United States Military Academy

West Point, New York

Jan. 10th, 1911.

Dear Reed:

I have delayed sending back the proof sheets of the third edition of your “Cadet Life at West Point” because I wanted to read them. This I have finally found time to accomplish, but I really have not the time to write out my views on the book as I would like to do for you can appreciate my situation when I tell you that we leave here on the 17th inst. and the house is completely torn up.

I think, however, that in addition to having written a very interesting book you have given the public one full of valuable information, particularly useful to young men who contemplate entering this academy. The book recalls many pleasant incidents of our own cadet life and conditions now are very little changed from our day, especially as we are to return to the four-year course with entrance for the new class back to June again.

With best wishes for the New Year,

Sincerely,

Fred H Sibley

Colonel Sibley was the Commandant of Cadets from February 1, 1909, to January 17, 1911.

Dedicated to the dear girls who adore the military.

“Entertaining personal reminiscences.”—Cleveland Plain Dealer.

“Most charming book.”—The (Philadelphia) Keystone.

“Especially entertaining to lads with military aspirations.”—(Boston) Waverly Magazine.

“Parents and sisters too come under its spell.”—(Chicago) Quarterly Book Review.

“The various troubles cadets have are clearly described.”—Cincinnati Commercial Tribune.

“The reader soon becomes interested.”—Richmond (Ind.) Palladium.

“Complete description of the life of a cadet.”—The (Chicago) Medical Standard.

“Through the trying days of plebedom.”—Indianapolis Journal.

“Until he finally doffs the cadet gray and dons the army blue.”—Chicago Tribune.

“The story is told in a very interesting way.”—(New York) American Stationer.

“A very spirited and interesting book.”—(New York) Scientific American.

“Stories, poems and accounts of graduation hops and other amusements.”—The (New York) Publishers’ Weekly.

“Also contains statistics which are of sufficient value alone to warrant publication.”—Chicago Journal.

“Charming in its personality.”—Army and Navy Journal.

“Answers many questions one would like to ask.”—Chicago Inter-Ocean.

“In such a happy vein as to charm American readers of all ages.”—Army and Navy Register.

“A pleasing style.”—(New York) Review of Reviews.

“The best description of cadet life and also of the workings of the academy.”—Wm. Ward, clerk in charge (for the last 60 years) of Cadet Records at West Point.

“Nothing quite like it in this country.”—(London, Eng.) Army and Navy Gazette.

“A complete book.”—(Orchard Lake, Mich.) Adjutant.

“Interesting reading.”—Chicago Times-Herald.

“About West Point, how to get there, etc.”—Indianapolis News.

“Just the thing.”—(Atlanta, Ga.) Southern Star.

“Of value to guardsmen.”—The (Columbus, O.) National Guardsman.

“Interesting reading even for laymen.”—(New York) Godey’s Magazine.

“Should be in both normal school and village libraries.”—Cortland (New York) Evening Standard.

Handsome cloth. 12mo. 315 pages. Illustrated. $1.50

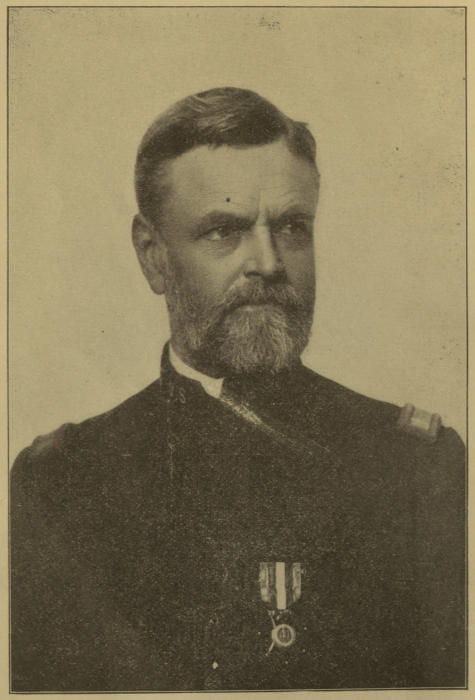

THE AUTHOR

CADET LIFE AT WEST POINT

BY

Col. Hugh T. Reed, Lieut. U. S. Army,

Late Inspector General of Indiana.

AUTHOR OF

Military Science and Tactics, Etc.

ILLUSTRATED

THIRD EDITION.

RICHMOND, INDIANA:

IRVIN REED & SON.

ALL RIGHTS RESERVED.

COPYRIGHT, 1896 AND 1911, BY HUGH T. REED.

Dedicated

TO THE DEAR GIRLS WHO ADORE THE MILITARY, ONE OF

WHOM HAVING PAID THE PENALTY OF HER ADMIRATION,

IS NOW MY SUPERIOR OFFICER.

I believe it to be well established that the mental habits are fully as strong as the physical habits of man. That is, thought moves in grooves day after day and day after day as walks in life do. The habit of retrospectant thought fastened itself upon me several years ago, and the habit confined itself largely and almost irresistibly to my life at West Point. My reflections became almost realisms; I was to all intents and purposes oblivious of the intervening years; oblivious of accumulated griefs and sorrows, of successes and of contemporaneous ambitions—I was indeed a boy again, and at West Point, living over and over and over again all the scenes leading up to and creating my life at the Nation’s Military School.

In one of these moods, it occurred to me, entirely for my own gratification, and possibly to dispossess myself of the habit of thinking upon the subject, to write a little sketch of those days. I became interested in the work, and the pages grew in number as memory served me with inspiration for my narrative, until I had at last completed what might be called a volume of reminiscences.

As an amusement for him, I read chapter after chapter, as it was written, to a favorite nephew,[8] and when the manuscript was written and in a temporary binding, I loaned it to this young relative, who, in turn, with my consent, loaned it to friends of his, and it was read by these youngsters and passed from hand to hand. I could not help but realize the interest that was taken by these young readers in what I had so carelessly and indifferently written, but at the same time, I should never have undertaken the publication of my notes if my nephew had not attended a military school and bombarded me with appeals to send him the old manuscript, so that his comrades might read about life at West Point.

The old manuscript wouldn’t do, so I edited what I had written, re-wrote some of the pages, added a few lines here and there, and finally concluded to publish it without the least expectation that it will interest very many persons, or bring me any material reward.

I have tried to write it naturally and without any attempt at literary excellence, and beg most respectfully to offer it to the public as a grateful tribute of my happiest years.

For valuable data I am indebted to Colonel Charles W. Larned, Lieutenant Colonel F. W. Sibley, Commandant of Cadets, Captains W. E. Wilder, F. W. Coe and O. J. Charles, Adjutants, Lieut. M. B. Stewart, Tactical Officer, Dr. E. S. Holden, Librarian, and Mr. William Ward, in charge of Cadet Records from 1851 to 1911, all of the Military Academy, and to Lieutenant Charles Braden, editor of Cullum’s Biographical Register of West Point Graduates.

| Chapter. | Page. | |

| I. | The Appointment | 13 |

| II. | The Preparation | 21 |

| III. | The Candidate | 27 |

| IV. | The Plebe in Camp | 65 |

| V. | The Plebe in Barracks | 87 |

| VI. | The Yearling | 125 |

| VII. | The Furloughman | 153 |

| VIII. | The Graduate | 179 |

| IX. | The United States Military Academy | 259 |

| X. | The Appendix | 287 |

| The Author | Frontispiece |

| Might Be a Cadet | 15 |

| Topographical Sketch of West Point | 25 |

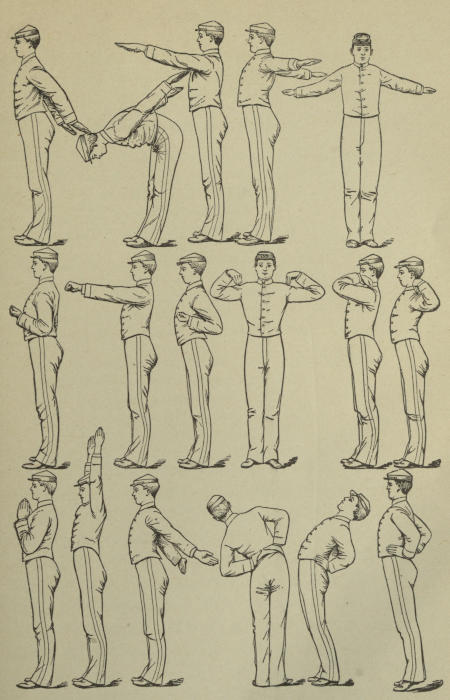

| Setting-up Exercises | 41 |

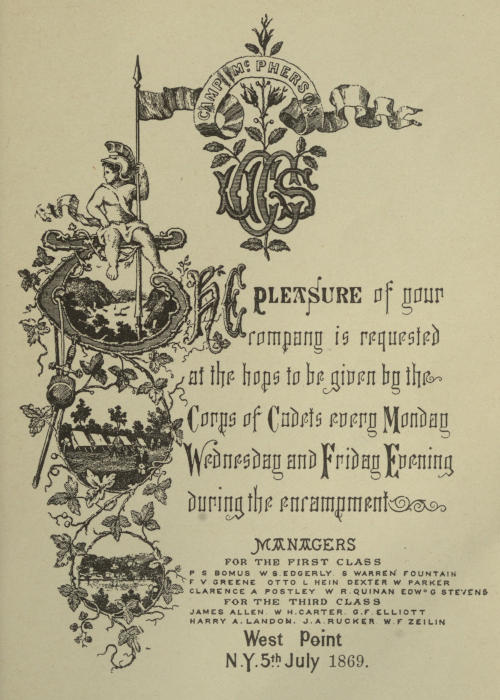

| Hop Invitation—Camp McPherson | 63 |

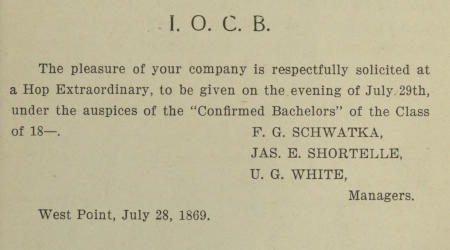

| Hop Invitation—I. O. C. B. | 81 |

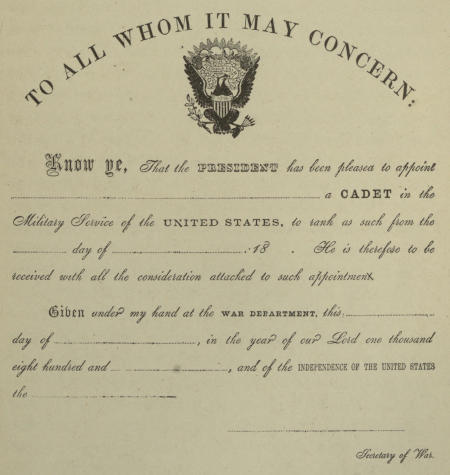

| Cadet Warrant | 111 |

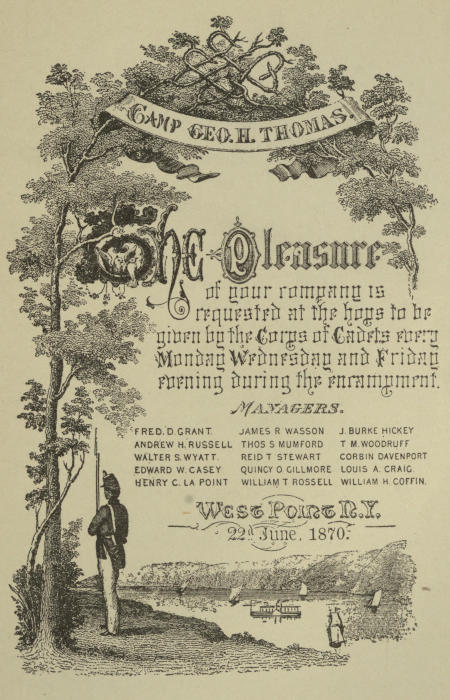

| Hop Invitation—Camp Geo. H. Thomas | 123 |

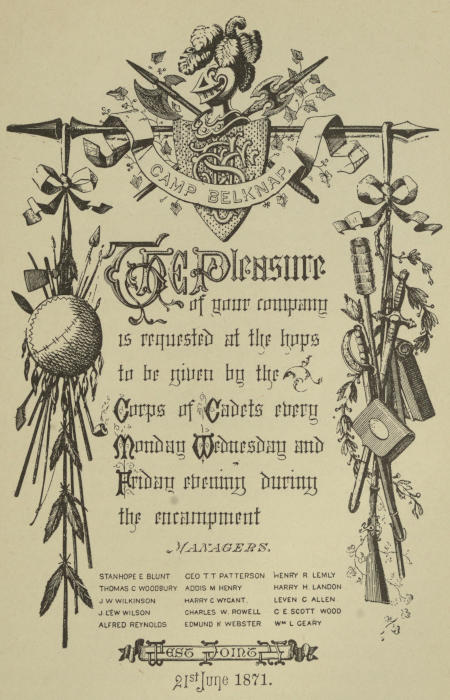

| Hop Invitation—Camp Belknap | 151 |

| Graduating Hop Invitation—Class of 1872 | 163 |

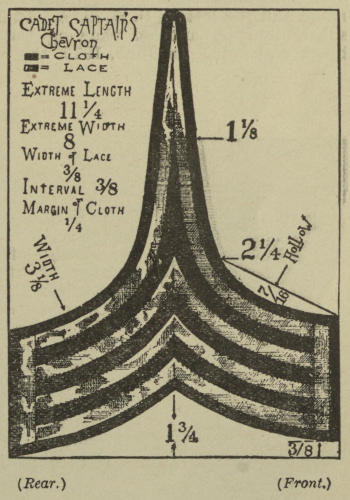

| Cadet Captain’s Chevron | 175 |

| Bell Button for Civilian Coats | 176 |

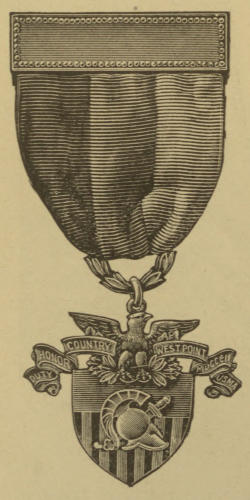

| Badge | 176 |

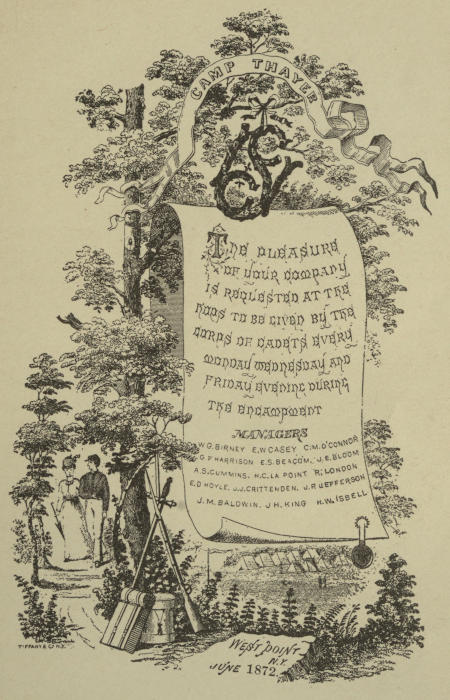

| Hop Invitation—Camp Thayer | 177 |

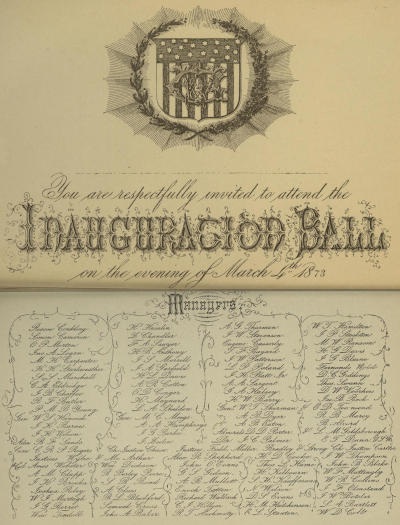

| Inaugural Ball Invitation | 198-9 |

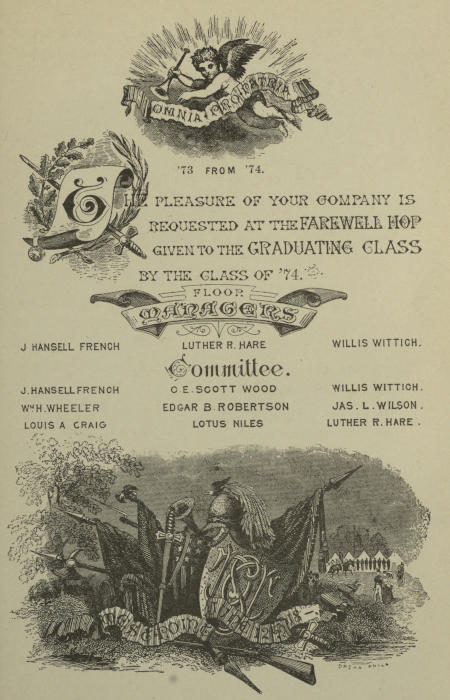

| Graduating Hop Invitation—Class of 1873 | 203 |

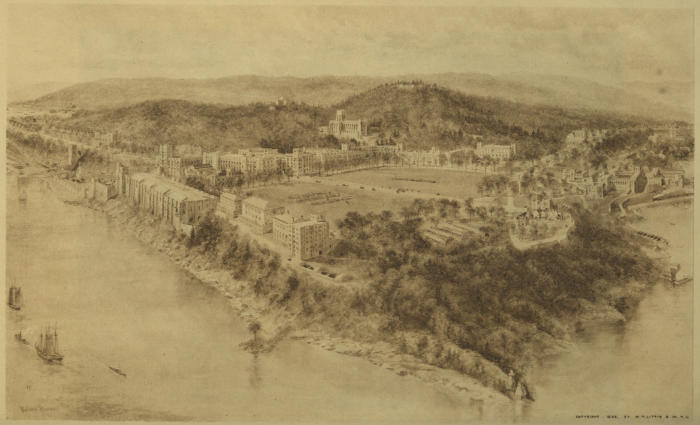

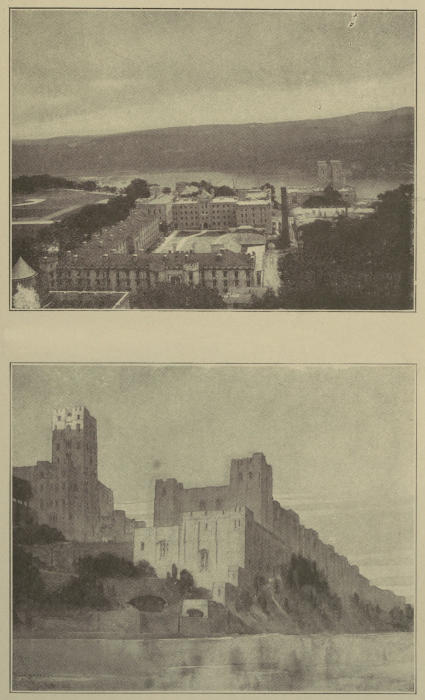

| Bird’s Eye View of West Point as It May Be in 1912 | 209 |

| Diploma | 211 |

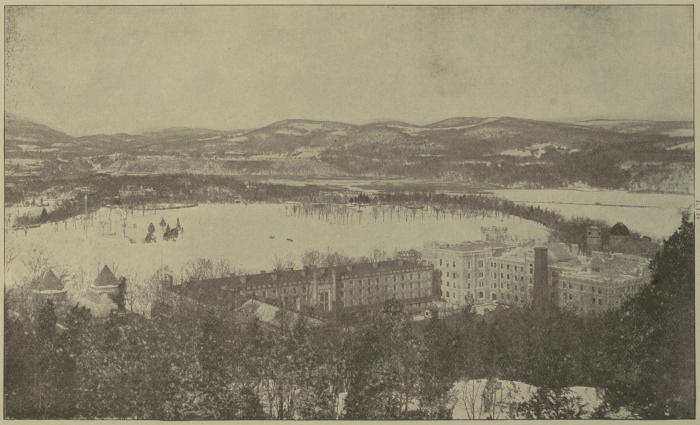

| Bird’s Eye View of West Point in 1902 | 213[10] |

| West Point in 1848 | 215 |

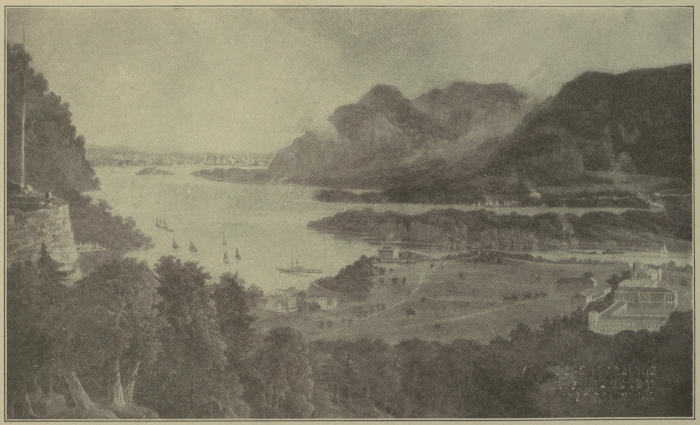

| West Point in 1825 | 217 |

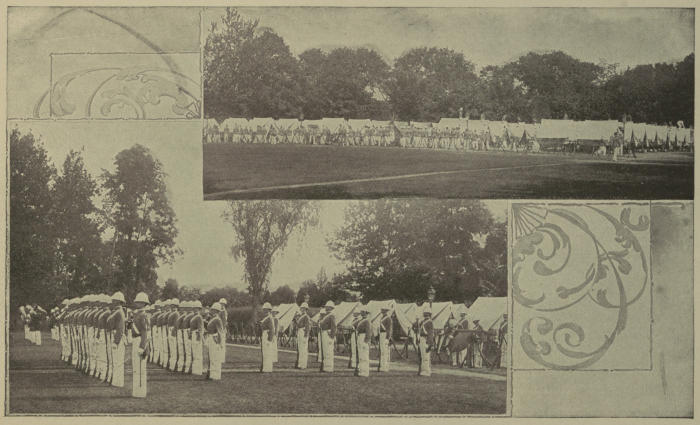

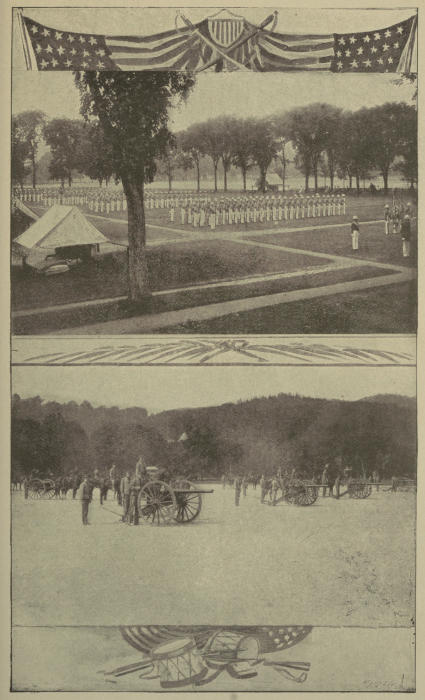

| Guard Mount in Camp | 219 |

| Color Line | 219 |

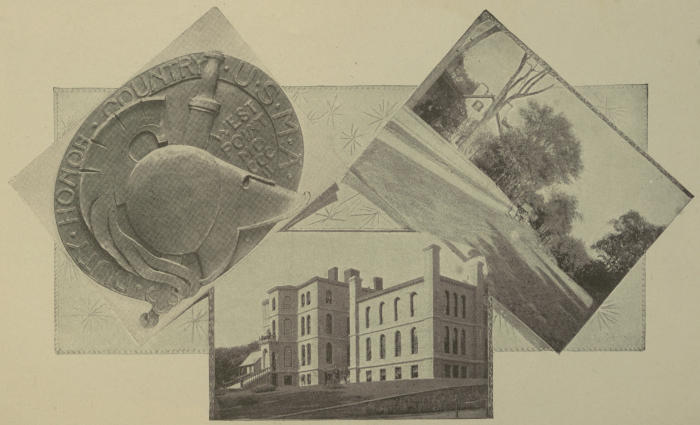

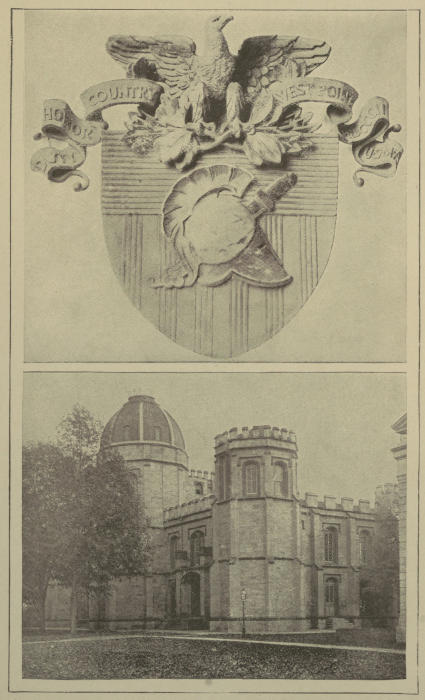

| Seal of the United States Military Academy | 221 |

| Cadet Hospital | 221 |

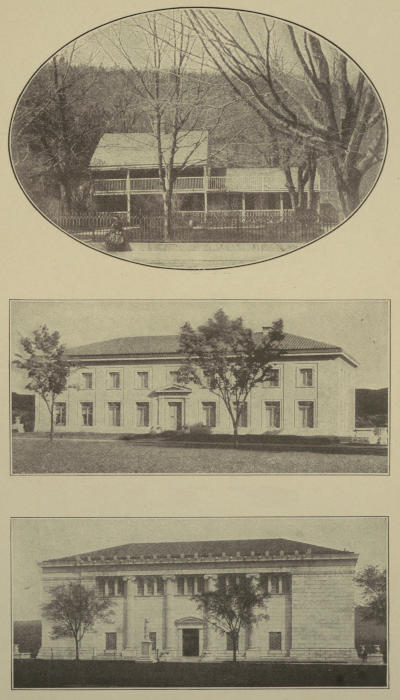

| Superintendent’s Quarters | 221 |

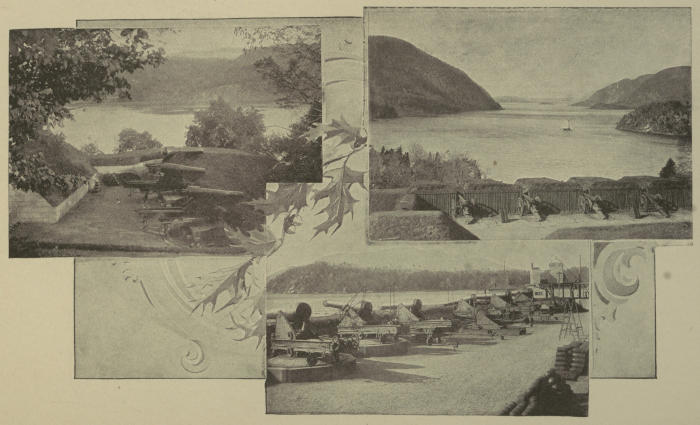

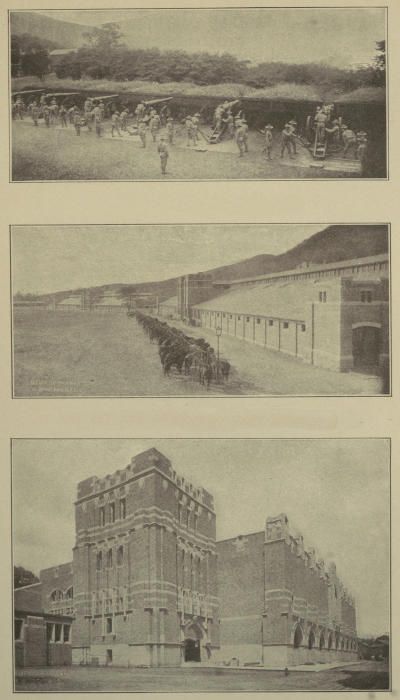

| Battery Knox | 223 |

| Sea Coast Battery | 223 |

| Siege Battery | 223 |

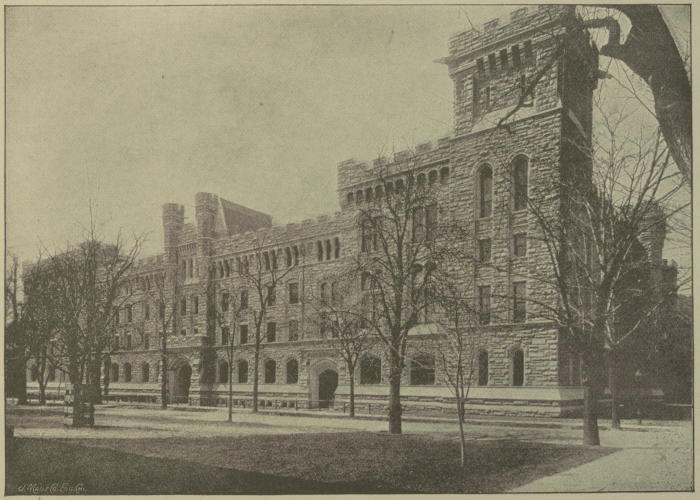

| The Academic Building | 225 |

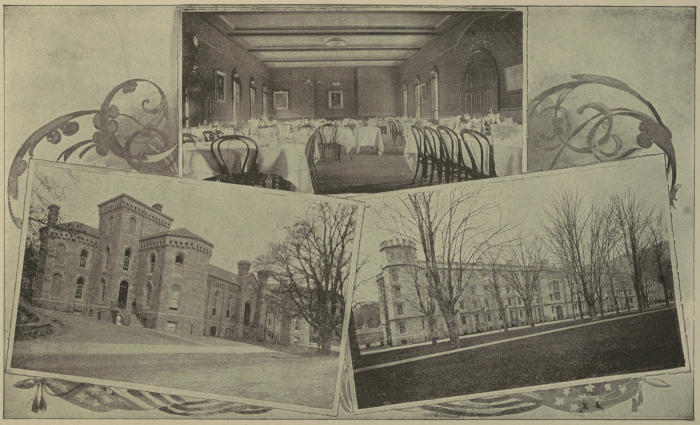

| Mess Hall | 227 |

| Dining Room | 227 |

| South Cadet Barracks | 227 |

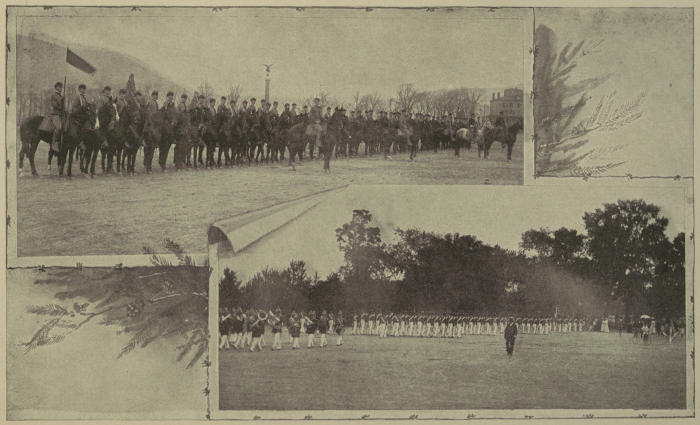

| Cavalry Drill | 229 |

| Battalion Marching from Camp to Barracks | 229 |

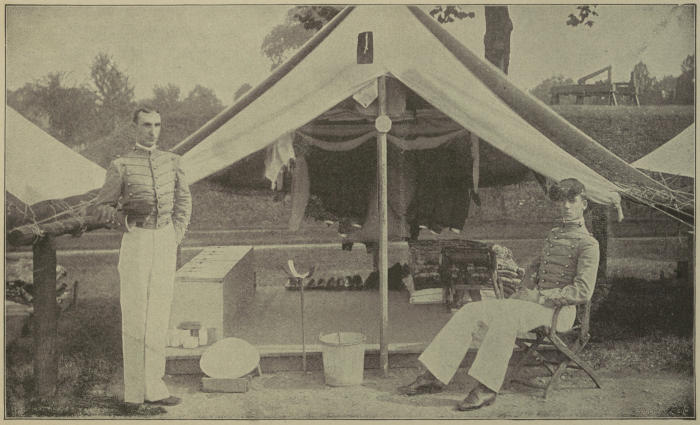

| Cadet Tent | 231 |

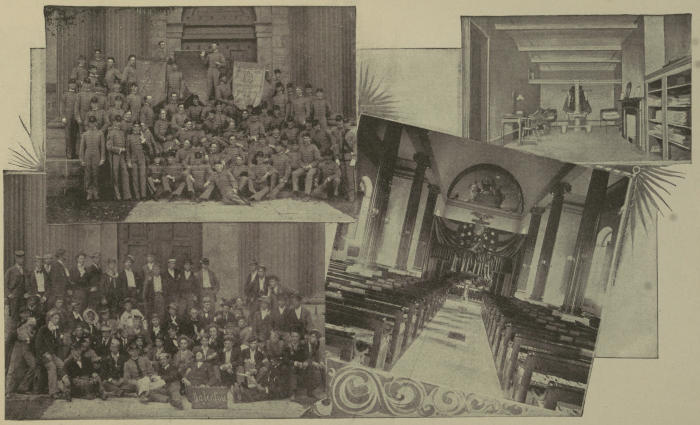

| Group of First Classmen | 233 |

| Group of Furloughmen | 233 |

| The Old Cadet Chapel | 233 |

| Cadet Room | 233 |

| Professors’ Row | 235 |

| Flirtation Walk | 235 |

| Kosciuszco’s Garden | 235 |

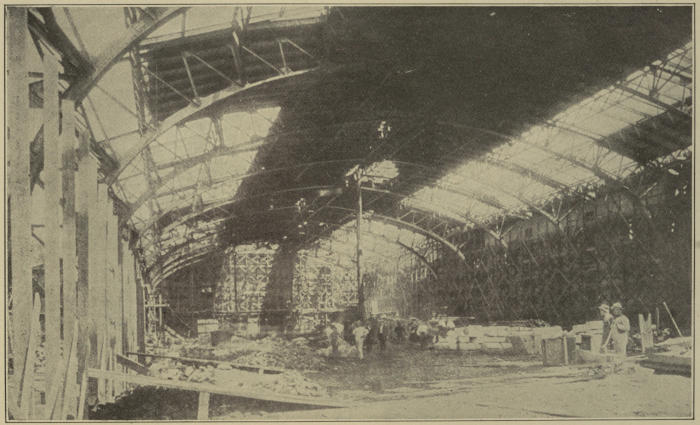

| The Old Riding Hall | 237 |

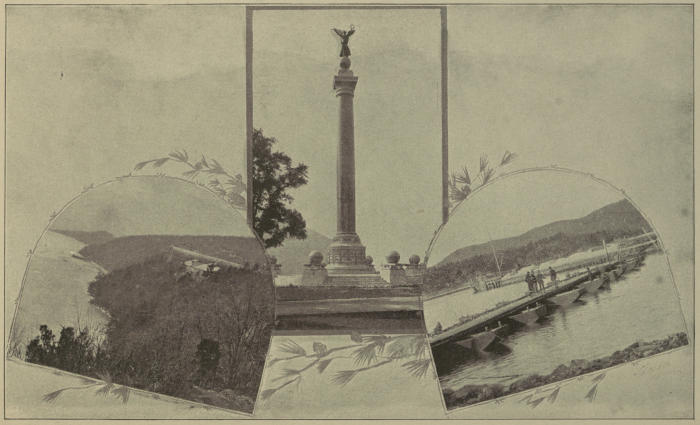

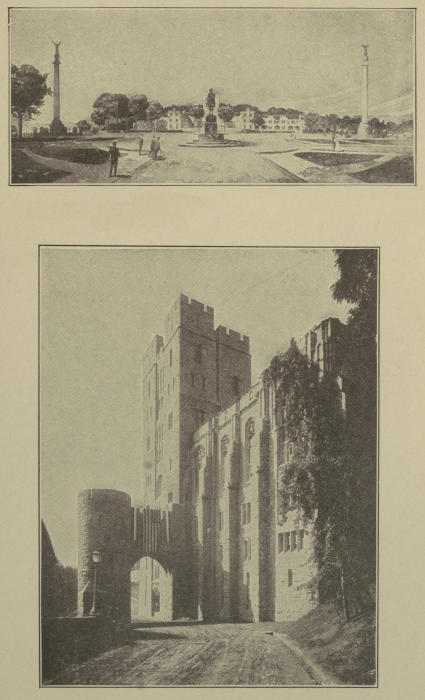

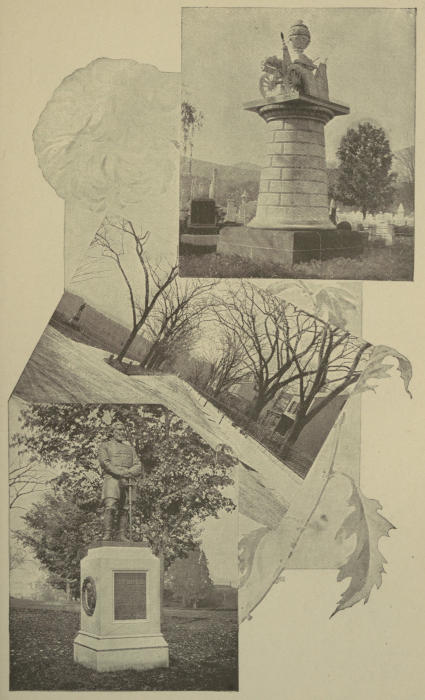

| Battle Monument | 237 |

| Ponton Bridge | 237 |

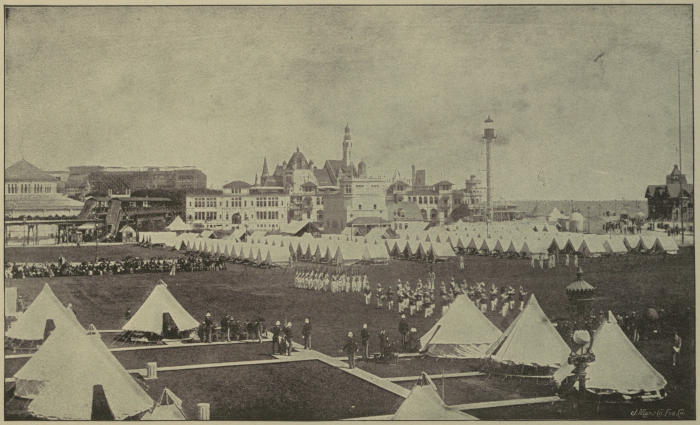

| Cadet Camp—World’s Fair, 1893 | 239 |

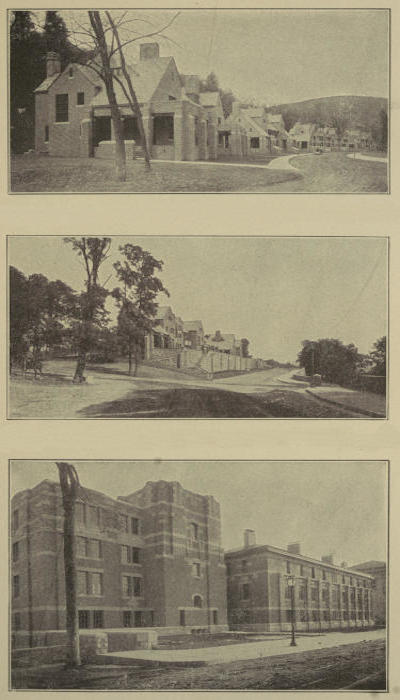

| Officers’ Quarters Above Old North Gate in 1910 | 241 |

| Officers’ Quarters Below Old South Gate in 1910 | 241 |

| Bachelor Officers’ Quarters in 1910 | 241 |

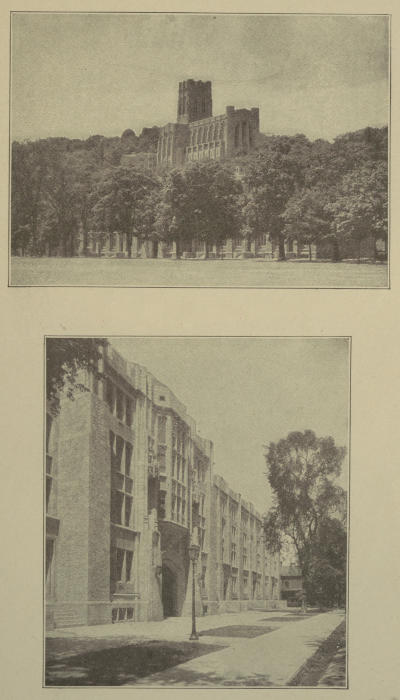

| The New Cadet Chapel in 1910 | 243 |

| The North Cadet Barracks in 1910 | 243 |

| The Old Washington Headquarters | 245 |

| Officers’ Mess in 1910 | 245 |

| Cullum Memorial Hall | 245 |

| Coat of Arms of the United States Military Academy | 247 |

| Library | 247 |

| Siege Battery Drill in 1910 | 249 |

| Artillery and Cavalry Group in 1910 | 249 |

| The New Gymnasium in 1910 | 249[11] |

| Proposed Staff Quarters | 251 |

| Headquarters Building | 251 |

| Inspection in Camp | 253 |

| Light Artillery Drill | 253 |

| Sedgwick’s Monument | 255 |

| Professors’ Row | 255 |

| Cadet Monument | 255 |

| Looking East from the New Chapel in 1910 | 257 |

| Perspective View from River on the East | 257 |

| Interior of New Riding Hall | 315 |

I was not more than eight years old when I first heard about West Point, and then I was told that it was Uncle Sam’s Military School; that the young men there were called cadets; that they were soldiers, and that they wore pretty uniforms with brass buttons on them. The impression made upon me at the time was such that I never tired talking and asking questions about West Point. I soon learned to indicate the site on the map, and I longed to go there, that I might be a cadet and wear brass buttons. I talked about it so much that my good mother made me a coat generous with brass buttons. I called it my cadet coat, and wore it constantly. Ah! for the day I should be a big boy and be a real cadet. With a wooden gun I played soldier, and when the war broke out and the soldiers camped in our old fair grounds, I was in their camp at every opportunity. The camp was about half-way between our home farm and father’s store in town, and many[14] is the time I have been scolded for being so much at the camp. My only regret at that time was that I was not old enough to enlist, for I loved to watch the drills and linger around the camp-fires, listening to stories of the war.

I learned a good deal from the soldiers about West Point. They told me that I could not go there until I was seventeen years old, and not then unless I was appointed as a cadet by my congressman. They also told me that I must be a good boy at school and study hard, for the reason that after securing the appointment I would have to pass a rigid examination at West Point before admission. This was bad news to me, because we farm boys never attended school longer than four or five months in a year. Fortunately, however, the family moved to “town” when I was fourteen years old. I was then assured that I would have my wish, and I never missed a day at school. I was so anxious to learn rapidly that I overtaxed my eyes, and was in a dark room for nearly a year. Still I did not give up hope, and when my eyesight permitted I returned to school again.

I found out that there could be only one cadet at a time at West Point from the same congressional district, and also that there was then a young man there from my district; still I had hopes of getting there myself before I got too old, that is, over twenty-one.[1] Then there was no[15] book published about West Point, and magazines and newspapers never described it.

“MIGHT BE A CADET.”

One day I saw by the paper that the Hon. G. W. Julian was at home on a short visit, and I knew that he was my congressman; hence I wanted to go at once to see him. I confided in my mother and obtained her permission to be absent from school that afternoon. So I saddled old John, my favorite horse, and rode six miles to Mr. Julian’s house. He was at home, and was very kind to me. He asked my father’s name, and also my name and age, and he made a note of my address, saying that he might write to me from Washington. He also said that there would be a vacancy at West Point, from his district, the next year in June, and that he would make the appointment soon; that I was the first young man to apply for the place, but if any one who had served in the war applied for the cadetship within the next few weeks he would appoint him—that such a person could be just under twenty-four years of age. Nevertheless, if no old soldier applied, he would appoint me, as he knew my father well. He then said that if he did appoint me I must be a good student the next year, and prepare for the examination at West Point. Upon my return home I did not talk about West Point any more, nor did I speak to any one except my mother about having seen Mr. Julian, and I had five brothers and a sister, too!

About two months after my visit to Mr. Julian,[18] I received a letter from him, taking it myself from the postoffice, but alas! the writing was such that I could not read it, although there were but eight words in it, so I hastened with it to my mother, but she could not read it, either. Then as I must confide in another person, I decided to speak to my father, and ask him to read the letter, under promise that he would not talk about West Point with any one except my mother and myself. He read the letter at once, and said that the writing was all right, but that the letter did not mean anything, as Mr. Julian had probably written the same to other boys. I did not believe this, and was surer than ever of obtaining the appointment. Many years have passed since then, but the words of that letter are still fresh in my memory. They are:

“Please inform me in reply your exact age.”

I wanted my father to write Mr. Julian in my behalf, but he declined to do so, saying that he did not want me to go to West Point. I then got him to promise not to write “that” to Mr. Julian, and I myself answered the letter by return mail.

About ten days after this I received another letter from the congressman, a great large one, in a long envelope, and all I could read of that was “I have recommended you”; but that was enough, as the appointment itself was enclosed, and I could read it, and I was a happy boy. I ran home to show the appointment to my mother, and then to[19] the store to show it to my father, and also to get him to read the letter to me, which was as follows:

“I have recommended you, and enclose herewith your conditional appointment as a cadet to West Point, together with certain other papers from the War Department. I shall now expect you to prepare yourself for the examination next June, and I hope you will graduate with high honors, and that afterwards you will be loyal and useful to your country.”

War Department.[2]

Washington, ________ 1868.

Sir: You are hereby informed, that the President has conditionally selected you for appointment as Cadet of the United States Military Academy, at West Point, New York.

Should you desire the appointment, you will report in person to the Superintendent of the Academy on the ____ day of ________, 1869, for examination. If it be found that you possess the qualifications required by law and set forth in the circular[3] herewith, you will be admitted, with pay from date of admission, and your warrant of appointment will be delivered to you.

Should you be found deficient in studies at the semi-annual or annual examinations, or should your conduct reports be unfavorable, you will be discharged from the military service, unless otherwise recommended for special reasons by the Academic Board, but will receive an allowance for traveling expenses to your home.

Your attention is particularly directed to the accompanying circular, and it is to be distinctly understood that this notification confers upon you no right to enter the Military Academy unless your qualifications agree fully with its requirements, and unless you report for examination at the time specified.

You are requested to immediately inform the Department of your acceptance or declination of the contemplated appointment upon the above conditions.

Very respectfully,

____________

Secretary of War.

To ____________

____________, 1868.

To the Honorable Secretary of War,[4] Washington, D. C.

Sir: I hereby respectfully acknowledge the receipt of your notification of my contemplated appointment as a Cadet of the United States Military Academy, with the appended circular, and inform you of my acceptance of the same upon the conditions named.

I certify, on honor, that I was born at ________, in the County of ________, State of ________, on the ____ day of ________, 18__, and that I have been an actual resident of the Congressional District of ________ for __ years and __ months.

(Signature of appointee) ____________

I hereby assent to the acceptance by my ________ of his conditional appointment as Cadet in the military service, and he has my full permission to sign articles binding himself to serve the United States eight years, unless sooner discharged.

I also certify, on honor, that the above statements are true and correct in every particular.

(Signature of parent or guardian) ____________

After examining the papers received from the War Department, I found one that required my father’s signature before I myself could accept the appointment. My parents both objected to my leaving home, and therefore did not wish me to go to West Point. I argued that I wanted to go to college somewhere, and why not let me go where Uncle Sam paid the bills. At last I won my mother on my side, and then my father, seeing that my heart was so fixed, signed the paper requiring his signature, and mailed it to the Honorable Secretary of War, Washington, D. C. This done, I let the secret out, and all of my boy friends wanted to know how I had gotten the appointment. I told part, but I did not tell just how I did get it.

After seeing the kind of examination[5] I would have to pass at West Point the next year, my father decided to send me to the High School at Ann Arbor, Mich., and to send my brother Charley there with me to prepare him for the University of Michigan. We entered the High School[22] early in September. About two weeks afterward the University of Michigan (also at Ann Arbor) opened, and we observed that many of the candidates for the freshman class seemed no farther advanced than we thought ourselves, so we applied, were examined, and admitted to the University. I thought that if I failed at West Point I could return and graduate at the University in three instead of four years.

There was a tall young man from Tennessee, who entered the High School with us, and afterward entered the University, too. He, like myself, had an appointment to West Point, and was going there the next June, so we became friends at once, and he and I agreed to study after Christmas for the West Point examination. After the sophomores quit hazing, all went well with us, and the year soon passed. I left Ann Arbor on the last day of April to return home via Lakes Huron and Michigan, and went to Detroit to take the first steamer of the season around the lakes to Chicago. Upon arriving in Detroit, I heard that there was to be a muster and inspection of a regiment of United States troops out at Fort Wayne, a short ride from Detroit, and as I was to be a soldier, I went to see the sight. As I looked at the troops (the First U. S. Infantry), I thought that I would like to be an officer of that regiment when I graduated from West Point, and singularly enough my wish was gratified. I remained so long at Fort Wayne that the boat had departed[23] when I returned to Detroit, so I took train and overtook the boat at Port Huron. While there I went to see Fort Gratiot, and strange to say, that was subsequently my first army station. When the steamer stopped at Mackinaw I visited the fort that was there at that time.

After my return home I reviewed the studies I was to be examined on in a few weeks, and then started east. I promised my father if I failed to pass the examination that I would return home at once. Arriving in the great city of New York, I took passage on the day steamer “Mary Powell,” and was charmed with the scenery along the Hudson. The first stop was at the south landing at West Point. I was on the upper deck at the time, and after seeing my trunk put ashore, I walked leisurely downstairs to disembark and to my great surprise the boat was fifty feet or more from shore when I got down. I thought that all steamers made long stops, for the only other boat that I had ever been on stopped for many hours every time she landed. The captain would not let me off, and said that I could get off at Cornwall and take a down boat the same evening. I was satisfied and went on the upper deck again and saw the passengers who had landed get into the West Point Hotel ’bus. All the trunks except mine were put on the top of the ’bus, and it was then driven up the hill, leaving my trunk all alone on the dock.

When the steamer stopped at Cornwall I this time promptly stepped ashore. It was about sunset. There were not more than half a dozen buildings in sight, and not a soul at the dock, and I was the only passenger landing at that point. I went to one of the houses and inquired the location of the hotel, and I was informed that it was not open, as it was too early for summer visitors. I then asked what time the down boat was due, and was informed that it would be along soon, but that it would not stop. The West Shore Railroad was not built at that time, and as there was no stage line over the mountains nor ferry on the river, I began to fear that I could not get away by the tenth of June, the last day for me to report. This bothered me more than the hotel accommodations, but I soon found obliging people and arranged for my lodging and breakfast, and also to be rowed to my destination the next day.

It was about ten o’clock in the morning of June 8, 1869, when I stepped from a rowboat on the dock near the Sea Coast Battery at West Point. The weather was perfect, and my heart was light and free. As there was neither any person nor conveyance at the dock, I followed the road winding up the hill to the plain. I stopped to admire the scenery. In front I beheld a level green plain of one hundred acres or more with massive buildings peeping through the large elm trees that fringe two sides of the plain; on either side were high hills; in my rear rolled the majestic Hudson between the Highlands, with Siege Battery at my feet. As I gazed around it was to me then, as it is to me now, the most beautiful of places.

I found my way to the Adjutant’s office in the Administration Building[6] and reported. I was courteously received and handed the “Instructions to Candidates” to read. I stated the fact[28] of my trunk having been put ashore on the south dock and of the Mary Powell carrying me to Cornwall the previous evening, and I was told that my trunk had undoubtedly been taken to the hotel, as there was then (and now is) but one hotel at the Point. And I was also informed that my trunk would be sent to the Cadet Barracks. After I had complied with the instructions, an orderly, at the sound of a bell, entered and was directed to escort me to the barracks. In going through the area we passed some cadets and I overheard such remarks as “He’ll learn to button his coat.” At the orderly’s suggestion I buttoned my coat. He took me into a hall, said “This is the door,” laid down my valise, and left me. The door was the first one on the right of the eighth division—how well I remember it! I knocked on the door, and heard a commanding voice say “Come in!”[7] With valise and umbrella in one hand and cap in the other, I entered. There were two cadets in the room, seated near a table, and before I had a chance to speak, I was greeted about as follows: “Leave your things in the hall. Don’t you know better than to bring them in here?” I stepped into the hall, left the door open, and while looking for a suitable place to put my things (for there was neither a hook nor a table), one of these two cadets cried out: “Lay them on the floor and come in, and don’t be all day about it, either. Move lively, I say. Shut the door. Stand there. Come to attention.[29] Put your heels together, turn out your toes, put your hands by your side, palms to the front, fingers closed, little fingers on the seams of the trousers, head up, chin in, shoulders thrown back, chest out, draw in your belly, and keep your eyes on this tack.” While one cadet was giving commands with great rapidity, the other one fixed my feet, hands, head and shoulders. “What’s your name? Put a Mr. before it. How do you spell it? What’s your first name? Spell it. What’s your middle name? Have none? What state are you from? What part? Put a sir on every answer. Where’s your trunk? Don’t know? Didn’t you bring one? Put on a sir; how often do you want me to speak about it?” I explained how my trunk and I had arrived at different times. “You’re too slow. You’ll never get along here. Keep your eyes on that tack; turn the palms of your hands squarely to the front. Did you bring all of the articles marked ‘thus’? You don’t know what they are? Put on a sir, I tell you. Didn’t you get a circular telling what articles you should bring? Didn’t you read it? Now answer me; did you bring the articles marked ‘thus’? Well, why didn’t you say so at first? Keep your eyes on that tack.” A wagon drove up and put a trunk on the porch near the window. “About face! Turn around the other way. Don’t you know anything? Is that your trunk? It is, is it? Now, let’s see you ‘about face’ properly. Steady. At the word ‘about’ turn on the left heel, turning the left toe[30] to the front, carrying the right foot to the rear, the hollow opposite to and three inches from the left heel, the feet perpendicular to each other. Don’t look at your feet. Head up. Stand at ‘attention’ till I give the command. Now, ‘about’ (one of the cadets fixed my feet); at the word ‘face,’ turn on both heels, raise the toe a little, face to the rear, when the face is nearly completed, raise the right foot and replace it by the left. Now, ‘face.’ Ah! turn on both heels. Fix your eyes on that tack again. Draw in your belly. Throw back your shoulders and stand up like a man. Now, ‘left, face.’ Don’t you know your left hand from your right? Face that door; open it. Ah! why don’t you step off with the left foot first? Pick up your things, follow me, and move lively.” My back was nearly broken, and I was glad to get out of that room. After going a few steps on the broad porch on the area side of barracks, a young man in civilian clothes came out of the next hallway carrying the palms of his hands to the front. “Come here, Mr. Howard, and help your room-mate carry his trunk upstairs; step lively, now.” With that introduction Mr. Howard and I took hold of the trunk. Just then the tall young Tennesseean, whom I knew at Ann Arbor, passed, carrying the palms of his hands to the front. We exchanged knowing winks, but did not venture to speak. “What’s the matter with you? Don’t be all day carrying that trunk upstairs.” Howard and I tugged away and finally got the[31] trunk upstairs and into the room designated. Candidates Howard and Knapp had already been assigned to the same room. “Stand attention, Mr. Knapp. Don’t you know enough to stand attention when I enter the room? Palms to the front. Put the trunk over there. Mr. R⸺d, open your trunk and valise and take out everything and make a list of all you have. Stand attention, Mr. Howard. Take out your things first and make a list afterward. Put the small articles on this part of the clothes-press, hang your clothes on those pegs and put your bedding over there. Study the regulations. Fold your things properly, put them in their places, and the next time I come in I want to see everything in place. What did you bring that umbrella for? You will never need it here. Mr. R⸺d, post your name over there on the ‘alcove,’ put it on the ‘Orderly Board’ under Mr. Knapp’s name, and put it there on the clothes-press. Whenever you hear the command, ‘Candidates, turn out,’ button your coats, hasten downstairs and ‘fall in’ in the Area.” Cadet Hood left the room then, and we sat down, prostrated. Then we proceeded to get acquainted with one another, and on comparing notes we found that each one of us had had about the same reception. As Howard and Knapp had reported the day before, they gave me many pointers, which I appreciated.

The room was good-sized, with two alcoves at the end opposite the window; but, oh! how uninviting it seemed. No bed, no carpet, no curtains,[32] and not even shades. The furniture that was in the room consisted of a clothes-press, that is, shelving arranged for two cadets, but to be used by three or four candidates, two small iron tables, a wash stand, an iron mantel and a steam coil with a marble slab on it. H⸺rd and K⸺p had already carried from the Commissary certain articles for use by all occupants of the room, as follows: A looking-glass, a wash basin, a water bucket, a cocoanut dipper, a slop bucket and a broom. They had also obtained such other articles as were required for their personal use, such as a chair and a pillow.

The following extract from the “Blue Book” shows the arrangement of rooms, etc.

White Helmet.—On the clothes-press.

Dress Hat.—On the gun-rack shelf.

Cartridge Box and Bayonet or Sword.—On pegs near gun-rack.

Caps and Sabres.—On pegs near gun-rack.

Rifle.—In gun-rack.

Spurs.—On peg with sabre.

Bedstead.—In alcove against side wall of room, head against rear wall.

Bedding.—Mattress, folded once; blankets, comforter and sheets, folded separately, so that the folds shall be the width of the pillow, and all piled against the head of the bedstead, thus: mattress, sheets, pillow, blankets and comforter; the end of the pile next to the alcove partition to be in line with the side of the bedstead; this end and the front of the pile to be vertical.

Clothes-Press.—Books on top against the wall, backs to the front; hair and clothes brushes, combs, shaving materials, such small boxes as are allowed, vials for medicines, etc., on top shelf; belts, collars, gloves, handkerchiefs, socks, etc., on second shelf from the top; sheets, pillow cases, shirts, drawers, pants, etc., on the other shelves.

Text-Books.—Those in daily use may be upon the tables, except during Sunday morning inspection.

Arrangement.—All articles of the same kind to be neatly placed in one pile, folded edges to the front and even with front edge of the shelves. Nothing to be between these piles and the back of the press, unless want of room renders it necessary.

Soiled Clothes.—In clothes bag.

Shoes.—To be kept clean, dusted and arranged in line, toes to the front, along the side near the foot of the bed. Shoe brush in the fireplace.

Woolen Clothing, Dressing Gown and Clothes Bag.—On pegs in alcove, arranged as follows: Overcoat, dressing gown, uniform coats, jackets, gray pants, clothes bag and night clothes.

Broom.—Behind the door.

Candle Box.—In fireplace.

Tables.—Against the wall under gas jet or near the window when the room is dark.

Chairs.—From 8 a. m. to 10 p. m. against the tables when not in use.

Mirror.—At center of mantel.

Wash Stand.—In front of and against alcove partition.

Wash Basin.—Inverted on top of wash stand.

Water Bucket.—Near to and on side of wash stand opposite the door.

Dipper.—In water bucket.

Slop Bucket.—Near to and on side of wash stand nearest the door.

Curtains.—Regulation only allowed.

Calendar.—A small, plain one may be placed on the wall over the gas fixture.

Clock.—A small plain one may be kept on the mantel.

Bath Towel.—May be hung in the alcove.

Trunks, Pictures, Splashers, Writing Desks, Etc.—Prohibited. There is a storeroom for trunks.

Floor.—To be kept clean and free from grease spots or stains.

Heating Apparatus.—To be kept clean and free from scratches.

Windows.—Cadets are forbidden to sit at the windows with feet on the woodwork, or to appear before windows improperly dressed, or to communicate through windows, or to raise the lower sash more than four inches during “call to quarters.”

Names.—Uniformly printed to be posted over gun-rack pegs, alcove, clothes-press and on orderly board over wash stand.

Hours of Recitation.—To be on the mantel on either side of the mirror.

Academic Regulations, Articles of War and the Blue Book.—To be kept on the mantel.

Laundry.—All clothes sent to the wash to be plainly marked with owner’s name.

Room Orderly.—Is responsible for the cleanliness and ventilation of the room, and that articles for joint use are in place.

After having folded and arranged my possessions according to the Blue Book, as I understood from a hasty perusal of it, I looked out of the window down into the Area of Barracks, where I saw old cadets passing to and fro. They carried themselves so very erect that we could not help but admire them and wish that we too were as straight and walked as well as they. We observed what small waists they had, and we wondered if they laced. Another thing we observed was that the cadets looked so much alike. I had unbuttoned my coat while arranging my effects, and forgot to button it again, when I heard a quick walk in the hall and then a sharp, firm, single rap on the door. We all sprang promptly to attention, palms to the front. Cadet Hood entered and began: “Button your coat, Mr. R⸺d.” He moved several piles on the clothes-press and disarranged my bedding, too, saying, “Not folded properly. Why don’t you study the Blue Book? Mr. Howard, fill your water bucket the first thing every morning. Get the water from one of the hydrants[8] in the Area. The floor is[36] very dirty; sweep it properly, invert your wash bowl, and don’t let me have occasion to speak about these things again.”

The first call for dinner sounded and then we heard, “Candidates, turn out promptly.” We hastened downstairs. The old cadets were gathering in four different groups, while the candidates were being put into another one. Cadets Hood, Allen and Macfarlan were on the watch for candidates, and they began thus:

“Button that coat. Get down here lively. ‘Fall in.’ Fall in in the rear; don’t you know better than to get in front of anybody? Palms to the front. Fix your eyes on the seam of the coat collar of the man in front of you, and at the second call, face to the left.” Some of the candidates faced one way and some another, but we were soon straightened out, and then, “Eyes to the front! What do you mean gazing about in ranks? Each candidate, as his name is called, will answer ‘Here’ in a clear and audible tone of voice.” The roll of the candidates was then called. “Why don’t you answer, Mr. H⸺? Well, then, speak up so that you can be heard. Mr. ⸺, don’t shout,” and so on till the last name was called. We were told how to “count fours,” and after the command came something like this: “Stop counting. Try it over. Count fours. Steady, Mr. ⸺; wait till the man on your right counts. Eyes to the front. Why don’t you count, Mr. ⸺! Speak out. Eyes to the front,” and so on. We were now told how to “wheel by fours,” and[37] at the command, “March,” to step off with the left foot first. There was a great time after the command, “Fours right, march,” was given. The cadets on duty over us were kept busy shouting at and pulling in place, first one candidate and then another, but after a fashion we got started and followed the cadets to the Mess Hall, and those on duty over us were kept busy all the way correcting mistakes made by the candidates.

While en route to dinner we were directed to remove our caps just before entering the Mess Hall and to put them on again just after leaving it. Of course we made blunders, and were gently (?) corrected for them. Upon entering the hall we were directed to certain tables, but told not to sit down until the command, “Candidates, take seats,” was given. When each one found a place behind an iron stool (that in my day resembled an hour glass in shape), the command, “A Company, take seats,” was given, and then the members of A Company all sat down promptly; then came “B Company, take seats,” “C Company, take seats,” “D Company, take seats,” and then “Candidates, take seats.” Immediately after the last command something like this came: “Sit down promptly. Do you want to be all day about it? Eat your dinner, and don’t leave the table until the command, ‘Candidates, rise.’”

Dinner was on the table, and there were a good many tables in the big hall. Each table had seats for twenty-two persons, ten on a side and one at either end. There were tablecloths, but no napkins,[38] and one waiter for every two long tables; the waiters did not pass anything, but brought water, bread, etc., when needed. The cadets (and candidates) at the ends of the tables did the carving, while those at the center of the long tables poured the water. At supper and breakfast there were no tablecloths. Tablecloths and napkins are now furnished for all meals, and there are cane seat chairs instead of the old iron stools. The tables of the cadets were divided crosswise in the center by an imaginary line into two parts, and each part was called a table. The cadets had seats according to rank, and they always sat in the same seats. First classmen sat near the end called the head of the table, second classmen next, third classmen (except the corporals) next, and then fourth classmen, the latter being at the center of the long tables. The corporals at the ends of the tables were the carvers, and the fourth classmen poured the water.[9]

After dinner we were marched back to barracks, and before being dismissed the candidates were informed that they could do as they pleased until the bugle sounded “Call to quarters” at 2 o’clock, and then they must repair promptly to quarters, that is, to their own rooms in the barracks. All the time that we were in ranks the usual volleys were fired at us, such as: “Eyes to the front. Head erect and chin in.” After we were dismissed we were constantly reminded to “carry palms of the hands to the front,” notwithstanding[39] the fact that we had been told to go where we pleased for a whole half hour. Some of the candidates went to the sink (i. e., water closet),[10] and some of the old cadets went there, too. A number of them surrounded a poor candidate, called him a plebe or an animal, and fired dozens of questions at him at once. The madder the plebe got the more fun it was for the old cadets. As the candidates were not acquainted with one another, and as they dreaded to meet the old cadets, they naturally drifted to their quarters, thinking that the safest place to be, but, alas! some of the old cadets called upon them there. While they did not mention their names, something like this generally occurred: “‘Shun, squad. Come to attention, plebes. Palms to the front. What’s your name? Spell it; spell it backwards. What state are you from? Who’s your predecessor?’ Say ‘Mr. ⸺.’ Do you think you can pass the ‘prelim’? Where is Newburg? Don’t know? How do you expect to get in here if you don’t know where Newburg is? Climb up on that mantel and be lively about it, too. Now move your arms and say ‘Caw, caw.’ Stop that laughing. Eyes to the front.” And so on, till the old cadets would slip out in time to go to their rooms for “Call to quarters.”

At two o’clock came the call, “Candidates, turn out promptly,” and every candidate turned out and “fell in.” A number were sent back for[40] towels, and upon returning to the Area were sent to the bathrooms, then in the basement of D Company quarters. After bathing, some were sent to the Cadet Hospital for physical examination, and were there told to strip to the skin, then called one at a time before three Army Surgeons, in full uniform, who examined the lungs, eyes, ears, teeth and feet, made the candidates hop first on one foot, then on the other, raise their hands high above the head, cough, bend over forward, etc. When my turn came I did not mention anything about ever having been troubled with my eyes.

Upon returning to the barracks we were sent to the Commissary, where each candidate was given the articles necessary for his own immediate use. As near as I now remember, I got a chair, a pillow, a piece of soap, an arithmetic, a slate, a copybook, a quire of “uniform” paper, a history, a grammar and a geography. Other candidates who, like myself, had brought the articles marked “Thus*” received the same as I, while those who had not brought them got two blankets in addition to what the rest of us got. The books mentioned above are not now issued to candidates.[41] Cadet H⸺d saw to it that candidates rooming together were provided with a wash bowl, a mirror, two buckets, etc. When all were fitted out we took up our loads and returned with them to Barracks, carrying them in our hands or on our shoulders, as was most convenient. This trip from the Commissary store across the grassy plain to Barracks has been described thus:

SETTING UP EXERCISES.

The setting up exercises are now taught by the Instructor of Military Gymnastics and Physical Culture.

Upon returning to Barracks we were ordered to our rooms, and then to the shoeblacks, at that time in the basement of B Company quarters, to have our shoes cleaned and polished, and told to go there, at certain hours, as often as necessary to keep our shoes in proper order. Candidates whose hair was considered too long by Cadet H⸺d were sent to the barber’s, at that time in the basement of C Company quarters. Candidates who had to shave were directed to shave themselves, as the barber was not permitted to do anything but cut hair.

At 4:15 p. m. we were turned out for “Squad[44] Drill.” We “fell in” promptly and were corrected in the manner indicated when we fell in for dinner. Even now I seem to hear Cadets A⸺n, H⸺d and M⸺n shouting themselves hoarse at us poor, stupid candidates. There were about twenty “yearlings,” classmates of Cadets A⸺n and H⸺d, standing around our line, waiting to get a chance at the candidates, so as to compete with them and with one another for “Corporal’s chevrons.” We were separated into squads of four or five to the squad, and a cadet instructor assigned to drill each squad. Cadet H⸺d had the squad I was in. After all details were adjusted, the command, “March off your Squads” was given, and then Babylon was let loose; the candidates could hear the commands of all of the instructors, and they did not know the voice of their own, hence there was much confusion. Some of the instructors acted as if they wanted to terrorize the candidates in their squads, and shouted: “Eyes to the front. Pay attention to me. What do you mean by listening to others? Palms to the front,” and so on, for ten or fifteen minutes, and then we were given a brief “rest.”

Then we were taught how to march and the instructor began thus: “At the word ‘forward’ throw the weight of the body upon the right leg, the left knee straight. At the word ‘march’ move the left leg smartly, without jerk, carry the left foot forward thirty inches from the right, the sole near the ground, the toe a little depressed, knee straight[45] and slightly turned out. At the same time throw the weight of the body forward (eyes to the front), and plant the foot without shock, weight of the body resting upon it; next, in like manner, advance the right foot and plant it as above. Continue to advance without crossing the legs or striking one against the other, keeping the face direct to the front. Now, ‘forward, common time, march.’ Depress the toe, so that it strikes the ground at the same time as the heel. (Palms of the hands squarely to the front. Head up.) When I count ‘one,’ plant the left foot, ‘two,’ plant the right, ‘three,’ plant the left again, ‘four,’ plant the right again, and so on. Now, ‘One,’ ‘two,’ ‘three,’ ‘four,’” etc. “Bring your feet down together. Depress your toes,” and so on.

We were taught many things, such as the facings, the exercises, rests, etc. “In place, rest,” was the most acceptable, but half the pleasure of that was taken away from the candidates by being often told to “keep one heel in place.” That first hour at squad drill is not soon forgotten. My every muscle was sore and I ached all over. Just before we were dismissed we were informed that we could go anywhere we pleased on Cadet Limits, so long as we were back a little before sunset, in time for dress parade. This seemed a great privilege, but wherever candidates went some old cadets were already there, and greeted them with “Depress your toes, plebes. Palms to the front. Are you going to be all summer learning how to march? Squad[46] halt. Right hand salute. What’s your name? Can you sing, dance or play on the piano? Come here ‘Dad,’ and see this ‘animal.’” And a thousand and one other equally pleasant sayings.

Dress parade came and went, but the candidates did not participate in the ceremony out on the grassy plain. They were kept in the Area, and their positions alternated between “Attention” and “Parade, Rest.” When the “Retreat Gun” was fired many of them jumped half out of ranks, and then were gently (?) informed that they were a fine lot of soldiers. “What do you mean by leaving ranks before you are dismissed?” When we had half a chance we enjoyed the music of the band, but it was very hard to hear it and our instructor’s commands at the same time. Soon after parade we fell in again and marched to supper. On the way to and from the Mess Hall we were constantly entertained by our cadet instructors by such commands as, “Eyes to the front,” “Depress your toes,” and “Palms to the front.” Before being dismissed after supper we were informed that we had half an hour before “Call to quarters,” and that during that half hour we could do as we pleased. But that half hour passed just as the other half hours had passed, that is, by the candidates furnishing amusement for the old cadets.

Upon going to our rooms at the signal of “Call to quarters,” Cadet H⸺d called to say that if we expected to pass our preliminary examination we had better “bone up” for it; he also informed[47] us that we could not retire until after “Tattoo.” A cadet’s bed is “made down,” when it is ready to get into, and it is “made up” when it is piled according to regulations and not ready for use. We were too tired to talk. At 9:30 we were turned out to Tattoo. After Tattoo I folded each blanket lengthwise and laid it on the floor, then spread the sheets and comforter on the blankets, undressed and got in bed, leaving H⸺rd, the room orderly, to turn out the gas. Our bones did not fit the hard floor very well, but we soon fell asleep. “Taps” sounded at 10 p. m., and, oh, how sweet and soothing it was. In a few moments more our room door was opened (for they are never locked), a dark lantern flashed in our faces and the door closed again. The same thing was repeated once more during the night, but this time by an officer of the army, called by the cadets a “Tactical Officer.” These inspections were made to make sure that our lights were out and that we were in bed. We slept in the alcoves, heads near the wall farthest from the door. H⸺rd, K⸺p and I, when fast asleep, were suddenly awakened. We had been “yanked,” that is, some old cadets had come into our room, seized our blankets, and with a quick jerk carried us some distance from the wall, and then ran out of the room. We fell asleep once more and slept soundly until we were awakened by the “Reveille Gun” that is fired at sunrise and followed by the beating off of “Reveille.” This music was very pretty, too, but we could not half[48] appreciate it, as we had to get up at once, fall in and begin another day. After reveille we made up our beds. H⸺rd swept out and brought a bucket of fresh water. Cadet H⸺d inspected our quarters twenty minutes after reveille, and said, “Mr. H⸺rd, your wash bowl is not inverted, and your floor not half swept. Attend to them at once.”

We had another hour’s drill before breakfast (omitted now), which made us very hungry. Sick call sounded soon after this drill, but while the candidates were all half sick, it was not medicine they wanted, so none of them went to the hospital. Breakfast was at seven o’clock, and after it the candidates furnished the cadets with the customary half-hour’s entertainment before call to quarters sounded. Cadet H⸺d again cautioned us to “bone up” when he inspected quarters about nine o’clock, and said: “The mantel is dusty, and the floor very dirty.” Captain H⸺t, a Tactical Officer of the Army, also inspected us before noon, but he did not say anything. While I had then been only a day at West Point, so much had happened that it seemed an age.

About a week passed with much the same routine as for the first day, except that we had Saturday afternoon, after inspection, to ourselves, that is, such part of it as we were not busy entertaining old cadets, and on Sunday morning we had inspection of quarters, and after this inspection we were all marched to church. On[49] Sunday afternoon we were permitted to make down and air, or use, our beds, and to enjoy lying on the soft side of the boards again. The candidates were all marched to the Episcopal Church, “the” church there at that day. In due time the Catholics and Methodists attended their own churches, but all cadets, except Jewish ones, had to attend some church once a week. After inspection of quarters on Sunday morning, K⸺p became room orderly for the next week. It was then his duty to sweep and dust the room and to carry the water needed for himself, H⸺rd and me. The dirt was swept into the hall to one side of the door, and left there. A policeman, that is, the janitor, swept the halls, carried out the waste water and scrubbed room and hall floors, when necessary. It is wonderful how soon we learned many things, such as to button our coats and spring to attention, palms to the front, at the sound of footsteps in our hall. At first we made mistakes, but we soon learned to distinguish the footsteps of our instructors from those of our fellow-candidates.

There was a story in my day of a gentleman who went with his son when the latter reported as a candidate, and that while Cadets H⸺d and A⸺n were putting the son through his first lesson in the office, the father turned his palms to the front, put his heels together, and otherwise assumed the position of the soldier.

At the first opportunity I wrote home, but I was[50] very careful not to mention the hardships I endured, for the reason that I had gone to West Point contrary to my parents’ wishes, and consequently I was determined to get through if I could. This reminds me, there were young men in my class whose parents had sent them there against the wishes of the candidates themselves, and many of these young men did not want to stay. Competitive examinations required by some Congressmen for appointments were not as common in my day as they are now. Some of my classmates purposely failed on the preliminary examination and West Point is no place for a young man unless the young man himself wants to go there.

One day Mr. B⸺dy, my predecessor, sent for me to go to his quarters. I did not know what new trials were in store for me, as I had never been in any old cadet’s quarters. Mr. B⸺dy invited me to sit down, which I did for the first time in an old cadet’s presence. We talked for a few moments about people we both knew at our native places. He then gave me his “white pants” (about twenty pairs), and said he hoped I would pass the “prelim” so as to be able to wear them, and that I would graduate higher than he would.

The “graduating ball” that year was on the night of June 14th, but as candidates were not expected to attend it, none were present. The next day the graduating class received their diplomas, discarded cadet gray, put on “Cit” clothes, said good-byes and left the Point, to return no more as[51] cadets. We did not know much of the graduating class, but I now remember the names of more men in that class than in any other at the Academy, excepting my own. This I account for from the fact that I was then so much impressed with the importance of a graduate of West Point. In my eyes he seemed to be a greater man than the Superintendent, in fact there was no comparison.

There was a change made on graduating day among the cadet officers. At the next drill Cadet H⸺d appeared with pretty gold lace chevrons on his coat. He wore them on the sleeves of his dress coat, below the elbow, and he was proud to have everybody know that he was a “Corporal” now. I promptly congratulated him, and he said, “Thank you, Mr. R⸺d,” instead of reprimanding me for speaking without having been first spoken to. In a few days more the new second class men put on “Cit” clothes, and left on furlough. It seemed strange to me that these cadets seemed just as anxious to take off the cadet gray as the candidates were to put it on.

Before the departure of the graduates and furloughmen the candidates learned that there were four trunk rooms[11] in the angle of Barracks, one for the cadets of each company. They learned this by carrying trunks from there to the rooms of the graduates and furloughmen. I soon learned that I got along the easiest by saying as little as possible and doing about as I was told. The candidates who talked much or who bragged on what they[52] knew, especially about military matters, had the hardest time. These poor fellows were called “too fresh,” or “rapid,” and, as the cadets expressed it, they had to be “taken down.”

It was a common thing for old cadets to enjoy a call upon candidates after supper and on Saturday afternoons. And it was difficult at first for candidates to become acquainted with one another, as so much of their leisure (?) time was taken up answering questions, standing on chairs, tables and mantels, reading press notices about themselves, singing, and in fact doing almost everything old cadets told them to do. I have heard many cadets when they were “plebes” or “animals,” declare that they would not do so and so, but they always did as they were told, and they were quick about it, too. It is strange what control old cadets have over “plebes.” They never laid hands on candidates except when they yanked them.

We soon discovered that the cadets who found especial delight in being in the society of plebes were generally “yearlings,” that is, those who had themselves been plebes only the year before. But “yearling” instructors[12] seldom deviled plebes in their own squads.

Mail arrived every day, and was sorted over, that for the cadets and plebes in each division was dropped on the floor in the halls near the entrances and the word mail called out in a loud tone of voice. Every one expecting mail buttoned up his[53] coat and hastened to get such as might be for him. Now the policemen deliver mail to the cadets in their rooms.[13]

In a few days more the candidates were sent in sections of about a dozen to the section for their preliminary or entrance examination. The section I was in was sent to a room having tables, chairs and writing materials, and we were here examined in writing and spelling. There was but one officer present, and after a certain time we put our names on and handed our papers to him whether we had finished them or not. We were next sent to another room, where there were about a half a dozen members of the Academic Board, and as many other army officers.[14] Each candidate, as his name was called, was assigned a subject and then sent to a blackboard. The first one called was numbered one, the second numbered two, and so on, until five or six candidates were sent to different blackboards. Each was directed to write his name and number at the upper right hand corner of the board, to put such data or work on the board as he wished, and when ready to recite to pick up a pointer in his right hand and face about. While those sent to the blackboard were getting ready to recite, another candidate was sent to the center of the room, facing the examiners, and then questioned by one of them. After finishing with the candidate on questions, No. 1 was called upon to recite, and after he was through, another candidate was assigned a subject and sent to the board,[54] and so on. Some of the candidates were self-possessed, and made good recitations and ready answers to questions, while others trembled all over and lost control over themselves, their hearts got up into their throats or went down into their boots. The examination here was in grammar, history, and geography. We were then sent to another room before as many other Professors and Army Officers for examination in arithmetic and reading. I was satisfied with my examination up to this time. After the assignments to the blackboards I was called upon to read. I began to tremble, and had much difficulty in turning to the page designated. I read very poorly, because I could not hold the book steady, and the words on the page danced so that it was hard for me to catch them. I was then told to put down the book and was questioned in arithmetic. Professor C⸺h asked me a number of questions, the answers to which I knew perfectly well, yet all the answer I could make was “I don’t know, sir.” Professor C⸺h then talked kindly and said how important it was to me, that I answer the questions, because if I did not answer properly that I would be found deficient and sent home. I then said that the old cadets had told me he would “find” me, and I believed he would. After having said this I got courage to ask to be sent to the blackboard. My request was granted, and I had no trouble in writing answers to every question, or to solve any problem given me, but for the life of me I could[55] not turn my back to the board and tell what I had put on it; but fortunately I could point to anything called for. The preliminary examinations the next year were written, and they have been written ever since, which is decidedly the best, as some of my class were so badly frightened that they did not know what they said, and some who failed were graduates of good schools, or had passed splendid competitive examinations for their appointments. In a few days the result of the examination was announced, and I was happy to write home that I was one of the lucky ones to enter West Point, and be a “new Cadet” instead of a “Candidate.” Those of us who were fortunate enough to pass were sent to the Commissary[15] for “plebe-skins,” that is, rubber overcoats, caps and white gloves, and we were measured for uniform, clothes and shoes, and for fear perhaps that we might get lazy another hour’s drill, from 11 a. m. to 12 m., was given us. From now on we wore caps and white gloves at all infantry drills.

The new cadet whose name comes first in alphabetical order is the “class-marcher” whenever the class is called out by itself, and it is his duty to call the roll of the class and to report absentees. After our preliminary examination Baily became the class-marcher, and he marched us over to the Library, where we took the oath of allegiance.[16] We were now assigned to Companies, the[56] tallest were put in A and D and the rest in B and C Companies, but the new cadets were still drilled by themselves in small squads, then in larger ones, and later on all in one squad as a company.

W⸺r of my class wore a plug hat when he reported, and he was sorry for it many times. He was the left file of Mr. H⸺d’s squad. One day we were drilling on the Cavalry plain,[17] and there were many ladies and gentlemen watching the drill. We were marching in line at double time, and Mr. H⸺d gave the command, “By the right flank, march.” Three of us marched to the right, but Mr. W⸺r went off to the left all by himself. Everybody near laughed, even Mr. H⸺d suppressed a grin, and then scolded the new cadets for laughing in ranks. Mr. W⸺r chewed tobacco, and this, too, caused him many unhappy moments, but after having been repeatedly reprimanded for chewing tobacco and told to spit it out he quit the practice in ranks.

There was a young man who could not keep step, yet he tried hard to do so. When in front he threw everybody behind him out of step and at other times he would walk all over the heels of the man in front of him. I do not remember whether he was found deficient physically or mentally, but he was not there long. This reminds me of the “Awkward Squad.” It was composed of those who were particularly slow in doing what they were told to do. Tired and sore as they were from[57] the frequent drills, I have seen members of the Awkward Squad practice alone, determined to get out of it, which, of course, they eventually did.

We studied the Blue Book, but the most of the regulations were learned by having them beaten into our heads by the old cadets. We did not then have a copy of the Drill Regulations to study, but we learned them in the same way that we learned most of the Regulations in the Blue Book.

We were now instructed in many things besides Squad Drill. For instance, we were informed that we would be reported for all delinquencies, that is, for all offenses committed against the Regulations, that the reports would be read out daily after parade, and be posted the next day in a certain place; that we must go there every day to see the list; that when there were reports against us we must copy the exact wording of each report and then write an explanation for it; that we must write as many explanations as there were reports against us, and further, that for all official communications we must use “Uniform Paper” (i. e., paper of a certain size) and no other.

New cadets are taught to use as few words as possible in their explanations. One evening at Dress Parade, a plebe raised his hand and of course he was reported for it, and the reason he gave in his explanation for raising his hand in ranks was, “Bug in ear.”

The following illustrates the character of the reports posted against cadets, to-wit:

REPORTS.

Floor not properly swept at A. M. inspection.

Bedding not properly folded at police inspection.

Late at dinner formation.

Calling for articles of food in an unnecessarily loud tone of voice at supper.

Gloves in clothes-press not neatly arranged at morning inspection.

Appearing in Mathematical Section Room with shoes not properly polished.

Inattention in Mathematical Section Room.

Shoulder belt too short at inspection.

Dust in chamber of rifle at inspection.

In dressing gown at A. M. inspection.

Shoes at side of bed not dusted at A. M. inspection.

Hair too long at weekly inspection.

Absent from formation for gymnasium at 12 M.

Orderly light in quarters after taps.

Late at reveille.

Absent from quarters 9 A. M.

Wheeling improperly by fours at drill.

Not seeing to it that a cadet who was late at breakfast was reported.

Coat not buttoned throughout at reveille.

Cap visor dusty at guard-mounting.

The discipline is very strict, more so by far than in the Army, but the enforcement of penalties for reports is inflexible rather than severe. The reports are made by Army Officers, and by certain cadets themselves, such as file-closers and section-marchers, and the cadets make by far the greatest number of reports against one another, but no cadet ever reports another except when it is his duty to do so. If he fails to report a breach of discipline he himself is reported for the neglect. Cadets may write explanations for all reports against them, but they must write an explanation for absence from any duty or from quarters; for communicating at blackboard in section room; for neglect of study or duty; for disobedience of orders; for failure to register for a bath, and for failure to report departure or return on permit where such report is required.

When the Commandant accepts an explanation as satisfactory he crosses off the report, and four days after the date of reports, for which either no explanations or unsatisfactory ones have been received, he forwards them to the Superintendent,[60] and he causes a certain number of demerits to be entered against a cadet for each report in a book kept for that purpose, and which the cadets may see once a week. Any cadet receiving more than one hundred demerits[18] in six months is dismissed from the Academy for deficiency in discipline. The result is that cadets invariably write explanations, and the form now used is as follows:

West Point, N. Y., ____ __, 19__.

Sir:

With reference to the report, “Absent from 9:20 A. M. class formation,” I have the honor to state that I did not hear the call for this formation. I was in my room at the time. The offense was unintentional.

Very respectfully,

John Jones,

Cadet prt. Co. “B,” 4th class.

For the first few weeks demerits are not counted against new cadets, but to teach them how to write them, explanations must be submitted for all reports. Whenever a cadet is reported absent, and he is on Cadet Limits, he is sure to write an [61]explanation stating this fact and anything more he may have to say, because if he fails to do so he is tried by Court-Martial.[19]

A “permit” is a document that grants certain privileges to the cadet named in it. A map of “Cadet Limits” is posted where all may see it, and when a cadet desires to visit friends at the hotel or at an Officer’s quarters, or go to the Dutch Woman’s, i. e., the confectioner’s, or to the dentist’s, he must write an official letter to the Commandant of Cadets (or to the Adjutant of the Military Academy, as the case may be), setting forth what duty, if any, he wishes to be excused from, and the exact time he wishes. This letter will be returned with an endorsement granting all, a part or none of his request, and the cadet must govern himself accordingly.

From now on we had to make out a list of such articles as we wanted or were instructed to get from the Commissary. An account is kept by the Treasurer with each cadet, who is credited with his deposit, and also with his pay,[20] and he is charged for everything furnished him, such as board, washing, wearing apparel, bedding, books, gas, policing barracks, polishing shoes, etc. At his option a cadet is also charged for boats, hops, etc., and when out of debt with such luxuries as new clothes, hop gloves, hop shoes, or $2.00 per month for confectioneries at the “Dutch Woman’s.”

As time wore away we felt less fatigue from drill, and found more pleasure in life, and letters borne were quite cheerful.

Note 1. At present the new 5th classman is received by cadet officers under the immediate supervision of an officer of the Tactical Department and his reception is strictly in accordance with the requirements of military discipline and courtesy. The discipline is, of course, of the strictest and is rigidly enforced, but the life of the newcomer is so hedged about by orders and is so carefully guarded by those who have him in charge, that it is doubtful if a young man entering any school or college in the country would be subjected to less annoyance or embarrassment than would fall to his lot at the Military Academy.

Note 2. At present each table seats 10 cadets, and the cadets are about equally divided among the different classes. One first classman sits at the head of each table; he is officially designated “The Commandant of Table,” and is responsible for order at his table.

Note 3. The mail is now received and distributed by company in the Cadet Guard House, and at a signal on the trumpet a cadet private from each division of barracks, detailed for a week at a time, reports at the Guard House, gets the mail for his division, and distributes it to the proper rooms.

Note 4. In addition to demerits cadets receive other punishments for certain classes of offenses; these consist of confinement to room during release from quarters for a certain number of days, or, of walking (equipped as a sentinel) for a certain number of hours on certain days in the area of barracks.

CAMP McPHERSON

The Pleasure of your company is requested at the hops to be given by the Corps of Cadets every Monday Wednesday and Friday Evening during the encampment

MANAGERS

FOR THE FIRST CLASS

P. S. BOMUS. W. S. EDGERLY. S. WARREN FOUNTAIN. F. V. GREENE. OTTO L. HEIN. DEXTER W. PARKER. CLARENCE A. POSTLEY. W. R. QUINAN. EDWD G. STEVENS.

FOR THE THIRD CLASS

JAMES ALLEN. W H. CARTER. G. F. ELLIOTT. HARRY A. LANDON. J. A. RUCKER. W. F. ZEILIN.

West Point

N.Y. 5th July 1869.

About two weeks after I reported we were directed to prepare to go to Camp McPherson, a half mile or so from Barracks, out beyond the Cavalry plain, near old Fort Clinton. We were told just what articles to take for use in camp, and that we must put the balance of our effects in our trunks and carry them to the trunk rooms in the angle. We sorted out our camp articles, and each cadet made a bundle of his small things, and used a comforter or a blanket to hold them. D⸺n, M⸺s, and I, having arranged to tent together, we helped one another store away our trunks. When the call sounded to “fall in” we fell in with our bundles, brooms and buckets, and marched over to the camp. There were trees all around the camp site, with quite a grove at the guard tents. The tents were all pitched and they looked very pretty through the trees, with the trees and green parapet of Fort Clinton as a background, which could be seen over the tops of the white tents as we approached the camp. The tent cords were not fastened to pegs in the ground, but to pegs in cross-pieces supported upon posts about four feet[66] high, which brought the Company tents only four or five feet apart. All of the tents for cadets were wall tents, and each had a “fly” on it. There was a wooden floor, a gun rack, and a keyless locker (that is, a four-compartment long box), and a swinging pole hung about eighteen inches below the ridge pole of the tent, and nothing else in it. After the assignment, which, of course, was made according to rank, we proceeded to our respective tents, that were to be our homes till the 29th of August, the day to return to Barracks.

The “Yearlings” and first classmen, too, began to take a greater interest in the plebes than ever. They were anxious to teach them how to fix up their tents, and this is the way they did: “Come here, Plebe, and I’ll show you how to fix up your tent. Untie those bundles, fold the blankets once one way then once the other way; that’s it. Now pile them in the rear corner over there, farthest from the locker; put the folded edges to the front and inside; that’s not right, turn them the other way; now that’s right. Lay the pillows on the blankets, closed ends toward the locker; that’s it; now fold the comforters just like you folded the blankets, and pile them the same way on top of the pillows; that’s it. Why, you’re an old soldier, ain’t you? Straighten the pile a little, so that the edges are vertical; that’s it. Now hang the mirror up there on the front pole; that’s it. Put the washbowl out there against the platform, bottom[67] outward; that’s it. Put the candle-box behind the rear tent pole. Put the white pants, underclothes, etc., in the locker. Throw the overcoats, gray pants, etc., on the pole. There, that’ll do. Say, wait a minute. When you go after water, why I want some; just set the bucket down there by the washbowl when you come back.” After having been given several lessons the plebes were permitted to fix up their own tents, and in a very short time every tent was ship-shape. The yearlings kindly showed the plebes how to clean rifles, too, and this is the way they did it: “Come here, Plebe, you’ll soon be getting your guns, so I’ll teach you how to clean yours; just get that gun over there in my rack; that’s the one; get the cleaning materials in the candle-box, take out a rag, put oil on it; that’s it. Lay the gun in your lap, muzzle to the left, half-cock the piece, open the chamber. Why, you’re doing well. See the rust in the breech block? Well, get a small stick out of the candle-box, put a bit of the rag over it, pour a little oil on the rag, now be quick, rub it on the rusty place, rub hard, elbow grease is what counts most, so don’t be afraid to use plenty of it,” and so on, till the yearling’s gun showed an improvement. “I’ll call you again soon to give you another lesson; that’ll do now.” Strange as it may appear, even the first classmen condescended to teach us some things, and even the cadet officers showed us how to clean their breast plates. The old cadets never told us, in so many words, to do[68] anything of a menial character, but their broad hints and insinuating ways were very persuasive. Every day the plebes were called to the tents of the Army Officers in charge of cadet companies, and asked if they had any complaints to make against upper classmen, and the plebes invariably answered “No, sir.”

We continued to take our meals in the Mess Hall, and we marched to and fro as usual, but as the distance was a half mile or more we were now cheered en route (notwithstanding the plebes still carried palms to the front) by the inspiring music of fifes and drums; and we now sat at tables with the old cadets, and had the pleasure of pouring water for them before helping ourselves, no matter how thirsty we might be, but such is the life of a plebe, and it is a necessary part of his training.

The first day in camp we were initiated in police duty; the other classmen turned out with us, and, as usual, they did the talking and we did the work. The detail from each company had a wheelbarrow, a shovel, and a broom. The grounds, to us plebes, seemed clean when we began, but we got half a wheelbarrow load of dirt all the same, which we dumped into “police hollow,”[21] near camp and just west of Fort Clinton. We gathered up burnt matches, cigar stumps, tobacco quids, bits of paper, etc. Whenever there was a sign of rain we turned out and loosened tent cords, and after a rain we turned out and tightened them—always by command, of course. We dreaded the nights[69] in camp, but we were not yanked often, unless we got too fresh or rapid, and then, of course, we had to be taken down.[22]

The parade ground was changed during camp from the grassy plain in front of Professor’s Row to the space between the guard tents and the west line of company tents. In fair weather the battalion stacked arms on the camp parade ground, and the colors were furled and laid on the center stack. The arms and colors, that is, the United States flag, were left there from after guard mount till 4 p. m., and a sentinel posted to require everybody crossing his post, which is known as the “Color Line,” to salute the colors by lifting the cap.

We plebes were very anxious to get guns, but after we did get them we wished we did not have them, for we were again put into small squads and drilled three times a day, notwithstanding the fact that our right arms were very sore, and each rifle seemed to weigh a ton, and, again, we had to spend several hours a day, for weeks, cleaning the guns before they would pass inspection. Each cadet knows his own gun by the number on it. The upper classmen had already taught us how to clean their guns, so we knew something about cleaning our own, and they now were considerate enough to allow us more time to ourselves, and some of the plebes finished cleaning their guns in less than an hour’s time. But, alas! at the first drill with arms the cadet instructors told them that their guns, cartridge boxes, and waist plates[70] were very dirty. After drill we set to work on them again, but still they were said to be dirty. In the course of time we were told that our guns were passable, and later on that they were in fair condition. We soon learned to attend to them immediately after a rain, as it was easier to clean them then than after they had stood awhile.

We were kept busy at first complying with requests (?) of upper classmen, but they were very considerate and dispensed with our services long enough to let us attend drills three times a day, police service twice a day, and to other military duties. We were still required, both in and out of ranks, to carry palms of the hands to the front, but nothing more was said about depressing the toes.

Cadets are encouraged to be patriotic, and they always celebrate Fourth of July. This year, as the Fourth fell on Sunday, the exercises were held on the next day.

Note 1. At my time hazing, or deviling, consisted of little more than harmless badgering, which had the effect of reducing a possibly conceited or bumptuous youth to a frame of mind more consistent with the requirements of military discipline. In time, however, it developed into practices which it was deemed advisable to discontinue, and hazing has entirely disappeared from the Academy.

UNITED STATES MILITARY ACADEMY.

July 5th, 1869.

President,

| Cadet E. E. Wood | Pennsylvania |

Marshal of the Day,

| Cadet J. Rockwell | New York |

PROGRAMME.

Overture.

Prayer.

Music.

Reading of the Declaration of Independence,

| Cadet E. M. Cobb | California |

Music.

Oration,

| Cadet E. S. Chapin | Iowa |

Music.

Benediction.

Music.

Plebe life was very trying, especially on H⸺e of my class, and he, being something of a poet, reduced his thoughts to writing, which he showed to his classmates. They said that he had expressed the situation very well, indeed. Some of the yearlings heard of H⸺e’s poetry, so he was persuaded (?) to read it to them, and then to sing it. His poetry was so well received by the yearlings that the first classmen wanted to hear it, too, so at their invitation (?) H⸺e both read and sang it for them. And, at the request of a number of upper classmen, he made copies of his songs for them. Other plebes were requested (?) to make copies of the copies, and the following are copies of H⸺e’s copies that were made for me by a plebe in my yearling camp, viz.:

There were a good many more verses to this song, and songs written by others of my class, but I have forgotten them.