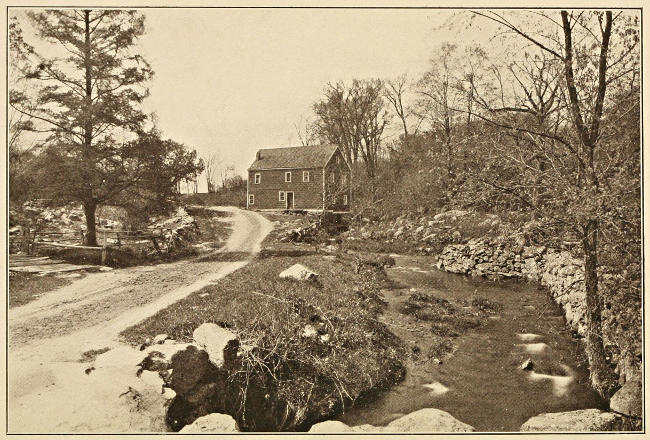

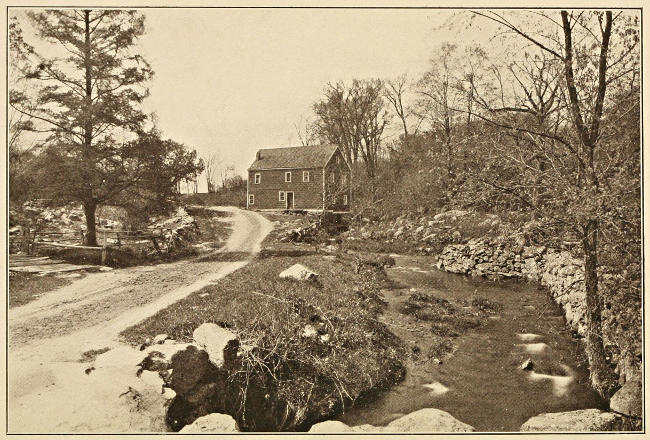

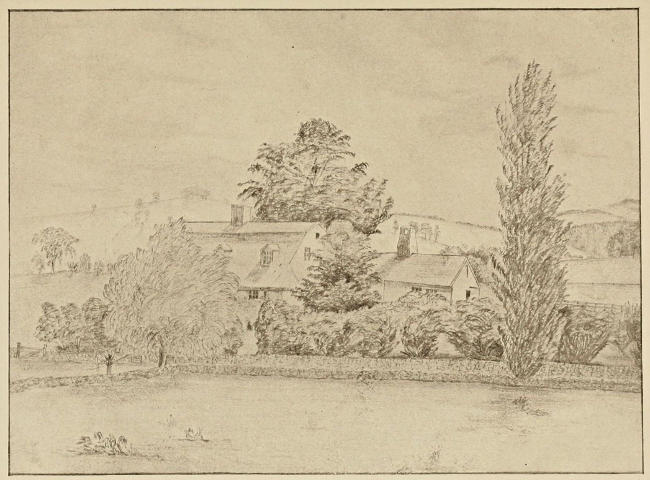

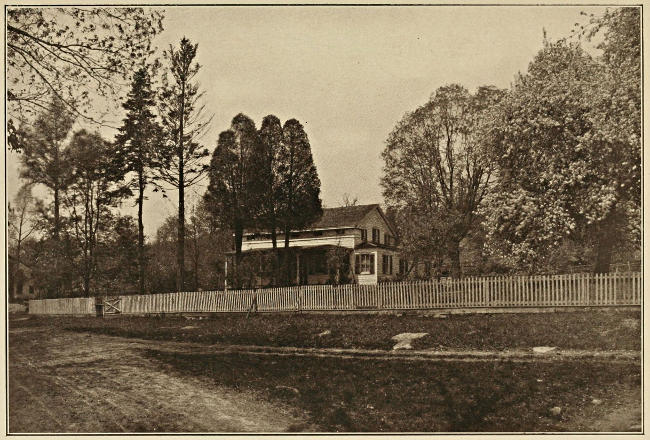

Grist mill at Fredericksburgh, now Kent, built by Colonel Henry Ludington about the time of the Revolution

Project Gutenberg's Colonel Henry Ludington, by Willis Fletcher Johnson

This eBook is for the use of anyone anywhere in the United States and most

other parts of the world at no cost and with almost no restrictions

whatsoever. You may copy it, give it away or re-use it under the terms of

the Project Gutenberg License included with this eBook or online at

www.gutenberg.org. If you are not located in the United States, you'll have

to check the laws of the country where you are located before using this ebook.

Title: Colonel Henry Ludington

A Memoir

Author: Willis Fletcher Johnson

Release Date: October 17, 2018 [EBook #58125]

Language: English

Character set encoding: UTF-8

*** START OF THIS PROJECT GUTENBERG EBOOK COLONEL HENRY LUDINGTON ***

Produced by David Edwards and the Online Distributed

Proofreading Team at http://www.pgdp.net (This file was

produced from images generously made available by The

Internet Archive)

Transcriber’s Note: Period documents are given with their original—and imperfect—spelling, punctuation and grammar.

Grist mill at Fredericksburgh, now Kent, built by Colonel Henry Ludington about the time of the Revolution

COLONEL HENRY LUDINGTON

A Memoir

BY

WILLIS FLETCHER JOHNSON

A.M., L.H.D.

WITH PORTRAITS, VIEWS,

FACSIMILES, ETC.

PRINTED BY HIS GRANDCHILDREN

LAVINIA ELIZABETH LUDINGTON AND

CHARLES HENRY LUDINGTON

NEW YORK

1907

Copyright, 1907, by

Lavinia Elizabeth Ludington and

Charles Henry Ludington

| CHAPTER | PAGE | |

| PREFACE | vii | |

| I | GENEALOGICAL | 3 |

| II | BEFORE THE REVOLUTION | 24 |

| III | THE BEGINNING OF THE REVOLUTION | 47 |

| IV | THE REVOLUTION | 77 |

| V | SECRET SERVICE | 114 |

| VI | BETWEEN THE LINES | 133 |

| VII | AFTER THE WAR | 191 |

| VIII | SOME LATER GENERATIONS | 215 |

| INDEX | 230 |

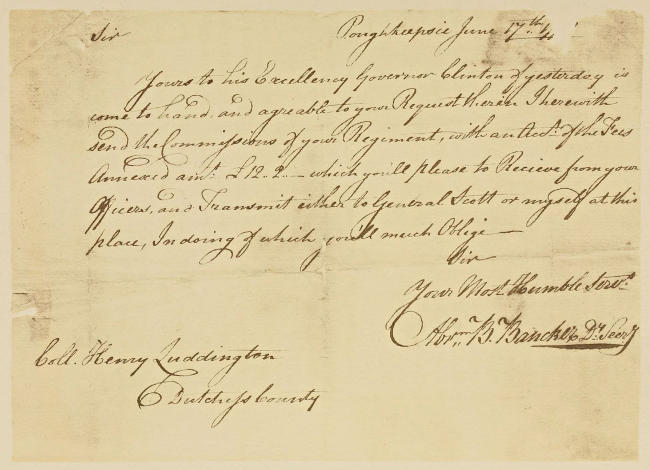

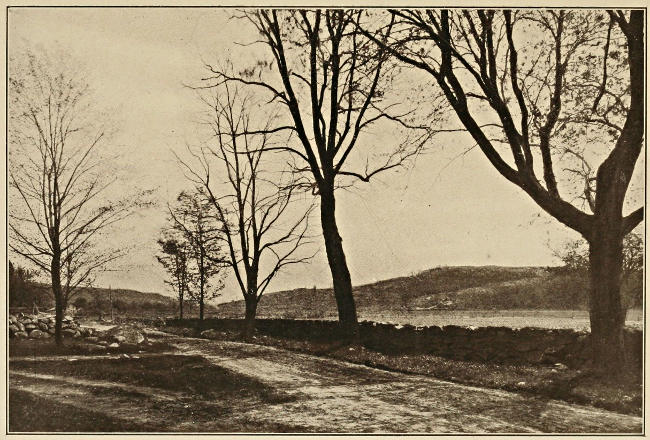

| Grist mill at Fredericksburgh, now Kent (Ludingtonville post-office), built by Col. Henry Ludington about the time of the Revolution | Frontispiece |

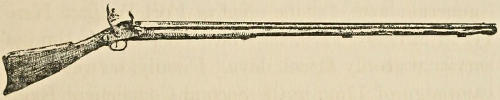

| Old gun used by Henry Ludington in the French and Indian War | 29 |

| FACING PAGE | |

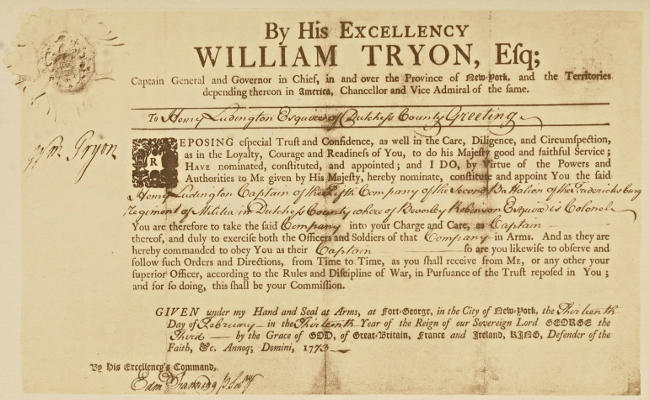

| Henry Ludington’s commission, from Governor Tryon, as captain in Col. Beverly Robinson’s regiment | 30 |

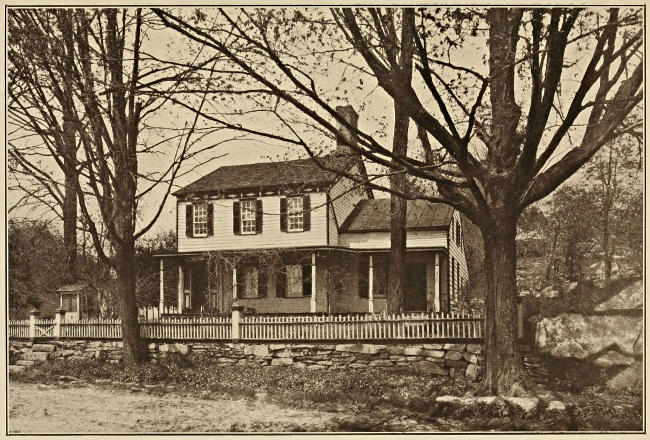

| Old Phillipse Manor House at Carmel, N. Y., in 1846 | 36 |

| View of Carmel, N. Y. | 38 |

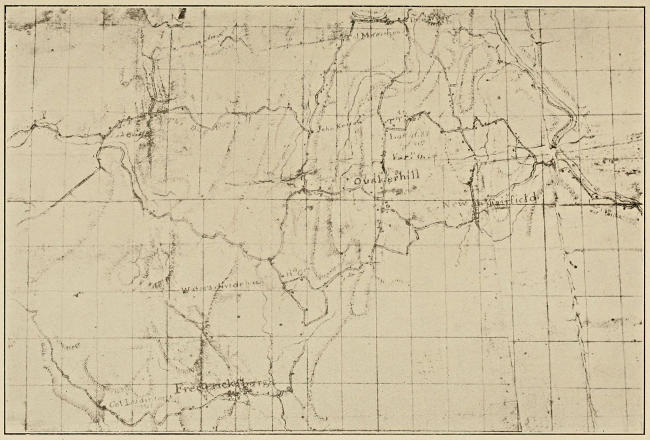

| Map of Quaker Hill and vicinity, 1778-80, showing location of Colonel Ludington’s place at Fredericksburgh | 50 |

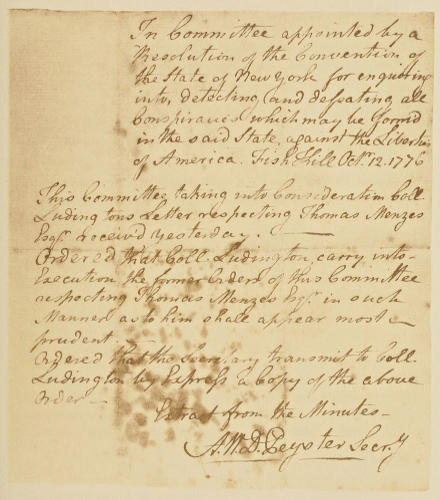

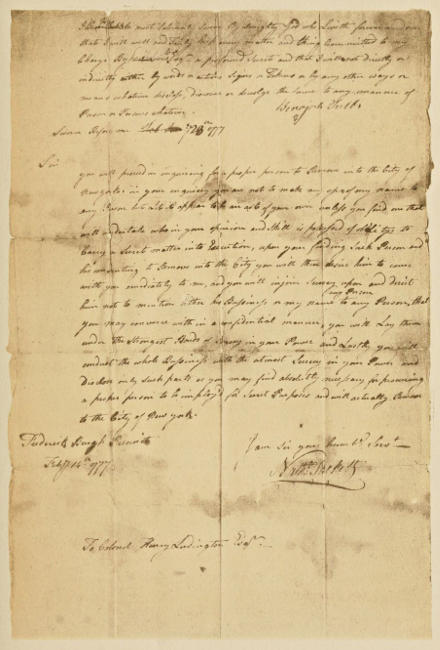

| Letter from Committee on Conspiracies to Colonel Ludington | 56 |

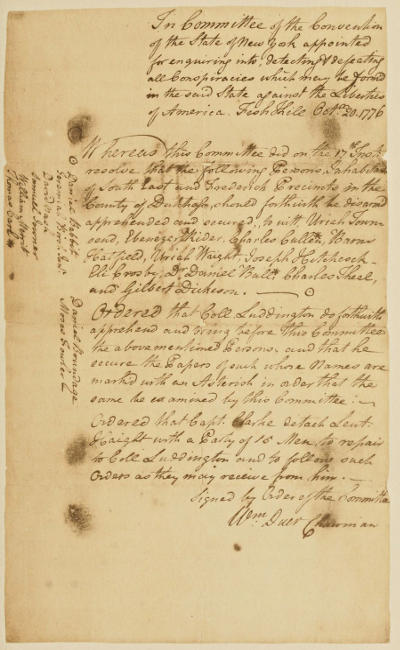

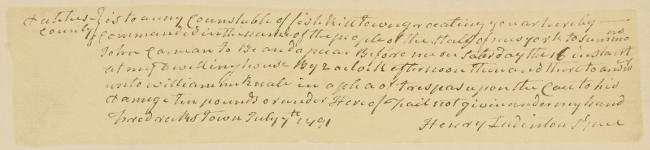

| Order of arrest from Committee on Conspiracies to Colonel Ludington | 58 |

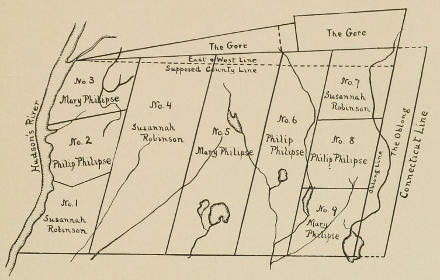

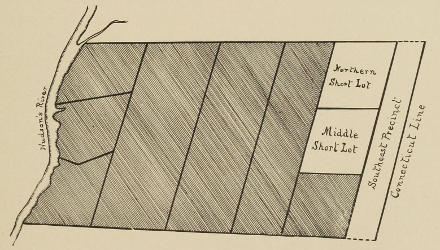

| Maps of Phillipse patent, showing original divisions and territory covered by Colonel Ludington’s regiment | 60 |

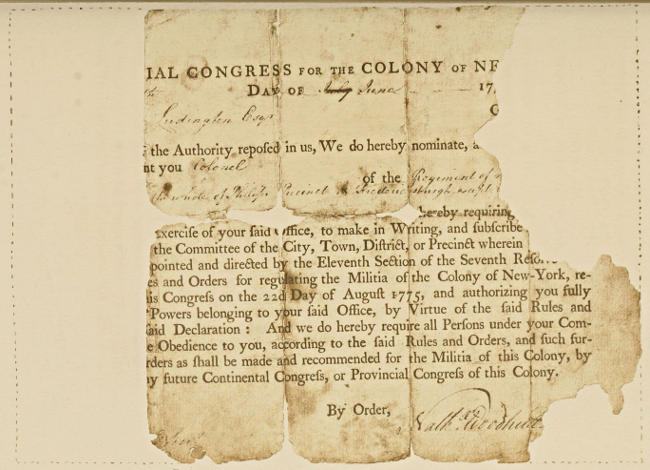

| Henry Ludington’s commission as colonel from Provincial Congress, 1776 | 70 |

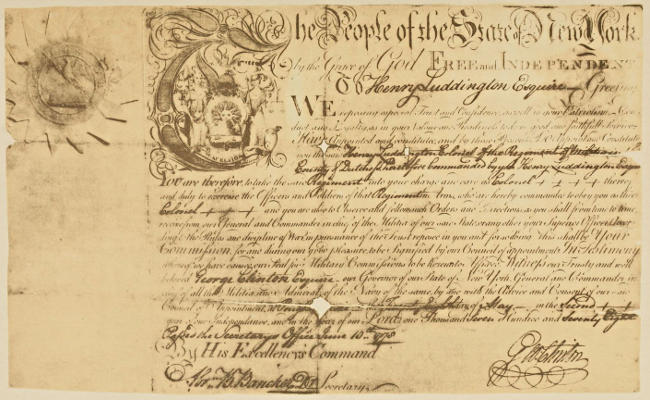

| Henry Ludington’s commission as colonel from State of New York, 1778 | 72 |

| Letter from Abraham B. Bancker to Colonel Ludington about militia | 74 |

| View of highroad and plains from site of Colonel Ludington’s house | 90 |

| Fac-simile of Colonel Ludington’s signature | 102 |

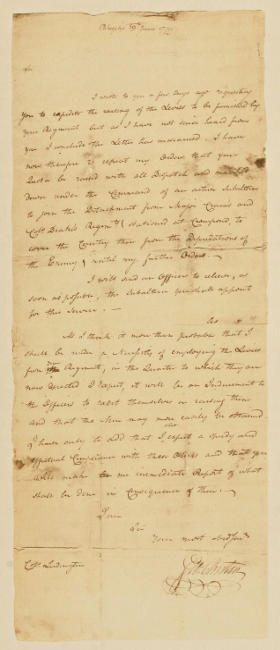

| Letter from Col. Nathaniel Sackett to Colonel Ludington on secret service | 114 |

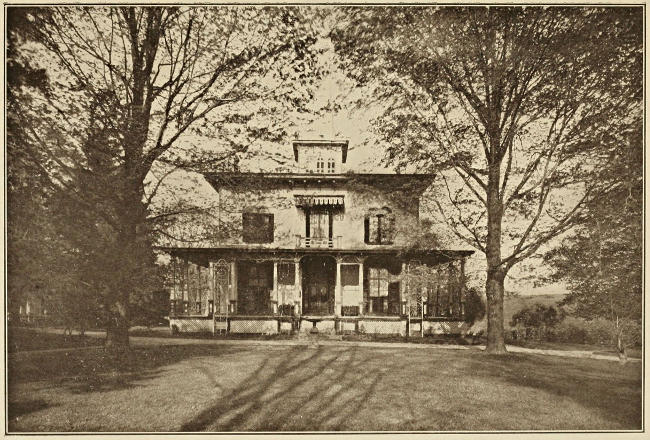

| [vi]Home of the late George Ludington on site of Colonel Ludington’s house | 132 |

| Home of the late Frederick Ludington, son of Colonel Ludington, at Kent | 134 |

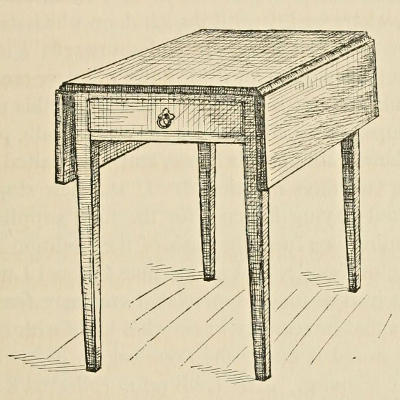

| Mahogany table used by Colonel Ludington, at which, according to family tradition, Washington and Rochambeau dined | 165 |

| Letter from Governor Clinton to Colonel Ludington about militia | 170 |

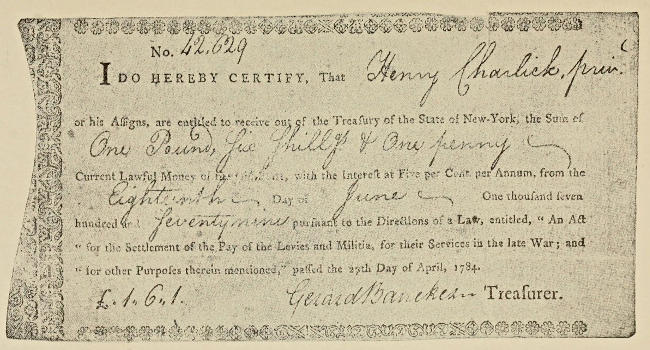

| Pay certificate of a member of Colonel Ludington’s regiment | 188 |

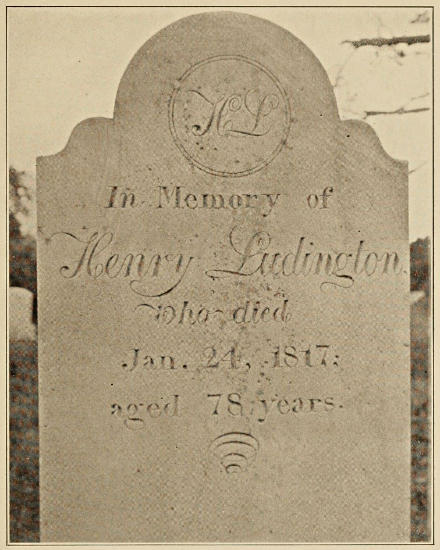

| Colonel Ludington’s tombstone at Patterson, formerly part of Fredericksburgh, N. Y. | 208 |

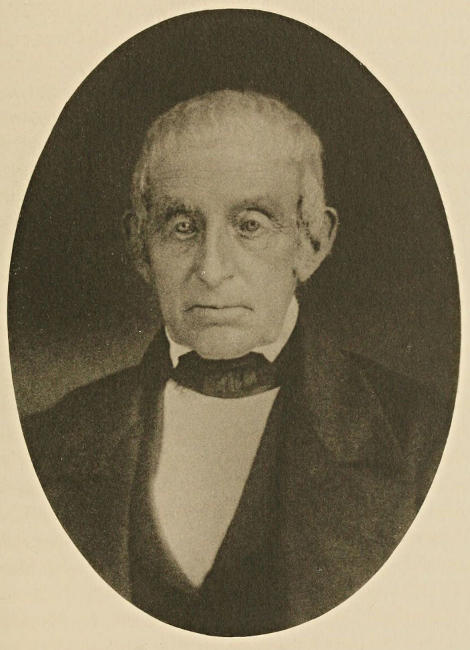

| Portrait of Frederick Ludington, son of Colonel Ludington | 216 |

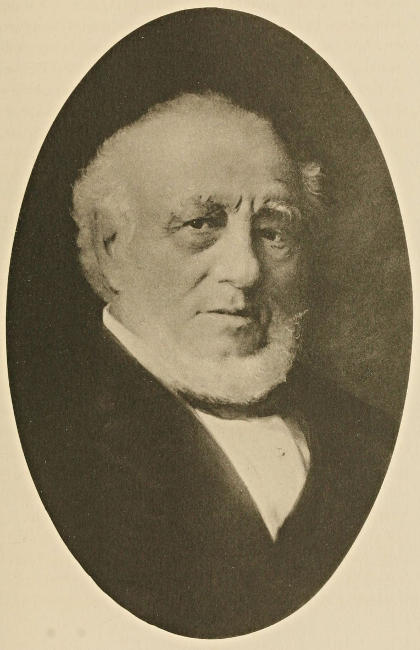

| Portrait of Gov. Harrison Ludington, grandson of Col. Ludington | 218 |

| Old store at Kent, built by Frederick and Lewis Ludington about 1808 | 220 |

| Home of the late Lewis Ludington, son of Colonel Ludington, at Carmel | 222 |

| Portrait of Lewis Ludington, son of Colonel Ludington | 224 |

| Portrait of Charles Henry Ludington, grandson of Colonel Ludington | 226 |

The part performed by the militia and militia officers in the War of the Revolution does not seem always to have received the historical recognition which it deserves. It was really of great importance, especially in southern New England and the Middle States, at times actually rivaling and often indispensably supplementing that of the regular Continental Army. It will not be invidious to say that of all the militia none was of more importance or rendered more valuable services than those regiments which occupied the disputed border country between the American and British lines, and which guarded the bases of supplies and the routes of communication. There was probably no region in which borderland friction was more severe and intrigues more sinister than that which lay between the British in New York City and the Americans at the Highlands of the Hudson, nor was there a highway of travel and communication more important than that which led from Hartford in Connecticut to Fishkill and West Point in New York.

It is the purpose of the present volume to present the salient features of the public career of a militia colonel who was perhaps most of all concerned in holding that troublous territory for the American[viii] cause, in guarding that route of travel and supply, and in serving the government of the State of New York, to whose seat his territorial command was so immediately adjacent. It is intended to be merely a memoir of Henry Ludington, together with such a historical setting as may seem desirable for a just understanding of the circumstances of his life and its varied activities. It makes no pretense of giving a complete genealogy of the Ludington family in America, either before or after his time, but confines itself to his own direct descent and a few of his immediate descendants. The facts of his life, never before compiled, have been gleaned from many sources, including Colonial, Revolutionary and State records, newspaper files, histories and diaries, correspondence, various miscellaneous manuscript collections, and some oral traditions of whose authenticity there is substantial evidence. The most copious and important data have been secured from the manuscript collections of two of Henry Ludington’s descendants, Mr. Lewis S. Patrick, of Marinette, Wisconsin, who has devoted much time and painstaking labor to the work of searching for and securing authentic information of his distinguished ancestor, and Mr. Charles Henry Ludington, of New York, who has received many valuable papers and original documents and records from a descendant of Sibyl Ludington Ogden, Henry Ludington’s first-born child. It is much regretted that among all these data, no portrait of Henry Ludington[ix] is in existence, and that therefore none can be given in this book. In addition, the old records of Charlestown and Malden, Massachusetts, and of Branford, East Haven and New Haven, Connecticut, the collections of the Connecticut Historical Society, the early annals of New York, especially in the French and Indian and the Revolutionary wars, and the publications of the New England Genealogical Society, have also been utilized, together with the Papers of Governor George Clinton, Lossing’s “Field Book of the Revolution,” Blake’s and Pelletreau’s histories of Putnam County, Smith’s “History of Dutchess County,” Bolton’s “History of Westchester County,” and other works, credit to which is given in the text of this volume. It is hoped that this brief and simple setting forth of the public services of Henry Ludington during the formative period of our country’s history will prove of sufficient interest to the members of his family and to others to justify the printing of this memoir.

“This family of the Ludingtons,” says Gray in his genealogical work on the nobility and gentry of England, “were of a great estate, of whom there was one took a large travail to the seeing of many countries where Our Saviour wrought His miracles, as is declared by his monument in the College of Worcester, where he is interred.” The immediate reference of the quaint old chronicler was to the Ludingtons of Shrawley and Worcester, and the one member of that family whom he singled out for special mention was Robert Ludington, gentleman, a merchant in the Levantine trade. In the pursuit of business, and also probably for curiosity and pleasure, he traveled extensively in Italy, Greece, Turkey, Egypt and Syria, at a time when such journeyings were more arduous and even perilous than those of to-day in equatorial or polar wildernesses. In accord with the pious custom of the age he also made a pilgrimage to Palestine, and visited the chief places made memorable in Holy Writ. He died at Worcester at the age of 76 years, in 1625, a few years before the first colonists of his name appeared in North America. The exact degree of relationship between[4] him and them is not now ascertainable, but it is supposable that it was close, while there is no reason whatever for doubting that the American Ludingtons were members of that same family “of a great estate,” whether or not they came from the particular branch of it which was identified with Shrawley and Worcester.

For the Ludington family in England antedated Robert Ludington of Worcester by many generations, and was established elsewhere in the Midlands than in Worcestershire. Its chief seat seems to have been in the Eastern Midlands, though its name has long been implanted on all the shires from Lincoln to Worcester, including Rutland, Leicester, Huntingdon, Northampton, and Warwick. There is a credible tradition that in the Third Crusade a Ludington was among the followers of Richard Cœur de Lion, and that afterward, when that adventurous monarch was a prisoner in Austria, he sought to visit him in the guise of a holy palmer, in order to devise with him some plan for his escape. Because of these loyal exploits, we are told, he was invested with a patent of nobility, and with the coat of arms thereafter borne by the Ludington family, to wit (according to Burke’s Heraldry): Pale of six argent and azure on a chief, gules a lion passant and gardant. Crest, a palmer’s staff, erect. Motto, Probum non penitet.

Authentic mention of other Ludingtons, honorable and often distinguished, may be found from[5] time to time in English history, especially in the annals of Tudor and Stuart reigns. In the reign of Henry VIII a Sir John Ludington was a man of mark in the north of England, and his daughter, Elizabeth Ludington, married first an alderman of the City of London, and second, after his death, Sir John Chamberlain. In the sixteenth century, the Rev. Thomas Ludington, M.A., was a Fellow of Christ Church College, Oxford, where his will, dated May 28, 1593, is still preserved. In the next century another clergyman, the Rev. Stephen Ludington, D.D., was married about 1610 to Anne, daughter of Richard Streetfield, at Chiddington, Kent. Afterward he was made prebendary of Langford, Lincoln, on November 15, 1641, and in June, 1674, resigned that place to his son, the Rev. Stephen Ludington, M.A. He was also rector of Carlton Scrope, and archdeacon of Stow, filling the last-named place at the time of his death in 1677. His grave is to be seen in Lincoln Cathedral. His son, mentioned above, was married to Ann Dillingham in Westminster Abbey in 1675.

It will be hereafter observed in this narrative that the family name of Ludington has been variously spelled in this country, as Ludington, Luddington, Ludinton, Ludenton, etc. Some of these variations have appeared also in England, together with the form Lydington, which has not been used here. These same forms have also been applied to the several towns and parishes which bear or have borne the[6] family name, and especially that one parish which is so ancient and which was formerly so closely identified with the Ludingtons that question has risen whether the parish was named for the family or the family derived its name from the parish. This place, at one time called Lydington, was first mentioned in the Domesday Book of William the Conqueror, where it was called Ludington—whence we may properly regard that as the original and correct form of the name. It was then a part of the Bishopric of Lincoln and of the county of Northampton; Rutlandshire, in which the place now is, not having been set off from Northampton until the time of King John. The Bishop of Lincoln had a residential palace there, which was afterward transformed into a charity hospital, and as such is still in existence. In the chapel of the hospital is an ancient folio Bible bearing the inscription “Ludington Hospital Bible,” and containing in manuscript a special prayer for the hospital, which is regularly read as a part of the service. The name of Loddington is borne by parishes in Leicestershire and Northamptonshire, that of Luddington by parishes in Lincolnshire and Warwickshire (the latter near Stratford-on-Avon and intimately associated with Shakespeare), and that of Luddington-in-the-Brook by one which is partly in Northamptonshire and partly in Huntingdonshire; all testifying to the early extent of the Ludington family throughout the Midland counties of England.

The earliest record of a Ludington in America occurs[7] in 1635. On April 6 of that year the ship Hopewell, which had already made several voyages to these shores, sailed from London for Massachusetts Bay, under the command of William Bundock. Her Company of eleven passengers was notable for the youthfulness of all its members, the youngest being twelve and the oldest only twenty-two years of age. Seven of them were young men, or boys, and four were girls. One of the latter, whose age was given as eighteen years, was registered on the ship’s list as “Christiom” Ludington, but other records, in London, show that the name, although very distinctly written in that form, should have been “Christian.” Concerning her origin and her subsequent fate, all records are silent. In John Farmer’s “List of Ancient Names in Boston and Vicinity, 1630-1644,” however, appears the name of “Ch. Luddington”; presumably that of this same young woman. Again, in the Old Granary burying ground in Boston, on Tomb No. 108, there appear the names of Joseph Tilden and C. Ludington; and a plausible conjecture is that Christian Ludington became the wife of Joseph Tilden and that thus they were both buried in the same grave. But this is conjecture and nothing more. So far as ascertained facts are concerned, Christian Ludington makes both her first and her last recorded appearance in that passenger list of the Hopewell.

The next appearance of the name in American annals, however,—passing by the mere undated mention[8] of one Christopher Ludington in connection with the Virginia colony,—places us upon assured ground and marks the foundation of the family in America. William Ludington was born in England—place not known—in 1608, and his wife Ellen—her family name not known—was also born there in 1617. They were married in 1636, and a few years later came to America and settled in the Massachusetts Bay colony, in that part of Charlestown which was afterward set off into the separate town of Malden. The date of their migration hither is not precisely known. Savage’s “Genealogical Register” mentions William Ludington as living in Charlestown in 1642; which is quite correct, though, as Mr. Patrick aptly points out, the date is by no means conclusive as to the time of his first settlement in that place. Indeed, it is certain that he had settled in Charlestown some time before, for in the early records of the colony, under date of May 13, 1640, appears the repeal of a former order forbidding the erection of houses at a distance of more than half a mile from the meeting house, and with the repeal is an order remitting to William Ludington the penalty for having disobeyed the original decree. That restriction of building was, of course, a prudent and probably a necessary one, in the early days of the colony, for keeping the town compact and thus affording to all its inhabitants greater security against Indian attacks. It seems to have been disregarded, however, by the actual building of some houses outside[9] of the prescribed line, and in such violation a heavy penalty was incurred. By 1640 the law became obsolete. Boston had then been founded ten years. The colonies of New Hampshire, Rhode Island, and Connecticut had been settled and organized. And three years before the Pequods had been vanquished. It was therefore fitting to rescind the order, and to let the borders of Charlestown be enlarged. We may assume that it was with a realization that this would speedily be done that William Ludington, either at the very beginning of 1640 or previous to that year, built his house on the forbidden ground, and thus incurred the penalty, which, however, was not imposed upon him; and we may further assume that it was this act of his which finally called official attention to the obsolete character of the law and thus brought about its repeal. In the light thus thrown upon him, William Ludington appears as probably a man of considerable standing in the community, and of high general esteem, else his disregard of the law would scarcely have been thus condoned.

Reckoning, then, that William Ludington was settled in his house in the outskirts of Charlestown—on the north side of the Mystic River, in what was later called Malden—before May 13, 1640, the date of his arrival in America must probably be placed as early as 1639, if not even earlier. He remained at Charlestown for a little more than twenty years, and was a considerable landowner and an important[10] member of the community. Many references to him appear in the old colonial records, with some apparent conflicts of date, which are doubtless due to the transition stage through which the calendar was then passing. Most of the civilized world adopted the present Gregorian calendar in the sixteenth century, but it was not until 1751 that Great Britain and the British colonies did so. Consequently during most of our colonial history, including the times of William Ludington, the year began on March 25 instead of January 1, and all dates in the three months of January, February and March (down to the 24th) were credited to a different year from that to which we should now credit them. In many cases historians have endeavored to indicate such dates with accuracy by giving the numbers of both years, thus: March 1, 1660-61. But in many cases this has not been done and only a single year number is given, thus causing much uncertainty and doubt as to which year is meant. There were also other disturbances of chronology, and other differences in the statement of dates, involving other months of the year; especially that of two months’ difference at what is now the end of the year. Thus the birth of William Ludington’s daughter Mary is variously stated to have occurred on December 6, 1642, December 6, 1642-43, February 6, 1643, and February 6, 1642-43. Also the birth and death of his son Matthew are credited, respectively, to October 16, 1657, and November 12, 1657, and to December 16, 1657, and January 12,[11] 1658. There is record of the purchase, on October 10, 1649, of a tract of twenty acres of land at Malden, by William Ludington, described in the deed as a weaver, from Ralph Hall, a pipe-stave maker, and also of the sale of five acres by William Ludington to Joseph Carter, a currier. The deed given by Ralph Hall is entitled “A Sale of Land by Ralph Hall unto William Luddington, both of Charlestowne, the 10th day of the 10th moneth, 1649,” and runs as follows:

Know all men by these presents, That I, Ralph Hall, of Charletowne in New England, Pipe stave maker, for a certaine valluable consideration by mee in hand Received, by which I doe acknowledge myselfe to be fully satisfied, and payed, and contented; Have bargained, sould, given, and granted, and doe by these presents Bargaine, sell, give, and grant unto william Luddington of Charletowne aforesayd, Weaver, Twenty Achors of Land, more or less, scituate, Lying, and Beeing in Maulden, That is to say, fifteen Acres of Land, more or less which I, the sayd Ralph formerly purchased at the hand of Thomas Peirce, of Charltowne, senior, Bounded on the Northwest by the land of Mr. Palgrave, Phisition, on the Northeast by the Lands of John Sybly, on the South Easte by the Lands of James Hubbert, and on the South west by the Land of widdow Coale, And the other five Acres herein mencioned sould to the sayd William, Are five Acres, more, or less, bounded on the southeast by the Land of Widdow Coale aforesaid, on[12] the southwest by Thomas Grover and Thomas Osborne, Northeast by the Ground of Thomas Molton, and Northwest by the forsayde fifeteen Acres: which five acres I formerly purchased of Mr. John Hodges, of Charltowne. To Have and to hould the sayd fifeteen acres, and five Acres of Lands, with all the Appurtenances and priviledges thereoff To Him, the sayd William Luddington his heigres and Assignees for ever: And by mee, the sayd Ralph Hall, and Mary my wife, to bee bargained sould, given, and confirmed unto him, the sayd william, and his heigres and assignes for him, and them peasable and quietly to possess, inioy, and improve to his and their owne proper use and usses for ever, and the same by us by vertue hereoff to bee warrantedtised (sic) mayntained, and defended from any other person or persons hereafter Laying clayme to the same by any former contract or agreement concerning the same: In witness whereof, I, the sayd Ralph Hall with Mary my wife, for our selves, our heires, executors and Administrators, have hereunto sett our hands and seales.

Dated this Tenth day of December 1649.

This is testified before the worshipfull Mr. Richard Bellingham.

On November 30, 1651, William Ludington was mentioned in the will of Henry Sandyes, of Charlestown, as one of the creditors of his estate, and in 1660 he was enrolled as a juror in Malden. Early in the latter year, however, he removed from Malden or Charlestown to the New Haven, Connecticut, colony,[13] and there settled at East Haven, adjoining Branford, on the east side of the Quinnipiac River. Five years before there had been established at that place the first iron works in Connecticut. The raw material used was the rich bog ore which was then found in large quantities in the swamps of North Haven and elsewhere, precisely like that which at a still later date was abundantly found and worked in the swamps of southern New Jersey, where the name of “Furnace” is still borne by more than one village on the site of a long-abandoned foundry. This industry flourished at East Haven until about 1680, when the supply of bog ore was exhausted and the works were closed. Although William Ludington had been a weaver at Malden, he appears to have been interested in these iron works, and indeed probably removed to East Haven for the sake of connecting and identifying himself with them. But his career there was short. On March 27, 1660, evidently soon after his arrival there, he was complainant in a slander suit, and in either the same year or the next year he died, at the East Haven iron works. The manner of his death, whether from sickness or from accident, is unknown. But it evidently produced some impression in the community, since it is the only death specially recorded in the early annals of the place.

The precise date of his death, even the year in which it occurred, is a matter of uncertainty. Mr. Patrick quotes a passage from the East Haven records[14] which says: “In 1662 John Porter obtained a piece of land to set his blacksmith shop upon … and about the same time William Ludington died.” Therefore he concludes that William Ludington died in 1662. But was it 1662 according to the chronology of those times or according to that of our time? Wyman’s records of Charlestown and Malden, which mention William Ludington’s departure thence for East Haven, relate that on October 1, 1661, John White made petition for the appointment of an administrator of William Ludington’s estate in Middlesex County, Massachusetts, and Pope’s “Pioneers of Massachusetts” confirms that record, giving the name of the petitioner as Wayte or Waite, and adding that the inventory of the estate was filed by James Barrat, or Barret, on April 1, 1662. Mr. Patrick has the name Bariat and the date February 1, 1662. Here we have, then, the same discrepancy of exactly two months in statement of date which was noticed in the case of Matthew Ludington’s birth and death. Of course, if the petition for administration of William Ludington’s estate was made on October 1, 1661, his death must have occurred before that date, instead of in 1662 as the East Haven records suggest. The explanation of the apparent conflict of dates is doubtless to be found in the changes of calendar to which reference has been made, one historian giving the date according to the chronology then prevailing and another according to that of the present day. Concerning the date of the[15] probating of his estate at East Haven, however, there is apparently no doubt, since in the records of it the dual year-dates are given. That estate was inventoried and appraised by John Cooper and Matthew Moulthrop, and their inventory, according to Hoadly’s “New Haven Colonial Records,” was filed in court at New Haven on March 3, 1662, according to the chronology of that time, or 1663 according to ours. This interesting document was entitled “An Inventory of ye Estate of William Ludington, late of New Haven, deceased, amounting to £183 and 10s., upon Oath attested yt ye Aprizents was just to the best of their light, by John Cooper, Sen., and Matthew Moulthrop in Court at New Haven, 1662-63.” It ran in detail as follows:

| lbs | sh | d. | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Inv’ty ⅌ bd’s, boulsters pillows, coverlits, rugs, curtains—value | 20 | 07 | 02 |

| ” ⅌ sheets, pillow covers, table clothes and a blanket | 05 | 16 | 00 |

| ” ⅌ five yards ¾ of krosin | 02 | 00 | 00 |

| ” ⅌ four yards of red kersey | 01 | 00 | 00 |

| ” ⅌ six yards of kersey | 02 | 14 | 00 |

| ” ⅌ five yards of serze at 7s | 01 | 15 | 00 |

| ” ⅌ eight yards blew kersey at 7s | 02 | 16 | 00 |

| ” ⅌ twelve yards of serge at 6s | 00 | 18 | 00 |

| ” ⅌ 1¾th of wosted yarns | 00 | 12 | 00 |

| [16]” ⅌ 1¼th of woolen yarns | 00 | 05 | 00 |

| ” ⅌ 4 guns, 2 swords and a piece of a sword | 05 | 16 | 00 |

| ” ⅌ 3 chests and three boxes | 02 | 00 | 00 |

| ” ⅌ pewter, chamber pots, spoons and 2 sauce pans | 02 | 13 | 02 |

| ” ⅌ 2 dripping pans, 1 cup, 4 cream pots, some eartyn ware | 00 | 08 | 02 |

| ” ⅌ 3 bottles and a tu mill | 00 | 02 | 06 |

| ” ⅌ warming pan, 2 iron pots, kettle, brass pot 2 skillets, frying pan | 03 | 15 | 00 |

| ” ⅌ iron dogs, tramell, share and coulter and an iron square | 01 | 01 | 06 |

| ” ⅌ tooles, wedges, sithes & a payre of still yards & a 7lb waight | 05 | 04 | 00 |

| ” ⅌ a smoothing iron, a parcell of wayles, a hogshead & 2 chests | 01 | 08 | 06 |

| ” ⅌ sheeps wooll and cotton wooll | 02 | 10 | 09 |

| ” ⅌ Indyan corne, 7lb 10s; 10 bush turnips, 18s | 08 | 08 | 00 |

| ” ⅌ 2 loomes and furniture, 3 chayres | 05 | 09 | 00 |

| ” ⅌ wooden ware, a table & forme, a sieve, some trenches & bagges | 01 | 09 | 04 |

| [17]” ⅌ house and land 60lbs | 60 | 00 | 00 |

| ” ⅌ 3 cowes & two calves, 2 sowes & 3 shoates | 16 | 06 | 08 |

| ” ⅌ 6 loads of hay, 50s, and some other thinges in all | 30 | 07 | 00 |

| 185 | 02 | 09 | |

| The Estate Cr. | 00 | 15 | 00 |

| The Estate Dr. | 02 | 07 | 09 |

| Which being deducted there remains | 183 | 10 | 00 |

The marke, i. e. of

| John Cooper, | } Apprisers. |

| Mathew Moulthrop, |

Again, in the “Records of the Proprietors of New Haven” we find that “At a Court held at New Haven March 3, 1662-3 … an inventory of the Estate of Willm. Luddington deceased whas presented.… The widdow upon oath attested to the fulness of it to the best of her knowledge.… The widdow being asked if her husband made noe will answered that she knew of none for she was not at home when he died.… The matter respecting the childrens portions was deferred till next court & the … widdow with him that shee was to marry & all her children above fourteen years of age was ordered then to appear.…” At this date, therefore, William Ludington’s widow was engaged to be married again, and that engagement was publicly announced.[18] Moreover, she was actually married to her second husband, John Rose, a few weeks later, for on May 5 following, in 1662-63, according to the “Proprietors’ Records,” the court was again in session, and “John Rose who married widdow Ludington was called to know what security he would give for the childrens portions that was not yet of age to receive them.” It is true that in those days the period of mourning before remarriage was sometimes abbreviated, but it is scarcely conceivable that this widow’s marriage took place within a few months of her husband’s death, or sooner than a year thereafter. It may therefore be assumed that William Ludington’s death, at the East Haven iron works, occurred at least as early as March or April, 1661-62.

There is reason to believe that William Ludington was not only a man of note in the East Haven community but that also he was a man of considerable property—more than would be suggested by the item of “house and land 60 lbs.” in the inventory. For the New Haven Land Records show that in 1723 his son, William Ludington, 2nd, sold to Thomas Robinson “part of that tract of land set out to my father, William Luddington, which tract contains 100 acres.” This property was in East Haven, just across the river from Branford.

The children of William and Ellen Ludington were seven in number. The first was Thomas, who was born (probably in England) in 1637. He removed to Newark, New Jersey, in 1666, and became[19] a farmer—since when in 1689 he sold some land with a house and barn at New Haven he described himself in the deed as a husbandman. He was an assessor and a surveyor of highways at Newark, and left children whose descendants are now to be found in the northern part of New Jersey. His oldest child, John, remained at New Haven, married, and had issue, his first-born, James, being a soldier in the French and Indian war and being killed in battle on September 8, 1756. The second child of William and Ellen Ludington was John Ludington, who was born (probably at Charlestown, Massachusetts) in 1640. He was living at East Haven in 1664, and afterward, Mr. Patrick thinks, removed to Vermont. The third child was Mary, of whose birth various dates are given, as already noted. The fourth was Henry Ludington, the date of whose birth is not known, but who was killed in the war with King Philip, at the end of 1675 or beginning of 1676, as appears in the “New Haven Probate Records,” where is found an inventory of the estate of “Henry Luddington late of N. haven slayne in the warre taken & apprised by Mathew Moulthrop & John Potter Janry. 3, 1676.” The fifth child was Hannah, the dates of whose birth and death are unknown. The sixth child was William Ludington, 2nd, who was born about 1655 and died in February, 1737. His first wife was Martha Rose, daughter of his stepfather, John Rose, and his second was Mercy Whitehead. According to Dodd’s “East Haven Register”[20] he was a man of means, of intelligence, of ability, and of important standing in the community. He had two sons and one daughter by his first wife, and two sons and six daughters by his second. His first-born, the son of Martha Rose, was Henry Ludington, who was born in 1679, was a carpenter, married Sarah, daughter of William Collins, on August 20, 1700, had eight sons and four daughters, and died in the summer of 1727—of whom, or of his descendants, we shall presently hear much more. Finally, the seventh child of William and Ellen Ludington was Matthew, who as already related was born at Malden and died in infancy. Despite the removal of Thomas Ludington to Newark, and that of John Ludington (probably) to Vermont, they appear to have retained much interest in the New Haven colony, since in the “Colony Record of Deeds” of Connecticut we find Thomas, John, and William Ludington enumerated among the proprietors of New Haven in 1685, who were, presumably, the above mentioned first, second, and sixth children of William and Ellen Ludington.

Recurring for a moment to the family of William Ludington, 2nd, and passing by for the time his first-born, Henry Ludington, it is to be observed that his second child, Eleanor, married Nathaniel Bailey, of Guilford, Connecticut, and had issue; his third, William Ludington, 3rd, married Anna Hodge, lived at Waterbury and Plymouth, Connecticut, and had issue, his sixth son, Samuel, serving in[21] the French and Indian war, and his grandson, Timothy, son of William 3rd’s first-born, Matthew, also serving in that war and being killed in battle at East Haven in the War of the Revolution; the fourth, Mercy, married Ebenezer Deanes or Dains, of Norwich, Connecticut, and had issue; the fifth, Mary, married John Dawson, of East Haven, and had issue; the sixth, Hannah, married Isaac Penfield, of New Haven, and had issue; the seventh, John, married Elizabeth Potter, and had issue, his son Jude serving in the French and Indian war; the eighth, Eliphalet, married Abigail Collins, and had issue, his third son, Amos, serving in the French and Indian war; the ninth, Elizabeth, died in childhood; the tenth, Dorothy, married Benjamin Mallory and had issue; and the eleventh, Dorcas, married James Way and had issue.

Returning now to Henry Ludington, eldest son of William Ludington, 2nd, who was the sixth child of the original William Ludington, it is to be observed that his first child, Daniel, married first Hannah Payne, and second Susannah Clark, and had issue, his second child, Ezra, serving in the French and Indian war, and his ninth, Collins, in the War of the Revolution; his second, William Ludington, married first Mary Knowles, of Branford, and second Mary Wilkinson, of Branford, and had issue—of whom we shall hereafter hear much more; his third, Sarah, died in childhood; his fourth, Dinah, married Isaac Thorpe; his fifth, Lydia, married Moses[22] Thorpe; his sixth, Nathaniel, married first Mary Chidsey, and second Eunice (Russell) Smith, and had issue; his seventh, Moses, married Eunice Chidsey; his eighth, Aaron, died at sea; his ninth, Elisha, died in infancy; his tenth, also named Elisha, settled in Phillipse Precinct, Dutchess County, New York, married, and had a daughter, Abigail, of whom more hereafter; his eleventh, Sarah, probably died unmarried, though Dodd’s “East Haven Register” says she married Daniel Mead; and his twelfth, Thomas, was drowned, unmarried.

Turning back, once more, to the William Ludington last mentioned, who was the second son of Henry Ludington, we find that he was born at Branford, Connecticut, on September 6, 1702. He married Mary Knowles, of Branford, on November 5, 1730. She died on April 16, 1759, and on April 17, 1760,—just a day after the year of mourning had elapsed!—he married for his second wife Mary Wilkinson, also of Branford. His eight children, all of his first wife, were as follows: First, Submit, who married Stephen Johnson, of Branford; second, Mary; third, Henry, of whom we shall hear more, since he forms the chief subject of this book; fourth, Lydia, who married William (or, according to Dodd, Aaron) Buckley, of Branford; fifth, Samuel; sixth, Rebecca; seventh, Anne; and eighth, Stephen. On the night of Monday, May 20, 1754, part of William Ludington’s house at Branford was destroyed by fire, and his sixth and seventh children, Rebecca and Anne, aged[23] seven and four years, respectively, perished in the flames.

Attention is thus finally centered upon the second Henry Ludington, who was the third child of William Ludington, who was the second child of the first Henry Ludington, who was the first child of the second William Ludington, who was the sixth child of the first William Ludington, who was the founder of the Ludington family in America. The sources of information concerning him and his career, which have been mentioned in the preface to this volume, are varied and numerous rather than copious or comprehensive; but they are sufficient to indicate that he was a man of more than ordinary force of character and of more than average importance and influence in his time and place, and that he is entitled to remembrance and to enrolment among those who contributed materially, and with no little sacrifice of self, to the making of the State of New York and of the United States of America.

Henry Ludington, the third child of William and Mary (Knowles) Ludington, was born at Branford, Connecticut, on May 25, 1739. Some records give the date as 1738, but the weight of authority indicates the later year. Branford, originally called Totoket, was a part of the second purchase at New Haven in 1638, but was not successfully settled until two years later, when a dissatisfied company from Wethersfield, headed by William Swayne, secured a grant of it. Together with Milford, Guilford, Stamford, Southold (Long Island), and New Haven, it made up the separate jurisdiction of New Haven, under an ecclesiastical government, until 1665, when all were merged into the greater Colony of Connecticut, Branford being erected into an organized town with representation in the General Court, in 1651. The place won lasting distinction in 1700, when it was the scene of the practical founding of Yale College; ten ministers, who had been named as trustees of “The School of the Church,” each laying upon the table in their meeting-room a number of books, with the words, “I give these books for the founding of a college in this[25] colony.” The next year the college was chartered and was formally opened at Saybrook, and in 1716-17 it was permanently removed to New Haven. At the time of Henry Ludington’s birth, therefore, New Haven had become fully established as the metropolis of that part of the colony, and Branford, which had at first been its peer and rival, had become reconciled to the status of a suburban town. The educational facilities of Branford were similar to those of other colonial towns; to wit, primitive in character and chiefly under church control. To what extent young Ludington availed himself of them does not appear, but so far as may be judged from his letters and other papers in after years he was an indifferent scholar, probably thinking more of action than of study.

Such as his schooling was, however, it was ended at an early date and the school-boy became a man of action when only half-way through his teens. The epoch-making struggle commonly known as the French and Indian War, which was really a part of the Seven Years’ War in Europe, and which secured for the English absolute dominance in North America and transformed the maps of two continents, began when he was fifteen years old, and made a strong appeal to his adventurous and daring disposition; and at an early date, probably in 1755, though the meager records now in existence are not conclusive on that point, he enlisted in those Colonial levies which formed so invaluable an adjunct to the regular[26] British Army in all the campaigns of that war. No complete roster of the Connecticut troops is now in existence, but the “East Haven Register” tells us that many men from East Haven and Branford were enlisted for service with the British Army near the Great Lakes, of whom the greater part were lost through sickness and in battle. In these levies were several members of the Ludington family, beside Henry Ludington. Our genealogical review has already indicated the service in that war of James, Ezra, Timothy, Samuel, Jude, and Amos Ludington, uncles and cousins of Henry Ludington. As some of the Ludingtons had, years before the war, removed from Connecticut to Dutchess County, New York, some members of the family were also among the troops from the latter region. Old records tell that in Captain Richard Rea’s Dutchess County regiment were two young farmers, Comfort Loudinton and Asa Loudinton—obviously meaning Ludington—respectively 19 and 17 years old; the former with brown eyes and dark complexion, the latter with brown eyes and fresh complexion.

Henry Ludington enlisted in Captain Foote’s company of the Second Connecticut Regiment, a notable body of troops which was put forward to bear much of the brunt of the campaign. The regiment was at first commanded by Colonel Elizur Goodrich, and later by Colonel Nathan Whiting, one of the most distinguished Colonial officers of that war. The regiment was assigned to duty under[27] Major-General (afterward Sir) William Johnson, who, with a Colonial army and numerous Indian allies under the famous Mohawk chieftain Hendrick, was moving to meet the French at Lake George. The march from New Haven was made by way of Amenia and Dover, in Dutchess County, New York, to the Hudson River, and thence northward to the “dark and bloody ground” of the North Woods. Young Ludington was of a lively and venturesome disposition and, as family traditions show, had a propensity to practical joking which more than once put him in peril of not undeserved punishment, which, however, he managed to avoid.

It was early in September, 1755, when he was in only his seventeenth year, that the young soldier received his “baptism of fire” in the desperate battle of Lake George, near the little sheet of water afterward known as Bloody Pond because of the hue its water took from the gory drainage of the battlefield. General Johnson, with his Colonial troops and Indian allies, was moving northward. Baron Dieskau, with a French and Indian army, moving southward, embarked at Fort Frederick, Crown Point, came down the lake in a fleet of small boats, and landed at Skenesborough, now Whitehall. On the night of Sunday, September 7, word came to Johnson that the enemy was marching down from Fort Edward to Lake George, and early the next morning plans were made to meet them. It was at first suggested that only a few hundred men be sent forward to hold the[28] enemy in check until the main army could dispose and fortify itself, but Hendrick, the shrewd Mohawk warrior, objected to sending so small a force. “If they are to fight,” he said, “they are too few; if they are to be killed, they are too many.” Accordingly the number was increased to 1,200, comprising and, indeed, led by the Connecticut troops. Colonel Ephraim Williams, a brave and skilful officer, was in command, with Colonel Nathan Whiting, of New Haven, as his chief lieutenant. They came upon the enemy at Rocky Brook, about four miles from Lake George, and found the French and Indians arrayed in the form of a crescent, the horns of which extended for some distance on both sides of the road which there led through a dense forest. The devoted Colonial detachment marched straight at the center of the crescent, and was quickly attacked in front and on both flanks at the same time. Williams and Hendrick were among the first to fall, and their followers were cut down in great numbers. Thereupon Colonel Whiting succeeded to the general command, and perceiving that the Colonials were outnumbered and outflanked, ordered a retreat, which was skilfully conducted, with little further loss. When the army was thus reunited, hasty preparations were made to meet the onslaught of the foe, and at noon the conflict began in deadly earnest. The forces were commanded, respectively, by Johnson and Dieskau in person, until the former was disabled by a wound, when his place was taken by General Lyman, who[29] fulfilled his duties with singular ability and success. After four hours of fighting on the defensive, the English and Colonials leaped over their breastworks and charged the foe with irresistible fury. The French and Indians were routed with great slaughter, and Baron Dieskau himself, badly wounded, was taken prisoner.

Old gun used by Henry Ludington in the French and Indian War. Now owned by Frederick Ludington, son of the late Governor Harrison Ludington, of Wisconsin.

(From sketch made by Miss Alice Ludington, great-great-granddaughter of Henry Ludington.)

Henry Ludington was in the thickest of both parts of this battle, having been in the detachment which was sent forward in advance. He came off unscathed, but he had the heartrending experience of seeing both his uncle and his cousin shot dead at his side. These were probably his uncle Amos Ludington (called Asa in the “East Haven Register,” as already noted), son of Eliphalet Ludington, and his cousin Ezra, son of Daniel Ludington. The uncle fell first, pierced by a French bullet. The cousin sprang to his side and stooped to lift him, and in the act was himself shot, and a few moments later both died. Soon after this battle the term of enlistment of the Connecticut militia expired, but reënlistments[30] were general. According to the French and Indian War Rolls, and the Connecticut Historical Collections as searched by Mr. Patrick, Henry Ludington again enlisted on April 19, 1756, served under Colonel Andrew Ward at Crown Point, and was discharged at the expiration of his term on November 13, 1756. Again, he was in Lieutenant Maltbie’s company, under Colonel Newton, at the time of the “general alarm” for the relief of Fort William Henry, in August, 1757, on which occasion his time of service was only fifteen days. Finally, he was in the campaign of 1759, in the Second Connecticut Regiment, under Colonel Nathan Whiting, being a member of David Baldwin’s Third Company. In this year he enlisted on April 14, and was duly discharged on December 21, 1759. During this memorable period of service the young soldier marched with the British and American troops to Canada, and participated in the crowning triumph at Quebec, on September 13, 1759, and a little later was intrusted with the charge of a company of sixty wounded or invalid soldiers, who were to return to New England. The march was made across country, from Quebec to Boston, in the dead of the very severe winter of 1759-60, and the labors and perils of the journey were sufficient to tax to the utmost the skill and resourcefulness of the youth of only twenty years. For many nights their camp consisted of caves or burrows in the snowdrifts, where they slept on beds of spruce boughs, wrapped in their blankets. Provisions failed, too,[31] and some meals were made of the bark and twigs of birch trees and the berries of the juniper. Through all these hardships young Ludington led his comrades safely to their destination. Then, in the spring of 1760, he proceeded from Boston to Branford, and thus terminated for the time his active military career. In recognition of his services he received from King George II the commission of a lieutenant in the British Colonial Army, which he held until, in the succeeding reign, news came of the enactment of the Stamp Act, when he resigned it. Later, on February 13, 1773, he accepted a captain’s commission from William Tryon, the last British governor of New York, which he held until the beginning of the Revolution. This commission was in the regiment commanded by Beverly Robinson, that eminent British Loyalist who was the intermediary between Sir Henry Clinton and Benedict Arnold. It was at Robinson’s country mansion that much of Arnold’s plotting was done, and it was there, while at dinner, that the traitor received the news of the failure of his treason through the capture of his agent, Major André.

Reduced Fac-simile of the Commission of Henry Ludington as Captain in Col. Beverly Robinson’s Regiment.

From William Tryon last British Governor of the Province of New York.

(Original in possession of Charles H. Ludington, New York City.)

One other incident of Henry Ludington’s service demands passing attention. In one of the returns of his regiment, in connection with the fifteen days’ service in August, 1757, he is recorded as “Deserted.” Generally speaking, no worse blot than that can well be put upon a soldier’s record. But it is quite obvious that in this case it is devoid of its usual serious[32] significance. It is certain that he did not actually desert in the ordinary present meaning of that term. This we know, because there is no record nor intimation of any steps ever being taken to punish him for what would have been regarded as a heinous crime; because soon after that entry against him he was serving with credit in the army and continued so to do; because thereafter he was intrusted with the important march to Boston which has been described; and because, after having honorably completed his service in the army, he received a royal commission as an officer. In those early days, when an army was campaigning in an almost trackless wilderness and warfare was largely of the most irregular description, it was not difficult for a soldier to become detached and practically lost from the rest of his army, and perhaps not be able to rejoin it for some time. Such a mishap might the more easily have befallen an impetuous and adventurous youth such as Henry Ludington was. And of course the record “Deserted” might naturally enough have been put against his name when he failed to respond to roll-call and no explanation of his absence was forthcoming.

In the French and Indian War the Colonial troops were paid for their services by the various Colonial governments, which latter were afterward reimbursed for such expenditures by the British Government. It was, however, with a view to compelling the Colonies to bear the cost of the war, by levying taxes upon them at the will of Parliament, that the[33] British Government entered upon the fatal policy which a few years later cost it the major part of its American possessions. Because of that change of government, no pension system was ever created for the veterans of that war. In 1815, however, near the close of Henry Ludington’s life, such pensions were proposed, and with a view to establishing his eligibility to receive one, in the absence of the authoritative records of the Connecticut troops, he secured from two of his former comrades in arms the following affidavits—here reproduced verbatim et literatim:

State of New York

Putnam County

Jehoidah Wheton, of the town of Carmell in said county, being duly sworn doth depose and say that he is now personally acquainted with Henry Ludington, who lives in the Town of Fredericks in said county and that the deponent has known him for many years past. The deponent knows that the above named Henry Ludington was in the service in the years 1756 and 1757 under the King’s pay, and belonged to the State troops of Connecticut, and that the deponent was personally acquainted with the said Henry Ludington during the service above stated, and the deponent was with him the two campaigns, and further the deponent saith that from certain information which he the deponent knows to be true from the above named Henry Ludington of certain transactions which took place in the year 1759 to me the deponent now[34] told he verrily believes that the said Henry Ludington was in the service that year, and that the deponent places confidence in the truth and veracity of the said Henry Ludington, and the deponent saith that he together with the above named Henry Ludington was under Capt. Foot in Colonel Nathan Whiting’s Ridgement in the service aforesaid; and further this deponent saith not.

X

Jehoidah Wheaton

his mark

Sworn and subscribed the 14th day of September 1815 before me John Phillips, one of the masters in the cort of Chy. in and for sd. State.

I, John Byington, of Redding in Fairfield County and State Connecticut, of lawful age depose and say

that I am well acquainted with Henry Ludington of Fredericks, state of New York, that he enlisted under the King’s proclamation and served with the Connecticut troops in the war with France, three campaigns, in the company of Capt. Foot, under whom I also served; that he rendered the above service between the year 1756 & 1764, and further say not.

John Byington.

State Connecticut, County Fairfield, Ss. Redding the 15th day of September 1815 personally apperd John Byington the above deponent & made oath to the truth of the above deposition.

Lemuel Sanford, Justice Peace.

Both of the foregoing affidavits or depositions are taken from copies of the originals, made by Lewis Ludington, son of Henry Ludington, on September 19, 1815, and now in possession of Lewis Ludington’s son.

We have seen that Henry Ludington, at the age of twenty-one, escorted a company of invalided soldiers from Quebec to Boston in the winter of 1759-60, and thereafter returned to civil life. One of his first acts was to get married, his bride being his cousin, Abigail Ludington, daughter of his father’s younger brother, Elisha Ludington. As already noted, Elisha Ludington upon his marriage had removed from Connecticut to Dutchess County, New York, and had settled in what was known as the Phillipse Patent. The exact date of that migration is not recorded, but it was probably some years before the French and Indian war. As the Connecticut troops on their way to that war marched across Dutchess County, through Dover and Amenia, it is to be presumed that Henry Ludington on that momentous journey called at his uncle’s home, and saw his cousin, afterward to be his wife, who had been born on May 8, 1745, and was at that time consequently a child of about ten years. Whether they met again until his return from Quebec is not surely known, but we may easily imagine the boy soldier’s carrying with him into the northern wilderness an affectionate memory of his little cousin, perhaps the last of his kin to bid him good-by, and also her cherishing[36] a romantic regard for the lad whom she had seen march away with his comrades. At any rate, their marriage followed close upon his return, taking place on May 1, 1760, when he was not yet quite twenty-one and she just under fifteen. Soon afterward the young couple, apparently accompanied by the rest of Henry Ludington’s immediate family, removed to Dutchess County, New York, to be thereafter identified with that historic region.

Old Phillipse Manor House at Carmel, N. Y.

(From sketch made in 1846 by Charles Henry Ludington)

Dutchess County was one of the twelve counties into which the Province of New York was divided on November 1, 1683, the others being Albany, Cornwall (now a part of the State of Maine), Duke’s (now a part of Massachusetts), King’s, New York, Orange, Queen’s, Richmond, Suffolk, Ulster, and Westchester. Dutchess then comprised what is now Putnam County, which was set off as a separate county in 1812 and was named for General Israel Putnam, who was in command of the forces there during much of the Revolutionary War. In 1719 Dutchess County was divided into three wards, known as Northern, Middle, and Southern, each extending from the Hudson River to the Connecticut line. Again, in 1737, these wards were subdivided into seven precincts, called Beekman, Charlotte, Crom Elbow, North, Poughkeepsie, Rhinebeck, and Southeast; and at later dates other precincts, or towns, were formed, to wit: North East in 1746; Amenia in 1762; Pawlings in 1768; and Frederickstown in 1772. Fishkill and Rombout were also constituted[37] in colonial times. Frederickstown, where the Ludingtons settled and with which we have most to do, was a part of the Phillipse Patent, in the Southern Ward of Dutchess County, now Putnam County. It derived its name from Frederick Phillipse, a kinsman of Adolphe Phillipse, the patentee of Phillipse Manor or Patent. It has now been divided and renamed, its old boundaries comprising the present towns of Kent, Carmel, and Patterson, and a part of Southeast, the present village of Patterson occupying the site of the former Fredericksburgh. The name of Kent was taken from the family of that name, of which James Kent, the illustrious jurist and chancellor of the State of New York, was a member. It may be of interest to recall at this point, also, that a certain strip of land at the eastern side of Dutchess County was in dispute between New York and Connecticut. This was known as The Oblong, or the Oblong Patent, from its configuration, and comprised 61,440 acres, in a strip about two miles wide, now forming parts of Dutchess, Putnam, and Westchester counties and including part of the Westchester town of Bedford, and also Quaker Hill, near Pawling, in Dutchess County, which was once suggested as the capital of the State, and which gets its name from having been first settled by Quakers. The dispute over the New York-Connecticut boundary and the consequent ownership of this land arose before 1650, when the Dutch were still owners of New York, or New Netherlands as the latter was[38] then called, and it was continued between the two Colonies when they were both under British rule. The settlement was effected by confirming New York in possession of The Oblong, and granting to Connecticut in return a tract of land on Long Island Sound, eight miles by twelve in extent, which was long called the “Equivalent Land,” and which is now occupied by Greenwich, Stamford, and other towns. The final demarcation of the boundary was not, however, effected until as late as 1880.

CARMEL, PUTNAM COUNTY, NEW YORK.

From a Painting by Jamee M. Hart, 1858.

(In possession of Charles H. Ludington, New York City.)

The precise date of Henry Ludington’s settlement in Dutchess County is not now known. Neither his nor his father’s name appears in the 1762 survey of Lot No. 6 of the Phillipse Patent, and it has been assumed that therefore his arrival there must have been at a later date than that. This reasoning must, however, be challenged on the ground that—as we shall presently see—on March 12, 1763, he was officially recorded as a sub-sheriff of Dutchess County. It is scarcely likely that he would have been appointed to that office immediately upon his arrival in the county, and we must therefore conclude that he settled there at least early in 1762, if not before that year. He made his home on a tract of 229 acres of land in Frederickstown, at the north end of Lot No. 6 of the Phillipse Patent, on the site of what was afterward appropriately, though with awkward etymology, called Ludingtonville. This land he was not able to purchase outright, but leased for many years from owners who clung to the old feudal notions of tenure;[39] but at last, on July 15, 1812, he effected actual purchase and received title deeds from Samuel Gouverneur and his wife. On that property he built the first grist- and saw-mills in that region, there being no others nearer than the “Red Mills” at Lake Mahopac and those built by John Jay on the Cross River, in the town of Bedford, Westchester County—which latter, by the way, remained in continuous operation, with much of the original framework and sheathing, until 1906, when they were destroyed to make room for one of the Croton reservoirs. Ludington’s mills were of course operated by water power, generated by a huge “overshot” wheel, supplied with water conveyed from a neighboring stream in a channel or mill-race made of timber.

Near-by stood the house, which was several times enlarged. The main building was two stories in height, with an attic above. Through the center ran a broad hall, with a stairway broken with a landing and turn. At one side was a parlor and at the other a sitting or living room, and back of each of these was a bedroom. The parlor was wainscoted and ceiled with planks of the fragrant and beautiful red cedar. Beyond the sitting room, at the side of this main building, was the “weaving room,” an apartment unknown to our modern domestic economy, but essential in colonial days. It was a large room, fitted with a hand-loom, and a number of spinning wheels, reels, swifts, and the other paraphernalia for the manufacture of homespun fabrics of different kinds.[40] This room also contained a huge stone fireplace. Beyond it, at the extreme east of the house, was the kitchen, with its great fireplace and brick or stone oven. The house fronted toward the south, and commanded a fine outlook over one of the picturesque landscapes for which that region is famed. Years ago the original house was demolished, and a new one was built on the same site by a grandson, George Ludington. The location was a somewhat isolated one, neighbors being few and not near, and the nearest village, Fredericksburgh, on the present site of Patterson, being some miles distant. The location was, however, important, being on the principal route from Northern Connecticut to the lower Hudson Valley, the road leading from Hartford and New Milford, Connecticut, through Fredericksburgh, past Colonel Ludington’s, to Fishkill and West Point—a circumstance which was of much interest and importance to Colonel Ludington in the Revolution, as we shall see. The population of the county at that time was small and scattered. In 1746, or about the time when Elisha Ludington went thither and Abigail Ludington was born, the census showed a population of 8,806, including 500 negro slaves. By 1749 the numbers had actually diminished to 7,912, of whom only 421 were negroes. In 1756, however, there were 14,148 inhabitants, including 859 negroes, and Dutchess was the most populous county in the colony, excepting Albany, which had 17,424 inhabitants. The county was at that time able to contribute[41] to the army about 2,500 men. It had enjoyed exemption from the Indian wars which had ravaged other parts of the colony, and its situation and natural resources gave it the advantages of varied industries. It had the Hudson River at one side for commerce, it was well watered and wooded, its open fields were exceptionally fertile, it had abundant water-power for mills, and it had—though this was not realized until after the colonial period—much mineral wealth.

Such was the community in which Henry Ludington established himself at the beginning of his manhood and married life, and in which he quickly rose to prominence. The extent of his holdings of land, and the fact of his proprietorship of important mills, made him a leading factor in business affairs, while his bent for public business soon led him into both the civil and the military service. At that time, from 1761 to 1769, James Livingston was sheriff of Dutchess County, and early in 1763 Henry Ludington became one of his lieutenants, as sub-sheriff. The Protestant dynasty in England was so newly established that elaborate oaths of abjuration and fealty were still required of all office-holders, of whatever rank or capacity, and on March 12, 1763, Henry Ludington, as sub-sheriff, took and subscribed to them, as follows:

I, Henry Ludington, Do Solemnly and Sincerely, in the Presence of God, Profess, Testify,[42] and Declare, That I do Believe, that in the Sacrament of the Lord’s Supper, there is not any Transubstantiation, of the Elements of Bread and Wine, in the Body and Blood of Christ at or after the Consecration Thereof, by any Person whatsoever. And that the Invocation, or Adoration, of the Virgin Mary, or Any other Saint, and the Sacrifice of the Mass, as they are now Used in the Church of Rome, are Superstitious and Idolatrous, and I do Solemnly in the presence of God, Profess, Testify, and Declare, that I make this Declaration, and Every Part thereof, in the plain and Ordinary Sence of the Words read to me, as they are Commonly Understood by English Protestants, Without any Evasion, Equivocation, or Mental Reservation whatsoever, and Without any Dispensation Already Granted to me for this purpose by the Pope, or any other Authority Whatsoever, or Without Thinking that I am Acquitted, before God or Man, or Absolved of this Declaration, or any Part thereof, Although the Pope, or any Person or Persons, or Power Whatsoever, Should Dispence with or Annul the same and Declare that it was Null or Void, from the Beginning.

I, Henry Ludington, do Sincerely Promise & Swear, that I will be faithful and bear true Allegiance to his Majesty King George the Third, and I do Swear that I do from my heart Abhor, Detest, and Abjure, as Impious and Heretical, that Damnable Doctrine and Position, that Princes Excommunicated and Deprived by the Pope, or Any Authority of the See of Rome, May Be Deposed by Their Subjects or any other[43] Whatsoever, and I do Declare that no Foreign Prince, Person, Prelate, State or Potentate hath or ought to have, any Jurisdiction, Power, Superiority, Pre-eminence, or Authority Ecclesiastical or Spiritual, Within this Realm, and I do Truly and Sincerely acknowledge and profess, Testify and Declare, in my conscience before God and the World, That Our Sovereign Lord King George the Third of this Realm, and all other Dominions and Countrys Thereunto Belonging, and I do Solemnly and Sincerely Declare, that I do believe in my conscience that the person pretended to be Prince of Wales During the Life of the Late King James the Second, and since his Decease, Pretending to be and Taking upon himself the Stile and Title of King of England, by the Name of James the Third, or of Scotland by the name of James the Eighth, or Stile and Title of the King of Great Britain, hath not any right or Title whatsoever, to the Crown of this Realm, or any other Dominions Thereunto Belonging, and I do Renounce, Refuse, and Abjure, any Allegiance or Obedience to him, and I do Swear, that I will bear Faith, and True Allegiance to his Majesty King George the Third and him will defend, to the utmost of my Power, against all Traiterous Conspiracies and Attempts Whatsoever, which shall be made Against his Person, Crown or Dignity, and I will do my Utmost Endeavors to Disclose and Make Known to his Majesty and his Successors all Treasons and Traiterous Conspiracies which I shall know to be against him, or any of them, and I faithfully promise to the Utmost of my Power to Support, Maintain and Defend the Successors of the[44] Crown against him the said James and all other Persons Whatsoever, Which Succession by an Act entitled An Act for the further Limitation of the Crown Limited to the Late Princess Sophia, Electress and Dowager of Hanover, and the Heirs of Her Body, being Protestants, and all these things I do plainly and Sincerely Acknowledge and Swear according to the Express words by me spoken and according to the Plain and Common Sence and Understanding of the same Words Without any Equivocation, Mental Evasion, or Sinister Reservation Whatsoever, and I do make this Recognition, Acknowledgement, Abjuration, Renunciation and Promise heartily, Willingly and Truly, upon the True Faith of a Christian. So help me, God!

Thus qualified by the taking of these oaths, Henry Ludington began public services which lasted, in one capacity and another, for more than a generation in the Colony and State of New York. The first entry in his ledger bears date of “May, A.D. 1763,” and runs as follows: “James Livingston Sheriff Dr to Serving county writs (seven in number) the price for serving each writ being from 11s. 9d. to £1—10—9.” There follow, under dates of October, 1763, and May, 1764, entries for serving other writs. Among the names of attorneys in the suits appear those of Cromwell, Livingston, Jones, Snedeker, Ludlow, Snook, and Kent; and among those of parties to suits, etc., are those of Joseph Weeks, Jacob Ellis, Uriah Hill, Jacob Griffen, George Hughson,[45] Ebenezer Bennett, and Joseph Crane. In 1764 first appears the name of Beverly Robinson, as the plaintiff in a suit against one Nathan Birdsall. There is also mention of a suit brought in the name of the “Earl of Starling” as plaintiff before the Supreme Court of the colony—probably William Alexander, or Lord Stirling, the patriot soldier of the Revolution.

At this home in Frederickstown the children of Henry and Abigail Ludington, or all of them but the eldest, were born. These children, with the dates of their births, were as follows, as recorded by Henry Ludington in his Family Register, which was inscribed on a fly-leaf of the ledger already quoted:

Of these it is further recorded in the same register that Sibyl was married to Edward Ogden (the name is elsewhere given as Edmund or Henry Ogden) on[46] October 21, 1784; that Mary was married to David Travis on September 12, 1785; that Archibald was married to Elizabeth ⸺ on September 23, 1790; and that Rebecca was married to Harry Pratt on May 7, 1794.

In order justly to appreciate the circumstances in which Henry Ludington and his young family found themselves about fifteen years after his return from the French and Indian war, it will be desirable to recall briefly the political and social conditions generally prevailing throughout the Colonies at that time, which were nowhere more marked than in New York City and the rural counties lying just north of it. During the two or three years before the actual declaration of American independence, or secession from England, the people of the Colonies were divided into two parties, the Patriots and the Loyalists or Tories. The latter maintained the right of England to govern the Colonies as she pleased, and regarded even a protest against the maladministration of George III’s ministers as little short of sacrilege. The former were by no means as yet committed to the idea of American separation from the mother country, but they were most resolute in their demand for local self-government, and for government according to the needs of the Colonies rather than the caprices of English ministers. When they first placed the legend “Liberty and Union” upon their colonial flag, and called it the “Grand Union Flag,” they had in[48] mind liberty under the British constitution and continued union with England. Nevertheless, antagonism between the two parties became as bitter as ever it was between Roundhead and Cavalier in Stuart days; and while in some respects Boston and Philadelphia figured more conspicuously in the pre-revolutionary agitation and operations than did New York, there was probably no place in all the Colonies where the people were more evenly and generally divided between the two parties, or where passions rose higher or were more strongly maintained, than in and about the last-named city. No ties of neighborliness, friendship, or even family relationship sufficed to prevent or to quell the animosities which arose over the political interests of the Colonies. Nowhere had the Patriots a more ardent or persuasive leader than young Alexander Hamilton, or the Tories a more uncompromising champion than Rivington, the printer, whose office was at last sacked and gutted by wrathful Patriots. An illuminating side-light is thrown upon the New York state of mind by an item in the New York “Journal” of February 9, 1775, as follows:

A company of gentlemen were dining at a house in New York. One of them used the word Tory several times. His host asked him, “Pray, Mr. ⸺, what is a Tory?” He replied, “A Tory is a thing whose head is in England, and its body in America, and its neck ought to be stretched!”

Nor were these passions by any means confined to the urban but not always urbane community on[49] Manhattan Island. They prevailed with equal force in the rural regions of Westchester and Dutchess counties. During the Revolutionary War that border region, between the British garrison on Manhattan Island and the American strongholds in the Highlands of the Hudson, was the fighting ground of the belligerents, and was also unmercifully harried and ravaged by the irregular succors of both sides, the “Cow Boys” and “Skinners,” and others, celebrated in the unhappy André’s whimsical ballad of “The Cow Chase.” Patriots from Westchester County were foremost among those who wrecked Rivington’s Tory printing shop, and an aggravated sequel to the item just cited from the New York “Journal” is provided in the annals of Dutchess County a little later in the same year. At that time a County Committee, or Committee of Safety—of which we shall presently hear much more—had been formed in that county, for the purpose of holding the Tories in check, and it had forcibly deprived some men of their arms and ammunition. The despoiled Tories made appeal to the Court of Common Pleas for redress, and James Smith, a justice of that court, according to a contemporary narrative, “undertook to sue for and recover the arms taken from the Tories by order of said committee, and actually committed one of the committee who assisted at disarming the Tories; which enraged the people so much that they rose and rescued the prisoner, and poured out their resentment on this villanous retailer of the law.” The[50] “resentment” seems to have been poured out of buckets and pillows, for we are told that Justice Smith and his relative, Coen Smith, were “very handsomely tarred and feathered, for acting in open contempt of the resolves of the County Committee!”

In or near that part of Dutchess County in which Henry Ludington lived a third small but not insignificant factor was involved in the problem. This was provided by the members of the Society of Friends, who were settled at Quaker Hill, near Pawling, in The Oblong. This was the first community in America to abolish negro slavery, in 1775, and on that account it was probably regarded with some suspicion. But worse still was the regard given to it in the strife between Patriots and Tories. There can be little doubt that the sentiments and wishes of the Quakers were largely with the Patriots. Yet their religious principle of non-resistance forbade them to take up arms or to engage in forcible conflict of any kind. They were therefore generally looked upon by the Patriots as Tories, and were on that account sometimes fined and otherwise punished, while on the other hand, the Tories made themselves free to quarter troops upon them and to demand aid of them at will. On the whole, however, they appear to have commanded the respect of the Patriots, for their sincerity, and thus to have been far more leniently dealt with than were the more militant Tories outside the Society of Friends.

Map of Quaker Hill and Vicinity, 1778-80, showing location of Colonel Ludington’s place at Fredericksburgh

The earliest organization of the Patriots in and[51] about New York was a Committee of Vigilance, the chief functions of which were to watch for oppressive acts of the British Government and incite colonial protests against them. This was in 1774 superseded by a Committee of Fifty-One, and it in turn in the same year gave place to a Committee of Inspection, of sixty members. In both of these latter John Jay, who was a neighbor and friend of Henry Ludington, was conspicuous, and it is to be presumed that Henry Ludington himself was either a member of the committees or at least was in active sympathy with their work. In April, 1775, came a crisis and the turning point in the movement for independence. The old Colonial Assembly of New York went out of existence on April 3. Then came the news of the first clash of arms at Lexington and Concord, acting as a spark in a powder-magazine. “Astonished by accounts of acts of hostility in the moment of expectation of terms of reconciliation,” said the lieutenant-governor of New York in his account of the occurrence, “and now filled with distrust, the inhabitants of the city burst through all restraint on the arrival of the intelligence from Boston, and instantly emptied the vessels laden with provisions for that place, and then seized the city arms and in the course of a few days distributed them among the multitude, formed themselves into companies and trained openly in the streets; increased the number and power of the committee before appointed to execute the association of the Continental Congress, convened themselves by[52] beat of the drum for popular resolutions, have taken the keys of the custom house by military force; shut up the port, drawn a small number of cannon into the country; called all parts of the country to a Provincial Convention; chosen twenty delegates for this city, formed an association now signing by all ranks, engaging submission to committees and congresses, in firm union with the rest of the continent, and openly avow a resolution not only to resist the acts of Parliament complained as grievances, but to withhold succors of all kinds from the troops and to repel every species of force, wherever it may be exerted, for enforcing the taxing claims of Parliament at the risk of their lives and fortunes.” This only half coherent but wholly intelligible and graphic narrative tells admirably how the Patriot sentiment of New York startled into life and action. A year later it was forcibly repressed by the British garrison on Manhattan Island, but in the counties at the north it continued dominant and triumphant.

The “association now signing by all ranks” was promptly entered into by Henry Ludington and his neighbors in Dutchess County, as the following transcript, from the MS. collection of Mr. Patrick, shows, the date of the original being April 29, 1775:

A General Association agreed to and subscribed by the Freeholders and Inhabitants of the County of Dutchess:

Persuaded: That the Salvation of the Rights & Liberties of America depends, under God, on the[53] firm Union of its Inhabitants in a Vigorous Prosecution of the Measures necessary for its Safety; and Convinced of the Necessity of preventing the Anarchy & Confusion which attend the Dissolution of the Powers of Government, We, the Freeholders and Inhabitants of the County of Dutchess, being greatly alarmed at the avowed Design of the Ministry to raise a Revenue in America, and shocked by the bloody Scene now acting in the Massachusetts Bay, Do, in the most solemn Manner, Resolve, never to become Slaves; and do associate under all the Ties of Religion, Honour and Love to our Country, to adopt and endeavor to carry into execution, whatever Measures may be recommended by the Continental Congress, or resolved upon by our Provincial Conventions, for the Purpose of preserving our Constitution and opposing the execution of the several arbitrary and oppressive Acts of the British Parliament, until a Reconciliation between Great Britain and America, on Constitutional Principles (which we most ardently desire) can be obtained: And that we will in all things, follow the Advice of our General Committee, respecting the Purposes aforesaid: the Preservation of peace and good Order and the Safety of Individuals, and private property.