by Leonard Lockhard

Leonard Lockhard is an experienced patents attorney who can slip the glovelike surfaces of an inventor’s nightmare on his writing hand with a dexterity glorious to behold. We suspect he even does so in his dreams, chuckling right merrily until the dawn breaks through. You’ll chuckle too, we think, at one of the most uproariously funny SF yarns it has ever been our privilege to publish.

Krome was Mr. Patent Office in person—and a hard man to needle. But Marchare’s underground diving suit had a very sharp point to it.

The interoffice buzzer on my phone rang. It was Helix Spardleton, patent attorney extraordinary—and my boss.

“Saddle?” Helix said. “Marchare is on the phone. Take care of him, will you?” And he hung up.

For a moment I just sat there, phone in hand. Marchare! My palms were suddenly moist. Other patent lawyers had nice normal scientists to work with—people who invented new and patentable plastics, pharmaceuticals, and insecticides.

I had Marchare. My mind ran back over some of his inventions—synthetic babies, supersonic washing machines, hair-growing chemicals. Collectively they had netted him a small fortune, but they had brought nothing but headaches to me. Now he was on the phone again. Another invention undoubtedly.

My forefinger shook a little as I stabbed it at the lighted button on the phone. “Saddle speaking,” I said.

“Good morning, Carl!” came cheerily. “This is Marchare. You sound a little weak. You’re not ill, I hope?”

“Well, I’m not feeling exactly—”

“Glad to hear it. Look, I wonder if you could drop over at my lab. I’ve run across something interesting, and I think we ought to investigate the patent possibilities.”

I swallowed dryly. “What is it?”

“A diving suit.”

I pondered his reply suspiciously. Was it conceivable that “Doc” had finally thought up a beautiful routine invention for me to work with—one that wouldn’t get me all fouled up with the Patent Office? It wasn’t too likely. Still—a diving suit. How could I get into trouble with a mere diving suit? Surely I was on safe ground there.

I said, “Fine, Doc. Shall I come over now?”

“The sooner the better,” he replied. “I’ll wait for you.”

“Is there anything I should bring along? The camera?”

“Your notebook is all you’ll need,” he assured me. “I’m not yet ready to test it underground. See you soon.” He hung up.

I hung up myself and had half risen from my desk when I suddenly stiffened. Underground. His diving suit worked underground! I was plenty startled, but as I thought it over I decided that Marchare must have been mistaken. He’d meant underwater—just a slip of the tongue. Sure, that was it. Who ever heard of a diving suit that went underground? It was too fantastic.

I felt better almost immediately. I got my hat and notebook and went out into the bright sunshine and hailed a cab.

On the way to Marchare’s laboratory I did some thinking. He was a brilliant man capable of almost anything, a man who seldom made mistakes. His tongue wouldn’t slip—not on a thing like that. If he said underground he meant underground. It was a statement I had to accept.

By the time the cab pulled up in front of Marchare’s laboratory in Alexandria I knew exactly where I stood. I knew for sure that he had gone and invented a diving suit that would go underground.

“Doc” Marchare was dressed in his usual clothes, which is just another way of saying he looked as though he’d only recently got back from an unsuccessful, but jovial panhandling expedition.

“You got over here quickly, Carl. You’re anxious to get going, eh?”

I forced a sickly smile.

“That’s the spirit,” he said, thumping me on the shoulder. “Come along, let’s have a look at it.”

He led me down the hall and into a cluttered work room where Hamilton Eskew, his cadaverous assistant, was working on something that looked like a large pair of coveralls.

Marchare said, “I’ll describe the suit to you, If you have any questions just break in and ask them. It’s really quite simple.”

I said, “Uh-huh,” pulled out my notebook, flexed my fingers, and was all set.

“Externally,” he said, “it closely resembles any self-contained underwater suit. The body portion is all in one piece. The helmet clamps down over the head, and the pack on the back contains the power supply. Any power supply can be used so long as it delivers approximately ten amperes at ten thousand volts for a reasonable period of time.”

I scribbled busily. “Got it,” I told him.

“The current passes to a cabbagite crystal, then to a selector box, and finally to the surface of the suit,” he went on. “Control dials mounted inside the hands of the suit enable the operator to control the amount of current at various places on the surface.”

I broke in, “Cabbagite sounds familiar. Precisely what is it?”

“Well,” said Marchare, “I’m not quite certain. Carbon, you see, occurs in two allotropic crystalline forms—diamonds and graphite. I’ve prepared a third allotrope that I call cabbagite. It is a twinned crystal with peculiar properties, to say the least. When an electromotive force is impressed at one end of it the other end emits energy of varying wave lengths. The bombardment of this energy seems to nullify the cohesive forces between the molecules of matter.

“Up until now the only use I could find for it was in transforming oxygen to ozone. When you plug it into the wall socket, you have a wonderful cabbage-cooking deodorizer, Spardleton filed a case on that use a couple of years ago. A few weeks ago I discovered the crystal had other possibilities. I’ve now discovered that it works on solid matter as well as oxygen. The solid matter yields and flows when pushed on by a conductive object that is connected to an activated cabbagite crystal.”

I asked, “But how does the cabbagite crystal allow the diving suit to move around underground—through solid earth?”

Out of the corner of my eye I noticed that Eskew was shaking his head in sneering compassion for my slow-witted grasp of the technical details. But Marchare didn’t mind a bit, having had long experience with patent attorneys.

“Well,” he said, “the energy from the crystal goes first to a selector unit. From there it passes to the surface of the suit by means of thousands of tiny wire leads. These leads connect to a wire fabric imbedded in the thin rubber from which the suit is made. Is that clear?”

“Of course,” I assured him loftily, ignoring Eskew’s subdued snicker.

“The control dials work this way,” continued Marchare. “Once the diver is underground he can cut off the energy field beneath the soles of his feet. Thus he will have something solid to stand on. When he walks, though, he will have to keep the soles of his feet pointed away from the direction of his advance, or retreat, because only the ground under his soles will always be solid. Either that, or he can adjust the controls each time he moves his foot.

“The control built into the right hand will control the right half of the suit; the left-hand one will control the left, The energy field over the rest of the suit isn’t so important as long as it is strong enough to soften the surrounding earth. But even so we’re going to make it possible for the diver to control the energy field on the entire surface. That way he could even lie down if he wanted to.”

“Since you haven’t finished the suit yet,” I said, “how do you know it will work?”

Eskew looked up at me as though I had just taken a dime from a five-year-old.

Marchare never turned a hair. “Oh, it will work all right. We’ve already made a great many tests. We’ve thrust objects through walls and rocks and metals. Hamilton hasn’t actually finished the diving suit. But when he does, you can rest assured it will come up to expectations.”

“What,” I asked, “happens to the diver if the crystal stops functioning while he’s underground?”

“Now there’s a disturbing thought,” mused Marchare. “I guess the suit would be lost. Gravity would pull it down to the center of the earth.”

Eskew cackled mirthlessly. “And would the diver be burned up.”

Marchare smiled indulgently. “A card, that Hamilton. Actually, there’d be no pain. Ham has timed the air supply to fail long before the diver can reach the center of the earth.”

The hair on the back of my neck relaxed a little. I forced myself to consider only the legal aspects of the subject at hand. “When will the suit be ready?” I asked.

“In about four months,” grunted Eskew. “Possibly a little sooner.”

“That’s good,” I told him. “I think the Patent Office may want a demonstration. If I can prepare and file the application within the next two weeks, the Office will probably take it up just about the time the suit is ready.”

“What I don’t understand,” said Marchare, “is how we can file a patent application on something that doesn’t yet exist. Won’t it be perjury for me to sign the inventor’s oath?”

“That would depend on what oath you sign,” I told him. “Fortunately there are two kinds. In one you swear that everything in the application is true. In the second you merely swear that the object described in the specifications is your invention. I never heard of any inventor using the first kind. You don’t think Selden ever actually made the automobile he patented, do you?”

“I see,” he said, with an expression that said he didn’t at all.

I looked over my notes. Mr. Spardleton had previously explained that it was useless to take notes on a new invention because the attorney’s version never agreed with the inventor’s. What was even worse, neither bore any resemblance to the hash the patent examiners would inevitably make of it. My notes were sufficiently confused to gladden the heart of any practicing patent attorney.

“Well, I guess that’s it,” I said.

I shook hands with Marchare, returned Eskew’s sneer cordially, and headed back to town. Plans for the coming tussle with the Patent Office were beginning to take shape in my head. But I foresaw no great difficulty. This was real invention. Imagine. A diving suit that went underground. Even the Examiner would have to admit that this was creative originality of the highest order. He couldn’t turn me down. He wouldn’t dare.

When I got back to the office I went in and explained the whole thing to Spardleton. He heard me all the way through without an interruption. When I had exhausted my vocabulary of superlatives he sat quietly for a moment thinking. Then he said, “Yes, it seems straightforward enough. I’ll tell you what. Make a search and pull a couple of patents that describe the usual diving suits. You will be able to use large portions of the specifications.”

“How can I?” I asked. “Those patents will only describe diving suits that go underwater. They won’t—”

He cut me off with an airy wave of his hand. “Whenever you hit the word ‘underwater,’ change it to ‘underground.’ When you hit the word ‘sea,’ change it to ‘ground’ or ‘earth.’ You’ll save a lot of time that way. Okay, you’re on your own. But let me see the spec before you file it.”

I left and went over to the Patent Office to make the search. I flipped through the patents in Class 2, Subclass 2.1, and selected two patents to serve as models. I realized almost immediately that I’d be able to use large portions of them. It seemed like a good idea at the time.

During the next ten days I wrote and re-wrote. I consulted with Marchare on several occasions, and I worked closely with Eskew to make sure that his drawings would be comprehensible to a man from Mars—or a patent examiner. Even at lunch Susan, our secretary, and I talked about the diving suit and hardly anything else. I ate, slept, and breathed the suit. I became convinced that it was going to be a perfect application. The Patent Office wouldn’t get to first base with its exotic logic this time.

Susan was a gem. She never even frowned when I changed my mind several times about how best to drive home a telling point. She just tore up the old copy and made a new one from my dictation. Sometimes, though, she had a funny little half-smile on her face as though she knew something which I didn’t. I asked her about it once. She didn’t say a word, just reached over and patted me on top of the head. Somehow it made me feel like a Pekinese. But I refused to let it worry me. I was too busy creating a perfect patent specification.

The opening paragraph in my specification read:

This invention relates to a suit of apparel, particularly designed for the protection of a diver, and has for its object to provide a diving suit of novel construction that may be comfortably worn by a person, be capable of yielding at all the joints of the wearer’s body, be earthproof and airtight, be self-contained as to air supply, be light, strong, and durable, afford means for the descent of a diver in various depths of dirt, and enable the deepground diver to move around freely through rock, stone, and earth of varying composition.

The final draft consisted of seven pages of drawings, ten pages of spec, and twenty-eight claims. I sat at my desk for a good thirty minutes pridefully staring at the lovely stack of papers. I read over some of the more brilliant passages, rolling the words on my tongue, amazed at what a clear picture they painted. Convinced that it was now a masterpiece of logic and persuasiveness, I took it in for Spardleton’s approval.

He picked it up and began to read. I waited confidently, convinced that he could hardly fail to see in it the sure hand of genius. He finished it far more rapidly than I would have thought possible. “Um,” he said, tossing it back to me, “It’ll do. File it.”

Susan made out a check for thirty-eight dollars and I mailed the whole mess to the Patent Office.

The next couple of months passed swiftly. Under Spardleton’s expert tutelage my working fund of patent knowledge blossomed and grew. I learned how to write page after page of patent specification without actually saying anything. I achieved an amazing degree of tonal control over my voice. By simply saying to an Examiner, “I don’t quite agree with you there,” I was able to suggest by the tone of my voice alone that I knew he had received his scientific education by the rudimentary osmotic process of sitting on his text books. Sometimes it worked.

Then one day Spardleton sent for me.

He was evidently busy trying to decipher an Office Action when I entered. Webster’s Unabridged stood open on its stand beside his desk and at least six volumes of the Britannica were scattered about on the floor. The desk itself was littered with thesauruses and handbooks and I noticed particularly Partridge’s Dictionary of Slang and Unconventional English.

As soon as I walked in he asked, “Did you ever hear of the word ‘sludutiferous?’”

“I’m afraid not,” I said.

“Well, there is such a word. I found it here.” He waved vaguely at the forest of books on his desk. “And I must say I’m a little disappointed in the Examiner. I don’t know what the Patent Office is coming to when they begin using words that are actually in existence.” He looked at the initials in the upper left-hand corner of the Office Action. “Oh,” he said, brightening considerably. “Maybe that explains it. Old Nailgood. He’s just allowed several claims in Marchare’s cabbagite deodorizer case. He must be slipping fast.”

His smile vanished and his brows drew together. “Still, there’s something phony here. Cabbagite is a real invention. It’s a money maker for Marchare, and a boon to the housewife. There’s something remotely similar in the prior art. It’s very odd, therefore, that the office is willing to give us a patent on it. Unless—”

“Unless what?”

“Unless they want to allow it, in order to use the allowed claims to reject Marchare on some other application of even greater importance. Does he have any co-pending applications relating to cabbagite?”

“None that I know of,” I said.

“How about that diving suit?” I stared at him, startled, “Surely you don’t mean they’d reject a diving suit on a deodorizer? What kind of sanity is that?”

He gave me a puzzled look. “Sanity? What’s sanity got to do with it?”

I hadn’t got around to answering him when Susan walked in and handed Spardleton a letter—clearly a communication from an Examiner. He tore it open and scanned it quickly.

“Ah, hah,” he said. “Look here. This explains everything.”

I circled around behind him. It was an Office Action, all right. And it was in reference to the diving suit application.

The first thing I noticed were the initials in the upper left-hand corner: H. K. Herbert Krome! Mister Patent Office himself—the evil genius who handled patent lawyers the way an animal trainer handles big cats. A single glance showed me how serious—and nasty—it was.

“This application has been examined

Art cited:

Anderson et al—

1,022,997 April 9, 1912 2/2.1

Browne—

2,388,674 Nov. 13, 1945 2/2.1

Claims 1-28 are rejected as based on inoperable structure in the absence of a demonstration.

Claims 1-28 are further rejected on the allowed claims in applicant’s co-pending S.N. 162,465, directed to the cabbagite crystal. Since it is known that cabbagite rearranges matter (302→203) it would be obvious to attach it to the well-known diving suit of Browne to obtain applicant’s result.

No claim is allowed.

Examiner.

“See?” said Spardleton, his features dark, “Just as I thought. He’s using our own application against us.”

We were quiet for a moment.

“There’s another matter,” said Spardleton. “Marchare says the Department of Defense has been dickering with him for rights under his diving suit application. I told him to stall them until he gets an allowance. If he can’t get a patent, the government can award manufacturing rights to anyone and not have to pay Marchare a nickel.

“Actually, they prefer a license under a patent: It avoids any chance of suits in the U. S. Court of Claims by twenty or more halfbaked inventors who think Defense stole the idea from them. So time is of the essence.”

I said, “If I could demonstrate a suit to Krome, I’m sure he’d allow the case immediately. But I don’t think the suit has been completed yet. Have you heard from Marchare?”

“I phoned him about it a couple of weeks ago,” said Spardleton. “He told me it wasn’t quite ready. When I asked him to be specific he mumbled something about bugs in the control system.” Spardleton studied me thoughtfully.

“I can at least show the suit to Krome,” I said uneasily.

“I think it’ll take more than that,” Spardleton said.

“Maybe I could fill it with rocks and let it down into the ground on a rope,” I suggested brightly.

“Krome won’t buy that.” Spardleton frowned and seemed lost in thought for a moment. “Still, if I know Krome as well as I think I do it may work out all right. You’d better arrange for an interview this afternoon, and then run out and get the suit—as is. Marchare said you could have it anytime.”

As I left to take care of things, a slow introspective smile was spreading over Spardleton’s face.

Each patent lawyer must develop his own technique for interviewing Examiners. Some shout and rave and rant. But that is foolhardy. One slip, and the show is over. Others play dumb and act as if they haven’t the slightest idea what the score is. That encourages the Examiner to talk himself out on a limb. Still others employ the yakety-yak system wherein they never give the Examiner a chance to open his mouth. It is a subterfuge which is only used by those who don’t dare meet the Examiner in fair and open combat. Others use the buddy-to-buddy approach in which the attorney manages to convince the Examiner that he and the Examiner—and especially the Examiner—are the only two people in the whole world who really understand patents.

After due consideration I had decided to use an absolutely unique approach, one never thought of before.

I was going to be myself.

I had a good invention, the application was well-written and everything was just as it should be. I had no need to resort to deception, or evasion. Besides, I had seen what Krome could do to attorneys with a system. He took the system, rolled it up in a compact ball, and fanned them out with it, scoring his three strikes without once unbending.

At two o’clock sharp, with the diving suit under my arm, I stepped up to Mr. Krome’s desk.

“Mr. Krome?” I inquired, with just the proper amount of rhetorical deference.

“Yes, yes. What is it?” he said without even looking up.

“I’d like to talk to you, sir, if I may. It’s about the Marchare case, the diving suit—”

I knew Krome quite well, but still he asked me coldly, “Are you the attorney of record?”

“Yes, sir,” was my instant reply. He knew I was—and he knew I knew that he knew. But it was part of his routine, and I didn’t want to irritate him by abbreviating the amenities.

“I can spare you ten minutes,” he grumbled. “I have an important appointment with the Commissioner at two-thirty.”

I said, “Ten minutes will be quite sufficient.”

“Just a second while I get the case,” he said. He got up and disappeared into the Clerk’s room.

Five minutes later he returned, and steamed back to his desk, my application clutched tightly in his hand.

“Yes,” he said, without even looking at it, “part of my rejection was on probable inoperability. Have you got a working model there?”

“I certainly have,” I replied. “Though you might not believe it even when you see it. This is absolutely the most—”

“Why won’t I believe it when I see it?” he demanded.

“Well, I just meant—”

“Is this a trick of some kind?” he bridled.

“No. Oh, no. I just—”

“Well, why won’t I believe it when I see it?”

“I didn’t mean it that way,” I said quickly. “I meant—”

“I heard what you said. Let me remind you of Rule Three. Interviews with Examiners must be conducted with decorum. No frivolity, understand?”

“I’m sorry,” I apologized. “You’ll believe it. Honest you will.” He stared at me suspiciously. “We’ll see. Bring it into the next room.” He stalked off. I picked up the box, and staggered after him into the conference room.

“Open it up,” he commanded.

I dumped the suit on the table.

He felt the texture of the cloth. “It doesn’t look like much,” he said. “And look here.” Very deliberately he stretched the diving suit out full length. “Doesn’t that look just like an ordinary diving suit?” he asked.

“Yes, but—”

“Isn’t its design similar to that of any diving suit?”

“Yes, but—”

“And a diver underground acts the same as a diver underwater.”

“Well, sure. But—”

“And, as a matter of fact, listen to this.” Krome picked up the application and read a few paragraphs to me. “Now,” he said, “all I have to do is change the word ‘underground’ to ‘underwater,’ change the word ‘ground’ or ‘earth’ to ‘sea,’ and I have a perfect description of a deepsea diving suit. Am I right?”

“I know all that,” I said. “But—”

“Well, then—there is no invention here. Once the cabbagite crystal is known it becomes so obvious that any routineer could use it in a diving suit. A new use of an old thing or an old process cannot be patented. Regar & Sons, Incorporated versus Scott and Williams, Incorporated.”

I protested, “But wait a minute. Wait until I demonstrate it for you. I’ll tie this rope on and then—”

“No you don’t,” he said. “You don’t pull any rope tricks on me. I’ve read the spec. I know how it’s supposed to work. I’ll put it on.” And he began to climb into it.

“Kindly stop opening and closing your mouth,” he said, “and help me with the helmet.”

“Please,” I gasped. “The controls aren’t—”

“Put the helmet on,” he said.

“But the controls aren’t—”

“Put the helmet on,” he insisted.

With nerveless fingers I obeyed. I can remember wondering whether there was anything in his life insurance policy that would have covered a possibly fatal outcome. I hoped they wouldn’t make his widow and children wait seven years.

I turned to glance at the door to see if there were any witnesses. No one was watching. I turned back to Krome and noticed with alarm that he appeared to have grown shorter. For a moment I thought he had fallen to his knees. But then I saw that he was slowly sinking through the floor.

I made gestures with my hands in front of his face plate in a frantic attempt to show him how to operate the controls. Lower and lower he sank. I followed him right down to the floor until he disappeared through it, leaving me on my hands and knees staring at the blank and dusty tiles.

Then I realized with horror that we were on the seventh floor.

I turned and rushed out of the room and down the hall to the stairway. I tore down the stairs, and out into the hall below. I ran for the room directly underneath the one where Krome had been. Before I could reach it several sickeningly-curdled screams resounded through the corridor, and I heard the muffled bangs of things crashing to the floor. A few loose papers floated out through the open door.

I pulled up in the doorway, and looked in.

There were five patent attorneys in the room, waiting their turn to be heard by the Board of Appeals. Krome was in the middle of the room up to his waist in the floor. His arms flailed wildly as he tried to keep his balance.

The panic-stricken attorneys stood on tables and chairs hurling whatever they could lay their hands on at the monster that confronted them. Books, inkwells, and brief cases rained around Krome’s helmeted figure. Finally one of the attorneys reached down and hoisted a chair high over his head.

Krome saw it and raised an arm in terrified protest. For the first time his voice came out through the speaker attached to the diving suit. “No! No!” he screamed. But it did no good. With fear-driven muscles the attorney launched the chair at Krome. It struck him sharply across the chest.

The two shattered ends of the chair hurtled past him, and crashed against the opposite wall. The middle portion that had hit his body flattened out like water against the suit. Part of it flowed down, and formed wooden puddles on the floor. Other parts splashed out sideways in little streamlets that solidified into splinters and sprinkled all over the floor.

The attorneys stared bug-eyed at what had happened to the chair. For a brief instant they were paralyzed. Then, moving as a single man, all five of them made a dive for the doorway. I was directly in their path, and I never had a chance.

I was a wreck when the stampede had passed over me. My nose was bleeding profusely, my left trouser-leg was ripped off at the knee, and my right sleeve was gone. There were even footprints on my naked chest.

I crawled back to the door and looked in. Krome was gone. I got to my feet and slowly started to walk toward the stairs. I tried in vain to stem the flow of blood with my shirttail. One eye was swelling fast, and a front tooth had worked loose.

I wandered out into the next lower corridor in search of Krome. I looked in at the doorway of what seemed to be the proper room. It was. The Primary Examiner was sitting at his desk talking to an ashen-faced young fellow. Neither of them was saying anything. Their eyes were fixed on a stationary point at one corner of the Primary’s desk. At first I couldn’t tell what it was. Then I caught a movement, and my heart sank.

Krome had descended on the Primary’s desk. Apparently he had thrashed around while trying to get his balance, and now he was half-stuck in the desk. I got there just in time to see the helmet, right side up at last, take up a fixed position at one end of a shelf of books.

“Oh,” said the Primary peering in through the faceplate. “I’m glad you dropped in, Krome. I’d like you to meet Jones, our newest junior Examiner. He just joined us today. Mr. Jones, Mr. Krome.” There was a bitter, almost savage irony in his voice.

Krome nodded curtly, only his head visible above the desk top. His arm came out of the desk as he started to shake hands. But he thought better of it and his arm dropped out of sight again. Jones just sat there, white, tense.

The Primary nodded. “Some misguided applicant has just cut his own throat by persuading Mr. Krome to try out his invention.” He turned to Jones. “There’s a good lesson here. The inventor has merely substituted stone for water. In processes it’s a common expedient to substitute one ordinary medium for another. Diving suits are no exception. Mere gadgeteering.”

Jones just sat there staring at Krome’s head. I don’t think he heard anything the Primary said. I could see that if anybody was going to defend my application, I’d have to do it myself. I walked into the room and took up the battle.

“But how,” I demanded, “can you reject an inventor on his own co-pending application-one that hasn’t even been issued as a patent?”

Krome gave me a pained look through the quartz porthole. “Section one hundred and two, A, says the invention must not have been known before the invention by the applicant. There’s no inventive advance in the diving suit over Marchare’s prior cabbagite application. Hence, in effect, the diving suit invention was known when Marchare invented cabbagite.”

I blinked at his steady black eyes. “You mean,” I said, “like jet planes were known when the Chinese invented the sky rocket?”

“Precisely. This concept of patent law is so sound, so logical, that I can’t understand why the Supreme Court took nearly a hundred and fifty years to swing around to it. And, of course, when it’s the inventor’s own prior work that’s used to reject a current application, the situation is a double strike against him.” He leered at me triumphantly. “How can a man be smarter than himself?”

“But even the Supreme Court says you can’t reject an application on a combination merely because you can find all its elements in the prior art,” I protested. “There can still be a patentable invention in combining those elements. Here the invention consists of combining cabbagite and a diving suit. Nobody ever thought of that before.”

“Of course they never thought of it before,” he explained patiently. “They couldn’t, because they never heard of cabbagite before.”

“Then nobody but Marchare could invent the diving suit.”

“Quite true. But the minute he invented it, it became non-invention, because, since it was he who invented it, it didn’t require invention.”

The new Examiner finally recovered his faculties, He slapped both hands on his knees, got up, and said, “Well, so long, sir. By resigning right now I may have a fighting chance of retaining my sanity.” And he walked out the side door shaking his head.

“What’s the matter with him?” asked the Primary in a puzzled voice.

Krome said, “I don’t know. Perhaps he—” He stopped. The helmet had suddenly dropped a couple of inches further into the desk. It hung there a split second, then dropped a few inches more. Step by step he was slipping down. We heard his muffled voice coming out of the desk through the cracks around the drawers, but we couldn’t understand what he said. The Primary and I leaned over to look under the desk. We watched the floor close over the helmet.

The Primary straightened up, and glared at me. “Well,” he said. “If you’ll excuse me, I have lots of work to do.”

“Oh, sure,” I said. “I have to go find Mr. Krome anyway. Goodbye, and thanks for your trouble.”

“No trouble, no trouble,” he retorted with a venomous inflection, picking up a document from his desk top and beginning to read it.

I trotted on down to the room underneath.

The door was closed, and on it in big letters were the words NARCOTICS BUREAU. I carefully opened the door and looked inside.

It was a small room, and there were only four men in it. Three of them were bent intently over their desks. But the fourth man had tilted back in his chair for a moment’s reflection and contemplation. His hands were clasped behind his head, and everything about him was normal—except his eyes. No human eyes should ever protrude the way his did.

Krome hung suspended from the ceiling. Everything below his collar bone was in plain sight, and most of it was thrashing around noiselessly. For about ten seconds it continued thus—the immobile narcotics expert, the quivering Krome. Then Krome managed to turn on the energy field in the upper part of the suit. Without a sound he slipped out of the ceiling, fell through the floor, and disappeared.

Nobody saw him go except me and the thinker. That amazing gentleman swallowed hard and sat upright. A quick glance convinced him that none of the others had noticed anything wrong. He swallowed again, sighed heavily, and then methodically began to clean out his desk.

As I was sadly closing the door, I realized with sudden consternation that Krome was dropping toward the Search Room on the ground floor. And the ceiling there was over twenty feet high. I began to run again.

The Search Room was quiet when I burst into it, holding my tattered and blood-caked clothing tightly around me. The occupants of the room gave me strange looks, but they were so used to having screwballs around that nobody said anything. I kept my eyes on the ceiling.

For a moment there was no sign of Krome. Then off to one side, over near the entrance where the patent bundles were kept, a foot appeared from the ceiling. It moved around as if seeking a firm place to stand, and then quickly withdrew back into the ceiling. It cautiously reappeared a moment later, closer to the huge pillars that stretched down to the floor. Again it sought a footing.

I heaved a sigh of relief. Krome evidently knew where he was, and was taking no chances. As I stared the foot vanished for the second time.

It came into view again an instant later, this time about eighteen inches from the arch at the summit of the pillars. It flitted around and found the pillar. Hands flashed through the ceiling as Krome paddled himself over, and then carefully lowered himself out of the ceiling and into the arch at the top. Large portions of him were now in plain view.

The uproar from the floors above had been steadily increasing in volume. The people in the Search Room were glancing questioningly at one another. And just as Krome was about to complete his transfer to the pillar one of the patent stenographers saw him.

Her screams all but shattered every window in the block-long room. Everybody froze. All eyes followed the stenographer’s hand that was pointing to where Krome was just beginning to descend, half in and half out of the pillar. A long moment of stark silence gave a kind of funeral dirge significance to what followed.

There were only two exits. I was smart this time. I stood off to one side as the terrified occupants of the room leaped over the search tables like gazelles fleeing from a lion. Chairs were crushed to pulpwood. Many people had been back in the stacks when the commotion started, and were now emerging with their arms loaded with bundles of patents. Instantly the air was thick with flying documents.

I couldn’t help but admire the consummate skill with which Krome descended the column. His rear end protruded as he stepped slowly down. Every four or five feet, he’d stop, turn around, and thrust his head out to make sure where he was. Then he’d disappear for a moment, out would come his backside again, and the slow descent would resume.

There was a revolving fan fastened to the pillar about seven feet above the floor. I watched, fascinated, as Krome got closer and closer to it. Finally fan and fanny met. The blades flowed into long slivers of metal that shot across the room and spanged off the walls. The motor, relieved of its load, began to race faster and faster.

Krome must have felt the gentle blows of the blades because his hand reached out of the pillar and brushed at them as though he were shooing a fly. His hand passed through the fan support. There was a shower of sparks and a little smoke curled up. The fan sagged forward on its support and then solidified as Krome’s hand moved on through. I never saw a sorrier looking device than that fan once Krome got through with it. The electricians would be in for a bad few hours trying to figure out what had happened to it.

Krome finally reached the floor, stepped out of the pillar, turned off the suit, and heaved a big sigh. He turned around and for the first time got a good look at the Search Room. Most of the chairs were reduced to rubble. Many of the large search tables were overturned and broken and Krome himself stood knee-deep in patents.

Krome gave one puzzled and uncomprehending glance at all this. Then he looked at the clock over the door. “Good grief!” he groaned. “Two thirty-five! The Commissioner!” He turned and ran through one of the archways that opened into the stacks. I lit out after him.

He had turned the suit on again, except for the soles of the feet. This gave him a decided advantage over me. He could take short cuts through solid walls. He went through the back wall of the stacks without even slowing down.

I cut off to one side through the door that led into the foreign art. I stopped and listened. From the other end of the long law room I heard a sudden splintering crash. I raced on in trepidation. A man was standing near the Swedish art. A broken pint bottle lay at his feet and whiskey was lapping at the soles of his shoes. His forefinger was half-crooked in front of his face. But it was his bulging eyes, aimed at a section of the wall, which pointed out the direction Krome had taken. As I turned from him he collapsed, head in hands, and began to sob quietly.

I quickly found my way to the back corridor. As I proceeded down it, the now-familiar ruckus started up in the Mail Room. Women screamed, men shouted, and heavy objects thumped on the floor. Krome had used very poor judgment in cutting through the Mail Room. But how was he to know that the people in it were not scientifically-minded?

I waited until one of the doors stopped spewing people, and then leaped resolutely inside. One glance convinced me that the Patent Office would not be running smoothly for a considerable period to come. Several of the clerks had dropped to their knees and were praying, some quietly, some loudly.

There were papers everywhere. And an empty mailbag dangled limply from an overhead light, looking startlingly like the victim of an over-wrought hangman. One man sat on the floor in front of a pile of thousands of newly-arrived applications. He was laughing insanely and tossing repeated handfuls of applications high overhead. Petitions, checks, notarized oaths, drawings, and fragments of applications slithered through the air like snowflakes in a blizzard. Krome had passed through, all right.

I walked amidst the bedlam unnoticed seeking some sign of Krome. I couldn’t figure out where he had gone. Then suddenly I had it—his two-thirty appointment with the Commissioner.

I jumped to a window and looked out. My heart almost stopped beating at what I saw.

A girl was walking away from me along the sidewalk, her hips swinging up and down like the ends of a seesaw. Krome was plowing along right behind her, completely out of control, getting closer all the time. He was tilted forward pawing at the ground with his hands, now submerged to his neck, now above ground to his ankles. The girl had ignored his first frantic warnings, so Krome shouted again. She threw an annoyed glance back over one shoulder and—the seesaw froze.

Krome churned closer and closer. My heart was in my mouth. I had no idea what would happen when the diving suit bumped into a live human being. I stopped breathing.

Closer and closer! Then just as a collision seemed inevitable Krome executed a rather neat surface dive into the pavement which carried him safely and spectacularly underneath her feet. Almost instantly he reappeared on the other side doing a strong overhand stroke which quickly put a safe distance between himself and the grievously threatened young lady. She toppled over in a dead faint.

I dashed into the next building, into an office where a short, heavyset man stood bending over a huge desk. I recognized him in a flash. The Commissioner of Patents!

At the Commissioner’s desk side sat a man in uniform—a two-star general.

It added up. I thought fast. Krome—the Commissioner—the general.

I cleared my throat as they looked up blankly. “I beg your pardon,” I said politely. “I’m Mr. Saddle, Dr. Marchare’s attorney in the diving suit case. Mr. Krome suggested I be here during his appointment on this matter.”

“Really?” grunted the Commissioner. “And where is Mr. Krome?”

“He said he’d be passing through any moment now,” I said hurriedly. Just then Krome walked in through the north wall. Fortunately neither the general nor the Commissioner saw him until he stepped out from the wall.

The Commissioner glared at Krome, then at his desk clock. “You’re late,” he chided. “However, since you brought the suit, that’ll save time. Gentlemen, this is General Bond, Secret Weapons Bureau, Department of Defense.”

Krome got it immediately too. But, like other people who live by their wits, my reflexes were faster. I said smoothly, “Mr. Krome and I have just been giving the suit a tryout, and he invited me along to the conference.” I beamed sideways at Krome. “He finds all the claims allowable, and my client stands prepared to license the Secretary of Defense to manufacture, at a very reasonable royalty, any and all—”

“But—” sputtered Krome.

“Mr. Krome has applied to most stringent tests.” I continued hurriedly as I sidled over toward the encased, protesting figure. And in patting him jovially on the back, I somehow brushed against the mike button, chopping off the torrent in mid-cascade. “Oops, how careless of me! Oh, well, Mr. Krome will tell you himself, as soon as I get the helmet off.”

“How long will that take?” demanded General Bond.

“Not more than three or four hours,” I said. “If it doesn’t jam.”

“Can’t wait.” He turned curtly to the Commissioner. “Phone me the patent number as soon as the application is passed to issue.”

“Yes, sir,” the Commissioner replied.

“And you, Mr. Saddle,” said the general sternly, “had better inform Dr. Marchare about the penalties of profiteering against his government. We’ll give him a trial order for ten thousand suits, but if he holds out for more than five thousand dollars per suit, we’ll seize the patent by Eminent Domain.”

“I suppose the good doctor won’t mind taking a loss on a small trial order,” I said reluctantly, “But, of course, on a mass scale, my client would at least have to make expenses, particularly if he adds certain improved features.”

“Hey, wait a minute,” declared the Commissioner. “There’s something funny about this. Look at Krome. Tears are pouring down his cheeks!”

“I’m sure that’s sweat.” I mopped my face hurriedly. “It’s warm in here too, isn’t it? Dr. Marchare intends to air-condition the suit. That’ll bring it up to an even six thousand.”

“Five thousand five hundred,” clipped the general.

I hesitated a moment. “You’re a hard man, general,” I sighed. “But—all right, five thousand five hundred it is.”

And I led Krome out of the room.

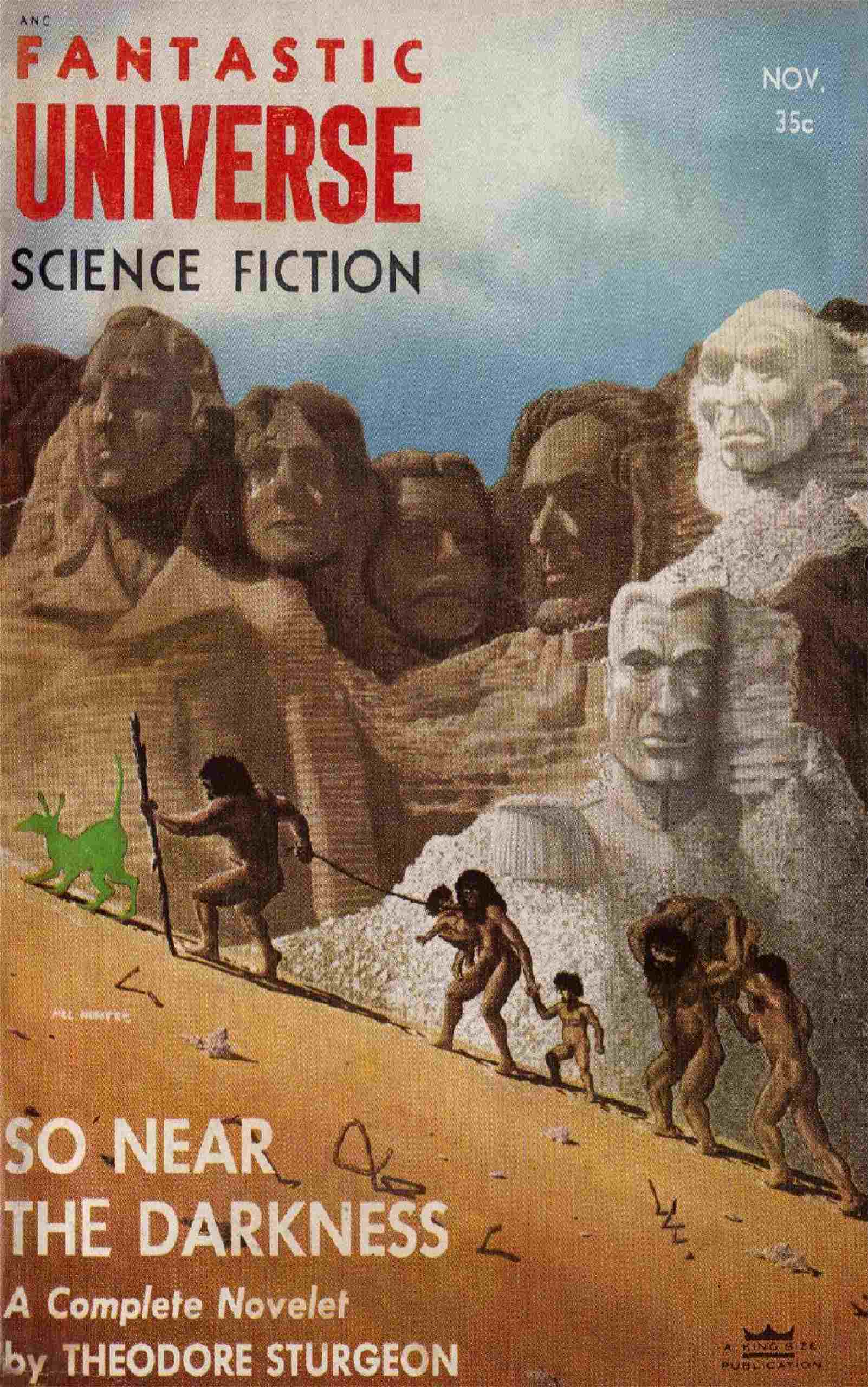

This etext was produced from Fantastic Universe, November 1955 (Vol. 4, No. 4.). Extensive research did not uncover any evidence that the U.S. copyright on this publication was renewed.

Obvious errors have been silently corrected in this version, but minor inconsistencies have been retained as printed.