Being

An Account of the History, Religions, Customs, Legends, Fables and

Songs of Gilgit, Chilas, Kandia (Gabrial) Yasin, Chitral,

Hunza, Nagyr and other parts of the Hindukush,

AS ALSO A SUPPLEMENT TO THE SECOND EDITION OF

THE HUNZA AND NAGYR HANDBOOK

And An Epitome of

PART III OF THE AUTHOR’S “THE LANGUAGES AND RACES

OF DARDISTAN”

By

G. W. LEITNER M.A., PH.D., LL.D., D.O.L., ETC.

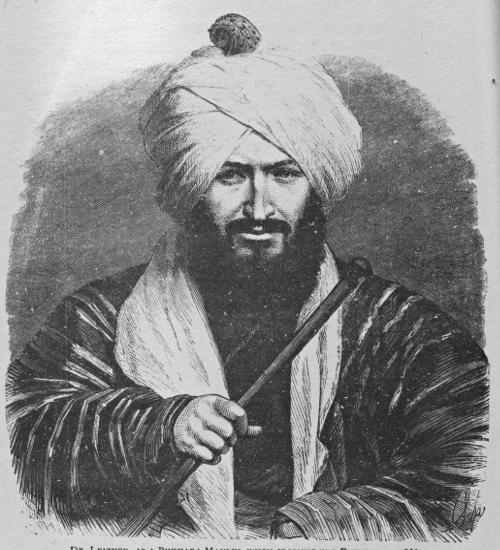

(With appendices on recent events, a map and

numerous illustrations)

MANJUSRI PUBLISHING HOUSE

Kumar Gallery, 11, Sunder Nagar Market,

NEW DELHI (India)

PUBLISHED BY VIRENDRA KUMAR JAIN FOR MANJUSRI PUBLISHING HOUSE

KUMAR GALLERY, SUNDER NAGAR MARKET—NEW DELHI-110003 INDIA

Transcriber’s Note: click map for larger version.

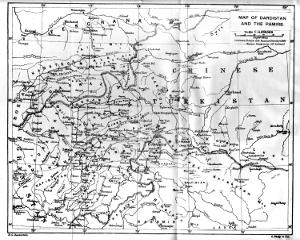

MAP OF DARDISTAN AND THE PAMIRS

E. G. Ravenstein G. Philip & Son

| PAGE | |

| A Map of Dardistan and of the Pamirs | |

| Introduction. A Note on Classical Allusions to the Dards and to Greek Influence in India (4 pages) | |

| Legends, Songs, Customs, and History, of Dardistan (with Illustrations) | |

| A. Demons—Yatsh | 1 |

| B. Fairies—Barái | 6 |

| C. Wizards and Witches—Dayáll | 7 |

| D. Historical Legend of the Origin of Gilgit | 9 |

| The Feast of Firs and Songs | 14 |

| Bujóni—Riddles, Proverbs, and Fables | 17 |

| Songs—(Gilgiti, Astóri, Guraizi, and Chilási) | 22 |

| Manners and Customs: | |

| (a) Amusements (Polo, Dances, etc.) | 33 |

| (b) Beverages (beer, wine) | 38 |

| (c) Birth Ceremonies | 41 |

| (d) Marriage Ceremonies (Song to the Bride) | 42 |

| (e) Funerals | 46 |

| (f) Holidays | 48 |

| (g) The Religious Ideas of the Dards | 49 |

| (h) Form of Government among the Dards | 53 |

| (i) Habitations | 57 |

| (j) Divisions of the Dard race | 58 |

| (k) Castes | 62 |

| Legends regarding Animals, and note thereon | 64 |

| Genealogies and History of Dardistan (pages 67 to 111) | 67 |

| Rough Chronological Sketch from 1800 to 1872 | 70 |

| Note on Events since 1872, and in 1891 and 1892 | 75 |

| Introduction to “The Dard Wars with Kashmîr” | 77 |

| Routes to Chilás | 79 |

| I. Struggles for the Conquest of Chilás | 80 |

| II. Wars for the possession of Gilgit | 88 |

| III. Wars on Yasin, and the massacre of its inhabitants | 95 |

| IV. War with Nagyr and Hunza (1864) | 98 |

| V. War with Dareyl (Yaghistán) (1866) | 101 |

| Mir Wali and Mulk Aman (with a note on the murder of Hayward) | 104 |

| Account of Kashmîr atrocities | 106 |

| Remarks on Dardistan in 1893 | 108 |

| Treaty of the British Government with Kashmîr | 110 |

| Note on the Hunza-Nagyr Genealogy | 111 |

| Appendices: | |

| I. Hunza, Nagyr, and the Pamir Regions. (With an Autograph Letter of the Tham of Nagyr, and other Illustrations) | 24 pages |

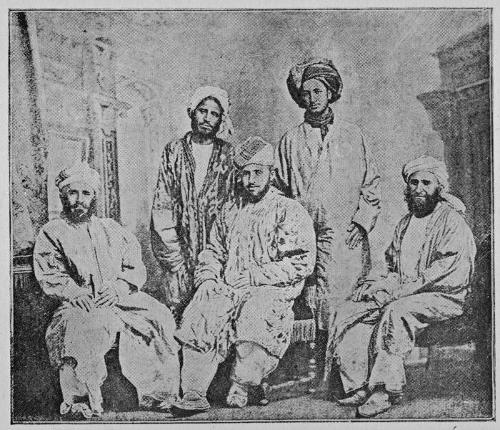

| II. Notes on Recent Events in Chilás and Chitrál, with a photograph of H. H. the present Mihtar of Chitrál, Nizám-ul-Mulk, his former Yasin Council and Chitráli Musicians | 19 pages |

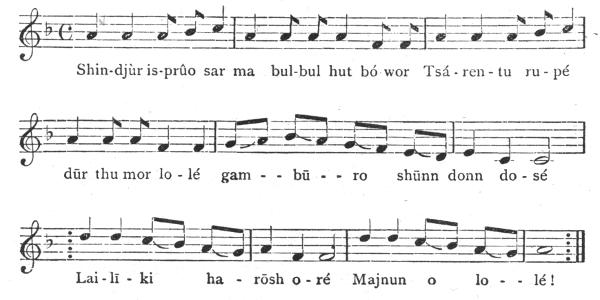

| III. Fables, Legends, and Songs of Chitrál (one in musical notation), by H. H. Mihtar Nizám-ul-Mulk | 14 pages |

| IV. Races and Languages of the Hindukush [The Kohistán, Gabriál, etc.], with a Note on Polo in Hunza-Nagyr | 18 pages |

| V. Anthropological Observations and Measurements | 8 pages |

| VI. Rough Itineraries in the Hindukush and to Central Asia, Routes i, ii, and iii | 12 pages |

| VII. (a) A Secret Religion in the Hindukush and in the Lebanon | 14 pages |

| (b) The Kelám-i-pîr and Esoteric Muhammadanism | 9 pages |

| VIII. On the Sciences of Language and of Ethnography, with special reference to the Language and Customs of Hunza (a separate pamphlet) | 16 pages |

| Illustrations in the Text. | |

| 1. | Map of Dardistan and of the Pamirs (abridged from Dr. Leitner’s large Map of Dardistan and a number of Native Maps and Itineraries). |

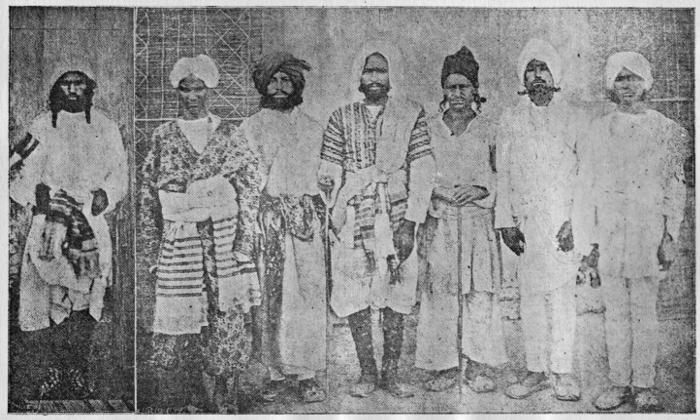

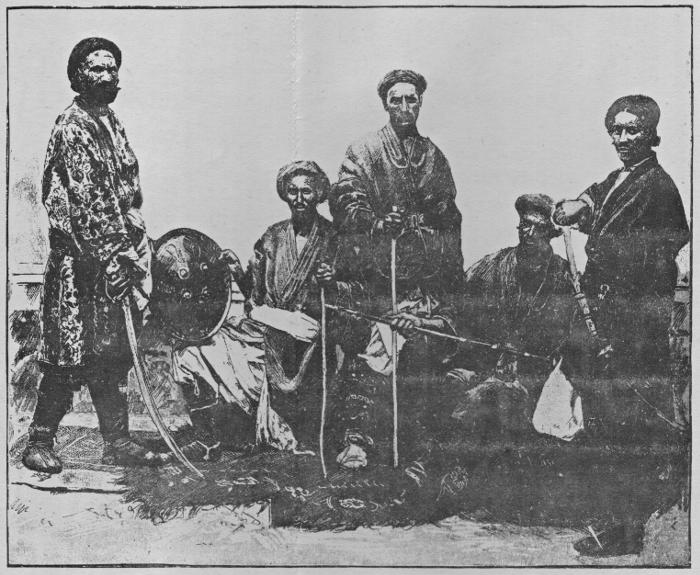

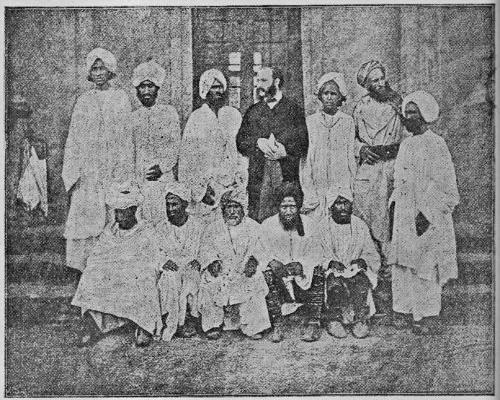

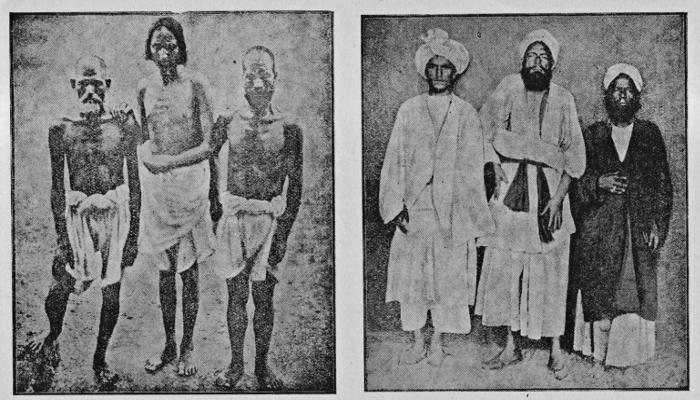

| 2. | First Group of Dards, etc., taken in 1866. (Facing page 1.) |

| 3. | Group of Natives from Hunza, Yasin, and Nagyr, listening to a Chitráli and a Badakhshi Musician. (Facing page 22.) |

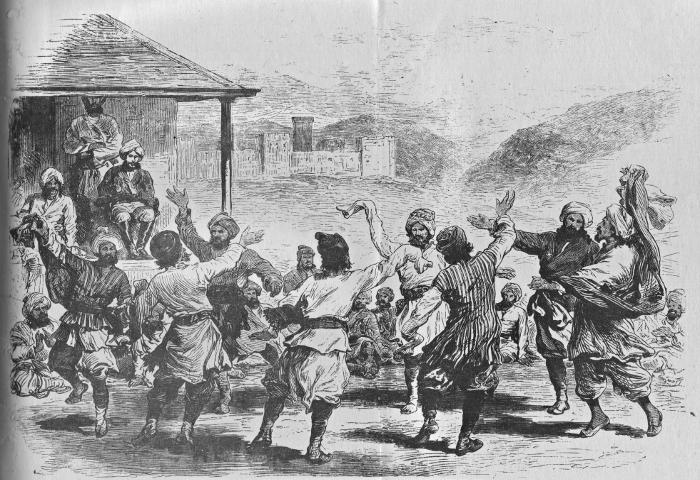

| 4. | A Dance at Gilgit. (Facing page 36.) |

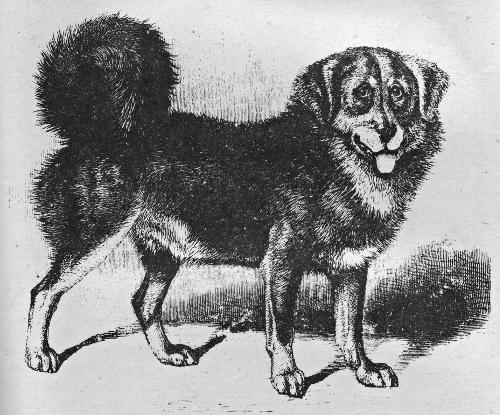

| 5. | Dr. Leitner’s Tibet Dog, “Chang.” (Facing page 66.) |

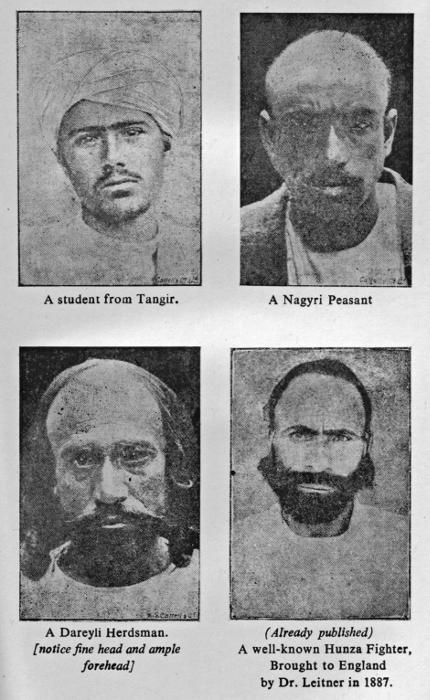

| 6. | “Our Manufactured Foes:” a Tangir Student, a Nagyri Peasant, a Dareyli Herdsman, and a Hunza Fighter (the first Hunza man taken to Europe in 1886). (Facing page 76.) |

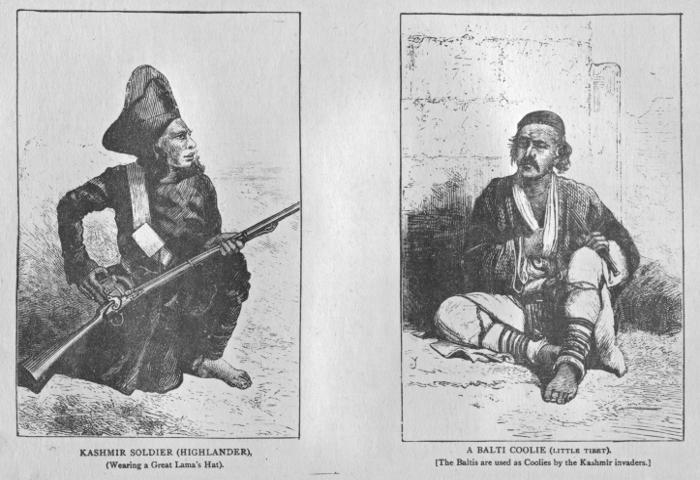

| 7. | A Kashmir Soldier and a Balti Coolie. (Facing page 77.) |

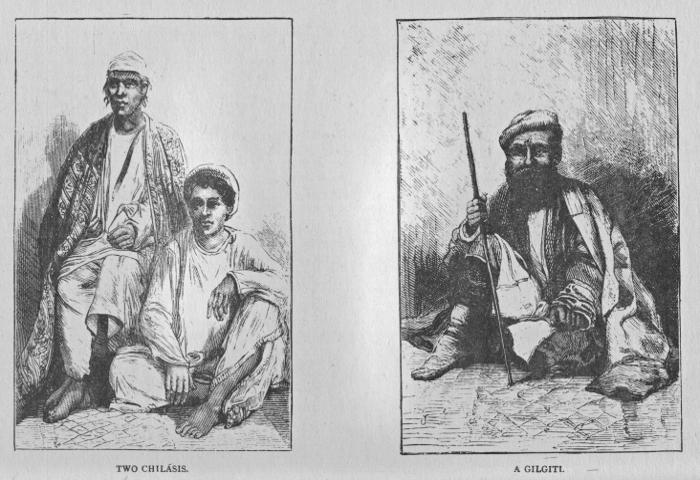

| 8. | Two Chilásis and a Gilgiti. (Facing page 80.) |

| Illustrations in the Appendices. | |

| Appendix I.—(Hunza-Nagyr and the Pamir Regions.) | |

| 9. | Specimens of Burishkis of Hunza, Nagyr, and Yasin. (Facing page 1 of Appendix I.) “Hunza and Nagyri Warriors, separated by Yasinis.” |

| 10. | Autograph Letter from the Chief (Tham) of Nagyr, Za’far Khan. (Facing page 5.) |

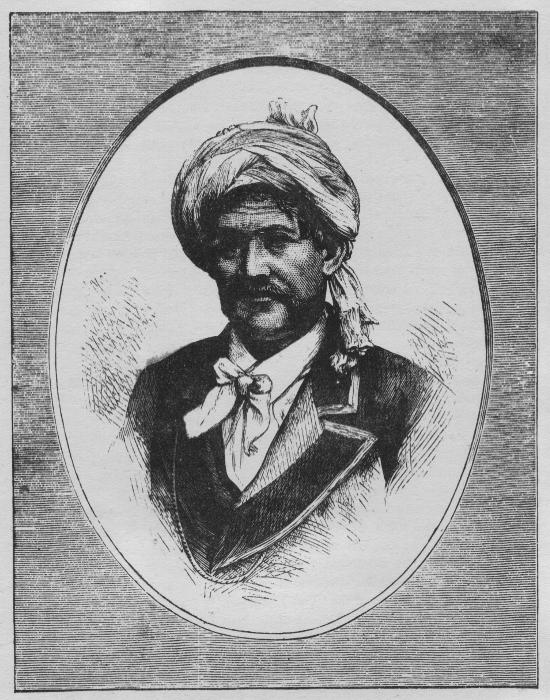

| 11. | Dr. Leitner as a Bokhara Maulvi in 1866. (Facing page 17.) |

| Appendix II.—(Recent Events in Chilás and Chitrál.) | |

| 12. | Mihtar Nizám-ul-Mulk and his Yasin Council in 1886. (Facing page 6.) |

| 13. | Chitráli Players and the Badakhshi Poet, Taighûn Shah. (Facing page 7.) |

| Appendix IV.—(Races and Languages of the Hindukush.) | |

| 14. | Group of Natives from Nagyr, Koláb, Chitrál, Gabriál, Badakhshan, and Hunza. (Facing page 1.) |

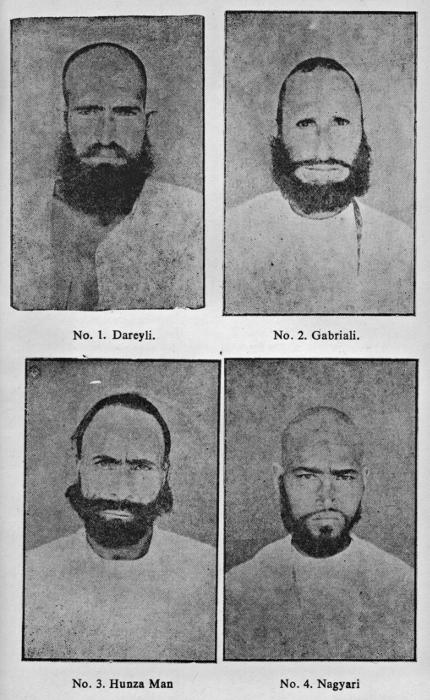

| 15. | Heads of Natives from Dareyl, Gabriál, Hunza, and Nagyr. (Facing page 2.) |

| Appendix V.—(Anthropological Observations and Measurements.) | |

| 16. | Ethnological and Anthropological Groups. (Facing page 1.) |

| 17. | Jamshêd, the first Siah Pôsh Kafir taken to Europe (in 1872). (Facing page 4.) |

| 18. | Comparative Table of Measurements of Dards and Kafirs. |

Herodotus (III. 102-105) is the first author who refers to the country of the Dards, placing it on the frontier of Kashmir and in the vicinity of Afghanistan. “Other Indians are those who reside on the frontiers of the town ‘Kaspatyros’ and the Paktyan country; they dwell to the north of the other Indians and live like the Baktrians; they are also the most warlike of the Indians and are sent for the gold,” etc. Then follows the legend of the gold-digging ants (which has been shown to have been the name of a tribe of Tibetans by Schiern), and on which, as an important side-issue, consult Strabo, Arrian, Dio Chrysostomus, Flavius Philostratus the elder, Clemens Alexandrinus, Ælian, Harpokration, Themistius Euphrades, Heliodorus of Emesa, Joannes Tzetzes, the Pseudo-Kallisthenes and the scholiast to the Antigone of Sophocles[1]—and among Romans, the poems of Propertius, the geography of Pomponius Mela, the natural history of the elder Pliny and the collections of Julius Solinus.[2] The Mahabharata also mentions the tribute of the ant-gold “paipilika” brought by the nations of the north to one of the Pandu sons, king Yudhisthira.

In another place Herodotus [IV. 13-27] again mentions the town of Kaspatyros and the Paktyan country. This is where he refers to the anxiety of Darius to ascertain the flow of the Indus into the sea. He accordingly sent Skylax with vessels. “They started from the town of Κασπάτυρος and the Πακτυική χώρη towards the east to the sea.” I take this to be the point where the Indus river makes a sudden bend, and for the first time actually does lie between Kashmir and Pakhtu-land (for this, although long unknown, must be the country alluded to),[3] in other words, below the Makpon-i-Shang-Rong, and at Bunji, where the Indus becomes navigable.[4] The Paktyes are also mentioned as one of the races that followed Xerxes in his invasion of Hellas (Herod. VII. 67-85). Like our own geographers till 1866, Herodotus thought that the Indus from that point flowed duly from north to south, and India being, according to his system of geography, the most easterly country, the flow of the Indus was accordingly described as being easterly. I, in 1866, and Hayward in 1870, described its flow from that point to be due west for a considerable distance (about one hundred miles). (The Paktyes are, of course, the Afghans, called Patans, or more properly Pakhtus, the very same Greek word). “Kaspatyros” is evidently a mis-spelling for “Kaspapyros,” the form in which the name occurs in one of the most accurate codes of[2] Herodotus which belonged to Archbishop Sancroft (the Codex Sancroftianus) and which is now preserved at Emmanuel College, Cambridge. Stephanus Byzantianus (A.V.) also ascribes this spelling to Hekatœus of Miletus.[5]

Now Kaspapyros or Kaspapuros is evidently Kashmir or “Kasyapapura,” the town of Kasyapa, the founder of Kashmir, and to the present day one may talk indifferently of the town of Kashmir, or of the country of Kashmir, when mentioning that name, so that there is no necessity to seek for the town of Srinagar when discussing the term Kaspatyrus, or, if corrected, Kaspapuros, of Herodotus.

Herodotus, although he thus mentions the people (of the Dards) as one neighbouring (πλησιοχώροι) on Kashmir and residing between Kashmir and Afghanistan, and also refers to the invasions which (from time immemorial it may be supposed, and certainly within our own times) this people have made against Tibet for the purpose of devastating the goldfields of the so-called ants, does not use the name of “Dard” in the above quotations, but Strabo and the elder Pliny, who repeat the legend, mention the very name of that people as Derdæ or Dardæ, vide Strabo XV., ἐν Διρδαις ἔθνει μεγάλω τῶν προσεώων καὶ ὀρείνων Ἰνδῶν. Pliny, in his Natural History, XI. 36, refers to “in regione Septentrionalium Indorum, qui Dardæ vacantur.” Both Pliny and Strabo refer to Megasthenes as their authority in Chapter VI., 22. Pliny again speaks of “Fertilissimi sunt auri Dardæ.” The Dards have still settlements in Tibet where they are called Brokhpa (see page 60 of text). The Dards are the “Darada” of the Sanscrit writers. The “Darada” and the “Himavanta” were the regions to which Buddha sent his missionaries, and the Dards are finally the “Dards, an independent people which plundered Dras in the last year, has its home in the mountains three or four days’ journey distant, and talks the Pakhtu or Daradi language. Those, whom they take prisoners in these raids, they sell as slaves” (as they do still). (Voyage par Mir Izzetulla in 1812 in Klaproth’s Magasin Asiatique, II., 3-5.) (The above arrangement of quotations is due to Schiern.)[6]

The most important contribution to this question, however, is Plutarch’s Speech on Alexander’s fortune and virtue (περὶ Ἀλεξάνδρου τύχης καὶ ἀρετῆς), the keynote to which may be found in the passage which contains the assertion that he Κατέσπειρε τὴν Ἀσίαν ἑλληνικοῖς τέλεσι, but the whole speech refers to that marvellous influence.

That this influence was at any rate believed in, may be also gathered from a passage in Aelian, in which he speaks of the Indians and Persian kings singing Homer in their own tongues. I owe the communication of this passage to Sir Edward Fry, Q.C., which runs as follows; Ὄτι Ἰνδοὶ τῆ παρα σφίσιν ἐπιχωριά φωνη τά Ὁμήρου μεταγράψαντις ᾄδουσιν οὐ μάνοι, ἀλλὰ[3] καὶ οἲ Περσῶν βασιλεῖς εὶ τι χρη πιστεύειν τοῖς ὕπερ τούτων ἱστοροῦσι.—Aeliani Variæ Historiæ, Lib. XII., Cap. 48. [I find from a note in my edition that Dio Chrysostom tells the same story of the Indians in his 53rd Oration.—E.F.]

I trust to be able to show, if permitted to do so, in a future note (1) that the Aryan dialects of Dardistan are, at least, contemporaneous with Sanskrit, (2) that the Khajuná is a remnant of a prehistoric language, (3) that certain sculptors followed on Alexander’s invasion and taught the natives of India to execute what I first termed “Græco-Buddhistic” sculptures, a term which specifies a distinct period in history and in the history of Art.

G. W. Leitner.

P.S. in 1893.—The above, which appeared in “the Calcutta Review” of January 1878, was also reprinted in the Asiatic Quarterly Review of April 1893 with reference to Mr. J. W. McCrindle’s recent work on “Ancient India: Its Invasion by Alexander the Great,” in which he omits to draw attention to the importance of Plutarch’s Speech on the civilizing results of Alexander’s invasion, and makes no mention whatever of the traces which Greek art has left on the Buddhistic sculptures of the Panjab.

He only just mentions Plutarch’s speech on page 13 of his otherwise excellent work, published by Messrs. Constable of 14 Parliament Street, London. As that speech, which is divided into two parts, is, however, of the utmost importance in showing what were believed to be in Plutarch’s days the results of Alexander’s mission, I think it necessary to quote some of the most prominent passages from it relating to the subject under inquiry. I also propose to show in a monograph on the græco-buddhistic sculptures, now at the Woking Museum, which I brought from beyond the Panjab frontier, that Alexander introduced not only Greek Art but also Greek mythology into India. I will specially refer to the “Pallas Athene,” “the rape of Ganymede,” and “the Centaur” in my collection, leaving such sculptures as “Olympian games,” “Greek soldiers accompanying Buddhist processions,” “the Buddhist Parthenon,” [if not also Silanion’s “Sappho with the lyre,”]—all executed by Indian artists—to tell their own tale as to the corroborations in sculpture of passages in ancient Greek and Roman writers relating to the genial assimilation of Eastern with Western culture which the Great Conqueror of the Two Continents, “the possessor of two horns,” the “Zu’l-Qarnein” (Al-Asghar) of the Arabs, endeavoured to bring about.

The following passages from Plutarch’s Speech may, I hope, be read with interest. The author endeavours to answer his question as to whether Alexander owed his success “to his fortune or to his virtue” by showing that he was almost solely indebted to his good qualities:

“The discipline of Alexander ... oh marvellous philosophy, through which the Indians worship the Greek gods.”

“When Alexander had recivilized Asia, they read Homer and the children of the Persians ... sang the tragedies of Euripides and Sophocles.” “Socrates was condemned in Athens because he introduced foreign Gods ... but, through Alexander, Bactria and the Caucasus worshipped the[4] Greek Gods.” “Few among us, as yet, read the laws of Plato, but myriads of men use, and have used, those of Alexander, the vanquished deeming themselves more fortunate than those who had escaped his arms, for the latter had no one who saved them from the miseries of life, whilst the conqueror had forced the conquered to live happily.”

“Plato only wrote one form of Government and not a single man followed it because it was too severe, whereas Alexander founded more than 70 cities among barbarous nations and permeating Asia with Hellenic Institutions....” Plutarch makes the conquered say that if they had not been subdued “Egypt would not have had Alexandria nor India Bucephalia,” that “Alexander made no distinction between Greek and Barbarian, but considered the virtuous only among either as Greek and the vicious as Barbarian” and that he by “intermarriages and the adaptation of customs and dresses sought to found that union which he considered himself as sent from heaven to bring about as the arbitrator and the reformer of the universe.” “Thus do the wise unite Asia and Europe.” “By the adoption of (Asiatic) dress, the minds were conciliated.” Alexander desired that “One common justice should administer the Republic of the Universe.”

“He disseminated Greece and diffused throughout the world justice and peace.” Alexander himself announces to the Greeks, “Through me you will know them (the Indians) and they will know you, but I must yet strike coins and stamp the bronze of the barbarians with Greek impressions.” The fulfilment of this statement is attested by the Bactrian coins. I submit that he who left his mark on metal did so also on sculpture, as I have endeavoured to show since 1870 when I first called my finds “græco-buddhistic,” a term which has, at last, been adopted after much opposition, as descriptive of a period in History and in the history of Art and Religion.

[The above quotations are all from the 1st Part of Plutarch’s oration; the second is reserved for the proposed monograph.]

G. W. Leitner.

For “Divisions of the Dard Race” and the countries which they occupy see page 58.

FIRST GROUP OF DARDS, ETC., TAKEN IN 1866.

| Gulam Muhammad, of Gilgit (A Shiah Muhammadan). | Gharib Shah and Friend, Both of Chilas (Sunni Muhammadans). | Mirza beg, of Astor (Sunni). | Kazim, From Skardo (Little Tibet). (Shiah). | Malek and Batshu (Kalasha and Bashgali Kafirs) (Subjects of Chitral). |

1. Dardu Legends, in Shiná (the language, with dialectic modifications, of Gilgit, Astor, Guraiz, Chilas, Hódur, Dareyl, Tangîr, etc., and the language of historical songs in Hunza and Nagyr).

(Committed to writing for the first time in 1866,

By Dr. G. W. Leitner,

from the dictation of Dards. This race has no written character of its own.)

Demons are of a gigantic size, and have only one eye, which is on the forehead. They used to rule over the mountains and oppose the cultivation of the soil by man. They often dragged people away into their recesses. Since the adoption of the Muhammadan religion, the demons have relinquished their possessions, and only occasionally trouble the believers.

They do not walk by day, but confine themselves to promenading at night. A spot is shown near Astor, at a village called Bulent, where five large mounds are pointed out which have somewhat the shape of huge baskets. Their existence is explained as follows. A Zemindar (cultivator) at Grukot, a village farther on, on the Kashmir road, had, with great trouble, sifted his grain for storing, and had put it into baskets and sacks. He then went away. The demons came—five in number—carrying huge leather-sacks,[2] into which they put the grain. They then went to a place which is still pointed out and called “Gué Gutume Yatsheyn gau boki,” or “The place of the demons’ loads at the hollow”—Gué being the Shiná name for the present village of Grukōt. There they brought up a huge flat stone—which is still shown—and made it into a kind of pan, “tawa,” for the preparation of bread. But the morning dawned and obliged them to disappear; they converted the sacks and their contents into earthen mounds, which have the shape of baskets and are still shown.

A Shikari (sportsman) was once hunting in the hills. He had taken provisions with him for five days. On the sixth day he found himself without any food. Excited and fatigued by his fruitless expedition, he wandered into the deepest mountain recesses, careless whither he went as long as he could find water to assuage his thirst, and a few wild berries to allay his hunger. Even that search was unsuccessful, and, tired and hungry, he endeavoured to compose himself to sleep. Even that comfort was denied him, and, nearly maddened with the situation, he again arose and looked around him. It was the first or second hour of night, and, at a short distance, he descried a large fire blazing a most cheerful welcome to the hungry, and now chilled, wanderer. He approached it quietly, hoping to meet some other sportsman who might provide him with food. Coming near the fire, he saw a very large and curious assembly of giants, eating, drinking, and singing. In great terror, he wanted to make his way back, when one of the assembly, who had a squint in his eye, got up for the purpose of fetching water for the others. He overtook him, and asked him whether he was a “child of man.” Half dead with terror, he could scarcely answer that he was, when the demon invited him to join them at the meeting, which was described to be a wedding party. The Shikari replied: “You are a demon, and will destroy me”; on which the spirit took an oath, by the sun and the moon, that[3] he certainly would not do so. He then hid him under a bush and went back with the water. He had scarcely returned when a plant was torn out of the ground and a small aperture was made, into which the giants managed to throw all their property, and, gradually making themselves thinner and thinner, themselves vanished into the ground through it. Our sportsman was then taken by the hand by the friendly demon, and, before he knew how, he himself glided through the hole and found himself in a huge apartment, which was splendidly illuminated. He was placed in a corner where he could not be observed. He received some food, and gazed in mute astonishment on the assembled spirits. At last, he saw the mother of the bride taking her daughter’s head into her lap and weeping bitterly at the prospect of her departure into another household. Unable to control her grief, and in compliance with an old Shîn custom, she began the singing of the evening by launching into the following strains:

SONG OF THE MOTHER.

Original:—

Translation:—

“Oh, Biráni, thy mother’s own; thou, little darling, wilt wear ornaments, whilst to me, who will remain here at Buldar Butshe, the heavens will appear dark. The prince of Lords of Phall Tshatshe race is coming from Nagyr; and Mirkann, thy father, now distributes corn (as an act of welcome). Be (as fruitful and pleasant) as the water of seven rivers, for Shadu Malik (the prince) is determined to start, and now thy father Mirkann is distributing ghee (as a compliment to the departing guest).”

The Shikari began to enjoy the scene and would have liked to have stayed, but his squinting friend told him now that he could not be allowed to remain any longer. So he got up, but before again vanishing through the above-mentioned aperture into the human world, he took a good look at the demons. To his astonishment he beheld on the shoulders of one a shawl which he had safely left at home. Another held his gun; a third was eating out of his own dishes; one had his many-coloured stockings on, and another disported himself in pidjamas (drawers) which he only ventured to put on, on great occasions. He also saw many of the things that had excited his admiration among the property of his neighbours in his native village, being most familiarly used by the demons. He scarcely could be got to move away, but his friendly guide took hold of him and brought him again to the place where he had first met him. On taking leave he gave him three loaves of bread. As his village was far off, he consumed two of the loaves on the road. On reaching home, he found his father, who had been getting rather anxious at his prolonged absence. To him he told all that had happened, and showed him the remaining loaf, of which the old man ate half. His mother, a good housewife, took the remaining half and threw it into a large granary, where, as it was the season of Sharó (autumn), a sufficient store of flour had been placed for the use of the family during the winter. Strange to say, that half-loaf brought luck, for demons mean it sometimes kindly to the children of men, and only hurt them when they consider themselves offended. The granary remained always full, and the people of the village rejoiced with the family, for they were liked and were good people.

It also should be told that as soon as the Shikari came home he looked after his costly shawl, dishes, and clothes, but he found all in its proper place and perfectly uninjured. On inquiring amongst his neighbours he also found that they too had not lost anything. He was much astonished at all this, till an old woman who had a great reputation for wisdom,[5] told him that this was the custom of demons, and that they invariably borrowed the property of mankind for their weddings, and as invariably restored it. On occasions of rejoicings amongst them they felt kindly towards mankind.

Thus ends one of the prettiest tales that I have heard.

Something similar to what has just been related, is said to have happened at Doyur, on the road from Gilgit to Nagyr. A man of the name of Phûko had a son named Laskirr, who, one day going out to fetch water was caught by a Yatsh, who tore up a plant (“reeds”?) “phuru” and entered with the lad into the fissure which was thereby created. He brought him to a large palace in which a number of goblins, male and female, were diverting themselves. He there saw all the valuables of the inhabitants of his village. A wedding was being celebrated and the mother sang:—

Translation:—

On his departure, the demon gave him a sackful of coals, and conducted him through the aperture made by the tearing up of the reed, towards his village. The moment the demon had left, the boy emptied the sack of the coals and went home, when he told his father what had happened. In the emptied sack they found a small bit of coal, which, as soon as they touched it, became a gold coin, very much to the regret of the boy’s father, who would have liked his son to have brought home the whole sackful.

They are handsome, in contradistinction to the Yatsh or Demons, and stronger; they have a beautiful castle on the top of the Nanga Parbat or Dyarmul (so called from being inaccessible). This castle is made of crystal, and the people fancy they can see it. They call it “Shell-battekōt” or “Castle of Glass-stone.”

Once a sportsman ventured up the Nanga Parbat. To his surprise he found no difficulty, and venturing farther and farther, he at last reached the top. There he saw a beautiful castle made of glass, and pushing one of the doors he entered it, and found himself in a most magnificent apartment. Through it he saw an open space that appeared to be the garden of the castle, but there was in it only one tree of excessive height, and which was entirely composed of pearls and corals. The delighted sportsman filled his sack in which he carried his corn, and left the place, hoping to enrich himself by the sale of the pearls. As he was going out of the door he saw an innumerable crowd of serpents following him. In his agitation he shouldered the sack and attempted to run, when a pearl fell out. It was eagerly swallowed by a serpent which immediately disappeared. The sportsman, glad to get rid of his pursuers at any price, threw pearl after pearl to them, and in every case it had the desired effect. At last, only one serpent remained, but for her (a fairy in that shape?) he found no pearl; and urged on by fear, he hastened to his village, Tarsing, which is at the very foot of the Nanga Parbat. On entering his house, he found it in great agitation; bread was being distributed to the poor as they do at funerals, for his family had given him up as lost. The serpent still followed and stopped at the door. In despair, the man threw the corn-sack at her, when lo! a pearl glided out. It was eagerly swallowed by the serpent, which immediately disappeared. However, the man was not the same being as before. He was ill for days, and in about a fortnight after the events narrated, died, for fairies never forgive a man who has surprised their secrets.

It is not believed in Astor that fairies ever marry human beings, but in Gilgit there is a legend to that effect. A famous sportsman, Kibá Lorí, who never returned empty-handed from any excursion, kept company with a fairy to whom he was deeply attached. Once in the hot weather the fairy said to him not to go out shooting during “the seven days of the summer,” “Caniculars,” which are called “Bardá,” and are supposed to be the hottest days in Dardistan. “I am,” said she, “obliged to leave you for that period, and, mind, you do not follow me.” The sportsman promised obedience and the fairy vanished, saying that he would certainly die if he attempted to follow her. Our love-intoxicated Nimrod, however, could not endure her absence. On the fourth day he shouldered his gun and went out with the hope of meeting her. Crossing a range, he came upon a plain, where he saw an immense gathering of game of all sorts and his beloved fairy milking a “Kill” (markhor) and gathering the milk into a silver vessel. The noise which Kibá Lorí made caused the animal to start and to strike out with his legs, which upset the silver vessel. The fairy looked up, and to her anger beheld the disobedient lover. She went up to him and, after reproaching him, struck him in the face. But she had scarcely done so when despair mastered her heart, and she cried out in the deepest anguish that “he now must die within four days.” “However,” she said, “do shoot one of these animals, so that people may not say that you have returned empty-handed.” The poor man returned crestfallen to his home, lay down, and died on the fourth day.

The gift of second sight, or rather the intercourse with fairies, is confined to a few families in which it is hereditary. The wizard is made to inhale the fumes of a fire which is lit with the wood of the tshili[10] (Panjabi = Padam), a kind[8] of fir-wood which gives much smoke. Into the fire the milk of a white sheep or goat is poured. The wizard inhales the smoke till he apparently becomes insensible. He is then taken on the lap of one of the spectators, who sings a song which restores him to his senses. In the meanwhile, a goat is slaughtered, and the moment the fortune-teller jumps up, its bleeding neck is presented to him, which he sucks as long as a drop remains. The assembled musicians then strike up a great noise, and the wizard rushes about in the circle which is formed round him and talks unintelligibly. The fairy then appears at some distance and sings, which, however, only the wizard hears. He then communicates her sayings in a song to one of the musicians, who explains its meaning to the people. The wizard is called upon to foretell events and to give advice in cases of illness, etc. The people believe that in ancient times these Dayalls invariably spoke correctly, but that now scarcely one saying in a hundred turns out to be true. Wizards do not now make a livelihood by their talent, which is considered its own reward.

There are few legends so exquisite as the one which chronicles the origin, or rather the rise, of Gilgit. The traditions regarding Alexander the Great, which Vigne and others have imagined to exist among the people of Dardistan, are unknown to, at any rate, the Shiná race, excepting in so far as any Munshi accompanying the Maharajah’s troops may, perhaps, accidentally have referred to them in conversation with a Shîn. Any such information would have been derived from the Sikandarnama of Nizámi, and would, therefore, possess no original value. There exist no ruins, as far as I have gone, to point to an occupation of Dardistan by the soldiers of Alexander. The following legend, however, which not only lives in the memories of all the Shîn people, whether they be Chilasis, Astoris, Gilgitis, or Brokhpá (the latter, as I discovered, living actually side by side with the Baltis in Little Tibet), but which also an annual festival commemorates, is not devoid of interest from either a historical or a purely literary point of view.

“Once upon a time there lived a race at Gilgit, whose origin is uncertain. Whether they sprang from the soil, or had immigrated from a distant region, is doubtful; so much is believed, that they were Gayupí = spontaneous, aborigines, unknown. Over them ruled a monarch who was a descendant of the evil spirits, the Yatsh, that terrorized over the world. His name was Shiribadatt, and he resided at a castle, in front of which there was a course for the performance of the manly game of Polo. (See my Hunza Nagyr Handbook.) His tastes were capricious, and in every one of his actions his fiendish origin could be discerned. The natives bore his rule with resignation, for what could they effect against a monarch at whose command even magic aids were placed? However, the country was rendered fertile and round the capital bloomed attractive gardens.

“The heavens, or rather the virtuous Peris, at last grew tired of his tyranny, for he had crowned his iniquities by indulging in a propensity for cannibalism. This taste had been developed by an accident. One day his cook brought him some mutton broth, the like of which he had never tasted. After much inquiry as to the nature of the food on which the sheep had been brought up, it was eventually traced to an old woman, its first owner. She stated that her child and the sheep were born on the same day, and losing the former, she had consoled herself by suckling the latter. This was a revelation to the tyrant. He had discovered the secret of the palatability of the broth, and was determined to have a never-ending supply of it. So he ordered that his kitchen should be regularly provided with children of tender age, whose flesh, when converted into broth, would remind him of the exquisite dish he had once so much relished. This cruel order was carried out. The people of the country were dismayed at such a state of things, and sought slightly to improve it by sacrificing, in the first place, all orphans and children of neighbouring tribes! The tyrant, however, was insatiable, and soon was his cruelty felt by many families at Gilgit, who were compelled to give up their children to slaughter.

“Relief came at last. At the top of the mountain Ko, which it takes a day to ascend, and which overlooks the village of Doyur, below Gilgit, on the side of the river, appeared three figures. They looked like men, but much more strong and handsome. In their arms they carried bows and arrows, and turning their eyes in the direction of Doyur, they perceived innumerable flocks of sheep and cattle grazing on a prairie between that village and the foot of the mountain. The strangers were fairies, and had come (perhaps from Nagyr?) to this region with the view of ridding Gilgit of the monster that ruled over it. However, this intention was confined to the two elder ones. The three strangers were brothers, and none of them had been born at the same time. It was their intention to make Azru Shemsher, the youngest, Rajah of Gilgit, and, in order to achieve their purpose, they hit upon the following plan.

“On the already-noticed plain, which is called Didingé, a sportive calf was gamboling towards and away from its mother. It was the pride of its owner, and its brilliant red colour could be seen from a distance. ‘Let us see who is the best marksman,’ exclaimed the eldest, and saying this, he shot an arrow in the direction of the calf, but missed his aim. The second brother also tried to hit it, but also failed. At last, Azru Shemsher, who took a deep interest in the sport, shot his arrow, which pierced the poor animal from side to side and killed it. The brothers, whilst descending, congratulated Azru on his sportsmanship, and on arriving at the spot where the calf was lying, proceeded to cut its throat, and to take out from its body the titbits, namely the kidneys and the liver.

“They then roasted these delicacies, and invited Azru to partake of them first. He respectfully declined, on the ground of his youth; but they urged him to do so, ‘in order,’ they said, ‘to reward you for such an excellent shot.’ Scarcely had the meat touched the lips of Azru, than the brothers got up, and vanishing into the air, called out, ‘Brother! you have touched impure food, which Peris never should eat, and we have made use of your ignorance[11] of this law, because we want to make you a human being,[11] who shall rule over Gilgit; remain therefore at Doyur.’

“Azru in deep grief at the separation, cried, ‘Why remain at Doyur, unless it be to grind corn?’ ‘Then,’ said the brothers, ‘go to Gilgit.’ ‘Why,’ was the reply, ‘go to Gilgit, unless it be to work in the gardens?’ ‘No, no,’ was the last and consoling rejoinder; ‘you will assuredly become the king of this country, and deliver it from its merciless oppressor.’

“No more was heard of the departing fairies, and Azru remained by himself, endeavouring to gather consolation from the great mission which had been bestowed on him. A villager met him, and, struck by his appearance, offered him shelter in his house. Next morning he went on the roof of his host’s house, and calling out to him to come up, pointed to the Ko mountain, on which, he said, he plainly discerned a wild goat. The incredulous villager began to fear he had harboured a maniac, if no worse character; but Azru shot off his arrow, and accompanied by the villager (who had assembled some friends for protection, as he was afraid his young guest might be an associate of robbers, and lead him into a trap), went in the direction of the mountain. There, to be sure, at the very spot that had been pointed out, though many miles distant, was lying the wild goat, with Azru’s arrow transfixing its body. The astonished peasants at once hailed him as their leader, but he exacted an oath of secrecy from them, for he had come to deliver them from their tyrant, and would keep his incognito till such time as his plans for the destruction of the monster were matured.

“He then took leave of the hospitable people of Doyur, and went to Gilgit. On reaching the place, which is scarcely four miles distant from Doyur, he amused himself by prowling about in the gardens adjoining the royal residence. There he met one of the female companions of Shiribadatt’s daughter (goli in Hill Punjabi, Shadróy in Gilgiti) fetching water for the princess, a lady both[12] remarkably handsome, and of a sweet disposition. The companion rushed back, and told the young lady to look from over the ramparts of the castle at a wonderfully handsome young man whom she had just met. The princess placed herself in a spot from which she could observe any one approaching the fort. Her maid then returned, and induced Azru to come with her on the Polo ground, the “Shavaran,” in front of the castle; the princess was smitten with his beauty and at once fell in love with him. She then sent word to the young prince to come and see her. When he was admitted into her presence, he for a long time denied being anything else than a common labourer. At last, he confessed to being a fairy’s child, and the overjoyed princess offered him her heart and hand. It may be mentioned here that the tyrant Shiribadatt had a wonderful horse, which could cross a mile at every jump, and which its rider had accustomed to jump both into and out of the fort, over its walls. So regular were the leaps which that famous animal could take, that he invariably alighted at a distance of a mile from the fort and at the same place.

“On that very day on which the princess had admitted young Azru into the fort, King Shiribadatt was out hunting, of which he was desperately fond, and to which he used sometimes to devote a week or two at a time. We must now return to Azru, whom we left conversing with the princess. Azru remained silent when the lady confessed her love. Urged to declare his sentiments, he said that he would not marry her unless she bound herself to him by the most stringent oath; this she did, and they became in the sight of God as if they were wedded man and wife.[12] He then announced that he had come to destroy her father, and asked her to kill him herself. This she refused; but as she had sworn to aid him in every way she could, he finally induced her to promise that she would ask her father where his soul was. ‘Refuse food,’ said Azru, ‘for three or four days, and your father, who is devotedly fond[13] of you will ask for the reason of your strange conduct; then say, “Father, you are often staying away from me for several days at a time, and I am getting distressed lest something should happen to you; do reassure me by letting me know where your soul is, and let me feel certain that your life is safe.”’ This the princess promised to do, and when her father returned refused food for several days. The anxious Shiribadatt made inquiries, to which she replied by making the already-named request. The tyrant was for a few moments thrown into mute astonishment, and finally refused compliance with her preposterous demand. The love-smitten lady went on starving herself, till at last her father, fearful for his daughter’s life, told her not to fret herself about him, as his soul was [of snow?] in the snows, and that he could only perish by fire. The princess communicated this information to her lover. Azru went back to Doyur and the villages around, and assembled his faithful peasants. Them he asked to take twigs of the fir-tree or tshi, bind them together and light them—then to proceed in a body with the torches to the castle in a circle, keep close together, and surround it on every side. He then went and dug out a very deep hole, as deep as a well, in the place where Shiribadatt’s horse used to alight, and covered it with green boughs. The next day he received information that the torches (talên in Gilgiti and Lome in Astori) were ready. He at once ordered the villagers gradually to draw near the fort in the manner which he had already indicated.

“King Shiribadatt was then sitting in his castle; near him his treacherous daughter, who was so soon to lose her parent. All at once he exclaimed, ‘I feel very close; go out, dearest, and see what has happened.’ The girl went out, and saw torches approaching from a distance; but fancying it to be something connected with the plans of her husband, she went back, and said it was nothing. The torches came nearer and nearer, and the tyrant became exceedingly restless. ‘Air, air,’ he cried, ‘I feel very, very ill; do see, daughter, what is the matter.’ The dutiful[14] lady went, and returned with the same answer as before. At last, the torch-bearers had fairly surrounded the fort, and Shiribadatt, with a presentiment of impending danger, rushed out of the room, saying ‘that he felt he was dying.’ He then ran to the stables and mounted his favourite charger, and with one blow of the whip made him jump over the wall of the castle. Faithful to its habit, the noble animal alighted at the same place, but alas! only to find itself engulfed in a treacherous pit. Before the king had time to extricate himself, the villagers had run up with their torches. ‘Throw them upon him,’ cried Azru. With one accord all the blazing wood was thrown upon Shiribadatt, who miserably perished. Azru was then most enthusiastically proclaimed king, celebrated his nuptials with the fair traitor, and, as sole tribute, exacted the offering of one sheep, instead of that of a human child, annually from every one of the natives.[13] This custom has prevailed down to the present day, and the people of Shin, wherever they be, celebrate their delivery from the rule of a monster, and the inauguration of a more humane government, in the month preceding the beginning of winter—a month which they call Dawakió or Daykió—after the full moon is over and the new moon has set in. The day of this national celebration is called ‘nôs tshilí,’ ‘the feast of firs.’ The day generally follows four or five days after the meat provision for the winter has been laid in to dry. A few days of rejoicing precede the special festivity, which takes place at night. Then all the men of the villages go forth, having torches in their hands, which, at the sound of music, they swing round their heads, and throw in the direction of Gilgit, if they are at any distance from that place; whilst the people of Gilgit throw them indifferently about the plain in which that town, if town it may be called, is situated. When the throwing away of the brands is over, every man[15] returns to his house, where a curious custom is observed. He finds the door locked. The wife then asks: ‘Where have you been all night? I won’t let you come in now.’ Then her husband entreats her and says, ‘I have brought you property, and children, and happiness, and everything you desire.’ Then, after some further parley, the door is opened, and the husband walks in. He is, however, stopped by a beam which goes across the room, whilst all the females of the family rush into an inner apartment to the eldest lady of the place. The man then assumes sulkiness and refuses to advance, when the repenting wife launches into the following song:—

Original:—

Translation:—

“Then the husband relents and steps over the partition beam. They all sit down, dine together, and thus end festivities of the ‘Nôs.’ The little domestic scene is observed at Gilgit; but it is thought to be an essential[16] element in the celebration of the day by people whose ancestors may have been retainers of the Gilgit Raja Azru Shemsher, and by whom they may have been dismissed to their homes with costly presents.

“The song itself is, however, well known at Gilgit.

“When Azru had safely ascended the throne, he ordered the tyrant’s palace to be levelled to the ground. The willing peasants, manufacturing spades of iron, ‘Killi’, flocked to accomplish a grateful task, and sang whilst demolishing his castle:

Original:—

Translation:—

“‘My nature is of a hard metal,’ said Shiri and Badatt. ‘Why hard? I Khoto, the son of the peasant Dem Singh, am alone hardy; with this iron spade I raze to the ground thy kingly house. Behold now, although thou art of race accursed, of Shatsho Malika, I, Dem Singh’s son, am of hard metal; for with this iron spade I level thy very palace; look out! look out!’”

During the Nauroz [evidently because it is not a national festival] and the Eed, none of these national Shîn songs are sung. Eggs are dyed in different colours and people go about amusing themselves by trying which eggs are hardest by striking the end of one against the end of another. The possessor of the hard egg wins the broken one. The women, however, amuse themselves on those days by tying ropes to trees and swinging themselves about on them.

1. Tishkóreya ushkúrey halól.

“The perpendicular mountain’s sparrow’s nest. The body’s sparrow’s hole.”

“Now listen! My sister walks in the day-time and at night stands behind the door.” As “Sas” “Sazik” also means a stick, ordinarily called “Kunali” in Astori, the riddle means: “I have a stick which assists me in walking by day and which I put behind the door at night.”

3. The Gilgitis say “méy káke tré pay; dashtea” = my brother has three feet; explain now. This means a man’s two legs and a stick.

4. Astóri mió dádo dimm dáwa-lók; dáyn sarpa-lók, buja.

My grandfather’s body [is] in Hades; his beard [is in] this world, [now] explain!

This riddle is explained by “radish” whose body is in the earth and whose sprouts, compared to a beard, are above the ground. Remarkable above all, however, is that the unknown future state, referred to in this riddle, should be called, whether blessed or cursed, “Dawalók” [the place of Gods] by these nominal Muhammadans. This world is called “Sarpalók,” = the world of serpents. “Sarpe” is also the name for man. “Lók” is “place,” but the name by itself is not at present understood by the Shins.

The top of the Hooka is the dadi’s or grandmother’s head.

viz., “out of the dark sheath the beautiful, but destructive, steel issues.” It is remarkable that the female Yatsh should be called “Rûi.”

7. Lólo bakuró shé tshá lá há—búja!

In the red sheep’s pen white young ones many are—attend!

This refers to the Redpepper husk in which there are many white seeds.

To an old man people say:

“You are old and have got rid of your senses.”

Old women are very much dreaded and are accused of creating mischief wherever they go.

“When young I gave away, now that I am old you should support me.”

10. Ek damm agáru dáddo dugúni shang thé!

Once in fire you have been burnt, a second time take care!

11. Ek khatsh látshek bilo búdo donate she.

One bad sheep if there be, to the whole flock is an insult = One rotten sheep spoils the whole flock.

12. Ek khatsho manújo budote sha = one bad man is to all an insult.

13. A. Mishto manújo—katshi béyto, to mishto sitshé

Katsho manujo—katshi béyto, to katsho sitshe

When you [who are bad?] are sitting near a good man you learn good things.

When you [who are bad?] are sitting near a bad man you learn bad things.

This proverb is not very intelligible, if literally translated.

14. Tús máte rá: mey shughulo ró hun, mas tute rám: tu ko hanu = “Tell me: my friend is such and such a one, I will tell you who you are.”

15. Sháharè kéru gé shing shém thé—konn tshiní tey tshiní téyanú.

“Into the city he went horns to place (acquire), but ears he cut thus he did. He went to acquire horns and got his ears cut off.”

Dî dé, putsh kàh = “give the daughter and eat the son,” is a Gilgit proverb with regard to how one ought to treat an enemy. The recommendation given is: “marry your daughter to your foe and then kill him,” [by which you get a male’s head which is more valuable than that of a female.] The Dards have sometimes acted on this maxim in order to lull the suspicions of their Kashmir enemies.[17]

Moral.—

Anésey maní aní haní = the meaning of this is this:

Translation.

A woman had a hen; it used to lay one golden egg; the woman thought that if she gave much food it would lay two eggs; but she lost even the one, for the hen died, its stomach bursting.

Moral.—People often lose the little they have by aspiring to more.

“A sparrow who tried to kick the mountain himself toppled over.”

The bat is in the habit of sleeping on its back. It is believed to be very proud. It is supposed to say as it lies down and stretches its legs towards heaven, “This I do so that when the heavens fall down I may be able to support them.”

“A kettle cannot balance itself on one stone; on three, however, it does.”

Ey pûtsh! èk gutur-yá dêh nè quriyein; tré[18] gútúrey á dek quréyn.

Oh son! one stone on a kettle not stops; three stones on a kettle stop.

The Gilgitis instead of “ya” = “upon” say “dja.”

“Gutur” is, I believe, used for a stone [ordinarily “bàtt”] only in the above proverb.

“If I speak, the water will rush against my mouth, and if I keep silent I will die bursting with rage.”

This was said by a frog who was in the water and angry at something that occurred. If he croaked, he would be drowned by the water rushing down his throat, and if he did not croak he would burst with suppressed rage. This saying is often referred to by women when they are angry with their husbands, who may, perhaps, beat them if they say anything. A frog is called “manok.”

When a man threatens a lot of people with impossible menaces, the reply often is “Don’t act like the fox ‘Lóyn’ who was carried away by the water.” A fox one day fell into a river: as he swept past the shore he cried out, “The water is carrying off the universe.” The people on the banks of the river said, “We can only see a fox whom the river is drifting down.”

“The fox wanted to eat pomegranates: as he could not reach them, he went to a distance and biting his lips [as “tshàmm” was explained by an Astori although Gilgitis call it “tshappé,”] spat on the ground, saying, they are too sour.” I venture to consider the conduct of this fox more cunning than the one of “sour grapes” memory. His biting his lips and, in consequence, spitting on the ground, would make his disappointed face really look as if he had tasted something sour.

Once upon a time a Mogul army came down and surrounded the fort of Gilgit. At that time Gilgit was governed by a woman, Mirzéy Juwāri[20] by name. She was the widow of a Rajah supposed to have been of Balti descent. The Lady seeing herself surrounded by enemies sang:

The meaning of this, according to my Gilgiti informant, is: Juwari laments that “I, the daughter of a brave King, am only a woman, a cup of pleasures, exposed to dangers from any one who wishes to sip from it. To my misfortune, my prominent position has brought me enemies. Oh, my dear son, for whom I would sacrifice myself, I have sacrificed you! Instead of preserving the Government for you, the morning-star which shines on its destruction has now risen on you.”

In ancient times there was a war between the Rajahs of Hunza and Nagyr. Muko and Báko were their respective Wazeers. Muko was killed and Báko sang:

Gilgiti.

English.

Group of Natives from Hunza, Yasin, and Nagyr listening to Musicians from Chitrál and Badakhshán.

Translation.

“The bullet of Kashiru sends many to Paradise. He has gone to the wars, oh my child and mother of Sahib Khan! Will the sun ever shine for me by his returning? It is true that he has taken by assault the ravine of Mutshutshul, but yet, oh beloved child, my soul is in fear for his fate, as the danger has not passed, since the village Doloja yet remains to be conquered.”

Shammi Shah Shaíthing was one of the founders of the Shín rule. His wife, although she sees her husband surrounded by women anxious to gain his good graces, rests secure in the knowledge of his affections belonging to her and of her being the mother of his children. She, therefore, ridicules the pretensions of her rivals, who, she fancies, will, at the utmost, only have a temporary success. In the above still preserved song she says, with a serene confidence, not shared by Indian wives.

Translation.

The Wife:

The Husband:

Translation of “A Woman’s Song.”

The deserted wife sings:—My Pathan! oh kukúri, far away from me has he made a home; but, aunt, what am I to do, since he has left his own! The silk that I have been weaving during his absence would be sufficient to bind all the animals of the field. Oh, how my darling is delaying his return!

The faithless husband sings:—[My new love] Azari is like a royal Deodar; is it not so, my love? for Azari I am sick with desire. She is a Wazeer’s princess; is it not so, my love? Let me put you in my waist. The sun on yonder mountain, and the tree on this nigh mountain, ye both I love dearly. I will recline when this white hawk and her black fragrant tresses become mine; encircling with them my head I will recline [in happiness.]

The above describes the dream of a lover whose sweetheart has married one older than herself; he says:

Translation.

This Song was composed by Rajah Bahadur Khan, now at Astŏr, who fell in love with the daughter of the Rajah of Hunza to whom he was affianced. When the war between Kashmir and Hunza broke out, the Astoris and Hunzas were in different camps; Rajah Bahadur Khan, son of Rajah Shakul Khan, of the Shíah persuasion,[31] thus laments his misfortunes:

Chorus falls in with “hai, hai, armân bulbúl” = “oh, oh, the longing [for the] nightingale!”[33]

Translation.

After having discharged my usual religious duties in the early morning, I offer a prayer which, oh thou merciful God, accept from thy humble worshipper. [Then, thinking of his beloved.] Her teeth are as white as ivory, her body as graceful as a reed, her hair is like musk. My whole longing is towards you, oh sweet nightingale.

Chorus: Alas, how absorbing this longing for the nightingale.

This district used to be under Ahmad Shah of Skardo, and has since its conquest by Ghulab Singh come permanently under the Maharajah of Kashmîr. Its possession used to be the apple of discord between the Nawabs of Astor and the Rajahs of Skardo. It appears never to have had a real Government of its own. The fertility of its valleys always invited invasion. Yet the people are of Shîná origin and appear much more manly than the other subjects of Kashmîr. Their loyalty to that power is not much to be relied upon, but it is probable that with the great intermixture which has taken place between them and the Kashmîri Mussulmans for many years past, they will become equally demoralized. The old territory of Guraiz used in former days to extend up to Kuyam or Bandipur on the Wular Lake. The women are reputed to be very chaste, and Colonel Gardiner told me that the handsomest women in Kashmîr came from that district. To me, however, they appeared to be tolerably plain, although rather innocent-looking, which may render them attractive, especially after one has seen the handsome, but sensual-looking, women of Kashmîr. The people of Guraiz are certainly very dirty, but they are not so plain as the Chilásis. At Guraiz three languages are spoken: Kashmîri, Guraizi (a corruption of a Shiná dialect), and Panjabi—the[29] latter on account of its occupation by the Maharajah’s officials. I found some difficulty in getting a number of them together from the different villages which compose the district of Guraiz, the Arcadia of Kashmir, but I gave them food and money, and after I got them into a good humour they sang:

GURAIZI HUNTING SONG.

| Guraizi. | English. |

|---|---|

| Pere, tshaké, gazàri meyaru | = Look beyond! what a fine stag! |

| Beyond, look! a fine stag. | |

| Chorus. Pére, tshaké, djôk maar âke dey. | = Chorus. Look beyond! how gracefully he struts. |

| Beyond, look! how he struts! | |

| Pére, tshaké, bhapûri bay bâro | = Look beyond! he bears twelve loads of wool. |

| Beyond, look! shawl wool 12 loads. | |

| Chorus. Pére, tshaké, djôk maarâke dey. | = Chorus. Look beyond! how gracefully he struts. |

| Beyond, look! how he does strut! | |

| Pére, tshaké, dòni shilélu | = Look beyond! his very teeth are of crystal. |

| Beyond, look! [his] teeth are of crystal [glass] | |

| Chorus. Pére, tshaké, djôk maarâke dey. | = Chorus. Look beyond! how gracefully he struts. |

This is apparently a hunting song, but seems also to be applied to singing the praises of a favourite.

There is another song, which was evidently given with great gusto, in praise of Sheir Shah Ali Shah, Rajah of Skardo.[34] That Rajah, who is said to have temporarily conquered Chitrál, which the Chilasis call Tshatshál,[35] made a road of steps up the Atsho mountain which overlooks Bûnji, the most distant point reached before 1866 by[30] travellers or the Great Trigonometrical Survey. From the Atsho mountain Vigne returned, “the suspicious Rajah of Gilgit suddenly giving orders for burning the bridge over the Indus.” It is, however, more probable that his Astori companions fabricated the story in order to prevent him from entering an unfriendly territory in which Mr. Vigne’s life might have been in danger, for had he reached Bûnji he might have known that the Indus never was spanned by a bridge at that or any neighbouring point. The miserable Kashmîri coolies and boatmen who were forced to go up-country with the troops in 1866 were, some of them, employed, in rowing people across, and that is how I got over the Indus at Bûnji; however to return from this digression to the Guraizi Song:

| Guraizi. | English. |

|---|---|

| Sheir Shah Ali Shah | = Sheir Shah Ali Shah. |

| Nōmega djong | = I wind myself round his name.[36] |

| Ká kōlo shing phuté | = He conquering the crooked Lowlands. |

| Djar súntsho taréga | = Made them quite straight. |

| Kâne Makponé | = The great Khan, the Makpon. |

| Kâno nom mega djong | = I wind myself round the Khan’s name. |

| Kó Tshamūgar bòsh phuté | = He conquered bridging over [the Gilgit river] below Tshamûgar. |

| Sar[37] súntsho taréga | = And made all quite straight. |

I believe there was much more of this historical song, but unfortunately the paper on which the rest was written down by me as it was delivered, has been lost together with other papers.

“Tshamūgar,” to which reference is made in the song, is a village on the other side of the Gilgit river on the Nagyr side. It is right opposite to where I stayed for two nights[31] under a huge stone which projects from the base of the Niludâr range on the Gilgit side.

There were formerly seven forts at Tshamūgar. A convention had been made between the Rajah of Gilgit and the Rajah of Skardo, by which Tshamūgar was divided by the two according to the natural division which a stream that comes down from the Batkôr mountain made in that territory. The people of Tshamūgar, impatient of the Skardo rule, became all of them subjects to the Gilgit Rajah, on which Sher Shah Ali Shah, the ruler of Skardo, collected an army, and crossing the Makpon-i-shagaron[38] at the foot of the Haramûsh mountain, came upon Tshamūgar and diverted the water which ran through that district into another direction. This was the reason of the once fertile Tshamūgar becoming deserted; the forts were razed to the ground. There are evidently traces of a river having formerly run through Tshamūgar. The people say that the Skardo Rajah stopped the flow of the water by throwing quicksilver into it. This is probably a legend arising from the reputation which Ahmad Shah, the most recent Skardo ruler whom the Guraizis can remember, had of dabbling in medicine and sorcery.[39]

[The Chilasis have a curious way of snapping their fingers, with which practice they accompany their songs, the thumb running up and down the fingers as on a musical instrument.]

The last word in each sentence, as is usual with all Shín songs, is repeated at the beginning of the next line. I may also remark that I have accentuated the words as pronounced in the songs and not as put down in my Vocabulary.

Translation.

MESSAGE TO A SWEETHEART BY A FRIEND.

The second song describes a quarrel between two brothers who are resting after a march on some hill far away from any water or food wherewith to refresh themselves.

2nd Verse.

The ideas and many of the words in this prayer were evidently acquired by my two Kafirs on their way through Kashmir:

“Khudá, tandrusti dé, prushkári rozì de, abattì kari, dewalat man. Tu ghóna asas, tshik intara, tshik tu faidá káy asas. Sat asmán tì, Stru suri mastruk mótshe dé.”

The Chaughan Bazi or Hockey on horseback, so popular everywhere north of Kashmir, and which is called Polo by the Baltis and Ladakis, who both play it to perfection and in a manner which I shall describe elsewhere, is also well known to the Ghilgiti and Astori subdivisions of the Shina people. On great general holidays as well as on any special occasion of rejoicing, the people meet on those grounds which are mostly near the larger villages, and pursue the game with great excitement and at the risk of casualties. The first day I was at Astor, I had the greatest difficulty in restoring to his senses a youth of the name of[34] Rustem Ali who, like a famous player of the same name at Mardo, was passionately fond of the game, and had been thrown from his horse. The place of meeting near Astor is called the Eedgah. The game is called Tope in Astor, and the grounds for playing it are called Shajaran. At Gilgit the game is called Bulla, and the place Shawaran. The latter names are evidently of Tibetan origin.

The people are also very fond of target practice, shooting with bows, which they use dexterously but in which they do not excel the people of Nagyr and Hunza. Game is much stalked during the winter. At Astor any game shot on the three principal hills—Tshhamô, a high hill opposite the fort, Demídeldèn and Tshólokot—belong to the Nawab of Astor—the sportsman receiving only the head, legs and a haunch—or to his representative, then the Tahsildar Munshi Rozi Khan. At Gilgit everybody claims what he may have shot, but it is customary for the Nawab to receive some share of it. Men are especially appointed to watch and track game, and when they discover their whereabouts notice is sent to the villages from which parties issue, accompanied by musicians, and surround the game. Early in the morning, when the “Lóhe” dawns, the musicians begin to play and a great noise is made which frightens the game into the several directions where the sportsmen are placed.

The guns are matchlocks and are called in Gilgiti “turmàk” and in Astór “tumák.” At Gilgit they manufacture the guns themselves or receive them from Badakhshan. The balls have only a slight coating of lead, the inside generally being a little stone. The people of Hunza and Nagyr invariably place their guns on little wooden pegs which are permanently fixed to the gun and are called “Dugazá.” The guns are much lighter than those manufactured elsewhere, much shorter and carry much smaller bullets than the matchlock of the Maharajah’s troops. They carry very much farther than any native Indian gun and are fired with almost unerring accuracy. For “small shot”[35] little stones of any shape—the longest and oval ones being preferred—are used. There is one kind of stone especially which is much used for that purpose; it is called “Balósh Batt,” which is found in Hanza, Nagyr, Skardo, and near the “Demídeldèn” hill already noticed, at a village called Pareshinghi near Astor. It is a very soft stone and large cooking utensils are cut out from it, whence the name, “Balósh” Kettle, “Batt” stone, “Balósh Batt.” The stone is cut out with a chisel and hammer; the former is called “Gútt” in Astori and “Gukk” in Gilgiti; the hammer “toá” and “Totshúng” and in Gilgiti “samdenn.” The gunpowder is manufactured by the people themselves.[42]

The people also play at backgammon, [called in Astóri “Patshis,” and “Takk” in Gilgiti,] with dice [called in Astóri and also in Gilgiti “dall.”]

Fighting with iron wristbands is confined to Chilasi women who bring them over their fists which they are said to use with effect.

The people are also fond of wrestling, of butting each other whilst hopping, etc.

To play the Jew’s harp is considered meritorious as King David played it. All other music good Mussulmans are bid to avoid.

The “Sitara” [the Eastern Guitar] used to be much played in Yassen, the people of which country as well as the people of Hunza and Nagyr excel in dancing, singing and playing. After them come the Gilgitis, then the Astoris, Chilasis, Baltis, etc. The people of Nagyr are a comparatively mild race. They carry on goldwashing which is constantly interrupted by kidnapping parties from[36] the opposite Hunza. The language of Nagyr and Hunza is the Non-Aryan Khajuná and no affinity between that language and any other has yet been traced. The Nagyris are mostly Shiahs. They are short and stout and fairer than the people of Hunza [the Kunjûtis] who are described[43] as “tall skeletons” and who are desperate robbers. The Nagyris understand Tibetan, Persian and Hindustani. Badakhshan merchants were the only ones who could travel with perfect safety through Yassen, Chitral and Hunza.

Fall into two main divisions: “slow” or “Búti Harip” = Slow Instrument and Quick “Danni Harip,” = Quick Instrument. The Yassen, Nagyr and Hunza people dance quickest; then come the Gilgitis; then the Astóris; then the Baltis, and slowest of all are the Ladakis.

When all join in the dance, cheer or sing with gesticulations, the dance or recitative is called “thapnatt” in Gilgiti, and “Burró” in Astóri.

When there is a solo dance it is called “nàtt” in Gilgiti, and “nott” in Astóri.

“Cheering” is called “Halamush” in Ghilgiti, and “Halamùsh” in Astóri. Clapping of hands is called “tza.” Cries of “Yú, Yú dea; tza theá, Hiú Hiú dea; Halamush thea; shabâsh” accompany the performances.

There are several kinds of Dances. The Prasulki nate, is danced by ten or twelve people ranging themselves behind the bride as soon as she reaches the bridegroom’s house. This custom is observed at Astor. In this dance men swing above sticks or whatever they may happen to hold in their hands.

A Dance at Gilgit (Dr. Leitner and his Panjabi Attendants looking on).

The Buró natt is a dance performed on the Nao holiday, in which both men and women engage—the women forming a ring round the central group of dancers, which is composed of men. This dance is called Thappnatt at[37] Gilgit. In Dareyl there is a dance in which the dancers wield swords and engage in a mimic fight. This dance Gilgitis and Astòris call the Darelâ nat, but what it is called by the Dareylis themselves I do not know.

The mantle dance is called “Goja nat.” In this popular dance the dancer throws his cloth over his extended arm.

When I sent a man round with a drum inviting all the Dards that were to be found at Gilgit to a festival, a large number of men appeared, much to the surprise of the invading Dogras, who thought that they had all run to the hills. A few sheep were roasted for their benefit; bread and fruit were also given them, and when I thought they were getting into a good humour, I proposed that they should sing. Musicians had been procured with great difficulty, and after some demur, the Gilgitis sang and danced. At first, only one at a time danced, taking his sleeves well over his arm so as to let it fall over, and then moving it up and down according to the cadence of the music. The movements were, at first, slow, one hand hanging down, the other being extended with a commanding gesture. The left foot appeared to be principally engaged in moving or rather jerking the body forward. All sorts of “pas seuls” were danced; sometimes a rude imitation of the Indian Nátsh; the by-standers clapping their hands and crying out “Shabâsh”; one man, a sort of Master of Ceremonies, used to run in and out amongst them, brandishing a stick, with which, in spite of his very violent gestures, he only lightly touched the bystanders, and exciting them to cheering by repeated calls, which the rest then took up, of “Hiù, Hiù.” The most extraordinary dance, however, was when about twelve men arose to dance, of whom six went on one side and six on the other, both sides then, moving forward, jerked out their arms so as to look as if they had all crossed swords, then receded and let their arms drop. This was a war dance, and I was told that properly it ought to have been danced with swords, which, however, out of suspicion of the Dogras,[38] did not seem to be forthcoming. They then formed a circle, again separated, the movements becoming more and more violent till almost all the bystanders joined in the dance, shouting like fiends and literally kicking up a frightful amount of dust, which, after I had nearly become choked with it, compelled me to retire.[45] I may also notice that before a song is sung the rhythm and melody of it are given in “solo” by some one, for instance

Fine corn (about five or six seers in weight) is put into a kettle with water and boiled till it gets soft, but not pulpy. It is then strained through a cloth, and the grain retained and put into a vessel. Then it is mixed with a drug that comes from Ladak which is called “Papps,” and has a salty taste, but in my opinion is nothing more than hardened dough with which some kind of drug is mixed. It is necessary that “the marks of four fingers” be impressed upon the “Papps.” The mark of “four fingers” make one stick, 2 fingers’ mark ½ a stick, and so forth. This is scraped and mixed with the corn. The whole is then put into an earthen jar with a narrow neck, after it has received an infusion of an amount of water equal to the proportion of corn. The jar is put out into the sun—if summer—for twelve days, or under the fire-place—if in winter—[where a separate vault is made for it]—for the same period. The orifice is almost hermetically closed with a skin. After twelve days the jar is opened and contains a drink possessing intoxicating qualities. The first infusion is much prized, but the corn receives a second and sometimes even a third supply of water, to be put out again in a similar manner and to provide a kind of Beer for the consumer. This Beer is called “Mō,” and is much[39] drunk by the Astóris and Chilasis [the latter are rather stricter Mussulmans than the other Shiná people]. After every strength has been taken out of the corn it is given away as food to sheep, etc., which they find exceedingly nourishing.

The Gilgitis are great wine-drinkers, though not so much as the people of Hunza. In Nagyr little wine is made. The mode of the preparation of the wine is a simple one. The grapes are stamped out by a man who, fortunately before entering into the wine press, washes his feet and hands. The juice flows into another reservoir, which is first well laid round with stones, over which a cement is put of chalk mixed with sheep-fat which is previously heated. The juice is kept in this reservoir; the top is closed, cement being put round the sides and only in the middle an opening is made over which a loose stone is placed. After two or three months the reservoir is opened, and the wine is used at meals and festivals. In Dareyl (and not in Gilgit, as was told to Vigne,) the custom is to sit round the grave of the deceased and eat grapes, nuts and Tshilgōzas (edible pine). In Astor (and in Chilâs?) the custom is to put a number of Ghi (clarified butter) cakes before the Mulla, [after the earth has been put on the deceased] who, after reading prayers over them, distributes them to the company who are standing round with their caps on. In Gilgit, three days after the burial, bread is generally distributed to the friends and acquaintances of the deceased. To return to the wine presses, it is to be noticed that no one ever interferes with the store of another. I passed several of them on my road from Tshakerkōt onward, but they appeared to have been destroyed. This brings me to another custom which all the Dards seem to have of burying provisions of every kind in cellars that are scooped out in the mountains or near[40] their houses, and of which they alone have any knowledge. The Maharajah’s troops when invading Gilgit often suffered severely from want of food when, unknown to them, large stores of grain of every kind, butter, ghi, etc., were buried close to them. The Gilgitis and other so-called rebels, generally, were well off, knowing where to go for food. Even in subject Astor it is the custom to lay up provisions in this manner. On the day of birth of anyone in that country it is the custom to bury a stock of provisions which are opened on the day of betrothal of the young man and distributed. The ghi, which by that time turns frightfully sour, and [to our taste] unpalatable and the colour of which is red, is esteemed a great delicacy and is said to bring much luck.

The chalk used for cementing the stones is called “San Bàtt.” Grapes are called “Djatsh,” and are said, together with wine, to have been the principal food of Ghazanfar, the Rajah of Hunza, of whom it is reported that when he heard of the arrival of the first European in Astor (probably Vigne) he fled to a fort called Gojal and shut himself up in it with his flocks, family and retainers. He had been told that the European was a great sorcerer, who carried an army with him in his trunks and who had serpents at his command that stretched themselves over any river in his way to afford him a passage. I found this reputation of European sorcery of great use, and the wild mountaineers looked with respect and awe on a little box which I carried with me, and which contained some pictures of clowns and soldiers belonging to a small magic lantern. The Gilgitis consider the use of wine as unlawful; probably it is not very long since they have become so religious and drink it with remorse. My Gilgitis told me that the Mughullí—a sect living in Hunza, Gojal, Yassen and Punyal[47]—considered the use of wine with prayers to be rather meritorious than otherwise. A Drunkard is called “Máto.”

As soon as the child is born the father or the Mulla repeats the “Bâng” in his ear “Allah Akbar” (which an Astóri, of the name of Mirza Khan, said was never again repeated in one’s life!). Three days after the reading of the “Bâng” or “Namáz” in Gilgit and seven days after that ceremony in Astor, a large company assembles in which the father or grandfather of the newborn gives him a name or the Mulla fixes on a name by putting his hand on some word in the Koran, which may serve the purpose or by getting somebody else to fix his hand at random on a passage or word in the Koran. Men and women assemble at that meeting. There appears to be no pardah whatsoever in Dardu land, and the women are remarkably chaste.[48] The little imitation of pardah amongst the Ranis of Gilgit was a mere fashion imported from elsewhere. Till the child receives a name the woman is declared impure for the seven days previous to the ceremony. In Gilgit 27 days are allowed to elapse till the woman is declared pure. Then the bed and clothes are washed and the woman is restored to the company of her husband and the visits of her friends. Men and women eat together everywhere in Dardu land. In Astór, raw milk alone cannot be drunk together with a woman unless thereby it is intended that she should be a sister by faith and come within the prohibited degrees of relationship. When men drink of the same raw milk they thereby swear each other eternal friendship. In Gilgit this custom does not exist, but it will at once be perceived that much of what has been noted above belongs to Mussulman custom generally. When a son is born great rejoicings take place, and in Gilgit a musket is fired off by the father whilst the “Bâng” is being read.

In Gilgit it appears to be a more simple ceremony than in Chilâs and Astór. The father of the boy goes to the father of the girl and presents him with a knife about 1½ feet long, 4 yards of cloth and a pumpkin filled with wine. If the father accepts the present the betrothal is arranged. It is generally the fashion that after the betrothal, which is named: “Shéir qatar wíye, ballí píye, = 4 yards of cloth and a knife he has given, the pumpkin he has drunk,” the marriage takes place. A betrothal is inviolable, and is only dissolved by death so far as the woman is concerned. The young man is at liberty to dissolve the contract. When the marriage day arrives the men and women who are acquainted with the parties range themselves in rows at the house of the bride, the bridegroom with her at his left sitting together at the end of the row. The Mulla then reads the prayers, the ceremony is completed and the playing, dancing and drinking begin. It is considered the proper thing for the bridegroom’s father, if he belongs to the true Shín race, to pay 12 tolas of gold of the value [at Gilgit] of 15 Rupees Nanakshahi (10 annas each) to the bride’s father, who, however, generally, returns it with the bride, in kind—dresses, ornaments, &c., &c. The 12 tolas are not always, or even generally, taken in gold, but oftener in kind—clothes, provisions and ornaments. At Astór the ceremony seems to be a little more complicated. There the arrangements are managed by third parties; an agent being appointed on either side. The father of the young man sends a present of a needle and three real (red) “múngs” called “lújum” in Chilâsi, which, if accepted, establishes the betrothal of the parties. Then the father of the bride demands pro formâ 12 tolas [which in Astór and Chilâs are worth 24 Rupees of the value of ten annas each.]