| Previous Part | Main Index | Next Part |

|

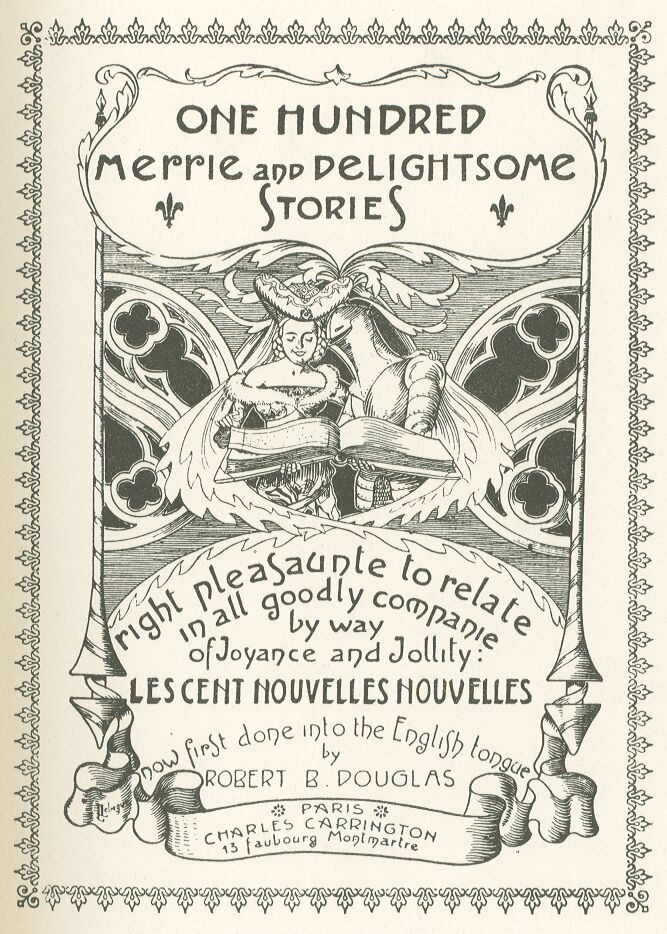

44.jpg The Match-making Priest. |

STORY THE FORTY-FIRST — LOVE IN ARMS.

Of a knight who made his wife wear a hauberk whenever he would do you

know what; and of a clerk who taught her another method which she almost

told her husband, but turned it off suddenly.

STORY THE FORTY-SECOND — THE MARRIED PRIEST.

Of a village clerk who being at Rome and believing that his wife was

dead became a priest, and was appointed curé of his own town, and when

he returned, the first person he met was his wife.

STORY THE FORTY-THIRD — A BARGAIN IN HORNS.

Of a labourer who found a man with his wife, and forwent his revenge

for a certain quantity of wheat, but his wife insisted that he should

complete the work he had begun.

STORY THE FORTY-FOURTH —THE MATCH-MAKING PRIEST.

Of a village priest who found a husband for a girl with whom he was in

love, and who had promised him that when she was married she would do

whatever he wished, of which he reminded her on the wedding-day, and the

husband heard it, and took steps accordingly, as you will hear.

STORY THE FORTY-FIFTH — THE SCOTSMAN TURNED WASHERWOMAN

Of a young Scotsman who was disguised as a woman for the space of

fourteen years, and by that means slept with many girls and married

women, but was punished in the end, as you will hear.

STORY THE FORTY-SIXTH — HOW THE NUN PAID FOR THE PEARS.

Of a Jacobin and a nun, who went secretly to an orchard to enjoy

pleasant pastime under a pear-tree; in which tree was hidden one who

knew of the assignation, and who spoiled their sport for that time, as

you will hear.

STORY THE FORTY-SEVENTH —TWO MULES DROWNED TOGETHER.

Of a President who knowing of the immoral conduct of his wife, caused

her to be drowned by her mule, which had been kept without drink for a

week, and given salt to eat—as is more clearly related hereafter.

STORY THE FORTY-EIGHTH — THE CHASTE MOUTH.

Of a woman who would not suffer herself to be kissed, though she

willingly gave up all the rest of her body except the mouth, to her

lover—and the reason that she gave for this.

STORY THE FORTY-NINTH —THE SCARLET BACKSIDE.

Of one who saw his wife with a man to whom she gave the whole of her

body, except her backside, which she left for her husband and he made

her dress one day when his friends were present in a woollen gown on the

backside of which was a piece of fine scarlet, and so left her before

all their friends.

STORY THE FIFTIETH — TIT FOR TAT.

Of a father who tried to kill his son because the young man wanted to

lie with his grandmother, and the reply made by the said son.

STORY THE FIFTY-FIRST — THE REAL FATHERS.

Of a woman who on her death-bed, in the absence of her husband, made

over her children to those to whom they belonged, and how one of the

youngest of the children informed his father.

STORY THE FIFTY-SECOND — THE THREE REMINDERS.

Of three counsels that a father when on his deathbed gave his son, but

to which the son paid no heed. And how he renounced a young girl he had

married, because he saw her lying with the family chaplain the first

night after their wedding.

STORY THE FIFTY-THIRD — THE MUDDLED MARRIAGES.

Of two men and two women who were waiting to be married at the first

Mass in the early morning; and because the priest could not see well, he

took the one for the other, and gave to each man the wrong wife, as you

will hear.

STORY THE FIFTY FOURTH — THE RIGHT MOMENT.

Of a damsel of Maubeuge who gave herself up to a waggoner, and refused

many noble lovers; and of the reply that she made to a noble knight

because he reproached her for this—as you will hear.

STORY THE FIFTY-FIFTH — A CURÉ FOR THE PLAGUE.

Of a girl who was ill of the plague and caused the death of three men

who lay with her, and how the fourth was saved, and she also.

STORY THE FIFTY-SIXTH — THE WOMAN, PRIEST, SERVANT, AND WOLF.

Of a gentleman who caught, in a trap that he laid, his wife, the

priest, her maid, and a wolf; and burned them all alive, because his

wife committed adultery with the priest.

STORY THE FIFTY-SEVENTH — THE OBLIGING BROTHER.

Of a damsel who married a shepherd, and how the marriage was arranged,

and what a gentleman, the brother of the damsel, said.

STORY THE FIFTY-EIGHTH — SCORN FOR SCORN.

Of two comrades who wished to make their mistresses better inclined

towards them, and so indulged in debauchery, and said, that as after

that their mistresses still scorned them, that they too must have played

at the same game—as you will hear.

STORY THE FIFTY-NINTH — THE SICK LOVER.

Of a lord who pretended to be sick in order that he might lie with the

servant maid, with whom his wife found him.

STORY THE SIXTIETH — THREE VERY MINOR BROTHERS.

Of three women of Malines, who were acquainted with three cordeliers,

and had their heads shaved, and donned the gown that they might not be

recognised, and how it was made known.

Of a knight who made his wife wear a hauberk whenever he would do you know what; and of a clerk who taught her another method which she almost told her husband, but turned it off suddenly.

A noble knight of Haynau, who was wise, cunning, and a great traveller, found such pleasure in matrimony, that after the death of his good and prudent wife, he could not exist long unmarried, and espoused a beautiful damsel of good condition, who was not one of the cleverest people in the world, for, to tell the truth, she was rather dull-witted, which much pleased her husband, because he thought he could more easily bend her to his will.

He devoted all his time and study to training her to obey him, and succeeded as well as he could possibly have wished. And, amongst other matters, whenever he would indulge in the battle of love with her—which was not as often as she would have wished—he made her put on a splendid hauberk, at which she was at first much astonished, and asked why she was armed, and he replied that she could not withstand his amorous assaults if she were not armed. So she was content to wear the hauberk; and her only regret was that her husband was not more fond of making these assaults, for they were more trouble than pleasure to him.

If you should ask why her lord made her wear this singular costume, I should reply that he hoped that the pain and inconvenience of the hauberk would prevent his wife from being too fond of these amorous assaults; but, wise as he was, he made a great mistake, for if in each love-battle the hauberk had broken her back and bruised her belly, she would not have refused to put it on, so sweet and pleasant did she find that which followed.

They thus lived together for a long time, till her husband was ordered to serve his prince in the war, in another sort of battle to that above-mentioned, so he took leave of his wife and went where he was ordered, and she remained at home in the charge of an old gentleman, and of certain damsels who served her.

Now you must know that there was in the house a good fellow, a clerk, who was treasurer of the household, and who sang and played the harp well. After dinner he would often play, which gave madame great pleasure, and she would often come to him when she heard the sound of his harp.

She came so often that the clerk at last made love to her, and she, being desirous to put on her hauberk again, listened to his petition, and replied;

"Come to me at a certain time, in such a chamber, and I will give you a reply that will please you."

She was greatly thanked, and at the hour named, the clerk did not fail to rap at the door of the chamber the lady had indicated, where she was quietly awaiting him with her fine hauberk on her back.

She opened the door, and the clerk saw her armed, and thinking that some one was concealed there to do him a mischief, was so scared that, in his fright, he tumbled down backwards I know not how many stairs, and might have broken his neck, but luckily he was not hurt, for, being in a good cause, God protected him.

Madame, who saw his danger, was much vexed and displeased; she ran down and helped him to rise, and asked why he was in such fear? He told her that truly he thought he had fallen into an ambush.

"You have nothing to fear," she said, "I am not armed with the intention of doing you any hurt," and so saying they mounted the stairs together, and entered the chamber.

"Madame," said the clerk, "I beg of you to tell me, if you please, why you have put on this hauberk?"

She blushed and replied, "You know very well."

"By my oath, madame, begging your pardon," said he, "if I had known I should not have asked."

"My husband," she replied, "whenever he would kiss me, and talk of love, makes me dress in this way; and as I know that you have come here for that purpose, I prepared myself accordingly."

"Madame," he said, "you are right, and I remember now that it is the manner of knights to arm their ladies in this way. But clerks have another method, which, in my opinion is much nicer and more comfortable."

"Please tell me what that is," said the lady.

"I will show you," he replied. Then he took off the hauberk, and the rest of her apparel down to her chemise, and he also undressed himself, and they got into the fair bed that was there, and—both being disarmed even of their chemises—passed two or three hours very pleasantly. And before leaving, the clerk showed her the method used by clerks, which she greatly praised, as being much better than that of knights. They often met afterwards, also in the same way, without its becoming known, although the lady was not over-cunning.

After a certain time, her husband returned from the war, at which she was not inwardly pleased, though outwardly she tried to pretend to be. His coming was known, and God knows how great a dinner was prepared. Dinner passed, and grace being said, the knight—to show he was a good fellow, and a loving husband—said to her,

"Go quickly to our chamber, and put on your hauberk." She, remembering the pleasant time she had had with her clerk, replied quickly,

"Ah, monsieur, the clerks' way is the best."

"The clerks' way!" he cried. "And how do you know their way?" and he began to fret and to change colour, and suspect something; but he never knew the truth, for his suspicions were quickly dissipated.

Madame was not such a fool but what she could see plainly that her husband was not pleased at what she had said, and quickly bethought herself of a way of getting out of the difficulty.

"I said that the clerks' way is the best; and I say it again."

"And what is that?" he asked.

"They drink after grace."

"Indeed, by St. John, you speak truly!" he cried. "Verily it is their custom, and it is not a bad one; and since you so much care for it, we will keep it in future."

So wine was brought and they drank it, and then Madame went to put on her hauberk, which she would willingly have done without, for the gentle clerk had showed her another way which pleased her better.

Thus, as you have heard, was Monsieur deceived by his wife's ready reply. No doubt her wits had been sharpened by her intercourse with the clerk, and after that he showed her plenty of other tricks, and in the end he and her husband became great friends.

Of a village clerk who being at Rome and believing that his wife was dead became a priest, and was appointed curé of his own town, and when he returned, the first person he met was his wife.

In the year '50 (*) just passed, the clerk of a village in the diocese of Noyon, that he might gain the pardons, which as every one knows were then given at Rome (**), set out in company with many respectable people of Noyon, Compeigne, and the neighbouring places.

(*) 1450

(**) Special indulgences were granted that year on account

of the Jubilee

But, before leaving, he carefully saw to his private affairs, arranged for the support of his wife and family, and entrusted the office of sacristan, which he held, to a young and worthy clerk to hold until his return.

In a fairly brief space of time, he and his companions arrived at Rome, and performed their devotions and their pilgrimage as well as they knew how. But you must know that our clerk met, by chance, at Rome, one of his old school-fellows, who was in the service of a great Cardinal, and occupied a high position, and who was very glad to meet his old friend, and asked him how he was. And the other told him everything—first of all that he was, alas! married, how many children he had, and how that he was a parish clerk.

"Ah!" said his friend, "by my oath! I am much grieved that you are married."

"Why?" asked the other.

"I will tell you," said he; "such and such a Cardinal has charged me to find him a secretary, a native of our province. This would have suited you, and you would have been largely remunerated, were it not that your marriage will cause you to return home, and, I fear, lose many benefits that you cannot now get."

"By my oath!" said the clerk, "my marriage is no great consequence, for—to tell you the truth—the pardon was but an excuse for getting out of the country, and was not the principal object of my journey; for I had determined to enjoy myself for two or three years in travelling about, and if, during that time, God should take my wife, I should only be too happy. So I beg and pray of you to think of me and to speak well for me to this Cardinal, that I may serve him; and, by my oath, I will so bear myself that you shall have no fault to find with me; and, moreover, you will do me the greatest service that ever one friend did another."

"Since that is your wish," said his friend, "I will oblige you at once, and will lodge you too if you wish."

"Thank you, friend," said the other.

To cut matters short, our clerk lodged with the Cardinal, and wrote and told his wife of his new position, and that he did not intend to return home as soon as he had intended when he left. She consoled herself, and wrote back that she would do the best she could.

Our worthy clerk conducted himself so well in the service of the Cardinal, and gained such esteem, that his master had no small regret that his secretary was incapable of holding a living, for which he was exceedingly well fitted.

Whilst our clerk was thus in favour, the curé of his village died, and thus left the living vacant during one of the Pope's months. (*) The Sacristan who held the place of his friend who had gone to Rome, determined that he would hurry to Rome as quickly as he could, and do all in his power to get the living for himself. He lost no time, and in a few days, after much trouble and fatigue, found himself at Rome, and rested not till he had discovered his friend—the clerk who served the Cardinal.

After mutual salutations, the clerk asked after his wife, and the other, expecting to give him much pleasure and further his own interests in the request he was about to make, replied that she was dead—in which he lied, for I know that at this present moment (**) she can still worry her husband.

(*) During eight months of the year, the Pope had the right

of bestowing all livings which became vacant.

(**) That is when the story was written.

"Do you say that my wife is dead?" cried the clerk. "May God pardon her all her sins."

"Yes, truly," replied the other; "the plague carried her off last year, along with many others."

He told this lie, which cost him dear, because he knew that the clerk had only left home on account of his wife, who was of a quarrelsome disposition, and he thought the most pleasant news he could bring was to announce her death, and truly so it would have been, but the news was false.

"And what brings you to this country?" asked the clerk after many and various questions.

"I will tell you, my friend and companion. The curé of our town is dead; so I came to you to ask if by any means I could obtain the benefice. I would beg of you to help me in this matter. I know that it is in your power to procure me the living, with the help of monseigneur, your master."

The clerk, thinking that his wife was dead, and the cure of his native town vacant, thought to himself that he would snap up this living, and others too if he could get them. But, all the same, he said nothing to his friend, except that it would not be his fault if the other were not curé of their town,—for which he was much thanked.

It happened quite otherwise, for, on the morrow, our Holy Father, at the request of the Cardinal, the master of our clerk, gave the latter the living.

Thereupon this clerk, when he heard the news, came to his companion, and said to him,

"Ah, friend, by my oath, your hopes are dissipated, at which I am much vexed."

"How so?" asked the other.

"The cure of our town is given," he said, "but I know not to whom. Monseigneur, my master, tried to help you, but it was not in his power to accomplish it."

At which the other was vexed, after he had come so far and expended so much. So he sorrowfully took leave of his friend, and returned to his own country, without boasting about the lie he had told.

But let us return to our clerk, who was as merry as a grig at the news of the death of his wife, and to whom the benefice of his native town had been given, at the request of his master, by the Holy Father, as a reward for his services. And let us record how he became a priest at Rome, and chanted his first holy Mass, and took leave of his master for a time, in order to return and take possession of his living.

When he entered the town, by ill luck the first person that he chanced to meet was his wife, at which he was much astonished I can assure you, and still more vexed.

"What is the meaning of this, my dear?" he asked. "They told me you were dead!"

"Nothing of the kind," she said. "You say so, I suppose, because you wish it, as you have well proved, for you have left me for five years, with a number of young children to take care of."

"My dear," he said, "I am very glad to see you in good health, and I praise God for it with all my heart. Cursed be he who brought me false news."

"Amen!" she replied.

"But I must tell you, my dear, that I cannot stay now; I am obliged to go in haste to the Bishop of Noyon, on a matter which concerns him; but I will return to you as quickly as I can."

He left his wife, and took his way to Noyon; but God knows that all along the road he thought of his strange position.

"Alas!" he said, "I am undone and dishonoured. A priest! a clerk! and married! I suppose I am the first miserable wretch to whom that ever occurred!"

He went to the Bishop of Noyon, who was much surprised at hearing his case, and did not know what to advise him, so sent him back to Rome.

When he arrived there, he related his adventure at length to his master, who was bitterly annoyed, and on the morrow repeated it to our Holy Father, in the presence of the Sacred College and all the Cardinals.

So it was ordered that he should remain priest, and married, and curé also; and that he should live with his wife as a married man, honourably and without reproach, and that his children should be legitimate and not bastards, although their father was a priest. Moreover, that if it was found he lived apart from his wife, he should lose the living.

Thus, as you have heard, was this gallant punished for believing the false news of his friend, and was obliged to go and live in his own parish, and, which was worse, with his wife, with whose company he would have gladly dispensed if the Church had not ordered it otherwise.

Of a labourer who found a man with his wife, and forwent his revenge for a certain quantity of wheat, but his wife insisted that he should complete the work he had begun.

There lived formerly, in the district of Lille, a worthy man who was a labourer and tradesman, and who managed, by the good offices of himself and his friends, to obtain for a wife a very pretty young girl, but who was not rich, neither was her husband, but he was very covetous, and diligent in business, and loved to gain money.

And she, for her part, attended to the household as her husband desired; who therefore had a good opinion of her, and often went about his business without any suspicion that she was other than good.

But whilst the poor man thus came and went, and left his wife alone, a good fellow came to her, and, to cut the story short, was in a short time the deputy for the trusting husband, who still believed that he had the best wife in the world, and the one who most thought about the increase of his honour and his worldly wealth.

It was not so, for she gave him not the love she owed him, and cared not whether he had profit or loss by her. The good merchant aforesaid, being out as usual, his wife soon informed her friend, who did not fail to come as he was desired, at once. And not to lose his time, he approached his mistress, and made divers amorous proposals to her, and in short the desired pleasure was not refused him any more than on the former occasions, which had not been few.

By bad luck, whilst the couple were thus engaged, the husband arrived, and found them at work, and was much astonished, for he did not know that his wife was a woman of that sort.

"What is this?" he said. "By God's death, scoundrel, I will kill you on the spot."

The other, who had been caught in the act, and was much scared, knew not what to say, but as he was aware that the husband was miserly and covetous, he said quickly:

"Ah, John, my friend, I beg your mercy; pardon me if I have done you any wrong, and on my word I will give you six bushels of wheat."

"By God!" said he, "I will do nothing of the kind. You shall die by my hands and I will have your life if I do not have twelve bushels."

The good wife, who heard this dispute, in order to restore peace, came forward, and said to her husband.

"John, dear, let him finish what he has begun, I beg, and you shall have eight bushels. Shall he not?" she added, turning to her lover.

"I am satisfied," he said, "though on my oath it is too much, seeing how dear corn is."

"It is too much?" said the good man. "Morbleu! I much regret that I did not say more, for you would have to pay a much heavier fine if you were brought to justice: however, make up your mind that I will have twelve bushels, or you shall die."

"Truly, John," said his wife, "you are wrong to contradict me. It seems to me that you ought to be satisfied with eight bushels, for you know that is a large quantity of wheat."

"Say no more," he replied, "I will have twelve bushels, or I will kill him and you too."

"The devil," quoth the lover; "you drive a bargain; but at least, if I must pay you, let me have time."

"That I agree to, but I will have my twelve bushels."

The dispute ended thus, and it was agreed that he was to pay in two instalments,—six bushels on the morrow, and the others on St. Remy's day, then near.

All this was arranged by the wife, who then said to her husband.

"You are satisfied, are you not, to receive your wheat in the manner I have said?"

"Certainly," he replied.

"Then go," she said, "whilst he finishes the work he had begun when you interrupted him; otherwise the contract will not be binding."

"By St. John! is it so?" said the lover.

"I always keep my word," said the good merchant. "By God, no man shall say I am a cheat or a liar. You will finish the job you have begun, and I am to have my twelve bushels of wheat on the terms agreed. That was our contract—was it not?"

"Yes, truly," said his wife.

"Good bye, then," said the husband, "but at any rate be sure that I have six bushels of wheat to-morrow."

"Don't be afraid," said the other. "I will keep my word." So the good man left the house, quite joyful that he was to have twelve bushels of wheat, and his wife and her lover recommenced more heartily than ever. I have heard that the wheat was duly delivered on the dates agreed.

Of a village priest who found a husband for a girl with whom he was in love, and who had promised him that when she was married she would do whatever he wished, of which he reminded her on the wedding-day, and the husband heard it, and took steps accordingly, as you will hear.

In the present day they are many priests and curés who are good fellows, and who can as easily commit follies and imprudences as laymen can.

In a pretty village of Picardy, there lived formerly a curé of a lecherous disposition. Amongst the other pretty girls and women of his parish, he cast eyes on a young and very pretty damsel of nubile age, and was bold enough to tell her what he wanted.

Won over by his fair words, and the hundred thousand empty promises he made, she was almost ready to listen to his requests, which would have been a great pity, for she was a nice and pretty girl with pleasant manners, and had but one fault,—which was that she was not the most quick-witted person in the world.

I do not know why it occurred to her to answer him in that manner, but one day she told the curé, when he was making hot love to her, that she was not inclined to do what he required until she was married, for if by chance, as happened every day, she had a baby, she would always be dishonoured and reproached by her father, mother, brothers, and all her family, which she could not bear, nor had she strength to sustain the grief and worry which such a misfortune would entail.

"Nevertheless, if some day I am married, speak to me again, and I will do what I can for you, but not otherwise; so give heed to what I say and believe me once for all."

The cure was not over-pleased at this definite reply, bold and sensible as it was, but he was so amorous that he would not abandon all hope, and said to the girl;

"Are you so firmly decided, my dear, not to do anything for me until you are married?"

"Certainly, I am," she replied.

"And if you are married, and I am the means and the cause, you will remember it afterwards, and honestly and loyally perform what you have promised?"

"By my oath, yes," she said, "I promise you."

"Thank you," he said, "make your mind easy, for I promise you faithfully that if you are not married soon it will not be for want of efforts or expense on my part, for I am sure that you cannot desire it more than I do; and in order to prove that I am devoted to you soul and body, you will see how I will manage this business."

"Very well, monsieur le curé," she said, "we shall see what you will do."

With that she took leave of him, and the good curé, who was madly in love with her, was not satisfied till he had seen her father. He talked over various matters with him, and at last the worthy priest spoke to the old man about his daughter, and said,

"Neighbour, I am much astonished, as also are many of your neighbours and friends, that you do not let your daughter marry. Why do you keep her at home when you know how dangerous it is? Not that—God forbid—I say, or wish to say, that she is not virtuous, but every day we see girls go wrong because they do not marry at the proper age. Forgive me for so openly stating my opinion, but the respect I have for you, and the duty I owe you as your unworthy pastor, require and compel me to tell you this."

"By the Lord, monsieur le curé," said the good man, "I know that your words are quite true, and I thank you for them, and do not think that I have kept her so long at home from any selfish motive, for if her welfare is concerned I will do all I can for her, as I ought. You would not wish, nor is it usual, that I should buy a husband for her, but if any respectable young man should come along, I will do everything that a good father should."

"Well said," replied the curé, "and on my word, you could not do better than marry her off quickly. It is a great thing to be able to see your grandchildren round you before you become too old. What do you say to so-and-so, the son of your neighbour?—He seems to me a good, hard-working man, who would make a good husband."

"By St. John!" said the old man, "I have nothing but good to say about him. For my own part, I know him to be a good young man and a good worker. His father and mother, and all his relatives, are respectable people, and if they do me the honour to ask my daughter's hand in marriage for him, I shall reply in a manner that will satisfy them."

"You could not say more," replied the curé, "and, if it please God, the matter shall be arranged as I wish, and as I know for a fact that this marriage would be to the benefit of both parties, I will do my best to farther it, and with this I will now say farewell to you."

If the curé had played his part well with the girl's father, he was quite as clever in regard to the father of the young man. He began with a preamble to the effect that his son was of an age to marry, and ought to settle down, and brought a hundred thousand reasons to show that the world would be lost if his son were not soon married.

"Monsieur le curé," replied also the second old man, "there is much truth in what you say, and if I were now as well off as I was, I know not how many years ago, he would not still be unmarried; for there is nothing in the world I desire more than to see him settled, but want of money has prevented it, and so he must have patience until the Lord sends us more wealth than we have at present."

"Then," said the curé, "if I understand you aright, it is only money that is wanting."

"Faith! that is so," said the old man. "If I had now as much as I had formerly, I should soon seek a wife for him."

"I have concerned myself," said the curé, "because I desire the welfare and prosperity of your son, and find that the daughter of such an one (that is to say his ladylove) would exactly suit him. She is pretty and virtuous, and her father is well off, and, as I know, would give some assistance, and—which is no small matter—is a wise man of good counsel, and a friend to whom you and your son could have recourse. What do you say?"

"Certainly," said the good man, "if it please God that my son should be fortunate enough to be allied to such a good family; and if I thought that he could anyhow succeed in that, I would get together what money I could, and would go round to all my friends, for I am sure that he could never find anyone more suitable."

"I have not chosen badly then," said the curé. "And what would you say if I spoke about this matter to her father, and conducted it to its desired end, and, moreover, lent you twenty francs for a certain period that we could arrange?"

"By my oath, monsieur le curé," said the good man, "you offer me more than I deserve. If you did this, you would render a great service to me and mine."

"Truly," answered the curé, "I have not said anything that I do not mean to perform; so be of good cheer, for I hope to see this matter at an end."

To shorten matters, the curé, hoping to have the woman when once she was married, arranged the matter so well that, with the twenty francs he lent, the marriage was settled, and the wedding day arrived.

Now it is the custom that the bride and bridegroom confess on that day. The bridegroom came first, and when he had finished, he withdrew to a little distance saying his orisons and his paternosters. Then came the bride, who knelt down before the curé and confessed. When she had said all she had to say, he spoke to her in turn, and so loudly, that the bridegroom, who was not far off, heard every word, and said,

"My dear, I beg you to remember now the promise you formerly made me. You promised me that when you were married that I should ride you; and now you are married, thank God, by my means and endeavours, and through the money that I have lent."

"Monsieur le curé," she said, "have no fear but what I will keep the promise I have made, if God so please."

"Thank you," he replied, and then gave her absolution after this devout confession, and suffered her to depart.

The bridegroom, who had heard these words, was not best pleased, but nevertheless thought it not the right moment to show his vexation.

After all the ceremonies at the church were over, the couple returned home, and bed-time drew near. The bridegroom whispered to a friend of his whom he dearly loved, to fetch a big handful of birch rods, and hide them secretly under the bed, and this the other did.

When the time came, the bride went to bed, as is the custom, and kept to the edge of the bed, and said not a word. The bridegroom came soon after, and lay on the other edge of the bed without approaching her, or saying a word and in the morning he rose without doing anything else, and hid his rods again under the bed.

When he had left the room, there came several worthy matrons who found the bride in bed, and asked her how the night had passed, and what she thought of her husband?

"Faith!" she said, "there was his place over there"—pointing to the edge of the bed—"and here was mine. He never came near me, and I never went near him."

They were all much astonished, and did not know what to think, but at last they agreed that if he had not touched her, it was from some religious motive, and they thought no more of it for that once.

The second night came, and the bride lay down in the place she had occupied the previous night, and the bridegroom, still furnished with his rods, did the same and nothing more; and this went on for two more nights, at which the bride was much displeased, and did not fail to tell the matrons the next day, who knew not what to think.

"It is to be feared he is not a man, for he has continued four nights in that manner. He must be told what he has to do; so if to-night he does not begin,"—they said to the bride—"draw close to him and cuddle and kiss him, and ask him if married people do not do something else besides? And if he should ask you what you want him to do? tell him that you want him to ride you, and you will hear what he will say."

"I will do so," she said.

She failed not, for that night she lay in her usual place, and her husband took up his old quarters, and made no further advances than he had on the previous nights. So she turned towards him, and throwing her arms round him, said;

"Come here husband! Is this the pleasant time I was to expect? This is the fifth night I have slept with you, and you have not deigned to come near me! On my word I should never have wished to be married if I had not thought married people did something else."

"And what did they tell you married people did?" he asked.

"They say," she replied, "that the one rides the other. I want you to ride me."

"Ride!" he said. "I would not like to do that.—I would not be so unkind."

"Oh, I beg of you to do it—for that is what married people do."

"You want me to do it?" he asked.

"I beg of you to do it," she said, and so saying she kissed him tenderly.

"By my oath!" he said, "I will do it, since you ask me to though much to my regret, for I am sure that you will not like it."

Without saying another word he took his stock of rods, and stripped his wife, and thrashed her soundly, back and belly, legs and thighs, till she was bathed in blood. She screamed, she cried, she struggled, and it was piteous to see her, and she cursed the moment that she had ever asked to be ridden.

"I told you so," said her husband, and then took her in his arms and "rode" her so nicely that she forgot the pain of the beating.

"What do you call that you have just done?" she asked.

"It is called," he said, "'to blow up the backside'."

"Blow up the backside!" she said. "The expression is not so pretty as 'to ride', but the operation is much nicer, and, now that I have learned the difference, I shall know what to ask for in future."

Now you must know that the curé was always on the look-out for when the newly married bride should come to church, to remind her of her promise. The first time she appeared, he sidled up to the font, and when she passed him, he gave her holy water, and said in a low voice,

"My dear! you promised me that I should ride you when you were married! You are married now, thank God, and it is time to think when and how you will keep your word."

"Ride?" she said. "By God, I would rather see you hanged or drowned! Don't talk to me about riding. But I will let you blow up my backside if you like!"

"And catch your quartain fever!" said the curé, "beastly dirty, ill-mannered whore that you are! Am I to be rewarded after all I have done for you, by being permitted to blow up your backside!"

So the curé went off in a huff, and the bride took her seat that she might hear the holy Mass, which the good curé was about to read.

And thus, in the manner which you have just heard, did the curé lose his chance of enjoying the girl, by his own fault and no other's, because he spoke too loudly to her the day when he confessed her, for her husband prevented him, in the way described above, by making his wife believe that the act of 'riding' was called 'to blow up the backside'.

Of a young Scotsman who was disguised as a woman for the space of fourteen years, and by that means slept with many girls and married women, but was punished in the end, as you will hear.

None of the preceding stories have related any incidents which happened in Italy, but only those which occurred in France, Germany, England, Flanders, and Brabant,—therefore I will relate, as something new, an incident which formerly happened in Rome, and was as follows.

At Rome was a Scotsman of the age of about 22, who for the space of fourteen years had disguised himself as a woman, without it being publicly known all that time that he was a man. He called himself Margaret, and there was hardly a good house in Rome where he was not known, and he was specially welcomed by all the women, such as waiting-women, and wenches of the lower orders, and also many of the greatest ladies in Rome.

This worthy Scotsman carried on the trade of laundress, and had learned to bleach sheets, and called himself the washerwoman, and under that pretence frequented, as has been said, all the best houses in Rome, for there was no woman who could bleach sheets as he did.

But you must know that he did much else beside, for when he found himself with some pretty girl, he showed her that he was a man. Often, in order to prepare the lye, he stopped one or two nights in the aforesaid houses, and they made him sleep with the maid, or sometimes with the daughter; and very often, if her husband were not there, the mistress would have his company. And God knows that he had a good time, and, thanks to the way he employed his body, was welcome everywhere, and many wenches and waiting maids would fight as to who was to have him for a bedfellow.

The citizens of Rome heard such a good account of him from their wives, that they willingly welcomed him to their houses, and if they went abroad, were glad to have Margaret to keep house along with their wives, and, what is more, made her sleep with them, so good and honest was she esteemed, as has been already said.

For the space of fourteen years did Margaret continue this way of living, but the mischief was at last brought to light by a young girl, who told her father that she had slept with Margaret and been assaulted by her, and that in reality she was a man. The father informed the officers of justice, and it was found that she had all the members and implements that men carry, and, in fact, was a man and not a woman.

So it was ordered that he should be put in a cart and led through all the city of Rome, and at every street corner his genitals should be exposed.

This was done, and God knows how ashamed and vexed poor Margaret was. But you must know that when the cart stopped at a certain corner, and all the belongings of Margaret were being exhibited, a Roman said out loud;

"Look at that scoundrel! he has slept more than twenty nights with my wife!"

Many others said the same, and many who did not say it knew it well, but, for their honours sake, held their tongue. Thus, in the manner you have heard, was the poor Scotsman punished for having pretended to be a woman, and after that punishment was banished from Rome; at which the women were much displeased, for never was there such a good laundress, and they were very sorry that they had so unfortunately lost her.

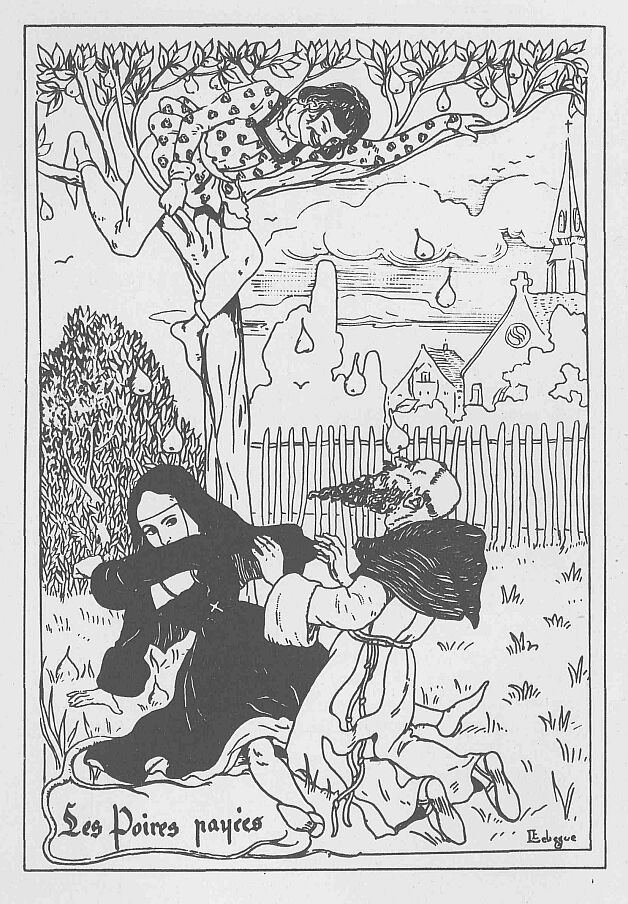

Of a Jacobin and a nun, who went secretly to an orchard to enjoy pleasant pastime under a pear-tree; in which tree was hidden one who knew of the assignation, and who spoiled their sport for that time, as you will hear.

(*) The name of the author of this story is spelled in four

different ways in different editions of these tales—Viz,

Thieurges, Thienges, Thieuges and Thianges.

It is no means unusual for monks to run after nuns. Thus it happened formerly that a Jacobin so haunted, visited, and frequented a nunnery in this kingdom, that his intention became known,—which was to sleep with one of the ladies there.

And God knows how anxious and diligent he was to see her whom he loved better than all the rest of the world, and continued to visit there so often, that the Abbess and many of the nuns perceived how matters stood, at which they were much displeased. Nevertheless, to avoid scandal, they said not a word to the monk, but gave a good scolding to the nun, who made many excuses, but the abbess, who was clear-sighted, knew by her replies and excuses that she was guilty.

So, on account of that nun, the Abbess restrained the liberty of all, and caused the doors of the cloisters and other places to be closed, so that the poor Jacobin could by no means come to his mistress. That greatly vexed him, and her also, I need not say, and you may guess that they schemed day and night by what means they could meet; but could devise no plan, such a strict watch did the Abbess keep on them.

It happened one day, that one of the nieces of the Abbess was married, and a great feast was made in the convent. There was a great assemblage of people from the country round, and the Abbess was very busy receiving the great people who had come to do honour to her niece.

The worthy Jacobin thought that he might get a glimpse of his mistress, and by chance be lucky enough to find an opportunity to speak to her. He came therefore, and found what he sought; for, because of the number of guests, the Abbess was prevented from keeping watch over the nun, and he had an opportunity to tell his mistress his griefs, and how much he regretted the good time that had passed; and she, who greatly loved him, gladly listened to him, and would have willingly made him happy. Amongst other speeches, he said;

"Alas! my dear, you know that it is long since we have had a quiet talk together such as we like; I beg of you therefore, if it is possible, whilst everyone is otherwise engaged than in watching us, to tell me where we can have a few words apart."

"So help me God, my friend," she replied, "I desire it no less than you do. But I do not know of any place where it can be done; for there are so many people in the house, and I cannot enter my chamber, there are so many strangers who have come to this wedding; but I will tell you what you can do. You know the way to the great garden; do you not?"

"By St. John! yes," he said.

"In the corner of the garden," she said, "there is a nice paddock enclosed with high and thick hedges, and in the middle is a large pear-tree, which makes the place cool and shady. Go there and wait for me, and as soon as I can get away, I will hurry to you."

The Jacobin greatly thanked her and went straight there. But you must know there was a young gallant who had come to the feast, who was standing not far from these lovers and had heard their conversation, and, as he knew the paddock, he determined that he would go and hide there, and see their love-making.

He slipped out of the crowd, and as fast as his feet could carry him, ran to this paddock, and arrived there before the Jacobin; and when he came there, he climbed into the great pear-tree—which had large branches, and was covered with leaves and pears,—and hid himself so well that he could not be easily seen.

He was hardly ensconced there when there came trotting along the worthy Jacobin, looking behind him to see if his mistress was following; and God knows that he was glad to find himself in that beautiful spot, and never lifted his eyes to the pear-tree, for he never suspected that there was anyone there, but kept his eyes on the road by which he had come.

He looked until he saw his mistress coming hastily, and she was soon with him, and they rejoiced greatly, and the good Jacobin took off his gown and his scapulary, and kissed and cuddled tightly the fair nun.

They wanted to do that for which they came thither, and prepared themselves accordingly, and in so doing the nun said;

"Pardieu, Brother Aubrey, I would have you know that you are about to enjoy one of the prettiest nuns in the Church. You can judge for yourself. Look what breasts Î what a belly! what thighs! and all the rest."

"By my oath," said Brother Aubrey, "Sister Jehanne, my darling, you also can say that you have for a lover one of the best-looking monks of our Order, and as well furnished as any man in this kingdom," and with these words, taking in his hand the weapon with which he was about to fight, he brandished it before his lady's eyes, and cried, "What do you say? What do you think of it? Is it not a handsome one? Is it not worthy of a pretty girl?"

"Certainly it is," she said.

"And you shall have it."

"And you shall have," said he who was up in the pear-tree, "all the best pears on the tree;" and with that he took and shook the branches with both hands, and the pears rattled down on them and on the ground, at which Brother Aubrey was so frightened that he hardly had the sense to pick up his gown, but ran away as fast as he could without waiting, and did not feel safe till he was well away from the spot.

The nun was as much, or more, frightened, but before she could set off, the gallant had come down out of the tree, and taking her by the hand, prevented her leaving, and said; "My dear, you must not go away thus: you must first pay the fruiterer."

She saw that a refusal would appear unseasonable, and was fain to let the fruiterer complete the work which Brother Aubrey had left undone.

Of a President who knowing of the immoral conduct of his wife, caused her to be drowned by her mule, which had been kept without drink for a week, and given salt to eat—as is more clearly related hereafter.

In Provence there lived formerly a President of great and high renown, who was a most learned clerk and prudent man, valiant in arms, discreet in counsel, and, in short, had all the advantages which man could enjoy. (*)

(*) Though not mentioned here by name, the principal

character in this story has been identified with Chaffrey

Carles, President of the Parliament of Grenoble. On the

front of a house in the Rue de Cleres, in Grenoble is carved

a coat of arms held by an angel who has her finger on her

lips. The arms are those of the Carles family and the figure

is supposed to refer to this story. At any rate the secret

was very badly kept, for the story seems to have been widely

known within a few years of its occurrence.

One thing only was wanting to him, and that was the one that vexed him most, and with good cause—and it was that he had a wife who was far from good. The good lord saw and knew that his wife was unfaithful, and inclined to play the whore, but the sense that God had given him, told him that there was no remedy except to hold his tongue or die, for he had often both seen and read that nothing would cure a woman of that complaint.

But, at any rate, you may imagine that a man of courage and virtue, as he was, was far from happy, and that his misfortune rankled in his sorrowing heart. Yet as he outwardly appeared to know or see nothing of his wife's misconduct, one of his servants came to him one day when he was alone in his chamber, and said,

"Monsieur, I want to inform you, as I ought, of something which particularly touches your honour. I have watched your wife's conduct, and I can assure you that she does not keep the faith she promised, for a certain person (whom he named) occupies your place very often."

The good President, who knew as well or better than the servant who made the report, how his wife behaved, replied angrily;

"Ha! scoundrel, I am sure that you lie in all you say! I know my wife too well, and she is not what you say—no! Do you think I keep you to utter lies about a wife who is good and faithful to me! I will have no more of you; tell me what I owe you and then go, and never enter my sight again if you value your life!"

The poor servant, who thought he was doing his master a great service, said how much was due to him, received his money and went, but the President, seeing that the unfaithfulness became more and more evident, was as vexed and troubled as he could be. He could not devise any plan by which he could honestly get rid of her, but it happened that God willed, or fortune permitted that his wife was going to a wedding shortly, and he thought it might be made to turn out lucky for him.

He went to the servant who had charge of the horses, and a fine mule that he had, and said,

"Take care that you give nothing to drink to my mule either night or day, until I give you further orders, and whenever you give it its hay, mix a good handful of salt with it—but do not say a word about it."

"I will say nothing," said the servant, "and I will do whatever you command me."

When the wedding day of the cousin of the President's wife drew near, she said to her husband,

"Monsieur, if it be your pleasure, I would willingly attend the wedding of my cousin, which will take place next Sunday, at such a place."

"Very well, my dear; I am satisfied: go, and God guide you."

"Thank you, monsieur," she replied, "but I know not exactly how to go. I do not wish to take my carriage; your nag is so skittish that I am afraid to undertake the journey on it."

"Well, my dear, take my mule—it looks well, goes nicely and quietly, and is more sure-footed than any animal I ever saw."

"Faith!" she said, "I thank you: you are a good husband."

The day of departure arrived, and all the servants of Madame were ready, and also the women who were to serve her and accompany her, and two or three cavaliers who were to escort Madame, and they asked if Madame were also ready, and she informed them that she would come at once.

When she was dressed, she came down, and they brought her the mule which had not drank for eight days, and was mad with thirst, so much salt had it eaten. When she was mounted, the cavaliers went first, making their horses caracole, and thus did all the company pass through the town into the country, and on till they came to a defile through which the great river Rhone rushes with marvellous swiftness. And when the mule which had drank nothing for eight days saw the river, it sought neither bridge nor ford, but made one leap into the river with its load, which was the precious body of Madame.

All the attendants saw the accident, but they could give no help; so was Madame drowned, which was a great misfortune. And the mule, when it had drunk its fill, swam across the Rhone till it reached the shore, and was saved.

All were much troubled and sorrowful that Madame was lost, and they returned to the town. One of the servants went to the President, who was in his room expecting the news; and with much sorrow told him of the death of his wife.

The good President, who in his heart was more glad than sorry, showed great contrition, and fell down, and displayed much sorrow and regret for his good wife. He cursed the mule, and the wedding to which his wife was going.

"And by God!" he said, "it is a great reproach to all you people that were there that you did not save my poor wife, who loved you all so much; you are all cowardly wretches, and you have clearly shown it."

The servant excused himself, as did the others also, as well as they could, and left the President, who praised God with uplifted hands that he was rid of his wife.

He gave his wife's body a handsome funeral, but—as you may imagine—although he was of a fit and proper age, he took care never to marry again, lest he should once more incur the same misfortune.

Of a woman who would not suffer herself to be kissed, though she willingly gave up all the rest of her body except the mouth, to her lover—and the reason that she gave for this.

A noble youth fell in love with a young damsel who was married, and when he had made her acquaintance, told her, as plainly as he could, his case, and declared that he was ill for love of her,—and, to tell truth, he was much smitten.

She listened to him graciously enough, and after their first interview, he left well satisfied with the reply he had received. But if he had been love sick before he made the avowal, he was still more so afterwards. He could not sleep night or day for thinking of his mistress, and by what means he could gain her favour.

He returned to the charge when he saw his opportunity, and God knows, if he spoke well the first time, he played his part still better on the second occasion, and, by good luck, he found his mistress not disinclined to grant his request,—at which he was in no small degree pleased. And as he had not always the time or leisure to come and see her, he told her on that occasion of the desire he had to do her a service in any manner that he could, and she thanked him and was as kind as could be.

In short, he found in her so great courtesy, and kindness, and fair words, that he could not reasonably expect more, and thereupon wished to kiss, but she refused point-blank; nor could he even obtain a kiss when he said farewell, at which he was much astonished.

After he had left her, he doubted much whether he should ever gain her love, seeing that he could not obtain a single kiss, but he comforted himself by remembering the loving words she had said when they parted, and the hope she had given him.

He again laid siege to her; in short, came and went so often, that his mistress at last gave him a secret assignation, where they could say all that they had to say, in private. And when he took leave of her, he embraced her gently and would have kissed her, but she defended herself vigorously, and said to him, harshly;

"Go away, go away! and leave me alone! I do not want to be kissed!"

He excused his conduct as he best could, and left.

"What is this?" he said to himself. "I have never seen a woman like that! She gives me the best possible reception, and has already given me all that I have dared to ask—yet I cannot obtain one poor, little kiss."

At the appointed time, he went to the place his mistress had named, and did at his leisure that for which he came, for he lay in her arms all one happy night, and did whatsoever he wished, except kiss her, and that he could never manage.

"I do not understand these manners," he said to himself; "this woman lets me sleep with her, and do whatever I like to her; but I have no more chance of getting a single kiss than I have of finding the true Cross! Morbleu! I cannot make it out; there is some mystery about it, and I must find out what it is."

One day when they were enjoying themselves, and were both gay, he said,

"My dear, I beg of you to tell me the reason why you invariably refuse to give me a kiss? You have graciously allowed me to enjoy all your fair and sweet body—and yet you refuse me a little kiss!"

"Faith! my friend," she replied, "as you say, a kiss I have always refused you,—so never expect it, for you will never get it. There is a very good reason for that, as I will tell you. It is true that when I married my husband, I promised him—with the mouth only—many fine things. And since it is my mouth that swore and promised to be chaste, I will keep it for him, and would rather die than let anyone else touch it—it belongs to him and no other, and you must not expect to have anything to do with it. But my backside has never promised or sworn anything to him; do with that and the rest of me—my mouth excepted—whatever you please; I give it all to you."

Her lover laughed loudly, and said;

"I thank you, dearest! You say well, and I am greatly pleased that you are honest enough to keep your promise."

"God forbid," she answered, "that I should ever break it."

So, in the manner that you have heard, was this woman shared between them; the husband, had the mouth only, and her lover all the rest, and if, by chance, the husband ever used any other part of her, it was rather by way of a loan, for they belonged to the lover by gift of the said woman. But at all events the husband had this advantage, that his wife was content to let him have the use of that which she had given to her lover; but on no account would she permit the lover to enjoy that which she had bestowed upon her husband.

Of one who saw his wife with a man to whom she gave the whole of her body, except her backside, which she left for her husband and he made her dress one day when his friends were present in a woollen gown on the backside of which was a piece of fine scarlet, and so left her before all their friends.

I am well aware that formerly there lived in the city of Arras, a worthy merchant, who had the misfortune to have married a wife who was not the best woman in the world, for, when she saw a chance, she would slip as easily as an old cross-bow.

The good merchant suspected his wife's misdeeds, and was also informed by several of his friends and neighbours. Thereupon he fell into a great frenzy and profound melancholy; which did not mend matters. Then he determined to try whether he could know for certain that which was hardly likely to please him—that is to see one or more of those who were his deputies come to his house to visit his wife.

So one day he pretended to go out, and hid himself in a chamber of his house of which he alone had the key. The said chamber looked upon the street and the courtyard, and by several secret openings and chinks upon several other chambers in the house.

As soon as the good woman thought her husband had gone, she let one of the lovers who used to come to her know of it, and he obeyed the summons as he should, for he followed close on the heels of the wench who was sent to fetch him.

The husband, who as has been said, was in his secret chamber, saw the man who was to take his place enter the house, but he said not a word, for he wished to know more if possible.

"When the lover was in the house, the lady led him by the hand into her chamber, conversing all the while. Then she locked the door, and they began to kiss and to cuddle, and enjoy themselves, and the good woman pulled off her gown and appeared in a plain petticoat, and her companion threw his arms round her, and did that for which he came. The poor husband, meanwhile, saw all this through a little grating, and you may imagine was not very comfortable; he was even so close to them that he could hear plainly all they said. When the battle between the good woman and her lover was over, they sat upon a couch that was in the chamber, and talked of various matters. And as the lover looked upon his mistress, who was marvellously fair, he began to kiss her again, and as he kissed her he said;

"Darling, to whom does this sweet mouth belong?"

"It is yours, sweet friend," she replied.

"I thank you. And these beautiful eyes?"

"Yours also," she said.

"And this fair rounded bosom-does that belong to me?" he asked.

"Yes, by my oath, to you and none other," she replied.

Afterwards he put his hand upon her belly, and upon her "front" and each time asked, "Whose is this, darling?"

"There is no need to ask; you know well enough that it is all yours."

Then he put his hand upon her big backside, and asked smiling,

"And whose is this?"

"It is my husband's," she said. "That is his share; but all the rest is yours."

"Truly," he said, "I thank you greatly. I cannot complain, for you have given me all the best parts. On the other hand, be assured that I am yours entirely."

"I well know it," she said, and with that the combat of love began again between them, and more vigorously than ever, and that being finished, the lover left the house.

The poor husband, who had seen and heard everything, could stand no more; he was in a terrible rage, nevertheless he suppressed his wrath, and the next day appeared, as though he had just come back from a journey.

At dinner that day, he said that he wished to give a great feast on the following Sunday to her father and mother, and such and such of her relations and cousins, and that she was to lay in great store of provisions that they might enjoy themselves that day. She promised to do this and to invite the guests.

Sunday came, the dinner was prepared, those who were bidden all appeared, and each took the place the host designated, but the merchant remained standing, and so did his wife, until the first course was served.

When the first course was placed on the table, the merchant who had secretly caused to be made for his wife a robe of thick duffle grey with a large patch of scarlet cloth on the backside, said to his wife, "Come with me to the bedroom."

He walked first, and she followed him. When they were there, he made her take off her gown, and showing her the aforesaid gown of duffle grey, said, "Put on this dress!"

She looked, and saw that it was made of coarse stuff, and was much surprised, and could not imagine why her husband wished her to dress in this manner.

"For what purpose do you wish me to put this on?" she asked. "Never mind," he replied, "I wish you to wear it." "Faith!" she replied, "I don't like it! I won't put it on! Are you mad? Do you want all your people and mine to laugh at us both?"

"Mad or sane," he said, "you will wear it." "At least," she answered, "let me know why." "You will know that in good time." In short, she was compelled to put on this gown, which had a very strange appearance, and in this apparel she was led to the table, where most of her relations and friends were seated.

But you imagine they were very astonished to see her thus dressed, and, as you may suppose, she was very much ashamed, and would not have come to the table if she had not been compelled.

Some of her relatives said they had the right to know the meaning of this strange apparel, but her husband replied that they were to enjoy their dinner, and afterwards they should know.

The poor woman who was dressed in this strange garb could eat but little; there was a mystery connected with the gown which oppressed her spirits. She would have been even more troubled if she had known the meaning of the scarlet patch, but she did not.

The dinner was at length over, the table was removed, grace was said, and everyone stood up. Then the husband came forward and began to speak, and said;

"All you who are here assembled, I will, if you wish, tell you briefly why I have called you together, and why I have dressed my wife in this apparel. It is true that I had been informed that your relative here kept but ill the vows she had made to me before the priest, nevertheless I would not lightly believe that which was told me, but wished to learn the truth for myself, and six days ago I pretended to go abroad, and hid myself in an upstairs chamber. I had scarcely come there before there arrived a certain man, whom my wife led into her chamber, where they did whatsoever best pleased them. And amongst other questions, the man demanded of her to whom belonged her mouth, her eyes, her hands, her belly, her 'front', and her thighs? And she replied, 'To you, dear'. And when he came to her backside, he asked, 'And whose is this, darling?' 'My husband's' she replied. Therefore I have dressed her thus. She said that only her backside was mine, and I have caused it it to be attired as becomes my condition. The rest of her have I clad in the garb which is befitting an unfaithful and dishonoured woman, for such she is, and as such I give her back to you."

The company was much astonished to hear this speech, and the poor woman overcome with shame. She never again occupied a position in her husband's house, but lived, dishonoured and ashamed, amongst her own people.

Of a father who tried to kill his son because the young man wanted to lie with his grandmother, and the reply made by the said son.

Young men like to travel and to seek after adventures; and thus it was with the son of a labourer, of Lannoys, who from the age of ten until he was twenty-six, was away from home; and from his departure until his return, his father and mother heard no news of him, so they often thought that he was dead.

He returned at last, and God knows what joy there was in the house, and how he was feasted to the best of such poor means as God had given them.

But the one who most rejoiced to see him was his grandmother, his father's mother. She was most joyful at his return, and kissed him more than fifty times, and ceased not to praise God for having restored her grandson in good health.

After the feasting was over, bed-time came. There were in the cottage but two beds—the one for the father and mother, and the other for the grandmother. So it was arranged that the son should sleep with his grandmother, at which she was very glad, but he grumbled, and only complied to oblige his parents, and as a makeshift for one night.

When he was in bed with his grandmother, it happened, I know not how, that he began to get on the top of her.

"What are you doing?" she cried.

"Never you mind," he replied, "and hold your tongue." When she saw that he really meant to ravish her, she began to cry out as loud as she could for her son, who slept in the next room, and then jumped out of bed and went and complained to him, weeping bitterly meanwhile.

When the other heard his mother's complaint, and the unfilial conduct of his son, he sprang out of bed in great wrath, and swore that he would kill the young man.

The son heard this threat, so he rose quickly, slipped out of the house, and made his escape. His father followed him, but not being so light of foot, found the pursuit hopeless, so returned home, where his mother was still grieving over the offence her grandson had committed.

"Never mind, mother!" he said. "I will avenge you."

I know not how many days after that, the father saw his son playing tennis in the town of Laon, and drawing his dagger, went towards him, and would have stabbed him, but the young man slipped away and his father was seized and disarmed.

There were many there who knew that the two were father and son; so one said to the son,

"How does this come about? What have you done to your father that he should seek to kill you?"

"Faith! nothing," he replied. "He is quite in the wrong. He wants to do me all the harm in the world, because, just for once, I would ride his mother—whereas he has mounted mine more than five hundred times, and I never said a word about it."

All those who heard this reply began to haugh heartily, and swore that he must be a good fellow. So they did their best to make peace for him with his father, and at last they succeeded, and all was forgiven and forgotten on both sides.

Of a woman who on her death-bed, in the absence of her husband, made over her children to those to whom they belonged, and how one of the youngest of the children informed his father.

There formerly lived in Paris, a woman who was married to a good and simple man—he was one of our friends and it would have been impossible to have had a better. This woman was very beautiful and complaisant, and, when she was young, she never refused her favours to those who pleased her, so that she had as many children by her lovers as by her husband—about twelve or thirteen in all.

When at last she was very ill, and about to die, she thought she would confess her sins and ease her conscience. She had all her children brought to her, and it almost broke her heart to think of leaving them. She thought it would not be right to leave her husband the charge of so many children, of some of which he was not the father, though he believed he was, and thought her as good a woman as any in Paris.

By means of a woman who was nursing her, she sent for two men who in past times had been favoured lovers. They came to her at once, whilst her husband was gone away to fetch a doctor and an apothecary, as she had begged him to do.

When she saw these two men, she made all her children come to her, and then said;

"You, such an one, you know what passed between us two in former days. I now repent of it bitterly, and if Our Lord does not show me the mercy I ask of Him, it will cost me dear in the next world. I have committed faults, I know, but to add another to them would be to make matters worse. Here are such and such of my children;—they are yours, and my husband believes that they are his. You cannot have the conscience to make him keep them, so I beg that after my death, which will be very soon, that you will take them, and bring them up as a father should, for they are, in fact, your own."

She spoke in the same manner to the other man, showing him the other children:

"Such and such are, I assure you, yours. I leave them to your care, requesting you to perform your duty towards them. If you will promise me to care for them, I shall die in peace."

As she was thus distributing her children, her husband returned home, and was met by one of his little sons, who was only about four years old. The child ran downstairs to him in such haste that he nearly lost his breath, and when he came to his father, he said,

"Alas, father! come quickly, in God's name!"

"What has happened?" asked his father. "Is your mother dead?"

"No, no," said the child, "but make haste upstairs, or you will have no children left. Two men have come to see mother, and she is giving them most of my brothers and sisters. If you do not make haste, she will give them all away."

The good man could not understand what his son meant, so he hastened upstairs, and found his wife very ill, and with her the nurse, two of his neighbours, and his children.

He asked the meaning of the tale his son had told him about giving away his children.

"You will know later on," she said; so he did not trouble himself further, for he never doubted her in the least.

The neighbours went away, commending the dying woman to God, and promising to do all she had requested, for which she thanked them.

When the hour of her death drew near, she begged her husband to pardon her, and told him of the misdeeds she had committed during the years she had lived with him, and how such and such of the children belonged to a certain man, and such to another—that is to say those before-mentioned—and that after her death they would take charge of their own children.

He was much astonished to hear this news, nevertheless he pardoned her for all her misdeeds, and then she died, and he sent the children to the persons she had mentioned, who kept them.

And thus he was rid of his wife and his children, and felt much less regret for the loss of his wife than he did for the loss of the children.

Of three counsels that a father when on his deathbed gave his son, but to which the son paid no heed. And how he renounced a young girl he had married, because he saw her lying with the family chaplain the first night after their wedding.

Once upon a time there was a nobleman who was wise, prudent, and virtuous. When he was on his deathbed, he settled his affairs, eased his conscience as best he could, and then called his only son to whom he left his worldly wealth.

After asking his son to be sure and pray for the repose of his soul and that of his mother, to help them out of purgatory, he gave him three farewell counsels, saying; "My dear son, I advise you first of all never to stay in the house of a friend who gives you black bread to eat. Secondly, never gallop your horse in a valley. Thirdly, never choose a wife of a foreign nation. Always bear these three things in mind, and I have no doubt you will be fortunate,—but, if you act to the contrary, be sure you would have done better to follow your father's advice."

The good son thanked his father for his wise counsels, and promised that he would heed them, and never act contrary to them.

His father died soon after, and was buried with all befitting pomp and ceremony; for his son wished to do his duty to one to whom he owed everything.

Some time after this, the young nobleman, who was now an orphan and did not understand household affairs, made the acquaintance of a neighbour, whom he constantly visited, drinking and eating at his house.

This friend, who was married and had a beautiful wife, became very jealous, and suspected that our young nobleman came on purpose to see his wife, and that he was in reality her lover.

This made him very uncomfortable but he could think of no means of getting rid of his guest, for it would have been useless to have told him what he thought, so he determined that little by little he would behave in such a way that, if the young man were not too stupid, he would see that his frequent visits were far from welcome.

To put this project into execution, he caused black bread to be served at meals, instead of white. After a few of these repasts, the young nobleman remembered his father's advice. He knew that he done wrong, and secretly hid a piece of the black bread in his sleeve, and took it home with him, and to remind himself, he hung it by a piece of string from a nail in the wall of his best chamber, and did not visit his neighbour's house as formerly.

One day after that, he, being fond of amusement, was in the fields, and his dogs put up a hare. He spurred his horse after them, and came up with them in a valley, when his horse, which was galloping fast, slipped, and broke its neck.

He was very thankful to find that his life was safe, and that he had escaped without injury. He had the hare for his reward, and as he held it up, and then looked at the horse of which he had been so fond, he remembered the second piece of advice his father had given him, and which, if he had kept in mind, he would have been spared the loss of his horse, and also the risk of losing his life.

When he arrived home, he had the horse's skin hung by a cord next to the black bread; to remind him of the second counsel his father had given him.

Some time after this, he took it in his head to travel and see foreign countries, and having arranged all his affairs, he set out on his journey, and after seeing many strange lands, he at last took up his abode in the house of a great lord, where he became such a favourite that the lord was pleased to give him his daughter in marriage, on account of his pleasant manners and virtues.

In short, he was betrothed to the girl, and the wedding-day came. But when he supposed that he was to pass the night with her, he was told that it was not the custom of the country to sleep the first night with one's wife, and that he must have patience until the next night.

"Since it is the custom of the country," he said, "I do not wish it broken for me."

After the dancing was over, his bride was conducted to one room, and he to another. He saw that there was only a thin partition of plaster between the two rooms. He made a hole with his sword in the partition, and saw his bride jump into bed; he saw also the chaplain of the household jump in after her, to keep her company in case she was afraid, or else to try the merchandise, or take tithes as monks do.

Our young nobleman, when he saw these goings on, reflected that he still had some tow left on his distaff, and then there flashed across his mind the recollection of the counsel his good father had given him, and which he had so badly kept.

He comforted himself with the thought that the affair had not gone so far that he could not get out of it.

The next day, the good chaplain, who had been his substitute for the night, rose early in the morning, but unfortunately left his breeches under the bride's bed. The young nobleman, not pretending to know anything, came to her bedside, and politely saluted her, as he well knew how, and found means to surreptitiously take away the priest's breeches without anyone seeing him.

There were great rejoicings all that day, and when evening came, the bride's bed was prepared and decorated in a most marvellous manner, and she went to bed. The bridegroom was told that that night he could sleep with his wife. He was ready with a reply, and said to the father and mother, and other relations.

"You know not who I am, and yet you have given me your daughter, and bestowed on me the greatest honour ever done to a foreign gentleman, and for which I cannot sufficiently thank you. Nevertheless, I have determined never to lie with my wife until I have shown her, and you too, who I am, what I possess, and how I am housed."

The girl's father immediately replied,

"We are well aware that you are a nobleman, and in a high position, and that God has not given you so many good qualities without friends and riches to accompany them. We are satisfied, therefore do not leave your marriage unconsummated; we shall have time to see your state and condition whenever you like."