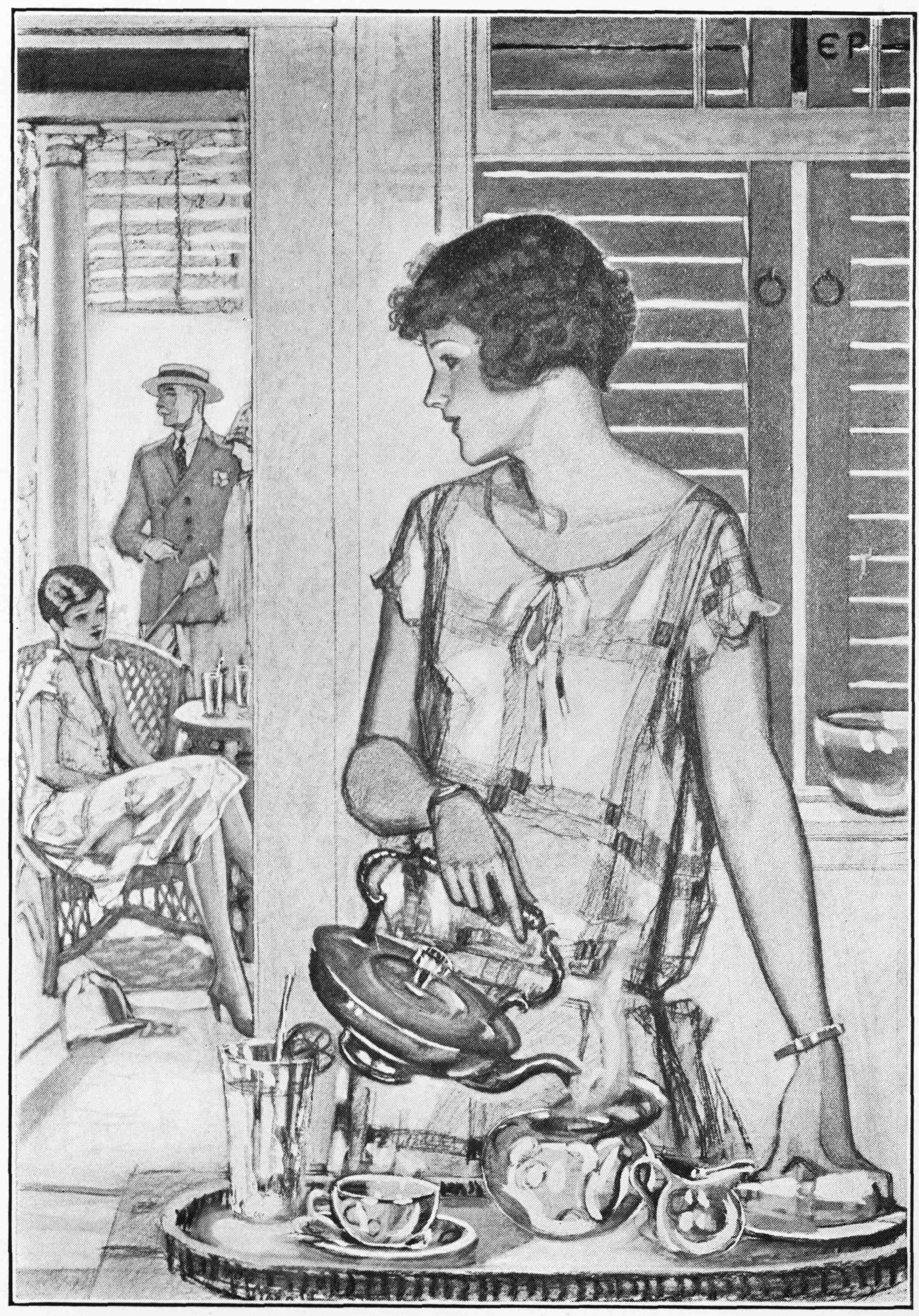

PEGGY HAD HER HANDS FULL BEHIND THE SCENES

THE GREEN DOLPHIN

PEGGY HAD HER HANDS FULL BEHIND THE SCENES

by

Sara Ware Bassett

Author of “The Harbor Road,” etc.

THE PENN PUBLISHING

COMPANY · PHILADELPHIA

1926

COPYRIGHT

1926 BY

THE PENN

PUBLISHING

COMPANY

The Green Dolphin

First Printing, September, 1926

Second Printing, October, 1926

Third Printing, October, 1926

Fourth Printing, December, 1926

Fifth Printing, February, 1927

Made in the United States of America

Probably the thought most remote from the mind of Asaph Holmes, as his dingy wagon gritted along the ribbon of sand that bound together the hamlets of Belleport and Wilton, was matrimony.

He was a shy man with only a limited acquaintance among women. Moreover he considered himself to be well enough off as he was. His small cottage overlooking the horseshoe enclosure of Belleport harbor was cosy as a schooner’s cabin and within it he could do as he pleased without running the risk of being nagged, prodded or reformed.

Just why Asaph should have associated a wife with this trilogy of vices was an enigma, for his mother, gentle soul, had never been a nagging, prodding, or reforming woman and hers was the only marriage he had had opportunity to study at close range. Certainly the theory had not been deduced from viewing her tyrannies, and from what source Asaph had evolved it was a puzzle difficult of solution.

Perchance Hannah Dole was responsible for the credo.

She was a lean, stern-visaged Cape Codder who came periodically from the village to clean him up. Asaph Holmes dreaded her visits as he dreaded the Day of Judgment and would joyfully have done away with them had they not become indispensable. Gradually, however, it had developed that whenever his solitary existence waxed too complex and he found himself face to face with a state of things he was powerless to untangle, he summoned Hannah Dole, that paragon of method and orderliness, to extricate him from his unhappy dilemma.

The feat sounded simple enough and under ordinary conditions would doubtless have proved so, but in Asaph’s case the conditions were not ordinary.

Unfortunately he was possessed of two hobbies: an admiration for Daniel Webster abnormal in its proportions; and a passion for horticulture in consequence of which he collected everything having even a remote connection with this delightful pursuit. He sent far and wide for flower catalogues; he invested in patent seed shakers, pruning shears, and self-watering window boxes; he dabbled in every heralded variety of fertilizer and insecticide; he spent his last jingling copper for perennials that never came up. To these heterogeneous treasures he added reels of wire, tags, balls of twine, markers, volumes of garden lore, not to mention innumerable clippings culled from every periodical he could lay hands on.

It was these latter intellectual wisps that complicated his existence. He could have managed very well had he not had them to reckon with. But as they were of a precarious nature and must be guarded against the gusts that howled through his wind-swept abode, he found it necessary to make them secure by weighting them down with books, vases, candlesticks, or any other object that chanced to be within reach. He tucked pearls of wisdom beneath the clock, behind the mirror, under the chair legs. He was never separated from his pocket scissors and whenever he read (and he read a great deal), snip, snip, snip they went and more information was added to his mounting pile of knowledge.

As a result his dwelling was a place perilous of habitation. Whenever the door opened a snowstorm of whirling paper greeted the visitor, forcing him to grope his way through its blinding thickness as through a winter’s blizzard. Ordinarily Asaph was a mild-tempered person who seldom raised his voice in anger; but on such occasions he would bawl shrilly:

“Shut that door, can’t you, you blasted idiot! Don’t you see you’re turnin’ loose all my cuttin’s?”

Then the unlucky invader, startled by this wrathful reception, would bang the door with a vim that did but increase the havoc he sought to check. What a scramble would ensue forthwith, what a chase to recapture the winged fragments of learning! Behind pictures they skimmed; they lodged in odd cracks and unfrequented corners, sailing away as if bewitched. Often, in the excitement of the moment, the hunters would inadvertently release wisdom already imprisoned and this would augment the squall.

When at length as many items as it was possible to corral had been gathered together and anchored, Asaph Holmes would drop panting into a chair, if he could find one not already preëmpted as a paper-weight; but when it proved that every seat the room possessed had been pressed into service and the interior rendered uncomfortable he would gaze about him for a moment in helpless irritation, then sigh deeply, and tiptoeing out would turn the key in the door and move into the adjoining apartment where in due time he repeated the drama.

A month of hoarding would usually throw the four modestly proportioned rooms on the ground floor out of commission and another month serve to make the bedrooms uninhabitable; and then, chagrined and mortified, Asaph Holmes would creep out the back window to the shed roof, drop softly to the ground, lock up his abode and flee to Lemmy Gill’s, from which haven he would telephone Hannah Dole to come and set him to rights.

Hannah was quite accustomed to the summonses; indeed she looked for them as a means of making both ends meet and would have been disappointed enough had they not been received. It was never necessary, therefore, to explain details or give her instructions. She arrived with her apron under her arm, took the key from behind the kitchen blind, and opening the door just wide enough for her spare body to wriggle through the crack she went to work. She knew before leaving home exactly what she would find and she invariably found precisely what she expected.

Her only comment was a muttered: “Humph! At it again!”

With that she would start in unceremoniously gathering up the clippings and jamming them along with hundreds of their predecessors into the faded blue sea chest beneath the stairs. It mattered not to her that they were gems of learning. Helter-skelter, in they went! Then she would collect the stray trowels, shears, envelopes of seed, boxes of sifted loam, and, having sorted the collection, would transfer it to the destination she deemed most suitable. The tools she carted to the shed; armfuls of pamphlets and catalogues were borne to the attic; boxes of sprouting plants were thrust out of doors. Afterward, having emptied the various poisonous sprays out of pails, teapots and pitchers and scoured the premises from top to bottom, she would return the key to its accustomed peg behind the blind and telephone the master of the house that he might come home.

She never supplemented the permission with social pleasantries nor did he. There was a quality in her tone that discouraged airy nothings even had Asaph been skilled to utter them. The crisp timbre of her voice and her scantily worded message was courteous enough but somehow it conveyed a rebuke that caused the proprietor of the estate to shrivel and feel sheepish as a whipped schoolboy. To carry off the situation and make possible a continuance of their relations he habitually scrawled a jaunty line of commendation and, enclosing it with his check, sent it promptly away to the autocrat by mail.

He could as well have left the money behind the blind in advance, for Mrs. Dole was unimpeachably honest, and, being a rutty creature, never varied her charges by the fraction of a cent. But, although he knew beforehand what the bill would be, he invariably mailed the wage. The more formal method restored to some extent his injured dignity and at the same time avoided the possibility of an encounter with his rescuer. He had not looked Hannah in the face since he could remember. The acquaintance of these two being of such limited and laconic a character, it can easily be seen that to accuse Hannah Dole of naggin’, proddin’ an’ reformin’ was base injustice. And yet so cameo-cut are certain personalities that all unvoiced their opinions emanate from them. Thus it was with Mrs. Dole.

Never in her life had she been guilty of uttering the assertion that Asaph Holmes was a disorderly old fogy or framed the sarcasm that he never would glance a second time at the litter of printed matter he amassed. Yet in spite of her forbearance she might as well have voiced the charges, for they breathed in the very corner-to-corner precision with which the seed catalogues were stacked and the firmness with which the cover of the sea chest was clamped down.

Nevertheless, if the spirited and flawless performance of her task was intended as an example, the lesson she sought to convey made but a shallow imprint on Asaph Holmes’s conscience, for, beyond the fact that he shrank more timidly each time from sending for his deliverer and confessing he had again perpetrated the crimes he knew her to deplore, he did no better for all her teaching.

Whenever he returned from exile he would beam upon his domain from the threshold and after a second or two of pleased contemplation would proceed to search out the sprouting seeds and the dislodged trowels. Other penates, too, he would restore to their accustomed haunts until before an hour had elapsed one might well have questioned whether the beneficent presence of Hannah Dole had pervaded the place or not.

Still, there undeniably was in the interior a subtle sense of spaciousness that awakened in its owner a feeling of luxury and the impulse to expand. With zeal he immediately set about culling more clippings, mixing fresh sprays, recruiting additional catalogues even though all the time he was doing it he was dimly aware of the abyss of disgrace into which such backsliding would lead him. Hence by the end of the allotted two months he was again an outlaw and compelled to subpoena Hannah Dole.

As this cycle of events made its rotation, he resolved every time that this visit should be her last. He would no longer submit to the ignominy of being chided by a supercilious female. Tomorrow he would begin to peruse, classify, and arrange his cuttings and paste them into books. He would sort his bulb from his seed catalogues and tie them in bundles. But the utopian tomorrow he pictured never came.

Having been born into the world with a personality of this ilk, is it to be marvelled at that Asaph Holmes prized his bachelorhood as his brightest jewel and in no unmistakable terms derided matrimony?

As he bowled along to Zenas Henry Brewster’s to haggle about the wood he proposed to purchase, who would have imagined an event of such stupendous proportions impended? Certainly not he. He turned into the yard trustingly as a child and, pulling up at the back door, dismounted from his wagon. Even when he entered the kitchen he had no premonition that Fate stood jeering impishly at his elbow.

Then without warning he spied the woman!

She was, as it happened, washing dishes, but she might as well have been gathering the apples of the Hesperides, so glorified seemed her task.

Meantime Abbie, Zenas Henry’s wife, came forward.

“Good-mornin’, Asaph,” ejaculated she. “Why, we haven’t seen you for weeks. Where have you been keepin’ yourself? Pity Zenas Henry or the Captains ain’t in. They were speakin’ of you only the other day. Draw up a chair. I want to make you acquainted with my friend Althea Morton who’s up from Provincetown visitin’ me.”

In a haze of wonder such as that in which Adam must have first surveyed Eve, Asaph turned toward the woman. He had, however, one advantage over his distinguished progenitor—he had previously beheld the sex. But alas! his superiority did him no good for the woman he now confronted was like unto no other woman he had ever set eyes upon.

Not that she was so different in appearance, although with her bright color, vivacity, encouraging smile, and well-proportioned figure she presented a bewildering ensemble. The characteristic he found novel and appealing was the gracious simplicity with which she welcomed him. Females were wont to scent out the fact that he was shy in their presence and make scant effort to draw him out. But this one either failed to recognize his limitations or, having detected them, overleaped them as matters of no consequence. Never had he been approached with such a degree of understanding, never addressed with so much courtesy and ease. Under the genial spell he waxed fluent or thought he did until he afterward discovered that it was Circe and not he who had done the talking. But he could have talked, that was the miracle. His tongue was unloosed and to its tip came a score of observations he might have uttered had the conversation lagged.

Half an hour later he drove home conscious that he had been transformed into another being altogether. The silent, serene man who had gone to Wilton to bargain for wood—where was he?

Next day he went to the Brewsters’ again, having recollected that he had forgotten in his confusion to stipulate that he wished the wood split, and once more he beheld Althea Morton. How full of spirit she was! How wholesome and natural! He could not recall ever having met so enthralling a woman. Asaph’s mental processes, however, were slow and therefore the possibility of securing the continual companionship of this peerless creature did not occur to him until a fortnight later, during which interval he had repeatedly pondered on what a desirable wife Althea would make for some lonely, quiet man like himself. How her alert, ingratiating personality would enliven a home! Then gradually out of these abstractions the realization took form that he was quiet and lonely and Althea Morton might enliven him. It was a new and disturbing idea yet withal a pleasant one. Idly conceived, it grew until it assumed such compelling force that might became must and Asaph set resolutely to work to possess himself of this gem of womanhood.

There was nothing to hinder the marriage, for he was well-to-do and his solitary home stood ready to receive a mistress. Moreover, he had neither kith nor kin to oppose the match. There was no one to object, no one to rate the inspiration as preposterous except Lemuel Gill.

Here Asaph paused, his enthusiasm experiencing a check.

What was Lemmy going to think of the amazing move—Lemmy, who up to the present moment had been the paramount consideration of his life?

He knew all too well without asking and if he entertained doubts he could have them forever set at rest by inquiring, for not only was Lemmy honesty itself but between the two men existed a friendship tough of fibre and redolent with frankness. Lemmy could be depended upon to state without reserve exactly what his opinion of the venture was.

Then of a sudden it came over Asaph that he did not want to know what Lemuel thought, did not care. Should his crony’s judgment be unfavorable to the plan it would in no way hinder it. It would merely create disagreement and hard feeling. For Lemuel would disapprove, that he knew perfectly well. Had they not often exchanged felicitations on their untrammeled independence and dwelt with satisfaction on the compensations of single blessedness?

Furthermore, his friend knew him through and through and was acquainted with every quirk of his character—his absorption in books, his horticultural bent, his unmethodical habits. These idiosyncrasies he would feel it his Christian duty to drag into the daylight as barriers to any matrimonial enterprise.

Indeed Asaph himself had been obliged to acknowledge there was something to be said for such arguments. Having granted this, however, he considered he had done all that honesty required and finding the facts disagreeable he forthwith swept them aside. Much better reflect on Althea and her varied charms.

But although he valiantly attempted to do this the thought of Lemmy Gill would persist. It was going to be awkward to explain his change of heart to Lemuel; to make clear just why he, who had revelled in pursuing his tastes unmolested, should now prefer a stranger’s continual companionship. Besides, Lemmy was sensitive and easily aggrieved. It was going to cut him to the quick to have a third person come between them.

Asaph frowned.

The entanglement in which he found himself was embarrassing and unluckily it was not one from which Hannah Dole could deliver him. He must face the perplexity alone.

He admitted it was only just, only decent, to consult Lemmy before taking a step so revolutionary. Why, the two had never so much as planted a rose-bush without first discussing for a good half-day all the pros and cons of the project. But with regard to this larger and more vital issue he confessed, after searching examination, he had not the courage to take Lemuel into his confidence. He was determined to wed Althea Morton whether or no, with Lemuel’s consent or without it. That was what the matter sifted down to.

The discovery of this monstrous breach of friendship appalled and dismayed him. What enchantment was upon him? What magic spell? It was the first time during the long span of years they had known one another that he had ever kept a secret from Lemuel Gill.

Asaph’s mighty secret would have been less easy to guard had Althea Morton been staying at Belleport, for gossip travels quickly in a small Cape Cod village and before a day had elapsed all the town would have been cognizant of the romance. As it was his pilgrimages to Wilton had to be explained.

“I’m negotiatin’ with Zenas Henry about some wood,” announced he in offhand fashion at the post-office, and forthwith the excuse sped about the hamlet and further speculation was silenced.

But to satisfy Lemuel Gill’s curiosity was not such a simple matter. Friendship granted him the privilege of asking questions, any number of them, and no snub or subtle display of reticence discouraged him in the least.

“Goin’ over to Zenas Henry’s about that load of wood again?” queried he. “But you’ve been to the Brewsters’ about that blamed wood twice already. What you goin’ a third time for?”

The sharp little eyes bored like gimlets through his colleague. Nevertheless there was nothing offensive in Lemuel’s gaze. He was interested, that was all, and the inquisitiveness he now manifested was no greater than that in which he had habitually indulged for the past quarter of a century. Under other circumstances Asaph would scarce have noticed it or would even have welcomed the interrogations, cheerfully replying to them with a good-humored grin and a statement as to his exact reason for making another journey to the adjoining village. Furthermore he would, in all probability, have urged Lemuel to accompany him.

But today he did none of these things.

Instead he flushed irritably and tried to shift the conversation into another channel.

“So I have,” he murmured. “Still, you can’t get nothin’ in this world without takin’ some trouble about it.”

“But a load of wood,—” pressed Lemuel. “Why ’tain’t worth goin’ eight miles for once, let alone travellin’ the distance three times. You’ll double its cost in wear to your wagon.”

“Mebbe. Still the ride’s a pleasant one an’—”

“Oh, if you’re just goin’ a-ridin’!” sniffed the inquisitor. “But with the work you’ve got laid out—cultivatin’, weedin’ an’ the like, I didn’t look for you to go ridin’ out. You said yesterday you figgered on sprayin’ your roses this mornin’.”

“So I did! So I did,” hedged Asaph.

“You certainly don’t expect to do it when you get back; ’twill be near noon.”

“Likely I may not be gone that long an’ if I am I can do my sprayin’ tomorrow.”

“You told me I could use the sprayer tomorrow,” came from Lemmy in an aggrieved tone.

“You can an’ welcome.”

“But I’ve no notion of borrowin’ it when you’re plannin’ to use it yourself.”

“I can wait. It don’t matter a mite when I do my roses.”

Through wide-open blue eyes Lemuel Gill scanned his friend’s countenance.

“Why, Asaph Holmes, you were declarin’ not three days ago that every one of them roses in that front bed bid fair to be et up by aphids unless you got after ’em straight away.”

In sickly fashion Asaph grinned.

“I reckon I was sorter het up when I made that statement, Lemmy.”

“Still, there’s aphids on your Dorothy Perkins’s. I saw ’em myself.”

“I’m goin’ to tend to ’em.”

“When?”

“Late this afternoon, mebbe.”

“’Tain’t good to spray roses toward nightfall. You read that to me out of one of your clippin’s once and cautioned me against doin’ it.”

“Did I? I’ve got so many of them confounded clippin’s I can’t for the life of me remember what half of ’em say.”

The jauntiness of the tone more than the words that accompanied it caught Lemuel’s attention, and spreading his legs far apart, he riveted his eyes on his comrade’s face.

“Say, Asaph, what’s the matter with you anyway?” he demanded.

Here was Asaph Holmes’s golden opportunity! If he was ever going to impart to Lemmy Gill the great tidings of his contemplated change of plans, a natural opening now presented itself. In one sentence he could clear his conscience of the load that weighed it down. The secret trembled on the tip of his tongue. He glanced furtively at Lemmy.

Standing there in the sunshine, his eyes starry with curiosity and his sandy hair up-ended in the breeze, his crony’s short figure appeared ridiculously youthful—too youthful to be entrusted with such important intelligence. Moreover, Asaph remembered his artlessness, and how prone he was to prattle ingenuously to the first person he met any news that interested him. No, he dared not impart so fragile a tale as his love affair to Lemuel. Indeed, when all was said and done, what was it but a dream, a mad and beautiful imagining? Why, he had only seen Althea Morton twice! On the strength of those two short interviews it would be preposterous to assert he was going to marry her.

Therefore he fumbled with the button on his cuff and responded nonchalantly:

“Nothin’ in the world. Mebbe after all I had better put off the Wilton trip till afternoon an’ do my sprayin’ now.”

“You’d much better,” beamed Lemuel, wholly satisfied. “Delay goin’ till after dinner an’ I’ll flax round an’ go with you.”

“Oh, I’ll have to be leavin’ before that time,” Asaph hastened to protest. “I’ve got a peck of errands to do. Were I to wait till noon I wouldn’t get ’em done before nightfall.”

“What you goin’ to buy?” asked Lemmy, too much interested to let the rebuff he had received ruffle him.

“Collars, chicken-feed—lots of things.”

“Goin’ to get ’em at Wilton?”

“I may’s well, long’s I’m drivin’ through.”

“’Twill hurt Eben Snow’s feelin’s to have you go patronizin’ the Wilton store instead of his.”

“He won’t know nothin’ about it.”

“Oh, he’ll know all right. Everybody knows everything in this town. Folks read your inmost thoughts almost before you think ’em.”

At the words Asaph colored uncomfortably.

“Nobody’s goin’ to read my inmost thoughts,” he answered with a touch of humor. “Eb Snow ain’t goin’ to be the wiser for any shoppin’ I do unless you tell him.”

“I sha’n’t tell him nothin’. But he’ll know for all that. People will see you drivin’ home an’ spy the bags of grain in the wagon.”

“I can’t help it,” returned Asaph with a mild suggestion of impatience. “I’ve got the right to buy things where I please, ain’t I?”

“It’ll be nuts for Silas Nickerson to have you comin’ to Wilton to shop. He’ll make no end of talk about it. He’ll tell folks you couldn’t get no collars nor chicken-feed in Belleport an’ so had to tote over there for ’em. He’s always crackin’ up his town. I thought he’d never have done talkin’ when Bijah Sole picked a Wilton wife. Si said that evidently our place couldn’t boast a smart woman. But when Lyman Bearse up an’ answered that the trouble was the Belleport women were too smart to marry Bijah he kinder quit braggin’.”

Asaph, however, failed to echo the guffaw that concluded the story.

He had started precipitately for the house.

“I must get to sprayin’,” called he, “before the sun rises higher.”

As he disappeared into the shed he caught a glimpse of Lemmy jogging off down the lane, and to make sure no hard feeling existed between them he waved cordially to his comrade. Then as he bent to stir into a can a turquoise mixture of Bordeaux his brow wrinkled.

It was not pleasant to reflect that Silas Nickerson would probably make similar assertions with regard to his marriage. Still Belleport would be more ready to forgive him for wedding a Provincetown wife than if she were a native of Wilton. That was some comfort.

Feverishly he sprayed his roses, and by keeping a tight rein on his inclinations and not allowing himself to be led into hunting cut-worms, thinning out his poppies, which sorely needed it, or weeding his iris border, by eleven o’clock he was ready to set out for the adjoining town. As he stole off as quietly as he could in his wagon he felt guilty and selfish not to have delayed until afternoon and taken Lemmy with him. The little man had no horse and keenly enjoyed a drive.

“But I just can’t take him today,” replied he to his conscience. “Things are too ticklish. He might mess up everything. Some day I’ll make it up to him. He shall have three or four rides—half a dozen.”

Thus quieting the accusations that assailed him, he turned into the highway that edged the Belleport shore.

It was a day when to the very horizon the ocean was a dazzling reach of blue flecked into splendor by the gold of the sun and the snowy sails of scudding schooners. Little creeks that gave back the azure of the sky cut paths across the marshes, dredging channels for themselves amid swaying sedge, tough, salt, and vividly green. Inland in the bordering swamps azalea was just coming into bloom and purple flags stained to amethyst the dark pools of tide water. A vague satisfaction in this beauty mingled with Asaph’s reveries as he drove along. The sea, the ships, the tiny winding inlets were things he loved, things he would not have been parted from at any price and yet things he every day passed by with nothing more than a subconscious realization of their existence.

Today his mind was much more engrossed by the thought of Althea or even the collars and chicken-feed than by the glory of the world about him. Nevertheless, he could not have been oblivious to it for he drank in the cool breeze with pleasure and was dimly aware of the perfume of sun-dried pine and budding roses.

The riot of color had faded into dull mist when he returned, and Lemuel Gill was sitting on the front steps awaiting him.

“You’ve been an awful while,” called he in a tone of relief. “I was ’most afraid somethin’ had befell you.”

“Oh, no.”

“But you’ve been gone so long. I s’pose you ran afoul of Silas Nickerson an’ couldn’t make your escape. What a critter he is for wormin’ gossip out of folks! He’d keep a man in that store till doomsday pumpin’ him. Get your collars?”

“No, I didn’t.”

“Don’t tell me Silas didn’t have the size! My eye! Sorry as I am you should be disappointed, I’m tickled to death he was out of ’em. Reckon he was peeved enough to have somebody from Belleport ketch him nappin’. He prides himself no end on never lettin’ his goods run out of stock. Wait till I tell Eben Snow there warn’t a sixteen collar in the place. He’ll be so pleased ’twill mor’n make up to him for your goin’ to Wilton to shop.”

As Lemuel rubbed his hands and smiled, a dull red flush rose to Asaph’s forehead.

“Silas warn’t out of collars fur’s I know.”

“What?”

“I didn’t ask for ’em.”

“O-h! Forgot ’em, eh?”

Receiving no answer he waited; then his face, clouded with ebbing triumph, brightened.

“But you got your chicken-feed,” ventured he.

“I didn’t get anything. I didn’t go near the Wilton post-office.”

“What on earth have you been doin’ till this time of night?”

“Visitin’ at Zenas Henry’s.”

“You mean to say you’ve been at Brewsters’ ever since eleven o’clock this mornin’?”

“I didn’t get there till close onto noon,” explained Asaph, a warning note of annoyance giving crispness to his embarrassment.

“An’ you’ve been hangin’ round there till now?”

The picture presented was so unflattering the lover flinched.

“I’ve been there, yes.”

“What doin’?”

“Talkin’.”

“Zenas Henry must have had an awful lot to say. What was the news?”

Lemmy drew closer, his eyes avid with interest.

“I warn’t talkin’ with him. He warn’t home.”

“Oh, the Three Captains were holdin’ forth, were they? Benjamin Todd’s a great gossip. He can spin a yarn out of most anythin’. I like to listen to him myself when he gets well a-goin’.”

There was no help for it. Asaph saw the truth must out.

“None of the Captains were home, neither. They’d gone fishin’.”

“Wal’, Abbie Brewster is an entertainin’ woman but I never knew of your spendin’ hours in her company before.”

“She warn’t there. She’d gone to Brockton.”

Mystified, Lemmy stroked his chin.

“Then who in tunket was you talkin’ to?” he burst out.

“A friend of Abbie’s who’s a-visitin’.”

“A woman?”

Asaph nodded.

Lemuel looked dazed.

“Seems to me I did hear down to the store the Brewsters had somebody stayin’ with ’em,” said he slowly. “But you certainly warn’t talkin’ to her from high noon till most supper time.”

“’Twarn’t really long when you come to think of it.”

“’Twas about five hours.”

“Mebbe.”

“’Twas all of that.” Lemuel appeared for a moment to be bereft of words. Then he added with a touch of malice: “She must ’a’ been almighty interestin’.”

“She was,” was the curt retort.

Something in its tartness, something in his friend’s flushed countenance and the sudden movement he made to bend and pull a blade of grass from the roadside caused Lemuel Gill to crumple up weakly against the picket fence.

“Lord!” he murmured.

“It ain’t goin’ to make a mite of difference twixt you an’ me, Lemmy,” his companion declared eagerly. “We’re goin’ on with our gardenin’ an’ all same’s before. Althea’s got to expect that. In fact as I figger it, I’m goin’ to have more time for diggin’ round an’ workin’ at my plants married than single. More leisure for readin’ too, I hope. Althea’s an awful nice woman, Lemmy. You’ll like her. You can’t help it. She’s a fine cook, too. I had a chance to sample some of her bakin’ this noon an’ ’twas good as any I ever ate. Take everything together seems to me I’m goin’ to be better off than I ever was in my life. If only you—” The onrush of his words was halted by sudden timidity.

“If I don’t mind, you mean?” Lemmy contrived to stammer. “Pshaw! ’Course I don’t. ’Most everybody marries—some of ’em two an’ three times. I’d be a great kind of a friend if I was to stand in the way of your bein’ happy. Don’t go worryin’ about me. Most likely I sha’n’t give the matter a second thought.”

For all his bluster, the bravado the little man tried to maintain weakened toward the final clause of his sentence and there was a quaver in the words.

A wave of self accusation swept over Asaph.

Only too well he realized his happiness had been purchased at a price—the price of Lemmy Gill’s.

It was July when Asaph Holmes made Althea his wife and brought her home to Belleport. The marriage was a quiet one, taking place at Abington, the residence of her sister, and even Lemuel Gill did not attend it.

“’Course I’ll go, Asaph, if you say the word,” asserted the little man, “though it does seem kinder foolish for me to traipse way up there for a ten-minute ceremony. Nevertheless if there’s aught of comfort in havin’ me at hand I’m ready to stand by.”

“I know you are, Lemmy,” was the earnest reply. “But there wouldn’t be the least use in your goin’.”

“I ’magined there wouldn’t,” Lemuel answered with evident relief. “It’s one of them times, I guess, when only heaven can help you. So I reckon the best thing I can do is to stay behind an’ keep a weather eye on your belongin’s. There’ll be ice to get in against your return, an’ butter, too; an’ should the weather be dry the garden will need waterin’. You can’t leave the whole place to go to the dogs even if you are gettin’ married.”

The tart comment that concluded Lemuel’s words was the first he had uttered and his crony generously passed it by.

“It will be mighty reassurin’ to know somebody’s at this end of the route,” declared he. “A house gets musty when it’s shut up an’ though I don’t plan to be away mor’n a few days I’ll feel a lot easier with you on the spot. Of course there’ll be Hannah Dole. I had to send for her to come an’ straighten things up. There’s been so many odds an’ ends round lately owin’ to spring plantin’ an’ all that I’ve run into one of them crowded spells. However, this visit will be her last—thank the Lord for that!”

For the first time he smiled into the eyes of his colleague—one of his frank, whimsical smiles—and Lemuel smiled back.

“Under those conditions you may’s well give Hannah your blessin’ an’ let her do her darndest,” drawled he.

Each man drew a breath of relief that the delicate situation had been so amicably adjusted.

Lemuel never went on journeys now-a-days. In the past he had been a continual wanderer, cruising as cook on a freighter to almost every port under the sun and having no permanent abode. But now that he had abandoned the sea and had a domicil of his own he could not be coaxed away from it. For years he had not been out of Belleport. Having indulged himself in this stay-at-home habit he had become so unaccustomed to travel that its complexities terrified him until even a short detour from his own threshold assumed the nerve-racking proportions of a voyage round the globe.

In the particular instance of Asaph’s marriage, he not only dreaded going away but also shrank from braving through in the presence of strangers an event which at best could be nothing for him but an ordeal. Besides, he had nothing to wear—a feminine reason, he humorously conceded, but in his case a very real one. His wardrobe was not a thing that normally interested him. Indeed it was the last consideration in his budget (if he boasted a budget). So long as his garments could be coaxed to hang together he wore them regardless of their appearance, rating such accessories as shirt and collars of very slight importance when weighed against the possession of a Lafayette rose. It was calamity enough that so large a percentage of his meagre income must be expended for bread and butter; but he had long ago discovered one could exist with astonishingly few coats and trousers.

All these facts Asaph understood far better than Lemmy could have explained them and therefore was only too glad to spare his pal not alone the expense but also the exactions the Abington trip would entail. Moreover, everybody did not appreciate Lemuel and he had a premonition that perhaps Althea’s relatives might not. He was an unconventional creature. Too sincere for pretense, he made no effort to appear other than he was—a shabby, simple-minded, ingenuous fisherman into whose cheek was burned the brine of the deep and whose eyes were faded by the glitter of its dancing waters.

Asaph Holmes was not ashamed of Lemmy. On the contrary he was far too proud of him, too sensitive to his worth to place him where he might not be appraised in his true value. Abington was a bigger town than Belleport and the Tylers liable to be governed by more worldly standards than those that prevailed in his own village. But more weighty than any of these arguments was the fact that Althea had never yet seen Lemuel and he was eager the first impression she received of his friend should be under the most favorable of circumstances. Lemmy, awkward and ill at ease in city clothes and irritated by the unaccustomed restraints of collar and tie, would, he realized, present anything but an ingratiating appearance.

Even Asaph himself winced before the prospect of the approaching festivities and inwardly confessed he should be heartily glad when they were over and he and his bride safe at home. However, the tomfoolery had to be gone through with, and buoying up his courage by the philosophy that everything has an end he struggled not to betray to Lemuel his perturbation.

“Thank goodness I ain’t got to stay at Abington with them Tylers forever,” muttered he when alone. “I guess I can manage to stand ’em for a couple of days. Once I get Althea away from ’em I don’t plan to do much visitin’ in that quarter, nor mean she shall neither. Abington’s a good distance off. I’m almighty thankful it’s no nearer.”

Yet, in spite of this stoical point of view, when the moment for his departure came he was obviously nervous and so was Lemuel Gill who, fighting to conceal his emotion, bravely watched him out of sight down the road that edged the harbor.

Everything had been left in what the prospective groom termed apple-pie order. The key for Hannah Dole hung on its peg behind the blind; a saucer of fish had been put out for the cat; the annuals sending up delicate green shoots in the shelter of the hollyhocks had been carefully cultivated.

“The place is in the pink of condition, Lemmy,” he asserted as the two friends parted. “I’ve sprayed every rose an’ pulled up every durn weed. You won’t find a thing to do.”

Notwithstanding the declaration, however, no sooner was the owner of the establishment out of sight than Lemuel decided to investigate.

“He’s so addle-pated ’bout that woman he much as ever knows which way he’s goin’,” soliloquized he. “He ain’t been himself since first he clapped eyes on her. An’ tellin’ me his marryin’ warn’t goin’ to make no difference. Lord! Why, he’s changed a’ready. He’s begun to worry even now lest Althea won’t like this an’ won’t like that, an’ will go shiftin’ things around when she gets here. An’ she will, too—mark my words. She’ll start straight in reformin’ the premises before her hat’s off. See if she don’t. All women do. It’s in their blood.

“Look at Hannah Dole. Is she content to kinder dust off Asaph’s possessions an’ leave ’em where she finds ’em? Not she! Nothin’ will satisfy her but to heave round every article in the place an’ whisk a broom where ’twas standin’. Let a room just get so’st things are handy an’ easy of reach an’ in she comes an’ begins cartin’ off everything in sight till it’s a marvel Asaph ever finds ’em again. She relishes doin’ it, too, even if she does pretend the job is almost mor’n she can bear.”

There may have been an element of truth in Lemuel’s accusation.

Certainly when Mrs. Dole came hither on this, her final pilgrimage, the weathered cottage on the bluff received an extra overhauling. Her zeal was as the zeal of ten. She beat and brushed, mopped and scoured with a zest never before equalled.

“Poor Asaph!” lamented Lemuel, who had crept up to peep through the blinds at the unconscious toiler. “He’ll be a month locatin’ his tools an’ catalogues. The very devil seems to be at Hannah’s heels this time. Most likely she realizes it’s her last chance; or mebbe she has a notion to demonstrate to another woman what she can do in the cleanin’ line when once she puts every ounce of elbow grease she’s got into the job. Anyhow she’s scrubbin’ like a demon. Almost before light she was out emptyin’ all the sprayin’ mixtures into the glory-hole an’ rinsin’ out the cans. Asaph won’t thank her for that. He’ll just have to stir more together soon’s her back is turned. But there’s no use tellin’ her so. Once she sets out on a course there’s no stoppin’ her. Besides, Hannah ain’t one you’d dare meddle with. Were I to object to what she’s doin’ she might up an’ leave an’ then where’d I be? No, she better be left free rein to do her worst unmolested. The foundations of the house are firm an’ the roof’s nailed on.”

Hence Lemuel placed no restraining hand on Mrs. Dole’s efforts. But after her sweeping orgy was over and she had hung the key in its usual place he came to get it, and viewing with consternation the spotless stark interior she had left behind her, exclaimed:

“My eye! It looks more as if there’d been a funeral goin’ on here than a weddin’. It actually seems as if I’d oughter strew somethin’ round to make the place seem homelike. Still, I figger I’ll not tinker with Hannah’s handiwork; she might come back an’ discover it. Besides, ’tain’t as if the rooms were goin’ to stay this way. Once Asaph returns he’ll have ’em all easy an’ comfortable again in no time.”

But when Lemuel beheld Althea he did not feel so certain of this sanguine prophecy coming true.

He was at the gate to welcome the newly wedded couple on their arrival, having spent the entire morning in preparation for the event. Awake at sunrise, he resolved to offer on the altar of friendship his dearest treasure, and steeling himself to the sacrifice he cut an armful of his choicest peonies and delphinium and arranged the flowers in a vase beneath the red worsted motto: God Bless Our Home.

Then he aired the house; purchased ice, bread, butter and sufficient provisions to tide over the mistress of the domain until she should have opportunity to assume for herself these domestic cares. Afterward, having plucked the last straggling weed from Asaph’s garden, clipped from the rose bed the fading blooms, and watered the window boxes, he sat down to wait, turning his back on the house lest he yield to the persistent temptation to strew a few catalogues and clippings about the interior.

As the moment of meeting drew nearer misgivings assailed him. Suppose he did not like Althea? Or, what was more terrifying, suppose she did not like him. The latter was the possibility that alarmed him, for he was determined to vanquish the former contingency. Indeed, he would not give the thought of not liking Althea harborage. He was going to like her. Asaph did. Why should not he?

Nevertheless, stoutly as he maintained this attitude he realized full well that do what he might he could not control Althea’s preferences. What if she should regard him with animosity and make no effort to check the impulse?

That was the dread that weighed on his spirits and that was why he today donned collar and tie, put on fresh overalls, plastered his rebellious locks sleek to his forehead, and cut the spires of larkspur that it wrung his heart to sever from the stalks.

“I’ve got to expect to make some effort to please her,” reasoned he. “Then if I do my full part an’ fail to make a go of it, I’ll have nothin’ to cuss myself for. A lot depends on the three of us startin’ right.”

Apparently Asaph also realized this truth, for during the homeward journey, naturally as an April shower falls from the clouds, the name of his crony fell from his lips.

“You’re goin’ to like Lemmy, Althea,” he remarked as they drove along. And later he said:

“I’m bankin’, Althea, on you an’ Lemmy bein’ great friends.”

And when at last a curve of the shore was reached from which the silvery grey cottage could be seen, with an anxiety he could no longer conceal he ventured earnestly:

“I do hope you are goin’ to take to Lemmy for he’s the best friend I have on earth—that is, outside of you,” he amended with haste. “You won’t, mebbe, find him much at first. He ain’t great on appearances, Lemmy ain’t. But the heart inside him—” Emotion halted further utterance and to bridge his embarrassment Althea inquired kindly:

“Tell me about him.”

“Lord! I thought I had. Seems to me I’ve been talkin’ of him most of the time I’ve been away. You mean his looks? Wal, I ain’t sure’s I can. I’ve never thought much about ’em.”

“But you know whether he’s short or tall.”

“He’s short, I guess. Yes, he must be, ’cause I recollect he’s always havin’ to take a slice off the legs of his new overalls quick’s he buys ’em.”

The bride laughed. She had fine white teeth and was at her best when showing them. Asaph liked to see her laugh.

“He’s short, then; that’s settled. Now for his complexion. Surely after all these years you should know whether he is light or dark.”

“I reckon I should,” agreed her husband, “but I’m not certain I do. You see I’ve never picked Lemmy to pieces. I’ve just taken him as he was. Mebbe his eyes are blue. They’d oughter be ’cause his hair is sorter light—carroty, some folks call it; but I don’t consider it that color. It may be sandy an’ I reckon ’tis. But it ain’t carroty—it certainly ain’t that.”

“Does Mr. Gill—”

“Oh, for pity sakes don’t call him Mr. Gill, Althea. Nobody ever called him that in his life an’ should you begin doin’ it ’twould scare him so’st he’d most likely start runnin’ an’ never stop. Furthermore, he ain’t Mister. If you must put a handle before his name (which I pray you won’t) make it Captain.”

“Oh, he has commanded a ship, has he?”

Asaph looked disconcerted.

“Wal’, no—not quite that—at least, not exactly. But he was somethin’ important aboard a freighter once an’ so folks have dropped into speakin’ of him as Cap’n.”

It did not seem opportune just then to explain to his wife precisely the nature of the important post Lemuel had held aboard the Clara D.

“I hope he’s goin’ to like me,” mused Althea aloud.

“Like you! ’Course he is. Lemmy likes everybody.” Then, sensing the assurance contained no great compliment, he foundered on: “Furthermore, my likin’ you will be enough for Lemmy.”

“But I want him to like me for myself,” protested Althea prettily.

Here was a chance for a courtier’s tongue, and had Asaph been skilled in making graceful speeches he would doubtless have seized on the opportunity to bestow on the lady beside him a few words of delicate flattery; lacking this training he answered instead:

“Oh, he will; don’t you fret about that. Lemuel ain’t hard to please. Give him a little time. Folks can learn to like anything if they keep tryin’ long enough. I remember as a lad I never could abide turnips; but my mother fed ’em to me till now I’ve come to relish ’em most as much as any other vegetable.”

Althea drew in her chin. Then her sense of humor came to her aid, and reaching over she patted the hand of the big, clumsy man at her elbow.

There was time for no further demonstration for just at this juncture the stage drew up before Asaph’s door, and Lemuel Gill, hatless and smiling, came forward to greet the travelers.

His welcome carried something that would instantly have disarmed antagonism had Althea been armed with it. Good will spoke in his every gesture, and even a tender solicitude was evident in the care with which he helped her out of the grimy wagon and took her bag.

His eyes, as Asaph had surmised, were blue, and they shone now with bright, unwavering friendliness. But prejudiced indeed must one have been who failed to recognize his hair as carroty. Yet, notwithstanding the hue of his locks and the casualness of the garments that covered his loose, slouching figure, there was a buoyant youthfulness about him, a warmth and sincerity that charmed.

Althea gave him her hand and felt the color flood her face as with curiosity his artless gaze swept it.

Then Asaph put to rout the tension of the moment by exclaiming jovially:

“Bless my soul, Lemmy! If you ain’t all dolled out in a collar an’ necktie! Althea can’t say you ain’t paid her the highest honors.”

“I meant to,” was the grave retort.

What woman could resist such homage?

Certainly not Althea, who saw in the little man a quality all women love.

“I hope we’re goin’ to be friends—you an’ I,” she responded timidly.

“We’re goin’ to if it rests with me,” beamed Lemuel.

They had gone indoors and the bride turned to look about her.

“My, Asaph, how neat your house looks!” commented she. “I’m glad to find you such an orderly housekeeper. If there’s anything I can’t abide it’s dirt an’ untidiness.”

Lemuel cast a quick glance at his comrade, and seeing him on the brink of a confession interrupted with feverish haste:

“Asaph’s an all-right housekeeper in his way, marm; but his biggest talents show outdoors. Did you twig his garden as you came along?”

“Phoo, phoo, Lemmy—nonsense! Why, I ain’t ever raised a thing could compare with your lilies an’ delphinium.”

They were sauntering from the hall into the sitting room and a cry from Althea cut short the argument.

“Oh!” murmured she, pointing to the mass of bloom that all but concealed the motto opposite her.

“You didn’t cut down your larkspur, Lemmy,” gasped Asaph, aghast at the sight.

“I snipped some of it off,” answered Lemuel, lightly. “Folks ain’t married every day.”

“But your best hybrids—an’ the peonies!”

“They’re beautiful,” broke in Althea softly. “I couldn’t have had, Lemmy, a present that would have pleased me more.”

With feminine understanding she laid her hand shyly on the arm of the little man.

The Rubicon had been crossed. They were friends.

“I reckon ’twas worth it,” drawled Lemmy Gill, when, that evening, alone in his garden, he ruefully surveyed the naked stalks that towered into the gloom. “Flowers have a way of sayin’ for you things you can’t say yourself. Had I tried a lifetime I couldn’t ’a’ made clear to Althea what them delphiniums did.”

Belleport experienced no slight shock in the whirlwind courtship and marriage of Asaph Holmes, and immediately the romance became the chief topic of interest in the town’s social calendar. Curiosity to see the bride and hear about her obsessed old and young.

A few of the villagers had been fortunate enough to meet Althea at the Brewsters, and these found themselves besieged with queries concerning her. She must be a paragon indeed to have transformed a confirmed bachelor like Asaph into a benedict. Why, nobody dreamed he would ever marry. He wasn’t the marrying sort. Moreover, were not he and Lemuel Gill almost twin souls?

What did poor Lemmy think of the affair? It must have been a staggering blow to him.

Thus they whispered and speculated together.

It was not malicious gossip, merely the chatter of neighbors who had known Asaph from boyhood and known his father and mother before him. Not a twist of his character was there with which they were not familiar. They knew of his veneration for Webster; his garden, his clippings, his catalogues; knew, too, of the visitations of Hannah Dole with an intimacy that would have appalled the shy man had he been aware of their knowledge. Oh, there was little about him they did not know. Hence when it came to checking him up there was no need for them to give his personal history more than a cursory glance.

But the woman he had married, this outlander from down the Cape, who was she and what was her ancestry? These were the burning questions. The seal of friendship set upon her by the Brewsters counted, to be sure, for something, for they were persons of standing whose sanction carried weight. Sensing this and hopeful of wresting from them more information, some of the more inquisitive Belleporters made a pilgrimage to Wilton to glean from Zenas Henry and his wife such facts as were procurable. Zeke Barker, in the meantime, outdid them in enterprise and became the hero of the hour by driving to Provincetown and acquiring from Althea’s neighbors additional data with which to augment the common fund. By piecing these scattered fragments together, and putting with them items contained in a letter Mattie Bearse received from her Abington cousin, a fairly accurate idea of Althea Holmes and her forebears was obtained, and, disappointed that the investigation yielded such a meagre foothold for scandal, the populace was obliged to concede there seemed to be nothing in the past of Asaph’s bride for which she need blush.

Apparently she came of the same rugged Cape stock as did they themselves, and her history paralleled that of the average New Englander of sea-faring ancestry. This summary must content them until such time as she should make her advent into the community and they be granted a more intimate glimpse of her.

When, therefore, the happy pair arrived in town the waiting hamlet was a-tiptoe with excitement, and immediately a stream of visitors began to flow toward the silver cottage on the bluff. Some came to bear friendly greetings; others to invite the wedded couple to supper or urge Althea to join the Ladies’ Sewing Circle, the Eastern Star, or the Reading Club.

To the master of the house this influx of guests was a novel and, it must be owned, a not altogether welcome experience. Shy by nature and having fostered the tendency by a hermit-like existence, he found the rôle of jovial host a difficult one to portray. He had at his command little talk that did not relate to his hobbies and it hardly seemed worthwhile to offer this to the flitting herd that swarmed his doors. Furthermore, years of solitary living had solidified the ruts in which he moved until to be jolted out of them by intruders jarred and irritated.

When at last he had been constantly interrupted until the weeds were knee deep in his iris border and his roses showed signs of blackspot, he felt it necessary to offer the suggestion of an apology to Lemuel Gill.

“’Course I s’pose it’s to be expected folks will come troopin’ here at first,” remarked he. “Likely they consider it polite. Their galavantin’ will soon be over, though, an’ their curiosity gratified, an’ then I’ll have a chance to get to work. I’m about beat out with company an’ I guess Althea is, too.”

Later he ventured to commiserate his bride on their common misfortune.

“It’s too bad you’ve been so pestered with folks comin’ to see you,” he said sympathetically. “I reckon, though, there’s nothin’ to be done about it but brave through the hurricane till it blows over. Our marryin’ seems to have stirred up quite a tempest. But it’ll calm down before long an’ the public will leave us alone.”

Althea glanced quickly into his face.

“I hope not,” answered she. “I like visitors. At home folks were always droppin’ in to talk or borrow somethin’. It livened us up an’ kept us from gettin’ lonesome.”

Her husband sobered.

“I hope you ain’t goin’ to be lonesome here, Althea,” he returned, a note of anxiety in his voice.

“I don’t look to be,” was the grave response. “I’ve my housework, an’ plenty to do don’t leave a body leisure for mopin’. Besides, ain’t you here to cheer me up?”

The great fellow colored with pleasure. Until lately Althea had maintained toward him a piquing reserve that continually left him speculating as to the heights and depths of her regard; but since marriage, although still charmingly elusive, she had gradually lowered the bars that held him in check, a fact that delighted her husband. Had he been of more intuitive a nature he would have understood that this change of demeanor was largely the result of his own attitude toward her. Asaph Holmes had been brought up under the tutelage of a good mother, who early in life had instilled into him both chivalry and consideration for all womanhood. Hence, although his circle of feminine acquaintances did not extend any great radius beyond his own doorsill, he was much better versed in what constituted a happy marriage than was many a man of wider experience. This Althea was learning, and in proportion as the truth seeped in upon her she gave freer rein to her affection, congratulating herself that her union with this silent, awkward man had been no mistake. To marry was at best a venture, and to embark on the experiment late in life was, her level head told her, a madness to be matched by no other human undertaking. Yet in her sudden romance there had been qualities that convinced her the affair could not culminate in disaster.

Had Asaph Holmes been an ardent, hot-blooded wooer she would have feared to trust his promises. But this man, earnest, pleading, self-effacing, scorning to pledge himself to more than he knew he could honestly perform, appealed to her truth-seeking heart. What mattered it that his words were few; that he was studious, matter-of-fact, and a good ten years her senior? He could be trusted, and experience told her every man could not. Long ago, in girlhood, a lover dashing and debonair had crossed her path, and the black shadow he had left behind him caused her even yet to shrink from any repetition of his type.

But Sarah Tyler, more worldly-minded and eager for family advancement, could see in the match little to commend it.

“I can’t for the life of me, Althea, understand why you should want to go marryin’ that big, hulkin’ fisherman. Not only is he years older than you but he’s dumb as an oyster. A whistlin’ buoy off the coast would be cheerful company compared to him. With your looks and figger you ought to be able to do better’n that.”

Althea did not vouchsafe to this criticism any of the several retorts she might have been justified in offering. She did not, for example, reply that Asaph Holmes had plenty to say to anyone who had the brains to talk with him; neither did she utter the tart response that when it came to husbands she did not see that Sarah herself had selected from the myriad masculine varieties with which the universe was peopled, a particularly flawless specimen of the sex. She did not even trouble to lay bare for her sister’s inspection the heart that like a jewel lay beneath Asaph’s prosaic exterior. Instead, she laughed off the comment by declaring good-humoredly:

“After all, Sarah, it’s I and not you that’s got to live with him,” and ruefully acknowledging the truth of the assertion, Mrs. Tyler said no more.

In Belleport, however, where Asaph was known and universally respected, judgment assumed precisely the opposite tack.

“A woman don’t half know how lucky she is to get a husband like Asaph Holmes,” announced Marcia Snow to the assembled sewing circle. “He may be deliberate and scant of talk, but he’s kindness itself an’ as dependable as the sun. He won’t go whiskin’ round an’ start chasin’ off in some other direction after he’s married. The wife that’s got him has got him for life.

“But what’s he drawn, I’d like to know? Oh, I’ve seen her an’ I don’t deny she’s pleasant to meet; good lookin’, too, with her curly hair, red cheeks an’ all. But what kind of a wife is she goin’ to make him—that’s the question I’m askin’? She must be younger than he by a dozen years an’ is evidently one of those chatty, sociable creatures that’ll drag him round a-visitin’ an’ break up all the quiet of his home. She ain’t a-goin’ to be no person to live out on that lonely point of sand with a bookworm like Asaph Holmes. She’ll never be contented there in the world. Before a year’s out there’ll be ructions—you see if there ain’t!”

The pair concerning whom this dubious prophecy was uttered were in the meantime evidently oblivious to their impending fate, and not anticipating any violent domestic upheaval Althea took possession of her new home with interest. She hung ruffled curtains at the windows, invested in additional china, put plants, table-covers, and bric-à-brac about, made fresh sofa cushions.

With conflicting emotions her husband surveyed her innovations. There was no disputing the fact that they rendered the cottage more pretentious and up to date. But did they make it more homelike? Amid the galaxy of objects that now adorned the rooms little space was to be found for his catalogues and clippings. To be sure he still collected them, tucking them into obscure corners, since he dared not weight them down with Althea’s bridal ornaments. As a result they more frequently took wing. For these literary cyclones he was always apologetic and his wife forgiving. Nevertheless, beneath their courtesy simmered mutual irritation.

Then there were the tools, the cans of insecticide, the boxes of loam, the strings, wires, and markers that gradually stole beyond the confines allotted them by Hannah Dole. Althea did not allude to their presence at first, and mistaking tolerance for sanction her helpmate gave his repressed impulses freer scope and proceeded to drag out his entire array of agricultural paraphernalia. He splashed Bordeaux and Pyrox about the shed until its floor was blue; he brewed bottle after bottle of evil brown, yellow, or black liquids and whistled with complete contentment as he stirred the deadly mixtures, thinking all the while what a fortunate marital choice he had made and what a blessing wedlock was under conditions such as these. Had a woman been created purposely for him she could not have been a more perfect wife.

Occasional clouds, to be sure, blurred his sunshine. There was no denying Lemuel Gill was sensitive, and Althea—well, perhaps all women were jealous. Be that as it may, jars did occur and moments of tension when he was compelled to flit solicitously between the opposing factions, soothing Lemmy and comforting Althea. Gradually he realized that this rôle of peacemaker was to be a more or less permanent one. It was a taxing post, the office of interpreter between the two individuals who loved him best; but since the friction rose because of him, he granted he was preeminently the one to bear its annoyances. Moreover, the strife never expanded into open warfare; it remained petty and unacknowledged, taking vent in a toss of the head, an upward tilt of the chin, or a whiffle out the front gate.

In the meantime, notwithstanding these rifts in the general serenity, the months wore tranquilly along, and by the time winter came the trio had learned to adapt themselves more amiably to one another’s crooks and corners. This was indeed fortunate, for as the Holmeses and Lemuel Gill were the sole residents of the bluff where their houses stood, they had few outside resources and were continually thrown upon each other’s society.

Asaph had never found cold weather irksome. Incontestably gales did howl round his cottage, and a northeaster with the ocean lashed into fury and sending the spray high in air was a sight not to be lightly contemplated. Nevertheless, there was grandeur and exhilaration in the spectacle as well as awe and terror. Besides, the sea was not always in cruel humor. Often it was merely sullen, its leaden expanse flooding out to meet a lowering sky. Or the sun shone on it from a cloudless heaven flashing on waves that curled white and fretted with feathery beauty the vast sweep of sapphire. Oh, there was many and many a winter’s day when in spite of snow-buried dunes and tingling fingers it was good to be alive!

These kaleidoscopic moods of the deep Asaph Holmes knew and loved, and the season meant to him a warm kitchen; a high-backed rocker before the fire; chowder steaming on the stove; and a well-thumbed volume of Webster or one of his precious seed annuals before him. At such moments Paradise had seemed very near, and now, with Althea and her knitting added to the picture, it seemed nearer than ever.

Each morning Lemuel Gill dropped in to bring the mail and retail the village gossip, and while the men talked, smoked, and built air castles around their summer gardens, Althea baked, cleaned, and mended. Sometimes she would join them; but more frequently she seized the opportunity to steal off by herself and pursue interests of her own.

She always returned, however, in time to press Lemmy to remain to dinner, which he usually did after having protested there were a hundred reasons why he must immediately return to his shanty.

Thus the winter passed, and with spring all unforeseen came the earthquake that turned peace into chaos and the grey cottage on the Belleport sands into a maelstrom of activity.

Alas for Asaph! Alas, too, for Lemuel Gill!

Out of a sky placid as a noonday in June fell the bolt that left the former man dazed and breathless and the latter murmuring to himself:

“Certainly marriage does lead folks into unexpected byways!”

Of course it was all Althea. But for her it would never have happened. One must, however, be just, and taking the bitter with the sweet concede that had Asaph Holmes never ventured upon matrimonial seas he would have missed immeasurable depths of happiness. Indeed, he himself granted that after having once been blessed with such a wife he looked back on the empty years that preceded his marriage and marvelled how he had even contrived to get on without this peerless woman.

It was not yet a year since the wedding, and in that brief interval Althea had become a prop he could not well have lived without. How capable she was! What a caretaker!

Before her advent he had often been wont, when engrossed in horticultural pursuits or the allurements of a Websterian oration, to become oblivious to the milk bottles, the ice card, or the pan beneath the refrigerator. Now these nagging duties along with a score of others like them Althea had taken into her keeping. She never suffered lapses of memory; never even tied strings round her finger to help her to remember details. Responsibility came so easily to her one felt she could carry in her head ten times the number of things she did, and still not be conscious of having anything on her mind.

Care, on the other hand, nettled her husband. When in addition to weeding and transplanting he had the milk bottles, the ice card and the refrigerator to remember, he veered as close to irritation as his phlegmatic temperament ever approached. This Althea speedily sensed, and after her arrival it took her not more than twenty-four hours to shift from his shoulders to her own all the harassing routine of the household.

She did not, however, make the transfer to the blowing of trumpets. That was the delightful part of it. So quietly was the exchange accomplished that Asaph could not have told the moment when the burden slipped from him. All he was conscious of was his wife’s voice announcing with a finality not to be questioned:

“I will attend to the ice-chest and the other things in future, dear.”

And yet for all her amazing executive ability Althea was very modest. She did not perch herself on a pedestal and from its elevation look down with superiority on her less capable helpmate. In fact it is doubtful whether the idea that she was superior ever occurred to her. She was a proud woman, to whom the bare notion of being linked with an inferior husband would have been unendurable. No, she certainly did not hold Asaph to be lower down the evolutionary ladder than herself. Instead, she evidently considered he maintained the intellectual balance of their union by making up in information with regard to Saturn’s rings, the campaigns of Napoleon, and Webster’s reply to Haine what he lacked in knowledge concerning the catch on the back door or the leak in the shed roof. She was immensely proud of his learning. Not every woman in Belleport was married to a man who could tell offhand the name of the hero who first glimpsed the Pacific. To be sure, Balboa and his discoveries offered no remedy for the door that continually blew open, nor were they of assistance in tarring over the shed roof. Nevertheless as a background they lent dignity to these commonplace phenomena.

When, therefore, such a pillar as Althea casually declared on an afternoon in late May: “I’ve had a letter from Sister Sarah, Asaph, an’ she sounds to be in such a sea of trouble that I’ve decided to go up to Abington an’ straighten her out,” what wonder the blow was more overwhelming than the fall of Sebastopol or the destruction of the Spanish Armada?

Asaph cringed before it in consternation.

Not that Abington was far away. In actual miles it was no great distance off. But it might as well have been at the other end of the world if Althea were to betake herself hither. As Mercutio remarked of his death wound, it would serve.

Deep in his heart Asaph cursed Sarah Tyler. She was constantly foundering into calamities that all but submerged her, and then appealing to Althea to rescue her from them. He did not for the moment appreciate that he himself committed dozens of similar offenses, and if he had he would doubtless have offered the excuse that a husband’s privileges were very different from those of a sister. If he chose to amble into seas of tribulation and then shout to Althea for help he had a perfect right to do so; but Sarah Tyler should keep her troubles to herself.

Possibly had the hapless Sarah been born with a relative less capable she would have pursued this very policy; but to be linked with Althea by ties of blood and aware of her ability was fatal. Why endure the slings and arrows of outrageous fortune when succor so potential was within reach? In every crisis of her life Althea had been her guiding star. Why shift pilots at this late hour? Therefore, if the children had the mumps (and they had a faculty for catching everything within catching distance); if Jabez was out of work; if her taffeta silk had to be made over, Sarah sat down and graphically described on paper the nature of her dilemma; then having gummed her trials up in a pale blue envelope and hurried them into the mail box she sat serenely down to await the magic solution which experience had taught her would surely follow.

Asaph had come to dread the appearance of those blue envelopes. Had he dared, he would have burned them unopened as fast as they arrived. Not possessing this measure of courage he habitually delivered them to his wife with the edged interrogation:

“Well, what’s up with the Tylers now?”

For it was safe to assume something was up. When affairs went prosperously Sarah never wrote at all.

This time a heavier thunderbolt than usual assailed her. Teddie had had a bad fall and his mother must take him to Boston for an X-ray examination. Could Althea come in the meantime and keep house for the family? There was no one else she dared leave the children with. Surely in such an emergency she could be spared, especially as she would not be long away.

Asaph grunted ungraciously. How ready some people were to settle everybody else’s affairs for them! Nevertheless he was a tender-hearted man and of all the Tyler brood Teddie was his favorite. The present catastrophe certainly justified Althea’s being summoned, and under ordinary conditions he would have urged her to go and do what she could. But just now the conditions were not ordinary. Althea herself must realize that. Was it not she who was responsible for them?

Vividly Asaph called to mind the fatal evening when the adventure of the Green Dolphin had first been presented to him. He and his wife had been sitting together in the March twilight, he absorbed in the Bunker Hill oration and she silent over her knitting. The click of her needles and the faraway sobbing of the surf were the only sounds in the room, and he had thought how delightful the stillness was. Often through the winter they had sat thus, and his serenity had been so profound it had not occurred to him that Althea was not finding their wordless companionship as satisfying as did he.

Then suddenly, without warning of any sort, she had burst out:

“I wish to goodness, Asaph, this house stood on the main road!”

Startled not alone by the words, but by an unusual quality in her voice, her husband crashed down from the heights amid which he was soaring.

“W—hat?” stammered he.

“I say,” repeated Althea, “that I wish to mercy we lived on the main road; then there’d be some passin’.”

“It wouldn’t be so quiet,” objected the man uncomprehendingly.

“I don’t want it so quiet,” was the sharp answer. “It’s all very well for you to have it still, readin’ as you do day in an’ day out. But I’d like somethin’ goin on—like to see folks an’ talk to ’em.”

Aghast, Asaph stared.

“Why, Althea, I never dreamed but you were contented enough.”

“I am contented,” returned his wife. “Nevertheless, that doesn’t prevent me from wantin’ to get a look at my kind once in a while, does it? A woman enjoys a bit of gossip an’ an occasional peep at what the rest of the world is doin’.”

“My soul an’ body!” was all her spouse contrived to ejaculate.

“It ain’t no crime as I see,” went on Althea, gaining eloquence now that the subject was fairly launched. “We ain’t all made alike. You could sit in one spot an’ read that talk of Daniel Webster’s till the chair dropped to pieces under you; but I’m different. I like sociability, meetin’ people an’ hearin’ what they have to say. I can put up with a certain amount of quiet; but when it nears spring I begin to long for some sound besides the boomin’ of the sea.”

“My soul!” reiterated Asaph under his breath.

“Now if we were on the main road there’d be folks goin’ by from April till October—Enoch Morton in his fish cart, the butcher, an’ Ephraim Wise with the mail.”

“Humph!”

“They’d be better’n nothin’,” asserted Althea, instantly on the defensive. “Besides, there’d be the summer people—streams of ’em in their automobiles.”

“Precious little good they’d do you, shootin’ by as if the devil was at their heels,” sniffed the man with sarcasm.

“They’d do me good if I was on the main road,” was the significant response.

“I don’t see how.”

“I’d open a tea-room. Other women do it an’ make money hand over fist.”

“But you ain’t in want of money, are you?” inquired her husband, concern evident in his face. “I thought—”

“No, Asaph,” answered Althea more gently. “No, I don’t lack anything. You’ve been very generous an’ given me whatever I needed ever since we were married. ’Tain’t that. It’s just that I’d like the fun of havin’ folks comin’ an’ goin’ here same’s they do over at Mattie Bearse’s Yaller Fish. Why, there’s days when Mattie has much as a dozen or fifteen people at the house drinkin’ tea an’ laughin’, talkin’, an’ havin’ a good time. It’s most like livin’ in a hotel.”

Without intending to, Asaph shuddered.

“Mattie has opened up every room in the house; an’ she’s usin’ her pink lustre china as well as her gold banded set. An’ what do you think? The first day she had the lustre out some lady from the city wanted to buy it right off the table—offered fifty dollars for it an’ would hardly take no for an answer. Of course Mattie didn’t sell it. She told me she was afraid the woman warn’t right in her head to set such a price on that old stuff. Moreover, Mattie warn’t anxious to part with it, it havin’ belonged to her Great-aunt Experience Howland. Still, it was gratifyin’ to have outsiders take a fancy to it. It gave Mattie somethin’ to talk of for days.”

“An’ you’d like to have a parcel of strangers come here an’ try to buy the dishes you were eatin’ off of?”

Althea laughed good-humoredly, showing her strong white teeth.

“Yes, I would,” admitted she without a blush. “It would amuse me same’s readin’ Daniel Webster amuses you. This ain’t the first time I’ve thought of it. All winter I’ve been kinder drawin’ plans in my head as to how I could manage. It’s been most entertainin’. While you were busy with that long history of the Civil War, I’ve been doin’ it.”

Asaph opened his mouth; then uttering only a faint gasp closed it again.

It was incredible that anyone presenting the peaceful appearance Althea had displayed should in the meantime have been engaged in so monstrous a mental mutiny. While in imagination he was marching through the South with Sheridan, he had not thought to question what she was doing. Had he speculated at all on her pursuits he would have rated her as being intent on fashioning socks to ward off the winter’s cold. And all the time her mind had been on teacups, gossips, and silliness! He could scarcely credit her with such frivolity.

“Yes,” continued his wife, shamelessly, “I planned it all out just how we could arrange tables on the screened-in porch, the sittin’-room an’ the dinin’ room. There’d be space enough to do things real tasty.”

As with rapidity she sketched her plans Asaph became wordless before the magnitude of her conception. The screened-in porch—his favorite refuge on a July day! And the sitting room where he always took his afternoon nap! Of course the possibility of these quiet corners being infested by unending tea parties was preposterous, but the thought nevertheless disquieted him.

Meanwhile, mistaking the trend of his silence Althea hastened on:

“There’s quite a few broken chairs in the shed that you could fix up an’ paint—old ladder-backed things that came from Provincetown along with my other stuff. Mattie says folks like ’em an’ they’d save buyin’ more. I’ve figgered that for a hundred dollars, or a hundred an’ fifty at most, we could get all that would be necessary to make a start.”

Spellbound the man listened.

Why, she actually spoke as if the enterprise were a practical scheme and as if she meant to drag him into it with her! The absurdity of it!

“You know I’ve never touched a penny of the money that belonged to Mother,” she went on, “though you’ve urged me times without number to spend it for somethin’ I’d really take pleasure in doin’. Up to the minute I’ve never found the thing I wanted to use it for. But now I’ve decided I’d like to lay out part of it startin’ the Green Dolphin.”

“The—the—what?”

“The Green Dolphin,” repeated Althea, impatient at his stupidity. “A tea-room has to have a name, you know. They all do. Mattie’s is the Yaller Fish an’ the one over at Sawyer’s Falls is the Blue Whale.”

“An’ darn silly names they are,” retorted Asaph, his scientific mind offended by the inaccuracy of the terms and his irritation accumulating. “There ain’t any such thing as a blue whale.”

“That’s just it!” agreed the undaunted Althea. “Of course there ain’t. But that’s no hinderance. Folks like queer names. The queerer they are the better. They attract attention.”

“An’ you think a Green Dolphin would catch people’s eyes?”

“Yes, I do,” nodded his wife with spirit. “The very sound of one would set me wonderin’; wouldn’t it you? We’d have to do more, though, than just call the place that. We’d have to have a carved dolphin over the door an’ mebbe one in the front yard.”