From photo by the Author.

[4]

[5]

A POPULAR INTRODUCTION TO THE

WILD LIFE OF THE BRITISH SHORES

BY

EDWARD STEP, F.L.S.

AUTHOR OF “WAYSIDE AND WOODLAND BLOSSOMS,” “BY VOCAL WOODS AND WATERS,” “BY SEASHORE, WOOD, AND MOORLAND,” ETC.

WITH 122 ILLUSTRATIONS BY P. H. GOSSE, W. A. PEARCE, AND MABEL STEP

THIRD EDITION

LONDON

JARROLD & SONS, 10 & 11, WARWICK LANE, E.C.

[All Rights Reserved]

1896

[6]

[7]

| I. | The Sea and its Shores | 11 |

| II. | Low Life | 20 |

| III. | Sponges | 28 |

| IV. | Zoophytes | 37 |

| V. | Jelly-Fishes | 49 |

| VI. | Sea-Anemones | 64 |

| VII. | Sea-Stars and Sea-Urchins | 86 |

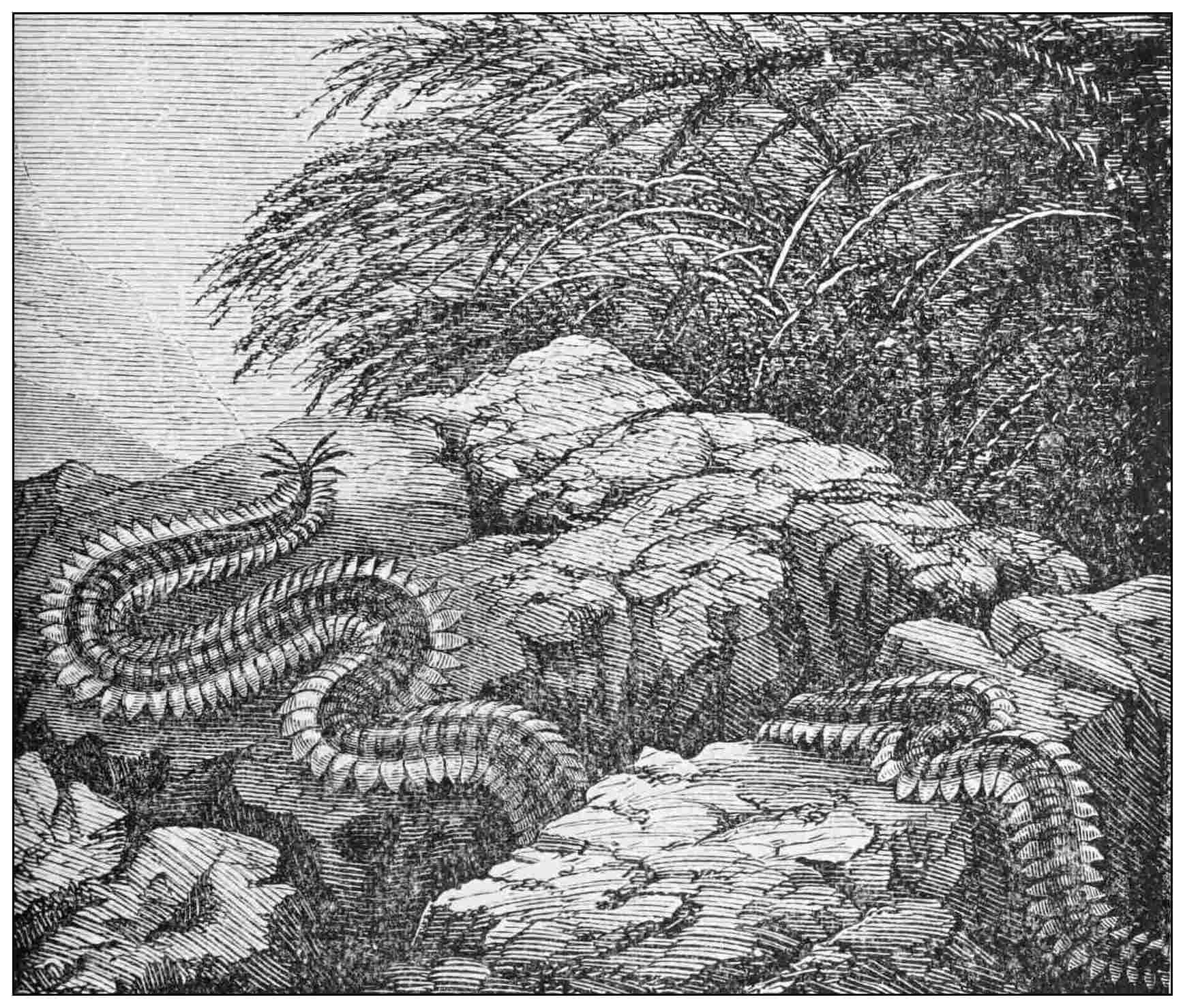

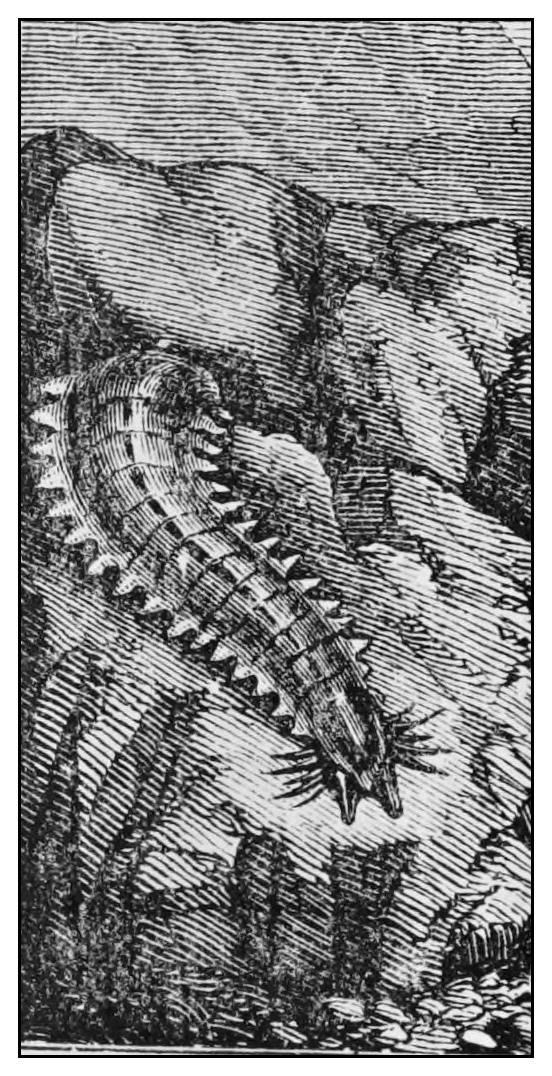

| VIII. | Sea-Worms | 107 |

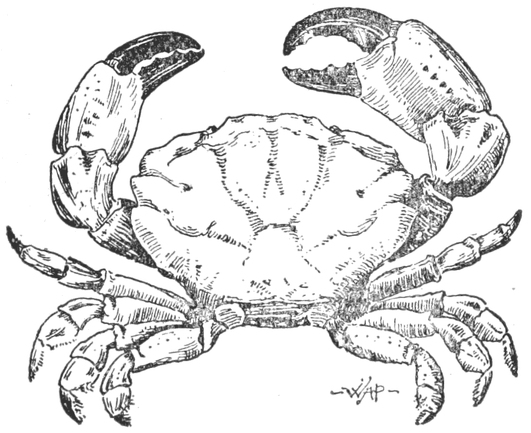

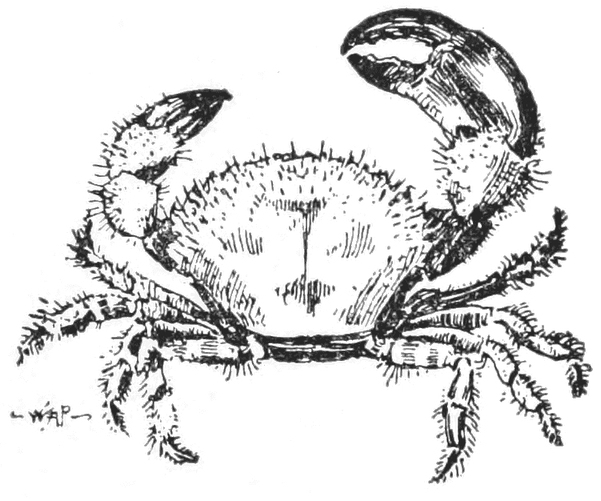

| IX. | Crabs and Lobsters | 130 |

| X. | Shrimps and Prawns | 160 |

| XI. | Some Minor Crustaceans | 172 |

| XII. | Barnacles and Acorn-Shells | 176 |

| XIII. | “Shell-Fish” | 185 |

| XIV. | Sea-Snails and Sea-Slugs | 207 |

| XV. | Cuttles | 231 |

| XVI. | Sea-Squirts | 236 |

| XVII. | Shore Fishes | 246 |

| XVIII. | Birds of the Sea-Shore | 277 |

| XIX. | Seaweeds | 288 |

| XX. | Flowers of the Shore and Cliffs | 303 |

| Classified Index of Species referred to in Text | 309 | |

| Alphabetical Index | 315 |

[9]

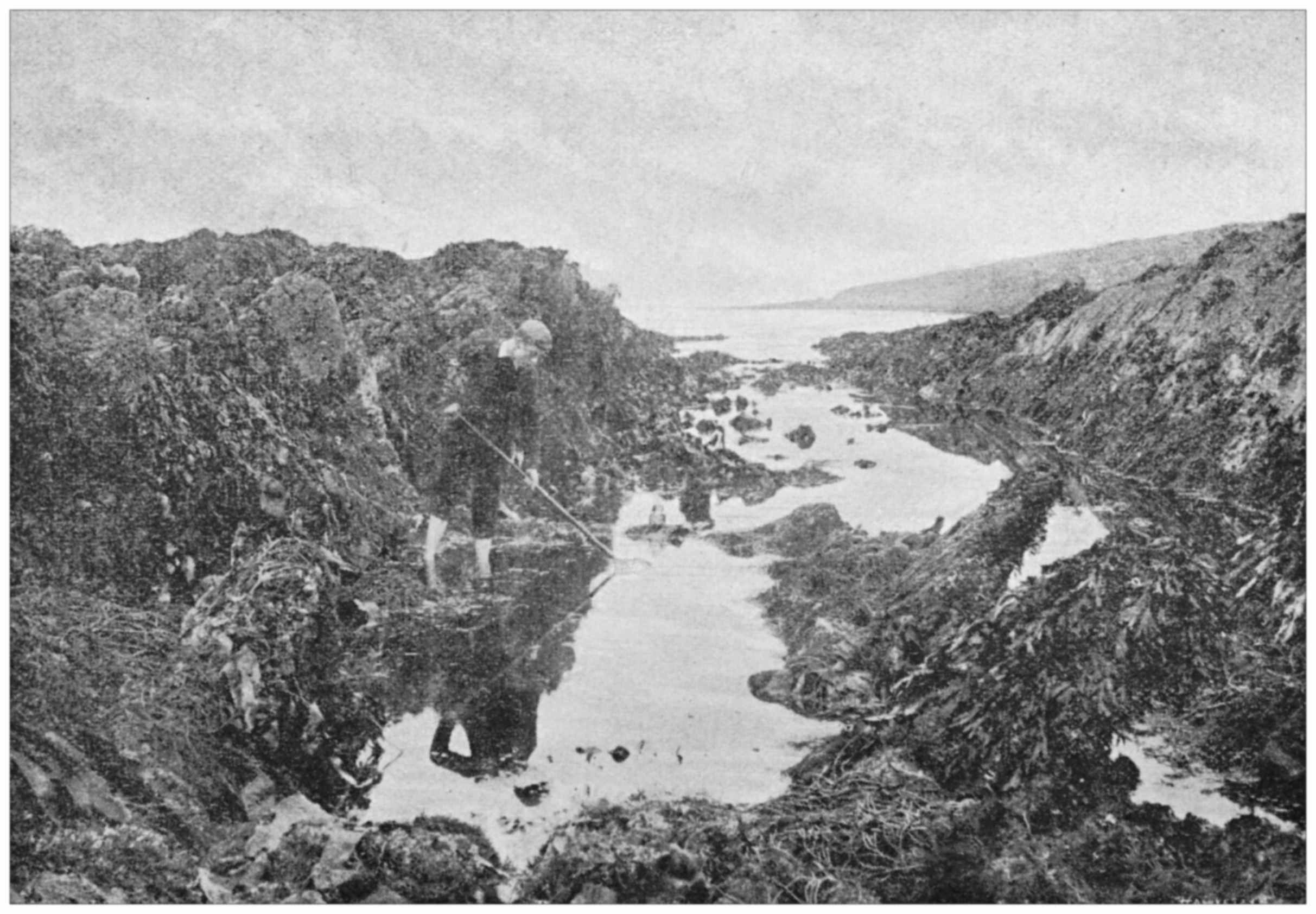

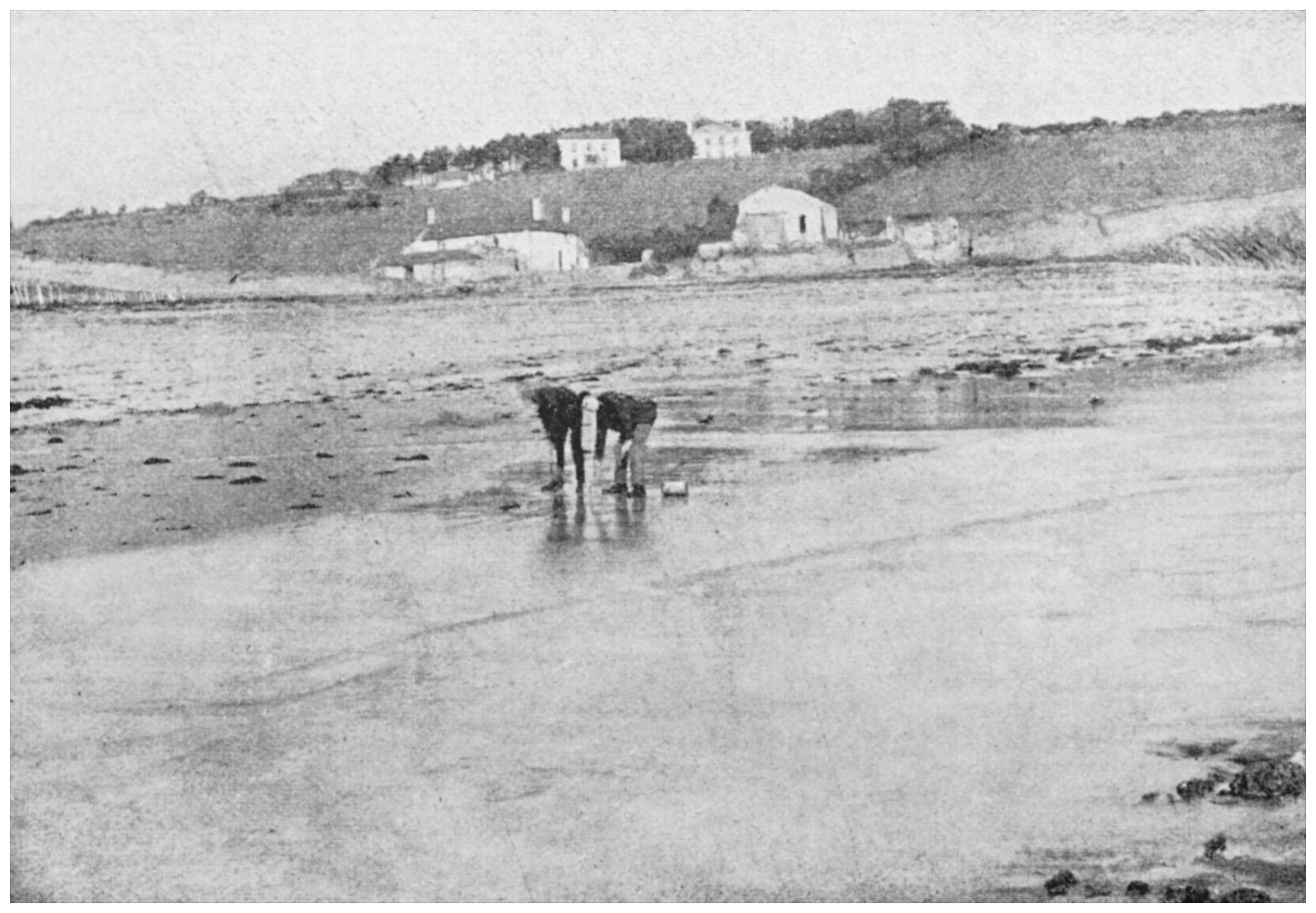

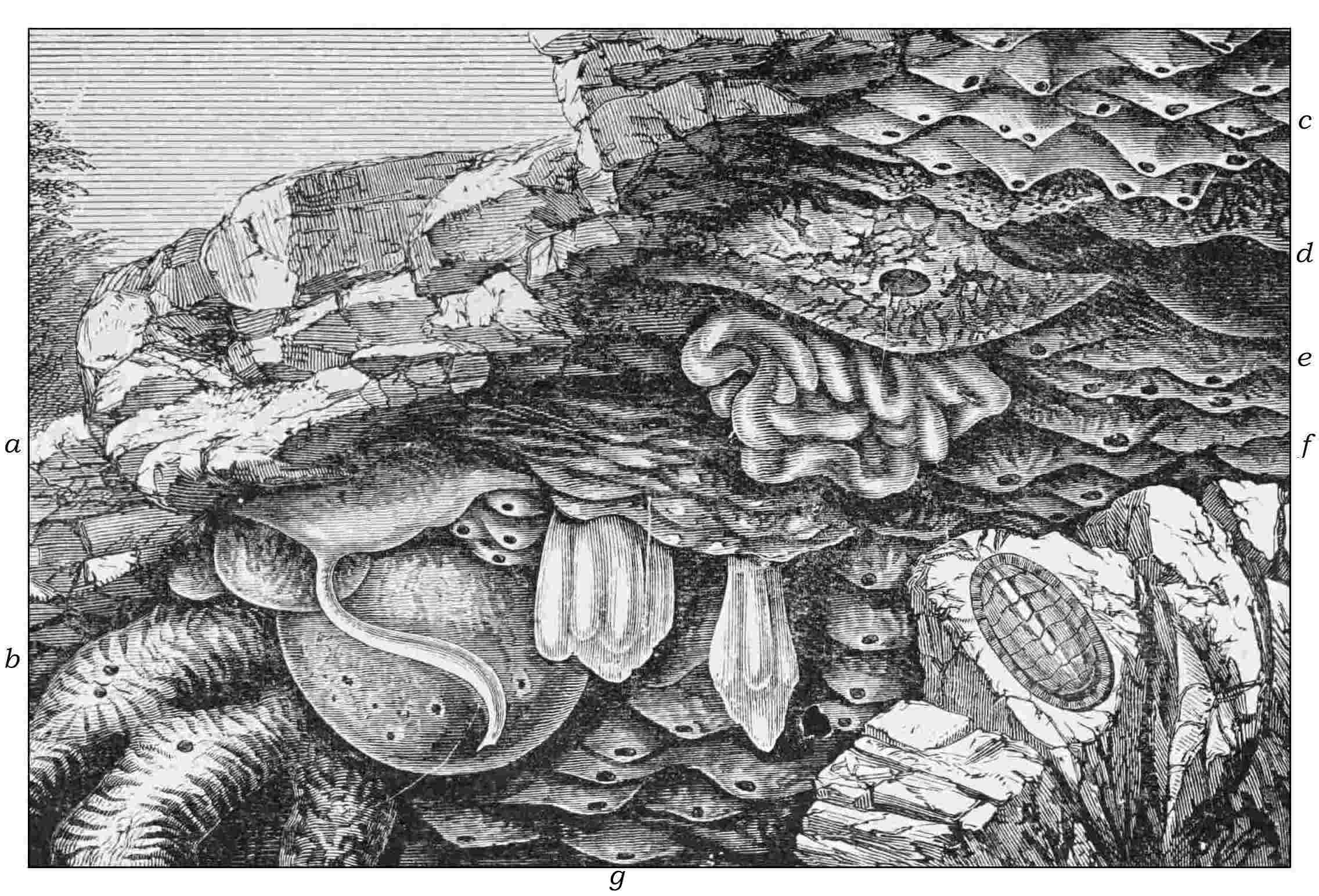

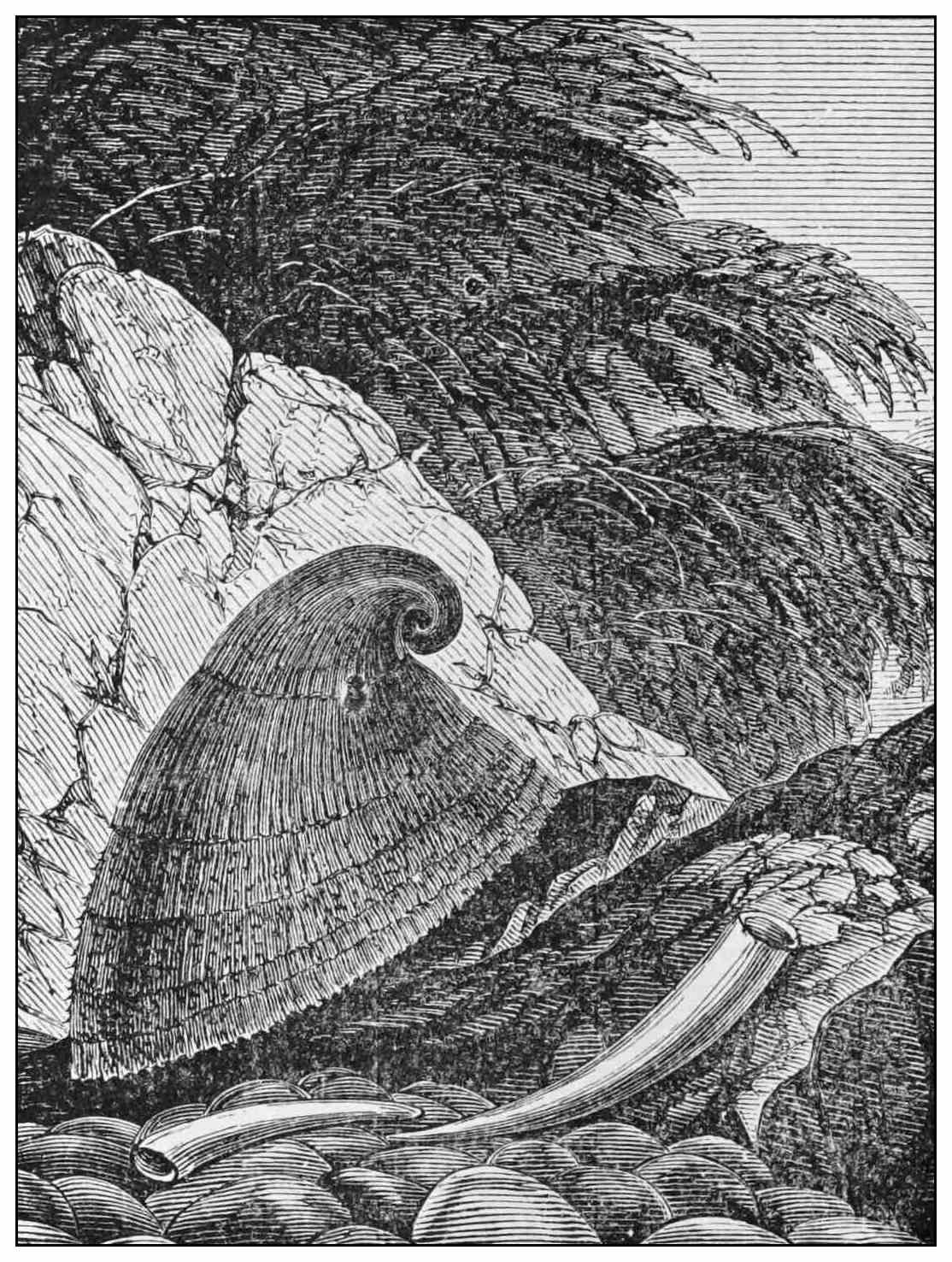

| The Rocky Shore at Low-water | Frontispiece |

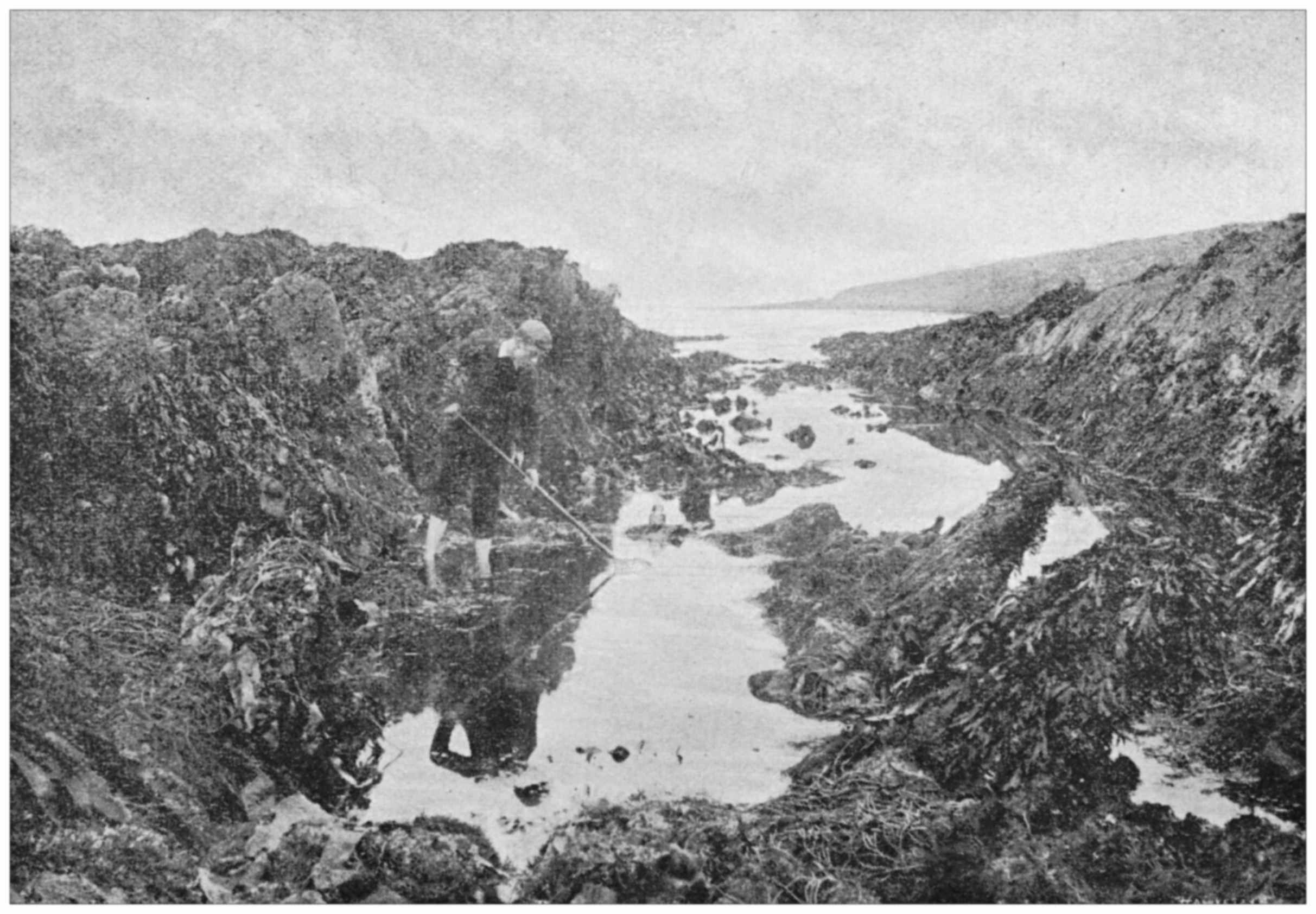

| The Sandy Shore at Low-water | facing 11 |

| Foraminifera | 22 |

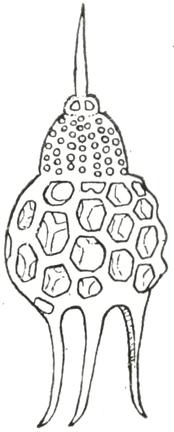

| Polycistin | 23 |

| Sponges | 29 |

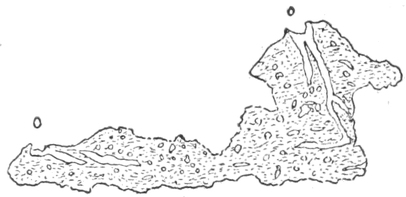

| Section through Crumb-of-Bread Sponge | 32 |

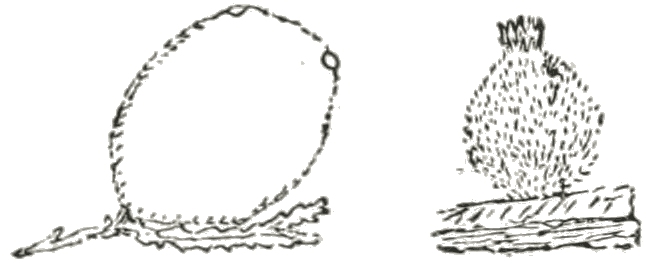

| Grantia compressa | 35 |

| Grantia ciliata | 35 |

| Sea Oak Coralline | 39 |

| Calycles of Sertularia enlarged | 39 |

| Plumularia pinnata | 43 |

| Plumularian, portion enlarged | 43 |

| Haliclystus | 45 |

| Sea-Mat (Flustra) | 46 |

| Larvæ of Aurelia | 53 |

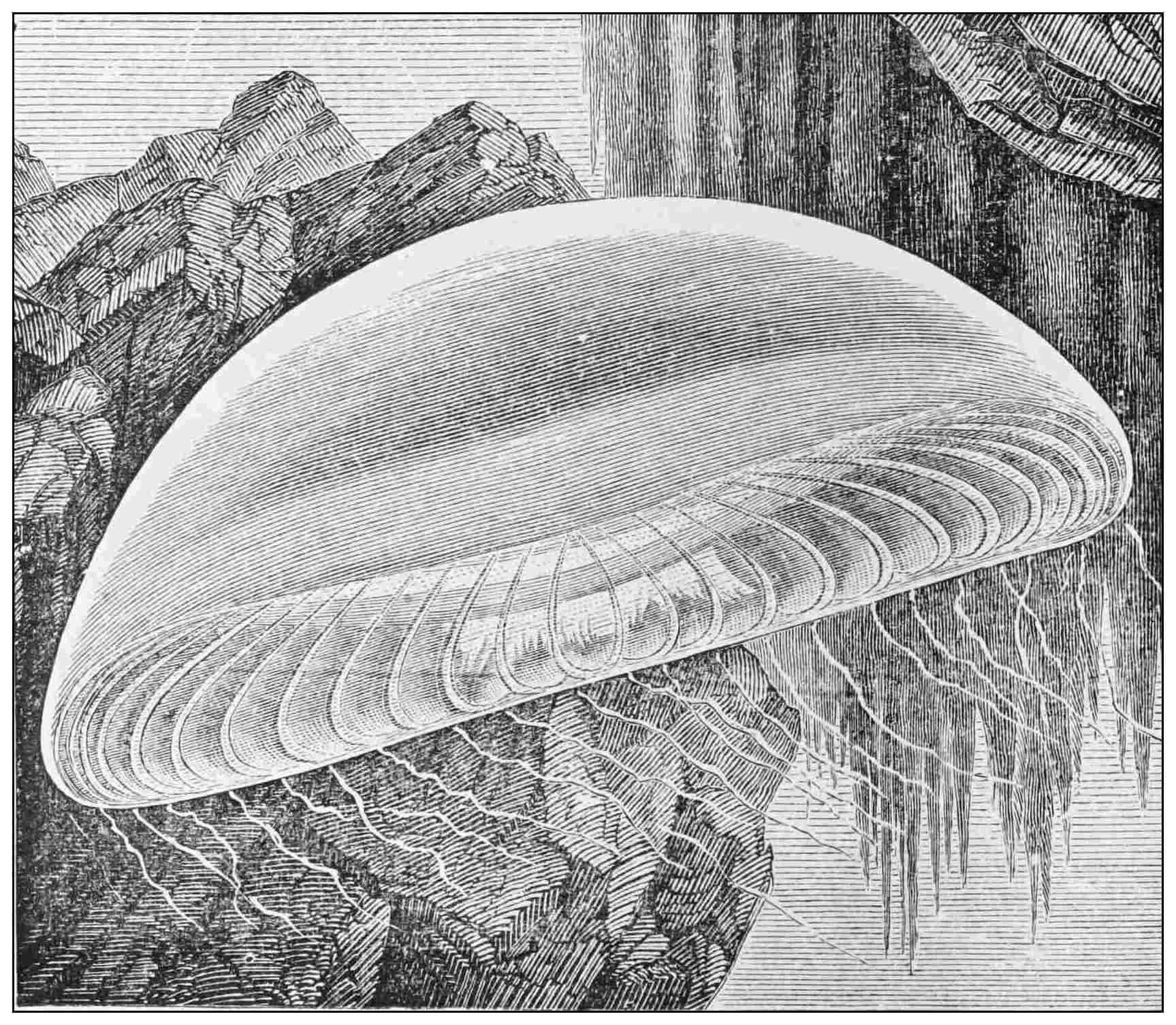

| Marigold (Aurelia aurita) | 54 |

| Portuguese Man o’ War | 56 |

| Tube-mouthed Sarsia | 57 |

| Forbes’ Æquorea | 58 |

| Beröe and Young | 61 |

| Beadlet | 65 |

| Snowy Anemone | 68 |

| Rosy Anemone | 68 |

| Orange-disk Anemone | 69 |

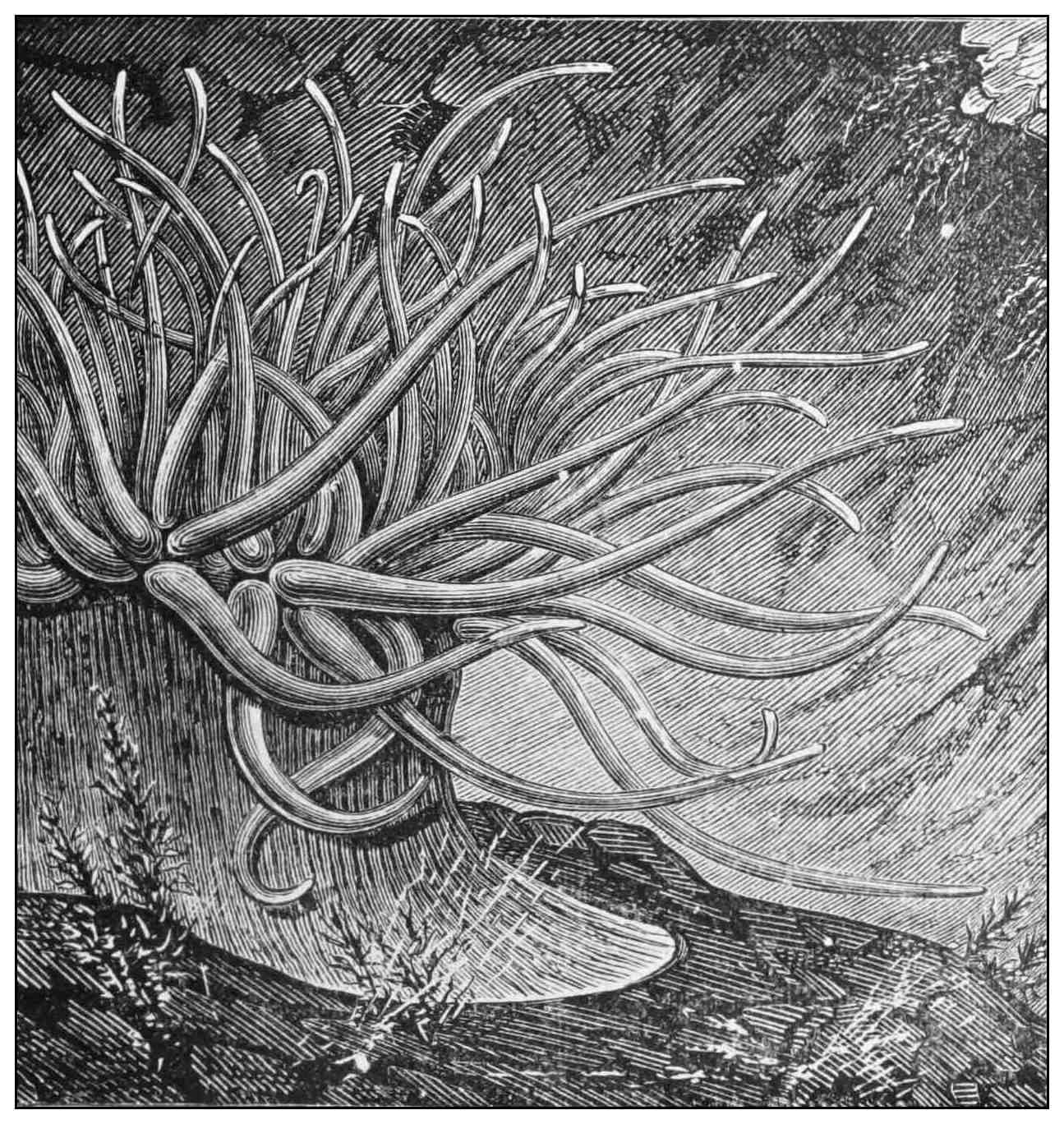

| Opelet | 73 |

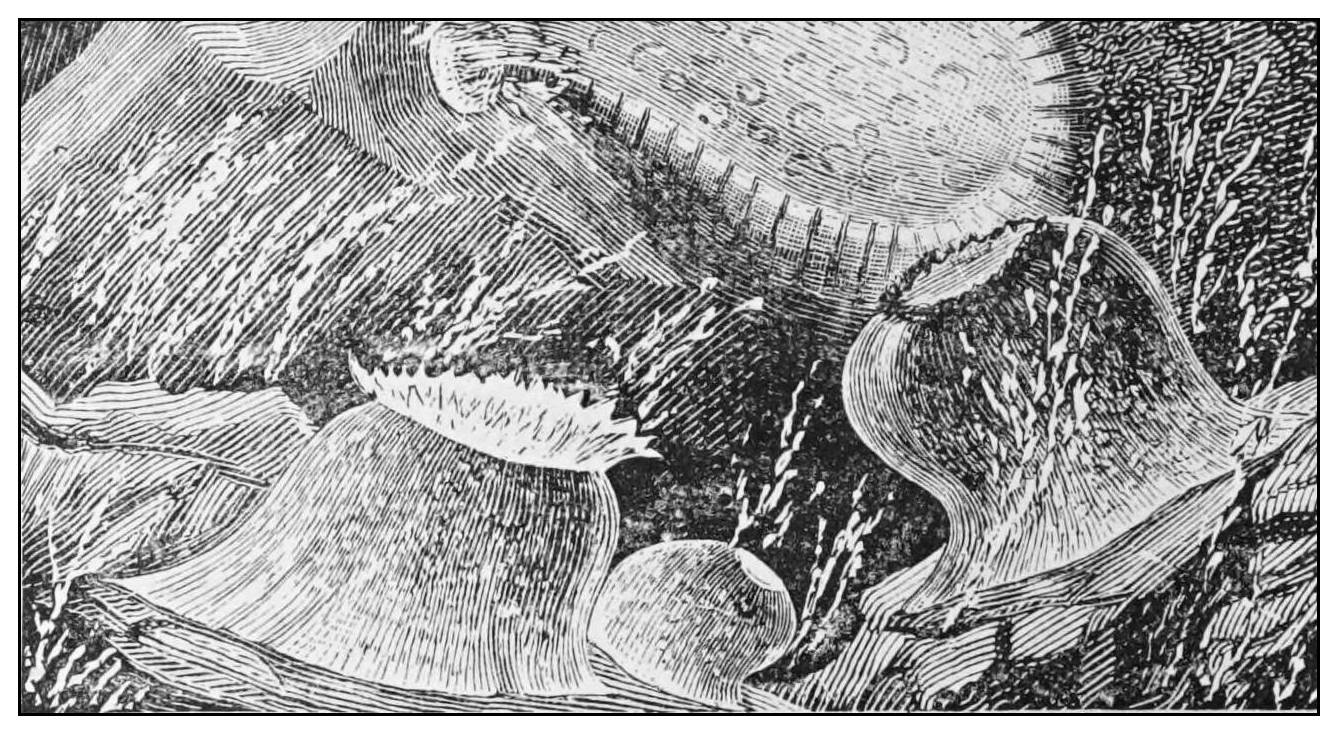

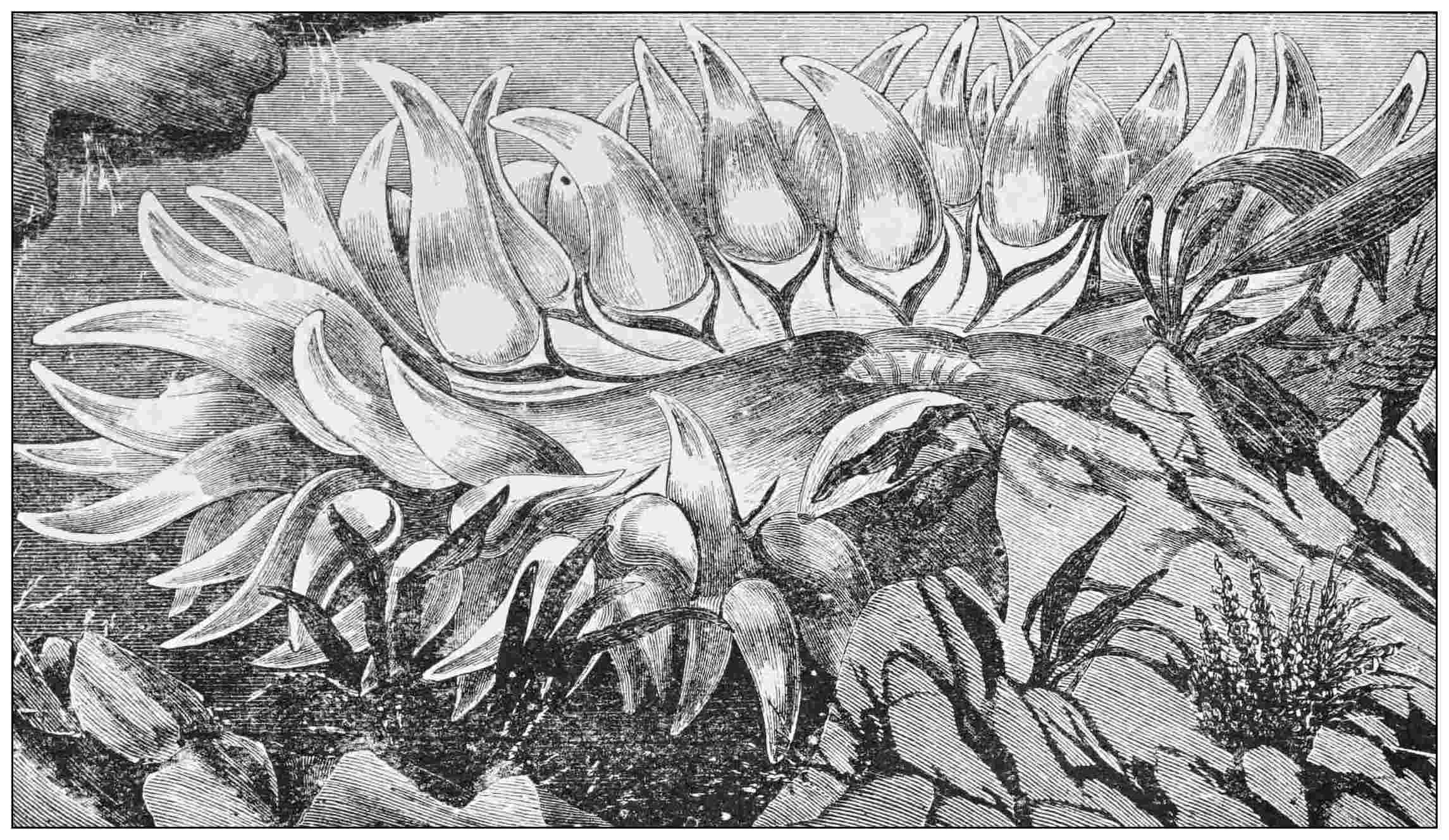

| Dahlia Wartlet | 81 |

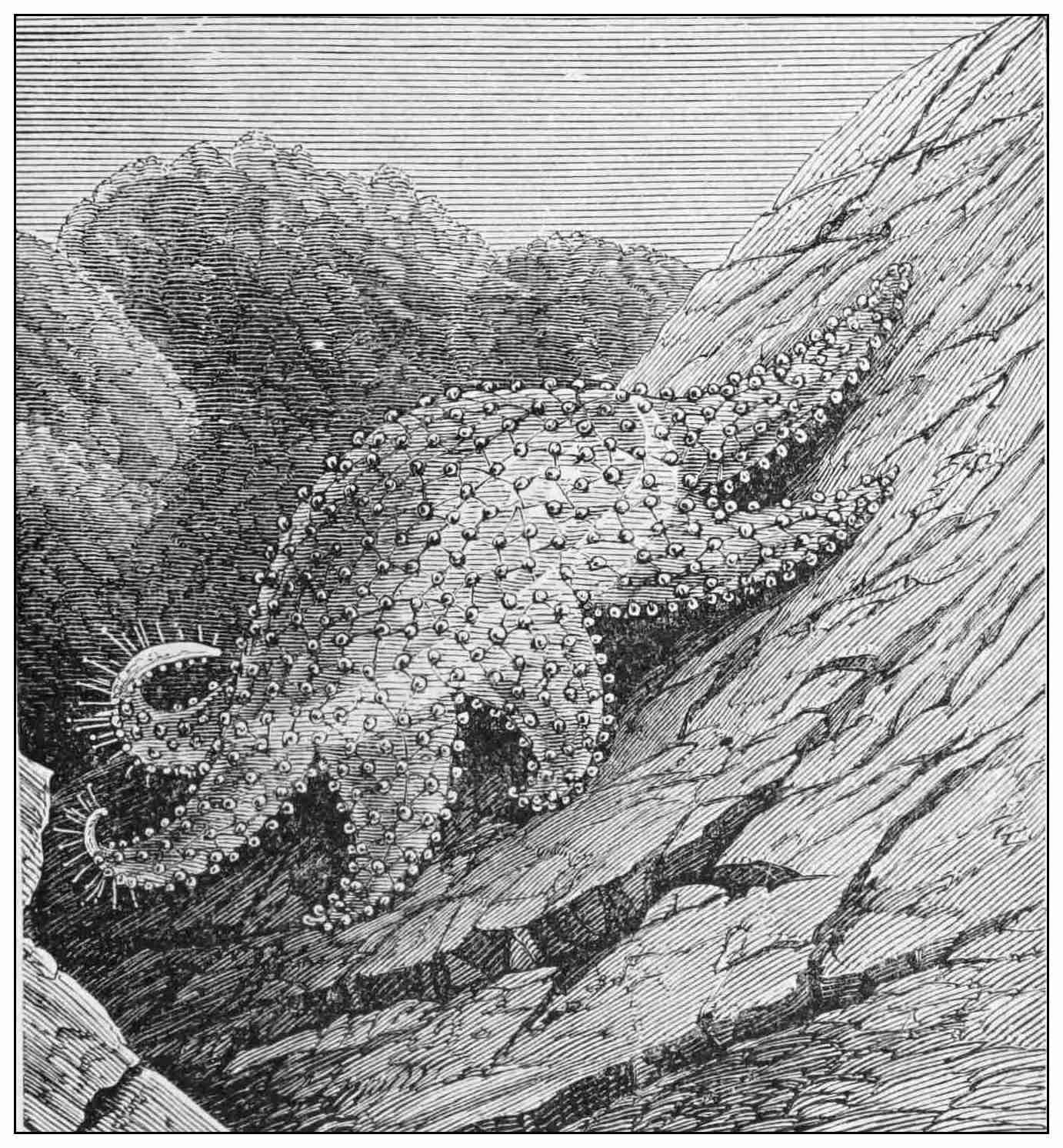

| Sun Star | 91 |

| Purple-tipped Urchin | 93 |

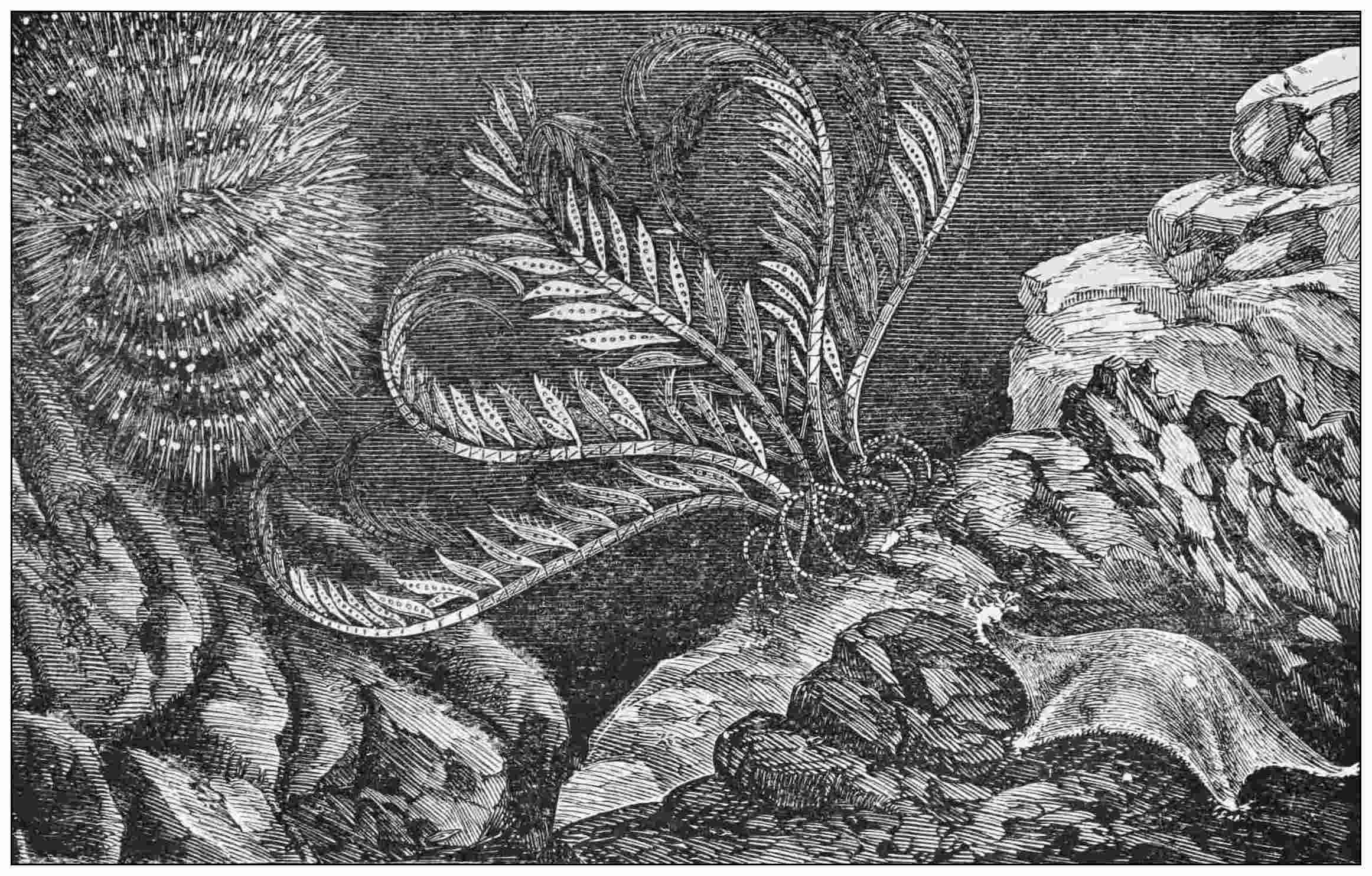

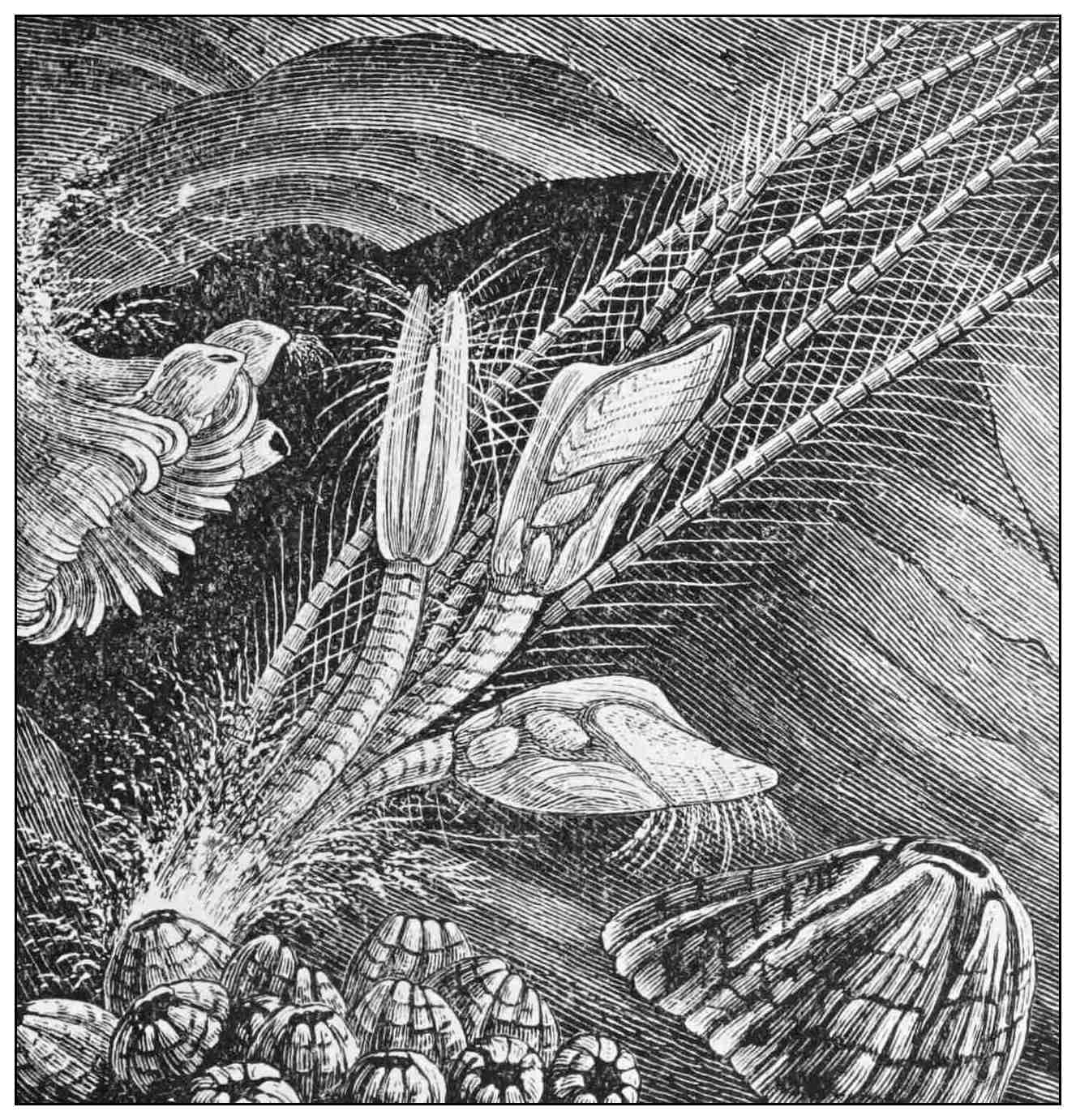

| Feather-star | 93 |

| Starlet | 93 |

| Granulate Brittle-star | 95 |

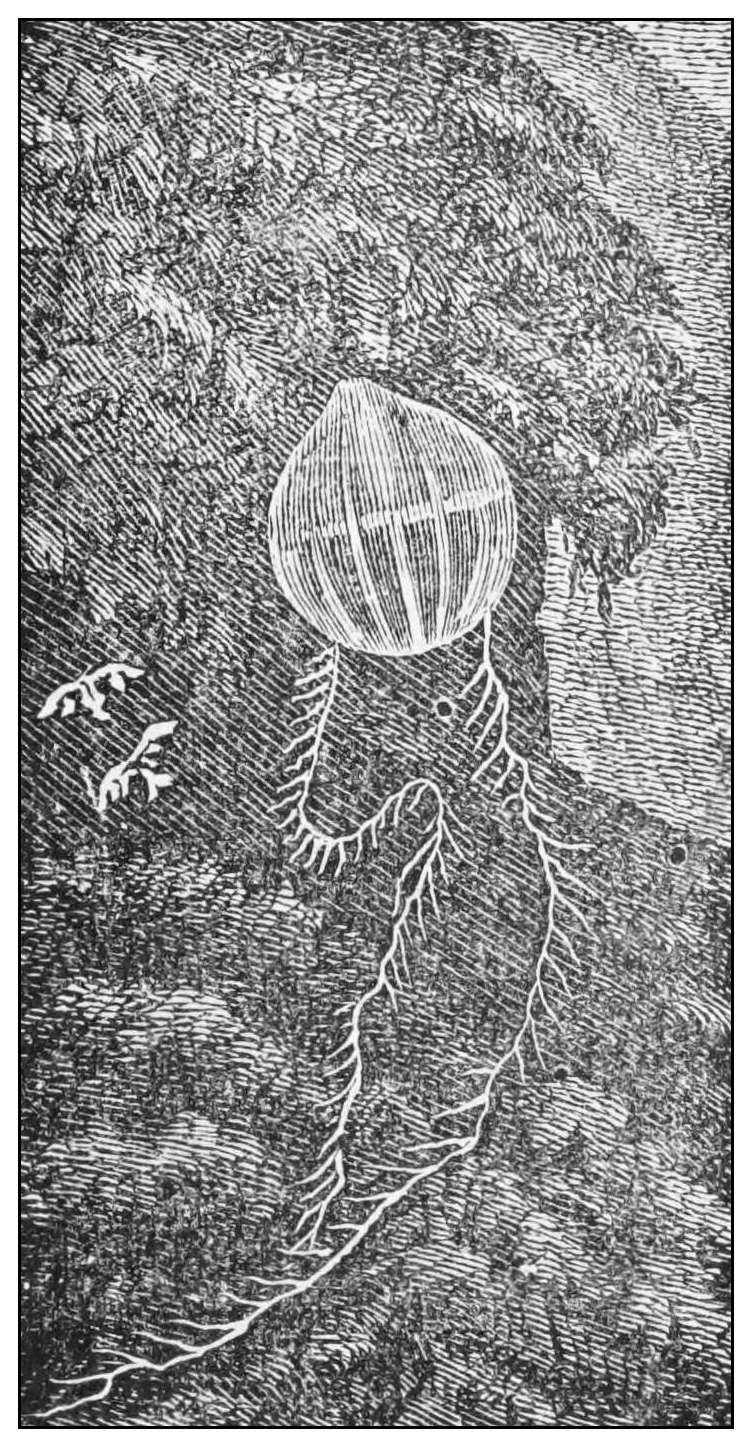

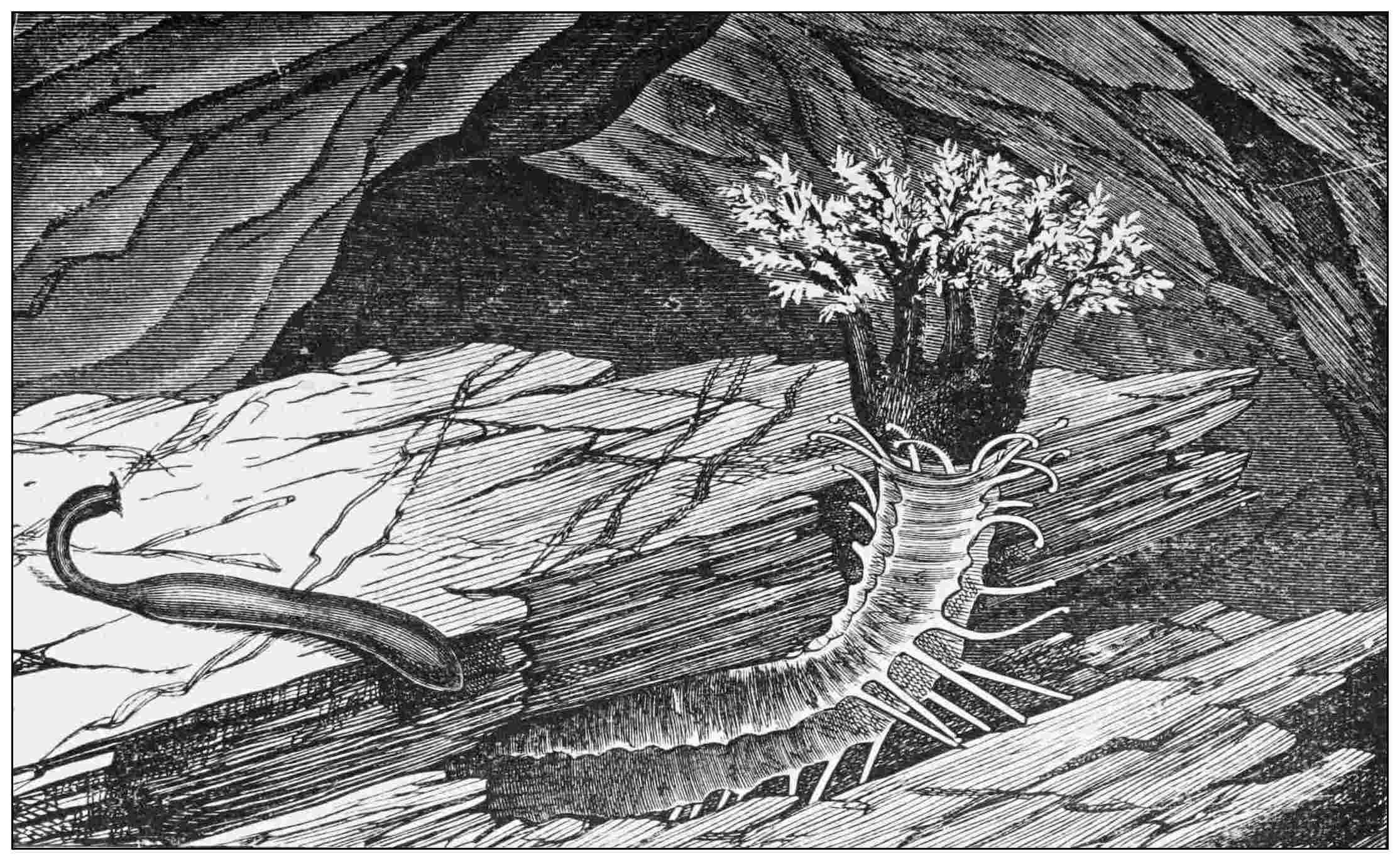

| Sipunculus | 103 |

| Sea-cucumber | 103 |

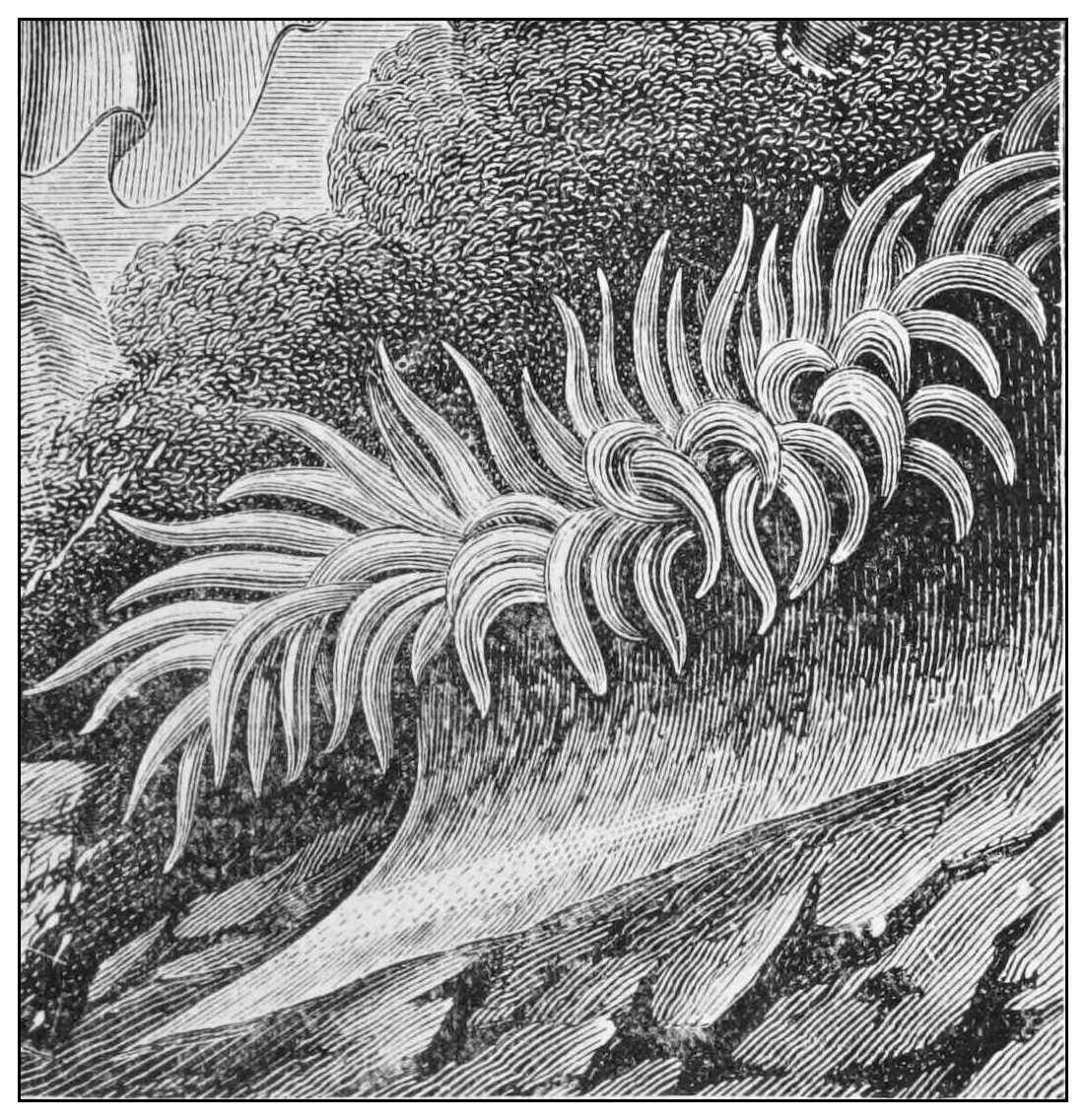

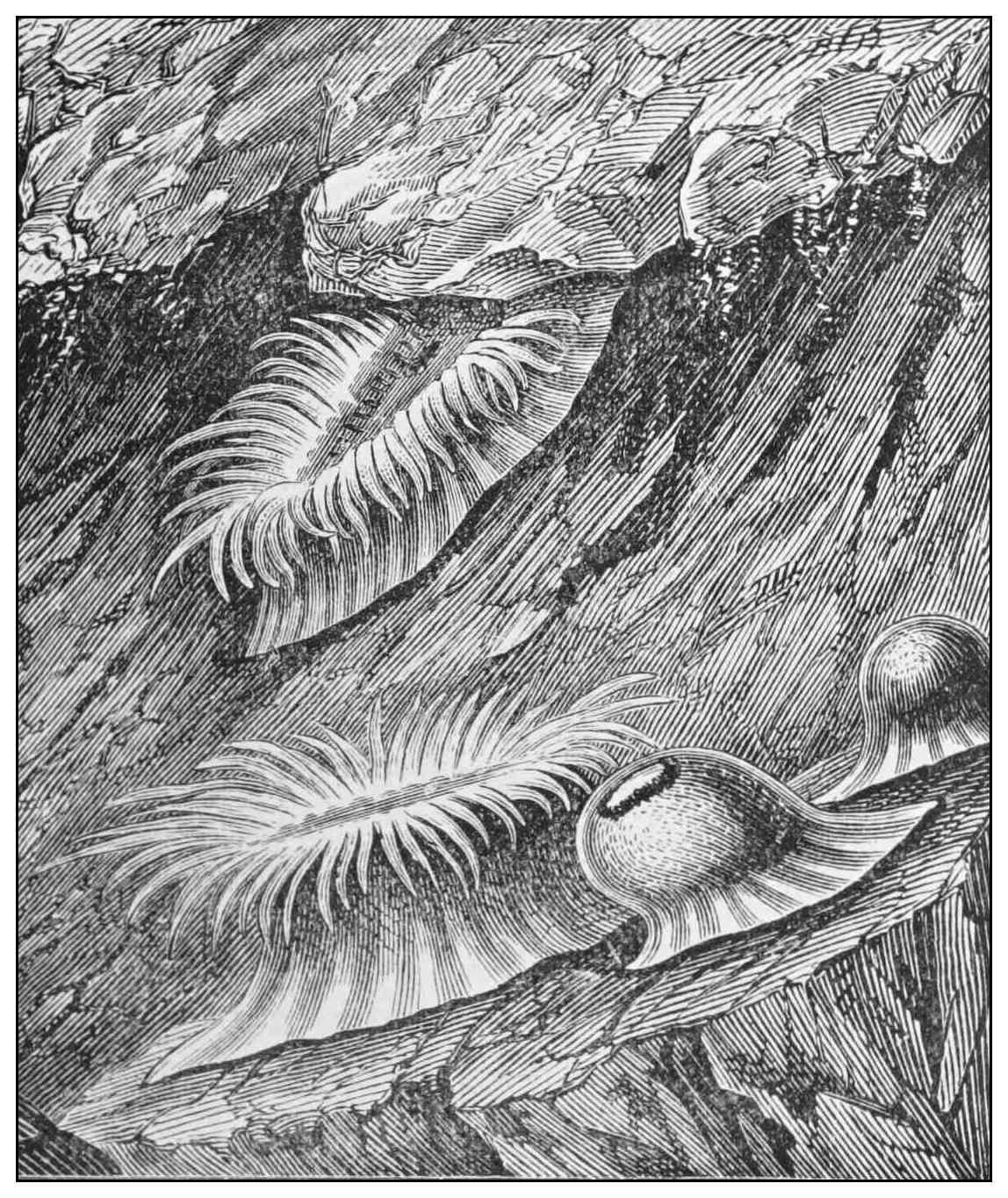

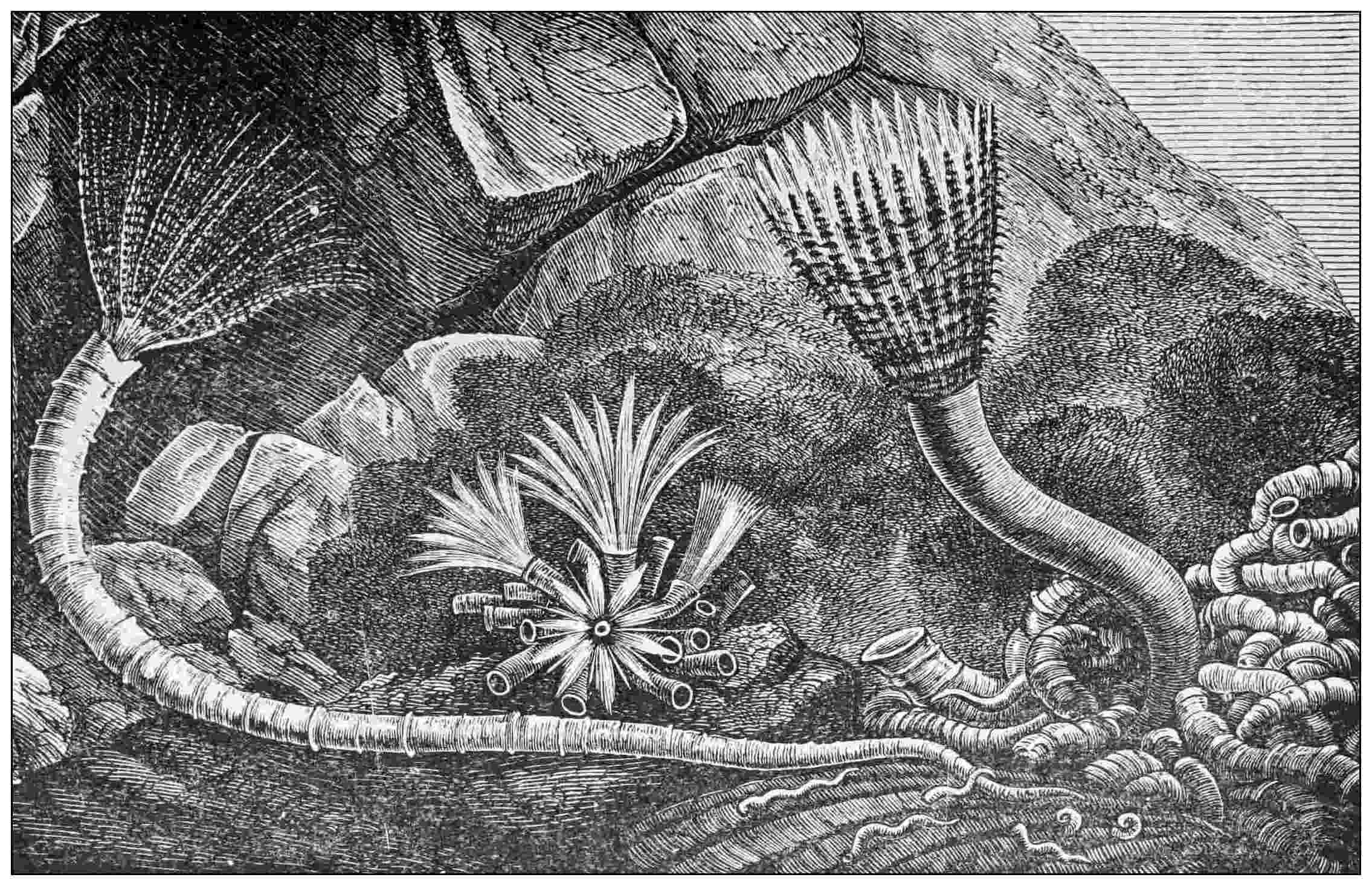

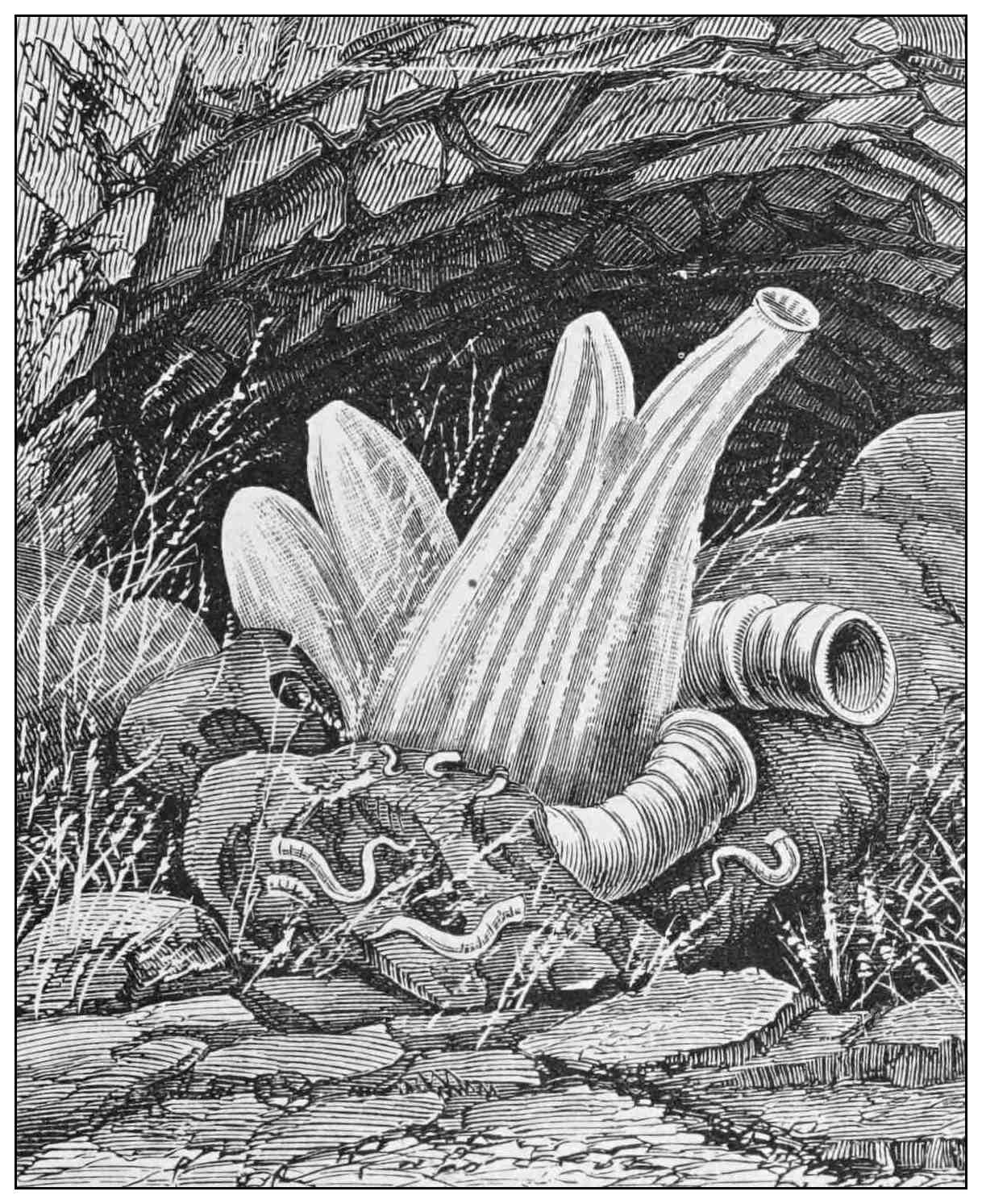

| Trumpet Sabella | 109 |

| Brush Sabella | 109 |

| Common Sabella | 109 |

| Scarlet Serpula | 113 |

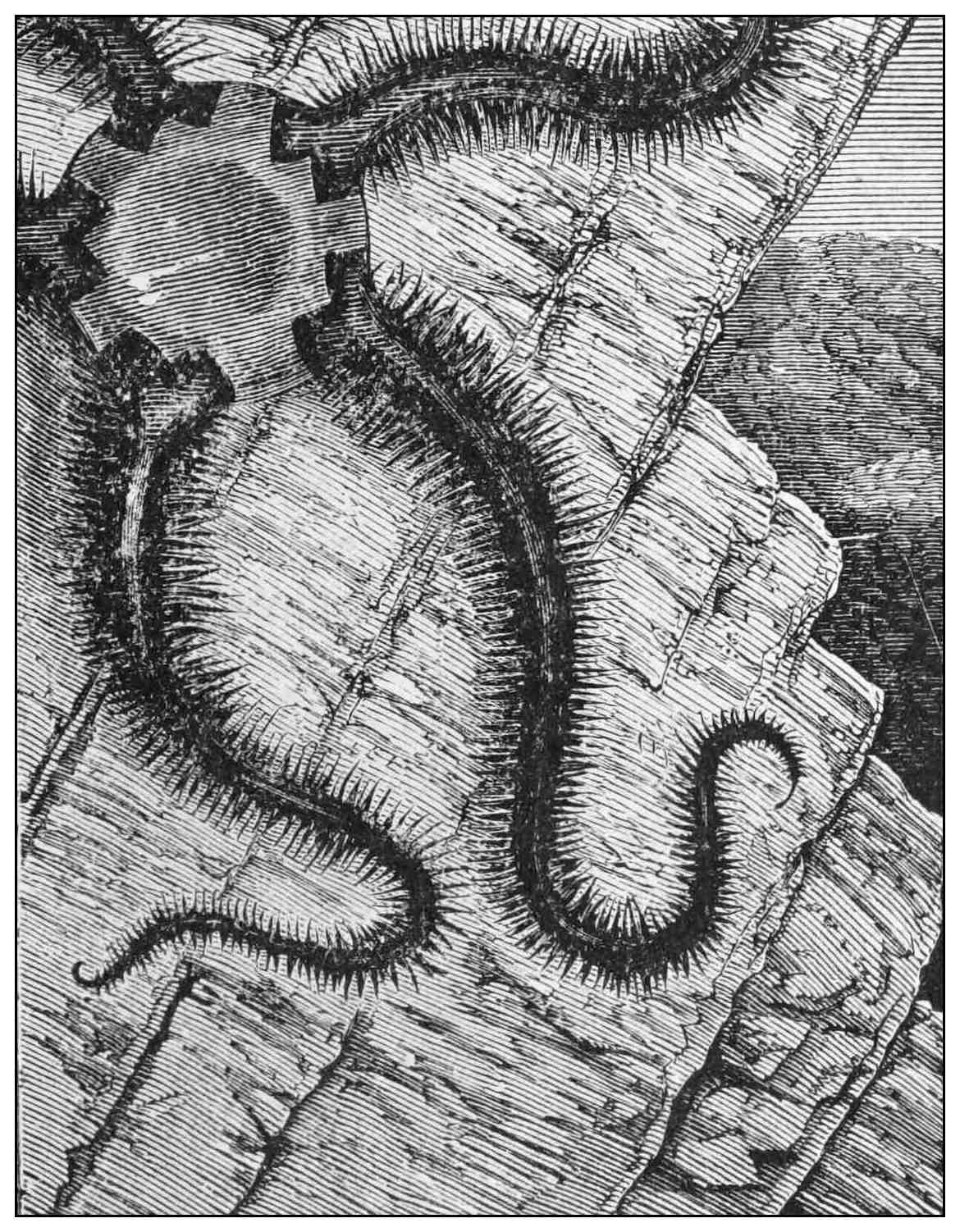

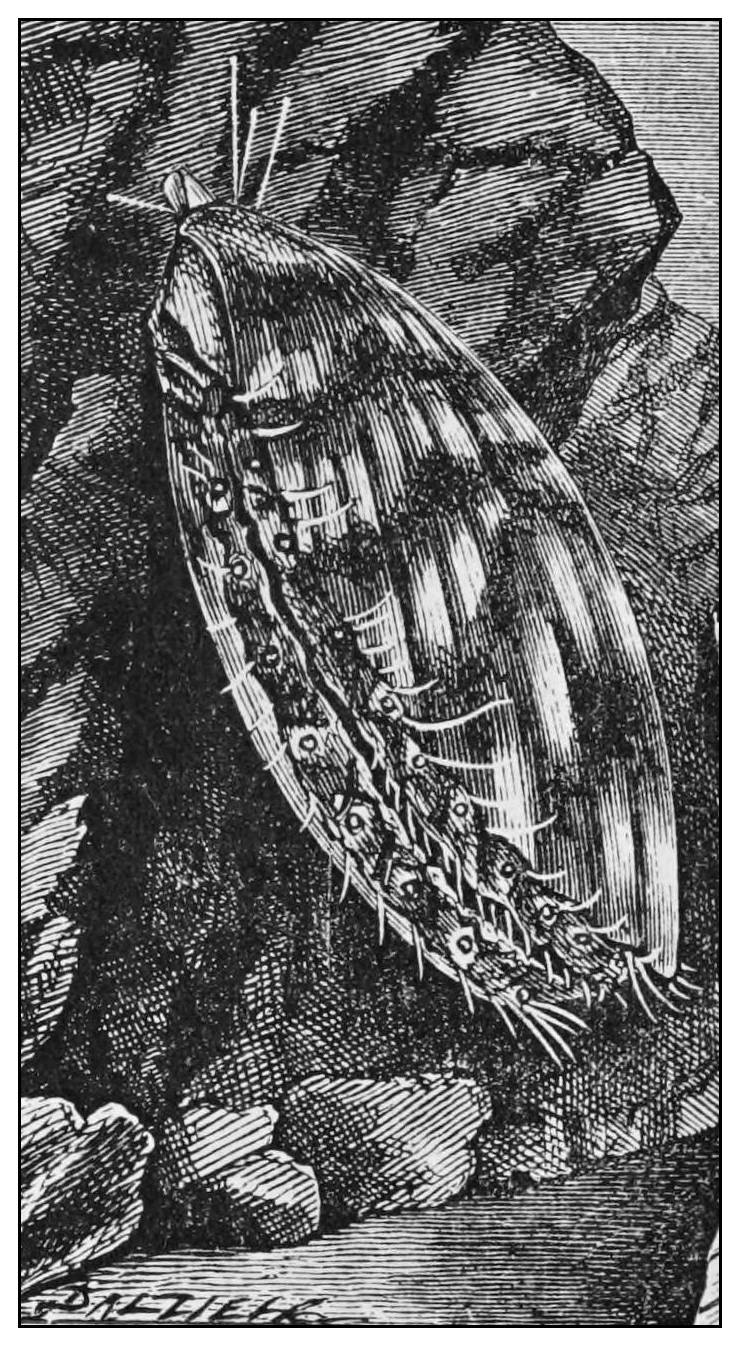

| Pearly Nereis | 118 |

| Rainbow Leaf-worm | 119 |

| Banded Flat-worm | 125 |

| Long Worm | 125 |

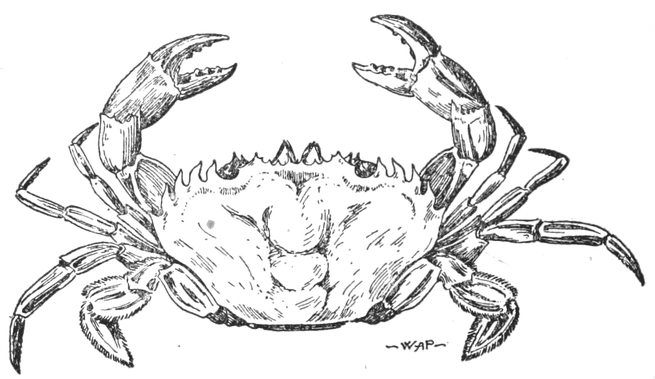

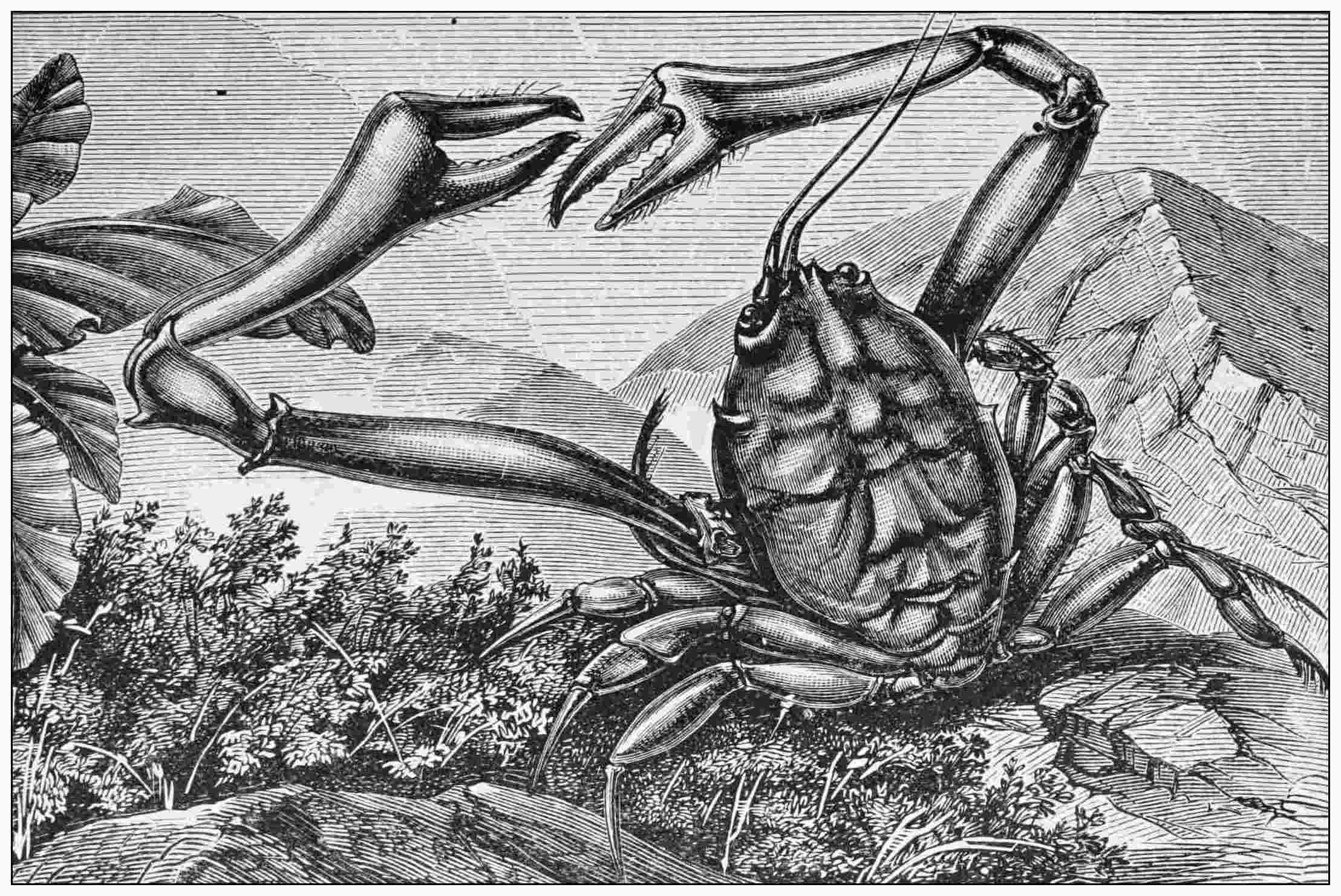

| Zebedee (Xantho incisus) | 137 |

| Hairy-crab | 138 |

| Velvet Fiddler | 140 |

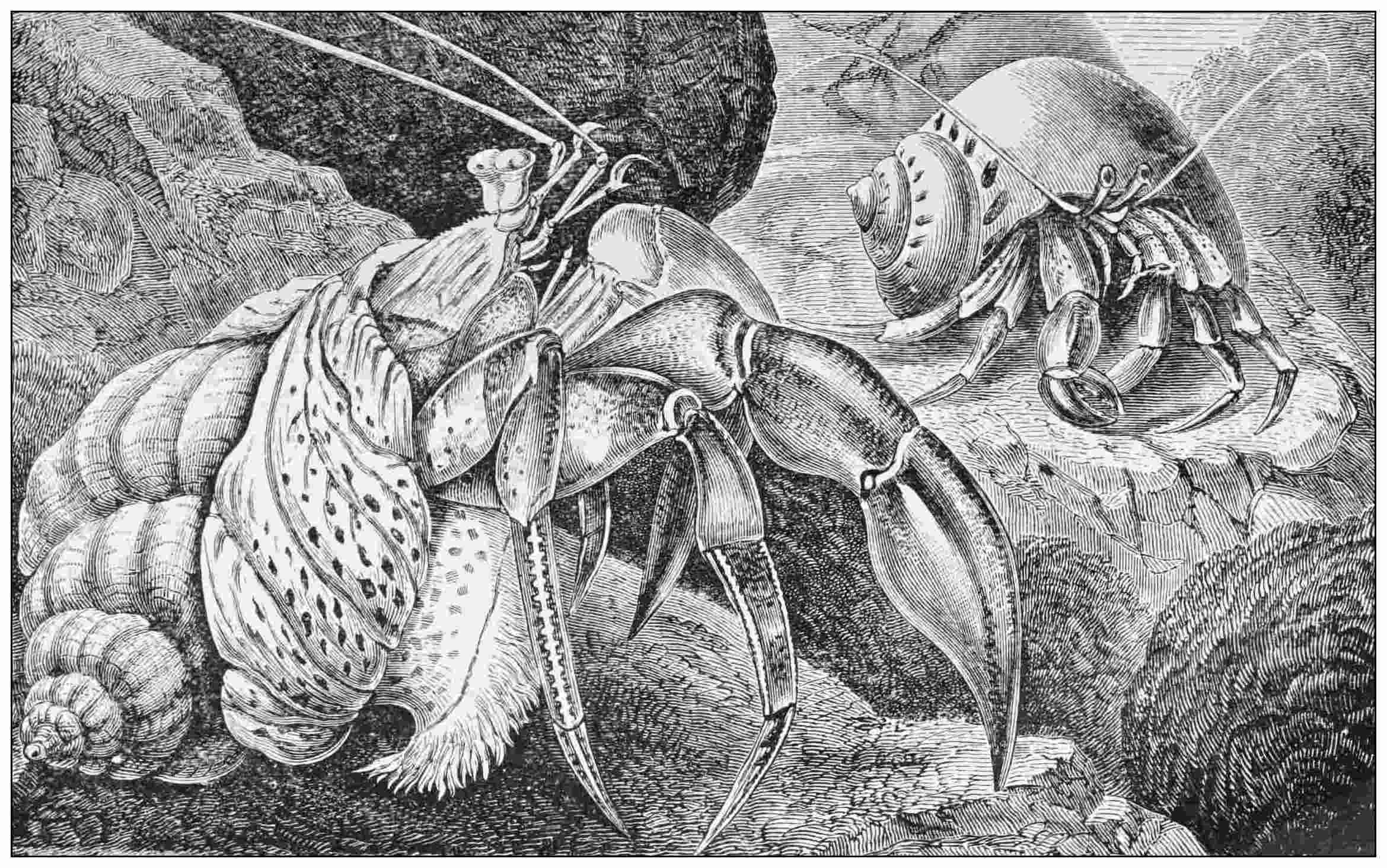

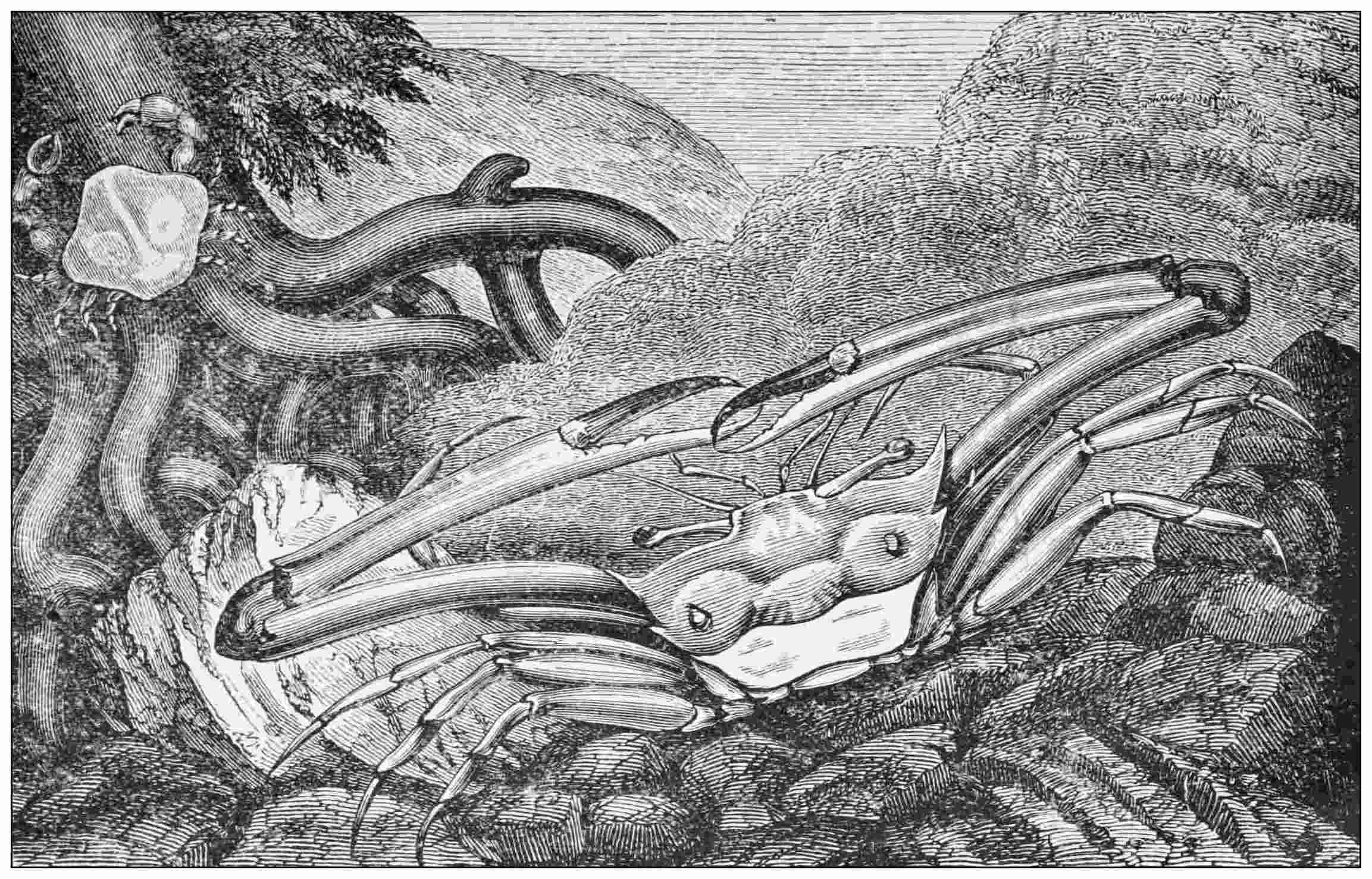

| The Hermit-crab and the Cloaklet Anemone | 145 |

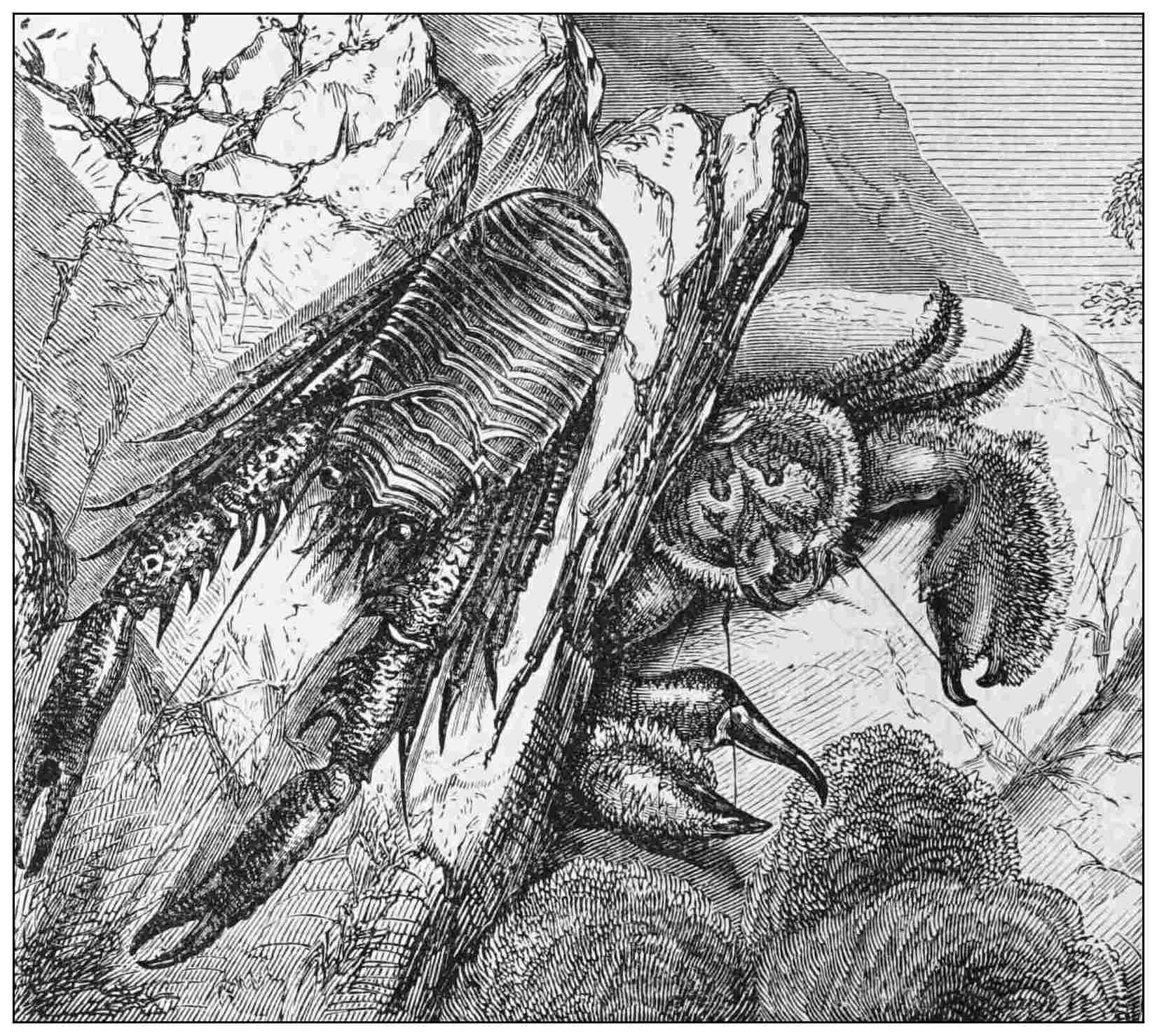

| Scaly Squat-lobster | 148 |

| Broad-claw | 148 |

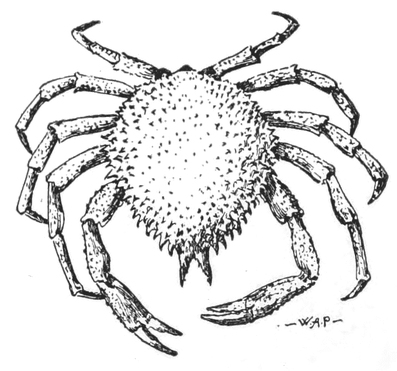

| Prickly Spider-crab | 152 |

| The Masked-crab (male) | 153 |

| Nut-crab | 157 |

| Angular-crab | 157 |

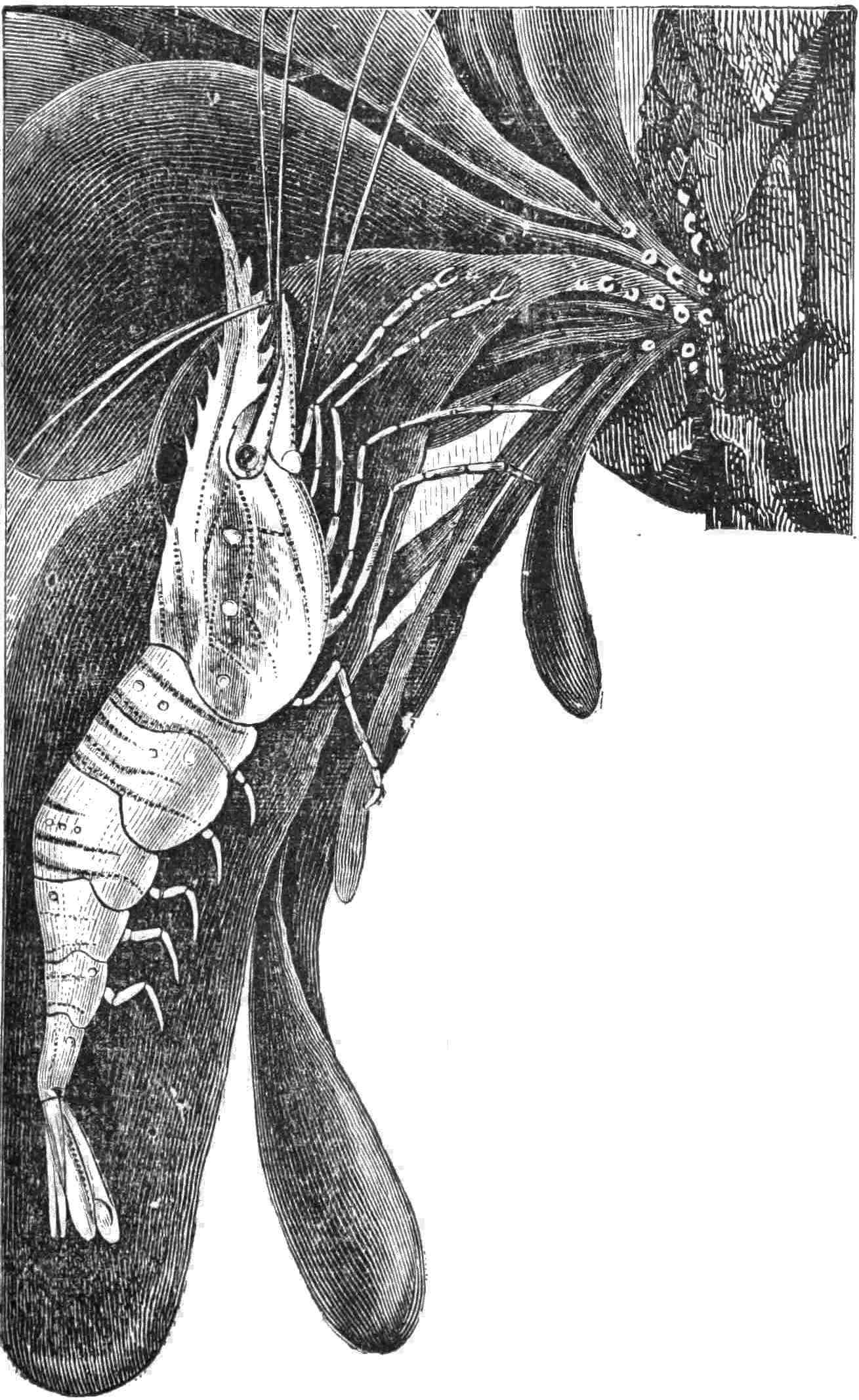

| The Prawn | 163 |

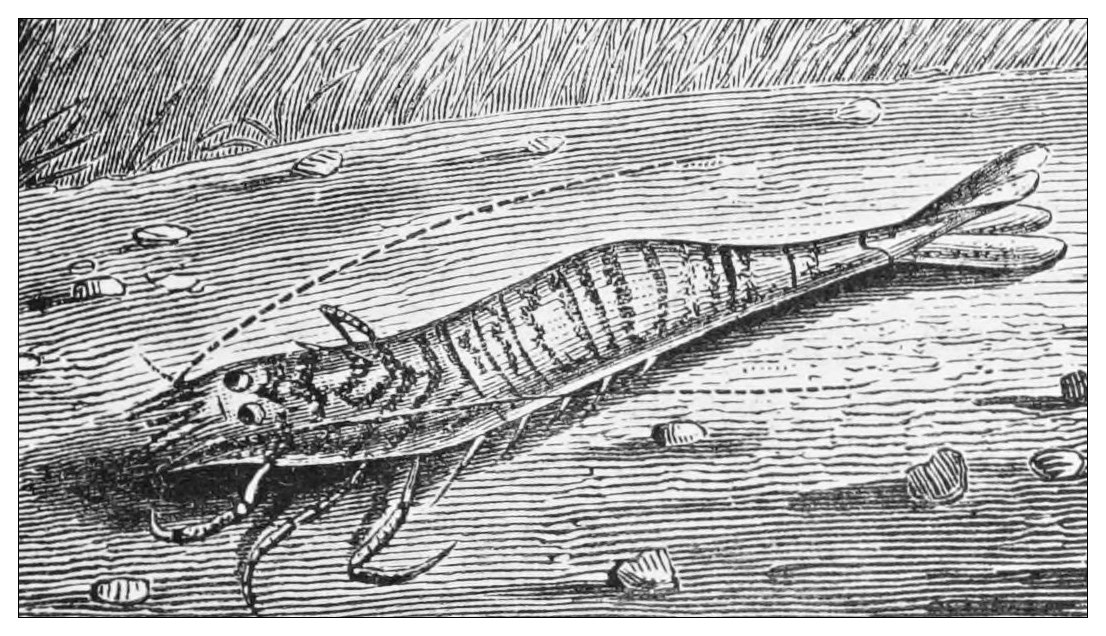

| Common Shrimp | 167 |

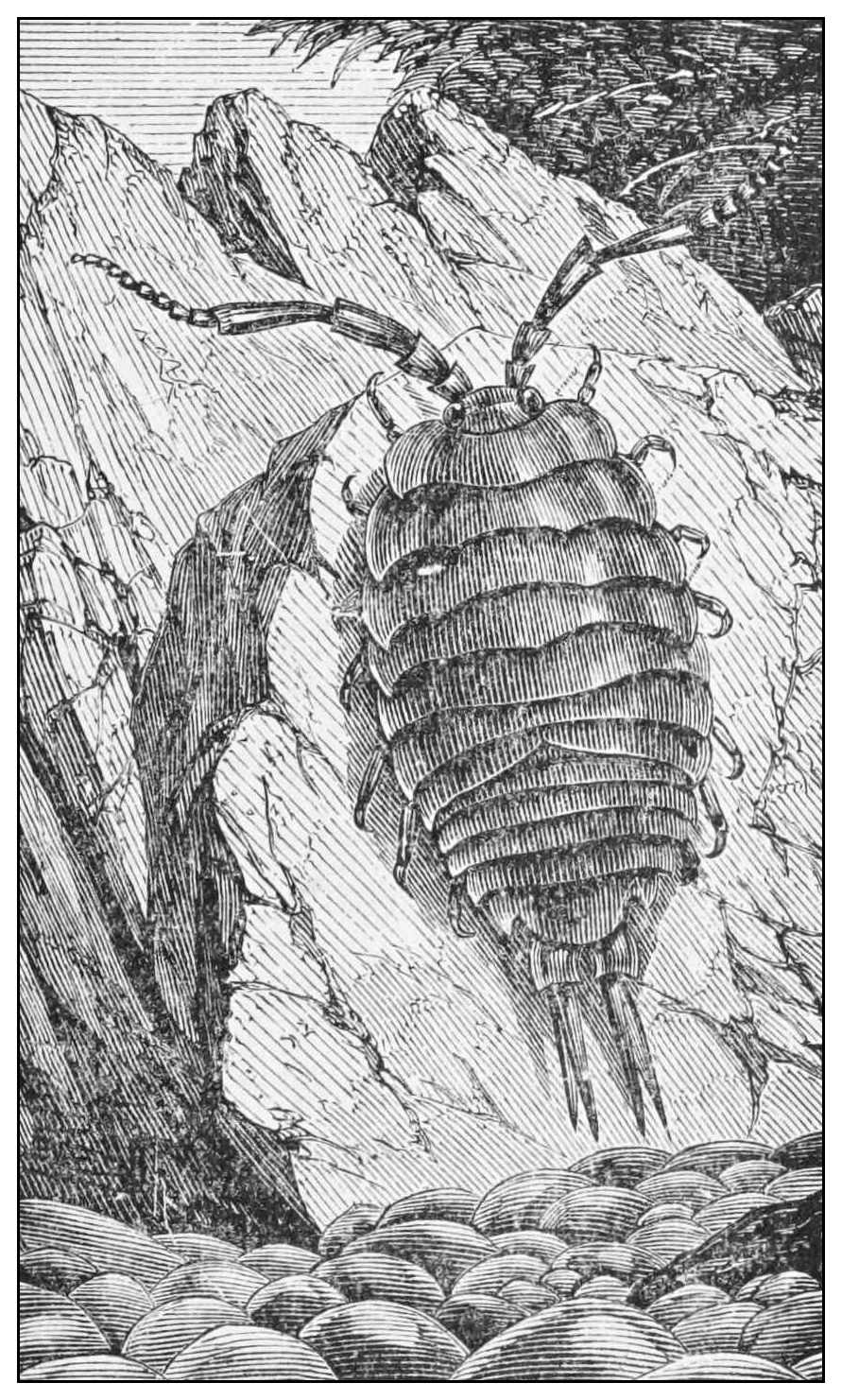

| Sea Slater | 173 |

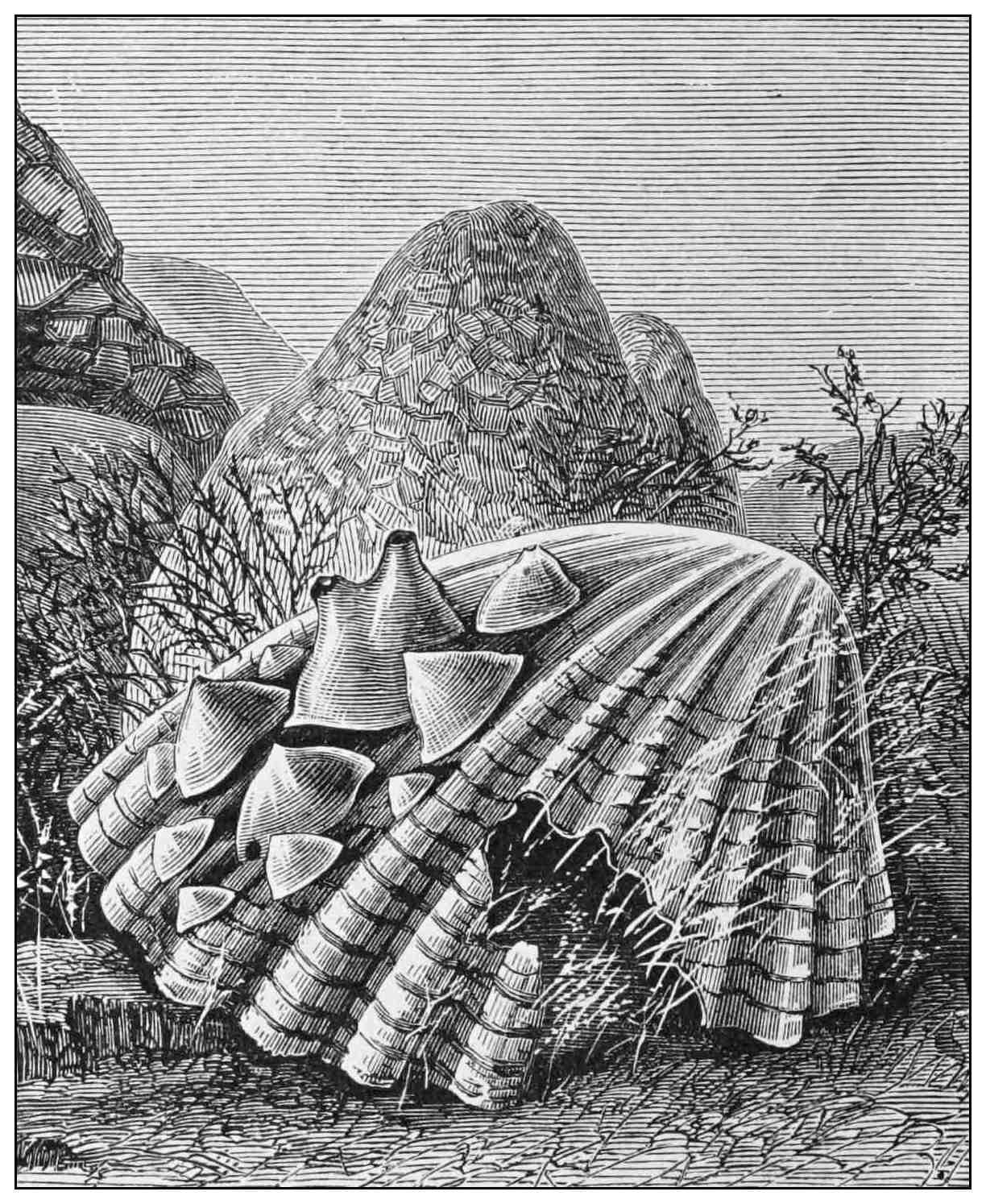

| Ship-barnacle | 177 |

| Pyrgoma | 183 |

| Scalpellum | 183 |

| Porcate barnacle | 183 |

| Acorn-shell | 183 |

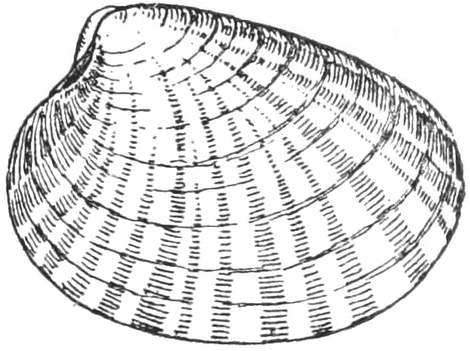

| Spiny Cockle | 186 |

| Banded Venus | 186 |

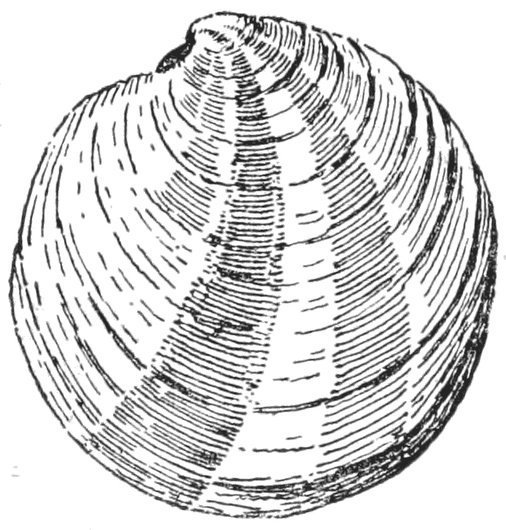

| Smooth Venus | 191 |

| Rayed Artemis | 192 |

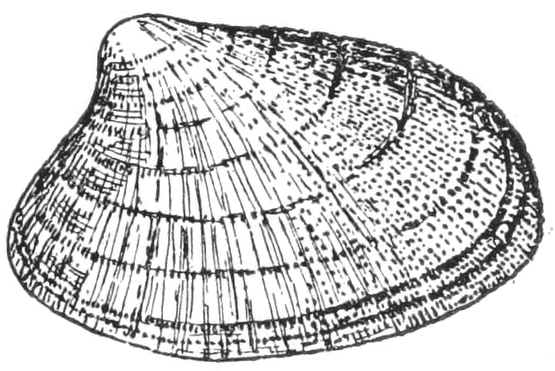

| Cross-cut Carpet-shell | 193 |

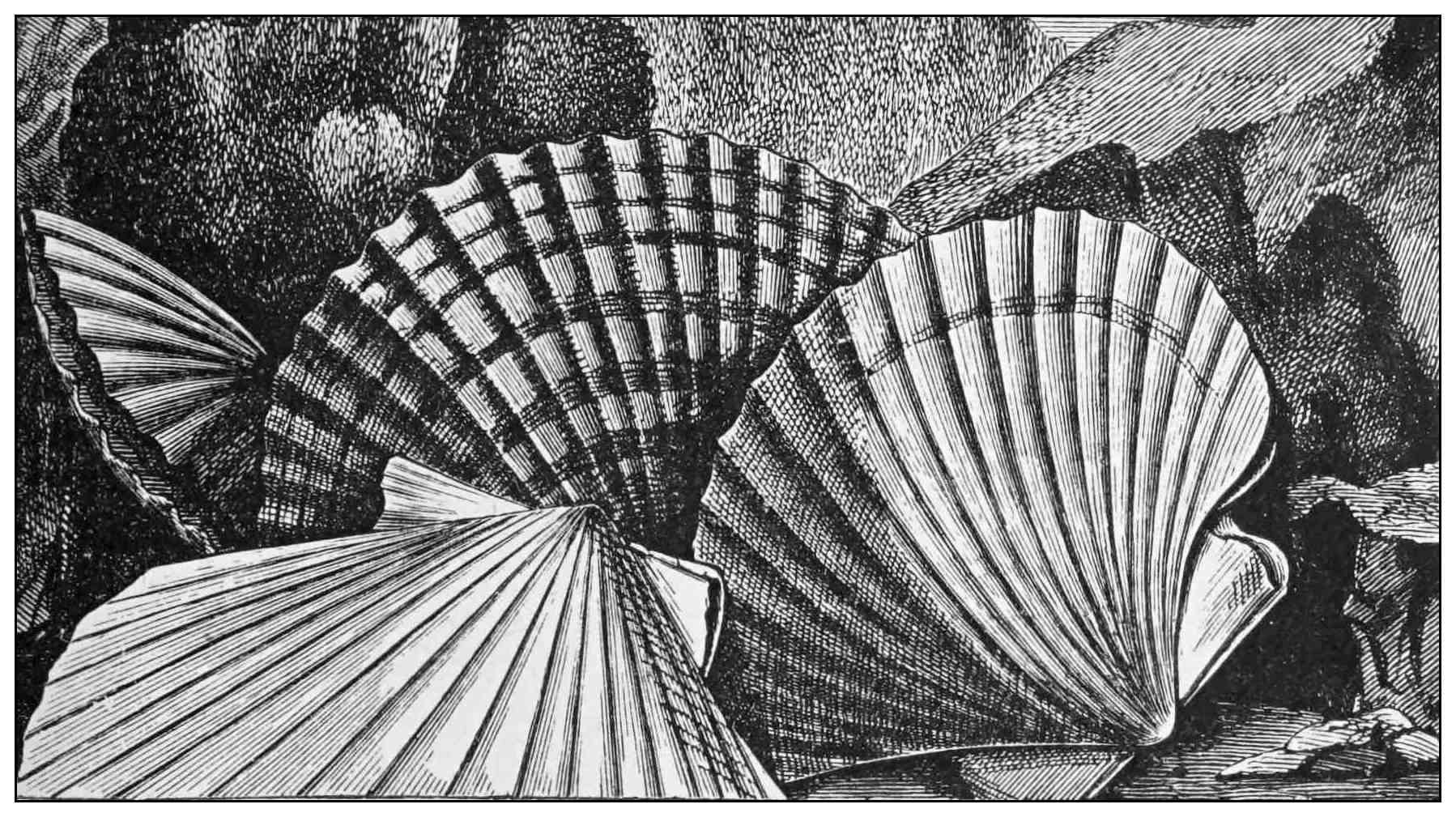

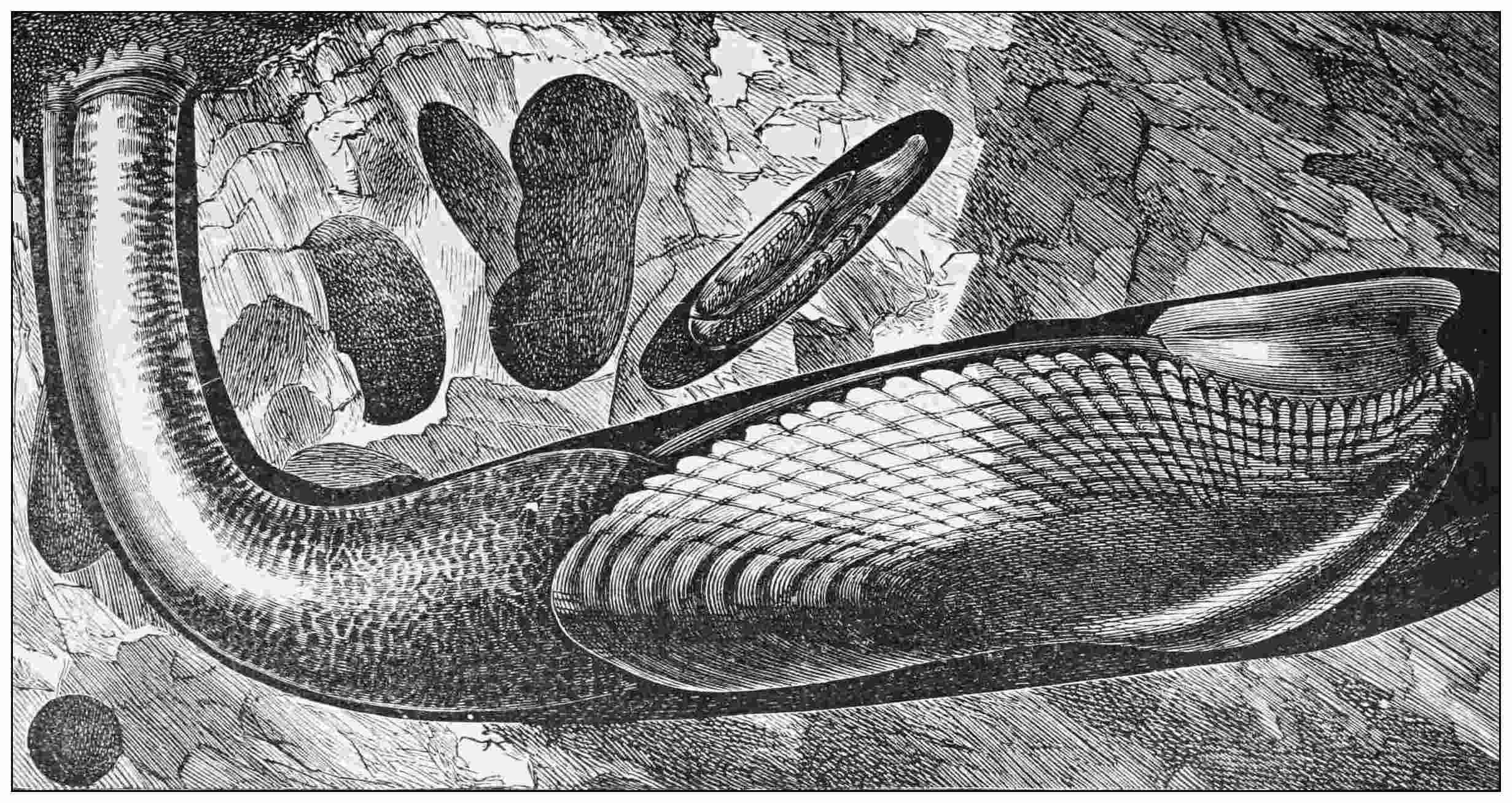

| Common Scallops | 195 |

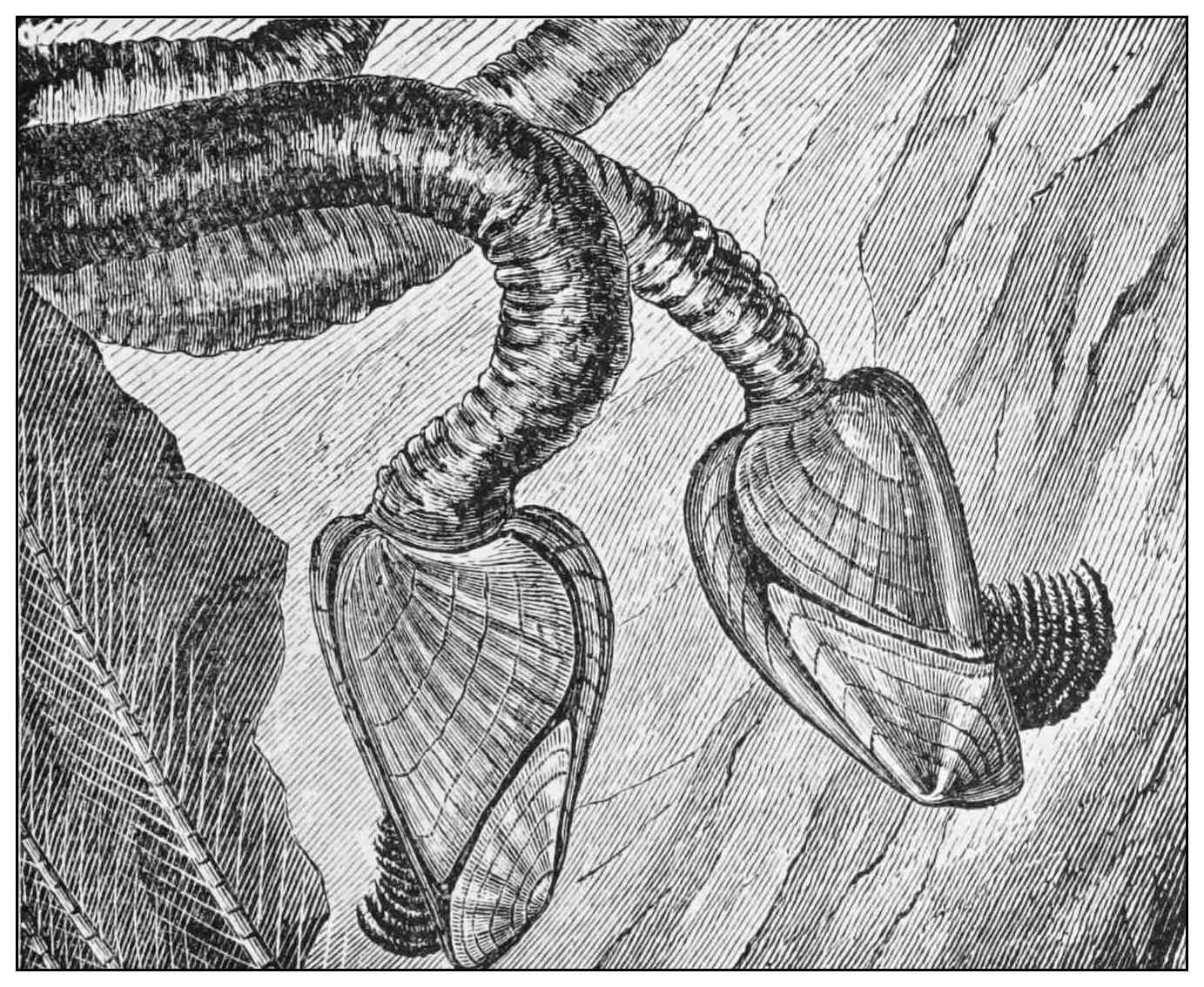

| Scallop hung up | 196 |

| Comb-shell | 198 |

| Rayed Trough-shell | 199 |

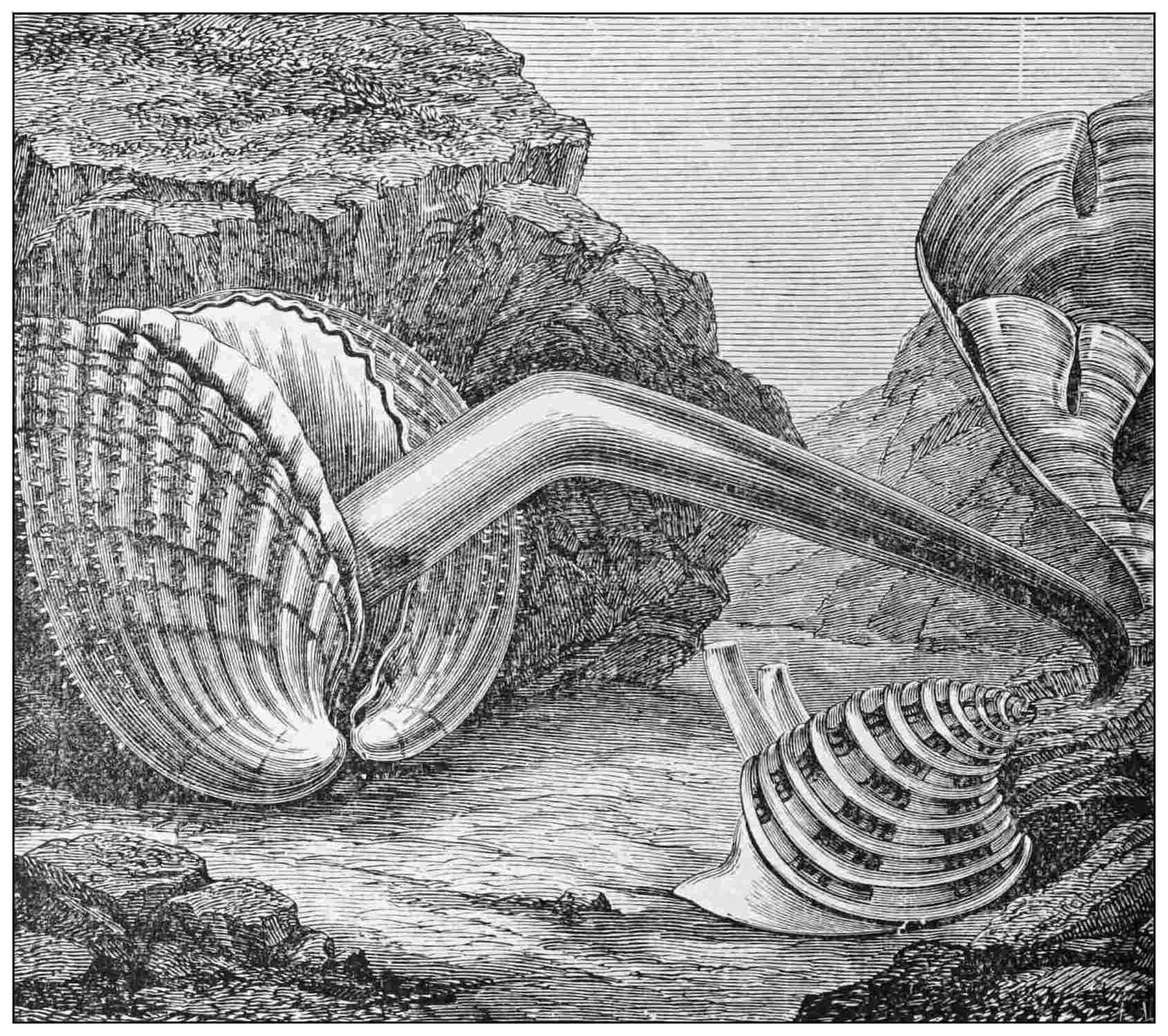

| Red-nosed Borer | 203 |

| Piddock | 203 |

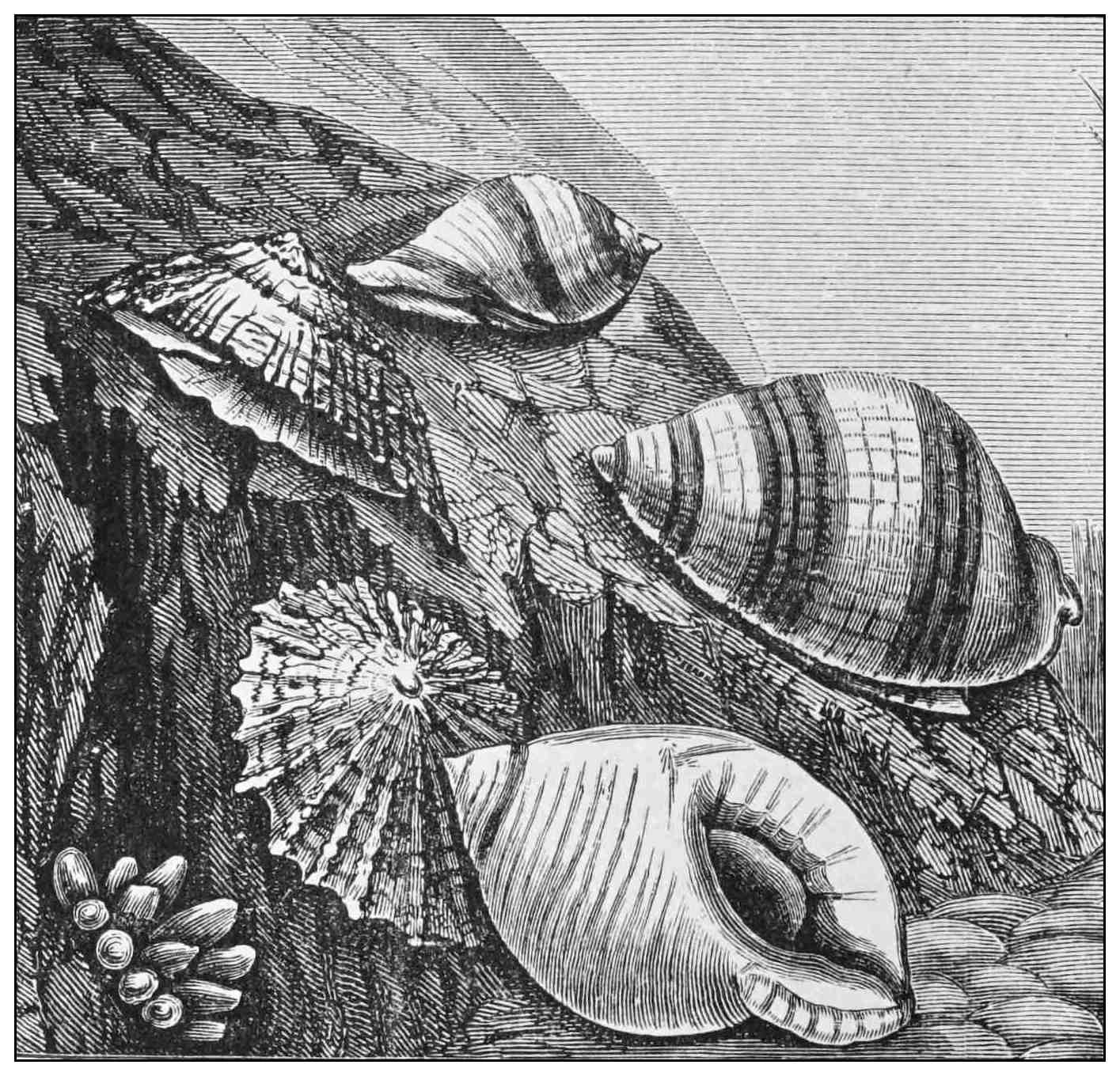

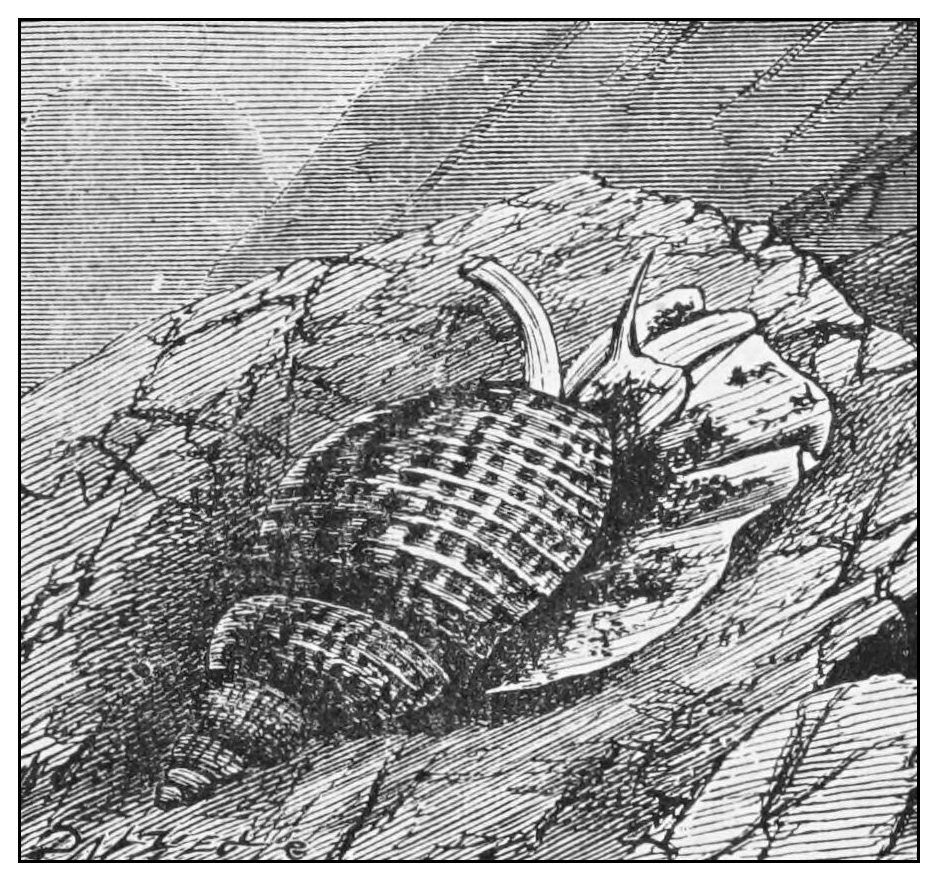

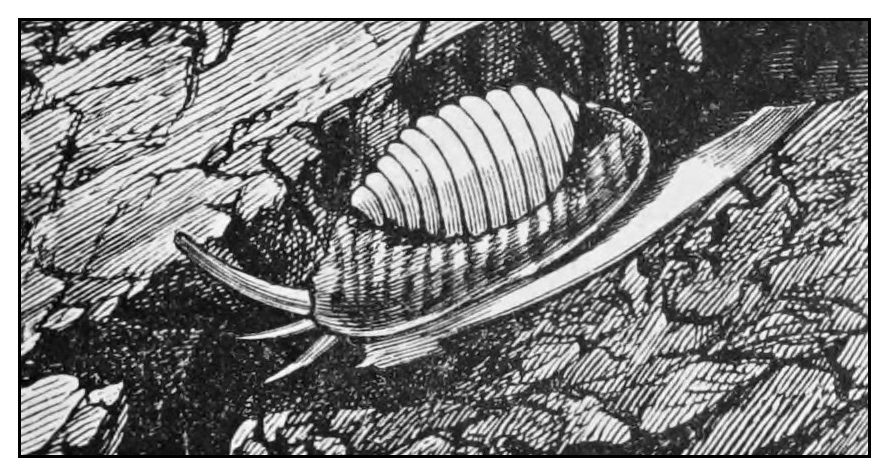

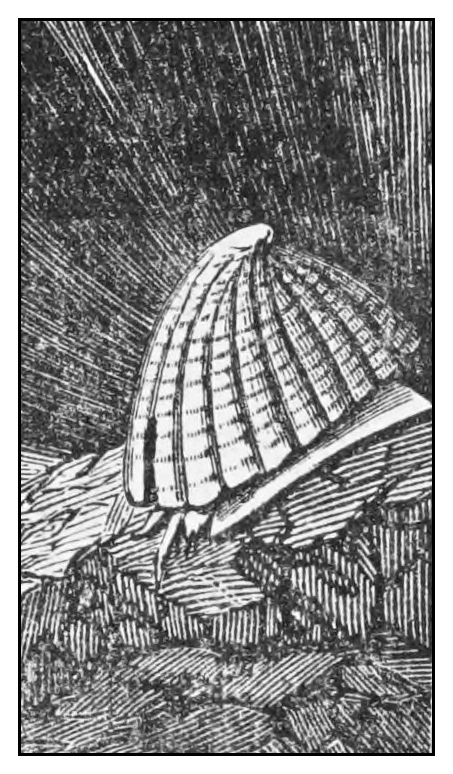

| Limpets | 208 |

| Purples | 208 |

| Smooth Limpet | 211 |

| Smooth Limpet, thick variety | 211 |

| Netted Dog-whelk | 213 |

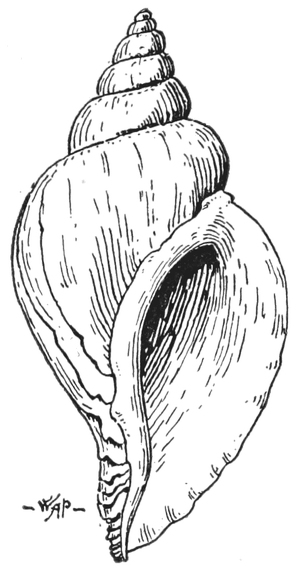

| Red Whelk | 214 |

| Cowry | 215 |

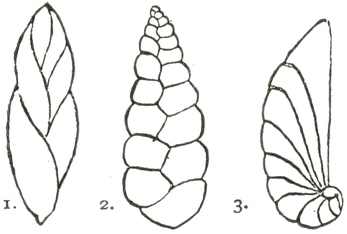

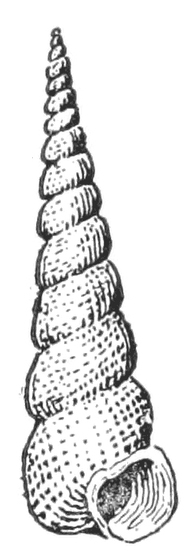

| Horn-shell | 218 |

| Pelican’s-foot | 220 |

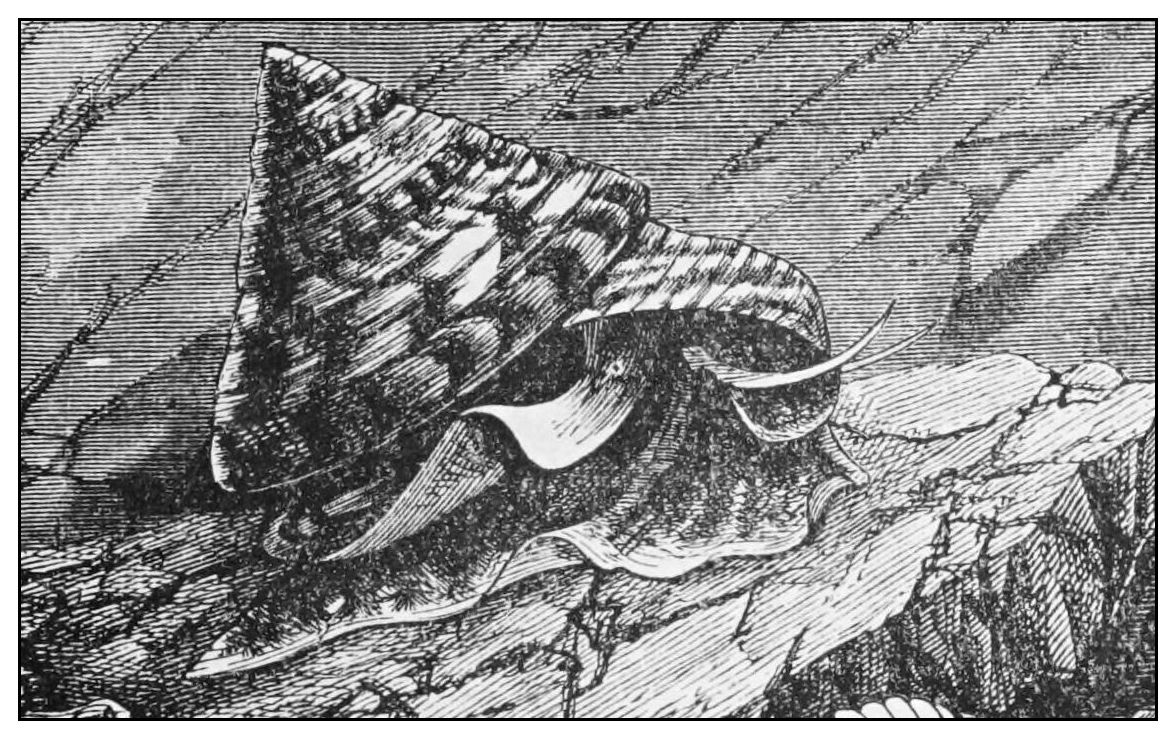

| The Common Top | 221 |

| Violet-shell | 222 |

| Raft of Violet-shell | 222 |

| Slit Limpet | 223 |

| Hungarian Cap | 224 |

| Tusk-shell | 224 |

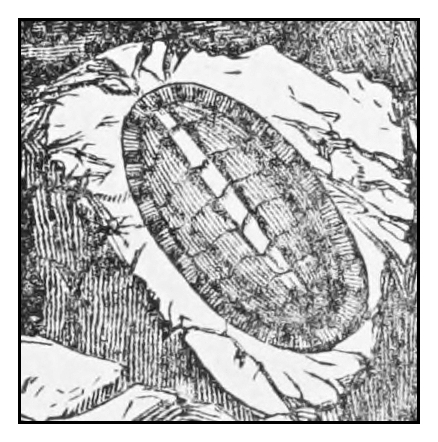

| Smooth Mail-shell | 225 |

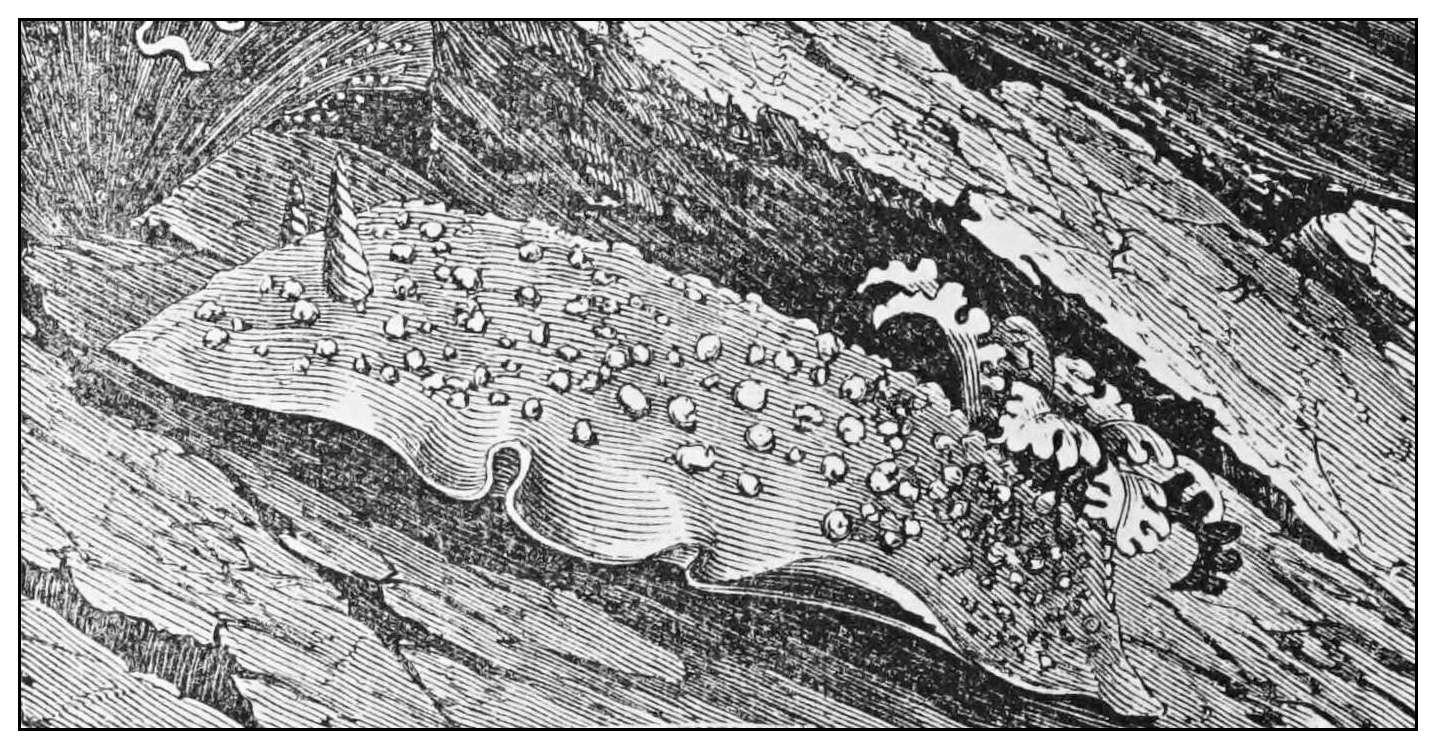

| Sea Lemon | 226 |

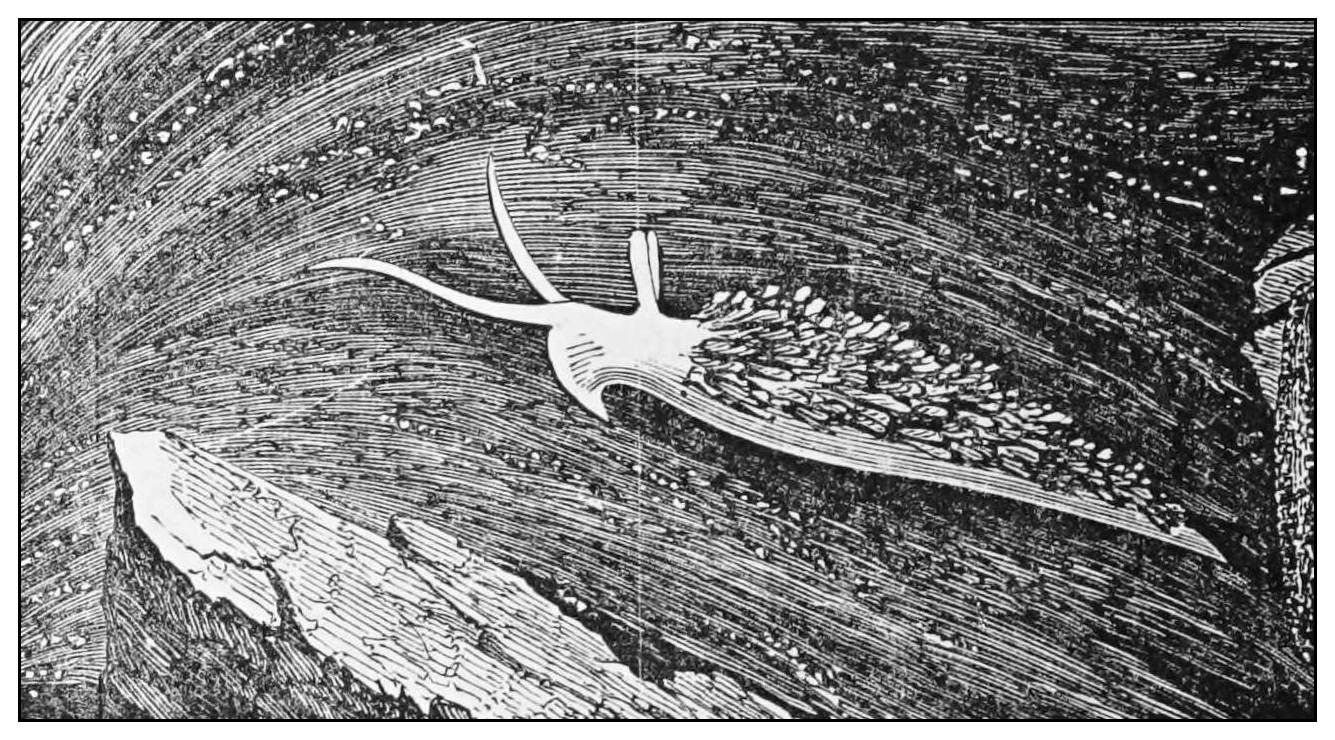

| Crowned Eolis | 228 |

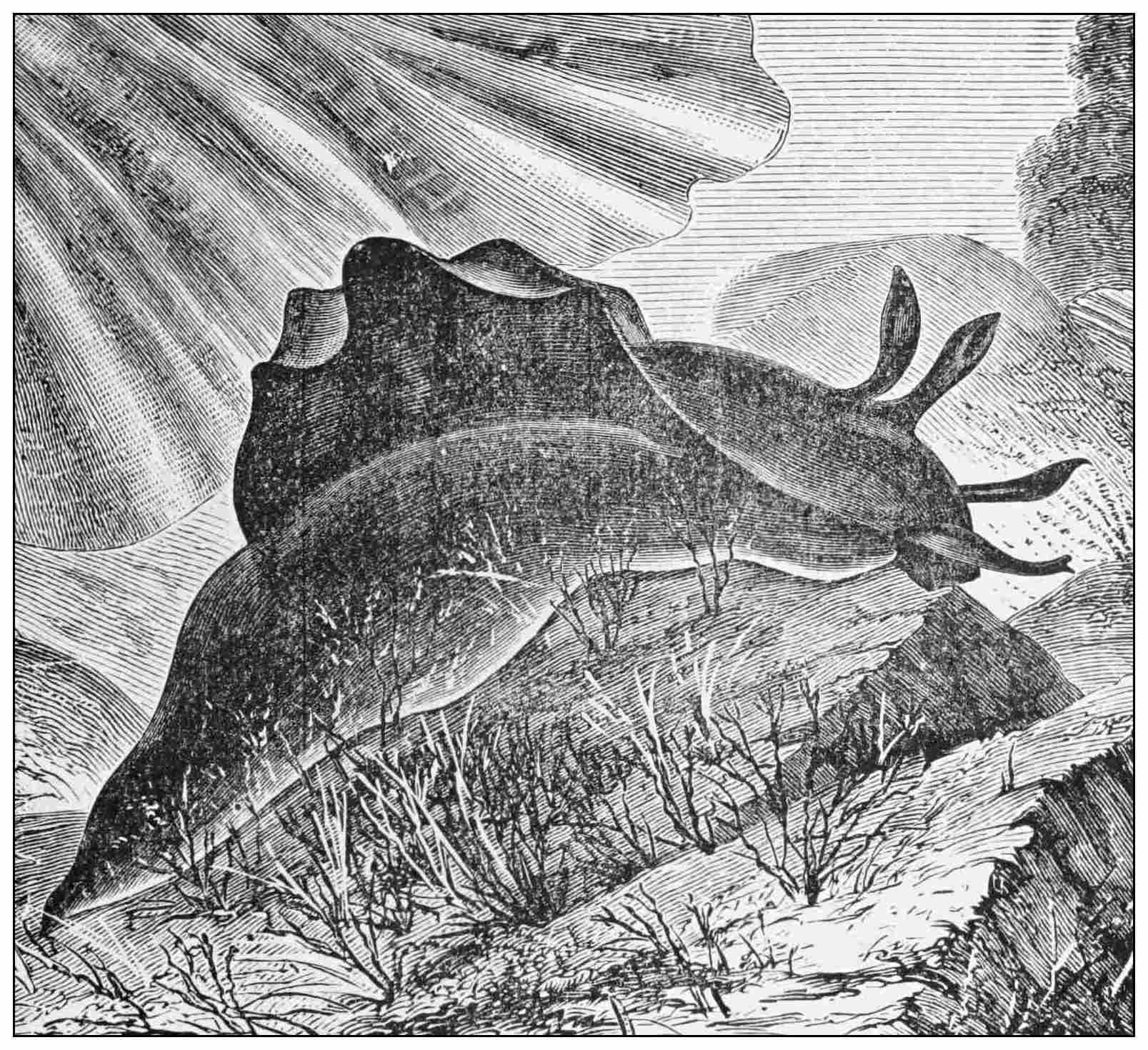

| Sea-hare | 229 |

| Sea-hare, front view | 230 |

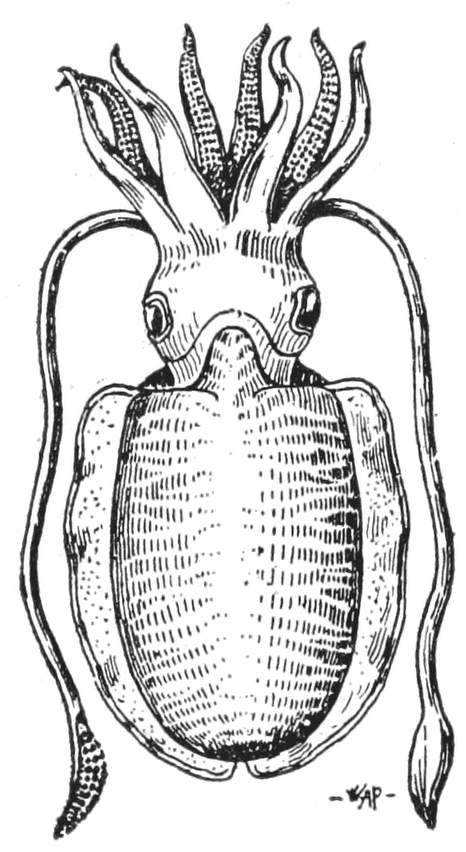

| Octopus | 232 |

| Sepia | 234 |

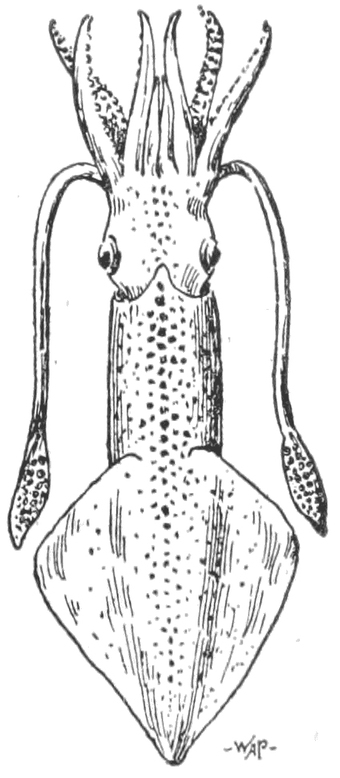

| Squid (loligo) | 235 |

| Ascidia virginea | 237 |

| Cynthia quadrangularis | 237 |

| Diagrammatic section of an Ascidian | 238 |

| Orange-spotted Squirt (Cynthia aggregata) | 239 |

| Ascidia mentula | 240 |

| Currant-squirter (Styela grossularia) | 240 |

| Clavelina | 241 |

| Salpa maxima | 242 |

| Part of a chain of Salpæ | 242 |

| Botryllus | 243 |

| Botryllus violaceus | 244 |

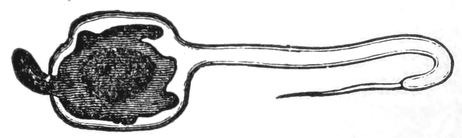

| Larva of a Tunicate | 245 |

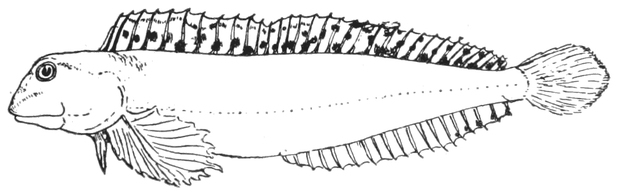

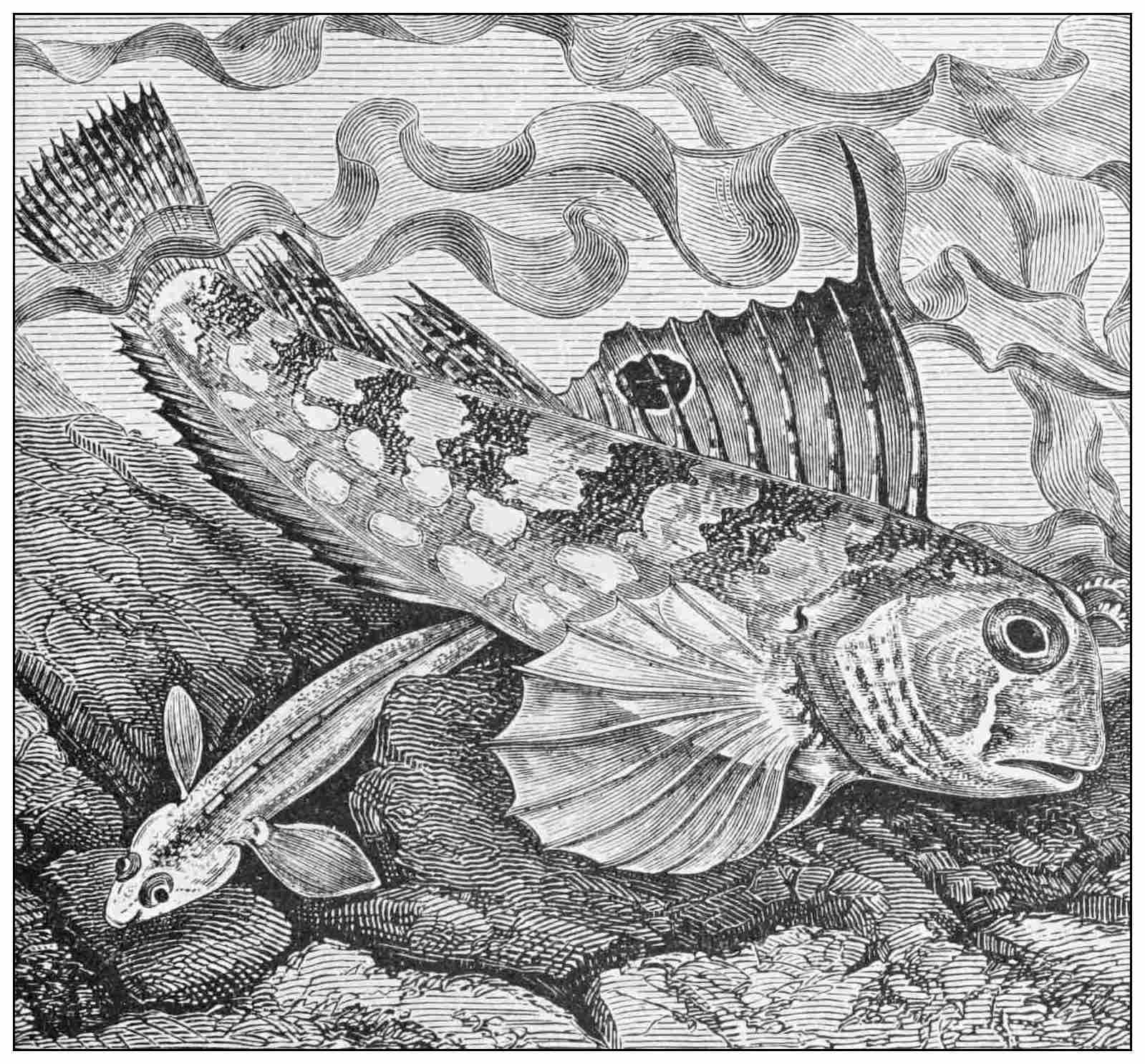

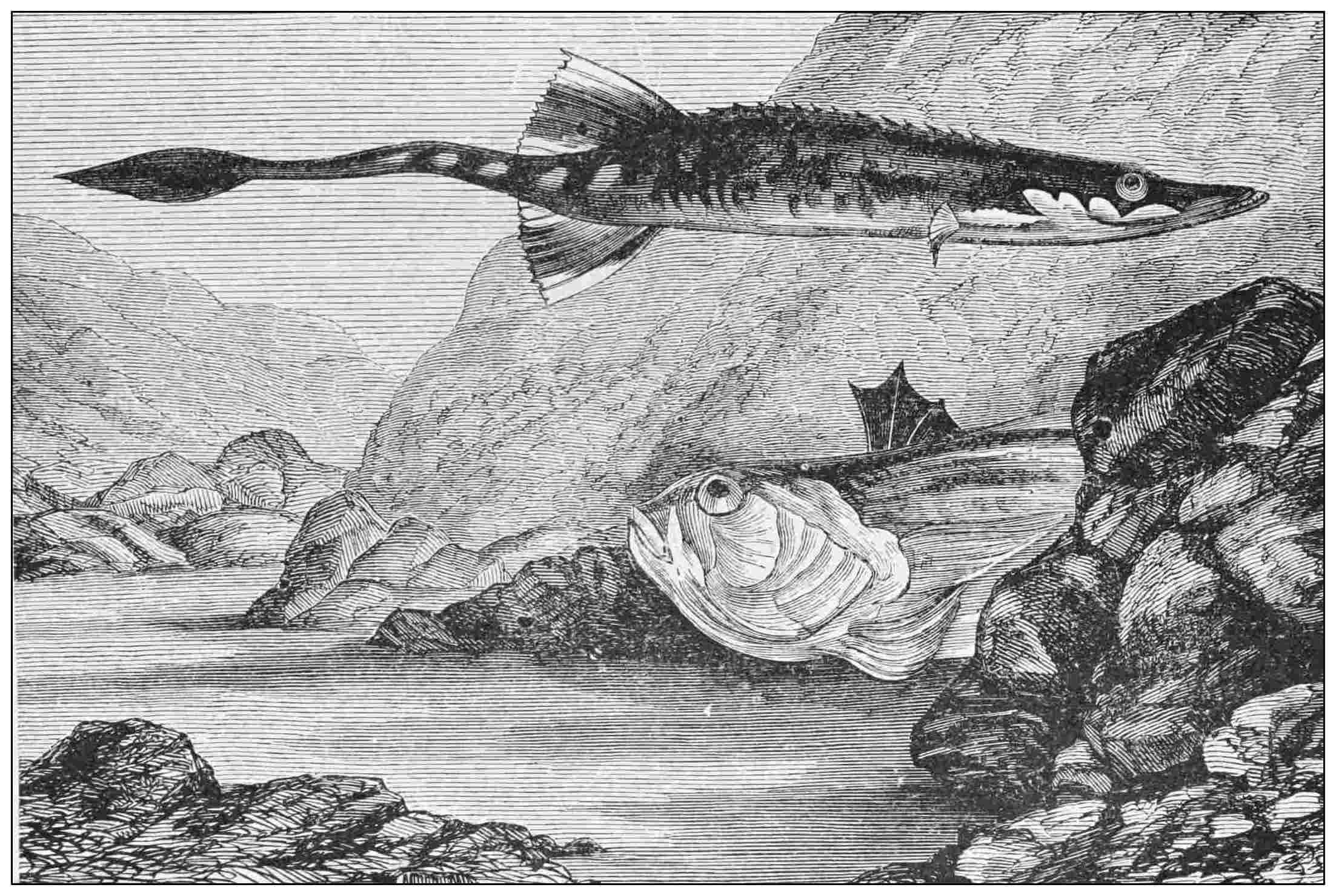

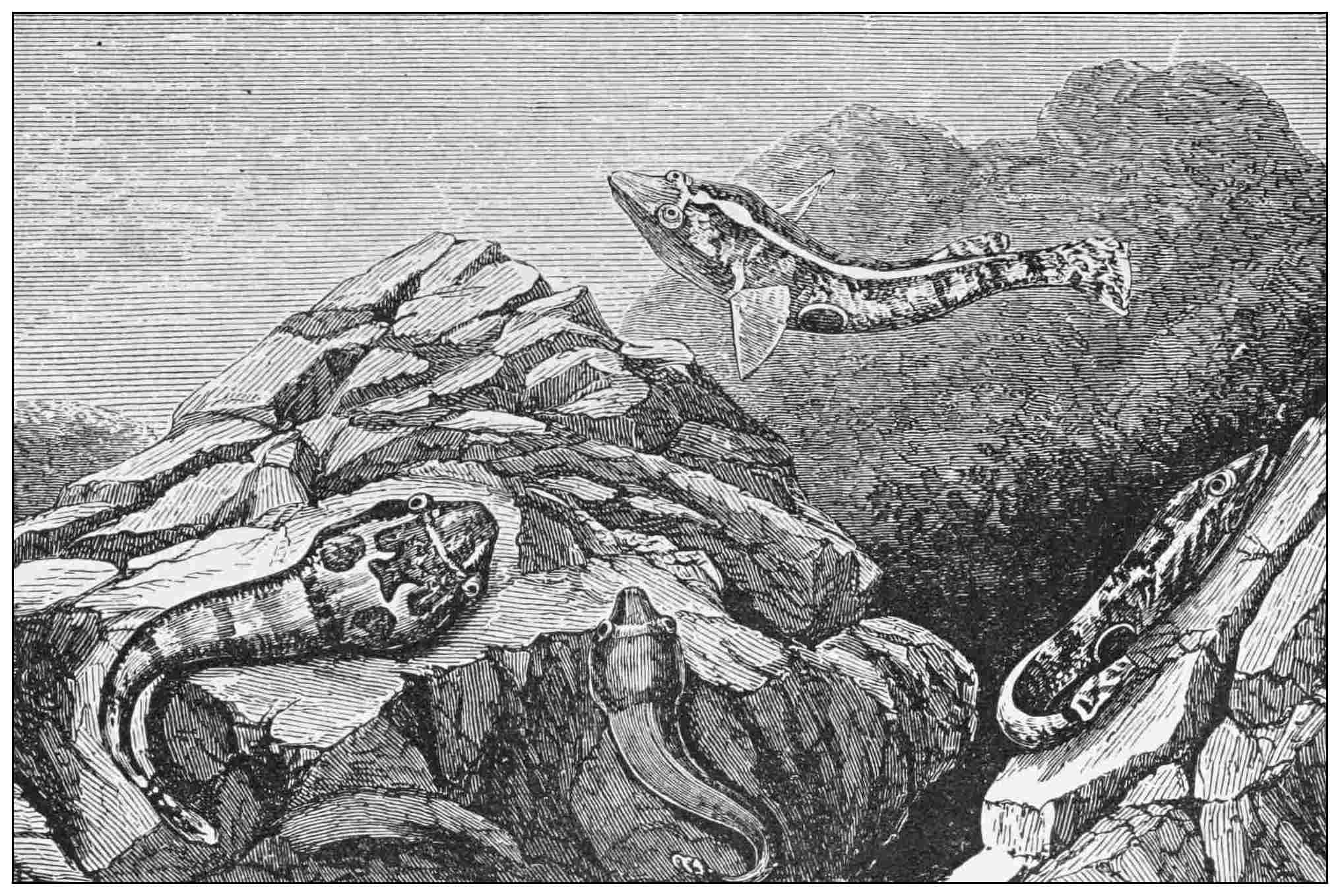

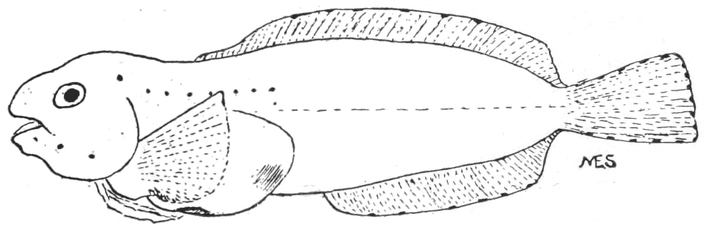

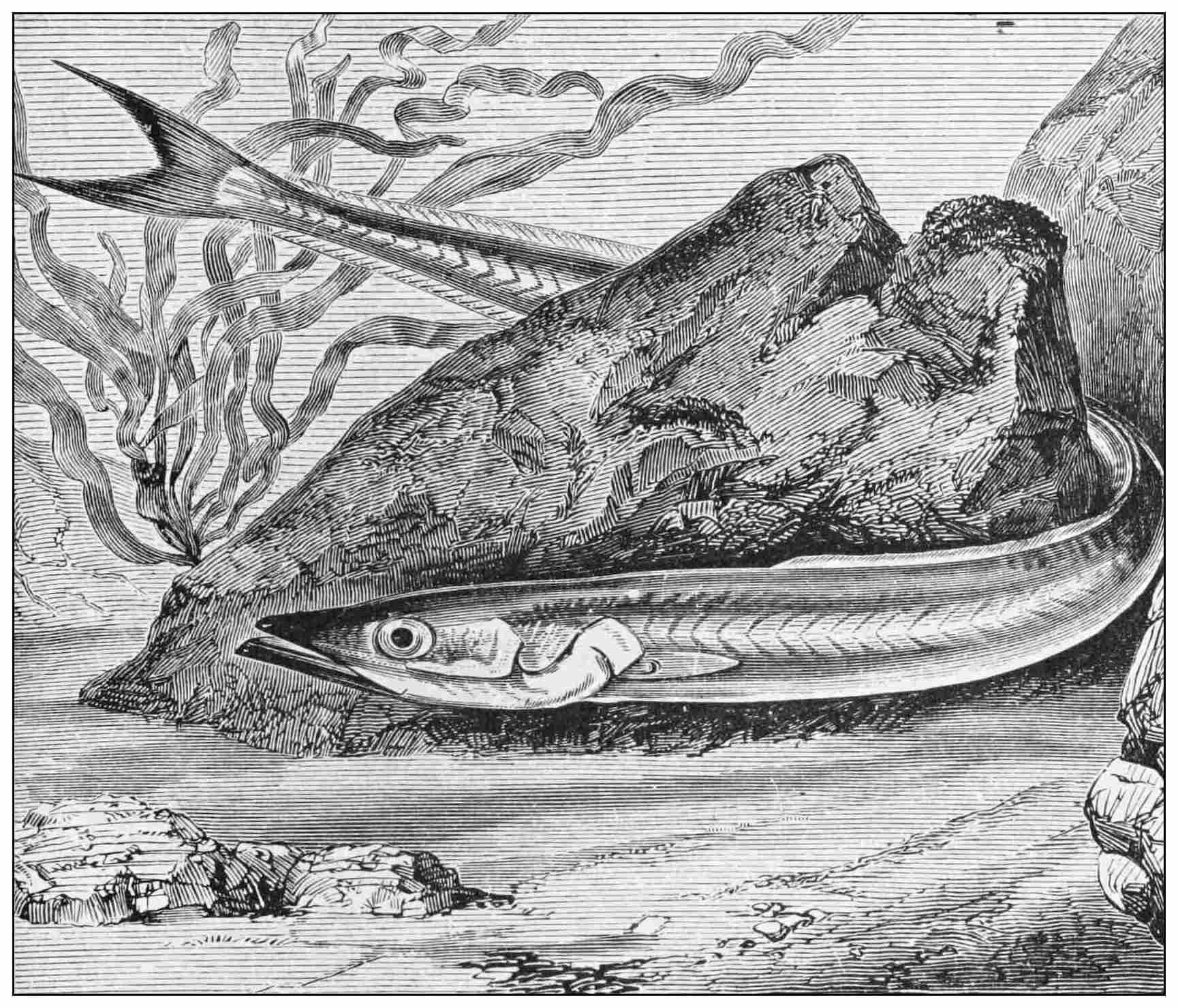

| Shanny | 247 |

| Father Lasher | 251 |

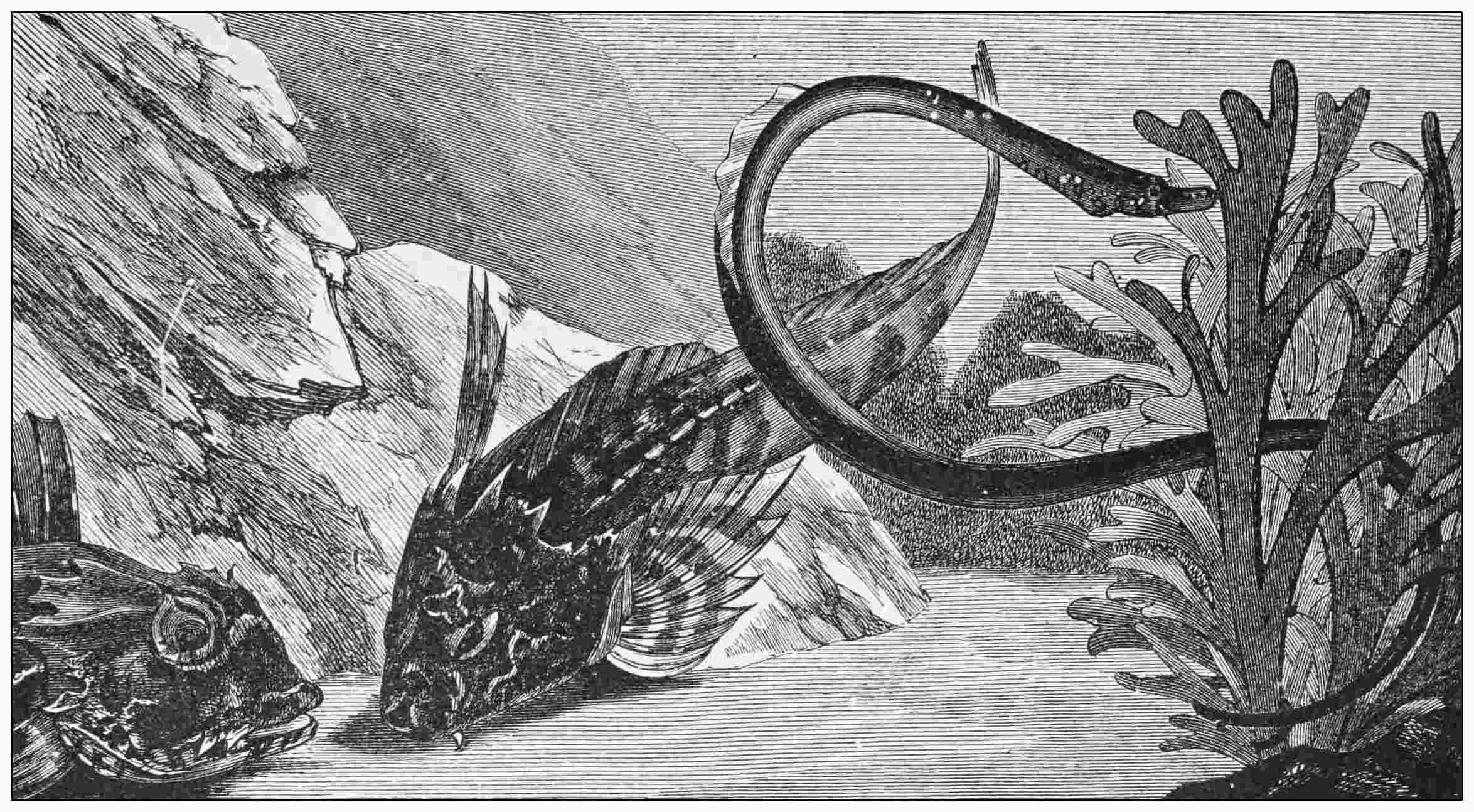

| Worm Pipe-fish | 251 |

| Little Goby | 257 |

| Butterfly Blenny | 257 |

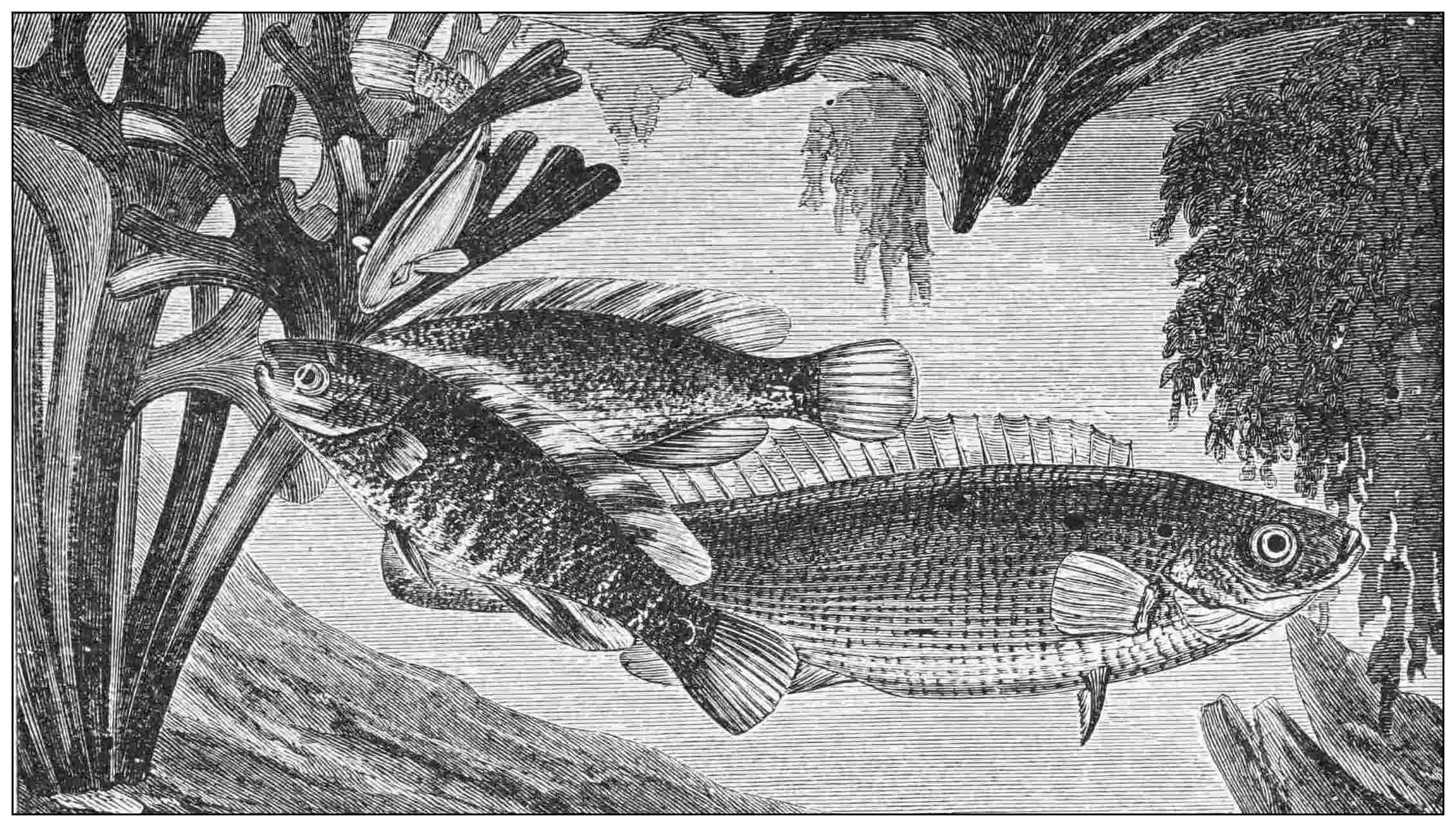

| Corkwing Wrasse | 259 |

| Gunnel | 264 |

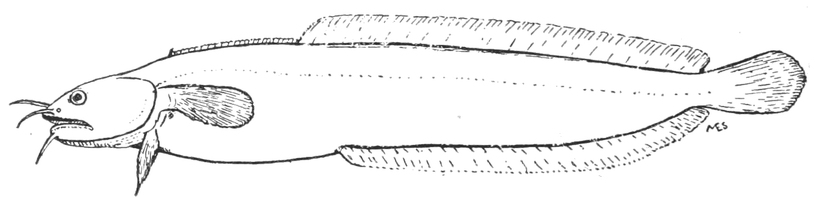

| Three-bearded Rockling | 266 |

| Fifteen-spined Stickleback | 267 |

| Lesser Weever | 267 |

| Two-spotted Sucker | 271 |

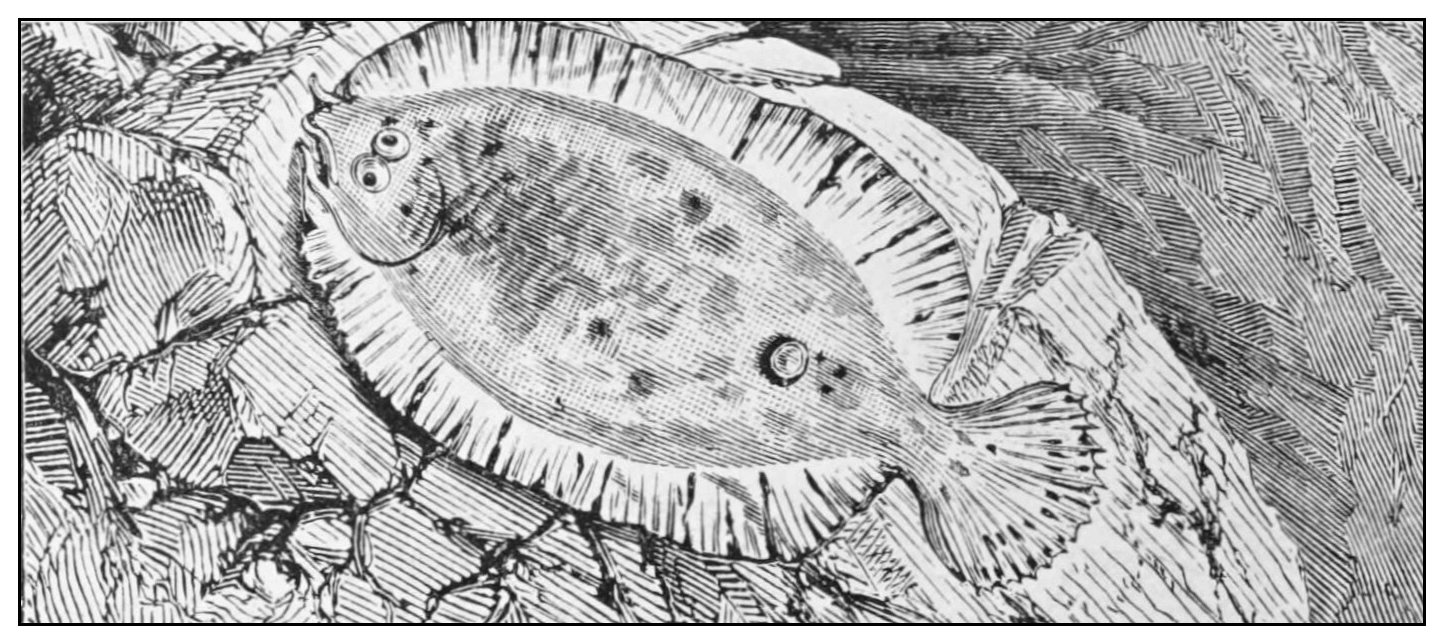

| Montagu’s Sucker | 273 |

| Topknot | 274 |

| Lesser Launce or Sand-eel | 275 |

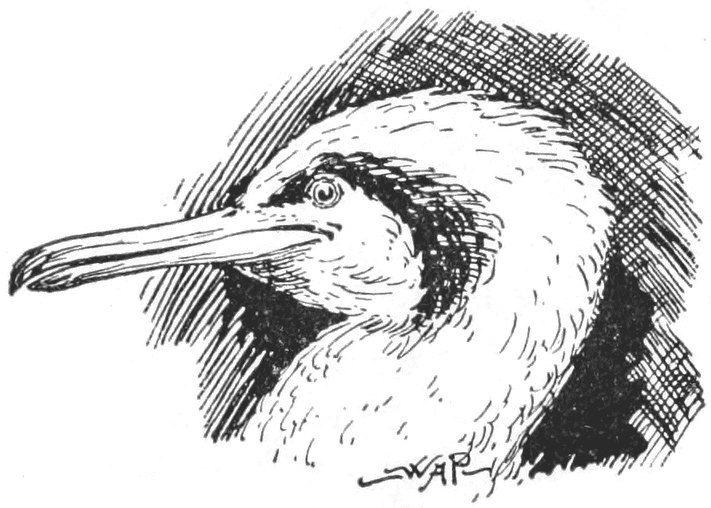

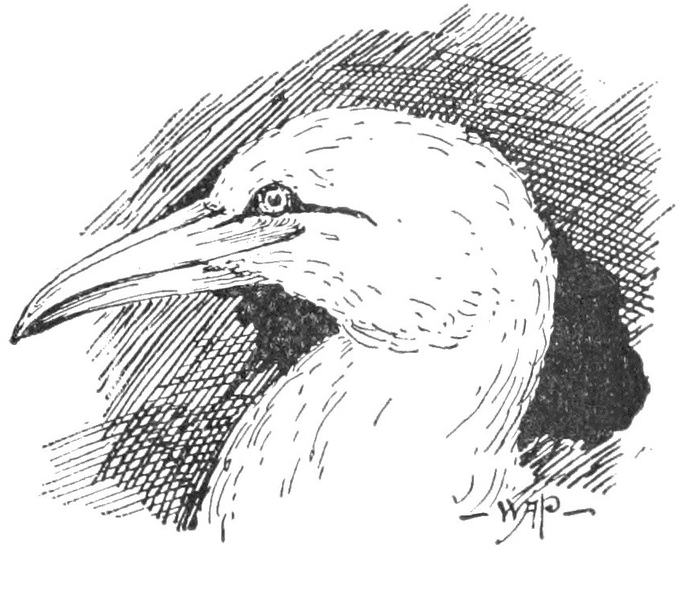

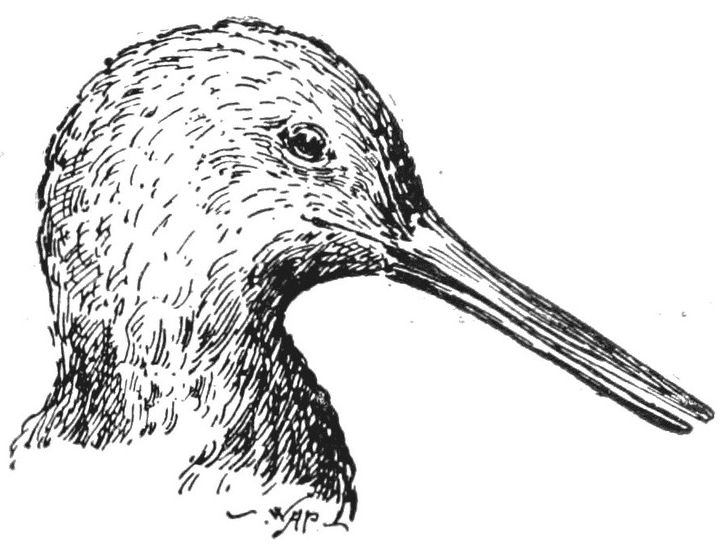

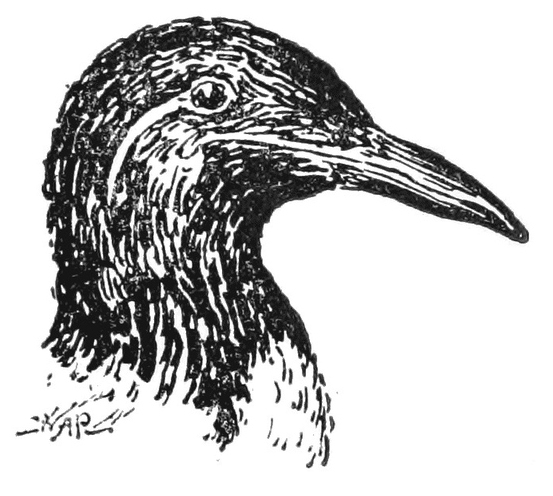

| Shag | 279 |

| Solan Goose | 281 |

| Oyster Catcher | 281 |

| Razorbill | 285 |

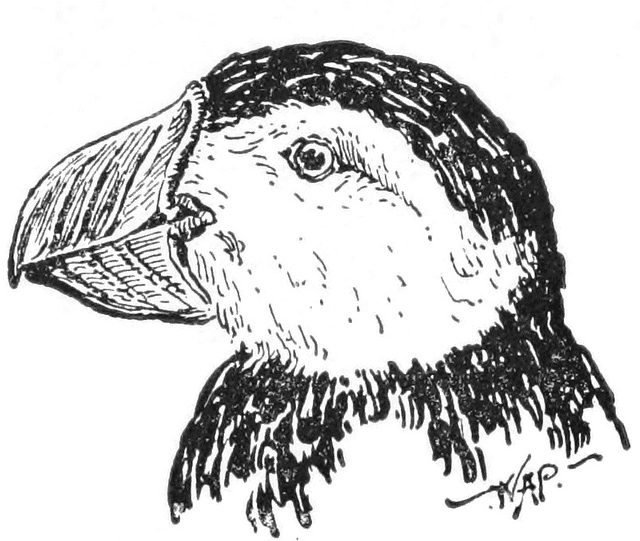

| Puffin | 285 |

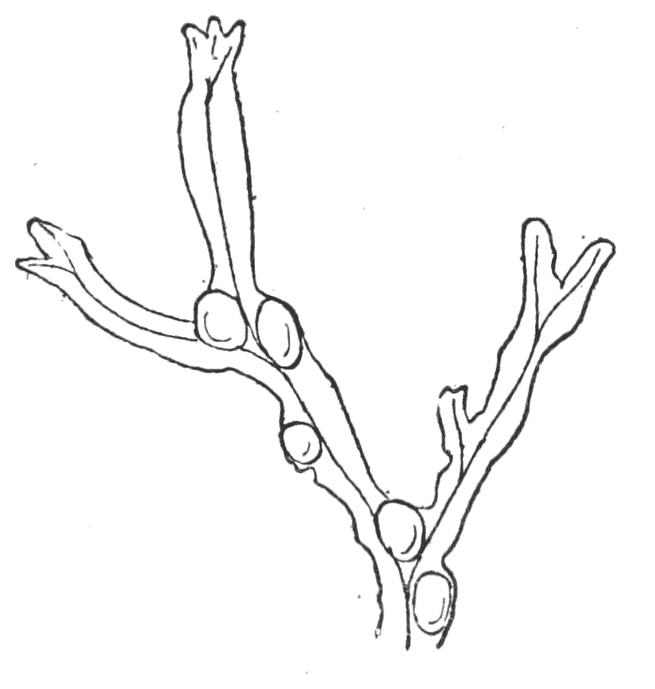

| Channelled Wrack | 289 |

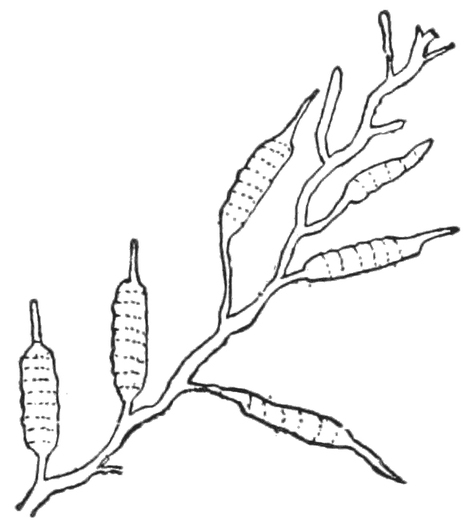

| Bladder Wrack | 291 |

| Saw-edged Wrack | 291 |

| Pod-weed | 292 |

| Peacock’s Tail | 296 |

| Chondrus crispus | 299 |

| Ash-leaved Seaweed | 300 |

[11]

The sea is the very fountain and reservoir of the life of this globe. As the heart is to man and his fellow vertebrates, so is the ocean to the world. It is the centre of the circulatory system; and that system means the life, the health, the sustenance of the body through which it sends its fluids. With the destruction of the heart the human life must cease; and with the annihilation of the sea, could such a thing be possible, all life on the globe must come to an end. We know it is the source of all our vitalizing showers, of every fertilizing stream, of every commerce-laden river. The sun and the winds distil its waters, and carry the sponge-like clouds over the lands, to drop their moisture in rain and mist and snow, making vegetation possible, and giving man two-thirds of his entire substance; for there are ninety-eight pounds of water in the man of ten stone!

The ocean does almost everything for man. Consider this statement well, and you will be astounded at the way in which we are everywhere dependent, directly or indirectly, upon the sea as the great reservoir of the world’s water, and as the manufacturer, by means of its myriads of living contents, of new and useful material from the old and worn-out rubbish, the very refuse and filth, that we daily pour into it. In fact, one[12] of the principal occupations of civilised man may be said to consist in making clean water dirty; and one of the greatest operations of Nature is to make the dirty water clean and pure again. Like the man in the fairy story, the sea gives us new lamps for our old battered and bruised ones; and it is mainly enabled to do this by reason of its immensity and the enormous variety of its population, each able to turn some portion of our rubbish to account. According to the most recent estimates, the cubical contents of the ocean is fourteen times greater than the bulk of the land, and this means that the whole of the land could be lost in the oceans. Not only so, but if all the continents and all the islands were dumped down into the Atlantic, there would still be two-thirds of that great ocean quite clear, and the whole of the other oceans would be undisturbed. It is calculated that the entire surface of the globe is 188 millions of square miles, and of this, the small portion of 51 millions of square miles represents the land surface, whilst the Pacific Ocean alone has a surface area of 67 millions of square miles.

It is no wonder that the immensity and mystery of the sea have always exercised a fascination over man. Emerson declares that “the Scandinavians in our race still hear in every age the murmurs of their mother, the ocean;” but he need not thus have limited the thought—in this respect, at least, we are all Vikings, and the murmurs of our mother still draw us to her side. Whether we be Scandinavians or Celts, the sea has power to bring us to her to-day as strong as ever it had over our forefathers, who found in the seas that lap our little isles the secret of national liberty, wealth, and power, such as no other country has ever enjoyed. What a part the sea has played in the making of the great Anglo-Saxon race! It is but meet that we should try to understand something of that great heart of Nature; and for years we have been sending expeditions here and there to sound its depths, and collect facts that shall one day enable us to know it thoroughly. We cannot all undertake, or accompany, such expeditions, and must, therefore,[13] be content to read with delight of their results; but great numbers of us make our annual pilgrimage to the sea-shore, and, if we will, may learn much of its wonders and beauties without running into danger, experiencing the discomfort of sea-sickness, or risking more than the wetting of a foot.

In the present volume it is the author’s desire to act as a friendly go-between, introducing the unscientific seaside visitor to a large number of the wonderful and interesting creatures of the rocks, the sands, and the shingle beach. Some may think this a work of supererogation, for already many volumes have been issued with a similar object. It is true that there are a number of manuals upon the wonders and the common objects of the shore, but the best are out-of-date or out-of-print, and the recent ones are such shocking examples of bookmaking without much knowledge of the subject in hand, that the practical ’long-shore naturalist smiles and writhes alternately as he turns their pages. Whatever else the present effort may lack, I claim for it this merit, that it has been written in close contact with the things it describes—not only of cabinet specimens, but of the living creatures under natural conditions. There is not a line in the whole volume that has not been written within a few yards of, and in full view of the rocks where the waves forever break, sometimes gently with a low murmuring, almost a whisper; at other times rearing their white crests a mile away, then sweeping across the bay, flinging their malachite curves upon the rocks with giant force and thunderous roar, whilst the foam flakes flying high tap softly at my window.

As far as possible I have dealt with the fauna of the rocky shore separately from that of the sands or the shingly beach, but it must be understood that in Nature there is a good deal of overlapping. It will also be no surprise to the reader that the rocky shore bulks more largely in these pages than sand or shingle; the rocks with their cracks and caves and pools affording protection to many delicate organisms against the fury of the waves.[14] Naturalists have marked off the sea-bed into a series of zones, an arrangement which may seem somewhat arbitrary, but which is found very useful in practice. The first or highest of these zones is known as the Littoral zone (Latin, litoralis, the shore), and includes all the shore, be it rocks, sand, shingle, or mud, that lies between the highest and the lowest of spring-tide marks. Next to this comes the Laminarian zone, so-called because between very low tide and a depth of about fifteen fathoms of water, the Laminaria digitata, or Oar-weed, grows profusely over the rocky ground, and forms a splendid cover for the luxuriant animal life that haunts it. Our district is the Littoral zone, and the Laminarian zone forms our seaward boundary, which we cannot cross, for its exploration needs the use of boat and dredge. It is a very tempting province to enter, for it contains the oyster-banks, and many interesting forms of life.

He who would see the most that the shore has to exhibit to him, must consult the local tide-table, and the table of the moon’s changes. If his stay at the seaside is to be brief, he must endeavour to let the date of his start be governed by lunar considerations. Many business men cannot get away for more than a fortnight, and if any such should wish to make the best use of his time in connection with natural history, we should advise him to begin his holiday at the period of the moon’s first or third quarter. He will thus arrive at the time of neap-tides; that is, when high-water is low, and low-water not much lower—when, in a word, there is the least difference between high and low water. The local weekly newspaper will in all probability contain the times of high-water for every day in the coming week. If not, he must find out on his first day at what hour low-water is reached, and for at least an hour before that time he must be on the shore with basket of wide-mouthed bottles—glass jam-jars are the best, for they are easily obtained everywhere, and should an accident happen to one through collision with a rock, no[15] great harm is done. Now bear in mind that the time of low- or high-water will be about forty-five minutes later to-morrow than it was to-day, and the same number of minutes must be added on each day to give the correct time for your visit to the shore. Arrived there, it is best to keep close to the ebbing tide, and as it goes further and further back, to turn over the stones and weeds that have just been left by it. In this way you will get acquainted with the best manner of proceeding, according to the peculiarities of the special bit of coast you are on, so that when, a week after your arrival, there comes the spring-tides, you will be able to make far better use of your opportunities than if you had arrived in the locality just at the period of spring-tides.

The lowest tide is the third after New and Full Moon. Then the water goes out to a great distance, and if on a rocky shore you will be able just to step over the border among the Laminaria, and hunt for specimens on its roots and under its long broad fronds. If you really desire to see and find as much as possible with the greatest amount of comfort, then pay attention to your dress before seeking the shore. You should don an old suit of clothes that has become too shabby for ordinary wear. If it is a bicycling outfit, so much the better, for the knickerbockers will be more handy for wading. There is, of course, no necessity for wading, but often it will be found that a “likely” looking rock is cut off from us by a few feet of shallow water, too wide to jump. In such a case wading pays. But it is really best to make up the mind to wade. Take with you an old pair of shoes, and above high-water mark you will find some safe place in the rocks for depositing your walking-shoes, socks, and such other articles of clothing as you wish to doff. Put the old shoes on your naked feet, and roll up your trousers or knickerbockers as high as they will go. You thus run little risk of getting your clothes wet, and your feet will be protected from the sharp edges of newly-fractured rocks and broken shells, or even from the nip of a too-familiar crab.[16] Should the idea of old clothes be an objectionable one to you, and you have a preference for something appropriate, I would strongly advise a good knitted Jersey, worn without a coat—at least when the collecting ground is reached. Such a garment is warm without being heavy, and is a protection against the changes of temperature that frequently take place by the sea; there are no tails to get wet when you sit or kneel on low rocks, and no pockets out of which things can fall when you stoop. For the head a cloth cap is best; whilst at work wear it with the peak behind, otherwise when you peer closely into a pool it will get wet.

If you visit the village shop or store you can buy for a few pence one of the handy open chip baskets with handle across the middle, that are so much used for gardening purposes. In this you can store your glass-jars, and have them always handy without any lid to open, and can find room for seaweeds, shells, etc. If you are going to the sands you should carry a garden trowel; if to the rocks, a good strong putty knife with straight edge. You will find in most cases this will do instead of the more cumbersome cold-chisel and hammer that you may have to use on special occasions. With it you can separate the upper flake of a slaty rock upon which are desired specimens, by driving the knife in at the edge. For getting anemones off rocks you will find this knife very valuable. In such situations the anemone’s base usually rests upon a crust of old acorn-shells, sponge, coralline, or other foreign growth on the rock. The edge of the knife should be driven through this crust at a little distance from the desired specimen, and then pushed firmly towards and under it. It will come off with its base—the most delicate part of an anemone—uninjured and undisturbed, so that when placed in an aquarium it will spontaneously glide off the crumbling rubbish and obtain a firmer footing.

Some of the anemones and other fixed objects in the rock-pools you will find are in too great a depth of water to be got at with ease or comfort; but by using one of your bottles as a[17] baler you can rapidly reduce the level of the water to a working height. I have in this way almost completely emptied a deep and narrow rock basin, where there was no play for the arms. You need have no scruples about destroying a natural aquarium by so doing, for the rising tide will soon put that matter right again. Where I have had to reduce the water in a large pool that would have taken a long time to bale out in this fashion, I have taken down a portable garden pump with splendid results.

In working a “drang” or rock gulley at low-water, pay special attention to the lower part of the perpendicular rock-walls, that are most protected from the full force of the waves in stormy weather. Where such a fissure runs parallel with the cliffs, the most productive wall will be that which faces the cliffs, for it is easy to see that in heavy seas this is the part that is protected from the sledge-hammer force of the waves and the big stones with which they batter and bombard the land; therefore, it is the part where soft and delicate organisms have the best chance of flourishing. It will be well also to carefully scrutinise the opposite wall, but when there is only a brief time at disposal devote it to the one we have indicated as the best.

Should you desire to obtain specimens for preservation in the cabinet instead of the aquarium, then you must take a jar of fresh water, which should be of a distinctive shape or material, to prevent mistakes. Most of the marine creatures are killed by immersion in fresh-water, which has the advantage of not altering their colours, as spirit does in too many cases—notably among the Crustacea. A few of the corked glass tubes that most naturalists use, will be found handy for minute specimens, which are liable to be overlooked if put into the general collecting jars with larger creatures. Overcrowding of the live stock must be avoided, or all will be dead or dying before your collecting is well through.

For small fish, shrimps, and other swimming creatures, you[18] will require a small net, or rather two nets, for one that is suitable for catching the small and delicate forms one finds in the rock-pools or swimming near the surface of a smooth sea, will not be strong enough for drawing through the rough weeds. The one should be of fine muslin to retain minute forms; the other should be really a “net,” of the very smallest mesh possible.

On the rocky shore you will find the greatest abundance and variety of the marine algæ or seaweeds, most of the crustaceans, nearly all the anemones of the littoral zone, a number of species of fishes, many of the tube-worms, the sponges, the tunicates, and such molluscan forms as the periwinkle family, the limpets, dog-whelk, tops, slit limpet, smooth limpet, cowry, and sea lemon. On the sandy beaches you will find only such seaweeds as have been washed in by the waves, shrimps, the masked crab and the angled crab, launce or sand-eel, the razor-shell, cockle, tellen-shells, horn-shells, the natica, and other shells.

On the shingle beach little will be found besides empty shells and heaps of more or less damaged seaweeds, which, however, are well worth examining, for occasionally one may find uncommon kinds there, and among them specimens of animal life. But it is to the rocky shore we advise our readers to give most attention. The rocks, their pools and crannies, will engross the attention more, and the harvest will be greater. By a little local study it will be found that certain winds will cause the heaping up of certain shells on one particular part of a beach, whilst other winds bring other things to the same or different parts. This knowledge acquired, you will put it to practical use by finding out what was the direction of that stiff gale that blew last night, and then bending your steps in a particular direction, you will be able to take your pick of the shells before the hinges have become broken and the valves separated. There are many species of mollusca whose shells you will only acquire in this way, unless you are able to go[19] dredging, and thus get up the living creature from the sea-bottom. All such shells, though they may look perfectly clean, should be carefully washed in fresh water, to get rid of the salt, that would otherwise hang about them, and prevent them becoming absolutely dry, as cabinet specimens should be.

Probably, after you have really seen something of the exceeding beauty of the rock-pools and the little marine caverns, you will be fired with the ambition to start a small marine aquarium when you return to your own home. You really ought to be filled with this desire a month or so before you seek the shore, so that you might provide a suitable vessel or vessels, and allow the sea-water to settle down and the contained germs of vegetation to start into active life, and so be ready to support animal life. We will suppose you have made some provision of this sort before leaving home, and now desire a suitable selection of creatures to fill it. My advice is, be modest in scheming, and for a first experiment start with creatures that consume very little oxygen—you cannot have better subjects than the anemones. These should be conveyed not in water, but each specimen wrapped lightly and separately in soft weed, and the whole packed in more weed in a light wooden box. The pools should be searched for a rough, uneven piece of rock, upon which small green weeds are growing, and this should also be placed in your aquarium as a suitable base for the anemones. Most marine animals travel better in weed than in water, which rapidly becomes foul in travelling, and destroys all that have been entrusted to it.

[20]

Some persons go to the seaside every year for several weeks, and yet know little of its treasures. Take away the bands, the bathing machines, the itinerant entertainers of various kinds, the bustling crowds that pass and repass on the grand parade, and they are lonely, miserable, with nothing to occupy their minds. Of the illimitable sea, the cliffs, the sands, the passing sails they soon tire. For a very small sum, as money is considered to-day, such a person could acquire a tolerable microscope, and a very little application to books would put him in the way of getting an absolutely endless fund of interest, knowledge, even amusement from it. Through the magic glasses he enters another world; or, rather they enable him to see that other half of Creation with which he has been rubbing shoulders all his life, yet without seeing the creatures. With such an instrument and the knowledge how to use it, a man may defy the demon ennui wherever he may be. With such an instrument at home a person who is not a naturalist may be induced to look into a rock-pool, to take samples of its fauna and flora, and by and by to become a naturalist without intending or knowing it.

Behold how easy a thing it is! He has but to take away a phial full of the water, a tiny bunch of coralline, the finer green weed, or a snippet of sponge from the walls of the pool, and he has abundance of material whose marvellous beauties of form and colour will delight and astonish him when he has had time to examine it under the microscope. For the coralline tuft and the lowly weed, when washed out in the sea-water,[21] will yield him multitudes of Infusoria, Rhizopoda, and the infantile stages of many of the higher groups of life.

The Foraminifera are the minute creatures which have so largely contributed to the formation of the enormous beds of chalk we find in Surrey, Kent, Sussex, and other counties, such as the explorations of the Challenger showed us are being formed in the deep sea at the present time. So minute are they that one hundred and fifty of them placed side by side would not measure more than one inch, and of such insignificant creatures the chalk is almost entirely composed. What are they? How are they fashioned? How do they live? These questions probably occur to the reader, and I must do my best to briefly answer them.

There is a minute creature, plentiful in ditches and similar accumulations of stagnant water into which decaying vegetation has fallen. It is a minute speck of animated jelly, without form, substance, or limbs. There is, in fact, no closer analogy than the speck of almost clear jelly, to which in some mysterious way life has been given. In the words of the late Dr. W. B. Carpenter, who made a special study of these creatures: “A little particle of homogeneous jelly[1] arranging itself into a greater variety of forms than the fabled Proteus, laying hold of its food without members, swallowing it without a mouth, digesting it without a stomach, appropriating its nutritious material without absorbent vessels or a circulating system, moving from place to place without muscles, feeling without nerves, propagating itself without genital apparatus, and not only this, but in many instances forming shelly coverings for symmetry and complexity not surpassed by those of any testaceous animal.”

[1] It is now known that this jelly-like material is not of so simple a character as was supposed a few years since: the most modern microscopes prove it to be not devoid of structure.

With the exception of the last three-and-twenty words the above description refers to the Amæba and its allies; but in the Foraminifera we have a sort of advanced type of amæbæ,[22] a more æsthetic race that have taken to build themselves houses, in most cases of graceful form, such as are referred to in Dr. Carpenter’s concluding words. One of the fresh-water amæbæ is named Difflugia, and it distinguishes itself by coating the greater part of its small body with particles of sand and other matter picked up as the Difflugia rolls along. The Foraminifera do not resort to so clumsy a method of satisfying their architectural instincts. In the course of their feeding they take into their primitive systems a good deal of carbonate of lime, and instead of casting this out as innutritious, useless stuff, they secrete it as shell, in many cases not unlike the shells of mollusks, but with minute pores (foramina) all over them. From this character they derived their name Foraminifera or pore-bearers.

Within these perforated shells live the amæba-like animals, and through all these minute pores they protrude still more minute threads or wisps of their living jelly to use as limbs wherewith to pull themselves along, and to catch their food. There is a very ancient conundrum which asks: “What is smaller than a mite’s mouth?” a mite being formerly considered to be the least of all animals and a very minute thing indeed; therefore, to imagine the mouth of a mite was to conceive of something so very small as to be almost beyond conception. But then came the answer: “That which goes into it!” Of course, if a mite had a mouth it must have it for the purpose of eating, so that though nothing were known smaller than a mite, yet a mite must have a mouth, and that could scarcely be quite as large as the mite, and its food must be smaller than its mouth. A naturalist would say that this line of reasoning is weak, and it undoubtedly is so, for there are creatures that contrive to swallow[23] things that are much larger than their mouths; but there is no occasion to split hairs just now. These Foraminifera are in some cases invisible to the unassisted vision, but as each is pierced with many pores, it follows that the individual pore must be almost inconceivably small, though still smaller are the wisps of jelly that protrude through them and invest the outside of the shell. For it must not be supposed that these structures are secreted like the shell of the snail, that the animal may live within it; rather it is like our own skeleton, built up within our bodies.

Some of these shells have but one chamber, like Lagena, which is flask-shaped, and Entosolenia, in which the long neck of the flask has been pushed down inside the globose portion. Others have many compartments, but these are subject to great variety of arrangement, each species having its own special form. Dentalina has the chambers placed one behind the other in a straight or curved line. In Nonionina, Polystomella, Rotalina, Globigerina, and others they are rolled in a spiral, and resemble the chambered shell of the Nautilus; or they may be twined, not spirally, round an axis, each making a half-turn.

In some respects similar to the Foraminifera are the Polycistina, which are equally minute creatures, whose skeletons are of flint instead of chalk, and the perforations are so large and so close together that the term pore no longer adequately expresses their proportionate size. They are more like windows, but with little intervening stonework. The jelly-substance, called sarcode, flows out through all these windows in the form of threads (called pseudopodia or false feet) as in the Foraminifera, spreading over the outer surface and acting as legs and arms by means of which the creature moves and captures its food. They feed upon infusoria of various kinds, and the diatoms and desmids,[24] which appear to be paralysed by contact with the pseudopodia. They also seem to derive part of their nutriment from the exertions of some minute yellow-bodies, a species of algæ (Xanthellæ) that are lodgers within their substance. These lowly plants, which have sometimes been incorrectly alluded to as parasites, elaborate starchy products by the aid of their chlorophyll, and on their death this material is available for the nutrition of the Polycistin, which also can make use of the oxygen given off by the plant.

There is one of these low forms of life in which almost all visitors to the sea-shore take an interest—or rather they are interested in certain signs of its vital activity—the mysterious phosphorescence of the sea. There is no moon visible, the sea is quiet, and our reader late in the evening takes a stroll along the edge of the waves, “before turning in.” He is charmed to see the ripples as they break upon the shore brightly outlined with glow-worm light, and stays long to enjoy the elfish illumination. Now my advice is, do not stay long, but hasten back to your “diggings” and get a bottle; then return and fill it with sea-water at a spot where the phosphorescence is most abundant. You can then examine the creature that produces the strange light.

If now you continue your stroll along to that part of the sea-wall where the male villagers most chiefly congregate to spin yarns with a more or less saline flavour, and to discuss village politics, you will probably hear them talking about fishing prospects, and if it is in early summer, mackerel will be in their talk. “Well,” says one, “there’s no doubt the fish are about, and I propose that we get the sean-boats ready, and to-morrow night we’ll try the briming.” The meaning of which dark saying is that to-morrow evening they will row across the bay till they come under the shadow of the great headland, and there they will adapt the focus of their eyes to seeing below the surface of the crystal waters, and watching for the streaks of phosphorescent light that break from the fins and tails and scales of the mackerel as they pass through the sea.[25] This light is the “briming” of the fishermen. It is due to the movement of the fish exciting the light-producer, just as in a marine aquarium in a dark room you can produce a similar effect by blowing the surface of the water into ripples. The six long oars of the big sean-boat every time they dip into the water send a spray of light into the air, and as they again leave it a shower of glowing pearls drops from each. The prow of the boat sends up a fountain of pale heatless fire on either side, and an ever-widening track of the same mysterious light marks the way the boat has come.

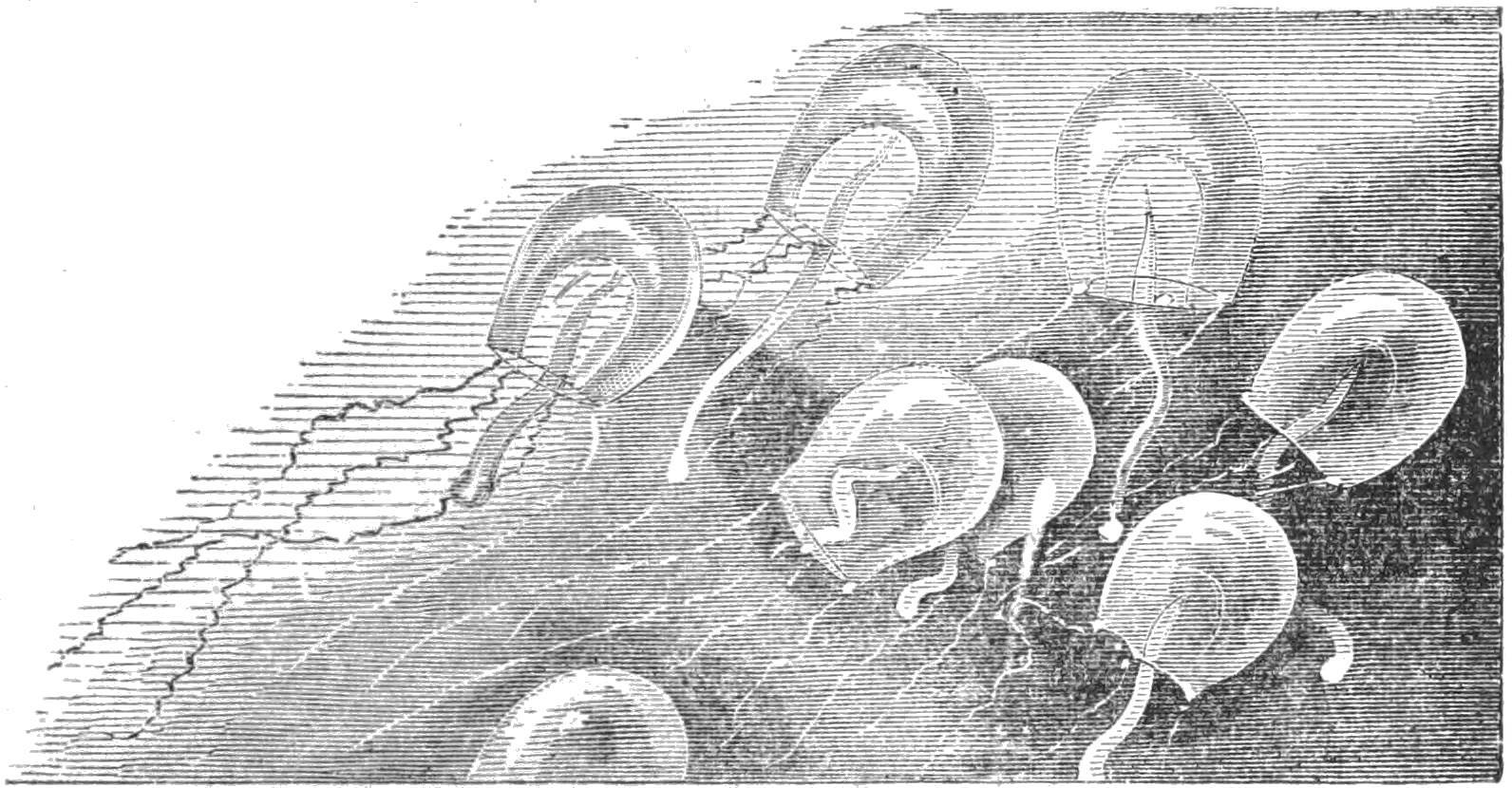

All these brilliant effects are produced by millions of a tiny Infusorian, individually so small that twenty of the finest specimens, placed closely together in Indian file, would only produce a procession one inch in length, whilst of mediocre examples it would require from fifty to eighty to cover the same space. Its size may be insignificant, but it has a name which will at least inspire respect with some persons—Noctiluca miliaris—which may be Englished as the Sea Night-light. If now we go together to your lodgings and examine that bottle of sea-water with a lens we shall be able to make out a large number of these creatures swimming about, and by means of a pipette or dipping tube we can isolate a specimen and place it under the microscope. There it is revealed to us as a peach-shaped individual, the spherical mass being partly mapped into two lobes by the slight groove that, as in the peach, runs down from the depression in which the stalk is attached. The stalk in this microscopic night-light is represented by a long flexible tentacle, or flagellum, by means of which Noctiluca moves through the waters, much as a fisherman will propel his boat by the skilful use of a single paddle at the stern. There is a shell-like envelope of transparent material through which may be seen a meshwork of granular material, denser than the body-mass. A funnel, opening near the flagellum, becomes lost in this granular matter; this is the creature’s mouth and gullet, within which lies a smaller[26] flagellum. The gullet simply opens into the central protoplasm; no continuing alimentary canal has yet been made out. Reproduction is effected by several methods: one is the division of the creature transversely into two, each complete, but for the time smaller; a second method is the conjugation of two individuals and the subsequent breaking up of the protoplasm into numerous spores, each provided with a flagellum. But this breaking up process may occur independently of conjugation. The spores move by the lashing of the flagellum, and gradually develop into the adult form. The light is produced in flashes just under the clear cell wall, and pure sea-water, rich in oxygen, is necessary for its continued brilliancy. At times, on summer evenings, Noctiluca is extremely abundant in the littoral zone, and it is then impossible to take up a glass of water without getting thousands of specimens.

If you occasionally indulge in boating, many forms of low life, or the larval condition of higher forms may be obtained without difficulty. Take a piece of thin, round cane—about the thickness used in training a child in the way he should go—and bend it into a hoop. The two ends should be cut half through for an inch of their length, so that their flat surfaces can be brought together and secured by several turns of a piece of thin copper wire. Now to this cane secure a small flat piece of lead, so that when thrown into the water the hoop will assume an erect position. If you should have a couple of inches of “compo” gas-tubing handy, this will do admirably, and may be slipped over the cane before the ends are lashed together. Upon the hoop now stitch a muslin bag to serve as a net; and to three or four equi-distant points on the frame attach short, strong strings of equal length, and join their ends to a length (say three fathoms) of fishing line. This may be made fast to one of the thwarts of the boat, or held in the hand, whilst the net is thrown overboard. The movement of the boat will cause the net to collect a large number of minute[27] creatures that float on the surface or immediately below it. From time to time it should be hauled in, and the bag turned inside out and washed in a glass jar of sea-water. In this way many interesting forms may be secured. A calm, sunny afternoon should be selected for this work, and the boat should be rowed gently.

[28]

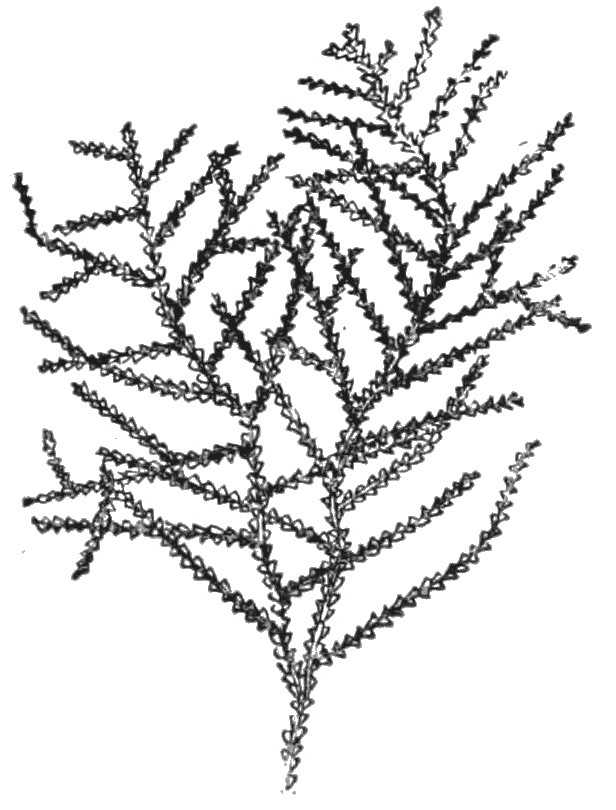

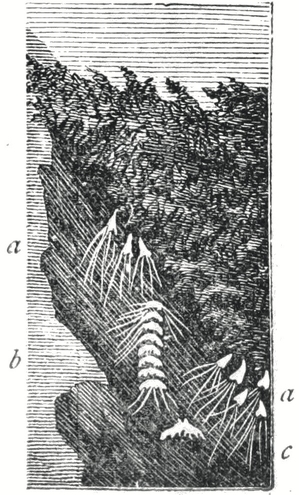

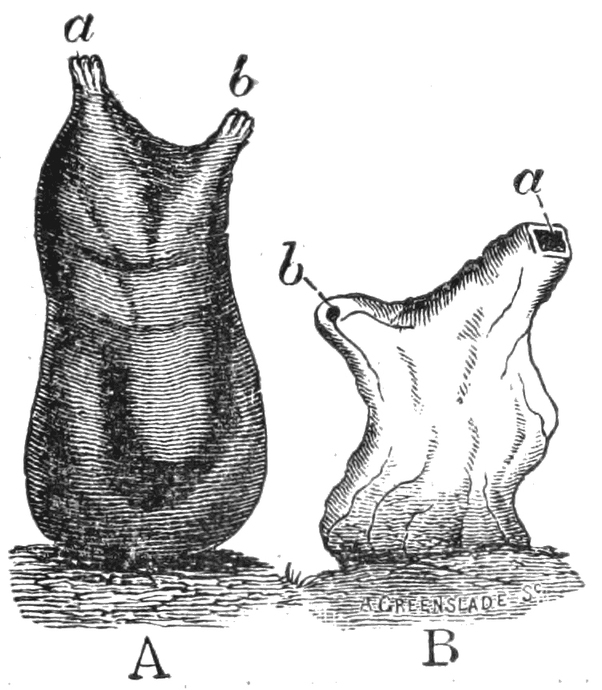

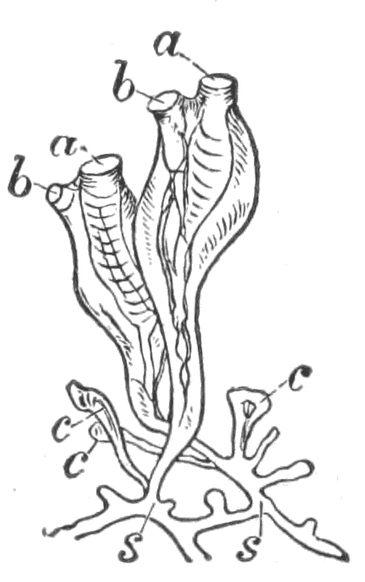

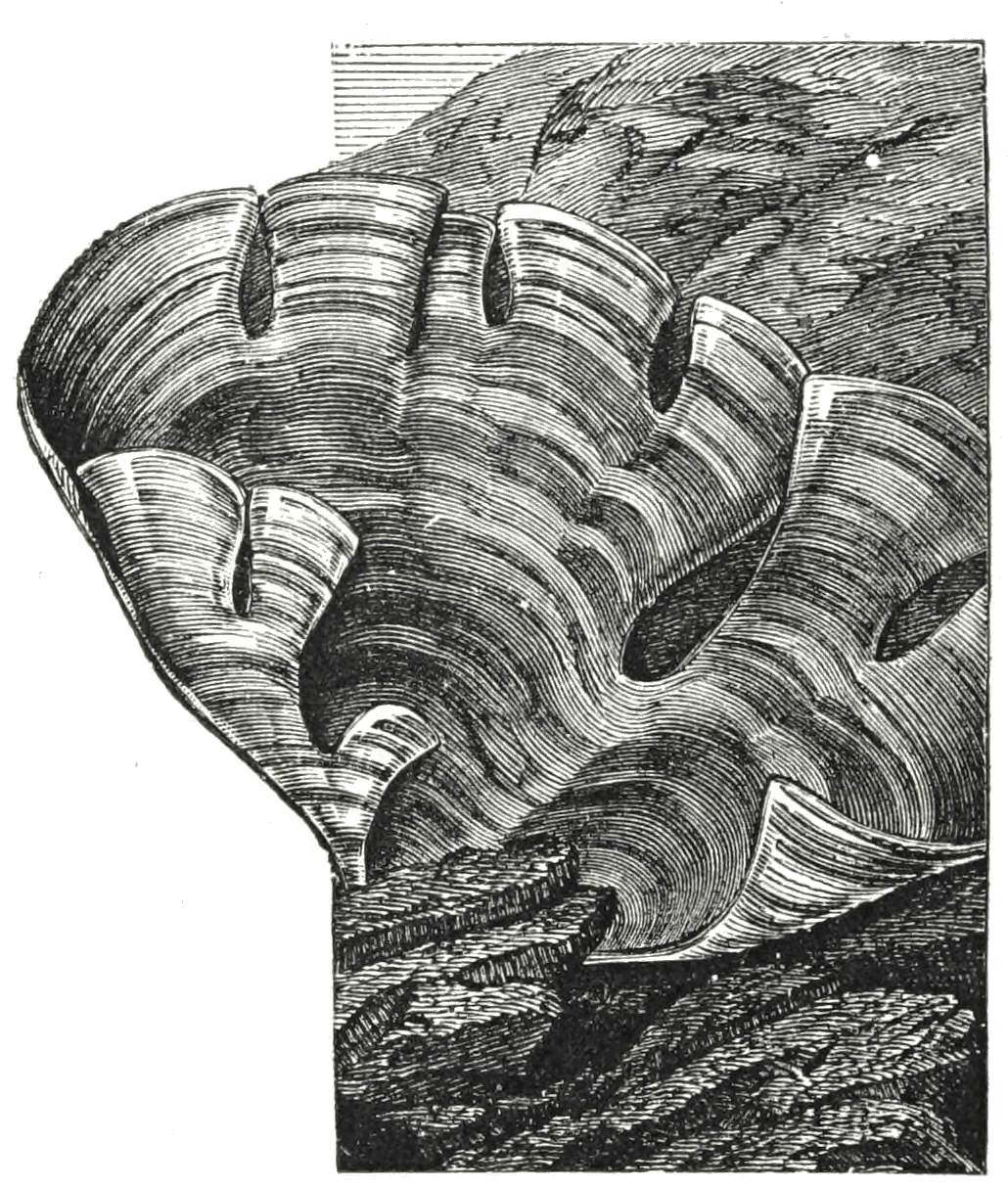

To many persons the statement that we are going for a ramble among the rocks in quest of sponges will merely suggest the idea of wreckage, and they will suppose that we have had information that a vessel, part of whose cargo was Turkey sponges, has gone to grief on the rocks near, and that sponges are to be had for the trouble of picking them up. And should they venture to accompany you on so promising an expedition, they would certainly consider you demented as, having reached the rocks that are only uncovered at very low tides, you proceeded to point out the green and orange and brown and whity-yellow expanses that coat the vertical faces of the rocks. All these things to them bear no resemblance to the only sponges they know—the ones they use daily for purposes of ablution. You can show them something approaching nearer to their ideal, if you hunt among the thick stems of the shrubby weeds on the rock. There, encrusting a branch, is a yellowish-brown form with rough surface and large pores very much like those they know all about. And attached to various weeds are others of the shape, size, and colour of melon seeds, with porous surface and open end.

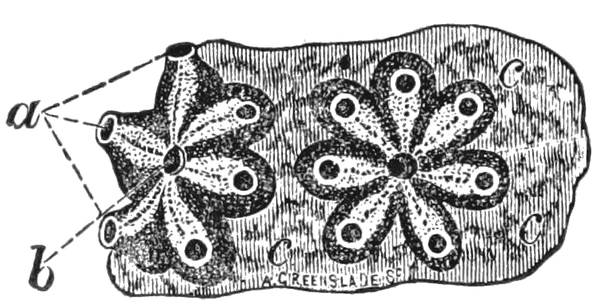

a. Hymeniacidon albescens;

b. Pachymatisma johnstoni;

c. Halichondria panicea;

d. Grantia coriacea;

e. Halichondria incrustans;

f. Leuconia nivea;

g. Leuconia gossei.

Your friend, though disappointed, maybe, that he is not to share in the salvage of some splendid bath sponges from the supposed wreck, cannot help feeling some interest in the extensive layers of colour on the rocks, some of it raised into conical hillocks, and suggesting a fairy plain thickly studded with volcanoes. You tell him that these are really aquatic volcanoes so-to-speak, and that if you could get a portion off[31] the rock, you could exhibit the phenomenon to him at work in a shallow dish of sea-water. Thereupon he, thinking to be of service to you tears off a slice of the pale green, hillocky sponge (Halichondria panicea) and breaks it up hopelessly. However, we will turn his clumsiness to account and take a view of the interior thus violently exposed. We see that these crater-like openings are the outlets to tubular spaces running through the sponge, and from these passages smaller branches go off at right angles, whilst these and the larger openings are surrounded by tissues that are very like bread in consistence; and that is really only a way of explaining that they are spongy. Now the whole of the substance of these sponges, as you may see by microscopical examination, is composed of myriads of minute flint spicules, finer than the most delicate fragments of “spun glass,” and of beautiful forms. Some are simple rods, straight and curved; others forked at one end; some like a gribble; others what is known as quadriradiate in form.

Now in some species these spicules are not arranged in any order; they are merely jumbled together, and their remarkable forms make it easy for them to become entangled. When so entangled they form the skeleton of the sponge. Each sponge is a co-operative colony containing many thousands of members, and these are represented to our view, through my pocket lens, in the mass only, as a thin clear jelly investing the spicule-tangles, or rather the spicules are imbedded in the sarcode as this living matter is termed. If we were to chip off a thin flake of rock with its investing sponge intact, and place the whole in a glass vessel full of water, we could observe the movements which manifest its vitality. A little finely powdered indigo or other colouring matter should be dropped into the water near the specimen. On closely observing it would be seen that many of these minute granules were flowing towards the sponge, then that they entirely disappeared through the very fine openings in the surface. A little later these particles[32] will reappear, not where they went in, but in a denser stream issuing from one of the craters, which are scientifically designated oscula to distinguish them from the minute pores.

If we dissect the sponge under a microscope, we shall find that from one of these oscula a broad passage runs through the centre of the mass, and from the walls of this the minute pores run off to the outer surface. This central cavity is invested by a living membrane which, when examined through a higher power of the microscope, is seen to consist of myriads of organisms closely packed together side by side, and each resembling a glass vase, spherical below, with a wide neck, and from its centre there issues a long antenna-like process. This is called the flagellum (Latin, a whip), because its office is to lash the water. These flask-like organs, with their flagella, present a wonderful likeness to some free infusoria known as collared monads, and over this likeness and all that it may or may not imply to the systematic naturalist much ink has been shed, and the sounds of controversial strife it engendered, though now faint, are still audible. Into that question we do not go.

The combined lashing of these little whips in unison sets a strong current of water flowing through the central passages and out at the oscula. To feed this stream, water flows in automatically through all the little pores, and brings with it the infusoria and other minute particles of life with which the sea is swarming. These come in contact with the lips of the flasks in the interior over which the living jelly of the sponge is steadily flowing. The infusoria flow with it and are carried away by the current to a little clear space (vacuole) in the lower part of the flask, where it is digested, and the refuse portions are thrust out to go in the general stream and be[33] carried out through the oscula. Each of these cells may be taken therefore as a separate individual, enjoying home rule, yet taking part in general efforts for the whole sponge-community, for we find that by some strangely communicated understanding, all these cells cease lashing the water for a time as though resting (or digesting their food), and the craters cease to pour forth their streams. But then after a time activity is resumed, the craters belch forth again, and we know thereby that the flagella are in active operation down below, not merely capturing and digesting food, but also absorbing oxygen from the inflowing streams, whereby vital energy is maintained.

After the cells have become full grown, they split transversely or longitudinally, and so increase their number, which means that the size of the colony increases. But some of these divided portions develop into eggs, which after fertilization are swept out into the ocean by the outflowing current, and settling upon some rock become glued down and grow, gradually, by division and subdivision, producing a new colony. Such is a highly condensed account of the general phenomena of sponge life. There are variations upon it in the life-history of well-nigh every species; but this will suffice to give my reader a general idea of what sponges are. For the rest, he must go down among the rocks, and search out the various species of many forms, and endeavour to add to the general sums of knowledge by some fresh observations respecting British Sponges.

However startling the statement may sound, there is no lack either of specimens or species on the British coasts. Some of the most conventionally sponge-like of these must be sought by the dredge in deep waters, but our own hunting ground, the rocks that mark the shoreward-bounds of the laminarian zone, if carefully inspected at low spring tides, will afford more specimens in half an hour than we can exhaust the interest of in a week. That this is no mere[34] figure of speech you will agree when I add that Dr. Bowerbank published a work in three volumes dealing only with British Sponges, and to these a supplementary posthumous volume, edited by Dr. Norman, has since been added.

Where the rocks rise high above the shore with their upper portions tilted towards the cliffs, we shall find several species incrusting the vertical or overhanging surfaces of these rocks, such as Halichondria incrustans, whose buff-coloured bread-like surface is diversified with slightly raised oscula. Its principal spicules are knobbed at one end, in which respect it differs from the similar Halichondria panicea which is peculiar in having only one type of spicules—a rounded rod, slightly curved or quite straight, but pointed at each end. Ellis called this species the Crumb-of-bread sponge, a name which is reflected in the scientific cognomen panicea. It is one of the most plentiful of the encrusting species, and may be readily known by the greenish-yellow or distinctly green colour of its extensive patches.

Not far from the Crumb-of-bread will in all probability be found the similar Sanguine sponge (Halichondria sanguinea), of a bright red colour. The conical elevations of the oscula in these species distinguish them readily from the plump, though narrow bands of Microciona carnosa, a plentiful species that creeps extensively between the other kinds, its pale red branches being very unequal in width, and alternately contracting and swelling out, joining and separating. This will be found figured in the lower left-hand corner of our illustration on page 29.

A very noticeable species on account of its neat compact shape will be found attached to various red seaweeds, with which its whitish colour contrasts well. It is a small oval, usually from a quarter to an inch in length, very flat, but yet hollow, with a large vent at the free and larger end. This is the Grantia compressa. Careful search among the indescribable medley of “unconsidered trifles” that crust the rocks[35] beneath the shelter of the Fucus-growth, will reward us with a little spherical sponge with tubular oscula at the summit formed of spicules, and its general surface bristling with long spicules. This is the Grantia ciliata, looking like a little gooseberry.

There are many other forms, for which I must refer my readers to Dr. Bowerbank’s work, where also will be found descriptions and figures of many deep-water species, such as the more conventional sponge-like Chalina oculata, in branching masses nine or ten inches high.

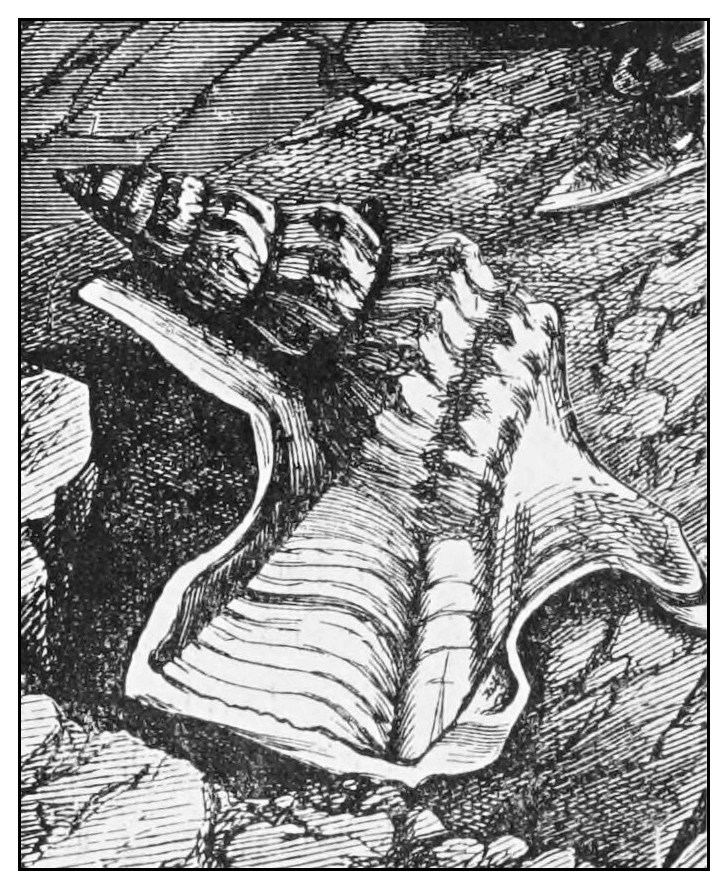

There is, however, one other we must mention; the so-called Boring sponge (Cliona celata), which attacks various shells and stones. It is quite a common occurrence for the rambler along the shore to pick up the shell of some mollusk, and find it so tunnelled, the borings branching in every direction, that what would otherwise be as strong as stone is now as weak as poor strawboard, and will yield to very slight pressure or strain. On breaking such a shell across we get both cross and longitudinal sections of these tunnels and chambers, and find some of them to be lined with a dark brown filmy tissue, the remains of some past inhabitant; others contain portions of this Cliona sponge, living or dead; others again contain little bivalve shells that just fit the aperture, whilst yet another set exhibit clean walls that may not have had any animal inmate. Much controversy has raged over the question whether these excavations have been made by the sponge, or by some boring worm, and there have not been wanting as advocates of either view men whose authority on sponge matters is unquestioned. Where such doctors differ how shall humble observers venture to give a verdict? For my part, I cannot give my support to the contention that the sponge has bored the clean holes, hollows, and tubes that I[36] have seen in the large numbers of attacked shells I have broken; neither am I prepared with an opinion as to the creature that did make them. I believe that on this matter, as on many others connected with natural history, we have much still to learn, and every student of Nature should have his eyes and his mind ever open to receive hints from Nature herself as to her methods. One of these days, some lonely wanderer by the margin of the wave will show us how simply this boring is accomplished, and we shall all wonder that we never thought of the possibility before. But whatever views or lack of views we may have upon the question, “who made the burrows?” there is no doubt that the sponge does exist in some of them, and its spicules embedded in the yellow sarcode are well worthy of minute observation.

[37]

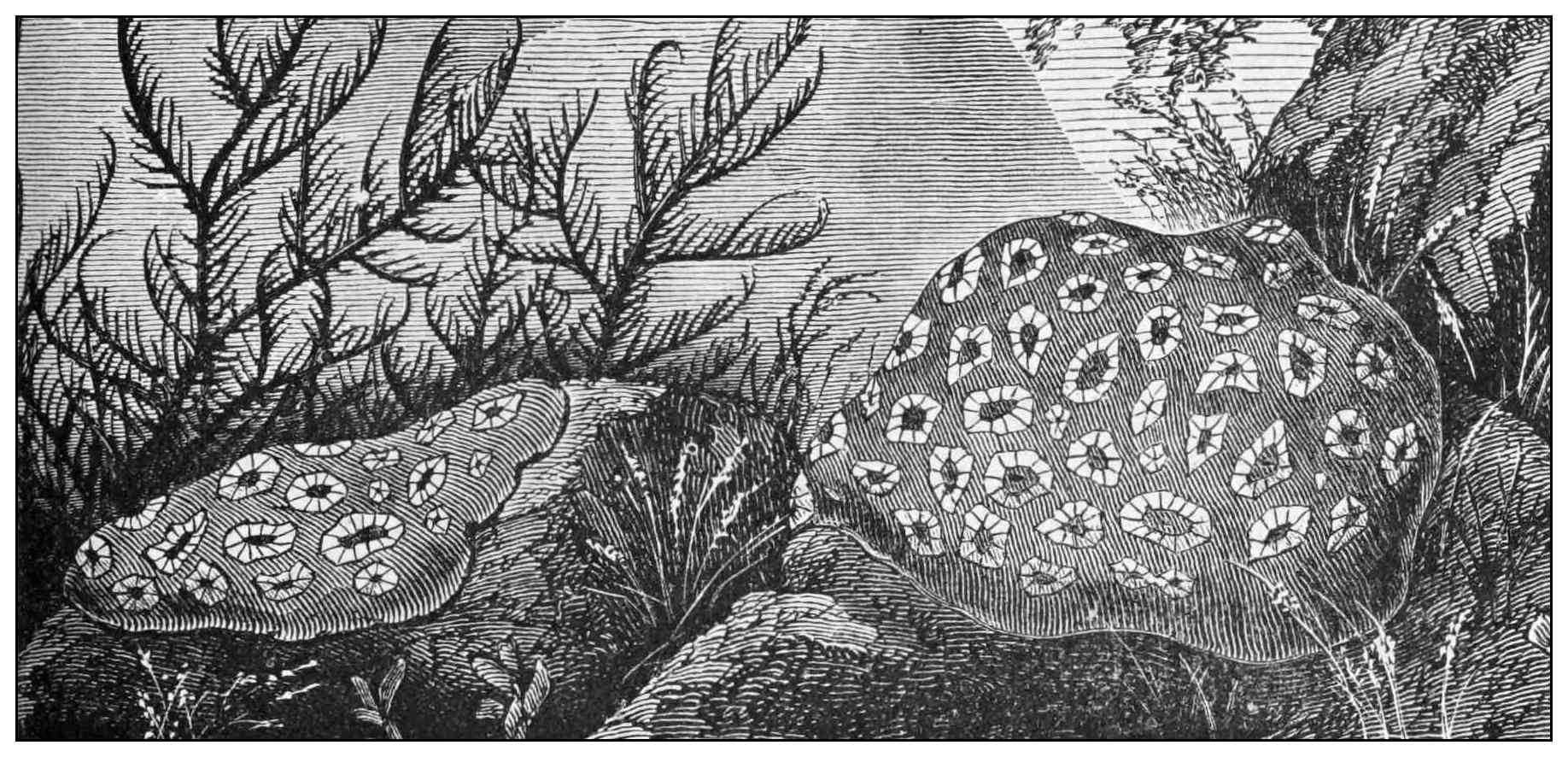

Not many years ago our knowledge of the lower forms of life was very imperfect, and it was believed that the gulf between the animal and vegetable kingdoms was bridged over by certain creatures which could not properly be classed in either, because they appeared to unite the characters and organization of each. Such was the case with the sponges, already dealt with, and with the creatures now to be considered. These last were on that account called Zoophytes, or animal plants, a term which we must render to-day as plant-like animals. Some of us have again got to the notion that there is no sharp division between animal and plant-life; but with increased knowledge we have put back the debatable or common ground much lower in the scale of life.

With the whole of the families included in this division of life, I do not propose to deal in the present chapter: the Sea-Anemones and the Sea-Jellies, for instance, being treated in succeeding chapters, for each group deserves and demands a chapter to itself. It is characteristic of the Zoophytes that they form a bag of jelly-like material, with an opening at one end which may be regarded as a mouth, though it is without tongue or teeth, and opens directly into the stomach. Around this mouth are set a number of limb-like organs, called tentacles, which are used for seizing the prey and conveying it within the orifice. Their entire structure is very simple, and apart from primitive muscular and nervous systems, and the possession of stinging threads, which can be quickly extruded through the exterior walls of the body, they appear to be[38] almost innocent of organs. This form of structure is generally referred to as a Polypite, and its appearance has been made familiar by the descriptions and figures of the Hydra or Polyp of our stagnant fresh-water ponds. From their general agreement in structure with the Hydra, the creatures to which much of this chapter will be devoted, are called Hydroid Zoophytes. There are, however, but few species that occur solitarily, like the Hydra. In most cases they are associated in inseparable colonies. The egg of a zoophyte gives rise, it is true, to an organism resembling Hydra, but this individual does not long remain solitary; it produces many buds, which rapidly develop, and in turn produce other buds, so that before long there is a colony that may number its thousands of polypites. However numerous the individuals may be, we may be sure that the colony has been the production of a single egg. One came from that egg, but all the others were produced vegetatively by budding from the original polypite, or as later generations from such bud-originated polyps.

A slight examination of such a colony will show that the polypites themselves are held in association by an investing substance (cœnosarc), which takes the form of a living tube of thin flesh, which adheres to rock or shell or seaweed, acting as a support for the community, and also reproducing the polypites. It consists of two distinct layers, an inner and an outer, and sometimes there is a third layer of a different kind between these two, muscular in character. In most cases the outer wall of this tube secretes a sheath of a substance called chitin, of which the external skeletons of insects are composed. This sheath is known as the polypary, because into it the individual polypite withdraws itself. It is this polypary that the seaside visitor finds attached to weeds or shells, and concludes, from its moss-like aspect, it is a seaweed, and probably adds it to his collection as such.

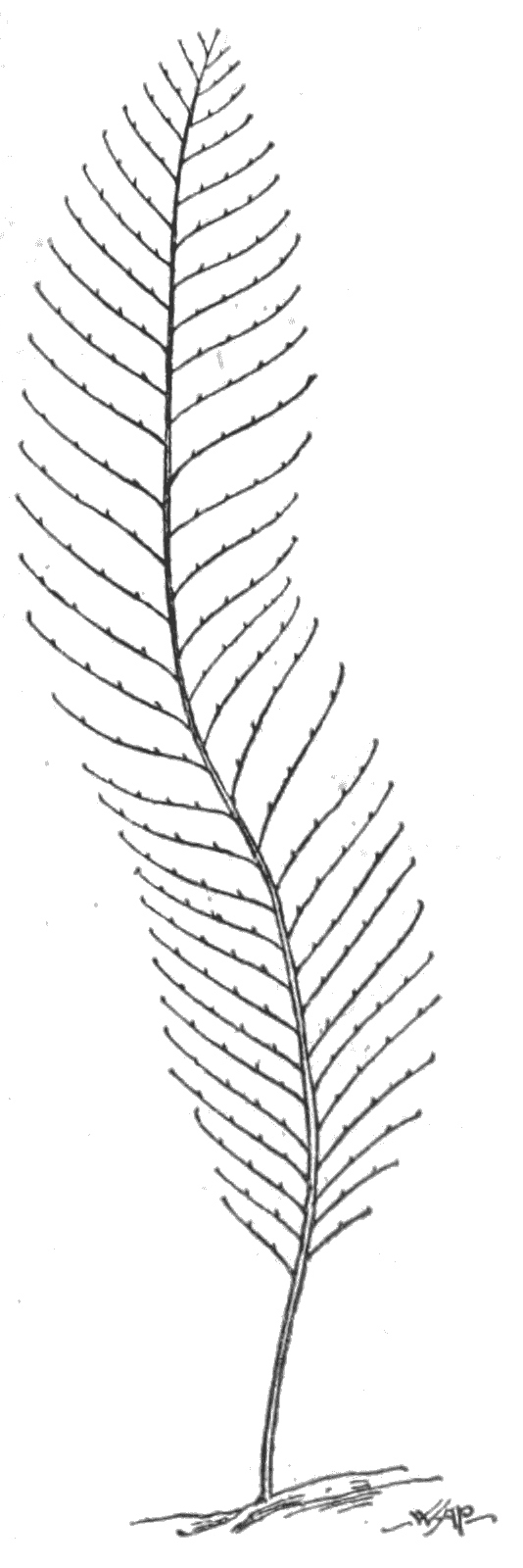

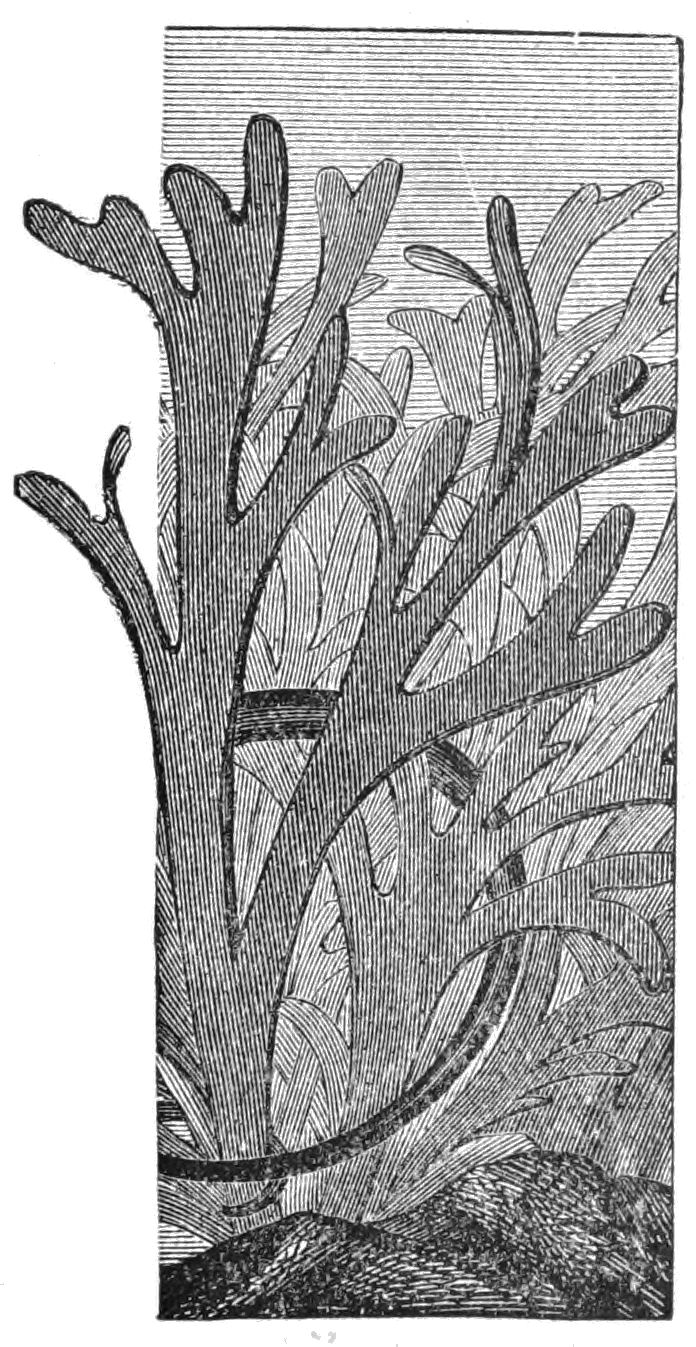

Now if we get down among the rocks near low-water, and look among the coarse brown weeds, we shall not look long[39] before we find one whose stem and parts of the frond are covered with a plantation of erect-growing “somethings,” that look like the backbones of some small fishes. They are only about an inch in height, very slender, and regularly notched on each side. Some of the specimens have one or two branches, but most of them are simple erect stems. It is known as the Sea Oak Coralline (Sertularia pumila), and if we examine it with our lens, we shall find that each of the notches represents the space between the elegant crystal vases that are arranged symmetrically along each side of the stem. These vases are known as calycles, and in each there stands a polypite, reaching out its upper portion and waving its tentacles. In case of danger the polypite can be withdrawn into the calycle; and certain species have an automatic contrivance for closing the mouth of the vase when they have retreated within. All genera have not these calycles.

Returning to the animal for a moment, it should be explained that its organization is so low that there is no true circulatory system for the renewal of the body, by the carrying of elaborated food from the stomach to distant parts of the body; but by the activity of innumerable eye-lash-like hairs on the surface the whole of the particles of food digested in the stomach are carried all over the system to be then assimilated by different parts.

Within the circle of tentacles is the mouth, which is sometimes cut into lobes, and is generally borne upon a very mobile proboscis, which may be withdrawn or protruded, and in some genera takes a trumpet-shape; in others it is conical. In the winter the cœnosarc may frequently be found with all its[40] calycles empty; and it might then be supposed that the zoophyte is dead and only its skeleton remains. But this is not necessarily so, and a closer inspection may convince us that the organism is alive. In spring it will furnish its calycles with new polypites, and all will go merrily again. At certain seasons buds of a peculiar structure are formed, which develop into polypites, whose function it is to produce eggs, instead of catching and digesting food for the colony. These are known as gonophoræ, and sometimes they remain where they were produced, simply bursting to discharge their contents. In other cases they detach themselves from the parent colony at a certain stage in their development, and float off, having all the appearance of minute jelly-fishes. Some of these, instead of remaining small, attain an enormous size, so that it is difficult to credit their origin to the so-called coralline upon which they were produced, and of which in turn they are really the egg-bearers. The eggs they scatter will develop into plant-like growths such as they were produced by; from the edge of their jelly-umbrella and from its handle, buds are given off, which open as jelly-fish like itself.

Growth proceeds rapidly among these creatures, and if a balk of timber be immersed in the sea, it is not long ere there is a fine forest in miniature upon its surface, and that forest will consist of some of these corallines. The species are generally distributed along our coasts, but a few are local. Thus the finest of all the British species of Sertularia—Diphasia pinnata—is found only on the coasts of Devon and Cornwall, where most other species attain their maxima of beauty and luxuriance. Its relative Diphasia alata, as well as Calycella fastigiata and Aglaophenia tubulifera, have been found in Britain, only in Cornwall, Shetland, the Hebrides, and on the west coast of Scotland. On the other hand, certain species belong to the north, and such species as Salacia abietina, the Sea-fir, and Sertularia tricuspidata are not found on our shores below the north-east coast. Sertularia fusca is similarly confined,[41] so far as our seas are concerned, to the east coast of Scotland and the north-east of England; and Thuiaria thuja, found on the east coast, is rare in Devon and Cornwall; whilst the species of Aglaophenia are plentiful on our south-west and north-west coasts, and rarely seen on the north-east.

Although some species are distinctly deep-water forms, necessitating the dredge for their capture, the vast majority inhabit the littoral and laminarian zones. Among the littoral species are many of the rarer forms, and some of these are found only on special species of seaweeds, or on the shells of particular mollusks. Mr. Hincks, whose beautiful work on the “Hydroid Zoophytes” you must see, gives some very good advice as to collecting in the littoral zone. He recommends my own favourite plan of lying flat beside the rock-pool, and bringing the eye close to the water. “He should bring his eye to the edge of the pool, and look down the side, so as to catch the outline of any zoophytes that may be attached to it amidst the tufts of minute Algæ. He must not be content with a hasty glance, but look and look again until his eye is familiar with the scene, and may accurately discriminate its various elements. And let him watch for the shadows; for in following them he will often secure the reality. I have frequently detected the tiny Campanulariæ and Plumulariæ in this way, by means of the images of their frail forms which the light had sketched on the rock beneath them. For tools, the hunter must have his stout, flat, sharp-edged, collecting knife, a long-armed and substantial forceps, and a varied array of bottles, ranging from the homœopathic tube to the pickle-jar. If his choice of ground be good, and his patience proof, and his eye quick, he will have an ample reward for his labour in the rich spoil of beauty which he will bear away, even if he should not hit upon any novelty; but amongst the minute zoophytes there is still, I have no doubt, much to be done in the discovery of new forms, as there certainly is in working out thoroughly the history of those that are known.”[42] I hope that in the foregoing remarks I have made it quite clear that our Sea Oak Coralline is not an individual but a community of individuals—a community on the strictest of co-operative principles, in which the good fortune accruing to one of the polypites by food falling in its way, is shared by all alike; for a polypite cannot digest it and retain it to its own selfish use, instead, it goes to the nutriment of the commonwealth.

Some of these Hydroid Zoophytes, though sharing the communist character, are much simpler in form, and we shall find a common example ready to our hand on almost anything in the way of stone or shell removed from a rock-pool. It is a minute creature, as stout as a “short white” pin, and about a third of the length, white or pinkish; a number of them spring in a row from a creeping stem of firmer substance, in which are well-defined tubular openings, in which the upright bodies stand. These answer to the calycles of Sertularia, just as the upright bodies agree with the polypites of that genus. The name of this creature is Clava multicornis, and it may conveniently be called the Many-horned Club. It gets its name Clava from the shape of the polypite which thickens towards the top, and then tapers off again to the summit, where its mouth is situated. It has a number of tentacles, varying from ten to forty, according to age, but these do not form a regularly disposed crown round the mouth; instead, they are placed anyhow on the thickened part of the polypite. The name multicornis refers to these many-horns or tentacles. An advance on this type is seen in Coryne pusilla, a much larger but equally common inhabitant of our rock-pools, in which the tentacles are knobbed, and are arranged in a series of more definite whorls.

There is another group which is more likely to be confounded with the Sertularians by those who are content with hasty glances at things; but species of the one group may be readily distinguished from the other by the aid of a simple lens.[43] The Sertularians, as we have seen, have the calycles arranged symmetrically on each side of the axis. The Plumularians, as the other group are called, have their calycles arranged along one side only of stem and branches. The Sertularians are frequently spoken of as Sea-firs, the arrangement of the calycles giving some species a very close resemblance to the branches of fir-trees. In the Plumularians, the resemblance much more nearly approaches a feather.

Hincks, describing Plumularia cornucopiæ says:—“In the present species a conspicuous band of opaque white encircles the body, like a girdle, a little below the tentacles, and adds much to the beauty of a colony in full life and activity, when its many polypites are in eager pursuit of prey, stretching themselves forward, and casting forth their flower-like wreaths, now suddenly clasping their arms together, and then as suddenly flinging them back; now holding them motionless, the tips elegantly recurved, and then on some alarm shrinking into half their size, and folding them together like flowers closing their petals when the sun has gone.”

In addition to the calycles in which the polypites live, there are special reproductive chambers as in the Sertularians. In this species (P. cornucopiæ) “they assume the shape of an inverted[44] horn, and are formed of material translucent as the finest glass. Each one of them, in fact, is a little crystal cornucopia, in which is lodged one of the reproductive members of the commonwealth, a class totally distinct from that which is charged with the function of alimentation. These graceful receptacles are several times larger than the calycles, from the base of which they spring, singly or in pairs, and within them the ova are produced and the embryos matured which are to give rise to new colonies.”

One of this group, the Lobster-horn or Sea-beard (Antennularia antennina), shown at the back of the illustration of acorn-shells on page 183, has the calycles arranged in whorls all around the axis, which produces a very singular appearance, not at all unlike the antennæ of some of the larger crustacea.

In the Creeping Bell (Calycella syringa) so common on seaweeds, etc., the calycles are more bell-shaped, and the mouth of the bell is fringed with a series of large triangular teeth, similar to the peristome of many moss-fruits. When the polypite withdraws into his calycle, these teeth bend inwards, and so close the opening.

Many of the forms of Jelly-fish to be described in the next chapter, though they are described with separate names, are now known to be merely stages in the history of some of these Hydrozoa or Hydroid Zoophytes—the developed free-swimming gonophoræ previously mentioned.

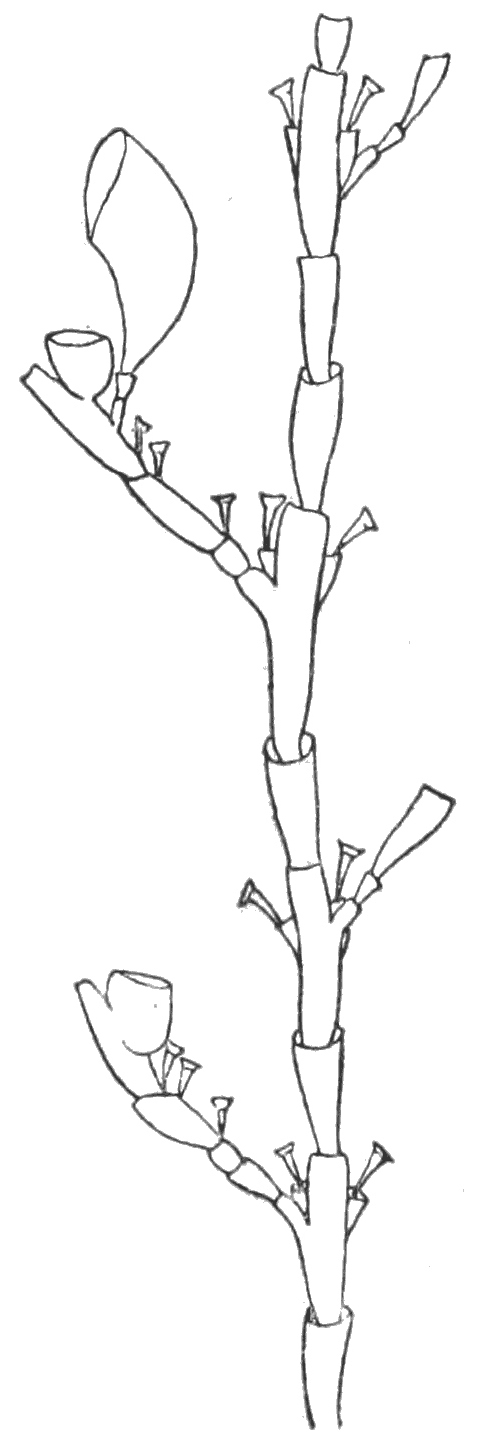

A singular member of the group has the form of a jelly-fish, but does not act as one. This was formerly named Lucernaria, but is now known as Haliclystus octoradiatus. It was thought to swim like a jelly-fish, but it really creeps. Its form is like a ladies’ sunshade that, instead of being the ordinary umbrella shape, tapers off to the stick at the top. What would be the ferrule of the sunshade is the footstalk of Haliclystus. By this footstalk it attaches itself to a weed, say, and hangs down its eight arms with their connecting web, and by means of a little knob on the edge of the web alternating with its[45] “arms,” it is able to take hold until it has “looped” like a geometer caterpillar, by bringing its footstalk forward and taking fresh hold. The extremities of the eight arms (or ribs of the sunshade) are ornamented with tassels of tentacles, and it uses these after the manner of a sea-anemone when it wishes to secure food. It, in fact, has some of the peculiarities of both jelly-fish and anemone, though it will not act quite consistently with either character. I have found it on Laminaria and other weeds at low water, and a few months since I picked one off the plumage of a dead guillemot, that had been drowned in a storm and afterwards washed ashore.

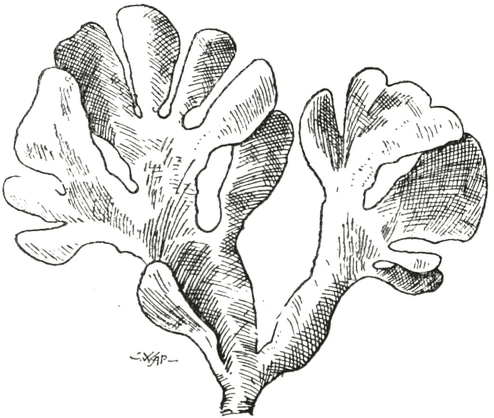

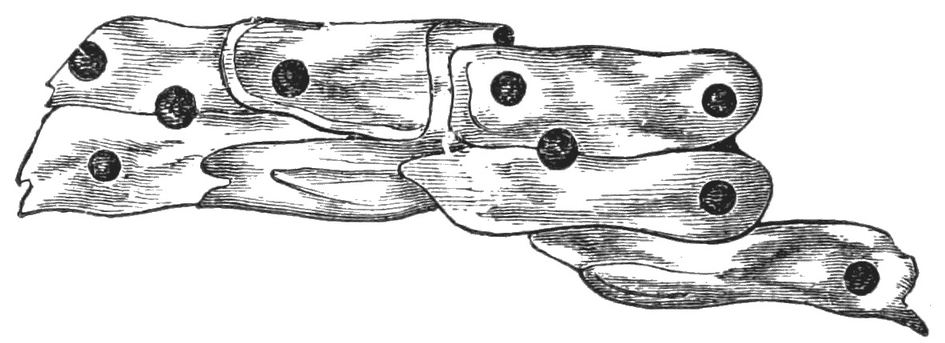

There is an important group of incrusting organisms that you will find represented on almost the first specimen of Fucus you pick up, and which you may be tempted to class with these zoophytes; but they occupy a much higher position in the scale of life. I refer to the Sea-mats, the Sea-scurfs, the Bird’s-head Coralline, and allied forms, whose proper designation is Marine Polyzoa. They are more nearly allied to the mollusks, the structure approaching towards that of the Lamp shells. They are associated in colonies (zoaria), but there is no connecting cœnosarc as in the Hydrozoa, although there is communication between the chambers by wisps of animal matter. Each chamber of the Sea-mat marks the habitation of a complete individual, who catches, eats, and digests for himself alone, not for the colony. These chambers are of a horny, persistent character, secreted of course by the polypide; with a small opening through which the creature protrudes its mouth and fringe of tentacles. Its body consists of a thin bag filled with a clear fluid, in which can be traced the gullet enlarging into a simple stomach, contracting again into the intestine. There are muscles by means of which the upper part of the sac with the mouth and tentacles are withdrawn inside the lower part. Add to this a nerve-ganglion[46] beside the gullet, sexual organs within the sac, and the polypide is fully described.

The original founder of the colony was produced from an egg, and was for a time a restless larva, swimming and creeping and whirling around by the aid of cilia. Finally it settles down on weed or stone, and becomes anchored; drops its cilia and develops its horny chamber and its crown of tentacles. Having reached its full degree of growth, it buds at the sides, and originates other creatures like itself. Just as the solitary daisy root or chrysanthemum throws out what the gardener terms suckers, and soon becomes the centre of a clump of similar plants; so the solitary Sea-mat soon becomes only one in a symmetrically arranged colony, containing hundreds of individuals, all produced by budding from the original egg-produced polypide.

Some of these colonies have a number of queer adjuncts, which bear a startling likeness to the head of a bird of prey, with moveable jaws, that are for ever snapping. These have, of course, given rise to many theories to account for them; but it appears now to be generally accepted that the “bird’s-head” is a specialised member of the zoarium who serves some purpose, probably of defence, or of scavenging, that is of advantage to the whole colony. In some species, this differentiation of individuals takes the form of a long whip-like process, constantly lashing, instead of the snapping jaws. The forms of the marine polyzoa are very varied, but we shall be unable[47] to do more than indicate a few of them here, leaving the reader to make wider acquaintance with a most interesting group by studying the species in Hincks’s British Marine Polyzoa.

The Sea-mat (Flustra foliacea) is a deep-water form, whose colonies take the shape of fronds, resembling Fucus serratus in outline; but it is thrown up on the beach in great quantities, and it will be one of the first things you will find on the shore, especially if you rout about among the weeds washed up by every tide. Creeping over these flat frond-like masses you will probably find other species that take a more branching form, such as the common Creeping Coralline (Scrupocellaria reptans), or the more bushy Bird’s-head Coralline (Bugula avicularia). The Tufted Ivory Coralline (Crisea eburnea) has tubular chambers of ivory whiteness; it is of branching habit, and occurs on some of the red seaweeds. The Foliaceous Coralline (Membranipora pilosa) runs in very narrow ribbons, covered with a “pile” of bristles, up the stems of various weeds; and many another of the nearly two hundred and fifty British species will be sure to fall to the patient and sharp-eyed investigator.

The horny cell in which the polypide resides is really its own cuticle or outer skin, to which it is inseparably attached. If careful examination be made, it will be found that at the mouth of the so-called cell the horny material suddenly changes its character and becomes a very fine and delicate tissue, capable of the greatest freedom of movement and folding such as is absolutely impossible with the horny portion. This remarkable change of character in the two portions of the same cuticle allows the anterior portion of the polypide, with its crown of tentacles, to be suddenly and completely withdrawn out of danger, just as easily as the tip of a glove-finger can be withdrawn into its lower portion.

The tentacles that encircle the mouth of the polypide are hollow, and covered with ever-waving cilia, whose beating[48] causes currents of water to set in towards the animal’s mouth, bringing food with them. These tentacles appear to be also the only sense organs possessed by the polypide, and to serve the further purpose of gills. None of the Polyzoa to which we here make reference possesses a heart or blood-vessels.

[49]

It has been remarked that we get our best ideas of geography from the newspaper-man’s special correspondence in war time. Certainly, at such times certain places that are not even marked on ordinary maps are thrust into such prominence that they become familiar to thousands who otherwise would never have known of their existence. In a similar fashion many scraps and fragments of useful knowledge that will stick in the memory will be picked up by the newspaper reader who is simply bent on following the moves in the great political game. For instance, it is not many years since a well-known Scots peer, in order to cast ridicule upon his opponents, enlightened the world upon the subject of Jelly-fish organization. The party he held up to scorn resembled Jelly-fishes in his estimation because they were invertebrate—they possessed no backbone, and could make no progress against the tide, but were forced to float aimlessly with the current. The political small-fry took up the parable from the venerable duke, some reproducing it with variations that appeared marvellous indeed to the mere naturalist; but it was soon quite generally known without recourse to text-books, that the Jelly-fish was not a vertebrate animal, and that it had no muscular power sufficient to enable it to move against the tide.

Now these facts in the natural history of the Medusæ, elementary though they be, are such as in the ordinary way might have taken generations to get fixed on the public mind. Many persons who spend their autumnal holiday at the seaside,[50] become fairly familiar with the more or less broken and lifeless forms of one or two common species, as they get drifted upon the beach and are unable to get off again; but they have probably little idea of the beauty and elegance of these frail creatures when fully expanded and pulsating with life a short distance from the shore.

There are two things which stand in the way of a more familiar knowledge of these Jelly-fish, on the part of the public. First, they are almost entirely composed of water, and, having no muscular tissue, are soft and flabby to the touch—a characteristic which inspires feelings of abhorrence in the average man or woman. A man may courageously face a dangerous wild beast, and yet shrink with loathing and disgust from contact with a slug or a Jelly-fish—though, with strange inconsistency, he may swallow a living oyster with gusto! Having found a stranded Jelly-fish on the beach, he will probably turn it over with his stick, call to mind the Duke of Argyll’s political simile, and pass on.

The second reason is that certain common forms have an unpleasant trick of stinging slightly. This is a power given to them for the purpose of paralysing small creatures they secure as food, but they have sometimes mistakenly exerted it upon a timorous thin-skinned bather, against whom they have drifted.

There are, however, only two or three of our native species that have that power, and though they have been known from ancient days as Sea-nettles, Stingers, and Stangers, there is no doubt that their virulence has been greatly exaggerated. This exaggeration probably owes something to the graphic word-picture of the late Professor Forbes, in which he described the Hairy Stinger (Cyanea capillata). In picturesque language he depicted it as “a most formidable creature, and the terror of tender-skinned bathers. With its broad, tawny, festooned and scalloped disk, often a full foot or more across, it flaps its way through the yielding waters, and drags after[51] it a long train of riband-like arms, and seemingly interminable tails, marking its course, when the body is far away from us. Once tangled in its trailing ‘hair,’ the unfortunate, who has recklessly ventured across the monster’s path, soon writhes in prickly torture. Every struggle but binds the poisonous threads more firmly round his body, and then there is no escape, for when the winder of the fatal net finds his course impeded by the terrified human wrestling in his coils, seeking no combat with the mightier biped, he casts loose his envenomed arms and swims away. The amputated weapons, severed from their parent body, vent vengeance on the cause of their destruction, and sting as fiercely as if their original proprietor gave the word of attack.”

No doubt Forbes had good grounds for his statement in the experience of one of these delicate and nervous persons who suffer more mentally than physically, and whose imaginative powers would create a horror out of their contact with a spider, or even its web. The mischief is that the bookmakers, who have no practical knowledge of their subjects, go on quoting Forbes approvingly, and on this slight foundation characterise the whole jelly-fish race as stinging creatures. It seems very probable that some of the larger tropical forms that have the stinging power are far more virulent than those inhabiting British seas; but I have handled the Hairy Stinger and lifted it from the water with my bare hands and experienced no discomfort from the operation.

The Rev. J. G. Wood improved upon Forbes, and described the pain inflicted by Cyanea as being at first like that following contact with the stinging nettle of our hedgerows; getting more severe it causes a sharp pain to flit right through the nervous system, the heart and lungs suffer spasmodically. This state of affairs lasts for ten or twelve hours, and then for several days the skin is so sensitive that the sufferer can scarcely bear the contact of clothes; and it is months before the shooting pains depart.

[52]

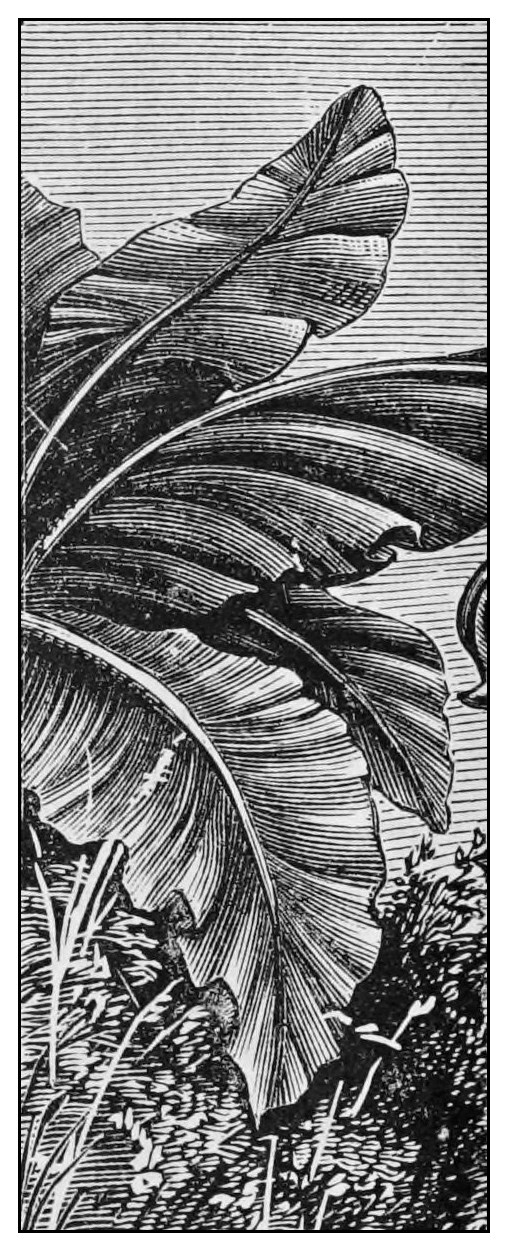

With such a character it is little wonder that the unscientific public should decline an intimate acquaintance with the family. And yet the story they have to tell is as marvellous as any that will be found in the whole range of Mr. Lang’s Blue, Red, and Green Fairy Books. It is the story of the insignificant and despised dwarf, who one day bursts through his squalid exterior and stands revealed as the handsome prince magnificently attired, whom all the princesses desire to marry. It begins in the orthodox way with, Once upon a time there was a simple and very tiny creature, with soft white flesh and no bones, who dwelt on a rock on the sea-shore. He was just a little tube of jelly, and though he had a mouth he had no head. His many arms were arranged in a circle round his mouth, and from his body sprouted out several creatures like himself, but much smaller. Learned men had examined him and declared that his proper name was Hydra tuba. He remained fixed to this rock from the autumn right through the winter’s storms, and in the spring it was noticed that he was getting old, for a large number of wrinkles appeared on his tubular body. Weeks went by and the wrinkles became deeper and the edges of them turned up, so that the upper part of the creature’s body looked like a dozen saucers piled up one in the other. Then these saucers each grew a series of eight arms from its edge, and the uppermost of the pile broke away from the others and began to float off through the water. The next, and the next, and every one of the remaining saucers floated off in the same fashion, and those who watched them do so, say that they gradually grew into glorious Marigolds or Sea-Jellies, with umbrella-like bodies of clear jelly, marked on the top with rings and streaks of red, and all around its edge each had a delicate fringe looking like the finest of silk. And so they floated off to see the world and seek their fortunes.

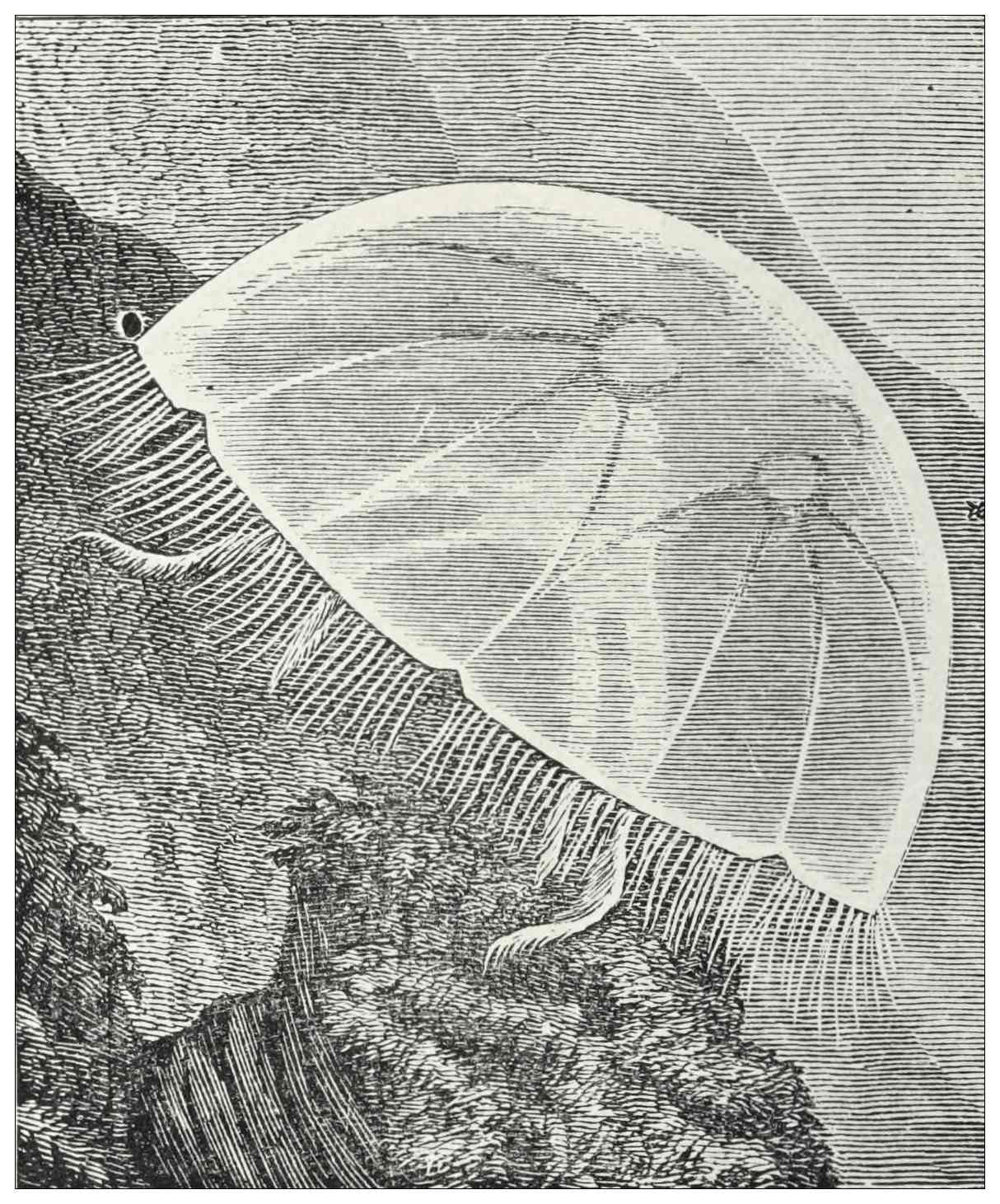

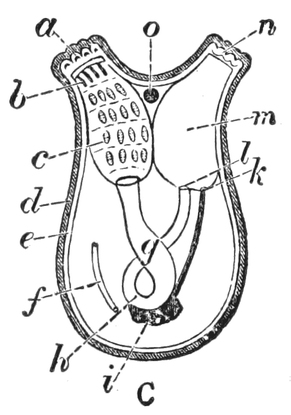

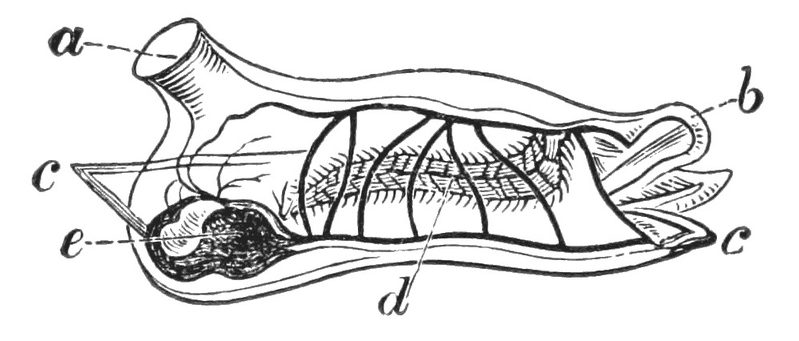

The Jelly-fish produces ova, which develop cilia—eye-lash-like processes, by means of which they swim through the water.[53] Settling on a rock or shell, they develop into Hydra tuba, with long tentacles, as at a a. Then comes the saucer-like stage, as at b; finally the free-swimming segment, c, which ultimately becomes the huge creature of our next illustration, which is so plentiful in our seas during summer and early autumn.

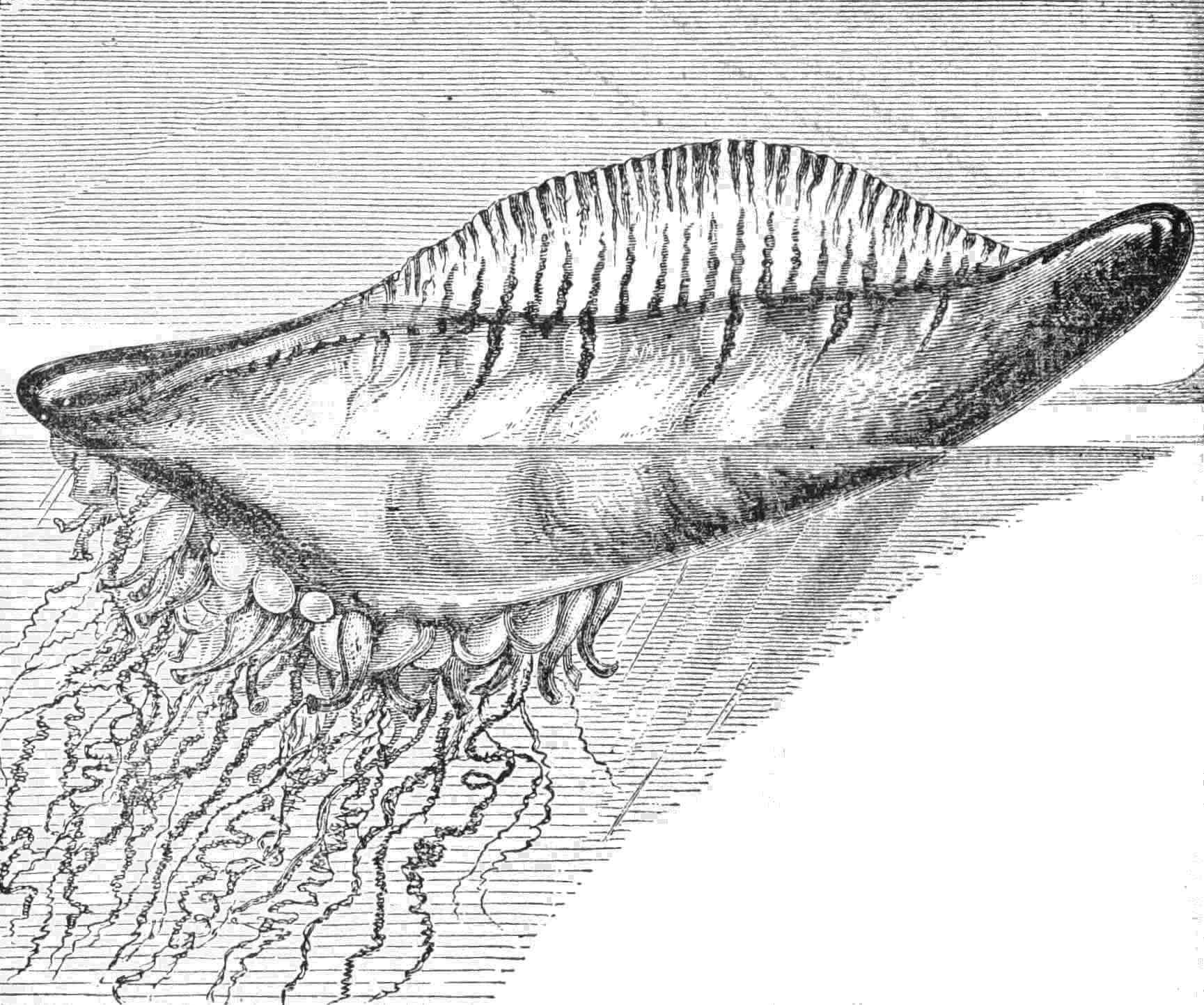

Every person that has any acquaintance with Jelly-fishes at all knows this species well—by sight. It is probable that many of those who think they know it would be somewhat puzzled if asked to point out the creature’s mouth and to give a rough outline of its organization. It may be described roughly as umbrella-shaped. There is an arched disk, from the centre of which, on the concave or lower surface there depends a thick cylindrical body, the manubrium or handle, sometimes erroneously termed the polypite, which finally terminates in four lobes assuming the form of trailing ribbons. In the centre of these lobes is the creature’s mouth, and the stomach is continued from the mouth up the middle of the manubrium. Here digestion takes place, and the nutriment thus obtained is carried up to the centre of the umbrella, and thence distributed to all parts by means of nutrient tubes which may be seen running straight from the centre to the circumference.