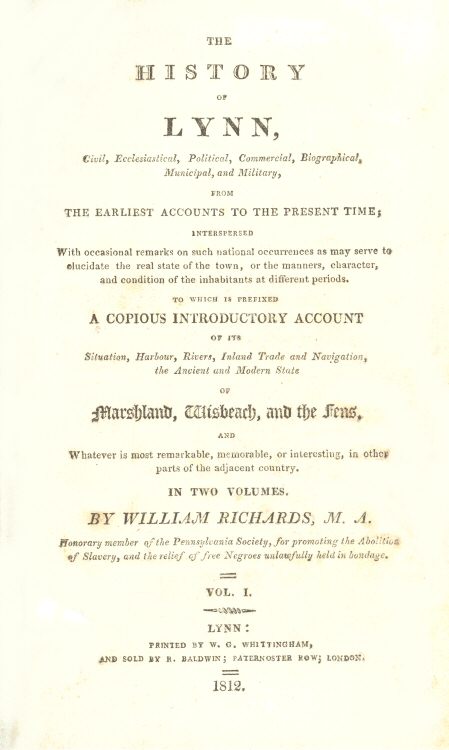

Transcribed from the 1812 W. G. Whittingham edition by David Price, email ccx074@pglaf.org

THE

HISTORY

OF

LYNN,

Civil,

Ecclesiastical, Political, Commercial,

Biographical,

Municipal, and Military,

FROM

THE EARLIEST ACCOUNTS TO THE PRESENT TIME;

INTERSPERSED

With occasional remarks on such national occurrences as may serve

to

elucidate the real state of the town, or the manners,

character,

and condition of the inhabitants at different periods.

TO WHICH IS

PREFIXED

A COPIOUS INTRODUCTORY ACCOUNT

OF ITS

Situation, Harbour, Rivers, Inland Trade

and Navigation,

the Ancient and Modern State

OF

Marshland, Wisbeach, and the Fens,

AND

Whatever is most remarkable, memorable, or interesting, in

other

parts of the adjacent country.

IN TWO VOLUMES.

BY WILLIAM RICHARDS, M.A.

Honorary member of the

Pennsylvania Society, for promoting the Abolition

of Slavery, and the relief of free Negroes unlawfully

held in bondage.

VOL. I.

~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~

LYNN:

PRINTED BY W. G. WHITTINGHAM,

AND SOLD BY R. BALDWIN; PATERNOSTER ROW;

LONDON.

1812.

Materials for a history of Lynn have been collected as long ago as the reign of Charles II. by Guybon Goddard, then recorder of this town, and brother-in-law of Sir William Dugdale. At his death, which happened, if we are not mistaken, about 1677, those materials came into the possession of his son Tho. Goddard Esq; from whom our corporation soon after endeavoured to obtain them; but we cannot learn that they then succeeded; nor does it appear that they ever came into their hands. What became of them, whether still in being or not, we have never been able to learn: and it is presumed that all the present members of our body Corporate are equally uninformed. See p. 831.

About forty years after the death of Guybon Goddard, another attempt was made to produce or compile a history of this town, by a nameless person, but evidently a learned, ingenious, and industrious man. Unfortunately his attention was chiefly engaged about the churches, and especially p. ivthe monuments and monumental inscriptions which they contained. These he took no small pains with, and made fair drawings of most of them. This work he carefully arranged, and fairly wrote out. It forms a moderate folio volume, and is now in the possession, or at least in the hands, of Mr. Thomas King of this town, for we are informed that Dr. Adams is the real owner of it. There are at the end of it some curious documents relating to divers ancient customs and occurrences, of which the compiler of the present history has in some measure availed himself. The volume was finished in 1724, and the author, it seems, died soon after.

Within a few years after his death, the work fell into the hands of Mr. B. Mackerell, who, after making a few paltry additions to it, actually published the greatest part of it verbatim under his own name, and it constitutes the bulk of that volume which has ever since been called, Mackerell’s History of Lynn. This act or achievement is disreputable to Mackerell’s memory; but the plagiarism has been scarcely known or noticed till now. He makes, in his preface, some slight obscure mention of the MS. but deigns not to tell the author’s name, though it must have been well known to him. He also boasts of his having had free access to the town records, and having “diligently searched and perused them, for a considerable time together.” For aught we know, this may be all very true; but if it be so, he p. vmust have laboured to very small purpose, as all the discoveries he has been able to make amount to very little, and may be comprised within a very narrow compass.

Parkin also, in his continuation of Bloomfield’s History of Norfolk, and in his Topography of Freebridge Hundred and Half, has published a history of Lynn, of above fifty large folio pages. It is in few hands, and little known; and though it contains much useful information, (very ill arranged,) it has no pretension to the character of a complete history of the town. The same may be said of what has since appeared, in the octavo history of Norfolk published at Norwich, and, more recently, in the Norfolk Tour, and the Beauties of England; the former from the pen of Mr. Beatniffe, and the latter from that of Mr. Britton. All these are mere Epitomes, and never fail to excite in their readers a wish to see a more copious and complete history of the place. Such a wish has been often and very generally expressed; and some years ago, a young man, of the name of Delamore, offered to gratify it, and supply this deficiency and lack of service. He accordingly circulated printed proposals for publishing, by subscription, a larger account of the town than any that had yet appeared. But not meeting with sufficient encouragement, he dropt the design, and soon after quitted this vicinity. What materials he possessed, or how competent he was for the undertaking, the present writer is not able p. vito say. But it is very clear that the public were not disposed to favour his proposal.

For some years after the last mentioned occurrence, there was no talk or expectation of a new history of Lynn. But somewhat more than seven years ago, a sudden and severe domestic affliction (from the effects of which he has never recovered) obliged the present writer to seek in solitude some alleviation of his sorrow, which he despaired of finding in the way of social intercourse, and even found himself incapable of attempting it, without offering unbearable violence to his feelings. Thus shut up in retirement, and buried among books, he tried to beguile his melancholy, by forming and pursuing certain literary projects; among which was an ecclesiastical history of Wales, which had often before employed his thoughts; and likewise a general history of Lynn, which has been his place of residence now near forty years, and whose history had also, not unfrequently, engaged his attention. In both these works he made some progress; which coming to the knowledge of his friends, they urged him to publish, but they were not agreed which should be published first: some called for the former work, of which some hundreds of copies were soon subscribed for; others advised him to complete and publish the History of Lynn first, and these prevailed—it being more convenient for him just then to attend to this than to the other. An agreement was consequently made with one of the book-sellers p. viifor its publication; and the public manifested a disposition to encourage the undertaking.

When the work was sent to the press, it was fully intended that it should all be comprised in one volume; and this intention was persisted in, till 7 or 800 pages had been printed off. By that time the author had received a large and unexpected quantity of new matter, much of it very curious and interesting, which many of his subscribers wished him to make use of and insert. He was therefore induced and constrained to depart from his original design, and extend the work to two volumes. But as it was then too late to have the pages numbered accordingly, they were of course continued in a regular series through both volumes, so as to amount in all to above 1200.

The enlargement or extension of the work, beyond the original design, has occasioned some derangement of the author’s first plan, so as to give the latter part of the work somewhat of the appearance of disorder and confusion; which the author sincerely regrets, but it was perhaps unavoidable, as the case stood. Had he possessed at first all the materials he has since obtained, he flatters himself that the task he undertook had been much better executed. Some of the latter or lately received documents were found to cast a new light on divers facts previously stated, so as to convince the author that he had been in several p. viiiinstances mistaken. He therefore never failed to seize the earliest opportunity to rectify those mistakes; for he was fully resolved to make his history the vehicle of truth, as far as it lay in his power. Of this he thinks he has given frequent proofs. Yet even this very practice, of rectifying, without loss of time, any mistakes which he found he had previously fallen into, will probably be classed, by some, among the defects of this performance. Be it so. He is more desirous of being classed among honest men, and lovers of truth, than among polished writers, or methodical and elegant historians.

As to the Critics, annual, and quarterly, as well as monthly, he has but little to say to them. He is very sensible of the defects of the work; many of which however were unavoidable, in existing circumstances, or in a first attempt like his, where many of the necessary materials were not in his possession, or at his command, and seemed for a long while unobtainable. Should the work come before their high tribunal, he asks no favour. They will doubtless see in it many defects, but not more perhaps than he is himself conscious of. They are welcome however to be as severe as they please, provided they deal fairly, or with reason and justice. It may be less cruel to exercise their severity here, than upon some young authors, who are in quest of, and panting for popular applause, or literary fame; neither of which has ever been sought for by the present writer.

p. ixThe work being now finished, after many unforeseen delays, the author respectfully submits it to the examination and judgment of the candid and intelligent reader, by whom, he doubts not, both its merits and demerits will be rightly estimated. Whatever may be said or thought of the execution, he thinks it must be admitted, that there is here brought together such a mass of interesting information relating to this town, as few people could have expected to see, when the design of this publication was first advertised. So that there may now be obtained as much knowledge of the ancient and modern affairs of this town, as of most towns in the county, or in the kingdom. He regrets that so many typographical errors escaped him in revising the sheets; the chief of which he has now pointed out, in a table of errata, (which will be found in each volume,) by the direction of which he requests the subscribers forthwith to correct the reading.

It may have been expected, that this work would contain a list of our mayors; but as no such list was known of, that might be depended upon for its correctness, it has been omitted: nor did it seem to be at all material, unless it had also been accompanied with lists of the recorders, and other functionaries, which appeared unobtainable.—It was intended to add an alphabetical Index; but as it would take up some time, and increase too much the size of the concluding number, (already almost three times as large at p. xany of the others,) the design was given up. The Table of contents it is hoped, will supply, in a great measure, the want of an index. Be that as it may, the work is now left to take its chance and make its own way in the world—the author consoling himself with the consciousness of having faithfully and honestly performed the task he had undertaken.

Lynn, July, 1812.

Site of Lynn—Account of its harbour, and that of Wisbeach—Ancient and present state of its rivers—Inland Navigation—Drainage—Projects of improvement—State of its shipping, commerce, and population, at different periods.

Situation of the town—its distance from the sea, &c.—its harbour—river Ouse and its tributary streams.

Lynn is situated on the eastern side of Marshland, and of the Great Level, or Fen Country, about 12 miles from the Sea, 42 from Norwich, 46 from Cambridge, and 98 from London. [1] It stands partly on each side of the Ouse, but chiefly on its eastern banks; though it is supposed to have stood originally all on the opposite shore, and hence that part of it is still called Old Lynn.

p. 2The Haven or Harbour is capacious, but the entrance to it is accounted somewhat difficult, and even dangerous, owing to the numerous sandbanks, and the frequent shiftings of the channel, occasioned by the loose and light nature of the sandy and silty soil at the bottom. On which account it is not deemed safe for ships to go in or out without pilots, who are, or ought always to be well acquainted with the variations and actual state of the channel. In the ages proceeding the 13th century this harbour, compared with its present width, is said to have been very narrow, being only a few perches over, though its depth of water was then, probably, no less, if not greater than it is at present.

The Ouse over against the town, is reckoned about as wide as the Thames above London Bridge. Its name is evidently of British origin, [2] and corresponds with those of several others of our rivers; such as the Usk, Esk, Ex, Isis, &c. The word signifies, a stream, or the river, by way of eminence. It is called the great Ouse, to distinguish it from that called the little or lesser Ouse, which is now one of its tributary streams, and joins it some way below Ely, though it had formerly no connection with it. It is also called the eastern Ouse, to distinguish it from the northern, or Yorkshire river of the same name.

As Lynn owes most of its consequence to this river, which forms its communication with the sea, and gives it so great an extent of inland navigation, and consequently p. 3such a vast commercial intercourse with the interior parts of the country, it will not be improper here to give some account of it, together with its principal branches, or those tributary streams which render it so considerable among the British navigable rivers.

Kinderley, many years ago, has given the following account of this river and its several branches: “The Ouse (says he) formerly Usa or Isa, which is the most famous of all the rivers that pass through this Level, has its original head on a gentle rising ground full of springs, under Sisam in Northamptonshire, 54 miles from Erith bridge, at which place it first touches the Isle of Ely. It falls by Brackley, Buckingham, Newport Pagnel, Bedford, Huntingdon, and St. Ives, to Erith, and so on till it comes to Lynn. It has 5 rivers emptying themselves into it, beside many brooks and rills; Grant, Mildenhall, Brandon, Stoke, and the river Lenne, or Sandringham Ea [otherwise Nare,] which rises under Lycham, and comes by Castleacre, Narford, and Sechy.” [He omits the Nene, which surely he ought to have mentioned.] Afterward he adds, “That the Ouse by its situation, and having so many navigable rivers falling into it from eight several counties, does therefore afford a great advantage to trade and commerce, since hereby two cities, and several great towns are therein served; as Peterborough, Ely, Stamford, Bedford, St. Ives, Huntingdon, St. Neots, Northampton, Cambridge, Bury St. Edmunds, Thetford, &c. with all sorts of heavy commodities from Lynn, as Coals, Salt, Deals, Fir-timber, Iron, Pitch, Tar, and Wine, thither p. 4imported; and from these parts great quantities of Wheat, Rye, Coleseed, Barley, &c. are brought down these rivers, whereby a great foreign and inland trade is carried on, and the breed of seamen is increased. The Port of Lynn supplies six counties wholly, and three in part.”

But of the Ouse and the other Lynn rivers, no one, perhaps, has given so full and so good an account as Mr. Skrine, in his general account of the British rivers.

“The Ouse (he says,) traverses a very considerable part of the Midland counties of England, rising in two branches, not far from Brackley and Towcester on the borders of Northamptonshire and Oxfordshire, from whence its course is eastward, a little inclined to the north, through Buckinghamshire, joined at Newport Pagnel by a small stream from Ivinghoe in the south; to reach Bedford it descends by many windings toward the south, and then joined by the Hyee from Woburn, and the Ivel from Biggleswade, it pursues its original direction to Huntingdon, where a combination of streams from the south-west contributes to its increase. From thence it passes nearly eastward through the centre of the Fens of Cambridgeshire, where it receives the Cam near Ely from the south-west, and afterwards the lesser Ouse from Woolpit and Ixworth in the south-east, joined by the Larke from Bury St. Edmunds; it then inclines more and more to the north, till it falls into the great Gulph of the sea between the projecting coasts of Norfolk and Lincolnshire, beneath the walls of Lynn Regis.

“The Ouse is generally a stagnant stream, neither giving p. 5nor receiving much beauty in all the great tract through which it passes. Its course is uniformly dull and unimportant to Buckingham; nor is it at all an object from the princely territory of Stowe, which abounds in grand scenes and buildings.”

This river “does not improve much,” (he further observes) “as it traverses the plain counties of Bedford and Huntingdon, though it adds some consequence to their capitals, being there navigable; at St. Ives it sinks into those great marshes which abound on this part of the eastern coast, through Norfolk, Huntingdonshire, Cambridgeshire, Northamptonshire and Lincolnshire.

“The Hyee which meets it a little below Bedford, passes near the Duke of Bedford’s noble domain at Woburn Abbey, and the Ivel flows northward to it through a dull uninteresting tract of country.

“The Cam is composed of two branches, one of which rises on the borders of Bedfordshire, and unites with the other, which bears the classic name of Granta, flowing from the confines of Essex, through the highly ornamented grounds of Audley End. They unite near Cambridge, and then run nearly eastward till the Ouse receives them, a little way from Ely.

“The Cam receives no small portion of beauty from the academical shades of Cambridge, being crossed by bridges from most of the principal Colleges, whose gardens join the public walks on its banks, which are finely planted and laid out. The stream itself is but stagnant p. 6and muddy, yet it adds something to the peculiar traits of the landscape, with the several stone bridges; nor do the fronts of the colleges, as they appear in succession, intermixed with thick groves, any where shew themselves to such advantage. The Area in front of Clare Hall, and the new building of King’s College, with its superb chapel, matchless in that species of Gothic Architecture which has been called “the improved,” exhibit one of the most striking displays in England. Soon afterward the Cam sinks into the Fens, where the proud pile and towers of Ely Cathedral appear finely elevated over the level, just above the junction of the Cam and the Ouse.

“A dreary tract of Marsh accompanies these united rivers to Downham in Norfolk; nor does the country much improve afterwards, but the channel becomes very considerable, and the exit of these rivers is splendid, where the flourishing port and great trade of Lynn present a croud of vessels.”

To the above account by Skrine, which is but imperfect, other rivers might be added, which join the Ouse in the latter part of its progress, and which ought not to be left here unnoticed; as the Nene, from Peterborough, Whittlesea, and March; the Wissey or Winson, from Stoke, and the Lenne or Nare, from Narborough and Sechhithe. The former, a large branch of which joins the Ouse at Salter’s Lode, is a Northamptonshire river, and rises near Catesby, under Anby Hill, in that county, and making Northampton in its way, passes from thence to Wellingborough, and along p. 7by Higham Ferrers, Thrapston, Oundle, Walmsford or Wandesford, Castor, Peterborough, Whittlesea, March, and on to Salter’s Lode and Lynn. The Wissey or Winson rises in the neighbourhood of Necton and Bradenham, in Norfolk, and running by Pickingham, Cressingham, Ikborough, Northwould, Stoke, and Helgay, enters the Ouse some way above Downham. The Lenne or Nare, otherwise Sandringham Ea, is also a Norfolk river, which after running by Litcham, Lexham, Castleacre, Westacre, Narford, Narborough, Pentney, and Sechhithe enters the Ouse at the South or upper end of the town of Lynn. It is a narrow, but in some places a deep and rapid river, and navigable a good way into the country; but has no very beautiful or striking sceneries any where upon or near its banks. [7] Like all the rivers of this low, flat, and dull country, it presents nothing that can be called striking or very remarkable, unless it be, a perpetual succession, or uniformity of dullness.

Further account of the river Ouse—remarkable phenomenon—the poet Cowper—supposed etymology of the name of Wisbeach—the Ouse diverted from its ancient course and outlet—King John’s disastrous passage over that river, in his last progress from Lynn—Extract from Vancouver.

In the respectable work called The Beauties of England, this remarkable circumstance is quoted from Walsingham relating to the river Ouse—That on the first of January 1399 it suddenly ceased to flow between the villages of Snelson and Harrold near Bedford, leaving its channel so bare of water that the people walked at the bottom for full three miles. [8] So strange a phenomenon seems not very easy to account for. It is said to have been for a long time considered as ominous of those dire dissentions and bloody wars which the opposite claims of the rival Houses of York and Lancaster shortly afterward occasioned. Nor is it at all wonderful that such an idea should gain credit in those dark and superstitious times: but to men of enlightened minds it must appear a very idle and pitiful conceit. A Dr. Childrey endeavoured to account for the said phenomenon, by supposing the stream above to have been congealed by a sudden frost: but this also is very properly deemed untenable by the writers of the work above mentioned; and they assign, as the most probable cause, in their opinion, that the earth had suddenly sunk in some part of the channel, so as to form there a deep and capacious cavity, into which the waters flowed till it was filled up, p. 9leaving the channel below in the mean time nearly dry, so that people might then actually walk at the bottom, as the story asserts. This appears reasonable enough, and was probably the real case; but as it cannot be now very interesting there seems no need to investigate it any further.

Dull and uninspiring, and in no sense classical ground, or a favourite haunt of the muses, as the banks of the Ouse have been generally, and perhaps justly considered, it must not be forgotten that they are become of late entitled to no small portion of celebrity, by the distinguished productions of the ingenious and excellent Cowper, one of the best, if not the very best of all our English poets of these latter days. He spent the greatest part of his time, and composed most of his works in the vicinity of this river. Henceforth it may therefore be deemed a classic stream: but it will be long, perhaps, before its banks shall have again the honour of numbering among their inhabitants a poet or a man of equal worth, genius, or renown. [9]

Here it may be proper further to observe, that the Ouse did not always visit Lynn, or pass that way in its progress to the Ocean. In ancient times its course is said to have been by Wisbeach, to which that town probably owes its name: Wis, or Wys, being apparently p. 10but another name of the Ouse, and Wisbeach the very same thing with Ousebeach, and signifying the beach, side, or bank of the Ouse; in other words, a place or town on the Shore and near the mouth of that river. [10]

What diverted this river from its ancient and original course is said to have been a great inland flood, which, meeting with obstruction, choked up the channel (already become bad and neglected) broke over the banks, and deluged the fens to a vast extent; from the effects of which they have never been fully recovered to this day.

This flood so deprived of a passage to the sea by the usual channel, and consequently overflowing the adjacent country to a great depth, became a most grievous and ruinous annoyance to the Fen people. At last, in order to remove so unbearable and terrible a nuisance, instead of taking common sense for their guide, and following nature, by opening the channel to the ancient p. 11outfall at Wisbeach, they determined, seemingly, to force nature, and set common-sense at defiance, by opening a passage for the inundating waters, and consequently for the future course of the great Ouse, the Cam, and the Larke into the narrow bed of the lesser Ouse, from Little-port Chair to Priests Houses, across that ridge, or higher ground, by which nature seemed to have forbidden the union of these rivers. [11]

In this ill judged and preposterous measure most of the existing evils in regard to the bad state of the Lynn and Wisbeach Harbours, the inland navigation and the drainage of the Fens have probably originated. The Ouse and the other rivers before mentioned have ever since followed the same new and unnatural track: Nor is it now very likely that they will ever again be permitted to follow any other. This memorable event, according to Dugdale, happened in the reign of Henry the third: so that in the reign of King John, the great patron of Lynn, the river or body of fresh water which flowed that way was but very small and narrow; and it was in crossing the Ouse, which did not then pass by Lynn, that he lost his baggage and treasures, and probably many of his men. Ancient records say that it was in crossing Wellstream, which was then the name of p. 12the Ouse in its approach to Wisbeach and the Sea, that the said King suffered those losses. [12]

The following Extract from Vancouver’s Appendix to his Agricultural Report will serve, it is thought, to corroborate some of the foregoing observations.—

“From the highlands in Suffolk (between the Mildenhall and Brandon rivers) to the east of Welney, Outwel, Emneth, and thence to the sea a positive dividing ground exists, formed by the hand of nature, strongly marked, and distinctly to be seen between the waters of the Lynn and of the Wisbeach Ouse. The hanging level, or natural inclination of the Country on the north side of this dividing ground draws the waters off to the sea through the lesser Ouse to the outfall of Lynn; and on the south side of it draws them off to the sea through the greater Ouse to the outfall of Wisbeach. To the cutting through this dividing ground, in order to force the water of the greater into the lesser Ouse, are all the evils of the south and middle levels of the fens, and of the country below originally and solely to be ascribed. At this time the bed of the Ouse where Denver Sluices now stand, was at least 13 feet below the general surface of the surrounding country; and then it was that, by the free action and reaction of the tides the waters flowed five hours in the haven of Lynn, ascended unto the Stoke and Brandon rivers, and into other streams which nature had wisely appropriated to be discharged p. 13through that outfall; forming the bed of the Ouse to one gradually inclined plain from the junction of the principal branches of that river into the low country to the level of the Ocean, very near or in the harbour of Lynn. The Counteracting this disposition of nature by forcing a greater quantity of water into the river than it could discharge into the sea during the time of ebb, necessarily occasioned the highland and foreign waters to override all those, which during the time of ebb, would naturally have drained into the Lynn river, and gave the waters of Buckingham and Bedford an exit into the sea in preference to those which lay inundating the country within a few miles, of their natural outfall.—In this condition at present are all the lower parts of the country bordering upon the Lynn Ouse; and the country above Denver Sluices, Downham, Marshland, and Bardolph fens, exhibits the most important of many other melancholy examples and evidences of it. In the higher parts of the country the consequences of this measure seem to have been severely experienced on the lands exposed to the unembanked waters of the old Ouse, between Hermitage and Harrimere. The Old Bedford river was then cut from Erith to Salter’s Lode, as a slaker to the Ouse, to relieve the country through which the Ouse flowed, from Erith to Ely. The Ouse waters thus divided a great part of them descended through the Old Bedford river in a straight line of twenty miles into the Lynn Ouse. But as that work was judged insufficient and defective, the New Bedford, or one hundred foot river was determined upon, and Sluices were erected at Hermitage to drive all the water of old p. 14Ouse from Erith (through the One hundred foot) into the Lynn Ouse; but that river not having sufficient capacity to utter them to sea, they reverted up the Ouse, the Stoke and Brandon rivers, drowning the whole of that country, and finally urging the necessity of erecting Denver Sluices, as the only apparent cure for the evils with which the country was then oppressed, and seemed further threatened with. In the execution of this business, with a view of bringing the bottom of the Ouse on a level with that of the hundred foot river (which was cut only five feet deep) it was judged expedient to raise a Dam eight feet high across the bed of the Ouse, upon the top of which the Sole or base of Denver Sluices was laid. This measure has not only defeated the purpose it was designed to promote, but has been the unfortunate cause of a body of sand and sea sediment being deposited in the bed of the Lynn Ouse at least eight feet deep at Denver Sluices, and only terminating in its injurious consequences at the mouth of the Lynn Channel. This shews to every calm and candid mind the necessity of duly considering the probable effects of counteracting the laws of nature, in cases where nature appears experimentally to have had success on her side.—From a due consideration of the obstacles which appear at this time to exist in what has long been considered the principal outfalling drain to the Middle and South levels of the fens, it is surely reasonable to direct our attention to the general inclination of the country with respect to the sea, and to what has all along been pointed out by nature as the main outlet thither, for the waters of the middle and south levels, and see if some p. 15means cannot yet be devised for recovering the general course of the ancient and voluntary passage of the waters through their natural channel of Wisbeach to the sea.”

The above passage merits serious and particular attention. The undisputed and indisputable fact, that the course of the Ouse lay formerly by Wisbeach, seems a clear and decisive proof that it was its natural course, and so may be considered as corroborating a great part at least of the above reasoning. Upon the whole, therefore, it seems highly probable that the evils now existing and complained of, as to the bad state of the Wisbeach and Lynn harbours, the inland navigation and fen drainage, have mostly originated in the abovementioned desertion of the Ouse from its ancient and natural outfall, and the forcing of it to Lynn through the channel of the lesser Ouse, in the 13th century, and reign of Henry III. as was before observed.

Effects of the desertion of the Ouse and Nene on Wisbeach and parts adjacent.

After the above mentioned disastrous aberration of the Ouse some plans, it seems, were formed, and royal Commissions issued to bring it back again into its old deserted channel by Wisbeach, but all proved in the end ineffectual and fruitless, so that the port of Wisbeach, of course would be materially injured. “Of old time” (says Badeslade—that is, while the Ouse and the Nene p. 16discharged themselves that way) “ships of great burden resorted to Wisbeach”—but after those rivers had deserted their ancient outlet, that town soon ceased to be accessible to large vessels. The bed or channel below the town being forsaken by the said rivers, (or at most occupied only by an inconsiderable branch of the Nene, which must have been insufficient to grind or scour it to its former or usual depth,) would gradually be filled up in time with silt and sand; and which evidently has been the case. This is confirmed by a remarkable circumstance related by Dugdale—That in deepening the Wisbeach river in 1635, (about 300 years after the desertion of the Ouse,) “the workmen, at eight feet below the then bottom came to another bottom which was stony, and there at several distances found seven boats that had lain there overwhelmed with sand for many ages.” [16a]

Atkins, who wrote in 1608, and dedicated his paper to Andrews bishop of Ely, speaks of the Wisbeach channel as “anciently an arm of the sea;” [16b] and says that the time was when all the waters of the Ouse, even those which then passed from Littleport Chair to Lynn had their passage by Welney and Well to the North Seas at Wisbeach, and from thence to the Washes—and he further observes that writers have said, that King John’s people perished in the Waters of Well. [16c] p. 17From Thorney Red Book he also shews, that Well Stream was an ancient appellation of the Wisbeach river. He further adds, that this outfall, or arm of the sea, had Holland and a part of the Isle on one side, and Marshland on the other; these were defended from it by great sea-banks, which in the time of Henry VI were ordained to be made and maintained fifty feet high. Hither of old resorted (he says) ships and vessels of great burden. But the sea, still forsaking the Isle, made the whole passage between Wisbeach and the Washes high marshes and sands; and by the decay of the river, the channel, or outfall, became so shallow and weak, as to admit of people often going over on foot, bare legged under the knees. He also imputes much blame to the people about Wisbeach, in not scouring and dyking the river, as by ancient laws and presentments they ought to have done; and not preserving and maintaining the petty sewers and drains. In consequence of these omissions, not only the fens were drowned, but the means were also lost of draining 13 or 14000 acres of inland grounds, the support of three or four towns on the North of Wisbeach.

That the bad effects of the desertion of the Ouse and Nene from their ancient outfall at Wisbeach, soon became very grievous to that town and the adjacent country, appears by the frequent complaints made, and laws enacted for their relief. Some of those laws were made in the reign of Henry VI, and measures were taken, it seems, in consequence of them, for the relief and benefit p. 18of the sufferers. The most important and beneficial of all those measures appears to be that adopted toward the latter part of the 15th century under the direction of bishop Morton. [18] “That prelate finding (says Atkins) that beside its being a very chargeable course to his people of the hundred of Wisbeach, once in four or five years to dyke this river, and that notwithstanding this dyking of the river, the outfall below to the seaward nevertheless decayed; and finding that without a great head of fresh waters, to scour both the river and the outfall, all would be lost, took a part of Hercules’ labour upon him, and strove to bring in great abundance of fresh waters, by divers courses, out of the Fens, to maintain this channel: viz. the rivers Nene and Welland from Southea, and the river of the great cross, or Plantwater, from the united branches of Nene and Ouse, descending by Benwick.” But the bishop’s principal undertaking seems to have been the cut of 14 miles, from Peterborough to Guyhorn, by which a large portion of the Nene was brought down p. 19to Wisbeach, and proved of up small benefit to that town and harbour, as well as to the drainage of the country. This cut has transmitted the bishop’s name deservedly and honourably to posterity; it being ever since known and distinguished under the denomination of Morton’s Leam. Happy had it been for the world, if all those of his order had deserved so well of their neighbours and of their country. [19]

“By this doing” (says Atkins, referring to the works of bishop Morton) “Wisbeach Fens were made good Sheep pastures, and the fall of the water at Wisbeach became so great, that no man would adventure under the bridge, with a boat, but by veering through, &c. But succeeding ages (he further observes) neglecting these p. 20good provisions, have thereby lost the benefit.” The blame of this neglect, both Atkins and Sir Clement Edmunds seem to lay entirely on the total want of public spirit, or the selfish and sordid disposition of the people of Wisbeach, who strove at all events to avoid the expence, alleging that the benefit of cleansing and dyking the outfall would altogether accrue to the behoof of the upland country, and therefore that they [the inhabitants of the said upland country] ought to put their hands to the work, and contribute towards it in some reasonable measure. The uplanders, on the other hand, produced divers presentments, some of them as high as Henry VI, shewing, that they ought not to be charged; at the same time expressing a willingness to yield a reasonable aid, when the work was done, if it proved serviceable. But those of Wisbeach required a previous contribution, to be expended as the work should proceed. Their selfishness and perverseness, on these occasions, carried them, it seems, to very extravagant and ridiculous lengths, to elude the charge: “one while saying, they cared not if Wisbeach were a dry town; another while by thinking to keep it as a standing pool; [and again] another while enforcing [or urging] the making of a Sluice between the town and the sea, that the tide should not silt up the river, saying that otherwise the charge of dyking the river would be but cast away.—And to the charge of this Sluice they would call in the high-country people, such as they knew would not easily be brought to it, so that nothing might be done.” This preposterous conduct of the Wisbeachers appears to have effectually frustrated every reasonable and salutary proposal. Atkins, however, gives it p. 21as his firm opinion, “that were there in the Isle of Ely again another bishop Morton the country might well be regained by such means as might be easily set down.” [21a] But it does not appear that another bishop Morton has yet risen in the Isle, whatever may be said of the regeneration, reformation, or amendment of the good people of Wisbeach.

Nothing of any consequence appears to have been attempted since, for the benefit of the port or navigation of Wisbeach, except Kinderley’s Cut, made in 1721 and 1722, by order of the Board of Adventurers, and not without the consent of the town of Wisbeach likewise; only the adventurers [it seems] ought to have had their consent under their hands: at least so says Mr Kinderly. This cut, had it gone forward, would probably have been of great advantage to the river. But by the time that it was completed, and a dam was making across the old channel, to turn the river into the new one, “the Wisbeach gentlemen, falsely, or by mistake, apprehending the advantage of a wide indraught over all those spreading sands, and complaining that this new cut was not wide enough, (though it was wider than the river at Wisbeach by twenty feet) and that therefore their river would immediately be choked up, and their navigation lost. [So they now] violently opposed it, and raised the Country for demolishing the works; and after that obtained an injunction from the Lord Chancellor to stop all further progress.” [21b] A long vexatious Law Suit ensued, but the p. 22Adventures could not recover the Money they had laid out, amounting to nearly £2000, and the gentlemen of Wisbeach gave ample proof that they still inherited, in full measure, the genuine spirit of their ancestors, before mentioned. Their Harbour has been for some years in a most miserable state, and seems to stand in need of the aid of a Morton or a Kinderly as much as ever.

The Effects on Lynn, and on its Harbour and Navigation, of the great accession of Fresh Waters in the reign of Henry III.

Let us now attend to the Ouse and its sister streams, in their now or modern course, by Denver, Downham, St. German’s, and Lynn. By the addition of so many large rivers to its former waters, Lynn might be expected to have its Haven, by degrees, both widened and deepened, so as to contribute materially to its future naval consequence, and commercial importance. Previously to this great accession of water, the bed or channel of the river, about St. German’s, has been represented as so very narrow, that in some places a man might throw himself over with a pikestaff; and in Lynn Haven it is said to have been but six poles, or about an hundred feet wide. But afterward, by the said accession of fresh waters, Lynn Haven and channel were made in time so wide and deep as to become famous for Navigation. [22]

p. 23Things appear to have continued pretty much in this favourable state, till sometime after the erection of the Sluices at Denver; which by preventing the tides from going further up into the country, as before, proved very prejudicial to the harbour and Navigation of Lynn; and the effects are felt, it seems, and much complained of to this day. The free admission of the tides, and the natural course of the freshes are said to have kept other rivers open and navigable; and this appears to have been the case with the Ouse itself, while it possessed those advantages, or till the adventurers erected the said sluices across its channel, which are thought to have proved so very prejudicial, not only to the navigation of Lynn, Cambridge, &c. but even to the draining of the Fen districts and Marshland.

Before the erection of those sluices, the tide is said to have gone up the rivers a very great way. Into the Ouse, and Grant, or Cam, it went, according to Badeslade, five miles above their junction, or 48 above Lynn; into the Larke, or Mildenhall river, eight miles above its month, or 42 above Lynn; into the lesser Ouse, or Brandon river, ten miles above its mouth, or 36 above Lynn; into the Wessey, or Stoke river, six miles above its mouth, or 24 above Lynn; and into the Nene, p. 24seven miles above its mouth, or 23 above Lynn. [24a]—These rivers are said to be then completely supplied with water from the sea, in the driest seasons, to serve for inland navigation.—The Nene, to Well, Marsh, and Peterborough, &c. with vessels of 15 tuns in the driest times: the Ouse, with vessels of 40 tuns, 36 miles, at least, from Lynn, in ordinary neap tides; and to Huntingdon, St. Neots, Bedford, and even as far as 90 miles from Lynn, with vessels of 15 tuns. The tides then raised the waters at Salters Lode 12 feet above low-water mark. These waters in their return scoured the channel, and kept it clear and deep. This seems to have been the case before the erection of the sluices; but whether it would have continued so to this time, may, perhaps, be doubted. Badeslade and Kinderly seem to have entertained different and opposite opinions on the subject; as the reader may see by consulting their respective publications.

In a course of time, Lynn Haven is said to wear from 6 or 8 to 40 poles wide; which seems not improbable, considering the situation of it, and the accession of so many large rivers. In Badeslade’s time, as he says, [24b] it was from 50 to 60 poles in the narrowest part; and p. 25now it can be no less. The Lynn river, however, has been thought to be still narrower than any other of equal size so near its outfall. Before the erection of the said Dams, or Sluices no complaints appear to have been made of either the haven, or yet the rivers above wanting a competent depth of water. Barges carrying 40 chalders could then go up the Ouse 36 miles, and those that carried from 26 to 30 chalders passed with ease to the very town of Cambridge. Whereas, in Badeslade’s time, flat bottom lighters, with eight or ten chalders, could hardly pass. Nor does it appear that things have gotten to a better state since. As to the haven, or harbour of Lynn, it was at those times wide, deep, and commodious. In 1645 its breadth is said to have been about a furlong. Ships then, and for some years after, rode at the south end of the town, and the west side in two fathoms, at low water. So they also did at the Crutch; and the largest ships could go to sea at neap tides. Two parts of the harbour were then remarkably deep; the one called Fieln’s Road, at the end of the west channel; and the other Ferrier’s Road, at the end of the east channel; and both of them three and half fathoms at low water. The tides too were then so strong as to make it necessary to use stream cables to moor the ships. Guybon Goddard, Esq. a former Recorder of Lynn (and brother in law to Sir Wm. Dugdale) who died about 1677, says, that at the World’s End in the Harbour of Lynn, there was not in any man’s remembrance less than ten or eleven feet at low water; and at a place called the Mayor’s Fleet 8 or 9 feet. The channel p. 26to seaward, below the haven, he says, near half mile wide at low water, was yet of a depth sufficient for a Ship of 12 foot water to be brought up in any one tide without wind. [26a] Upon the whole, it appears that the state of Lynn Harbour, and of the rivers which discharge themselves that way, was before the erection of the Sluices much superior to what it has been since. [26b]

As to the State of the Ouse and the other rivers up in the country above Lynn, it seems to have been much better before the undertaking for a general drainage and erection of the Sluices than since that period, as appears from the views of the Sewers taken June 25, 1605, by Sir Robert Bevill, Sir John Peyton, &c. at Salters Lode, where the Nene falls into the Ouse. The commissioners declared the fall from the soil of the Fens to low watermark as no less than ten feet, beside the natural descent of the grounds from the uplands of Huntingdonshire thither; which shews the bottom of the Ouse to be there much deeper then than it was afterward. Dugdale also, in his History of Embanking, says, that at Salter’s Lode there was ten feet fall of the fens at low water mark. p. 27From these statements it must necessarily follow, that the lands in the South Level, though unembanked, must in general have been in a comparatively good condition before the undertaking for a general drainage and erection of the Sluices; for, the fall being so great, no water could lie long upon them; and if at any time, by the descent of the upland waters, they became overflowed, they would not long continue in that state. At present, the case, it seems, is very different.

Of the Eabrink Cut, and other projects of former times—with some slight hints on the comparative state of the Shipping—Commercial consequence and population of Lynn at different periods.

It seems allowed on all hands that Lynn Harbour has grown much worse in the memory of the present inhabitants, and that it is daily getting more and more so. To remedy this growing and alarming evil, as well as to promote and facilitate the inland navigation and drainage of the Fen Districts, a project was formed some few years ago to open a straight cut from Eabrink, about three miles above the town, into the upper part of the said harbour, with the view of scouring, deepening, and improving the same; and an Act of Parliament was obtained for that purpose. The work however, has been hitherto postponed: it being, it seems, found difficult to raise a fund adequate to the occasion. Vast benefits are p. 28said to be confidently expected by many from the execution of this project; while others appear much less sanguine in their expectations, and even consider it as in no small degree dubious and problematical.

The opening a straight cut from Eabrink to Lynn Haven is not indeed, properly speaking, a new or a late project. It was suggested and recommended many years ago, as a part of a far more extensive undertaking, by Mr Kinderley, who wrote a large pamphlet on the subject, the second and last edition of which was published in 1751.—His favourite scheme was to continue the Cut from Lynn, through the marshes below the Wottons, Babingley and Wolverton, into what is called the Old Road; and to bring the Wisbeach river from the mouth of the Shiredam across Marshland into Lynn Harbour. The Welland also or Spalding river, he proposed to conduct by another cut to Boston, there to join the Witham, and pass along with it to the sea by a new outlet, so that there might be but two outlets instead of four, for all the great Fen rivers. The accomplishment of this vast plan, as he imagined, would not fail of being productive of many and most important benefits:—The harbours of Lynn and Boston, of course, would become more accessible, and be otherwise greatly improved:—The two washes would inevitably and soon be filled up, by the abundance of silt and mud which the tides would lodge there, and which would shortly be converted into firm and fertile land.—Also an extensive district larger than all Marshland, and almost as large as the whole county of Rutland, and of far p. 29greater value, would in no very long time be gained from the sea, and brought into a condition to be effectually secured by embankments from any future annoyance from the briny element.—Moreover, a good turnpike road, straight as an arrow, might and would be made across this recovered country, all the way from Lynn to Boston, to the no small convenience and comfort of travellers, (as the obstructions and dangers of the Washes would no longer exist) and to the facilitating and perpetuating a safe and easy intercourse between the inhabitants of Lincolnshire, as well as of all the north of England and those of Norfolk, Suffolk and the whole eastern coast of the Kingdom. The scheme or project, however, was not adopted, nor perhaps ever sufficiently attended to; and it may not now be worth while to inquire into the cause of its miscarriage or rejection. Whether this same scheme shall hereafter be ever adopted, executed, or realized, no mortal at present is capable of divining.

Between Mr Kinderley and Mr Badeslade there seems to have existed a considerable difference of opinion on some points. The former ascribed the increasing foulness and decay of Lynn Harbour to the increasing width of the channel below, the loose and light nature of the sand there, subject to the powerful action of the tides, continually driving up those sands and lodging them in the harbour and river above: whereas the latter seems to ascribe it chiefly, if not solely to the Sluices, or the obstruction which they occasioned to the free influx and p. 30efflux of the waters. [30a] Each writer supports his own opinion with great confidence; but the question remains undecided. Both of them, perhaps, might be right in many or most of their ideas and reasonings.

Very unlike most other great Sea-port towns, whose shipping and trade have vastly increased within the last hundred years, Lynn appears to have remained, in a great measure, stationary. As long ago as 1654 we hear of fourscore vessels or more belonging to the port of Lynn, (some of them drawing 13 or 14 feet water) and that they used then to make from 15 to 18 Voyages annually to Newcastle, for coals, Salt, &c. Also that Ship-building was at that period very briskly carried on in the town, to keep up the stock. Moreover the number of seamen and watermen, then employed here, is said to amount to, at least, fifteen hundred; and the whole number of inhabitants was probably equal to that of any subsequent period. It seems, indeed, to be now the prevailing opinion, that the present population of Lynn exceeds that of any former time; which yet may be deemed somewhat doubtful, if not quite improbable; especially as it is known to have been formerly a manufacturing town, [30b] which is not its case at present. The p. 31point, however, may not now be very easy to determine. But it seems very evident, that the trade of Lynn has not increased to the degree or extent that might have been expected, from the great opulence of its merchants and the vast extent of its inland navigation. The real or probable cause of this will not become here the subject of enquiry; but it may not be unworthy of investigation.

Of Marshland and the adjoining parts, or Great Fen Country.—View of their situation and revolutions in remote ages, or Sketch of their ancient history.

Account of their state before and after the arrival of the Romans—Character of that people—establishment of their power here—improvements made by them in these parts.

As Lynn may be considered as the Capital or Metropolis of Marshland and the Fens, it will not be improper to give here some account of those remarkable districts from the earliest times. All this flat and level country is thought to have been originally a vast forest, which was afterwards in some measure cleared, and converted into good cultivated land, fertile fields, rich pastures, and numerous habitations of industrious men. After that however, it was, it seems, for no short period, covered by the sea, occasioned, perhaps, by an earthquake, or some such convulsive event, which might considerably lower or sink the whole surface of the country, and so make way for the violent influx of the ocean. The overflowing waters in time gradually covering the original surface of the ground with silt and sand to a very p. 33great depth, or rather height, would at last recede. The present face of the country, composed of silt to a vast depth,(and which seems no other than marine sediment) confirms this hypothesis. Still however the parts next the sea, such as Marshland and the low-lands on the eastern side of Lincolnshire would remain as a great salt marsh, occasionally overflowed, especially at spring-tides.—This seems to have been the case when Julius Cæsar invaded this country, and when Claudius afterwards reduced it to the state of a Roman Province.

The Romans, with all their faults, were certainly a wonderful people. Like all other invaders and conquerors they were in general very hard masters, and in some respects most vile oppressors and tyrants. In other respects, however, they may be said to have been eventually real benefactors to many, if not to most of the countries and nations which they subdued, as they were the means of greatly improving those countries, and of introducing among their inhabitants the rudiments of useful knowledge, habits of industry, and the laws of civilization.

Julius Cæsar’s invasion of Britain seems to have proved upon the whole unsuccessful; for he withdrew to the continent, without being able to effect its subjugation, or to retain the conquests which he is supposed to have made; which may be thought to furnish a pretty strong argument in favour of the independent spirit, and high military character of the British nation at that time. Nor does it appear that the Romans ever attempted to give p. 34our ancestors any further disturbance afterward, till the reign of Claudius, whose general, Aulus Plautius, a person of senatorial dignity, was the first that established the power of that people, or gave them a firm footing in this island. This was near a hundred years after the retreat or departure of Julius Cæsar; and the success of Plautius is said to have been chiefly or greatly owing to the bitter dissentions which then raged among the British chieftains, some of whom had invited the Romans hither, and afterward joined them against their own country-men. Claudius himself came over sometime after, and completed the conquest of a great part of South Britain, including, it seems, the country of the Iceni, which comprehended the present counties of Norfolk and Suffolk, with most, if not the whole of those of Cambridge and Huntingdon, and probably some part of Lincolnshire. So that the parts adjoining the Fens became subject to the Romans among their earliest acquisitions in Britain. The inhabitants of these parts are also said to have made the least resistance to them, at first, of any of the British States, and therefore to have been for sometime more highly favoured by them than any of the rest. Claudius at his departure from this island, which is said to have been in the year 43 of the Christian Era, left here a considerable force under Plautius, Vespasian (afterwards emperor) and other experienced and able Generals, who were succeeded by others, no way their inferiors, in experience, ability, or military fame; among whom were Ostorius Scapula, Suetonius Paulinus, and Julius Agricola. Besides Julius Cæsar, Claudius, and Vespasian, several others of the Roman p. 35emperors are said to have spent some part of their time in this island; and particular Hadrian, Severus, Constantius Chlorus, and his son Constantine the Great. The latter is supposed to have been born here, and his mother is said to have been a Briton. His father, as well as his predecessor Severus, died at York, a place of no small consequence and celebrity in those times.

After the country was reduced, and made a part or province of the empire, the Romans soon began to view it as a very important acquisition. Accordingly they set in good earnest about improving it; and there are still to be seen numerous proofs and monuments of their laborious, ingenious, and successful exertions. Among their important improvements here were included the draining of the Fens, and the embanking of the Marshes, to secure them against the violence and destructive inroads of the ocean. Marshland and the low lands of Lincolnshire, as was before observed, they found in the miserable condition of a salt marsh, occasionally and frequently overflowed by the tides. This country they secured by very strong and extensive embankments, which bear their name to this day. [35a]

These improvements in the Fens and Marshes are said to have been the works of a colony of foreigners, [35b] brought over, probably, from Belgium, a country of a similar description, whose natives, from their previous knowledge and habits, would be eminently fitted for p. 36such employments. Not that those works can be supposed to have been effected without the powerful co-operation of the native Britons, who would sometimes loudly complain of the hardships they endured in labours of this kind, imposed upon them by the Romans: a plain proof that they bore their full share of them. Catus Decianus, it seems, was the name of the Roman officer who had the chief direction or superintendence of the improvements then projected and carried on in the Fens. [36] He was probably the first Roman Procurator of the province of the Iceni, and continued to be so for many years. Some things recorded of him, during his government here exhibit him in a very unamiable and detestable light; and it may be presumed that he was an unfeeling and severe task-master to the workmen whom he employed in the fens and marshes, as well as elsewhere; so that we need not wonder that they should sometimes loudly complain of the hardships they underwent. The public works of which he had the direction and superintendence seem, however, to have been carried on by him with no small energy and effect, and to have been soon brought to a state of considerable forwardness and perfection.

The Fens must have been in a very dismal state before the arrival of the Romans; and their exertions, undoubtedly, wrought a mighty, and most happy change in the face of the country. Houses, villages, and towns would now appear in places that were before perfectly desolate and dreary. At this period we may venture to p. 37date the origin of Lynn; for it may be pretty safely concluded that it owes its rise to the schemes formed by the Romans for the recovery and improvement of these fens and marshes. It is also very probable, not only that it was the first town built in these parts, on that occasion, but also that it was built and inhabited by those foreign colonists above mentioned, and derived its name from them. This however is not the proper place for the further elucidation of this point: our present business being with the history of the Fens.

Further strictures on the ancient state of this country, and on a wonderful change it appears to have undergone, at a very remote and unknown period; from De Serra’s account of a submarine Forest on the coast of Lincolnshire.

Some very remote ages ago, the land, it seems, extended much further out on the Lincolnshire coast than it does at present; and it appears that whole forests once existed in places now wholly occupied by the ocean; which must tend to corroborate what has been already suggested, that the whole face of the fens was originally a forest. A remarkable Paper, giving an account of a Submarine Forest on the said coast, appeared in the Philosophical Transactions for 1799. Part I. written by Joseph Correa De Serra L.L.D. F.R.S. and A.S. in which the Author informs us of a report in Lincolnshire, that a large extent of islets of moor, p. 38situated along the coast, and visible only in the lowest ebbs of the year, was chiefly composed of decayed trees. That report induced him to take a journey thither for the purpose of inspecting so singular a curiosity. Those islets, he observes, are marked in Mitchell’s Chart of that coast by the name of Clay huts; and the Village of Huttoft, opposite to which they principally lie, he supposes to have derived its name from them.

“In the Month of September 1796, (says he) I went to Sutton, on the coast of Lincolnshire, in the company of the right honourable the President of the Royal Society, in order to examine their nature and extent. The 19th of the month being the day after the equinoctial full moon, when the lowest ebbs were to be expected, we went in a boat, about half past twelve at noon, and soon set foot on one of the largest islands then appearing. Its exposed surface was about 30 yards long, and 25 wide when the tide was at the lowest. A great number of smaller islets were visible around us to the eastward and southward; and the fishermen whose authority in this point is very competent, say that similar moors are to be found along the whole coast from Skegness to Grimsby, particularly off Addlethorpe and Mablethorpe. The channels dividing the islets were, at the time we saw them, wide and of various depths; the islets themselves ranging generally from east to west in their largest dimensions.

“We visited them again in the ebbs of the 20th and 21st.; and though it did not generally ebb so far as we expected, we could notwithstanding ascertain that they consisted almost entirely of roots, trunks, branches, and p. 39leaves of trees and shrubs, intermixed with some leaves of aquatic plants. The remains of some of these trees were still standing on their roots, while the trunks of the greater part lay scattered on the ground in every possible direction. The barks of trees and roots appeared generally as fresh as when they were growing; in that of the branches particularly, of which a great quantity was found, even the thin silver membranes of outer skin were discernible. The timber of all kinds on the contrary, was decomposed, and soft in the greatest part of the trees: in some, however, it was firm, especially in the roots. The people of the country have often found among them very sound pieces of timber, fit to be employed for several economical purposes. The sorts of wood which are still distinguishable are, birch, fir, and oak. Other woods evidently exist in these islets, of some of which we found the leaves in the soil; but our present knowledge of the comparative anatomy of timber is not so far advanced as to afford us the means of pronouncing with confidence respecting their species. In general the trunks, branches, and roots of the decayed trees were considerably flattened, which is a phenomenon observed in the Surtarbrand, or fossil wood of Iceland, and which Scheuchzer remarked also in the fossil wood found in the neighbourhood of the lake Thun in Switzerland.

“The soil to which the trees are fixed, and in which they grew, is a soft greasy clay; but for many inches above the surface, the soil is composed of rotten leaves, scarcely distinguishable to the eye, many of which may p. 40be separated by putting the soil in water and dexterously and patiently using the Spatula, or blunt knife. By this method I obtained some imperfect leaves of the Ilexaquifolium, which are now in the Herbarium of the right honourable Sir Joseph Banks; and some other leaves, though less perfect, seem to belong to some species of willow. In this stratum of rotten leaves we could also distinguish some roots of Arundo Phragmites.

“These islets, according to the most accurate information, extend at least twelve miles in length, and about a mile in breadth, opposite to Sutton shore. The water without them toward the sea, generally deepens suddenly, so as to form a steep bank. The channels between the several islets, when the islets are dry, in the lowest ebbs of the year, are from four to twelve feet deep: their bottoms are clay or sand, and their direction is generally from east to west.

“A well, dug at Sutton by Joshua Searby, shews that a moor of the same nature is found under ground in that part of the country, at the depth of sixteen feet, consequently very nearly on the same level with that which constitutes the islets. The disposition of the strata was found to be nearly as follows: clay sixteen feet; moor, similar to that of the islets, three or four ditto; soft moor, like the scourings of a ditch bottom, mixed with shells and silt, twenty feet; marly clay, one foot; chalky rock, from one to two feet; clay, thirty-one yards; gravel and water; the water has a chalybeate taste. In order to ascertain the course of this subterraneous p. 41stratum of decayed vegetables, Sir Joseph Banks directed a boring to be made in the fields belonging to the royal Society in the parish of Mablethorpe. Moor of a similar nature to that of Searby’s well, and the islets, was found very nearly on the same level, about four feet thick, and under a soft clay.

“The whole appearance of the rotten vegetables we observed, perfectly resembles, according to the remark of Sir Joseph Banks, the moor which, in Blakeney Fen, and in other parts of the East Fen in Lincolnshire, is thrown up in the making of banks; barks like those of the birch-tree being there also abundantly found. The moor extends over all the Lincolnshire fens, and has been traced as far as Peterborough, more than sixty miles to the south of Sutton. On the north side, according to the fishermen, the moory islets extend as far as Grimsby, situated on the south side of the Humber: and it is a remarkable circumstance, that in the large tracts of low land which lie on the south banks of that river, a little above its mouth, there is a subterraneous stratum of decayed trees and shrubs, exactly like those we have observed at Sutton; particularly at Axolme isle, a tract of ten miles in length by five in breadth; and at Hatfield chace, which comprehends 180,000 acres. Dugdale had long ago made this observation in the first of these places; and Dela Prime in the second. The roots are there likewise standing in the places where they grew: the trunks lie prostrate. The woods are of the same species as at Sutton. Roots of aquatic plants and reeds p. 42are likewise mixed with them; and they are covered by a stratum of some yards of soil, the thickness of which, though not ascertained with exactness by the abovementioned observers, we may easily conceive to correspond with what covers the stratum of decayed wood at Sutton, by the circumstances of the roots being (according to Mr. Richardson’s observations) only visible when the water is low, where a channel was cut which has left them uncovered.

“Little doubt can be entertained of the moory islets of Sutton being a part of this extensive and subterraneous stratum, which, by some inroad of the sea, has there been stripped of its covering of soil. The identity of the levels; that of the species of trees; the roots of these affixed in both to the soil where they grew; and above all, the flattened shape of the trunks, branches, and roots, found in the islets (which can only be accounted for by the heavy pressure of a superinduced stratum) are sufficient reasons for this opinion.”

Further observations from the same Paper—Epoch of the destruction of the said Forest—Agency by which it was effected, &c.—Similar appearances eastward along the Norfolk coast.

“Such a wide-spread assemblage of vegetable ruins, lying almost in the same level, and that level generally under the common mark of low water, must naturally strike the observer, and give birth to the following questions: p. 431. What is the epoch of this destruction? 2. By what agency was it effected?

“In answer to these questions I will venture to submit the following reflections: The fossil remains of vegetables hitherto dug up in so many parts of the globe, are, on a close inspection, found to belong to two different states of our planet. The parts of vegetables and their impressions, found in mountains, of a colaceous and schistous, or even sometimes of a calcareous nature, are chiefly of plants now existing between the tropics, which would neither have grown in the latitudes in which they are dug up, nor have been carried and deposited there by any of the acting forces under the present constitution of nature. The formation indeed of the very mountains in which they are buried, and the nature and position of the materials which compose them, are such as we cannot account for by any actions and re-actions which in the actual state of things take place on the surface of the earth. We must necessarily recur to that period in the history of our planet, when the surface of the ocean was at least so much above its present level as to cover even the summits of those secondary mountains which contain the remains of tropical plants. The changes which these vegetables have suffered in their substance is almost total; they commonly retain only the external configuration of what they were. Such is the state in which they are found in England by Lhwyd; in France by Jussicu; and in the Netherlands by Burtin; not to mention instances in more distant countries. Some of the impressions or remains of plants p. 44found in soils of this nature which were, by the more ancient and enlightened oryctologists, supposed to belong to plants actually growing in temperate and cold climates, seem, on accurate investigation, to have been part of exotic vegetables. In fact, whether we suppose them to have grown near the spot where they are found, or to have been carried thither from different parts by the force of an impelling flood, it is equally difficult to conceive how organized beings, which, in order to live, require such a vast difference in temperature and seasons, could live on the same spot, or how their remains could (from climates so widely distant) be brought together in the place by one common dislocating cause. To this ancient order of fossil vegetables belong whatever retains a vegetable shape found in or near coalmines, and (to judge from the places where they have been found) the greater part of the agatized woods. But from the species and state of the trees which are the subject of this memoir, and from the situation and nature of the soil in which they are found, it seems very clear that they do not belong to the primeval order of vegetable ruins.

“The second order of fossil vegetables comprehend those which are found in the strata of clay or sand; materials which are the result of slow depositions of the sea and of rivers, agents still at work under the present constitution of our planet. These vegetable remains are found in such flat countries as may be considered to be a new formation. The vegetable organization still subsists, at least in part; and their vegetable substance has suffered a change only in colour, smell, or consistence; alterations p. 45which are produced by the development of their oily and bitumenous parts, or by their natural progress towards rottenness. Such are the fossil vegetables found in Cornwall by Borlase; in Essex, by Derham; in Yorkshire by Dela Prime and Richardson; and in foreign countries by other naturalists. These vegetables are found at different depths; some of them much below the present level of the sea, but in clayey and sandy strata (evidently belonging to modern formation); and have, no doubt, been carried from their original place and deposited there by the force of great rivers or currents, as it has been observed with respect to the Mississippi. In many instances, however, these trees and shrubs are found standing on their roots, and generally in low or marshy places above, or very little below the level of the sea.

“To this last description of fossil vegetables the decayed trees here described certainly belong. They have not been transported by currents or rivers; but though standing in their native soil, we cannot suppose the level in which they are found to be the same as that in which they grew. It would be impossible for any of these trees or shrubs to vegetate so near the sea, and below the common level of its water. The waves would cover such tracts of land, and hinder any vegetation. We cannot conceive that the surface of the ocean has ever been any lower than it is now; on the contrary we are led, by numberless phenomena to believe that the level of the water in our globe is now below what it was in former periods. We must therefore conclude, that the forest here described grew in a level high enough to permit p. 46its vegetation; and that the force (whatever it was) which destroyed it, lowered the level of the ground where it stood.

“There is a force of subsidence (particularly in soft ground) which being a natural consequence of gravity, slowly, though imperceptibly operating, has its action sometimes quickened and rendered sudden by extraneous causes; for instance, by earthquakes. The slow effects of this force of subsidence have been accurately remarked in many places: examples also of its sudden action are recorded in almost every history of great earthquakes.—In England, Borlase has given in the Philosophical Transactions a curious observation of a subsidence of at least sixteen feet in the ground between Sampson and Trecaw islands in Scilly. The soft and low grounds between the towns of Thorne and Gowle in Yorkshire, a space of many miles, has so much subsided in latter times, that some old men of Thorne affirmed, “that whereas they could before see little of the Steeples (of Gowle) they now see the church yard wall.” The instances of similar subsidence which might be mentioned, are innumerable.

“The force of subsidence, suddenly acting by means of some earthquake, seems to me the most probable cause to which the usual submarine situation of the forest we are speaking of may be ascribed. It affords a simple easy explanation of the matter; its probability is supported by numberless instances of similar events; and it is not liable to the strong objections which exist against the hypothesis of the ultimate depression and elevation p. 47of the level of the ocean; an opinion which, to be credible, requires the support of a great number of proofs less equivocal than those which have hitherto been urged in its favour, even by the genius of Lavoisier.

“The stratum of soil, sixteen feet thick, placed above the decayed trees, seems to remove the epoch of their sinking and destruction far beyond the reach of any historical knowledge. In Cæsar’s time the level of the north sea appears to have been the same as in our days. He mentions the separation of the Wahal branch of the Rhine, and its junction with the Meuse; noticing the then existing distance from that junction to the sea, which agrees according to D’Anville’s inquiries, with the actual distance. Some of the Roman roads, constructed according to the order of Augustus, under Agrippa’s administration, leading to the maritime towns of Belgium, still exist, and reach the present shore. The description which Roman authors have given of the coast, ports, and mouths of rivers, on both sides of the North sea, agree in general with their present state; except in places ravaged by the inroads of this sea, more apt from its force to destroy the surrounding countries than to increase them.

“An exact resemblance exists between maritime Flanders and the opposite coast of England, both in point of elevation above the sea, and of the internal structure and arrangement of the soils. On both sides strata of clay, silt, and sand, (often mixed with decayed vegetables) are found near the surface; and in both, these p. 48superior materials cover a very deep stratum of blueish or dark coloured clay, unmixed with extraneous bodies. On both sides they are the lowermost part of the soil, existing between two ridges of high lands, on their respective sides of the same narrow sea. These two countries are certainly coeval; and whatever proves that maritime Flanders has been for many ages out of the sea, must, in my opinion, prove also that the forest we are speaking of was long before that time destroyed and buried under a stratum of soil. Now it seems proved from historical records, carefully collected by several learned members of the Brussels Academy, that no material change has happened in the lowermost part of maritime Flanders during the period of the last two thousand years.

“I am therefore inclined to suppose the original catastrophe which buried this forest to be of very ancient date; but I suspect the inroad of the sea which uncovered the decayed trees of the islands of Sutton, to be comparatively recent. The state of the leaves and of the timber, and also the tradition of the neighbouring people concur to strengthen this suspicion.”

The reader, it is hoped, will excuse, and even approve the length of this curious extract, as it seems so well calculated to account for and elucidate divers striking phenomena in the natural history of the Fens.

Here it may not be improper further to observe, that the forest above described seems to have extended from the coast of Lincolnshire a considerable way along the Norfolk coast; as there is on the shore, near Thornham p. 49in that county, at low water, the appearance of a large forest having been, at some period, interred and swallowed up by the waves. Stools of numerous large timber trees, and many trunks, are to be seen, but so rotten, that they may be penetrated by a spade. These lie in a black mass of vegetable fibres, consisting of decayed branches, leaves, rushes, flags, &c. The extent of this once sylvan tract [on the Norfolk coast] must have been great, from what is discoverable; and at high water, now covered by the tides, is in one spot from five to six-hundred acres. No hint of the manner, or the time, in which this submersion happened, can be traced. Nothing like a bog is near, and the whole beach besides is composed of a fine ooze, or marine clay. [49]

Some further geological observations relating to the Fens, extracted from Dugdale’s Letters to Sir Thomas Browne.