THE TREASURE TRAIL

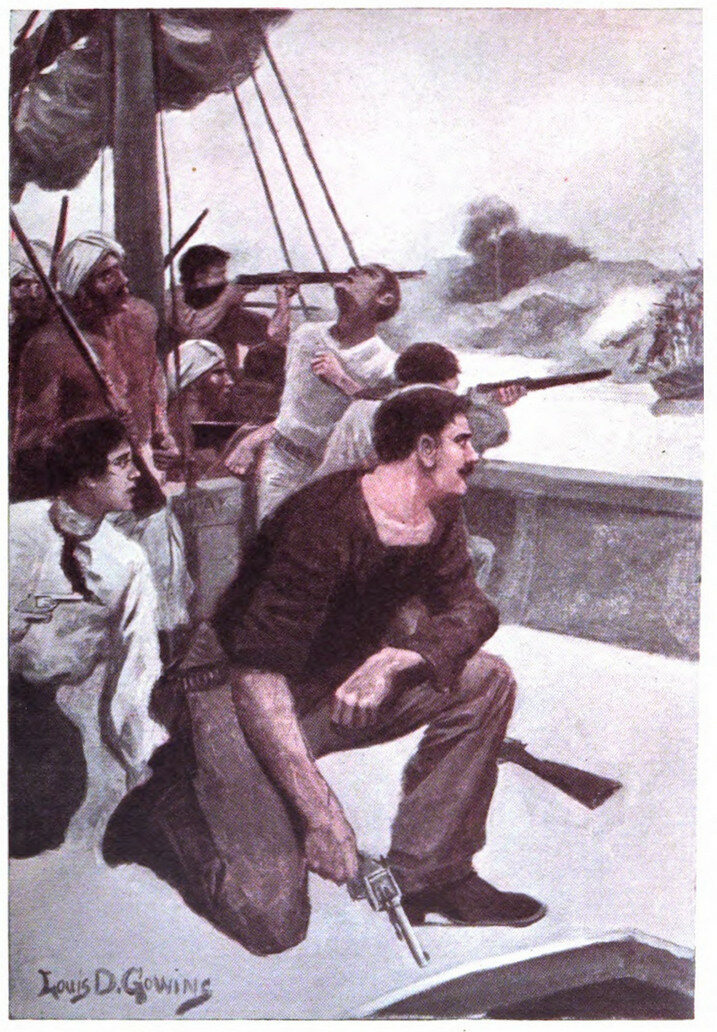

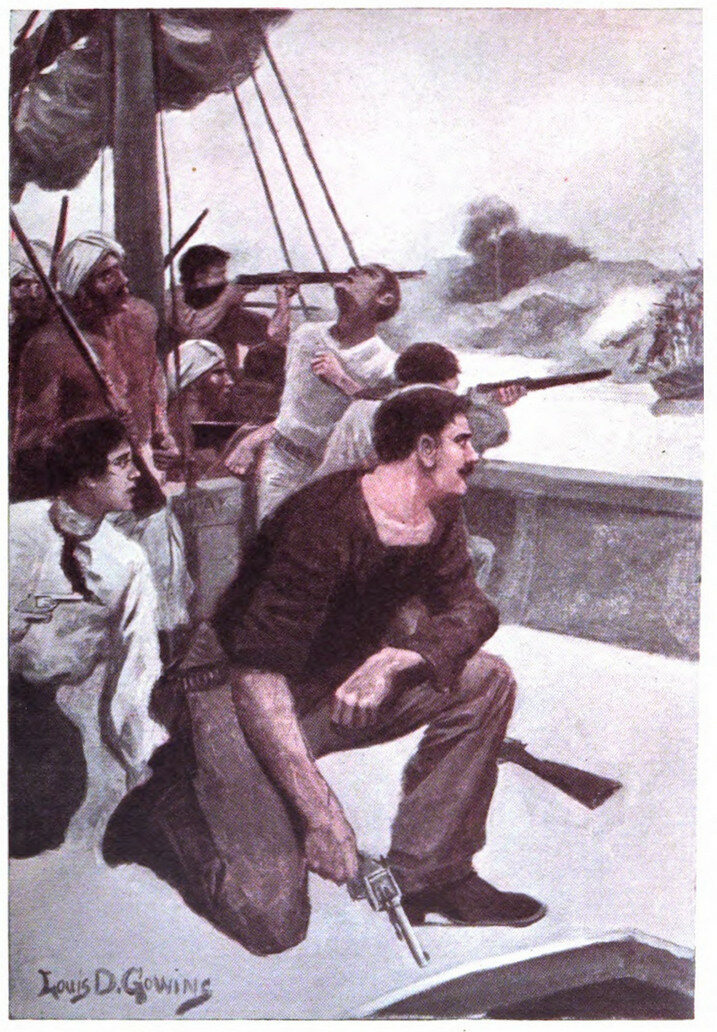

“Suddenly Sullivan stood up jerkily on the deck.”

“Suddenly Sullivan stood up jerkily on the deck.”

| I. | The New Leaf |

| II. | The Open Road |

| III. | The Adventurer |

| IV. | The Fate of the Treasure Ship |

| V. | The Ace of Diamonds |

| VI. | The Mystery of the Mate |

| VII. | The Indiscretion of Henninger |

| VIII. | The Man from Alabama |

| IX. | On the Trail |

| X. | A Lost Clue |

| XI. | Illumination |

| XII. | Open War |

| XIII. | First Blood |

| XIV. | The Clue Found |

| XV. | The Other Way Round the World |

| XVI. | The End of the Trail |

| XVII. | The Treasure |

| XVIII. | The Battle on the Lagoon |

| XIX. | The Second Wreck |

| XX. | The Rainbow Road |

“Lord! what a haul!” Elliott murmured to himself, glancing over his letter while he waited with the horses for Margaret, who had said that she would be just twelve minutes in putting on her riding-costume. The letter was from an old-time Colorado acquaintance who was then superintending a Transvaal gold mine, and, probably by reason of the exigencies of war, the epistle had taken over two months to come from Pretoria. Elliott had been able to peruse it only by snatches, for the pinto horse with the side-saddle was fidgety, communicating its uneasiness to his own mount.

“And managed to loot the treasury of over a million in gold, they say, and got away with it all. The regular members of the Treasury Department were at the front, I suppose, with green hands in their places,” he read.

It was a great haul, indeed. Elliott glanced absently along the muddy street of the Nebraska capital, and his face hardened into an expression that was not usual. It was on the whole a good-looking face, deeply tanned, with a pleasant mouth and a small yellowish moustache that lent a boyishness to his whole countenance, belied by the mesh of fine lines about the eyes that come only of years upon the great plains. The eyes were gray, keen, and alive with a spirit of enterprise that might go the length of recklessness; and their owner was, in fact, reflecting rather bitterly that during the past ten years all his enterprises had been too reckless, or perhaps not reckless enough. He had not had the convictions of his courage. The story of the stealings of a ring of Boer ex-officials had made him momentarily regret his own passable honesty; and it struck him that in his present strait he would not care to meet the temptation of even less than a million in gold, with a reasonable chance of getting away with it.

This subjective dishonesty was cut short by Margaret, who hurried down the veranda steps, holding up her brown riding-skirt. She surveyed the pinto with critical consideration.

“Warranted not to pitch,” Elliott remarked. “The livery-stable man said a child could ride him.”

“You’d better take him, then. I don’t want him,” retorted Margaret

“This one may be even more domestic. What in the world are you going to do with that gun?”

“Don’t let Aunt Louisa see it; she’s looking out the window,” implored Margaret, her eyes dancing. “I want to shoot when we get out of town. Put it in your pocket, please,—that’s against the law, you know. You’re not afraid of the law, are you?”

“I am, indeed. I’ve seen it work,” Elliott replied; but he slipped the black, serviceable revolver into his hip pocket, and reined round to follow her. She had scrambled into the saddle without assistance, and was already twenty yards down the street, scampering away at a speed unexpected from the maligned pinto, and she had crossed the Union Pacific tracks before he overtook her. From that point it was not far to the prairie fields and the barbed-wire fences. The brown Nebraska plains rolled undulating in scallops against the clear horizon; in the rear the great State House dome began to disengage itself from a mass of bare branches. The road was of black, half-dried muck, the potent black earth of the wheat belt, without a pebble in it, and deep ruts showed where wagons had sunk hub-deep a few days before.

A fresh wind blew in their faces, coming strong and pure from the leagues and leagues of moist March prairie, full of the thrill of spring. Riding a little in the rear, Elliott watched it flutter the brown curls under Margaret’s grey felt hat, creased in rakish affectation of the cow-puncher’s fashion. Now that he was about to lose her, he seemed to see her all at once with new eyes, and all at once he realized how much her companionship had meant to him during these past six months in Lincoln,—a half-year that had just come to so disastrous an end.

Margaret Laurie lived with her aunt on T Street, and gave lessons in piano and vocal music at seventy-five cents an hour. Her mother had been dead so long that Elliott had never heard her mentioned; the father was a Methodist missionary in foreign parts. During the whole winter Elliott had seen her almost daily. They had walked together, ridden together, skated together when there was ice, and had fired off some twenty boxes of cartridges at pistol practice, for which diversion Margaret had a pronounced aptitude as well as taste. She had taught him something of good music, and he confided to her the vicissitudes of the real estate business in a city where a boom is trembling between inflation and premature extinction. It had all been as stimulating as it had been delightful; and part of its charm lay in the fact that there had always been the frankest camaraderie between them, and nothing else. Elliott wished for nothing else; he told himself that he had known enough of the love of women to value a woman’s friendship. But on this last ride together he felt as if saturated with failure—and it was to be the last ride.

Margaret broke in upon his meditations. “Please give me the gun,” she commanded. “And if it’s not too much trouble, I wish you’d get one of those empty tomato-cans by the road.”

“You can’t hit it,” ventured Elliott, as he dismounted and tossed the can high in the air. The pistol banged, but the can fell untouched, and the pinto pony capered at the report.

“Better let me hold your horse for you,” Elliott commented, with a grin.

“No, thank you,” she retorted, setting her teeth. “Now,—throw it up again.”

This time, at the crack of the revolver, the can leaped a couple of feet higher, and as it poised she hit it again. Two more shots missed, and the pinto, becoming uncontrollable, bolted down the road, scattering the black earth in great flakes. Elliott galloped in pursuit, but she was perfectly capable of reducing the animal to submission, and she had him subjected before he overtook her.

“It’s easier than it looks,” Margaret instructed him, kindly. “You shoot when the can poises to fall, when it’s really stationary for a second.”

“Thank you—I’ve tried it,” Elliott responded, as they rode on side by side, at the easy lope of the Western horse. The wind sang in their ears, though it was warm and sunny, and it was bringing a yellowish haze up the blue sky.

hummed Margaret, softly.

“What a truly Western combination,—horses, Wagner, and gun-play!” remarked Elliott.

“Of course it is. Where else in the world could you find anything like it? It’s the Greek ideal—action and culture at once.”

“It may be Greek. But I know it would startle the Atlantic coast.”

“I don’t care for the Atlantic coast. Or—yes, I do. I’m going to tell you a great secret. Do you know what I’ve wanted more than anything else in life?”

“Your father must be coming home from the South Seas,” Elliott hazarded.

“Dear old father! He isn’t in the South Seas now; he’s in South Africa. No, it isn’t that. I’m going to Baltimore this fall to study music. I’ve been arguing it for weeks with Aunt Louisa. I wanted to go to New York or Boston, but she said the Boston winter would kill me, and New York was too big and dangerous. So we compromised on Baltimore.”

“Hurrah!” said Elliott, with some lack of enthusiasm. “Baltimore is a delightful town. I used to be a newspaper man there before I came West and became an adventurer. I wish I were going to anything half so good.”

“You’re not leaving Lincoln, are you?” she inquired, turning quickly to look at him.

“I’m afraid I must.”

“When are you going, and where?” she demanded, almost peremptorily.

“I don’t exactly know. I had thought of trying mining again,” with a certain air of discouragement.

Margaret looked the other way, out across the muddy sheet of water known locally as Salt Lake, where a flock of wild ducks was fluttering aimlessly over the surface; and she said nothing.

“I suppose you know that the bottom’s dropped out of the land boom in Lincoln,” Elliott pursued. “I’ve seen it dropping for a month; in fact, there never was any real boom at all. Anyhow, the real estate office of Wingate Elliott, Desirable City Property Bought and Sold, closed up yesterday.”

“You don’t mean that you have—”

“Failed? Busted? I do. I’ve got exactly eighty-two dollars in the world.”

She began to laugh, and then stopped, looking at him half-incredulously.

“You don’t appear to mind it much, at least.”

“No? Well, you see it’s happened so often before that I’m used to it. Good Lord! it seems to me that I’ve left a trail of ineffectual dollars all over the West!”

“You do mind it—a great deal!” exclaimed Margaret, impulsively putting a hand upon his bridle. “Please tell me all about it. We’re good friends—the very best, aren’t we?—but you’ve told me hardly anything about your life.”

“There’s nothing interesting about it; nothing but looking for easy money and not finding it,” replied Elliott. He was scrutinizing the sky ahead. “Don’t you think we had better turn back? Look at those clouds.”

The firmament had darkened to the zenith with a livid purple tinge low in the west, and the wind was blowing in jerky, powerful gusts. A growl of thunder rumbled overhead.

“It’s too early for a twister, and I don’t mind rain. I’ve nothing on that will spoil,” said Margaret, almost abstractedly. She had scarcely spoken when there was a sharp patter, and then a blast of drops driven by the wind. A vivid flash split the clouds, and with the instantaneous thunder the patter of the rain changed to a rattle, and the black road whitened with hail. The horses plunged as the hard pellets rebounded from hide and saddle.

“We must get shelter. The beasts won’t stand this,” cried Elliott, reining round. The lumps of ice drove in cutting gusts, and the frightened horses broke into a gallop toward the city. For a few moments the storm slackened; then a second explosion of thunder seemed to bring a second fusilade, driving almost horizontally under the violent wind, stinging like shot.

Across an unfenced strip of pasture Elliott’s eye fell upon the Salt Lake spur of the Union Pacific tracks, where a mile of rails is used for the storage of empty freight-cars. He pulled his horse round and galloped across the intervening space, with Margaret at his heels, and in half a minute they had reached the lee of the line of cars, where there was shelter. He hooked the bridles over the iron handle of a box-car door that stood open, and scrambled into the car, swinging Margaret from her saddle to the doorway.

It was a perfect refuge. The storm rattled like buckshot on the roof and swept in cloudy pillars across the Salt Lake, where the wild ducks flew to and fro, quacking from sheer joy, but the car was clean and dry, slightly dusted with flour. They sat down in the door with their feet dangling out beside the horses, that shivered and stamped at the stroke of chance pellets of hail.

“This is splendid!” said Margaret, looking curiously about the planked interior of the car. “Why do you want to leave Lincoln?” she went on in a lower tone, after a pause.

“I don’t want to leave Lincoln.”

“But you said just now—”

“It seems to me, by Jove, that I’ve done nothing but leave places ever since I came West!” Elliott exclaimed, impatiently. “That was ten years ago. I came out from Baltimore, you know. I was born there, and I learned newspaper work on the Despatch there, and then I came West and got a job on the Denver Telegraph.”

“At a high salary, I suppose.”

“So high that it seemed a sort of gold mine, after Eastern rates. But it didn’t last. The paper was sold and remodelled inside a year, and most of the reporters fired. I couldn’t find another newspaper job just then, so I went out with a survey party in Dakota for the winter and nearly froze to death, but when I got back and drew all my accumulated salary, I bought a half-interest in a gold claim in the Black Hills. Mining in the Black Hills was just beginning to boom then, and I sold my claim in a couple of months for three thousand. I made another three thousand in freighting that summer, and if I had stayed at it I might have got rich, but I came down to Omaha and lost it all playing the wheat market. I had a sure tip.”

“Six thousand dollars! That’s more money than I ever saw all at once,” Margaret commented.

“It was more money than I saw for some time after that; but that’s a fair specimen of the way I did things. Once I walked into Seattle broke, and came out with four thousand dollars. I cleaned up nearly twenty thousand once on real estate in San Francisco. Afterwards I went down to Colorado, mining. I could almost have bought up the whole Cripple Creek district when I got there, if I had had savvy enough, but I let the chance slip, and when I did go to speculating my capital went off like smoke. The end of it was that I had to go into the mines and swing a pick myself.”

“You were game, it seems, anyway,” said Margaret, who was listening with absorbed interest. The sky was clearing a little, and the hail had ceased, but the rain still swept in gusty clouds over the brown prairie.

“I had to be. It did me good, and I got four dollars a day, and in six months I was working a claim of my own. By this time I thought I was wise, and I sold it as soon as I found a sucker. I got ten thousand for it, and I heard afterwards that he took fifty thousand out of it.”

“What a fraud!” cried Margaret, indignantly.

“Anyhow, I bought a little newspaper in a Kansas town that was just drawing its breath for a boom. I worked for it till I almost got to believe in that town myself. At one time my profits in corner lots and things—on paper, you know—were up in the hundreds of thousands. In the end, I had to sell for less than one thousand, and then I came to Lincoln and worked for the paper here. That was two years ago, when I first met you. Do you remember?”

“I remember. You only stayed about four months. What did you do then?”

“Yes, it seemed too slow here, too far east. I went back to North Dakota, mining and country journalism. I did pretty well too, but for the life of me I don’t know what became of the money. After that I did—oh, everything. I rode a line on a ranch in Wyoming; I worked in a sawmill in Oregon; I made money in some places and lost it in others. Eight months ago I had a nice little pile, and I heard that there was a big opening in real estate here in Lincoln, so I came.”

“And wasn’t there an opening?”

“There must have been. It swallowed up all my little pile without any perceptible effect, all but eighty-two dollars.”

“And now—?”

“And now—I don’t know. I was reading a letter just now from a man I know in South Africa telling of a theft of a million in gold from the Pretoria treasury during the confusion of the war. Do you know, I half-envied those thieves; I did, honour bright. A quick million is what I’ve always been chasing, and I’d almost steal it if I got the chance.”

“You wouldn’t do any thing of the sort. I know you better than that. You’re going to do something sensible and strong and brave. What is it to be?”

“But I don’t know,” cried Elliott. “There are heaps of things that I can do, but I tell you I feel sick of the whole game. I feel as if I’d been wasting time and money and everything.”

“So you have, dear boy, so you have,” agreed Margaret. “And now, if you’d let me advise you, I’d tell you to find out what you like best and what you can do best, and settle down to that. You’ve had no definite purpose at all.”

“I have. It was always a quick fortune,” Elliott remonstrated. “I’ve got it yet. There are plenty of chances in the West for a man to make a million with less capital than I’ve got now. This isn’t a country of small change.”

“Yes, I know. I’ve heard men talk like that,” said Margaret, more thoughtfully. “But it seems to me that you’ve been doing nothing but gamble all your life, hoping for a big haul. Of course, I’ve no right to advise you. Nebraska is all I know of the world, but I don’t like to think of you going back to the ‘game,’ as you call it. Do you know that it hurts me to think of you making money and losing it again, year after year, and neglecting all your real chances? Too many men have done that. A few of them won, but nobody knows where most of them died. There are such chances to do good in the world, to be happy ourselves and make others happy, and when I think of a man like my father—”

“You wouldn’t want me to go to Fiji as a missionary?” Elliott interrupted. He was shy on the subject of her father, whom Margaret had seen scarcely a dozen times since she could remember, but who was her constant ideal of heroism, energy, and virtue.

“Of course not. But don’t you like newspaper work?”

“I like it very much.”

“And isn’t it a good profession?”

“Very fair, if one works like a slave. That is, I might reach a salary of five thousand dollars a year. The best way is to buy out a small country daily and build it up as the town grows. There’s money in that sometimes.”

“Why not do it, then? It’s not for the sake of the money. I hate money; I’ve never had any. But I don’t believe any one can be really happy after he’s twenty-five without a definite purpose and a kind of settled life. Some day you’ll want to marry—”

“Don’t say that. I’ve been a free lance too long!” cried Elliott.

“I’ve always been afraid of matrimony, too,” said Margaret, with a quick flush. “I want my own life, all my own.”

“But what you say is right, dead right,” said Elliott, after a reflective pause that lasted for several minutes. “It’s just what my own conscience has been telling me.” He stopped to meditate again.

“I’ll tell you what I think I’ll do,” he proceeded, at last. “I’ll go over to Omaha and look for a job on one of the dailies there. I expect I can get it, and it’ll give me time to think over my plans.

“You’re not going East till fall, and I can run across here often, so that I’ll be able to see you. I may go East this fall myself. You’ve just crystallized what I’ve been thinking. I will do something to surprise you, and I’ll make a fortune with it. Will you shake hands on it?”

She pulled off the riding-gauntlet and put out her hand, meeting his eyes squarely. The deep flush still lingered in her cheeks.

“We are good friends,” he exclaimed, feeling a desire to say something, he scarcely knew what.

“The very best!” said Margaret, looking bright-eyed at him. “I hope we always will be. Come,” she cried, pulling her hand away. “The storm’s over. Let’s go back.”

The rain had made the road very sticky, and they rode slowly side by side, while Margaret chattered vivaciously of her own future, of her music, of the coming winter in the East. She was full of plans, and Elliott sunk his own perplexities to share in her enthusiasm. He was himself imbued with the cheerfulness that comes of good resolutions, whose difficulties are yet untried.

“When are you going to Omaha?” she asked him, as he left her at the gate.

“In a couple of days. I’ll see you, of course, before I go.”

He packed his two trunks that night. He did not see her again, however, for she happened to be out when he called to make his farewell. He was unreasonably annoyed at this disappointment, and thought of delaying his departure another day, but he was afraid that she would consider it weak. Anyhow, he expected to be back in Lincoln within a fortnight, and he left that night for Omaha.

The next couple of days he spent in a round of visits to the offices of the various Omaha newspapers. He found every staff filled to its capacity. There was a prospect of a vacancy in about a month, but it was too long to wait, and, happening to hear that the St. Joseph Post was looking for a new city editor, he went thither with a letter of introduction from the manager of the Omaha Bee.

“That’s number eighteen, and the red,” said the croupier behind the roulette-table, raking in the checks that the player had scattered about the checkered layout. Round went the ball again with a whirr, though there were no fresh stakes placed.

In fact, Elliott had no more to place. The stack of checks he had purchased was exhausted, and he had no mind to buy more. He slid down from the high stool and stepped back, and with the fever of the game still throbbing in his blood, he watched the little ivory ball as it spun. It slackened speed; in a moment it would jump; and Elliott suddenly felt—he knew—what the result would be. He thrust his hand into his pocket where a crumpled bill lingered, and it was on his lips to say “Five dollars on the single zero, straight,” when the ball tripped on a barrier and fell.

“That’s the single zero,” said the croupier, and spun the ball again.

Elliott turned away, shrugging his shoulders. “That’s enough for me to-night,” he remarked, with an affectation of unconcern. He had no luck; he could predict the combinations only when he did not stake.

The sleepy negro on guard drew the bolt for him to pass out, and he went down the stairs to the precipitous St. Joseph streets, at that hour, silent and deserted. It was a mild spring night, and the air smelled sweet after the heavy atmosphere of the gaming-rooms. A full moon dimmed the electric lights, and his steps echoed along the empty street as he walked slowly toward the river-front, where the muddy Missouri rolled yellow in the sparkling moonlight.

As the coolness quieted his nerves he was filled with sickening disgust at his own folly and weakness. “Why had he done it?” he asked himself. He had never been a gambler, in the usual sense of the word. His ventures had always been staked upon larger and more vital events than the turn of a card or of a wheel, but after finding that he had come to St. Joseph upon a fruitless quest, after all, he had gone to the gaming-rooms with one of the Post’s reporters, who was showing him the town. In his depression and weariness and curiosity he had begun to stake small sums and to win. He remembered scarcely anything more. He had won largely; then the luck changed. He had sat down at the table with nearly seventy dollars. How much was left?

He had reached the bottom of the street, and, crossing the railway tracks, he walked out upon the long pier that extends into the river and sat down upon a pile of planks. A freight-train outbound for St. Louis shattered the night as it banged over the noisy switches, and then silence fell again upon the yellow river. In the unsleeping railway-yards to the east there was an incessant flash and flicker of swinging lanterns.

He turned out his pockets. There was the five-dollar bill that he had saved from the wheel, and a quantity of loose silver,—eighty-five cents. With a lively emotion of pleasure he discovered another folded five-dollar bill in his pocketbook which he had not suspected. Ten dollars and eighty-five cents was the total amount. It was all that was left of his former capital, or it was the nucleus of his new fortunes, as he should choose to consider it.

At the memory of the promises he had made scarcely a hundred hours ago to Margaret Laurie, he shivered with shame and self-reproach, and in his remorse he realized more clearly than ever the truth of her words. He was wasting his life, his time, and his money; and already the endless chase of the rainbow’s end began to seem no longer desirable. In an access of gloom he foresaw years and years of such unprofitable existence as he had already spent, alternations of impermanent success and real disaster, of useless labour, of hardship that had lost its romance and come to be as sordid as poverty, and for the sum of it all, Failure. The fitful fever of such a life could have no place for the quiet and graceful pleasures that he had almost forgotten, but which seemed just then to lie at the basis of happiness and success; and suddenly in his mind there arose a vision of the old city on the Chesapeake Bay, its crooked and narrow streets named after long dead colonial princes, its shady gardens, the Southern indolence, the Southern quiet and perfume.

That was where Margaret was going, and there perhaps he had left what he should have clung to; and, as he turned this matter over in his mind, he remembered another fact of present importance. One of the men with whom he had worked on the Baltimore Mail had within the last year become its city editor. He had written offering Elliott a position should he want it, but Elliott had never seriously considered the proposition.

Now, however, he jumped at it. “The West’s too young for me,” he reflected. “I’d better get out of the game.” He would write to Grange for the job that night, and he would be in Baltimore long before Margaret would arrive there. No, he would start for the East that night without writing,—and then he was chilled by the memory of his reduced circumstances. A ticket to Baltimore would cost thirty-five dollars at least.

But the Westerner’s first lesson is to regard distance with contempt. Elliott had travelled without money before, but it was where he knew obliging freight conductors who would give him a lift in the caboose, while between the Mississippi and the Atlantic was new ground to him. Nevertheless he was unable to bring himself to regard the thousand odd miles as a real obstacle. He could walk to the Mississippi if he had to; it would be no novelty. Once on the river he could get a cheap deck passage to Pittsburg, or he might even work his passage. Probably, however, he could get a temporary job in St. Louis which would supply expenses for the journey. As for his baggage, it would go by express C. O. D., and he could draw enough advance salary in Baltimore to pay for it.

As he walked back to his hotel, he felt as if he were already in Baltimore, regardless of the long and probably hard road that had first to be travelled. That part of it, indeed, struck him rather in the light of a joke. A few rough knocks were needed to seal his good resolutions firmly this time, and the tramp to the Mississippi would be a sort of penance, a pilgrimage.

He debated whether to write to Margaret, and decided that he had better not. It would not be pleasant to confess; at least it would be preferable to wait until he was launched upon the new and industrious career which he had planned. He would write from Baltimore, not before.

That night he laid out his roughest suit, and it was still early the next morning when he tramped out of St. Joseph. His baggage was in the hands of the express company, and he carried no load; despite his penury he preferred to buy things than to “pack” them. He followed the tracks of the Burlington Railroad with the idea that this would give him a better and straighter route than the highway, as well as a greater certainty of encountering villages at regular intervals. He was unencumbered, strong, and hopeful, and he rejoiced, smoking his pipe in the cool air, as he left the last streets behind, and saw the steel rails running out infinitely between the brown corn-fields and the orchards, straight into the shining West.

For a long time Elliott remembered that day as one of the most enjoyable he ever spent. It was warm enough to be pleasant; the track, ballasted heavily with clay, made a delightfully elastic footpath; on either side were pleasant bits of woodland dividing the brown fields where the last year’s cornstalks were scattered, and farmhouses and orchards clustered on the rolling slopes. Where they lay beside the track the air was full of the hoarse “booing” of doves; and, after the rawness of the treeless plains, this seemed to Elliott a land of ancient comfort, of long-founded homesteads, and all manner of richness.

He had intended to ask for dinner at one of the farmhouses, where they would charge him only a trifle, but he developed a nervous fear of being taken for a tramp. Again and again he selected a house in the distance where he resolved to make the essay; approached it resolutely—and weakly passed by, finding some excuse for his hesitation. It was too imposing, or too small; it looked as if dinner were not ready, or as if it were already over; and all the time hunger was growing more acute in his vitals. About one o’clock, however, he came to a little village, just as his appetite was growing uncontrollable. He cast economy to the dogs, went to the single hotel, washed off the dust at the pump, and fell upon the hot country dinner of coarse food supplied in unlimited quantity. It cost twenty-five cents, but it was worth it; and after it was all over he strolled slowly down the track, and finally sat down in the spring sun and smoked till he softly fell asleep.

He was awakened by the roar of an express-train going eastward, and it occurred to him that his baggage must be aboard that train, travelling in ease while its owner plodded between the rails. It was after two o’clock; he had rested long enough, and he returned to the track and took up the trail again.

At sunset he reached Hamilton, and his time-table folder indicated that he had travelled twenty-seven miles that day. At this rate he would reach the Mississippi in less than a week, and he felt only an ordinary sense of healthy fatigue and an extraordinary appetite.

He was charged a quarter for supper that evening at a farmhouse, and before dark he had reached the next village. There was a bit of woodland near by where he imagined that he could encamp, and as it had been a warm day he thought a fire would be unnecessary. So in the twilight he scraped together a heap of last year’s leaves, and spread his coat blanket-wise over his shoulders. It reminded him of many camps in the mountains, and he went to sleep almost at once, for he was very tired.

A sensation of extreme cold awoke him. It was dark; the stars were shining above the trees, and, looking at his watch by a match flare, he learned that it was a quarter to twelve. But the cold was unbearable; he lay and shivered miserably for half an hour, and then got up to look for wood for a fire. In the darkness he could find nothing, and, thoroughly awake by this time, he abandoned the camp and went back through the gloom to the railway station, where half a dozen empty box cars stood upon the siding. Clambering into one of these, it appeared comparatively warm; it reminded him of Margaret and of the hail upon Salt Lake,—things which already seemed very far away.

His rest that night was shattered at frequent intervals by the crash of passing freight-trains. They stopped, backed, and shunted within six feet of him with a clatter of metal like a collapsing foundry, a noise of loud talking and swearing, and a swinging flash of lanterns. Drowsily Elliott fancied that his car was likely to be attached to some train and hauled away, perhaps to St. Louis, perhaps to St. Joseph, but in the stupefaction of sleep he did not care where he went; and, in fact, when he awoke he saw the little village still visible through the open side door, looking strange and unfamiliar in the gray dawn. Grass and fences were white with hoarfrost.

At five o’clock that afternoon Elliott was twenty-two miles nearer the Mississippi. He had just passed a small station. His time-table told him that there was another eight miles away, and he decided to reach it and spend the night in one of its empty freight-cars, for he had learned that camping without a fire was not practicable.

He reached the desired point just as it was growing dark. Point is the word, for it was nothing else. There was no depot there, no houses, no siding,—nothing whatever but a name painted on a mocking plank beside the track. It was a crossroads flag-station. Elliott had failed to notice the “f” opposite the name in the time-table.

The sun had set in clouds and a fine cold rain was beginning. The sky looked black as iron. A camp in the rain was out of the question. The next village was five miles away, but he would have to reach it.

It was a dark night, but it never grows entirely dark in the open air, as house-dwellers imagine, and as he went on he could make out looming masses of forest on either hand. The country seemed to be growing marshy; he came to several long trestles, which he crossed in fear of an inopportune train.

Presently the track plunged into a sort of swamp, where the trees came close and black on both sides. The rain pattered in pools of water, and through the wet air darted great fireflies in streaks of bluish light. Their fading trails crossed among the rotting trees, and from the depths of the marsh sounded such a chorus of frog voices as he had never dreamed of, in piccolo, tenor, bass, screeching and thrumming. In the deepest recesses some weird reptile emitted at regular intervals a rattling Mephistophelean laugh. It impressed Elliott with a kind of horror,—the blue witch-fires flashing through the rain, the reptilian voices, and that ghastly laugh from the decaying woods; and he hastened to leave it behind.

It proved a very long five miles to the next station, and he was wet through and stumbling with weariness when he reached it. The village was pitch-dark; not a light burned about the station except the steady switch-lamps; not a freight-car stood upon the siding. There was not even a roof over the platform, and, too tired to look for shelter, Elliott dropped upon a pile of lumber by the track, and went heavily to sleep in the rain.

The hideous clangour of a passing express-train awoke him; he was growing accustomed to such awakenings. It was an hour from sunrise. Close to him stood the little red station and a great water-tank. The village was still asleep among the dripping trees. Not a smoke arose from any chimney.

It had stopped raining, and the east was clearer. Elliott was wet through, cold and stiff, and he found his feet sore and swollen. He was not in training for so much pedestrian exercise, and he had overdone it.

But the solitary hotel of the village awoke early, and Elliott did not have to wait long for breakfast. Shortly after sunrise, strengthened with hot coffee, he was renewing the march, finding every step exquisitely painful. The romance of this sort of vagabondage was fast evaporating, and the thought of the seventy dollars that he had wasted in St. Joseph infuriated him.

When the sun rose high enough to dry his garments, he sat down, removed his coat, and steamed gently. After this respite the pain in his blistered soles was worse than ever, but he trudged stoically on. After an hour it grew dulled till he scarcely noticed it, and about noon he reached Redwood.

Near the station there was a small lunchroom, where Elliott satisfied his appetite, and he returned to the railway, sat upon a pile of ties, lighted his pipe, and reflected. The endless line of shining rails running eternally eastward was loathsome to his eyes.

“I’ve overdone it at the start. I ought to lie up and rest for a day or two,” he said to himself. But even walking appeared preferable to idling in the scraggly village, and he suddenly determined that he would neither idle nor yet walk, but nevertheless he would be in Hannibal in two days.

He sat on the pile of ties for over an hour. A ponderous freight-train dragged up to the station, went upon the siding and waited till the fast express flashed past without stopping. Then the freight got clumsily under way again with a tremendous clank and clamour. At it rolled slowly past, Elliott saw a side door half-open. He ran after it, swung himself up by his elbows, and tumbled head first into the car.

The train went on, gradually gaining speed. There were loose handfuls of corn scattered about the car from its last load. Elliott slid the door almost shut and sat down on the floor, wondering if the crew had seen him get aboard.

The train was attaining a considerable speed and the car was flung over the rails with shattering jolts. Through the cranny of the door Elliott saw trees and fields sweep by, and he was considering pleasantly that he had already travelled an hour’s walk, when a heavy trampling of feet sounded on the roof of the pitching car.

He listened with some uneasiness. The feet reached the end of the car; he heard them coming down the iron ladder, and then a face, a grimed but not unfriendly face, topped by a blue cap, appeared at the little slide in the end.

“Hello!” called the brakeman, peering into the dark interior. “I know you’re there. I seen you get in. I kin see you now.”

At this culminative address, Elliott came out of his dusky corner.

“Where you goin’?” demanded the brakeman.

“Why, I’d like to stay right with this train. It’s going my way,” replied Elliott. “You don’t mind, do you?”

“Dunno as I do,—but you can’t ride this train free.”

“Oh, that’s all right,” responded the trespasser. “I’m pretty short or else I’d be on the cushions instead of here, but I don’t mind putting up a quarter. Does that go?”

“I reckon,” said the brakeman, unhesitatingly. “This train don’t go only to Brookfield; that’s the division point. Keep the door shet, an’ don’t let nobody see you.”

He went back to the top of the train. Elliott felt as if he had been swindled, for Brookfield was only twenty-five miles away. However, he hoped to catch another freight that afternoon and make as many more miles before sunset, and he settled himself as comfortably as possible on the jolting floor and lighted his pipe.

He had time to smoke many pipes before reaching Brookfield, for it was nearly two hours before the heavy train rolled into the yards. Elliott climbed out upon the side-ladder and swung to the ground before the train stopped, to avoid a possible railway constable. Considerably to his surprise, he saw half a dozen rusty-looking vagrants hanging to the irons and jumping off at the same time. He had had more fellow passengers than he had suspected, and it struck him that freight-breaking must be rather a lucrative employment.

All the rest of that afternoon Elliott watched the freight-yards, but, though some trains departed eastward, they appeared to contain no empty cars. After supper he returned to the railroad, and remained there till it grew dark. Trains came and went; there were engines hissing and panting without cease; all the dozen tracks were crowded with cars, and up and down the narrow alleys between them hastened men with lanterns, talking and swearing loudly. The crash and jar of coupling and shunting went on ceaselessly, and this activity did not lessen, and the night passed, for Brookfield was one of the “division points” on the main line of a great railroad.

It was nearly midnight when Elliott observed that a train was being made up with the caboose on the western end. He walked its length; the switchmen paid no attention to him, and he discovered an empty box car about the middle of the train, and into it he climbed without delay. For another half-hour, however, the manipulation of the cars continued, with successive violent shocks as fresh cars were coupled on. The whole train seemed to be broken and shuffled in the darkness, and it was hauled up and down till Elliott began to doubt whether it were going ahead at all. But at last he heard the welcome two blasts from the locomotive ahead, and in another minute the long train was labouring out.

This time he suffered no interference from any brakeman. The train was a fast freight; it made no stop for nearly two hours, and then continued after the briefest delay. The speed was high enough to make the springless car most uncomfortable, till the jolts seemed to shake the very bones loose in Elliott’s body. Every position he tried seemed more uncomfortable than the last, but he was determined to stay with the train as far as it went. After a few hours of being tossed about, he became somewhat stupefied, and even dozed a little, and between sleep and waking the night passed. In the first gray of morning the train pulled up at the great water-tank at Palmyra Junction, fifteen miles from Hannibal. He had travelled ninety miles that night.

The train went no farther. After waiting an hour or two for another, Elliott decided to walk the rest of the way, and he left Palmyra at nine o’clock, arriving in Hannibal, very tired and dusty, at a little after three. At the bottom of the long street he caught a glimpse of the broad Mississippi rolling yellow between its banked levees. The first stage of the journey was accomplished; the next would be upon the river.

When he went down to the levee an hour or two later, Elliott found no boats preparing to sail, and a general lack of activity about the steamer wharves. Sitting upon a stack of cotton-bales, he perceived a young man of rather less than his own age, smoking with something of the air of a busy man who finds a moment for relaxation. He was very much tanned; he wore a flannel shirt and a black tie, and his clothes were soiled with axle-grease and coal-dust. By these tokens Elliott recognized that he had been for some time in contact with the railways, but he did not look like a railway man, and his face wore a bright alertness that distinguished it unmistakably from that of the joyless hobo. Elliott took him for an amateur vagrant like himself.

“Seems to be nothing doing on the river. Do you know when there’s a boat for St. Louis?” he asked, pausing beside the cotton-bales.

The lounger took stock of Elliott, keenly but with good nature.

“There ought to be one leaving about six o’clock, but I don’t see any sign of her yet,” he responded. “Going down the river?”

“I thought I’d try it. Do you reckon the mate would take me on, even if it was only to work my passage?”

“What do you want to do that for?” queried the other, with a sort of astonished amusement.

“Why, I wanted to get to St. Louis, and after that up to Pittsburg or Cincinnati.”

“If you want to get there easy, and get there alive, I don’t see why you don’t swim,” remarked the stranger, dryly. “You don’t know much about these river boats, do you? Man, they’re floating hells. The crew is all niggers, and the toughest gang of pirates in America. They knife a man for a chew of tobacco. The officers themselves don’t hardly dare go down on the lower deck after dark,—but, Lord! they do take it out of the black devils when they tie up at a wharf and start to unload. If you can’t work for ten hours at a stretch toting a hundred-pound crate in each hand, live on corn bread, and kill a man every night, don’t try the boats. A white man wouldn’t last any longer in that crowd than an icicle in hell.”

“The deuce!” said Elliott, disconcerted. “I’m very anxious to get to Cincinnati, anyway, and the fact is I’m sort of strapped. I thought I’d be all right when I got to the river.”

“Tried freights?”

“Yes, and they don’t suit me too well.”

“I’m going to St. Louis,” said the stranger, after a pause. “I’m going to leave early in the morning, and I expect to get there in three hours, and I don’t intend that it shall cost me a cent. To tell the truth, I’m in something of the same fix as you are.”

“How’ll you manage it?” Elliott inquired, with much curiosity.

“Ride a passenger-train, on the top. I’ve just come from Seattle that way,” he continued, after a meditative pause. “There’s no great amount of fun in it, but I did it in six days.”

“The deuce!” exclaimed Elliott again. “Do you mean to say that you came all the way from Seattle in six days, beating passenger-trains?”

“Every inch of it. I was in a hurry, and I’m in a hurry yet. Mostly I rode the top, and sometimes the blind, and once I tried the trucks, but next time I’ll walk first. The beast of a conductor found that I was there, and poured ashes down between the cars.”

“You’re a genius,” said Elliott, looking at the audacious traveller with admiration. “That’s beyond me.”

“Not a bit of it. I don’t do this sort of thing professionally, nor you, either. Excuse me, I can see that you’re no more a bum than I am. But a man ought to be able to do anything,—beat the hobo at his own game if he’s driven to it. I simply had to get to Nashville, and I hadn’t the money for a ticket. I did it, or I’ve nearly done it, and you could have done it, too.

“Of course you could,” he went on, as Elliott looked doubtful. “Come with me in the morning, if you’re game, and I’ll guarantee to land you in St. Louis by eight o’clock.”

“Oh, I’m game all right,” cried Elliott, “if you’re sure I won’t be troubling you.”

“Didn’t I say that I’m going, anyway. I mighty seldom let anybody trouble me. Now look here: the fast train from Omaha gets here a little before three, daylight. You meet me at the passenger depot at, say, three o’clock. Better get as much sleep as you can before that, for you sure won’t get any after it.”

He glanced at Elliott with a smile that had the effect of a challenge. “Oh, I won’t back out,” Elliott assured him. “I’ll be there, sharp on time. So long, till morning.”

Elliott went away a little puzzled by his new comrade, and not altogether satisfied. The young fellow—he did not know his name—evidently was in possession of an almost infernal degree of energy. Plainly he was no “bum,” as he had said; it was equally plain that he was, undeniably, not quite a gentleman; and, plainest of all, that he was a man of much experience of the world and ability to take care of himself in it. Elliott could not quite place him. He was a little like a professional gambler down on his luck. It was quite possible that he was a high-class crook escaping from the scene of his latest exploit, and it was this consideration that roused Elliott’s uneasiness. It was bad enough, he thought, to be obliged to dodge yard watchmen and railway detectives without risking arrest for another man’s safe-cracking.

Still, the association would last only for a few hours, and he went to bed that night resolved to carry the agreement through. He was staying at a cheap hotel, and there were times when he would have regarded its appointments as impossible, but it struck him just now that he had never known before what luxury was. It was four nights since he had slept in a bed, and, as he stretched himself luxuriously between the sheets, the idea of getting up at three o’clock seemed a fantastic impossibility.

A thundering at the door made it real, however. He had left orders at the desk to be called, and he pulled his watch from under the pillow. There was no mistake; it was three o’clock, and, shivering and still sleepy, he got up and lighted the gas.

Near the waterfront he found an all-night lunchroom, and hot coffee and a sandwich effected a miraculous mental change. With increasing cheerfulness he went on toward the depot through the deserted streets. It was still dark and the stars were shining, but there was an aromatic freshness in the air, and low in the east a tinge of faintest pallor.

He found his prospective fellow traveller lounging about the triangular walk that surrounds the depot, and saluted him with a flourish of his pipestem. An almost imperceptible grayness was beginning to fill the air, and sparrows chirped in the blackened trees about the station.

“She’ll be along in a few minutes,” said the expert, referring to the train. “By the way, my name’s Bennett; what’ll I call you? Any old name’ll do.”

“Call me Elliott. That happens to be my real name, anyway. But say, won’t it be a little too light soon for us to sit up in plain sight on the roof of that train?”

“A little. But she doesn’t make any stop all the way to St. Louis, I believe, and of course the people on board can’t see us. It’s easier to climb up there by daylight, too, and—there she whistles.”

The few early passengers hurried out upon the platform. In half a minute the train rolled into the station, its windows closely curtained and the headlight glaring through the gray dawn. The passengers went aboard; there was no demand for tickets at the car steps, and Bennett and Elliott went straight to the smoker, where they sat quietly till the train started again, after the briefest delay.

“Now come along,” muttered Bennett, and Elliott followed him across the platforms and through the three day coaches full of dishevelled, dozing passengers. The Pullmans came next, and luckily the juncture was not vestibuled.

Without the slightest hesitation Bennett climbed upon the horizontal brake-wheel, and put his hands on the roof of the sleeper. Then with a vigorous spring he went up, crept to a more level portion of the roof, and beckoned Elliott to follow him.

The train was now running fast, and the violent oscillation of the cars made the feat look even more difficult and dangerous than it was. But the idea that the conductor might come through and find him there stimulated Elliott amazingly, and he clambered nervously upon the wheel, and got his hands upon the grimy roof that was heaving like a boat on a stormy sea. Securing a firm hold, he attempted to spring up, but a violent lurch at that moment flung him aside, and he was left dangling perilously till Bennett scrambled to his relief and by strenuous efforts hauled him up to more security.

A furious blast of smoke and cinders struck his face. Before him writhed the dark, reptilian back of the train, ending in the locomotive, that was just then wreathed in a vivid glare from the opened firebox. From that view-point the engine seemed to leap and struggle like a frenzied horse, and all the cars plunged, rolling, till it appeared miraculous that they did not leave the rails. Even as he lay flat on the roof of the bucking car it was not easy to avoid being pitched sideways. The cinders came in suffocating blasts with the force of sleet, and presently, following Bennett’s example, Elliott turned about with his head to the rear and lay with his face buried in his arms. The roar of the air and of the train made speech out of the question.

The position had its discomforts, but it seemed an excellent strategic one. An hour went by, and it was now quite light. The fast express continued to devour the miles with undiminished speed.

Little sleeping villages flashed by, as Elliott saw occasionally when he ventured to raise his head Two hours; they were within forty miles of St. Louis, when the train unexpectedly slackened speed and came to a stop.

Elliott jumped to the conclusion that it had stopped for the sole purpose of putting him off, but he observed immediately that it was to take water. He glanced at Bennett, who was looking about with an air of disgusted surprise.

There were men about the little station, and the trespassers flattened themselves upon the car roof, hoping to escape notice, but some one must have seen them. A gold-laced brakeman presently thrust his head up from below, mounted upon the brake-wheel.

“Come now, get down out of that!” he commanded.

His conductor was looking on, and there was no possibility of coming to an arrangement with him. Elliott slid down to the platform, much crestfallen, followed by Bennett. Cinders fell in showers from their clothing as they moved, and a number of passengers watched them with unsympathetic curiosity as they walked away.

“By thunder, I hate to be ditched like that!” muttered Bennett, glancing savagely about. “Let’s try the blind baggage, if there is one. We’ll beat this train yet.”

Elliott doubted the wisdom of this second attempt, but they went forward, looking for the little platform, usually “blind,” or doorless, which is to be found at the front end of most baggage-cars. It was there; none of the crew appeared to be looking that way, and they scrambled aboard just as the train started.

It was a much more comfortable position than the top, for there were iron rails to cling to and a platform to sit upon, while they were out of the way of smoke and cinders. Immediately before them rose the black iron hulk of the tender and it was not long before the fireman discovered them as he shovelled coal, but he made no hostile demonstration beyond playfully shaking his fist.

“We’re safe for St. Louis now. There won’t be another stop, and nobody can see us or get at us while she’s moving,” remarked Bennett, with satisfaction. He glanced over his shoulder, turned and looked again, and his face suddenly fell. After a moment’s sober stare, he burst into a fit of laughter.

“Done again! This ‘blind’ isn’t blind at all,” he cried, pointing to the car-end.

It was hideously true. There was a narrow door which they had not observed in the end of the car. Just then it was closed fast enough, but there was no telling when it might be opened.

“Anyhow,” said Elliott, plucking up courage, “we’re making nearly forty miles an hour, and every minute they leave us in peace means almost another mile gained.”

“Yes, and there’s just a chance that nobody opens this door. I think that if we stop again we’d better give this train up.”

They watched the door anxiously as the minutes and the miles went past, but it remained unopened. The little stations flew past—Clarksville, Annada, Winfield. It was not far to West Alton, and that was practically St. Louis.

The end was almost in sight. But the door opened suddenly, and the brakeman they had before encountered came out.

“I told you fellows to get off half an hour ago.”

“Now, look here,” said Bennett, persuasively. “We’re not doing this train any harm at all. We’re not going inside; we’ll stay right here, and we’ll jump the minute she slows for Alton. We’re no hobos. We’re straight enough, only we’re playing in hard luck just now and we’ve simply got to stay on this train. Now you go away, and just fancy you never saw us, and you’ll be doing us a good turn.”

The brakeman reflected a moment, looked at them with an expression more of sorrow than of anger, and returned to the car without saying anything.

“He’s all right,” said Elliott.

“And every minute means a mile,” Bennett added.

But in less than a mile the brakeman returned, and the conductor came with him.

“Come now, get off!” commanded the chief, crisply.

“We’ll get off if we have to,” said Bennett. “You must slow up for us, though.”

“Slow hell!” returned the conductor. “I’ve lost time enough with you bums. Hit the gravel, now!”

Elliott glanced down. The gravel was sliding past with such rapidity that the roadway looked smooth as a slate.

“Great heavens, man, you wouldn’t throw us off with the train going a mile a minute. It would be sure murder,” pleaded Bennett.

“I’ve no time to talk. Jump, or I’ll throw you off.” The conductor advanced menacingly, with the brakeman at his shoulder.

Bennett lifted his arm with a gesture that the conductor mistook for aggression. He whipped out his revolver and thrust it in Bennett’s face. The adventurer, startled, stepped quickly back, clean off the platform, and vanished.

A wave of rage choked Elliott’s throat, and he barely restrained himself from flying at the throats of his uniformed tormentors.

“Now you’ve done it,” he said, finding speech with difficulty. “You’ve killed the man.”

The conductor, looking conscience-stricken and anxious, leaned far out and gazed back, and then pulled the bell-cord.

“He needn’t have jumped. I wouldn’t have thrown him off; never did such a thing in my life,” he muttered.

“He didn’t jump. You assaulted him, when all he wanted was to get off quietly. You pulled your gun on him, when neither of us was armed. It’s murder, and you’ll be shown what that means.”

Elliott felt that he had the moral supremacy. The conductor made no reply, and the train came to a stop.

“You’d better go back and look after your partner,” he said, in a subdued manner. “I’m mighty sorry. I’d never have hurt him if he’d stayed quiet. It’s only a couple of miles to Alton,” he added, as Elliott jumped down, “and you can take him into St. Louis all right, if he isn’t hurt bad. I’d wait and take you in myself if I wasn’t eighteen minutes late already.”

The train was moving ahead again before Elliott had reached its rear. He ran as fast as he could, and while still a great way off he was relieved to see Bennett sitting up among the weeds near the fence where he had been pitched by the fall. He was leaning on his arms and spitting blood profusely.

“Are you hurt much, old man? I thought you’d be killed!” cried Elliott, hurrying up.

Bennett looked at him in a daze. His face was terribly cut and bruised with the gravel, and the blood had made a sort of paste with the smoke-dust on his cheeks. His clothes were rent into great tatters.

“Don’t wait for me,” he muttered, thickly. “Go ahead. Don’t miss the train. I’m—all right.”

But his head drooped helplessly, and he sank down. The ditch was full of running water, and Elliott brought his hat full and bathed the wounded man’s head and washed off the blood and grime. Bennett revived at this, and looked up more intelligently.

Elliott examined him cursorily. His right arm was certainly broken, and something appeared wrong with the shoulder-joint; it looked as if it might be dislocated. There must be a rib broken as well, for Bennett complained of intense pain in his chest, and continued to spit blood.

“That conductor certainly ditched us, didn’t he?” he murmured. “Did he throw you off too? I was a fool not to see that door.”

None of the injuries appeared fatal, or even very serious, with proper medical care, and Elliott felt sure that the right thing was to get his comrade into St. Louis and the hospital at once. But Bennett was quite incapable of walking, and Elliott was not less unable to carry him. He became feverish and semidelirious again; he talked vaguely of war and shipwreck, but in his lucid moments he still adjured Elliott to leave him.

Elliott remained beside him, though with increasing anxiety. After an hour or two, however, he was relieved by the appearance of a gang of section workers with their hand-car, to whom Elliott explained the situation without reserve. They were sympathetic, and carried both Elliott and Bennett into Alton on their car, where they waited for two hours for a train to St. Louis.

Bennett was got into the smoker with some difficulty; he remained almost unconscious all the way, and at the Union Station in St. Louis there was more difficulty. Elliott was afraid to call a policeman and ask for the ambulance, lest admission should be refused on the ground that Bennett was an outsider. So, half-supporting and half-carrying the injured man, he got him out of the station and a few yards along the street. It was impossible to do more. A policeman came up, and Elliott briefly explained that this man was badly hurt and would have to go to the hospital at once. Then he hurried off, lest any questions should be asked.

Elliott watched the arrival of the ambulance from a distance, for he felt certain that he looked a thorough tramp, with his rough dress and the clinging coal grime of the railroad. Yet he did not wish to leave the city without at least seeing Bennett again, and hearing the medical account of his condition; and he was surprised to find how much liking he felt for this light-hearted and resourceful vagabond whom he had known for less than twenty-four hours.

Though his money was running dangerously short, he lodged himself at a not wholly respectable hotel on Market Street, and next morning he made what improvement he could in his appearance, and went to the hospital. Visitors, it turned out, were not admitted that day, but he was told that his friend was in a very bad way indeed. The young doctor in white duck evidently did not consider his shabby-looking inquirer as capable of comprehending technical details, and seemed himself incapable of furnishing any other, but Elliott gathered that Bennett had been found to have two or three ribs broken and his shoulder dislocated, besides a broken arm and more or less severe lacerations of the lungs. He was quite conscious, however, and the doctor said that, if he grew no worse, it was likely that Elliott would be permitted to see him on the next visiting day, which would be the morrow.

At three o’clock the next afternoon, therefore, Elliott applied, and was admitted without objection. A wearied-looking nurse led him through the ward, where there seemed a visitor for every cot. Bennett, she said, appeared a little better. His temperature had gone down and he seemed to be recovering well from the shock, but Elliott was startled at the pallor of the face upon the pillow. The brown tan looked like yellow paint upon white paper, but Bennett greeted him cheerfully and seemed nervously anxious to talk.

“Sit down here. This is mighty good of you,” he said. “I never got ditched like that before. Did that conductor throw you off, too?”

“Oh, no. He stopped the train for me to get off. His conscience was hurting him, I think.”

“Well, it’s going to cost the road something, I think. But you’ve stayed by me like a brother,” Bennett went on, deliberatively, “and I’ll make it up to you if I can, and I think I can. There’s something I want to tell you about. It’s no small thing, and it’ll take an hour or two, so you’ll have to come to-morrow afternoon, and bring a note-book. We can’t talk with all these visitors swarming around. They’ll let you in; I’ve fixed it up with the doctor. They said that it was liable to kill me, but I told them that it was a matter of life and death, and they gave in. It is a life and death business, too, for a couple of dozen men have been killed in it already, and there’s a round million, at least, in solid gold. What do you think of that?”

Elliott thought that his comrade was becoming delirious again, but he did not say so. The nurse, who had been keeping an eye on him, came up.

“I really think you’ve talked long enough,” she said, with a sweetness that had the force of a command.

“All right,” said Elliott, getting up. “I’ll see you to-morrow, then. Good-bye.”

“Will it really be all right, nurse, for me to have a long talk with him to-morrow?” he inquired, as soon as he was out of Bennett’s hearing.

“No, it isn’t all right, but the house surgeon has given his consent. I think it’s decidedly dangerous, but your friend said it was an absolute matter of life and death, and it may do him good to get it off his mind. Come, since you’ve got permission; and if it seems to excite him too much, I’ll send you away.”

Elliott felt a good deal of curiosity as to the secret which was to be confided to him, for which a couple of dozen men had died already. Probably it had something to do with Bennett’s rapid journey across the continent, and Elliott felt some apprehension that he might be about to be made the involuntary accessory to some large and unlawful exploit.

His curiosity made him willing to take chances, however, and he waited impatiently for the next afternoon. When it came, he found Bennett propped up on three pillows and looking better. The nurse said that he really was better, that all would probably go well, but that it would be slow work, and this slowness seemed to irritate the patient most of all.

“First,” he said, when the nurse was out of earshot, “I’ll tell you what you must do for me. You’ll have to go out of your way to do it, but, unless I’m mistaken, you’ll find it worth your while. I want you to go to Nashville, Tennessee, and I want you to go at once. It’s a case for hurry. I can’t write now, and I daren’t telegraph. Maybe the men I want aren’t there, but you can find where they’re gone. Will you go?”

Elliott hesitated half a moment, wishing he knew what was coming next, but he promised—with a mental reservation.

“That’s all right, then,” said Bennett, “because I know you’re square,”—a remark which touched Elliott’s conscience. “It’s quite a tale that I want you to carry to them, and I’ll have to cut it as short as I can, and you’d better make notes as I go along, for every detail is important.

“I told you how I’d crossed the country from the Coast. I had come as straight as I could from South Africa. I wasn’t in any army there; that’s not in my line. It don’t matter what I was doing; I was just fishing around in the troubled waters.

“Anyway, I had a big deal on that was going to make or break me, and it broke me. I was in Lorenzo Marques then, and it was the most God-awful spot I ever struck. It was full of all the scum of the war, every sort of ruffians and beats, Portuguese and Dutch and Boers and British deserters, and gamblers and mule-drivers from America, all rowing and knifing each other, and it was blazing hot and they had fever there, too.

“I’ve seen a good many wicked places, but I never went against anything like that, and I wanted to get back to America. The American consul wouldn’t do anything for me at all, but I saw an American steamer out in the river,—the Clara McClay of Philadelphia,—loading for the East Coast and then Antwerp. She was the rottenest sort of tramp, but she caught my eye because she was the only American ship I ever saw in those waters. So I went aboard and asked the mate to sign me on as a deck-hand to Antwerp, and he just kicked me over the side.

“Anyway, I was determined to go on that ship, mate or no mate, for there wasn’t anything else going my way, and I expected to die of fever if I waited. So I went aboard again the night before she sailed, and they were getting in cargo by lantern light, and there was such a stir on the decks that nobody paid any attention to me. I got below, and dropped through the hatch into the forehold. They had pretty nearly finished loading by that time, and pretty soon they put the hatches on. It was as dark as Egypt then, and hotter than Henry, with an awful smell, but after awhile I went to sleep, and when I woke up she was at sea, and rolling heavily.

“When I thought she must be good and clear of land, I started to go up and report myself, but when I’d stumbled around in the dark for awhile, I found that the bales and crates were piled up so that I couldn’t get near the hatch. So I sat down and thought it over. I had a quart bottle of water with me, but nothing to eat, and I began to be horribly hungry.

“When I’d been there ten or twelve hours, I guess, I tried moving some of the crates to get to the hatchway, but they were too heavy. But while I was lighting matches to see where I was, I saw a lot of cases just alike, and all marked with the stencil of a Chicago brand of corned beef, and it looked like home. I thought it must be a providential interposition, for I was pretty near starving, and it struck me that I might rip one of the boards off, get out a can or two, and nail the case up again.

“The cases were big and heavy, and they were all screwed up and banded with sheet iron, but I had regularly got it into my head that I was going to get into one of them, and at last I did burst a hole. When I stuck my hand in, it nearly broke my heart. There wasn’t anything there at all, so far as I could make out, but a lot of dry grass.

“It occurred to me that this must be another commissary fraud, but when I tried to move the case it seemed heavy as lead. I poked my arm down into the grass and rummaged around. At last I struck something hard and square down near the middle, but it didn’t feel like a meat tin. I worked it out, and lit a match. It was a gold brick, and it must have weighed ten pounds.”

“Solid, real gold?” cried Elliott, with a sudden memory of Salt Lake.

“The real thing. It didn’t take me long to gut that box, and I dug out nineteen more bricks, nearly fifty thousand dollars’ worth, I reckoned. No wonder it was heavy. Then I looked over the rest of the cases, and they all looked just alike, and there were twenty-three of them, so I figured up that there must be considerably over a million in those boxes.”

“Stolen from the Pretoria treasury!” Elliott exclaimed.

“I believe it was, but what made you think of that?”

“Never mind; I’ll tell you later. Go on.”

“Well, I felt pretty certain that this gold came from the Rand, of course, but who it belonged to, or why he had shipped it on this old tramp steamer was what I couldn’t make out. Of course, if he was going to ship it on this boat, it was easy to understand that it might be safer to pass it as corned beef, but the whole thing looked queer and crooked to me.

“At first I was fairly off my head at the find, but when I came to think it over, it looked like there wasn’t anything in it for me, after all. I couldn’t walk off with those bricks. They might be government stuff, and I didn’t want any trouble with Secret Service men. So after awhile I packed up the box again as well as I could and fixed the lid.

“I thought I’d lie low for awhile, and I stayed in that black hole till I’d drunk all my bottle of water and was pretty near ready to eat my boots. When I couldn’t stand it any longer, I raised a devil of a racket, yelling, and hammering on the deck overhead with a piece of plank, and I kept this up, off and on, for half a day before they hauled the hatch off and took me out. It was dark night, with a fresh wind, and the ship rolling, and I never smelt anything so good as that open air.

“The first thing they did was to drag me before that same mate for judgment, and he cursed me till he was blue. He’d have murdered me if he’d recognized me, and he nearly did anyway, for he sent me down to the stoke-hold.

“I couldn’t stand that. I’d had a touch of fever in Durban, and I was weak with hunger anyway, and the first thing I knew I was tumbling in a heap on the coal. Somebody threw a bucket of water over me, but it was no use. I couldn’t stagger, and they took me up and made a deck-hand of me.

“This suited me all right, and the fresh air soon fixed me up. I wouldn’t have minded the job at all, but for the mate. The crew were afraid of him as death. His name was Burke, Jim Burke; he was a big Irishman, with a fist like a ham, and he made that ship a hell. He nearly killed a man the first night I was on deck, and I’ve got some of his marks on me yet. The captain wasn’t so bad, but I didn’t see so much of him. I was in the mate’s watch,—worse luck!

“But all this time I didn’t forget that gold below, and I was trying to see through the mystery. But I couldn’t make any sense of it till I saw the passengers we had.

“There were four of them that I saw. Three of them I spotted at once as from Pretoria. I’d seen the office-holding Boer often enough to recognize him, and they always talked among themselves in the Taal. Two of them were native Boers, I was sure, but the third looked like some sort of German. Besides these fellows, there was a middle-aged Englishman that looked like a missionary, and I heard something of another man who never showed himself, but I didn’t pay any attention to any one but the Boers.

“Because when I saw them, I saw through the whole thing. The war was going well for the Boers just then, but there were plenty of them wise enough to see that they couldn’t fight England to a finish, and crooked enough to try to feather their nests while they had a chance. Pretoria was all disorganized with the war-fever; half the government was at the front, and I’d heard of the careless ways they handled the treasury at the best of times.”

“You were right,” said Elliott. “I happen to know something about it.” And he imparted to Bennett the story of the official plundering which the mine superintendent in the Rand had written to him.

“Well, I thought that must have been it,” went on Bennett. “I wondered if the officers of the steamer knew the gold was there, but I didn’t think so. I was sure they didn’t,—not if the Boer was as ‘slim’ as he ought to be. I wouldn’t have trusted a box of cigars to that crowd.

“But all this detective work didn’t put me any forwarder, and the mate kept me from meditating too much. The boat was the worst old scow I ever saw. Twelve knots was about her best speed, and then we always expected the propeller to drop off, and she rolled like an empty barrel when there was the slightest sea. I’m no sailor, and that was the first time I’d ever bunked with the crew, but I could see easy enough that she was rotten.

“For the first few days the weather was pretty fair, but on the fourth after I came on deck it turned rougher. There wasn’t very much wind, but a heavy swell, as if there was a big gale somewhere out in the Indian Ocean. It was the sixth day from port, and I reckoned that we must be getting pretty well through the Mozambique Channel.

“It came on cloudy that evening, and when I came on deck it was dark as pitch and raining hard. There was a light, cool south wind with a tremendous black swell. The big oily rollers hoisted her so that the screw was racing half the time, and every little while she’d take it green, with an awful crash. Everybody was in oilskins but me, and I hadn’t any.

“The mate was on the bridge, and it wasn’t long before we found out that he was drunk, and he must have had a bottle up there with him, for he kept getting drunker. Once in awhile he’d come down and raise Cain, and then go back and curse us from up there till everybody was in a blue fright. We didn’t know what he might do with the ship, and the watch below came on deck without being called.

“Just a little before six bells struck, I heard a yell, and I found that he’d pitched the helmsman clear off the bridge, and taken the wheel himself. That part of the channel is full of reefs and islands, and we heard surf in about half an hour,—straight ahead the breakers sounded, and the mate appeared to be running her dead on them.

“Three or four of the men made a rush for the bridge to take the wheel away from him, and some one went down to call the captain. But before the mutineers were half-way up the iron ladder, the mate had his pistol out, and shot the top man through the head, and he knocked down the rest as he fell. By this time we could see the surf, spouting tall and white like geysers, but it was too dark to see the land. The captain came on deck, half-dressed and looking wild, but he was hardly up when the mate gave a whoop, rang for full speed ahead, and ran her square on the reef.

“She struck with a bang that seemed to smash everything on board. I was pitched half the length of the deck, it seemed to me, and next minute a big roller picked her up and lifted her over the reef and set her down hard, with another terrific bump.

“When we’d picked ourselves up we couldn’t see anything at all, and the spray was flying over us in bucketfuls. The steam was blowing off, all the lights had gone out, and the old boat was lying almost on her port rails, shaking like a leaf at every big sea. Still there didn’t seem to be much danger of her breaking up right away, and we settled down after awhile to wait for daylight.

“When the light came back we saw that we were up against a long, barren island, about half a mile across I should think, with one rocky hill, and no trees, no natives, nor anything. We were stuck on a bunch of reefs nearly a mile from shore, and we were half-full of water. When we looked her over, we found that she was cracking in two, so we got ready to launch the boats. Two of the men were missing, and we never saw any more of the captain; we supposed that they had been pitched overboard when she struck. The mate had been knocked off the bridge and appeared to be hurt. He was lying groaning against the deckhouse, but nobody paid any attention to him.

“We got one of the starboard boats into the water with six men in it, and it was smashed and swamped against the side before it was fairly afloat. We threw lines and things, but only fished out one of the crew. I got into the second boat myself, and we managed to fend off from the ship, and got on pretty well till we came close to the shore. It was a bad landing-place when there was any sea running, but we tried it, and piled her all up in the surf. I got tossed on shore somehow,—I don’t know how,—but presently I found myself half in the water and half out, with a bleeding crack in my head, and most of the skin scraped off my arms and legs. I looked for the rest of the boat’s crew, but none of them came ashore—alive, that is.

“In about half an hour I saw them put another boat overboard, but this one shared the fate of the first, and I don’t think anybody was saved. There was still too much sea running to launch boats.

“I lay around on the shingle in a sort of silly state from the crack on my head, waiting for some one to come and find me, but nobody came. About noon, I guess, I saw another boat skimming round the corner of the island with a sail set, and four or five men in her. I tried to signal her, but she went out of sight, and that was the last I saw of any of the people of the Clara McClay.

“Everybody seemed to be off the ship, and it looked like I was the only one to get to the island. That night the wind and sea got up tremendously; the spray flew clean over the island, and I got up on the hill to keep from being washed off. In the morning I saw that the ship had cracked right open and broken in two, with her stern sticking on the rocks and the bow part slipping forward into the lagoon. All sorts of things were cast ashore that day,—but, say, there isn’t anything in the Robinson Crusoe business. There was about fifty tons of wreckage and cargo scattered over the beach, but I couldn’t do anything with wood and hardware, and I had all I could do to find grub enough for a square meal. Later I found more.”

“Did any of the gold cases come ashore?” asked Elliott.

“Oh, no. They were too heavy. But in a day or so, when the weather had gone down, I rafted myself out to the wreck on some spars. But the forward half of the ship was sunk in about eight fathoms; it just showed above the surface, and I couldn’t get at the hold. The stern part was out of water and I rummaged around for something to eat, but everything was spoiled by the salt water.