To return to the use of the scape animal as a means of

expelling disease. In Berâr, if cholera is very severe, the

people get a scapegoat or young buffalo, but in either case it must be

a female and as black as possible, the latter condition being based on

the fact that Yamarâja, the lord of death, uses such an animal as

his vehicle. They then tie some grain, cloves and red lead (all demon

scarers) on its back and turn it out of the village. A man of the

gardener caste takes the goat outside the boundary, and it is not

allowed to return.74 So among the Korwas of

Mirzapur, when cholera begins, a black cock, and when it is severe, a

black goat, is offered by the Baiga at the shrine of the village

godling, and he then drives the animal off in the direction of some

other village. After it has gone a little distance, the Baiga, who is

protected from evil by virtue of his holy office, follows it, kills it

and eats it. Among the Patâris in cholera epidemics the elders of

the village and the Ojha wizard feed a black fowl with grain and drive

it beyond the boundary, ordering it to take the plague with it. If the

resident of another village finds such a fowl and eats it, cholera

comes with it into his village. Hence, when disease prevails, people

are very cautious about meddling with strange fowls. When these animals

are sent off, a little oil, red lead, and a woman’s forehead

spangle are put upon it, a decoration which, perhaps, points to a

survival of an actual sacrifice to appease the demon of disease. When

such an animal comes into a village, the Baiga takes it to the local

shrine, worships it and [170]then passes it on quietly outside

the boundary. Among the Kharwârs, when rinderpest attacks the

cattle, they take a black cock, put some red lead on its head, some

antimony on its eyes, a spangle on its forehead, and fixing a pewter

bangle to its leg, let it loose, calling to the

disease—“Mount on the fowl and go elsewhere into the

ravines and thickets; destroy the sin!” This dressing up of the

scape animal in a woman’s ornaments and trinkets is almost

certainly a relic of some grosser form of expiation in which a human

being was sacrificed. We have another survival of the same practice in

the Panjâb custom, which directs that when cholera prevails, a

man of the Chamâr or currier caste, one of the hereditary

menials, should be branded on the buttocks and turned out of the

village.75

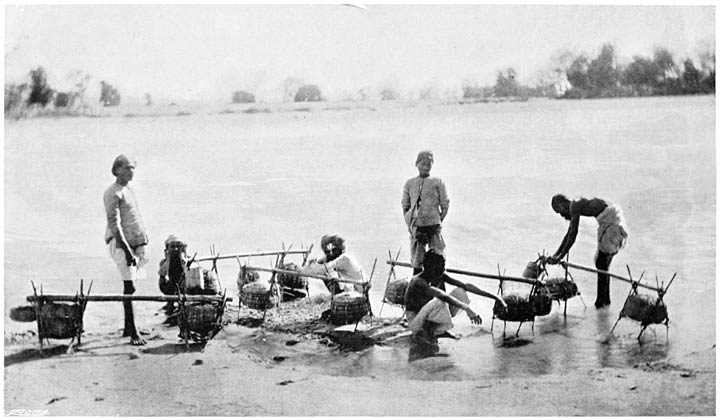

A curious modification of the ordinary scape animal, of which it is

unnecessary to give any more instances, comes from Kulu.76 “The people occasionally perform an

expiatory ceremony with the object of removing ill-luck or evil

influence, which is supposed to be brooding over the hamlet. The

godling (Deota) of the place is, as usual, first consulted through his

disciple (Chela) and declares himself also under the influence of a

charm and advises a feast, which is given in the evening at the temple.

Next morning a man goes round from house to house, a creel on his back,

into which each family throws all sorts of odds and ends, parings of

nails, pinches of salt, bits of old iron, handfuls of grain, etc. The

whole community then turns out and perambulates the village, at the

same time stretching an unbroken thread round it, fastened to pegs at

the four corners. This done, the man with the creel carries it down to

the river bank and empties the contents therein, and a sheep, fowl, and

some small animals are sacrificed on the spot. Half the sheep is the

property of the man who dares to carry the creel, and he is also

entertained from house to house on the following night.”

It is obvious that this exactly corresponds with the old English

custom of sin-eating. Thus we read:77—“Within

[171]the memory of our fathers, in Shropshire, when a

person died, there was a notice given to an old sire (for so they

called him), who presently repaired to the place where the deceased

lay, and stood before the door of the house, when some of the family

came out and furnished him with a cricket on which he sat down facing

the door. Then they gave him a groat, which he put in his pocket; a

crust of bread, which he ate; and a full bowl of ale, which he drank

off at a draught. After this he got out from the cricket and

pronounced, with a composed gesture, the ease and rest of the soul

departed, for which he would pawn his own soul.”

There are other Indian customs based on the same principle.78 Thus, in the Ambâla District a

Brâhman named Nathu stated “that he had eaten food out of

the hand of the Râja of Bilâspur, after his death, and that

in consequence he had for the space of one year been placed on the

throne at Bilâspur. At the end of the year he had been given

presents, including a village, and had then been turned out of

Bilâspur territory and forbidden apparently to return. Now he is

an outcast among his co-religionists, as he has eaten food out of the

dead man’s hand.” So at the funeral ceremonies of the late

Rânî of Chamba, it is said that rice and ghi were placed in

the hands of the corpse, which a Brâhman consumed on payment of a

fee. The custom has given rise to a class of outcast Brâhmans in

the Hill States about Kângra. In another account of the funeral

rites of the Rânî of Chamba, it is added that after the

feeding of the Brâhman, as already described, “a stranger,

who had been caught beyond Chamba territory, was given the costly

wrappings round the corpse, a new bed and a change of raiment, and then

told to depart, and never to show his face in Chamba again.” At

the death of a respectable Hindu the clothes and other belongings of

the dead man are, in the same way, given to the Mahâbrâhman

or funeral priest. This seems to be partly based on the principle that

he, by using these articles, passes them on for the use of the deceased

in the land of death; but the detestation and contempt [172]felt

for this class of priest may be, to some extent, based on the idea that

by the use of these articles he takes upon his head the sins of the

dead man.79

Again, writing of the customs prevailing among the Râjput

tribes of Oudh which practise female infanticide, Gen. Sleeman

writes:80—“The infant is destroyed in the room

where it was born, and there buried. The room is then plastered over

with cow-dung, and on the thirteenth day after, the village or family

priest must cook and eat his food in this room. He is provided with

wood, ghi, barley, rice, and sesamum. He boils the rice, barley, and

sesamum in a brass vessel, throws the ghi over them when they are

dressed, and eats the whole. This is considered as a Homa or burnt

offering, and by eating it in that place, the priest is supposed to

take the whole Hatya or sin upon himself, and to cleanse the family

from it.”

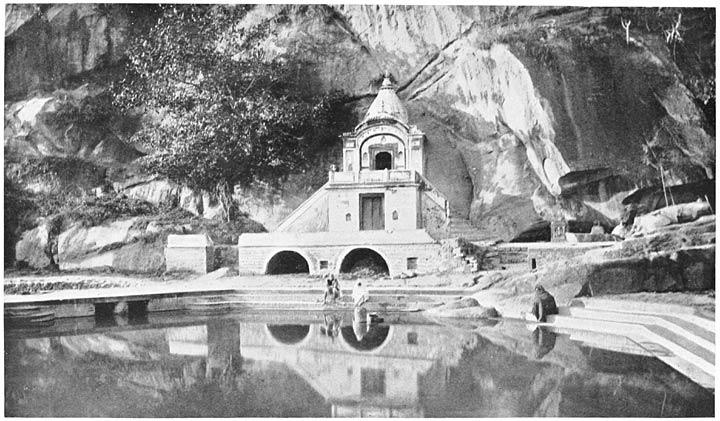

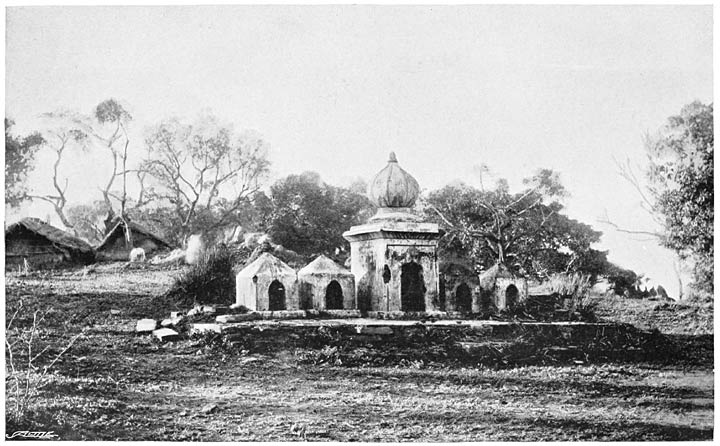

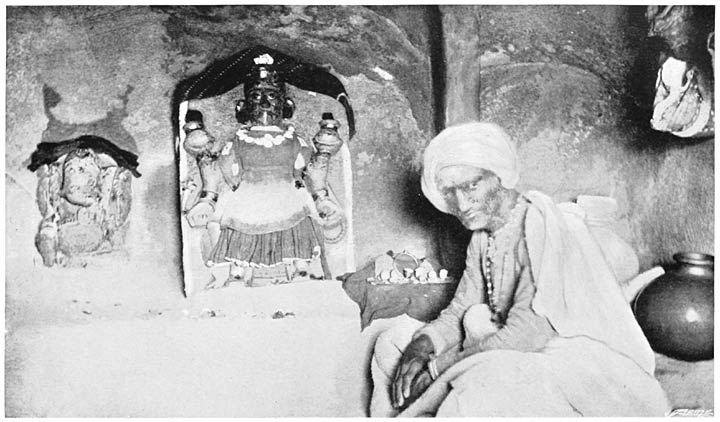

So, in Central India the Gonds in November assemble at the shrine of

Gansyâm Deo to worship him. Sacrifices of fowls and spirits, or a

pig, occasionally, according to the size of the village, are offered,

and Gansyâm Deo is said to descend on the head of one of the

worshippers, who is suddenly seized with a kind of fit, and after

staggering about for a while, rushes off into the wildest jungles,

where the popular theory is that, if not pursued and brought back, he

would inevitably die of starvation, and become a raving lunatic. As it

is, after being brought back by one or two men, he does not recover his

senses for one or two days. The idea is that one man is thus singled

out as a scapegoat for the sins of the rest of the village.

In the final stage we find the scape animal merging into a regular

expiatory sacrifice. Other examples will be given in another connection

of the curious customs, like that of the Irish and Manxland rites of

hunting the wren, which are almost certainly based on the principle of

a sacrifice. Here it may be noted that at one of their festivals, the

Bhûmij [173]used to drive two male buffaloes into a small

enclosure, while the Râja and his suite used to witness the

proceedings. They first discharged arrows at the animals, and the

tormented and enraged beasts fell to and gored each other, while arrow

after arrow was discharged. When the animals were past doing very much

mischief, the people rushed in and hacked them to pieces with axes.

This custom is now discontinued.81

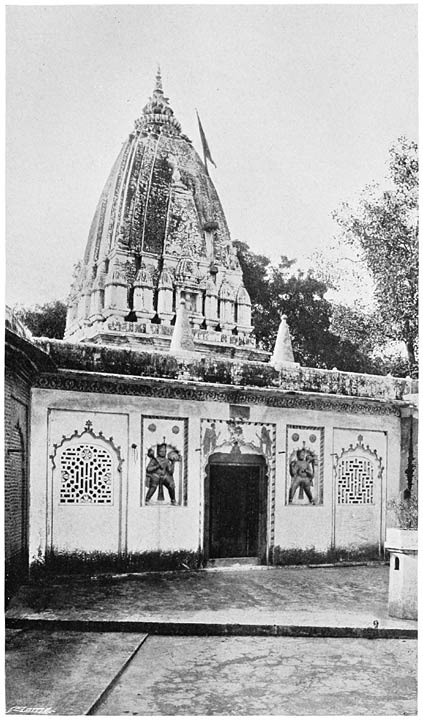

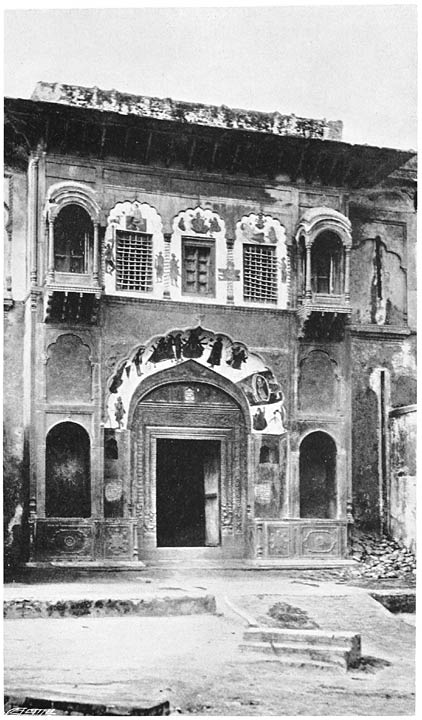

Similarly in the Hills, at the Nand Ashtamî, or feast in

honour of Nanda, the foster father of Krishna, a buffalo is specially

fed with sweetmeats, and, after being decked with a garland round the

neck, is worshipped. The headman of the village then lays a sword

across its neck and the beast is let loose, when all proceed to chase

it, pelt it with stones, and hack it with knives until it dies. It is

curious that this savage rite is carried out in connection with the

worship of the Krishna Cultus, in which blood sacrifice finds no

place.82

In the same part of the country the same rite is performed after a

death, on the analogy of the other instances, which have been already

quoted. When a man dies, his relations assemble at the end of the year

in which the death occurred, and the nearest male relative dances naked

(another instance of the nudity charm, to which reference has been

already made) with a drawn sword in his hand, to the music of a drum,

in which he is assisted by others for a whole day and night. The

following day a buffalo is brought and made intoxicated with Bhang or

Indian hemp, and spirits, and beaten to death with sticks, stones and

weapons.

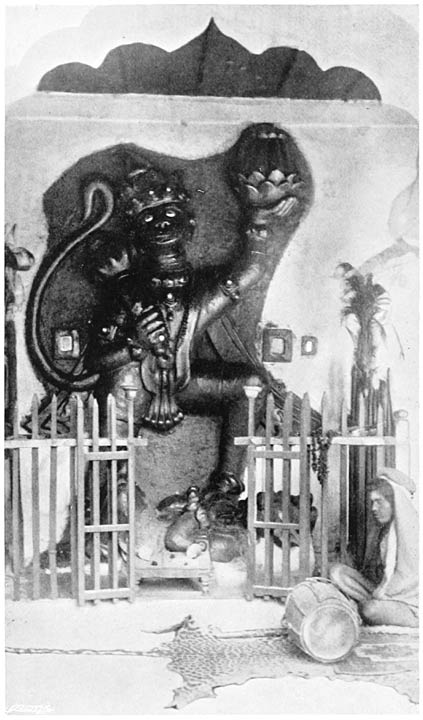

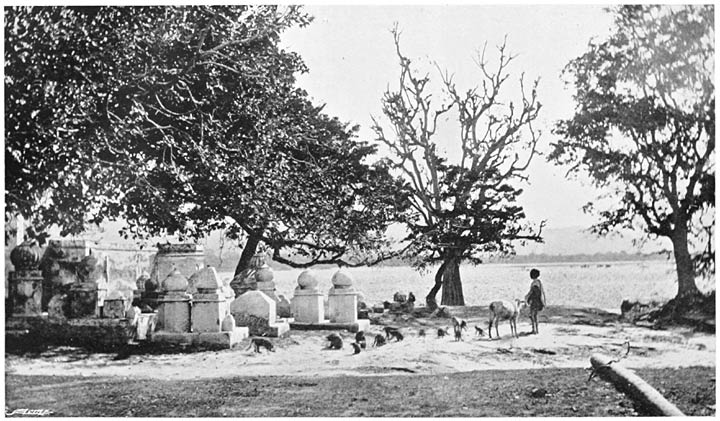

So, the Hill Bhotiyas have a feast in honour of the village god, and

towards evening they take a dog, make him drunk with spirits and hemp,

and kill him with sticks and stones, in the belief that no disease or

misfortune will visit the village during the year.83 At the

periodical feast in honour of the mountain goddess of the

Himâlaya, Nandâ Devî, it is said that a four-horned

goat is invariably born and accompanies the pilgrims. When unloosed on

the mountain, the [174]sacred goat suddenly disappears and as

suddenly reappears without its head, and then furnishes food for the

party. The head is supposed to be consumed by the goddess herself, who

by accepting it with its load of sin, washes away the transgressions of

her votaries. [175]