THE

OR,

FIRST LESSONS IN GEOLOGY,

AND

THE STUDY OF ORGANIC REMAINS.

VOL. I.

"If we look with wonder upon the great remains of human works, such as the columns of Palmyra, broken in the midst of the desert; the temples of Pæstum, beautiful in the decay of twenty centuries; or the mutilated fragments of Greek sculpture in the Acropolis of Athens, or in our own museums, as proofs of the genius of artists, and power and riches of nations now past away; with how much deeper feeling of admiration must we consider those grand monuments of nature which mark the revolutions of the Globe; continents broken into islands; one land produced, another destroyed; the bottom of the ocean become a fertile soil; whole races of animals extinct, and the bones and exuviæ of one class covered with the remains of another; and upon the graves of past generations—the marble or rocky tombs, as it were, of a former animated world—new generations rising, and order and harmony established, and a system of life and beauty produced out of chaos and death; proving the infinite power, wisdom, and goodness of the Great Cause of all things!"—Sir H. Davy.

MEDALS OF CREATION

THE

OR,

FIRST LESSONS IN GEOLOGY,

AND

THE STUDY OF ORGANIC REMAINS.

BY

GIDEON ALGERNON MANTELL, LL.D. F.R.S. V.P.G.S.

PRESIDENT OF THE WEST LONDON MEDICAL SOCIETY, ETC. AUTHOR OF THE WONDERS OF GEOLOGY, ETC.

"Voilà! une nouvelle espèce de médailles, beaucoup plus importantes, et incomparablement plus anciennes, que toutes celles des Grecs et des Remains!"—Knorr, Monumens des Catastrophes.

Gideon Algernon Mantell

IN TWO VOLS.—VOL. 1.

CONTAINING

SECOND EDITION, ENTIRELY REWRITTEN.

LONDON:

HENRY G. BOHN, YORK STREET, COVENT GARDEN.

MDCCCLIV

LONDON:

R. CLAY, PRINTER, BREAD STREET HILL.

TO

MY SONS,

WALTER MANTELL,

OF WELLINGTON, NEW ZEALAND,

AND

REGINALD NEVILLE MANTELL,

OF KENTUCKY, UNITED STATES,

MY LAST ATTEMPT TO PROMOTE THE ADVANCEMENT

OF SCIENTIFIC KNOWLEDGE,

IS MOST AFFECTIONATELY INSCRIBED.

G. A. M.

Chester Square, Pimlico,

Feb. 3, 1853.

[The above having been penned by the much-lamented author of the "Medals" some months previous to his decease, it is retained in this posthumous edition of his favourite work as an appropriate dedication, dictated by the parental affection of one of the chief promoters of geological science in England, and addressed to his absent sons, whose works have already shown them to be enthusiastic labourers in the same field, both at home and in distant parts of the world.]

PREFATORY NOTE TO THE SECOND EDITION.

The untimely Decease of the lamented Author of the "Medals of Creation" during the progress of the present edition through the press has unavoidably delayed its publication.

The First Volume has been wholly rewritten by the Author.

The materials of the Second Volume had been elaborately revised and much enlarged by Dr. Mantell previously to his Decease. The Editor has laboured to carry out the intentions of the Author in rendering this part of the Work as complete a compendium as possible of the Palæontological history of the Organic Beings of which it treats, and in adapting it to the requirements of the Geological Student of the present time.

The various sources from which palæontological and zoological information has been derived have, for the most part, been adverted to in the text or in the footnotes. « viii » The Editor, however, has especially to acknowledge the kindness of Mr. J. Morris, F.G.S., in allowing him to refer to the proof-sheets of the forth-coming edition of his "Catalogue of British Fossils," and thereby affording him important assistance in making correct statements of the distribution of the Fossil Remains of the Crustacea, Insecta, and Vertebrata, in the strata of the British Islands.

T. Rupert Jones.

PREFACE TO THE FIRST EDITION.

In the first edition of the Wonders of Geology, an intention was expressed of immediately publishing, as a sequel to those volumes, "First Lessons," or an Introduction to the Study of Petrifactions, for persons wholly unacquainted with the nature of Fossil Remains; but the completion of the contemplated work was unavoidably postponed, from year to year, by the long and severe indisposition of the Author.

In the meanwhile several works professing the same object have issued from the press; and an enlarged edition of Sir C. Lyell's "Elements" has also appeared, in which the elementary principles of physical Geology are fully illustrated, and numerous figures given of the characteristic fossils of the several formations, or groups of strata. But that department of the science which especially treats of Organic Remains is necessarily considered in a cursory manner; and a work upon the plan originally contemplated by the Author seems still to be required, to initiate the young and uninstructed in the study of those Medals of Creation—those electrotypes of nature—the mineralized remains of the plants and animals which successively flourished in the earlier ages of our planet, in periods incalculably remote, and long antecedent to all human history and tradition.

With this conviction the present volumes are offered, with such modifications of the original plan as circumstances have rendered necessary, as a guide for the Student and the Amateur Collector of fossil remains; for the intelligent Observer who may desire to possess a general knowledge of the subject, without intending to pursue Geology as a science; and for the Tourist who may wish, in the course of his travels, to employ profitably a leisure hour in quest of those interesting memorials of the ancient physical revolutions of our globe, which he will find everywhere presented to his observation.

Crescent Lodge,

Clapham Common,

May, 1844.

ADDRESS TO THE READER.

"Some books are to be tasted—others to be swallowed—and some few to be chewed and digested; that is, some Books are to be read only in parts—others to be read, but not curiously—and some few to be read wholly and with diligence and attention."—Lord Bacon's Essays.

Anxious that the "Courteous Reader" should derive from this work all the information it is designed to impart, the Author presumes to offer a few words in explanation of the plan upon which it has been constructed, and some suggestions as to the best means of rendering its contents most available to the varied tastes and pursuits of different classes of readers.

In its arrangement, a three-fold object was had in view; namely, in the first place, to present such an epitome of Palæontology, the science which treats of the fossil remains of the ancient inhabitants of the Globe, as shall enable the intelligent Observer to comprehend the nature of the principal discoveries in modern Geology, and the method of investigation by which such highly interesting, and unexpected results, have been obtained..

Secondly, to assist the Collector in his search for Organic Remains,—directing attention to those objects which possess the highest interest, and are especially deserving of accurate examination—instructing him in the art of developing and « xii » preserving the specimens he may discover—and pointing out the means to be pursued, for ascertaining their nature, and their relation to existing plants or animals.

Thirdly, to place before the Student a familiar exposition of the elementary principles of Palæontology, based upon a general knowledge of the structure of vegetable and animal organization; to excite in his mind a desire for further information, and prepare him for the perusal and study of works of a higher order than these unpretending volumes; and to point out the sources from which the required instruction may be derived.

Although fully aware of the imperfect manner in which these intentions are fulfilled, the Author hopes that the indulgence claimed by one of the most able writers of our times may be extended to him; and that, "if the design be good upon the whole, the work will not be censured too severely for those faults, from which, in parts, its very nature would scarcely allow it to be free."[1]

[1] Sir E. B. Lytton—preface to the second edition of "The Disowned."

With regard to the best means of making use of these volumes, the advice of the great founder of Inductive Philosophy, on the Study of Books in general, expressed in the quotation prefixed to this address, is peculiarly applicable to the different classes of readers for whom the work is designed.

Thus, "the Book may be tasted, that is, read only in parts," by the intelligent reader, who requires but a general acquaintance with the subjects it embraces. The perusal of the introductory and concluding remarks of each chapter, of the « xiii » general descriptions of fossil remains, and of the circumstances under which they occur,—omitting the scientific terms and descriptions,—and a cursory examination of the illustrations, will probably satisfy his curiosity; and the work may be transferred to the library for occasional reference, or taken as a travelling companion and guide to some interesting geological district.

But the Book "must be swallowed, that is, read, but not curiously," by the reader desirous of forming a collection of organic remains. A general acquaintance with its contents, and a careful investigation of the characters of the fossils, and comparison with the figures and descriptions, will be requisite to enable the amateur collector to determine the nature of the specimens he may discover.

By the Student the Book "must be digested, that is, read wholly, and with diligence and attention." He should fully comprehend one subject before he advances to the consideration of another, and should test the solidity of his knowledge by practical research. He should visit some of the localities described; collect specimens, and develope them with his own hands; examine their structure microscopically; nor rest satisfied until he has determined their general characters, and ascertained their generic and specific relations. Nor is this an arduous or irksome task; by a moderate degree of attention, a mind of average ability may quickly overcome the apparent difficulties, and will find in the knowledge thus acquired, and in the accession of mental vigour which such investigations never fail to impart, an ample reward for any expenditure of time and trouble.

It is, indeed, within the power of every intelligent reader, by assiduity and perseverance, to attain the high privilege of those who walk in the midst of wonders, in circumstances where the uninformed and uninquiring eye can perceive neither novelty nor beauty; and of being

VOL. I.

Dedication, p. v.

Prefatory Note to the Second Edition, vii.

Preface to the First Edition, ix.

Address to the Reader, xi.

Table of Contents, xv.

Description of the Plates, xix.

List of Lignographs in Vol. I., xxxi.

Introduction, 1.

Preliminary Remarks:—On the Plan of the Work and the Arrangement and Subdivision of the subjects it embraces, 8. Works of Reference, 8. Explanation of Terms, 11. List of subjects, 12.

PART I.—Stratigraphy of the British Islands, and the Nature of Fossils, 15.

Chapter I.—On the Nature and Arrangement of the British Strata and their Fossils, 15.

Chapter II.—Synopsis of the British Strata, 23. Chronological Arrangement of the British Formations; Modern or Human Epoch; Post-Pliocene, 23. Tertiary Epochs, 24. Secondary Epochs, 25. Palæozoic Epochs, 30. Hypogene Rocks, 34. Volcanic Rocks, 35.

Chapter III.—On the Nature of Fossils or Organic Remains, 37. Incrustations, 38. Silicification, 40. Animal Remains, 43. Hints for Collecting Fossil Bones, 45.

PART II.—Fossil Botany, 51.

Chapter IV.—Fossil Botany, 51. Fossil Vegetables, 51. On the investigation of the Fossil Remains of Vegetables, 54. Endogenous Stems, 56. Exogenous Stems, 56. Structure of Coniferæ, 57. Botanical principles, 58. Exogens, 59. Endogens, 59. Investigation of Fossil Stems, 61. Fossil Leaves, 64. On the Microscopical Examination of Fossil Vegetables, 65. Mode of preparing slices of Fossil Wood, 66.

Chapter V.—On Peat-wood, Lignite, and Coal, 69. Submerged Forests; Peat, 70. Lignite, Brown-coal, Cannel-coal, 71. Bovey-coal, 72. Jet, 72. Wealden Coal, 73. Coal, 76. Stratification of a Coal-field, 80. Origin and Nature of Coal, 82.

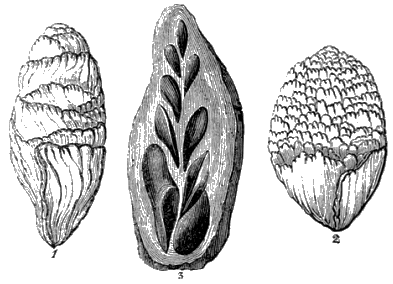

Chapter VI.—Fossil Vegetables, 86. Fossil Cryptogamia, 87. Recent Diatomaceæ, 88. Fossil Diatomaceæ, 93. Fossil Coniferæ, 100. Fossil Fucoids, 101. Chondrites, 101. Moss-agates and Mocha-stones, 103. Equisetaceæ, 105. Calamites, 107. Filicites or Fossil Ferns, 109. Pachypteris, 112. Sphenopteris, 112. Cyclopteris, 114. Neuropteris, 115. Glossopteris, 115. Odontopteris, 116. Anomopteris, 116. Tœniopteris, 117. Pecopteris, 118. Lonchopteris, 119. Phlebopteris, 120. Clathropteris, 121. Stems of Arborescent Ferns, 122. Caulopteris, 123. Psarolites, 123. Sigillariæ and Stigmariæ, 125. Internal Structure of Sigillariæ, 130. Stigmaria, 132. Lepidodendron, 137. Lepidostrobus, 140. Triplosporite, 142. Lycopodites, 143. Halonia and Knorria, 143. Asterophyllites, 145. Sphenophyllum, 147. Cardiocarpon, 147. Trigonocarpum, 148. Fossil Cycadaceæ, 150. Pterophyllum, 152. Zamites, 152. Trunks and Stems of Cycadaceæ, 156. Mantellia, 157. Clathraria, 159. Endogenites, 163. Fossil Coniferæ, 164. Fossil Coniferous Wood, 167. Palæoxylon, 167. Pence, 168. Araucarites, 168. Sternbergia, 168. Petrified Forests of Conifers, 169. Coniferous Wood in Oxford Clay, 172. Coniferous Wood in Chalk, 173. Tertiary Coniferous Wood, 175. Fossil Foliage and Fruit of Coniferæ, 175. Araucaria, 175. Pinites, 176. Walchia, 177. Abietites, 178. Thuites, 180. Voltzia, 180. Taxites, 181. Nœggerathia, 181. Fossil Resins and Amber, 181. Fossil Palms, 183. Fossil Palm-leaves, 185. Fossil Fruits of Palms, 186. Fossil Fruits from the Isle of Sheppey, 186. Nipadites, 190. Fossil Fruit of Pandanus, 192. Wood perforated by Teredines, 193. Fossil Liliaceæ, 194. Fossil Fresh-water Plants, 195. Fossil Fruits of Chara, 195. Fossil Nymphaeæ, 197. Fossil Flowers, 197. Fossil Angiosperms, 197. Fossil Flora of Œningen, 200. Carpolithes, 202. Fossil Dicotyledonous Trees, 203. Dicotyledons of the Cretaceous Epoch, 205. Retrospect of Fossil Botany, 206. On Collecting British Fossil Vegetables, 211. British localities of Fossil Vegetables, 213.

PART III.—Fossil Zoology, 216.

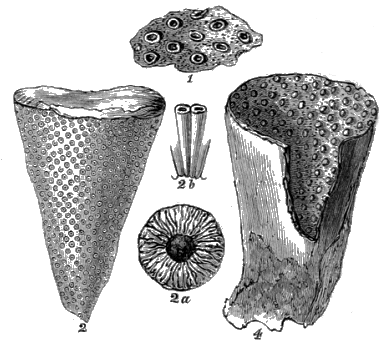

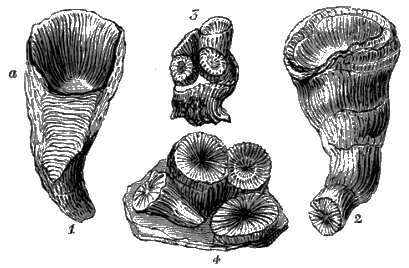

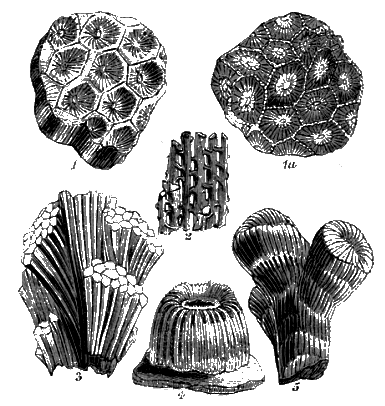

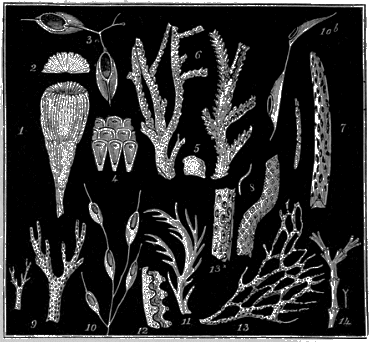

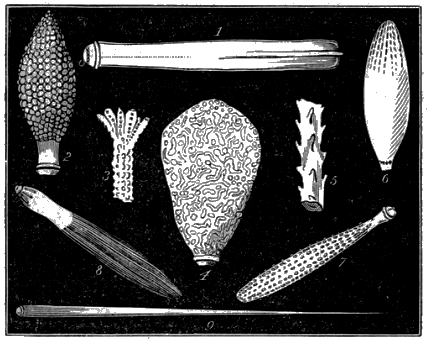

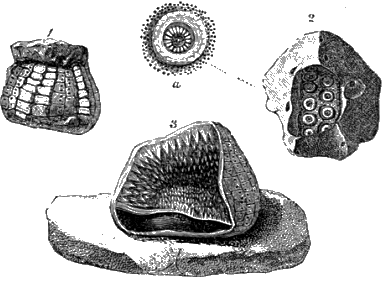

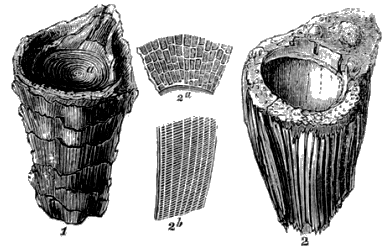

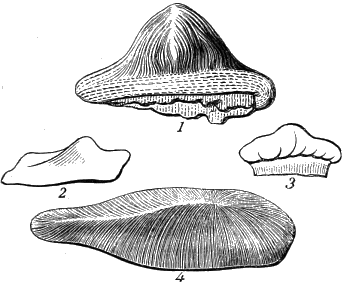

Chapter VII.—Fossil Zoophytes; Porifera or Amorphozoa; Polypifera or Corals; Bryozoa or Molluscan Zoophytes, 218. Fossil Porifera, 219. On the Sponges in Chalk and Flint, 222. Spongites, 223. Fossil Zoophytes of Faringdon, 226. Scyphia, 227. Cnemidium, 228. Chenendopora, 228. Tragos, 229. Siphonia, 230. Choanites, 233. Paramoudra, 236. Clionites, 238. Spicula of Sponges, 238. Spiniferites, 239. Ventriculites, 242. Polype in Flint, 250. Fossil Polypifera, 251. Graptolites, 255. Fungia, 256. Anthophyllum, 257. Turbinolia, 257. Caryophillia, 257. Favosites, 258. Catenipora, 259. Springopora, 259. Lithostrotion, 260. Cyathophyllum, 260. Astræa, 262. Madrepora, 264. Millepora, 264. Lithodendron, 264. Gorgonia, 265. Fossil Bryozoa, 265. Flustra, 266. Crisia, 269. Retepora, 269. Fenestrella, 270. Petalæpora, 270. Pustulopora, 270. Homœsolen, 271. Idmonea, 271. Verticillipora, 273. Lunulites, 273. Geological Distribution of Fossil Zoophytes, 273. On Collecting Fossil Corals, 276. British localities, 278.

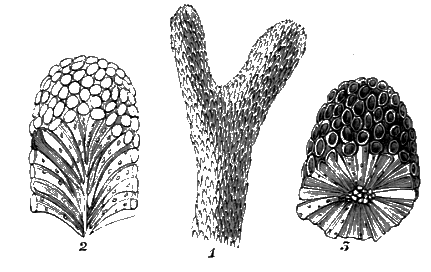

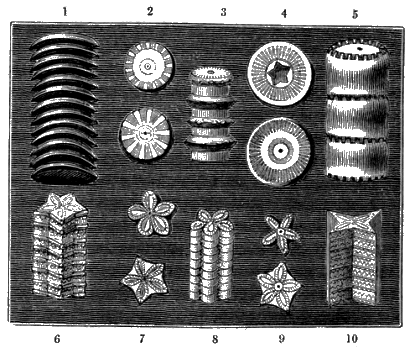

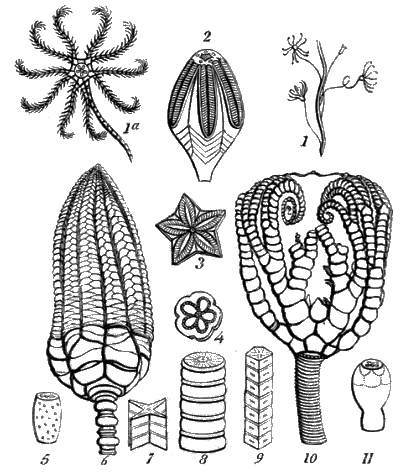

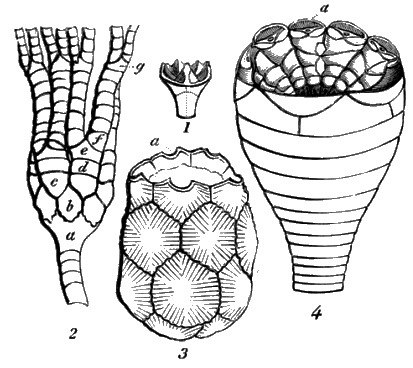

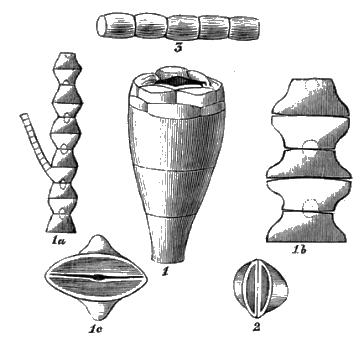

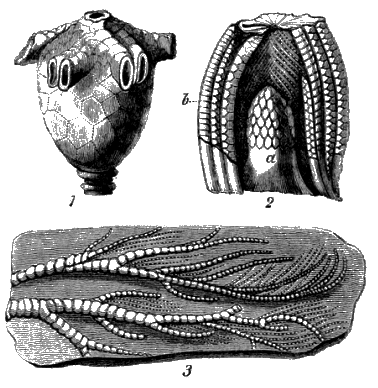

Chapter VIII.—Fossil Stelleridæ; comprising the Crinoidea and the Asteriadæ, 280. Crinoidea, 281. Pentacrinus, 282. Fossil Crinoidea, 283. Fossil Stems of Crinoidea, 284. Pulley-stones, 285. Apiocrinus, 288. Bourqueticrinus, 291. « xvii » Encrinus, 292. Pentacrinites, 293. Actinocrinus, 295. Cyathocrinus, 295. Rhodocrinus, 297. Eugeniacrinus, 297. Pentremites, 297. Cystidea, 298. Marsupites, 299. Fossil Asteriadæ, 301. Fossil Ossicula of Star-Fishes, 303. Ophiura, 304. Goniaster, 306. Asterias, 307. Geological Distribution of the Crinoidea, 308.

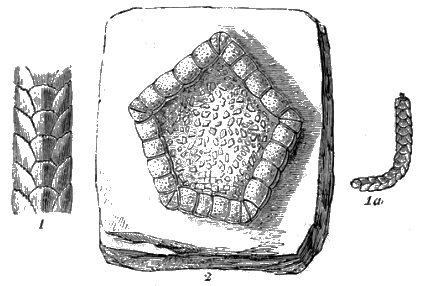

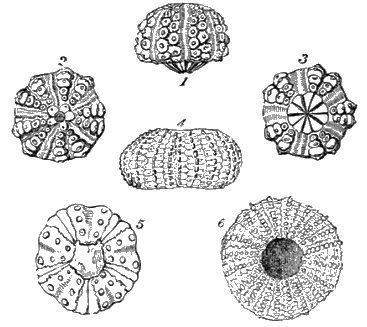

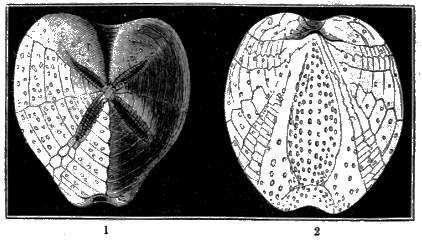

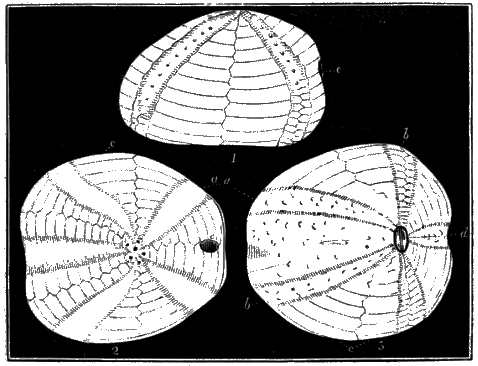

Chapter IX.—Fossil Echinidæ, 311. Cidaritidæ, 314. Cidaris, 316. Diadema, 318. Echinus, 318. Salenia, 318. Spines of Cidarites, 319. Flint Casts of Cidarites, 320. Cidaritidæ of the Palæozoic Rocks, 321. Clypeasteridæ, 322. Galerites, 322. Holectypus, 324. Discoidea, 324. Clypeideæ, 325. Clypeus, 325. Nucleolites, 326. Spatangidæ, 326. Ananchytes, 327. Micraster, 328. Toxaster, 329. Holaster, 330. Geological Distribution of Echinites, 330. On Collecting and Developing Echinodermata, 331.

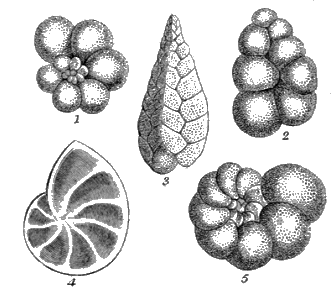

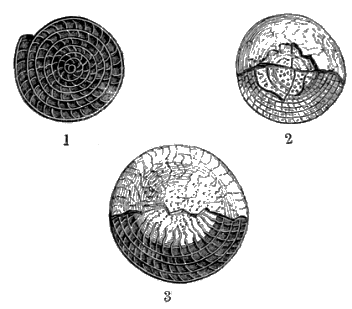

Chapter X.—Fossil Foraminifera; and Microscopical Examination of Chalk and Flint, 336. Foraminifera, 339. Classification of the Foraminifera, 342. Nummulites, 344. Orbitoides, 346. Siderolina, 346. Fusulina, 346. Nodosaria, 347. Cristellaria, 348. Flabellina, 348. Polystomella, 348. Lituola, 348. Spirolina, 349. Globigerina, 350. Nonionina, 350. Rotalia, 351. Rosalina, 351. Textularia, 352. Verneuilina, 352. Strata composed of Foraminifera, 352. Foraminifera of the Chalk and Flint, 355. Fossil Remains of the Soft Parts of Foraminifera, 357. Foraminifera-Limestones of India, 362. Foraminifera-deposit at Charing, 363. Foraminifera of the Oolite, Lias, &c. 364. Foraminifera-deposits of the United States, 364. Foraminifera of the Carboniferous Formations, 365. Foraminifera-Limestone of New Zealand, 366. Tertiary Foraminifera, 366. Foraminifera of the Fens of Lincolnshire and Cambridgeshire, 367. Recent Foraminifera-deposit at Brighton, 368. Geological Distribution of the Foraminifera, 369. Instructions for the Microscopical Examination of Chalk, Flint, and other Rocks, 371.

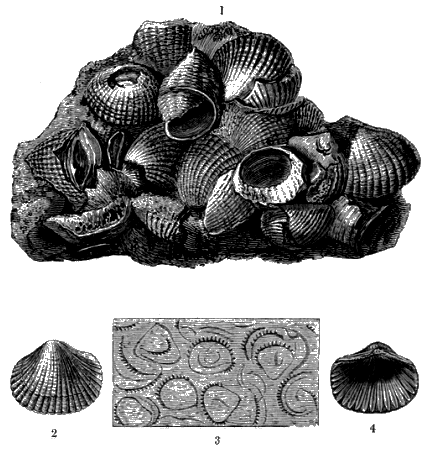

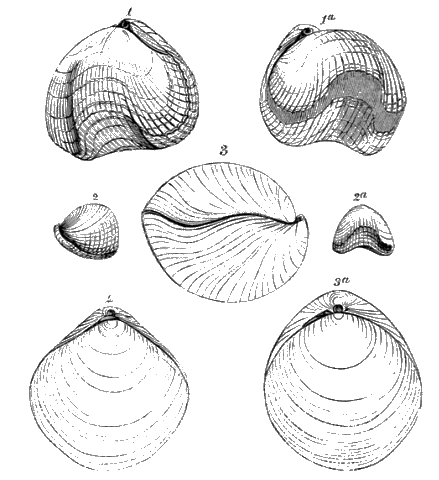

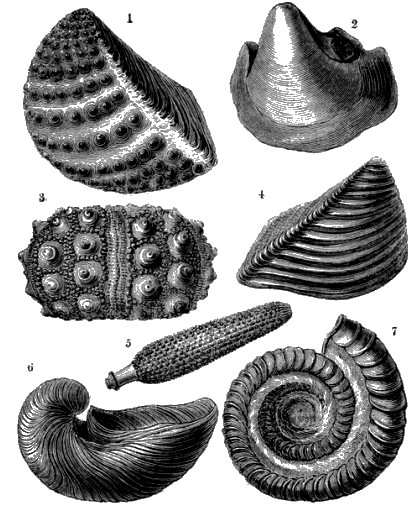

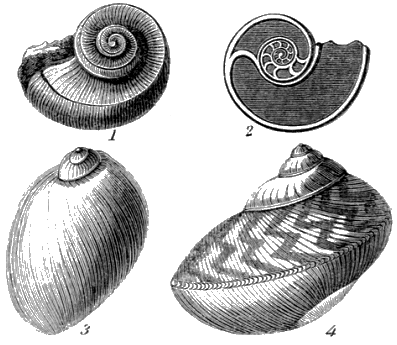

Chapter XI.—Fossil Testaceous Mollusks, or Shells, 374. Mollusca, 374. Acephala, 375. Encephala, 378. Fossil Bivalve Shells, 381. Shell-Rocks, 382. Fossil Brachiopoda, 388. Terebratula, 389. Spirifer, 390. Rhynchonella, 391. Pentamerus, 391. Orthis, Leptæna, and Productus, 392. Calceola, 392. Crania, 392. Orbicula, 392. Obolus, 392. Lingula, 393. Hippurites, 393. Fossil Shells of the Lamellibranchiates, 394. Monomyaria, 395. Ostrea, 395. Gryphæa, 396. Spondylus, 398. Plagiostoma, 399. Plicatula, 400. Pecten, 400. Inoceramus, 401. Avicula, 404. Dimyaria, 404. Venericardia, 405. Pectunculus, 405. Nucula, 406. Pinna, 406. Mytilus, 407. Modiola, 407. Pholadomya, 408. Pholas, 408. Teredo, 410. Trigonia, 412. Fossil Fresh-water Bivalves, 413. Unio, 414. Cyclas, 416. Fossil Pteropoda, 417. Fossil Gasteropoda, 417. Fresh-water Univalves, 421. Paludina, 421. Limnæus, 423. Planorbis, 423. Melanopsis, 424. Marine Univalves, 424. Fusus, 425. Pleurotoma, 425. Cerithium, 425. Potamides, 425. Rostellaria, 426. Dolium, 426. Trochus,426. Solarium, 426. Conus, 426. Pleurotomaria, 427. Euomphalus, 429. Murchisonia, 430. Sphærulites, 430. Molluskite, 432. Geological Distribution of Bivalve and Univalve Mollusks, 436. On the Collecting and Arranging Fossil Shells, 441. British Localities of Fossil Shells, 443.

CONTENTS OF VOL. II.

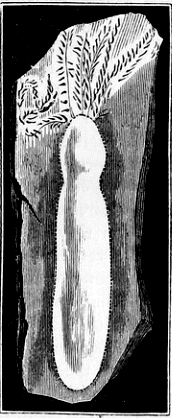

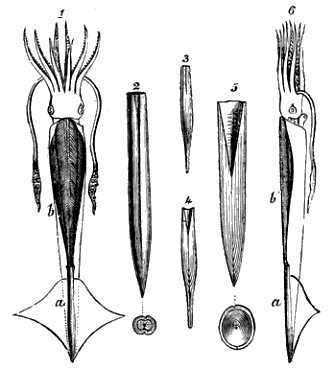

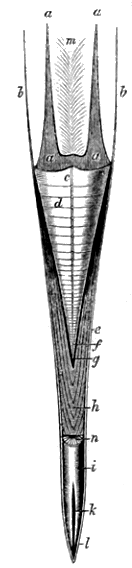

Description of Frontispiece (Plate II.)

List of Lignographs in Vol. II.

PART III.—continued.

Chapter XII.—Fossil Cephalopoda, 447.

Chapter XIII.—Fossil Articulata, 503.

Chapter XIV.—Fossil Ichthyology; Sharks, Rays, and other Placoid Fishes, 562.

Chapter XV.—Fossil Ichthyology; Ganoid, Ctenoid, and Cycloid Fishes, 600.

Chapter XVI.—Fossil Reptiles; Enaliosaurians and Crocodiles, 643.

Chapter XVII.—Fossil Reptiles; Dinosaurians, Lacertians, Pterodactyles, Turtles, Serpents, and Batrachians, 684.

Chapter XVIII.—Fossil Birds, 759.

Chapter XIX.—Fossil Mammals, 775.

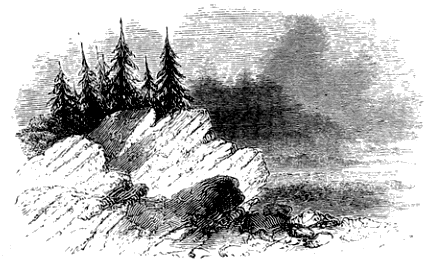

PART IV.—Geological Excursions, 827.

Miscellaneous, 905.

General Index, 909.

DIRECTIONS TO THE BINDER.

Plate I.—Frontispiece to Vol. I.

Plate II. Frontispiece to Vol. II.

Plates III., IV., V., and VI., to follow the Table of Contents, and be placed opposite the description of each.

Lign. 247, to face page 770.

DESCRIPTION

OF THE

FRONTISPIECE OF VOL. I.

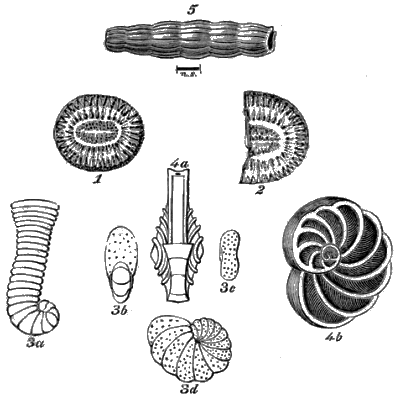

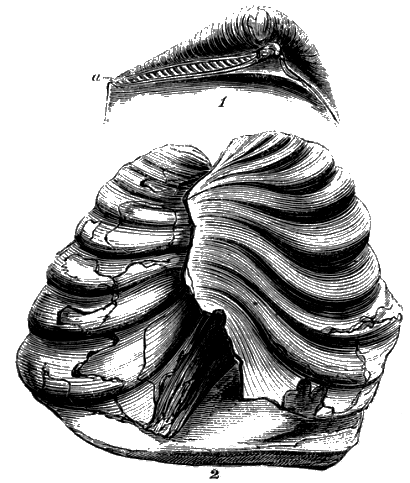

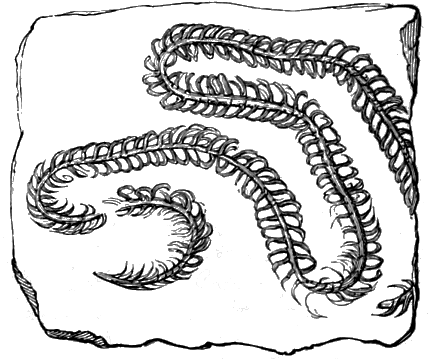

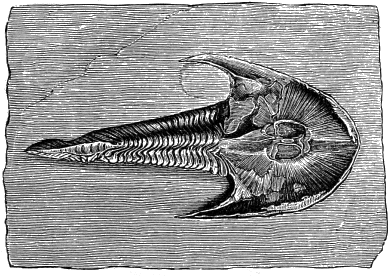

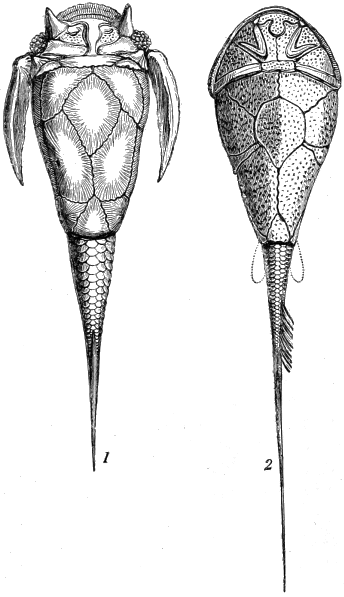

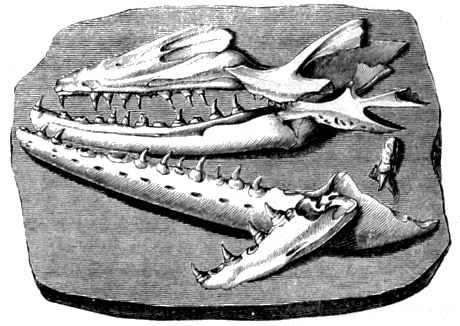

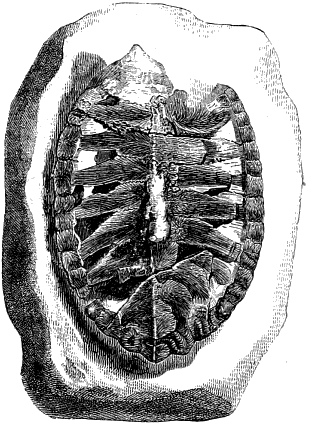

| Fig. | 1.— | A Fern in Coal-shale, from Leicestershire. |

| 2.— | A Crustacean in Limestone, from Solenhofen. | |

| 3.— | A Fish (Pycnodus rhombus) in Limestone; from near Castel-a-mare. | |

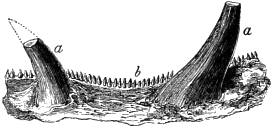

| 4.— | Half the Lower Jaw of a Hyena, from a fissure in a sandstone rock, near Maidstone. | |

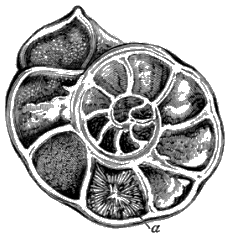

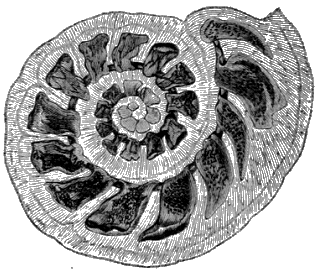

| 5.— | An Ammonite, from the Isle of Portland. |

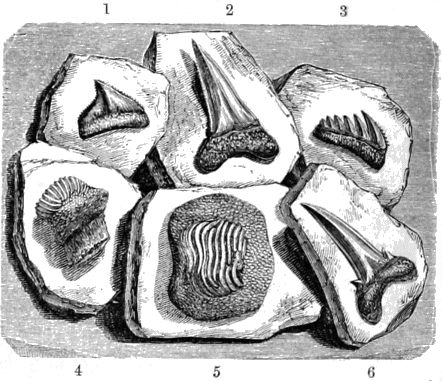

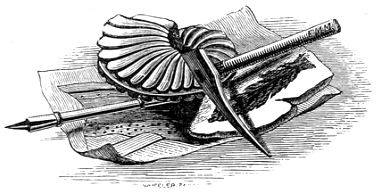

DESCRIPTION OF THE VIGNETTE OF VOL. I.

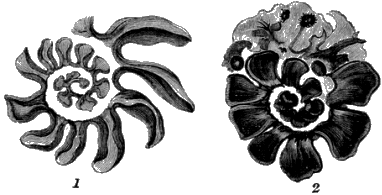

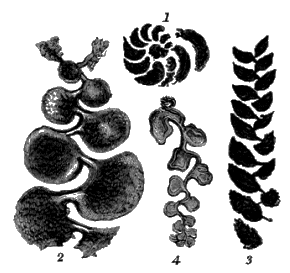

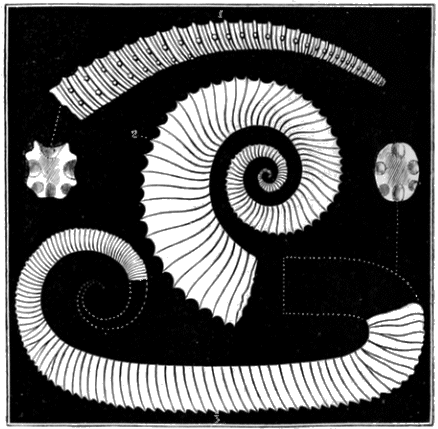

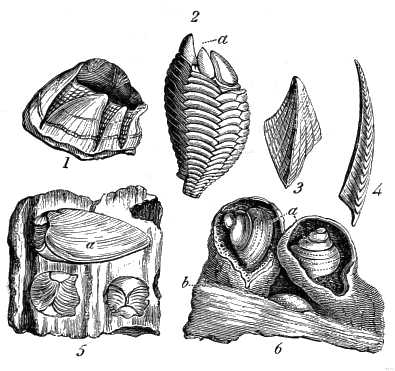

A Group of Fossils, containing

Ammonites Mantellii, from the Chalk-marl, Sussex.

Turrilites costatus, from the Lower Chalk, Rouen.

Chondrites Bignoriensis, from the Chalk-marl, Sussex.

Echinus and Fusus, from Tertiary strata, Palermo.

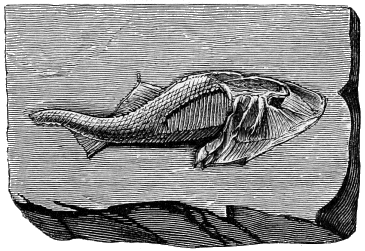

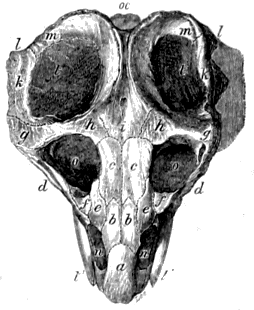

DESCRIPTION OF PLATE II.

A Fossil Fish of the Salmon tribe, allied to the Smelt; from the Chalk, near

Lewes, in Sussex.

[See Vol. II. pages 626 and 628.]

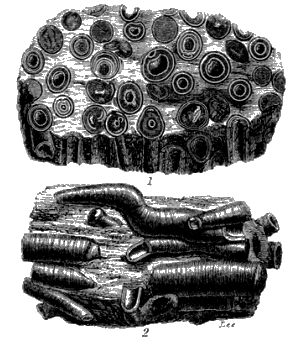

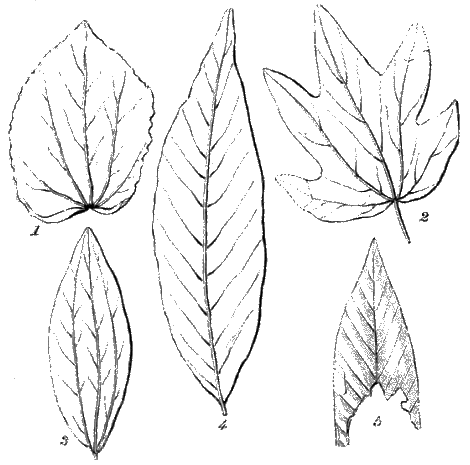

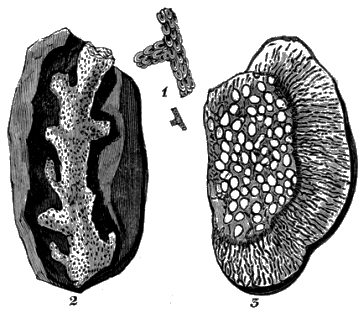

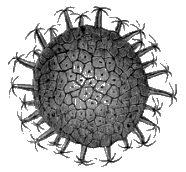

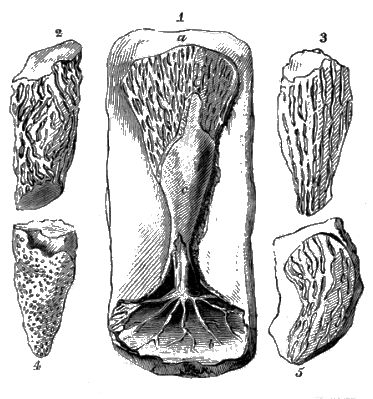

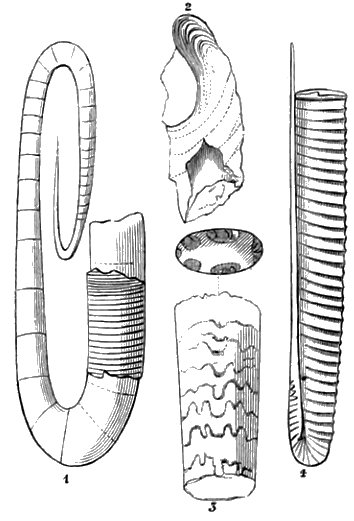

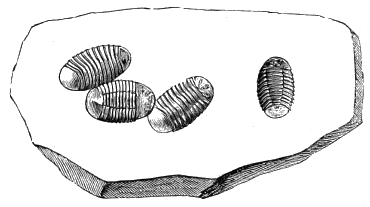

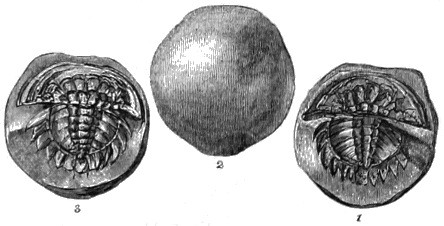

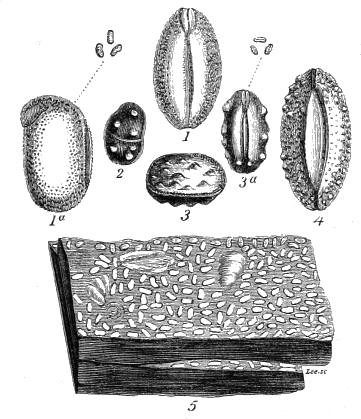

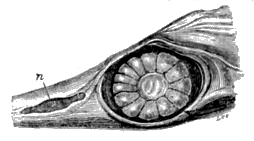

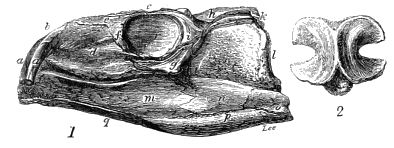

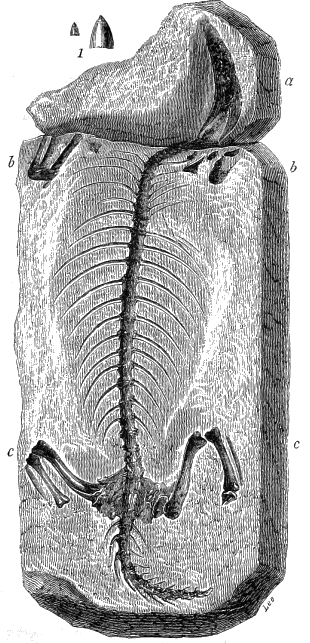

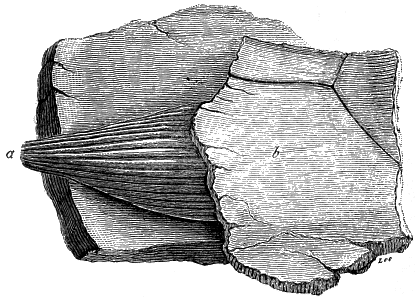

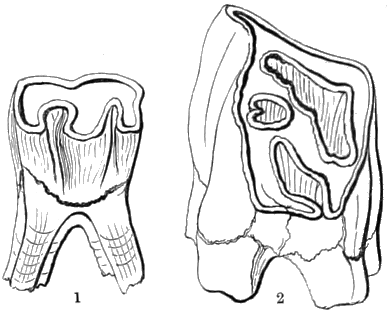

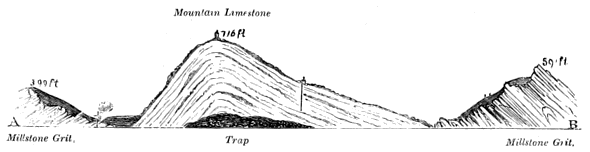

DESCRIPTION OF PLATE III.

Incrustations, and Fossil Plants.

| Figs. | 1, 2, 3.— | Twigs of Larch and Hawthorn, coated with tufa, or travertine, from having been exposed to the dripping of an incrusting spring; from Russia; see p. 39. |

| 5.— | A branch of recent Chara, with its fruit, with a thin pellicle of incrustation. Matlock. | |

| 6, 7.— | Hazel-nuts, from Belfast Lough: fig. 6 is lined with crystals of calcareous spar; fig. 7 is filled with a solid mass of the same mineral; see p. 71. | |

| 4, 8.— | Impressions of Dicotyledonous Leaves in Gypseous Marlstone, from Stradella, near Pavia; see p. 201. | |

| 9.— | Eocene Lacustrine or Fresh-water Limestone, from East Cliff Bay, Isle of Wight, with stems and seeds of Charge: slightly magnified; see p. 195. | |

| 10.— | Encrusted Twigs, from Matlock; the vegetable matter has perished, and left tubular cavities; see p. 39, and p. 873. |

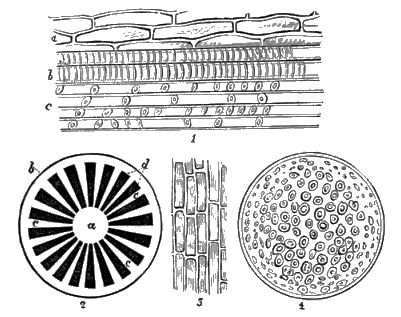

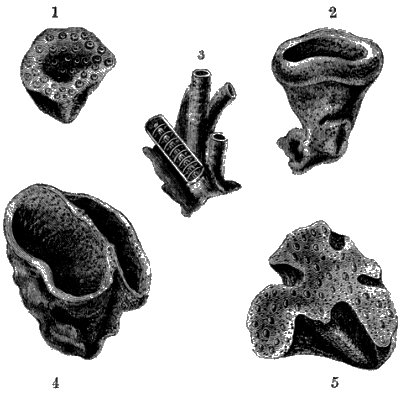

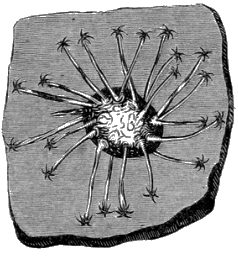

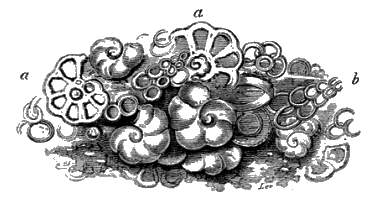

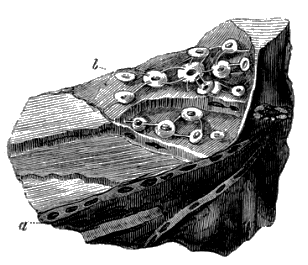

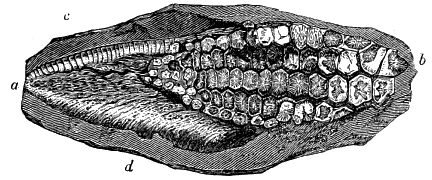

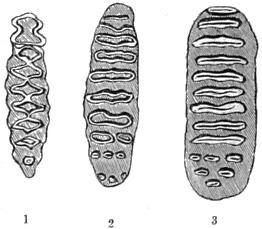

DESCRIPTION OF PLATE IV.

Various species of recent Diatomaceæ, to illustrate the Fossil remains of this Tribe of Vegetables.

For detailed descriptions, see pages 87-100.

| Figs. | 1 to 5.— | Various kinds of Xanthidia: figs. 2, 3, 4, found in a pond on Clapham Common, and fig. 1. living in a pond near Westpoint, United States. |

| 1.— | Xanthidium furcatum: 1/24 of a line in diameter. | |

| 2.— | ———— hirsutum: 1/36. | |

| 3.— | ———— aculeatum: 1/24. | |

| 4.— | ———— fasciculatum: 1/24. | |

| 5.— | —————————— variety of the above. | |

| 2*.— | Pyxidicula operculata; Carlsbad, Bohemia: 1/48 of a line in diameter. | |

| 6.— | Bacillaria vulgaris. 1/36 of a line in diameter. Pond on Clapham Common. | |

| 7.— | Cocconeis scutellum: from the Baltic: 1/24 of a line. | |

| 8.— | Navicula viridis: 1/6 of a line. Ponds on Clapham Common. | |

| 9.— | The same; a side view; showing the currents produced in the water by the animal when in locomotion. | |

| 10.— | Gallionella lineata: 1/36 of a line. Ponds on Clapham Common. | |

| 11.— | Gallionella moniliformis: 1/72 of a line. | |

| 12.— | Synhedra ulna: 1/9 of a line: the point a, marks the pedicle of attachment. Ponds on Clapham and Wandsworth Commons. | |

| 13.— | Podosphenia gracilis: 1/12 of a line; attached to a thread of Calothria and having by self-division formed a radiating cluster. Common in the ditches communicating with the Thames in Battersea-fields. | |

| 14.— | Navicula splendida: 1/12 of a line in diameter. | |

| 15.— | Lateral view of the same. « xxvi » | |

| 16.— | Eunotia turgida: 1/14 of a line; the empty shell, with sixty-five ribs, viewed laterally. | |

| 17.— | A living group of the same: 1/20 of a line: a piece of Conferva rivularis, beset with these animalcules. The smaller species are E. Westermanni. |

[All the above organisms were figured and described by Ehrenberg as animals (Polygastrica), and are comprised in his family Bacillaria; they are now, however, regarded as unquestionably vegetable structures, belonging to the family of Algæ, termed Diatomaceæ.]

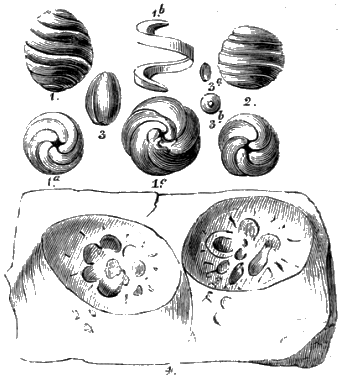

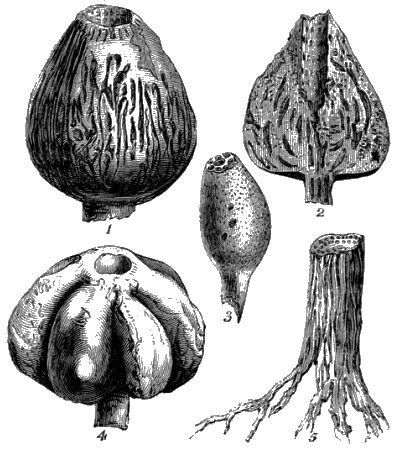

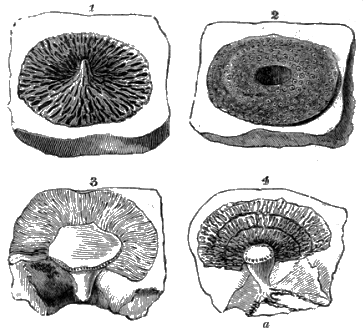

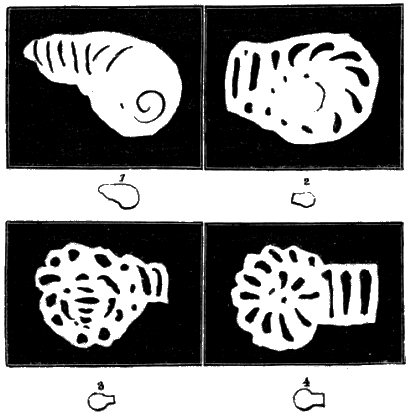

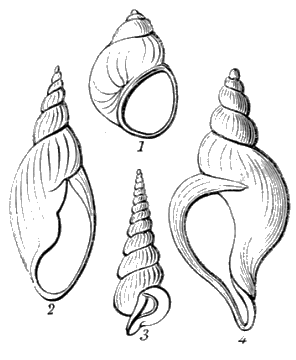

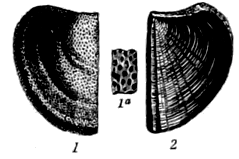

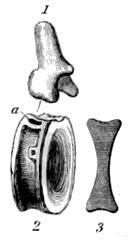

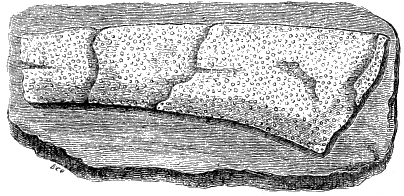

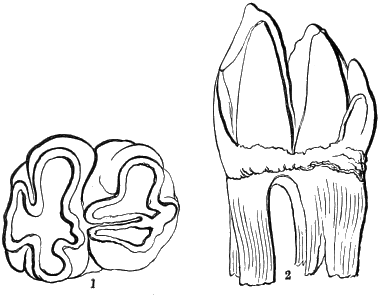

DESCRIPTION OF PLATE V.

Illustrative of the Structure of Fossil Vegetables.

| Fig. | 1.— | Polished transverse section of silicified Monocotyledonous Wood, from Antigua; p. 185. |

| 1a.— | Magnified 20 times linear. | |

| 1b.— | Magnified 75 times linear. | |

| 2a.— | Transverse section of silicified Coniferous Wood (Abies Benstedi) from the Kentish Rag, near Maidstone (Iguanodon quarry), × 120 linear; p. 173. | |

| 2b.— | Vertical or longitudinal section of the same, × 250 linear. | |

| 3a.— | Transverse section of calcareous coniferous wood, from Willingdon, Sussex, × 80 linear; p. 173. | |

| 3b.— | Longitudinal section of the above, × 120 linear. | |

| 4.— | Slice of a transverse section of a recent Dicotyledonous Stem; showing, 1st, Pith or medullary column, occupying the centre; 2d, Four bands of woody layers, separated by condensed lines of elongated tissue in series, and having large regular openings of vessels, with numerous medullary rays running continuously from the central pith to the bark; 3d, the bark. (From Mr. Witham.) | |

| 5.— | Slice of a transverse section of a recent gymnospermous phanerogamic stem (of a Cycas), having a central pith, with woody layers separated by a condensed line, and consisting of elongated cellular tissue, arranged in a regular series; medullary rays and bark. (From Mr. Witham.) | |

| 6.— | Bundles of vascular tissue in Stigmaria ficoides, × 12 linear. See p. 135. The two strands of vessels that appear as if on the surface (and are of a looser texture) are part of the vascular tissue of the stem, and become inflected (that is, bent over), and give rise to a band of vessels (the darker band seen between the above), that passes towards the bark or cortical covering. « xxviii » | |

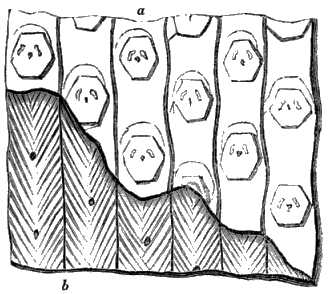

| 7.— | Portion of a transverse section of one of the bundles of vascular tissue of Sigillaria elegans, × 20 linear. (From M. Brongniart.) See p. 131. | |

| The convex portion on the left, and which in the original stem is situated towards the centre, is composed of the medullary vascular tissue formed of vessels irregularly disposed. | ||

| The longitudinal bundles are the woody fibres arranged in a radiated circle: the smooth interspaces are medullary rays. | ||

| The two distinct roundish spots of vascular tissue on the right of the ligneous zone occur irregularly on the outside of the woody circle, and are supposed to be detached bundles of the ligneous zone extending towards the leaves. See p. 131. |

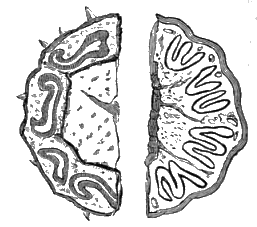

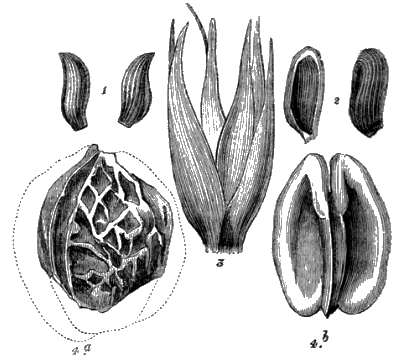

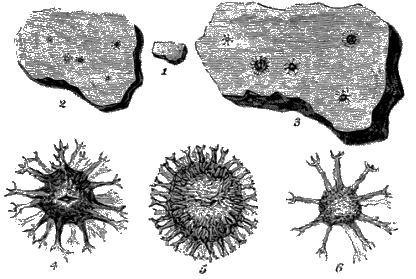

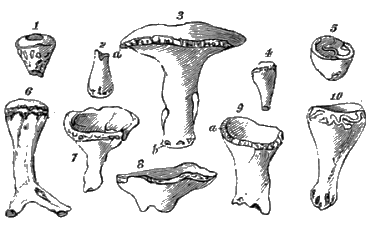

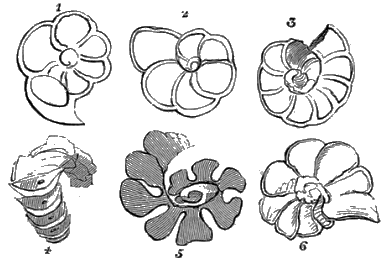

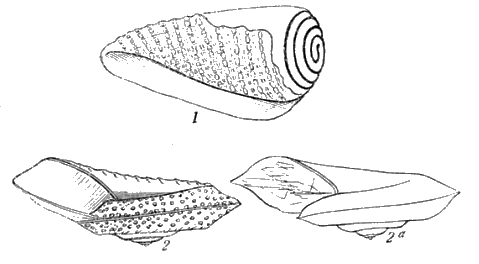

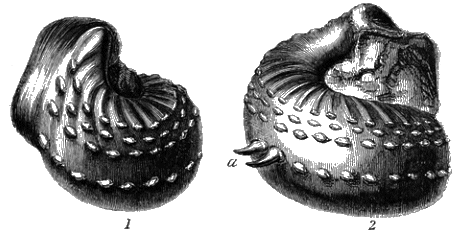

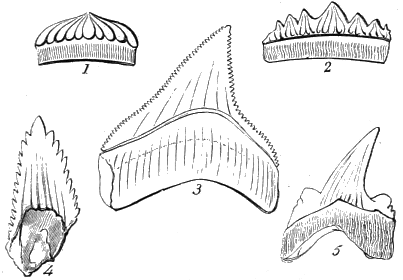

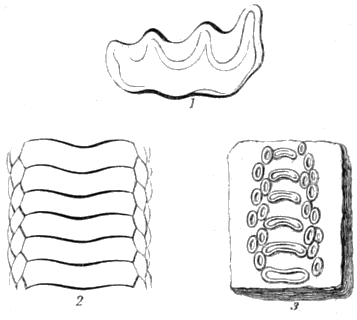

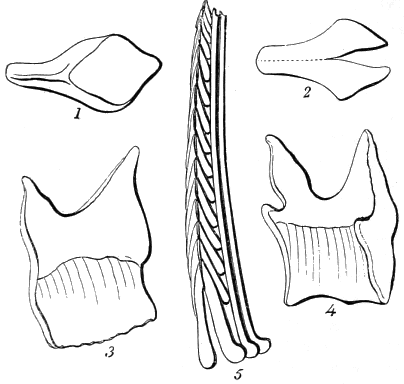

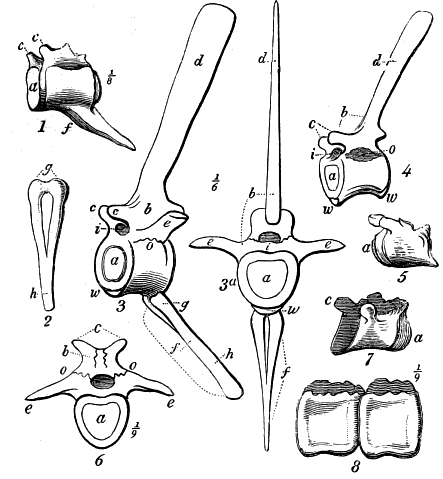

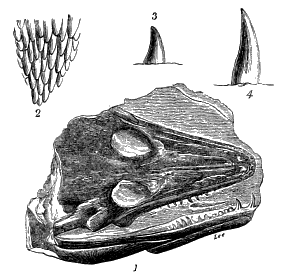

DESCRIPTION OF PLATE VI.

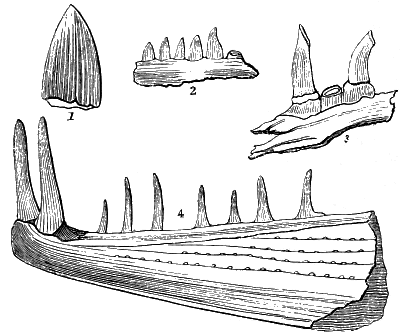

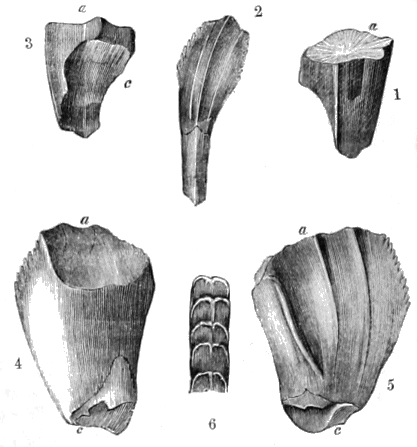

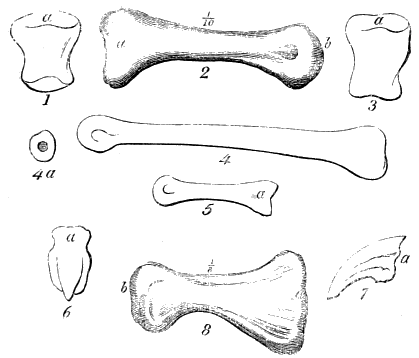

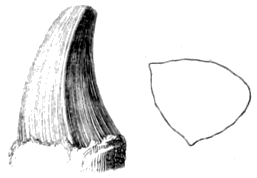

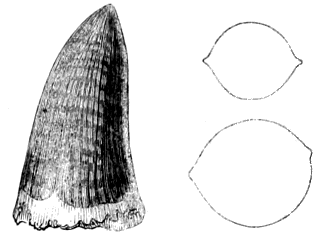

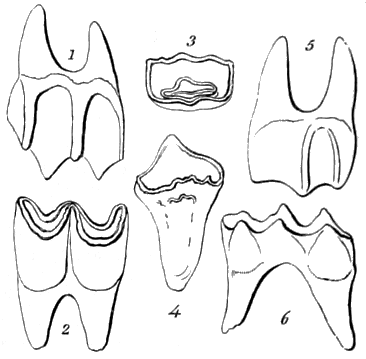

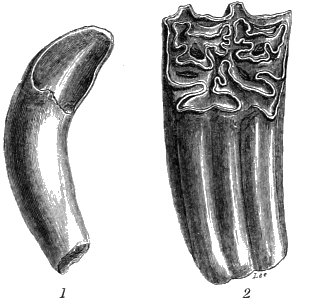

Illustrative of the Structure of Fossil Teeth.

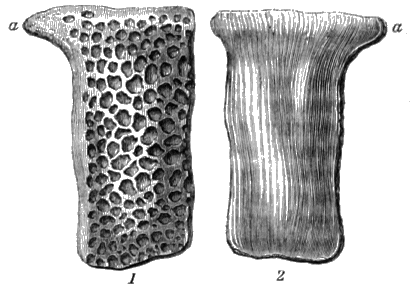

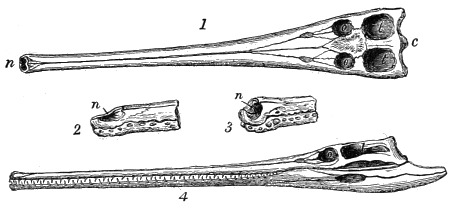

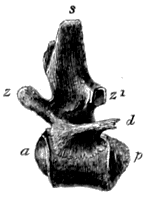

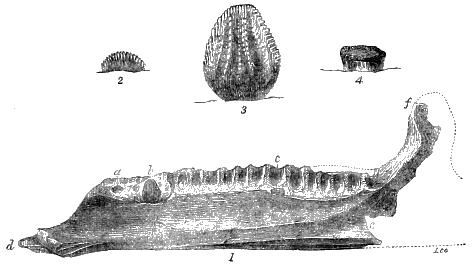

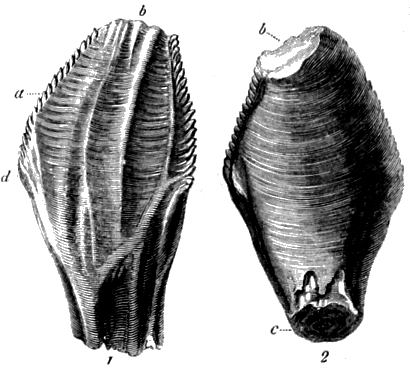

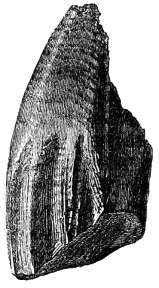

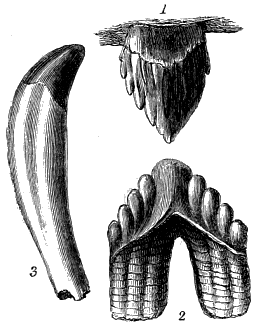

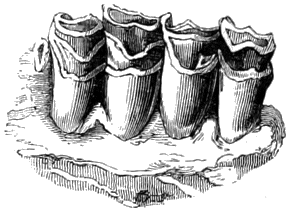

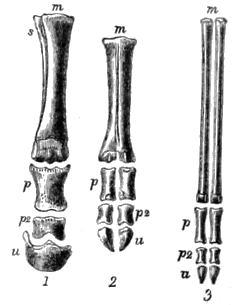

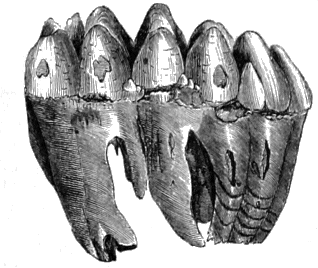

| Fig. | 1a.— | Tooth of Psammodus porosus, from the Mountain Limestone. See p. 587. |

| 1b.— | Vertical section, a portion × 75 linear. | |

| 1c.— | Transverse section of the same, × 75. | |

| 2a.— | Tooth of Ptychodus polygurus, from the Chalk, near Lewes. See p. 585. | |

| 2b.— | Portion of longitudinal section, × 20. | |

| 2c.— | Portion of transverse section, × 20. | |

| 3b.— | Tooth of the Labyrinthodon Jægeri, from the New Red sandstone near Wirtemberg; half the natural size: the specimen presented by Dr. Jæger. See p. 742. | |

| 3a.— | A moiety of a transverse polished section, × 20. | |

| 3b.— | Portion of a vertical section near the apex, × 20. | |

| 3c.— | One of the anfractuosities of fig. 3a × ×. | |

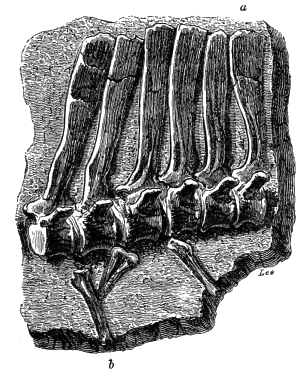

| 4a.— | Crown or upper portion of a tooth of a young Iguanodon, from Tilgate Forest. See p. 697. | |

| 4b.— | Portion of a vertical section of the above, × 20. | |

| 4c.— | A small portion of a transverse section of the same, × 20. | |

| 5.— | Tooth of Goniopholis, Tilgate Forest: half the natural size. See p. 678. | |

| 6a.— | Tooth of a reptile (probably of the Hylæosaurus), from Tilgate Forest; half the natural size. See p. 690. | |

| 6b.— | Portion of a vertical section of the same, × 20. | |

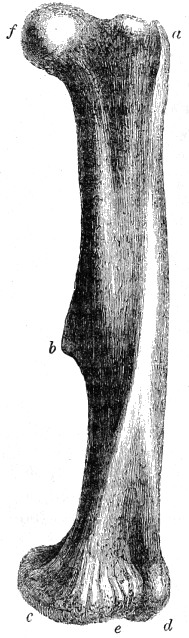

| 7a.— | Tooth of Megalosaurus, from Tilgate Forest. See p. 687. | |

| 7b.— | Portion of a vertical section of the same, × 10. | |

| 8.— | A small portion of a vertical section of a tooth of Dendrodus. See p. 618. | |

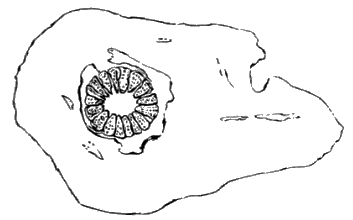

| 9.— | Portion of a transverse section of the base of a tooth of Ichthyosaurus, × 20. See p. 665. | |

| 10a.— | Tooth of Lepidotus, Tilgate Forest. See p. 606. | |

| 10b.— | The upper figure is a transverse section, and the lower a vertical section of the same, × 20. |

(Illustrative of Fossil Botany.)

| LIGN. | PAGE | |

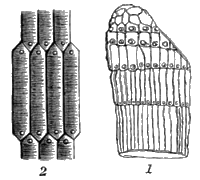

| 1. | Sections of Recent Vegetables | 55 |

| 2. | Sections of Fern-Stems | 62 |

| 3. | Nodule of Ironstone, enclosing a Fern Leaf | 69 |

| 4. | Siliceous Frustules of Diatomaceæ, and Spicules of Spongillæ | 94 |

| 5. | Fossil Gallionellæ | 96 |

| 6. | Organic Bodies in Porcelain Earth | 97 |

| 7. | Microphytes from the Tertiary deposits at Richmond, U.S. | 98 |

| 8. | Confervites Woodwardii | 101 |

| 9. | Chondrites Bignoriensis | 102 |

| 10. | Delesserites (Fucoides) Lamourouxii | 103 |

| 11. | Moss and Conferva in transparent quartz | 104 |

| 12. | Equisetum Lyellii | 105 |

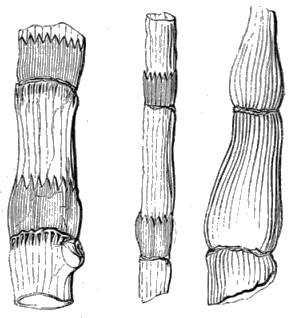

| 13. | Equisetites columnaris | 106 |

| 14. | Calamites decoratus | 107 |

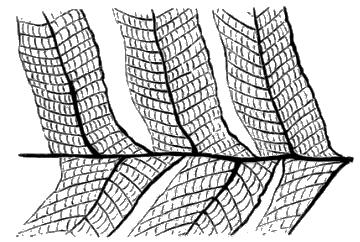

| 15. | Calamites in Coal-shale | 108 |

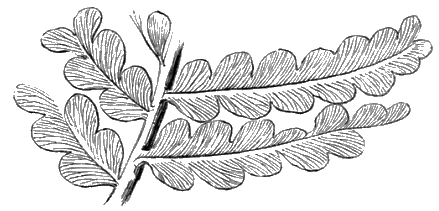

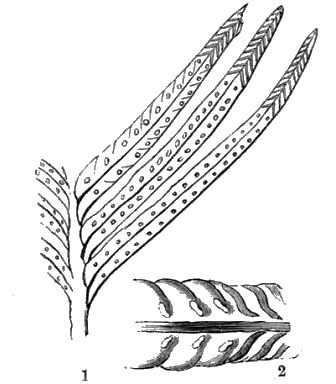

| 16. | Pecopteris Sillimani | 110 |

| 17. | Pachypteris lanceolata | 112 |

| 18. | Sphenopteris elegans | 112 |

| 19. | Sphenopteris nephrocarpa | 113 |

| 20. | Sphenopteris Mantellii | 113 |

| 21. | Cyclopteris trichomanoides | 114 |

| 22. | Neuropteris acuminata | 115 |

| 23. | Glossopteris Phillipsii | 116 |

| 24. | Odontopteris Schlotheimii | 116 |

| 25. | Anomopteris Mougeotii | 117 |

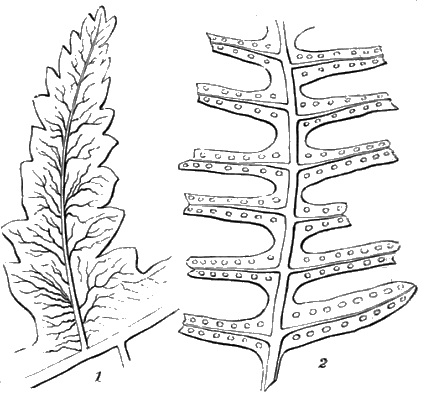

| 26. | Tœniopteris latifolia | 118 |

| 27. | Fig. 1, Pecopteris Murrayana | 118 |

| 2, Pecopteris lonchitica | 118 | |

| 28. | Lonchopteris Mantellii | 119 |

| 29. | Fig. 1, Phlebopteris Phillipsii | 120 |

| 2, Phlebopteris propinqua | 120 | |

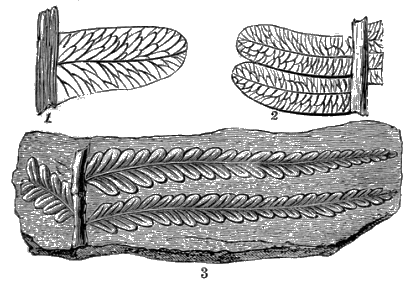

| 30. | Clathropteris meniscoides | 121 |

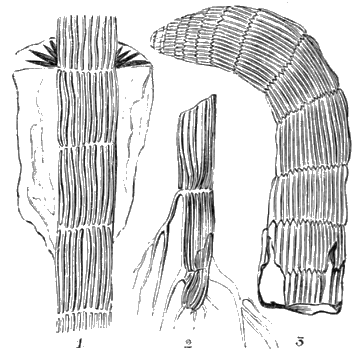

| 31. | Caulopteris macrodiscus | 123 |

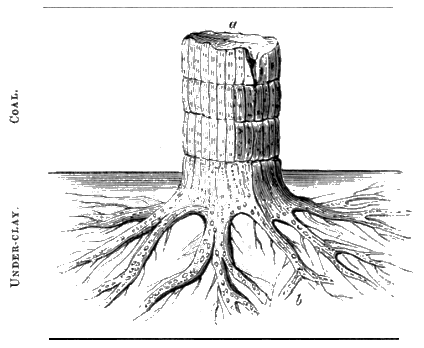

| 32. | Base of a Trunk of a Sigillaria, with root | 126 |

| 33. | Sigillariæ, in Coal Shale | 128 |

| 34. | Sigillaria Saullii | 129 |

| 35. | Silicified Stem of Sigillaria elegans | 130 |

| 36. | Stigmaria ficoides | 133 |

| 37. | Transverse section of Stigmaria ficoides | 135 |

| 38. | Erect Stem of a Sigillaria, with Roots | 136 |

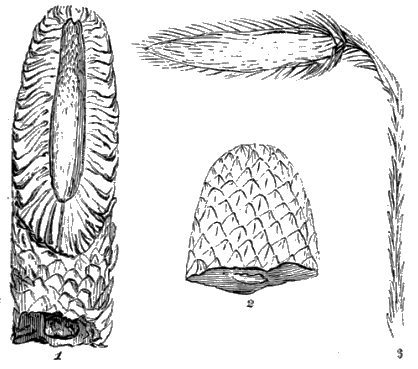

| 39. | A Terminal Branch of a Lepidodendron | 138 |

| 40. | Lepidostrobi, the Fruit of Lepidodendra | 141 |

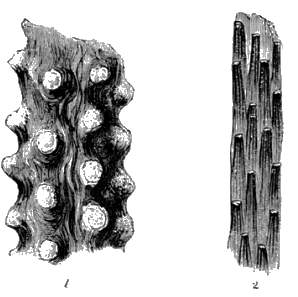

| 41. | Stems of Halonia and Knorria, from the Coal Formation | 144 |

| 42. | Asterophyllites equisetiformis | 147 |

| 43. | Fig. 1, Sphenophyllum Schlotheimii | 148 |

| 2, Sphenophyllum erosum | 148 | |

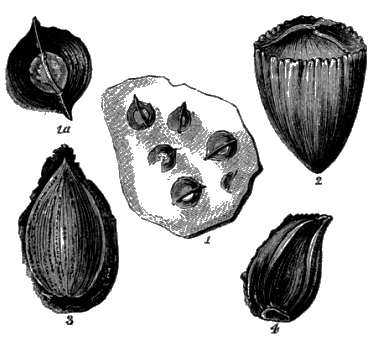

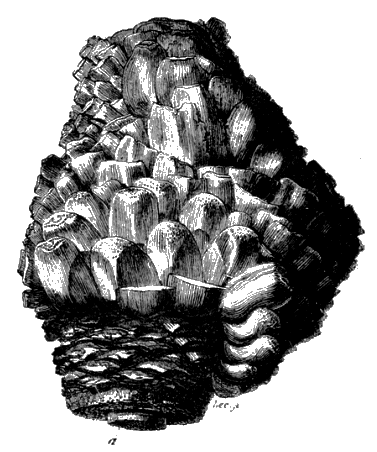

| 44. | Fossil Fruits, or Seed Vessels | 149 |

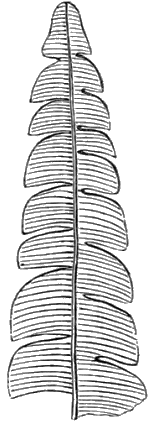

| 45. | Foliage and upper part of the Stem of Cycas revoluta (recent) | 150 |

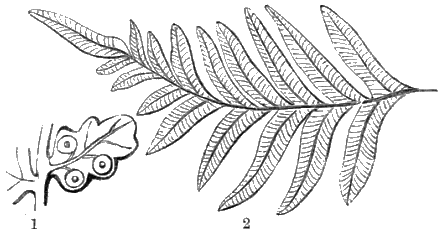

| 46. | Part of a leaf of Pterophyllum comptum | 152 |

| 47. | Part of a leaf of Zamites pectinatus | 153 |

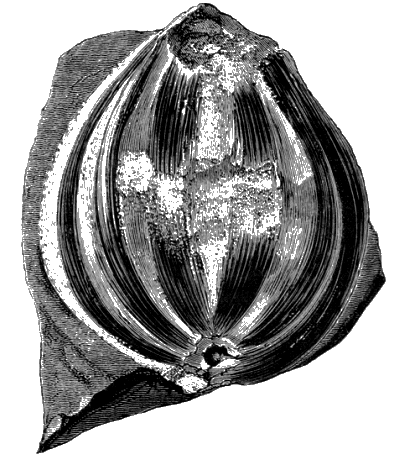

| 48. | Fruit of Zamites Mantellii | 154 |

| 49. | Fossil Fruits of Cycadeous Plants | 156 |

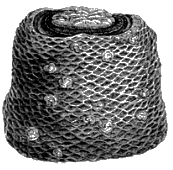

| 50. | Mantellia nidiformis « xxxi » | 157 |

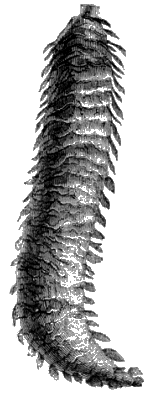

| 51. | Mantellia cylindrica | 158 |

| 52. | Clathraria Lyellii, inner Axis of the Stem of | 159 |

| 53. | Clathraria Lyellii, Stem of | 160 |

| 54. | Clathraria Lyellii, part of Stem of | 161 |

| 55. | Clathraria Lyellii, Petiole of | 161 |

| 56. | Clathraria Lyellii, summit of Stem, with petioles | 162 |

| 57. | Clathraria Lyellii, water-worn Stem of | 163 |

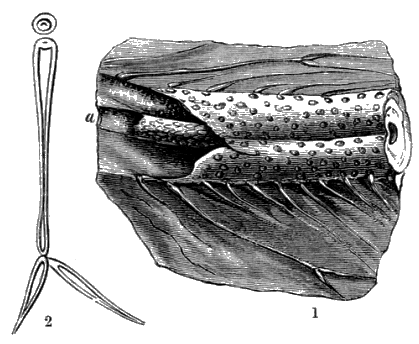

| 58. | Fragment of Coniferous Wood in Flint | 174 |

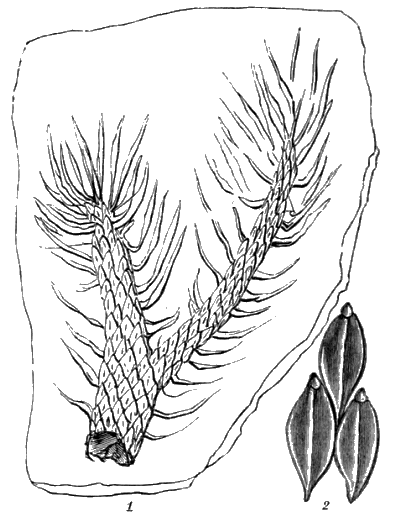

| 59. | Fig. 1, Part of a Branch of Araucaria peregrina | 176 |

| 2, Calamites nodosus, with foliage | 176 | |

| 60. | Walchia hypnoides | 178 |

| 61. | Abietites Dunkeri | 179 |

| 62. | Thuites Kurrianus | 180 |

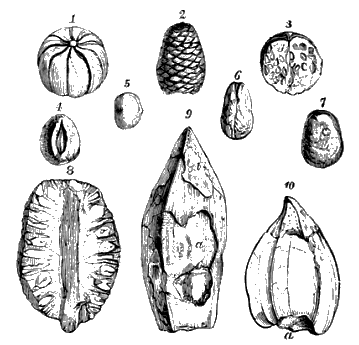

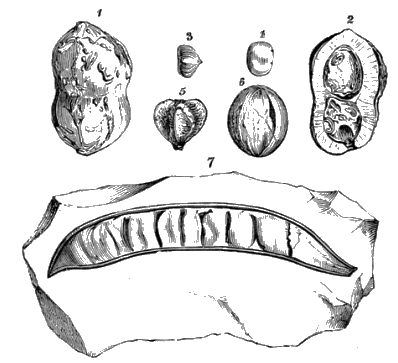

| 63. | Nipadites and other Fossil Fruits from the Isle of Sheppey | 188 |

| 64. | Fossil Fruits from the Isle of Sheppey | 189 |

| 65. | Fossil Wood perforated by Teredines | 193 |

| 66. | Fossil Fresh-water Plants | 196 |

| 67. | Fossil Fruits and Flower | 198 |

| 68. | Imprints of Dicotyledonous leaves in Gypseous Marlstone | 201 |

(lllustrative of Fossil Zoology.) |

||

| 69. | Coral and Spongites | 224 |

| 70. | Fossil Zoophytes | 227 |

| 71. | Fossil Sponge | 228 |

| 72. | Fossil Zoophytes | 229 |

| 73. | Siphoniæ from the Greensand | 231 |

| 74. | Polypothecia dichotoma | 232 |

| 75. | Choanites Königi | 234 |

| 76. | Paramoudra in the Chalk | 237 |

| 77. | A group of Spiniferites in Flint | 239 |

| 78. | Spiniferites Reginaldi | 241 |

| 79. | Spiniferites palmatus | 241 |

| 80. | Flints, the forms of which are derived from Zoophytes | 243 |

| 81. | Ventriculites radiatus | 244 |

| 82. | Portions of Ventriculites | 245 |

| 83. | Ventriculites alcyonoides | 248 |

| 84. | A Coral Polype, in flint | 250 |

| 85. | Graptolites in Wenlock Limestone | 255 |

| 86. | Favosites polymorpha | 258 |

| 87. | Corals from the Dudley Limestone | 261 |

| 88. | Fossil Corals | 262 |

| 89. | Corals from the Chalk and Mountain Limestone | 268 |

| 90. | Stems of Encrinites and Pentacrinites | 284 |

| 91. | Recent Comatula and Fossil Crinoidea | 286 |

| 92. | Fossil Crinoidea | 289 |

| 93. | Apiocrinites | 291 |

| 94. | Actinocrinites and Pentacrinite | 294 |

| 95. | Cyathocrinites planus | 296 |

| 96. | Marsupites Milleri | 300 |

| 97. | Fossil remains of Star-fishes | 305 |

| 98. | Goniaster Mantelli | 306 |

| 99. | Asterias prisca | 308 |

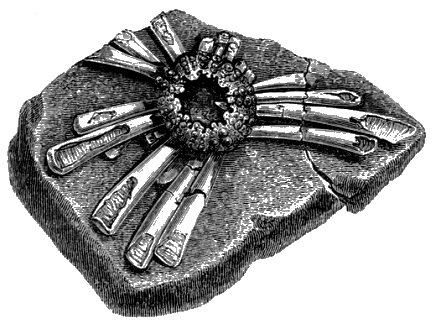

| 100. | Fossil Turban Echinus with its Spines | 311 |

| 101. | Cidarites from the Oolite and Chalk | 316 |

| 102. | Fossil Spines of Cidarites | 319 |

| 103. | Echinital remains in flint | 320 |

| 104. | Echinites from the Chalk | 323 |

| 105. | Holectypus inflatus | 324 |

| 106. | Discoidea castanea | 325 |

| 107. | Micraster cor-anguinum | 328 |

| 108. | Toxaster complanatus | 329 |

| 109. | Foraminifera from the Chalk | 342 |

| 110. | Nummulites, or Nummulina | 344 |

| 111. | Foraminifera from the Chalk | 347 |

| 112. | Spirolinites in flint | 349 |

| 113. | Nonionina Germanica (recent) | 350 |

| 114. | Foraminifera in Chalk and flint | 351 |

| 115. | Chalk-dust, chiefly composed of Foraminifera | 355 |

| 116. | Section of a Rotalia in flint | 356 |

| 117. | Rotalia in flint, with the fossilized body of the animal in the shell | 358 |

| 118. | Soft Bodies of Foraminifera extracted from the Chalk | 359 |

| 119. | Remains of Foraminifera in chalk and flint | 361 |

| 120. | Fossil Oyster, from the Chalk | 374 |

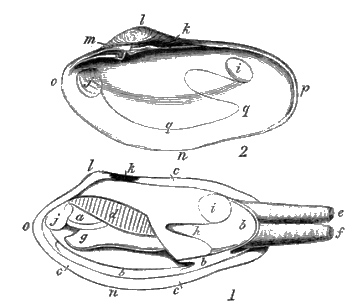

| 121. | Recent Bivalve Mollusc, showing the several parts of the shell and the animal « xxxii » | 377 |

| 122. | Turritellæ from Bracklesham | 383 |

| 123. | Shell-Conglomerate | 385 |

| 124. | Shell-Limestone, from the mouth of the Thames | 386 |

| 125. | Terebratula and Rhynchonella | 388 |

| 126. | Terebratula and Spirifer | 390 |

| 127. | Shells and Echinite from the Oolite and Lias | 397 |

| 128. | Spondylus spinosus in Chalk-flint | 399 |

| 129. | Inoceramus Cuvieri of the Chalk | 401 |

| 130. | Flint with fragments of Inoceramus perforated by Clionites | 403 |

| 131. | Unio Valdensis | 415 |

| 132. | Cyclas and Melanopsis | 416 |

| 133. | Fossil Shells of Gasteropoda | 418 |

| 134. | Polished Slab of Purbeck Marble | 422 |

| 135. | Univalves from the Chalk of Touraine | 427 |

| 136. | Univalves from the Mountain Limestone | 428 |

| 137. | Murchisonia bilineata | 430 |

| 138. | Sphærulites from the Chalk | 431 |

| 139. | Coprolites and Molluskite | 432 |

THE

MEDALS OF CREATION.

"Geology, in the magnitude and sublimity of the objects of which it treats, ranks next to Astronomy in the scale of the Sciences."—Sir J. F. W. Herschel.

Geology, a term signifying a discourse on the Earth, (from two Greek words: viz. γἡ, ge, the earth; and λὁγος, logos, a discourse,) is the science which treats of the physical structure of the planet on which we live, and of the nature and causes of the successive changes which have taken place in the organic and inorganic kingdoms, from the remotest period to the present time, and is therefore intimately connected with every department of natural philosophy.

While in common with other scientific pursuits it yields the noblest and purest pleasures of which the human mind is susceptible, it has peculiar claims on our attention, since it offers inexhaustible and varied fields of intellectual research, and its cultivation, beyond that of any other science, is in a great measure independent of external circumstances; for « 2 » it can be followed in whatever condition of life we maybe placed, and wherever our fortunes may lead us.

The eulogium passed by a distinguished living philosopher on scientific knowledge in general, is strikingly applicable to geological investigations. "The highest worldly-prosperity, so far from being incompatible with them, supplies additional advantages for their pursuit; they may be alike enjoyed in the intervals of the most active business, while the calm and dispassionate interest with which they fill the mind, renders them a most delightful retreat from the agitations and dissensions of the world, and from the conflict of passions, prejudices, and interests, in which the man of business finds himself continually involved."[2]

[2] Sir J. F. W. Herschel, "Discourse on the Study of Natural Philosophy."

From the present advanced state of geological science, particularly of that department which it is the more especial object of these volumes to elucidate, namely Palæontology,[3] or the study of Organic Remains,—it seems scarcely credible, that but little more than a century ago it was a matter of serious question with naturalists, whether the petrified shells imbedded in the rocks and strata were indeed shells that had been secreted by molluscous animals; or whether these bodies, together with the teeth, bones, leaves, wood, &c. found in a fossil state, were not formed by what was then termed the plastic power of the earth; in like manner as minerals, metals, and crystals.

[3] Palæontology: from παλαιος, palaios, ancient—οντα, onta, beings—λὁγος, logos, a discourse.

In a "Natural History of England," published towards the end of the last century, it is gravely observed that at Bethersden in Kent, a kind of stone is found full of shells, "which is a proof that shells and the animals we find in them living, have no necessary connexion." Another amusing instance of the ignorance on such subjects which « 3 » prevailed at no remote period, occurs in a "History of the County of Surrey," in which it is stated that in a search for coal near Guildford the borers broke, and "this was thought by Mr. Peter Lely, the Astrologer, to have been the work of subterranean spirits, who wrenched off the augers of the miners, lest their secret haunts should be invaded."

But in the latter part of the seventeenth century, there were several eminent men in England who were greatly in advance of the age in which they lived, and strenuously exerted themselves to discover and promulgate the true principles of Geology. Among these, Dr. Martin Lister, physician to Queen Anne, was one of the most distinguished. This accomplished naturalist, in his great work on shells, which remains to this day a splendid monument of his labours, and of the talents and filial affection of his two daughters, by whom all the plates were engraved, figures and describes many fossil shells as real animal productions, and carefully compares them with recent species. He also recognised the distinction of strata by the organic remains they contain; and to him the honour is due of having first suggested the construction of geological maps;[4] he was likewise well acquainted with the position and extent of the Chalk and other strata of the South of England.[5]

[4] See Notes on the Progress of Geology in England, by W. H. Fitton, M.D. &c. Philos. Mag. vols. i. and ii. for 1832 and 1833.

[5] This celebrated physician and British geologist died in 1712, and was interred in the old church at Clapham; where a tablet to his memory is affixed to the outside of the north wall of St. Paul's Chapel.

From the foreign writers, who at an early period had obtained some correct notions of the structure of our planet, and of the nature of the revolutions it had undergone, I select the following beautiful and philosophical illustration of the physical mutations to which the surface of the earth is perpetually « 4 » subjected. It is from an Arabic manuscript of the thirteenth century;[6] the narrative is supposed to be related by Rhidhz, an allegorical personage.

[6] Quoted by Sir C. Lyell in his "Principles of Geology."

"I passed one day by a very ancient and populous city, and I asked one of its inhabitants how long it had been founded? 'It is, indeed, a mighty city,' replied he; 'we know not how long it has existed, and our ancestors were on this subject as ignorant as ourselves.' Some centuries afterwards I passed by the same place, but I could not perceive the slightest vestige of the city; and I demanded of a peasant, who was gathering herbs upon its former site, how long it had been destroyed? 'In sooth, a strange question,' replied he, 'the ground here has never been different from what you now behold it.' 'Was there not,' said I, 'of old a splendid city here?' 'Never,' answered he, 'so far as we know, and never did our fathers speak to us of any such.'

"On revisiting the spot, after the lapse of other centuries, I found the sea in the same place, and on its shores were a party of fishermen, of whom I asked how long the land had been covered by the waters? 'Is this a question,' said they, 'for a man like you? this spot has always been what it is now.'

"I again returned ages afterwards, and the sea had disappeared. I inquired of a man who stood alone upon the ground, how long ago the change had taken place, and he gave me the same answer that I had received before.

"Lastly, on coming back again, after an equal lapse of time, I found there a flourishing city, more populous and more rich in buildings than the city I had seen the first time; and when I fain would have informed myself regarding its origin, the inhabitants answered me, 'Its rise is lost in remote antiquity—we are ignorant how long it has existed, and our fathers were on this subject no wiser than ourselves.'"

We may smile at the ignorance of the inhabitants of the fabled cities, but are we in a condition to give a more satisfactory reply should it be inquired of us, "What are the physical changes which the country you inhabit has undergone?"—and yet cautious observation, and patient and unprejudiced investigation, are alone necessary to enable us to answer the interrogation.

Dismissing from his mind all preconceived opinions, the student must be prepared to learn that the earth's surface has been, and still is, subject to perpetual mutation,—that the sea and land are continually changing place,—that what is now dry land was once the bottom of the deep, and that the bed of the present ocean will, in its turn, be elevated above the water and become land,—that all the solid materials of the globe have been in a softened, fluid, or gaseous state,—that the relics of countless myriads of animals and plants are entombed in the rocks and strata,—and that vast mountain-chains, and extensive regions, are wholly composed of the petrified remains of beings that lived and died in periods long antecedent to the creation of the human race. Astounding as are these propositions, they rest upon evidence so clear and incontrovertible, that they cannot fail to be admitted by every intelligent and unprejudiced reader, who will bestow but a moderate share of attention to the examination of the phenomena, of which the following pages present a familiar exposition.

I cannot conclude these introductory observations, without adverting to the incalculable benefits which result from scientific pursuits in general, and of Geology in particular. An able modern writer has justly remarked:—"It is fearfully true, that nine-tenths of the immorality which pervades the better classes of society, originate from the want of an interesting occupation to fill up the vacant time; and as the study of the natural sciences is as attractive as it is beneficial, it must necessarily exert a moral and even religious influence upon the young and inquiring mind. The youth who is fond of scientific pursuits will not enter into revelry, for frivolous or vicious excitements will have no fascination for him. The overflowing cup, the unmeaning or dishonest game, will not entice him. If any one doubts the beneficial influence of these studies on the morals and character, I would ask him to point out the immoral young « 6 » man who is devotedly attached to any branch of natural science: I never knew such an one. There may be such individuals—for religion only can change the heart—but if there be, they are very rare exceptions; and the loud clamours which are always raised against the man of science who errs, prove how rarely the study of the works of the Creator fails to exert an ennobling effect upon a well-regulated mind. Fortunate, indeed, are the youth of either sex, who early imbibe a taste for natural knowledge, and whose predilections are not thwarted by injudicious friends."

And while Geology exerts this hallowing influence on the character, it possesses the great advantage of presenting subjects adapted to every capacity; on some of its investigations the highest intellectual powers and the most profound acquirements in exact science are required; while many of its problems may be solved by any one who has eyes and will use them; and innumerable facts illustrative of the ancient condition of our planet, and of its inhabitants, may be gathered by any diligent and intelligent observer.

But it is surely unnecessary to dwell on the interest and importance of a study, which instructs us that every pebble we tread upon bears the impress of the Almighty's hand, and affords evidence of Creative wisdom; that every grain of sand, every particle of dust scattered by the wind, may be composed of the aggregated skeletons of beings, so minute as to elude our unassisted vision, but which possessed an organization as marvellous as our own;—a science whose discoveries have realized the wildest imaginings of the poet,—whose realities far surpass in grandeur and sublimity the most imposing fictions of romance;—a science, whose empire is the earth, the ocean, the atmosphere, the heavens;—whose speculations embrace all elements, all space, all time;—objects the most minute, objects the most colossal;—carrying its researches into the smallest atom which the « 7 » microscope can render accessible to our visual organs,—and comprehending all the phenomena in the boundless Universe, which the powers of the telescope can reveal.

And as no branch of natural philosophy can more strongly impress the mind with that deep sense of humility and dependence, which the contemplation of the works of the Eternal is calculated to inspire, so none can more powerfully encourage our aspirations after truth and wisdom. Every walk we take offers subjects for profound meditation,—every pebble that attracts our notice, matter for serious reflection; and contemplating the incessant dissolution and renovation which are taking place around us in the organic and inorganic kingdoms of nature, we are struck with the force and beauty of the exclamation of the poet—

ON THE PLAN OF THE WORK, AND THE ARRANGEMENT AND SUBDIVISION OF THE SUBJECTS IT EMBRACES.

With the view of economizing space, I would refer the reader to the following volumes for figures and descriptions of such fossils as are illustrated therein: by this arrangement I hope to afford the student a comprehensive view of Palæontology, and yet restrict this work within the limits which as a manual it would be inconvenient to exceed; at the same time it will be complete in itself, and afford all the information required by the amateur collector and general reader.

I. Dr. Buckland's Bridgewater Treatise: 2 vols. 8vo.—These volumes contain numerous excellent figures of organic remains; and as the work is, or ought to be, found in every good public or private library in the kingdom, it will be accessible to most of my readers.

II. The Wonders of Geology, or a Familiar Exposition of Geological Phenomena; sixth edition, in two vols, with coloured plates, and numerous figures; by the Author. Price 18s.—This work is designed to afford a general view of Geological phenomena, divested as much as possible of scientific language: it is illustrated by numerous figures of organic remains.

III. Geological Excursions round the Isle of Wight and along the adjacent Coasts of Hampshire and Dorsetshire. One volume, richly illustrated. By the Author. Price 12s.

IV. Petrifactions and their Teachings; or a Hand-book to the Gallery of Organic Remains in the British Museum. One vol. with many original figures of the most interesting objects. By the Author.[7] Price 5s.

[7] The three works above named consist of four volumes uniform with the present edition of the "Medals of Creation:" this series of six volumes comprises the popular geological works of the Author.

V. A Pictorial Atlas of Fossil Remains; consisting of Coloured Illustrations selected from "Parkinson's Organic Remains of a Former World," and Artis' "Antediluvian Phytology." 1 vol. 4to. with seventy-four coloured plates, and several lignographs, containing nearly 900 figures of fossils. By the Author. Price 2l. 2s.

To the above may be added Dana's Mineralogy, which treats of the various mineral substances that enter into the composition of the rocks and strata in which the fossil remains are imbedded.

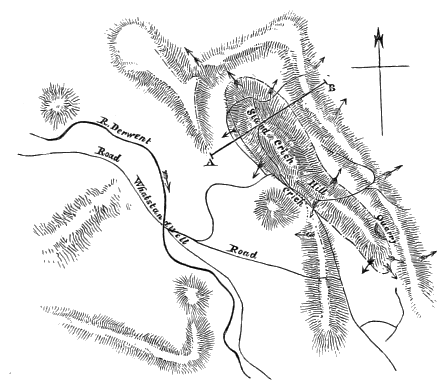

A good geological map of Great Britain is indispensable. The small map published by the Society for the Diffusion of Useful Knowledge, edited by Sir R. Murchison, price 5s., is an excellent compendium; but Mr. Knipe's large "Geological Map of the British Isles" is the most complete and convenient for the traveller: price 3l. 3s. By reference to the map, the geological structure, and the prevailing fossils of a district, may be ascertained.

The above works are referred to as follows: viz.

Bd. Dr. Buckland's Treatise.

Wond. The Wonders of Geology.

Geol. I. of W. Geology of the Isle of Wight.

Petrifactions. Petrifactions and their Teachings.

Pict. Atlas. Pictorial Atlas of Organic Remains.

The following works, to which reference will often be made, are thus denoted:—

Foss. Flor. The Fossil Flora of Great Britain, by Dr. Lindley, and W. Hutton, Esq. 3 vols. 8vo.

Vég. Foss. Histoire des Végétans: Fossiles, par M. Adolphe Brongniart. 1 vol. 4 to.

Geol. Trans. Transactions of the Geological Society of London. 5 vols. 4to.; and New Series, in 5 vols.

Geol. Proc. Geological Proceedings.

—— Journ. ————— Quarterly Journal.

Sil. Syst. The Silurian System, by Sir R. I. Murchison. 2 vols. 4to. with plates and map.

Org. Rem. Parkinson's Organic Remains of a Former World. 3 vols. 4to.

Oss. Foss. Ossemens Fossiles, par Baron Cuvier. 5 vols. 4to. 5me. edit.

Min. Conch. Sowerby's Mineral Conchology. 6 vols. 8vo.

Odont. Odontography; a Treatise on the Comparative Anatomy of the Teeth, by Professor Owen. 2 vols. 8vo.

Brit. Mam. British Fossil Mammalia; by the same Author. 1 vol. 8vo.

Brit. Rep. Reports on British Fossil Reptiles in the British Association Transactions for 1839, and 1841; by the same Author.

Phil. York. Geology of Yorkshire, by Professor John Phillips. 2 vols. 4to.

South. D. Fossils of the South Downs, 1 vol. 4to. 42 plates by the Author. 1822.

Geol. S. E. Geology of the South-east of England. 1 vol. 8vo. by the same.

Tilg. For. Fossils of Tilgate Forest. 1 vol. 4to. 20 plates; by the same. 1827.

Poiss. Foss. Recherches sur les Poissons Fossiles, par M. Agassiz. 4 vols. 4to, and 2 vols, folio.

Man. Geol. Manual or Elements of Geology, by Sir C. Lyell. 1 vol. 8vo. Edit. 1852.

The following abbreviations are also employed:—

§ 1. Relative to the Rocks or Strata.

Drift. Alluvial deposits, or Drift.

Tert. Tertiary. Lond. C. London clay.

Cret. Cretaceous formation. U. Ch. Upper chalk. L. Ch. Lower chalk.

Trias. New Red Sandstone, or Triassic deposits.

Carb. Carboniferous or Coal formation.

Mt. L. Mountain or Carboniferous limestone.

Devon. Devonian or Old Red Sandstone formation.

Sil. Syst. Silurian System, or formation.

§ 2. Relative to Organic Remains.

nat. Natural size.

× Magnified in diameter: e.g. × 8, magnified eight diameters, &c.

× × Highly magnified; the degree not accurately determined.

inv. Invisible to the naked eye.

— Less than natural: e.g. —2/3, reduced to two-thirds the diameter of the original.

Lign. Lignograph or woodcut.

Explanation of Terms.—Upon the occurrence of a scientific word apparently requiring explanation, the meaning, where practicable, is for the most part given in a parenthesis; for example, Caulopteris (fern-stem); Phascotherium (pouch-animal); carboniferous (coal-bearing); except in the case of arbitrary names, and of those whose derivation cannot be concisely expressed.[8] With the view of rendering these volumes more generally useful, English terminology is in many instances made use of, though involving inelegance of expression.

[8] Upwards of 300 scientific terms are explained in the Glossary, "Wonders," vol. ii. p. 915-921.

The work is divided into four parts: the first is an Introduction to the Study of Organic Remains; the second treats of Fossil Botany; the third embraces Fossil Zoology; and the fourth, under the head of Geological Excursions, illustrates the principles enunciated in the course of the work, by practical observations on a few instructive British localities.

PART I.

|

PART II.

FOSSIL BOTANY.

|

Classification of Fossil Vegetables.

Retrospect. British Localities of Fossil Plants. |

PART III.

FOSSIL ZOOLOGY.

|

On the Fossil Remains of the Animal Kingdom.

Retrospect. |

PART IV.

| I. | Geological Excursions in various parts of England, illustrative of the method of observing geological phenomena, and of collecting Fossil Remains. |

| II. | Miscellaneous. On the prices of Fossils; lists of Dealers, &c. |

| III. | Appendix. |

ON THE NATURE AND ARRANGEMENT OF THE BRITISH STRATA, AND THEIR FOSSILS.

"To discover order and intelligence in scenes of apparent wildness and confusion is the pleasing task of the geological inquirer."—Dr. Paris.

The solid materials of which the earth is composed, from the surface to the greatest depths within the reach of human observation, consist of minerals and fossils.

Minerals are inorganic substances formed by natural operations, and are the product of chemical or electro-chemical action.

Fossils are the durable remains of animals and vegetables which have been imbedded in the strata by natural causes in remote periods, and subsequently more or less altered in structure and composition by mechanical and chemical agencies.

The soft and delicate parts of animal and vegetable organisms rapidly decompose after death; but the firmer and denser structures, such as the bones and teeth of the former, and the woody fibre of the latter, possess considerable durability, and under certain conditions will resist decay for « 16 » many years, or even centuries; and when deeply imbedded in the earth, protected from atmospheric influences, and subjected to the conservative effects of various mineral solutions, the most perishable tissues often resist decomposition, and becoming transformed into stone, may endure for incalculable periods of time. The calcareous and siliceous cases or frustules of numerous microscopic plants are so indestructible, and occur in such inconceivable quantities, that the belief of some eminent naturalists of the last century, that every grain of flint and lime in certain rocks, may have been elaborated by the energies of vitality, can no longer be regarded as an extravagant hypothesis. Some idea may be formed of the large proportion of the solid materials of the globe that has unquestionably originated from this source, by a reference to the list of strata which are wholly, or in great part, composed of animal and vegetable structures, given in the "Wonders of Geology," p. 888.

There are also immense tracts of country that consist in a great measure of the remains of plants in the state of anthracite, coal, lignite, &c.; and districts covered with peat-bogs and subterranean forests.

Although these relics of animal and vegetable organisms are found in almost every sedimentary deposit, yet they occur far more abundantly, and in a better state of preservation, in some strata than in others: nor are they equally distributed throughout the same bed, but are heaped together in particular localities, and occur but sparingly, or are altogether absent, in other layers of the same rock. Neither are the remains of the same kinds of animals and plants found indiscriminately in strata of different ages: on the contrary, many species are restricted to the most ancient, others to the most recent formations; while some genera range through the entire series of deposits, and also appear as denizens of the existing seas. Hence organic remains « 17 » acquire a high degree of importance, not only from the intrinsic interest they possess as objects of natural history, but also for the light they shed on the physical condition of our planet in the remotest ages, and for the data they afford as to the successive physical revolutions which the surface of the earth has undergone.

Fossils have been eloquently and appropriately termed Medals of Creation; for as an accomplished numismatist, even when the inscription of an ancient and unknown coin is illegible, can from the half-obliterated effigy, and from the style of art, determine with precision the people by whom, and the period when, it was struck; in like manner the geologist can decipher these natural memorials, interpret the hieroglyphics with which they are inscribed, and from apparently the most insignificant relics, trace the history of beings of whom no other records are extant, and ascertain the forms and habits of unknown types of organization whose races were swept from the face of the earth, ere the creation of man and the creatures which are his contemporaries. Well might the illustrious Bergman exclaim, "Sunt instar nummorum memorialium, quæ de præteritis globi nostri fatis testantur, ubi omnia silent monumenta historica."

To derive from these Medals of Creation all the information they are capable of affording, regard therefore must be had not only to their peculiar characters, but also to the geological relations of the strata in which they are imbedded. Data may be thus obtained by which the relative age of a formation or group of strata can be determined, as well as the mode of deposition, and the agency by which it was effected; whether in the bed of an ocean, or of a lake, or estuary,—by the action of the sea, or of rivers, or running streams,—by the effects of icebergs or glaciers,—by slow processes through long periods of time, or by sudden inundations or deluges,—or by the agency of volcanoes and earthquakes.

The discovery that particular fossils are confined to certain deposits, was soon productive of important results, which greatly tended to the advancement of modern Geology; for although Dr. Lister, more than a century before, had obtained a glimpse of this law, its principles were neither understood nor regarded in this country until the late Dr. William Smith, by his own unaided exertions, proved by numerous observations on the British strata, its value and applicability for the identification of a deposit, in districts remote from each other.

This phenomenon did not escape the notice of the distinguished French philosophers, MM. Cuvier and Brongniart, who in their admirable work, "Géographie Minéralogique des Environs de Paris," enunciated the same principle:—

"Le moyen que nous avons employé pour reconnoitre au milieu d'un si grand nombre de lits calcaires, un lit déjà, observé, dans un canton très-éloigné, est pris de la nature des fossiles renfermés dans chaque couche; ces fossiles sont toujours généralement les mêmes dans les couches correspondantes, et présentent d'un système de couche à un autre système, des différences d'espèces assez notables. C'est un signe de reconnoissance qui jusqu'à présent ne nous a pas trompés."[9]

[9] Géog. Min. Oss. Foss. tom. ii. p. 266.

Now, though recent discoveries have shown that this rule has many exceptions, and that its too stringent adoption has been productive of some erroneous generalizations, yet if employed with due caution it is fraught with the most interesting results, and is the only certain basis of our knowledge respecting the appearance, continuance, and extinction, of the lost races of animals and plants, which were once denizens of our planet.

In the "Wonders of Geology" will be found a comprehensive sketch of the composition and arrangement of the several formations or groups of strata; and a reference to that work will afford the student the necessary information « 19 » on this branch of Geology. For the convenience of the general reader I subjoin a synoptical view of the characters and relations of the British fossiliferous deposits.

The total thickness of the entire series of rocks within the scope of human examination, is estimated at from fifteen to twenty miles, reckoning from the summits of the highest mountains to the greatest depths hitherto penetrated; and as this vertical section scarcely amounts to 1/400th of the diameter of the globe, it is familiarly termed the Earth's crust. The substances of which the sedimentary strata are composed have been deposited by the action of water, and subsequently more or less modified in structure and composition by heat, and by electro-chemical forces. The superficial accumulations of water-worn detritus, consisting of gravel, boulders, sand, clay, &c. are termed Drift, or Alluvial deposits. When the successive layers in which the sediments subsided are obvious, the deposits are said to be stratified; when the nature of the materials has been altered by igneous action or high temperature, but the lines of stratification are not wholly effaced, the rocks are denominated metamorphic (transformed). When all traces of organic remains and of sedimentary deposition are lost, and the mass is crystalline, and composed of known products of igneous action, such rocks are named plutonic, as granite, sienite, trap, basalt, porphyry, and the like. Lastly, rocks resembling the lavas, scoria, and other substances emitted by burning mountains still in activity, are called volcanic.

The sedimentary origin ascribed to ancient crystalline rocks is, of course, hypothetical, since all evidence of aqueous deposition is wanting, and the minerals (mica, quartz, and felspar) of which they are so largely constituted, are not readily soluble in water under ordinary circumstances. But rocks unquestionably deposited by water, when exposed to intense heat under great pressure, acquire a crystalline structure (Wond. p. 864); and a series of changes, from a « 20 » loose earthy deposit, to compact volcanic lava, may be traced in numerous instances, so as to leave but little doubt that the rocks called primitive or primary, may have originally been either argillaceous, siliceous, or calcareous strata, abounding in organic remains (Wond. p. 873). These crystalline masses have been formed at successive periods; for granite is found of all ages, occurring in the most ancient, as well as in comparatively modern epochs. The difference between the composition and aspect of these rocks, and those of recent volcanoes, is with much probability ascribed to the fact that the latter are of sub-aerial origin; that is, were erupted on the surface, and the gaseous products in consequence escaped; while the former were ejected at great depths, either beneath the sea, or under immense accumulations of other deposits, and being thus subjected to great pressure, the volatile elements were confined, and formed new combinations: in like manner as chalk when burnt in the open air is converted into lime, the carbonic acid gas escaping; but when exposed to the same degree of heat in a closed iron tube, is transformed into granular marble (Wond. p. 104).

From these ancient crystalline rocks generally underlying the sedimentary deposits, and never appearing as if they had been ejected from a crater, the term hypogene[10] (nether-formed) is employed by Sir C. Lyell to designate the whole class; and they are subdivided into, 1. plutonic, those in which all traces of sedimentary origin are lost, as granite; and 2. metamorphic, those which still manifest traces of stratification, as mica-schist, &c.

[10] Nether-formed, from ιπο, hypo, under; and γἱνομαι, ginomai, to be formed.

The fossiliferous rocks are, for the convenience of study, separated into three grand divisions.

1. The Tertiary; comprising the deposits between the Chalk and the superficial Drift and modern Alluvium.

2. The Secondary; from the Chalk to the Trias or New Red, inclusive.

3. The Palæozoic; from the Permian to the Silurian; including the vast series of unfossiliferous slate rocks termed the Cambrian, in which all traces of organic remains are lost.

In the following arrangement the strata are enumerated as if lying in regular sequence, one beneath the other; but in nature such an unbroken series has never been observed. A few groups only occur in a serial order, and these but rarely in their original position. The beds are for the most part disrupted, and lie in various angles of inclination; sometimes they are completely retroverted, the newer strata underlying those upon which they were originally deposited. The order of succession has been ascertained by careful observation of the relative superposition of the respective members of the series in different countries; and from an immense number of facts collected by able observers in every part of the globe.

This synopsis presents a chronological arrangement of the rocks according to the present state of geological knowledge, but it must not be supposed that these rigid distinctions, these hard lines, which are necessary to facilitate the acquisition of a general idea of the phenomena attempted to be explained, exist in nature. By whatever names we designate geological periods, there appear to be no clearly defined boundaries between them in reference to the whole earth: such well marked lines may be seen in particular localities, but daily experience teaches us that there is a blending, and a gradual and insensible passage, from the lowest to the highest sedimentary strata, particularly in respect of fossil remains. The terms employed to designate formations can only be considered as expressing the « 22 » predominance of certain characters, to be used provisionally, as a convenient mode of classifying and generalizing the facts collected, whilst that knowledge is accumulating which in after times will reveal the nature and order of succession of the principal events in the earth's physical history.[11]

[11] "Wonders of Geology," p. 892.

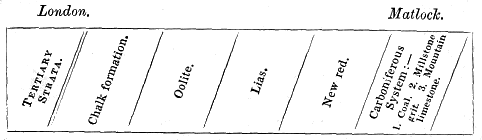

Dr. Buckland's "Bridgewater Treatise" (Vol. II. frontispiece) contains a comprehensive Diagram of the rocks and strata of which the crust of the earth is composed; it was drawn by the late Mr. Thomas Webster.

SYNOPSIS OF THE BRITISH STRATA.

"Hard lines are admissible in Science, whose object is not to imitate Nature, but to interpret her works."—Greenough.

The classification of the stratified rocks is based on three principal characters; namely, 1, the mineral structure; 2, the order of superposition; and 3, the nature of the organic remains; the following synopsis has been drawn up in accordance with these principles.[12]

[12] See "Wonders of Geology," vol. i. pp. 200-207, for a Synoptical Table of the principal rocks.

CHRONOLOGICAL ARRANGEMENT OF THE BRITISH FORMATIONS.

COMMENCING WITH THE UPPERMOST OR NEWEST DEPOSITS.

Alluvial Deposits: remains of Man and existing species of mammalia.

Drift; Boulder clay; Till; &c. comprising the superficial irregular accumulations of transported materials, consisting of gravel, boulders, sand, clay, &c.

Observations.—These beds have been formed by a variety of causes; by land-floods and inundations, by irruptions of the sea, and by the « 24 » agency of glaciers and icebergs. They are the catacombs of the extinct colossal mammalia—of the mastodon, mammoth, rhinoceros, hippopotamus, elk, horse, ox, whale, &c. They cannot be definitively separated from those of the Modern or Human epoch, for the gravel beds near Geneva, which closely resemble the newest tertiary drift in materials and position, abound in bones of animals, almost all of which belong to existing species.[13]

[13] See M. Pictet's "Palæontologie."

An extensive series, comprising many isolated groups of marine and lacustrine deposits, containing fossil remains of animals and vegetables of all classes; the greater number of genera and species in the most ancient or lowermost beds belong to extinct types.

Subdivisions:—

1. The Pliocene[14] (more new, or recent.[15] Wond. p. 221); strata in which the shells are for the most part of recent species, having only about ten per cent of extinct forms. (Norwich Crag.)

2. The Miocene (less recent,[16] Wond. p. 221); containing about 20 per cent of recent species of shells. (Suffolk Crag.)

3. The Eocene (dawn of recent,[17] in allusion to the first appearance of recent species—Wond. p. 226); the most ancient tertiary strata contain but very few existing species of shells; not more than five per cent. (London, Hants, and Paris basins.)

[14] In the present state of our knowledge, this arrangement is of great utility, but it will probably require considerable modification, and must, perhaps, hereafter be abandoned; for it cannot be doubted, that strata in which no recent species have yet been found, may yield them to more accurate and extended observations, and those in which only a few recent species are associated with a large number of extinct forms, may have these proportions reversed.

[15] From πλειων, pleion, more; and καινος, kainos, recent.

[16] From μεἱων, meion, less, and recent.

[17] From ἠως, eos, the dawn or commencement, and recent.

Obs.—The marine are often associated with fresh-water deposits, and the general characters of the Tertiary system are alternations of marine and lacustrine strata. In England the most important Tertiary deposits are those of the London basin, the Isle of Sheppey, the south-western coasts of Sussex and Hampshire, the north of the Isle of Wight, and the eastern coasts of Essex, Norfolk, Suffolk. (Wond. p. 226.)

The Cretaceous or Chalk Formation. (Wond. p. 296). A marine formation, comprising a vast series of beds of limestone, sandstone, marl, and clay, &c.; characterized by remains of extinct zoophytes, mollusks, cephalopods, echinoderms, crustaceans, fishes, &c.; lacertians, crocodilians, chelonians, and other extinct reptiles; drifted coniferous and dicotyledonous wood and foliage, fuci, &c.

Subdivisions:—

| 1. | The Maestricht beds. Friable coralline and shelly limestones, with flints and chert. | ||

| 2. | Upper Chalk, with flints | } | Craie blanche of the French geologists. |

| 3. | Lower Chalk, without flints | ||

| 4. | Chalk-marl | Craie tufeau. | |

| 5. | Firestone, Malm-rock, Upper Greensand, or Glauconite | } | Glauconie crayeuse. |

| 6. | Galt, or Folkstone-marl | Glauconie sableuse. | |

| 7. | Shanklin, or Lower Greensand. | { | Formation néocomien; which is divided into N. supérieur, the English upper divisions of the Greensand or Kentish rag; and N. inférieur, the lower beds of sand and clay, of the southern shore of the Isle of Wight, at Atherfield.[18] |

[18] Another subdivision, with other names (chiefly derived from French localities), has lately been proposed by M. D'Orbigny; which I notice with the more regret, since this eminent naturalist formerly repudiated the censurable practice of many modern systematists, of changing established names of strata and fossils, without any just cause. The British geologist will smile to see the Wealden Formation—so eminently distinguished in England and Germany by its extent, thickness, and remarkable fauna and flora,—ranked as a subordinate member of the "Formation néocomien," of France.

Obs.—The Maestricht beds are chiefly composed of fawn-coloured limestones of friable texture; containing peculiar species of corals, shells, fishes, reptiles, &c. The Chalk is generally white, but in some localities is of a deep red, in others of a yellow colour; nodules, layers, and veins of flint occur in the upper, but are seldom present in the lower chalk. The Marl is an argillaceous limestone, which generally prevails beneath the white chalk; it sometimes contains a large intermixture of green or chlorite sand, and then is called Firestone, or Glauconite. The Galt is a stiff, blue or blackish clay, abounding in shells which frequently retain their pearly lustre. The Greensand is a triple alternation of sands and sandstones with clays; and beds of cherty limestone called Kentish Rag.

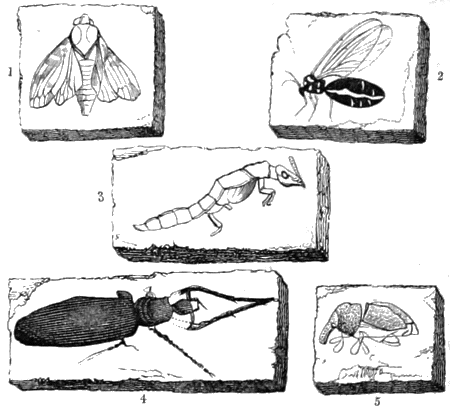

The Wealden; a formation, whose fluviatile character was first observed and established by the researches of the author (Wond. p. 360). A series of clays, sands, sandstones and limestones, with layers of lignite, and extensive coal-fields; characterized by the remains of several peculiar terrestrial reptiles, namely, Iguanodon, Hylæosaurus, Pelorosaurus, Megalosaurus; Crocodilians and Chelonians; Enaliosaurians; Pterodactyles, &c.; Fishes of fluviatile and marine genera; Insects of several orders; fresh-water mollusks and crustaceans; conifers, cycads, ferns, &c.

Subdivisions:—

| 1. | Weald-clay, with Sussex or Petworth marbles. |

| 2. | Tilgate-grit, and Hastings sands. |

| 3. | Ashburnham clays, shales, and grey limestones. |

| 4. | Purbeck beds; argillaceous and calcareous shales, and fresh-water limestones and marbles. Petrified forest, and layers of vegetable earth; with Cycads and Conifers. |

Obs.—Clays and limestones, almost wholly composed of fresh-water snail-shells, and minute crustaceans, generally occupy the « 27 » uppermost place in the series in Sussex; sands and sandstones, with shales, and lignite, prevail in the middle; while in the lowermost, argillaceous beds, with shelly marbles or limestones, again appear; and, buried beneath the whole, is a petrified pine-forest, with the trees still erect, and the vegetable mould undisturbed! The upper clay beds and marbles form the deep valleys or Wealds of Kent and Sussex, and the middle series constitutes the Forest-Ridge. The Purbeck strata are obscurely seen in some of the deepest valleys of eastern Sussex; they emerge on the Dorsetshire coast, form the Island or Peninsula whose name they bear, and surmount the northern brow of the Isle of Portland. On the southern coast of the Isle of Wight, the Wealden beds emerge from beneath the Greensand strata between Atherfield and Compton Bay on the western limit, and in Sandown Bay on the eastern; and their characteristic fossils are continually being washed up on the sea-shore.

The Jurassic or Oolitic Formation. (Wond. pp. 202, and 491). A marine formation of great extent and thickness, consisting of strata of limestone and clay, which abound in extinct species and genera of marine shells, Corals, Insects, Fishes, and terrestrial and marine Reptiles. Land plants of many peculiar types, and the remains of two genera of Mammalia.

Subdivisions:—

Upper Oolite of Portland, Wilts, Bucks, Berks, &c.

| 1. | Portland Oolite. Limestone of an oolitic structure, abounding in ammonites, trigoniæ, &c. and other marine exuviæ. Green and ferruginous sands—layers of chert. |

| 2. | Kimmeridge clay. Blue clay, with septaria, and bands of sandy concretions—marine shells and other organic remains—ostrea deltoidea. Beds of lignite. |

Middle Oolite of Oxford, Bucks, Yorkshire, &c.

| 1. | Coral oolite, or Coral rag. Limestone composed of corals, with shells and echinites. |

| 2. | Oxford clay; with septaria and numerous fossils. Beds of calcareous grit, called Kelloway-rock swarming with organic remains. |

Lower Oolite of Gloucestershire, Oxfordshire, and Northamptonshire.

| 1. | Cornbrash—a coarse shelly limestone. |

| 2. | Forest marble; concretions of fissile arenaceous limestone—coarse shelly oolite—sand, grit, and blue clay. |

| 3. | Great oolite—calcareous oolitic limestone and freestone; reptiles, corals, &c., upper beds full of shells. |

| Stonesfield slate;—terrestrial plants, insects, reptiles, Mammalia. | |

| 4. | Fullers earth beds;—marls and clays, with fuller's earth—sandy limestones and shells. |

| 5. | Inferior oolite—coarse limestone—conglomerated masses of terebratulæ and other shells—ferruginous sand, and concretionary blocks of sandy limestone, and shells. |

Lower Oolite, of Brora in Scotland.

| 1. | Shelly Limestones—alternation of sandstones, shales, and ironstone; land-plants. |

| 2. | Ferruginous limestone, with carbonized wood and shells. |

| 3. | Sandstone and shale; with two beds of coal. |

Lower Oolite of the Yorkshire coast.

| 1. | Cornbrash—a provincial term for a bluish grey rubbly limestone, with intervening layers of clay. |

| 2. | Sandstones and clays, with land-plants, thin beds of coal and shale—calcareous sandstone and shelly limestone. |

| 3. | Sandstone—often carbonaceous, with clays; coal-beds, and ironstone, with remains of vegetables. |

| 4. | Limestone; ferruginous and concretionary sands. |