Is Tomorrow Hitler’s?

H. R. KNICKERBOCKER

200 Questions

On the Battle of Mankind

Reynal & Hitchcock : New York

COPYRIGHT, 1941, BY H. R. KNICKERBOCKER

All rights reserved, including the right to

reproduce this book, or portions

thereof, in any form

Second Printing

PRINTED IN THE UNITED STATES OF AMERICA

BY THE CORNWALL PRESS, CORNWALL, N. Y.

To Agnes[vii]

NOTE: This descriptive table of contents gives only a

sampling of the many provocative questions discussed.

| CHAPTER | PAGE | |

| Foreword | xi | |

| Introduction | xv | |

| 1. | Germany | 1 |

| Have you ever met Hitler? | ||

| What impression does he make when you meet him? | ||

| Does Hitler’s personality grow upon closer acquaintance? | ||

| Is Hitler personally brave? | ||

| Is it true that Hitler is a homosexual? | ||

| Are women attracted to Hitler? | ||

| What kind of public speaker is Hitler? | ||

| What is the secret of Hitler’s power? | ||

| Do you think Hitler is personally responsible for the war? | ||

| Is Hitler the real boss of Germany? | ||

| Are any of the men around Hitler of a calibre to succeed him? | ||

| Does Hitler actually direct his battles as did Napoleon? | ||

| Why didn’t Hitler attack England after Dunkirk? | ||

| What was Hitler’s second mistake? | ||

| Isn’t there anything constructive about Hitlerism? | ||

| How has Hitler run his show without money, without gold, without foreign exchange? | ||

| Can the Nazi economy continue to run indefinitely? | ||

| How can you describe the German people as hysterical? | ||

| What would happen if Hitler were killed? | ||

| Why doesn’t somebody kill Hitler? | ||

| What was the explanation of the bombing attempt on Hitler in the Munich Beer Hall? | ||

| Were the Nazi atrocity stories exaggerated? | ||

| Do you consider Out of the Night authentic? | ||

| Hasn’t Hitler proved he is an enemy of Bolshevism by attacking Russia? | ||

| What should we do with Hitler after he is defeated?[viii] | ||

| 2. | Russia | 88 |

| What is the best way for the United States to help the Russians? | ||

| How can the Russian resistance to the German attack be explained? | ||

| What do the Russians fight for? | ||

| Is it true that the Soviet government has restored freedom of worship? | ||

| Are we running a risk if we support the Russians? | ||

| Can Stalin be trusted? | ||

| Under what circumstances would Stalin make a separate peace? | ||

| What would be the effect of such a compromise peace on Great Britain and the United States? | ||

| What is the NKVD? | ||

| Are the peasants better off on collective farms? | ||

| How about the Soviet elections of which we hear? | ||

| Why do you give so much importance to the Soviet Terror? | ||

| How do you explain Russian inefficiency and wastefulness? | ||

| How has the Red Army been able to stand up so well? | ||

| Could Stalin carry on with the resources of the Urals? | ||

| 3. | England | 139 |

| What place will Churchill have in history? | ||

| Is Churchill really backed by the English people? | ||

| Can Churchill be trusted? | ||

| What does Churchill think of the United States? | ||

| What are Churchill’s characteristics as a person? | ||

| Would the British Navy survive the fall of the British Isles? | ||

| How can the flight of Hess be explained? | ||

| What is the secret of Churchill’s success? | ||

| What are Churchill’s principal interests? | ||

| 4. | War Aims | 184 |

| What are Britain’s war aims? | ||

| What was the meaning of the Churchill-Roosevelt meeting? | ||

| How can the gains of victory be consolidated? | ||

| Will the United States come out of the war in a better economic condition than others? | ||

| What will the peace conference be like? | ||

| In what sense will the conquered peoples be slaves? | ||

| How could we compete with Hitler after a German victory?[ix] | ||

| Can’t American labor produce better and cheaper than slave labor? | ||

| What are Hitler’s plans for Europe? | ||

| What kind of negotiated peace would be acceptable to the Axis? | ||

| What is the text of Hitler’s terms? | ||

| What chance has Communism in a defeated Germany? | ||

| Is there any way to render Germany impotent? | ||

| Is the problem of the Germans insoluble? | ||

| Will England come out of the war with a socialist system? | ||

| What is to be done with all the former nations of Europe? | ||

| 5. | France | 234 |

| Why did France fall? | ||

| Were there traitors on the French General Staff? | ||

| How did treason manifest itself in the operations of the army? | ||

| Who gave the orders? | ||

| What is the opinion of informed Frenchmen? | ||

| Is Pétain a patriot or traitor, or misguided? | ||

| Is Pétain moved by personal ambition? | ||

| What would Hitler do if he finally tired of fooling with Vichy? | ||

| What about Darlan? And Laval? | ||

| Has Laval a chance to seize power? | ||

| In what way are we Americans very much like the French? | ||

| Are there any encouraging differences between ourselves and the unfortunate French? | ||

| Is there any hope that the French may come back? | ||

| Will Hitler’s treatment of France be different later? | ||

| How was the French indemnity fixed? | ||

| How does this compare with the reparations paid by Germany after the World War? | ||

| What is Hitler doing with French industry? | ||

| Should we continue diplomatic relations with Vichy? | ||

| 6. | The United States | 293 |

| What is the greatest danger we face as a nation today? | ||

| Is our morale very bad? | ||

| What is the state of our armament? | ||

| If we have nothing to fight with, how can we go to war? | ||

| Could Hitler succeed in invading the British Isles? | ||

| Why doesn’t Ireland allow Britain to take over naval bases?[x] | ||

| Is it true that Hitler wants to destroy the United States? | ||

| Haven’t we plenty to do at home without getting into a foreign war? | ||

| Why do you think we ought to go to war with Germany today? | ||

| Why would a declaration of war be worth so much immediately? | ||

| What effect would a declaration of war have on the morale of the Army? | ||

| But weren’t we suckers in the last war? | ||

| Would an American declaration of war have any effect on the morale of the Germans? | ||

| Would another A.E.F. be required? | ||

| Might a new League of Nations be successful? | ||

| 7. | Fifth Columnists | 339 |

| What makes Lindbergh the way he is? | ||

| Are we fair in calling Lindbergh a Copperhead? | ||

| What is the reason for the divorce between Lindbergh and the American people? | ||

| Why did Lindbergh attack the Jews? | ||

| What is to be the fate of the Jews? | ||

| What are Lindbergh’s arguments against our entering the war? | ||

| What is the answer to America’s Fifth Columnists? | ||

[xi]

I met H. R. Knickerbocker way back in 1927 or thereabouts. Those were the good old days. They were the days of the Long Armistice. No one had ever heard of the Rome-Berlin Axis, Stuka dive bombers, or the Haushofer Plan. Mr. Roosevelt was out of politics, Mr. Churchill was a chancellor of the Exchequer, and Mr. Lindbergh had just flown the Atlantic. We talked of such neolithic creatures as Pilsudski of Poland and Alexander of Jugoslavia, and most of us thought that Hitler was a bad Austrian joke, more or less. Those were the good old days. Even so, thunderheads were gathering.

I first met Mr. Knickerbocker in Berlin. This was fitting, since Berlin was his bailiwick. We all had bailiwicks in those days. Duranty was in Moscow, Raymond Swing was in London, and Dorothy Thompson had just left Berlin. I was bouncing all over the place. I didn’t have my bailiwick yet. We were all very good friends. We formed a kind of fluid international community. We were buzzards in every foreign office, and kings on every wagon-lit.

We didn’t meet often, since we lived in different cities, and it took something of a catastrophe to bring us all together. When we did meet, the vault of heaven shook. I remember days—and nights—in Geneva, Bucharest, Cairo, Helsingfors. I think of Sheean, the Mowrers, Webb Miller, Shirer, Jay Allen, Fodor, Whitaker, and many more. Don’t let me sound nostalgic. I am thinking merely that we have all grown up. We are not cameras any longer.

This foreword is not about Mr. Knickerbocker’s book. Let that speak for itself. Knick is the most pertinacious, plausible, and inquisitive question-asker I ever met. In this book he answers questions[xii] instead of asking them. I like to see the tables turned. I don’t know that I agree with all his answers. But let him answer them.

This foreword is about Mr. Knickerbocker himself. His flaming red hair, his flaming red personality (I mean “red” chromatically, not politically) are famous on four continents. He needs no introduction. But certain nuggets of memory stay fixed in mind. I remember the time he fed me caviar inside a baked potato, at Horcher’s in Berlin, and I remember the time I fed him a dinner in London that, deliberately, we planned so that it would cost exactly five pounds. I remember the time that he took me to hear Putzi Hanfstaengl hammer out a tornado of Wagner in the Hotel Kaiserhof, and I remember the time I took him across the freezing Danube, on the way to Sofia, in what was supposed to be a rowboat. I remember week-ends on the Semmering, bad oysters in Madrid, evenings in the Café Royal, drinks in Rome, Budapest, and points beyond.

Knick’s career has been spectacular in more than one dimension. He once set out to fly the Atlantic, as a passenger in a German plane, long before the Lindbergh flight; he was the only correspondent during the Ethiopian war to glimpse the front from the air; he has had more interviews with European heads of state, I imagine, than any other newspaper man alive.

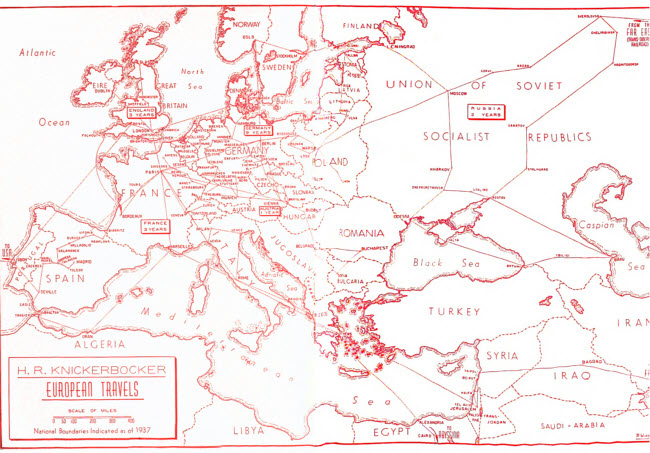

Mr. Knickerbocker was born in Texas in 1898. He went to Europe in 1923, and, a student of psychiatry at the University of Munich, walked straight into Hitler’s Beerhall Putsch. He studied briefly in Vienna, and then got a job in Berlin on the New York Evening Post-Philadelphia Public Ledger foreign service. Since then his career has been a calendar of most of the great events of our time. He spent two years in Moscow as correspondent for the International News Service (this was in 1924-26, when Trotsky was declining and the N.E.P. expanding), and in 1928 took over Dorothy Thompson’s job as chief correspondent in Berlin for the Public Ledger. He won a Pulitzer prize for distinguished foreign[xiii] correspondence—a series of articles on Russia’s Five Year Plan, but for almost ten years Berlin was the blazing focus of his life.

Meantime there were trips to take. In 1933 he travelled all over Europe for a series, “Will War Come in Europe?” for I.N.S. He saw the death of Dollfuss in Vienna, and the burial of Hindenburg in Germany. He met Mussolini, Masaryk, King Alexander, King Boris, Otto Habsburg, and hosts of others. He did one series of articles on Russia and the Baltic states, comparing living standards under communism and capitalism, and another surveying economic aspects of the Europe that was crumbling. Came the war in Ethiopia in 1935, which he covered on Haile Selassie’s side. I will never forget the agitated days in London when Knick was accumulating the vast equipment he took along. In 1936 came the Spanish civil war, and the next year the war in China. He saw bombings all the way from Toledo to Nanking. He returned to Europe to cover the Anschluss crisis and the Munich disaster; then he dipped briefly into South America, and reached Peru. Then Europe called again; he saw the beginning of World War II in London and France, and in 1940 accompanied the French armies till they collapsed, and then saw the battle of Britain at its fiercest climax, in September.

But let me go back to those days in Berlin. The main point I want to make has to do with Knickerbocker in Berlin. During the turbulent 1930’s he was much more than a journalist covering Germany; he was a definite public character in German political life. After Hindenburg and Hitler, he was practically the best known man in the country. His réclame was fabulous, personally and politically. Everyone knew the lithe, active, red-haired Herr Knickerbocker (pronounce the K, please). Once a musical comedy was named for him—supreme tribute!

Partly this was because he published half a dozen books in German, compiled from the long newspaper articles he wrote,[xiv] which appeared serially in the Vossische Zeitung or the Berliner Tageblatt. The books were extraordinarily successful in Germany; they introduced German readers to a new type of American journalism. Among them were Der Rote Handel Droht!, Der Rote Handel Lockt!, Kommt Europe Wieder Hoch?, Rote Wirtschaft und Weisse Wohlstand!, England’s Wirtschaft und Schwarzhemden!, Deutschland So oder So!, and Kommt Krieg in Europa?

Knick knew practically every human being of consequence in Germany. He explored the country from top to bottom. He talked to Hitler, Spengler, Brüning, Goering, Goebbels. Then Hitler came to power. At the time Knickerbocker was in the middle of a German lecture tour that had begun in the Lessing Hochschule in Berlin. Knick watched the Nazi revolution crushingly obliterate all opposition. He wrote a series exposing the Brown Terror that caused violent comment in New York as well as Berlin. Presently he was excluded from the country. There are hate affairs as well as love affairs. The hate affair between Hitler and Knickerbocker is one of the most torrid in political history.

But this should not detract from the main point, which is that Knick knows the real Germany, loves it, and respects it. He is a Nazi-hater, but not a German-hater. His authority on the subject is authentic and complete.

John Gunther

[xv]

There is no such thing as winning a fight without passion. France went to war apologetically; France fought the war without music, and so France lost. Britain went to war apologetically, but Britain had the inestimable advantage of being bombed, and today for the first time in 100 years Britain is angry and is fighting as she has never fought before. We, the United States, are today apologetic, so sorry that it seems we after all are called upon to fight, and some of us still say we should not fight, and others say we must fight only with aviators and sailors, and never with infantrymen, and very few indeed are the strains of martial music throughout the land. From all sides we are called upon to restrain our emotions, and it is said that the cool head is the shrewd head, and that is correct, of course, but a cool head without a hot heart is useless on a battlefield. Without anger there can be no victory and useful anger is based upon understanding. Unless the American people can be brought to understand that our national existence and our individual security are today in peril, and unless the American people become angry at the enemy, we shall become a part of Hitler’s Reich.

History may eventually record that Britain was saved by the bombs Hitler has rained upon her since the fall of France. Unless they annihilate the British, these bombs will have fulfilled a function Hitler never imagined. He thought they would terrorize the British into surrender; instead the bombs aroused a resistance such as no other population has ever shown, for the prolonged punishment of Britain’s cities has been worse than anything we know of elsewhere, including Belgrade, Warsaw, Rotterdam, Madrid, Barcelona,[xvi] or Chungking. The British required this experience to awaken them. They had been at war eight months when the Germans finally attacked in the West, but they had not given up the grand old British custom of the Friday to Tuesday week end. It took the German break-through on the Meuse, and then the German bombs on London, to shock every inhabitant of the British Isles into the realization that they faced death for their nation and death or slavery for themselves unless they fought with a ferocity even greater than that of their jungle enemies.

We are today as sound asleep as the British were before May 1940. We are as sound asleep as the French were before they saw their fortifications fall and their army of 4,500,000 soldiers with the tradition of Napoleon dissolve between May 10 and June 17, in five weeks of the greatest military debacle of all time. We have had no bombs on America, and presumably shall not have them until it is time to trek for the Rocky Mountains. A sober American patriot remarked, “How fortunate Britain has been to have had the bombs to arouse her martial spirit before it was too late. If Hitler were to have a lapse in judgment and send just half a dozen bombers over New York, and drop just half a dozen bombs, it might be the salvation of America.” But Hitler will do no such thing. He is glad to accommodate those Americans who refuse to believe they are threatened until they are physically attacked. When and if the Germans break through upon America we shall awake to find ourselves alone, cut off, surrounded, outnumbered, outgunned, and outlawed amid a world of enemies.

A few of us, chiefly correspondents formerly in Germany, have been trying to do duty for German bombs on America, and for the German break-through. We have been called alarmists. For years the world of international observers was divided into two groups: the one composed of nearly everybody on earth outside of Germany, who understood nothing of the true character of Hitler’s Third Reich; and the second tiny group, small enough to[xvii] be contained within a lecture hall, composed of correspondents, diplomats, and a few businessmen who had firsthand knowledge of what the Nazis mean. Today a good many persons without this intimate knowledge of Nazi Germany have been able to decide for themselves about the character of a regime which has overrun fifteen countries in three years, but the danger to America still looks very remote and impersonal to millions of patriotic citizens. I have been talking to about 100,000 of these citizens, during a lecture series.

My thesis was in brief: That the United States should be in a state of formal, shooting war with Germany as speedily as possible because only by this means can we make the world safe for America; and that we must realize that after going to war we have only begun a task which may last for many years and one which we can fulfill only by learning to fight with even more fervor than the demoniac Nazi shock troops, and by greater national self-sacrifice than we have ever been called upon to make.

On this thesis I was asked around 3,000 questions during the question period following the lectures. For this book I have chosen around 200 as representative of what the American people are thinking. I have arranged the questions in categories and have added many recent ones to bring the Forum up to date. Eager, painful, almost agonizing concern for the future of America was the background of these queries from audiences in 128 communities, including two-thirds of all cities of more than 100,000 population and scores of towns and villages. The people with whom I talked ranged from millionaire winter tourists in Florida to coal miners in Pennsylvania, applegrowers in Yakima, oilmen in Oklahoma, college boys in the Great Lakes states, farmers in the Midwest, workers, bankers, club ladies, teachers, cowhands, Catholics, Jews, Protestants, atheists, Yankees, Southerners, Texans, Westerners—Americans.

I am convinced that these earnest Americans, representing[xviii] through their family and friendly connections at least ten times their number, or more than 1,000,000 persons, are far in advance of the President’s moves toward active defense, just as the President has always been far ahead of the Congress. They wanted action even before the President offered it. Among 3,000 questioners there were not more than six openly hostile hecklers from the floor. Would it be too hopeful to say that America is 2,994 to 6 in favor of liberty?

[1]

Q. Have you ever met Hitler?

A. Many times. From 1923 until today I have watched and studied him and a good part of that time I was close enough to have opportunities for firsthand observation. I first heard him speak in August 1923, not long before his unsuccessful attempt to seize power, in the famous Beer Hall Putsch, and then I witnessed the Putsch, and reported his trial with Ludendorff for treason. He was released from Landsberg Prison in December 1924 where he had been held in comfortable “fortress confinement” just long enough for him to have time conveniently to write Mein Kampf. I interviewed him for the first time in the Brown House in Munich in 1932. Thereafter I had a series of interviews with him, and was present at many of the great moments of his career.

Q. What impression does he make when you meet him?

A. The first impression he makes upon any non-German is that he looks silly. Not to a German, mind you, and I suppose he did not look silly to any of those heads of European states who crawled to Berchtesgaden to get their orders. But to a foreigner not subject to his commands he certainly looks silly. I know that is a strong word to use about a man who has already conquered a continent but it fits.

I remember well the first time I ever laid eyes on him, in August 1923, when he was speaking at the Zirkus Krone in Munich—I broke out laughing. Even if you had never heard of him you[2] would be bound to say, “He looks like a caricature of himself.” The moustache and the lock of hair over the forehead help this look, but chiefly it is the expression of his face, and especially the blank stare of his eyes, and the foolish set of his mouth in repose. Sometimes he looks like a man who ought to go around with his mouth open, chin hanging in the style of a surprised farm hand. Other times he clamps his lips together so tightly and juts out his jaw with such determination that again he looks silly, as though he were putting on an act.

Indeed Hitler is, more than anything else, an actor. He will go on being one the rest of his life, a great actor who in his role as tyrant conqueror will have affected the destinies of more millions of people than any other human being in history, but an actor to the last, a tragedian whom no one would take seriously until he began shooting at his audience. Even in the midst of his triumphs he manages to look silly to any outsider capable for the moment of detaching himself from horrified contemplation of the fate inflicted upon his victims.

I remember watching him roll down the Ringstrasse in Vienna standing beside the chauffeur in a cream-colored Mercedes car, with his arm outstretched in the stiff salute he affects on such occasions, the hand rigidly held at a slight angle downward. It was the moment of his conquest of Austria. The streets were crowded with half a million people, a few cheering sincerely, many cheering out of fear, and hundreds of thousands grim-faced, weeping inwardly.

At that moment when I, too, felt like weeping at the abasement of the city where I had worked and danced and studied and played when I first came to Europe fifteen years before, even at such a moment I found myself smiling and saying to friends looking out the window of my room in the Hotel Bristol, “Doesn’t he look silly?” That oversized cap of his, the military cap with the too-large[3] crown and the visor which completely hides his low forehead!

There is something absurd even about his stance as he rides his victorious chariot through freshly conquered cities. He is softly fat about the hips and this gives his figure a curiously female appearance. A scientist friend of mine watching him once remarked that Hitler seemed afflicted by steatopygia, which he defined as “an excessive development of fat on the buttocks, especially in females.” It is possible that the strongly feminine element in Hitler’s character is one of the reasons for his violence. He realizes his femininity, is ashamed of it, wishes to be a man, and overcompensates by brutal behavior. This little fatty-hipped, slope-shouldered, lonely figure, standing so inflexibly, his arm outstretched so tautly, his eyes staring over the heads of his subjects, is incredible. “No,” you say to yourself, “this can’t be true.”

If this odd creature finally conquers the world, his last victims, we once proud Americans, would still be saying as we filed into concentration camp, “It’s impossible. He looks too silly.” But he is not silly. My friend, Captain Philippe Barres of the French Army, one of those who did not surrender, remarked to another Frenchman: “You say Hitler is merely a madman, an idiot. I suppose you must be one of those Frenchmen who prefer to have been conquered by an idiot than by a clever man.”

Oh no, he certainly is not an idiot; but is it not incredible that this mighty conqueror, now master over two hundred and fifty million Europeans—more civilized white human beings than ever before came under the tyranny of a single despot—and now reaching out to drive another thousand million under his yoke, that this man usually looks completely insignificant? I am sure that was the first impression Mussolini had of him. I saw the two dictators when they first met and Hitler never looked sillier in his life than at that time.

[4]

Q. How did the two behave toward each other? Did they seem to like each other?

A. Not much. It was June 14, 1934 when Hitler first visited Italy to meet the Duce and discuss with him the fate of Austria. Hitler had not yet created his army and Mussolini could still talk on terms of equality, or even a little better. Mussolini wanted to impress his guest as much as possible with the power and glory of Fascist Italy. Hitler had to try to impress Mussolini with the coming strength of Nazi Germany. Mussolini, being at home, had all the advantage. For Hitler the trip itself must have been a great experience because it was the first time he had ever been out of Germany or Austria in his whole life, if you except the time he spent as a soldier in the trenches of Northern France.

Mussolini proved a great stage manager. He arranged the meeting to take place in Venice, and had his guest land on the airfield of the Lido. The fact that it was an island made it easy for the authorities to exclude the public, and when Hitler arrived he stepped directly into a perfectly appointed theater.

There were representatives of all the Italian armed forces, companies of Bersaglieri, Alpini, Sailors, Airmen, and the Black Shirt Fascist Militia, and a group of the highest civilian officials in black uniform with the black-tasseled fez caps of the party, surrounding the Duce himself who was in the powder-blue uniform of a Corporal of the Fascist Militia.

Mussolini used to think of himself as the successor to the Corsican Corporal. I remember once noticing that the only ornament on his desk was a framed portrait of Napoleon. I remarked on it, and Mussolini exclaimed, “A great Italian!” One of the Duce’s most ambitious literary ventures was a play called The Hundred Days. Whether he is still able after Greece, Libya, and Ethiopia to fancy himself in the role of a conqueror when he meets Hitler[5] now, he still appears in the uniform of a corporal as when he met Hitler the first time.

The only persons on the field not in uniform were the foreign correspondents and we looked very dim compared with the brilliant Italians. Mussolini appeared a few minutes early and when he strode down the line and looked over his warriors he made a most vigorous impression. He had an electric step; his feet seemed to bounce off the ground, and the air vibrated with his personality. After he finished reviewing his troops he came over and stood within a few feet of us and we waited.

Presently Hitler’s Junkers plane roared down out of the sky, landed, taxied up to us, and came to a full stop. The door opened. The Italian troops, dazzling in full dress, presented arms. The Fascist officials stood at attention. The sunshine sparkled on Mussolini’s gold braid and the Duce, stepping close to the open door of the airplane, flung out his arm in a Roman salute with so much energy that it seemed as though he might lose his hand. He trembled with passion. Then, out of the shadow of the door, emerged Hitler. There, before the splendid Italians, he stood, a faint little man arrayed in his old worn raincoat, his blue serge suit, and a brand-new Fedora hat. His right hand faltered up in the Nazi salute.

He gives the salute two ways. For reviewing his own troops or crowds he gives it stiff-arm. This is his Prussian style. For greeting individuals he gives the salute, Viennese style, with a limp hand, the arm not outstretched but bent at the elbow and the hand flopping back until it almost touches his shoulder, then flopping forward feebly. He used the Viennese version on Mussolini. Hitler was embarrassed. Later we learned he had threatened to dismiss Baron von Neurath, then chief of protocol, for having advised him to come in civilian clothes.

The Fuehrer stood for a moment, blinking in the sunlight, then awkwardly came down the steps, and the two dictators shook[6] hands. They were not over three yards from me, and I was fascinated to watch the expressions on their faces. Beneath the obligatory cordiality I fancied I could see an expression of amusement in Mussolini’s eyes and of resentment in Hitler’s. At any rate Hitler’s embarrassment did not diminish, for when Mussolini led him down the line of troops he did not know how to carry it off. This was the first time he had ever had to inspect foreign troops, but that was not the chief trouble. The chief trouble was his hat.

He had taken it off as a salute to the Italian flag, and he started to put it back on his head, thought better of it, and held it in his right hand. Then, as he walked beside the Duce, who was chattering all the time in his fluent German, Hitler shifted the hat to his left hand, then back to the right, and so back and forth until one could feel he would have given anything to be able to throw the hat away. Finally, when they reached the end of the line, he clapped the hat back on his head, but he had not yet recovered his poise because when they came to the launch which was to carry them to Venice, Hitler, flustered, tried to insist that Mussolini, the host, precede him on board. The Duce finally got behind the Fuehrer and shooed him down the gangplank first.

Mussolini arranged that his visitor should constantly be reminded that although Germany might have her great man, Italy had a greater. With true totalitarian courtesy Mussolini ordered thousands of young Black Shirts to cheer him and keep up a continuous howl of “Duce, Duce, Duce!” whenever Hitler appeared. They jammed St. Mark’s square and that night when Mussolini gave his guests a banquet in the wonderful old Palace of the Doges, the Black Shirts yelled so much and so powerfully that nobody could hear the speeches. Finally Mussolini had to send word for the boys to quiet down.

The show had its desired effect as far as the Italian populace was concerned. The climax of the evening was a procession on the Grand Canal. They had taken from museums the most treasured[7] old gondolas, and decorated them with lanterns. You may imagine what a spectacle they made under a June moon. My wife had a gondolier who spoke a few words of broken English. She asked him, “What do you think of Hitler?” “Oh,” said the gondolier, “Eetlaire, Eetlaire is only a piccolo Mussolini.” I wonder if the gondolier still thinks Hitler is a “little Mussolini”?

Q. What did the two dictators accomplish by their meeting? Did they lay the basis for the Axis there?

A. No, just the contrary. They laid the basis for nearly going to war with each other. The Axis was not formed until much later, after Mussolini had been compelled to recognize Hitler’s supremacy and take orders from him. At the time they first met, Mussolini still fancied himself Hitler’s superior. At Venice they were supposed to negotiate an agreement about Austria.

At that time Mussolini wanted very much to take Austria himself, or to keep it independent as a buffer state between Italy and the Germany which he felt was going some day to become strong enough to menace him as well as the rest of Europe. Hitler, on the other hand, was bent upon the Anschluss, upon annexing Austria as the first item on his program of expansion.

Mussolini had an army of unknown quality but big enough compared with Hitler’s to make the Duce feel superior and Hitler feel cautious. So they talked on this basis and Count Ciano, Mussolini’s son-in-law and already Propaganda Minister, took me aside the afternoon of the second day and triumphantly whispered that a “gentleman’s agreement” had been reached that both parties would respect the integrity and independence of Austria. It was all I could do to restrain myself from putting in my cable some obvious crack about the agreement between those two notable “gentlemen,” but one does not do that under censorship.

What happened then? I must say that everything that has happened[8] in Europe since the gangsters took over has the quality of a caricature. Sure enough, Hitler and Mussolini made their “gentlemen’s agreement” to keep hands off Austria on June 15, and just forty days later, on July 25, Hitler sent a band of Nazi revolutionaries to seize the Austrian government. They murdered Chancellor Dollfuss, but were overpowered by loyal troops, and before Hitler could move, Mussolini had mobilized on the Brenner mechanized forces strong enough to make Hitler back down and disavow the whole action. I reached Vienna and the Ballhaus Platz while the loyal troops were still besieging the Reichskanzlei. Dollfuss had not died yet. In the midst of it all I had to laugh at the thought of that “gentlemen’s agreement.”

Q. That must have made Mussolini cocky, to make Hitler back down?

A. Decidedly! I went from Vienna where I had covered the Dollfuss Putsch, back to Berlin for the death of Hindenburg—and incidentally for a sidelight on Hitler, let me remark this. You still hear repeated the wishful thought that the German Army will some day “do something” about Hitler. Nobody who knows anything about Germany believes that for a moment now, but I admit I thought it possible until the day Hindenburg died that the army might stop Hitler.

That was August 7, 1934, and at the moment Goebbels announced on the radio the death of the President he also announced that Hitler had assumed the presidency, which meant he was commander in chief of the armed forces as well as Reichs Chancellor, and thus had sole executive power. That morning I came early to the office in Berlin and as I entered the door Goebbels’ voice began to come over the radio. I worked on the cables until mid-afternoon and then Dosch-Fleurot and I went out to witness the[9] swearing in of the Berlin garrison. That was where I learned that the army would from then on do nothing to stop Hitler.

The regiment was drawn up in hollow square and in the middle stood the commanding general on a platform. Every one of the 2,000 men and officers held his right hand above his head with the two fingers extended as in taking an oath in court. The general repeated the words two at a time and the troops repeated in sonorous chorus, “I swear—by God—eternal allegiance—to my Fuehrer—Adolf Hitler—to obey him,” and so on, with no word about the flag, the Constitution, or even the Fatherland. The oath was a personal oath to Hitler himself, as commander in chief. I believe it is unique; at any rate I have never heard of such an oath in any other army.

The officers corps knew what it meant, so much so that thousands of officers absented themselves that day from duty “on account of illness,” but when they came back each had to take the oath individually. The significance of that is that no German army has ever mutined, and this oath bound every soldier of Germany to the person of Adolf Hitler. It was a most impressive ceremony and I carried away from it the conviction that this army would never break its oath and turn on Hitler until it met defeat. I am still convinced this is true.

Q. Yes, but what about Mussolini? You said he was decidedly cocky about defeating Hitler over Austria.

A. I started to say that after having covered the death of Hindenburg and the accession to the Presidency of Hitler, I went down and reported the Nuremberg Party Congress, and directly thereafter went to Rome and met Mussolini. It was October 1934. I had met him several times previously and he always used to insist on asking more questions than he answered; so he began our conversation[10] by saying, “I hear you have been to Nuremberg—what did you learn there? What did they think of me?”

I answered that frankly the Italians were not popular in Nuremberg, and that one of my English colleagues, Chris Holmes of Reuters, who is tall, dark, and handsome, had once been mistaken for an Italian and had some trouble with Nazi Storm Troopers until he identified himself. “So we are unpopular there,” Mussolini ruminated. “And go on, what else did you observe in that line?”

“Well,” I continued, “one night I met a group of officers of the SS [Schutzstaffel] and we were talking about affairs, and one of them asked me what you, Your Excellency, would have done with those troops you mobilized on the Brenner during the Dollfuss Putsch if you had marched into Austria.” “Yes,” said the Duce leaning forward. “Yes, yes, go on, what did they want to know?” “Well,” I hesitated, “they wanted to know if you had marched into Austria, would you have stopped there, or would you have gone on and marched into Germany?” Mussolini put his hands on the desk and leaned halfway over it, and a great smile came on his face as he ejaculated, “Ahhhh! Were they afraid?” I laughed and he laughed and it was agreed that the Germans had been afraid, and if ever there was a delighted man it was Mussolini, reveling in the thought that he had frightened his gentlemen friends.

Q. You have told us that the first impression one gets of Hitler is that he looks silly, but you remarked that this was a false impression.... Do you imply that on closer acquaintance his personality grows upon you?

A. In a way, perhaps. At any rate you realize after several meetings that the silly appearance is due to superficialities. His moustache, the lock of hair over his forehead, and his staring eyes make his face easy work for a cartoonist, and a world of them have taken[11] advantage of it. It is almost like a mask. He frequently looks as though he were gazing into space when he is looking straight at you. He has terrific power of concentration and sometimes when he talks he appears to forget his surroundings, and to be conversing with himself, although he may be shouting loud enough to be heard by a great multitude.

His manner is various, and he can be quietly affable just as another time he may rave and bellow until his voice breaks. Once, during his trial for treason, I heard him bellow and then surrender to a louder voice. This was an incident worth recording, because as far as I know it is the only time Hitler has been literally shouted down. All during his trial the courtroom was dominated by the figure of Ludendorff, the great Ludendorff who for the last two years of the war had been master of Germany. Ludendorff of course was as guilty of treason as Hitler, and if the court had done its duty both Ludendorff and Hitler would have been sentenced to death and executed. Ludendorff, however, had such prestige that even this republican court was afraid to find him guilty, and as you know, they acquitted him. And having acquitted Ludendorff it was not possible to sentence Hitler to death. They gave him the lightest possible sentence, fortress confinement for five years, and later commuted by a general amnesty to less than a year.

Ludendorff used to bark at the court in Kommandostimme, the tone of the parade ground, every syllable clipped harsh, and when his imperious voice rose, the little Chief Justice in the middle of the Bench would quiver until his white goatee flickered so badly he had to seize it to keep it quiet. Hitler at that time had nothing like the authority of Ludendorff but he made up for that by his volubility and his rough treatment of the witnesses against him. As defendant he had the right to question witnesses and he bullied them unmercifully until the turn came of General von Lossow, the chief witness for the state. Von Lossow was in command of the Bavarian Reichswehr.

[12]

A few days before the Putsch, Hitler had given his personal word of honor to von Lossow that he would not try a revolution. On the night of the Putsch, Hitler, brandishing a revolver, forced von Lossow to join the revolution and yield the Bavarian Reichswehr to the new Hitler government. But the moment von Lossow was free, he mobilized his troops and crushed the Putsch. So the two men hated each other, and each considered the other a double-crosser.

When von Lossow took the stand, Hitler stood up and yelled a question. Thereupon the General, a tall bony man, with a corrugated shaven head and a jaw of steel, pulled himself up to his full height and began yelling at Hitler and throwing his long forefinger as if it were a weapon at Hitler’s face. Hitler started to shout back, but the General shouted so much louder, and looked so menacing, that presently Hitler fell back in his seat as if he had collapsed under a physical blow. Hitler had his revenge on June 30, 1934 when he had von Lossow assassinated along with the hundreds of others who perished in the Blood Purge. In retrospect it is fascinating to reflect that Hitler, the most successful bully our world has seen, can himself be bullied.

Q. Do you think that Hitler is personally responsible, or largely responsible, for this war? Is it possible to ascribe that much importance to one individual?

A. I do ascribe that much importance to the individual Hitler. We would no more have had this war, in the form it has taken, and at the time it has taken place, without Hitler, than we would have had the Napoleonic wars without Napoleon. Without Hitler, Germany would either have forged slowly ahead as she was doing under the Weimar Republic, or she would have come under some other leader of Pan-German Imperialism who would have attempted on a lesser and not so successful scale something like the[13] thing Hitler has attempted. It is extremely unlikely that anyone else could have been found with Hitler’s genius. It is more likely that the Weimar Republic would have persisted. Remember, when Hitler was sentenced to fortress confinement for his 1923 Putsch, his National Socialist German Workers Party practically disappeared, but immediately upon his emergence from prison it began to grow until by 1928 he had 12 seats, and in 1930, 130 seats in the Reichstag.

You may say this growth of a radical party would have been inevitable under the circumstances of economic crisis, unemployment, and so on. I agree that the growth of radical votes would have been inevitable, but it was far from inevitable that so many of these radical votes should be canalized into one great, super-efficient, terroristic, militaristic party. This was the accomplishment of one man, Adolf Hitler.

I was a correspondent in Germany from 1923 on, and during that particular decade, 1923 to 1933, when Hitler took power, two-thirds of the German electorate voted consistently in favor of some form of collectivism, either Social Democracy, or National Socialism, or Communism. I contend that it was solely the genius of Adolf Hitler which eventually brought the whole country under his particular brand of collectivism. Without him the votes given the Nazis would have been split in half a dozen ways, and the probability is that the conservative parties representing one-third of the votes, with the Social Democrats who wanted a democratic republican collectivism, would have won out in the long run, and we should have had a republican Germany today and no war. This is sheer retrospective speculation, but it is useful to point out the importance of the personality of Hitler.

The Marxists have always insisted that individuals do not count; that history is made by economic and social forces which in the long run accomplish their destiny no matter who lives or dies. The[14] longer I live the less I believe in this explanation of history, at any rate as it applies to our span of life.

Over centuries it may be that the great forces carry mankind irresistibly along no matter what leaders it has, but within a single generation we are bound to feel that the history of our nation would have been quite different if this or that individual had not existed. Objectively it may be true that over long periods of time the individual leader counts for little. But subjectively, for short periods of time, the individual leader counts for nearly everything. What a difference it would have made for the Jews of the whole world, if a Hitler had not obtained control of the collectivist movement in Germany.

There was nothing inherently anti-Semitic in the German yearning for a Gemeinschaft, a collective. Anti-Semitism need not have played any part in National Socialism any more than it did in Communism or Social Democracy. Yet, because Hitler from his early youth had been infected with this curious kind of psychic sickness, anti-Semitism became a part of the German state religion, and from this accident of history has grown the tragedy of twelve million people.

Q. Is Hitler really the boss of Germany, or is there not someone behind the throne?

A. There is nobody behind the throne. Hitler is the whole regime, its author, its parent, its spirit, its brains, and its boss.

Q. What about the men around Hitler; are any of them of the caliber to succeed him?

A. None of them is of the caliber to succeed Hitler, but Hitler has publicly announced Goering as his successor, and he would automatically take the position if der Fuehrer should die now. In[15] the Party there is nobody to compete with him. The bloodthirsty Himmler, head of the SS Elite Guards and the Gestapo, is merely a policeman, one of great ability, ranking perhaps with the notorious Fouché of the French Revolution, but out of the question as Fuehrer. Goebbels, the advertising director, is the cleverest man in the Party, but he would be lucky to remain alive twenty-four hours after Hitler’s protective hand was removed. He and Himmler are rivals in unpopularity. Who are the rest? Minor figures, as Foreign Minister Ribbentrop, the upstart “Bismarck” of the champagne trade, who if anything is more widely disliked and despised than Goebbels. Hess, of course, has fled. Dr. Ley, the head of the Labor Front, is the type of drunken, racketeering labor gangster who in this country would have gone to the penitentiary under the lash of Westbrook Pegler. Alfred Rosenberg, the Party’s “brain,” could no more succeed Hitler than he could take Joe Louis’s place.

The more one scrutinizes the German scene the more one realizes that the war has moved all the big party figures far into the background, leaving only Goering a modest place miles beneath the Fuehrer. The outside world has believed Goering would be an improvement on Hitler, in that he would be more amenable to reason, less aggressive. He would be an improvement only in that he would be weaker. His instincts and intentions are not more Christian than Hitler’s. He would have neither Hitler’s magic hold on the German people nor Hitler’s genius in action, but he is as cruel a man as ever exercised power in a modern state. At the same time he has all the sentimentality which is an almost invariable accompaniment of brutality in this type of German. During the period of the worst Terror, the active Nazi revolution in 1933, Goering was over Himmler in charge of the concentration camps, and at the moment when the Nazi sadists and criminals in charge of the camps were beating to death and torturing and hanging[16] scores of men daily, Goering decreed the severest law against cruelty to animals ever to be passed anywhere.

Goering’s most marked characteristics, aside from his high animal spirits, his callous cruelty, and his sentimentality, are his energy, courage, and will power. He looks too fat to be self-disciplined, but he twice cured himself of the morphine habit, which he had contracted after his wounding in the World War, and again after his wounding on the Odeon’s Platz during the Munich Putsch. A glandular derangement resulting from his wounds made him monstrously obese, but appears to have endowed him with an excess of energy which he demonstrates by doing the work of half a dozen men. He works incomparably harder than Hitler who by any ordinary standards is a fitful worker, given to long spells of dreamy idleness.

Everybody else in Germany quails before Goering, but Reichs Marshal Goering becomes a trembling, whipped child when Hitler yells at him, despite fanciful newspaper stories about Goering’s disputing with der Fuehrer. The Army prefers Goering to any other Nazi leader except Hitler, because Goering is the only soldier and the only gentleman by birth among the Nazi chiefs. Yet when one has reviewed all the points in favor of Goering’s position, it becomes more and more obvious that the war has made a successor to Hitler almost unthinkable. Hitler has the power now more than ever, but the power now is the Army; it is no longer, as it was until September 1939, the Party. If Goering were to take over automatically, after Hitler’s death, how long could he keep the apparatus running; what would the Army do; how would the German people and the people of Europe respond to their new and obviously so immensely inferior master? The more one considers the condition of Germany today the more it seems that Hitler is indispensable to German success. His successors would probably succeed one another with Blitz speed.

[17]

Q. What about Karl Haushofer, who is said to be his one-man brain trust?

A. Haushofer is one of the men Hitler consults. Hitler likes Haushofer’s theory of what they call Geopolitik because it fits in with Hitler’s own theory that politics should always go ahead of economics, which is his particular way of proving the Marxists wrong. But Haushofer has no more influence than perhaps half a dozen of Hitler’s advisers. Hitler hates experts, because they advance objections to his projects. The only experts who have a chance with him are yes-men, except in the Army. He listens to technical advice from generals he respects, although even from them he would tolerate no shadow of opposition to his grand strategy. You may be sure Haushofer has never said no.

Q. Is Hitler also in the military sphere the real war lord? Does he actually direct his battles as did Napoleon?

A. Hitler is the nearest thing to Napoleon since Napoleon. I remember just before the beginning of the war, in August 1939, I asked a Colonel of the French General Staff if they had heard that Hitler had taken over active command of the Army, in fact, and that when war began he would direct the fighting. The French Colonel said yes, that the French General Staff knew that was true. Then he surprised me by saying that they did not like it.

I had expected him to rub his hands and exclaim over French good luck in having an amateur at the head of the German Army. Not at all. This French Colonel went on to explain that Hitler had already demonstrated the most miraculous sense of timing, and this was perhaps the most important talent a field marshal could have, and that with the technical advice of his generals, Hitler might prove a formidable adversary indeed. Less than a year later the[18] French Colonel who had foreseen so well was one of the vast army of military refugees fleeing before the New Napoleon.

I do not mean to say that Hitler blueprints each battle and determines where each division is to go. He simply determines the grand strategy, names the objective, and sets the time. For instance, in the case of Poland, some time before the German attack, Hitler called his General Staff together and said, “Gentlemen, I want you to work out a plan for the crushing of Poland as swiftly as possible. The problem is how to knock out Poland before the French and British can bring any help or alleviation by attacking in the West. Now, how many divisions can we have fully mobilized within a month? So, and how many do we need to hold the French? So. That will leave us so and so many for the Polish campaign. Now, gentlemen, at how many different points can we attack Poland, from every available entrance? You say five, including East Prussia. All right, now within forty-eight hours I want you to bring me a sketch plan of attack, with the outline of the number of divisions to attack at each point.”

With these data in hand Hitler orders the general disposition of the troops. Then he waits, and takes into account each of a score or hundred other factors besides military factors that may enter into the supreme decision to choose the exact time to strike. He considers the attitude of all the powers involved, the British and French morale, their military strength, the weather, the attitude of Poland’s neighbors, the Polish preparations, and finally when he is ready he gives the fateful order to march at 2 A.M. on September 1, 1939. Before the order reaches the commanding generals probably not more than half a dozen men in the world know the time.

He may meet technical criticism from his generals; he often does. But unlike Mussolini, whose staff is so subservient and sycophantic that they say “Yes” when the Duce has outlined some impossible campaign such as his fiasco in Greece, the German generals voice their objections. If the objections are valid, Hitler[19] may change his plans. As a rule, however, Hitler’s grand strategy is seldom affected, because the great sweeping decisions are based upon Hitler’s appreciation of the problem, the campaign, the scene as a whole. His generals will be thinking of the local problem, and their opinion in this respect carries weight. But Hitler will be thinking in terms first of the whole war, second of the whole campaign, as against Poland. To these great decisions the generals invariably bow.

Q. Why? How has this man who was able to become only a corporal in the last war suddenly obtained such an ascendancy over the German Army and in particular over the General Staff? I always understood that the General Staff of the German Army was one of the proudest, most professionally capable, and vain and exclusive organizations in the whole world.

A. How has Hitler done it? By being always right. Well, nearly always. He has so far made two mistakes, either or both of which may prove fatal, or not, as destiny will have it. The first was when, instead of launching an all-out assault on Britain immediately after Dunkirk, he pursued the crumbling French Army, which as he later learned, could not have been a danger to him; thus he postponed too late his attack on Britain.

Q. Why didn’t he attack England at that time?

A. Because Hitler did not expect France to collapse as speedily as she did. Neither he nor anyone else in the world expected it. He may say he did but the best proof that he did not is the fact that he failed to take advantage of it. When the German armies broke through the Low Countries, and began to press upon the French line at the famous “hinge” at Montmedy, they were like a man who is pressing hard on a locked and bolted door when suddenly[20] the bolt breaks, the door flies open, and the man pitches forward into the room.

So the German armies pitched forward into France when they broke across the Meuse and staggered on, almost losing their balance for lack of the opposition they had expected to find. They lurched on until at the end of five weeks the French Army had dissolved; the French government had surrendered; the nation of France had ceased to exist. Then Hitler pulled his army together, turned it around, started it for the Channel ports. But it takes time to turn an army around; it takes time to establish air bases and collect the thousands of flat-bottomed vessels to ferry an army across the channel.

The time required was fifty-five days from June 17, the day the French asked for an armistice, to August 8, when the Germans made their first mass air attack on Britain as preliminary to invasion. It was those fifty-five days which saved Britain. I arrived in London on June 20, full of the apprehension that Hitler’s army was about to sweep the world. After all it is impressive to have believed all your life that the French Army was the best in the world and then to witness it disappear in thirty-seven days of fighting.

It is more impressive to become a refugee. I had established in Paris the first home I had had in twenty years of vagabond newspaper work. As the German armies came closer to the French capital I congratulated myself that I could now live at home and motor daily to the front. Then one night around midnight the American military attaché, my old friend Colonel Horace M. Fuller, our wisest professional observer of the war abroad, and Lieutenant-Commander Hillenkoetter, our naval attaché, veteran submarine expert, called on me and said: “Knick, you must leave tonight; the Germans will be here by morning.”

In Edgar Mowrer’s overfull Ford, followed by Lilian Mowrer valiantly driving her tiny Simca, we left Paris about three o’clock[21] in the morning, passing through empty streets, the great boulevards stretching wide and forlorn without so much as a policeman in sight, while fog eddied above the paving. We passed through the gates of the city where not even a sentry stood.

Paris was already broken, already humiliated. We fled on down, stopping with the demoralized government at Tours, and then on to Bordeaux where with 1,600 other refugees I found a place on the British India Line S.S. Madura, built to accommodate 160. On the way from Paris to Bordeaux we had traveled with six to eight million other refugees, the largest number of fugitives ever to assemble on the roads of the Western World. Flight, flight, flight! Anything to get away! That was the panic spirit which had gripped the whole population of France, as of the Low Countries.

The German Army could not even come in contact with the main body of refugees, except in the contact of murder when the Luftwaffe machine-gunned the roads. From the moment, eleven days after the grand assault began, when the Germans reached the sea at Abbeville, May 21, from that moment on French resistance disappeared. But Hitler could not begin to attack England until the British Expeditionary Force and the Northern French Army were destroyed. Actually the B.E.F. escaped from Dunkirk June 4, and from that date on Hitler was free to turn in either direction, and many observers believed he would drive straight at England.

Instead, he chose to pursue the French Army another thirteen days, until it surrendered. If Hitler, immediately after Dunkirk, had concentrated every resource on invading England, nobody can say what would have happened. Dunkirk had shocked the British more deeply than anything in 100 years, but the French capitulation shocked them worse.

By the time I arrived at Falmouth, after four days on deck with my fellow refugees, the British were still dazed, dismayed, not panicky, but desperately aware that they stood closer to national destruction than ever in 1,000 years. The truth was they had no[22] army, or rather their army had no weapons. The B.E.F., which had possessed about 75 per cent of all the weapons possessed by all the British Land Forces, had been compelled to leave behind at Dunkirk all their tanks, cannon, and most of their machine guns and even their rifles. It was terrifying to stand on the curb in London and watch battalions of the Guards march by with only half a dozen rifles to a battalion.

The British Land Forces immediately after Dunkirk were practically weaponless. The R.A.F. which was soon to give so gallant an account of itself, needed reorganization; all the units which had been in France had to be brought back and reintegrated for the defense of the island. If ever the German invasion could succeed, it could have succeeded then, but Hitler did not move until the night of August 8, when he sent over his first mass of 400 bombers and fired the docks of London in a blaze so high I was able to read a newspaper by its light on the roof of the Ministry of Information building, eight miles from the fire. Had that attack been launched June 8 or even June 18, instead of August 8, who knows what the result would have been? By August 8 the British had been transformed.

Three things had happened to them which had not happened for over 100 years, since the time of Napoleon. First, they had become frightened; second, they had become angry; third, they had been forced, again I repeat, for the first time in 100 years, forced to go to work. Until the fall of France the British had been as easygoing as we are now, despite the fact they had been formally at war for eight months; but after the fall of France every able-bodied human being in the United Kingdom went to work at the rate of ten to twelve hours a day seven days a week.

In a miraculously short time they tripled their production of weapons, planes, ammunition; meanwhile we sent them 1,000 cannon, many machine guns, and 750,000 rifles. The R.A.F. trained, reorganized, expanded, laid out new fields. In short, when Hitler[23] attacked he struck a new Britain, aroused as never since 1066. It was a dazzling example of what danger can do to a people. The British of August 1940 were not the British of June 1940.

Historians will wonder why Hitler did not move earlier against England. I suppose they will go on wondering why for centuries, even after Hitler has explained it in his memoirs, for his own benefit, and to the satisfaction of few. My estimate is that he simply overvalued the French Army and undervalued the British spirit. Surprised by the French collapse he was carried along by the momentum of his drive to destroy the possibility of further French resistance before trying to invade England. He lost thereby what may prove to have been his greatest chance when he failed to throw his whole air force, army, and navy at England in the moment of her greatest weakness.

Q. What was Hitler’s second mistake?

A. His second mistake was when he went into Russia, apparently expecting the Red Army to fold up at least as fast as the French Army, probably hoping to be able to turn around and launch a second attack on Britain in 1941 before American aid became effective. The initial effect of the invasion of Russia was a disappointment to Hitler, however it may eventually end. So was the First Battle of Britain, but the final outcome of both battles must be awaited to determine how they will affect Hitler’s reputation as a master of war.

Meanwhile his generals have not had reason to change fundamentally the judgment they formed on the basis of their experience with him since 1933. That experience began when he took over the Presidency and obtained the oath of allegiance which, as we have seen, laid at least a legal foundation for his ascendancy over the armed forces. Then he set out to build out of the 100,000-man[24] Reichswehr the mightiest military machine the world has ever known.

He denounced the military clauses of the Versailles treaty, and thus relieved the Army of its crushing sense of being condemned forever to inferiority. He boldly announced the creation of an Air Force, and assigned to it the explosive energies of his first Paladin, Goering. Thereafter, all the resources of the nation were poured into the armed forces. Nothing was too good for the troops. They were given barracks such as no European army had ever had, as good as anything the United States Army has ever known. The food of the army and navy and air force was improved until it was on the average far better, even in peacetime, than anything the German soldier had to eat at home.

Discipline was kept at its highest point, but at the same time a new spirit of comradeship came into the German armed forces. For the first time in the history of the German Navy, officers and men would eat at the same table. All this was bound to have its effect upon the services and to make them think at any rate gratefully of Hitler, but of course the test had still to come. What would this commander in chief order his troops to do? Would he lead them into some impossible adventure prematurely? Would this amateur after building his beautiful machine sacrifice it in some vainglorious maneuver? It seemed as though he would do just that.

The first test of Hitler’s fitness to command his army came on March 7, 1936, when he ordered it into the Rhineland to reoccupy that portion of Germany adjoining France which had been demilitarized by the Versailles treaty. France had insisted that Germany should promise never to quarter troops on the right bank of the Rhine. This was to make up for the fact that France had been prevented from occupying the right bank of the Rhine, and for the fact that the United States in 1919 had refused to join the proposed[25] tripartite pact of France, England, and the United States, to guarantee the French from invasion by Germany.

As long as the Germans kept out of the Rhineland, France was safe. If the Germans ever reoccupied the Rhineland, it meant that they intended sooner or later to use it as a jumping-off-place from which to attack France. France therefore had insisted upon and had obtained this clause in the Versailles treaty, and had thereafter frequently announced that its violation would mean war. Nevertheless, Hitler toward the middle of February 1936 informed his General Staff that in the first week of March he intended to reoccupy the Rhineland. At that moment Hitler met his first opposition from the Army. The generals protested that they could not be responsible for what would happen, because if the French mobilized and fought, the German Army was not strong enough—it would have to retreat. Unspoken was the conclusion that if the German Army retreated, it would mean the end of the Nazi regime, the end of Hitler.

Hitler replied that it was the duty of the Army to obey orders; it was his duty as Fuehrer to give orders which could be successfully obeyed. “I know,” he told them, “that the French will not mobilize. I know the French will not fight. I know the English don’t want them to fight. Don’t ask me how I know. I know. It is my business to know.”

When I was in Spain during the Spanish Civil War, I learned under unusual circumstances something of what went on inside the German General Staff during those days of March 1936, which were to decide the history of the continent. At Burgos, headquarters of Franco’s government, I met Major von der Osten, who was ostensibly in charge of certain economic investigations or negotiations, but as a matter of fact was the chief of the German Gestapo in Spain. He was an agreeable fellow, father of eight children, highly intelligent, amusing, and it did not matter to me that some months before, his organization, the Gestapo, had had me arrested[26] and thrown into a death cell in San Sebastian for thirty-six hours, whence I escaped by the determined vocal and political efforts of my friend and fellow correspondent, Randolph Churchill.

The Major knew that I knew that he was chief of the Gestapo and he knew that I would do all I could to get information from him of value to me, as I knew he would do likewise with me. So we got along famously, and one day he included me in a picnic with several other correspondents. There, on the banks of a clear stream while the Major’s soldier servants served us grilled frankfurters and Rhine wine, I led the conversation into discussion of what the Army thought of Hitler. The theme reached the reoccupation of the Rhineland, and at this the Major became enlightening.

“I was assigned to the Bendlerstrasse [headquarters of the General Staff] then,” the Major said. “I can tell you that for five days and five nights not one of us closed an eye. We knew that if the French marched, we were done. We had no fortifications, and no army to match the French. If the French had even mobilized, we should have been compelled to retire.” He confirmed that the opinion of virtually the entire General Staff was against Hitler; they considered the move suicidal, and when they did move, it was only to obey orders, not because they were convinced it was right.

“And what did they think after the thing was all over and Hitler had been proved right? Did they think that Hitler had proved himself a genius or that he just had extraordinarily good luck?”

The Major smiled. “We thought there was a good deal of kind fortune concerned,” he said.

That was Hitler’s first brush with his army, and his generals may well have put him down as lucky. He won, and later events proved how tremendous his victory was. For the occupation of the Rhineland enabled Hitler to build there his Siegfried line, and the Siegfried line enabled him eventually to hold France until he was ready to fall upon and destroy her as he did in 1940.

This first demonstration that he was “always right,” strengthened[27] his position with the General Staff enormously. The second test was accordingly easier. It was Austria.

Just as in the case of the Rhineland, so in the case of Austria, France had often declared that any German attempt to annex Austria would be a cause of war. This made good sense, just as it had made good sense for the French to have said they would go to war to prevent reoccupation of the Rhineland. Once the Germans had the Rhineland and began to fortify it, they made it difficult for the French to defend Austria. Once the Germans had Austria they made it difficult for the French to defend Czechoslovakia. Once the Germans had Czechoslovakia they made it difficult for the French to defend France.

The German generals understood this series of steps as well as or better than the French, and therefore they could not believe that the French would allow each step to be taken without trying to stop it. Therefore, as Hitler ordered each step taken, his generals protested, since like all generals they did not want to start a war without the certainty of winning.

They protested vigorously over the decision to go into Austria, but once again Hitler said: “Gentlemen, it is your business to take the action I direct. It is my business to direct only action which will be successful. I can assure you now, as I assured you on the reoccupation of the Rhineland, that now also France will not move, the British will not move; we can do as we like.” He was right again, and now with two major victories to his credit, he could face his generals with an even more momentous and critical order—to occupy Czechoslovakia.

This third move, against Czechoslovakia, was the most critical, because here France was pledged by her solemn word of honor to fight for her ally, and because the possession of Czechoslovakia would make it possible finally to attack France herself. These two facts were of course amply known to the German generals and once more they assumed that the French generals and the French[28] government would now awaken and fight for the life of their country.

So, in spite of the two lessons Hitler had given them, the German generals once more pointed out the dangers. Their Siegfried line was not nearly complete. If they threw crushing weight at Czechoslovakia, they would have to weaken their West Front so badly that the French, if they wished to plunge, might break through. Hitler this time was beside himself. He not only knew the French and British would not fight if the Czechs asked them to fight, but he believed, and I think he was right, that the French and British would not have fought even if the Czechs had fought.

So he wanted above all things at this juncture to meet a little opposition to blood his sword. He wanted the Czechs to fight, and knowing he would have them alone, he longed for a chance to show what his vast army and air force could do with overwhelming odds on their side. In my opinion it is just the opposite of true to say that Hitler wanted another bloodless victory. He did not. He wanted a bloody one, the blood of course, to be shed by the hopelessly outnumbered enemy. It seemed to him absolutely idiotic that any of his generals should object. They did, but feebly.

Once more Hitler overrode them, with the same arguments. “France will not fight. The British will not fight. We can do as we like with the Czechs. I only hope they do fight.” Hitler this time got everything he wanted but one thing. The Czechs, brutally betrayed by their ally France and bullied by England, did not fight. Hitler was cheated of his desire to do violence. At Munich the bad temper he displayed when Chamberlain and Daladier gave in to him on every point was caused by the fact that he realized these good gentlemen were going to make the Czechs surrender. He was not going to be given the chance to drop one bomb. He had to wait a whole year for his bloodshed.

If you doubt this analysis of Hitler’s bloodthirstiness, recollect that he never gave Poland a chance to imitate Czechoslovakia’s[29] surrender. Would it not be a matter for wonderment if the German generals had failed to be impressed by this third example of the Fuehrer’s infallibility?

Yet when he proposed to destroy Poland even after the British and French had “guaranteed” her, some of Hitler’s generals still cautiously offered objections on the grounds that this would inevitably mean the Great War and maybe they could not win the Great War. For the fourth time Hitler overcame constantly lessening opposition of “timid” generals. He explained that he would knock out Poland before the French or British could strike, if indeed they intended to strike at all.

There was some doubt whether the Allies would really fight. Ribbentrop insisted Britain was through, and although they might declare war and mobilize, the British would do so only to save face, and would take the first opportunity to quit with a negotiated peace. But even if the British and the French did go to war, Hitler explained, he would finish Poland swiftly, and then turn such heat on France, bring such terrific forces to bear on the Western Front, that she would probably also be ready to negotiate peace, and if not he would knock her out also. That he was sure he could do, and once he had done that, the British would capitulate.

If there was any opposition lingering among the generals, it disappeared upon the signature of the Russo-German Pact, August 23, 1939. This most brilliant of all Hitler’s foreign political coups convinced his generals first that they would not have to fight a war on two major fronts, second that they were in the hands of an invincible military-political genius of the first category.

How gloriously right Hitler seemed to be. At first everything appeared to depend upon the speed with which Hitler could knock out the Poles, whether he could finish them off before the French could mobilize for a great offensive on the West. Optimistic Poles said they could hold out for three years; pessimistic Poles said one year. The French thought the Poles could hold for six months.[30] The German generals thought it would take three months to break the Poles. Hitler gave them six weeks to do the job. They conquered Poland in eighteen days!

Then came Norway and then came France!

No matter what the German generals had thought before, by May 1940 they had the feeling Hitler was another Napoleon. Sure enough, on May 10, they attacked and on June 17 the French Army, the mighty French Army of 4,500,000 men only three generations from Napoleon, surrendered. The Germans, led by Hitler, had accomplished the greatest victory in the history of the German Army, and had inflicted upon their age-old enemy the most colossal defeat in the history of France. Indeed from the point of view of the numbers of men involved, and the issues at stake, it may be said to be dimensionally the greatest victory of military history.

How can anyone now wonder that after the fall of France the German General Staff with all its professional vanity would be proud to take and if necessary blindly obey orders from Corporal Hitler?

Hitler had brought his General Staff to this position of unquestioning obedience when he gave the orders to attack Russia. Here was truly the place for caution. If Hitler was another Napoleon, here was the same Russia. It meant a two-front war. It would give time for United States aid to become effective. At the best it meant lengthening the war by years.

“No,” Hitler ordered, “we shall conquer Russia before the summer is out, and conquer England before the year is out and before the United States can do anything about it. Vorwaerts!” Only the prestige built up by Hitler’s uninterrupted series of victories from the Rhineland to Crete could have won the acquiescence of the German General Staff to the Russian adventure.

Q. Is Hitler personally brave?

[31]

A. It is hard to say. I could put it this way: Hitler is not the sort of man about whom one would unhesitatingly say that he is personally brave, as one would say about Churchill, for example. Perhaps we shall not count the story he told me about his winning the Iron Cross in the last war, since many Germans say it is not a true story. Yet it is an interesting one. He told it to me the night of March 11, 1932 on the eve of the Presidential election when he ran against Hindenburg and scored eleven million to Hindenburg’s eighteen million votes.

I asked him how he had won his Iron Cross. He always wore it but his political enemies declared there was no record in the army archives of its having been awarded him and neither in Mein Kampf nor elsewhere could there be found any account of how he got it. I was afraid when I asked the question that it might irritate him, but he seemed amused, and even pleased.