ii

The “Roswell Incident” has assumed a central place in American folklore since the events of the 1940s in a remote area of New Mexico. Because the Air Force was a major player in those events, we have played a key role in executing the General Accounting Office’s tasking to uncover all records regarding that incident.

Our objective throughout this inquiry has been simple and consistent: to find all the facts and bring them to light. If documents were classified, declassify them; where they were dispersed, bring them into a single source for public review.

In July 1994, we completed the first step in that effort and later published The Roswell Report: Fact vs. Fiction in the New Mexico Desert. This volume represents the necessary follow-on to that first publication and contains additional material and analysis. I think that with this publication we have reached our goal of a complete and open explanation of the events that occurred in the Southwest many years ago.

Beyond that achievement, this inquiry has shed fascinating light into the Air Force of that era and revitalized our appreciation for the dedication and accomplishments of the men and women of that time. As we celebrate the Air Force’s 50th Anniversary, it is appropriate to once again reflect on the sacrifices made by so many to make ours the finest air and space force in history.

This publication contains the complete report as submitted to the Secretary of the Air Force. The exceptions are the statements found in Appendix B. Due to Privacy Act restrictions and by request, the addresses of the individuals making these statements have been deleted.

This volume is divided into two sections, eight subsections, eleven sidebar discussions, and three appendices. Section One examines alleged events at two locations in rural New Mexico. Section Two examines the alleged activities at the Roswell Army Airfield Hospital.

Appendix A is a table listing the launch and landing locations of test equipment for U.S. Air Force scientific research projects High Dive and Excelsior. Appendix B is a collection of signed sworn statements based on in-person interviews conducted for this report by U.S. Air Force researchers. The exception is the statement of Lt. Col. William C. Kaufman, which was not sworn due to equipment failures at the time of interview.

Appendix C contains transcripts of interviews of alleged witnesses presented by UFO theorists. The interviews of Gerald Anderson, Alice Knight, and Vern Maltais were excerpted in their entirety from unedited interviews used to prepare the video, Recollections of Roswell, Part II (1993), and appear courtesy of the Fund for UFO Research. The interview of Mr. W. Glenn Dennis was provided by the interviewer, Karl T. Pflock. The transcript of the interview of Mr. James Ragsdale was provided by Kevin Randle, the coauthor of the Truth About the UFO Crash at Roswell (Avon Books, 1994), in which direct quotes from this transcript appear.

A selected bibliography of technical reports and how to obtain them are found on page 221. For additional information on this subject, see Headquarters United States Air Force, The Roswell Report: Fact vs. Fiction in the New Mexico Desert (Washington D.C.: U.S. Government Printing Office, 1995).

vi

CAPTAIN JAMES MCANDREW serves as an Intelligence Applications Officer assigned to the Secretary of the Air Force Declassification and Review Team, The Pentagon, Washington, D.C.. Captain McAndrew was the coauthor, with Col. Richard L. Weaver, of The Roswell Report: Fact vs. Fiction in the New Mexico Desert (1995), the first Air Force work on the alleged “Roswell Incident.” He participated in the declassification of the Gulf War Air Power Survey (1993) and has served special tours of duty with the Drug Enforcement Administration and High Intensity Drug Trafficking Area (HIDTA) Task Force. He holds a BS degree with honors, from Metropolitan State College, Denver, Colo. and is a native of Washington, D.C.

Page |

|

| Foreword | iii |

| Guide for Readers | v |

| Introduction | 1 |

| SECTION ONE Flying Saucer Crashes and Alien Bodies |

5 |

| 1.1 The “Crash Sites,” Scenarios, and Research Methods | 11 |

| 1.2 High Altitude Balloon Dummy Drops | 23 |

| 1.3 High Altitude Balloon Operations | 37 |

| 1.4 Comparison of Witnesses Accounts to U.S. Air Force Activities | 55 |

| SECTION TWO Reports of Bodies at Roswell Army Air Field Hospital |

75 |

| 2.1 The “Missing” Nurse and the Pediatrician | 81 |

| 2.2 Aircraft Accidents | 93 |

| 2.3 High Altitude Research Projects | 101 |

| 2.4 Comparison of the Hospital Account to the Balloon Mishap | 109 |

| Conclusion | 123 |

| Notes | |

| Section One | 127 |

| Section Two | 139 |

| viii

APPENDIX A Anthropomorphic Dummy Launch and Landing Locations |

155 |

| APPENDIX B Witness Statements |

|

| Charles E. Clouthier |

160

|

| Charles A. Coltman, Jr., Col., USAF, MC (Ret) | 162 |

| Dan D. Fulgham, Col., USAF (Ret) | 164 |

| Bernard D. Gildenberg, GS-14 (Ret) | 166 |

| Ole Jorgeson, MSgt., USAF (Ret) | 169 |

| William C. Kaufman, Lt. Col., USAF (Ret) | 171 |

| Joseph W. Kittinger, Jr., Col., USAF (Ret) | 174 |

| Roland H. Lutz, CMSgt., USAF (Ret) | 178 |

| Raymond A. Madson, Lt. Col. USAF (Ret) | 180 |

| Frank B. Nordstrom, M.D. | 182 |

| APPENDIX C Interviews |

|

| Gerald Anderson | 187 |

| Glenn Dennis | 197 |

| Alice Knight |

213

|

| Vern Maltais | 214 |

| James Ragsdale | 215 |

| Selected Bibliography of Technical Reports |

221 |

| Index | 225 |

| Tables | |

| SECTION ONE | |

| 1.1 Comparison of Testimony to Actual Air Force Equipment and Procedures Used to Launch and Recover Anthropomorphic Dummies | 69 |

| SECTION TWO | |

| 2.1 Persons Described and Periods of Service at Roswell AAF/Walker AFB | 91 |

| ix 2.2 Fatal Air Force Aircraft Accidents by Year in the Vicinity of Walker AFB—1947–1960 | 93 |

| 2.3 Analysis of Air Force Aircraft Accidents by Year in the Vicinity of Walker AFB—1947–1960 | 94 |

| 2.4 U.S. Air Force Manned High Altitude Balloon Flights | 104 |

| Figures | |

| SECTION ONE | |

| The Roswell Report: Fact vs. Fiction In The New Mexico Desert. | |

| The International UFO Museum and Research Center, Roswell, N.M. | |

| Drawing of Project Mogul Balloon Train. | |

| Maj. Jesse Marcel With “Flying Disc” Debris. | |

| ML-307B/AP Radar Target on Ground. | |

| ML-307B/AP Radar Target in Flight. | |

| “Harassed Rancher Who Located ‘Saucer’ Sorry He Told About It,” Roswell Daily Record, July 9, 1947. | |

| Announcement from November 4, 1992 Socorro (N.M.) Defensor Chieftain. | |

| B.D. “Duke” Gildenberg. | |

| Charles B. Moore. | |

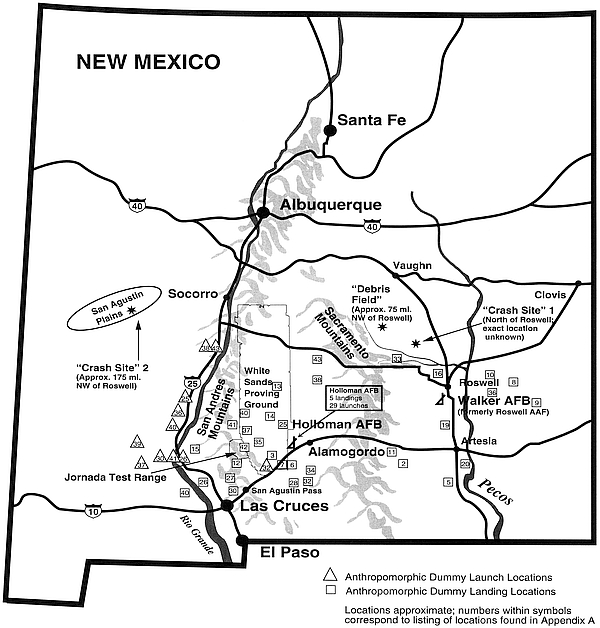

| Map of New Mexico Depicting “Crash Sites” and “Debris Field.” | |

| Missile Recovery Scene. | |

| Drone Recovery Scene. | |

| “Sierra Sam” Type Anthropomorphic Dummy. | |

| National Transportation Highway Safety Administration Advertisement Featuring “Vince and Larry.” | |

| “Dummy Joe” with J.J. Higgins and Guy Ball, McCook Field, Ohio, 1920. | |

| Rope and Sandbag Parachute Drop Dummy on Ground. | |

| Rope and Sandbag Parachute Drop Dummy Descending at Wright Field, Ohio. | |

| Ted Smith Model Anthropomorphic Dummy in Ejection Seat. | |

| Anthropomorphic Dummy “Oscar Eightball” at Muroc AAF, Calif. | |

| “Sierra Sam” Anthropomorphic Dummy in Ejection Seat. | |

| Alderson Laboratories Anthropomorphic Dummies Hanging in Laboratory. | |

| Project High Dive Dummy Launch. | |

| x | Map of New Mexico Depicting Dummy Landing Locations. |

| Capt. Joseph W. Kittinger, Jr.’s Record Parachute Jump. | |

| Article In December 1960 National Geographic Featuring Project Excelsior. | |

| Magazine Covers Depicting U.S. Air Force Aero-Medical Experiments. | |

| M-342 Five-Ton Wrecker. | |

| Project High Dive Gondola and “Sierra Sam” Type Anthropomorphic Dummy. | |

| 1st Lts. Raymond A. Madson and Eugene M. Schwartz with “Sierra Sam” Type Anthropomorphic Dummy. | |

| M-35 Two-Ton Cargo Truck. | |

| M-37 ¾-Ton Cargo Truck. | |

| Lt. Col. John P. Stapp Preparing for Rocket Sled Test. | |

| Cover of September 12, 1955 Time Magazine Depicting Lt. Col. John P. Stapp. | |

| Anthropomorphic Dummy with Missing Fingers. | |

| Anthropomorphic Dummy Falling from Balloon Gondola. | |

| Memo from Project High Dive Files. | |

| Hanging Anthropomorphic Dummies and Hospital Gurney. | |

| Anthropomorphic Dummy in Insulation Bag. | |

| High Altitude Balloon Dummy Drops Report Covers. | |

| Inflation of High Altitude Balloon for Project Viking. | |

| Lobby Card from On The Threshold of Space. | |

| Promotional Photo From On The Threshold of Space. | |

| Promotional Photo From On The Threshold of Space. | |

| Relative Sizes of High Altitude Balloon, Airliner, and Hot Air Balloon. | |

| Target Balloon Launch Near Holloman AFB, N.M. | |

| Discoverer Nosecone Rigged for High Altitude Balloon Flight. | |

| Discoverer Capsule Aboard the USS Haiti Victory. | |

| Viking Spaceprobe at Martin Marietta Corp., Denver, Colo. | |

| Balloon Launch Of Voyager-Mars Space Probe. | |

| Viking Space Probe at Roswell Industrial Airport, Roswell, N.M. | |

| Viking Space Probe Awaiting Recovery at White Sands Missile Range. | |

| xi | Drawing of Alleged UFO. |

| “Vee” Balloon at Holloman AFB, N.M. | |

| Current Members of the Holloman AFB Balloon Branch. | |

| B.D. Gildenberg, Capt. Joseph W. Kittinger, Jr., and Lt. Col. David G. Simons (MC). | |

| Ranch Family with Panel from Project Stargazer. | |

| Balloon Recovery Personnel and “The Hermit.” | |

| Mule Borrowed for Balloon Payload Recovery. | |

| Bulldozer Used for Balloon Payload Recovery. | |

| M-43 Ambulance. | |

| Unusual Balloon Payloads. | |

| U.S. Army Communications Payload. | |

| Scientific Balloon Payload Flown for The Johns Hopkins University. | |

| Balloon Payload Flown from Holloman AFB, N.M. | |

| Project High Dive Anthropomorphic Dummy Launch. | |

| Vehicles Present at High Altitude Balloon Launch and Recovery Sites. | |

| Alderson Laboratories Anthropomorphic Dummies. | |

| Anthropomorphic Dummies Attached to Rack. | |

| Anthropomorphic Dummy with “Bandaged” Head. | |

| Anthropomorphic Dummy with Torn Uniform. | |

| Promotional Photo From On The Threshold of Space. | |

| L-20 Observation Aircraft. | |

| C-47 Transport Aircraft. | |

| Balloon Crew Preparing Balloon for Launch. | |

| Anthropomorphic Dummy Launch Scene. | |

| Typical High Altitude Balloon Launch Scene. | |

| Map of New Mexico. | |

| SECTION TWO | |

| The International UFO Museum and Research Center. | |

| Capt. Eileen M. Fanton. | |

| “Flying Saucer Swindlers,” True Magazine, August 1956. | |

| “The Flying Saucers and the Mysterious Little Green Men,” True Magazine, September 1952. | |

| xii | Col. Lee F. Ferrell and U.S. Senator Dennis Chavez. |

| Lt. Col. Lucille C. Slattery. | |

| KC-97 Aircraft. | |

| 4036th USAF Hospital, Walker AFB, N.M., 1956. | |

| Ballard Funeral Home, Roswell, N.M. | |

| Maj. David G. Simons (MC), Otto C. Winzen, and Capt. Joseph W. Kittinger, Jr. | |

| Capt. Joseph W. Kittinger, Jr. in Man High Capsule. | |

| Lt. Col. David G. Simons. | |

| Bernard D. “Duke” Gildenberg and 1st Lt. Clifton McClure. | |

| Capt. Joseph W. Kittinger, Jr. and the Excelsior High altitude Balloon Gondola. | |

| Capt. Joseph W. Kittinger, Jr. and William C. White with Stargazer Gondola. | |

| Capt. Grover Schock and Otto C. Winzen. | |

| Capt. Dan D. Fulgham and Capt. William C. Kaufman. | |

| Thirty-foot Polyethylene Training Balloon. | |

| Maj. Joseph W. Kittinger, Jr. in Vietnam. | |

| A2C Ole Jorgeson and M-43 Ambulance Converted to a Communications Vehicle. | |

| Stenciled Letters Described as “Hieroglyphics.” | |

| A2C Ole Jorgeson in Rear of M-43 Ambulance. | |

| Polyethylene Balloon on Ground After High Altitude Flight. | |

| Hospital Dispensary, Building 317, Walker AFB, N.M., 1954. | |

| Main Gate at Walker AFB, N.M., 1954. | |

| Capt. Joseph W. Kittinger, Jr. and Dr. J. Allen Hynek. | |

| Clinical Record Cover Sheet of Capt. Dan D. Fulgham. | |

| Capt. Dan D. Fulgham at Wright-Patterson AFB, Ohio. | |

| Maj. Dan D. Fulgham, James Lovell, Hilary Ray, and Alan Bean. | |

| Maj. Dan D. Fulgham at Ubon AB, Thailand. | |

| Memorial Plaque at Holloman AFB, N.M. | |

| Nenninger Balloon Launch Facility at Holloman AFB, N.M. | |

| Capt. Joseph W. Kittinger, Jr. Following Excelsior I. | |

In July 1994, the Office of the Secretary of the Air Force concluded an exhaustive search for records in response to a General Accounting Office (GAO) inquiry of an event popularly known as the “Roswell Incident.” The focus of the GAO probe, initiated at the request of New Mexico Congressman Steven Schiff, was to determine if the U.S. Air Force, or any other U.S. government agency, possessed information on the alleged crash and recovery of an extraterrestrial vehicle and its alien occupants near Roswell, N.M. in July 1947.

Reports of flying saucers and alien bodies allegedly sighted in the Roswell area in 1947, have been the subject of intense domestic and international media attention. This attention has resulted in countless newspaper and magazine articles, books, a television series, a full-length motion picture, and even a film purported to be a U.S. government “alien autopsy.”

The July 1994 Air Force report concluded that the predecessor to the U.S. Air Force, the U.S. Army Air Forces, did indeed recover material near Roswell in July 1947. This 1,000-page report methodically explains that what was recovered by the Army Air Forces was not the remnants of an extraterrestrial spacecraft and its alien crew, but debris from an Army Air Forces balloon-borne research project code named Mogul.[1] Records located describing research carried out under the Mogul project, most of which were never classified (and publicly available) were collected, provided to GAO, and published in one volume for ease of access for the general public.*

Although Mogul components clearly accounted for the claims of “flying saucer” debris recovered in 1947, lingering questions remained concerning anecdotal accounts that included descriptions of “alien” bodies. The issue of “bodies” was not discussed extensively in the 1994 report because there were not any bodies connected with events that occurred in 1947. The extensive Secretary of the Air Force-directed search of Army Air Forces and U.S. Air Force records from 1947 did not yield information that even suggested the 1947 “Roswell” events were anything other than the retrieval of the Mogul equipment.[2]

2

Subsequent to the 1994 report, Air Force researchers discovered information that provided a rational explanation for the alleged observations of alien bodies associated with the “Roswell Incident.” Pursuant to the discovery, research efforts compared documented Air Force activities to the incredible claims of “flying saucers,” “aliens” and seemingly unusual Air Force involvement. This in-depth examination revealed that these accounts, in most instances, were of actual Air Force activities but were seriously flawed in several major areas, most notably: the Air Force operations that inspired reports of “bodies” (in addition to being earthly in origin) did not occur in 1947. It appears that UFO proponents have failed to establish the accurate dates for these “alien” observations (in some instances by more than a decade) and then erroneously linked them to the actual Project Mogul debris recovery.

This report discusses the results of this further research and identifies the likely sources of the claims of “alien” bodies. Contrary to allegations that the Air Force has engaged in a cover-up and possesses dark secrets involving the Roswell claims, some of the accounts appear to be descriptions of unclassified and widely publicized Air Force scientific achievements. Other descriptions of bodies appear to be descriptions of actual incidents in which Air Force members were killed or injured in the line of duty.

3

The conclusions of the additional research are:

• Air Force activities which occurred over a period of many years have been consolidated and are now represented to have occurred in two or three days in July 1947.

• “Aliens” observed in the New Mexico desert were probably anthropomorphic test dummies that were carried aloft by U.S. Air Force high altitude balloons for scientific research.

• The “unusual” military activities in the New Mexico desert were high altitude research balloon launch and recovery operations. The reports of military units that always seemed to arrive shortly after the crash of a flying saucer to retrieve the saucer and “crew,” were actually accurate descriptions of Air Force personnel engaged in anthropomorphic dummy recovery operations.

• Claims of bodies at the Roswell Army Air Field hospital were most likely a combination of two separate incidents:

1) a 1956 KC-97 aircraft accident in which 11 Air Force members lost their lives; and,

2) a 1959 manned balloon mishap in which two Air Force pilots were injured.

This report is based on thoroughly documented research supported by official records, technical reports, film footage, photographs, and interviews with individuals who were involved in these events.

The most puzzling and intriguing element of the complex series of events now known as the Roswell Incident, are the alleged sightings of alien bodies. The bodies turned what, for many years, was just another flying saucer story, into what many UFO proponents claim is the best case for extraterrestrial visitation of Earth. The importance of bodies and the assumptions made as to their origin is illustrated in a passage from a popular Roswell book:

Crashed saucers are one thing, and could well turn out to be futuristic American or even foreign aircraft or missiles. But alien bodies are another matter entirely, and hardly subject to misinterpretation.[3]

The 1994 Air Force report determined that project Mogul was responsible for the 1947 events. Mogul was an experimental attempt to acoustically detect suspected Soviet nuclear weapon explosions and ballistic missile launches.[4] Mogul utilized acoustical sensors, radar reflecting targets and other devices attached to a train of weather balloons over 600 feet long. Claims that the U.S. Army Air Forces recovered a “flying disc” in 1947, were based primarily on the lack of identification of the radar targets, an element of weather equipment used on the long Mogul balloon train. The oddly constructed radar targets were found by a New Mexico rancher during the height of the first U.S. flying saucer wave in 1947.[5] The rancher brought the remnants of the balloons and radar targets to the local sheriff after he allegedly learned of the broadcasted reports of flying discs. However, following some initial confusion at Roswell Army Air Field, the “flying disc” was soon identified by Army Air Forces officials as a standard radar target.[6]

From 1947 until the late 1970s, the Roswell Incident was essentially a non-story. The reports that existed contain only descriptions of mundane materials that originated from the Project Mogul balloon train—“tinfoil, paper, tape, rubber, and sticks.”[7] The first claim of “bodies” appeared in the late 1970s, with additional claims made during the 1980s and 1990s. These claims were usually based on anecdotal accounts of second- and third-hand witnesses collected by UFO proponents as much as 40 years after the alleged incident. The same6 anecdotal accounts that referred to bodies also described massive field operations conducted by the U.S. military to recover crash debris from a supposed extraterrestrial spaceship.

A technique used by some UFO authors to collect anecdotal corroboration for their theories was to solicit cooperating witnesses through newspaper announcements. For example, one such solicitation appeared in the Socorro (N.M.) Defensor Chieftain on November 4, 1992, on behalf of7 Don Berliner and Stanton T. Friedman, the authors of the book Crash at Corona. This request solicited persons to provide information about the supposed crashes of alien spacecraft in the Socorro area.[8]*

8

In response to the newspaper announcement, two scientists central to the actual explanation of the “Roswell” events, Professor Charles B. Moore, a former U.S. Army Air Forces contract engineer, and Bernard D. Gildenberg, retired Holloman AFB Balloon Branch Physical Science Administrator and Meteorologist, came forward with pertinent information.[9] According to Moore and Gildenberg, when they met with the authors their explanations that some of the Air Force projects they participated in were most likely responsible for the incident, they were summarily dismissed. The authors even went so far as to suggest that these distinguished scientists were participants in a multifaceted government cover-up to conceal the truth about the Roswell Incident.

9

Since many of the Roswell accounts and allegations were collected by irregular methods and are not specifically documented, the series of events as alleged by UFO theorists has become very complex and requires clarification. Therefore, the following section will briefly examine some of the more confusing elements of the Roswell stories, specifically, the multiple crash sites and complex scenarios, in order to facilitate an objective analysis of actual events.

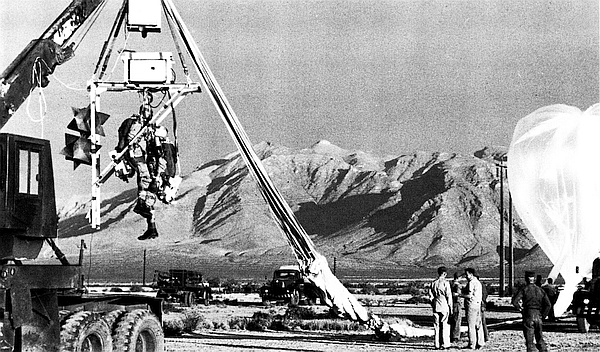

From 1947 until the late 1970s, the Roswell Incident was confined to one alleged crash site. This site, located on the Foster Ranch approximately 75 miles northwest of the city of Roswell, was the actual landing site of a Project Mogul balloon train in June 1947.[10] The Mogul landing site is referred to in popular Roswell literature as the “debris field.”

In the 1970s, the 1980s and throughout the 1990s, additional witnesses came forward with claims and descriptions of two other alleged crash sites. One of these sites was supposedly north of Roswell, the other site was alleged to have been approximately 175 miles northwest of Roswell in an area of New Mexico known as the San Agustin Plains.[11] What distinguished the two new crash sites from the original debris field were accounts of alien bodies.

12

UFO enthusiasts have attempted to explain the obvious contradiction of multiple impact sites involving only one alien craft through the introduction of complicated scenarios. These scenarios have become increasingly convoluted since the proponents of each crash site must make allowances to have “their” flying saucer at the correct time and place—the actual Mogul balloon train landing site in early July, 1947—in order to “fit” with the rest of the story. The actual Project Mogul landing site, 75 miles northwest of Roswell, lends credibility, and more importantly establishes a time frame, for the other accounts that include reports of bodies. Flying saucer enthusiasts use the documented presence of U.S. Army Air Forces personnel at the Mogul site in July 1947, who were there to retrieve the Mogul balloon train, to provide the nucleus of unrelated and much later accounts that include reports of “bodies.” It must be emphasized that the claims of “bodies” only became part of the Roswell Incident after 1978, when they were erroneously linked to the July 1947 retrieval of Project Mogul components.

In general, “Roswell Incident” scenarios claim that a disabled alien craft momentarily touched down at the site 75 miles northwest of Roswell, leaving behind parts of the spaceship (material that has been subsequently identified as components of a Mogul balloon train) to create the original “debris field.” The scenarios further contend that the damaged craft again became airborne and flew to its final crash site, at either the location north of Roswell or 175 miles northwest of Roswell on the San Agustin Plains.

Regardless of the dispute over the location, an element common to most scenarios was that, once recovered, the bodies were supposedly transported to the hospital at Roswell Army Air Field for autopsy. Also common to these theories is that the bodies were later shipped from Roswell AAF to another facility, usually Wright-Patterson AFB, Ohio (or a host of other facilities—this is another area of further disagreement among UFO theorists) for further evaluation and ultimate deep-freeze storage.

In an attempt to untangle this collection of complicated assertions and determine if there was any validity to the reports of bodies, Air Force researchers faced the task of sorting through and examining anecdotal testimony of hundreds of witnesses. However, a large number of the accounts were eliminated by applying previously established facts to the testimonies. The July 1994 report to the Secretary of the Air Force clearly presented and documented these facts:

a. The U.S. Army Air Forces did not recover an extraterrestrial vehicle and alien crew. This conclusion was based on extensive research that included a thorough review of both classified and13 unclassified materials at record depositories, archives, libraries and research facilities throughout the nation. Of the millions of pages of material reviewed, there was no mention of any activities that even tangentially suggested such an event. Additionally, former and retired Air Force members and civilian contract scientists were located and released from any possible nondisclosure agreements they may have entered into regarding past classified activities. This release allowed them to freely discuss with Air Force researchers, or any other persons, information related to this issue. These releases were issued at the express written direction of the Secretary of the Air Force. Interviews with these persons yielded no information supporting extraterrestrial claims or any other unusual activities.

b. The reports of bodies were not associated with Project Mogul. The Mogul balloon train did not, was not designed to, nor could it carry passengers. Neither did it carry hazardous materials that would have caused injury, death, or mutilation to persons who may have come in contact with any of its components.

c. Actual events, if any, that inspired reports of bodies did not occur in 1947. Based on extensive examinations of U.S. Army Air Forces activities in 1947, no evidence was found to support allegations that the Army Air Forces was involved in any uncommon operations other than the retrieval of the Mogul balloon train in the Roswell area in July 1947. Examination of research and development projects, aircraft crashes, errant missiles and possible nuclear accidents yielded no information to support a 1947 claim.

In light of these documented facts, the hundreds of anecdotal accounts were reduced to a few. Eliminated were accounts that were likely descriptions of materials known to be part of the Project Mogul balloon train and accounts describing transportation of these materials.

From the remaining testimony, Air Force researchers developed the following set of working hypotheses to assist in identifying the actual events, if any, matching those described by the witnesses.

a. Due to the number and great detail provided in some of the accounts, it was likely that some event(s) actually did occur.

b. Due to the many similarities of the two crash site descriptions and the considerable distance between them, it was likely that more than one event with similar characteristics was the basis for these accounts.

c. Since the account of bodies at the Roswell Army Air Field hospital did not contain elements similar to reports of the two14 crash sites, it was likely that this account was unrelated to the crash site accounts. (The hospital account will be addressed separately in Section Two of this report.)

The remaining testimony was examined with regard both to the facts and to working hypotheses to determine if there were common threads or links connecting any of the accounts. If similarities were found, the next step was to determine if they were related to an actual event. Finally, if there were actual event(s), were they part of U.S. Air Force or U.S. Government activities?

Careful examination of the testimony revealed that primary witnesses of the two “crashed saucer” locations contained descriptions common to both. These areas of commonality contained both general and detailed characteristics. However, before continuing, the accounts were carefully examined to determine if the testimony related by individual witnesses were of their own experiences and not a recitation of information given by other persons. While many aspects of the remaining accounts were judged to be similar, other aspects were found to be significantly different. The accounts on which the analysis is based were determined, in all likelihood, to have been independently obtained or observed by the witnesses.

General Similarities. The testimony presented for both crash sites generally followed the same sequence of events. The witnesses were in a rural and isolated area of New Mexico. In the course of their travels in this area, they came upon a crashed aerial vehicle. The witnesses then proceeded to the area of the crash to investigate and at some distance they observed strange looking “beings” that appeared to be crewmembers of the vehicle. Soon thereafter, a convoy of military vehicles and soldiers arrived at the site. Military personnel allegedly instructed the civilians to leave the area and forget what they had seen. As the witnesses left the area, the military personnel commenced with a recovery operation of the crashed aerial vehicle and “crew.”

Detailed Similarities. Along with general similarities in the testimonies, there also existed a substantial amount of similar detailed descriptions of the “aliens,” and the military vehicles and procedures allegedly used to recover them.

The first obvious similarity was the descriptions of the aliens. Mr. Gerald Anderson, an alleged witness of events at the site 175 miles northwest of Roswell, recalled, “I thought they were plastic dolls.”[12] Mr. James Ragsdale, an alleged witness of the site north of Roswell, stated, “They were using dummies in those damned things.”[13] Another alleged witness to a “crash” north of Roswell, Frank J. Kaufman, recalled that there was “talk” that perhaps an “experimental plane with dummies in it” was the source of the claims.[14]

15

Additional similarities were also noted. Mr. Vern Maltais, a secondhand witness of the site 175 miles northwest of Roswell, described the hands of the “aliens” as, “They had four fingers.”[15] Anderson characterized the hands as, “They didn’t have a little finger.”[16] He also described the heads of the aliens as “completely bald”[17] while Maltais described them as “hairless.”[18] The uniforms of the aliens were independently described by Anderson as “one-piece suits ... a shiny silverish-gray color”[19] and by Maltais as “one-piece and gray in color.”[20] The date of this event was also not precisely known. Maltais recalled that it may have occurred “around 1950”[21] and another secondhand witness, Alice Knight stated, “I don’t recall the date.”[22]

Witnesses of different sites also used the terms “wrecker”[23] and “six-by-six”[24] when they described the military vehicles present at the different recovery sites. One witness described seeing a “medium sized Jeep/truck”[25] and another witness described seeing a “weapons carrier”[26] (a weapons carrier is a mid-sized Jeep-type truck).

When the general and specific similarities were combined, a profile emerged describing the event or activity that might have been observed. The profile, which contains elements common to at least two, and in some cases, all of the accounts, established a set of criteria used to determine what the witnesses may have observed. The profile is as follows:

a. An activity that, if viewed from a distance, would appear unusual.

b. An activity of which the exact date is not known.

c. An activity that took place in two rural areas of New Mexico.

d. An activity that involved a type of aerial vehicle with dolls or dummies that had four fingers, were bald, and wore one-piece gray suits.

e. An activity that required recovery by numerous military personnel and an assortment of vehicles that included a wrecker, a six-by-six, and a weapons carrier.

Based on this profile, research was begun to identify events or activities with these characteristics. Due to the location of the sites, attention was focused on Roswell AAF (renamed Walker AFB in 1948), White Sands Missile Range and Holloman AFB, N.M. The aerial vehicles assigned or under development at these facilities were aircraft, missiles, remotely-piloted drones, and high altitude balloons. The operational characteristics and areas where these vehicles flew were researched to determine if they played a role in the events described by the witnesses.

16

Missiles and Drones. Missiles and drones were determined not to have been responsible for the accounts.* The areas where the alleged crashes took place were, in all likelihood, too far from the White Sands Missile Range. Missiles were equipped with a self-destruct mechanism that was activated if it strayed off-course or out of the White Sands Missile Range. There was never a program that required a dummy or doll to be placed inside a missile or a drone. However, missiles were launched from White Sands carrying monkeys and other small animals aloft for scientific research.[27] These projects were well documented, and none of these missiles landed near either of the two crash sites.

Aircraft. Aircraft seemed just as unlikely as missiles to have been responsible for the extraterrestrial claims as outlined in the profile. Although additional research revealed the significant role dummies played in the test and evaluation of aircraft emergency escape systems, these dummies were used on board aircraft and on the high-speed test track at Holloman AFB. However, aircraft test flights demanded strict adherence to established flight profiles over the instrumented portions of the White Sands Missile Range, many miles from the alleged crash sites. Dummies used on the high-speed track remained in the immediate vicinity of the track facilities at Holloman AFB. This geographical impossibility ruled out dummies that were ejected from aircraft and those used on the high-speed track as a cause of alleged alien sightings. (Aircraft accidents will be discussed extensively in Section Two of this report.)

17

High Altitude Research Balloons. The only vehicles not yet evaluated as a possible source of the accounts were high altitude research balloons. Previous reviews of early research balloon flight records revealed that trajectories of high altitude balloons were, at times, unpredictable and did not usually remain over Holloman AFB or White Sands Missile Range.[28] Many of the scientific payloads required recovery so the data collected during flight could be returned to the laboratory for analysis.

These characteristics seemed to fit at least some of the research profile. Atmospheric sampling apparatus or weather instruments, the typical payload of many high altitude balloons, could hardly have been mistaken for space aliens. A careful examination of the instruments carried aloft by the high altitude balloons revealed that one unique project used a device that very likely could be mistaken for an alien—an anthropomorphic dummy.

An anthropomorphic dummy is a human substitute equipped with a variety of instrumentation to measure effects of environments and situations deemed too hazardous for a human. These abstractly human dummies were first used in New Mexico in May 1950, and have been used on a continuous basis since that time.[29]

In the 1950s, anthropomorphic dummies were not widely exposed outside of scientific research circles and easily could have been mistaken for something they were not. Today, anthropomorphic dummies, better known as crash test dummies, are easily identifiable and are even the “stars” of their own automotive safety advertising campaign. During the 1950s when the U.S. Air Force dropped the odd-looking test devices from high altitude balloons in its program to study high altitude human free-fall characteristics, public awareness and stardom were decades away. It seems likely that someone who unexpectedly observed these dummies at a distance would believe they had seen something unusual. In retrospect, when interviewed over 40 years later, they could accurately report that they had seen something very unusual.

With the introduction of anthropomorphic dummies as a possible explanation for the reports of bodies, another element of the research profile appeared to be satisfied. Specific information that described the locations, methods, and procedures used to employ the dummies was required before any definitive conclusions could be drawn. To gather this detailed information, research efforts were concentrated on high altitude balloon operations and the specific projects that utilized balloon-borne anthropomorphic dummies.

18

Since the beginning of manned flight, designers have sought a substitute for the human body to test hazardous new equipment. Early devices used by the predecessors of the U.S. Air Force were simply constructed parachute drop test dummies with little similarity to the human form. Following World War II, aircraft emergency escape systems became increasingly sophisticated and engineers required a dummy with more humanlike characteristics.

Parachute Drop DummiesDuring World War I research and development of the first U.S. military parachute was underway at McCook Field, Ohio. To test the parachute, engineers experimented with several types of dummies, settling on a model constructed of three-inch hemp rope and sandbags with the approximate proportions of a medium-sized man.[30] The new invention was soon known by the nickname “Dummy Joe.” Dummy Joe is said to have made more than five thousand “jumps” between 1918 and 1924.[31]

By 1924, parachutes were required on military aircraft with their serviceability tested by dummies dropped from aircraft.[32] For this routine testing, several types of dummies were used. The most common type is shown in figures 17 and 18. Parachutes were individually drop-tested from aircraft until the early stages of World War II, when, due both to increased reliability and large numbers of parachutes in service, this routine practice was discontinued. Nonetheless, test dummies were still used frequently by the Parachute Branch of Air Materiel Command (AMC) at Wright Field, Ohio, to test new parachute designs.

Fig. 16. “‘Dummy Joe,’ the hero of five thousand jumps” is shown here with engineers J.J. Higgins (left) and Guy Ball at McCook Field, Ohio in 1920. (U.S. Air Force photo)20

Fig. 17. (Left) Early rope and sandbag dummy used to test parachutes. (U.S. Air Force photo)

Fig. 18. (Right) Parachute drop dummies in use at Wright Field, Ohio. The historic Flight Test hangars, Hangars 1 and 9, can be seen in the background. (U.S. Air Force photo)Anthropomorphic DummiesThe ejection seat had been developed and used successfully by the German Luftwaffe during the latter stages of World War II. The utility of this invention was realized when the U.S. Army Air Forces obtained an ejection seat in 1944.[33] To properly test the ejection seat, the Army Air Forces required a dummy that had the same center of gravity and weight distribution as a human, characteristics that parachute drop dummies did not possess. In 1944, the USAAF Air Materiel Command contracted with the Ted Smith Company of Upper Darby, Pa. to design and manufacture the first dummy intended to accurately represent a human.[34] The dummy had the same basic shape as a human, but with only abstract human features, and “skin” made of canvas.

Figs. 19 & 20. (Left & Right) These early anthropomorphic dummies, manufactured by the Ted Smith Co., of Upper Darby, Pa., were used by the Army Air Forces beginning in 1944. They were replaced by a more realistic dummy in 1949.

(Right) “Oscar Eightball,” the name given to this early model anthropomorphic dummy by Col. John P. Stapp, is shown following a run of the high-speed track at Muroc AAF (now Edwards AFB), Calif., in 1947. (U.S. Air Force photos)21

In 1949, the U.S. Air Force Aero Medical Laboratory submitted a proposal for an improved model of the anthropomorphic dummy.[35] This request was originated by the renowned Air Force scientist and physician John P. Stapp, now a retired Colonel, who conducted a series of landmark experiments at Muroc (now Edwards) AFB, Calif., to measure the effects of acceleration and deceleration during high-speed aircraft ejections.[36] Stapp required a dummy that had the same center of gravity and articulation as a human, but, unlike the Ted Smith dummy, was more human in appearance. A more accurate external appearance was required to provide for the proper fit of helmets, oxygen masks, and other equipment used during the tests. Stapp requested the Anthropology Branch of the Aero Medical Laboratory at Wright Field to review anthropological, orthopedic, and engineering literature to prepare specifications for the new dummy.[37] Plaster casts of the torso, legs, and arms of an Air Force pilot were also taken to assure accuracy.[38] The result was a proposed dummy that stood 72 inches tall, weighed 200 pounds, had provisions for mounting instrumentation, and could withstand up to 100 times the force of gravity or 100Gs.

In 1949, a contract was awarded to Sierra Engineering Company of Sierra Madre, Calif., and deliveries began in 1950.[39] This dummy quickly became known as “Sierra Sam.”

In 1952, a contract for anthropomorphic dummies was awarded to Alderson Research Laboratories, Inc., of New York City.[40] Dummies constructed by both companies possessed the same basic characteristics: a skeleton of aluminum or steel, latex or plastic skin, a cast aluminum skull, and an instrument cavity in the torso and head for the mounting of strain gauges, accelerometers, transducers, and rate gyros.[41] Models used by the Air Force were primarily parachute drop and ejection seat versions with center of gravity tolerances within one quarter inch.

Over the next several years the two companies improved and redesigned internal structures and instrumentation, but the basic external appearance of the dummies remained relatively constant from the mid 1950s to the late 1960s. Dummies of these types were most likely the “aliens” associated with the “Roswell Incident.”

From 1953 to 1959, anthropomorphic dummies were used by the U.S. Air Force Aero Medical Laboratory as part of the high altitude aircraft escape projects High Dive and Excelsior.[42] The object of these studies was to devise a method to return a pilot or astronaut to earth by parachute, if forced to escape at extreme altitudes.[43]

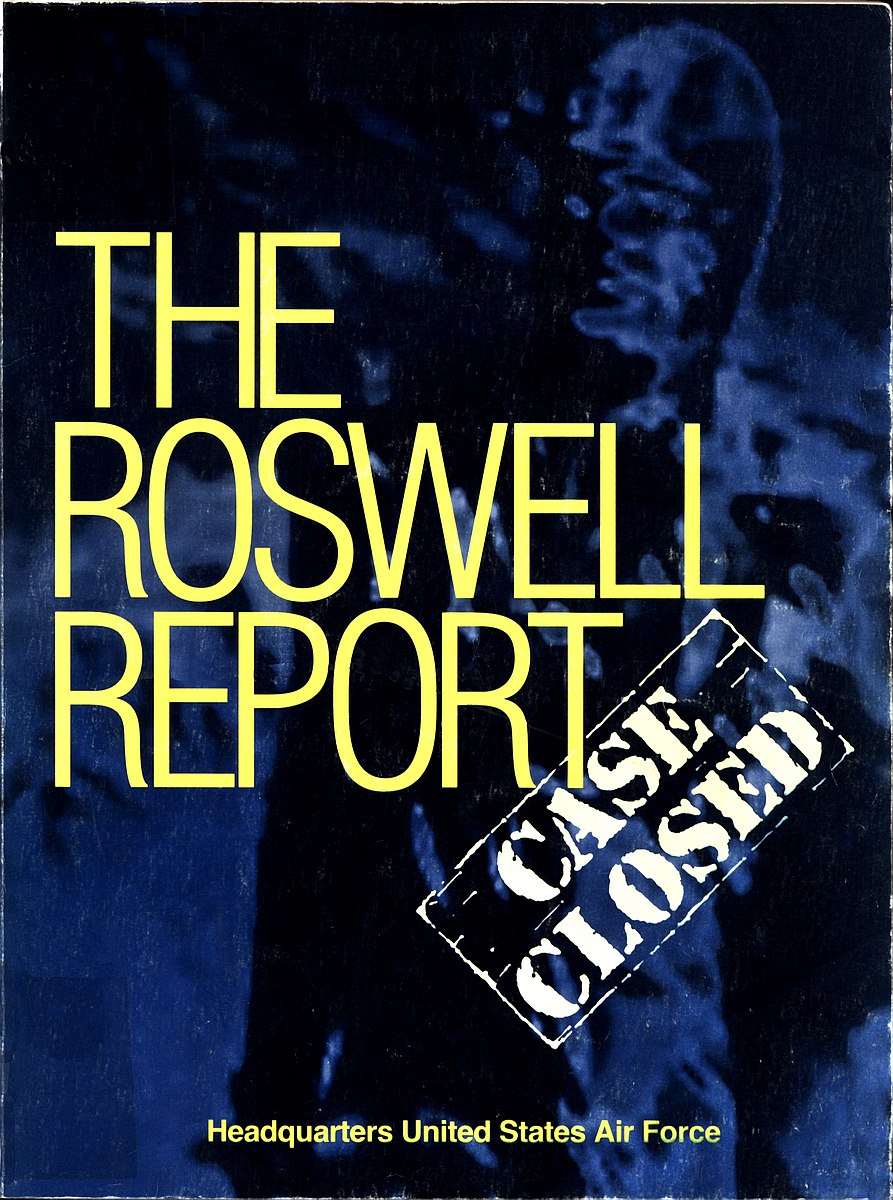

Anthropomorphic dummies were transported to altitudes up to 98,000 feet by high altitude balloons. The dummies were then released for a period of free-fall while body movements and escape equipment performance were recorded by a variety of instruments. Forty-three high altitude balloon flights carrying 67 anthropomorphic dummies were launched and recovered throughout New Mexico between June 1954 and February 1959.[44] Due to prevailing wind conditions, operational factors and ruggedness of the terrain, the majority of dummies impacted outside the confines of military reservations in eastern New Mexico, near Roswell, and in areas surrounding the Tularosa Valley in south central New Mexico.[45] Additionally, 30 dummies were dropped by aircraft over White Sands Proving Ground, N.M. in 1953. In 1959, 150 dummies were dropped by aircraft over Wright-Patterson AFB, Ohio (possibly accounting for alleged alien “sightings” at that location).[46]

24

25

A number of these launch and recovery locations were in the areas where the “crashed saucer” and “space aliens” were allegedly observed.

Following the series of dummy tests, a human subject, test pilot Capt. Joseph W. Kittinger, Jr., now a retired Colonel, made three parachute jumps from high altitude balloons. Since free-fall tests from these unprecedented altitudes were extremely hazardous, they could not be accomplished by a human until a rigorous testing program using anthropomorphic dummies was completed.

Countering claims of a cover-up, Air Force projects that used anthropomorphic dummies and human subjects were unclassified and widely publicized in numerous newspaper and magazine stories, books, and television reports. These included a book written by test pilot Kittinger, The Long, Lonely Leap, another book, Man High, by Man High Project Scientist, Lt. Col. David G. Simons (MC), a feature article in National Geographic, and cover stories in Life, Collier’s, Popular Mechanics, and Time.[47] A characterization of Kittinger’s record parachute jump even appeared in the adolescent magazine, MAD.[48] The intense public interest in High Dive, Excelsior and other aero medical projects conducted at Holloman AFB also resulted in a 1956 Twentieth Century Fox full-length motion picture, On the Threshold of Space (see page 38).

27

28

For the majority of the tests, dummies were flown to altitudes between 30,000 and 98,000 feet attached to a specially designed rack suspended below a high altitude balloon.[49] On several flights the dummies were mounted in the door of an experimental high altitude balloon gondola.[50] Upon reaching the desired altitude, the dummies were released and free-fell for several minutes before deployment of the main parachute.

The dummies used for the balloon drops were outfitted with standard equipment of an Air Force aircrew member. This equipment consisted of a one-piece flightsuit, olive drab, gray (witnesses had described seeing aliens in gray one-piece suits) or fuchsia in color, boots, and a parachute pack.[51] The dummies were also fitted with an29 instrumentation kit that contained accelerometers, pressure transducers, an oscillograph, and a camera to record movements of the dummy during free-fall.[52]

30

Recoveries of the test dummies were accomplished by personnel from the Holloman AFB Balloon Branch.[53] Typically, eight to twelve civilian and military recovery personnel arrived at the site of an anthropomorphic dummy landing as soon as possible following impact. The recovery crews operated a variety of aircraft and vehicles. These included a wrecker, a six-by-six, a weapons carrier, and L-20 observation and C-47 transport aircraft—the exact vehicles and aircraft described by the witnesses as having been present at the crashed saucer locations.[54] On one occasion, just southwest of Roswell, a High Dive project officer, 1st Lt. Raymond A. Madson, even conducted a search for dummies on horseback[55] (see statement in Appendix B).

To expedite the recoveries, crews were prepositioned with their vehicles along a paved highway in the area where impact was expected.[56] 31 On a typical flight the dummies were separated from the balloon by radio command and descended by parachute.[57] Prompt recovery of the dummies and their suspension racks, which usually did not land in the same location resulting in extensive ground and air searches, was essential for researchers to evaluate information collected by the instrumentation and cameras. To assist the recovery personnel, a variety of methods were used to enhance the visibility of the dummies: smoke grenades, pigment powder, and brightly colored parachute canopies.[58] Also, recovery notices promising a $25 reward were taped to an exposed portion of a dummy.[59] Local newspapers and radio stations were contacted when equipment was lost.[60]

America was introduced to Col. John Paul Stapp on December 10, 1954, when he became known as both the “the bravest” and “the fastest” man on earth. Stapp earned these titles following a rocket sled test that accelerated him to 632 miles per hour. He reached this speed in just five seconds—faster than a .45 caliber bullet—and was decelerated to a stop in 1.4 seconds, subjecting his body to more than 42 times the force of gravity! While this was America’s introduction to Col. Stapp, the 1954 rocket sled test that examined aircraft restraint devices and human responses to accelerative/decelerative forces and windblast, was just one of many achievements of this legendary Air Force physician.

Born in Bahia, Brazil to American missionary parents, Stapp sold pots and pans door to door during the Depression while he earned both undergraduate and graduate degrees in zoology and chemistry at Baylor University. He went on to earn a doctorate in biophysics from the University of Texas, and a doctorate in medicine from the University of Minnesota.

Fig. 33. The first “space doctor,” Lt. Col. John P. Stapp (now a retired Colonel) being strapped into the rocket sled Sonic Wind No 1, on December 10, 1954, at Holloman AFB, N.M. Courageously, Stapp was his own volunteer subject on 29 rocket sled tests and earned two awards of the Legion of Merit and the Cheney Award for valor and self-sacrifice. (U.S. Air Force photo)In 1944 Stapp entered the U.S. Army Air Forces and became a flight surgeon. From 1946 to 1963, due to his unique qualifications in biophysics and medicine, he conducted a series of acceleration/deceleration experiments on the high-speed track at Muroc (now Edwards AFB), Calif.,[61] and later at Holloman AFB, N.M. Developments from these and other studies resulted32 in innovations which have saved many lives. These included improved safety belt restraint systems and design specifications for aircraft and automobiles, aircraft ejection and emergency escape systems, refinement of automobile airbag systems, and development of the modern anthropomorphic test dummy.

As commander of the U.S. Air Force Aeromedical Field Laboratory at Holloman AFB, N.M. and later the Aero Medical Laboratory at Wright-Patterson AFB, Ohio, Stapp won support for the Air Force manned high altitude balloons projects—Man High and Excelsior. As a testament to his thorough safety preparations, these and other extremely hazardous projects administered by Stapp, did not result in a single debilitating injury to a test subject. These projects helped pave the way for future flights of both high altitude aircraft such as the X-15, and of spacecraft for the Mercury, Gemini, and Apollo programs. In fact, Stapp’s expertise was called upon to assist in the selection of the initial cadre of astronauts, the “Mercury Seven.”

He retired from the Air Force in 1970, but not before amassing a collection of awards and honors. These included two awards of the Legion of Merit for rocket sled experiments, the Cheney Award for 1954, and membership in the National Aviation Hall of Fame.

In association with the Society of Automotive Engineers, Stapp continues to participate in annual conferences in which industry experts assemble to discuss vehicle safety issues. The conferences, now in their 40th year bear his name: the Stapp Car Crash Conferences.

In 1991, in recognition of a lifetime of unselfish dedication to scientific research, Stapp was awarded the National Medal of Technology, bestowed upon him at the White House by President George Bush.

He is married to the former Lillian Lanese, a former soloist with the Ballet Theater of New York, and resides in Alamogordo, N.M. At 87 years old he continues to maintain a dizzying pace of travel and lectures.

It is not an exaggeration that virtually every person who has safely operated, or ridden in, an automobile, aircraft, or spacecraft, has benefited from the genius of Col. John Paul Stapp, and owes this brave scientist, physician, and visionary, a great deal of thanks.

33

Despite these efforts, the dummies were not always recovered immediately; one was not found for nearly three years and several were not recovered at all.[62] When they were found, the dummies and instrumentation were often damaged from impact.[63] Damage to the dummies included loss of heads, arms, legs and fingers.[64] This detail, dummies with missing fingers, appears to satisfy another element of the research profile—aliens with only four fingers.

Fig. 35. Rough treatment and parachute failures during

balloon drops often caused damage to the hands of the dummies. This

detail, “beings” with “four fingers,” was related by two witnesses as a

distinguishing feature of the Roswell aliens. (U.S. Air Force photo)

Fig. 35. Rough treatment and parachute failures during

balloon drops often caused damage to the hands of the dummies. This

detail, “beings” with “four fingers,” was related by two witnesses as a

distinguishing feature of the Roswell aliens. (U.S. Air Force photo)34

35

What may have contributed to a misunderstanding if the dummies were viewed by persons unfamiliar with their intended use, were the methods used by Holloman AFB personnel to transport them. The dummies were sometimes transported to and from off-range locations in wooden shipping containers, similar to caskets, to prevent damage to fragile instruments mounted in and on the dummy.[65] Also, canvas military stretchers and hospital gurneys were used (a procedure recommended by a dummy manufacturer) to move the dummies in the laboratory or retrieve dummies in the field after a test.[66] The first 10 dummy drops also utilized black or silver insulation bags, similar to “body bags” in which the dummies were placed for flight to guard against equipment failure at low ambient temperatures of the upper atmosphere.[67]

36

On one occasion northwest of Roswell, a local woman unfamiliar with the test activities arrived at a dummy landing site prior to the arrival of the recovery personnel.[68] The woman saw what appeared to be a human embedded head first in a snowbank and became hysterical. The woman screamed, “He’s dead!, he’s dead!”[69]

It now appeared that anthropomorphic dummies dropped by high altitude balloons satisfied the requirements of the research profile. However, the review of high altitude balloon operations revealed what appeared to be explanations for some other sightings of odd objects in the deserts and skies of New Mexico.

Research has shown that many high altitude balloons launched from Holloman AFB, N.M., were recovered in locations, and under circumstances, that strongly resemble those described by UFO proponents as the recovery of a “flying saucer” and “alien” crew. When these descriptions were carefully examined, it was clear that they bore more than just a resemblance to Air Force activities. It appears that some were actually distorted references to Air Force personnel and equipment engaged in scientific study through the use of high altitude balloons.

Since 1947, U.S. Air Force research organizations at Holloman AFB, N.M., have launched and recovered approximately 2,500 high altitude balloons. The Air Force organization that conducted most of these activities, the Holloman Balloon Branch, launched a wide range of sophisticated, and from most perspectives, odd looking equipment into the stratosphere above New Mexico. In fact, the very first high altitude data gathering balloon flight launched from Alamogordo Army Airfield (now Holloman AFB), N.M., on June 4, 1947, was found by the rancher and was the first of many unrelated events now collectively known as the “Roswell Incident.”

In 1956, Twentieth Century Fox released On the Threshold of Space, a full-length motion picture based on Air Force aero medical projects conducted at Holloman AFB, N.M. Starring Guy Madison, John Hodiak, and Dean Jagger, this drama chronicled the high altitude balloon experiments of projects High Dive/Excelsior and the high-speed track studies conducted by Col. John P. Stapp. Filmed on location at Holloman AFB, Air Force personnel, high altitude balloons, aircraft, vehicles, and other equipment, including the actual anthropomorphic dummies responsible for sightings of aliens, were used in the making of this film.

In an ironic twist, in 1990 the television program Unsolved Mysteries, featured a segment on the Roswell Incident. The program, hosted by actor Robert Stack, depicted a dramatized version of the claims of “aliens,” space ships and mysterious government recovery crews. Interestingly, a review of newspapers from 1956 announcing the Hollywood premiere of On the Threshold of Space, listed Stack among the persons scheduled to attend this star-studded event.[70]

39

40

In 1946, as a result of research conducted for project Mogul, Charles B. Moore, a New York University graduate student working under contract for the U.S. Army Air Forces, made a significant technological discovery: the use of polyethylene for high altitude balloon construction.[71] Polyethylene is a lightweight plastic that can withstand stresses of a high altitude environment that differed drastically from, and greatly exceeded, the capabilities of standard rubber weather balloons used previously. Moore’s discovery was a breakthrough in technology. For the first time, scientists were able to make detailed, sustained studies of the upper atmosphere. Polyethylene balloons, first produced in 1947 for Project Mogul, are still widely used today for a host of scientific applications.

High altitude polyethylene balloons and standard rubber weather balloons differ greatly in size, construction, and utility. The difference between these two types of balloons historically has been the subject of misunderstandings in that the term “weather balloon” is often used to describe both types of balloons.

High altitude polyethylene balloons are used to transport scientific payloads of several pounds to several tons to altitudes of nearly 200,000 feet. Polyethylene balloons do not increase in size and burst with increases in volume as they rise, as do standard rubber weather balloons. They are launched with excess capacity to accommodate the increase in volume. This characteristic of polyethylene balloons makes them substantially more stable than rubber weather balloons and capable of sustained constant level flight, a requirement for most scientific applications.

The initial polyethylene balloons had diameters of only seven feet and carried payloads of five pounds or less.[72] As balloon technology advanced, payload capacities and sizes of balloons increased. Modern polyethylene balloons, some as long as several football fields when on41 the ground, expand at altitude to volumes large enough to contain many jet airliners. Polyethylene balloons flown by the U.S. Air Force have reached altitudes of 170,000 feet and lifted payloads of 15,000 pounds.[73]

During the late 1940’s and 1950’s, a characteristic associated with the large, newly invented, polyethylene balloons, was that they were often misidentified as flying saucers.[74] During this period, polyethylene balloons launched from Holloman AFB, generated flying saucer reports on nearly every flight.[75] There were so many reports that police, broadcast radio, and newspaper accounts of these sightings were used by Holloman technicians to supplement early balloon tracking techniques.[76] Balloons launched at Holloman AFB generated an especially high number of reports due to the excellent visibility in the New Mexico region. Also, the balloons, flown at altitudes of approximately 100,000 feet, were illuminated before the earth during the periods just after sunset and just before sunrise. In this instance, receiving sunlight before the earth, the plastic balloons appeared as large bright objects against a dark sky. Also, with the refractive and translucent qualities of polyethylene, the balloons appeared to change color, size, and shape.

The large balloons generated UFO reports based on their radar tracks.[77] This was due to large metallic payloads that weighed up to several tons and echoed radar returns not usually associated with balloons. In later years, balloons were equipped with altitude and position reporting transponders and strobe lights that greatly diminished the numbers of both visual and radar UFO sightings.

One classic misidentification of a Holloman balloon that was mistaken for a UFO, was launched on October 27, 1953.[78] According to the following account published in a widely distributed 1958 history of Air Force balloon operations, Contributions of Balloon Operations to Research and Development at the Air Force Missile Development Center Holloman Air Force Base, N. Mex. 1947–1958, a suspected Holloman balloon was tracked both visually and by radar over London, England on November 3, 1953.

“English accounts of the incident contained such statements as ‘tremendous speed,’ ‘practically motionless,’ ‘circular or spherical and white in color,’ ‘emitting or reflecting a fierce light.’ Altitude was reported as 61,000 feet—and as no research balloon had recently been sent up from Britain, there was ample room for local saucer enthusiasts to claim the ‘unidentified flying object’ as proof of their theories. A much likelier explanation, however, is that this was really the balloon launched from Holloman on 27 October.”[79]

Over the years, payloads transported by high altitude polyethylene balloons ranged from simple radio transmitters to anthropomorphic dummies to sophisticated satellite components and NASA interplanetary space probes. Many of these payloads, some of42 which weighed many tons, were not what someone would typically envision as being associated with a balloon. Examples of payloads flown in New Mexico by Air Force high altitude balloons can be found on pages 52 and 53 at the end of this section.

Research projects of the late 1940’s and 1950’s conducted at Holloman AFB which began with the Project Mogul flights in June 1947, covered a wide spectrum of scientific research. One important experiment in space biology measured the effects of exposure to cosmic ray particles on living tissues.[80] Other projects gathered meteorological data and collected air samples to determine the composition of the atmosphere.[81] The first high altitude photographic reconnaissance project, a forerunner to today’s reconnaissance satellites, Project 119L, also used high altitude balloons launched at Holloman AFB.[82]

As early as May 1948, polyethylene balloons coated or laminated with aluminum were flown from Holloman AFB and the surrounding area.[83] Beginning in August 1955, large numbers of these balloons were flown as targets in the development of radar guided air to air missiles.[84] Various accounts of the “Roswell Incident” often described thin, metal-like materials that when wadded into a ball, returned to their original shape. These accounts are consistent with the properties of polyethylene balloons laminated with aluminum. These balloons were typically launched from points west of the White Sands Proving Ground, floated over the range as targets, and descended in the areas northeast of White Sands Proving Ground where the “strange” materials were allegedly found.

In 1958 the first manned stratospheric balloon flights were made from Holloman AFB (see page 102). In 1960, balloon tests of components of the first U. S. reconnaissance satellite were also flown at Holloman AFB. In the 1960’s, 70’s, and 80’s high altitude balloons were used in support of Air Force, and other U.S. Government and university sponsored research projects. Instrument testing of atmospheric entry vehicles for the National Aeronautics and Space Administration (NASA) space probes is one prominent example.

An illustration of the important contributions of the Holloman AFB Balloon Branch, and the necessity for a rapid recovery of a high altitude balloon payload, were evaluations of components of the first U.S. satellite-based reconnaissance system, code named Corona.

The Soviet Union had already beaten the U.S. into space with the launch and orbit of Sputnik I on October 4, 1957. The next achievement in the quest for space superiority were the physical recovery of a payload that had been in orbit.[85] The Discoverer satellite, the sensor used in the Corona program, was to be propelled into orbit and then eject a capsule containing an American flag to enable the U.S. to claim this honor.[86]

The Discoverer program had been plagued by failure with 10 unsuccessful missions in 1959 and 1960. With the eyes of the nation watching, and the Soviets testing a similar system, more failures could not be tolerated. To test the faulty components of the Discoverer, U.S. Air Force high altitude balloons at Holloman AFB were determined to be the most expedient method of conducting the evaluations.

In April 1960, Discoverer XI, on the launch pad at Vandenberg AFB, Calif., was put into a hold pending results of the balloon tests.[87] The first test at Holloman AFB on April 5th was unsatisfactory due to a parachute failure.[88] On April 8th, with pressure mounting, the Balloon Branch launched another balloon with the Discoverer capsule. This test, in which the capsule was dropped over White Sands Missile Range and recovered immediately, was a total success.[89] The results were relayed by telephone from the Balloon Control Center at Holloman AFB to the launch pad at Vandenberg AFB where the countdown resumed.[90] Despite the successful balloon drop, Discoverer XI and Discoverer XII were failures.[91] Therefore, balloon testing continued throughout the summer of 1960.

44

Finally, on August 11, 1960, Discoverer XIII successfully ejected a capsule and, amid much fanfare, the first recovery of a manmade object that had orbited the earth was accomplished.[92] This first successful mission of an American satellite, made possible in part by Holloman AFB high altitude balloons, enabled the U.S. to beat the Soviets and claim the honor of the first space recovery by only nine days.[93]

The Surveyor (Moon), Voyager-Mars (Mars), Viking (Mars), Pioneer (Venus), and Galileo (Jupiter) spacecraft were tested by Air Force high altitude balloons before they were launched into space.

Viking and Voyager-Mars Space Probes. Examples of unusual payloads, not likely to be associated with balloons, were qualification trials of NASA’s Voyager-Mars and Viking space probes. Both of these spacecraft looked remarkably similar to the classic dome-shaped “flying saucer.”

In 1966–67 and 1972, eight of the UFO lookalikes were launched by the Balloon Branch from the former Roswell Army Air Field (now Roswell Industrial Air Center), N.M.[94] The spacecraft were transported by Air Force balloons to altitudes above 100,000 feet and released for a period of self-propelled, supersonic, free-flight prior to landing on the White Sands Missile Range.[95] While the origins of the “Roswell” scenarios cannot be specifically traced to these vehicles, their flying saucer-like appearance, and the fact that they were launched exclusively from the original “Roswell Incident” location, leaves an impression that perhaps these odd balloon payloads may have played some role in the unclear and distorted stories of at least some of the “Roswell” witnesses.

45

Tethered Balloons. The Holloman Balloon Branch, in addition to high altitude research activities, also conducted low altitude tethered balloon flights. It appears that descriptions of these balloons may have become part of the “Roswell Incident.”

Most standard shaped tethered balloons are readily identified when near the ground or when the tether is visible. Other experimental46 tethered balloons are not so easily identified. During the 1960s, Balloon Branch personnel flew experimentally shaped tethered balloons from deep canyons of central New Mexico. To a distant observer, from a vantage point above the canyon rim, where the tether and ground anchors are not visible, an experimental tethered balloon might lead some persons to speculate as to the oddly shaped balloon’s origin and purpose. One design of a low altitude tethered balloon may have inspired at least one account of an “alien” craft. In The Truth About the UFO Crash at Roswell, the authors published a drawing of a crashed alien spaceship allegedly based on a drawing given to them by an anonymous witness.[96] When this drawing is compared to a photograph of an experimental tethered balloon flown at Holloman AFB in March 1965, the similarities are undeniable.[97] The tethered balloon and the NASA space probes are just two examples of the uncommon technologies that were flown in New Mexico by the Holloman Balloon Branch.

Today, the Air Force maintains a reduced but still highly capable high altitude balloon program at Holloman AFB. The Space and Missile Command, Test and Evaluation Unit (SMC/TE, OL-AC) represents the sole Department of Defense high altitude research balloon capability. The ability of a U.S. Air Force high altitude balloon to lift a scientific payload to more than 100,000 feet, above 99 per cent of the earth’s atmosphere, for days at a time, presents a profoundly useful scientific tool at a fraction of the cost of a space research platform. Recent tests that utilized Holloman balloons included atmospheric sampling and gravity measurement experiments, high altitude astronomic studies, weapons systems evaluations, and gamma ray detection experiments. While most tests continue to be launched from the permanent47 balloon launch facility at Holloman AFB, U.S. Air Force balloon crews have recently launched balloons from numerous field locations in the U.S. (including two sites in Roswell), as well as Alaska, Panama, and Antarctica.

UFO theorists support their claims of an extraordinary occurrence in the New Mexico desert by describing mysterious U.S. military personnel, operating a variety of vehicles and aircraft that always seem to arrive shortly after the crash of a “flying saucer.” When carefully scrutinized, the descriptions of the mystery crews, their equipment, methods, and the areas where the recoveries allegedly occurred—in targeted high altitude balloon recovery areas—indicates that Holloman Balloon Branch activities were most likely responsible for the claims.

To successfully recover high altitude balloons, balloon recovery technicians regularly ventured far from Holloman AFB. In most instances the balloons and their scientific payloads were recovered from predetermined recovery areas. These regularly targeted areas, located in Arizona, West Texas, and New Mexico, included the area surrounding Roswell.[98] From 1947 to the present, the Roswell area has been the site of hundreds of balloon and payload recoveries (including those that carried anthropomorphic dummies).[99]

The regularly targeted areas were the result of the evolution of high altitude balloon control techniques developed at Holloman AFB. These techniques were based on meteorological, geographical, and operational conditions that exist in New Mexico. These factors, combined with ample amounts of skill and experience of balloon controllers at Holloman AFB, determined the impact points of Holloman high altitude balloons.

48

Many of the procedures used to position Air Force balloons are described in General Philosophy and Techniques of Balloon Control, and Meteorological Aspects of Constant-Level Balloon Operations in the Southwestern United States, both by Bernard D. Gildenberg (see statement in Appendix B).[100] Gildenberg served as the Holloman Balloon Branch Meteorologist, Engineer, and Physical Science Administrator from 1951 until 1981. During this period, Gildenberg, a recognized world expert in upper atmospheric wind patterns, pioneered methods to launch, control, track, and recover high altitude balloons. Many of these methods are still used today by the U.S. Air Force and by research organizations throughout the world.

In several accounts, unsubstantiated allegations have been made that military personnel who retrieved equipment from rural areas of New Mexico intimidated and threatened civilians. Contrary to these charges, Balloon Branch personnel enjoyed good relations with the local community and often solicited their assistance in the area of a balloon or payload49 landing. In the flat, featureless desert areas of southeastern New Mexico near Roswell, the parachutes, payloads, the balloons themselves, and circling chase aircraft often drew crowds of curious onlookers from the local community. In fact, so many civilians were often present at balloon or payload landing sites, the scene was described by longtime civilian Balloon Branch recovery supervisor, Robert Blankenship, as being like the “circus coming to town.”[101]

Allegations that civilians were threatened or told to “forget what they saw” are profoundly inaccurate. Threats, intimidation, or other types of misconduct by Balloon Branch personnel would have served no purpose since without the cooperation of local persons, many recoveries would not have been possible.[102]

Most balloon recoveries were coordinated in advance with local law enforcement agencies.[103] If a balloon or payload landed on private property and the owner could not be located, Balloon Branch operating instructions dictated that the local sheriff or police must be contacted.[104] In situations where local persons arrived at balloon landing sites before the recovery crews, they were simply asked to “step back” to allow recovery personnel to secure the balloon equipment.[105] If these persons inquired as to the purpose of a balloon flight, they were informed by technicians that it was a U.S. Air Force scientific study and were given a telephone number at Holloman AFB if they required additional information. At Holloman AFB, individuals qualified to answer detailed questions responded to these50 inquiries. There was never a reason to mislead or threaten individuals who observed balloon operations. Relations with local citizens were good, and Balloon Branch personnel and equipment were a common sight to residents in areas with high incidences of balloon operations.

In a few instances, situations arose when persons not familiar with the procedures and equipment used by the Balloon Branch misunderstood their activities. Such misunderstandings occurred several times during the 1970s and 1980s when recovery crews not only attracted the attention of local citizens while coordinating balloon recoveries, but also drew the attention of federal law enforcement agencies.[106]

Checks with the local sheriff revealed that the trucks and circling aircraft in the desert near Roswell were part of a balloon recovery mission, and not a drug smuggling operation. Apparently, balloon recoveries appeared to be something suspicious even to federal agents.

51

52

53

Were they aliens or dummies? This question can be answered by comparing witness testimony and the Air Force projects of the 1950s, High Dive and Excelsior. Both of these projects employed anthropomorphic dummies flown by high altitude balloons and appeared to satisfy the requirements of the previously established research profile:

a. An activity that if viewed from a distance would appear unusual.

b. An activity for which the exact date was not likely to have been known because many dummies were dropped over a six-year period (1953–1959).

c. An activity that took place in many areas of rural New Mexico.

d. An activity that involved a type of aerial vehicle with dummies that had four fingers, were bald and wore one-piece gray suits.

e. An activity that required recovery by numerous military personnel and an assortment of vehicles that included a wrecker, a six-by-six, and a weapons carrier.

The testimony used in the following comparison, an undocumented mixture of firsthand and secondhand re-countings, are the actual statements, not the interpretations of UFO proponents, that are presented to “prove” the Earth was visited by extraterrestrial beings and the U.S. Air Force has covered up this fact since 1947. This comparison is augmented by references to photographs whenever possible to illustrate the undeniable similarities between the descriptions provided by the witnesses and the equipment and methods employed by the Air Force projects.

56

This summarized account is the basis for the alleged “flying saucer” crash site north of Roswell.* The exact location is not known since the witness, Mr. James Ragsdale, in two separate sworn statements, has described two different sites, many miles apart.[107] This account was excerpted from an interview with Mr. Ragsdale by author Donald Schmitt. A transcript of the complete interview is included in Appendix C.

“They was using dummies in those damned things”[108]

Testimony attributed to Ragsdale, who is deceased, states that he and a friend were camping one evening and saw something fall from the sky. The next morning, when they went to investigate, they saw a crash site:

“One part [of the craft] was kind of buried in the ground and one part of it was sticking our [out] of the ground.” “I’m sure that [there] was bodies ... either bodies or dummies.” “The federal government could have been doing something they didn’t want anyone to know what this was. They was using dummies in those damned things ... they could use remote control ... but it was either dummies or bodies or something laying there. They looked like bodies. They were not very long ... [not] over four or five foot long at the most.” “We didn’t see their faces or nothing like that ... we had just gotten to the site and the Army ... and all [was] coming and we got into a damned jeep and took off.”

This testimony then describes an assortment of military vehicles used to recover the “bodies”: “It was two or three six-by-six Army trucks a wrecker and everything. Leading the pack was a ’47 Ford car with guys in it.... It was six or eight big trucks besides the pickup, weapons carriers and stuff like that.” Ragsdale also said that before he left the area he observed the military personnel “gathering stuff up” and “they cleaned everything all up.”