The Project Gutenberg EBook of Catalogue of the Retrospective Loan Exhibition of European Tapestries, by Phyllis Ackerman This eBook is for the use of anyone anywhere at no cost and with almost no restrictions whatsoever. You may copy it, give it away or re-use it under the terms of the Project Gutenberg License included with this eBook or online at www.gutenberg.org/license Title: Catalogue of the Retrospective Loan Exhibition of European Tapestries Author: Phyllis Ackerman Contributor: J. Nilsen Laurvik Release Date: July 16, 2018 [EBook #57518] Language: English Character set encoding: ISO-8859-1 *** START OF THIS PROJECT GUTENBERG EBOOK CATALOGUE *** Produced by Jane Robins and the Online Distributed Proofreading Team at http://www.pgdp.net (This file was produced from images generously made available by The Internet Archive)

SAN FRANCISCO MUSEUM OF ART

CATALOGUE

OF THE

RETROSPECTIVE LOAN EXHIBITION

OF

EUROPEAN TAPESTRIES

BY

PHYLLIS ACKERMAN

M.A.; PH.D.

WITH A PREFACE BY

J. NILSEN LAURVIK

DIRECTOR

SAN FRANCISCO

PUBLISHED BY THE MUSEUM

MCMXXII

Published September 29, 1922, in an edition of 2000 copies. Copyright, 1922, by San Francisco Museum of Art. Reprinted November 15, 1922, 500 copies.

Printed by TAYLOR & TAYLOR, San Francisco. In the making of the type-design for the cover, the printer has introduced an illuminated fifteenth-century woodcut by an unknown master. Its original appears, illuminated as shown, in "L'Istoire de la Destruction de Troye la Grant," a book printed at Paris, dated May 12, 1484, of which only a single copy is known to exist, that in the Royal Library at Dresden, this reproduction having been made from the excellent facsimile of the block shown in Claudin's "Histoire de l'Imprimerie en France." The border-design of the cover is composed of the names of the chief tapestry-producing cities in Europe during the Gothic and Renaissance periods.

Halftones made by Commercial Art Company, San Francisco.

This historical exhibition of European Tapestries is the fourth in a series of retrospective exhibitions which we have planned to illustrate the chronological development of some important phase of world-art, as in the Old Masters Exhibition, held in the fall of 1920, or of the art of an individual in whose work is significantly reflected the spirit of his age, as in the J. Pierpont Morgan Collection of drawings and etchings by Rembrandt, exhibited here in the spring of 1920.

In its scope and general lines this exhibition follows closely the plan of our Exhibition of Paintings by Old Masters, and, as will at once be apparent from the subject-matter and treatment, covers the same period of European history. Although important exhibitions of European tapestries have been held at various times both here and abroad, it has remained for our museum to arrange the first complete historical survey of this art given in America. This collection presents in unbroken sequence the main currents influential in the development and decadence of the great art of tapestry-weaving in Europe, from the XIVth century down to and including the early XIXth century, as exhibited in the work of the foremost designers and weavers of the period, in examples that, for the most part, are brilliantly typical and always characteristic of their particular style.

Virtually, every loom of importance in France, Flanders, Germany, Switzerland, Spain, England, and Russia is here represented by historically famous pieces which run the entire gamut of subjects that engaged the interest of the most celebrated designers and weavers of each epoch, from allegorical, classical, historical, and mythological to genre subjects, landscapes, religious pieces, and even portraits and still-life subjects. The only omissions of any consequence are the Italian looms and Soho, and the output of these was relatively small and the examples extant are very scarce. However, their absence does not materially affect the historical integrity of the exhibition as a whole. On the other hand, the Gothic series is perhaps the most complete assemblage of all the most important types ever brought together at one time in this country, and every important type of Renaissance design is here included; the collection comprises two of the excessively rare products of the Fontainebleau ateliers, as well as unusually fine specimens of the relatively scarce examples of the Spanish and Russian looms.

My chief concern in organizing this exhibition has been to make it exemplify, first, the history of tapestry, and, second, its æsthetic qualities as these have appeared during the different periods of its changing and varying development, which, like the art of painting, had its naïve, primitive beginnings, its glorious culmination, and its decline. Therefore, every piece has been selected both to represent a distinct and significant type in the chronology of the art and to illustrate the artistic merits of that type, and all the tapestries shown are of the highest worth in their particular category and many of them are among the supreme masterpieces of European art, considered from whatever point of view one may choose to regard them. Only too long have these noble products of the loom been relegated to a[6] secondary place in the history of European culture, which they did so much to celebrate. I sincerely trust that this exhibition, culled from seventeen collections in New York, San Francisco, and Paris, may successfully contribute something toward abolishing the hypnotic spell of the gold-framed oil-painting, that artistic fetish which too long has held the uncritical enthralled to the exclusion of other and ofttimes more authentic manifestations of the human spirit in art.

Regarded from the standpoint of design alone, the extraordinary co-ordination of color and pattern (not to speak of the depth and richness of the inner content) exhibited in certain of these pieces is a sharp challenge to the oft-repeated distinction drawn between the major and the minor arts, and one is constrained, after studying these tapestries, to conclude that there are no major or minor arts, only major and minor artists, and that greatness transfigures the material to the point of art, be it paint or potter's clay, and a simple Tanagra transcends in worth all the gilded and bejeweled banalities of Cellini, whose essentially flamboyant soul sought refuge in gold and precious stones. This truth, too rarely insisted upon, is of prime importance in any consideration of art, whether it be "fine" or applied art, and a collection such as this should do much to make it clear. Here one may observe how the principles of design and color that animate the immortal masterpieces of mural painting are identical with those that give life and vitality to these masterpieces of the loom, and thereby apprehend something of that mysterious law governing the operation of the creative impulse which finds its expression in all the arts, irrespective of time and place, whether it be in rugs, porcelains, Persian tiles and manuscripts, in European primitives, or in the works of Chinese and Japanese old masters, transcending racial differences and attaining a universal affinity that makes a Holbein one with a Chinese ancestral portrait. Surely such opulent fantasy of design and color as is revealed in Nos. 1, 3, 5, and 17, to mention only four of the Gothic pieces in the collection, is deserving of something better than the left-handed compliment of a comparison with painting.

In their masterly filling of the allotted space, in the fine subordination of the varied details to the general effect, as well as in the loftiness and intensity of the emotion expressed, these glorious products of the loom are worthy exemplars of the highest ideals of mural decoration no less than of the aristocratic art of tapestry-weaving. Reflections such as these are the natural consequence of a comparative study of art, and these and kindred reasons are the impelling causes prompting one to exhibit, not only tapestries, but rugs and textiles of all kinds, in an art museum and to give them the same serious study one would accord a Leonardo, a Giotto, a Rembrandt. Æsthetically and racially, they are no less revealing and frequently more interesting in that they are the products of the earliest expressions of those æsthetic impulses the manifestation of which has come to be called art; nor are they less authentic and expressive because communicated with the force and directness of the primitive loom, which give to all its products a certain character and worth rarely equaled by the more sophisticated products of the so-called fine arts.

It is our hope that this catalogue will serve as a helpful guide to all those wishing to make such use of this collection. Every serious student of the subject no less than every unbiased specialist will, I am sure, appreciate at its true worth the scholarly work done by Dr. Ackerman, whose researches have made such a text possible. Bringing to the task a critical judgment and a scientific method of analysis hitherto applied almost exclusively to the identification and interpretation of primitive paintings, the author has been able to correct several well-established errors and to throw new light on many doubtful and obscure points which are so well documented as should make them contributions of permanent value to the literature of the subject.

In conclusion we wish to thank Messrs. William Baumgarten & Company, C.

Templeton Crocker, Demotte, Duveen Brothers, P. W. French & Company, A. J.

Halow, Jacques Seligmann & Company, Dikran K. Kelekian, Frank Partridge, Inc.,

W. & J. Sloane, William C. Van Antwerp, Wildenstein & Company, and Mesdames

James Creelman, William H. Crocker, Daniel C. Jackling, and Maison Jamarin of

Paris, for their kindness in lending us these priceless examples of the European

weavers' art that constitute this notable assemblage of tapestries, and to record our

deep appreciation of the generous co-operation of the patrons and patronesses whose

sponsorship has made the exhibition possible by guaranteeing the very considerable

expense involved in bringing the collection to San Francisco. And last, but not

least, we wish to express our grateful appreciation of the unremitting thought and

attention devoted by the printer to designing and executing the very fitting typographical

form that contributes so largely to making the varied material contained

herein readily available to the reader, and to acknowledge, on behalf of the author,

the friendly help of Arthur Upham Pope, whose suggestions and criticisms have

been found of real value in the preparation of the text of the catalogue.

J. NILSEN LAURVIK, Director

San Francisco, September 29, 1922.

The patrons and patronesses of the Exhibition are: Messrs. William C. Van Antwerp, Edwin Raymond Armsby, Leon Bocqueraz, Francis Carolan, C. Templeton Crocker, Sidney M. Ehrman, William L. Gerstle, Joseph D. Grant, Walter S. Martin, James D. Phelan, George A. Pope, Laurance Irving Scott, Paul Verdier, John I. Walter, Michel D. Weill, and Mesdames A. S. Baldwin, C. Templeton Crocker, Henry J. Crocker, William H. Crocker, Marcus Koshland, Eleanor Martin, George A. Pope, and Misses Helen Cowell and Isabel Cowell, and The Emporium.

BOARD OF TRUSTEES

WILLIAM C. VAN ANTWERP, EDWIN RAYMOND ARMSBY

ARTHUR BROWN, JR., FRANCIS CAROLAN, CHARLES W. CLARK

CHARLES TEMPLETON CROCKER

WILLIAM H. CROCKER, JOHN S. DRUM, SIDNEY M. EHRMAN

JOSEPH D. GRANT, DANIEL C. JACKLING

WALTER S. MARTIN, JAMES D. PHELAN, GEORGE A. POPE

LAURANCE I. SCOTT, RICHARD M. TOBIN

JOHN I. WALTER

DIRECTOR

J. NILSEN LAURVIK

THE MUSEUM IS HOUSED IN THE PALACE OF FINE ARTS

ERECTED BY THE PANAMA-PACIFIC INTERNATIONAL

EXPOSITION IN 1915

For a detailed list of the tapestries

catalogued herein see the subject and title index at

the end of the volume

| PREFACE | Page 5 |

| INTRODUCTION | 11 |

| CATALOGUE | 25 |

| LIST OF WEAVERS | 58 |

| BIBLIOGRAPHY | 59 |

| SUBJECT AND TITLE INDEX | 61 |

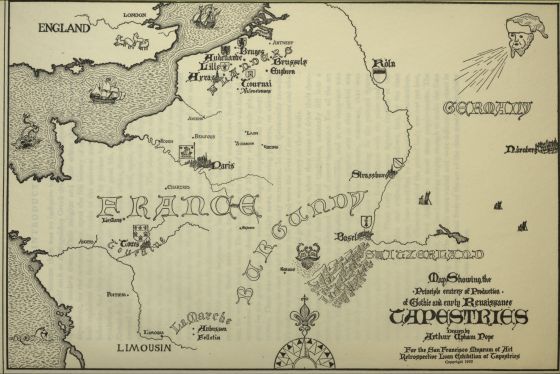

| MAP | Facing Page 16 |

| Showing the principal centers of production of Gothic and early Renaissance tapestries |

|

| TAPESTRIES | |

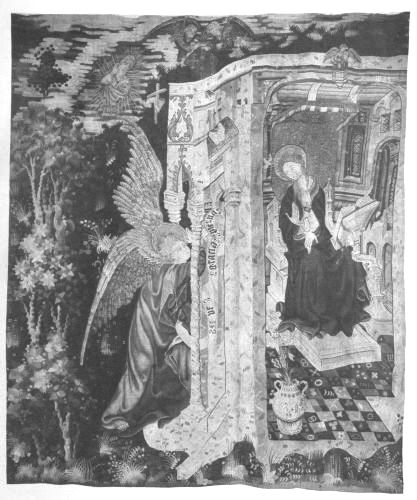

| The Annunciation | Facing Page 24 |

| The Chase | 25 |

| The Annunciation, the Nativity, and the Announcement to the Shepherds | 26 |

| Scenes from the Roman de la Rose | 27 |

| The Vintage | 30 |

| Entombment on Millefleurs | 31 |

| Millefleurs with Shepherds and the Shield of the Rigaut Family | 32 |

| Pastoral Scene | 33 |

| The Creation of the World | 34[10] |

| Four Scenes from the Life of Christ | 35 |

| The Triumph of David | 38 |

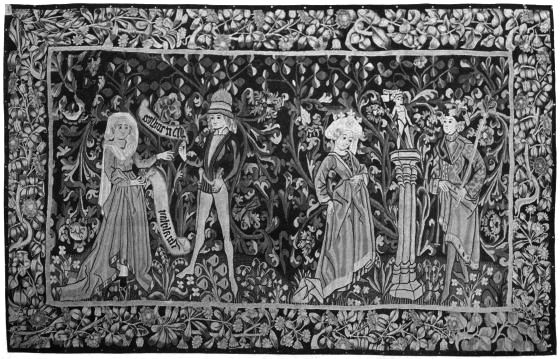

| Two Pairs of Lovers | 39 |

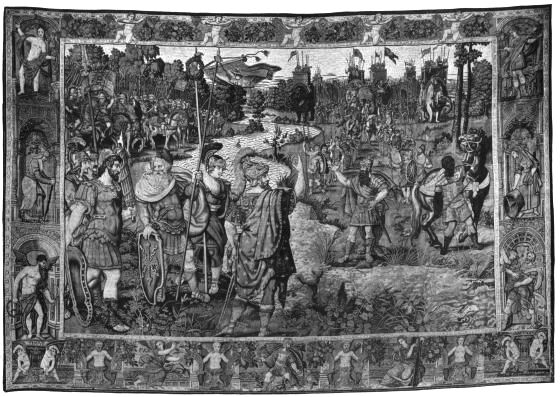

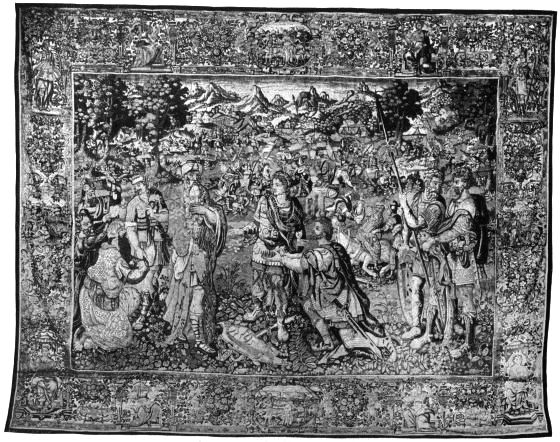

| Hannibal Approaches Scipio to Sue for Peace | 40 |

| Cyrus Captures Astyages, His Grandfather | 41 |

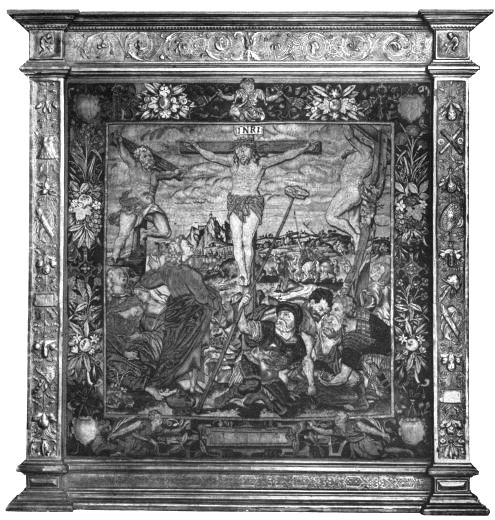

| The Crucifixion | 42 |

| Grotesques | 43 |

| Triumph of Diana | 46 |

| The Niobides | 47 |

| Scene from the History of Cleopatra | 48 |

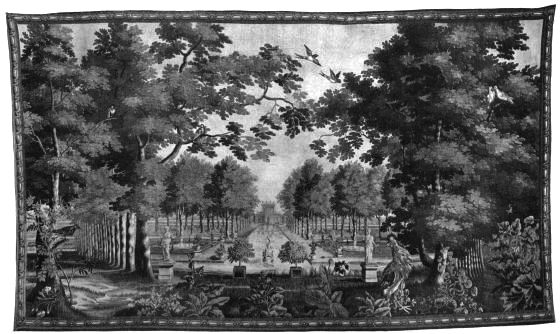

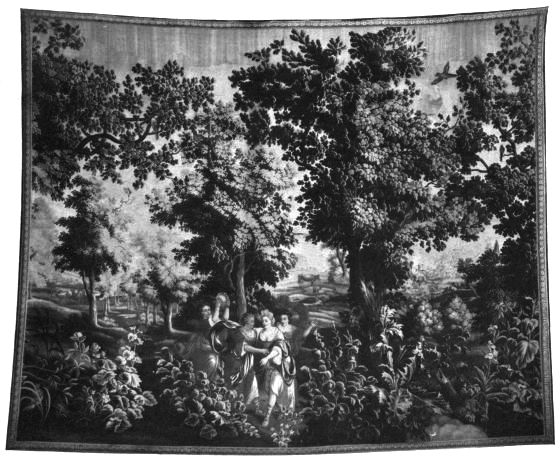

| Verdure | 49 |

| Verdure with Dancing Nymphs | 50 |

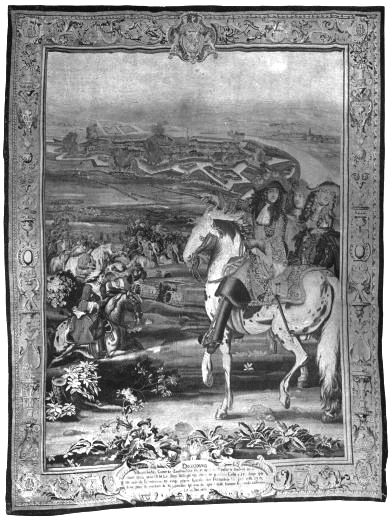

| The Conquest of Louis the Great | 51 |

| The Poisoning of a Spy | 54 |

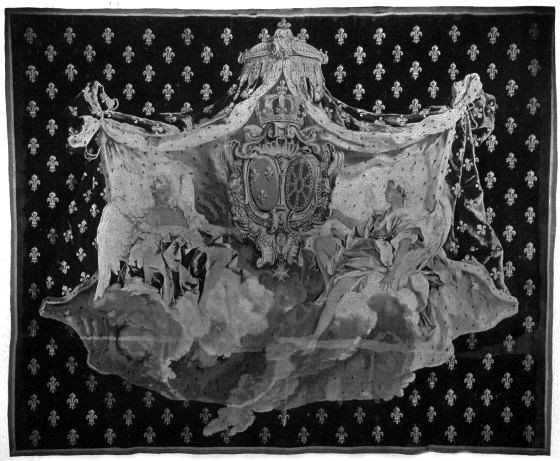

| The Arms of France and Navarre | 55 |

Tapestry is a compound art. It stands at the meeting-point of three other arts, and so is beset by the problems of all three. In the first place, it is illustrative, for while there are tapestries that show only a sprinkling of flowers, a conventionalized landscape, or an armorial shield, the finest and most typical pieces are those with personnages that represent some episode from history, myth, or romance, or give a glimpse of the current usages of daily life. In the second place, tapestry is a mural decoration. It is part of the architectural setting of the rooms, really one with the wall. And, in the third place, it is a woven material—a solid fabric of wool or silk in the simplest of all techniques.

Since a tapestry is an illustration, it must be realistic and convincing, accurate in details and clearly indicative of the story. Because it is also a wall decoration, it cannot be too realistic, but must be structural in feeling and design, and the details must fall into broad masses that carry a strong effect from a distance. And since it is a woven material, even if it be structural, it must be flexible, and must have a fullness of ornament that will enrich the whole surface so that none of it will fall to the level of mere cloth.

But if the tapestry designer have a difficult problem in resolving these conflicting demands of the different aspects of his art, he has also wider opportunities to realize within those limitations. As an illustration, if he handle it with skill, he can make the design convey all the fascination of romance and narrative. As a mural decoration his design can attain a dignity and noble reserve denied to smaller illustrations, splendid in itself, and valuable for counterbalancing the disproportionate literary interest that the subject sometimes arouses. And the thick material, with its soft, uneven surface, lends, even to a trivial design, a richness and mellowness that the painter can achieve only in the greatest moments of his work.

The designer of tapestry can steer his way among the difficulties of the three phases of his art, and win the advantages of them all only if he have a fine and sensitive feeling for the qualities that he must seek. A realism flattened to the requirement of mural decoration and formalized to the needs of the technique of weaving, that still retains the informality and charm of the illustration, can best be won by considering the design as a pattern of silhouettes; for a silhouette is flat, and so does not violate the structural flatness of the wall by bulging out in high modeling. Moreover, it does give a broad, strong effect that can carry across a large room. And, finally, it permits both of adaptation in attitude and gesture[12] to the needs of the story and of easy-flowing lines that can reshape themselves to the changing folds of a textile. So, to make good silhouettes, the figures in a good tapestry design will be arranged in the widest, largest planes possible, as they are in a fine Greek relief, and they will be outlined with clear, decisive, continuous lines, definitive of character, expressive and vivacious.

The strength and vivacity of the outline is of prime significance in tapestry design, even though in its final effect it appears not primarily as a linear art, but rather as a color art. The outlines have to be both clearly drawn in the cartoon and forcefully presented in the weave; for they bear the burden both of the illustrative expressiveness and of the decorative definition. If they are weakened in delineation or submerged by the glow of the colors, the tapestry becomes confused in import, weak in emphasis, and blurred in all its relations, while the charm and interest of detail is quite lost. The too heavy lines of some of the primitive tapestries are less a defect than the too delicate lines of the later pieces designed by those who were primarily painters, and which were too much adapted to the painting technique. The outlines in the best tapestries are not only indicated with a good deal of force, but these lines themselves have unflagging energy, unambiguous direction, diversified movement, and unfaltering control.

In order to complete and establish the silhouette effect, the color in the best tapestries is laid on in broad flat areas, each containing only a limited number of tones. A gradual transition of tone through many shades is undesirable, because such modulations convey an impression of relief modeling, which is inappropriate and superfluous in an art of silhouette. Then, again, these gradations at a little distance tend to fuse, and thus somewhat blur the force and purity of the color; and, finally, a considerable number of color transitions are ill-adapted to the character of a textile, as they tend to make it appear too much like painting. Nor are fluctuating tones and minute value-gradations necessary for a soft and varied effect. The very quality of tapestry material accomplishes that—first, because the ribbed surface breaks up the flatness of any color area and gives it shimmering variations of light and shade, and, second, because the wide folds natural to the material throw the flat tones now into dark and now into light, thus by direct light and shade differentiating values that in the dyes themselves are identical. Color in tapestry can thus be used in purer, more saturated masses than in any form of painting, not excepting even the greatest murals.

Flat silhouetted figures cannot of course be set in a three-dimensional world. They would not fit. So the landscape, too, must be flattened out into artificially simplified stages. This is also necessary both for the architectural and the decorative effect of tapestry, for otherwise the remote vistas tend to give the effect of holes in the wall, and the distance, dimmed by atmosphere, is too pallid and empty to be interesting as textile design. Yet the fact of perspective cannot be altogether denied. Often the designer can avoid or limit the problem by cutting off the farther views with a close screen of trees and buildings, and this has also the advantage of giving a strong backdrop against which the figures stand out firm[13] and clear. But there are occasions in which a wider field is essential for the purposes of illustration. The problem is how to show a stretch of country and still keep it flat and full of detail. In the most skillful periods of tapestry design the difficulty was met by reducing the perspective to three or four sharply stepped levels of distance, laid one above the other in informal horizontal strips. Aerial perspective was disregarded, each strip being filled with details, all sharply drawn but diminishing in size. The scene was thus kept relatively flat, was adapted to flat figures, and was also filled with interesting details.

This fullness of detail is important in tapestries and is the source of much of their richness and charm. The great periods of weaving made lavish use of an amazing variety of incidents and effects: the pattern of a gown, jewels, the chasing or relief on a piece of armor, bits of decorative architecture, carved furniture, and the numerous household utensils, quaint in shape or suddenly vivid in color—all these, with the innumerable flowers, the veritable menagerie of beasts, real and imaginary, gayly patterned birds, as well as rivers, groves, and mountains, make up the properties with which the designer fills his spaces and creates a composition of inexhaustible resource and delight.

So with flat figures, strong outlines, deep, pure, and simple colors, a flattened setting, and a wealth of details, the artist can make a tapestry that will be at the same time both a representative and an expressive illustration, an architectural wall decoration, and a sumptuous piece of material. But even then he has not solved every difficulty; for the tapestry cannot be merely beautiful in itself. It has to serve as a background for a room and for the lives lived in it; so it must be consonant in color and line quality with the furniture current at the time it is made, and it must meet the prevailing interests of the people. Moreover, while it must be rich enough to absorb the loitering attention, it must also have sufficient repose and reserve and aloofness not to intrude unbidden into the eye and not to be too wearyingly exciting—and this last was sometimes no easy problem to solve when the designer was bidden to illustrate a rapidly moving and dramatic tale. Sometimes, in truth, he did not solve it, but sometimes he employed with subtle skill the device of so dispersing his major points of action that until they are examined carefully they merge into a general mass effect.

While the designers have at different periods met these various problems in different ways and with varying skill, the technique of the weaving has never been modified to any extent. For centuries this simple kind of weaving has been done. In essentials it is the same as that used in the most primitive kind of cloth manufacture. The warps are stretched on a frame that may rest horizontally or stand upright. The shuttle full of thread of the desired color is passed over and under the alternate warps, the return reversing the order, now under the warps where it was before over, and over where it was under. A comb is used to push the wefts thus woven close together so that they entirely cover the warps. In the finished tapestry the warps run horizontally across the design. A change of colors in the weft-threads creates the pattern. In the more complex patterns of later[14] works the weaver follows the design drawn in outline on his warps, or sometimes, in the horizontal looms, follows the pattern drawn on a paper laid under his warps so that he looks down through them. His color cues he takes from the fully painted cartoon suspended somewhere near in easy view. Occasionally, in later pieces, to enrich the effect, the simple tapestry weave is supplemented with another technique, such as brocading (cf. No. 52), but this is rare.

All the earliest examples left to us of this kind of weaving are akin to tapestry as we usually know it only in technique. They have practically no bearing on the development of its design. Of the very earliest we have no evidence left by which to judge. Homer, the Bible, and a number of Latin authors all mention textiles that probably could be classed as tapestries; but the references are too general to give us any definite clue as to the treatment of the design. But from the VIth to the VIIIth century, the Copts in Egypt produced many pieces, showing, usually in very small scale, birds and animals and foliage, and even groups of people. Of these we have many samples left. From various parts of Europe, primarily from Germany, in the next two centuries we have a few famous examples. But these are almost wholly without significant relation to the central development of tapestry design. Tapestry, in our sense of the word, begins, as far as extant examples are concerned, with the XIVth century.

From the XIVth to the end of the XVth century was the Gothic period. Then tapestry was at its greatest height. More of the requisites of its design were met, and met more adequately and more naturally, than by any subsequent school of designers or any looms. As illustration, the tapestry of the Gothic period is interesting, vivid, and provocative. The stories and episodes that it presents were, to be sure, all part of the mental content of the audience, so that they comprehended them more immediately than we; but even without the literary background we follow them readily, so adequate is their delineation. Moreover, they carry successfully almost every narrative mood—humor, romance, lyricism, excitement, pathos, and pure adventure—and, except in the traditional religious scenes, they wisely eschew such tenser dramatic attitudes as a momentous climax, long-sustained suspense, or profound tragedy. Finally, when they had a good tale to tell, the Gothic designers rendered their episodes with a fullness of incident and a vivacity of detail never again equaled.

As mural decorations, too, the Gothic tapestries are equally successful. For the figures are always flat and, even while natural and animated, are often slightly formalized and structural in drawing (cf. No. 10); the outlines are clean and active, the colors strong and broad, the vistas either eliminated as in the millefleurs (cf. No. 11) or completely simplified (cf. No. 13), while the details are abundant and delightful. Finally, they are among the most sumptuous textiles ever woven in the Western World—sumptuous, not because of costly material, for they only rarely use metal thread, and even silk is unusual, but sumptuous because of the variety and magnificence of their designs and the splendor and opulence of their color.

Thus the Gothic designers both appreciated and employed to the full all of[15] the æsthetic conditions of their art; yet they did not do this from any theoretical comprehension of the medium. The supremacy of Gothic tapestry rests on a broad basis. It is the final product of one of the most vital and creative epochs in the history of art; its designers were brought up in a great tradition, surrounded everywhere by the most magnificent architectural monuments, accustomed to the habit of beauty in small as well as great things, still inspired and nourished by the fertile spirit that had created and triumphantly solved so many problems in the field of art. A passion for perfection and an elevated and sophisticated taste animated all of the crafts, of which tapestry was but one. The full flowering of tapestry is contemporaneous with that of Limoges enamel, paralleling it in many ways, even to the employment of the same designers (cf. No. 7). Great armor was being made at the same time—armor that exemplified as never before or since its inherent qualities and possibilities: perfection of form and finish, a sensitive and expressive surface, and exquisite decoration logically developed out of construction. Furniture also achieved at that time a combination of strength with natural and imaginative embellishments that still defies copy, while the first publishers were producing the most beautiful books that have ever been printed, unsurpassable in the clear and decorative silhouette of the type, in the perfection of tone, and in the balanced spacing of the composition. Other textile arts, such as that of velvet and brocade weaving, reached the utmost heights of subtlety and magnificence. This easy achievement of masterpieces in kindred fields, so characteristic of great epochs, doubtless stimulated tapestry-weaving as it did every other art.

This great achievement of the Gothic period in so many fields of art was the natural flowering of the spirit of the time. Life for all was limited in content, education as we understand it meager and ill-diffused, opportunities for advancement for the individual about non-existent. Despite these limitations—partly, indeed, because of them—and despite the physical disorders of the age, there were, none the less, a simplicity and unity of mind and an integrity of spirit that provided the basis for great achievement. The spontaneous and tremendous energy, the inexhaustible fertility that was an inheritance from their Frankish and Germanic forbears were now moulded and controlled by common institutions, by the acceptance of common points of view and the consciousness of unified and fundamental principles of life, the acceptance of an authoritative social system that defined and limited each man's ambitions. All these factors prevented the protracted self-analysis, the aimless criticism, the uncertainties and confusion of individual aims that consume our energies, detract from our will, and impoverish our accomplishments. Theirs was in no sense an ambiguous age; they were conscious of a universal spirit, continuously pressing for expression in art which could fortunately forge straight ahead to objective embodiment.

The stimulation of all of the arts had come in part, too, from the inrush of culture from the Byzantine Empire, where traditions and riches had been heaping up continuously ever since the Greek civilization had at its height spilled over into the East. Every flood-tide of culture is created by various streams of ideas and customs[16] that have for generations taken separate courses. All competent ethnologists are agreed that, no matter what the native equipment of a people is, no matter how abundant are their natural resources, how friendly and encouraging is their environment or how threatening and stimulating, one stream of culture flowing alone never rises to great heights. Invention, evolved organization, and artistic production come only with the meeting and mingling of ideas and habits. The East had first fertilized European intellectual creativeness when the numerous Crusades and the sacking of Constantinople by the Franks brought a wealth of novel and exciting ideas into France and the neighboring territories in the XIth and XIIth centuries. There followed the great period of cathedral-building with all the minor accompanying artistic developments of the sculpture, the glass-painting, the manuscript illuminating, the enameling, the lyrics of Southern France, and the romances and fabliaux of Northern. This tide was ebbing slowly when a second rush from the East incident to the fall of Constantinople in 1453 lifted it again. The art of tapestry was especially sensitive to this second Byzantine influence. The industry was coming to its height; the demand was already prodigious, the prices paid enormous, the workers highly skilled and well organized. Tapestry was ready to assimilate any relevant contribution. It enthusiastically took unto itself the sumptuous luxury of the decadent Orient with its splendid fabrics, encrusted architecture, complex patterns, and heavy glowing colors. The simple Frankish spirit of the earlier pieces (cf. No. 2) was almost submerged by the riotously extravagant opulence of the East (cf. Nos. 17, 18). On the other hand, too, from the jewelry of Scandinavia, a remote descendant of an ancient Oriental precedent, tapestry adopted examples of heavy richness of design. And at the same time it took also from the Byzantine some of the formality, the thickness of elaborate drapery, the conventionalization of types, and the rigidity of drawing that had paralyzed the art of Byzantium, but that in tapestry enhanced the architectural character and so constituted a real addition. The tendency of the late XIVth century to an absorption in an exact naturalism which might have immediately rushed French and Flemish taste into the scientific realism of the Florentine Renaissance was checked and deflected by the example and the memory of the stiff carven form, the arrested gestures, and the fixed draperies of the mosaics and manuscript illuminations of the Eastern Empire (cf. No. 8).

But aside from these general considerations, which were vital for the creation of great tapestries, there was at work a specific principle perhaps even more important. The manner of treatment which the tapestry medium itself calls for was one which was native to the mind of the time and which declared itself in a great variety of forms.

In the first place, the Middle Ages were in spirit narrative. The bulk of their literature was narrative—long historical or romantic poems with endless sequences of continued episodes that never came to any dominating climax. Their drama, too, was narrative, a story recounted through a number of scenes that could be cut short at almost any point or could be carried on indefinitely without destroying[17] the structure, because there was no inclusive unity in them, no returning of the theme on itself such as distinguishes Greek drama or Shakespeare and which we demand in modern times. Their religion and their ethics also were narrative, dependent, for the common man, upon the life history of sacred individuals that both explained the fundamental truths of the universe and set models for moral behavior. And they were supplemented, too, by profane histories with moralizing symbolism contrived to point the way to the good life, such as we find in the Roman de la Rose (cf. No. 4). Even their lesser ethics, their etiquette, was narrative, derived from the fabric of chivalric romance. And, again, their greatest art, their architecture, was adorned with narrative, ornamented with multiple histories, so that even the capital of a column told a tale. The whole world about them was narrative, so that the painters and designers must needs think in narrative terms, and hence as illustrators. The narrative features of the other arts also lent them valuable examples for their tapestries. Most of their renderings of religious stories were taken direct from the Mystery Plays (cf. No. 14), and some of their scenes were already familiar to them in stained glass and church sculptures.

Moreover, narrative decorations were interesting and important to the people of the XVth century because they had only very limited resources for intellectual entertainment. Books were scarce, but even if plentiful would have been of little use, for very few could read. The theatre for the mass of the people was limited to occasional productions on church holidays of Mystery and Miracle plays, and even for the great dukes these were only meagerly supplemented by court entertainers. There was no illustrated daily news, no moving pictures, no circuses, no menageries, no easy travel to offer ready recreation. In our distractedly crowded life today we are apt to forget how limited were the lives of our ancestors and what pleasure, as a result, they could get from a woven story on their walls.

In the second place, the Gothic designers, when they came to draw their decorative illustrations, because of their inherited traditions, naturally fell into a technique adapted to the architectual forms of mural decoration. For all the art of the Middle Ages was the derivative of architecture, and at its inception was controlled by it. The original conception of the graphic arts in this period was the delineation on a flat surface of sculpture—sculpture, moreover, that was basically structural, because made as part of a building. So the painted figures were heavily outlined silhouettes in a few broad planes with the poise and the restraint essential to sculpture. These early statuesque figures, familiar in the primitive manuscript illumination and stained-glass windows, had, by the time the tapestries reached their apogee, been modified by a fast-wakening naturalism. But the underlying idea of the silhouette and of the poised body was not yet lost, and so it was natural for tapestry designers to meet these requirements. The naturalism, on the other hand, was just becoming strong enough to make the lines more gracefully flowing and the details more varied and more delicate and exact in drawing, so that the very transitional form of the art of the time made it especially well adapted to a woven rendition.

In the third place, the cartoons, even if they were not quite right in feeling when they came from the painter's hand, would be modified in the translation into the weave by the workmen themselves; for the weavers at that time were respected craftsmen with sufficient command of design to make their own patterns for the less important orders, and were therefore perfectly able to modify and enrich the details of the cartoon of even a great painter. And no designer in the one medium of paint can ever fit his theme to the other medium of wool quite as aptly as the man who is doing the weaving himself.

Thus because the Gothic period happened to be a time when it was natural for the artists to make vivacious and decorative illustrations in clear, flat silhouettes with rich details, most of the Gothic tapestries have some measure of artistic greatness, sufficient to put them above all but the very greatest pieces of later times. Even when we discount the additions that time and our changed attitude make, the beauty of softened and blended colors, the charm of the unaccustomed and the quaint, the interest of the unfamiliar costumes, the literary flavor of old romantic times—even discounting these, they are still inherently superior. To be sure, they are rarely pretty and are sometimes frankly ugly, but with a tonic ugliness which possesses the deepest of all æsthetic merits, stimulating vitality. They have verve, energy, a pungent vividness that sharply reminds the beholder that he is alive. Their angular emphatic silhouettes and pure, highly saturated, abruptly contrasted colors catch and hold the attention and quicken all the vital responses that are essential to clear perception and full appreciation. They are a standing refutation of the many mistaken theories that would make the essence of beauty consist merely in the balanced form and symmetry, or smooth perfection of rendition, or photographic accuracy of representation. They are a forceful and convincing demonstration that in the last analysis beauty is the quality that arouses the fullest realization of life.

Within the common Gothic character there are clearly recorded local differences: the division between the French and the Flemish, not marked until the middle of the XVth century, because up to that time the Franco-Flemish school was really one and continuous. It amalgamated influences from both regions and absorbed a rather strong contribution from Italy. The center of activity was at first Paris and then at the courts of the Burgundian dukes. But after the middle of the century the divergence is rapid and clear. The French is characterized by greater simplicity, clarity, elegance, and delicacy. Even the strong uprush of realism was held in check in France by decorative sensitiveness. The most characteristic designs of the time are the millefleurs, the finer being made in Touraine (cf. No. 8), the coarser in La Marche. The Flemish decoration, on the other hand, is sumptuous, overflowing, sometimes confused, always energetic, and strongly varied in detail. Nothing checks the relentless realism that sometimes runs even to caricature and often is fantastic (cf. the punishment scenes in No. 4). Typical of Flemish abundance are the cartoons with multiple religious scenes, heavy with rich draperies and gorgeous with infinite detail, yet not subordinating to theme[19] the human interest of many well-delineated types of character (cf. No. 18). Brussels was the great center for the production of work of this kind, but beautiful pieces were being produced in almost every city of the Lowlands—Bruges, Tournai, Arras, and many more.

The German Gothic tapestry is quite different from both of these. It was developed almost entirely independently, under quite other conditions. While the French and Flemish shops grew up under the patronage of the great and wealthy nobles, and worked primarily for these lavish art-patrons, in Germany the nobles were impoverished and almost outcast; there was scarcely a real court, and all the wealth lay in the hand of the burghers, solid, practical folk who did not see much sense in art. So while in France and in the Lowlands the workshops were highly organized under great entrepreneurs, and the profits were liberal, in Germany the workshops were very small, and many of the pieces were not made professionally at all, but were the work of nuns in the convents or of ladies in their many idle hours. Thus the industry that in France and Flanders was definitely centered in the great cities such as Paris and Brussels, in Germany was scattered through many towns, primarily, however, those of south Germany and Switzerland. And, too, while the designs for the French and Flemish pieces were specially made by manuscript illuminators, painters, or professional cartoon designers, some of whom, like Maître Philippe (cf. Nos. 17-19), conducted great studios, for the German pieces the weavers themselves adapted the figures from one of the woodcuts that were the popular art of the German people or from some book illustration. So while the French and Flemish tapestries reached great heights of skill and luxury, and really were a great art, the German tapestry remained naïve and simple and most of its artistic value is the product of that very naïveté.

Toward the close of the XVth century a change begins to appear in the character of tapestry design. More and more often paintings are exactly reproduced down to the last detail. At first sporadic products, the reproductions of the work of such masters as Roger Van der Weyden and Bernard Van Orley become more and more frequent until by the end of the first quarter of the XVIth century they are a commonplace. Yet even though tapestry is no longer entirely true to itself, these tapestry paintings are nevertheless beautiful and fit. A woven painting has not yet become an anomaly because painting in Northern Europe is still narrative and decorative. There are still poise and restraint and clear flat silhouette and rich detail.

It was not until tapestry plunged full into the tide of the Italian Renaissance that it entirely lost its Gothic merits. But when, beginning in 1515 with the arrival of Raphael's cartoons for the Pope's Apostle series, the weavers of the North began to depend more and more for their designs on the painters of the South and on painters trained in the South, the character of tapestry completely changed. True, tapestry in the old style was still made for two decades, but in diminishing numbers. The Renaissance had the field. In place of endlessly varied detail, the designers sought for instantly impressive effects, and these are of necessity obvious. Every-thing[20] grew larger, coarser, more insistent on attention. Figures were monumental, floreation bold and strong, architecture massive. Even the verdures developed a new manner; great scrolling acanthus-leaves and exotic birds (cf. No. 33) took the place of the delicate field flowers and pigeons and songsters. Drama took the place of narrative. On many pieces metal thread was lavished in abundance. The whole flagrant richness of the newly modern world was called into play.

For the first time also with Renaissance tapestry, it becomes relevant to ask, Do they look like the scenes they depict?—for realism was in the full tide of its power. A hundred and fifty years before the Renaissance realism had begun to develop, inspired by the naturalism of Aristotle, whose influence had gradually filtered down from the schools to the people, and throughout the XIVth and early XVth century it had been slowly growing. The hunting tapestries of the first part of the XVth century are early examples of it. But the Gothic realism was an attempt to convey the impression of the familiar incidents of life, to get expressive gestures, to record characteristic bits of portraiture, whether of people or things or episodes, so that a Gothic tapestry can be adjudged naturalistically successful if it carries strongly the spirit and effect of a situation regardless of whether the drawing is quite true or not (cf. No. 2). Renaissance realism, on the other hand, is not satisfied with the impression, but strives for the fact. It wishes to depict not only the world as one sees it, but as one knows it to be—knows it, moreover, after long and careful study. So in all Renaissance graphic art correct anatomy becomes of importance, solid modeling is essential, and all details must be specific.

Yet, though tapestry in the Renaissance was no longer illustrative in the old sense, it still was decoratively fine; for the painting of Italy was founded on a mural art, and the decorative traditions still held true. Outlines are still clear and expressive. There was respect for architectural structure, and details, if less complex and sensitive, are still rich and full. Color, too, is still strong and pure, though the key is heightened somewhat and the number of tones increased. Moreover, the Renaissance introduced two important new resources, the wide border and the grotesque. Hitherto the border had been a narrow floral garland, a minor adjunct easily omitted. Now it became of major importance, always essential to the beauty of the piece, often the most beautiful part of it, designed with great resource and frequently interwoven with gold and silver. The grotesque, from being originally a border decoration, soon spread itself over the whole field (cf. No. 36), mingling with amusing incongruity but with decorative consistency goats and fair ladies, trellis, flowers, and heraldic devices. What the Renaissance lacked in subtlety it made up in abundance.

During the Renaissance the tapestry industry was dominated by the Flemish cities, with Brussels at the head. She had the greatest looms, great both for the exceeding skill of the workers and for the enormous quantity of the production. Some workshops, of which the most famous was that of the Pannemaker family, specialized in exquisitely fine work rendered in the richest materials. Of this class, the most typical examples are the miniature religious tapestries in silk and metal thread,[21] in which all the perfection of a painting was united with the sumptuousness of a most extravagant textile (cf. No. 35). But sometimes full-sized wall-hangings too were done with the same perfection and elaboration (cf. Nos. 23-25). Other shops sacrificed the perfection of workmanship to a large output, but even in the most commercially organized houses the weavers of Flanders in the XVIth century were able and conscientious craftsmen.

These same Flemish workmen were called to different countries in Europe to establish local looms. So Italy had several small temporary ateliers at this period, as did England also (cf. No. 32). But though these shops were in Italy and England, they were still predominantly Flemish. The character of local decoration and local demand influenced the design somewhat, but fundamentally the products both in cartoon and in weave were still those of the mother country. In France, however, the Flemish workmen were made the tools of the beginning of a new national revival of the art. A group of weavers was called to Fontainebleau, where, under the extravagant patronage of Francis I, the French Renaissance was taking form. These Flemings, weaving designs made by Italians, nevertheless created decorative textiles that are typically French in spirit (cf. No. 37). France alone had a strong enough artistic character to refashion the conventions of Italy and the technique of Flanders to a national idiom.

In the next century this revival of the art which survived at Fontainebleau barely fifty years was carried on in several ateliers at Paris. The workmen were still predominantly Flemish, but again their work was unmistakably French (cf. No. 38). In Trinity Hospital looms had been maintained since the middle of the XVIth century. In the gallery of the Louvre looms were set up about 1607. And the third and most important shop was established by Marc de Comans and François de la Planche at the invitation of the king. This was most important, because it later was moved to the Bièvre River, where the Gobelins family had its old dye-works, and it eventually became the great state manufactory.

Thereafter for the next two centuries the looms of Flanders and France worked in competition. Now one, now the other took precedence, but France had a slowly increasing superiority that by the middle of the XVIIIth century put her two royal looms, the Gobelin and Beauvais, definitely in the forefront of the industry.

For cartoons the looms of the two countries called on the great painters of the time, often requisitioning the work of the same painters, and sometimes even using the very same designs. Thus Van der Meulen worked both for Brussels manufacturers (cf. Nos. 53-56) and for the French state looms (cf. No. 52), and the Gobelin adapted to its uses the old Lucas Months that had originated in Flanders (cf. Nos. 57, 58.)

But though they did thus parallel each other in cartoons, the finished tapestries nevertheless retained their national differences. As in the Gothic period, the Flemish tapestries in all respects showed a tendency to somewhat overdo. Their figures were larger, their borders crushed fuller of flowers and fruit, their verdures heavier, their grotesques more heterogeneous, their metal threads solider. Their[22] abundance was rich and decorative, but lacking in refinement and grace. The French, on the other hand, kept always a certain detachment and restraint that made for clarity and often delicacy. When the Baroque taste demanded huge active figures, the French still kept theirs well within the frame. Their borders were always spaced and usually more abstract. The verdures of Aubusson can be distinguished from those of Audenarde by the fewer leaves, the lighter massing, the more dispersed lights and shades. The grotesques of France, especially in the XVIIIth century, often controlled the random fancy popularized among the Flemish weavers by introducing a central idea, a goddess above whom they could group the proper attributes (cf. No. 36), or a court fête (cf. No. 59). And when the French used metal thread it was to enrich a limited space rather than to weight a whole tapestry. In a way the opulence of the Flemish was better adapted to the medium. Certainly it produced some very beautiful tapestries. But the refinement of the French is a little more sympathetic to an overcivilized age.

With the accession of Louis XV, tapestry joined the other textile arts and painting in following furniture styles. Thereafter, until the advent of machinery put an end to tapestry as a significant art, the cabinetmaker led all the other decorators. Small pieces with small designs, light colors, delicate floral ornaments, and the reigning temporary fad—now the Chinese taste (cf. No. 71), now the pastoral (cf. No. 68)—occupied the attention of the cartoonmakers, so that the chief occupations of the court beauties of each successive decade can be read in the tapestries.

During this time France was dictating the fashions of all the Western World, so other countries were eager not only to have her tapestries, but to have her workmen weave for them in their own capitals. Accordingly, the royal family of Russia, always foreign in its tastes, sent for a group of weavers to set up a royal Russian tapestry works. Similarly, Spain sent for a Frenchman to direct her principal looms, those at Santa Barbara and Madrid, which for a decade or so had been running under a Fleming.

And meanwhile tapestry was steadily becoming more and more another form of painting. Until the middle of the XVIIIth century it remains primarily illustrative. The Renaissance designers continued to tell historical and biblical stories and to fashion the designs in the service of the tale they had to tell. With the influence of Rubens and his school (cf. No. 44), the story becomes chiefly the excuse for the composition; but the story is nevertheless still there and adequately presented. The artists of Louis XIV, when called upon to celebrate their king in tapestry, respected this quality of the art by depicting his history and his military exploits (cf. No. 52). But illustration already begins to run thin in the series of the royal residences done by the Gobelins during his reign, and with the style of his successor it runs out almost altogether. If Boucher paints the series of the Loves of the Gods it is not for the sake of the mythology, but for the rosy flesh and floating drapes, and Fragonard does not even bother to think of an excuse, but makes his languid nudes simply bathers (cf. No. 69). So when Louis XV is[23] to be celebrated by his weavers the designers make one effort to invent a story by depicting his hunts, and then abandon episode and substitute portraiture (cf. No. 64).

Throughout most of the Renaissance, tapestry remained decorative as a mural painting is decorative, but in the XVIIth century, with the degeneration of all architectual feeling, tapestry lost entirely its architectual character. It was still decorative—it was decorative as the painting of the time was. The tapestries of the XVIIth century are giant easel paintings, and of the XVIIIth century woven panel paintings.

As to the textile quality, during the XVIIth century the very scale of the pieces kept them somewhat true to it. The large figures, heavy foliage, and big floral ornaments can fall successfully into wide, soft folds. But most of the tapestry of the XVIIIth century must be stretched and set in panels or frames. That they are woven is incidental, a fact to call forth wonder for the skill of the workmen, both of the dyers who perfected the numberless slight gradations of delicate tones and kept them constant, and of the almost unbelievably deft weavers who could ply the shuttle so finely and exactly and grade these delicate tones to reproduce soft modeled flesh, fluttering draperies, billowing clouds, spraying fountains, and the sheen and folds of different materials. But that they are woven is scarcely a fact to be considered in the artistic estimate. The only advantage of the woven decorations over the painted panel is that they present a softer surface to relieve the cold glitter of rooms. Otherwise as paintings they stand or fall. Even the border has usually been reduced to a simulated wood or stucco frame.

During this gradual change through five hundred years in the artistic qualities of tapestry the technical tricks of the weavers underwent corresponding modification. In the Gothic period the drawing depended primarily upon a strong dark outline, black or brown, that was unbroken, and that was especially important whether the design was affiliated rather with panel painting (cf. No. 1) or with the more graphic miniature illustration (cf. No. 5). Even the lesser accessories were all drawn in clear outline. Within a given color area, transitions from tone to tone were made by hatchings, little bars of irregular length of one of the shades that fitted into alternate bars of the other shade, like the teeth of two combs interlocked. And for shadows and emphasis of certain outlines, some of the Gothic weavers had a very clever trick of dropping stitches (cf. No. 1), so that a series of small holes in the fabric takes the place of a dark line. During the Renaissance the outline becomes much narrower, and is used only for the major figures, a device that sometimes makes the figures look as if they had been cut out and applied to the design. Hatching, if used at all, is much finer than in the earlier usage, consisting now of only single lines of one color shading into the next. In the work of Fontainbleau (cf. Nos. 36, 37), the dotted series of holes between colors is still used to give a subordinate outline. During the XVIIth century hatching is scarcely used at all, and the outline has practically disappeared. During the XVIIIth century the French weavers perfected a trick which obviated any break[24] in the weave where the color changes, thus enabling tapestry to approximate even closer to painting effects.

To the weavers who adjusted these tricks to the varying demands of the cartoons, and so translated painted patterns in a woven fabric, is due quite as much credit for the finished work of art as to the painters who first made the design. Famous painters did prepare tapestry designs. Aside from the masters of the Middle Ages to whom tapestries are attributed, we have positive evidence that, among others, Jacques Daret, Roger Van der Weyden, Raphael, Giulio Romano (cf. Nos. 23-25), Le Brun, Rubens, Coypel (cf. Nos. 62, 63), Boucher (cf. Nos. 67, 68), Watteau, Fragonard (cf. No. 69), and Vernet (cf. No. 70), all worked on tapestry designs. The master weavers who could transpose their designs deserve to rank with them in honor.

Yet we know relatively little of these master weavers. Many names of tapicers appear in tax-lists and other documents, but not until the XVIIIth century do the names often represent to us definite personalities, and until then we can only occasionally credit a man with his surviving work. From the long lists of names and the great numbers of remaining tapestries a few only can be connected. Among the greatest of these is Nicolas Bataille, of Paris, who wove the famous set of the Apocalypse now in the Cathedral of Angers; Pasquier Grenier, of Tournai, to whom the Wars of Troy and related sets can be accredited (cf. No. 7), but who apparently was an entrepreneur rather than a weaver; Pieter Van Aelst, who was so renowned that the cartoons of Raphael were first entrusted to him; William Pannemaker, another Brussels man, who had supreme taste and skill, and his relative Pierre, almost as skilful; Marc Comans and François de la Planche, the Flemings who set up the looms in Paris that developed into the Gobelins (cf. No. 38); Jean Lefébvre, who worked first in the gallery of the Louvre and then had his studio in the Gobelins (cf. Nos. 39, 40); the Van der Beurchts, of Brussels (cf. Nos. 42, 56), and Leyniers (cf. Nos. 26, 27), and Cozette, most famous weaver of the Gobelins. Such men as these, and many more whose names are lost or are neglected because we do not know their work, were in their medium as important artists as the painters whose designs they followed.

With the passing of such master craftsmen the art of tapestry died. When men

must compete with machines their work is no more respected, and so tapestry is

no longer the natural medium of expression for the culture of the times. Tapestries

are still being made, but there is no genuine vitality in the art and little merit

in its product. It exists today only as an exhausted and irrelevant persistence

from the past, and, as a fine art, doomed to failure and ultimate extinction.

P.A.

The Annunciation No. 1

The Chase No. 2

Abbreviations: H. (Height); W. (Width); ft. (Feet); in. (Inches). "Right" & "Left," refer to right & left of the spectator

1 FRANCO-FLEMISH, POSSIBLY ARRAS, BEGINNING OF XV OR END OF XIV CENTURY

THE ANNUNCIATION: The Virgin, in a blue robe lined with red, is seated before a reading-desk in a white marble portico with a tile floor. Behind her is a red and metal gold brocade. The lily is in a majolica jar. The angel, in a green robe with yellow high lights lined with red, has alighted in a garden without. In the sky, God the Father holding the globe and two angels bearing a shield.

The treatment of the sky in two-toned blue and white striations, as well as the conventional landscape without perspective, with small oak and laurel trees, is characteristic of a number of tapestries of the opening years of the XVth century. Most of them depicted hunting scenes. But there was one famous religious piece, the Passion of the Cathedral of Saragossa. In the drawing of the figures and some of the details the piece is closely related to the paintings of that Paris school of which Jean Malouel is the most famous member. The work is by no means by Malouel, but it is similar to that of one of his lesser contemporaries, whose only known surviving work is a set of six panels painted on both sides, two of which are in the Cuvellier Collection at Niort and the others in the Mayer Van der Bergh Collection at Antwerp. The very primitively rendered Eternal Father is almost identical with the one that appears in several of the panels; the roughly indicated shaggy grass is the same, the rather unusual angle of the angel's wings recurs in the Cuvellier Annunciation, as does the suspended poise of the Virgin's attitude. The Virgin's reading-desk, too, is almost identical, though shown in the panel at the other side of the scene. The long, slim-fingered hands and the pointed nose and chin of the Virgin are characteristic of the school.

The tiles in the portico, so carefully rendered, are of interest because they are very similar to the earliest-known tile floor still in position—that of the Caracciolo Chapel in Naples. Some of the same patterns are repeated, notably that of the Virgin's initial and the star, which is more crudely rendered. The colors, too, are approximately the same, the brown being a fair rendering of the manganese purple of the chapel tiles. The majolica vase is also interesting as illustrating a type of which few intact examples are left.

The piece maintains a high level of æsthetic expression. The religious emotion is intensely felt and is adequately conveyed in the wistful sadness of the Virgin's face and the expectant suspense of her poised body. The portico seems removed from reality and flooded by a direct heavenly light, in its shining whiteness contrasting[26] with the deep blue-green background. This tapestry by virtue of its intense and elevated feeling, purified by æsthetic calm and by its exceptional decorative vividness, ranks with the very great masterpieces of the graphic arts.

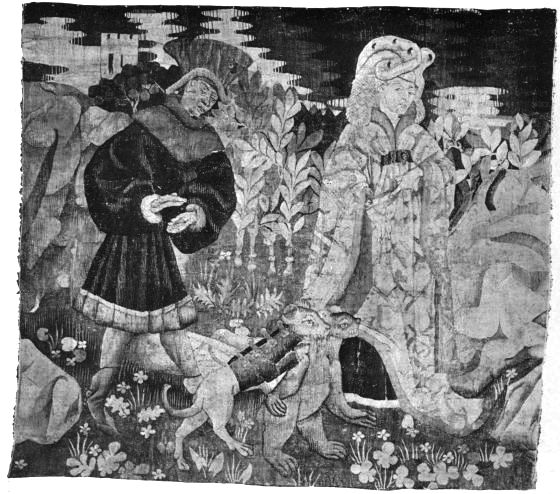

2 FRANCO-FLEMISH, EARLY XV CENTURY

THE CHASE: A man in a long dark-blue coat and high red hat and a lady in a brown brocade dress and ermine turban watch a dog in leather armor attack a bear. A landscape with trees and flowers is indicated without perspective and a castle in simple outline is projected against a blue and white striated sky.

This tapestry is an important example of a small group of hunting scenes of the early XVth century. It is closely related in style to the famous pair of large hunting tapestries in the collection of the Duke of Devonshire. It is not definitely known where any of these pieces were woven, but Arras is taken as a safe assumption, as that was the center of weaving at the time, and these tapestries are the finest production known of the period.

The very simple figures sharply silhouetted against the contrasting ground have a decidedly architectural quality, perfectly adapted to mural decoration. Yet the scene seems very natural and the persons have marked and attractive personalities.

These exceedingly rare pieces mark the great wave of naturalism that began sweeping over Europe about 1350 and they exemplify strikingly one of the finest qualities of the primitive—the impressive universality and objectivity that come from the freshness of the artist's vision. Looking straight at the thing itself, free from all the presuppositions that come from an inherited convention, the draftsman saw the essentials and recorded them directly without any confusing elaboration of technique. He was completely absorbed by the unsolved problems of the task, too occupied with the difficulty of rendering the central outstanding features of the scene to be diverted by personal affectations. His realization thus became vivid and intimate, his rendition achieved a singularity and epic force never again to be found in tapestry.

This is one of the few tapestries that have been improved by age. Time has spread over it a slight gray bloom that seems to remove it from the actual world, giving it the isolation that is so important a factor in æsthetic effect; yet the depth and strength of the colors have not been weakened, for we interpret the grayness as a fine veil through which the colors shine with their original purity.

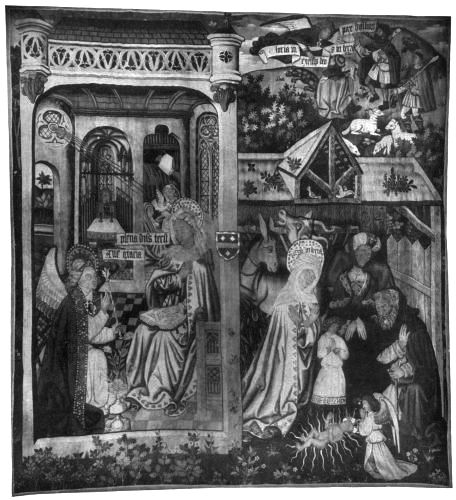

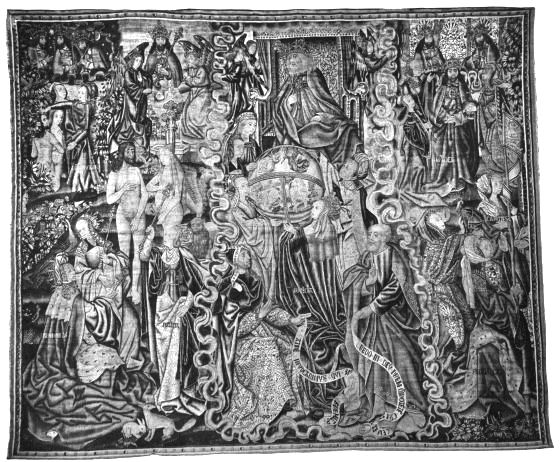

3 FLANDERS, MIDDLE XV CENTURY

THE ANNUNCIATION, THE NATIVITY, AND THE ANNOUNCEMENT TO THE SHEPHERDS: At the left in a Gothic chapel the Annunciation. The Virgin, in a richly jeweled and brocaded robe, reads the Holy Book. The angel in rich robes kneels before her. The lilies are in a dinanderie vase. Through the open door a bit of[27] landscape is seen, and in a room beyond the chapel two women sit reading. The Nativity, at the right, is under a pent roof. The Virgin, Joseph, and Saint Elizabeth kneel in adoration about the Holy Babe, who lies on the flower-strewn grass. John kneels in front of his mother, and in the foreground an angel also worships. Above and beyond the stable the three shepherds sit tending their flocks, and an angel bearing the announcement inscribed on a scroll flutters down to them from Heaven. Oak-trees, rose-vines, and blossoming orange-trees in the grass.

The Annunciation, The Nativity, and The Announcement to the Shepherds No. 3

Scenes from the Roman de la Rose No. 4

This tapestry belongs to a small and very interesting group, all evidently the work of one designer. The three famous Conversations Galantes (long erroneously called the Baillée des Roses) in the Metropolitan Museum are by the same man, as are the four panels of the History of Lohengrin in Saint Catherine's Church, Cracow, the fifth fragmentary panel of the series being in the Musée Industrielle, Cracow. A fragment from the same designer showing a party of hunters is in the Church of Notre Dame de Saumur de Nantilly, and another fragment depicting a combat is in the Musée des Arts Decoratifs. Three small fragments—one with a single figure of a young man with a swan, like the Metropolitan pieces, on a striped ground, another showing a king reading in a portico very similar to the portico of the Annunciation, and the third showing a group of people centered about a king—were in the Heilbronner Collection.

Schmitz points out[1] a connection between the three Metropolitan pieces and the series of seven pieces depicting the life of Saint Peter in the Beauvais Cathedral, with an eighth piece in the Cluny Musée, and it is quite evident that the cartoons are the work of the same man. But whereas the other pieces all have the same characteristics in the weaving, this series shows a somewhat different technique in such details as the outline and the hatchings, so that one must assume they were woven on another loom.

Fortunately, there is documentary information on one set of the type that enables us to say definitely where and when the whole group was made. The Lohengrin set was ordered by Philip the Good from the first Grenier of Tournai in 1462. There can be no reasonable doubt that the set in Saint Catherine's Church is the same, for in this set the knight is quite apparently modeled after Duke Philip himself, judging from the portraits of him in both the Romance of Gerard de Rousillon (Vienna Hof-bibliothèque) and in the History of Haynaut (Bibliothèque Royale, Brussels).

Schmitz asserts that it is almost certainly useless to seek the author of these cartoons among contemporary painters, as they are probably the work of a professional cartoon painter, of which the Dukes of Burgundy kept several in their service—and this is probably true. But artists were not as specialized then as they are now, and even a professional tapestry designer might very well on occasion turn his hand to illustrating a manuscript or making a sketch for an enamel, so that it is not impossible that further research in the other contemporary arts may bring to light more information about this marked personality who created so individual a style.

This tapestry is exceedingly interesting, not only for its marked style of drawing and its quaint charm, but for the direct sincerity of the presentation and the brilliant and rather unaccustomed range of colors.

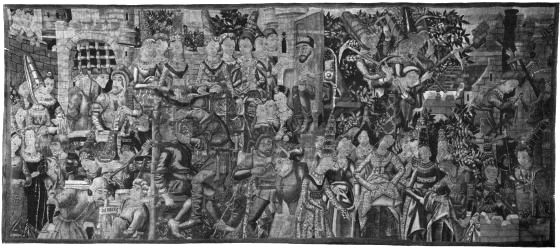

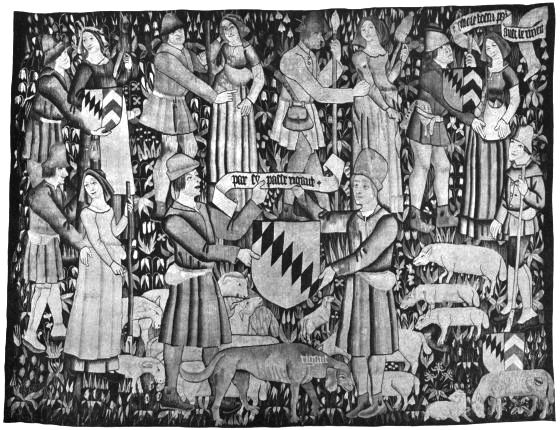

4 FLANDERS, MIDDLE XV CENTURY

SCENES FROM THE ROMAN DE LA ROSE: This piece illustrates one of the most popular romances of the Middle Ages, the Romance of the Rose, the first part of which was written in 1337 by Guillaume de Lorris, the second part in 1378 by Jean de Meung, and translated into English by Chaucer. The culminating scenes are represented. Jealousy has imprisoned Bel Acceuil in a tower because he helped the Lover see the Rose after Jealousy had forbidden it. The Lover calls all his followers, Frankness, Honor, Riches, Nobility of Heart, Leisure, Beauty, Courage, Kindness, Pity, and a host of others, to aid him in rescuing the prisoner. In the course of the struggle Scandal, one of Jealousy's henchmen, is trapped by two of the Lover's followers posing as Pilgrims, who cut his throat and cut out his tongue. With the aid of Venus, the Lover finally wins.

The piece is very close in drawing to the illustrations of the Master of the Golden Fleece,[2] whom Lindner has identified as Philip de Mazarolles. The long bony, egg-shaped heads that look as if the necks were attached as an afterthought, the shoe-button eyes, flat mouths, and peaked noses all occur in his many illustrations. Characteristic of him, too, are the crowded grouping of the scene and the great care in presenting the accessories, every gown being an individual design, whereas many of his contemporary illustrators contented themselves with rendering the general style without variations. The conventional trees are probably the weaver's interpolations. The top of the tapestry being gone, there is no possibility of knowing whether his customary architectural background was included or not.

The tapestry is interesting, not only because it is quaint, but because it is a vivid illustration of the spirit of the time—virile, cruel, yet self-consciously moralistic.

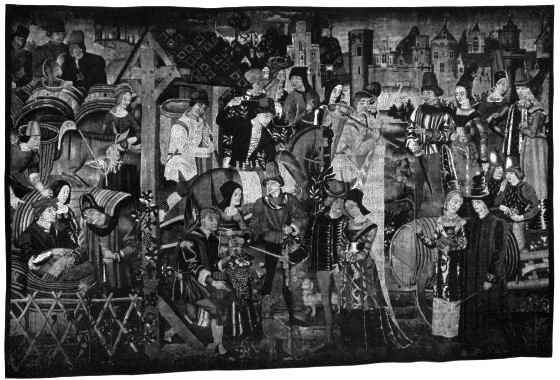

5 FLANDERS, MIDDLE XV CENTURY

THE VINTAGE: This piece was probably originally one of a series of the Months, representing September. Groups of lords and ladies have strolled down from the castle in the background to watch the peasants gathering and pressing the grapes.

The costumes and the drawing indicate that the piece was made in Burgundy at the time of Philip the Good. In fact, it is so close to the work of one of the most prolific of the illustrators who worked for Philip the Good that it is safe to assume that the original drawing for the cartoons was his work. In the pungency of the[29] illustration and the vivacity of the episodes as well as in numerous details it follows closely the characteristics of Loysot Lyedet. Here are the same strong-featured faces with large prominent square mouths, the same exaggeratedly long and thin legs with suddenly bulging calves on the men, the same rapidly sketched flat hands, and the same attitudes. The very exact drawing of the bunches of grapes parallels the exactness with which he renders the household utensils in his indoor scenes, and the dogs, while they are of types familiar in all the illustrations of the time, have the decided personalities and alert manner that he seemed to take particular pleasure in giving them.

Another tapestry that seems to be from the same hand is Le Bal de Sauvages in l'Eglise de Nantilly de Saumur.

The piece is one of the most vivid and convincing illustrations of the life of the time that has come down to us in tapestry form. The silhouetting of the figures against contrasting colors and the structural emphasis of the vertical lines give the design great clarity and strength.

Loysot Lyedet was working for the Dukes of Burgundy in 1461. He died about 1468. Among the most famous of his illustrations are those of the History of Charles Martel (Bibliothèque Royale, Brussels) History of Alexander (Bibliothèque Nationale, Paris) and the Roman History (Bibliothèque de l'Arsenal, Paris.)

6 GERMANY, PROBABLY NUREMBERG, MIDDLE XV CENTURY

SCENES FROM THE LIFE OF CHRIST: The Life of Christ is shown in eight small scenes, beginning with the Entrance into Jerusalem, the Farewell to his Mother, the Last Supper, the Agony in the Garden, the Carrying of the Cross, the Crucifixion, the Pieta, and the Entombment.

The scenes in this tapestry were apparently adapted from the illustrations from a Nuremberg manuscript of the middle of the XVth century. Of course, the weaving may have been done later. The simplified arrangement of the scenes with a reduction to a minimum of the number of actors, the relative size of the figures to the small squares of the compositions, the marked indebtedness in the use of line and light and shade to woodcuts, and the courageous but not altogether easy use of the direct profile, all bring the pieces into close relationship with such book illustrations as those of George Pfinzing's book of travels (The Pilgrimage to Jerusalem), now in the City Library of Nuremberg.[3] In fact, the parallelism is so very close, the tapestry may well have been adapted from illustrations by the same man, the curiously conventionalized line-and-dot eyes being very characteristic of the Pfinzing illustrations and not common to all the school.

In weaving many of the figures the warp is curved to follow the contours.

The naïve directness and unassuming sincerity of the piece give it great interest.

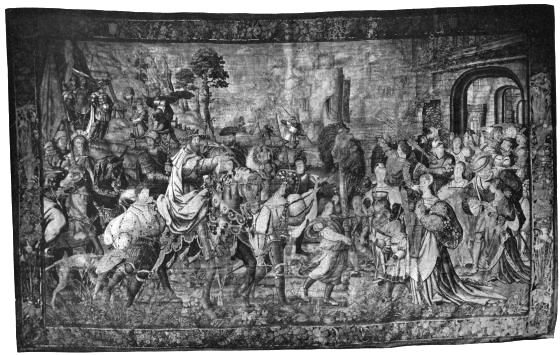

7 TOURNAI, THIRD QUARTER XV CENTURY

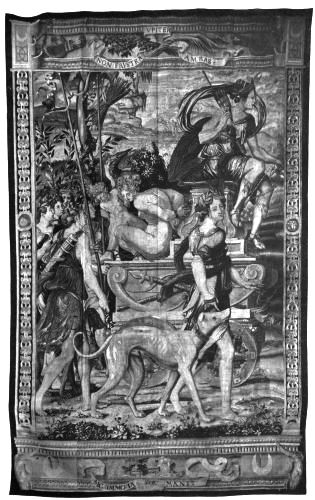

THE HISTORY OF HERCULES: Hercules, clad in a magnificent suit of shining black armor, rides into the thickest tumult of a furious battle; with sword in his right hand, he skillfully parries the thrust of a huge lance, while with the other hand he deals a swinging backhand blow that smites an enemy footman into insensibility. His next opponent, obviously bewildered and frightened, has half-turned to flee. The whole apparatus of mediæval combat is shown in intense and crowded action. The piece is incomplete.

This tapestry illustrates one of the favorite stories of the Middle Ages, and was undoubtedly originally one of a set. In design it is closely related to the famous Wars of Troy series, many examples of which are known and some of the first sketches for which are in the Louvre. It is also closely related to the History of Titus set in the Cathedrale de Notre Dame de Nantilly de Saumur.[4] Both of these sets are signed by Jean Van Room, and this piece also is undoubtedly from his cartoon. All of these pieces were probably woven between 1460 and 1470.

Jean Van Room (sometimes called de Bruxelles) is one of the most interesting personalities connected with the history of Gothic tapestry. He was a cartoon painter and probably conducted a large studio, judging from the number of pieces of his which are left to us. Fortunately, he had a habit of signing his name on obscure parts of the designs, such as the borders of garments. His work extends over sixty years and changes markedly in style during that time, adapting itself to the changing taste of his clients. This piece illustrates his earliest manner. In the succeeding decades he is more and more affected by the Renaissance and the Italian influence, until his latest pieces (cf. No. 21) are quite unlike these first designs. At the close of the century he began to collaborate with Maître Philippe, evidently a younger man, who had had Italian instruction and was less restrained by early Gothic training (cf. Nos. 17-19).

Jean Van Room seems to have done designs for enamels, also, that were executed in the studio of the so-called Monvaerni. In the collection of Otto H. Kahn is a Jesus before Pilate very close in style to Jean Van Room's early work,[5] on which appear the letters M E R A, which might even be a pied misspelling of Room, for similar confused signatures appear on tapestries known to be his. A triptych with Crucifixion in the collection of Charles P. Taft[6] has figures very close to the Crucifixion tapestry in the Cathedral of Angers done by Van Room in his middle period. According to Marquet de Vasselot, this enamel bears the letters JENRAGE, but M. de Vasselot also comments on its illegibility in the present condition of the enamel. Could he have misread a letter or two? Still another triptych with Crucifixion, in the Hermitage,[7] actually repeats two figures from the Angers Crucifixion with only very slight variations.

Jean Van Room borrowed liberally from various other artists at different stages of[31] his career. In the Wars of Troy, the History of Titus, and this piece he seems to have relied primarily on Jean le Tavernier for his models, the affiliation being especially close in the Wars of Troy. Le Tavernier is known to have illustrated the Wars of Troy,[8] and Jean Van Room, judging from the close stylistic relations of his Troy tapestries with le Tavernier's drawings, evidently took his hints from this lost manuscript.

The Vintage No. 5

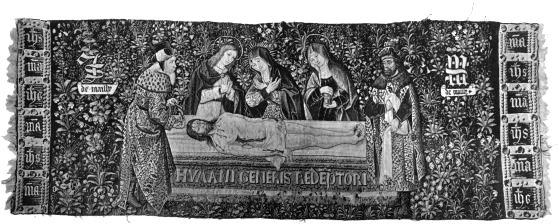

Entombment on Millefleurs No. 8

This piece was probably woven under Pasquier Grenier at Tournai, as were the Wars of Troy, on which there are some documents.

This tapestry presents with extraordinary vividness the fury, din, excessive effort, hot excitement, and blinding confusion of crowded hand-to-hand conflicts that marked mediæval warfare. It must have been conceived and rendered by an eye-witness who knew how to select and assemble the raw facts of the situation with such honesty and directness that an overwhelming impression of force and tumult is created, and it was woven for patrons, the fighting Dukes of Burgundy, by whom every gruesome incident would be observed with relish and every fine point of individual combat noted with a shrewd and appraising eye.

8 FRANCE, END XV CENTURY

ENTOMBMENT ON MILLEFLEURS: Christ lies on the tomb which is inscribed "Humani Generis Redeptori." John in a red cloak, the Virgin in a blue cloak over a red brocaded dress, and Mary Magdalene in a red cloak over a green dress stand behind the tomb. At the head, removing the crown of thorns, stands Joseph of Arimathea and at the foot Nicodemus. Both Joseph and Nicodemus are in richly brocaded robes. Borders at the sides only of alternate blue and red squares inscribed I H S and M A surrounded by jeweled frames. Millefleurs on a blue ground. In the upper left corner the monogram I S and in the upper right W S, with a scroll under each bearing the inscription "de Mailly."