The Project Gutenberg EBook of The Library of Work and Play: Guide and

Index, by Cheshire L. Boone

This eBook is for the use of anyone anywhere at no cost and with

almost no restrictions whatsoever. You may copy it, give it away or

re-use it under the terms of the Project Gutenberg License included

with this eBook or online at www.gutenberg.org

Title: The Library of Work and Play: Guide and Index

Author: Cheshire L. Boone

Release Date: July 29, 2014 [EBook #46445]

Language: English

Character set encoding: ISO-8859-1

*** START OF THIS PROJECT GUTENBERG EBOOK LIBRARY OF WORK AND PLAY: INDEX ***

Produced by Chris Curnow, Chris Jordan and the Online

Distributed Proofreading Team at http://www.pgdp.net (This

file was produced from images generously made available

by The Internet Archive)

Transcriber's Note: This book is a summary and index to a series of

books that can also be found in the Project Gutenberg collection.

Details of these books can be found in the

notes at the

end of this volume.

THE LIBRARY OF WORK AND PLAY

GUIDE AND INDEX

THE

LIBRARY OF WORK AND PLAY

| Carpentry and Woodwork |

| By Edwin W. Foster |

| |

| Electricity and Its Everyday Uses |

| By John F. Woodhull, Ph.D. |

| |

| Gardening and Farming |

| By Ellen Eddy Shaw |

| |

| Home Decoration |

| By Charles Franklin Warner, Sc.D. |

| |

| Housekeeping |

| By Elizabeth Hale Gilman |

| |

| Mechanics, Indoors and Out |

| By Fred T. Hodgson |

| |

| Needlecraft |

| By Effie Archer Archer |

| |

| Outdoor Sports, and Games |

| By Claude H. Miller, Ph.B. |

| |

| Outdoor Work |

| By Mary Rogers Miller |

| |

| Working in Metals |

| By Charles Conrad Sleffel |

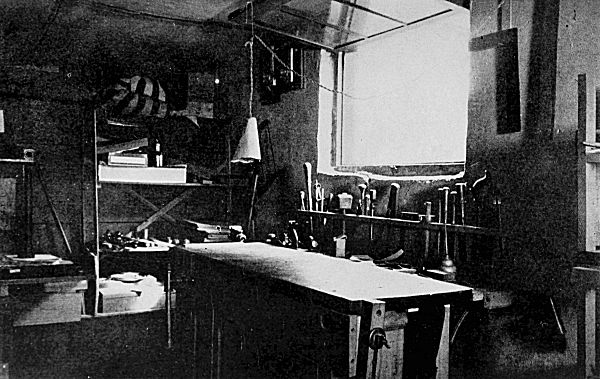

Wireless Station and Workroom of George Riches, Montclair, N. J. George made most of the Apparatus

at Home or in the School Shop

The Library of Work and Play

GUIDE and INDEX

BY

CHESHIRE L. BOONE

Garden City New York

DOUBLEDAY, PAGE & COMPANY

1912

ALL RIGHTS RESERVED, INCLUDING THAT OF TRANSLATION

INTO FOREIGN LANGUAGES, INCLUDING THE SCANDINAVIAN

COPYRIGHT, 1912, BY DOUBLEDAY, PAGE & COMPANY

THE COUNTRY LIFE PRESS, GARDEN CITY, N. Y.

| CHAPTER | | PAGE |

| I. | Significance of the Crafts in the Life of a People | 3 |

| II. | The Cultivation of Taste and Design | 16 |

| III. | The Real Girl | 28 |

| IV. | That Boy | 47 |

| V. | A House and Lot—Especially the Lot | 67 |

| VI. | Vacations, Athletics, Scouting, Camping, Photography | 78 |

| Index | | 85 |

[vii]

| Wireless station and workroom of George Riches | Frontispiece |

| | FACING PAGE |

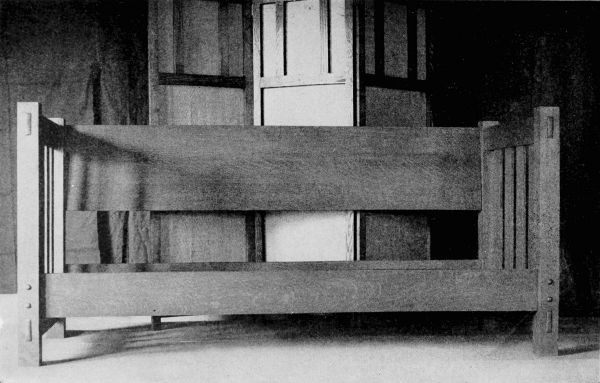

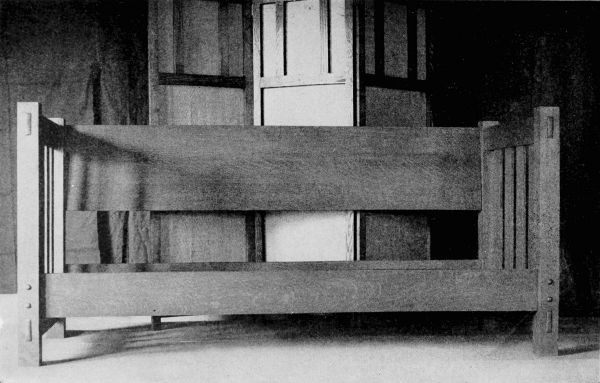

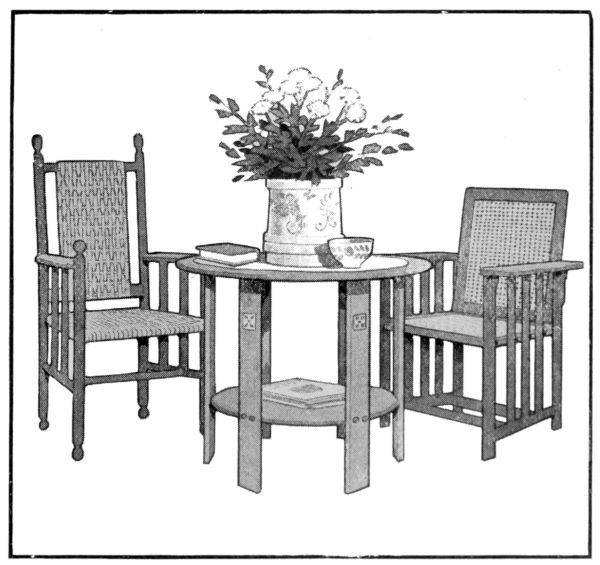

| An example of furniture such as boys like | 4 |

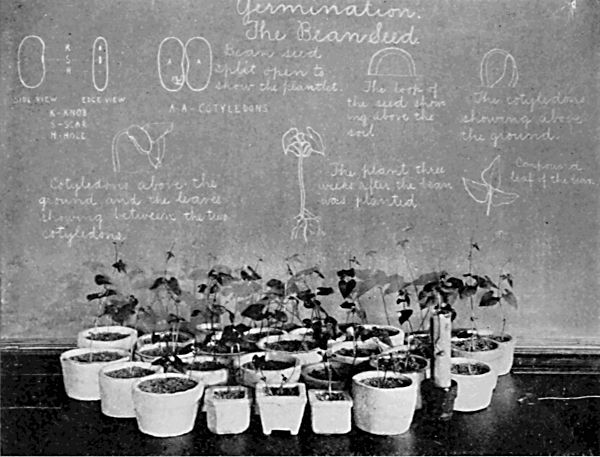

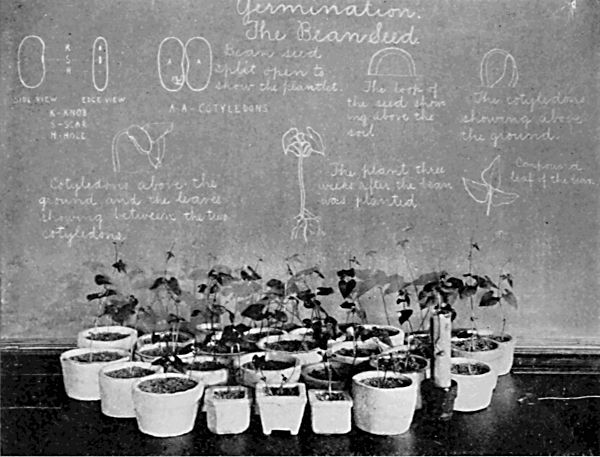

| Clay pots made for germination experiments | 5 |

| The work of children between ten and eleven years of age | 5 |

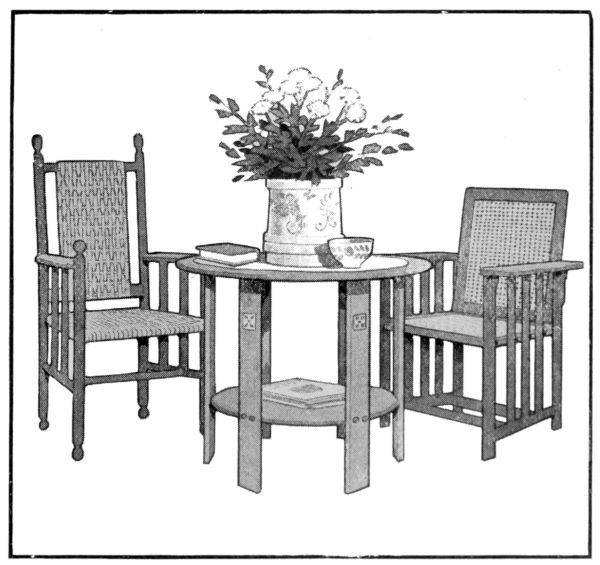

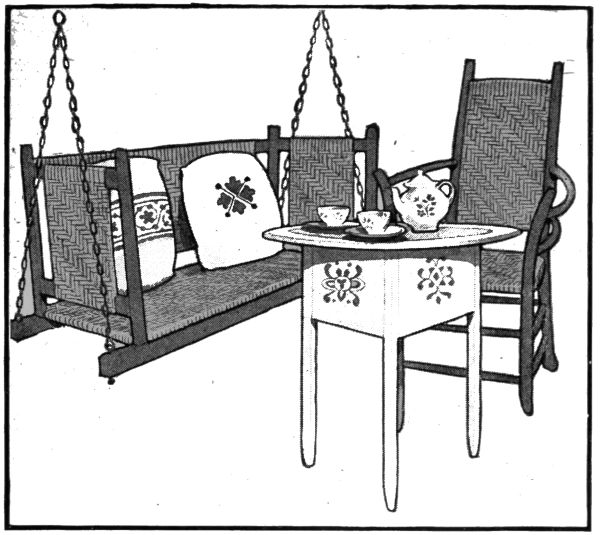

| Two examples of furniture grouping for the porch or outdoors | 18 |

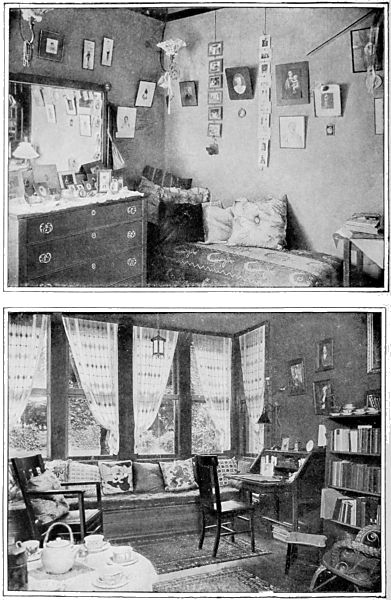

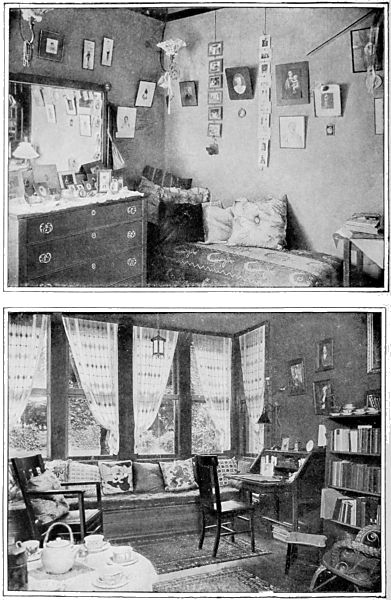

| The numerous photographs suggest disorder and dust | 19 |

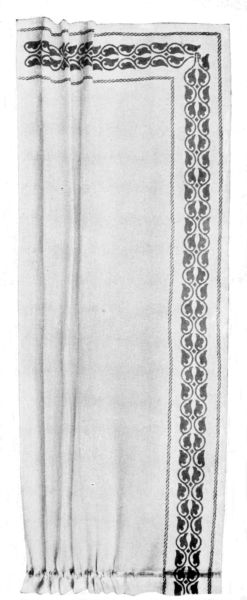

| An interesting curtain which might be duplicated by any girl | 20 |

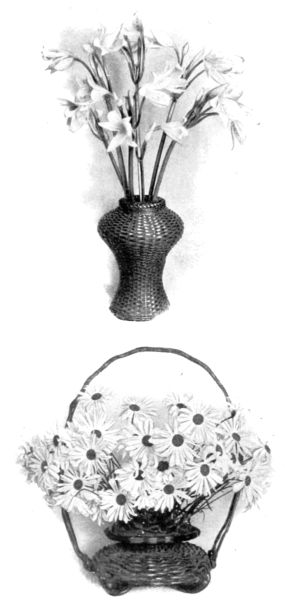

| Since flowers are so beautiful in themselves, is it not worth while to arrange them with judgment? | 21 |

| A school garden in Jordan Harbour, Ontario, Can. | 28 |

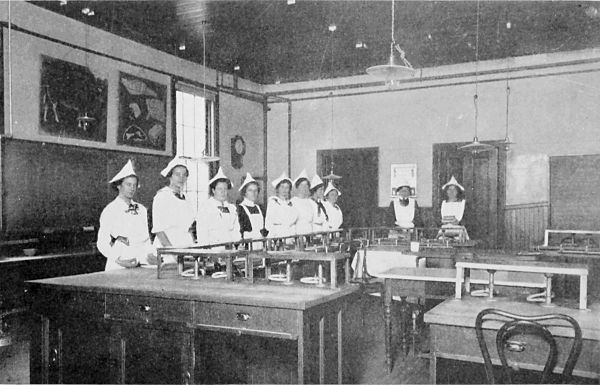

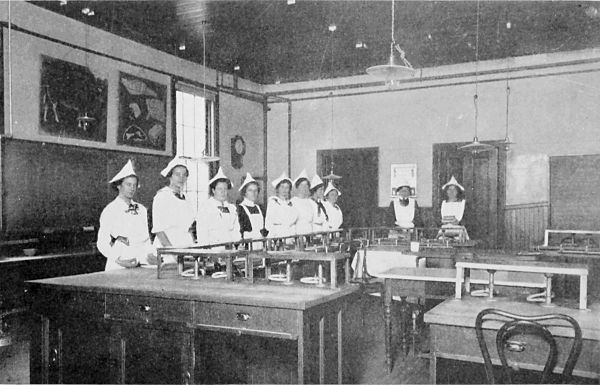

| Domestic science class | 29 |

| The work of girls in the public schools | 30 |

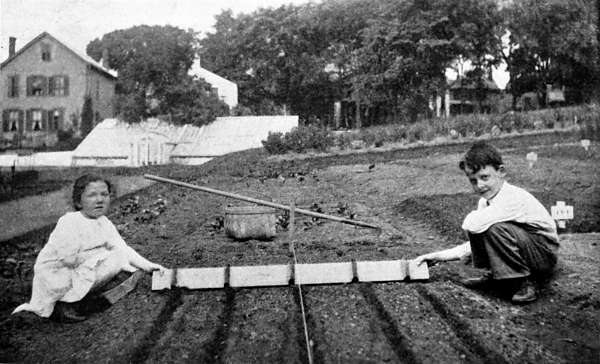

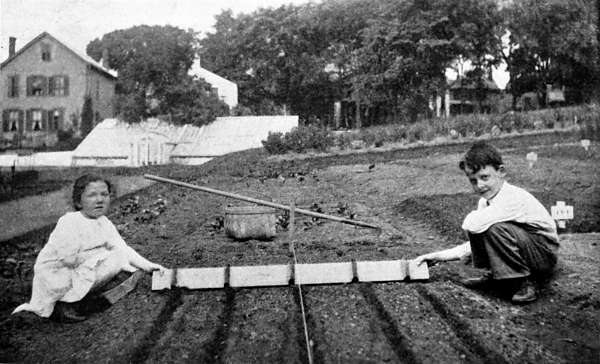

| A children's garden gives fresh air and sunshine | 31 |

| All children love to play at being "grown up" | 32 |

| Girls must sometime learn of the conventions and customs of domestic arrangement | 33 |

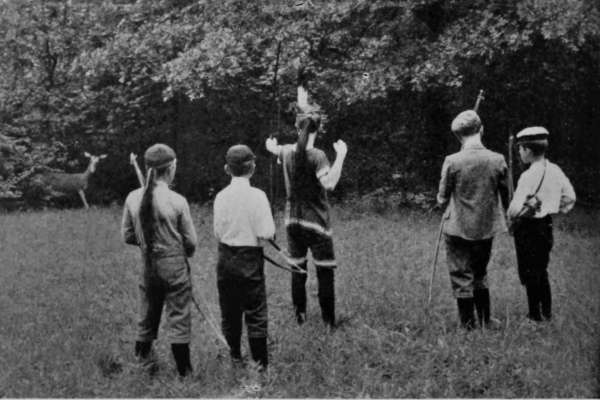

| A boys' camp with Ernest Thompson Seton | 48 |

| The play idea very soon grows toward the representation of primitive though adult customs and actions | 49 |

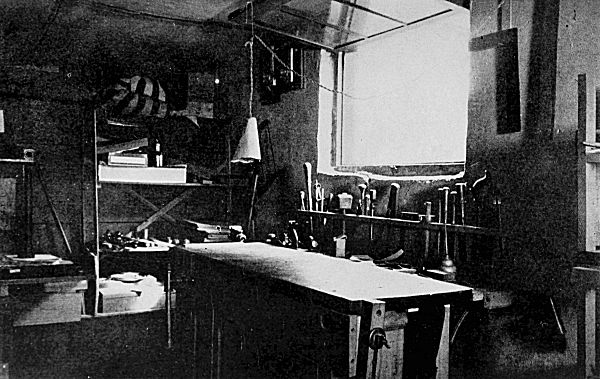

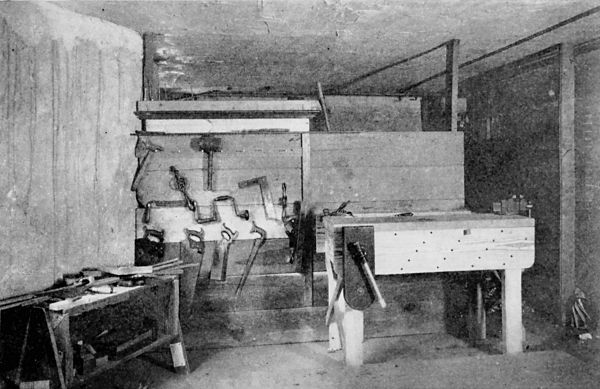

| [viii]A typical boy's workroom and shop | 50 |

| The kind of shop which one may have at home | 51 |

| The kite fever is an annual disease | 52 |

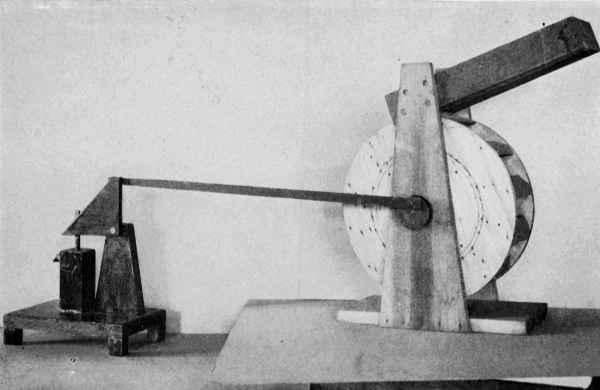

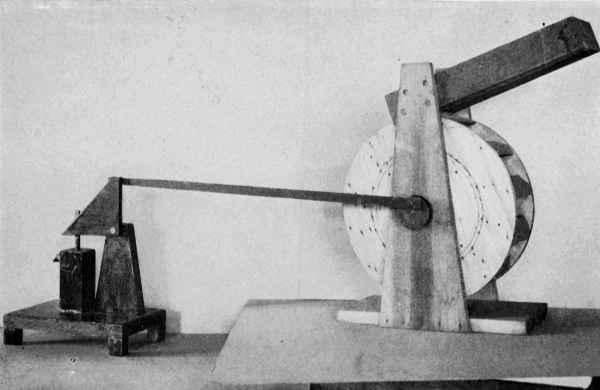

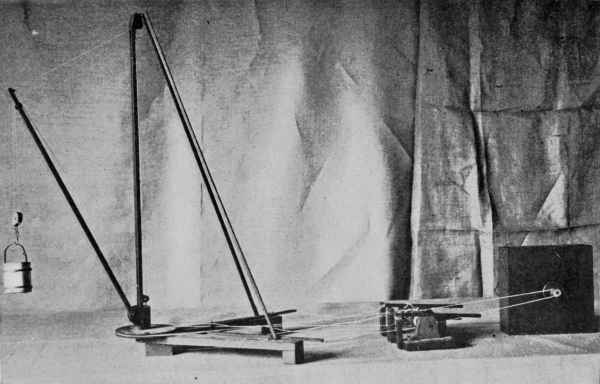

| Pump and waterwheel | 53 |

| Boat made by Percy Wilson and Donald Mather | 54 |

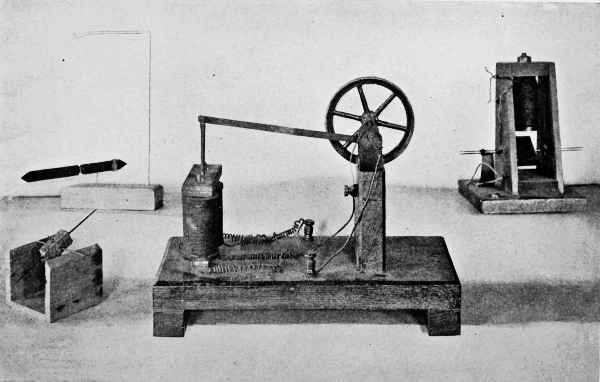

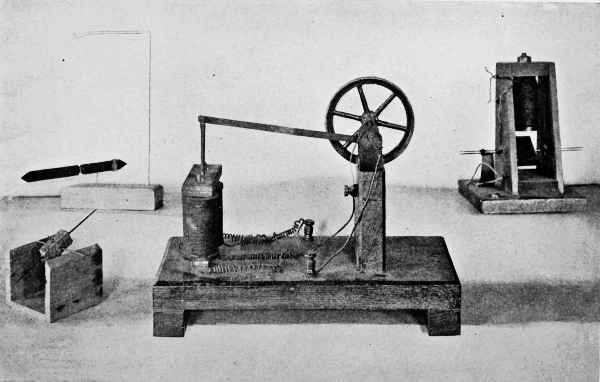

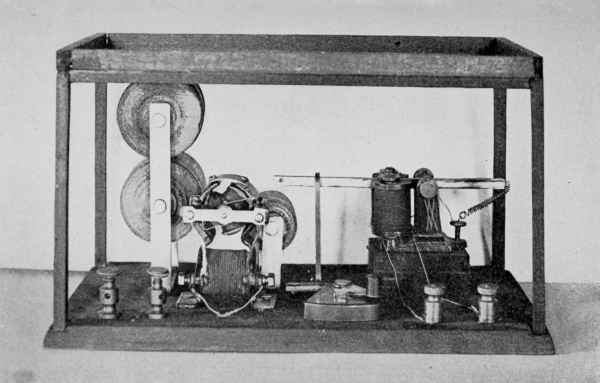

| These are the forerunners of numerous other electrical constructions | 55 |

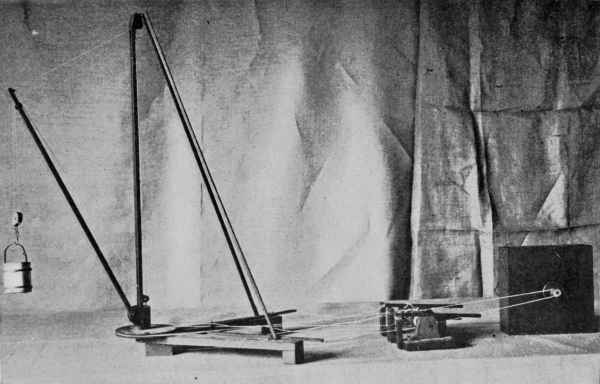

| A real derrick in miniature | 56 |

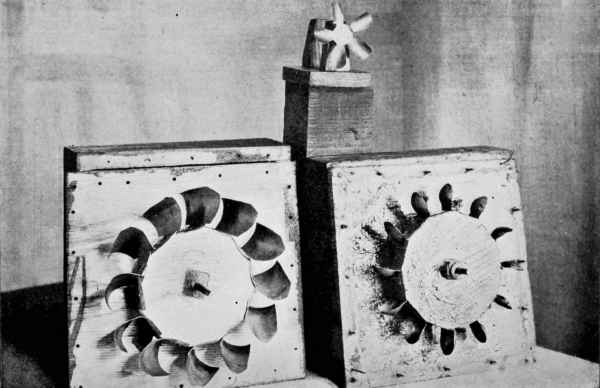

| Waterwheels and fan | 57 |

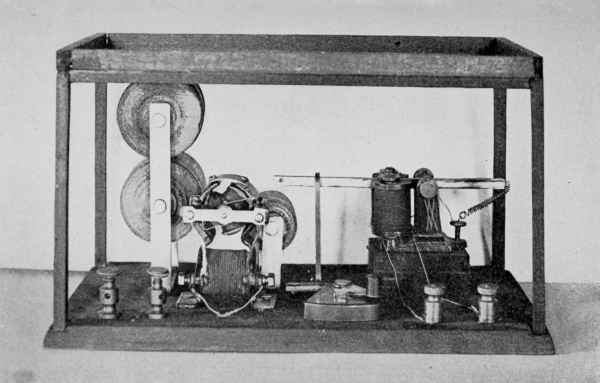

| A self-recording telegraph receiver | 58 |

| Wireless station and workroom of Donald Huxom | 59 |

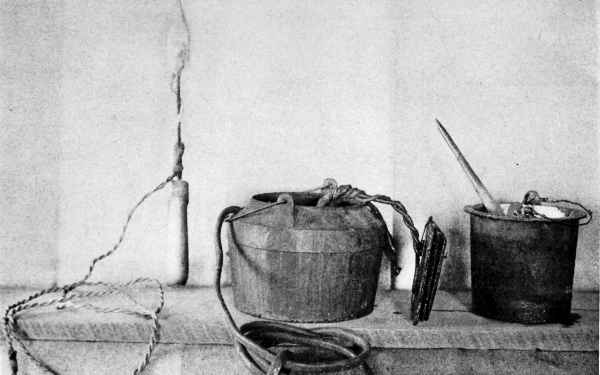

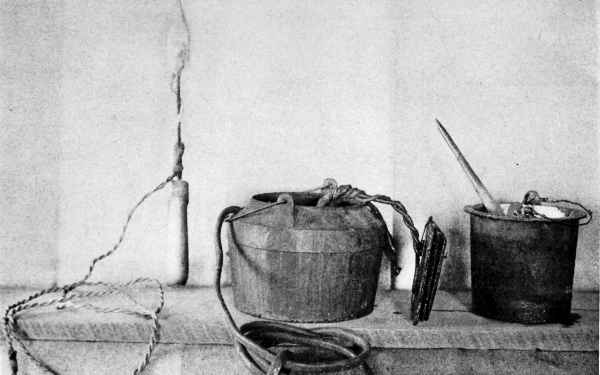

| An electrical soldering iron and glue-pot | 60 |

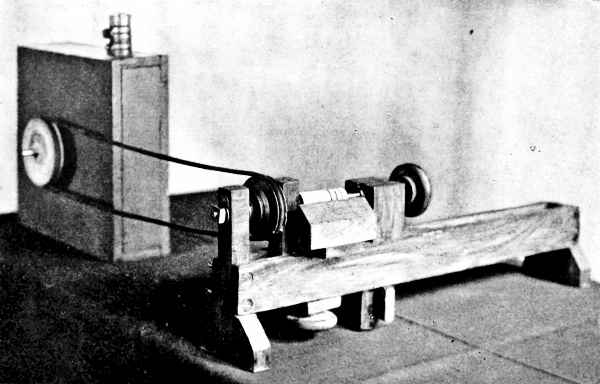

| Waterwheel connected with model lathe | 61 |

| Excellent examples of high school work | 62 |

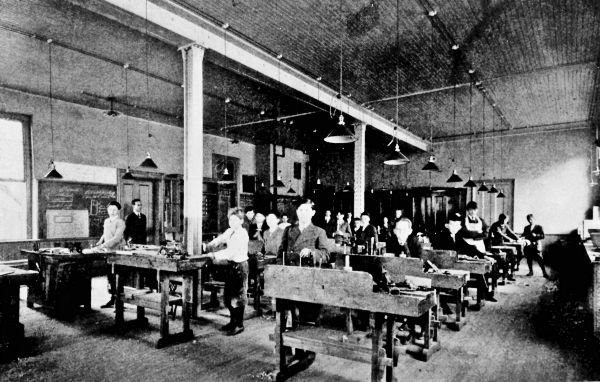

| A manual training shop | 63 |

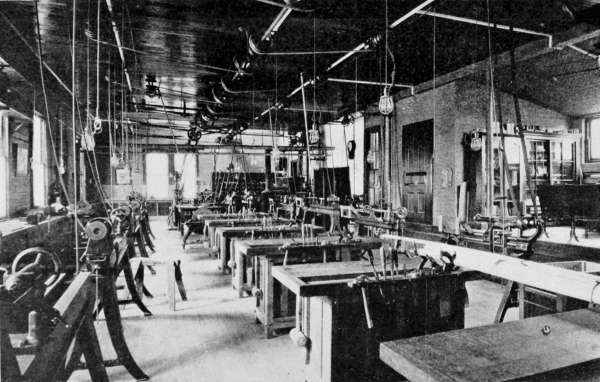

| The machine shop | 64 |

| The study of aeroplane construction | 65 |

| A successful machine | 64 |

| Finished aeroplanes | 65 |

| The boy who does not love to camp is unique | 68 |

| This and other illustrations of homes, show such places as people make when they care about appearance | 69 |

| Even the most beautiful house must have a background | 70 |

| One should build a house as one builds a reputation | 71 |

| Trees, shrubbery and lawn form the frame of the picture | 72 |

| There was a time not long since, when people built houses according to style | 73 |

| A school garden | 74 |

| The Watchung School garden | 75 |

| [ix]There is a fascination about raising animals whether for sale or as pets | 76 |

| Two more illustrations which will suggest plans for the future | 77 |

| Every child, and especially the boy, needs active outdoor exercise | 78 |

| Organized play (woodcraft) under Ernest Thompson Seton | 79 |

| More woodcraft. Has the boy had a chance at this kind of experience? | 80 |

| Even the technical process of photography has been reduced to popular terms | 81 |

| In these days photography has become so simplified that every child can use a camera to advantage | 81 |

[3]

CHAPTER I

SIGNIFICANCE OF THE CRAFTS IN THE LIFE OF A

PEOPLE

There was never a time in the history of the

world when each race, each nation, each

community unit, each family almost, did

not possess its craftsmen and artists. In every

instance, these so-called gifted members were by

no means the least important citizens; their names

appeared again and again in the stream of tradition

as wonder workers and idols of the people. This

is still true in the very midst of a materialistic age,

when money and mechanics work hand in hand to

produce the most in the least time for economic

reasons, and when the individual worships "hand-made

things." They may even be poorly made or

bizarre, but "handwork" satisfies the untutored.

Now it is quite possible for the machine to produce

a bit of jewelry, textile, or woodwork—even carving—quite

as pleasing as any made by hand alone, and

it is being done every day. But the machine-made[4]

article must be produced in large quantities (duplicates)

for profit, whereas the work of hand alone

is unique. There lies the reason for reverence of

"handwork." It is always individual and characteristic

of the workman in style or technique and

has no duplicate; it is aristocratic. Among the

primitives, the pot, necklace, or utensil was wrought

by infinite labor, and, being valuable because unique,

was embellished with all the wealth of current

symbolism. It was preserved with care and became

more valuable to succeeding generations as a tangible

record of race culture and ideals. And so

down to the present time, the handiwork of the

craftsman and skilled artisan has always stood as

the one imperishable record of racial development.

The degree of finish, the intricacy of design and

nicety of construction are evidences of skill and

fine tools, well-organized processes, familiarity with

material and careful apprenticeship: the pattern,

color, ornament, and symbolism point to culture,

learning, and standards of taste and beauty. A

crude domestic economy, rude utensils, coarse,

garish costume and of simple construction, are

characteristic of an undeveloped social order. In

fact, all the arts of both construction and expression

exhibit at a given period the degree of civilization;[5]

art products are true historical documents. Since

then through their arts and crafts it is possible

for one to know a people, does it not follow that

one entrance to sympathy with the ideals and taste

of the present time is through practice in the arts?

Of course a considerable mass of information about

them can be conveyed in words, especially to adults

who have passed the formative period in life and

have not the same work-incentive as have children.

But even the adult never really secretes much real

knowledge of the arts unless he has worked in them.

He acquires rather a veneer or artistic polish which

readily loses its lustre in even a moderately critical

atmosphere: he learns artistry and the laws pertaining

thereto as he would learn the length of the

Brooklyn Bridge or the population of El Paso. He

merely learns to talk about art. But children learn

primarily and solely by doing, and the foundations

of taste and culture need to be put down early that

they may build upon them the best possible superstructure

which time and opportunity permit.

Copyright, 1909, by Cheshire L. Boone

An Example of Furniture such as Boys Like and which They Can Make Under Direction

Copyright, 1909, by Cheshire L. Boone

Clay Pots Made for Germination Experiments in Grade IV. of the

Public School. The Boys of this Grade Built a Small Kiln in which

these Pots were Fired

The Work of Children between Ten and Eleven Years of Age

The foregoing paragraphs will perhaps have opened

the way for questions: "What kind of knowledge

is of most worth? Why do children—practically

all of them—try to make things, and what is their

choice?" And when these queries have been answered[6]

so far as may be, do the answers possess

immediate value?

At the outset it will be evident that no sort of

knowledge will be of much avail until it is put in

such form that the student can use it to advantage.

Mere knowledge of any kind is inherently static—inert

and often seemingly indigestible, like green

fruit and raw meat. One too frequently meets

college graduates, both men and women, equipped

with so-called education, who are economic failures.

These people are full of information, well up to date,

but they seemingly cannot use it. Their assortment

of knowledge is apparently in odd mental sizes

which do not fit the machinery of practical thinking

as applied to life: it is like gold on a desert isle.

What the boy and girl need and desire is (1) a favorable

introduction to the sources of information, and

(2) the key to its use. They will have to be shown

simple facts and truths, and have their mental

relations and importance explained. By gradually

introducing new knowledge as occasion offers, the

field of study is sufficiently widened. Children

profit little by books and tools alone: they crave

encouragement and some direct constructive criticism.

In such an atmosphere their endeavors become

significant and profitable, and the accumulated[7]

learning will be applied to business or economic

ideas which result in progressive thinking, which

uses information as a tool, not an end in itself.

If then the arts of a people stand as monuments

to its beliefs and ideals, an intimate understanding

of some of the arts ought to be provided for in every

scheme of education both at home and in school.

The child is by nature interested in the attributes

of things associated with his life and upbringing.

He wants to know about them, how they are made,

and learn their uses by means of experiment. The

elements of science, mechanics and natural phenomena,

business and household art, and finally

play (which is often adult living in miniature)—these

comprise a large portion of the subject matter

which is of prime importance to children. It is

just such material as this which bids fair to serve

in the future as the basis for public school curricula,

simply because of its strong appeal to youth and

its potential worth in forming the adult.

The boy makes a kite, a telegraph outfit, or sled

in order to give to his play a vestige of realism.

He seeks to mold the physical world to personal

desires, as men do. Incidentally he taps the general

mass of scientific facts or data and extracts therefrom

no small amount of very real, fruitful information.[8]

The result possesses marvelously suggestive

and lasting qualities because it came through effort;

because the boy wanted above all things to see his

machine or toy work, move, or obey his guiding hand,

he was willing to dig for the necessary understanding

of the problem. His study brought about contact

with numerous other lines of work which were

not at the time, perhaps, germain to the subject,

but were suggestive and opened various side lines

of experiment to be considered later. Therein lies

the lure of mechanics and craft work, gardening,

outdoor projects, camping, etc.: the subject is never

exhausted, the student can never "touch bottom."

There is always an unexplored path to follow up.

The intensity of interest in mechanical things and

in nature is the one influence which can hold the

boy in line. Turn him loose among mechanical

things where nicety of fitting and accurate workmanship

are essential and he appreciates construction

immediately, because it is clear that workmanship

and efficiency go hand in hand. It is very much

the same with the girl: she may not enjoy the

tedium of mere sewing, but when the sewing serves

a personal end, when sewing is essential to her

greatest needs, these conditions provide the only,

inevitable, sure stimulus to ambition and effort.

[9]

The school of the past, and often that of the

present, has sought to produce the adult by fertilizing

the child with arithmetic, grammar, geography,

and language. The process resulted in all kinds

of crooked, stunted, oblique growth, the greatest

assortment of "sports" (to use a horticultural

term) the world has ever seen. It isn't intellectual

food the child needs most (though some is very

necessary); the real need is intensive cultivation.

Within himself he possesses, like the young plant,

great potential strength and virility, enough to

produce a splendid being absolutely at one with his

time and surroundings; he simply requires the

chance to use the knowledge and opportunities

which lie at hand. It is, then, the common subjects

of every-day interest—science, business, nature

and the like—which are the sources of knowledge

which has greatest worth to children.[A] They are

the valuable ones because they are of the type which

first attracts and holds the child's attention; they

are concrete. Through them one may learn language

and expression, because one has something

worth saying.

The second question, "Why do children like to

make things and what is their choice?" in the light[10]

of what has been said practically answers itself.

Children work primarily in response to that law of

nature which urges the young to exercise their

muscles, to become skilful and accurate in movement,

for the sake of self-preservation and survival.

It is another phase of the same law which makes one

carry out in work, in concrete form, the ideas which

come tumbling in from all conceivable sources.

The child can only think and learn in terms of

material things. Finally, the child's interests, the

things he desires to make and do, are such as will

minister to his individual or social needs, his play

and imitation, and such as will satisfy his desire

to produce articles of purpose. The need may be

a temporary, minor one, but every child is stubborn

on this one point, that everything he does must

lead to utility of a sort; through such working with

a purpose he in time rises to an appreciation of

beauty and other abstract qualities.

Now this complex condition of child and school

and society, in which there is seemingly so much

waste—"lost motion"—has always existed; the

facts are not new ones by any means. It is a condition

where the child is always curious, inquisitive

and ready to "hook a ride" on the march of business,

science and learning, but the school sternly commands[11]

"learn these stated facts because they are

fundamental" (philosophically), while society, represented

by the parent, alternately abuses the

school, which is collectively his own institution,

or spoils the child by withholding the tools for

learning easily. In the meantime the child, with

the native adaptability and hardiness of true need,

thrives in barren, untoward surroundings, and matures

notwithstanding. In other words, the school

and society have always tended toward misunderstanding—toward

a lack of mutual interest. In

this period of uncertainty, of educational groping,

the child is found in his leisure hours pushing along

the paths which connect most directly with life

and action, shunning the beaten but roundabout

highways of custom and conservatism.

The deductions are evident and clear-cut. If

one accepts the foregoing statement of the case,

and there is ample evidence in any community of

size, it will be clear that certain definite opportunities

should be opened to the boy or girl to make the most

of native talent and enthusiasm. Encourage the

young business adventurer or artisan to make the

most of his chosen hobby (and to choose a hobby

if he has not one already), to systematize it, develop

it, make it financially profitable if that is the desire;[12]

but first, last and all the time to make it a study

which is intensive enough to satisfy his or her productive

ambitions. At this age (up to the high

school period) the boy or girl may not have been

able to decide upon a profession or business, but

he is working toward decision, and he is the only one

who can choose. Instead of trying to select an

occupation for him, father and mother would do

well to put the child at the mercy of his own resources

for amusement, recreation and business,

merely lending a hand now and then in their full

development. It will preserve the freshness of

youth beyond the ordinary time of its absorption

by a blasé attitude toward the world, and lead toward

a more healthy and critical kind of study than the

haphazard lonesomeness, or the destructive gang

spirit of the modern community.[B]

Perhaps it would not be amiss to indicate just

how this unofficial study may be promoted, and to

name the resources of the parent for the purpose.

First of all, nine children out of ten will definitely

choose a hobby or recreation or indicate some preference,

as photography, animal pets, woodwork,

electricity, drawing, sport, one or more of the[13]

domestic arts, collecting coins, stamps, etc.; there

are as many tastes as children. The child may get

his suggestion from the school or companions. Any

legitimate taste should be actively encouraged and

supplemented by books which really explain and

by tools and materials with which to use the books.

If it is a shop he wants, try to give him the use of

some corner for the specific purpose so that the

occupation may be dignified according to its juvenile

worth. Second, endeavor to emphasize the

economic and social significance of the work done

and urge right along some definite aim. If a boy

wants a shop, or pets, see that they are kept in condition,

attended to, and if possible give some measure

of tangible return on the outlay of money and energy.

Third, connect the boy's or girl's chosen avocation

with real living in every possible manner. Girls

are rather fond of those decorative arts which contribute

to artistic pleasure, and should they make

experiments with stenciling, block-printing, and

the like, have them use them also in embellishing

their own rooms, the summer camp or club. Fourth,

make the child feel that a given hobby is not to be

satisfied for the mere asking. Put some limit on

the money expenditure until it is clear that the

interest is genuine and honest, and that the child[14]

is either producing results which are sincere, or

acquiring real knowledge. Fifth and last, but perhaps

most important of all, support the school in

its effort to solve the problem of formal education,

because the heavy burden rests there. It is quite

essential that the home give the boy and girl every

possible chance to develop along original and specific

lines at their own pace, to experiment with the

world's activities in miniature, and establish the

probable trend of individual effort for the future.

But this can only supplement and point the way for

the formal training which the institution (school)

gives. The school, being democratic and dependent

upon the general public for existence, takes

its cue therefrom, and creating ideals in consonance

with public needs perfects the method of reaching

them. When father and mother believe in a

vigorous, efficient education, rooted deeply in the

child's fundamental attitude toward the world

and its affairs, then will the public approve and

urge the proper kind of organized training. Even

so, the school cannot really educate the child—he

educates himself through the agents aforementioned—it

simply organizes information and gives

the pupil access to methods of using facts and

ideas.

[15]

In closing this chapter there is one more word to

be said concerning the main theme. The arts and

crafts[C] of expression and construction fulfil that

precise function in the child's preliminary training

which they did in the early history of the race.

They indicate just that degree of manual skill and

constructive ability of which both the youthful

individual and the young race are capable; they

serve as indices and guides to the development of

design, taste and constructive thinking. As the

child matures he may elevate a given craft to an

art or science, but the early familiarity, the simple

processes, he should have, because they are essential

to childhood. Hence, the large amount of handwork

in the kindergarten and primary school; it is the

necessary complement to academic work and balances

the educational diet.

[16]

CHAPTER II

THE CULTIVATION OF TASTE AND DESIGN

It will be evident to the thinking man or woman

that art or any phase of it is not to be taught

successfully as a profession through books.

The very most that one can expect from reading is

a knowledge about art matters and acquaintance

with the conventions and rules which obtain therein.

But even this slight result may be the precursor of

a fuller, more intimate familiarity with the principles

of good taste and design.

One may be able to say "that is a beautiful room"

or "a fine garden" or "a charming gown" and yet

be unable to produce any such things. How is

it possible then to know if one cannot do? The

answer is that, potentially, every individual who

really sees and appreciates beauty can produce it

through some form of artistic expression; the power

to execute and the power of invention are merely

undeveloped. And as for the artist or craftsman

who can make beautiful things, but who cannot[17]

explain how he does it—he is unique, like the mathematical

genius; he just sees the answer; it is a

gift. Though there are born in every generation a

few with the divine spark of genius, the mass of

men and women has always learned by effort.

In other words, it has been possible to teach the

subjects which were found necessary to culture

and education; it is quite possible to present the

ordinary phases of art to the lay mind in such a

way, even through books, that one may have worthy

ideals, and a healthy point of view. The present

chapter will be devoted to showing how books such

as these[D] for boys and girls can contribute to the

development of taste.

Frankly, taste has much less to do with fine art

than with the arrangement and choice of the ordinary

externals of living. Of course fine art does in the

last analysis pass judgment upon form, color and

design in clothes, furnishings and architecture, but

the common home variety of taste is derived directly

from custom, comfort, and convention, not from art

at all. Only in the later stages of refinement does

the lay mind succumb to direct supervision by art.

On the other hand, all conventions and ideals are

the result or sum total of general experience, in[18]

which art has played its part, and has left some

impress on the individual, giving rise to belief in a

few principles so common as to be accepted by all.

Principles of this kind are not always serviceable

or effective, because they are not stated in precise

language, and cannot therefore become standard.

In truth, so far as design is concerned, there are very

few absolute rules for guidance, and a book like

"Home Decoration" cannot tell the child or parent

how to make a beautiful, inspiring home. Its mission

is to create the desire for fine surroundings,

to suggest ways and means for studying design,

especially those phases of decoration associated

with the crafts, and above all such a book invites

and helps to maintain a receptive attitude of mind

toward artistic matters. In the effort to produce

work of merit, one becomes critical, and seeks

reasons and precedents for judgment. This is the

beginning of design study: and the fact that one has

real interest in taste is indicative of the desire of the

cultured mind for ideals. If a child is allowed to grow

up in the "I know what I like" atmosphere, without

reasonable contact with choice things, and without the

necessity for selection based upon reason, there is

small chance that such a child will ever acquire any

sense of fitness or taste in material surroundings.

Two Examples of Furniture Grouping for the Porch or

Outdoors. These Few Pieces Suggest Comfort, Cleanliness

and Moderate Expense

The Numerous Photographs in the Upper Illustration Suggest

Disorder and Dust. They do not Decorate. Sometimes a lack of

Small, Insignificant Objects like these is the Secret of Successful

Decoration

[19]

The aims of all practical books for boys and girls

may be summarized about as follows:

(a) To absorb the overflow of youthful energy

and turn it into profitable channels.

(b) To develop organized thinking and accomplishment,

and eliminate wasted, aimless, non-productive

action. This is the complement to the

routine of formal training in academic subjects,

which are in themselves, normally un-useful.

(c) To explore the field of accomplishment in

order to select intelligently a future occupation.

(d) To develop and foster standards and ideals

of efficiency, comfort, enjoyment, beauty and social

worth. This last purpose includes taste and is the

one of concern here.

The peculiar ęsthetic standards which interest

young people are of the most practical kind. They

apply every day and to everybody. And they are

fundamental. The illustrations given below will indicate

the common-sense way in which design should

be approached:

Color. The tones of the color scale have not yet

been systematized so well as those of music, but

each year students of design and artists move a

little toward agreement. Now, suppose one wishes

to use two or more tones in a room, how may[20]

harmonious effect be secured? The very word

"harmony" means agreement, and suggests similarity,

likeness, relationship. Therefore the tones one would

use in the embellishment of a room should possess

some common quality for the harmonizing element.

Each tone having that quality as characteristic

is similar in that one respect to all other tones having

the same quality. Hence they are related in a

way. The relation may be made strong or weak

by the manipulation of the bond which holds the

tones together. For instance:

Red and green are not related at all. By mixing

gray with each, red and green become related

through gray. By mixing yellow, orange or blue,

etc., with red and green, the relationship may be

established in the same way.

Yellow and green have a common quality—yellow,

and in so far tend toward harmony. But

it may not be a pleasing one, and it will be necessary

to bring them still closer together by introducing

other bonds, as gray or a color. Yellow is very

light and green is dark: they will work together

better if brought nearer together in value.

An Interesting Curtain which might be

Duplicated by almost any Girl—If She

Wanted Curtains

Since Flowers are so Beautiful in Themselves,

is it not Worth While to Arrange

Them with Judgment?

It is by such simple means that all color combinations

are brought into line and rendered satisfactory.

No rule can be given for mixing or choosing the actual[21]

colors, but it is a safe rule to select those of a kind

in some respect. The popular belief in low-toned

(grayed) color schemes is a sound one, and the principle

can be used very comfortably by the amateur

decorator in furnishing a home. She can have any

colors she wishes, and make them pleasing, if she

will unite them by some harmonizing tone. Of

course, all grays even are not rich and beautiful,

but they are better than unadulterated color. Mr.

Irwin in one of his breezy skits quotes the ęsthete

as saying: "Good taste should be like the policeman

at parade; he should permit the assembled

colors to make an orderly demonstration but not

to start a riot." The moment the unskilled amateur

tries to use white woodwork, red wallpaper, and

gilt furniture in combination, he or she courts failure

simply because the choice lacks the pervading tone

which would modify the three. There are ways to

secure harmony even under the most adverse conditions,

but the technical details are not pertinent

here.

Another characteristic which stands in the way

of harmony is emphasis. The moment any one

tone becomes greatly different from its neighbors in

value or otherwise, it stands out, attracts attention,

just as in material objects, unusual, curious shapes[22]

and sizes invite notice, often beyond their just dues.

Hence a brilliant yellow house, a bright green gown,

large figured wallpaper, are over-emphatic. Clothes,

which by their color and style are loud in their

clamor for inspection, are out of key and bear the

same relation to surroundings which foreign, exotic

manners and customs bear to domestic conventions.

And ordinarily one does not seek such prominence.

This question of taste is a vital one to children,

and these books about "Needlecraft," "Home

Decoration," "Outdoor Work," "Gardening," etc.,

are indirectly most useful because they put the

child in a position to choose. The girl who sews and

helps run the home is bound to cross the path of

design a dozen times a day. She is faced with

problems of arrangement, color and utility at every

turn. Her own clothes, her room, the porch and

garden, whatever she touches, are inert, lifeless

things which await artistic treatment. It is when

the child is faced with the problem of personal

interest and pleasure that these elementary conceptions

of design may be proposed.

Form and Line. Each year fashion decrees for

both men and women certain "correct" styles. At

slightly longer intervals the shops offer new models

of furniture, hangings, jewelry, pottery, etc. Have[23]

these new things been devised to meet a change in

public taste? Not at all; they are inventions to

stimulate trade. Most of such productions are

out of place, incongruous, in company with present

possessions. One must have a pretty sound sense

of fitness and selection in order to use them to advantage

or to resist their lure. As single examples,

many of the new things are beautiful in color and

line, though they may have nothing whatever in

common with what one already owns.

One chooses a given pattern in furniture first,

because of its utility; second, because of its harmony

in line and size with other furniture already owned;

and third, because of its intrinsic beauty. It is

much less difficult to furnish a house throughout

than to refurnish an old room in consonance with

others already complete. All the household things

need not be of one kind, though the closer one clings

to a clear-cut conception of harmony (relationship

of some kind) the better the result. Hence clothes

may either beautify or exaggerate personal physique,

and the garden may attach itself to the house and

grounds or stand in lonely, painful isolation. Down

at bottom design aims to assemble elements and

parts into proper groups, and in the common questions

of home decorations and dress the student can[24]

usually work on just that simple basis. It is usually

the incongruous, over-prominent, conspicuous, or isolated

factor in decoration which causes trouble.

This fragmentary discussion will perhaps suggest

some of the benefit which may come from the pursuit

of crafts and occupations. The illustrations here

given are in some detail because it is so easy to overlook

design at home and in common things. Everything

is so familiar there, one is so accustomed to

the furniture, rugs and their arrangement, that it

never comes to mind that the situation might be

improved. It must be remembered that, when

children begin to apply design to their own handicraft,

their fundamental conceptions of beauty

originate in the home. Either the children must

lose faith in home taste, or, as they grow and learn, be

allowed to bring their new-found knowledge back

into the home and "try it on." This is where the

craft does its real work. The true privilege conferred

upon children by the possession of such books

as these on various special occupations is a chance

to obtain, first-hand, individual standards of perfection

and beauty. Before this they have merely

accepted the home as it stood, with no thought of

what was choice or otherwise.

Since taste and design are merely implied, or[25]

indirectly included in the several volumes, save

"Home Decoration," the latter should be used as

a supplementary reference in connection with the

others. As has already been said, it is not possible

or advisable to systematically teach good taste. It

will be better and more effective to just include taste

in the several activities the child undertakes. When

the girl begins to make things for herself, help her

to select materials which are appropriate in every

way. Have her seek materials for the purpose.

Have her choose decoration and color rather than

take the first handy suggestion or copy the plans

of another. She would do well to experiment independently.

The girl should create her own room

down to the last detail, not make everything herself,

but plan it, plan its arrangement, its color

(tone) if possible, and make those small decorative

articles like pillows, runners, curtains, etc. But

before beginning such a comprehensive experiment

in decoration have her look about a bit and note

the conditions imposed. The light and exposure,

size of the room, furniture which must be used,

treatment of hangings—these are all stubborn

factors, but they respond to gradual treatment.

Then the room is hers in reality. The boy's attitude

toward taste is totally different. He cares less than[26]

the girl for the charm of tone and arrangement; he

is quite willing to despise the niceties of decoration.

He must approach the question obliquely through

interest in the efficiency of a given effort; he appreciates

the utility phase of design most of all. The

boy will come to see gradually that his pets and

chickens should be decently housed, and that it is

good business to do so. He should not be allowed

to impose upon his own family or their neighbors a

slovenly yard or garden. He will find that those

tools work best which are sharp and clean and always

in place. His final lesson in design grows out of

association with his mates. When he begins to go

to parties, to enter the social world in a small way,

a new body of conventions in taste appear and he

must be taught to appreciate them if he would be

well liked. But the real training in design arises

from manual work—the playthings, toys and

utensils the boy makes for use. They need not be

beautiful nor is there excuse for clumsiness in construction.

One cannot expect even the mature

child to take much interest in design in the abstract,

but when he meets the subject on a common-sense

basis, as a part of some personal problem, design—even

taste in color and form—acquires definite

standing in his esteem. It has earned the right.[27]

Hence a liberal contact with youthful amusements

and occupations encourages both boy and girl to

build ideals of working, and among these ideals

taste is bound to appear in some guise—usually

unbidden. The book on design or decoration is

but a reference, an inspiration, a stimulant, never

a text of instruction. The ability to choose, to

secure appropriate, beautiful, accurate results, is

largely a by-product of judicious reading combined

with persistent effort. It remains for the parent

to skim off this by-product as it appears and infuse

a little of it into each problem the child presents

for inspection.

[28]

CHAPTER III

THE REAL GIRL

What Is the Ideal Home?

A School Garden in Jordan Harbor, Ontario, Canada. Any Child Who has had this Experience, Who Has

Produced or Helped Nature to Produce such Wonderful Things, will be Richer in Sympathy for Fine Things

Domestic Science Class. These Girls not only Cook but Learn about Foods, Housekeeping, Entertaining,

and Themselves Keep Open House at the School Occasionally

Strange as it may seem, most of the plans

for industrial training, the majority of school

courses of study, and probably seventy-five

per cent. of the books on the crafts and arts have

been devised for the use of boys. Now there are

hosts of girls in this world, probably as many girls

as boys, and these girls are just as keen, intelligent,

ambitious and curious about things and how to

make them, as are boys. In very early childhood

when both boys and girls have the same interests,

similar books of amusement are used by both. But

as girls develop the feminine point of view and need

the stimulus of suggestion and aid in creative work,

the literature for them seems meagre; they have

somehow been passed by save for a manual now and

then on cooking or sewing, left as a sop to their

questioning and eagerness. This state of affairs[29]

is more than unfortunate, it is fundamentally wrong

for two very good reasons. (1) The girl up to the age

of twelve or thirteen has practically the same

interests, pleasures and play instincts as the boy.

She is perhaps not so keenly alive to the charm of

mechanical things as the boy, but like all children

regardless of sex, she seeks to be a producer. She is

just as much absorbed in pets and growing things,

in nature, in the current activities of her environment,

and requires the same easy outlet for her play

instincts as the boy. (2) The girl, when a woman

grown, becomes the creator of the home, and too

often enters upon her domestic career with a minimum

of skill or taste in the great body of household

arts, which in the aggregate, give us the material

comforts and homely pleasures. Moreover, since

she, as a girl, probably did not have the chance to

satisfy her play desires and consequently never

learned to do things herself, she is at a loss to understand

the never ceasing, tumultuous demands of her

own children for the opportunity to experiment.

To quote Gerald Lee in the "Lost Art of Reading,"

which is one of the real modern books: "The experience

of being robbed of a story we are about to read,

by the good friend who cannot help telling how it

comes out, is an occasional experience in the lives of[30]

older people, but it sums up the main sensation of

life in the career of a child. The whole existence of

a boy may be said to be a daily—almost hourly—struggle

to escape being told things ... it is

doubtful if there has ever been a boy as yet worth

mentioning, who did not wish we would stand a little

more to one side—let him have it out with things.

There has never been a live boy who would not

throw a store-plaything away in two or three hours

for a comparatively imperfect plaything he had

made himself...."

When one goes deep enough—below the showy

veneer of present-day living—one comes to agree

with Mr. Lee. The normal child, especially the boy,

is potentially a creator, a designer, discoverer, and

we have committed the everlasting sin of showing

him short cuts, smoothing away difficulties, saying

"press here." No child can survive the treatment.

Father and mother have the very simple obligation

to furnish the place, raw material (books, tools, etc.),

and encouragement.

Copyright, 1909, by Cheshire L. Boone

The Work of Girls in the Public Schools, Montclair, N. J. These Girls are only Eleven

Years of Age

A Children's Garden gives Fresh Air and Sunshine, and Best of All, Brings Nature very Near. To Be Really

Happy One Must Make Nature's Acquaintance

For these reasons, if for no other, the girl ought to

have a permanent outlet for her native ingenuity

and constructive skill in such crafts and occupations

as are adapted to her strength, future responsibilities

and possible interests. A home should comprise[31]

other elements than food and clothes, which are

bare necessities; and though these may be expanded

and multiplied, becoming in their preparation real

art products, they alone are deficient in interest.

Look over any well-ordered household, note the

multiplicity of things it contains which are primarily

woman's possessions, and collecting all one knows

about them, the amount of real knowledge is surprisingly

small. How much does the embryo housekeeper

know about textiles, curtains, carpets, hangings,

linens, brass, china, furniture? Where do all

these charming things come from? Many of the

hangings, table linen, embroidery, etc., are home

products. They cannot be bought at all. The

simple stenciled curtain which one likes so much

draws attention by virtue of its personal quality.

To have such things in any abundance the girl must

create them, and this she is more than willing to do.

How may one explain the restful atmosphere of

certain homes visited? How many housewives have

intelligent insight concerning home management

and administration; of simple domestic chemistry

or sanitation? Yet these are vital elements in the

domestic machine. One never mistakes a proper

household, orderly, smooth running for the showy

establishment—gay outside and sad inside. Even[32]

the most untutored child unconsciously responds

to the healthy influence of selected material environment

and conditions, when these are combined

harmoniously. There are systematic ways of creating

pleasant rooms, fine grounds, comfortable places

for living, places imbued with the spirit of contentment.

The people who produce such places are

seldom the professional decorator, landscape architect,

and hired housekeeper. It is the woman

of the family, who, having practised some of the

arts, or at least been their disciple, has learned to

appreciate order and love beauty. Therewith comes

an almost instinctive knowledge of how to use them

to advantage. One can never really have beautiful

baskets, pottery, sewing, gardens, until one has

made them. One surely cannot appreciate the true

worth of clean linen, a spotless house, and perfect

routine anywhere so thoroughly as in one's own house.

It naturally follows that the girl, like the boy,

should be a producer, not a mere purchaser, of

personal or domestic commodities. She may have

unlimited means, but the place where she lives as

a girl and the home she seeks to create in adult life

will always be impersonal, detached, hotel-like, unless

she personally builds it. She must know the

structure, composition, and functions of inanimate[33]

things; this knowledge comes easiest and persists

longer through use and experience.

All Children Love to Play at Being "Grown Up," even Beyond the Time of Childhood. These Girls will

make Real Women, because They are Normal and Happy

Girls must sometime Learn of the Conventions and Customs of Domestic Arrangement, and too often

Their Only Opportunity Lies in such Classes as These

There is a good bit of psychology behind the suggestions

offered, and the reasoning is simple. All

our ideas, our plans, and conceptions are just ideas

and nothing more until they have been worked up

into concrete form—put to test. There is nothing

tangible about an idea. But living is real; hence

all the details which comprise living are real too

and mere thinking about them without action is

futile. One must execute, arrange, and experiment

with the raw materials of everyday use. The result

is either pleasant or otherwise; if otherwise, the

effort has somehow failed, and one should do it

again and learn thereby; if pleasant, one is the richer

and happier for a bit of success, and is warmed by

the presence of mere accomplishment.

This last phrase reveals the nub of the whole

question—accomplishment. Material surroundings

and comforts of course go far to make one happy,

and they are the evidence of success, but the

ideal home is also composed of people each of whom

is or should be a contributor to the work of the world.

The ideal home contains no drones, and therefore no

discontent. Now the girl cannot plunge headfirst

into the maelstrom of domestic management. She[34]

must learn her strength and acquire confidence, and

there are simple occupations for early years, occupations

which train the muscles, sharpen the wits;

occupations which through suggestion gradually lead

to a wider and wider intellectual horizon, and which,

by a cumulation of information and experience,

mature both judgment and taste. These occupations

form, as it were, some chapters in the unwritten

grammar of culture and efficiency whereby the girl

grows in self-reliance and maturity.

There are, for instance, a number of crafts which,

in their delicacy of technique and the artistic worth

of the finished product, are splendid occupations

for girls, and some few of which every girl should

know. The girl who cannot sew is an object for

sympathy; it is the typical feminine craft for the

reason heretofore named—that one cannot know

how things should be unless one is familiar with

the process involved. Gowns are manufactured of

pieces of cloth cut in proper shape and sewn together

in some, to the male, occult fashion, and this complex

operation only explains itself even to a woman

by going through the experience. One has always

been accustomed to think that the accomplished

mistress is also an expert needle-woman or skilled

worker in textiles of some kind. Products of the[35]

needle and loom have always been her intimate,

personal possessions, and the charm of old hangings,

lace, needlecraft of all kinds, rests in the main on

this personal quality. Without a doubt the most

precious belongings of the young girl are her own

room with its contents of decorations and furnishing,

and the garments which emphasize her inherent

feminine charm. It is not only a girl's right, but

her duty, to maintain her place as the embodiment

of all that is fresh, cleanly and attractive. To this

end clothes and the various other products of the

needle contribute not a little; a clean-cut, thorough

experience in manufacturing things for herself is

the best assurance of future taste, which will spread

out and envelop everything she touches. It is

much the same with clothes and furnishings as with

other matters, what one makes is one's own, characteristic,

appropriate, adequate, with the touch of

enjoyment in it; the purchased article is devoid of

sentiment, it is a makeshift and substitute.

Then by all means let the girl learn to sew, learn

to do for herself, to study her own needs and desires,

to find as she progresses, ways to master the details

of woman's own craft, and it is hoped, lay up a store

of just the sort of experience which will enable her

to supervise the work of others in her behalf when[36]

the time comes. But sewing, valuable as it is in

connection with the young girl's problems, is not

the only craft at hand. In recent years craftworkers

have revived a number of old methods of using or

preparing textiles for decorative purposes, and some

of these have proven increasingly worth while in

the household. Stenciling, block-printing, dyeing,

decorative darning, and even weaving itself, since

they have been remodeled and brought out in simple

form, offer opportunities to the wideawake girl. The

results in each case may be very beautiful, and perhaps

more in harmony with the individual taste

and scheme of living of the particular girl than any

materials she could buy, because they may be designed

and executed for a specific place. Few people,

least of all a child, work just to be busy; there is

always a motive. With the girl it is a scarf, a belt,

collar, curtain, or sofa pillow; is it not well worth

while if she can make these for herself or her room,

in her chosen design motif, (as rose, bird, tree, etc.)

and color? It may be an ordinary design, peculiar

color, but they satisfy a personal sentiment which,

by the way, can be modified and improved as time

goes on. One must needs allow children to begin

with the bizarre, distorted, seemingly unreasonable,

archaic desires they have and cross-fertilize these[37]

with better ones in the hope of producing a fine,

wholesome, sturdy attitude of mind.

Among the minor crafts which may be a source

of real pleasure and good taste, two are prominent:

pottery and basketry. The technique, decorative

possibilities, and functions of the finished products

as elements in household economy and ornament

place these crafts high in the list of those especially

suitable for girls, though boys and adults do find

them equally interesting. Pottery is so closely associated

with flowers and growing things, with the

decoration of fine rooms, with choice spots of color,

and with those receptacles and utensils which belong

to the household, that it makes a strong appeal to the

feminine mind. Here is a craft which vies with textiles

in age and beauty of design, and possesses even

greater charm of manipulation because it is plastic.

One can imagine no finer outlet for creative effort.

Lastly, there is the eternal, magnificent, womanly

craft—home-making. When one stops to think

that the home is the one imperishable, absolute

social unit, the power which creates it must take

rank with other vital forces of constructive economics.

Mothers' clubs and women's organizations

of divers kinds, or, rather, the individuals who

comprise such societies, are continually drifting into[38]

the discussion of the worries, difficulties, and trials

which attend the household. The instant household

routine becomes awkward or inadequate it

affects adversely each individual member of the

family, and naturally the mistress who is responsible

shoulders a burden. There are times when the

maid leaves, or the cooking goes wrong, or the house

is cold, or just a time when one gets started for the

day badly. There are times when the innate perversity

of humans and material things runs riot.

One is led to believe that such untoward occasions,

since they have been in the past, will in all likelihood

continue to crop up to the end of time, though one

cannot find any good reason why they should.

There are homes unacquainted with any household

rumble or squeak, where the domestic machinery

is always in order, and flexible enough to care for

sudden overloading, or absorb any reasonable shock.

In many such places, devoid of servants and confined

to a modest income, the mistress is ever an

expert; the chances are that her daughters will be

equally resourceful. Really, the only sure way to

bring up an adequate number of fine, competent,

resourceful wives and home-makers is to train them

definitely for the profession. The girls must be made

acquainted with every detail of the business which[39]

they will surely inherit. The people who would live

in hotels and frankly abandon home-making themselves

merely emphasize the charm of the household,

because hotels have nothing in common with homes.

It seems rather strange that a business so old

as housekeeping does not, and never has, applied

to its development the laws of commercial enterprise.

When the community or corporation state

sees the need for workmen, foremen or directors, it

tries to educate individuals for the purpose. The

supply of competent men and women is not left

to chance. Whereas, womankind trusts to a very

fickle fortune, that every girl will somehow learn

to steer the domestic craft and be conversant with

methods of preserving family ideals. Contrast the

far-sighted plans of business to fill its ranks with the

casual training the average girl undergoes to fit her

for the future. What is her chance of success? Is

it reasonable to suppose that one who has never

made a home, or even helped actively to run one

made for her, can on demand "make good?" It is

a lasting tribute to the inherent genius and indefatigable

patience of the modern woman that she

has achieved so much with a minimum of experience.

Hence, in order to properly equip one's children

for a practically inevitable future, let the girls into[40]

the secret of domestic planning; let them know of

costs and shopping, income and expenditure; of

materials and uses; the care of possessions, repairs

and cleaning; try to show them that the menu is

not a haphazard combination of ingredients and

foods, but a conscious selection of viands which will

entice the appetite, furnish proper nutrition and

accord with the season. By all means emphasize

the fact that housekeeping, like any business, can be

systematized so that the hundred and one activities

may succeed one another in orderly procession through

the weeks and months. Wash day and housecleaning

should be absorbed into the domestic program, and

never present their grisly features to the home-coming

male, with sufficient trouble of his own.

Recent issues of the magazines have contained

much discussion of the household tangle, and most

of them have ended with the slogans "industrial

education," "back to the kitchen," and such.

Granted that girls need this training, and that schools

in time will give it; granted that the social position

of the servant is a source of discussion and friction;

that the demands of modern living are exacting;

and, finally, granting the insistent prominence of

all the other economic disturbances, who is, in the

last analysis, to blame? Would a business man[41]

think for one moment of handing over any department

of his affairs to one not trained for the particular

duties involved? Industry in every branch

seeks men and women fitted to take charge of even

minor matters. And when trained assistants are

scarce the obvious policy is to prepare other promising

workers for such special places. On the other

hand, mothers too often prepare their daughters for

marriage, not for home-making, seemingly blind to

the fact that marriage is an inert, barren, static condition,

save in the stimulating atmosphere of a fine

home. How can the servant question ever be settled

by untutored girls who get no closer to the domestic

question than fudge, welsh rarebit and salted

peanuts? The school can and does now, in all well-ordered

communities, give a very satisfactory formal,

technical training in domestic art and science.[E]

There students learn to cook and sew; they learn a

good deal about food values, dietetics and simple

food chemistry, simple sanitation, etc. But the

management of a real house, system and everyday

routine, that fine sense of adjustment to the conditions

as they exist—these essentials can only be

learned in the home itself. The efforts of the school can[42]

largely supplement but never replace home guidance,

experience and responsibility. Keeping house ought to

be a science and art rather than a game of chance.

Definite Suggestions

In the "Library of Work and Play," to which the

present book is the introductory volume, one will

find a collection of books replete with suggestion.

But these are not manuals, or courses to be followed

from end to end, because children do not profit

most by such a plan. The child is like a pebble

dropped into still water. It communicates its energy

of momentum to the surrounding fluid and makes

a circular ripple, which in turn makes another and

wider ripple, until the energy is exhausted. In

much the same way the child, landed in the midst

of a more or less inert material world, acts upon it

with energy, which, however, is never exhausted, producing

the results which become more and more

extended. He begins in the middle of a given subject

and works in all possible directions, which gives

one the clue to how to make the most of books like

these.[F]

If the girl has not already indicated a decided

preference for some recreation or play, place at hand

the books which show the possibilities open to her.[43]

It would be well for one to go over them rather

carefully first in order to know what they contain.

Let the girl take her leisure in searching the chapters

and illustrations for the suggestion which strikes a

responsive chord. Ofttimes it will be quite in order

to point to chapters which have a bearing on some

personal need or desire. At any rate, the book or

chapters which seem to be most significant at the

time should be followed up. Read over with

her such a volume as "Home Decoration" or

"Housekeeping." Let her discuss the plans offered

and try them out in her own home. Every girl

wants and should have a dainty, inspiring, beautiful

room of her own, and as she grows older she also

wants the rest of the house to match, so that she

can entertain her friends with pride and confidence.

If one will take "Housekeeping," "Home Decoration,"

and "Needlecraft" as texts, and select from

them first those suggestions which are immediately

apt in a particular home, the girl will shortly find

herself looking at home problems from several

different and very important angles. But it is

desirable also that the study be taken up first in a

very simple way, in order to tie it to real living and

needs. New curtains, pillows for the porch or den,

stenciled scarf, the decorations and menu for a[44]

small party, additional linen: these are some of

the problems always coming up, which may be used

as a beginning. And once the start is made the girl

should have the chance to try other experiments

along the same line. Read with her the chapter

on menus and marketing, or housecleaning, and

turn the house over to the daughter for a time

to manage—absolutely. There is nothing in the

world which children love more or which develops

them more quickly than responsibility, and the

mutual consideration of household affairs gives the

girl real partnership in the domestic business.

She may use the "Housekeeping" book as a kind

of reference, to be sought when new problems in

management fall to her share.

The question of home decoration is so vital that it

deserves special statement. The text[G] deals with

all those details of interior furnishing and embellishment

which indicate taste. All of these are not

equally important, nor do they interest all girls to

the same extent, and in using the book one can

profit most by the study of those topics which touch

the individual or particular family. But everywhere

there is the problem of furniture arrangement,

wall decorations, color schemes, and the skilful[45]

use of flowers, pottery and textiles. Give the young

people, and especially the girls, an insight into how the

interior should be treated. Have them look up pertinent

questions in the text and then try their 'prentice

hands at creating a pleasant, restful, homelike house

with the furnishings at hand plus whatever they can

make or secure. Really, the book is as much a volume

of suggestion for the mother, to which she can refer her

daughter, as a text for the child. There is very keen

interest in taste in recent years, among young people

as well as parents, and the elements hitherto lacking

have been (1) accessible information and (2) opportunity

to "try it out." Offer that opportunity; a flat

is just as fruitful a field for experiment as a house,

perhaps more.

The active participation in outdoor life, nature-study

propaganda and the multiplication of popular

scientific (nature) literature has greatly opened

another field to children—that of raising pets,

gardening, etc. Here the boy or girl will readily

make some choice at an early day, if there has been

any contact with such things. If not, a volume of

this kind[H] will be a real stimulant and inspiration,

as it should be, not a lesson manual. Place the[46]

book in a child's hands, help him look over the conditions,

available ground, cost, care, etc.; let him

send for circulars and catalogues, or if possible visit

some one interested in the same hobby and the

experiment is under way with irresistible momentum.

It is a godsend to any child to give him a

simple, direct statement of what can be done; he

furnishes the steam and imagination for future

development, and father and mother comprise the

balance wheel of the business. This volume and

the one on "Outdoor Sports" contain a mass of

information which touch the interests of practically

all boys and girls at some time in their first sixteen

years. When the child is old enough to launch out

in any personal undertaking, old enough for even

minor responsibilities, when he or she expresses the

desire for possession and money, then give them

books like these. Let them soak in and digest.

Encourage only those requests which are convincing,

but give them all the scope possible. Every

child will eventually select the pastimes which are

best for her though she may stumble in doing so;

she will make fewer mistakes, and waste less time

if she have access to books which will crystallize

and guide her ambitions.

[47]

CHAPTER IV

THAT BOY

"The prime spur to all industry (effort) was and is to own and use the

finished product."—Hall.

One day the pedagogue, who was a learned

man and addicted to study, shut himself

up in his library, bent on devising a method

for training boys into men. This master was well

versed in the sciences so that he could follow the

stars in their courses, make the metals and substances

of the earth obey his will, and guide the

plants in their growth from seed to blossom. Nor

was this scholar lacking in sympathy for the arts,

if they were not too fine, for his desires all led to

systems and orderly arrangements of matter, and

those subjects which would not succumb to analysis

he looked upon coldly.

A Boy's Camp with Ernest Thompson Seton. There Was Never a Boy Who Did Not "Make-Believe,"

and Here the Play Spirit, under Stimulating Guidance, Becomes a Powerful Factor in Developing the

Appreciation of Community Effort

The Play Idea very soon Grows Toward the Representation of Primitive though Adult Customs and

Actions, in which Several Join a Common Body or Company. Hence City Gangs which Merely Seek

Romantic Expression

Hence in this problem of education he made a

careful survey of the history and development of

learning from the beginning—seeking those ideals[48]

and standards of culture which had been approved

for the scholar, because scholars have always been

held in high esteem by those patrons who, being

ignorant themselves, wanted scholarship nearby.

It was found in the course of his delving that the

sciences had originated and developed in about

this order, mathematics, astronomy, geology, botany,

biology, etc. The arts of expression had of course

developed as a group, but chiefly through literature

from the beginning. There seemed to be a good deal

of recent interest in machines and engineering, and

of course certain classes had always tilled the soil,

because one must have food; but the study of these

activities could not lead to culture, because culture

had always had to do with thinking, not manual

labor. Therefore it became clear to the master

that up to the present time, since the end of all

scholarly ambition had been a profession (law,

medicine, theology, etc.), education must be a

very simple matter. All one had to do was to

prepare certain capsules of mathematics, grammar,

Greek and Latin, and a few, very few, odd pellets

of science, etc., and at stated intervals stimulate

the boy's mental organism with the various toxins in

rotation. Were these subjects not the very basis

of culture, and what would be more logical than[49]

direct systematic presentation of the fundamental

principles? If the patient did not respond nothing

could be done but to use more medicine, more

lessons; there could be but one line of treatment.

With this question settled the good savant signified

his readiness to instruct youth in such branches as

were desirable for the educated man, and pupils

came in numbers to obtain the precious learning,

for the pedagogue was favorably known as a great

scholar. But these pupils who came, like the

master, happened to live in or about the year 1912,

when the chief interests of the people were business,

science, and engineering; when transportation and

communication had become highly developed and

systematized; when farming and agriculture were

almost arts, the whole welfare of the nation

rested on industry, and utility held high rank as

an element in culture among the people who worked.

Even when a boy of this period did not seek industrial

honors and follow in the footsteps of his father,

he must needs be interested as a citizen in so important

a source of prosperity. Hence the children

who set out to become pupils of the learned teacher

were alive to the business and activities of their time

and surroundings, and were more than willing to

learn when the learning led to a useful end. But[50]

the scheme proposed by their mentor was such a

queer scheme. Of course it was better to go to

school than do nothing and one must study a few

things, but how much more fascinating and worth

while to talk about birds and animals, trolley cars,

the railway, electricity, machines, and doing things

with a purpose, than to discuss impossible stories

written by people who evidently knew very, very

little about young people, to learn unending pages

of numbers and definitions and facts, which, since

one had no use for them, were speedily forgotten

to make room for better material?

A Typical Boy's Workroom and Shop. Pride of Personal Possession Develops rather Early and the Boy

Should Have a Place of His Own

The Kind of Shop which One May Have at Home

Now these children were obedient and reverent

toward learning and did the tasks assigned them by

their master, but in their leisure hours they did a

good bit of experimenting along other lines, and

found several other studies which were not in the

master's scheme much more to their taste. Animals

and pets were not only nice, live, soft, downy, fuzzy

things to play with, but they had such queer ways

and were so useful that one could talk about them

forever. And then if one raised numbers of them,

often neighbors would desire to purchase, and behold,

a business began whereby it was just possible one

could make a profit now and then. Again, it was

fine if one had even a few tools so that one could put[51]

together the toys and playthings necessary to every-day

amusement. Of course it was needful to measure

and calculate and scheme about materials and

costs, but all this scheming led to real purpose,

while the questions proposed by the teacher were

just questions after all and it couldn't make

much difference whether one found the answer or

not.

Now the usual thing happened. Because of their

reverence for traditional learning and respect for

its apostle the youths continued to attend upon the

master and go through the ceremonial form of

intellectual purification. But really their hearts

were outside, wrapped up in the work of the world,

where they had found just the tonics which were good

for them.

In just so far as the school and home open ways

which "enable the student to earn a livelihood and

to make life worth living" do we see the passing

of the old type school (suggested above) and ideal

of training. Not only are there comparatively

few in this world capable of receiving high polish

through the so-called culture studies, but the definition

of culture has changed; now any activity

is cultural which arouses one's best efforts. Moreover,

the boy of the present is on the lookout for a[52]

new type of instructor, one born of the new era of

industrial success, a teacher who will unlock the

mysteries of modern nature, science, engineering

and business, and who will make it possible for the

student to find his special abilities or bent at an

early age. It is no argument at all to say that the

boy is too young to know what is best for him, that

the mature mind is the only safe guide. The adult

teacher and parent becomes a true guide only when

he uses as a basis for guidance those qualities and

instincts of childhood which cannot be smothered

or eradicated. The child, whether boy or girl,

knows instinctively some of the kinds of information

which do not agree with him, because they possess

no significance at the time and he cannot assimilate

and fatten on them. The child needs a new and

more nutritious mental diet. Father and mother

cannot be of great direct assistance because, strange

to say, they are not experts with children, they

merely know a child (their own) passably well,

but they can provide a most effective, indirect,

contributory stimulus through outside opportunities

for healthy play and experiment which will supplement

the formal instruction of the school. And

children of all ages up to the time they go to college

need some strong outside interest, or group of them,[53]

which will serve as a finder to determine the trade,

profession, or business of the future man.

The Kite Fever is an Annual Disease. Common to practically the

Whole Country. But it is a Disease which Flourishes only among

Normal Children, chiefly Boys

Pump and Waterwheel. A Type of Mechanical Problem which the Boy May Begin With, Both In and Out

of School, because It Touches His Keenest Interest

The children who enter the school, from whatever

grade of society or given race, are all much

alike—lively little animals that sleep, eat and

talk continuously, and play, though play and expression

are one and the same. They do what all

animals do—keep on the move, acquire muscular

skill and precision, and endeavor by every possible

means to express their ideas and convey them

to others. This expression takes on a constructive

phase when children play at store, keeping house,

fire engine, and make toys of paper and cardboard,

and such amusement is the forerunner of that

intense mechanical interest which overtakes boys

about the age of ten or eleven.[I] Girls have an

equally positive leaning which is characteristic and

will be noted elsewhere. Watch any group of boys

of average parentage and surroundings and make a

list of the things they construct for themselves, for

their own ends. In any such list extending over a

period of several months will be found, according

to locality, such things as wagons, sleds, whistles,

kites, dog houses, pigeon roosts, chicken coops,[54]

boats, guns, etc., etc. The young artisan uses

whatever raw material he can; he is chiefly concerned

with the plan, and makes the best of conditions

and materials. The things he makes are

always for real use, a principle held in high esteem

in all the arts. In making these toys the boy acquires

some exceedingly valuable information and

a physical skill and perfection which can only be