The Project Gutenberg EBook of Coronation Rites, by Reginald Maxwell Woolley

This eBook is for the use of anyone anywhere in the United States and

most other parts of the world at no cost and with almost no restrictions

whatsoever. You may copy it, give it away or re-use it under the terms

of the Project Gutenberg License included with this eBook or online at

www.gutenberg.org. If you are not located in the United States, you'll

have to check the laws of the country where you are located before using

this ebook.

Title: Coronation Rites

Author: Reginald Maxwell Woolley

Editor: H. B. Swete

J. H. Srawley

Release Date: May 30, 2019 [EBook #59634]

Language: English

Character set encoding: UTF-8

*** START OF THIS PROJECT GUTENBERG EBOOK CORONATION RITES ***

Produced by deaurider and the Online Distributed

Proofreading Team at http://www.pgdp.net (This file was

produced from images generously made available by The

Internet Archive)

The Cambridge Handbooks of Liturgical Study

General Editors:

CAMBRIDGE UNIVERSITY PRESS

C. F. CLAY, Manager

London: FETTER LANE, E.C.

Edinburgh: 100 PRINCES STREET

New York: G. P. PUTNAM’S SONS

Bombay, Calcutta and Madras: MACMILLAN AND CO., Ltd.

Toronto: J. M. DENT AND SONS, Ltd.

Tokyo: THE MARUZEN-KABUSHIKI-KAISHA

All rights reserved

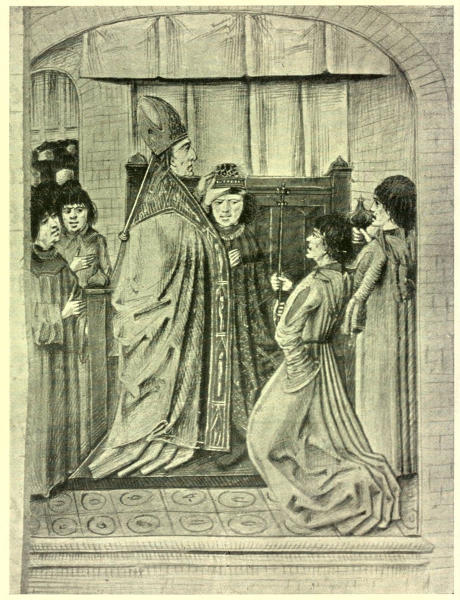

The Coronation of Henry I of England

CORONATION RITES

BY

REGINALD MAXWELL WOOLLEY, B.D.

Rector and Vicar of Minting

Examining Chaplain to the Lord Bishop of Lincoln

Cambridge:

at the University Press

1915

Cambridge:

PRINTED BY JOHN CLAY, M.A.

AT THE UNIVERSITY PRESS

The purpose of The Cambridge Handbooks of Liturgical Study is to offer to students who are entering upon the study of Liturgies such help as may enable them to proceed with advantage to the use of the larger and more technical works upon the subject which are already at their service.

The series will treat of the history and rationale of the several rites and ceremonies which have found a place in Christian worship, with some account of the ancient liturgical books in which they are contained. Attention will also be called to the importance which liturgical forms possess as expressions of Christian conceptions and beliefs.

Each volume will provide a list or lists of the books in which the study of its subject may be pursued, and will contain a table of Contents and an Index.

The editors do not hold themselves responsible for the opinions expressed in the several volumes of the series. While offering suggestions on points of detail, they have left each writer to treat his subject in his own way, regard being had to the general plan and purpose of the series.

H. B. S.

J. H. S.

While it is hoped that this book may prove of service to those who wish to study the history and structure of the Coronation Rite, it will be evident that a subject so large can only be treated, in the space at my disposal, in outline. Those who wish for more detailed information must be referred to the texts themselves.

May I also here point out that since the Rite was probably never used twice in identically the same form in any country, and since it was thus in a continually fluid state, the ‘Recensions’ into which the rites of the different countries are here and generally divided, are to a certain extent arbitrary, and must be taken as marking periods at which the rites reached certain stages of developement?

Both Dr Swete and Dr Srawley have by their criticisms added considerably to the accuracy of the book. To Dr Srawley in particular I am much indebted for his patience in the discussion of various[vii] doubtful points that arose, and also for the trouble he has taken with the proof during the passage of the book through the Press. I am indebted, too, to the Rev. Chr. Schmidt for going over my translation of the Scandinavian documents. I have to thank M. H. Omont for permission to reproduce the miniature of Nicephorus Botoniates, and Mr H. Yates Thompson for like permission in the case of the picture of St Louis. All the photographs, except of this last named picture, were made by Mr Donald Macbeth. Lastly I must express my sense of obligation to the readers and printers of the University Press for the care with which they have printed the book.

R. M. W.

August 23, 1915.

| PAGE | ||

| Bibliography | xi | |

| CHAP. | ||

| I. | Early conceptions of Kingship, and religious rites in connection with a King’s accession | 1 |

| II. | Ceremonies in connection with the Inauguration of a Roman Emperor in pre-Christian times. The Origin of the Christian Coronation Rite in the fifth century. The Byzantine Rite of the tenth century and its developements. The Coronation of a Russian Czar. The Abyssinian Rite | 7 |

| III. | The Origin of the Rite in the West. A twofold source. The seventh-century Rite of the Consecration of a King in Spain, and the Imperial Rite of the Holy Roman Empire | 32 |

| IV. | The Western Imperial Rite of the Coronation of an Emperor at Rome. The accounts of the Coronation of Charlemagne. The earliest forms and their later developements | 37 |

| [ix]V. | The Coronation of a King. The Anglo-Saxon Consecration. The Rite of the so-called Pontifical of Egbert, and the developement of the English Rite | 56 |

| VI. | The French Rite and its developements. The Coronation of Napoleon | 91 |

| VII. | The Roman Rite of the Coronation of a King and its developements | 109 |

| VIII. | The Rite of Milan and its developements | 114 |

| IX. | The German Rite | 120 |

| X. | The Hungarian Rite | 126 |

| XI. | The early accounts of the Rite of the Consecration of a King in Visigothic Spain. The Rites of Aragon and Navarre | 128 |

| XII. | Other countries. Protestant Rites. Scotland. Bohemia. The Prussian Rite of 1701. Denmark. Sweden. Norway | 137 |

| XIII. | The Papal Coronation | 159 |

| XIV. | The Inter-relation of the different Rites | 165 |

| XV. | The Unction, the Vestments, and the Regalia | 177 |

| XVI. | The Significance of the Rite | 188 |

| General Index | 200 | |

| Index of Forms | 203 | |

| I. | The Coronation of Henry I of England | Frontispiece |

| (Reproduced from B.M. Royal MS. 15. E. iv. Photograph by Donald Macbeth.) | ||

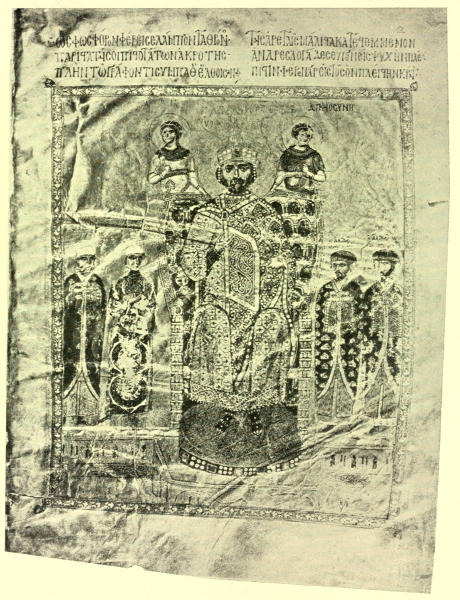

| II. | The Emperor Nicephorus Botoniates in his imperial robes | to face p. 25 |

| (MS. Coislin 79 fol. 2, bibl. nationale Paris. Reproduced from Omont, H., Fac-similés des miniatures des plus anciens MSS grecs de la bibliothèque nationale. Photograph by Donald Macbeth.) | ||

| III. | The Emperor Charles V in his Coronation robes | to face p. 55 |

| (Reproduced from F. Bock, Kleinodien des heiligen römischen Reiches deutscher Nation. Photograph by Donald Macbeth.) | ||

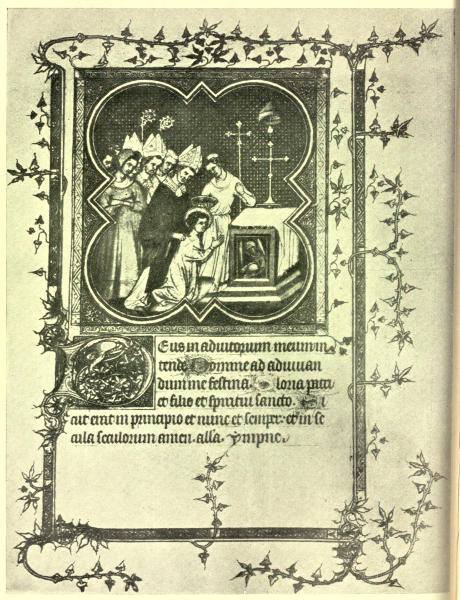

| IV. | The Anointing of St Louis of France | to face p. 99 |

| (Reproduced from H. Yates Thompson, Book of Hours of Joan II, Queen of Navarre.) |

Codinus Curopalates. De officiis Constantinopolitanis. (Bonn, 1839.)

Constantinus Porphyrogenitus. De caerimoniis aulae Byzantinae. (Bonn, 1829.)

Goar, J. Euchologion. (Paris, 1647.)

Theophanes. Chronographia. (Bonn, 1839.)

Maltzew, A. Die heilige Krönung. In Bitt-Dank- und Weihe-Gottesdienste der orthodox-katholischen Kirche des Morgenlandes. (Berlin, 1897.)

Metallinos, E. Imperial and Royal Coronation. (London, 1902.)

Lobo, Jeronymo. Voyage Historique d’Abissinie, Traduite du Portugais, continuée et augmentée de plusieurs Dissertations, Lettres, et Mémoires. Par M. Le Grand, Prieur de Neuville-les-Dames et de Prevessin. (Paris, MDCCXXVIII.)

Tellez, Balthasar. The Travels of the Jesuits in Ethiopia translated into English. (London, 1710.)

Duchesne, L. Liber Pontificalis. 2 vols. (Paris, 1886-92.)

Hittorp, Melchior. De divinis Catholicae Ecclesiae officiis. Paris, 1610.

Mabillon, J. Museum Italicum, 2 vols. (Paris, 1687-9.) For Ordines Romani, see also Migne, P.L. LXXVIII.

Martène, E. De antiquis ecclesiae ritibus. (Antwerp, 1763.)

(The first edition of this work published in 1702 does not contain all the documents which are found in the editions of 1736 onwards.)

Panvinius and Beuther. Inauguratio, Coronatio, Electioque aliquot Imperatorum, etc. (Hanover, 1612.)

Pertz, G. H. Monumenta Germaniae Historica. (Hanover, 1826.)

Pontificale Romanum. (Venice, 1520.)

Pontificale Romanum Clementis VIII et Urbani PP. VIII auctoritate recognitum. (Louvain, n.d. Other edd., Paris, 1664, Rome, 1738-40.)

Waitz, G. Die Formeln der deutschen Königs- und der römischen Kaiser-Krönung. (Göttingen, 1872.)

Greenwell, W. The Pontifical of Egbert Archbishop of York. (Surtees Soc., vol. XXVII. 1853.)

Wickham Legg, J. Missale ad usum Ecclesiae Westmonasteriensis, vols. II. and III. (H.B.S., 1893-6.)

Wickham Legg, J. Three Coronation Orders. (H.B.S., 1900.)

Wickham Legg, J. The Order of the Coronation of King James I. (Russell Press, London, 1902.)

Wickham Legg, L. G. English Coronation Records. (Westminster, 1901.)

Wordsworth, Chr. The Manner of the Coronation of King Charles I of England. (H.B.S., 1892.)

The Form and Order of the Service that is to be performed and of the Ceremonies that are to be observed in the Coronation of Their Majesties King Edward VII and Queen Alexander in the Abbey Church of S. Peter, Westminster, on Thursday, the 26th day of June, 1902. (Cambridge, 1902.)

The Form and Order of the Service that is to be performed and of the Ceremonies that are to be observed in the Coronation of Their Majesties King George V and Queen Mary in the Abbey Church of S. Peter, Westminster, on Thursday, the 22nd day of June, 1911. (Oxford, 1911.)

Ménard, H. D. Gregorii Papae I. Liber Sacramentorum. Paris, 1642. (Reprinted in Migne, P.L. LXXVIII.)

Dewick, E. S. The Coronation Book of Charles V of France. (H.B.S., 1899.)

Francorum Regum Capitularia, in Migne, P.L. CXXXVIII.

Godefroy, T. Le Cérémonial François. (Paris, MDCXLIX.)

Martène, op. cit.

Masson, F. Le sacre et le couronnement de Napoléon. (Paris, 1908.)

Procès-Verbal de la Cérémonie du Sacre et du Couronnement de LL. MM. L’Empereur Napoléon et L’Impératrice Joséphine. (Paris, An XIII. = 1805.)

Hittorp, op. cit.

Martène, op. cit.

Mabillon, op. cit.

Pontificale Romanum.

Magistretti, M. Pontificale in usum eccles. Mediolanensis necnon Ordines Ambrosiani. (Milan, 1897.)

Pertz, op. cit.

Pertz, op. cit.

Martène, op. cit.

Martène, op. cit.

Panvinius and Beuther, op. cit.

de Blancas, J. Coronaçiones. (Çaragoça, 1641.)

Çurita, Geronymo. Los cinco libros primeros de la segunda parte de los anales de la corona de Aragon. (Çaragoça, MDCX.)

Férotin, M. Liber ordinum. (Paris, 1904.)

Yanguas y Miranda, J. M. Cronica de los Reyes de Navarra. (Pamplona, 1843.)

Lector, Lucius. Le Conclave. (Paris, 1894.)

Lector, Lucius. L’Élection papale. (Paris, 1896.)

Mabillon, op. cit.

Grissell, H. de la G. Sede vacante. (Oxford, 1903.)

Sacrarum caerimoniarum sive rituum ecclesiasticorum S. Rom. Ecclesiae Libri tres. (Venetiis, MDLXXXII.)

Acta Bohemica. ([Prague], 1620.)

Actus Coronationis seren. Dn. Frederici Com. Pal. Rheni ... et Dom. Elisabethae ... in Regem et Reginam Bohemiae. (Prague, 1619.)

Allernaadigst approberet Ceremoniel ved Deres’ Majestæter Kong Christian den Ottendes og Dronning Caroline[xv] Amalias forestaaende, höie Kronings-og Salvings-Act paa Frederiksborg Slot, Sondagen den 28ᵈᵉ Juni, 1840. Hendes Majestæt Dronninges allerhöieste Födselsdag. A. Seidelin. (Kjöbenhavn, 1840.)

Bute, John Marquess of. Scottish Coronations. (Alex. Gardner, 1902.)

Cooper, J. Four Scottish Coronations. (Aberdeen, 1902.)

Ceremoniel ved deres Majestæter Kong Haakon den Syvende’s og Dronning Maud’s Kroning i Trondhjem’s Domkirke Aar 1906. Steen’ske Bogtrykkeri, Kr. A., 1906.

Kurtze Beschreibung wie Ihr. Königl. Majest. zu Schweden Karolus XI: zu Upsahl ist gekrönet worden. Aus dem Schwedischen verdeutschet. (1676.)

Ordning vid Deras Majestäter Konung Carl den Femtondes och Drottning Wilhelmina Frederika Alexandra Anna Lovisas Kröning och Konungens Hyllning vid Riksdagen i Stockholm. 1860.

Wickham Legg, J. An Account of the Anointing of the First King of Prussia in 1701, in Arch. Journ. LVI. pp. 123 ff. 1899.

Bock, F. Die Kleinodien des heil. römischen Reiches deutscher Nation. (Leipzig, 1864.)

Brightman, F. E. The Coronation Vestments. In The Pilot, vol. VI. pp. 136, 137.

Wickham Legg, L. G., op. cit.

Bouquet, M. Recueil des historiens des Gaules. (Paris, 1738.)

Brightman, F. E. Byzantine Imperial Coronations. In Journal of Theological Studies, II. 369 f. (Cited as J. Th. St.)

Desdevises du Dezert, G. Don Carlos d’Aragon. (Paris, 1889.)

Diemand, A. Das Ceremoniell der Kaiserkrönungen von Otto I bis Friedrich II. (München, 1894.)

Heylin, P. Cyprianus Anglicus. (London, MDCLXVIII.)

Leclercq, H. Dictionnaire d’archéologie et de liturgie chrétienne. (Paris. In progress.) Cited as DACL, ‘Charlemagne.’

Liebermann, F. Die Gesetze der Angelsachsen. (Halle, 1903.)

Prynne. Canterburie’s Doome. (London, 1646.)

Wilson, H. A. The English Coronation Orders. J. Th. St. II. 481 ff.

Kingship is one of the most ancient institutions of civilisation. At the very dawn of history the king is not only already existent, but is regarded with a reverential awe that shews that the institution must have had its beginnings in very remote times. His functions are twofold, civil and religious; not only is he set apart from those over whom he rules, but by virtue of his other function, that of mediator between God and his people, we find him invested as it were with a halo of quasi-divinity. And so in early times we find the king possessing certain priestly prerogatives. Pharaoh was not an ordinary man but the son of Horus, and almost as one of the Gods. The kings of the Semites were priest-kings. In Homer the king is Θεῖος[1], he is set upon his throne by Zeus, he is invested with the divine sceptre as in the case[2] of Agamemnon[2] and stands in a very special relation to the Deity. In ancient Rome it was the same; and when in Rome and Athens kingship was abolished, still it was necessary to have an ἄρχων βασιλεύς or a Rex Sacrorum to perform the special priestly functions hitherto belonging to the king.

In view then of the sacred character of the king it is only natural to expect to find some religious ceremonial accompanying his accession to his office, and although in the West there is little or no direct evidence of this, in the East there is found in very early times a solemn religious ceremony consecrating the king to his office.

The first actual reference to the consecration of a king occurs in the Tel-el-Amarna correspondence. In one of the letters Ramman-Nirari a Syrian king writing to Pharaoh speaks of the consecration of his father and grandfather, and that by unction with oil[3].

In the Old Testament there are a number of instances of the consecration of a king by anointing[3] with oil, a rite parallel to the consecration of a priest or prophet. In the parable of the trees of Lebanon in the Book of Judges (ix. 15), the consecration of a king by anointing with oil is regarded as the general and accepted custom. Accordingly we read (1 Sam. ix-xi) of the first Israelitish king Saul being solemnly anointed by the prophet Samuel on his election as king. In the account of the inauguration of Saul, if we may use the term, three distinct features are noticeable—

(1) He is anointed with oil, and so is endowed with special gifts, for the Spirit of the Lord comes upon him.

(2) There is a ‘Recognition’ or acceptance of him as king by the people.

(3) King and people make a joint covenant with God.

David was anointed at first privately by Samuel, and by this unction he was endowed with the Spirit of the Lord ‘from that day forward’ (1 Sam. xvi. 13). But he was twice again anointed as king publicly, and in each case in connection with his recognition by the people, on the first occasion when he was made king by the men of Judah (2 Sam. ii. 4), and on the second when he was made king over all Israel (2 Sam. v. 3). Moreover on the second occasion we read of a covenant being made—‘King David made a league with them in Hebron before the Lord: and they anointed David king over Israel.’ In the case of Solomon (1 Kings i. 38-40), we are given more information as to the ceremonial used. Solomon[4] riding on the royal mule goes in procession to Gihon; he is anointed from a horn of oil out of the tabernacle by Zadok the high-priest; trumpets are blown and the people acclaim him with the cry ‘God save King Solomon.’ He is brought and enthroned on David’s throne.

In Israel and Syria we find kings consecrated in like manner by unction. Thus we read of Elijah being charged to anoint Hazael to be king over Syria and Jehu king over Israel (1 Kings xix. 15, 16). The somewhat informal manner in which Jehu was anointed by a son of the prophets (2 Kings ix. 1 ff.) may have been due to the special circumstances of the case, or it is possible that there was a more gradual development of the ceremonial in Israel than in orthodox Judah.

The fullest account given in the Old Testament of a coronation is that of Jehoiada (2 Kings xi. 12 ff.). Here is the first actual mention of the crowning, and there are a number of separate ceremonial acts.

(1) The crown is set on the king’s head by the high-priest.

(2) The king is given the ‘testimony,’ for which we should probably read the regal ‘bracelets[4].’

(3) He is made king and anointed.

(4) He is acclaimed by the people, ‘God save the King.’

(5) A covenant is made not only between the[5] Lord and the king and the people, but also between the king and the people.

Here then we have investiture with crown and perhaps with other regal ornaments. A recognition is probably implied in the expression ‘they made him king.’ He is anointed and acclaimed. The covenant made between king and people is, to use a later phraseology, the coronation oath. It was his refusal to make a satisfactory covenant with his people that was the occasion of trouble between Rehoboam and Israel.

At a much later period Isaiah refers to Cyrus as ‘the Lord’s anointed.’ The prophet’s language may be merely metaphorical, but on the other hand may imply that the anointing of a king at his accession was a rite common to the whole East. In later times there was a ceremonial crowning of a Persian king, as we happen to know from Agathias’ story of unusual circumstances attendant upon the coronation of Sapor[5].

Reference has been made above to certain regal ornaments mentioned in the accounts of the coronations of various Jewish kings. The crown and regal bracelets are mentioned among Saul’s kingly ornaments (2 Sam. i. 10). To these may perhaps be added the shield (2 Sam. i. 21), and the spear (1 Sam. xviii. 10, xxvi. 7, 22)[6].

Ezekiel (xxi. 26) mentions the crown and diadem in connection with Zedekiah as the special insignia of the king. There is also special reference made to royal robes distinctive of kingly rank (1 Kings xxii. 10, 30), but there is no evidence as to the nature of these robes.

If the book of Esther can be relied on, there was a definite royal apparel used by the Persian kings as well as a ‘crown royal’ (Esth. vi. 8); and a ‘crown royal’ is also mentioned in connection with the queen, in the case of both Vashti and Esther (i. 11, ii. 17). There can be little doubt that crown and royal vesture reach back to remotest antiquity.

The Christian rite of the sacring of kings does not derive its origin from the older Jewish rite, though doubtless during the process of its developement it borrowed details from the older ceremony.

The origin of the rite must be sought in Constantinople, and from the Byzantine ritual the idea of the Western rite is ultimately derived. But what then is the origin of the Byzantine rite itself? It is the Christian developement of the ceremonies connected with the inauguration of the Roman Emperors in pre-Christian times. Of these ceremonies we have no very full or detailed account, but although we have no exact and complete record of the actual ritual used, yet certain historians tell us in somewhat general terms of what happened on the accession of various Emperors. For example, the circumstances of the election of Tacitus to the Empire in 275 were as follows[7].

The Senate was convoked and asked to elect an Emperor, and Tacitus the Princeps Senatus on rising to give his opinion was suddenly acclaimed Emperor by the whole Senate, with the acclamation ‘Tacitus Augustus, the Gods preserve you. You are our choice, we make you Princeps, to you we commit the care of the republic and the world. Take up the Empire by the Senate’s authority. The honour which you deserve is in keeping with your life, your rank, your character’ etc., and the acclamations conclude with the repetition of the formal words, ‘Tacitus Augustus, the Gods preserve you.’ He was thereupon elected, and the Senate proceeded to the Campus Martius, where its choice is announced to the people in these words, ‘You have here, Sanctissimi Milites et Sacratissimi Quirites, the prince whom the Senate has elected in pursuance of the vote of all the armies, I mean the most august Tacitus; so that he who has hitherto helped the republic by his votes, will now help it by his commands and decrees.’ The people greet the announcement with the acclamation: ‘Most fortunate Augustus Tacitus, the Gods preserve you,’ and the rest that it is customary to say. Lastly the Senate’s choice is proclaimed to the army, and the customary Donative is given.

Pertinax was suddenly and irregularly acclaimed by army and populace without waiting for the Senate to make an election. Thereupon he proceeded to the Senate, and after delivering an address to the senators he was acclaimed by all, and received from[9] them all honour and reverence, and ‘was sent to the temple of Jupiter and the other sanctuaries, and having celebrated the sacrifice for the Empire, he returned to the palace[8].’

Thus we see that in theory the new Emperor was first elected by the Senate, and then accepted or recognised in the Campus Martius by the people and army with acclamations which followed a definite and fixed ritual, and finally the Donative originated by the Emperor Claudius, and followed by his successors, was bestowed. But in actual fact the election by the Senate tended to become more and more a very perfunctory affair, and the choice of an Emperor came more and more to fall into the hands of the armies.

The Emperor had, however, some power in providing his successor. He could and often did nominate a colleague who would normally possess a right of succession. But while he was merely colleague in the Empire, though he was invested with some of the marks and functions of the Imperial dignity, he had no actual ‘imperium.’

There were also certain definite imperial insignia, such as the purple cloak, once the mark of a general in the field; the laurel wreath, which the Emperor habitually wore; the purple-striped toga and tunic; and the scarlet senatorial shoes.

The ceremonies of the inauguration naturally tended in process of time to develope. The election by the Senate, as has been remarked, became more[10] and more of a form, and new customs gradually came into being. A considerable developement is noticeable in the account of the inauguration of Julian, though the whole ceremony in his case was under the circumstances somewhat informal and makeshift. It is the army which elects him. In spite of his protests he is acclaimed as Emperor; he is then elevated on a shield; and finally he is crowned, a torque serving temporarily to represent the diadem. Afterwards, we are told, he assumed a gorgeous diadem at Vienne[9]. The elevation on a shield, which henceforward always occurs in the inauguration ceremonies, appears for the first time at Julian’s accession to the imperial throne. It was a custom followed among the Teutonic tribes[10], and was doubtless introduced by the Teutonic soldiers who formed so important a part of the Roman armies at this time. The diadem, which is of oriental origin, was perhaps introduced by Aurelian. It seems to have been habitually used by Constantine, and there was a gradual advance during this period in the matter of ceremonial and the sumptuousness of the imperial vestments.

There is no sign, for some time after the acceptance of Christianity as the religion of the Empire, of any Christian influence on the rites of inauguration. It is not until the time of the Emperor Leo I that we meet with the coronation rite in the religious sense of the term. In the year 457 the Emperor Leo I[11] was formally crowned and invested as Emperor with religious rites. Constantine Porphyrogenitus[11], to whom we owe so much of our knowledge of the court functions and ceremonial of the Byzantine period, describes the rite which took place at the accession of Leo. The new Emperor, accompanied by the high officials of the Empire, went down in state to the Hippodrome, in which was gathered together a vast concourse of people. Here he ascended a lofty tribunal in view of all the people and was greeted with acclamations. A maniakis (apparently a kind of fillet) is placed upon his head, and another in his hand, amid the cheers of the people. Then under the cover of a testudo, raised by the candidati, he is arrayed in the imperial vestments, and so shews himself to the people, with the diadem on his head and the imperial shield and spear in his hands. He is thereupon greeted with the ritual formula, Mighty and victorious and august, prosperously, prosperously. Many years, Leo Augustus, thou shalt reign. God will keep this realm, God will keep this Christian realm, and other such things. The Emperor then makes a speech to the people, and promises the customary Donative.

Nicephorus, Theodore the Reader, and Theophanes, assert that Leo was elected by the Senate, and that the diadem was set upon his head by the Patriarch Anatolius[12], but Constantine does not make any[12] reference to any act of coronation by the Patriarch, and does not mention him at all, except as being among the high officials who accompanied the Emperor to the Hippodrome. Evidently as yet the Patriarch took no very public or prominent part in the ceremonial.

We are told more, however, in connection with the inauguration of the Emperor Anastasius I in 491[13]. On the death of Zeno, the choice of his successor to the Empire was left in the hands of the Empress Ariadne. The Senate summoned the Patriarch to exhort her to make a worthy choice, and she chose as Emperor Anastasius the Silentiary. After the funeral of Zeno, Anastasius takes up his position before the portico of the great Triclinium and the magistrates and Senate require of him an oath that he will retain no private grudge against anyone, and that he will rule the Empire well and justly. The Patriarch Euthymius then demands an oath in writing[14] that he will make no change in the Faith or Church, and that he shall sign the Chalcedonian dogmas. Anastasius then proceeds to the Hippodrome and enters the triclinium from which the Emperor is wont at race times to receive the adoration of the Senate. He is clothed in the golden-striped Dibetesion (a tunic reaching to the knees), girdle, greaves, and royal buskins, his head being uncovered. The military standards are in the meanwhile lying[13] on the ground, to signify, apparently, the vacancy of the throne. The people acclaim him, he is raised on a shield, and a campiductor places a torque about his head. This last is perhaps a perpetuation of the makeshift coronation of Julian with a military torque. The standards are then lifted up, and people and soldiery together acclaim the Emperor. The Emperor re-enters the triclinium, and is invested with the regalia. The Patriarch says a prayer which is followed by the Kyrie eleeson, and then the Patriarch invests the Emperor with the imperial chlamys (the purple robe), and sets a gorgeous crown upon his head. After this the Emperor goes to the Kathisma and shews himself to the people, who greet him with the cry Auguste, Σεβαστέ. The Emperor then proceeds to address the people in a special ritual formulary, a book containing which is put into his hand for the purpose.

Emperor. It is manifest that human power depends on the will of the supreme Glory.

People. Abundance to the world! As thou hast lived, so rule. Incorrupt rulers for the world! and so on.

Emp. Since the most serene Augusta Ariadne with the assent of the illustrious nobles and by the election of the glorious Senate and mighty armies, and the consent of the sacred people, have advanced me, though unwilling and hesitating, that I should assume the care of the Empire of the Romans, agreeably to the clemency of the Divine Trinity....

Peo. Kyrie eleeson. Son of God, have mercy upon[14] him. Anastasie Auguste, tu vincas! God will keep the pious Emperor. God gave thee, God will keep thee! and so on.

Emp. I am not ignorant how great a weight is laid upon me for the common safety of all.

Peo. Worthy of the Empire! Worthy of the Trinity! Worthy of the City. Out with the informers. (This last is doubtless an unauthorised interpolation.)

Emp. I pray Almighty God that as ye hoped me to be, in this common choice of yours, so ye may find me to be in the conduct of affairs.

Peo. He in whom thou believest will save thee. As thou hast lived, so reign. Piously hast thou lived, piously reign. Ariadne, thou conquerest! Many be the years of the Augusta! Restore the army, restore the forces. Have mercy on thy servants. As Marcian reigned, so do thou ... (and much more to the same effect).

Emp. Because of the happy festival of our Empire, I will bestow 5 solidi and a pound of silver on each man.

Peo. God will keep the Christian Emperor. These are the prayers of all. These are the prayers of the whole world. Keep, O Lord, the pious Emperor. Holy Lord, raise up thy world. The fortune of the Romans conquers. Anastasius Augustus, thou conquerest! Ariadne Augusta, thou conquerest! God hath given you, God will keep you.

Emp. God be with you.

The Emperor then proceeds to the church of[15] St Sophia and lays aside his crown in the Mutatorium, and it is deposited in the sanctuary. He then offers his gifts, and returning to the Mutatorium reassumes his crown, and thence returns to the palace.

In the account which he gives of the inauguration of Leo the Younger in 474[15], Constantine illustrates the ceremonies observed at the inauguration of one associated in the Empire during his father’s lifetime.

The reigning Emperor, accompanied by the Senate and by the Patriarch Acacius, proceeds to the Hippodrome, where the populace and soldiery are already assembled. The Emperor standing before his throne begins to address the troops, who pray him to be seated. Saluting the people the Emperor seats himself and the concourse greeting him with cries of ‘Augustus,’ beseeches him to crown the new Emperor. The Magister and Patricians then lead forward the Caesar, and place him on the Emperor’s left hand. The Patriarch recites a prayer to which all answer ‘Amen.’ The Praepositus then hands a crown to the Emperor, who himself sets it on the Caesar’s head, the people shouting ‘Prosperously, prosperously, prosperously.’ The Emperor seats himself, while the new Emperor addresses the people who greet him with shouts of ‘Augustus.’ The Eparch of the city and the Senate come forward and present the new Emperor, according to custom, with a modiolon, or crown of gold. Finally the Emperor addresses the soldiery, and promises the usual Donative.

In these descriptions we still find a reminiscence of the old election by the Senate, ratified by the soldiery and people. The military assent is signified by the raising aloft on the shield, and by the imposition of the military torque, which was retained as late as the time of Justin II. Leo I also received a second torque in his right hand, which may perhaps be identified with the second golden crown given to Leo II. The meaning of this second crown is not clear, but Mr Brightman[16] has suggested that it may represent authority to crown consorts in the Empire. The acclamations evidently follow a fixed ritual, and the imperial speech is a written document.

We are told in these accounts of inaugurations something of the imperial insignia. The imperial tunic (στιχάρις διβητήσις αὐρόκλαβος, αὐρόκλαβον διβητήσιον) was of white, and when girded with the belt reached to the knees. The belt (ζωνάριον) was a cincture of gold jewelled. The gaiters (τουβία) were purple hose. The buskins (καμπάγια) were of crimson, with gold embroideries and rosettes. The purple paludamentum reached to the ankles, was apparelled with gold, and was fastened on the right shoulder with a jewelled morse. The diadem was a broad gold jewelled circlet with pendants over the ears.

It is to be noticed that the inauguration of an Emperor took place at first in the Hippodrome. It is not until the days of Phokas (602) that we find the ceremony being performed in a church. The Emperor Phokas was crowned by the Patriarch Cyriacus in St John in the Hebdomon; Heraclius (610) by the Patriarch in St Philip in the Palace; Heraclius II in[17] St Stephen in Daphne. The Empress, unless crowned with her consort or father, was not crowned in church, and if crowned at all, the ceremony was of a private and domestic nature and took place in the palace, the Emperor himself setting the diadem upon the head of the Empress.

We have not much information as to the developement of the rite during the seventh and eighth centuries. The following description is given by Theophanes of the coronation of Constantine VI by his father Leo IV in 780[17].

On Good Friday an oath of allegiance was taken to the new Emperor by all classes in writing. On the Saturday the imperial procession went down to St Sophia. There the Emperor, according to custom, arrayed himself in the imperial vestments, and accompanied by his son and the Patriarch ascended into the Ambo, the written oaths of allegiance being deposited on the Holy Table. The Emperor informed the people that he had acceded to their request, and had associated his son with himself in the Empire. ‘Lo, ye receive him from the Church and from the hand of Christ.’ The people respond, ‘Answer us, Son of God; for from thy hand we receive the Lord Constantine as Emperor, to guard him and to die for him.’ On Easter Day the Emperor proceeds to the Hippodrome, where an antiminsion (a portable altar) having been set up, in the sight of all the people the Patriarch recites a prayer, and the Emperor sets the[18] crown on the head of his son. Thereupon the procession returns to the Great Church.

In the tenth century we have from the pen of Constantine Porphyrogenitus[18] a full description of the ceremonial of the coronation of an Emperor, except for the actual prayers used. These however can be found elsewhere, for there are extant two patriarchal Euchologia belonging to this same period, one of the end of the eighth century, the famous Barberini uncial codex, and the other the Grotta Ferrata codex of the twelfth century[19]. These both contain the rite, and it is noticeable that it is the same in both books, except for the fact that the second includes the coronation of an Empress. The rite therefore had remained unchanged from at least the end of the eighth century until the twelfth.

The description given by Constantine is as follows.

The Emperor proceeds to the church of St Sophia and enters the Horologion, and the veil being raised, passes into the Metatorion, where he vests himself with the Dibetesion and the Tzitzakion (a mantle, probably flowered), and over them the Sagion (a light cloak). Entering the church with the Patriarch he lights tapers at the silver gates between the narthex and the nave, and passes down the nave until he comes to the platform before the sanctuary, which is called the Soleas. Here before the Holy Doors leading through the Eikonostasis he prays and lights more[19] candles. The Emperor and the Patriarch then go up into the Ambo, where the Chlamys or imperial robe, and the Stemma or crown, have already been set out on a table. The Patriarch then says the ‘Prayer over the Chlamys,’ and the chamberlains put it on the Emperor. The Patriarch next says the ‘Prayer over the Crown,’ and at the end of it takes the crown and sets it on the Emperor’s head, and the people cry Holy, holy, holy, Glory be to God on high and on earth peace, three times; and then acclaim him, Many be the years of N., the great Emperor and Augustus.

If it is the son of a reigning Emperor who is being crowned as an associate Emperor, the Patriarch gives the crown into the hands of the Emperor, who himself sets it on his son’s head, the people crying, He is worthy, and the standards are dipped in obeisance.

After the Coronation the ‘Laudes’ follow.

Cantors. Glory be to God on high, and on earth peace. The people likewise thrice.

Cant. Goodwill among Christian men. The people likewise thrice.

Cant. God has had mercy on his people. The people likewise thrice.

Cant. This is the great day of the Lord. The people likewise thrice.

Cant. This is the day of the life of the Romans. The people likewise thrice.

Cant. This is the joy and glory of the world. The people likewise.

Cant. On which the crown of the kingdom.... The people likewise.

Cant. ... has worthily been set upon thy head. The people likewise thrice.

Cant. Glory be to God the Lord of all. The people likewise.

Cant. Glory be to God who hath crowned thy head. The people likewise.

Cant. Glory be to God who declared thee (τῷ ἀναδείξαντί σε) Emperor. The people likewise.

Cant. Glory be to God who hath thus glorified thee. The people likewise.

Cant. Glory be to God who hath thus approved thee. The people likewise.

Cant. And He who hath crowned thee, N., with his own hand.... The people likewise.

Cant. ... will preserve thee long time in the purple. The people likewise.

Cant. With the consort Augustae and the Princes born in the purple. The people the same.

Cant. Unto the glory and uplifting of the Romans. The people the same.

Cant. May God hear your people. The people likewise.

Cant. Many, many, many.

℟. Many years, for many years.

Cant. Long life to you, N N., Emperors of the Romans.

℟. Long life to you.

Cant. Long life to you, servants of the Lord.

℟. Long life to you.

Cant. Long life to you, N N., Augustae of the Romans.

℟. Long life to you.

Cant. Long life to you: prosperity to the sceptres.

℟. Long life to you.

Cant. Long life to you, N., crowned of God.

℟. Long life to you.

Cant. Long life to you, Lords, and to the Augustae, and to the Princes born in the purple.

℟. Long life to you.

The cantors proceed; But the Creator and Lord of all things, (the people repeat) who hath crowned you with his own hand, (the people repeat) will multiply your years with the Augustae and the Princes born in the purple, (the people repeat) unto the perfect stabiliment of the Romans.

Both choirs then chant Many be the years of the Emperors, etc., and the Emperor descends, wearing the crown, into the Metatorion, and seated upon his throne, the nobles come and do homage, kissing his knees. After which the Praepositus says At your service, and they wish him Many and prosperous years.

The Liturgy now proceeds, and the Emperor makes his Communion.

The ceremonial at the coronation of an Empress[20] was much the same as that observed in the case of the Emperor. The coronation act, however, was performed not by the Patriarch but by the Emperor himself. If the Emperor was married after his[22] accession, the whole ceremony of the crowning of his consort took place immediately after the wedding, and not publicly in the church of St Sophia, but as a private court function in the Augusteum.

The Euchologia, as has been mentioned above, give the text of the prayers used, which Constantine only indicates. They are as follows[21].

As the Emperor stands with bowed head with the Patriarch in the Ambo a deacon says the Ectene or Litany.

The Patriarch then says the prayer over the Chlamys, secretly:

O Lord our God, King of kings, and Lord of lords, who through Samuel the prophet didst choose thy servant David, and didst anoint him to be king over thy people Israel; hear now the supplication of us though unworthy, and look forth from thy holy dwelling place, and vouchsafe to anoint with the oil of gladness thy faithful servant N., whom thou hast been pleased to establish as king over thy holy people which thou hast made thine own by the precious blood of thine Only-begotten Son. Clothe him with power from on high; set on his head a crown of precious stones; bestow on him length of days; set in his right hand a sceptre of salvation; stablish him upon the throne of righteousness; defend him with the panoply of thy Holy Spirit; strengthen his arm; subject to him all the barbarous nations; sow in his heart the fear of Thee, and feeling for his subjects; preserve him in the blameless faith; make him manifest as the[23] sure guardian of the doctrines of thy Holy Catholic Church; that he may judge thy people in righteousness, and thy poor in judgement, (and) save the sons of those in want; and may be an heir of thy heavenly kingdom. (He goes on aloud) For thine is the might, and thine is the kingdom and the power. Amen.

The Patriarch then hands the Chlamys with its fibula to the Vestitores, who array the Emperor in it. (If however it is the son, or daughter, or the wife of an emperor who is to be crowned, the Patriarch hands the vestment to the Emperor, who himself puts it on the person to be crowned.)

The Patriarch then says the ‘Prayer over the Crown.’

Patriarch. Peace be to all.

Deacon. Bow your heads.

Patriarch. To Thee alone, King of mankind, has he to whom thou hast entrusted the earthly kingdom bowed his neck with us. And we pray Thee, Lord of all, keep him under thine own shadow; strengthen his kingdom; grant that he may do continually those things which are pleasing to Thee; make to arise in his days righteousness and abundance of peace; that in his tranquillity we may lead a tranquil and quiet life in all godliness and gravity. For Thou art the King of peace, and the Saviour of our souls and bodies, and to Thee we ascribe glory. Amen.

The Patriarch then takes the crown from the table, and sets it on the Emperor’s head, saying:

In the name of the Father, and of the Son, and of the Holy Ghost.

The Emperor is then communicated.

Here however there is apparently a disagreement between the Euchologia and the account of Constantine Porphyrogenitus. The Barberini Euchologion of the eighth century states that the Patriarch ‘celebrating the liturgy of the Presanctified administers to him the lifegiving communion,’ and the Grotta Ferrata Euchologion of the twelfth century speaks of the communicating the Emperor with the presanctified Sacrament, while Constantine says nothing of the Emperor being communicated in the reserved Sacrament, but implies that he was communicated in the ordinary course of the Liturgy. It has been suggested by Mr Brightman[22] that ‘the apparent discrepancy may be explained by supposing that the ecclesiastical rubrics are drawn up on the assumption that the Coronation will not necessarily be a festival with a Mass, while the Court ceremonial assumes that it will be.’ He goes on to point out that ‘in ordinary cases of accession the coronation was generally performed at once, festival or no festival: in the case of a consort, when the day could be chosen, it was generally a festival.’

The Greek rite in its final development is found in the writings attributed to Codinus Curopalates[23] (c. 1400).

The Emperor Nicephorus Botoniates in his imperial robes

The Emperor proceeds to the church of St Sophia, and there makes his profession of faith both in writing and orally, reciting the Nicene Creed and declaring[25] his adhesion to the seven Oecumenical Councils, professing himself a servant and protector of the Church, and promising to rule with clemency and justice. Then he proceeds to the triclinium called the Thomaite[24], and medals are scattered among the people, and he is raised aloft on a shield. He then proceeds once more to St Sophia, where screened by a wooden screen erected for the purpose he is clothed in the imperial vestments; the Sakkos (the dibetesion or dalmatic), and the Diadema (girdle)[25], which have already been blessed by bishops. The Liturgy is now begun, and before the Trisagion, at the Little Entrance, the Patriarch enters the Ambo and summons the Emperor. There in the Ambo the Patriarch recites the ‘Prayers composed for the anointing of Emperors,’ part secretly and part aloud, and the Emperor having uncovered his head, the Patriarch anoints him in the form of a cross saying, ‘He is holy,’ the people repeating the words thrice. The Patriarch then sets the crown on the Emperor’s head saying, ‘He is worthy,’ the people repeating this also thrice. Thereupon the Patriarch again recites prayers, doubtless the second prayer ‘To Thee alone.’ If however the Emperor to be crowned is a consort, associated during his father’s lifetime, the Patriarch gives the crown to the Emperor, who himself crowns his colleague.

If the Empress is to be crowned, she takes up her position in front of the Soleas, and the Emperor receiving the already consecrated crown from the Patriarch, himself sets it on her head.

The Emperor and Empress being now crowned, they go to their thrones, the Emperor holding in his hand the Cross-sceptre; the Empress her Baion or wand, both remaining seated except at the Trisagion, Epistle, and Gospel. When the Cherubic Hymn is begun at the Great Entrance the chief deacons summon the Emperor to the entrance of the Prothesis and he is invested with the golden Mandyas (a vestment something like a cope) over his Sakkos and Diadema, and so vested, holding in his right hand the Cross-sceptre and in his left a Narthex or wand[26], he leads the procession at the Great Entrance in virtue of his ecclesiastical rank as Deputatus or Verger. He goes up to the Patriarch and salutes him, and is then censed by the second deacon, who says, ‘The Lord God remember the might of thy kingdom in his Kingdom, always, now and ever, and for ever and ever,’ all the clergy repeating the words. The Emperor greets the Patriarch, and putting off the mandyas returns to his throne, rising only at the Creed, the Lord’s Prayer, and the Elevation. If he is not prepared to communicate he remains seated until the end of the Liturgy. If however he is prepared to communicate, he is escorted to the sanctuary by the deacons, and censes the altar and the Patriarch, and is censed by the Patriarch.[27] Then committing his crown to the deacons he is communicated after the manner of a priest. When he has made his communion, he replaces his crown and returns to his throne. After the Liturgy is over, he receives the Antidoron, and is blessed by the Patriarch and by the bishops present, and kisses their hands. The choirs sing an anthem called the ἀνατείλατε, and the Emperor is acclaimed by the people, and so returns in procession to the palace.

In this account the most important feature is the explicit mention of the unction. There is no definite allusion hitherto in any account to any anointing in the Eastern rite, until the time of the intruding emperor Baldwin I, who was crowned with a Latin rite in 1214.

In 1453 Constantinople was taken by the Turks, and the Greek Empire came to an end. But the Greek coronation rite still survives, and is used in the Russian tongue at the coronation of the Czars of Russia[27], who regard themselves as the successors of the Greek Caesars.

The Russian Czar is crowned at Moscow in the Cathedral of the Assumption (Uspenski Sobor). The imperial procession is met at the church door by the Metropolitan, who blesses the Emperor and Empress with holy water and censes them. Entering the church they make their devotions and ascend to their thrones. The 101st Psalm is sung, after which the[28] Emperor is interrogated as to his belief, and recites in a loud voice the Nicene Creed. Then is sung the hymn ‘O Heavenly King, O Paraclete,’ and after the Litany (Synapte) the hymn, ‘O Lord, save thy people’ is sung thrice, and the lections follow at once; the Prophecy (Is. xlix. 13-19), the Epistle (Ro. xii. 1-7), and the Gospel (Matt. xxii. 15-22). The Emperor now assumes the purple robe, assisted by the Metropolitan who says, ‘In the name of the Father,’ etc. The Emperor bares his head and the Metropolitan making the sign of the cross over it and laying on his hand recites the prayer, ‘O Lord our God’ (cp. p. 22), and then the prayer of the Bowing of the head, ‘To Thee alone’ (cp. p. 23). The Metropolitan now presents the Crown to the Emperor, who puts it on his head, the Metropolitan saying, ‘In the name of the Father,’ etc., and then proceeding to explain the symbolical meaning of the crown. Next the Metropolitan gives the Sceptre into the Czar’s right hand and the Orb into his left, saying, ‘In the name of the Father,’ etc., and explaining the symbolical meaning of these ornaments.

The Czar then seats himself on his throne and the Czarina is summoned. The Czar takes off his Crown and with it touches the brow of the Czarina, and then replaces it on his head. He then sets a smaller Crown on the Czarina’s head, and she immediately assumes the purple robe and the Order of St Andrew.

Thereupon the Archdeacon proclaims the titles of the Czar and Czarina, and the clergy and the assembled[29] company do homage by making three obeisances to the Czar.

The Czar then gives the Sceptre and Orb to the appointed officers, and kneeling down says a prayer for himself that he may worthily fulfil his high office, after which the Metropolitan says a prayer on his behalf. Te Deum is sung and the Liturgy proceeds.

The Anointing takes place after the Communion hymn (κοινωνικόν). Two bishops summon the Czar, who takes his stand near the Royal Gates, the Czarina a little behind him, both in their purple robes, and there the Czar is anointed on the forehead, eyes, nostrils, mouth, ears, breast, and on both sides of his hands by the senior Metropolitan, who says: ‘The seal of the gift of the Holy Ghost.’ The Czarina is then anointed with the same words, but on her forehead only.

After he has been anointed, the Czar is conducted through the Royal Gates and receives the Holy Sacrament in both kinds separately, as if he were a priest, and then are given the Antidoron and wine with warm water, and water to wash his mouth and hands. The Czarina is communicated in the usual manner at the Royal Gates, and is given the Antidoron, wine, and water.

The Father Confessor reads before the imperial pair, who have returned to their seats, the Thanksgiving for Communion. After the dismissal the Archdeacon says the royal anthem, πολυχρόνιον, the choir repeating thrice the last part, ‘Many years,’ and the clergy and laity then present congratulate[30] their Majesties, bowing thrice towards them. The Metropolitan presents the cross for the Czar and Czarina to kiss, and the imperial procession leaves the church.

A curious and unique variety of the Eastern rite survives to this day in Abyssinia[28].

The Negus enters Axum in state, accompanied by his principal officers. At a little distance from the church he alights, and his progress is barred by a cord held across the road by young girls. Thrice they ask him who he is, and at first he answers that he is King of Jerusalem, or King of Sion, and at the third interrogation he draws his sword and cuts the cord, the girls thereupon crying out that he verily is their king, the King of Sion. He is met at the entrance of the church (or sometimes apparently in a tent which is perhaps a moveable church)[29] by the Abuna and the clergy, and enters to the accompaniment of music. He is anointed by the Abuna with sweet oil, all the priests present singing psalms the meanwhile. He is next invested with a royal mantle. Finally a crown of gold and silver, in the shape of a[31] tiara and surmounted by a cross, is set on his head, and a naked sword denoting Justice is placed in his hand. The liturgy is then celebrated, and the Negus receives the Holy Sacrament. When he leaves the church the first chaplain ascends a lofty place and proclaims to the people that N. has been made to reign, and the assembly greet the new monarch with acclamations and good wishes, and come forward in order to kiss his hand.

Unfortunately none of the forms of this rite are accessible. The chief point of interest in it lies in the fact that the Negus is anointed. In view of the obscurity which shrouds the history of Abyssinia during the six centuries which followed the Arab conquest of Egypt it would be precarious to say whence this rite with the accompanying anointing was derived. It may have been an independent development in Abyssinia, derived from the accounts of the anointing of kings found in the Old Testament, more especially as many Judaising practices survive in Abyssinia.

The Eastern rite was one and one only. There was only one monarch in the East to be crowned, and therefore the rite was subject only to a natural and internal development.

When, however, we turn to the history of the Western rite, we approach a very much more intricate matter, for the contemporary western documents give only general accounts and are not explicit as to details.

In the old Empire the coronation of the Emperor took place always at Constantinople and never at Rome, and therefore the old rite was essentially Eastern. When, however, the Neo-Roman Western Empire came into existence, and Charlemagne was crowned at Rome on Christmas day 800, there came into existence a Western Imperial rite. There is no record of the forms used, nor do we even know for certain what took place on that occasion, but we may perhaps presume that the Pope intended to do what was proper on the occasion of the accession of[33] an emperor, and followed the Constantinopolitan ritual in outline, while it seems probable that the actual prayers used were Roman compositions made for the occasion. Here, at any rate, in the coronation of Charlemagne we have the beginnings of the Roman Imperial rite.

But if the coronation of Charlemagne marks the origin of the Western imperial rite, it does not mark the introduction into the West of the rite of the consecration of a king, for such a rite had already been in existence in Spain some two centuries before this time. Whether this Spanish rite, which appears to have been well established in the seventh century, was an independent religious developement of the ceremonies which seem to have been observed at the inauguration of a new chieftain among most of the northern peoples, or whether the idea of it was in any way borrowed from Constantinople, there is not sufficient evidence to show.

The Spanish rite was, as has been said, well established in the seventh century. In the canons of the sixth council of Toledo in 638 a reference is made to the oath taken by a Spanish monarch. Julian Bishop of Toledo in his Historia Wambae[30] gives a short description of the anointing of King Wamba, at which he himself was present in 672, and in his account speaks of the customs observed on such occasions. It is then abundantly clear that a consecration ceremony was observed at the accession[34] of the kings of Spain some two centuries before the rite of the coronation was introduced at Rome.

But not only in Spain did such a rite exist before the introduction of the imperial rite at Rome. It is found in existence in the eighth century in France, and probably it was used there before this date. We read how the first of the Carolingian kings sought the official recognition of his dynasty from the Church, and that in response to his appeal Pope Zacharias, ‘lest the order of Christendom should be disturbed, by his apostolic authority ordered Pippin to be created king and to be anointed with the unction of holy oil[31].’ He was accordingly consecrated in 750 by St Boniface, on which occasion we are told that he was elected king according to the custom of the Franks[32]; and to make assurance doubly sure he was a second time consecrated by Pope Stephen himself, who came over the Alps for the purpose and ‘confirmed Pippin as king with the holy unction, and with him anointed his two sons Carl and Carloman to the royal dignity[33].’

For England, if we leave out of consideration the Pontifical of Egbert, which cannot be ascribed to Egbert with any confidence, and of which the date is uncertain, we have only scanty evidence of the[35] existence of any coronation ceremony before the tenth century, though we read of two isolated instances in which, in Northumbria and in Mercia, under special circumstances, kings are said to have been ‘consecrated’ during the eighth century[34].

There remains the fact, then, that in Spain in the seventh century it was the custom to consecrate the Visigothic kings with unction, and a similar practice appears in France during the eighth century in connection with the new dynasty inaugurated by Pippin. For England the evidence is slight, though we read of kings being consecrated in two isolated instances. This evidence is earlier in date than the period at which the exigencies of the Roman Empire called an imperial rite into existence at Rome. Thus there were in the West two separate and distinct introductions of the consecration rite, the first into the Visigothic kingdom of Spain from which, in all probability, the Frankish and Anglo-Saxon rites were derived; the second in Rome on the occasion of the renaissance of the Western Empire. About the end of the ninth century these two rites began to influence one another, and from the Roman rite of the coronation of an Emperor a Roman rite of the coronation of a King was produced.

In the consideration of the different Western rites and their developements, perhaps the method most convenient to follow is, first to treat of the imperial rite, and then of the royal. Though this method has its disadvantages from the point of view of the[36] interaction of the two rites upon each other, yet on the whole it is the simplest and clearest way of treating the many varieties of rite that accumulated in process of time.

There seems to be no evidence of the existence of any coronation rite among the Britons. Gildas is sometimes quoted as evidencing the existence of a British rite. He says as follows; ‘Kings were anointed, and not by God, but such as stood out more cruel than other men; and soon they would be butchered, not in accordance with the investigation of the truth, for others more cruel were chosen in their place[35].’ It is plain that this language is merely metaphorical.

There is a passage occurring in Adamnan’s life of St Columba which is more to the point[36]. It speaks of an ‘ordination’ (ordinatio) of King Aidan by the saint. ‘And there (i.e. in Iona) Aidan coming to him in those same days he ordained (ordinavit) as king, as he had been bidden. And among the words of ordination he prophesied things to be of his sons and grandsons. And laying his hands upon his head, ordaining him, he blessed him.’

I do not think that this occurrence can be regarded in any sense of the word as a consecration of Aidan. It appears to be nothing more than a very solemn blessing. The word Ordinatio is curious, but it is probably referring to the laying on of the hand in benediction.

The Western coronation rite came into existence on the foundation of the Neo-Roman or Holy Roman Empire by Charlemagne. The rite by which he was crowned was evidently regarded as the equivalent to that used at Constantinople, for the contemporary accounts claim that the ceremony was carried out ‘more antiquorum.’

The two earliest accounts of the coronation of Charlemagne agree closely but give only scanty details. The Chronicle of Moissac[37] describes the event thus. ‘Now on the most holy day of the Nativity of the Lord, when the king arose from prayer at Mass before the tomb of the blessed apostle Peter, Leo the Pope with the counsel of all the bishops and priests and the Senate of the Franks and also of the Romans, set a golden crown on his head, in the presence also of the Roman people, who cried: “To Charles the Augustus crowned of God, great and[38] pacific Emperor of the Romans, life and victory.” And after the Laudes had been chanted by the people, he was also adored by the Pope after the manner of the former princes.’

Very much the same is the account given by the Liber Pontificalis[38]. ‘After these things, the day of the Nativity of our Lord Jesus Christ arriving, they were all again gathered together in the aforesaid basilica of the blessed Apostle Peter. And then the venerable and beneficent pontiff with his own hands crowned him with a most precious crown. Then all the faithful Romans, seeing the great care and love he had towards the holy Roman Church and its Vicar, unanimously with loud voice cried out, by the will of God and the blessed Peter, key-bearer of the kingdom of the heavens, “To Charles, the most pious Augustus crowned of God, great and pacific Emperor of the Romans, life and victory.” Before the sacred tomb of the blessed Apostle Peter, invoking many saints[39], thrice was it said; and he was constituted by all Emperor of the Romans. In the same place the most holy priest and pontiff anointed[39] with holy oil Charles, his most noble son, as king, on that same day of the Nativity of our Lord Jesus Christ.’

The forms by which Charlemagne was crowned have not survived and we have only such short descriptions as these as to what took place, and a comparison in other cases of such descriptions with the rites actually used warns us how precarious it is to rely too much on the accounts even of eyewitnesses.

In the two accounts given above it will be noticed that the Chronicle of Moissac seems to desire to keep up the old fiction of a constitutional election when it speaks of the coronation as taking place ‘with the counsel of all the bishops and priests, and the Senate of the Franks and also of the Romans’; and also some sort of recognition by the people seems to be implied by the statement of the Liber Pontificalis that Charlemagne ‘was constituted by all Emperor of the Romans.’

Einhard[40], in his Life of Charles, expressly states that Charles had no idea beforehand of the intention of the Pope to crown him as Emperor, and that if he had known he would not have entered St Peter’s on that eventful Christmas Day. But the words of the Chronicle of Moissac certainly imply that it was a prearranged thing, and if Charlemagne was really taken by surprise, it was probably the method of the coronation, at the hands of the Pope, which[40] constituted the surprise. The occurrence of the Laudes need not present any difficulties to the view that the whole affair was unexpected, for as we have seen they were a familiar part of great public functions, and it is possible that the people were led on such occasions by official cantors, as we know was the practice at Constantinople.

But the most important question connected with Charlemagne’s coronation is, Was Charles anointed? There is no reference whatever to any anointing in the contemporary accounts of the Chronicle of Moissac and the Liber Pontificalis, nor yet in other almost contemporary matter such as the verses of the Poeta Saxo[41], or the Chronicle of Regino[42]. To this must be added the fact, inconclusive in itself, that there is no mention of any unction in the earliest extant Order of the Western imperial rite, that of the Gemunden Codex. On the other hand it is expressly stated by a contemporary eastern historian, Theophanes, that Charlemagne was anointed ‘from head to foot[43],’ and this statement is repeated by a later Greek writer of the twelfth century, Constantine Manasses, who adds, ‘after the manner of the Jews[44].’

If Charlemagne was not anointed but only crowned[41] by the Pope, then his coronation was strictly in accordance with the rite of Constantinople, for it is probable that there was no unction in the Eastern rite at this date, and thus the Western rite on its first introduction into the West would be similar in its outstanding feature to the Eastern rite.

Of course the use of an unction at the consecration of a king had long been the central feature of the Western rite of the consecration of a King. But it must be borne in mind that Charlemagne was here being crowned as Roman Emperor, and that he had been anointed as King of the Franks on the occasion long ago of his father Pippin’s anointing as Frankish King at the hands of Pope Stephen. Moreover it is added in the Liber Pontificalis that after the coronation of Charlemagne as Emperor, the Pope anointed his son Charles as King. Duchesne finds here the explanation of the statement of Theophanes that Charlemagne was anointed, and thinks that he has confused the two events which took place on the same occasion, the coronation of Charlemagne as Emperor, and the anointing of the younger Charles as King.

It may be noticed, before we leave Charlemagne, that at the coronation of his grandson Louis the Pious in 813 as associate in the Empire, he himself crowned Louis with his own hands, thus following exactly the Eastern precedent in such a case. It may be that here we have the explanation of the alleged dissatisfaction and surprise of Charlemagne at his coronation on Christmas Day, 800. He may[42] have intended to crown himself instead of being crowned by the Pope.

The earliest Roman forms used at the coronation of an Emperor are found in the Gemunden Codex, and constitute Martène’s Ordo III[45]. This rite is very early, being of the ninth century, and it is possible that with some such forms as these Charlemagne himself was crowned.

The rite begins with a short prayer for the Emperor: Exaudi Domine preces nostras et famulum tuum illum, etc., and then follows at once the prayer Prospice Omnipotens Deus serenis obtutibus hunc gloriosum famulum tuum illum, etc., at the end of which the Emperor is crowned with a golden crown with the words, Per eum cui est honor et gloria per infinita saecula saeculorum. Amen. Next follows the Traditio Gladii, with the form Accipe gladium per manus episcoporum licet indignas, vice tamen et auctoritate sanctorum Apostolorum consecratas tibi regaliter impositum, nostraeque benedictionis officio in defensione sanctae ecclesiae divinitus ordinatum; et esto memor de quo Psalmista prophetavit dicens: Accingere gladio super femur tuum potentissime, ut in hoc per eundem vim aequitatis exerceas.

The Laudes[46] are then chanted.

Cantors. Exaudi Christe.

R. Domino nostro illi a Deo decreto summo Pontifici et universali Papae vitam.

C. Exaudi Christe.

R. Exaudi Christe.

C. Salvator mundi.

R. Tu illum adiuva.

C. Exaudi Christe.

R. Domino nostro illi Augusto, a Deo coronato magno et pacifico imperatori vitam.

C. Sancta Maria (thrice).

R. Tu illum adiuva.

C. Exaudi Christe.

R. Tuisque praecellentissimis filiis regibus vitam.

C. Sancte Petre (thrice).

R. Tu illos adiuva.

C. Exaudi Christe.

R. Exercitui Francorum, Romanorum, et Teutonicorum vitam et victoriam.

C. Sancte Theodore (thrice).

R. Tu illos adiuva.

C. Christus vincit, Christus regnat, Christus imperat. (Twice, and R. the same.)

C. Rex regum, Christus vincit, Christus regnat. (R. the same.)

Here follow a series of acclamations.

Rex noster Christus vincit, Christus regnat. Spes nostra Christus vincit. Gloria nostra Christus vincit. Misericordia nostra Christus vincit. Auxilium nostrum Christus vincit. Fortitudo nostra Christus[44] vincit. Victoria nostra Christus vincit. Liberatio et redemptio nostra Christus vincit. Victoria nostra Christus vincit. Arma nostra Christus vincit. Murus noster inexpugnabilis Christus vincit. Defensio nostra et exaltatio Christus vincit. Lux, via, et vita nostra Christus vincit. Ipsi soli imperium, gloria, et potestas per immortalia saecula, Amen. Ipsi soli virtus, fortitudo, et victoria per omnia saecula saeculorum, Amen. Ipsi soli honor, laus, et iubilatio per infinita saecula saeculorum, Amen.

In conjunction with this rite Martène gives another very close to it but differing in some respects. The form at the crowning is different, Accipe coronam a Domino Deo tibi praedestinatam. Habeas, teneas, possideas, ac filiis tuis post te in futurum ad honorem, Deo auxiliante, derelinquas. Then follows at once the prayer Deus Pater aeternae gloriae. The Collect is given of the Mass, Deus regnorum. It is to be noted that the earliest Milanese rite[47] of the coronation of a king, of the ninth century, is almost identical with this rite of the Gemunden Codex.

What may be regarded as a second recension of the Roman rite is the Order of the Coronation of an Emperor given in Hittorp’s Ordo Romanus[48]. This[45] is of the tenth or eleventh century. It differs considerably from the last recension, and is more fixed and definite in character, but is still definitely Roman.

First the Emperor takes the oath as follows: In nomine Christi promitto, spondeo, atque polliceor ego N. imperator coram Deo et beato Petro apostolo, me protectorem ac defensorem esse huius ecclesiae sanctae Romanae in omnibus utilitatibus in quantum divino fultus fuero adiutorio, secundum scire meum ac posse.

As he enters St Peter’s the Cardinal Bishop of Albano meets him at the silver door, and recites the prayer, Deus in cuius manu corda sunt regum, a new form. Inside the church the Cardinal Bishop of Porto says the prayer Deus inenarrabilis auctor mundi, another new form, and after the Litany has been said, before the Confessio of St Peter, the Cardinal Bishop of Ostia anoints the Emperor on the right arm and between the shoulders with the oil of catechumens, using the form Domine Deus Omnipotens cuius est omnis potestas—again another new form, which however is found in the rite by which Pope John VIII crowned Louis II of France at Troyes in 877. The Pope then crowns the Emperor, using one of three forms which are given, Accipe signum gloriae in nomine Patris, etc., or (alia) Accipe coronam a Domino Deo praedestinatam, or (alia) with the prayer Deus Pater aeternae gloriae.

A third recension of the Roman rite may be seen in a group of orders of the twelfth century, that of the Pontifical of Apamea[49], the Order of the Pontifical of Arles[50], and Ordo III of Waitz[51]. It must be borne in mind that the rite was in a continual process of developement in all lands, and therefore however convenient it may be to trace its history by means of recensions, yet these ‘recensions’ must be to some extent arbitrary, and indeed even in a group chosen to illustrate any given recension the documents vary to some extent from each other.

The second of the orders mentioned above was that by which the Emperor Frederick I was crowned in 1155.

The Emperor first takes the oath on the Gospels in the church of St Mary in Turri to defend the Roman Church; thither he is attended by two archbishops or bishops of his own realm, and thence he proceeds to St Peter’s, where he is met at the entrance by the Bishop of Albano, who says the prayer Deus in cuius manu. Inside the church the Bishop of Porto says the prayer Deus inenarrabilis auctor mundi. The Emperor then goes up into the[47] choir, and the Litany is said, he lying prostrate the while before the altar of St Peter. The Litany over, he is anointed by the Bishop of Ostia on the right arm and between the shoulders, before the altar of St Maurice. The three orders do not quite agree in the prayers of consecration. In the two orders of Martène the prayer of anointing is Domine Deus cuius est omnis potestas, or Deus Dei Filius, this latter perhaps a non-Roman form, and here first found in the Roman rite. In the Ordo of Waitz the consecration prayer is Deus qui es iustorum gloria, the unction being made at the words Accende, quaesumus, cor eius ad amorem gratiae tuae per hoc unctionis oleum, unde unxisti sacerdotes, etc., followed by Domine Deus omnipotens cuius est, etc. Then the Pope sets the crown on his head, with the form (M. VIII and W.) Accipe signum gloriae, W. also adding the prayer Coronet te Deus.

M. VI is more developed here. After the anointing the Pope gives the Emperor the sword at the altar of St Peter, Accipe gladium imperialem ad vindictam quidem malorum, etc., and kisses him; he then girds the sword on him with the words Accingere gladio tuo super femur, etc., and kisses him; and the Emperor brandishes it and then returns it to its sheath. Then the sceptre is delivered with the words Accipe sceptrum regni, virgam videlicet virtutis; and finally the Pope crowns him, saying: Accipe signum gloriae, and once more kisses him. The Teutons then chant the Laudes in their own tongue, and Mass is celebrated.

The rite is still simple at this period, but two[48] developements in the ceremonial have taken place. The Emperor from this time forward takes the oath in the church of St Mary in Turri; and is no longer anointed before the Confessio of St Peter, but in the chapel of St Maurice, no one henceforth being anointed before the Confessio but the Pope at his consecration[52].

The account given by Robert of Clary[53] of the coronation of the first Latin Emperor of Constantinople, Baldwin of Flanders, in 1204, shews it to have been a purely Western ceremony.

The Emperor accompanied by the clergy and nobles went in procession from the imperial palace to the church of St Sophia. Here he was arrayed in his royal vesture in a chamber specially prepared for him. He was anointed kneeling before the altar, and was then crowned by all the bishops. There is no mention of any other investiture, though the sword, sceptre, and orb are all referred to. Finally he was enthroned holding the sceptre in his right hand and the orb in his left, and Mass was celebrated.

The account given by Robert is very meagre, but the rite described is clearly Western, and apparently one very similar to the third recension of the Roman rite.

The end of the twelfth century is marked by a further developement in the rite contained in the Liber Censuum of Cardinal Cenci[54]. This particular rite was probably used at the coronation of Henry VI and the Empress Constantia by Pope Celestine III in 1191[55].

The Emperor and Empress go in procession to St Mary in Turri, the choir singing Ecce mitto angelum, and there the Emperor takes the oath to defend the Roman Church. The oath has become longer and the Emperor swears fealty to the Pope and to his successors and that he will be a defender of the Roman Church[56], and kisses the Pope’s foot. The Pope gives him the Peace, and the procession sets out to St Peter’s, singing Benedictus Dominus Deus Israel. At the silver door of St Peter’s the Bishop of Albano meets the Emperor and recites the prayer Deus in cuius manu sunt corda regum. As[50] the Pope enters the Responsory Petre amas me is sung. Then under the Rota the Pope puts to the Emperor a series of questions concerning his faith and duty, and while the Pope retires to vest, the Bishop of Porto recites the prayer Deus inenarrabilis auctor mundi. Next the Emperor is vested in the chapel of St Gregory with amice, alb and girdle, and is led to the Pope, who ‘facit eum clericum,’ and he is thereupon vested with tunic, dalmatic, pluviale, mitre, buskins, and sandals. The Bishop of Ostia then proceeds to the silver door, where the Empress has been waiting, and recites the prayer Omnipotens aeterne Deus fons et origo bonitatis, and she is then led to St Gregory’s altar to await the Pope’s procession. The Pope proceeds to the Confessio of St Peter and Mass is begun. After the Kyrie the Litany is said by the archdeacon, the Emperor and Empress lying prostrate the while. The Emperor is then anointed (apparently before the altar of St Maurice)[57] by the Bishop of Ostia with the oil of exorcism on the right arm and between the shoulders with the prayer Dominus Deus Omnipotens cuius est omnis potestas, followed by the prayer (once an alternative) Deus Dei Filius. The benediction of the Empress follows, Deus qui solus habes immortalitatem, and she is anointed on the breast with the[51] form Spiritus Sancti gratia humilitatis nostrae officio copiosa descendat, etc. The Pope, the anointing over, descends to the altar of St Maurice, on which the crowns have been deposited, and delivers a ring to the Emperor with the form Accipe anulum signaculum videlicet sanctae fidei, etc., followed by a short prayer, Deus cuius est omnis potestas, a much shortened form of the prayer already used at the anointing; next the sword is girt on with the form Accipe hunc gladium cum dei benedictione tibi collatum, and the prayer Deus qui providentia; and he crowns the Emperor with the form Accipe signum gloriae, etc. The Empress is then crowned with the form Accipe coronam regalis excellentiae, etc. The Pope delivers the sceptre to the Emperor with the form Accipe sceptrum regiae potestatis, virgam scilicet rectam regni, virgam virtutis, etc., followed by the prayer Omnium Domine fons bonorum. Then at the altar of St Peter the Gloria in excelsis is sung, and the special collect Deus regnorum omnium follows. The Laudes are now sung and then the Mass proceeds, the Emperor offering bread, candles, and gold; and the Emperor offering wine, the Empress the water for the chalice. Both communicate, and on leaving St Peter’s the Emperor swears, at three different places, to maintain the rights and privileges of the Roman people.

The most noticeable thing in this recension is the appearance of the investiture with the ring, which comes from non-Roman sources and disappears again in the next recension.

In the fourteenth century further developements appear. The order used at the coronation of Henry VII[58], and the Ordo Romanus XIV of Mabillon[59], may be taken as representative of this period.