No sooner had our launch reached the landing place,

than we bounded ashore, eager for information about our mules and their

drivers. We asked the sable matron who, with her equally sable

daughters, waited at the brink to greet us, if the mules had come. She

replied laconically, “No, Señor.” “Have you

heard anything about them?” “No, Señor.”

“Is there anyone here,” and I glanced at the swarthy youth

hard by, “that would be willing, if well rewarded, to go forward

and hasten the arrival of men and mules?” “No,

Señor.”

What was to be done? We could not continue our journey alone and

afoot, even if we were disposed to leave our baggage behind us. And it

soon became evident that it would not be safe to remain long at

Barrigón. There was but one rude hut there, and that was

surrounded by mud and pools of water covered by “Spawn, weeds and

filth

and leprous-scum”—certainly not a very inviting place to

abide any length of time.

Besides, the family had nothing to eat, at least they said they had

not, except a few platanos, and these they required for their own use.

We had almost exhausted the supply we had brought from Trinidad, and

the little that was still left, we intended for our three-days trip to

Villavicencio. We were not sure that we could get anything on the way,

and we did not wish to run any risk of being without food where it

might be most needed.

Something had to be done, and that quickly, if we did not wish to

expose ourselves to the pangs of hunger and the danger of fever in that

filthy, miasmatic hole. In the dry [196]season, we might return to

Cabuyaro, where we could secure horses or mules, and go thence to our

next objective point, Villavicencio. During the rainy season, however,

this was impossible. We had been told the night before, that several of

the caños and rivers between Cabuyaro and Villavicencio were

quite impassable, as there were neither bridges nor ferries, and that

the currents were so swift that it was quite out of the question for

man or beast to cross them by swimming.

We were certainly in a quandary, if not in a very serious

predicament. It was useless to go backwards, unless we wished to return

to Orocué, and thence to Trinidad. Even if we returned to Orocué,

we could not get a steamer down the river for several months, and to

make the long trip to Ciudad Bolivar in a bongo was not to be thought

of. We were confronted by the first really grave difficulty of our

journey, and when we considered all the circumstances, it was enough to

depress the stoutest heart.

“But why had not our men and mules arrived,” we asked ourselves

time and again? Our telegram

ordering them had been received and satisfactorily answered. Just

before leaving Orocué we had sent a second telegram advising our

vaqueano—guide—when he should meet us but we had not

awaited a reply, taking it for granted that there would be no hitch in

our plans. It now occurred that we had acted unwisely in not waiting

for a response to our second telegram, so as to be sure that it had

been received and was properly understood.

The telegraph line to Orocué had only recently been put

up—just a few weeks before our arrival there—and had never

been in satisfactory working order. In fact, owing to a break in the

wire, which lasted a fortnight, we had not been able to get into

communication with Villavicencio—the place whence our mules were

to come—until a few days before we started for Barrigón.

Might there not have been another interruption in the line after we

sent our second message? And did this message ever reach [197]its

destination? It is true that a week had elapsed since our departure

from Orocué, and, if the line had been severed, it might have

been repaired.

But then again this was far from certain. The wire passed through

dense and interminable forests—where there were no roads of any

kind—and it might require several days to reach the break after

it was located. And then after our vaqueano got our telegram it would

require three days for him to go from Villavicencio to Barrigón,

supposing that he had the mules and saddles in readiness. If they were

not ready there would be another delay in starting. Altogether the

outlook was far from reassuring. Our animals and men might arrive at

any hour, and then again we might be obliged to wait for them for

weeks.

While occupied in these far from comforting reflections, we

remembered that the mail from Bogotá to Orocué was due.

The men who would bring it would also bring a certain amount of freight

for various points on the Meta. Here, then, was a ray of hope. If our

own men and animals should fail us, we might be able to prevail on the

mail carriers to give us the necessary means of transportation for

ourselves and baggage. This consideration tended to relieve somewhat

the suspense which was the most unpleasant feature of our hapless

situation. We resolved, accordingly, to take a more optimistic view of

things, and to trust to our star which, so far, had ever been in the

ascendant.

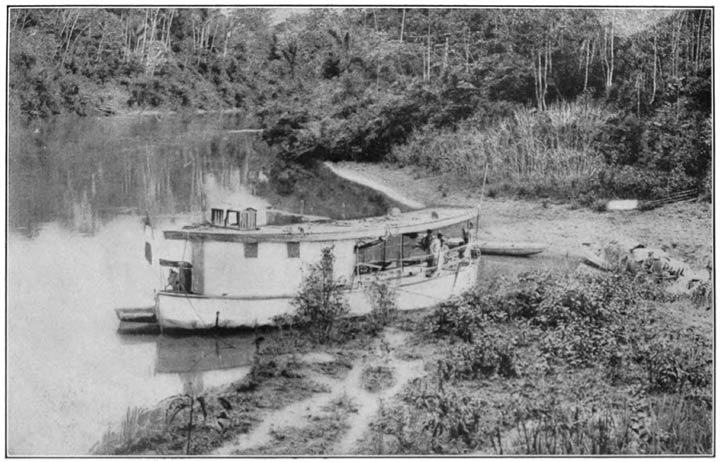

What had greatly contributed to the gloominess of the outlook on our

arrival at Barrigón was the thought that we should be obliged to

leave our launch—where we were so comfortable—for the

dismal, steaming pest-hole on the river’s bank. We did not for a

moment think of asking for shelter in the filthy shack occupied by the

negro family. That would be tantamount to courting

paludismo—malarial fever—in its worst form.

Fortunately, we had a good tent with us, and in this we could be

shielded from sun and rain, and, at the same time, escape some of the

unsanitary [198]features that rendered this spot so forbidding

and dangerous. It was really the first place that we had yet visited

from which we instinctively shrank and from which we wished to depart

at the earliest possible moment.

While thus preoccupied and devising ways and means for rendering our

enforced detention at this spot as endurable as circumstances would

permit, our captain, God bless him! observing our distress, came to us,

and with a kindness and courtesy we can never forget, said,

“No se preocupen, Señores, la lancha

quedará aquí hasta que vengan las bestias.” Do

not worry, gentlemen, the launch will remain here until the arrival of

your animals.

What a relief this kind and considerate act was—performed when

and where it counted for so much to us—only those can realize who

have been placed in similar situations. Everything was now as well

provided for as might be, except food. Where that was to come from was

a mystery, as we did not wish to draw on the very limited supply we had

brought with us.

Our first meal consisted of plátanos—some boiled and

some fried—with a cup of black coffee. I had never eaten a dozen

bananas in any form before coming to South America, but I gradually

became accustomed to them, although I never relished them. Here,

however, there was nothing else in sight, except two or three ducks

that were quacking about the green, miasmatic pools that surrounded the

negro shanty. We endeavored to purchase these, but, although we offered

the old dame several times what they were worth, she would not part

with them. No African ever held on more tenaciously to his fetish or

rabbit-foot than did this swart Ethiopian hag of Puerto Nuevo to her

prized webfeet.

For our dinner we fared better. Fortunately and quite unexpectedly,

someone succeeded in landing a large and delicious fish, which was

quite sufficient to furnish a meal for ourselves and crew. A new source

of food-supply was now indicated, but try as we would, it was

impossible to [199]catch another fish—large or small. The

impetuous current of the muddy river was decidedly adverse to our

rising piscatorial hopes. But we determined not to worry on account of

our lack of success as anglers. “Sufficient for the day is the

evil thereof.” Providence, we were sure, would provide for the

morrow. Probably our men and mules would arrive. If not, the mail

carriers would undoubtedly come, and then no Deus ex machina

would be necessary to extricate us from our embarrassing situation.

A dreary day passed and a more dreary night. What with the suspense

and the lack of proper food, and the confinement to a disagreeable spot

in the impenetrable forest, our position was such as not to encourage

slumber by night or rapturous admiration of tropical flora during the

day. Nevertheless, we still instinctively felt that relief would not be

long in coming.

The second morning we had our usual desayuno of black coffee and

plátanos. And to our amazement, there was added to this simple

fare a fine roast chicken. Where did it come from? We had seen no

chickens anywhere about the premises, and could not have been more

surprised if it had dropped from the blue sky. I asked the captain, and

he quietly replied with a smile, “Un poco de diplomacia. Nada

mas.” A little diplomacy. Nothing more. Ever considerate

about our comfort and needs, he had instituted a search for provisions,

and learned that the la vieja—the old woman, as he called

her—had some chickens concealed not far from the house, and,

whether by persuasion or threats, he would not say, he induced her to

part with one of them, and intimated that the same diplomacy he had

employed in getting the first, would, if necessary, avail in securing

others. The outlook was still brightening, and we now felt more than

ever that our deliverance was near.

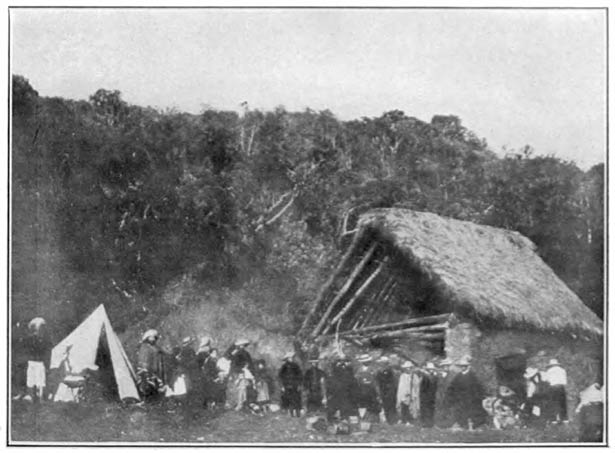

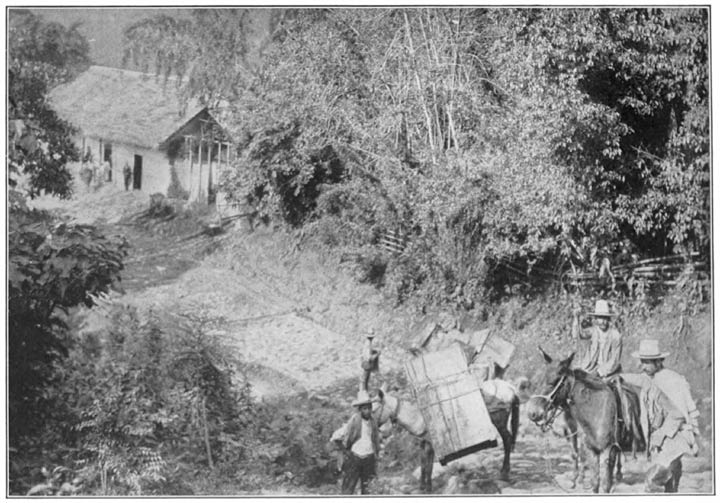

Shortly after midday, while we were taking our usual siesta in the

launch, we were suddenly startled by an unearthly noise. All the dogs

and whelps of the place and all the “curs of low

degree”—and there were many of [200]them—began to bark at once. And then in

the forest near by there was such shouting and screaming on the part of

men and boys, accompanied by the neighing of horses and the braying of

mules, that it seemed that a troop of guerrillas was bearing down upon

us. Never before had we heard anything like it, except possibly a Sioux

or Navajo war whoop. They seemed to desire to frighten us to death

before attacking us vi et armis. But no music could have been

more grateful to our ears than were those discordant notes emitted by

man and beast. We knew at once what it all meant, and, almost before we

could reach the top of the bank, our animals and men were all gathered

in the small free space in front of the cabin, and with them were the

bearers of the Bogotá mail. There were about thirty mules and

horses, and more than a dozen men.

We had telegraphed for mules only, as we did not think we should be

able to get horses, but to our delight we found that we were to have

two good saddle horses for our personal use, besides the mules destined

for our baggage. As, however, both men and animals needed rest, after

their long tiresome trip from Villavicencio, it was deemed best to

defer our departure until the following morning. The animals were then

turned loose to browse on whatever they could find to appease hunger,

and their masters were soon ensconced in their hammocks, slung wherever

they could find a suitable place for them.

It was arranged with our vaqueano that we should all be ready for

our journey across the llanos de madrugada—at early

dawn—the following morning. We had a long day’s ride before

us, as the nearest stopping place, where we could hope to find food and

shelter, was at a place called Barrancas, where was the house of the

owner of a large hato—cattle farm.

Bright and early, then, the next morning, our peons and vaqueano

were busy saddling our horses and packing our baggage on the backs of

the mules. The mail bongo from Orocué—which had left that

place ten days before we did[201]—arrived a few hours before

our departure, and all mail matter was hurriedly put on the backs of

other mules by those in charge of the mail destined for Bogotá

and intervening points.

It was not without a pang that we bade farewell to our devoted crew,

who had done so much to render our voyage on the Meta and Humea as

pleasant as it was memorable. From the ever-courteous and thoughtful

captain to our good-natured and obliging Guahibo, we were always the

recipients of delicate attentions of every kind. We might travel far

before again meeting with men so kind and so sympathetic as were those

four whom it was our good fortune to meet in an isolated village of

far-off Colombia. “God bless you all!” we said in parting.

“Nothing is too good for you.”

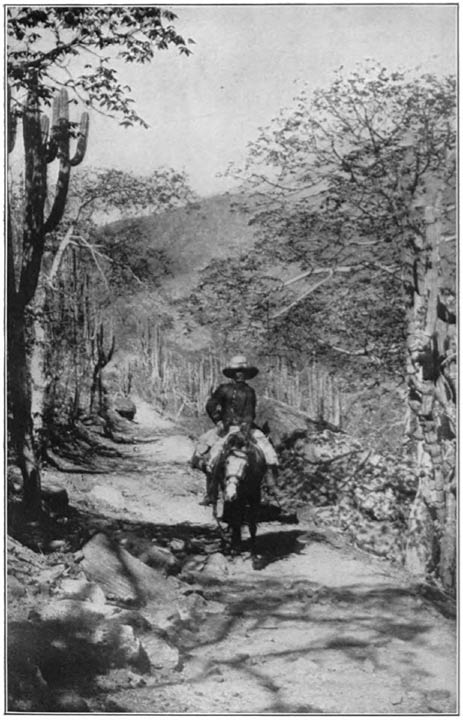

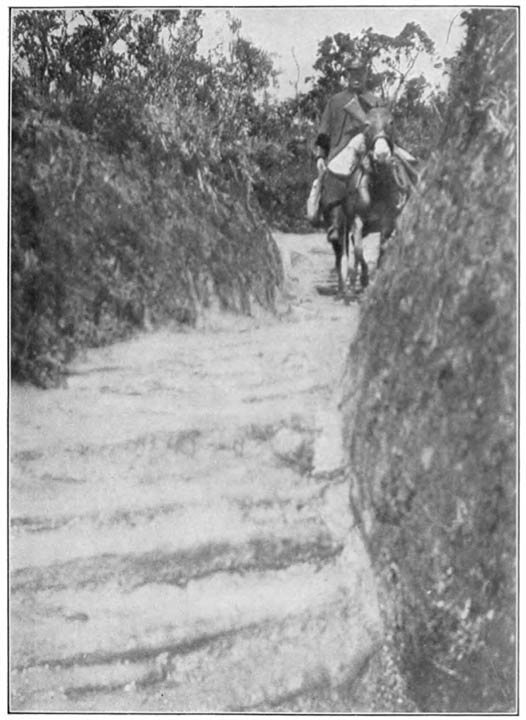

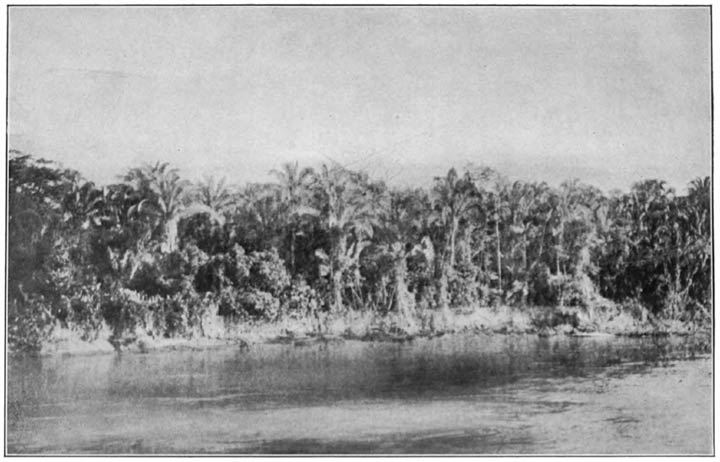

During the first hour after starting we had to struggle through what

the natives call the montaña. It had nothing mountainous

about it, as the name would seem to indicate, but was a dark, nearly

impervious wood almost on a level with the waters of the Humea. In the

dry season, I doubt not, the path through this forest would present no

difficulty, but during the rainy season it was next to impassable.

Everywhere there was deep, sticky mud and deeper pools and dirty

stagnant water. Often our horses sank to the saddle-girths in the

tenacious slime, and it was only by the greatest effort that they were

able to extricate themselves. At times, where the mud and water were

unusually deep, we were forced, for short stretches, to make our way

through the pathless forest. Then every step was impeded by branches

and lianas and progress was next to impossible. Finally, with great

difficulty for the animals and not a little danger to ourselves, we

succeeded in effecting our exit from this terrible montaña, and,

before we were aware of it, we found ourselves on high and dry ground

on the edge of a beautiful, smiling prairie of apparently limitless

extent.

What a relief it was to get once more into the

open—[202]into the broad llanos of Colombia—where we

could have an unimpeded view for miles in every direction. We had been

in the depths of the forest so long, getting only occasional glimpses

of the llanos on our way up the river, that we felt like a prisoner

given his liberty after a long term of confinement. Not that we had not

enjoyed the forests while we were in them. Far from it. We had enjoyed

every moment of the time spent in studying their richness and beauty.

But now that we had reached the llanos, to which we had so long looked

forward, and were no longer confined to the limited quarters of our

launch; now that we were on our willing steeds and could move as we

chose in any direction and as far afield as fancy might suggest, we

experienced a sense of freedom and agility that surprised ourselves. We

felt as if we had suddenly been transferred to another world, so

different was our new environment from that in which we had spent so

many weeks.

Never did the earth seem so green or the sky so blue, or the sun so

bright; never did the face of nature appear so ravishingly beautiful as

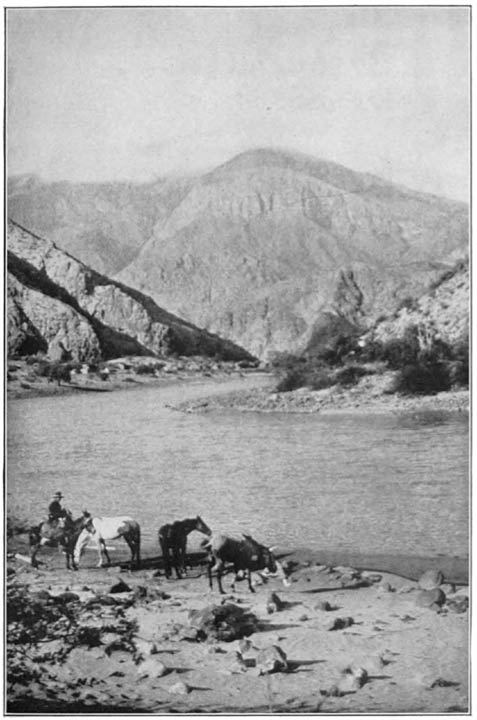

on that glorious May morning near the picturesque Humea. And away to

the west, partly veiled by haze and cloud, loomed up higher than ever

those vast mountains of majesty and mystery that seemed to overhang the

world. Yes, we were slowly but surely approaching the Andes, and in a

few days more, Deo volente, we should be scaling its

dizzy heights and exulting in the splendid panoramas that would be

presented to our enchanted gaze.

The landscape before us was indeed beautiful, entrancing as a

vision, fair as the Happy Valley of Rasselas. Exulting in a new sense

of freedom, and stirred by many overmastering emotions, we could but

exclaim with Byron,

“Beautiful!

How beautiful is all this beautiful world!

How glorious in its action and itself!”

[203]

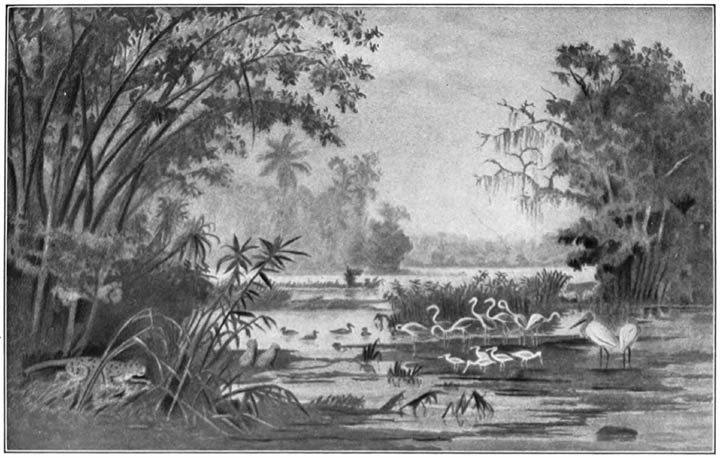

I have called the part of the llanos we were then entering a

prairie, but it was far more beautiful than any of our plains known by

that name. It was more like the palm-besprent delta of the Nile than

the tame and almost treeless reaches of land which characterize so much

of our western prairies. Here and there were coppices of graceful

shrubs made melodious by feathered songsters whose notes were new to

us, but everywhere, at no greater distance from one another, were our

old friends that had accompanied us all the way from the mouth of the

Orinoco—the ever-attractive moriche palms.

We saw also several other species of palm that excited our interest,

but none more so than the strange corneto palm. Like various species of

the Oenocarpus and Iriartea, it is remarkable for its

adventitious or secondary roots, which, springing from the trunk in

large numbers, lift it above the ground, and give it the appearance of

a large column supported on a cone of smaller columns inclined to it

obliquely. These roots vary from a fraction of an inch to several

inches in diameter. They have at times a length of from six to ten feet

and embrace a space of ground from five to eight feet in diameter. They

are frequently covered by vines and parasites so as to form a natural

bower which is used as a retreat by wild animals. Even the Indians have

recourse to these fantastic arbors as a place of refuge during rain

storms.

Here, as in the land of the Aruacs, the moriche palm is not only a

thing of beauty, but, for the Indians, a source of comfort and joy.

This and other palms, notably a kind of date palm, and the

Cumana, which bears a fruit similar to the wild olive, supply

the Indians, during certain months of the year, with all the food they

consume. Speaking of the palm, Padre Rivero declares it to be

“the earthly paradise of the Guahibos and Chiricoas. It is their

delight, their general larder, their all. It is the subject matter of

their thoughts and conversations. About it they dream, [204]and

without it life would possess no joy for them.”1

Like the cocoa palm, “By the Indian Sea, on the isles of

balm,” of which Whittier so sweetly sings, the palm on the Meta

and its affluents, as well as on the lower Orinoco, is for the child of

the forest

“A gift divine,

Wherein all uses of man combine,—

House and raiment and food and wine.”

When contemplating the bountiful provisions of Nature

in favor of the inhabitants of the tropics, as evinced in various

species of food-producing palms, we are forcibly reminded of the

statement of Linnæus that the first home of our race was

somewhere in the tropics. “Man,” says this illustrious

botanist, “dwells naturally within the tropics, and lives on food

furnished by the palm tree; he exists in other parts of the world and

subsists on flesh and cereals.”2

The llanos in places are quite level, and intersected by numerous

caños and streams. Some of them are so large that they could

easily be converted into navigable canals for small craft. In other

places the plains are undulating and are ideal grazing lands during the

rainy season. There is always an abundance of water, even in the dryest

summer, and the numerous groves and clumps of trees suffice to furnish

shade at all times for the largest herds.

We had not proceeded far when we met a large herd of cattle in care

of herdsmen quietly reposing beneath some umbrageous moriche palm or

singing some favorite Llanero [205]song. Contrary to what we

expected, the cattle were not so wild as those we had seen in Venezuela

and, although we passed within a few yards of them, they barely noticed

us. They were quite as tame as any one would find in the pasture lands

of an Illinois farm.

But what a fine breed of cattle they were and in what splendid

condition! They were as fat, sleek and large as any we had ever seen on

the plains of Texas or Nebraska, and would, I am sure, command as high

prices in the stockyards of Chicago.

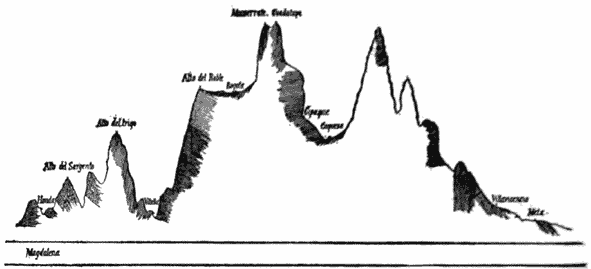

We were deeply impressed with the future possibilities of the

Venezuelan grazing lands, but we are now convinced that even a greater

future awaits the llanos of Colombia when properly exploited. To extend

the Cucuta railway so as to place Casanare and Villavicencio in

connection with Lake Maracaibo would be a far less difficult and costly

undertaking than many other railroad enterprises in South America that

have been carried to a successful issue, and that, too, when the

traffic hoped for was far less than it would be in this instance. Such

an extension, which would not need to be more than two or three hundred

miles in length, would put the Colombian llanos in direct communication

with the chief ports of the United States and Europe. By using fast

steamers, freight could then be carried from the heart of the llanos to

Mobile or New York in a week. What an immense development of the cattle

industry this would at once effect is beyond calculation. It would be a

greater source of revenue to the Republic of Colombia than all its

mines combined.

At the first blush this project may appear Utopian to those who are

unfamiliar with the country or who have never given thought to the

feasibility of the enterprise. Colombia, to most people in the United

States, is little better known than the territory of the Congo. Even to

the Colombians themselves, the llanos—la parte oriental,

as they call it—is a terra incognita. Outside of the

Llaneros—cattle men—who have interests there, it is rarely

[206]visited by any one connected with the

administration of the government. To reach the llanos from

Bogotá means a long and tiresome journey across the eastern

Cordilleras, and few are willing to undertake such a trip out of

curiosity or for the purpose of informing themselves about the

resources of this distant and neglected part of their country.

And yet, far away as they may seem, the llanos are not half so

distant from the United States as England is, and, with the steamship

and railway facilities above indicated, they could be brought as near

to New York in time as is London at the present.

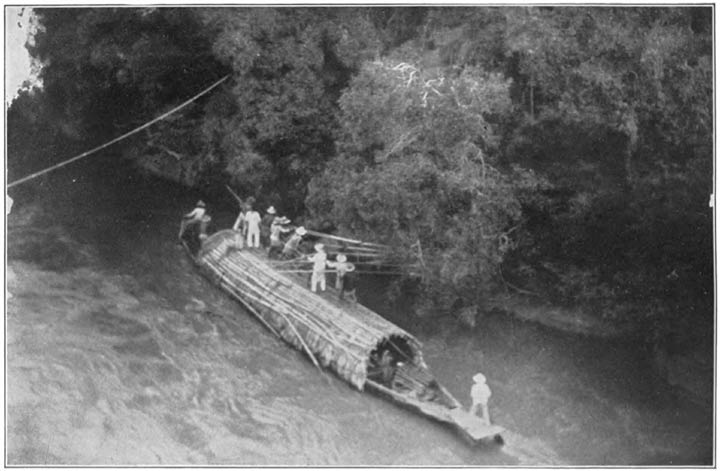

Probably a more economical way of reaching the llanos would be by

the Orinoco and the Meta. During the rainy season, as we have seen,

boats of light draft, but of considerable tonnage, can safely traverse

these rivers as far as Cabuyaro or Barrigón. A few hundred tons

of dynamite judiciously applied would effect a wonderful change for the

better in the beds of the two rivers named, and would render navigation

quite safe for the whole, or at least a greater part of the year.

When we note the magnitude of the beef trade between Australia and

the Argentine and the different ports of Europe, we are amazed to

observe that so little has been attempted towards developing a similar

but a more profitable trade with regions that are comparatively at our

doors. If these fertile and favored lands, instead of belonging to a

country long known, and looked at askance by capitalists and business

men, were a new discovery, there would be as great a rush towards them

on the part of colonists as there has frequently been to those Indian

lands that have, from time to time, been opened to white settlers in

Oklahoma and elsewhere in the West.

Now that our people are beginning to realize that the cattle in the

United States are not increasing in proportion to the demands of its

rapidly-growing population, they [207]may be induced to turn their

eyes towards the vast plains of our two sister republics of Colombia

and Venezuela, where there is, all the year round, abundant pasturage

of the richest kind for millions of cattle. There are vast fortunes

awaiting those who are willing to venture into these long-neglected

fields.

According to the reports of our Bureau of Animal Industry, the

United States has been for some years past suffering from fever ticks

and other plagues an annual loss of more than sixty million dollars.

This fact, coupled with the increasing demand for beef, renders it

imperative to seek for an adequate supply elsewhere. The cheapest and

best place in which to secure this extra supply is, me judice,

in the marvelous llanos so near our own country, which should, in the

manner indicated above, be brought much nearer than they are at

present.

I know that people will hesitate about investing in countries whose

governments are as unstable as those of the two nations mentioned, and

where foreign investors have found so little encouragement and

sympathy. There is, however, reason to believe that the age of

revolutions is coming to an end, and that it will, in the near future,

be succeeded by the reign of law. Peace congresses, arbitration

agreements, the spread of education, and the construction of railroads

have produced splendid results in other parts of the world, where

progress had long been unsatisfactory, and who will say that we may not

hope to see the same beneficent results realized in Venezuela and

Colombia? If all else fail, it is quite certain that our government

will know how to safeguard the rights of those of its citizens who may

have interests in these countries about whose validity there can be no

question. Now that all are so desirous of seeing improved commercial

relations established between the United States and the various

countries of Latin America, it would seem to be a matter of prime

importance not any longer to ignore the golden opportunities that in

the regions bordering the [208]Caribbean have so long eluded

American energy and enterprise.

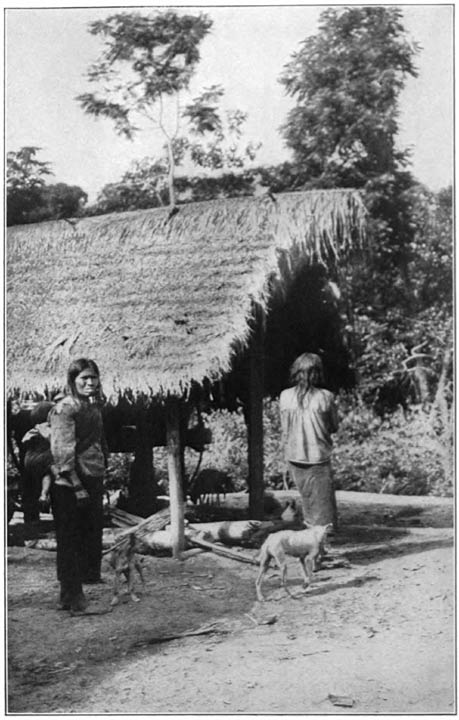

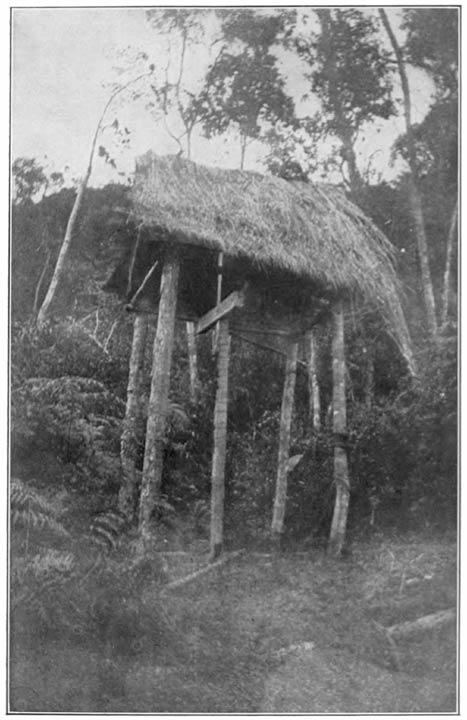

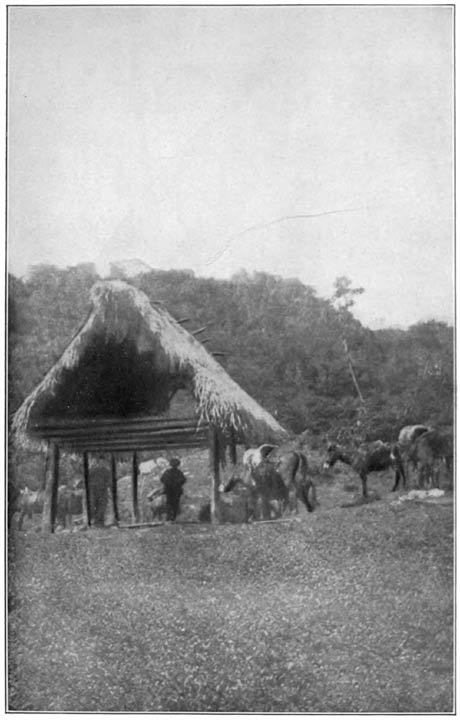

It was about four o’clock in the afternoon when we arrived at

Barrancas. We found here a good-sized house with an open

shed—enramada—near by. This latter structure is used

as a shelter for farming implements, harness, saddles, etc., and as a

place where peons and herdsmen may swing their hammocks and sleep

during the night. The house, to our surprise, had a tile roof, the

first we had seen since leaving Ciudad Bolivar.

The proprietor of the hato, whose home and family were in

Bogotá, received us cordially and did everything in his power to

make us comfortable. He also gave us his own room, which had a board

floor, another novelty to us. We were soon provided with a frugal

repast, after which we were entertained by our host’s experiences

on the llanos. He was one of eighteen children of the same mother. He

and his eleven brothers own a number of ranches and have many thousand

cattle in different parts of the republic.

“During the last war,” he said, “the soldiers

appropriated a thousand of our steers.” “Did you put in a

claim to the government for damages?” I asked. “Yes,”

he replied, “but it did no good. I never got a centavo and

never expect to. If I had been a foreigner, especially if I had been an

American, I should have received compensation for my loss. The

government always pays foreign claims when just, but the citizens of

the country must be satisfied with promises. It always promises to

reimburse us for any losses sustained during revolutions but the fact

is that we never get anything more substantial than

promises.”

The labor problem was as serious with him as with a Kansas farmer

during harvest time. “Es muy dificil conseguir

brazos aquí,”—it is very difficult to secure

laborers here—he told me in a tone of sadness. “So many men

lost their lives during the last war, that the country is now suffering

for a lack of working men.” [209]

And yet, notwithstanding his losses and his troubles, our host was a

thoroughly loyal Colombian. He loved to talk about his country, its

marvelous resources, and the great future in store for it. He spent

most of the year in the capital, coming to Barrancas only for a few

weeks at a time, and that only when business demanded his personal

supervision.

I was curious to learn from him, a Llanero, and therefore an expert

horseman, the shortest possible time in which the trip could be made to

Bogotá from Barrigón. Some books I had read stated that

the distance from the head of navigation on the Meta—and we had

reached that point—to Bogotá was only twenty miles, while

certain Venezuelans I had met had assured me that the trip could be

made in two days. His answer was conclusive. “The shortest

possible time without a relay of horses,” he said, “is four

days. To attempt to cover the distance in less time would be fatal to

the horse. I never try to reach Bogotá from here in less than

four days, and even this means hard riding.”3

“But what brings you up the Orinoco and the Meta at this

season of the year,” he enquired. “You are certainly

[210]the first Americans to come here—rio

arriba—up the river. Others may have come to the llanos from

the capital, but, if they did, I am not aware of it. And why did you

select the rainy season for your journey? Why did you not wait until

summer, when it is dry, and when the roads are in better

condition?” We then explained to him that no boats ascended the

Meta during the summer season and that we were thus forced to come

during the winter. Strange as it may appear, this had never occurred to

him. And yet he was an intelligent man and well informed about his

country and presumably about the means of communication with the

countries adjacent.

The Colombian Llanero is a most interesting character. He is

absolutely unique among his countrymen. The only people with whom he

can be compared are the inhabitants of the Apure plains and the Gauchos

of the Argentine pampas. Like these he regards as “fortunate the

man who has received from heaven the means of safeguarding life and

property—a good horse and a good lance.”4 Having

these two essentials of defense and offense, he is happy and

independent.

This is readily understood from his manner of life, which is quite

akin to that of the Arabian nomad. The desert in which he lives and his

eternal struggle against a physical environment that is as savage as it

is grandiose; his occupation as a herdsman and his roving life in the

boundless plain, have given the Llanero a character that is as original

as it is interesting.

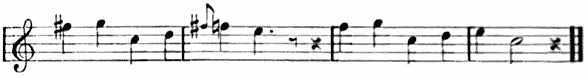

As a son of the desert, he is a lover of music and poetry, and will

spend an entire night or several consecutive nights dancing, playing

his rude guitar, scarcely larger than the hand that twangs it, or a

huge banjo, and singing verses either of his own composition, or those

of some other poet [211]of the plains. For strange as it may

appear, poets abound in the llanos as scarcely anywhere else. They may

be unable to read or write but they are nevertheless able to produce

songs—tonos or trovas llaneras—that

are frequently marked by rare beauty and depth of feeling. Considering

their limitations, their faculty for versification is often really

remarkable, and it is not unusual to find among them a singer that will

improvise with as much facility as an Italian improvisatore.

The Llaneros have a poetry of their own which they never abandon.

They compose what they sing and sing what they compose. And, although

they cannot as yet point to one of their poets who has had the

advantages of education and culture, they can, nevertheless, point with

pride to many of their number who have produced metrical compositions

of marked excellence and power of expression. The pity is that so far

we have no anthology of these poets of the plains. There is certainly a

rich field here for research awaiting some lover of the fresh and the

novel in literature and it is to be hoped that some one may soon

explore a domain that is so promising in results.

Their favorite compositions are ballads or rhymed romances, called

galerones, which are sung as recitatives. They closely resemble

the popular rhymed romances of Spain, and refer generally to deeds of

prowess performed by their own heroes in their constant struggles with

the wild and unsubdued nature in which their life is cast. In these

galerones valor and not love is the protagonist. Love, in the

metrical compositions of the plains, is always a secondary

character.

Two stanzas from a poem entitled En Los

Llanos—On the Plains—will exhibit the character of

these poems, and show, at the same time, that the Llanero has a keen

eye for the beautiful and sublime in nature and that his heart is open

to the sweetest sentiment and the deepest piety and reverence.

[212]

“Lejos, muy lejos del hogar querido

Paréceme que estoy en un desierto,”

“Far, far away from my hearth,” he

laments, “meseems I am in a desert.” And he gives his

reason.

“Cuando entre vivo rosicler la aurora

Muestra la fresca faz en el Oriente

En vano busco a mi gentil señora,

En vano á la hija que mi alma adora,

Para besarlas ambas en la frente.”5

For the Llanero a view of the beauty and grandeur of

his surroundings is a call to prayer, as is evinced by the following

lines:

“O que prodigios! que beldad! El hombre

Debil se siente y pobre en su presencia.

No hay nada aqui que el corazón no asombre,

En todo escrito está de Dios el nombre,

Todo pregona aquí su

Omnipotencia.”6

Before daylight next morning, the vaqueano knocked at

our door, announcing that it was time to rise, as we had another long

ride before us and must start early. Coffee was soon ready for us and

also a roast chicken. The latter, however, was prepared in such a way

that we did not relish it. Then it was, indeed, that we missed our

Indian cooks of the Meta. We asked for some milk for our coffee, but

although surrounded by large herds of cattle, there was not a drop of

milk in the house. When we expressed surprise at this, the cook

replied: “We never milk the cows here. We leave the milk for the

calves.”

I had often had a similar experience in the large ranches

[213]of the trans-Missouri region and was not,

therefore, specially surprised at the answer. However, a little

persuasion induced one of the peons to secure us a calabash of milk,

although his task was not an easy one. The cows, unaccustomed to being

milked, refuse to stand still, and in this instance, the peon had to

tie one of them to a tree. Even then, he was obliged to call in the aid

of an assistant before he could get the milk we craved.

On the cattle farms of Venezuela, where the cows are quite wild, it

is necessary to throw a noose around the horns of the animal to be

milked, and for one of the dairymen to hold it secure by a long pole,

while another does the milking in the usual way. Our peon, fortunately,

was not obliged to resort to such a drastic, time-consuming method.

Although it had rained heavily the greater part of the night, there

was no indication that the downpour would soon cease. On the contrary,

it looked as if it were to continue raining all day. Fortunately, we

were provided with good waterproof ponchos, and were prepared for any

aguacero—heavy shower—that Jupiter Pluvius might

choose to send from the heavy, lowering clouds that, pall-like,

overcast the sky.

Before we left Orocué, at the suggestion of the prefect of

the place, we had telegraphed to Villavicencio for a couple of

bayetones—a special kind of poncho—and these our

vaqueano had delivered to us at Barrigón.

To the inhabitants, especially the Indians of South America, and

more particularly those living in the Cordilleras, the poncho is what a

mantle was to an Irishman in the days of the poet Spenser. “When

it rayneth it is his pent howse; when it blowes it is his tent; when it

freezeth, it is his tabernacle. In sommer he can weare it loose, in

winter he can weare it close; at all times he can use it, never heavy,

never cumbersome.” In a word, this “weede is theyr howse,

theyr bedd, and theyr garment.”7 [214]

The poncho or bayeton,8 usually made of wool, in fully

six feet square with a hole in the centre to admit the head. Our

bayetones—called “nabby-tonys” by C.—were

really double ponchos, made by sewing together two blankets, one red,

the other blue. When the weather is damp and cloudy, the blue side is

exposed, whereas it is the red that is kept outside when the sun is

shining. The wearers of this useful garment have learned by experience

that these two colors are differently acted upon by heat and light and

they accordingly adjust it so as to secure the maximum of comfort. The

manta is a lighter covering made of white linen and is sometimes

highly embroidered. It is used when the sun’s rays are more

intense, because it reflects the solar rays better than the red woolen

garment. It is, however, rather an ornament than a necessity, and its

use is confined almost entirely to the better classes.

Provided with a poncho, a hammock and a many-pocketed

saddle—which are almost as indispensable as his horse—the

Llanero is always at home. The two former, he carries in a bundle

behind his saddle, where they are always ready for him at a

moment’s notice. In camping out he slings his hammock in any

convenient place, and, if it be in the open, the poncho is, by means of

a rope, held over it in such wise that he can defy the most violent

storm of the tropics, and sleep as soundly and be as well protected

from the rain as if he were under his own roof-tree.

Our trail was one of the numerous cattle paths that intersect the

llanos in every direction. The one we followed was a narrow ditch

filled with from one to two feet of water. Our vaqueano, who was in the

lead, trotted along as if we were following a dry path, and we had to

keep up with him or be lost. It was then that we realized the

impossibility of traveling over these extensive plains without a guide,

especially on a cloudy day during the rainy season. As well might one

try to cross the ocean without a compass as attempt to make one’s

way over the [215]llanos without a vaqueano. There was so many

caños—those natural channels, like deep ditches,

connecting streams and rivers—and morasses to cross that were

quite impassable except in certain places known only to the Llaneros,

who are thoroughly familiar with the country, that a stranger traveling

alone would soon find progress quite impeded.

To attempt to reach one’s destination by relying on the oral

directions of a Llanero would be quite hopeless. They would, probably,

be worded somewhat as follows:

“Continue your course over the savanna—arriba,

arriba—up, up, until you reach that bunch of cattle you see

yonder. You see them, don’t you?” queries the Llanero. They

are some cows and young bullocks, lost in the distance. Not having an

Indian’s keenness of vision you discern absolutely nothing, and

yet, unwilling to admit the fact, you declare that you distinguish them

perfectly. Your informant then vouchsafes further information which, if

you carefully heed and are able to follow, will without fail, conduct

you to your desired goal. “Then,” he continues, “go

to a clump of algarroba trees, but leave that aside and veer towards a

group of palms which you will see from there. When you reach the palm

group, coast along the foothills, across the Caño del Cayman,

for that is the name of the caño, until you come to the

Caño del Tigre. Next, you come to a copse of bamboos, and then

after that to the Caño de Chaparro Negro. Near it you will find

the Paso del Caño. Cross it and you will come to a

morichal at your left, but leave it behind, and continue a

little to the right for half an hour, and you will see the place you

are looking for.”

Years ago I had received similar directions from an old woman in the

mountains of Conamara, but there, all I had to do was to keep on the

road, and stop at the place I was seeking when I reached it. In the

llanos, where there are no roads, outside the hundreds of cattle paths

extending in every direction, it would be natural for the traveler,

[216]depending on directions like the above, promptly

to lose himself.

Fortunately, we had a good vaqueano, one who knew every cowpath and

caño and clump of trees between Barrigón and

Villavicencio, and we felt thoroughly at ease under his guidance. At

times, it is true, we found it somewhat difficult to keep up with him.

He seemed to have reserved the speediest animal for himself, or he knew

better how to keep up a sustained trot than we did. But, be that as it

may, we managed never to permit him to vanish from sight.

As we were riding over the plains we observed a large number of

vultures—Gallinazos—on a tree near our path. Hard by was

the carcass of an ox, that had just died, on which a single king

vulture—Sarcoramphus Papa—like the one we fancied

that preyed on the liver of Tityus—was making his morning repast.

The Gallinazos appear to stand in awe of the king vulture, and were

patiently waiting till he was satiated before making any attempt to

appease their own voracious appetites. The two species are never seen

to feed on the same carcass together. We saw several other such vulture

banquets on our way, but never did we see so many of these scavengers

congregated around the same carrion.

After six hours of hard riding, most of the time in a heavy rain, we

reached Los Pavitos. It consisted of a small bamboo hut and a number of

sheds. Here we dismounted for our midday meal, which consisted of a few

boiled eggs, and a cup of café à la

llanera—that is, coffee without milk or sweetening of any

kind—sin dulce—as the natives phrase it—and

some crackers that we had in an improvised haversack.

The family living in the hut consisted of three persons—man,

wife and their little daughter, a sweet child of about four years of

age. Both mother and child were neatly dressed, and had a genteel

appearance that was in marked contrast with their surroundings. The

child wore [217]a tidy pink dress, tastefully ornamented, and

seemed as if she had just come from the class-room of a convent school.

The family impressed us as having seen better days, and had evidently

not lived always so far away from their fellows.

Near the house stood a large calabash tree, bearing the largest

fruit of the kind we had yet observed. Some of the specimens of this

tree looked not unlike green pumpkins, and were fully from ten to

twelve inches in diameter. It is well named the crockery tree, because,

in the tropics, it supplies to a great extent the kitchen utensils

which are elsewhere made from clay.

Within a few steps of the tree mentioned was a broad, murmuring

stream—shaded on both sides by large, overhanging trees—of

pure crystal water. It was the first time in many weeks that we had

seen clear, flowing water, and then was brought home to us, as never

before, the truth of old Captain John Hawkins’ expressive words

that there is nothing “so toothsome as running water.”

While on the Orinoco and the Meta, we always had with us large

earthenware filters, for it was not safe to drink the muddy waters of

these rivers, often containing more or less decaying animal matter.

The last thing we did before leaving our launch was to fill our

canteen with filtered water. But more than a day had elapsed since

then, and our supply was exhausted. We accordingly proceeded to

replenish our canteen with water from the neighboring stream, but, as

soon as the lady of the house saw what we were about, she begged us to

permit her to render us this little service. “I know where the

water is best,” said she, and, taking the canteen, she waded out

almost to the middle of the stream and in a few moments returned with a

new supply of water fresh from the Andes.

As we prepared to leave, mother and child—the father was sick

abed with malaria—both expressed their regret that we could not

remain longer. “We feel greatly honored,” [218]the

good woman said, “by your visit, and, if you ever come this way

again, you must be sure to come to Los Pavitos. Dios

guarde á VV. y feliz viaje.” May God protect you and

may you have a happy journey.

Such were the parting words of this gentle soul in the wilderness,

words of tenderest charity and sweetest benediction. For hours

afterwards her touching accents seemed like music in our ears, and the

image of her lovely child, her darling niñita, nestling

by her side, with her little hands waving us a fond adieu, was before

our eyes long after we had left the llanos far behind us.

What was it in these gentle creatures, whom we saw for only a few

moments, that appealed to us so strongly? Was it that secret bond of

sympathy—highly intensified by circumstances and

environment—that makes all the world akin? Was it the same

sentiment that touched the artistic soul of Raphael, when, on passing

through an Italian village, he saw the mother and child whom he has

immortalized in his Madonna della Sedia. Or were we

just then in the mood that impelled Goethe to indite his soul-subduing

ballad Der Wanderer? Perhaps. Let the reader judge

from the following stanza:—

“Farewell!

O Nature, guide me on my way!

The wandering stranger guide,

“To a sheltering place,

From north winds safe!

“And when I come

Home to my cot

At evening,

Illumined by the setting sun,

Let me a woman see like this,

Her infant in her arms!”

After leaving Los Pavitos, we still had a three-hours

ride ahead of us before reaching Las Palmas, where we [219]purposed stopping for the night. Fortunately, it

had ceased raining and our trail was now in a much better condition

than it had been since leaving Barrancas.

It contributed much to our comfort, too, that we were able to

complete our day’s journey under sun-proof clouds. So far we had

not suffered the slightest inconvenience from the exaggerated heat of

the plains. Some of our Ciudad Bolivar friends had told us that the

heat of the llanos was so intense that it would be necessary, if we

would avoid sunstroke, to travel by night. As a matter of fact, the

temperature was never above 80° F. During the greater part of the

time it was several degrees below this figure. Besides, to attempt to

cross the llanos in the rainy season, during the pitch-dark nights that

usually prevail, would be like trying to find one’s way through a

Cimmerian bog. Not even the most experienced vaqueano would venture on

such a foolhardy journey.

We arrived at Las Palmas just as the rays of the setting sun were

beginning to throw a veil of crimson and purple over the distant

summits of the Cordilleras. Here we met with the same cordial reception

as elsewhere on the llanos. As, however, there was not room enough in

the small choza and enramada for our entire party, we had

recourse to our portable tent, which we always had with us for such

emergencies. When we enquired of our host what he could offer us for

comida, he sadly replied he had nothing but bananas, which were

at our disposition. There were no eggs or chickens, and, although there

were herds of cattle all around us, it was quite impossible to get a

draught of milk. The cows would not permit anyone to milk them.

We then remembered that we yet had in our haversack a small tin box,

still unopened, of sliced Chicago bacon. This, with some crackers, was

all that was left of the little store of provisions that we had brought

with us. It was not without grave misgivings that we proceeded to open

this remnant of our food-supply. We had, on several former occasions,

found that our canned goods were unfit [220]for use, and what if

the contents of this last box should be spoiled? It meant that we

should be reduced to extremely short rations until we should reach

Villavicencio, and there was no certainty when that would be. We had

still another montaña to pass, many rivers and

caños to cross, and, above all, the terrible Ocoa, which, on

account of the floods that had been overflowing its banks during the

past week, our vaqueano said, might delay us for several days.

But the good God, who takes care of the birds of the air and clothes

the lily of the field, had not forgotten us. We found the contents of

the box as fresh and wholesome as when first enclosed in the far-off

metropolis on Lake Michigan, and very pleasant was it, as the reader

can imagine, for us, who had so long fared on chicken, eggs and

bananas, to have a change in our aliment, in the form of sweet, nutty,

breakfast bacon and that, too, from the glorious land of the Stars and

Stripes.

Early the next morning we were again in the saddle. Before bidding

us adieu our kindly host expressed his regret that he was unable to

give us better entertainment. He wished us to understand that it was

through lack of means and not of good will. “Dispense la mala posada,” excuse our poor lodging house,

he said—and his wife and daughter, a fair young girl just

entering her teens, re-echoed his apologies and in accents that left no

doubt as to their sincerity.

During the latter part of the night at Las Palmas, there was a

genuine tropical aguacero—the heaviest downpour that we

had yet witnessed. When we started from there the next morning it was

still raining heavily, and with no indication that there was to be a

change until late in the day, if then. Now, more than ever, we

congratulated ourselves on having secured our bayetones just when they

were so much needed. They were all they had been represented to be and

more. Although we had already spent many hours in continuous rainfalls,

not a drop of moisture had yet reached our persons, and we had remained

as dry as [221]if we had traveled under a cloudless sky. The

raincoats we had brought with us, although guaranteed to be the best

waterproofs made, would never have served the purpose that our

bayetones answered so admirably.

After about an hour’s ride, we entered a montaña

similar to the one near Barrigón, but greater in extent. The mud

was not so deep, but there were more caños and streams to cross.

Some of them were quite deep, and in a few instances, the current was

so strong that our horses had difficulty in keeping themselves on their

feet. Several times we turned to our vaqueano to enquire if a

particularly large stream was the much-dreaded Ocoa. “No, Señores,” he always replied; “El Ocoa es más grande”—the Ocoa is

larger.

We noticed that he was quite pensive and apparently as much

preoccupied about the Ocoa as we were ourselves. He then informed us

that he had learned at Las Palmas that the Ocoa had been impassable for

several days past, and he feared we should be detained there for some

time. Just then we came to the largest and widest torrent that we had

yet met. We effected the passage of this with the greatest difficulty,

and not without considerable risk to both mount and rider. After we had

safely gotten across I turned again to our guide and said: “That

is surely the Ocoa, is it not?” “No,

Señor, el Ocoa es todavia más grande y más

bravo.” No, Sir, the Ocoa is still larger and more

turbulent.

Finally, after we had been about three hours in the montaña,

the rain continuing all the while without cessation; after we had

narrowly escaped being mired several times, or being carried away by

several of the impetuous water courses that obstructed our

path—there were by actual count more than thirty of them; after a

long struggle against the dread that was so greatly depressing our

vaqueano, and trying to take an optimistic view of our situation, we

had our attention directed to a loud roaring noise immediately in front

of us. We knew at once what that [222]meant, and did not need the

information then volunteered by our guide, “He

aquí el Ocoa, Señores.” That is the Ocoa,

Sir.

A few minutes more and we were on its banks. Swollen to an unusual

height by the recent heavy rainfalls in the Andes, it was now a raging,

roaring mountain torrent that had attained the magnitude of a

tumultuous river which swept everything before it. It must have been

such a torrent that the poet Schiller had before his mind’s eye

when he wrote The Diver, of which the following stanza is a

part:—

“And it seethes and roars, it welters and

boils,

As when water is showered upon fire;

And skyward the spray agonizingly toils

And flood over flood sweeps higher and higher,

Upheaving, downrolling, tumultuously,

As though the abyss would bring forth a young

sea.”

C., who had never witnessed in Trinidad such

exhibitions of storm and flood, was in despair. Our peons, finding

their worst forebodings an actuality, were distressed and disconsolate.

If they could but reach the other side of the river, they would be

almost in sight of their homes from which they had been absent for more

than a week.

“How long shall we be obliged to wait before we can

cross?” someone timorously inquired. “If it does not rain

any more,” the reply came, “we may get over to-morrow

evening. If there is another aguacero in the mountains, Dios

sabe,”—God knows—“how long we may be

detained here.” Just then, one of the peons who claimed superior

knowledge about the behavior of such rios bravos as the one

before us, gave it as his candid opinion, that, even if there were no

further rain, it would be quite impossible to effect a passage inside

of three days.

To one unfamiliar with the suddenness with which mountain streams

become raging torrents,9 and the quickness [223]with

which they subside, these declarations of opinion were depressing

enough. I had, however, spent many years among the Rocky and Sierra

Madre mountains, and had often had occasion to study the modus

operandi of the cloud-bursts that are there of so frequent

occurrence. Besides this, while our peons were disputing among

themselves as to what was best to be done in our embarrassing

situation, I had been carefully observing the height of the water line

and found, to my great delight, that it was gradually becoming lower.

After making a few measurements, I found that, if there were no further

rainfall, we should be able to cross to the other side before

sundown.

As it was now long past noon, and we had had nothing to eat since

early morning, it was suggested that we take a little luncheon, while

waiting for the river to become fordable. Suiting the action to the

word, a fire was started, our kit of kitchen utensils was drawn from

its sack, and in a short time we had a large cup of fragrant, black

coffee, and the remnant of our breakfast bacon fried in a manner to do

credit to a New York chef. We still had a few soda crackers, and

these, together with the coffee and bacon, furnished us with a repast

that left nothing to be desired.

Having no doubt about our ability to reach Villavicencio before

nightfall, we gave all the remaining eatables to our vaqueano and

peons. They thankfully partook of the coffee and crackers, but a mere

taste of the bacon quite satisfied them. They had evidently never eaten

any before and, far from relishing it, found it positively distasteful.

They had yet to acquire a taste for bacon as others acquire a taste for

snails and frogs’ legs. They still had with them a few

platanos—their staff of life—which they roasted, and with

these and the crackers and coffee we gave them they fared even better

than usual.

After luncheon was finished, it was found that the river had fallen

enough to justify an attempt to cross it. Great caution, however, was

necessary to prevent any possible mishap. First, the largest and

strongest mule in the drove [224]was relieved of his burden and

forced to cross the river alone. He examined it very suspiciously and

at first hesitated about entering the water. But he was so belabored

with sticks and clubs that the poor beast had no alternative. After he

had started towards the other side the peons all kept up such an

unearthly yell that he was afraid to venture back. After a terrific

struggle he succeeded in reaching the opposite bank.

The current was evidently still too strong to warrant another

experiment of this kind. So we waited about a half an hour, when a

second mule—a smaller one—was driven into the water. He had

barely reached the middle of the river when he was lifted off his feet,

and carried some distance down stream. It looked, for a few moments, as

if he was going to be lost, but, by vigorous exertion, he got on his

feet again, and stood in mid-river breasting the full force of the

current and looking piteously towards his masters for assistance. But

they merely jeered at him vociferously and asked him if he wished to

return to Barrigón.

Seeing no help forthcoming, the terrified brute made a supreme

effort and succeeded in getting back to the bank from which he had

started. There he stood for a while panting heavily, after the

strenuous efforts he had made, but all the while looking wistfully at

his companion on the opposite bank of the Ocoa. After he was somewhat

rested, and before any one realized what he was about to do, the mule

was again in the water, making, of his own accord, a second attempt to

reach the other side of the river, where his companion was awaiting

him. After battling with the current for some minutes, he was

successful in his venture, for which he received the unstinted applause

of his masters. No sooner had he emerged from the water than he gave a

long, loud bray of victory which awoke the echoes in the woods for

miles around. The whole performance was so comical that it provoked

roars of laughter from our entire party. As an illustration of

mule-headedness in a good [225]cause, in face of apparently

insuperable difficulties, it was superb.

Having proved the fordableness of the river by mules, the peons

determined to match their own strength against the still-impetuous

current. Accordingly, one of their number, a giant in strength, taking

the end of a hundred-foot lariat between his teeth, carefully entered

the water, and, after successfully buffeting the angry billows, landed

on the opposite bank, whence the two mules had watched his struggles

with apparent interest and sympathy.

Now that the lariat was firmly stretched between the two banks, and

that the river was still falling, it was a matter of only a short time

to transfer the remaining mules and the baggage to the other side.

The jurungos10—a Llanero epithet for

strangers—were the last to cross. Elevating our feet as much as

possible, to avoid getting wet, we were soon in mid-stream. The motion

of the water in one direction while our horses were struggling in the

other, had a tendency to induce vertigo, but as we had to be on the

alert every instant, in order to preclude all danger of miscarriage, we

soon found ourselves happily landed, with the dread Ocoa at last in our

rear.

It was now only a short ride to Villavicencio, over comparatively

dry and slightly rising ground. Ere the sun had dropped behind the

Andes we had alighted before our lodging house near the plaza on the

main street of the town. Our host, who was awaiting us at the door,

gave us a most cordial greeting, but seemed to be much surprised and

embarrassed. He then explained that he had misunderstood the telegram

that he had received from [226]Orocué announcing our

arrival and requesting him to have

piezas—rooms—reserved for us. “I inferred from

the telegram,” he said, “that you were Colombians and

never, for an instant, dreamed that I should have the honor of

entertaining foreigners. Had I known whom I was to have as my guests, I

should have made more elaborate preparations for your reception. As it

is, I can offer you only an unfurnished room. It is the best I have,

and I trust you will excuse my not making better provisions for your

comfort during your sojourn in our midst. We have no hotels here, and

our people, when traveling, are accustomed to lodge with their friends,

or take an apartment like the one reserved for you.”

The good man’s explanation was quite unnecessary, as we were

more than satisfied with our room. It was large and airy, and, although

devoid of furniture of every kind, it had a clean board floor, and that

was a great deal for travelers, who, like ourselves, had been roughing

it on the Meta and the llanos.

He was much relieved when he saw how easy it was to satisfy his

guests, and without more ado, he proceeded to order dinner for us

without delay. While dinner was preparing we had our dufflebags brought

into our apartment, and, in a very short time, our camp chairs were

unfolded and our cots and bedding arranged for the night. A table was

next brought in from an adjoining house, and soon a young Indian maid

arrived to make the necessary preparations for our evening repast. Our

meals, it had been arranged, were to be served from a restaurant a few

doors away. The señora in charge, and her daughter, who belonged

to an old Colombian family, now in reduced circumstances, left nothing

undone to insure the most satisfactory service possible.

A bountiful dinner, such as we had not had since leaving

Orocué, was soon on the table. There were meats, vegetables and

various kinds of fruits and, what we found specially agreeable, good

wheaten bread. Besides all these [227]viands, there was an

additional and unexpected luxury in the form of a quart bottle of

generous old Bordeaux. It goes without saying that we showed due

appreciation of the señora’s culinary skill. Never did the

dishes of a Parisian restaurateur seem more inviting. Now came to us

with special force the old saying that “appetite is the best

sauce,” and that for travelers like ourselves, “Il vaut mieux découvrir un nouveau plat qu’

un nouveau planète,” it is better to discover a new

dish than a new planet.

As we had resolved to remain a few days in Villavicencio before

essaying the trip across the Cordilleras, we felt a sense of relief, by

anticipation, in the thought that we should not, before daybreak the

following morning, be obliged to hearken, as hitherto, to the usual

announcement of our vaqueano, “Vamonos,

Señores—Gentlemen, it is time to start.”

As we were both quite fatigued, we did not delay long in seeking

repose on our ever-restful cots. And it was but a very short time

before at least one of the travelers was in the land of dreams. And one

of the visions that appeared to him was that of a little child in a

pink frock, standing beside her mother under a totuma tree, near a

crystal stream in the llanos, waving her tiny hand and lisping a sweet

Adiosito to two strangers from beyond the sea, whose

course was towards the western sky, where the giant Andes stood to

salute the approaching lord of day. [228]