The Project Gutenberg EBook of The Principles of Psychology, Volume 2 (of 2), by William James This eBook is for the use of anyone anywhere in the United States and most other parts of the world at no cost and with almost no restrictions whatsoever. You may copy it, give it away or re-use it under the terms of the Project Gutenberg License included with this eBook or online at www.gutenberg.org. If you are not located in the United States, you'll have to check the laws of the country where you are located before using this ebook. Title: The Principles of Psychology, Volume 2 (of 2) Author: William James Release Date: August 4, 2018 [EBook #57634] Language: English Character set encoding: UTF-8 *** START OF THIS PROJECT GUTENBERG EBOOK PRINCIPLES OF PSYCHOLOGY *** Produced by Clare Graham & Marc D'Hooghe at Free Literature (Images generously made available by the Hathi Trust)

Sensation, 1

Its distinction from perception, 1. Its cognitive function—acquaintance

with qualities, 3. No pure sensations after the first

days of life, 7. The 'relativity of knowledge,' 9. The law of

contrast, 13. The psychological and the physiological theories

of it, 17. Hering's experiments, 20. The 'eccentric projection'

of sensations, 31.

Imagination, 44

Our images are usually vague, 45. Vague images not necessarily

general notions, 48. Individuals differ in imagination;

Gabon's researches, 50. The 'visile' type, 58. The 'audile'

type, 60. The 'motile' type, 61. Tactile images, 65. The neural

process of imagination, 68. Its relations to that of sensation, 72.

The Perception of 'Things,' 76

Perception and sensation, 76. Perception is of definite and

probable things, 82. Illusions, 85;—of the first type, 86;—of

the second type, 95. The neural process in perception, 103.

'Apperception,' 107. Is perception an unconscious inference?

111. Hallucinations, 114. The neural process in hallucination,

122. Binet's theory, 129. 'Perception-time,' 131.

The Perception of Space, 134

The feeling of crude extensity, 134. The perception of spatial

order, 145. Space-'relations,' 148. The meaning of localization,

158. 'Local signs,' 155. The construction of 'real' space, 166.

The subdivision of the original sense-spaces, 167. The sensation[Pg iv]

of motion over surfaces, 171. The measurement of the sense-spaces

by each other, 177. Their summation, 181. Feelings of

movement in joints, 189. Feelings of muscular contraction, 197.

Summary so far, 202. How the blind perceive space, 203.

Visual space, 211. Helmholtz and Reid on the test of a sensation,

216. The theory of identical points, 222. The theory of projection,

228. Ambiguity of retinal impressions, 231;—of eye-movements,

234. The choice of the visual reality, 237. Sensations which

we ignore, 240. Sensations which seem suppressed, 243. Discussion

of Wundt's and Helmholtz's reasons for denying that

retinal sensations are of extension, 248. Summary, 268. Historical

remarks, 270.

The Perception of Reality, 283

Belief and its opposites, 283. The various orders of reality,

287. 'Practical' realities, 293. The sense of our own bodily

existence is the nucleus of all reality, 297. The paramount reality

of sensations, 299. The influence of emotion and active impulse

on belief, 307. Belief in theories, 311. Doubt, 318. Relations

of belief and will, 320.

Reasoning, 323

'Recepts,' 327. In reasoning, we pick out essential qualities,

329. What is meant by a mode of conceiving, 332. What is

involved in the existence of general propositions, 337. The two

factors of reasoning, 340. Sagacity, 343. The part played by

association by similarity, 345. The intellectual contrast between

brute and man: association by similarity the fundamental human

distinction, 348. Different orders of human genius, 360.

The Production of Movement, 373

The diffusive wave, 373. Every sensation produces reflex

effects on the whole organism, 374.

Instinct, 383

Its definition, 383. Instincts not always blind or invariable,

389. Two principles of non-uniformity in instincts: 1) Their

inhibition by habits, 394; 2) Their transitoriness, 398. Man has[Pg v]

more instincts than any other mammal, 403. Reflex impulses,

404. Imitation, 408. Emulation, 409. Pugnacity, 409. Sympathy,

410. The hunting instinct, 411. Fear, 415. Acquisitiveness,

422. Constructiveness, 426. Play, 427. Curiosity, 429.

Sociability and shyness, 430. Secretiveness, 432. Cleanliness,

434. Shame, 435. Love, 437. Maternal love, 439.

The Emotions, 442

Instinctive reaction and emotional expression shade imperceptibly

into each other, 442. The expression of grief, 443; of

fear, 446; of hatred, 449. Emotion is a consequence, not the

cause, of the bodily expression, 449. Difficulty of testing this

view, 454. Objections to it discussed, 456. The subtler emotions,

468. No special brain-centres for emotion, 472. Emotional differences

between individuals, 474. The genesis of the various

emotions, 477.

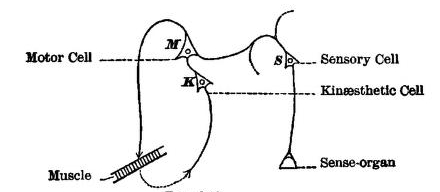

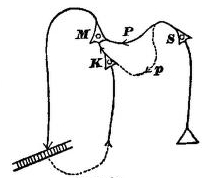

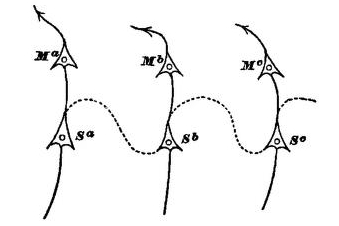

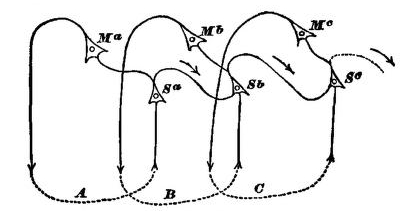

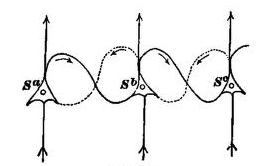

Will, 486

Voluntary movements: they presuppose a memory of involuntary

movements, 487. Kinæsthetic impressions, 488. No need

to assume feelings of innervation, 503. The 'mental cue' for a

movement may be an image of its visual or auditory effects as

well as an image of the way it feels, 518. Ideo-motor action, 522.

Action after deliberation, 528. Five types of decision, 531. The

feeling of effort, 535. Unhealthiness of will: 1) The explosive

type, 537; 2) The obstructed type, 546. Pleasure and

pain are not the only springs of action, 549. All consciousness is

impulsive, 551. What we will depends on what idea dominates

in our mind, 559. The idea's outward effects follow from the

cerebral machinery, 560. Effort of attention to a naturally

repugnant idea is the essential feature of willing, 562. The

free-will controversy, 571. Psychology, as a science, can safely

postulate determinism, even if free-will be true, 576. The education

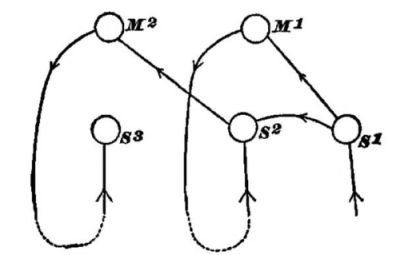

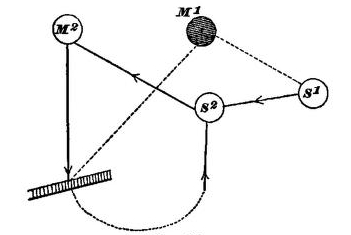

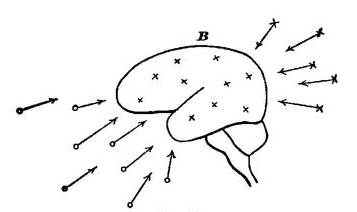

of the Will, 579. Hypothetical brain-schemes, 582.

Hypnotism, 594

Modes of operating and susceptibility, 594. Theories about

the hypnotic state, 596. The symptoms of the trance, 601.

Necessary Truths and the Effects of Experience, 617

Programme of the chapter, 617. Elementary feelings are

innate, 618. The question refers to their combinations, 619.

What is meant by 'experience,' 620. Spencer on ancestral experience,

620. Two ways in which new cerebral structure arises:

the 'back-door' and the 'front-door' way, 625. The genesis of

the elementary mental categories, 631. The genesis of the

natural sciences, 633. Scientific conceptions arise as accidental

variations, 636. The genesis of the pure sciences, 641. Series of

evenly increasing terms, 644. The principle of mediate comparison,

645. That of skipped intermediaries, 646. Classification,

646. Predication, 647. Formal logic, 648. Mathematical

propositions, 652. Arithmetic, 653. Geometry, 656. Our doctrine

is the same as Locke's, 661. Relations of ideas v. couplings

of things, 663. The natural sciences are inward ideal schemes

with which the order of nature proves congruent, 666. Metaphysical

principles are properly only postulates, 669. Æsthetic

and moral principles are quite incongruent with the order of

nature, 672. Summary of what precedes, 675. The origin of

instincts, 678. Insufficiency of proof for the transmission to the

next generation of acquired habits, 681. Weismann's views, 683.

Conclusion, 688.

After inner perception, outer perception! The next three chapters will treat of the processes by which we cognize at all times the present world of space and the material things which it contains. And first, of the process called Sensation.

The words Sensation and Perception do not carry very definitely discriminated meanings in popular speech, and in Psychology also their meanings run into each other. Both of them name processes in which we cognize an objective world; both (under normal conditions) need the stimulation of incoming nerves ere they can occur; Perception always involves Sensation as a portion of itself; and Sensation in turn never takes place in adult life without Perception also being there. They are therefore names for different cognitive functions, not for different sorts of mental fact. The nearer the object cognized comes to being a simple quality like 'hot,' 'cold,' 'red,' 'noise,' 'pain,' apprehended irrelatively to other things, the more the state of mind approaches pure sensation. The fuller of relations the object is, on the contrary; the more it is something classed, located, measured, compared, assigned to a function, etc., etc.; the more unreservedly do we call the state of mind a perception, and the relatively smaller is the part in it which sensation plays.

Sensation, then, so long as we take the analytic point of[Pg 2] view, differs from Perception only in the extreme simplicity of its object or content.[1] Its function is that of mere acquaintance with a fact. Perception's function, on the other hand, is knowledge about[2] a fact; and this knowledge admits of numberless degrees of complication. But in both sensation and perception we perceive the fact as an immediately present outward reality, and this makes them differ from 'thought' and 'conception,' whose objects do not appear present in this immediate physical way. From the physiological[Pg 3] point of view both sensations and perceptions differ from 'thoughts' (in the narrower sense of the word) in the fact that nerve-currents coming in from the periphery are involved in their production. In perception these nerve-currents arouse voluminous associative or reproductive processes in the cortex; but when sensation occurs alone, or with a minimum of perception, the accompanying reproductive processes are at a minimum too.

I shall in this chapter discuss some general questions more especially relative to Sensation. In a later chapter perception will take its turn. I shall entirely pass by the classification and natural history of our special 'sensations,' such matters finding their proper place, and being sufficiently well treated, in all the physiological books.[3]

A pure sensation is an abstraction; and when we adults talk of our 'sensations' we mean one of two things: either certain objects, namely simple qualities or attributes like hard, hot, pain; or else those of our thoughts in which acquaintance with these objects is least combined with knowledge about the relations of them to other things. As we can only think or talk about the relations of objects with which we have acquaintance already, we are forced to postulate a function in our thought whereby we first become aware of the bare immediate natures by which our several objects are distinguished. This function is sensation. And just as logicians always point out the distinction between substantive terms of discourse and relations found to obtain between them, so psychologists, as a rule, are ready to admit this function, of the vision of the terms or matters meant, as something distinct from the knowledge about them and of their relations inter se. Thought with the former function is sensational, with the latter, intellectual. Our earliest thoughts are almost exclusively sensational. They merely give us a set of thats, or its, of subjects[Pg 4] of discourse, with their relations not brought out. The first time we see light, in Condillac's phrase we are it rather rather than see it. But all our later optical knowledge is about what this experience gives. And though we were struck blind from that first moment, our scholarship in the subject would lack no essential feature so long as our memory remained. In training-institutions for the blind they teach the pupils as much about light as in ordinary schools. Reflection, refraction, the spectrum, the ether-theory, etc., are all studied. But the best taught born-blind pupil of such an establishment yet lacks a knowledge which the least instructed seeing baby has. They can never show him what light is in its 'first intention'; and the loss of that sensible knowledge no book-learning can replace. All this is so obvious that we usually find sensation 'postulated' as an element of experience, even by those philosophers who are least inclined to make much of its importance, or to pay respect to the knowledge which it brings.[4]

But the trouble is that most, if not all, of those who admit it, admit it as a fractional part of the thought, in the old-fashioned atomistic sense which we have so often criticised.

Take the pain called toothache for example. Again and again we feel it and greet it as the same real item in the universe. We must therefore, it is supposed, have a distinct pocket for it in our mind into which it and nothing else will fit. This pocket, when filled, is the sensation of toothache; and must be either filled or half-filled whenever and under whatever form toothache is present to our thought, and whether much or little of the rest of the mind be filled at the same time. Thereupon of course comes up the paradox and mystery: If the knowledge of toothache be pent up in this separate mental pocket, how can it be known cum alio or brought into one view with anything else? This pocket knows nothing else; no other part of the mind knows toothache. The knowing of toothache cum alio must be a miracle. And the miracle must have an Agent. And the Agent must be a Subject or Ego 'out of time,'—and all the rest of it, as we saw in Chapter X. And then begins the well-worn round of recrimination between the sensationalists and the spiritualists, from which we are saved by our determination from the outset to accept the psychological point of view, and to admit knowledge whether of simple toothaches or of philosophic systems as an ultimate fact. There are realities and there are 'states of mind,' and the latter know the former; and it is just as wonderful for a state of mind to be a 'sensation' and know a simple pain as for it to be a thought and know a system[Pg 6] of related things.[5] But there is no reason to suppose that when different states of mind know different things about the same toothache, they do so by virtue of their all containing faintly or vividly the original pain. Quite the reverse. The by-gone sensation of my gout was painful, as Reid somewhere says; the thought of the same gout as by-gone is pleasant, and in no respect resembles the earlier mental state.

Sensations, then, first make us acquainted with innumerable things, and then are replaced by thoughts which know the same things in altogether other ways. And Locke's main doctrine remains eternally true, however hazy some of his language may have been, that

"though there be a great number of considerations wherein things may be compared one with another, and so a multitude of relations; yet they all terminate in, and are concerned about, those simple ideas[6] either of sensation or reflection, which I think to be the whole materials of all our knowledge.... The simple ideas we receive from sensation and reflection are the boundaries of our thoughts; beyond which, the mind whatever efforts it would make, is not able to advance one jot; nor can it make any discoveries when it would pry into the nature and hidden causes of those ideas."[7]

The nature and hidden causes of ideas will never be unravelled till the nexus between the brain and consciousness is cleared up. All we can say now is that sensations are first things in the way of consciousness. Before conceptions can come, sensations must have come; but before sensations come, no psychic fact need have existed, a nerve-current is enough. If the nerve-current be not given, nothing else will take its place. To quote the good Locke again:

"It is not in the power of the most exalted wit or enlarged understanding, by any quickness or variety of thoughts, to invent or frame[Pg 7] one new simple idea [i.e. sensation] in the mind.... I would have any one try to fancy any taste which had never affected his palate, or frame the idea of a scent he had never smelt; and when he can do this, I will also conclude that a blind man hath ideas of colors, and a deaf man true distinct notions of sounds."[8]

The brain is so made that all currents in it run one way. Consciousness of some sort goes with all the currents, but it is only when new currents are entering that it has the sensational tang. And it is only then that consciousness directly encounters (to use a word of Mr. Bradley's) a reality outside itself.

The difference between such encounter and all conceptual knowledge is very great. A blind man may know all about the sky's blueness, and I may know all about your toothache, conceptually; tracing their causes from primeval chaos, and their consequences to the crack of doom. But so long as he has not felt the blueness, nor I the toothache, our knowledge, wide as it is, of these realities, will be hollow and inadequate. Somebody must feel blueness, somebody must have toothache, to make human knowledge of these matters real. Conceptual systems which neither began nor left off in sensations would be like bridges without piers. Systems about fact must plunge themselves into sensation as bridges plunge their piers into the rock. Sensations are the stable rock, the terminus a quo and the terminus ad quem of thought. To find such termini is our aim with all our theories—to conceive first when and where a certain sensation may be had, and then to have it. Finding it stops discussion. Failure to find it kills the false conceit of knowledge. Only when you deduce a possible sensation for me from your theory, and give it to me when and where the theory requires, do I begin to be sure that your thought has anything to do with truth.

Pure sensations can only be realized in the earliest days of life. They are all but impossible to adults with memories and stores of associations acquired. Prior to all impressions on sense-organs the brain is plunged in deep sleep and consciousness is practically non-existent. Even the first weeks[Pg 8] after birth are passed in almost unbroken sleep by human infants. It takes a strong message from the sense-organs to break this slumber. In a new-born brain this gives rise to an absolutely pure sensation. But the experience leaves its 'unimaginable touch' on the matter of the convolutions, and the next impression which a sense-organ transmits produces a cerebral reaction in which the awakened vestige of the last impression plays its part. Another sort of feeling and a higher grade of cognition are the consequence; and the complication goes on increasing till the end of life, no two successive impressions falling on an identical brain, and no two successive thoughts being exactly the same. (See Vol. I, p. 230 ff.)

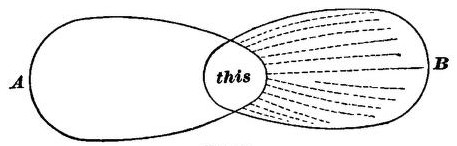

The first sensation which an infant gets is for him the Universe. And the Universe which he later comes to know is nothing but an amplification and an implication of that first simple germ which, by accretion on the one hand and intussusception on the other, has grown so big and complex and articulate that its first estate is unrememberable. In his dumb awakening to the consciousness of something there, a mere this as yet (or something for which even the term this would perhaps be too discriminative, and the intellectual acknowledgment of which would be better expressed by the bare interjection 'lo!'), the infant encounters an object in which (though it be given in a pure sensation) all the 'categories of the understanding' are contained. It has objectivity, unity, substantiality, causality, in the full sense in which any later object or system of objects has these things. Here the young knower meets and greets his world; and the miracle of knowledge bursts forth, as Voltaire says, as much in the infant's lowest sensation as in the highest achievement of a Newton's brain. The physiological condition of this first sensible experience is probably nerve-currents coming in from many peripheral organs at once. Later, the one confused Fact which these currents cause to appear is perceived to be many facts, and to contain many qualities.[9] For as the currents vary, and the brain-paths[Pg 9] are moulded by them, other thoughts with other 'objects' come, and the 'same thing' which was apprehended as a present this soon figures as a past that, about which many unsuspected things have come to light. The principles of this development have been laid down already in Chapters XII and XIII, and nothing more need here be added to that account.

To the reader who is tired of so much Erkenntnisstheorie I can only say that I am so myself, but that it is indispensable, in the actual state of opinions about Sensation, to try to clear up just what the word means. Locke's pupils seek to do the impossible with sensations, and against them we must once again insist that sensations 'clustered together' cannot build up our more intellectual states of mind. Plato's earlier pupils used to admit Sensation's existence, grudgingly, but they trampled it in the dust as something corporeal, non-cognitive, and vile.[10] His latest followers[Pg 10] seem to seek to crowd it out of existence altogether. The only reals for the neo-Hegelian writers appear to be relations, relations without terms, or whose terms are only speciously such and really consist in knots, or gnarls of relations finer still in infinitum.

"Exclude from what we have considered real all qualities constituted by relation, we find that none are left." "Abstract the many relations from the one thing and there is nothing.... Without the relations it would not exist at all."[11] "The single feeling is nothing[Pg 11] real." "On the recognition of relations as constituting the nature of ideas, rests the possibility of any tenable theory of their reality."

Such quotations as these from the late T. H. Green[12] would be matters of curiosity rather than of importance, were it not that sensationalist writers themselves believe in a so-called 'Relativity of Knowledge,' which, if they only understood it, they would see to be identical with Professor Green's doctrine. They tell us that the relation of sensations to each other is something belonging to their essence, and that no one of them has an absolute content:

"That, e.g., black can only be felt in contrast to white, or at least in distinction from a paler or a deeper black; similarly a tone or a sound only in alternation with others or with silence; and in like manner a smell, a taste, a touch, only, so to speak, in statu nascendi, whilst, when the stimulus continues, all sensation disappears. This all seems at first sight to be splendidly consistent both with itself and with the facts. But looked at more closely, it is seen that neither is the case."[13]

The two leading facts from which the doctrine of universal relativity derives its wide-spread credit are these:

1) The psychological fact that so much of our actual knowledge is of the relations of things—even our simplest sensations in adult life are habitually referred to classes as we take them in; and

2) The physiological fact that our senses and brain must have periods of change and repose, else we cease to feel and think.

Neither of these facts proves anything about the presence or non-presence to our mind of absolute qualities with which we become sensibly acquainted. Surely not the psychological fact; for our inveterate love of relating and comparing things does not alter the intrinsic qualities or nature of the things compared, or undo their absolute givenness. And surely not the physiological fact; for the length of time during which we can feel or attend to a quality is altogether irrelevant to the intrinsic constitution of the quality felt. The time, moreover, is long enough in many instances, as sufferers from neuralgia know.[14] And the doctrine of relativity, not proved by these facts, is flatly disproved by other facts even more patent. So far are we from not knowing (in the words of Professor Bain) "any one thing by itself, but only the difference between it and another thing," that if this were true the whole edifice of our knowledge would collapse. If all we felt were the difference between the C and D, or c and d, on the musical scale, that being the same in the two pairs of notes, the pairs themselves would be the same, and language could get along without substantives. But Professor Bain does not mean seriously what he says, and we need spend no more time on this vague and popular form of the doctrine.[15] The facts which seem to hover before the minds[Pg 13] of its champions are those which are best described under the head of a physiological law.

I will first enumerate the main facts which fall under this law, and then remark upon what seems to me their significance for psychology.[16]

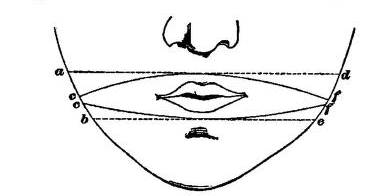

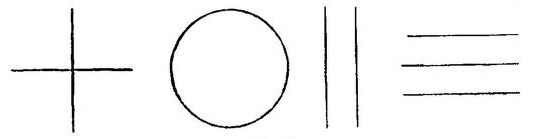

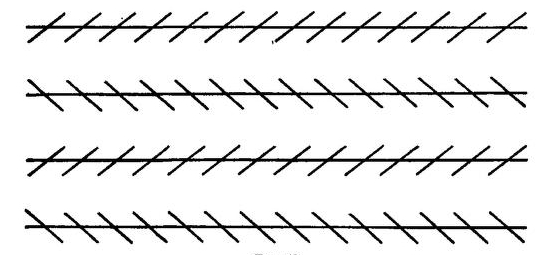

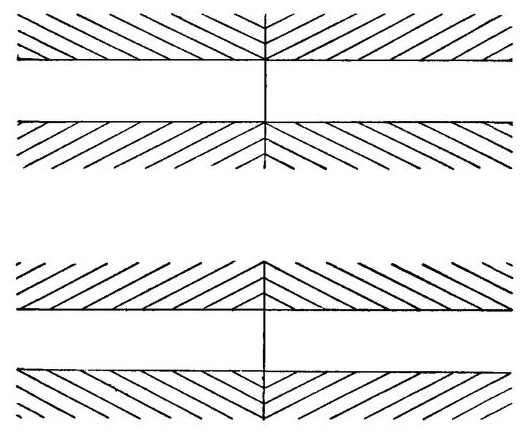

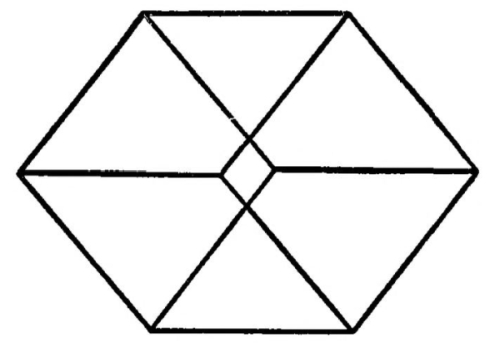

[Nowhere are the phenomena of contrast better exhibited, and their laws more open to accurate study, than in connection with the sense of sight. Here both kinds—simultaneous and successive—can easily be observed, for they are of constant occurrence. Ordinarily they remain unnoticed, in accordance with the general law of economy which causes us to select for conscious notice only such elements of our object as will serve us for æsthetic or practical utility, and to neglect the rest; just as we ignore the double images, the mouches volantes, etc., which exist for everyone, but which are not discriminated without careful attention. But by attention we may easily discover the general facts involved in contrast. We find that in general the color and brightness of one object always apparently affect the color and brightness of any other object seen simultaneously with it or immediately after.

In the first place, if we look for a moment at any surface and then turn our eyes elsewhere, the complementary color and opposite degree of brightness to that of the first surface tend to mingle themselves with the color and the brightness of the second. This is successive contrast. It finds its explanation in the fatigue of the organ of sight, causing it to respond to any particular stimulus less and less readily the longer such stimulus continues to act. This is shown clearly in the very marked changes which occur in case of continued fixation of one particular point of any field. The field darkens slowly, becomes more and more indistinct, and finally, if one is practised enough in holding the eye perfectly[Pg 14] steady, slight differences in shade and color may entirely disappear. If we now turn aside the eyes, a negative after-image of the field just fixated at once forms, and mingles its sensations with those which may happen to come from anything else looked at. This influence is distinctly evident only when the first surface has been 'fixated' without movement of the eyes. It is, however, none the less present at all times, even when the eye wanders from point to point, causing each sensation to be modified more or less by that just previously experienced. On this account successive contrast is almost sure to be present in cases of simultaneous contrast, and to complicate the phenomena.

A visual image is modified not only by other sensations just previously experienced, but also by all those experienced simultaneously with it, and especially by such as proceed from contiguous portions of the retina. This is the phenomenon of simultaneous contrast. In this, as in successive contrast, both brightness and hue are involved. A bright object appears still brighter when its surroundings are darker than itself, and darker when they are brighter than itself. Two colors side by side are apparently changed by the admixture, with each, of the complement of the other. And lastly, a gray surface near a colored one is tinged with the complement of the latter.[17]

The phenomena of simultaneous contrast in sight are so complicated by other attendant phenomena that it is difficult[Pg 15] to isolate them and observe them in their purity. Yet it is evidently of the greatest importance to do so, if one would conduct his investigations accurately. Neglect of this principle has led to many mistakes being made in accounting for the facts observed. As we have seen, if the eye is allowed to wander here and there about the field as it ordinarily does, successive contrast results and allowance must be made for its presence. It can be avoided only by carefully fixating with the well-rested eye a point of one field, and by then observing the changes which occur in this field when the contrasting field is placed by its side. Such a course will insure pure simultaneous contrast. But even thus it lasts in its purity for a moment only. It reaches its maximum of effect immediately after the introduction of the contrasting field, and then, if the fixation is continued, it begins to weaken rapidly and soon disappears; thus undergoing changes similar to those observed when any field whatever is fixated steadily and the retina becomes fatigued by unchanging stimuli. If one continues still further to fixate the same point, the color and brightness of one field tend to spread themselves over and mingle with the color and brightness of the neighboring fields, thus substituting 'simultaneous induction' for simultaneous contrast.

Not only must we recognize and eliminate the effects of successive contrast, of temporal changes due to fixation, and of simultaneous induction, in analyzing the phenomena of simultaneous contrast, but we must also take into account various other influences which modify its effects. Under favorable circumstances the contrast-effects are very striking, and did they always occur as strongly they could not fail to attract the attention. But they are not always clearly apparent, owing to various disturbing causes which form no exception to the laws of contrast, but which have a modifying effect on its phenomena. When, for instance, the ground observed has many distinguishable features—a coarse grain, rough surface, intricate pattern, etc.—the contrast effect appears weaker. This does not imply that the effects of contrast are absent, but merely that the resulting sensations are overpowered by the many other stronger[Pg 16] sensations which entirely occupy the attention. On such a ground a faint negative after-image—undoubtedly due to retinal modifications—may become invisible; and even weak objective differences in color may become imperceptible. For example, a faint spot or grease-stain on woollen cloth, easily seen at a distance, when the fibres are not distinguishable, disappears when closer examination reveals the intricate nature of the surface.

Another frequent cause of the apparent absence of contrast is the presence of narrow dark intermediate fields, such as are formed by bordering a field with black lines, or by the shaded contours of objects. When such fields interfere with the contrast, it is because black and white can absorb much color without themselves becoming clearly colored; and because such lines separate other fields too far for them to distinctly influence one another. Even weak objective differences in color may be made imperceptible by such means.

A third case where contrast does not clearly appear is where the color of the contrasting fields is too weak or too intense, or where there is much difference in brightness between the two fields. In the latter case, as can easily be shown, it is the contrast of brightness which interferes with the color-contrast and makes it imperceptible. For this reason contrast shows best between fields of about equal brightness. But the intensity of the color must not be too great, for then its very darkness necessitates a dark contrasting field which is too absorbent of induced color to allow the contrast to appear strongly. The case is similar if the fields are too light.

To obtain the best contrast-effects, therefore, the contracting fields should be near together, should not be separated by shadows or black lines, should be of homogeneous texture, and should be of about equal brightness and medium intensity of color. Such conditions do not often occur naturally, the disturbing influences being present in case of almost all ordinary objects, thus making the effects of contrast far less evident. To eliminate these disturbances and to produce the conditions most favorable for the appearance of good contrast-effects,[Pg 17] various experiments have been devised, which will be explained in comparing the rival theories of explanation.

There are two theories—the psychological and the physiological—which attempt to explain the phenomena of contrast.

Of these the psychological one was the first to gain prominence. Its most able advocate has been Helmholtz. It explains contrast as a deception of judgment. In ordinary life our sensations have interest for us only so far as they give us practical knowledge. Our chief concern is to recognize objects, and we have no occasion to estimate exactly their absolute brightness and color. Hence we gain no facility in so doing, but neglect the constant changes in their shade, and are very uncertain as to the exact degree of their brightness or tone of their color. When objects are near one another "we are inclined to consider those differences which are clearly and surely perceived as greater than those which appear uncertain in perception or which must be judged by aid of memory,"[18] just as we see a medium-sized man taller than he really is when he stands beside a short man. Such deceptions are more easily possible in the judgment of small differences than of large ones; also where there is but one element of difference instead of many. In a large number of cases of contrast, in all of which a whitish spot is surrounded on all sides by a colored surface—Meyer's experiment, the mirror experiment, colored shadows, etc., soon to be described—the contrast is produced, according to Helmholtz, by the fact that "a colored illumination or a transparent colored covering appears to be spread out over the field, and observation does not show directly that it fails on the white spot."[19] We therefore believe that we see the latter through the former color. Now

"Colors have their greatest importance for us in so far as they are properties of bodies and can serve as signs for the recognition of bodies.... We have become accustomed, in forming a judgment in regard to the colors of bodies, to eliminate the varying brightness and[Pg 18] color of the illumination. We have sufficient opportunity to investigate the same colors of objects in full sunshine, in the blue light of the clear sky, in the weak white light of a cloudy day, in the reddish-yellow light of the sinking sun or of the candle. Moreover the colored reflections of surrounding objects are involved. Since we see the same colored objects under these varying illuminations, we learn to form a correct conception of the color of the object in spite of the difference in illumination, i.e. to judge how such an object would appear in white illumination; and since only the constant color of the object interests us, we do not become conscious of the particular sensations on which our judgment rests. So also we are at no loss, when we see an object through a colored covering, to distinguish what belongs to the color of the covering and what to the object. In the experiments mentioned we do the same also where the covering over the object is not at all colored, because of the deception into which we fall, and in consequence of which we ascribe to the body a false color, the color complementary to the colored portion of the covering."[20]

We think that we see the complementary color through the colored covering,—for these two colors together would give the sensation of white which is actually experienced. If, however, in any way the white spot is recognized as an independent object, or if it is compared with another object known to be white, our judgment is no longer deceived and the contrast does not appear.

"As soon as the contrasting field is recognized as an independent body which lies above the colored ground, or even through an adequate tracing of its outlines is seen to be a separate field, the contrast disappears. Since, then, the judgment of the spatial position, the material independence, of the object in question is decisive for the determination of its color, it follows that the contrast-color arises not through an act of sensation but through an act of judgment."[21]

In short, the apparent change in color or brightness through contrast is due to no change in excitation of the organ, to no change in sensation; but in consequence of a false judgment the unchanged sensation is wrongly interpreted, and thus leads to a changed perception of the brightness or color.

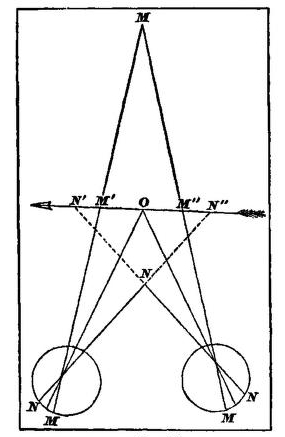

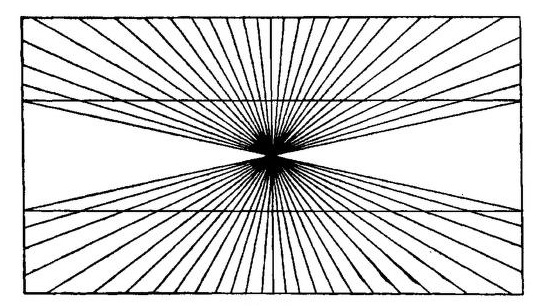

In opposition to this theory has been developed one which attempts to explain all cases of contrast as depending[Pg 19] purely on physiological action of the terminal apparatus of vision. Hering is the most prominent supporter of this view. By great originality in devising experiments and by insisting on rigid care in conducting them, he has been able to detect the faults in the psychological theory and to practically establish the validity of his own. Every visual sensation, he maintains, is correlated to a physical process in the nervous apparatus. Contrast is occasioned, not by a false idea resulting from unconscious conclusions, but by the fact that the excitation of any portion of the retina—and the consequent sensation—depends not only on its own illumination, but on that of the rest of the retina as well.

"If this psycho-physical process is aroused, as usually happens, by light-rays impinging on the retina, its nature depends not only on the nature of these rays, but also on the constitution of the entire nervous apparatus which is connected with the organ of vision, and on the state in which it finds itself."[22]

When a limited portion of the retina is aroused by external stimuli, the rest of the retina, and especially the immediately contiguous parts, tends to react also, and in such a way as to produce therefrom the sensation of the opposite degree of brightness and the complementary color to that of the directly-excited portion. When a gray spot is seen alone, and again when it appears colored through contrast, the objective light from the spot is in both cases the same. Helmholtz maintains that the neural process and the corresponding sensation also remain unchanged, but are differently interpreted; Hering, that the neural process and the sensation are themselves changed, and that the 'interpretation' is the direct conscious correlate of the altered retinal conditions. According to the one, the contrast is psychological in its origin; according to the other, it is purely physiological. In the cases cited above where the contrast-color is no longer apparent—on a ground with many distinguishable features, on a field whose borders are traced with black lines, etc.,—the psychological theory, as we have seen, attributes this to the fact that under these circumstances we judge the smaller patch of color to be an[Pg 20] independent object on the surface, and are no longer deceived in judging it to be something over which the color of the ground is drawn. The physiological theory, on the other hand, maintains that the contrast-effect is still produced, but that the conditions are such that the slight changes in color and brightness which it occasions become imperceptible.

The two theories, stated thus broadly, may seem equally plausible. Hering, however, has conclusively proved, by experiments with after-images, that the process on one part of the retina does modify that on neighboring portions, under conditions where deception of judgment is impossible.[23] A careful examination of the facts of contrast will show that its phenomena must be due to this cause. In all the cases which one may investigate it will be seen that the upholders of the psychological theory have failed to conduct their experiments with sufficient care. They have not excluded successive contrast, have overlooked the changes due to[Pg 21] steady fixation, and have failed to properly account for the various modifying influences which have been mentioned above. We can easily establish this if we examine the most striking experiments in simultaneous contrast.

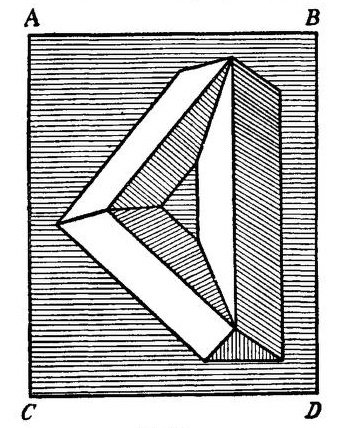

Of these one of the best known and most easily arranged is that known as Meyer's experiment. A scrap of gray paper is placed on a colored background, and both are covered by a sheet of transparent white paper. The gray spot then assumes a contrast-color, complementary to that of the background, which shines with a whitish tinge through the paper which covers it. Helmholtz explains the phenomenon thus:

"If the background is green, the covering-paper itself appears to be of a greenish color. If now the substance of the paper extends without apparent interruption over the gray which lies under it, we think that we see an object glimmering through the greenish paper, and such an object must in turn be rose-red, in order to give white light. If, however, the gray spot has its limits so fixed that it appears to be an independent object, the continuity with the greenish portion of the surface fails, and we regard it as a gray object which lies on this surface."[24]

The contrast-color may thus be made to disappear by tracing in black the outlines of the gray scrap, or by placing above the tissue paper another gray scrap of the same degree of brightness, and comparing together the two grays. On neither of them does the contrast-color now appear.

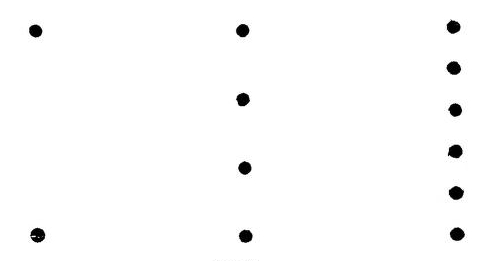

Hering[25] shows clearly that this interpretation is incorrect, and that the disturbing factors are to be otherwise explained. In the first place, the experiment can be so arranged that we could not possibly be deceived into believing that we see the gray through a colored medium. Out of a sheet of gray paper cut strips 5 mm. wide in such a way that there will be alternately an empty space and a bar of gray, both of the same width, the bars being held together by the uncut edges of the gray sheet (thus presenting an appearance like a gridiron). Lay this on a colored background—e.g. green—cover both with transparent paper, and above all put a black frame which covers all the edges, leaving visible only the bars, which are now alternately[Pg 22] green and gray. The gray bars appear strongly colored by contrast, although, since they occupy as much space as the green bars, we are not deceived into believing that we see the former through a green medium. The same is true if we weave together into a basket pattern narrow strips of green and gray and cover them with the transparent paper.

Why, then, if it is a true sensation due to physiological causes, and not an error of judgment, which causes the contrast, does the color disappear when the outlines of the gray scrap are traced, enabling us to recognize it as an independent object? In the first place, it does not necessarily do so, as will easily be seen if the experiment is tried. The contrast-color often remains distinctly visible in spite of the black outlines. In the second place, there are many adequate reasons why the effect should be modified. Simultaneous contrast is always strongest at the border-line of the two fields; but a narrow black field now separates the two, and itself by contrast strengthens the whiteness of both original fields, which were already little saturated in color; and on black and on white, contrast-colors show only under the most favorable circumstances. Even weak objective differences in color may be made to disappear by such tracing of outlines, as can be seen if we place on a gray background a scrap of faintly-colored paper, cover it with transparent paper and trace its outlines. Thus we see that it is not the recognition of the contrasting field as an independent object which interferes with its color, but rather a number of entirely explicable physiological disturbances.

The same may be proved in the case of holding above the tissue paper a second gray scrap and comparing it with that underneath. To avoid the disturbances caused by using papers of different brightness, the second scrap should be made exactly like the first by covering the same gray with the same tissue paper, and carefully cutting a piece about 10 mm. square out of both together. To thoroughly guard against successive contrast, which so easily complicates the phenomena, we must carefully prevent all previous excitation of the retina by colored light. This may be done by arranging thus: Place the sheet of tissue paper[Pg 23] on a glass pane, which rests on four supports; under the paper put the first gray scrap. By means of a wire, fasten the second gray scrap 2 or 3 cm. above the glass plate. Both scraps appear exactly alike, except at the edges. Gaze now at both scraps, with eyes not exactly accommodated, so that they appear near one another, with a very narrow space between. Shove now a colored field (green) underneath the glass plate, and the contrast appears at once on both scraps. If it appears less clearly on the upper scrap, it is because of its bright and dark edges, its inequalities, its grain, etc. When the accommodation is exact, there is no essential change, although then on the upper scrap the bright edge on the side toward the light, and the dark edge on the shadow side, disturb somewhat. By continued fixation the contrast becomes weaker and finally yields to simultaneous induction, causing the scraps to become indistinguishable from the ground. Remove the green field and both scraps become green, by successive induction. If the eye moves about freely these last-named phenomena do not appear, but the contrast continues indefinitely and becomes stronger. When Helmholtz found that the contrast on the lower scrap disappeared, it was evidently because he then really held the eye fixed. This experiment may be disturbed by holding the upper scrap wrongly and by the differences in brightness of its edges, or by other inequalities, but not by that recognizing of it 'as an independent body lying above the colored ground,' on which the psychological explanation rests.

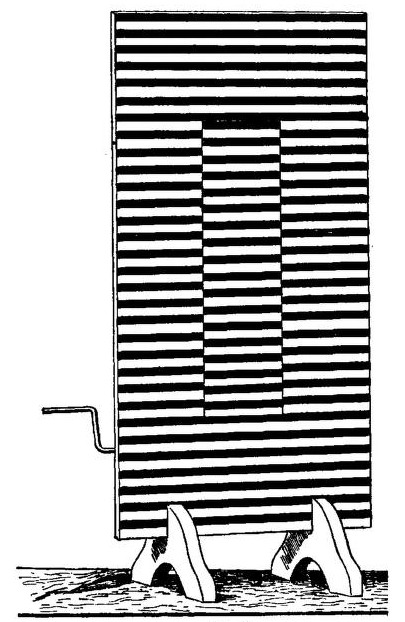

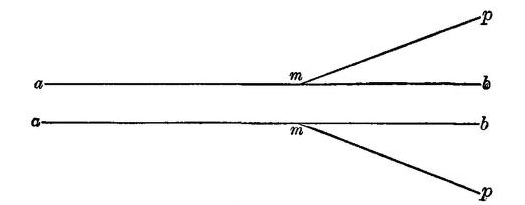

In like manner the claims of the psychological explanation can be shown to be inadequate in other cases of contrast. Of frequent use are revolving disks, which are especially efficient in showing good contrast-phenomena, because all inequalities of the ground disappear and leave a perfectly homogeneous surface. On a white disk are arranged colored sectors, which are interrupted midway by narrow black fields in such a way that when the disk is revolved the white becomes mixed with the color and the black, forming a colored disk of weak saturation on which appears a gray ring. The latter is colored by contrast with[Pg 24] the field which surrounds it. Helmholtz explains the fact thus:

"The difference of the compared colors appears greater than it really is either because this difference, when it is the only existing one and draws the attention to itself alone, makes a stronger impression than when it is one among many, or because the different colors of the surface are conceived as alterations of the one ground-color of the surface such as might arise through shadows falling on it, through colored reflexes, or through mixture with colored paint or dust. In truth, to produce an objectively gray spot on a green surface, a reddish coloring would be necessary."[26]

This explanation is easily proved false by painting the disk with narrow green and gray concentric rings, and giving each a different saturation. The contrast appears though there is no ground-color, and no longer a single difference, but many. The facts which Helmholtz brings forward in support of his theory are also easily turned against him. He asserts that if the color of the ground is too intense, or if the gray ring is bordered by black circles, the contrast becomes weaker; that no contrast appears on a white scrap held over the colored field; and that the gray ring when compared with such scrap loses its contrast-color either wholly or in part. Hering points out the inaccuracy of all these claims. Under favorable conditions it is impossible to make the contrast disappear by means of black enclosing lines, although they naturally form a disturbing element; increase in the saturation of the field, if disturbance through increasing brightness-contrast is to be avoided, demands a darker gray field, on which contrast-colors are less easily perceived; and careful use of the white scrap leads to entirely different results. The contrast-color does appear upon it when it is first placed above the colored field; but if it is carefully fixated, the contrast-color diminishes very rapidly both on it and on the ring, from causes already explained. To secure accurate observation, all complication through successive contrast should be avoided thus: first arrange the white scrap, then interpose a gray screen between it and the disk, rest the eye, set the wheel in motion, fixate the scrap, and then have the screen[Pg 25] removed. The contrast at once appears clearly, and its disappearance through continued fixation can be accurately watched.

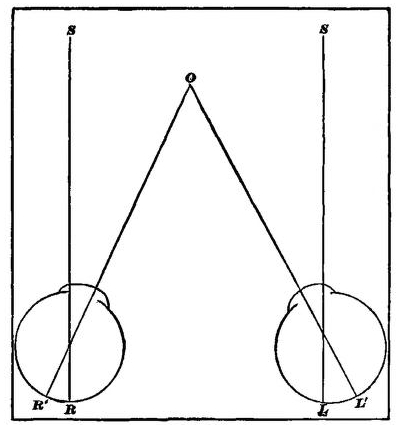

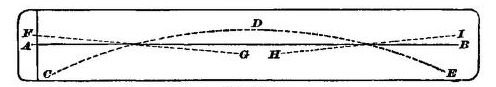

Brief mention of a few other cases of contrast must suffice. The so-called mirror experiment consists of placing at an angle of 45º a green (or otherwise colored) pane of glass, forming an angle with two white surfaces, one horizontal and the other vertical. On each white surface is a black spot. The one on the horizontal surface is seen through the glass and appears dark green, the other is reflected from the surface of the glass to the eye, and appears by contrast red. The experiment may be so arranged that we are not aware of the presence of the green glass, but think that we are looking directly at a surface with green and red spots upon it; in such a case there is no deception of judgment caused by making allowance for the colored medium through which we think that we see the spot, and therefore the psychological explanation does not apply. On excluding successive contrast by fixation the contrast soon disappears as in all similar experiments.[27]

Colored shadows have long been thought to afford a convincing proof of the fact that simultaneous contrast is psychological in its origin. They are formed whenever an opaque object is illuminated from two separate sides by lights of different colors. When the light from one source is white, its shadow is of the color of the other light, and the second shadow is of a color complementary to that of the field illuminated by both lights. If now we take a tube, blackened inside, and through it look at the colored shadow, none of the surrounding field being visible, and then have the colored light removed, the shadow still appears colored, although 'the circumstances which caused it have disappeared.' This is regarded by the psychologists as conclusive evidence that the color is due to deception of judgment. It can, however, easily be shown that the persistence of the color seen through the tube is due to fatigue of the retina through the prevailing light, and that when the colored light is removed the color slowly disappears as the[Pg 26] equilibrium of the retina becomes gradually restored. When successive contrast is carefully guarded against, the simultaneous contrast, whether seen directly or through the tube, never lasts for an instant on removal of the colored field. The physiological explanation applies throughout to all the phenomena presented by colored shadows.[28]

If we have a small field whose illumination remains constant, surrounded by a large field of changing brightness, an increase or decrease in brightness of the latter results in a corresponding apparent decrease or increase respectively in the brightness of the former, while the large field seems to be unchanged. Exner says:

"This illusion of sense shows that we are inclined to regard as constant the dominant brightness in our field of vision, and hence to refer the changing difference between this and the brightness of a limited field to a change in brightness of the latter."

The result, however, can be shown to depend not on illusion, but on actual retinal changes, which alter the sensation experienced. The irritability of those portions of the retina lighted by the large field becomes much reduced in consequence of fatigue, so that the increase in brightness becomes much less apparent than it would be without this diminution in irritability. The small field, however, shows the change by a change in the contrast-effect induced upon it by the surrounding parts of the retina.[29]

The above cases show clearly that physiological processes, and not deception of judgment, are responsible for contrast of color. To say this, however, is not to maintain that our perception of a color is never in any degree modified by our judgment of what the particular colored thing before us may be. We have unquestionable illusions of color due to wrong inferences as to what object is before us. Thus Von Kries[30] speaks of wandering through evergreen forests covered with snow, and thinking that through the interstices of the boughs he saw the deep blue of pine-clad mountains, covered[Pg 27] with snow and lighted by brilliant sunshine; whereas what he really saw was the white snow on trees near by, lying in shadow].[31]

Such a mistake as this is undoubtedly of psychological origin. It is a wrong classification of the appearances, due to the arousal of intricate processes of association amongst which is the suggestion of a different hue from that really before the eyes. In the ensuing chapters such illusions as this will be treated of in considerable detail. But it is a mistake to interpret the simpler cases of contrast in the light of such illusions as these. These illusions can be rectified in an instant, and we then wonder how they could have been. They come from insufficient attention, or from the fact that the impression which we get is a sign of more than one possible object, and can be interpreted in either way. In none of these points do they resemble simple color-contrast, which unquestionably is a phenomenon of sensation immediately aroused.

I have dwelt upon the facts of color-contrast at such great length because they form so good a text to comment on in my struggle against the view that sensations are immutable psychic things which coexist with higher mental functions. Both sensationalists and intellectualists agree that such sensations exist. They fuse, say the pure sensationalists, and make the higher mental function; they are combined by activity of the Thinking Principle, say the intellectualists. I myself have contended that they do not exist in or alongside of the higher mental function when that exists. The things which arouse them exist; and the higher mental function also knows these same things. But just as its knowledge of the things supersedes and displaces their knowledge, so it supersedes and displaces them, when it comes, being as much as they are a direct resultant of whatever momentary brain-conditions may obtain. The psychological theory of contrast, on the other hand, holds the sensations still to exist in themselves unchanged before the mind, whilst the 'relating activity' of the latter[Pg 28] deals with them freely and settles to its own satisfaction what each shall be, in view of what the others also are. Wundt says expressly that the Law of Relativity is "not a law of sensation but a law of Apperception;" and the word Apperception connotes with him a higher intellectual spontaneity.[32] This way of taking things belongs with the philosophy that looks at the data of sense as something earth-born and servile, and the 'relating of them together' as something spiritual and free. Lo! the spirit can even change the intrinsic quality of the sensible facts themselves if by so doing it can relate them better to each other! But (apart from the difficulty of seeing how changing the sensations should relate them better) is it not manifest that the relations are part of the 'content' of consciousness, part of the 'object,' just as much as the sensations are? Why ascribe the former exclusively to the knower and the latter to the known? The knower is in every case a unique pulse of thought corresponding to a unique reaction of the brain upon its conditions. All that the facts of contrast show us is that the same real thing may give us quite different sensations when the conditions alter, and that we must therefore be careful which one to select as the thing's truest representative.

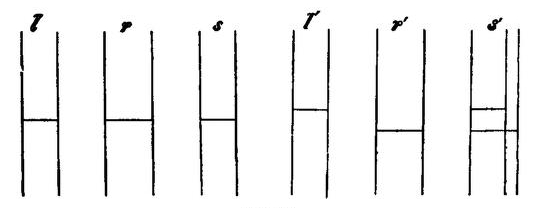

There are many other facts beside the phenomena of contrast which prove that when two objects act together on us the sensation which either would give alone becomes a different sensation. A certain amount of skin dipped in hot water gives the perception of a certain heat. More skin immersed makes the heat much more intense, although of course the water's heat is the same. A certain extent as well as intensity, in the quantity of the stimulus is requisite for any quality to be felt. Fick and Wunderli could not distinguish heat from touch when both were applied through a[Pg 29] hole in a card, and so confined to a small part of the skin. Similarly there is a chromatic minimum of size in objects. The image they cast on the retina must needs have a certain extent, or it will give no sensation of color at all. Inversely, more intensity in the outward impression may make the subjective object more extensive. This happens, as will be shown in Chapter XIX, when the illumination is increased: The whole room expands and dwindles according as we raise or lower the gas-jet. It is not easy to explain any of these results as illusions of judgment due to the inference of a wrong objective cause for the sensation which we get. No more is this easy in the case of Weber's observation that a thaler laid on the skin of the forehead feels heavier when cold than when warm; or of Szabadföldi's observation that small wooden disks when heated to 122° Fahrenheit often feel heavier than those which are larger but not thus warmed;[33] or of Hall's observation that a heavy point moving over the skin seems to go faster than a lighter one moving at the same rate of speed.[34]

Bleuler and Lehmann some years ago called attention to a strange idiosyncrasy found in some persons, and consisting in the fact that impressions on the eye, skin, etc., were accompanied by distinct sensations of sound.[35] Colored hearing is the name sometimes given to the phenomenon, which has now been repeatedly described. Quite lately the Viennese aurist Urbantschitsch has proved that these cases are only extreme examples of a very general law, and that all our sense-organs influence each other's sensations.[36] The hue of patches of color so distant as not to be recognized was immediately, in U.'s patients, perceived when a tuning-fork was sounded close to the ear. Sometimes, on the contrary, the field was darkened by the sound. The acuity of vision was increased, so that letters too far off to be read could be read when the tuning-fork was heard. Urbantschitsch, varying his experiments, found that their[Pg 30] results were mutual, and that sounds which were on the limits of audibility became audible when lights of various colors were exhibited to the eye. Smell, taste, touch, sense of temperature, etc., were all found to fluctuate when lights were seen and sounds were heard. Individuals varied much in the degree and kind of effect produced, but almost every one experimented on seems to have been in some way affected. The phenomena remind one somewhat of the 'dynamogenic' effects of sensations upon the strength of muscular contraction observed by M. Féré, and later to be described. The most familiar examples of them seem to be the increase of pain by noise or light, and the increase of nausea by all concomitant sensations. Persons suffering in any way instinctively seek stillness and darkness.

Probably every one will agree that the best way of formulating all such facts is physiological: it must be that the cerebral process of the first sensation is reinforced or otherwise altered by the other current which comes in. No one, surely, will prefer a psychological explanation here. Well, it seems to me that all cases of mental reaction to a plurality of stimuli must be like these cases, and that the physiological formulation is everywhere the simplest and the best. When simultaneous red and green light make us see yellow, when three notes of the scale make us hear a chord, it is not because the sensations of red and of green and of each of the three notes enter the mind as such, and there 'combine' or 'are combined by its relating activity' into the yellow and the chord, it is because the larger sum of light-waves and of air-waves arouses new cortical processes, to which the yellow and the chord directly correspond. Even when the sensible qualities of things enter into the objects of our highest thinking, it is surely the same. Their several sensations do not continue to exist there tucked away. They are replaced by the higher thought which, although a different psychic unit from them, knows the same sensible qualities which they know.

The principles laid down in Chapter VI seem then to be corroborated in this new connection. You cannot build up one thought or one sensation out of many; and only direct[Pg 31] experiment can inform us of what we shall perceive when we get many stimuli at once.

We often hear the opinion expressed that all our sensations at first appear to us as subjective or internal, and are afterwards and by a special act on our part 'extradited' or 'projected' so as to appear located in an outer world. Thus we read in Professor Ladd's valuable work that

"Sensations... are psychical states whose place—so far as they can be said to have one—is the mind. The transference of these sensations from mere mental states to physical processes located in the periphery of the body, or to qualities of things projected in space external to the body, is a mental act. It may rather be said to be a mental achievement [cf. Cudworth, note 10, as to knowledge being conquering], for it is an act which in its perfection results from a long and intricate process of development.... Two noteworthy stages, or 'epoch-making' achievements in the process of elaborating the presentations of sense, require a special consideration. These are 'localization,' or the transference of the composite sensations from mere states of the mind to processes or conditions recognized as taking place at more or less definitely fixed points or areas of the body; and 'eccentric projection' (sometimes called 'eccentric perception') or the giving to these sensations an objective existence (in the fullest sense of the word 'objective') as qualities of objects situated within a field of space and in contact with, or more or less remotely distant from, the body."[37]

It seems to me that there is not a vestige of evidence for this view. It hangs together with the opinion that our sensations are originally devoid of all spatial content,[38] an opinion which I confess that I am wholly at a loss to understand. As I look at my bookshelf opposite I cannot frame to myself an idea, however imaginary, of any feeling which I could ever possibly have got from it except the feeling of[Pg 32] the same big extended sort of outward fact which I now perceive. So far is it from being true that our first way of feeling things is the feeling of them as subjective or mental, that the exact opposite seems rather to be the truth. Our earliest, most instinctive, least developed kind of consciousness is the objective kind; and only as reflection becomes developed do we become aware of an inner world at all. Then indeed we enrich it more and more, even to the point of becoming idealists, with the spoils of the outer world which at first was the only world we knew. But subjective consciousness, aware of itself as subjective, does not at first exist. Even an attack of pain is surely felt at first objectively as something in space which prompts to motor reaction, and to the very end it is located, not in the mind, but in some bodily part.

"A sensation which should not awaken an impulse to move, nor any tendency to produce an outward effect, would manifestly be useless to a living creature. On the principles of evolution such a sensation could never be developed. Therefore every sensation originally refers to something external and independent of the sentient creature. Rhizopods (according to Engelmann's observations) retract their pseudopodia whenever these touch foreign bodies, even if these foreign bodies are the pseudopodia of other individuals of their own species, whilst the mutual contact of their own pseudopodia is followed by no such contraction. These low animals can therefore already feel an outer world—even in the absence of innate ideas of causality, and probably without any clear consciousness of space. In truth the conviction that something exists outside of ourselves does not come from thought. It comes from sensation; it rests on the same ground as our conviction of our own existence.... If we consider the behavior of new-born animals, we never find them betraying that they are first of all conscious of their sensations as purely subjective excitements. We far more readily incline to explain the astonishing certainty with which they make use of their sensations (and which is an effect of adaptation and inheritance) as the result of an inborn intuition of the outer world.... Instead of starting from an original pure subjectivity of sensation, and seeking how this could possibly have acquired an objective signification, we must, on the contrary, begin by the possession of objectivity by the sensation and then show how for reflective consciousness the latter becomes interpreted as an effect of the object, how in short the original immediate objectivity becomes changed into a remote one."[39]

Another confusion, much more common than the denial of all objective character to sensations, is the assumption that they are all originally located inside the body and are projected outward by a secondary act. This secondary judgment is always false, according to M. Taine, so far as the place of the sensation itself goes. But it happens to hit a real object which is at the point towards which the sensation is projected; so we may call its result, according to this author, a veridical hallucination.[40] The word Sensation, to[Pg 34] begin with, is constantly, in psychological literature, used as if it meant one and the same thing with the physical impression either in the terminal organs or in the centres, which is its antecedent condition, and this notwithstanding that by sensation we mean a mental, not a physical, fact. But those who expressly mean by it a mental fact still leave to it a physical place, still think of it as objectively inhabiting the very neural tracts which occasion its appearance when they are excited; and then (going a step farther) they think that it must place itself where they place it, or be subjectively sensible of that place as its habitat in the first instance, and afterwards have to be moved so as to appear elsewhere.

All this seems highly confused and unintelligible. Consciousness, as we saw in an earlier chapter (vol. I p. 214) cannot properly be said to inhabit any place. It has dynamic relations with the brain, and cognitive relations with everything and anything. From the one point of view we may say that a sensation is in the same place with the brain (if we like), just as from the other point of view we may say that it is in the same place with whatever quality it may be cognizing. But the supposition that a sensation primitively feels either itself or its object to be in the same place with the brain is absolutely groundless, and neither a priori probability nor facts from experience can be adduced to show that such a deliverance forms any part of the original cognitive function of our sensibility.

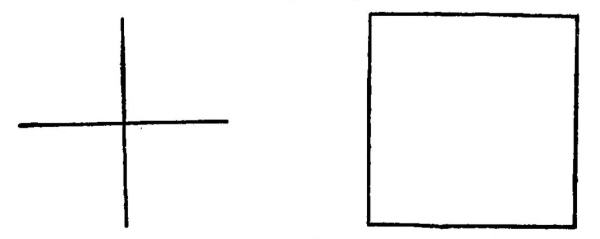

Where, then, do we feel the objects of our original sensations to be?

Certainly a child newly born in Boston, who gets a sensation from the candle-flame which lights the bedroom, or from his diaper-pin, does not feel either of these objects to[Pg 35] be situated in longitude 72° W. and latitude 41° N. He does not feel them to be in the third story of the house. He does not even feel them in any distinct manner to be to the right or the left of any of the other sensations which he may be getting from other objects in the room at the same time. He does not, in short, know anything about their space-relations to anything else in the world. The flame fills its own place, the pain fills its own place; but as yet these places are neither identified with, nor discriminated from, any other places. That comes later. For the places thus first sensibly known are elements of the child's space-world which remain with him all his life; and by memory and later experience he learns a vast number of things about those places which at first he did not know. But to the end of time certain places of the world remain defined for him as the places where those sensations were; and his only possible answer to the question where anything is will be to say 'there,' and to name some sensation or other like those first ones, which shall identify the spot. Space means but the aggregate of all our possible sensations. There is no duplicate space known aliunde, or created by an 'epoch-making achievement' into which our sensations, originally spaceless, are dropped. They bring space and all its places to our intellect, and do not derive it thence.

By his body, then, the child later means simply that place where the pain from the pin, and a lot of other sensations like it, were or are felt. It is no more true to say that he locates that pain in his body, than to say that he locates his body in that pain. Both are true: that pain is part of what he means by the word body. Just so by the outer world the child means nothing more than that place where the candle-flame and a lot of other sensations like it are felt. He no more locates the candle in the outer world than he locates the outer world in the candle. Once again, he does both; for the candle is part of what he means by 'outer world.'

This (it seems to me) will be admitted, and will (I trust) be made still more plausible in the chapter on the Perception of Space. But the later developments of this perception are so complicated that these simple principles get[Pg 36] easily overlooked. One of the complications comes from the fact that things move, and that the original object which we feel them to be splits into two parts, one of which remains as their whereabouts and the other goes off as their quality or nature. We then contrast where they were with where they are. If we do not move, the sensation of where they were remains unchanged; but we ourselves presently move, so that that also changes; and 'where they were' becomes no longer the actual sensation which it was originally, but a sensation which we merely conceive as possible. Gradually the system of these possible sensations, takes more and more the place of the actual sensations. 'Up' and 'down' become 'subjective' notions; east and west grow more 'correct' than 'right' and 'left' etc.; and things get at last more 'truly' located by their relation to certain ideal fixed co-ordinates than by their relation either to our bodies or to those objects by which their place was originally defined. Now this revision of our original localizations is a complex affair; and contains some facts which may very naturally come to be described as translocations whereby sensations get shoved farther off than they originally appeared.

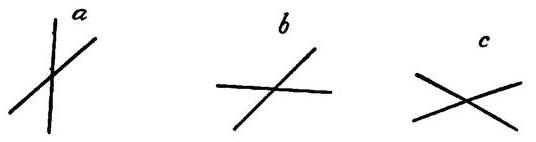

Few things indeed are more striking than the changeable distance which the objects of many of our sensations may be made to assume. A fly's humming may be taken for a distant steam-whistle; or the fly itself, seen out of focus, may for a moment give us the illusion of a distant bird. The same things seem much nearer or much farther, according as we look at them through one end or another of an opera-glass. Our whole optical education indeed is largely taken up with assigning their proper distances to the objects of our retinal sensations. An infant will grasp at the moon; later, it is said, he projects that sensation to a distance which he knows to be beyond his reach. In the much quoted case of the 'young gentleman who was born blind,' and who was 'couched' for the cataract by Mr. Chesselden, it is reported of the patient that "when he first saw, he was so far from making any judgment about distances, that he thought all objects whatever touched his eyes (as he expressed it) as what he felt did his skin." And other patients born blind, but relieved by surgical[Pg 37] operation, have been described as bringing their hand close to their eyes to feel for the objects which they at first saw, and only gradually stretching out their hand when they found that no contact occurred. Many have concluded from these facts that our earliest visual objects must seem in immediate contact with our eyes.

But tactile objects also may be affected with a like ambiguity of situation.

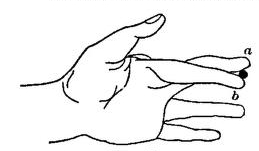

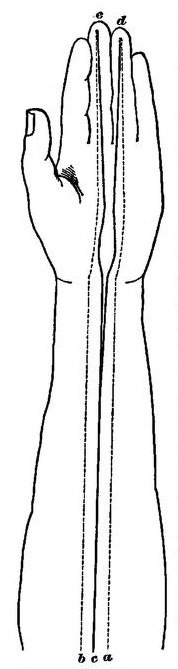

If one of the hairs of our head be pulled, we are pretty accurately sensible of the direction of the pulling by the movements imparted to the head.[41] But the feeling of the pull is localized, not in that part of the hair's length which the fingers hold, but in the scalp itself. This seems connected with the fact that our hair hardly serves at all as a tactile organ. In creatures with vibrissæ, however, and in those quadrupeds whose whiskers are tactile organs, it can hardly be doubted that the feeling is projected out of the root into the shaft of the hair itself. We ourselves have an approach to this when the beard as a whole, or the hair as a whole, is touched. We perceive the contact at some distance from the skin.

When fixed and hard appendages of the body, like the teeth and nails, are touched, we feel the contact where it objectively is, and not deeper in, where the nerve-terminations lie. If, however, the tooth is loose, we feel two contacts, spatially separated, one at its root, one at its top.

From this ease to that of a hard body not organically connected with the surface, but only accidentally in contact with it, the transition is immediate. With the point of a cane we can trace letters in the air or on a wall just as with the finger-tip; and in so doing feel the size and shape of the path described by the cane's tip just as immediately as, without a cane, we should feel the path described by the tip of our finger. Similarly the draughtsman's immediate perception seems to be of the point of his pencil, the surgeon's[Pg 38] of the end of his knife, the duellist's of the tip of his rapier as it plunges through his enemy's skin. When on the middle of a vibrating ladder, we feel not only our feet on the round, but the ladder's feet against the ground far below. If we shake a locked iron gate we feel the middle, on which our hands rest, move, but we equally feel the stability of the ends where the hinges and the lock are, and we seem to feel all three at once.[42] And yet the place where the contact is received is in all these cases the skin, whose sensations accordingly are sometimes interpreted as objects on the surface, and at other times as objects a long distance off.

We shall learn in the chapter on Space that our feelings of our own movement are principally due to the sensibility of our rotating joints. Sometimes by fixing the attention, say on our elbow-joint, we can feel the movement in the joint itself; but we always are simultaneously conscious of the path which during the movement our finger-tips describe through the air, and yet these same finger-tips themselves are in no way physically modified by the motion. A blow on our ulnar nerve behind the elbow is felt both there and in the fingers. Refrigeration of the elbow produces pain in the fingers. Electric currents passed through nerve-trunks, whether of cutaneous or of more special sensibility (such as the optic nerve), give rise to sensations which are vaguely localized beyond the nerve-tracts traversed. Persons whose legs or arms have been amputated are, as is well known, apt to preserve an illusory feeling of the lost hand or foot being there. Even when they do not have this feeling constantly, it may be occasionally brought back. This sometimes is the result of exciting electrically the nerve-trunks buried in the stump.

"I recently faradized," says Dr. Mitchell, "a case of disarticulated shoulder without warning my patient of the possible result. For two years he had altogether ceased to feel the limb. As the current affected the brachial plexus of nerves he suddenly cried aloud, 'Oh the hand,—the hand!' and attempted to seize the missing member. The phantom[Pg 39] I had conjured up swiftly disappeared, but no spirit could have more amazed the man, so real did it seem."[43]

Now the apparent position of the lost extremity varies. Often the foot seems on the ground, or follows the position of the artificial foot, where one is used. Sometimes where the arm is lost the elbow will seem bent, and the hand in a fixed position on the breast. Sometimes, again, the position is non-natural, and the hand will seem to bud straight out of the shoulder, or the foot to be on the same level with the knee of the remaining leg. Sometimes, again, the position is vague; and sometimes it is ambiguous, as in another patient of Dr. Weir Mitchell's who

"lost his leg at the age of eleven, and remembers that the foot by degrees approached, and at last reached the knee. When he began to wear an artificial leg it reassumed in time its old position, and he is never at present aware of the leg as shortened, unless for some time he talks and thinks of the stump, and of the missing leg, when ... the direction of attention to the part causes a feeling of discomfort, and the subjective sensation of active and unpleasant movement of the toes. With these feelings returns at once the delusion of the foot as being placed at the knee."

All these facts, and others like them, can easily be described as if our sensations might be induced by circumstances to migrate from their original locality near the brain or near the surface of the body, and to appear farther off; and (under different circumstances) to return again after having migrated. But a little analysis of what happens shows us that this description is inaccurate.