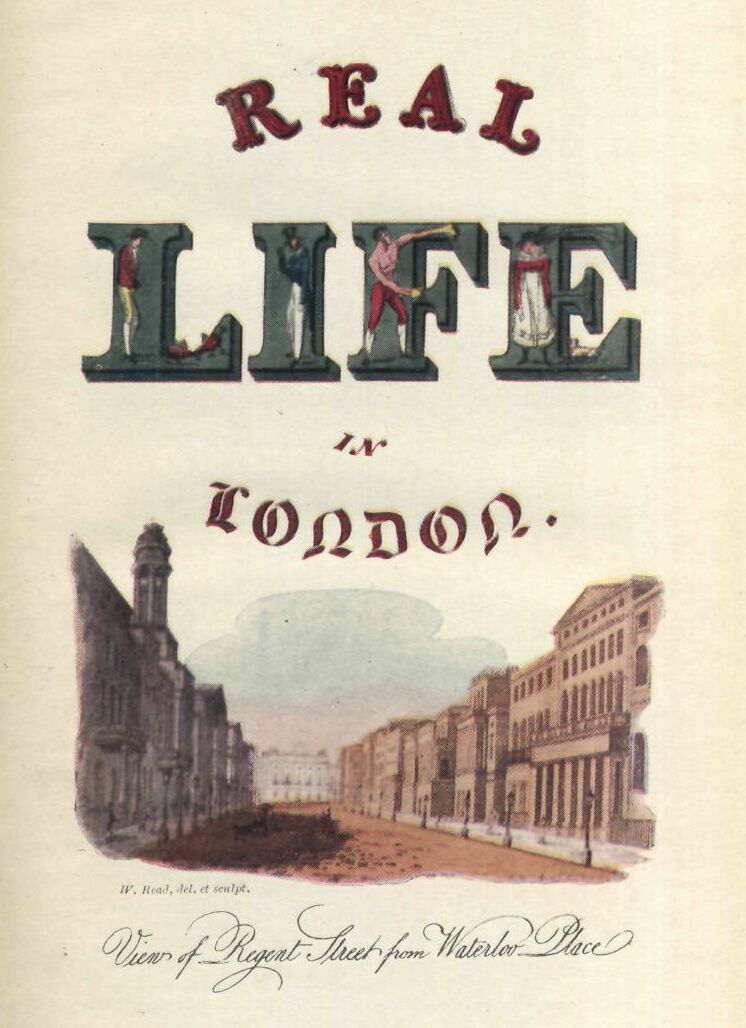

| Main Index |

| Volume I. Part 2 |

| Volume II. Part 1 |

| Volume II. Part 2 |

|

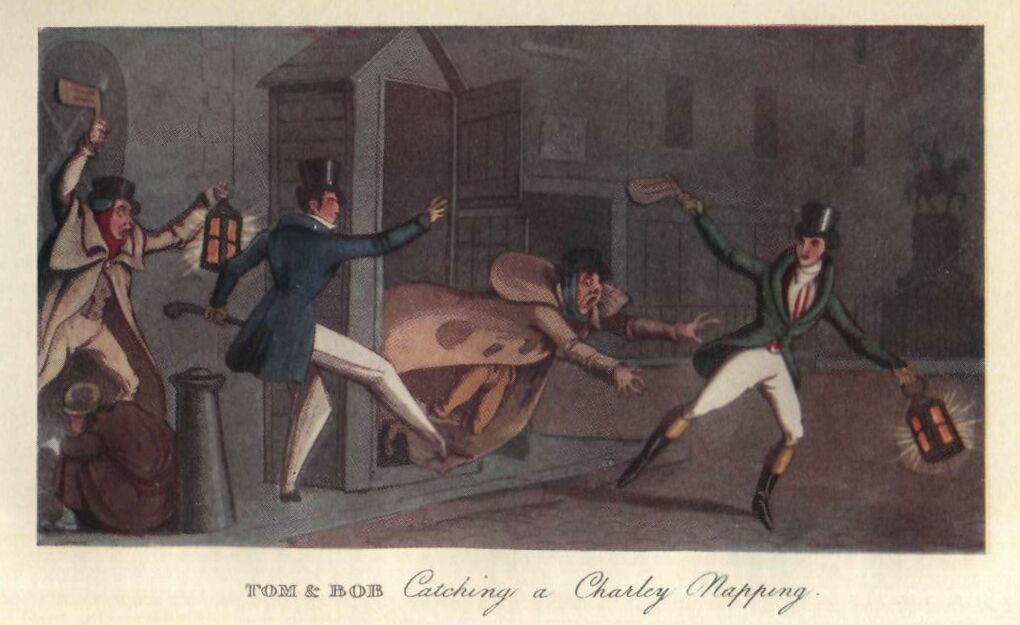

Page92 Catching a Charley Napping |

CONTENTS:

Chapter I.

Seduction from rural simplicity, page 2. Pleasures of the

table, 3. Overpowering oratory, 4. A warm dispute, 5.

Amicable arrangement, 6.

Chapter II.

Philosophical reflections, 7. A great master, 8. Modern

jehuism, 9. A coach race, 10. A wood-nymph, 11. Improvements

of the age, 12. An amateur of fashion, 13. Theatrical

criticism, 14. Reflections, 15.

Chapter III.

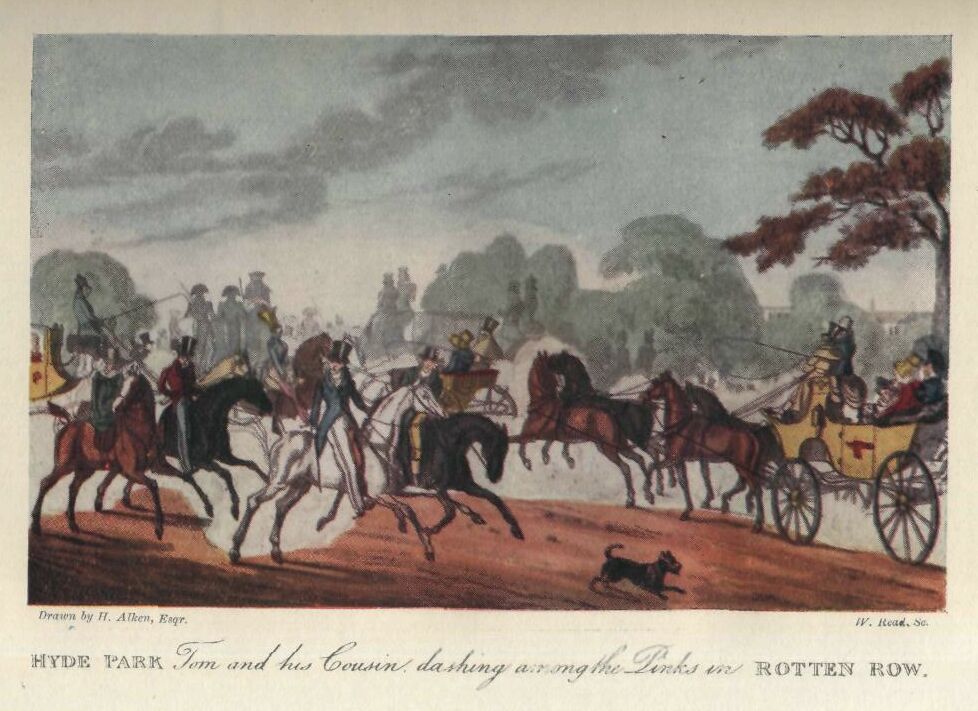

Hyde Park, and its various characters, 16. Sir F——s B——

tt, 22, Delightful reverie, 23.

Chapter IV.

Fresh game sprung, 24. Lord C——e, alias Coal-hole George,

25. Rot at Carlton Palace, 28. Once-a-week man, 29. Sunday

promenader, 30. How to raise the wind, 31. Lord Cripplegate

and his Cupid, 32. Live fish, 33. Delicacy, 34. A breathless

visitor, 35.

Chapter V.

A fashionable introduction, 36. A sparkling subject, 37. The

true spur to genius, 38. An agreeable surprise, 39. A

serious subject, 40. A pleasant fellow, 41. Lively gossip,

42. Living in style, 43. Modern good breeding, 45. Going to

see "you know who," 46.

Chapter VI.

Early morning amusements, 47. Frightening to death, 48.

Improvements of the age, 49. Preparing for a swell, 50. The

acmé of barberism, 51. A fine specimen of the art, 52. Duels

by Cupid and Apollo, 53. Fashionable news continued, 54. Low

niggardly notions, 55. Scenes from Barber-Ross-a, 56. A snip

of the superfine, 59. The enraged Managers, 60. Cutting out,

and cutting up, 61. The whipstitch mercury, 62. All in the

wrong again, 63. A Venus de Medicis, 64. Delicacy alarmed,

65.

Chapter VII.

Preparing for a ramble, 66. A man of the town, 67. Bond

Street, 68. A hanger on, 70. A man of science, 71. Dandyism,

72. Dandy heroism, 74. Inebriety reproved, 75. My uncle's

card, 76. St. James's Palace, 77. Pall Mall-Waterloo Place,

etc., 79. An Irish Paddy, 80. Incorrigible prigs, 81. A hue

and cry, 82. A capture, 83. A wake, with an Irish howl, 84.

Vocabulary of the new school, 85. Additional company, 87.

Chapter VIII.

Public Office, Bow Street, 88. Irish generosity, 89. A bit

of gig, 90. "I loves fun," 91. A row with the Charleys, 92.

Judicial sagacity, 93. Watch-house scenes, 94. A rummish

piece of business, 95. The Brown Bear well baited, 96.

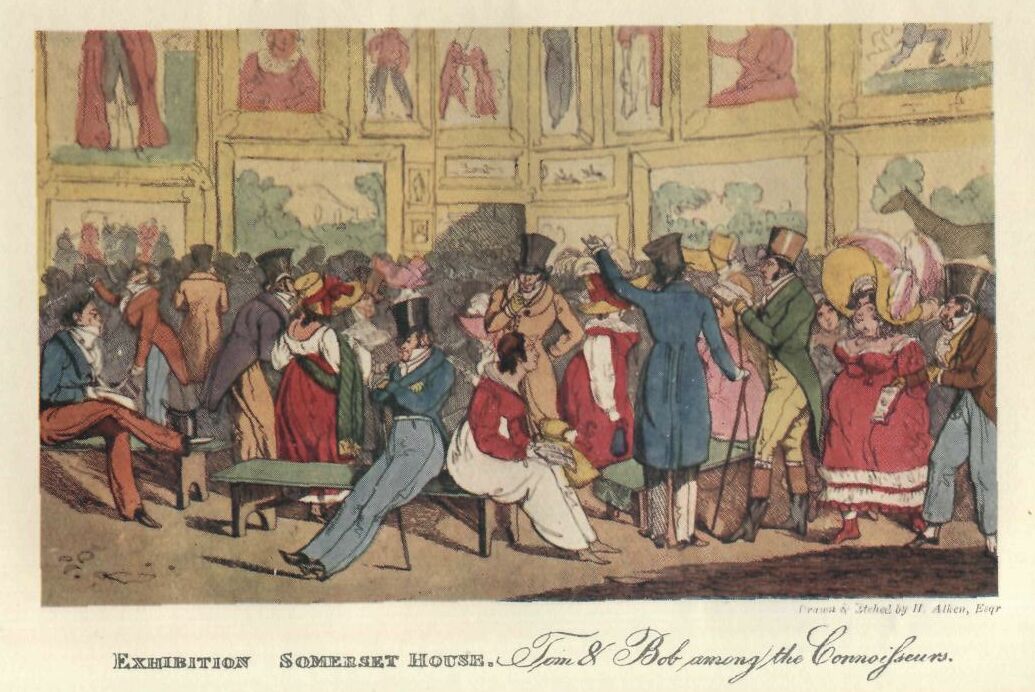

Somerset House, 97. An importunate customer, 99.

Peregrinations proposed, 100.

Chapter IX.

The Bonassus, 101. A Knight of the New Order, 102. Medical

quacks, 103. Medical (not Tailors') Boards, 105. Superlative

modesty, 106. Hard pulling and blowing, 107. Knightly

medicals, 108. Buffers and Duffers, 109. Extremes of

fortune, 110. Signs of the Times, 111. Expensive spree, 112.

The young Cit, 113. All in confusion, 115. Losses and

crosses, 116. Rum customers, 117. A genteel hop, 118. Max

and music, 119. Amateurs and actors, 120. A well-known

character, 121. Championship, 122. A grand spectacle, 123.

Adulterations, 124. More important discoveries, 125. Wonders

of cast-iron and steam, 126. Shops of the new school, 127.

Irish paper-hanging, 128.

Chapter X.

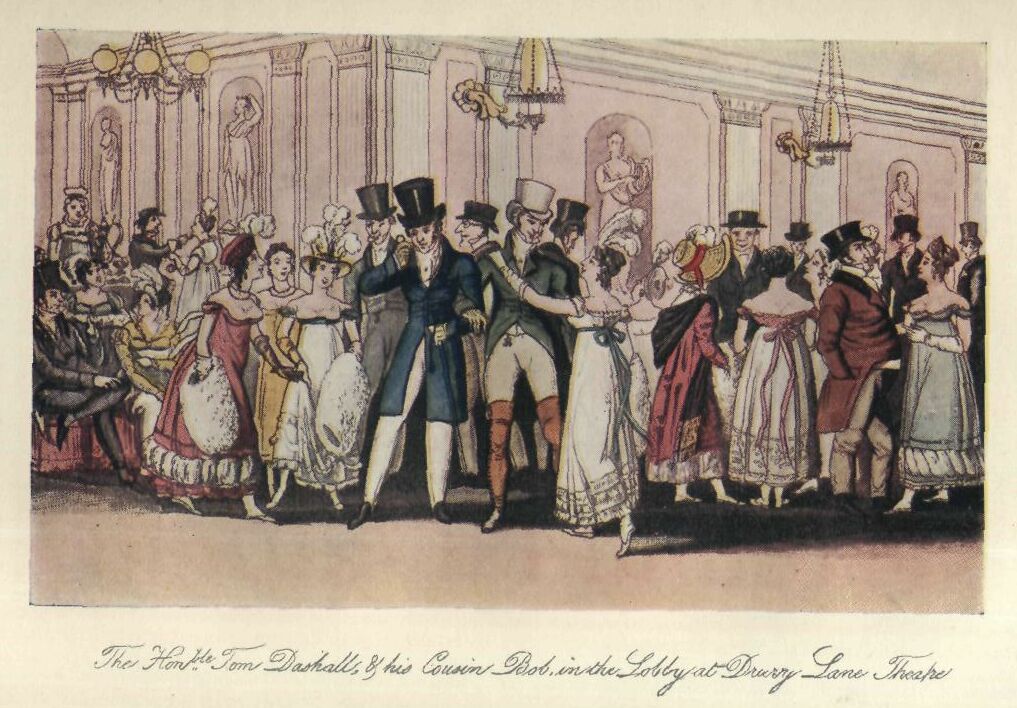

Heterogeneous mass, 129. Attractions of the theatre, 130.

Tragedy talk, 131. Authors and actors, 132. Chancery

injunctions, 133. Olympic music, 134. Dandy larks and

sprees, 135. The Theatre, 136. Its splendid establishment,

137. Nymphs of the saloon, 138. Torments of love and gout,

139. Prostitution, 140. A shameful business, 141. Be gone,

dull care, 142. Convenient refreshment, 143. A lushy cove,

144. The sleeper awake, 145. All on lire, 146. A short

parley, 147.

Chapter XI.

Fire, confusion and alarm, 148. Snuffy tabbies and boosy

kids, 149. A cooler for hot disputes, 150. An overturned

Charley, 151. Resurrection rigs, 152. Studies from life,

154. An agreeable situation, 155. A nocturnal visit to a

lady, 156. Sharp's the word, 157. Frolicsome fellows, 158.

Retirement, 159.

Chapter XII.

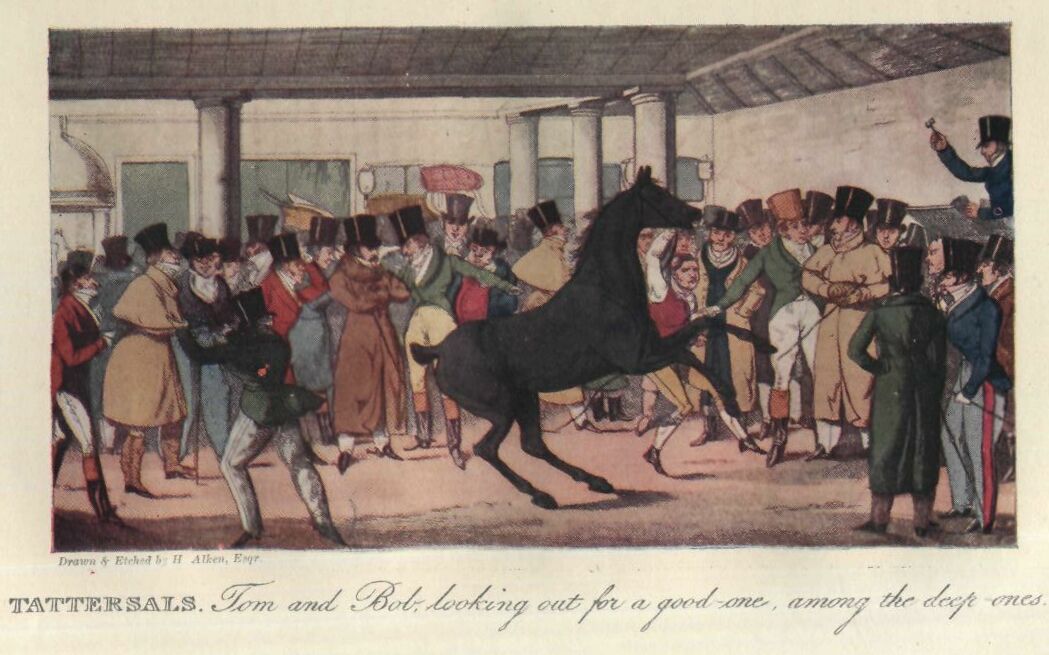

Tattersall's, 160. Friendly dealings, 161. Laudable company,

162. The Sportsman's exchange, 163. An unlimited order, 164.

How to ease heavy pockets, 165. Body-snatchers and Bum-

traps, 166. The Sharps and the Flats, 167. A secret

expedition, 168. A pleasant rencontre, 169. Accommodating

friends, 170. The female banker, 171. A buck of the first

cut, 172. A highly finished youth, 173. An addition to the

party, 174.

Chapter XIII.

A promenade, 175. Something the matter, 176. Quizzical hits,

177. London friendship, 178. Fashion versus Reason, 179.

Dinners of the Ton, 180. Brilliant mob of a ball-room, 181.

What can the matter be? 182. Something-A-Miss, 183.

Chapter XIV.

The centre of attraction, 185. The circulating library, 186.

Library wit, 187. Fitting on the cap, 188. Breaking up, 189.

Gaming, 190. Hells-Greeks-Black-legs, 191. How to become a

Greek, 192. Valuable instructions, 193. Gambling-house à la

Française, 194. Visitors' cards, 195. Opening scene, 196.

List of Nocturnal Hells, 197. Rouge et Noir Tables, 198.

Noon-day Hells, 199. Hell broke up, and the devil to pay,

200. A story, 202. Swindling Jews, 205. Ups and downs, 206.

High fellows, 207. Mingled company, 208. Severe studies,

209.

Chapter XV.

Newspaper recreations, 210. Value of Newspapers, 211. Power

of imagination, 212. Rich bill of fare, 213. Proposed Review

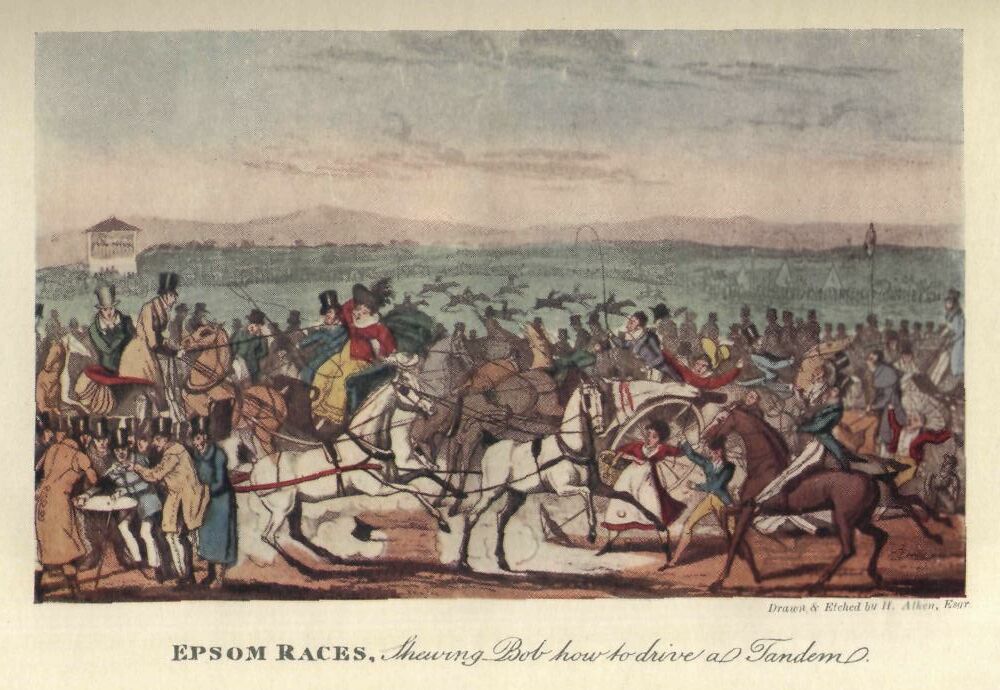

of the Arts, 214. Demireps and Cyprians, 215. Dashing

characters, 216. Female accommodations, 217. Rump and dozen,

218. Maggot race for a hundred, 219. Prime gig, larks and

sprees, 220. Female jockeyship, 221. Delicate amusements for

the fair sex, 222. Female life in London, 224. Ciphers in

society, 225. Ciphers of all sorts, 226. Hydraulics, 227.

Watery humours, 228. General street engagement, 229. Harmony

restored, 230.

Chapter XVI.

The double disappointment, 231. Heading made easy, 232.

Exhibition of Engravings, 233. How to cut a dash, 235.

Dashing attitude, costume, etc., 236. A Dasher-Street-

walking, etc., 237. Dancing—"all the go," 238. Exhibition,

Somerset House, 239. Royal Academy, Somerset House, 240. The

Sister Arts, 241. Character-Caricature, etc., 242. Moral

tendency of the Arts, 243. Fresh game sprung, 244. Law and

Lawyers, 245. Law qualifications, 247. Benchers, 248. Temple

Libraries-Church, 249. St. Dunstan's Bell-thumpers, 250.

Political Cobbler, 251. Coffee-houses, 252. Metropolitan

accommodations, 253. Chop-house delights and recreations,

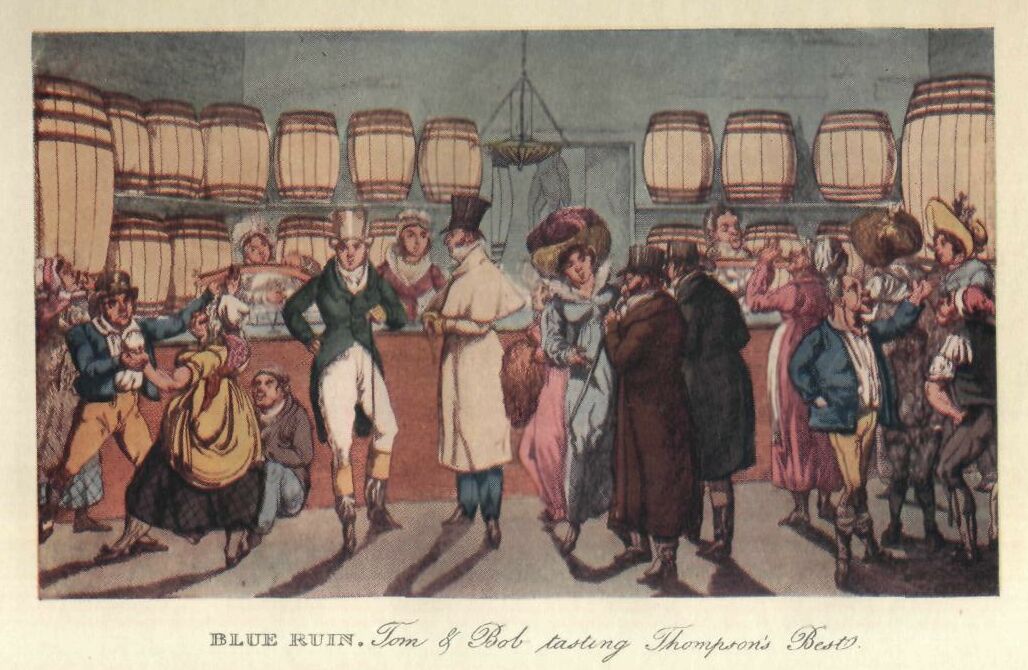

254. Daffy's Elixir, Blue Ruin, etc., 256. The Queen's gin-

shop, 257.

Chapter XVII.

Globe Coffee-house, 258. A humorous sort of fellow, 259. A

Punster, 260. Signals and Signs, 261. Disconcerted

Professors, 262. A learned Butcher, 263. A successful

stratagem, 264. A misconception, 265. A picture of London,

266. All in high glee, 268.

Chapter XVIII.

A Slap at Slop, 269. A Nondescript, 270. Romanis, 271. Bow

steeple-Sir Chris. Wren, 272. The Temple of Apollo, 273.

Caricatures, 274. Rich stores of literature, 275. Pulpit

oratory, 276. Seven reasons, 277. Street impostors and

impositions, 278. Impudent beggars, 280. Wise men of the

East, 281. A Royal Visitor and Courtier reproved, 282.

Confusion of tongues, 284. Smoking and drinking, 285.

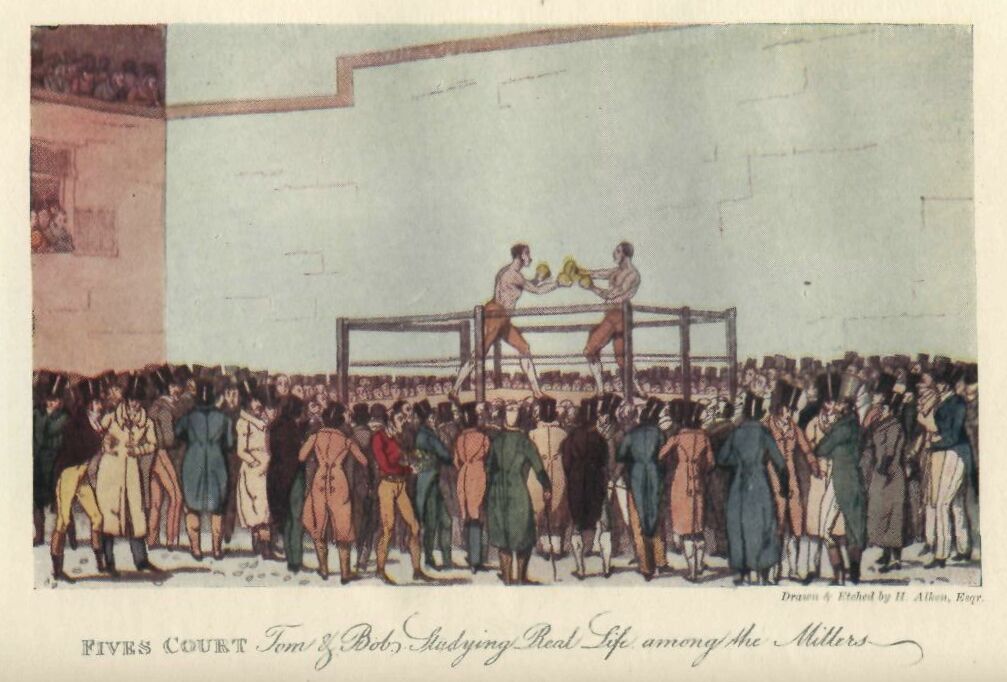

Knights of the Round Table, 286. The joys of milling, 287.

Noses and nosegays, 288. A Bumpkin in town, 289. Piggish

propensities, 2907 Joys of the bowl, 291.

Chapter XIX.

Jolly boys, 292. Dark-house Lane, 293. A breeze sprung up,

294. Business done in a crack, 295. Billingsgate, 296.

Refinements in language, 297. Real Life at Billingsgate,

298. The Female Fancy, 299. The Custom House, Long Room,

etc., 300. Greeting mine host, 302. A valuable customer,

303. A public character, 304.

Chapter xx.

The Tower of London, 305. Confusion of titles, 306. Interior

of the Trinity House, 307. Rag Fair commerce, 308. Itinerant

Jews and Depredators, 309. Lamentable state of the Jews,

310. Duke's Place and Synagogue, 311. Portuguese Jews, 312.

Bank of England, 313. An eccentric character, 314.

Lamentable effects of forgery, 315. Singular alteration of

mind, 316. Imaginary wealth, 317. Joint Stock Companies,

318. Auction Mart-Courtois, 319. Irresistible arguments,

320. Wealth without pride, 321. Royal Exchange, 322. A

prophecy fulfilled, 323. Lloyd's-Gresham Lecture, etc., 324.

The essential requisite, 325. Egress by storm, 326.

Chapter XXI.

Incident "ad infinitum," 327. A distressed Poet, 328.

Interesting calculations, 329. Ingenuity in puffing, 330.

Blacking maker's Lauréat, 331. Miseries of literary

pursuits, 332. Suttling house, Horse Guards, 333. Merits of

two heroes, 334. Hibernian eloquence, 335. A pertinacious

Disputant, 336. Peace restored-Horse Guards, 337. Old

habits-The Miller's horse, 338. Covent Garden-Modern Drury,

339 A more than Herculean labour, 340. Police Office scene,

341. Bartholomew Fair, 342. A Knight of the Needle, 343.

Variance of opinion, 344. A visit to the Poet, 345. Produce

of literary pursuits, 346. Quantum versus Quality, 347.

Publishing by subscription, 348. Wealth and ignorance, 349.

Mutual gratification, 350.

Chapter XXII.

Symptoms of alarm, 351. Parties missing, 352. A strange

world, 353. Wanted, and must come, 354. Expectation alive,

355. A cure for melancholy, 356. Real Life a game, 357. The

game over, 358. Money-dropping arts, 359. Dividing a prize,

360. The Holy Alliance broke up, 361. New method of Hat

catching, 362. Dispatching a customer, 363. Laconic

colloquy, 364. Barkers, 365. A mistake corrected, 366.

Pawnbrokers, 367. The biter bit, 368. Miseries of

prostitution, 369. Wardrobe accommodations, 370. New species

of depredation, 371.

Chapter XXIII.

The Lock-up House, 372. Real Life with John Doe, etc., 373.

Every thing done by proxy, 374. Lottery of marriage, 375.

Sharp-shooting and skirmishing, 376. A fancy sketch, 377.

The universal talisman, 378. Living within bounds, 379. How

to live for ten years, 380. An accommodating host, 381. Life

in a lock-up house, 382.

Chapter XXIV.

A successful election, 383. Patriotic intentions, 384.

Political dinner, 385. Another bear-garden, 386. Charley's

theatre, 387. Bear-baiting sports, 388. The coronation, 389.

Coronation splendour, 390.

Chapter XXV.

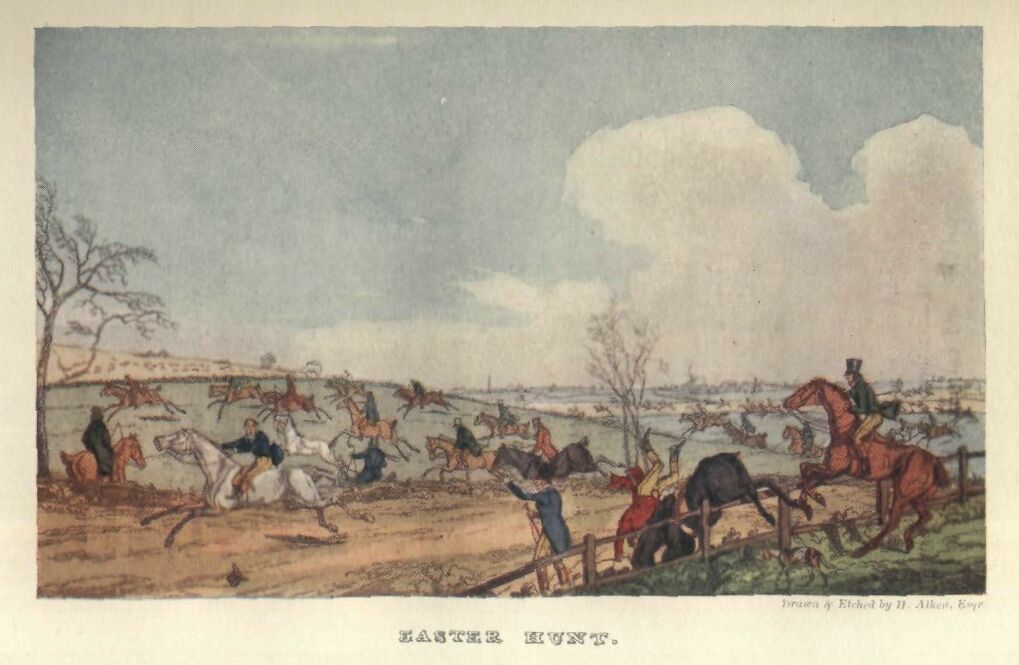

Fancy sports, 392. Road to a fight, 393. New sentimental

journey, 394. Travelling chaff, 395. Humours of the road,

396. Lads of the fancy, 397. Centre of attraction, 398. A

force march, 399. Getting to work, 400. True game, 401. The

sublime and beautiful, 402. All's well-good night, 403.

Chapter XXVI.

Promenading reflections, 404. Anticipation, 405. Preliminary

observations, 406. Characters in masquerade, 407. Irish

sympathy, 408. Whimsicalities of character, 409. Masquerade

characters, 410. The watchman, 411. New characters, 412. The

sport alive, 413. Multifarious amusements, 414. Doctors

disagree, 415. Israelitish honesty, 416.

Chapter XXVII.

Ideal enjoyments, 417. A glance at new objects, 418. Street-

walking nuisances, 419. Cries of London-Mud-larks, etc.,

420. The Monument, 421. London Stone, 422. General Post-

Office, 423. Preparations for returning, 424. So endeth the

volume, 425.

Triumphant returning at night with the spoil,

Like Bachanals, shouting and gay:

How sweet with a bottle and song to refresh,

And lose the fatigues of the day.

With sport, wit, and wine, fickle fortune defy,

Dull 'wisdom all happiness sours;

Since Life is no more than a passage at best,

Let's strew the way over with flowers.

[1]"THEY order these things better in London," replied the Hon. Tom Dashall, to an old weather-beaten sportsman, who would fain have made a convert of our London Sprig of Fashion to the sports and delights of rural life. The party were regaling themselves after the dangers and fatigues of a very hard day's fox-chace; and, while the sparkling glass circulated, each, anxious to impress on the minds of the company the value of the exploits and amusements in which he felt most delight, became more animated and boisterous in his oratory—forgetting that excellent regulation which forms an article in some of the rules and orders of our "Free and Easies" in London, "that no more than three gentlemen shall be allowed to speak at the same time." The whole party, consisting of fourteen, like a pack in full cry, had, with the kind assistance of the "rosy god," become at the same moment most animated, not to say vociferous, orators. The young squire, Bob Tally ho, (as he was called) of Belville Hall, who had recently come into possession of this fine and extensive domain, was far from feeling indifferent to the pleasures of a sporting life, and, in the chace, had even acquired the reputation of being a "keen sportsman:" but the regular intercourse which took place between him and his cousin, the Hon. Tom Dashall, of Bond Street notoriety, had in [2]some measure led to an indecision of character, and often when perusing the lively and fascinating descriptions which the latter drew of the passing scenes in the gay metropolis, Bob would break out into an involuntary exclamation of—"Curse me, but after all, this only is Real Life; "—while, for the moment, horses, dogs, and gun, with the whole paraphernalia of sporting, were annihilated. Indeed, to do justice to his elegant and highly-finished friend, these pictures were the production of a master-hand, and might have made a dangerous impression on minds more stoical and determined than that of Bob's. The opera, theatres, fashionable pursuits, characters, objects, &c. all became in succession the subjects of his pen; and if lively description, blended with irresistible humour and sarcastic wit, possessed any power of seduction, these certainly belonged to Bob's honourable friend and relative, as an epistolary correspondent. The following Stanzas were often recited by him with great feeling and animation:—

Parent of Pleasure and of many a groan,

I should be loath to part with thee, I own,

Dear Life!

To tell the truth, I'd rather lose a wife,

Should Heav'n e'er deem me worthy of possessing

That best, that most invaluable blessing.

I thank thee, that thou brought'st me into being;

The things of this our world are well worth seeing;

And let me add, moreover, well worth feeling;

Then what the Devil would people have?

These gloomy hunters of the grave,

For ever sighing, groaning, canting, kneeling.

Some wish they never had been born, how odd!

To see the handy works of God,

In sun and moon, and starry sky;

Though last, not least, to see sweet Woman's charms,—

Nay, more, to clasp them in our arms,

And pour the soul in love's delicious sigh,

Is well worth coming for, I'm sure,

Supposing that thou gav'st us nothing more.

Yet, thus surrounded, Life, dear Life, I'm thine,

And, could I always call thee mine,

I would not quickly bid this world farewell;

But whether here, or long or short my stay,

I'll keep in mind for ev'ry day

An old French motto, "Vive la bagatelle!"

Misfortunes are this lottery-world's sad blanks;

Presents, in my opinion, not worth thanks.

The pleasures are the twenty thousand prizes,

Which nothing but a downright ass despises.

It was not, however, the mere representations of Bob's friend, with which, (in consequence of the important result,) we commenced our chapter, that produced the powerful effect of fixing the wavering mind of Bob—No, it was the air—the manner—the je ne sais quoi, by which these representations were accompanied: the curled lip of contempt, and the eye, measuring as he spoke, from top to toe, his companions, with the cool elegant sang froid and self-possession displayed in his own person and manner, which became a fiat with Bob, and which effected the object so long courted by his cousin.

After the manner of Yorick (though, by the bye, no sentimentalist) Bob thus reasoned with himself:—"If an acquaintance with London is to give a man these airs of superiority—this ascendancy—elegance of manners, and command of enjoyments—why, London for me; and if pleasure is the game in view, there will I instantly pursue the sport."

[3]The song and toast, in unison with the sparkling glass, followed each other in rapid succession. During which, our elegant London visitor favoured the company with the following effusion, sung in a style equal to (though unaccompanied with the affected airs and self-importance of) a first-rate professor:—

SONG.

If to form and distinction, in town you would bow,

Let appearance of wealth be your care:

If your friends see you live, not a creature cares how,

The question will only be, Where?

A circus, a polygon, crescent, or place,

With ideas of magnificence tally;

Squares are common, streets queer, but a lane's a disgrace;

And we've no such thing as an alley.

A first floor's pretty well, and a parlour so so;

But, pray, who can give themselves airs,

Or mix with high folks, if so vulgarly low

To live up in a two pair of stairs?

The garret, excuse me, I mean attic floor,

(That's the name, and it's right you should know it,)

Would he tenantless often; but genius will soar,

And it does very well for a poet.

These amusements of the table were succeeded by a most stormy and lengthened debate, (to use a parliamentary phrase) during which, Bob's London friend had with daring heroism opposed the whole of the party, in supporting the superiority of Life in London over every pleasure the country could afford. After copious libations to Bacchus, whose influence at length effected what oratory had in vain essayed, and silenced these contending and jarring elements, "grey-eyed Morn" peeped intrusively amid the jovial crew, and Somnus, (with the cart before the horse) stepping softly on tip-toe after his companion, led, if not by, at least accompanied with, the music of the nose, each to his snoring pillow.[4]

——"Glorious resolve!" exclaimed Tom, as soon as his friend had next morning intimated his intention,—"nobly resolved indeed!—"What! shall he whom Nature has formed to shine in the dance and sparkle in the ring—to fascinate the fair—lead and control the fashions—attract the gaze and admiration of the surrounding crowd!—shall he pass a life, or rather a torpid existence, amid country bumpkins and Johnny-raws? Forbid it all ye powers that rule with despotic sway where Life alone is to be found,—forbid it cards—dice—balls—fashion, and ye gay et coteras,—forbid"——"Pon my soul," interrupted Bob, "you have frightened me to death! I thought you were beginning an Epic,—a thing I abominate of all others. I had rather at any time follow the pack on a foundered horse than read ten lines of Homer; so, my dear fellow, descend for God's sake from the Heroics."

Calmly let me, at least, begin Life's chapter,

Not panting for a hurricane of rapture;

Calm let me step—not riotous and jumping:

With due decorum, let my heart

Try to perform a sober part,

Not at the ribs be ever bumping—bumping.

Rapture's a charger—often breaks his girt,

Runs oft", and flings his rider in the dirt.

[5]"However, it shall be so: adieu, my dear little roan filly,—Snow-ball, good by,—my new patent double-barrelled percussion—ah, I give you all up!—Order the tandem, my dear Tom, whenever you please; whisk me up to the fairy scenes you have so often and admirably described; and, above all things, take me as an humble and docile pupil under your august auspices and tuition." Says Tom, "thou reasonest well."

The rapidity with which great characters execute their determinations has been often remarked by authors. The dashing tandem, with its beautiful high-bred bits of blood, accompanied by two grooms on horsebaek in splendid liveries, stood at the lodge-gate, and our heroes had only to bid adieu to relatives and friends, and commence their rapid career.

Before we start on this long journey of one hundred and eighty miles, with the celerity which is unavoidable in modern travelling, it may be prudent to ascertain that our readers are still in company, and that we all start fairly together; otherwise, there is but little probability of our ever meeting again on the journey;—so now to satisfy queries, remarks, and animadversions.

"Why, Sir, I must say it is a new way of introducing a story, and appears to me very irregular.—What! tumble your hero neck and heels into the midst of a drunken fox-hunting party, and then carry him off from his paternal estate, without even noticing his ancestors, relatives, friends, connexions, or prospects—without any description of romantic scenery on the estate—without so much as an allusion to the female who first kindled in his breast the tender passion, or a detail of those incidents with which it is usually connected!—a strange, very strange way indeed this of commencing."

"My dear Sir, I agree with you as to the deviation from customary rules: but allow me to ask,—is not one common object—amusement, all we have in view? Suppose then, by way of illustration, you were desirous of arriving at a given place or object, to which there were several roads, and having traversed one of these till the monotony of the scene had rendered every object upon it dull and wearisome, would you quarrel with the traveller who pointed out another road, merely because it was a new one? Considering the impatience of our young friends, the one to return to scenes in which alone he can [6]live, and the other to realize ideal dreams of happiness, painted in all the glowing tints that a warm imagination and youthful fancy can pourtray, it will be impossible longer to continue the argument. Let me, therefore, entreat you to cut it short—accompany us in our rapid pursuit after Life in London; nor risk for the sake of a little peevish criticism, the cruel reflection, that by a refusal, you would, probably, be in at the death of the Author—by Starvation."

"The panting steed the hero's empire feel,

Who sits triumphant o'er the flying wheel,

And as he guides it through th' admiring throng,

With what an air he holds the reins, and smacks the silken thong!"

ORDINARY minds, in viewing distant objects, first see the obstacles that intervene, magnify the difficulty of surmounting them, and sit down in despair. The man of genius with his mind's-eye pointed steadfastly, like the needle towards the pole, on the object of his ambition, meets and conquers every difficulty in detail, and the mass dissolves before him as the mountain snow yields, drop by drop, to the progressive but invincible operation of the solar beam. Our honourable friend was well aware that a perfect knowledge of the art of driving, and the character of a "first-rate whip," were objects worthy his ambition; and that, to hold four-in-hand—turn a corner in style—handle the reins in form—take a fly off the tip of his leader's ear—square the elbows, and keep the wrists pliant, were matters as essential to the formation of a man of fashion as dice or milling: it was a principle he had long laid down and strictly adhered to, that whatever tended to the completion of that character, should be acquired to the very acmé of perfection, without regard to ulterior consequences, or minor pursuits.

In an early stage, therefore, of his fashionable course of studies, the whip became an object of careful solicitude; and after some private tuition, he first exhibited his prowess about twice a week, on the box of a Windsor stage, tipping coachy a crown for the indulgence and improvement it afforded. Few could boast of being more fortunate during a noviciate: two overturns only occurred in the whole course of practice, and except the trifling accident of an old lady being killed, a shoulder or two dislocated, and about half a dozen legs and arms [8]broken, belonging to people who were not at all known in high life, nothing worthy of notice may be said to have happened on these occasions. 'Tis true, some ill-natured remarks appeared in one of the public papers, on the "conduct of coachmen entrusting the reins to young practitioners, and thus endangering the lives of his majesty's subjects;" but these passed off like other philanthropic suggestions of the day, unheeded and forgotten.

The next advance of our hero was an important step. The mail-coach is considered the school; its driver, the great master of the art—the Phidias of the statuary—the Claude of the landscape-painter. To approach him without preparatory instruction and study, would be like an attempt to copy the former without a knowledge of anatomy, or the latter, while ignorant of perspective. The standard of excellence—the model of perfection, all that the highest ambition can attain, is to approach as near as possible the original; to attempt a deviation, would be to bolt out of the course, snap the curb, and run riot. Sensible of the importance of his character, accustomed to hold the reins of arbitrary power; and seated where will is law, the mail-whip carries in his appearance all that may be expected from his elevated situation. Stern and sedate in his manner, and given to taciturnity, he speaks sententiously, or in monosyllables. If he passes on the road even an humble follower of the profession, with four tidy ones in hand, he views him with ineffable contempt, and would consider it an irreparable disgrace to appear conscious of the proximity. Should it be a country gentleman of large property and influence, and he held the reins, and handled the whip with a knowledge of the art, so to "get over the ground," coachy might, perhaps, notice him "en passant," by a slight and familiar nod; but it is only the peer, or man of first-rate sporting celebrity, that is honoured with any thing like a familiar mark of approbation and acquaintance; and these, justly appreciating the proud distinction, feel higher gratification by it than any thing the monarch could bestow: it is an inclination of the head, not forward, in the manner of a nod, but towards the off shoulder, accompanied with a certain jerk and elevation from the opposite side. But here neither pen nor pencil can depict; it belongs to him alone whose individual powers can nightly keep the house [9]in a roar, to catch the living manner and present it to the eye.

"——A merrier man

Within the limit of becoming mirth,

I never spent an hour's talk withall:

His eye begets occasion for his wit;

For every object that the one doth catch

The other turns to a mirth-moving jest."

And now, gentle reader, if the epithet means any thing, you cannot but feel disposed to good humour and indulgence: Instead of rattling you off, as was proposed at our last interview, and whirling you at the rate of twelve miles an hour, exhausted with fatigue, and half dead in pursuit of Life, we have proceeded gently along the road, amusing ourselves by the way, rather with drawing than driving. 'Tis high time, however, we made some little progress in our journey: "Come Bob, take the reins—push on—keep moving—touch up the leader into a hand-gallop—give Snarler his head—that's it my tight one, keep out of the ruts—mind your quartering—not a gig, buggy, tandem, or tilbury, have we yet seen on the road—what an infernal place for a human being to inhabit!—curse me if I had not as lief emigrate to the back settlements of America: one might find some novelty and amusement there—I'd have the woods cleared—cut out some turnpike-roads, and, like Palmer, start the first mail"——"Stop, Tom, don't set off yet to the Illinois—here's something ahead, but what the devil it is I cant guess—why it's a barge on wheels, and drove four-in-hand."—"Ha, ha—barge indeed, Bob, you seem to know as much about coaches as Snarler does of Back-gammon: I suppose you never see any thing in this quarter but the old heavy Bridgewater—why we have half a dozen new launches every week, and as great a variety of names, shape, size, and colour, as there are ships in the navy—we have the heavy coach, light coach, Caterpillar, and Mail—the Balloon, Comet, Fly, Dart, Regulator, Telegraph, Courier, Times, High-flyer, Hope, with as many others as would fill a list as long as my tandem-whip. What you now see is one of the new patent safety-coaches—you can't have an overturn if you're ever so disposed for a spree. The old city cormorants, after a gorge of mock-turtle, turn into them for a journey, and drop off in a [10]nap, with as much confidence of security to their neck and limbs as if they had mounted a rocking-horse, or drop't into an arm-chair."—"Ah! come, the scene improves, and becomes a little like Life—here's a dasher making up to the Safety—why its—no, impossible—can't be—gad it is tho'—the Dart, by all that's good! and drove by Hell-fire Dick!—there's a fellow would do honour to any box—drove the Cambridge Fly three months—pass'd every thing on the road, and because he overturned in three or four hard matches, the stupid rascals of proprietors moved him off the ground. Joe Spinum, who's at Corpus Christi, matched Dick once for 50, when he carried five inside and thirteen at top, besides heavy luggage, against the other Cambridge—never was a prettier race seen at Newmarket—Dick must have beat hollow, but a d——d fat alderman who was inside, and felt alarmed at the velocity of the vehicle, moved to the other end of the seat: this destroyed the equilibrium—over they went, into a four-feet ditch, and Joe lost his match. However, he had the satisfaction of hearing afterwards, that the old cormorant who occasioned his loss, had nearly burst himself by the concussion."

"See, see!—Dick's got up to, and wants to give the Safety the go by—gad, its a race—go it Dick—now Safety—d——d good cattle both—lay it in to 'em Dick—leaders neck and neck—pretty race by G——! Ah, its of no use Safety—Dick wont stand it—a dead beat—there she goes—all up—over by Jove "——"I can't see for that tree—what do you say Tom, is the race over?"—"Race, ah! and the coach too—knew Dick would beat him—would have betted the long odds the moment I saw it was him."

The tandem had by this time reached the race-course, and the disaster which Tom had hardly thought worth noticing in his lively description of the sport, sure enough had befallen the new 'patent Safety, which was about mid way between an upright and a side position, supported by the high and very strong quicksett-hedge against which it hath fallen. Our heroes dismounted, left Flip at the leader's head, and with Ned, the other groom, proceeded to offer their services. Whilst engaged in extricating the horses, which had become entangled in their harness, and were kicking and plunging, their attention was arrested by the screams and outrageous vociferations of a very fat, middle-aged woman, who had [11]been jerked from her seat on the box to one not quite so smooth—the top of the hedge, which, with the assistance of an old alder tree, supported the coach. Tom found it impossible to resist the violent impulse to risibility which the ludicrous appearance of the old lady excited, and as no serious injury was sustained, determined to enjoy the fun.

"If e'er a pleasant mischief sprang to view,

At once o'er hedge and ditch away he flew,

Nor left the game till he had run it down."

Approaching her with all the gravity of countenance he was master of—"Madam," says he, "are we to consider you as one of the Sylvan Deities who preside over these scenes, or connected in any way with the vehicle?"—"Wehicle, indeed, you hunhuman-brutes, instead of assisting a poor distressed female who has been chuck'd from top of that there safety-thing, as they calls it, into such a dangerous pisition, you must be chuckling and grinning, must you? I only wish my husband, Mr. Giblet, was here, he should soon wring your necks, and pluck some of your fine feathers for you, and make you look as foolish as a peacock without his tail." Mrs. Giblet's ire at length having subsided, she was handed down in safety on terra firma, and our heroes transferred their assistance to the other passengers. The violence of the concussion had burst open the coach-door on one side, and a London Dandy, of the exquisite genus, lay in danger of being pressed to a jelly beneath the weight of an infirm and very stout old farmer, whom they had pick'd up on the road; and it was impossible to get at, so as to afford relief to the sufferers, till the coach was raised in a perpendicular position. The farmer was no sooner on his legs, than clapping his hand with anxious concern into an immense large pocket, he discovered that a bottle of brandy it contained was crack'd, and the contents beginning to escape: "I ax pardon, young gentleman," says he, seizing a hat that the latter held with great care in his hand, and applying it to catch the liquor—"I ax pardon for making so free, but I see the hat is a little out of order, and can't be much hurt; and its a pity to waste the liquor, such a price as it is now-a-days."—"Sir, what do you mean, shouldn't have thought of your taking such liberties indeed, but makes good the old saying—impudence and [12]ignorance go together: my hat out of order, hey! I'd have you to know, Sir, that that there hat was bought of Lloyd, in Newgate-street,{1} only last Thursday,-and cost eighteen shillings; and if you look at the book in his vindow on hats, dedicated to the head, you'll find that this here hat is a real exquisite; so much for what you know about hats, my old fellow—I burst my stays all to pieces in saving it from being squeezed out of shape, and now this old brute has made a brandy-bottle of it."—"Oh! oh! my young Miss in disguise," replied the farmer, "I thought I smelt a rat when the Captain left the coach, under pretence of walking up the hill—what, I suppose vou are bound for Gretna, both of vou, hev young Lady?"

Every thing appertaining to the coach being now righted, our young friends left the company to adjust their quarrels and pursue their journey at discretion, anxious to reach the next town as expeditiously as possible, where they purposed sleeping for the night. They mounted the tandem, smack went the whip, and in a few minutes the stage-coach and its motley group had disappeared.

Having reached their destination, and passed the night comfortably, they next morning determined to kill an hour or two in the town; and were taking a stroll arm in arm, when perceiving by a playbill, that an amateur of fashion from the theatres royal, Drury Lane and Haymarket, was just come in, and would shortly come out,

1 It would be injustice to great talents, not to notice,

among other important discoveries and improvements of the

age, the labours of Lloyd, who has classified and arranged

whatever relates to that necessary article of personal

elegance, the Hat. He has given the world a volume on the

subject of Hats, dedicated to their great patron, the Head,

in which all the endless varieties of shape, dependent

before on mere whim and caprice, are reduced to fixed

principles, and designated after the great characters by

which each particular fashion was first introduced. The

advantages to gentlemen residing in the country must be

incalculable: they have only to refer to the engravings in

Mr. Lloyd's work, where every possible variety is clearly

defined, and to order such as may suit the rank or character

in life they either possess, or wish to assume. The

following enumeration comprises a few of the latest fashions:

—The Wellington—The Regent—The Caroline—The

Bashful—The Dandy—The Shallow—The Exquisite—The Marquis

—The New Dash—The Clerieus—The Tally-ho—The Noble Lord—

The Taedum—The Bang-up—The Irresistible—The Bon Ton—The

Paris Beau—The Baronet—The Eccentric—The Bit of Blood,

&c.

[13]in a favourite character, they immediately directed their steps towards a barn, with the hope of witnessing a rehearsal. Chance introduced them to the country manager, and Tom having asked several questions about this candidate, was assured by Mr. Mist:

"Oh! he is a gentleman-performer, and very useful to us managers, for he not only finds his own dresses and properties, but 'struts and frets his hour on the stage without any emoluments. His aversion to salary recommended him to the lessee of Drury-lane theatre, though his services had been previously rejected by the sub-committee."

"Can it be that game-cock, the gay Lothario," said Tom, "who sports an immensity of diamonds?"—

Of Coates's frolics he of course well knew, Rare pastime for the ragamuffin crew! Who welcome with the crowing of a cock, This hero of the buskin and sock.

"Oh! no," rejoined Mr. Mist, "that cock don't crow now: this gentleman, I assure you, has been at a theatrical school; he was instructed by the person who made Master Bettv a young Roscius."

Tom shook his head, as if he doubted the abilities of this instructed actor. To be a performer, he thought as arduous as to be a poet; and if poeta nascitur, non fit—consequently an actor must have natural abilities.

"And pray what character did this gentleman enact at Drury-lane Theatre?"

"Hamlet, Prince of Denmark," answered Mr. Mist—"Shakespeare is his favourite author."

"And what said the critics—'to be, or not to be'—I suppose he repeated the character?"

"Oh! Sir, it was stated in the play-bill, that he met with great applause, and he was announced for the character again; but, as the Free List was not suspended, and our amateur dreaded some hostility from that quarter, he performed the character by proxy, and repeated it at the Little Theatre in the Haymarket."

"Then the gentlemen of the Free List," remarked Bob, "are free and easy?"

"Yes—yes—they laugh and cough whenever they please: indeed, they are generally excluded whenever a [14]full house is expected, as ready money is an object to the poor manager of Drury-lane Theatre. The British Press, however, is always excepted."

"The British press!—Oh! you mean the newspapers," exclaimed Tom—"then I dare say they were very favourable to this Amateur of Fashion?"

"No—not very—indeed; they don't join the manager in his puffs, notwithstanding his marked civility to them: one said he was a methodist preacher, and sermonized the character—another assimilated him to a school-boy saying his lesson—in short, they were very ill-natured—but hush—here he is—walk in, gentlemen, and you shall hear him rehearse some of King Richard"—

"King Richard!" What ambition! thought Bob to himself—"late a Prince, and now—a king!"

"I assure you," continued Mr. Mist, "that all his readings are new; but according to my humble observation, his action does not always suit the word—for when he exclaims—' may Hell make crook'd my mind,' he looks up to Heaven"—

"Looks up to Heaven!" exclaimed Tom; "then this London star makes a solecism with his eyes."

Our heroes now went into the barn, and took a private corner, when they remained invisible. Their patience was soon exhausted, and Bob and his honourable cousin were both on the fidgits, when the representative of King Richard exclaimed—

"Give me a horse——"

"—Whip!" added Tom with stunning vociferation, before King Richard could bind up his wounds. The amateur started, and betrayed consummate embarrassment, as if the horsewhip had actually made its entrance. Tom and his companion stole away, and left the astounded monarch with the words—"twas all a dream."

While returning to the inn, our heroes mutually commented on the

ambition and folly of those amateurs of fashion, who not only sacrifice

time and property, but absolutely take abundant pains to render

themselves ridiculous. "Certainly," says Tom, "this cacoethes ludendi

has made fools of several: this infatuated youth though not possessed

of a single requisite for the stage, no doubt flatters himself he is

a second Kean; and, regardless [15]of his birth and family, he will

continue his strolling life

Till the broad shame comes staring in his face,

And critics hoot the blockhead as he struts."

Having now reached the inn, and finding every thing adjusted for their procedure, our heroes mounted their vehicle, and went in full gallop for Real Life in London.

"Round, round, and round-about, they whiz, they fly,

With eager worrying, whirling here and there,

They know, nor whence, nor whither, where, nor why.

In utter hurry-scurry, going, coming,

Maddening the summer air with ceaseless humming."

[16]OUR travellers now approached at a rapid rate, the desideratim of their eager hopes and wishes: to one all was novel, wonderful, and fascinating; to the other, it was the welcome return to an old and beloved friend, the separation from whom had but increased the ardour of attachment.—"We, now," says Dashall, "are approaching Hyde-Park, and being Sunday, a scene will at once burst upon you, far surpassing in reality any thing I have been able to pourtray, notwithstanding the flattering compliments you have so often paid to my talents for description."

They had scarcely entered the Park-gate, when Lady Jane Townley's carriage crossed them, and Tom immediately approached it, to pay his respects to an old acquaintance. Her lady-ship congratulated him on his return to town, lamented the serious loss the beau-monde had sustained by his absence, and smiling archly at his young friend, was happy to find he had not returned empty-handed, but with a recruit, whose appearance promised a valuable accession to their select circle. "You would not have seen me here," continued her ladyship, "but I vow and protest it is utterly impossible to make a prisoner of one's self, such a day as this, merely because it is Sunday—for my own part, I wish there was no such thing as a Sunday in the whole year—there's no knowing what to do with one's self. When fine, it draws out as many insects as a hot sun and a shower of rain can produce in the middle of June. The vulgar plebeians flock so, that you can scarcely get into your barouche without being hustled by the men-milliners, linen-drapers, and shop-boys, who [17]have been serving you all the previous part of the week; and wet, or dry, there's no bearing it. For my part, I am ennuyée, beyond measure, on that day, and find no little difficulty in getting through it without a fit of the horrors.

"What a legion of counter-coxcombs!" exclaimed she, as we passed Grosvenor-gate. "Upon the plunder of the till, or by overcharging some particular article sold on the previous day, it is easy for these once-a-week beaux to hire a tilbury, and an awkward groom in a pepper and salt, or drab coat, like the incog. of the royal family, to mix with their betters and sport their persons in the drive of fashion: some of the monsters, too, have the impudence of bowing to ladies whom they do not know, merely to give them an air, or pass off their customers for their acquaintance: its very distressing. There!" continued she, "there goes my plumassier, with gilt spurs like a field-officer, and riding as importantly as if he were one of the Lords of the Treasury; or—ah! there, again, is my banker's clerk, so stiff and so laced up, that he might pass for an Egyptian mummy—the self-importance of these puppies is insufferable! What impudence! he has picked up some groom out of place, with a cockade in his hat, by way of imposing on the world for a beau militaire. What will the world come to! I really have not common patience with these creatures. I have long since left off going to the play on a Saturday night, because, independently of my preference for the Opera, these insects from Cornhill or Whitechapel, shut up their shops, cheat their masters, and commence their airs of importance about nine o'clock. Then again you have the same party crowding the Park on a Sunday; but on the following day, return, like school boys, to their work, and you see them with their pen behind their ear, calculating how to make up for their late extravagances, pestering you with lies, and urging you to buy twice as much as you want, then officiously offering their arm at your carriage-door."

Capt. Bergamotte at this moment came up to the carriage, perfumed like a milliner, his colour much heightened by some vegetable dye, and resolved neither to "blush unseen," nor "waste his sweetness on the desert air." Two false teeth in front, shamed the others a little in their ivory polish, and his breath savoured of myrrh like a heathen sacrifice, or the incense burned in [18]one of their temples. He thrust his horse's head into the carriage, rather abruptly and indecorously, (as one not accustomed to the haut-ton might suppose) but it gave no offence. He smiled affectedly, adjusted his hat, pulled a lock of hair across his forehead, with a view of shewing the whiteness of the latter, and next, that the glossiness of the former must have owed its lustre to at least two hours brushing, arranging, and perfuming; used his quizzing-glass, and took snuff with a flourish. Lady Townley condescended to caress the horse, and to display her lovely white arm ungloved, with which she patted the horse's neck, and drew a hundred admiring eyes.

The exquisite all this time brushed the animal gently with a highly-scented silk handkerchief, after which he displayed a cambric one, and went through a thousand little playful airs and affectations, which Bob thought would have suited a fine lady better than a lieutenant in his Majesty's brigade of guards. Applying the lines of an inimitable satire, (The Age of Frivolity) to the figure before him, he concluded:

"That gaudy dress and decorations gay,

The tinsel-trappings of a vain array.

The spruce trimm'd jacket, and the waving plume,

The powder'd head emitting soft perfume;

These may make fops, but never can impart

The soldier's hardy frame, or daring heart;

May in Hyde-Park present a splendid train,

But are not weapons for a dread campaign;

May please the fair, who like a tawdry beau,

But are not fit to check an active foe;

Such heroes may acquire sufficient skill

To march erect, and labour through a drill;

In some sham-fight may manfully hold out,

But must not hope an enemy to rout."

Although he talked a great deal, the whole amount of his discourse was to inform her Ladyship that (Stilletto) meaning his horse, (who in truth appeared to possess more fire and spirit than his rider could either boast of or command,) had cost him only 700 guineas, and was prime blood; that the horse his groom rode, was nothing but a good one, and had run at the Craven—that he had been prodigiously fortunate that season on the turf—that he was a bold rider, and could not bear himself without a fine high spirited animal—and, that being engaged to dine at [19]three places that day, he was desperately at a loss to know how he should act; but that if her Ladyship dined at any one of the three, he would certainly join that party, and cut the other two.

At this moment, a mad-brained ruffian of quality, with a splendid equipage, came driving by with four in hand, and exclaimed as he flew past, in an affected tone,—"All! Tom, my dear fellow,—why where the devil have you hid yourself of late?" The speed of his cattle prevented the possibility of reply. "Although you see him in such excellent trim," observed Tom to Lady Jane, "though his cattle and equipage are so well appointed, would you suppose, it, he has but just made his appearance from the Bench after white-washing? But he is a noble spirited fellow," remarked the exquisite, "drives the best horses, and is one of the first whips in town; always gallant and gay, full of life and good humour; and, I am happy to say, he has now a dozen of as fine horses as any in Christendom, bien entendu, kept in my name." After this explanation of the characters of his friend and his horses, he kissed his hand to her Ladyship, and was out of sight in an instant, "Adieu, adieu, thou dear, delightful sprig of fashion!" said Lady Jane, as he left the side of the carriage.—"Fashion and folly," said Tom, half whispering, and recalling to his mind the following lines:—

"Oh! Fashion, to thy wiles, thy votaries owe

Unnumber'd pangs of sharp domestic woe.

What broken tradesmen and abandon'd wives

Curse thy delusion through their wretched lives;

What pale-faced spinsters vent on thee their rage,

And youths decrepid e're they come of age."

His moralizing reverie was however interrupted by her Ladyship, who perceiving a group of females decked in the extreme of Parisian fashions, "there," said she, "there is all that taffeta, feathers, flowers, and lace can do; and yet you see by their loud talking, their being unattended by a servant, and by the bit of straw adhering to the pettycoat of one of them, that they come all the way from Fish Street Hill, or the Borough, in a hackney-coach, and are now trying to play off the airs of women of fashion."

Mrs. Marvellous now drew up close to the party. "My dear Lady Jane," said she, "1 am positively suffocated with dust, and sickened with vulgarity; but to be sure we [20]have every thing in London here, from the House of Peers to Waterloo House. I must tell you about the trial, and Lady Barbara's mortification, and about poor Mr. R.'s being arrested, and the midnight flight to the Continent of our poor friend W——."

With this brief, but at the same time comprehensive introduction, she lacerated the reputation of almost all her acquaintance, and excited great attention from the party, which had been joined by several during her truly interesting intelligence. Every other topic in a moment gave way to this delightful amusement, and each with volubility contributed his or her share to the general stock of slander.

Scandal is at all times the sauce piquante that currys incident in every situation; and where is the fashionable circle that can sit down to table without made dishes?—Character is the good old-fashioned roast beef of the table, which no one touches but to mangle and destroy.

"Lord! who'd have thought our cousin D

Could think of marrying Mrs. E.

True I don't like such things to tell;

But, faith, I pity Mrs. L,

And was I her, the bride to vex,

I would engage with Mrs. X.

But they do say that Charlotte U,

With Fanny M, and we know who,

Occasioned all, for you must know

They set their caps at Mr. O.

And as he courted Mrs. E,

They thought, if she'd have cousin D,

That things might be by Colonel A

Just brought about in their own way."

Our heroes now took leave, and proceeded through the Park. "Who is that fat, fair, and forty-looking dame, in the landau?" says Bob.—"Your description shews," rejoined his friend, "you are but a novice in the world of fashion—you are deceived, that lady is as much made up as a wax-doll. She has been such as she now appears to be for these last five and twenty years; her figure as you see, rather en-bon point, is friendly to the ravages of time, and every lineament of age is artfully filled up by an expert fille de chambre, whose time has been employed at the toilette of a celebrated devotee in Paris. She drives through the Park as a matter of course, merely to furnish an opportunity for saying that she has been there: but the more important business of the morning will be transacted [21]at her boudoir, in the King's Road, where every luxury is provided to influence the senses; and where, by daily appointment, she is expected to meet a sturdy gallant. She is a perfect Messalina in her enjoyments; but her rank in society protects her from sustaining any injury by her sentimental wanderings.

"Do you see that tall handsome man on horseback, who has just taken off his hat to her, he is a knight of the ... ribbon; and a well-known flutterer among the ladies, as well as a vast composer of pretty little nothings."—"Indeed! and pray, cousin, do you see that lady of quality, just driving in at the gate in a superb yellow vis-à-vis,—as you seem to know every body, who is she?"

"Ha! ha! ha!" replied Tom, almost bursting with laughter, yet endeavouring to conceal it, "that Lady of Quality, as you are inclined to think her, a very few years since, was nothing more than a pot-girl to a publican in Marj'-le-bone; but an old debauchee (upon the look out for defenceless beauty) admiring the fineness of her form, the brilliancy of her eye, and the symmetry of her features, became the possessor of her person, and took her into keeping, as one of the indispensable appendages of fashionable life, after a month's ablution at Margate, where he gave her masters of every description. Her understanding was ready, and at his death, which happened, luckily for her, before satiety had extinguished appetite, she was left with an annuity of twelve hundred pounds—improved beauty—superficial accomplishments—and an immoderate share of caprice, insolence, and vanity. As a proof of this, I must tell you that at an elegant entertainment lately given by this dashing cyprian, she demolished a desert service of glass and china that cost five hundred guineas, in a fit of passionate ill-humour; and when her paramour intreated her to be more composed, she became indignant—called for her writing-desk in a rage—committed a settlement of four hundred a year, which he had made but a short time previously, to the flames, and asked him, with, a self-important air, whether he dared to suppose that paltry parchment gave him an authority to direct her actions?"

"And what said the lover to this severe remonstrance?"

"Say,—why he very sensibly made her a low bow, thanked her for her kindness, in releasing him from his bond, and took his leave of her, determined to return no more."

[22]"Turn to the right," says Tom, "and yonder you will see on horseback, that staunch patriot, and friend of the people, Sir——, of whom you must have heard so much."

"He has just come out of the K——B——, having completed last week the term of imprisonment, to which he was sentenced for a libel on Government, contained in his address to his constituents on the subject of the memorable Manchester Meeting."

"Ah! indeed, and is that the red-hot patriot?—well, I must say I have often regretted he should have gone to such extremes in one or two instances, although I ever admired his general character for firmness, manly intrepidity, and disinterested conduct."

"You are right, Bob, perfectly right; but you know, 'to err is human, to forgive divine,' and however he may err, he does so from principle. In his private character, as father, husband, friend, and polished gentleman, he has very few equals—no superior.

"He is a branch of one of the most ancient families in the kingdom, and can trace his ancestors without interruption, from the days of William the Conqueror. His political career has been eventful, and perhaps has cost him more, both in pocket and person, than any Member of Parliament now existing. He took his seat in the House of Commons at an early age, and first rendered himself popular by his strenuous opposition to a bill purporting to regulate the publication of newspapers.

"The next object of his determined reprehension, was the Cold-Bath-Fields Prison, and the treatment of the unfortunates therein confined. The uniformly bold and energetic language made use of by the honourable Baronet upon that occasion, breathed the true spirit of British liberty. He reprobated the unconstitutional measure of erecting what he termed a Bastile in the very heart of a free country, as one that could neither have its foundation in national policy, nor eventually be productive of private good. He remarked that prisons, at which private punishments, cruel as they were illegal, were exercised, at the mercy of an unprincipled gaoler—cells in which human beings were exposed to the horrors of heart-sickening solitude, and depressed in spirit by their restriction to a scanty and exclusive allowance of bread and water, were not only incompatible with the spirit of the constitution, but were likely to prove injurious to the spirit of the [23]people of this happy country; for as Goldsmith admirably remarks,

"Princes and Lords may nourish or may fade,

A breath can make them as a breath hath made,

But a bold peasantry their country's pride,

When once destroyed can never be supplied."

"And if this be not tyranny" continued the philanthropic orator, "it is impossible to define the term. I promise you here that I will persevere to the last in unmasking this wanton abuse of justice and humanity." His invincible fortitude in favour of the people, has rendered him a distinguished favourite among them: and though by some he is termed a visionary, an enthusiast, and a tool of party, his adherence to the rights of the subject, and his perseverance to uphold the principles of the constitution, are deserving the admiration of every Englishman; and although his fortune is princely, and has been at his command ever since an early age, he has never had his name registered among the fashionable gamesters at the clubs in St. James's-street, Newmarket, or elsewhere. He labours in the vineyard of utility rather than in the more luxuriant garden of folly; and, according to general conception, may emphatically be called an honest man. "But come," said Tom, "it is time for us to move homeward—the company are drawing off I see, we must shape our course towards Piccadilly."

They dashed through the Park, not however without being saluted by many of his fashionable friends, who rejoiced to see that the Honourable Tom Dashall was again to be numbered among the votaries of Real Life in London; while the young squire, whose visionary orbs appeared to be in perpetual motion, dazzled with the splendid equipages of the moving panorama, was absorbed in reflections somewhat similar to the following:

"No spot on earth to me is half so fair

As Hyde-Park Corner, or St. James's Square;

And Happiness has surely fix'd her seat

In Palace Yard, Pall Mall, or Downing Street:

Are hills, and dales, and valleys half so gay

As bright St. James's on a levee day?

What fierce ecstatic transports fire my soul,

To hear the drivers swear, the coaches roll;

The Courtier's compliment, the Ladies' clack,

The satins rustle, and the whalebone crack!"

"Together let us beat this ample field

Try what the open, what the covert yield:

The latent tracts, the giddy heights explore

Of all who blindly creep, or sightless soar;

Eye nature's walks, shoot folly as it flies,

And catch the manners living as they rise."

[24]IT was half past five when the Hon. Tom Dashall, and his enraptured cousin, reached the habitation of the former, who had taken care to dispatch a groom, apprizing Mrs. Watson, the house-keeper, of his intention to be at home by half past six to dinner; consequently all was prepared for their reception. The style of elegance in which Tom appeared to move, struck Tallyho at once with delight and astonishment, as they entered the drawing-room; which was superbly and tastefully fitted up, and commanded a cheerful view of Piccadilly. "Welcome, my dear Bob!" said Tom to his cousin, "to all the delights of Town—come, tell me what you think of its first appearance, only remember you commence your studies of Life in London on a dull day; to-morrow you will have more enlivening prospects before you." "'Why in truth," replied Bob, "the rapidity of attraction is such, as at present to leave no distinct impressions on my mind; all appears like enchantment, and I am completely bewildered in a labyrinth of wonders, to which there appears to be no end; but under your kind guidance and tuition I may prove myself an apt scholar, in unravelling its intricacies." By this time they had approached the window.

"Aye, aye," says Dashall, "we shall not be long, I see, without some object to exercise your mind upon, and dispel the horrors.

"Oh for that Muse of fire, whose burning pen

Records the God-like deeds of valiant men!

Then might our humble, yet aspiring verse,

Our matchless hero's matchless deeds rehearse."

[25]Bob was surprised at this sudden exclamation of his cousin, and from the introduction naturally expected something extraordinary, though he looked around him without discovering his object.

"That," continued Tom, "is a Peer"—pointing to a gig just turning the

corner, "of whom it may be said:

To many a jovial club that Peer was known,

With whom his active wit unrivall'd shone,

Choice spirit, grave freemason, buck and blood,

Would crowd his stories and bon mots to hear,

And none a disappointment e'er need fear

His humour flow'd in such a copious flood."

"It is Lord C——, who was formerly well known as the celebrated Major H——, the companion of the now most distinguished personage in the British dominions! and who not long since became possessed of his lordly honours. Some particulars of him are worth knowing. He was early introduced into life, and often kept both good and bad company, associating with men and women of every description and of every rank, from the highest to the lowest—from St. James's to St. Giles's, in palaces and night-cellars—from the drawing-room to the dust-cart. He can drink, swear, tell stories, cudgel, box, and smoke with any one; having by his intercourse with society fitted himself for all companies. His education has been more practical than theoretical, though he was brought up at Eton, where, notwithstanding he made considerable progress in his studies, he took such an aversion to Greek that he never would learn it. Previous to his arrival at his present title, he used to be called Honest George, and so unalterable is his nature, that to this hour he likes it, and it fits him better than his title. But he has often been sadly put to his shifts under various circumstances: he was a courtier, but was too honest for that; he tried gaming, but he was too honest for that; he got into prison, and might have wiped off, but he was too honest for that; he got into the coal trade, but he found it a black business, and he was too honest for that. At drawing the long bow, so much perhaps cannot be said—but that you know is habit, not principle; his courage is undoubted, having fought three duels before he was twenty years of age.

Being disappointed in his hope of promotion in the army, he resolved, in spite of the remonstrances of his [26]friends, to quit the guards, and solicited an appointment in one of the Hessian corps, at that time raising for the British service in America, where the war of the revolution was then commencing, and obtained from the Landgrave of Hesse a captain's commission in his corps of Jagers.

Previous to his departure for America, finding he had involved himself in difficulties by a profuse expenditure, too extensive for his income, and an indulgence in the pleasures of the turf to a very great extent, he felt himself under the necessity of mortgaging an estate of about 11,000L. per annum, left him by his aunt, and which proved unequal to the liquidation of his debts. He remained in America till the end of the war, where he distinguished himself for bravery, and suffered much with the yellow fever. On his return, he obtained an introduction to the Prince of Wales, who by that time had lanched into public life, and became one of the jovial characters whom he selected for his associates; and many are the amusing anecdotes related of him. The Prince conferred on him the appointment of equerry, with a salary of 300L. a year; this, however, he lost on the retrenchments that were afterwards made in the household of His Royal Highness. He continued, however, to be one of his constant companions, and while in his favour they were accustomed to practice strange vagaries. The Major was always a wag, ripe and ready for a spree or a lark.

"To him a frolic was a high delight,

A frolic he would hunt for, day and night,

Careless how prudence on the sport might frown."

At one time, when the favourite's finances were rather low, and the mopusses ran taper, it was remarked among the 60 vivants of the party, that the Major had not for some time given them an invitation. This, however, he promised to do, and fixed the day—the Prince having engaged to make one. Upon this occasion he took lodgings in Tottenham-court Road—went to a wine-merchant—promised to introduce him to the royal presence, upon his engaging to find wine for the party, which was readily acceded to; and a dinner of three courses was served up. Three such courses, perhaps, were never before seen; when the company were seated, two large dishes appeared; one was placed at the top of the table, and one at the bottom; all was anxious expectation: [27]the covers being removed, exhibited to view, a baked shoulder of mutton at top, and baked potatoes at the bottom. They all looked around with astonishment, but, knowing the general eccentricity of their host, they readily fell into his humour, and partook of his fare; not doubting but the second course would make ample amends for the first. The wine was good, and the Major apologized for his accommodations, being, as he said, a family sort of man, and the dinner, though somewhat uncommon, was not such an one as is described by Goldsmith:

"At the top, a fried liver and bacon were seen;

At the bottom was tripe, in a swinging tureen;

At the sides there were spinach and pudding made hot;

In the middle a place where the pasty—was not."

At length the second course appeared; when lo and behold, another baked shoulder of mutton and baked potatoes! Surprise followed surprise—but

"Another and another still succeeds."

The third course consisted of the same fare, clearly proving that he had in his catering studied quantity more than variety; however, they enjoyed the joke, eat as much as they pleased, laughed heartily at the dinner, and after bumpering till a late hour, took their departure: it is said, however, that he introduced the wine-merchant to his Highness, who afterwards profited by his orders.{1}

1 This remarkable dinner reminds us of a laughable

caricature which made its appearance some time ago upon the

marriage of a Jew attorney, in Jewry-street, Aldgate, to the

daughter of a well-known fishmonger, of St. Peter's-alley,

Cornhill, when a certain Baronet, Alderman, Colonel, and

then Lord Mayor, opened the ball at the London Tavern, as

the partner of the bride; a circum-stance which excited

considerable curiosity and surprise at the time. We know the

worthy Baronet had been a hunter for a seat in Parliament,

but what he could be hunting among the children of Israel

is, perhaps, not so easily ascertained. We, however, are not

speaking of the character, but the caricature, which

represented the bride, not resting on Abraham's bosom, but

seated on his knee, surrounded by their guests at the

marriage-feast; while to a panel just behind them, appears

to be affixed a bill of fare, which runs thus:

First course, Fish!

Second course, Fish!!

Third course, Fish!!!

Perhaps the idea of the artist originated in the anecdote

above recorded.

[28]It is reported that the Prince gave him a commission, under an express promise that when he could not shew it, he was no longer to enjoy his royal favour. This commission was afterwards lost by the improvident possessor, and going to call on the donor one morning, who espying him on his way, he threw up the sash and called out, "Well, George, commission or no commission?" "No commission, by G——, your Highness?" was the reply.

"Then you cannot enter here," rejoined the prince, closing the window and the connection at the same time.

"His Lordship now resides in the Regent's Park, and may almost nightly be seen at a public-house in the neighbourhood, where he takes his grog and smokes his pipe, amusing the company around him with anecdotes of his former days; we may, perhaps, fall in with him some night in our travels, and you will find him a very amusing and sometimes very sensible sort of fellow, till he gets his grog on board, when he can be as boisterous and blustering as a coal-heaver or a bully. His present fortune is impaired by his former imprudence, but he still mingles with the sporting world, and a short time back had his pocket picked, at a milling match, of a valuable gold repeater. He has favoured the world with several literary productions, among which are Memoirs of his own Life, embellished with a view of the author, suspended from (to use the phrase of a late celebrated auctioneer) a hanging wood; and a very elaborate treatise on the Art of Rat-catching. In the advertisement of the latter work, the author engages it will enable the reader to "clear any house of these noxious vermin, however much infested, excepting only a certain great House in the neighbourhood of St. Stephen's, Westminster."{1}

1 It appears by the newspapers, that the foundation of a

certain great house in Pall Mall is rotten, and giving-way.

The cause is not stated; but as it cannot arise from being

top-heavy, we may presume that the rats have been at work

there. Query, would not an early application of the Major's

recipe have remedied the evil, and prevented the necessity

of a removal of a very heavy body, which of course, must be

attended with a very heavy expense? 'Tis a pity an old

friend should have been overlooked on such an occasion.

[29]"Do you," said Tom, pointing to a person on the other side of the way, "see that young man, walking with a half-smothered air of indifference, affecting to whistle as he walks, and twirling his stick? He is a once-a-week man, or, in other words, a Sunday promenader—Harry Hairbrain was born of a good family, and, at the decease of his father, became possessed of ten thousand pounds, which he sported with more zeal than discretion, so much so, that having been introduced to the gaming table by a pretended friend, and fluctuated between poverty and affluence for four years, he found himself considerably in debt, and was compelled to seek refuge in an obscure lodging, somewhere in the neighbourhood of Kilburn, in order to avoid the traps; for, as he observes, he has been among the Greeks and pigeons, who have completely rook'd him, and now want to crow over him: he has been at hide and seek for the last two months, and, depending on the death of a rich old maiden aunt who has no other heir, he eventually hopes to 'diddle 'em.'"

This narrative of Hairbrain was like Hebrew ta Tallyho, who requested his interesting cousin, as he found himself at falt, to try back, and put him on the right scent.

"Ha! ha! ha!" said Tom, "we must find a new London vocabulary, I see, before we shall be able to converse intelligibly; but as you are now solely under my tuition, I will endeavour to throw a little light upon the subject.

"Your once-a-week man, or Sunday promenader, is one who confines himself, to avoid confinement, lodging in remote quarters in the vicinity of the Metropolis, within a mile or two of the Bridges, Oxford Street, or Hyde-Park Corner, and is constrained to waste six uncomfortable and useless days in the week, in order to secure the enjoyment of the seventh, when he fearlessly ventures forth, to recruit his ideas—to give a little variety to the sombre picture of life, unmolested, to transact his business, or to call on some old friend, and keep up those relations with the world which would otherwise be completely neglected or broken.

"Among characters of this description, may frequently be recognised the remnant of fashion, and, perhaps, the impression of nobility not wholly destroyed by adversity and seclusion—the air and manners of a man who has [30]outlived his century, with an assumption of sans souci pourtrayed in his agreeable smile, murmur'd through a low whistle of 'Begone dull care,' or 'No more by sorrow chased, my heart,' or played off by the flourishing of a whip, or the rapping of a boot that has a spur attached to it, which perhaps has not crossed a horse for many months; and occasionally by a judicious glance at another man's carriage, horses, or appointments, which indicates taste, and the former possession of such valuable things. These form a part of the votaries of Real Life in London. This however," said he (observing his cousin in mute attention) "is but a gloomy part of the scene; vet, perhaps, not altogether uninteresting or unprofitable."

"I can assure you," replied Tallyho, "I am delighted with the accurate knowledge you appear to have of society in general, while I regret the situation of the actors in scenes so glowingly described, and am only astonished at the appearance of such persons."

"You must not be astonished at appearances," rejoined Dashall, "for appearance is every thing in London; and I must particularly warn you not to found your judgment upon it. There is an old adage, which says 'To be poor, and seem poor, is the Devil all over.' Why, if you meet one of these Sunday-men, he will accost you with urbanity and affected cheerfulness, endeavouring to inspire you with an idea that he is one of the happiest of mortals; while, perhaps, the worm of sorrow is secretly gnawing his heart, and preying upon his constitution. Honourable sentiment, struggling with untoward circumstances, is destroying his vitals; not having the courage to pollute his character by a jail-delivery, or to condescend to white-washing, or some low bankrupt trick, to extricate himself from difficulty, in order to stand upright again.

"A once-a-week man, or Sunday promenader, frequently takes his way through bye streets and short cuts, through courts and alleys, as it were between retirement and a desire to see what is going on in the scenes of his former splendour, to take a sly peep at that world from which he seems to be excluded."

"And for all such men," replied Bob, "expelled from high and from good society, (even though I were compelled to allow by their own imprudence and folly) I [31]should always like to have a spare hundred, to send them in an anonymous cover."

"You are right," rejoined Tom, catching him ardently by the hand, "the sentiment does honour to your head and heart; for to such men, in general, is attached a heart-broken wife, withering by their side in the shade, as the leaves and the blossom cling together at all seasons, in sickness or in health, in affluence or in poverty, until the storm beats too roughly on them, and prematurely destroys the weakest. But I must warn you not to let your liberality get the better of your discretion, for there are active and artful spirits abroad, and even these necessities and miseries are made a handle for deception, to entrap the unwary; and you yet have much to learn—Puff lived two years on sickness and misfortune, by advertisements in the newspapers."

"How?" enquired Bob.

"You shall have it in his own words," said Dashall.

"I suppose never man went through such a series of

"calamities in the same space of time! Sir, I was five

"times made a bankrupt and reduced from a state of

"affluence, by a train of unavoidable misfortunes! then

"Sir, though a very industrious tradesman, I was twice

"burnt out, and lost my little all both times! I lived

"upon those fires a month. I soon after was confined by a

"most excruciating disorder, and lost the use of my limbs!

"That told very well; for I had the case strongly attested,

"and went about col—called on you, a close prisoner

"in the Marshalsea, for a debt benevolently contracted

"to serve a friend. I was afterwards twice tapped

"for a dropsy, which declined into a very profitable

"consumption! I was then reduced to—0—no—then,

"I became a widow with six helpless children—after

"having had eleven husbands pressed, and being left

"every time eight months gone with child, and without

"money to get me into an hospital!"

"Astonishing!" cried Bob, "and are such things possible?"

"A month's residence in the metropolis," said Dashall, "will satisfy your enquiries. One ingenious villain, a short time back, had artifice enough to defraud the public, at different periods of his life, of upwards of one hundred thousand pounds, and actually carried on his fraudulent schemes to the last moment of his existence, for he [32]defrauded Jack Ketch of his fee by hanging himself in his cell after condemnation."{1}