Project Gutenberg's The Eastern, or Turkish Bath, by Erasmus Wilson This eBook is for the use of anyone anywhere in the United States and most other parts of the world at no cost and with almost no restrictions whatsoever. You may copy it, give it away or re-use it under the terms of the Project Gutenberg License included with this eBook or online at www.gutenberg.org. If you are not located in the United States, you'll have to check the laws of the country where you are located before using this ebook. Title: The Eastern, or Turkish Bath Author: Erasmus Wilson Release Date: March 1, 2019 [EBook #58990] Language: English Character set encoding: UTF-8 *** START OF THIS PROJECT GUTENBERG EBOOK THE EASTERN, OR TURKISH BATH *** Produced by Christopher Wright, deaurider and the Online Distributed Proofreading Team at http://www.pgdp.net (This file was produced from images generously made available by The Internet Archive)

WORKS BY ERASMUS WILSON, F.R.S.

Popular Series.

I.

HEALTHY SKIN: a Popular Treatise on the Skin and Hair, their Preservation and Management. Foolscap 8vo, Sixth Edition. 2s. 6d.

II.

HUFELAND'S ART OF PROLONGING LIFE. Edited by Erasmus Wilson, F.R.S. Foolscap 8vo. 2s. 6d.

III.

THE EASTERN, OR TURKISH BATH: its History, Revival in Britain, and Application to the Purposes of Health. Foolscap 8vo. 2s.

A THREE WEEKS' SCAMPER THROUGH THE SPAS OF GERMANY AND BELGIUM. With an Appendix on the Nature and Uses of Mineral Waters. Post 8vo, cloth, 6s. 6d.

THE HISTORY OF THE MIDDLESEX HOSPITAL DURING ITS FIRST CENTURY. 8vo, cloth, 10s. 6d.

Medical Series.

PORTRAITS OF DISEASES OF THE SKIN. Folio. Twelve fasciculi, 20s. each, half-bound, £13.

ON DISEASES OF THE SKIN. Fourth Edition. 8vo, cloth, 16s.; or, with Coloured Plates, 34s.

ON RINGWORM; its Pathology and Treatment. 12mo. With a Plate, cloth, 5s.

THE ANATOMIST'S VADEMECUM: a System of Human Anatomy. Eighth Edition. Foolscap 8vo, cloth, 12s. 6d.

THE DISSECTOR'S MANUAL OF PRACTICAL AND SURGICAL ANATOMY. Second Edition. 12mo, cloth, 12s. 6d.

ANATOMICAL PLATES; illustrating the Structure of the Human Body. Edited by Jones Quain, M.D., and Erasmus Wilson, F.R.S. Folio. Five vols.

THE

EASTERN,

OR

TURKISH BATH.

BY

ERASMUS WILSON, F.R.S.

LONDON:

JOHN CHURCHILL, NEW BURLINGTON STREET.

MDCCCLXI.

It is now about twelve months since, that my attention was first attracted to the Eastern Bath. I thought I knew as much of baths as most men: I knew the hot, the warm, the tepid, and the cold; the vapour, the air, the gaseous, the medicated, and the mud bath; the natural and the artificial; the shower, the firework, the needle, the douche, and the wave bath; the fresh-river bath and the salt-sea bath, and many more beside: I knew their slender virtues, and their stout fallacies; they had my regard, but not my confidence; and I was not disposed to yield easily to any reputed advantages that might be represented to me in favour of baths. Mr. Urquhart talked to me, but without producing any other than a passing impression; he had, many years before, illustrated, under my observation, the beneficial effects of heat and moisture on his own person; but it bore no fruits in me; for where could I find another man who would submit to a process of so much severity? Without being prejudiced against the whole family of baths, I was not to be enticed into any belief or trust in them, without some posi[viii]tive and undoubted proof. Such was the state of my opinion with regard to baths, when an earnest man, with truth flashing from his eyes, one day stood before me, and challenged me to the trial of the Eastern Bath. I would, if no engagement occurred to prevent me. "Let nothing stand in your way, for there are few things of common life of more importance!" was the appeal of my visitor. "On Saturday, at four o'clock?" "So be it." And on Saturday, at four o'clock, with the punctuality of Nelson, I stood in Mr. George Witt's Thermæ.

To George Witt, F.R.S., the metropolis is indebted for a knowledge of the Eastern Bath. Mr. Urquhart struck the spark in "The Pillars of Hercules;" Dr. Barter caught it in Ireland, and fanned it into a blaze; another spark was attracted by Mr. George Crawshay and Sir John Fife, and burst into a flame in Newcastle-on-Tyne and the North of England. Mr. Urquhart himself applied the match in Lancashire; but Mr. George Witt introduced the Bath to London and its mighty ones. Rank, intellect, learning, art, all met, as companions of the new "order of the Bath," in Prince's Terrace, Hyde Park. And all will remember, with kindness and affection, the generous disinterestedness and earnest truthfulness of their host.

When I stepped into the Calidarium for the first time; when I experienced the soothing warmth of the atmosphere; when, afterwards, I perceived the gradual thaw of the rigid frame, the softening of[ix] the flesh, the moistening of the skin, the rest of the stretched cords of the nervous system, the abatement of aches and pains, the removal of fatigue, and the calm flow of imagination and thought,—I understood the meaning of my friend's zeal, and I discovered that there was one Bath that deserved to be set apart from the rest—that deserved, indeed, a careful study and investigation.

The Bath that cleanses the inward as well as the outward man, that is applicable to every age, that is adapted to make health healthier, and alleviate disease whatever its stage or severity, deserves to be regarded as a national institution, and merits the advocacy of all men, and particularly of medical men; of those whose special duty it is to teach how health may be preserved, how disease may be averted. My own advocacy of the Bath is directed mainly to its adoption as a social custom, as a cleanly habit; and, on this ground, I would press it upon the attention of every thinking man. But, if, besides bestowing physical purity and enjoyment, it tend to preserve health, to prevent disease, and even to cure disease, the votary of the Bath will receive a double reward.

Having, in my own person, and in the experience afforded me by its regular use, become convinced of the power and importance of the Bath, I felt it to be a duty to make my impressions known to the Medical Profession. With this object I addressed an essay, entitled, "Thermo-therapeia, the Heat-cure,"[x] to the British Medical Association, at their meeting at Torquay in August, 1860. In this paper, I urged upon the members of the medical profession, particularly in the provinces and rural districts, to erect a bath for themselves, as an auxiliary armament against disease, as an addition to their pharmacopœia; and to give their support to the establishment in every village and hamlet in Britain of an Eastern Bath.

In September, 1860, I was invited to address a paper on the "Revival of the Eastern Bath, and its Application to the Purposes of Health," to the National Association for the Promotion of Social Science, at their meeting in Glasgow; an abstract of that paper will be found in the second chapter of this treatise. And, having subsequently been called upon to deliver a popular lecture at the Parochial Institution of Richmond, I penned the historical account of the Bath which is embodied in the first chapter. This explanation I hope my readers will accept as accounting for a certain degree of repetition which occurs in this volume; and which, without the devotion of more time to the labour than I have at my disposal, could not be avoided.

It will be guessed, and with truth, that I am no longer a sceptic of the value of the Bath, when the Bath embraces the virtues which are possessed by the Eastern Bath. That it is a source of much enjoyment may be inferred from the suddenness with which it has spread through the metropolis of[xi] London. Turkish Baths meet our eye in almost every quarter of the town, and three Companies have been formed, or are in course of formation, for the establishment of Eastern Baths on correct principles. One of these Companies, under the presidency of Mr. Stewart Rolland, professes to draw its inspiration directly from Constantinople, and will take, as its especial model, the Turkish Bath.

When adopted as a social custom, the Turkish model is clearly that which ought to be imitated, on account of the moderate temperature which belongs to it. The higher temperatures are upon their trial; they are not a necessity of the process, they may have their uses in disease; but it would be best to treat them with caution, or, as a medicine, leave them wholly in medical hands. The Bath for the public should be one that they may adopt with as much safety as the basin of water with which they wash their hands.

The use of an elevated temperature is founded on the well-known power of heat of destroying organic impurity—such as odour, miasma, and animal poison. But, in this acceptation, when applied to the human body, it becomes a medicine of the most potent kind; and should, therefore, be left to medical management.

Henrietta Street, Cavendish Square,

March, 1861.

| Ground-plan of the Palæstra or Gymnasium of the Greeks: after Vitruvius | p. xix |

| Plan of the Roman Thermæ, from a drawing taken from the walls of the Baths of Titus | p. xxi |

| The Hypocaustum of the Roman Bath at Chester | p. xxiii |

| The Calidarium of Mr. George Witt's Bath | p. xxv |

| Mr. Urquhart's Bath at Riverside | p. xxvii |

| Ground-plan of my own Bath at Richmond Hill | p. xxix |

| The Dureta; the Moorish, and probably Phœnician, Couch, adopted by the Emperor Augustus | p. xxxi |

| The person reclining on this couch is so completely supported that he feels as though he were suspended in air. | |

CHAPTER I.

| The Bath, an animal instinct; coeval with the earliest existence of man; common to every rank; a ceremony of his birth, and a funereal rite; discovery of thermal springs; the Scamander; commemoration of the hot-bath by Homer; the hot-baths of Hercules; estimation of hot-baths by the Phœdrians; frequency of thermal springs; Hamâms of the East, Hamâm Ali, near ancient Nineveh; Hamâm Meskhoutin in Algeria; Baths of Nero in Italy; German thermal springs, Carlsbad, Wiesbaden, Ems, Aix-la-Chapelle; the Geysers of Iceland; thermal springs of Amsterdam Island; of America; of England, Bath, Bristol, Buxton, Matlock | pp. 1-5 [xiv] |

| Primitive idea of the artificial hot-vapour bath; Bath of the American Indians; ancient Irish Bath, or sweating-house, the Tig Allui; Mexican Bath; Moorish Bath; the Hypocaust | pp. 5-9 |

| Eastern origin of the bath; Mr. Urquhart's discovery of the vestiges of the Phœnician Bath among the ruins of Baalbeck; Syrian Bath; Gazul, its nature and properties; Gazul and the Strigil derived from Mauritania; probable irradiation of the knowledge of the bath from Phœnicia | pp. 9-12 |

| Hypocaust of the Moorish, Mexican, Greek, and Roman Bath; the only method of heating houses in Greece and Rome; the common practice in China; Chinese vapour bath, | pp. 12-13 |

| Baths of Greece; Gymnasia; Gymnasium or Palæstra; Lyceum Academia; Cynosarges | pp. 14-18 |

| Thermæ and Balneæ of Rome; Baths of Agrippa, Titus, Paulus Æmilius, Diocletian, and Caracalla; magnificence of the Roman Thermæ; Roman Baths of England; decline of the bath in Rome; construction of the Roman Bath; excessive indulgence in the bath by the Romans; Pliny's description of his own bath; Seneca's reproof of the luxury and wanton extravagance of the Romans | pp. 18-29 |

| Roman Baths of England; Uriconium; Chester | pp. 29-33 |

| The bath lost by the Romans; preserved by the Turks; the Turkish Hamâm; construction of the Hamâm; costume of the bath; mode of taking the bath; the outer Hall, or Mustaby, the middle room, the inner room; shampooing; rolling and peeling the scarf-skin; soaping and rinsing; return to the Mustaby; the couch of repose; special characteristics of the Turkish Hamâm—vapoury atmosphere, low temperature; the Turkish process contrasted with the Roman; the order, the decorum, the dignity of the Turkish Bath; Lady Mary Wortley Montagu's description of the Women's Bath in Turkey | pp. 33-46 |

| The Egyptian Bath; the Bath of Siout; the Bath at Cairo; Mr. Thackeray's experiences; Egyptian shampooing; M. Savary's description of the Egyptian Bath and Egyptian shampooing; its intellectual and medicative properties; Tournefort's experience | pp. 46-50 [xv] |

| Introduction of the Turkish Bath to Britain; Mr. Urquhart and the "Pillars of Hercules"; Mr. Urquhart's advocacy of the Bath; Mr. Urquhart erects a bath at Blarney for Dr. Richard Barter; spread of the Turkish Bath in Ireland | pp. 50-52 |

| Pioneers of the Bath in England, Mr. Urquhart, Mr. George Crawshay, Sir John Fife, Mr. George Witt, Mr. Stewart Rolland; private Turkish Baths in England; Mr. Witt's Bath; construction; process of the bath; costume of the bath; "Companions of the Bath;" first impressions; effect of the Bath in the removal of pain | pp. 52-55 |

| The delights of free perspiration; differences between the practised bather and the neophyte; thirst; beads upon the rose; counting our beads; freedom of perspiration in labourers exposed to high temperatures; a nutritive drink | pp. 55-58 |

| Temperature of the bath; mutual relations between temperature, size of apartment, moisture of atmosphere, and number of bathers; temperature relative to these conditions; effects of temperature in water, vapour, and air; man's capability of supporting temperatures of remarkable altitude in dry air; Mr. Urquhart's Laconicum; Sir Charles Blagden's experiments; Sir Francis Chantrey's oven; Chabert, the Fire King | pp. 58-61 |

| The best temperature for the purposes of Health; practice of the Romans, who lost the bath, compared with that of the Turks, who have preserved it; philosophy of the bath; talking and thinking to be avoided in the bath; inconveniences of the bath to the novitiate; the cause and its remedy; advice; peculiarities or idiosyncrasies of constitution; wisdom of the Turks | pp. 61, 63 |

| Duration of the bath; influenced by temperature and idiosyncrasy, | pp. 63-64 |

| Second operation of the bath; shampooing; proper moment for the process; the Turkish process; the Moorish process; Captain Clark Kennedy's description of the Moorish Bath, and the operation of shampooing; the British shampooer, | pp. 64-72 [xvi] |

| Third operation of the bath; the peeling of the scarf-skin; manner of performance; the camel's-hair or goat's-hair glove | pp. 72-74 |

| Fourth operation of the bath; soaping; the wisp of lyf; the warm shower; the cold douche; alternate hot and cold douche; closure of the pores; restoration of the warmth of the skin | pp. 74-76 |

| The Frigidarium; the process of cooling; the purified skin; sensations after the bath; the ordinary dress resumed; illustration of the use and effects of the bath in dispelling the cravings of hunger and fatigue | pp. 77-79 |

| Mr. Urquhart's bath; the Laconicum; the spiracle of sweet perfumes; the Lavatrina; the cold pool; the hot and cold douche; breakfast; kuscoussoo; the chemistry of the preparation of food; its value to man | pp. 79-87 |

| My own bath at Richmond Hill | pp. 88-89 |

CHAPTER II.

REVIVAL AND SANITARY PURPOSES OF THE EASTERN BATH.

| General idea of the bath; and of its sanitary application; its popularity with the working classes | pp. 90-92 |

| Construction of the bath, illustrated by the description of Mr. Witt's bath; the Calidarium; the heating apparatus; materials of construction; the flue; the dureta; Mr. Stewart Rolland's bath; the Lavatorium; the Frigidarium, | pp. 93-102 |

| Operation of the bath; costume of the bath; sensations of the bath; perspiration; the body washed in its own moisture; unpleasant sensations; contrast of the uneducated and educated skin; object of the bath; use of the cold douche; the cooling and drying process | pp. 103-110 [xvii] |

| Sanitary purposes of the bath; importance of the skin in the animal economy; structure and functions of the skin; exposure of the skin to the air; resistance of cold; costume of ancient Britons; defensive powers of the bath against catarrh; weakening of the skin by clothing; comparison of physical qualities of healthy and unhealthy skin; sensibility of the skin; hardening of the skin; nutritive properties of the skin; training; influence of the bath in the prevention of disease; curative powers of the bath | pp. 111-127 |

CHAPTER III.

RATIONAL USE OF THE BATH.

| Proper employment of the bath; proper temperature; proper time for taking the bath; duration and frequency of taking the bath; customs of the Moslem; unfounded apprehension of taking "cold;" the bath cannot give cold; disturbance of nutritive function occasioned by the bath; strengthening and restoring properties of the bath: Mr. Urquhart's evidence; Sir Alexander Burnes's evidence; health of shampooers | pp. 128-141 |

| Medical properties of the bath; on what principles founded; its chemical and electrical powers; its preservation of the balance of the nutritive functions; it supersedes the necessity for exercise; estimation of the medical powers of the bath in Turkey; its influence in producing longevity; it removes fat; gives power of exercise; removes rheumatism, and cures spasm and cramp; example of cure of wry-neck, | pp. 141-152 |

CHAPTER IV.

APPLICATION OF THE BATH TO HORSES AND CATTLE,

FOR TRAINING AND THE CURE OF DISEASE.

| Adaptation of the Turkish Bath to the horse, dog, oxen, cows, sheep, swine, &c.; its application to the purpose of training; Mr. Goodwin's management of horses after severe exercise; his remarks on the use of the bath in the stable, | pp. 153-159 [xviii] |

| The skin a respiratory organ; ventilation of the skin; clipping and singeing horses | pp. 159-161 |

| Dr. Barter's application of the bath to the treatment of the diseases of animals; report of a committee appointed to inquire into the utility of Dr. Barter's bath for the cure of distemper in cattle | pp. 162-164 |

| Observations on the use of the bath; and rules to be followed in taking it | pp. 165-167 |

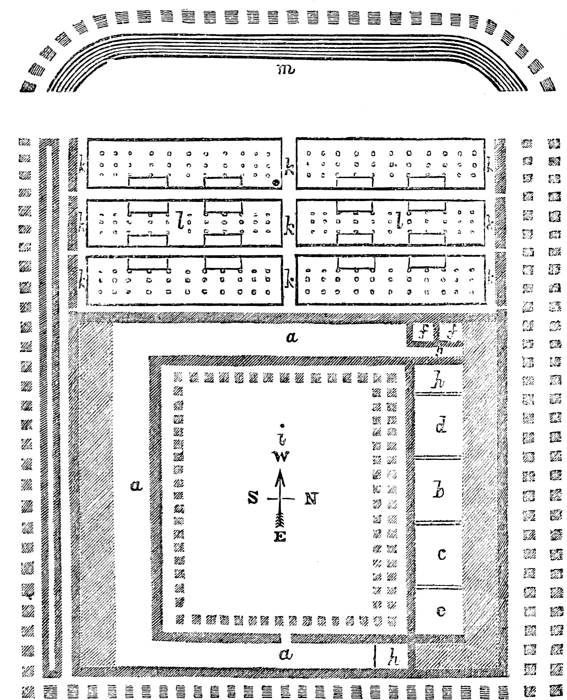

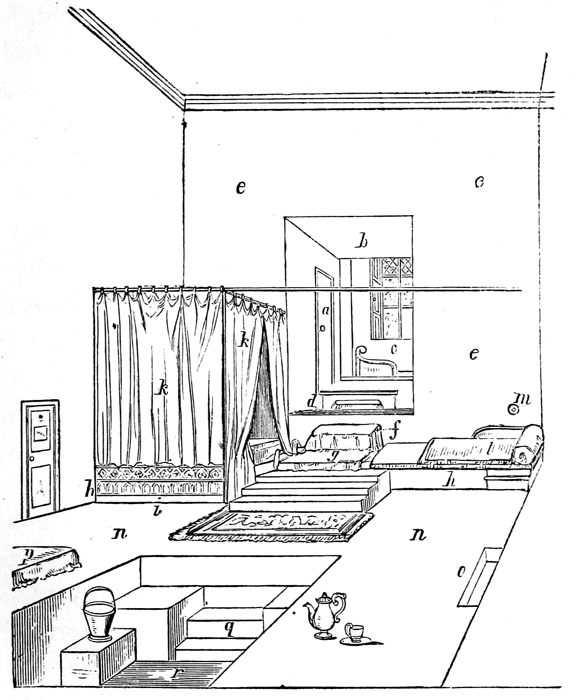

Ground-plan of the Palæstra or Gymnasium, after Vitruvius. (Page 15.)

a a. The portico. b. The Ephebeum, the room of the Ephebi or youths, c. The Apodyterium and Gymnasterium. d. The Elaiothesium, or anointing room. e. The Konisterium, or dusting room. f f. The hot baths. g. The stove or Laconicum. h. The cold bath. i. The Peristylium or Piazza, which includes the Sphæristerium, and Palestra. k k. Xysti. l l. Xysticus silvis. m. The Stadium.

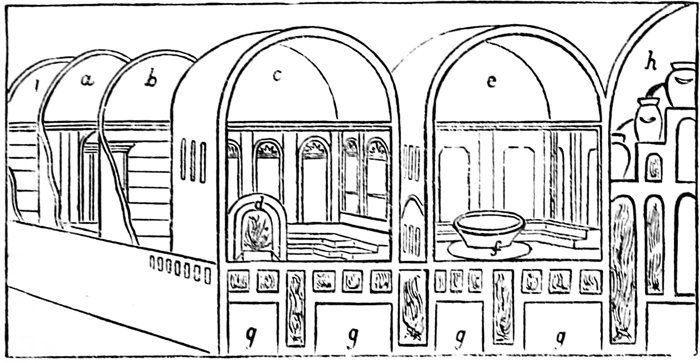

Plan of the Roman Thermæ, from a Drawing taken from the walls of the Baths of Titus. (Page 22.)

a. The Frigidarium, or cool room. b. The Tepidarium, or room of middle temperature. c. The Calidarium, sudatorium, or concamerata sudatio; around this apartment are seen several ranges of platforms of marble. d. A vaulted stove, covered by an arched cover, clipeus: this stove gave additional heat to the part of the room wherein it was situated, and constituted the Laconicum. e. The Lavatorium or Balneum; there are marble platforms in this apartment, and in its centre is an open bath, called, from its large everted lip upon which the bather sat, labrum. g g. The Hypocaustum. h. The room in which the water is stored and heated. In the uppermost vase the water is cold, as is indicated by the absence of fire beneath it. In the second vase the water is warm, being placed at a considerable height above the fire. In the lowest vase the water is hot. i. The Elaiothesium, or anointing room, from which the bather passes to the Vestiarium or Spoliatorium.

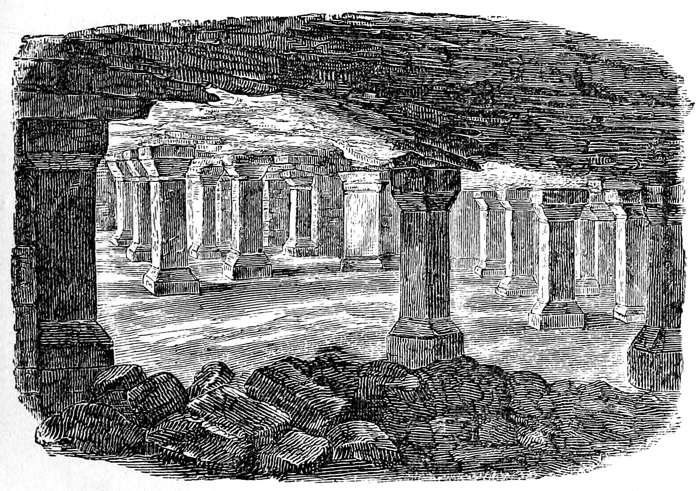

The Hypocaustum of the Roman Bath at Chester. (Page 31.)

In the foreground are seen three of the short pillars or pilæ, with square shafts and expanded heads and bases. Between these more distant pilæ are visible, seemingly arranged in rows. The floor on which the burning embers lay is uneven; while the roof, which is the under part of the floor of the bath, exhibits evidences of the corroding action of the fire. The Hypocaustum, in the Roman Thermæ, occupied the whole of the under surface of the Calidarium, and the ruins bear evidence of the use of fires of prodigious extent.

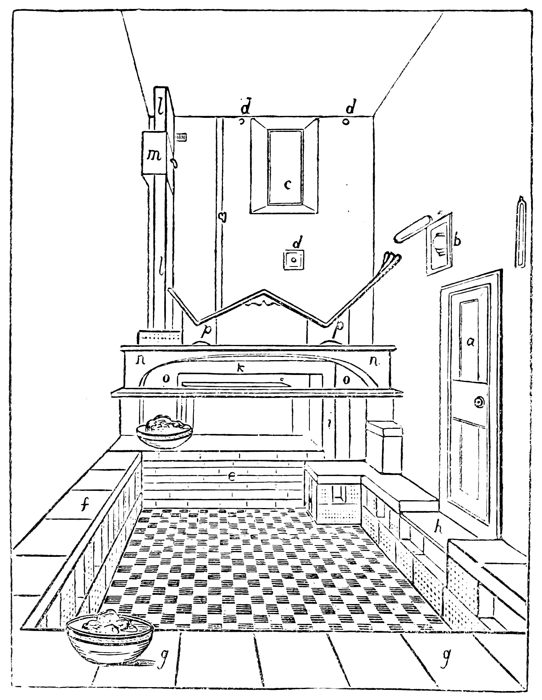

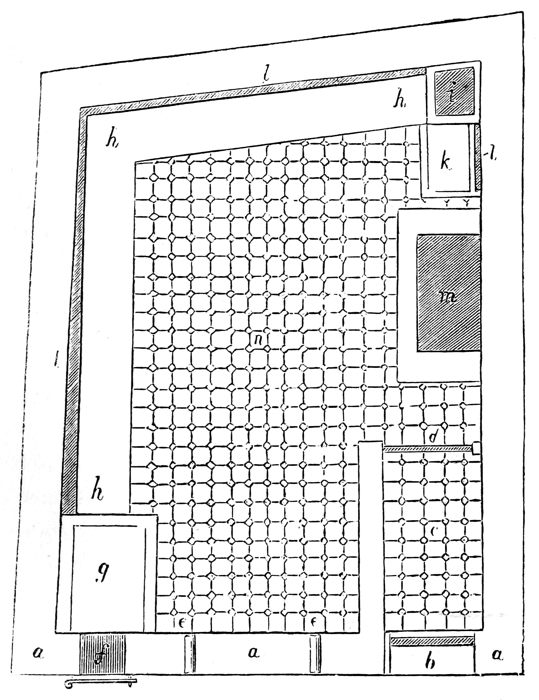

Mr. George Witt's Bath; the Calidarium. (Page 53.)

a. The entrance door. b. A small window looking into the Frigidarium; a gas lamp, for use at night, is seen through the pane. c. A thick plate of glass in the outer wall, for admitting light. d d. Ventilating holes; the lower one is furnished with a wooden plug. e. The masonry which encloses the furnace. f. The flue, proceeding from the furnace along the side of the room. g g. The flue crossing the end of the room. h. The flue returning along the opposite side of the room. i. The ascending flue. k. The flue crossing above the furnace, and then ascending, l l, the angle of the room, to terminate in the chimney. f g g h, support a wooden seat, on which the bathers sit; along the front of this seat, as at f, h, are perforated tiles and spaces, which give passage to the heated air. m. The warm water tank. n n. A platform, which also serves as a seat; the feet resting on the step o o. p p. The dureta; the letters are placed on the feet of the couch. The floor is tesselated; and on the seat are seen two wooden basins, containing soap and a bunch of lyf.

Mr. Urquhart's Bath; the Bath at Riverside. (Page 79.)

a. The door of entrance. b. The ceiling of the vestibule of the Bath. The side or rather the end of the vestibule c is occupied by an immense sheet of plate glass, through which are seen the Frigidarium, and the window of the Frigidarium, with a trellis of roses beyond. d. The floor of the vestibule. e e. One side of the great Hall of the Bath. f. A step covered with a Turkish towel. g. A platform, under which the hypocaust, h h, extends from one side to the other of the Hall. i. An ornamental grating, through which heated air enters the Hall directly from the furnace. k k. The tent, or enclosed chamber immediately over the furnace, where the highest degree of heat exists; the Laconicum. l. A couch, of lower temperature, but still hot, from being over the hypocaust. m. The spiracle of perfume from the mignionette bed. n. The floor of the Hall. o. The Lavatrina. p. A couch of less heat than l. q. Steps leading to the pool of cold water. r. The piscina or cold pool.

Ground-plan of my own Bath at Richmond-Hill. (Page 88.)

a a. Front wall. b. Door of entrance from a lobby, leading from the Frigidarium. c. Vestibule. d. Inner door. e e. Spiracles or ventilators. f. Mouth of the furnace. g. Furnace of fire-brick, enclosed in a jacket of hollow brick. h h h. Flue. i. Chimney. k. Returned flue, supporting a tank for warm water. l l. Outer wall; the dark shade between l h, and l k, indicates the interval between the flue and outer wall. m. The Lavatrina. n. Tesselated pavement.

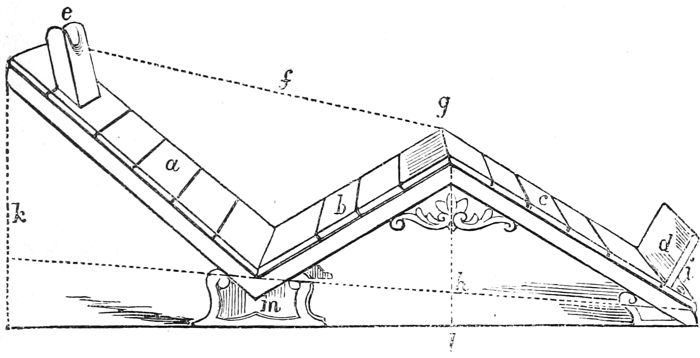

The Dureta, or Reclining Couch, used in the Bath; both in the Calidarium and Frigidarium. (Pages 53, 97.)

a. The plane for supporting the back. b. The thigh-plane. c. The leg-plane. d. The foot-piece, which is movable, and admits of adjustment, to suit the comfort of the bather. e. The head-piece, for supporting the head. f. Arc of the angle a-b. g. The angle corresponding with the bend of the knee. h. Arc of the angle b-c. i. Lower hole, for the foot-piece. k. Elevation of the trunk-plane from the ground-line, l. m. One of the feet of the couch.

This figure is intended to exhibit the construction of the dureta, the best lines of angle, and the size the most convenient for a person of medium stature—say five feet, eight inches. If the person be taller or shorter, a corresponding difference must be made in the length of the three principal pieces. The dureta is constructed of deal boards, 20 inches long, nailed on a pair of lateral rails; the rails being supported by a firm foot, m, and steadied by a bracket at the angle g. The measurements are as follow:—a, 28 inches; b, 18-1/2 inches; c, from g to the foot-piece, 19 inches; and from g to the extreme end, below the letter i, 23 inches. The holes for the foot-piece are two inches apart; and the head-piece may be made movable. The arc of the angle a-b, measured at f, from the upper angle of a to g is 38 inches; the arc of the angle b-c, measured at h from the angle m to the end of the plane c, is 37 inches; the height of the upper end at k is 24-1/2 inches; the height of the angle g at l is 14-1/2 inches; and the dotted line from the angle m to the perpendicular k, 21 inches; the height of the angle m from the point where the dotted line touches to the ground is 6-1/4 inches; and the height of the end at i is simply the depth of the rail—namely between two and three inches.

The dureta after the above model is manufactured by Mr. Allen, 7, Great Smith-street, Westminster.

The Bath is an animal instinct: and, par excellence, a human instinct; it is as much a necessity of our nature as drink. We drink because we thirst—an interior sense. We bathe because water, the material of drink, is a desire of the outward man—an exterior sense. An animal, whether beast or bird, pasturing or straying near a limpid stream, first satisfies the inward sense, and then delights the outward sense. A man, be he savage or civilized, can no more resist the gratification of bathing his wearied limbs in a warm transparent pool than he can resist the cup of water when athirst. Instinct bids him bathe and be clean. To inquire—Who invented the act of drinking? would be as reasonable as to ask—Who invented the bath?

The bath is coeval with the earliest existence of man. Can it be doubted that our first parents bathed their newly-created limbs in the river that[2] "went out of Eden to water the garden"? History teaches us, that the Phœnicians and ancient Greeks of all ranks, from the daughters of their kings down to the poorest citizens, were wont to bathe in rivers and in the sea, for the purpose of cleansing their bodies and refreshing and invigorating their frames. They had recourse to the bath when they ceased from sorrow and mourning, after great fatigues of whatever kind, before and during their meals, and at the conclusion of their battles. Bathing was the first act of their lives, and it was a part of their funereal rites. The birth of Jupiter, the Thunderer, is celebrated by the poet Callimachus in the following lines:—

Again, of Alcestis, when about to lay down her life for her husband Admetus, it is written:—

Plato, also, records how the good old philosopher Socrates, before he drank the fatal cup of hemlock that was to consign him to Hades, bathed and washed himself, that he might save the women, whose duty it was, their troublesome office.[1] [3]

A short stage in the history of the bath leads us to the discovery of springs of hot water, hot vapour, and hot air; and these very possibly suggested to man's inventive mind the means of procuring so great a luxury by his own contrivance. Homer commends one of the sources of the Scamander for its warmth, and tells us how Andromache, with matronly care, prepared a hot bath for her husband Hector, against his return from battle:—

We are taught also that Vulcan, or, as others say, Minerva, discovered certain hot baths ([Greek: Hêrakleea loutra]) to Hercules, that he might replenish his strength after undergoing severe exertion and fatigue. And the Phœdrians, according to Homer, laid great stress upon the importance to the health and happiness of man of frequent changes of apparel, comfortable beds, and hot baths.

It is one of the marvels of the earth's history, that hot springs, or thermal springs, bubble upwards to the light, not only on Mount Ida, the source of the Scamander, but in countless other places and countries on the world's surface. These hot springs would appear to have invited man to their use by their pleasant aspect and by their warmth; and their enjoyment to have suggested the possibility of contriving artificially a similar luxury nearer to his threshold.

[4] The word Hamâm, which is equivalent to thermal springs, is not unfrequently met with in the East as the name of a town or village in or near to which hot springs are found. Hamâm Ali, in the neighbourhood of ancient Nineveh, is an example of this kind. "The thermal spring is covered by a building, only commodious for half-savage people, yet the place is much frequented by persons of the better classes both from Baghdad and Mósul."[2] Captain Kennedy, in his "Travels in Algeria and Tunis," tells us of the hot springs of Hamâm Meskhoutin, which rise to the surface at a temperature of 203° of Fahrenheit, only 9° short of boiling, and are so abundant as to burst forth through any opening made accidentally in the ground. "The thermal waters, in flowing over the bank of the rivulet, have formed a calcareous deposit of great beauty, resembling a cascade of the purest white marble, tinged here and there with various shades of green and orange."

In Italy, near the town of Pozzuoli, are some natural thermal springs—the ancient Posidianæ, now called the Baths of Nero, of which the temperature of the water is 185°, while that of the vapour which rises from it is 122°. The spring is situated in a rocky cavern at the end of a long passage formed by a fissure in the rock, and in this way constitutes a natural bathing house.

In Germany, among others, are the thermal springs of Borcette, with a temperature of 171°; Carlsbad, in Bohemia, 165°; Wiesbaden, Ems, and Schlangenbad, in Nassau; Baden-Baden; Aix-la-Chapelle; Wildbad; and Ischl.

In Iceland are the far-famed Geysers; in the Southern Ocean the hot springs of Amsterdam Island; and many more are dispersed over the Continent of America; while in England there are the thermal springs of Bath, Bristol, Buxton, and Matlock.

The heated rock and the vaporization of water would seem to have originated the primitive idea of a hot-air and hot-vapour bath; and this idea we find carried out simultaneously in various parts of the world and amongst the rudest nations. Mr. Gent, in his "History of Virginia," describes the hot-vapour bath as employed by the American Indians.

"The doctor," he says, "takes three or four large stones, which, after having heated red-hot, he places in the middle of the stove, laying on them some of the inner bark of oak, beaten in a mortar, to keep them from burning; this being done, they (the Indians) creep in, six or eight at a time, or as many as the place will hold, and then close up the mouth of the stove, which is usually made like an oven in some bank near the water-side; in the meanwhile, the doctor, to raise a steam, after they have been stewing a little time, pours cold water on the stones, and now and then sprinkles the men to keep them[6] from fainting; after they have sweat as long as they can well endure it, they sally out, and (though it be in the depth of winter) forthwith plunge themselves over head and ears in cold water, which instantly closes up the pores and preserves them from taking cold." After the bath, they are anointed like the Romans, the pomatum of the Indians being for the most part bear's-grease, containing a powder obtained by grinding the root of the yellow alkanet.

But we find this primitive form of bath nearer home than the American Continent—namely, in Ireland, although both the American and the Irish bath may, Mr. Urquhart suggests, have been derived from the same ancestry—that of the Phœnicians. In a foot-note appended to a page on the universality of the bath, in his "Pillars of Hercules,"[3] Mr. Urquhart gives the following very curious and very interesting account of the practice of sweating employed in former times in Ireland, as reported to him by a lady as a recollection of her childhood:—

"With respect to the sweating-houses, as they are called, I remember about forty years ago seeing one in the island of Rathlin, and shall try to give you a description of it. It was built of basalt stones, very much in the shape of a bee-hive, with [7]a row of stones inside, for the person to sit on when undergoing the operation. There was a hole at the top, and one near the ground, where the person crept in and seated him or herself, the stones having been heated in the same way as an oven for baking bread is, the hole on the top being covered with a sod while being heated, but I suppose removed to admit the person to breathe. Before entering, the patient was stripped quite naked, and on coming out, dressed again in the open air. The process was reckoned a sovereign cure for rheumatism and all sorts of pains and aches."

Dr. Haughton on the same subject remarks that:—"Two varieties of Tig Allui, or sweating-houses, exist in Ireland, one kind being capable of containing a good many persons, and the other only intended for a single occupant." The former is that just described: it is heated in the same way as an oven, by making a large fire of wood in the middle of the floor, and after the wood is burnt out, sweeping away the ashes. Besides the cure of rheumatism, the young girls who have tarnished their complexion in the process of burning kelp or sea-weed for the manufacture of soda, also resort to the Tig Allui for the purpose of clearing their skin. The usual time for remaining in the bath is under the half hour.

The second kind of Tig Allui—namely, that for the reception of a single person only—is described by Dr. Tucker, of Sligo, as follows:—

"It is built of stone and mortar, and brought to a round top. It is sufficiently large for one person to sit on a chair inside, the door being merely large enough to admit a person on his hands and knees. When any of the old people of the neighbourhood, men or women, are seized with pains, they at once have recourse to the sweat-house, which is brought to the proper temperature by placing therein a large turf fire, after the manner of an oven, which is left until it is burned quite down, the door being a flat stone and air-tight, and the roof, or outside of the house, being covered with clay, to the depth of about a foot, to prevent the least escape of heat. When the remains of the fire are taken out, the floor is strewn with green rushes, and the person to be cured is escorted to the bath by a second person carrying a pair of blankets. The invalid, having crept in, plants himself or herself in a chair, and there remains until the perspiration rolls off in large drops. When sufficiently operated on, he or she, as the case may be, is anxious to get out, and the person in waiting swaddles him up in the blankets, and off home, and then to bed. I have heard old people say that they would not have been alive, twenty years ago, only for the sweating-house.... Remains of the Tig Allui are also found in the county Tyrone, of the following dimensions:—five feet in height, nine in length, and four in width, being built of solid masonry, and shaped like a bee-hive at the top."

Another, and a very important step in the progress of the bath was the contrivance of a mode of heating by means of which the temperature might be made uniform, and might be regulated in any manner that should be required. The hot stones of the North American medicine-man were clearly a very bungling and uncertain expedient; little better than the warm skin of a newly-killed animal; and the wood fire of the Irish sweating-houses was more objectionable still, not only on account of the impossibility of regulating the heat, but also from the resulting impurity of the atmosphere and the danger of leaving fragments of the heated ashes on the floor. The next contrivance, and that which has continued to be the practice up to the present day, was the construction of a furnace under the floor—in other words, a hypocaust. Mr. Urquhart, speaking of the existence of baths among the Mexicans and their probable introduction by the Phœnicians, remarks:—"However magnificent their public monuments," their baths were "such as are found in almost every house in Morocco,—a small apartment seven feet square, with a cupola roof five to six feet high, and a slightly convex floor, under one side of which there is a fire, and a small low door to creep in by."

Reviewing the probable rise and progress of the bath, there seems little doubt that the bath took its origin in the East, the dwelling-place of our first parents, the birth-place of civilization and know[10]ledge. It was known at a very early period in Phœnicia. Mr. Urquhart, in his recent work, "The Lebanon,"[4] relates his discovery of a Phœnician temple, or crypt, among the ruins of Baalbeck, or Baalbeth, the House of Baal—the Heliopolis, or City of the Sun, of the Greeks; in which were traces of the existence of the bath. "But the Phœnician crypt was not my only discovery. In a gap opening a few feet into the masonry, I found mortar hard as stone where exposed to the air, but soft within. Yet it was unlike other mortar; it was dark grey, with particles of charcoal; when I brought out some, it was recognised at once, and called kissermil, or ashes from the bath. Those ashes are still used in this country for mortar, which with this addition becomes as hard as stone. According to the old construction, the baths were heated as an oven is, brushwood and dung being used as well as wood. The combustion not being complete, there remain various chemical compounds, alkali, ammonia, sulphate and carbonate of lime, and carbon, which by entering into new combinations, bind the mortar into a distinct substance."

"One thing is clear, there were baths at Baalbeck. In the elaborately finished bath of Emir Beshir at Ibtedeen, one peculiarity struck me as evidencing their high antiquity in this land. It was the absence of cocks; instead of which simple [11]plugs or clots of cloth were used for the pipes which brought the water into the basins. As the Romans and Greeks used cocks, the art of the bath had not been derived from them, but traced beyond them. Still it was curious to observe these ashes in the midst of Cyclopic blocks. And yet why should not the bath have belonged to the very earliest period of human society? It is sufficiently excellent to be from the beginning."

"I remembered that in opening up the pavement of an ancient bath on the western coast of Africa, I had come upon a somewhat similar deposit, in large quantities, under the floor. This was gazul, the product of a certain mountain in Morocco, resembling soapstone, but composed of an admixture of silex, alumina, magnesia, and lime, and which has the peculiar property of polishing the skin when rubbed upon it, and so cleaning off the dead epidermis. Being used for this purpose largely in the baths, the grey deposit under the ruin in question is easily accounted for. Might not this same gazul, mixed with kissermil, have been the deposit which I took for mortar at Baalbeck?"

For the purpose of removing the dead epidermis from the surface of the skin, "four processes have been adopted throughout the families of the human race, and in successive times. The simple, the natural, the first hit upon, was the rubbing down with the ball of the hand, which is still the process used in this country for currying horses of high[12] breed. The three others, of a more refined and, I may say, historical character, are, scraping, rolling, and polishing. The scraping is with the strigil, which we know of from the Romans and Greeks, but which is figured on the tombs of Lycia, and the Roman name of which is derived from Mauritania. The rolling is that which we see to-day practised by the Turks. The polishing is with the gazul, and practised by the Moors, to whom it is confined, and who alone possess the admirable substance which is used for it. Now, if gazul was used by the early inhabitants of Baalbeck, their bathing process belonged to the last of these systems, and they carried on a traffic with Morocco."

From Phœnicia, from the coast of Tyre and Sidon, a knowledge of the bath may have spread along the southern coast of the Mediterranean, through Egypt, Tripoli, and Algiers, to Morocco and the Pillars of Hercules; or it may, as Mr. Urquhart suggests, have been earliest in use among the nations of Mauritania, and have been carried by the Moors into the countries of the East. From Phœnicia, the knowledge of the bath may have followed the line of caravan communication into Russia, Persia, China, and Hindostan; while the ships of the then greatest maritime country in the world would have carried it to Greece, to Ireland, and to America. The bath is a common practice in Russia; it is also well known in Persia, Hindostan, and China; and, as we have already seen, its[13] use in North America, in Mexico, and Ireland, probably dates back to a very early age. Its progress in Europe we shall presently see.

Speaking of the mode of heating the bath in Mexico and Morocco, I have used the word hypocaust; this word is of Greek origin, and signifies under-fire—that is, the fire is placed under the thing to be heated; for example, under the foundation of the bath or of the house. The Greeks and the Romans had no other means of heating their houses than this; there was no open fire, but a fire under the foundation, from which flues were carried upwards in the walls of the building. When a great heat was required, as in the baths, the foundation was supported on short columns (pilæ), and the entire space between the columns was occupied with fire, while numerous ascending flues distributed the heat around the rooms. Now it is curious to find that at the present hour the Chinese continue the same means of heating their houses.

That they also employ the sudatory process of bathing, is shown by the following extract from Mr. Henry Ellis's "Journal of an Embassy to China," published in 1817:—

"Near this temple (at Nankin) is a public vapour bath, called, or rather miscalled, the Bath of Fragrant Water, where dirty Chinese may be stewed clean for ten chens, or three farthings; the bath is a small room of one hundred feet area, divided into four compartments, and paved with[14] coarse marble; the heat is considerable, and as the number admitted into the bath has no limit but the capacity of the area, the stench is excessive; altogether, I thought it the most disgusting cleansing apparatus[5] I had ever seen, and worthy of this nasty nation."

The Baths of Greece are celebrated for their magnificence; they formed parts of buildings of vast extent and grandeur, termed Gymnasia. The gymnasium was an institution of the Spartans of Lacedæmonia or Laconia, and spread thence to other parts of Greece, and notably to the metropolis of Attica, the famed city, Athens. The gymnasium was sufficiently large to accommodate several thousands of persons, and afforded space for the assembly of philosophers, men of science, and poets, who delivered lectures to their scholars and recited their verses; and for the pursuit of the favourite games and exercises of their youths and men—namely, leaping, running, throwing the disc or quoit, and wrestling; the purpose of these exercises being to give strength to the people and make them accomplished warriors.

The different parts of a gymnasium or palæstra, were as follows:—

1. The Porticos, in which were numerous rooms[15] furnished with seats for the professors and their scholars.

2. The Ephebeum, a large space in which the ephebi or youths planned and practised their exercises.

3. The Apodyterium, or undressing room; also called Gymnasterium, or the room for becoming nude.

4. The Elaiothesium, or anointing room, which was equally used by those who were preparing for exercise, and those who had completed their bath.

5. The Konisterium, or dusting room, where the bodies of the wrestlers and other athletæ, after being anointed, were well dusted over; probably as a defence to the skin against injury.

6. The Palæstra, or wrestling courts, which were bedded with sand more or less deep, like the modern circus, in order to break the fall of the combatants when they were thrown to the ground.

7. The Sphæristerium, or court for ball exercise and raquets.

8. The Peristyle, or Piazza, within which was the area of the Peristyle, for walking, and the exercises of leaping, quoits, ball, and wrestling.

9. Then there were Xysti, or covered courts, for the use of the wrestlers in bad weather; Xysta, which were walks between walls open at the top and intended for hot weather; and a Xystic Sylvis, or forest; the intervals of the numerous[16] ornamental columns of the building being so called, and being devoted to walking exercise.

10. Next came the Baths, which were hot, cold, and tepid water baths; and a stove, or Laconicum, named after the city of Laconia and the Lacedæmonians, from whom the Athenians derived their knowledge of the hot-air bath.

11. And lastly, there was the Stadium, a segment of an ellipse, which received its name from being one hundred paces long, equal to six hundred feet, or something less than an eighth of a mile. The Stadium was furnished with rows of seats for spectators, and was intended for the exhibition of feats of running and exercises upon a large scale.

The most remarkable Stadium known was one erected by Lycurgus on the banks of the river Ilissus. It was built of Pentellick marble, and was so magnificent a structure, that Pausanias the historian, in describing it, informs his readers that they would not believe what he was about to tell them, "it being a wonder to all that beheld it, and of that stupendous bigness that one would judge it a mountain of white marble."

There were several gymnasia in Athens, the most noteworthy being, the Lyceum, the Academia, and the Cynosarges.

The Lyceum, founded on the banks of the river Ilissus, was consecrated to Apollo; and not without reason, says Plutarch, but upon a good and rational account, since from the same deity that[17] cures our diseases and restores our health, we may reasonably expect strength and ability to contend in our exercises. The Lyceum is also interesting to us as being the institution in which Aristotle taught philosophy. Aristotle was wont to lecture to his scholars while walking, and his disciples were therefore called Peripatetics; he continued his teaching daily until the hour of anointing, which, with the Greeks, was a preparation for dinner.

The Academia was situated in the suburbs of the city, on a piece of ground that had been reclaimed from the marsh by draining and planting. It was called after an old hero named Academicus. Plutarch informs us that it was beset with shady woods and solitary walks fit for study and meditation; in witness whereof another writer says:—

"In Academus' shady walks;"

and Horace writes:—

"In Hecademus' groves to search the truth."

Plato taught philosophy in the Academia; but having in consequence of the unhealthy nature of the soil caught the ague, he was advised to relinquish it for the Lyceum. "No!" said the old man, "I prefer the Academy, for that it keeps the body under, lest by too much health it should become rebellious, and more difficult to be governed by the dictates of reason; as men prune vines when they spread too far, and lop off the branches that grow too luxuriant."

The Cynosarges was also in the suburbs of Athens, not far distant from the Lyceum. It was dedicated to the god of strength, Hercules; and was interesting from its admission of strangers, and half-blood Athenians. Its name is derived from the circumstance of a white dog seizing upon a part of the victim that was being sacrificed to Hercules by Diomus; and was the origin of the sect of philosophers known as the "Cynics."

Baths of Rome.—When Greece was subjugated by the Romans, the Romans carried back with them to Italy the taste for the bath. They erected thermæ of great magnificence, and in so great number, that at one period there were nearly nine hundred public baths in Rome. Agrippa alone is said to have built one hundred and sixty, while Mecænas has the credit of possessing the first private bath. The most famed of the public baths were those of Titus, Paulus Æmilius, Diocletian, Caracalla, and Agrippa. In these baths was centred all that was most perfect in material, elaborate in workmanship, elegant in design, and beautiful in art. Nothing was thought too grand or too magnificent for their decoration. Superb marbles brought from the most distant parts of the world; the choicest selections from the riches of their conquests, the curious and wonderful in nature and in art; precious gems and metals; and the finest works of the painter and the sculptor.[19] That beautiful production of the sculptor's art, the Laocoon, was discovered among the ruins of the Baths of Titus, and the celebrated Farnese Hercules in those of Caracalla.

The Baths of Agrippa were constructed of brick coated with enamel. Those of Nero were supplied with water from the sea, as well as fresh water. The Baths of Caracalla were a mile in circumference; they possessed two hundred marble columns, sixteen hundred seats of marble, and were capable of accommodating nearly two thousand persons; while those of Diocletian surpassed all others in grandeur, and occupied 140,000 men for many years in their construction.

Within the bath was collected all that contributed to the enjoyment, the luxury, and the gaiety of existence of the Romans. Here they practised their games, their athletic sports; here they came to learn the news of the day, to listen to recitations of poetry and prose,[6] to hear the eloquent harangues of their orators, and to be entranced with the chords of melodious music. There were temples devoted to dancing, to refreshment, to the [20]bath; and in their abundant gratitude they raised up appropriate statues to the gods who were supposed to preside over their several enjoyments. The great hall of their bath was ornamented with the statues of Hercules, the god of strength; Hygeia, the goddess of health; and Æsculapius, the god of medicine.

It is not to be wondered at, that, reared in the midst of the luxury, in the enjoyment of their Balneæ or Thermæ, the Romans should have carried with them their longing for the bath wheresoever they went, wheresoever their victorious armies forced themselves a way; and that, possessing a mastery over England and Wales, which they maintained for nearly four hundred years, they should have founded baths in their chief settlements in this country. Thus we have remains of Roman baths in London, in Chester, in Bath, at Wroxeter (Uriconium) in the neighbourhood of Shrewsbury, at Cirencester (Corinium), at Carisbrooke, in Colchester (Camulodunum), and in several other places besides.

But here we are compelled to draw a line of distinction between those grand institutions of their own metropolis, which comprised, as I have just described, their places of recreation, of exercise, of amusement, of diversion, as well as their temples of health; which were, in fact, a centralization of almost all the public institutions of their city into one—and those particular parts of these insti[21]tutions which were specially devoted to health. Although the remains of the Roman thermæ in England are large, although their construction evinces a great perfection in many of the arts of social life, particularly in the manufacture of bricks and pottery, yet they scarcely bear comparison with the grander thermæ of ancient Rome, and for this reason: that all that was simply ornamental—or, if I might be permitted to say so, that was superfluous—has been omitted, and nothing but the substantial and the wholesome allowed to remain—that portion, in fact, which was purely devoted to health and strength. We thus prune the bath down to its simpler elements, and we prepare the way for the consideration of the bath as it has been revived amongst us at the present day.

Without some explanation, it would be difficult to understand how an institution which was regarded with so much veneration by ancient Rome, should have totally fallen into decay in modern Rome; and that the thermæ shall have ceased to have an existence in Rome at the present day. It is clear that the games which were once played, and the exercises which were practised, within the narrow limits of the thermæ, grand though they were, have now sought a wider sphere: the paintings of their great artists have been gathered into the ecclesiastical edifices and academies; the statues and sculpture have found their way into museums,[22] or have been applied to the decoration of modern palaces; refreshment is more conveniently obtained in the cafés and restaurants; music and singing have been transferred to the opera; recitation to the theatre; poetry and prose to the library; and dancing to the assemblies; nay, the great hall of the Bath of Agrippa is now, in all its integrity, a place of Christian worship. In a word, the thermæ has become decentralized; whether as the result of the adoption of foreign fashions, or as a matter of convenience, it may be difficult to say; but so it is, and nothing of it now remains but the bath—that temple of the ancient thermæ over which Hercules, and Hygeia, and Æsculapius presided of old, and over which (in its humbler shape) they will continue to preside to the end of time.

The Baths of Titus have fortunately preserved to us a drawing, taken from its walls, which illustrates the construction and the mode of taking the bath among the Romans.

Beneath the bath is shown the furnace, or hypocaustum, for heating the rooms, as also the water used in the latter stages of the process.

Then follows a series of rooms, of which the principal are:—

1. The Apodyterium, Gymnasterium, or Vestiarium: the undressing and dressing-room.

2. The Tepidarium, which is warmed to a moderate temperature, and is intended to prepare and[23] season the body before entering the hotter apartment.

3. The Caldarium, or Calidarium, sometimes called the Sudatorium, and in the figure (Fig. 2), concamerata sudatio, was a room of higher temperature, in which the perspiratory process was accomplished. In this apartment there was commonly a recess, of a higher temperature still, which was intended for special purposes, and was named Laconicum, in compliment to the Spartans of Laconia.

4. After the Calidarium followed a Lavatorium (Lavatrina, Latrina), called in the figure Balneum, in which the body was washed after the process of perspiration was complete. The mode of washing was to sit on the everted edge or lip of a large marble trough—the labrum—and to be rinsed with warm water poured over the body by means of a cup or small basin (pelvis).

5. The bather then went into the Frigidarium, where he received an affusion of cold water, and where he reclined, or sat, or walked about, until he was cool or dry.

6. From the Frigidarium the bather passed into the Elaiothesium, or anointing room, where he was smeared with fragrant oils previously to resuming his dress in the Vestiarium.

Besides these, which were the principal rooms, there were others devoted to additional processes, such as shaving, hair-cutting, depilation, and hair-plucking.

The Romans carried the indulgence and decoration of their baths to so unreasonable a pitch of luxury and extravagance as to call forth State restrictions upon their use, and the reproof of their philosophers. Juvenal levels a shaft of satire against those who make the bath the instrument of gluttony; and Pliny scolds the doctors for declaring that the bath assists digestion, and for withholding their denunciations against its excessive abuse. Moreover, the Emperor Titus is said to have lost his life through excess of the bath, having spent in it many hours of the day. We cannot, therefore, be surprised that the time devoted to bathing should be limited by imperial edict, as happened in the reign of the Emperor Hadrian, the hours when the bath was open to the public being confined to two,—namely, from three until five.

Pliny the Consul, in his admirable letters, speaks in most affectionate language of the bath. "How stands Comum" (meaning Como, his birthplace), says he, "that favourite scene of yours and mine? What have you to tell me of the firm yet soft gestatio,[7] the sunny bath?" In another letter, addressed to a lady, he says:—"The elegant accommodations which are to be found at Narnia ... particularly the pretty bath."

Describing his winter villa, Laurentium, after painting a series of rooms, he continues:—

"From thence you enter into the grand and spacious cooling-room belonging to the baths, from the opposite walls of which two round basins project, large enough to swim in. Contiguous to this is the perfuming-room, then the sweating-room, and beyond that the furnace which conveys the heat to the baths. Adjoining are two other little bathing-rooms, which are fitted up in an elegant rather than costly manner: annexed to this is a warm bath of extraordinary workmanship, wherein one may swim, and have a prospect at the same time of the sea. Not far from hence stands the tennis-court, which lies open to the warmth of the afternoon sun."

"Between the garden and this gestatio runs a shady walk of vines, which is so soft that you may walk barefoot upon it without any injury."

Alluding to the mode of life of one of his friends, he observes:—

"When the baths are ready, which in winter is about three o'clock, and in summer about two, he undresses himself, and if there happens to be no wind, he walks for some time in the sun. After this he plays a considerable time at tennis, for by this sort of exercise, too, he combats the effects of old age. When he has bathed, he throws himself upon his couch till supper[8] time."

Seneca reproves the extravagance and self-indul[26]gence of his countrymen in a memorable letter (his eighty-sixth), which is as follows:—

"I write from the very villa of Scipio Africanus, having first invoked his manes, and that altar which I take to be the sepulchre of so great a man.

"I behold a villa built of squared stone; the wall encloses a wood, and has towers after the style of a fortification; the reservoir lies below the buildings and the walks, large enough for the use of an army; the bath is close and confined, dark, after the old fashion, for our forefathers united heat with obscurity.

"I was struck with an inward pleasure when I compared these times of Scipio with our own. In this nook did that dread of Carthage—to whom our city owes her having been but once taken—wash his limbs, wearied with labour; for, according to the ancient custom, he tilled his fields himself. Under this mean roof did he live—him did this rude pavement sustain.

"But who at this time would submit to bathe thus? A person is held to be poor and sordid, whose house does not shine with a profusion of the most precious materials, the marbles of Egypt being inlaid with those of Numidia; unless the walls are ornamented with an elaborate and variegated stucco, after the fashion of painting; unless the chambers are covered with glass; unless the Thasian stone, formerly a curiosity worthy of being placed in our temples, surrounds the pools into which we cast our[27] bodies weakened with immoderate sweating; unless the water is conveyed through silver pipes.

"As yet, I have confined my remarks to private baths only. What shall I say when I come to our public baths? What a profusion of statues. What a number of columns do I see supporting nothing; but placed as an ornament, merely on account of their expense. What quantities of water murmuring down steps. We are come to that pitch of luxury, that we disdain to tread upon anything but precious stones.

"In this Bath of Scipio are small holes rather than windows, cut through the wall, so as to admit the light without interfering with its resemblance to a fortification.

"But now we reckon a bath fit only for moths and vermin, whose windows are not so disposed as to receive the rays of the sun during his whole career; unless we are washed and sunburnt at the same time; unless from the bathing-vessel we have a prospect of the sea and land. In fact, that which excited the admiration of mankind, when first built, is now rejected as old and useless. Thus it is that luxury finds out something new in which to obliterate her own works.

"Formerly, baths were few in number, and not much ornamented; for why should a thing of common life be ornamented, which was invented for use, and not for the purposes of elegance? The water in those days was not poured down in drops like a[28] shower, neither did it run always as if fresh from a hot spring; nor was its clearness considered a matter of consequence. But, ye gods! what pleasure was there in entering those obscure and vulgar baths when prepared under the direction of the Cornelii, of Cato, or of Fabius Maximus? For the most renowned of the ædiles had, by virtue of their office, the inspection of those places where the people assembled, to see that they were kept clean and of a proper and wholesome degree of temperature; not of a heat like that of a furnace, such as has been lately found out, proper only for the punishment of slaves convicted of the highest misdemeanors. We now seem to make no distinction between being warm and burning.

"How many do I hear ridiculing the simplicity of Scipio, who did not admit the day into his sweating-places, or suffer himself to be baked in a hot sunshine. Unhappy man! He knew not how to enjoy life!

"The water he washed in was not clear and transparent, but, after rain, even thick and muddy. This, however, concerned him but little; he came to the bath to refresh himself after his labour, not to wash away the perfumes of a pomatumed body. What think you some will say of this? I envy not Scipio: he lived in exile indeed, who bathed in this manner.

"Should you be told further, that he bathed not every day—for those who relate to us the traditions[29] of early times, say that our forefathers bathed their whole bodies on market-days only—it will be answered, Then they were very uncleanly. How, think ye, they smelt? Like men of labour and fatigue.

"Since dainty baths have been invented, we are become more nasty. Horace, when describing a man infamous for his dissipation, what does he reproach him with? With smelling of perfumed balls! 'Pastillos Rufillus olet.'"

Of the ancient Roman bath in England, we have several examples, the most interesting being that which has been lately brought to light in the ancient Roman city, Uriconium, in the neighbourhood of Shrewsbury. Uriconium is close to the village of Uroxeter, commonly pronounced Wroxeter, five miles from Shrewsbury. It is situated on the property of the Duke of Cleveland, and is known to have existed at the beginning of the second century of the Christian era, when the Romans held dominion over England, and when England was a part, and a highly-treasured part, of the Roman Empire.

It was of considerable size, having a boundary wall three miles in circumference, and was, doubtless, a flourishing city; but fell a victim to the ravages of fire and the sword during the fifth century, and has since lain buried and unnoticed until the last few years, when a society was formed for the purpose of excavating it.

The walls of the houses are remarkable for their[30] thickness, namely, three feet; while that of the wall of the town is four feet. They are constructed upon a plan commonly adopted by the Romans—namely, a facing of stone on each side, and the space between filled in with rubble and that remarkable stone-like enduring mortar which has suggested the name of a better kind of cement of the present time, known as "Roman cement." The height of the houses was thirty feet; but they had no upper storey, and there is no trace of staircase.

Of the mode of warming the houses and, par excellence, the baths, the Rev. Thomas Wright[9] observes:—"The Romans did not warm their apartments by fires lighted in them.... The floor of the house, formed of a considerable thickness of cement, was laid upon a number of short pillars formed usually of square Roman tiles placed one upon another, and from two to three feet high. Those of the largest hypocausts yet found at Wroxeter were rather more than three feet high. Sometimes these supports were of stone, and in one or two cases in discoveries made in this country they were round. They were placed near to each other and in rows, and upon them were laid, first, larger tiles, and over these a thick mass of cement, which formed the floor, and upon which the tesselated pavements were set. Sometimes small parallel walls forming flues instead of rows of columns [31]supported the floor.... Flue tiles—that is, square tubes made of baked clay with a hole on one side or sometimes on two sides—were placed against the walls endways one upon another so as to run up the walls."

My friend Mr. George Witt, having recently visited the ruins of the ancient Roman bath still existing at No. 117, Bridge-street, Chester, describes it as follows:—

"The most interesting of all the Roman antiquities of this ancient city are the remains of a private Roman bath, showing the Hypocaustum, or heating place beneath, in a state of great preservation. The hypocaust is 18 feet long by 8 feet wide, and 3 feet high. The roof was supported on thirty-two stone pillars (of a single block), broader at the base and the top, and narrower in the middle; of these twenty-eight still remain. On the top of the columns are placed, by way of capitals, strong tiles from 17 to 23 inches square, and 3 inches thick, reaching from pillar to pillar, thus forming, at the same time, the roof of the hypocaust and the floor of the room above. Over all these is a bed of hard concrete, 9 or 10 inches thick, the whole suited to bear any amount of heat. The pillars are made of the red sandstone of the district, and are so far worthy of note, that they differ from the tile-columns of most of the Roman hypocausts found in other parts of England, which are chiefly formed of piles of 8-inch tiles, 2 inches thick.

"The room above the hypocaust, which was the hot-chamber of the bath, called the Caldarium, has unfortunately been so dismantled, that little or nothing can now be learned of its character or proportions, two of the side walls only remain. The walls of these hot-chambers are generally on the inside by ranges of hollow flue-tiles, coming up from the hypocaust below, varying in number, according to the degree of heat required.

"There is nothing whatever here left of the Frigidarium, or cooling-room, nor any other of the apartments of the bath, nor of any of the contrivances used therein, except a sort of tank, 7 feet deep, 10 feet long, and 4 feet wide, situate near the mouth of the furnace, which may have served either as a receptacle for warm water, or as a place for a plunge in cold water, after the previous processes of the bath had been completed.

"Like modern Rome, the present city of Chester stands some feet above the level of the old Roman city; the visitors, therefore, must be prepared to descend into a dark cellar, to inspect the hypocaust and so-called bath! and to emerge therefrom, with a bitter feeling of humiliation and regret, that our forefathers could have so ruthlessly destroyed these interesting evidences of the manners and customs of that wonderful people, who for upwards of four hundred years held dominion over this island—a people to whom we are indebted for the fundamental principles of our social civilization; for the intro[33]duction of architecture, sculpture, coinage of money, construction of roads, and for innumerable other arts and adornments of life. There can be no more instructive proof of the mental darkness of those ages which followed the overthrow of the Roman Empire, than the wholesale destruction of the buildings of that great people, of which this is an example; and it is to be lamented that this barbarism, in regard to such monuments of antiquity, has not yet altogether disappeared."

And where, it may be asked, is the bath now; the conquering Romans have ceased to be other than a name, or a weary lesson for schoolboys; the Romans are gone, the Roman bath is lost. But here an eloquent modern author, Mr. Urquhart, helps us in our difficulty with a quotation:—"A people who know neither Latin nor Greek have preserved this great monument of antiquity on the soil of Europe, and present to us, who teach our children only Latin and Greek, this Institution in all its Roman grandeur and its Grecian taste. The bath, when first seen by the Turks, was a practice of their enemies, religious and political; they were themselves the filthiest of mortals; yet no sooner did they see the bath than they adopted it, made it a rule of their society, a necessary adjunct to every settlement, and Princes and Sultans endowed such institutions for the honour of their name." This, then, is the answer to the question—Where is the bath now? The ancient Roman bath lives in its[34] modern offspring, the Turkish Bath—the Turkish Hamâm.

When, therefore, we see the words "Turkish Bath" in grand letters paraded through our metropolis; when we see a human being performing the part of a sandwich, with a broadsheet of Turkish bath in front, and a similar sheet behind, himself representing a flattened anchovy between the two slices, we shall know that the ancient Roman bath, after being kept alive for many centuries by the fostering care of the Turks, has at last come back to revisit its ancient haunts, and to offer to modern Britons the enjoyments from which our forefathers turned away with contempt as a custom of their conquerors. And we are led to recognise the truth of my preliminary proposition—that the bath is an instinct, and that, being an instinct, its survival of a race is no longer a wonder, but is a law of nature—a law of the universe.

Let me now describe the Hamâm, or Turkish Bath as it exists at the present moment in Constantinople; and in this description I shall take as my groundwork the account given of it by Mr. Urquhart. It is a large building, with a domed roof, a square massive body, from which minarets shoot up, and against which wings abut containing side apartments. The essential apartments of the hamâm are three in number—a great hall or mustaby, a middle chamber, and an inner chamber. We raise the curtain which covers the entrance to the street, and we find[35] ourselves in the mustaby, a circular or octagonal hall, maybe a hundred feet high, with a domed roof, and open in the centre to the vault of heaven. In the middle of the floor is a basin of water four feet high, with a fountain playing in the centre, and around it are plants and trellises; and resting against it, at some one point, the stall whence comes the supply of coffee and pipes or chibouques.

Around the circumference of the hall is a low platform, from four to twelve feet in breadth and three feet high. This is divided by dwarf balustrades into small compartments, each containing one or more couches. These compartments are the dressing-rooms, and the couches, shaped like a straddling letter W, and adapted by their angles to the bends of the body, are the couches of repose. It is here that the bather disrobes; his clothes are folded and placed in a napkin, and the napkin is carefully tied up. He then assumes the bathing garb; a long Turkish towel (peshtimal or futa) is wound turban-wise around his head; a second around his hips, descending to the middle of the leg; and a third, disposed like a scarf over one or both shoulders. Two attendants shield him from view while changing his linen, by holding a napkin before him; and when he is ready, the same attendants help him to descend from the platform; they place wooden pattens (called nalma in Turkish, and cob cob in Arabic) on his feet, and taking each arm, lead him to the middle apartment. The[36] wooden pattens are intended to protect the feet from the heat of the inner rooms, and from the dirty water and slop of the passages.

"The slamming doors are pushed open, and you enter the region of steam;" this is the second chamber, it is low, dark, and small; it feels warm without being hot or oppressive, and the air is moistened with a thin vapour. It is paved with white marble, and a marble platform eighteen inches high occupies its two sides, while the space between serves as the passage from the mustaby to the inner hall. A mattress and cushion are laid on the marble platform, and here the bather reclines; he smokes his chibouque, sips his coffee, and converses in subdued and measured tones with his neighbour. This is the Tepidarium of the Roman bath; here the bather courts a "natural and gentle flow of perspiration," and to this end are adapted the warm temperature, the bath coverings, the hot coffee, and the tranquil rest.

"The bath is essentially sociable, and this is the portion of it so appropriated; this is the time and place where a stranger makes acquaintance with a town or village. While so engaged, a boy kneels at your feet and chafes them, or behind your cushion, at times touching or tapping you on the neck, arm, or shoulder, in a manner that causes the perspiration to start."

After a while the bath attendant arrives; he passes his hand under the linen coverings of the[37] bather; if he find the skin sufficiently moist and softened, the bather is again taken by the arms, his feet are replaced in the wooden pattens, another slamming door is opened, and he is ushered into the inner apartment, "a space such as the centre dome of a cathedral," lighted by means of "stars of stained glass in the vault." The temperature of this apartment, the Calidarium or Sudatorium of the Romans, is considerably higher than that of the middle room; the atmosphere is filled with "curling mists of gauzy and mottled vapour," the steam being raised by throwing water on the floor. In the middle of the apartment is "an extensive platform of marble slabs," and on this the bather is laid on his back, his scarf being placed beneath him to protect his skin from the heated marble, and the napkin that served as his turban being rolled up as a pillow to his head.

The bather is now subjected to the process of shampooing—that is, his muscles are pressed and squeezed, his joints are stretched until they snap, and they are forcibly bent in various directions. In the hands of the professional shampooer the process is elevated to an art, and words fail to convey other than a very imperfect idea of its nature.

After the shampooing, the bather is brought to the side of the hall—around which are placed marble basins two feet in diameter, supplied by means of taps with hot and cold water—and made to sit on a board near to one of these basins. The[38] attendant draws on a camel's-hair glove. "He stands over you; you bend down to him, and he commences from the nape of the neck in long sweeps down the back till he has started the skin; he coaxes it into rolls, keeping them in and up till within his hand they gather volume and length; he then successively strikes and brushes them away, and they fall right and left as if spilt from a dish of macaroni. The dead matter which will accumulate in a week forms, when dry, a ball of the size of the fist." In the course of his frictions he pours water from the basin over the skin by means of a copper cup, to rinse off the impurities.

In the next place, a large wooden bowl is placed by the side of the bather; this bowl contains soap and a wisp of lyf, the woody fibre of the Mecca palm, and the body is thoroughly soaped and washed twice over from the head to the feet, and, as a coup de grâce, a bowl of warm water is dashed over the entire body.

An attendant now approaches with warm napkins; the hip-cloth, or cummerbund, is dropped, and a warm dry napkin is selected to supply its place; another is thrown over the shoulders, and the bather is placed on a seat. The shoulder napkin is then raised, a fresh dry one put in its place, and the first over it; a fourth is wrapped around the head; "your feet are already in the wooden pattens. You are wished health; you return the salute, rise, and are conducted by both arms to the outer hall."

In the outer hall, the bather is led to his box; he drops the pattens as he steps on a napkin spread on the matting of the platform; and he stretches his limbs on the couch of repose. "The attendants then reappear, and gliding like noiseless shadows, stand in a row before him. The coffee is poured out and presented; the pipe follows; or if so disposed he may have sherbet or fruit; the sweet or water-melons are preferred, and they come in piles of lumps large enough for a mouthful; and if inclined to make a positive meal at the bath, this is the time. The hall is open to the heavens, but nevertheless, a boy with a fan of feathers, or a napkin, drives the cool air upon him." The linen is twice changed; and when the cooling is complete, "the body has come forth shining like alabaster, fragrant as the cistus, sleek as satin, and soft as velvet. The touch of the skin is electric." "The time occupied is from two to four hours, and the operation is repeated once a week." At the conclusion of the process, "the crispness of the skin returns, the fountains of strength are opened: you seek again the world and its toils; and those who experience these effects and vicissitudes for the first time, exclaim—'I feel as if I could leap over the moon.'"