The Author of La Araucana

[i]

HISPANIC

NOTES & MONOGRAPHS

ESSAYS, STUDIES, AND BRIEF

BIOGRAPHIES ISSUED BY THE

HISPANIC SOCIETY OF AMERICA

HISPANIC AMERICAN SERIES

I

[ii]

OTHER BOOKS BY THE SAME

AUTHOR ON THE COLONIAL

PERIOD IN SOUTH AMERICA

The Establishment of Spanish Rule in America.

The Spanish Dependencies in South America, 2 vols.

Spain’s Declining Power in South America.

South America on the Eve of Emancipation.

The Author of La Araucana

[iii]

BY

BERNARD MOSES, Ph. D., LL.D.,

Professor Emeritus in the University of California,

Honorary Professor in the University of Chile

The Hispanic Society of America

LONDON : NEW YORK

1922

[iv]

PRINTED AT THE

SHAKESPEARE HEAD PRESS

STRATFORD-UPON-AVON

Copyright 1922 by

THE HISPANIC SOCIETY OF AMERICA

[v]

No intelligent person is likely to deny the importance of official documents as the basis of a nation’s history; but these documents do not tell the whole story. There are social activities, currents of national thought, and waves of popular sentiment, which are not fully described either in laws or governmental proclamations. Tradition sometimes conveys a knowledge of these aspects of society, but tradition undergoes such modifications in the course of time that it does not render the same account to all later generations or centuries. Only what is written remains fixed.

Each century writes the literature it reads. This is especially true of historical literature. It is also true that each century, in the various forms of its literature, writes its own history; and it is to this literature, not to the later critical writings that one must refer, who would know how any [vi]given period of the past appeared to those then living. It was once said of a distinguished modern historian of Rome that he knew more about the affairs of Rome than the Romans themselves knew; which was to say, that his works presented a view of Rome such as no Roman ever had. The critical history of the society of any given period of the past is so completely an artificial creation that it would hardly be recognized by a member of that society. It takes its character, in a considerable part, from knowledge, ideas, and emotions that were foreign to him. Therefore, in order to know a nation’s life as known at any given epoch, or to visualise the worldly show that passed before the thoughtful contemporary mind, one should refer, not to the artificial creation of the modern historian, with its twentieth-century atmosphere, but to what men wrote of their own times or times near their own. Our ancestors’ vision of the world and the reaction which the world produced in their minds are revealed in the various forms of their literature.

The material for an intellectual reconstitution [vii]of the view of their society entertained by the Spanish colonists of South America is much less abundant than that which the twenty-third-century historian will have for reproducing our view of our times. There were in the Spanish colonies no congressional or parliamentary debates, no popular orators describing social conditions and setting forth economic and political doctrines, no discussion of social programmes, and, more significant than all else, no periodical press recording from day to day and from month the events and ideas of the period in question. But in the books, the reports, and the relaciones there is a larger mass of written evidence than the comparatively rude state of colonial society would lead one to expect; and it is the purpose of this book to point out the principal documents of this colonial literature, and to introduce the reader to the men of letters in the colonies who wrote under the inspiration of their experience in the New World, whether their contributions were in the realm of poetry, history, geographical description, or ecclesiastical [viii]discussion. All this is brought together under a general title in which the term “literature” is consciously expanded from its narrower meaning to cover whatever was written on any of these general subjects; and by helping the reader to a knowledge of this literature it is believed that through it he will be enabled to acquire a more or less distinct view of the colonial society as it appeared in any period to men of that period.

It is presumed that copies of this book will fall into the hands of persons not completely versed in the Spanish language, and for this reason a somewhat broad view of Spanish accentuation has been carried out as an assistance in the pronunciation of such Spanish words and titles as it has been found advisable to introduce. It will, moreover, be noted that all titles and quotations from the texts of early colonial writers are given in modernized Spanish.

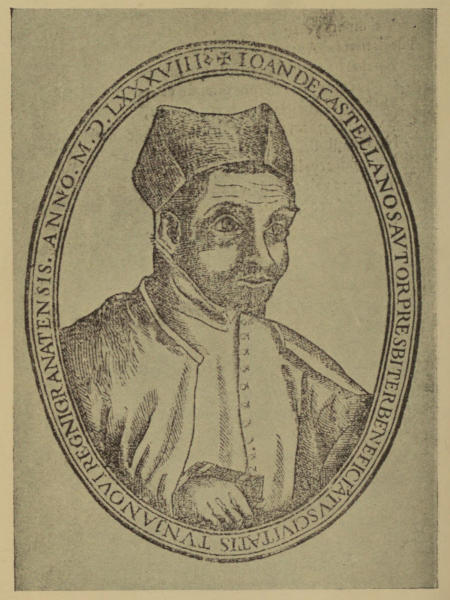

The portraits here presented help to show that the intellectual life of the colonies was not limited to a single class, but embraced friars, parish priests, and bishops; private [ix]soldiers and officers of the army; governors, judges, and viceroys.

It is not to be expected that a book covering the number and wide range of facts here included will be without errors; but there are fewer errors in this volume than would have appeared but for the valuable editorial assistance of Mr. A. H. Wykeham-George, who suggested and formed the Appendix, directed the preparation of the illustrations, and supervised the passing of the whole through the press. For that assistance I take this occasion to express my cordial appreciation; and at the same time I would gratefully acknowledge the important contribution to the undertaking rendered by Miss Janet Hunter Perry, Lecturer in Spanish at King’s College, and the very friendly and helpful attention given by the authorities of the British Museum, particularly by Dr. Henry Thomas, Assistant Keeper of Printed Books.

Bernard Moses.

Paris, June 3rd, 1922.

[x]

[xi]

| CHAPTER I | |

| Introduction | Page 1 |

| CHAPTER II Early Writers of Tierra Firme |

|

| I. Bartolomé de Las Casas. II. Gonzalo Fernández de Oviedo y Valdés. III. Pascual de Andagoya. | Page 28 |

| CHAPTER III Contemporary Accounts of the Conquest of Peru |

|

| I. Francisco de Xerés. II. Pedro Sancho. III. Tomás de San Martín; Benito Peñalosa Mondragón. IV. Pedro Pizarro; Cristóbal de Molina. V. Alonso Enríquez de Guzmán; Diego Fernández. VI. Agustín de Zárate. VII. Pedro Cieza de León. VIII. Girolamo Benzoni; Juan Fernández. | Page 59[xii] |

| CHAPTER IV Peruvian and Chilean Historians, 1550-1600 |

|

| I. José de Acosta. II. Garcilaso de la Vega. III. Pedro Sarmiento de Gamboa; Polo de Ondegardo. IV. Cristóbal de Molina; Cabello de Balboa. V. Pedro de Valdivia. VI. Alonso de Góngora Marmolejo. VII. Pedro Mariño de Lovera. | Page 102 |

| CHAPTER V | |

| Alonso de Ercilla y Zúñiga: La Araucana | Page 158 |

| CHAPTER VI Ercilla’s Imitators |

|

| I. Pedro de Oña. II. Juan de Mendoza Monteagudo. III. Fernando Álvarez de Toledo. IV. Diego de Santistevan Osorio. | Page 189 |

| CHAPTER VII | |

| Juan de Castellanos | Page 211 |

| CHAPTER VIII | |

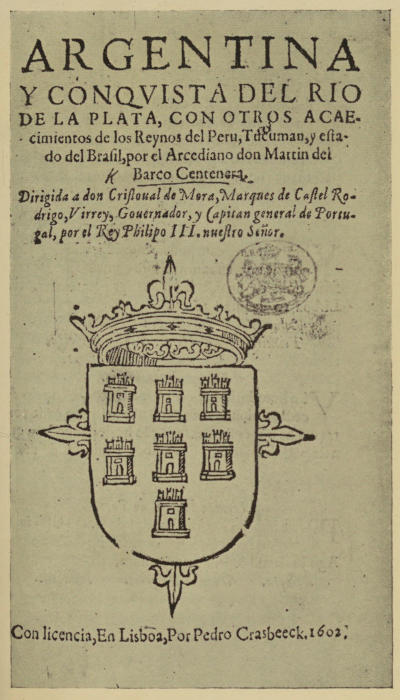

| Martín del Barco Centenera: La Argentina | Page 222[xiii] |

| CHAPTER IX Writers on Chilean History, 1600-1650 |

|

| I. Alonso González de Nájera. II. Francisco Núñez de Pineda Bascuñán. III. Caro de Torres. IV. Melchor Xufré del Águila. V. Alonso de Ovalle. VI. Miguel de Aguirre. VII. Francisco Ponce de León. VIII. Diego de Rosales. IX. Santiago de Tesillo. | Page 243 |

| CHAPTER X Writers of Peru and New Granada, 1600-1650 |

|

| I. Juan Bautista Aguilar. II. Francisco Vásquez; Toribio de Ortiguera. III. Cristóbal de Acuña. IV. Diego de Torres Bollo. V. Antonio de la Calancha. VI. Bernabé Cobo. VII. Alonso Mesía Venegas. VIII. Pedro Simón. IX. Rodríguez Fresle; Alonso Garzón de Tahuste. X. Pedro Fernández de Quiros; Gobeo de Victoria; Fernando Montesinos. | Page 288 |

| CHAPTER XI The Last Half of the Seventeenth Century |

|

| I. Juan de Barrenechea y Albis; Luis de Oviedo y Herrera; Juan del Valle y Caviedes. II. Ignacio [xiv] de Arbieto; Jacinto Barrasa; José de Buendía. III. Jerónimo de Quiroga; Anello Oliva; Diego Ojeda Gallinato; Martín Velasco. IV. Lucas Fernández de Piedrahita. V. Pedro Claver; Juan Flórez de Ocáriz. VI. Anales del Cuzco. VII. Manuel Rodríguez; Samuel Fritz. | Page 330 |

| CHAPTER XII The Early Years of the Eighteenth Century |

|

| I. Jorge Juan y Santacilla and Antonio de Ulloa. II. Alonso de Zamora; José de Oviedo y Baños. III. Joseph Luis Cisneros and Francisca Josefa de Castillo y Guevara. IV. Pedro José de Peralta Barnuevo; Juan de Mira. V. Juan Rivero; José Cassani; José Gumilla. VI. Some minor ecclesiastical writers. | Page 360 |

| CHAPTER XIII On Paraguay |

|

| I. Alvar Núñez Cabeza de Vaca; Ulrich Schmidel. II. Early Sources of Information about Paraguay; Nicolás de Techo. III. Pedro Lozano. IV. José Guevara. V. Dobrizhoffer; Pauke; Falkner; [xv] Orosz; Cardiel, Quiroga, Jolís, Peramás, Muriel, Juárez, Sánchez Labrador. VI. Juan Patricio Fernández; Matías de Anglés. | Page 395 |

| CHAPTER XIV Some Ecclesiastics and their Religious Books |

|

| I. Bishop Lizárraga. II. Bishop Luis Jerónimo de Oré. III. Bishop Gaspar de Villarroel. IV. Minor religious writers. | Page 428 |

| CHAPTER XV Government and Law |

|

| I. Melchor Calderón; Francisco Falcón; Francisco Carrasco del Saz. II. Nicolás Polanco de Santillana; Juan Matienzo; Juan de Solórzano Pereira; Gaspar de Escalona y Agüero. III. The brothers Antonio, Diego, and Juan de León Pinelo; Juan del Corral Calvo de la Torre. IV. Jorge Escobedo y Alarcón; José Rezabal y Ugarte. V. Alonso de la Peña Montenegro. | Page 460[xvi] |

| CHAPTER XVI Late Eighteenth Century Historians |

|

| I. José Eusebio Llano y Zapata. II. Miguel de Olivares; Pedro de Córdoba y Figueroa. III. José Pérez García; Vicente Carvallo y Goyeneche. IV. Geographical Description; Molina and Vidaurre. V. Dionisio and Antonio Alcedo; Zamacola; Segurola; Martínez y Vela. VI. Concolorcorvo. | Page 491 |

| CHAPTER XVII Outlook towards Emancipation |

|

| I. The intellectual movement after the expulsion of the Jesuits. II. Political Reformers. III. Poets. IV. Literary periodicals: Mercurio Peruano, Gaceta de Lima. V. Contributors to Mercurio Peruano. VI. El Telégrafo Mercantil. VII. Tadeo Haenke. VIII. El Volador. | Page 531 |

| APPENDIX | |

| A Catalogue, under Authors’ Names, of the Books mentioned in the text. | Page 585 |

| GENERAL INDEX | Page 651 |

[xvii]

| Alonso de Ercilla y Zúñiga | Frontispiece |

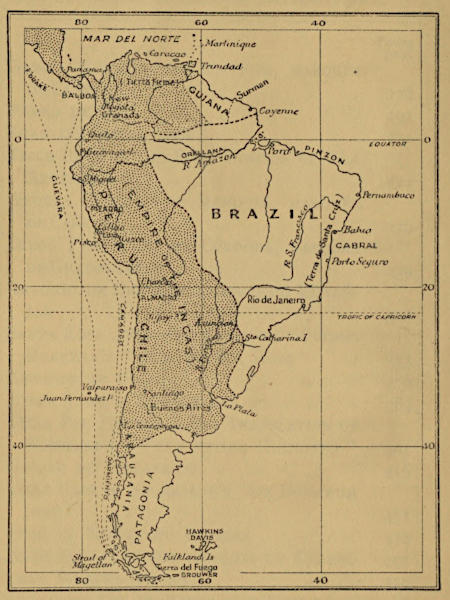

| A Map of South America | Page xx |

| Facing page | |

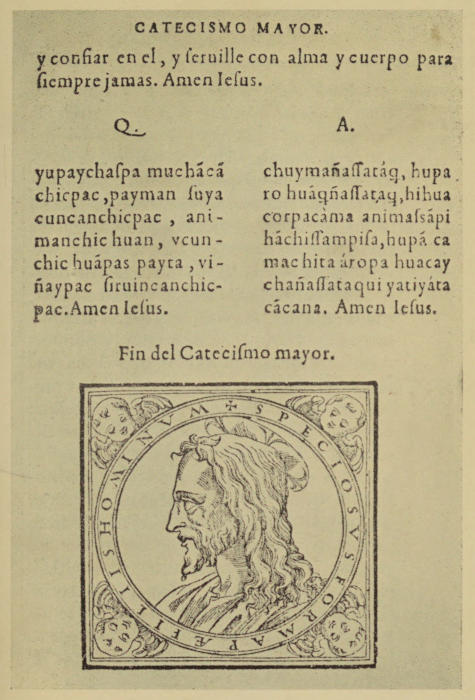

| Page from first book to be printed in South America | 6 |

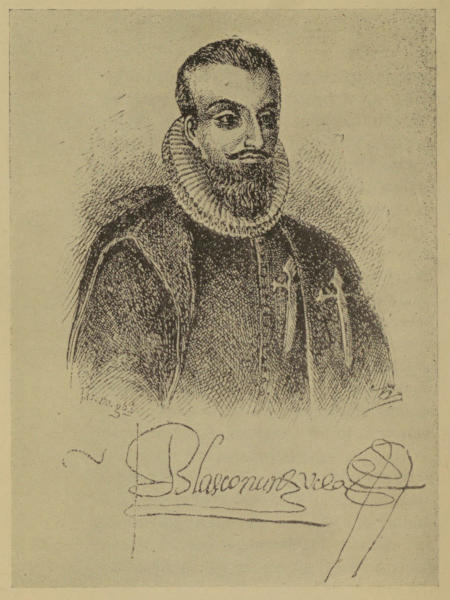

| Blasco Núñez de Vela | 11 |

| Manuel Omms de Santa Pau, marqués de Casteldosríus | 16 |

| Bartolomé de las Casas | 33 |

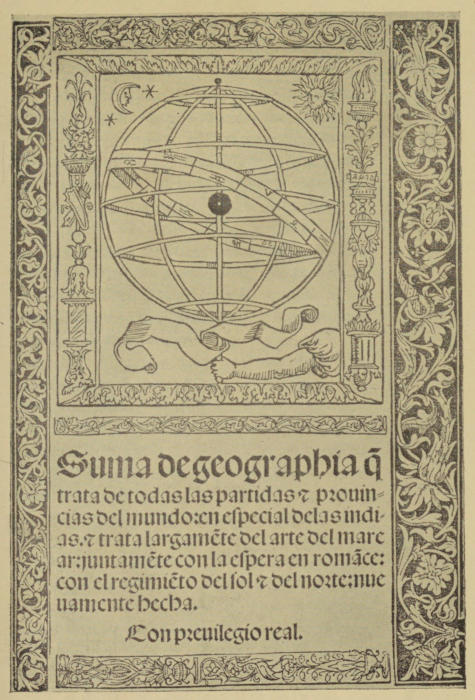

| Title Page of “Suma de Geografía” | 54 |

| Francisco Pizarro | 59 |

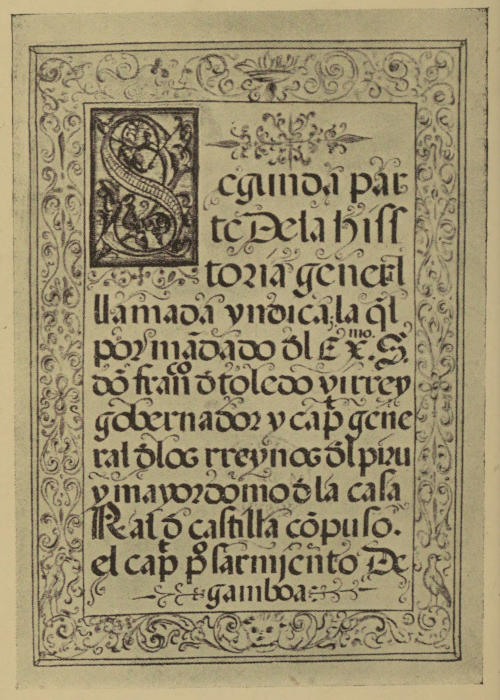

| Page from MS. of Sarmiento de Gamboa’s “Historia General” | 129 |

| Francisco de Toledo | 144 |

| Pedro de Valdivia | 147 |

| Jerónimo de Alderete | 151 |

| Francisco de Villagra | 154 |

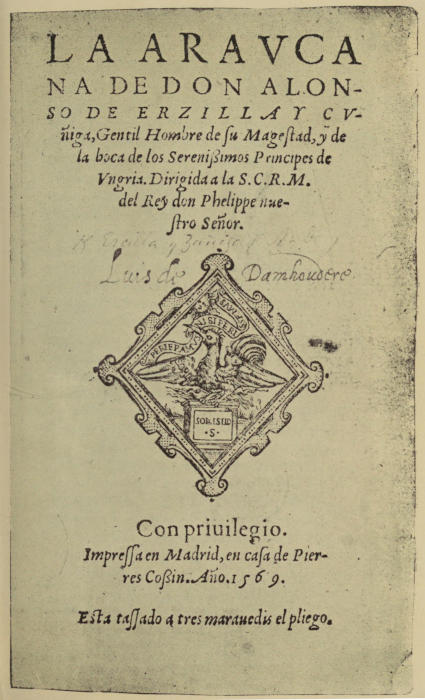

| Title Page of the First Edition of “La Araucana” | 158 |

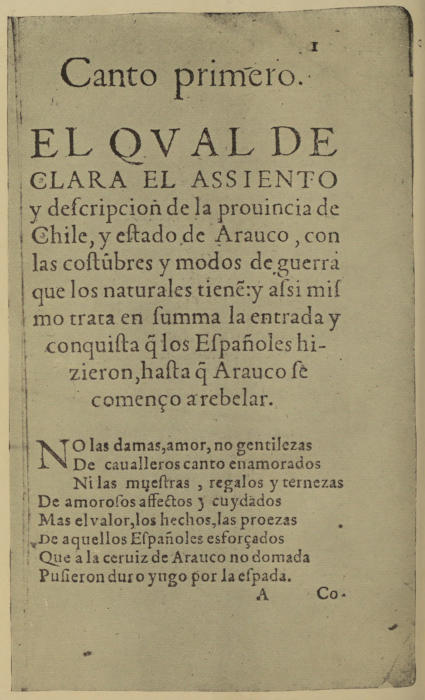

| Page from the First Edition of “La Araucana” | 165 |

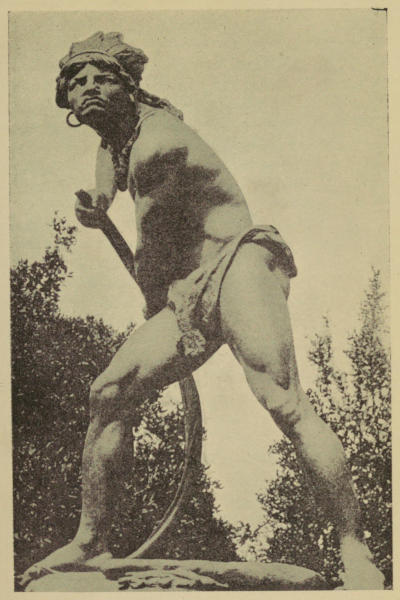

| Statue of Caupolicán | 172[xviii] |

| García Hurtado de Mendoza, marqués de Cañete | 178 |

| Pedro de Oña | 191 |

| Juan de Castellanos | 211 |

| Title Page of the First Edition of “La Argentina” | 222 |

| Andrés Hurtado de Mendoza, marqués de Cañete | 226 |

| Diego Fernández de Córdoba, marqués de Guadalcázar | 239 |

| Antonio de Mendoza, marqués de Mondéjar | 324 |

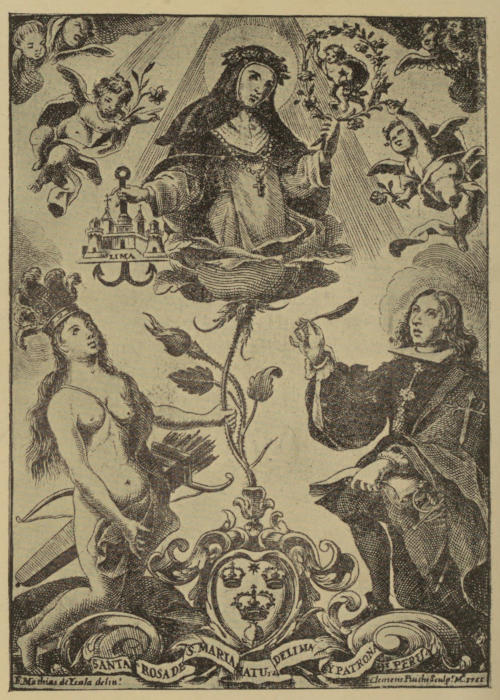

| Santa Rosa; from 1st Edition of Oviedo Herrera’s “Vida de Sta Rosa” | 333 |

| Antonio de Ulloa | 370 |

| Jorge Juan y Santacilla | 383 |

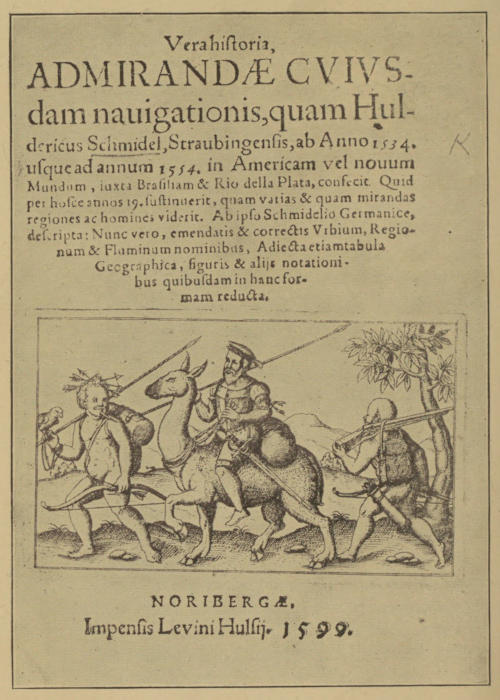

| Title Page of the Latin Translation of Schmidel’s “Warhafftige Historien” | 401 |

| Gaspar de Villarroel | 416 |

| Title Page of Solórzano’s “De Indiarum jure” | 471 |

| Juan de Solórzano Pereira | 474 |

| Ambrosio O’Higgins, marqués de Osorno | 497 |

| Juan Ignacio Molina | 512 |

| Francisco Gil de Taboada y Lemus | 558 |

[xix]

[xx]

Map of South America, showing (shaded) the Spanish Colonial Possessions

[1]

The literary activity of the Spanish Colonies in South America extended over a period of somewhat more than two hundred and fifty years, in which Spain organized and carried on her great colonial enterprise. In this undertaking the king, assisted by the Council of the Indies and the Casa de Contratación, held the colonies as royal dependencies. He was the common link between the ordinary government of Spain and the government of the Spanish possessions in America. Emigration to the colonies was controlled through the Casa de Contratación, while the Council of the Indies stood as the supreme governmental ministry. The occupation of the country was conducted largely as a material and spiritual [2]conquest, in which conspicuous parts were played by soldiers and priests, the soldiers giving to the process of colonisation the appearance of a military campaign, while the activity of the priests was supported by the idea that the acceptance of the Christian doctrine transferred the Indians from barbarism to the status of civilization.

The agencies of control in the colonial undertaking, whether military, ecclesiastical or civil, were directed from Spain. These agencies, in their final organization, were gathered into three important groups, or viceroyalties: Peru, New Granada, and Río de la Plata. The viceroy in each of these semi-independent states was assisted by a small body called an audiencia, which performed the functions both of a ministry and of a supreme court. In the several subdivisions of the territory local officers, known as corregidores, carried on a practically arbitrary administration, under which the Indians were oppressed and impoverished; and in the larger town a cabildo, or municipal council, exercised a certain [3]degree of control, when not impeded by a superior authority. Over the government and the inhabitants, in the course of time, the Inquisition extended its paralysing force; and in the presence of spies and malicious reporters men put off their intellectual independence, and either remained silent or conformed their utterances to the prescriptions of the Holy Office. This restraint naturally limited the range of ideas that found expression either orally or in writing. Authors had continually to face the possibility of seeing their manuscripts refused the privilege of publication. The subjects not liable to this embarrassment were the history of the colonies discreetly treated, the geography and natural history of the Indies, and the doctrines and history of the Church. Writings on these subjects, therefore, constitute the bulk of the colonial literature of South America.

Nature as displayed in the unspoiled wilderness of the New World attracted more attention than it had received in Spain, and writers of the history of the Indies gave much space to descriptions of their unfamiliar [4]environment. Great writers of Italy had made verse a preferred form of literature in the sixteenth century, and there is no doubt that, in addition to their example, the exaltation of spirit maintained by the unaccustomed adventures of early colonial life contributed powerfully to the extensive adoption of this form of utterance. It was undoubtedly the new and inspiring scenes and events attending the campaigns against the Araucanians that moved Ercilla to give a poetic record of his experience, in La Araucana. When Barco Centenera under similar influences undertook to write an account of the Spanish occupation of the south eastern part of the continent, the result was an “historical poem” called La Argentina; and Peralta Barnuevo’s extended history of the early development of Spanish society in Peru assumed the metrical form in Lima fundada. The form of Castellanos’ chronicle was practically determined by the success of Ercilla’s verses. And after these came a troop of chroniclers, whose verses were the product of imitation rather than the result of original inspiration.

[5]

Much that was written in the colonies has not been printed, sometimes because the manuscript was not approved by the censor, sometimes because the funds needed to cover the cost were not available, and sometimes because the manuscript was lost. The liability to loss was especially great during most of the colonial period, since manuscripts designed for printing had to be sent to Europe, and were exposed to dangers from shipwreck, the attacks of pirates, and the neglect of the persons to whom they were entrusted. It was only late that presses were established in the dependencies of South America; and even after they were provided, the quality of the work done was poor and the expense high. Printing was introduced into Mexico earlier than into South America, and it was from Mexico that Peru received its first printer. This was Antonio Ricardo, who had been a printer in Mexico for ten years. He decided to remove to Peru in 1579, but encountered serious obstacles to his proposed emigration, partly due to the fact that he was not a native of Spain. He encountered other obstacles [6]in seeking permission to undertake the business of printing in Peru after his arrival in that country. Finally, when the catechism prepared by the Jesuits at the request of the ecclesiastical council was completed, the audiencia, on February the thirteenth, 1584, decreed that Ricardo might be permitted to print it. But the work was interrupted in order to print instructions concerning corrections in the calendar, under the title Pragmática sobre los diez días del año. The authorization of this publication was given by the audiencia on the fourteenth of July, 1584, and this first product of the South American press appeared a little later. The catechism became the second publication.[1]

After this beginning the business of printing grew rapidly, in spite of the high cost of paper, receiving its principal impulse from a strong demand for primary books for schools and little manuals of devotion. News-sheets followed, issued at irregular intervals, and after twenty-five years, it became [7]customary to issue them on the arrival of ships bringing news from Spain. As early as 1621 Jerónimo de Contreras, who had been a printer in Seville, appeared as the publisher of these news-sheets; and for the next hundred years he and members of his family were the leading printers of Lima. His son, José de Contreras, succeeded him in 1641, and continued his business until 1688. Two years before this last date, in 1686, José de Contreras, a grandson of the founder of the house, organized an independent printing establishment, which held a practical monopoly of printing in Lima until 1712. The printing of books for primary instruction in the local schools brought to the head of this new establishment considerable profits, and by a decree of the crown José de Contreras acquired the title of Royal Printer. The Inquisition, the University of San Marcos, and various other institutions resorted to his press for the printing required. After the death of the Royal Printer his brother, Jerónimo de Contreras, carried on the business for a number of years, and the establishment maintained [8]itself without essential change of character until 1779.

Page from the First Book to be printed in South America

Early printing elsewhere in South America was almost exclusively the work of the Jesuits. They had a press at the mission station of Juli near Lake Titicaca, in the second decade of the seventeenth century, but it was only after about a hundred years that a press was set up in any other part of South America. In the missions of Paraguay the first book printed by the Jesuits appeared in 1705. This was entitled De la diferencia entre lo temporal y eterno, by Padre Juan Eusebio Nieremberg, translated into Guaraní by Joseph Serrano.[2]

The Jesuits established a printing press at Córdoba in connexion with the college of Monserrat, but after the expulsion of the order from South America the press was transferred to Buenos Aires in 1780. About eight years later the authorities of the college [9]felt the need of the press that had been removed, and sent Manuel Antonio Talavera to Buenos Aires to request that it might be replaced by another. The negotiations ended, however, without any immediate result.

In 1741 Alejandro Coronado, a resident of Quito, petitioned the Council of the Indies for permission to establish a printing press in that city, where previously no facilities for printing had existed. This petition was granted, and by a subsequent act of the Council this privilege was extended to his heirs, in case of Coronado’s death before the projected press had been set up. Coronado’s plan was not carried out, and nearly twenty years later the Jesuits, who had a press in Ambato, removed it to Quito at the beginning of 1760. The first printing in Quito was done on that press in the early part of that year.[3]

The beginning of printing in Bogotá is assigned to various dates. According to Vergara, the press was established there in [10]1740, but other statements maintain that there was no printing in Bogotá until 1789.[4]

The development of literature in the Spanish dependencies of South America was hindered, not only by the very imperfect facilities for printing, but also by the extremely rigid restrictions on the publication and importation of books. These restrictions were, however, an after-thought of Spanish legislation. A law of 1480, relating to the introduction of books into Spain, provided that “no duties whatsoever shall be paid for the importation of foreign books into these kingdoms; considering how profitable and honourable it is that books from other countries should be brought to these kingdoms, in order that by them men may become learned”.[5]

Blanco Núñez de Vela, 1st Viceroy of Peru

But this wise and liberal law remained valid for only a few years. It was supplanted by legislation conceived in fear of foreign influences that might threaten the traditions of the nation and the accepted [11]ecclesiastical doctrines. The new law, the law of July the eighth, 1502, was issued to prohibit the publication or sale of a book on any subject whatsoever without royal authorization, or the importation of any book except after submission to a rigorous censorship and on receipt of permission. In September, 1543, Charles V ordered the viceroys, the audiencias, and the governors to prevent the printing, selling, holding, or the bringing into their districts, of books of fiction treating of profane subjects, and to provide that neither Spaniards nor Indians should read them. This legislation was designed to prevent the publication, sale, and reading of the romances of chivalry, which were held to have a demoralizing influence on the spirit of the Spaniards. A law of 1556 provided that the judges and justices “shall not permit any book to be printed or sold which treats of subjects relating to the Indies, without having a special licence issued by the Council of the Indies; and they shall cause to be collected and shall collect and send to that body all the books which they shall find, and no printer may [12]print, hold, or sell them, under penalty of 200,000 maravedis and the loss of his printing office.” Moreover, the sending of manuscripts to Spain to be examined by the Council of the Indies was attended with very great risks; and when an American author had secured the printing of his book in Spain or in any other European country, great difficulties were encountered in his attempts to have copies of it returned to America; for it was provided by law that no printed book treating of American subjects, whether issued in Spain or in a foreign country, could be taken to the Indies until it had been examined and approved by the Council of the Indies.[6]

The inconvenience of sending manuscripts to Spain to be examined and approved or disapproved by the Council of the Indies is illustrated by Bishop Villarroel’s experience. He sent the manuscript of El gobierno eclesiástico pacífico to Spain, but the vessel carrying it was wrecked, and only by great good fortune was the manuscript saved. He sent another work in four volumes [13]to Madrid, and solicited permission to publish it. The issuing of the licence was delayed three years, and in the meantime the manuscript was lost. The legal obstacles and the practical difficulties in the way of obtaining permission to print help to explain why many manuscripts, written in America or about America, remained unpublished until after the overthrow of Spanish rule in the Indies. Even after the establishment of presses in America, the great cost of paper furnished an obstacle to their extensive use, and except in Mexico and Lima there were few printing presses until late in the colonial period.

While the Inquisition tended to destroy free intellectual activity in the Spanish colonies, the Church in other ways contributed to a certain cultivation along lines approved by itself. It helped to preserve old-world traditions in some departments of life. By the study of the Indian languages, which it encouraged, and the formation and the publication of grammars, it made public and preserved a knowledge of these languages. It, moreover, founded [14]and supported schools, that maintained the light of learning, though a feeble and fluctuating light, within a narrow ecclesiastical horizon. But all efforts in favour of liberal enlightenment were counteracted by governmental measures in opposition to the importation of books, particularly secular books of all kinds.

But the range of learning was limited. Until near the end of the colonial period instruction in the colleges and universities retained its mediæval character. The curriculum of studies embraced little, if anything, besides Latin, philosophy, and theology. Having attained proficiency in Latin the student was admitted to the courses on philosophy under the faculty of arts. After three years with this faculty he passed to the study of theology, which was continued for four, and later for five, years. The first enlargement of this curriculum was effected by the addition of jurisprudence, or Roman law. This change was not made until near the end of the eighteenth century.[7]

[15]

The expulsion of the Jesuits in 1767 was a very severe blow to scholarly and literary activity in colonial society. The Jesuits had a school or a college in every important town of the dependencies, and their instruction was clearer and more effective than that of the other schools, although one is sometimes disposed to regard their employment of a rigid mould of predetermined form, in which to cast all minds, as the greatest educational error of history. But under conditions where, outside of the chief towns, the dominating influences made either for the roughness of the camp or the brutishness of semi-barbarism, a system of instruction that trained the mind to a definite standard was not without its merits, although that standard was the inelastic standard of the Jesuits.[8]

The universities presumed a more or less extensive group of cultivated persons in the towns where they were established; and when these towns were also the principal seats of government, as were Lima, Bogotá, [16]Santiago de Chile, and Caracas, the officials of the administration formed another superior element in the population. Lima, as the viceroy’s residence, was the social capital of the dependencies. The powers of the viceroy were practically those of an autocratic ruler, during the period of his incumbency, and there were brought to Lima from Spain many of the forms and ceremonies of the Spanish court. The viceroy appeared in public with much of the state affected by European monarchs of the seventeenth and eighteenth centuries. Sometimes he used the influence of his high position to encourage learning and literary activity. The viceregal palace, in the reign of the viceroy Casteldosríus, was the meeting-place of a society where authors assembled every Monday to present their writings and discuss subjects of interest to men of letters. Dr. Pedro Peralta Barnuevo, the author of Lima fundada, was a member of this academy. But the “high society” of Lima had a lower conception of literature and literary men than the learned viceroy, and expressed regret that the [17]ancient customs and dignity of the viceregal office had been violated by the participation of the head of the state in the proceedings of a literary society. The victory of the French under Vendome over the Austrians under Starhemberg was celebrated at the palace by the production of Barnuevo’s comedy called Triunfos de amor y poder; and there were more regrets by the aristocracy that the palace of the viceroy had been turned into a theatre.

El Marqués de Casteldosríus, 24th Viceroy of Peru 1707-1710

Lima at this time, the beginning of the eighteenth century, had about seventy thousand inhabitants, Europeans, mestizos, Indians, and negro slaves. Gold and silver flowed into the city from the mines, and the buildings that were constructed after the earthquake of 1687 were superior to those which had been destroyed; they gave Lima an appearance of prosperity; they suggested a degree of luxury that had not been evident earlier. The creoles, always fond of display, sought to avoid the simplicity and rudeness of the smaller towns. They made their wealth conspicuous by their possession of paintings from Italy and Spain, by their [18]extravagant dress, and by their abundant ornaments of gold, pearls, diamonds, and other precious stones; and it is said that the nobles of Lima exceeded in luxury the aristocracy of Spain. The Peruvian capital was enlivened not only by the presence of the fifteen hundred students of the University of San Marcos, but also by a large number of convents or monasteries, in which the conflicts attending the elections of their officers often ran so high that large sections of the population became involved, and the secular authorities were called upon forcefully to interfere.

Bogotá, Caracas, Quito, Santiago, Asunción, and Buenos Aires were capitals, like Lima, but on a smaller scale. Common fundamental characteristics prevailed in all, except as these were modified by the different material interests and opportunities of the several cities. In the very small towns and in the country the Indians and the mestizos predominated, suggesting barbarism rather than civilization.

The colonial society of Spanish South America had no notion of social or political [19]equality like that entertained by the British colonists in North America, and consequently recognized marked class distinctions as a phase of the normal social order. The authorities in Spain, charged with the government of the colonies, maintained the traditional view of social inequality, and encouraged its practical development by creating a titled nobility and conferring upon encomenderos a status of superiority over their dependents not greatly unlike the relation of superior and inferior that prevailed during the period of European feudalism. Under this social order the subdued Indians became an element, naturally a subordinate element, in the composite society of the colonies, instead of drifting into irreconcilable hostility to Europeans, as happened in British North America.

An analysis of Spanish colonial society in South America would reveal a body of officials composed almost exclusively of men born in Spain, and educated in accordance with the ideas and traditions of Spain’s conservative administration. These were the viceroys, the judges of the audiencias, [20]the royal treasurers, and the corregidores, or governors of small districts. Hardly less important than the civil officials were the ecclesiastics, who were sent to the colonies by the authorities in Spain, and paid out of the royal revenues of the colonies. These members of the clergy became teachers, missionaries, and parish priests, many of whom were friars belonging to the various religious orders. A third group was composed of soldiers, who were sent from Spain for a period of four or five years, and a more or less extensive body of militia. This military force was employed in putting down insurrections, defending the frontiers and extending the dominion of the Spaniards. And it was in this group that a number of the most noteworthy writers of South America appeared.

Some of the officials, in the exercise of their practically irresponsible authority, often made illegitimate appropriations from the public funds that passed under their control; and the parish priests, in many cases, and the petty governors almost universally, extorted whatever was to be had [21]from the Indians by a systematic process of merciless oppression.

The dishonesty of officials, coupled with the fact that they were almost exclusively Spaniards, sent from Spain to occupy their posts for a few years, at length alienated the sympathies of the creoles and the mestizos from the Spanish administration. The creoles, persons of pure Spanish blood born in America, in many cases took advantage of the instruction offered in the colonial universities, and in some instances continued their studies in Spain. They became men of cultivation and sober judgment; they knew the circumstances and needs of the society of which they were members; they had a patriotic interest and an instinctive pride in their communities or commonwealths; yet they were practically barred from office, and their advice was seldom, or never, solicited. By this egoistical and stupid conduct of the government in Spain the creoles and the mestizos were thrown into an attitude of opposition; a rigid line was drawn between them and the Spaniards; and on the American side of this line the [22]creoles and mestizos formed a new society which increased in numbers and self-confidence with the passing decades. Finally, these two classes, merged into one and supported by the civilized Indians, asserted their determination to abolish Spanish domination and be independent. But throughout the two centuries and a half of colonial existence, under the influence of Spanish conservatism, the colonies remained, to a very great extent, in a state of social stagnation until near the end of the eighteenth century.

The industrial and commercial life of the colonies suffered under restrictions quite as effective as those that burdened the cause of letters. Importation to the dependencies of South America was limited by positive laws, and the exportation of certain products was made practically impossible, because they could not successfully compete with similar commodities produced elsewhere, on account of the greater cost of transportation from the western ports of South America. Agriculture was limited by the prohibitory cost of transporting its [23]products, and by the fact that the small population offered only a restricted demand for them, a demand that was insufficient to bring into cultivation the available fertile land or to employ the available labourers. This limited domestic demand and the impossibility of exporting the products constituted an effective restriction on agricultural progress; and this restriction was intensified by arbitrary governmental prohibition affecting certain branches of cultivation, notably wine and sugar. But mining for gold and silver was free from all restrictions, and the fact that the crown received one-fifth of the products was a reason for governmental encouragement of the industry. This freedom in the development of mining and the hindrances encountered by other forms of industry caused the population and the appliances of civilization to increase more rapidly in the mining regions, in the inhospitable high lands of Upper Peru, than in the fertile valleys of Chile or on the rich Argentine plains. Potosí, for instance, became a bustling city of 150,000 inhabitants before Buenos Aires and the [24]towns of Chile had emerged from the condition of dirty frontier villages.[9]

But the most effective factor in determining the character of colonial society was the spiritual inheritance from Spain. In government it was the spirit of autocracy, producing a political administration in no respect controlled by the popular will, an administration imposed by the king advised by the Council of the Indies. In matters of religion the spirit of the Spanish church passed to the colonies, and carried over to them the ecclesiastical traditions of the mother country, with no break, like that which appeared between the Puritans and the dominant Church of England. This was important for the aesthetic life of the colonies, for the artistic notions and sentiments entertained by the Church as a social body were transferred to Spanish America, and manifested their creative force in developing a somewhat original church architecture, and in elaborating the courts and interiors of secular [25]buildings. The aesthetic sense displayed in the Spanish colonies stands in interesting contrast with the Puritanic barrenness of the British colonies in artistic matters. The Spanish colonies, moreover, contained more abundant survivals of mediæval ideas and traditions, and the lines of connexion with the European past tended to maintain the colonies for many decades in a state of social stagnation. This inheritance of conservatism helped to keep alive, in at least some part of the population, the sentiment of human dignity as a force counteracting the vulgarizing and brutalizing influences that attended life on the frontier of civilization. In this attitude the persons asserting their superiority were convinced of the value of their ideas and experience, and were moved to convey to posterity their opinions and a knowledge of the organization and growth of the colonial communities in which their lives were passed.

In considering the volume of literary production in the Spanish dependencies in comparison with the inferior amount produced in the British colonies, one must take account [26]of two important facts bearing on this subject. In the first place, there was in the Spanish colonies a very large number of men, soldiers and priests, who derived their support from the state, and were thus relieved from the necessity of acquiring a livelihood by their personal efforts or by expending mental energy in forming plans, and in executing them by the employment of their time and force. In the second place, a relatively large number of men in the Spanish colonies were celibates, and consequently their time, their thoughts, and their energies were not absorbed in providing for the current wants of families, or in accumulating property to be passed as an inheritance to a succeeding generation. In the British colonies there was practically no subsidized class; and every man was interested in providing for a family and in accumulating property for the benefit of his heirs. This was the absorbing thought of the British colonists as they pressed back the aborigines and advanced upon the wilderness. They, moreover, conceived the affairs of the colonies as their own affairs [27]and felt no need of sending elaborate reports to the king, or of writing geographical descriptions and historical narratives for the enlightenment of the nation they had abandoned. They were content with a minimum of communication with the mother country. The Spanish colonies, on the other hand, lived by their connexion with Spain and by action of the Spanish government.

The intellectual class of Spain had more interest in the American possessions than was manifested by any class in Great Britain with respect to the British colonies; and this superior interest of Spaniards constituted a demand for information concerning the New World, which encouraged persons in Spanish America by their writings to meet this demand.

These introductory suggestions help to explain the remarkable literary activity in the colonies during the period under consideration.

[28]

I. Bartolomé de las Casas. II. Gonzalo Fernández de Oviedo y Valdés. III. Pascual de Andagoya.

The letters and reports of the adventurers, the discoverers, and the early settlers, during the period of exploration and conquest, constitute a noteworthy introduction to the literary history of the Spanish colonies in America; and the intellectual vigour of some of these writers was quite in keeping with the practical energy and daring displayed by their Spanish contemporaries in exploring and subduing the wilderness.

The extension of the Spanish occupation from Santo Domingo, as an early seat of the administration, to the South American [29]mainland, belongs to the first decades of the sixteenth century. During this period the Spaniards founded Santa Marta and Cartagena; explored and occupied the Isthmus; and Andagoya established his brief authority on the Pacific coast south of Panama.

It was in this period, moreover, that the Spanish government granted to the German company of the Welsers a charter to an extensive region of Tierra Firme, where the agents of this company devoted their activity, almost exclusively to hunting Indians for the slave-market. On a part of the northern coast of South America Bartolomé de las Casas proposed to plant a proletariat colonial administration as the beginning of a practical reform of Spain’s colonial policy. When this enterprise was wrecked by its internal weakness, Las Casas turned to the business of the Church and to unsparing criticism of the Spanish government. On its practical side the conduct of the government doubtless required modification, but the plan to introduce Spanish labourers and negroes to perform all the work of the colony, if it had been thoroughly [30]and successfully carried out, would indeed have lifted the burden of labour from the Indians, but it would also have made it impossible for the Indians to have a place in the new society. The performance of a certain amount of work was an essential condition of the Indian’s existence in regions occupied by the Spaniards. He had to work or disappear, as he disappeared before the British settlers in North America, who made no provision for incorporating him in the communities which they organized. The Spaniards had a very different plan for the social development of their American colonies. They proposed to form communities with important mediæval features; they recognized distinct classes and feudal superiority and dependence. This method of social organization provided a place for the Indians, although a subordinate place, nevertheless a place where their continued existence would be assured on condition of performing a certain amount of labour. But when Las Casas faced the question of reforming the Spanish policy, he appears to have advocated, if not the worst possible [31]solution, at least a project that could have had no happy outcome for the Indians.

The facts of Las Casas’ life hardly need to be recited here. His prodigious defence of the Indian’s right to liberty has made him widely known and given him an exalted position in the estimation of those in sympathy with his purposes. He was born in Seville about eighteen years before the discovery of America: the date of his birth is usually set down as 1474. His studies, begun in his native city, were continued at Salamanca, where he was graduated as “Licenciado”. His first knowledge of the Indians appears to have been obtained through one who had been brought from America to Spain by his father, and was attached to Bartolomé at the University in the capacity of a servant. Las Casas went to the West Indies with Nicolás de Obando, governor of Santo Domingo. This was in 1502. In 1510 he became a priest, and a year later he accompanied Governor Velásquez to Cuba. In these nine years he witnessed certain acts of barbarity by the Spaniards, which seemed to presage the [32]diminution of the native population, and intensified his sympathy for the oppressed race.

In the islands, on the mainland, or as Bishop of Chiapas, one dominating purpose controlled his actions, it was to ameliorate the condition of the Indians, and, in planning for their welfare, the welfare of no other race mattered. Las Casas’ ideal of the Indians, which helped to inspire his zeal for their liberty is set forth in this passage from the Brevísima relación:

“All the territory that has been discovered down to the year forty-one is full of people, like a hive of bees, so that it seems as though God had placed all, or the greater part, of the entire human race, in these countries. God has created all these numberless peoples to be the simplest, without malice or duplicity, the most obedient, the most faithful to their natural Lords, and to the Christians, whom they serve, the most humble and patient, the most peaceful and calm, without strife or tumults, nor wrangling or querulous, as free from rancour, hate, and desire for revenge as any in the [33]world. They are likewise the most delicate people, weak and of feeble constitution, and they are less able than any other to bear fatigue, and they succumb readily to whatever disease attacks them, so that not even the sons of our princes or nobles, brought up in luxury and effeminate ways, are weaker than they; although there are among them some who belong to the class of labourers. They are also very poor people, who have few worldly goods, nor wish to possess them.”

Bartolomé de Las Casas

It was beings answering to this ideal that fascinated Las Casas, and a large part of the civilized world has been disposed to honour him for his marvellous service in the interest of an oppressed and outraged people; but when his eulogists announce him as the champion of universal human liberty, they make too large a claim. A champion of the liberty of the Indians he surely was, a champion of rare devotion and unflagging zeal, but with little concern as to the social cost of securing that liberty by his method. He was, moreover, so thoroughly absorbed in his own ideas and plans that he had no mind [34]to consider the ideas and plans of others, or to deliberate with other persons in an attitude of possible compromise. He did not hesitate to seek with unslacking energy the execution of his plan, even when he was aware that it involved extending negro slavery, with all the horrors of the transoceanic shipment of slaves.

Las Casas’ project to introduce Spaniards into America to undertake the common work which the Indians were required to perform, or to throw the burden upon negroes, necessarily ran counter to the views of those Spaniards to whom Indians had been assigned by the government in Spain, and who depended upon the labour of the Indians to cultivate the lands that had been granted to them, to work their mines, and to carry on their manufacturing enterprises. The encomenderos had come to regard themselves as the foundation of the economic system of the colonies, and they naturally considered the government under obligation to defend them against attacks designed to destroy that system. But Las Casas had enthusiastic partisans, who praised [35]extravagantly his devotion to the Indian and were apparently blind to the consequences of extending negro slavery with respect to the development of society in America. The intense hostility displayed towards Las Casas in the colonies did not proceed solely from his proposed interference with the interests of the encomenderos, but was in a large measure provoked by his reckless denunciation of opponents.

The views set forth in Brevísima relación de la destrucción de las Indias found an enthusiastic reception, particularly in England, promoted by the political friction existing between that country and Spain, and by the rage of militant Protestantism, which found in Las Casas’ denunciation at least a partial expression of its own detestation of Catholicism and of all measures favoured by the Pope. The titles given to translations of the Brevísima relación are evidence of the force of that sentiment.[10]

[36]

This pamphlet was published in 1552, and aroused in the minds of some of the Spaniards an opposition only a little less marked than the favour with which it was received by the English. Bernardo de Vargas Machuca was one of those who rose to combat the views presented by Las Casas. His refutation appeared in Apologías y discursos de las conquistas occidentales. On the title-page of this pamphlet the author announces that it is written “in opposition to the treatise on the ruin of the Indies.”[11] [37]The question concerning the servitude or the freedom of the Indians raised by Las Casas was discussed by a professor in the University of Córdoba, who wrote Fasti novi orbis under the name of Cyriacus Morelli. His book was published in Venice in 1776. Dr. Juan Ginés de Sepúlveda, a distinguished Spanish theologian and jurist, opposed vigorously the ideas presented by Las Casas, and argued in support of the Spanish policy regarding the Indians. A similar attitude was assumed by Gonzalo Fernández de Oviedo, whose education at the Spanish court, and whose later service under appointment by the king naturally disposed him to justify the conduct of the government. This subject continued to engage the attention of writers as long as the Spanish régime lasted. A work by Giovanni Nuix translated from the Italian by Pedro Varela y Ulloa, entitled in Spanish Reflexiones imparciales sobre la humanidad [38]de los españoles en las Indias, contra los pretendidos filósofos y políticos, was published in Madrid in 1782. The writer characterized the views of Las Casas as false or exaggerated, and defended the thesis that the conquests made by the Spaniards in America were just, or at least as just as those made by other nations; and he attributed whatever covetousness or cruelty was displayed by the Spaniards to the great distance of the colonies from the supreme authority, under which local officers served in the colonies without adequate supervision. He distinguished clearly, moreover, between the benevolent designs of the crown and the unjust and cruel acts of governmental subordinates and irresponsible private persons.

Besides the Brevísima relación a number of other pamphlets were printed in 1552 and 1553, but the more important of Las Casas’ writings remained in manuscript until long after the author’s death. These are the Historia general de las Indias and Historia apologética de las Indias, apparently designed in the beginning to constitute [39]a single work; but in the process of their composition, the character of each became more and more distinct, and they finally appeared in print as separate productions. The former is an account of the occupation of the West Indies and the mainland during the early years of Spanish rule, describing the condition of the native inhabitants, their mental state and their customs, with special emphasis on the treatment they received under the Spanish administration; the latter, the Historia apologética de las Indias, treats of the character of soil and climate of the occupied lands, of the natural and social position of the inhabitants, but does not contain a narrative of the events incident to the establishment and progress of Spanish settlements. Like other writers of his time, and even of later times, Las Casas faced the problem of the relation of the different races to one another, and of the capacity of the less developed race to rise to the highest form of civilization, and, like most of his countrymen, he regarded the fundamental difference between the races as consisting in the [40]fact that the Spaniards were Christians, while the Indians were pagans, and that the conversion and baptism of the Indians necessarily removed the main feature of difference, and transferred the Indian from the status of barbarism to civilization. But one-remedy reformers have not been found merely among Spanish missionaries. When the government of the United States conferred the right of suffrage upon the emancipated negro slaves, this action was supported by the extravagant expectation that the possession of this right would exercise a transforming influence on the quality of the subject. This hopeful view of the missionary’s work was doubtless the principal source of Las Casas’ inspiration; it was also the source of his intolerance.

The King and the Council of the Indies, in granting lands to Spaniards establishing themselves in America, and distributing Indians among them to become labourers on these lands, had as one of their purposes an end not greatly different from the object of the missionary’s striving. They hoped that by gathering the Indians on these [41]estates to make them immediately subject to Christians who would be required to provide opportunities and facilities for the Indians to acquire a knowledge of Christian doctrine. Thus one of the features of the colonial organization against which Las Casas directed his vehement eloquence was in some part the product of a design formed to further the conversion of the Indians. If it did not attain its high aim or respond to the exalted purpose of Las Casas, it failed for the same reason that some of Las Casas’ plans had failed: it was conceived in imperfect knowledge of American conditions, and was entrusted for execution to selfish, in other words, human agents.

An attempt less radical than that of Las Casas to improve Spain’s colonial administration was made by Gonzalo Fernández de Oviedo y Valdés, author of the Historia general y natural de las Indias. Although Oviedo’s posthumous fame rests almost exclusively on his writings, his reputation during his lifetime was based chiefly on his [42]practical activity. A contemporary of Las Casas, he was born in Madrid in 1478, and very early entered the service of Don Alfonso de Aragón, the second duke of Villahermosa, a nephew of King Ferdinand. Here his early years were spent under the influence of persons interested in literary cultivation, and where the circumstances tended to stimulate his natural intelligence. At the age of thirteen he became attached to the court of the Catholic Kings as a page. Two years later the sovereigns entered upon the campaign against Granada, and Gonzalo followed the Court to Santa Fe. There as a youth he saw some of Spain’s most distinguished men of the time. He saw Columbus, whose distinction was yet to be won, and who appeared asking assistance to enable him to find a new world.

After the death of Prince Juan, on October the fourth, 1497, Oviedo visited Italy, where the art and literature of that country exerted a powerful influence on his intellectual development. In 1500, after three years of varied service, he appeared at Rome, claiming the jubilee indulgence granted to the [43]faithful by the Pope. Subsequently he entered the service of the King of Naples, but in 1501 he left Naples in the train of Queen Juana for Palermo, and in May, 1502, he left Palermo for Valencia, where he took leave of the Queen’s service and went to Madrid. In Madrid he married Margarita de Vergara, who died ten months later. Under the impression of this loss, he turned to service in the army, but he soon abandoned his plans for a military career, and became again attached to the court. Shortly after Oviedo’s return to the court, preparations were made for the expedition of Pedrarias Dávila to Castilla de Oro, and he was appointed to inspect the production of gold in Tierra Firme.

The fleet sailed from San Lucar on April 11, 1514, and arrived at Santa Marta on the following 12th of June. At the end of June the company reached the gulf of Urabá, and proceeded to Santa María del Antigua, where they found the colony overwhelmed in misfortune, now rendered more distressing by the tyranny and cruelty of Pedrarias. Oviedo, out of favour with the [44]authorities, returned to Spain to seek a remedy for the state of things he had observed. After years of waiting to have his memorial considered by the court, he encountered at Barcelona Bartolomé de las Casas, who was present on a somewhat similar mission. They both sought reform in the Indies, but with divergent views. Oviedo contemplated a reform in Darien through the efforts of a wise and just governor and a bishop devoid of covetousness, who would aim effectively at holding the clergy under proper regulations. Las Casas, on the other hand, a religious anarchist, advocated removing the governors, the captains, and the soldiers from the Indies, agreeing to maintain the territory of Cumaná in the power of the crown without other instrumentalities than a few hundred simple labourers and fifty knights of the cross.

In April, 1520, Oviedo embarked at Seville on his second voyage to America. Learning at Santo Domingo that Lope de Sosa, who had been appointed through his influence to supersede Pedrarias, had died on the outward voyage, Oviedo had little [45]reason to expect that friendly relations would be established between himself and Pedrarias, and, in spite of the courteous reception extended to him, he discovered very early that his anticipations were realized. In fact, the governor’s hostility appears to have been one of the influences that led Oviedo to abandon Antigua for Panama and to induce the colonists to remove to the new capital. Pedrarias’ hostility and his desire to compromise and ruin the prestige of Oviedo, moreover, led the governor to appoint him to be his lieutenant or deputy.

The efforts of Oviedo to abate the evils of the colony only intensified the hostility of the governor and his supporters and led him to withdraw the deputy’s appointment. Oviedo then, in 1523, returned to Spain to call the king’s attention to the scandalous conduct of Pedrarias. The part of his voyage between Santo Domingo and the Peninsula was made in company with Diego Columbus. The charges presented specified with much detail the abuses and crimes of the governor; they were made not for the redress of personal wrongs Oviedo had [46]suffered, but to preserve the colony from utter corruption and destruction; and, in spite of the vigorous attempt made to reply to them, Pedrarias was superseded by Pedro de los Ríos as governor of Castilla de Oro. Oviedo, not content to leave his proposed reform half accomplished, offered his services to the new governor, and embarked with him for America on the 30th of April, 1526. It was in this year, 1526, that he published by order of the emperor at Toledo his Sumario de la natural historia de las Indias, a work quite distinct from the larger work issued later under a similar title. Oviedo arrived at Nombre de Dios on the 20th of July. After four years of varying fortune in Castilla de Oro, Nicaragua, and Santo Domingo he returned again to Spain in 1530. Wishing to be relieved of the duties of his office as inspector of gold-smelting, he presented his resignation, and petitioned that his son might be appointed to succeed him. Not only was the petition granted, but the emperor appointed him General Chronicler of the Indies.

After his experience in the warmer regions [47]of America, he no longer found the climate of Spain agreeable, and in the autumn of 1532 he returned to the New World, establishing himself in the city of Santo Domingo. Here the citizens showed their appreciation of his decision, and on the death of Francisco de Tapia, the alcaide, or governor of the fortress of the city, petitioned for the appointment of Oviedo to the vacant post. This petition was granted, and the appointment was confirmed by a decree dated October 25, 1533.

In 1534 Oviedo went to Spain, published the first part of his Historia general y natural de las Indias, the printing of which was completed on September 30, 1535. In the following January he was once more in Santo Domingo. From this time forward the practical affairs of his office as alcaide engaged much of his attention. The fort had fallen into decay through neglect, and the increasing danger of pirates and the new wars into which Spain was plunged induced Oviedo to solicit from the King and the Council of the Indies more effective artillery and other means for making the defence [48]more complete. At the same time stories of Pizarro’s exploits began to arrive from Peru, and the affairs of the island were thrown into confusion by emigration to that country. The tales of great wealth acquired by the invaders had the effect of news from newly discovered gold mines.

As Oviedo approached the end of life, he turned to Spain as his final residence, in spite of his lively interest in the New World. He therefore resigned his office of alcaide, retaining the post of honorary regidor of Santo Domingo. In June, 1556, he took final leave of America, where he had resided thirty-four years, and during this period had crossed the Atlantic at least twelve times.

During these last years his efforts were directed chiefly to giving to the world a complete and corrected edition of his Historia general y natural de las Indias. The printing was begun, but before it was finished the author succumbed to an acute fever at the age of seventy-nine. The undertaking was interrupted, and it was only after nearly three hundred years that the complete [49]work appeared in print. The whole work was originally divided into three parts comprising fifty books. The first part published during his lifetime consisted of nineteen or nineteen and a half books. In 1557 the twentieth book was printed separately in Valladolid, but the rest of it remained in manuscript until the publication of the complete edition issued by the Academy of History in the middle of the nineteenth century. Oviedo wrote as the authorized chronicler of the Indies, and in this capacity he had access to official documents. His other works deal chiefly with the affairs of the Peninsula. Harrisse reports the existence of two collections of Oviedo’s letters and diaries, and suggests the desirability of their publication. In referring to this principal work of Oviedo Las Casas manifests his ruling passion in affirming that Oviedo should have written at the top of his history: “This book was written by a conqueror, robber, and murderer of the Indians, whole populations of whom he consigned to the mines, where they perished.”[12]

[50]

The first chapter of the Sumario presents a description of the navigation between Seville and America. A number of the following chapters are devoted to the Indians of the islands and Tierra Firme, and these are followed by a series of chapters enumerating and describing the animals, birds, reptiles, trees, and other living things, succeeded by an account of mines and pearl-fishing. Of this latter business Oviedo gives a brief account:

“It is off Cubagua and Cumaná that pearl fishing is chiefly carried on, as I have been fully informed by Indians and Christians, who say that many Indians go from the island of Cubagua. These belong to crews in the service of private persons, residents of Santo Domingo and San Juan. They go out in a boat or barge in the morning, in companies of four, five, six or more, [51]and when it seems to them, or they know already, that there are pearls at the point they have reached, they stop there, and the Indians dive into the water and swim until they reach the bottom; one remains in the boat, which he holds in place as well as he can, waiting for those in the water to appear, and after the Indian has been down a long time, he comes to the surface and is taken into the boat, presenting and putting into it the oysters which he has brought up, for in the oysters are found the valuable pearls. He rests a little, eats a mouthful, and then enters the water again, and stays as long as he is able, and again comes up with the oysters which he has found this time and does as before, and in this manner all the rest proceed who are divers in this operation. And when night comes, and it appears to be time to rest, they go home to the island, and turn over the oysters to the major domo of the proprietor, who has charge of the Indians, and who gives them their supper, and places the oysters in a receptacle, and when he has a large number of them, he causes them to be opened, and in [52]them are found pearls of two, three, four, five, six or more grains, as nature has placed them there.”

This quotation from Oviedo’s Sumario offers a glimpse of an occupation, which sooner or later proved fatal to immense numbers of the Indians forced into it. Many of those engaged in pearl-fishing were compelled to re-enter the water before they had recovered their normal condition after a previous descent, and either never returned to the surface alive, or returned hopelessly exhausted. But in connexion with this account our author makes no mention of the perilous and destructive character of the work, through which the population of the islands and the neighbouring coast was greatly depleted. Doubtless Oviedo wished to reform abuses in the colonies, but his relation to the court and his part in the public administration naturally rendered him reluctant to make conspicuous in his writings the abuses that were brought to his attention. The presence of these abuses produced in his mind a very different reaction from that observed in the fiery spirit of Las Casas.

[53]

The reference, in the Brevísima relación, to the pearl fishing described by Oviedo reveals the contrast between Las Casas’ lively sympathy with the Indians and Oviedo’s unconcern and official indifference:

“The tyranny exercised by the Spaniard upon the Indians in fishing pearls is as cruel and damnable a thing as can be found in the world. On land there is no life so desperate and infernal in this century that may be compared with it, although that of digging gold in the mines is in its kind exceedingly severe and difficult. They let the Indians down into the sea, three and four and five fathoms deep, from the morning till sunset, where they are swimming under water without respite, gathering the oysters in which the pearls grow; they come up to breathe, bringing up little nets full of oysters. There is a very cruel Spaniard in a boat, and if they linger resting, he beats them with his fists, and, taking them by the hair, throws them into the water to go on fishing.... Their food is fish, and the fish that contain the pearls, and a little cazabi, or maize bread, which are kinds of [54]native bread; the one gives very little sustenance, and the other is very difficult to make, so with such food they are never sufficiently nourished. Instead of giving them beds at night, they put them in stocks on the ground to prevent them from running away.

“Many of the Indians throw themselves into the sea while fishing or hunting for pearls, and never come up again, because dolphins or sharks, which are two kinds of very cruel sea animals that swallow a man whole, kill and eat them.... With this insupportable toil, or rather infernal trade, the Spaniards completed the destruction of all the Indians of the Lucayan Islands, who were in the islands when they set themselves to making these gains.”

A number of persons who became especially conspicuous in colonial affairs, besides Oviedo, accompanied Pedrarias on his expedition to the Isthmus. Among these were Bishop Quevedo; Enciso, some time governor of Darien and author of Suma de [55]geografía; Benalcázar, who became governor of Popayán; Hernando de Soto; and Pascual de Andagoya, whose varied experience and the events associated with Pedrarias form the matter of a document which has been translated into English by Sir Clements R. Markham. The title of Markham’s translation is Narrative of the proceedings of Pedrarias Dávila in the provinces of Tierra Firme, or Castilla del Oro, and of what happened in the discovery of the South Sea, and the coasts of Peru and Nicaragua.[13]

Title page of Fernández de Enciso’s “Suma”

Andagoya, the author of this narrative, was born in the valley of Cuartango in the province of Alava. The account of his life as narrated by himself begins with his departure from Spain. On the Isthmus and in regions lying north and south of Panama, he was engaged in various exploring expeditions, during which by observation he appears to have acquired much knowledge of the manners and customs of the Indians. A weaker and less positive character than Oviedo, he was consequently less [56]disposed than Oviedo to revolt against the régime of Pedrarias; in fact, he went with him to Panama, and received from him an encomienda, and became one of the first regidores of Panama, after that settlement had been declared a city. In 1521 and 1522 he was inspector-general of the Indians on the Isthmus. He was the first to receive information concerning the Inca Kingdom of Peru, but, lacking the health, perhaps also the initiative, to become the leader of an expedition against it, he communicated his knowledge to Pizarro and his partners.

“In this province (Birú) I received accounts both from chiefs and from merchants and interpreters, concerning all the coast, and everything that has since been discovered, as far as Cuzco, especially with regard to the inhabitants of each province, for in their trading these people extend their wanderings over many lands. Taking new interpreters, and the principal chief of that land, who wished of his own accord to go with me, and show me other provinces of the coast that obeyed him, I descended to the sea. The ships followed the coast at [57]some little distance from the land, while I went close in, in a canoe, discovering the ports. While thus employed, I fell into the water, and if it had not been for the chief, who took me in his arms and pulled me on to the canoe, I should have been drowned. I remained in this position until a ship came to succour me, and while they were helping the others, I remained for more than two hours wet through. What with the cold air and the quantity of water I had drunk, I was laid up next day, unable to turn. Seeing that I could not now conduct this discovery along the coast in person, and that the expedition would thus come to an end, I resolved to return to Panama with the chief and interpreters who accompanied me, and report the knowledge I had acquired of all that land.

“The land had never been discovered either by Castilla de Oro, or by way of the gulf of San Miguel, and the province was called Pirú, because one of the letters of Birú has been corrupted, and so we call it Pirú, but in reality there is no country of that name.

[58]

“As soon as Pedrarias heard the great news which I had brought he was also told by the doctors that time alone could cure me, and in truth it was fully three years before I was able to ride on horseback. He therefore, asked me to hand over the undertaking to Pizarro, Almagro, and Father Luque, who were partners, in order that so great a discovery might be followed up, and he added that they would repay me what I had expended. I replied that, so far as the expedition was concerned, I must give it up, and that I did not wish to be paid, because if they paid me my expenses, they would not have sufficient to commence the business, for at that time they had not more than sixty dollars. Accordingly, these three, and Pedrarias, which made four, formed a company, each partner taking a fourth share.”[14]

Francisco Pisarro

[59]

I. Francisco de Xerés. II. Pedro Sancho. III. Tomás de San Martín; Benito Peñalosa Mondragón. IV. Pedro Pizarro; Cristóbal de Molina. V. Alonso Enríquez de Guzmán; Diego Fernández. VI. Agustín de Zárate. VII. Pedro Cieza de León. VIII. Girolamo Benzoni; Juan Fernández.

The especially important event in South America in the first half of the sixteenth century was the conquest of Peru. If the story as it has been frequently told has exaggerated somewhat the magnificence of the kingdom destroyed, this presentation has only perpetuated the impression made on the Spanish mind by contemporary rumours [60]and reports. These reports and rumours inspired and kept alive for many decades the hope of finding other kingdoms equally wealthy, by the spoils of which the conquerors might be enriched.

Until the discovery of the Pacific and the voyage along the western coast, knowledge of America had been only very slowly increased, and in this process no especially startling statements had been received in Europe. But reports that an empire had been discovered, that the emperor had been captured, and that his subjects had offered untold amounts of gold and silver as his ransom, fired the imagination of the Spaniards and appealed to their cupidity. After this the business of exploration and conquest moved with greater rapidity. The number of persons in Spain wishing to emigrate or to join expeditions bound for the New World increased, and the settlements already established in the islands lost a large part of their inhabitants, carried away to Peru by the desire for adventure and the wealth to be obtained; and the eagerness to get information from America was greatly [61]intensified. Reports and letters sent from Peru to satisfy this demand tended to augment the popular excitement, and in so far as they have been preserved they constitute an important part of the historical record of Pizarro’s enterprise in Peru. Those that were directed to the King or the Council of the Indies concerning the events of the conquest were usually deposited in the archives, and only a part of them have come to light. Among documents of this class belong some of the contemporary accounts of the conquest of Peru. Francisco de Xerés, the writer of such a document, was Pizarro’s secretary, who left Spain in January, 1530. His account was written in Peru at the request or by the order of Pizarro. He returned to Spain in July, 1534, and his report was printed in Seville in that year. Three years later a second edition was printed in Salamanca. The edition most frequently referred to is that of 1749. Xerés was an actor in, or a witness of, the remarkable events which he describes, and his narrative has the freshness and vividness of a story by one writing of what he saw. The [62]Hakluyt Society included a translation of it into English in a volume entitled Reports on the Discovery of Peru. This volume contains also a translation of Hernando Pizarro’s letter to the audiencia of Santo Domingo. This letter gives a summary of the events of the conquest prior to November, 1533. There is given here, moreover, a translation of Miguel de Astete’s report on Hernando Pizarro’s expedition to Pachacamac.[15]

The paragraph describing the capture of Atahualpa may serve as an illustration of Xerés’ style of narration:

“Then the Governor put on a jacket of cotton, took his sword and dagger, and, with the Spaniards who were with him, entered amongst the Indians most valliantly, and, with only four men who were able to follow him, he came to the litter where Atahualpa was, and fearlessly seized him by the arm, crying out ‘Santiago.’ Then the guns were fired off, the trumpets were sounded, and the troops, both horse and [63]foot, sallied forth. On seeing the horses charge many of the Indians who were in the open space fled, and such was the force with which they ran that they broke down part of the wall surrounding it and many fell over one another. The horsemen rode them down, killing and wounding and following them in pursuit. The infantry made so good an assault upon those who remained that in a short time most of them were put to the sword. The governor still held Atahualpa by the arm, not being able to pull him out of the litter because he was raised so high. Then the Spaniards made such a slaughter among those who carried the litter that they fell to the ground, and, if the governor had not protected Atahualpa, that proud man would there have paid for all the cruelties he had committed. The governor, in protecting Atahualpa received a slight wound in the hand. During the whole time no Indian raised his arms against a Spaniard. So great was the terror of the Indians at seeing the governor force his way through them, at hearing the fire of the artillery and beholding the charging [64]of the horses, a thing never before heard of, that they thought more of flying to save their lives than of fighting. All those who bore the litter of Atahualpa appeared to be principal chiefs. They were all killed, as well as those who were carried in the other litters and hammocks. One of them was a page of Atahualpa and a great lord, and the others were lords of many vassals and his counsellors. The chief of Caxamalca was also killed, and others; but, the number being very great, no account was taken of them, for all who came in attendance on Atahualpa were great lords. The governor went to his lodging with his prisoner Atahualpa despoiled of his robes, which the Spaniards had torn off in pulling him out of the litter. It was a very wonderful thing to see so great a lord taken prisoner in so short a time, who came in such power.”