Of the numerous groupes of islands which constitute

the maritime division of Asia, the Phillippines, in situation, riches,

fertility, and salubrity, are equal or superior to any. Nature has here

revelled in all that poets or painters have thought or dreamt of

unbounded luxuriance of Asiatic scenery. The lofty chains of

mountains—the rich and extensive slopes which form their

bases—the ever-varying change of forest and savannah—of

rivers and lakes—the yet blazing volcanoes in the midst of

forests, coeval perhaps with their first eruption—all stamp her

work with the mighty emblems of her creative and destroying powers.

Java alone can compete with them in fertility; but in riches, extent,

situation, and political importance, it is far inferior.

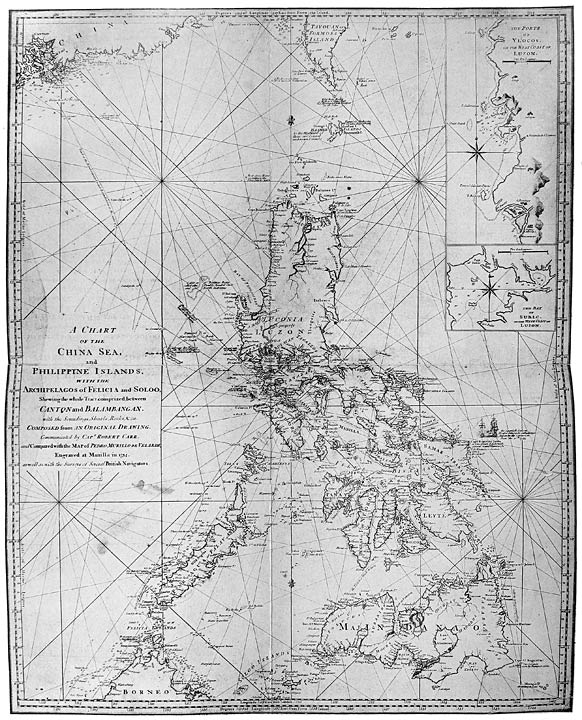

Their position, whether in a political or commercial point of view,

is strikingly advantageous. With India and the Malay Archipelago on the

west and south, the islands of the fertile Pacific and the rising

empires of the new world on the east, the vast market of China at their

doors, their insular position and numerous rivers affording a facility

of communication and defence to every part of them, an active and

industrious population, climates of almost all varieties, a soil so

fertile in vegetable and mineral productions as almost to exceed

credibility; the Phillippine [75]Islands alone, in the hands of an

industrious and commercial nation, and with a free and enlightened

government, would have become a mighty empire:—they are—a

waste!

This archipelago presents, in common with all the islands which form

the southern and eastern barrier of Asia, those striking features which

mark a recent or an approaching convulsion of nature: they are

separated by narrow, but deep, and frequently unfathomable channels;

their steep and often tremendous capes and headlands, though clothed

with verdure to the very brink, appear to rise almost perpendicularly

from the ocean; they have but few reefs or shoals, and those of small

extent; and in the interior of the islands, numerous volcanoes, in

activity or very recently so, boiling springs and mineral waters of all

descriptions, minerals of all kinds on the very surface of the earth,

and frequent shocks of earthquakes, all point to this conclusion, and

offer a rich and unexplored field to the geologist2 and

mineralogist, as do their plants and animals to the botanist and

zoologist;3 the few attempts that have hitherto been made to

examine them, having from various causes failed, or only extended to a

short distance round the capital.4 [76]

The climate of these islands is remarkably temperate and salubrious.

The thermometer in Manila is sometimes as low as 70°, and rarely

exceeds 90° in the house during the N. E. monsoon. In the interior

[77]it is sometimes as low as 68° in the mornings,

which are remarkably cool, so much so as to require at time$ woolen

clothing. None of the mountains are within the limits of perpetual

congelation; but I think some cannot be far from it, as I have seen

something much resembling snow on the Pico de Mindoro, and there may be

higher ones in the interior of Magindanao.6

Both natives and Spaniards live to a tolerable age, in spite of the

indolent habits of the latter, and the debauches of both. The Spaniards

are most commonly carried off by chronic dysentery, which is called by

them “la enfermedád del pays”

(the illness of the country): from its very frequent occurrence, at

least 7 out of 10 of those who exceed the age of 40, fall victims to

this disorder.7 Acute [78]liver complaints are very rare,

as is also the chronic affection of that organ, unless as connected

with the preceding disorder.

Fevers are not common amongst Europeans, in Manila. Amongst

the natives, the intermittent is of common occurrence, particularly

after the rains (in September and October), and in woody or marshy

situations.8 This appears to be owing as much to the thinness

and want of clothing, together with their habits of bathing

indiscriminately at all hours, as to miasmata; and, as their fevers are

generally neglected, they often superinduce other and more fatal

disorders, as obstructions, &c. Tetanos in cases of wounds is of

common occurrence, and generally fatal.

Their population, by a census taken in 1817–18, amounted to

2,236,000 souls, and is increasing rapidly. In one province, that of

Pampanga, from 1817 to 1818, there was an increase of 6,737 souls, the

whole population being in 1817, 22,500; but I suspect some inaccuracy

in this. The total increase from 1797 to 1817, 25 [sic] years,

is by this statement 835,500, or 3,360 per annum! In this census are

included only [79]those subject to Spanish laws. About three

quarters of a million more may be added for the various independent

tribes,9 which may be said to possess the whole of the

interior of the islands, on some of which, as the large one of Mindanao

(called by the natives Magindanao) there are only a few contemptible

[Spanish] posts, the interior and a great part of the coast being still

subject to the Malay sultans, originally of Arab race.

The population of the Marianas and Calamianes Islands, with that of

Palawan, which are all included in “The Kingdom of the

Phillippines,” are [80]comprised in this number, but the

whole of these does not exceed 19,000.

Of this number about 600 only are European Spaniards, with

some few foreigners: the remainder are divided into various classes, of

which the principal are, 1st, The Negroes, or aborigines; 2d, the

Malays (or Indians, as they are called by the Spaniards); and the

Mestizos and Creoles, who are about as 1 to 5 of the Indian

population.

The Negroes [i.e., Negritos]10 are in all

probability the original inhabitants of these islands, as they appear

at some remote epoch to have been of almost all the eastern

archipelago. The tide of Malay emigration, from whatever cause and part

it proceeded, has on some islands entirely destroyed them. Others, as

New Guinea, it has not yet reached, a circumstance which seems to point

to the west as the original cradle of the Malay race. In the

Phillippines, it has driven them from the coast to the mountains, which

by augmenting the difficulty of procuring subsistence, may have much

diminished their numbers. Still, however, they form a distinct, and

perhaps a more numerous class of men than is generally suspected. They

have in the present day undisturbed possession of nearly ⅔ds of

the island of Luzon, and of others a still larger proportion.

These people are small in stature, some of them almost dwarfish,

woolly-headed, and thick-lipped, like the negroes of Africa, to whom

indeed they bear [81]a striking resemblance, though the different

tribes vary much in their stature and general appearance. They subsist

entirely on the chase, or on fruits, herbs, roots, or fish when they

can approach the coast. They are nearly, and often quite naked, and

live in huts formed of the boughs of trees, grass &c., or in the

trees themselves, when on an excursion or migration. Their mode of life

is wandering and unsettled, seldom remaining long enough in one place

to form a village. They sometimes sow a little maize or rice, and wait

its ripening, but not longer. These are the habits of the tribes which

border on the Spanish settlements. Farther within the mountains they

are more settled, and even form villages of considerable size, in the

deep vallies by which the chains of mountains are intersected. The

entrances to these they fortify with plantations of the thorny bamboo,

pickets of the same, set strongly in the earth and sharpened by fire,

ditches and pit-falls; in short all the means of defence in their power

are employed to render these places inaccessible. Here they cultivate

corn, rice, and tobacco; the last they sell to Indians, who smuggle it

into the towns. This being a contraband article, as it is monopolized

by government, the defences are used against the Spanish revenue

officers and troops, who on this account never fail to destroy their

establishments when they can do so, though many are impregnable to any

force they can bring against them, from the nature of the passes, and

from the activity of the negroes, who use their bows with wonderful

expertness. There are indeed instances of their repulsing bodies of one

or two hundred native troops, but affairs of this magnitude are very

rare.

To this predatory kind of warfare, as well as to [82]the

defective qualities, and often very reprehensible conduct of the

missionaries, generally Indian priests (Clerigos), are

perhaps to be in some measure attributed their unsettled habits. Those

nearest the Spanish settlements carry on a little commerce, receiving

wrought iron, cloth, and tobacco, but oftener dollars, in

exchange for gold-dust, &c., or for wax, honey, and other products

of their mountains. The circumstance of their receiving dollars, which

they rarely use in their purchases, is a curious one; but it is a fact,

and very large quantities of money are supposed to be thus buried; from

what motive, except a superstitious one, cannot be imagined.11

Of their manners or customs little or nothing is known. Like all

savage nations, they are abundantly tinctured with superstitions,

fickle, and hasty. One of their customs best known is, that upon the

death of a chief, they plant themselves in ambush on some frequented

track, and with their arrows assassinate the first unfortunate

traveller who passes, and not unfrequently two or three; the bodies are

carried off as sacrifices to the manes of the deceased.12 The communications between the Spanish

settlements are often interrupted by this circumstance, as no Indian

will venture out when the negroes are known to be “de luto” (in mourning): they are also said to

have a “throwing of spears,” similar to those of New

Holland, at the death of any eminent person. In fact, upon this, as

upon all other points unconnected with masses and sermons, there exists

a degree of ignorance which is almost incredible. The early

missionaries, [83]in their rage for nominal conversion,

appear to have neglected entirely the history or origin of their

neophytes; and, as in America, where the monuments of ages were

crumbled to the dust to plant the cross, all that related to the

history of their converts was considered as unprofitable, if not as

impious, the devil13 being compendiously supposed to

preside over their political as well as religious institutions in all

cases. In this belief, and in its consequent effects, the modern

missionaries, who are mostly Indian priests, are worthy successors of

their Spanish predecessors.

The government have many missions established for the purpose of

converting them, but with little success. Like most savages, their mode

of life has to them charms superior to civilization, or rather to

Christianity (for here the terms are not synonimous); and they rarely

remain, should they even consent to be baptized, but on the first

caprice, or exaction of tribute, which immediately takes place, and

sometimes even precedes this ceremony, return again to their

mountains.

Exposed to all inclemencies of the weather, and with an unwholesome

and precarious diet, they perhaps rarely attain more than forty years

of age. Their numbers are supposed rather to diminish than increase;

and in a few years this race of men, with their language, will probably

be extinct. It is indeed a curious subject of enquiry, whether the

language of those of the eastern islands has any, and what resemblance

to those of Africa, or the southern parts of New Holland and Van

Dieman’s Land?14 [84]

They are not represented as very mischievous; but if strangers

venture too far into their woods, they consider it an aggression, and

repel it accordingly [85]with their arrows. Those who frequent the

Spanish settlements are rather of a mild character; and there are

instances of Spanish vessels being wrecked on the [86]coast,

whose people, particularly the Europeans, have been treated by them in

the kindest manner, and carefully conducted to the nearest settlement.

[87]

The character of the different tribes appears, however, to vary in

this particular: some are described as treacherous and cruel, and those

which inhabit the [88]north western coasts of the Bay of Manila are

accused of having frequently attacked the boats of ships, when these

were not sufficiently guarded in their intercourse with them. The

natives of the town in the Bay of Mariveles, at the entrance of that of

Manila, assured the writer of these pages, that it would be madness to

attempt accompanying them into the woods, even in disguise; and in this

they persisted, though money was offered them to allow him to proceed

with them.

The Indians are the descendants of the various Malay tribes which

appear to have emigrated to this country at different times, and from

different parts of Borneo and Celebes. Their languages, though all

derived from one stock (the Malay), has a number of dialects differing

very materially; so much so, that those from different provinces

frequently do not understand each other.

They differ too in their character, and slightly in their manners

and customs. The most numerous class of them are the Bisayas,18 (a Spanish name, from their [89]anciently painting their bodies, and using

defensive armour). These inhabit the largest part of the southern

islands. Luzon contains several tribes, of which the most remarkable

are the Ylocos, Cagayanes, Zambales, Pangasinanes, Pampangos, and

Tagalos. These still retain their national distinctions and characters

to such a degree, that they often occasion quarrels amongst each other.

Of their general character as a nation we are now to speak.

The Indian of the Phillippine Islands has been strangely

misrepresented. He is not the being that oppression, bigotry,

and indolence, have for 300 years endeavoured to make him, or he is so

only when he has no other resource. Necessity, and the force of example

have made those of Manila, what the whole are generally

characterized as—traitors, idlers, and thieves.

How, under such a system as will be afterwards described, should

they be otherwise? Say rather, that all considered, it is surprising to

find them what they are; for they are in general (I speak of the Indian

of the provinces), mild, industrious, as far as they dare to be so,

hospitable, kind, and ingenuous. The Pampango is brave,19 faithful, and active; the fidelity of the Cagayan

is proverbial; the Yloco and the Pangasinanon are most industrious; the

Bisayan is brave and enterprising almost to fool-hardiness:—they

are all a spirited, a proudly-spirited race of men; and such materials,

in other hands, would form the foundation of all that is great and

excellent in human nature.

But for 300 years they have been ground to the earth with

oppression. They have been crushed by [90]tyranny; their spirit has

been tortured by abuse and contempt, and brutalized by ignorance; in a

word, there is no injustice that has not been inflicted on them, short

of depriving them of their liberty; and in a work published at Madrid

in 1819 (Estado de las Yslas Filipinas, par

[sic; for por] Don Tomas Comyn), whose author

was a factor of the Phillippine company, a whole chapter (the 4th) is

devoted to the mild and humane project “of establishing Spanish

agriculturists throughout the islands,” who are, “to

require a certain number of Indians from the governors of towns and

provinces, who are to be driven to the plantations, where they are to

be obliged to work a certain time, the price of their labour

being fixed, and then to be relieved by a fresh drove!”20

Such a system, incredible as it may appear, has been proposed to a

Spanish cortes; and still more wonderful, plans like these excited no

reprobation in Manila. Such were Spanish ideas of governing Indians!

Justice would almost tempt us to wish that this scheme had been carried

into execution, and that the Indian had risen and dashed his chains on

the heads of the authors of such an infernal project. And yet the

Indian is marked out as little better than a brute; so many of them

are, but to the system of government, and not to the Indian, is the

fault to be ascribed.

It is not here meant to accuse the Spanish laws; many of them are

excellent, and would appear to [91]have been dictated by the very

spirit of philanthropy. But these are rarely enforced, or if they are,

delay vitiates their effect. That this colony, the most favoured

perhaps under heaven by nature, should have remained till the present

day almost a forest, is a circumstance which has generally excited

surprise in those who are acquainted with it, and has as generally been

accounted for by attributing it to the laziness of the Spaniards

and Indians. This is but a superficial view of the subject; one of

those general remarks which being relatively a little flattering to

ourselves, pass current as facts, and then “we wonder how any one

can doubt of what is so generally received.”—The cause lies

deeper, man is not naturally indolent. When he has supplied his

necessities, he seeks for superfluities—if he can enjoy them in

security and peace;—if not—if the iron gripe of despotism

(no matter in what shape, or through what form it is felt), is ready to

snatch his earnings from him, without affording him any

equivalent—then indeed he becomes indolent, that is, he merely provides

for the wants of to-day. This apathy is perpetuated through numerous

generations till it becomes national habit, and then we falsely call it

nature. It cannot be too often repeated, that from the poles to the

equator, man is the creature of his civil institutions, and is active

in proportion to the freedom he enjoys. Who that has perused the

History of Java by Sir S. Raffles,21 and seen the effects of

government planned [92]by the talents of Minto in the spirit

of the British constitution in that country, will now accuse the

Javanese of unwillingness to work, if the fruits of his labour are

secured to him? And yet we remember when a Javanese was another name

for every thing that is detestable. It is ever thus—we blame the

race, because that flatters our pride—we should first look to

their institutions. I return to the Phillippines.

The cause, then, of their little progress is “because there

is no security for property;” or in other words, the

smallness of the salaries of the officers of justice, as well as of

other members of government, and the profligacy inseparable from all

despotic governments, have laid the inhabitants under that curse of all

societies, venal courts of justice. Does an unfortunate Indian scrape

together a few dollars to buy a buffalo, in which consists their whole

riches? Woe to him if it is known; and if his house is in a lonely

situation—he is infallibly robbed. Does he complain, and is the

robber caught? In three months he is let loose again (perhaps with some

trifling punishment), to take vengeance on his accuser, and renew his

depredations.

Hundreds of Indian families are yearly ruined in this manner.

Deprived of their cattle, on which they [93]depend for subsistence,

they grow desperate and careless of future exertion, which can but lead

to the same results, and thus either drag on a miserable existence from

day to day, or join with the robbers23 to pursue

the same mode of life, and to exonerate themselves from paying tributes

and taxes, in return for which no protection is granted. In many

provinces this has been carried to such an extent, that whole districts

are rendered impassable by the robbers,24 who even

lay villages under contribution!

This is the state of the inland towns. On the coasts, and while a

flotilla of gun-boats is maintained at an expense of upwards of half a

million of dollars annually, there is no part safe from the attacks of

the Malay pirates from Borneo, Sooloo, and Mindanao. These make regular

cruises to procure slaves, and have even not unfrequently carried them

off, not only from the bay of Manila,25 but even

from within gun-shot of its ramparts! The very soldiers and sailors

sent for their protection plunder them. An Indian in whose

neighbourhood troops are posted, [94]or who sees the gun-boats

approaching, can no longer consider his property safe; and in the very

vicinity of Manila, soldiers ramble about with their loaded muskets,

and pilfer all they lay hands upon at midday!26

Does the Indian, in spite of all this, escape, and by patient

industry make a little way in the world? he is vexed with offices; he

is chosen Alguazil, Lieutenant, and Captain of his town; to these

offices no pay is attached, they always occasion expenses and create

him enemies; he is pinched or cheated by the Mestizos, a forestalling,

avaricious, and tyrannical race. Does he suffer in silence? it is a

signal for new oppressions: does he complain? a law suit. The Mestizos

are all connected, they are rich, and the Indian is poor.

The imperfect mode of trial, both in civil and criminal cases (by

written declarations and the decisions of judges alone), lays

them open to a thousand frauds; for if the magistrate be supposed

incorruptible, his notaries or writers (escribanos and escribientes) are not

so; and from their knavery, declarations are often falsified, or one

paper is exchanged for another whilst in the act of or before signing

them.

To such a degree does this exist, that few Indians, even of those

who can read Spanish tolerably, will sign a declaration made before a

magistrate without threats, or without having some one on whom they

[95]can depend, to assure them they may safely do so.

Nor is this to be wondered at, when it is known that declarations on

which the life or fortune of an individual may depend are left, often

for days, in the power of writers or notaries, any of whom may be

bought for a doubloon; and some of them are even the menial servants of

the magistrate! This applies to Luzon. In the other islands, this

miserable system is yet worse: they have seldom but one communication a

year with the capital, to which all causes of any magnitude are sent

for decision or confirmation; and, as the papers are often (purposely)

drawn up with some informality, the cause, after suffering all the

first ordeal of chicane and knavery, experiences a year’s delay

before it is even allowed a chance of being exposed to that which

awaits it at Manila. Or should the cause be at length carried to the

Audiencia, or Supreme Court, and there, as is sometimes the

case, be judged impartially, the delay of the decision renders it

useless—the sentence is evaded—or treated with contempt!

This may appear almost incredible, but known to any person who has

resided in Manila.

While the civil power is thus shamefully corrupt or negligent of its

duties, the church has not forgotten that she too has claims on the

Indian. She has marked out, exclusive of Sundays, above 40 days in the

year on which no labour can be performed throughout the islands.

Exclusive of these are the numerous local feasts in honor of the patron

saints of towns and churches.27 The influence of these extends

[96]often through a groupe of many islands, always to

many leagues round their different sanctuaries; and often lasting three

or four days, sometimes a week, according to his or her reputation for

sanctity; so that including Sundays, the average cannot be less than

110 or 120 days lost to the community in a year. This alone is a heavy

tax on the agricultural classes, by whom it is most severely felt; but

its consequences are more so, from the habits of idleness and

dissipation which it engenders and perpetuates. These feasts are

invariably, after the procession is over, scenes of gambling, drinking,

and debauchery of every description.

“And mony jobs that day begun,

Will end in houghmagandie.”29

Thus they unsettle and disturb the course of their

labours [97]by calling off their attention from their domestic

cares; and by continually offering occasions of dissipation destroy

what little spirit of economy or foresight may exist amongst so rude

and ignorant a people. Nor is this all; they are subject to numerous

other vexations and impositions under the title of church-services;

such are, in some towns, five or six men attendant daily in rotation to

bring the sick to the church to confess, or to carry the

“Padre” with the host to their houses, and many others; all

of which, though in themselves trifles, are more harassing, from their

unsettling tendency, than pecuniary imposts. An encouragement to

celibacy and its consequent evils is also to be found in the (to them)

heavy expenses attendant on all the domestic offices of religion, as

matrimony, baptism, &c., as well as in the increase of the poll-tax

on married persons, for the whole of which the husband is responsible.

The ecclesiastical expenses of a marriage between the poorer classes

are about five dollars: the others, as christenings, buryings, &c.,

in proportion. These appear trifles; but if to these are added the

confessions, bulas, [i.e., of the Crusade] and other

exactions, it will be seen that these constitute no trifling part of

the oppressive and ill managed system which has so much contributed to

debase their real character.

I say nothing here of the natural effect of the Roman Catholic

religion on an ignorant people, who imagine, that verbal confession and

pecuniary atonements (rarely to the injured person) are a salvo

for crimes of all magnitudes: that such is the case, is notorious to

every one who has visited Catholic countries. [98]

Let us for a moment retrace this picture. To whom after this is it

attributable that the Indian is often a vicious and degraded being,

particularly in the neighborhood of Manila?

If he sees all around him thieving and enjoying their plunder with

impunity, what wonder is it that he should thieve also? If his

tribunals of all descriptions afford him no redress, or place that

redress beyond his reach, what resource has he but private

revenge?30 If he cannot enjoy the fruits of his labour in

peace, why should he work? If he is ignorant, why has he not been

instructed? There exist scarcely any schools to teach him his duties:

the few that do exist teach him Latin! prayers! theology!

jurisprudence! and some little reading and writing;31 but he

[99]is only taught to read the lives of the saints,

and the legends of the church, whose gloomy, fanatical doctrines and

sanguinary histories have not a little contributed to make him at times

revengeful and intolerant. Does he prevaricate and flatter? It is

because [100]he dare not speak the truth, and because

a long system of oppression has broken his spirit.

Does he endeavour to advance himself a few steps in civilization?

his attempts are treated with ridicule and contempt;32 hence he

becomes apathetic, careless of advancement, and often insensible to

reproach. The best epithets he hears from Spaniards (often as ignorant

as himself) are “Indio!” The God of

nature made him so. “Bruto!” He has

been and is brutalized by his masters. “Barbaro!” He is often so by force, example, or even

by precept. “Ignorante!” He has no

means of learning; the will is not wanting. In a word, the spirit of

the followers of Cortes and Pizarro, appears to have left its last

vestiges here, and perhaps the Indian has been saved from its

persecutions only by the weakness of the Spaniard.

Such are some of the causes which have marked the character of the

Indian, which is not naturally bad, with some of its prominent

blemishes. I am far from holding up the Indian of the Phillippines as a

faultless being; he is not so; the Indian of Manila34 [101]has all the vices attributed to

him; but I assert, that the Phillippine islander owes the greater

part of his vices to example, to oppression, and above all to

misgovernment; and that his character has traits, which under a

different system, would have produced a widely different result.

To sum up his character:—He is brave, tolerably faithful,

extremely sensible to kind treatment, and feelingly alive to injustice

or contempt; proud of ancestry, which some of them carry to a remote

epoch; fond of dress and show, hunting, riding, and other field

exercises; but prone to gambling and dissipation. He is active,

industrious, and remarkably ingenious. He possesses an acute ear, and a

good taste for music and painting, but little inclination for abstruse

studies. He has from nature excellent talents, but these are useless

for want of instruction. The little he has received, has rendered him

fanatical in religious opinions; and long contempt and hopeless misery

has mingled with his character a degree of apathy, which nothing but an

entire change of system and long perseverance will efface from

it.36 [102]

The Mestizos are the next class of men who inhabit these islands:

under this name are not only included the descendants of Spaniards by

Indian women and their progeny, but also those of the Chinese, who are

in general whiter than either parent, and carefully distinguish

themselves from the Indians. [103]The Mestizos are, as the name

denotes, a mixed class, and, with the creoles of the country, like

those of all colonies, when uncorrected by an European education,

inherit the vices of both progenitors, with but few of the virtues of

either. Their character has but few marked traits; the principal ones

are [104]their vanity, industry, and trading ingenuity:

as to the rest, money is their god; to obtain it they take all shapes,

promise and betray, submit to everything, trample and are trampled on;

all is alike to them, if they get money; and this, when obtained, they

dissipate in lawsuits, firing cannon, fireworks, illuminations,

[105]processions on feast days and rejoicings, in

gifts to the churches, or in gambling. This anomaly of actions is the

business of their lives. Too proud to consider themselves as Indians,

and not sufficiently pure in blood to be acknowledged as Spaniards,

they affect the manners of the last, with the dress of the first, and

despising, are despised by both.37 They however, cautiously

mark on all occasions the lines which separate them from the Indians,

and have their own processions, ceremonies, inferior officers of

justice, &c., &c. The Indian repays them with a keen contempt,

not unmixed with hatred. And these feuds, [106]while they contribute

to the safety of a government too imbecile and corrupt to unite the

good wishes of all classes, have not unfrequently given rise to affrays

which have polluted even the churches and their altars with blood.

Such are the three great classes of men which may be considered as

natives of the Phillippine Islands. The Creole38 Spaniards,

or those whose blood is but little mingled with the Indian ancestry,

pass as Spaniards. Many of them are respectable merchants and men of

large property; while others, from causes which will be seen hereafter,

are sunk in all the vices of the Indian and Mestizo.

The government of the Phillippine Islands is composed of a governor,

who has the title of Captain General, with very extensive powers; a

Teniente Rey, or Lieutenant Governor; the Audiencia or Supreme Court,

who are also the Council. This tribunal is composed of three judges,

the chief of whom has the title of Regent, and two Fiscals or Attorney

Generals, the one on the part of the king, the other on that of the

natives, and this last has the specious title of “Defensor de los

Indios.” The financial affairs are under the direction of an

Intendant, who may be called a financial governor. He has the entire

control and administration of all matters relative to the revenue, the

civil and military auditors and accountants being under him. Commercial

affairs [107]are decided by the Consulado, or chamber of

commerce, composed of all the principal, and, in Manila, some of the

inferior merchants. From this is an appeal to a tribunal “de

Alzada” [i.e., of appeal] composed of one judge and two

merchants, and from this to the Audiencia, without whose approbation no

sentence is valid.

The civic administration is confided to the Ayuntamiento (Courts of

Aldermen or Municipality). This body, composed of the two Alcaldes,

twelve Regidors (or Aldermen) and a Syndic, enjoy very extensive

privileges, approaching those of Houses of Assembly; their powers,

however, appear more confined to remonstrances and protests,

representations against what they conceive arbitrary or erroneous in

government, or recommendations of measures suggested either by

themselves or others. They have, in general, well answered the object

of their institution as a barrier against the encroachments of

government, and as a permanent body for reference in cases where local

knowledge was necessary, which last deficiency they well supply.

The civil power and police are lodged in the hands of a Corregidor

and two Alcaldes: the decision of these is final in cases of civil

suits, where the value in question is small, 100 dollars being about

the maximum.39 Their criminal jurisdiction extends only to

slight fines and corporal punishments, and imprisonment preparatory to

trial. The police is confided to the care of the Corregidor, who has

more extensive powers, and also the inspection and control of the

prisons.

To him are also subject the Indian Captains and [108]Officers of towns, who are annually elected by

the natives. These settle small differences, answer for disturbances in

their villages, execute police orders, impose small contributions of

money or labour for local objects, such as repairs of roads, &c.

&c. They also have the power of inflicting slight punishments on

the refractory. To them is also confided the collection of the

capitation or poll-tax, which is done by dividing the population of the

town or village into tens, each of which has a Cabeça (or head),

who is exempt from tribute himself, but answerable for the amount of

the ten under him. This tax is then paid to the Alcalde or Corregidor,

and from him to the treasury. The Mestizos and Chinese have also their

captains and heads, who are equally answerable for the poll-tax.

The different districts and islands, which are called provinces, and

are 29 in number, are governed by Alcaldes. The more troublesome ones,

or those requiring a military form of government, by military officers,

who are also Corregidors. Samboangan on the south west coast of

Mindanao, and the Marianas, have governors named from Manila, and these

are continued from three to five years in office.

These Alcaldeships are a fertile source of abuses and oppression:

their pay is mean to the last degree, not exceeding 350 dollars per

annum, and a trifling per centage on the poll-tax. They are in general

held by Spaniards of the lower classes, who finding no possible

resource in Manila, solicit an Alcadeship. This is easily obtained, on

giving the securities [109]required by government for

admission to these offices, which consist in two sureties40 to an amount proportionable to the value of the

taxes of the province, which all pass through the Alcalde’s

hands.

Of the nature and amount of these abuses an idea will be better

formed from the following abridged quotations, which are translated

from the work of Comyn before quoted (p. 16).41

“It is indeed common enough to see the barber or lacquey of a

governor, or a common sailor, transformed at once into the Alcalde in

chief of a populous province, without any other guide or council than

his own boisterous passions.

“Without examining the inconvenience which may arise from

their ignorance, it is yet more lamentable to observe the consequences

of their rapacious avarice, which government tacitly allows them to

indulge, under the specious title of permissions to trade (indultos).

——“and these are such that it may be asserted,

that the evil which the Indian feels most severely is derived from

the very source which was originally intended for his assistance and

protection, that is, from the Alcaldes of the provinces, who,

generally speaking, are the determined enemies and the real oppressors

of their industry. [110]

“It is a well known fact, that far from promoting the felicity

of the provinces to which he is appointed, the Alcalde is exclusively

occupied with advancing his private fortune, without being very

scrupulous as to the means he employs to do so: hardly is he in office

than he declares himself the principal consumer, buyer, and exporter of

every production of the province. In all his enterprises he requires

the forced assistance of his subjects, and if he condescends to

pay them, it is at least only at the price paid for the royal works.

These miserable beings carry their produce and manufactures to him, who

directly or indirectly has fixed an arbitrary price for them. To offer

that price is to prohibit any other from being offered—to

insinuate is to command—the Indian dares not hesitate—he

must please the Alcalde, or submit to his persecution: and thus, free

from all rivalry in his trade, being the only Spaniard in the province,

the Alcalde gives the law without fear or even risk, that a

denunciation of his tyranny should reach the seat of government.

“To enable us to form a more correct idea of these iniquitous

proceedings, let us lift a little of the veil with which they are

covered, and examine a little their method of collecting the

‘tributo’ (poll-tax).

“The government, desirous of conciliating the interests of the

natives with that of the revenue, has in many instances commuted the

payment of the poll-tax into a contribution in produce or manufactures:

a year of scarcity arrives, and this contribution, being then of much

higher value than the amount of the tax, and consequently the payment

in produce a loss, and even occasioning a serious want in their

families, they implore the Alcalde to make a representation

[111]to government that they may be allowed to pay

the tribute for that year in money. This is exactly one of those

opportunities, when, founding his profits on the misery of his people,

the Alcalde can in the most unjust manner abuse the power confided to

him. He pays no attention to their representations. He is the zealous

collector of the royal revenues;—he issues proclamations and

edicts, and these are followed by his armed satellites, who seize on

the harvests, exacting inexorably the tribute, until nothing more is to

be obtained. Having thus made himself master of the miserable

subsistence of his subjects, he changes his tone on a sudden—he

is the humble suppliant to government in behalf of the unfortunate

Indians, whose wants he describes in the most pathetic terms, urging

the impossibility of their paying the tribute in produce—no

difficulty is experienced in procuring permission for it to be paid in

money—to save appearance, a small portion of it is collected in

cash, and the whole amount paid by him into the treasury, while

he resells at an enormous profit, the whole of the produce (generally

rice) which has been before collected!” Comyn, p. 134 to

138.

This extract, though long, is introduced as an evidence from a

Spaniard (not of the lower order, or a disappointed adventurer, but a

man of high respectability), of the shameless abuses which are daily

practiced in this unfortunate country, and of which the Indian is

invariably the victim: and it is far from being an overcharged

one. Hundreds of other instances might be cited,42 but this

one will perhaps [112]suffice to exonerate the writer of these

remarks from suspicion of exaggeration, in pointing out some of the

most prominent of them.

While treating of the government of the Phillippines, we must not

forget the ministers of their religion, and the share which they have

in preserving these islands as dominions to the crown of Spain. This

influence dates from the earliest epoch of their discovery. The

followers of Cortes and Pizarro, with their successors, were employed

in enriching themselves in the new world; and the spirit of conquest

and discovery having found wherewith to satiate the brutal avarice by

which it was directed, abandoned these islands to the pious efforts of

the missionaries by whom, rather than by force of arms, they were in a

great measure subdued; and even in the present day, they still preserve

so great an influence, that the Phillippines may be almost said to

exist under a theocracy approaching to that of the Jesuits in

Paraguay.

The ecclesiastical administration is composed of an Archbishop (of

Manila), who has three suffragans, Ylocos, Camarines, and Zebu; the

first two on Luzon, the last on the island of the same name. The

revenue of the Archbishop is 4000, and that of the bishops 3000 dollars

annually. The regular Spanish clergy of all orders are about 250, the

major part of which are distributed in various convents in [113]the

different islands, though their principal seats are in that of Luzon;

and many of them, from age or infirmity, are confined to their convents

in Manila.

The degree of respect in which “the Padre” is held by

the Indian, is truly astonishing. It approaches to adoration, and must

be seen to be credited. In the most distant provinces, with no other

safeguard than the respect with which he has inspired the Indians, he

exercises the most unlimited authority, and administers the whole of

the civil and ecclesiastical government, not only of a parish, but

often of a whole province. His word is law—his advice is taken on

all subjects. No order from the Alcalde, or even the

government43 is executed without his counsel and approbation,

rendered too in many cases the more indispensable from his being the

only person who understands Spanish in the village.44 To their

high honour be it spoken, the conduct of these reverend fathers in

general fully justifies [114]and entitles them to this

confidence. The “Padre” is the only bar to the oppressions

of the Alcalde: he protects, advises, comforts, remonstrates, and

pleads for his flock; and not unfrequently has he been seen, though

bending beneath the weight of years and infirmity, to leave his

province, and undertake a long and often perilous voyage to Manila, to

stand forward as the advocate of his Indians; and these gratefully

repay this kind regard for their happiness by every means in their

power.

Their hospitality is equally praiseworthy. The stranger who is

travelling through the country, no matter what be his nation or his

religion,45 finds at every town the gates of the convent open

to him, and nothing is spared that can contribute to his comfort and

entertainment. They too are the architects and mechanists: many of them

are the physicians and schoolmasters of the country, and the little

that has been done towards the amelioration of the condition of the

Indian, has generally been done by the Spanish clergy.

It is painful, however, to remark, that much that [115]might have been done, has been left undone. The

exclusive spirit of the Roman church, which confines its knowledge to

its priests, is but too visible even here: they appear to be more

anxious to make Christians, than citizens, and by neglecting this last

part of their duty, have but very indifferently fulfilled the

first,—the too common error of proselytists of all denominations,

which has probably its source in that vanity of human nature, which is

as insatiable beneath the cowl as under any garb it has yet

assumed.

Some of them too have furnished a striking but melancholy proof of

the eloquent moral,

“It is not good for man to be alone.”

Let us draw a veil over these infirmities. He who has

lived amidst the busy hum of crowds, amidst the wild whirl of human

passions and interests, can have but little conception of the state of

that mind, which perhaps feeling alive to the blessings of social

intercourse, is cut off for years from civilized men; and thus buried

mentally, is constrained to seek all its resources within

itself.46 That heart is one of powerful fibre which does

not sometimes show itself to be human ….

There are instances indeed of some of them forgetting in a great

measure their language! and of others who have become almost idiots

while yet in the vigour of life!47 [116]

The next and lowest order of ecclesiastics are the Indian clergy

(clerigos); they are in number from 800 to 1000, and

though from the want of Spaniards, the administration of many large

districts and towns is confided to them, they are as a body far from

being worthy of such an important charge. The majority of them are

ignorant to the last degree, proud, debauched, and indolent: in a word,

they unite the vices of the priesthood to those of the Indian, and form

a class of men who may almost be said to be distinguished by

their vices only.

This arises from various causes, of which the principal appears to

be that of their being entirely excluded from the higher ecclesiastical

situations. This alone, by depriving them of the most powerful stimulus

to correct conduct, together with the very confined education they

receive, and the impassable line drawn between them and the Spanish

clergy, whom they are never allowed to approach, and who treat them

with much contempt, are sufficient to account, in a great measure, for

their apparent demerit. The fact, however, is such, whatever be its

cause; and seldom a week passes, or at most a month, but [117]some

of them are brought before the ecclesiastical tribunals, under

accusations but little creditable to their cloth.

Their ordinary resort at Manila is the cockpit or the gaming table,

where they shew an avidity and keenness which are disgraceful and

shameless to the last degree. Yet to the guidance of beings like these

is the unfortunate Indian in a great measure abandoned, even in his

last moments: for from the very great proportion of these to the

Spanish priests, and from the recluse lives of the latter, nearly

nine-tenths of all the clerical duties are performed by the Indian

clerigos, such as I have described them. The few who

do form an exception, are men whose conduct is highly creditable to

themselves, and more striking from its unfrequent occurrence.

A keen and deadly jealousy subsists between these and the Spanish

ecclesiastics, or rather a hatred on the one side, and a contempt on

the other. The Indian clergy accuse these last of a neglect of their

ecclesiastical duties, of vast accumulations of property in lands,

&c., which, say they, “belong to us the

Indians.” The Spaniards in return treat them with silent

contempt, continuing to enjoy the best benefices, and living at their

ease in the convents. From what has been said, it will be easily seen,

“that much may be said on both sides;” but these

recriminations have the bad effect of debasing both parties in the eyes

of the natives, and are the germs of a discord which may one day

involve these countries in all the horrors of religious

dissentions.48 [118]

Such are the civil and ecclesiastical government of the

Phillippines. We turn now to the Revenue and Expenditure, Military

establishments, &c.

Until very lately these rich islands have been a constant burden to

the crown of Spain, money having been annually sent from Mexico to

supply their expenses. The establishment of the monopoly of tobacco has

principally contributed to supply this deficiency. It was established

by an active and intelligent governor (Vasco) about 1745 [sc.,

1785] and still continues to be the principal revenue of the country;

and large sums have been from time to time sent home to Spain, as a

balance against those received from Mexico. The sales of this article

amount more or less to a million of dollars per annum. The extensive

establishment which is kept up to prevent smuggling, and the expenses

of purchase and manufacture, reduce its net produce to 500,000 dollars

per annum. The plant is cultivated in the districts of Gapan in

Pampanga, in a part of the province of Cagayan, and in the island

Marinduque to the south of Luzon. It is delivered in by the cultivators

at fixed prices, and sent to Manila, where it is manufactured in a

large range of buildings dedicated to that purpose, and retailed to the

public at about 18 to 19½ dollars per arroba of 25 lbs.

(Spanish), the prices varying a little according to the harvests.

The administration, inspection, and manufacture [119]of

this article, employ several thousand persons of both sexes (the

manufacturing process being almost wholly carried on by women). This is

not only the most productive, but the best conducted branch of the

revenue; while it is at the same time the least vexatious in its

operations, though not exempt from those objections which are common to

all government monopolies.

Another of these monopolies is that of Coco wine, as it is called

(vino de Coco y nipa). This is a weak spirit produced from the juice of

the Toddy tree (Borassus gomutus),49 and from the nipa (Cocos

nypa): of this, large quantities are used by the natives. The expense

of collection is about 80,000 dollars, the net revenue to government

varying from 2 to 300,000.

The poll-tax (tributo) is the other great branch of the revenue; the

manner of collecting it is described in p. 29. Its amount to each

individual is, with some exceptions and variations in different

provinces, 14 rials, or 1¾ dollars for every married Indian,

from the age of 24 to 60. The Mestizos pay 24 rials or 3 dollars, and

the Chinese 6 dollars each: this last branch is generally farmed. The

amount of Indian and Mestizo tribute may be stated in round numbers at

800,000 dollars: the expense of collecting it diminishes it to about

640,000. The exemptions [120]from it are disbanded soldiers,

who pay less than others, men above 60 years of age, and the

cultivators of tobacco, or makers of wine for the royal monopolies.

The collection of this tax is always attended with much trouble, and

it is detested by the Indians to the last degree. The exaction of it

from the newly converted tribes,50 and the extensive frauds

which, as already detailed, are practised by means of it, render it the

most oppressive of all impositions. The natives consider it (perhaps

with some justice), as giving money to no purpose; and infallibly evade

it by every means in their power.

The customs produce from 1 to 300,000 dollars per annum. The

remaining part of the revenue is derived from various minor sources:

such are the cockpits, which are farmed, and produce a net revenue of

25 to 40,000 dollars;—the Chinese poll-tax, 30,000

dollars;—“Bulas,”51 (the sale of which is [121]farmed, and produces from 10 to 12,000

dollars);—cards, powder (a monopoly), stamps, and other articles

of minor importance; amongst which was formerly the monopoly of betel

nut, which is now abolished.

The expenses of administration are as follows. The civil and

ecclesiastical officers of government, 250,000 dollars. The military,

including all classes, about 600,000; and the marine, about

550,000.

The excess of revenue over the expenditure is stated by Comyn to

have been in 1809 about 450,000 dollars, but in this is included

250,000 received from Mexico.

In 1817, by an account published by order of the Ayuntamiento of

Manila, the amount of the revenue was—

Receipts

|

Dollars |

| Poll Tax |

638,976 |

| Rentas (monopolies, farms, &c.) |

810,784 |

| Total |

1,449,76052 |

of which a surplus would remain when all the expenses were

liquidated. In preceding years, some surplus has been remitted to

Spain.

The military establishment consists of three regiments of infantry,

one of dragoons, a squadron of hussars, and a battalion of artillery,

in all about 4500 regulars. The militia are numerous, but only one

[122]regiment is under arms: the total of men may be

estimated at 5000, but on an emergency, large bodies of irregulars can

be called into activity. In 1804, the governor, Don J. M. de Anguilar,

[i.e., Aguilar] is said to have had upwards of 20,000 men

under arms, being in expectation of an attack from the English.

These troops (which are all natives) are in general badly

disciplined and officered, mostly by country-born officers, without the

advantage of an European education, ignorant of their military duties

to the last degree, many of them (more especially in the Mestizo

regiments) connected with the soldiers by relationship, or at least by

the tie of mutual indulgence, the soldier performing every menial

office for the officer, who in return winks at the excesses of the

soldier. This is carried to such an extent, that, not to mention such

trifles as a garden wall or gate, a bathing house, or a stable, or at

times a little smuggling; there are instances on record, where the

commanding officer of a regiment has built himself a country house! the

whole of the masonry and carpentry being performed by soldiers of his

regiment! Another is of a captain collecting his debts by means of a

piquet of infantry; taking possession of his debtor’s house until

payment was made!

It will be easily conceived, that where these things are permitted,

the soldiers are made subservient to other purposes; accordingly they

have been employed to punish the paramours of their officers’

wives—to eject a troublesome tenant—or at times to take

vengeance for affronts, in cases where it might not be safe for the

injured person to do so.53 [123]

These remarks apply more particularly to the Mestizo officers. The

Spaniards, and some of the creoles, who are but very few in number,

form a respectable class of military men, of whom some few may be cited

as models of spirit and discipline: but they are not sufficiently

numerous for their example to influence the despicable beings with whom

they are unavoidably associated; and the wealth and influence being

generally on the side of the native-born officers, these abuses are

permitted, and the complaints of others disregarded.

It is but just, however, to remark, that their pay is excessively

mean; it is a bare, and miserable subsistence; and due weight should be

given to this circumstance in extenuation. A captain of regulars has

not more than 80 dollars per month! and so on in proportion, and when

we reflect, that from the low value of the circulating medium, a dollar

will barely command more than a rupee in any part of India, much must

be allowed for men so situated.

Hence, though the men, arms, and accoutrements are not bad, the

troops are, from abuses, embezzlement, and neglect, miserably deficient

in a military point of view, and but poorly calculated to answer any

efficient purpose. To this description, the regiment [124]of

artillery and Pampango militia are exceptions: the style of equipment

and discipline of the first are a high testimony of the activity and

military talents of their colonel. The queen’s regiment is by far

the most respectable of the infantry.

Their cavalry are badly mounted, the horses being very small, and by

no means good. The men too are clumsily equipped, with swords

manufactured apparently in the 14th century, being straight,

disproportionably long, and furnished with a steel poignet or basket,

above which is a cross, resembling the rapiers of that time.

Their marine is still more miserably deficient in the requisite

qualities for essential service, and suffers more from the

mal-administration of its various branches. All work done in the royal

arsenal is computed to cost at least 40 per cent. more than that by

individuals! The marine consists of a flotilla of 40 or 50 gun-boats,

and as many feluccas,54 of which about one half, or

fewer, may be in constant activity; with what effect has been already

remarked.

Like the army, the navy is almost entirely officered by creoles and

Mestizos, whose pay is but a subsistence, and consequently no prospect

is offered to young men of family and enterprise who may have other

resources.

The arsenal at Cavite, about 10 miles from Manila, is well provided

with officers and workmen, but has no docks. Vessels, however, may

heave down [125]with great safety; and the work, though

expensive, is remarkably well executed.

The agriculture of this very fertile country is yet in its infancy.

Oppressed with so many enemies to his advancement, and placed in a

climate where the slightest exertion insures subsistence, the Indian

has, like the majority of his Malay brethren, been content with

supplying his actual wants, without seeking for luxuries. Hence, and

from the expulsion of the Jesuits, they have made no advances beyond

the common attainments of the surrounding islanders.

This spirited and indefatigable order of men, who, both by precept

and example, encouraged agriculture, not only as the source of national

greatness, but as preparatory to, and inseparable from, conversion to

Christianity, which they well knew did not consist alone in

ceremonies, but in fulfilling the duties of citizens and men, and who,

whatever were their political sins, certainly possessed more than any

other the talent of converting men from savage to civilized life, have

left in the Phillippines some striking monuments of their

wide-spreading and well-directed influence. Extensive convents (the

ground stories of which were magazines), in the centre of fertile

districts formerly in the highest state of cultivation, but now more

than half abandoned,—tunnels,—canals,—reservoirs and

dams, by which extensive tracts were irrigated for the purposes of

cultivation, attest the spirit with which they encouraged this science;

and if their expulsion was a political necessity, it certainly appears

to have been in this country a moral evil.

The restraints imposed on commerce were another insuperable bar to

their prosperity, as depriving [126]them of a market for their

produce. Since foreigners have been allowed free intercourse with them,

their agriculture has in some degree improved by the increased demand

of produce; but under the present system, but little can be expected

from it.55

The soil is in general a rich red mould, with a great proportion of

iron, and in some districts volcanic matters; it is easily worked and

very productive: that in the immediate vicinity of Manila, and for four

or five miles round it, extending to that distance from the coast of

the Bay, is an alluvial soil, formed by the confluence of the numerous

rivers with the ocean; it is stiff, and in all respects very inferior

to the other. In some parts are extensive tracts, the reservoirs of the

waters from the mountains in the rainy season, which first yield an

amazing supply of fish,56 and then a good crop of rice or

pasture for the buffaloes.

The frequent rains, and the numerous rivers and streams with which

the country is every-where intersected, adds to its extraordinary

fertility: it is seldom, [127]if ever, afflicted with droughts,

but is at times devastated by locusts (perhaps once in 10 or

15 years), and these make dreadful havoc amongst the canes. Their

attacks, however, are partial, and generally take place after the rice

is harvested, in December, disappearing before the rains. In 1818,

nearly the whole of the canes were destroyed by them, and the

Ayuntamiento of Manila expended from 60 to 80,000 dollars in

purchasing large quantities of them, which were thrown into the

sea.58

The buffalo is universally used in all field labours, [128]for

which, however, he is but poorly calculated: the slowness of his pace,

and his great suffering from heat, which obliges the labourer to bathe

him frequently, occasion a very considerable loss of time, which is

scarcely compensated by his great strength and little expense in

keeping. Indeed, the bullock should perhaps be on all occasions

substituted for him, excepting only in the cultivation of rice fields.

In a few districts, this is the case; but it is with reluctance that

the native uses him in preference to the buffalo.

Their breed of horses is small, but very hardy: they are never used

for agricultural purposes, though but few of the peasants are without

one for riding, and many of them have two or three. In the province of

Pampanga (the finest tribe of Indians in the Phillippines), they risk

considerable sums on races! of which they are very fond.

Their plough is of Chinese origin: it has but one handle, and no

coulter or mould-board, the upper part of the share, which is flat, and

turned to one side, performing this part of the work. The common harrow

is composed of five or six pieces of the stems of the thorny bamboos,

which at the lower part are almost solid; these are united by a long

peg of the same, passing through all the pieces: to these the hard

branches of thorns are left appending, and being cut off at a short

distance from the stem, form the teeth of the instrument, which, rude

as it is, performs its work well, and usefully, and is seldom out of

order.

For cleaning and finally pulverizing the ground, they have another

harrow of Chinese origin, (or an invention of the Jesuits?) It is of

wrought iron, and [129]for simplicity and utility it is, I think,

unequalled. By means of it they can extirpate the Lallang grass

(Andropogon caricosum), called by them Cogon,60 and which no other instrument will perform so

well, that I am acquainted with.

A hoe, like that of the West Indies, answers the purposes of a

spade; and (with the basket) of a shovel. A large knife (the Malay

Parang), called “Bolo,” completes the list of their

agricultural instruments. Machinery they cannot be said to possess,

except a rude mill of two cylinders for cane, and another for grinding

their rice, can be called such. The greater part of the rice is beaten

from the husk in wooden mortars, and by hand.

The rainy season commences with the S. W. monsoon, and ends in

October. The rice (the aquatic sorts) is planted by hand in July and

August, and reaped in December. The upland rice, of which they have two

varieties, is planted earlier, and comes sooner to maturity. The cane

is planted in the manner called “en canon” by the French,

that is, the plant piece is stuck diagonally into the ground; and thus,

from the roots being often on the surface, the plant suffers frequently

from drought, and they have seldom two crops from a piece of cane:

their sugar, though clumsily manufactured, is of excellent grain, and

highly esteemed by the refiners of Europe.

The indigo plant is very fine; and though, as in all countries, a

precarious crop, yet it is far from being so much so as in India: it

has been manufactured equal to Guatemala, but in the present day

is of a very inferior quality: this arises from various causes, of

which the principal are ignorance in the manufacture [130]of

it, a want of capital, and spirit of enterprise. They have no tanks of

masonry, the whole process being carried on in two wooden vats of a

very moderate size, from which the fecula is taken once a week. It is

needless to remark, that the quality of the indigo is materially

injured by this alone: it is also subject to many adulterations in the

hands of the Mestizos, before being brought to market.

The coffee plant was almost entirely unknown about 40 years ago, a

few plants only existing in the gardens about Manila. It was gradually

transported from thence to the towns in the neighbourhood of the lake,

where it has been since multiplied to an amazing degree by an

extraordinary method. A species of civet cat with which the woods

abound, swallows the berries,61 and these passing through the

animal entire, take root, and thus the forests are filled with wild

plants. This fact may be depended upon, and the major part of all the

coffee exported from Manila is produced from the wild plants, and is

equal or superior in flavour to that of Bourbon. The government, in

1795 or 96, made an attempt to force its cultivation in the province of

Bulacan, but forgot, as one of their own officers naivement observes, “Que no habia

compradores ni consumidores”—that there were neither

consumers or customers for it! It [131]of course fell to the ground,

and in the next passage of the same work, the Indian is partly

blamed for it!

The cultivation of cotton is as yet but very partial. It is of the

herbaceous species, of a very fine quality, almost equalling the

Bourbon, but excessively adherent to the grain: so much so indeed, that

none of the attempts to separate it from the seed by machinery have

hitherto succeeded; the grains passing through the rollers, and

staining the cotton. It is cleared by the natives by means of a

hand-mill, very clumsy in its construction, and performing so little

work, that the cleaning costs six dollars per pekul.

The principal part of the cotton comes from the province of Ylocos,

where large quantities of stuffs are manufactured. The brown cotton,

for which a prize was offered in 1818 by the Society of Arts, grows in

great quantities, and is manufactured into durable cloths and blankets.

The prices of agricultural labour vary from 1 rial63 per day

near Manila to ¾ and ½ rial in the provinces—a

plough with two buffaloes and a man, 2½ rials. The workmen, like

day labourers in all countries, are often “looking for

sunset;” but when allowed task work, are willing and industrious.

A plough will go over rather more than a loan64 of ground

in a day—about a quinion in three months. [132]

Of the produce of any given cultivation, it is difficult to speak

with any degree of correctness: calculations of this kind are difficult

to make amongst a people labouring each for himself, and all for the

wants of the day: for, unaccustomed to generalize, each gives his

own as the average, and hence the discrepancy which every person

must have remarked who has had occasion to make inquiries of this

description in half civilized countries, where a main point, the value

of the labourer’s time, and of that of his animals, is invariably

left out, as is also the difference of work for himself and for a

master. The tables given at the conclusion of Comyn’s work are,

as far as regards the vicinity of the capital, very erroneous. They are

also very deficient in many [133]points.67 The

following is a much nearer approximation.

A quinion of land requires four ploughings and three harrowings, say

six ploughings in all.

|

Ds. |

Rs. |

| Now as 1 Quinion will occupy a hired

labourer about 90 days at 2½ Rials = 28 Dollars 1 Rial, which

for six times is |

168 |

6 |

| Fencing, 12 Ds.; Grubbing, &c., 15; Cane

Slips, 25; Planting, 18; Weeding and Hoeing, 30; Carriage, 18;

Manufacture, 45; Pilones, &c., 12 |

175 |

0 |

| Cost |

343 |

6 |

| Produce at low average, 150 Pilones,68 salable at 3½ Ds. |

487 |

4 |

| Profit |

143 |

6 |

This supposes the proprietor of the cane to be possessed

[134]of a mill, buffaloes, &c. for the wear of

which no estimate is made.

The 150 pilones of sugar, each weighing about 150 lbs. gross, will

produce the refiner who has purchased them about 100 piculs of sugar,

of which

|

S. |

Ds. |

| 80 1st sort, worth 6¼ Dollars |

500 |

0 |

| 20 2d ditto, and Molasses, &c. 3¾ |

75 |

0 |

|

575 |

0 |

| They have cost him about |

487 |

4 |

| Refiner’s allowance on 100

Pilones, S. Ds. |

47 |

8 |

The profits of the refiner would appear high; and

[135]they have been so; but are far from what this

statement appears to give, from various reasons, of which the chief

are, the heavy capital sunk in buildings, interest on advances, &c.

and from a want of knowledge, the enormous waste of labour in the

process. A glance at this may give an idea of what trade is at these

antipodes of commercial knowledge.

I have termed the process “refining;” it should rather

be called claying and sorting—and it is as clumsily managed as

the ingenuity of man could well devise. The trade is principally in the

hands of three or four capitalists; advances are made by these to

brokers, the provincial merchants, who annually bring their produce to

the capital in small vessels,69 and to the masters of coasting

traders, in which the [136]sugar merchants have shares. These

are made to a large amount, 80 to 100,000 dollars; and as the interest

of this must at least run for six months at 9 per cent. it forms a

heavy item. Losses and defaulters form another, say ½ per cent.

in all 5 per cent.

The pilones are delivered from November to May and June, and are

received into extensive warehouses, which are provided with large

court-yards and terraced roofs. Here the upper part of the pilone is

cut off, and a quantity of manufactured sugar being pressed down on the

top of it, a thin layer of the river mud is put on it; this is watered

from time to time and changed once or twice, the pilone standing on a

small foot, with the small hole at its apex left open, through which

the molasses slowly drains, leaving the upper and broader part of the

pilone of a fine white, gradually decreasing in goodness to the bottom,

where it is little more than molasses—the pilone is then cut in

two; the darker part is put by as second quality (or reboiled), and the

whiter portion as firsts, of the sugar, the care taken in the process,

the kind of mud used, &c. About two piculs of sugar from three

pilones is a fair average, when these are of a good size. That from the

province of Pampanga is by far the best; it is produced from a small

red cane70 [137]about four feet high, and of the

thickness of a good walking stick.

The sugar being thus clayed, is now to be mixed, pounded, and dried.

The last process is performed by laying it on small mats in the sun, on

the terraces and pavements of the court-yards. On the slightest

appearance of rain, it must be hurried under cover, and brought out

again when this is past. So that in a manufacture of any size, when

from 3 to 400 Chinese are employed at 4½ dollars per month,

fully ⅓d of their labour is expended on this operation alone. The

management of the rest requires no comment.

The cost of production of any of the other articles cannot be

estimated to any degree of correctness, from the very small scale on

which they are cultivated, and the limited knowledge of the writer of

these remarks. Those of Comyn are erroneous.

The Indians are the principal and almost the only cultivators of the

soil, very few Mestizos or Chinese71 being engaged in it. The

few Spaniards and other Europeans who have attempted it, have been

obliged to abandon their attempts to form plantations. These failures,

or rather determination to [138]abandon their speculations (even

when in a promising state), have arisen from various causes; but the

general one may be stated to be the very little security for life and

property, in a country such as has been described. This is with the

major part an insuperable objection; for from the moment they are

established, and known to possess money for the payment of their

workmen, they must be in expectation of an attack, and prepared to

defend themselves; nor can they lie down at night free from the

apprehension of seeing their establishments in flames before morning!

either from robbers, or from malice of any individual who may think

himself aggrieved:—the impossibility of obtaining justice so

generally experienced by the Indians, and the many chances of escaping

punishment, being strong inducements to the ill-disposed to adopt these

modes of revenge. To this it may be added, that even were the foreigner

to kill the most determined robber in the country, the circumstance of

having done so in defence of his life and property, would by no means

exonerate him from a fleecing by the inferior officers of justice, and

from a long and tiresome process of depositions, declarations, &c.

during which his affairs must be entirely neglected.73

[139]

In addition to this he must lay his account with another obstacle,

and this none of the smallest—the chance of bad faith on the part

of those with whom he is connected; a chance which by no means will

diminish in proportion to his success; for, let no foreigner deceive

himself on this head in Manila; if he cannot flatter as low, or bribe

as high as his adversary, his cause is lost by some means or other.

The Phillippines also produce cacao of an excellent quality, though

not sufficient for their consumption, a large quantity being imported

from New Spain.

Pepper is also an article of exportation, but in very limited

quantities, the utmost the Phillippine Company have been able to

procure being about 60,000 lbs. in favourable years.

To these may be added the Abaca (Musa

textilis), a species of plantain, from which the beautiful

fibres are procured known by that name. This is becoming a very

considerable article of exportation, both raw, and manufactured into

cordage. The natives also consume large quantities of it in cordage,

and as shirting cloth, into which a large portion of the interior

[140]and finer fibres are manufactured. Some of it is

equal to the coarser sort of China grass cloth.74

In Gogo,76 a gigantic climbing plant, whose trunk attains

the size of a man’s body, is another remarkable production of