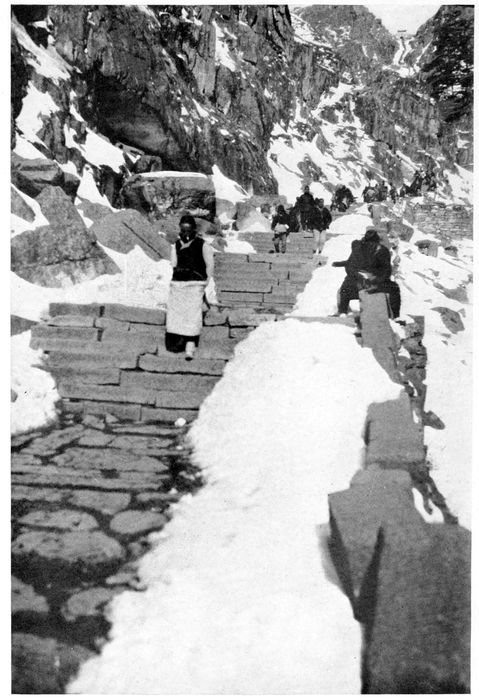

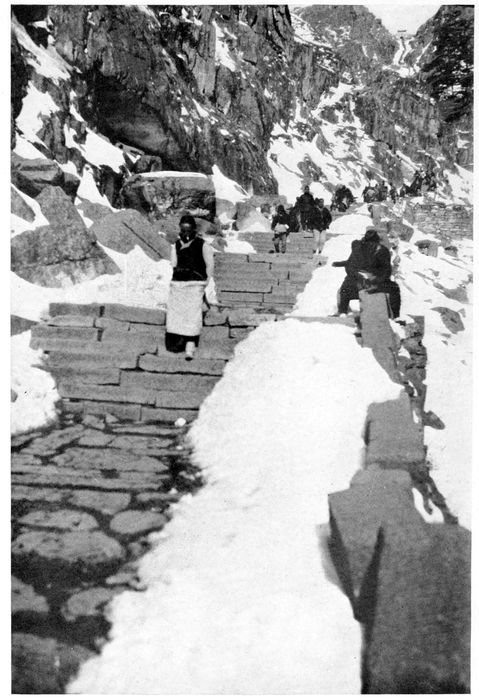

A constant stream of pilgrims, largely blue-clad coolies on foot, passed up and down the sacred stairway

Transcriber’s Note:

The cover image was created by the transcriber and is placed in the public domain.

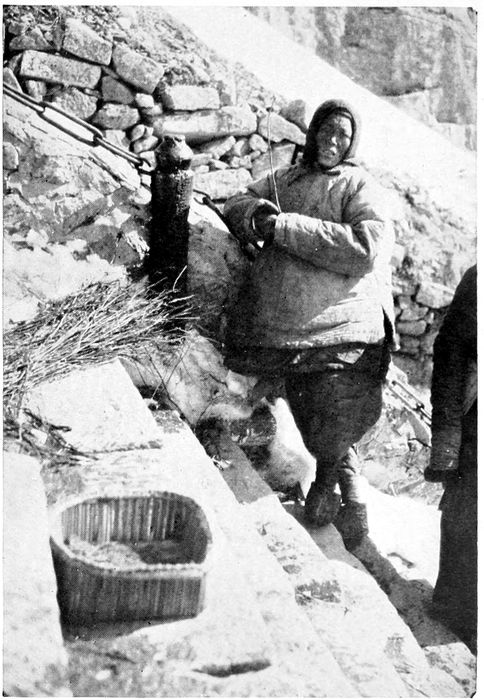

A constant stream of pilgrims, largely blue-clad coolies on foot, passed up and down the sacred stairway

There is no particular plan to this book. I found my interest turning toward the Far East, and as I am not one of those fortunate persons who can scamper through a country in a few weeks and know all about it, I set out on a leisurely jaunt to wherever new clues to interest led me. It merely happened that this will-o’-the-wisp drew me on through everything that was once China, north of about the thirty-fourth parallel of latitude. The man who spends a year or two in China and then attacks the problem of telling all he saw, heard, felt, or smelled there is like the small boy who was ordered by the teacher to write on two neat pages all about his visit to the museum. It simply can’t be done. Hence I have merely set down in the following pages, in the same leisurely wandering way as I have traveled, the things that most interested me, often things that others seem to have missed, or considered unimportant, in the hope that some of them may also interest others. Impressions are unlike statistics, however, in that they cannot be corrected to a fraction, and I decline to be held responsible for the exact truth of every presumption I have recorded. If I have fallen into the common error of generalizing, I hereby apologize, for I know well that details in local customs differ even between neighboring villages in China. What I say can at most be true of the north, for as yet I know nothing of southern China. On the other hand, there may be much repetition of customs and the like, but that goes to show how unchanging is life among the masses in China even as a republic.

Lafcadio Hearn said that the longer he remained in the East the less he knew of what was going on in the Oriental mind. An “old China hand” has put the same thing in more popular language: “You can easily tell how long a man has been in China by how much he doesn’t know about it. If he knows almost everything, he has just recently arrived; if he is in doubt, he has been here a few years; if he admits that he really knows nothing whatever about the Chinese people or their probable future, you may take it for granted that he has been out a very long time.”

But as I have said before, the “old-timer” will seldom sit down to tell even what he has seen, and in many cases he has long since lost his way through the woods because of the trees. Or he may have other and viiimore important things to do. Hence it is up to those of us who have nothing else on hand to pick up and preserve such crumbs of information as we can; for surely to know as much of the truth about our foreign neighbors as possible is important, above all in this new age. In our own land there are many very false ideas about China; false ideas that in some cases are due to deliberate Chinese propaganda abroad. While I was out in the far interior I received a clipping outlining the remarks of a Chinese lecturing through our Middle West, and his résumé left the impression that bound feet and opium had all but completely disappeared from China, and that in the matter of schools and the like the “republic” is making enormous strides. No sooner did the Lincheng affair attract the world’s attention than American papers began to run yarns, visibly inspired, about the marvelous advances which the Chinese have recently accomplished. Such men as Alfred Sze are often mistaken in the United States as samples of China. Unfortunately they are nothing of the kind; in fact, they are too often hopelessly out of touch with their native land. There has been progress in China, but nothing like the amount of it which we have been coaxed or lulled into believing, and some of it is of a kind that raises serious doubts as to its direction. For all the telephones, airplanes, and foreign clothes in the coast cities, the great mass of the Chinese have been affected barely at all by this urge toward modernity and Westernism—if that is synonymous with progress. As some one has just put it, “the Chinese still wear the pigtail on their minds, though they have largely cut it off their heads.” How great must be the misinformation at home which causes our late President to say that all China really needs is more loans, thereby making himself, and by extension his nation, the laughing-stock of any one with the rudiments of intelligence who has spent an hour studying the situation on the spot. England is a little better informed on the subject than we, because she is less idealistic, more likely to look facts in the face instead of trying to make facts fit preconceived notions of essential human perfection. China may need more credits, but any fool knows that you should stop the hole in the bottom of a tub before you pour more water into it. At times, too, it is laughable to think of us children among nations worrying about this one, thousands of years old, which has so often “come back,” and may still be ambling her own way long after we have again disappeared from the face of the earth.

Though it is impossible to leave out the omnipresent entirely, I have said comparatively little about politics. My own interest in what ixwe lump together under that word reaches only so far as it affects the every-day life of the people, of the mudsill of society, toward which, no doubt by some queer quirk in my make-up, I find my attention habitually focusing. I have tried, therefore, to show in some detail their lives, slowly changing perhaps yet little changed, and to let others conclude whether “politics” has done all that it should for them. Besides, the Far East swarms with writers on politics, men who have been out here for years or decades and have given their attention almost entirely to that popular subject; and even these disagree like doctors. Some of us, I know, are frankly tired of politics, at least for a space, important as they are; moreover, political changes are so rapid, especially in the “never changing” East, that it is impossible to keep abreast of the times in anything less than a daily newspaper.

At home there are numbers of young men, five or ten years out of college, who can tell you just what is the matter with the world, and exactly how to remedy it. I am more or less ready to agree with them that the world is going to the dogs. What of it? You have only to step outdoors on any clear night to see that there are hundreds of other worlds, which may be arranging their lives in a more intelligent manner. The most striking thing about these young political and sociological geniuses sitting in their suburban gardens or their city flats is that while they can toss off a recipe guaranteed to cure our own sick world overnight, if only some one can get it down its throat, they seldom seem to have influence enough in their own cozy little corner of it to drive out one grafting ward-heeler. In other words, if you must know what is to be the future of China, I regret that I have not been vouchsafed the gift of prophecy and cannot tell you.

In the minor matter of Chinese words and names, I have deliberately not tried to follow the usual Romanization, but rather to cause the reader to pronounce them as nearly like what they are on the spot as is possible with our mere twenty-six letters. Of course I could not follow this rule entirely or I must have called the capital of China “Bay-jing,” have spoken of the evacuation of “Shahn-doong,” and so on; so that in the case of names already more or less familiar to the West I have used the most modern and most widely accepted forms, as they have survived on the ground. At that I cannot imagine what ailed the men who Romanized the Chinese language, but that is another story.

| CHAPTER | PAGE | |

|---|---|---|

| I | In the Land We Call Korea | 3 |

| II | Some Korean Scenes and Customs | 23 |

| III | Japanese and Missionaries in Korea | 36 |

| IV | Off the Beaten Track in Cho-sen | 53 |

| V | Up and Down Manchuria | 71 |

| VI | Through Russianized China | 82 |

| VII | Speeding across the Gobi | 108 |

| VIII | In “Red” Mongolia | 124 |

| IX | Holy Urga | 135 |

| X | Every One His Own Diplomat | 160 |

| XI | At Home under the Tartar Wall | 174 |

| XII | Jogging about Peking | 195 |

| XIII | A Journey to Jehol | 230 |

| XIV | A Jaunt into Peaceful Shansi | 252 |

| XV | Rambles in the Province of Confucius | 265 |

| XVI | Itinerating in Shantung | 288 |

| XVII | Eastward to Tsingtao | 308 |

| XVIII | In Bandit-Ridden Honan | 330 |

| XIX | Westward through Loess Cañons | 349 |

| XX | On to Sian-fu | 366 |

| XXI | Onward through Shensi | 387 |

| XXII | China’s Far West | 405 |

| XXIII | Where the Fish Wagged His Tail | 423 |

| XXIV | In Mohammedan China | 447 |

| XXV | Trailing the Yellow River Homeward | 468 |

| XXVI | Completing the Circle | 485 |

| A constant stream of pilgrims, largely blue-clad coolies on foot, passed up and down the sacred stairway | Frontispiece |

| FACING PAGE | |

|---|---|

| Map of the author’s route | 12 |

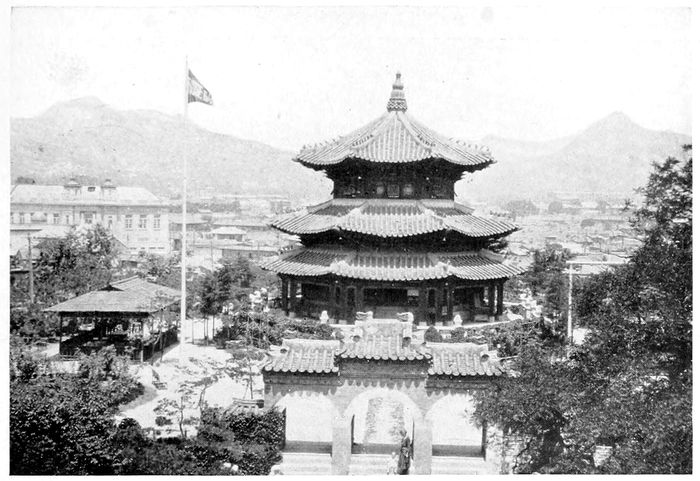

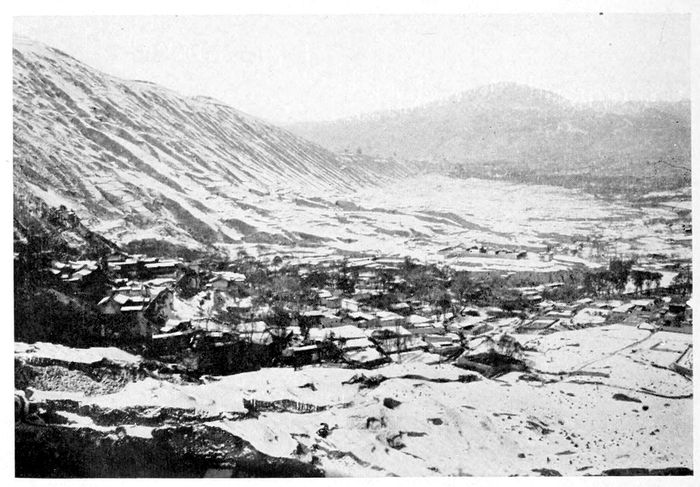

| Our first view of Seoul, in which the former Temple of Heaven is now a smoking-room in a Japanese hotel garden | 16 |

| The interior of a Korean house | 16 |

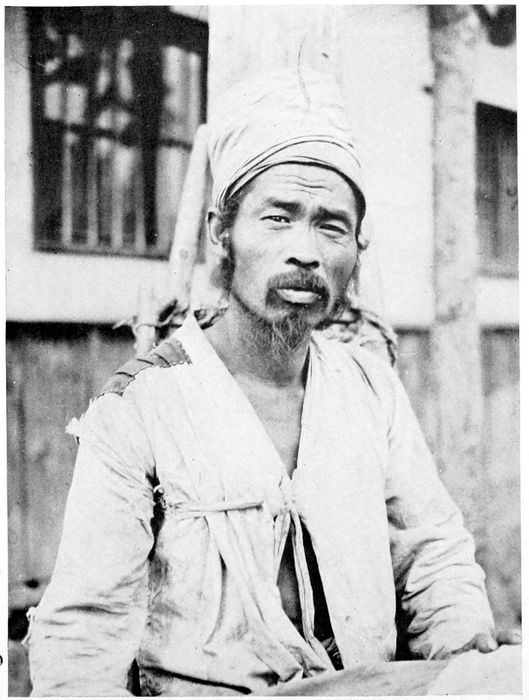

| Close-up of a Korean “jicky-coon,” or street porter | 17 |

| At the first suggestion of rain the Korean pulls out a little oiled-paper umbrella that fits over his precious horsehair hat | 17 |

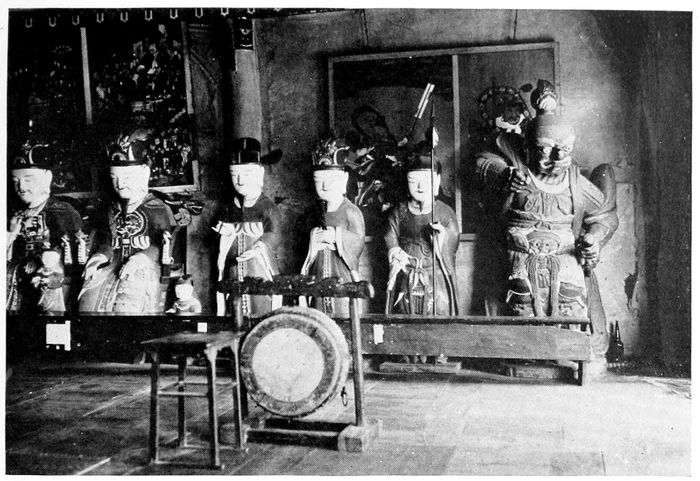

| Some of the figures, in the gaudiest of colors, surrounding the Golden Buddha in a Korean temple | 32 |

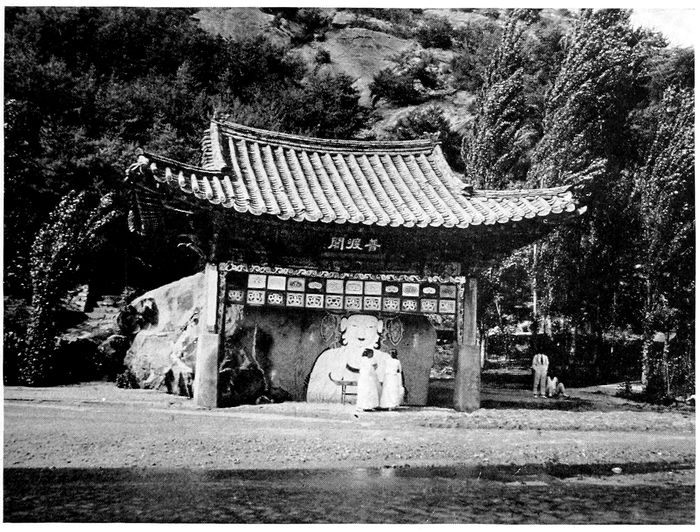

| The famous “White Buddha,” carved, and painted in white, on a great boulder in the outskirts of Seoul | 32 |

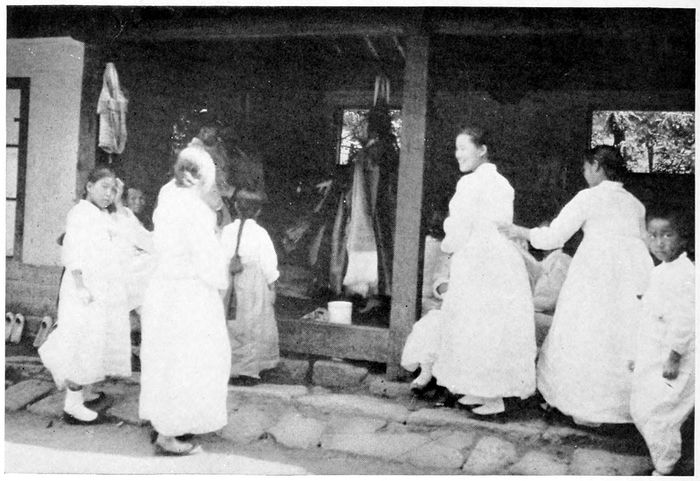

| One day, descending the hills toward Seoul, we heard a great jangling hubbub, and found two sorceresses in full swing in a native house, where people come to have their children “cured” | 33 |

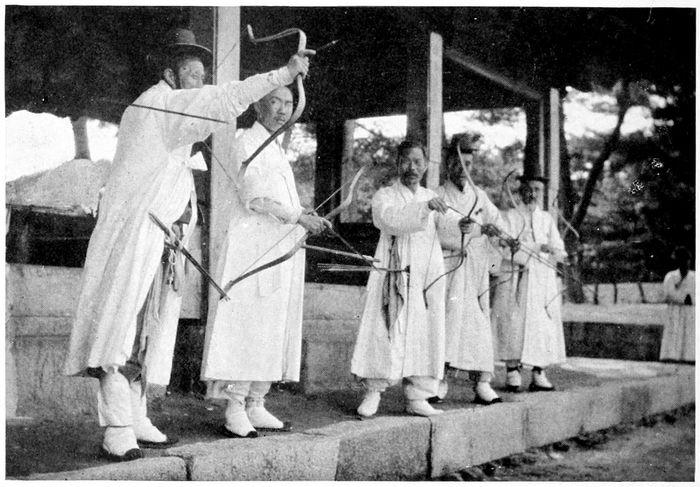

| The yang-ban, or loafing upper class of Korea, go in for archery, which is about fitted to their temperament, speed, and initiative | 33 |

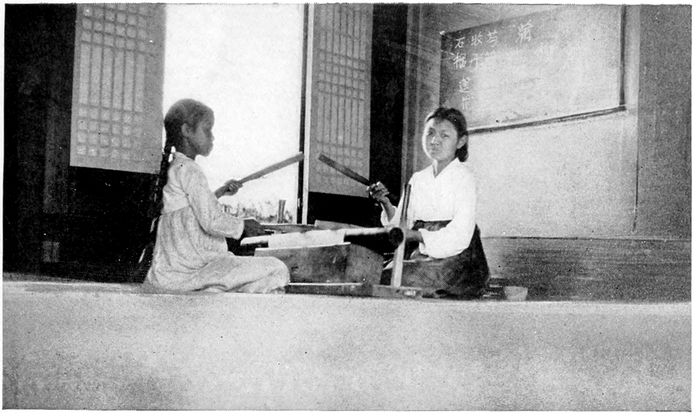

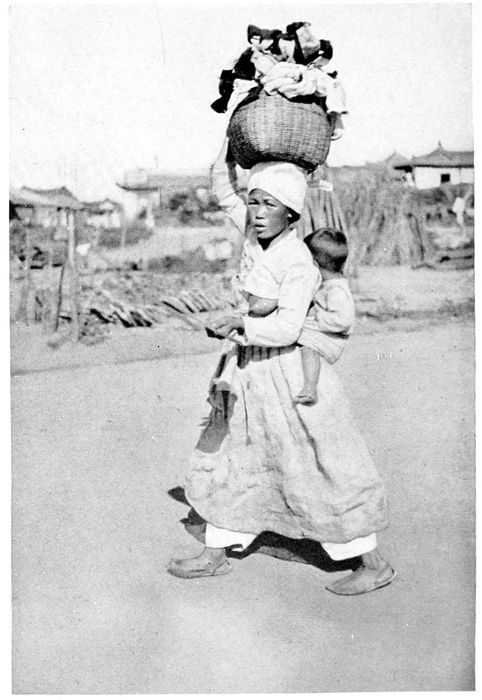

| The Korean method of ironing, the rhythmic rat-a-tat of which may be heard day and night almost anywhere in the peninsula | 40 |

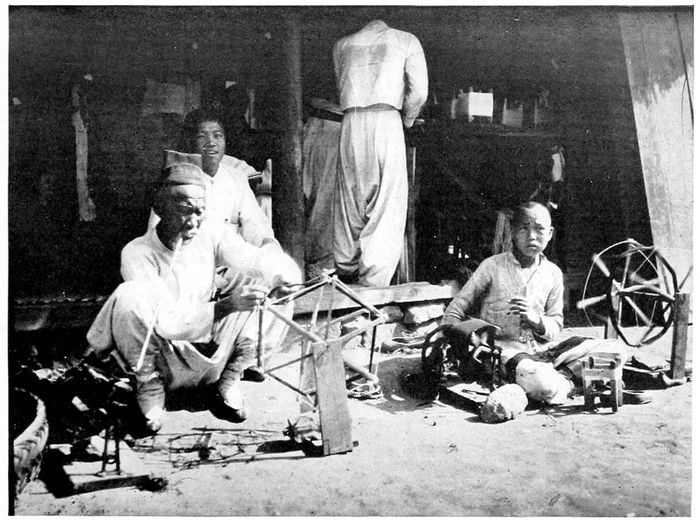

| Winding thread before one of the many little machine-knit stocking factories in Ping Yang | 40 |

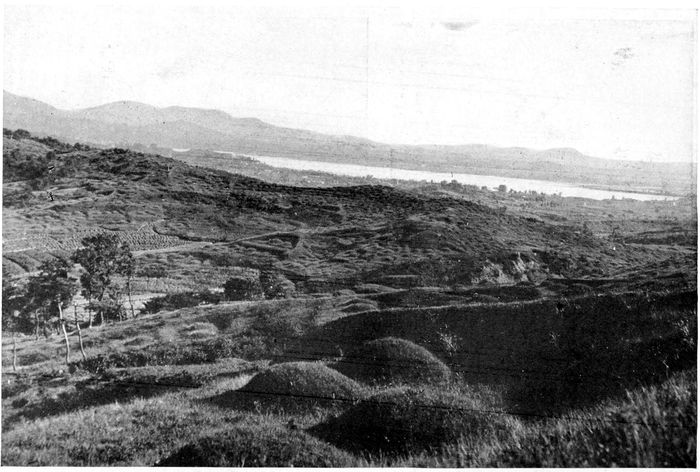

| The graves of Korea cover hundreds of her hillsides with their green mounds, usually unmarked, but carefully tended by the superstitious descendants | 41 |

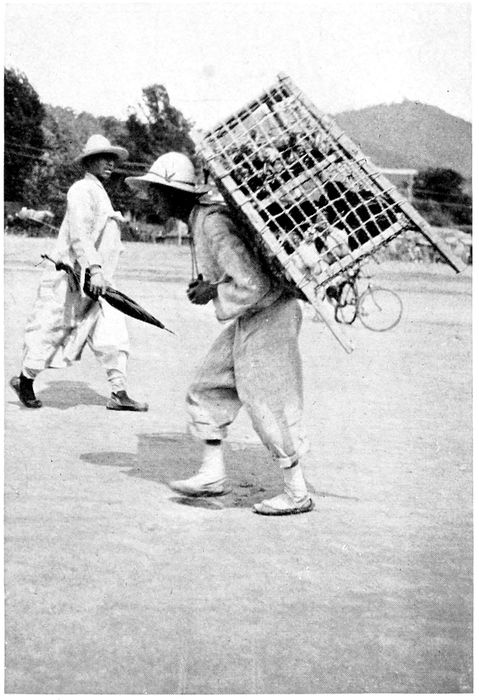

| A chicken peddler in Seoul | 48 |

| A full load | 48 |

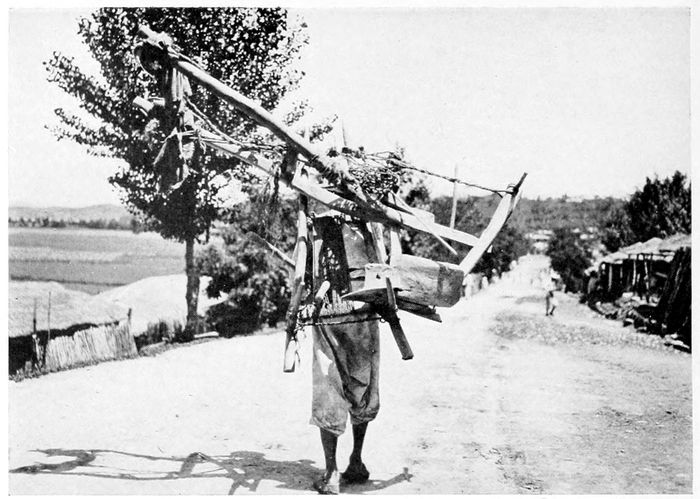

| The plowman homeward wends his weary way—in Korean fashion, always carrying the plow and driving his unburdened ox or bull before him. One of the most common sights of Korea | 49 |

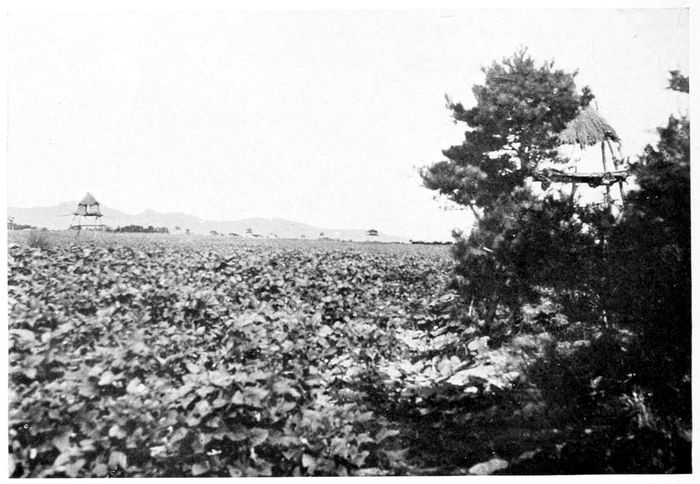

| The biblical “watch-tower in a cucumber patch” is in evidence all over Korea in the summer, when crops begin to ripen. Whole families often sleep in them during this season, when they spring up all over the country, and often afford the only cool breeze | 49 |

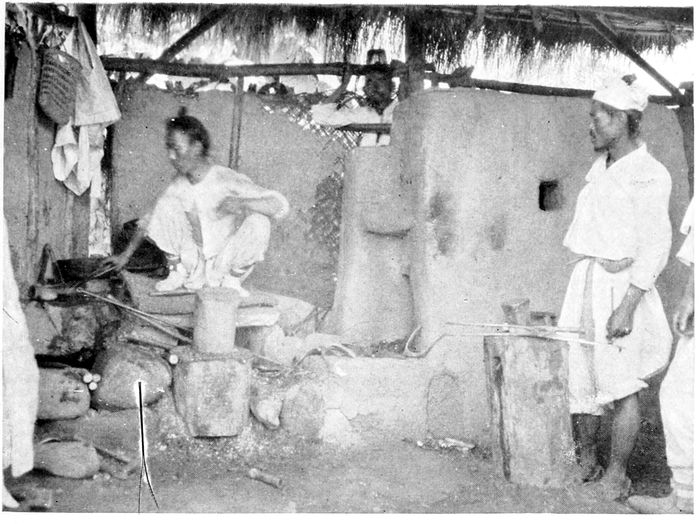

| A village blacksmith of Korea. Note the bellows-pumper in his high hat at the rear | 64 |

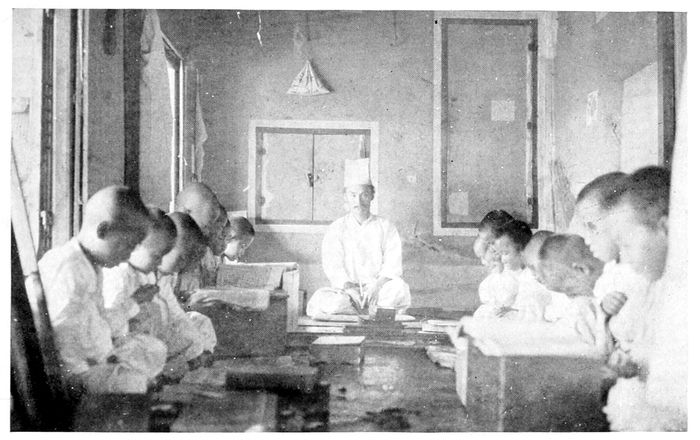

| The interior of a native Korean school of the old type,—dark, dirty, swarming with flies, and loud with a constant chorus | 64 |

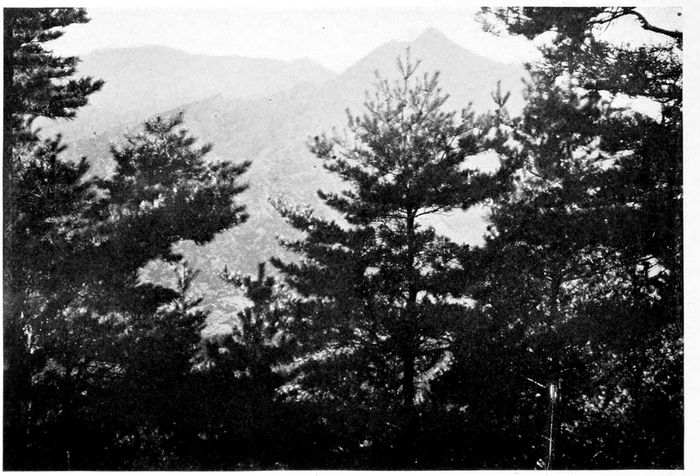

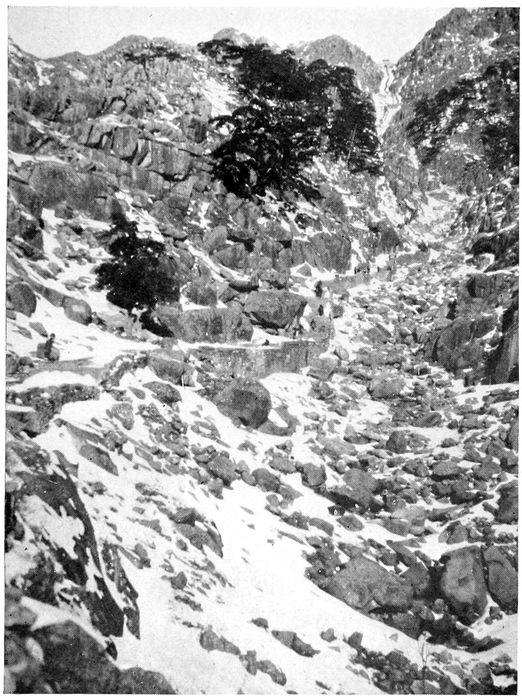

| In Kongo-san, the “Diamond Mountains” of eastern Korea | 65 |

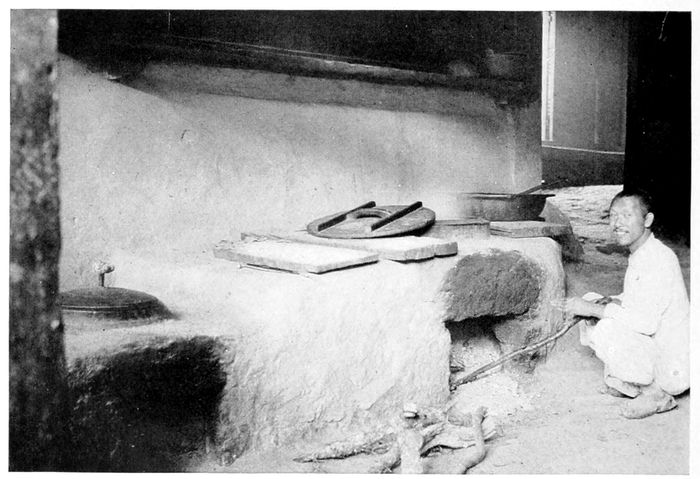

| The monastery kitchen of Yu-jom-sa, typical of Korean cooking | 65 |

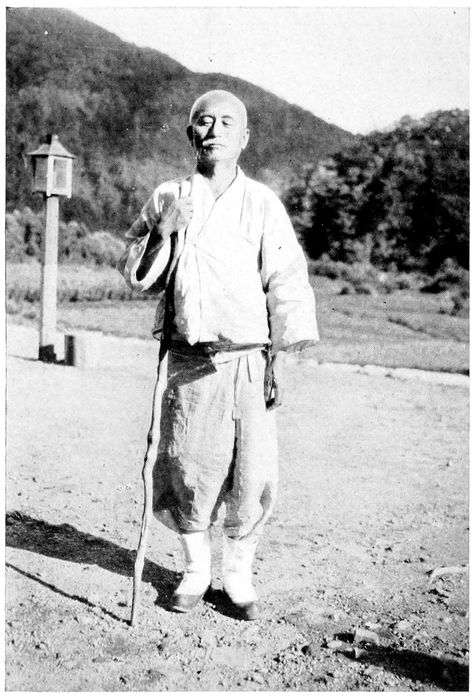

| xivOne of the monks of Yu-jom-sa | 68 |

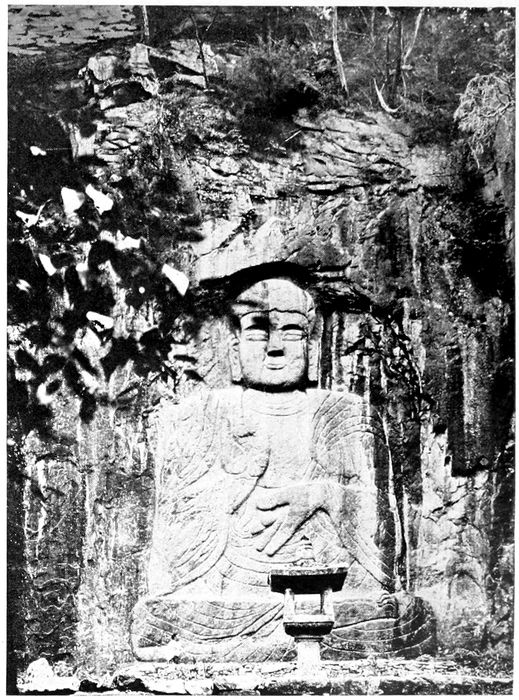

| This great cliff-carved Buddha, fifty feet high and thirty broad, was done by Chinese artists centuries ago. Note my carrier, a full-sized man, squatting at the lower left-hand corner | 68 |

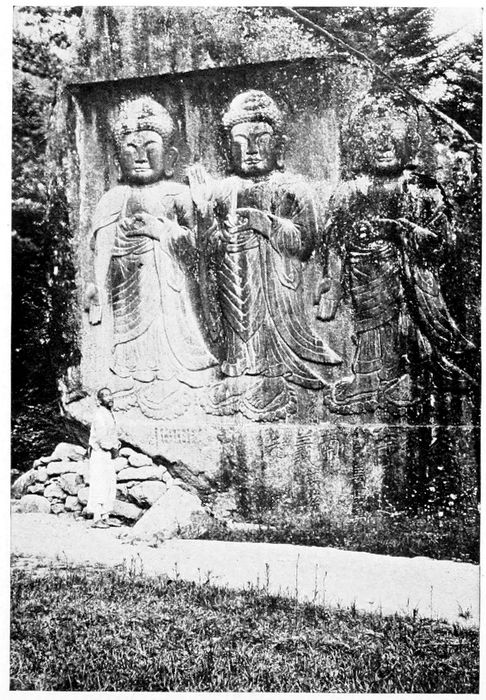

| The carved Buddhas of Sam-pul-gam, at the entrance to the gorge of the Inner Kongo, were chiseled by a famous Korean monk five hundred years ago | 69 |

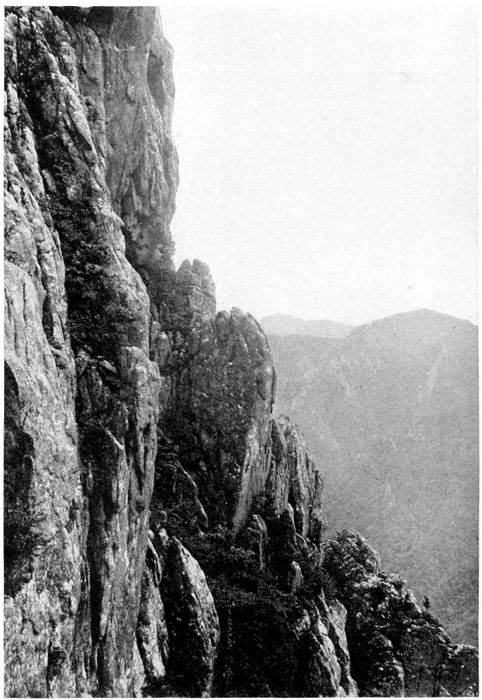

| The camera can at best give only a suggestion of the sheer white rock walls of Shin Man-mul-cho, perhaps the most marvelous bit of scenery in the Far East | 69 |

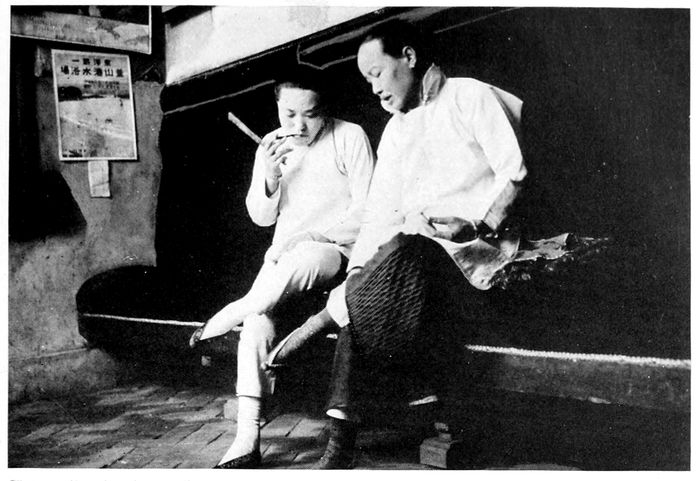

| Two ladies in the station waiting-room of Antung, just across the Yalu from Korea, proudly comparing the relative inadequacy of their crippled feet | 76 |

| The Japanese have made Dairen, southern terminus of Manchuria and once the Russian Dalny, one of the most modern cities of the Far East | 76 |

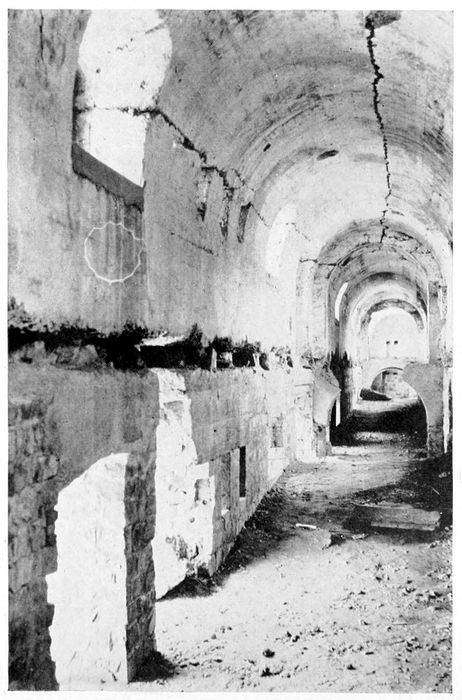

| A ruined gallery in the famous North Fort of the Russians at Port Arthur. Hundreds of such war memorials are preserved by the Japanese on the sites of their first victory over the white race | 77 |

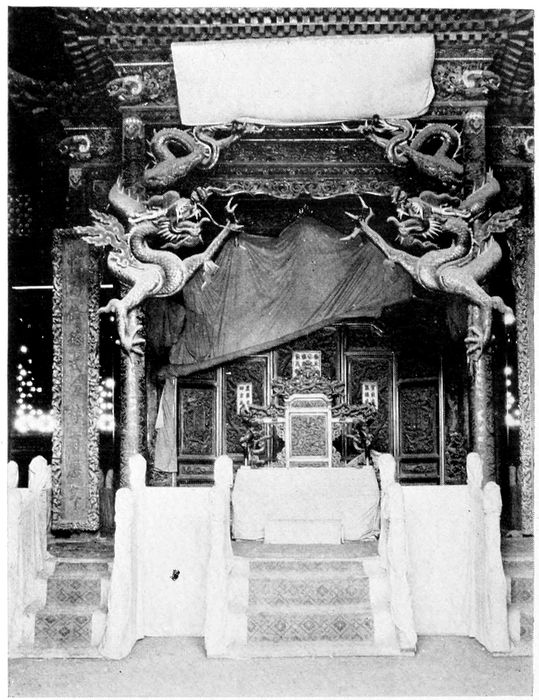

| The empty Manchu throne of Mukden | 77 |

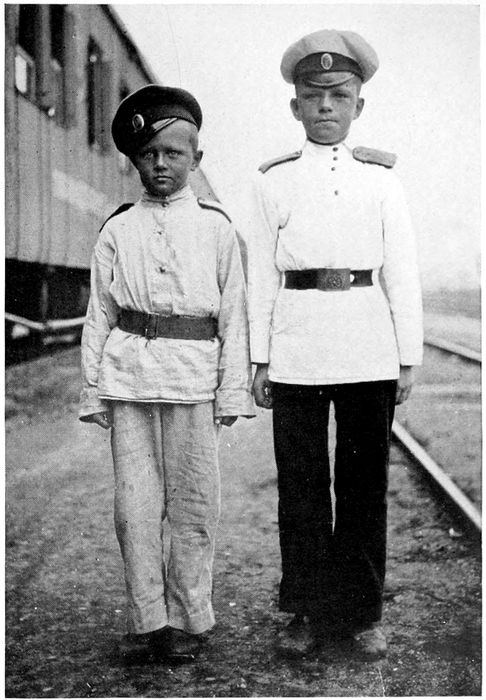

| The Russian so loves a uniform, even after the land it represents has gone to pot, that even school-boys in Vladivostok usually wear them,—red bands, khaki, black trousers, purple epaulets | 80 |

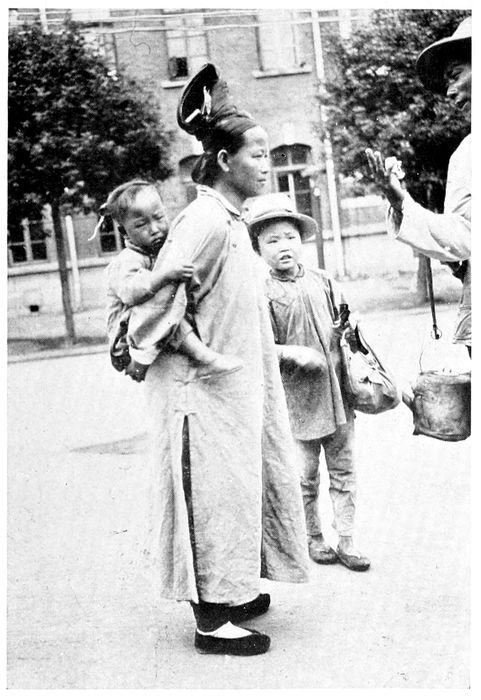

| A Manchu woman in her national head-dress, bargaining with a street vender of Mukden for a cup of tea | 80 |

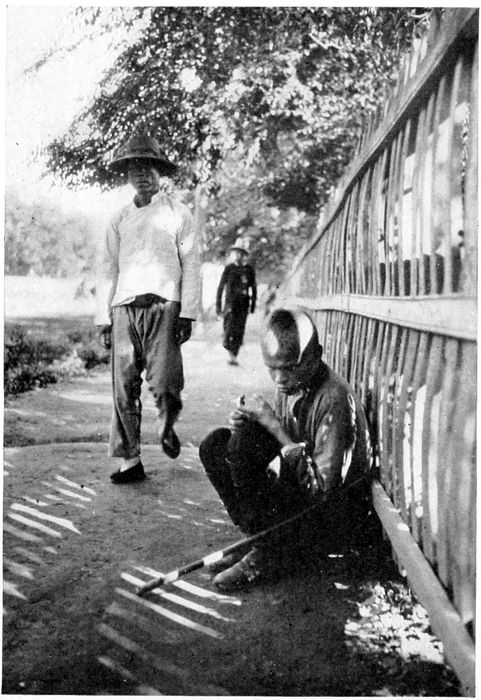

| A common sight in Harbin,—a Russian refugee, in this case a blind boy, begging in the street of passing Chinese | 81 |

| A Russian in Harbin—evidently not a Bolshevik or he would be living in affluence in Russia | 81 |

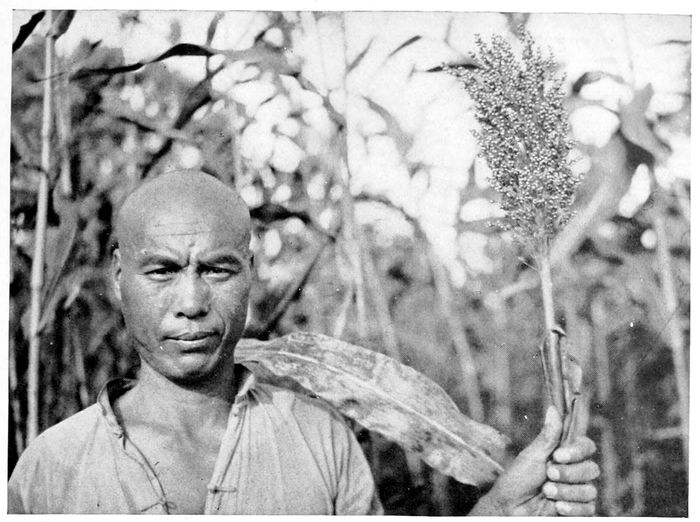

| The grain of the kaoliang, one of the most important crops of North China. It grows from ten to fifteen feet high and makes the finest of hiding-places for bandits | 96 |

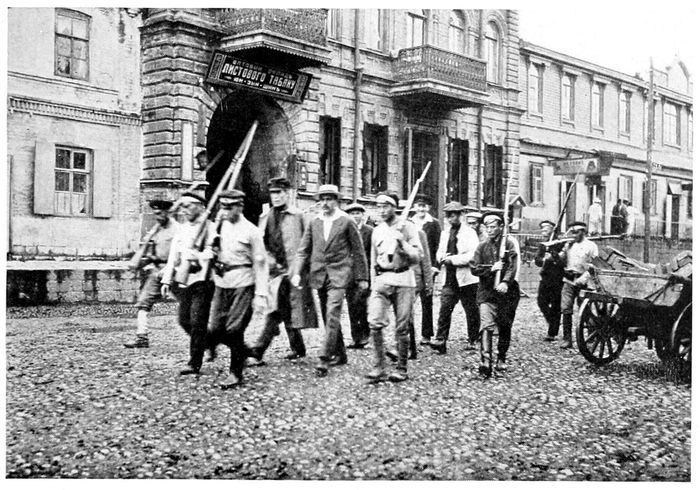

| A daily sight in Vladivostok,—a group of youths suspected of opinions contrary to those of the Government, rounded up and trotted off to prison | 96 |

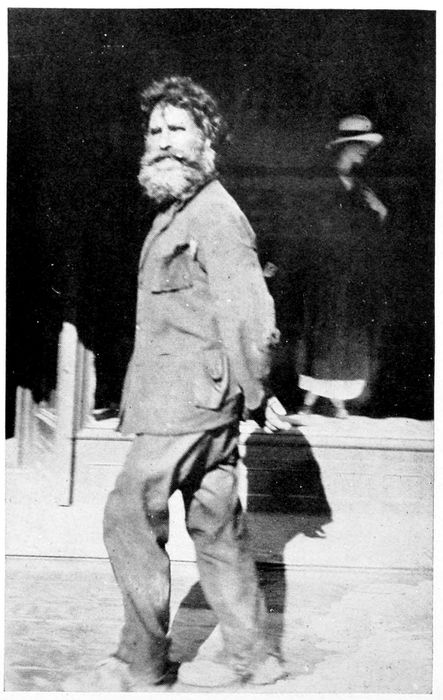

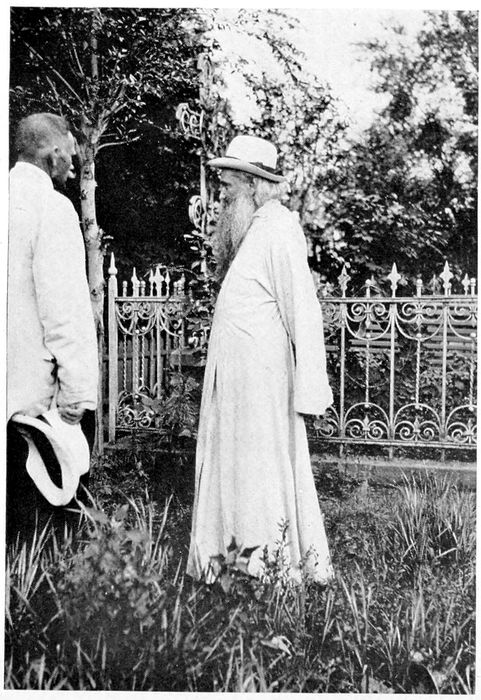

| A refugee Russian priest, of whom there were many in Harbin | 97 |

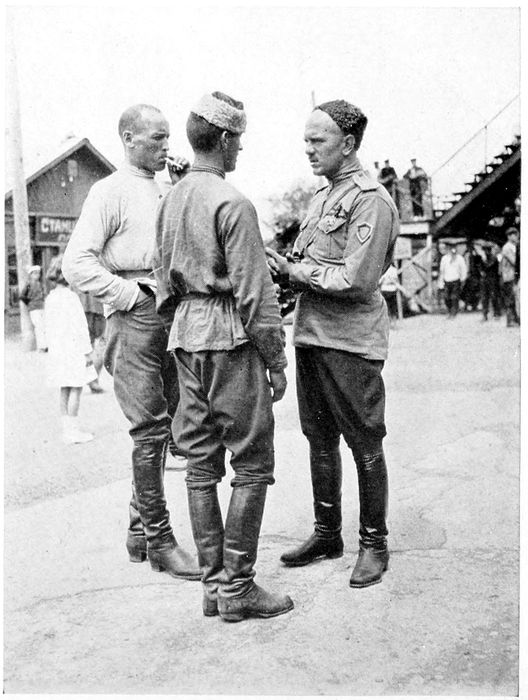

| Types of this kind swarm along the Chinese Eastern Railway of Manchuria, many of them volunteers in the Chinese army or railway police | 97 |

| One of the Russian churches in Harbin, a creamy gray, with green domes and golden crosses, with much gaudy trimming | 100 |

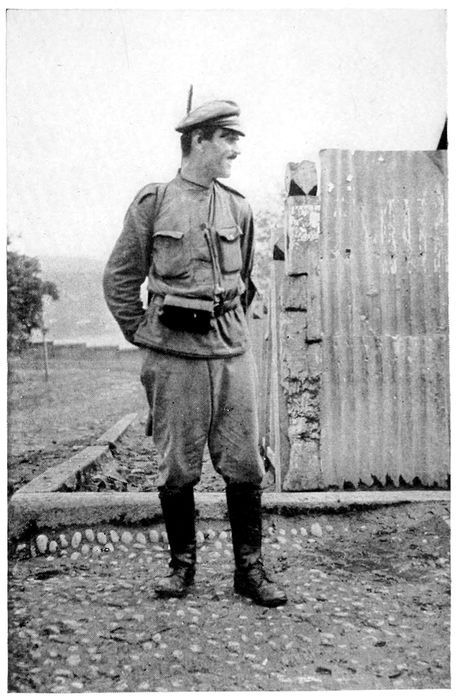

| A policeman of Vladivostok, where shaving is looked down upon | 100 |

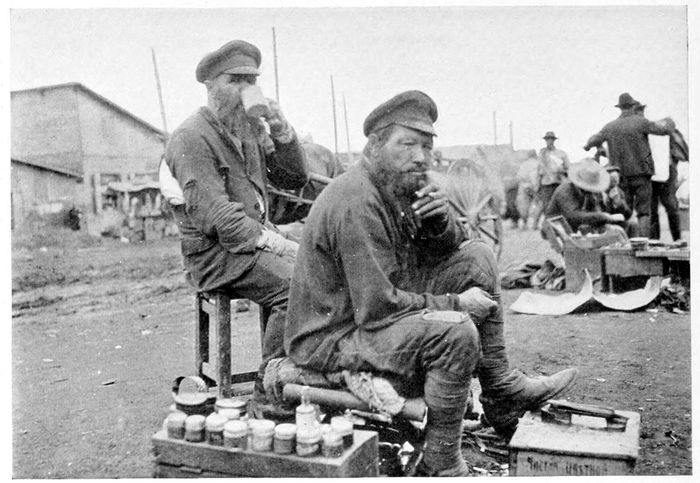

| Two former officers in the czar’s army, now bootblacks in the “thieves” market of Harbin—when they catch any one who can afford to be blacked | 101 |

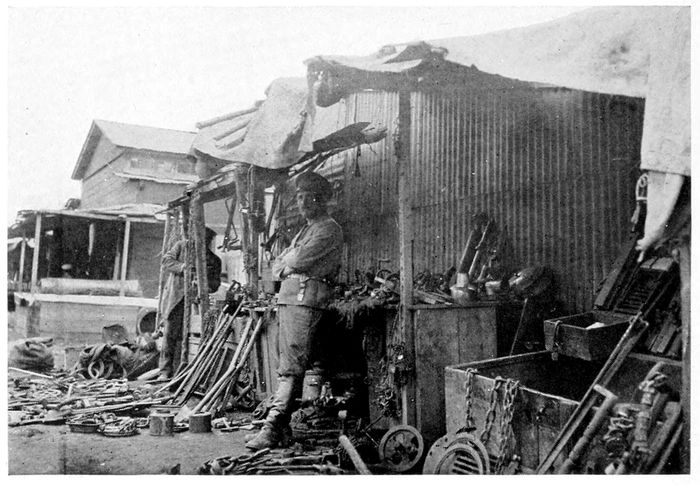

| Scores of booths in Harbin, Manchuli, and Vladivostok, selling second-hand hardware of every description, suggest why the factories and trains of Bolshevik Russia have difficulty in running | 101 |

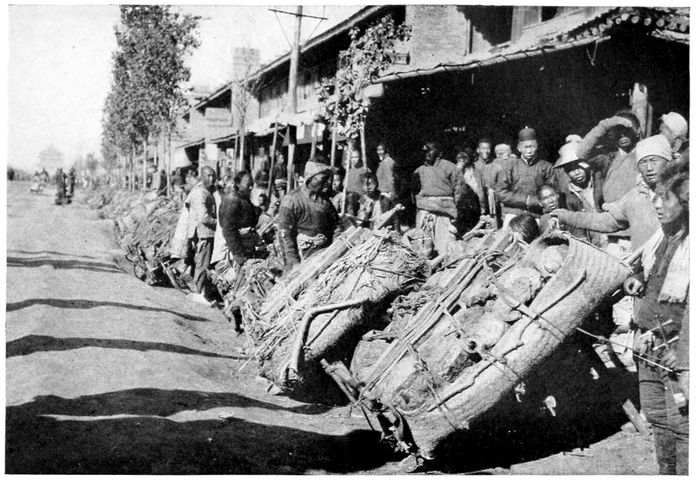

| The human freight horses of Tientsin, who toil ten or more hours a day for twenty coppers, about six cents in our money | 108 |

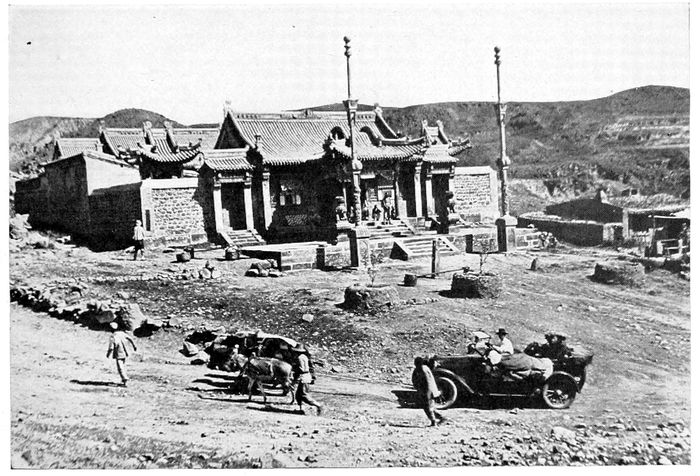

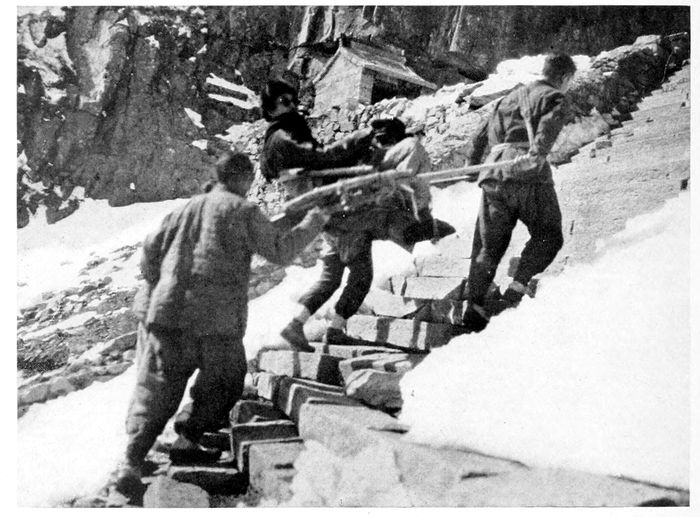

| Part of the pass above Kalgan is so steep that no automobile can climb to the great Mongolian plateau unassisted | 108 |

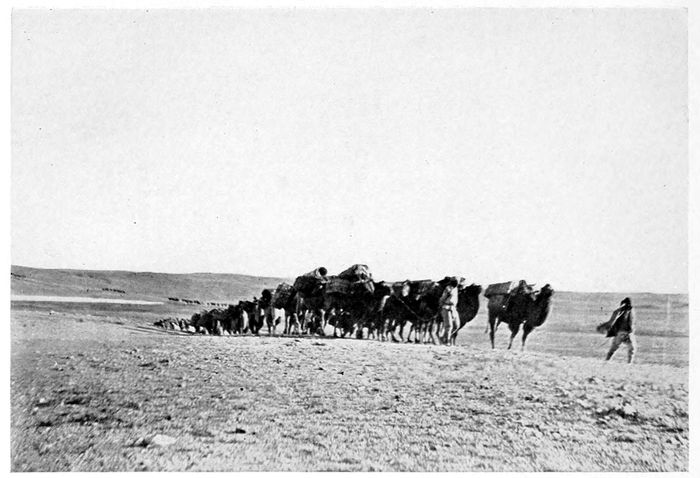

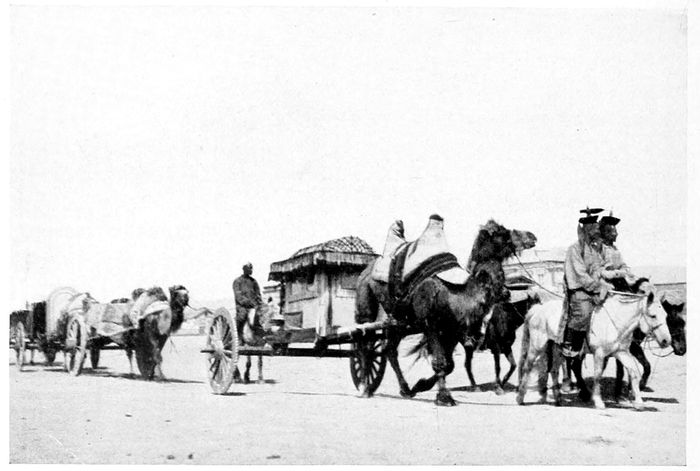

| xvSome of the camel caravans we passed on the Gobi seemed endless. This one had thirty dozen loaded camels and more than a dozen outriders | 109 |

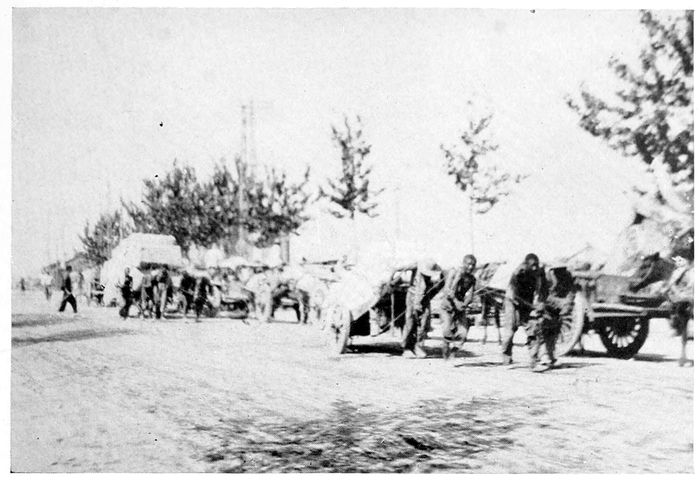

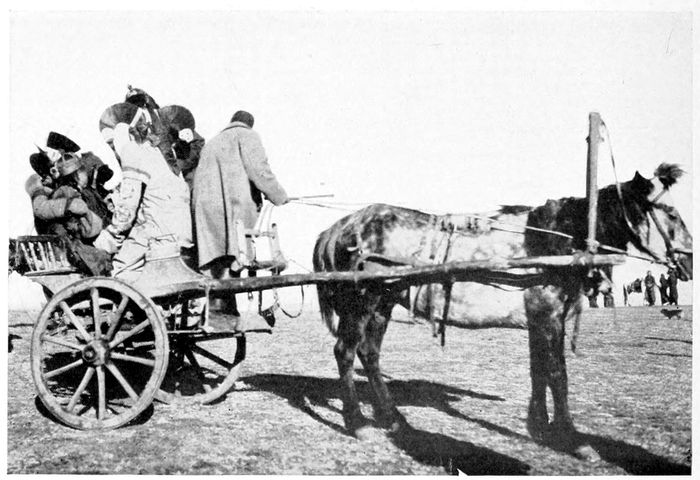

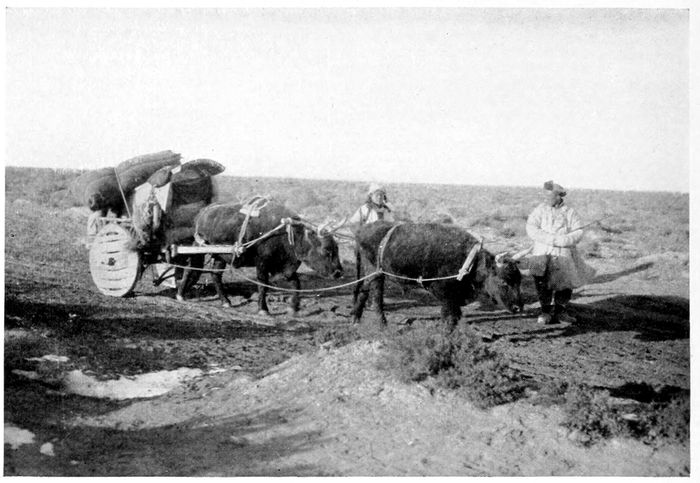

| But cattle caravans also cross the Gobi, drawing home-made two-wheeled carts, often with a flag, sometimes the Stars and Stripes, flying at the head | 109 |

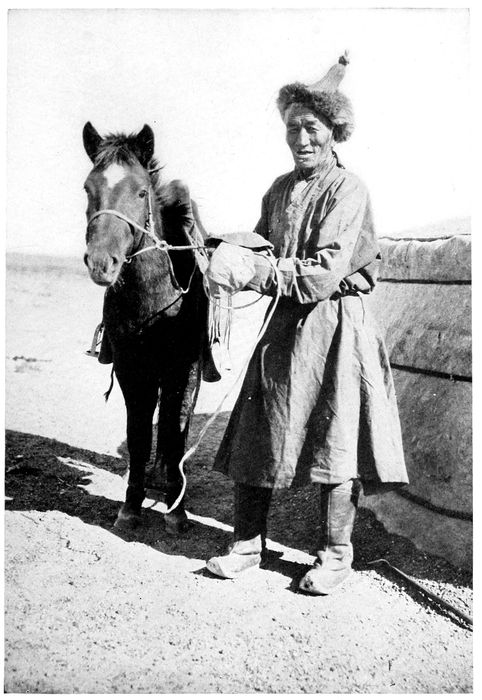

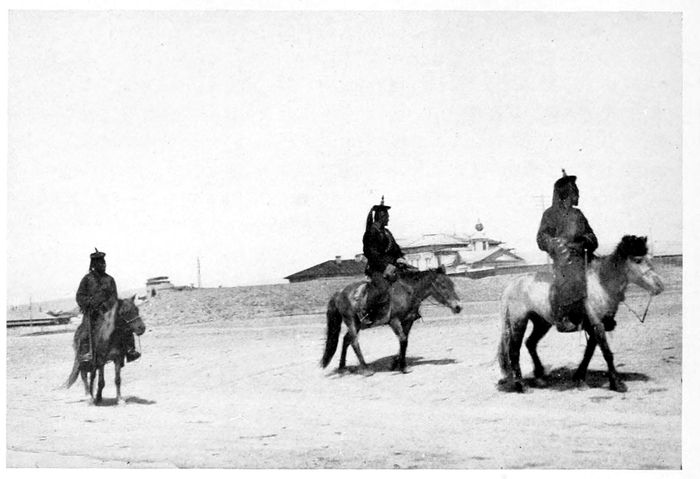

| The Mongol would not be himself without his horse, though to us this would usually seem only a pony | 112 |

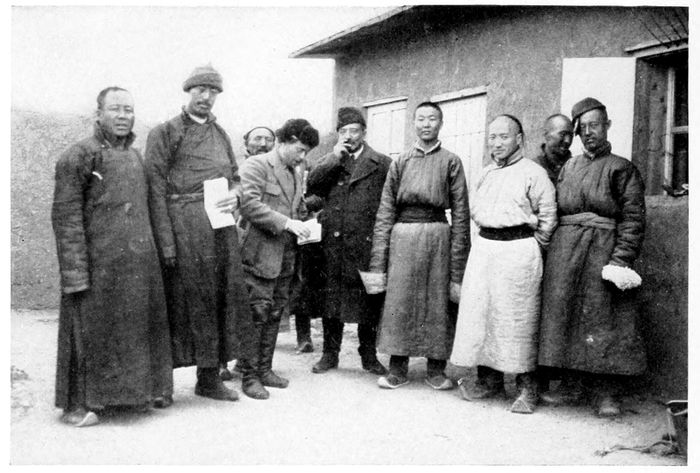

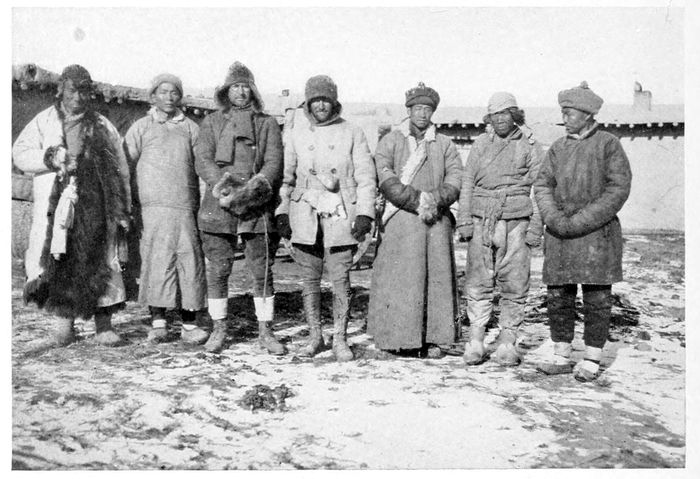

| Mongol authorities examining our papers, which Vilner is showing, at Ude. Robes blue, purple, dull red, etc. Biggest Chinaman on left | 113 |

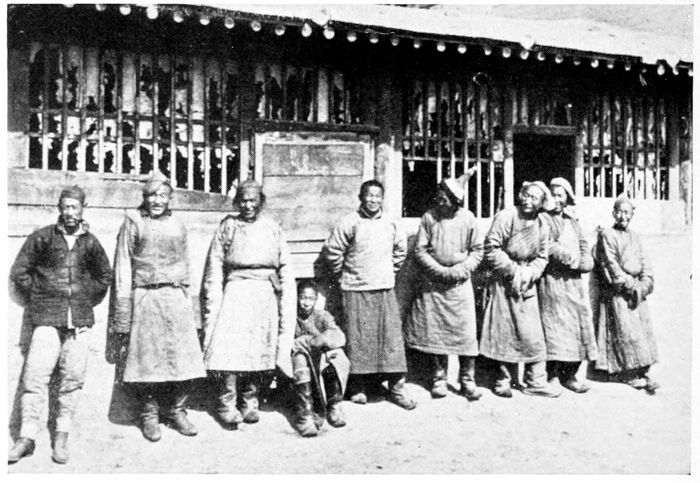

| A group of Mongols and stray Chinese watching our arrival at the first yamen of Urga | 113 |

| The frontier post of Ude, fifty miles beyond the uninhabited frontier between Inner and Outer Mongolia, where Mongol authorities examine passports and very often turn travelers back | 128 |

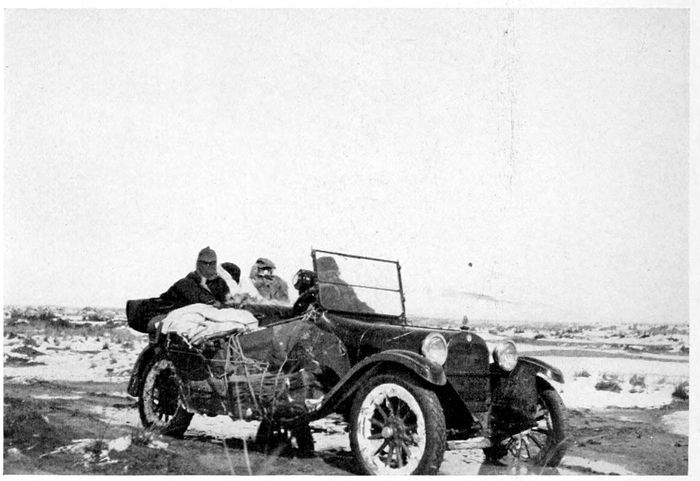

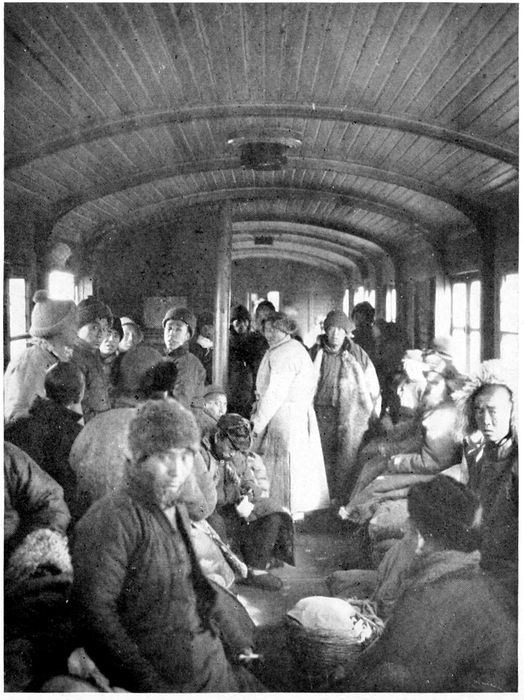

| Chinese travelers on their way to Urga. It is unbelievable how many muffled Chinamen and their multifarious junk one “Dodge” will carry | 128 |

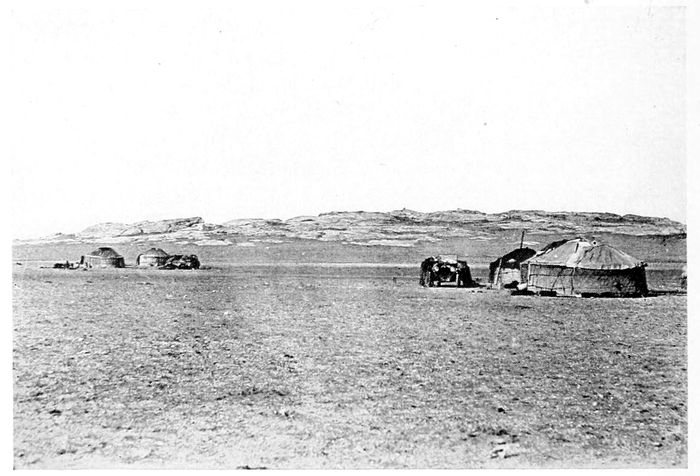

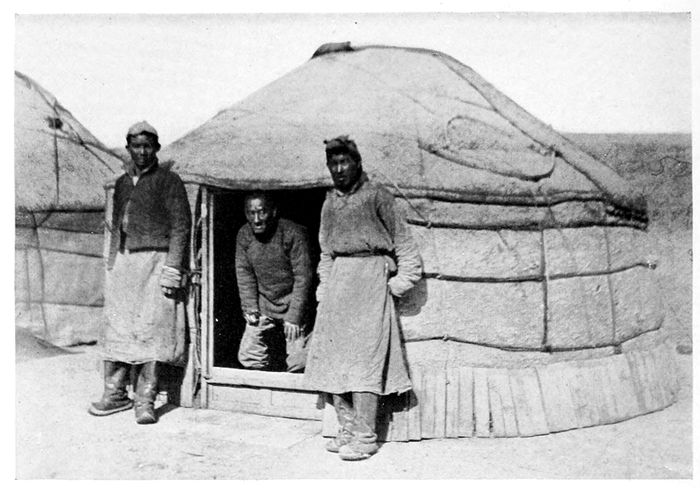

| The Mongol of the Gobi lives in a yourt made of heavy felt over a light wooden framework, which can be taken down and packed in less than an hour when the spirit of the nomad strikes him | 129 |

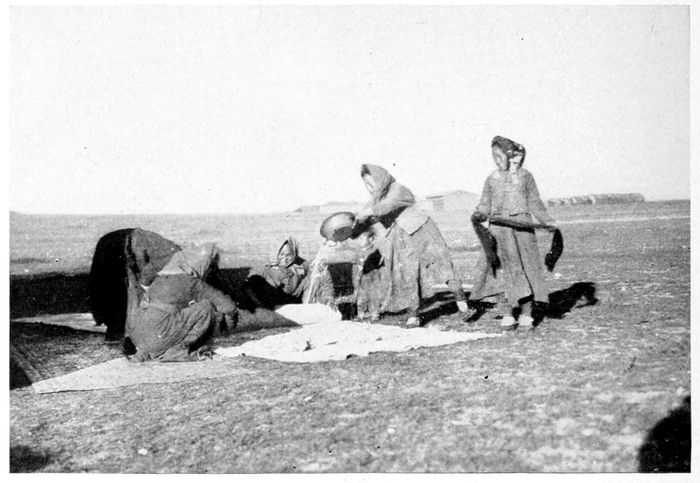

| Mongol women make the felt used as houses, mainly by pouring water on sheep’s wool | 129 |

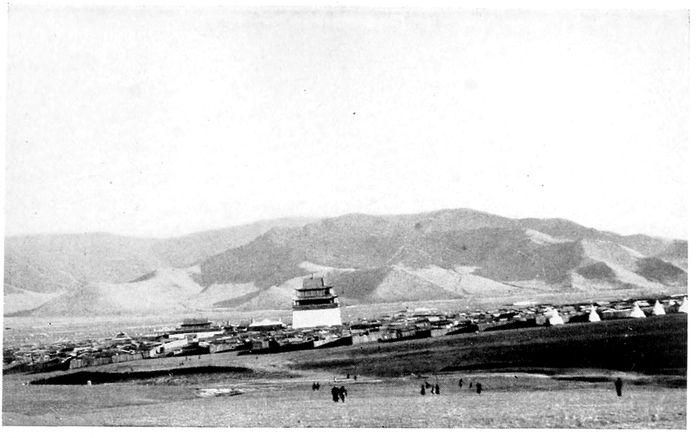

| The upper town of Urga, entirely inhabited by lamas, has the temple of Ganden, containing a colossal standing Buddha, rising high above all else. It is in Tibetan style and much of its superstructure is covered with pure gold | 144 |

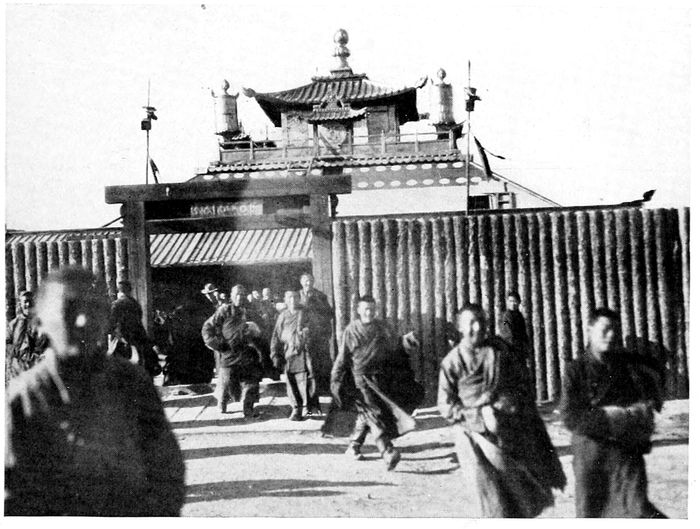

| Red lamas leaving the “school” in which hundreds of them squat tightly together all day long, droning through their litany. They are of all ages, equally filthy and heavily booted. Over the gateway of the typical Urga palisade is a text in Tibetan, and the cylinders at the upper corners are covered with gleaming gold | 144 |

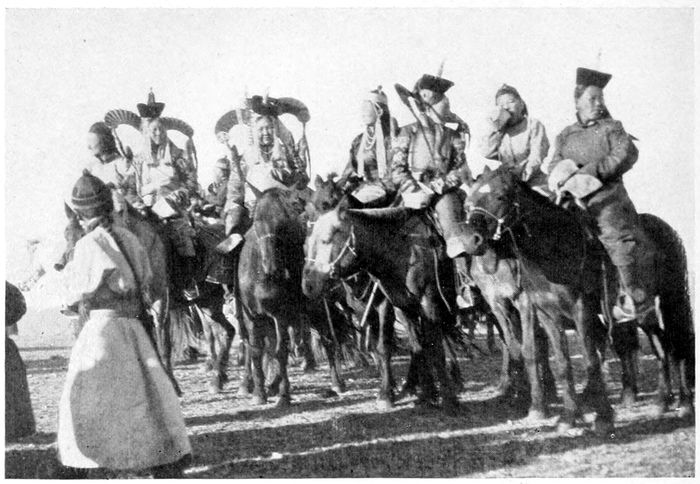

| High class lamas, in their brilliant red or yellow robes, great ribbons streaming from their strange hats, are constantly riding in and out of Urga. Note the bent-knee style of horsemanship | 145 |

| A high lama dignitary on his travels, free from the gaze of the curious, and escorted by mounted lamas of the middle class | 145 |

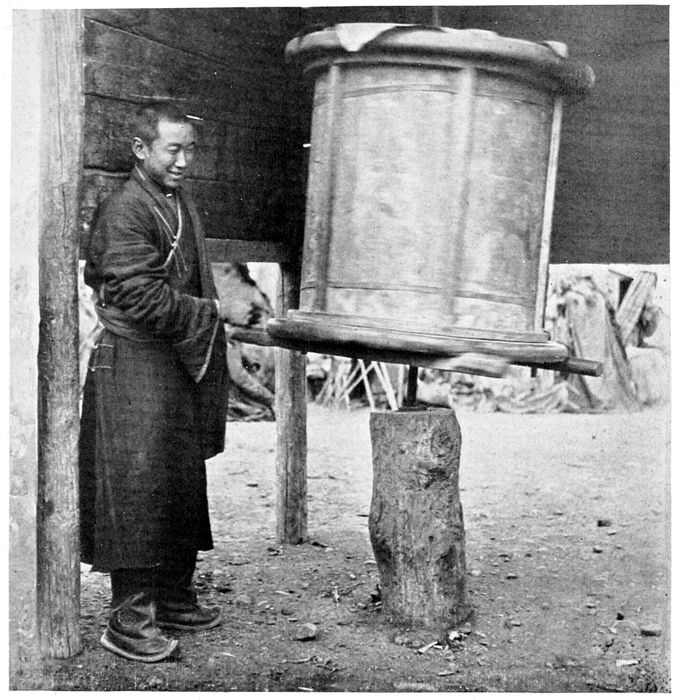

| A youthful lama turning one of the myriad prayer-cylinders of Urga. Many written prayers are pasted inside, and each turn is equivalent to saying all of them | 152 |

| The market in front of Hansen’s house. The structure on the extreme left is not what it looks like, for they have no such in Urga, but it houses a prayer-cylinder | 152 |

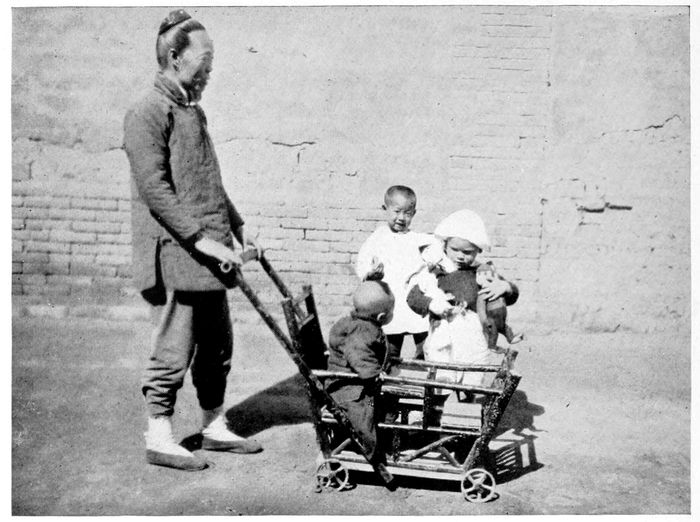

| Women, whose crippled feet make going to the shops difficult, do much of their shopping from the two-boxes-on-a-pole type of merchant, constant processions of whom tramp the highways of China | 153 |

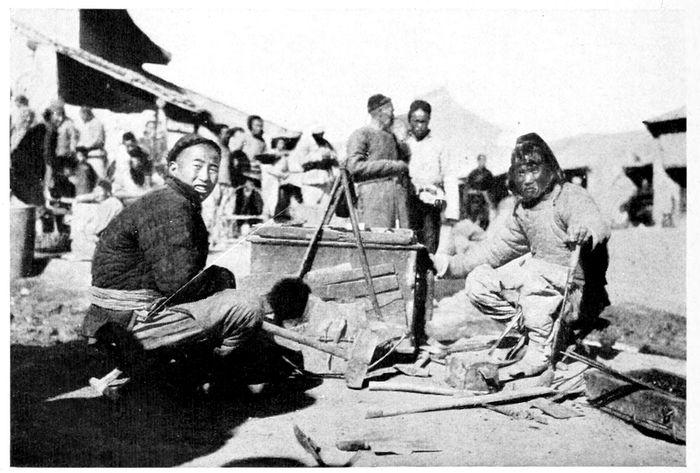

| An itinerant blacksmith-shop, with the box-bellows worked by a stick handle widely used by craftsmen and cooks in China | 153 |

| Pious Mongol men and women worshiping before the residence of the “Living Buddha” of Urga, some by throwing themselves down scores of times on the prostrating-boards placed for that purpose, one by making many circuits of the place, now and again measuring his length on the ground | 160 |

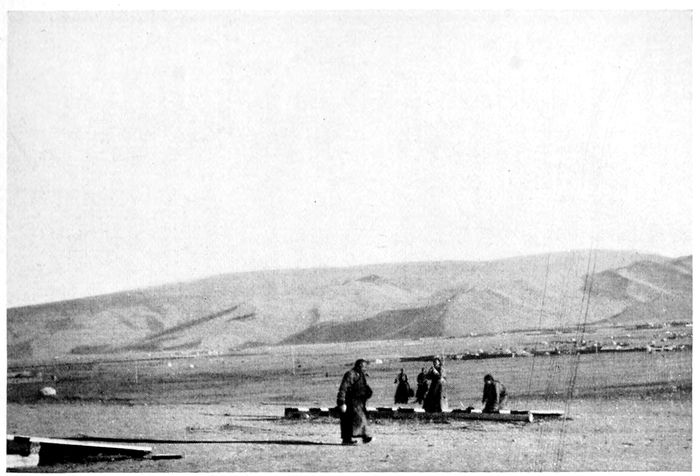

| xviThe Mongols of Urga disposed of their dead by throwing the bodies out on the hillsides, where they are quickly devoured by the savage black dogs that roam everywhere | 160 |

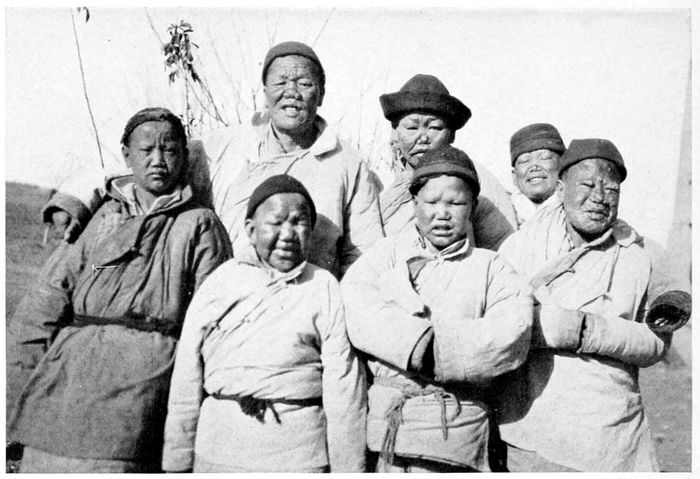

| Mongol women in full war-paint | 161 |

| Though it was still only September, our return from Urga was not unlike a polar expedition | 161 |

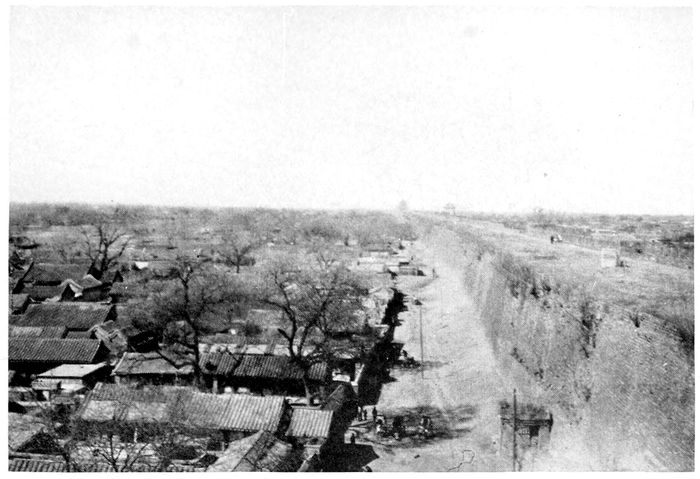

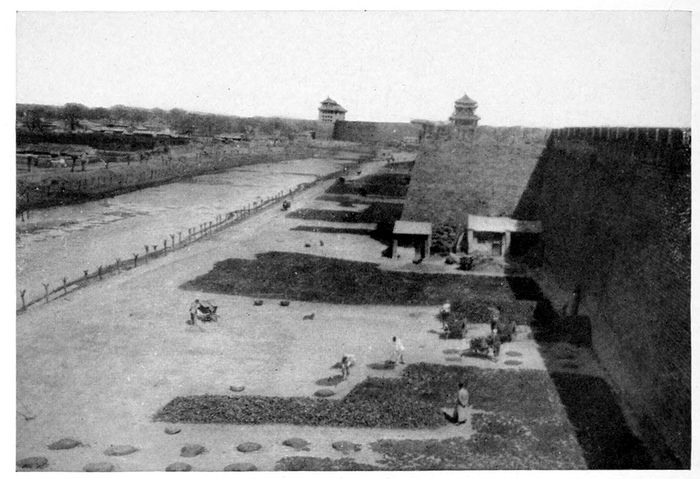

| Our home in Peking was close under the great East Wall of the Tartar City | 176 |

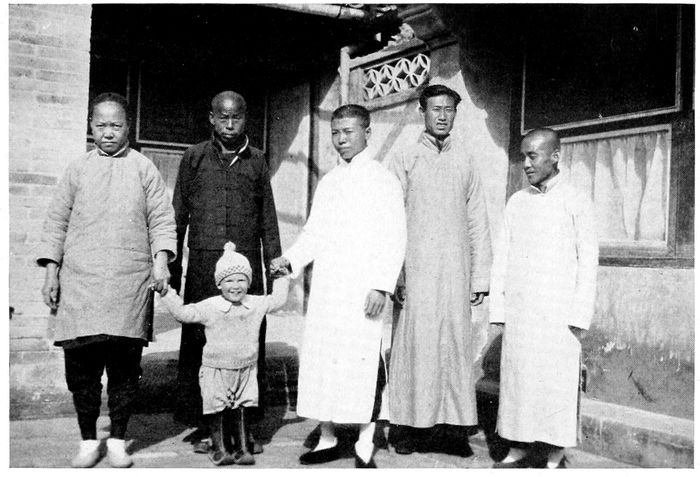

| The indispensable staff of Peking housekeeping consists of (left to right) ama, rickshaw-man, “boy,” coolie, and cook | 176 |

| A chat with neighbors on the way to the daily stroll on the wall | 177 |

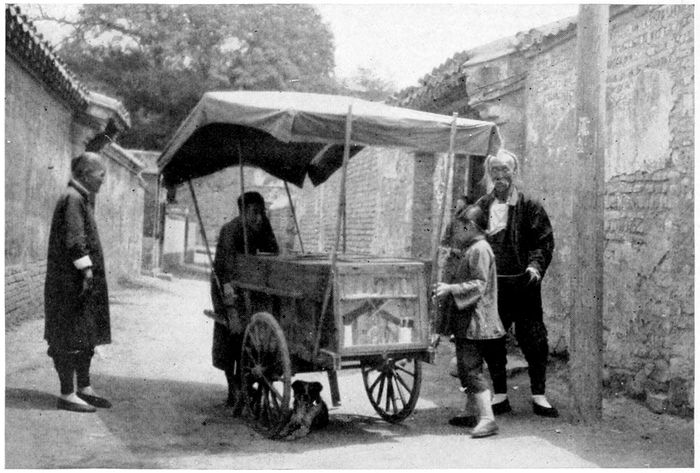

| Street venders were constantly crying their wares in our quarter | 177 |

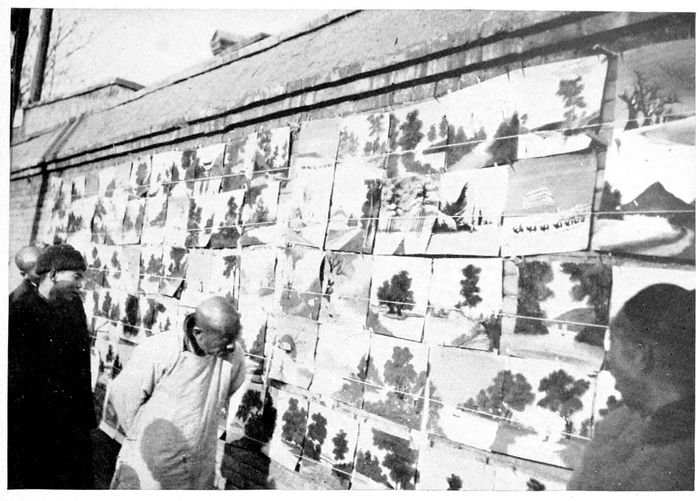

| At Chinese New Year the streets of Peking were gay with all manner of things for sale, such as these brilliantly colored paintings of native artists | 192 |

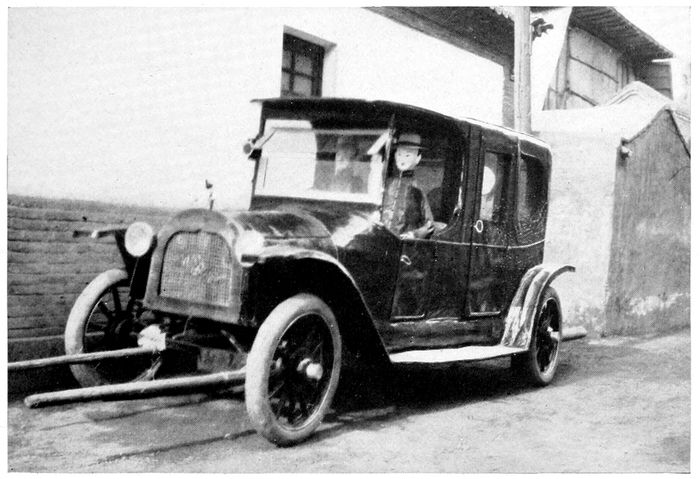

| A rich man died in our street, and among other things burned at his grave, so that he would have them in after-life, were this “automobile” and two “chauffeurs” | 192 |

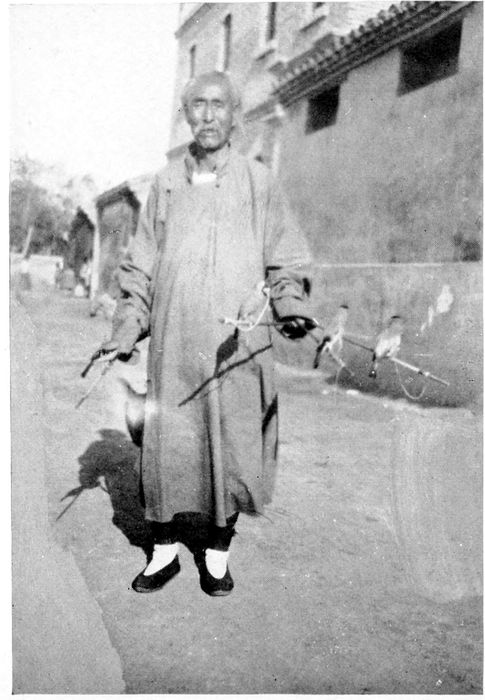

| A neighbor who gave his birds a daily airing | 193 |

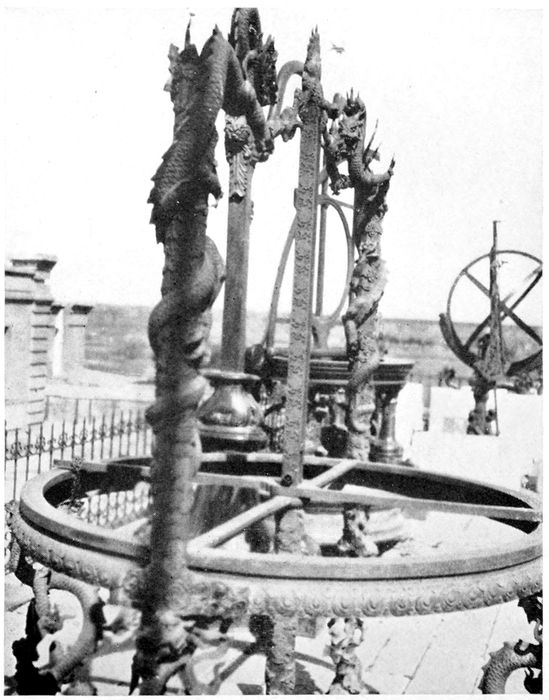

| Just above us on the Tartar Wall were the ancient astronomical instruments looted by the Germans in 1900 and recently returned, in accordance with a clause in the Treaty of Versailles | 193 |

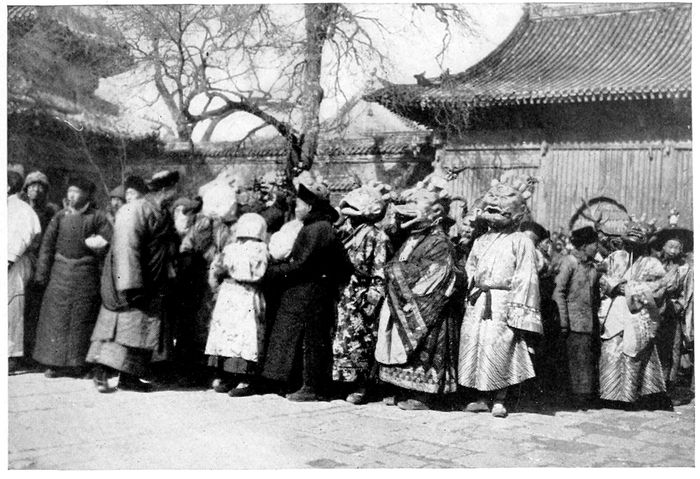

| Preparing for a devil dance at the lama temple in Peking | 208 |

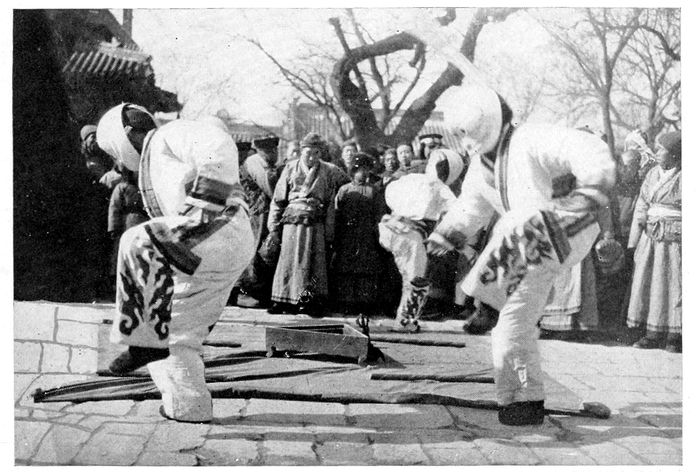

| The devil dancers are usually Chinese street urchins hired for the occasion by the languid Mongol lamas of Peking | 208 |

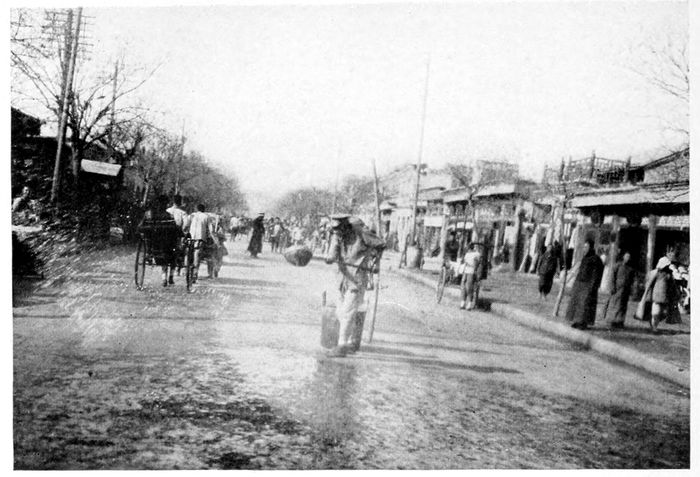

| The street sprinklers of Peking work in pairs, with a bucket and a wooden dipper. This is the principal street of the Chinese City “outside Ch’ien-men” | 209 |

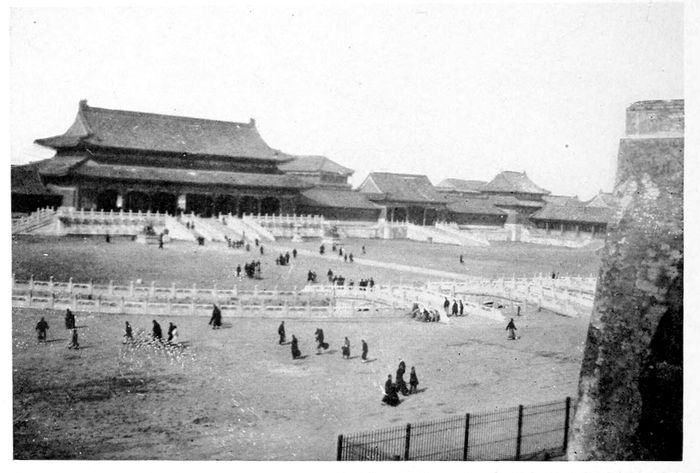

| The Forbidden City is for the most part no longer that, but open in more than half its extent to the ticket-buying public | 209 |

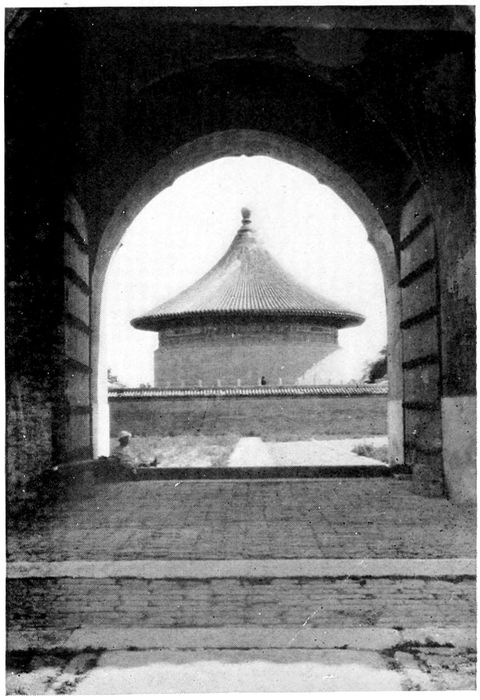

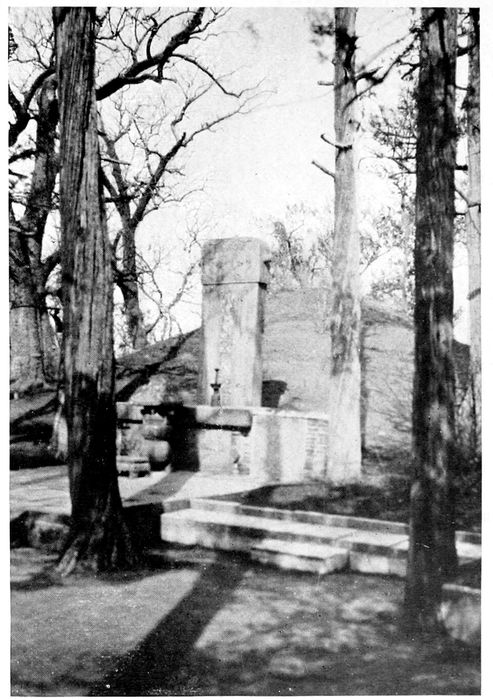

| In the vast compound of the Altar of Heaven | 224 |

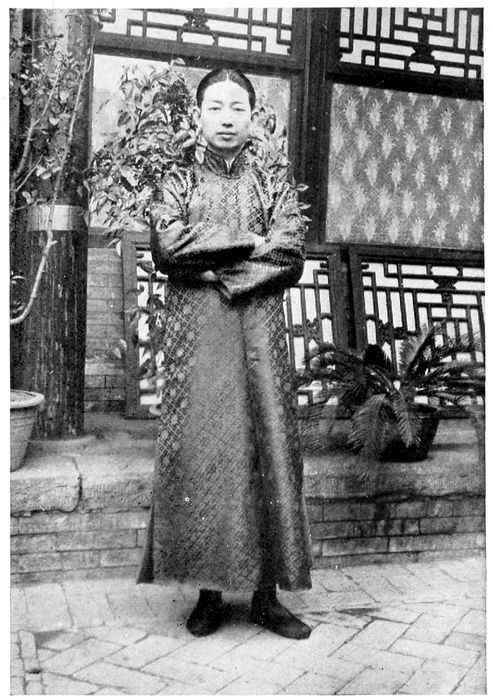

| Mei Lan-fang, most famous of Chinese actors, who, like his father and grandfather before him, plays only female parts | 224 |

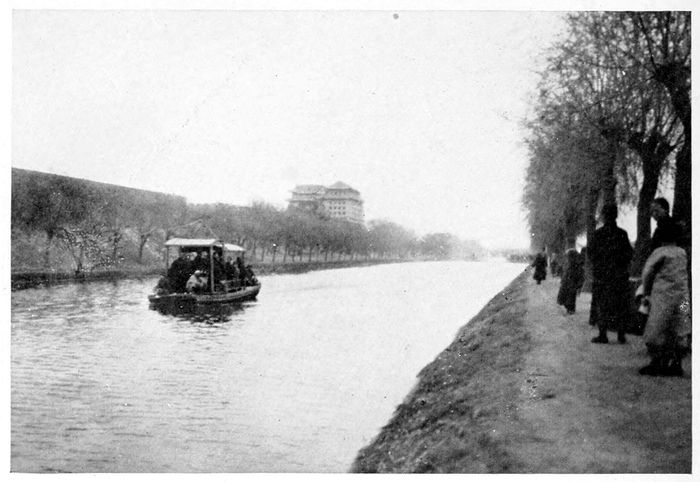

| Over the wall from our house boats plied on the moat separating us from the Chinese City | 225 |

| Just outside the Tartar Wall of Peking the night soil of the city, brought in wheelbarrows, is dried for use as fertilizer | 225 |

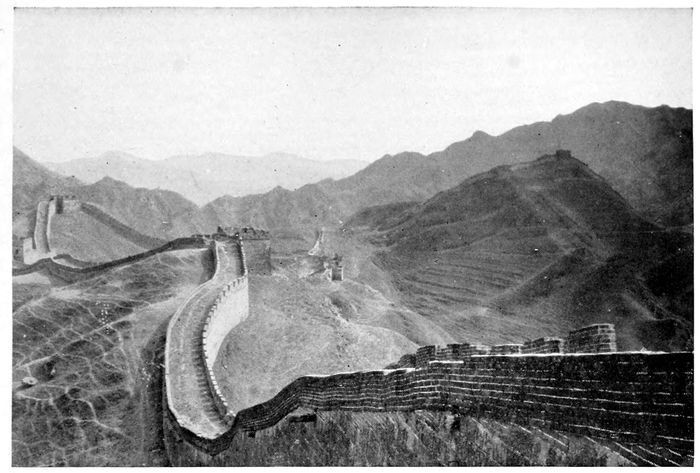

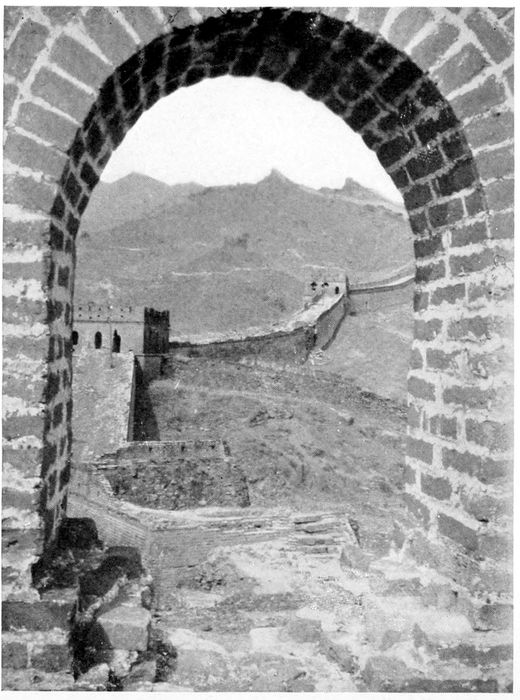

| For three thousands miles the Great Wall clambers over the mountains between China and Mongolia | 240 |

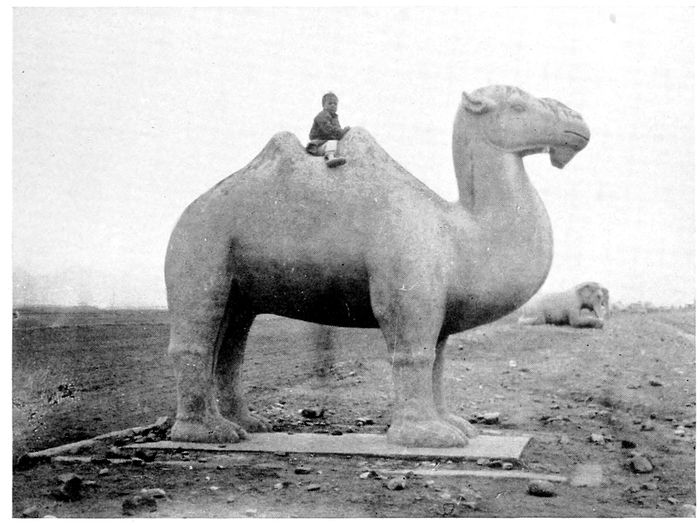

| One of the mammoth stone figures flanking the road to the Ming Tombs of North China, each of a single piece of granite | 240 |

| Another glimpse of the Great Wall | 241 |

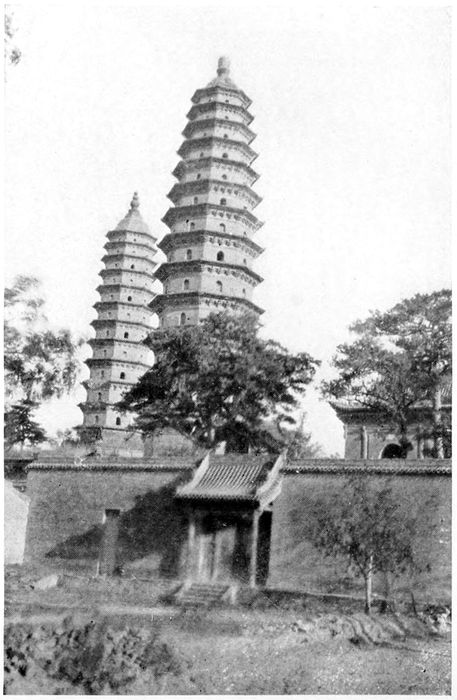

| The twin pagodas of Taiyüan, capital of Shansi Province | 241 |

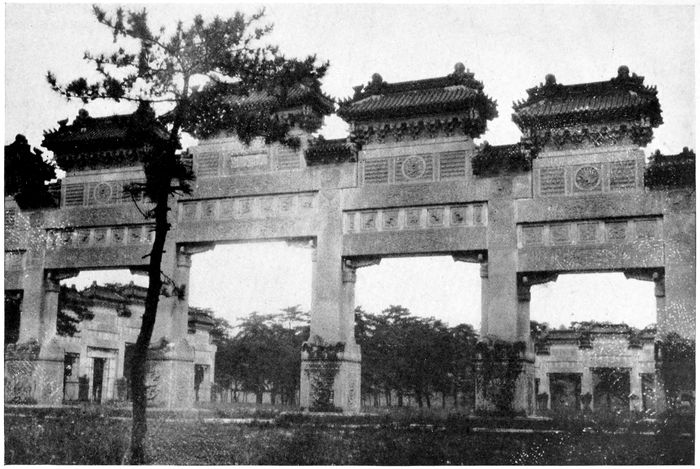

| The three p’ai-lous of Hsi Ling, the Western Tombs | 248 |

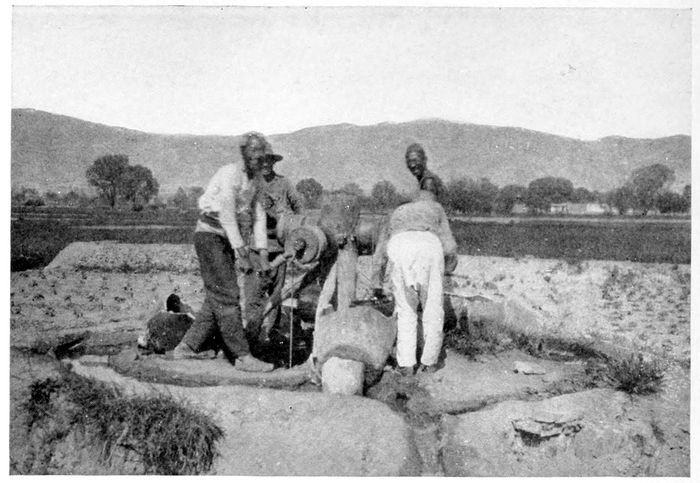

| In Shansi four men often work at as many windlasses over a single well to irrigate the fields | 249 |

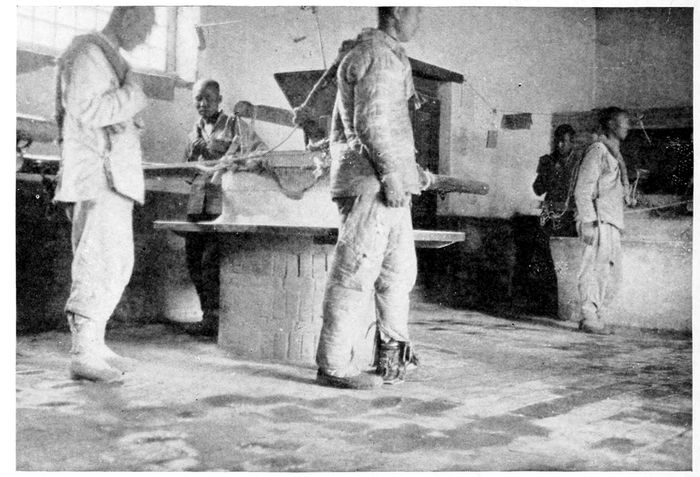

| Prisoners grinding grain in the “model prison” of Taiyüan | 249 |

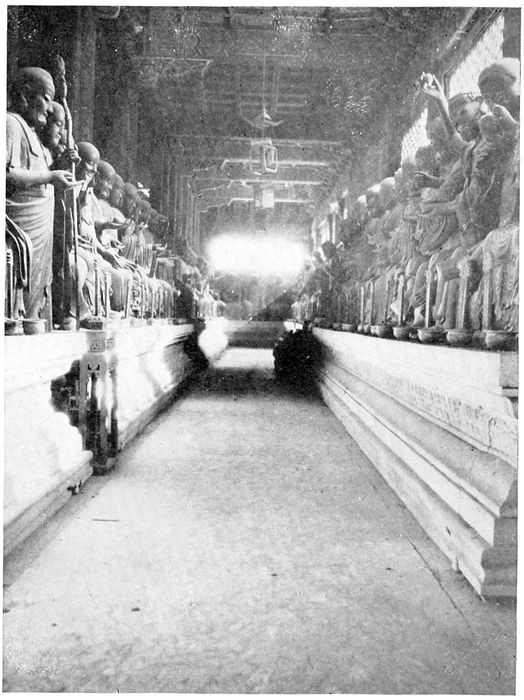

| A few of the 508 Buddhas in one of the lama temples of Jehol | 256 |

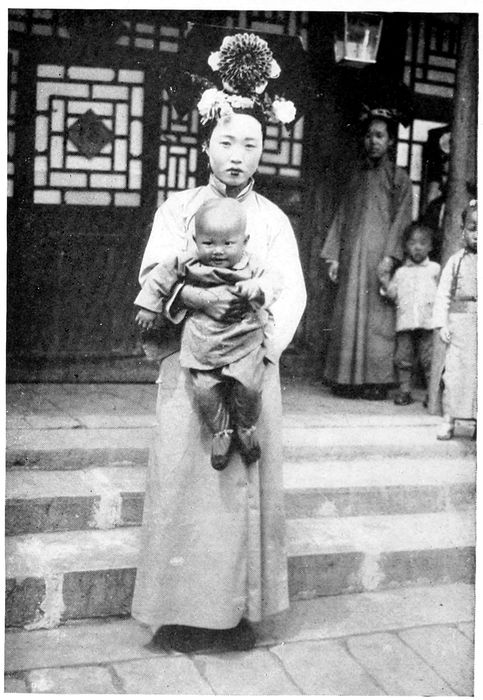

| xviiThe youngest, but most important—since she has borne him a son—of the wives of a Manchu chief of one of the tomb-tending towns of Tung Ling | 256 |

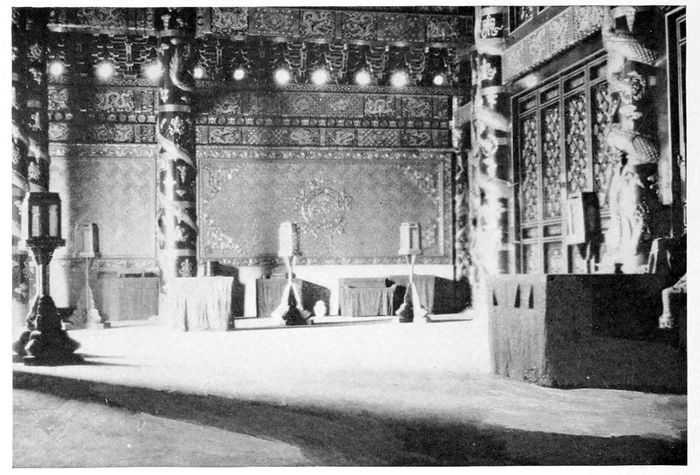

| Interior of the notorious Empress Dowager’s tomb at Tung Ling, with her cloth-covered chair of state and colors to dazzle the stoutest eye | 257 |

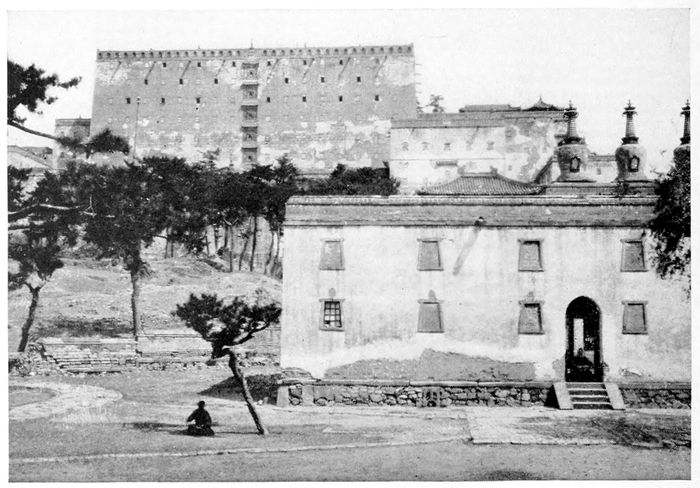

| The Potalá of Jehol, said to be a copy, even in details, of that of Lhasa. The windows are false and the great building at the top is merely a roofless one enclosing the chief temple | 257 |

| Behind Tung Ling the great forest reserve which once “protected” the tombs from the evil spirits that always come from the north was recently opened to settlers, and frontier conditions long since forgotten in the rest of China prevail | 260 |

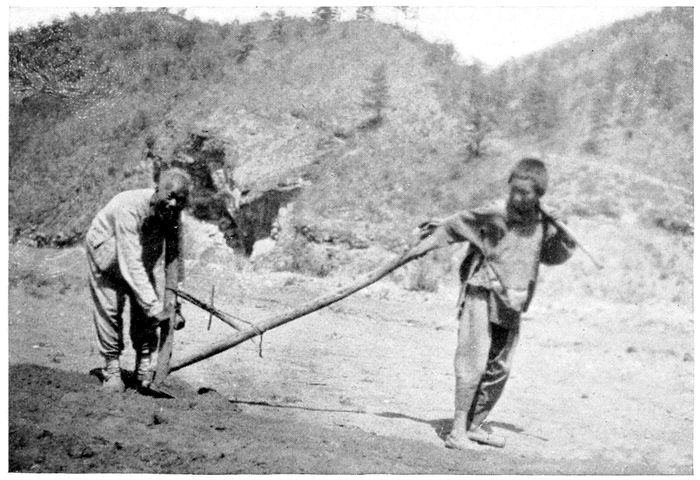

| Much of the plowing in the newly opened tract is done in this primitive fashion | 260 |

| The face of the mammoth Buddha of Jehol, forty-three feet high and with forty-two hands. It fills a four-story building, and is the largest in China proper, being identical, according to the lamas, with those of Urga and Lhasa | 261 |

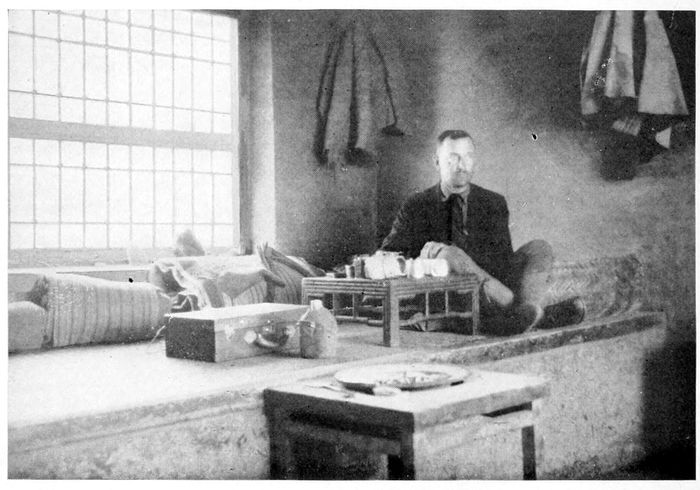

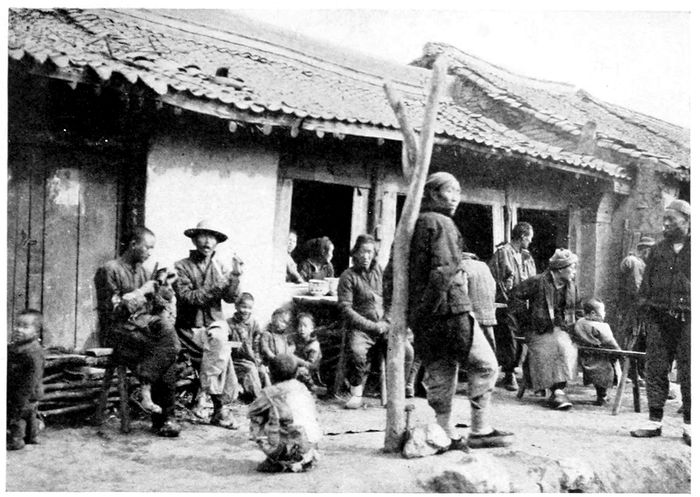

| A Chinese inn, with its heated k’ang, may not be the last word in comfort, but it is many degrees in advance of the earth floors of Indian huts along the Andes | 261 |

| The upper half of the ascent of Tai-shan is by a stone stairway which ends at the “South Gate of Heaven,” here seen in the upper right-hand corner | 268 |

| One of the countless beggar women who squat in the center of the stairway to Tai-shan, expecting every pilgrim to drop at least a “cash” into each basket | 268 |

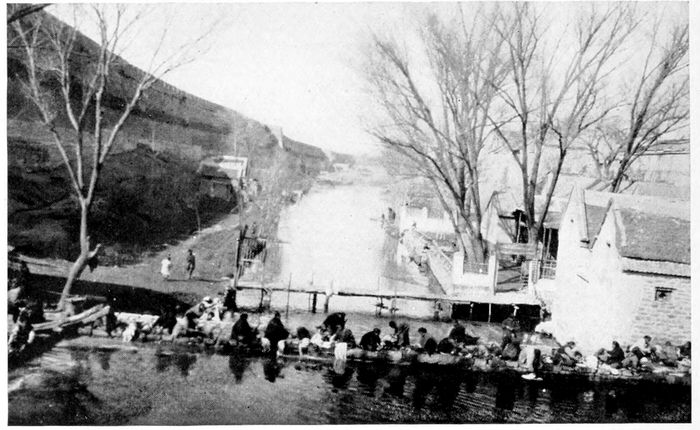

| Wash-day in the moat outside the city wall of Tzinan, capital of Shantung | 269 |

| A traveler by chair nearing the top of Tai-shan, most sacred of the five holy peaks of China | 269 |

| A priest of the Temple of Confucius | 272 |

| The grave of Confucius is noted for its simplicity | 272 |

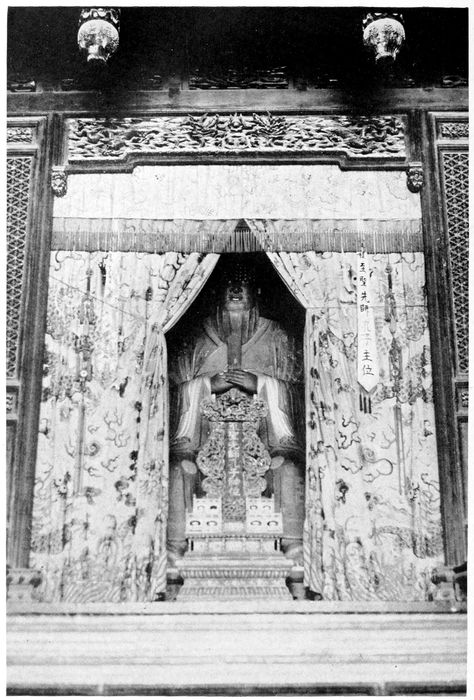

| The sanctum of the Temple of Confucius, with the statue and spirit—tablet of the sage, before which millions of Chinese burn joss-sticks annually | 273 |

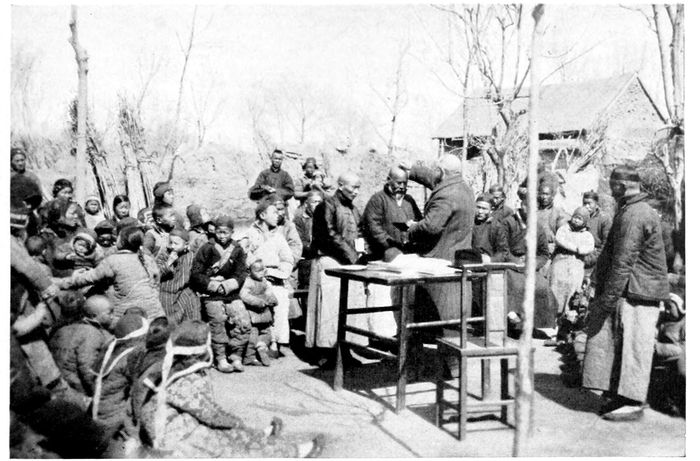

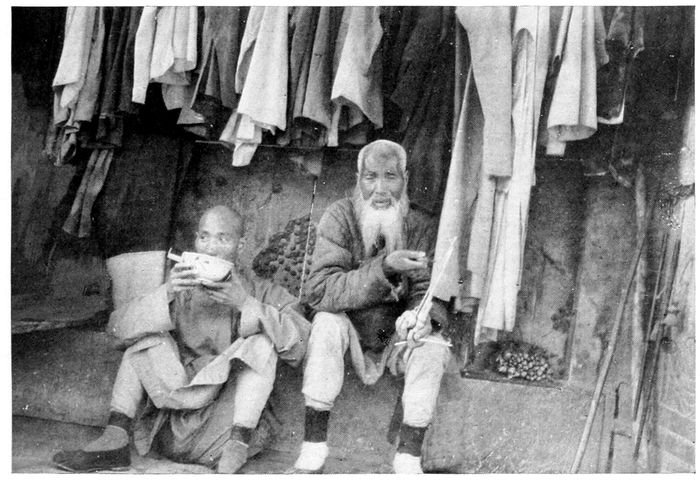

| Making two Chinese elders of a Shantung village over into Presbyterians | 288 |

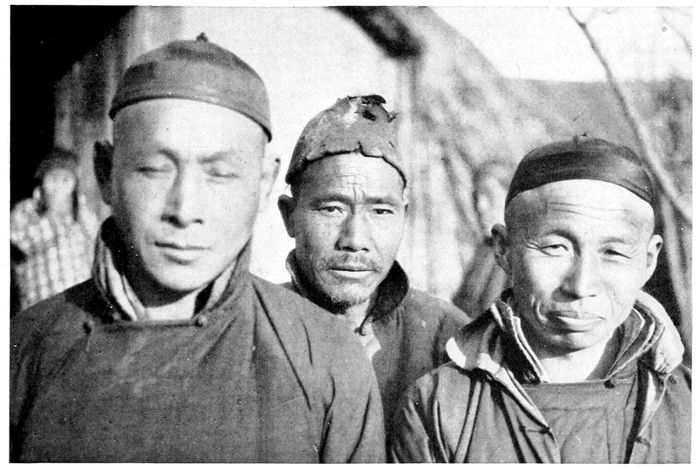

| Messrs. Kung and Meng, two of the many descendants of Confucius in Shantung flanking one of those of Mencius | 288 |

| Some of the worst cases still out of bed in the American leper-home of Tenghsien, Shantung, were still full of laughter | 289 |

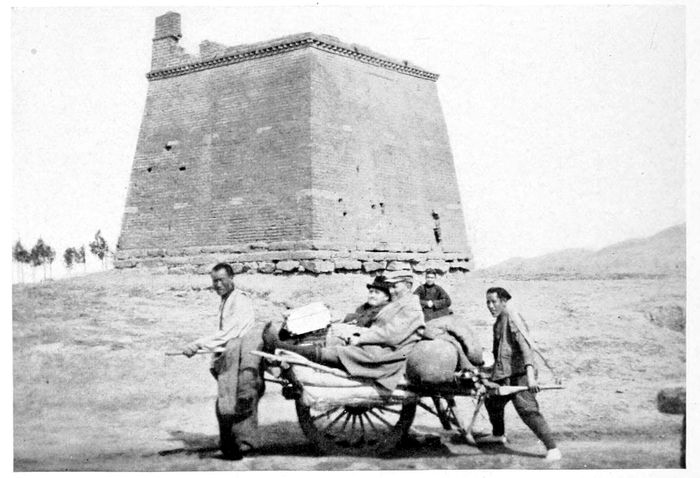

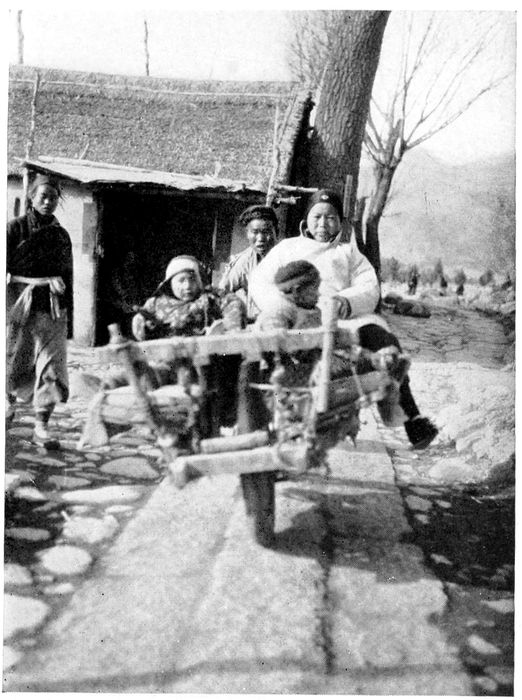

| Off on an “itinerating” trip with an American missionary in Shantung, by a conveyance long in vogue there. Behind, one of the towers by which messages were sent, by smoke or fire, to all corners of the old Celestial Empire | 289 |

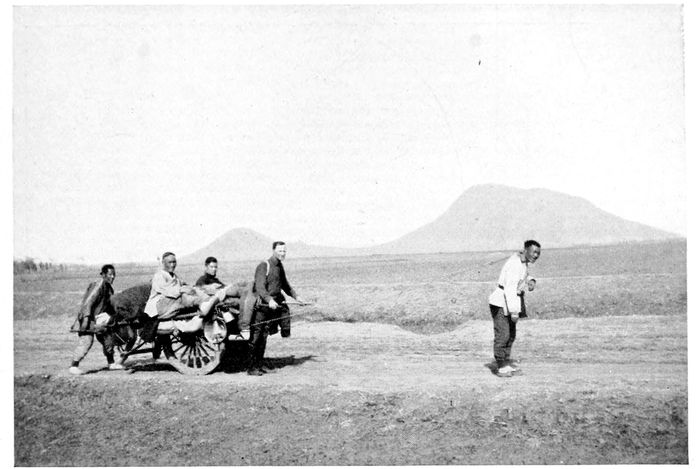

| On the way home I changed places with one of our three wheelbarrow coolies, and found that the contrivance did not run so hard as I might otherwise have believed | 304 |

| The men who use the roads of China make no protest at their being dug up every spring and turned into fields | 304 |

| Sons are a great asset to the wheelbarrowing coolies of Shantung | 305 |

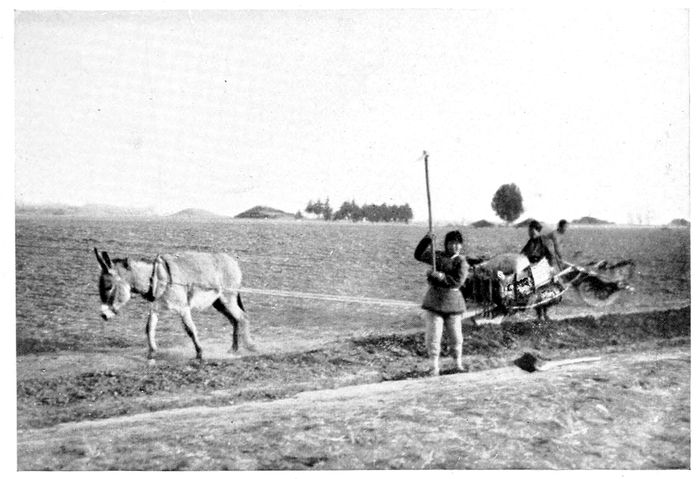

| A private carriage, Shantung style | 320 |

| xviiiShackled prisoners of Lao-an making hair-nets for the American market | 320 |

| School-girls in the American mission school at Weihsien, Shantung | 321 |

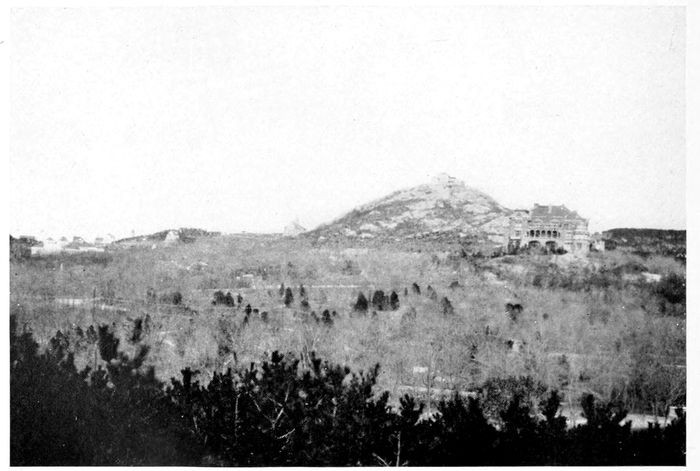

| The governor’s mansion at Tsingtao, among hills carefully reforested by the Germans, followed by the Japanese, has now been returned to the Chinese after a quarter of a century of foreign rule | 321 |

| Chinese farming methods include a stone roller, drawn by man, boy, or beast, to break up the clods of dry earth | 336 |

| Kaifeng, capital of Honan Province, has among its population some two hundred Chinese Jews, descendants of immigrants of centuries ago | 336 |

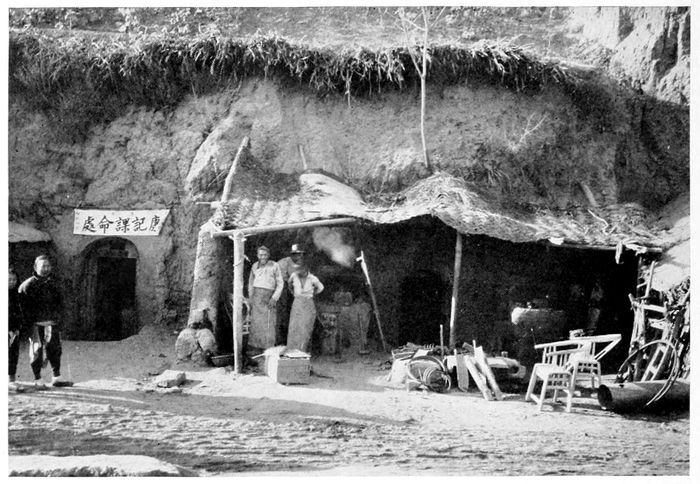

| A cave-built blacksmith and carpenter-shop in Kwanyintang where the Lunghai railway ends at present in favor of more laborious means of transportation | 337 |

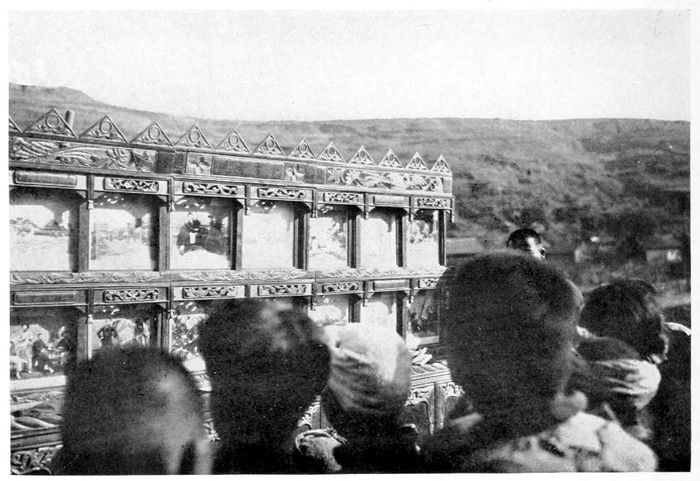

| An illustrated lecture in China takes place outdoors in a village street, two men pushing brightly colored pictures along a two-row panel while they chant some ancient story | 337 |

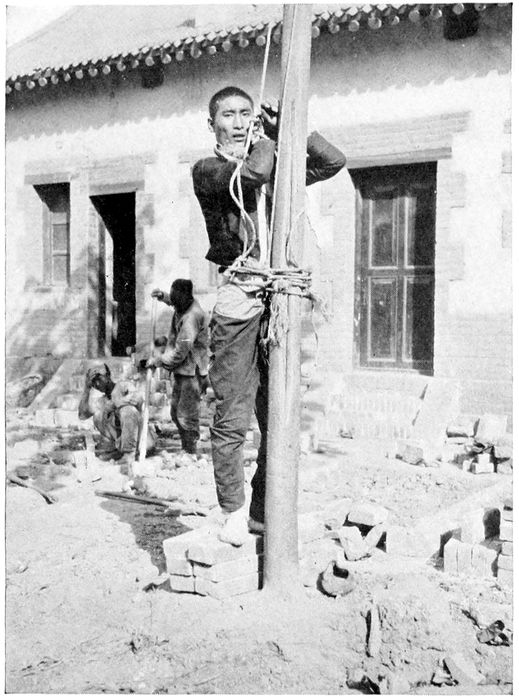

| In the Protestant Mission compound of Honanfu the missionaries had tied up this thief to stew in the sun for a few days, rather than turn him over to the authorities, who would have lopped off his head | 344 |

| Over a city gate in western Honan two crated heads of bandits were festering in the sun and feeding swarms of flies | 344 |

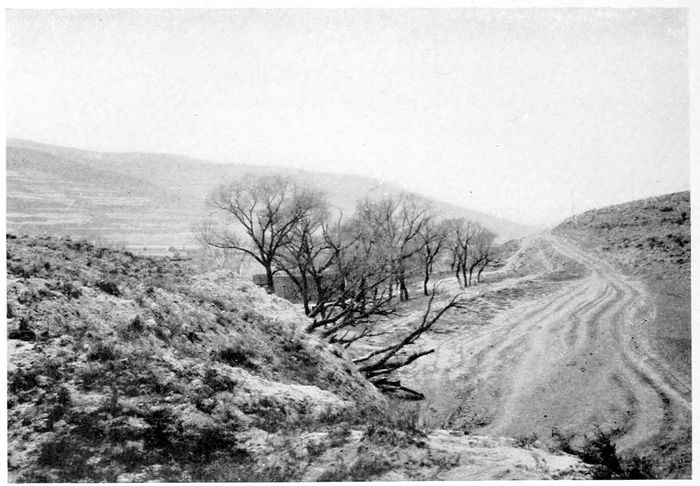

| A village in the loess country, which breaks up into fantastic formations as the stoneless soil is worn away by the rains and blown away by the winds | 345 |

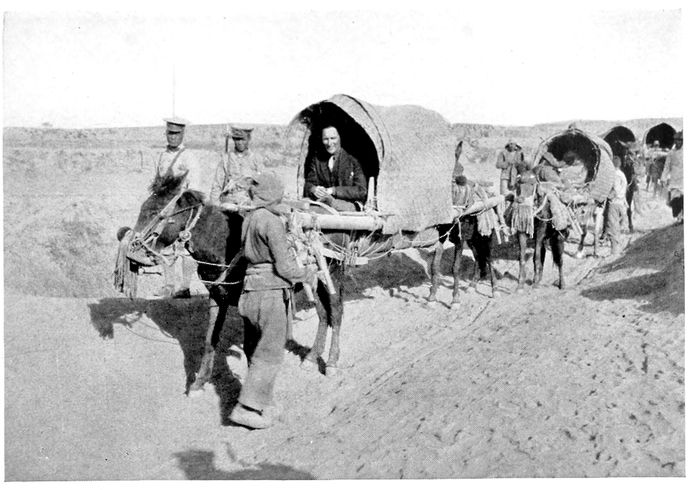

| I take my turn at leading our procession of mule litters and let my companions swallow its dust for a while | 352 |

| The road down into Shensi. Once through the great arch-gate that marks the provincial boundary, the road sinks down into the loess again, and beggars line the way into Tungkwan | 352 |

| Hwa-shan, one of the five sacred mountains of China | 353 |

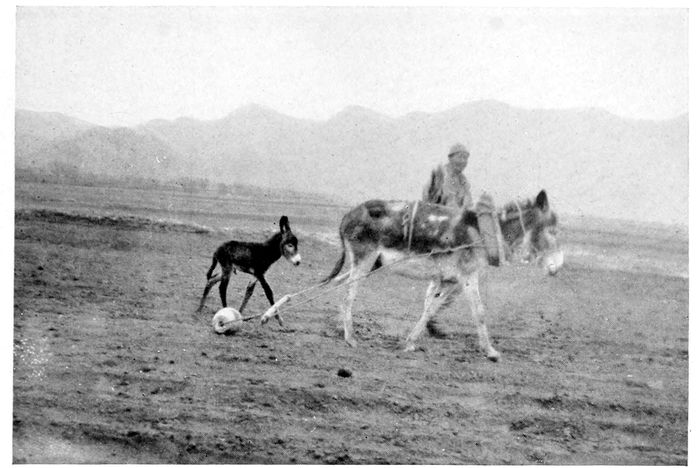

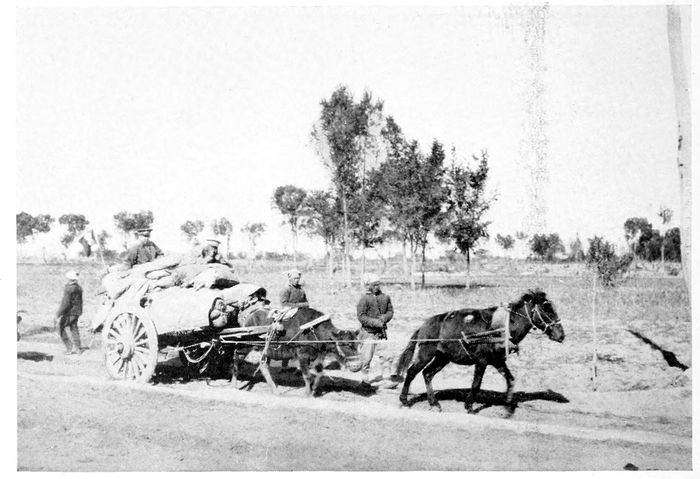

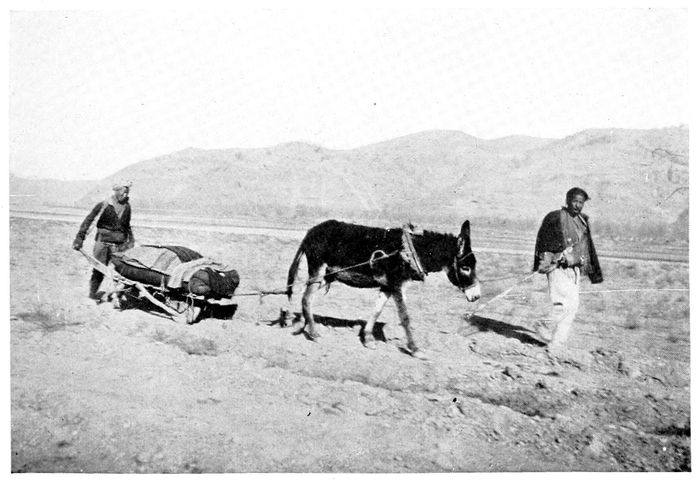

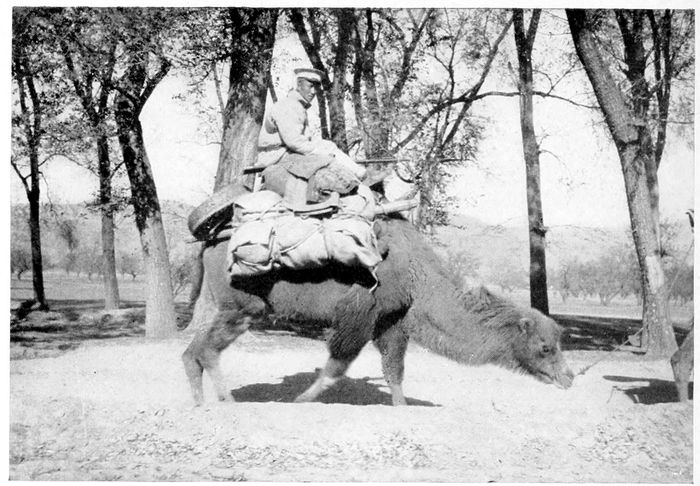

| An example of Chinese military transportation | 353 |

| Coal is plentiful and cheap in Shensi, and comes to market in Sian-fu in wheelbarrows, there to await purchasers | 360 |

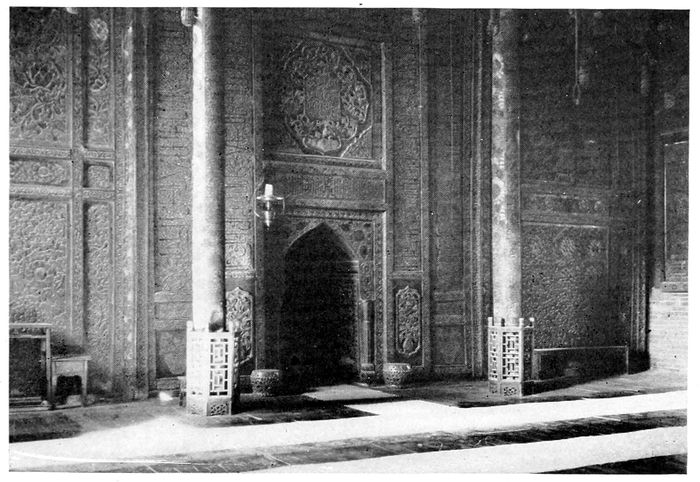

| The holy of holies of the principal Sian-fu mosque has a simplicity in striking contrast to the demon-crowded interiors of purely Chinese temples | 360 |

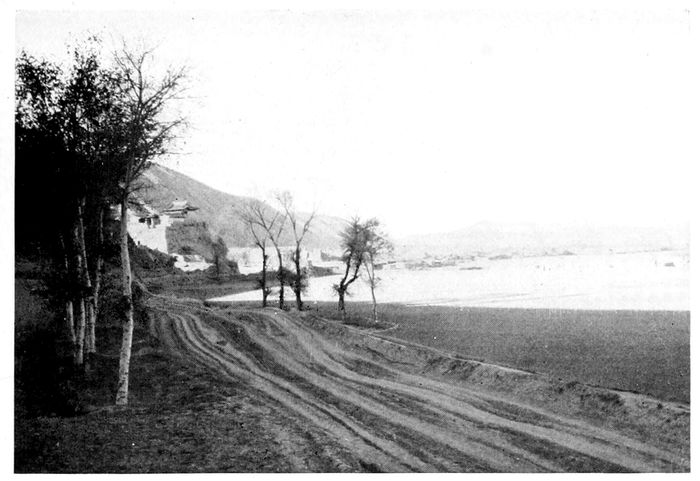

| Our carts crossing a branch of the Yellow River fifty li west of the Shensi capital | 361 |

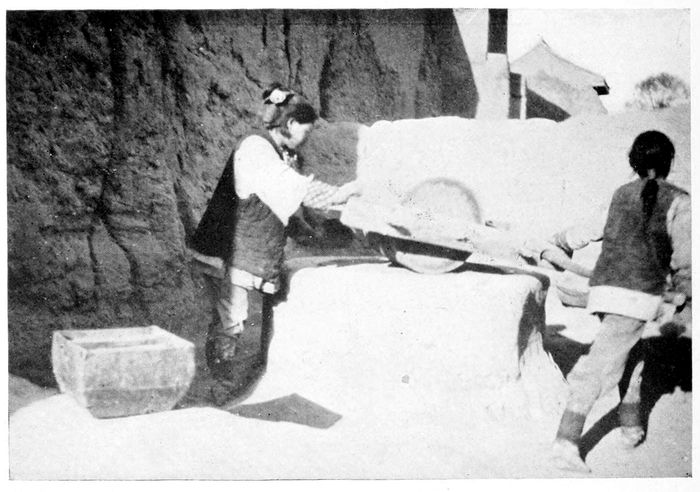

| Women and girls do much of the grinding of grain with the familiar stone roller of China, in spite of their bound feet | 361 |

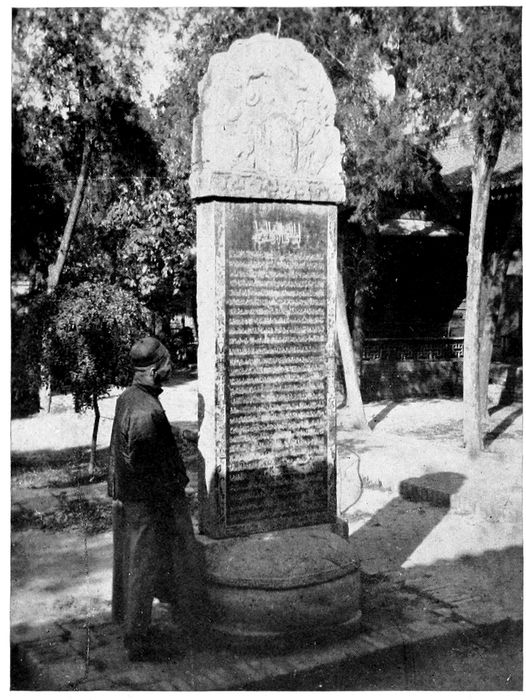

| An old tablet in the compound of the chief mosque at Sian-fu, purely Chinese in form, except that the base has lost its likeness to a turtle and the writing is in Arabic | 368 |

| This famous old portrait of Confucius, cut on black stone, in Sian-fu is said to be the most authentic one in existence | 368 |

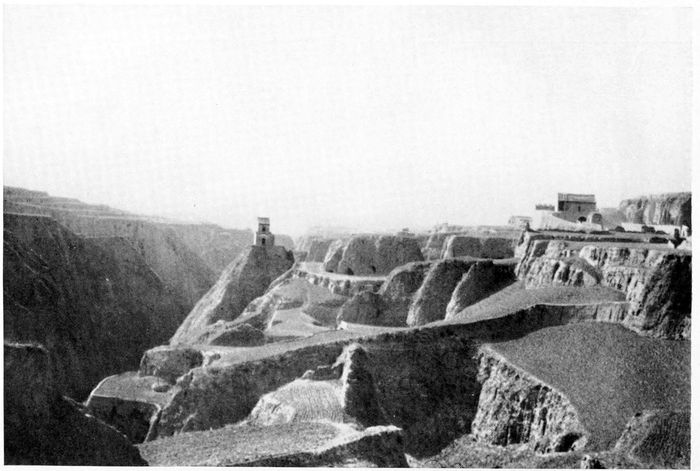

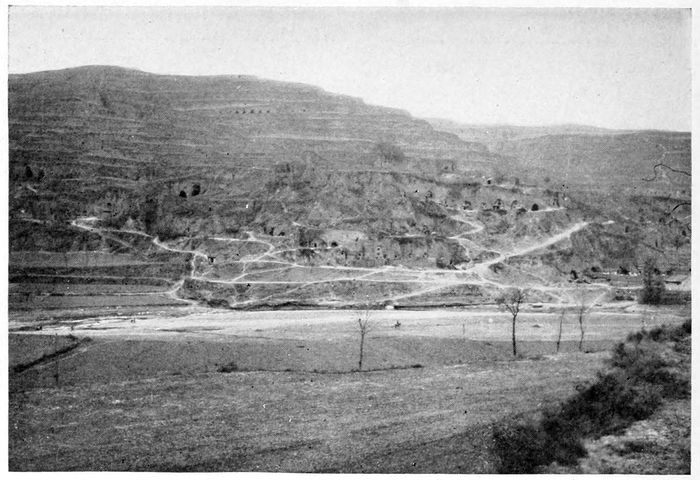

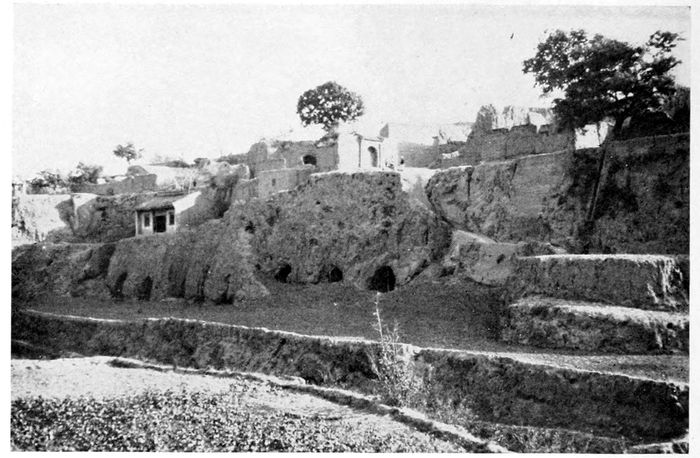

| A large town of cave-dwellers in the loess country, and the terraced fields which support it | 369 |

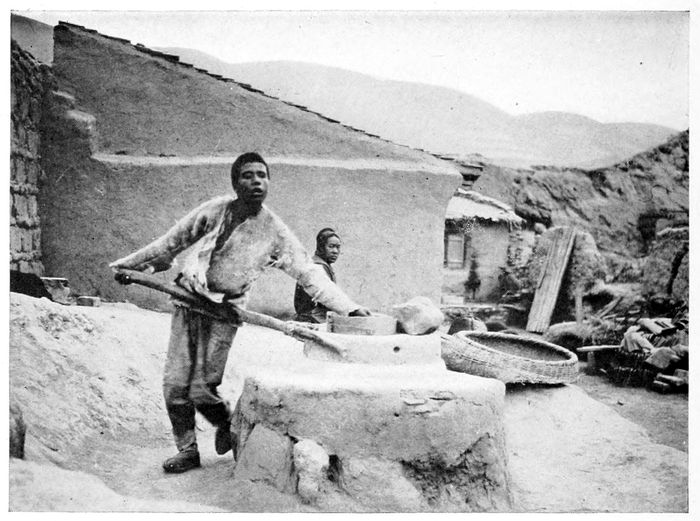

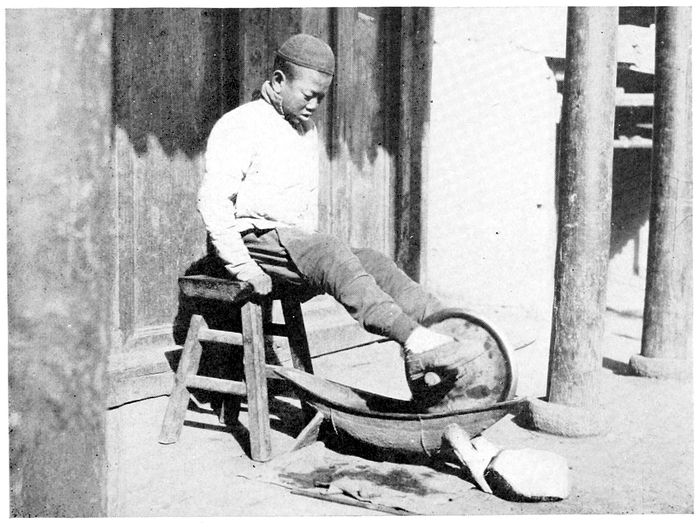

| Samson and Delilah. This blind boy, grinding grain all day long, marches round and round his stone mill with the same high lifted feet and bobbing head of the late Caruso in the opera of that name | 369 |

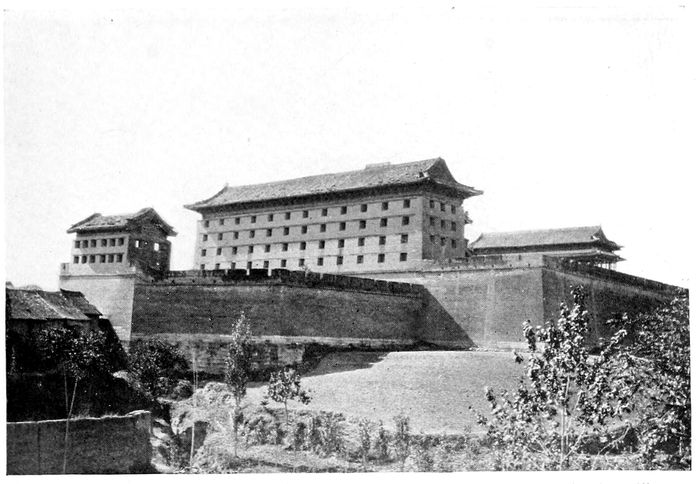

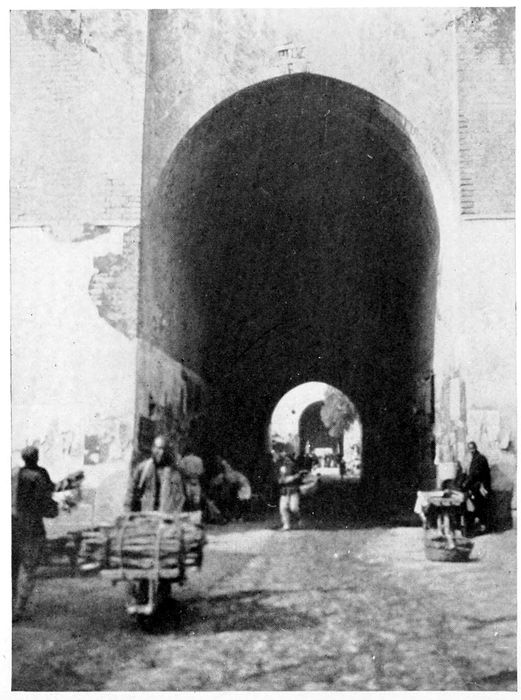

| xixThe East Gate of Sian-fu, by which we entered the capital of Shensi, rises like an apartment-house above the flat horizon | 384 |

| All manner of aids to the man behind the wheelbarrow are used in his long journey in bringing wheat to market, some of them not very economical | 384 |

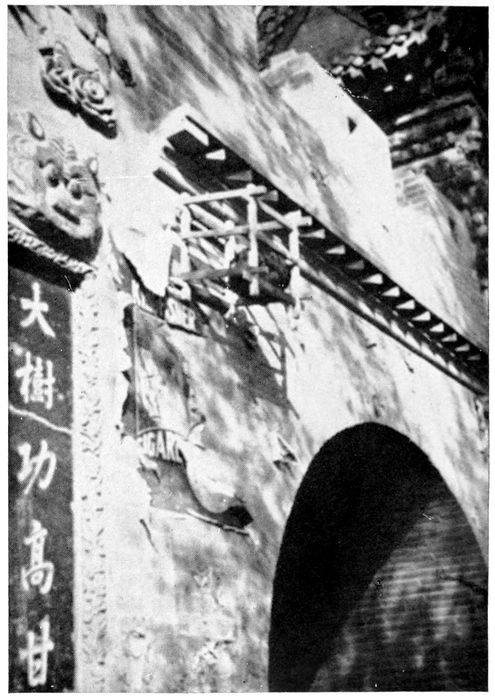

| The Western Gate of Sian-fu, through which we continued our journey to Kansu | 385 |

| A “Hwei-Hwei,” or Chinese Mohammedan, keeper of an outdoor restaurant | 385 |

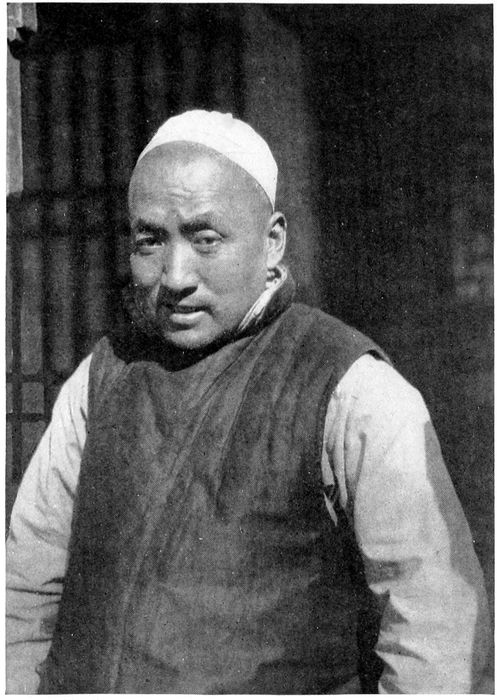

| In the Mohammedan section of Sian-fu there are men who, but for their Chinese garb and habits, might pass for Turks in Damascus or Constantinople | 400 |

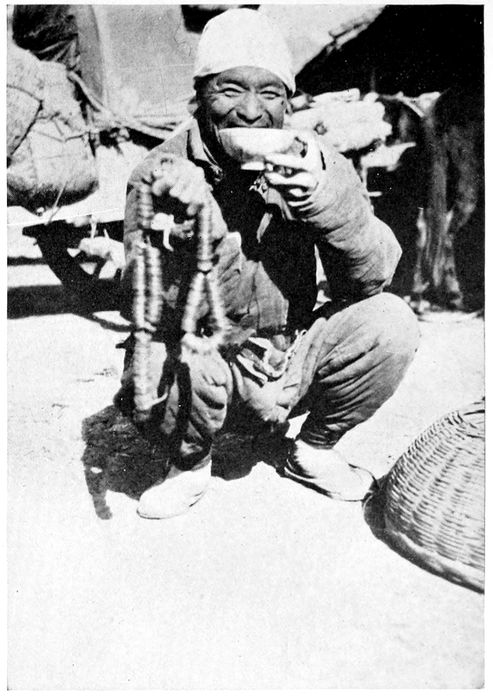

| Our chief cartman eating dinner in his favorite posture, and holding in one hand the string of “cash,” one thousand strong and worth about an American quarter, which served him as money | 400 |

| A bit of cliff-dwelling town in the loess country, where any other color than a yellowish brown is extremely rare | 401 |

| A corner of a wayside village, topped by a temple | 401 |

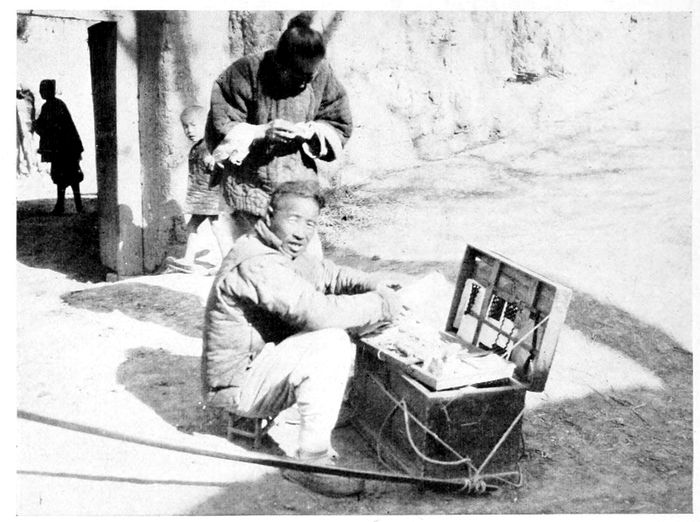

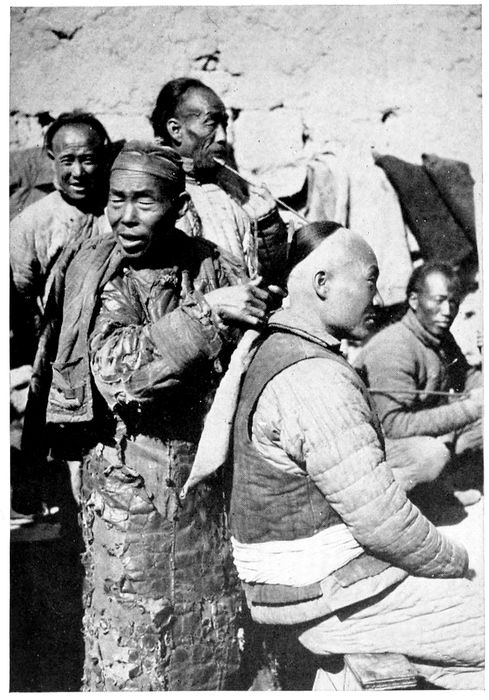

| The Chinese coolie gets his hair dressed about once a month by the itinerant barber. This one is just in the act of adding a switch. Note the wooden comb at the back of the head | 408 |

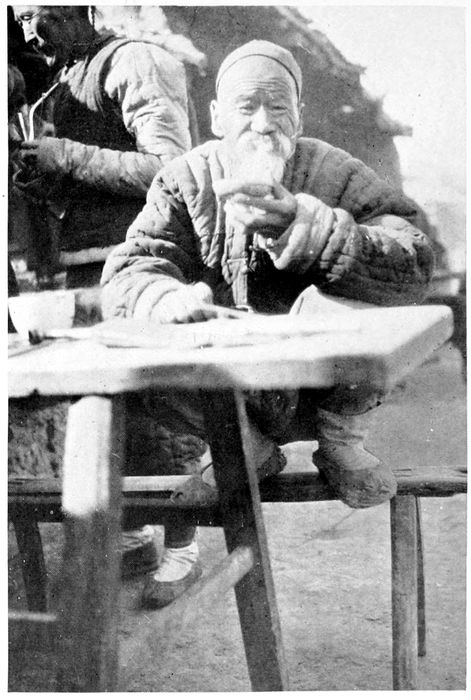

| An old countryman having dinner at an outdoor restaurant in town on market day has his own way of using chairs or benches | 408 |

| A Chinese soldier and his mount, not to mention his worldly possessions | 409 |

| Mongol women on a joy-ride | 409 |

| Two blind minstrels entertaining a village by singsonging interminable national ballads and legends, to which they keep time by beating together resonant sticks of hard wood | 416 |

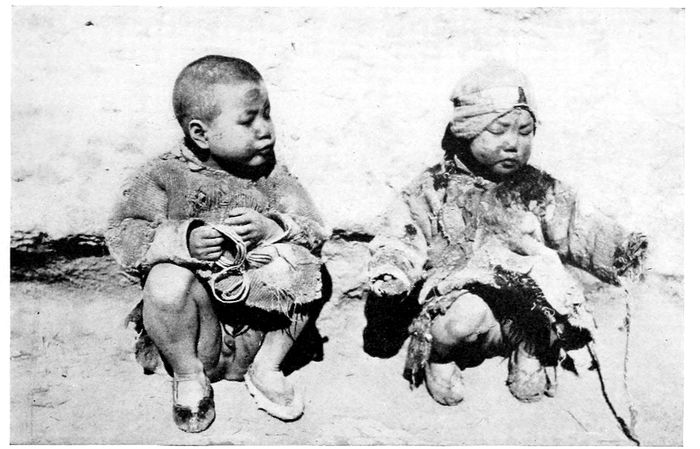

| The boys and girls of western China are “toughened” by wearing nothing below the waist and only one ragged garment above it, even in midwinter | 416 |

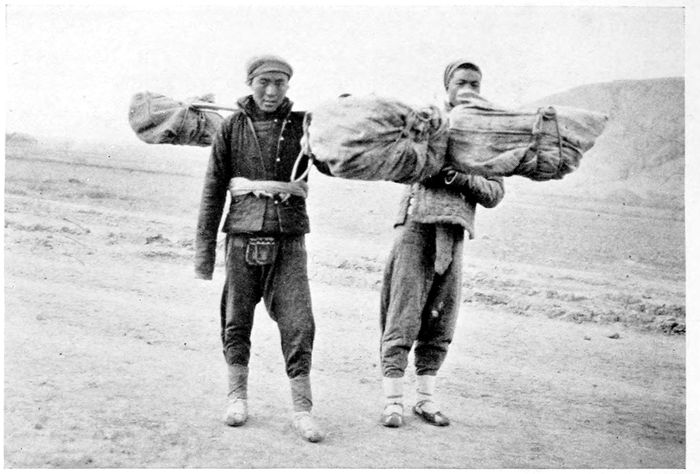

| The “fast mail” of interior China is carried by a pair of coolies, in relays of about twenty miles each, made at a jog-trot with about eighty pounds of mail apiece. They travel night and day and get five or six American dollars a month | 417 |

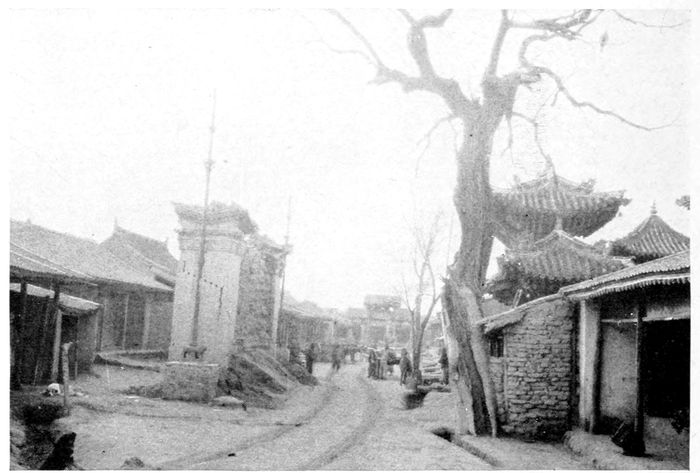

| A bit of the main street of Taing-Ning, showing the damage wrought by the earthquake of two years before to the “devil screen” in front of the local magistrate’s yamen | 417 |

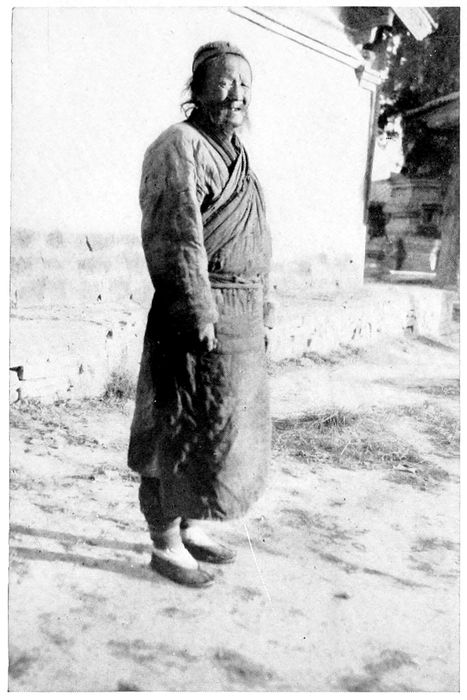

| This begging old ragamuffin is a Taoist priest | 436 |

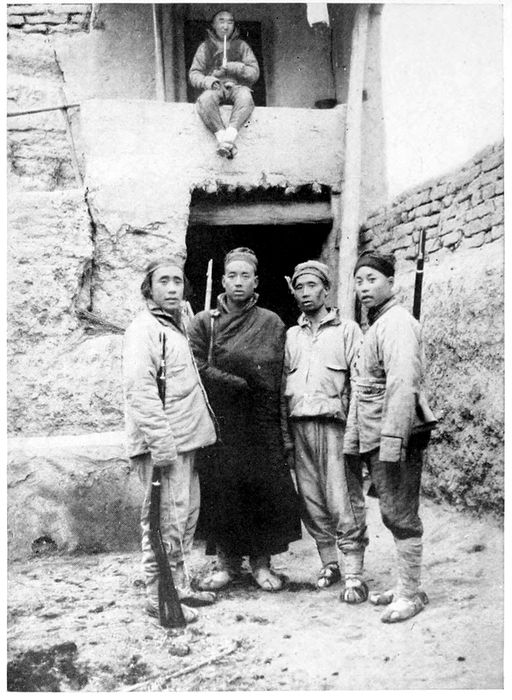

| A local magistrate sent this squad of “soldiers” to escort us through the earthquake district, though whether for fear of bandits, out of mere respect for our high rank, or because the “soldiers” needed a few coppers which he could not give them himself, was not clear | 436 |

| Where the “mountain walked” and overwhelmed the old tree-lined highway. In places this was covered hundreds of feet deep for miles, in others it had been carried bodily, trees and all, a quarter-mile or more away | 437 |

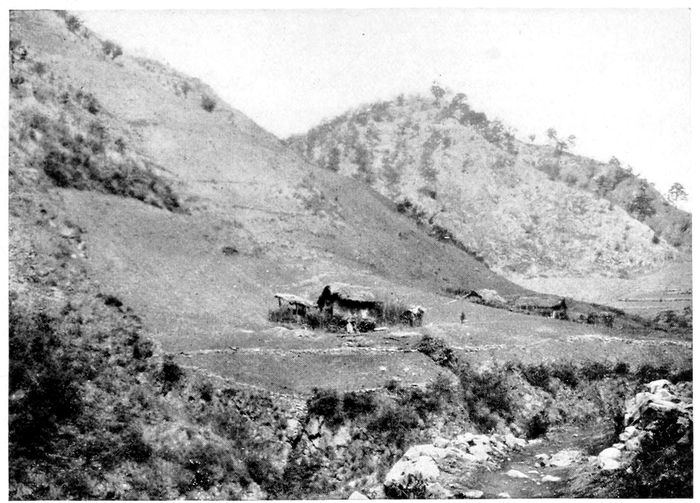

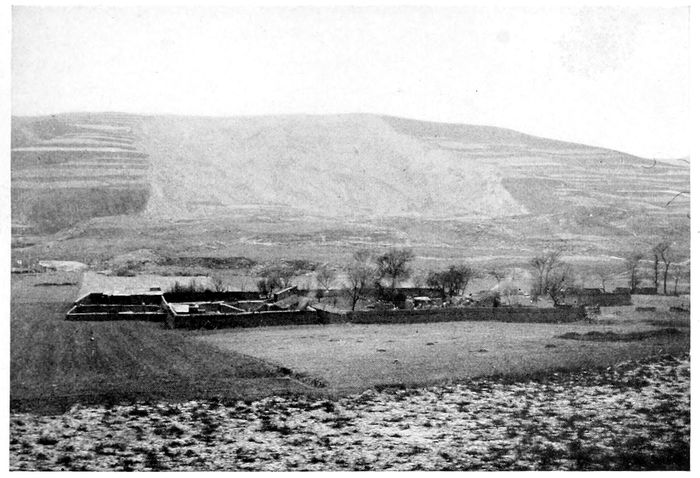

| xxIn the earthquake district of western China whole terraced mountain-sides came down and covered whole villages. In the foreground is a typical Kansu farm | 437 |

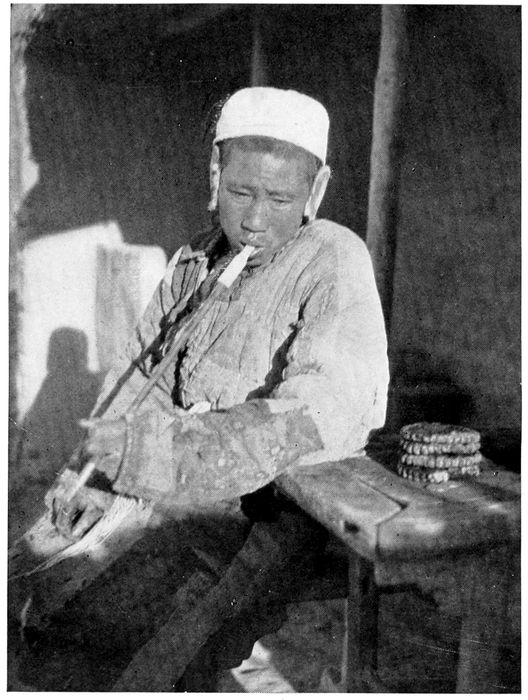

| Kansu earlaps are very gaily embroidered in colored designs of birds, flowers, and the like. Pipes are smaller than their “ivory” mouthpieces | 444 |

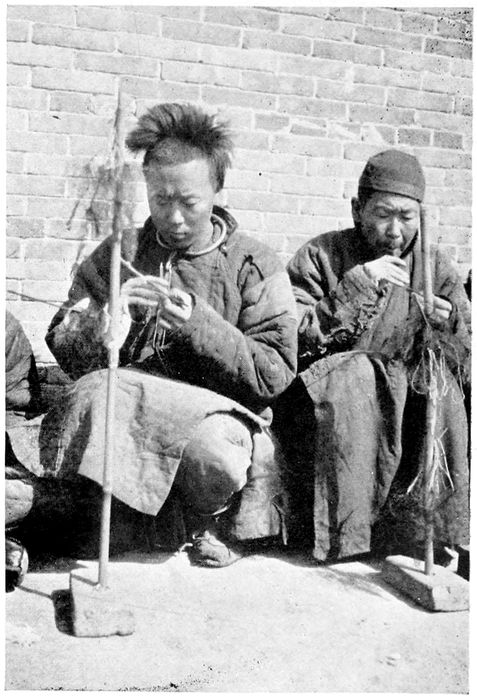

| It is a common sight in some parts of Kansu to see men knitting, and still more so to meet little girls whose feet are already beginning to be bound | 444 |

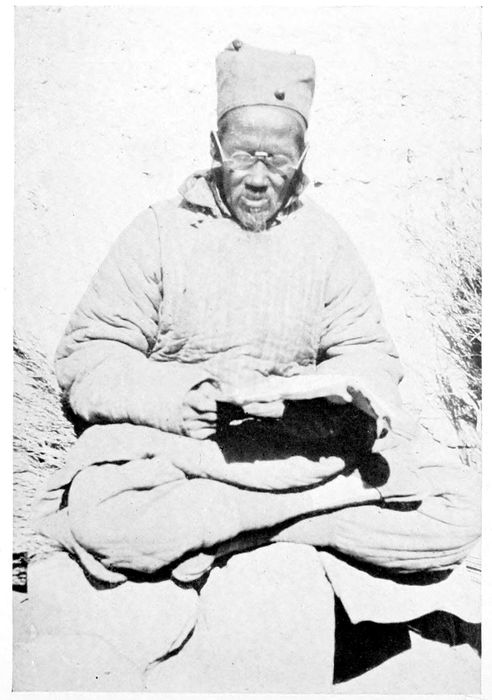

| The village scholar displays his wisdom by reading where all can see him—through spectacles of pure plate-glass | 445 |

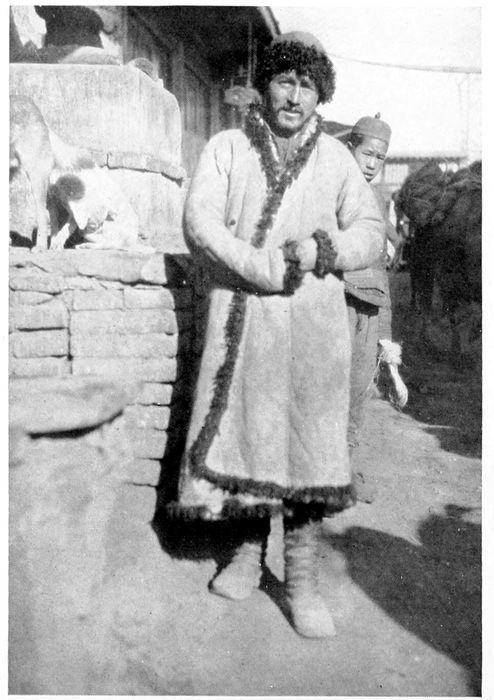

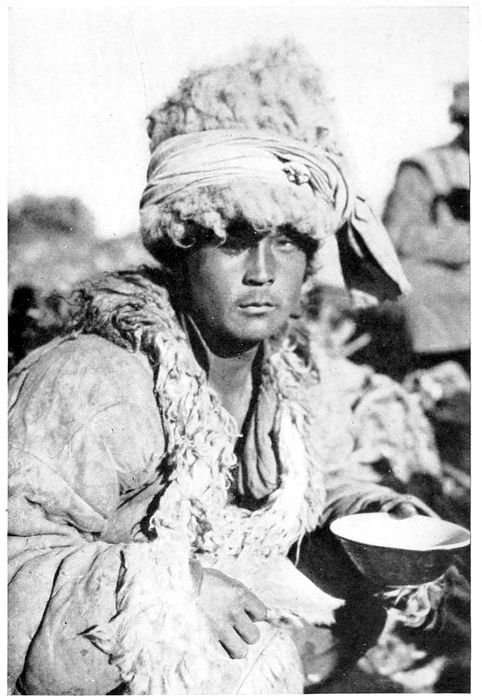

| A Kirghiz in the streets of Lanchow, where many races of Central Asia meet | 445 |

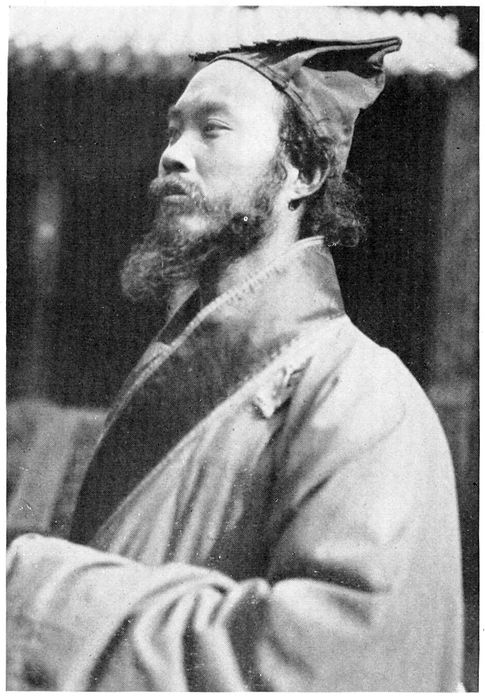

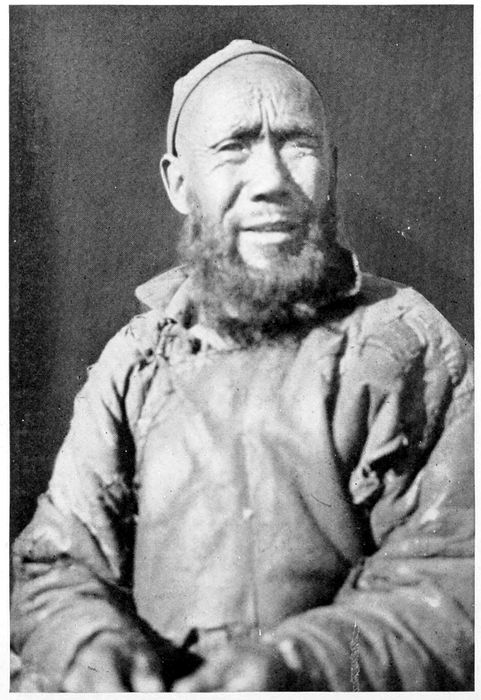

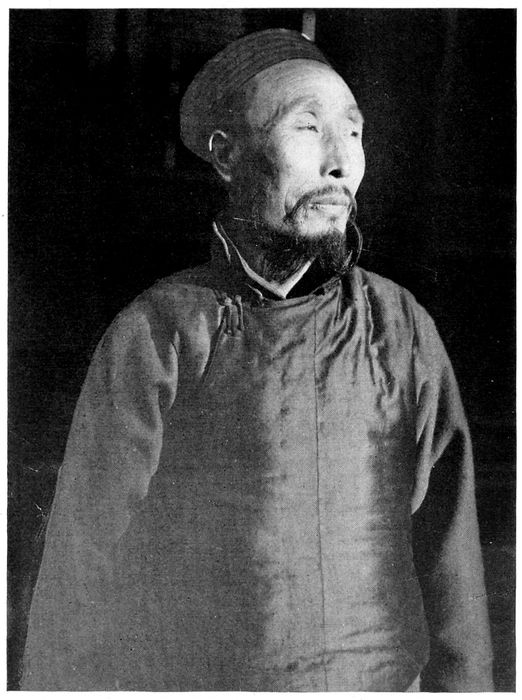

| An ahong, or Chinese Mohammedan mullah of Lanchow | 448 |

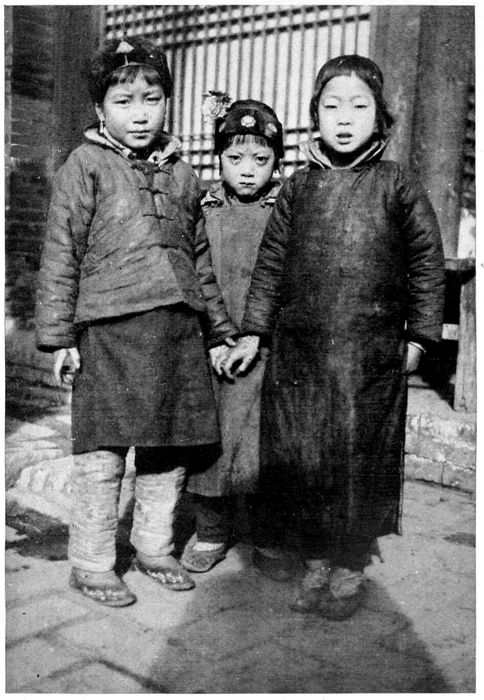

| Mohammedan school-girls, whose garments were a riot of color | 448 |

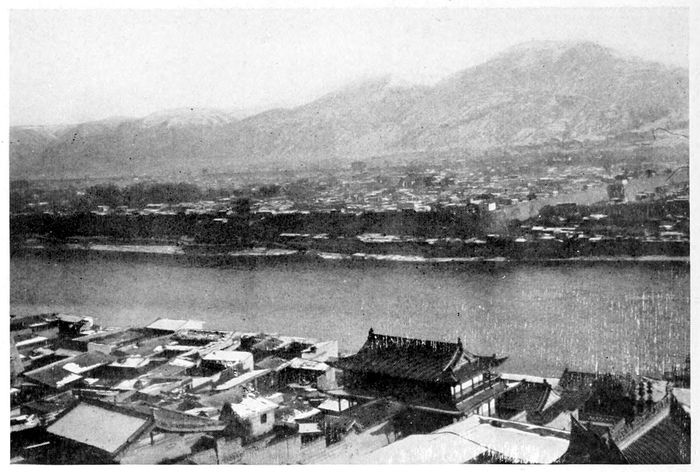

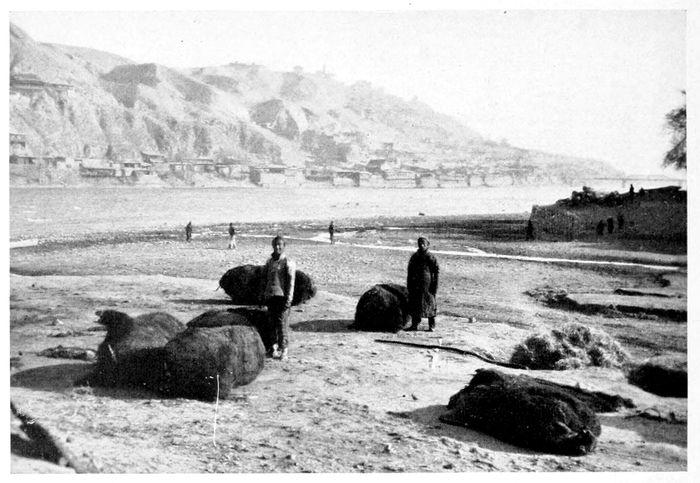

| A glimpse of Lanchow, capital of China’s westernmost province, from across the Yellow River | 449 |

| Looking down the valley of Lanchow, across several groups of temples at the base of the hills, to the four forts built against another Mohammedan rebellion | 449 |

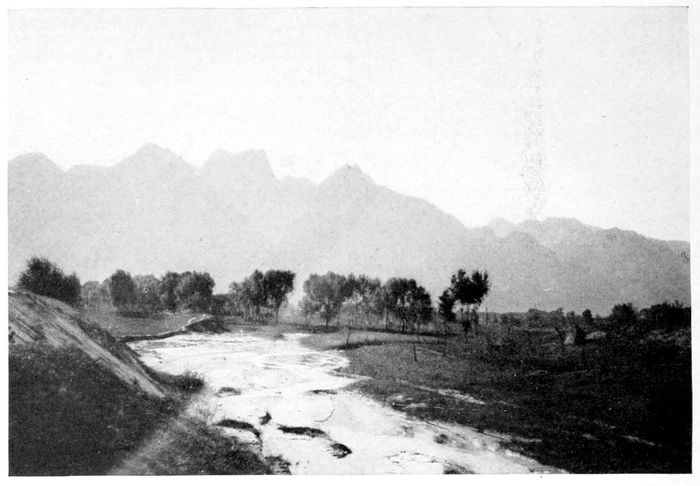

| A Kansu vista near Lanchow, where the hills are no longer terraced, but where towns are numerous and much alike | 464 |

| This method of grinding up red peppers and the like is wide-spread in China. Both trough and wheel are of solid iron | 464 |

| Oil is floated down the Yellow River to Lanchow in whole ox-hides that quiver at a touch as if they were alive | 465 |

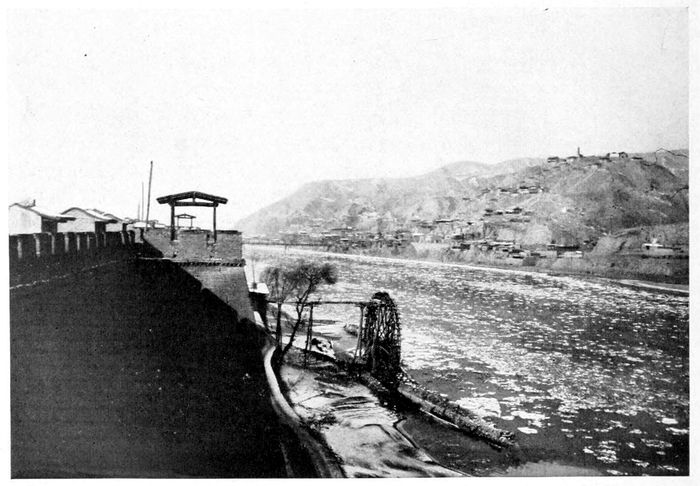

| The Yellow River at Lanchow, with a water-wheel and the American bridge which is the only one that crosses it in the west | 465 |

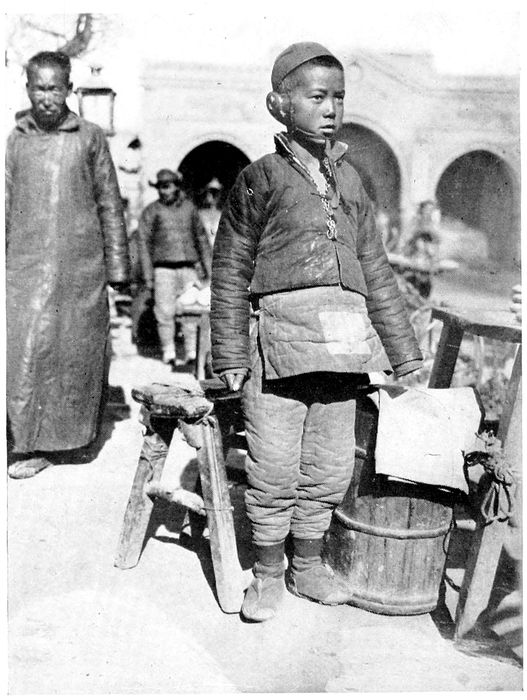

| The Chinese protect their boys from evil spirits (the girls do not matter) by having a chain and padlock put about their necks at some religious ceremony, which deceives the spirits into believing that they belong to the temple. Earlaps embroidered in gay colors are widely used in Kansu in winter | 480 |

| Many of the faces seen in Western China hardly seem Chinese | 480 |

| A dead man on the way to his ancestral home for burial, a trip that may last for weeks. Over the heavy unpainted wooden coffin were brown bags of fodder for the animals, surmounted by the inevitable rooster | 481 |

| Our party on the return from Lanchow,—the major and myself flanked by our “boys” and cook respectively, these in turn by the two cart-drivers, with our alleged mafu, or groom for our riding animals, at the right | 481 |

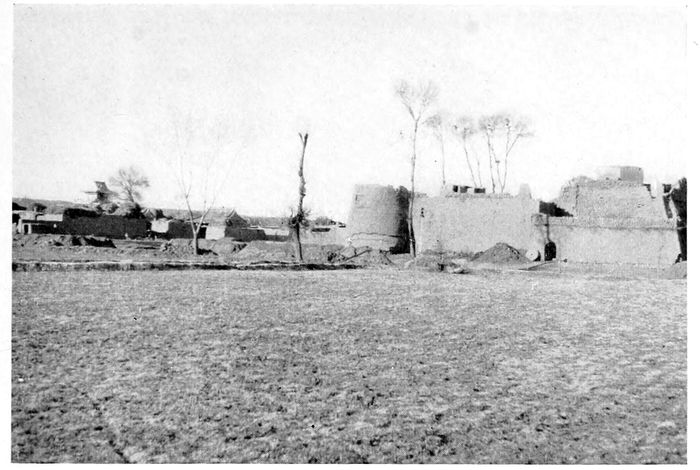

| A typical farm hamlet of the Yellow River valley in the far west where some of the farm-yards are surrounded by mud walls so mighty that they look like great armories | 496 |

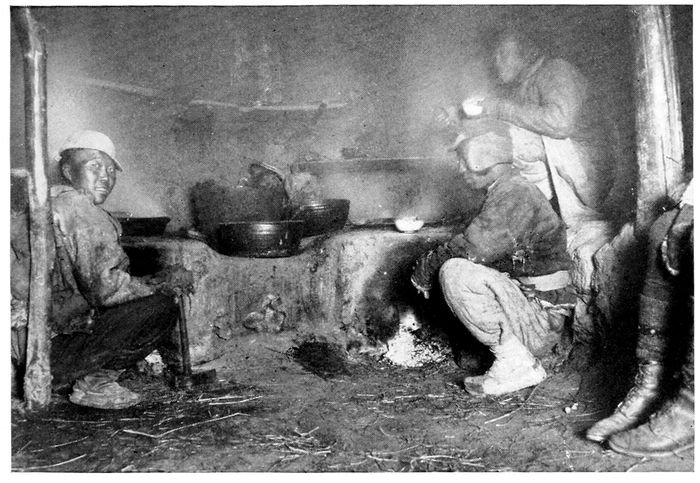

| The usual kitchen and heating-plant of a Chinese inn, and the kind on which our cook competed with hungry coolies in preparing our dinners | 496 |

| The midwinter third-class coach in which I returned to Peking | 497 |

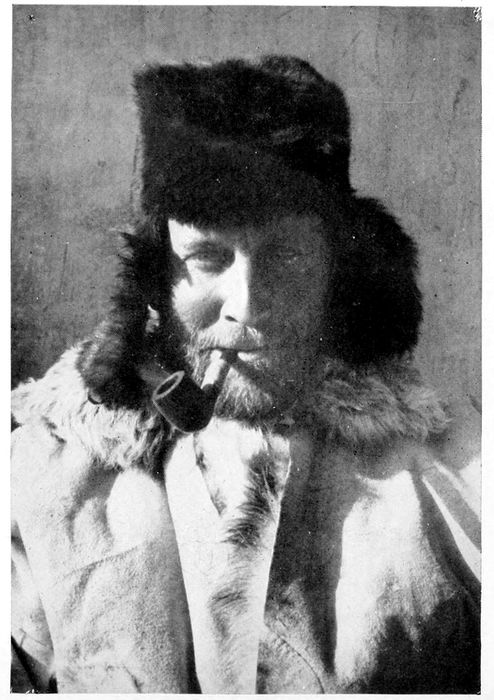

| No wonder I was mistaken for a Bolshevik and caused family tears when I turned up in Peking from the west | 497 |

The author gratefully acknowledges his indebtedness to Mr. Edwin S. Mills of Peking, China, for the use of the pictures of Urga.

The traveler from Japan to the peninsula still known to the Western world as Korea has a sense of being wafted on some magic carpet thousands of miles while he slept, a sensation which the splendid steamers bridging the Straits of Tsushima several times a day do not dispel. It is surprising how different two lands separated only by a few hours on the sea can be. A fortnight on a Nippon Yusen Kaisha liner and six weeks of wandering from end to end of the Island Empire gave us a Japanese background against which many of the problems of the Far East stood out more clearly, but it did very little to prepare us for the physical aspects of the “Cho-sen” over which the banner of the rising sun now waves. Those who have listened to the long and heated controversy over the adding of this large slice of mainland to the mikado’s realm must often have heard the apologists’ assertion that the two peoples, Japanese and Koreans, are so nearly alike as to be virtually the same. Perhaps they are; but if so, all the outward evidences the casual visitor must depend upon to form an opinion are deceiving. Superficially, at least, Japan and Korea are as different as two Oriental lands and races could well be. In landscape, customs, costumes, point of view, general characteristics, even in the details of personal appearance, the two shores of the Sea of Japan strike the new-comer as having very little in common.

Perhaps the most outstanding feature of Korea, to any one newly arrived from Japan, is her treelessness. The lack of forests is, with the possible exception of exclamations of incredulity over her extraordinary costumes, almost certain to be the subject of any Occidental’s first paragraph of Korean notes. In our own case this denuded 4aspect of the peninsula was emphasized by the blazing, cloudless sunshine that beat relentlessly down during all our first day of travel northward to the old capital, and on many another to follow. The bare and sun-scorched landscape suggested some victim of barbarian cruelty, who, stripped of his garments, was being tortured to death by slow roasting. Possibly we should have been prepared for this, but we were not. We had heard much of the doings of Japan in Korea; we knew something of the opera-bouffe hats of the men and the startlingly short waists of the women, but no one had ever told us of the curiously pure and molten sunshine of “Cho-sen,” of the vividness of its shadows and the filtered transparency of its air, nor, for that matter, of the incessant heat we must endure because chance allotted us from June to August in what was once the Hermit Kingdom.

Trees as sparse as the hairs of a Korean beard stood out in lonely isolation across the more or less flat lands of all that first day’s journey; beyond these, usually rather near at hand, rose scarred and repulsive hillsides as unsightly as the faces of those countless inhabitants along the way who had been visited by the “honorable spirit” of smallpox. It was not merely the barrenness of a naturally treeless country, a barrenness as dreary as those upper reaches of the Andes to which real vegetation never attains, but one which, like the denuded plains of Spain, visibly complains of the wanton violence of man. To be sure, many of the rocky hills that sometimes rose to be almost mountains were here and there thinly covered with evergreen shrubs which might some day be trees, and even forests. But these, travelers are informed with what becomes tiresome persistency, were planted by the new Government. The Japanese policy of reforestation, we were eventually to know, has already done excellent things for Korea, and that not merely, as those who resent the rape of the peninsula assert, where it will attract the passing tourist’s eye, and it promises in time to accomplish something worth while; but it is an unfortunate Japanese trait to fear that good deeds will not speak loudly enough for themselves.

The reducing of a once well wooded land to its present nude state is characteristic of the Korean, we were to learn, suggestive of his general point of view. In the olden days the people were often driven to the hills by their savage or demented rulers, and as the rigorous winters that contrast with the tropical summers came on, they not only burned the trees, but as roots make excellent charcoal they dug up even these, leaving nothing that might by any chance sprout again. To replant in better times, to take any serious thought for the morrow, 5would have been un-Korean. The Korean even of to-day who covets the half-dozen cherries or plums on a limb does not usually take the trouble to pick them; he breaks off the branch and goes his way munching the fruit, with never a thought of next year. Translate this improvidence, this almost complete lack of foresight, into all the details of daily life, and the condition and the final fate of Korea become understandable, in fact inevitable.

Woods survive to any great extent in Korea only in two places—about royal tombs and up along the Yalu River which forms the northern frontier. Elsewhere in the peninsula, with minor exceptions, there are only groups of trees planted by foreign missionaries, and rows of pine shrubs set out directly by the Japanese Government, or by local authorities, school children, or private individuals, under Japanese influence. This treelessness is not the unimportant detail many may think; it is the wanton destruction of her forests of long ago that gives the Korea of to-day her mainly mud houses, much of her filth, dust, and swarming flies, and those devastating floods of the rainy season which sweep roads, bridges, fields, and even villages before them.

There were many other things which gave the Korean landscape its strikingly un-Japanese aspect. Fewer people were working in the larger and less garden-like fields; the village roofs thatched with rice-straw had a flatter, smoother look than the homes of Japanese peasants; the towns themselves seemed to huddle together as closely and inconspicuously as possible, as if to escape, or join in resisting, the rapacious tax-gatherers of the olden days that are not forgotten. Koreans in white, their inevitable color, so rare in Japan, were everywhere, though more often in the shade of villages or rare wayside trees or huts than out in the baking sunshine. The suggestion forced itself upon us that perhaps the fields were larger because the people could not coax themselves to work alone. In Japan it had been unusual to see more than a peasant and his wife in the same field; here work seemed to be done almost entirely by gangs. In spite of the general aridness of the landscape, there were many flooded rice-fields, and in nearly all of them waded a soldier-like line of often a dozen laborers, as many women as men among them. Much of the country showed no signs of the languid hand of man, yet even in the drier sections scattered rows of these peasants, their garments still almost snow-white at a distance, gleamed forth in the otherwise mainly reddish landscape.

Similar groups stood in semicircles on earth threshing-floors flailing 6grain in a way that is familiar to the Western world, but which we had never seen in Japan. Nor were there any reminders of the Island Empire in the clusters of women kneeling at the edge of every bit of a stream or mud-hole paddling clothes with a sort of cricket-bat. The ways of life, the very architecture, were strangely reminiscent of lands inhabited by negroes.

The most primitive of plows, drawn by bulls, dragged their way to and fro in a field here and there. Along what passed for roads others of these lumbering animals plodded almost hidden under loads of new-cut grain or brushwood, at a pace which seemed to fit the languid temperament of the country. In places a highway, constructed by the new rulers, tried to preserve an unbroken march; but wherever a bridge should have been they almost invariably pitched headlong down into the bed of a stream as waterless as those of summer-time Spain. Even the Japanese, we were to learn before leaving the peninsula, are poor bridge-builders, while the Korean remains true to his natural improvidence in constructing flimsy things of branches and earth, with totally inadequate abutments, which the first dash of the rainy season down the treeless hillsides converts into scattered masses of rubbish.

All the day long the scene varied little from these first few glimpses. There was a certain rough beauty in the tawny hillsides and the broad stretches of sun-flooded rice lands, but of a similarity that grew monotonous, while the ways of the people, until opportunity should come to see them in closer detail, were such as the fleeting tourist is wont to sum up under the outworn word “picturesque” and quickly lose from between the pages of memory. Korea has often been called a land of villages, and in all the two hundred and eighty miles from the southern point of the peninsula to Seoul there was little more than a frequent succession of smooth-thatched, closely snuggled towns varying, outwardly at least, only in size. Not until later on, and by more primitive means of travel, were we to know of the remnants of bygone civilization, the pine-grove tombs of royalty, the ruined palaces of fallen dynasties, and the welter of modern problems with which the peninsula teems.

The Korean wardrobe has so little in common with that of the Occident, and includes so many startling absurdities, that it merits a few words in detail, even though some of its more striking features are fairly familiar to those interested in foreign lands. To begin with the basis of all wardrobes, there is that ingenious contrivance with 7which the Korean gentleman protects his other garments from perspiration during the blazing months of summer. A missionary who carried home a set of these and offered them to any one in his native parish who could identify them recorded forty-two guesses, all equally wide of the mark, which was the simple phrase “summer underwear.” Out of their environment these useful garments look more like primitive bird-cages or light baskets than what they really are. In their entirety they consist of a kind of waistcoat, a high collar of the Elizabethan period, and cuffs so long as to be almost sleeves—all made of small strips of ratan very loosely woven together. That they are effective in allowing the free circulation of air, and at the same time preserve the cloth garments from contact with the perspiring body, one is willing to grant without the evidence of actual personal experience. Now and again one runs across a Japanese petty official who, in an effort to mitigate his midsummer sufferings, has adopted at least the cuffs; but on the whole this ingenious contribution is likely to suffer the common fate of never finding appreciation beyond its native habitat.

Over his ratan skin-protectors the Korean gentleman wears a kind of waistcoat-shirt, trousers (if so commonplace a term may be used for so uncommonplace a garment) which are more than voluminous even in use and, when hung out to dry, suggest the mainsails of a wind-jammer, and finally a turamaggie, an overcoat reaching to the calves and tied together with a bow over the right breast. All these articles are snow-white, and in summer are made of a vegetable fiber so thin as to suggest starched cheese-cloth. The mainsail trousers are fastened tightly about the ankles with a winding of cloth, which also supports the carefully foot-shaped and curiously thick white socks, which are thrust into low slippers cut well away at the instep, slippers formerly of leather richly embroidered or otherwise decorated, but now rapidly giving way to the white or reddish rubber ones made in Japan which are ruining the feet of Korea. The crowning glory and absurdity of this de rigueur costume, however, is the head-dress. About the brow is bound, so tightly as to cause violent headaches when first adopted and to leave lifelong marks, a black band about four inches wide and reaching well up over the curve of the head. On top of this sits a brimless cap shaped like a fez with an L-shaped indentation in its front, and finally over all else reigns an uncollapsible opera-hat. Both the hat and the cap beneath it are made of horsehair, or cheap imitations thereof, and are so loosely woven and screen-like in their transparency that facetious and unkindly foreigners are wont 8to refer to them as “fly-traps.” This term is as unwarranted as it is offensive, for the one place in Korea which is free from flies in season is the hat-protected crown of the adult Korean male. One need not take the word of “old-timers,” but will find ample evidence in photographs of a decade or more ago that the opera-bouffe contraption with which the Korean gentleman tops himself off once had brim enough to do duty almost as a real hat. Such utilitarian days are past, however; perhaps it is that universal bugbear of the human family, the high cost of living, which has reduced the brim to little more than a ledge. The fact remains that a fly must walk with caution now in making a circuit which in the good old days he might safely have accomplished after sipping long and generously at the edge of a bowl of sool. However, let there be no misapprehension, no uncalled for sympathy under the impression that this shrinking has worked hardship upon the wearer. The Korean hat was not designed to be a protection for the head and a shade for the face. Its purpose in life is far more serious and is concentrated on one single object,—to protect from evil spirits the precious topknot which is the badge of full Korean manhood. Hence its duty is not merely an outdoor one; wicked beings of the invisible world have no compunction in taking unfair advantage of their victims, so that to this day it is a common practice for the Korean man to lay him down to sleep—on his bare papered floor, using a hardwood brick as a pillow—with his precious top-hat still in place.

However, we have not yet completely garbed our yang-ban, our gentleman of the Land of Morning Calm. His hat, being light, almost ethereal, in fact, must be held in place, whether in sleep or in the slightest breeze, for which purpose a black ribbon under the chin serves the ordinary man and a string of amber beads his haughtier fellow-citizen. Add to this the unfailing collapsible fan, and a pipe as long and heavy as a cane, with a bowl the size of the end of the thumb, and you may vizualize in his entirety the proud gentleman who sallies forth from his mud hut and picks his way leisurely between the mud-holes and offal-heaps of any town or city street. The fan is rarely inactive, now dispensing a breeze to the copper-tinted face of its owner, now shading it from the direct rays of a burning sun. The pipe, bowl down, swings with the jaunty aggressiveness of an Englishman’s “stick”; above all else the features remain fixed and unalterable in their serenity, for in the code of the genuine Korean gentleman of the old school there is no greater vulgarity than to show in public either mirth, anger, curiosity, or annoyance. Nothing could be more 9specklessly white than this dignified apparition, for do not his servant-wives spend their days, and no small portion of their nights, in preparing his garments for the daily sortie and mingling with his fellows? Behold him, then, as he joins the latter, in a shop-door or on a shaded street-corner, where he squats with them in that fashion which has caused a row of Korean males to be likened to penguins, letting his spotless starched turamaggie spread out on the unswept earth with a carelessness which seems a boast of his ability to command unlimited female labor.

We must come back again, however, to the incredible hat, as the eyes and the attention constantly will as long as one remains in Korea. If the Japanese are commonplace and unoriginal in their head-dress, certainly their newly captured fellow-subjects make up for it. Set usually at a jaunty angle, whether by design, breeze, or cranial malformation, a jauntiness enhanced by its scarcity of brim, the “fly-trap” hat furnishes Korea half its picturesqueness. Graduates of modern mission or Japanese government schools, self-complacent young men who have been abroad, native Christian pastors, may wear the Panama or the felt of the West above their otherwise national white garb, but the “fly-trap” is still the prevailing head-dress throughout the length, breadth, and social strata of the peninsula. Far and wide, in city or village, in crowded marts or on lonely country roads, indoors or out, awake or asleep, the high hat is seldom missing. It persists to the very edge of the frontier, then disappears as suddenly as it had sprung up at the other extremity of the country. After one has weathered the first shock it does not look so greatly out of place on your city gentleman, but I never learned to behold it with proper equanimity on the heads of porters, plasterers, and peasants. Even the workman without it, however, is still conspicuous. Tattered, soiled, and sun-scorched men wandering across the country with a kind of tramp’s pack on their backs wear the horsehair bird-cage on their heads; perhaps the most incongruous sight of all is to behold a battered old man of the rice-fields solemnly squatting on a garbage-heap in his mud hamlet, with his opera hat perched on guard above his gray and scanty topknot.

Once or twice we caught a glimpse of the light-brown hat formerly worn by all men about to be married, or to add a new wife to their collection of servants; once the custom was wide-spread of painting the hat white in sign of mourning, but to-day black is almost universal, and an excellent foil to the otherwise white garb. Bridegrooms no longer feel compelled publicly to announce their happy status, and there 10is another and more effective means of showing grief at bereavement,—a mourner’s hat like a large, finely woven, inverted basket with scalloped edges, which completely hides the afflicted face of the wearer. As he ambles along under this ample protection instead of blistering beneath a horsehair cage, surely a feeling of gratitude toward the departed relative must pervade the thoughts of the bereaved, particularly as the Korean term of mourning lasts for three years. There is a still more enormous, very coarsely woven, sunshade worn by peasants in the midsummer months, while Buddhist priests, otherwise indistinguishable from layman tramps and beggars, wear a smaller hat of similar shape to that of the mourners, but raised on bamboo stilts well above the head. The horsehair hat is costly, by Korean standards, the better ones even by our own, and, being put together with glue, is frail and perishable. Water is particularly fatal to it. Let the first drop of a shower fall, therefore, and from within the garments of every Korean man appears a hat-umbrella, a little cone-shaped cover of oiled paper or silk, like a miniature Japanese parasol, which is quickly opened and slipped over the precious hat. As to the rest of the male garb, no damage is possible which cannot be repaired by the return of sunshine or a few hours’ labor by the women at home. Thus on a rainy day the black heads above white bodies characteristic of all Korea turn to drenched cheese-cloth surmounted by oily yellow clowns’ caps.

It is fitting that the wardrobe of the insignificant sex should be simpler, and more easily described. Except that anything in the way of head-dress is denied them, lest they compete with the decorative male, the garb of the Korean women is in the main a crude replica of that of the men. All reasonably available evidence goes to show that the women are never permitted the luxury of wickerwork undergarments. Trousers, socks, and slippers are similar to those worn by the male; above these is the thinnest and slightest of garments, which barely covers the shoulders, and over the trousers is worn a white skirt fastened well up above the floating ribs. In summer at least that is all, except in a few old-fashioned communities, where a muffling white cloak covering everything except the eyes and the feet is still occasionally seen. That, I repeat, is all, and from our puritanical point of view it is not enough. For the Korean woman insists that the waistline is at the armpits, and makes no provision to have the upper and lower garments contiguous, with the result that she displays to the 11public gaze exactly that portion of the torso which the women of most nations take pains to conceal. Missionaries, who are as prone as the rest of us to lose their native point of view through long contact with other races, assure us that Korean women are extremely modest. In general deportment the statement holds water; but a married lady of Korea, marching down the main thoroughfare of one of our cities in her native garb, would be granted anything but modesty. One might fancy that the costume was prescribed by some lascivious tyrant of olden days; those who have looked deeply into the matter, however, assure us that it is due to the pride of motherhood. The fact remains that, though the precept and example of Western nations have tended to lengthen the upper garment among better-class women of the cities, and particularly among those who have attended modern schools, the great majority of the adult female sex in Korea still wear their breasts outside their clothing. Sun-browned and leather-textured as the face, the plumpness of matrons or the withered rags of age are almost always in plain, not to say insistent, evidence. In fact neither the men nor the women of the masses often succeed in making both garments meet; males below the turamaggie class as habitually display their navels as their wives do their bosoms.

White is as universally the color of Korean garments in winter as in summer; the only difference is that they thicken from cheese-cloth to cotton-padded ones as the cold season advances. The incongruous sight of skaters in what looks like tropical garb, of whole towns of people wading through the snow from which they are barely distinguishable, provokes the wonder of winter visitors. The whiteness of a Korean crowd can be duplicated nowhere on earth. Within the lifetime of any one capable of reading these lines the glimpse of a figure in dark or colored garments anywhere in the peninsula betrayed it at once as that of a foreigner. The first record of any variation from this rule was when, a decade ago, the upper classmen of a mission school in Seoul agreed by resolution to adopt dark European trousers, in order to spare their wives or mothers some of their incessant washing and ironing.

The sounds of these two occupations are never silent in Korea. Stand on an eminence above any town or city of the land, and to the ears will be borne the similar yet easily distinguishable rat-a-tat-rat-a-tat of a hundred housewives busy with one or the other of their two principal duties. How they attain the snowy whiteness required by their unaffectionate masters by paddling their garments at the edge 12of any mud-hole or trickle of sewage is one of the mysteries of the East; yet not a roadside puddle or a hollowed rock but is turned into a wash-tub, and never is the visible result outwardly anything but spotless purity. In contrast to the dull plump-a-plump of washing paddles is this falsetto tone of ironing, prolonged far into every night. Nay, wake up at any hour and it will be strange if you do not catch the sound of some distant housewife putting the finishing touches on the garments in which her lord will strut forth into the world in the morning. For in Korea the hot iron is not in vogue, except a tiny one used along the sewed or pasted seams. Instead, the clothing is folded over a hardwood cylinder and beaten with two miniature baseball-bats, beaten with an endless persistency that suggests an unsuspected durability in the apparently flimsy material, and with a rhythm that has grown almost musical with centuries of practice.

Children are often dressed in colors, and unmarried maidens may wear garments of a green or bluish tinge; but all soon succumb to the omnipresent white. Huge hats not unlike those of men in mourning were once universally required for young women not yet sentenced to the servitude of a husband, that their faces might not be disclosed to the male sex. Missionaries by no means gray in the service recall how half-acres of these basket-hats used to lie stacked up before native churches on days of service. But the old order passes, even in the once Hermit Kingdom, and one may travel far afield now and still perhaps look in vain for any survival of this long prevalent custom. As in Japan, the head-dress of the women of Korea is now a matter of hair, in this case drawn smoothly and tightly down over the scalp, like a cap of oily black velvet, and tied in a compact little knot behind, decorated perhaps with a red cloth rosette and thrust through with what looks almost like one of our new-fashioned nickel-plated lead-pencils.

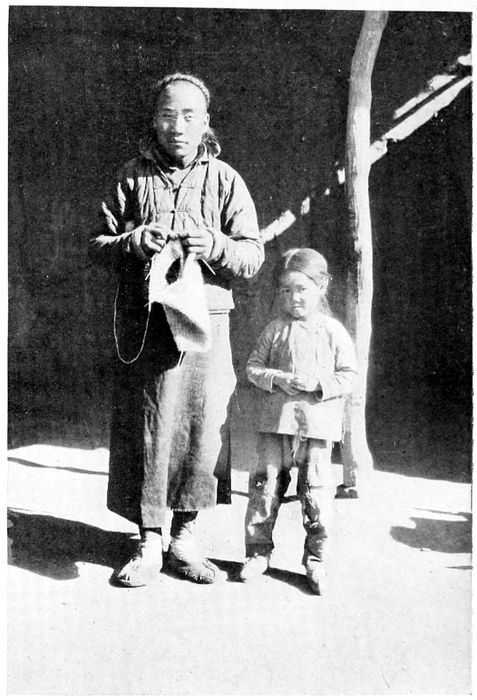

The Koreans have never been reduced to any such crude expedient as a bachelor-tax to keep up their marriage-rate. Until very recent years all boys wore their hair in a long braid up to the day they took a wife. Even now this custom survives in some outlying districts, though none yielded more swiftly to the influx of foreign influence. As long as a man wore a braid he was rated a minor; when he approached manhood he became more and more a community butt, and shame and ridicule rarely failed to drive him into an early marriage. Girls, too, had powerful reasons for not long persisting in the dreadful condition of maidenhood, not the least among which was the custom, still widely practised, of burying the body of an unmarried woman in the public highway, to the everlasting shame of her family to its remotest branches. Moreover, a Korean woman is not given a name of her own until she has borne a son, after which she is forever known as “Mother of So-and-So.” Before that her title, even to her husband, is “Yea!” or the slightly more honorable “Yea-bo!” which correspond fairly closely to our affectionate “Heh!” or “Heh, you!”

13When the happy day comes that is to put an end to the ridicule of his fellows and the shame of his parents, the youth transforms his braid into a topknot, a tightly braided, twisted, and doubled mass of hair an inch in diameter and about three inches high, standing bolt upright in the center of his head, and transfixed with a nickeled or silver ornament similar to that worn by the women. Unlike the cue of the Chinese, forced upon them as a sign of alien subjection, the topknot is the Korean’s badge of manhood, his proudest and most precious possession. Thenceforth one of his most serious problems in life is to protect it from the powers of evil. About his brow is placed the painfully tight band that he is seldom again to be seen without this side of the grave, and he sallies forth under his gleaming new horsehair hat with the masterly air that befits a man of family cares and advantages. To its wearers the Korean top-hat must have become, as even the worst eyesores of human costume will with long use, a thing of beauty; for though many are the men, and myriad the youths, who now cut their hair in Western fashion, numbers even of these still cling to the native hat, while shopkeepers with close-cropped heads, or those whom the evil spirits have outwitted and left bald, may be seen squatting among their wares virtually without clothing but with the discredited head-gear precariously perched upon their bare heads.

Once in a dog’s age even now a country youth turns up at a government or a mission school wearing the braid that not long ago was universal among unmarried males, or, since early marriages are still in vogue, with a topknot; but it is seldom that the end of the first week does not find his fashion changed. Pseudo-pathetic stories still come in from the outlying districts of mothers who wept their eyes red at the cutting of a son’s braid, or of conservative old fathers wrathfully driving from home youths who have sacrificed the topknot that stands for manhood. But the shearing goes steadily on, and thus is passing one of Korea’s most conspicuous idiosyncrasies. The bachelor braid down the back yielded swiftly to foreign influence; a generation hence the topknot, perhaps even the stovepipe screen that surmounts it, may 14be as unknown in the peninsula as the pre-Meiji male head-dress is now in Japan.

If one takes heed not to carry the likeness too far, the Korean might be described as a cross between the Japanese and the Chinese. Some of his traits and customs resemble those of one or the other of his immediate neighbors, but a still greater number seem to be peculiar to himself alone. He builds his house, for example, somewhat like those of Japan; he heats it somewhat after the fashion in China, yet in neither case is the similarity more than approximate. Certainly he is content with as few comforts as any race, with the possible exception of the Chinese, that ever reached the degree of civilization to which he once attained. This, of course, is partly due to the centuries of atrocious misrule under which he lived, when it was unsafe for even the wealthiest of men to attract the ravenous tax-gatherers, turned loose upon the kingdom in rival bands by both king and court, by living in anything more than a thatched mud hovel.

Thus it is that even the larger Korean cities are little more than numerous clusters of such hovels, huddled together along haphazard alleyways of dust or mud, except where the hand of the new rulers of the peninsula, or of those Westerners who have been striving for more than three decades to Christianize it, show themselves. The typical Korean house, whether of country or town, is made of adobe bricks or odds and ends of stone completely plastered over, inside and out, with mud. Thus the walls remain, until they crumble or wash away, for neither paint nor whitewash is used to disguise their milk-and-coffee tint. Except in rare cases, or a few special localities, a rice-straw roof covers them, a roof so smooth and almost glossy, so low and nearly flat, that a village suggests a cluster of dead mushrooms. The accepted shape of the dwelling is that of the half of a square, though in its poorer form it may be merely a hut somewhat longer than it is wide, and in the more pretentious cases it sometimes completes the whole square. Whether it does or not, it must be wholly shut off from the outside world, usually by a wall or screen of woven straw as high as the eaves and enclosing a wholly untended dust-bin of a yard between the two ells. The well built and spick and span servants’ houses erected by a missionary community near Seoul were unpopular with the domestics because they looked off across a pretty valley to the mountains, instead of being shut in by the customary mat-fence.

The outside of the half-square has no openings whatever, but 15presents to the world a perfectly blank face. The inside, on the other hand, is little else than openings, across which may be pushed paper walls or doors somewhat similar to those of Japan. Like the Japanese, the Koreans are squatters rather than sitters, so that the three living-rooms of the average dwelling are barely six feet high, and not much more than that in their other dimensions. The floors are raised somewhat above the level of the ground outside, and are made of stone and mud, like the walls, covered with plaster, or sometimes wood, and this in turn by a heavy, yellow-brown native paper of a consistency between cardboard and oil-cloth. None of the thick soft mats of the Japanese, nor of his cushions or padded quilts, soften life by night or day in a Korean home. When sleep suggests itself, the inmates merely stretch out on the floor on which they have been squatting, thrust a convenient oak brick under their heads, and drift into slumber. Rarely do they make any change of clothing at retiring or rising, the men, as I have said before, often wearing their top-hats all night. Shoes, or, more exactly, slippers, are dropped as the wearers come indoors as unfailingly as in Japan on the ledge of polished wood which forms a cross between a porch and a step along the front of the house. To the Western eye the lack both of space and furniture is surprising. In the center of the house, and usually wide open, is a kind of parlor or sitting-room, at most ten or twelve feet long, flanked at either end by two little living-rooms no longer than they are wide, and the house nowhere has a width much greater than the height of the average Western man. Eating, sleeping, the whole domestic life, in fact, is carried on in a constant proximity exceeding that of our most crowded tenements. It looks more like “playing house,” like a building meant for children to amuse their dolls in, than like the actual lifelong residence of human beings. This impression is enhanced by the miniature furniture, usually as scarce as it is small. There are, of course, no chairs, and no tables unless the little tray with six-inch legs on which food is served be counted as one. If there is a student in the family, or the father is engaged in business, there may be a little writing-desk without legs set flat on the floor; probably there is a chang, or legless chest of drawers, and one of the famous Korean chests, both more than generously bound in brass, or even silver if the family is more prosperous than the exterior of the building ever suggests. That is usually about all, except perhaps a little sewing-machine run by hand, and the few trinkets and inconspicuous odds and ends which the women and children gather about them.

16In the ell, flanking one of the little square living-rooms, is the kitchen, with earth floor and the crudest of stone-and-plaster stoves and implements. Next to this, or perhaps across the dusty, sun-baked yard in the other right-angled extension, is a rough store-room, which commonly alternates in location with an indispensable chamber offering much less privacy and convenience than a Westerner could wish. The walls of the floored rooms are usually covered with plain paper, white or cream-colored, though sometimes figured in a way that recalls both Japan and China. In the yard sit half a dozen or more enormous earthenware jars of the color of chocolate. In one or two of these water is kept; others are filled with preserved or pickled food, particularly the Korean’s favorite delicacy, kimshee, a kind of sauer-kraut of cabbage and turnips generously treated with salt and time and rarely missing from the native menu except in the hot months when it is perforce out of season.

When it comes to heating his house the Korean takes complete leave of his island neighbor and turns his face westward. Under the stone floor runs a large flue, the entire length of the house, connected with the kitchen at one end and springing out of the ground in the form of a crude chimney or stovepipe at the other. None of this shivering over a hibachi filled with a few glowing coals for the otherwise comfort-scorning Korean; he will have his dwelling well heated from end to end, not merely his k’ang, or stone bed, after the Chinese fashion, but every nook and corner within doors. While the cooking is going on he may lie on the papered floor and toast himself to his heart’s content; or a bundle of brushwood—almost the only fuel left him in his deforested land—thrust into the business end of the flue in the morning and another at night makes winter a mere laughing matter. It is an ingenious scheme, yet not without its drawbacks. In the blazing summer-time, for instance, there is no way of shutting off the kitchen heat, and the house-warming goes as merrily on as in January. Not that the native seems to mind; he is as immune to a hot bed as to a hard one. But many is the foreign itinerant missionary who, having found lodging on a frosty night with hosts who would outdo themselves in hospitality, has gratefully stretched out on a nicely warmed floor and fallen luxuriously asleep—to awaken half an hour later dripping with perspiration, and toss the night through in a vain effort to shake off the nightmare impression of having brought up in that very section of the after-world which all his earthly efforts had been designed to avoid.

Our first view of Seoul, in which the former Temple of Heaven is now a smoking-room in a Japanese hotel garden

The interior of a Korean house

Close-up of a Korean “jicky-coon,” or street porter

At the first suggestion of rain the Korean pulls out a little oiled-paper umbrella that fits over his precious horsehair hat

17Like his neighbors, the Korean eats with chop-sticks, but he uses a flat metal spoon with his rice. This grain is the basis of the better-class meal, but is not so highly polished as in Japan; and it is too costly for the common people, who replace it with cheaper grains, especially millet. What may seem a hardship is really a blessing. The poverty which denies them some of the refinements of the table imposes upon the people of Korea a more healthful diet than that of their island neighbors; in the mass they are more sturdily built; if all other signs are insufficient one can usually distinguish a Korean from a Japanese by the excellence of his teeth. Besides his beloved kimshee, no Korean meal is complete without a pungent sauce made from beans pressed together into what looks like a grindstone and then soaked in brine, a sauce into which at least every other mouthful is dipped. Meat is more often eaten than in Japan; fish, as generally. But tea is not widely used; in its place the average Korean uses plain water, or the water in which barley or millet has been cooked, or, best of all, sool, cousin of the fiery sake or samshu of the neighboring lands. Then come a dozen little side-dishes,—pickled vegetables, some strange, some familiar to us, cucumbers cut up rind and all, green onions, and some distant member of the celery family, all immersed in vinegar-and-oil baths, slices of hot red peppers, tiny pieces of some hardy tuber, brittle sheets of seaweed cooked in oil until they look as if they had been varnished, a jet-black kind of lettuce, and other odds and ends for which there are no equivalents in our language. Sugar is hardly used at all, and the adaptable traveler who learns to be otherwise satisfied with a native dinner usually rises to his feet with a longing for a bit of chocolate or some similar delicacy.

It is curious how geographical names often persist in our languages of the West long after they have become antiquated and even unknown in the places to which we apply them. The name “Korea,” for instance, means nothing to those who live in the peninsula we call by that term; nor for that matter did the word “Korai” from which we took it ever refer to more than a third of the country, and that long centuries ago. Ever since they absorbed the former kingdom the Japanese have striven to get the world to adopt the native name “Cho-sen” (the “s” is soft), a word already legitimized by several hundred years of use. But the world is notoriously backward in making such changes; perhaps it is suspicious of the motives of Japan, and a bit resentful at her attempt to render whole pages of our geographies out of date. Yet 18there is nothing mysterious or tricky in the wholesale alterations in nomenclature which she has wrought in her new possession, though there is often irksome annoyance. Every province, every city, almost every slightest hamlet has been given a new name; but this has come about as naturally as the Frenchman’s persistent obstinacy in calling a horse a cheval. It is a mere matter of pronunciation. A given Chinese ideograph stands, and has stood for centuries, for a given town or village of Korea. The Korean looks at the character and pronounces it, let us say, “Wonju”; the Japanese knows as well as we know the word “cat” that the proper pronunciation is “Genshu”—and there you are. It is hardly a dispute, but it is at least a new means of harassing the traveler. If he is American or English, or even French or German, for that matter, he will find that nearly all his fellow-countrymen resident in the country, mainly missionaries, have lived there, or been trained by those who have, since before the Japanese took possession, and that they know only the Korean names. If he has a guide-book, which is rather essential, it is almost certainly concocted by the new rulers or under their influence, and insists on using the Japanese names. So do the railway time-tables, all government documents, and the like. Thus he discovers that it is almost impossible to talk with his own people, at least on geographical matters.

“Have you ever been in Heijo?” he begins, with the purpose of pumping a compatriot for information on that second city of the peninsula.

“Never heard of it,” replies the old resident, with a puzzled air, whereupon the new-comer gives him up as a hopeless recluse and goes his way, perhaps to learn a few days later that this very man was for ten years the most influential foreigner in that very city, but that to him it has always been, and still is, “Ping Yang.” Thus it goes, throughout the length and breadth of the peninsula, so that the man who would mingle with both sides must know that “Kaijo” is “Song-do,” that “Chemulpo” is “Jinsen,” that what the guide-book and time-table call “Kanko” has always been “Ham-hung” to the missionaries, that every last handful of huts in Korea is known by two separate and distinct names, though the erratic slashes with a weazel-hair brush which stands for it in the ridiculous calligraphy of the East never varies. Long before his education has reached this fine point the traveler will have completely forgotten his resentment at finding, as he rumbles into it at the end of a long summer day, that the city he has known since has early school-days as “Seoul” is now officially called “Keijo.”

19It doesn’t greatly matter, however, for the chances are that he has always spoken of it as “Sool,” which is the native fire-water, instead of using the proper pronunciation of “Sow-ohl”; and to learn the new name is easier than to change the old. Our own impressions of what was for more than five centuries the capital of Ch’ao-Hsien, the Land of Morning Calm, and is still the seat of the Government-General of Cho-sen, started at delight, sank very near to keen disappointment, then gradually climbed to somewhere in the neighborhood of calm enjoyment. Seen from afar, the jagged rows of mountain peaks that surround it should quicken the pulse even of the jaded wanderer. The promise that here at last he will find that spell of the ancient East which romancers have enticed him to seek, in the face of his cold better judgment, seems to rise in almost palpable waves from among them. Then he descends at a railway station that might be found in any prairie burg of our central West, and is bumped away by Ford into a city that is flat and mean in its superficial aspect, commonplace in form, and swirling with a fine brown dust. But next morning, or within a day or two of random wandering, according to the pace at which his moods are geared, interest reawakens from its lethargy, and something akin to romance and youthful enthusiasm grows up out of the details of the strange life about him.

There are, of course, almost no real streets, in the American sense, in the Far East; hence only those wholly unfamiliar with that region will be greatly surprised to find that the “many broad avenues” of Seoul, emphasized by semi-propagandist scribblers, are rather few in number and, with one or two exceptions, are sun-scorched stretches of dust which the rainy season of July and August will turn to oozing mud. But the eye will soon be caught by the queer little shops crowded tightly together along most of them, particularly by the haphazard byways that lead off from them into the maze of mushroom hovels that make up the native city. From out of these dirty alleys comes jogging now and then a gaudy red and gold palanquin in which squats concealed some lady of quality, though these conveyances now are almost confined to weddings and funerals; the miserable little mud hovels disgorge haughty gentlemen in spotless white who would be incredible did not the falsetto rat-a-tat of ironing and the groups of women kneeling along the banks of every slightest stream explain them. There is constant movement in the streets of Keijo, a movement that might almost be called kaleidoscopic, were it not for the whiteness of Korean dress; but it strikes one as rather an aimless movement, a 20leisurely if constant going to and fro that rarely seems to get anywhere. Dignified yangbans, that still numerous class of Korea, and especially of the capital, which in the olden days was rated just below the nobility, strut past in their amber beads and their huge tortoise-shell goggles as if they were really going somewhere; but if one takes the trouble to follow them he will probably find them doubling back on their tracks without having reached any objective. In the olden days they could at least go to the government offices where they pretended to do something for their salaries; since Japan has taken away their sinecures without removing the pride that forbids them to work, there is little else than this random strolling left for them to do.