| Main Index |

| Volume I. Part 1 |

| Volume I. Part 2 |

| Volume II. Part 2 |

Chapter I.

A return to the metropolis, 2. Instance of exorbitant

charges, 3. Field-marshal Count Bertrand, 4. Lines on the

late Napoleon, 5. A mysterious vehicle, 6. The devil in Long

Acre, 7. The child in the hay, 8. A family triumvirate, 9.

Egyptian monuments, 10. Relations of Gog and Magog

discovered, 11. The Theban ram, 12. Egyptian antiquities,

13. Egyptian mummies, &c. 14. Curiosities of the museum, 15.

Statues of Bedford and Fox, 16. The knowing one deceived,

17. Covent Garden Market, 18. Miss Linwood's exhibition, 19.

Chapter II.

Tothill-fields Bridewell, 20. Perversion of justice, 21. A

laudable resolution, 22. Success and disappointment, 23. A

story out of the face, 24. A critical situation, 25. A hair-

breadth escape, 26. Kidnappers, or crimps, 27. Summary

justice averted, 28. Swindling manoeuvres, 29. Estates, &c.

in nubibus, 30. Fetters and apathy, 31. Urchin thief

picking-pockets, 32. Juvenile depravity, 33.

Chapter III.

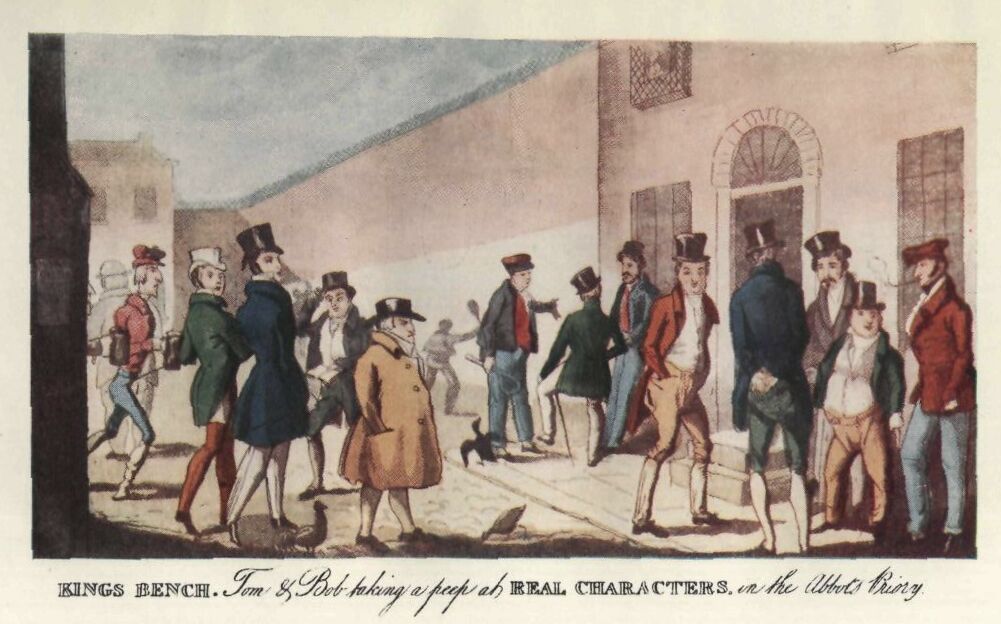

Life in St. George's Fields, 34. Chums—Day rules, &c. 35.

Hiring a horse—A bolter, 36. Characters of Abbot's priory,

37. Introductory sketch, 38. The flying pieman, 39.

Commercial activity, 40. A cutting joke, 41. Magdalen

Hospital, 42. Curious anecdote, 43. Surrey Theatre, &c, 44.

Admixture of characters, &c. 45.

Chapter IV.

Entry to Abbott's park, 46. A world within walls, 47.

Finding a friend at home, 48. Exterior of the chapel, 49. A

finish to education, 50. The walking automaton, 51. The

parliamentary don, 52. The tape merchant, &c. 53. A morning

in the Bench, 54. Prison metamorphoses, 55. Friendly

congratulations, 56. Preparations for a turn to, 57. The

college cries, 58. Another real character, 59. A mutual

take-in, 60. A college dinner, 61. Free from college rules,

62. A heavy-wet party, 63. Keeping the game alive, 64. An

agreeable surprise, 65. Harmony disturbed, 66.

Chapter V.

London munificence, 67. Vauxhall Bridge, 68. Millbank

Penitentiary, 69. Metamorphoses of time, 70. Cobourg

Theatre, 71. Retrospection, 72. Intellectual progress, 73.

Wonders of the moderns, 74. Bridge-Street association, 75.

Infidel pertinacity, 76. City coffee house, 77. St. Paul's

Cathedral, 78. Clockwork and great bell, 79. Serious

cogitations disturbed, 80. A return homeward, 81.

Chapter VI.

Westminster Abbey, 82. Monuments—Poets' corner, 83. Henry

Seventh's chapel, 84. Interesting prospect, 85. Fees exacted

for admission, 86. Westminster Hall—Whitehall, 87. Sir

Robert Wilson, 88. Temptations to depredation, 89. Sympathy

excited, 90. A sad story strangely told, 91. Fleet Street—

Doctor Johnson, 92. Fleet Market, 93. The market in an

uproar, 94. The rabbit pole-girl, 95. Princess of

Cumberland, 96. Doubts of royal legitimacy, 97. Mud-larks,

picking up a living, 98. The boil'd beef house, 99. A

spunger, 100. Gaol of Newgate, 101. Jonathan Wild's

residence, 102. Entering the Holy Land, 103. The Holy Land,

104. Salt herrings and dumplings, 105. Deluge of beer, 106.

Mrs. C*r*y, 107. Andrew Whiston, 108.

Chapter VII.

A dinner party, 109. Complimentary song, 110. Irish posting,

111. Extraordinary robbery, 112. Follies of fashion—ennui,

113. A set-to in a gambling house, 114. A nunnery—the Lady

abbess, 115. Life in a cellar, 116. Advantageous offer

rejected, 117. "Bilge water not whiskey," 118. Aqua fortis

and aqua fifties, 119. A quarrel—appeal to justice, 120.

Finale of a long story, 121.

Chapter VIII.

An unexpected visitor, 122. Private accommodations, 123. The

hero of Waterloo, 124. "The lungs of the metropolis," 125.

How to cut up a human carcass. 126. Resurrectionists, 127. A

perambulation of discovery, 128. Irish recognition, 129. A

discovery—Mother Cummings, 130. Wife hunting, 131.

Elopement, 132. Female instability, 133. Manouvres Return to

town, 134. Making the most of a good thing, 135. Ingenious

female shop-lifter, 136.

Chapter IX.

Thieves of habit and necessity, 137. A felicitous meeting,

138. Shopping—Ludicrous anecdote, 139. A tribute of

respect, 140. Royal waxworks, Fleet Street, 141. Sir Felix

as Macbeth, 142. Irish love, 143. Apathy in the midst of

danger, 144. "No wassel in the lob," 145. The bear at

Kensington Palace, 146.

Chapter X.

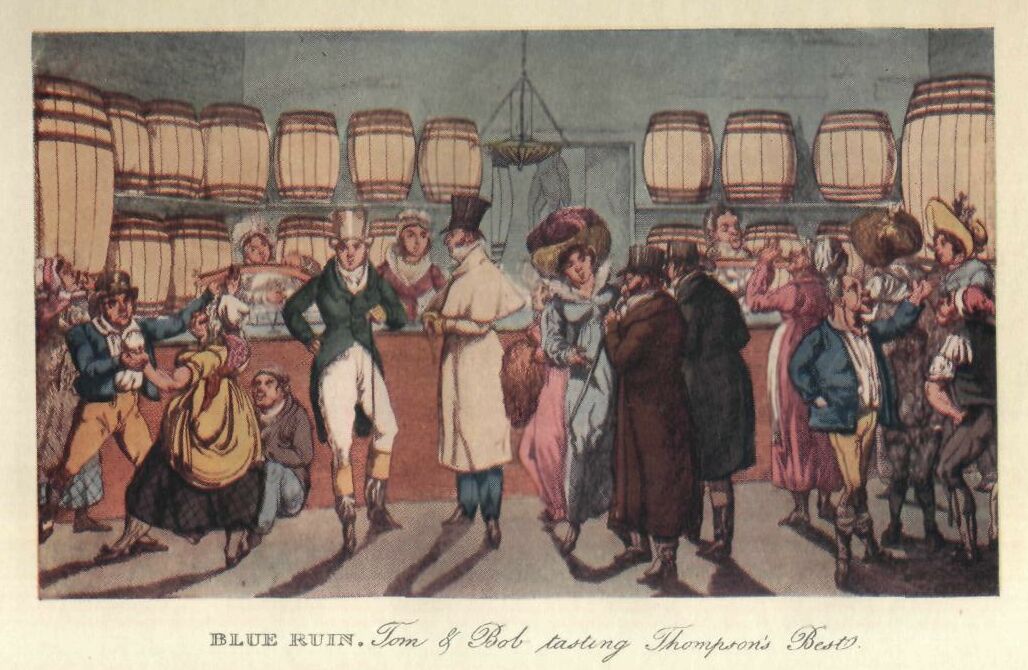

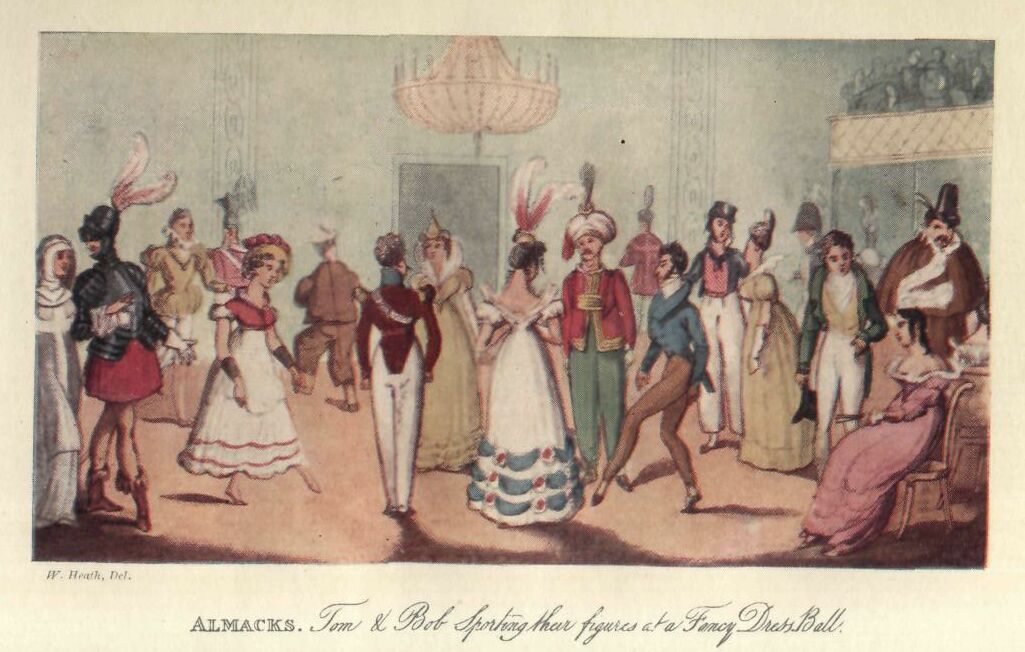

A change of pursuits, 147. Almack's Rooms, 148. A fancy-

dress ball, 149. Selection of partners, 150. Family

portraits, 151. A rout and routed, 152. Pleasures of

matrimony, 153. The discomfited Virtuoso, 154.

Chapter XI.

Frolics of Greenwich fair, 155. Dr. Eady—Wall chalking,

156. Packwood and puffing, 157. Greenwich Hospital, 158.

Greenwich pensioners, 159. Veterans at ease, 160. The old

commodore, 161. "Fought his battles o'er again," 162. The

Chapel—Hall, &e. 163.

Chapter XII.

An early hour in Piccadilly, 164. Cleopatra's needle, 165. A

modest waterman, 166. Interesting scenery, 167. Philosophy

in humble life, 168. Southwark Bridge, 169. London Bridge-

The Shades, 170. Itinerant musicians, 171. "Do not leave

your goods," 172. Riches of Lombard Street, 173. Mansion

House, 174. Curious case in justice room, 175. A reasonable

proposition, 176.

Chapter XIII.

An hour in the Sessions House, 177. A piteous tale of

distress, 178. Low life, 179. Serious business, 180. A

capture, 181. Johnny-raws and green-horns, 182. Decker the

prophet, 183. A devotee in danger, 184.

Chapter XIV.

A morning at home, 185. High life, 186. Converting felony

into debt, 187. Scene in a madhouse, 188. Apathy of

undertakers, 189. A provident undertaker, 190. A bribe

rejected, 191. Antiquated virginity, 192. Arrangements for

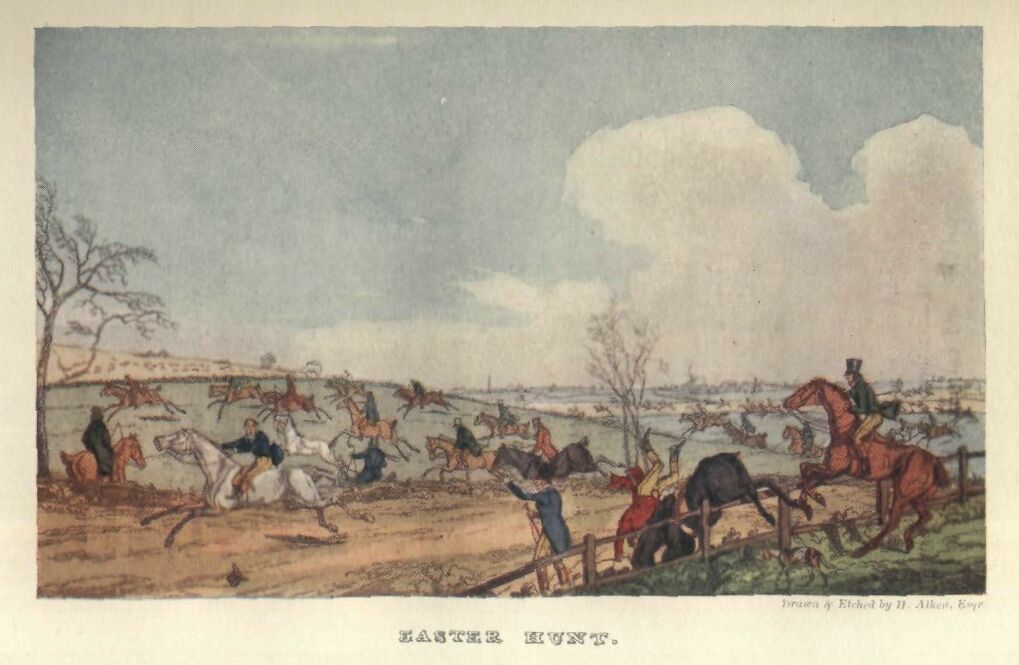

Easter, 193. A Sunday morning lounge, 194. Setting out for

Epping hunt, 195. Involuntary flight, 196. Motley groups on

the road, 197. Disasters of cockney sportsmen, 198. A

beautiful crature of sixty, 199. Tothill-fields fair, 200.

Whimsical introduction, 201. Ball at the Mansion-House, 202.

Chapter XV.

Guildhall, 203. Palace Yard—Relieving Guard, 204. The

regions below, 205. An old friend in the dark, 206. Seeing

clear again, 207. A rattler, 208.

Chapter XVI.

Civic festivity, 209. Guildhall, 210. Council chamber—

Paintings, 211. City public characters, 212. A modern

Polyphemus, 213. A classic poet, 214. Rhyming contagious,

215. Smithfield prad-sellers, 216. Jockeyship in the east,

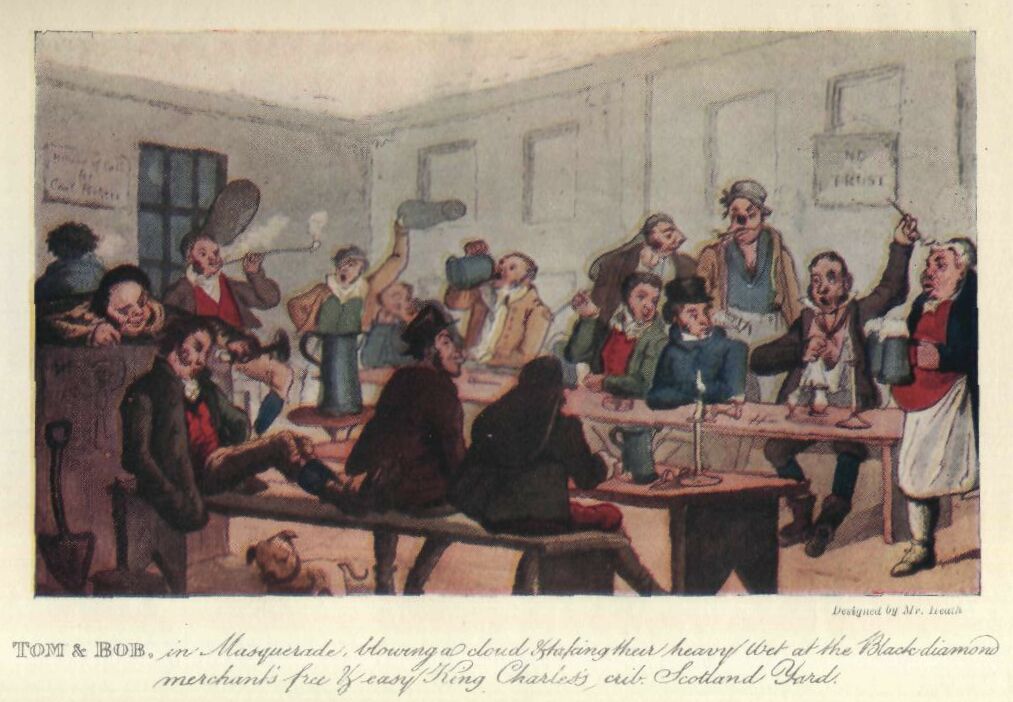

217. A peep at the Theatre, 218. The Finish, Covent Garden,

219. Wags of the Finish, 220. Smoking and joking, 222.

Chapter XVII.

A morning visit, 223. The fine arts, 224. Public

exhibitions, 225. Living artists, 226. Horse Guards—

Admiralty, 227. Westminster Bridge, 228. Promenade Rooms,

229. Improvements in the Park, 230. Ludicrous anecdote, 231.

A crazy fabric, 232. Regal splendour, 233. Marlborough

House, 234. Limmer's Hotel, 235. Laconic prescription, 236.

How to take it all, 237. How to get a suit of clothes, 238.

Ingenious swindling, 239. Talent perverted, 240.

Chapter XVIII.

The Harp, Drury Lane, 241. Wards of city of Lushington, 242.

The social compact, 243. A popular election, 244. Close of

the poll, 245. Oratorical effusions, 246. Harmony and

conviviality, 247. Sprees of the Market, 248. A lecture on

heads, 249. A stroll down Drury Lane, 250. A picture of real

characters, 251. "The burning shame," 253. Ludicrous

procession, 254.

Chapter XIX.

An old friend returned, 255. A good object in view, 256. An

alarming situation, 257. Choice of professions, 258. Pursuit

of fortune, 259. Advantages of law, 260. A curious law case,

261. Further arrangements, 262.

Chapter XX.

St. George's day, 263. Royalty on the wing, 264. Progress to

the levee, 265. An unfortunate apothegm, 266. How to adjust

a quarrel, 267. Wisdom in wigs, 268. A classical

acquaintance, 269. Royal modesty, 270. Ludicrous anecdote,

271. A squeeze in the drawing-room, 272. Pollution of the

sanctorum, 273. Procession of mail coaches, &c. 274. A

parody, 275. Two negatives make a positive, 276. Remarkable

anecdote, 277. Marrow-bones and cleavers, 278. The king and

the laureat, 279. A remonstrance, 280. Hint at retrenchment,

281.

Chapter XXI.

Diversity of opinions, 282. A fresh start, 283. A critique

on names, 284. The Cafe Royale, Regent Street, 285. A

singular character, 286. Quite inexplicable, 287.

Development, 288. Aquatic excursion, 289. A narrow escape,

290. Tower of London, 291. The lost pilot found, 295. River

gaiety, 296. Rowing match, 297.

Chapter XXII.

The tame hare, 298. Ingenuity of man, 299. London sights and

shows, 300. Automaton chess player, 301. South sea bubble,

302. New City of London tavern, 303. Moorfields, 304.

Epitaph collector, 305. Monumental gleanings, 307.

Voluminous collectors, 309. A horned cock, 310.

Extraordinary performance, 311. Female salamander, 312.

Regent's Canal, 313. Anecdote of a gormandizer, 314. Eating

a general officer alive, 315. A field orator, 316.

Chapter XXIII.

Munster simplicity, 317. A visit to an astrologer, 318. A

peep into futurity, 319. Treading-mill, 320. An unexpected

occurrence, 321. The sage taken in, 322. Statue of ill luck,

323. A concatenation of exquisites, 324. How to walk the

streets, 325. How to make a thoroughfare, 326. Dog stealers,

327. Canine knavery, 328. A vexatious affair, 329. How to

recruit your finances, 330. A domestic civic dinner, 331.

The very respectable man, 332.

Chapter XXIV.

Vauxhall Gardens, 334, Various amusements, 335. Sober

advice, 336. Fashionable education, 337. University

education, 338. Useful law proceedings, 339. How to punish a

creditor, 340. Exalted characters, 341. Profligacy of a

peer, 342. Mr. Spankalong, 343. Other characters of ton,

344. Sprig of fashion, 345. An everlasting prater, 346. And

incorrigible fribble, 347. Kensington Gardens and Park, 348.

Statue of Achilles, 349.

Chapter XXV.

A medley of characters, 353. Fashionables, 354. More

fashionables, 355. More life in St. Giles's, 356.

Reconnoitring—a discovery, 357. Tragedy prevented, 358.

Fat, fair, and forty, 359. Philosophic coxcombs, 360 Blanks

in society, 361.

Chapter XXVI.

A ride, 362. Exceptions to trade rivalship, 363. Effects of

superior education, 364. Affectation in names, 365.

Portraits of governesses, 366. Road to matrimony, 367.

Villainy of private madhouses, 369. Appearances may deceive,

370.

Chapter XXVII.

Pleasing intelligence, 371. Moralizing a little, 373. Cries

of London, 374. The Blacking Poet, 375. Literary squabble

376. Curious Merchandise, 377.

Chapter XXVIII.

A new object of pursuit, 378. Royal visit to Scotland, 379.

Embarkation, 381. Royal recollections, 38'2.

Chapter XXIX.

Port of London, 383. Descriptive entertainment, 384. A rea

swell party, 385. An Irish dancing master, 386. Female

disaster, 387. Blackwall—East India Docks, 388. Sir Robert

Wigram, 389. Domestic happiness, 390. West India Docks, 391.

Loudon Docks, 393. News from home, 394.

Chapter XXX.

Travelling preparations, 395. Whimsical associations, 396.

Antiquity and origin of signs, 397. Signs of altered times,

398. Ludicrous corruptions, 399. A curious metamorphosis,

400. A sudden breeze, 401. A smell of powder, 402.

Chapter XXXI.

An unexpected visitor, 403. Sketches of fashionable life,

404. A Corinthian rout, 405. A Corinthian dinner party, 406.

A new picture of real life, 409. More wise men of the East,

411.

Chapter XXXII.

Anticipation of danger, 415. Smoke without fire, 416.

Fonthill Abbey, 417. Instability of fortune, 419. Wealth

without ostentation, 420. Eccentricity of character, 421.

Extremes meeting, 422.

Chapter XXXIII.

Sketches of new scenes, 423. A critical essay on taste, 424.

The pleasures of the table, 425. A whimsical exhibition,

426. Canine sobriety, 427.

Chapter XXXIV.

Anticipation, 428. Obligation, 429. Change of subjects, 430

Magasin de Mode, 431. Bell, Warwick Lane, 432. Bull and

Mouth Street, 433. Bull and Mouth Inn, 434. Jehu chaff, 435.

Adieu to London, 436.

With what unequal tempers are we form'd!

One day the soul, elate and satisfied,

Revels secure, and fondly tells herself

The hour of evil can return no more:

The next, the spirit, pall'd and sick of riot,

Turns all to discord, and we hate our being,

Curse our past joys, and think them folly all.

[1]MATTER and motion, say Philosophers, are inseparable, and the doctrine appears equally applicable to the human mind. Our country Squire, anxious to testify a grateful sense of the attentions paid him during his London visit, had assiduously exerted himself since his return, in contributing to the pleasures and amusements of his visitors; and Belville Hall presented a scene of festive hospitality, at once creditable to its liberal owner, and gratifying to the numerous gentry of the surrounding neighbourhood.

But however varied and numerous the sports and recreations of rural life, however refined and select the circle of its society, they possessed not the endless round of metropolitan amusement, nor those ever-varying delights produced amid "the busy hum of men," where every street is replete with incident and character, and every hour fraught with adventure.

Satiety had now evidently obtruded itself amid the party, and its attendants, lassitude and restlessness, were not long in bringing up the rear. The impression already made upon the mind of Bob by the cursory view he had taken of Life in London was indelible, and it required little persuasion on the part of his cousin, the Hon. Tom Dashall, to induce him again to return to scenes of so much delight, and which afforded such inexhaustible stores of amusement to an ardent and youthful curiosity.

[2]A return to the Metropolis having therefore been mutually agreed upon, and every previous arrangement being completed, the Squire once more abdicated for a season his paternal domains, and accompanied by his cousin Dashall, and the whole ci-devant party of Belville Hall, arrived safe at the elegant mansion of the latter, where they planned a new system of perambulation, having for its object a further investigation of manners, characters, objects, and incidents, connected with Real Life in London.

"Come," cried Dashall, one fine morning, starting up immediately after breakfast—

"——rouse for fresh game, and away let us haste,

The regions to roam of wit, fashion, and taste;

Like Quixote in quest of adventures set out,

And learn what the crowds in the streets are about;

And laugh when we must, and approve when we can,

Where London displays ev'ry feature of man."

"The numerous hotels, bagnios, taverns, inns, coffee-houses, eating-houses, lodging-houses, &c. in endless variety, which meet the eye in all parts of the metropolis, afford an immediate choice of accommodation, as well to the temporary sojourner as the permanent resident; where may be obtained the necessaries and luxuries of life, commensurate with your means of payment, from one shilling to a guinea for a dinner, and from sixpence to thirty shillings a night for a lodging!

"The stranger recommended to one of these hotels, who regales himself after the fatigues of a journey with moderate refreshment, and retires to rest, and preparing to depart in the morning, is frequently surprised at the longitudinal appearance and sum total of his bill, wherein every item is individually stated, and at a rate enormously extravagant. Remonstrance is unavailable; the charges are those common to the house, and in failure of payment your luggage is under detention, without the means of redress; ultimately the bill must be paid, and the only consolation left is, that you have acquired a useful, though expensive lesson, how to guard in future against similar exaction and inconvenience."{1}

1 Marlborough Street.—Yesterday, Mrs. Hickinbottom, the

wife of Mr. Hickinbottom, the keeper of the St. Petersburgh

Hotel in Dover Street, Piccadilly, appeared to a summons to

answer the complaint of a gentleman for unlawfully detaining

his luggage under the following circumstances: The

complainant stated, that on Thursday evening last, on his

arrival in town from Aberdeen, he went to the White Horse

Cellar, Piccadilly; but the house being full, he was

recommended to the St. Petersburgh Hotel in Dover Street;

where, having taken some refreshment and wrote a letter, he

went to bed, and on the following morning after break-fast,

he desired the waiter to bring him his bill, which he did,

and the first item that presented itself was the moderate

charge of one pound ten shillings for his bed; and then

followed, amongst many others, sixpence for a pen, a

shilling for wax, a shilling for the light, and two and

sixpence for other lights; so that the bill amounted in the

whole to the sum of two pounds one shilling for his night's

lodging! To this very exorbitant charge he had refused to

submit; in consequence of which he had been put to great

inconvenience by the detention of his luggage. The

magistrate animadverted with much severity on such

extravagant charges on the part of the tavern-keeper, and

advised that upon the gentleman paying fifteen shillings,

the things might be immediately delivered up. To these

terms, however, Mrs. Hickinbottom refused to accede, adding

at the same time, that the gentleman had only been charged

the regular prices of the house, and that she should insist

upon the whole amount of the bill being paid, for that the

persons who were in the habit of coming to their house never

objected to such, the regular price of their lodgings being

ten guineas per week! The magistrate lamented that he had

no power to enforce the things being given up, but he

recommended the complainant to bring an action against the

tavern-keeper for the detention.

[3] These were the observations directed by Dashall to his friend, as they passed, one morning, the Hotel de la Sabloniere in Leicester Square.

"Doubtless," he continued, "in those places of affluent resort, the accommodations are in the first style of excellence; yet with reference to comfort and sociability, were I a country gentleman in the habit of occasionally visiting London, my temporary domicile should be the snug domesticated Coffee-house, economical in its charges and pleasurable in the variety of its visitors, where I might, at will, extend or abridge my evening intercourse, and in the retirement of my own apartment feel myself more at home than in the vacuum of an hotel."

The attention of our perambulators, in passing through the Square, was attracted by a fine boy, apparently about eight years of age, dressed in mourning, who, at the door of Brunet's Hotel, was endeavouring with all his little strength and influence to oppose the egress of a large Newfoundland dog, that, indignant of restraint, seemed desirous in a strange land of introducing himself to [4] canine good fellowship. The boy, whose large dark eyes were full of animation, and his countenance, though bronzed, interestingly expressive, remonstrated with the dog in the French language. "The animal does not understand you," exclaimed Tallyho, in the vernacular idiom of the youth, "Speak to him in English." "He must be a clever dog," answered the boy, "to know English so soon, for neither him nor I have been in England above a week, and for the first time in our lives."—"And how is it," asked Tallyho, "that you speak the English language so fluently?" "O," said the little fellow, "my mother taught it me; she is an English woman, and for that reason I love the English, and am much fonder of talking their language than my own." There was something extremely captivating in the boy. The dog now struggling for freedom was nearly effecting his release, when the two friends interposed their assistance, and secured the pre-meditating fugitive at the moment when, to inquire the cause of the bustle, the father of the child made his appearance in the person of Field Marshal Count Bertrand. The Count, possessing all the characteristics of a gentleman, acknowledged politely the kind attention of the strangers to his son, while, on the other hand, they returned his obeisance with the due respect excited by his uniform friendship and undeviating attachment to greatness in adversity. The discerning eye of Field Marshal Bertrand justly appreciated the superior rank of the strangers, to whom he observed, that during the short period he had then been in England, he had experienced much courtesy, of which he should always retain a grateful recollection. This accidental interview was creative of reciprocal satisfaction, and the parties separated, not without an invitation on the part of the boy, that his newly found acquaintances would again visit the "friends of the Emperor."{1}[5]

1 LINES SUPPOSED TO HAVE BEEN WRITTEN BY

THE EX-EMPEROR NAPOLEON IN HIS LAST ILLNESS.

Too slowly the tide of existence recedes

For him in captivity destined to languish,

The Exile, abandon'd of fortune, who needs

The friendship of Death to obliviate his anguish.

Yet, even his last moments unmet by a sigh,

Napoleon the Great uncomplaining shall die!

Though doom'd on thy rock, St. Helena, to close

My life, that once presag'd ineffable glory,

Unvisited here though my ashes repose,

No tablet to tell the lone Exile's sad story,—

Napoleon Buonaparte—still shall the name

Exist on the records immortal of Fame!

Posterity, tracing the annals of France,

The merits will own of her potent defender;

Her greatness pre-eminent skill'd to advance,

Creating, sustaining, her zenith of splendour;

Who patroniz'd arts, and averted alarms,

Till crush'd by the union of nations in arms!

I yield to my fate! nor should memory bring

One moment of fruitless and painful reflection

Of what I was lately—an Emperor and King,

Unless for the bitter, yet fond recollection

Of those, who my heart's best endearments have won,

Remote from my death-bed—my Consort and SON!

Denied in their arms even to breathe my last sigh,

No relatives' solace my exit attending;

With strangers sojourning, 'midst strangers I die,

No tear of regret with the last duties blending.

To him, the lorn Exile, no obsequies paid,

Whose fiat a Universe lately obey'd!

Make there then my tomb, where the willow trees wave,

And, far in the Island, the streamlet meanders;

If ever, by stealth, to my green grassy grave

Some kind musing spirit of sympathy wanders—

"Here rests," he will say, "from Adversity's pains,

Napoleon Buonaparte's mortal remains!"

We have no disposition to enter into the character of the

deceased Ex-Emperor; history will not fail to do justice

alike to the merits and the crimes of one, who is inevitably

destined to fill so portentous a page on its records. At the

present time, to speak of the good of which he may have been

either the intentional or the involuntary instrument,

without some bias of party feeling would be impossible.

"Hard is his fate, on whom the public gaze

Is fix'd for ever, to condemn or praise;

Repose denies her requiem to his name,

And folly loves the martyrdom of fame."

At all events, he is now no more; and "An English spirit

wars not with the dead."

"The Count," said Dashall to his Cousin, as they pursued their walk, "remains in England until he obtain [6] permission from the King of France to return to his native country: that such leave will be given, there is little doubt; the meritorious fidelity which the Count has uniformly exemplified to his late unfortunate and exiled Master, has obtained for him universal esteem, and the King of France is too generous to withhold, amidst the general feeling, his approbation."

Passing through Long Acre in their progress towards the British Museum, to which national establishment they had cards of admission, the two friends were intercepted in their way by a concourse at a coach-maker's shop, fronting which stood a chariot carefully matted round the body, firmly sewed together, and the wheels enveloped in hay-bands, preparatory to its being sent into the country. Scarcely had these precautionary measures of safety been completed, when a shrill cry, as if by a child inside the vehicle, was heard, loud and continuative, which, after the lapse of some minutes, broke out into the urgent and reiterated exclamation of—"Let me out!—I shall be suffocated!—pray let me out!"

The workmen, who had packed up the carriage, stared at each other in mute and appalling astonishment; they felt conscious that no child was within the vehicle; and when at last they recovered from the stupor of amazement, they resisted the importunity of the multitude to strip the chariot, and manfully swore, that if any one was inside, it must be the Devil himself, or one of his imps, and no human or visible being whatsoever.

Some, of the multitude were inclined to a similar opinion. The crowd increased, and the most intense interest was depicted in every countenance, when the cry of "Let me out!—I shall die!—For heaven's sake let me out!" was audibly and vehemently again and again repeated.

The impatient multitude now began to cut away the matting; when the workmen, apprehensive that the carriage might sustain some damage from the impetuosity of their proceedings, took upon themselves the act of dismantling the mysterious machine; during which operation, the cry of "Let me out!" became more and more clamorously importunate. At last the vehicle was laid bare, and its door thrown open; when, to the utter amazement of the crowd, no child was there—no trace was to be seen of aught, human or super-human! The [7] assemblage gazed on the vacant space from whence the sounds had emanated, in confusion and dismay. During this momentary suspense, in which the country 'Squire participated, a voice from some invisible agent, as if descending the steps of the carriage, exclaimed—"Thank you, my good friends, I am very much obliged to you—I shall now go home, and where my home is you will all know by-and-by!"

With the exception of Dashall and Tallyho, the minds of the spectators, previously impressed with the legends of superstition and diablerie, gave way under the dread of the actual presence of his satanic majesty; and the congregated auditors of his ominous denunciation instantaneously dispersed themselves from the scene of witchery, and, re-assembling in groupes on distant parts of the street, cogitated and surmised on the Devil's visit to the Coachmakers of Long Acre!

Tallyho now turned an inquisitive eye on his Cousin, who answered the silent and anxious enquiry with an immoderate fit of laughter, declaring that this was the best and most ingenious hoax of any he had ever witnessed, and that he would not have missed, on any consideration whatsoever, the pleasure of enjoying it. "The Devil in Long Acre!—I shall never forget it," exclaimed the animated Cousin of the staring and discomfited 'Squire.

"Explain, explain," reiterated the 'Squire, impatiently.

"You shall have it in one word,"answered Dashall—"Ventriloquism!"{1}

1 This hoax was actually practised by a Ventriloquist in the

manner described. It certainly is of a less offensive nature

than that of many others which have been successfully

brought for-ward in the Metropolis, the offspring of folly

and idleness.—"A fellow," some years ago, certainly not "of

infinite humour," considering an elderly maiden lady of

Berner Street a "fit and proper subject" on whom to

exercise his wit, was at the trouble of writing a vast

number of letters to tradesmen and others, magistrates and

professional men, ordering from the former various goods,

and requiring the advice, in a case of emergency, of the

latter, appointing the same hour, to all, of attendance; so

that, in fact, at the time mentioned, the street, to the

annoy-ance and astonishment of its inhabitants, was crowded

with a motley group of visitants, equestrian and pedestrian,

all eagerly pressing forward to their destination, the old

lady's place of residence. In the heterogeneous assemblage

there were seen Tradesmen of all denominations, accompanied

by their Porters, bearing various articles of household

furniture; Counsellors anticipating fees; Lawyers engaged

to execute the last will and testament of the heroine of the

drama, and, not the least conspicuous, an Undertaker

preceded by his man with a coffin; and to crown the whole,

"though last not least in our esteem," the then Lord Mayor of

London, who, at the eager desire of the old Lady, had, with

a commendable feeling of humanity, left his civic dominions,

in order to administer, in a case of danger and difficulty,

his consolation and assistance. When, behold! the clue was

unravelled, the whole turn'd out an hoax, and the Author

still remains in nubibus!!!

[8] "And who could have been the artist?" enquired Tallyho.

"Nay," answered his friend, "that is impossible to say; some one in the crowd, but the secret must remain with himself; neither do I think it would have been altogether prudent his revealing it to his alarmed and credulous auditory."

"A Ventriloquist," observed the 'Squire, "is so little known in the country, that I had lost all reminiscence of his surprising powers; however, I shall in future, from the occurrence of to-day, resist the obtrusion of superstition, and in all cases of 'doubtful dilemma' remember the Devil in Long Acre!"{l}

"Well resolved," answered Dashall; and in a few minutes they gained Great Russel Street, Bloomsbury, without further incident or interruption.

1 The child in the hat.—Not long since, a Waggoner coming

to town with a load of hay, was overtaken by a stranger, who

entered into familiar conversation with him. They had not

pro-ceeded far, when, to the great terror of Giles Jolt, a

plaintive cry, apparently that of a child, issued from the

waggon. "Didst hear that, mon?" exclaimed Giles. The cry was

renewed—"Luord! Luord! an there be na a babe aneath the

hay, I'se be hanged; lend us a hand, mon, to get un out, for

God's sake!" The stranger very promptly assisted in

unloading the waggon, but no child was found. The hay now

lay in a heap on the road, from whence the cry was once more

long and loudly reiterated! In eager research, Giles next

proceeded to scatter the hay over the road, the cry still

continuing; but when, at last, he ascertained that the

assumed infantine plaint was all a delusion, his hair stood

erect with horror, and, running rapidly from his companion,

announced that he had been associated on the road by the

Devil, for that none else could play him such a trick! It

was not without great difficulty that the people to whom he

told this strange story prevailed on him to return, at last,

to his waggon and horses; he did so with manifest

reluctance. To his indescribable relief, his infernal

companion hail vanished in the person of the Ventriloquist,

and Jolt still believes in the supernatural visitation!

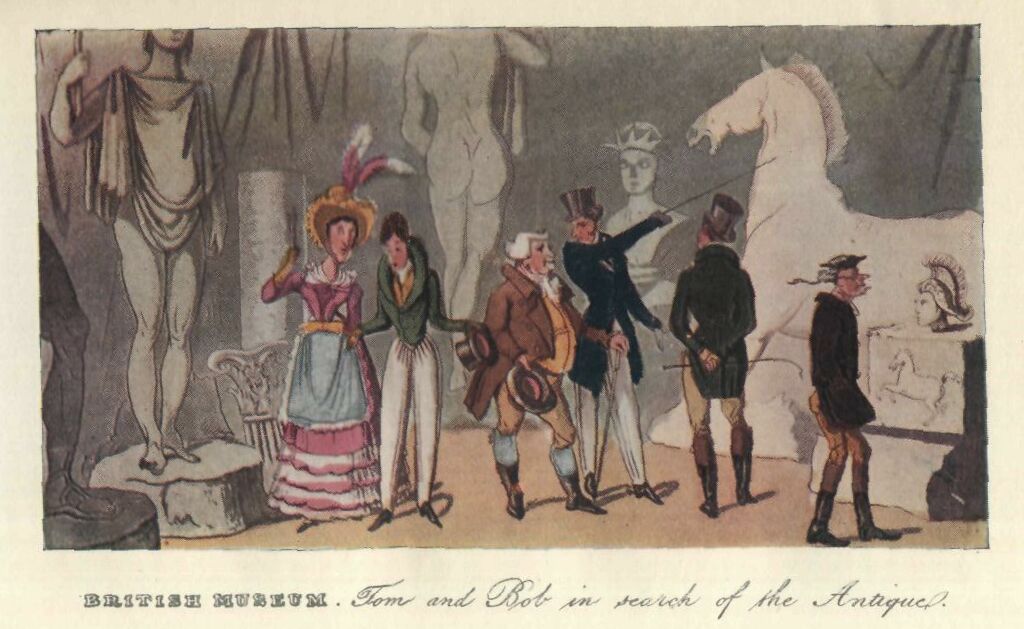

[9] Amongst the literary and scientific institutions of the Metropolis, the British Museum, situated in Great Russel Street, Bloomsbury, stands pre-eminent.

Entering the spacious court, our two friends found a party in waiting for the Conductor. Of the individuals composing this party, the reconnoitering eye of Dashall observed a trio, from whence he anticipated considerable amusement. It was a family triumvirate, formed of an old Bachelor, whose cent per cent ideas predominated over every other, wheresoever situated or howsoever employed; his maiden Sister, prim, starch and antiquated; and their hopeful Nephew, a complete coxcomb, that is, in full possession of the requisite concomitants—ignorance and impudence, and arrayed in the first style of the most exquisite dandyism. This delectable triumviri had emerged from their chaotic recess in Bearbinder-lane; the Exquisite, to exhibit his sweet person along with the other curiosities of the Museum; his maiden Aunt, to see, as she expressed it, the "He-gipsyian munhuments, kivered with kerry-glee-fix;" and her Brother, to ascertain whether, independent of outlandish baubles, gimcracks and gewgaws, there was any thing of substantiality with which to enhance the per contra side in the Account Current between the British Museum and the Public!

Attaching themselves to this respectable trio, Dashall and Tallyho followed, with the other visitants, the Guide, whose duty it that day was to point out the various curiosities of this great national institution.

The British Museum was established by act of parliament, in 1753, in pursuance of the will of Sir Hans Sloane, who left his museum to the nation, on condition that Parliament should pay 20,000L. to his Executors, and purchase a house sufficiently commodious for it. The parliament acted with great liberality on the occasion; several other valuable collections were united to that of Sir Hans Sloane, and the whole establishment was completed for the sum of 85,000L. raised by lottery. At the institution of this grand treasury of learning, it was proposed that a competent part of 1800L. the annual sum granted by parliament for the support of the house, should be appropriated for the purchase of new books; but the salaries necessary for the officers, together with the contingent expenses, have always exceeded the allowance; so that the Trustees have been repeatedly [10] obliged to make application to defray the necessary charges.

Mr. Timothy Surety, the before mentioned Bearbinder-lane resident, of cent per cent rumination; his accomplished sister, Tabitha; his exquisite nephew, Jasper; and the redoubtable heroes of our eventful history, were now associated in one party, and the remaining visitants were sociably amalgamated in another; and each having its separate Conductor, both proceeded to the inspection of the first and most valuable collection in the universe.

On entering the gate, the first objects which attracted attention were two large sheds, defending from the inclemency of the seasons a collection of Egyptian monuments, the whole of which were taken from the French at Alexandria, in the last war. The most curious of these, perhaps, is the large Sarcophagus beneath the shed to the left, which has been considered as the exterior coffin of Alexander the Great, used at his final interment. It is formed of variegated marble, and, as Mrs. Tabitha Surety observed, was "kivered with Kerry-glee-fix."

"Nephew Jasper," said his Uncle, "you are better acquainted with the nomenclature, I think you call it, of them there thing-um-bobs than I am—what is the name of this here?"

"My dear Sir," rejoined the Exquisite, "this here is called a Sark o' Fegus, implying the domicile, or rather, the winding-sheet of the dead, as the sark or chemise wound itself round the fair forms of the daughters of O'Fegus, a highland Chieftain, from whom descended Philip of Macedon, father of Alexander the Great; and thence originated the name subsequently given by the highland laird's successors, to the dormitory of the dead, the Sark o' Fegus, or in the corruption of modern orthography, Sarcophagus."

Timothy Surety cast an approving glance towards his Nephew, and whispering Dashall, "My Nephew, Sir, apparently a puppy, Sir, but well informed, nevertheless—what think you of his definition of that hard word? Is he not, I mean my Nephew Jaz, a most extraordinary young man?"

"Superlatively so," answered Dashall, "and I think you are happy in bearing affinity to a young man of such transcendent acquirements."

[11]"D—n his acquirements!" exclaimed Timothy; "would you think it, they are of no use in the way of trade, and though I have given him many an opportunity of doing well, he knows no more of keeping a set of books by double-entry, than Timothy Surety does of keeping a pack of hounds, who was never twenty miles beyond the hearing of Bow bells in all his lifetime!"

This important communication, having been made apart from the recognition of the Aunt and Nephew, passed on their approach, unanswered; and Dashall and his friend remained in doubt whether or not the Nephew, in his late definition of the word Sarcophagus, was in jest or earnest: Tallyho inclined to think that he was hoaxing the old gentleman; on the other hand, his Cousin bethought himself, that the apparent ingenuity of Jaz's definition was attributable entirely to his ignorance.

Here also were two statues of Roman workmanship, supposed to be those of Marcus Aurelius and Severus, ancient, but evidently of provincial sculpture.

Mrs. Tabitha, shading her eyes with her fan, and casting a glance askew at the two naked figures, which exhibited the perfection of symmetry, enquired of her Nephew who they were meant to represent.

His answer was equally eccentric with that accorded to his Uncle on the subject of the Sarcophagus.

"My dear Madam!" said Jaz, "these two figures are consanguineous to those of Gog and Magog in Guildhall, being the lineal descendants of these mighty associates of the Livery of London!"

"But, Jaz" rejoined the antique dame, "I always understood that Messieurs Gog and Magog derived their origin from quite a different family."

"Aunt of mine," responded Jaz, "the lofty rubicunded Civic Baronet shall not be 'shorn of his beams;' he claims the same honour with his brainless brothers before us-he is a scion of the same tree; Sir W*ll**m, the twin brothers of Guildhall, and these two sedate Gentlemen of stone, all boast the honour of the same extraction!"

Behind them, on the right, was a ram's head of very curious workmanship, from Thebes.

"Perhaps, Sir," said Mrs. Tabitha, graciously addressing herself to 'Squire Tallyho, "you can inform us what may be the import of this singular exhibition?"

"On my honour, Madam," answered the 'Squire, "I cannot satisfactorily resolve the enquiry; I am a country [12] gentleman, and though conversant with rains and rams' horns in my own neighbourhood, have no knowledge of them with reference to the connexion of the latter with the Citizens of London or Westminster!"

Jaz again assumed the office of expositor.—"My very reverend Aunt," said Jaz, "I must prolegomenize the required explanation with a simple anecdote:—

"When Charles the Second returned from one of his northern tours, accompanied by the Earl of Rochester, he passed through Shoreditch. On each side the road was a huge pile of rams' horns, for what purpose tradition saith not. 'What is the meaning of all this?' asked the King, pointing towards the symbolics. 'I know not,' rejoined Rochester, 'unless it implies that the Citizens of London have laid their heads together, to welcome your Majesty's return!' In commemoration of this witticism, the ram's head is to the Citizens of London a prominent feature of exhibition in the British Museum."

This interpretation raised a laugh at the expense of Timothy Surety, who, nevertheless, bore it with great good humour, being a bachelor, and consequently not within the scope of that ridicule on the basis of which was founded the present sarcastic fabric.

It was now obvious to Dash all and his friend, that this young man, Jasper Surety, was not altogether the ignoramus at first presumed. They had already been entertained by his remarks, and his annotations were of a description to warrant the expectancy of further amusement in the progress of their inspection.

From the hall the visitors were led through an iron gateway to the great staircase, opposite the bottom of which is preserved a model in mahogany, exhibiting the method used by Mr. Milne in constructing the works of Blackfriars' Bridge; and beneath it are some curious fragments from the Giant's Causeway in Ireland.

These fragments, however highly estimated by the naturalist and the antiquary, were held in derision by the worldly-minded Tim. Surety, who exclaimed against the folly of expending money in the purchase of articles of no intrinsic value, calculated only to gratify the curiosity of those inquisitive idlers who affect their admiration of every uninteresting production of Nature, and neglect the pursuit of the main chance, so necessary in realizing the comforts of life.

[13] These sordid ideas were opposed by Dashall and the 'Squire, to whom they seemed particularly directed. Mrs. Tabitha smiled a gracious acquiescence in the sentiments of the two strangers, and Jasper expressed his regret that Nuncle was not gifted and fated as Midas of ancient times, who transformed every thing that he touched into gold!

The Egyptian and Etruscan antiquities next attracted the attention of the visitors. Over a doorway in this room is a fine portrait of Sir William Hamilton, painted by Sir Joshua Reynolds. Dashall and Tallyho remarked with enthusiasm on these beautiful relics of the sculpture of former ages, several of which were mutilated and disfigured by the dilapidations of time and accident. Of the company present, there stood on the left a diminutive elderly gentleman in the act of contemplating the fragment of a statue in a posterior position, and which certainly exhibited somewhat of a ludicrous appearance; on the right, the exquisite Jasper pointed out, with the self-sufficiency of an amateur, the masculine symmetry of a Colossian statue to his Aunt of antiquated virginity, whose maiden purity recoiling from the view of nudation, seemed to say, "Jaz, wrap an apron round him!" while in the foreground stood the rotunditive form of Timothy Surety, who declared, after a cursory and contemptuous glance at the venerable representatives of mythology, "That with the exception of the portrait of Sir William Hamilton, there was not in the room an object worth looking at; and as for them there ancient statutes," (such was his vernacular idiom and Bearbinder barbarism) "I would not give twopence for the whole of this here collection, if it was never for nothing else than to set them up as scare-crows in the garden of my country house at Edmonton!"

Jasper whispered his aunt, that nuncks was a vile bore; and the sacrilegious declaration gave great offence to the diminutive gentleman aforesaid, who hesitated not in pronouncing Timothy Surety destitute of taste and vertu; to which accusation Timothy, rearing his squat form to its utmost altitude, indignantly replied, "that there was not an alderman in the City of London of better taste than himself in the qualities of callipash and callipee, and that if the little gemmen presumed again to asperse his vartue, he would bring an action against him tor slander and defamation of character." The minikin man gave Timothy a glance of ineffable disdain, and left the room. Mrs. [14] Tabitha, in the full consciousness of her superior acquirements, now directed a lecture of edification to her brother, who, however, manfully resisted her interference, and swore, that "where his taste and vartue were called in question he would not submit to any she in the universe."

Mrs. Tabitha, finding that on the present occasion her usual success would not predominate, suspended, like a skilful manoeuvreist, unavailable attack, and, turning to her nephew, required to know what personage the tall figure before them was meant to represent. Jasper felt not qualified correctly to answer this enquiry, yet unwilling to acknowledge his ignorance, unhesitatingly replied, "One of the ancient race of architects who built the Giant's Causeway in the north of Ireland." This sapient remark excited a smile from the two friends, who shortly afterwards took an opportunity of withdrawing from further intercourse with the Bearbinder triumviri, and enjoyed with a more congenial party the remaining gratification which this splendid national institution is so well calculated to inspire.

Extending their observations to the various interesting objects of this magnificent establishment, the two prominent heroes of our eventful history derived a pleasure only known to minds of superior intelligence, to whom the wonders of art and nature impart the acmé of intellectual enjoyment.

Having been conducted through all the different apartments, the two friends, preparing to depart, the 'Squire tendered a pecuniary compliment to the Guide, in return for his politeness, but which, to the surprise of the donor, was refused; the regulations of the institution strictly prohibiting the acceptance by any of its servants of fee or reward from a visitor, under the penalty of dismissal.{1}

1 Although the limits of this work admit not a minute detail

of the rarities of the British Museum, yet a succinct

enumeration of a few particulars may not prove unacceptable

to our Readers.

In the first room, which we have already noticed, besides

the Egyptian and Etruscan antiquities, is a stand filled

with reliques of ancient Egypt, amongst which are numerous

small representatives of mummies that were used as patterns

for those who chose and could afford to be embalmed at their

decease.

The second apartment is principally devoted to works of art,

be-ginning with Mexican curiosities. The corners opposite

the light are occupied by two Egyptian mummies, richly

painted, which were both brought from the catacombs of

Sakkara, near Grand Cairo.

The third room exhibits a rich collection of curiosities

from the South Pacific Ocean, brought by Capt. Cook. In the

left corner is the mourning dress of an Otaheitean lady, in

which taste and barbarity are curiously blended. Opposite

are the rich cloaks and helmets of feathers from the

Sandwich Islands.

The visitor next enters the manuscript department, the first

room of which is small, and appropriated chiefly to the

collections of Sir Hans Sloane. The next room is completely

filled with Sir Robert Harley's manuscripts, afterwards Earl

of Oxford, one of the most curious of which is a volume of

royal letters, from 1437 to the time of Charles I.. The next

and last room of the manuscript department is appropriated

to the ancient royal library of manuscripts, and Sir Robert

Cotton's, with a few-later donations. On the table, in the

middle of the room, is the famous Magna Charta of King John;

it is written on a large roll of parchment, and was much

damaged in the year 1738, when the Cotton library took fire

at Westminster, but a part of the broad seal is yet annexed.

We next reach the great saloon, which is finely ornamented

with fresco paintings by Baptiste. Here are a variety of

Roman remains, such as dice, tickets for the Roman theatres,

mirrors, seals for the wine casks, lamps, &c. and a

beautiful bronze head of Homer, which was found near

Constantinople.

The mineral room is the next object of attention. Here are

fossils of a thousand kinds, and precious stones, of various

colours and splendours, composing a collection of

astonishing beauty and magnificence.

Next follows the bird room; and the last apartment contains

animals in spirits, in endless variety. And here the usual

exhibition of the house closes.

[15] Issuing from the portals of the Museum, "Apropos," said Dashall, "we are in the vicinity of Russell-square, the residence of my stock-broker; I have business of a few moments continuance to transact with him—let us proceed to his residence."

A lackey, whose habiliment, neat but not gaudy, indicated the unostentatious disposition of his master,, answered the summons of the knocker: "Mr. C. was gone to his office at the Royal Exchange."

"The gentleman who occupies this mansion," observed Dashall to his friend, as they retired from the door, "illustrates by his success in life, the truth of the maxim so frequently impressed on the mind of the school-boy, that perseverance conquers all difficulties. Mr. C, unaided by any other recommendation than that of his own unassuming modest merit, entered the very [16] respectable office of which he is now the distinguished principal, in the situation of a young man who has no other prospect of advancement than such as may accrue from rectitude of conduct, and the consequent approbation and patronage of his employer. By a long exemplary series of diligence and fidelity, he acquired the confidence of, and ultimately became a partner in the firm. His strictly conscientious integrity and uniform gentlemanly urbanity have thus gained him a preference in his profession, and an ample competency is now the well-merited meed of his industry."

"Combining with its enjoyment," responded the 'Squire, "the exercise of benevolent propensities."

"Exactly so much so, that his name appears as an annual subscriber to nearly all the philanthropic institutions of the metropolis, and his private charities besides are numerous and reiterated."

"This, then, is one of the few instances (said the 'Squire) of Real Life in London, where private fortune is so liberally applied in relief of suffering humanity—it is worthy of indelible record."

Circumambulating the square, the two observers paused opposite the fine statue of the late Francis Duke of Bedford.

The graceful proportion, imposing elevation, and commanding attitude of the figure, together with the happy combination of skill and judgment by the artist, in the display on the pedestal of various agricultural implements, indicating the favourite and useful pursuits of this estimable nobleman, give to the whole an interesting appearance, and strongly excite those feelings of regret which attend the recollection of departed worth and genius. Proceeding down the spacious new street directly facing the statue, our perambulators were presently in Bedford-square, in which is the effigy of the late eminent statesman Charles James Fox: the figure is in à sitting posture, unfavourable to our reminiscences of the first orator of any age or country, and is arrayed in the Roman toga: the face is a striking likeness, but the effect on the whole is not remarkable. The two statues face each other, as if still in friendly recognition; but the sombre reflections of Dashall and his friend were broke in upon by a countryman with, "Beant that Measter Fox, zur?" "His effigy, my [17]friend." "Aye, aye, but what the dickens ha've they wrapt a blanket round un vor?"

Proceeding along Charlotte Street, Bloomsbury, the associates in search of Real Life were accosted by a decent looking countryman in a smock-frock, who, approaching them in true clod-hopping style, with a strong provincial accent, detailed an unaffectedly simple, yet deep tale of distress:

"——Oppression fore'd from his cot,

His cattle died, and blighted was his corn!"

The story which he told was most pathetic, the tears the while coursing each other down his cheeks; and Dashall and his friend were about to administer liberally to his relief, the former observing, "There can be no deception here," when the applicant was suddenly pounced upon by an officer, as one of the greatest impostors in the Metropolis, who, with the eyes of Argus, could transform themselves into a greater variety of shapes than Proteus, and that he had been only fifty times, if not more, confined in different houses of correction as an incorrigible rogue and vagabond, from one of which he had recently contrived to effect his escape. The officer now bore off his prize in triumph, while Dashall, hitherto "the most observant of all observers," sustained the laugh of his Cousin at the knowing one deceived, with great good humour, and Dashall, adverting to his opinion so confidently expressed, "There can be no deception here," declared that in London it was impossible to guard in every instance against fraud, where it is frequently practised with so little appearance of imposition.

The two friends now bent their course towards Covent Garden, which, reaching without additional incident, they wiled away an hour at Robins's much to their satisfaction. That gentleman, in his professional capacity, generally attracts in an eminent degree the attention of his visitors by his professional politeness, so that he seldom fails to put off an article to advantage; and yet he rarely resorts to the puff direct, and never indulges in the puff figurative, so much practised by his renowned predecessor, the late knight of the hammer, Christie, the elder, who by the superabundancy of his rhetorical [18]flurishes, was accustomed from his elevated rostrum to edify and amuse his admiring auditory.{1}

Of the immense revenues accruing to his Grace the Duke of Bedford, not the least important is that derived from Covent Garden market. As proprietor of the ground, from every possessor of a shed or stall, and from all who take their station as venders in the market, a rent is payable to his Grace, and collected weekly; considering, therefore, the vast number of occupants, the aggregate rental must be of the first magnitude. His Grace is a humane landlord, and his numerous tenantry of Covent Garden are always ready to join in general eulogium on his private worth, as is the nation at large on the patriotism of his public character.

Dashall conducted his friend through every part of the Market, amidst a redundancy of fruit, flowers, roots and vegetables, native and exotic, in variety and profusion, exciting the merited admiration of the Squire, who observed, and perhaps justly, that this celebrated emporium unquestionably is not excelled by any other of a similar description in the universe.

1 The late Mr. Christie having at one time a small tract of

land under the hammer, expatiated at great length on its

highly improved state, the exuberant beauties with which

Nature had adorned this terrestrial Paradise, and more

particularly specified a delightful hanging wood.

A gentleman, unacquainted with Mr. Christie's happy talent

at exaggerated description, became the highest bidder, paid

his deposit, and posted down into Essex to examine his new

purchase, when, to his great surprise and disappointment, he

found no part of the description realized, the promised

Paradise having faded into an airy vision, "and left not a

wreck behind!" The irritated purchaser immediately returned

to town, and warmly expostulated with the auctioneer on the

injury he had sustained by unfounded representation; "and as

to a hanging wood, Sir, there is not the shadow of a tree on

the spot!" "I beg your pardon, Sir," said the pertinacious

eulogist, "you must certainly have overlooked the gibbet on

the common, and if that is not a hanging wood, I know not

what it is!"

Another of Mr. Christie's flights of fancy may not unaptly

be termed the puff poetical. At an auction of pictures,

dwelling in his usual strain of eulogium on the unparalleled

excellence of a full-length portrait, without his producing

the desired effect, "Gentlemen," said he, "1 cannot, in

justice to this sublime art, permit this most invaluable

painting to pass from under the hammer, without again

soliciting the honour of your attention to its manifold

beauties. Gentlemen, it only wants the touch of Prometheus

to start from the canvass and fall abidding!"

[19] Proceeding into Leicester Square, the very extraordinary production of female genius, Miss Linwood's Gallery of Needlework promised a gratification to the Squire exceeding in novelty any thing which he had hitherto witnessed in the Metropolis. The two friends accordingly entered, and the anticipations of Tallyho were superabundantly realized.

This exhibition consists of seventy-five exquisite copies in needlework, of the finest pictures of the English and foreign schools, possessing all the correct drawing, just colouring, light and shade of the original pictures from whence they are taken, and to which in point of effect they are in no degree inferior.

From the door in Leicester Square the visitants entered the principal room, a fine gallery of excellent proportions, hung with scarlet broad-cloth, gold bullion tassels, and Greek borders. The appearance thus given to the room is pleasing, and indicated to the Squire a still more superior attraction. His Cousin Dashall had frequently inspected this celebrated exhibition, but' to Tallyho it was entirely new.

On one side of this room the pictures are hung, and have a guard in front to keep the company at the requisite distance, and for preserving them.

Turning to the left, a long and obscure passage prepares the mind, and leads to the cell of a prison, on looking into which is seen the beautiful Lady Jane Gray, visited by the Abbot and keeper of the Tower the night before her execution.

This scene particularly elicited the Squire's admiration; the deception of the whole, he observed, was most beautiful, and not exceeded by any work from the pencil of the painter, that he had ever witnessed. A little farther on is a cottage, the casement of which opens, and the hatch at the door is closed; and, on looking in at either, our visitants perceived a fine and exquisitely finished copy of Gainsborough's Cottage Children standing by the fire, with chimney-piece and cottage furniture compleat. Near to this is Gainsborough's Woodman, exhibited in the same scenic manner.

Having enjoyed an intellectual treat, which perhaps in originality as an exhibition of needlework is no where else to be met with, our perambulators retired, and reached home without the occurrence of any other remarkable incident.[20]

"Look round thee, young Astolpho; here's the place

Which men (for being poor) are sent to starve in;—

Rude remedy, I trow, for sore disease.

Within these walls, stifled by damp and stench,

Doth Hope's fair torch expire, and at the snuff,

Ere yet 'tis quite extinct, rude, wild, and wayward,

The desperate revelries of fell Despair,

Kindling their hell-born cressets, light to deeds

That the poor Captive would have died ere practised,

Till bondage sunk his soul to his condition."

The Prison.—Act I. Scene III.

TRAVERSING the streets, without having in view any particular object, other than the observance of Real Life in London, such as might occur from fortuitous incident; our two perambulators skirted the Metropolis one fine morning, till finding themselves in the vicinity of Tothill-fields Bridewell, a place of confinement to which the Magistrates of Westminster provisionally commit those who are supposed to be guilty of crimes. Ingress was without much difficulty obtained, and the two friends proceeded to a survey of human nature in its most degraded state, where, amidst the consciousness of infamy and the miseries of privation, apathy seemed the predominant feeling with these outcasts of society, and reflection on the past, or anticipation of the future, was absorbed in the vacuum of insensibility. Reckless of his destiny, here the manacled felon wore, with his gyves, the semblance of the most perfect indifference; and the seriousness of useful retrospection was lost in the levity of frivolous amusement. Apart from the other prisoners was seated a recluse, whose appearance excited the attention of the two visitants; a deep cloud of dejection overshadowed his features, and he seemed studiously to keep aloof from the obstreperous revelry of his fellow-captives. There was in his manner a something inducing a feeling of commiseration which could not be extended to his callous [21] companions in adversity. His decayed habiliment indicated, from its formation and texture, that he had seen better days, and his voluntary seclusion confirmed the idea that he had not been accustomed to his present humiliating intercourse. His intenseness of thought precluded the knowledge of approximation on his privacy, until our two friends stood before him; he immediately rose, made his obeisance, and was about to retire, when Mr. Dashall, with his characteristic benevolence, begged the favour of a few moments conversation.

"I am gratified," he observed, "in perceiving one exception to the general torpitude of feeling which seems to pervade this place; and I trust that your case of distress is not of a nature to preclude the influence of hope in sustaining your mind against the pressure of despondency."

"The cause of my confinement," answered the prisoner, "is originally that of debt, although perverted into crime by an unprincipled, relentless creditor. Destined to the misery of losing a beloved wife and child, and subsequently assailed by the minor calamity of pecuniary embarrassment, I inevitably contracted a few weeks arrears of rent to the rigid occupant of the house wherein I held my humble apartment, when, returned one night to my cheerless domicil, my irascible landlord, in the plenitude of ignorance and malevolence, gave me in charge of a sapient guardian of the night, who, without any enquiry into the nature of my offence, conducted me to the watch-house, where I was presently confronted with my creditor, who accused me of the heinous crime of getting into his debt. The constable very properly refused to take cognizance of a charge so ridiculous; but unluckily observing, that had I been brought there on complaint of an assault, he would in that case have felt warranted in my detention, my persecutor seized on the idea with avidity, and made a declaration to that effect, although evidently no such thought had in the first instance occurred to him, well knowing the accusation to be grossly unfounded. This happened on a Saturday night, and I remained in duresse and without sustenance until the following Monday, when I was held before a Magistrate; the alleged assault was positively sworn to, and, maugre my statement of the suspicious, inconsistent conduct of my prosecutor, I was immured in the lock-up house for the remainder of the day, on the affidavit of [22] perjury, and in the evening placed under the friendly care of the Governor of Tothill-fields Bridewell, to abide the issue at the next Westminster sessions."

"This is a most extraordinary affair," said the Squire; "and what do you conjecture may be the result?"

"The pertinacity of my respectable prosecutor," said the Captive, "might probably induce him to procure the aid of some of his conscientious Israelitish brethren, whom 1 never saw, towards substantiating the aforesaid assault, by manfully swearing to the fact; but as I have no desire of exhibiting myself through the streets, linked to a chain of felons on our way to the Sessions House, I believe I shall contrive to pay the debt due to the perjured scoundrel, which will ensure my enlargement, and let the devil in due season take his own!"

"May we enquire," said Dashall, "without the imputation of impertinent inquisitiveness, what has been the nature of your pursuits in life?"

"Multitudinous," replied the other; "my life has been so replete with adventure and adversity in all its varieties, and in its future prospects so unpropitious of happiness, that existence has long ceased to be desirable; and had I not possessed a more than common portion of philosophic resignation, I must have yielded to despair; but,

"When all the blandishments of life are gone, The coward sneaks to death,—the brave live on!"

"Thirty years ago I came to London, buoyant of youth and hope, to realize a competency, although I knew not by what means the grand object was to be attained; yet it occurred to me that I might be equally successful with others of my country, who, unaided by recommendation and ungifted with the means of speculation, had accumulated fortunes in this fruitful Metropolis, and of whom, fifteen years ago, one eminently fortunate adventurer from the north filled the civic chair with commensurate political zeal and ability.

"Some are born great; others achieve greatness, And some have greatness thrust upon them!"

"Well, Sir, what can be said of it? I was without the pale of fortune, although several of my school-mates, who had established themselves in London, acquired, by dint of perseverance, parsimony and servility, affluent [23]circumstances; convinced, however, that I was not destined to acquire wealth and honour, and being unsolaced even with the necessaries of life, I abandoned in London all hope of success, and emigrated to Ireland, where I held for several years the situation of clerk to a respectable Justice of the Quorum. In this situation I lived well, and the perquisites of office, which were regularly productive on the return of every fair and market day, for taking examinations of the peace, and filling up warrants of apprehension against the perpetrators of broken heads and bloody noses, consoled me in my voluntary exile from Real Life in London. I was in all respects regarded as one of the family; had a horse at my command, visited in friendly intimacy the neighbouring gentry; and, above all, enjoyed the eccentricities of the lower Irish; most particularly so when before his honour, detailing, to his great annoyance, a story of an hour long about a tester (sixpence), and if he grew impatient, attributing it to some secret prejudice which he entertained against them.{1}

1 Their method is to get a story completely by heart, and to

tell it, as they call it, out of the face, that is, from the

beginning to the end without interruption.

"Well, my good friend, I have seen you lounging about these

three hours in the yard, what is your business?"

"Plase your honour, it is what I want to speak one word to

your honour."

"Speak then, but be quick. What is the matter?"

"The matter, plase your honour, is nothing at all at all,

only just about the grazing of a horse, plase your honour,

that this man here sold me at the fair of Gurtishannon last

Shrove fair, which lay down three times with myself, plase

your honour, and kilt me; not to be telling your honour of

how, no later back than yesterday night, he lay down in the

house there within, and all the children standing round, and

it was God's mercy he did not fall a-top of them, or into

the fire to burn himself. So, plase your honour, to-day I

took him back to this man, which owned him, and after a

great deal to do I got the mare again I swopped (exchanged)

him for; but he won't pay the grazing of the horse for the

time I had him, though he promised to pay the grazing in

case the horse didn't answer; and he never did a day's work,

good or bad, plase your honour, all the time he was with me,

and I had the doctor to him five times, any how. And so,

plase your honour, it is what I expect your honour will

stand my friend, for I'd sooner come to your honour for

justice than to any other in all Ireland. And so I brought

him here before your honour, and expect your honour will

make him pay me the grazing, or tell me, can I process him

for it at the next assizes, plase your honour?"

The defendant now, turning a quid of tobacco with his

tongue into some secret cavern in his mouth, begins his

defence with

"Plase your honour, under favour, and saving your honour's

presence, there's not a word of truth in all this man has

been saying from beginning to end, upon my conscience, and I

would not for the value of the horse itself, grazing and

all, be after telling your honour a lie. For, plase your

honour, I have a dependance upon your honour that you'll do

me justice, and not be listening to him or the like of him.

Plase your honour, it is what he has brought me before your

honour, because he had a spite against me about some oats I

sold your honour, which he was jealous of, and a shawl his

wife got at my shister's shop there without, and never paid

for, so I offered to set the shawl against the grazing, and

give him a receipt in full of all demands, but he wouldn't,

out of spite, plase your honour; so he brought me before

your honour, expecting your honour was mad with me for

cutting down the tree in the horse park, which was none of

my doing, plase your honour;—ill luck to them that went

and belied me to your honour behind my back. So if your

honour is plasing, I'll tell you the whole truth about the

horse that he swopped against my mare, out of the face:—

Last Shrove fair I met this man, Jemmy Duffy, plase your

honour, just at the corner of the road where the bridge is

broke down, that your honour is to have the present for this

year—long life to you for it! And he was at that time

coming from the fair of Gurtishannon, and 1 the same way:

'How are you, Jemmy?' says I. 'Very well, I thank you,

Bryan,' says he: 'shall we turn back to Paddy Salmon's, and

take a naggin of whiskey to our better acquaintance?' 'I

don't care if I did, Jemmy,' says I, 'only it is what I

can't take the whiskey, because I'm under an oath against it

for a month.' Ever since, plase your honour, the day your

honour met me on the road, and observed to me I could hardly

stand, I had taken so much—though upon my conscience your

honour wronged me greatly that same time—ill luck to them

that belied me behind my back to your honour! Well, plase

your honour, as I was telling you, as he was taking the

whiskey, and we talking of one thing or t'other, he makes me

an offer to swop his mare that he couldn't sell at the fair

of Gurtishannou, because nobody would be troubled with the

beast, plase your honour, against my horse; and to oblige

him I took the mare—sorrow take her, and him along with

her! She kicked me a new car, that was worth three pounds

ten, to tatters, the first time I ever put her into it, and

I expect your honour will make him pay me the price of the

car, any how, before I pay the grazing, which I have no

right to pay at all at all, only to oblige him. But I leave

it all to your honour; and the whole grazing he ought to be

charging for the beast is but two and eight pence halfpenny,

any how, plase your honour. So I'll abide by what your

honour says, good or bad; I'll leave it all to your honour."

I'll leave it all to your honour, literally means, I'll

leave all the trouble to your honour.

[25]But this pleasant life was not decreed much longer to endure, the insurrection broke out, during which an incident occurred that had nearly terminated all my then cares in this life, past, present, and to come.

"In my capacity as clerk or secretary, I had written one morning for the worthy magistrate, two letters, both containing remittances, the one 150L. and the other 100L. in bank of Ireland bills. We were situated at the distance of fifteen miles from the nearest market town, and as the times were perilous and my employer unwilling to entrust property to the precarious conveyance of subordinate agency, he requested that I would take a morning ride, and with my own hands deliver these letters at the post-office. Accordingly I set out, and had arrived to within three miles of my destination, when my further progress was opposed by two men in green uniform, who, with supported arms and fixed bayonets, were pacing the road to and fro as sentinels, in a very steady and soldier-like manner. On the challenge of one of these fellows, with arms at port demanding the countersign, I answered that I had none to give, that I was travelling on lawful business to the next town, and required to know by what authority he stopt me on the King's highway, "By the powers," he exclaimed, "this is my authority then," and immediately brought his musket to the charge against the chest of my horse. I now learnt that the town had been taken possession of that morning by a division of the army of the people, for so the insurgents had styled themselves. "You may turn your nag homewards if you choose," said the sentry; "but if you persist in going into the town, I must pass you, by the different out-posts, to the officer on duty." The business in which I was engaged not admitting of delay, I preferred advancing, and was ushered, ultimately, to the notice of the captain of the guard, who very kindly informed me, that his general would certainly order me to be hanged as a spy, unless I could exhibit good proof of the contrary. With this comfortable assurance, I was forthwith introduced into the presence of the rebel general. He was a portly good-looking man, apparently about the age of forty, not more; wore a green uniform, with gold embroidery, and was engaged in signing dispatches, which his secretary successively sealed and superscribed; his staff were in attendance, and a provost-marshal in waiting to perform the office of summary execution on those to whom the general might attach suspicion. The insurgent leader [26]now enquiring, with much austerity, my name, profession, from whence I came, the object of my coming, and lastly, whether or not I was previously aware of the town being in possession of the army of the people, I answered these interrogatories by propounding the question, who the gentleman was to whom I had the honour of addressing myself, and under what authority I was considered amenable to his inquisition. "Answer my enquiries, Sir," he replied, "without the impertinency of idle circumlocution, otherwise I shall consider you as a spy, and my provost-marshal shall instantly perform on your person the duties of his office!" I now resorted to my letters; I had no other alternative between existence and annihilation. Explaining, therefore, who I was, and by whom employed, "These letters," I added, "are each in my hand-writing, and both contain remittances; I came to this town for the sole purpose of putting them into the post-office, and I was not aware, until informed by your scouts, that the place was in the occupation of an enemy." He deigned not a reply farther than pointing to one of the letters, and demanding to know the amount of the bill which it enveloped; I answered, "One hundred and fifty pounds." He immediately broke the seal, examined the bill, and found that it was correct. "Now, Sir," he continued, "sit down, and write from my dictation." He dictated from the letter which he had opened, and when I had finished the copy, compared it next with the original characters, expressed his satisfaction at their identity, and returning the letters, licensed my departure, when and to where I list, observing, that I was fortunate in having had with me those testimonials of business, "Otherwise," said he, "your appearance, under circumstances of suspicion, might have led to a fatal result."—"You may be assured, gentlemen," continued the narrator, "that I did not prolong my stay in the town beyond the shortest requisite period; two mounted dragoons, by order of their general, escorted me past the outposts, and I reached home in safety. These occurrences took place on a Saturday. The triumph of the insurgent troops was of short duration; they were attacked that same night by the King's forces, discomfited, and their daring chieftain taken prisoner. On the Monday following his head, stuck upon a pike, surmounted the market-house of Belfast. The scenes of anarchy and desperation in which that [27] unfortunate country became now involved, rendered it no very desirable residence. I therefore procured a passport, bid adieu to the Emerald Isle, Erin ma vorneen slan leet go bragh! and once more returned to London, to experience a renewal of that misfortune by which I have, with little interval, been hitherto accompanied, during the whole period of my eventful life."

The two strangers had listened to the narrative with mingled sensations of compassion and surprise, the one feeling excited by the peculiarity, the other by the pertinacity of his misfortunes, when their cogitations were interrupted by a dissonant clamour amongst the prisoners, who, it appeared, had united in enmity against an unlucky individual, whom they were dragging towards the discipline of the pump with all the eagerness of inflexible vengeance.

On enquiry into the origin of this uproar, it was ascertained that one of the prisoners under a charge of slight assault, had been visited by this fellow, who, affecting to commiserate his situation, proposed to arrange matters with his prosecutor for his immediate release, with other offers of gratuitous assistance. This pretended friend was recognised by one of the prisoners as a kidnapper.