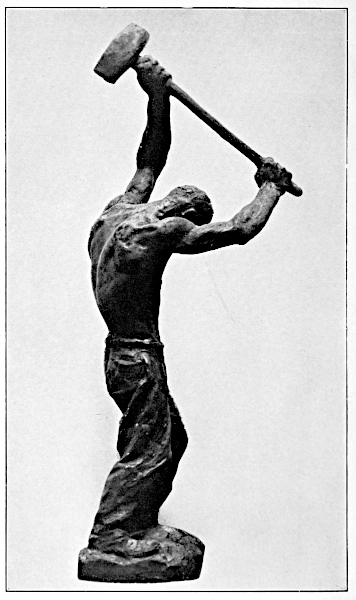

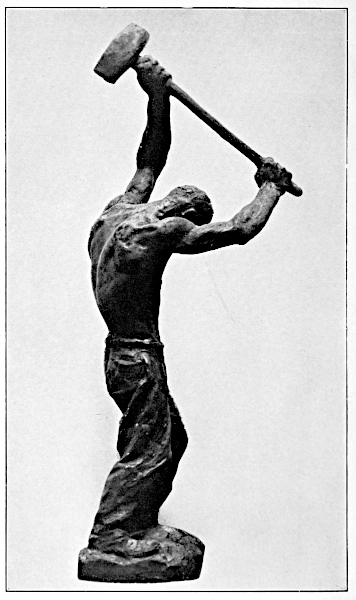

THE HEAVY SLEDGE

MAHONRI YOUNG

(American sculptor, born 1877)

THE HEAVY SLEDGE

MAHONRI YOUNG

(American sculptor, born 1877)

An Anthology of the Literature

of Social Protest

THE WRITINGS OF PHILOSOPHERS, POETS, NOVELISTS,

SOCIAL REFORMERS, AND OTHERS WHO HAVE

VOICED THE STRUGGLE AGAINST

SOCIAL INJUSTICE

SELECTED FROM TWENTY-FIVE LANGUAGES

Covering a Period of Five Thousand Years

Edited by

UPTON SINCLAIR

Author of “Sylvia,” “The Jungle,” Etc.

With an Introduction by

JACK LONDON

Author of “The Sea Wolf,” “The Call of the Wild,”

“The Valley of the Moon,” Etc., Etc.

ILLUSTRATED WITH REPRODUCTIONS

OF SOCIAL PROTEST IN ART

Published by

UPTON SINCLAIR

NEW YORK CITY AND PASADENA, CALIFORNIA

Dr. John R. Haynes, of Los Angeles, very generously purchased from the publishers the plates and copyright of this book, in order to make possible the issuing of this edition. I asked Dr. Haynes if he would let me make acknowledgment to him in the book, and he answered: “Dedicate the book to those unknown ones, who by their dimes and quarters keep the Socialist movement going; to the poor and obscure people who sacrifice themselves in order to bring about a better world, which they may never live to see. Write this as eloquently as you can, and it will be the best possible dedication to ‘The Cry for Justice’.”

I decided, after thinking it over, to combine my own idea with the idea of Dr. Haynes.

Copyright, 1915, by

The John C. Winston Co.

This anthology, I take it, is the first edition, the first gathering together of the body of the literature and art of the humanist thinkers of the world. As well done as it has been done, it will be better done in the future. There will be much adding, there will be a little subtracting, in the succeeding editions that are bound to come. The result will be a monument of the ages, and there will be none fairer.

Since reading of the Bible, the Koran, and the Talmud has enabled countless devout and earnest right-seeking souls to be stirred and uplifted to higher and finer planes of thought and action, then the reading of this humanist Holy Book cannot fail similarly to serve the needs of groping, yearning humans who seek to discern truth and justice amid the dazzle and murk of the thought-chaos of the present-day world.

No person, no matter how soft and secluded his own life has been, can read this Holy Book and not be aware that the world is filled with a vast mass of unfairness, cruelty, and suffering. He will find that it has been observed, during all the ages, by the thinkers, the seers, the poets, and the philosophers.

And such person will learn, possibly, that this fair world so brutally unfair, is not decreed by the will of God nor by any iron law of Nature. He will learn that the world can be fashioned a fair world indeed by the humans who inhabit it, by the very simple, and yet most difficult process of coming to an understanding of the world. Understanding, after all, is merely sympathy in its fine correct sense. And such sympathy, in its genuineness, makes toward unselfishness. Unselfishness inevitably[4] connotes service. And service is the solution of the entire vexatious problem of man.

He, who by understanding becomes converted to the gospel of service, will serve truth to confute liars and make of them truth-tellers; will serve kindness so that brutality will perish; will serve beauty to the erasement of all that is not beautiful. And he who is strong will serve the weak that they may become strong. He will devote his strength, not to the debasement and defilement of his weaker fellows, but to the making of opportunity for them to make themselves into men rather than into slaves and beasts.

One has but to read the names of the men and women whose words burn in these pages, and to recall that by far more than average intelligence have they won to their place in the world’s eye and in the world’s brain long after the dust of them has vanished, to realize that due credence must be placed in their report of the world herein recorded. They were not tyrants and wastrels, hypocrites and liars, brewers and gamblers, market-riggers and stock-brokers. They were givers and servers, and seers and humanists. They were unselfish. They conceived of life, not in terms of profit, but of service.

Life tore at them with its heart-break. They could not escape the hurt of it by selfish refuge in the gluttonies of brain and body. They saw, and steeled themselves to see, clear-eyed and unafraid. Nor were they afflicted by some strange myopia. They all saw the same thing. They are all agreed upon what they saw. The totality of their evidence proves this with unswerving consistency. They have brought the report, these commissioners of humanity. It is here in these pages. It is a true report.

But not merely have they reported the human ills.[5] They have proposed the remedy. And their remedy is of no part of all the jangling sects. It has nothing to do with the complicated metaphysical processes by which one may win to other worlds and imagined gains beyond the sky. It is a remedy for this world, since worlds must be taken one at a time. And yet, that not even the jangling sects should receive hurt by the making fairer of this world for this own world’s sake, it is well, for all future worlds of them that need future worlds, that their splendor be not tarnished by the vileness and ugliness of this world.

It is so simple a remedy, merely service. Not one ignoble thought or act is demanded of any one of all men and women in the world to make fair the world. The call is for nobility of thinking, nobility of doing. The call is for service, and, such is the wholesomeness of it, he who serves all, best serves himself.

Times change, and men’s minds with them. Down the past, civilizations have exposited themselves in terms of power, of world-power or of other-world power. No civilization has yet exposited itself in terms of love-of-man. The humanists have no quarrel with the previous civilizations. They were necessary in the development of man. But their purpose is fulfilled, and they may well pass, leaving man to build the new and higher civilization that will exposit itself in terms of love and service and brotherhood.

To see gathered here together this great body of human beauty and fineness and nobleness is to realize what glorious humans have already existed, do exist, and will continue increasingly to exist until all the world beautiful be made over in their image. We know how gods are made. Comes now the time to make a world.

Honolulu, March 6, 1915.

The editor has used his best efforts to ascertain what material in the present volume is protected by copyright. In all such cases he has obtained the permission of author and publisher for the use of the material. Such permission applies only to the present volume, and no one should assume the right to make any other use of it without seeking permission in turn. If there has been any failure upon the editor’s part to obtain a necessary consent, it is due solely to oversight, and he trusts that it may be overlooked. The following publishers have to be thanked for the permissions which they have kindly granted; the thanks applying also to the authors of the works.

Mitchell Kennerley

Patrick MacGill, “Songs of the Dead End.” Harry Kemp, “The Cry of Youth.” Charles Hanson Towne, “Manhattan.” Hjalmar Bergström, “Lynggaard & Co.” Donald Lowrie, “My Life in Prison.” John G. Neihardt, “Cry of the People.” Frank Harris, “The Bomb.” Vachel Lindsay, “The Eagle that is Forgotten” and “To the United States Senate.” Frederik van Eeden, “The Quest.” Edwin Davies Schoonmaker, “Trinity Church.” Walter Lippman, “A Preface to Politics.” L. Andreyev, “Savva.” J. C. Underwood, “Processionals.” Bliss Carman, “The Rough Rider.” Percy Adams Hutchison, “The Swordless Christ.”

Doubleday, Page & Co.

Frank Norris, “The Octopus.” Helen Keller, “Out of the Dark.” Frederik van Eeden, “Happy Humanity.” Bouck White, “The Call of the Carpenter.” Alexander Irvine, “From the Bottom Up.” John D. Rockefeller, “Random Reminiscences.” G. Lowes Dickinson, “Letters from a Chinese Official.” Ben B. Lindsey and Harvey J. O’Higgins, “The Beast.” Franklin P. Adams, “By and Large.” Edwin Markham, “The Man with the Hoe and Other Poems.” Gerald Stanley Lee, “Crowds.” Woodrow Wilson, “The New Freedom.”

Houghton Mifflin Co.

William Vaughn Moody, “Poems.” Vida D. Scudder, “Social Ideals.” Florence Wilkinson Evans, “The Ride Home.” Peter Kropotkin, “Mutual Aid” and “Memoirs of a Revolutionist.” Helen G. Cone, “Today.” T. B. Aldrich, “Poems.” T. W. Higginson, “Poems.”

Charles Scribner’s Sons

H. G. Wells, “A Modern Utopia.” Björnstjerne Björnson, “Beyond Human Power.” Edith Wharton, “The House of Mirth.” John Galsworthy, “A Motley.” Maxim Gorky, “Fóma Gordyéeff.” J. M. Barrie, “Farm Laborers.” Walter Wyckoff, “The Workers.”

The Macmillan Co.

John Masefield, “Dauber” and “A Consecration.” Jack London, “The People of the Abyss” and “Revolution.” Robert Herrick, “A Life for a Life.” Israel Zangwill, “Children of the Ghetto.” Albert Edwards, “A Man’s World” and “Comrade Yetta.” Walter Rauschenbusch, “Christianity and the Social Crisis.” Winston Churchill, “The Inside of the Cup.” Rabindranath Tagore, “Gitanjali.” Thorstein Veblen, “The Theory of the Leisure Class.” Edward Alsworth Ross, “Sin and Society.” W. J. Ghent, “Socialism and Success.” Vachel Lindsay, “The Congo.” Wilfrid Wilson Gibson, “Fires.” Percy Mackaye, “The Present Hour.” Robert Hunter, “Violence and the Labor Movement.” Ernest Poole, “The Harbor.”

The Century Co.

Louis Untermeyer, “Challenge.” Richard Whiteing, “No. 5 John Street.” George Carter, “Ballade of Misery and Iron.” James Oppenheim, “Songs for the New Age.” H. G. Wells, “In the Days of the Comet.” Alex. Irvine, “My Lady of the Chimney Corner.” Edwin Björkman, “Dinner à la Tango.”

Small, Maynard & Co.

Charlotte P. Gilman, “In this Our World” and “Women and Economics.” Finley P. Dunne, “Mr. Dooley.”

Brentano

G. Bernard Shaw, “Preface to Major Barbara” and “The Problem Play.” Eugene Brieux, “The Red Robe.” W. L. George, “A Bed of Roses.”

Duffield & Co.

Elsa Barker, “The Frozen Grail.” H. G. Wells, “Tono-Bungay.”

B. W. Huebsch

James Oppenheim, “Pay Envelopes.” Gerhart Hauptmann, “The Weavers.” Maxim Gorky, “Tales of Two Countries.”

G. P. Putnam Sons

Antonio Fogazzaro, “The Saint.” J. L. Jaurès, “Studies in Socialism.”

George H. Doran Co.

Will Levington Comfort, “Midstream.” Charles E. Russell, “These Shifting Scenes.”

Frederick A. Stokes Co.

Robert Tressall, “The Ragged Trousered Philanthropists.” Wilhelm Lamszus, “The Human Slaughter House.” Olive Schreiner, “Woman and Labor.” Alfred Noyes, “The Wine Press.”

McClure Publishing Co.

Dana Burnet, “A Ballad of Dead Girls.” Lincoln Steffens, “The Dying Boss” and “The Reluctant Grafter.”

The “Masses”

John Amid, “The Tail of the World.” Dana Burnet, “Sisters of the Cross of Shame.” Carl Sandburg, “Buttons.” J. E. Spingarn, “Heloise sans Abelard.” Louis Untermeyer, “To a Supreme Court Judge.”

James Pott & Co.

David Graham Phillips, “The Reign of Gilt.”

Barse & Hopkins

R. W. Service, “The Spell of the Yukon.”

University of Chicago Press

August Bebel, “Memoirs.”

Charles H. Sergel Co.

Verhaeren, “The Dawn: Translation by Arthur Symons.”

Albert and Charles Boni

Horace Traubel, “Chants Communal.”

A. C. McClurg & Co.

W. E. B. du Bois, “The Souls of Black Folk.”

Mother Earth Publishing Co.

A. Berkman, “Prison Memories of an Anarchist.” Voltairine de Cleyre, “Works.” Emma Goldman, “Anarchism.”

Moffat, Yard & Co.

Reginald Wright Kauffman, “The House of Bondage.”

John Lane

Anatole France, “Penguin Island.” William Watson, “Poems.”

Bobbs-Merrill Co.

Brand Whitlock, “The Turn of the Balance.”

E. P. Dutton & Co.

Patrick MacGill, “Children of the Dead End.”

Charles H. Kerr Co.

“When the Leaves Come Out.”

Hillacre Bookhouse

Arturo Giovannitti, “The Walker.”

Henry Holt & Co.

Romain Rolland, “Jean-Christophe.”

Richard G. Badger (Poet Lore)

Andreyev, “King Hunger.” Gorky, “A Night’s Lodging.”

Mrs. Arthur Upson

Poems by Arthur Upson.

New York Times

Elsa Barker, “Breshkovskaya.”

Collier’s Weekly

Herman Hagedorn, “Fifth Avenue, 1915.”

Poetry: A Magazine of Verse

F. Kiper Frank, “A Girl Strike Leader.”

Life

Max Eastman, “To a Bourgeois Litterateur.”

Walter Scott Publishing Co.

(P. P. Simmons Co., New York)

Joseph Skipsey, “Mother Wept.” Jethro Bithell’s translation of Verhaeren in “Contemporary Belgian Poetry” and of Dehmel in “Contemporary German Poetry.” Rimbaud’s “Waifs and Strays” in “Contemporary French Poetry.”

Elkin Mathews & Co.

William H. Davies, “Songs of Joy.”

Constable & Co.

Harold Monro, “Impressions.”

Duckworth & Co.

Hilaire Belloc, “The Rebel.”

Swan, Sonnenschein & Co.

Edward Carpenter, “Towards Democracy.”

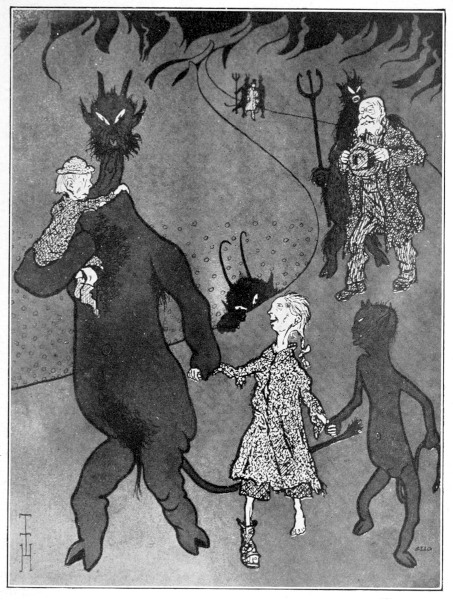

Acknowledgments have also to be made to the following artists, who have kindly consented to have their works used in the volume: Mahonri Young, Wm. Balfour Ker, Ryan Walker, Charles A. Winter, Abastenia Eberle, John Mowbray-Clarke, Isidore Konti, Walter Crane, and Will Dyson. Also to Life Publishing Co. and the New Age, London, for permission to use a drawing from their files.

| BOOK | PAGE | |

|---|---|---|

| I. | Toil | 27 |

| II. | The Chasm | 73 |

| III. | The Outcast | 121 |

| IV. | Out of the Depths | 179 |

| V. | Revolt | 227 |

| VI. | Martyrdom | 289 |

| VII. | Jesus | 345 |

| VIII. | The Church | 383 |

| IX. | The Voice of the Ages | 431 |

| X. | Mammon | 485 |

| XI. | War | 551 |

| XII. | Country | 593 |

| XIII. | Children | 637 |

| XIV. | Humor | 679 |

| XV. | The Poet | 725 |

| XVI. | Socialism | 783 |

| XVII. | The New Day | 835 |

| The Heavy Sledge, Mahonri Young | Frontispiece |

| PAGE | |

|---|---|

| The Man with the Hoe, E. M. Lilien | 32 |

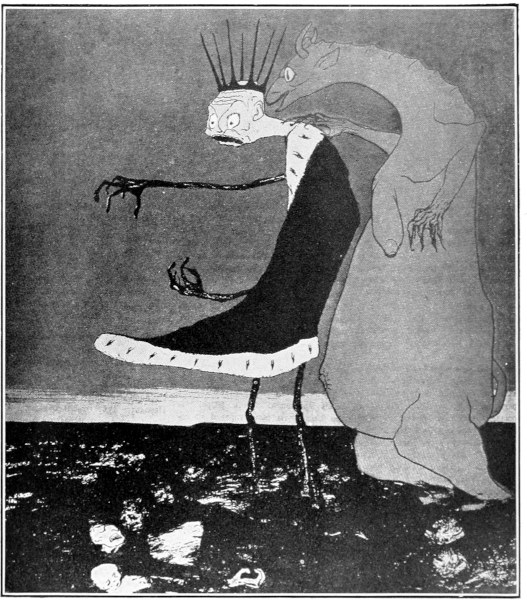

| The Vampire, E. M. Lilien | 33 |

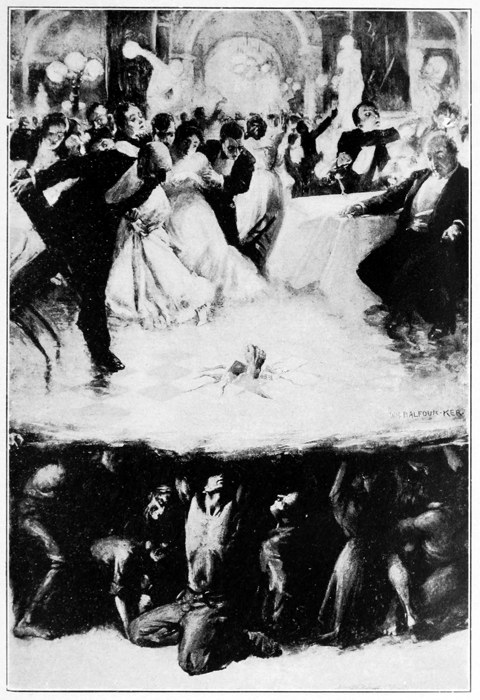

| King Canute, William Balfour Ker | 93 |

| The Hand of Fate, William Balfour Ker | 92 |

| Without a Kennel, Ryan Walker | 136 |

| The White Slave, Abastenia St. Leger Eberle | 137 |

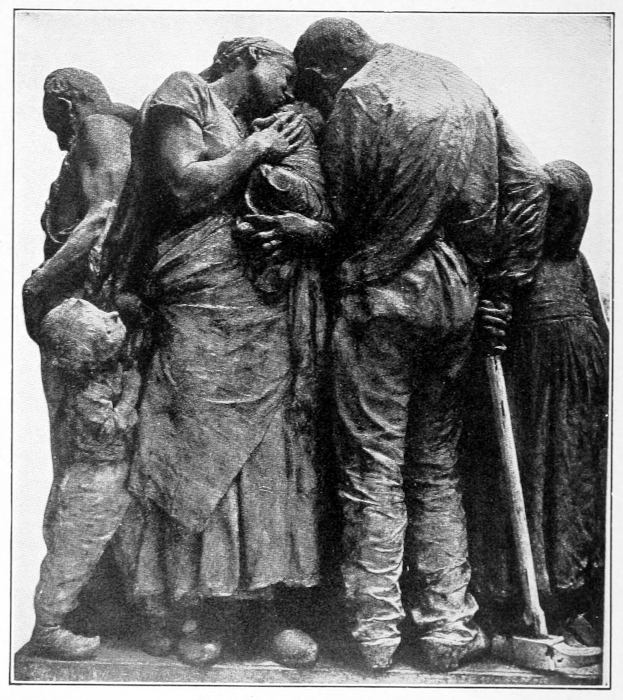

| Cold, Roger Bloche | 200 |

| The People Mourn, Jules Pierre van Biesbroeck | 201 |

| The Liberatress, Theophile Alexandre Steinlen | 233 |

| Outbreak, Käthe Kollwitz | 232 |

| The End, Käthe Kollwitz | 297 |

| The Surprise, Ilyá Efímovitch Repin | 296 |

| Ecce Homo, Constantin Meunier | 368 |

| Despised and Rejected of Men, Sigismund Goetze | 369 |

| “To Sustain the Body of the Church, if You Please,” Denis Auguste Marie Raffet | 392 |

| Christ, John Mowbray-Clarke | 393 |

| The Despotic Age, Isidore Konti | 456 |

| “Courage, Your Majesty, Only One Step More!” | 457 |

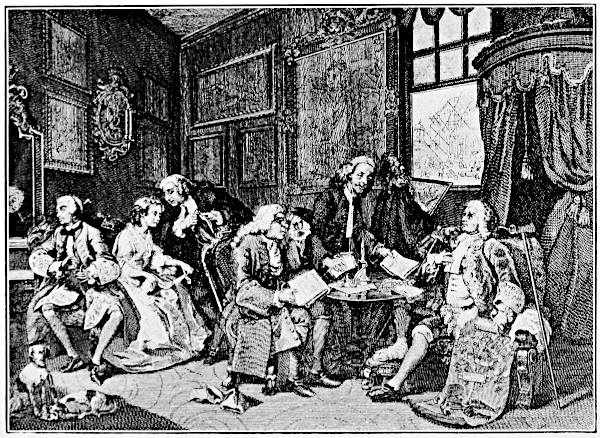

| Marriage à la Mode, William Hogarth | 489 |

| Mammon, George Frederick Watts | 488 |

| War, Arnold Böcklin | 584 |

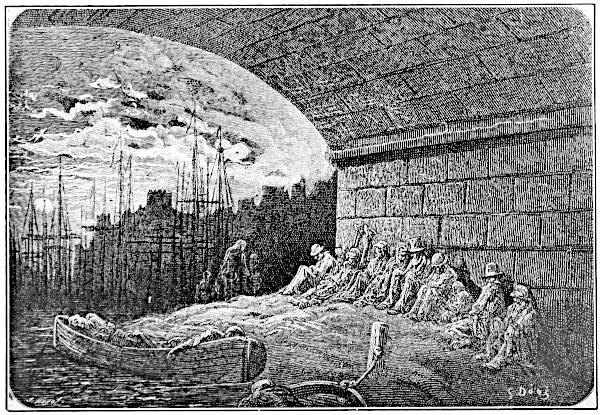

| London, Paul Gustave Doré | 585 |

| A Citizen Lost, Ryan Walker | 649 |

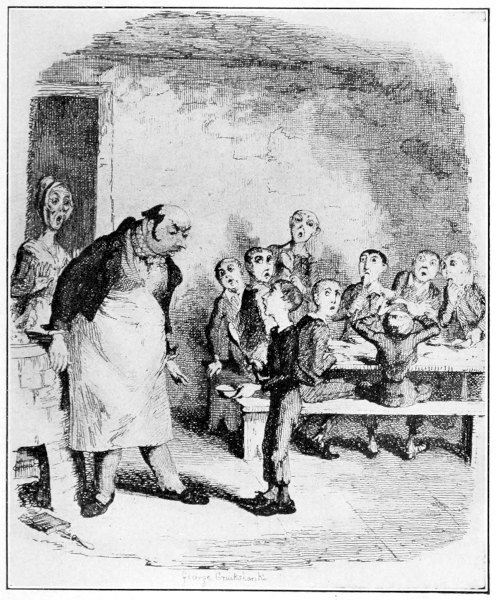

| “Oliver Twist Asks for More,” George Cruikshank | 648 |

| The Coal Famine, Thomas Theodor Heine | 680 |

| My Solicitor Shall Hear of This, Will Dyson | 681 |

| The Militant, Charles A. Winter | 744 |

| The Death of Chatterton, Henry Wallis | 745 |

| Once Ye Have Seen My Face Ye Dare Not Mock | 808 |

| [16]Justice, Walter Crane | 809 |

When the idea of this collection was first thought of, it was a matter of surprise that the task should have been so long unattempted. There exist small collections of Socialist songs for singing, but apparently this is the first effort that has been made to cover the whole field of the literature of social protest, both in prose and poetry, and from all languages and times.

The reader’s first inquiry will be as to the qualifications of the editor. Let me say that I gave nine years of my life to a study of literature under academic guidance, and then, emerging from a great endowed university, discovered the modern movement of proletarian revolt, and have given fifteen years to the study and interpretation of that. The present volume is thus a blending of two points of view. I have reread the favorites of my youth, choosing from them what now seemed most vital; and I have sought to test the writers of my own time by the touchstone of the old standards.

The size of the task I did not realize until I had gone too far to retreat. It meant not merely the rereading of the classics and the standard anthologies; it meant going through a small library of volumes by living writers, the files of many magazines, and a dozen or more scrap-books and collections of fugitive verse. At the end of this labor I found myself with a pile of typewritten manuscript a foot high; and the task of elimination was the most difficult of all.

To a certain extent, of course, the selection was self-determined. No anthology of social protest could omit[18] “The Song of the Shirt,” and “The Cry of the Children,” and “A Man’s a Man for A’ That”; neither could it omit the “Marseillaise” and the “Internationale.” Equally inevitable were selections from Shelley and Swinburne, Ruskin, Carlyle and Morris, Whitman, Tolstoy and Zola. The same was true of Wells and Shaw and Kropotkin, Hauptmann and Maeterlinck, Romain Rolland and Anatole France. When it came to the newer writers, I sought first their own judgment as to their best work; and later I submitted the manuscript to several friends, the best qualified men and women I knew. Thus the final version was the product of a number of minds; and the collection may be said to represent, not its editor, but a whole movement, made and sustained by the master-spirits of all ages.

For this reason I may without suspicion of egotism say what I think about the volume. It was significant to me that several persons reading the manuscript and writing quite independently, referred to it as “a new Bible.” I believe that it is, quite literally and simply, what the old Bible was—a selection by the living minds of a living time of the best and truest writings known to them. It is a Bible of the future, a Gospel of the new hope of the race. It is a book for the apostles of a new dispensation to carry about with them; a book to cheer the discouraged and console the wounded in humanity’s last war of liberation.

The standards of the book are those of literature. If there has been any letting down, it has been in the case of old writings, which have an interest apart from that of style. It brings us a thrill of wonder to find, in an ancient Egyptian parchment, a father setting forth to his son how easy is the life of the lawyer, and what a[19] dog’s life is that of the farmer. It amuses us to read a play, produced in Athens two thousand, two hundred and twenty-three years ago, in which is elaborately propounded the question which thousands of Socialist “soap-boxers” are answering every night: “Who will do the dirty work?” It makes us shudder, perhaps, to find a Spaniard of the thirteenth century analyzing the evil devices of tyrants, and expounding in detail the labor-policy of some present-day great corporations in America.

Let me add that I have not considered it my function to act as censor to the process of social evolution. Every aspect of the revolutionary movement has found a voice in this book. Two questions have been asked of each writer: Have you had something vital to say? and Have you said it with some special effectiveness? The reader will find, for example, one or two of the hymns of the “Christian Socialists”; he will also find one of the parodies on Christian hymns which are sung by the Industrial Workers of the World in their “jungles” in the Far West. The Anarchists and the apostles of insurrection are also represented; and if some of the things seem to the reader the mere unchaining of furies, I would say, let him not blame the faithful anthologist, let him not blame even the writer—let him blame himself, who has acquiesced in the existence of conditions which have driven his fellow-men to the extremes of madness and despair.

In the preparation of this work I have placed myself under obligation to so many people that it would take much space to make complete acknowledgments. I must thank those friends who went through the bulky manuscript, and gave me the benefit of their detailed criticism: George Sterling, Max Eastman, Floyd Dell, Clement Wood, Louis Untermeyer, and my wife. I am[20] under obligation to a number of people, some of them strangers, who went to the trouble of sending me scrap-books which represented years and even decades of collecting: Elizabeth Balch, Elizabeth Magie Phillips, Frank B. Norman, Frank Stuhlman, J. M. Maddox, Edward J. O’Brien, and Clement Wood. Among those who helped me with valuable suggestions were: Edwin Björkman, Reginald Wright Kauffman, Thomas Seltzer, Jack London, Rose Pastor Stokes, May Beals, Elizabeth Freeman, Arthur W. Calhoun, Frank Shay, Alexander Berkman, Joseph F. Gould, Louis Untermeyer, Harold Monro, Morris Hillquit, Peter Kropotkin, Dr. James P. Warbasse, and the Baroness von Blomberg. The fullness of the section devoted to ancient writings is in part due to the advice of a number of scholars: Dr. Paul Carus, Professor Crawford H. Toy, Professor William Cranston Lawton, Professor Charles Burton Gulick, Professor Thomas D. Goodell, Professor Walton Brooks McDaniels, Rev. John Haynes Holmes, Professor George F. Moore, Prof. Walter Rauschenbusch, and Professor Charles R. Lanman.

With regard to the illustrations in the volume, I endeavored to repeat in the field of art what had been done in the field of literature: to obtain the best material, both old and new, and select the most interesting and vital. I have to record my indebtedness to a number of friends who made suggestions in this field—Ryan Walker, Art Young, John Mowbray-Clarke, Martin Birnbaum, Odon Por, and Walter Crane. Also I must thank Mr. Frank Weitenkampf and Dr. Herman Rosenthal of the New York Public Library, and Dr. Clifford of the Library of the Metropolitan Museum of Art. To the artists whose copyrighted work I have used I owe my thanks for their permission: as likewise to the many[21] writers whose copyrighted books I have quoted. Elsewhere in the volume I have made acknowledgments to publishers for the rights they have kindly granted. Let me here add this general caution: The copyrighted passages used have been used by permission, and any one who desires to reprint them must obtain similar permission.

One or two hundred contemporary authors responded to my invitation and sent me specimens of their writings. Of these authors, probably three-fourths will not find their work included—for which seeming discourtesy I can only offer the sincere plea of the limitations of space which were imposed upon me. I am not being diplomatic, but am stating a fact when I say that I had to leave out much that I thought was of excellent quality.

What was chosen will now speak for itself. Let my last word be of the hope, which has been with me constantly, that the book may be to others what it has been to me. I have spent with it the happiest year of my lifetime: the happiest, because occupied with beauty of the greatest and truest sort. If the material in this volume means to you, the reader, what it has meant to me, you will live with it, love it, sometimes weep with it, many times pray with it, yearn and hunger with it, and, above all, resolve with it. You will carry it with you about your daily tasks, you will be utterly possessed by it; and again and again you will be led to dedicate yourself to the greatest hope, the most wondrous vision which has ever thrilled the soul of humanity. In this spirit and to this end the book is offered to you. If you will read it through consecutively, skipping nothing, you will find that it has a form. You will be led from one passage to the next, and when you reach the end you will be a wiser, a humbler, and a more tender-hearted person.

By John Masefield

Toil

The dignity and tragedy of labor; pictures of the actual conditions under which men and women work in mills and factories, fields and mines.

By Edwin Markham

(This poem, which was written after seeing Millet’s world-famous painting, was published in 1899 by a California school-principal, and made a profound impression. It has been hailed as “the battle-cry of the next thousand years”)

(From “The Village”)

By George Crabbe

(One of the earliest of English realistic poets, 1754-1832; called “The Poet of the Poor”)

By Richard Jefferies

(English essayist and nature student, 1848-1887)

For weeks and weeks the stark black oaks stood straight out of the snow as masts of ships with furled sails frozen and ice-bound in the haven of the deep valley. Never was such a long winter.

One morning a laboring man came to the door with a spade, and asked if he could dig the garden, or try to, at the risk of breaking the tool in the ground. He was starving; he had had no work for six months, he said, since the first frost started the winter. Nature and the earth and the gods did not trouble about him, you see. Another aged man came once a week regularly; white as the snow through which he walked. In summer he worked; since the winter began he had had no employment, but supported himself by going round to the farms in rotation. He had no home of any kind. Why did he not go into the workhouse? “I be afeared if I goes in there they’ll put me with the rough ‘uns, and very likely I should get some of my clothes stole.” Rather than go into the workhouse, he would totter round in the face of the blasts that might cover his weak old limbs with drift. There was a sense of dignity and manhood left still; his clothes were worn, but clean and decent; he was no companion of rogues; the snow and frost, the straw of the outhouses, was better than that. He was struggling against age, against nature, against circumstances; the entire weight of society, law and order pressed upon him to force him to lose his self-respect and liberty. He would rather risk his life in the snow-drift. Nature, earth and the gods did not help him; sun and stars, where were they? He knocked at the doors of the farms and found good in man only—not in Law or Order, but in individual man alone.

By James Matthew Barrie

(English poet, playwright and novelist, born 1860)

Grand, patient, long-suffering fellows these men were, up at five, summer and winter, foddering their horses, maybe, hours before there would be food for themselves, miserably paid, housed like cattle, and when rheumatism seized them, liable to be flung aside like a broken graip. As hard was the life of the women: coarse food, chaff beds, damp clothes their portion, their sweethearts in the service of masters who were loath to fee a married man. Is it to be wondered that these lads who could be faithful unto death drank soddenly on their one free day; that these girls, starved of opportunities for womanliness, of which they could make as much as the finest lady, sometimes woke after a holiday to wish that they might wake no more?

(From “Sartor Resartus”)

By Thomas Carlyle

(One of the most famous of British essayists, 1795-1881; historian of the French Revolution, and master of a vivid and picturesque prose-style)

It is not because of his toils that I lament for the poor: we must all toil, or steal (howsoever we name our stealing), which is worse; no faithful workman finds his task a pastime. The poor is hungry and athirst; but for[32] him also there is food and drink: he is heavy-laden and weary; but for him also the Heavens send sleep, and of the deepest; in his smoky cribs, a clear dewy haven of rest envelops him, and fitful glitterings of cloud-skirted dreams. But what I do mourn over is, that the lamp of his soul should go out; that no ray of heavenly, or even of earthly, knowledge should visit him; but only, in the haggard darkness, like two spectres, Fear and Indignation bear him company. Alas, while the body stands so broad and brawny, must the soul lie blinded, dwarfed, stupefied, almost annihilated!, Alas, was this too a Breath of God; bestowed in heaven, but on earth never to be unfolded!—That there should one Man die ignorant who had capacity for Knowledge, this I call a tragedy, were it to happen more than twenty times in the minute, as by some computations it does. The miserable fraction of Science which our united Mankind, in a wide universe of Nescience, has acquired, why is not this, with all diligence, imparted to all?

(From “Songs of the Dead End”)

By Patrick MacGill

(A young Irishman, called the “Navvy poet”; born 1890. From the age of twelve to twenty a farm laborer, ditch-digger and quarry-man. As this work goes to press, he is fighting with his regiment in Flanders)

(From “Dauber”)

By John Masefield

(An English poet who has had a varied career as sailor, laborer and even bartender upon the Bowery, New York. Born 1873, his narrative poems of humble life made him famous almost over night)

(From “The Cry of Youth”)

By Harry Kemp

(A young American poet who has wandered over the world as sailor, harvest hand and tramp; born 1883)

(From “The Harbor”)

By Ernest Poole

(American playwright and novelist, born 1880)

We crawled down a short ladder and through low passageways, dripping wet, and so came into the stokehole.

This was a long narrow chamber with a row of glowing furnace doors. Wet coal and coal-dust lay on the floor. At either end a small steel door opened into bunkers that ran along the sides of the ship, deep down near the bottom, containing thousands of tons of soft coal. In the stokehole the fires were not yet up, but by the time the ship was at sea the furnace mouths would be white hot and the men at work half naked. They not only shovelled coal into the flames, they had to spread it as well, and at intervals rake out the “clinkers” in fiery masses on the floor. On these a stream of water played, filling the chamber with clouds of steam. In older ships, like this one, a “lead stoker” stood at the head of the line and set the pace for the others to follow. He was paid more to keep up the pace. But on the big new liners this pacer was replaced by a gong.

“And at each stroke of the gong you shovel,” said Joe. “You do this till you forget your name. Every time the boat pitches the floor heaves you forward, the fire spurts at you out of the doors, and the gong keeps on like a sledge-hammer coming down on top of your mind. And all you think of is your bunk and the time when you’re to tumble in.”

From the stokers’ quarters presently there came a burst of singing.

“Now let’s go back,” he ended, “and see how they’re getting ready for this.”

As we crawled back, the noise increased, and swelled to a roar as we entered. The place was pandemonium. Those groups I had noticed around the bags had been getting out the liquor, and now at eight o’clock in the morning half the crew were already well soused. Some moved restlessly about. One huge bull of a creature with limpid shining eyes stopped suddenly with a puzzled stare, and then leaned back on a bunk and laughed uproariously. From there he lurched over the shoulder of a thin, wiry, sober man who, sitting on the edge of a bunk, was slowly spelling out the words of a newspaper aeroplane story. The big man laughed again and spit, and the thin man jumped half up and snarled.

Louder rose the singing. Half the crew was crowded close around a little red-faced cockney. He was the modern “chanty man.” With sweat pouring down his cheeks and the muscles of his neck drawn taut, he was jerking out verse after verse about women. He sang to an old “chanty” tune, one that I remembered well. But he was not singing out under the stars, he was screaming at steel walls down here in the bottom of the ship. And although he kept speeding up his song, the crowd were too drunk to wait for the chorus; their voices kept tumbling in over his, and soon it was only a frenzy of sound, a roar with yells rising out of it. The singers kept pounding each other’s backs or waving bottles over their heads. Two bottles smashed together and brought a still higher burst of glee.

“I’m tired!” Joe shouted. “Let’s get out!”

I caught a glimpse of his strained frowning face. Again it came over me in a flash, the years he had spent in holes like this, in this hideous rotten world of his, while I had lived joyously in mine. And as though he had read the thought in my disturbed and troubled eyes, “Let’s go up where you belong,” he said.

I followed him up and away from his friends. As we climbed ladder after ladder, fainter and fainter on our ears rose that yelling from below. Suddenly we came out on deck and slammed an iron door behind us. And I was where I belonged.

I was in dazzling sunshine and keen, frosty autumn air. I was among gay throngs of people. Dainty women brushed me by. I felt the softness of their furs, I breathed the fragrant scent of them and of the flowers that they wore, I saw their trim, fresh, immaculate clothes. I heard the joyous tumult of their talking and their laughing to the regular crash of the band—all the life of the ship I had known so well.

And I walked through it all as though in a dream. On the dock I watched it spell-bound—until with handkerchiefs waving and voices calling down good-byes, that throng of happy travellers moved slowly out into midstream.

And I knew that deep below all this, down in the bottom of the ship, the stokers were still singing.

(From “Challenge”)

By Louis Untermeyer

(American poet, born 1885)

(From “The Jungle”)

By Upton Sinclair

(A novel portraying the lives of the workers in the Chicago stockyards; published in 1906)

His labor took him about one minute to learn. Before him was one of the vents of the mill in which the fertilizer was being ground—rushing forth in a great brown river, with a spray of the finest dust floating forth in clouds. Jurgis was given a shovel, and along with half a dozen others it was his task to shovel this fertilizer into carts. That others were at work he knew by the sound, and by the fact that he sometimes collided with them; otherwise they might as well not have been there, for in the blinding dust-storm a man could not see six feet in front of his face. When he had filled one cart he had to grope around him until another came, and if there was none on hand he continued to grope till one arrived. In five minutes he was, of course, a mass of fertilizer from head to feet; they gave him a sponge to tie over his mouth, so that he could breathe, but the sponge did not prevent his lips and eyelids from caking up with it and his ears from filling solid. He looked like a brown ghost at twilight—from hair to shoes he became the color of the building and of everything in it, and for that matter a hundred yards outside it. The building had to be left open, and when the wind blew Durham and Company lost a great deal of fertilizer.

Working in his shirt-sleeves, and with the thermometer at over a hundred, the phosphates soaked in through every pore of Jurgis’ skin, and in five minutes he had a[44] headache, and in fifteen was almost dazed. The blood was pounding in his brain like an engine’s throbbing; there was a frightful pain in the top of his skull, and he could hardly control his hands. Still, with the memory of his four jobless months behind him, he fought on, in a frenzy of determination; and half an hour later he began to vomit—he vomited until it seemed as if his inwards must be torn into shreds. A man could get used to the fertilizer-mill, the boss had said, if he would only make up his mind to it; but Jurgis now began to see that it was a question of making up his stomach.

At the end of that day of horror, he could scarcely stand. He had to catch himself now and then, and lean against a building and get his bearings. Most of the men, when they came out, made straight for a saloon—they seemed to place fertilizer and rattlesnake poison in one class. But Jurgis was too ill to think of drinking—he could only make his way to the street and stagger on to a car. He had a sense of humor, and later on, when he became an old hand, he used to think it fun to board a street-car and see what happened. Now, however, he was too ill to notice it—how the people in the car began to gasp and sputter, to put their handkerchiefs to their noses, and transfix him with furious glances. Jurgis only knew that a man in front of him immediately got up and gave him a seat; and that half a minute later the two people on each side of him got up; and that in a full minute the crowded car was nearly empty—those passengers who could not get room on the platform having gotten out to walk.

Of course Jurgis had made his home a miniature fertilizer-mill a minute after entering. The stuff was half an inch deep in his skin—his whole system was full of it,[45] and it would have taken a week not merely of scrubbing, but of vigorous exercise, to get it out of him. As it was, he could be compared with nothing known to man, save that newest discovery of the savants, a substance which emits energy for an unlimited time, without being itself in the least diminished in power. He smelt so that he made all the food at the table taste, and set the whole family to vomiting; for himself it was three days before he could keep anything upon his stomach—he might wash his hands, and use a knife and fork, but were not his mouth and throat filled with the poison?

And still Jurgis stuck it out! In spite of splitting headaches he would stagger down to the plant and take up his stand once more, and begin to shovel in the blinding clouds of dust. And so at the end of the week he was a fertilizer-man for life—he was able to eat again, and though his head never stopped aching, it ceased to be so bad that he could not work.

By James Oppenheim

(American poet and novelist; born 1882)

(From “Children of the Dead End”)

By Patrick MacGill

(See page 32)

At that time there were thousands of navvies working at Kinlochleven waterworks. We spoke of waterworks, but only the contractors knew what the work was intended for. We did not know, and we did not care. We never asked questions concerning the ultimate issue of our labors, and we were not supposed to ask questions. If a man throws red muck over a wall today and throws it back again tomorrow, what the devil is it to him if he keeps throwing that same muck over the wall for the rest of his life, knowing not why nor wherefore, provided he gets paid sixpence an hour for his labor? There were so many tons of earth to be lifted and thrown somewhere else; we lifted them and threw them somewhere else; so many cubic yards of iron-hard rocks to be blasted and carried away; we blasted and carried them away, but never asked questions and never knew what results we were laboring to bring about. We turned the Highlands into a cinder-heap, and were as wise at the beginning as at the end of the task. Only when we completed the job, and returned to the town, did we learn from the newspapers that we had been employed on the construction of the biggest aluminium factory in the kingdom. All that we knew was that we had gutted whole mountains and hills in the operations....

Above and over all, the mystery of the night and the[48] desert places hovered inscrutable and implacable. All around the ancient mountains sat like brooding witches, dreaming on their own story of which they knew neither the beginning nor the end. Naked to the four winds of heaven and all the rains of the world, they had stood there for countless ages in all their sinister strength, undefied and unconquered, until man, with puny hands and little tools of labor, came to break the spirit of their ancient mightiness.

And we, the men who braved this task, were outcasts of the world. A blind fate, a vast merciless mechanism, cut and shaped the fabric of our existence. We were men despised when we were most useful, rejected when we were not needed, and forgotten when our troubles weighed upon us heavily. We were the men sent out to fight the spirit of the wastes, rob it of all its primeval horrors, and batter down the barriers of its world-old defences. Where we were working a new town would spring up some day; it was already springing up, and then, if one of us walked there, “a man with no fixed address,” he would be taken up and tried as a loiterer and vagrant.

Even as I thought of these things a shoulder of jagged rock fell into a cutting far below. There was the sound of a scream in the distance, and a song died away in the throat of some rude singer. Then out of the pit I saw men, red with the muck of the deep earth and redder still with the blood of a stricken mate, come forth, bearing between them a silent figure. Another of the pioneers of civilization had given up his life for the sake of society....

The plaintive sunset waned into a sickly haze one evening, and when the night slipped upwards to the mountain peaks never a star came out into the vastness[49] of the high heavens. Next morning we had to thaw the door of our shack out of the muck into which it was frozen during the night. Outside the snow had fallen heavily on the ground, and the virgin granaries of winter had been emptied on the face of the world.

Unkempt, ragged, and dispirited, we slunk to our toil, the snow falling on our shoulders and forcing its way insistently through our worn and battered bluchers. The cuttings were full of slush to the brim, and we had to grope through them with our hands until we found the jumpers and hammers at the bottom. These we held under our coats until the heat of our bodies warmed them, then we went on with our toil.

At intervals during the day the winds of the mountain put their heads together and swept a whirlstorm of snow down upon us, wetting each man to the pelt. Our tools froze until the hands that gripped them were scarred as if by red-hot spits. We shook uncertain over our toil, our sodden clothes scalding and itching the skin with every movement of the swinging hammers. Near at hand the lean derrick jibs whirled on their pivots like spectres of some ghoulish carnival, and the muck-barrows crunched backwards and forwards, all their dirt and rust hidden in woolly mantles of snow. Hither and thither the little black figures of the workers moved across the waste of whiteness like shadows on a lime-washed wall. Their breath steamed out on the air and disappeared in space like the evanescent and fragile vapor of frying mushrooms....

When night came on we crouched around the hot-plate and told stories of bygone winters, when men dropped frozen stiff in the trenches where they labored. A few tried to gamble near the door, but the wind that[50] cut through the chinks of the walls chased them to the fire.

Outside the winds of the night scampered madly, whistling through every crevice of the shack and threatening to smash all its timbers to pieces. We bent closer over the hot-plate, and the many who could not draw near to the heat scrambled into bed and sought warmth under the meagre blankets. Suddenly the lamp went out, and a darkness crept into the corners of the dwelling, causing the figures of my mates to assume fantastic shapes in the gloom. The circle around the hot-plate drew closer, and long lean arms were stretched out towards the flames and the redness. Seldom may a man have the chance to look on hands like those of my mates. Fingers were missing from many, scraggy scars seaming along the wrists or across the palms of others told of accidents which had taken place on many precarious shifts. The faces near me were those of ghouls worn out in some unholy midnight revel. Sunken eyes glared balefully in the dim unearthly light of the fire, and as I looked at them a moment’s terror settled on my soul. For a second I lived in an early age, and my mates were the cave-dwellers of an older world than mine. In the darkness, near the door, a pipe glowed brightly for a moment, then the light went suddenly out and the gloom settled again.

(From “The Spell of the Yukon”)

By Robert W. Service

(Canadian poet, born 1876. His poems of Alaska and the great Northwest have attained wide popularity)

By Charles Hanson Towne

(American poet, born 1877)

(From “The House of Bondage”)

By Reginald Wright Kauffman

(American novelist, born 1877)

Katie Flanagan arrived at the Lennox department store every morning at a quarter to eight o’clock. She passed through the employees’ dark entrance, a unit in a horde of other workers, and registered the instant of her arrival on a time-machine that could in no wise be suborned to perjury. She hung up her wraps in a subterranean cloak-room, and, hurrying to the counter to which she was assigned, first helped in “laying out the stock,” and then stood behind her wares, exhibiting, cajoling, selling, until an hour before noon. At that time she was permitted to run away for exactly forty-five minutes for the glass of milk and two pieces of bread and jam that composed her luncheon. This repast disposed of, she returned to the counter and remained behind it, standing like a war-worn watcher on the ramparts of a beleaguered city, till the store closed at six, when there remained to her at least fifteen minutes more of work before her sales-book was balanced and the wares covered up for the night. There were[54] times, indeed, when she did not leave the store until seven o’clock, but those times were caused rather by customers than by the management of the store, which could prevent new shoppers from entering the doors after six, but could hardly turn out those already inside.

The automatic time-machine and a score of more annoying, and equally automatic, human beings kept watch upon all that she did. The former, in addition to the floor-walker in her section of the store, recorded her every going and coming, the latter reported every movement not prescribed by the regulations of the establishment; and the result upon Katie and her fellow-workers was much the result observable upon condemned assassins under the unwinking surveillance of the Death Watch.

If Katie was late, she was fined ten cents for each offense. She was reprimanded if her portion of the counter was disordered after a mauling by careless customers. She was fined for all mistakes she made in the matter of prices and the additions on her salesbook; and she was fined if, having asked the floor-walker for three or five minutes to leave the floor in order to tidy her hair and hands, in constant need of attention through the rapidity of her work and the handling of her dyed wares, she exceeded her time limit by so much as a few seconds.

There were no seats behind the counters, and Katie, whatever her physical condition, remained on her feet all day long, unless she could arrange for relief by a fellow-worker during that worker’s luncheon time. There was no place for rest save a damp, ill-lighted “Recreation Room” in the basement, furnished with a piano that nobody had time to play, magazines that nobody had[55] time to read, and wicker chairs in which nobody had time to sit. All that one might do was to serve the whims and accept the scoldings of women customers who knew too ill, or too well, what they wanted to buy; keep a tight rein upon one’s indignation at strolling men who did not intend to buy anything that the shop advertised; be servilely smiling under the innuendoes of the high-collared floor-walkers, in order to escape their wrath; maintain a sharp outlook for the “spotters,” or paid spies of the establishment; thwart, if possible, those pretending customers who were scouts sent from other stores, and watch for shop-lifters on the one hand and the firm’s detectives on the other.

“It ain’t a cinch, by no means”—thus ran the departing Cora Costigan’s advice to her successor—“but it ain’t nothin’ now to what it will be in the holidays. I’d rather be dead than work in the toy-department in December—I wonder if the kids guess how we that sells ’em hates the sight of their playthings?—and I’d rather be dead an’ damned than work in the accounting department. A girl friend of mine worked there last year,—only it was over to Malcare’s store—an’ didn’t get through her Christmas Eve work till two on Christmas morning, an’ she lived over on Staten Island. She overslept on the twenty-sixth, an’ they docked her a half-week’s pay.

“An’ don’t never,” concluded Cora, “don’t never let ’em transfer you to the exchange department. The people that exchange things all belong in the psychopathic ward at Bellevue—them that don’t belong in Sing Sing. Half the goods they bring back have been used for days, an’ when the store ties a tag on a sent-on-approval opera cloak, the women wriggle the tag inside, an’ wear it to the theatre with a scarf draped over the string. Thank God, I’m goin’ to be married!”

(From the Yiddish of Morris Rosenfeld)

(The poet of the East Side Jews of New York City, born 1861. His poems appeared in Yiddish newspapers and leaflets, and are the genuine voice of the sweat-shop workers. The following translation is by Charles Weber Linn)

(From “A Motley”)

By John Galsworthy

(English novelist and dramatist, born 1867)

She held in one hand a threaded needle, in the other a pair of trousers, to which she had been adding the accessories demanded by our civilization. One had never seen her without a pair of trousers in her hand, because she could only manage to supply them with decency at the rate of seven or eight pairs a day, working twelve hours. For each pair she received seven farthings, and used nearly one farthing’s worth of cotton; and this gave her an income, in good times, of six to seven shillings a week. But some weeks there were no trousers to be had and then it was necessary to live on the memory of those which had been, together with a little sum put by from weeks when trousers were more plentiful. Deducting two shillings and threepence for rent of the little back room, there was therefore, on an average, about two shillings and ninepence left for the sustenance of herself and husband, who was fortunately a cripple, and somewhat indifferent whether he ate or not. And looking at her face, so furrowed, and at her figure, of which there was not much, one could well understand that she, too, had long established within her such internal economy as was suitable to one who had been “in trousers” twenty-seven years, and, since her husband’s accident fifteen years before, in trousers only, finding her own cotton.... He was a man with a round, white face, a little grey mustache curving[58] down like a parrot’s beak, and round whitish eyes. In his aged and unbuttoned suit of grey, with his head held rather to one side, he looked like a parrot—a bird clinging to its perch, with one grey leg shortened and crumpled against the other. He talked, too, in a toneless, equable voice, looking sideways at the fire, above the rims of dim spectacles, and now and then smiling with a peculiar disenchanted patience.

No—he said—it was no use to complain; did no good! Things had been like this for years, and so, he had no doubt, they always would be. There had never been much in trousers; not this common sort that anybody’d wear, as you might say. Though he’d never seen anybody wearing such things; and where they went to he didn’t know—out of England, he should think. Yes, he had been a carman; ran over by a dray. Oh! yes, they had given him something—four bob a week; but the old man had died and the four bob had died too. Still, there he was, sixty years old—not so very bad for his age....

They were talking, he had heard said, about doing something for trousers. But what could you do for things like these, at half a crown a pair? People must have ’em, so you’d got to make ’em. There you were, and there you would be! She went and heard them talk. They talked very well, she said. It was intellectual for her to go. He couldn’t go himself owing to his leg. He’d like to hear them talk. Oh, yes! and he was silent, staring sideways at the fire as though in the thin crackle of the flames attacking the fresh piece of wood, he were hearing the echo of that talk from which he was cut off. “Lor’ bless you!” he said suddenly. “They’ll do nothing! Can’t!” And, stretching out his dirty hand he took from[59] his wife’s lap a pair of trousers, and held it up. “Look at ’em! Why you can see right throu’ ’em, linings and all. Who’s goin’ to pay more than ‘alf a crown for that? Where they go to I can’t think. Who wears ’em? Some institution I should say. They talk, but dear me, they’ll never do anything so long as there’s thousands like us, glad to work for what we can get. Best not to think about it, I says.”

And laying the trousers back on his wife’s lap he resumed his sidelong stare into the fire.

By Thomas Hood

(Popular English poet and humorist; 1799-1845)

(From “The People of the Abyss”)

By Jack London

(California novelist and Socialist; born 1876. The story of his life will be found on p. 732. For the work here quoted London lived among the people whose misery he describes)

A spawn of children cluttered the slimy pavement, for all the world like tadpoles just turned frogs on the bottom of a dry pond. In a narrow doorway, so narrow that perforce we stepped over her, sat a woman with a young babe, nursing at breasts grossly naked and libelling all the sacredness of motherhood. In the black and narrow hall behind her we waded through a mess of young life, and essayed an even narrower and fouler stairway. Up we went, three flights, each landing two feet by three in area, and heaped with filth and refuse.

There were seven rooms in this abomination called a house. In six of the rooms, twenty-odd people, of both sexes and all ages, cooked, ate, slept, and worked. In[63] size the rooms averaged eight feet by eight, or possibly nine. The seventh room we entered. It was the den in which five men sweated. It was seven feet wide by eight long, and the table at which the work was performed took up the major portion of the space. On this table were five lasts, and there was barely room for the men to stand to their work, for the rest of the space was heaped with cardboard, leather, bundles of shoe uppers, and a miscellaneous assortment of materials used in attaching the uppers of shoes to their soles.

In the adjoining room lived a woman and six children. In another vile hole lived a widow, with an only son of sixteen who was dying of consumption. The woman hawked sweetmeats on the street, I was told, and more often failed than not to supply her son with the three quarts of milk he daily required. Further, this son, weak and dying, did not taste meat oftener than once a week; and the kind and quality of this meat cannot possibly be imagined by people who have never watched human swine eat.

“The w’y ‘e coughs is somethin’ terrible,” volunteered my sweated friend, referring to the dying boy. “We ‘ear ’im ‘ere, w’ile we’re workin’, an’ it’s terrible, I say, terrible!”

And, what of the coughing and the sweetmeats, I found another menace added to the hostile environment of the children of the slums.

My sweated friend, when work was to be had, toiled with four other men in his eight-by-seven room. In the winter a lamp burned nearly all the day and added its fumes to the over-loaded air, which was breathed, and breathed, and breathed again.

In good times, when there was a rush of work, this[64] man told me that he could earn as high as “thirty bob a week.”—“Thirty shillings! Seven dollars and a half!

“But it’s only the best of us can do it,” he qualified. “An’ then we work twelve, thirteen, and fourteen hours a day, just as fast as we can. An’ you should see us sweat! Just runnin’ from us! If you could see us, it’d dazzle your eyes—tacks flyin’ out of mouth like from a machine. Look at my mouth.”

I looked. The teeth were worn down by the constant friction of the metallic brads, while they were coal-black and rotten.

“I clean my teeth,” he added, “else they’d be worse.”

After he had told me that the workers had to furnish their own tools, brads, “grindery,” cardboard, rent, light, and what not, it was plain that his thirty bob was a diminishing quantity.

“But how long does the rush season last, in which you receive this high wage of thirty bob?” I asked.

“Four months,” was the answer; and for the rest of the year, he informed me, they average from “half a quid” to a “quid,” a week, which is equivalent to from two dollars and a half to five dollars. The present week was half gone, and he had earned four bob, or one dollar. And yet I was given to understand that this was one of the better grades of sweating.

So far has the divorcement of the worker from the soil proceeded, that the farming districts, the civilized world over, are dependent upon the cities for the gathering of the harvests. Then it is, when the land is spilling its ripe wealth to waste, that the street folk, who have been driven away from the soil, are called back to it[65] again. But in England they return, not as prodigals, but as outcasts still, as vagrants and pariahs, to be doubted and flouted by their country brethren, to sleep in jails or casual wards, or under the hedges, and to live the Lord knows how.

It is estimated that Kent alone requires eighty thousand of the street people to pick her hops. And out they come, obedient to the call, which is the call of their bellies and of the lingering dregs of adventure-lust still in them. Slums, stews, and ghetto pour them forth, and the festering contents of slums, stews, and ghetto are undiminished. Yet they overrun the country like an army of ghouls, and the country does not want them. They are out of place. As they drag their squat, misshapen bodies along the highways and byways, they resemble some vile spawn from underground. Their very presence, the fact of their existence, is an outrage to the fresh, bright sun and the green and growing things. The clean, upstanding trees cry shame upon them and their withered crookedness, and their rottenness is a slimy desecration of the sweetness and purity of nature.

Is the picture overdrawn? It all depends. For one who sees and thinks life in terms of shares and coupons, it is certainly overdrawn. But for one who sees and thinks life in terms of manhood and womanhood, it cannot be overdrawn. Such hordes of beastly wretchedness and inarticulate misery are no compensation for a millionaire brewer who lives in a West End palace, sates himself with the sensuous delights of London’s golden theatres, hobnobs with lordlings and princelings, and is knighted by the king. Wins his spurs—God forbid! In old time the great blonde beasts rode in the battle’s van and won their spurs by cleaving men from pate to[66] chin. And, after all, it is finer to kill a strong man with a clean-slicing blow of singing steel than to make a beast of him, and of his seed through the generations, by the artful and spidery manipulation of industry and politics.

(From “Merrie England”)

By Robert Blatchford

(This book is probably the most widely-circulated of Socialist books in English. Over two million copies have been sold in Great Britain, and probably a million in America. The author is the editor of the London Clarion; born 1851)

Some years ago a certain writer, much esteemed for his graceful style of saying silly things, informed us that the poor remain poor because they show no efficient desire to be anything else. Is that true? Are only the idle poor? Come with me and I will show you where men and women work from morning till night, from week to week, from year to year, at the full stretch of their powers, in dim and fetid dens, and yet are poor—aye, destitute—have for their wages a crust of bread and rags. I will show you where men work in dirt and heat, using the strength of brutes, for a dozen hours a day, and sleep at night in styes, until brain and muscle are exhausted, and fresh slaves are yoked to the golden car of commerce, and the broken drudges filter through the poor-house or the prison to a felon’s or a pauper’s grave! I will show you how men and women thus work and suffer and faint and die, generation after generation; and I will show you how the longer and the harder these wretches toil[67] the worse their lot becomes; and I will show you the graves, and find witnesses to the histories of brave and noble and industrious poor men whose lives were lives of toil, and poverty, and whose deaths were tragedies.

And all these things are due to sin—but it is to the sin of the smug hypocrites who grow rich upon the robbery and the ruin of their fellow-creatures.

By Georg Herwegh

(German poet, 1817-1875; took part in the attempt at revolution in Baden in 1848)

By Max Nordau

(A Hungarian Jewish physician, born 1849, whose work, “Degeneration,” won an international audience)

The modern day laborer is more wretched than the slave of former times, for he is fed by no master nor any one else, and if his position is one of more liberty than the slave, it is principally the liberty of dying of hunger. He is by no means so well off as the outlaw of the Middle Ages, for he has none of the gay independence of the free-lance. He seldom rebels against society, and has neither means nor opportunity to take by violence or treachery what is denied him by the existing conditions of life. The rich is thus richer, the poor poorer than ever before since the beginnings of history.

By Frederic Harrison

(English essayist and philosopher, born 1831; President of the Positivist Society)

I cannot myself understand how any one who knows what the present manner is can think that it is satisfactory. To me, at least, it would be enough to condemn modern society as hardly an advance on slavery or serfdom, if the permanent condition of industry were to be that which we behold; that ninety per cent of the actual producers of wealth have no home that they can call their own beyond the end of the week;[69] have no bit of soil, or so much as a room that belongs to them; have nothing of value of any kind, except as much old furniture as will go in a cart; have the precarious chance of weekly wages, which barely suffice to keep them in health; are housed for the most part in places that no man thinks fit for his horse; are separated by so narrow a margin from destitution that a month of bad trade, sickness or unexpected loss brings them face to face with hunger and pauperism. In cities, the increasing organization of factory work makes life more and more crowded, and work more and more a monotonous routine; in the country, the increasing pressure makes rural life continually less free, healthful and cheerful; whilst the prizes and hopes of betterment are now reduced to a minimum. This is the normal state of the average workman in town or country, to which we must add the record of preventable disease, accident, suffering and social oppression with its immense yearly roll of death and misery. But below this normal state of the average workman there is found the great band of the destitute outcasts—the camp-followers of the army of industry, at least one-tenth of the whole proletarian population, whose normal condition is one of sickening wretchedness. If this is to be the permanent arrangement of modern society, civilization must be held to bring a curse on the great majority of mankind.

The Chasm

The contrast between riches and poverty; the protest of common sense against a condition of society where one-tenth of the people own nine-tenths of the wealth.

By Robert Southey

(One of the so-called “Lake School” of English poets, which included Wordsworth and Coleridge; 1774-1843. Poet-Laureate for thirty years. The refrain of this song was the motto of Wat Tyler’s rebels, who marched upon London in 1381)

(From “Sartor Resartus”)

By Thomas Carlyle

(See page 31)

“The furniture of this Caravanserai consisted of a large iron Pot, two oaken Tables, two Benches, two Chairs, and a Potheen Noggin. There was a Loft above (attainable by a ladder), upon which the inmates slept; and the space below was divided by a hurdle into two apartments; the one for their cow and pig, the other for themselves and guests. On entering the house we discovered the family, eleven in number, at dinner; the father sitting at the top, the mother at the bottom, the children on each side, of a large oaken Board, which was scooped out in the middle, like a trough, to receive the contents of their Pot of Potatoes. Little holes were cut at equal distances to contain Salt; and a bowl of Milk stood on the table; all the luxuries of meat and beer, bread, knives and dishes, were dispensed with.” The Poor-Slave himself our Traveller found, as he says, broad-backed, black-browed, of great personal strength, and mouth from ear to ear. His Wife was a sun-browned but well-featured woman; and his young ones, bare and chubby, had the appetite of ravens. Of their Philosophical or Religious tenets or observances, no notice or hint.

But now, secondly, of the Dandiacal Household:

“A Dressing-room splendidly furnished; violet-colored curtains, chairs and ottomans of the same hue. Two full-length Mirrors are placed, one on each side of a table, which supports the luxuries of the Toilet. Several Bottles of Perfume, arranged in a peculiar fashion, stand[75] upon a smaller table of mother-of-pearl; opposite to these are placed the appurtenances of Lavation richly wrought in frosted silver. A Wardrobe of Buhl is on the left; the doors of which, being partly open, discover a profusion of Clothes; Shoes of a singularly small size monopolize the lower shelves. Fronting the wardrobe a door ajar gives some slight glimpse of the Bathroom. Folding-doors in the background.—”Enter the Author,” our Theogonist in person, “obsequiously preceded by a French Valet, in white silk Jacket and cambric Apron.”

Such are the two sects which, at this moment, divide the more unsettled portion of the British People; and agitate that ever-vexed country. To the eye of the political Seer, their mutual relation, pregnant with the elements of discord and hostility, is far from consoling. These two principles of Dandiacal Self-worship or Demon-worship, and Poor-Slavish or Drudgical Earth-worship, or whatever that same Drudgism may be, do as yet indeed manifest themselves under distant and nowise considerable shapes: nevertheless, in their roots and subterranean ramifications, they extend through the entire structure of Society, and work unweariedly in the secret depths of English national Existence; striving to separate and isolate it into two contradictory, uncommunicating masses.

In numbers, and even individual strength, the Poor-Slaves or Drudges, it would seem, are hourly increasing. The Dandiacal, again, is by nature no proselytizing Sect; but it boasts of great hereditary resources, and is strong by union; whereas the Drudges, split into parties, have as yet no rallying-point; or at best only co-operate by means of partial secret affiliations. If, indeed, there[76] were to arise a Communion of Drudges, as there is already a Communion of Saints, what strangest effects would follow therefrom! Dandyism as yet affects to look down on Drudgism; but perhaps the hour of trial, when it will be practically seen which ought to look down, and which up, is not so distant.

To me it seems probable that the two Sects will one day part England between them; each recruiting itself from the intermediate ranks, till there be none left to enlist on either side. These Dandiacal Manicheans, with the host of Dandyizing Christians, will form one body; the Drudges, gathering round them whosoever is Drudgical, be he Christian or Infidel Pagan; sweeping-up likewise all manner of Utilitarians, Radicals, refractory Potwallopers, and so forth, into their general mass, will form another. I could liken Dandyism and Drudgism to two bottomless boiling Whirlpools that had broken-out on opposite quarters of the firm land; as yet they appear only disquieted, foolishly bubbling wells, which man’s art might cover-in; yet mark them, their diameter is daily widening; they are hollow Cones that boil-up from the infinite Deep, over which your firm land is but a thin crust or rind! Thus daily is the intermediate land crumbling-in, daily the empire of the two Buchan-Bullers extending; till now there is but a foot-plank, a mere film of Land between them; this too is washed away; and then—we have the true Hell of Waters, and Noah’s Deluge is outdeluged!

Or better, I might call them two boundless, and indeed unexampled Electric Machines (turned by the “Machinery of Society”), with batteries of opposite quality; Drudgism the Negative, Dandyism the Positive; one attracts hourly towards it and appropriates all the Posi[77]tive Electricity of the nation (namely, the Money thereof); the other is equally busy with the Negative (that is to say the Hunger) which is equally potent. Hitherto you see only partial transient sparkles and sputters; but wait a little, till the entire nation is in an electric state; till your whole vital Electricity, no longer healthfully Neutral, is cut into two isolated portions of Positive and Negative (of Money and of Hunger); and stands there bottled-up in two World-Batteries! The stirring of a child’s finger brings the two together; and then—What then? The Earth is but shivered into impalpable smoke by that Doom’s-thunderpeal; the Sun misses one of his Planets in Space, and thenceforth there are no eclipses of the Moon.

(French bishop and statesman, 1754-1838)

Society is divided into two classes; the shearers and the shorn. We should always be with the former against the latter.

By Alfred Tennyson

(Probably the most popular of English lyrical poets; 1809-1892. Made Poet-laureate in 1850, and a baron in 1884)

By Charles Kingsley

(English clergyman and novelist, 1819-1875; founder of the Christian Socialist movement. In the scene here quoted, a young University man is taken by a game-keeper to see the degradation of English village life)

“Can’t they read? Can’t they practice light and interesting handicrafts at home, as the German peasantry do?”

“Who’ll teach ’em, sir? From the plough-tail to the reaping-hook, and back again, is all they know. Besides,[79] sir, they are not like us Cornish; they are a stupid pig-headed generation at the best, these south countrymen. They’re grown-up babies who want the parson and the squire to be leading them, and preaching to them, and spurring them on, and coaxing them up, every moment. And as for scholarship, sir, a boy leaves school at nine or ten to follow the horses; and between that time and his wedding-day he forgets every word he ever learnt, and becomes, for the most part, as thorough a heathen savage at heart as those wild Indians in the Brazils used to be.”

“And then we call them civilized Englishmen!” said Lancelot. “We can see that your Indian is a savage, because he wears skins and feathers; but your Irish cotter or your English laborer, because he happens to wear a coat and trousers, is to be considered a civilized man.”

“It’s the way of the world, sir,” said Tregarva, “judging carnal judgment, according to the sight of its own eyes; always looking at the outsides of things and men, sir, and never much deeper. But as for reading, sir, it’s all very well for me, who have been a keeper and dawdled about like a gentleman with a gun over my arm; but did you ever do a good day’s farm-work in your life? If you had, man or boy, you wouldn’t have been game for much reading when you got home; you’d do just what these poor fellows do—tumble into bed at eight o’clock, hardly waiting to take your clothes off, knowing that you must turn up again at five o’clock the next morning to get a breakfast of bread, and, perhaps, a dab of the squire’s dripping, and then back to work again; and so on, day after day, sir, week after week, year after year, without a hope or chance of being anything but[80] what you are, and only too thankful if you can get work to break your back, and catch the rheumatism over.”

“But do you mean to say that their labor is so severe and incessant?”

“It’s only God’s blessing if it is incessant, sir, for if it stops, they starve, or go to the house to be worse fed than the thieves in gaol. And as for its being severe, there’s many a boy, as their mothers will tell you, comes home night after night, too tired to eat their suppers, and tumble, fasting, to bed in the same foul shirt which they’ve been working in all the day, never changing their rag of calico from week’s end to week’s end, or washing the skin that’s under it once in seven years.”

“No wonder,” said Lancelot, “that such a life of drudgery makes them brutal and reckless.”

“No wonder, indeed, sir: they’ve no time to think; they’re born to be machines, and machines they must be; and I think, sir,” he added bitterly, “it’s God’s mercy that they daren’t think. It’s God’s mercy that they don’t feel. Men that write books and talk at elections call this a free country, and say that the poorest and meanest has a free opening to rise and become prime minister, if he can. But you see, sir, the misfortune is, that in practice he can’t; for one who gets into a gentleman’s family, or into a little shop, and so saves a few pounds, fifty know that they’ve no chance before them, but day-laborer born, day-laborer live, from hand to mouth, scraping and pinching to get not meat and beer even, but bread and potatoes; and then, at the end of it all, for a worthy reward, half-a-crown-a-week of parish pay—or the work-house. That’s a lively hopeful prospect for a Christian man!” ...

Into the booth they turned; and as soon as Lancelot’s[81] eyes were accustomed to the reeking atmosphere, he saw seated at two long temporary tables of board, fifty or sixty of “My brethren,” as clergymen call them in their sermons, wrangling, stupid, beery, with sodden eyes and drooping lips—interspersed with more girls and brazen-faced women, with dirty flowers in their caps, whose sole business seemed to be to cast jealous looks at each other, and defend themselves from the coarse overtures of their swains.

Lancelot had been already perfectly astonished at the foulness of language which prevailed; and the utter absence of anything like chivalrous respect, almost of common decency, towards women. But lo! the language of the elder women was quite as disgusting as that of the men, if not worse. He whispered a remark on the point to Tregarva, who shook his head.

“It’s the field-work, sir—the field-work, that does it all. They get accustomed there from their childhood to hear words whose very meanings they shouldn’t know; and the elder teach the younger ones, and the married ones are worst of all. It wears them out in body, sir, that field-work, and makes them brutes in soul and in manners....”

Sadder and sadder, Lancelot tried to listen to the conversation of the men round him. To his astonishment he hardly understood a word of it. It was half articulate, nasal, guttural, made up almost entirely of vowels, like the speech of savages. He had never before been struck with the significant contrast between the sharp, clearly defined articulation, the vivid and varied tones of the gentleman, or even of the London street-boy, when compared with the coarse, half-formed growls, as of a company of seals, which he heard round him. That[82] single fact struck him, perhaps, more deeply than any; it connected itself with many of his physiological fancies; it was the parent of many thoughts and plans of his after-life. Here and there he could distinguish a half sentence. An old shrunken man opposite him was drawing figures in the spilt beer with his pipe-stem, and discoursing of the glorious times before the great war, “when there was more food than there were mouths, and more work than there were hands.” “Poor human nature!” thought Lancelot, as he tried to follow one of those unintelligible discussions about the relative prices of the loaf and the bushel of flour, which ended, as usual, in more swearing, and more quarrelling, and more beer to make it up—“Poor human nature! always looking back, as the German sage says, to some fancied golden age, never looking forward to the real one which is coming!”

“But I say, vather,” drawled out some one, “they say there’s a sight more money in England now, than there was afore the war-time.”

“Eees, booy,” said the old man; “but it’s got into too few hands.”

“Well,” thought Lancelot, “there’s a glimpse of practical sense, at least.” And a pedler who sat next him, a bold, black-whiskered bully from the Potteries, hazarded a joke—

“It’s all along of this new sky-and-tough-it farming. They used to spread the money broad cast, but now they drills it all in one place, like bone-dust under their fancy plants, and we poor self-sown chaps gets none.”

This garland of fancies was received with great applause; whereat the pedler, emboldened, proceeded to observe, mysteriously, that “donkeys took a beating, but horses kicked at it; and that they’d found out that in Stafford[83]shire long ago. You want a good Chartist lecturer down here, my covies, to show you donkeys of laboring men that you have got iron on your heels, if you only knowed how to use it....”

Blackbird was by this time prevailed on to sing, and burst out as melodious as ever, while all heads were cocked on one side in delighted attention.

“Coorus, boys, coorus!”

And the chorus burst out—

And again the boy’s delicate voice rang out the ferocious chorus, with something, Lancelot fancied, of fiendish exultation, and every worn face lighted up with a coarse laugh, that indicated no malice—but also no mercy....

Lancelot almost ran out into the night—into a triad of fights, two drunken men, two jealous wives, and a brute who struck a poor, thin, worn-out woman, for trying to coax him home. Lancelot rushed up to interfere, but a man seized his uplifted arm.

“He’ll only beat her all the more when he getteth home.”

“She has stood that every Saturday night for the last seven years, to my knowledge,” said Tregarva; “and worse, too, at times.”