The Project Gutenberg EBook of The World Crisis, Volume I (of VI), by Winston S. Churchill This eBook is for the use of anyone anywhere in the United States and most other parts of the world at no cost and with almost no restrictions whatsoever. You may copy it, give it away or re-use it under the terms of the Project Gutenberg License included with this eBook or online at www.gutenberg.org. If you are not located in the United States, you'll have to check the laws of the country where you are located before using this ebook. Title: The World Crisis, Volume I (of VI) Author: Winston S. Churchill Release Date: June 23, 2019 [EBook #59794] Language: English Character set encoding: UTF-8 *** START OF THIS PROJECT GUTENBERG EBOOK THE WORLD CRISIS, VOLUME I (OF VI) *** Produced by Richard Tonsing and the Online Distributed Proofreading Team at http://www.pgdp.net (This file was produced from images generously made available by The Internet Archive)

Transcriber’s Note:

The cover image was created by the transcriber and is placed in the public domain.

From October 25, 1911, to May 28, 1915, I was, in the words of the Royal Letters Patent and Orders in Council, “responsible to Crown and Parliament for all the business of the Admiralty.” This period comprised the final stage in the preparation against a war with Germany; the mobilisation and concentration of the Fleet before the outbreak; the organisation of the Blockade; the gathering in 1914 of the Imperial forces from all over the world; the clearance from the oceans of all the German cruisers and commerce destroyers; the reinforcement of the Fleet by new construction in 1914 and 1915; the frustration and defeat of the first German submarine attack upon merchant shipping in 1915; and the initiation of the enterprise against the Dardanelles. It was marked before the war by a complete revision of British naval war plans; by the building of a fast division of battleships armed with 15–inch guns and driven by oil fuel; by the proposals, rejected by Germany, for a naval holiday; and by the largest supplies till then ever voted by Parliament for the British Fleet. It was distinguished during the war for the victories of the Heligoland Bight, of the Falkland Islands and the Dogger Bank; and for the attempt to succour Antwerp. It was memorable for the disaster to the three cruisers off the Dutch Coast; the loss of Admiral Cradock’s squadron at Coronel; and the failure of the Navy to force the Dardanelles.

Many accounts of these matters have been published both here and abroad. Most of the principal actors have unfolded their story. Lord Fisher, Lord Jellicoe, Lord French, Lord Kitchener’s biographer, Lord Haig’s Staff, and many others viof less importance, have with the utmost fullness and freedom given their account of these and other war-time events and of the controversies arising out of them. The German accounts are numerous and authoritative. Admirals von Tirpitz and Scheer have told their tales. Sir Julian Corbett, the Official Historian, has in a thousand pages recorded the conduct of the naval war during the whole of my administration. Eight years have passed since I quitted the Admiralty.

In all these circumstances I feel it both my right and my duty to set forth the manner in which I endeavoured to discharge my share in these hazardous responsibilities. In doing so I have adhered to certain strict rules. I have made no important statement of fact relating to naval operations or Admiralty business, on which I do not possess unimpeachable documentary proof. I have made or implied no criticism of any decision or action taken or neglected by others unless I can prove that I had expressed the same opinion in writing before the event.

Many of the accounts which I have mentioned above enjoy the great advantage of having been written some considerable time after the events with which they deal, when the results of schemes and operations set on foot in the early days of the war could be clearly seen, and when the ideas and impressions of 1914 and 1915 could be reviewed in the broad and certain experience and science of 1918 and after. There are no doubt obvious conveniences in this way of treating the subject. Actors in these great situations are able to dwell with certainty upon those of their opinions and directions which have effectively been vindicated by the subsequent course of the war, and they are not, on the other hand, obliged to disturb the public mind by dwelling on any errors of neglect or commission into which they may possibly have been betrayed. I have followed a different method.

In every case where the interests of the State allow, I have viiprinted the actual memoranda, directions, minutes, telegrams or letters written by me at the time, irrespective of whether these documents have been vindicated or falsified by the march of history and of time. The only excisions of relevant matter from the documents have been made to avoid needlessly hurting the feelings of individuals, or the pride of friendly nations. For such reasons here and there sentences have been softened or suppressed. But the whole story is recorded as it happened, by the actual counsels offered and orders given in the fierce turmoil of each day. The principal minutes by which Admiralty business was conducted embody in every case decisions for which, as the highest executive authority in the department, I was directly responsible, and are in all cases expressed in my own words. I am equally accountable, together with the First Sea Lord at the time, for the principal telegrams which moved fleets, squadrons and individual ships, all of which (unless the contrary appears) bear my initials as their final sanction.

The number of minutes and telegrams published in these volumes is, of course, only a fraction of the whole. Restricted space and the fear of wearying the reader have excluded much. But lest it should be thought that there have been any material suppressions, or that what is published does not truly represent what occurred, or the way things were done, I affirm my own willingness to see every document of Admiralty administration for which I am responsible made public provided it is presented in its fair context. Sometimes a dozen or even a score of important decisions had to be taken in a single day. Complicated directions and recommendations were given in writing as fast as they could be dictated, and were acted upon without recall thereafter. Nothing of any consequence was done by me by word of mouth. A complete record therefore exists both of executive and administrative action.

If in the great number of decisions and orders which these viiipages recount and which deal with so many violent and controversial affairs, mistakes can be found which led to mishap, the fault is mine. If, on the other hand, favourable results were achieved, that should be counted to some extent as an offset. Where the decision lay outside my powers and was taken contrary to my advice, I rest on the written record of my warning. Should it be objected that in any of these matters, many of them so highly technical, a landsman and layman could form no valuable opinion, I point to the documents themselves. They can be judged as they stand, but lest, on the other hand, it should be thought that I am seeking to claim credit which is not mine, it must be remembered that throughout this period I enjoyed the assistance, loyal, spontaneous and unstinted, of the best brains of the Royal Navy, that every treasure of every branch of the Admiralty and the Fleet was lavished upon my instruction, and that I had only to apply my own reason and instinct to the arguments of those who I believe stood in the foremost rank of the naval experts of the world.

Taking a general view in after years of the transactions of this terrific epoch, I commend with some confidence the story as a whole to the judgment of my countrymen. It has long been the fashion to disparage the policy and actions of the Ministers who bore the burden of power in the fateful years before the War, and who faced the extraordinary perils of its outbreak and opening phases. Abroad, in Allied, in neutral, and above all, in enemy States, their work is regarded with respect and even admiration. At home, criticism has been its only meed. I hope that this account may be agreeable to those at least who wish to think well of our country, of its naval service, of its governing institutions, of its political life and public men; and that they will feel that perhaps after all Britain and her Empire have not been so ill-guided through the great convulsions as it is customary to declare.

Lastly, I must record my thanks to Vice-Admiral Thomas ixJackson and others who have aided me in the preparation and revision of this work, especially in its technical aspect, and to those who have given me permission to quote correspondence or conversations in which they were concerned.

| CHAPTER | PAGE | ||

|---|---|---|---|

| I | The Vials of Wrath | 1 | |

| II | Milestones to Armageddon | 19 | |

| III | The Crisis of Agadir | 38 | |

| IV | Admirals All | 68 | |

| V | The German Navy Law | 95 | |

| VI | The Romance of Design | 125 | |

| VII | The North Sea Front | 149 | |

| VIII | Ireland and the European Balance | 179 | |

| IX | The Crisis | 203 | |

| X | The Mobilisation of the Navy | 228 | |

| XI | War: The Passage of the Army | 247 | |

| XII | The Battle in France | 281 | |

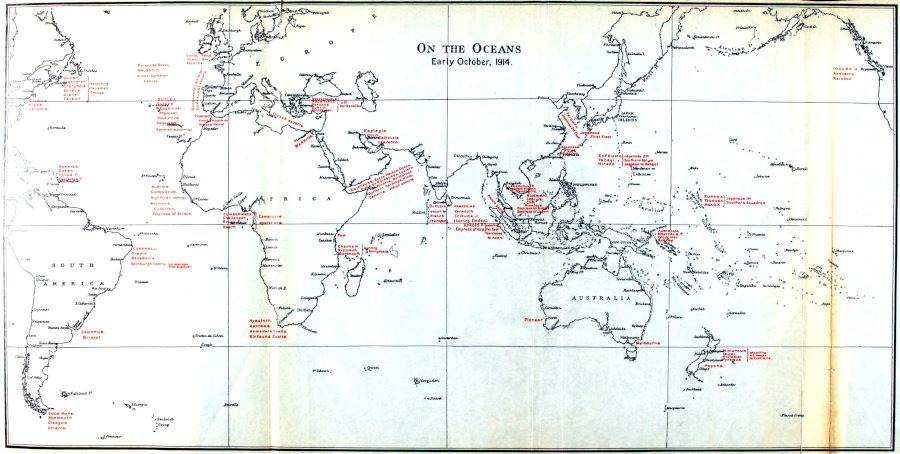

| XIII | On the Oceans | 305 | |

| XIV | In the Narrow Seas | 330 | |

| XV | Antwerp | 355 | |

| XVI | The Channel Ports | 391 | |

| XVII | The Grand Fleet and the Submarine Alarm | 413 | |

| xiiXVIII | Coronel and the Falklands | 442 | |

| XIX | With Fisher at the Admiralty | 479 | |

| XX | The Bombardment of Scarborough and Hartlepool | 502 | |

| XXI | Turkey and the Balkans | 522 | |

| Appendix A | Naval Staff Training | 552 | |

| Appendix B | Tables of Fleet Strength | 558 | |

| Appendix C | Trade Protection | 562 | |

| Appendix D | Mining | 566 | |

| Appendix E | First Lord’s Minutes | 570 | |

| Index | 579 | ||

| AT PAGE | ||

|---|---|---|

| I | Home Waters | 224 |

| II | The Escape of the “Goeben” | 274 |

| III | On the Oceans | 328 |

| IV | Antwerp and the Belgium Coast | 360 |

| V | Coronel and the Falklands | 476 |

| VI | The 16th December, 1914 | 518 |

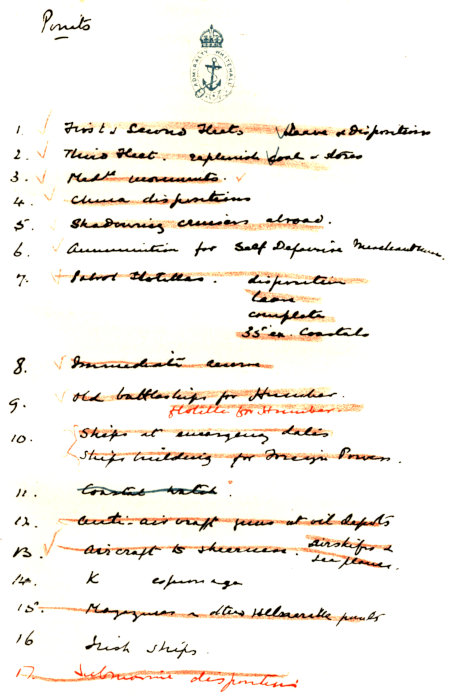

| The Seventeen Points of the First Lord | 206 | |

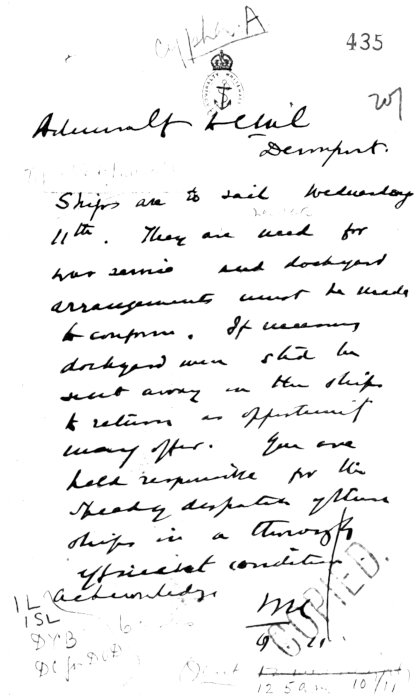

| Facsimile of Admiralty’s Instructions to the Commander-in-Chief at Devonport | facing page | 474 |

The Unending Task—Ruthless War—The Victorian Age—National Pride—National Accountability—The Franco-German Feud—Bismarck’s Apprehension—His Precautions and Alliances—The Bismarckian Period and System—The Young Emperor and Caprivi—The Franco-Russian Alliance, 1892—The Balance of Power—Anglo-German Ties—Anglo-German Estrangement—Germany and the South African War—The Beginnings of the German Navy—The Birth of a Challenge—The Anglo-Japanese Alliance—The Russo-Japanese War—Consequences—The Anglo-French Agreement of 1904—Lord Rosebery’s Comment—The Triple Entente—Degeneration in Turkey and Austria—The Long Descent—The Sinister Hypothesis.

It was the custom in the palmy days of Queen Victoria for statesmen to expatiate upon the glories of the British Empire, and to rejoice in that protecting Providence which had preserved us through so many dangers and brought us at length into a secure and prosperous age. Little did they know that the worst perils had still to be encountered and that the greatest triumphs were yet to be won.

Children were taught of the Great War against Napoleon as the culminating effort in the history of the British peoples, and they looked on Waterloo and Trafalgar as the supreme achievements of British arms by land and sea. These prodigious victories, eclipsing all that had gone before, seemed the fit and predestined ending to the long drama of our island race, which had advanced over a thousand years from small and weak beginnings to a foremost position in the world. Three 2separate times in three different centuries had the British people rescued Europe from a military domination. Thrice had the Low Countries been assailed; by Spain, by the French Monarchy, by the French Empire. Thrice had British war and policy, often maintained single-handed, overthrown the aggressor. Always at the outset the strength of the enemy had seemed overwhelming, always the struggle had been prolonged through many years and across awful hazards, always the victory had at last been won: and the last of all the victories had been the greatest of all, gained after the most ruinous struggle and over the most formidable foe.

Surely that was the end of the tale as it was so often the end of the book. History showed the rise, culmination, splendour, transition and decline of States and Empires. It seemed inconceivable that the same series of tremendous events through which since the days of Queen Elizabeth we had three times made our way successfully, should be repeated a fourth time and on an immeasurably larger scale. Yet that is what has happened, and what we have lived to see.

The Great War through which we have passed differed from all ancient wars in the immense power of the combatants and their fearful agencies of destruction, and from all modern wars in the utter ruthlessness with which it was fought. All the horrors of all the ages were brought together, and not only armies but whole populations were thrust into the midst of them. The mighty educated States involved conceived with reason that their very existence was at stake. Germany having let Hell loose kept well in the van of terror; but she was followed step by step by the desperate and ultimately avenging nations she had assailed. Every outrage against humanity or international law was repaid by reprisals often on a greater scale and of longer duration. No truce or parley mitigated the strife of the armies. The wounded died 3between the lines: the dead mouldered into the soil. Merchant ships and neutral ships and hospital ships were sunk on the seas and all on board left to their fate, or killed as they swam. Every effort was made to starve whole nations into submission without regard to age or sex. Cities and monuments were smashed by artillery. Bombs from the air were cast down indiscriminately. Poison gas in many forms stifled or seared the soldiers. Liquid fire was projected upon their bodies. Men fell from the air in flames, or were smothered, often slowly, in the dark recesses of the sea. The fighting strength of armies was limited only by the manhood of their countries. Europe and large parts of Asia and Africa became one vast battlefield on which after years of struggle not armies but nations broke and ran. When all was over, Torture and Cannibalism were the only two expedients that the civilised, scientific, Christian States had been able to deny themselves: and these were of doubtful utility.

But nothing daunted the valiant heart of man. Son of the Stone Age, vanquisher of nature with all her trials and monsters, he met the awful and self-inflicted agony with new reserves of fortitude. Freed in the main by his intelligence from mediæval fears, he marched to death with sombre dignity. His nervous system was found in the twentieth century capable of enduring physical and moral stresses before which the simpler natures of primeval times would have collapsed. Again and again to the hideous bombardment, again and again from the hospital to the front, again and again to the hungry submarines, he strode unflinching. And withal, as an individual, preserved through these torments the glories of a reasonable and compassionate mind.

In the beginning of the twentieth century men were everywhere unconscious of the rate at which the world was growing. It required the convulsion of the war to awaken the nations 4to the knowledge of their strength. For a year after the war had begun hardly anyone understood how terrific, how almost inexhaustible were the resources in force, in substance, in virtue, behind every one of the combatants. The vials of wrath were full: but so were the reservoirs of power. From the end of the Napoleonic Wars and still more after 1870, the accumulation of wealth and health by every civilised community had been practically unchecked. Here and there a retarding episode had occurred. The waves had recoiled after advancing: but the mounting tides still flowed. And when the dread signal of Armageddon was made, mankind was found to be many times stronger in valour, in endurance, in brains, in science, in apparatus, in organisation, not only than it had ever been before, but than even its most audacious optimists had dared to dream.

The Victorian Age was the age of accumulation; not of a mere piling up of material wealth, but of the growth and gathering in every land of all those elements and factors which go to make up the power of States. Education spread itself over the broad surface of the millions. Science had opened the limitless treasure-house of nature. Door after door had been unlocked. One dim mysterious gallery after another had been lighted up, explored, made free for all: and every gallery entered gave access to at least two more. Every morning when the world woke up, some new machinery had started running. Every night while the world had supper, it was running still. It ran on while all men slept.

And the advance of the collective mind was at a similar pace. Disraeli said of the early years of the nineteenth century, “In those days England was for the few—and for the very few.” Every year of Queen Victoria’s reign saw those limits broken and extended. Every year brought in new thousands of people in private stations who thought about their own country and its story and its duties towards other countries, to the world and to the future, and understood the 5greatness of the responsibilities of which they were the heirs. Every year diffused a wider measure of material comfort among the higher ranks of labour. Substantial progress was made in mitigating the hard lot of the mass. Their health improved, their lives and the lives of their children were brightened, their stature grew, their securities against some of their gravest misfortunes were multiplied, their numbers greatly increased.

Thus when all the trumpets sounded, every class and rank had something to give to the need of the State. Some gave their science and some their wealth, some gave their business energy and drive, and some their wonderful personal prowess, and some their patient strength or patient weakness. But none gave more, or gave more readily, than the common man or woman who had nothing but a precarious week’s wages between them and poverty, and owned little more than the slender equipment of a cottage, and the garments in which they stood upright. Their love and pride of country, their loyalty to the symbols with which they were familiar, their keen sense of right and wrong as they saw it, led them to outface and endure perils and ordeals the like of which men had not known on earth.

But these developments, these virtues, were no monopoly of any one nation. In every free country, great or small, the spirit of patriotism and nationality grew steadily; and in every country, bond or free, the organisation and structure into which men were fitted by the laws, gathered and armed this sentiment. Far more than their vices, the virtues of nations ill-directed or mis-directed by their rulers, became the cause of their own undoing and of the general catastrophe. And these rulers, in Germany, Austria, and Italy; in France, Russia or Britain, how far were they to blame? Was there any man of real eminence and responsibility whose devil heart conceived and willed this awful thing? One rises from the study of the causes of the Great War with a prevailing sense 6of the defective control of individuals upon world fortunes. It has been well said, “there is always more error than design in human affairs.” The limited minds even of the ablest men, their disputed authority, the climate of opinion in which they dwell, their transient and partial contributions to the mighty problem, that problem itself so far beyond their compass, so vast in scale and detail, so changing in its aspect—all this must surely be considered before the complete condemnation of the vanquished or the complete acquittal of the victors can be pronounced. Events also got on to certain lines, and no one could get them off again. Germany clanked obstinately, recklessly, awkwardly towards the crater and dragged us all in with her. But fierce resentment dwelt in France, and in Russia there were wheels within wheels. Could we in England perhaps by some effort, by some sacrifice of our material interests, by some compulsive gesture, at once of friendship and command, have reconciled France and Germany in time and formed that grand association on which alone the peace and glory of Europe would be safe? I cannot tell. I only know that we tried our best to steer our country through the gathering dangers of the armed peace without bringing her to war or others to war, and when these efforts failed, we drove through the tempest without bringing her to destruction.

There is no need here to trace the ancient causes of quarrel between the Germans and the French, to catalogue the conflicts with which they have scarred the centuries, nor to appraise the balance of injury or of provocation on one side or the other. When on the 18th of January, 1871, the triumph of the Germans was consolidated by the Proclamation of the German Empire in the Palace of Versailles, a new volume of European history was opened. “Europe,” it was said, “has lost a mistress and has gained a master.” A new and 7mighty State had come into being, sustained by an overflowing population, equipped with science and learning, organised for war and crowned with victory. France, stripped of Alsace and Lorraine, beaten, impoverished, divided and alone, condemned to a decisive and increasing numerical inferiority, fell back to ponder in shade and isolation on her departed glories.

But the chiefs of the German Empire were under no illusions as to the formidable character and implacable resolves of their prostrate antagonist. “What we gained by arms in half a year,” said Moltke, “we must protect by arms for half a century, if it is not to be torn from us again.” Bismarck, more prudent still, would never have taken Lorraine. Forced by military pressure to assume the double burden against his better judgment, he exhibited from the outset and in every act of his policy an extreme apprehension. Restrained by the opinion of the world, and the decided attitude of Great Britain, from striking down a reviving France in 1875, he devoted his whole power and genius to the construction of an elaborate system of alliances designed to secure the continued ascendancy of Germany and the maintenance of her conquests. He knew the quarrel with France was irreconcilable except at a price which Germany would never consent to pay. He understood that the abiding enmity of a terrific people would be fixed on his new-built Empire. Everything else must be subordinated to that central fact. Germany could afford no other antagonisms. In 1879 he formed an alliance with Austria. Four years later this was expanded into the Triple Alliance between Germany, Austria and Italy. Roumania was brought into this system by a secret alliance in 1883. Not only must there be Insurance; there must be Reinsurance. What he feared most was a counteralliance between France and Russia; and none of these extending arrangements met this danger. His alliance with Austria indeed, if left by itself, would naturally tend to draw France and Russia together. Could he not make a league of 8the three Emperors—Germany, Austria, and Russia united? There at last was overwhelming strength and enduring safety. When in 1887 after six years, this supreme ideal of Bismarck was ruptured by the clash of Russian and Austrian interests in the Balkans, he turned—as the best means still open to him—to his Reinsurance Treaty with Russia. Germany, by this arrangement, secured herself against becoming the object of an aggressive combination by France and Russia. Russia on the other hand was reassured that the Austro-German alliance would not be used to undermine her position in the Balkans.

All these cautious and sapient measures were designed with the object of enabling Germany to enjoy her victory in peace. The Bismarckian system, further, always included the principle of good relations with Great Britain. This was necessary, for it was well known that Italy would never willingly commit herself to anything that would bring her into war with Great Britain, and had, as the world now knows, required this fact to be specifically stated in the original and secret text of the Triple Alliance. To this Alliance in its early years Great Britain had been wholly favourable. Thus France was left to nurse her scars alone; and Germany, assured in her predominance on the Continent, was able to take the fullest advantage of the immense industrial developments which characterised the close of the nineteenth century. The policy of Germany further encouraged France as a consolation to develop her colonial possessions in order to take her thoughts off Europe, and incidentally to promote a convenient rivalry and friction with Great Britain.

This arrangement, under which Europe lived rigidly but peacefully for twenty years, and Germany waxed in power and splendour, was ended in 1890 with the fall of Bismarck. The Iron Chancellor was gone, and new forces began to assail the system he had maintained with consummate ability so long. There was a constant danger of conflagration in the Balkans 9and in the Near East through Turkish misgovernment. The rising tides of pan-Slavism and the strong anti-German currents in Russia began to wash against the structure of the Reinsurance Treaty. Lastly, German ambitions grew with German prosperity. Not content with the hegemony of Europe, she sought a colonial domain. Already the greatest of military Empires, she began increasingly to turn her thoughts to the sea. The young Emperor, freed from Bismarck and finding in Count Caprivi, and the lesser men who succeeded him, complacent coadjutors, began gaily to dispense with the safeguards and precautions by which the safety of Germany had been buttressed. While the quarrel with France remained open and undying, the Reinsurance Treaty with Russia was dropped, and later on the naval rivalry with Britain was begun. These two sombre decisions rolled forward slowly as the years unfolded. Their consequences became apparent in due season. In 1892 the event against which the whole policy of Bismarck had been directed came to pass. The Dual Alliance was signed between Russia and France. Although the effects were not immediately visible, the European situation was in fact transformed. Henceforward, for the undisputed but soberly exercised predominance of Germany, there was substituted a balance of power. Two vast combinations, each disposing of enormous military resources, dwelt together at first side by side but gradually face to face.

Although the groupings of the great Powers had thus been altered sensibly to the disadvantage of Germany, there was in this alteration nothing that threatened her with war. The abiding spirit of France had never abandoned the dream of recovering the lost provinces, but the prevailing temper of the French nation was pacific, and all classes remained under the impression of the might of Germany and of the terrible consequences likely to result from war.

10Moreover, the French were never sure of Russia in a purely Franco-German quarrel. True, there was the Treaty; but the Treaty to become operative required aggression on the part of Germany. What constitutes aggression? At what point in a dispute between two heavily armed parties, does one side or the other become the aggressor? At any rate there was a wide field for discretionary action on the part of Russia. Of all these matters she would be the judge, and she would be the judge at a moment when it might be said that the Russian people would be sent to die in millions over a quarrel between France and Germany in which they had no direct interest. The word of the Tsar was indeed a great assurance. But Tsars who tried to lead their nations, however honourably, into unpopular wars might disappear. The policy of a great people, if hung too directly upon the person of a single individual, was liable to be changed by his disappearance. France, therefore, could never feel certain that if on any occasion she resisted German pressure and war resulted, Russia would march.

Such was the ponderous balance which had succeeded the unquestioned ascendancy of Germany. Outside both systems rested England, secure in an overwhelming and as yet unchallenged, naval supremacy. It was evident that the position of the British Empire received added importance from the fact that adhesion to either Alliance would decide the predominance of strength. But Lord Salisbury showed no wish to exploit this favourable situation. He maintained steadily the traditional friendly attitude towards Germany combined with a cool detachment from Continental entanglements.

It had been easy for Germany to lose touch with Russia; but the alienation of England was a far longer process. So many props and ties had successively to be demolished. British suspicions of Russia in Asia, the historic antagonism to France, memories of Blenheim, of Minden and of Waterloo, the continued 11disputes with France in Egypt and in the Colonial sphere, the intimate business connexions between Germany and England, the relationship of the Royal Families—all these constituted a profound association between the British Empire and the leading State in that Triple Alliance. It was no part of British policy to obstruct the new-born Colonial aspirations of Germany, and in more than one instance, as at Samoa, we actively assisted them. With a complete detachment from strategic considerations, Lord Salisbury exchanged Heligoland for Zanzibar. Still even before the fall of Bismarck the Germans did not seem pleasant diplomatic comrades. They appeared always to be seeking to enlist our aid and reminding us that they were our only friend. To emphasise this they went even farther. They sought in minor ways to embroil us with France and Russia. Each year the Wilhelmstrasse looked inquiringly to the Court of St. James’s for some new service or concession which should keep Germany’s diplomatic goodwill alive for a further period. Each year they made mischief for us with France and Russia, and pointed the moral of how unpopular Great Britain was, what powerful enemies she had, and how lucky she was to find a friend in Germany. Where would she be in the councils of Europe if German assistance were withdrawn, or if Germany threw her influence into the opposing combination? These manifestations, prolonged for nearly twenty years, produced very definite sensations of estrangement in the minds of the rising generation at the British Foreign Office.

But none of these woes of diplomatists deflected the steady course of British policy. The Colonial expansion of Germany was viewed with easy indifference by the British Empire. In spite of their rivalry in trade, there grew up a far more important commercial connexion between Britain and Germany. In Europe we were each other’s best customers. Even the German Emperor’s telegram to President Kruger on the Jameson Raid in 1896, which we now know to have been no personal act but a decision of the German Government, 12produced only a temporary ebullition of anger. All the German outburst of rage against England during the Boer War, and such attempts as were made to form a European coalition against us, did not prevent Mr. Chamberlain in 1901 from advocating an alliance with Germany, or the British Foreign Office from proposing in the same year to make the Alliance between Britain and Japan into a Triple Alliance including Germany. During this period we had at least as serious differences with France as with Germany, and sufficient naval superiority not to be seriously disquieted by either. We stood equally clear of the Triple and of the Dual Alliance. We had no intention of being drawn into a Continental quarrel. No effort by France to regain her lost provinces appealed to the British public or to any political party. The idea of a British Army fighting in Europe amid the mighty hosts of the Continent was by all dismissed as utterly absurd. Only a menace to the very life of the British nation would stir the British Empire from its placid and tolerant detachment from Continental affairs. But that menace Germany was destined to supply.

“Among the Great Powers,” said Moltke in his Military Testament, “England necessarily requires a strong ally on the Continent. She would not find one which corresponds better to all her interests than a United Germany, that can never make claim to the command of the sea.”

From 1873 to 1900 the German Navy was avowedly not intended to provide for the possibility of “a naval war against great naval Powers.” Now in 1900 came a Fleet Law of a very different kind. “For the protection of trade and the Colonies,” declared the preamble of this document, “there is only one thing that will suffice, namely, a strong Battle Fleet.”

In order to protect German trade and commerce under existing conditions, only one thing will suffice, namely, Germany must possess a battle fleet of such a strength that, 13even for the most powerful naval adversary, a war would involve such risks as to make that Power’s own supremacy doubtful.

For this purpose it is not absolutely necessary that the German Fleet should be as strong as that of the greatest naval Power, for, as a rule, a great naval Power will not be in a position to concentrate all its forces against us. Even if it were successful in bringing against us a much superior force, the defeat of a strong German Fleet would so considerably weaken the enemy that, in spite of the victory that might be achieved, his own supremacy would no longer be assured by a fleet of sufficient strength.

For the attainment of this object, viz., protection of our trade and colonies by assuring peace with honour, Germany requires, according to the strength of the great naval Powers and with regard to our tactical formations, two double squadrons of first-class battleships, with the necessary attendant cruisers, torpedo boats, etc. Since the Fleet Law provides for only two squadrons, the construction of third and fourth squadrons is proposed. Two of these four squadrons will form one fleet. The tactical formation of the second fleet should be similar to that of the first as provided for in the Fleet Law.

And again:—

In addition to the increase of the Home Fleet an increase of the foreign service ships is also necessary.... In order to estimate the importance of an increase in our foreign service ships, it must be realised that they represent the German Navy abroad, and that to them often falls the task of gathering fruits which have ripened as a result of the naval strength of the Empire embodied in the Home Battle Fleet.

And again:—

If the necessity for so strong a Fleet for Germany be recognised, it cannot be denied that the honour and welfare of the Fatherland authoritatively demand that the Home Fleet be brought up to the requisite strength as soon as possible.

The determination of the greatest military Power on the Continent to become at the same time at least the second 14naval Power was an event of first magnitude in world affairs. It would, if carried into full effect, undoubtedly reproduce those situations which at previous periods in history had proved of such awful significance to the Islanders of Britain.

Hitherto all British naval arrangements had proceeded on the basis of the two-Power standard, namely, an adequate superiority over the next two strongest Powers, in those days France and Russia. The possible addition of a third European Fleet more powerful than either of these two would profoundly affect the life of Britain. If Germany was going to create a Navy avowedly measured against our own, we could not afford to remain “in splendid isolation” from the European systems. We must in these circumstances find a trustworthy friend. We found one in another island Empire situated on the other side of the globe and also in danger. In 1901 the Alliance was signed between Great Britain and Japan. Still less could we afford to have dangerous causes of quarrel open both with France and Russia. In 1902 the British Government, under Mr. Balfour and Lord Lansdowne, definitely embarked upon the policy of settling up our differences with France. Still, before either of these steps were taken the hand was held out to Germany. She was invited to join with us in the alliance with Japan. She was invited to make a joint effort to solve the Moroccan problem. Both offers were declined.

In 1904, the war between Russia and Japan broke out. Germany sympathised mainly with Russia; England stood ready to fulfil her treaty engagements with Japan, while at the same time cultivating good relations with France. In this posture the Powers awaited the result of the Far Eastern struggle. It brought a surprise to all but one. The military and naval overthrow of Russia by Japan and the internal convulsions of the Russian State produced profound changes in the European situation. Although German influence had leaned against Japan, she felt herself enormously strengthened 15by the Russian collapse. Her Continental predominance was restored. Her self-assertion in every sphere became sensibly and immediately pronounced. France, on the other hand, weakened and once again, for the time being, isolated and in real danger, became increasingly anxious for an Entente with England. England, whose statesmen with penetrating eye alone in Europe had truly measured the martial power of Japan, gained remarkably in strength and security. Japan, her new ally, was triumphant: France, her ancient enemy, sought her friendship: the German fleet was still only a-building, and meanwhile all the British battleships in China seas could now be safely brought home.

The settlement of outstanding differences between England and France proceeded, and at last in 1904 the Anglo-French Agreement was signed. There were various clauses; but the essence of the compact was that the French desisted from opposition to British interests in Egypt, and Britain gave a general support to the French views about Morocco. This agreement was acclaimed by the Conservative forces in England, among whom the idea of the German menace had already taken root. It was also hailed somewhat short-sightedly by Liberal statesmen as a step to secure general peace by clearing away misunderstandings and differences with our traditional enemy. It was therefore almost universally welcomed. Only one profound observer raised his voice against it. “My mournful and supreme conviction,” said Lord Rosebery, “is that this agreement is much more likely to lead to complications than to peace.” This unwelcome comment was indignantly spurned from widely different standpoints by both British parties, and general censure fell upon its author.

Still, England and all that she stood for had left her isolation, and had reappeared in Europe on the opposite side to 16Germany. For the first time since 1870 Germany had to take into consideration a Power outside her system which was in no way amenable to threats, and was not unable if need be to encounter her single-handed. The gesture which was to sweep Delcassé from power in 1905, the apparition “in shining armour” which was to quell Russia in 1908, could procure no such compliance from the independent Island girt with her Fleet and mistress of the seas.

Up to this moment the Triple Alliance had on the whole been stronger than France and Russia. Although war against these two Powers would have been a formidable undertaking for Germany, Austria and Italy, its ultimate issue did not seem doubtful. But if the weight of Britain were thrown into the adverse scale and that of Italy withdrawn from the other, then for the first time since 1870 Germany could not feel certain that she was on the stronger side. Would she submit to it? Would the growing, bounding ambitions and assertions of the new German Empire consent to a situation in which, very politely no doubt, very gradually perhaps, but still very surely, the impression would be conveyed that her will was no longer the final law of Europe? If Germany and her Emperor would accept the same sort of restraint that France, Russia and England had long been accustomed to, and would live within her rights as an equal in a freer and easier world, all would be well. But would she? Would she tolerate the gathering under an independent standard of nations outside her system, strong enough to examine her claims only as the merits appealed to them, and to resist aggression without fear? The history of the next ten years was to supply the answer.

Side by side with these slowly marshalling and steadily arming antagonisms between the greatest Powers, processes of degeneration were at work in weaker Empires almost equally dangerous to peace. Forces were alive in Turkey which threatened with destruction the old regime and its 17abuses on which Germany had chosen to lean. The Christian States of the Balkans, growing stronger year by year, awaited an opportunity to liberate their compatriots still writhing under Turkish misrule. The growth of national sentiment in every country created fierce strains and stresses in the uneasily knit and crumbling Austro-Hungarian Empire. The Balkan States saw also in this direction kinsmen to rescue, territory to recover, and unities to achieve. Italy watched with ardent eyes the decay of Turkey and the unrest of Austria. It was certain that from all these regions of the South and of the East there would come a succession of events deeply agitating both to Russia and to Germany.

To create the unfavourable conditions for herself in which Germany afterwards brought about the war, many acts of supreme unwisdom on the part of her rulers were nevertheless still necessary. France must be kept in a state of continued apprehension. The Russian nation, not the Russian Court alone, must be stung by some violent affront inflicted in their hour of weakness. The slow, deep, restrained antagonism of the British Empire must be roused by the continuous and repeated challenge to the sea power by which it lived. Then and then only could those conditions be created under which Germany by an act of aggression would bring into being against her, a combination strong enough to resist and ultimately to overcome her might. There was still a long road to travel before the Vials of Wrath were full. For ten years we were to journey anxiously along that road.

It was for a time the fashion to write as if the British Government during these ten years were either entirely unconscious of the approaching danger or had a load of secret matters and deep forebodings on their minds hidden altogether from the thoughtless nation. In fact, however, neither of these alternatives, taken separately, was true; 18and there is a measure of truth in both of them taken together.

The British Government and the Parliaments out of which it sprang, did not believe in the approach of a great war, and were determined to prevent it; but at the same time the sinister hypothesis was continually present in their thoughts, and was repeatedly brought to the attention of Ministers by disquieting incidents and tendencies.

During the whole of those ten years this duality and discordance were the keynote of British politics; and those whose duty it was to watch over the safety of the country lived simultaneously in two different worlds of thought. There was the actual visible world with its peaceful activities and cosmopolitan aims; and there was a hypothetical world, a world “beneath the threshold,” as it were, a world at one moment utterly fantastic, at the next seeming about to leap into reality—a world of monstrous shadows moving in convulsive combinations through vistas of fathomless catastrophe.

‘Enmities which are unspoken and hidden are more to be feared than those which are outspoken and open.’

A Narrower Stage—The Victorian Calm—The Chain of Strife—Lord Salisbury Retires—Mr. Balfour and the End of an Epoch—Fall of the Conservative Government—The General Election of 1906—The Algeciras Conference—Anglo-French Military Conversations—Mr. Asquith’s Administration—The Austrian Annexations—The German Threat to Russia—The Admiralty Programme of 1909—The Growth of the German Navy—German Finance and its Implications—The Inheritance of the New German Chancellor.

If the reader is to understand this tale and the point of view from which it is told, he should follow the authors mind in each principal sphere of causation. He must not only be acquainted with the military and naval situations as they existed at the outbreak of war, but with the events which led up to them. He must be introduced to the Admirals and to the Generals; he must study the organisation of the Fleets and Armies and the outlines of their strategy by sea and land; he must not shrink even from the design of ships and cannon; he must extend his view to the groupings and slow-growing antagonisms of modern States; he must contract it to the humbler but unavoidable warfare of parties and the interplay of political forces and personalities.

The dramatis personæ of the previous Chapter have been great States and Empires and its theme their world-wide balance and combinations. Now the stage must for a while be narrowed to the limits of these islands and occupied by the 20political personages and factions of the time and of the hour.

In the year 1895 I had the privilege, as a young officer, of being invited to lunch with Sir William Harcourt. In the course of a conversation in which I took, I fear, none too modest a share, I asked the question, “What will happen then?” “My dear Winston,” replied the old Victorian statesman, “the experiences of a long life have convinced me that nothing ever happens.” Since that moment, as it seems to me, nothing has ever ceased happening. The growth of the great antagonisms abroad was accompanied by the progressive aggravation of party strife at home. The scale on which events have shaped themselves, has dwarfed the episodes of the Victorian era. Its small wars between great nations, its earnest disputes about superficial issues, the high, keen intellectualism of its personages, the sober, frugal, narrow limitations of their action, belong to a vanished period. The smooth river with its eddies and ripples along which we then sailed, seems inconceivably remote from the cataract down which we have been hurled and the rapids in whose turbulence we are now struggling.

I date the beginning of these violent times in our country from the Jameson Raid, in 1896. This was the herald, if not indeed the progenitor, of the South African War. From the South African War was born the Khaki Election, the Protectionist Movement, the Chinese Labour cry and the consequent furious reaction and Liberal triumph of 1906. From this sprang the violent inroads of the House of Lords upon popular Government, which by the end of 1908 had reduced the immense Liberal majority to virtual impotence, from which condition they were rescued by the Lloyd George Budget in 1909. This measure became, in its turn, on both sides, the cause of still greater provocations, and its rejection by the Lords was a constitutional outrage and political blunder almost beyond compare. It led directly to the two General Elections of 1910, to the Parliament Act, and to the Irish struggle, in which our 21country was brought to the very threshold of civil war. Thus we see a succession of partisan actions continuing without intermission for nearly twenty years, each injury repeated with interest, each oscillation more violent, each risk more grave, until at last it seemed that the sabre itself must be invoked to cool the blood and the passions that were rife.

In July, 1902, Lord Salisbury retired. With what seems now to have been only a brief interlude, he had been Prime Minister and Foreign Secretary since 1885. In those seventeen years the Liberal Party had never exercised any effective control upon affairs. Their brief spell in office had only been obtained by a majority of forty Irish Nationalist votes. During thirteen years the Conservatives had enjoyed homogeneous majorities of 100 to 150, and in addition there was the House of Lords. This long reign of power had now come to an end. The desire for change, the feeling that change was impending, was widespread. It was the end of an epoch.

Lord Salisbury was followed by Mr. Balfour. The new Prime Minister never had a fair chance. He succeeded only to an exhausted inheritance. Indeed, his wisest course would have been to get out of office as decently, as quietly, and, above all, as quickly as possible. He could with great propriety have declared that the 1900 Parliament had been elected on war conditions and on a war issue; that the war was now finished successfully; that the mandate was exhausted and that he must recur to the sense of the electors before proceeding farther with his task. No doubt the Liberals would have come into power, but not by a large majority; and they would have been faced by a strong, united Conservative Opposition, which in four or five years, about 1907, would have resumed effective control of the State. The solid ranks of Conservative members who acclaimed Mr. Balfour’s accession as First Minister were however in no mood to be dismissed 22to their constituencies when the Parliament was only two years old and had still four or five years more to run. Mr. Balfour therefore addressed himself to the duties of Government with a serene indifference to the vast alienation of public opinion and consolidation of hostile forces which were proceeding all around him.

Mr. Chamberlain, his almost all-powerful lieutenant, was under no illusions. He felt, with an acute political sensitiveness, the ever-growing strength of the tide setting against the ruling combination. But instead of pursuing courses of moderation and prudence, he was impelled by the ardour of his nature to a desperate remedy. The Government was reproached with being reactionary. The moderate Conservatives and the younger Conservatives were all urging Liberal and conciliatory processes. The Opposition was advancing hopefully towards power, heralded by a storm of angry outcry. He would show them, and show doubting or weary friends as well, how it was possible to quell indignation by violence, and from the very heart of reaction to draw the means of popular victory. He unfurled the flag of Protection.

Time, adversity and the recent Education Act had united the Liberals; Protection, or Tariff Reform as it was called, split the Conservatives. Ultimately, six Ministers resigned and fifty Conservative or Unionist members definitely withdrew their support from the Government. Among them were a number of those younger men from whom a Party should derive new force and driving power, and who are specially necessary to it during a period of opposition. The action of the Free Trade Unionists was endorsed indirectly by Lord Salisbury himself from his retirement, and was actively sustained by such pillars of the Unionist Party as Sir Michael Hicks-Beach and the Duke of Devonshire. No such formidable loss had been sustained by the Conservative Party since the expulsion of the Peelites.

23But if Mr. Balfour had not felt inclined to begin his reign by an act of abdication, he was still less disposed to have power wrested from his grasp. Moreover, he regarded a Party split as the worst of domestic catastrophes, and responsibility for it as the unforgivable sin. He therefore laboured with amazing patience and coolness to preserve a semblance of unity, to calm the tempest, and to hold on as long as possible in the hope of its subsiding. With the highest subtlety and ingenuity he devised a succession of formulas designed to enable people who differed profoundly, to persuade themselves they were in agreement. When it came to the resignation of Ministers, he was careful to shed Free Trade and Protectionist blood as far as possible in equal quantities. Like Henry VIII, he decapitated Papists and burned hot Gospellers on the same day for their respective divergencies in opposite directions from his central, personal and artificial compromise.

In this unpleasant situation Mr. Balfour maintained himself for two whole years. Vain the clamour for a general election, vain the taunts of clinging to office, vain the solicitations of friends and the attempts of foes to force a crucial issue. The Prime Minister remained immovable, inexhaustible, imperturbable; and he remained Prime Minister. His clear, just mind, detached from small things, stood indifferent to the clamour about him. He pursued, as has been related, through the critical period of the Russo-Japanese War, a policy in support of Japan of the utmost firmness. He resisted all temptations, on the other hand, to make the sinking of our trawlers on the Dogger Bank by the Russian Fleet an occasion of war with Russia. He formed the Committee of Imperial Defence—the instrument of our preparedness. He carried through the agreement with France of 1904, the momentous significance of which the last chapter has explained. But in 1905 political Britain cared for none of these things. The credit of the Government fell steadily. The process of 24degeneration in the Conservative Party was continuous. The storm of opposition grew unceasingly, and so did the unification of all the forces opposed to the dying regime.

Late in November, 1905, Mr. Balfour tendered his resignation as Prime Minister to the King. The Government of Sir Henry Campbell-Bannerman was formed, and proceeded in January to appeal to the constituencies. This Government represented both the wings into which the Liberal Party had been divided by the Boer War. The Liberal Imperialists, so distinguished by their talents, filled some of the greatest offices. Mr. Asquith went to the Exchequer; Sir Edward Grey to the Foreign Office; Mr. Haldane became Secretary of State for War. On the other hand the Prime Minister, who himself represented the main stream of Liberal opinion, appointed Sir Robert Reid, Lord Chancellor and Mr. John Morley, Secretary of State for India. Both these statesmen, while not opposing actual war measures in South Africa, had unceasingly condemned the war; and in Mr. Lloyd George and Mr. John Burns, both of whom entered the Cabinet, were found democratic politicians who had gone even farther. The dignity of the Administration was enhanced by the venerable figures of Lord Ripon, Sir Henry Fowler, and the newly returned Viceroy of India, Lord Elgin.

The result of the polls in January, 1906, was a Liberal landslide. Never since the election following the great Reform Bill, had anything comparable occurred in British parliamentary history. In Manchester, for instance, which was one of the principal battle-grounds, Mr. Balfour and eight Conservative colleagues were dismissed and replaced by nine Liberals or Labour men. The Conservatives, after nearly twenty years of power, crept back to the House of Commons barely a hundred and fifty strong. The Liberals had gained a majority of more than one hundred over all other parties combined. Both great parties harboured deep grievances against the other; and against the wrong of the Khaki Election 25and its misuse, was set the counter-claim of an unfair Chinese Labour cry.

Sir Henry Campbell-Bannerman was still receiving the resounding acclamations of Liberals, peace-lovers, anti-jingoes, and anti-militarists, in every part of the country, when he was summoned by Sir Edward Grey to attend to business of a very different character. The Algeciras Conference was in its throes. When the Anglo-French Agreement on Egypt and Morocco had first been made known, the German Government accepted the situation without protest or complaint. The German Chancellor, Prince Bülow, had even declared in 1904 that there was nothing in the Agreement to which Germany could take exception. “What appears to be before us is the attempt by the method of friendly understanding to eliminate a number of points of difference which exist between England and France. We have no objection to make against this from the standpoint of German interest.” A serious agitation most embarrassing to the German Government was, however, set on foot by the Pan-German and Colonial parties. Under this pressure the attitude of the Government changed, and a year later Germany openly challenged the Agreement and looked about for an opportunity to assert her claims in Morocco. This opportunity was not long delayed.

Early in 1905 a French mission arrived in Fez. Their language and actions seemed to show an intention of treating Morocco as a French Protectorate, thereby ignoring the international obligations of the Treaty of Madrid. The Sultan of Morocco appealed to Germany, asking if France was authorised to speak in the name of Europe. Germany was now enabled to advance as the champion of an international agreement, which she suggested France was violating. Behind this lay the clear intention to show France that she could not afford in consequence of her agreement with Britain, 26to offend Germany. The action taken was of the most drastic character. The German Emperor was persuaded to go to Tangiers, and there, against his better judgment, on March 31, 1905, he delivered, in very uncompromising language chosen by his ministers, an open challenge to France. To this speech the widest circulation was given by the German Foreign Office. Hot-foot upon it (April 11 and 12) two very threatening despatches were sent to Paris and London, demanding a conference of all the Signatory Powers to the Treaty of Madrid. Every means was used by Germany to make France understand that if she refused the conference there would be war; and to make assurance doubly sure a special envoy[1] was sent from Berlin to Paris for that express purpose.

France was quite unprepared for war; the army was in a bad state; Russia was incapacitated; moreover, France had not a good case. The French Foreign Minister, Monsieur Delcassé, was, however, unwilling to give way. The German attitude became still more threatening; and on June 6 the French Cabinet of Monsieur Rouvier unanimously, almost at the cannon’s mouth, accepted the principle of a conference, and Monsieur Delcassé at once resigned.

So far Germany had been very successful. Under a direct threat of war she had compelled France to bow to her will, and to sacrifice the Minister who had negotiated the Agreement with Great Britain. The Rouvier Cabinet sought earnestly for some friendly solution which, while sparing France the humiliation of a conference dictated in such circumstances, would secure substantial concessions to Germany. The German Government were, however, determined to exploit their victory to the full, and not to make the situation easier for France either before or during the conference. The conference accordingly assembled at Algeciras in January, 1906.

Great Britain now appeared on the scene, apparently quite 27unchanged and unperturbed by her domestic convulsions. She had in no way encouraged France to refuse the conference. But if a war was to be fastened on France by Germany as the direct result of an agreement made recently in the full light of day between France and Great Britain, it was held that Great Britain could not remain indifferent. Sir Henry Campbell-Bannerman therefore authorised Sir Edward Grey to support France strongly at Algeciras. He also authorised, almost as the first act of what was to be an era of Peace, Retrenchment, and Reform, the beginning of military conversations between the British and French General Staffs with a view to concerted action in the event of war. This was a step of profound significance and of far-reaching reactions. Henceforward the relations of the two Staffs became increasingly intimate and confidential. The minds of our military men were definitely turned into a particular channel. Mutual trust grew continually in one set of military relationships, mutual precautions in the other. However explicitly the two Governments might agree and affirm to each other that no national or political engagement was involved in these technical discussions, the fact remained that they constituted an exceedingly potent tie.

The attitude of Great Britain at Algeciras turned the scale against Germany. Russia, Spain and other signatory Powers associated themselves with France and England. Austria revealed to Germany the limits beyond which she would not go. Thus Germany found herself isolated, and what she had gained by her threats of war evaporated at the Council Board. In the end a compromise suggested by Austria, enabled Germany to withdraw without open loss of dignity. From these events, however, serious consequences flowed. Both the two systems into which Europe was divided, were crystallised and consolidated. Germany felt the need of binding Austria more closely to her. Her open attempt to terrorise France had produced a deep impression upon French 28public opinion. An immediate and thorough reform of the French Army was carried out, and the Entente with England was strengthened and confirmed. Algeciras was a milestone on the road to Armageddon.

The illness and death of Sir Henry Campbell-Bannerman at the beginning of 1908 opened the way for Mr. Asquith. The Chancellor of the Exchequer had been the First Lieutenant of the late Prime Minister, and, as his chief’s strength failed, had more and more assumed the burden. He had charged himself with the conduct of the new Licensing Bill which was to be the staple of the Session of 1908, and in virtue of this task he could command the allegiance of an extreme and doctrinaire section of his Party from whom his Imperialism had previously alienated him. He resolved to ally to himself the democratic gifts and rising reputation of Mr. Lloyd George. Thus the succession passed smoothly from hand to hand. Mr. Asquith became Prime Minister; Mr. Lloyd George became Chancellor of the Exchequer and the second man in the Government. The new Cabinet, like the old, was a veiled coalition. A very distinct line of cleavage was maintained between the Radical-Pacifist elements who had followed Sir Henry Campbell-Bannerman and constituted the bulk both of the Cabinet and the Party on the one hand, and the Liberal Imperialist wing on the other. Mr. Asquith, as Prime Minister, had now to take an impartial position; but his heart and sympathies were always with Sir Edward Grey, the War Office and the Admiralty, and on every important occasion when he was forced to reveal himself, he definitely sided with them. He was not, however, able to give Sir Edward Grey the same effectual countenance, much as he might wish to do so, that Sir Henry Campbell-Bannerman had done. The old chief’s word was law to the extremists of his Party. They would accept almost anything from him. 29They were quite sure he would do nothing more in matters of foreign policy and defence than was absolutely necessary, and that he would do it in the manner least calculated to give satisfaction to jingo sentiments. Mr. Asquith, however, had been far from “sound” about the Boer War, and was the lifelong friend of the Foreign Secretary, who had wandered even further from the straight path into patriotic pastures. He was therefore in a certain sense suspect, and every step he took in external affairs was watched with prim vigilance by the Elders. If the military conversations with France had not been authorised by Sir Henry Campbell-Bannerman, and if his political virtue could not be cited in their justification, I doubt whether they could have been begun or continued by Mr. Asquith.

Since I had crossed the Floor of the House in 1904 on the Free Trade issue, I had worked in close political association with Mr. Lloyd George. He was the first to welcome me. We sat and acted together in the period of opposition preceding Mr. Balfour’s fall, and we had been in close accord during Sir Henry Campbell-Bannerman’s administration, in which I had served as Under-Secretary of State for the Colonies. This association continued when I entered the new Cabinet as President of the Board of Trade, and in general, though from different angles, we leaned to the side of those who would restrain the froward both in foreign policy and in armaments. It must be understood that these differences of attitude and complexion, which in varying forms reproduce themselves in every great and powerful British Administration, in no way prevented harmonious and agreeable relations between the principal personages, and our affairs proceeded amid many amenities in an atmosphere of courtesy, friendliness and goodwill.

It was not long before the next European crisis arrived. On October 5, 1908, Austria, without warning or parley, 30proclaimed the annexation of Bosnia and Herzegovina. These provinces of the Turkish Empire had been administered by her under the Treaty of Berlin, 1878; and the annexation only declared in form what already existed in fact. The Young Turk Revolution which had occurred in the summer, seemed to Austria likely to lead to a reassertion of Turkish sovereignty over Bosnia and Herzegovina, and this she was concerned to forestall. A reasonable and patient diplomacy would probably have secured for Austria the easements which she needed. Indeed, negotiations with Russia, the Great Power most interested, had made favourable progress. But suddenly and abruptly Count Aerenthal, the Austrian Foreign Minister, interrupted the discussions by the announcement of the annexation, before the arrangements for a suitable concession to Russia had been concluded. By this essentially violent act a public affront was put upon Russia, and a personal slight upon the Russian negotiator, Monsieur Isvolsky.

A storm of anger and protest arose on all sides. England, basing herself on the words of the London Conference in 1871, “That it is an essential principle of the law of nations that no Power can free itself from the engagements of a Treaty, nor modify its stipulations except by consent of the contracting parties,” refused to recognise either the annexation of Bosnia and Herzegovina or the declaration of Bulgarian independence which had synchronised with it. Turkey protested loudly against a lawless act. An effective boycott of Austrian merchandise was organised by the Turkish Government. The Serbians mobilised their army. But it was the effect on Russia which was most serious. The bitter animosity excited against Austria throughout Russia became a penultimate cause of the Great War. In this national quarrel the personal differences of Aerenthal and Isvolsky played also their part.

Great Britain and Russia now demanded a conference, 31declining meanwhile to countenance what had been done. Austria, supported by Germany, refused. The danger of some violent action on the part of Serbia became acute. Sir Edward Grey, after making it clear that Great Britain would not be drawn into a war on a Balkan quarrel, laboured to restrain Serbia, to pacify Turkey, and to give full diplomatic support to Russia. The controversy dragged on till April, 1909, when it was ended in the following remarkable manner. The Austrians had determined, unless Serbia recognised the annexation of Bosnia and Herzegovina, to send an ultimatum and to declare war upon her. At this point the German Chancellor, Prince von Bülow, intervened. Russia, he insisted, should herself advise Serbia to give way. The Powers should officially recognise the annexation without a conference being summoned and without any kind of compensation to Serbia. Russia was to give her consent to this action, without previously informing the British or French Governments. If Russia did not consent, Austria would declare war on Serbia with the full and complete support of Germany. Russia, thus nakedly confronted by war both with Austria and Germany, collapsed under the threat, as France had done three years before. England was left an isolated defender of the sanctity of Treaties and the law of nations. The Teutonic triumph was complete. But it was a victory gained at a perilous cost. France, after her treatment in 1905, had begun a thorough military reorganisation. Now Russia, in 1910, made an enormous increase in her already vast army; and both Russia and France, smarting under similar experiences, closed their ranks, cemented their alliance, and set to work to construct with Russian labour and French money the new strategic railway systems of which Russia’s western frontier stood in need.

It was next the turn of Great Britain to feel the pressure of the German power.

32In the spring of 1909, the First Lord of the Admiralty, Mr. McKenna, suddenly demanded the construction of no less than six Dreadnought battleships. He based this claim on the rapid growth of the German Fleet and its expansion and acceleration under the new naval law of 1908, which was causing the Admiralty the greatest anxiety. I was still a sceptic about the danger of the European situation, and not convinced by the Admiralty case. In conjunction with the Chancellor of the Exchequer, I proceeded at once to canvas this scheme and to examine the reasons by which it was supported. The conclusions which we both reached were that a programme of four ships would sufficiently meet our needs. In this process I was led to analyse minutely the character and composition of the British and German Navies, actual and prospective. I could not agree with the Admiralty contention that a dangerous situation would be reached in the year 1912. I found the Admiralty figures on this subject were exaggerated. I did not believe that the Germans were building Dreadnoughts secretly in excess of their published Fleet Laws. I held that our margin in pre-Dreadnought ships would, added to a new programme of four Dreadnoughts, assure us an adequate superiority in 1912, “the danger year” as it was then called. In any case, as the Admiralty only claimed to lay down the fifth and sixth ships in the last month of the financial year, i. e., March, 1910, these could not affect the calculations. The Chancellor of the Exchequer and I therefore proposed that four ships should be sanctioned for 1909, and that the additional two should be considered in relation to the programme of 1910.

Looking back on the voluminous papers of this controversy in the light of what actually happened, there can be no doubt whatever that, so far as facts and figures were concerned, we were strictly right. The gloomy Admiralty anticipations were in no respect fulfilled in the year 1912. The British margin was found to be ample in that year. There were no secret 33German Dreadnoughts, nor had Admiral von Tirpitz made any untrue statement in respect of major construction.

The dispute in the Cabinet gave rise to a fierce agitation outside. The process of the controversy led to a sharp rise of temperature. The actual points in dispute never came to an issue. Genuine alarm was excited throughout the country by what was for the first time widely recognised as a German menace. In the end a curious and characteristic solution was reached. The Admiralty had demanded six ships: the economists offered four: and we finally compromised on eight. However, five out of the eight were not ready before “the danger year” of 1912 had passed peacefully away.

But although the Chancellor of the Exchequer and I were right in the narrow sense, we were absolutely wrong in relation to the deep tides of destiny. The greatest credit is due to the First Lord of the Admiralty, Mr. McKenna, for the resolute and courageous manner in which he fought his case and withstood his Party on this occasion. Little did I think, as this dispute proceeded, that when the next Cabinet crisis about the Navy arose our rôles would be reversed; and little did he think that the ships for which he contended so stoutly would eventually, when they arrived, be welcomed with open arms by me.

Whatever differences might be entertained about the exact number of ships required in a particular year, the British nation in general became conscious of the undoubted fact that Germany proposed to reinforce her unequalled army by a navy which in 1920 would be far stronger than anything up to the present possessed by Great Britain. To the Navy Law of 1900 had succeeded the amending measure of 1906; and upon the increases of 1906 had followed those of 1908. In a flamboyant speech at Reval in 1904 the German Emperor had already styled himself, “The Admiral of the Atlantic.” All sorts of sober-minded people in England began to be profoundly disquieted. What did Germany want this great 34navy for? Against whom, except us, could she measure it, match it, or use it? There was a deep and growing feeling, no longer confined to political and diplomatic circles, that the Prussians meant mischief, that they envied the splendour of the British Empire, and that if they saw a good chance at our expense, they would take full advantage of it. Moreover it began to be realised that it was no use trying to turn Germany from her course by abstaining from counter measures. Reluctance on our part to build ships was attributed in Germany to want of national spirit, and as another proof that the virile race should advance to replace the effete overcivilised and pacifist society which was no longer capable of sustaining its great place in the world’s affairs. No one could run his eyes down the series of figures of British and German construction for the first three years of the Liberal Administration, without feeling in presence of a dangerous, if not a malignant, design.

In 1905 Britain built 4 ships, and Germany 2.

In 1906 Britain decreased her programme to 3 ships, and Germany increased her programme to 3 ships.

In 1907 Britain further decreased her programme to 2 ships, and Germany further increased her programme to 4 ships.

These figures are monumental.

It was impossible to resist the conclusion, gradually forced on nearly every one, that if the British Navy lagged behind, the gap would be very speedily filled.

As President of the Board of Trade I was able to obtain a general view of the structure of German finance. In 1909 a most careful report was prepared by my direction on the whole of this subject. Its study was not reassuring. I circulated it to the Cabinet with the following covering minute:—

Believing that there are practically no checks upon German naval expansion except those imposed by the increasing difficulties of getting money, I have had the enclosed report prepared with a view to showing how far those limitations are becoming effective. It is clear that they are becoming terribly effective. The overflowing expenditure of the German Empire strains and threatens every dyke by which the social and political unity of Germany is maintained. The high customs duties have been largely rendered inelastic through commercial treaties, and cannot meet the demand. The heavy duties upon food-stuffs, from which the main proportion of the customs revenue is raised, have produced a deep cleavage between the agrarians and the industrials, and the latter deem themselves quite uncompensated for the high price of food-stuffs by the most elaborate devices of protection for manufactures. The splendid possession of the State railways is under pressure being continually degraded to a mere instrument of taxation. The field of direct taxation is already largely occupied by State and local systems. The prospective inroad by the universal suffrage Parliament of the Empire upon this depleted field unites the propertied classes, whether Imperialists or State-right men, in a common apprehension, with which the governing authorities are not unsympathetic. On the other hand, the new or increased taxation on every form of popular indulgence powerfully strengthens the parties of the Left, who are themselves the opponents of expenditure on armaments and much else besides.

Meanwhile the German Imperial debt has more than doubled in the last thirteen years of unbroken peace, has risen since the foundation of the Empire to about £220,000,000, has increased in the last ten years by £105,000,000, and practically no attempt to reduce it has been made between 1880 and the present year. The effect of recurrent borrowings to meet ordinary annual expenditure has checked the beneficial process of foreign investment, and dissipated the illusion, cherished during the South African War, that Berlin might supplant London as the lending centre of the world. The credit of the German Empire has fallen to the level of that of Italy. It is unlikely that the new taxes which have 36been imposed with so much difficulty this year will meet the annual deficit.

These circumstances force the conclusion that a period of severe internal strain approaches in Germany. Will the tension be relieved by moderation or snapped by calculated violence? Will the policy of the German Government be to soothe the internal situation, or to find an escape from it in external adventure? There can be no doubt that both courses are open. Low as the credit of Germany has fallen, her borrowing powers are practically unlimited. But one of the two courses must be taken soon, and from that point of view it is of the greatest importance to gauge the spirit of the new administration from the outset. If it be pacific, it must soon become markedly pacific, and conversely.

This is, I think, the first sinister impression that I was ever led to record.