| Previous Part | Main Index | Next Part |

|

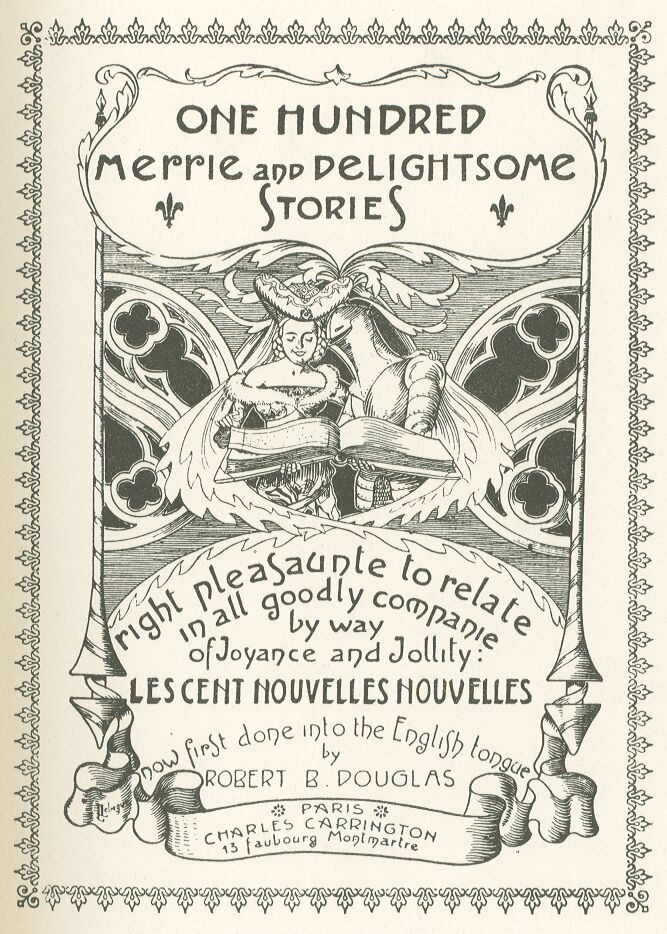

23.jpg The Lawyer's Wife Who Passed The Line. 27.jpg The Husband in The Clothes-chest. 32.jpg The Women Who Paid Tithe. 34.jpg The Man Above and The Man Below. 37.jpg The Use of Dirty Water. |

STORY THE TWENTY-FIRST — THE ABBESS CURED

Of an abbess who was ill for want of—you know what—but would not have

it done, fearing to be reproached by her nuns, but they all agreed to do

the same and most willingly did so.

STORY THE TWENTY-SECOND — THE CHILD WITH TWO FATHERS.

Of a gentleman who seduced a young girl, and then went away and joined

the army. And before his return she made the acquaintance of another,

and pretended her child was by him. When the gentleman returned from the

war he claimed the child, but she begged him to leave it with her second

lover, promising that the next she had she would give to him, as is

hereafter recorded.

STORY THE TWENTY-THIRD — THE LAWYER'S WIFE WHO PASSED THE LINE.

Of a clerk of whom his mistress was enamoured, and what he promised to

do and did to her if she crossed a line which the said clerk had made.

Seeing which, her little son told his father when he returned that he

must not cross the line; or said he, "the clerk will serve you as he did

mother."

STORY THE TWENTY-FOURTH — HALF-BOOTED.

Of a Count who would ravish by force a fair, young girl who was one of

his subjects, and how she escaped from him by means of his leggings,

and how he overlooked her conduct and helped her to a husband, as is

hereafter related.

STORY THE TWENTY-FIFTH — FORCED WILLINGLY.

Of a girl who complained of being forced by a young man, whereas

she herself had helped him to find that which he sought;—and of the

judgment which was given thereon.

STORY THE TWENTY-SIXTH —THE DAMSEL KNIGHT.

Of the loves of a young gentleman and a damsel, who tested the loyalty

of the gentleman in a marvellous and courteous manner, and slept three

nights with him without his knowing that it was not a man,—as you will

more fully hear hereafter.

STORY THE TWENTY-SEVENTH — THE HUSBAND IN THE CLOTHES-CHEST.

Of a great lord of this kingdom and a married lady, who in order

that she might be with her lover caused her husband to be shut in a

clothes-chest by her waiting women, and kept him there all the night,

whilst she passed the time with her lover; and of the wagers made

between her and the said husband, as you will find afterwards recorded.

STORY THE TWENTY-EIGHTH —THE INCAPABLE LOVER.

Of the meeting assigned to a great Prince of this kingdom by a damsel

who was chamber-woman to the Queen; of the little feats of arms of the

said Prince and of the neat replies made by the said damsel to the Queen

concerning her greyhound which had been purposely shut out of the room

of the said Queen, as you shall shortly hear.

STORY THE TWENTY-NINTH — THE COW AND THE CALF.

Of a gentleman to whom—the first night that he was married, and after

he had but tried one stroke—his wife brought forth a child, and of

the manner in which he took it,—and of the speech that he made to his

companions when they brought him the caudle, as you shall shortly hear.

STORY THE THIRTIETH — THE THREE CORDELIERS.

Of three merchants of Savoy who went on a pilgrimage to St. Anthony

in Vienne, and who were deceived and cuckolded by three Cordeliers who

slept with their wives. And how the women thought they had been with

their husbands, and how their husbands came to know of it, and of the

steps they took, as you shall shortly hear.

STORY THE THIRTY-FIRST — TWO LOVERS FOR ONE LADY.

Of a squire who found the mule of his companion, and mounted thereon

and it took him to the house of his master's mistress; and the squire

slept there, where his friend found him; also of the words which passed

between them—as is more clearly set out below.

STORY THE THIRTY-SECOND — THE WOMEN WHO PAID TITHE.

Of the Cordeliers of Ostelleria in Catalonia, who took tithe from the

women of the town, and how it was known, and the punishment the lord of

that place and his subjects inflicted on the monks, as you shall learn

hereafter.

STORY THE THIRTY-THIRD — THE LADY WHO LOST HER HAIR.

Of a noble lord who was in love with a damsel who cared for another

great lord, but tried to keep it secret; and of the agreement made

between the two lovers concerning her, as you shall hereafter hear.

STORY THE THIRTY-FOURTH — THE MAN ABOVE AND THE MAN BELOW.

Of a married woman who gave rendezvous to two lovers, who came and

visited her, and her husband came soon after, and of the words which

passed between them, as you shall presently hear.

STORY THE THIRTY-FIFTH — THE EXCHANGE.

Of a knight whose mistress married whilst he was on his travels, and on

his return, by chance he came to her house, and she, in order that she

might sleep with him, caused a young damsel, her chamber-maid, to go to

bed with her husband; and of the words that passed between the husband

and the knight his guest, as are more fully recorded hereafter.

STORY THE THIRTY-SIXTH — AT WORK.

Of a squire who saw his mistress, whom he greatly loved, between

two other gentlemern, and did not notice that she had hold of both of

them till another knight informed him of the matter as you will hear.

STORY THE THIRTY-SEVENTH — THE USE OF DIRTY WATER.

Of a jealous man who recorded all the tricks which he could hear or

learn by which wives had deceived their husbands in old times; but at

last he was deceived by means of dirty water which the lover of the said

lady threw out of window upon her as she was going to Mass, as you shall

hear hereafter.

STORY THE THIRTY-EIGHTH — A ROD FOR ANOTHER'S BACK.

Of a citizen of Tours who bought a lamprey which he sent to his wife

to cook in order that he might give a feast to the priest, and the said

wife sent it to a Cordelier, who was her lover, and how she made a woman

who was her neighbour sleep with her husband, and how the woman was

beaten, and what the wife made her husband believe, as you will hear

hereafter.

STORY THE THIRTY-NINTH — BOTH WELL SERVED.

Of a knight who, whilst he was waiting for his mistress amused himself

three times with her maid, who had been sent to keep him company that

he might not be dull; and afterwards amused himself three times with

the lady, and how the husband learned it all from the maid, as you will

hear.

STORY THE FORTIETH — THE BUTCHER'S WIFE THE GHOST IN THE CHIMNEY.

Of a Jacobin who left his mistress, a butcher's wife, for another woman

who was younger and prettier, and how the said butcher's wife tried to

enter his house by the chimney.

Of an abbess who was ill for want of—you know what—but would not have it done, fearing to be reproached by her nuns, but they all agreed to do the same and most willingly did so.

In Normandy there is a fair nunnery, the Abbess of which was young, fair, and well-made. It chanced that she fell ill. The good sisters who were charitable and devout, hastened to visit her, and tried to comfort her, and do all that lay in their power. And when they found she was getting no better, they commanded one of the sisters to go to Rouen, and take her water to a renowned doctor of that place.

So the next day one of the nuns started on this errand, and when she arrived there she showed the water to the physician, and described at great length the illness of the Lady Abbess, how she slept, ate, drank, etc.

The learned doctor understood the case, both from his examination of the water, and the information given by the nun, and then he gave his prescription.

Now I know that it is the custom in many cases to give a prescription in writing, nevertheless this time he gave it by word of mouth, and said to the nun;

"Fair sister, for the abbess to recover her health there is but one remedy, and that is that she must have company with a man; otherwise in a short time she will grew so bad that death will be the only remedy."

Our nun was much astonished to hear such sad news, and said,

"Alas! Master John! is there no other method by which our abbess can recover her health?"

"Certainly not," he replied; "there is no other, and moreover, you must make haste to do as I have bid you, for if the disease is not stopped and takes its course, there is no man living who could cure it."

The good nun, though much disconcerted, made haste to announce the news to the Abbess, and by the aid of her stout cob, and the great desire she had to be at home, made such speed that the abbess was astonished to see her returned.

"What says the doctor, my dear?" cried the abbess. "Is there any fear of death?"

"You will be soon in good health if God so wills, madam," said the messenger. "Be of good cheer, and take heart."

"What! has not the doctor ordered me any medicine?" said the Abbess.

"Yes," was the reply, and then the nun related how the doctor had looked at her water, and asked her age, and how she ate and slept, etc. "And then in conclusion he ordered that you must have, somehow or other, carnal connection with some man, or otherwise you will shortly be dead, for there is no other remedy for your complaint."

"Connection with a man!" cried the lady. "I would rather die a thousand times if it were possible." And then she went on, "Since it is thus, and my illness is incurable and deadly unless I take such a remedy, let God be praised! I will die willingly. Call together quickly all the convent!"

The bell was rung, and all the nuns flocked round the Abbess, and, when they were all in the chamber, the Abbess, who still had the use of her tongue, however ill she was, began a long speech concerning the state of the church, and in what condition she had found it and how she left it, and then went on to speak of her illness, which was mortal and incurable as she well knew and felt, and as such and such a physician had also declared.

"And so, my dear sisters, I recommend to you our church, and that you pray for my poor soul."

At these words, tears in great abundance welled from all eyes, and the heart's fountain of the convent was moved. This weeping lasted long, and none of the company spoke.

After some time, the Prioress, who was wise and good, spoke for all the convent, and said;

"Madam, your illness—what it is, God, from whom nothing is hidden, alone knows—vexes us greatly, and there is not one of us who would not do all in her power to aid your recovery. We therefore pray you to spare nothing, not even the goods of the Church, for it would be better for us to lose the greater part of our temporal goods than be deprived of the spiritual profit which your presence gives us."

"My good sister," said the Abbess, "I have not deserved your kind offer, but I thank you as much as I can, and again advise and beg of you to take care of the Church—as I have already said—for it is a matter which concerns me closely, God knows; and pray also for my poor soul, which hath great need of your prayers."

"Alas, madam," said the Prioress, "is it not possible that by great care, or the diligent attention of some physician, that you might be restored to health?"

"No, no, my good sister," replied the Abbess. "You must number me among the dead—for I am hardly alive now, though I can still talk to you."

Then stepped forth the nun who had carried the water to Rouen, and said;

"Madam, there is a remedy if you would but try it." "I do not choose to," replied the Abbess. "Here is sister Joan, who has returned from Rouen, and has shown my water, and related my symptoms, to such and such a physician, who has declared that I shall die unless I suffer some man to approach me and have connection with me. By this means he hopes, and his books informed him, that I should escape death; but if I did not do as he bade me, there was no help for me. But as for me, I thank God that He has deigned to call me, though I have sinned much. I yield myself to His will, and my body is prepared for death, let it come when it may."

"What, madam!" said the infirmary nun, "would you murder yourself? It is in your power to save yourself, and you have but to put forth your hand and ask for aid, and you will find it ready! That is not right; and I even venture to tell you that you are imperilling your soul if you die in that condition."

"My dear sister," said the Abbess, "how many times have I told you that it is better for a person to die than commit a deadly sin. You know that I cannot avoid death except by committing a deadly sin. Also I feel sure that even by prolonging my life by this means, I should be dishonoured for ever, and a reproach to all. Folks would say of me, 'There is the lady who ——'.

"All of you,—however you may advise me—would cease to reverence and love me, for I should seem—and with good cause—unworthy to preside over and govern you."

"You must neither say nor think that," said the Treasurer. "There is nothing that we should not attempt to avoid death. Does not our good father, St. Augustine, say that it is not permissible to anyone to take his own life, nor to cut off one of his limbs? And are you not acting in direct opposition to his teaching, if you allow yourself to die when you could easily prevent it?"

"She says well!" cried all the sisters in chorus. "Madam, for God's sake obey the physician, and be not so obstinate in your own opinion as to lose both your body and soul, and leave desolate, and deprived of your care, the convent where you are so much loved."

"My dear sisters," replied the Abbess, "I much prefer to bow my head to death than to live dishonoured. And would you not all say—'There is the woman who did so and so'."

"Do not worry yourself with what people would say: you would never be reproached by good and respectable people."

"Yes, I should be," replied the Abbess.

The nuns were greatly moved, and retired and held a meeting, and passed a resolution, which the Prioress was charged to deliver to the Abbess, which she did in the following words.

"Madam, the nuns are greatly grieved,—for never was any convent more troubled than this is, and you are the cause. We believe that you are ill-advised in allowing yourself to die when we are sure you could avoid it. And, in order that you should comprehend our loyal and single-hearted love for you, we have decided and concluded in a general assembly, to save you and ourselves, and if you have connection secretly with some respectable man, we will do the same, in order that you may not think or imagine that in time to come you can be reproached by any of us. Is it not so, my sisters?"

"Yes," they all shouted most willingly.

The Abbess heard the speech, and was much moved by the testimony of the love the sisters bore her, and consented, though with much regret, that the doctor's advice should be carried out. Monks, priests, and clerks were sent for, and they found plenty of work to do, and they worked so well that the Abbess was soon cured, at which the nuns were right joyous.

Of a gentleman who seduced a young girl, and then went away and joined the army. And before his return she made the acquaintance of another, and pretended her child was by him. When the gentleman returned from the war he claimed the child, but she begged him to leave it with her second lover, promising that the next she had she would give to him, as is hereafter recorded.

Formerly there was a gentleman living at Bruges who was so often and so long in the company of a certain pretty girl that at last he made her belly swell.

And about the same time that he was aware of this, the Duke called together his men-at-arms, and our gentleman was forced to abandon his lady-love and go with others to serve the said lord, which he willingly did. But, before leaving, he provided sponsors and a nurse against the time his child should come into the world, and lodged the mother with good people to whose care he recommended her, and left money for her. And when he had done all this as quickly as he could, he took leave of his lady, and promised that, if God pleased, he would return quickly.

You may fancy if she wept when she found that he whom she loved better than any one in the world, was going away. She could not at first speak, so much did her tears oppress her heart, but at last she grew calmer when she saw that there was nothing else to be done.

About a month after the departure of her lover, desire burned in her heart, and she remembered the pleasures she had formerly enjoyed, and of which the unfortunate absence of her friend now deprived her. The God of Love, who is never idle, whispered to her of the virtues and riches of a certain merchant, a neighbour, who many times, both before and since the departure of her lover, had solicited her love, so that she decided that if he ever returned to the charge he should not be sent away discouraged, and that even if she met him in the street she would behave herself in such a way as would let him see that she liked him.

Now it happened that the day after she arrived at this determination, Cupid sent round the merchant early in the morning to present her with dogs and birds and other gifts, which those who seek after women are always ready to present.

He was not rebuffed, for if he was willing to attack she was not the less ready to surrender, and prepared to give him even more than he dared to ask; for she found in him such chivalry, prowess, and virtue that she quite forgot her old lover, who at that time suspected nothing.

The good merchant was much pleased with his new lady, and they so loved each other, and their wills, desires, and thoughts so agreed, that it was as though they had but a single heart between them. They could not be content until they were living together, so one night the wench packed up all her belongings and went to the merchant's house, thus abandoning her old lover, her landlord and his wife, and a number of other good people to whose care she had been recommended.

She was not a fool, and as soon as she found herself well lodged, she told the merchant she was pregnant, at which he was very joyful, believing that he was the cause; and in about seven months the wench brought forth a fine boy, and the adoptive father was very fond both of the child and its mother.

A certain time afterwards the gentleman returned from the war, and came to Bruges, and as soon as he decently could, took his way to the house where he had left his mistress, and asked news of her from those whom he had charged to lodge her and clothe her, and aid her in her confinement.

"What!" they said. "Do you not know? Have you not had the letters which were written to you?"

"No, by my oath," said he. "What has happened?'

"Holy Mary!" they replied, "you have good reason to ask. You had not been gone more than a month when she packed up her combs and mirrors and betook herself to the house of a certain merchant, who is greatly attached to her. And, in fact, she has there been brought to bed of a fine boy. The merchant has had the child christened, and believes it to be his own."

"By St. John! that is something new," said the gentleman, "but, since she is that sort of a woman, she may go to the devil. The merchant may have her and keep her, but as for the child I am sure it is mine, and I want it."

Thereupon he went and knocked loudly at the door of the merchant's house. By chance, the lady was at home and opened the door, and when she recognised the lover she had deserted, they were both astonished. Nevertheless, he asked her how she came in that place, and she replied that Fortune had brought her there.

"Fortune?" said he; "Well then, fortune may keep you; but I want my child. Your new master may have the cow, but I will have the calf; so give it to me at once, for I will have it whatever may happen."

"Alas!" said the wench, "what will my man say? I shall be disgraced, for he certainly believes the child is his."

"I don't care what he thinks," replied the other, "but he shall not have what is mine."

"Ah, my friend, I beg and request of you to leave the merchant this child; you will do him a great service and me also. And by God! you will not be tempted to have the child when once you have seen him, for he is an ugly, awkward boy, all scrofulous and mis-shapen."

"Whatever he is," replied the other, "he is mine, and I will have him."

"Don't talk so loud, for God's sake!" said the wench, "and be calm, I beg! And if you will only leave me this child, I promise you that I will give you the next I have."

Angry as the gentleman was, he could not help smiling at hearing these words, so he said no more and went away, and never again demanded the child, which was brought up by the merchant.

Of a clerk of whom his mistress was enamoured, and what he promised to do and did to her if she crossed a line which the said clerk had made. Seeing which, her little son told his father when he returned that he must not cross the line; or said he, "the clerk will serve you as he did mother."

Formerly there lived in the town of Mons, in Hainault, a lawyer of a ripe old age, who had, amongst his other clerks, a good-looking and amiable youth, with whom the lawyer's wife fell deeply in love, for it appeared to her that he was much better fitted to do her business than her husband was.

She decided that she would behave in such a way that, unless he were more stupid than an ass, he would know what she wanted of him; and, to carry out her design, this lusty wench, who was young, fresh, and buxom, often brought her sewing to where the clerk was, and talked to him of a hundred thousand matters, most of them about love.

And during all this talk she did not forget to practise little tricks: sometimes she would knock his elbow when he was writing; another time she threw gravel and spoiled his work, so that he was forced to write it all over again. Another time also she recommenced these tricks, and took away his paper and parchment, so that he could not work,—at which he was not best pleased, fearing that his master would be angry.

For a long time his mistress practised these tricks, but he being young, and his eyes not opened, he did not at first see what she intended; nevertheless at last he concluded he was in her good books.

Not long after he arrived at this conclusion, it chanced that the lawyer being out of the house, his wife came to the clerk to teaze him as was her custom, and worried him more than usual, nudging him, talking to him, preventing him from working, and hiding his paper, ink &c.

Our clerk more knowing than formerly, and seeing what all this meant, sprang to his feet, attacked his mistress and drove her back, and begged of her to allow him to write—but she who asked for nothing better than a tussle, was not inclined to discontinue.

"Do you know, madam," said he, "that I must finish this writing which I have begun? I therefore ask of you to let me alone or, morbleu, I will pay you out."

"What would you do, my good lad?" said she. "Make ugly faces?"

"No, by God!*

"What then?"

"What?"

"Yes, tell me what!"

"Why," said he, "since you have upset my inkstand, and crumpled my writing, I will well crumple your parchment, and that I may not be prevented from writing by want of ink, I will dip into your inkstand."

"By my soul," quoth she, "you are not the man to do it. Do you think I am afraid of you?"

"It does not matter what sort of man I am," said the clerk, "but if you worry me any more, I am man enough to make you pay for it. Look here! I will draw a line on the floor, and by God, if you overstep it, be it ever so little, I wish I may die if I do not make you pay dearly for it."

"By my word," said she, "I am not afraid of you, and I will pass the line and see what you will do," and so saying the merry hussy made a little jump which took her well over the line.

The clerk grappled with her, and threw her down on a bench, and punished her well, for if she had rumpled him outside and openly, he rumpled her inside and secretly.

Now you must know that there was present at the time a young child, about two years old, the son of the lawyer. It need not be said either, that after this first passage of arms between the clerk and his mistress, there were many more secret encounters between them, with less talk and more action than on the first occasion.

You must know too that, a few days after this adventure, the little child was in the office where the clerk was writing, when there came in the lawyer, the master of the house, who walked across the room to his clerk, to see what he wrote, or for some other matter, and as he approached the line which the clerk had drawn for his wife, and which still remained on the floor, his little son cried,

"Father, take care you do not cross the line, or the clerk will lay you down and tumble you as he did mother a few days ago."

The lawyer heard the remark, and saw the line, but knew not what to think; but if he remembered that fools, drunkards, and children always tell the truth, at all events he made no sign, and it has never come to my knowledge that he ever did so, either through want of confirmation of his suspicions, or because he feared to make a scandal.

Of a Count who would ravish by force a fair, young girl who was one of his subjects, and how she escaped from him by means of his leggings, and how he overlooked her conduct and helped her to a husband, as is hereafter related.

I know that in many of the stories already related the names of the persons concerned are not stated, but I desire to give, in my little history, the name of Comte Valerien, who was in his time Count of St. Pol, and was called "the handsome Count". Amongst his other lordships, he was lord of a village in the district of Lille, called Vrelenchem, about a league distant from Lille.

This gentle Count, though of a good and kind nature, was very amorous. He learned by report from one of his retainers, who served him in these matters, that at the said Vrelenchem there resided a very pretty girl of good condition. He was not idle in these matters, and soon after he heard the news, he was in that village, and with his own eyes confirmed the report that his faithful servants had given him concerning the said maiden.

"The next thing to be done," said the noble Count, "is that I must speak to her alone, no matter what it may cost me."

One of his followers, who was a doctor by profession, said, "My lord, for your honour and that of the maiden also, it seems to me better that I should make known to her your will, and you can frame your conduct according to the reply that I receive."

He did as he said, and went to the fair maiden and saluted her courteously, and she, who was as wise as she was fair and good, politely returned his salute.

To cut matters short, after a few ordinary phrases, the worthy messenger preached much about the possessions and the honours of his master, and told her that if she liked she would be the means of enriching all her family.

The fair damsel knew what o'clock it was. (*) Her reply was like herself—fair and good—for it was that she would obey, fear, and serve the Count in anything that did not concern her honour, but that she held as dear as her life.

(*) A literal translation. La bonne fille entendit tantost

quelle heure il estoit.

The one who was astonished and vexed at this reply was our go-between, who returned disappointed to his master, his embassy having failed. It need not be said that the Count was not best pleased at hearing of this proud and harsh reply made by the woman he loved better than anyone in the world, and whose person he wished to enjoy. But he said, "Let us leave her alone for the present. I shall devise some plan when she thinks I have forgotten her."

He left there soon afterwards, and did not return until six weeks had passed, and, when he did return it was very quietly, and he kept himself private, and his presence unknown.

He learned from his spies one day that the fair maiden was cutting grass at the edge of a wood, and aloof from all company; at which he was very joyful, and, all booted as he was, set out for the place in company with his spies. And when he came near to her whom he sought, he sent away his company, and stole close to her before she was aware of his presence.

She was astonished and confused, and no wonder, to see the Count so close to her, and she turned pale and could not speak, for she knew by report that he was a bold and dangerous man to women.

"Ha, fair damsel," said the Count, "you are wondrous proud! One is obliged to lay siege to you. Now defend yourself as best you can, for there will be a battle between us, and, before I leave, you shall suffer by my will and desire, all the pains that I have suffered and endured for love of you."

"Alas, my lord!" said the young girl, who was frightened and surprised. "I ask your mercy! If I have said or done anything that may displease you, I ask your pardon; though I do not think I have said or done anything for which you should owe me a grudge. I do not know what report was made of me. Dishonourable proposals were made to me in your name, but I did not believe them, for I deem you so virtuous that on no account would you dishonour one of your poor, humble subjects like me, but on the contrary protect her."

"Drop this talk!" said my lord, "and be sure that you shall not escape me. I told you why I sent to you, and of the good I intended to do you," and without another word, he seized her in his arms, and threw her down on a heap of grass which was there, and pressed her closely, and quickly made all preparations to accomplish his desire.

The young girl, who saw that she was on the point of losing that which she held most precious, bethought her of a trick, and said,

"Ah, my lord, I surrender! I will do whatever you like, and without refusal or contradiction, but it would be better that you should do with me whatever you will by my free consent, than by force and against my will accomplish your intent."

"At any rate," said my lord, "you shall not escape me! What is it you want?"

"I would beg of you," said she, "to do me the honour not to dirty me with your leggings, which are greasy and dirty, and which you do not require."

"What can I do with them?" asked my lord.

"I will take them off nicely for you," said she, "if you please; for by my word, I have neither heart nor courage to welcome you if you wear those mucky leggings."

"The leggings do not make much difference," said my lord, "nevertheless if you wish it, they shall be taken off."

Then he let go of her, and seated himself on the grass, and stretched out his legs, and the fair damsel took off his spurs, and then tugged at one of his leggings, which were very tight. And when with much difficulty she had got it half off, she ran away as fast as her legs could carry her with her will assisting, and left the noble Count, and never ceased running until she was in her father's house.

The worthy lord who was thus deceived was in as great a rage as he could be. With much trouble he got on his feet, thinking that if he stepped on his legging he could pull it off, but it was no good, it was too tight, and there was nothing for him to do but return to his servants. He did not go very far before he found his retainers waiting for him by the side of a ditch; they did not know what to think when they saw him in that disarray. He related his story, and they put his boots on for him, and if you had heard him you would have thought that she who thus deceived him was not long for this world, he so cursed and threatened her.

But angry as he was for a time, his anger soon cooled, and was converted into sincere respect. Indeed he afterwards provided for her, and married her at his own cost and expense to a rich and good husband, on account of her frankness and loyalty.

Of a girl who complained of being forced by a young man, whereas she herself had helped him to find that which he sought;—and of the judgment which was given thereon.

The incident on which I found my story happened so recently that I need not alter, nor add to, nor suppress, the facts. There recently came to the provost at Quesnay, a fair wench, to complain of the force and violence she had suffered owing to the uncontrollable lust of a young man. The complaint being laid before the provost, the young man accused of this crime was seized, and as the common people say, was already looked upon as food for the gibbet, or the headsman's axe.

The wench, seeing and knowing that he of whom she had complained was in prison, greatly pestered the provost that justice might be done her, declaring that without her will and consent, she had by force been violated and dishonoured.

The provost, who was a discreet and wise man, and very experienced in judicial matters, assembled together all the notables and chief men, and commanded the prisoner to be brought forth, and he having come before the persons assembled to judge him, was asked whether he would confess, by torture or otherwise, the horrible crime laid to his charge, and the provost took him aside and adjured him to tell the truth.

"Here is such and such a woman," said he, "who complains bitterly that you have forced her. Is it so? Have you forced her? Take care that you tell the truth, for if you do not you will die, but if you do you will be pardoned."

"On my oath, provost," replied the prisoner, "I will not conceal from you that I have often sought her love. And, in fact, the day before yesterday, after a long talk together, I laid her upon the bed, to do you know what, and pulled up her dress, petticoat, and chemise. But my weasel could not find her rabbit hole, and went now here now there, until she kindly showed it the right road, and with her own hands pushed it in. I am sure that it did not come out till it had found its prey, but as to force, by my oath there was none."

"Is that true?" asked the provost.

"Yes, on my oath," answered the young man.

"Very good," said he, "we shall soon arrange matters."

After these words, the provost took his seat in the pontifical chair, surrounded by all the notable persons; and the young man was seated on a small bench in front of the judges, and all the people, and of her who accused him.

'"Now, my dear," said the provost, "what have you to say about the prisoner?"

"Provost!" said she, "I complain that he has forced me and violated me against my will and in spite of me. Therefore I demand justice."

"What have you to say in reply?" asked the provost of the prisoner.

"Sir," he replied, "I have already told how it happened, and I do not think she can contradict me."

"My dear!" said the provost to the girl, "think well of what you are saying! You complain of being forced. It is a very serious charge! He says that he did not use any force, but that you consented, and indeed almost asked for what you got. And if he speaks truly, you yourself directed his weasel, which was wandering about near your rabbit-hole, and with your two hands—or at least with one—pushed the said weasel into your burrow. Which thing he could never have done without your help, and if you had resisted but ever so little he would never have effected his purpose. If his weasel was allowed to rummage in your burrow, that is not his fault, and he is not punishable."

"Ah, Provost," said the girl plaintively, "what do you mean by that? It is quite true, and I will not deny it, that I conducted his weasel into my burrow—but why did I do so? By my oath, Sir, its head was so stiff, and its muzzle so hard, that I was sure that it would make a large cut, or two or three, on my belly, if I did not make haste and put it where it could do little harm—and that is what I did."

You may fancy what a burst of laughter there was at the end of this trial, both from the judges and the public. The young man was discharged,—to continue his rabbit-hunting if he saw fit.

The girl was angry that he was not hanged on a high forked tree for having hung on her "low forks" (*). But this anger and resentment did not last long, for as I heard afterwards on good authority, peace was concluded between them, and the youth had the right to ferret in the coney burrow whenever he felt inclined.

(*) A play upon words, which is not easily translatable, in

allusion to the gallows.

Of the loves of a young gentleman and a damsel, who tested the loyalty of the gentleman in a marvellous and courteous manner, and slept three nights with him without his knowing that it was not a man,—as you will more fully hear hereafter.

In the duchy of Brabant—not so long ago but that the memory of it is fresh in the present day—happened a strange thing, which is worthy of being related, and is not unfit to furnish a story. And in order that it should be publicly known and reported, here is the tale.

In the household of a great baron of the said country there lived and resided a young, gracious, and kind gentleman, named Gerard, who was greatly in love with a damsel of the said household, named Katherine. And when he found opportunity, he ventured to tell her of his piteous case. Most people will be able to guess the answer he received, and therefore, to shorten matters, I omit it here.

In due time Gerard and Katherine loved each other so warmly that there was but one heart and one will between them. This loyal and perfect love endured no little time—indeed two years passed away. Love, who blinds the eyes of his disciples, had so blinded these two that they did not know that this affection, which they thought secret, was perceived by every one; there was not a man or a woman in the chateau who was not aware of it—in fact the matter was so noised abroad that all the talk of the household was of the loves of Gerard and Katherine.

These two poor, deluded fools were so much occupied with their own affairs that they did not suspect their love affairs were discussed by others. Envious persons, or those whom it did not concern, brought this love affair to the knowledge of the master and mistress of the two lovers, and it also came to the ears of the father and mother of Katherine.

Katherine was informed by a damsel belonging to the household, who was one of her friends and companions, that her love for Gerard had been discovered and revealed both to her father and mother, and also to the master and mistress of the house.

"Alas, what is to be done, my dear sister and friend?" asked Katherine. "I am lost, now that so many persons know, or guess at, my condition. Advise me, or I am ruined, and the most unfortunate woman in the world," and at these words her eyes filled with tears, which rolled down her fair cheeks and even fell to the edge of her robe.

Her friend was very vexed to see her grief, and tried to console her.

"My sister," she said, "it is foolish to show such great grief; for, thank God, no one can reproach you with anything that touches your honour or that of your friends. If you have listened to the vows of a gentleman, that is not a thing forbidden by the Court of Honour, it is even the path, the true road, to arrive there. You have no cause for grief, for there is not a soul living who can bring a charge against you. But, at any rate, I should advise that, to stop chattering tongues which are discussing your love affairs, your lover, Gerard, should, without more ado, take leave of our lord and lady, alleging that he is to set out on a long voyage, or take part in some war now going on, and, under that excuse, repair to some house and wait there until God and Cupid have arranged matters. He will keep you informed by messages how he is, and you will do the same to him; and by that time the rumours will have ceased, and you can communicate with one another by letter until better times arrive. And do not imagine that your love will cease—it will be as great, or greater, than ever, for during a long time you will only hear from each other occasionally, and that is one of the surest ways of preserving love."

The kind and good advice of this gentle dame was followed, for as soon as Katherine found means to speak to her lover, Gerard, she told him how the secret of their love had been discovered and had come to the knowledge of her father and mother, and the master and mistress of the house.

"And you may believe," she said, "that it did not reach that point without much talk on the part of those of the household and many of the neighbours. And since Fortune is not so friendly to us as to permit us to live happily as we began, but menaces us with further troubles, it is necessary to be fore-armed against them. Therefore, as the matter much concerns me, and still more you, I will tell you my opinion."

With that she recounted at full length the good advice which had been given by her friend and companion.

Gerard, who had expected a misfortune of this kind, replied;

"My loyal and dear mistress, I am your humble and obedient servant, and, except God, I love no one so dearly as you. You may command me to do anything that seems good to you, and whatever you order shall be joyfully and willingly obeyed. But, believe me, there is nothing left for me in the world when once I am removed from your much-wished-for presence. Alas, if I must leave you, I fear that the first news you will hear will be that of my sad and pitiful death, caused by your absence, but, be that as it may, you are the only living person I will obey, and I prefer rather to obey you and die, than live for ever and disobey you. My body is yours. Cut it, hack it, do what you like with it!"

You may guess that Katherine was grieved and vexed at seeing her lover, whom she adored more than anyone in the world, thus troubled. Had it not been for the virtue with which God had largely endowed her, she would have proposed to accompany him on his travels, but she hoped for happier days, and refrained from making such a proposal. After a pause, she replied;

"My friend you must go away, but do not forget her who has given you her heart. And that you may have courage in the struggle which is imposed on you, know that I promise you on my word that as long as I live I will never marry any man but you of my own free-will, provided that you are equally loyal and true to me, as I hope you will be. And in proof of this, I give you this ring, which is of gold enamelled with black tears. If by chance they would marry me to some one else, I will defend myself so stoutly that you will be pleased with me, and I will prove to you that I can keep my promise without flinching from it. And, lastly, I beg of you that wherever you may stop, you will send me news about yourself, and I will do the same."

"Ah, my dear mistress," said Gerard, "I see plainly that I must leave you for a time. I pray to God that he will give you more joy and happiness than I am likely to have. You have kindly given me, though I am not worthy of it, a noble and honourable promise, for which I cannot sufficiently thank you. Still less do I deserve it, but I venture in return to make a similar promise, begging most humbly and with all my heart, that my vow may have as great a weight as if it came from a much nobler man than I. Adieu, dearest lady. My eyes demand their turn, and prevent my tongue from speaking."

With these words he kissed her, and pressed her tightly to his bosom, and then each went away to think over his or her griefs.

God knows that they wept with their eyes, their hearts, and their heads, but ere they showed themselves, they concealed all traces of their grief, and put on a semblance of cheerfulness.

To cut matters short, Gerard did so much in a few days that he obtained leave of absence from his master—which was not very difficult, not that he had committed any fault, but owing to his love affair with Katherine, with which her friends were not best pleased, seeing that Gerard was not of such a good family or so rich as she was, and could not expect to marry her.

So Gerard left, and covered such a distance in one day that he came to Barrois, where he found shelter in the castle of a great nobleman of the country; and being safely housed he soon sent news of himself to the lady, who was very joyful thereat, and by the same messenger wrote to tell him of her condition, and the goodwill she bore him, and how she would always be loyal to him.

Now you must know that as soon as Gerard had left Brabant, many gentlemen, knights and squires, came to Katherine, desiring above all things to make her acquaintance, which during the time that Gerard had been there they had been unable to do, knowing that her heart was already occupied.

Indeed many of them demanded her hand in marriage of her father, and amongst them was one who seemed to him a very suitable match. So he called together many of his friends, and summoned his fair daughter, and told them that he was already growing old, and that one of the greatest pleasures he could have in the world was to see his daughter well married before he died. Moreover, he said to them;

"A certain gentleman has asked for my daughter's hand, and he seems to me a suitable match. If your opinion agrees with mine, and my daughter will obey me, his honourable request will not be rejected."

All his friends and relations approved of the proposed marriage, on account of the virtues, riches, and other gifts of the said gentleman. But when they asked the opinion of the fair Katherine, she sought to excuse herself, and gave several reasons for refusing, or at least postponing this marriage, but at last she saw that she would be in the bad books of her father, her mother, her relatives, friends, and her master and mistress, if she continued to keep her promise to her lover, Gerard.

At last she thought of a means by which she could satisfy her parents without breaking her word to her lover, and said,

"My dearest lord and father, I do not wish to disobey you in anything you may command, but I have made a vow to God, my creator, which I must keep. Now I have made a resolution and sworn in my heart to God that I would never marry unless He would of His mercy show me that that condition was necessary for the salvation of my poor soul. But as I do not wish to be a trouble to you, I am content to accept this condition of matrimony, or any other that you please, if you will first give me leave to make a pilgrimage to the shrine of St. Nicolas at Varengeville (*) which pilgrimage I vowed and promised to make before I changed my present condition."

(*) A town of Lorraine, on the Meurthe, about six miles from

Kancy. Pilgrims flocked thither from all parts to worship

the relics of St. Nicolas.

She said this in order that she might see her lover on the road, and tell him how she was constrained against her will.

Her father was rather pleased to hear the wise and dutiful reply of his daughter. He granted her request, and wished to at once order her retinue, and spoke to his wife about it when his daughter was present.

"We will give her such and such gentlemen, who with Ysabeau, Marguerite and Jehanneton, will be sufficient for her condition."

"Ah, my lord," said Katherine, "if it so please you we will order it otherwise. You know that the road from here to St. Nicolas is not very safe, and that when women are to be escorted great precautions must be taken. I could not go thus without great expense; moreover, the road is long, and if it happened that we lost either our goods or honour (which may God forfend) it would be a great misfortune. Therefore it seems good to me—subject to your good pleasure—that there should be made for me a man's dress and that I should be escorted by my uncle, the bastard, each mounted on a stout horse. We should go much quicker, more safely, and with less expense, and I should have more confidence than with a large retinue."

The good lord, having thought over the matter a little while, spoke about it to his wife, and it seemed to them that the proposal showed much common sense and dutiful feeling. So everything was prepared for their departure.

They set out on their journey, the fair Katherine and her uncle, the bastard, without any other companion. Katherine, who was dressed in the German fashion very elegantly, was the master, and her uncle, the bastard, was the serving man. They made such haste that their pilgrimage was soon accomplished, as far as St. Nicolas was concerned, and, as they were on their return journey-praising God for having preserved them, and talking over various matters Katherine said to her uncle,

"Uncle, you know that I am sole heiress to my father, and that I could bestow many benefits upon you, which I will most willingly do if you will aid me in a small quest I am about to undertake—that is to go to the castle of a certain lord of Barrois (whom she named) to see Gerard, whom you know. And, in order that when we return we may have some news to tell, we will demand hospitality, and if we obtain it we will stop there for some days and see the country, and you need be under no fear but that I shall take care of my honour, as a good girl should."

The uncle, who hoped to be rewarded some day, and knew she was virtuous, vowed to himself that he would keep an eye upon her, and promised to serve her and accompany her wherever she wished. He was much thanked no doubt, and it was then decided that he should call his niece, Conrad.

They soon came, as they desired, to the wished-for place, and addressed themselves to the lord's major-domo, who was an old knight, and who received them most joyfully and most honourably.

Conrad asked him if the lord, his master, did not wish to have in his service a young gentleman who was fond of adventures, and desirous of seeing various countries?

The major-domo asked him whence he came, and he replied, from Brabant.

"Well then," said the major-domo, "you shall dine here, and after dinner I will speak to my lord."

With that he had them conducted to a fair chamber, and ordered the table to be laid, and a good fire to be lighted, and sent them soup and a piece of mutton, and white wine while dinner was preparing.

Then he went to his master and told him of the arrival of a young gentleman of Brabant, who wished to serve him, and the lord was content to take the youth if he wished.

To cut matters short, as soon as he had served his master, he returned to Conrad to dine with him, and brought with him, because he was of Brabant, the aforesaid Gerard, and said to Conrad;

"Here is a young gentleman who belongs to your country."

"I am glad to meet him," said Conrad.

"And you are very welcome," replied Gerard.

But he did not recognise his lady-love, though she knew him very well.

Whilst they were making each other's acquaintance, the meat was brought in, and each took his place on either hand of the major-domo.

The dinner seemed long to Conrad, who hoped afterwards to have some conversation with her lover, and expected also that she would soon be recognised either by her voice, or by the replies she made to questions concerning Brabant; but it happened quite otherwise, for during all the dinner, the worthy Gerard did not ask after either man or woman in all Brabant; which Conrad could not at all understand.

Dinner passed, and after dinner my lord engaged Conrad in his service; and the major-domo, who was a thoughtful, experienced man, gave instructions that as Gerard and Conrad came from the same place, they should share the same chamber.

After this Gerard and Conrad went off arm in arm to look at their horses, but as far as Gerard was concerned, if he talked about anything it was not Brabant. Poor Conrad—that is to say the fair Katherine—began to suspect that she was like forgotten sins, and had gone clean out of Gerard's mind; but she could not imagine why, at least, he did not ask about the lord and lady with whom she lived. The poor girl was, though she could not show it, in great distress of mind, and did not know what to do; whether to still conceal her identity, and test him by some cunning phrases, or to suddenly make herself known.

In the end she decided that she would still remain Conrad, and say nothing about Katherine unless Gerard should alter his manner.

The evening passed as the dinner had done, and when they came to their chamber, Gerard and Conrad spoke of many things, but not of the one subject pleasing to the said Conrad. When he saw that the other only replied in the words that were put into his mouth, she asked of what family he was in Brabant, and why he left there, and where he was when he was there, and he replied as it seemed good to him.

"And do you not know," she said, "such and such a lord, and such another?"

"By St. John, yes!" he replied.

Finally, she named the lord at whose castle she had lived; and he replied that he knew him well, but not saying that he had lived there, or ever been there in his life.

"It is rumoured," she said, "there are some pretty girls there. Do you know of any?"

"I know very little," he replied, "and care less. Leave me alone; for I am dying to go to sleep!"

"What!" she said. "Can you sleep when pretty girls are being talked about? That is a sign that you are not in love!"

He did not reply, but slept like a pig, and poor Katherine began to have serious doubts about him, but she resolved to try him again.

When the morrow came, each dressed himself, talking and chattering meanwhile of what each liked best—Gerard of dogs and hawks, and Conrad of the pretty girls of that place and Brabant.

After dinner, Conrad managed to separate Gerard from the others, and told him that the country of Barrois was very flat and ugly, but Brabant was quite different, and let him know that he (Conrad) longed to return thither.

"For what purpose?" asked Gerard. "What do you see in Brabant that is not here? Have you not here fine forests for hunting, good rivers, and plains as pleasant as could be wished for flying falcons, and plenty of game of all sorts?"

"Still that is nothing!" said Conrad. "The women of Brabant are very different, and they please me much more than any amount of hunting or hawking!"

"By St. John! they are quite another affair," said Gerard. "You are exceedingly amorous in your Brabant, I dare swear!"

"By my oath!" said Conrad, "it is not a thing that can be hidden, for I myself am madly in love. In fact my heart is drawn so forcibly that I fear I shall be forced to quit your Barrois, for it will not be possible for me to live long without seeing my lady love."

"Then it was a madness," said Gerard, "to have left her, if you felt yourself so inconstant."

"Inconstant, my friend! Where is the man who can guarantee that he will be constant in love. No one is so wise or cautious that he knows for certain how to conduct himself. Love often drives both sense and reason out of his followers."

The conversation dropped as supper time came, and was not renewed till they were in bed. Gerard would have desired nothing better than to go to sleep, but Conrad renewed the discussion, and began a piteous, long, and sad complaint about his ladylove (which, to shorten matters, I omit) and at last he said,

"Alas, Gerard, and how can you desire to sleep whilst I am so wide awake, and my soul is filled with cares, and regrets, and troubles. It is strange that you are not a little touched yourself, for, believe me, if it were a contagious disease you could not be so close to me and escape unscathed. I beg of you, though you do not feel yourself, to have some pity and compassion on me, for I shall die soon if I do not behold my lady-love."

"I never saw such a love-sick fool!" cried Gerard. "Do you think that I have never been in love? I know what it is, for I have passed through it the same as you—certainly I have! But I was never so love-mad as to lose my sleep or upset myself, as you are doing now. You are an idiot, and your love is not worth a doit. Besides do you think your lady is the same as you are? No, no!"

"I am sure she is," replied Conrad; "she is so true-hearted."

"Ah, you speak as you wish," said Gerard, "but I do not believe that women are so true as to always remain faithful to their vows; and those who believe in them are blockheads. Like you, I have loved, and still love. For, to tell you the truth, I left Brabant on account of a love affair, and when I left I was high in the graces of a very beautiful, good, and noble damsel, whom I quitted with much regret; and for no small time I was in great grief at not being able to see her—though I did not cease to sleep, drink, or eat, as you do. When I found that I was no longer able to see her, I cured myself by following Ovid's advice, for I had not been here long before I made the acquaintance of a pretty girl in the house, and so managed, that—thank God—she now likes me very much, and I love her. So that now I have forgotten the one I formerly loved, and only care for the one I now possess, who has turned my thoughts from my old love!"

"What!" cried Conrad. "Is it possible that, if you really loved the other, you can so soon forget her and desert her? I cannot understand nor imagine how that can be!"

"It is so, nevertheless, whether you understand it or not." "That is not keeping faith loyally," said Conrad. "As for me, I would rather die a thousand times, if that were possible, than be so false to my lady. However long God may let me live, I shall never have the will, or even the lightest thought, of ever loving any but her."

"So much the greater fool you," said Gerard, "and if you persevere in this folly, you will never be of any good, and will do nothing but dream and muse; and you will dry up like the green herb that is cast into the furnace, and kill yourself, and never have known any pleasure, and even your mistress will laugh at you,—if you are lucky enough to be remembered by her at all."

"Well!" said Conrad. "You are very experienced in love affairs. I would beg of you to be my intermediary, here or elsewhere, and introduce me to some damsel that I may be cured like you."

"I will tell you what I will do," said Gerard. "Tomorrow I will speak to my mistress and tell her that we are comrades, and ask her to speak to one of her lady friends, who will undertake your business, and I do not doubt but that, if you like, you will have a good time, and that the melancholy which now bears you down will disappear—if you care to get rid of it."

"If it were not for breaking my vow to my mistress, I should desire nothing better," said Conrad, "but at any rate I will try it."

With that Gerard turned over and went to sleep, but Katherine was so stricken with grief at seeing and hearing the falsehood of him whom she loved more than all the world, that she wished herself dead and more than dead. Nevertheless, she put aside all feminine feeling, and assumed manly vigour. She even had the strength of mind to talk for a long time the next day with the girl who loved the man she had once adored; and even compelled her heart and eyes to be witnesses of many interviews and love passages that were most galling to her.

Whilst she was talking to Gerard's mistress, she saw the ring that she had given her unfaithful lover, but she was not so foolish as to admire it, but nevertheless found an opportunity to examine it closely on the girl's finger, but appeared to pay no heed to it, and soon afterwards left.

As soon as supper was over, she went to her uncle, and said to him;

"We have been long enough in Barrois! It is time to leave. Be ready to-morrow morning at daybreak, and I will be also. And take care that all our baggage is prepared. Come for me as early as you like."

"You have but to come down when you will," replied the uncle.

Now you must know that after supper, whilst Gerard was conversing with his mistress, she who had been his lady-love went to her chamber and began to write a letter, which narrated at full length the love affairs of herself and Gerard, also "the promises which they made at parting, how they had wished to marry her to another and how she had refused, and the pilgrimage that she had undertaken to keep her word and come to him, and the disloyalty and falsehood she had found in him, in word, act, and deed. And that, for the causes mentioned, she held herself free and disengaged from the promise she had formerly made. And that she was going to return to her own country and never wished to see him or meet him again, he being the falsest man who ever made vows to a woman. And as regards the ring that she had given him, that he had forfeited it by passing it into the hands of a third person. And if he could boast that he had lain three nights by her side, there was no harm, and he might say what he liked, and she was not afraid."

Letter written by a hand you ought to know, and underneath Katherine etc., otherwise known as Conrad; and on the back, To the false Gerard etc.

She scarcely slept all night, and as soon as she saw the dawn, she rose gently and dressed herself without awaking Gerard. She took the letter, which she had folded and sealed, and placed it in the sleeve of Gerard's jerkin; then in a vow voice prayed to God for him, and wept gently on account of the grief she endured on account of the falseness she had met with.

Gerard still slept, and did not reply a word. Then she went to her uncle, who gave her her horse which she mounted, and they left the country, and soon came to Brabant, where they were joyfully received, God knows.

You may imagine that all sorts of questions were asked about their adventures and travels, and how they had managed, but whatever they replied they took care to say nothing about their principal adventure.

But to return to Gerard. He awoke about 10 o'clock on the morning of the day when Katherine left, and looked to see if his companion Conrad was already risen. He did not know it was so late, and jumped out of bed in haste to seek for his jerkin. When he put his arm in the sleeve, out dropped the letter, at which he was much astonished, for he did not remember putting it there.

At any rate, he picked it up, and saw that it was sealed, and had written on the back, To the false Gerard. If he had been astonished before, he was still more so now.

After a little while he opened it and saw the signature, Katherine known as Conrad etc.

He did not know what to think, nevertheless he read the letter, and in reading it the blood mounted to his cheeks, and his heart sank within him, so that he was quite changed both in looks and complexion.

He finished reading the letter the best way he could, and learned that his falseness had come to the knowledge of her who wished so well to him, and that she knew him to be what he was, not by the report of another person, but by her own eyes; and what touched him most to the heart was that he had lain three nights with her without having thanked her for the trouble she had taken to come so far to make trial of his love.

He champed the bit, and was wild with rage, when he saw how he had been mystified. After much thought, he resolved that the best thing to do was to follow her, as he thought he might overtake her.

He took leave of his master and set out, and followed the trail of their horses, but did not catch them up before they came to Brabant, where he arrived opportunely on the day of the marriage of the woman who had tested his affection.

He wished to kiss her and salute her, and make some poor excuse for his fault, but he was not able to do so, for she turned her back on him, and he could not, all the time that he was there, find an opportunity of talking with her.

Once he advanced to lead her to the dance, but she flatly refused in the face of all the company, many of whom took note of the incident. For, not long after, another gentleman entered, and caused the minstrels to strike up, and advanced towards her, and she came down and danced with him.

Thus, as you have heard, did the false lover lose his mistress. If there are others like him, let them take warning by this example, which is perfectly true, and is well known, and happened not so very long ago.

Of a great lord of this kingdom and a married lady, who in order that she might be with her lover caused her husband to be shut in a clothes-chest by her waiting women, and kept him there all the night, whilst she passed the time with her lover; and of the wagers made between her and the said husband, as you will find afterwards recorded.

It is not an unusual thing, especially in this country, for fair dames and damsels to often and willingly keep company with young gentlemen, and the pleasant joyful games they have together, and the kind requests which are made, are not difficult to guess.

Not long ago, there was a most noble lord, who might be reckoned as one of the princes, but whose name shall not issue from my pen, who was much in the good graces of a damsel who was married, and of whom report spoke so highly that the greatest personage in the kingdom might have deemed himself lucky to be her lover.

She would have liked to prove to him how greatly she esteemed him, but it was not easy; there were so many adversaries and enemies to be outwitted. And what more especially annoyed her was her worthy husband, who kept to the house and played the part of the cursed Dangier, (*) and the lover could not find any honourable excuse to make him leave.

(*) Allegorical personage typifying jealousy, taken from Le

Romaunt de la Rose.

As you may imagine, the lover was greatly dissatisfied at having to wait so long, for he desired the fair quarry, the object of his long chase, more than he had ever desired anybody in all his life.

For this cause he continued to importune his mistress, till she said to him.

"I am quite as displeased as you can be that I can give you no better welcome; but, you know, as long as my husband is in the house he must be considered."

"Alas!" said he, "cannot you find any method to abridge my hard and cruel martyrdom?"

She—who as has been said above, was quite as desirous of being with her lover as he was with her—replied;

"Come to-night, at such and such an hour, and knock at my chamber door. I will let you in, and will find some method to be freed from my husband, if Fortune does not upset our plans."

Her lover had never heard anything which pleased him better, and after many gracious thanks,—which he was no bad hand at making—he left her, and awaited the hour assigned.

Now you must know that a good hour or more before the appointed time, our gentle damsel, with her women and her husband, had withdrawn to her chamber after supper; nor was her imagination idle, but she studied with all her mind how she could keep her promise to her lover. Now she thought of one means, now of another, but nothing occurred to her by which she could get rid of her cursed husband; and all the time the wished-for hour was fast approaching.

Whilst she was thus buried in thought, Fortune was kind enough to do her a good turn, and her husband a bad one.

He was looking round the chamber, and by chance he saw at the foot of the bed his wife's clothes-chest. In order to make her speak, and arouse her from her reverie, he asked what that chest was used for, and why they did not take it to the wardrobe, or some other place where it would be more suitable.

"There is no need, Monseigneur," said Madame; "no one comes here but us. I left it here on purpose, because there are still some gowns in it, but if you are not pleased, my dear, my women will soon take it away."

"Not pleased?" said he. "No, I am not; but I like it as much here as anywhere else, since it pleases you; but it seems to me much too small to hold your gowns well without crumpling them, seeing what great and long trains are worn now."

"By my word, sir," said she, "it is big enough."

"It hardly seems so," replied he, "really; and I have looked at it well."

"Well, sir," said she, "will you make a bet with me?"

"Certainly I will," he answered; "what shall it be?"

"I will bet, if you like, half a dozen of the best shirts against the satin to make a plain petticoat, that we can put you inside the box just as you are."

"On my soul," said he, "I will bet I cannot get in."

"And I will bet you can."

"Come on!" said the women. "We will soon see who is the winner."

"It will soon be proved," said Monsieur, and then he made them take out of the chest all the gowns which were in it, and when it was empty, Madam and her women put in Monsieur easily enough.

Then there was much chattering, and discussion, and laughter, and Madam said;

"Well, sir; you have lost your wager! You own that, do you not?"

"Yes," said he, "you are right."

As he said these words, the chest was locked, and the girls all laughing, playing, and dancing, carried both chest and man together, and put it in a big cupboard some distance away from the chamber.

He cried, and struggled, and made a great noise; but it was no good, and he was left there all the night. He could sleep, or think, or do the best he could, but Madam had given secret instructions that he was not to be let out that day, because she had been too much bothered by him already.

But to return to the tale we had begun. We will leave our man in his chest, and talk about Madam, who was awaiting her lover, surrounded by her waiting women, who were so good and discreet that they never revealed any secrets. They knew well enough that the dearly beloved adorer was to occupy that night the place of the man who was doing penance in the clothes-chest.

They did not wait long before the lover, without making any noise or scare, knocked at the chamber door, and they knew his knock, and quickly let him in. He was joyfully received and kindly entertained by Madam and her maids; and he was glad to find himself alone with his lady love, who told him what good fortune God had given her, that is to say how she had made a bet with her husband that he could get into the chest, how he had got in, and how she and her women had carried him away to a cupboard.

"What?" said her lover. "I cannot believe that he is in the house. By my word, I believed that you had found some excuse to send him out whilst I took his place with you for a time."

"You need not go," she said. "He cannot get out of where he is. He may cry as much as he will, but there is no one here likes him well enough to let him out, and there he will stay; but if you would like to have him set free, you have but to say so."

"By Our Lady," said he, "if he does not come out till I let him out, he will wait a good long time."

"Well then, let us enjoy ourselves," said she, "and think no more about him."

To cut matters short, they both undressed, and the two lovers lay down in the fair bed, and did what they intended to do, and which is better imagined than described.

When day dawned, her paramour took leave of her as secretly as he could, and returned to his lodgings to sleep, I hope, and to breakfast, for he had need of both.

Madam, who was as cunning as she was wise and good, rose at the usual hour, and said to her women;

"It will soon be time to let out our prisoner. I will go and see what he says, and whether he will pay his ransom."

"Put all the blame on us," they said. "We will appease him."

"All right, I will do so," she said.

With these words she made the sign of the Cross, and went nonchalantly, as though not thinking what she was doing, into the cupboard where her husband was still shut up in the chest. And when he heard her he began to make a great noise and cry out, "Who is there? Why do you leave me locked up here?"

His good wife, who heard the noise he was making replied timidly, as though frightened, and playing the simpleton;

"Heavens! who is it that I hear crying?"

"It is I! It is I!" cried the husband.

"You?" she cried; "and where do you come from at this time?"

"Whence do I come?" said he. "You know very well, madam. There is no need for me to tell you—but what you did to me I will some day do to you,"—for he was so angry that he would willingly have showered abuse upon his wife, but she cut him short, and said;

"Sir, for God's sake pardon me. On my oath I assure you that I did not know you were here now, for, believe me, I am very much astonished that you should be still here, for I ordered my women to let you out whilst I was at prayers, and they told me they would do so; and, in fact, one of them told me that you had been let out, and had gone into the town, and would not return home, and so I went to bed soon afterwards without waiting for you."

"Saint John!" said he; "you see how it is. But make haste and let me out, for I am so exhausted that I can stand it no longer."

"That may well be," said she, "but you will not come out till you have promised to pay me the wager you lost, and also pardon me, or otherwise I will not let you out."

"Make haste, for God's sake! I will pay you—really."

"And you promise?"

"Yes—on my oath!"

This arrangement being concluded, Madam opened the chest, and Monsieur came out, tired, cramped, and exhausted.

She took him by the arm, and kissed him, and embraced him as gently as could be, praying to God that he would not be angry.

The poor blockhead said that he was not angry with her, because she knew nothing about it, but that he would certainly punish her women.

"By my oath, sir," said she, "they are well revenged upon you—for I expect you have done something to them."

"Not I certainly, that I know of—but at any rate the trick they have played me will cost them dear."

He had hardly finished this speech, when all the women came into the room, and laughed so loudly and so heartily that they could not say a word for a long time; and Monsieur, who was going to do such wonders, when he saw them laugh to such a degree, had not the heart to interfere with them. Madame, to keep him company, did not fail to laugh also. There was a marvellous amount of laughing, and he who had the least cause to laugh, laughed one of the loudest.

After a certain time, this amusement ceased, and Monsieur said;

"Mesdames, I thank you much for the kindness you have done me."

"You are quite welcome, sir," said one of the women, "and still we are not quits. You have given us so much trouble, and caused as so much mischief, that we owed you a grudge, and if we have any regret it is that you did not remain in the box longer. And, in fact, if it had not been for Madame you would still be there;—so you may take it how you will!"

"Is that so?" said he. "Well, well, you shall see how I will take it. By my oath I am well treated, when, after all I have suffered, I am only laughed, at, and what is still worse, must pay for the satin for the petticoat. Really, I ought to have the shirts that were bet, as a compensation for what I have suffered."

"By Heaven, he is right," said the women. "We are on your side as to that, and you shall have them. Shall he not have them, Madame?"

"On what grounds?" said she. "He lost the wager."

"Oh, yes, we know that well enough: he has no right to them,—indeed he does not ask for them on that account, but he has well deserved them for another reason."

"Never mind about that," said Madame. "I will willingly give the material out of love for you, mesdames, who have so warmly pleaded for him, if you will undertake to do the sewing."

"Yes, truly, Madame."

Like one who when he wakes in the morning has but to give himself a shake and he is ready, Monsieur needed but a bunch of twigs to beat his clothes and he was ready, and so he went to Mass; and Madame and her women followed him, laughing loudly at him I can assure you.

And you may imagine that during the Mass there was more than one giggle when they remembered that Monsieur, whilst he was in the chest (though he did not know it himself) had been registered in the book which has no name. (*) And unless by chance this book falls into his hands, he will never,—please God—know of his misfortune, which on no account would I have him know. So I beg of any reader who may know him, to take care not to show it to him.

(*) The Book of Cuckolds.

Of the meeting assigned to a great Prince of this kingdom by a damsel who was chamber-woman to the Queen; of the little feats of arms of the said Prince and of the neat replies made by the said damsel to the Queen concerning her greyhound which had been purposely shut out of the room of the said Queen, as you shall shortly hear.

If in the time of the most renowned and eloquent Boccaccio, the adventure which forms the subject of my tale had come to his knowledge, I do not doubt but that he would have added it to his stories of great men who met with bad fortune. For I think that no nobleman ever had a greater misfortune to bear than the good lord (whom may God pardon!) whose adventure I will relate, and whether his ill fortune is worthy to be in the aforesaid books of Boccaccio, I leave those who hear it to judge.

The good lord of whom I speak was, in his time, one of the great princes of this kingdom, apparelled and furnished with all that befits a nobleman; and amongst his other qualities was this,—that never was man more destined to be a favourite with the ladies.

Now it happened to him at the time when his fame in this respect most flourished, and everybody was talking about him, that Cupid, who casts his darts wherever he likes, caused him to be smitten by the charms of a beautiful, young, gentle and gracious damsel, who also had made a reputation second to no other of that day on account of her great and unequalled beauty and her good manners and virtues, and who, moreover, was such a favourite with the Queen of that country that she shared the royal bed on the nights when the said Queen did not sleep with the king.