[Pg i]

[Pg ii]

[Pg iii]

THE SECRETS

OF

STAGE CONJURING

By ROBERT-HOUDIN

TRANSLATED AND EDITED, WITH NOTES

BY

PROFESSOR HOFFMANN

AUTHOR OF “MODERN MAGIC.”

WITH ILLUSTRATIONS

LONDON

GEORGE ROUTLEDGE AND SONS, Limited

BROADWAY, LUDGATE HILL

1900.

[Pg iv]

[Pg v]

TO THE ORIGINAL EDITION.

In the volume published by Robert-Houdin under the title of Les Secrets de la Prestidigitation et de la Magie,[1] the author expressed his intention of issuing at an early date a sequel to that work. Death unhappily prevented his carrying his design into execution; but he left behind him materials sufficient, if not, as he had wished, for an exhaustive treatise on the art of conjuring, at least for the compilation of a new work of a highly interesting character.

It is this posthumous work which is now offered to the public. Not only is it both [Pg vi]instructive and amusing, as revealing the curious secrets of the professional wizard, but, further, with the aid of the diagrams with which the text is illustrated, it will enable the hitherto uninitiated to repeat on their own account those experiments which Robert-Houdin modestly describes as “tricks,” but which are in reality marvellous applications of mechanical and physical science, worthy in many instances of the genius of a Vaucanson.

[Pg vii]

[1] An English version of the above extremely interesting work, by the present translator, is published by Messrs. George Routledge and Sons, under the title of “The Secrets of Conjuring and Magic.”

[Pg 9]

THE SECRETS

OF

STAGE CONJURING

Before I proceed to the practical discussion of my subject, it may be as well perhaps to give a few particulars concerning the theatre founded by me under the title of the Théâtre des Soirées Fantastiques de Robert-Houdin,[3] in which I exhibited, during a long series of years, the majority of the illusions which I am about to describe in this book. And I fancy it may be agreeable to the reader if I prelude my description by an anecdote whose details (if I may judge from the effect which its mere recollection, after twenty years’ interval, produces on myself) cannot fail to excite his lively interest.

[Pg 10]

I have related in my Confidences[4] how from a mechanician I had developed into a conjuror; but I was not then at liberty, from reasons which will presently appear, to state the singular circumstance to which I am indebted for having been enabled to build my theatre with pecuniary resources much more limited than such an undertaking would ordinarily demand. I may now speak freely upon the subject, and shall do so with the greater pleasure that I am thereby afforded an opportunity of paying a grateful tribute to one whose noble nature and delicate generosity the following narrative will illustrate. This exordium will further serve as a dedication [Pg 11]to the memory of my deeply regretted benefactor and friend.

In 1843, when I was as yet only a clockmaker and constructor of mechanical curiosities, I chanced to sell a chronometer-clock to the Count de l’Escalopier. This clock, to which I had devoted special attention, was the cause of my noble client paying me sundry visits in order to express his satisfaction with its performance. I had some reason to think, however, that my customer, who was passionately devoted to the arts in general, and to mechanics in particular, was rather glad to avail himself of the excuse of offering a fairly-earned compliment to the mechanician, in order to pay me an occasional call. He was sure to find, at each visit, some new curiosity in course of construction, and he used, without ceremony, to take his seat beside my workbench in order to watch me at work.

At the date I speak of, as I have elsewhere mentioned, while employed with my workpeople in the production of articles of a saleable character, I was engaged in the fabrication of sundry [Pg 12]mechanical pieces destined to figure, though possibly at a very remote date, in the public performances which I intended some day to give.

A kind of intimacy having thus become established between M. de l’Escalopier and myself, I was naturally led to talk to him of my projects of appearing in public; and, in order to justify them, I had given him, on more than one occasion, specimens of my skill in sleight-of-hand. Prompted doubtless by his friendly feelings, my spectator steadily applauded me, and gave me the warmest encouragement to put my schemes into actual practice. Count de l’Escalopier, who was the possessor of a considerable fortune, lived in one of those splendid houses which surround the square which has been called Royale, or des Vosges, according to the colour of the flag of our masters of the time being. I myself lived in a humble lodging in the Rue de Vendôme, in the Marais, but the wide disproportion in the style of our respective dwelling-places did not prevent the nobleman [Pg 13]and the artist from addressing each other as “my dear neighbour,” or sometimes even as “my dear friend.”

My neighbour then being, as I have just stated, warmly interested in my projects, was constantly talking of them; and in order to give me opportunities of practice in my future profession, and to enable me to acquire that confidence in which I was then wanting, he frequently invited me to pass the evening in the company of a few friends of his own, whom I was delighted to amuse with my feats of dexterity. It was after a dinner given by M. de l’Escalopier to the Archbishop of Paris,[5] with whom he was on intimate terms, that I had the honour of being presented to the reverend prelate as a mechanician and future magician, and that I performed before him a selection of the best of my experiments.

At that period—I don’t say it in order to gratify a retrospective vanity—my skill in sleight-of-hand was of a high order. I am warranted in [Pg 14]this belief by the fact that my numerous audience exhibited the greatest wonderment at my performance, and that the Archbishop himself paid me, in his own handwriting, a compliment which I cannot refrain from here relating.

I had reserved for the last item of my programme a trick which, to use a familiar expression, I had at my fingers’ ends. In effect it was shortly as follows:—After having requested the spectators carefully to examine a large envelope sealed on all sides, I had handed it to the Archbishop’s Grand Vicar, begging him to keep it in his own possession. Next, handing to the prelate himself a small slip of paper, I requested him to write thereon, secretly, a sentence, or whatever he might choose to think of; the paper was then folded in four, and (apparently) burnt. But scarcely was it consumed and the ashes scattered to the winds, than, handing the envelope to the Archbishop, I requested him to open it The first envelope being removed a second was found, sealed in like manner; then another, until a dozen envelopes, one inside another, had been [Pg 15]opened, the last containing the scrap of paper restored intact. It was passed from hand to hand, and each read as follows:—

“Though I do not claim to be a prophet, I venture to predict, sir, that you will achieve brilliant success in your future career.”

I begged Monseigneur Affre’s permission to keep the autograph in question, which he very graciously gave me.[6]

After the evening above mentioned, M. de l’Escalopier never ceased urging me to “strike the decisive blow,” as he called it, and was frequently quite importunate upon the subject. In answer to these friendly solicitations I urged the non-completion of certain indispensable apparatus, which, however, was not the precise truth. The real cause of my successive delays was the inadequacy of my pecuniary resources.

[Pg 16]

Whether rightly or wrongly, I was too proud to admit the fact, trusting that hard work would sooner or later bring me to the desired goal. However, one day, being driven into a corner over our often repeated discussion, I was compelled to make a half admission of the truth.

“The very thing,” said the Count, in the heartiest manner possible; “I have at home, at this very moment, ten thousand francs or so, which I really don’t know what to do with. Do me the favour to borrow them for an indefinite period; you will be doing me an actual service.”

I was wholly unprepared for this generous offer, and declined it. Why I did so I scarcely know, save that I hesitated to risk the interests of a friend beforehand in the uncertainties of my speculation. M. de l’Escalopier tried various arguments to conquer my scruples, the cause of which he rightly conjectured; not succeeding, he left me, evidently somewhat annoyed.

It was some time before I saw him again, to my great regret—for I must own that his visits, which had till then been very regular, gave [Pg 17]me much pleasure, and afforded an excitement which greatly aided my labours; in fact, my noble neighbour had become indispensable to me; and I had all but made up my mind to go and look for him when, one afternoon, he made his appearance at my workshop. He looked greatly disturbed, and appeared to be labouring under some strong emotion.

“My dear neighbour,” he said, as he came in, “since you are resolved not to accept a favour from me, I have now come to beg one of you. This is the state of the case. My mother, my wife, and myself are threatened with a serious danger—I may say with a frightful calamity. This misfortune you may be able to guard us against. Listen, and judge for yourself. For the last year my desk has been robbed from time to time of very considerable sums of money. Not knowing who was the culprit, I have sent away my servants, one after another. I have adopted all possible kinds of safeguards and precautions—having the place watched, changing the locks, secret fastenings to the [Pg 18]doors, etc.—but none of these has foiled the villainous ingenuity of the thief. This very morning, I have just discovered that a couple of thousand-franc notes have disappeared. Only imagine,” added the Count, “what a frightful position the whole family is placed in; the robber, whoever he may be, judging by the cool audacity he has displayed, would be likely enough, if caught in the fact, to murder one or more of us in order to effect his escape. Do, pray, suggest, without delay, some means of discovering, and, if possible, catching this rascally thief.”

“Count,” I replied, “you know that my magic power, unfortunately, only extends to the tips of my fingers, and, in the present instance, I really don’t see how I can help you.”

“You don’t see how you can help us!” replied the Count. “Surely, you have a mighty aid in mechanics!”

“Mechanics! Stop a bit. You have given me an idea. I remember, in truth, that when I was a boy at school, I did, by the aid of a rather [Pg 19]primitive contrivance, find out a rascal who was in the habit of stealing my boyish possessions. Improving on the same idea, perhaps I may be able to contrive some new trap for the robber. Let me think the matter over, and to-morrow you shall hear the result.”

When I was left alone, urged on by that feverish excitement which an inventor can provoke at will, I had speedily found an answer to the problem propounded to me. I at once made a sketch of my intended contrivance, and set to work without delay, assisted by two of my workmen, who remained with me the whole of the night. At eight o’clock in the morning the apparatus was finished, and ready to be fixed.

M. de l’Escalopier, to whom I forthwith went, had been beforehand cautioned by a line from me, and had, under various pretexts, sent all his servants away from the house, so that no one should be aware of our visit.

While I was placing the apparatus in position, the Count, who did not know how it was [Pg 20]intended to operate, repeatedly expressed his surprise at seeing my right hand covered by a very thick padded glove. I would not, however, explain the secret until my arrangements were completely finished.

“Look,” I said, after I had closed the desk, “let us suppose that I am the robber. I put the key in the lock. I turn it as carefully as possible; but scarcely is the lid ever so little open, when—” here the report of a pistol was heard, and on the back of my glove, printed in indelible characters, appeared the word “Robber.”

Wishing to explain to the Count the effect which had been thus produced—

“The report of the pistol,” I said, “is to give the alarm, and summon you to the spot, in whatever part of the house you may chance to be. In the next place, you observe, as soon as the opening of the desk allows sufficient space, this claw-like apparatus, attached to a light rod and impelled by a spring, comes smartly down on the back of the hand which holds the key. The [Pg 21]‘claw’ is, in truth, a mere tattooing instrument; it consists of a number of very short but sharp points, so arranged as to form the word ROBBER. These points are brought through a pad impregnated with nitrate of silver, a portion of which is forced by the blow into the punctures, and makes the scars indelible for life.”

Upon hearing my explanation, M. de l’Escalopier looked very grave, not to say shocked.

“Good Heavens! my dear friend, that would be a fearful thing to do. Justice alone has the right to brand a criminal. Such an indelible mark, which the poor wretch could only get rid of by a horrible self-mutilation, would be but too likely, by classing him permanently among the enemies of society, to close the door of repentance to him altogether. Such a course would be inhuman, indeed, unjust. And besides,” he added, with a look of horror, “might it not happen that, through carelessness, forgetfulness, or some fatal mistake, one of our own people was the victim of our stern precautions; and then——”

[Pg 22]

I had, however, at the very first words of the Count perceived the justice of his apprehensions, and interrupting him—

“You are quite right,” I said, “I had not thought of those objections; but there is no harm done. I only ask an hour or two to make such an alteration in the apparatus as shall leave you nothing either to fear or to wish for.”

I hastened to shut myself up again in my workshop, and before the close of the day I had taken back the instrument in an altered form. In place of the branding apparatus, I had inserted a kind of cat’s-claw, which would make a slight scratch on the hand, a mere surface wound, capable of being easily cured. We closed the desk, and my neighbour and myself parted company, to wait further events.

In order to stimulate the cupidity of the robber, M. de l’Escalopier sent more than once for his stockbroker—money was ostentatiously passed from hand to hand—a pretence was made of going away from home, of a trip to a short distance, and complete absence of the [Pg 23]heads of the family. But the bait was a failure, for a week passed without any result whatever. The Count, who came to see me each morning, invariably saluted me with the same words, “Nothing as yet.”

The l’Escalopier household almost began to believe in the supernatural. For my own part, I racked my brains in vain to imagine the cause of my ill success.

We had reached the sixteenth day of waiting, and I had at last made up my mind not to bother myself any more about the affair, when, early in the morning, M. de l’Escalopier suddenly made his appearance, looking much excited.

“We have caught the thief at last,” he said, wiping his forehead, like a man who has just finished some laborious task; but before I tell you who he proves to be, I will relate exactly what has happened. I was this morning in my library, which, as you know, is some distance from my sleeping-room, when I heard a loud ‘bang.’ Recognizing at once the report of our [Pg 24]‘trap,’ but having no weapon at hand, I snatched up a battle-axe from a stand of armour, and ran to seize the robber. In the hurry of the moment, I acted, perhaps, rather rashly, for I had not the least notion what sort of adversary I might have to tackle, and my rather primitive weapon might have been but a scant protection. However, when I reached the spot, I pushed the door vigorously, and rushed boldly in. Imagine my astonishment, when I found myself face to face with Bernard,[7] my confidential servant, my factotum, I might almost say my friend—a man whom I have treated in the most familiar way for over twenty years. Completely bewildered, scarcely believing my own eyes, and not knowing what to think,—‘What Bernard,’ I stammered, ‘what was that noise, and how do you come to be just now in my room?’

“‘That is easily explained, Count,’ replied Bernard, in the coolest manner possible. ‘I came, as you yourself have done, at the sound [Pg 25]of the explosion, and as I got here, I saw a man just making his escape down the back stairs. I was so alarmed, that I hadn’t the power to follow him. He must be out of the house by this time.’

“Without a moment’s thought, I ran down to the foot of the staircase which he indicated. But the door was locked, and the key inside. A frightful thought struck me. Could Bernard himself be the culprit? I retrace my footsteps, and now the truth is evident, unpleasant though it be. I notice that Bernard keeps his right hand behind him. I drag it forcibly in sight, and showing the blood with which it is covered—

“‘Wretched man!’ I exclaim, flinging him from me with disgust, ‘there is the witness of your crime!’

“The rascal, who, up to the latest moment, had tried to keep up the deception, now threw himself at my feet, begging for mercy. I turned a deaf ear, and left him, taking care, however, to place him under lock and key first.

[Pg 26]

“You know,” added the Count, “my worthy doctor, G——; he is a man whose advice is always worth having. I hurried off in search of him, and told him what had taken place. After having discussed over the best course to adopt, we returned to my house.

“‘Now, then,’ I said sternly to Bernard, ‘how long have you been robbing me?’

“‘For nearly two years.’

“‘And how much have you taken, pray?’

“‘I cannot tell exactly. Perhaps 15,000 francs, or thereabouts.’

“‘We will call it 15,000 francs,’ I replied, ‘I will make you a present of the rest, for I have no doubt you are deceiving me still. And what have you done with the money?’

“‘I have invested it in Government Stock. The scrip is in my desk.’

“‘We took him to his room, where he handed over to us scrip equivalent to the amount which he admitted having robbed me of; after which, I made him write, then [Pg 27]and there, a declaration in the terms following:—

“‘I, the undersigned, hereby admit having stolen from the Count de l’Escalopier the sum of 15,000 francs, taken by me from his desk by the aid of false keys.

“‘Bernard X——.

“‘Paris, the — day of —, 18—.’

“Lastly, the doctor, addressing the culprit, said, sternly—

“‘It is to your own interest, beginning from to-day, to return to a life of honesty, and thereby to endeavour to redeem your shameful past; if otherwise, this document, which will remain in my hands, shall be handed over to the proper authorities, and you will be called upon to supply in a criminal court the details of this confession. Now, be off with you, and remember that you are forbidden ever to enter this house again.’”

[Pg 28]

(I may here mention that Bernard died the following year, and his former master, only too ready to forgive, shed a tear to his memory, telling me that he felt certain that the weight of his remorse had killed him.)

Having concluded his story, M. de l’Escalopier drew from his pocket a pocket-book, took from it some folded papers, and handing them to me with delightful cordiality—

“I do hope, my dear friend,” he said, “that you will no longer refuse me the pleasure of lending you this sum, which I owe entirely to your ingenuity and mechanical skill; take it, return it to me just when you like, with the understanding that it is only to be repaid out of the profits of your theatre.”

At this generous offer I was fairly overcome by emotion, and I remained for some moments without being able to get out a single word. At last, controlling myself by an effort, I rose, and flinging my arms round the neck of my noble-hearted friend—

“Etiquette be hanged!” I said; “you must [Pg 29]really let me embrace you for your generous kindness.”

This embrace was the only security which M. de l’Escalopier would accept from me.[8]

Thanks to this augmentation of my finances, I was able to give immediate effect to my architectural intentions, and without further delay I built, in the Palais Royal, a theatre whose interior and surroundings I propose briefly to describe.

The galleries which surround the garden of the Palais Royal are divided into successive arches, occupied by shops which are, with reason, reputed to contain the richest, most elegant, and most tasteful wares that Paris can boast. Above these arches there are, on the first floor, spacious suites of apartments, used as public assembly rooms, clubs, cafés, restaurants, etc. It was in the space occupied by one of these suites, at No. 164 of the Rue de Valois, that I [Pg 30]built my theatre, which extended, in width over three of the above mentioned arches; and in length the distance between the garden of the Palais Royal and the Rue de Valois, or, in other words, the whole depth of the building. The dimensions of my exhibition-room were therefore, as will be seen, very limited; a couple of hundred persons could barely be accommodated therein; it should, however, be mentioned that the benches were comfortably divided into separate seats. Though the seats were few in number, their prices were tolerably high, which made up for their scarcity, so far as my interests were concerned. The reader may judge by the table following—

Children were paid for as grown persons.

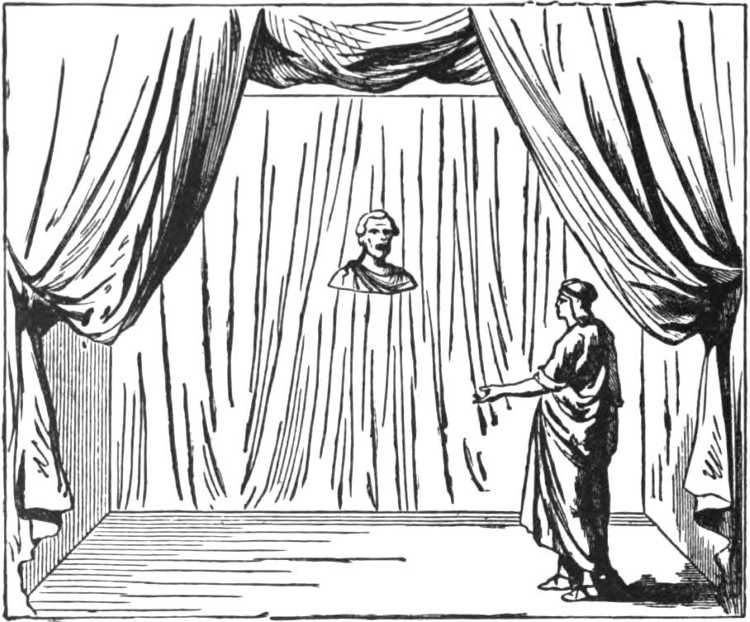

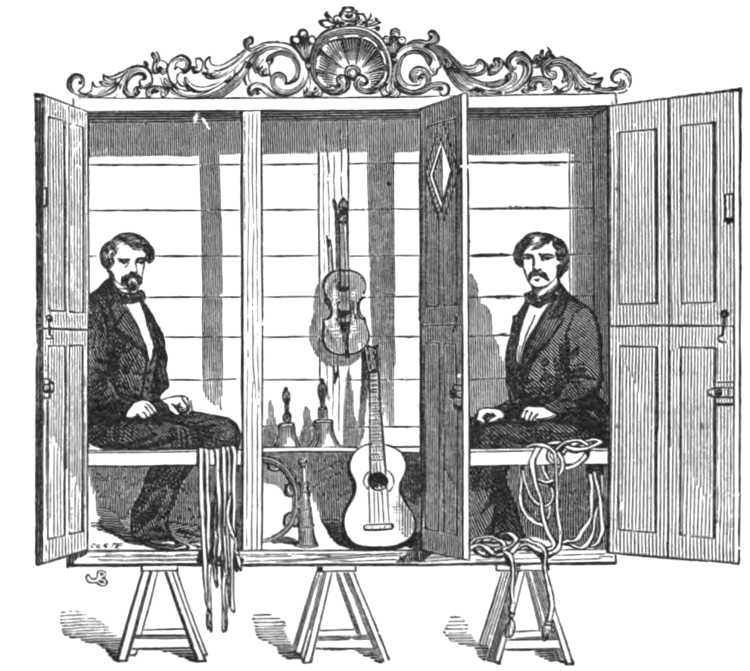

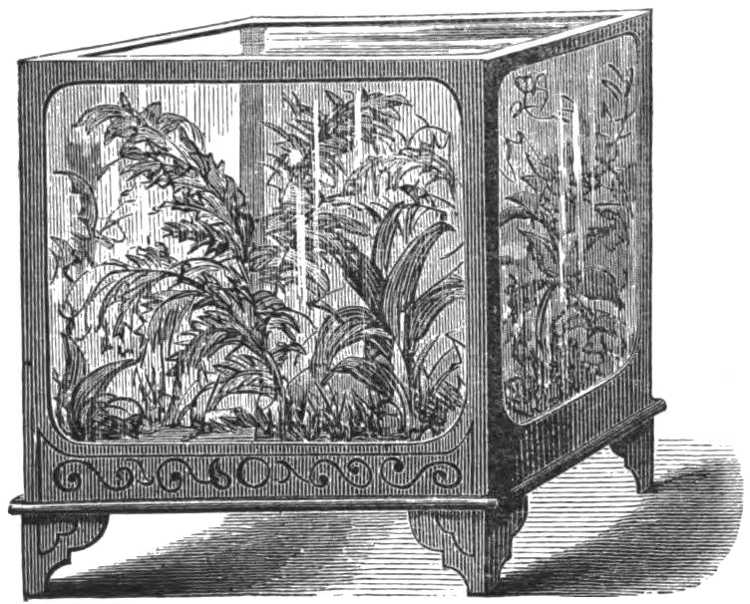

At the outset, the portion known as the amphitheatre was called the “pit,” which in [Pg 31]truth it was. But, later on, perceiving that many people were shy of occupying seats so described, I had recourse to an euphemism, and employed the word “amphitheatre,” to designate the seats in question. The alteration answered very well indeed, for among the occupants of these seats there was a large proportion of ladies. My stage was small, but in due proportion to the size of the auditorium; [Pg 32]it represented a sort of miniature drawing-room of the Louis XV. period, in white and gold, furnished solely with what was absolutely necessary for the purpose of my performance. There were a centre table, two consoles, and two small guéridons;[9] a broad shelf, in the same style, extended right across the back of the stage, on this I placed articles intended for use in my performance. The flooring was covered with an elegant carpet. On each side of the stage, right and left, was a pair of folding doors, the width of opening thereby created being necessary to allow of the passage of my mechanical pieces. The accompanying sketch (Fig. 1) will render my explanation complete.

The door on the right of the stage led to a room, in which, in the evening, I made my preliminary preparations for my tricks, and which, in the morning, served as my workshop. A large window, looking out over the [Pg 33]garden of the Palais Royal, made this a very pleasant room, and it was here that I contrived the greater number of the tricks which I am about to describe.

[2] In the original a chapter entitled “Introduction dans la demeure de l’Auteur” is here introduced, but being merely a reprint of a similar chapter in Les Secrets de la Prestidigitation et de la Magie, which has been already translated in our English version of that work, it is not here repeated.—Ed.

[3] The public materially shortened the above title, Théâtre Robert-Houdin now fully indicating both the place and the nature of the performance.—R.-H.

[4] Les Confidences d’un Prestidigitateur, the title under which Robert-Houdin wrote his autobiography.—Ed.

[5] Monseigneur Affre, killed at the barricades in 1849.—R.-H.

[6] This slip of paper I preserved as a religious relic. I kept it in a secret corner of a pocket-book which I always carried about my person. During my travels in Algeria I had the misfortune to lose both this pocket-book and the precious object which it contained.—R.-H.

[7] I change the name, for obvious reasons.—R.-H.

[8] The singular favour with which my performances were received by the public, enabled me to repay my generous creditor within a year after the opening of my theatre.—R.-H.

[Pg 34]

[9] Small round tables.

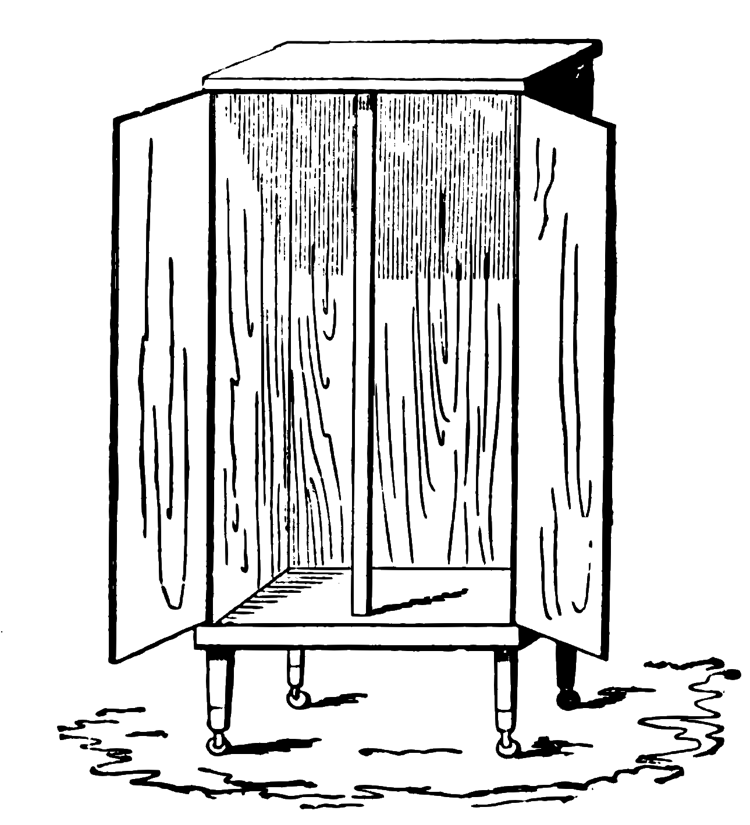

The furniture of a conjuror’s stage is not merely designed to please the eye of the spectator, but serves, in addition, to facilitate the execution of many of his marvels. The tables, in particular, have important duties to discharge, for by their aid is generally effected the appearance or disappearance of articles too bulky to be concealed in the hands or the pockets of the performer.

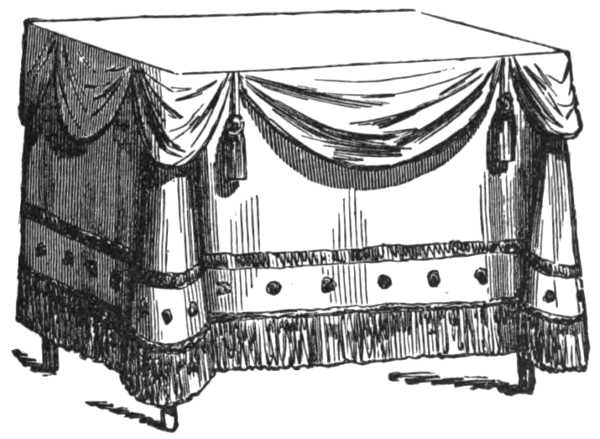

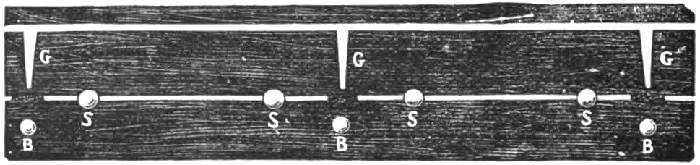

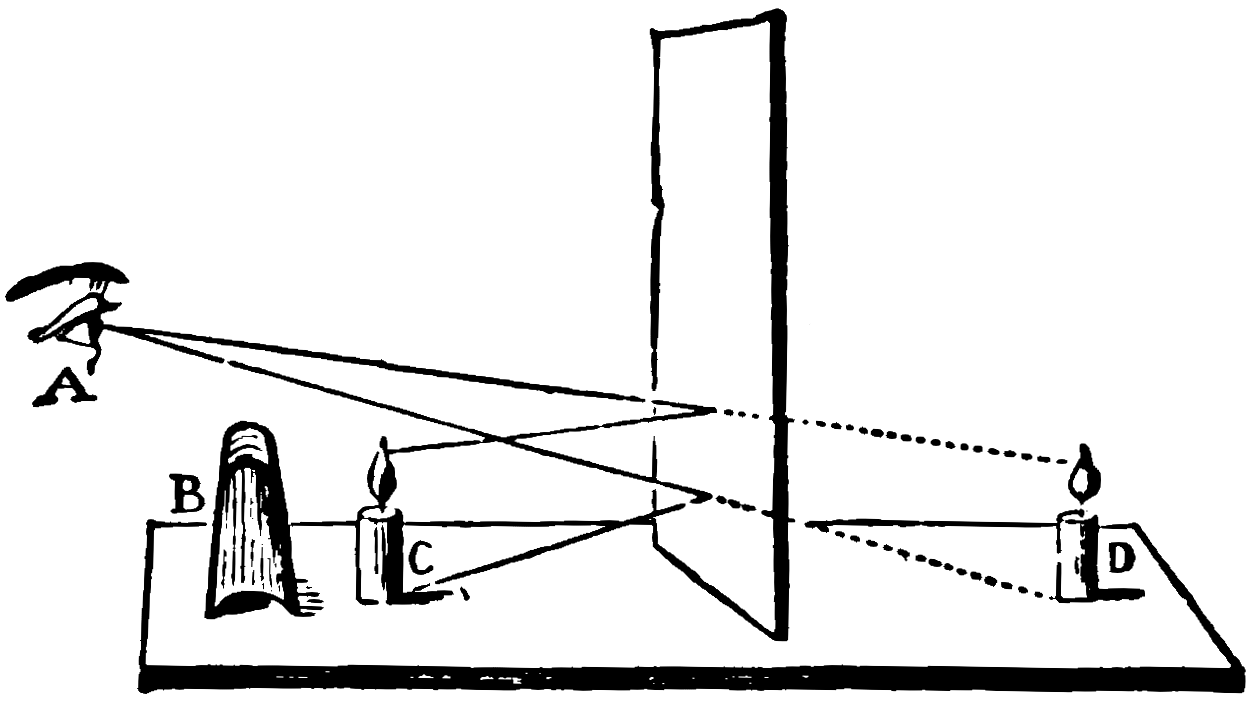

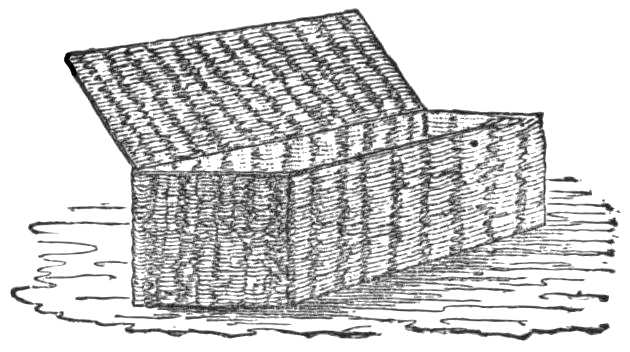

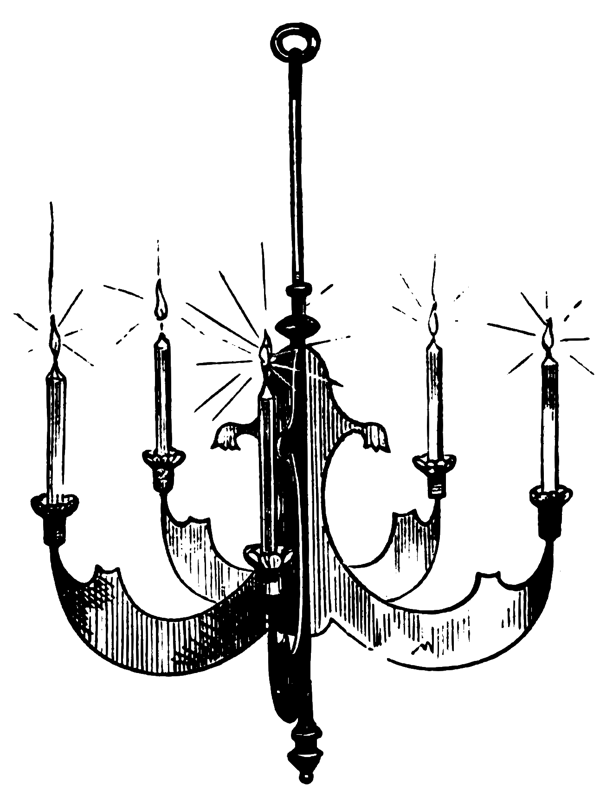

The conjurors of the old school[10] derived great assistance in this particular even from the ornamentation of their tables. These were covered with richly-embroidered cloths, [Pg 35]extending downwards to the floor, as shown in the accompanying figure (Fig. 2).

It was not uncommon to see four or five of these tables on the stage, and sometimes even more. In order to mislead the spectator as to their real purpose, they were loaded with candlesticks and other articles, ostensibly intended to be used for the purposes of the performance.

In the background, the principal object, extending quite from side to side, was a kind of sideboard composed of several stages, one above the other, also loaded with pieces of [Pg 36]apparatus made of polished brass, which, however, generally speaking, had no connection whatever with conjuring.

This miscellaneous but showy collection was rendered still more dazzling by a considerable number of lamps and wax candles.[11] This gorgeous exhibition, which the conjuror of that day denominated pallas,[12] was simply intended, to use a homely phrase, to throw dust in the eyes of the spectators.

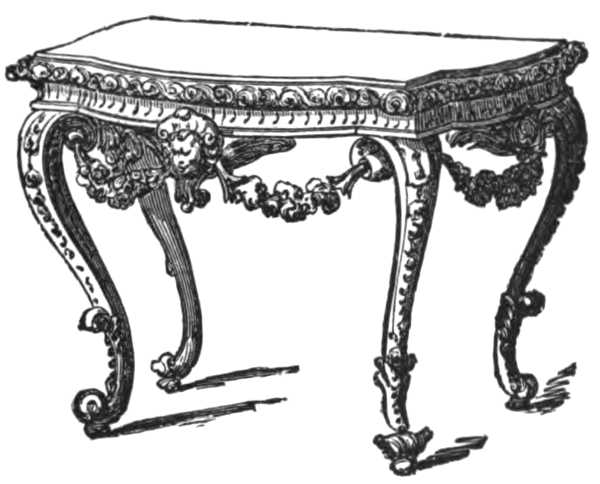

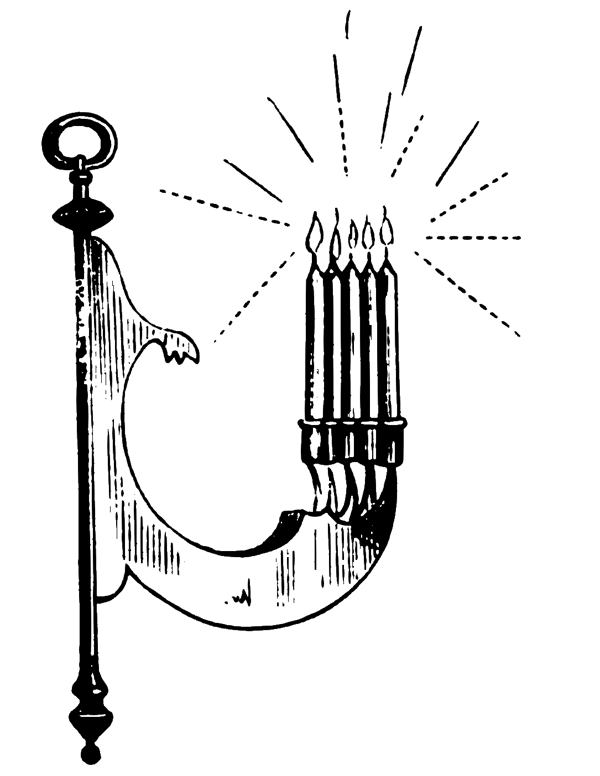

When, in the year 1844, I undertook the erection of my own theatre, I made very considerable alterations in my stage arrangements, as compared with those of my predecessors. The most important was the suppression of the long table-covers, under which the public always suspected, and not without reason, the presence of an assistant to facilitate the execution of the tricks performed. For these bulky “confederate-boxes,” I substituted gilt tables and consoles in the Louis XV. style, of which I subjoin a specimen (Fig. 3).

[Pg 37]

The number of these latter was very limited: a centre table (that represented by the figure), two side consoles, and two small light guéridons. At the back a broad shelf in the same style, on which were arranged the pieces of apparatus intended to be used in my performance.[13] Those [Pg 38]enormous metal covers, polished or japanned, under which articles to be vanished had hitherto been put, were no longer to be seen. I had replaced them with covers of glass, opaque or transparent, as the case might be. Boxes with false bottoms, and all apparatus of polished brass or tin, were completely banished from my stage.

The decoration of my miniature drawing-room was of white and gold. The visible lighting arrangements consisted simply of four girandoles, and two small candelabra of crystal, placed on my centre table. But in order that my audience might have a perfect view of the smallest details of my experiments, I had fitted my stage with special appliances, which gave a sufficiency of light without hurting the eyes of the spectators. For this purpose, I had fixed just behind the proscenium-border[14] a gas string-light,[15] with a reflector, which brightly illuminated my centre table and my two consoles, the only spots at which my feats of magic were executed.

[Pg 39]

The reforms which I had introduced in the form and ornamentation of the “tables” did not by any means render them less valuable than their predecessors for conjuring purposes, as the reader may judge by the following details:—

As I have already stated, there were on my stage but three tables—one in the centre and two at the sides; these last, which were in the form of consoles, were fixed to the panelling of the side-scene. I had also two little guéridons,[16] of the lightest possible description, which I brought forward, as occasion demanded, to the front of the stage, for any experiment which required close proximity to the spectators.

[Pg 40]

The majority of my tricks were performed at my centre table. The only specialities of this table were a servante, with its gibecière, and a set of “pistons.” I have already described in a preceding work, and illustrated by a diagram[17] the arrangement and utility of the servante. It is a shelf (behind the table on the side farthest away from the spectators) on which are placed the articles destined to be produced in the course of the performance. In the middle is placed a small square box (the gibecière) made of cloth padded with wadding, and quilted so as to give it a certain degree of stiffness. Its use is to receive noiselessly any article dropped therein.[18]

[Pg 41]

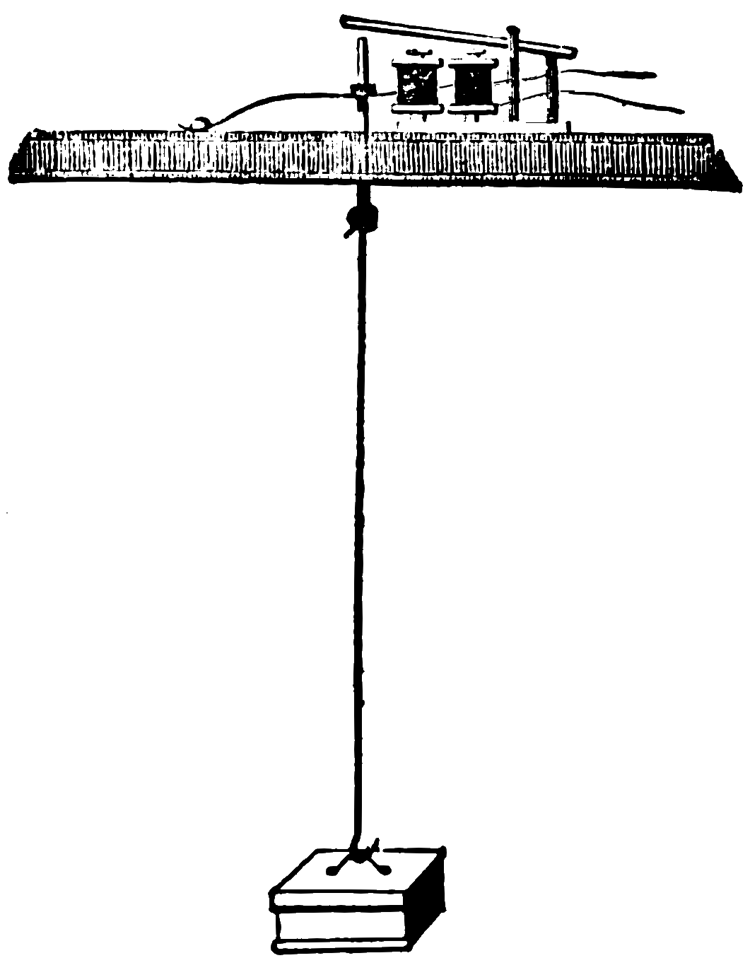

The set of pistons, which is fitted to the under surface of the table, serves to work the [Pg 42]automata and mechanical pieces exhibited to the spectators. These automata being supposed to obey the word of command, it is necessary that their mechanical intelligence should be guided by an assistant, and this result is obtained by the use of pistons.

A piston is a group of three steel rods; two of them are fixed, and form what in mechanical parlance is termed a cage, the third is movable, and may be made, by pulling the string attached to it, to rise above the other two. A spring placed beneath, serves to bring the rod down again as soon as the string is released.

When several of these pistons are placed side by side in a straight line, they form what is known as a set of pistons. Supposing that, [Pg 43]as in the case of my own table, the set is composed of ten pistons; the ten cords will travel right and left (over pulleys) down the legs of the table, and passing under the floor of the stage, will terminate at a “key-board,” to which they are attached in the same order which they occupy in the table.

When the piston-rods rise above the surface of the table, they come in contact with corresponding pedals in the base of the mechanical piece; which pedals move, as the case may be, the arm, the head, or any other part of the automaton, or whatever the apparatus may be.

The side tables, or consoles, fixed to the panels of the side-scene are furnished with various traps, specially adapted for different tricks. An opening made in the side-scene, immediately behind the console, enables the assistant to introduce his arm for the performance of whatever duty may devolve upon him. The under surface of the consoles forms a closed case, so that articles passed through the traps cannot fall on the floor. This case, which is [Pg 44]about seven inches deep, is concealed by the ornamental work of the table, and the gold fringe which surrounds its edges.

Besides these tables, which are intended for the general requirements of the performance, there are others specially designed for some one special trick, and which are placed on the stage as they happen to be needed. We may instance that which serves to vanish a human being, and which we shall describe later on, when we come to deal with the trick in question.[19]

The conjuror’s servant fills on the stage a like office to that which is discharged by the assistant of a lecturer on chemistry or natural science; it is his duty to provide the operator with all that is needed for the performance of his experiments, and not unfrequently he gives his personal assistance, unknown to the spectators, in aid of some particular trick. The [Pg 45]costume of the servant is a matter of taste, but he should be of smaller stature than the conjuror, so as not to draw too much attention to himself; a young lad answers the purpose very well. I used to be assisted on the stage by one of my sons, who wore the dress which the fashion of the day rendered appropriate to his age, who at that time (in 1844) was thirteen.

There is a second servant, of whose existence the spectators know nothing. This is the alter ego of the conjuror, the invisible hand which really effects sundry appearances, disappearances, and substitutions, of which magic has the credit. This servant remains behind the scenes, eye and ear constantly on the alert; and at certain moments, duly arranged beforehand, he lends a hand in ready aid of the skill and the “patter” of the principal performer. The due discharge of this office demands great dexterity, constant watchfulness, and, above all, instant readiness in execution. Women perform this duty to perfection.

[10] As, for example, Conus, Bosco, and Philippe, to name those only of whom many of the present generation will retain a recollection.—R.-H.

[11] Philippe may claim the credit of having reached the highest pitch of extravagance in these dazzling exhibitions; he used not less than five hundred wax candles on his stage.—R.-H.

[12] It was formerly a common thing, in speaking of a rich and showy mise en scène, to say, “C’est très pallaseux.”—R.-H.

[13] I should state that the other members of the profession quickly adopted these modifications, always excepting, however, Bosco the elder, who, to his latest hour, would give up neither his short sleeves nor his long table-covers.—R.-H.

[14] This is the term applied to the festooned drapery behind which the curtain is hidden when drawn up.—R.-H.

[15] A “string-” or “border-light,” in theatrical parlance, is a long gas-pipe, to which are fitted, at very short distances apart, fish-tail burners, forming a kind of ribbon of light the whole length of the stage.—R.-H.

[16] Small round stands or tables. See Fig. 1.—Ed.

[17] See “The Secrets of Conjuring and Magic,” p. 284

[18] For a detailed description of conjuring tables, and the various mechanical arrangements connected therewith, see “Modern Magic,” pp. 437 et seq. An improved table, not there noticed, is known as the “Lynn” table, after the well known professor who first used it in public, and claims to divide with a certain noble amateur the honour of its invention. Its speciality is that, by an ingenious mechanical arrangement, both back and front may be shown without suggesting the presence of a servante, and that to further prove its innocence of mechanism, a drawer, apparently occupying the whole body of the table, may be taken completely out, shown empty, and replaced, though the interior of the table is, in fact, fully “loaded” with the requirements of the performance. The table in question has been further improved, in certain details of construction, by Mr. Bland, of New Oxford Street, a leading manufacturer of magical apparatus, and in its final shape forms as perfect a conjuring table as any performer could desire.

We are indebted to Mr. Bland, above named, for the opportunity of examining a “magic chair,” which possesses many of the advantages of a mechanical table, in addition to sundry special faculties of its own. In appearance it is a handsome drawing-room chair, with a figured cloth seat and open back. In the first place, the upright centre rail of the back revolves, and so discloses a borrowed watch, after the manner of the Watch Target (see “Modern Magic,” p. 200). At the back of the top rail is a cunningly-devised apparatus for instantaneously producing three cards, which, by an ingenious arrangement, are made to fold down behind the back till wanted (in which condition they are quite invisible). At the word of the performer, they spring up above the top rail, at the same time spreading fanwise, the marvel being where they could possibly have been concealed.

The production of the cards and watch, as above, is effected by a single string, pulled by the assistant behind the scenes, and which may, at the pleasure of the performer, be made to produce either the cards only, the watch only, or both together. The seat of the chair contains a piston for working mechanical pieces, the same string already mentioned being made by an instantaneously effected alteration, to perform this duty also. Two other strings serve to actuate an elaborate mechanical trap in the seat, producing a succession of startling changes: while the hinder part of the seat, which is open on the side remote from the spectators, serves at need as a receptacle for a bowl of gold-fish, or any other article the performer may desire to produce or get rid of.—Ed.

[Pg 46]

[19] This intention was never carried into effect by Robert-Houdin. For a brief description of a similar table, see “Modern Magic,” p. 449.—Ed.

Among the articles which the spectators are in the habit of entrusting to conjurors for the execution of their tricks, handkerchiefs, both silk and cambric, play a prominent part.

I propose to give, in due course, a description of the various tricks in which handkerchiefs are specially concerned, such as the Orange Tree, the Handkerchief Cut up and Restored, the Instantaneous Combustion, etc.[20]

[Pg 47]

Here is, meanwhile, a pretty little trick (as yet unpublished) performed with a handkerchief, and which I used at my séances as a kind [Pg 48]of interlude. I can recommend it as producing a very great effect.

[Pg 49]

The Handkerchief which Vanishes in the Hand.—“The magicians of old,” you remark, “were not subject to any of the minor inconveniences of life. They felt neither cold, hunger, nor thirst, so long as they were engaged in their mystic rites. Their close relations, however, with the fiery potentates of another sphere exposed them pretty frequently to a very high temperature, the effect of which showed itself in copious perspiration.

“The wizards, thus playing with fire, were much troubled by water, which streamed from their countenances; but they removed it by wiping their faces with their handkerchiefs, just as ordinary mortals do.

“One of their number, who, I suppose, found this troublesome, hit upon a curious expedient for shortening the task of drying himself; he [Pg 50]caused his handkerchief, after having discharged its duty, to go back of its own accord into his pocket. I have discovered the secret of his cabalistic process, and, if agreeable to yourselves, I will repeat it in your presence.

“Let us suppose that, for the reasons I have suggested, I find it necessary to wipe my brow. I take my handkerchief from my pocket for that purpose. Here it is, you see.”

You wipe your forehead, and gently fan yourself with the handkerchief; then clapping your hands, with the handkerchief between them, it instantly vanishes.

“Do you know, gentlemen, where the handkerchief is? No? Then I will tell you. It has gone back into my pocket.”

You again take the handkerchief out of your pocket, and make it vanish a second time.

“You see, gentlemen, how much time this arrangement saves; you have only to take your handkerchief out of your pocket. You have no occasion whatever to put it back again.”

[Pg 51]

This amusing little interlude served the double purpose of gaining a few moments in my performance, and of affording a relaxation to the spectators.

The trick is performed as follows:—

This trick, I repeat, is extremely striking in effect. It may, perhaps, appear somewhat difficult, but let not the student be discouraged; with a very moderate degree of practice, it should readily be conquered.

[20] These promised explanations were never given. The effect of the “Orange Tree Trick,” as described by Robert-Houdin himself in his “Confidences d’un Prestidigitateur,” was as follows:—

“I borrowed a lady’s handkerchief. I rolled it into a ball, and placed it beside an egg, a lemon, and an orange upon the table. I then passed these four articles one into another, and when at last the orange alone remained, I used the fruit in question in the manufacture of a magical solution. The process was as follows: I pressed the orange between my hands, making it smaller and smaller, showing it every now and then in its various shapes, and finally reducing it to a powder, which I passed into a phial in which there was some spirits of wine. My assistant then brought me an orange-tree, bare of flowers or fruit. I poured into a cup a little of the solution I had just prepared, and set fire to it. I placed it near the tree, and no sooner had the vapour reached the foliage, then it was seen suddenly covered with flowers. At a wave of my wand, the flowers were transformed into fruit, which I distributed among the spectators.

“A single orange still remained on the tree. I ordered it to fall apart in four portions, and within it appeared the handkerchief I had borrowed. A couple of butterflies with moving wings took it each by a corner, and flying upwards with it, spread it open in the air.”

Without professing to give precise details, it is easy to form a general idea of the working of this very artistic trick. The borrowed handkerchief is of course exchanged for a substitute, and the original “passed off” to the assistant, who places it in position for the dénouement, and then brings forward the orange-tree. Meanwhile, the performer, partly by sleight-of-hand and partly by the aid of traps, causes the successive disappearance of the substitute handkerchief, the egg, and the lemon. (See the “Secrets of Conjuring and Magic,” pp. 284 et seq., and “Modern Magic,” pp. 437 et seq.). The orange is then changed for others of smaller size in due succession, and finally vanishes altogether. (For description of similar effects in the Crystal Balls, see “Modern Magic,” p. 426.) The supposed solution of the orange in the spirits of wine is, of course, merely a part of the boniment or mise en scène. The orange-tree, which is a marvel of mechanical ingenuity, is constructed as follows: The oranges, with one exception, are real, and are stuck on small upright spikes, and concealed by hemispherical wire screens, covered with foliage, which, when released by the upward pressure of a piston, make a half turn, and so disclose the fruit. The flowers are hidden behind smaller screens, similarly covered; in this instance, however, the screen does not revolve, but the flower rises above it. A single orange, near the top of the tree, is artificial, and made to open in four portions; while two butterflies flutter out one on each side of the tree, and draw out of the orange the borrowed handkerchief. The butterflies are attached to the upper extremities of two light arms of brass, at the back of the tree, working on a pivot at their lower ends. A mechanical arrangement compels these arms to rise up behind the tree, at the same time spreading apart, and so causes the butterflies to appear.

The handkerchief cut up and restored has been worked, in various forms, by successive generations of conjurors. (See “Modern Magic,” pp. 246-249.) Doubtless, the method adopted by Robert-Houdin bore (as indeed did everything he touched) the stamp of his original genius; but unfortunately we have not been able to obtain any note of his special working.

The instantaneous combustion was probably produced by means of what is now known as a “flash” handkerchief, i.e., a handkerchief so treated with a mixture of nitric and sulphuric acid as to transform the fabric, in effect, to gun-cotton. A handkerchief of this kind held to a lighted candle, or merely touched with a hot glass rod, disappears with a flash, leaving not even a shred of tinder behind.—Ed.

[Pg 54]

[21] In making this attachment, you must carefully avoid creating any impediment which might interfere with the passage of the handkerchief up the sleeve. This difficulty is best avoided by sewing the string to the handkerchief.—R.-H.

Among the illusions which I have, from time to time, contrived, in order—if I may venture to say it—to cheat my friendly spectators, I do not think, modesty apart, that I ever invented anything so daringly ingenious as the experiment I am about to describe.

I do not here allude to the “light and heavy chest,” whose secret I have already revealed in my autobiography,[22] but of an addition I made to that trick in order to throw the inquiring minds of the public off the scent.

Even at the risk of repeating myself in the eyes of those who have read the book above mentioned, I think I ought, in the first place, to say a few words as to the manner in which I performed my original experiment of the light and heavy chest; after which we will proceed to describe the trick to which I now refer.

[Pg 55]

The heavy chest was a small strong-box, which, placed in a particular spot among the audience, had the faculty of becoming light or heavy at my command. At one time a child could lift it without difficulty; at another, the most powerful man could not stir it from its place.

In order that the reader may fully comprehend the working of the trick, I must, in the first place, give a short explanation of certain electrical principles on which it is founded.

By the aid of electricity, as is now generally known, we can render a piece of iron temporarily magnetic. This artificial magnet, which is known as an electro-magnet,[23] retains its power of attraction so long as the electric current circulates around it; but the moment that the electric circuit is broken, the iron completely loses its magnetic force. By this means magnets may be produced of such immense power, that when a piece of iron is brought in contact with them, no human power can tear it away.

[Pg 56]

It was upon this principle that I based the secret of the trick of the “light and heavy chest,” which I produced in the course of my performances.

In the middle of the pit, and upon a broad plank which served as a “run-down” to enable me to communicate with the spectators, I made an opening in which was fixed a powerful electro-magnet, concealed by a thin cloth which covered it. The conducting wires were carried behind the scenes, whence, at the proper moment, the current necessary to magnetise the iron was to be despatched. On the under side of the strong-box, which was to be subjected to the magnetic influence, there was a stout iron [Pg 57]plate let into the wood, and disguised by a mahogany-coloured piece of paper, which apparently formed part of the substance of the box.

These arrangements being duly made beforehand, when I placed the strong-box upon the electro-magnet, a spectator would either lift it without difficulty, or exhaust himself in fruitless attempts to move it, according as my concealed assistant made or unmade the electric circuit.

When, in the year 1845, I performed this trick for the first time, the phenomena of electro-magnetism were wholly unknown to the general public. I took very good care not to enlighten my audience as to this marvel of science, and found it much more to the advantage of my performances to exhibit the “heavy chest” as an illustration of white magic, of which I alone possessed the secret. I also exhibited it as an imitation of a spiritualistic effect, the fiction with which I introduced it being as follows: “This chest,” I gravely announced, “serves me as a strong-box when I have any money to lock up; in such case, I don’t trouble myself in the [Pg 58]least to put it out of reach of thieves. I simply make a mesmeric pass over it, and I am quite certain to find it again wherever I may have left it. I will give you a proof of my assertion. Let us suppose that this chest, the lightness of which you have proved for yourselves, contains a few thousands of francs in bank-notes, which would be very easily run away with. Well, I have only to pass my hand over it, like this, and you may now satisfy yourselves that the strongest man would waste his strength in vain in the endeavour to remove it from its place.”

After sundry attempts had been made to no purpose, I added:—

“And yet, at my command, the chest is no longer heavy, and you see that I can raise it with ease with my little finger.”

At a later period, when electro-magnetism had become more generally known, I thought it advisable to make an addition to the “light and heavy chest,” in order to throw the public off the scent as to the principle on which the [Pg 59]illusion was based. The following was my method of presenting this new trick, which to the eyes of the public, was merely a second phase of that which had preceded it:—

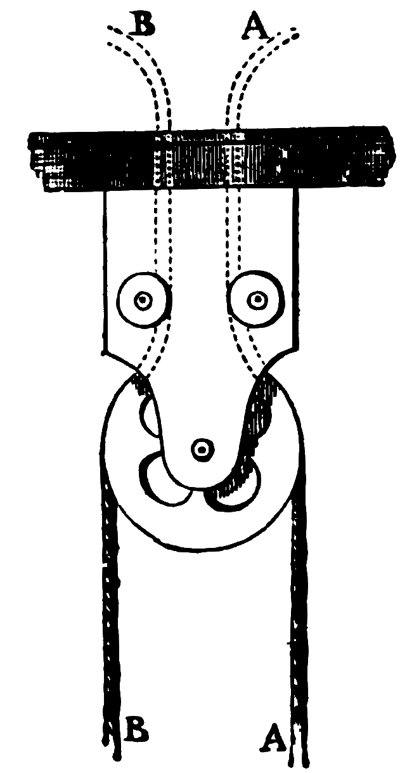

“Gentlemen,” I continued, “in order to prove to you that the additional weight which I impart to the chest is genuine, and does not depend on any external artifice, I will attach it to one end of this cord,” (a cord passing over a pulley attached to the ceiling), “and if you will hold the other, you will be able to form a fair estimate of the amount of its downward pressure.” So saying, I hooked the chest to the cord; after which, I requested one of the spectators to be good enough to keep it suspended by holding the other end of the cord, which he did with perfect ease. “Just at present,” I remarked, “the chest is extremely light; but as [Pg 60]it is about to become, at my command, very heavy, I must ask five or six other persons to help this gentleman, for fear the chest should lift him off his feet, or even carry him away altogether.”

No sooner was this done than the chest came heavily to the ground, dragging along and sometimes actually lifting off their feet all the spectators who were holding the cord.

This marvellous effect is produced entirely by mechanical means; but their operation is so well disguised, that no one could possibly suspect the truth.

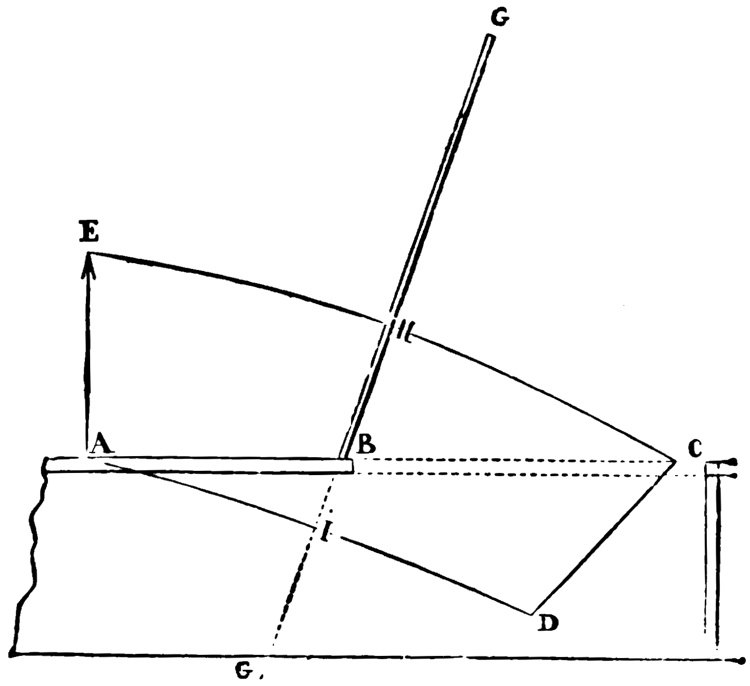

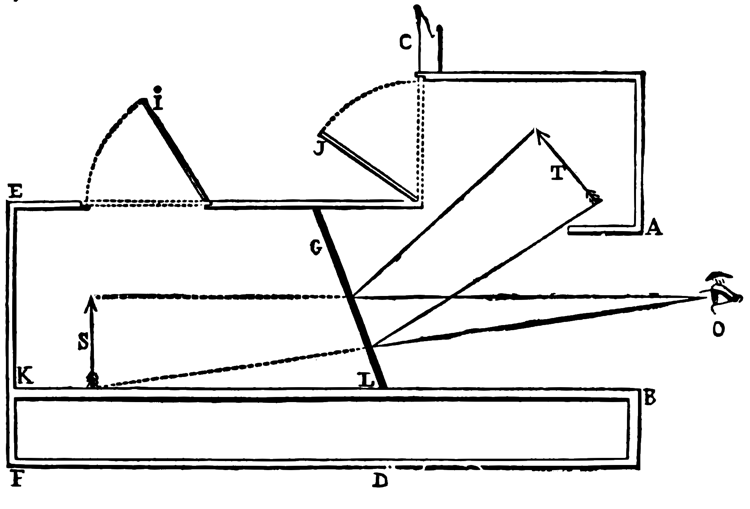

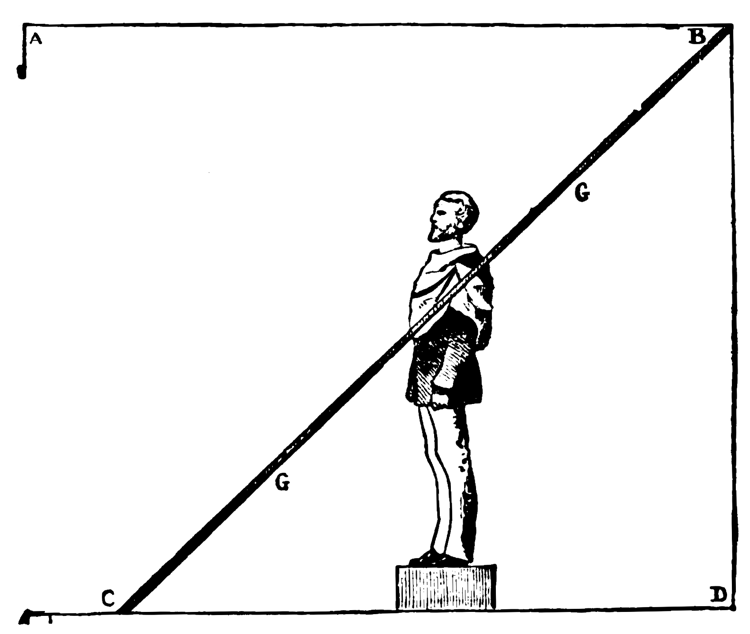

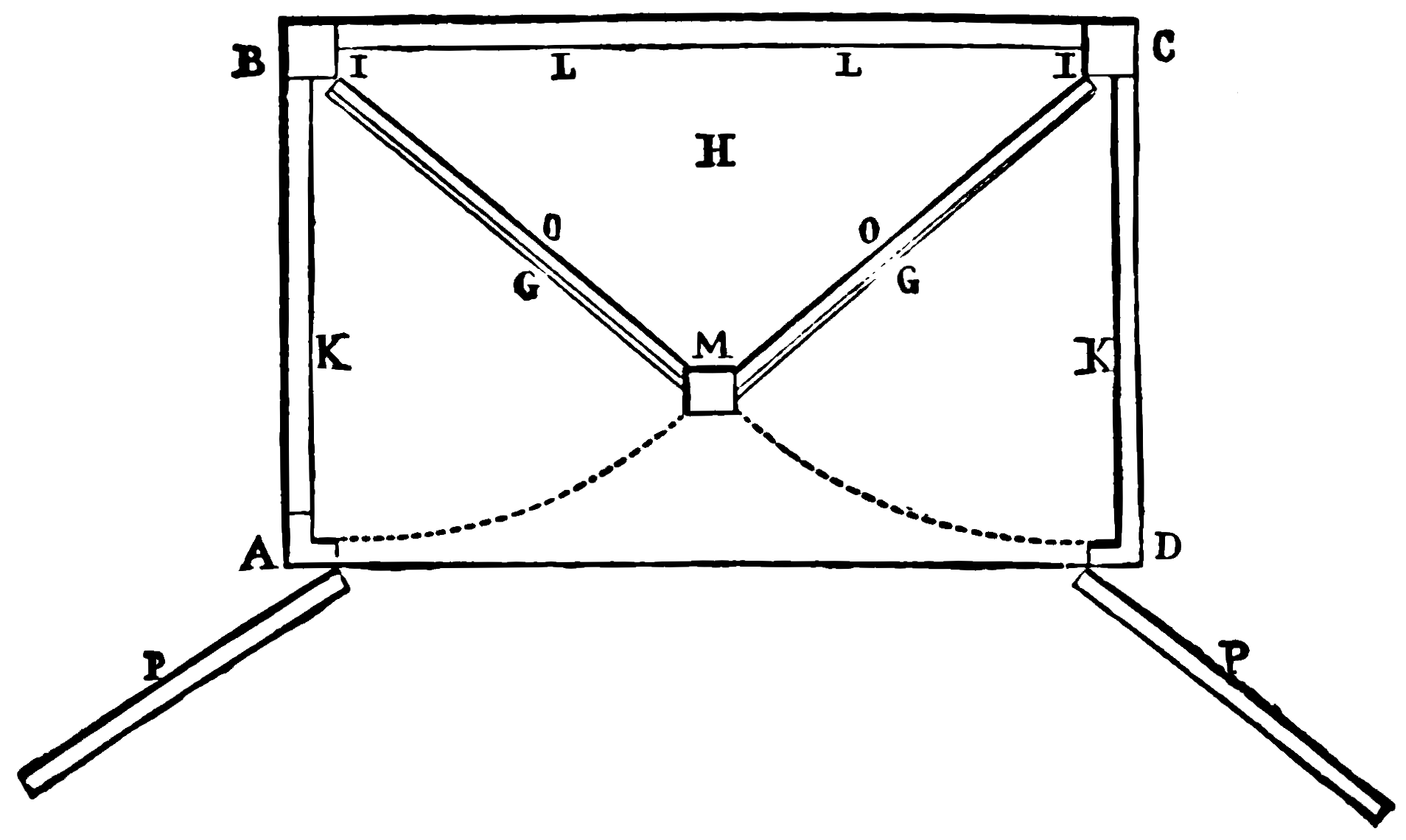

I shall now proceed to give a more detailed explanation, for the purpose of which I must refer the reader to the accompanying diagram:—

On a casual inspection of the pulley and block, everything appears to indicate that, as usual in such cases, the cord passes straight over the pulley, in on one side and out on the other; but such is not really the fact, as will be seen upon tracing the course of the dotted lines, which, passing through the block and through [Pg 61]the ceiling, are attached on either side to a double pulley fixed in the room above.

One circumstance that favours the illusion is that, before the box is hung on the hook, by pulling the latter the cord wound upon the double pulley above unwinds itself, while the portion of the cord on the opposite side is wound up to the same extent. Now, to the eye of the spectator, this pulling of the cord to right or left produces precisely the same effect as if the cord simply passed over the visible pulley.

To any one who has the most elementary acquaintance with the laws of mechanics, it will be obvious that the strength of the person who holds the handle of the windlass above is multiplied tenfold, and that he can easily overcome even the combined resistance of five or six spectators.

This experiment cannot well be performed save in a place of exhibition whose ceiling is not very lofty.

[22] “Confidences d’un Prestidigitateur,” vol. ii., p. 265, and “Secrets of Conjuring and Magic,” p. 79.

[Pg 62]

[23] For the construction of electro-magnets, the reader is referred to works treating of physical science, particularly those which treat specially of electricity, e.g., those of Count Dumoncel and Edmond Becquerel.—R.-H.

We say “the hundred candles,” in order to preserve to the trick the title under which it has been generally exhibited, but, as will presently be seen, even a larger number may be lighted, if desired.

This trick, which is, in truth, only the application on a large scale of an old scientific experiment known as the briquet électrique,[24] was first exhibited by the conjuror Döbler, in the course of the performances which he gave in 1840, at the St. James’s Theatre, in London.

[Pg 63]

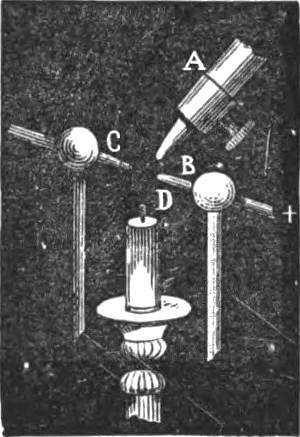

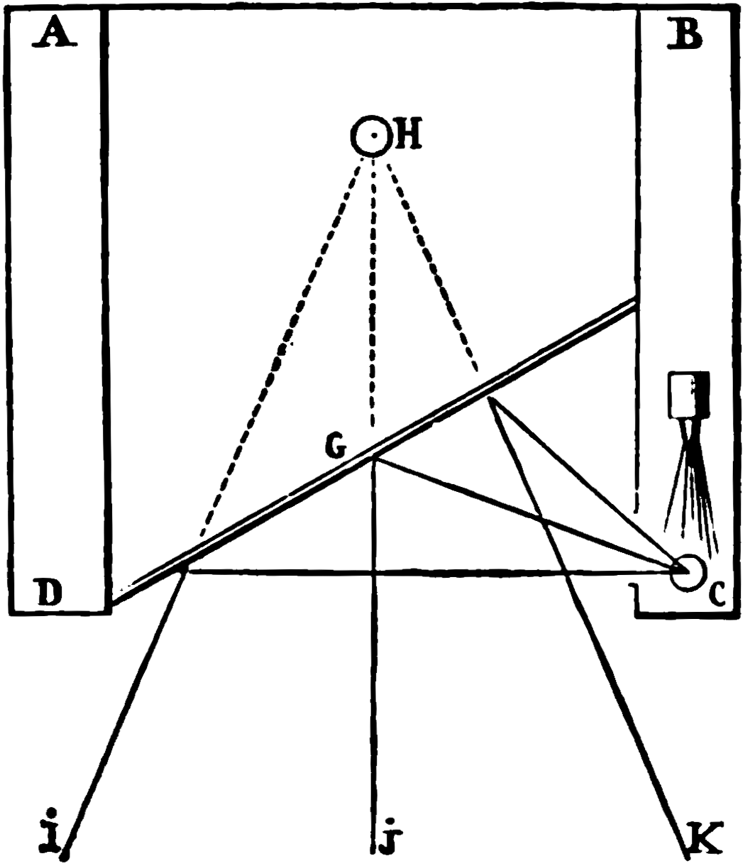

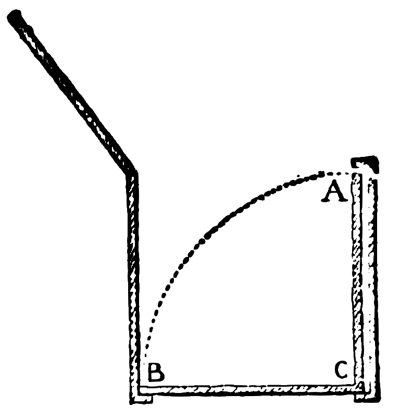

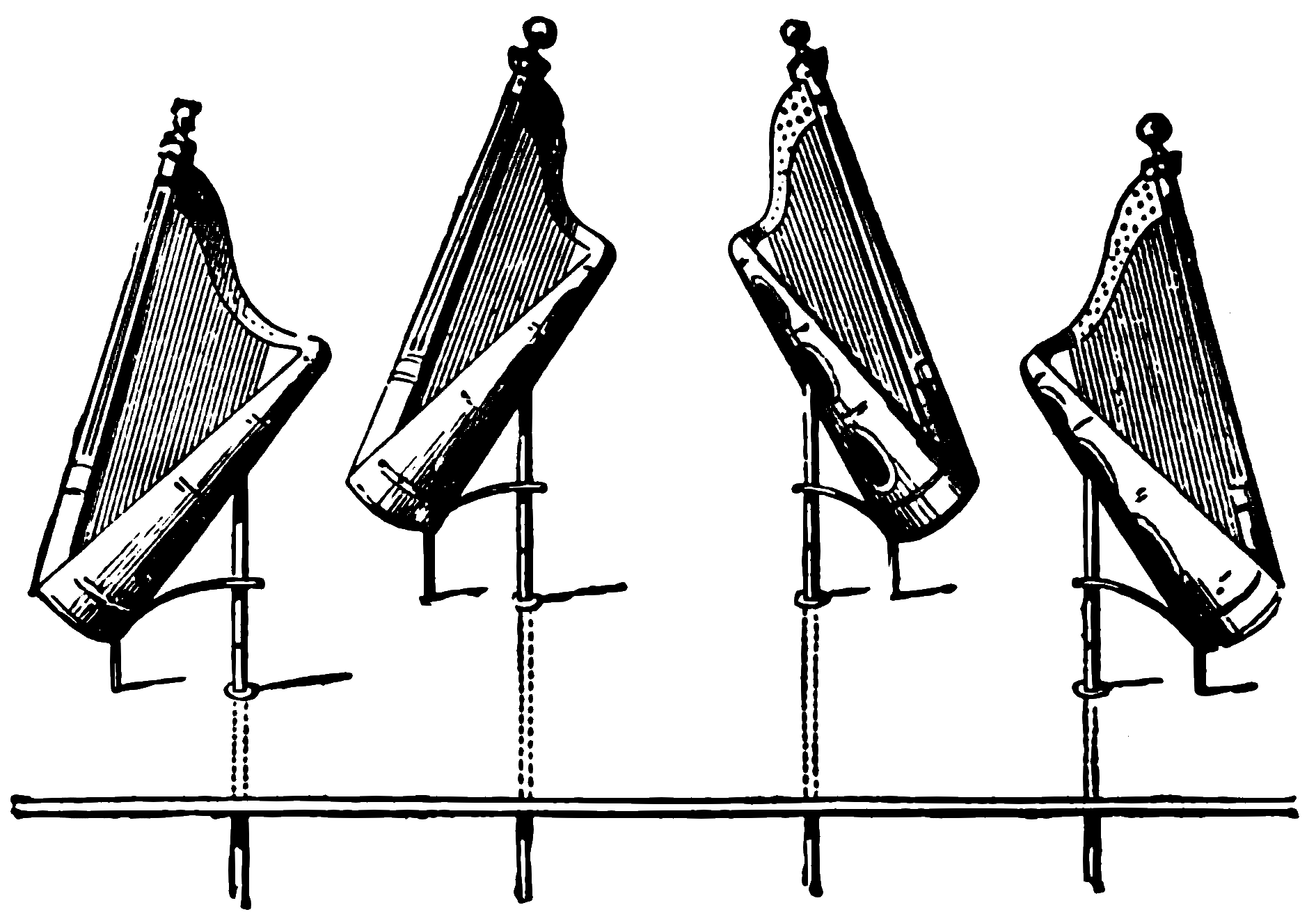

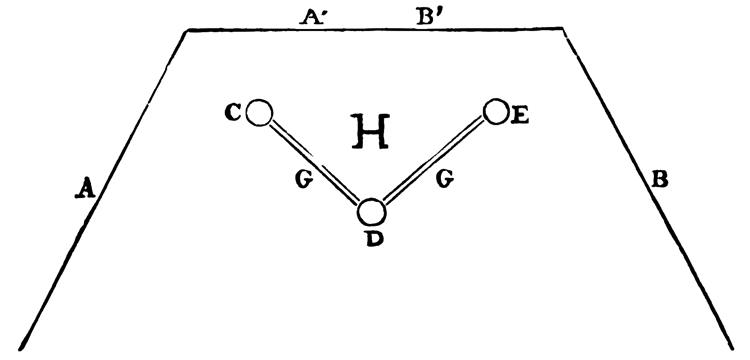

In order to enable the reader the better to comprehend the arrangements for the trick of the “hundred candles,” we will first recapitulate those of the briquet électrique. The accompanying diagram (Fig. 5) will assist our description.

A is the extremity of a tube or burner in communication with a reservoir of hydrogen gas; B and C are two thin metal wires, whose points are very near together. One of these wires (B) is insulated by means of a glass support; the other (C) is fixed on a brass rod in communication with the ground.

When the gas escapes from the burner A, it impinges directly upon the wick of the candle D, passing between the points B and C. If at the same instant an electric current is communicated to the point B, the spark will in its journey to the opposite point pass through the gas and [Pg 64]ignite it. The jet of flame thus created will in turn light the wick of the candle.

Given a few modifications in point of form, and increasing the number of the gas-jets, points, and candles, we have the experiment of M. Döbler.

In the illustration which next follows (Fig. 6), the reader will see the new arrangement complete. All the supports (S S S S) of the conducting wires, however numerous, with the exception of the last, are insulators. All the burners (G G G) are attached to a single pipe, which keeps them supplied with gas. The letters B B B indicate the position of the candles.

As in the experiment already described, the gas is turned on at the common main, and [Pg 65]escapes at each burner. At the same moment an electric current is brought in circuit with one of the insulated conducting rods, and instantly leaping over all the intervals, sets light, as we have said, to the gas-jets, and by their aid to the candles.

To ensure greater certainty in lighting, the wick of the candle is charred a little beforehand, and then moistened, by the aid of a camel-hair brush, with spirits of turpentine.

The greater the number of interruptions in the circuit, the stronger need be the current of electricity to enable it to conquer all the successive resistances to its flight.

Formerly the spark was produced by means of a large frictional machine, but however powerful such machine might be, it happened now and then, when the weather was damp, that the quantity of the electric fluid produced was inadequate, and that the experiment was a failure. At the present day, with the aid of the Rhumkorff induction coil, the [Pg 66]performer need have nothing to fear in this particular, so long as he takes care that the size of his coil is in due proportion to the number of candles he desires to set light to.

[Pg 67]

[24] Literally, “electric tinder-box.” We are not aware that the experiment in question has any special cognomen among English electricians.—Ed.

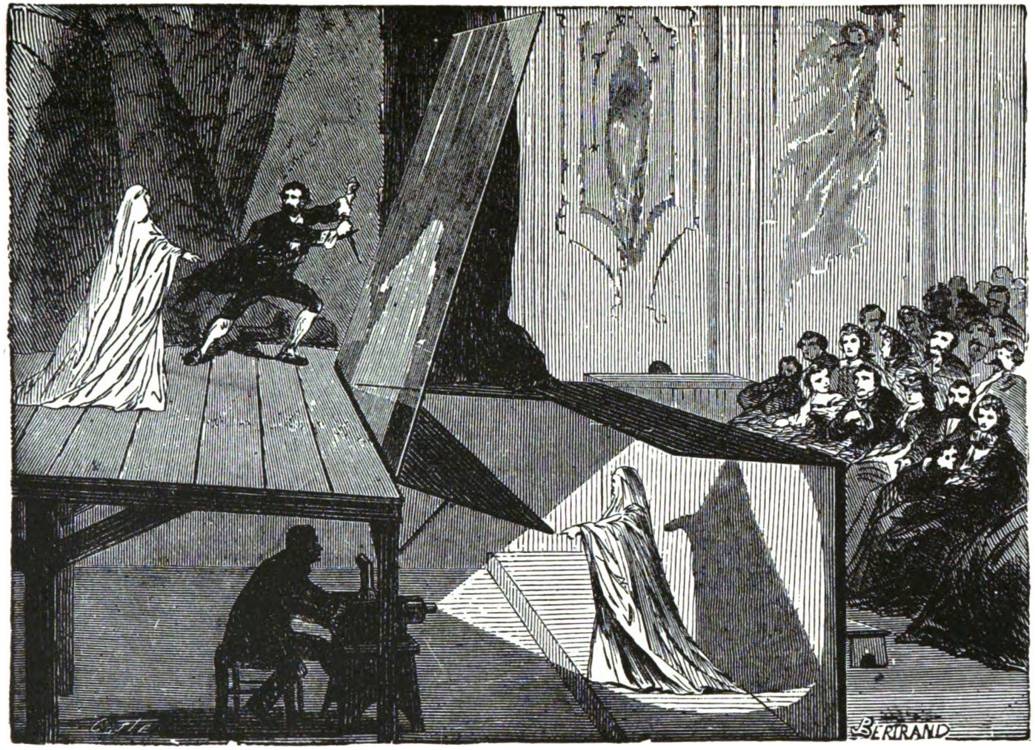

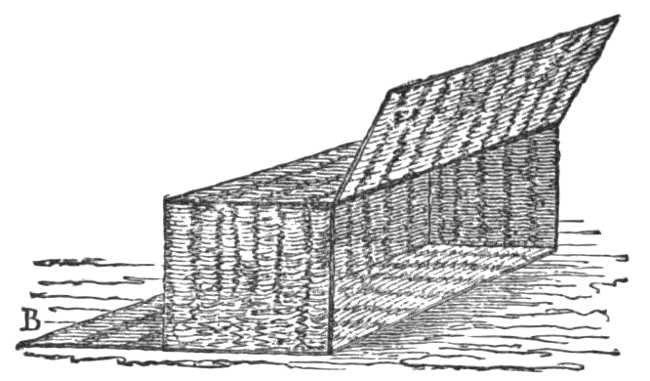

The trick known as the “ghost illusion” is one of the most curious ever produced by optical science. The apparitions produced by its means are most startling in effect, and leave the spectators scarcely room to question their actual existence.

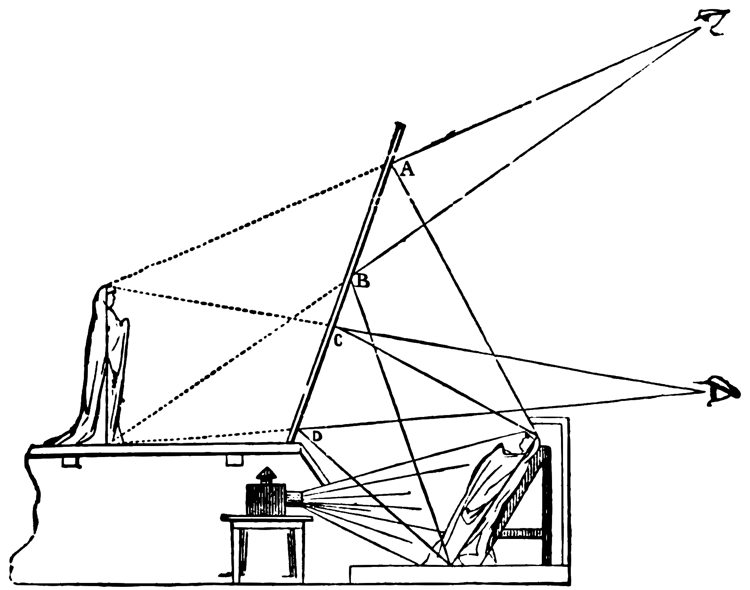

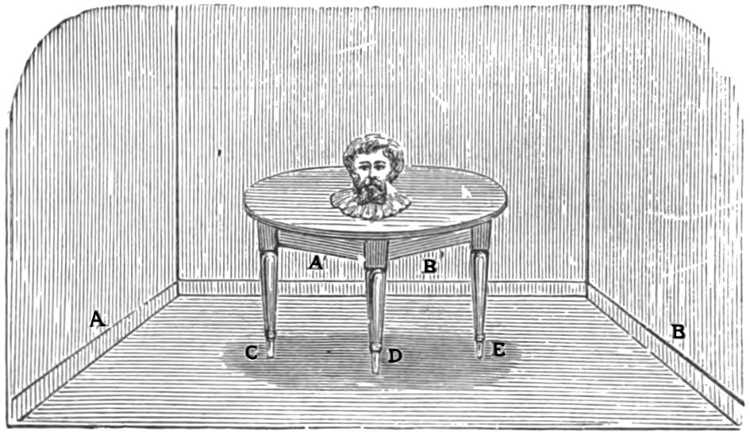

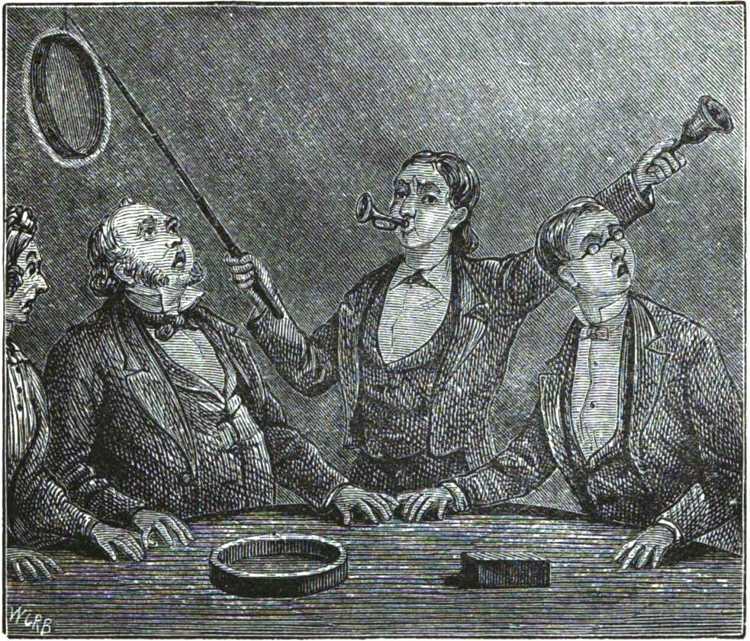

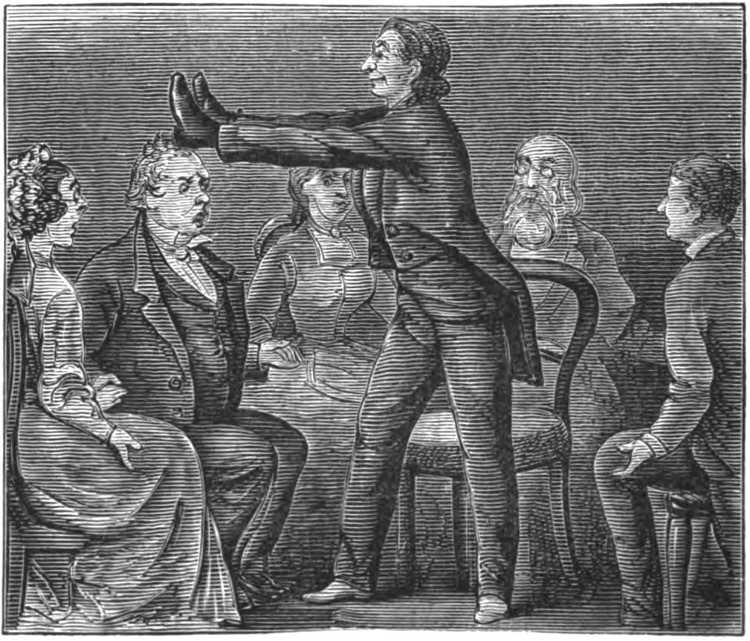

Two persons, for instance, as in the accompanying illustration (Fig. 7), are seen upon the stage. They walk and move in all directions, they are heard to converse with one another, and every indication leads to the belief that they are beings of like organization, though differently attired. In truth, however, the one is a flesh-and-blood personage, the other but a ghostly shade, an impalpable spectre.

The living personage tries in vain to grapple with the phantom. He slashes at it with his [Pg 68]sword, and even passes right through its body, as he might pass through a cloud of vapour. But the shadowy form shows no signs of injury; it remains intact, and gesticulates as though in defiance of its adversary, until at last it vanishes into thin air, and the mortal is left alone upon the stage.

This singular illusion depends upon certain optical principles, which we propose, in the first place, to explain, and to which we shall have occasion to recur a little later in describing the stage arrangements necessary for their dramatic development.

An illustration of the most simple character will at once enable the reader to understand the principle on which the phenomenon in question rests.

Place in a vertical position on a table a piece of unsilvered plate-glass, or if plate-glass cannot be obtained, then a piece of ordinary window glass free from air-bubbles or striæ, about ten inches in height, and the same in width.

[Pg 69]

[Pg 70]

Then place a lighted taper on your own side of the glass, at about three inches from it, and behind this place a book, which will serve the purpose of a screen. Fig. 8, below, will make clear the details of the arrangement.

On looking over the top of the book at the glass, you will see therein the reflected image of the taper C, which is screened by the book from your direct view, and this image will in effect appear to you to be at D, behind the glass, at the same distance as the real object, C, is removed from it.[25]

[Pg 71]

If, while still keeping the eye in the same position, you extend your hand behind the glass, you can pass your fingers right through the phantom taper, D, and this latter, which previously appeared to be substantial, will instantly become diaphanous and impalpable.

If, in the stead of the taper C, you place in the same position any white object strongly illuminated, you will have a miniature reproduction of the ghost illusion as represented on the stage.

It is of course understood that there must be no other light in the room save that which is essential to the experiment.

The effect produced as above may be explained as follows:—When a piece of unsilvered glass is placed in a position in which it receives equal light on both sides, there is no reflection from either the one or the other of its surfaces. Such, for instance, is the case with the panes of a window, so long as the outside and inside of the room receive the same amount of light. But if either side of the [Pg 72]glass is more strongly illuminated than the other, the latter, in such case, loses in transparency but gains in reflection, in precise proportion as the light is diminished, the darkness in this case serving the purpose of a more or less perfect “silvering.”

We will now proceed to trace the application of this principle in the stage trick known as the “Ghost Illusion” or “Living Phantoms.”

Fig. 7 represents a scene between a spectre and a living being; and indicates the general arrangement of the process employed to produce the illusion. A plate of unsilvered glass, inclined at a proper angle, is placed between the actors and the spectators. Beneath the stage, and just in front of this glass, is a person robed in a white shroud, and illuminated by the brilliant rays of the electric or the Drummond (oxy-hydrogen) light. Matters being thus arranged, the image of the actor who plays the part of spectre, being reflected by the glass, [Pg 73]becomes visible to the spectators, and stands, apparently, just as far behind the glass as its prototype is placed in front of it.

This image, in accordance with the principles of reflection which we have explained above, is only visible to the audience. The actor who is on the stage sees nothing of it, and in order that he may not strike at random in his attacks on the spectre, it is necessary to mark beforehand on the boards the particular spot at which, to the eyes of the audience, the phantom will appear.

In order that the experiment may be completely successful, it is necessary to pay particular attention to the following points:—

Dimensions of the Glass.—The dimensions of the glass which is to be used for the experiment are practically determined as follows:—

After having decided at what particular part of the stage the shadowy form is to appear, you fix, in an upright position on the spot in question, a deal board of the height and breadth of the phantom. Then fastening a thread to each side of the base of this board, you carry it straight across the flooring to the stage boxes, or those seats on the extreme right and left which are nearest to the stage.

[Pg 76]

The angle formed by these two will indicate the necessary width of the glass for any position on the stage in which you may decide to place it. The height is determined with equal facility. You fasten to the top of the board a third thread, which you carry in a straight line to the highest seat at the opposite side of the auditorium. This line will indicate the height to which the glass must extend, whatever be its angle of inclination. The three threads in question represent the extreme lines of sight of the audience. All eyes will therefore necessarily find space on the glass for the reflection of the spectral form.

It is obvious that in arranging the glass according to the limits defined by these lines, the nearer it is placed to the spectators the larger it must be, and vice versâ.

The Angle of Inclination of the Glass.—Let us suppose, as indicated in Fig. 9, that the phantom is to appear at the point A, distant five yards from the front edge of the stage.

Such being the case, let us place our glass, G, [Pg 77]a couple of yards in front of A, and incline it at an angle of 20°.

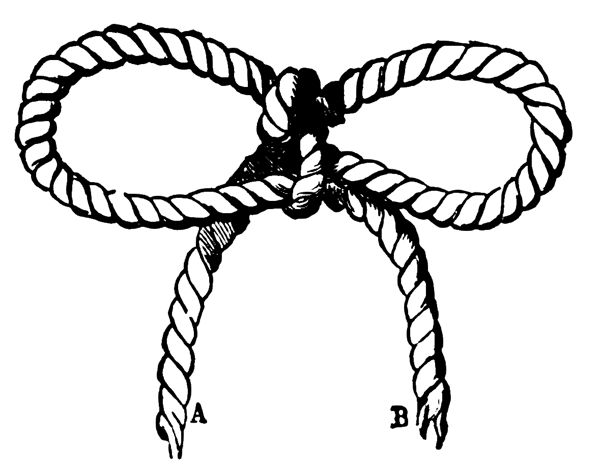

Position and Arrangement of the Ghost-Actor.—Let us continue the line G downwards upon the paper till it extends about three or four times the length of the glass. Taking the lower extremity of this line as a centre, let us describe with a pair of compasses two arcs, one extending from E to C, the other from A to D,[27] [Pg 78]and join them by a line, C D, which should form with the glass a like angle to that which the line E A forms therewith.

The plane and inclination of the line C D will be those which the actor must assume in order that his reflected image may appear in an upright position at the point A.

It will be readily understood that the more upright the glass, the less sloping will be the position of the actor; but, on the other hand, the higher will he be brought above the level of the stage. Under such circumstances, the portion around the opening, being necessarily made higher in order to conceal the actor, would also hide a portion of his reflected image from the spectators in the orchestra or stalls.

Fig. 10 exhibits the optical effect of a glass placed according to the conditions we have just described. The particular spot on which the reflection appears varies with each spectator, according to the position which such spectator occupies. Thus, for the spectators in the topmost [Pg 79]row, the reflection will be on the portion of the glass marked A B, while for spectators at the lowest level it will be on the portion marked C D. It will be observed that, whatever be the spot at which the image appears, the angle of incidence equals the angle of reflection, and that these same angles of incidence are likewise equal to the corresponding angles of the reflected image which we have traced behind the glass.

[Pg 80]

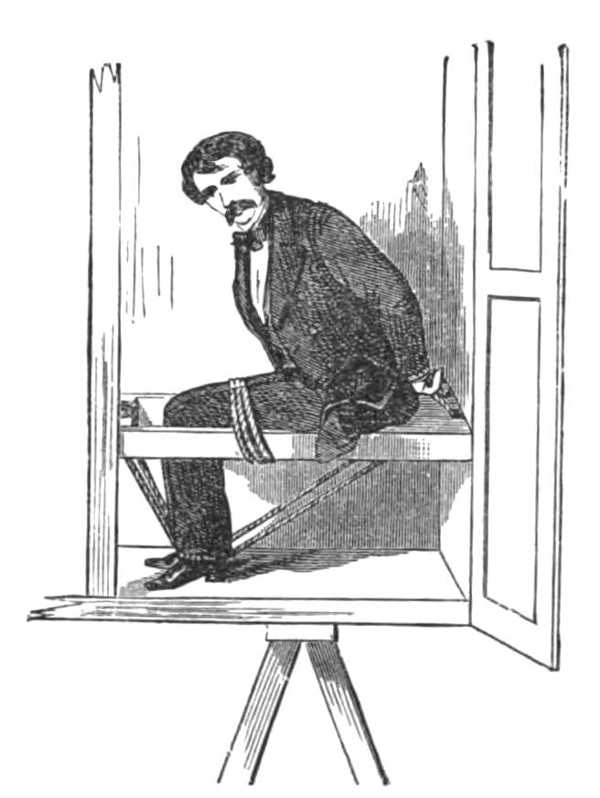

When the ghost-actor is not called upon to move from a given spot, he poses himself upon a support which is inclined at the necessary angle, and which leaves him still full power to move his limbs as may be desired. But if the exigencies of the scene require that he should move from one spot to another, the inclined position of the body creates a difficulty. However, as he can only be required to move in a direction parallel with the plane of the glass, he may, under cover of the robe with which he is attired, bend the leg on the side towards which he leans, which will enable him to walk without much difficulty with his body inclined at an angle of thirty-five to forty degrees. But the actor’s gait under such circumstances is sure to be a little awkward; and a better plan is to arrange behind him, at a proper angle, a support, moving on castors, and which is easily concealed by the drapery appropriate to his spectral character. This support does not prevent the actor from moving his legs, and, thus sustained, he is enabled to walk [Pg 81](apparently) backwards and forwards in the direction in which the support travels. In some cases, the actor himself keeps motionless, but the wheeled carriage on which he leans, being drawn forward by a cord, causes him to advance towards the living actor in genuine ghostly fashion. This movement produces a most startling effect.

The difficulty as to the inclined position of the actor may be avoided by arranging in the position which he would otherwise occupy, and parallel to the unsilvered glass, a mirror of comparatively small size (say of about six feet by three). Where this plan is adopted, the actor will stand upright before this mirror, and his reflected image therein will be again reflected to form the ghost.

The necessary light will be afforded by a lamp placed in front of the actor, and beside the mirror in question.

A Novel Application of the Ghost Illusion.—In the year 1868, there was exhibited at the [Pg 82]Ambigu Theatre, Paris, a melodrama (La Czarine) founded on an episode related in my Confidences,[28] and in which an automaton chessplayer, constructed by myself for that purpose, played an important part. My collaborateurs, Messrs. Adenis and Gastineau, had asked me to arrange a ghost effect for the last act. I had recourse to the “ghost illusion” above described, but I presented it in such guise as to give it a completely novel character, as the reader will be enabled to judge from the following description.

The scene is laid in Russia, in the reign of Catherine II. In the last act, an individual named Pougatcheff, who, on the strength of a personal likeness to Peter III., attempts to pass himself off as the deceased monarch, is endeavouring to incite the Russian populace to dethrone Catherine. A learned man, M. de Kempelen, who is devoted to the Czarina, [Pg 83]succeeds, by the aid of scientific expedients, in neutralizing the villainous designs of the sham prince.

The scene is a savage glen, behind which is seen a background of rugged rocks. Pougatcheff appears, surrounded by a crowd of noisy adherents. M. de Kempelen comes forward, denounces the impostor, and declares that, to complete his confusion, he will call up the spirit of the genuine Peter III. At his command a sarcophagus appears from the solid rock; it stands upright on end. The lid opens, and exhibits a corpse covered with a winding-sheet. The tomb falls again to the ground, but the phantom remains erect. The sham Czar, though a good deal frightened, makes a pretence of defying the apparition, which he treats as a mere illusion. But the upper part of the winding-sheet falls aside, and reveals the livid and mouldering features of the late sovereign. Pougatcheff, thinking that he can hardly be worsted in a fight with a corpse, draws his sword, and with one blow cuts off its [Pg 84]head, which falls noisily to the ground; but at the very same moment the living head of Peter III. appears on the ghostly shoulders. Pougatcheff, driven to frenzy by these successive apparitions, rushes at the figure, seizes it by its garments, and thrusts it violently back into the tomb. But the head remains unmoved; though severed from the body, it remains suspended in space, rolling its eyes in a threatening manner, and appearing to offer defiance to its persecutor. The frenzy of Pougatcheff reaches its culminating point. Grasping his sword with both hands, he tries to cleave in twain the head of his mysterious adversary; but his blade only passes through a shadowy being, who laughs to scorn his impotent rage. Again he raises his sword, but at the same moment the body of Peter III. in full imperial costume, and adorned with all the insignia of his rank, becomes visible beneath the head. The re-animate Czar hurls the impostor violently back, exclaiming, in a voice of thunder, “Hold, sacrilegious wretch!” [Pg 85]Pougatcheff, terror-stricken, and overwhelmed with confusion, confesses his imposture, and the phantom vanishes.

The stage arrangements to produce these effects are as follows. An actor, robed in the brilliant costume of Peter III. reclines against the support, which is sloped as above described. His body is covered with a wrapper of black velvet, which is designed to prevent, until the proper moment, any reflection in the glass. His head alone is uncovered, and ready to be reflected in the glass so soon as the rays of the electric light shall be directed upon it.

The phantom which originally comes out of the sarcophagus is a dummy, whose head is modelled from that of the actor who plays the part of the Czar. This head is made readily detachable from the body.

Everything is placed and arranged in such manner that the dummy image of Peter III. shall precisely correspond in position with the person of the actor who plays the part of Ghost.

[Pg 86]

At the same moment that the head of the former falls to the ground, the electric light is gradually made to shine on the head of the actor who plays the part of Peter III., which, being reflected in the glass, appears to shape itself on the body of the dummy ghost. After this latter is hurled to the ground, the veil which hides the body of the actor-Czar is quickly and completely drawn away, and the sudden flood of the electric light reflects his whole body where his head alone was previously visible.

Where it is desired to exhibit the ghost illusion in a hall which has no space beneath the stage, it becomes necessary to modify the reflective machinery, and to arrange it as shown in Fig. 11. Let us suppose A B C D to be the stage, C D being the front, A D and B C the “wings,” C the actor who plays the part of the spectre, H his image in the glass, and G the glass itself, set at an angle of 30° to the front of the stage.

The actor, C, is out of sight of the spectators; [Pg 87]but his body, brightly illuminated by the electric or oxy-hydrogen light, is reflected in the glass, G, and appears as if standing at the point H. The letters I, J, K, indicate various “points of sight” among the audience, and serve to show that, whatever be the position of the spectator in the hall, the spectre must, according to the laws of reflection, always appear at the point H.

After the various explanations above given, the reader will readily comprehend certain stage arrangements which I have had made for my [Pg 88]own use in order to produce at will spectral apparitions, or, as the English call them, “dissolving spectres.”[29]

The arrangement which I refer to is set up, for the amusement of myself and my friends, in a summer-house specially built for that purpose in the middle of my park.

In the case of this exhibition, there are no seats; the few spectators who may patronize it stand in front of an opening, A B (Fig. 12), representing in miniature the proscenium of a theatre. This proscenium, or stage front, indicated by the letters A B C D, is within the summer-house. The annexe, C E F D, is built out behind, and contains the stage on which my optical illusions are displayed. This annexe is so constructed that the sunlight may readily find its way in at the trap-doors, I, J, when opened.

G is the glass, which forms with the stage-floor, K, L, an angle of 70°. T is the object to be [Pg 89]reflected in the glass, so as to appear, when the daylight shines upon it, at S. This spot, S, is also designed for the placing of objects to be seen directly through the glass, G, by the spectators. The eye, O, indicates the mean point of vision of those present.

With the aid of these arrangements, the following effects, among others, may be produced. The scene becomes slowly lighter, passing by gentle gradations from the first glimmer of dawn to full daylight. There then appears, at S, an owl [Pg 90]perched on a tombstone. A few moments later, a statue of the Virgin appears, mixed up, so to speak, with the gloomy objects we have mentioned. The outline of this figure, growing gradually more and more defined, takes the place of the tomb, which fades away from view. The Virgin, in her turn, undergoes a transformation; her cheeks acquire a roseate tint, her features assume life and expression, and the figure becomes animate under the guise of a young girl, robed in white and wreathed with flowers. These flowers gradually increase till they assume the semblance of a gigantic bouquet, beneath which gradually appears a vase, which takes the place of the young girl.

This scene might be prolonged indefinitely, all that is needed being the substitution of new objects in place of those which have already appeared.

Explanation of the Preceding Scene.—Before the commencement of the exhibition, the tombstone we have referred to must be placed at [Pg 91]S, while the statuette of the Virgin is placed at T.

Both stage and “auditorium” must be in total darkness. To that end, all the openings, and especially the trap-doors, I, J, must be shut as closely as possible.

Now, if, by the aid of a cord, appropriately arranged, we gradually open the trap I, the daylight will by slow degrees illuminate the object placed at S, which will be seen directly by the spectators. After this trap is completely open, it should be again slowly closed, while the trap J is proportionately opened. The sunlight will now fall on the Virgin placed at T, and at a particular period it will be found that the two images (direct and reflected) receiving an equal share of light, will become confused the one with the other. But the image T, gradually receiving more light, while the image S gets less, will at last be alone visible to the spectators, and the substitution will be complete.

The stage being now left in darkness by [Pg 92]the closing of the trap I, the young girl will be able to take the place of the tombstone, which she may remove, or which may sink down below the stage, and she will remain invisible until the last-mentioned trap-door, again opening, shall bring the light to bear upon her. This opening is made simultaneously with the closing of the trap J, producing, as in the former instance, first confusion of the two images, and then substitution of the one for the other. When the Virgin is in her turn left in darkness, she is replaced by the vase of flowers, which is destined, to the eyes of the spectators, to take the place of the young girl by a repetition of the process already described.

Thus the spectator, placed at O, is made to see at S four different pictures—namely: 1st, the direct image of the tombstone; 2nd, the same object in combination with the reflected image of the Virgin placed at T, which is afterwards seen alone; 3rd, this latter image in combination with the direct image of the young girl [Pg 93]placed at S, which also is afterwards seen alone; 4th, this image in combination with the vase of flowers placed at T, and whose reflected image is finally left alone upon the scene.

In arranging this experiment, it is essential that the distances between the glass and the various objects should be the same, so that their real or reflected images shall meet at precisely the same points on the stage.

The “Ghost Illusion” was invented in 1863, by Professor Pepper, the manager of the London Polytechnic, and was exhibited at that Institution, where it excited the liveliest interest.

In the course of the same year, M. Hostein, manager of the Imperial Châtelet Theatre, purchased from Mr. Pepper the secret of the “Ghost,” in order to introduce it into a drama entitled Le Secret de Miss Aurore.[30] M. Hostein spared no expense in order to ensure the success of the illusion. Three [Pg 94]enormous sheets of unsilvered glass, each five yards square, were placed side by side, and presented an ample surface for the reflection of the ghost-actor and his movements. Two Drummond lights (oxy-hydrogen) were used for the purpose of the trick.

But before the trick was in working order at its new destination, several of the Parisian theatres, in the face of letters patent duly granted to Mr. Pepper, had already advertised performances wherein it was included.

M. Hostein had no means of preventing the piracy; unluckily for himself, and still more so for the inventor, the plagiarists had discovered among the French official records a patent taken out, ten years before, by a person named Séguin for a toy called the Polyoscope, which was founded on the same principle as the ghost illusion.

In view of this unfortunate precedent, of which he was wholly unaware, Mr. Pepper, though the undoubted inventor of the trick as above described, had no alternative but to give [Pg 95]way to his numerous imitators,[31] and to acknowledge the truth of the stern axiom, enforced by dint of many cogent illustrations, that “there is nothing new under the sun.”

[25] The reader will probably have noticed, in travelling by rail on a dark night, that the light in the carriage is accompanied by a ghostly “double” at a little distance outside. This is another illustration of the effect above described.—Ed.

[26] The illustration (Fig. 7) is faulty in this particular. With a black velvet background, there would not, as a matter of fact, be any visible shadow behind the figure. Were there such, it would be reflected with the figure on the glass.—Ed.

[27] The French illustrator, by an oversight, has made A to D a straight line, instead of an arc of a circle.—Ed.

[28] “Les Confidences d’un Prestidigitateur,” the title under which Robert-Houdin issued his autobiography.—Ed.

[29] Sic. Robert-Houdin is but an indifferent authority for English sayings or doings.—Ed.

[30] A French adaptation of “Aurora Floyd.”—Ed.

[Pg 96]

[31] Among these, the conjurors Robin and Lassaigne were the most successful, among Paris exhibitors, in presenting the illusion with adequate effect.—R.-H.

The Indian Basket Trick was exhibited in London in the year 1865, by Colonel Stodare, at his Theatre of Mystery, Egyptian Hall, Piccadilly.

It was asserted that the illusion in question had been brought over from India by the conjuror-colonel; but in such case, as the reader will judge from the following description, the original mise en scène of the Indian Basket Trick must have been very considerably modified in arranging it for exhibition before the British public.

Upon the rising of the curtain, the spectators beheld a wicker basket, of oblong shape, placed upon a light, undraped table.

[Pg 97]