THE WORLD-STRUGGLE FOR OIL

Some BORZOI Books

Midwinter, 1924

SOCIOLOGY AND POLITICAL THEORY

Harry Elmer Barnes

THE OLD AND THE NEW GERMANY

John Firman Coar

THE BASIS OF SOCIAL THEORY

Albert G.A. Balz

ESSAYS IN ECONOMIC THEORY

Simon Nelson Patten

THE TREND OF ECONOMICS

Various Writers

THE FABRIC OF EUROPE

Harold Stannard

THE WORLD-STRUGGLE FOR OIL

Translated from the French of Pierre l'Espagnol de la Tramerye by C. LEONARD LEESE

NEW YORK ALFRED · A · KNOPF MCMXXIV

COPYRIGHT, 1924, BY ALFRED A. KNOPF, INC.

Published, February, 1924

Set up, electrotyped, and printed by the Vail-Ballou Press, Inc., Binghamton, N.Y. Paper furnished by W.F. Etherington & Co., New York. Bound by H. Wolff Estate, New York.

MANUFACTURED IN THE UNITED STATES OF AMERICA

CONTENTS

PART I

THE WORLD'S OIL

"WHO HAS OIL HAS EMPIRE!"

The question of oil has become one of the most vital in all countries. Its importance is such that even the most solid political alliances are subordinate to it. The Great Powers have all an "oil policy." The United States, where the most powerful trust is an oil trust—the Standard Oil Company—the United States, which control 70 per cent. of the oil production of the world, have decided not to leave the question to private initiative alone, but to start a vigorous oil policy both at home and abroad. The American Senate recently decided to create the "United States Oil Corporation to develop new petroleum fields," while Mr. Bedford, Chairman of the Board of Directors of the Standard Oil Company, asked the Government to lend its support to any Americans who were soliciting oil concessions throughout the world. This support, which even Wilson—hostile to trusts as he was—did not refuse, was granted very energetically by Mr. Harding: three European States have just had experience of it.

Britain, with her usual foresight, understood long[Pg 10] ago the importance of oil, and took the necessary action. In the work of exploration alone she is at the present moment spending considerable sums, and she will soon have nearly all the remaining oil-fields of the world in her hands.

France alone remains behind, hesitates, changes her mind, and allows herself to be despoiled, not only of the region of Mosul, one of the richest oil-fields of the world, which was formally promised to her by the Agreements of 1916, but also of the few modest oil deposits which she possesses in her colonies. For these are almost all exploited by British firms; and by the Agreement of San Remo the French Government has, in addition, promised to reserve a large share for "British co-operation" in new companies which may be established there.

"Who has oil has Empire!" exclaimed Henry Bérenger, in a diplomatic note which he sent to Clemenceau on December 12, 1919, on the eve of the Franco-British conferences held in London to consider the future of Eastern Europe and Asia Minor. "Control of the ocean by heavy oils, control of the air by highly refined oils, and of the land by petrol and illuminating oils. Empire of the World through the financial power attaching to a substance more precious, more penetrating, more influential in the world than gold itself!" The nation which controls this precious fuel will see the wealth of the rest of[Pg 11] the world flowing towards it. The ships of other nations will soon be unable to sail without recourse to its stores of oil. Should it create a powerful merchant fleet, it becomes at once mistress of ocean trade. Now, the nation which obtains the world's carrying trade takes toll from all those whose goods it carries, and so has abundant capital. New industries arise round its ports, its banks become clearing houses for international payments. At one stroke the controlling centre of the world's credit is displaced. This is what happened already in the eighteenth century when, with the development of British shipping, it passed from Amsterdam to London. And British statesmen have had, at one time, a moment of anxiety lest it should move to New York!

Thus began the terrible struggle between Britain and the United States for possession of the precious "rock-oil."

"The country which dominates by means of oil," said Elliot Alves, head of the British Controlled Oil-fields, a semi-official, semi-private organization, which the British Government has specially commissioned to fight the Standard Oil Company, "will command at the same time the commerce of the world. Armies, navies, money, even entire populations, will count as nothing against the lack of oil."

The War proved it.

Whence does oil derive this formidable power, before which the whole world bows down? From the fact that the fundamental basis upon which the industrial life of modern nations rests is fuel. Before the War, Germany, Britain, and the United States owed the whole of their power and their wealth to coal. It would have been true to say that the British Empire rested upon a foundation of coal.

It is essential to have control over fuel in time of peace for economic prosperity, and in time of war to supply the navy and maintain control of the seas.

Now oil has considerable advantages over coal. Its extraction is remarkably easy compared with that of coal. What is the boring of a well and the installation of some simple machinery on the surface compared with the expensive subterranean workings which are involved in the exploitation of a coal-mine? An oil-boring before the War cost a few hundred thousand francs, while the simplest workings for a colliery always necessitated an expenditure of several millions. The installations once made, oil flows by itself into the reservoirs, whence it is conducted by pipe-lines to the sea-ports and there pumped into the ships. It may be refined before exportation or only on arrival in the country where[Pg 13] it is to be consumed. The expenditure upon labour in these various operations is extremely small, especially in undeveloped countries where native labour is employed. Thus, even at the present time, in the Dutch Indies the coolies are paid a florin a day. Now at the end of the War the employés of the Royal Dutch in the Dutch Indies numbered only 1,000 Europeans and 2,906 natives and Chinese for a production of 1,706,675 tons. A native earned only 300 gold francs a year for 80 tons of oil extracted, refined and transported to the coast.

After the Bolshevik revolution wages at Grosny were still only seven roubles a day, which, considering the depreciation of Russian money, represented very little. Generally the expenses of production in Russia did not exceed a few kopecks a pood (50 kopecks for one of the best-known firms, that of Akverdoff).

Thus oil is bound to become in future more and more important as a fuel, because of its peculiarity in necessitating so insignificant a charge for labour—which protects it from the inconveniences resulting from the social crises in the midst of which we live—and because its net cost is so small. For half a century it was used only for lighting purposes, and then it had to compete with gas and electricity. At one time there was talk of limiting production!

Between 1900 and 1910 the invention of the inter[Pg 14]nal-combustion engine and the enormous development of motoring gave it new impetus. Fine oils only had been used up to then. Under pressure of the demand, it became customary to raise and refine poorer and poorer oils, giving from 60 to 75 per cent. of waste products.

There remained the mazut[1] or fuel-oil, which required very high temperatures for combustion and which was very dirty in use.

Then the German, Diesel, invented the internal-combustion engine for heavy oil. The mazut, subjected to high pressure in a cylinder, produces an explosive mixture which, without sparking-plug or magneto, drives the pistons in the manner of a petrol engine. The installation is rather heavy, but no boiler is required, and it takes up much less space than a steam engine of the same power. A vessel fitted with a Diesel engine can sail for fifty-seven days without re-fuelling, while with a steam engine it could only sail for a fortnight. A ship fitted with a Diesel engine and having a speed of 20 knots could sail from France to Suez, India, Australia, New Zealand, and return by Cape Horn without re-fuelling. But, better than any words, the following little table, made out for two boats of the same power, will[Pg 15] give an idea of the great advantages of the Diesel engine:—

| Diesel. | Steam. | |

| H.P. | 21,000 | 21,000 |

| Weight of engine and accessories | 1,000 tons | 3,400 tons |

| Space required | 5,300 cu. m. | 10,000 cu. m. |

| Daily consumption | 100 tons | 360 tons |

| (heavy oil) | (coal) | |

| Consumption for a voyage of 15 days | 1,500 tons | 5,400 tons |

| Bunker space for a voyage of 15 days | 1,700 cu. m. | 7,000 cu. m. |

| Total space required for engine and fuel | 7,000 cu. m. | 17,000 cu. m. |

At first oil was used on fishing boats, then on small coasters. To-day the biggest British cargo boats, of the type of the Zeelandia or Sutlandia, are fitted with Diesel engines. All German submarines had them during the War. In 1917 Herr Ballin,[2] the great friend of William II and the head of the Hamburg-Amerika line, just before his suicide decided on the construction of a fleet of enormous ships fitted with internal-combustion engines. Scandina[Pg 16]via, Holland, Italy, all now use the Diesel engine. France alone remains behind in this respect. It has even been used on railways, a little-known fact. Diesel locomotives with four cylinders, built by Sulzer Brothers of Winterthur, have recently been run on the line from Berlin to Mannsfeld.

"The development of our metallurgy," wrote Admiral Degouy in April 1920, "will soon give us the assurance that we also shall be able to manufacture large-bore cylinders and pistons of flawless casting, like those made in Augsburg, Nuremberg, Stockholm, and Christiania, which will support for long periods without change (and consequently without leakage) the temperature of 1,000° C. which is developed by the combustion of mazut in these engines."

Since the invention of the internal-combustion engine, mazut has been introduced directly into the furnaces of great ships. The heating power of this formerly despised product is almost double that of coal: 1 kilogramme of liquid fuel produces the same results as 1.7 kilogrammes of coal. Its use allows of the reduction by five-eighths in bunker space, and by 70 to 80 per cent. of the stokers, since a single man can look after several boilers. The fuelling of a ship is effected cleanly and quietly in a few hours. Hundreds of tons of oil can be pumped into the cisterns in a negligible time, and[Pg 17] that even out at sea and in heavy weather. To give an idea of the difference in time and labour required for the loading of coal and oil before the sailing of a mail steamer of the tonnage of the Olympic or the Lusitania, I will quote the following figures:—

| Coal | 5 days | 500 men |

| Oil | 12 hours | 12 men |

The labour of stoking and clearing the furnaces is done away with; there is no longer either dust or smoke. Parts of the ship which are too restricted or too inconveniently placed for housing coal can be used for oil. It is stored in the double bottom of the boat, and by utilizing the coal bunkers for general cargo the available storage space is increased by 10 per cent. On the latest Cunard and White Star liners the economy of space thus realized has been as much as 33 per cent. And Admiral Lord Fisher drew attention to the fact that on the Mauretania—the sister ship to the Lusitania—the adoption of oil fuel allowed of the reduction of the crew by three hundred men.

The efficiency of a boiler heated by coal is not much more than 60 per cent.; that of one heated by oil reaches 80 per cent. On Japanese steamers of the type of the Temyo Maru, of 21,000 tons, with Parsons turbines of 20,000 horse-power, the con[Pg 18]sumption of oil is only 455 grammes to one effective horse-power, instead of 685 grammes of coal. The flexibility and ease of control are extraordinary.

Since 1911 the merchant fleet of the United States has been consuming 15 million barrels annually. Nearly all the nations have followed this example,[3] especially those which dream of the dominion of the seas for the use of oil in their warships gives them an incontestable superiority. The presence of a squadron sailing under coal is disclosed at a distance of more than 10 kilometres by enormous clouds of smoke; under oil its presence is almost imperceptible; it becomes visible only at the moment when it is about to attack. Ease of approach is enormously increased; and even if an enemy vessel is discovered by marine or aerial scouts it is very difficult for the gunners of the threatened vessel to take their aim at so vague a target as an almost invisible horizontal silhouette. "No smoke, not even a funnel!" exclaimed Lord Fisher in his strenuous campaign for the transformation of the British Navy. Many years elapsed, however, before he saw the triumph of the new fuel.

It has been objected that ships lose a little of the protection which is conferred upon them by their belts of coal bunkers; but this criticism is valueless.[Pg 19] For, as they gain considerably in lightness, it is possible to increase the thickness of the armour plate and the size of the guns. The abolition of funnels permits of a considerable increase in the field of fire of the artillery.

Moreover, with oil fuel fleets acquire an extreme mobility.[4] Half an hour after receiving the order to raise steam the ship is ready to start. Thirty-five minutes afterwards it is going at full speed. In six minutes it can pass from normal to maximum speed. Eleven minutes are needed to get a boiler under full pressure. A voyage at forced speed entails no extra fatigue for the crew: with coal it is hell!

Thus, since 1912, oil has been constantly used on twenty-eight German battleships, almost the whole of the fleets of Great Britain and the United States, and the Russian squadrons in the Baltic and the Black Sea. The American Navy has completely abandoned coal for its new units.

And France? France, which was the first to conceive the idea, had, at the moment when war broke out, only a few small boats burning oil, and not a single powerful modern vessel comparable with the Queen Elizabeth. And yet, as early as 1864, it was France that built the first ship, the Puebla, sailing under Lieutenant Farcy, to use the new fuel,[Pg 20] which aroused so much curiosity during the Second Empire. But the selfish opposition of our coal-owners overcame those who were favourably inclined, including Napoleon III himself.

No one gives a thought to these facts at the present time. France often points the way of progress; she never profits by it.

The most far-reaching revolutions have begun with a technical invention. The unknown monk who first mixed charcoal with sulphur and saltpetre razed feudal castles and created the great modern States. And he who balanced a magnetized needle on its pivot was the real founder of colonial empires.

We are just entering upon an economic period which will turn the whole world upside-down—the Revolution in Fuel, with its far-reaching consequences.

FOOTNOTES:

[1] "The famous petroleum wells of Baku ... yield crude naphtha, from which the petroleum or kerosene is distilled; while the heavier residue (mazut) is used as lubricating oil and for fuel."—Encyclopaedia Britannica, 11th ed., vol. iii, p. 230.—Translator's Note.

[2] "Herr Ballin committed suicide, foreseeing that unrestricted submarine warfare, which had then been decided upon, would be the downfall of Germany."—Revue des Deux Mondes: Contre-Admiral Degouy, "Oil and the Navy."

[3] Since 1920 the world tonnage of oil-burning steamers has exceeded that of steamers built to burn coal.

[4] At the battle of Jutland, only the oil-burning ships realized their trial speed.

OIL: ITS ORIGIN, DISCOVERY, AND HISTORY

The Great Producing States before 1914 and in 1921

Oil is found naturally in different forms. Sometimes it occurs as a volatile liquid at ordinary temperatures; it is then known as naphtha. Sometimes the volatile principles are only given off at higher temperatures; it is then called petroleum or rock-oil. Sometimes also it appears in a semi-solid form, asphalt, its volatile properties having already evaporated.

It is very rarely that oil is found on the surface or gushing up by itself without the help of pumps. It is usually met with at a great depth underground, in pockets in which oil and gas are found above water. Thus, in order to detect its presence, it is necessary to make borings. When one reaches a pocket in the neighbourhood of the gas, the latter escapes by the outlet which is offered. If the boring first reaches oil, and if the pressure of gas is sufficient, the oil gushes out and forms a spring. This[Pg 22] is what happened in the Caucasus, where certain wells spouted up to a height of eighty metres through the borings made by the prospectors. More often the gas pressure is not sufficient to raise the liquid to the surface, and it is necessary to install pumps driven by steam to empty the pocket. At the time of the boring, when the cylindrical metal drill, driven vertically by a metal cable and held vertical by the derrick (a sort of pyramidal framework of metal), reaches the deposit, the gas which has been accumulating for thousands of years escapes, driving, pushing, sucking up the oil, and making a fountain, a gusher, a sort of artesian well. The oil is led away in metal pipes, vertical till they reach the surface, horizontal to the refineries, ports, or other destinations. Once the well is capped, it is not touched again; it is alone in the desert, and only a metre records its daily output, while hundreds of thousands of men are obliged to work underground to wrest coal from the bowels of the earth by the strength of their arms!

The depth of the wells varies from 200 to 1,600 metres, according to the region. The duration of the flow is essentially variable, depending upon the magnitude of the deposit of oil. But it goes without saying that when a spring has flowed for seven years more or less, like the first one exploited by the Mexican Eagle, it gives out, yielding salt water.[Pg 23] The fact is quite ordinary, and is known in all competent circles, although it is sometimes brandished as a warning by interested people in order to lower the value of certain oil shares. One often hears of "pools," "rivers," or "veritable lakes of oil." These expressions are most inaccurate. Apart from certain exceptions, such as the famous well of the Colombia in Rumania in 1913, the deposits of oil are neither rivers nor pools. They are actually solid layers of sandstone, often very hard, impregnated, saturated with oil. This sandstone is very porous and contains thousands of cavities or pockets enclosing the precious "rock-oil." Its thickness varies from the usual 30 or 50 metres (giving wells of a yield of 200, 500, or 1,000 barrels a day) to one kilometre in certain wells of the Eagle (yielding 70,000 to 100,000 barrels a day, instead of 200 to 1,000). The Eagle is lucky, it must be admitted, and its history is unique in the annals of oil. Only its sister company, the Mexican Oil, which works in the same field, but for the Standard Oil group, can be compared with it.

Even a superficial examination of the chemical composition of oil, a hydrocarbon, in which the carbon, in a proportion of 80 to 88 per cent., is combined with hydrogen, and sometimes with a little oxygen, reveals in this compound a marvellous source of thermal energy, which may manifest itself[Pg 24] in various ways. For, from the greenish-brown oil which is lighter than water, no less than 128 chemical compounds are obtained, which are used in forty different industries. From the retort in which the crude oil is distilled comes an infinity of substances of basic importance in modern industry.

Although the intensive use of oil and its industrial applications are of comparatively recent date, the discovery of deposits of petroleum goes back to remote antiquity.

The history of oil is as old as the world, since there is already mention of it in the Book of Genesis. The wells of Baku were known long before the Christian era. In the peninsula of Apsheron, where they are situated, arose the cult of Zoroaster and the fire-worshippers. According to the latter, the flames which escaped from the soil would burn until the end of the world. They were, at any rate, famed throughout the world nearly three thousand years ago.

The Greeks and Romans were acquainted with oil. The latter called it bitumen. In Low Latin it was petroleus, from petra—stone, and oleum—oil; and the word has come down to us through the scholars of the seventeenth and eighteenth centuries who adopted it.

In ancient mythology and literature oil is often[Pg 25] mentioned. It is probably with oil that the Centaur—to avenge himself upon Hercules—was obliged to anoint the famous shirt of Nessus! "It is not without reason," says Plutarch, "that certain authors, wishing to restore truth to legend, assert that petroleum is the substance which Medea used to smear the crown and veil that play so great a part in the tragedies; for fire does not issue from them of itself, but when they are brought near a flame fire is communicated to them by some kind of attraction with such rapidity that the eye can scarcely follow it."

Herodotus, in his works, mentions the oil-fields of Zante; Pliny those of Agrigente in Sicily; Plutarch those of Ecbatana and Babylon. "The land of Babylon," he says, "is impregnated with fire.... It is as though the soil, agitated by the fiery substances which lie concealed in its bosom, has a sort of pulse which makes it quake." When Alexander conquered these regions he was particularly astonished, in the province of Ecbatana, at "a gulf from which rivers of flame streamed continually, as though from an inexhaustible source."[5] His return to Babylon was celebrated by the burning of two parallel streams flowing through the streets. And one of his courtiers, to amuse him, caused a young man to be anointed with oil; scarcely had it touched his body when he was enveloped in flames.

The Chinese have used oil for lighting from the most distant times; Europeans since the fourteenth century. It is difficult to go further back owing to the absence of documents during the Middle Ages. But what was Greek Fire, if not oil? In the fifteenth century we find traces of its use in medicine; and even at the present time the natives of Mosul and Bagdad use some of the purer varieties, which they call "mourn," as a dressing for serious wounds. Oil has some fame as a vermifuge; as, for example, the oil of Gabiau in the south of France. A curious memoir of François Clouet, who was entrusted with the task of embalming Francis I in 1547, mentions the use of an oil ("pétrolle") in the colouring of a waxen mask made in the dead king's likeness.

In the eighteenth century Apsheron was again the astonishment of British travellers seeking a route to India. "The Russians drink it as a tonic and as a beverage," writes Jonas Hanway, who visited these regions in 1754, speaking of petroleum. "It never intoxicates. Used internally, it is also an excellent cure for gravel. Used externally, it is a valuable remedy in cases of scurvy, gout, and cramp. It is very good for removing stains from fabrics, and would be in more frequent use if it did not leave behind it an abominable smell."

.

.

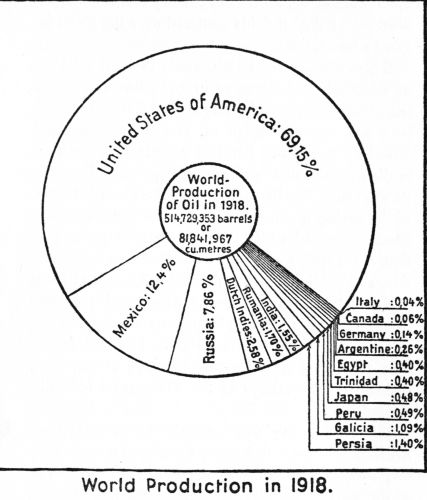

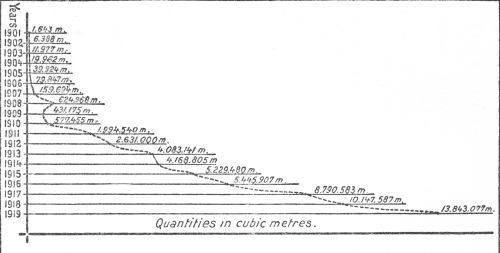

World Production in 1918.

Finally, the earliest settlers found oil in America, or, to be more exact, recognized the wells which had[Pg 28] already been dug by the Indians. But it was only in the middle of the nineteenth century that the real importance of the oil-fields scattered over the globe began to be realized.

While France about 1840 made the first trial use of shale oil, and Germany in 1853 invented the oil lamp, later perfected by Laydaw of Edinburgh, "the bold and inventive spirit of Young America undeterred by a series of fruitless experiments, set itself to discover the first springs of the precious liquid in Pennsylvania." In 1858 Colonel Edward Drake, while boring a salt-water well near Tytusville, was nearly engulfed with his workmen in a jet of oily liquid, the spring of which was apparently inexhaustible, and continued to furnish several thousand litres a day. It was subsequently discovered that this liquid after a very simple process of purification, would burn with a brilliant light. The "oil fever" then seized all America and myriads of searchers rushed into the valleys of the Alleghanies in Pennsylvania.

The oil industry was created. For a long time America was the only country producing the precious oil; forty years ago she still furnished two-thirds of the world's supplies. But although the oil-fields of the Alleghanies and of Ohio were developed rapidly, they have been far surpassed by the enormous deposits of Baku. In 1898 Russia outdistanced the[Pg 29] United States, and kept the first place until 1902, when America recovered it after a great struggle, thanks to the new oil basins of Texas, California, and the Mid-Continent, and above all those of Kansas and Oklahoma, with its famous "Glen Pool," which in 1908 produced the fantastic figure of 50,000 barrels a day.

Russia has never been able to retrieve her position. Her production, which in 1901 was 50 per cent. of that of the whole world, was not more than 20 per cent. two years before the War, and in 1918 had fallen to 7.86 per cent. The cause is chiefly the diminution of production of the "black region" of Baku, in the peninsula of Apsheron, which juts out into the Caspian Sea and is connected with the open seas by a railway and by a pipe 800 kilometres long, through which the annual flow of oil towards Europe before the great world catastrophe amounted to 400,000 tons. In five years the average yield of the wells diminished by 40 per cent., while the mean depth of the borings was increased by 25 per cent. It was necessary to dig more and more deeply to find less and less oil. The old oil-fields of Baku were nearing exhaustion. Now they alone furnished four-fifths of the production of Russia. That is why, in 1918, Russia lost the second place, which she had held so long, to her young rival Mexico. It is true that the two revolutions which she had to undergo in[Pg 30] this quarter century helped the process considerably. The revolution of 1905 caused the bloody disturbances of the Caucasus: the finest factories were burnt and numerous wells destroyed. Great unrest continued incessantly in this region until the triumph of Lenin. But there are still in Russia oil-fields of very considerable extent, scarcely touched before 1914, which the world cannot afford to dispense with.[6]

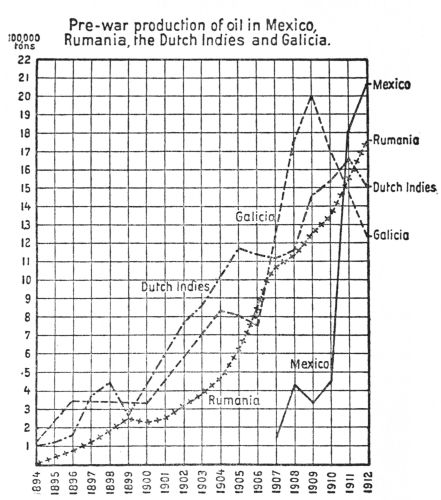

The United States, Russia, Mexico, Rumania, these were, in order of importance, the four chief oil-producing countries before the War. Rumania shares with America the distinction of being the first country in which rock-oil was extracted. The same year in which Colonel Drake made his experiments at Tytusville 250 tons were extracted from a well by hand-pumping: the oil was only just below the surface. Since then Rumanian production has continually increased. It was 500,000 tons when the region of Moreni, one of the richest in the world, was discovered. Foreign capital flowed in immediately, and Rumanian production reached its highest point in 1913 with 2 million tons. The War gave it an appreciable setback; at the present time it does not come to more than half this figure.[7]

Pre-war production of oil in Mexico, Rumania, the Dutch Indies and Galicia.

Although the production of Rumania, hampered by the lack of electricity which hinders the borings, has recovered with difficulty, that of Mexico, often a prey to civil war, has known no pause in its incredible progress. In ten years it has passed from 3 to 160 million barrels, carrying its share in world production from 1 per cent. to 23 per cent. The figures are worth quoting:—

| Year. | World Production 1910-21 (barrels). | Percentage from Mexico only. |

| 1910 | 328,000,000 | 1.10 |

| 1911 | 344,000,000 | 3.65 |

| 1912 | 352,500,000 | 4.70 |

| 1913 | 385,000,000 | 6.80 |

| 1914 | 400,000,000 | 5.30 |

| 1915 | 426,500,000 | 7.70 |

| 1916 | 459,500,000 | 8.70 |

| 1917 | 505,500,000 | 10.09 |

| 1918 | 515,000,000 | 12.40 |

| 1919 | 551,000,000 | 15.85 |

| 1920 | 684,000,000 | 23.35 |

| 1921 | 759,000,000 | 25.00 |

It is Mexico which saves the world to-day, for the United States—the greatest producers in the world—do not even supply enough for their own consumption, and are obliged to call in the help of Mexico to make good their deficit. In spite of all their efforts, they have only succeeded, during the last three years, in increasing production by 24 per cent., while Mex[Pg 33]ico has augmented hers by 130 per cent. The other countries follow at a considerable distance. Here is the record of each for 1921:—

| Barrels. | |

| United States | 469,639,000 |

| Mexico; | 195,064,000 |

| Russia | 28,500,000 |

| Dutch East Indies | 18,000,000 |

| Rumania | 8,347,000 |

| India | 6,864,000 |

| Poland (Galicia) | 3,665,000 |

| Peru | 3,568,000 |

| Japan and Formosa | 2,600,000 |

| Trinidad | 2,354,000 |

| Argentina | 1,747,000 |

| Egypt | 1,181,000 |

| Venezuela | 1,078,000 |

| France | 392,000 |

| Germany | 200,000 |

| Canada | 190,000 |

| Italy | 35,000 |

| Algeria | 3,000 |

| Great Britain | 3,000 |

| Other countries | 1,000,000 |

The total production was 759,000,000 barrels of 42 gallons, against 684,000,000 barrels in 1920. It exceeds 100 million tons, easily beating the records of the preceding years. If we remember that half a century ago, it was only 66,000 tons, and that between 1913 and 1920 it has almost doubled, we shall see what a tremendous stimulus the great world War has been.

But fears are increasingly felt. Will it be possible to satisfy the dizzy increase in the consumption of oil? And do not certain countries already fear to see the reserves contained in their soil exhausted?

FOOTNOTES:

[5] Plutarch's Lives, Alexander the Great, chap. xliv.

[6] Cp. chap. xvi, The Struggle for the Oil-fields of Russia.

[7] Having fallen to 920,000 tons in 1919, it had increased to 1,030,086 tons in 1920 (12 per cent. increase). This slight recovery is the first noted; for six years Rumanian production steadily decreased. The worst year was 1917.

AMAZING INCREASE IN CONSUMPTION

Fears of the United States

The consumption of oil is rising at a terrific rate. Entire branches of industry are transformed, and it may be said that all modern transport is increasingly dependent upon the use of the new fuel. Automobilism and aviation owe their existence to it. Not only do steam engines tend to give place to the oil motor in a great number of cases, but they themselves begin to use oil instead of coal. Locomotives and the engines of ships more and more seek the source of their energy in oil. No more smoke, no more troublesome ash, and double the calorific power. The work of a fireman, formerly so exhausting, is reduced to the opening and closing of a tap. If coal is replaced by mazut in the furnaces of ships, their radius of action is increased by 50 per cent.; it is more than tripled if the internal-combustion engine is used. Certain British engineers are not afraid to assert that one ton of mazut, used in a Diesel engine for ships, is equivalent to at least six tons of coal.

Few countries hesitate in face of such advantages. Since 1885 the railways of Southern Russia have been run on oil; those of Rumania since 1887. The railway companies of the United States consumed 20 million barrels even in 1909—that is, one-tenth of the production at that time. And the last few years have been marked by the conclusion of contracts by the United States Railroad Administration for the delivery of 50 million barrels. The engines of the Southern Pacific Railway have been aptly described as veritable monsters. Their boilers are two metres in diameter and fourteen and a half metres long. Their heating-surface is double that of ordinary locomotives. The driver's place is in front, which allows him to see the track.

Mexico has long since followed the example set by the United States. So also has Austria for her Alpine railways. France has made experiments which have been much talked of; and the Argentine, only a few months ago, has concluded important contracts with the Shell Transport and Trading Company for the supply of oil for her railways. Everywhere the substitution of oil for coal is going on, and consumption is developing with such rapidity that the supply is no longer anything like equal to the demand. Even if Russia recovered, the discrepancy between the needs of the world and the quantity available would be considerable. That is why the[Pg 36] price of liquid fuel, which requires little labour in its production, remains so high.

Since North America supplies 80 per cent. of the world production, the dollar has become the standard currency for oil. At the present time, Rumanian oil, delivered in Hungary, is sold at the same price as American oil. The market-price is therefore fixed for the whole world by New York.

Very few people realize at all clearly what will be the consumption of oil in a few years' time. It is natural enough, for it is only a short time since our great and instructive Press began—very timidly, however—to entertain its readers with this burning topic. There is no one, at present, who does not know that the question of fuel is of supreme importance to the whole industrial life of Europe.

Now, the world-production of coal was, in 1920, about 100 million tons short, compared with the production in 1913. The directors of colliery companies endeavour to increase the output of the mines, but they obtain in general only disappointing results, which is not strange when we observe the increasing number of miners' strikes, the rise in wages, and the fact that laws are continually passed to reduce the hours of labour.

In producing steam, one ton of mazut gives almost the same result as two tons of coal; more than 50 mil[Pg 37]lion tons of fuel-oil are therefore required to make good this enormous deficit.

Now, in 1919 the world production of mazut did not exceed 75 million tons. After making good the shortage of coal, this would leave only 25 million tons to satisfy the ordinary demand. This comparison of figures makes clear how great is the need of oil, at a time when the use of oil, in preference to coal, is becoming more and more the order of the day. Now, the great and general increase in consumption is not equalled by the production which, though far from stationary, is none the less much below the needs which are predicted for the future in competent circles. An American oil journal recently published the following figures for the consumption of the United States:—

1907 24 million tons

1918 57 million tons

1919 75 million tons

And even at the beginning of 1920 an increase of 25 per cent. over 1919 was noted. The rate of increase was such that, in January and February 1921, the American consumption was greater by 230,729 barrels a day than the national production. The stock of oil in the United States, both national and Mexican, has recently been considerably reduced, and[Pg 38] does not amount to more than 114,000,000 barrels, representing only four months' consumption, although for years past it has alw ays been sufficient to meet the consumption for six months. It must be remarked that motor-cars are terrible gluttons for petrol, and that in the United States every farmer has his car. In a self-respecting family there are generally three—a limousine for use in town, an open car for touring, and a Ford for the servants to fetch provisions. It has been calculated that there is on an average one motor-car to every thirteen inhabitants. The Ford works alone are capable of turning out three million annually.

And, as if that was not enough, America is planning to develop, by motor traction, the means of transport in Asia, the continent without railways. We may predict for this a consumption of 120 million tons in the near future.

The United States consume twice as much oil as the rest of the world, while their resources do not amount to more than one-seventh of those of the world.

Their consumption increased in 1920 by 25 per cent.; their production only by 11 per cent. And already fears are entertained that it may diminish. Two-thirds of the oil-fields of Oklahoma, which state alone produces nearly one-quarter of the total, have been developed; and the number of borings tends to diminish.

If the increase in world-consumption of oil continues at the rate that it has done during the past few years, the oil reserves of the United States, calculated on the basis of 70 barrels to each inhabitant, without allowing for increase of population, would, according to the Smithsonian Institute, come to an end about the year 1927.

These figures seem to me a little exaggerated, for the reserves contained in the soil of the United States cannot possibly be completely exploited in so short a time. But the figures published by the Geological Survey of the Department of the Interior shows that other countries consume half as much oil as the United States, while their soil contains seven times more.

"These countries consume at the present time two million barrels a year; at this rate, they have reserves sufficient for 250 years. The United States consume 400 million barrels a year; they have only enough for 18 years.[8]

"The total amount of oil which can still be extracted from the soil of the entire world has been computed at 60,000 million barrels—43,000 million have already been brought to the surface by successful borings.

"Of the 60,000 million which remain to be ex[Pg 40]tracted, 7,000 million are to be found in the United States and in Alaska; 53,000 million in the rest of the world."

That is why the American Navy, having in view the treatment of bituminous shale by distillation, has reserved to itself the rights over immense deposits, chiefly in Colorado and Utah. If the United States do not succeed in acquiring new oil-fields in the rest of the world, the position will become so serious that they will only be able to avoid war at the price of economic vassalage.

There is oil in all parts of the world, and yet dominion over oil is one of the most concentrated possible.

From Alaska almost to Tierra del Fuego, every country in the New World possesses some.

Alaska.

Canada: its presence was discovered in 1789 by Sir Alexander Mackenzie.

United States.

Mexico.

Central America.

Venezuela.

Trinidad, Guiana.

Colombia.

Ecuador, Peru, Bolivia.

Chili, the Argentine.

Brazil and Uruguay: it is hoped that oil will be found shortly.

In Europe it is less evenly distributed:

Hanover (Wenigsen).

Alsace.

Italy.

Poland. The Ukraine. Rumania.

Hungary: a subsidiary company of the Anglo-Persian, the D'Arcy Exploration, found oil deposits in March 1921.

Asia is nearly as rich as America:

The Caucasus.

Persia, Mesopotamia.

Dutch Indies.

Siam, Burma.

China.

Japan and Formosa.

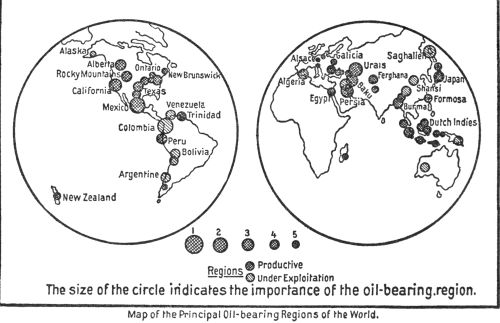

Map of the Principal Oil-bearing Regions of the World.

Africa and Oceania, on the contrary, seem to possess only small quantities of the precious oil. There is some in North Africa, in Egypt, and possibly in Madagascar. The great British prospecting group, which I have already mentioned in connection with Hungary, is making a thorough search at this moment in Western Australia and New Zealand.

Now nearly all these oil-fields, scattered in the four corners of the world, and in so many different countries, are at the present moment in the hands of two great trusts—one American, the Standard Oil, and the other Anglo-Dutch, the Royal Dutch-Shell—and certain companies controlled by the British Government.

FOOTNOTES:

[8] Cp. Part III, chap. xiv, How the United States Lost Supremacy over Oil.

PART II

THE STRUGGLE OF THE

TRUSTS

THE STANDARD OIL COMPANY

Although it sometimes happens that governments oppose each other openly in the struggle for oil, as in the case of Poland, Rumania, the Caucasus, and Turkey, they prefer, in general, to hide behind trusts.

There exist in the United States numerous oil concerns whose power is far from negligible, such as the Sinclair Oil Company, with a capital of 500 million dollars, and the Texas and the Doheny interests, which together represent another 500 million dollars. But all these independent producers must bow before the unchallenged supremacy of the Standard Oil.

The Standard Oil, a purely American concern, preceded the Royal Dutch—a Dutch company with considerable British, and recently a little French, capital[9]—by twenty years.

As a matter of fact, there is no longer to-day one Standard Oil, but forty companies, all bearing this name followed by that of a town or State:

The Standard Oil of New Jersey,

The Standard Oil of Pennsylvania,

The Standard Oil of Kansas,

The Standard Oil of Ohio.

The first is the most important. All are federated under one great administrative body.

The Chairman of the Board of Directors of Standard Oil Companies is at the present time Mr. Bedford, formerly Chairman of the Standard Oil of New Jersey, where his place has been taken by Walter Teagle. This great Council is the real brain of the Standard, from which emanates the general policy of this federation of companies, as powerful as the Government of the United States—more powerful sometimes.

Its history, like that of all American trusts, has something of the marvellous. At the beginning of a great undertaking there is always a great man: the founder of the Standard was John Rockefeller, a small dealer in oil, who, in 1865, conceived the idea of forming a federation of all American oil-dealers.

There were in 1870, in the United States, 250 refineries, which waged among themselves a merciless price-war.

It was to put an end to this struggle, which was so advantageous to the consumer, that the Standard Oil Company was created, a combine of refiners, not of producers. Following a strict and constant princi[Pg 47]ple, which it has always observed, the Standard has refrained from seeking raw oil, leaving this task entirely to the prospectors and producers. But as soon as it reaches the surface, the oil, wherever it is found, becomes the exclusive property of the Company, to whose innumerable refineries it is conducted by pipe-lines. The original Standard Oil Company, that of Ohio, began humbly with a capital of a million dollars, and the small consumption of 600 barrels a day. Established in Cleveland, it grouped together all the interests in the refining and transport of oil acquired in Pennsylvania since 1865 by Rockefeller, Andrews, Harckess and Flager. Two years later, not only had it brought all the refineries in the neighbourhood of Cleveland under its own control, but it had built others at Baltimore, Philadelphia, New York, Boston, and Pittsburgh.

Six years after its inauguration, it already acquired the greater part of the crude oil produced in the United States. Moreover, its capital had been twice increased, in 1872 and 1874.

At the end of ten years, it transported and distributed 95 per cent. of the American output.

In 1881 it amalgamated thirty-nine oil companies. The trust was constituted and already disposed of a capital of 75 million dollars. The first cycle of its growth was finished. Supreme in the United States market and sure of its monopoly, it completed the[Pg 48] laying of its first pipe-line to the Atlantic. The Standard Oil was about to lay claim to Europe.

The Agreement of January 2, 1882

Such fortunes were not built up by entirely honourable methods. The directors of the Standard Oil of Ohio had formed pools. They imposed buying and selling prices on every company which participated. This system, which in a dozen years gave such wonderful results, was not without its faults. There was friction between members of the pool. The need for establishing unity of direction was soon felt. It was with this object that the Standard Oil Trust was founded in 1882.

It was the first time that the word "Trust" appeared in the name of a firm. A Committee of nine members, or trustees, was formed. It comprised all the Rockefeller family: John Rockefeller, Payne, William Rockefeller, Bestwick, Flager, Warden, Pratt, Brewster, Archbold. The nine trustees became the sole delegates and depositories of all the 39 companies conjointly engaged. They received from each concern the shares and the corresponding voting powers. Trust Certificates, of a nominal value of 100 dollars, were exchanged for shares only in the proportion of the value of each undertaking to the total value of all the undertakings constituting the Trust.

The Agreement of 1882 which sealed the pact, provided for the admission into the Trust of new companies and the eventual formation of a Standard Oil Company in each State of the Union.

Companies of four kinds entered the combine of 1882:—

1. Fourteen companies in which the whole of the shares were held by the trustees. Among these were the Atlantic Refining Company, the Standard of Ohio, and the Standard of Pittsburgh. The first of these companies succeeded in recovering its liberty in 1911.

2. Rich private individuals, having an interest in the oil industry and holders of large parcels of shares, such as W.C. Andrews and John Archbold.

3. Twenty-four companies in which the majority of the shares were held by the trustees:—

Central Refining Company of Pittsburgh,

Germania Mining,

Empire Refining,

Keystone Refining,

National Transit Company, etc.

These twenty-four companies placed themselves under the control of the Trust from 1882 onward. Two others have come in under compulsion:—

(1) The Tide-water Pipe-line Company, having constructed pipe-lines itself, entered into fierce competition with the Standard. On October 9, 1883, it was compelled to negotiate with the National Company. Under the resulting contract, it agreed to provide 11-1/2 per cent. of the quantity sent to the ports by pipe-lines as its share of the traffic, and was guaranteed an annual profit of at least half a million dollars for fifteen years.

(2) The Producers' Associated Oil Company, born of a concerted effort of independent producers to fight the Standard, gave in in October, 1887.

4. One other company alone forms the fourth class. The Trust has an interest in this but has never been able, whatever its efforts, to obtain the majority of the shares and to control the company. This is the United States Pipe-Line Company. This company experienced many difficulties and mortifications. After having struggled against the inertia of the railways devoted to the Standard Oil, and spent more than 15,000 dollars on law costs alone, it succeeded in pushing its lines up to Washington, but could never get any further, nor reach the coast; the Standard bought up the intervening territory.

At its zenith, in 1911, when it was declared illegal[Pg 51] by the Supreme Court of the United States, the Standard owned 90 per cent. of the pipe-lines and controlled 86-1/2 per cent. of the oil production of America. A single company, the Pure Oil Company, founded in 1895, whose field of exploitation was Germany, was able to maintain its independence. The seventy-five small refineries existing outside the Trust did not refine, all put together, a fifth as much as the Standard. The refinery which the latter possessed at Bayonne was by itself more important than ten of these competing refineries.

The European market was almost completely conquered. Everywhere the Standard operated by means of its subsidiary companies:—

The Anglo-American Oil Company in Great Britain.

The American Petroleum in Holland.

The Deutsche Amerikanische Petroleum Gesellschaft in Germany.

The Société pour la Vente du Pétrole in Belgium.

The Vacuum Oil in Austria-Hungary.

The Societa Italo-Americana per Petrollo in Italy.

The Romana-Americana in Rumania.

The Danske Petroleum Altieselskabet in Denmark.

The Swenska Petroleum Altiebolage in Sweden.

The International Oil in Japan.

In Galicia, the Trust held its own against all similar indigenous enterprises. The Rumanian refiners[Pg 52] were obliged to come to an understanding with it; otherwise it would, with its powerful means of pressure, have created a monopoly for itself. And the French Oil Cartel was at its mercy.

Causes of the Success of the Standard

The difficulty is not to produce oil, but to transport it, for it is generally found in more or less desert regions. Hence Rockefeller's brilliant idea, to construct pipe-lines bringing the oil direct to the great centres! Thenceforward, since the oil was transported almost automatically, its price dropped considerably. All the producers became tributaries of the pipe-lines, and the Standard obtained practically complete control of the market.

This was the first cause of the success of the Standard. All the small producing companies became compulsorily its clients. As controller of the market, it fixed the price in draconian fashion.

There is a second cause: its alliance with the great railway companies, and the support which it received from the railway magnates—Scott of the Pennsylvania Railroad, Vanderbilt of the New York Central, Jewet of the Erie Railroad, Watson of the Lake Shore, and many others less well known.

Its subsidiary, the South Improvement Company, on January 18, 1872, made contracts with the railway companies, by which it fixed the proportionate[Pg 53] shares in the transport of oil to the Atlantic seaboard as follows:—

27-1/2 per cent. to the Erie,

27-1/2 per cent. to the New York Central,

45 per cent. to the Pennsylvania.

The companies thus favoured by the Standard made their competitors pay double rates. One of these latter produced before the Inter-State Commerce Commission the scandalous tariffs demanded of them:

On the Louisville and Nashville Railroad, increased rates to competitors of 87 to 333 per cent.;

On the Cincinnati, New Orleans, and Texas Pacific, from 63 to 267 per cent.;

On the St. Louis, Iron Mountain and Southern, from 82 to 257 per cent.

Systematic negligence in transport was proved with regard to competitors. The Union Tank Line Company, which owns tank-wagons as the International Sleeping Car Company owns restaurant cars, would only put them at the disposal of the Standard, and compelled its adversaries to dispatch their oil in barrels, which is much more costly. The Trust alone was entitled to lay its pipe-lines beside the railway-lines or underneath the track. It possessed 35,000[Pg 54] miles of such lines at the end of last century—or rather the National Transit Line, which acts as its instrument, owned them. Such abuses could not be allowed to continue. The inquiry by the Hepburn Committee revealed a multitude of crying injustices. For example, it was enough for the Standard or the South Improvement to telegraph "Wilkinson and Co. have received a truck which only paid $41.50; screw them up to $57.50," and the order was executed.

The Charter of the South Improvement, which had even succeeded in acquiring the right of expropriation in order to construct its pipe-lines, was withdrawn under the pressure of indignant oil-producers. But the Federal Government of the United States will never succeed in crushing the Standard Oil.

Its Two Dissolutions—Roosevelt's Fight against the Standard Oil

Twice over, in 1892 and 1911, its constitution was judged illegal, but in vain.

In 1892 the system of nine trustees was declared illegal by the Supreme Court of Ohio. The trustees voted the dissolution of the Trust, but continued to administer all the corporations in the same way until 1899. The Trust was apparently divided into twenty distinct companies; the nine old trustees distributed the shares in such a way as to possess the majority[Pg 55] in each one. Thus they made sure, as before, of unity of direction. Rockefeller had reversed the judgment of the court.

Here is the legal formula, which is dignified in its simplicity: "John Rockefeller has placed in the hands of the said attorney 256,854/292,500 of the total shares held by the said trustees on July 1, 1892, in each of the companies whose shares were deposited."

Still better, after receiving the shares which were granted them in each company, the old trustees took them and sold them to the Standard Oil Company of New Jersey, which has a capital of 100 million dollars of common stock, and only ten million dollars of preferred stock. For the Standard has a monarchical constitution. All power to the holders of preferred stock! The holders of common stock have none but that of drawing dividends. Though they may be in an enormous majority, they count for nothing in the direction of the enterprise.

About 1900 Rockefeller went still further. He increased the number of ordinary shares, and reduced that of the privileged shares. A memorandum of the Industrial Commission drew attention to this. "During the year 1900, the common stock has been increased by 38,550,700 dollars and the preferred stock has been reduced by 3,968,400 dollars."

In short, Rockefeller makes the concern more and[Pg 56] more autocratic. The Standard forms a veritable State within a State, which nothing can bend. The Trust was reconstituted, with a holding company, the Standard Oil Company of New Jersey, holding the title-deeds of all the other companies.

It was then that Roosevelt undertook to destroy a power before which everything bowed down. The Federal Government brought an action before the Court of St. Louis, under the Sherman Anti-Trust Law. The Standard Oil and the seventy companies dependent on it were accused of "conspiracy, coercion, intimidation, rebating and other illegal acts in restraint of trade." The Federal Court of St. Louis ordered the dissolution of the Trust in 1909. The Standard entered an appeal before the Supreme Court of the United States, which confirmed the dissolution in 1911, after five years of inquiries, prosecutions, judgments and appeals. The struggle had been going on since 1906. Many judgments had to be reversed. Thus, the Standard Oil Company of Indiana, with a capital of only a million dollars, was ordered to pay a fine of 29 million dollars for an illicit understanding with the Chicago and Alton Railway. It was paying only six cents a hundredweight for transport, while its competitors paid eighteen. This judgment was reversed in July 1908 by the Court of Appeal of Chicago. "It is strange," ran the decision "that a company with a capital of a mil[Pg 57]lion dollars should be fined a sum representing twenty-nine times this capital." The first tribunal had found 1,462 infringements proved, and had zealously applied the maximum for each case; that is how it had arrived at the incredible figure of 29 million dollars.

The Standard Oil was given six months to dissolve. The result was the same as in 1892. There were simply thirty-four companies apparently independent. In the midst of this new constellation, the Standard Oil Company of New Jersey, whose capital has risen to 600 million dollars, merely shines with a greater brilliance than its satellites. And the Standard has no longer to fear attack from the Government of the United States, which bows obediently to its will. Even better, the late President Harding energetically supported its claims throughout the world. Whoever attacks the Standard attacks the Federal Government itself.

To think of Rockefeller's modest company in 1870, with its 600 barrels a day and its small capital of a million dollars, and to see what it has become to-day, is to be lost in amazement. In 1920, the Great Council of the Standard controlled a capital of a thousand million dollars; representing almost equal profits, and a daily consumption of two hundred million barrels, which it even hopes to see presently increased to three hundred million. Here are the[Pg 58] original and the present positions; they are widely different:—

Capital has increased from 1 to 1,000.

Profits have increased from 1 to 100,000.

Production has increased from 1 to 300,000.

The Standard has soared so high because it was a national enterprise. Every bank, every shipping company, every railway in the United States, was interested in the success of the Trust, for this great corporation exported to the four corners of the world a commodity drawn from the soil of the Union, and brought into the country, one year with another, more than a hundred million dollars. It looked as though all competition was impossible, and yet a European company has been found bold enough to attack, not only in Europe and Asia, but on its own ground of the United States, this financial power, whose turn-over must be estimated at twelve thousand million francs at least, or more than twice the pre-War budget of a nation like France.

FOOTNOTES:

[9] Forty per cent. of the capital of the Royal Dutch is in French hands, but France unfortunately has no voice in the direction of this undertaking.

THE ROYAL DUTCH-SHELL

In face of the formidable hegemony which the Standard Oil exercised over the oil markets of the world, an opposition arose, at first timid, then bolder in proportion as success attended its efforts.

This was the Royal Dutch allied to the Shell. Thirty years have sufficed to give it a unique position in the world.

It was in 1890, at The Hague, that the Royal Dutch Oil Company[10] was founded, with a capital of 1,300,000 florins. As a result of borings carried out in the Sunda Islands, the Government of the Dutch Indies granted it concessions at Sumatra. After some years, as the sale of crude oil did not give a sufficient return on the capital already sunk, the directors of the young company resolved to erect a refinery on the spot. It was necessary for this purpose to increase the capital to 1,700,000 florins in 1892. A strange fact to relate to-day, this issue was a failure.[Pg 60] The capitalists of the day had lost confidence in an undertaking whose net profits for two years had been nil. In spite of these initial difficulties, the board of directors persevered. It even acquired new concessions, whose more profitable exploitation allowed of a first dividend in 1894 of 8 per cent. This distribution restored the confidence of the public, and the Royal Dutch was able to increase its capital without difficulty in 1895 to 2,300,000 florins, with a view to extending its sphere of action. In the same year it was able to distribute a dividend of 44 per cent. Considering the importance of its operations, the company decided in 1897 to increase its capital to 5,000,000 florins, in order to obtain tank steamers to transport its products. The dividends had then risen to 52 per cent., but it could not keep up for long so exceptional a rate. For, from 1898 onward, the Standard, becoming uneasy, tried to obtain control over its rival. To escape from its grip, the Royal Dutch was compelled to issue one and a half million preference shares, which were allotted to friendly groups. A bitter economic struggle followed. The Royal Dutch maintained its independence, but the Standard, to destroy its young rival, did not hesitate to sell in extra-American markets at less than cost, and the steady lowering of the price of oil compelled the Dutch company to reduce its dividend to 6 per cent. It was maintained[Pg 61] at this rate the following year, but began to rise again in 1900, and reached 24 per cent. in 1901.

Since then the Royal Dutch has progressively increased its capital to the present fantastic figure, under conditions which were so many windfalls for its shareholders. Its dividends during the great world War rose to the enormous rates of 45, 48 and even 49 per cent. There were some years when it went so far as to distribute to its shareholders dividends in shares of 200 per cent., thus tripling its nominal capital.

The Alliance with the Shell

The early career of the Royal Dutch was as modest as that of the Standard Oil and far more troubled. At its very beginning it found in the East a young British firm, the Shell Transport and Trading Company, which put up a keen competition, the more disastrous because the latter possessed a fleet of tank steamers, while the Royal Dutch as yet had none. The Shell was directed by Sir Marcus Samuel, one of the cleverest business men in London.

Samuel had begun humbly as a trader in sea-shells. His business prospering more and more, he hunted about for some commodity to exchange for the shells which he brought from the East. He decided upon oil, and became himself a producer in Borneo.

In 1897 the Shell was registered in Great Britain, with the view of absorbing the business of Samuel and Company and certain other similar concerns. The new company had a large number of tank steamers and hundreds of depots.

The Royal Dutch had then amalgamated the greater number of the independent producers of the Sunda Islands, but was experiencing some difficulty in getting its oil to Europe, and so decided to negotiate with the Shell.

Hence the agreement of 1902, by which the two companies entrusted the sale of their products to a company which they created specially for the purpose, the Asiatic Petroleum. Its capital was subscribed as follows:—

1/3 by the Royal Dutch,

1/3 by the Shell Transport,

1/3 by the Rothschilds.

This simple alliance became a complete union ten years later. The Royal Dutch and the Shell amalgamated on the following basis:—

On January 1, 1907, the two groups transferred their assets to two companies, one Dutch, one British. These were the Bataafsche Petroleum Maatschappij and the Anglo-Saxon Petroleum.

The Bataafsche, or Batavian Oil Company, which now has a capital of 200 million florins, was[Pg 63] specially entrusted with the extraction of oil and with everything concerning its production. Its oil-fields are situated in Java, Sumatra and Borneo, and it exploits them directly or by subsidiary companies. It has interests in the Mexican Corona company and in many Russian companies.

Although this last part of its program has not hitherto been productive, the Bataafsche has distributed during the last few years dividends representing annually nearly half its capital. Directly or indirectly, it is responsible for almost the whole production of the Dutch Indies, which amounts to nearly 20 million barrels annually, and is steadily rising. To meet this increase, the Batavian Oil Company is obliged every year to construct new reservoirs. In 1920 their capacity had reached more than 900,000 tons.

The Anglo-Saxon Petroleum, with its head-quarters in London, was entrusted with everything concerning the transport and sale of oil, that is to say, with the commercial side of the business. Unlike the Bataafsche, this company undertakes no direct exploitation, although it controls the production of a large number of subsidiary companies in Ceylon, British India, Malay, Northern and Southern China, Siam, the Philippines, Australia, New Zealand and South Africa. For the Royal Dutch-Shell has an almost organic structure. Instead of reproducing itself in[Pg 64] new companies, always the same, like the Standard Oil, it only receives new adherents for distinct functions. One company is entrusted with the distribution of its products, another with the exploitation of oil-fields or with refining. The Royal Dutch and the Shell have become to-day holding companies. In 1907 the Royal Dutch ceased to be an industrial enterprise and became an omnium of oil securities.

Forty per cent. of the profits resulting from this co-operation were to come to the Shell, 60 per cent. to the Royal Dutch, which has reserved the lion's share for itself.

At the time of signing this agreement the Shell was not without a certain anxiety. Thus it was agreed, in order to safeguard its interests, that the Royal Dutch would buy, on January 1, 1907, half a million ordinary shares of the Shell at the price of thirty shillings, and would undertake not to sell again without the consent of the board of directors of the Shell.

In case of liquidation or sale by private contract before January 1, 1932, it was stipulated that the net product of the liquidation, up to £9,000,000 sterling, was to be divided equally between the Shell and the Royal Dutch, and that only above this amount the products should be shared in the proportion of 40[Pg 65] and 60 per cent. We see how closely these two concerns are allied. The only difference which exists between them is that, officially, one is Dutch, the other British.

Deterding's First Victory. The Chinese Campaign

Freed from all obstacles in the Dutch Indies and allied with one of the most powerful British firms, the Royal Dutch, under the skilful guidance of Henry Deterding, was ready to attempt a conquest of the world.

But for the second time it came up against the hostility of the Standard Oil, which waged a bitter warfare in the Far East—the famous price-war of 1910.

The Standard Oil of New York considered China as its private property. It had taught the Chinese to use kerosene by distributing, free of charge, lamps inscribed Mei Foo, or Good Luck. When this method became too expensive it sold them at cost price, and when the Royal Dutch appeared as a competitor it was selling, in this way, two million lamps a year. With a population of 400 million Chinese, this produced an unlimited market for kerosene, for which, in comparison with petrol, the American demand is small.

The Standard tried to fight by selling refined oil below cost price in foreign markets, while keeping the price very high in America in the shelter of the tariff wall. It even went so far as to sell in the Far East 50 per cent, lower than in Holland, although the latter market was nearer the American oil-fields. At the same time the refined American oil, which was quoted in England at the end of August 1910 at 6-1/4d. a gallon, fell at the end of November to 5-3/4d., and in December to 5-1/2d. Deterding's receipts from the sale of kerosene were reduced by 3,750,000 dollars. But he would not give way. He did not leave China; he stood his ground and fought. Although his oil was of an inferior quality to that of the Standard, it was near at hand, and had not to be transported for long distances like that of its rival (which involved the latter in great expense). An agreement was finally made. The Standard, which had taken possession of the Chinese market in 1903, gave up 50 per cent, of that trade to the Royal Dutch. The latter's share has even been increased recently to 60 per cent. For the first time Deterding had conquered!

Perhaps he would not have triumphed so easily if the Standard Trust had not been dissolved just at that time by the Supreme Court of the United States. But two such powerful groups could not have con[Pg 67]tinued indefinitely to struggle for the international market without making sure of some stability and limiting their respective zones of operation.

After many attempts they have come to an understanding.

In 1907 an agreement fixed the quota of oil that each group might send to the British market.

In 1912 an agreement of a similar kind put an end to the struggle that had been going on in the Far East.

The absence of a definite general agreement between the two great Trusts did not exclude the possibility of tacit agreements, which regulated their operations in the international market and assured to both an extraordinary prosperity. The Standard has several times made very tempting offers of close co-operation to the Royal Dutch, leaving this group free to make its own conditions. The Royal Dutch-Shell has always refused, for the future is its own. What will happen to the Standard, an almost exclusively American concern, when the oil resources of the United States are exhausted? Since 1919 it has been endeavouring to acquire oil-fields in the rest of the world, to guard against this danger, but everywhere it finds the "closed door." The Royal Dutch, aided by the British Government, has taken possession of all that remain in the world.

New Struggle with the Standard Oil for the Conquest of the World

One day, to the great astonishment of everybody interested in the American oil industry, Mr. Deterding brought a cargo of oil to the United States and sold it under the very nose of the directors of the Standard Oil. Emboldened by this first success, he tried to establish himself in the United States, and with this aim in view bought oil-bearing properties in Oklahoma. The Royal Dutch rapidly increased its territory.

By a bold policy and without recourse to the sharp practices of the directors of the Standard Oil, Deterding revenged himself for the attack upon him in the Far East. The Royal Dutch sent large quantities of petrol to America and sold them at rates as high as those of the Standard. This enabled it to make good its losses in the Old World and to emerge victorious from the struggle.

During his Chinese campaign Deterding had been handicapped by the inferiority of the oil from Borneo. To remedy this he proposed to obtain possession of various Californian wells.

Of all the wars that Deterding has waged, that of California is the most interesting and perhaps the most strenuous. It required a remarkable audacity for the Royal Dutch to establish itself on the very[Pg 69] territory of the Standard in America. Would it not meet there the coalition of this great firm and the independent oil companies? And yet Deterding triumphed. He created the Roxana Petroleum Company in Oklahoma, the Shell Company of California on the shores of the Pacific, and then extended his conquests to Texas, New Mexico, Colorado, Utah, Arizona, Montana, Dakota and Nevada. Everywhere the Royal Dutch brings with it its curious methods. It begins by taking an option for six months on an oil bearing property, giving it the right to examine the books of the company and to make an inquiry. At the end of six months it takes an option on another property, and continues in this way throughout the region. After leaving nearly all the options without sequel, the Royal Dutch is ready to begin boring operations on its own account in selected places.

This method, adopted for the first time in California, is to-day the habitual method of the Royal Dutch-Shell. Thus this company rarely makes miscalculations in the oil-fields it exploits. Its agents have orders to report the minutest details to head-quarters.

In order to interest the American public in the success of his enterprise, Deterding was clever enough to place upon the New York market, in 1916, 220,000 so-called American shares. This issue was a great success, and it has thus become against the in[Pg 70]terest of many Yankees for the United States Government to start reprisals against the Royal Dutch, of which the late President Harding has often spoken.

In 1915 the Royal Dutch already controlled one-ninth of the American output. One-third of its total production comes to-day from the United States. It has obtained for its pipe-lines the right of passage to St. Louis and the river, and its surveys of Virginia and Louisiana are complete. It owns the great refineries of Martinez, near San Francisco, and of St. Louis and New Orleans.

Seventy-five per cent. of the Californian output, which exceeds ten million tons, now escapes the control of the Standard Oil.

But more than this, the Royal Dutch is gaining possession of the deposits of Mexico and Venezuela. The oil-bearing territories of Tampico and Panuco, the railway, and the local oil companies belong to Mr. Deterding. The importance of this region is well known. Its geographical position, a few miles from the sea, and its nearness to the Panama Canal double its value. Three hundred and fifty kilometres by sea, one hundred and seventy-five by pipe-line across the isthmus of Tehuantepec, and the oil can be delivered at a centre which commands the whole South American market.

Not content with conquering the Standard Oil on its own ground, Deterding also caused it to lose its[Pg 71] "Algeria." Master of the Mexican Eagle, which he bought from its founder, Lord Cowdray, in 1918 for more than a thousand million francs, he controls to-day the bulk of Mexican production. By this master-stroke he increased by 50 per cent. the quantity of oil that the Royal Dutch can offer to the world.

The Americans felt the loss very keenly, for hitherto all the output of the Mexican Eagle had gone to the Standard Oil.

The Mexican Eagle had a large number of tank steamers, the acquisition of which brought up the fleet of the Royal Dutch-Shell to more than a million tons.

Moreover, the directors of the Royal Dutch do not hesitate to assert that the oil-bearing district of Venezuela, of which, since their agreements with the General Asphalt Company, they control more than 15,000 square miles, is as rich in oil as the district of Tampico. That is why they have put up enormous buildings, both warehouses and refineries, at Curaçao. The Shell, which has operated for four or five years in Venezuela, has just overcome the difficulties of approaching the coast by constructing a flotilla of tankers of very small draught, thus permitting the transport of oil from Maracaibo to Curaçao.

The Panama Canal itself is seriously menaced. The United States have spent more than 300 million[Pg 72] dollars in constructing the canal, and now American vessels are going to be dependent upon the Royal Dutch for oil. Mr. Deterding has a depot at one end of the canal and another at the entrance to the gulf. He dominates American commerce.

This is indeed a work of conquest. Mr. Deterding follows the commercial example of Great Britain. He has stations at all the strategic points of the world. He also controls the Suez Canal at both ends. The capacity of the refinery at Suez has been increased by 7,000 barrels a day, on account of the increase in the tonnage passing through the canal during the War. Mr. Deterding is building a station on the Cape Verde Islands, situated just half-way between Africa and America. He has establishments at the Antipodes, in the East and West Indies, on the west coast of South America, on the coast of Africa, and at the Azores. The European market, in particular the French, is dependent on him. Through the instrumentality of M. Deutsch de la Meurthe, the oil deposits in Asia, owned by the Rothschilds, have come under the Royal Dutch trust, which possesses 90 per cent. of the capital of the oil companies of the Caspian and Black Seas and 25 per cent. of that of the New Russian Standard Company of Grosny. In August 1920 the Shell bought the Mantasheff and the Lianosoff, together with a 40 per cent. interest in the Tsatouroff, fearing to see the Standard Oil[Pg 73] acquire the Nobel properties at Baku. The contract was signed in London, but was incompletely carried out, for Great Britain hoped to treat directly with the Soviets at Genoa and to have no more responsibility towards the former owners.[11]

A large part of the Rumanian production is controlled by the Royal Dutch.

In Germany the Royal Dutch-Shell has an interest in the Erdol und Kohle Veränderung Aktien Gesellschaft, the Aktien Gesellschaft für Petroleum Industrie and the Deutsche Bergin Aktien Gesellschaft.

Since 1912 it has established itself in Sweden as the Anglo-Swedish Oil Company, to drive out the Standard Oil, until then mistress of the market. Everywhere the Royal Dutch insinuates itself into the good graces of governments, thanks to its elastic methods and to the cleverness of some of its directors, such as the brilliant Armenian Gulbenkian, who has been well named the "Talleyrand of Oil." In co-operation with the Belgrade Government, it has just formed a new company at Agram, with a capital of 50 million crowns, to exploit the oil of Jugo-Slavia.

As the Financial Times wrote: "Following the creation in France of the [Pg 74]Société Maritime des Pétroles and the Société pour l'Exploitation des Pétroles, the Royal Dutch is able to obtain from the French Government an important interest in the oil-fields which remain at its disposal."

Its last triumph was its entry into Spain. The eminently suggestive list of companies controlled by the Royal Dutch will give an idea of the network which it has spread over the whole world:—

Shell Transport and Trading Company.

Asiatic Petroleum Company.

Anglo-Saxon Petroleum.

Bataafsche Petroleum Maatschappij.

Erdol und Kohle Veränderung Aktien Gesellschaft.

Aktien Gesellschaft für Petroleum Industrie.

Deutsche Bergin A.G.

Anglo-Swedish Oil Company.

Asiatic Petroleum (Ceylon).

Asiatic Petroleum (Egypt).

Asiatic Petroleum (Federated Malay States).

Asiatic Petroleum (India).

Asiatic Petroleum (Northern China).

Asiatic Petroleum (Philippines).

Asiatic Petroleum (Siam).

Asiatic Petroleum (Southern China).

Asiatic Petroleum (Straits Settlements).

Anglo-Egyptian Oil-fields.

British Imperial Company (Australia).

[Pg 75]British Imperial Company (New Zealand).

British Imperial Company (South Africa).

Astra Romana.

Caribbean Petroleum.

Dordesche Petroleum Industrie Maatschappij.

Dordesche Petroleum Company.

Sumatra Palembang.

Nederlandsche Indische Tanks Troomboat.

Vereinigte Benzinwerke, Hamburg.

Home Light Oil Company.

British Petroleum Company.

Norsk Encelska Mineralojeanie Colaget.

Shell Marketing Company.

Italian Company for the Import of Oil.

British Tanker Company.

Moebi Hid.

Ceram Petroleum.

Ceram Oil Syndicate.

Société Bnito.

North Caucasian.

Russian Standard of Grosny.

Mazut Company.

Ural-Caspian Company.

Grosny Sundja Oil-fields.

New Shibaïeff Petroleum.