| Main Index |

| Volume I. Part 1 |

| Volume I. Part 2 |

| Volume II. Part 1 |

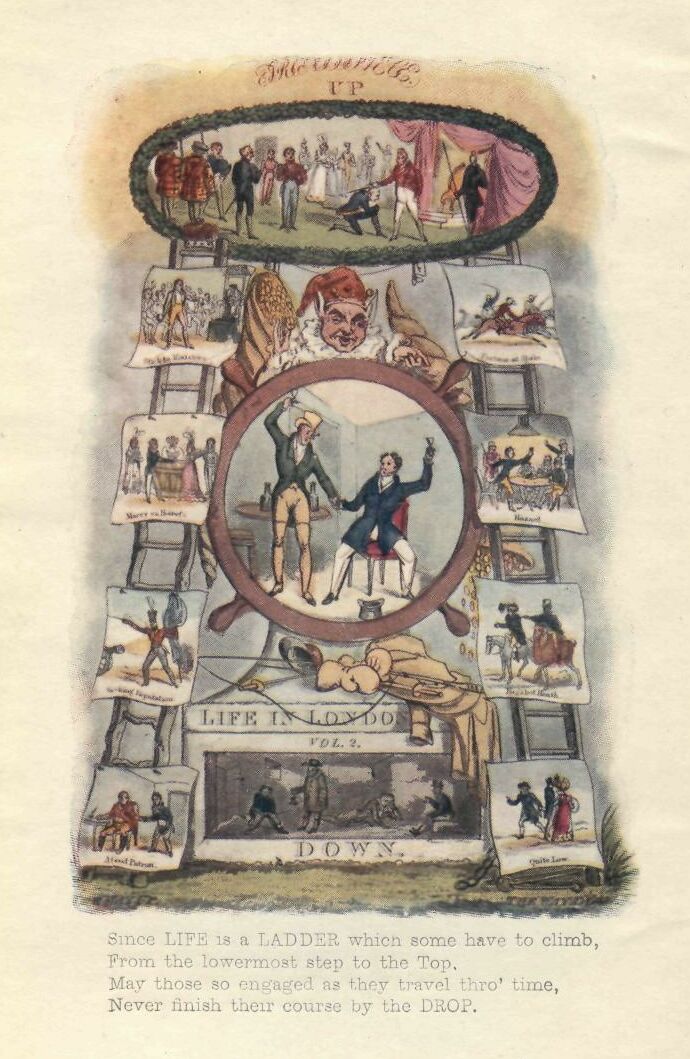

"All London is full of vagaries,

Of bustle of splendour and show,

At every turn the scene varies,

Whether near, or still further we go.

Each lane has a character in it,

Each street has its pauper and beau:

And such changes are making each minute,

Scarce one from the other we know.

The in and out turnings of life,

Few persons can well understand;

But in London the grand source of strife,

Is of fortune to bear the command.

Yet some who are high up to day,

Acknowledged good sober and witty,

May to-morrow be down in decay,

In this great and magnanimous city."

[203] "Apropos," said the Hon. Tom Dashall, laying down the Times newspaper after breakfast, "a fine opportunity is offered to us to day, for a peep at the Citizens of London in their Legislative Assembly, a Court of Common Council is announced for twelve o'clock, and I think I can promise you much of entertaining information, by paying a visit at Guildhall and its vicinity. We have several times passed it with merely taking a view of its exterior, but the interior is equally deserving of attention, particularly at a period when it is graced by the personages and appendages which constitute its state and dignity. London is generally spoken of as the first commercial city in the known world, and its legislators, as a corporate body, becomes a sort of rallying post for all others in the kingdom. We have plenty of time before us, and may lounge a little as we march along to amuse or refresh ourselves at leisure." "With all my heart," said Tallyho, "for I have heard much about the Lord Mayor, the Sword Bearer, and the Common Hunt, all in a bustle,—though I have never yet had an opportunity of seeing any of them."

[204]"They are interesting subjects, I can assure you, so come along, we will take a view of these Gogs and Magogs of civic notoriety," and thus saying, they were quickly on the road for the city. The morning being fine, they took their way down St. James's Street, at the bottom of which their ears were attracted by the sounds of martial music approaching.

"We have nicked the time nicely indeed," said Dashall, "and may now enjoy a musical treat, before we proceed to the oratorical one. The Guards in and about the Palace, are relieved every morning about this time, for which purpose they are usually mustered at the Horse-Guards, in the Park, where they are paraded in regular order, and then marched here. It forms a very pleasing sight for the cockney loungers, for those out of employ, and those who have little inclination to be employed; and you see the crowds that are hastening before them, in order to obtain admission to Palace Yard, before their arrival—let us join the throng; there is another detachment stationed there ready to receive them, and while they are relieving the men actually on duty, the two bands alternately amuse the officers and the bye-standers with some of the most admired Overtures and Military Airs."

They now passed the gate, and quickly found themselves in a motley group of all descriptions, crowding to the seat of action, and pouring in from various avenues. Men, women, and children, half-drill'd drummers, bandy-legged fifers, and suckling triangle beaters, with bags of books and instruments in their hands to assist the band. The colours were mounted as usual on a post in the centre, the men drawn up in ranks, and standing at ease, while the officers were pacing backwards and forwards in the front, arm-in-arm with each other, relating the rencontres of the preceding day, or those in anticipation of the ensuing. This order of things was however quickly altered, as the relieving party entered, and at the word "attention," every officer was at his post, and the men under arms. Our friends now moved under the piazzas so as to be in the rear of the party who had the first possession, and after hearing with great admiration the delightful airs played by the two bands, which had been the principal object of attraction with them—they proceeded through the Park and reached Charing Cross, by the way of Spring Gardens.

[205] "Zounds," said Tallyho, "this is a very unworthy entrance to a Royal Park."

"Admitted, it is so," was the reply, "and a degradation to the splendid palace, I mean internally, which is so close to it, and which is the present residence of Majesty." They now proceeded without any thing further of consequence worthy of remark, till they reached Villiers-street.

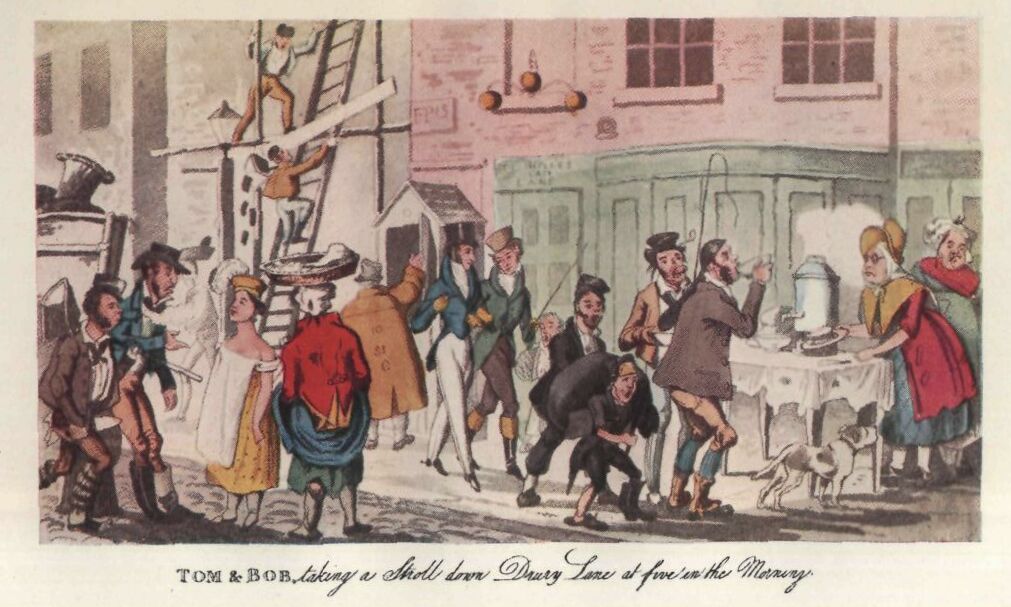

"Come," said Tom, "I perceive we shall have time to take a look at the world below as well as the world above; "when crossing into the Adelphi, and suddenly giving another turn, he entered what to Bob appeared a cavern, and in one moment was obscured from his sight.—"Hallo," said Tallyho, "where the devil are you leading me to?"—"Never mind," was the reply; "keep on the right side, and you are safe enough; but if you get into the centre, beware of the Slough of Despond—don't be afraid."

Upon this assurance Bob groped his way along for a few paces, and at a distance could discover the glimmering of a lamp, which seemed but to make darkness more visible. Keeping his eye upon the light, and more engrossed with the idea of his own safety in such a place than any thing else, for he could neither conjecture where he was nor whence he was going, he presently came in violent contact with a person whom he could not see, and in a moment found himself prostrate on the ground.

"Hallo," cried a gruff voice, which sounded through the hollow arches of the place with sepulchral tone—"who the devil are you—why don't you mind where you go—you must not come here with your eyes in your pocket;" and at the same time he heard a spade dug into the earth, which almost inspired him with the idea that he should be buried alive.

"Good God protect," (exclaimed Bob,) "where is Dashall—where am I?"

"Where are you—why you're in the mud to be sure—and for aught I know, Dashall and all the rest may be in the clouds; what business have you dashing here—we have enough of the Dandies above, without having them below—what have you lost your way, or have you been nibbling in the light, and want to hide yourself—eh?"

[206] "Neither, neither, I can assure you; but I have been led here, and my friend is on before."

"Oh, well, if that's the case, get up, and I'll hail him, —ey-ya-ap"—cried he, in a voice, which seemed like thunder to our fallen hero, and which was as quickly answered by the well known voice of his Cousin, who in a few minutes was at his elbow.

"What now," vociferated Tom, "I thought I gave you instructions how to follow, and expected you was just behind me."

"Why for the matter of that," cried the unknown, "he was not before you, that's sartin; and he knocked himself down in the mud before ever I spoke to him, that's all I know about it—but he don't seem to understand the navigation of our parts."

"I don't wonder at that," replied Tom; "for he was never here before in his life—but there is no harm done, is there?"

"None," replied Bob; "all's right again now—so proceed."

"Nay," replied the unknown, "all's not right yet; for if as how this is your first appearance in the shades below, it is but fair you should come down."

"Down," said Bob, "why I have been down—you knock'd me down."

"Well, never mind, my master, I have set you on your pins again; and besides that, I likes you very well, for you're down as a hammer, and up again like a watch-box—but to my thinking a drap o'somut good would revive you a little bit; and I should like to drink with you—for you ought to pay your footing."

"And so he shall," continued Tom—"So come along, my lad."

By this time Bob had an opportunity of discovering that the person he had thus unfortunately encountered, was no other than a stout raw-boned coalheaver, and that the noise he had heard was occasioned by his sticking his pointed coal-shovel in the earth, with intention to help him up after his fall. Pursuing their way, and presently turning to the right, Bob was suddenly delighted by being brought from utter darkness into marvellous light, presenting a view of the river, with boats and barges passing and repassing with their usual activity.

"What place is this?" inquired Tallyho.

[207] "Before you," replied his Cousin, "is the River Thames; and in the front you will find wharfs and warehouses for the landing and housing of various merchandize, such as coals, fruit, timber, &c.: we are now under the Adelphi Terrace, where many elegant and fashionable houses are occupied by persons of some rank in society; these streets, lanes, and subterraneous passages, have been constructed for the convenience of conveying the various articles landed here into the main streets of the metropolis, and form as it were a little world under ground."

"And no bad world neither," replied the coalheaver, who upon inspection proved to be no other than Bob Martlet, whom they had met with as one of the heavy wet party at Charley's Crib—"For there is many a family lives down here, and gets a good bit of bread too; what does it signify where a man gets his bread, if he has but an honest appetite to eat it with: aye, and though I say it, that house in the corner there, just down by the water's edge, can supply good stuff at all times to wash it down with, and that you know's the time of day, my master: this warm weather makes one dryish like, don't it?"

Tom thought the hint dry enough, though Bob was declaring he was almost wet through; however, they took their road to the Fox under the Hill, as it is termed. On entering which a good fire presented itself, and Tallyho placed himself in front of it, in order to dry his clothes, while Bob Martlet was busy in inquiring of the landlord for a brush to give the gemman a wipe down, as, he observed, he had a sort of a trip up in these wild parts—though to be sure that there was no great wonder, for a gentleman who was near sighted, and didn't wear spectacles; "however," continued he, "there an't no harm done; and so the gemman and I are going to drink together—arn't we, Sir?"

Tallyho, who by this time had got well roasted by the fire-side, nodded his assent, and Dashall inquired what he would like.

[208] "Why, my master, as for that, it's not much matter to me; a drap of sky blue in a boulter of barley,{1} with a dollop of sweet,{2} and a little saw dust,{3} is no bad thing according to my thinking; but Lord bless you! if so be as how a gemman like you offers to treat Bill Martlet,

1 A boulter of barley—a drink—or a pot of porter.

2 A dollop of sweet—sugar.

3 Saw-dust—a cant term for ginger or nutmeg grated.

why Bill Martlet never looks a gift horse in the mouth, you know, as the old saying is; but our landlord knows how to make such rum stuff, as I should like you to taste it—we call it hot, don't us, landlord?—Come, lend us hold of the brush?" "Ave, and brush up, Mr. Landlord," said the Hon. Tom Dashall; "let us have a taste of this nectar he's talking of, for we have not much time to stop."

"Lord bless your eye sight," replied Martlet, "there an't no occasion whatsomdever for your honours to stay—if you'll only give the order, and push about the possibles, the business is all done. Come, shovel up the sensible," continued he to the landlord, "mind you give us the real double XX. I don't think your coat is any the worse, it would sarve me for a Sunday swell toggery for a twelve-month to come yet; for our dirt down here is as I may say clean dirt, and d———me if I don't think it looks all the better for it."

"Thank you, my friend," said Bob; "that will do very well," and the landlord having by this time completed his cookery, produced the good stuff, as Martlet termed it.

"Come, gentlemen, this is the real right sort, nothing but the bang-up article, arn't it, my master? But as I always likes the landlord to taste it first, by way of setting a good example, just be after telling us what you think of it."

"With all my heart," said the landlord; who declared it was as prime a pot of hot as he had made for the last fortnight. .

With this recommendation our friends tried it; and after tipping, took their departure, under the positive assurance of Martlet, that he should be very glad to see them again at any time.

They now pursued their way through other subterraneous passages, where they met waggons, carts, and horses, apparently as actively and usefully employed as those above ground.

"Come," said Tom, "we have suffered time to steal a inarch upon us," as they reached the Strand; "we will therefore take the first" rattler we can meet with, and make the best of our way for the City."—This was soon accomplished, and jumping into the coach, the old Jarvey was desired to drive them as expeditiously as possible to the corner of King-street, Cheapside.[209]

"How wretched those who tasteless live,

And say this world no joys can give:

Why tempts yon turtle sprawling,

Why smoaks the glorious haunch,

Are these not joys still calling

To bless our mortal paunch?

O 'tis merry in the Hall

When beards wag all,

What a noise and what a din;

How they glitter round the chin;

Give me fowl and give me fish,

Now for some of that nice dish;

Cut me this, Sir, cut me that,

Send me crust, and send me fat.

Some for tit bits pulling hauling,

Legs, wings, breast, head,—some for liquor, scolding, bawling,

Hock, port, white, red, here 'tis cramming, cutting, slashing,

There the grease and gravy splashing,

Look, Sir, look, Sir, what you've done,

Zounds, you've cut off the Alderman's thumb."

The Hon. Tom Dashall, who was fully aware that City appointments for twelve o'clock mean one, was nevertheless anxious to arrive at their place of destination some time before the commencement of the business of the day; and fortunately meeting with no obstruction on the road, they were set down at the corner of King-street, about half-past twelve.

"Come," said he, "we shall now have time to look about us at leisure, and observe the beauties of this place of civic festivity. The Hall you see in front of you, is the place devoted to the entertainment usually given by the Lord Mayor on his entrance upon the duties and dignities of his office. It is a fine gothic building, in which the various courts of the city are held. The citizens also meet there for the purpose of choosing their representatives in Parliament, the Lord Mayor, Sheriffs, &c. It was originally built in the year 1411, previous to which period the public, or as they term it the Common Hall, was held at a small room in Aldermanbury.

[210] The expense Of the building was defrayed by voluntary subscription, and its erection occupied twenty years. It was seriously damaged by the fire of 1666, since which the present edifice, with the exception of the new gothic front, has been erected. That, however, was not finished till the year 1789, and many internal improvements and decorations have been introduced since. There is not much of attraction in its outward appearance. That new building on the right has recently been erected for the accommodation of Meetings of Bankrupts; and on the left is the Justice-Room, where the Aldermen attend daily in rotation as magistrates to decide petty causes; but we must not exhaust our time now upon them."

On entering the Hall, Tallyho appeared to be highly pleased with its extent, and was presently attracted by the monuments which it contains. "It is a noble room," said he.—"Yes," replied Tom, "this Hall is 153 feet in length, 48 in breadth, and the height to the roof is 55." Tallyho was, however, more engaged in examining the monument erected to the memory of Lord Nelson, and an occasional glance at the two enormous figures who stand at opposites, on the left of the entrance.—Having read the tablet, and admired the workmanship of the former, he hastily turned to the latter. "And who in the name of wonder are these?" he inquired.

"These," replied his communicative Cousin, "are called Gog and Magog. They are two ancient giants carved in wood, one holding a long staff suspending a ball stuck with pikes, and the other a halbert, supposed to be of great antiquity, and to represent an ancient Briton and a Saxon. They formerly used to stand on each side of that staircase which leads to the Chamberlain's Office, the Courts of King's Bench and Common Pleas, the Court of Aldermen, and the Common Council Chamber. At the other end are two fine monuments, to the memory of Lord Chatham, the father of Mr. Pitt, and his Son. The windows are fine specimens of the revived art of painting on glass. There is also a monument of Mr. Beckford."

While they were taking a view of these several objects of curiosity, their attention was suddenly attracted by a confused noise and bustle at the door, which announced the arrival of the Lord Mayor and his attendants, who passed them in state, and were followed by our friends to the Council Chamber; on entering which, they were [211] directed by the City Marshall, who guarded the door, to keep below the bar. Tallyho gazed with admiration and delight on the numerous pictures with which the Chamber is decorated, as well as the ceiling, which forms, a dome, with a skylight in the centre. The Lord Mayor having first entered the Court of Aldermen, the business of the day had not yet commenced. Tom directed his Cousin's eye in the first instance to the very large and celebrated painting by Copley, which fronts the Lord Mayor's chair, and represents the destruction of the floating batteries before Gibraltar, to commemorate the gallant defence of that place by General Elliott, afterwards Lord Heath field, in 1782. The statue of the late King George the Third; the death of David Rizzio, by Opie; the miseries of Civil War, from Shakespeare; Domestic Happiness, exemplified in portraits of an Alderman and his family; the death of Wat Tyler; the representation of the Procession of the Lord Mayor to Westminster Hall, by water; and the ceremony of swearing in the Lord Mayor at Guildhall, in 1781; containing portraits of all the principal members of the Corporation of London at that time. Meanwhile the benches were filling with the Deputies and Common Councilmen from their several wards. At one o'clock, the Lord Mayor entered the Court, attended by several Aldermen, who took their seats around him, and the business of the day commenced. Among those on the upper seats, Tom gave his Cousin to understand which were the most popular of the Aldermen, and named in succession Messrs. Waithman, Wood, Sir Claudius Stephen Hunter, Birch, Flower, and Curtis; and as their object was not so much to hear the debates as to see the form and know the characters, he proposed an adjournment from their present rather uncomfortable situation, where they were obliged to stand wedged in, by the crowd continually increasing, during which they could take a few more observations, and he could give some little clue to the origin and present situations of the persons to whom he had directed his Cousin's attention. Making the best of their way out of the Court, they found themselves in an anti-room, surrounded by marshalmen, beadles of Wards waiting for their Aldermen, and the Lord Mayor's and Sheriffs' footmen, finding almost as much difficulty to proceed, as they had before encountered.

[212] Having struggled through this formidable phalanx of judicial and state appendages,

"Now," said Dashall, "we shall be enabled to breathe again at liberty, and make our observations without fear; for where we have just quitted, there is scarcely any possibility of making a remark without having it snapped up by newspaper reporters, and retailers of anecdotes; here, however, we can indulge ad libitum."

"Yes," replied Tallyho, "and having seen thus far, I am a little inquisitive to know more. I have, it is true, at times seen the names of the parties you pointed out to me in the daily prints, but a sight of their persons in their official stations excites stronger curiosity."

"Then," said Tom, "according to promise I will give you a sort of brief sketch of some of them. The present Lord Mayor is a very eminent wholesale stationer, carrying on an extensive trade in Queen-street; he ought to have filled the chair before this, but some temporary circumstances relative to his mercantile concerns induced him to give up his rotation. He has since removed the obstacle, and has been elected by his fellow-citizens to the high and important office of Chief Magistrate. I believe he has not signalized himself by any remarkable circumstance, but he has the character of being a worthy man. Perhaps there are few in the Court of Aldermen who have obtained more deservedly the esteem of the Livery of London, than Alderman Waithman, whose exertions have long been directed to the correction of abuses, and who represented them as one of their members during the last Parliament, when he displaced the mighty Alderman Curtis. Waithman is of humble origin, and has, like many others of Civic notoriety, worked his way by perseverance and integrity as a linen-draper, to respectable independence, and the hearts of his fellow-citizens: he has served the office of Sheriff, and during that time acted with a becoming spirit at the death of the late Queen, by risking his own life to save others. His political sentiments are on the opposition side, consequently he is no favorite with ministers."

"And if he were," replied Tallyho, "that would scarcely be considered an honour."

"True," continued Tom, "but then it might lead to profit, as it has done with many others, though he appears to hold such very light.

[213] "Alderman Wood has not yet been so fortunate as the celebrated Whittington, whom you may recollect was thrice Lord Mayor of London; but he has had the honour to serve that office during two succeeding years: he is a member of Parliament, and his exertions in behalf of the late Queen, if they have done him no great deal of good among the higher powers, are at least honourable to his heart.

"Of Sir Claudius Stephen Hunter there is but little to be said, except that he has served the office, and been a Colonel of the City Militia—led off the ball at a Jew's wedding—used to ride a white charger—and is so passionately fond of military parade, that had he continued another year in the office, the age of chivalry would certainly have been revived in the East, and knights-errant and esquires have completely superseded merchants, traders, and shopkeepers.

"Alderman Birch is an excellent pastry-cook, and that perhaps is the best thing that can be said of him: he has written some dramatic pieces; but the pastry is beyond all comparison best of the two, and he needs no other passport to fame, at least with his fellow-citizens.

"But last, though not least, under our present consideration, comes the renowned Sir William, a plain bluff John Bull; he is said to be the son of a presbyterian citizen, and was rigidly educated in his father's religion. He obtained the alderman's gown, and represented the City in the year 1790: he is a good natured, and, I believe, a good hearted man enough, though he has long been a subject for satirical wit. He was Lord Mayor in 1796: you may recollect what was related of him by the literary labourer we met with in the Park—anecdotes and caricatures have been published in abundance upon him: he may, however, be considered in various points of view—as an alderman and a biscuit baker—as a fisherman "—

"How!" cried Tallyho!

"Why, as a fisherman, he is the Polyphemus of his time.

"His rod was made out of the strongest oak,

His line a cable which no storm e'er broke,

His hook was baited with a dragon's tail,

He sat upon a rock and bobb'd for a whale."

"Besides which," continued Dashall, "he is a great sailor; has a yacht of his own, and generally accompanies

[214] Royalty on aquatic excursions. I remember a laughable caricature, exhibiting the alderman in his own vessel, with a turtle suspended on a pole, with the following lines, in imitation of Black-eyed Susan, said to be written by Mr. Jekyll:—

"All in the Downs the fleet lay moor'd,

The streamers waving in the wind,

When Castlereagh appeared on board,

'Ah where shall I my Curtis find.

Tell me ye jovial sailors, tell me true,

Does my fat William sail among your crew.'"

He is a banker, a loan-monger, and a contractor, a member of Parliament, and an orator; added to which, he may be said to be a man of wit and humour—at all events he is the cause of it in others. His first occupations have procured him great wealth, and his wit and humour great fame.

"The worthy Alderman's hospitality to the late good humoured and gossiping James Boswell, the humble follower and biographer of Dr. Johnson, is well known; and it is probable that the pleasures of the table, in which no man more joyously engaged, shortened his life. To write the life of a great man is no easy task, and to write that of a big one may be no less arduous. Whether the Alderman really expected to be held up to future fame by the Biographer of Johnson, cannot be very easily ascertained; however that wish and expectation, if it ever existed, was completely frustrated by the death of poor Boswell.

"I recollect to have seen some lines of the worthy Alderman, on the glorious victory of the Nile, which shew at once his patriotism, his wit, and his resolution, in that he is not to be laughed out of the memorable toast he once gave—

"Great Nelson, in the grandest stile,

Bore down upon the shores of Nile,

And there obtained a famous victory,

Which puzzled much the French Directory.

The impudence of them there fellows,

As all the newspapers do tell us,

Had put the grand Turk in a pet,

Which caus'd him send to Nelson an aigrette;

Likewise a grand pelisse, a noble boon—

Then let us hope—a speedy peace and soon."{1}

1 Whether the following lines are from the same hand or not,

we are unable to ascertain; at least they wear a great

similarity of character:

I give you the three glorious C's.

Our Church, Constitution, and King;

Then fill up three bumpers to three noble Vs.

Wine, Women, and Whale fish-ing.

[215] "Egad," said Bob, "if this be true, he appears to knock up rhymes almost as well as he could bake biscuits" (smothering a laugh.)

"Why," replied Dashall, "I believe that it has not been positively ascertained that these lines, which unlike other poetry, contain no fiction, but plain and undeniable matter of fact, were wholly indicated by the worthy Alderman; indeed it is not impossible but that his worship's barber might have had a hand in their composition. It would be hard indeed, if in his operations upon the Alderman's pericranium, he should not have absorbed some of the effluvia of the wit and genius contained therein; and in justice to this operator on his chin and caput, I ought to give you a specimen which was produced by him upon the election of his Lordship to the Mayoralty—

"Our present Mayor is William Curtis,

A man of weight and that your sort is."

"This epigrammatic distich, which cannot be said to be destitute of point, upon being read at table, received, as it deserved, a large share of commendation; and his Lordship declared to the company present, that it had not taken his barber above three hours to produce it extempore."

Tallyho laughed heartily at these satirical touches upon the poor Alderman.

"However," continued Tom, "a man with plenty of money can bear laughing at, and sometimes laughs at himself, though I suspect he will hardly laugh or produce a laugh in others, by what he stated in his seat in the House of Commons, on the subject of the riots{1} at Knightsbridge. I suspect his wit and good humour will hardly protect him in that instance."

1 On a motion made by Mr. Favell in the Court of Common

Council, on the 21st of March, the following resolution was

passed, indicative of the opinion that Court entertained of

the conduct of Alderman Curtis on the occasion here alluded

to:

"That Sir William Curtis, Bart, having acknowledged in his

place in this Court, that a certain speech now read was

delivered by him in the House of Commons, in which, among

other matters which he stated respecting the late riot at

Knightsbridge, he said, 'That he had been anxious that a

Committee should investigate this question, because he

wished to let the world know the real character of this

Great Common Council, who were always meddling with matters

which they had nothing to do with, and which were far above

their wisdom and energy. It was from such principles they

had engaged in the recent inquiry, which he would contend

they had no right to enter upon. Not only was evidence

selected, but questions were put to draw such answers as the

party putting them desired.'

"That the conduct of Sir William Curtis, one of the repre-

sentatives of this City in Parliament, lias justly merited

the censure and indignation of this Court and of his fellow

Citizens."

[216] After taking a cursory look into the Chamberlain's Office, the Court of King's Bench and Common Pleas, they took their departure from Guildhall, very well satisfied with their morning's excursion.

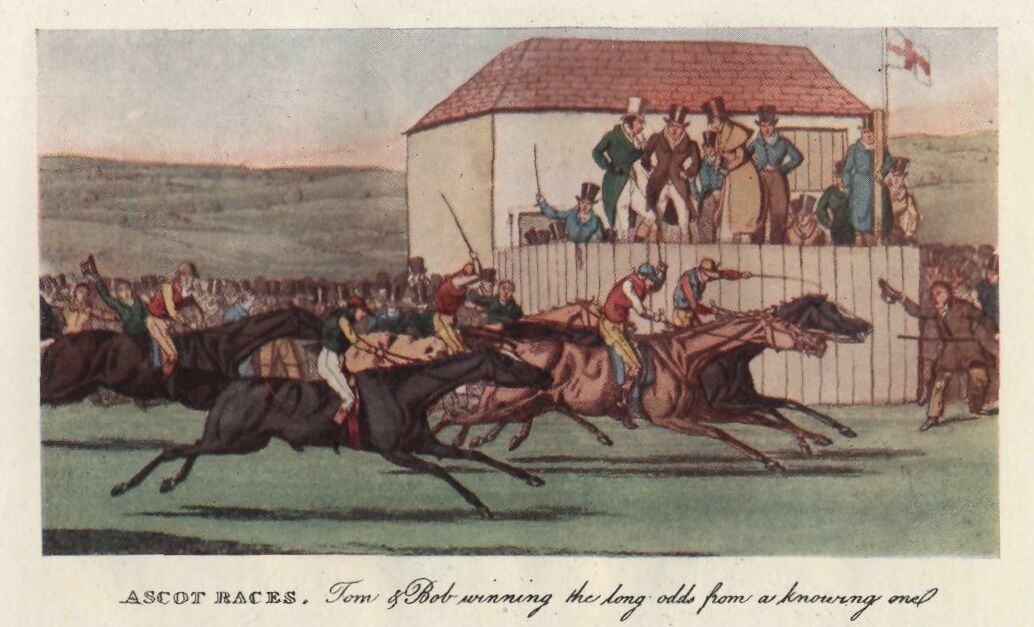

It was between three and four o'clock when our friends left the Hall. Tom Dashalt, being upon the qui vive, determined to give his Cousin a chevy for the remainder of the day; and for this purpose, it being on a Friday, he proposed a stroll among the Prad-sellers in Smithfield, where, after partaking of a steak and a bottle at Dolly's, they accordingly repaired.

"You will recollect," said Tom, "that you passed through Smithfield (which is our principal cattle market) during the time of Bartholomew Fair; but you will now find it in a situation so different, that you would scarcely know it for the same place: you will now see it full of horse-jockeys, publicans, pugilists, and lads upon the lark like ourselves, who having no real business either in the purchase or sale of the commodities of the market, are watching the manners and manouvres of those who have."

As Tom was imparting this piece of information to his attentive Cousin, they were entering Smithfield by the way of Giltspur-street, and were met by a man having much the appearance of a drover, who by the dodging movements of his stick directly before their eyes, inspired our friends so strongly with the idea of some animal being behind them which they could not see, and from which danger was to be apprehended, that they suddenly broke from each other, and fled forward for safety, at which a roar of laughter ensued from the byestanders, who [217] perceiving the hoax, recommended the dandies to take care they did not dirty their boots, or get near the hoofs of the prancing prads, Tom was not much disconcerted at this effort of practical jocularity, though his Cousin seemed to have but little relish for it.

"Come along," said Tom, catching him by the arm, and impelling him forward, "although this is not Bartholomew Fair time, you must consider all fair at the horse-fair, unless you are willing to put up with a horse-laugh."

Struggling through crowds who appeared to be buying, selling, or bargaining for the lame, the broken winded, and spavined prads of various sizes, prices, and pretensions,

"There is little difference," said Tom, "between this place as a market for horses, and any similar mart in the kingdom,

Here the friend and the brother

Meet to humbug each other,

except that perhaps a little more refinement on the arts of gulling may be found; and it is no very uncommon thing for a stolen nag to be offered for sale in this market almost before the knowledge of his absence is ascertained by the legal owner.—I have already given you some information on the general character of horse-dealers during our visit to Tattersal's; but every species of trick and low chicanery is practised, of which numerous instances might be produced; and though I admit good horses are sometimes to be purchased here, it requires a man to be perfectly upon his guard as to who he deals with, and how he deals, although the regulations of the market are, generally speaking, good."

"I wouldn't have him at no price," said a costermonger, who it appeared was bargaining for a donkey; "the h———y sulkey b——— von't budge, he's not vorth a fig out of a horses———."

"I knows better as that 'are," cried a chimney-sweeper; "for no better an't no vare to be had; he's long backed and strong legged. Here, Bill, you get upon him, and give him rump steaks, and he'll run like the devil a'ter a parson."

Here Bill, a little blear-eyed chimney-sweeper, mounted the poor animal, and belaboured him most unmercifully, without producing any other effect than kicking up behind, and most effectually placing poor Bill in the

[218] mud, to the great discomfiture of the donkey seller, and the mirth of the spectators. The animal brayed, the byestanders laughed, and the bargain, like poor Bill, was off.

After a complete turn round Smithfield, hearing occasionally the chaffing of its visitants, and once or twice being nearly run over, they took their departure from this scene of bustle, bargaining, and confusion, taking their way down King-street, up Holborn Hill, and along Great Queen-street.

"Now," said Tom, "we will have a look in at Covent Garden Theatre; the Exile is produced there with great splendour. The piece is certainly got up in a style of the utmost magnificence, and maintains its ground in the theatre rather upon that score than its really interesting dialogue, though some of the scenes are well worked up, and have powerful claims upon approbation. The original has been altered, abridged, and (by some termed) amended, in order to introduce a gorgeous coronation, a popular species of entertainment lately."

Upon entering the theatre, Tallyho was almost riveted in attention to the performance, and the latter scene closed upon him with all its splendid pageantry before he discovered that his Cousin had given him the slip, and a dashing cyprian of the first order was seated at his elbow, with whom entering into a conversation, the minutes were not measured till Dashall's return, who perceiving he was engaged, appeared inclined to retire, and leave the cooing couple to their apparently agreeable tete-a-tete. Bob, however, observing him, immediately wished his fair incognita good night, and joined his Cousin.

"D———d dull," said Tom,—"all weary, stale, flat, and unprofitable."

"But very grand," rejoined Bob.

"I have found nothing to look at," replied Tom; "I have hunted every part of the House, and only seen two persons I know."

"And I," said Tallyho, "have been all the while looking at the piece."

"Which piece do you mean, the one beside you, or the one before you?"

"The performance—The Coronation."

"I have had so much of that," said Tom, "that finding you so close in attention to the stage, that I could get no [219] opportunity of speaking to you, I have been hunting for other game, and have almost wearied myself in the pursuit without success; so that I am for quitting the premises, and making a call at a once celebrated place near at hand, which used to be called the Finish. Come along, therefore, unless you have 'mettle more attractive;' perhaps you have some engagements?"

"None upon earth to supersede the one I have with you," was the reply. Upon which they left the House, and soon found themselves in Covent Garden Market. "This," said Tom, "has been the spot of many larks and sprees of almost all descriptions, ana election wit has been as cheap in the market as any of the vegetables of the venders; but I am going to take you to a small house that has in former times been the resort of the greatest wits of the age. Sheridan, Fox, and others of their time, have not disdained to be its inmates, nor is it now deserted by the votaries of genius, though considerably altered, and conducted in a different manner: it still, however, affords much amusement and accommodation. It was formerly well known by the appellation of the Finish, and was not opened till a late hour in the night, and, as at the present moment, is generally shut up between 11 and 12 o'clock, and re-opened for the accommodation of the market people at 4 in the morning. The most respectable persons resident in the neighbourhood assemble to refresh themselves after the labours of the day with a glass of ale, spirits, or wine, as they draw no porter. The landlord is a pleasant fellow enough, and there is a pretty neat dressing young lass in the bar, whom I believe to be his sister—this is the house."

"House," said Bob, "why this is a deviation from the customary buildings of London; it appears to have no up stairs rooms."

"Never mind that," continued Dashall, "there is room enough for us, I dare say; and after your visit to the Woolpack, I suppose you can stand smoke, if you can't stand fire."

By this time they had entered the Carpenter's Arms, when turning short round the bar, they found themselves in a small room, pretty well filled with company, enjoying their glasses, and puffing their pipes: in the right hand corner sat an undertaker, who having just obtained a victory over his opposite neighbour, was humming a stave [220] to himself indicative of his satisfaction at the result of the contest, which it afterwards appeared was for two mighty's;{1} while his opponent was shrugging up his shoulders with a feeling of a very different kind.

"It's of no use," said Jemmy,{2} as they called him, "for you to enter the lists along with me, for you know very well I must have you at last."

"And no doubt it will prove a good fit," said an elderly shoemaker of respectable appearance, who seemed to command the reverence of the company, "for all of us are subject to the pinch."

"There's no certainty of his assertion, however," replied the unsuccessful opponent of Jemmy.

"Surely not,"{3} said another most emphatically, taking a pinch of snuff, and offering it to the shoemaker; "for you know Jemmy may come to the finch before John."

1 "Mighty."—This high sounding title has recently been

given to a full glass of ale,—the usual quantity of what is

termed a glass being half a pint, generally supplied in a

large glass which would hold more—and which when filled is

consequently subjected to an additional charge.

2 To those who are in the habit of frequenting the house,

this gentleman will immediately be known, as he usually

smokes his pipe there of an afternoon and evening.

"With his friend and his pipe puffing sorrow away, And with

honest old stingo still soaking his clay."

With a certain demonstration before him of the mortality of

human life, he deposits the bodies of his friends and

neighbours in the earth, and buries the recollection of them

in a cloud, determined, it should seem, to verify the words

of the song, that

"The right end of life is to live and be jolly."

His countenance and manners seldom fail to excite

risibility, not-withstanding the solemnity of his calling,

and there can be little doubt but he is the finisher of

many, after the Finish; he is, however, generally good

humoured, communicative, and facetious, and seldom refuses

to see any person in company for a mighty, usually

concluding the result with a mirthful ditty, or a doleful

countenance, according to the situation in which he is left

as a winner or a loser; and in either case accompanied with

a brightness of visage, or a dull dismal countenance,

indicative of the event, which sets description at defiance,

and can only be judged of by being seen.

3 "Surely not," are words in such constant use by one

gentleman who is frequently to be met in this room, that the

character alluded to can scarcely be mistaken: he is partial

to a pinch of snuff, but seldom carries a box of his own. He

is a resident in the neighbour-hood, up to snuff, and

probably, like other men, sometimes snuffy; this, however,

without disparagement to his general character, which is

that of a respectable tradesman. He is fond of a lark, a

bit of gig, and an argument; has a partiality for good

living, a man of feeling, and a dealer in felt, who wishes

every one to wear the cap that fits him.

[221] "Never mind," continued Jemmy, "I take my chance in this life, and sing toll de roll loll."

By this time our friends, being supplied with mighties, joined in the laugh which was going round at the witty sallies of the speakers.

"It is possible I may go first," said the undertaker, resuming his pipe; "and if I should, I can't help it."

"Surely not,—but I tell you what, Jemmy, if you are not afraid, I'll see you for two more mighties before I go, and I summons you to shew cause."

"D———n your summons,"{1} cried the former unsuccessful opponent of the risible undertaker, who at the word summons burst into a hearty laugh, in which he was immediately joined by all but the last speaker.

"The summons is a sore place," said Jemmy.

"Surely not. I did not speak to him, I spoke to you, Sir; and I have a right to express myself as I please: if that gentleman has an antipathy to a summons, am I to be tongue-tied? Although he may sport with sovereigns, he must be accountable to plebeians; and if I summons you to shew cause, I see no reason why he should interrupt our conversation."

1 "D——-n your summons." This, as one of the company

afterwards remarked, was a sore place, and uttered at a

moment when the irritation was strong on the affected part.

The speaker is a well known extensive dealer in the pottery,

Staffordshire, and glass line, who a short time since in a

playful humour caught a sovereign, tossed up by another

frequenter of the room, and passed it to a third. The

original possessor sought restitution from the person who

took the sovereign from his hand, but was referred to the

actual possessor, but refused to make the application. The

return of the money was formally demanded of the man of

porcelain, pitchers, and pipkins, without avail. In this

state of things the loser obtained a summons against the

taker, and the result, as might be expected, was compulsion

to restore the lost sovereign to the loving subject,

together with the payment of the customary expenses, a

circumstance which had the effect of causing great anger in

the mind of the dealer in brittle wares. Whether he broke

any of the valuable articles in his warehouse in consequence

has not been ascertained, but it appears for a time to have

broken a friendship between the parties concerned: such

breaches, however, are perhaps easier healed than broken or

cracked crockery.

[222] "Surely not," was reverberated round the room, accompanied with a general laugh against the interrupter, who seizing the paper, appeared to read without noticing what was passing.

The company was now interrupted by the entrance of several strangers, and our two friends departed on their return homeward for the evening.

"Roam where you will, o'er London's wide domains,

The mind new source of various feeling gains;

Explore the giddy town, its squares, its streets,

The 'wildered eye still fresh attraction greets;

Here spires and towers in countless numbers rise,

And lift their lofty summits to the skies;

Wilt thou ascend? then cast thine eyes below,

And view the motley groupes of joy and woe:

Lo! they whom Heaven with affluence hath blest,

Scowl with cold contumely on those distrest;

And Pleasure's maze the wealthy caitiffs thread,

While care-worn Merit asks in vain for bread;

Yet short their weal or woe, a general doom

On all awaits,—oblivion in the tomb!"

[223] Our heros next morning determined on a visit to their Hibernian friend and his aunt, whom they found had not yet forgot the entertainment at the Mansion-house, and which still continued to be the favorite topic of conversation. Sir Felix expressed his satisfaction that the worthy Citizens of London retained with increasing splendor their long established renown of pre-eminent distinction in the art of good living.

"And let us hope," said Dashall, "that they will not at any future period be reduced to the lamentable necessity of restraining the progress of epicurism, as in the year 1543, when the Lord Mayor and Common Council enacted a sumptuary law to prevent luxurious eating; by which it was ordered, that the Mayor should confine himself to seven, Aldermen and Sheriffs to six, and the Sword-bearer to four dishes at dinner or supper, under the penalty of forty shillings for each supernumerary dish!"

"A law," rejoined the Baronet, "which voluptuaries of the present times would find more difficult of observance than any enjoined by the decalogue."

The Squire suggested the expediency of a similar enactment, with a view to productive results; for were the [224] wealthy citizens (he observed) prohibited the indulgence of luxurious eating, under certain penalties, the produce would be highly beneficial to the civic treasury.

The Fine Arts claiming a priority of notice, the party determined on visiting a few of the private and public Exhibitions.

London is now much and deservedly distinguished for the cultivation of the fine arts. The commotions on the continent operated as a hurricane on the productions of

genius, and the finest works of ancient and modern times ave been removed from their old situations to the asylum afforded by the wooden walls of Britain. Many of them have, therefore, been consigned to this country, and are now in the collections of our nobility and gentry, chiefly in and about the metropolis.

Although France may possess the greatest number of the larger works of the old masters, yet England undoubtedly possesses the greatest portion of their first-rate productions, which is accounted for by the great painters exerting all their talents on such pictures as were not too large to be actually painted by their own hands, while in their larger works they resorted to inferior assistance. Pictures, therefore, of this kind, being extremely valuable, and at the same time portable, England, during the convulsions on the Continent, was the only place where such paintings could obtain a commensurate price. Such is the wealth of individuals in this country, that some of these pictures now described, belonging to private collections, were purchased at the great prices of ten and twelve thousand guineas each.

Amongst the many private collections of pictures, statues, &c. in the metropolis, that of the Marquis of Stafford, called the Cleveland Gallery, is the most prominent, being the finest collection of the old masters in England, and was principally selected from the works that formerly composed the celebrated Orleans Gallery, and others, which at the commencement of the French revolution were brought to this country. Thither, then, our tourists directed their progress, and through the mediation of Dashall access was obtained without difficulty.

The party derived much pleasure in the inspection of this collection, which contains two or three fine pictures of Raphael, several by Titian and the Caracas, some [225] capital productions of the Dutch and Flemish schools, and some admirable productions of the English school, particularly two by Wilson, one by Turner, and one by Vobson, amounting, in the whole, to 300 first-rate pictures by the first masters, admirably distributed in the new gallery, the drawing-room, the Poussin room (containing eight chef d'oeuvres of that painter), the passage-room, dining-room, old anti-room, old gallery, and small room. The noble proprietor has liberally appropriated one day in the week for the public to view these pictures. The curiosity of.the visitors being now amply gratified, they retired, Sir Felix much pleased with the polite attention of the domestic who conducted them through the different apartments, to whom Miss Macgilligan offered a gratuity, but the acceptance of which was, with courteous acknowledgments, declined.

Proceeding to the house of Mr. Angerstein, Pall Mall, our party obtained leave to inspect a collection, not numerous, but perhaps the most select of any in London, and which has certainly been formed at the greatest expense in proportion to its numbers. Among its principal ornaments are four of the finest landscapes by Claude; the Venus and Adonis, and the Ganymede, by Titian, from the Colonna palace at Rome; a very fine landscape by Poussin, and other works by Velasquez, Rubens, Murillo, and Vandyck: to all which is added the invaluable series of Hogarth's Marriage-a-la-mode.

Returning along Pall-Mall, our perambulators now reached the Gallery of the British Institution; a Public Exhibition, established in the year 1805, under the patronage of his late Majesty, for the encouragement and reward of the talents of British artists, exhibiting during half of the year a collection of the works of living artists for sale; and during the other half year, it is furnished with pictures painted by the most celebrated masters, for the study of the academic and other pupils in painting. The Institution, now patronised by his present Majesty, is supported by the subscriptions of the principal nobility and gentry, and the number of pictures sold under their influence is very considerable. The gallery was first opened on April 17, 1806.

In 1813, the public were gratified by a display of the best works of Sir Joshua Reynolds, collected by the industry and influence of the committee, from the private [226] collections of the royal family, nobility, and gentry; and in 1814, by a collection of 221 pictures of those inimitable painters, Hogarth, Gainsborough, and Wilson.{1}

1 That the Fine Arts engaged not a little of the attention

of the British Public during the late reign, is a fact too

notorious to require proof. The establishment of the Royal

Academy, in 1768, and its consequent yearly Exhibitions,

awakened the observation or stimulated the vanity of the

easy and the affluent, of the few who had taste, and of the

many who were eager to be thought the possessors of it, to a

subject already honoured by the solicitude of the sovereign.

A considerable proportion of the public was thus induced to

talk of painting and painters, and to sit for a portrait

soon became the fashion; a fashion, strange to say, which

has lasted ever since. Whether the talents of Sir Joshua

Reynolds as a painter, were alone the cause of his high

reputation, may, however, admit of a doubt. From an early

period of life, he had the good fortune to be associated in

friendship with several of the most eminent literary

characters of the age; amongst whom there were some whose

high rank and personal consequence in the country greatly

assisted him to realize one leading object which he had in

view, that of uniting in himself (perhaps for the first time

in the person of an English painter) the artist and the man

of fashion. From his acknowledged success in the attainment

of this object, tending as it did to the subversion of

ancient prejudices degrading to art, what beneficial effects

might not have resulted, had the President exerted his

influence to sustain the dignity of the artist in others!

But satisfied with the place in society which he himself had

gained, he left the rest of the Academy to follow his

example, if they could, seldom or never mixing with them in

company, and contenting himself with the delivery of an

annual lecture to the students. Genius is of spontaneous

growth, but education, independence, and never-ceasing

opportunity, are necessary to its full developement.

Since then they have regularly two annual exhibitions; one, of the best works of the old masters, for the improvement of the public taste, and knowledge of the artists, varied by some of the deceased British artists, alternately with that on their old plan of the exhibition and sale of the works of living artists.

The directors of this laudable Institution have also exhibited and procured the loan for study, of one or two of the inimitable cartoons of Raphael for their students. An annual private exhibition of their studies also takes place yearly; the last of which displayed such a degree of merit as no society or academy in Europe could equal.

Sir Felix, who on a former occasion had expressed a wish to acquire the art of verse-writing, was so much satisfied with his inspection of this exhibition, that he [227]became equally emulous of attaining the sister-art of painting; but Dashall requested him to suspend at present his choice, as perhaps he might alternately prefer the acquisition of music.

"In that case," rejoined the Baronet, "I must endeavour to acquire the knack of rhyming extempore, that I may accompany the discordant music with correspondent doggerels to the immortal memory of the heroic achievements of my revered Aunt's mighty progenitor—O'Brien king of Ulster."

This expression of contempt cast by the Baronet on the splendor of the ancient provincial sovereign of the north, had nearly created an open rupture between his aunt and him. Tallyho, however, happily succeeded in effecting an amnesty for the past, on promise under his guarantee of amendment for the future.

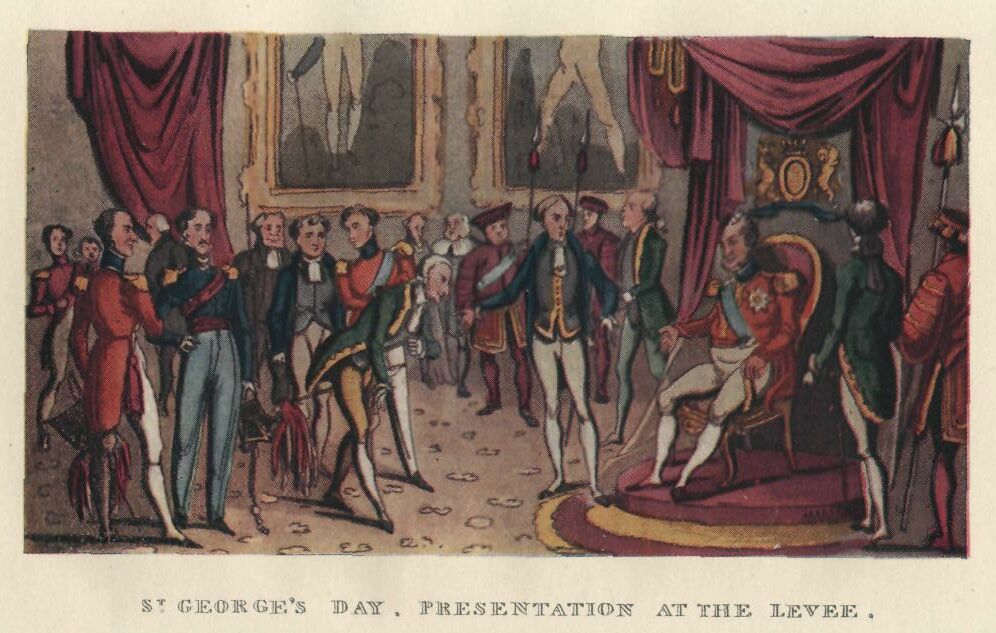

The party now migrated by Spring Garden Gate into the salubrious regions of St. James's Park, and crossing its eastern extremity, took post of observation opposite the Horse Guards, an elegant building of stone, that divides Parliament-street from St. James's Park, to which it is the principal entrance. The architect was Ware, and the building cost upwards of £30,000. It derives its name from the two regiments of Life Guards (usually called the Horse Guards) mounting guard there.

"Here is transacted," said Dashall, "all the business of the British army in a great variety of departments, consisting of the Commander-in-Chief's Office,—the Offices of the Secretary-at-War,—the Adjutant-General's Office,—the Quarter-Master-General's Office,—besides the Orderly Rooms for the three regiments of Foot Guards, whose arms are kept here. These three regiments, containing about 7000 men, including officers, and two regiments of Horse Guards, consisting together of 1200 men, at once serve as appendages to the King's royal state, and form a general military establishment for the metropolis. A body called the Yeomen of the Guard, consisting of 100 men, remains a curious relic of the dress of the King's guards in the fifteenth century. Some Light Horse are stationed at the Barracks in Hyde Park, to attend his Majesty, or other members of the Royal Family, chiefly in travelling; and to do duty on occasions immediately connected with the King's administration.

[228] "On the left is the Admiralty (anciently Wallingford House), containing the offices and apartments of the Lords Commissioners who superintend the marine department of this mighty empire.

"On the right is the Treasury and Secretary of State's Offices. Here, in fact, is performed the whole State business of the British Empire. In one building is directed the movements of those fleets, whose thunders rule every sea, and strike terror into every nation. In the centre is directed the energies of an army, hitherto invincible in the field, and which, number for number, would beat any other army in the world. Adjoining are the executive departments with relation to civil and domestic concerns, to foreign nations, and to our exterior colonies. And to finish the groupe, here is that wonderful Treasury, which receives and pays above a hundred millions per annum."

Entering Parliament-street from the Horse-Guards, our perambulators now proceeded to Westminster-bridge,{1} which passing, they paid a visit to Coade and Sealy's Gallery of Artificial Stone, Westminster-bridge-road.

1 Westminster Bridge. This bridge was built between the

years 1730 and 1750, and cost £389,000. It is 1223 feet

long, and 44 feet wide; containing 14 piers, and 13 large

and two small semicircular arches; and has on its top 28

semi-octangular towers, twelve of which are covered with

half domes. The two middle piers contain each 3000 solid

feet, or 200 tons of Portland stone. The middle arch is 76

feet wide, the two next 72 feet, and the last 25 feet. The

free-water way between the piers is 870 feet. This bridge is

esteemed one of the most beautiful in the world. Every part

is fully and properly supported, and there is no false

bearing or false joint throughout the whole structure; as a

remarkable proof of which, we may quote the extraordinary

echo of its corresponding towers, a person in one being able

to hear the whispers of a person opposite, though at the

distance of nearly 50 feet.

This place contains a great variety of elegant models from the antique and modern masters, of statues, busts, vases, pedestals, monuments, architectural and sculptural decorations, modelled and baked on a composition harder and more durable than any stone.

Animadverting on the utility of this work combining the taste of elegance with the advantage of permanent wear, the two friends, Tom and Bob, recollected having seen, in their rambles through the metropolis, many specimens of the perfection of this ingenious art, particularly at Carlton-House, the Pelican Office, Lombard-street, and almost all the public halls. The statues of the four [229]quarters of the world, and others at the Bank, at the Admiralty, Trinity House, Tower-hill, Somerset-place, the Theatres; and almost every street presents objects, (some of 20 years standing,) as perfect as when put up.

Retracing their steps homewards, our pedestrians again crossed the Park, and finding themselves once more in Spring Gardens, entered the Exhibition Rooms of the Society of Painters in Water Colours.

This, beyond any other gratification of the morning, pleased the party the most. The vivid tints of the various well-executed landscapes had a pleasing effect, and wore more the appearance of nature than any similar display of the fascinating art which they had hitherto witnessed.

This Society, which was formed in 1804, for the purpose of giving due emphasis to an interesting branch of art that was lost in the blaze of Somerset-House, where water-colours, however beautiful, harmonized so badly with paintings in oil, has, in its late exhibitions, deviated from its original and legitimate object, and has mixed with its own exquisite productions various pictures in oil.

The last annual exhibition of painting in oil and water colours, was as brilliant and interesting as any former one, and afforded unmixed pleasure to every visitor.

One more attraction remained in Spring Gardens, which Tom, who had all the morning very ably performed the double duty of conductor and explainer, proposed the company's visiting;—"That is," said he, "Wigley's Promenade Rooms, where are constantly on exhibition various objects of curiosity."

Thither then they repaired, and were much pleased with two very extraordinary productions of ingenuity, the first Mr. Theodon's grand Mechanical and Picturesque Theatre, illustrative of the effect of art in imitation of nature, in views of the Island of St. Helena, the City of Paris, the passage of Mount St. Barnard, Chinese artificial fireworks, and a storm at sea. The whole was conducted on the principle of perspective animation, in a manner highly picturesque, natural, and interesting.

Here also our party examined the original model of a newly invented travelling automaton, a machine which can, with ease and accuracy, travel at the rate of six miles an hour, ascend acclivities, and turn the narrowest corners, by machinery only, conducted by one of the persons seated within, without the assistance of either horse or steam.

[230] This extraordinary piece of mechanism attracted the particular attention of the Baronet, who minutely explored its principles, with the view, as he said, of its introduction to general use, in the province of Munster, in substitution of ricketty jaunting-cars and stumbling geldings. Miss Judith Macgilligan likewise condescended to honour this novel carriage with her approbation, as an economical improvement, embracing, with its obvious utility, a vast saving in the keep of horses, and superseding the use of jaunting-cars, the universal succedaneum, in Ireland, for more respectable vehicles; but which, she added, no lady of illustrious ancestry should resort to.

This endless recurrence to noble descent elicited from Sir Felix another "palpable hit;" who observed, that those fastidious dames of antiquity, to whatever country belonging, of apparent asperity to the present times, would do well in laying aside unfounded prejudices; that the age to which Miss Macgilligan so frequently alluded, was one of the most ignorant barbarism; and the unpolished females of that day unequal to a comparison with those of the present, as much so, as the savage squaws of America with the finished beauties of an Irish Vicegerent's drawing-room.{1}

1 The pride of ancestry, although prevalent in Ireland, is

not carried to the preposterous excess exemplified by

Cambrian vanity and egotism. A gentleman lately visited a

friend in Wales, who, among other objects of curiosity,

gratified his guest with the inspection of his family

genealogical tree, which, setting at naught the minor

consideration of antediluvian research, bore in its centre

this notable inscription,—About this time the world was

created!!!

Re-entering St. James's Park, our party directed their course towards the Mall, eastward of which they were agreeably amused by the appearance of groupes of children, who, under the care of attendant nursery maids, were regaling themselves with milk from the cow, thus presenting to these delighted juveniles a rural feast in the heart of the metropolis.

[231] Here Dashall drew the attention of his friends to a very important improvement. "Until within these few months," said he, "the Park at night-fall presented a very sombre aspect; being so imperfectly lighted as to encourage the resort of the most depraved characters of both sexes; and although, in several instances, a general caption, by direction of the police, was made of these nocturnal visitants, yet the evil still remained; when a brilliant remedy at last was found, by entirely irradiating the darkness hitherto so favourable to the career of licentiousness: these lamps, each at a short distance from the other, have been lately introduced; stretching along the Mall, and circumscribing the Park, they shed a noon-tide splendor on the solitude of midnight. They are lighted with gas, and continue burning from sunset to day-break, combining ornament with utility. Thus vice has been banished from her wonted haunts, and the Park has become a respectable evening promenade.

"This Park," continued the communicative Dashall, "which is nearly two miles in circuit, was enclosed by King Charles II., who planted the avenues, made the Canal and the Aviary adjacent to the Bird-cage Walk, which took its name from the cages hung in the trees; but the present fine effect of the piece of ground within the railing, is the fruit of the genius of the celebrated Mr. Brown."{1}

1 St. James's Park was the frequent promenade of King

Charles II. Here he was to be seen almost daily; unattended,

except by one or two of his courtiers, and his favorite

grey-hounds; inter-mixing with his subjects, in perfect

confidence of their loyalty and attachment. His brother

James one day remonstrating with him on the impolicy of thus

exposing his person,—"James," rejoined his majesty, "take

care of yourself, and be under no apprehension for me: my

people will never kill me, to make you king!"

In more recent times, Mr. Charles Townsend used every

morning, as he came to the Treasury, to pass by the Canal in

the Park, and feed the ducks with bread or corn, which he

brought in his pocket for that purpose. One morning having

called his affectionate friends, the duckey, duckey,

duckies, he found unfortunately that he had forgotten them;—

"Poor duckies!" he cried, "I am sorry I am in a hurry and

cannot get you some bread, but here is sixpence for you to

buy some," and threw the ducks a sixpence, which one of them

gobbled up. At the office he very wisely told the story to

some gentlemen with whom he was to dine. There being ducks

for dinner, one of the gentlemen ordered a sixpence to be

put into the body of a duck, which he gave Charles to cut

up. Our hero, sur-prised at finding a sixpence among the

seasoning, bade the waiter send up his master, whom he

loaded with epithets of rascal and scoundrel, and swore

bitterly that he would have him prosecuted for robbing the

king of his ducks; "for," said he, "gentlemen, this very

morning did I give this sixpence to one of the ducks in the

Canal in St. James's Park."

[232] The party now seated themselves on one of the benches in the Mall, opposite the spot where lately stood the Chinese or Pagoda bridge. Tallyho had often animadverted on the absurdity of the late inconvenient and heterogeneous wooden structure, which had been erected at a considerable public expense; its dangling non-descript ornaments, and tiresome acclivity and descent of forty steps each. "What," said he, "notwithstanding the protection by centinels of this precious memento of vitiated taste, has it become the prey of dilapidation?"

"Rather," answered Dashall, "of premature decay. Its crazy condition induced the sage authors of its origin to hasten its destruction; like the Cherokee chief, who, when the object of his regard becomes no longer useful, buries him alive!"

Contrasting the magnificent appearance of the adjacent edifices, as seen from the Park, with one of apparently very humble pretensions, Miss Macgilligan inquired to what purpose the "shabby fabric" was applied, and by whom occupied.

"That 'shabby fabric,' Madam," responded Dashall, "is St. James's Palace, erected by Henry VIII., in which our sovereigns of England have held their Courts from the reign of Queen Anne to that of his late Majesty George III." {1}

1 The state apartments, now renovated, comprehend six

chambers. The first is the guard chamber, at the top of the

stairs: this has been entirely repaired, and on the right

hand there is a characteristic chimney-piece, instead of the

ill-shaped clumsy fire-place which previously disgraced this

approach to the grand rooms. The next room, continuing to

advance, is the presence chamber. This chamber has been

remodelled, and a large handsome octagonal window

introduced. This produces the best effect, and has rendered

a gloomy room very light and cheerful. The privy chamber,

which forms the eastern end of the great suite that runs

from east to west, parallel to the Mall in the Park, and is,

strictly speaking, the immediate scene of the Court; this is

entirely new from the foundation, and is a continuation of

the old suite of state apartments. The chamber is of noble

dimensions, being nearly 70 feet in length, and having four

windows towards the garden and Park beyond. A magnificent

marble chimney-piece occupies the centre, on the east end.

The anti-drawing-room and the drawing-room, in which little

alteration appears, except in the introduction of splendid

chimney-pieces of statuary marble, taken from the library of

Queen Caroline in the Stable Yard, built by Kent. The

workmanship of these is amazingly fine, and the designs very

rich. The throne is at the upper end of the drawing room No.

5, and from the chimney of the room No. 3, the vista through

the middle doors of the anti-drawing-rooms is about 200

feet!! Thecoup d'oeil must be indescribably grand, when

all the three apartments are filled with rank and beauty.

The ceilings of the principal rooms, 3, 4, and 5, are coved

upon handsome cornices, carved and gilt. This gives the

apartments a spacious and lofty appearance; and there being

four large windows in each, the whole suite is very

imposing. The rooms are to be fitted with mirrors, and a

noble collection of the royal pictures. Over the chimney in

the drawing-room, Lawrence's splendid portrait of George

IV., surrounded by the fine old carvings of Grinling

Gibbons, of which many are preserved in the Palace, will be

the principal object. In the anti-drawing-room a portrait of

the venerable George III. will occupy a similar station; and

on each side will appear the victories which reflected the

highest lustre on his reign,—Trafalgar and Waterloo. In the

privy chamber, a portrait of Queen Anne will be attended by

the great Marlborough triumphs of Lisle and Tournay,

Blenheim, and other historical pieces. Other spaces will

exhibit a series of royal portraits, from the period of the

founder of the Palace, Henry VIII. to the present era;

including, of course, some of the most celebrated works of

Holbein and Vandyke. The unrivalled "Charles on

horseback," by the latter, is among the number, and the

gallery, altogether, must be inestimable, even as a panorama

of the arts in England for three centuries. On the whole,

these state apartments, when completed, will not be

excelled, if equalled, by any others in Europe. Holbein,

whom we have just mentioned, was a favourite of Henry VIII.

One day, when the painter was privately drawing a lady's

picture for the king, a nobleman forced himself into the

chamber. Holbein threw him down stairs; the peer cried out;

Holbein bolted himself in, escaped over the roof of the

house, and running directly to the king, fell on his knees,

and besought his majesty to pardon him, without declaring

the offence. The king promised to forgive him, if he would

tell the truth. Immediately arrives the lord with his

complaint. After hearing the whole, his majesty said to the

nobleman,—" You have behaved in a manner unworthy of your

rank. I tell you, of seven peasants I can make so many

lords, but not one Holbein. Be gone, and remember this, if

you ever presume to avenge yourself, I shall look on an

injury you do to the painter as done to me."

[233] The descendant of O'Brien was astonished, and connecting her ideas of the internal show of this Palace with its outward appearance, doubted not, secretly, that it was far inferior to the residence, in former times, of her royal progenitor.

Probably guessing her thoughts, Dashall proceeded to observe, that the Palace was venerable from age, and in its interior decoration that it fully corresponded in splendor with the regal purposes to which it had been so long applied; "It is now, however," he added, "about to assume a still more imposing aspect, being under alterations and adornments, for the reception of the Court of his present Majesty, which, when completed, will render it worthy the presence of the Sovereign of this great Empire."

[234] The sole use made lately of St. James's Palace, is for purposes of state. In 1808, the south-eastern wing of the building was destroyed by fire; the state apartments were, however, uninjured, and the Court of George the Third and his Queen was held here.

On the right of the Palace, the attention of the party was next attracted by Marlborough House. It was built in the reign of Queen Anne, by the public, at the expense of 40,000L. on part of the royal gardens, and given by the Queen and Parliament, on a long lease, to the great Duke of Marlborough. It is a handsome building, much improved of late years, and has a garden extending to the Park, and forms a striking contrast to the adjoining Palace of St. James's. It is now the town residence of his Royal Highness, Prince Leopold of Saxe Cobourg.

Our party now passed into St. James's-street, where Miss Macgilligan, whose acerbitude of temper had been much softened by the politeness of her friends during the morning's ramble, mentioned, that she had a visit to make on an occasion of etiquette, and requesting the honour of the gentlemen's company to dinner, she was handed by the Squire of Belville-hall, with all due gallantry and obeisance, into a hackney-chariot; Tom in the meanwhile noting its number, in the anticipation of its ultimately proving a requisite precaution.

The trio, now left to their own pursuits, lounged leisurely up St. James's-street, and pausing at the caricature shop, an incident occurred which placed in a very favorable point of view the Baronet's promptitude of reply and equanimity of temper. Having had recourse to his glasses, lie stood on the pavement, examining the prints, unobservant of any other object; when a porter with a load brushed hastily forward, and coming in contact with the Baronet, put him, involuntarily, by the violence of the shock, to the left about face, without the word either of caution or command. "Damn your spectacles!" at same time, exclaimed the fellow; "Thank you, my good friend," rejoined Sir Felix,—"it is not the first time that my spectacles have saved my eyes!"

[235] Remarking on this rencounter, Dashall observed, that the insolence of these fellows was become really a public nuisance. Armed in the panoply of arrogance, they assume the right of the footway, to the ejection, danger, and frequent injury of other passengers; moving in a direct line with loads that sometimes stretch on either side the width of the pavement, they dash onward, careless whom they may run against, or what mischief may ensue. "I would not," continued Dashall, "class them with beasts of burthen, and confine them to the carriage-way of the street, like other brutes of that description; but I would have them placed under the control of some salutary regulations, and humanized under the dread of punishment."

The Squire coincided with his friend in opinion, and added, by way of illustration, that it was only a few days since he witnessed a serious accident occasioned by the scandalous conduct of a porter: the fellow bore on his shoulders a chest of drawers, a corner of which, while he forced his way along the pavement, struck a young lady a stunning blow on the head, bringing her violently to the ground, and falling against a shop window, one of her hands went through a pane of glass, by which she was severely cut; thus sustaining a double injury, either of which might have been attended with fatal consequences.

The three friends had now gained the fashionable lounge of Bond-street, whence turning into Conduit-street, they entered Limmer's Coffee-house, for the purpose of closing, by refreshment, the morning's excursion.

Here Dashall recognized an old acquaintance in the person of an eminent physician, who, after an interchange of civilities, resumed his attention to the daily journals.

In the same box with this gentleman, and directly opposite, sat another, whose health was apparently on the decline, who finding that the ingenious physician had occasionally dropped into this coffee-house, had placed himself vis-a-vis the doctor, and made many indirect efforts to withdraw his attention from the newspaper to examine the index of his (the invalid's) constitution. He at last ventured a bold push at once, in the following terms: "Doctor," said he, "I have for a long time been very far from being well, and as I belong to an office, where I am obliged to attend everyday, the complaints I have prove very troublesome to me, [236] and I would be glad to remove them."—The doctor laid down his paper, and regarded his patient with a steady eye, while he proceeded. "I have but little appetite, and digest what I eat very poorly; I have a strange swimming in my head," &c. In short, after giving the doctor a full quarter of an hour's detail of all his symptoms, he concluded the state of his case with a direct question:—"Pray, doctor, what shall I take?" The doctor, in the act of resuming the newspaper, gave him the following laconic prescription:—"Take, why, take advice!"

This colloquy, and its ludicrous result, having been perfectly audible to the company present, afforded considerable entertainment, of which the manoeuvring invalid seemed in no degree willing to partake, for he presently made his exit, without even thanking the doctor for his gratuitous advice.{1}

1 Limmeb's Hotel.—This justly esteemed Hotel was much

frequented by the late unfortunate Lord Camelford. Entering

the coffee-room one evening, meanly attired, as he often

was, he sat down to peruse the papers of the day. Soon after

came in a "dashing fellow," a "first-rate blood," who threw

himself into the opposite seat of the same box with Lord C,

and in a most consequential tone hallowed out, "Waiter!

bring in a pint of Madeira, and a couple of wax candles, and

put them in the next box." He then drew to him Lord C.'s

candle, and set himself to read. His Lordship glanced at him

a look of indignation, but exerting his optics a little

more, continued to decypher his paper. The waiter soon re-

appeared, and with a multitude of obsequious bows, announced

his having completed the commands of the gentleman, who

immediately lounged round into his box. Lord Camelford

having finished his paragraph, called out in a mimic tone to

that of Mr.——-, "Waiter! bring me a pair of snuffers."

These were quickly brought, when his Lordship laid down his

paper, walked round to the box in which Mr.——-was, snuffed

out both the candles, and leisurely returned to his seat.

Boiling with rage and fury, the indignant beau roared out,