*** START OF THE PROJECT GUTENBERG EBOOK 77890 ***

Footnotes have been collected at the end of each chapter, and are

linked for ease of reference.

Minor errors, attributable to the printer, have been corrected. Please

see the transcriber’s note at the end of this text

for details regarding the handling of any textual issues encountered

during its preparation.

There are reproductions of sea charts some of which were quite

faded. These chart are provided with a link, accessed by clicking

on the chart, which will display a larger chart which may be inspected more closely.

Any corrections are indicated using an underline

highlight. Placing the cursor over the correction will produce the

original text in a small popup.

Any corrections are indicated as hyperlinks, which will navigate the

reader to the corresponding entry in the corrections table in the

note at the end of the text.

THE

AUTOBIOGRAPHY OF A SEAMAN.

VOL. II.

ILONDON

PRINTED BY SPOTTISWOODE AND CO.

NEW-STREET SQUARE

THE

AUTOBIOGRAPHY OF A SEAMAN.

BY

THOMAS, TENTH EARL OF DUNDONALD, G.C.B.

ADMIRAL OF THE RED, REAR-ADMIRAL OF THE FLEET,

ETC. ETC.

VOLUME THE SECOND.

Second Edition.

LONDON:

RICHARD BENTLEY, NEW BURLINGTON STREET,

Publisher in Ordinary to Her Majesty.

1861.

The right of translation is reserved.

vii

CONTENTS

OF

THE SECOND VOLUME.

| CHAPTER XXIV. |

| A NAVAL STUDY FOR ALL TIME. |

| |

|

| Charts, &c., supplied by the present Government.—Refused by a former Government.—Alteration made in the Charts.—Mr. Stokes’s Affidavits.—Letter to Sir John Barrow.—Singular Admiralty Minute.—Second Letter to Sir John Barrow.—The Charts again Refused.—My Departure for Chili.—Renewed Application to the Admiralty.—Kindness of the Duke of Somerset.—Difference of Opinion at the Admiralty |

Page 1 |

| |

|

| CHAP. XXV. |

| A NAVAL STUDY—continued. |

| |

|

| viiiFrench Hydrographic Charts.—One tendered by me to the Court.—Rejected by the President.—Grounds for its rejection.—The object of the rejected Chart.—Would have proved too much, if admitted.—Rejection of other Charts tendered by me.—Mr. Stokes’s Chart.—Its Fallacy at first sight.—Judge Advocate’s Reasons for Adopting it.—Its Errors detected by the President, and exposed here.—Probable Excuse for the Error.—Imaginary Shoal on the Chart.—Falsification of Width of Channel.—Lord Gambier’s Voucher for Stokes’s Chart.—Stokes’s Voucher for its Worthlessness.—Stokes’s Chart in a National point of View.—Taken Advantage of by the French |

15 |

| |

|

| CHAP. XXVI. |

| A NAVAL STUDY—continued. |

| |

|

| The Evidence of Officers present in Basque Roads.—Admiral Austen’s Opinions confirmatory of my Statements.—Fallacy of alleged Rewards to myself, in place of these Persecutions.—Treatment of my eldest Son, Lord Cochrane.—Letter from Capt. Hutchinson confirmatory of the Enemy’s Panic.—A Midshipman near taking the Flag-ship.—Evidence of Capt. Seymour, conclusive as to Neglect, which was the Matter to be inquired into, in not sending Ships to attack.—Attempt to Weather his Evidence.—Capt. Malcolm’s Evidence confirmatory of Capt. Seymour’s.—Capt. Broughton’s Testimony proves the complete Panic of the Enemy, and the Worthlessness of their Fortifications.—Lord Gambier declares them Efficient on Supposition arising from Hearsay.—Enemy unable to fight their Guns.—The imaginary Shoal.—A great Point made of it.—Mr. Fairfax’s Map.—Lord Gambier on the Explosion Vessels.—Contradicted by Mr. Fairfax.—Contrast of their respective Statements.—Fairfax’s Evasions.—His Letter to the Naval Chronicle.—These Matters a Warning to the Service |

40 |

| |

|

| CHAP. XXVII. |

| CONDUCT OF THE COURT-MARTIAL. |

| |

|

| ixLord Gambier’s Defence.—Second Despatch ignoring the First.—Attempt of the Court to stop my Evidence.—Evidence received because opposed to mine.—I am not permitted to hear the Defence. The Logs tampered with.—Lord Gambier’s Defence aimed at me under an erroneous Imputation.—My Letter to the Court confuting that Imputation.—Admiralty Accusation against Lord Gambier on my Refusal to accuse his Lordship.—His Insinuations against me uncalled for.—Assumes that I am still under his Command.—Enemy escaped from his own Neglect.—The Shoals put in the Chart to excuse this.—Attempt to impute blame to me and Captain Seymour.—The Truth proved by Captain Broughton that Lord Gambier had no Intention of Attacking.—Lord Howe’s Attack on the Aix Forts.—Clarendon’s Description of Blake. |

82 |

| |

|

| CHAP. XXVIII. |

| THE VOTE OF THANKS. |

| |

|

| My Motion for Minutes of Court-martial.—Mr. Tierney’s Opinion respecting them.—Mr. Whitbread’s Views.—The Minutes indispensable.—Mr. Wilberforce on the same point.—Lord Grey’s Opinion of the Ministry.—The Vote of Thanks leaves out my Name, yet the Credit of the Affair given to me.—Inconsistency of this.—I impugn the Decision of the House.—Sir Francis Burdett’s Opinion.—Mr. Windham’s.—Lord Mulgrave turns round upon me.—His Lordship’s Misrepresentations.—Yet admits the Service to be “Brilliant.”—Lord Mulgrave Rebuked by Lord Holland.—Earl Grosvenor’s Views.—Lord Melville hits upon the Truth, that I, being a Junior Officer, was left out.—Vote of Thanks in Opposition to Minutes.—The Vote, though carried, damaged the Ministry |

104 |

| |

|

| CHAP. XXIX. |

| REFUSAL OF MY PLANS FOR ATTACKING THE FRENCH FLEET IN THE SCHELDT. |

| |

|

| xRefused Permission to Rejoin my Frigate.—-I am regarded as a marked Man.—No Secret made of this.—Additional cause of Offence to the Ministry.—The Part taken by me on the Reform Question, though Moderate, resented.—Motion for Papers on Admiralty-Court Abuses.—Effect of the System.—Modes of evading it.—Robberies by Prize-Agents.—Corroborated by George Rose.—Abominable System of Promotion.—Sir Francis Burdett committed to the Tower.—Petitions for his Liberation intrusted to me.—Naval Abuses.—Pittances doled out to wounded Officers.—Sinecures cost more than all the Dockyards.—My Grandmother’s Pension.—Mr. Wellesley Pole’s Explanation.—Overture to quit my Party.—Deplorable Waste of Public Money.—Bad Squibs.—Comparison with the present Day.—Extract from Times Newspaper |

126 |

| |

|

| CHAP. XXX. |

| MY PLANS FOR ATTACKING THE FRENCH COAST REFUSED, AND MYSELF SUPERSEDED. |

| |

|

| Plans for Attacking the French Coast submitted to the First Lord, the Right Honourable Charles Yorke.—Peremptorily ordered to join my Ship in an inferior Capacity.—My Remonstrance.—Contemptuous Reply to my Letter.—Threatened to be superseded.—Mr. Yorke’s Ignorance of Naval Affairs.—Result of his Ill-treatment of me.—My Reply passed unnoticed, and myself Superseded |

151 |

| |

|

| CHAP. XXXI. |

| VISIT TO THE ADMIRALTY COURT AT MALTA. |

| |

|

| The Maltese Admiralty Court.—Its extortionate Fees, and consequent Loss to Captors.—My Visit to Malta.—I possess myself of the Court Table of Fees.—Ineffectual Attempts to arrest me.—I at length Submit, and am carried to Prison.—A mock Trial.—My Defence.—Refuse to answer Interrogatories put for the purpose of getting me to criminate myself.—Am sent back to Prison.—Am asked to leave Prison on Bail.—My Refusal, and Escape.—Arrival in England |

166 |

| |

|

| CHAP. XXXII. |

| NAVAL LEGISLATION HALF A CENTURY AGO. |

| |

|

| xiInquiry into the State of the Navy.—Condition of the Seamen.—The real Cause of the Evil.—Motion relative to the Maltese Court.—Its extortionate Charges.—My own Case.—A lengthy Proctor’s Bill.—Exceeds the Value of the Prize.—Officers ought to choose their own Proctors.—Papers moved for.—Mr. Yorke’s Opinion.—Sir Francis Burdett’s.—My Reply.—Motion agreed to.—Captain Brenton’s Testimony.—French Prisoners.—Their Treatment.—Ministers refuse to inquire into it.—Motion on my Arrest.—Circumstances attending it.—My right to demand Taxation.—The Maltese Judge refuses to notice my Communications.—Afraid of his own Acts.—Proceedings of his Officers illegal.—Testimony of eminent Naval Officers.—Proclamation on my Escape.—Opinion of the Speaker adverse.—Mr. Stephen’s erroneous Statement.—Motion Objected to by the First Lord.—My Reply |

181 |

| |

|

| CHAP. XXXIII. |

| OPENING OF PARLIAMENT, 1812. |

| |

|

| Sir Francis Burdett’s Address seconded by me.—Employment of the Navy.—Naval Defences.—The Address rejected.—Curious Letter from Captain Hall.—Perversion of Naval Force in Sicily.—A Nautico-military Dialect.—Uselessness of our Efforts under a false System, which excludes Unity of Purpose |

215 |

| |

|

| CHAP. XXXIV. |

| MY SECRET PLANS. |

| |

|

| My Plans submitted to the Prince of Wales.—Negotiations thereon.—A modified Plan submitted, which came to nothing.—Inconsiderate Proposition.—Recent Report on my Plans.—Opinions of the Commissioners.—Plans probably known to the French.—Faith kept with my Country in spite of Difficulties.—Injurious Results to myself both Abroad and at Home.—Opposition to my Plans inexplicable.—Their Social Effect.—The Subject of Fortifications: these greatly overrated.—-Reasons why.—The Navy the only Reliance |

227 |

| xiiCHAP. XXXV. |

| NAVAL AND OTHER DISCUSSIONS IN PARLIAMENT. |

| |

|

| Sinecures.—Admiralty Expenses ill directed.—What might be done with small Means.—Flogging in the Army and Navy attributable to a bad System: nevertheless, indispensable.—National Means wrongly applied.—Injurious Concessions to the French.—Denied by the Government.—Explanations of my Parliamentary Conduct on the Dissolution of Parliament.—Letter to my Constituents.—Appointment of Officers by Merit instead of political Influence the true Strength of the Navy.—My Re-election for Westminster.—Address to the Electors.—Ministerial Views.—Treatment of an Officer.—My Interference |

246 |

| |

|

| CHAP. XXXVI. |

| MY MARRIAGE. |

| |

|

| Romantic Character of my Marriage.—Unforeseen Difficulties.—Family Results |

269 |

| |

|

| CHAP. XXXVII. |

| NAVAL ABUSES. |

| |

|

| Greenwich Hospital.—Droits of Admiralty.—Pensions.—My Efforts fruitless.—Contradiction of my Facts.—The Manchester Petition.—Naval Debates.—Resolutions thereon.—Mr. Croker’s Reply.—Remarks thereon.—Sir Francis Burdett.—My Reply to Mr. Croker.—Resolutions negatived without a Division.—Sir Francis Burdett’s Motion.—Mr. Croker’s Explanation.—-His Attack on me confirming my Assertions.—The Truth explained.—Another unfounded Accusation.—Official Claptrap of his own Invention.—My Reply.—Its Confirmation by Naval Writers.—Lord Collingwood’s Opinion.—My Projects adopted in all important Points.—Official Admissions.—The Result to myself |

273 |

| xiii |

|

| CHAP XXXVIII. |

| THE STOCK-EXCHANGE TRIAL. |

| |

|

| Necessity for entering on the Subject.—Lord Campbell’s Opinion respecting it.—Lord Brougham’s Opinion.—His late Majesty’s.—My Restoration to Rank.—Refusal to Reinvestigate my Case.—The Reasons given.—Extract from Lord Brougham’s Works.—My first Knowledge of De Berenger.—How brought about.—The Stock-Exchange Hoax.—Rumours implicating me in it.—I return to Town in consequence.—My Affidavit.—Its Nature.—Improbability of my Confederacy.—My Carelessness of the Matter.—De Berenger’s Denial of my Participation.—Remarks thereon.—Significant Facts.—Remarks on the alleged Hoax common on the Stock-Exchange |

317 |

| |

|

| CHAP. XXXIX. |

| |

|

| Admiralty Influence against me.—Appointment of Mr. Lavie as Prosecutor.—The Trial.—Crane, the Hackney Coachman.—Indecision of his Evidence.—Lord Ellenborough’s Charge, and unjustifiable Assumptions.—Report of the Trial falsified; or rather made up for the Occasion.—Evidence, how got up.—Proved to be positive Perjury.—This confirmed by subsequent Affidavits of respectable Tradesmen.—Another Charge in Store for me, had not this succeeded.—The chief Witness’s Conviction.—His subsequent Transportation and Liberation.—Affidavits of my Servants, Thomas Dewman, Mary Turpin, and Sarah Bust.—My second Affidavit.—Appeal from my Conviction refused.—Expulsion from the House.—Minority in my Favour. |

344 |

| |

|

| CHAP. XL. |

| |

|

| xivRemarks on Lord Ellenborough’s Directions.—Proofs of this Fallacy.—His Assumption of things not in Evidence, and unwarrantable Conjectures, in positive Opposition to Evidence.—His Desire to Convict obnoxious Persons.—Leigh Hunt, Dr. Watson, and Hone.—Lord Ellenborough a Cabinet Minister at the time of my Trial.—My Conviction a ministerial Necessity.—Vain Attempts to get my Case reheard.—Letter to Lord Ebrington.—The Improbability of my Guilt.—Absurdity of such Imputation.—Letter of Sir Robert Wilson.—Letter of the late Duke of Hamilton.—Mr. Hume’s Letter.—Causes for my Persecution.—Treatment of the Princess Charlotte, who fled to her Mother’s Protection.—Sympathy of the Princess for my Treatment—My Popularity increased thereby.—Mine really a State Prosecution.—Restoration of Sir Robert Wilson.—My Restoration incomplete to this Day |

372 |

| |

|

| Appendices |

401 |

xvDIRECTIONS TO THE BINDER.

| Chart A |

to face page 15 |

| ” B |

” 101 |

| ” C |

” 24 |

| ” D |

” 37 |

1AUTOBIOGRAPHY OF A SEAMAN.

CHAPTER XXIV.

A NAVAL STUDY FOR ALL TIME.

CHARTS, ETC., SUPPLIED BY THE PRESENT GOVERNMENT.—REFUSED BY A

FORMER GOVERNMENT.—ALTERATION MADE IN THE CHARTS.—MR.

STOKES’S AFFIDAVITS.—LETTER TO SIR JOHN BARROW.—SINGULAR

ADMIRALTY MINUTE.—SECOND LETTER TO SIR JOHN BARROW.—THE

CHARTS AGAIN REFUSED.—MY DEPARTURE FOR CHILI.—RENEWED

APPLICATION TO THE ADMIRALTY.—KINDNESS OF THE DUKE OF

SOMERSET.—DIFFERENCE OF OPINION AT THE ADMIRALTY.

It will be asked, “How is it that the matters recorded

in the present volume are, after the lapse of fifty years,

for the first time made public?”

The reply is, that it was not till after the publication

of the preceding volume that I have been enabled to

place the subject in a comprehensible point of view[1],

and that only through the high sense of justice manifested

by the late and present First Lords of the

2Admiralty, in furnishing me with charts and logs,

access to which was prohibited by former Boards of

Admiralty. On several previous occasions the attempt

has been made, but from the obstinate refusal of

their predecessors to afford me access to documents

by which alone truth could be elicited, it has not

hitherto been in my power to arrive at any more

satisfactory result than that of placing my own personal

and unsupported statements in opposition to the sentence

of a court-martial.

The necessary materials being now conceded, in such

a way as to enable me to prepare them for publication

in detail, it is, therefore, for the first time in my power

to vindicate myself. A brief recapitulation of former

refusals, as well as of the manner in which I became

possessed of such documentary testimony as will henceforth

exhibit facts in a comprehensive point of view,

is desirable, as placing beyond dispute matters which

would otherwise be incredible.

My declaration previous to the court-martial—that

it was in my capacity as a member of the House of

Commons alone that I intended to oppose a vote of

thanks to Lord Gambier, on the ground that no

service had been rendered worthy of so high an

honour—will be fresh in the remembrance of the

reader[2]; and also that when, at the risk of intrenchment

on the privilege of Parliament, the Board of

Admiralty called upon me officially to accuse his lordship,

I referred them to the logs of the fleet for such

3information relative to the attack in Aix Roads as they

might require[3];—it nevertheless became evident that

I was regarded as his lordship’s prosecutor! though,

throughout the trial, excluded from seeing the charts

before the Court, hearing the evidence, cross-examining

the witnesses, or even listening to the defence![4]

On the acquittal of Lord Gambier, the ministry did

not submit the vote of thanks to Parliament till six

months afterwards, viz. in the session of the following

year, 1810. To myself, however, the consequences

were—as Lord Mulgrave had predicted—immediate;

bringing me forthwith under the full weight of

ministerial displeasure. The Board of Admiralty prohibited

me from joining the Impérieuse in the Scheldt.

The effect of this prohibition in a manner so marked

as to be unmistakeable as to its cause, produced on my

mind a natural anxiety to lay before the public the

reasons for a proceeding so unusual, and, as a first step, I

requested of the Board permission to inspect the charts

upon which—in opposition to the evidence of officers

present at the attack—the decision of the court-martial

had been made to rest. The request was evaded, both

then and afterwards, even though persisted in up to

the year 1818, when it was officially denied that the

original of the most material chart was in the possession

of the Admiralty. Even inspection of a copy

admitted to be in their possession was refused.

An assertion of this nature might be dangerous were

not ample proof at hand.

4It having come to my knowledge, from certain affidavits

filed in the Court of Admiralty by Mr. Stokes,

the master of Lord Gambier’s flagship, on whose chart

the acquittal of Lord Gambier had been based—that,

after the lapse of eight years from the court-martial!

material alterations had been made by permission of the

Board itself and under the direction of one of its officers—I

naturally became suspicious that the charts might

otherwise have been tampered with; the more so,

as neither at the court-martial, nor at any period subsequent

to it, had I ever been allowed to obtain even

a sight of the charts in question.

The very circumstances were suspicious. On the

application for head-money to the Court of Admiralty

in 1817, the Court had refused to receive Mr. Stokes’s

chart, on account of its palpable incorrectness. On

this, Mr. Stokes applied to the Admiralty for permission

to alter his chart! The permission was granted, and in

this altered state it was received by the Court of

Admiralty, which, on Mr. Stokes’s authority, decreed

that the head-money should be given to the whole fleet,

contrary to the Act of Parliament, instead of the ships

which alone had taken part in the destruction of the

enemy’s vessels.

Fearful that material erasures or additions had been

made, I once more applied to the Board for permission

to inspect the alterations. The request was again

refused, though my opponents had been permitted to

make what alterations and erasures they pleased.

The following are extracts from the above-mentioned

affidavits of Mr. Stokes:—

5Extract from the affidavit, sworn before the High Court of Admiralty

on the 13th of November, 1817, of Thomas Stokes, master

of the Caledonia, as to the truth of the MSS. chart, upon which

the acquittal of Lord Gambier was based; before the Court of

Admiralty rejected his chart, and before the alterations were made.

“And this deponent maketh oath that the annexed paper

writing marked with the letter A, being a chart of Aix Roads,

is a true copy[5] made by this deponent of an original French

chart found on board the French frigate L’Armide in September,

1806, which original chart is now in the Hydrographic

Office in the Admiralty, and by comparing the same

with the original chart he is enabled to depose, and does

depose that the said chart is correct and true, and that the

soundings therein stated accurately describe the soundings at

low water, to the best of his judgment and belief.”

Extract from a second affidavit, sworn by Mr. Stokes, before the

High Court of Admiralty, on the 17th of April, 1818, after the

Court had refused to admit his chart from its incorrectness; and

after the alterations had been made!

“Appeared personally, Thomas Stokes, master in the Royal

Navy, and made oath that the original MSS. chart found on

board the French frigate L’Armide, and marked A, annexed

to his affidavit of the 13th of November, 1817, were delivered

at the Hydrographic Office at the Admiralty, and this deponent

for greater convenience of reference! inserted a scale of a

nautic mile!! the original manuscript chart having only a

scale of French toises; that in inserting a scale of a nautic

mile, this deponent had allowed a thousand French toises to

a nautic mile, and that Mr. Walker, the Assistant-Hydrographer,

accordingly made the erasures which now appear

on the face of the chart!” &c.

In these affidavits Mr. Stokes first distinctly swore

6that his chart, copied from a French MSS. was correct;

2ndly—when detected by the Court of Admiralty—that

it was incorrect; 3rdly—that the original was deposited

in the Hydrographic Office at the Admiralty.

My application to Sir John Barrow, then Hydrographer

to the Admiralty, was as follows:—

“May 4th, 1818.

“Sir,—As it appears by the affidavit of which I enclose a

copy that two charts of Aix Roads, the one stated to be a

copy of the other, were deposited in the Hydrographic Office,

and that the one purporting to be the copy has been delivered

up for the purpose of being exhibited as evidence on the part

of my opponents in a cause now pending in the High Court of

Admiralty, and as it further appears that an alteration in the

last-mentioned chart was made by Mr. Stokes, and a further

alteration by Mr. Walker, Assistant-Hydrographer, I have

to request that the Right Honourable the Lords Commissioners

will be pleased to permit me to see the other or

original chart of Mr. Stokes still remaining at the Hydrographic

Office, in order that I may be enabled to judge

for myself of the nature and effect of the alterations now

acknowledged to have been made on the charts. The

reasonableness of this request will, I presume, be manifest to

their Lordships, and the more especially, seeing that my opponents

are not only allowed similar access, but have been

permitted to withdraw one of the said charts for the purpose

of exhibiting it in evidence, notwithstanding that a variation

from the original has been avowedly made therein.

“Sir John Barrow, Hydrographer, &c.”

To this request Sir John Barrow, on the 6th of

May, returned the following refusal:—

“As Mr. Stokes’s charts have been restored to him, and a

copy made for the use of the office, I am directed to acquaint

7your Lordship that my Lords cannot comply with your request

in respect to the original chart, and as to the copy of the

chart made in this office and now remaining here, their Lordships

do not feel themselves at liberty to communicate it.

“I have the honour, &c.

“John Barrow.”

This refusal was accompanied by the following copy

of a minute from the Admiralty: in which it was pretended

that Stokes had only lent the original chart

to the Hydrographer’s office, to be copied for the use of

the Hydrographic Department—though it had been

made use of to acquit an admiral, to the rejection of

the charts of the fleet, as will presently be seen.

“Mr. Stokes lent the original chart to the Hydrographer’s

office, to be copied for the use of that department.

“Mr. Stokes then went abroad.

“On his return he applied for his chart, which being

mislaid they gave him the copy.

“Stokes, finding the alteration objected to in a court of

law, applied about a month since for his own chart, the

original of which was restored to him, copy being made.”—23,

141, 147.

To this singular communication and minute I returned

the subjoined reply:—

“13, Henrietta Street, Covent Garden.

18th May, 1818.

“Sir,—Your letter of the 6th of May was delivered to me

as I was going out of town, consequently I had no opportunity

of referring to documents which I have since consulted,

in order to refute the statements which the Lords of the Admiralty

appear to have received.

“You inform me, by command of their Lordships, that

‘it appears by a report from the Hydrographer that Mr.

Stokes had become possessed of the original chart which he

8lent to the Hydrographer’s office for the use of that department.’

This appears to imply that Mr. Stokes became

possessed of the original chart at the time of the attack

in the Charente under Lord Gambier, whereas Mr. Stokes

made oath that it was taken from the Armide in 1806, two

years and a half previous to the attack in question. As it

does not appear from the Minutes of the court-martial on

Lord Gambier that the original chart was then produced,

and as it is not now forthcoming in the cause now pending

in the Court of Admiralty, I am compelled to disbelieve its

existence, or at least to believe that it underwent material

alterations after it came into Mr. Stokes’s possession. The

original ought to have been exhibited with the copy at the

trial of Lord Gambier, and both either were or ought to

have been filed in the office of the Admiralty with the

Minutes of the proceedings; but whether either are so filed

their Lordships have not permitted me to ascertain.

“If the original were filed, it could not afterwards have

been ‘lent by Mr Stokes to the Hydrographer’s office to be

copied for the use of that department.’ Even had the copy

only been filed—sworn as it was by Mr. Stokes ‘to be correct!’

there could have been no necessity—if Mr. Stokes

was deemed worthy of belief—for the Hydrographer to borrow

the original. Eight years having elapsed since the court-martial

on Lord Gambier, you inform me that ‘Mr. Stokes

on his return from abroad applied for his chart accordingly,

which chart happening to be mislaid, he was furnished with

the copy in question,’ viz. that ‘made for the use of the

Hydrographer’s department.’ It is important to observe that

this is completely at variance with the affidavit of Mr. Stokes,

who swears that ‘he himself made the copy,’ and that ‘both

the copy and the original were delivered at the Hydrographic

Office!’ It cannot fail to be observed, that to ‘deliver’ a chart

at the Hydrographic Office, and to ‘lend a chart to be copied

for the use of that department’—the language of the letter

before me—are different expressions, conveying widely different

meanings.

9“It is also material to observe that it is strange alterations

at all should have been made on a chart represented to be a

copy of an original, and exhibited as evidence in a court of

law. That such original is not forthcoming is a very material

and a very suspicious circumstance. If it be true, or if

there really be any other chart than that which is described

as a copy and admitted to be altered, I may fairly infer

that such altered copy differs so materially and so fraudulentlyfraudulently

from the original, or that the original—so called—is itself

so palpable a fabrication, or has so obviously been altered,

that Mr. Stokes and his employers do not dare to exhibit it

in a court of law; and have withdrawn it from the Hydrographer’s

office for the purpose of suppressing so convincing a

proof of the fraud practised on Lord Gambier’s trial.

“Exclusive of the glaring contradiction between the statements

of Mr. Stokes on the court-martial, and that which you

have been commanded to make to me, when it is considered

that Mr. Stokes is detected in having altered a document

which he exhibits in a court of law as a correct copy of an

original, and that he is no sooner detected than he endeavours

to defend the alteration by declaring that it proceeded from

the Hydrographer’s office, where the original was deposited;

and that upon such defence leading to an application for

leave to inspect the original, answer is made that such

original had merely been borrowed of Mr. Stokes, and had

been returned to him at his own request, and that request,

too, made in consequence of the alteration in the alleged copy

having been detected—it is impossible not to infer a juggle

between Mr. Stokes, the Hydrographic Office, and others

whom I shall not here undertake to name, for the purpose of

defeating the ends of justice.

“Cochrane.

“Sir John Barrow, Hydrographer, &c.”

Receiving no reply to this letter, I subsequently

addressed the following to the Secretary of the Admiralty.

10

“9, Bryanstone Street, Portman Square,

2nd July, 1818.

“Sir,—I feel it proper to inclose to you, as Secretary of

the Admiralty, a copy of an affidavit, accompanied by a

general outline of the chart of Basque Roads, the originals of

which are filed in the High Court of Admiralty, by which

their Lordships will clearly perceive that five more ships of

the line might and ought to have been taken or destroyed,

had the enemy been attacked between daybreak and noon

on the 12th of April. And I have to request, Sir, that you

will have the goodness to lay these documents before their

Lordships (as well as the inclosed printed case which they

have already partly seen in manuscript), with my respectful

and earnest desire that their Lordships may be pleased to

cause the facts therein set forth to be verified by comparing

them with the original documents, logs, charts, and records

in their Lordships’ possession. I am the more solicitous that

the present Lords Commissioners of the Admiralty should

adopt this mode of proceeding, as it will enable them decisively

to judge on a subject of great national importance,

and also to ascertain (what a portion of the public know)

that it is not by false evidence from amongst the lower class

of society alone that my character has been assailed, in order

not only to perpetuate the concealment of neglect of duty,

but to prevent an exposure of the perjury, forgery, and

fraud by which that charge was endeavoured to be refuted.

“I beg, Sir, that you will assure their Lordships on my

part, that as a deep sense of public duty alone induced me

formerly to express a hope that the thanks of Parliament

might not be pressed for the conduct of the affair in Basque

Roads, so, in addition to that feeling, which made me disregard

every private interest, I have formed a fixed determination

never, whilst I exist, to rest satisfied until I expose the

baseness and wickedness of the attempts made to destroy my

character, which I value more than my life.

“As the affidavits of Captains Robert Kerr and Robert

Hockings (which, as well as my own, are filed in the High

Court of Admiralty) may immediately be made the subject of

11indictment in a court of law, and as the proceedings in the

Admiralty Court have been put off under the pretence of

obtaining further evidence in support of the mis-statements

of these officers and the claim of Lord Gambier, I have

respectfully to request that when the Lords Commissioners of

the Admiralty shall have instituted an inquiry into the logs,

charts, and documents, and ascertained the conduct of the

before-named officers, they will be pleased to cause public

justice to be done in a matter involving the character of the

naval service so deeply.

“If, Sir, through their Lordships’ means, a fair investigation

shall take place, it will be far more gratifying than any other

course of proceeding.

“I have the honour to be, &c. &c.,

“Cochrane.

“Jno. Wilson Croker, Esq., Secretary, &c., Admiralty.”

After the above correspondence I gave up, as hopeless,

all further attempts to obtain even so much as a

sight of the charts without which any public explanation

on my part would have been unintelligible.

In the year 1819—when nearly ruined by law

expenses, fines, and deprivation of pay—in despair

moreover, of surmounting the unmerited obloquy which

had befallen me in England—I accepted from the

Chilian government an invitation to aid in its war of

independence; and removed with Lady Cochrane and

our family to South America, in the vain hope of finding,

amongst strangers, that sympathy which, though

interested, might, in some measure compensate for the

persecutions of our native land.[6] I will not attempt

12to describe the agonised feelings of this even temporary

exile under such circumstances from my

country, in whose annals it had been my ambition to

secure an honourable position. No language of mine

could convey the mental sufferings consequent on finding

aspirations—founded on exertions which ought to

have justified all my hopes—frustrated by the enmity

of an illiberal political faction, which regarded services

to the nation as nothing when opposed to the interests

of party.

On my return to England, from causes which will

appear in the sequel, the subject of the charts was not

again officially renewed.

Latterly, however, considering that at my advanced

age there was a probability of quitting the world with

the stigma attached to my memory of having been

the indirect cause of bringing my commander-in-chief

to a court-martial—though in reality the charges were

made by the Admiralty—I determined to make one

more effort to obtain those documents which alone

could justify the course I had deemed it my duty to

pursue. In the hope that the more enlightened policy

of modern times might concede the boon, which a

former period of political corruption had denied, I

applied to Sir John Pakington, late First Lord of the

Admiralty, for permission to inspect such documents

relative to the affair of Aix Roads as the Board might

possess.

13Permission was kindly and promptly granted by Sir

John Pakington; but Lord Derby’s ministry going out

of office before the boon could be rendered available, it

became necessary to renew the application to the successor

of the Right Honourable Baronet, viz. his Grace

the Duke of Somerset, who as promptly complied with

the request. The reader may judge of my surprise on

discovering, in its proper place, bound up amongst the

Naval Records, in the usual official manner, the very

chart the possession of which had been denied by a

former Board of Admiralty!

The Duke of Somerset, moreover, with a consideration

for which I feel truly grateful, ordered that whatever

copies of charts I might require, should be supplied

by the Hydrographic Office; so that by the kindness

of Captain Washington, the eminent hydrographer to

the Board, tracings of the suppressed charts have been

made, and are now appended to this volume. His

grace further ordered that the logs of Lord Gambier’s

fleet should be submitted to the inspection of Mr. Earp,

with permission to make extracts; an order fully carried

out by the courtesy of Mr. Lascelles, of the Record

Office, to the extent of the logs in his possession.

It is, therefore, only after the lapse of fifty-one years

and in my own eighty-fifth year,—a postponement too

late for my peace, but not for my justification,—that I

am, from official documents, and proofs deduced from

official documents which were from the first and still

are in the possession of the Government, enabled to

remove the stigma before alluded to, and to lay before

the public such an explanation of the fabricated chart,

14together with an Admiralty copy of the chart itself, as

from that evidence shall place the whole matter beyond

the possibility of dispute. It will in the present day be

difficult to credit the existence of such practices and

evil influences of party spirit in past times as could

permit an Administration, even for the purpose of preserving

the prestige of a Government to claim as a

glorious victory! a neglect of duty which, to use the

mildest terms, was both a naval and a national dishonour.

The point which more immediately concerns myself is,

however, this:—that the verdict founded on this fabricated

chart, together with the subsequent official enmity

directed against me in consequence of my determination

to oppose the vote of thanks to Lord Gambier, was

persevered in year after year, till it reached its climax

in the consequences of that subsequent trial which was

made the pretext for driving me from the navy, in

defiance of remonstrance at the Board of Admiralty

itself. I have not long been aware of the latter fact.

Admiral Collier has recently informed me that Sir

W.J. Hope, then one of the Naval Lords of the Admiralty,

told him that considering the sentence passed

against me cruel and vindictive, he refused to sign his

name to the decision of the Board by which my name

was struck off the Navy List.

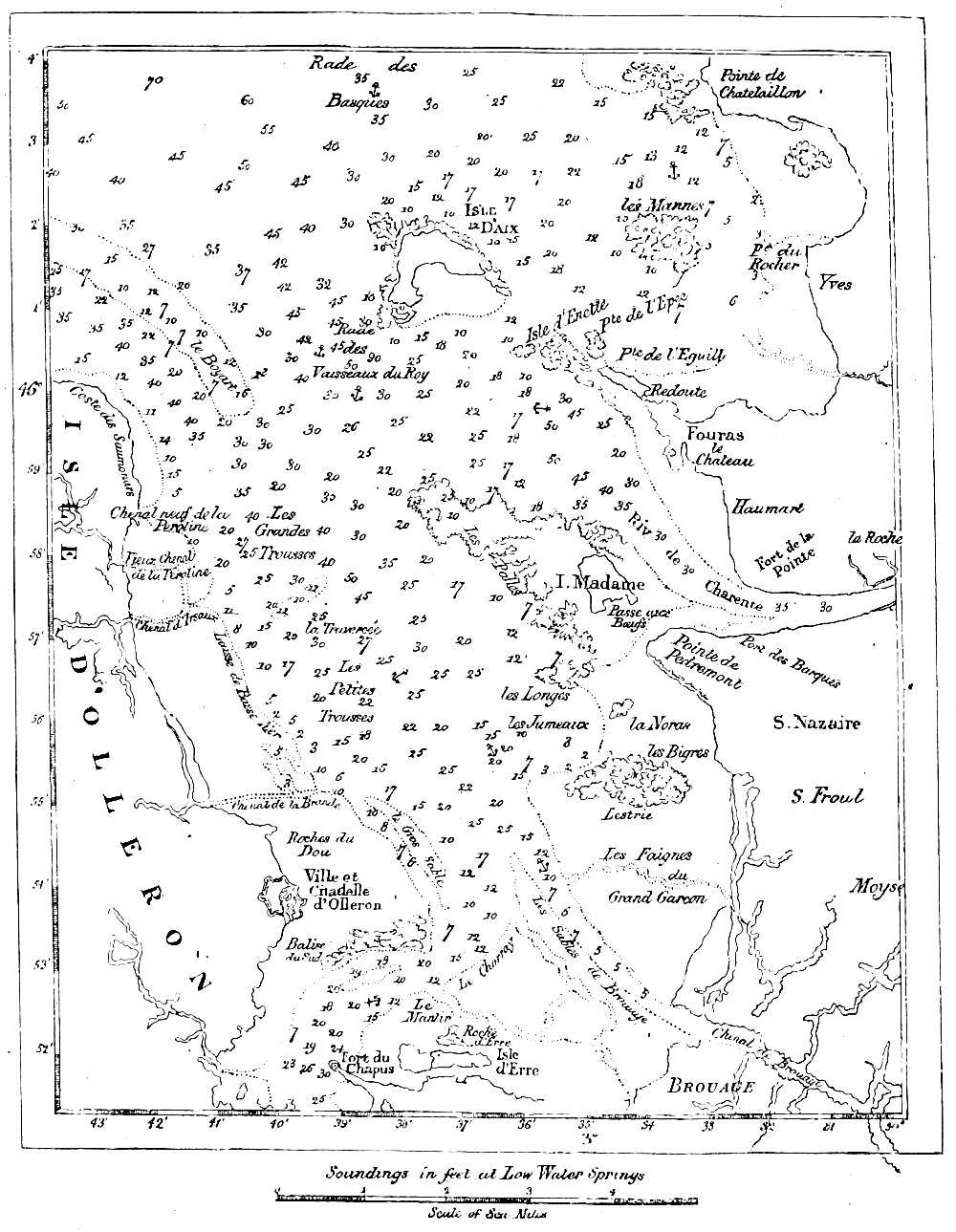

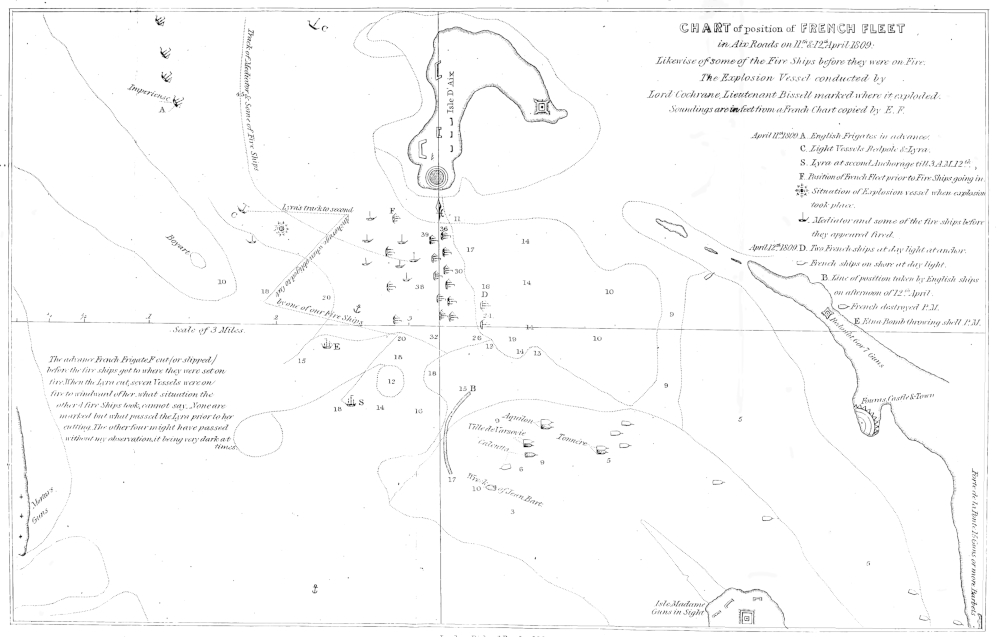

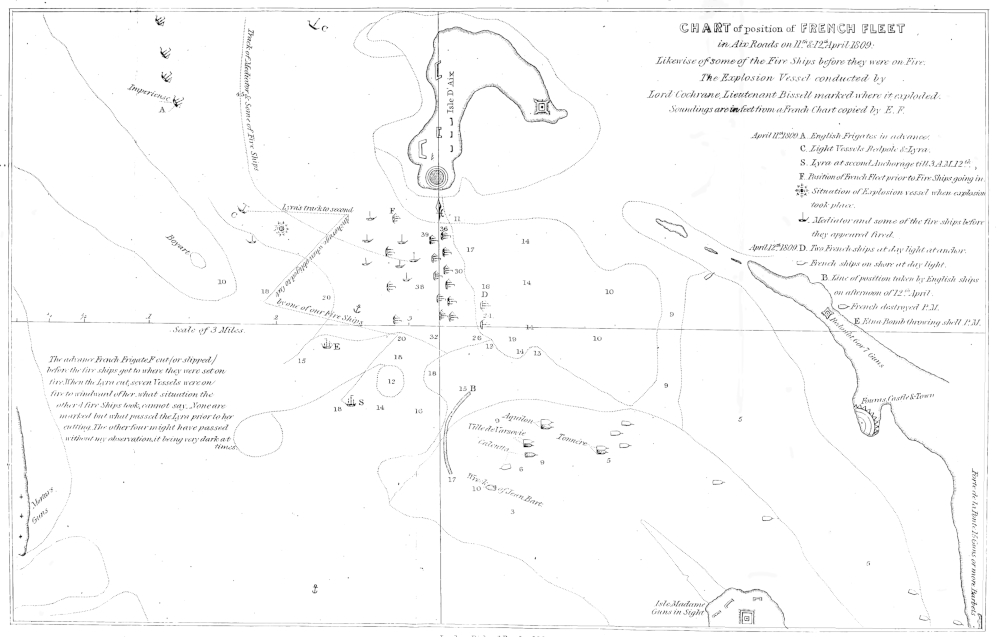

CHART A.

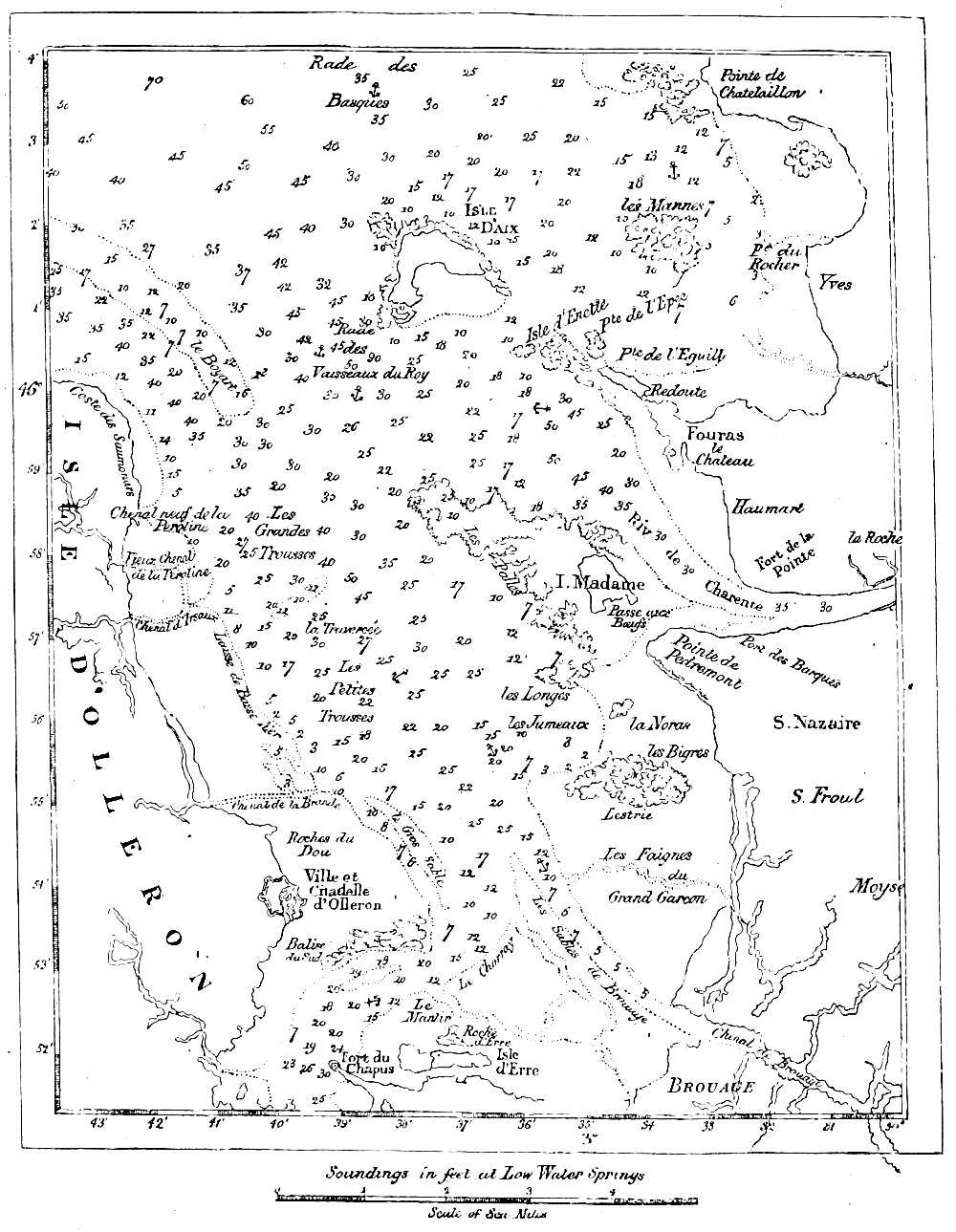

Tracing from the official French Chart of the isles of Ré and d’Olleron. Tendered to the Court-Martial by Lord Cochrane, and rejected.

Soundings in feet at Low Water Springs

London: Richard Bentley: 1860.

15

CHAP. XXV.

A NAVAL STUDY—continued.

FRENCH HYDROGRAPHIC CHARTS.—ONE TENDERED BY ME TO THE COURT.—REJECTED

BY THE PRESIDENT.—GROUNDS FOR ITS REJECTION.—THE

OBJECT OF THE REJECTED CHART.—WOULD HAVE PROVED TOO MUCH, IF

ADMITTED.—REJECTION OF OTHER CHARTS TENDERED BY ME.—MR.

STOKES’S CHART.—ITS FALLACY AT FIRST SIGHT.—JUDGE ADVOCATE’S

REASONS FOR ADOPTING IT.—ITS ERRORS DETECTED BY THE PRESIDENT,

AND EXPOSED HERE.—PROBABLE EXCUSE FOR THE ERROR.—IMAGINARY

SHOAL ON THE CHART.—FALSIFICATION OF WIDTH OF

CHANNEL.—LORD GAMBIER’S VOUCHER FOR STOKES’S CHART.—STOKES’S

VOUCHER FOR ITS WORTHLESSNESS.—STOKES’S CHART IN A NATIONAL

POINT OF VIEW.—TAKEN ADVANTAGE OF BY THE FRENCH.

The charts to which the reader’s attention is invited

are those alluded to in the last chapter, as having,

after the lapse of fifty-one years, been traced for me

by Captain Washington, by the order of his Grace

the Duke of Somerset. The subject being no longer

of personal but of historical interest, there can be no

impropriety in laying before the naval service, for its

judgment, materials so considerately supplied by the

present First Lord of the Admiralty.

is a correct tracing of Aix Roads from the Neptune

François, a set of charts issued by the French Hydrographical

Department—bound in a volume, and supplied

for the use of the French navy previous to

161809[7]; copies from the same source being at that

period supplied under the auspices of the Board of

Admiralty for the use of British ships on the French

coasts—these, in fact, forming the only guides available

at that period.

Chart A shows a clear entrance of two miles, without

shoal or hindrance of any kind, between Ile

d’Aix and the Boyart Sand; the soundings close to

the latter marking thirty-five feet at low water, with

from thirty to forty feet in mid-channel. The chart

shows, moreover, a channel leading to a spacious anchorage

between the Boyart and Palles Sands, marking

clear soundings at low water of from twenty to thirty

feet close to either sand, with thirty feet in mid-channel.

In this anchorage line-of-battle-ships could not only

have floated, without danger of grounding, but could

have effectively operated against the enemy’s fleet, even

in its entire state before the attack, wholly out of range

of the batteries on Ile d’Aix, as will hereafter be corroborated

by the logs and evidence of experienced

officers present in the attack, and therefore practically

acquainted with the soundings. To a naval eye, it will

be apparent that, by gaining this anchorage, it would

not at any time have been difficult for the British

force to have interposed the enemy’s fleet between itself

and the fortifications on Ile d’Aix in such a way as

completely to neutralise the fire of the latter.

Further inspection of the chart will indicate an inner

17anchorage, called Le Grand Trousse, to which any

British vessel disabled by the enemy’s ships—two only

of which, out of thirteen, remained afloat,—might have

retired with safety to an anchorage capable of holding

a fleet—the soundings in Le Grand Trousse marking

from thirty to forty feet at low water. Between these

anchorages it will be seen on the chart that there is

no shoal, nor any other danger whatever.[8]

The rise of tide marked on the chart was from ten

to twelve feet[9], consequently amply sufficient on a rising

tide for the two-deckers and frigates to have been sent

to the attack of the enemy’s ships aground on the

Palles Shoal, as testified by the evidence of Captains

Malcolm and Broughton.[10] The flood-tide making

about 7·0 A.M. gave assurance of abundant depth of

water by 11·0 A.M., which is the time marked in the

Commander-in-chief’s log[11] as that of bringing the British

ships to an anchor! in place of forwarding them to the

attack of ships on shore!

This chart was tendered by me to the Court, in explanation

of my evidence. It was, however, rejected,

18because I could not produce the French hydrographer

to prove its correctness! though copies of a similar

chart, as has been said, were furnished to British ships

for their guidance! Being thus repudiated, my chart

was flung contemptuously under the table, and neither

this nor any other official chart was afterwards allowed

to corroborate the facts subsequently testified by the

various officers present in the action, they being imperatively

ordered to base their observations on the

chart of Mr. Stokes alluded to in the last chapter, as

having been—eight years after the court-martial—pronounced

by the Court of Admiralty so incorrect as

to require material alteration before it could be put in

evidence in a court of law! To this point we shall

presently come.

A singular circumstance connected with the rejected

chart should rather have secured its reception, viz. that

it was taken by my own hands out of the Ville de

Varsovie French line-of-battle ship shortly before she

was set fire to, and therefore its authenticity, as having

been officially supplied by the French government for

the use of that ship, was beyond doubt or question.

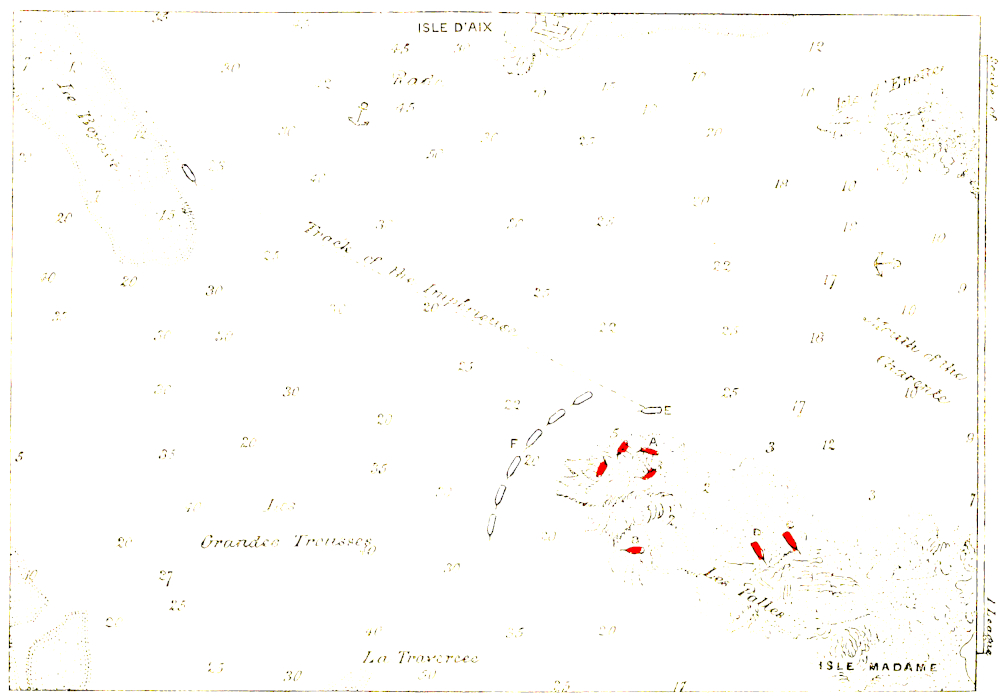

I also produced two similar charts, on which were

marked the places of the enemy’s ships aground at

daylight on the 12th of April, as observed from

the Impérieuse, the only vessel then in proximity.

The positions of the grounded vessels are marked on

Chart B.

The manner of the rejection by the Court—at the

suggestion of the Judge-Advocate—of the chart tendered

by me, is worthy of note.

President.—“I think your lordship said just now, that you

19thought there was water enough for ships of any draught

of water?”

Lord Cochrane.—“Yes.”

President.—“Have you an authenticated chart, or any

evidence that can be produced to show that there is actually

such a depth of water?”

Lord Cochrane (putting in the charts).—“It was actually

from the soundings we had going in, provided the tide does

not fall more than twelve feet, which I am not aware of. I

studied the chart of Basque Roads for some days before. The

rise of the tide, as I understand from that, is from ten to

twelve feet. It is so mentioned in the French chart. I have

no other means of judging.”[12]

Judge-Advocate.—“This chart is not evidence before

the Court, because his lordship cannot prove its correctness!!”

President.—“No! It is nothing more than to show upon

what grounds his lordship forms his opinion on the rise

and fall of the tide!!”[13]

It was not put in for any purpose of the kind—for

I had expressly said that I had no opinion as to the

rise and fall of the tide, except as marked on the

French official charts. The object of my putting in

those charts was to show the truth of the whole matter

before the Court. The president, however, flung the

chart under the table with as much eagerness as the

Judge-Advocate had evinced when objecting to its reception

in evidence.[14]

The object of the chart was in fact to prove, as indeed

was subsequently proved by the testimony of eminent officers,

and would have been proved even by the ships’ logs

had they been consulted, that there was plenty of channel

room to keep clear of the batteries on Ile d’Aix, together

with abundant depth of water[15]; and that the commander-in-chief,

in ordering all the ships to come to an

anchor, in place of sending a portion[16] of the British

21ships to the attack of the enemy’s vessels aground

on the north-west part of the Palles Shoal, on the

morning of the 12th of April, had displayed a “mollesse”—as

it was happily termed by Admiral Gravière—unbecoming

the Commander-in-chief of a British force,

superior in numbers, and having nothing to fear from

about a dozen guns on the fortifications of Aix; which,

had the ships been sent in along the edge of the

Boyart, could have inflicted no material damage, either

by shot or shell.[17]

These were precisely the points which the ministry

did not want proved, and which—as will presently be

seen—the Court was no less anxious to avoid proving.

Had the French chart been received in evidence, as

it ought to have been—I do not say mine, but

those on board the flagship itself, or indeed any copy

supplied by the Admiralty to the fleet—a vote of thanks

to Lord Gambier would have been impossible, and with

the impossibility would have vanished the Government

prestige of a great victory gained by their commander-in-chief,

under their auspices.[18]

The French official chart being thus adroitly got rid

of by the Judge-Advocate, the other charts tendered

by me to mark the positions of the enemy’s ships

22aground shared the like fate, though not open to the

same objection. The exactness of the positions was

moreover confirmed by the evidence of Mr. Stokes,

the master of the Caledonia, Lord Gambier’s flagship;

though his chart, substituted for those in use amongst

the British ships, was in direct contradiction to his

oral evidence.

The positions, of the ships aground as marked on my

charts, were as follows.

The Ocean, three-decker, bearing the flag of Admiral

Allemand, and forming a group with three other line-of-battle

ships close to her, lay aground on the north-west

edge of the Palles Shoal, nearest the deep water, where

even a gun-boat, had it been sent whilst they lay on their

bilge, could have so perforated their bottoms, that they

could not have floated with the rising tide. All were

immoveably aground, and were therefore incapable of

opposition to an attacking force[19]; whilst each of the

23group of three lay so much inclined towards each other

as to present the appearance of having their yards

locked together.[20] They had, in fact, drifted with the

same current, into the same spot, and being nearly of

the same draught of water, had grounded close to each

other. The one separate was a vessel of less draught

than these, and had gone a little further on the shoal.

The correctness of these positions, as marked on my

chart, was completely confirmed by Mr. Stokes, master

of the flag-ship, in his oral evidence as subjoined.

Question.—“State the situation of the enemy’s fleet on

the morning of the 12th of April.”

Mr. Stokes.—“At daylight I observed the whole of the

enemy’s ships, except two of the line, on shore. Four of them

lay in group, or lay together on the western part of the

Palles Shoal. The three-decker (L’Océan, flagship) was on

the north-west edge of the Palles Shoal, with her broadside

flanking the passage; the north-west point nearest the deep

water.”[20]—(Minutes, page 147.)

This was the truth as to the positions of the grounded

ships which escaped; these being referred to in Mr.

Stokes’s evidence precisely as marked on my rejected

chart. That is, his evidence showed, in corroboration

of my chart, the utter helplessness of an enemy which

a British admiral refrained from attacking, though

aground!

24The French charts produced by me being thus rejected,

those in the possession of the Commander-in-chief

not produced, and those connected with the fleet not

being called for, the court decided to rely upon two

charts professedly constructed for the occasion by the

master of the Caledonia, Mr. Stokes, and the master of

the fleet, Mr. Fairfax, neither of whom was present in

the attack.[21]

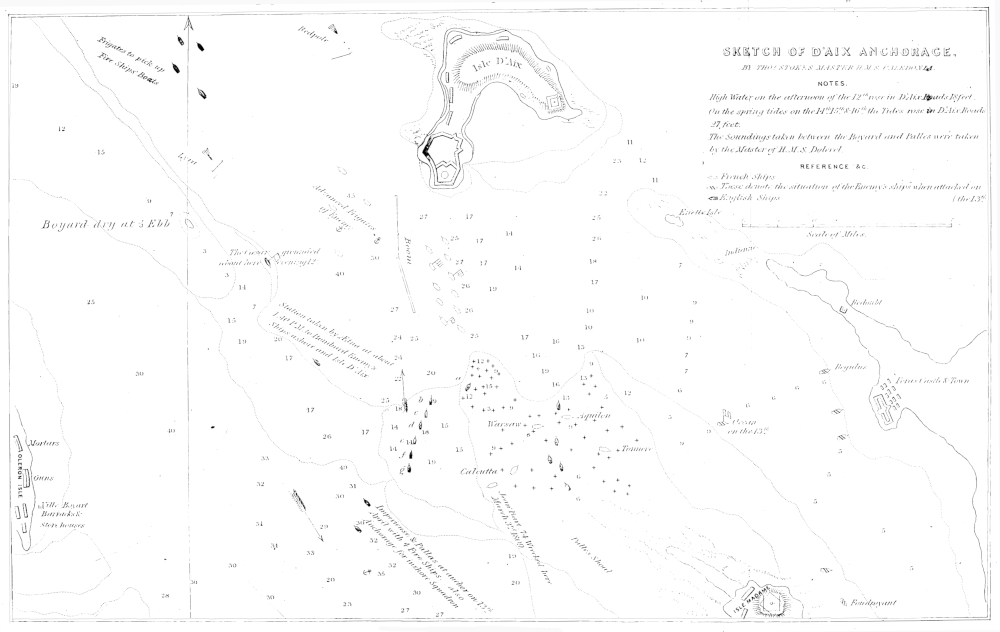

was tendered to the Court by Mr. Stokes, the master

of Lord Gambier’s flag-ship Caledonia.

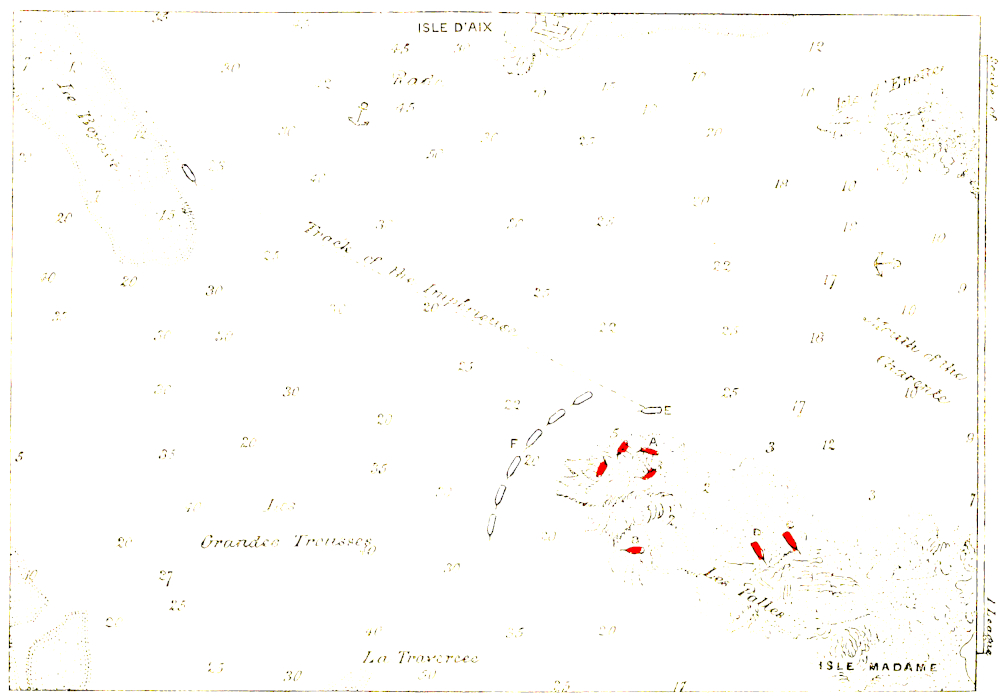

CHART C.

Constructed by Mr Stokes for the purposes of the Court Martial, and exclusively adopted, though it narrows the channel to Aix Roads to one mile only, the official French Charts marking two miles.

SKETCH OF D’AIX ANCHORAGE.

London: Richard Bentley, 1860.

This chart professed to show, and was sworn to by

Mr. Stokes as showing, the positions of the enemy’s

ships aground on the morning of the 12th of April, before

the Ocean three-decker, together with a group of

three outermost ships near her, had been permitted by

the delay of the Commander-in-chief to warp off and

escape. Instead, however, of placing these on his chart

as they lay helplessly aground “nearest the deep water”

as he had sworn in his evidence, they were placed in

25on the other side of the sand, in the positions occupied

after their escape! and to this Mr. Stokes swore as their

position when first driven ashore! The Ocean three-decker,

and group in particular, which, according to Mr.

Stokes’s oral evidence, must, as already stated, have

been an easy prey to a gunboat had such been sent

on the first quarter instead of the last quarter flood,

was thus placed on his chart where no vessel could

have approached them![22]

This falsehood on Mr. Stokes’s chart, in opposition

to his oral evidence just given, as well as to the evidence

of other officers, formed one of the principal

grounds of Lord Gambier’s acquittal; and it was for

this end that the official French charts presented by me

for the information of the court were rejected by the

judge-advocate.

On the presentation of Mr. Stokes’s chart to the

court, the subjoined colloquy took place as to the methods

adopted in its construction.

Mr. Bicknell.—“Produce a chart or drawing of the

anchorage at Isle d’Aix, with the relative positions of the

26British and French fleets, and other particulars, on and

previous to the 12th of April last.”

Mr. Bicknell.—“Did you prepare this drawing, and from

what documents, authorities, and observations; and are the

several matters delineated therein accurately delineated, to the

best of your knowledge and belief?”

Mr. Stokes.—“I prepared that drawing (Chart C),

partly from the knowledge I gained in sounding to the southward

of the Palles Shoal, and the anchorage of the Isle of

Aix.[23] The outlines of the chart are taken from the Neptune

François, and the position of the enemy’s fleet from Mr.

Edward Fairfax, and from the French captain of the Ville de

Varsovie, and the British fleet from my own observation.”

The distance between the sands was copied from a French

MS. which will be produced, and that I take it is correct.

Mr. Bicknell.—“Are the matters and things therein accurately

described?”

Mr. Stokes.—“They are.”

President (inspecting Mr. Stokes’s chart).—“There was

a large chart you lent me?”

27Mr. Stokes.—“That is the chart I allude to. This chart

I produce as containing the various positions.”

Judge-Advocate (to the President).—“This Chart is

produced to save a great deal of trouble!!” (Minutes,

pp. 23, 24.)

No doubt—the trouble of confirming the Commander-in-chief’s

neglect of duty in not following up a

manifest advantage, as would have been shown had

the court allowed the Neptune François itself to have

been put, in evidence; for it would have shown a

clear passage of two miles wide, extending beyond

reach of shot, instead of the one mile passage in Mr.

Stokes’s “accurate outlines” of the French chart, and

no shoal where he had marked only twelve feet of

water![24] That the president should have allowed this

to pass, after having himself detected the imposition

practised on the court, is a point upon which I will

not comment.

Mr. Stokes further admitted his chart to be valueless,

as regarded the position of the enemy’s fleet ashore, for

he said that position was taken “from Mr. Edward

Fairfax and the captain of the Ville de Varsovie”, and

the British fleet from “his own observations.” That

is, he confessed to know nothing but from hearsay as to

the position of the enemy’s fleet, the important object

before the court; but only of the position of the British

fleet, lying at anchor nine miles from the enemy’s fleet

ashore, a matter with which the court had nothing to do;

he being all the time on board the flagship, at that

distance. Yet the court insisted on this chart being exclusively

28referred to throughout the court-martial![25] It

is strange that such a chart should have been used at

all, when the charts of the fleet were available, but

more strange that, when the court saw the two miles

passage in the French chart was reduced to little more

than one mile in Mr. Stokes’s chart, he was not even

asked the reason why he had not conformed to the scale

of the French chart, to the correctness of the outlines of

which he had sworn!

But the most glaring contradiction of Mr. Stokes’s

chart is this: he swore to his chart as truly depicting the

positions of the Ocean and other grounded ships, as they

lay on the morning of the 12th of April, which was the

point before the Court; but being further questioned,

reluctantly admitted that he had marked the Ocean

29as she lay on the 13th of April, viz. on the following

day when an attack was made on her by the bomb

vessel! though he had just sworn to the positions of

the ships on the chart as being those on the morning of

the 12th, immediately after having run ashore to escape

destruction.

The fact was, as will be seen on inspection of the

chart, that not one of the ships under the cognizance of

the court is marked on Stokes’s chart as they lay on the

morning of the 12th, which position, and not that on

the 13th, was the subject of inquiry. Though as already

said this misrepresentation was detected by the President,

the court nevertheless persisted in the exclusive

use of Mr. Stokes’s chart throughout the trial, in accordance

with the suggestion of the Judge-Advocate,

that it was produced to “save a great deal of trouble.”

The President thus commented on the manifest contradiction.

President.—“I observe in the chart I had from you the

situation of the Ocean particularly is not marked on the

12th. She is marked on the 13th as advanced up the

Charente!”

Mr. Stokes.—“The only ships marked on the chart on

the 12th are those that were destroyed. The reason I marked

her on the 13th is, that a particular attack was made on her

by the bombs. I observed her from the mizentop of the

Caledonia[26], and I also had an observation from an officer,

so that I have no doubt her position is put down within a

cable’s length.” (Minutes p. 147.)

There is something in this evidence almost too repugnant

30for observation. Mr. Stokes first swore that

his chart accurately described the positions of the

enemy’s ships ashore on the morning of the 12th. He

then admitted that the most material ship of the enemy’s

fleet was marked as she lay on the 13th!! On this mis-statement

being detected by the president, he then

swore that the only ships marked on the 12th were those

which were destroyed, viz. on the evening and night of

the 12th!—a matter foreign to the subject of inquiry;

which was how the ships lay on the morning of the 12th,

and whether Lord Gambier was to blame for refraining

from attacking them at that particular time? So that

the positions of the enemy’s ships aground on the

morning of the 12th, according to Mr. Stokes’s own

admission, were not marked on his chart at all! though

he had sworn to this very chart as giving those positions

accurately to the best of his knowledge and belief; and

with the full knowledge that their position on the

morning of the 12th, when they were helplessly aground,

was the point before the court,—not their position

in the evening, and on the following day after their

escape to a spot where the British ships could not have

pursued them.

The fact is, Mr. Stokes swore to their positions after

their being warped off in consequence of the British fleet

being prematurely brought to an anchor—as being their

positions previous to their escape! which was the

matter of inquiry before the court, viz. as to whether

the Commander-in-chief had not committed a neglect

of duty in permitting them to escape by the

rising tide, when and before when the British force

could have operated with every advantage in its favour.

31The court had nothing whatever to inquire about

with regard to the ships which were destroyed, respecting

which there could be no question; the subject

of inquiry being whether the escape of the other

ships run ashore from terror of the explosion vessels on

the night of the 11th, and still ashore on the morning

of the 12th, ought to have been prevented.

Not so much as one of the ships marked on Mr.

Stokes’s chart formed part of the “group” to which

he had sworn, in his oral evidence, as lying on the

“western and northernmost edge of the Palles Shoal,

nearest the deep waterwater, all of which escaped towards

the Charente, where he truly enough placed the Ocean

three-decker, but as she lay on the 13th instead of

the 12th, he having sworn to the truth of his chart

as showing her position on the morning of the 12th!

It was a desperate venture, and can only be accounted

for by the supposition that, in reality, Mr. Stokes had

never seen the chart to which he was swearing. It

was no wonder, as proved in the first chapter, that

Mr. Stokes applied to the Admiralty for permission to

alter his chart before producing it in a court of law,

where it must have fallen under my inspection!

I will indeed so far exonerate Mr. Stokes from a

portion of blame, by declaring my belief that he never

had looked at the chart to which he had sworn. There

is little question in my mind but that this chart had

been fabricated under the auspices of Mr. Lavie, Lord

Gambier’s solicitor, the only hope of success consisting

in affirming a false position for the grounded ships;

the chart being then given to Stokes for paternity.

Had it been otherwise, Stokes could not possibly have

32sworn to a chart in diametrical opposition to his oral

evidence, which truly stated that on the morning of

the 12th, the Ocean and group lay on “the north-west

edge of the Palles shoal, nearest the deep water,” where

they were easily attackable. On his chart they were

placed on the opposite side of the shoal! where no ship

could have got near them.

Lord Gambier no doubt saw the mistake committed

by the evidence of his Master, and adroitly relieved

him from the dilemma, by putting a question of a

totally different nature. With this course the court

complacently complied, notwithstanding that the president

had detected a discrepancy so glaring.

Another material point on Mr. Stokes’s chart was his

marking a shoal between the Boyart and the Palles

Sands, where Capt. Broughton and others present in the

action, who actually sounded there, testify in corroboration

of the French chart to there being no shoal whatever.[27]

Yet Mr. Stokes marks only from twelve to

sixteen feet, in the deepest part. That this statement

was a misrepresentation on the part of Mr. Stokes, is

proved by Lord Gambier himself, who, in his defence,

says that “Mr. Stokes found on this bar or bank from

fourteen to nineteen feet”feet” (Minutes, p. 134). When closely

questioned on the point, Mr. Stokes deposed to these

soundings as “having been reported to him to have been

found”! (Minutes, p. 150.) The Neptune François

gives from twenty to thirty feet at low water, which

was no doubt correct.

But even had there been only nineteen feet of water

Mr. Stokes again forgot his chart when he gave oral

33evidence that “the rise of tide in Aix Roads is twenty-one

feet, which is more than we ever found in Basque Roads”

(Minutes, p. 150). I had put the rise of tide at

twelve feet only, so that by the oral evidence of Mr.

Stokes there was abundance of water for the British

force to have operated with full effect.

A still further falsification of the chart was, that it

reduced the channel by which the British fleet must

have passed to the attack to little more than a mile in

width, in defiance of the fact that on all the official

French charts the minimum distance between the

Boyart Sand and the fortifications on Ile d’Aix was

nearly two miles, and that Admiral Stopford, the

second admiral in command, confirmed the correctness

of the French charts so far as to admit a width of a

mile and a half. The object of Mr. Stokes’s statement

was to prove the danger to which, in a channel only a

mile wide, the British ships would have been exposed

from the batteries on Ile d’Aix had they been

sent to the attack. To this end was the chart no doubt

produced, and as narrowing the channel to a mile only—to

meet the occasion—gave a colour to this view,

his chart was accepted by the court, whilst the French

charts which marked two miles, were rejected.

A yet more flagrant contradiction is—that within

pistol shot of the western and north-western edge of the

Palles Shoal, where Mr. Stokes first truly swore “the

Ocean three-decker and a group of four lay aground on

the morning of the 12th,” he has placed the attacking

British ships, where their logs show that they never

touched the ground, notwithstanding that they took up

34their positions on a falling tide. If they could float

in safety much more could other ships have done so at

11 a.ma.m on a rising tide? How such a manifest discrepancy

could have passed without comment from

any member of the court-martial, is a point which is

not in my power to explain.

Such are some of the leading features of this famous

chart, upon which the acquittal of Lord Gambier was

made to rest, though the chart was admittedly constructed—not

from personal observation, otherwise than

from the mizentop of the Caledonia, nine miles off—but

from unofficial sources—from an anonymous manuscript,

and even from hearsay!

Yet Lord Gambier did not scruple to introduce this

chart for the guidance of the court, in the following

terms:

“I have to call the attention of the Court to the plan

drawn by Lord Cochrane of the position of the enemy’s ships

as they lay aground on the morning of the 12th of April,

and to that position marked upon the chart verified by Mr.

Stokes; the former laid down from uncertain data, the latter

from angles measured and other observations made on the

spot[28]; the difference between the two is too apparent to

escape the notice of the Court, and the respective merits of

these charts will not, I think, admit of a comparison.”

(Minutes, p. 133.)

This statement was made by Lord Gambier in face

of the admission previously made by Mr. Stokes,

that his observations were taken from the mizentop of

the Caledonia, three leagues off—that he had never

35sounded in Aix Roads—that the soundings were only

reported to him, the name of the reporter being

omitted—and that he had only marked upon his

chart, “the ships that were destroyed” on the evening

and during the night of the 12th, the destruction, in

fact, not being complete till the morning of the 13th.

This contradiction is so important to a right comprehension

of what follows, that I will, at the risk of

prolixity, bring into one focus Mr. Stokes’s admissions

as to his data for the construction of his chart.

“I prepared that drawing partly from the knowledge I

gained in sounding to the southward of the Palles Shoal.

The outlines of the chart are taken from the Neptune François

(narrowed from two miles to one!). The positions of

the enemy’s fleet are from Mr. Fairfax and the captain of the

Ville de Varsovie. For the distance between the sands I

must refer the court to a chart which I copied from a French

manuscript!” (Minutes, pp. 23, 24.)

For this confused jumble from unauthoritative

sources, the French charts were rejected as not being

trustworthy, and Lord Gambier did not hesitate to

endorse Mr. Stokes’s fabrication as being “from angles

measured and other observations taken on the spot;”

whilst by this act he decried the use of the French

charts by which his own fleet had been guided!

Comment, whether on Lord Gambier’s statement or

on Mr. Stokes’s involuntary contradiction thereof in

his oral evidence, is superfluous. If such were

wanted, it must be sought for in the fact already

adduced in the first chapter, viz. that, in 1817 and

1818, Mr. Stokes, when conscious that his fabrication

must become public, and that it might fall into my

36hands, thought it prudent to make affidavit before the

Court of Admiralty that this chart, produced at the

court-martial nine years before, was incorrect, and

therefore required alteration!! for which purpose the

Admiralty gave him back his chart, though this,

as already observed, remains to this day bound up

amongst the Admiralty records. The affidavits of Mr.

Stokes will be in the remembrance of the reader.

In a national point of view, Mr. Stokes’s chart has

another and even more important feature. A comparison

between the French chart and that produced by

Mr. Stokes will show that the latter narrowed the

entrance to Aix Roads—which on the French charts

is two miles wide—to one mile, and that it filled a

space with shoals where scarcely a shoal existed. Of

the imaginativeness of Mr. Stokes in this respect, the

French Government appears to have taken a very justifiable

naval advantage, calculated to deter any British

admiral in future from undertaking in Aix Roads

offensive operations of any kind.

A chart of the Aix Roads based on a modern French

chart has recently been shown me, as on the point of

being issued by the Board of Admiralty, on which

chart the main channel between Ile d’Aix and the

Boyart sand is laid down according to charts copied

from fabricated charts produced on Lord Gambier’s

court-martial, and not according to the hydrographic

charts of the Neptune François. The comparatively

clear anchorage shown in the new chart is also filled

with Mr. Stokes’s imaginary shoals! the result being

that no British admiral, if guided by the new chart,

37would trust his ships in Aix Roads at all, though both

under Admiral Knowles and at the attack in 1809

British ships found no difficulty whatever from want

of water, or other causes, when once ordered in.

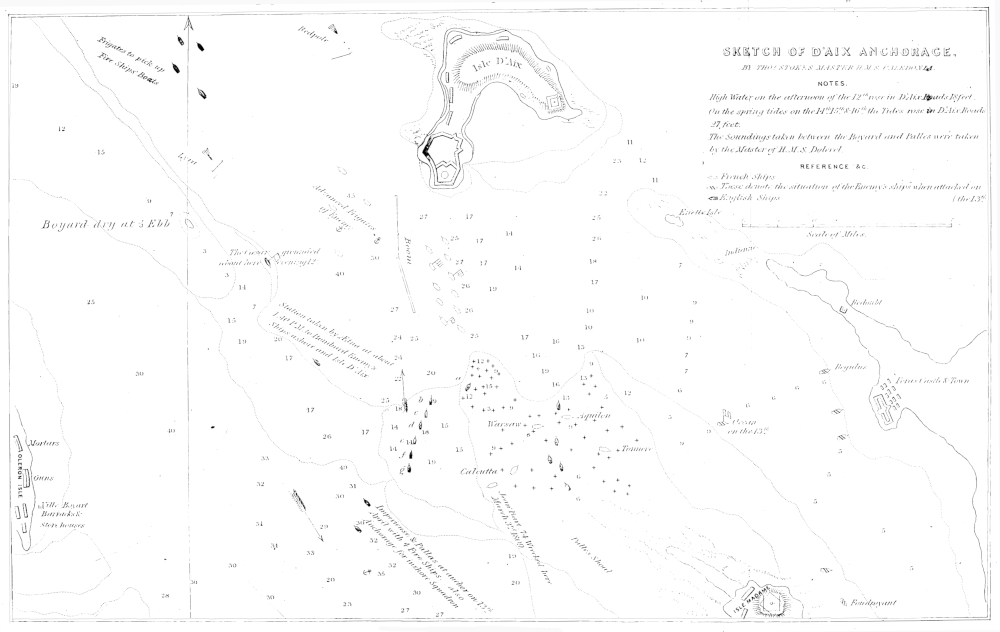

CHART D.

Constructed by Mr Fairfax and produced for the guidance of the Court Martial. Like Stokes’s Chart, it narrows the channel to Aix Roads from two miles to one mile though also like him professing to be an exact outline of the French Official Chart.]

London Richard Bentley, 1860

The solution of the matter is not difficult. For

the purpose of deterring a future British fleet from

entering Aix Roads, the modern French Government

appears to have followed the chart of Mr. Stokes in

place of their former official chart; and the British

Admiralty, having no opportunity of surveying the

anchorage in question, has copied this modern French

chart; so that in future the fabrications of Mr. Stokes

or rather I should say, the ingenuity of Lord Gambier’s

solicitor, or whoever may have palmed the chart on

Mr. Stokes, will form the best possible security to one

of the most exposed anchorages on the Atlantic coast

of France. Assuredly no British Admiral, with the

new chart in his hands,—should such be issued—would

for a moment think of operating in such an anchorage

as is there laid down, notwithstanding that former

British fleets have operated in perfect safety so far as

soundings were concerned.

was constructed by Mr. Fairfax, the Master of the

Fleet, and was used by the Court as confirmatory

of Mr. Stokes’s chart, agreeing with it, in fact, on

nearly every point; a circumstance not at all extraordinary,

as in his examination Mr. Stokes first

says that “his marks arose from the knowledge he

gained in sounding in the anchorage of Aix” (Minutes,

38p. 23), whilst Mr. Fairfax swore that he “gave Mr.

Stokes the marks.”!![29] A fact subsequently proved by

Mr. Stokes, who admitted that he had “never sounded

there at all.all.” The credibility of either witness may

be left to the reader’s judgment.

In one respect, the chart of Mr. Fairfax might have

been considered by those interested to be an improvement

on that of Mr. Stokes. The latter gentleman had

narrowed the two mile channel of the French charts to

a little more than a mile, but the chart of Mr. Fairfax

reduces it to a mile only!

Mr. Fairfax’s chart was introduced to the Court

with the same flourish as had been that of Mr. Stokes.

Mr. Fairfax.—“This chart shows the state of the enemy’s

ships at daylight on the 12th of April. This chart is correct,

except that the head of the Calcutta is placed by the engraver

too far to the southward. It should have been about

N.W. by compass, and the head of the three decker Ocean

is to the eastward, but not sufficiently far to the northward

by compass.”

Not much correctness here, but abundance of misrepresentation.

Mr. Fairfax is very particular about

the positions of the heads of the grounded ships, but,

like Mr. Stokes, not at all particular to a league or

two as to where they lay aground. For instance, he

is very sensitive about the position of the Ocean’s head,

yet the Ocean herself is not to be found on his chart!!

39though the names of other enemy’s ships aground, not

far from where she had lain before her escape, are

given, to mark the care with which the chart had

been constructed!

I will not in this place make any further observations

upon Mr. Fairfax’s chart, this being identical with

that of Mr. Stokes. The exposure of the one in the

next chapter will serve for the confutation of the other.

The reader will, from what has been stated, be able

to form a pretty correct idea as to why—in, and

subsequently to 1809—inspection of these charts was

refused to me. At that period it was in vain that

I published explanations, which, without access to

the charts, were incomprehensible to the public; my

unsupported declarations, as has been said, falling to the

ground unheeded, even if they were not the cause of

attributing to me malicious motives towards the commander-in-chief,

after his acquittal by sentence of a

court-martial. But for the consideration of his Grace

the Duke of Somerset a stigma must have followed me

to the grave. It is now otherwise, and I am content to

leave the matter to the judgment of posterity. I must,

however, remark, that neither the charts of Mr. Stokes

or Mr. Fairfax were shown to me on the court-martial,

though shown to nearly every other witness, one—Capt.

Beresford—being told that he “must” base his

observations on those charts. Had they been shown to

me, I should in an instant have detected their fallacy.

40

CHAP. XXVI.

A NAVAL STUDY—(continued).

THE EVIDENCE OF OFFICERS PRESENT IN BASQUE ROADS.—ADMIRAL

AUSTEN’S OPINIONS CONFIRMATORY OF MY STATEMENTS—FALLACY OF

ALLEGED REWARDS TO MYSELF, IN PLACE OF THESE PERSECUTIONS.—TREATMENT

OF MY ELDEST SON LORD COCHRANE.—LETTER FROM CAPT.

HUTCHINSON COMFIRMATORY OF THE ENEMY’S PANIC.—A MIDSHIPMAN

NEAR TAKING THE FLAG-SHIP.—EVIDENCE OF CAPT. SEYMOUR, CONCLUSIVE

AS TO NEGLECT, WHICH WAS THE MATTER TO BE INQUIRED

INTO, IN NOT SENDING SHIPS TO ATTACK.—ATTEMPT TO WEATHER

HIS EVIDENCE.—CAPT. MALCOLM’S EVIDENCE CONFIRMATORY OF CAPT.

SEYMOUR’S.—CAPT. BROUGHTON’S TESTIMONY PROVES THE COMPLETE

PANIC OF THE ENEMY, AND THE WORTHLESSNESS OF THEIR FORTIFICATIONS.—LORD

GAMBIER DECLARES THEM EFFICIENT ON SUPPOSITION

ARISING FROM HEARSAY.—ENEMY UNABLE TO FIGHT THEIR GUNS.—THE

IMAGINARY SHOAL.—A GREAT POINT MADE OF IT.—MR. FAIRFAX’S

MAP—LORD GAMBIER ON THE EXPLOSION VESSELS.—CONTRADICTED

BY MR. FAIRFAX.—CONTRAST OF THEIR RESPECTIVE STATEMENTS.—FAIRFAX’S

EVASIONS.—HIS LETTER TO THE “NAVAL

CHRONICLE.”—THESE MATTERS A WARNING TO THE SERVICE.

The matters related in the preceding chapter will

appear yet more extraordinary when contrasted with,

and confirmed by, the evidence of eminent officers

present in the action of Aix Roads; that is, of such

officers commanding ships as were permitted to give

their testimony, for those who were suspected of

not approving the Commander-in-chief’s conduct, were

not summoned to give evidence before the court-martial!

In one instance—that of Captain Maitland, of the

Bellerophon, whose opinions on the subject had been

freely expressed—this gallant officer was ordered to

41join the squadron in Ireland, so as to render his testimony

unavailable.

To a gallant officer still living, Admiral Sir Francis

William Austen, K.C.B., who was present in Basque

Roads, but, like other eminent officers, not examined

on the court-martial, I am indebted for a recently-expressed

opinion as to the causes why the majority

of the enemy’s ships were suffered to escape beyond

reach of attack, as well as of the persecution which

I afterwards underwent, in consequence of my conscientious

opposition to a vote of thanks to the Commander-in-chief.

The following is an extract from the gallant Admiral’s

letter:—

“I have lately been reading your book, the ‘Autobiography