Project Gutenberg's Harper's Young People, July 4, 1882, by Various

This eBook is for the use of anyone anywhere in the United States and most

other parts of the world at no cost and with almost no restrictions

whatsoever. You may copy it, give it away or re-use it under the terms of

the Project Gutenberg License included with this eBook or online at

www.gutenberg.org. If you are not located in the United States, you'll have

to check the laws of the country where you are located before using this ebook.

Title: Harper's Young People, July 4, 1882

An Illustrated Weekly

Author: Various

Release Date: December 10, 2018 [EBook #58448]

Language: English

Character set encoding: ISO-8859-1

*** START OF THIS PROJECT GUTENBERG EBOOK HERPER'S YOUNG PEOPLE, JULY 4, 1882 ***

Produced by Annie R. McGuire

| THROUGH THE TUNNEL. |

| INDEPENDENCE-DAY. |

| BURNING THE "TORO." |

| MR. STUBBS'S BROTHER. |

| PERIL AND PRIVATION. |

| THE LITTLE PATIENT. |

| A FOURTH-OF-JULY WARNING. |

| ONE NIGHT. |

| THE OLD, OLD STORY. |

| OUR POST-OFFICE BOX. |

| vol. iii.—no. 140. | Published by HARPER & BROTHERS, New York. | price four cents. |

| Tuesday; July 4, 1882. | Copyright, 1882, by Harper & Brothers. | $1.50 per Year, in Advance. |

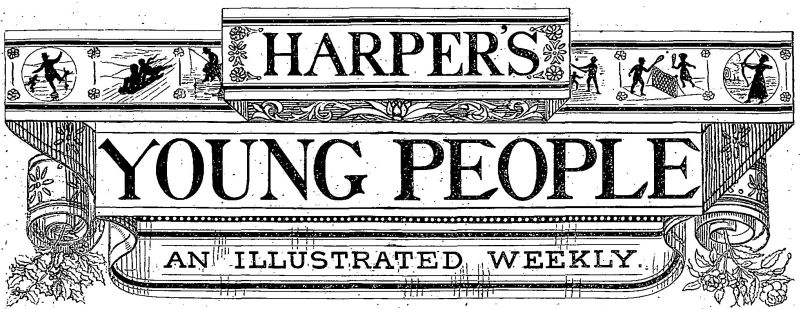

"ORDER ARMS!"

"ORDER ARMS!"

"Halloa, the house! Jedediah! Jedediah Petry! Mrs. Jedediah! Cadmus! Are you all deaf this morning? Come, come!"

Dr. Flaxman stood up in his old chaise before the door of the last white cottage in Wicketiquok village, and shouted until he was purple in the face. The nine-o'clock June sun shone bright upon the closed green blinds. A broom and a watering-pot rested in the open doorway; but the broom and the pot seemed to be the only members of the Petry family ready to receive an early morning call. No marvel that Dr. Flaxman grew impatient, said several things to himself, and was just making ready to get out of the chaise and tie his new horse, when all at once a boy came running around the house corner, calling: "Good-morning, Doctor. Did you call?"

"Did I call?" echoed the Doctor, cuttingly. "Well, Cadmus Petry, I should rather say that I did. Are you the only member of the family up at this time o' day? Cadmus, I want your father."

"Can't have him, Doctor," replied the lad. "Pop's gone up to Lafayette by the early train."

"There, now!" exclaimed the Doctor, appearing much disturbed by this answer. "So I've missed him, after all my trouble! Well, where's your mother?"

"Gone with father. I'm keeping house for 'em. They won't come back before evening. They were going to take dinner at Grandfather Fish's in the town, and then go to Lawyer Gable's, on some important business, they said; something about buying some more land, I believe."

"That's just it, Cadmus," said Dr. Flaxman, looking still more vexed and perplexed. He ran his sharp eye all over the boy from head to foot, and then continued: "Look a-here, Cadmus. You're a pretty smart youngster, and I think you'll have to help me—eh?"

"Yes, sir," replied Cadmus, quietly.

"Your father is going to buy a part of a farm to-day up in Lafayette, and he's getting it a good deal on my advice. He asked me to go and look at it and make some inquiries, and I did. Now I've got a letter here, my boy, that just alters my whole judgment of the matter. I wouldn't have your father make that bargain without first seeing this letter for anything you can think of. It came this morning. Now couldn't you go right up to Lafayette, catch your father and mother before they go to the lawyer's office, and give him this letter—without fail? I can't go myself, because Judge Kenipe's so low since yesterday; but I'll send a telegram ahead of you to tell your father to wait until you come."

Cadmus's face was puckered as he stood thinking. "You see, there's no train from here now, Doctor, until afternoon, and that'll be too late. The express don't stop, going through our village. Hello! I'll walk down to the Junction, and get on her there. She has to stop there always. That'll do it. Give me the letter, Doctor."

Dr. Flaxman looked greatly relieved. He laughed, and held it out of the chaise, with a regular battery of directions. "Now recollect, I depend on you, Cadmus," he added, switching his black horse, and moving away. "I'll send the dispatch. You've more than an hour to get down to the Junction. Got money enough for your fare? All right. Good-by." And the chaise rattled off.

Cadmus darted into the house, and locked that up securely. A moment later he was striding manfully down the road, bound for Rippler's Junction, a couple of miles below the village. Presently the daisy-bordered road crept alongside the level railway. A freight train, steaming and rumbling along, seemed to offer Cadmus a noisy hint, so he soon transferred himself to the track (a thing he had been soundly lectured for doing before this morning), and tramped along on the uneven ties, whistling as he rounded curves, like a locomotive itself—only locomotives don't, as a general thing, whistle "Captain Jinks." Soon Rippler's Mountain rose up in the distance before him. The railroad passed directly through this by a tunnel. At the other end of it lay Rippler's Junction, whither Cadmus was bound to catch that 10.15 express. A wagon-road ran smoothly over the top of the mountain, and came down into the town, and that was at his service. But Cadmus, hastening along toward the great black hole in the hill-side, and fancying himself to be in a much greater hurry than occasion at all required, began to ask himself why, if the railroad went through the mountain instead of over it, he, Cadmus Petry, shouldn't save time by doing the same thing.

Had not those dozen lectures as to walking on the railroad been given him? Hadn't Cadmus heard that even an old and experienced "hand" dislikes nothing worse than walking through a tunnel—had rather even do a regular job of repairing in it? Did not everybody know that the Rippler's Junction Tunnel was uncommonly narrow, close, and continually shot by freight, coal, or passenger trains? To meet such in quarters so dark and dangerous requires, indeed, a very cool head and steady nerves. There comes to every man or boy a time in his life when he does a foolish or a rash thing. This was such a moment for Cadmus Petry. The great hole loomed up before him in the hill's rocky side. He looked up. Over his head, nailed to the side of the brick facing, was a black sign-board, on which, in white letters, Cadmus read the following encouraging words:

The lad hesitated, wavered, then gave his head a rather defiant toss, and exclaiming, half aloud, "Sorry; but I'm in a hurry, and I can save ten minutes by you," walked forward into the smoky gloom before him, leaving sunlight and safety behind his back.

Cadmus was at first rather surprised to find his novel journey less odd and disagreeable than he had anticipated. There was very little smoke in the tunnel at so short a distance from one of its mouths. Daylight straggled in behind the boy's back, lighting up the road-bed with a gray distinctness. It brought out deep black shadows along the jagged walls of rock, and turned the rails before him to polished silver ribbons. Cadmus walked inward as fast as he could; occasionally he ran. By-and-by he noticed a curious sight upon turning his head. Far behind him lay the entrance by which he had come in, now dwindled to a third of its size, and with the air and landscape outside of it become a bright orange—an effect sometimes noticeable if one is well within the interior of a tunnel and looks outward. But the light amounted to worse than none by this time. Cadmus could not see his footing after a few yards further. He began stumbling badly in another minute. Hark! What was that low dull rattle that echoed to the boy's ears? The sound increased to a roll, then to a booming roar. A train was on its way toward him from daylight. From which end was it approaching? Cadmus dared not stop to think; he leaped aside, put out his hand, and felt the rough rocky wall.

He pressed himself closely against this, his heart thumping until he could scarcely stand. Was there space enough for safety between himself and the train rushing down toward him? He dared not try to determine now, for his ears were stunned, his breath taken away, as, ringing, hissing, and thundering in the darkness, what must have been a heavy freight train roared past the boy. Half choked with smoke, shaking in every limb and nerve, the[Pg 563] unlucky lad tottered from his terribly narrow station, and began running forward as well as he might. Never before had he imagined how terrible a thing was a train of cars at full speed. He shook with terror at the idea of meeting another. A quarter of a mile before him yet!

Another? Before he had thought the word again, his quick ear caught its shriek as it approached from the opening, which it seemed to Cadmus that he should never reach alive. He caught again the booming crash of its advent into the mountain's heart. Cadmus caught his breath, sick with nervousness and fear. This time the space between the rail and the rock seemed so dreadfully narrow—and it was, in truth, some inches less than a few yards back. Nevertheless, Cadmus staggered into it, stood as straight against the side wall as he could, his face toward it, and with his head thrown a little upward. His enemy sped toward him, and seemed to scorch and deafen and grind the boy with its whirling wheels as it shot behind his very shoulders. Cadmus's hat was blown off, and no more heard of, as no locomotive capped with a small brown chip astonished the natives on its way to Oswego. But a slight accident like the flying away of one's hat can be an important matter under such conditions. The sudden whizz of wind about him and the snap of his hat guard gave a start to the terrified boy. He lost his balance, and half crouched, half fell, not between those unseen wheels rolling so near, but sidelong.

The red flash of the lanterns on the platform of the last car fell on his bent figure as the train thundered away into the darkness beyond. Cadmus found his feet, doubtful if he were a hearing, breathing, and generally living boy or not. But the smoke rolled past. Gleams of light filtered through it. The worst was over, and Cadmus was safe—well scratched and bruised, and as close to being "frightened to death" as most persons ever have been.

A few moments later a hatless, grimy, almost unrecognizable boy emerged from the Junction end of the tunnel, and picked his way toward the dépôt, trembling, but quite bold enough to decline sharply to answer any questions that the interested switch-tenders and signal-men fired about his ears. There was a pump handy; so Cadmus contrived to make a very imperfect toilet before that 10.15 express came along, which spun him, bare-headed, back over the road he had come, toward Lafayette and his father.

Mr. and Mrs. Petry were sitting in the old dining-room at Grandfather Fish's, still in a state of mystification about the telegram they had received from the Doctor.

"What'll Lawyer Gable an' that man think of me?" exclaimed Mr. Petry. "Here 'tis half an hour after time, and Cadmus not here yet. How was he to come up with any letter, I'd like to know? He couldn't get aboard a train that didn't stop at Wicketiquok."

At which moment the door opened, and Cadmus strode manfully into the room. "Good-afternoon, grandpa," he exclaimed, quite composedly, holding out a very dirty white envelope toward the other members of the group. "Hello, father! here's that letter Dr. Flaxman telegraphed you about, and—and I walked through the tunnel to get the express. I suppose I'll have to be whipped."

Although it can not be said that Cadmus, in the course of the desired explanation which followed, succeeded in convincing Mr. and Mrs. Petry that his walking through the tunnel had been a very necessary part of his important errand, two things may be truthfully stated: first, that after reading Dr. Flaxman's letter, Mr. Petry at once decided not to buy "that farm"; and second, that Cadmus did not "have to be whipped," but went home with his parents on the afternoon train, quite subdued in spite of a brand-new straw hat. As they shot through the tunnel, his mother said, in a low voice, "What a mercy you weren't killed, Cadmus, you thoughtless fellow!"

That was about as true a thing as any one ever said about the affair.

Through the dusty street

And the broiling heat,

To the sound of the stirring drum,

With a martial grace

And measured pace,

See the proud young patriots come!

Why march they so,

With martial show,

These sons of patriot sires?

What glorious thought,

From the dim past caught,

Their brave young hearts inspires?

Sure the souls of boys

Love din and noise,

And they love to march along

To the ringing cheers

That greet their ears

From the loud-applauding throng.

But a grander thought

In their breasts hath wrought

Than the love of vain applause,

For strong and deep

Is the mighty sweep

Of their love for Freedom's cause.

They have heard the tale

Of the hero Hale,

They have read of Washington,

And they know full well

How Warren fell

Ere the fight was scarce begun.

And the long grand scroll

Of the muster-roll

Of Freedom's patriot band,

With hearts aflame

At each noble name,

Their eager eyes have scanned.

And now, as they hear

Loud cheer on cheer

Roll out like a mighty wave,

They think of the bold

Brave men of old,

And the land they died to save.

March on, brave boys,

With your din and noise,

Through the hot and dusty way,

And strong and sweet

May your hearts e'er beat

For glad Independence-day!

At sunrise on the Fourth of July the national flag is hoisted on all public buildings in the city of Mexico. Its pretty green, white, and red stripes wave as gayly in the sunshine as the star-spangled banner waves in the breeze sweeping over our own dear country, and the eagle in the white central stripe fiercely clutches the snake in its beak and claws as if it rejoiced in putting to death even a symbol of treachery.

Now the Fourth of July is not a holiday in Mexico, and if you were there you would wonder why so many flags were flying. Stop the first boy you meet in the street, no matter if he is a poor little Indian, and he will tell you it is because it is the Independence-day of the great sister republic, the United States of North America.

How many readers of Young People know the date of the Independence-day of the United States of Mexico? They have such a day, which is kept with great rejoicings, ringing of bells, booming of cannons, and no end of popping fire-crackers.

Spanish rule had long been very heavy and oppressive for the inhabitants of Mexico, and on the Sixteenth of September, 1810, a small company of men, led by a priest named Hidalgo, issued a proclamation calling upon the[Pg 564] Mexicans to rise against their tyrannical Spanish rulers. The people were not well organized; and although their desire for liberty was very strong, it took many years of hard fighting to drive the Spaniards out of the country. It was not until 1821 that Mexico gained her freedom. Hidalgo and other early leaders of the revolutionary movement had been killed by the Spaniards, and the people were not as yet wise enough to make good use of their liberty. They had been oppressed so many years that they did not know how to form a true republic. The first thing they did was to proclaim a man named Iturbide Emperor of Mexico. The people owed much to Iturbide, for it was by his skill and good generalship that they gained their freedom; but they should not have made him an Emperor. He oppressed the people so much that they soon had to rise again and drive him from the country.

It took the Mexicans many years to learn how to live under a republican government. They had many revolutions and much trouble, but they loved liberty, and went to work bravely to learn how to use it wisely. They abolished slavery more than fifty years ago, and the Constitution under which the people are now living peacefully and happily is very much like the Constitution of the United States. Every fourth year they elect a President. The name of the man now in office is Manuel Gonzalez.

The Sixteenth of September, the day on which the poor priest Hidalgo and his little band of patriots issued the proclamation against Spanish rule, is observed all over Mexico as a glorious Independence-day.

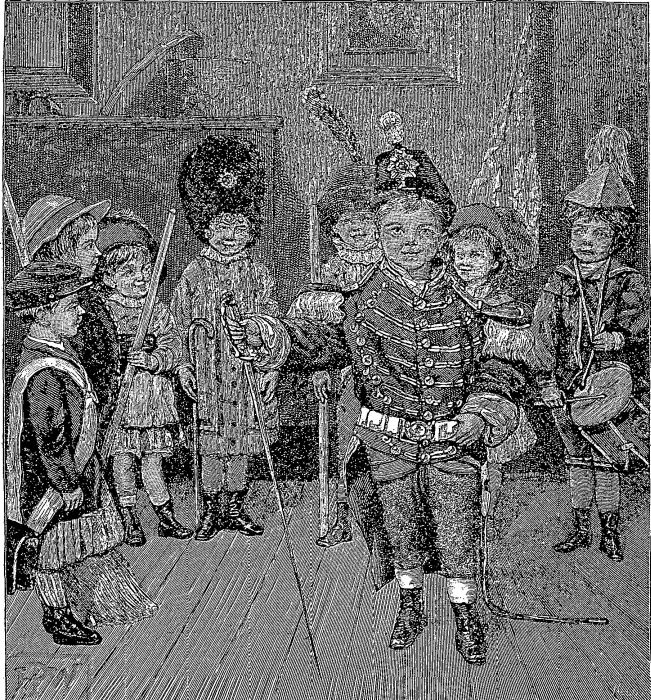

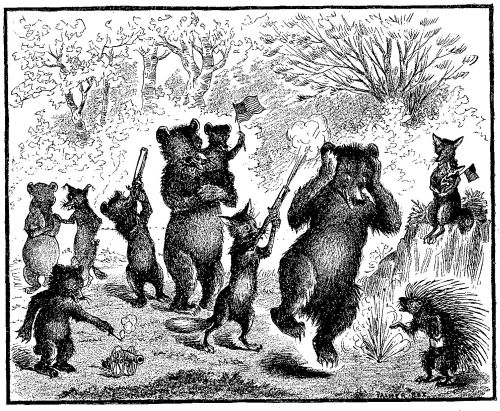

MEXICAN FIRE-WORKS—THE "TORO."

MEXICAN FIRE-WORKS—THE "TORO."

At sunrise the bells ring merrily, cannons are fired from all the forts, and thousands of little boys begin a lively sport with torpedoes and fire-crackers. Then during the day come public meetings with patriotic speeches, and splendid military parades with joyous martial music.

As evening draws near, the impatience, especially of the little Indian boys, grows so great for the fire-works to begin that long before sunset they send up fire-balloons of bright-colored paper, and when it is dark the air is full of these flying stars. The boys are very skillful in making these balloons, and a boy will often have a great number of them, which he has made himself, all ready to send up on that glorious Independence-night.

The fire-works are like those in this country. But there is one very curious piece, in which the Indians take special delight. They would not think it was Independence-night if they could not burn a "toro," the Spanish word for bull. The bull is made on a frame covered with thick leather, and pin-wheels and stars are fastened all over it. A light frame-work is built on the bull's back as a support for spiral fire-works and Roman candles. A young Indian takes this bull on his head, the projecting leather sides protecting him from any danger from falling sparks. A pin-wheel is ignited, which soon extends its fire over the bull's whole body. The young Indian scampers up and down the street, preceded by boys who make all the noise they can on little drums. The crowd of spectators runs after him, shouting with delight. The bull burns furiously, he shakes a fiery tail, his eyes are two glaring balls, and he darts green and red and yellow sparks from his nostrils. He is a very fierce creature, and the crowd of Indians laugh and scream as he rushes at them. His back is a tower of fire, sending forth small aerial bombs. At last his rage is over, the pin-wheels which covered his sides revolve slower and slower, and with a final sputter disappear. His eyes grow dim, and he is a very forlorn bull. The young Indian who has had the honor of carrying him in his glory and strength emerges from the blackened frame, and the crowd goes home to bed declaring that there never was such a fierce and magnificent bull.

On Fourth-of-July morning the readers of Young People must remember that the flags are flying in their honor in the city of Mexico, for in all honor done to our country every American boy and girl has a share.

And on the Sixteenth of September do not forget that it is Independence-day in Mexico, and that all the boys and girls in that country are having a "splendid time," and that at night the young Indians will be sure to burn a "toro."

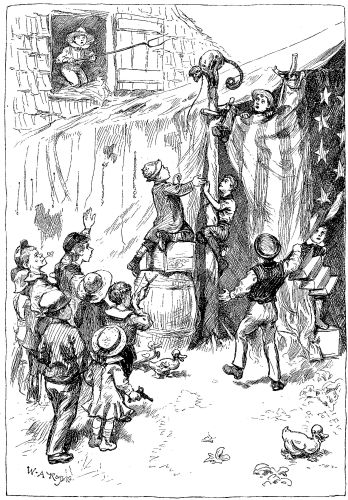

The sails were not in a remarkable state of preservation, or Captain Whetmore would not have taken them from his vessel; but Reddy explained that the holes could be closed up by pasting paper over them, or by each boy borrowing a sheet from his mother and pinning it up underneath.

One of the sails was considerably larger than the other; but Reddy had also thought of this, and proposed to make them look the same size by "tucking one in" at the end. Bob returned before the sails had been thoroughly inspected, and brought with him the coveted flag, thus showing he had been successful in his mission.

"Now let's put it right up, an' then we can build our ring, an' do our practicin' there instead of goin' up to the pasture," suggested Ben.

Since there was no reason why this should not be done, Bob and Ben started for the woods to cut some young trees with which to make a ridge-pole and posts, while the others carried the canvas out-of-doors, and made calculations as to where and how it should be put up.

When they commenced work, they had no idea but that it would be completed before supper-time; but when the village clock struck the hour of five, they had not finished making the necessary poles and pegs.

"We can't come anywhere near getting it done to-night," said Toby, surprised at the lateness of the hour, and wondering why Aunt Olive had not called him as she had promised. "Let's put the sails back in the barn, an' to-morrow mornin' we can begin early, an' have it all done by noon."

There was no hope that they could complete the work that night. Therefore Toby's advice was followed; and when the partners separated, each promised to be ready for work early the next morning.

Toby went into the house, feeling rather uneasy because he had not been called; but when Aunt Olive told him that Abner had aroused from his slumber but twice, and then only for a moment, he had no idea of being worried about his friend, although he did think it a little singular he should sleep so long.

That evening Dr. Abbot called again, although he had been there once before that day; and when Toby saw how troubled Uncle Daniel and Aunt Olive looked after he had gone, he asked, "You don't think Abner is goin' to be sick, do you?"

Uncle Daniel made no reply, and Aunt Olive did not speak for some moments; then she said, "I am afraid he staid out too long this morning; but the doctor hopes he will be better to-morrow."

If Toby had not been so busily engaged planning for Abner to see the work next day, he would have noticed[Pg 566] that the sick boy was not left alone for more than a few moments at a time, and that both Uncle Daniel and Aunt Olive seemed to have agreed not to say anything discouraging to him regarding his friend's illness.

When he went to bed that night he fancied Uncle Daniel's voice trembled as he said, "May the good God guard and spare you to me, Toby boy!" but he gave no particular thought to the matter, and the sandman threw dust in his eyes very soon after his head was on the pillow.

In the morning his first question was regarding Abner, and then he was told that his friend was not nearly so well as he had been; Aunt Olive even said that Toby had better not go into the sick-room, for fear of disturbing the invalid.

"Go on with your play by yourself, Toby boy, and that will be a great deal better than trying to have Abner join you until he is much better," said Uncle Daniel, kindly.

"But ain't he goin' to have a ride this mornin'?"

"No; he is not well enough to get up. You go on building your tent, and you will be so near the house that you can be called at any moment, if Abner asks for you."

Toby was considerably disturbed by the fact that he was not allowed to see his friend, and by the way Uncle Daniel spoke; but he went out to the barn, where his partners were already waiting for him, feeling all the more sad now because of his elation the day before.

He had no heart for the work, and after telling the boys that Abner was sick again, proposed to postpone operations until he should get better; but they insisted that as they were so near the house, it would be as well to go on with the work as to remain idle, and Toby could offer no argument to the contrary.

Although he did quite as much toward the putting up of the tent as the others did, it was plain to be seen that he had lost his interest in anything of the kind, and at least once every half-hour he ran into the house to learn how the sick boy was getting on.

All of Aunt Olive's replies were the same: Abner slept a good portion of the time, and during the few moments he was awake said nothing, except in answer to questions. He did not complain of any pain, nor did he appear to take any notice of what was going on around him.

"I think it's because he got all tired out yesterday, an' that he'll be himself again to-morrow," said Aunt Olive, after Toby had come in for at least the sixth time, and she saw how worried he was.

This hopeful remark restored Toby to something very near his usual good spirits; and when he went back to his work after that, his partners were pleased to see him take more interest in what was going on.

The tent was put up firmly enough to resist any moderate amount of wind, but it did not look quite so neat as it would have done had it not been necessary to perform the operation of "tucking in" one end, which made that side hang in folds that were by no means an improvement to the general appearance.

The small door of the barn, over which the tent was placed, served instead of a curtain to their dressing-room; and at one side of it, on an upturned barrel, arrangements were made for a band stand.

Mr. Mansfield's flag covered the one end completely, and all the boys thought it gave a better appearance to the whole than if they had made it wholly of canvas.

The ring, which Reddy marked out almost before the tent was up, occupied nearly the whole of the interior; but since they did not intend to have any seats for their audience, it was thought there would be plenty of room for all who would come to see them. The main point was to have the ring, and to have it as nearly like that of a regular circus as possible, while the audience could be trusted to take care of itself.

The animals to be exhibited were to be placed in small cages at each corner. Reddy had at first insisted that each cage should be on a cart to make it look well; but he gave up that idea when Bob pointed out to him that six mice or two squirrels would make rather a small show in a wagon, and that they would be obliged to enlarge their tent if they carried out that plan, even provided they could get the necessary number of carts, which was very doubtful.

MR. STUBBS'S BROTHER MISBEHAVES HIMSELF.

MR. STUBBS'S BROTHER MISBEHAVES HIMSELF.

In the matter of getting sheets from their mothers they had not been as successful as they had anticipated. No one of the ladies who had been spoken to on the subject was willing to have her bed-linen decorating the interior of a circus tent, even though the show was to be only a little one for three cents.

Reddy was quite sure he could mend one or two of the largest holes if he had a darning-needle and some twine; but after he got both from Aunt Olive, and stuck the needle twice in his own hand, once in Joe Robinson's, and then broke it, he concluded that it would be just as well to paste brown paper over the holes.

Of course, the fact that a tent had been put up by the side of Uncle Daniel's barn was soon known to every boy in the village, and the rush of visitors that afternoon was so great that Joe was obliged to begin his duties as door-keeper in advance, in order to keep back the crowd.

The number of questions asked by each boy who arrived kept Joe so busy answering them that, after every one in town knew exactly what was going on, Reddy hit upon the happy plan of getting a large piece of paper, and painting on it an announcement of their exhibition.

It was while he was absent in search of the necessary materials with which to carry out this work that the finishing touches were put on the interior; and the partners were counting the number of hand-springs Ben could turn without stopping, when a great shout arose from the visitors outside, and the circus owners heard a pattering and scratching on the canvas above their heads.

"Mr. Stubbs's brother has got loose, an' he's tearin' round on the tent!" shouted Joe, as he poked his head in through a hole in the flag, and at the same time struggled to keep back a small but bold boy with his foot.

Toby, followed by the other proprietors, rushed out at this alarming bit of news, and sure enough there was the monkey dancing around on the top of the tent like a crazy person, while the rope with which he had been tied dangled from his neck.

It seemed to Toby that no other monkey could possibly behave half so badly as did Mr. Stubbs's brother on that occasion. He danced back and forth from one end of the tent to the other, as if he had been a tight-rope performer giving a free exhibition; then he would sit down and try to find out just how large a hole he could tear in the tender canvas, until it seemed as if the tent would certainly be a wreck before they could get him down.

With their privations, insubordination increased. Some separated themselves from the rest, and settled a league away; some built a boat, and going up the lagoons about the island, were never heard of more. Worse than all, some in authority misbehaved themselves, especially a midshipman named Cozens, who had gained some influence over the men.

Cozens had a dispute with the surgeon; then he quarrelled with the purser, and was unquestionably of a mutinous disposition. Still it is certain that Captain Cheap exceeded his powers when he drew out a pistol and shot Cozens down. What was worse, he refused permission for the wounded man to be carried into the tent, "but allowed[Pg 567] him to languish for days on the ground, and with no other covering than a bit of canvas thrown over some bushes," until he died.

Unhappily Captain Cheap distinguished himself in nothing but severity. He never shared the sufferings of his men when he could help it; and though our narrator, Midshipman Byron, stuck to him to the last, it is plain he thought him a worthless creature.

This loyal young fellow was of good family, and became grandfather of the great Lord Byron, into whose imagination never entered stranger things than actually befell his ancestor.

The midshipman had built a little hut, just big enough to contain himself and a poor Indian dog he found straying in the woods. To this animal in his misery he became much attached. But a party of seamen came and took the dog by force, and killed and ate it. Indeed, three weeks afterward, when matters became much worse, Byron himself, recollecting the spot where the poor animal had been killed, "was glad to make a meal of the paws and skin which had been thrown aside."

The straits to which they were by that time reduced sharpened their ingenuity to the utmost. The boatswain's mate, having procured a water puncheon, lashed a log on each side of it, and actually put to sea in it, like the wise men of Gotham in their bowl, and with the assistance of this frail bark he provided himself with wild fowl while the others were starving. Eventually he suffered shipwreck, but was so little discouraged by it that out of an ox's hide and a few hoops he fashioned a canoe "in which he made several voyages."

In the mean time the hope of all these poor people lay in the building of a vessel out of the materials of the long-boat, with other timber added. This task was at last accomplished. Captain Cheap's plan was to seize a ship from the enemy, and to join the English squadron; but the majority of the hundred men, to which number starvation had reduced the castaways, were in favor of seeking a way home through the Straits of Magellan.

About this there arose a quarrel, and eventually the men threw off the Captain's authority altogether, left him on the island, and sailed away. A lieutenant of marines, Byron, and a few others remained with him. These were presently joined by some deserters who had settled on another portion of the island, so that their number now amounted to about twenty.

Their only chance of escape was in the barge and yawl, which in the absence of the carpenter were patched up so as to be fit for a fine-weather voyage. Even now their scanty stock of useful articles was diminished by theft, and two men were flogged by the Captain's orders, and one placed on a barren islet void of shelter. Two or three days later, on "going to the island with some little refreshment, such as their miserable circumstances would admit, and intending to bring him off, they found him stiff and dead."

All this time the weather was very tempestuous, but the occurrence of one fine day enabled them to hook up three casks of beef from the wreck, "the bottom of which only remained." These being equally divided, recruited for the time their lost health and strength.

On the 15th of December they embarked, twelve in the barge and eight in the yawl, and steered for a cape apparently about fifty miles away. But ere they reached it a heavy gale came on. The men were obliged to sit close together, to windward, in order to receive the seas on their backs, and prevent them from swamping the boats, and they were forced to throw everything overboard, including even the beef, to prevent themselves from sinking. As it was, the yawl was lost with half its crew.

The survivors, with the occupants of the barge, reached a small and swampy island, where bad weather confined them for days. There they ran along the coast, generally with nothing to eat but sea-tangle. At length they ate their very shoes, "which were of raw seal-skin."

It now became evident that the barge could not accommodate the whole party with safety, and as it had become a matter of indifference whether they should take their wretched chance in it or be left on this inhospitable coast, they separated. "Four marines were left ashore, to whom arms, ammunition, and some necessaries were given. At parting they stood on the beach and gave three cheers" (what cheers they must have been!) "for their comrades. A short time afterward they were seen helping one another over a hideous tract of rocks. In all probability they met with a miserable end."

Finding it impossible to double the cape, which had been the object of their journey, the rest returned to Mount Misery and Wager Island. Here they found some Indians, the chief of whom, on promise of the barge being given him, promised to guide them to the Spanish settlements.

Upon this voyage their sufferings, notwithstanding what they had already undergone, may be said to have commenced. Mr. Byron at first steered the barge, but one of the men dropping dead from fatigue and exhaustion, he had to take his oar. Just afterward, John Bosman, "the stoutest among them," fell from his seat under the thwarts with a cry for food. Captain Cheap had a large piece of boiled seal in his possession, but would not give up one mouthful. Byron having five dried shell-fish in his pocket, put one from time to time into the mouth of the poor creature, who expired as he swallowed the last of them.

Having landed in search of provisions, six of the sailors took an opportunity of deserting in the barge, leaving Captain Cheap, Lieutenant Hamilton, Mr. Byron, Mr. Campbell, and the surgeon—in short, all their surviving officers behind. The Cacique, as the Indian chief was called, had now no motive to assist them save the hope of possessing Byron's fowling-piece, and of receiving an immense reward should they ever be in a position to pay it. It was with difficulty that they could persuade him to continue his assistance. His wife, however, arrived in a canoe, and in this frail craft, which held but three persons, the chief took the young midshipman and Captain Cheap on a visit to his tribe. After two days' hard labor, in which we may be sure the Captain did not share, they landed at night near an Indian village. The Cacique gave the Captain shelter, but the poor midshipman was left to shift for himself. He ventured to creep into a wigwam where there was a fire, to dry his rags. In it were two women, "one young and handsome, the other old and hideous, who had compassion on him, gave him a large fish, and spread over him a piece of blanket made of the down of birds." The men of the village, fortunately for him, were absent, and for some time he was well cared for by his two kind hostesses.

Byron's life here was a romance in itself. The occupation of the women being to provide fish, he accompanied them in their canoe with the rest. "When in about eight or ten fathoms of water, they lay on their oars, and the younger of the women, taking a basket between her teeth, dived to the bottom, where she remained a surprising time. After filling the basket with sea-eggs, she rose to the surface, delivered them to her companion, and taking a short time to recover her breath, dived again and again."

When the husband of these two women returned, he expressed his dissatisfaction at the kindness they had shown the stranger by taking them in his arms and brutally dashing them against the ground. But notwithstanding this, these good creatures "still continued to relieve the young midshipman's necessities in secret, and at the hazard of their lives."

After a while the whole party returned to Mount Misery, where they found those they had left on the verge of starvation, and in the middle of March they embarked in[Pg 568] several canoes for the Spanish settlements. The surgeon now succumbed to his labors at the oar; Campbell and Byron rowed like galley-slaves, but Hamilton, strange to say, did not know how to row, and Captain Cheap "was out of the question." He and the Indians had seal to eat, but the rest only a bitter root to chew; and as to clothing, Byron's one shirt "had rotted off bit by bit."

BYRON CARRYING THE CAPTAIN'S SEAL.

BYRON CARRYING THE CAPTAIN'S SEAL.

The party landed, and the canoes were taken to pieces. Every one, man and woman, with the usual exception of Cheap, had to take his share of them; Byron had, besides, to carry for the Captain some putrid seal in canvas. "The way being through thick woods and quagmires, and stumps of trees in the water which obstructed their progress," the poor midshipman was left behind exhausted.

After two hours' rest, and feeling that if he did not overtake his companions he was lost indeed, he started after them without his burden. But on coming up with them he was so bitterly reproached by the Captain for the loss of his seal and canvas that he actually returned five miles for them. After two days of absence from his companions he again rejoined them, in the last extremity of fatigue, but "no signs of pleasure were evinced on their part."

Eventually, after days of terrible suffering, they reached the Spanish settlements at Castro, where, strange to say, they were received with humanity. But as to eating, "it would seem as if they never felt satisfied, and for months afterward would fill their pockets at meals in order that they might get up two or three times in the night to cram themselves." Even Captain Cheap was wont to declare that "he was quite ashamed of himself," from which we may certainly infer that their conduct was gluttonous indeed.

The Englishmen, though well fed, received no clothing, and were carried through the country by the Governor of Castro in a sort of triumphal progress. At one place a young woman, the niece of the parish priest, and bearing the appropriate name of Chloe, fell in love with young Byron. He did not wish for this union, but he confesses that what almost decided him to become her husband was the exhibition by her uncle of a piece of linen, which he was promised should be made up at once into shirts for him if he would consent. "He had, however, the resolution to withstand the temptation."

From Castro the English officers were taken to Santiago, the capital of Chili, where a Spanish officer generously cashed their drafts on the English consul at Lisbon. They received the sum of six hundred dollars, with which sum they purchased suitable equipments. They remained at Castro two years on parole, and eventually reached France, and thence escaped to England, after a series of hardships and adventures such as have rarely been equalled, and which were "protracted above five years."

The adventures of the eighty men who had left Wager Island in the long-boat were little less terrible. Many perished of starvation, and those who had money or valuables offered unheard-of prices for a little food. "On Sunday, the 15th of November," for example, "flour was valued at twelve shillings a pound, but before night it rose to a guinea." There was a boy on board, aged twelve years, son of a Lieutenant Capell, who had died on the island. His father had given twenty guineas, a watch, and a silver cross to one of the crew to take care of for the poor boy, who wanted to sell the cross for flour. His guardian told him it would buy clothes for him in the Brazils, whither they were bound. "Sir," cried the poor boy, "I shall never live to see the Brazils; I am starving. Therefore, for God's sake, give me my silver cross." But his prayers were vain. "Those who have not experienced such hardships," observes the narrator of this scene, "will wonder how people can be so inhuman.... But Hunger is void of compassion." Of the eighty men only thirty survived to reach England by way of Valparaiso.

Five of us farmer's children, and one from a city street

Who never in all his lifetime knew that the roses were sweet;

And he's come to us pale and frightened, but he'll soon grow plump and strong,

So, Rover, old fellow, you hear me: just gallop and gallop along,

And carry this poor little patient—for that's what he is, they say—

Down where the willows are gazing into the brook all day.

And go like the wind, dear Rover, you shall rest when the work is done

And we'll give you part of our dinner, and more than half of the fun.

Mother was ever so happy when father came up the road

Bringing this boy for a visit; he wasn't much of a load.

And we'll feed him on cream and biscuits, and give him the best of care,

A bed that is soft as clover, and the very freshest of air.

But, Rover, all that would be nothing—I see that you're looking wise,

And shaking your shaggy coat, dear, and laughing out of your eyes—

Nothing, unless we loved him, and gave him plenty of play

So hurrah for our little patient, and, Rover, scamper away.

I remember the accident well enough, though it happened nearly forty years ago.

There is no doubt about it, every genuine school-boy takes a keen delight in the Fourth of July. There is an inherent love of squibs and crackers, wheels and blue-lights, among lads, while a good flare-up of a bonfire is looked upon as almost indispensable.

When I was a boy I had a strong liking for cannon. I might have become an Armstrong, a Rodman, or a Dahlgren, if nothing had interfered to prevent the development of my tastes in that direction. But— Ah, that "but"! It is as troublesome as the "if" which spoils so many good things.

Would the boys like to hear the story? I began with a formidable piece of ordnance—an eighty-one-grain gun. It was an old key that I had picked up somewhere, and I tell you it made a very good miniature cannon. I was even more proud of it than of my first pair of boots, for I had manufactured it all myself. I felt that I had converted a useless old piece of iron into a weapon of modern warfare. At the end of the tube I filed a priming hole, fastened it to a wooden gun-carriage, and a jolly good bang I got out of it. Larger keys followed, and then brass cannon mounted on wheels, until somehow or other I got possessed—I can't remember how—of a monster cannon.

No common cast-brass toy this, but a homespun, wrought-iron gun: an iron bar, drilled, as near as I remember, with a three-quarter-inch drill; an unscientific-looking instrument, quite ignorant of lathe and emery-paper, but one that would and did go off.

Various small trial charges had been set off, until, on Fourth of July it was determined by a select committee on heavy ordnance, assembled in my father's garden, that in the evening an experiment should be made that would determine once for all its full powers.

We had had a good deal of fun of one kind and another all day, but for me nothing was one-half as interesting as that cannon. It seemed as if all the other boys in the neighborhood thought so too, for when the critical hour arrived there was something over two dozen of us in the garden. We formed a circle around my cannon, and the business of loading began. A fire-poker was secured for a ramrod, and a real good charge was rammed home. In the excitement of the moment the poker was left in the cannon!

A heap of soil at the end of the garden was chosen as the "earthwork," on which our big gun was fixed, pointing upward, though unnoticed by us, point-blank at the parlor windows. A small heap of shavings was put around the weapon, and one was appointed to light it. "To cover!" at once was the order, and each one rushed to a safe place. I tremble at this moment when I remember that, a second before the explosion, the inevitable small boy rushed from one cover to another right in front of the cannon's mouth.

What a bang! and what a crash! Oh, horror! Four panes of glass gone at once, the window-frame broken, and— We did not act the coward and fly. No, boys, never turn coward if you get into a scrape—and few boys of spirit but do sometimes get into one. Stand your ground, boys, and bear or pay whatever is fairly earned. Some of us stood our ground until father appeared. He had been a boy himself once, and though he looked very serious he did not scold us. At the first brush it was set down to atmospheric concussion, but on further investigation it was found that the brick-work was chipped and the wood-work broken; and, worse still, inside the parlor was found the fatal poker doubled up, having just escaped a splendid crystal chandelier hanging in the middle of the room. How crest-fallen I felt and looked! Father said that to remind me of the necessity of care in handling such a dangerous toy, I should pay for two of the panes. You can imagine I was glad not to be more severely punished.

That cannon was never again fired by me. The hair-breadth escape of that small boy haunts me even now. I have never fired a gun in my life; but for experimental purposes I have handled the strongest explosives, including the notorious dynamite; yet never in my life has such a thrill passed through me as did when I realized the almost miraculous escape of my playmate, when the doubled-up projectile was picked up on our parlor floor.

Boys, let an old one beg of you to be careful in handling explosives. Don't touch guns or pistols until you have a little more age upon you, lest some playmate or school-fellow meet with an untimely end. Don't reckon upon the lucky escape I had of being unintentionally a murderer.

"I'd like to have been Joan of Arc."

"And I, Queen Elizabeth."

"Who would you have chosen, Winnie?"

"The idea of asking a girl who is afraid in the dark!" said a sneering voice.

"It is rather absurd," replied brown-eyed Winnie, though she flushed a little uncomfortably, "but," she continued, "I have told you, Lulu, that I am trying to conquer that."

"What makes you afraid, anyhow?" queried Joan of Arc.

"I really don't know. I suppose somebody must have scared me when I was too little to remember."

"Pshaw! you're afraid of burglars," said Queen Elizabeth.

"Yes, she goes poking under her bed every night with a cane," said the sneering voice.

"I don't," said Winnie, indignantly.

"Well, who would you like to have been, Winnie?"

"Nobody."

"Oh, what a fib! Now don't get mad, Winnie, sweetie;" and Joan of Arc put her arm around her.

"I am not mad, but I just will not tell you who I admire most: tortures sha'n't get it out of me."

"Try her!" "Try her!" was shouted in chorus; and one seized her inkstand, another her pile of books, and a third was about to eat up her luncheon, when a tap of the bell announced that recess was over.

A week after this incident, one warm day in May, the teacher stopped the class as it was filing out, and said, "Who can go see why Jennie Jessup does not come to school?"

No one answered. It had been so tiresome a day, and all were eager to get home, Winnie especially, as she had been promised a little outing—a pleasant sail to Staten Island, an evening with friends, and a glimpse of blue waters and green fields. At the same time she thought to herself, "I pass the house she lives in. Perhaps I might just take time to stop."

The teacher seemed to divine her thoughts. "I wish you would go, Winnie. You're not afraid?"

"Afraid of what?"

"Well, she may be sick, and sometimes girls don't like to go to strange houses."

"I am not afraid. I'll go," said Winnie, just a little proudly, as the girl passed her who had twitted her with being afraid in the dark.

Winnie picked up her books and trudged off. "How nice it will be to get out of the hot city!" she thought; "and what lovely lilacs I shall bring home! I wonder if their roses are out yet, and the syringas! And what nice teas Mrs. Graham always has!—so much better than[Pg 571] a dinner such a day as this! And perhaps Rob will take us out sailing. Anyway, the trip up and down the bay will be delightful."

So she went on anticipating, until she came to Jennie Jessup's house. It was one of a block which had seen better days, but which now was degenerating from contact with the crowding business of the city.

She knocked at a door. No one replied. The occupants had gone to their daily duties, and had not returned. She mounted another pair of stairs. A partly open door had a small card tacked on it, upon which was the name "Jessup." She knocked. No answer. Again she tried. This time a far-away "Who is it?" was whispered.

"Can I come in?" asked Winnie, pushing the door gently before her.

"If you're not afraid," was the reply. It fairly stung Winnie.

"What should I be afraid of?"

"Why, of me," said Joan of Arc, in muffled accents. "Hush! don't wake mother; she's just tired out, and here am I sick in bed. Perhaps you had better not come in."

"I will, though," said Winnie; "that is, if it is right. I don't want to catch anything, and take it home to the children."

"I don't think it is catching. My head ached awfully, and the doctor was thinking it might turn out to be something contagious; but that fear is over. Oh, Winnie, is it not dreadful to be sick?"

Poor Joan of Arc was lying in a small, dark room, and in a large chair beside her was a pale-faced woman asleep. On an easel was an unfinished crayon head; here and there were sketches, scraps of pictures, as if done to test a color or a method. The afternoon sun was pouring a dusty flood of light on the faded carpet.

Winnie turned as if to go—were not Bob and Mary Graham waiting for her? she could fairly hear the splash of the water against the side of the boat. Joan of Arc turned a pale, longing face toward her.

"Oh, don't go, Winnie!"

"Do you want me?"

"Oh, so much! Mother is really ill herself. She has nursed me night and day, and tried to finish that crayon too—it is an order; but she is worn out—poor mother!"

Winnie moved about uneasily, thinking of lilacs and roses and syringas and the boat, but after a while she tore a slip from a copy-book and wrote a little note to her grandmother, telling the good old lady where she was. Then she turned to poor pale little Joan, bathed her, smoothed her pillows, and gave her the medicine which was to be taken.

Slowly the hours went by; no going to Staten Island this time. The clock ticked away, the jangling bells and whistles quieted down, doors opened and shut, people had their dinners and teas. The street grew quiet, and little pale-faced Joan slept softly and restfully, with one hand in Winnie's. Ten, eleven, twelve o'clock struck. Winnie must have dozed, but now she was wakened by little Joan's arousing.

"Oh, Winnie, I am so thirsty!"

"Yes, dear; here is some water."

"But I would so like to have some milk."

"Where is it, Jennie?"

"Down-stairs we have a closet under the stoop, and there's an ice-box there. A lump of ice in the milk would be so delicious!"

"So it would. Shall I get it?"

"Yes, only— Oh dear! Winnie, you don't like going down in the dark."

No, indeed, she didn't; but what was to be done?—waken poor Mrs. Jessup, and undo all the good that had been done? On the other hand rose visions of horror—bats, rats, meeting midnight prowlers, all sorts of indescribable fears without really any cause, the echoes of a frightened childhood, when some foolish nurse had used the rod of fear to control a sensitive nervous little one who could easily have been led by love.

"Where is the key, Jennie, and the pitcher?"

"The key is just here in this little drawer, and you will find a pitcher down there. But don't go if you are afraid, Winnie. I will try to wait till morning."

"Now or never," thought Winnie, and she plunged out into the darkness. The effort gave her courage. Down, down, down she went. The candle flared and flickered; she was sure it would go out, but she had put a match or two in her pocket. She reached the door, unlocked it, poured the milk, and cracked the ice, when with a chill of horror a hoarse laugh broke the midnight stillness.

It seemed close beside her, above her, around her. For an instant she stood as if paralyzed; then she would have sped like the wind, but a voice said, "Can't you let me in?"

Winnie looked up; there was a little grating over the heavy outer door. A face, young, handsome, but shadowed with the marks of ill-doing, was watching her curiously. Winnie shook her head.

"Who are you, anyhow, and what are you doing in my mother's closet?"

Winnie's voice shook. "I am a friend of Jennie's. She is sick. I am taking care of her. Do you live here?"

"Sometimes. It's a pretty time of night for a fellow to be out, isn't it? Well, if Jen's sick, I'll stay away. Here, give her this;" and between the narrow grating was slipped a bill.

Winnie picked it up. The face disappeared: ah! what a sorry tale it had told! She forgot her fears, but her heart ached for the toiling mother and sick little sister when son and brother was of this sort. Upstairs she went, seeing nothing alarming now in the darkness; all her visionary fears had fled. But little Joan saw her white face and wide-open eyes. Drinking the milk eagerly, she sank back on the pillow with a sigh of satisfaction. Winnie said nothing, and Joan slept like a baby.

When morning came, Mrs. Jessup arose rested, refreshed, and so grateful to Winnie that she felt repaid for the little sacrifice she had made; and then she told Mrs. Jessup of the night's occurrence, and gave her the money.

"My poor boy!" was all the mother said, as tears rolled down her face—"my poor boy!" but it told of sorrow, disappointment, and grief which even Winnie could hardly understand.

When Joan kissed Winnie good-by that morning, she whispered, "I know who you are like, and whom you would rather be than all the queens in the world."

"Who, Jennie?"

"Florence Nightingale."

"Yes, you have guessed rightly," answered Winnie, who not for one moment regretted her postponed jaunt, her sleepless night, nor anything she had done.

Once having conquered, she had now no more trouble with fears in the dark.

And the jaunt came in due time, and little Joan's room was made sweet and bright with roses and syringas that Florence Nightingale brought from her excursion.

But she never forgot that night.

We've had a most awful time in our house. There have been ever so many robberies in town, and everybody has been almost afraid to go to bed.

The robbers broke into old Dr. Smith's house one night. Dr. Smith is one of those doctors that don't give any medicine except cold water, and he heard the robbers, and came down-stairs in his nigown, with a big umbrella in his hand, and said, "If you don't leave this minute, I'll shoot you." And the robbers they said, "Oho! that umbrella[Pg 572] isn't loaded;" and they took him and tied his hands and feet, and put a mustard plaster over his mouth, so that he couldn't yell, and then they filled the wash-tub with water, and made him sit down in it, and told him that now he'd know how it was himself, and went away and left him, and he nearly froze to death before morning.

Father wasn't a bit afraid of the robbers, but he said he'd fix something so that he would wake up if they got in the house. So he put a coal-scuttle full of coal about half-way up the stairs, and tied a string across the upper hall just at the head of the stairs. He said that if a robber tried to come upstairs, he would upset the coal-scuttle, and make a tremendous noise, and that if he did happen not to upset it, he would certainly fall over the string at the top of the stairs. He told us that if we heard the coal-scuttle go off in the night, Sue and mother and I were to open the windows and scream, while he got up and shot the robber.

The first might, after father had fixed everything nicely for the robbers, he went to bed, and then mother told him that she had forgotten to lock the back door. So father he said, "Why can't women sometimes remember something," and he got up and started to go down-stairs in the dark. He forgot all about the string, and fell over it with an awful crash, and then began to fall down-stairs. When he got half-way down, he met the coal-scuttle, and that went down the rest of the way with him, and you never in your life heard anything like the noise the two of them made. We opened our windows, and cried murder and fire and thieves, and some men that were going by rushed in and picked father up, and would have taken him off to jail, he was that dreadfully black, if I hadn't told them who he was.

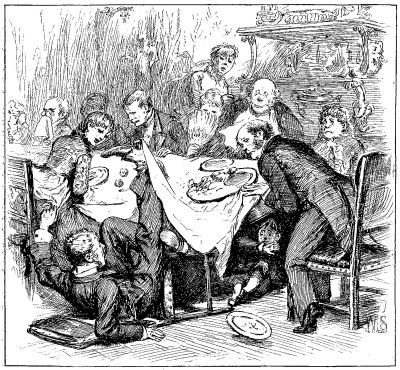

But this was not the awful time that I mentioned when I began to write, and if I don't begin to tell you about it, I sha'n't have any room left on my paper. Mother gave a dinner party last Thursday. There were ten ladies and twelve gentlemen, and one of them was that dreadful Mr. Martin with the cork leg, and other improvements, as Mr. Travers calls them. Mother told me not to let her see me in the dining-room, or she'd let me know; and I meant to mind, only I forgot, and went into the dining-room, just to look at the table, a few minutes before dinner.

I was looking at the raw oysters, when Jane—that's the girl that waits on the table—said, "Run, Master Jimmy; here's your mother coming." Now I hadn't time enough to run, so I just dived under the table, and thought I'd stay there for a minute or two, until mother went out of the room again.

It wasn't only mother that came in, but the whole company, and they sat down to dinner without giving me any chance to get out. I tell you, it was a dreadful situation. I had only room enough to sit still, and nearly every time I moved I hit somebody's foot. Once I tried to turn around, and while I was doing it I hit my head against the table so hard that I thought I had upset something, and was sure that people would know I was there. But fortunately everybody thought that somebody else had joggled, so I escaped for that time.

It was awfully tiresome waiting for those people to get through dinner. It seemed as if they could never eat enough, and when they were not eating, they were all talking at once. It taught me a lesson against gluttony, and nobody will ever find me sitting for hours and hours at the dinner table. Finally I made up my mind that I must have some amusement, and as Mr. Martin's cork leg was close by me, I thought I would have some fun with that.

There was a big darning-needle in my pocket, that I kept there in case I should want to use it for anything. I happened to think that Mr. Martin couldn't feel anything that was done to his cork leg, and that it would be great fun to drive the darning-needle into it, and leave the end sticking out, so that people who didn't know that his leg was cork would see it, and think that he was suffering dreadfully, only he didn't know it. So I got out the needle, and jammed it into his leg with both hands, so that it would go in good and deep.

"WASN'T THERE A CIRCUS IN THAT DINING-ROOM!"

"WASN'T THERE A CIRCUS IN THAT DINING-ROOM!"

Mr. Martin gave a yell that made my hair run cold, and sprang up, and nearly upset the table, and fell over his chair backward, and wasn't there a circus in that dining-room! I had made a mistake about the leg, and run the needle into his real one.

I was dragged out from under the table, and— But I needn't say what happened to me after that. It was "the old, old story," as Sue says when she sings a foolish song about getting up at five o'clock in the morning—as if she'd ever been awake at that time in her whole life!

"CHERRIES ARE RIPE."

"CHERRIES ARE RIPE."

Three cheers for the Fourth of July! What American boy does not love it? Where is the little girl who is not glad when it arrives? We hope you will all have a splendid time on the happy holiday, meet with no accidents, and when night comes, go to bed, to enjoy pleasant dreams.

Vacation has come to many of you by this time. You have said good-by to school and teachers, and have laid aside lessons and slates for a while. Be out-doors all you can in these bright summer days, and lay in a good stock of health for future use when the play spell is over.

We think you will all be pleased with the feast Our Post-office Box gives you in this Fourth-of-July number.

Orworth, Kansas.

Have you ever seen a Kansas dug-out? If you have not, I will write you a description of one. In the first place, a hole is dug in the ground four or five feet deep, and walled up with limestone or sandstone about six feet high, and covered with a dirt roof. They make these dirt roofs by putting a log lengthwise of the building, and laying poles crosswise; then they cover the poles with sunflowers, and place hay next, and on top of that usually a foot or more of dirt. They usually have earth floors, and sometimes there isn't a solitary window. I have seen dug-outs built of sod. Wouldn't you like to live in such a house, where it is a common thing for mice to tumble into the water bucket? The Wiggle I send is a picture of the dug-out we used to live in when we first came here. Will you please give it to the Wiggle master?

We had a beautiful sunset not very long ago. It was grand. It had been raining, and it slacked up as the sun was going down. Off in the north-west there were some very black clouds; one of them looked like a whale's back, another like a volcano in action. In a few minutes they changed shape, and the best idea I can give of them is a lot of giants contending together. The clouds seemed to come clear to the ground. Papa said he never saw anything like it before. The most beautiful of all was the rainbow. There was at first a perfect arch, with rays of glory coming from the centre. In a few minutes there was a reflected rainbow. All the time that the rainbows lasted there was a very peculiar light, which I can't describe.

Papa and I are alone here, and I have to do the cooking. We will begin to harvest next week. I am to have fifty cents per day for cooking. I hope my letter is not too long to be published.

Theodore G. B.

Philadelphia, Pennsylvania.

I am a little boy nine years old. Papa takes Harper's Young People for my sister and me, and we like it very much. I have had the pneumonia, and have been kept in the house two weeks, but that is not so bad as it is for the little boy I read about in Our Post-office Box who had to stay in the house two months, and can not walk yet. I feel so sorry for him! I have a pet cat, and I love it very dearly.

Ruliff Y. L. H.

By this time, Ruliff, I hope you are well, and able to fire off torpedoes as gayly as did the boys in Miss Porter's story.

London, Ontario, Canada.

I wrote a letter some time ago, and have been watching for it ever since, and I was much disappointed, and think perhaps you did not get it, and I thought I would try again. I have three little sisters, and they all enjoy Harper's Young People, and I think "Toby Tyler" was the best story in it, and we have great laughs over Jimmy Brown. We have five hens, and they all lay eggs; we get four or five every day. Papa and I are gardening to-day, and we have a lovely garden, and it is pretty hard work attending to it, and we have hard times looking after our chickens; they dig holes in the ground with their feet, and we are trying to shut them up for the summer.

Freddie W. F.

New York City.

I am a little girl nine years old. I have no pets except four dolls. One has not any head. Their names are Maud, Mabel, Emily, and Sadie. I wish somebody would write more fairy stories. I am very fond of them. I used to live in Brooklyn, and like it much better than here. I am glad Mr. Otis has written more about Toby Tyler, because I like him very much. My brother and I had scarlet fever this winter, but we are all well now. I like Harper's Young People very much. I have had it since it began. We have a parrot here who cries like a baby and then imitates a nurse singing to it. We go to the country every summer.

Bessie H.

What a charming parrot! Who taught him to cry and sing so cleverly? Dear Bessie, can not you put a new head on the poor dolly who has not any? I feel quite sad on her account.

Now, Bumble-bee, you just keep still; you needn't jump and buzz.

I've had such a time to catch you as never, never wuz.

I've chased you round the garden; a-cause I didn't look,

I almost fell right over into that drefful brook.

And I'm going to put you in it, though I s'pose you think you're hid.

For last week you stung my pussy; you know very well you did.

Yes, and you made us 'fraid that she was going to have a fit,

She jumped up so, and tried to catch the place where you had bit.

Yes, I shall surely drown you. But p'r'aps you've got a home,

And your little ones will wonder why you don't ever come;

And I think p'r'aps you're sorry you went and acted so:

If you'll only wait till I run away, I b'lieve I'll let you go.

Parkersburg, West Virginia.

I have been taking Young People ever since it was published, and I like it very much. This is the first letter I have ever written to Our Post-office Box. We have a nice little pet canary-bird and a little monkey. We have had the monkey four years, but we can not tame him. Last winter it was so cold that once he was almost frozen. At first we thought he was dead, and mamma was about to throw him away, when she saw him move. Then she took him by the stove to warm him, and he got well again.

Victoria R.

"Halloa! Walter, wake-up!" cried Georgie. "Don't you know it's the Fourth of July, and we must get up and celebrate it? All the rest of the folks are going to the Town-Hall to hear a speech and get their dinner, and we'll have a good time by ourselves. Do you know what the Fourth of July is for?"

"No," answered Walter, in a very sleepy way.

"Well, I do; mamma told me last night. It's the anniversary of the time when the United States made up their mind to take care of themselves. That was more than a hundred years ago; that's ever so long, mamma says. Now to-day, Walter, you and I will be like the United States, and take care of ourselves; that's what independence means, and this is Independence-day. Say, Walter, don't let anybody know that I told you, but I heard papa telling mamma that he's going to s'prise us each with lots of fire-works. Now I guess you'll wake up."

"Guess I will, too," said Walter, springing to his feet.

It did not take the boys long to dress. Sure enough they were surprised and delighted when to each was given a toy gun and a package of torpedoes, and then they were left to amuse themselves.

"Tell you what I'll do," said Georgie. "I'll make an oration, and you must be the audience, and when I get through, you must clap very hard, and make me do it all over again."

"All right," said Walter. "Jump up there on papa's desk, so I can hear you better."

Georgie mounted the desk, and began "Ladies and gentlemen,—I s'pose you know this is the Fourth of July." Then he couldn't think of anything else to say, so he jumped down. In doing so his foot hit the inkstand, and a black, black stream of ink followed him to the floor.

"Oh, dear! that's too bad!" he exclaimed. "Won't papa be sorry? Wish I hadn't made a speech. Hurry up, Walter; get something to wipe it off with."

Walter tried hard; but he could not wipe away all the ink. Several big spots remained.

"Never mind," he said; "we'd better go out-doors and forget about it. Let's play soldier. You and I'll be the Americans, and Brush can be the British."

Brush was the Newfoundland dog.

This plan suited Georgie, and he and Walter looked about for a red coat to put on Brush. They soon found Cousin Sarah's embroidered jacket, which they thought would do nicely. Then they went into the yard and coaxed Brush to be dressed up. He looked very funny when he stood on his hind-legs with the jacket buttoned around him.

"Now we must stand before him and present arms," said Georgie.

"Yes, and then I'll turn around quick, and fire a torpedo. Won't that frighten the old fellow?"

So, after presenting arms, Walter turned his back to the enemy, and threw a torpedo into the grass. Brush jumped after it, and in doing so he knocked both of the Americans to the ground. Walter was a little hurt, and he began to whimper, but Georgie helped him up, saying, "Don't you know that soldiers never cry?"

When the rest of the family came home, and found the ink spots in the parlor, and Cousin Sarah's jacket spoiled, they thought it was a poor plan to leave little boys to take care of themselves, even on the Fourth of July.

As our great national holiday approaches, perhaps the readers of Young People would like to hear something about Genoa, where the great Christoforo Colombo, as the Genoese call him, was born. Genoa is situated at the foot of the Appenine range. The town, which is a very ancient and picturesque one, commences at the river-front, and extends some distance up these mountains. A friend of mine writes that there you can not go up town in the sense that we do here, for so steep is the incline that all carriages have to be furnished with brakes, lest, after having once gone up town, one should not be able to get down town again. The drive overlooking the river is delightful. This place is a great stopping-point for ships plying the Mediterranean.

The seasons there are far in advance of ours, and at this present time the climate is intensely hot. Genoa has many beautiful buildings. The people are so proud of their favorite that they name their hotels after him, and also very many minor places of trade. Thus the name of Colombo meets the traveller nearly everywhere. These devoted countrymen have also erected a handsome monument to perpetuate his memory. Ancient as is the city, yet they regard this noble hero with the freshness of yesterday. Well may they be proud of a man capable of such grand achievements, the conception of which was regal in its grandeur.

You all know that to him we owe the blessing of our beautiful America. What wonder that we sing so sweetly and so often, "Hail, Columbia!"

Let us always revere his name as devoutly as his countrymen, who hug the memory of this noble hero as close as Patti did her doll, when at the age of ten she could not sing without it; it was an inspiration to the little songstress.

Let then this great man, Genoa's hero, command our love and gratitude, while it inspires to noble deeds.

Washington Heights, New York.

I have taken your paper for some time, and I look forward from week to week with so much pleasure, thinking of reading the pretty stories; and I am very much interested in the puzzles; I find the answers out myself. I am eleven years old, and have a little sister Mollie, who is a very quaint child. We love to read about all the little girls' pets, especially the cats and kittens, for we have two; the mother we call Dud, and her kitten Gipsy we nickname Gip. They are very knowing and cunning. Dud follows us when we go out, and sometimes, when she has gone very far, waits an hour in one place until we come back, delighted when she sees us, and runs along perfectly contented. Our birds, Pete and John, both died, one of old age, and the other of fits. We are to have a little dog soon. A gentleman has made us a present of him—an English fox terrier. We have never been to school, but are taught at home, and I have read quite a number of letters from little girls in Young People that have lessons at home also. We get along, because we study, and enjoy our books. I read music quite well, so can Moll; we practice an hour a day. We have each a baby doll that we are very fond of; Violet Depeyster is the name of mine, and Daisy Livingston Moll's, named after some aunties. They are very pretty and good; they have very many pretty things we make them, for we can both sew. I write to an uncle in Europe, and a little cousin in the country, and rather like letter-writing, and hope this is not too long.

Lulu K.

Your puzzle will appear before long. It is very nicely done.

Crete, Nebraska.

I want to tell you what I did two years ago, when I was six years old. My papa and uncle bought a drove of cattle in Colorado when they were in the western part of the State. Papa took me out there, and I rode one of the ponies, and helped to drive the cattle about two weeks. I could ride just as fast as the pony could go, and often beat the men in a race.

I have a little saddle. We had a tent, and camped out; it was rare fun, except when it rained. My sister Myrtle and I have a pair of pet doves, a Maltese cat, and two dogs. I like all the stories and letters very much.

George A. J.

Kau, Hawaii, Sandwich Islands.

We live on a sugar plantation, and the flume that carries the cane to the mill runs near our house. The whole length of the flume is eight miles. We have lots of hens, and we children take care of and feed them, and so mother lets[Pg 575] us sell some of them, and we saved the money and bought a cow. She had a calf, but she was so wild that we sold her and got another. She had a pretty little white calf; it is real tame. We call him David. He has a collar on, and we put a rope through the collar and lead him anywhere, and he kicks up his heels, and seems to enjoy the play. We children have three horses that we can ride whenever we like—Flora, Maud, and Nellie. Nellie is very small, because she lost her mother when she was small (a few weeks old), and had to be fed with a bottle, but she is very gentle now.

Fred N. H.

Of course you all think I am a pussy cat. No wonder, when folks call me Pussy. But you must know that one cold day in March I was hatched. Did you ever hear that a pussy was hatched, I'd like to know?

Laugh away, Sue and Ned, Joe and Tom, Mattie and Artie, Polly and Fanny! It is all true.

One day my master went out to the barn, and there were a whole dozen of us, shivering with cold. He brought us into the kitchen and put us right down by the stove. Everybody came to see us, and they all said: "Oh, the cunning little chicks! Where has the naughty mother hen gone?"

Then my mistress ran and brought a box, and lined it with soft wool and warmed it, and then all of us little brothers and sisters were crowded into it.

The others slept like good chicks all night, but I just cried and cried. Even the grandma was kept awake, and said, "That chicken will not live."

The next morning we were taken out to be fed, but my mistress said, when she saw me, "Oh, here is one poor little fellow dead.

"No," said grandma; "I think there is a little life in him still."

I tried hard, and made a faint motion of my eyes, and so I was put back under the stove. As I grew warm I kicked my little feet about, and then the children screamed, "The chick is alive; it was in a trance."

So for two days they called me Cat-a-lep-sy. When I began to run around and eat crumbs, they called me Puss-a-lep. By-and-by they named me Pussy-willow, when the pussy-willows pushed out their funny little fuzzy buds.

Do you know I have been a traveller? Yes, indeed. When I was two weeks old I was carried in a tiny basket over a hundred miles. Two children had me, and we went in the cars.

When we got to the new home, I was lifted out and set—where do you suppose? Why, right in the middle of the tea table. I tell you, things looked nice, I was so hungry.

It is June now, and I have grown so big that my old friends would not know me. I like the folks here. I eat out of their hands, I perch on their heads, and hop about after them all day long, and my name being Pussy, I try to behave as much like a kitten as possible.

That's all. Good-by.

Pussy-Chick ——.

You could not possibly find a prettier bit of verse than this to learn by heart or to copy in your book of choice quotations, even though you hunted through great volumes. It is by Lord Houghton (Richard Monckton Milnes), and we are sure he had some dear child in his mind's eye when he wrote it:

A fair little girl sat under a tree,

Sewing as long as her eyes could see;

Then smoothed her work, and folded it right,

And said, "Dear work, good-night, good-night."

Such a number of rooks came over her head,

Crying, "Caw, caw," on their way to bed;

She said, as she watched their curious flight,

"Little black things, good-night, good-night."

The horses neighed, and the oxen lowed,

The sheep's "Bleat, bleat," came over the road,

All seeming to say, with a quiet delight,

"Good little girl, good-night, good-night."

She did not say to the sun, "Good-night,"

Though she saw him there, like a ball of light;

For she knew he had God's time to keep

All over the world, and never could sleep.

The tall pink fox-glove bowed his head,

The violet courtesied, and went to bed,

And good little Lucy tied up her hair,

And said, on her knees, her favorite prayer.

And while on her pillow she softly lay,

She knew nothing more till again it was day—

And all things said to the beautiful sun,

"Good-morning, good-morning; our work is begun."