MALAY MAGIC

MACMILLAN AND CO., Limited

NEW YORK: THE MACMILLAN COMPANY

1900

All rights reserved

TO

SIR CECIL CLEMENTI SMITH

KNIGHT GRAND CROSS OF THE MOST DISTINGUISHED

ORDER

OF

ST. MICHAEL AND ST. GEORGE

AND FORMERLY

GOVERNOR OF THE STRAITS SETTLEMENTS

THIS BOOK IS (BY PERMISSION)

DEDICATED

PREFACE

The circumstances attending the composition and publication of the present work have thrown upon me the duty of furnishing it with a preface explaining its object and scope.

Briefly, the purpose of the author has been to collect into a Book of Malay Folklore all that seemed to him most typical of the subject amongst a considerable mass of materials, some of which lay scattered in the pages of various other works, others in unpublished native manuscripts, and much in notes made by him personally of what he had observed during several years spent in the Malay Peninsula, principally in the State of Selangor. The book does not profess to be an exhaustive or complete treatise, but rather, as its title indicates, an introduction to the study of Folklore, Popular Religion, and Magic as understood among the Malays of the Peninsula.

It should be superfluous, at this time of day, to defend such studies as these from the criticisms which have from time to time been brought against them. I remember my old friend and former teacher, Wan [viii]ʿAbdullah, a Singapore Malay of Trengganu extraction and Arab descent, a devout and learned Muhammadan and a most charming man, objecting to them on the grounds, first, that they were useless, and, secondly, which, as he emphatically declared, was far worse, that they were perilous to the soul’s health. This last is a point of view which it would hardly be appropriate or profitable to discuss here, but a few words may as well be devoted to the other objection. It is based, sometimes, on the ground that these studies deal not with “facts,” but with mere nonsensical fancies and beliefs. Now, for facts we all, of course, have the greatest respect; but the objection appears to me to involve an unwarrantable restriction of the meaning of the word: a belief which is actually held, even a mere fancy that is entertained in the mind, has a real existence, and is a fact just as much as any other. As a piece of psychology it must always have a certain interest, and it may on occasions become of enormous practical importance. If, for instance, in 1857 certain persons, whose concern it was, had paid more attention to facts of this kind, possibly the Indian Mutiny could have been prevented, and probably it might have been foreseen, so that precautionary measures could have been taken in time to minimise the extent of the catastrophe. It is not suggested that the matters dealt with in this book are ever likely to involve such serious issues; but, speaking generally, there can be no doubt [ix]that an understanding of the ideas and modes of thought of an alien people in a relatively low stage of civilisation facilitates very considerably the task of governing them; and in the Malay Peninsula that task has now devolved mainly upon Englishmen. Moreover, every notion of utility implies an end to which it is to be referred, and there are other ends in life worth considering as well as those to which the “practical man” is pleased to restrict himself. When one passes from the practical to the speculative point of view, it is almost impossible to predict what piece of knowledge will be fruitful of results, and what will not; prima facie, therefore, all knowledge has a claim to be considered of importance from a scientific point of view, and until everything is known, nothing can safely be rejected as worthless.

Another and more serious objection, aimed rather at the method of such investigations as these, is that the evidence with which they have to be content is worth little or nothing. Objectors attempt to discredit it by implying that at best it is only what A. says that B. told him about the beliefs B. says he holds, in other words, that it is the merest hearsay; and it is also sometimes suggested that when A. is a European and B. a savage, or at most a semi-civilised person of another breed, the chances are that B. will lie about his alleged beliefs, or that A. will unconsciously read his own ideas into B.’s [x]confused statements, or that, at any rate, one way or another, they are sure to misunderstand each other, and accordingly the record cannot be a faithful one.

So far as this objection can have any application to the present work, it may fairly be replied: first that the author has been at some pains to corroborate and illustrate his own accounts by the independent observations of others (and this must be his justification for the copiousness of his quotations from other writers); and, secondly, that he has, whenever possible, given us what is really the best kind of evidence for his own statements by recording the charms and other magic formulæ which are actually in use. Of these a great number has been here collected, and in the translation of such of the more interesting ones as are quoted in the text of the book, every effort has been made to keep to literal accuracy of rendering. The originals will be found in the Appendix, and it must be left to those who can read Malay to check the author’s versions, and to draw from the untranslated portions such inferences as may seem to them good.

The author himself has no preconceived thesis to maintain: his object has been collection rather than comparison, and quite apart from the necessary limitations of space and time, his method has confined the book within fairly well-defined bounds. Though the subject is one which would naturally lend itself to a comparative treatment, and though [xi]the comparison of Malay folklore with that of other nations (more particularly of India, Arabia, and the mainland of Indo-China) would no doubt lead to very interesting results, the scope of the work has as far as possible been restricted to the folklore of the Malays of the Peninsula. Accordingly the analogous and often quite similar customs and ideas of the Malayan races of the Eastern Archipelago have been only occasionally referred to, while those of the Chinese and other non-Malayan inhabitants of the Peninsula have been excluded altogether.

Moreover, several important departments of custom and social life have been, no doubt designedly, omitted: thus, to mention only one subject out of several that will probably occur to the reader, the modes of organisation of the Family and the Clan (which in certain Malay communities present archaic features of no common interest), together with the derivative notions affecting the tenure and inheritance of property, have found no place in this work. The field, in fact, is very wide and cannot all be worked at once. The folklore of uncivilised races may fairly enough be said to embrace every phase of nature and every department of life: it may be regarded as containing, in the germ and as yet undifferentiated, the notions from which Religion, Law, Medicine, Philosophy, Natural Science, and Social Customs are eventually evolved. Its bulk and relative importance seem to vary inversely with the [xii]advance of a race in the progress towards civilisation; and the ideas of savages on these matters appear to constitute in some cases a great and complex system, of which comparatively few traces only are left among the more civilised peoples. The Malay race, while far removed from the savage condition, has not as yet reached a very high stage of civilisation, and still retains relatively large remnants of this primitive order of ideas. It is true that Malay notions on these subjects are undergoing a process of disintegration, the rapidity of which has been considerably increased by contact with European civilisation, but, such as they are, these ideas still form a great factor in the life of the mass of the people.

It may, however, be desirable to point out that the complexity of Malay folklore is to be attributed in part to its singularly mixed character. The development of the race from savagery and barbarism up to its present condition of comparative civilisation has been modified and determined, first and most deeply by Indian, and during the last five centuries or so by Arabian influences. Just as in the language of the Malays it is possible by analysis to pick out words of Sanskrit and Arabic origin from amongst the main body of genuinely native words, so in their folklore one finds Hindu, Buddhist, and Muhammadan ideas overlying a mass of apparently original Malay notions. [xiii]

These various elements of their folklore are, however, now so thoroughly mixed up together that it is often almost impossible to disentangle them. No systematic attempt has been made to do so in this book, although here and there an indication of the origin of some particular myth will be found; but a complete analysis (if possible at all) would have necessitated, as a preliminary investigation, a much deeper study of Hindu and Muhammadan mythology than it has been found practicable to engage in.

In order, however, to give a clear notion of the relation which the beliefs and practices that are here recorded bear to the official religion of the people, it is necessary to state that the Malays of the Peninsula are Sunni Muhammadans of the school of Shafi’i, and that nothing, theoretically speaking, could be more correct and orthodox (from the point of view of Islām) than the belief which they profess.

But the beliefs which they actually hold are another matter altogether, and it must be admitted that the Muhammadan veneer which covers their ancient superstitions is very often of the thinnest description. The inconsistency in which this involves them is not, however, as a rule realised by themselves. Beginning their invocations with the orthodox preface: “In the name of God, the merciful, the compassionate,” and ending them with an appeal to the Creed: “There is no god but God, and Muhammad is the Apostle of God,” they are conscious [xiv]of no impropriety in addressing the intervening matter to a string of Hindu Divinities, Demons, Ghosts, and Nature Spirits, with a few Angels and Prophets thrown in, as the occasion may seem to require. Still, the more highly educated Malays, especially those who live in the towns and come into direct contact with Arab teachers of religion, are disposed to object strongly to these “relics of paganism”; and there can be no doubt that the increasing diffusion of general education in the Peninsula is contributing to the growth of a stricter conception of Islām, which will involve the gradual suppression of such of these old-world superstitions as are obviously of an “unorthodox” character.

This process, however, will take several generations to accomplish, and in the meantime it is to be hoped that a complete record will have been made both of what is doomed sooner or later to perish, and of what in all likelihood will survive under the new conditions of our time. It is as a contribution to such a record, and as a collection of materials to serve as a sound basis for further additions and comparisons, that this work is offered to the reader.

A list of the principal authorities referred to will be found in another place, but it would be improper to omit here the acknowledgments which are due to the various authors of whose work in this field such wide use has been made. Among the dead special mention must be made of Marsden, who will [xv]always be for Englishmen the pioneer of Malay studies; Leyden, the gifted translator of the Sĕjarah Malayu, whose early death probably inflicted on Oriental scholarship the greatest loss it has ever had to suffer; Newbold, the author of what is still, on the whole, the best work on the Malay Peninsula; and Sir William Maxwell, in whom those of us who knew him have lost a friend, and Malay scholarship a thoroughly sound and most brilliant exponent.

Among the living, the acknowledgments of the author are due principally to Sir Frank Swettenham and Mr. Hugh Clifford, who, while they have done much to popularise the knowledge of things Malay amongst the general reading public, have also embodied in their works the results of much careful and accurate observation. The free use which has been made of the writings of these and other authors will, it is hoped, be held to be justified by their intrinsic value.

It must be added that the author, having to leave England about the beginning of this year with the Cambridge scientific expedition which is now exploring the Northern States of the Peninsula, left the work with me for revision. The first five Chapters and Chapter VI., up to the end of the section on Dances, Sports, and Games, were then already in the printer’s hands, but only the first 100 pages or so had had the benefit of the author’s revision. For the arrangement of the rest of Chapter VI., and for [xvi]some small portion of the matter therein contained, I am responsible, and it has also been my duty to revise the whole book finally. Accordingly, it is only fair to the author to point out that he is to be credited with the matter and the general scheme of the work, while the responsibility for defects in detail must fall upon myself.

As regards the spelling of Malay words, it must be said that geographical names have been spelled in the way which is now usually adopted and without diacritical marks: the names of the principal Native States of the Peninsula (most of which are repeatedly mentioned in the book) are Kĕdah, Perak, Sĕlangor, Jŏhor, Păhang, Trĕngganu, Kĕlantan, and Pătani. Otherwise, except in quotations (where the spelling of the original is preserved), an attempt has been made to transliterate the Malay words found in the body of the book in such a way as to give the ordinary reader a fairly correct idea of their pronunciation. The Appendix, which appeals only to persons who already know Malay, has been somewhat differently treated, diacritical marks being inserted only in cases where there was a possible ambiguity, and the spelling of the original MSS. being changed as little as possible.

A perfect transliteration, or one that will suit everybody, is, however, an unattainable ideal, and the most that can be done in that direction is necessarily a compromise. In the system adopted in the [xvii]body of the work, the vowels are to be sounded (roughly speaking) as in Italian, except ĕ (which resembles the French e in que, le, and the like), and the consonants as in English (but ng as in singer, not finger; g as in go; ny as ni in onion; ch as in church; final k and initial h almost inaudible). The symbol ʿ represents the Arabic ʿain, and the symbol ’ is used (1) between consonants, to indicate the presence of an almost inaudible vowel, the shortest form of ĕ, and elsewhere (2) for the hamzah, and (3) for the apostrophe, i.e. to denote the suppression of a letter or syllable. Both the ʿain and the hamzah may be neglected in pronunciation, as indeed they are very generally disregarded by the Malays themselves. In this and other respects, Arabic scholars into whose hands this book may fall must not be surprised to find that Arabic words and phrases suffer some corruptions in a Malay context. These have not, as a rule, been interfered with or corrected, although it has not been thought worth while to preserve obvious blunders of spelling in well-known Arabic formulæ. It should be added that in Malay the accent or stress, which is less marked than in English, falls almost invariably on the penultimate syllable of the word. Exceptions to this rule hardly ever occur except in the few cases where the penultimate is an open syllable with a short vowel, as indicated by the sign ˘.

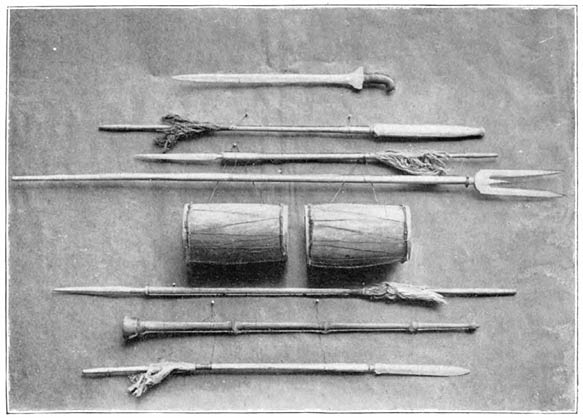

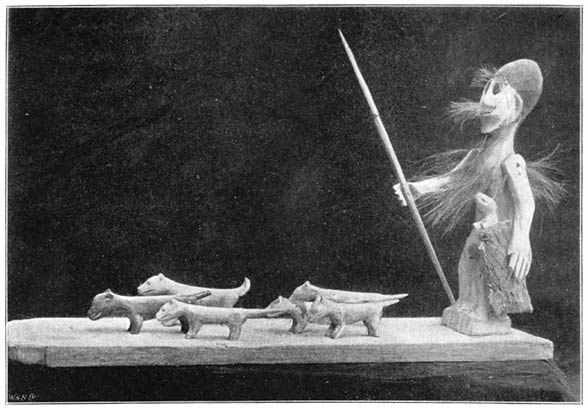

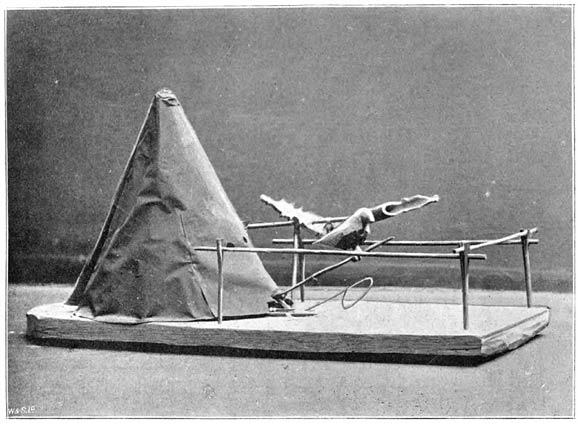

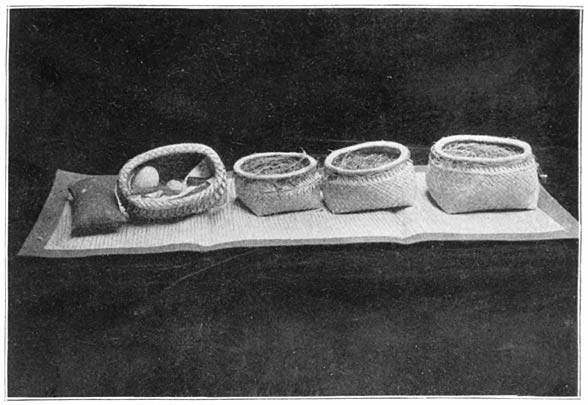

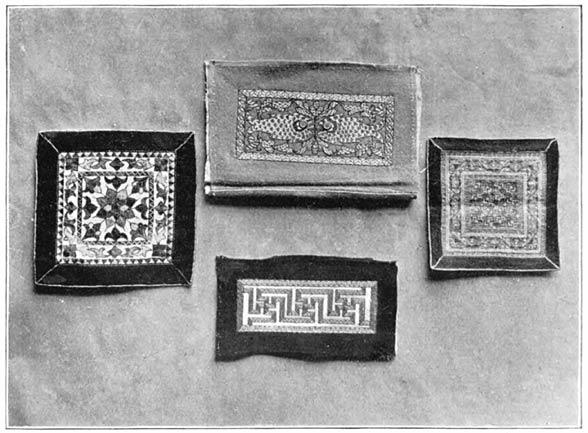

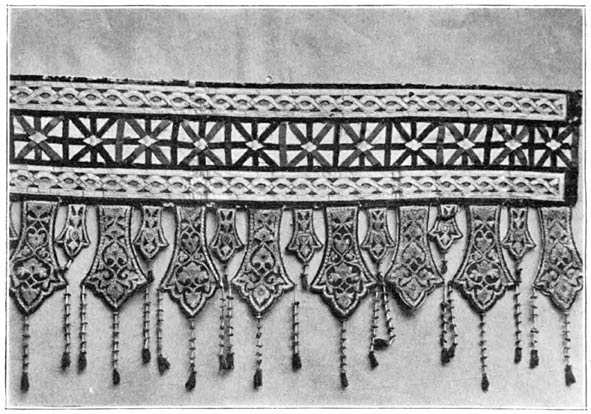

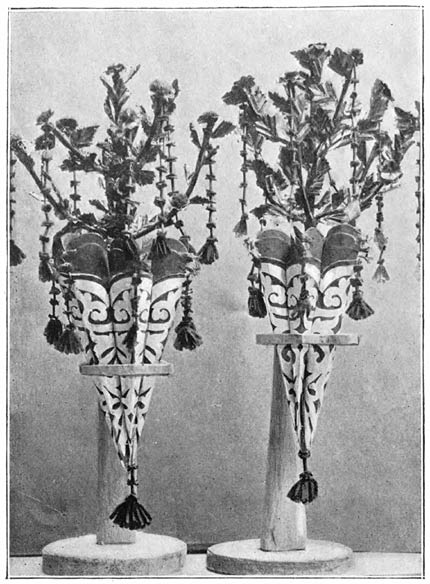

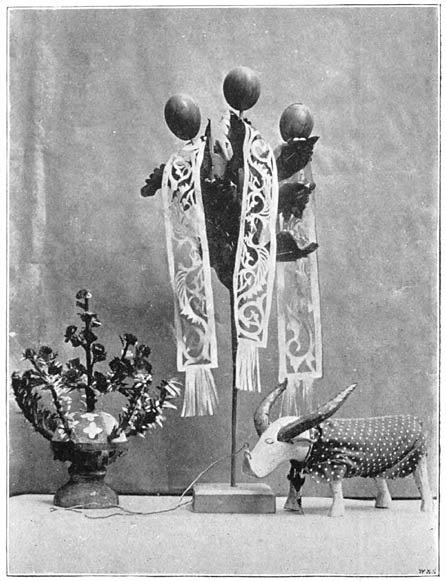

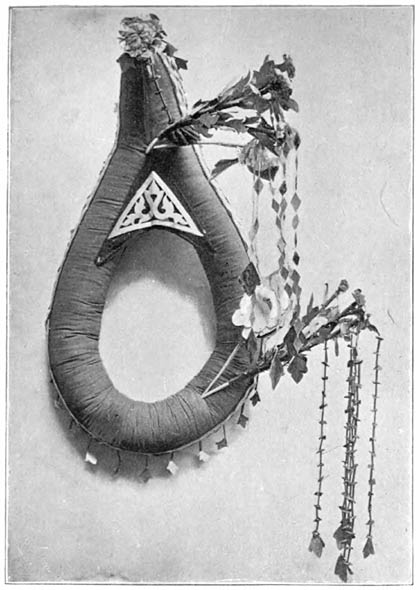

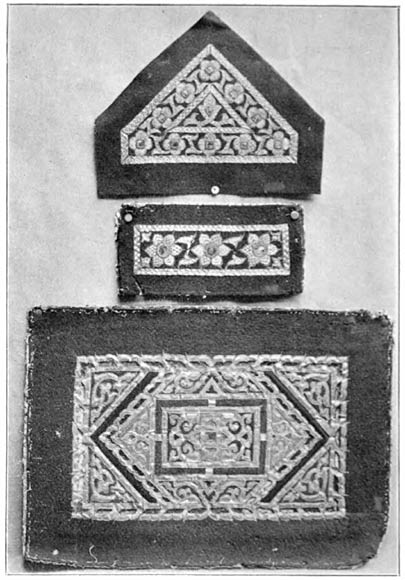

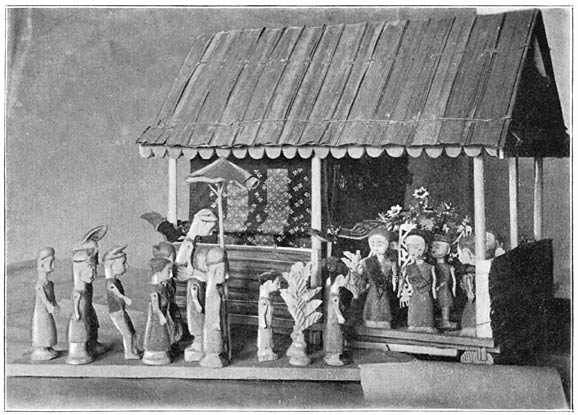

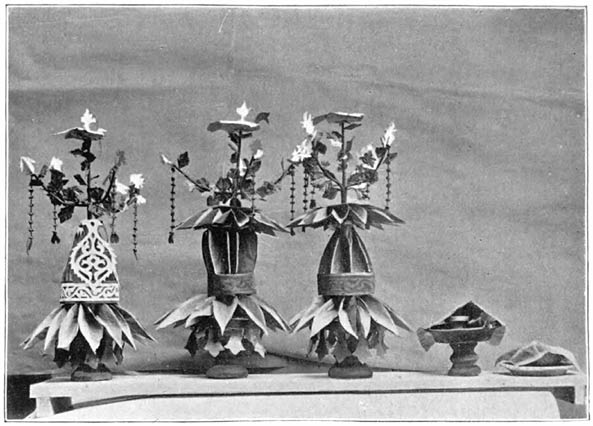

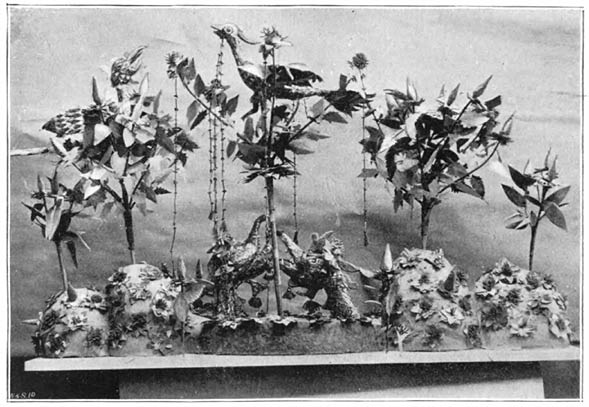

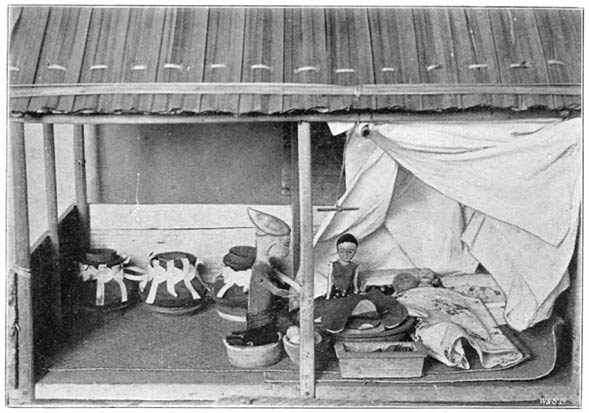

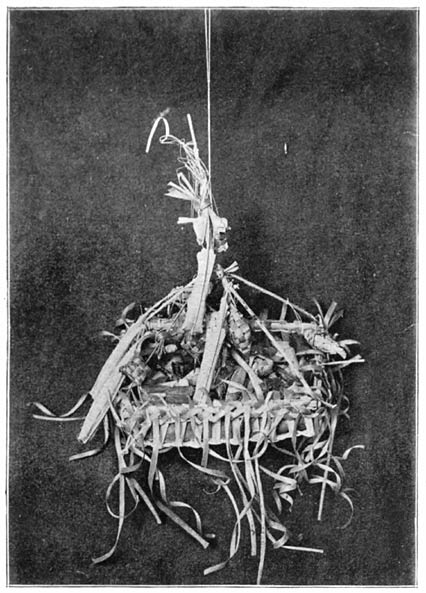

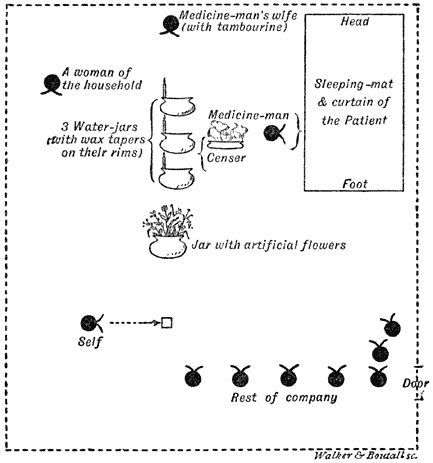

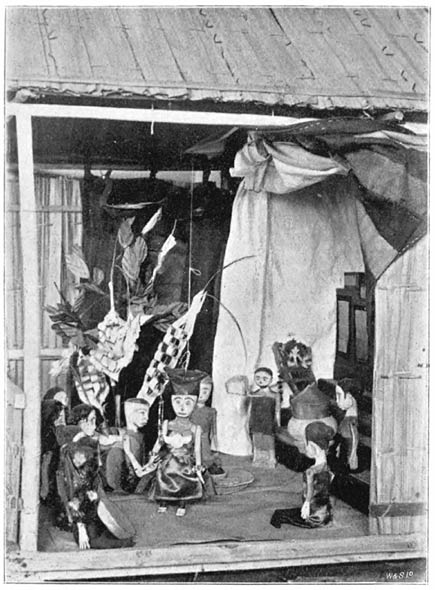

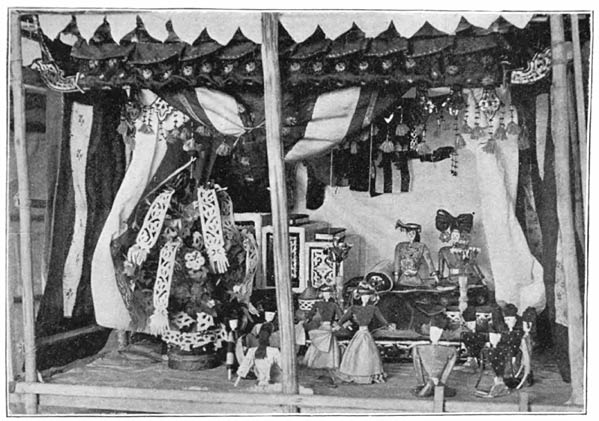

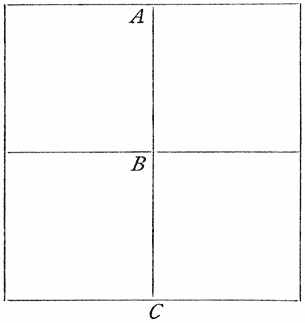

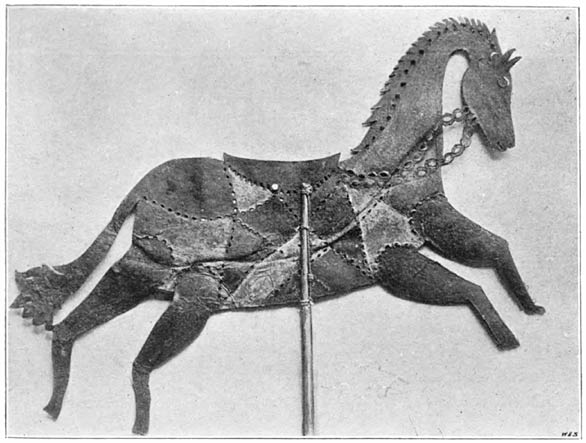

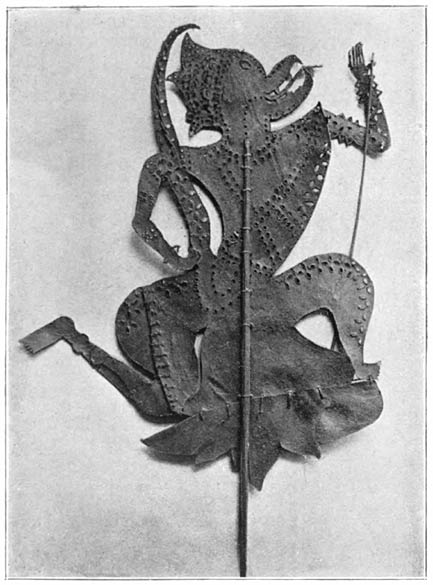

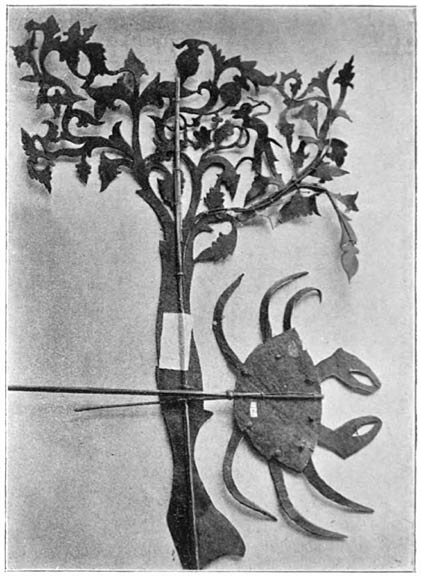

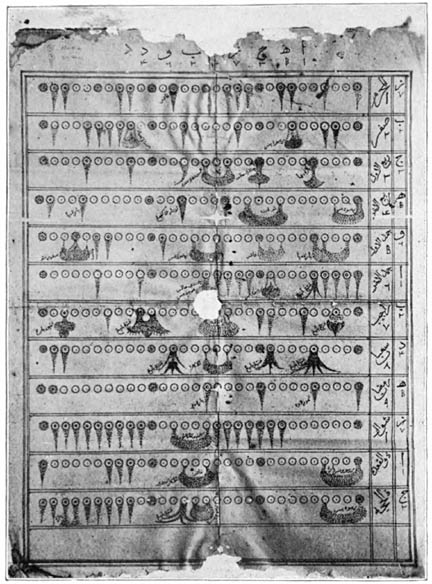

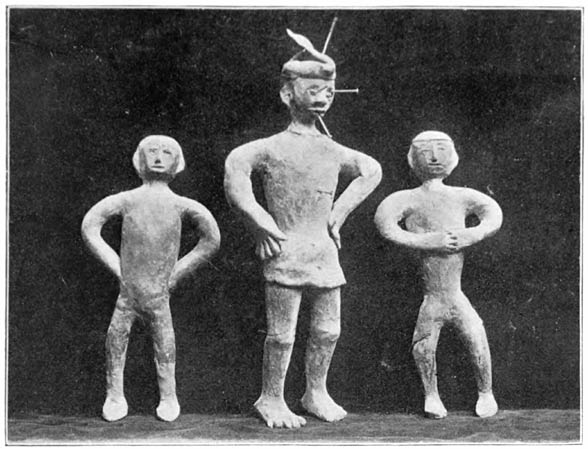

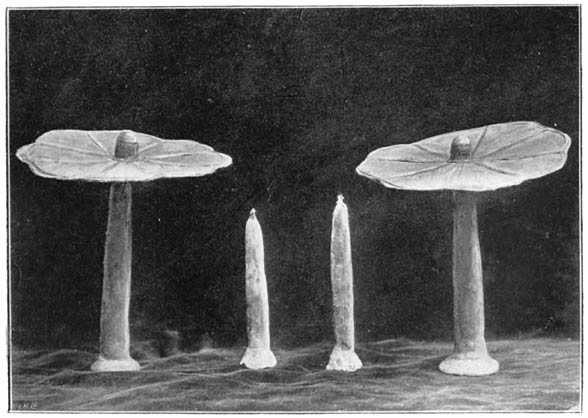

The illustrations are reproduced from photographs [xviii]of models and original objects made by Malays; most of these models and other objects are now in the Cambridge Archæological and Ethnological Museum, to which they were presented by the author.

The Index, for the compilation of which I am indebted to my wife, who has also given me much assistance in the revision of the proof-sheets, will, it is believed, add greatly to the usefulness of the work as a book of reference.

C. O. BLAGDEN.

Woking, 28th August 1899. [xix]

CONTENTS

CHAPTER I

Nature, pp. 1–15 PAGE

| (a) | Creation of the World | 1 | ||||

| (b) | Natural Phenomena | 5 | ||||

CHAPTER II

Man and His Place in the Universe, pp. 16–55

| (a) | Creation of Man | 16 | ||||

| (b) | Sanctity of the Body | 23 | ||||

| (c) | The Soul | 47 | ||||

| (d) | Animal, Vegetable, and Mineral Souls | 52 | ||||

CHAPTER III

Relations with the Supernatural World, pp. 56–82

| (a) | The Magician | 56 | ||||

| (b) | High Places | 61 | ||||

| (c) | Nature of Rites | 71 | ||||

CHAPTER IV

The Malay Pantheon, pp. 83–106

| (a) | Gods | 83 | ||||

| (b) | Spirits, Demons, and Ghosts | 93 | ||||

CHAPTER V

Magic Rites connected with the Several Departments of Nature, pp. 107–319

| (a) | Air—

|

|||||

| (b) | Earth—

|

|||||

| (c) | Water—

|

|||||

| (d) | Fire—

|

|||||

CHAPTER VI

Magic Rites as affecting the Life of Man, pp. 320–580

| 1. | Birth-Spirits | 320 | ||||

| 2. | Birth Ceremonies | 332 | ||||

| 3. | Adolescence [xxi] | 352 | ||||

| 4. | Personal Ceremonies and Charms | 361 | ||||

| 5. | Betrothal | 364 | ||||

| 6. | Marriage | 368 | ||||

| 7. | Funerals | 397 | ||||

| 8. | Medicine | 408 | ||||

| 9. | Dances, Sports, and Games | 457 | ||||

| 10. | Theatrical Exhibitions | 503 | ||||

| 11. | War and Weapons | 522 | ||||

| 12. | Divination and the Black Art | 532 | ||||

Appendix 581

LIST OF ILLUSTRATIONS

| Fig. | PAGE | |||||

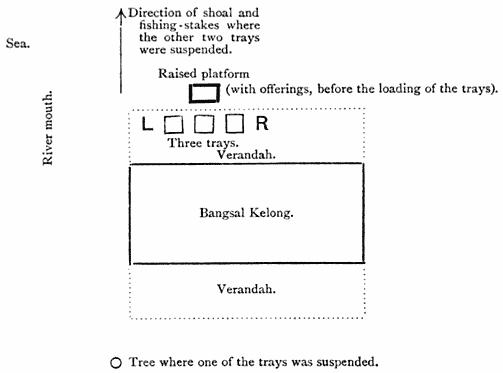

| 1. | Sacrificing at the Fishing Stakes | 311 | ||||

| 2. | Invoking the Tiger Spirit | 438 | ||||

| 3. | Stand used at Invocation of Spirits | 447 | ||||

| 4. | Main Galah Panjang | 500 | ||||

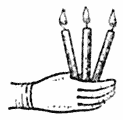

| 5. | Tapers used in exorcising Evil Spirits | 511 | ||||

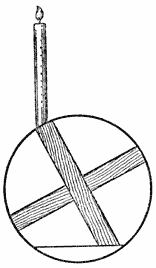

| 6. | Taper and Ring used in same Ceremony | 512 | ||||

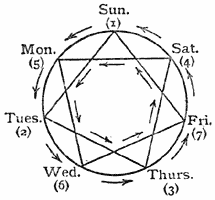

| 7. | Heptacle on which the Seven-Square is based | 558 | ||||

PLATES

| Plate | ||||||||||

| 1. | Selangor Regalia | 40 | ||||||||

| 2. | Spirits | 94 | ||||||||

| 3. | The Spectre Huntsman | 116 | ||||||||

| 4. | Pigeon Decoy Hut | 133 | ||||||||

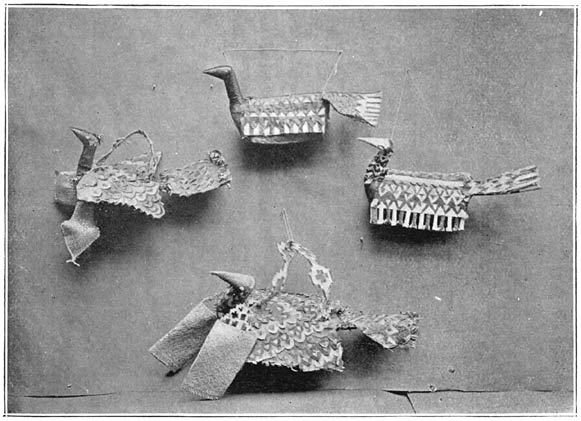

| 5. | Rice-Soul Baskets | 244 | ||||||||

| 6. | Bajang and Pĕlĕsit Charms | 321 | ||||||||

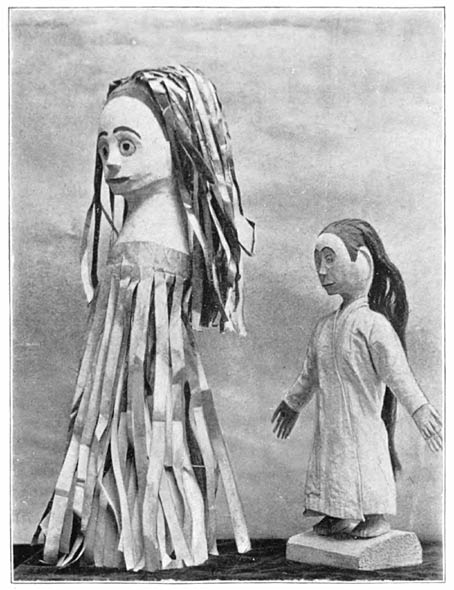

| 7. | Pĕnanggalan and Langsuir | 326 | ||||||||

| 8. | Betrothal Gifts | 365 | ||||||||

| 9. |

|

366 | ||||||||

| 10. | Curtain Fringe | 372 | ||||||||

| 11. | Fig. 1.—Bridal Bouquets | 375 | ||||||||

|

375 | |||||||||

| 12. | Fig. 1.—Bridegroom’s Headdress | 378 | ||||||||

|

378 | |||||||||

| 13. | Wedding Procession | 381 | ||||||||

| 14. | Poko’ Sirih | 382 | ||||||||

| 15. | Wedding Centrepiece with Dragons, etc. | 388 | ||||||||

| 16. | Bomor at Work | 410 | ||||||||

| 17. | Anchak | 414 | ||||||||

| 18. | Gambor | 464 | ||||||||

| 19. | Pĕdikir | 466 | ||||||||

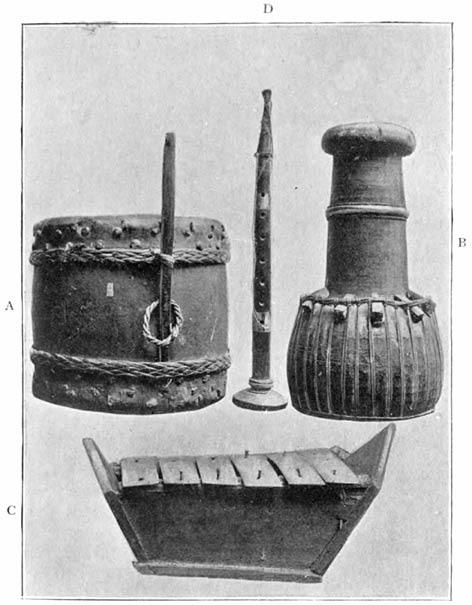

| 20. | Fig. 1.—Musical Instruments | 508 | ||||||||

|

508 | |||||||||

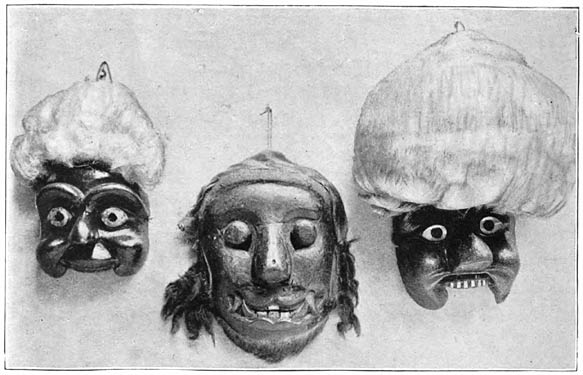

| 21. | Masks of Clowns and Demon | 513 | ||||||||

| 22. | Kuda Sĕmbrani | 514 | ||||||||

| 23. | Fig. 1.—Hanuman | 516 | ||||||||

|

516 | |||||||||

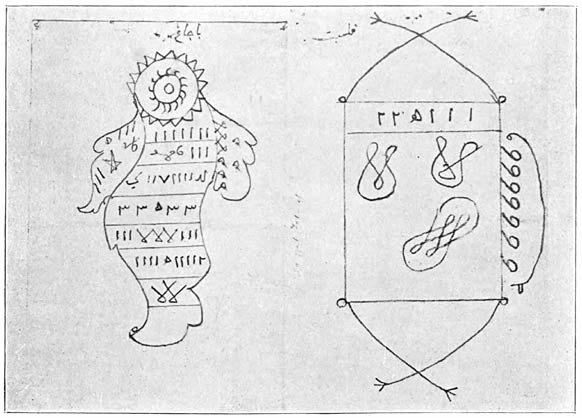

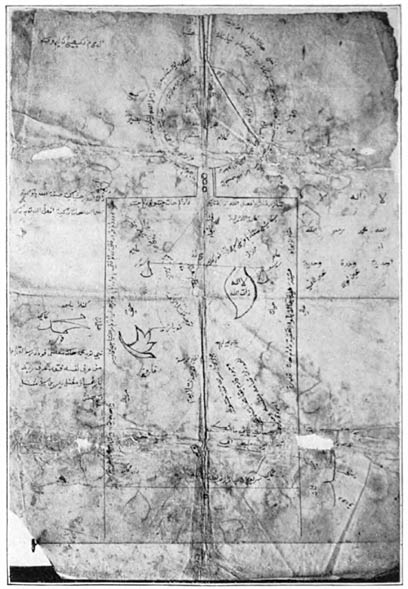

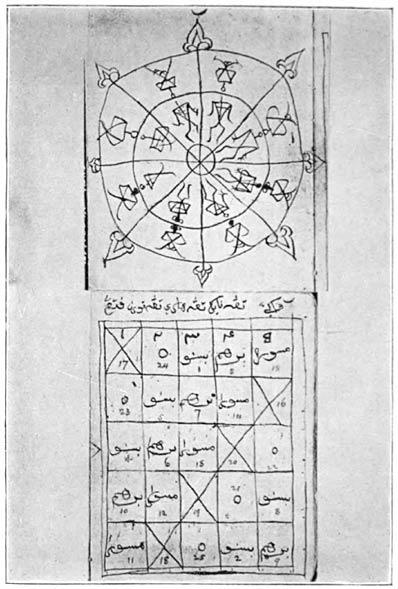

| 24. | Fig. 1.—Weather Chart | 544 | ||||||||

|

544 | |||||||||

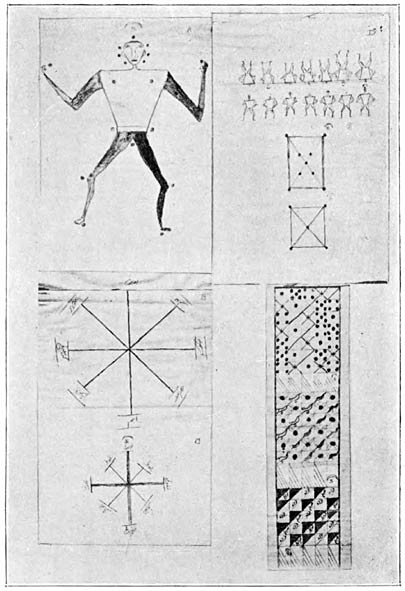

| 25. | Diagrams | 555 | ||||||||

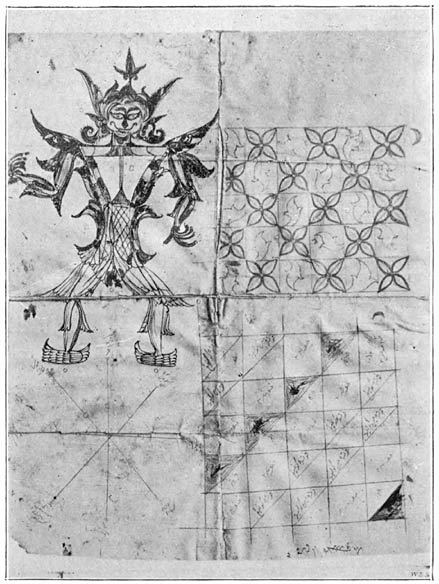

| 26. |

|

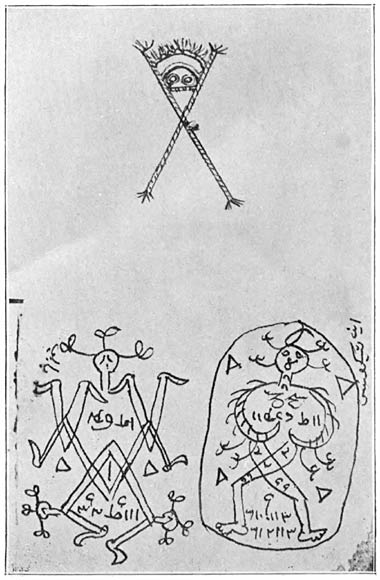

558 | ||||||||

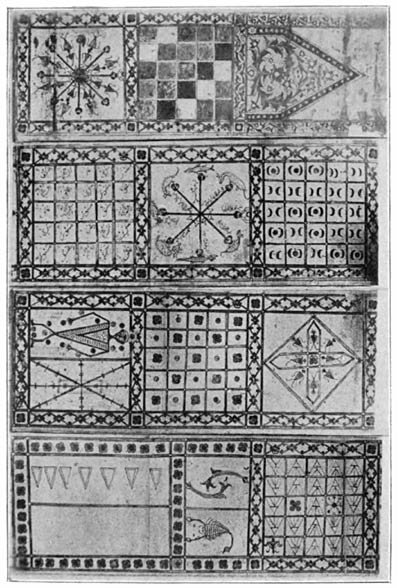

| 27. |

|

561 | ||||||||

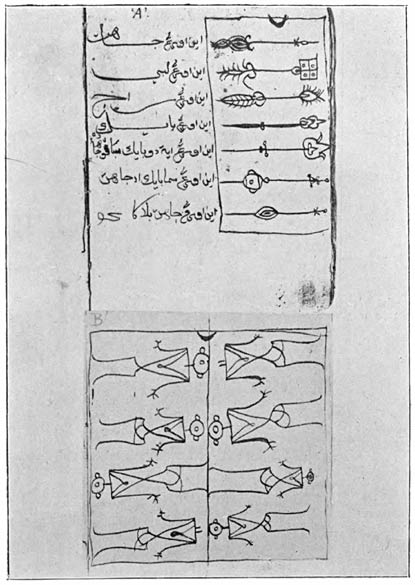

| 28. | Fig. 1.—Wax Figures | 570 | ||||||||

|

570 | |||||||||