The Cowboy and the Lady and Her Pa

The Gatlings threaded the trail like so many plodding ants and saw enough landscapes to fill all the souvenir post-card racks of the world.

The Gatlings threaded the trail like so many plodding ants and saw enough landscapes to fill all the souvenir post-card racks of the world.

From up on the first level of the first shelf of the wagon road above Avalanche Creek came the voice of Dad Wheelis, the wagon-train boss, addressing his front span. The mules had halted at the head of the steep grade to twist about in the traces and, with six ’cello-shaped heads stretched over the rim and twice that many somber eyes fixed on the abyss swimming in a green haze beneath them, to contemplate its outspread glories while they got their wind back. It became evident that Dad thought the breathing space sufficiently had been prolonged. On a beautiful clearness his words dropped down through the spicy dry air.

“Git up!” he bade the sextet with an affectionate violence, and you could hear his whip-lash where it crackled like a string of firecrackers above the drooping ears of the lead team. “Git up, you scenery-lovin’ so-and-soes!”

There was an agonized whine of tires and hubs growing faint and then fainter and Mrs. Hector Gatling sighed with a profound appreciation. “How prodigal nature is out in these Western wilds!” she said.

“Certainly does throw a wicked prod,” agreed her daughter, Miss Shirley Gatling. But her eyes were not fixed where her mother’s were.

“Such a climate!” affirmed the senior lady, flinching slightly that the argot of a newer and an irreverent generation should be invoked in this cathedral place. “Such views! Such picturesque types everywhere!”

“Not bad-looking mountains across over yonder, at that,” said Mr. Gatling, husband and father of the above, giving his gestured indorsement to an endless vista of serrated peaks of an average height of not less than seven thousand feet. “Not bad at all, so long as you don’t have to hoof up any of ’em.”

“Mong père, he also grows poetic, is it not?” murmured Miss Gatling. “Now, who’d have ever thunk it, knowing him in his native haunts back in that dear Pittsburgh!”

Her glance still was leveled in a different direction from the one in which her elders gazed. Mr. Gatling twisted about so that a foldable camp-chair creaked under his weight, and looked through his glasses in the same quarter where his daughter looked. His forehead drew into wrinkles.

Miss Gatling stood up, a slim, trim figure in her riding-boots and her well-tailored breeches and with a gay little shirt drawn snugly down inside her waistband and held there by a broad brilliant girdle of squaw’s beadwork. She settled a large sombrero on her bobbed hair and stepped away from them over the pine-needles and thence down toward the roaring creek. The morning sunlight came slanting through the lower tree boughs and picked out and made shiny glitters of the heavy Mexican silver spurs at her heels and the wide Navaho silver bracelet that was set on her right wrist. She passed between two squared boulders that might have been the lichened tombs for a couple of Babylon’s kings.

“Continue, I pray you, dear parents, to sit and invite your souls, if any,” she called back. “I go to make sure they’re putting plenty of cold victuals in the lunch kit. Yesterday noon, you’ll remember, we darn’ near starved. For you, the beckon and the lure of the wonderland. But for me and my girlish gastric juices—chow and lots of it!”

Mr. Gatling said nothing for a minute or two, but he took off his cap as though to make more room for additional furrows forming on his brow.

“Mmph!” he remarked presently. Mrs. Gatling emerged promptly from her own reverie. It was his commonest way of engaging her attention—that mmphing sound was. Lacking vowels though it did, its emphasis of uneasiness was quite apparent to her schooled ears.

“What’s wrong, dear?” she asked. “Still sore from all that dreadful horseback riding?”

“It’s that girl,” he told her; “that Shirley of ours. She’s the one I’m worried about.”

“Why, goodness gracious!” she cried. “What’s wrong with Shirley?”

“Look at her. That’s all I ask—just look at her.”

Mrs. Gatling, who was slightly near-sighted in more ways than one, squinted at the withdrawing figure.

“Why, the child never seemed happier or healthier in her life,” she protested, still peering. “Why, only last Monday—or was it Tuesday; no, Monday—I remember distinctly now it was Monday because that was the day we got caught in the snowstorm coming through Swift Current Pass—only last Monday you were saying yourself how well and rosy she was looking.”

“I don’t mean that—she’s a bunch of limber young whalebones. Look where she’s going! That’s what I mean. Look what she’s doing!”

“Why, what is she doing that’s out of the way, I’d like to know?” demanded his puzzled wife, now jealously on the defensive for her young.

“She’s doing what she’s been doing every chance she got these last four-five days, that’s what.” Mr. Gatling was manifesting an attitude somewhat common in husbands and fathers when dealing with their domestic problems. He preferably would flank the subject rather than bore straight at it, hoping by these roundabout tactics to obtain confirmation for his suspicions before he ever voiced them. “Got eyes in your head, haven’t you? All right then, use ’em.”

“Hector Gatling, for a sane man you do get the queerest notions in your brain sometimes! What on earth possesses you? Hasn’t the child a perfect right to stroll down there and watch those three guides packing up? You know she’s been trying to learn to make that pearl knot or turquoise knot or whatever it is they call it. What possible harm can there be in her learning how to tie a pearl knot?”

“Diamond hitch, diamond hitch,” he corrected her testily. “Not pearls, but diamonds; not knots, but hitches! You’d better try to remember it, too—diamonds and hitches usually figure in the thing that I’ve got on my mind. And, if you’ll be so kind as to observe her closely, you’ll see that it isn’t those three guides she’s so interested in. It’s one guide out of the three. And it’s getting serious, or I’m all wrong. Now then, do you get my drift, or must I make plans and specifications?”

“Oh!” The exclamation was freighted with shock and with sorrow but with incredulity too, and now she was fluttering her feathers in alarm, if a middle-aged lady dressed in tweed knickerbockers and a Boy Scout’s shirt may be said to have any feathers to flutter. “Oh, Hector, you don’t mean it! You can’t mean it! A child who’s traveled and seen the world! A child who’s had every advantage that wealth and social position and all could give her! A child who’s a member of the Junior League! A child who’s—who Hector, you’re crazy. Hector, you know it’s utterly impossible—utterly! It’s preposterous!” Womanlike, she debated against a growing private dread. Then, still being womanlike, she pressed the opposing side for proof to destroy her counter-argument: “Hector, you’ve seen something—you’ve overheard something. Tell me this minute what it was you overheard!”

“I’ve overheard nothing. Think I’m going snooping around eavesdropping and spying on Shirley? I’ve never done any of that on her yet and I’m too old to begin now and too fat. But I’ve seen a-plenty.”

“Oh, pshaw! I guess if there’d been anything afoot I’d have seen it myself first what with my mother’s intuition and all! Oh, pshaw!” But Mrs. Gatling’s derisive rejoinder lacked conviction.

“I’ve had the feeling for longer than these last few days,” continued Mr. Gatling despondently. “But I couldn’t put my hand on it, not at first. I tried to fool myself by saying it was this Wild Western flubdub and stuff getting into her blood and she’d get over it, soon as the attack had run its course. First loading up with all that Indian junk, then saying she felt as though she never wanted to do anything but be natural and stay out here and rough it for the rest of her life, and now here all of a sudden getting so much more flip and slangy than usual. That’s the worst symptom yet—that slang is.

“In your day, ma’am, when a girl fell in love or thought she had, she went and got all mushed-up and sentimental; went mooning around sentimentalizing and rhapsodizing and romanticking and everything. All of you but the strong-minded ones did and I guess they must have mushed-up some too, on the sly. Yes’m, that’s what you did—you mushed-up.” His tone was accusing, condemning, as though he dealt with ancient offenses which not even the passage of the years might condone. “But now it’s different with them. They get slangier and flippier and they let on to make fun of their own affections. And that’s what Miss Shirley is doing right now this very minute, or else I’m the worst misled man in the entire state of Montana.”

“Maybe—maybe——” The matron sputtered as her distress mounted. “Of course I’m not admitting that you’re right, Hector—the mere suggestion of such a thing is simply incredible—but on the bare chance that the child might be getting silly notions into her head maybe I’d better speak to her. I’m so much older than she is that——”

“You said it then!” With a grim firmness Mr. Gatling interrupted. “You’re so much older than she is; that’s your trouble. And I’m suffering from the same incurable complaint. People our age who’ve got children growing up go around bleating that young people are different from the way young people were when we were young. They’re not. They’re just the same as we were—same impulses, same emotions, same damphoolishness, same everything—but they’ve got a new way of expressing ’em. And then we say we can’t understand them. Knock thirty years off of our lives and we’d understand all right because then we’d be just the same as they are. So you’ll not say a word to that youngster of ours—not yet awhile, you won’t. Nor me, neither.” Grammar, considered as such, never had meant very much to Mr. Gatling, that masterful, self-educated man.

“But if I pointed out a few things to her—if I warned her——”

“Ma’am, you’ll perhaps remember your own daddy wasn’t so terribly happy over the prospect when I started sparking you. After I’d come courting and had gone on home again I guess it was as much as the old man could do to keep from taking a shovel and shoveling my tracks out of the front yard. But he had sense enough to keep his mouth shut where you were concerned. Suppose he’d tried to influence you against me, tried to break off the match—what would have happened? You’d have thought you were oppressed and persecuted and you’d have grabbed for me even quicker than you did.”

“Why, Hector Gatling, I never grabbed——”

“I’m merely using a figure of speech. But no, he had too much gumption to undertake the stern-father racket. He locked his jaw and took it out in nasty looks and let nature take its course, and the consequence was we got married in the First Methodist church with bridesmaids and old shoes and kinsfolks and all the other painful details instead of me sneaking you out of a back window some dark night and us running off together in a side-bar buggy. No, ma’am, if you’ll take a tip from an old retired yardmaster of the Lackawanna, forty-seven years, man and boy, with one road, you’ll——”

“You never worked a day as a railroad man and you know it.”

“Just another figure of speech, my dear. Understand now, you’re to keep mum for a while and I keep mum and we just sit back in our reserved seats up in the grand stand and see how the game comes out. A nice polite quiet game of watchful waiting—that’s our line and we’re both going to follow it. We’ll stand by for future developments and then maybe I’ll frame up a little campaign. With your valuable advice and assistance, of course!”

With a manner which she strove to make casual and unconcerned, the disturbed Mrs. Gatling that day watched. It was the manner rather of a solicitous hen with one lone chick, and she continually oppressed by dreads of some lurking chicken-hawk. It would have deceived no one who closely studied the lady’s bearing and demeanor. But then, none in the party closely studied these.

The camp dunnage being miraculously bestowed upon the patient backs of various pack-animals, their expedition moved. They overtook and passed Dad Wheelis and his crew, caravaning with provender for the highway contractors on up under the cloud-combing parapet of the Garden Wall, and behind them heard for a while his frank and aboveboard reflections upon the immediate ancestries, the present deplorable traits, the darkened future prospects of his work stock. Soon they swung away from the rutted wagon track and took the steeper horseback trail and for hours threaded it like so many plodding ants against the slant of a tilted bowl. They stopped at midday on a little plateau fixed so high toward heaven that it was a picture-molding on Creation’s wall above a vast mural of painted buttes and playful cataracts and a straggling timber-line and two jeweled glaciers.

They stretched their legs and uncramped their backs; they ate and remounted and on through the afternoon single-filed along the farther slope where a family herd of mountain-goats browsed among the stones and paid practically no heed to them. They saw a solitary bighorn ram with a twisted double cornucopia springing out of his skull and likewise they saw a pair of indifferent mule-deer and enough landscapes to fill all the souvenir post-card racks of the world; for complete particulars consult the official guide-book of Our National Playgrounds.

Evening brought them across a bony hip of the Divide to within sight of the distant rear boundary of the governmental domain. So they pitched the tents and coupled up the collapsible stove there in a sheltered small cove in the Park’s back yard and watched the sun go down in his glory. When the moon rose it was too good to believe. You almost could reach up and jingle the tambourines of little circling stars; anyhow, you almost thought you could. It was a magic hour, an ideal place for lovemaking among the young of the species. Realizing the which, Mrs. Gating had a severe sinking and apprehensive sensation directly behind the harness buckle on the ample belt which girthed her weary form amidships. She’d been apprehensive all day but now the sinking was more pronounced.

She strained at the tethers of her patience though until supper was over and it was near hushabye-time for the tired forms of the middle-aged. Within the shelter of their small tent she spoke then to her husband, touching on the topic so steadfastly uppermost in her brain.

“Oh, Hector,” she quavered, “I’m actually beginning to be afraid you’re right. They’ve been together this livelong day. Neither one of them had eyes for anything or anybody else. The way he helped her on and off her horse! The way he fetched and carried for her! And the way she let him do it! And they’re—they’re together outside now. Oh, Hector!”

“They certainly are,” he stated. “Sitting on a slab of rock in that infernal moonlight like a couple of feeble-minded turtledoves. Why in thunder couldn’t it ’a’ rained tonight—good and hard? Romola, I don’t want to harry you up any more than’s necessary but you take, say, about two or three more nights like this and they’re liable to do considerable damage to tender hearts.”

“Don’t I know it? Oh-h, Hector!”

“Well, anyhow, I had the right angle on the situation before you tumbled,” he said with a sort of melancholy satisfaction. “I can give myself credit for that much intelligence anyhow.” It was quite plain that he did.

He stepped, a broad shape in his thick pajamas and quilted sleeping-boots, to the door flap and he drew the canvas back and peeped through the opening.

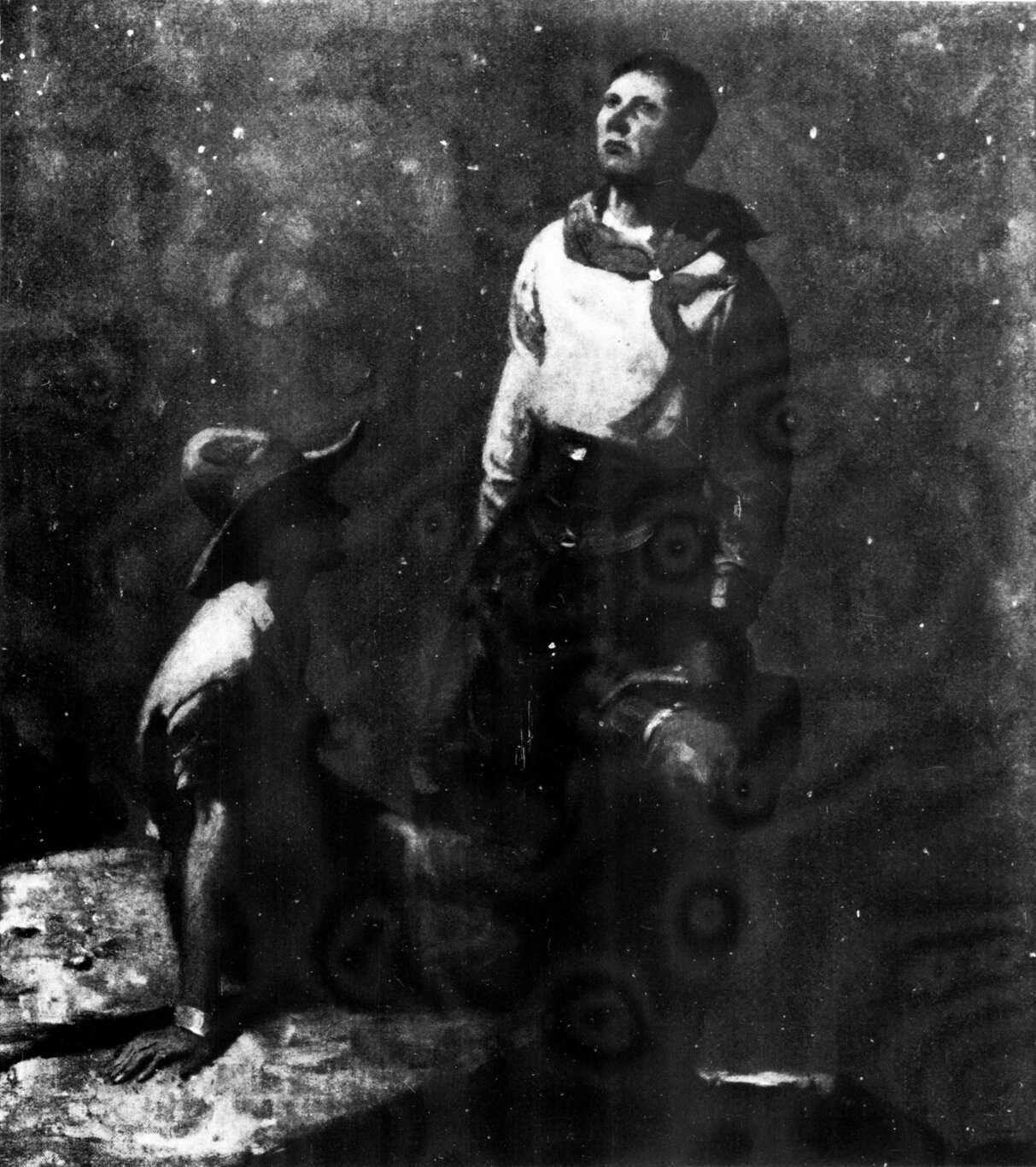

The pair under discussion had found the night air turning chill and their perch hard. They got up and stood side by side in the shimmering white glow. Against a background of luminous blue-black space, it revealed their supple figures in strong, sharp relief. The youth made a handsome shadowgraph. His wide-brimmed sugar-loaf hat; his blue flannel blouse; his Angora chaps with wings that almost were voluminous enough for an eagle’s wings; his red silk neckerchief reefed in by a carved bone ring to fit a throat which Mr. Gatling knew to be sun-tanned and wind-tanned to a healthy mahogany-brown; his beaded, deep-cuffed gauntlets; his sharp-toed, high-heeled, silver-roweled boots of a dude cowboy—they all matched and modeled in with the slender waist and the flat thighs and the sinewy broad shoulders and the alert head of the wearer.

His name was Hayes Tripler, but the other two guides generally called him “Slick” and they looked up to him, for he had ridden No Home, the man-killer, at last year’s Pendleton Round-up and hoped this year to be in the bulldogging money over the line at Calgary.

Hayes had ridden the man-killer at the Pendleton Round-up. And three moonlight nights hand-running had their effect on Shirley’s impressionable youth.

Within his limitations he was an exceedingly competent person and given to deporting himself accordingly.

At this present moment he appeared especially well pleased with his own self-cast horoscope. There was a kind of proud proprietary aura all about him.

The watcher inside the tent saw a caressing arm slip from about his daughter’s body and he caught the sounds but did not make out the sense of words that passed between them. Then the two silhouettes swung apart and the boy laughed contentedly and flung an arm aloft in a parting salute and began singing a catch as he went teetering off toward the spot where his mates of the outfit already were making the low tilt of a tarpaulin roof above them pulse to some very sincere snoring. But before she betook herself to quarters, the girl bided for a long minute on the verge of the cliff and looked off and away into the studded void beyond her.

Mr. Gatling drew the flaps together in an abstracted way and mmphed several times.

“Pretty dog-gone spry-looking young geezer at that,” he remarked absently.

“Who?”

“Him.”

“You actually mean that cowboy?”

“None other than which.”

“Oh, Hector! That—that vulgarian, that country bumpkin, that clodhopper!”

“Now hold on there, Romola. Let’s try to be just even if we are prejudiced. All the clods that kid ever hopped you could put ’em in your eye without interfering with your eyesight. He’s no farm-hand; he’s a cow-hand or was before he got this job of steering tourists around through these mountains—and that’s a very different thing, I take it. And what he knows he knows blame’ well. I wish I could mingle in with a horse the way he does. When he gets in a saddle he’s riveted there but I only come loose and work out of the socket. And I’d give about five years off my life to be able to handle a trout-rod like he can. I claim that in his departments he’s a fairly high-grade proposition. He’s aware of it, too, but I don’t so much blame him for that, either. If you don’t think well of yourself, who else is going to?”

“Why, Hector Gatling, I believe you’re really—but no, you couldn’t be! Look at the difference in their stations! Look at their different environments! Look at their different viewpoints!”

“I’m looking—just as hard as you are. You don’t get what I’m driving at. I wouldn’t fancy having this boy for a son-in-law any more than you would—although at that I’m not saying I couldn’t maybe make some use of him in another capacity. Still, you needn’t mind worrying so much about their respective stations in life. I didn’t have any station in life to start from myself—it was a whistling-post. And yet I’ve managed to stagger along fairly well. I’d a heap rather see Shirley tied up to pretty near any decent, ambitious, self-respecting young cuss that came along than to have her fall for one of those plush-headed lounge-lizards that keep hanging round her back home. I know the breed. In my day they used to be guitar-pickers—and some of ’em played a snappy game of Kelly pool. Now they’re Charleston dancers and the only place most of ’em carry any weight is on the hip.

“But that’s not the point. The point is that if Shirley fell for this party she’d probably be a mighty regretful young female when the bloom began to rub off the peach. They haven’t been raised to talk the same language—that’s the trouble. I don’t want her to make a mistake that’ll gum up her life before it’s fairly started. I don’t want her to have a husband that she’s liable later on to be ashamed to show him off before the majority of her friends, or anyhow one that she’d maybe have to go around making excuses for the way he handled his knife and fork in company; or something. Right now, the fix she’s in, she’s probably saying to herself that she could be perfectly satisfied to settle down in a cabin somewhere out here and wet-nurse a lot of calves for the next thirty, forty or fifty years. But that’s only her heart talking, not her head. After a while she’d get to brooding on Palm Beach and Paris.”

“But if she’s set her mind—and you know how stubborn she is when she gets her mind set—thank heavens she didn’t get that from my side of the family!—I say, if she’s set her mind on him, heavens above only knows what’s going to happen. She’s bewitched, she’s hypnotized; it’s this free and easy Western life that’s fascinated her. I can’t believe she’s in love with him!”

“Well, I don’t know. Maybe she’s in love with a half-gallon hat and a pair of cowboy pants with silver dewdabs down the sides, or then again on the other hand maybe it’s the real thing with her, or a close imitation of it. That’s for us to find out if we can.”

“I won’t believe it. She’s distracted, she’s glamoured, she’s——”

“All right, then, let’s get her unglammed.”

“But how?”

“Well, for one thing, by not rushing in and interfering with her little dream. By not letting either one of ’em see how anxious we are over this thing. By remaining as calm, cool and collected as we can.”

“And in the meanwhile?”

“Well, in the meanwhile I, for one, am going to tear off a few winks. I hurt all over and there’s quite a lot of me measured that way—all over.”

“You can go to sleep with that—that dreadful thought hanging over us?”

“I can and I will. Watch me for about another minute and you’ll hear me doing it.” He settled himself on his air mattress and drew the blankets over him.

Undeniably Mr. Hector Gatling could be one of the most aggravating persons on earth when he set out to be. Any husband can.

Speaking with regard to the ripening effect of summer nights upon the spirits of receptive and impressionable youth, Mr. Gatling had listed the cumulative possibilities of three moonlit ones hand-running. Specifically he had not included in his perilous category those languishing soft gloamings and those explosive sunrises and those long lazy mornings when the sun baked resiny perfumes out of the cedars and the unseen heart-broken little bird that the mountaineers call the lonesome bird sang his shy lament in the thickets; nor had he mentioned slow journeys through deep defiles where ferns grew with a tropical luxuriance; nor yet the fordings of tumbling streams when it might seem expedient on the part of a thoughtful young man to steady a young equestrian of the opposite sex while her horse’s hoofs fumbled over the slick, drowned boulders. But vaguely he had lumped all these contingencies in his symposium of contributory dangers.

Three more nights of moon it was with three noble days of pleasant adventuring in between; and on the late afternoon of the third day when camp was being made beside a river which mostly was rapids, Miss Shirley Gatling sought out her father in a secluded spot somewhat apart from the rest. It was in the nature of a rendezvous, she having told him a little earlier that presently she desired to have speech with him. Only, her way of putting it had been different.

“Harken, O most revered Drawing Account,” she said, dropping back on a broad place in the trail to be near him. “If you can spare the time from being saddle-sore I want to give you an earful as soon as this procession, as of even date, breaks up. You pick a quiet retreat away from the flock and wait there until I find you, savvy?”

So now he was waiting, and from yonder she came toward him stepping lightly, swinging forward from her hips with a sort of impudent freedom of movement; and to his father’s eyes she never had seemed more graceful or more delectable or more independent looking.

“Dad,” she began, without preamble, and meeting him eye to eye, “in me you behold a Sabine woman. I’m bespoken.”

“Mmph,” he answered, and the answer might be interpreted, by a person who knew him, in any one of half a dozen ways.

“Such is the case,” she went on, quite unafraid. “That caveman over there in the blue shirt”—she pointed—“he’s the nominee. We’re engaged.”

“I can’t plead surprise, kid,” he stated, taking on for the moment her bantering tone. “The report that you two had come to a sort of understanding has been in active circulation on this reservation for the past forty-eight hours or so—maybe longer.”

Her eyebrows went up. “I don’t get you,” she said. “Who circulated it?”

“You did, for one,” he told her. “And he did, for another. I may be failing, what with increasing age and all, but I’m not more than half blind yet. Have you been to your mother with this piece of news?”

“I came to you first. I—I”—for the first time she faltered an instant—“I figured you might be able to get the correct slant a little quicker then she would. This is only the curtain-raiser. I’m saving the big scene with the melodramatic touches for her. I have a feeling that she may be just a trifle difficult. So I picked on something easy to begin with.”

“I see,” he said. “Kind of an undress rehearsal, eh?” He held her off at arm’s length from him, studying her face hungrily. “But what’s the reason your young man didn’t come along with you or ahead of you, in fact? In my time it generally was the young man that brought the message to Garcia.”

“He wanted to come—he wasn’t scared. I wouldn’t let him. I told him I’d been knowing you longer than he had and I could handle the job better by myself. Well, that’s your cue. What’s it going to be, daddy—the glad hand of approval and the parental bless you my children, bless you, or a little line of that go-forth-ungrateful-hussy-and-never-darken-my-doors-again stuff? Only, we’re a trifle shy on doors around here.”

He drew her to him and spoke downward at the top of her cropped head, she snuggling her face against his wool-clad breast.

“Baby,” he said, “when all’s said and done, the whole thing’s up to you, way I look at it. I don’t suppose there ever was a man who really loved his daughter but what he figured that, taking one thing with another, she was too good for any man on earth. I’m not saying now what sort of a husband I’d try to pick out for you if the choice had been left to me. I’d probably want to keep you an old maid so’s I could have you around and then I’d secretly despise myself for doing it, too. What I’m saying is this: If you’re certain you know your own mind and if you’ve decided that this boy is the boy you want, why what more is there for me to do except maybe to ask you just one or two small questions?”

“Shoot!” she bade, without looking up, but her arms hugged him a little tighter. “Probably one of the nicest old meal-tickets in the world,” she added, confidentially addressing the top buttonhole of his sweater.

“Has it by any chance entered into your calculations at this early stage of the game, how you are going to live—you two? Or where? Or, if I may be so bold, what on?”

“That’s easy,” she said, and now she was peering up at him through a tousled short forelock. “You’re going to set us up on a place out here somewhere—a ranch. We’re going to raise beef. He knows about beef. And I’m going to learn. I aim to be the leading lady beefer of the Imperial Northwest.”

“Whose notion was that?” His voice had sharpened the least bit.

“Mine, of course. He doesn’t know anything about it. His idea is that we start in on what he can earn. But my idea is that we start in on a few of the simoleons that have already been earned—by you. And that’s the idea that’s going to prevail.”

“Lucky I brought a fountain pen and a check-book along,” he said. “Nothing like being prepared for these sudden emergencies. Still, I take it there’s no great rush. Now, I tell you what: You run along and locate your mother and get that over with. She knows how I stand—we’ve been discussing this little affair our own selves.”

“Oh,” she said. “Oh, you have?” She seemed disappointed somehow—disappointed and slightly puzzled.

“Oh yes, several times. And on your way kindly whisper to the young man that I’m lurking right here behind these rocks ready to have a few words with him.”

“Righto!” She reached up and kissed him and went swinging away, and for just a moment Mr. Gatling’s conscience smote him.

“I’ve got to do it,” he said to himself, excusing himself. “I’ve just got to find out—for her sake and ours—yes, and for his, too. It looks like an impossible bet and I’ve got to make sure.”

With young Tripier he had more than the few words he had specified. They had quite an interview and as they had it the youth’s embarrassment, which at the outset of the dialog had made him wriggle and mumble and kick with his toes at inoffensive pebbles, gradually wore off until it vanished altogether and his native assurance reasserted itself. A proposition was advanced. It needed little pressing; promptly he fell in with it. It appealed to him.

“So we’re agreed there,” concluded his prospective father-in-law, clinching the final rivets. “We’ll all go right ahead and finish out this tour—it’s only a couple of days more anyhow. Then I’ll take Shirley and her mother and run on out to Spokane. We’ll hustle one of the other boys back tomorrow to the entrance to tell my chauffeur to load some bags in the car and run around to this side and meet us where we come out. We’ll leave you there and you can dust back to the starting point through that short cut over the Garden Wall you were just speaking of. The business that I’ve got in Spokane will keep me maybe two or three days. That’ll give you time to get those new clothes of yours and then we’ll all meet over at Many Glacier—I’ll wire you in advance—and in a day or two we’ll all go on East together so’s you can get acquainted with Shirley’s friends and so forth. But of course, as I said before, that’s our secret—all that part of it is. You’ve never been East, I believe?”

“Well, I’ve been as far as Minot, North Dakota.”

“You’ll probably notice a good deal of territory the other side of there. You’ll enjoy it. Sure you can pick up all the wardrobe you need out in this country?” His manner was solicitous.

“Oh yes, sir, there’s those two swell fellows named Steinfelt and Immergluck I was telling you about that they’ve got the leading gents’ furnishing goods store down in Cree City.”

“Good enough! I’d suggest that when picking out a suit you get something good and brisk as to pattern. Shirley likes live colors.” Mr. Gatling next stressed a point which already had been dwelt upon: “You understand of course that she’s not to know a single thing about all this—it’s strictly between us two?”

“Yes, sir.”

“You see, that’ll make the surprise all the greater when she sees you all fixed up in a snappy up-to-date rigging like young college fellows your age wear back where she comes from. Seems like to me I was reading in an advertisement only here the other day where they’re going in for coats with belts on ’em this season. Oh yes, and full-bottomed pants; I read that, too.

“One thing more occurs to me: Your hair is a little bit long and shaggy, don’t you think? That’s fine for out here but back East a young fellow that wants to be in style keeps himself trimmed up sort of close. Now I saw a barber working on somebody about as old as you are just the other day. Let me see—where was it? Oh yes, it was the barber at that town of Cree City—I dropped in there for a shave when we motored down last week. He seemed to have pretty good ideas about trimming up a fellow’s bean, that barber.”

“I know the one you mean—Silk Sullivan. I’ve patronized him before.”

“That’s the one. Well, patronize him again before you rejoin us. He knows his business all right, your friend Sullivan does.... Now, mind you, mum’s the word. All this part of it is absolutely between us.”

“Oh yes, sir.”

“O. k. Shake on it.... Well, suppose we see how they’re coming along with supper.”

Mr. Gatling’s strategy ticked like a clock. After they got to Spokane he delayed the return by pretending a vexatious prolongation of a purely fictitious deal in ore properties, his privy intent being to give opportunity for Cree City’s ready-made clothing princes to work their will. Since a hellish deed must be done he craved that they do it properly. Then on the homeward journey when they had reached the Western Gate, he suddenly remembered he had failed to complete his purchases of an assortment of game heads at Lewis’s on Lake McDonald. He professed that he couldn’t round out the order by telephone; unless he personally checked his collection some grievous error might be made.

“You go on across on this train, Shirley,” he said. “I telegraphed your young man that we’d be there this morning and he’ll be on the lookout. Your mother and I’ll dust up to the head of the lake on the bus and I’ll finish up what I’ve got to do there and we’ll be along on the Limited this evening. After being separated for a whole week you two’ll enjoy a day together without any old folks snooping around. Meet us at the hotel tonight.”

So Shirley went on ahead. It perhaps was true that Shirley’s nerves had suffered after six days spent in the companionship of a devoted mother who trailed along with yearning, grief-stricken eyes fixed on her only child—a mother who at frequent intervals sniffed mournfully. Quite willingly Shirley went.

“I—I feel as though I were giving her up forever,” faltered Mrs. Gatling, following with brimming eyes her daughter’s departing form.

“Romola,” commanded Mr. Gatling, “don’t be foolish in the head. You’re going to be separated from her exactly nine hours.”

“But she tripped away so gaily—so gladly. It was exactly as though she wanted to leave us. And yet, heavens knows I’ve tried and tried ever since that—that terrible night to show her what she means to me——”

“You’ve done more than try, Romola—you’ve succeeded, if that’s any consolation to you. You’ve succeeded darned well.” He stared almost regretfully down the line at the rear of an observation-car swiftly diminishing into a small square dot where the rails came together. “Since you mention it, she did look powerfully chipper and cheerful a minute ago, hustling to climb aboard that Pullman—cheerfuller than she’s looked since we quit the trail last Wednesday. Lord, how I wish I could guarantee that kid was never going to have a minute’s unhappiness the rest of her life!” Something remotely akin to remorse was beginning to gnaw at Mr. Gatling’s heart cockles.

Indeed, something strongly resembling remorse beset him toward the close of this day. At the station when they detrained, no Shirley was on hand to greet them; nor was there sign of Shirley’s affianced, either. Up the slope from the tracks at the hotel a clerk wrenched himself from an importuning cluster of newly-arrived tourists for long enough to tell them Miss Gatling had left word she would be awaiting them in their rooms and wished them to come up immediately.

So they went up under escort of two college students serving as bell-hops. A bedroom door opened and out came Shirley—a crumpled, wobegone Shirley with a streaky swollen face.

“It’s all right, mater,” she said with a flickering trace of her usual jauntiness. “The alliance between the house of Gatling and the house of Tripier is off. So you can liven up. I’ll be your substitute for such crying as is done in this family during the next day or two. I’ve—I’ve been practising all afternoon.”

She eluded the lady’s outstretched arms and clung temporarily at her father’s breast.

“Dad,” she confessed brokenly, “I think I must have been a little bit loony these last two weeks. But, dad, I’ve taken the cure. It’s not nice medicine and it makes you feel miserable at first but I guess it’s good for what ails me.... Dad, have you seen—him?”

“Not yet.” Compassion for her was mixed in with his own secret exultation, as though he tasted a sweet cake that was iced with a most bitter icing.

“Well, when you do, you’ll understand. Even if he doesn’t!”

“Have you told him?”

“Of course I have. Did you think I’d try to wish that little job off on you? I didn’t tell him the real reason—I couldn’t wound him that much. I told him I’d changed. But he—he’s really the one that’s changed. That’s what makes it harder for me now. That’s what makes it hurt so.”

“Here, Romola,” he said, kissing the girl and relinquishing her into her mother’s grasp. “You swap tears awhile—you’ll enjoy that anyhow, Romola. I’ve got business downstairs—got to make some sleeper reservations for getting out of here in the morning. And as soon as we hit Pittsburgh I figure you two had better be booking up for a little swing around Europe.”

The lobby below was seething—seething is the word commonly used in this connection so we might as well do so, too—was seething with Easterners who mainly had dressed as they imagined Westerners would dress, and with Westerners who mainly had dressed as they imagined Easterners would dress, the resultant effect being that nobody was fooled but everybody was pleased. Working his way through the jam on the search for a certain one, Mr. Gatling’s eye almost immediately was caught by a startling color combination or rather a series of startling color combinations appertaining to an individual who stood half hidden by a column, leaning against it, head down, with his back to Mr. Gatling.

To begin at the top, there was, surmounting all, a smug undersized object of head-gear—at least, it would pass for head-gear—of a poisonous mustard shade. It perched high and, as it were, aloof upon the crest of its wearer’s skull. Below it, where the neck had been shaved, and a good portion of the close-clipped scalp as well, showed a sort of crescent of pink skin blazing forth in strong contrast to the abnormally long expanse of sunburnt surface rising above the cross-line of an exceedingly low, exceedingly shiny pink linen collar.

Straying on downward, Mr. Gatling’s wondering eye was aware of a high-waisted Norfolk jacket belted well up beneath the armpits, a garment of a tone which might not be called mauve nor yet lavender nor yet magenta but which partook subtly of all three shades—with a plaid overlay in chocolate superimposed thereon. Yet nearer the floor was revealed a pair of trousers extensively bell-bottomed and apparently designed with the intent to bring out and impress upon the casual observer the fact that their present owner had two of the most widely bowed legs on the North American continent; and finally, a brace of cloth-top shoes. Tan shoes, these were, with buttoned uppers of a pale fawn cloth, and bulldog toes. They were very new shoes, that was plain, and of an exceedingly bright and pristine glossiness.

This striking person now moved out of his shelter, his shoulders being set at a despondent hunch, and as he turned about, bringing his profile into view, Mr. Gatling recognized that the stranger was no stranger and he gasped.

“Perfect!” he muttered to himself; “absolutely perfect! Couldn’t be better if I’d done it myself. And, oh Lordy, that necktie—that’s the finishing stroke! Still, at that, it’s a rotten shame—the poor kid!”

He hurried across, overtaking the slumped figure, and as his hand fell in a friendly slap upon one drooped shoulder the transformed cowboy looked about him with two sad eyes.

“Howdy-do, sir,” he said wanly. Then he braced himself and squared his back, and Mr. Gatling perceived—and was glad to note—that the youngster strove to take his heartache in a manly fashion.

“Son,” said Mr. Gatling, “from what I’m able to gather I’m not going to have you for a son-in-law after all. But that’s no reason why we shouldn’t hook up along another line. I’ve been watching you off and on ever since we got acquainted and more closely since—well, since about a week ago, and it strikes me you’ve got some pretty good stuff in you. I’ve been thinking of trying a little flier in the cattle game out here. If you think you’d like a chance to start in as foreman or boss or superintendent or whatever you call it and maybe work up into a partnership if you showed me you had the goods, why, we’ll talk it over together at dinner. The womenfolks won’t be down and we can sit and powwow.”

“I’d like that fine, sir,” said young Tripier.

“Good boy! I’ll keep you so busy you won’t have time to brood on any little disappointment that you may be suffering from now.... Say, son, don’t mind my suggesting something, do you? If I was you I’d climb out of these duds you’ve got on and climb back into your regular working clothes—you don’t seem to match the picture the way you are now.”

“Why, you advised me to get ’em your own self, sir!” exclaimed the youth.

“That’s right, I did, didn’t I? Well, maybe you had better keep on wearing ’em.” A shrewd and crafty gleam flickered under his eyelids. “You see—yes—on second thoughts, I think I want a chance to get used to you in your stylish new outfit. Promise me you’ll wear ’em until noon tomorrow anyhow?”

“Yes, sir,” said his victim obediently.

Mr. Gatling winked a concealed, deadly wink.

THE END