| 1. THE “B. O. W. C.” |

| 2. THE BOYS OF GRAND PRÉ SCHOOL. |

| 3. LOST IN THE FOG. |

| 4. FIRE IN THE WOODS. |

| 5. PICKED UP ADRIFT. |

| 6. THE TREASURE OF THE SEAS. |

The Camp in the Woods.—Weapons of War.—An Interruption.—An old Friend.—A Mineral Bod.—Tremendous Excitement.—Captain Corbet on the Rampage.—A Pot of Gold.

The Old French Orchard.—The French Acadians.—The ruined Houses.—Captain Corbet in the Cellar.—Mysterious Movements.—The Mineral Bod—Where is the Pot of Cold?—Excitement.—Plans, Projects, and Proposals.

A Deed of Darkness.—The Money-diggers.—The dim Forest and the Midnight Scene.—Incantation assisted by Caesar, the Latin Grammar, and Euclid.—Sudden, startling, and terrific Interruption.—Flight of the “B. O. W. C.”—They rally again.

The Wonders of the upper Air.—Mr. Long calls upon the Boys for Help.—All Hands at hard Labor.—Captain Corbet on a Fence.—The Antelope comes to Grief.—Captain Corbet in the Grasp of the Law. Mr. Long to the Rescue.

A most mysterious Sound in a most mysterious Place.—What is it?—General Panic.—The adventurous Explorers.—They are baffled.—Is Pat at the Bottom of it?—Bart takes his Life in his Hand, and goes alone to encounter the Mystery of the Garret.

The great, the famous, and the never-to-be-forgotten Trial.—Captain Corbet hauled up before the Bar of Rhadamanthus.—Town and Gown.—Attitude of the gallant Captain.—The sympathizing Townsmen.—Old Zeke and his Bat.—Mr. Long’s eloquent Oration, ending in the Apotheosis of Captain Corbet’s Baby. (For meaning of above word—Apotheosis—see Dictionary.)

The Valley of the Gasper eaux.—Invading the Enemy’s Territory.—Defiance.—Returning Home to find their own Territory invaded.—The Camp.—The missing Ones.—Where are they?—The Gaspereaugians?

Bart and Solomon fall into an Ambush, and after a desperate Resistance are made Prisoners.—Bonds and Imprisonment.—Bruce and the Gaspereau-gians.—A Challenge, a Conflict, and a Victory.—Immense Sensation among the Spectators.—The Prisoners burst their Bonds.—Their Flight.—Recovery of the Spoils of War.

A Banquet begun, but suddenly interrupted.—The far-off Boar.—Off in Search of it.—Keeping Watch at the old French Orchard.—Another Boar, and another Chase.—Soliloquies of Solomon.—Sudden, amazing, paralyzing, and utterly confounding Discovery.—One deep, dark, dread Mystery stands revealed in a familiar but absurd Form.

Irrepressible Outburst of Feeling from the Grand Panjandrum.—He enlarges upon the Dignity of his Office.—Spades again.—Digging once more.—At the old Place, my Boy.—Resumption of an unfinished Work.—Uncovering the Money-hole.—The Iron Plate.—The Cover of the Iron Chest—A Tremendous but restrained Excitement.

Farther and farther down, and sudden Revelation of the Truth.—Rising superior to Circumstances.—The “Pot of Money,” and other buried Treasures.—They take all these exhumed Treasures to Dr. Porter.—Singular Reception of the excited Visitors.

The Doctor’s Proposal.—Blomidon.—The Expedition by Land.—The Drive by Morning Twilight.—The North Mountain.—Breakfasting amid the Splendors of Nature.—The illimitable Prospect.—The Doctor tells the Story of the French Acadians.

Plunging into the Depths of the primeval Forest.—Over Rock, Bush, and Brier.—A toilsome March.—The Barrens.—Where are we?—General Bewilderment of the Wanderers.—The Doctor has lost his Way.—Emerging suddenly at the Edge of a giant Cliff with the Boom of the Surf beneath

Woods, Precipices, Mists, and Ocean Waves.—The Party divided, and each Half departs to seek its separate Fortune.—Pat shows how to go in a straight Line.—Pat and the Porcupine.—In Chase after Pat.—Disappearance of Pat.—A lost Pat.—Wanderings in Search of the Lost.

All lost—The gathering Gloom of Fog and of Night—Sudden Discovery.—The lost One found.—A Turkey with four Legs.—A cheerful Discussion.—Five Hours of Wandering.—When will it end?—Once more upon the Tramp.

Sudden and unaccountable Reunion of the two wandering Bands.—A tremendous Circle described by Somebody.—Where are we going? Scott’s Bay, or Hall’s Harbor.—Descent into the Plain.—Twinkling Lights.—Sudden Sound of Sea Surf breaking in the Middle of a Prairie.

Old Bennie and Mrs. Bennie.—Old-fashioned Hospitality.—What old Bennie was able to spread before his famished Guests.—A Night on a Hay-mow.—A secluded Village.—A Morning Walk.—Behind Time.—Hurrah, Boys!

Great Excitement.—What is it?—Pat busy among the small Boys.—A great Supper, and a sudden Interruption.—The Midnight Knell.—General Uproar.—Flight of the Grand Panjandrum.—A solemn Time.—In the Dark.—Bold Explorers.—The Cupola, and the Abyss beneath.—The Discovery.

A puzzling Position.—How to meet the Emergency.—A strange Suggestion.—Diamond cut Diamond, or a Donkey in a Garret.—Surprise of Jiggins on seeing the Stranger.—The fated Moment comes.—The Donkey confronts the Garret Noises.—The Power of a Bray.

Full, complete, and final Revelation of the Great Garret Mystery.—Confession of Pat—Indignation of Solomon.—His Speech on the Occasion.—The Authorities of the School roused.—Pat and the “B. O. W. C.” are hauled up to give an Account.

Called to Account.—Mr. Long and the B. O. W. C.—They get a tremendous “Wigging.”—Pat to the Rescue.—Mr. Long relaxes.—The unhidden Guest.—Captain Corhet and the irrepressible Bobby.—Coming in Joy to depart in Tears.—The Relics again.—A Solemn Ceremony.—A Speech, a Poem, a Procession, all ending in a Consignment of the exhumed Treasure to its Resting-place.

The Boys in the Museum.—The Doctor’s Lecture.—The Acadians.—Louisbourg.—A Journey to the Wharf.—The Antelope.—Captain Pratt.

Inspection of the Schooner.—Captain Pratt to the Rescue.—His Engines and his Industry.—Up she rises!—Who’ll go for Captain Corbet?

Argument between Pat and Captain Corbet.—Meeting between Captain Corbet and the Antelope.—Pat alone with the Baby.—Corbet becomes an Exile, and vanishes into a Fog Bank.

The Camp in the Woods.—Weapons of War.—An Interruption.—An

old Friend.—A Mineral Bod.—Tremendous Excitement.—-Captain

Corbet on the Rampage.—A Pot of Gold.

THE

spring recess was over, and the boys of the Grand Pré School were now to

turn from play to study. The last day of their liberty was spent by the

“B. O. W. C.” at their encampment in the woods. They found it in so good a

condition, that it was even more attractive than when they left it. The

dam had proved water-tight; the pool was full to the brim; the trees

overhung with a denser foliage, while all around the fresh-turned earth

was covered with young grass, springing forth with that rapidity which

marks the growth of vegetation in these colder regions.

It was early in the day when they came up, and they were accompanied by the Perpetual Grand Panjandrum, who carried on his woolly head a basket crammed to the top with a highly-diversified and very luxurious lunch, which it had been the joy of that aged functionary to gather for the present occasion.

“Dar!” he exclaimed, as he put down his burden. “Ef you habn’t enough to feed you dis time, den I’m a nigga. Dar’s turkeys, an mutton pies, an hoe-cakes, an ham, an ginger-beer, an doughnuts, an de sakes ony knows what. All got up for de special benefit ob de Bee see double bubble Bredren, by de Gran Pan dandle drum. You’ll be de greatest specims ob chil’en in de woods dat ebber I har tell on. You gwine to be jes like wild Injins, and live in de wilderness like de prophets; an I’m gwine to be de black raven dat’ll bring you food. But now,” he added, “de black crow must fly back agen.”

“O, no, Solomon,” said they, as he started. “Don’t go. The ‘B. O. W. C.’ won’t be anything without you. Stay with us, and be the Grand Panjandrum.”

“Darsn’t!”

“O, yes, you must.”

“Can’t, no how.”

“Why not?”

“Darsn’t, De doctor’d knock my ole head off. De doctor mus hab ole Solomon. Can’t get along widout him. Yah, yah, yah! Why, de whole ’Cad-emy’d go to tarnal smash ef ole Solomon clar’d out dat way. Gracious sakes! Why, belubbed bred-ren, I’m sprised at you. An’ me de Gran Pandrum!”

“True,” said Bart, gravely. “Too true. It was very thoughtless in us, Grand Panjandrum; but don’t say that we asked you. Keep dark.”

“Sartin,” said old Solomon, with a grin. “Dar’s no fear but what I’ll keep dark. Allus been as dark as any ole darky could be. Yah, yah, yah!” And he rolled up his eyes till nothing could be seen but the whites of them, and chuckled all over, and then, with a face of mock solemnity, bobbed his old head, and said,—

“Far well, mos wos’ful, an’ all de res ob de belubbed breddren.”

And with these words he departed.

After this, the boys gave themselves up to the business of the day. And what was that? O, nothing in particular, but many things in general.

First and foremost, there was a grand jubilation to be made over the encampment of the “B. O. W. C.;” then a grand lamentation over the end of the recess. Then they talked over a thousand plans of future action. In these woods there were no bears, nor were there any wild Indians; but at any rate, there were squirrels to be shot at, and there were Gaspereaugians to be armed against.

It was certainly necessary, then, that they should have arms of offence and defence.

To decide on these arms was a matter that required long debate. One was in favor of clubs; another, of Chinese crackers; a third had a weakness for boomerangs; a fourth suggested lassos; and a fifth thought that an old cannon, with Bart’s pistol, and the gun, would form their most efficient means of defence. But in the course of a long discussion, all these opinions were modified; and the final result was in favor of the comparatively light and trifling arms—bows and arrows. In addition to these, whistles were thought to be desirable, in order to assist in decoying the unsuspecting squirrel, or in warning off the prowling Gaspereaugian.

One powerful cause of their unanimous decision was the pleasing fact, that bows, arrows, and whistles, could be manufactured on the spot by their own jackknives. Ash trees were all around, from which they could shape the elastic bow; tall spruce trees were there, from which they could fashion the light, straight shaft; and there, too, were the well-known twigs, from which they could whittle the willow whistle.

It was jolly—was it not? Could anything be more so? Certainly not. So they all thought, and they gave themselves up, therefore, to the joy of the occasion. They bathed in the pool. They dressed again, and lay on the grass in the sun. They gathered ash, and spruce, and willow. They collected also large quantities of fresh, soft moss, which they strewed over the floor of the camp, in which they at length sought refuge from the sun, and brought out their knives, and went to work.

Here they sat, then, working away like busy bees, two at bows, two at arrows, and one at whistles, laughing, singing, talking, joking, telling stories, and making such a general and indiscriminate hubbub as had never before been heard in these quiet woods; when suddenly they were startled by a dark shadow which fell in front of the doorway, and instantly retreated, followed by the crackling sound of dried twigs.

In a moment Bart was on his feet.

“Who goes there?” he cried, in a loud but very firm voice, while at the same instant the thought flashed into his mind, and into the minds of all the others,—The Gaspereaugians!—

Full of this thought, they all arose, even while Bart was speaking, with their souls full of a desperate resolution.

“Who goes there?” cried Bart a second time, in still louder tones.

A faint crackle among the dried twigs was the only respose that came.

“Who goes there?” cried Bart a third time, in a voice of deadly determination. “Speak or—I’ll fire!”

At this menacing and imperative summons there came a response. It came in the shape of a figure that stole forward in front of the doorway, slowly and carefully; a figure that disclosed to their view the familiar form, and the meek, the mild, the venerable, and the well-remembered face of Captain Corbet! Greeted with one universal shout of joy.

“Here we air agin, boys,” said the venerable commander, as he stepped inside, and looked all around with a scrutinizing glance. “We’ve ben together over the briny deep, an here’s the aged Corbet, right side up, in good health, and comes hopin to find you in the same.”

“Corbet! Corbet! Captain Corbet! Three cheers for the commander of the great expedition to Blomidon!”

And upon this there rang out three cheers as loud and as vigorous as could be produced by the united lungs of the five boys.

Captain Corbet regarded them with an amiable smile.

“Kind o’ campin’ out?” said he at last. “I thought by what you told me you’d be up to somethin like this, an I come down thinkin I’d find you; and here we air.”

“How’s the baby, captain?” asked Bart.

“In a terewly wonderful good state of health and sperits—kickin an crowin like mad; ony jest now he’s sound asleep—bless him. I’ve ben a-nussin of him ever sence I arrove, which I feel to be a perroud perrivelege, an the highest parental jy.”

“That’s right; and now sit down an sing us a song.”

“Wal, as to settin, I’ll set; but as to singin, I hain’t the time nor the vice. The fact is, I come down on business.”

At this Captain Corbet’s face assumed an expression of deep and dark mystery. He had a stick in his hand about a yard long, rather slender, and somewhat dirty. He now held out this stick, looked at it for a few moments in indescribable solemnity, then closed his eyes, then shook his head, and then, putting the stick behind his back, he drew a long breath, and looked hard at the boys.

“Business?” said Arthur; “what kind of business?”

Captain Corbet looked all around with an air of furtive scrutiny, and then regarded the boys with more solemnity than ever. He held out his stick again, and regarded it with profound earnestness.

“It’s a diskivery,” said he.

“A discovery?” asked Bart, full of wonder at Captain Corbet’s very singular manner; “a discovery? What kind of a discovery?”

“A diskivery,” continued Captain Corbet; “and this here stick,” he continued, holding it forth, “this here stick is the identical individooal article that’s made the diskivery to me. ’Tain’t everybody I’d tell; but you boys air different. I trust youns. Do you see that?” shaking the stick; “do you know what that air is? Guess, now.”

“That?” said Bart, somewhat contemptuously. “Why, what’s that? It’s only a common stick.”

At this Captain Corbet seemed deeply offended. He caressed the stick affectionately, and looked reproachfully at Bart.

“A stick?” said he at last; “a common stick? No, sir. ’Tain’t a stick at all. Excuse me. Thar’s jest whar you’re out of your reckonin. ’Tain’t a stick at all; no, nor anythin like it.”

“Well,” said Bart, “if that isn’t a stick, I should like to know what you call one.”

“O, you’ll know—you’ll know in time,” said Captain Corbet, whose air of mystery now returned, and made the boys more anxious than ever to find out the cause.

“If it isn’t a stick, what is it?” asked Bruce.

“Wal—it ain’t a stick, thar.”

“What is it, then?”

“It’s—a—ROD,” said Captain Corbet, slowly and impressively.

“A rod? Well, what then? Isn’t a rod a stick?”

“No, sir, not by a long chalk. Besides, this here’s a very pecooliar rod.” #

“How’s that?”

Captain Corbet rose, went to the door, looked on every side with eager scrutiny, then returned, and looked mysteriously at the boys; then he stepped nearer; then he bent down his head; and finally he said, in an eager and piercing whisper,—

“It’s a mineral rod!”

“A mineral rod?”

“Yes, sir,” said Captain Corbet, stepping back, and watching the boys eagerly, so as to see the full effect of this startling piece of intelligence.

The effect was such as might have satisfied even Captain Corbet, with all his mystery. A mineral rod! what could be more exciting to the imagination of boys? Had they not heard of such things? Of course they had. They knew all about them. They had read of mineral rods as they had read of other things. They had feasted their imaginations on pirates, brigands, wizards, necromancers, alchy-mists, astrologers, and all the other characters which go to make up the wonder-world of a boy; and among all the things of this wonder-world, nothing was more impressive than a mineral rod. This was the magic wand that revealed the secrets of the earth—this was the resistless “sesame” that opened the way to the hoarded treasures of the bandit—this was the key that would unlock the coffers, filled with gold, and buried deep in the earth by the robber chief or the pirate captain. What wonder, then, that the very mention of that word was enough to excite them all in an instant, and to turn their minds from good-natured contempt to eager and irrepressible curiosity?

“I’m no fool,” said Captain Corbet, impressively—“I know what I’m a doin. I got this mineral rod last year, and went round everywhar over the hull country. It didn’t come natral, at fust, but I kep on. You see I had a motive. It wan’t myself. It wan’t Mrs. Corbet. It was the babby! He’s a growin, and I’m a declinin; an afore he grows to be a man, whar’ll I be? I want to have somethin to leave him. That’s what sot me up to it. Nobody knows anythin about it. I darsen’t tell Mrs. Corbet. I have to do it on the sly. But when I saw you, I got to love you, an I knew I could trust you. For you see I’ve made a diskiv-ery, an I’m goin to tell you; an that’s what brought me down here. Besides, you’re all favored by luck; an ef I have your help, it’ll be all right.”

“But what is the discovery?” asked the boys, on whom these preliminary remarks made a still deeper impression.

“Wal—as I was a sayin,” resumed the captain—“I’ve been a prowlin round and round over the hull country with the mineral rod. It’s full of holes. Them old Frenchmen left lots of money. That’s what I’m a huntin arter, and that’s what I’ve found.”

These last few words, added in a low but penetrating whisper, thrilled the boys with strange excitement.

“Have you really found anything?” asked Bart, eagerly. “What is it? When? Where? How?”

Captain Corbet took off his hat very solemnly, and then, plunging his hand into his pocket, he drew forth a crowd of miscellaneous articles, one by one. He thus brought forth a button, a knife, a string, a fig of tobacco, a pencil, a piece of chalk, a cork, a stone, a bit of leather, a child’s rattle, a lamp-burner, a bit of ropeyarn, a nail, a screw, a hammer, a pistol barrel, a flint, some matches, a horse’s tooth, the mouthpiece of a fog-horn, a doll’s head, an envelope, a box of caps, a penholder, a nut, a bit of candy, a piece of zinc, a brass cannon, a pin, a bent knitting needle, some wire, a rat skin, a memorandum book, a bone, a squirrel’s tail, a potato, a wallet, half of an apple, an ink bottle, a lamp-wick, “Bonaparte’s Oraculum,” a burning glass, a corkscrew, a shaving brush, and very many other articles, all of which he put in his hat in a very grave and serious manner.

He then proceeded with his other hand to unload his other pocket, the contents of which were quite as numerous and as varied; but in neither of the pockets did he find what he wished.

“Wal, I declar!” he cried, suddenly. “I remember, now, I put it in my waistcoat pocket.”

Saying this, he felt in his waistcoat pocket, and drew forth a copper coin, which he held forth to the boys with a face of triumph.

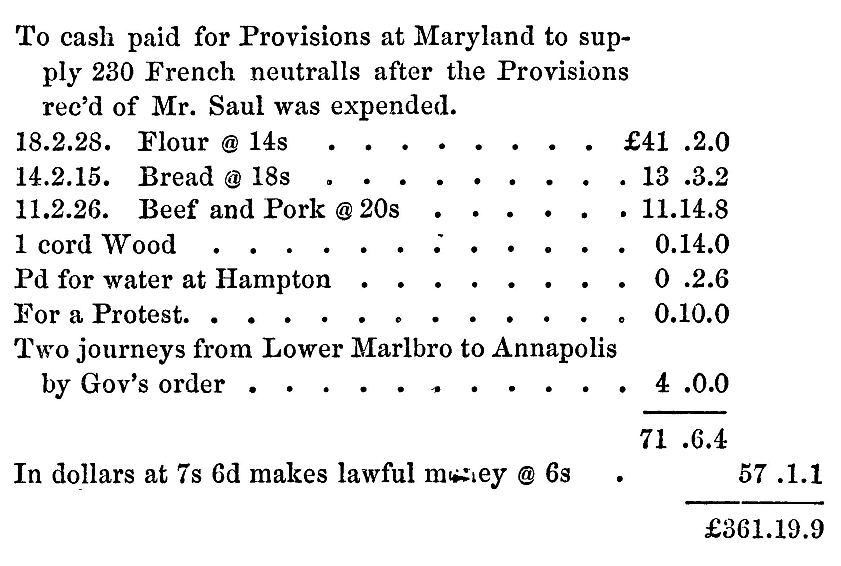

Bart took it, and the others crowded eagerly around him to look at it. It was very much worn; indeed, on one side it was quite smooth, and the marks were quite effaced; but on the other side there was a head, and around it were letters which were legible. They read this:

All of which sank deep into their souls.

“It’s an old French coin,” said Bruce at length. “Where did you get it? Did you find it yourself?”

Captain Corbet made no reply, but only held up his mineral rod, and solemnly tapped it.

“Did you find it with that?” asked Bart.

The captain nodded with mysterious and impressive emphasis.

“Where?”

“Mind, now, it’s a secret.”

“Of course.”

“Wal,” said Captain Corbet slowly, “it’s a very serous ondertakin; an ef it wan’t for the babby, an me hopin to leave him a fortin, I wouldn’t be consarned in it. Any how, you see, as I was tell-in, I ben sarchin; an not long before we sailed I was out one day with the mineral rod, an it pinted—it pinted—it did—in one spot. It’s an ole French cellar. Thar’s a pot of gold buried thar, boys—that I know. The mineral rod turned down hard.”

“And did you dig there?” asked Bart, anxiously. “Did you try it?”

Captain Corbet shook his head.

“I hadn’t a shovel. Besides, I was afeard I might be seen. Then, agin, I wanted help.”

“But didn’t you find this coin there?”

Captain Corbet again shook his head.

“No,” said he. “I found that thar kine in another cellar; but in that cellar the rod didn’t railly pint. So I didn’t dig. I went on a sarchin till I found one whar it did pint. It shows how things air. Thar’s money—thar’s other kines a buried in the ground. Now I tell you what. Let’s be pardners, an go an dig up that thar pot of gold. ’Tain’t at all in my line. ’Tain’t everybody that I’d tell. But you’ve got my confidence; an I trust on you. Besides, you’ve got luck. No,” continued the captain in a dreamy and somewhat mournful tone, “’tain’t in my line for me, at my age to go huntin arter buried treasure; but then that babby! Every look, every cry, every crow, that’s given by that bee-lessed offsprin, tetches my heart’s core; an I pine to be a de win somethin for him—to smooth the way for his infant feet, when poor old Corbet’s gone. For I can’t last long. Yes—yes—I must do it for the babby.”

Every word that Captain Corbet uttered, except, perhaps, his remarks about the “babby,” only added to the kindling excitement of the boys. A mineral rod! a buried treasure! What could be more overpowering than such a thought! In an instant the camp in the woods seemed to lose all its attractions in their eyes. To play at camping out—to humor the pretence of being bandits—was nothing, compared with the glorious reality of actually digging in the ground, under the guidance of a real mineral rod, for a buried pot of gold; yet it ought to be explained, that, to these boys, it was not so much the value of any possible treasure that might be buried and exhumed which excited them, as the idea of the enterprise itself—an enterprise which was so full of all the elements of romantic yet mysterious adventure. How tremendous was the secret which had thus been intrusted to them! How impressive was the sight of that mineral rod! How overpowering was the thought of a pot of gold, buried long ago by some fugitive Frenchman! How convincing was the sight of that copper coin! And, finally, how very appropriate was such an enterprise as this to their own secret society of the “B. O. W. C.”! It was an enterprise full of solemnity and mystery; beset with unknown peril; surrounded with secrecy and awe; a deed to be attempted in darkness and in silence; an undertaking which would supply the “B. O. W. C.” with that for which they had pined so long—a purpose.

“But is there any money buried?” asked Phil.

“Money buried?” said Bart. “Of course, and lots of it. When the French Acadians were banished, they couldn’t take their money away. They must have left behind all that they had. And they had lots of it. Haven’t you read all about ‘Benedict Bellefontaine, the wealthiest farmer of Grand Pré? Of course you have. Well, if he was the wealthiest, others were wealthy. That stands to reason. And if so, what did they do with their wealth? Where did they keep their money? They hadn’t any banks. They couldn’t buy stock, and all that sort of thing. What did they do with it, then? What? Why, they buried it, of course. That’s the way all half-civilized people manage. That’s what the Hindoos do, and the Persians, and the Chinese. People call it ‘hoarding.’ They say there’s enough gold and silver buried in the earth in India and China to pay olf the national debt; and I believe there’s enough money buried about here by the old Acadians to buy up all the farms of Grand Pré.”

Bart spoke earnestly, and in a tone of deep conviction which was shared by all the others. The copper coin and the mineral rod had done their work. They lost all taste for the camp, and its pool, and its overarching trees, and its seclusion, and were now eager to be off with Captain Corbet. Before this new enterprise even the greatest of their recent adventures dwindled into insignificance. Captain Corbet, with his magic wand, stood before them, inviting them to greater and grander exploits.

A long conversation followed, and Captain Corbet began to think that the pot of gold was already invested. The boys took his mineral rod, which he did not give up until he had been for a long time coaxed and entreated they passed it from hand to hand; each one closely inspected it, and balanced it on his finger so as to test the mode in which it worked; each one asked him innumerable questions about it, and gave it a long and solemn trial.

“But where is the place?” asked Bart. “Is it very far from here?”

Captain Corbet shook his head.

“’Tain’t very far off,” said he. “I’ll show you.”

“Which way?” asked Tom.

The captain waved his rod in the direction of the Academy.

“What! That way?” asked Bart. “Are the cellars there?”

“Yes.”

“You don’t mean those. What! Just behind the Academy?”

“Yes.”

“It’s the ‘Old French Orchard,’ then,” cried Bart—“the ‘Old French Orchard.’ The only cellars in that direction are under the old French apple trees, on the top of the hill. Is that the place you mean, captain?”

“That’s the indentical individool spot,” said Captain Corbet.

“The ‘Old French Orchard’!” exclaimed the other boys in surprise; for they had expected to be taken to some more remote and very different place.

“Wal,” said Captain Corbet, “that thar place’s a very pecooliar place. You see thar’s a lot o’ cellars jest thar, an then the ole apple trees—they’re somethin. The ole Frenchman, that lived up thar, must hev ben rich.”

“The fact is,” exclaimed Bart, “Captain Corbet’s right. The Frenchman that lived on that place must have been rich. For my part, I believe that he was no other than ‘Benedict Bellefontaine, the wealthiest farmer in Grand Pré.’ He buried all his money there, no doubt. This is one of his French sous. Come along, boys; we’ll find that pot of gold.”

And with these words they all set out along with Captain Corbet for the “Old French Orchard.”

The Old French Orchard.—The French Acadians.—The ruined

Houses.—Captain Corbet in the Cellar.—Mysterious Movements.—The

Mineral Bod—Where is the Pot of Cold?—Excitement.—Plans,

Projects, and Proposals.

THE hill on which Grand

Pré Academy was built sloped upwards behind it, in a gentle ascent, for

about a mile, when it descended abruptly into the valley of the

Gaspereaux. For about a quarter of a mile back of the Academy there were

smooth, cultivated meadows, which were finally bounded by a deep gully. At

the bottom of this there ran a brawling brook, and on the other side was

that dense forest in which the boys built their camps. Here, on the

cleared lands just by the gully, was the favorite play-ground of the

school. Happy were the boys who had such a play-ground. High up on the

slope of that hill, it commanded a magnificent prospect. Behind, and on

either side, were dense, dark woods; but in front there stood revealed a

boundless scene. Beneath was the Academy. Far down to the right spread

away the dike lands of Grand Pré, bounded by two long, low islands, which

acted as a natural barrier against the turbulent waters; and farther away

rose the dark outline of Horton Bluff, a wild, precipitous cliff, at the

mouth of the Gaspereaux River, marking the place where the hills advanced

into the sea, and the marsh lands ended. Beyond this, again, there spread

away the wide expanse of Minas Bay, full now with the flood tide—a

vast sheet of blue water, dotted with the white sails of passing vessels,

and terminated in the dim and hazy distance by those opposite shores,

which had been the scene of their late adventures—Parrsboro’,

Pratt’s Cove, and the Five Islands. Far away towards the left appeared

fields arrayed in the living green of opening spring; the wide plains of

Cornwallis, with its long reaches of dike lands, separated by ridges of

wood land, and bounded by the dark form of the North Mountain. Through all

this, from afar, flowed the Cornwallis River, with many a winding, rolling

now with a full, strong flood before them and beyond them, till, with a

majestic sweep, it poured its waters into that sea from which it had

received them. Finally, full before them, dark, gloomy, frowning, with its

crest covered with rolling fog-clouds, and the white sea-foam gleaming at

its base, rose the central object of this magnificent scene,—the

towering cliff—Blomidon.

Such was the scene which burst upon the eyes of the boys as they crossed the brook, and ascended the other side of the gully. Familiar that scene was, and yet, in spite of its familiarity, it had never lost its attractions to them; and for a moment they paused involuntarily, and looked out before them. For there is this peculiarity about the scenery of Grand Pré, that it is not possible for it to become familiar, in the common sense of the word. That scene is forever varying, and the variations are so great, that every day has some new prospect to offer. Land, sea, and sky, all undergo incessant changes. There is the Basin of Minas, which is ever changing from red to blue, from a broad sea to a contracted strait, hemmed in by mud flats. There is the sky, with its changes from deepest azure to dreamy haze, or impenetrable mist. There are rivers which change from fulness to emptiness, majestic at the flow of tide, indistinguishable at the ebb. There is Blomidon, which every day is arrayed in some new robe; sometimes pale-green, at other times deep purple; now light-gray, again dark-blue; and thus it goes through innumerable changes, from the pale neutral tints which it catches from the overhanging fogs, down through all possible gradations, to a darkness and a gloom, and a savage grandeur, which throw around it something almost of terror. Then come the seasons, which change the wide plains from brown to green, and from green to yellow, till winter appears, and robes all in white, and piles up for many a mile over the shallow shores, and in the deep channels of the rivers, the ever accumulating masses of heaped-up ice.

Yet all the time, through all the seasons, while field and flood, river and mountain, sea and forest, are thus changing their aspect, there hangs over all an atmosphere which brings changes more wonderful than these. The fog is forever struggling for an entrance here. The air in an instant may bring forth its hidden watery vapors. High over Blomidon the mist banks are piled, and roll and writhe at the blast of the winds from the sea. Here the mirage comes, and the eye sees the solid land uplifted into the air; here is the haze, soft and mysterious as that of Southern Italy, which diffuses through all the scene an unutterable sweetness and tenderness. Here, in an instant, a change of wind may whirl all the accumulated mists down from the crest of Blomidon into the vale of Cornwallis, and force vast masses of fog-banks far up into the Basin of Minas, till mountain and valley, and river and plain, and sea and sky, are all alike snatched from view, and lost in the indistinguishable gray of one general fog.

The boys then had not grown wearied of the scene. Every day they were prepared for some fresh surprise, and they found in this incessant display of the glory of nature, with its never-ending variety and its boundless scope, something which so filled their souls and enlarged their minds, that the perpetual contemplation of this was of itself an education. And so strong was this feeling in all of them, that for a moment all else was forgotten, and it was with an effort that they recollected the captain and his mineral rod.

Upon this they turned to carry out their purpose.

In this, place, and close by where they were standing, were several hollows in the ground, which were well known to be the cellars of houses once occupied by French Acadians. At a little distance were a number of apple trees, still growing, and now putting forth leaf, yet so old that their trunks and branches were all covered with moss, and the fruit itself, on ripening, was worthless. These trees also belonged to the former owners of the houses—the fallen—the vanished race.

And at the bottom of one of these holes Captain Corbet was standing, solemnly balancing the mineral rod on one finger, and calling to the boys to come and watch how it “pinted” to the buried pot of gold.

These cellars were but a few out of hundreds which exist over the country,

as sad memorials of those poor Acadians who were once so ruthlessly driven

into exile. The beautiful story of Evangeline has made the sorrows of the

Acadians familiar to all, and transformed Grand Pré into a place of

pilgrimage, where the traveller may find on every side these sad vestiges

of the former occupants. Into this beautiful land the French had come

first; they had felled the forests, drained the marshes, and reared the

dikes against the waters of the sea. Here they had increased and

multiplied, and long after Acadie had been ceded to the British they lived

here unmolested. They still cherished that patriotic love for France which

was natural, and in the wars did not wish to fight against their own

countrymen; but, on the other hand, they resisted the French agents who

were sent among them to excite insurrection. A few acted against the

British, but the majority were neutral. At length the British enlarged

their operations in Acadie, sent out thousands of emigrants, and began to

settle the province. Then came a life and death struggle between

Englishmen and Frenchmen, which spread over all America, far along the

Canadian frontier, and along the Ohio Valley, and southward to the Gulf of

Mexico. The Frenchmen of Acadie were looked on with suspicion. An effort

was soon to be made against Louisbourg and Quebec, by which it was hoped

that the French power would be crushed into the dust. But the Acadians

stood in the way. They were feared as being in league with the French and

the Indians. Their pleasant lands, also, were eagerly desired for an

English population. And so it was determined to banish them all, and in

the most cruel way conceivable. Ordinary banishment would not do; for then

they might wander to Canada, and add their help to their brethren: so it

was determined to send them away, and scatter them over the coast of

America. This plan was thoroughly carried out. From Grand Pré two thousand

were taken away—men, women, and children; families were divided

forever, the dearest friends were parted never to meet again. Their fields

were laid waste; their houses, and barns, and churches, were given to the

flames; and now the indelible traces of this great tragedy may be seen in

the ruined cellars which far and wide mark the surface of the country. Far

and wide also may be seen their trees,—the apple trees,—moss-grown,

and worn out, and gnarled, and decaying; the broad-spreading willow,

giving a grateful shade by the side of brooks; and the tall poplar, dear

to the old Acadian, whose long rows may be seen from afar, rising like so

many monuments over the graves of an extinct race.

Where is the thatch-roofed village, the home of Acadian

farmers,

Men whose lives glided on like rivers

that water the wood lands,

Darkened by shadows

of earth, but reflecting an image of heaven?

Waste

are those pleasant farms, and the farmers forever departed

Scattered like dust and leaves, when the mighty blasts of

October

Seize them, and whirl them aloft, and

sprinkle them far o’er the

ocean.

Nought but tradition remains of the beautiful village of

Grand Pré.

Now, the idea of the boys was not by any means so absurd as may be supposed. It was within the bounds of possibility that a pot of money might be in a French cellar. These Acadians had some wealth; they had been in the habit of hoarding it by burying it in the earth, and the bottom of the cellar was by no means an unlikely place. So sudden had been their seizure, that none of them had any time whatever to exhume any of their buried treasure, so as to carry it away with him. All had been left behind—cattle, flocks, herds, grain, houses, furniture, clothes, and of course money. Vague tradition to this effect had long circulated about the country, and there was a general belief that money was buried in the ground, where it had been left by the Acadians. So, after all, the boys were only the exponents of a popular belief.

The cellar might have originally been five or six feet in depth, but the falling of the walls and the caving in of the earth had given it a shape like a basin; and the depth at the centre was not more than four feet below the surrounding level. Around the edge were some stones which marked the old foundation.

The boys came up to Captain Corbet, and watched him quietly, yet very curiously. As for the illustrious captain, he felt to the utmost the importance of the occasion. He was now no longer the captain of a gallant bark. He had become transformed into a species of necromancer. Instead of the familiar tiller, he held in his hand the rod of the magician. All the solemnity of such a position was expressed in his venerable features. After throwing a benignant smile upon the boys, his eyes reverted to the rod, which was still balanced on his finger, and he walked about, with a slow and solemn pace, to different parts of the cellar. First he went around the sides, stopping at every third step, and looking solemnly at the rod. But the rod preserved its balance, and made no deflection whatever towards any place.

“Go down to the middle, captain,” said Bart, who, in common with the other boys, had been watching these mysterious proceedings with intense curiosity.

Captain Corbet shook his head solemnly, and lifted up his unoccupied hand with a warning gesture.

“H-s-s-s-s-s-s-s-s-s-s-s-s-s-s-s-s-h!” said Tom; “don’t interrupt him, Bart.”

Captain Corbet moved slowly about a little longer, and then descended to the middle of the cavity. Here he planted himself, and his face assumed, if possible, an expression of still profounder solemnity.

And now a strange sight appeared. The rod began to move!

Slowly and gradually one end of it lowered, so slowly, indeed, that at first it was not noticed; but at last they all saw it plainly, for it went down lower, yet in that gradual fashion; and the boys, as they looked, became almost breathless in suspense.

They drew nearer, they crowded up closer to Captain Corbet, and watched that rod as though all their future lives depended upon the vibration of that slender and rather dirty stick.

Not a word was spoken. Lower and lower went the rod.

It trembled on its balance! It quivered on Cap tain Corbet’s forefinger, as the lower end went down and dragged the rod out of its even poise. It slipped, and then—it fell.

It fell, down upon the very middle of the cellar, and lay there, marking that spot, which to the minds of the boys seemed now, beyond the possibility of a doubt, to be the place where lay the pot of gold.

“Thar,” said Captain Corbet, now breaking the silence. “Thar. You see with your own eyes how it pints. That thar is the actool indyvidool place; an this here’s the dozenth time it’s done it with me. O! it’s thar. I knowed it.”

As the rod fell, a thrill of tremendous excitement had passed through the hearts of the boys, and their belief in its mystic properties was so strong, that it did not need any assurances from Captain Corbet to confirm it. Yes, beyond a doubt, there it was, just beneath, a short distance down—the wonderful, the mysterious, the alluring pot of gold.

At last the silence was broken by Tom.

“Well, boys,” said he, “what are we going to do about it?”

“The question is,” said Phil, “shall we dig it or not? I move that we dig it.”

“Of course,” said Bruce, “we’ll dig it. There’s only one answer to that question. But when? The fellows are around here all the time.”

“We’ll have to do it after dark,” said Arthur.

“Early in the morning would be the best time, I think,” said Bruce, a little anxiously.

“No,” said Bart; “there’s only one time, and one hour, to dig money, and that time is midnight, and the hour twelve sharp. If we’re going to dig for a pot of money, we’ll have to do it up in proper shape.”

“Nonsense,” said Bruce, who still spoke in a rather anxious tone. “What are you talking about? Early morning is the time.”

“Early morning!” said Bart; “why, man alive, we’ll want several hours, and it’ll be early morning before we’re done. If we begin at early morning we can’t do anything. Some of the fellows are always up here before breakfast. No! From midnight to cock-crow, that’s the orthodox time. Besides,” added Bart, mysteriously, “there are certain ceremonies we’ll have to perform, that can only take place at night.”

“Nonsense!” said Bruce; “let’s tell the other fellows, and we’ll all dig together in broad day.”

“Tell the other fellows! What in the world do you mean?” cried Bart. “Bruce Rawdon, are you crazy?”

No! Bruce Rawdon was not crazy. He was only a little superstitious, and had a weakness with regard to ghosts. He had as brave and stout a heart as ever beat, with which to confront visible dangers and mortal enemies; but his stout heart quailed at the fanciful terrors of the invisible. Yet he saw that there was no help for it, and that he would have to choose the midnight hour. So he very boldly made up his mind to face whatever terrors the enterprise might have in store.

“The fact is,” said Bart, “we ourselves—we, the ‘B. O. W. C.’—must do it. It would be dishonor to invite the other boys. This belongs to us. We’re a secret and mystic order. We’ve never yet had anything in particular to do. Now’s our time, and here’s our chance. We’re bound to get at that pot of gold. The captain, of course, must be with us, and one other only; that is old Solomon. As Grand Panjandrum, he must be here, and share our labors.”

“We’ll have to get spades,” said Arthur. “I suppose Solomon can manage that.”

“Spades?” said Bart; “I should think so, and fifty other things. We must have lights. We’ll have to make a row of them around the edge of the hole.”

“A row of them?” said Phil. “Nonsense! Two will do.”

“No,” said Bart. “You must always have a row of burning lamps around whenever you dig for money. They must be kept burning too. One of us must watch the lamps: woe to us if any one of them should go out! You see it isn’t an ordinary work. It’s magic! Digging up a pot of gold must be done carefully. Every buried pot of gold can only be got up according to a regular fashion. I’ve got a book that tells all about it—how many lights, how many spades, the proper time, and all that. Above all, we’ll have to remember to keep as silent as death when we’re working, and never speak one word. Why, I’ve heard of cases where they touched the pot of gold, and just because they made a sort of cry of surprise, the pot at once sunk down ever so much farther. And so they had to do it all over again.” Did Bart believe all this nonsense that he was talking? It is very difficult to say. He was not at all superstitious; that is to say, his fancies never affected his actual life. He would walk through a graveyard at midnight as readily as he would go along a road. At the same time his brain contained such an odd jumble of wild fancies, and his imagination was so vivid, that his ordinary common sense was lost sight of. He could follow the leadings of a very vivid imagination to the most absurd extent. If he had been really, in his heart, superstitious, he would have shrunk from the terrors of this enterprise. But his real faith was not concerned at all. He was playing—very earnestly indeed, and with immense excitement, yet still he was only playing—at digging for money, just as he had been playing at being a bandit, or a pirate. He was quite ready, therefore, to comply with any amount of superstitious forms. The rest, also, were very much the same way, except Bruce. He alone looked upon the matter with anxiety; but he fought down his fear by an effort of pure courage.

It was only imagination, then; but still, so strong was their imagination, that it made the whole plan one of sober reality, and they discussed it as though it were so.

“You see,” said Bart, as he threw himself headlong into the excitement of the occasion—“you see, we’ve got to be careful. The pot of gold has been revealed by the mineral rod. If we had dug it up by accident, of course we could have got it without any trouble. But it has been revealed by magic, and must be gained by the laws of magic. I’ve got that Book of Magic, you know, and it tells all about it. Lights around, in number any multiple of three, or seven. Those are magic numbers. Our number inside the magic circle will be seven. That’s one reason why I want old Solomon. We’ll have to keep silent, and not say a word. We must not begin till midnight, and we cannot go on after cock-crow. O, we’ll manage it. Hurrah for the ‘B. O. W. C’!”

And so, after some further discussion, they decided to make the attempt that night. It was to be the last night of the holidays, and was more convenient than any other. Captain Corbet was to meet them with his rod and a spade. They were to come up with old Solomon, and all the other requisites.

With these arrangements they parted solemnly from Captain Corbet, and went back to the Academy, bowed down by the burden of a most tremendous secret.

A Deed of Darkness.—The Money-diggers.—The dim Forest and

the Midnight Scene.—Incantation assisted by Caesar, the Latin

Grammar, and Euclid.—Sudden, startling, and terrific Interruption.—Flight

of the “B. O. W. C.”—They rally again.

MIDNIGHT

came. Before that time the “B. O. W. C.” had prepared themselves for the

task before them. They were arrayed in the well-worn and rather muddy

clothes in which they had made their memorable expedition. Solomon was

with them, dressed in his robes of office. The venerable Grand Panjandrum

had gathered all the lanterns that he could collect; but as these were

only five in number, and as they wanted twenty-one, there had been some

difficulty. This had, at length, been remedied by means of baskets, pails,

and tin kettles; for it was thought that by putting a candle in a pail, or

something of that sort, it would be protected from the wind. Solomon also

was provided with matches, so as to kindle the light at once if it should

be blown out; and Bart tried, in the most solemn manner, to impress upon

him the necessity of watchfulness. It was Solomon’s duty to watch the

lights, and nothing else; the others were to dig. Besides the pails, pots,

lanterns, candlesticks, and tin kettles, they carried a pickaxe, four

spades, and the Bust,—which last was taken in order to add still

more to the solemnity of the occasion,—and after distributing this

miscellaneous load as equally as possible among the multitude, they at

length set out.

The Academy was all silent, and all were hushed in the depths of slumber; so they were able to steal forth unobserved, and make their way to the “Old French Orchard.”

The night was quite dark, and as they walked up the hill, the scene was one of deep impressiveness. Overhead the sky was overcast, and a fresh breeze, which was blowing, carried the thick clouds onward fast through the sky. The moon was shining; but the dense clouds, as they drove past, obscured it at times; and the darkness that arose from this obscurity was succeeded by a brighter light as the moon now and then shone forth. Before them rose the solemn outline of the dark forest, gloomy and silent, and the stillness that reigned there was not broken by a single sound.

After walking some distance, they stopped, partly to rest, and partly to see if they were followed. As they turned, they beheld beneath them a scene equally solemn, and far grander. Immediately below lay the dark outline of the Academy, and beyond this the scenery of Grand Pré; on the right extended the wide plains, now almost lost to view in the gloom of night; on the left the Cornwallis River went winding afar, its bed full, its waters smooth and gleaming white amid the blackness that bordered it on either side. Overhead the sky arose, covered over with its wildly-drifting clouds, between which the moon seemed struggling to shine forth. Beneath lay the dark face of the Basin of Minas, which faded away into the dimness of the opposite shore, while immediately in front,—now, as always, the centre of the scene,—rose Blomidon, black, frowning, sombre, as though this were the very centre from which emanated all the shadows of the night.

At the top of the hill they met Captain Corbet, who had a spade on his shoulder.

“It’s rayther dark,” said he, in a pensive tone. “Ef I’d aknowed it was to be so dark, I’d postponed it.”

“Dark!” said Bart, cheerily; “not a bit of it. It’s just right. We want it just this way. It’s the proper thing. You see, if it were moonlight, we’d be discovered; but this darkness hides us, The moon peeps out now and then, just enough to make the darkness agreeable. This is just the way it ought to be.”

They moved on in silence towards the spot. Here, on three sides, the forest encircled them; below them was the deep, dark gully; and the shadows of the forest were so heavy, that nothing could be distinguished at a distance. Captain Corbet, usually talkative, was now silent and pensive, and uttered an occasional sigh. As for Solomon, he did not say one word. The whole party stood for a moment in silence, looking into the cellar.

“Come, boys,” said Bart, at length, “hurry up. The first thing we’ve got to do is to make the arrangements. We must arrange the lamps.”

Saying this, they all proceeded to put down their lanterns, pots, kettles, pails, and baskets, around the cellar, so as to encircle it. Inside each of the pots, kettles, pails, and baskets, a candle was put, while the Bust was placed at the end of the cellar nearest the wood.

“Now,” said Bart, “let’s all go into the cellar, and Solomon will light the candles.”

They went into the cellar; but Solomon showed so much clumsiness in lighting them, that Bart had to do it. This was soon accomplished. The surrounding forest sheltered them from the wind, and the lights did not flicker very much, except at times when an occasional puff stronger than usual would be felt. Once a light was blown out; but Bart lighted it again, and then they all burned very well.

So there they stood, in the cellar, with the circle of lights around them, under a dark sky, at the midnight hour.

“I feel solemn,” said Captain Corbet, after a long silence; “I feel deeply solemn.”

“Solemn!” said Bart; “of course you do; so say we all of us. Why shouldn’t we?”

“I feel,” said Captain Corbet, “a kind of pinin feelin—a longin and a hankerin after the babby.”

“O, well, all right,” said Bart; “never mind the baby just now.”

“But I feel,” said Captain Corbet, in a voice of exceeding mournfnlness—“I feel as though I’d orter jine the infant.”

“O, never mind your feelings,” said Bart. “Have you got your mineral rod?”

“I hev.”

“Very well; try it.”

“I’d rayther not. I—I—Couldn’t we postpone this here? It’s so solemn!”

“Postpone it! Why, man, what are you thinking of? Postpone it! Nonsense! Think of your baby. Postpone it! And you pretend to be a father!”

Captain Corbet drew a long sigh.

“I feel,” said he, “rayther uncomfortable here;” and he pressed his hand against his manly bosom.

“Never mind,” said Bart. “Come; try the mineral rod.”

Captain Corbet took the rod, and tried to balance it on his finger; but his hand trembled so that it at once fell to the ground.

The boys gave a cry of delight. He had been standing, as before, in the middle of the cellar, and the rod fell in the former place.

“Not a bit of doubt about it!” cried Phil. “There it goes again! Come, let’s go to work, boys.”

“But we must have some ceremonies,” said Bart. “It would never do to begin to dig without something.”

“So I say,” remarked Captain Corbet, feebly.

Meanwhile Solomon had been standing in his robes, a little apart, looking nervously around.

“Hallo, Solomon!” cried Bart.

Solomon gave a start.

“Ya—ya—yas, sr.”

“You’re not watching the lights.”

“Ya—yasr.”

“That basket has fallen.”

“Ya, yasr,” said Solomon, whose teeth seemed to be chattering, and who seemed quite out of his senses.

Bart walked up to him, and saw at a glance how it was.

“Why, old Solomon,” said he, gently, “you’re not frightened—are you? It’s only our nonsense. Come, Grand Panjandrum, don’t take it in earnest. It’s all humbug, you know,” he added, dropping his voice. “Between you and me, we none of us take it in earnest. Come, you keep the lamps burning, and be the Grand Panjandrum.”

At this a little of Solomon’s confidence was restored. He ventured to the edge of the cellar, and lifted up the basket in time to save it from burning up; but scarce had he done this than he retreated; the gloom, the darkness, the magic ceremonies, were too awful.

“Come,” said Tom, “let’s begin the ceremonies.”

Captain Corbet gave another sigh.

“I feel dreadful anxious,” said he, “about the infant; I’m afeard somethins happened; I feel as if I’d orter be to hum.”

“All right, captain,” said Bart; “we’ll all be home before long, and with the pot of gold, you know. Come, cheer up, for the ceremonies are going to begin.”

“See here, now,” said Captain Corbet. “This here’s a solemn occasion. I feel solemn. It’s awful dark. We don’t know what’s buried here, or what will happen; so let’s don’t have any heathen ceremonies.”

“O, the ceremonies are not heathen,” said Bart. “Each of us is going to make an incantation in the most solemn language that we can think of; so, boys, begin.”

“The most solemn thing that I can think of,” said Phil, “is English history; so here goes.” And stretching forth his hand solemnly, he said, in a whining voice, like a boy reciting a lesson:—

“Britain was very little known to the rest of the world before the time of the Romans. The coasts opposite Gaul were frequented by merchants, who traded thither for such commodities as the natives were able to produce.”

“The most solemn thing, to me,” said Tom, “is Euclid.” And then he added in the same tone, “The square described on the hypothenuse of a right-angled triangle is equal to the sum of the squares described on the other two sides of the same.”

“And I,” said Arthur, “find Arnold’s Latin Exercises the worst. The most solemn thing for an invocation is,—’

“In temporibus Ciceronis Galli retinuerunt barbaram consuetudinem excercendæ virtutis omni occasione. Balbus odifcabat murum!”

“I,” said Bruce, “have something far more solemn.” And stretching out his hand, he said, in a loud, firm voice,—

“Dignus, indignus, content us, proditus, captus, and fretus, also natus, satus, ortus, editus, and the like, govern the—hem—nominative—no—the vocative—no—the ablative—all the same.”

“For my part,” said Bart, “the most solemn thing, to me, is Cæsar. The way they teach it here makes it a concentration of all the worst horrors of the Grammar, and Arnold, and History, with the additional horrors of an exact translation. O, brethren of the ‘B. O. W. C.,’ won’t you join with me in saying,—

“Gallia est omnis divisa in partes très, quarum unam incolunt Belgo, aliam Aquitani, tertiam, qui ipsorum lingua Celto, nostra Galli appellantur. Hi omnes lingua, institutis, legibus, inter se differunt. Gallos ab Aquitanis Garumna”

“Here!” cried Captain Corbet, suddenly interrupting Bart; “I can’t stand this any longer. It’s downwright heathenism—all that outlandish heathen stuff! Do ye mean to temp fate? Bewar, young sirs! It’s dangerous! ’Tain’t safe to stand here, at midnight, over a Frenchman’s bones, and jabber French at him.”

“French?” said Bart. “It’s not French.”

“That ain’t the pint,” said Captain Corbet, who had worked himself up into considerable excitement. “The pint is air it English? No, sir. Does any Christian onderstand sich? No, sir. We hain’t got no business with sich.”

“But it’s Latin,” said Bart.

“Wuss and wuss,” said Captain Corbet. “I take my stand by the patriarchs, the prophets, and the postles. Did they jabber Latin? No, sir. They were satisfied with good honest English. It was a solemn time with them thar. English did for them. So, on this solemn occasion, let us talk English, or forever after hold our peaces.”

“Well, what shall we do?” asked Bart.

“Do?” said Captain Corbet; “why, do somethin solemn. I should like—” he added, mildly. “Ef you could, it would be kind o’ sewthin ef you could sing a hime.”

“A hymn,” said Bart; “certainly.” Now, Bart had a quick talent for making

up jingling rhymes; so he immediately improvised the following, which he

gave out, two lines at a time, to be sung by the “B. O. W. C.” It was sung

to the mournful, the solemn, the venerable, and the very appropriate tune,

known as “Rousseau’s Dream.”

"Why did we

deprive the Frenchman

Of his lands against his

will,

Take possession of his marshes,

Raise a school-house on the hill?

”’Twas a foolish self-deceiving

By such tricks to hope for gain;

All that ever comes by thieving

Turns to sorrow, care, and pain.

"Ours is now the retribution;

See

the fate that falls on us—

Awful tasks

in Greek and Latin,

Algebra, and Calculus!

"Yet for all the tribulation

Which the morrow must behold,

We

may find alleviation

In the Frenchman’s pot

of gold!”

The wailing notes of the tune rose up into the dark night, and the tones, as they were dolefully droned out by the “B. O. W. C.,” died away in the dim forest around.

Captain Corbet gave a long sigh as they ended. “Solemner and solemner!” he slowly ejaculated. “I wish the biz was over.”

“Well,” said Bart, “the way to have it over is to begin as soon as possible. But remember this, all of you: after the first stroke of spade or pickaxe, not a word must be spoken—not a word—not one; no matter what may happen; no matter how surprised, astonished, terrified, horrified, mystified, or scarified we may be. Mum’s the word; any other word will break the spell; and then, where are we? And you, Solomon, mind the lights! Don’t you dare to let one of them go out: as you value your life, keep them going. Above all, mind that tin kettle in the corner; the wick is bad, and it’s flaring away at a tremendous rate. And don’t let the baskets upset. Have you got your matches?”

“Ya—yasr,” said Solomon, whose teeth were now chattering again, and who looked with utter horror at the row of lights which he was ordered to watch.

“Will you take the pickaxe, captain?”

“Wal,” said Captain Corbet, in a faint voice, “I hardly know; perhaps you’d better dig, an I’ll go over to the fence, and see that no one comes.”

“Go over to the fence!” cried Bart. “What! go out through that row of lights? and after our incantations? Why, Captain Corbet! Don’t you think of anything of the kind. We are seven. It’s a mystic number. You must stay with us.” Captain Corbet heaved a sigh.

“Wal,” said he, “I’ll take one of the spades.”

“I’ll take the pickaxe,” said Bruce. “Very well,” said Bart; “you begin. Stir up the earth, and we’ll all dig. But after the first stroke, remember—not one word!”

Bruce then seized the pickaxe with nervous energy, and raising it, he hurled it into the ground. As it struck, Solomon shuddered, and clasped his hands. Captain Corbet stepped back, and looked wildly around. Again and again Bruce wielded the pickaxe, dashing it into the earth with powerful blows, and then wrenching it so as to pry up the sods. The others looked on in silence. At length he had loosened the earth all about, and to a considerable depth. After this he stood back, and the other boys went to work with their spades. Bruce waited for a little time, and then, dropping the pickaxe, he seized a spade, and plunged it into the ground, and rapidly threw up the soil, doing as much work as any two of the others.

For some time they worked thus. The silence was profound, being only broken by the clash of the spades against the stones, and the hard breathing of the boys. At last they hod dug up all the earth that had been loosened by Bruce, and the hard soil began to present an insuperable barrier to the progress of the spades. Seeing this, Bruce seized the pickaxe once more, and again hurled it with vigorous blows into the ground, loosening the earth all around. At last, as he flung it down with all his force, it struck against something which gave so peculiar a sound that the boys all started, and caught one another’s arms, and looked at one another in the dim moonlight, each trying to see the face of the other. Bruce stopped for an instant, and then, swinging the pickaxe again over his head, he dashed it down with all his force. Again it struck that hard substance under ground, and again there was that peculiar sound. It was a sound that could not be mistaken. It was not such a sound as would be given by a stone, or by a stick of timber; it was something very different. It was hard, ringing,—metallic! And as that sound struck upon the ears of the “B. O. W. C.” there was but one thought, a thought which came simultaneously to the minds of all—the thought that Bruce’s pickaxe had reached the buried treasure. But the pot of gold now became to their imaginations an iron chest filled with coin, and it was against this iron chest that the pickaxe had struck, and it was this iron chest which had given forth the sound.

Yet so schooled were they, so determined upon success, that even the immensity of such a sensation could not make them forget their self-imposed silence. Not one word was spoken. They felt, they thought, but they did not speak.

Suddenly Bruce flung down the pickaxe, and seized his spade. At once all the others rushed forward to join in the task. Bruce was first; his spade was plunged deep into the loosened earth. Bight and left it was flung. The spades of the others were plunged in also. All of them were digging wildly and furiously, and panting heavily with their exertion and their excitement. Each one had felt his spade strike and grate against that hard metallic substance which the pickaxe had struck, and which they now fully believed to be the pot of gold. Each one was in the full swing of eager expectation, when suddenly there came an awful interruption.

They might have been digging five minutes, or an hour; they could never tell exactly. Afterwards, when they talked it over, and compared one another’s impressions, they could not come to any decision, for all idea of time had been lost. Engaged in their work, they took no note of minutes or hours. But while they were working Captain Corbet had stood aloof; he held a spade in his listless hands, but he did not use it. He was looking on nervously, and with a pale face, and his thoughts were such as cannot be described. Solomon also stood, with trembling frame and chattering teeth, a prey to superstitious terror. To Solomon had been committed the care of the lights; yet he did not dare to venture near them. For that matter, he did not dare even look at them. His gaze was fixed on the boys, while at times his eyes would roll fearfully over the dark outline of those dim and sombre woods whose shadows lowered gloomily before him.

Such, then, was the situation,—the boys busy and excited; Captain Corbet nervous, and idle, and fearful; Solomon trembling from head to foot, and overcome with a thousand wild and superstitious fancies,—when suddenly, close beside them, outside of the row of lights, just as their spades struck the metallic substance before mentioned,—suddenly, instantaneously, and without the slightest warning, there arose a sharp, a fearful, a terrible uproar; something midway between a shriek and a peal of thunder; a roar, in fact, so hideous, so wild, so unparalleled in its horrid accompaniments, that it shook the boldest heart in that small but bold company. It rose on high; it seemed to fill all the air; and its awful echoes prolonged themselves afar through the darkness of the midnight scene.

The boys started back from the hole; their spades dropped from their hands. They saw about half of the lights extinguished, and amid the gloom they could perceive two figures rushing in mad haste away from the spot. A panic seized upon them. Before a panic the stoutest heart is as weak as water. Even the “B. O. W. C.” yielded to its influence. They shrank back, they retreated, they passed the line of flickering lights.

They fled!

Away, away! back from this terrible place, back towards the Academy. So fled the “B. O. W. C.”

First of all the fugitives was Solomon.

He had been nearly frightened out of his wits long before. These proceedings, half in joke, had been no joke to him. In spite of Bart’s assurances he had stood a trembling spectator, neglectful of his duty. The wind had blown out the lights one by one. Far from lighting them again, he had not even watched them. Every moment his fear had increased, until at last his limbs were almost paralyzed with terror. But at length, when that awful roar had arisen, his stupor was dispelled. An overmastering horror had seized him. He burst through the line of lights; he fled across the field; he ran, with his official robes streaming behind him, towards the Academy. Off went his hat: he heeded it not; he kept on his way. He reached the door of the house; he burst in. Up the stairs, and up another flight, and up another flight, and yet another—so he ran, until at last he reached his room. Arriving here, he banged to the door, and moved his bedstead against it, and heaped upon the bedstead his trunk, his chairs, his table, his looking-glass, his boots, his washstand, and every movable in the room. Then tearing off the bedclothes, he rolled himself up in them, and crouching down in a corner of the room, he lay there sleepless and trembling till daybreak.

Nor was Solomon the only fugitive. Scarcely had he bounded away in his headlong flight before Captain Corbet, with a cry of “O, my babby!” plunged after him, through the line of lights into the gloom that surrounded the ill-omened spot.

And there, over that track which saw the college gown of Solomon and the coat tails of Captain Corbet streaming in the wind, there, fast and far, in wild confusion, in headlong panic, fled the “B. O. W. C.” Who ran first, and who came last, matters not. I certainly will never tell. Enough is it for me to say that they RAN! Such is the power of Panic.

Great, however, as was that panic, it did not last long; and by the time they reached the edge of the playground on the crest of the hill, they all slackened their pace and stopped by mutual consent. There they stood in silence for some time, looking back at the place from which they had fled, and where now a few lights were still flickering.

And there was one great question in all their minds.

What was It?

But this none of them could tell, and so they all kept silent.

That silence was at last broken by Bart.

“Well, boys,” said he, “what are we going to do now? Our shovels and lights are there; and, worst of all, our palladium—-the bust. Solomon has gone, and Captain Corbet; but we still remain. We’ve rallied; and now what shall we do? Shall we retreat, or go back again to the hole?”

Bart spoke, and silence followed. Overhead the clouds swept wrathfully before the face of the moon, and all around’ rose the dim forest shades.

In front flickered and twinkled the feeble, fitful lights. And there, by those lights, was That, whatever it was, from which they had fled.

“I’ll tell you what I’ll do, at any rate,” said Bruce, in a harsh, constrained voice; “I’ll go back to that hole, if I die for it.”

“You!” cried Bart.

“Yes,” said Bruce, standing with his fists close clinched, and his brow darkly frowning; “yes, I; you fellows may come or stay, just as you like.”

A man’s courage must be measured from his own idea of danger. A couple of hundred years ago many acts were brave which to-day are commonplace. To defy the superstitions of the age may be a sign of transcendent courage. Now, of all these boys Bruce was by far the most superstitious; yet he was the first who offered to go back to face That from which they had all fled. It was an effort of pure pluck. It was a grand recoil from the superstitious timidity of his weaker self. Buoyed up by his lofty pride and sense of shame, he crushed down the fear that rose within him, and his very superstition made his act all the more courageous. And as he spoke those last words, before the others had time to say anything in reply, he turned abruptly, and strode back with firm steps towards the cellar. So he stalked off, steeling his shaking nerves and rousing up the resources of his lofty nature. By that victory over the flesh he grew calm, and walked steadily back into the dark, ready to encounter any danger that might be lingering there—an example of splendid courage and conquest over fear.

But he did not long walk alone. Before he had taken a dozen steps the others were with him, and in a short time they were all in the hole again. Bart proceeded to light the extinguished candles, while Bruce quietly picked up the spades, assisted by the other boys. Soon all the lights were burning, and Bart joined the little knot of boys who were standing in the centre of the cellar.

“Well,” said he, coolly, “the old question is before us—What are we to do now? Shall we stay here and dig, or shall we go home and go to bed? For my part, if you wish to dig I’ll dig; but at the same time I think we’d better retire, taking our things with us, and postpone our digging till another time.”

“I won’t say anything about it,” said Bruce. “I’ll do either. One thing, however, I promise not to do; whatever happens, I won’t run again.”

“The fact is,” said Arthur, “there’s no use talking about digging any more to-night. It was all very well while we were in the humor. It was all fun; but the fun has gone; we’ve disgraced ourselves. What That was I don’t pretend to know; but it may have been a trick. If so, we’re watched. And I don’t think any of us feel inclined to dig here with some of the other fellows giggling at us from among the trees.”

“It may have been the Gaspereaugians,” said Phil.

Suddenly a heavy sigh was heard, not far away.

“Hu-s-s-s-s-s-s-h!” said Bart; “what’s that?”

“That? One of the cows,” said Tom.

“I tell you what it is, boys,” said Phil; “some of the fellows have got wind of our plan, and have been playing this trick on us. If so, we’ll never hear the end of it.”

“I’d rather have our fellows do it than the Gas-pereaugians,” said Bart, solemnly. “What a pity we didn’t think of this before we began! We’d not have been taken so by surprise.”

“Well,” said Phil, “I believe it was some trick; but how any human beings could contrive to make such an unearthly noise, such a mixture of thunder, and howling, and screeching, I cannot for the life of me imagine.”

“Still,” said Bruce, “it may not have been a trick. It may have been something which ought to make us afraid.”

“I believe,” said Tom, “that we’ll find out all about it yet. Let us only keep dark, say nothing, and keep our eyes and ears open. We’ll find it out some time.”

“Well,” said Arthur, “I suppose we’re all out of the humor for digging. If so, suppose we smooth over this hole; and then we can take away our lights and spades. My only idea in coming back was to get the things and destroy all traces of our digging.”

“All right,” said Bruce, seizing a spade.

The other boys did the same, and soon the hole was filled up. They placed the sods over it as neatly as they could, and though the soil bore marks of disturbance, yet they were not conspicuous enough to excite particular attention.

Then they proceeded to gather up the things so as to carry them away. In the midst of this there came a voice out of the darkness, a long, loud, shrill voice,—a voice of painful, eager, anxious inquiry.

“B-o-o-o-o-o-o-o-ys! O, b-o-o-o-o-o-o-o-o-o-ys!”

“It’s Captain Corbet!” cried Bart. “Hallo-o-o-o-o!” he shouted. “All ri-i-i-i-i-i-ght! We-e-e-’re h-e-e-e-re! All sa-a-a-a-a-a-afe! Come alo-o-o-o-o-o-o-ong!”

He stopped shouting then, and they all listened attentively. Soon they heard footsteps approaching, and before long they saw emerging from the gloom the familiar form and the reverend features of Captain Corbet. He came down into the hole, and after giving a furtive look all around, he said,—“So you’ve ben a toughin of it out, hev you? Wal, wal, wal!”

“No, captain,” said Bart; “we all ran as fast as we could.”

“You did!” cried Captain Corbet, while a gleam of joy illuminated his venerable face. “You ran! What actilly? Not railly?”

“Yes, we all ran; and stopped at the edge of the hill, and then, seeing nothing, we came back to get the things.”

“Wal,” said Captain Corbet, “that’s more’n I’d hev done. I’m terewly rejiced to find that you clar’d out, sence it makes me not so ’shamed o’ myself; but I wonder at your comin back, I do railly. It was a vice,” he continued, solemnly, “a vice o’ warnin. Hark! from the tombs a doleful sound! But it’s all right now. Sence you’ve ben an stopped up the hole, I ain’t afeard any more. But, boys,”—and he regarded them with a face full of awe,—“boys, let that vice be a warnin. Don’t you ever go a diggin any more for a pot of gold. I give up that thar biz now, and forevermore. See here, and bar witness, all.”

Saying this Captain Corbet took his mineral rod with both hands, and snapped it across his knee; then, letting the fragments fall on the ground, he put his feet over them.

“Thar, that’s done! I got that thar rod from a demon in human form,” he said. “It was old Zeke; I bought it from him. He showed me how to use it. It was not myself, boys. Old Corbet don’t want money; it was the babby. That pereshus infant demanded my parential care. I wanted to heap up wealth for his sake. But it’s all over. That vice has been a warnin. While diggin here, I pined arter the babby; an when that vice come, a soundin like thunder in my ears, I fe-led. I cut like lightnin across the fields, an got to my own hum. But when I got thar I thought o’ youns. I couldn’t go in to see my babby, and leave you here in danger. So I come back; an here we air again, all safe, at last. An the infant’s safe to hum; an the rod’s broke forevermore; an my dreams of gold hev ben therrown like dumb idols to the moulds and tew the bats,—to delude me no more forever. That’s so; an thar you hev it; an I remain yours till death shall us part.”

After some further conversation, the money-diggers gathered up all their pots, and kettles, and pans, and spades, and pickaxes, and shovels, and hoes, and candles, and lanterns, and finally the Bust. These they bore away, and bidding an affectionate adieu to Captain Corbet, they went to the Academy, and succeeded in reaching their rooms unobserved.

And during all the time that they lingered in the cellar there was no repetition of that sound, nor was there any interruption whatever.

The Wonders of the upper Air.—Mr. Long calls upon the Boys for Help.—All

Hands at hard Labor.—Captain Corbet on a Fence.—The Antelope

comes to Grief.—Captain Corbet in the Grasp of the Law. Mr. Long to

the Rescue.

THE next morning came. It was a glorious

sunrise. Nowhere out of Italy, I think, can be seen such sunrises and

sunsets as those of Grand Pré. And you may see all that can be presented

by even Italy in every part of its varied outline—on the plain, on

the mountain-top, or by the sea-side; you may’ traverse the Apennines, or

wander by the Mediterranean shore, or look over the waste Campagna, and

yet never find anything that can surpass those atmospheric effects which

may be witnessed along the shores that surround the Basin of Minas. Here

may be found that which would fill the soul of the poet or artist—the

dreamy haze, the soft and voluptuous calm, the glory of the sunlit sky,

the terror of the storm, the majesty of giant cloud masses piled up

confusedly, the rainbow tints cast by the rising or setting sun over

innumerable clouds.