The Project Gutenberg EBook of History of Lace, by Bury Palliser

This eBook is for the use of anyone anywhere in the United States and most

other parts of the world at no cost and with almost no restrictions

whatsoever. You may copy it, give it away or re-use it under the terms of

the Project Gutenberg License included with this eBook or online at

www.gutenberg.org. If you are not located in the United States, you'll have

to check the laws of the country where you are located before using this ebook.

Title: History of Lace

Author: Bury Palliser

Editor: M. Jourdain

Alice Dryden

Release Date: April 21, 2018 [EBook #57009]

Language: English

Character set encoding: ISO-8859-1

*** START OF THIS PROJECT GUTENBERG EBOOK HISTORY OF LACE ***

Produced by Keith Edkins, Constanze Hofmann, David Edwards

and the Online Distributed Proofreading Team at

http://www.pgdp.net (This file was produced from images

generously made available by The Internet Archive/American

Libraries.)

HISTORY OF LACE

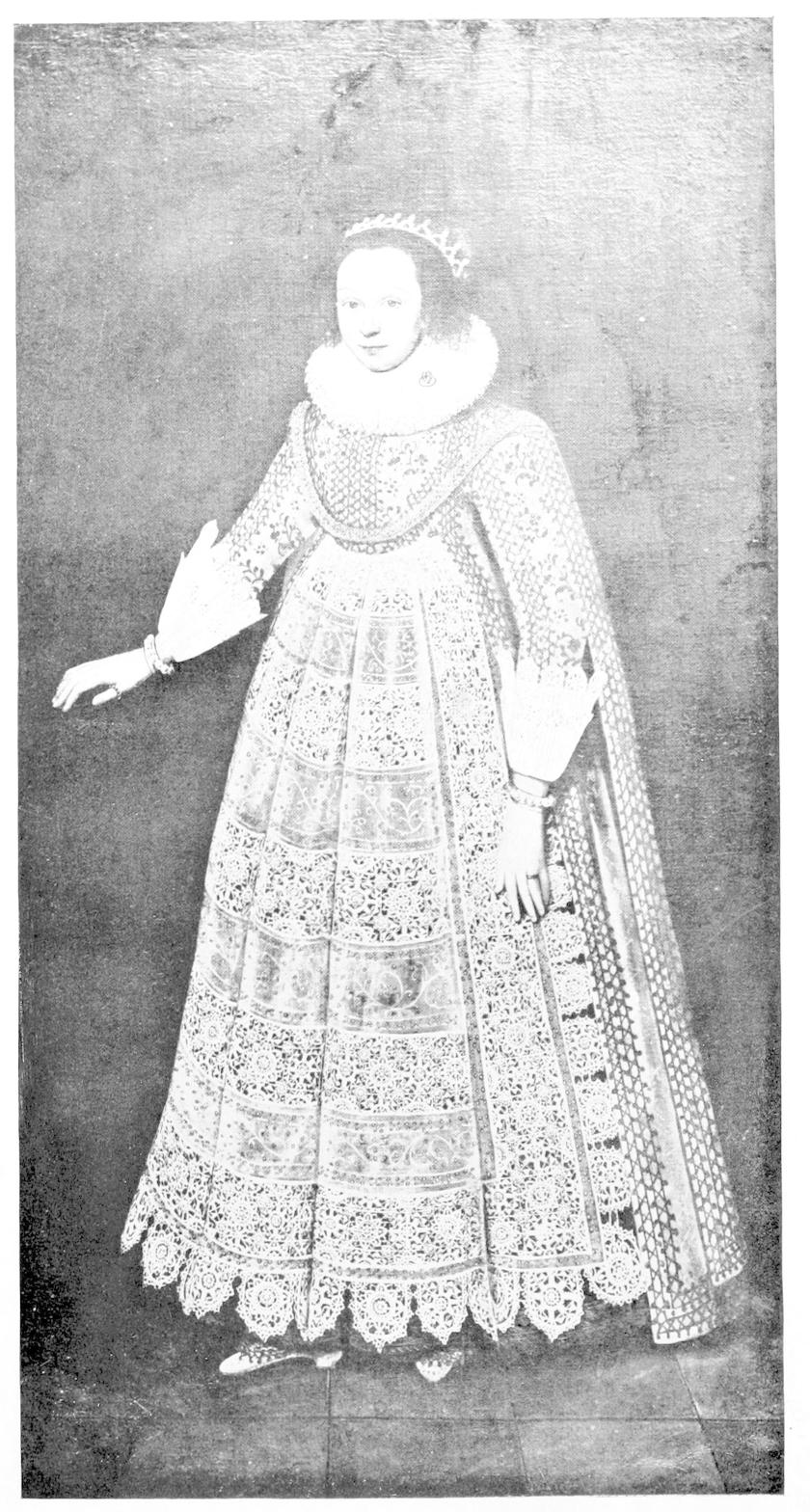

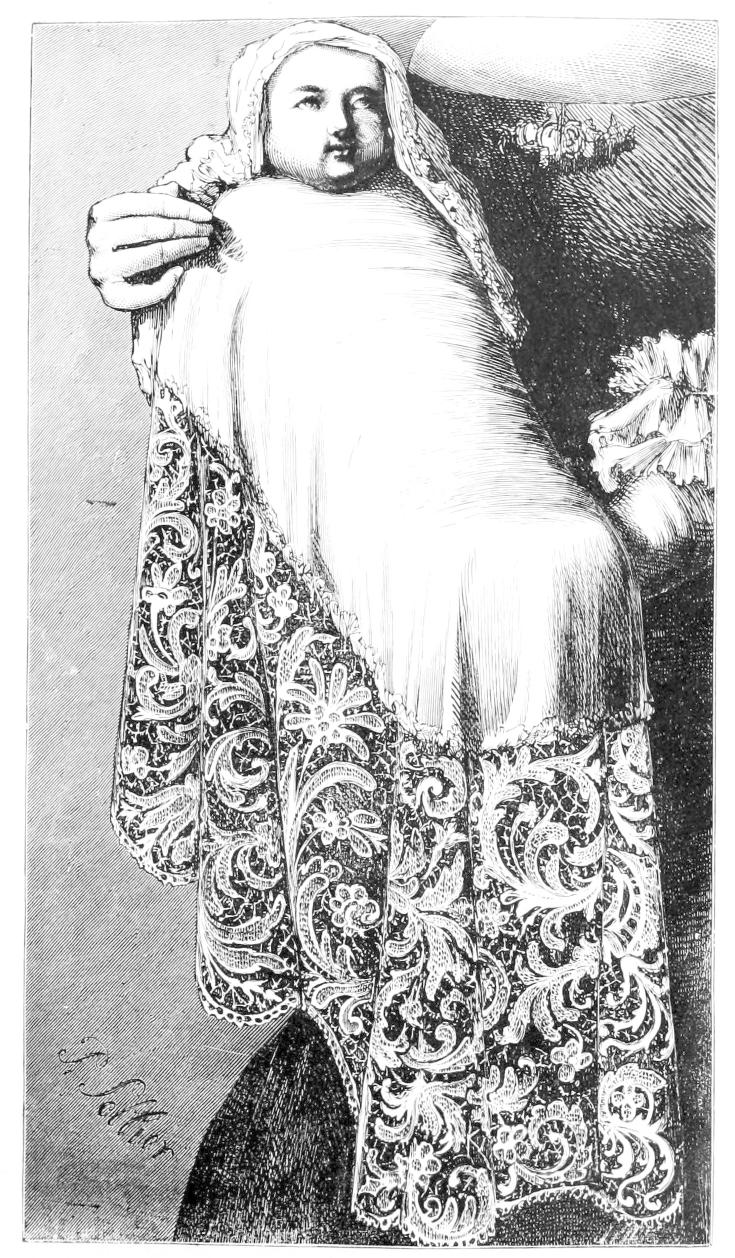

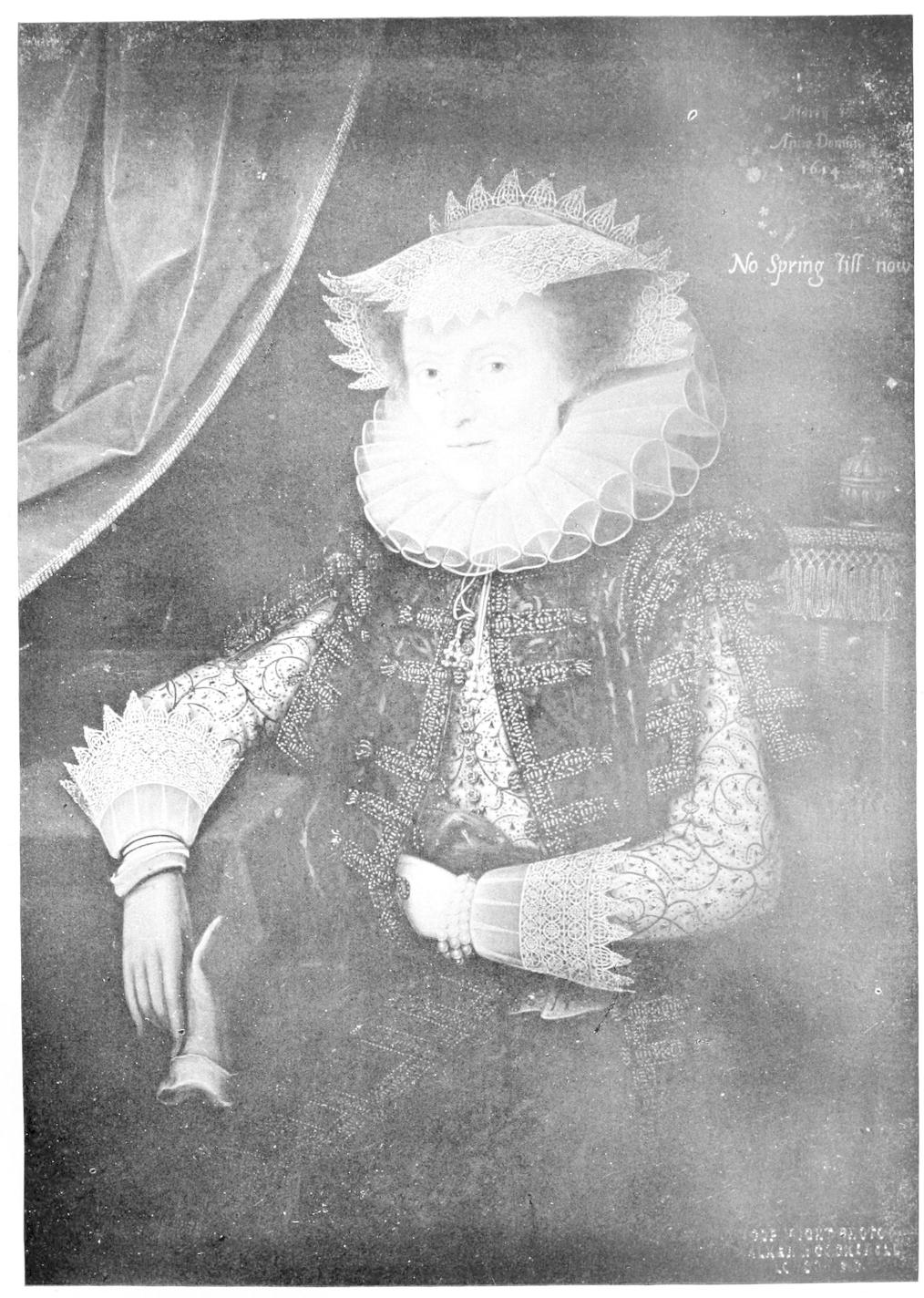

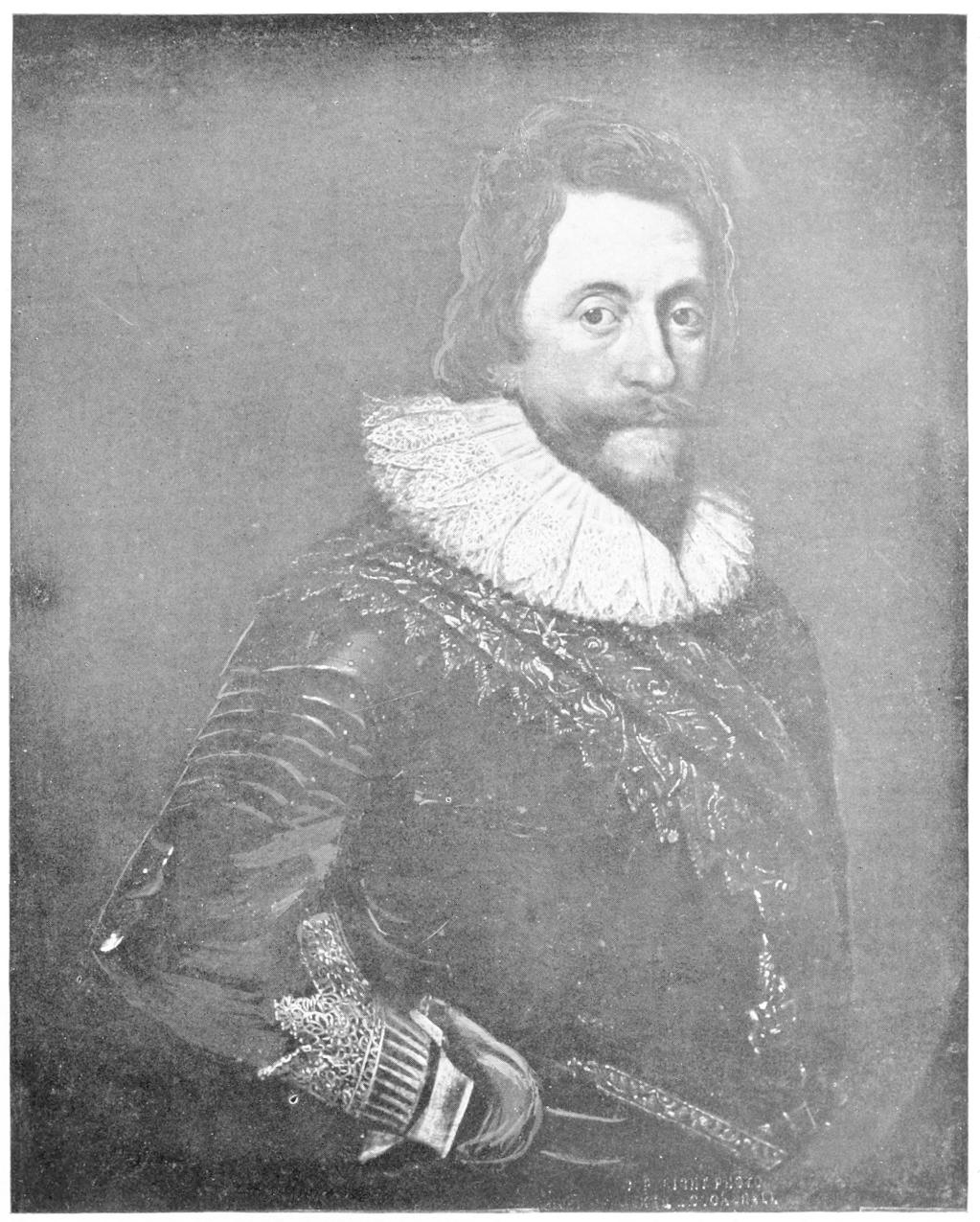

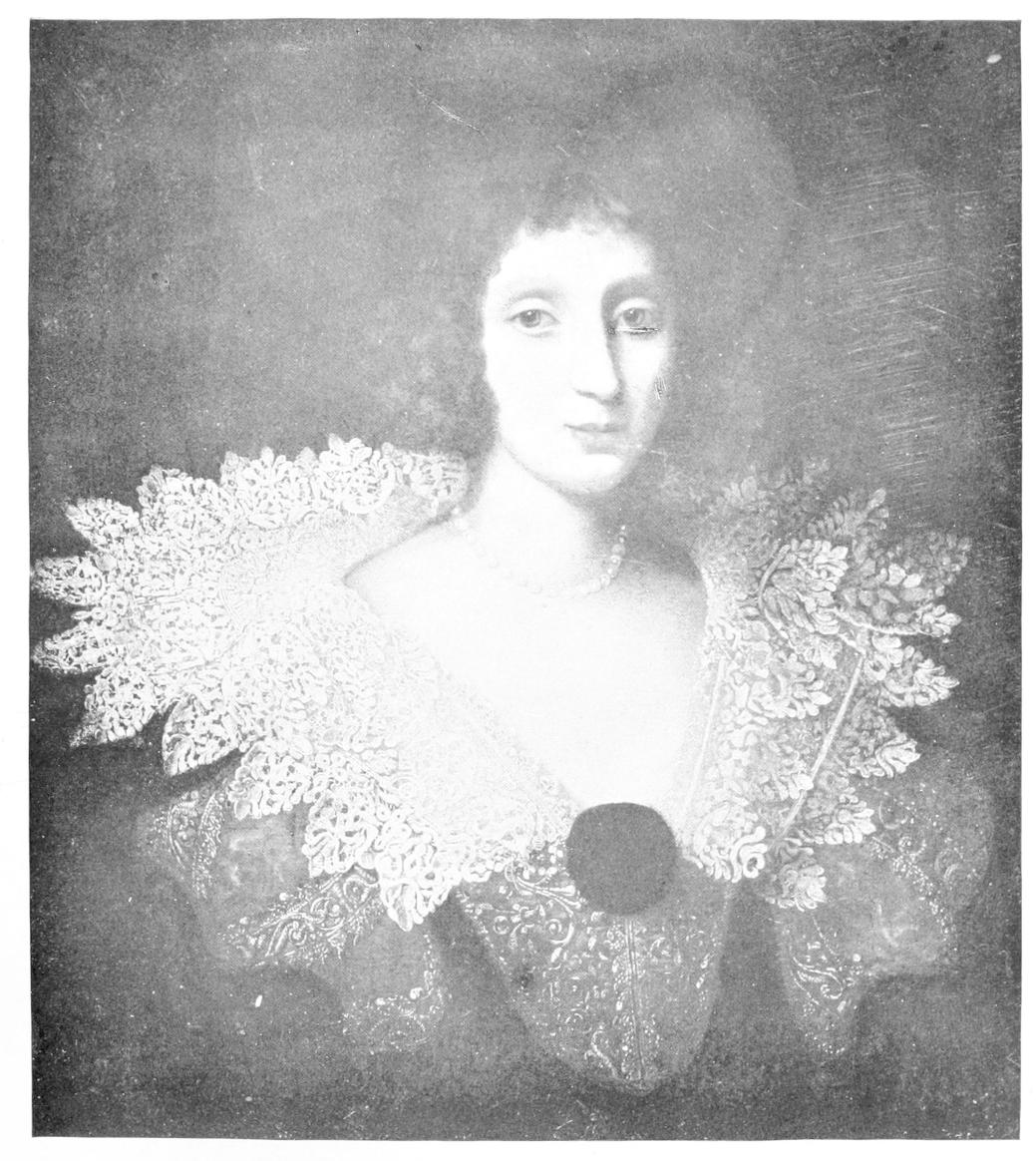

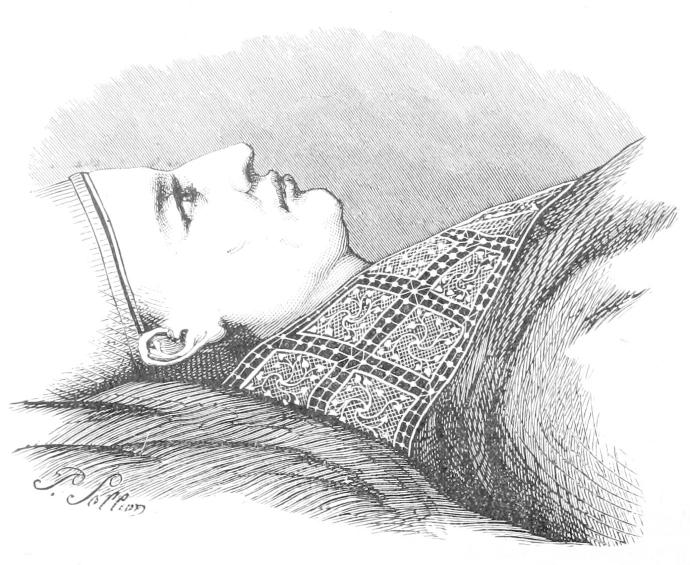

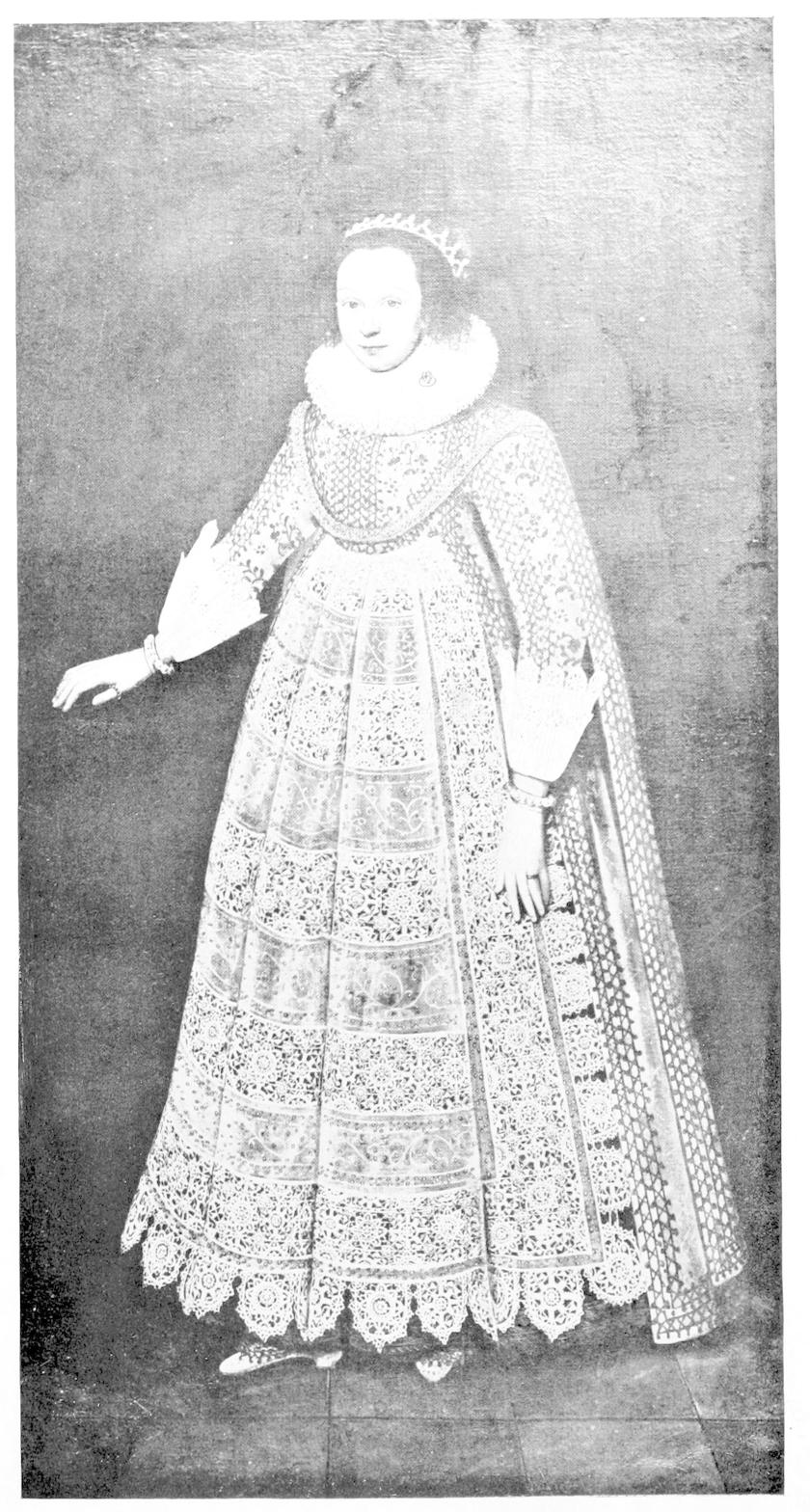

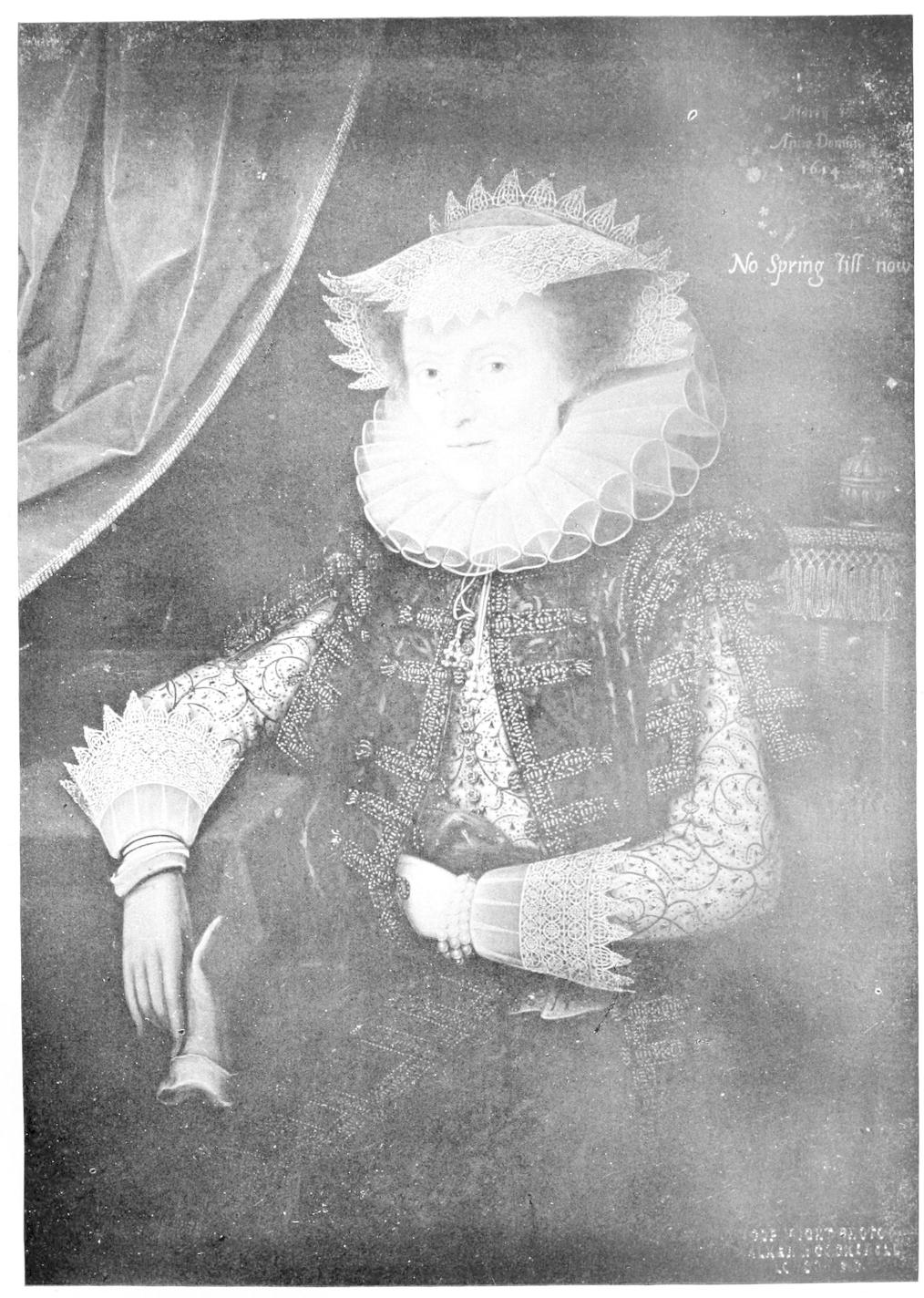

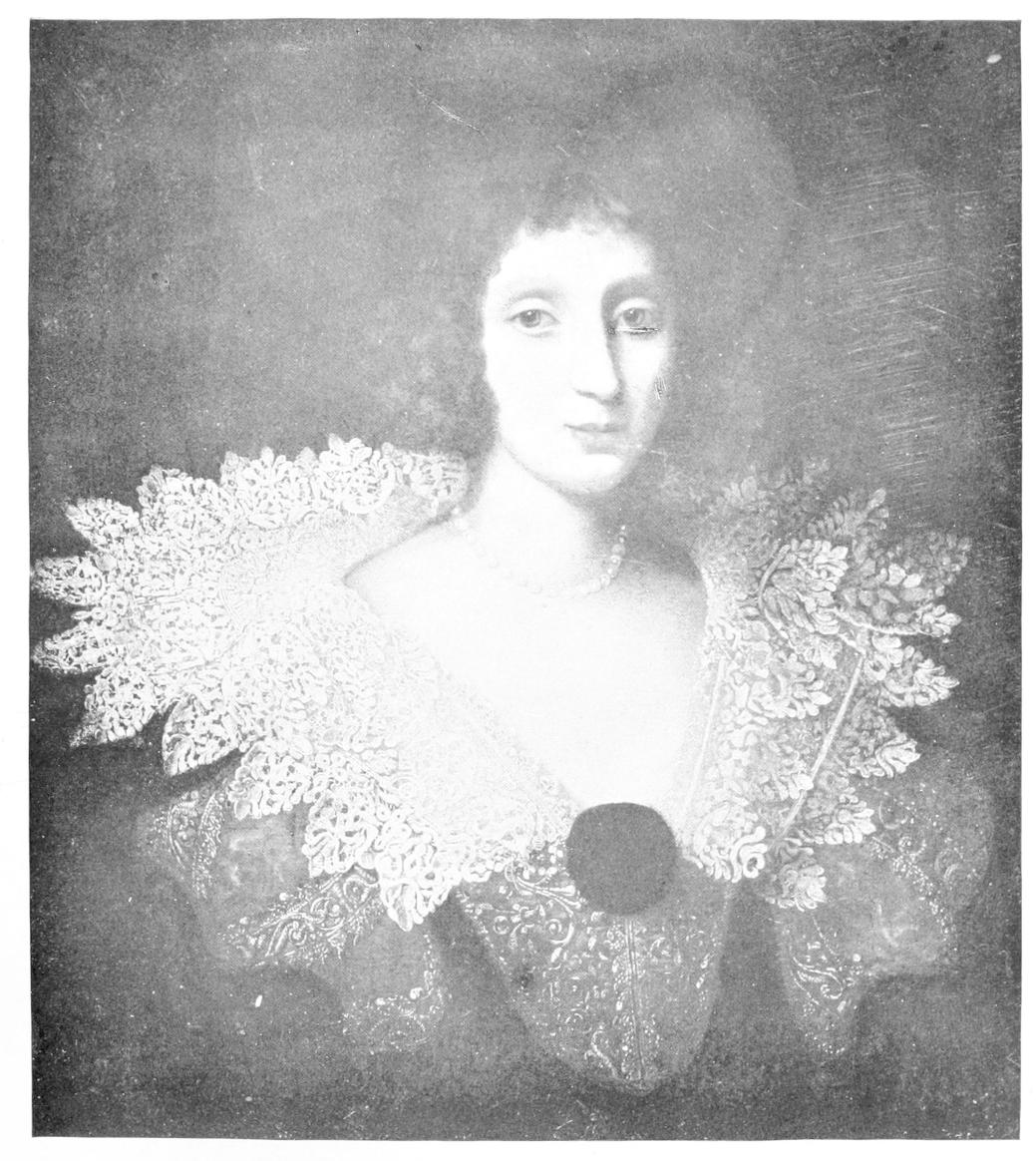

Anne, Daughter of Sir Peter Vanlore, Kt.,

first wife of Sir Charles Cæsar, Kt., about 1614.

The lace is probably Flemish, Sir Peter having come from Utrecht.

From the picture the property of her descendant, Captain Cottrell-Dormer.

Frontispiece.

History of Lace

BY

MRS. BURY

PALLISER

ENTIRELY REVISED, RE-WRITTEN,

AND ENLARGED

UNDER THE EDITORSHIP

OF

M.

JOURDAIN AND ALICE DRYDEN

WITH 266

ILLUSTRATIONS

NEW YORK

CHARLES SCRIBNER'S SONS

1902

LONDON:

PRINTED BY WILLIAM CLOWES AND SONS, LIMITED,

DUKE STREET, STAMFORD STREET, S.E., AND GREAT WINDMILL STREET, W.

PREFACE TO THE FOURTH

EDITION

Nearly thirty years have elapsed since the third edition of the History of

Lace was published. As it is still the classical work on the subject, and many developments

in the Art have taken place since 1875, it seemed desirable that a new and revised edition should

be brought out.

The present Revisers have fully felt the responsibility of correcting anything the late Mrs.

Palliser wrote; they have therefore altered as little of the text as possible, except where modern

research has shown a statement to be faulty.

The chapters on Spain, Alençon and Argentan, and the Introductory chapter on Needlework, have

been almost entirely rewritten. Much new matter has been added to Italy, England and Ireland, and

the notices of Cretan and Sicilian lace, among others, are new. The original wood-cuts have been

preserved with their designations as in the 1875 edition, which differ materially from the first

two editions. Nearly a hundred new illustrations have been added, and several portraits to show

different fashions of wearing lace.

The Revisers wish to record their grateful thanks to those who have assisted them with

information or lace for illustration; especially to Mrs. Hulton, Count Marcello and Cavaliere

Michelangelo Jesurum in Venice, Contessa di Brazza and Contessa Cavazza in Italy, M. Destrée in

Brussels, Mr. Arthur Blackborne, Salviati & Co., and the Director of the Victoria and Albert

Museum in London.

M. Jourdain.

Alice Dryden.

CONTENTS

LIST OF

ILLUSTRATIONS

| PAGE |

| Anne, Daughter of Sir Peter Vanlore, Kt. |

Frontispiece |

|

| Gold Lace found in a barrow |

Fig. 1 |

4 |

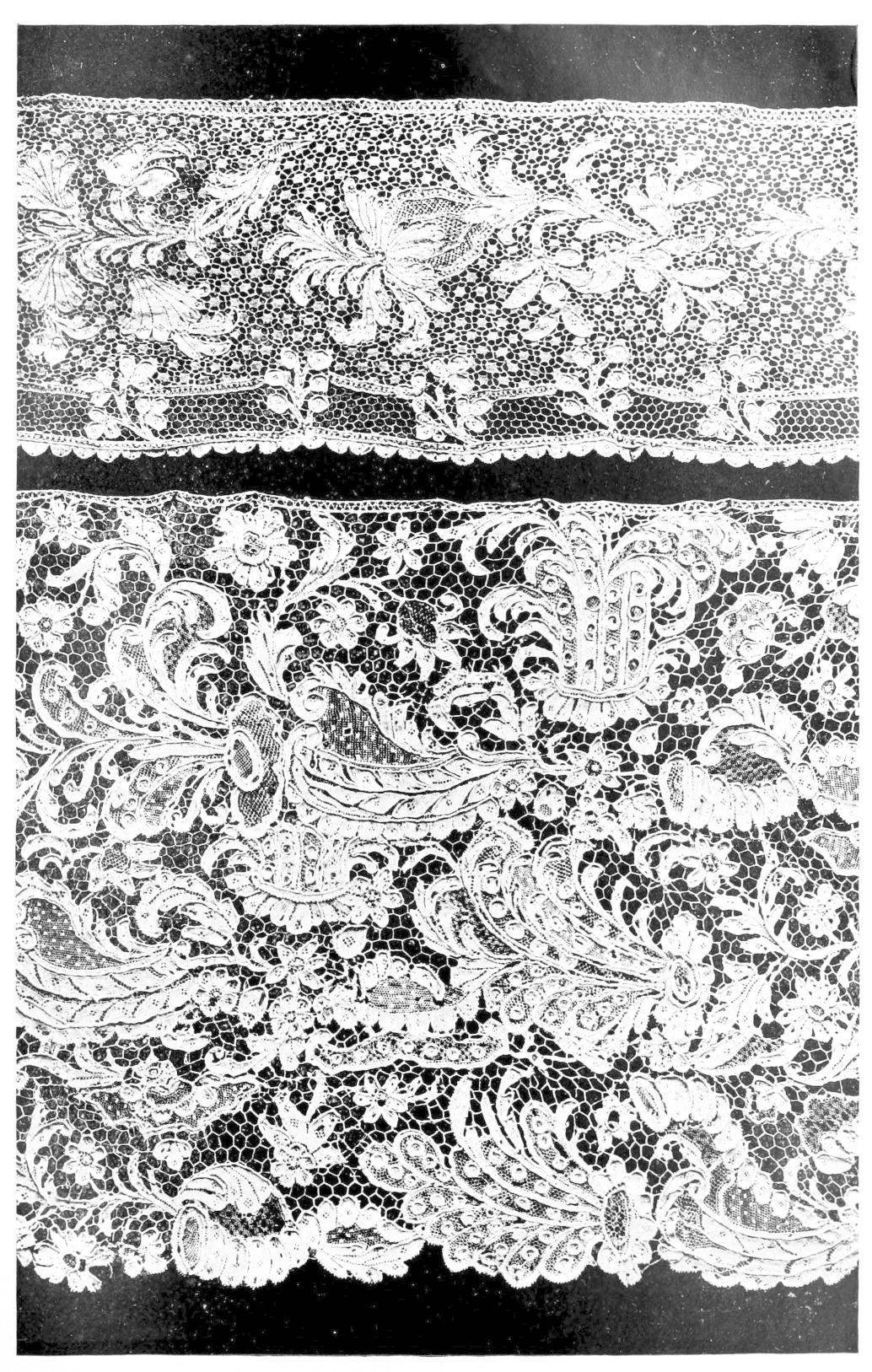

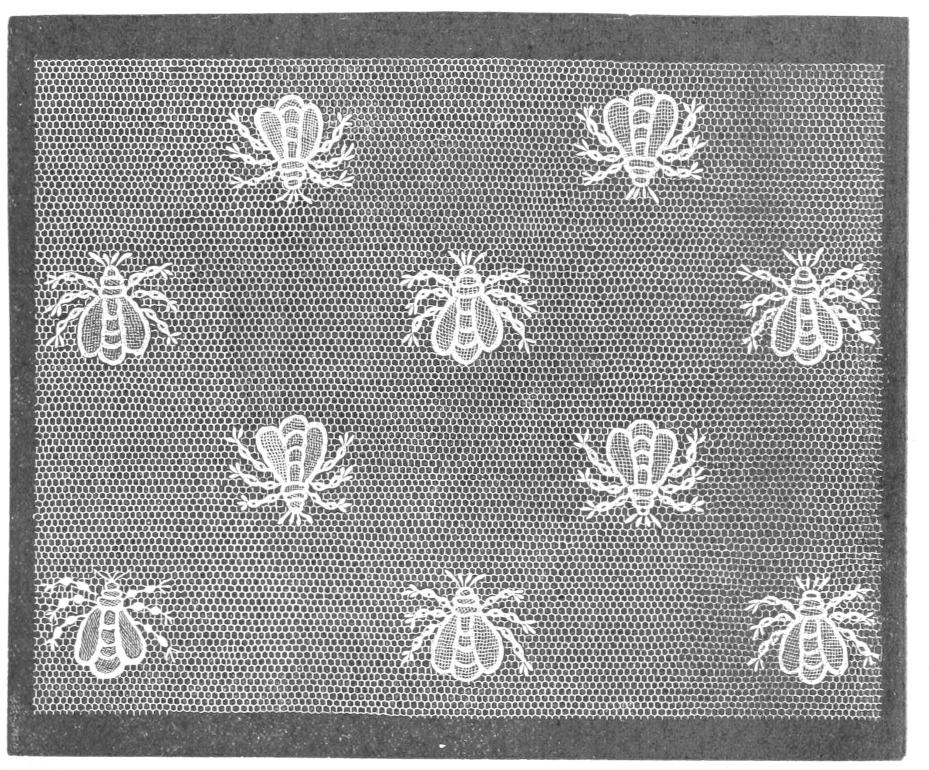

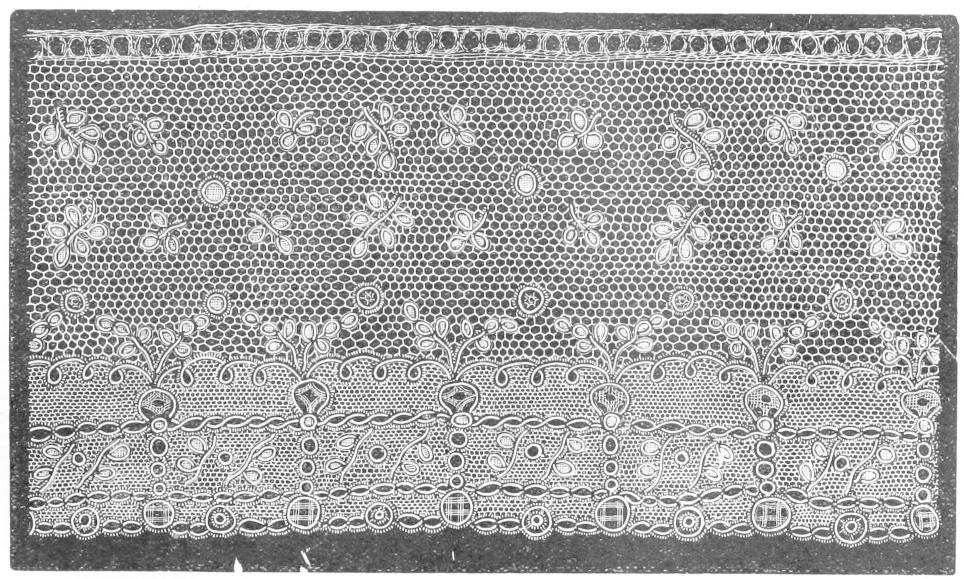

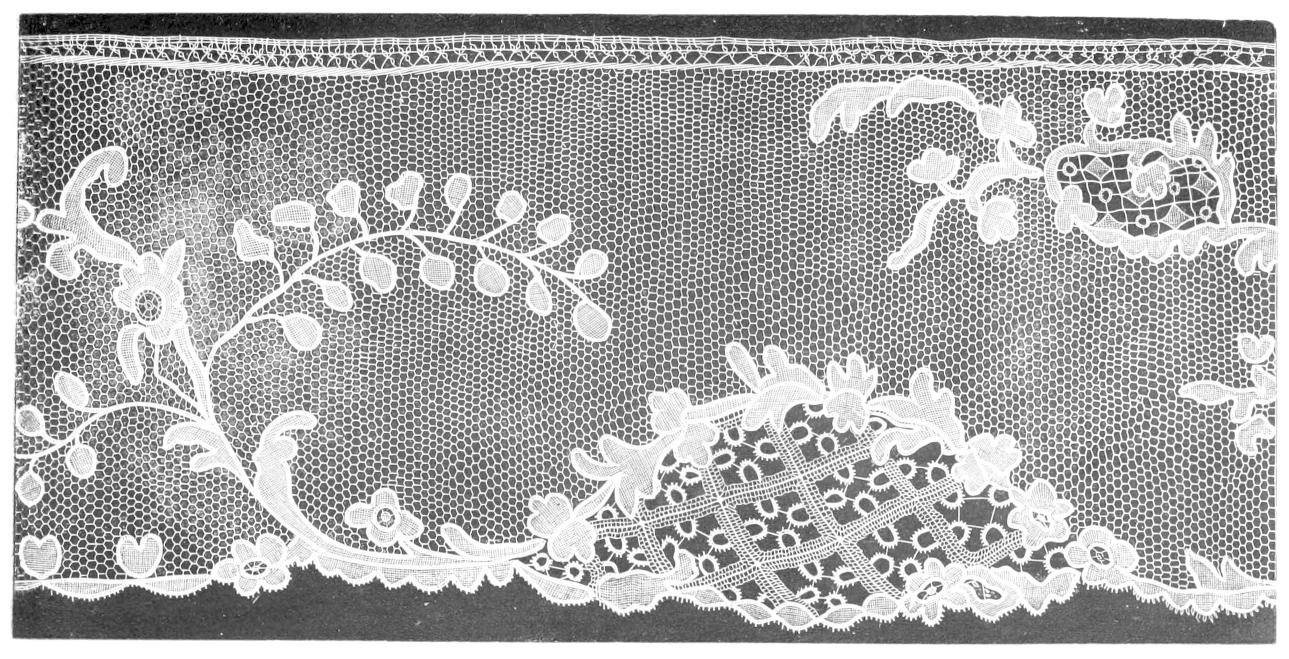

| Argentan.—Circular Bobbin Réseau; Venetian

Needlepoint |

Plate I |

12 |

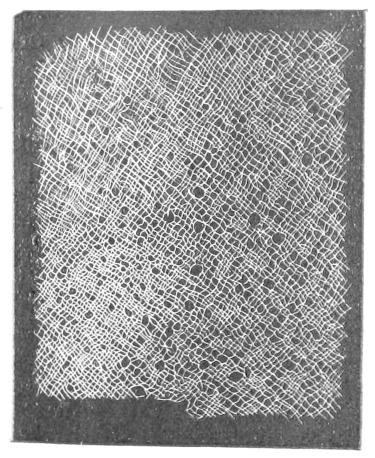

| Italian Bobbin Réseau; Six-pointed Star-meshed Bobbin Réseau;

Brussels Bobbin Réseau; Fond Chant of Chantilly and Point de Paris; Details of Bobbin Réseau

and Toile; Details of Needle Réseau and Buttonhole Stitches |

Plate II |

14 |

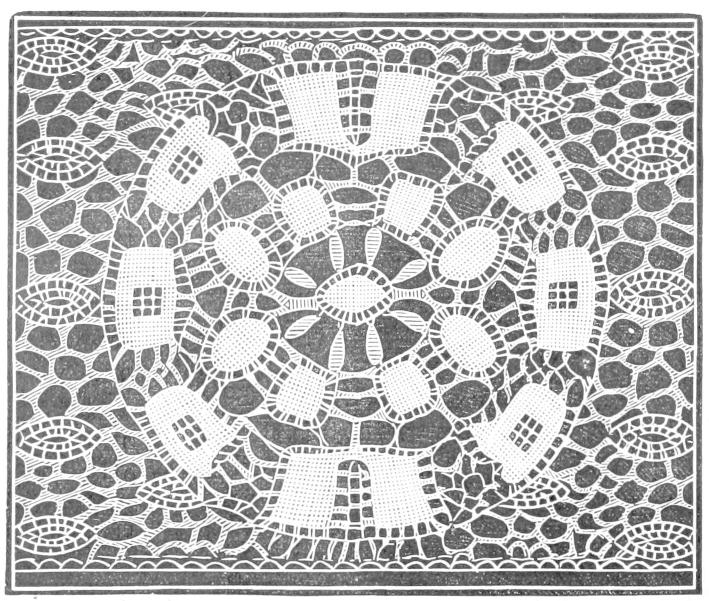

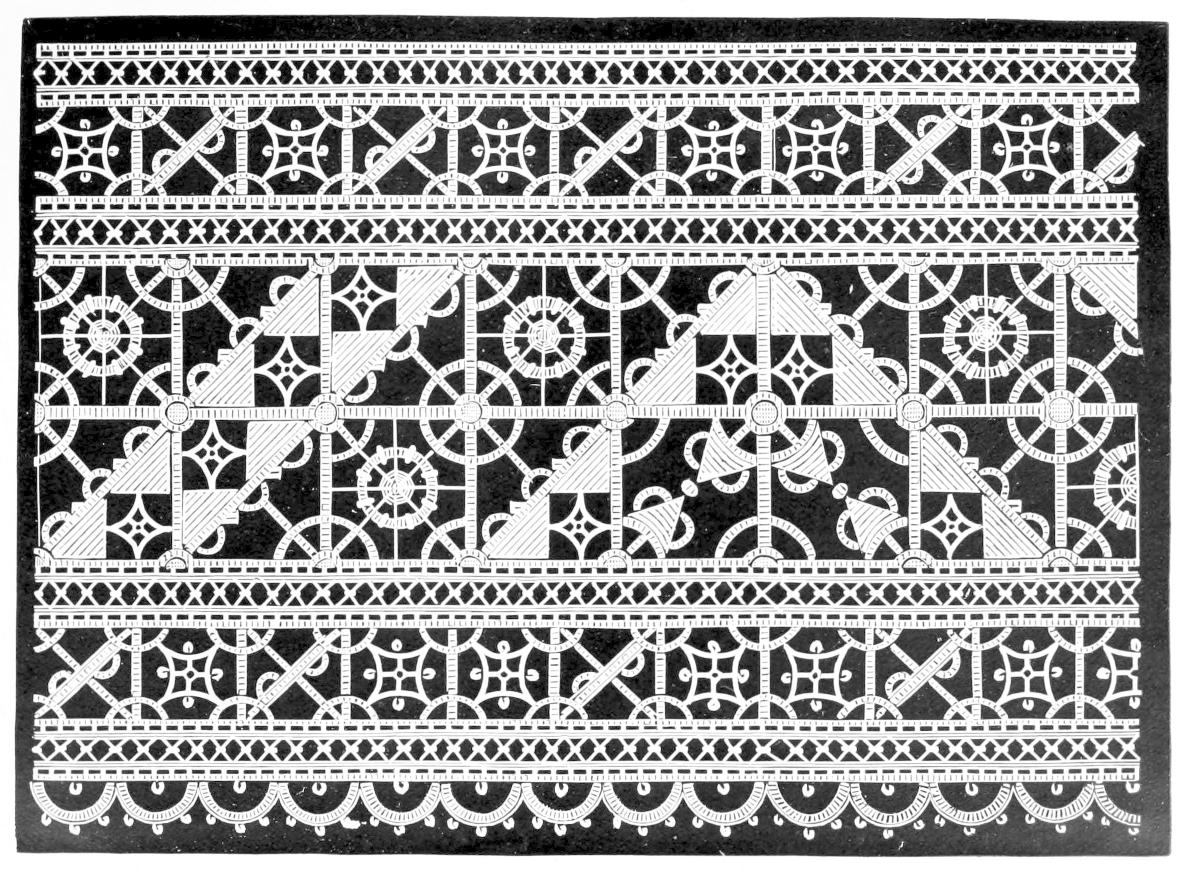

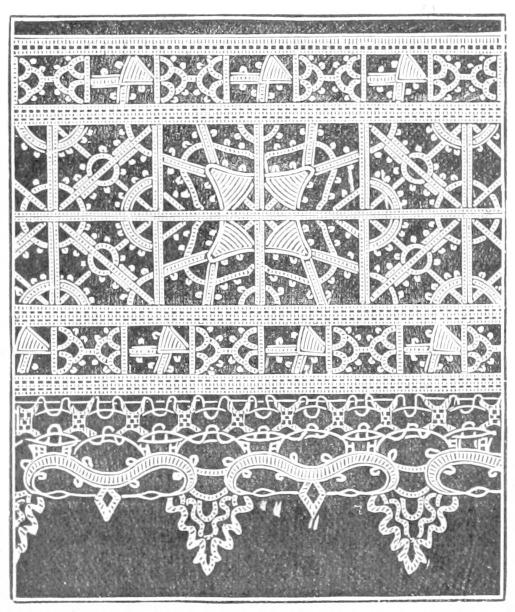

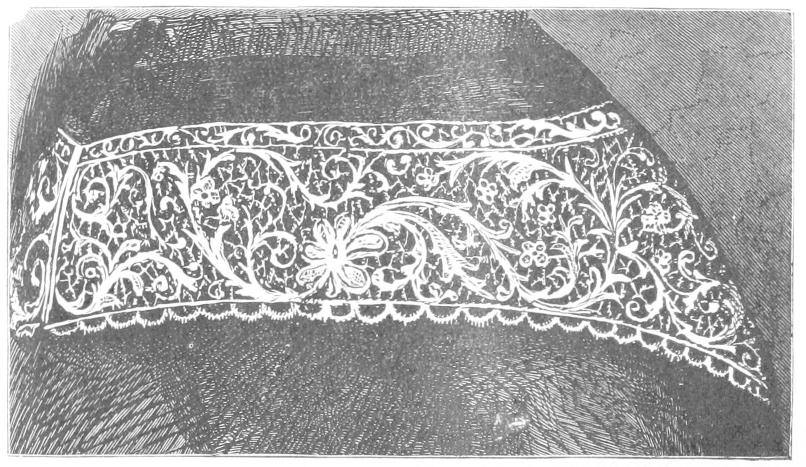

| Point Coupé |

Fig. 2 |

18 |

| Altar or Table-cloth of Fine Linen (probably

Italian) |

Plate III |

18 |

| Laces |

Fig. 3 |

19 |

| Elizabethan Sampler |

" 5 |

22 |

| Impresa of Queen Margaret of Navarre |

" 4 |

23 |

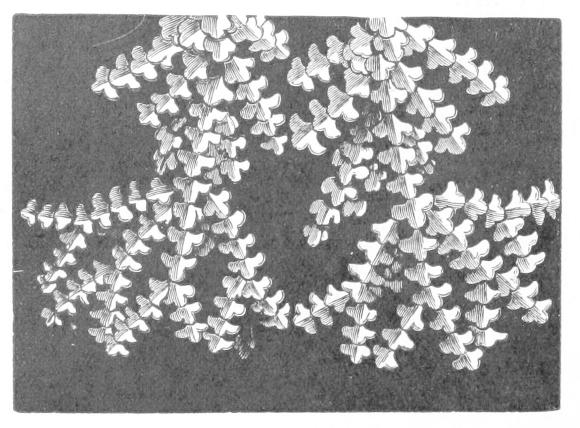

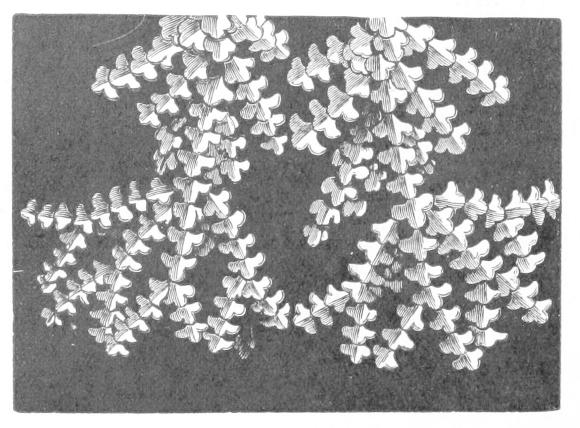

| Spider-work |

Figs. 6, 7 |

24 |

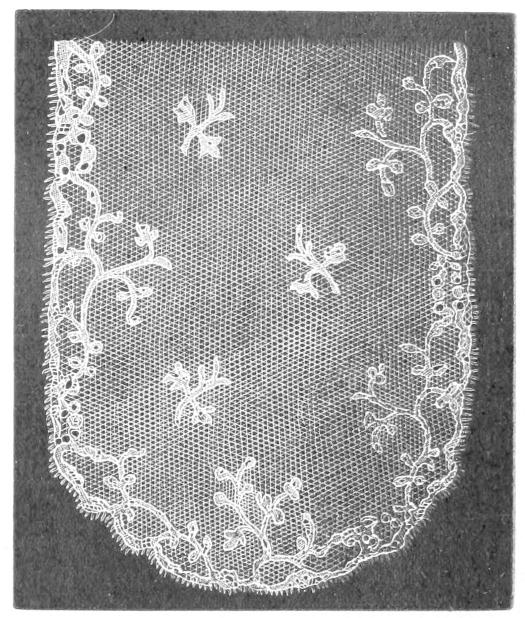

| Fan Made at Burano |

Plate IV |

24 |

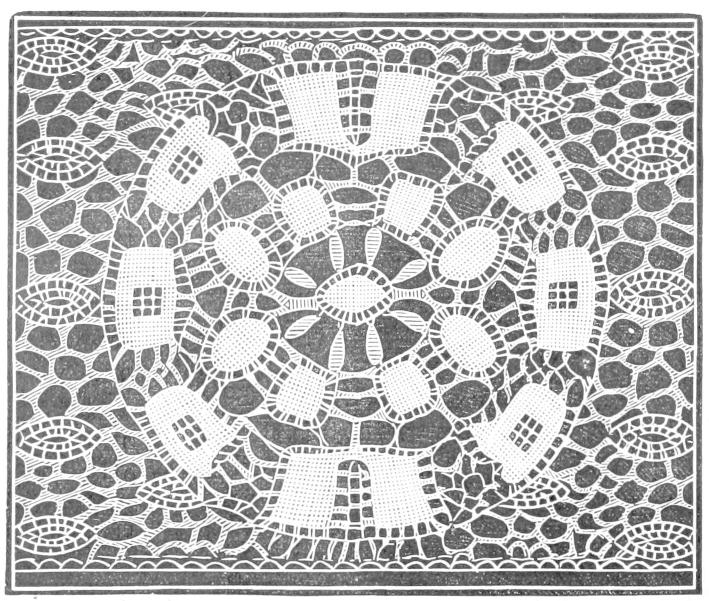

| Italian Punto Reale |

" V |

24 |

| Grande Dantelle au Point devant l'Aiguille |

Fig. 8 |

28 |

| Petite Dantelle |

Figs. 9-12 |

29 |

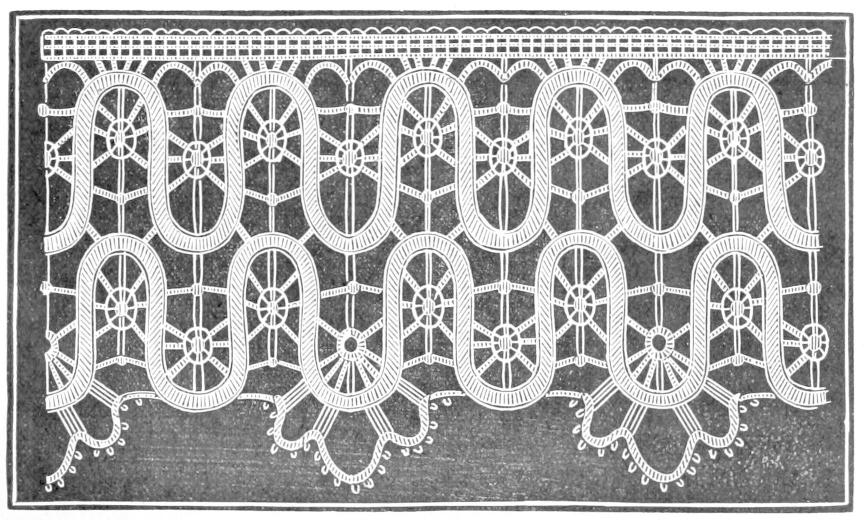

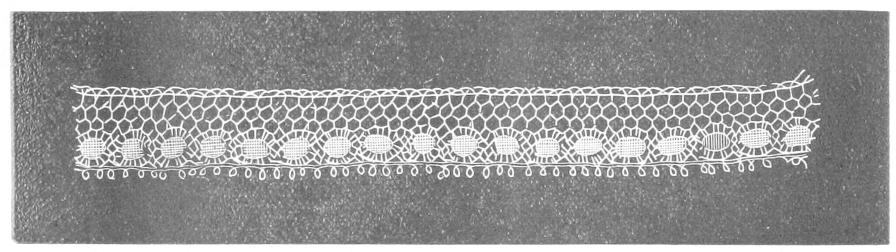

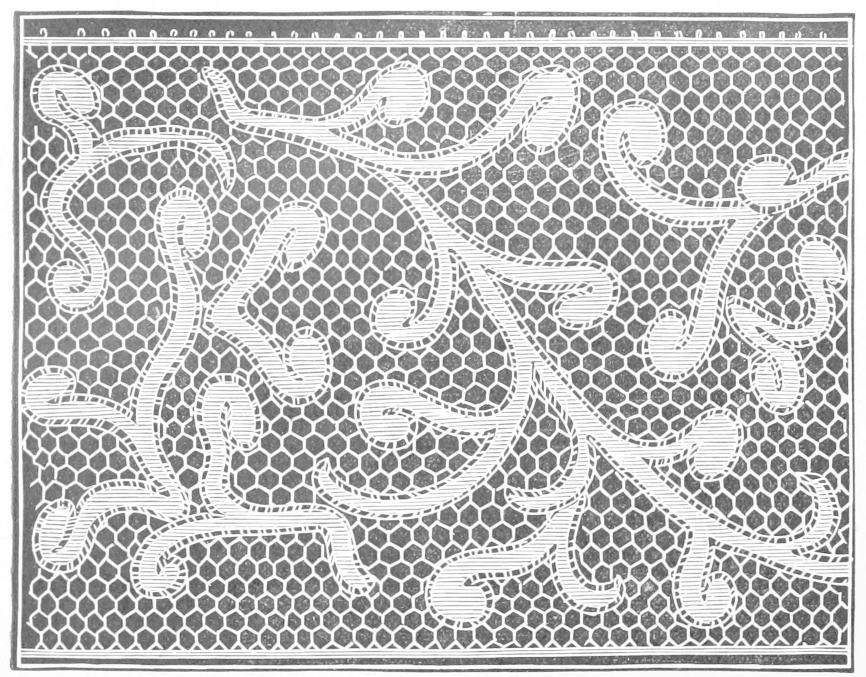

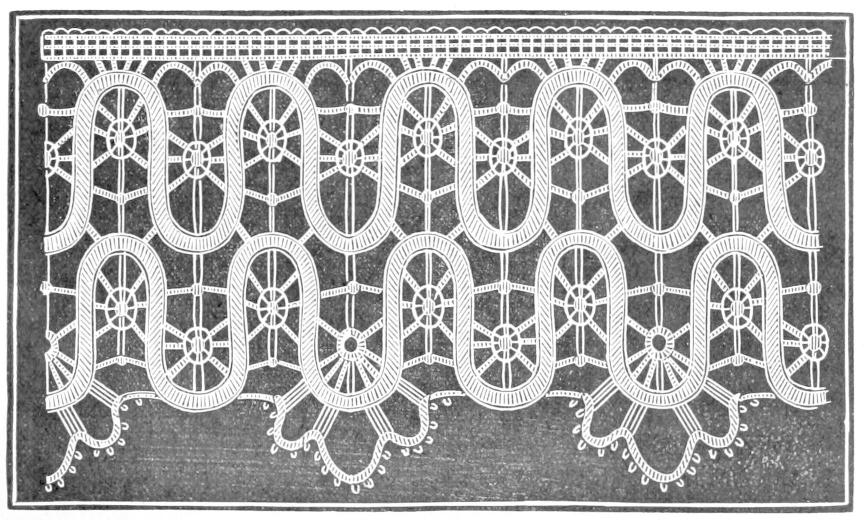

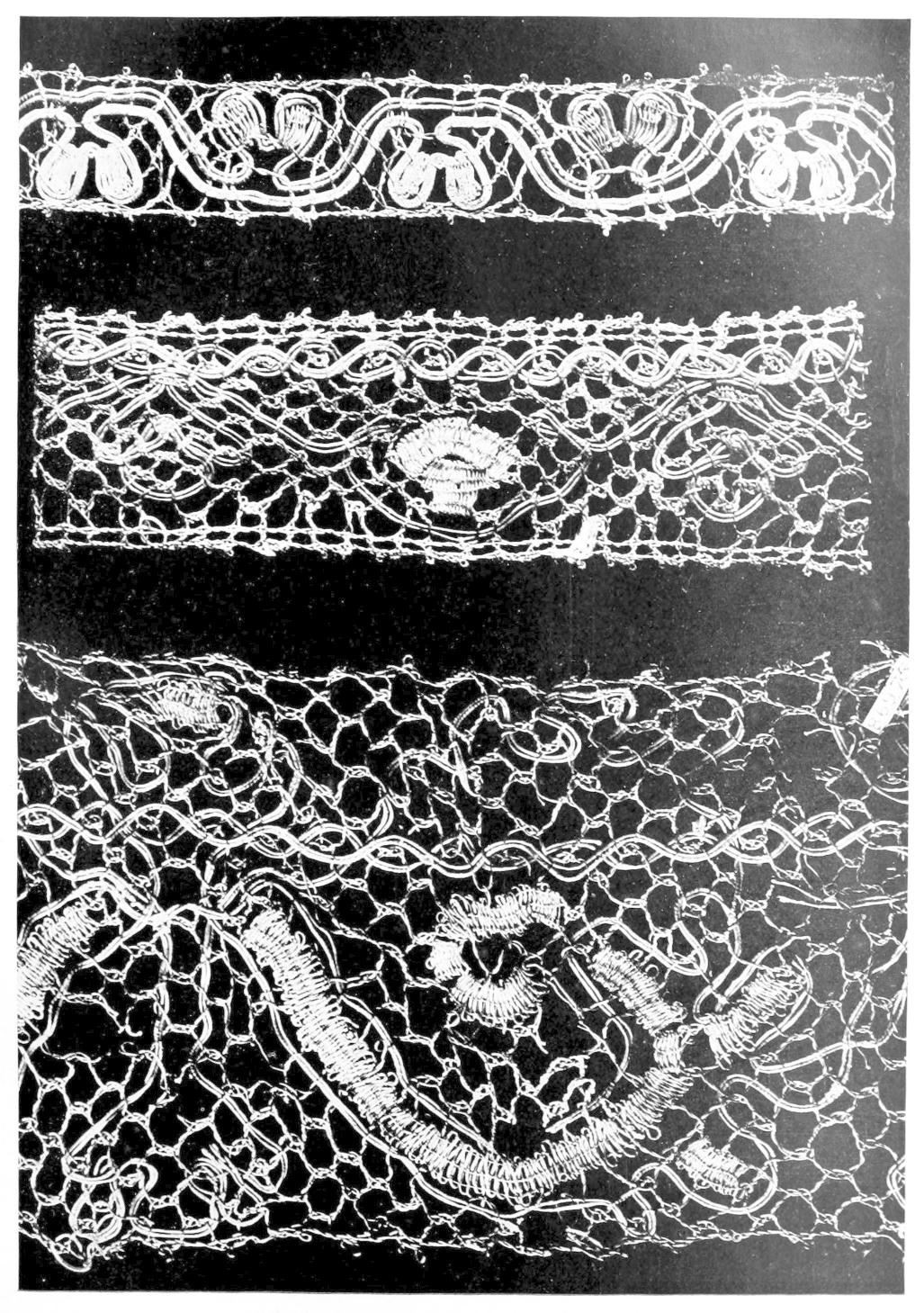

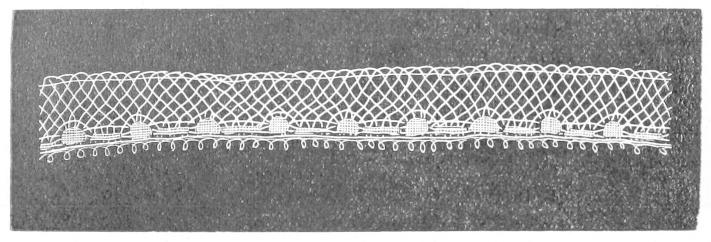

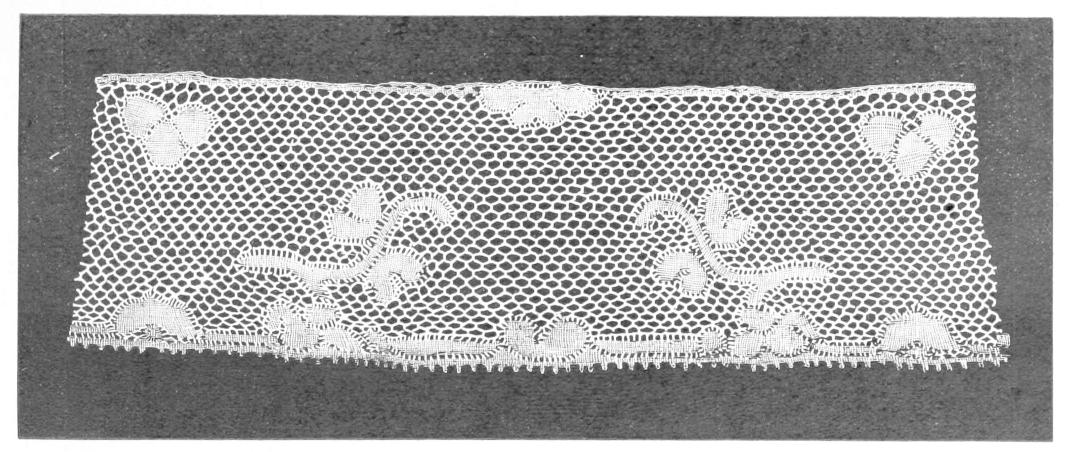

| Passement au Fuseau |

Figs. 13, 14 |

30 |

| Passement au Fuseau |

Fig. 15 |

31 |

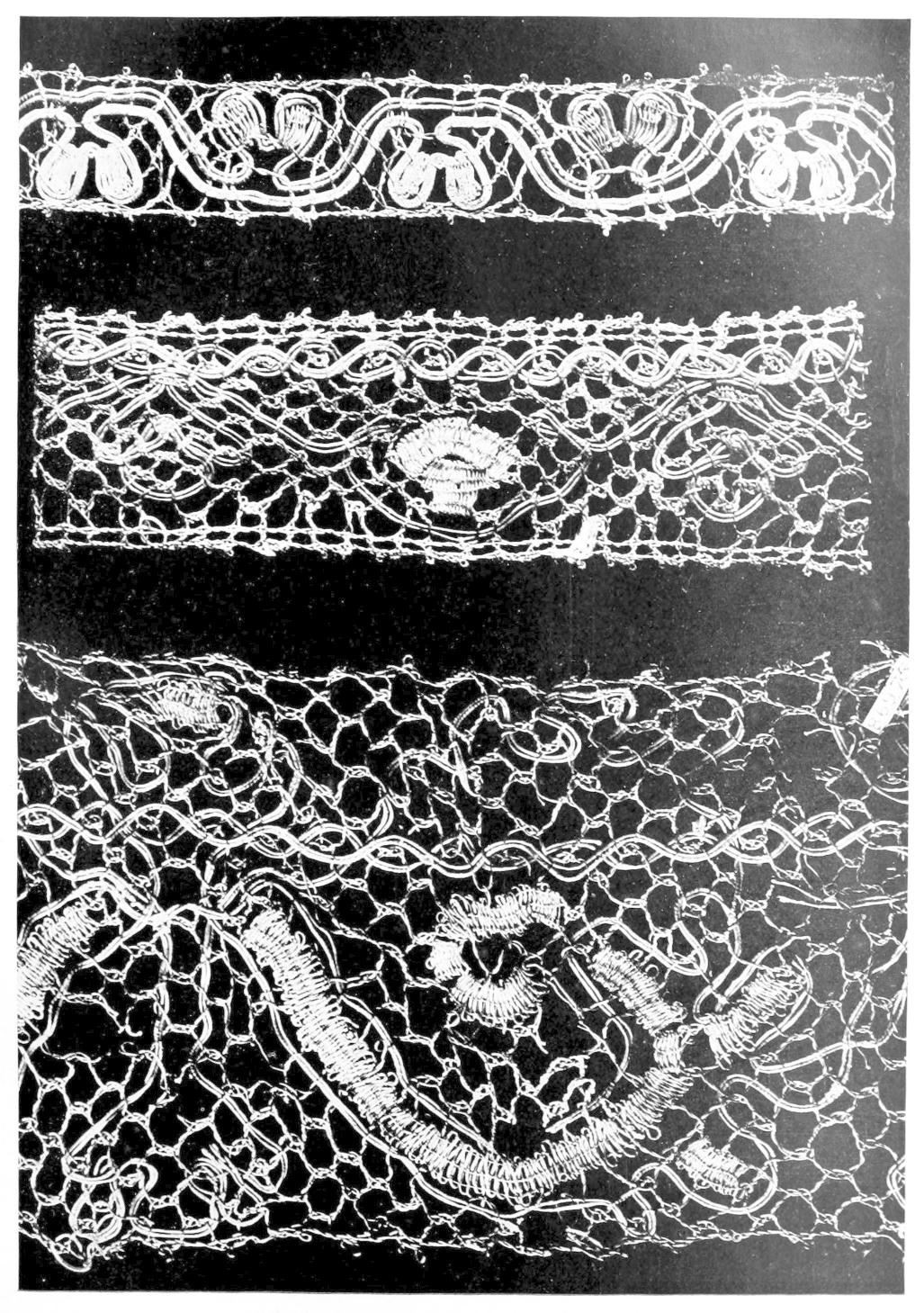

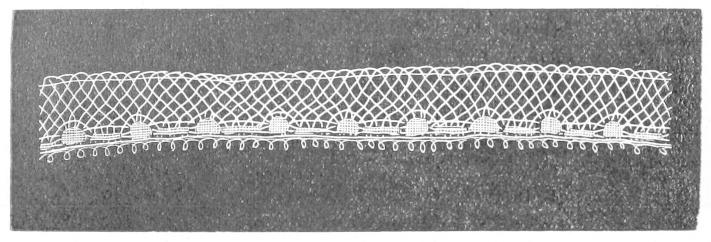

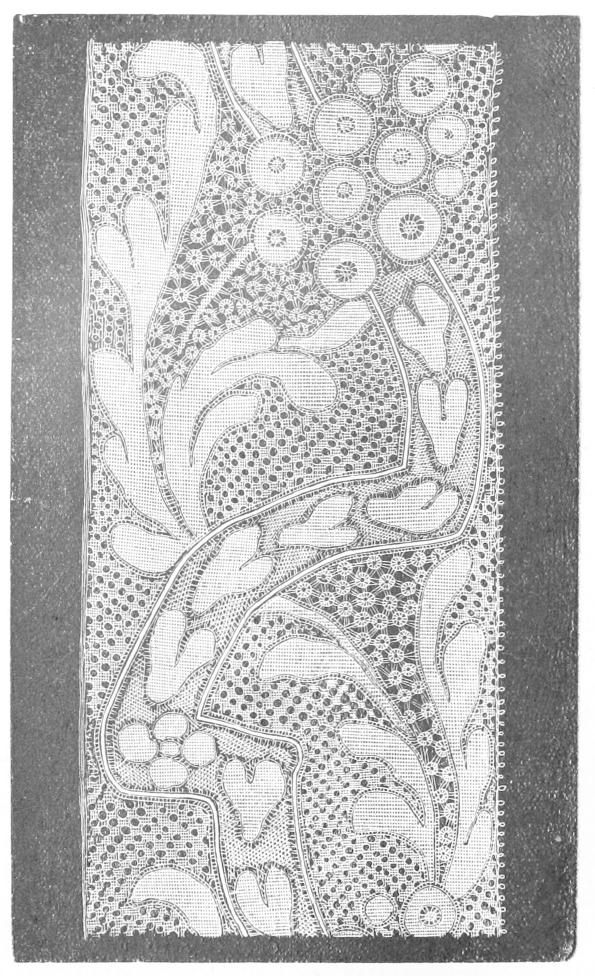

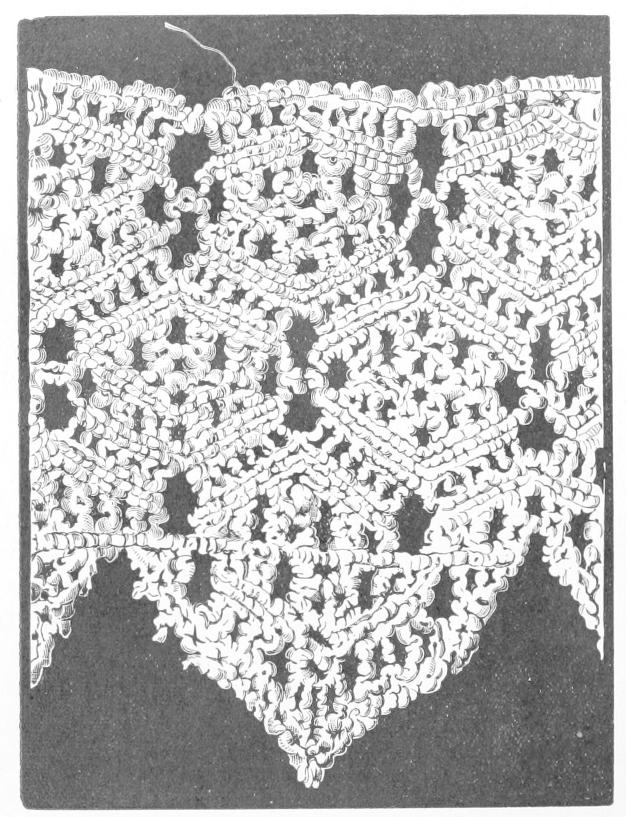

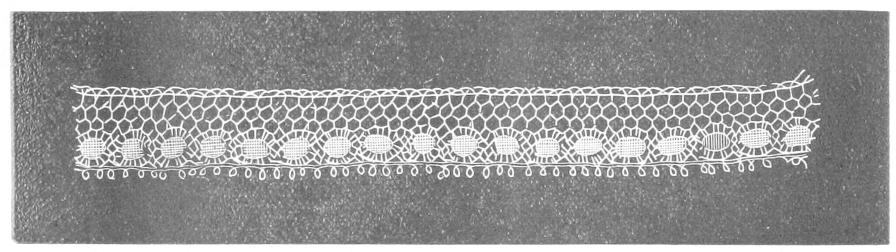

| Merletti a Piombini |

" 16 |

31 |

| Italian.—Modern Reproduction at Burano |

Plate VI |

32 |

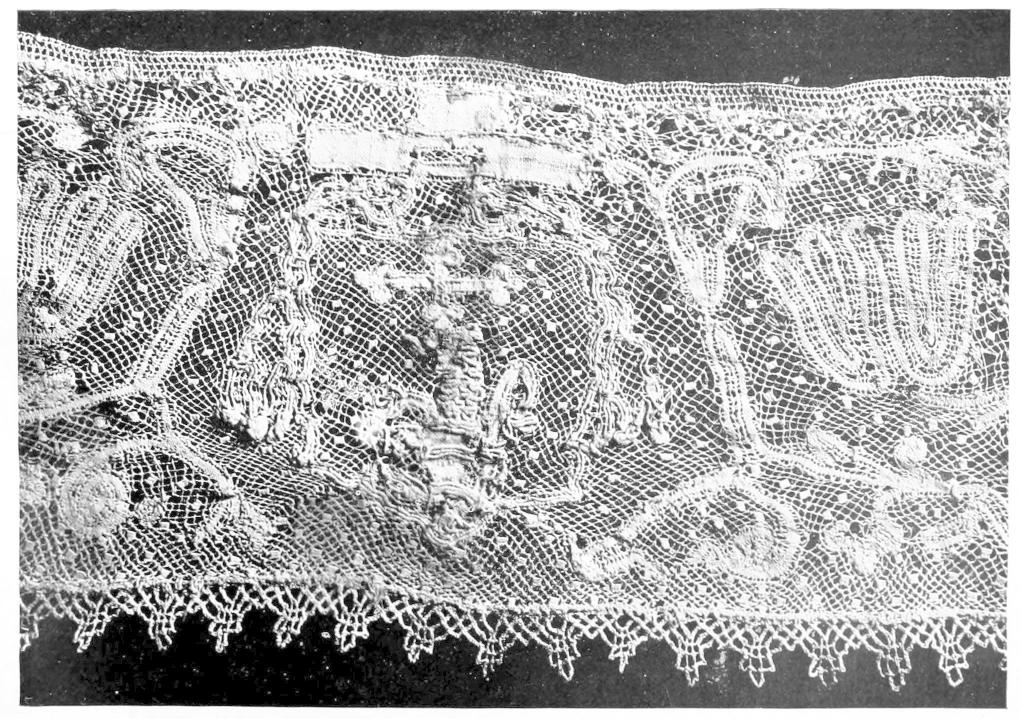

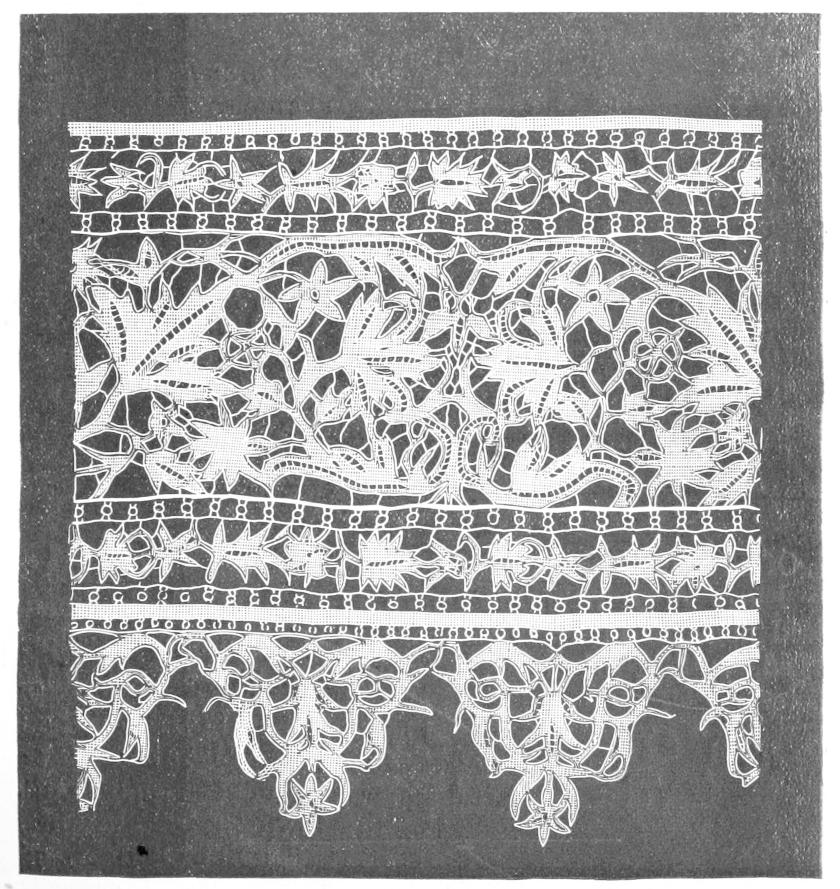

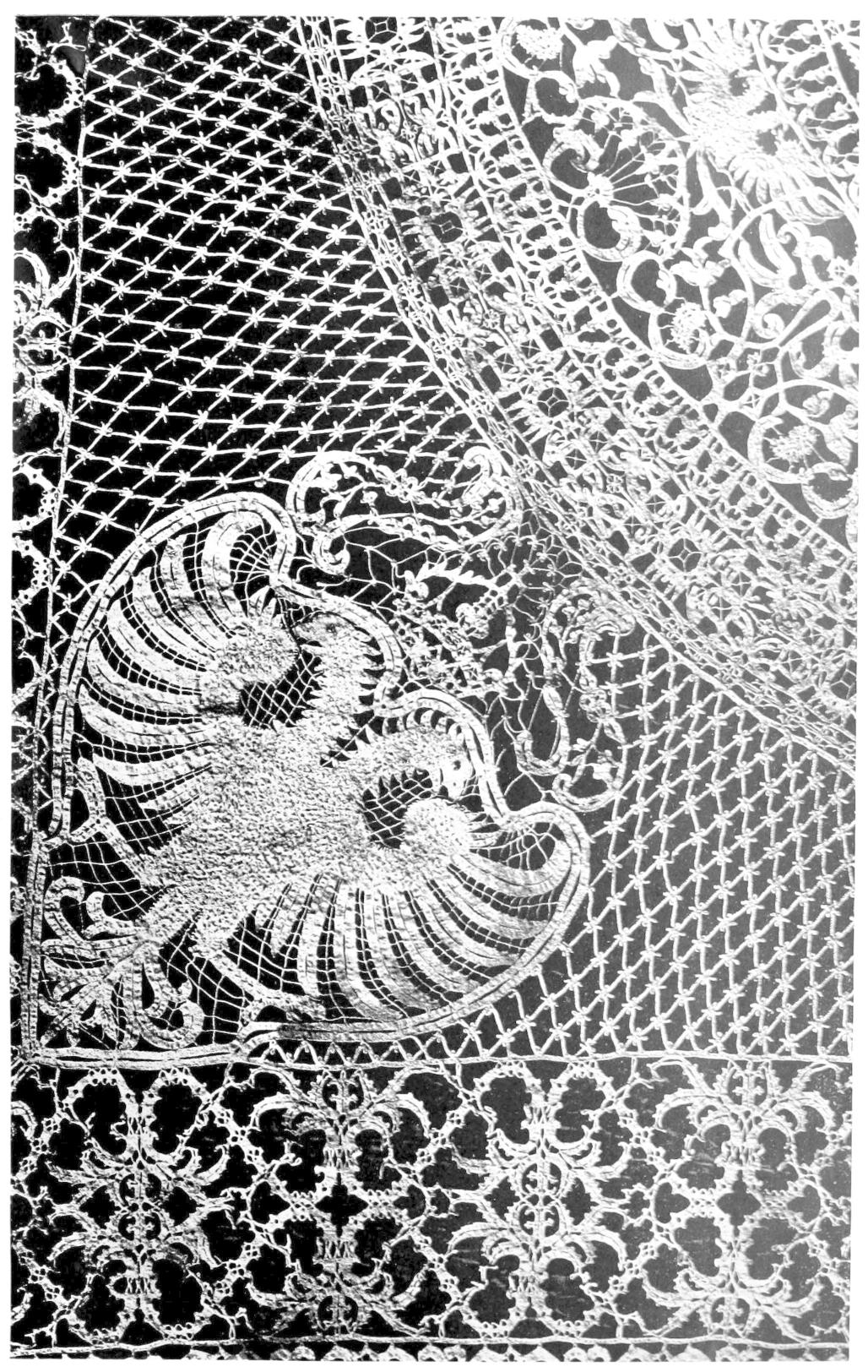

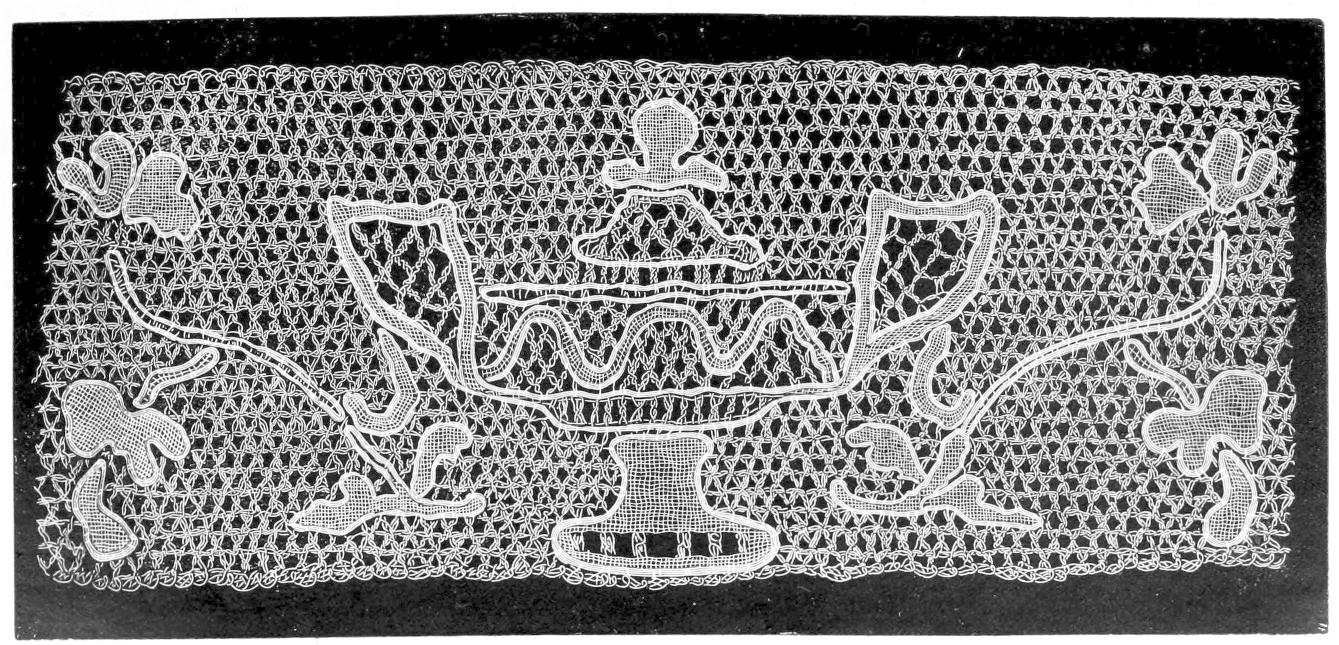

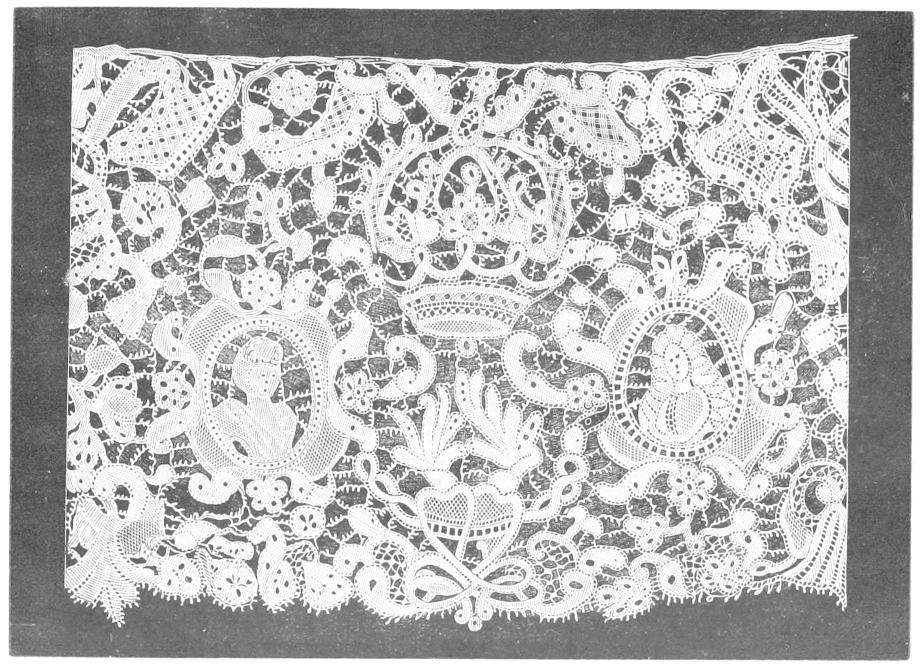

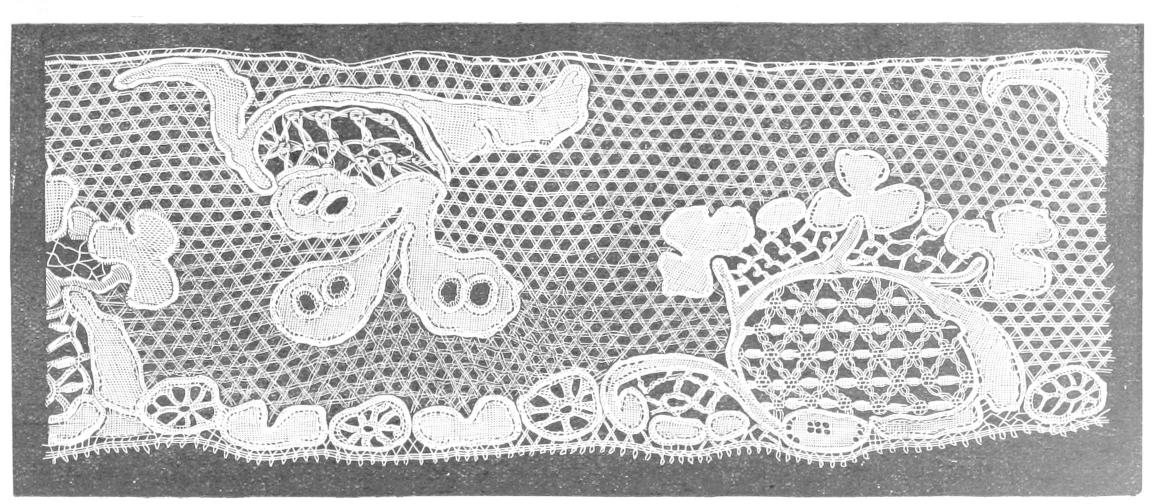

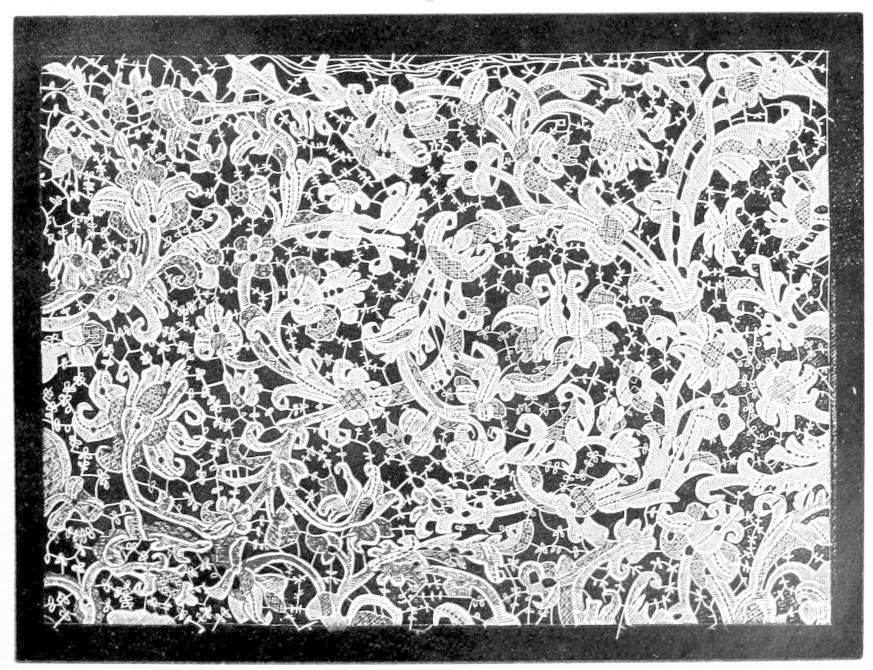

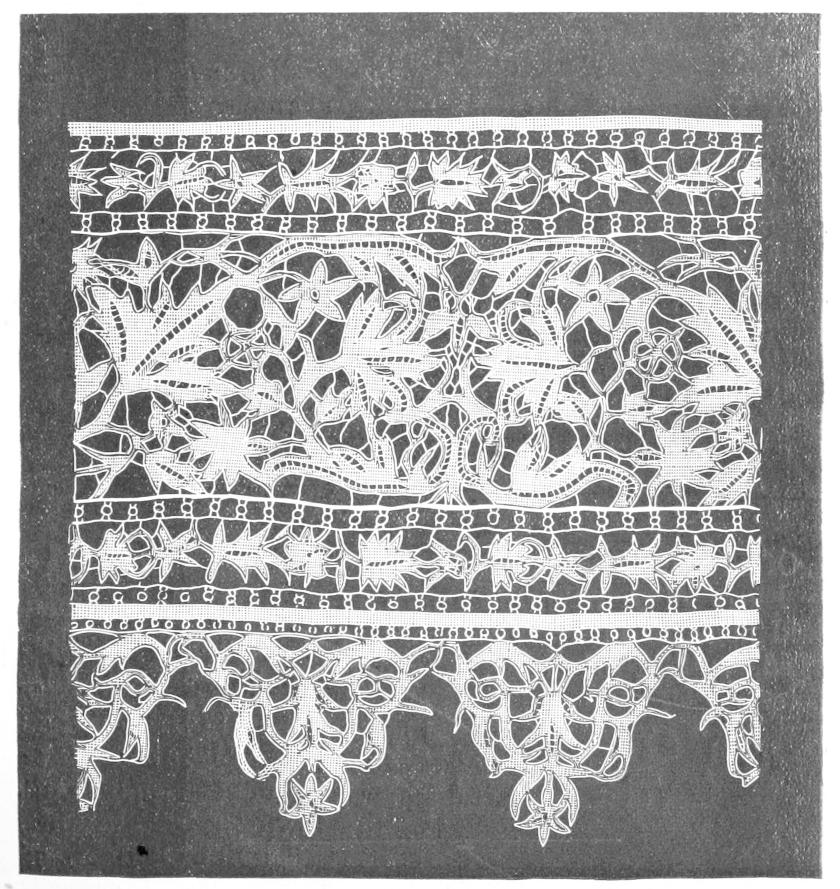

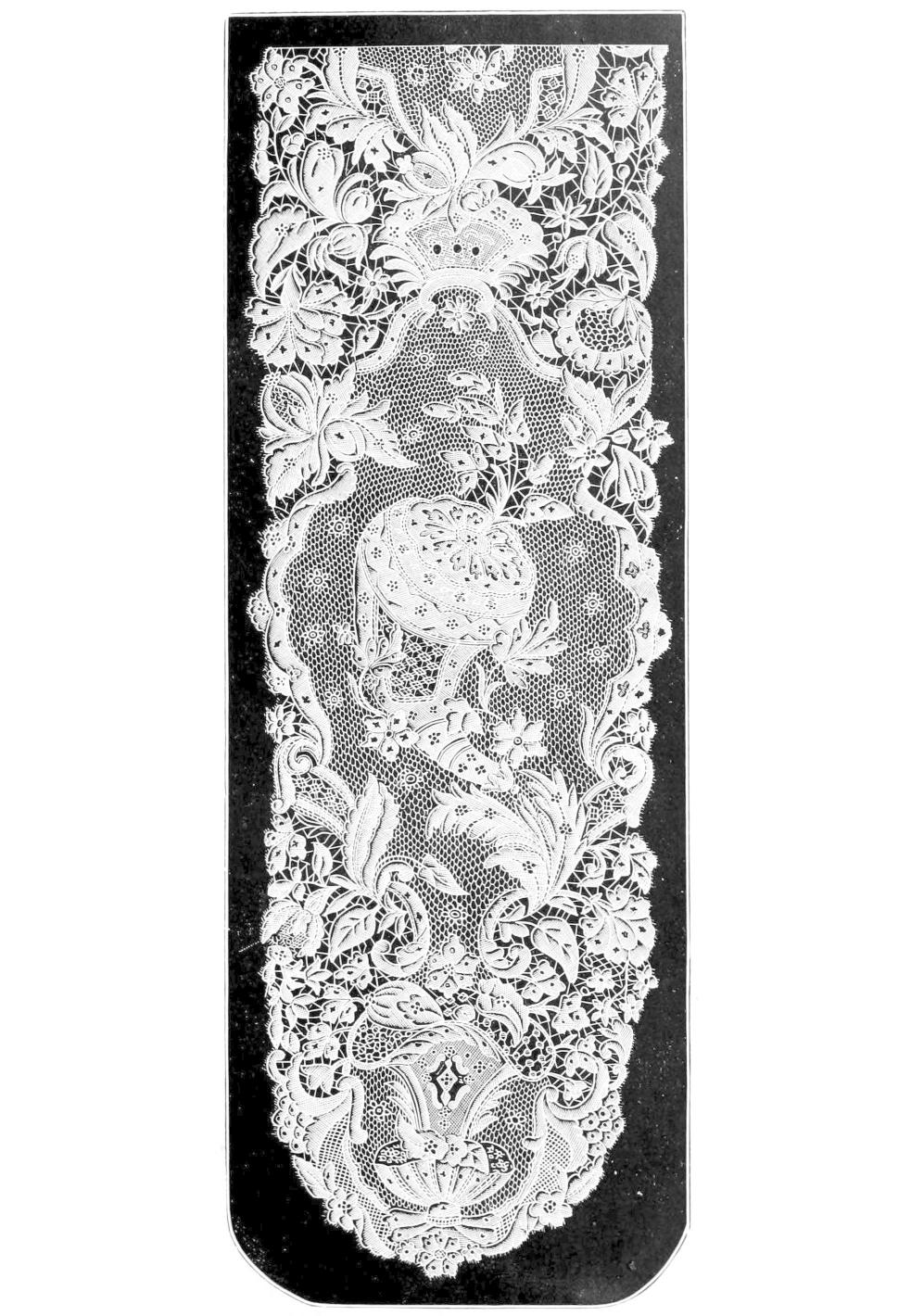

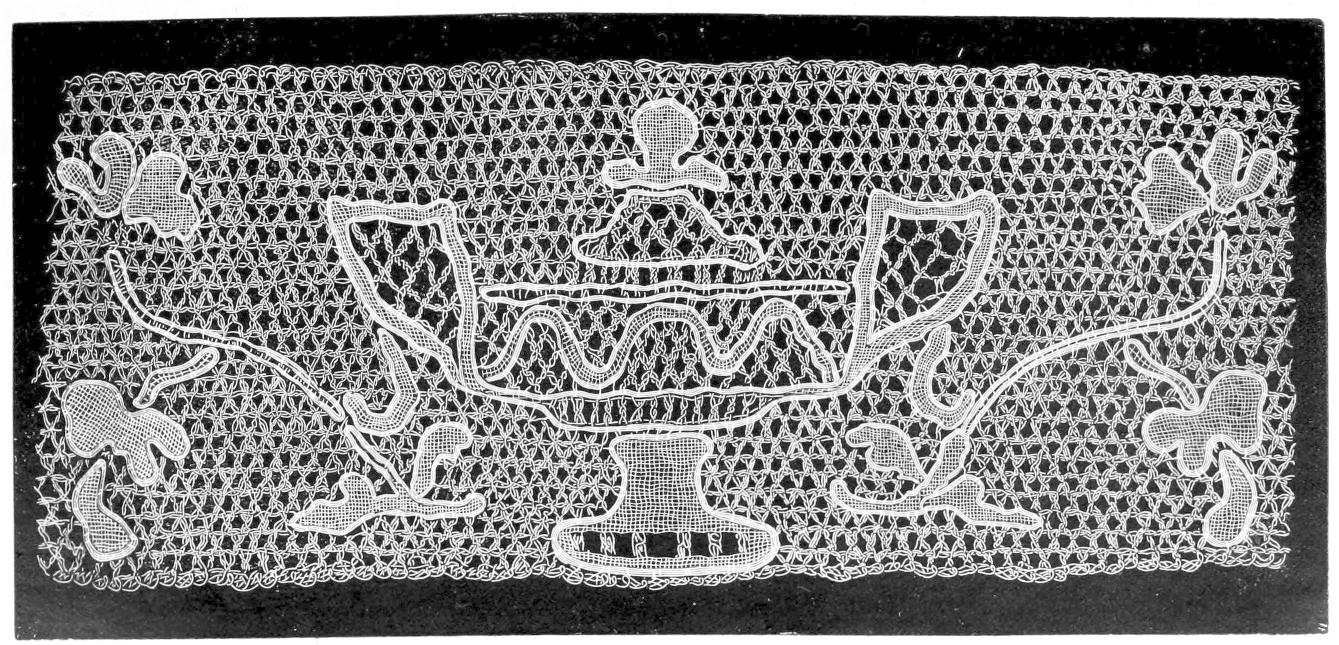

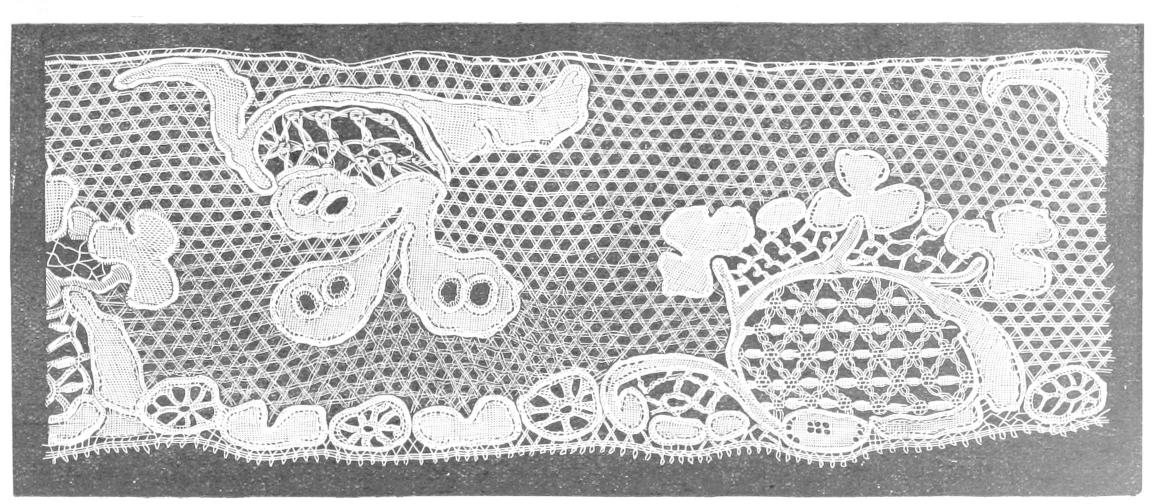

| Heraldic (Carnival Lace) |

" VII |

32 |

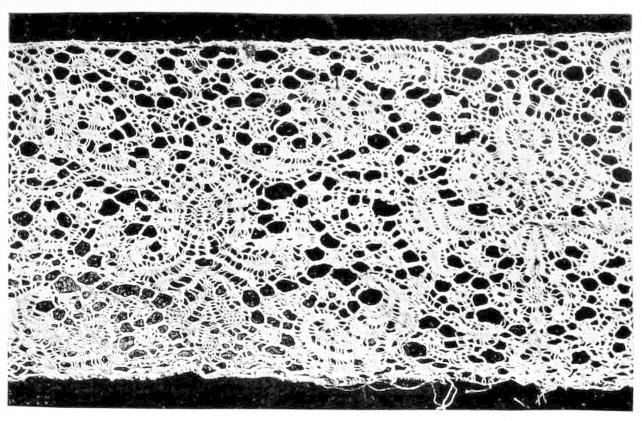

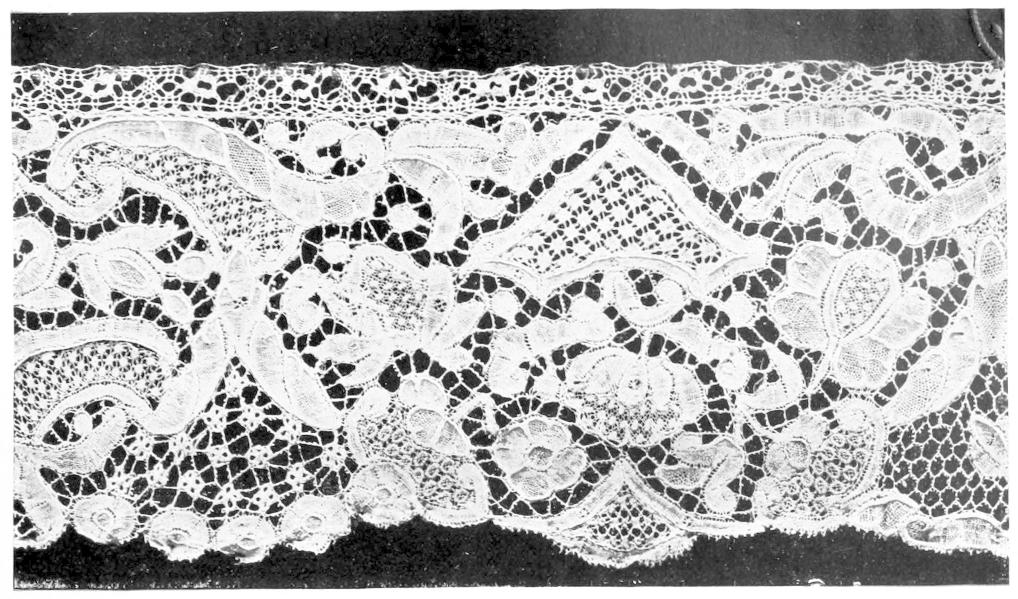

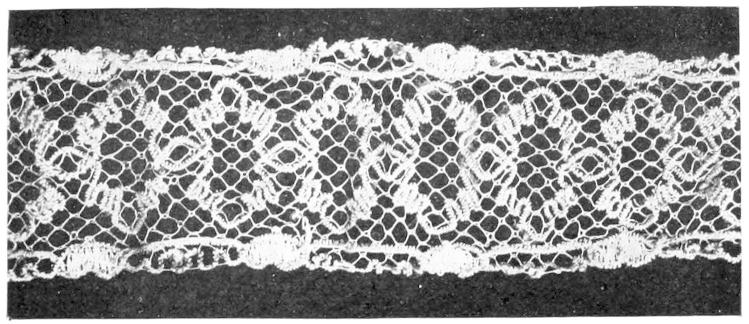

| Old Mechlin |

Fig. 17 |

35 |

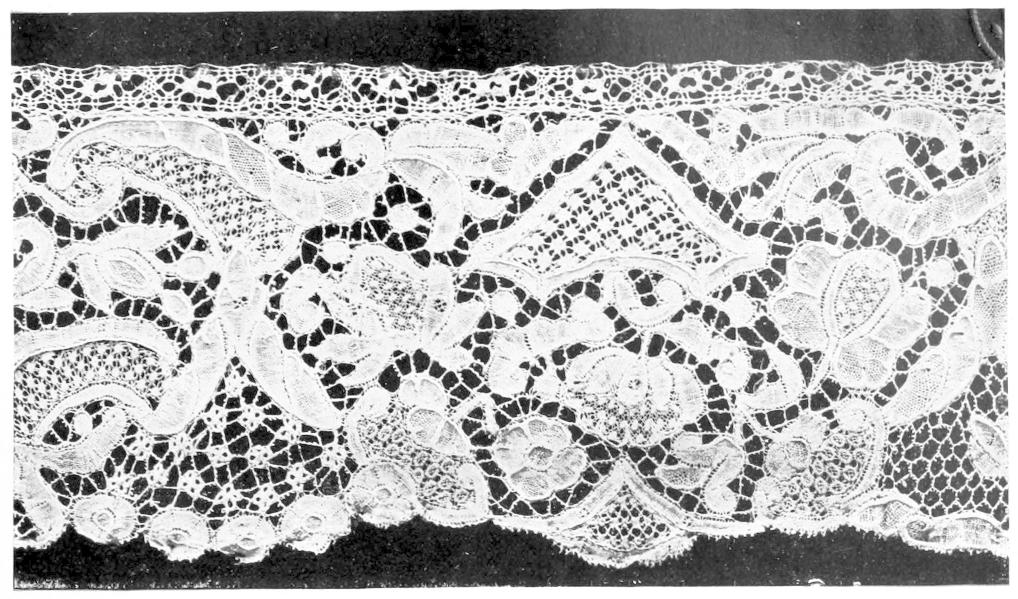

| Italian, Venetian, Flat Needle-point Lace |

Plate VIII |

36 |

| Portion of a Band of Needle-point Lace |

" IX |

36 |

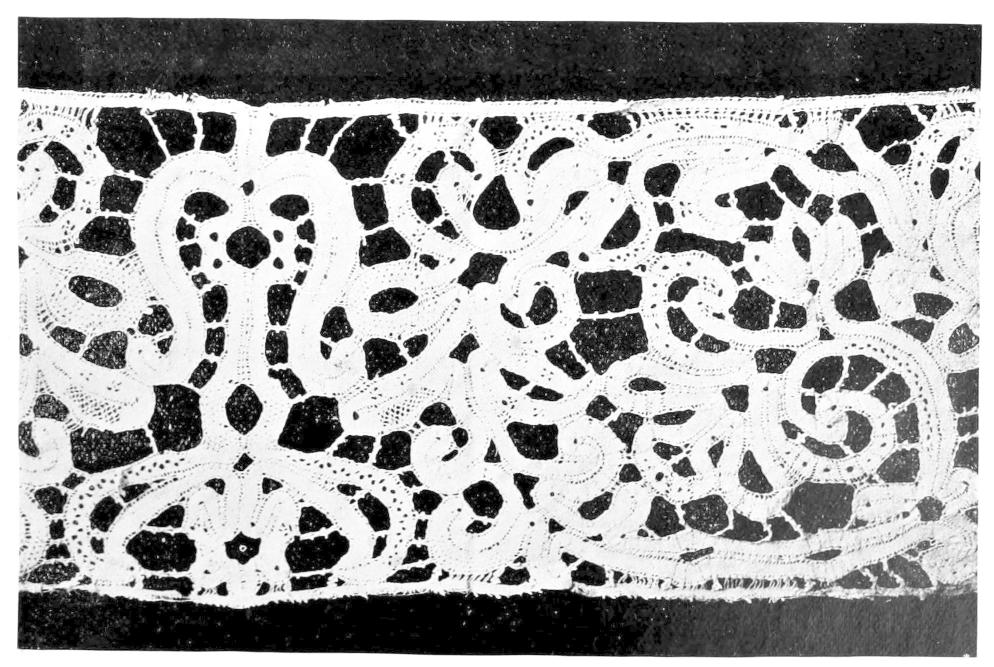

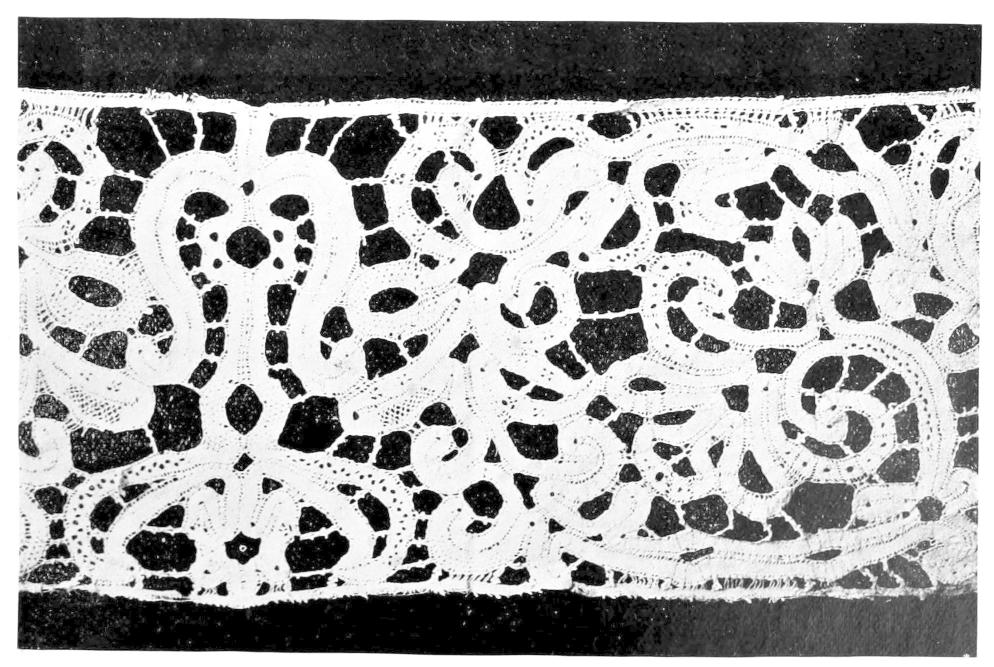

| Guipure |

Fig. 18 |

39 |

| Tape Guipure |

" 19 |

40 |

| Italian.—Point de Venise à la Rose |

Plate X |

44 |

| Italian.—Point Plat de Venise |

" IXI |

46 |

| Italian.—Point de Venise à Réseau |

" XII |

48 |

| Mermaid Lace |

Fig. 20 |

50 |

| Reticella |

" 21 |

50 |

| Punto a Gropo |

" 22 |

52 |

| Gros Point de Venise |

" 23 |

52 |

| Punto a Maglia |

" 24 |

53 |

| Punto Tirato |

" 25 |

54 |

|

Point de Venise à Bredes Picotées

|

" 26 |

54 |

| Venise Point |

" 27 |

55 |

| Gros Point de Venise |

" 28 |

56 |

| Point de Venise |

" 29 |

56 |

| Point Plat de Venise |

" 30 |

56 |

| Point de Venise à Réseau |

" 31 |

58 |

| Burano Point |

" 32 |

60 |

| Italian.—Modern Point de Burano |

Plate XIII |

60 |

| Italian.—Modern Reproduction at Burano |

" XIV |

62 |

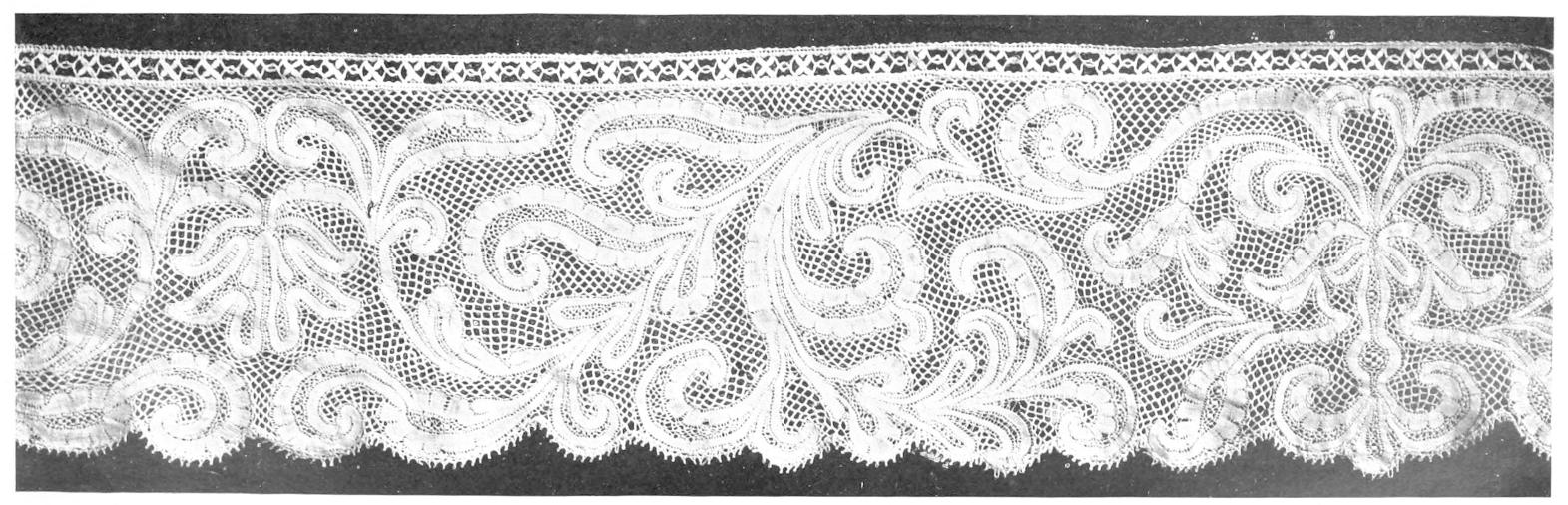

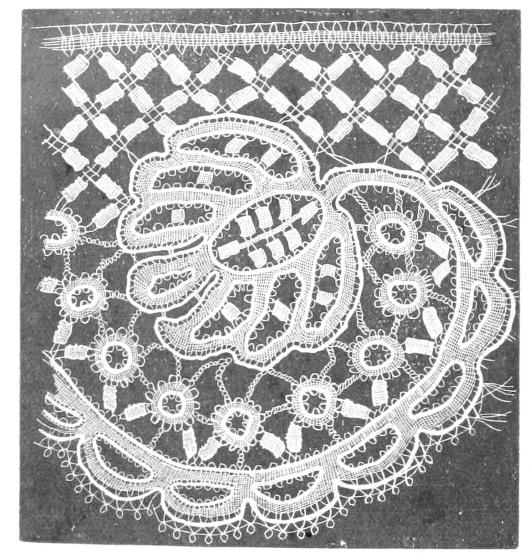

| Italian.—Milanese, Bobbin-made |

" IXV |

64 |

| Reticella from Milan |

Fig. 33 |

65 |

| Italian.—Venetian, Needle-made |

Plate XVI |

66 |

| Italian.—Milanese, Bobbin-made |

" XVII |

66 |

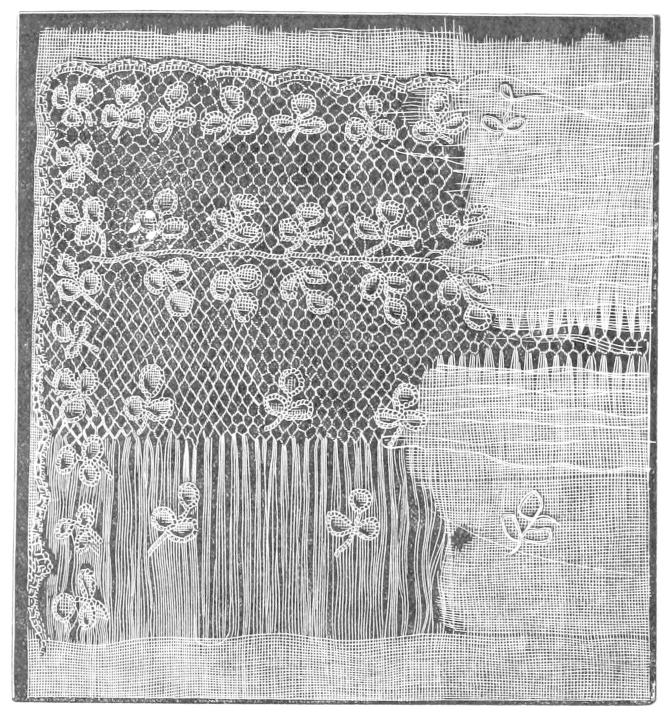

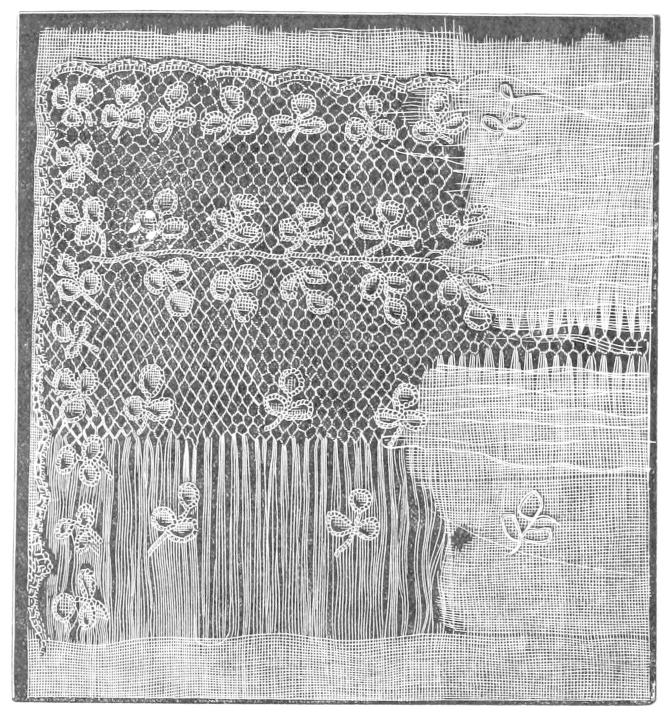

| Unfinished Drawn-work |

Fig. 34 |

69 |

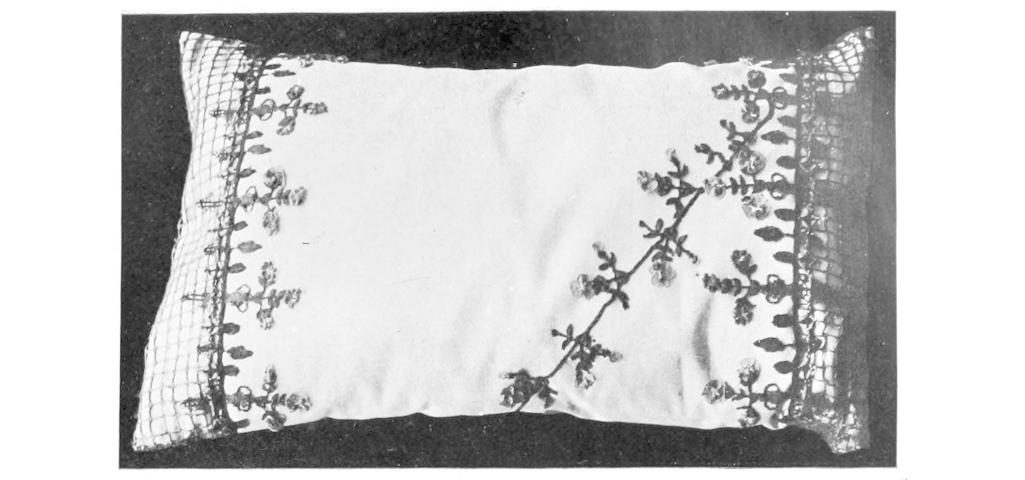

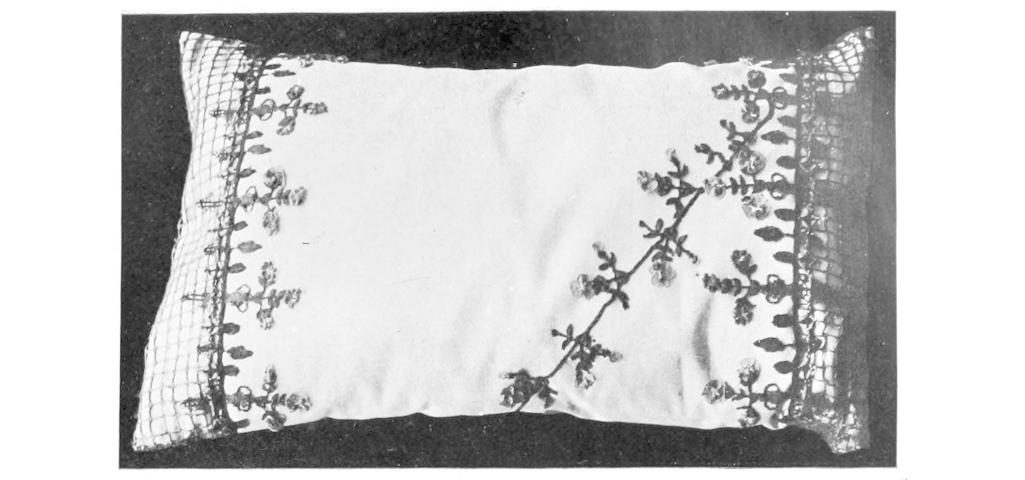

| Cushion made at the School |

Plate XVIII |

70 |

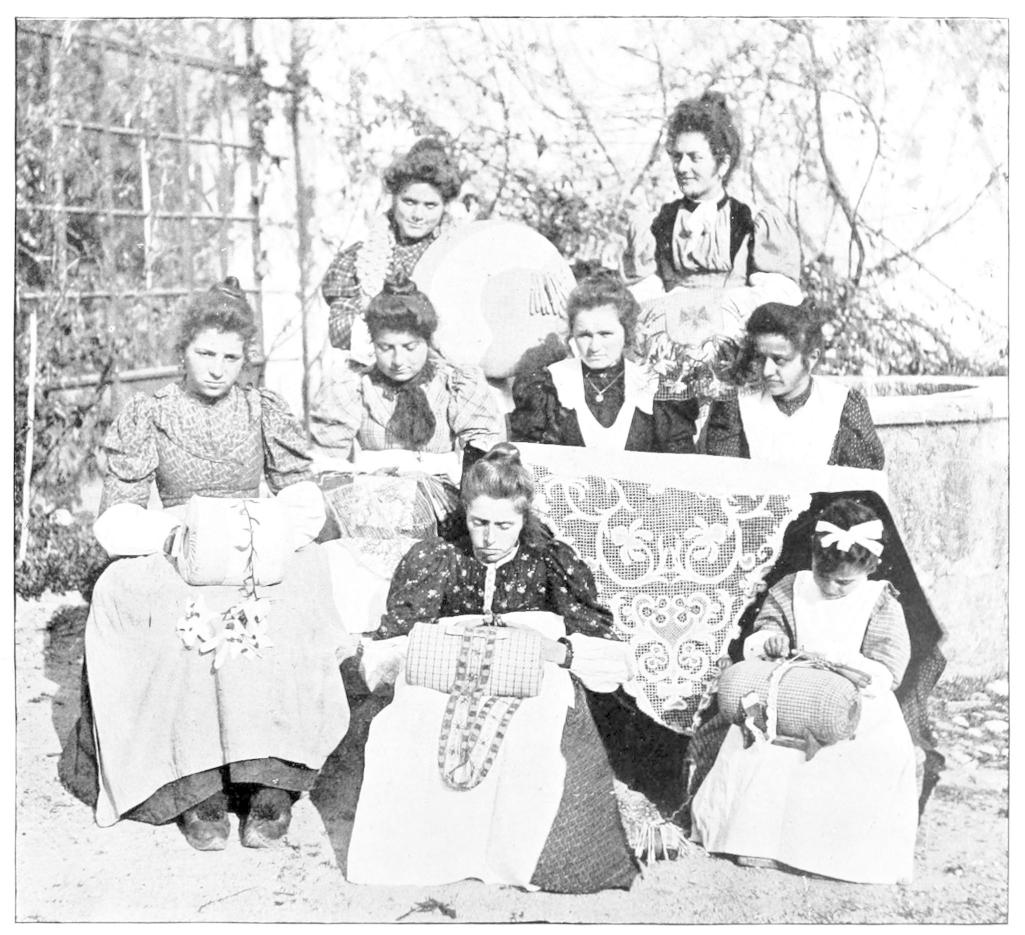

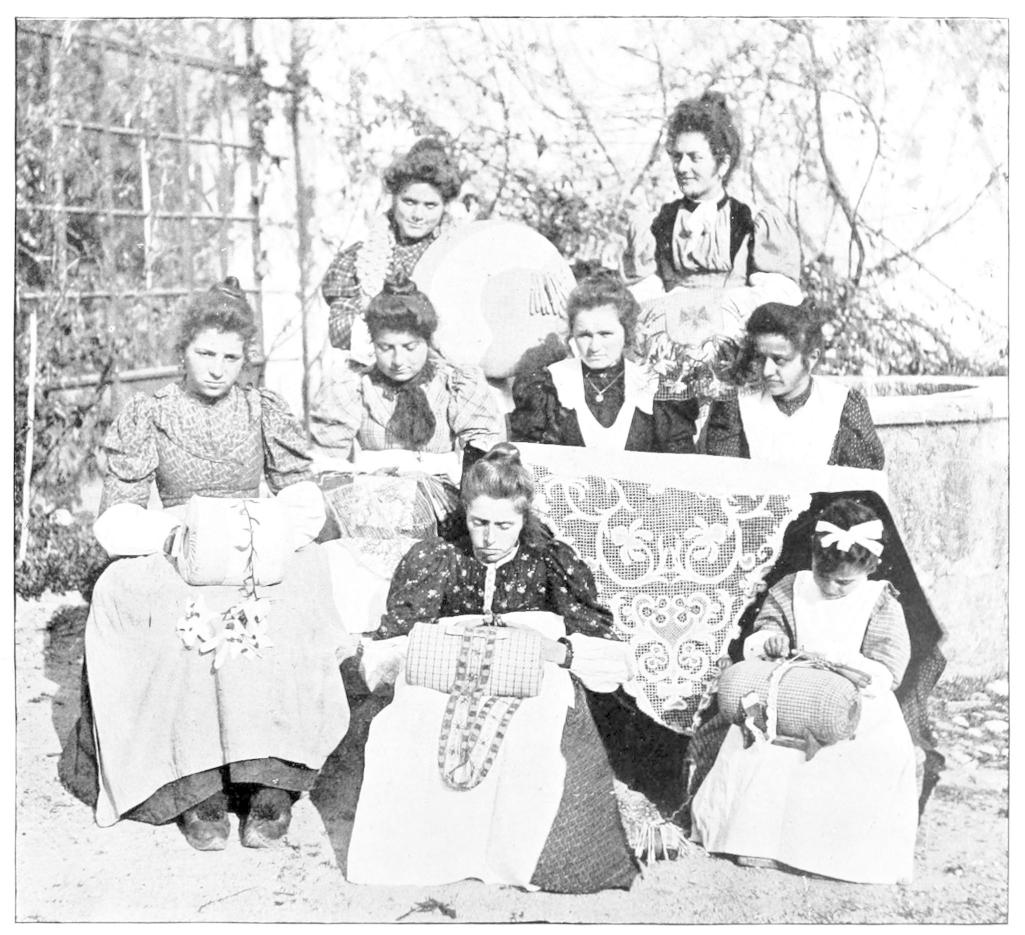

| Italy.—Group of Workers at Brazza School |

" XIX |

70 |

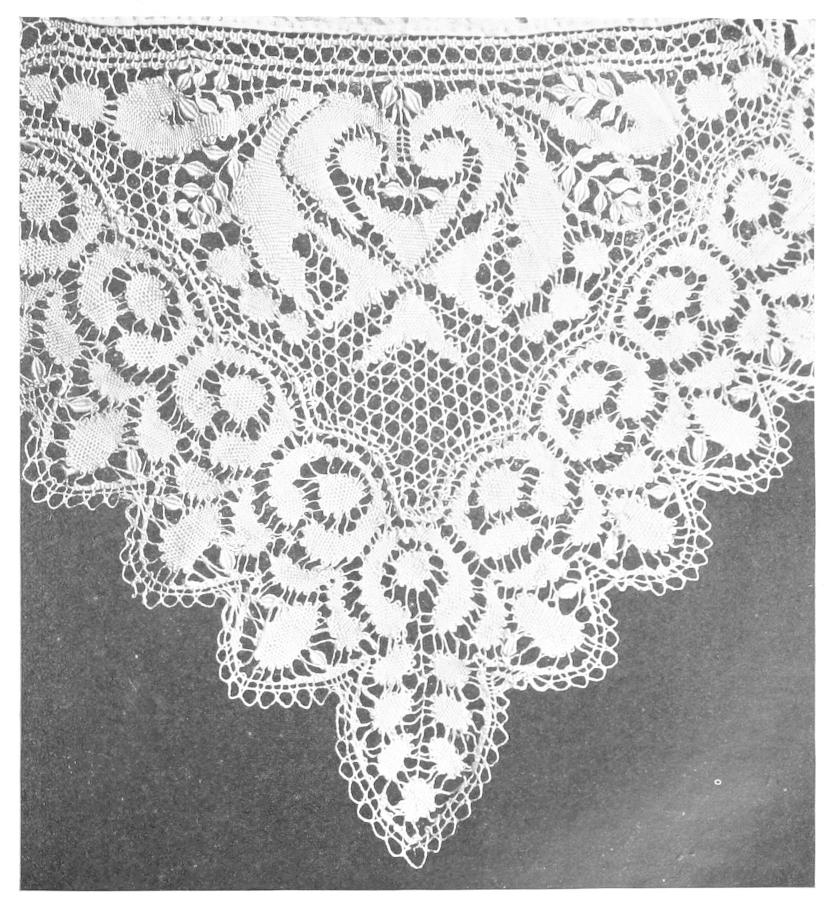

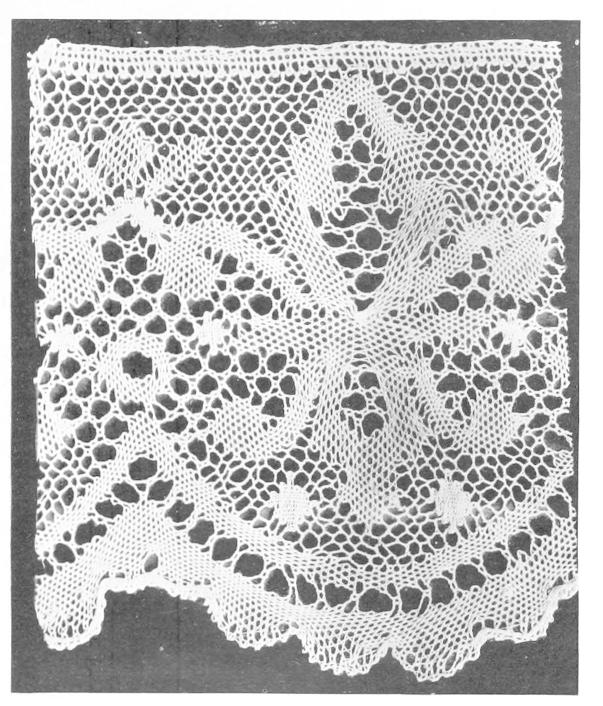

| Genoa Point, Bobbin-made |

Fig. 35 |

74 |

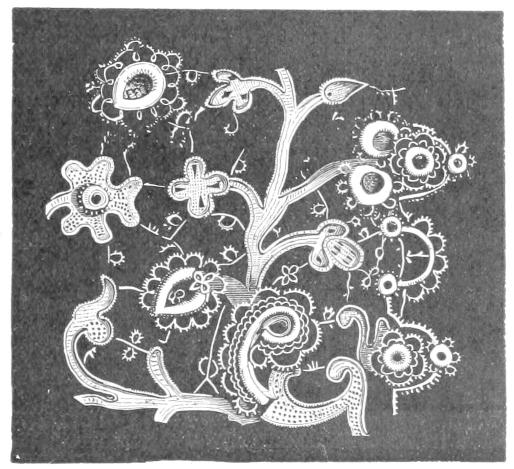

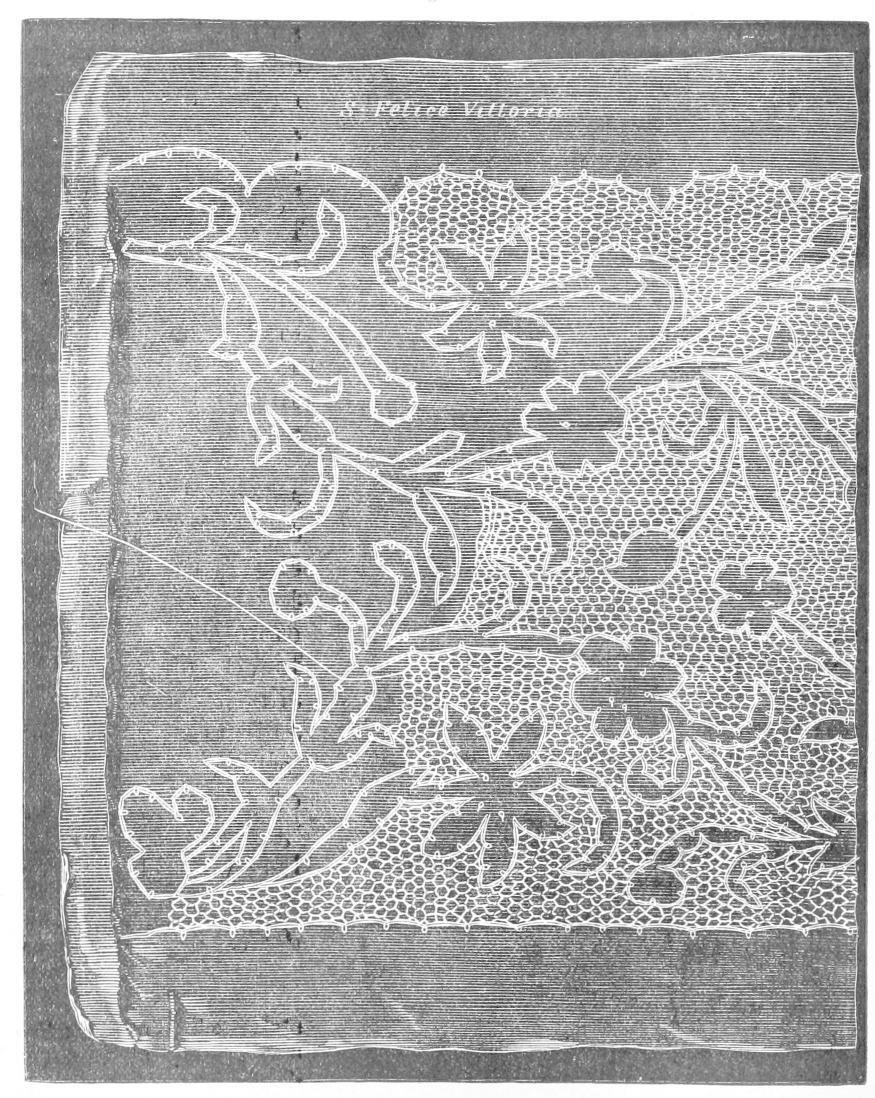

| Lace Pattern found in the Church at Santa Margherita |

" 36 |

76 |

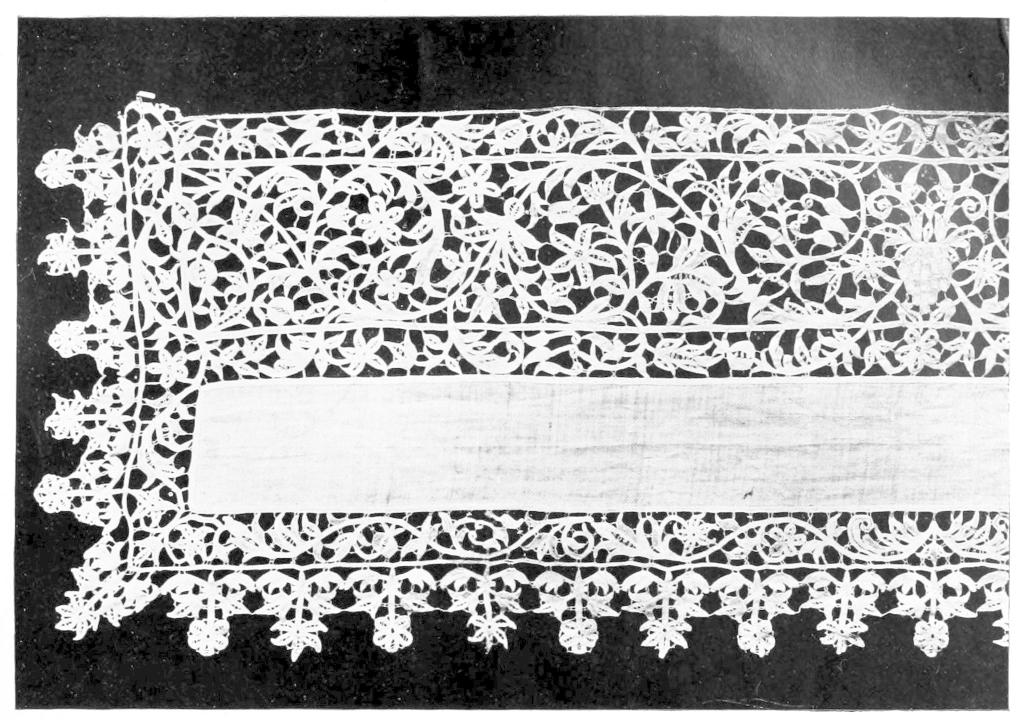

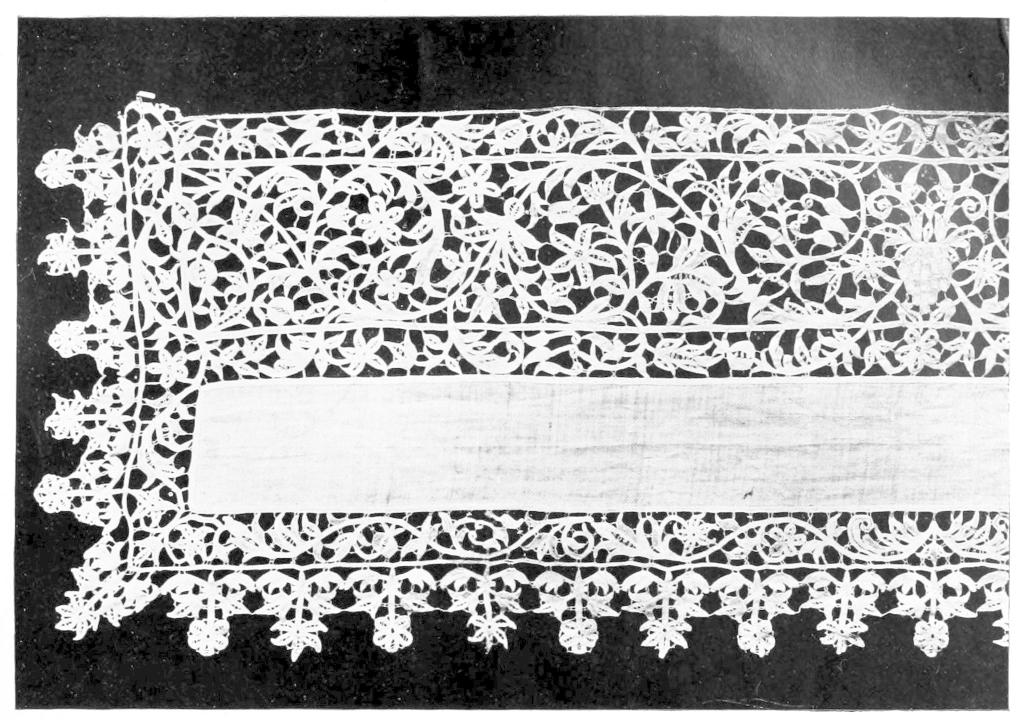

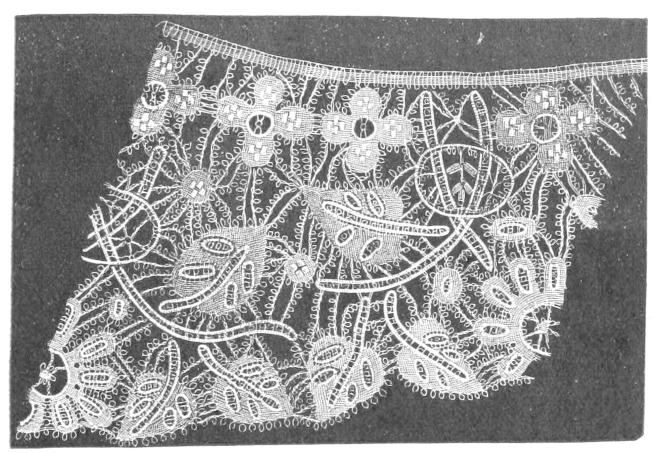

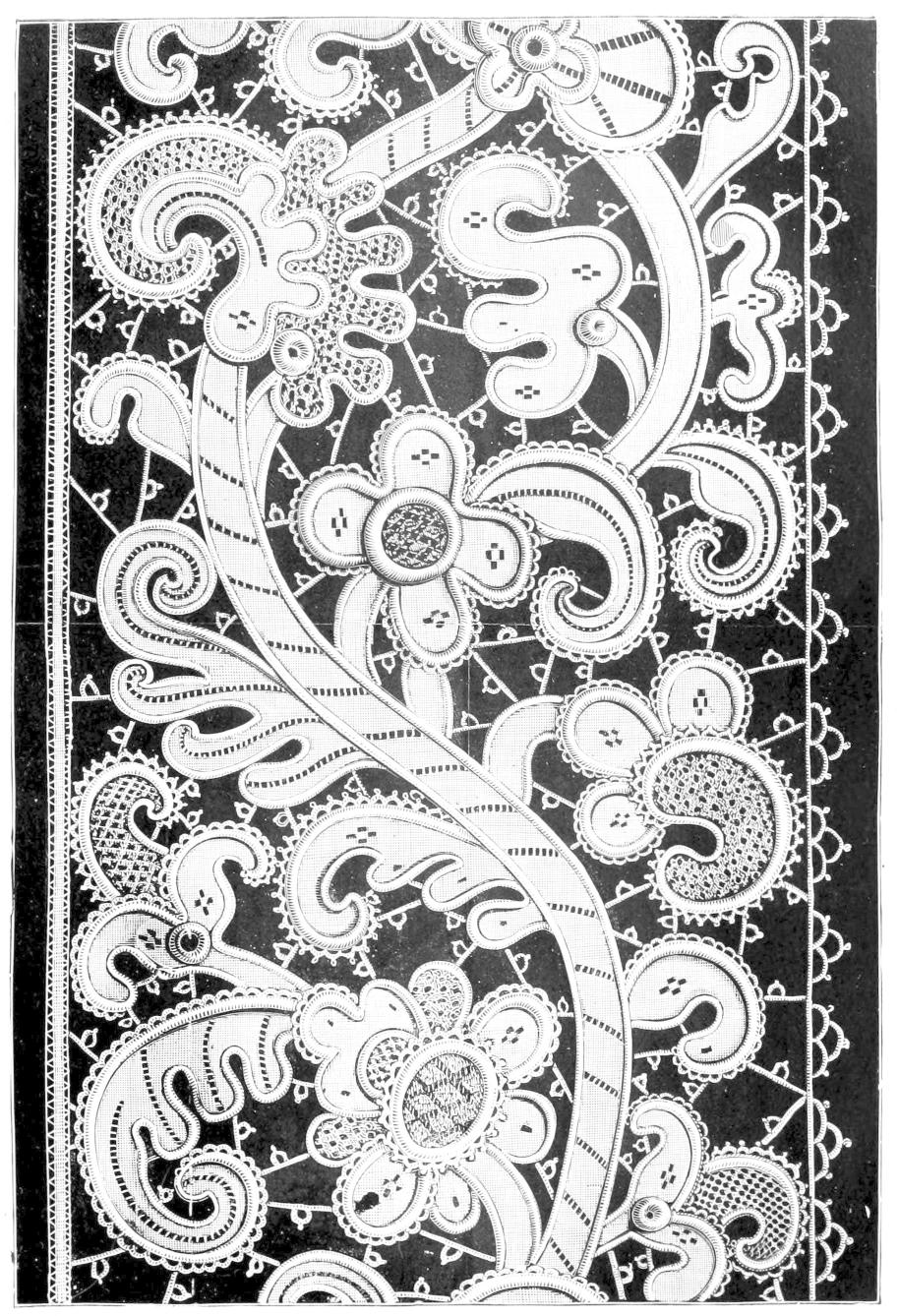

| Italian.—Bobbin Tape With Needle-made

Réseau |

Plate XX |

76 |

| Italian, Genoese.—Border |

" XXI |

76 |

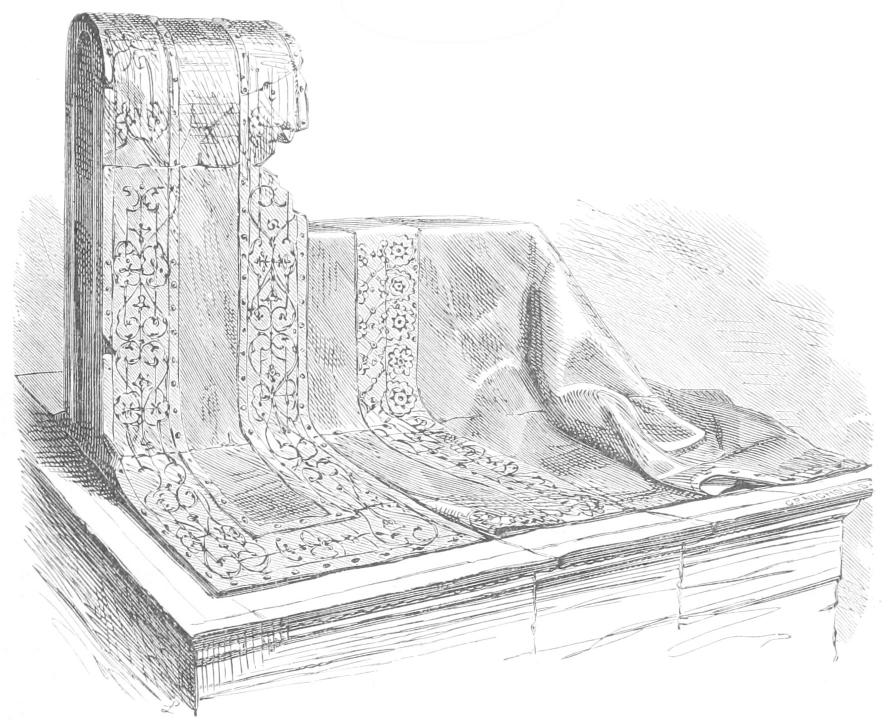

| Parchment Pattern used to cover a Book |

Fig. 37 |

77 |

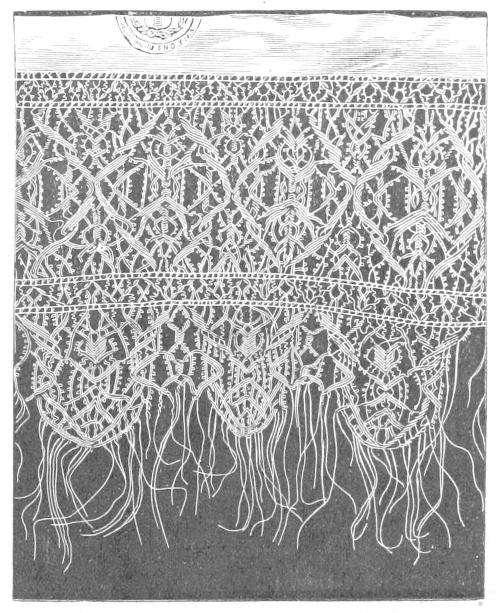

| Fringed Macramé |

" 38 |

80 |

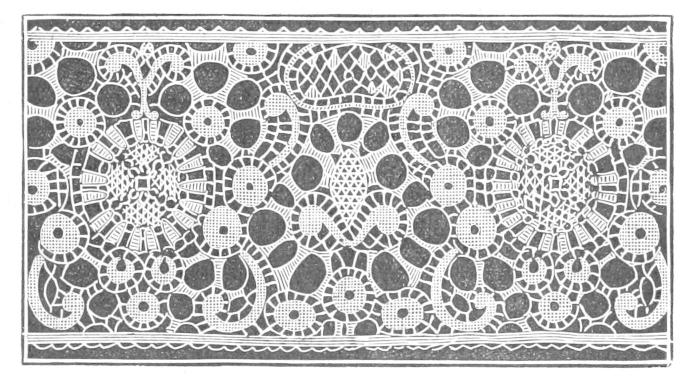

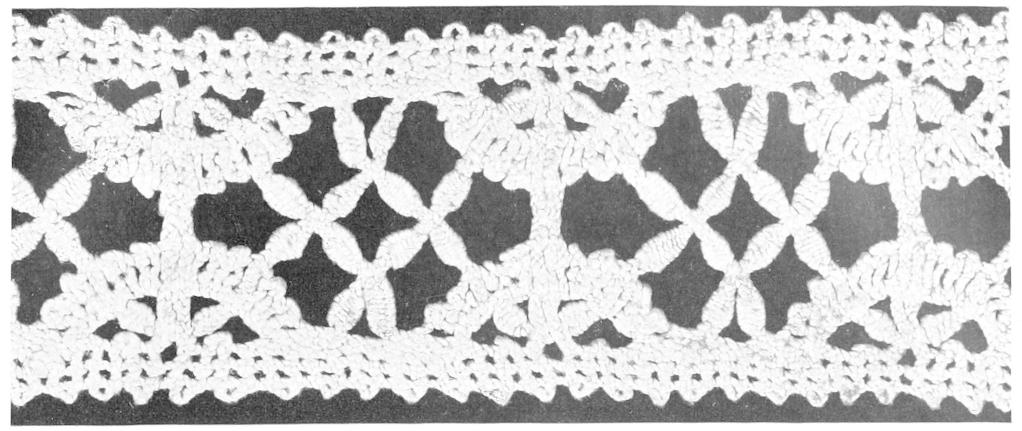

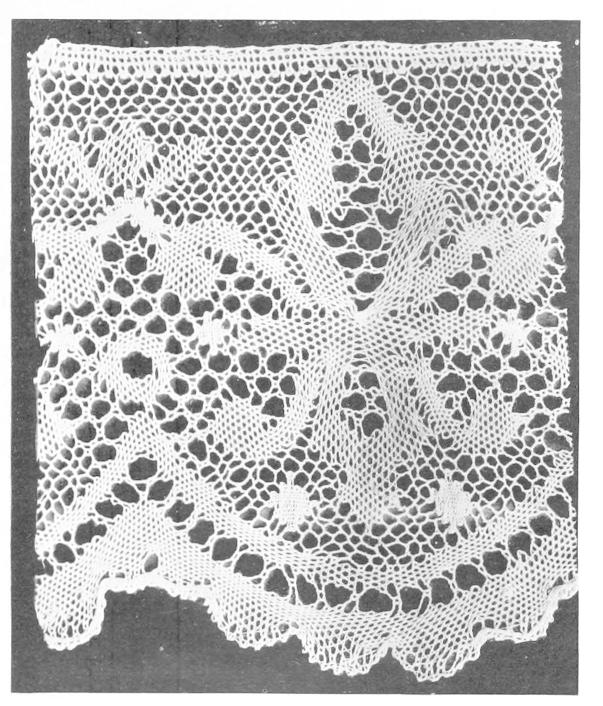

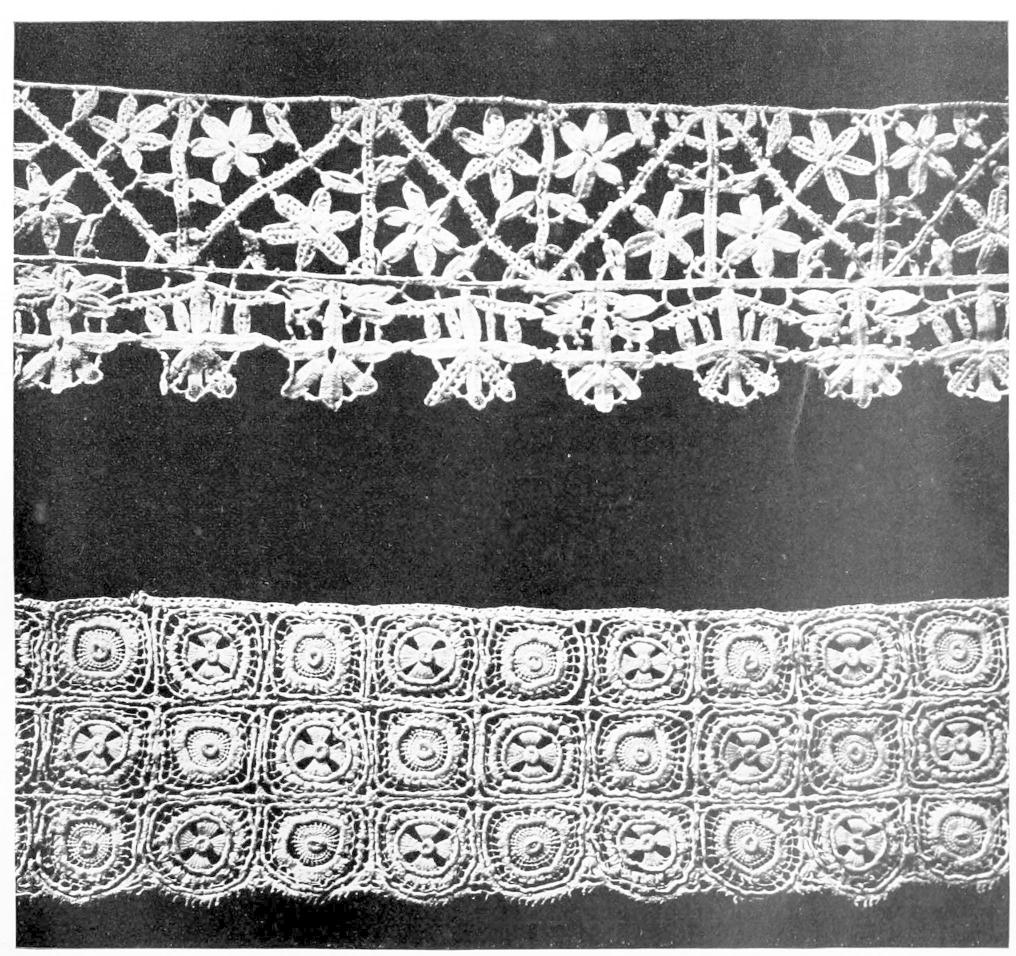

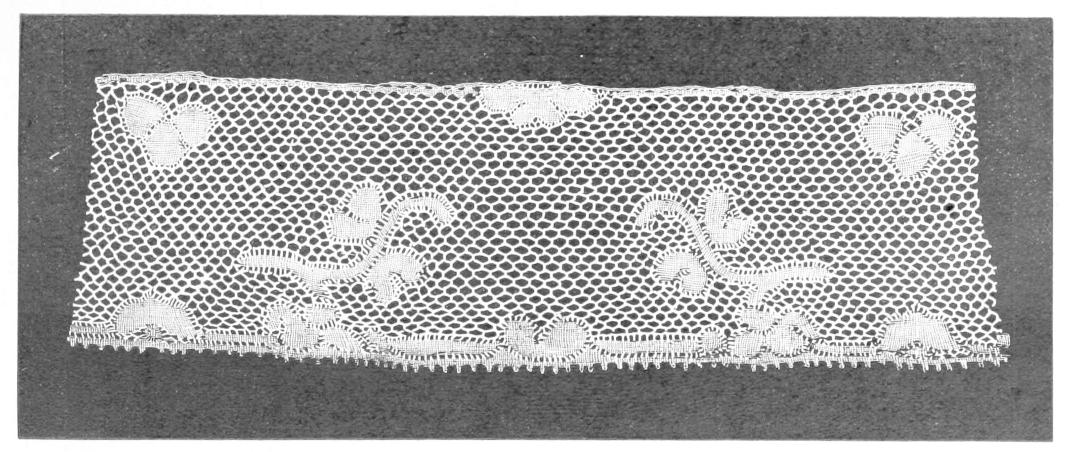

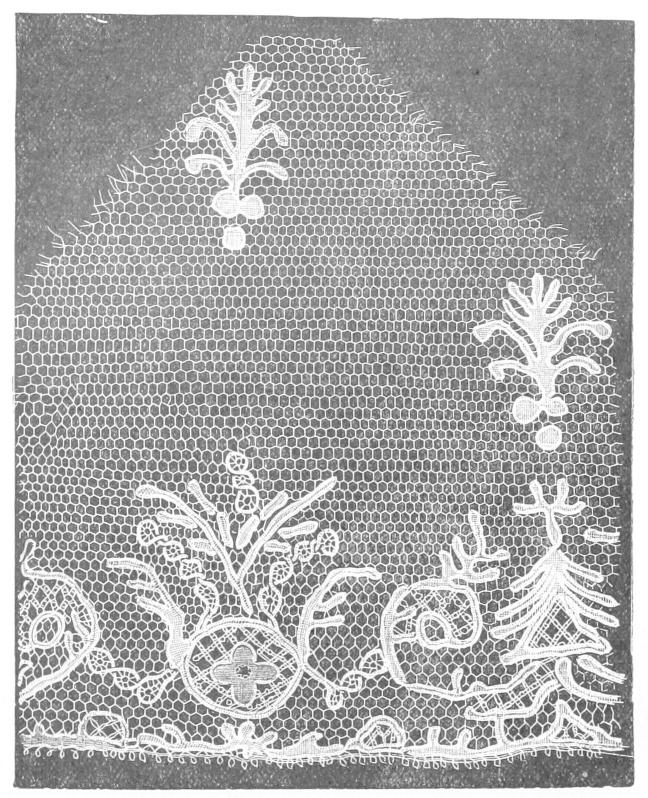

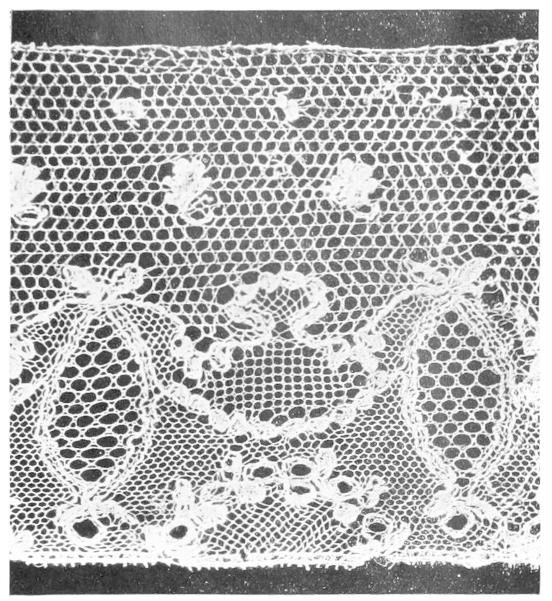

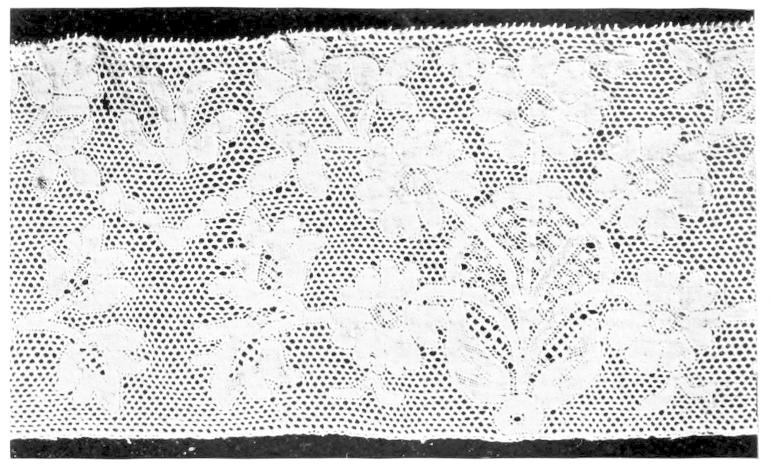

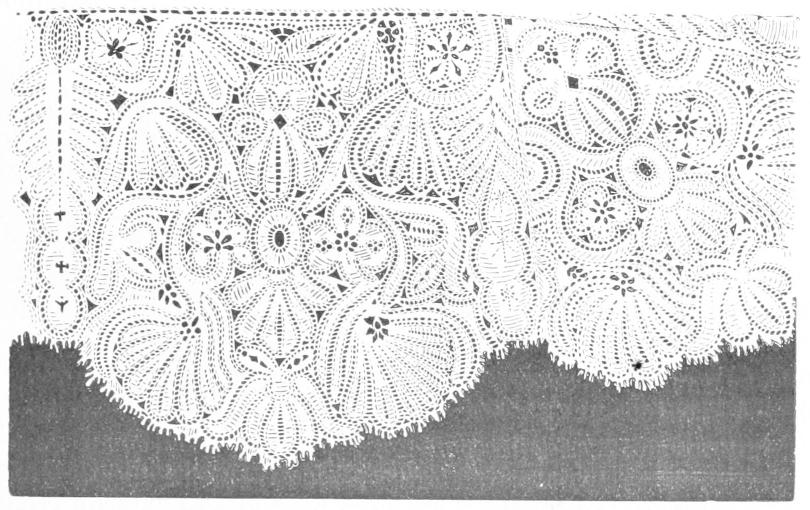

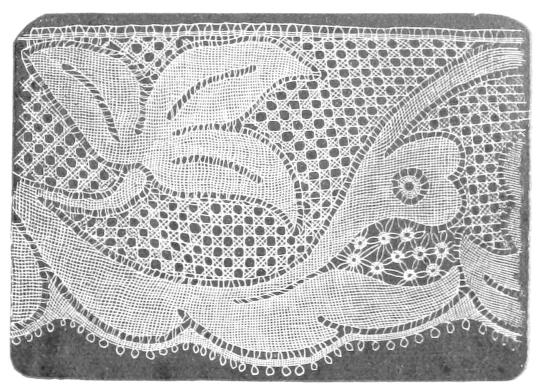

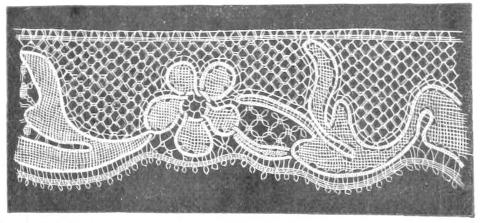

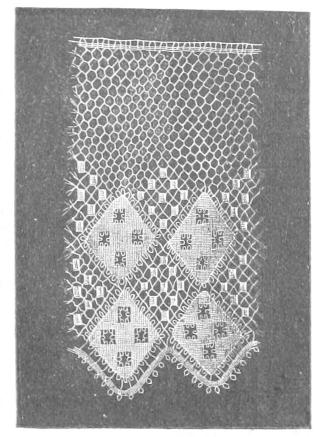

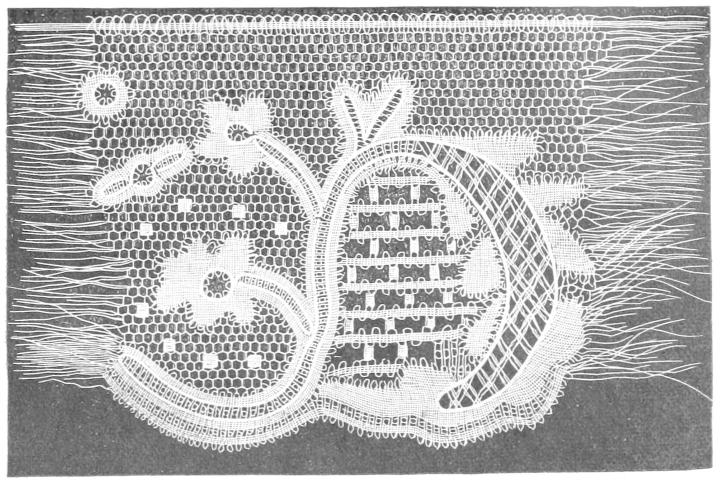

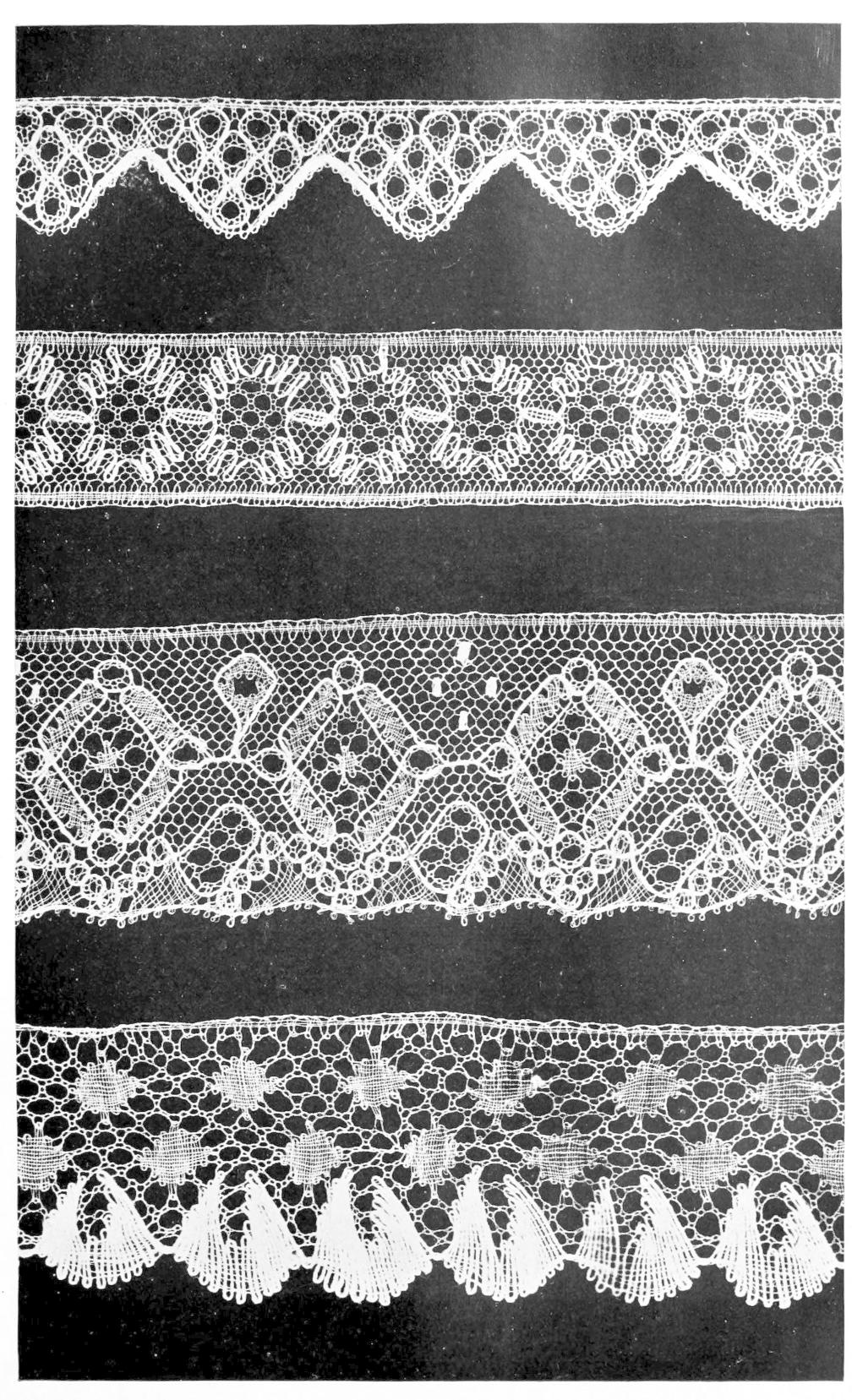

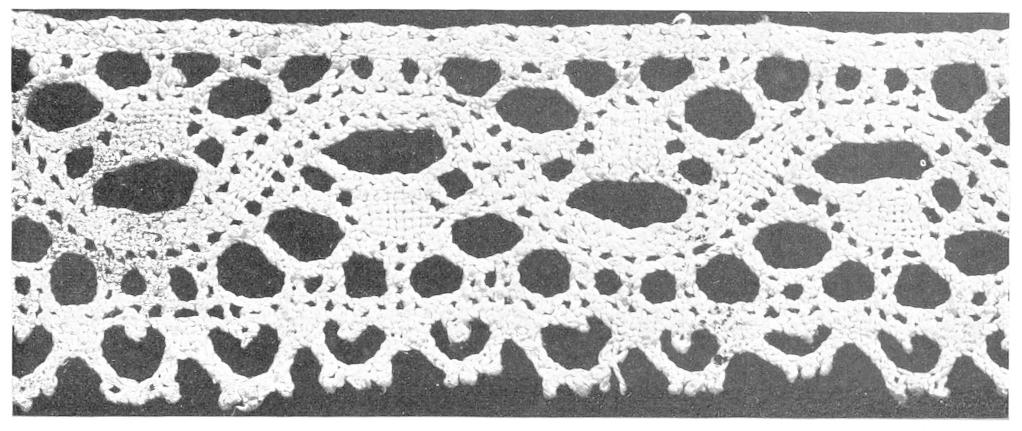

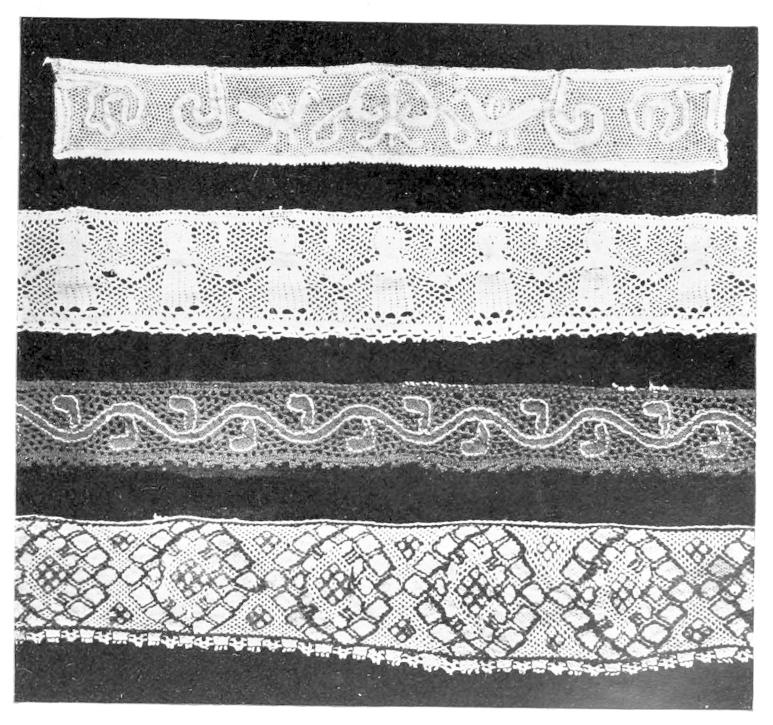

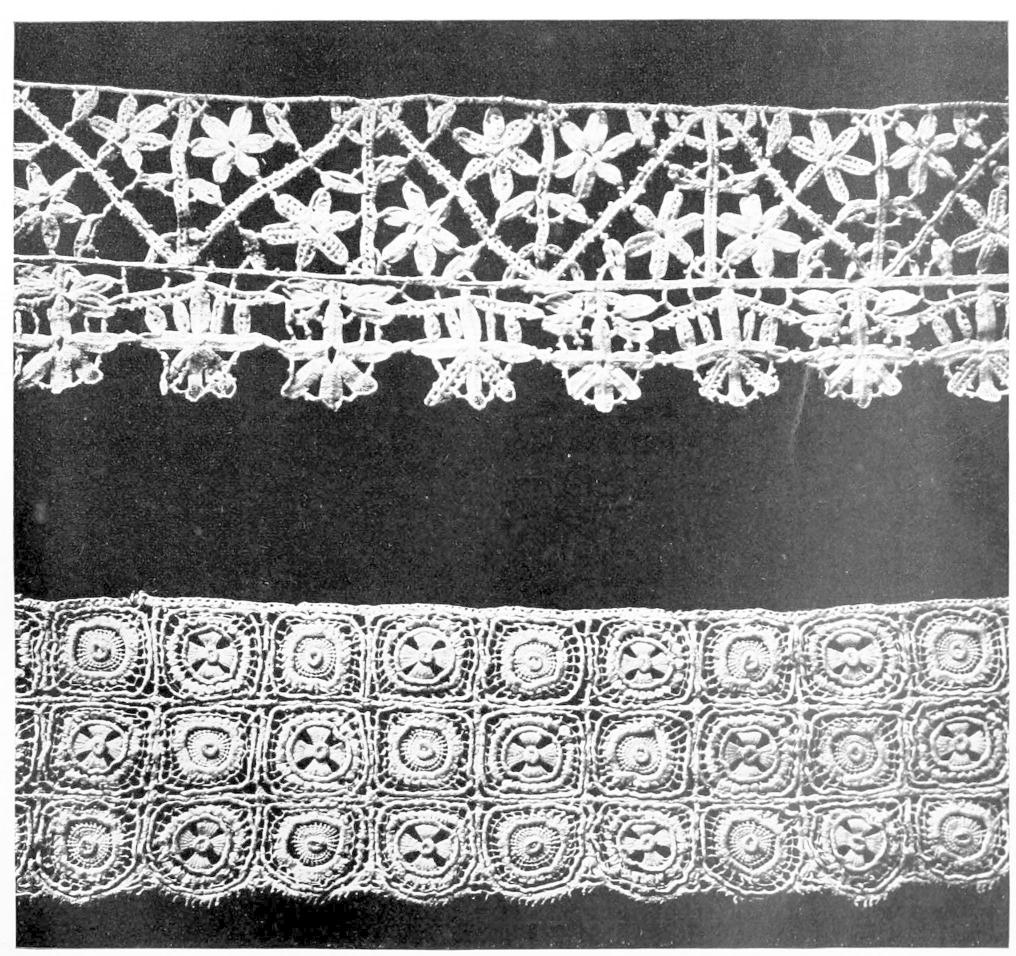

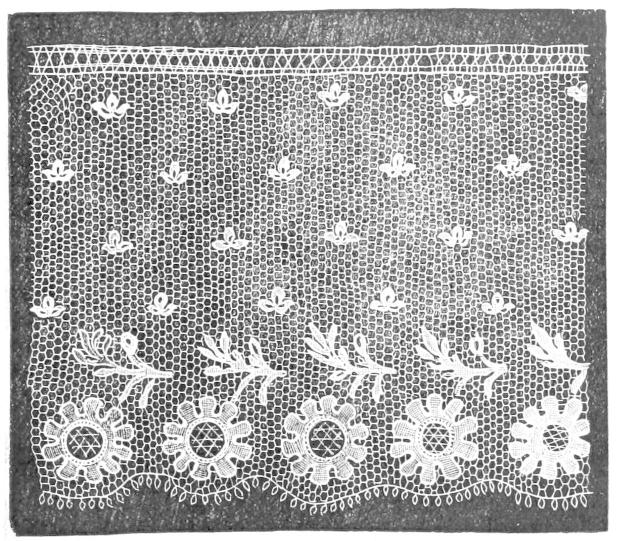

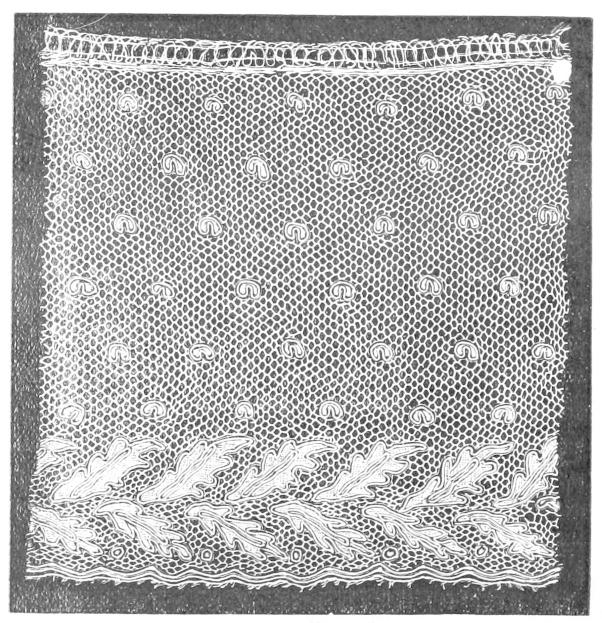

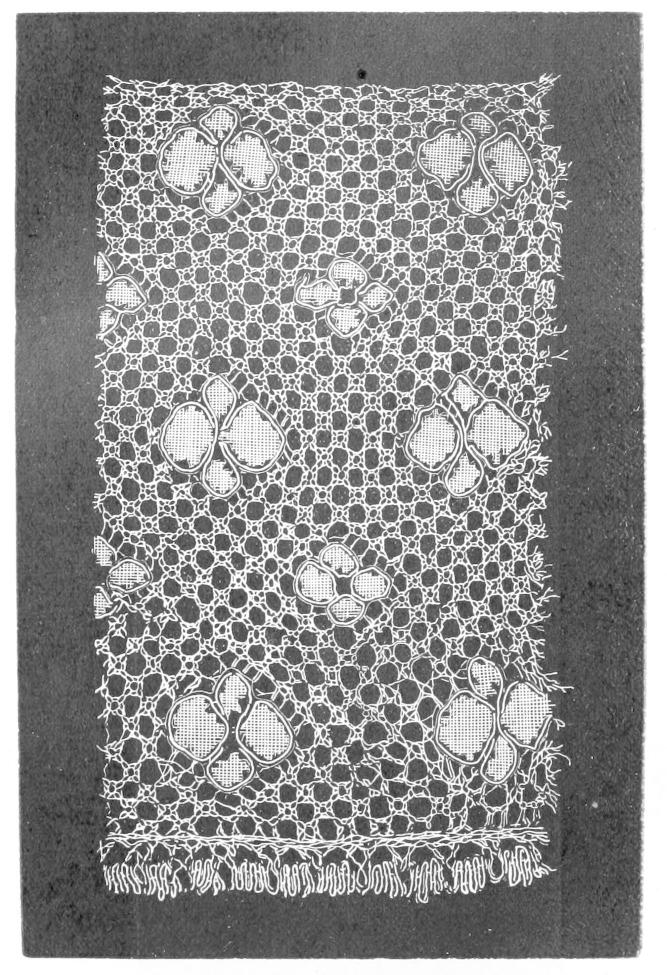

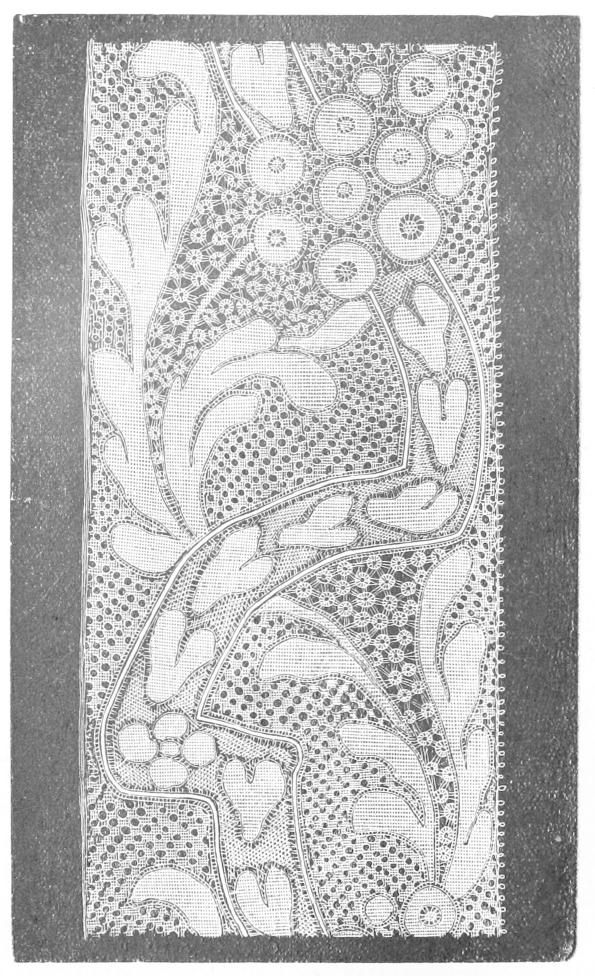

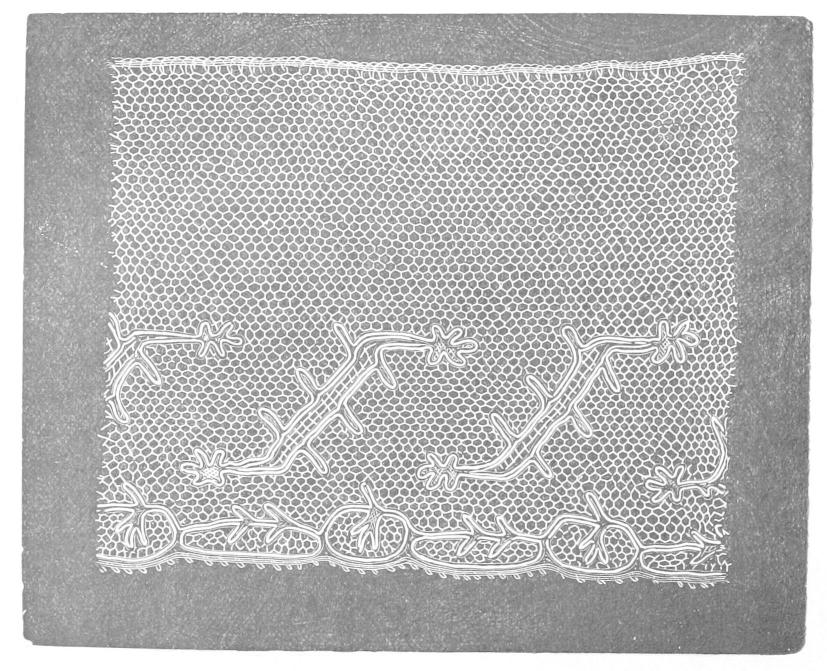

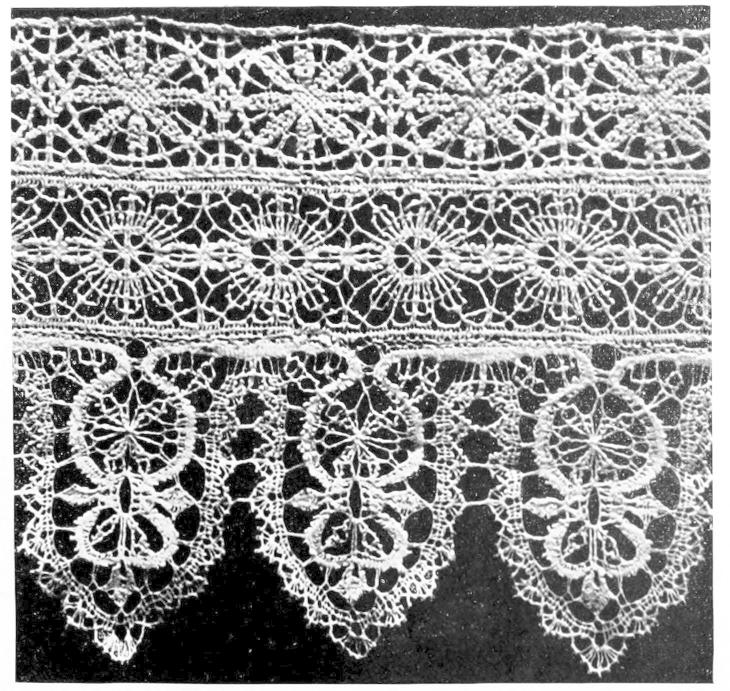

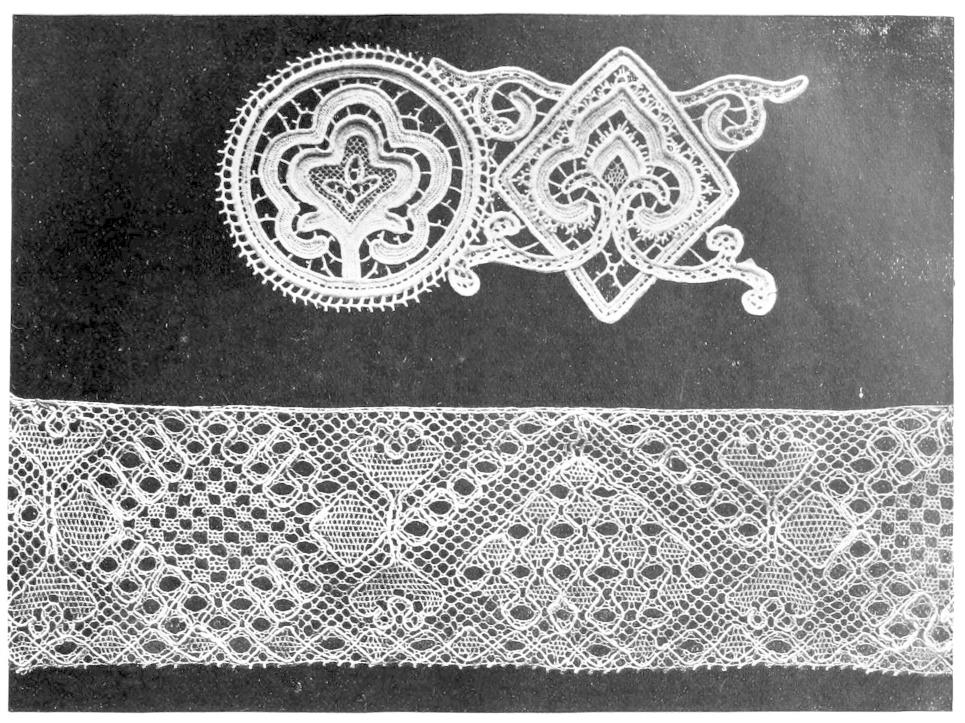

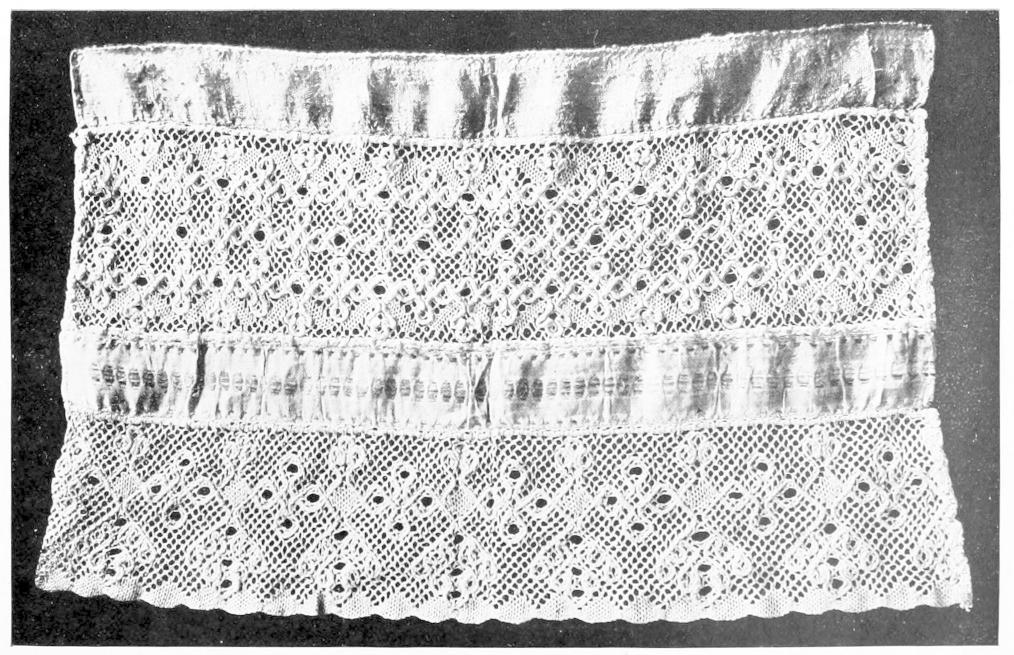

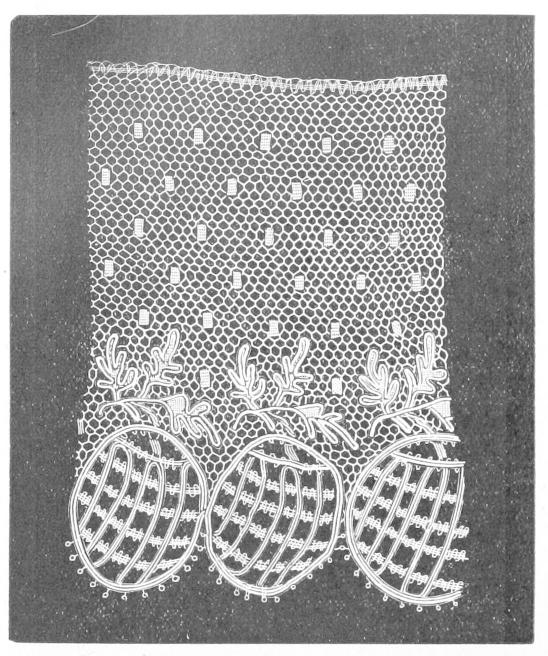

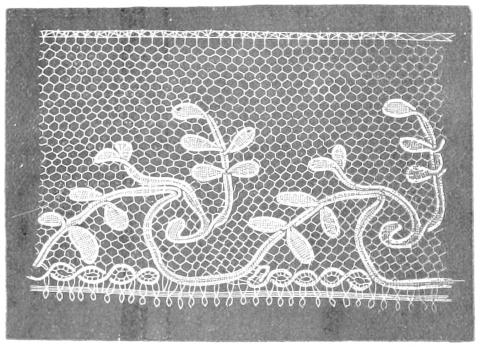

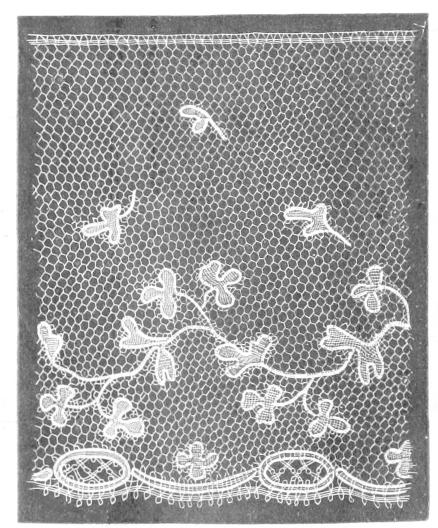

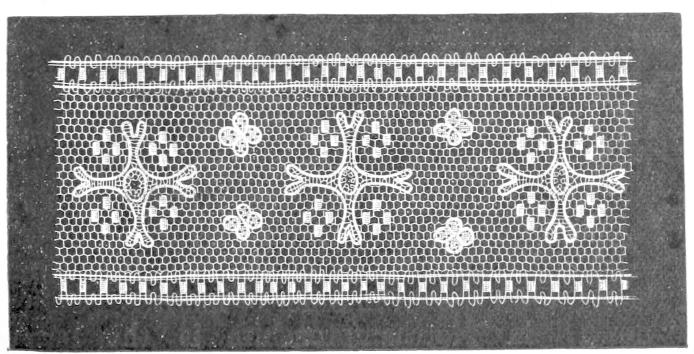

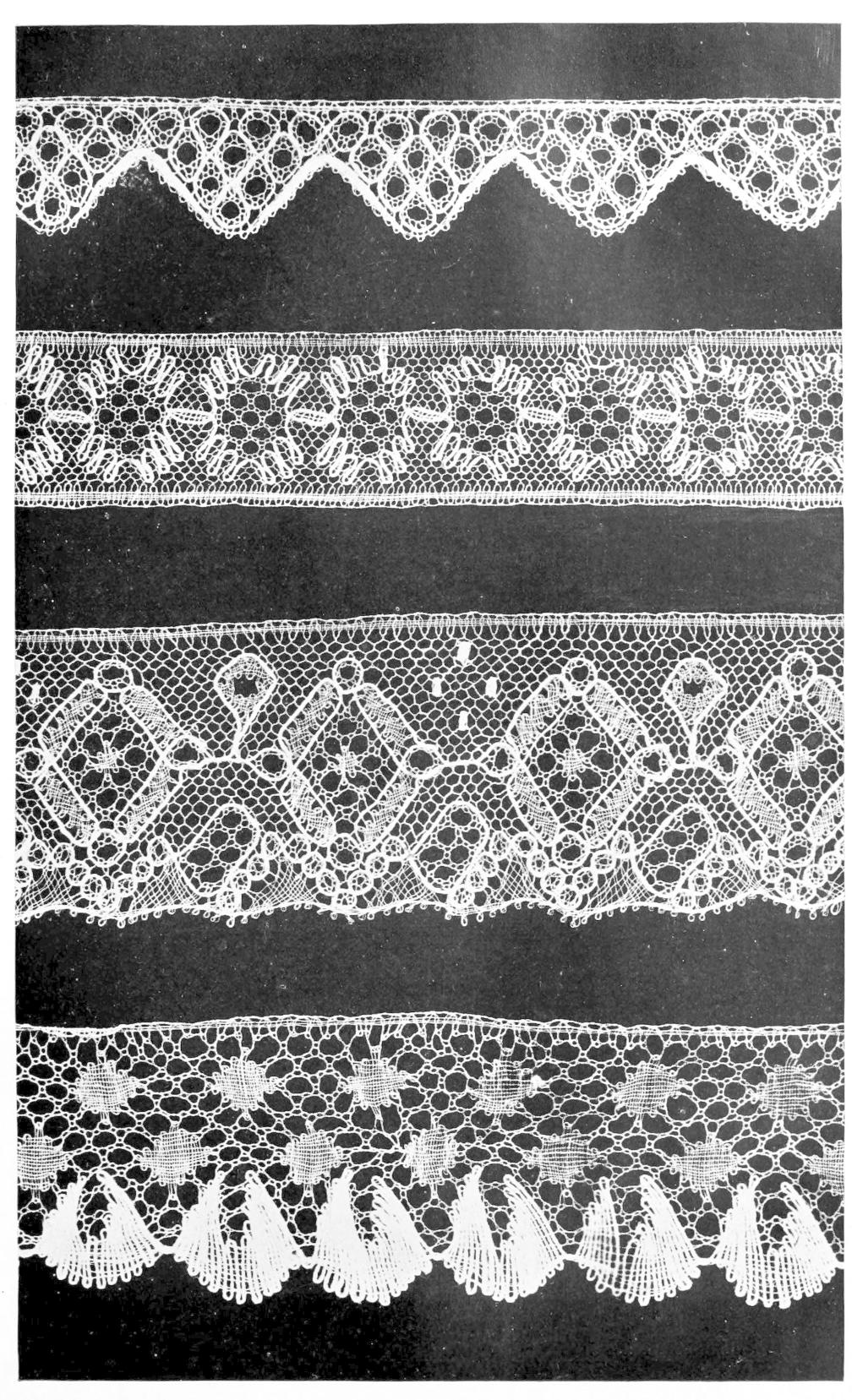

| Italian.—Old Peasant Laces, Bobbin-made |

Plates XXII, XXIII |

80 |

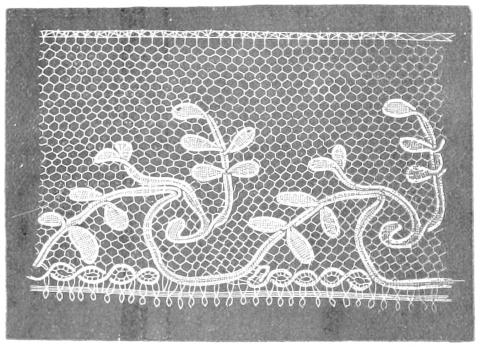

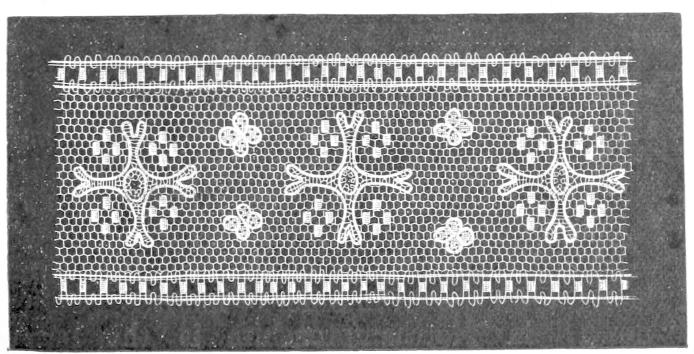

| Italian.—Modern Peasant Lace |

Plate XXIV |

80 |

| Silk Gimp Lace |

Fig. 39 |

84 |

| Sicilian.—Old Drawn-work |

Plate XXV |

84 |

| South Italian |

" XXVI |

84 |

| Reticella, or Greek Lace |

Fig. 40 |

85 |

| Loubeaux de Verdale |

" 41 |

88 |

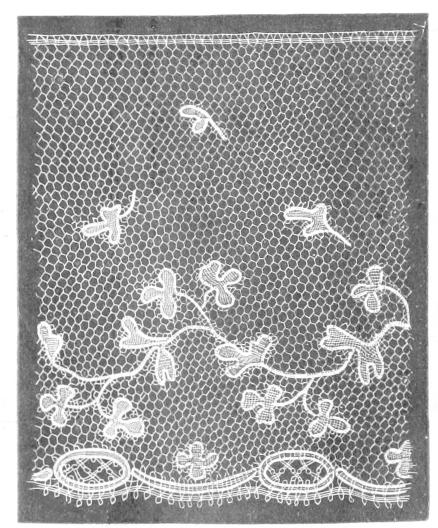

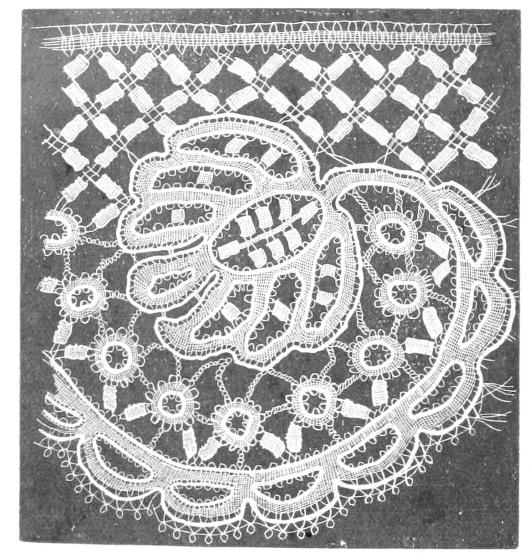

| Italian, Rapallo—Modern Peasant Lace |

Plate XXVII |

88 |

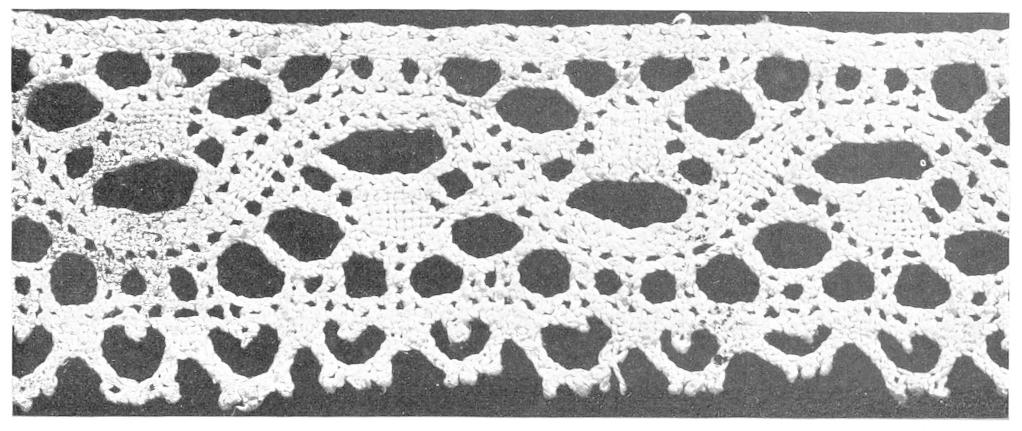

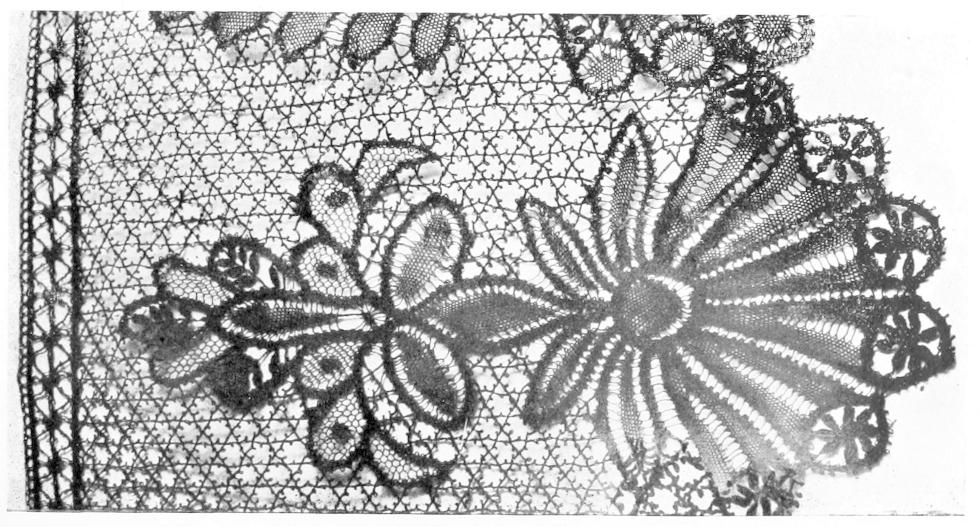

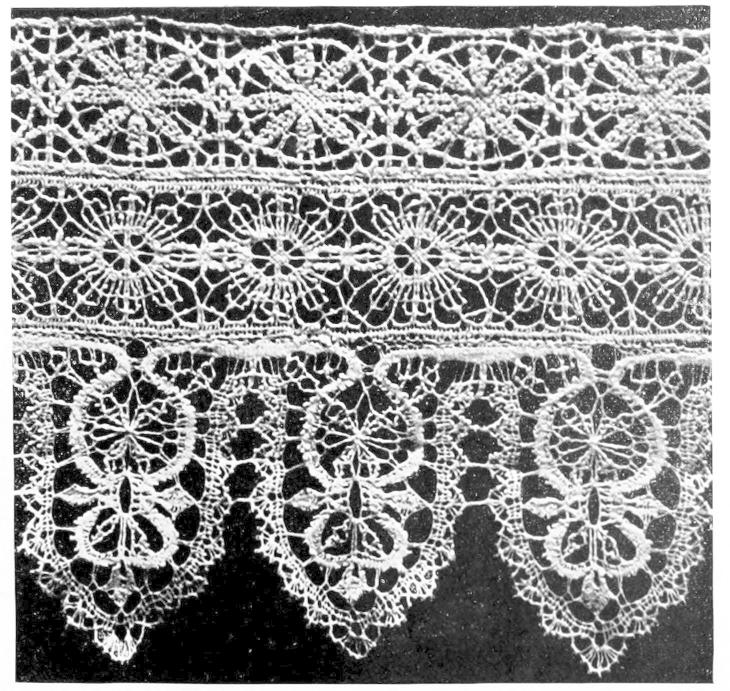

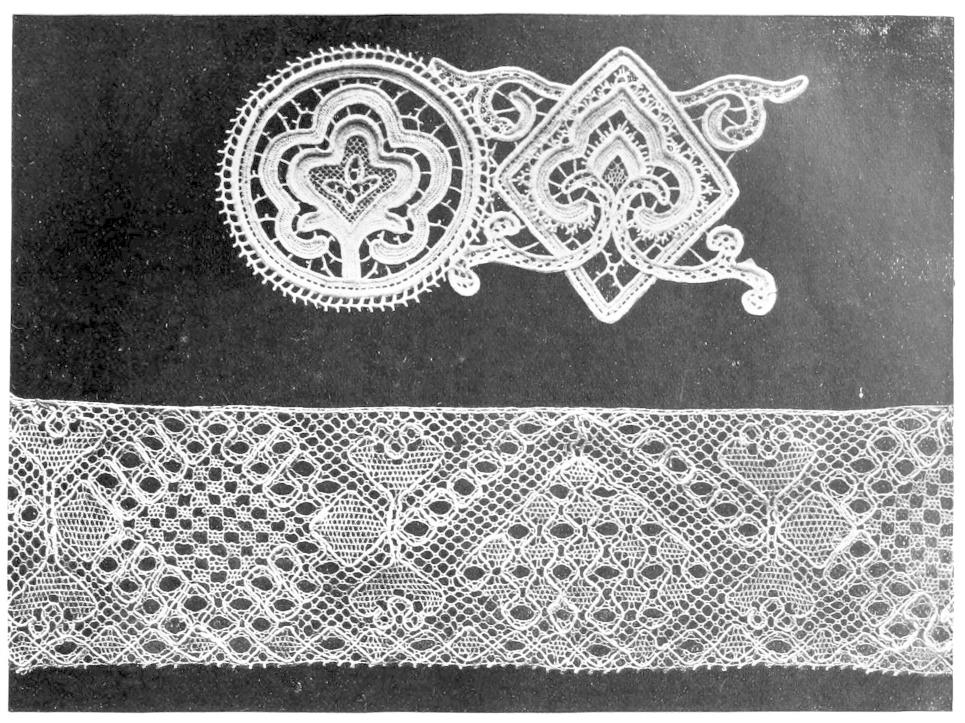

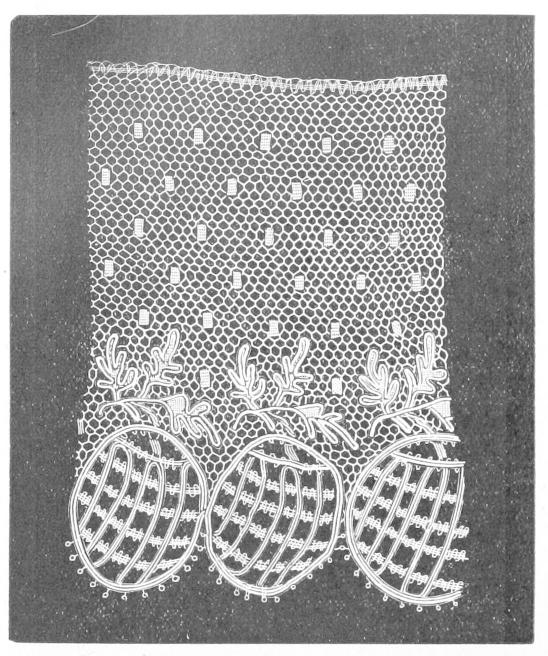

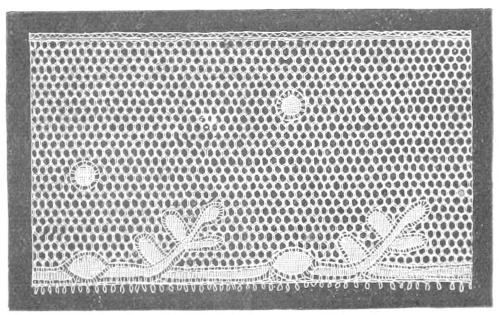

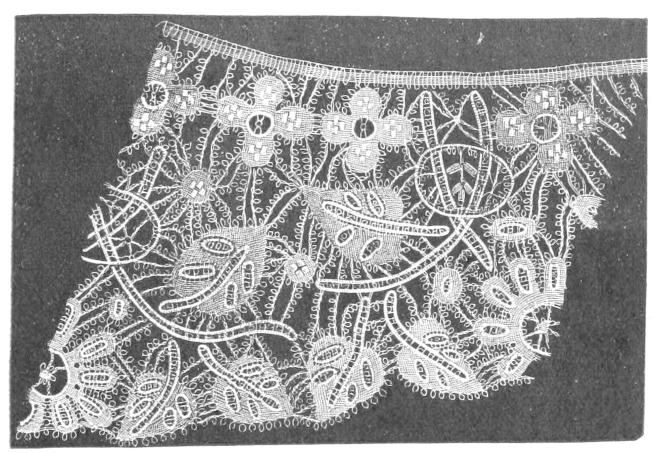

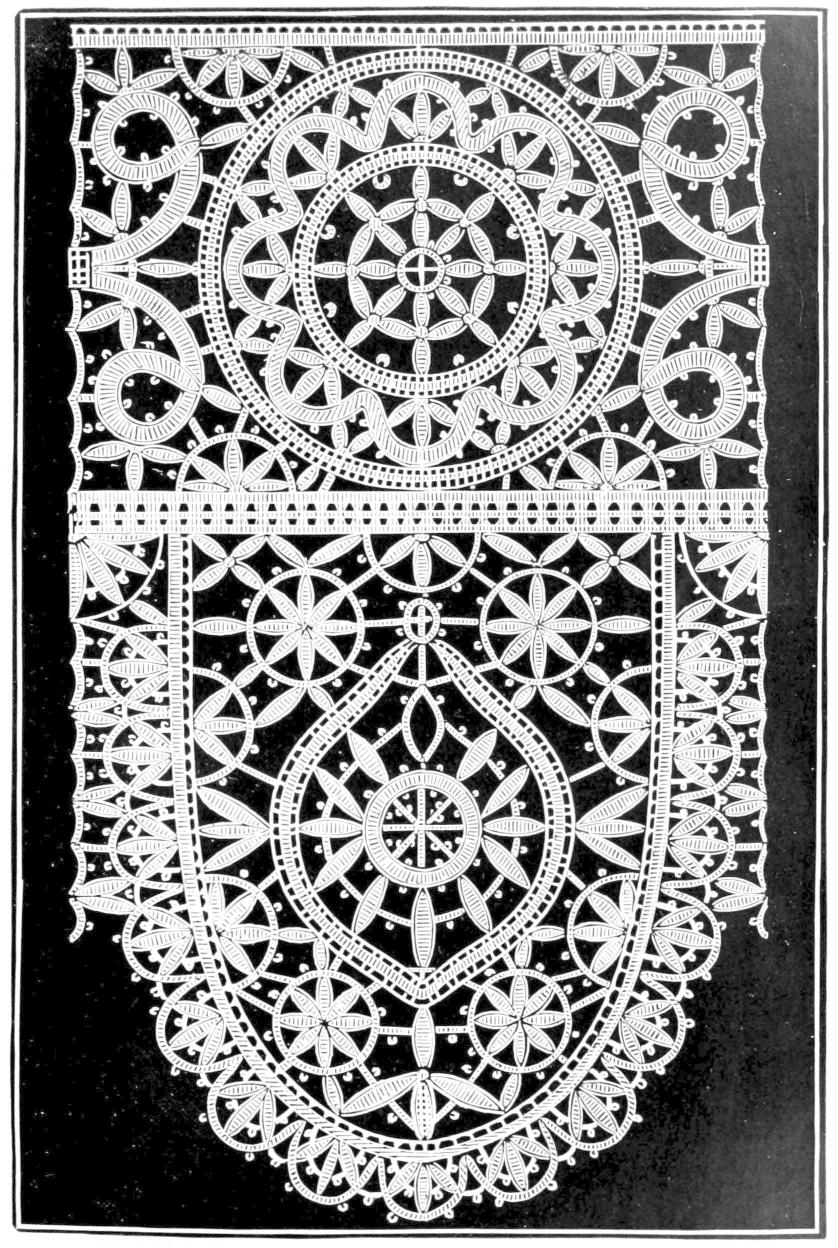

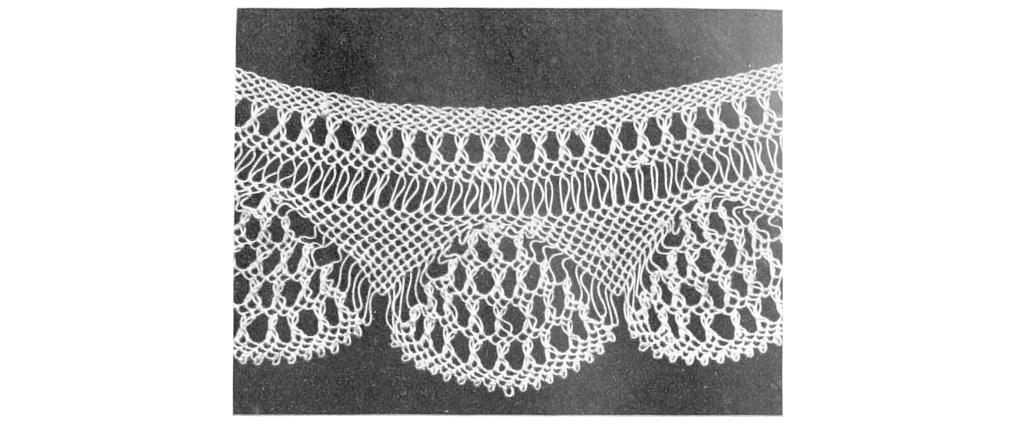

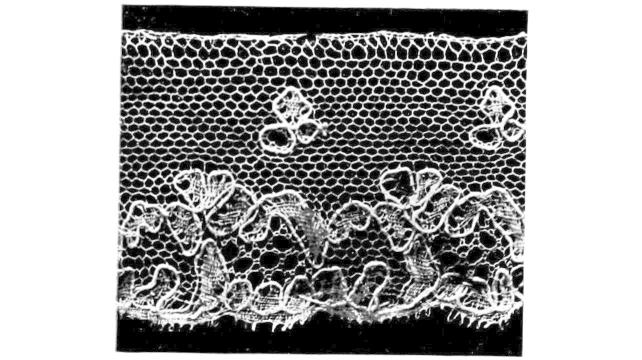

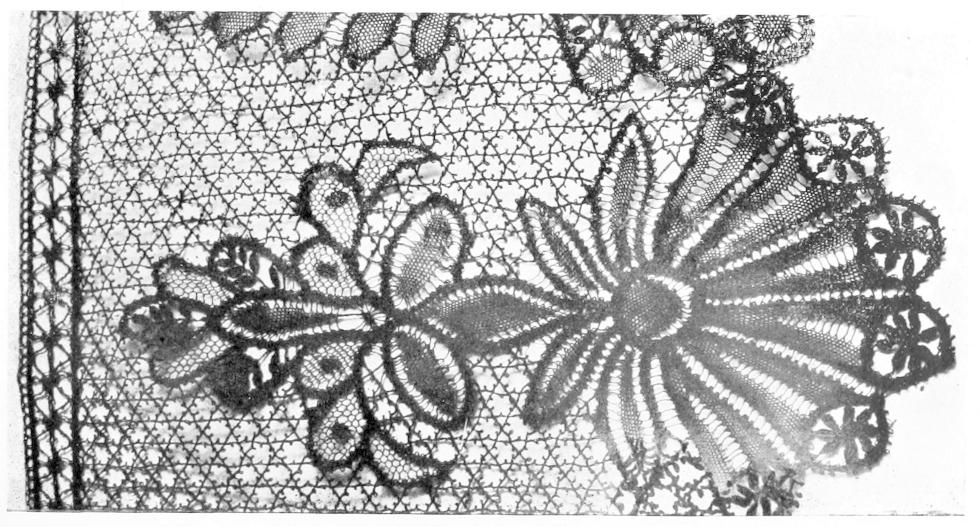

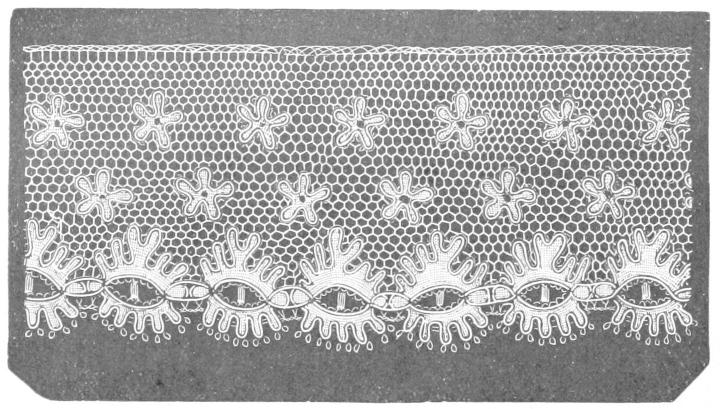

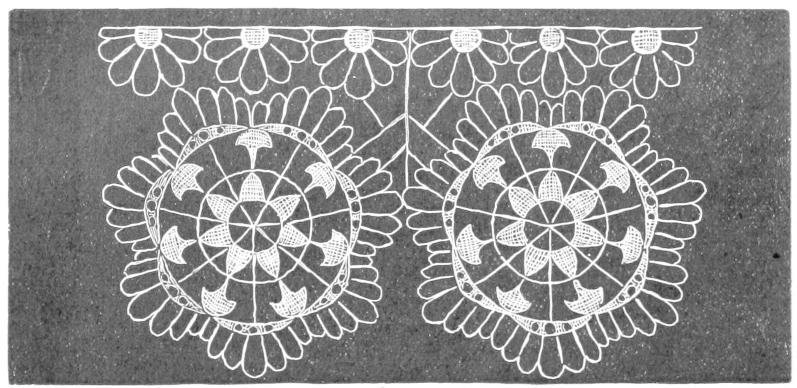

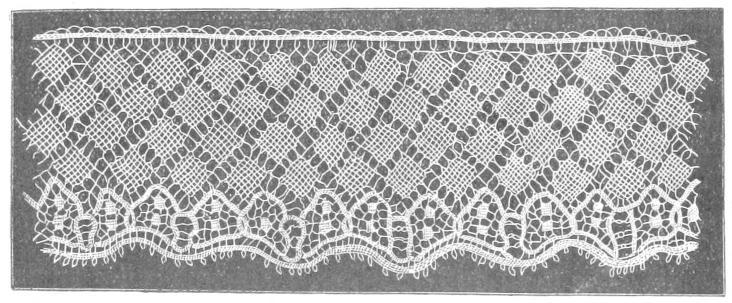

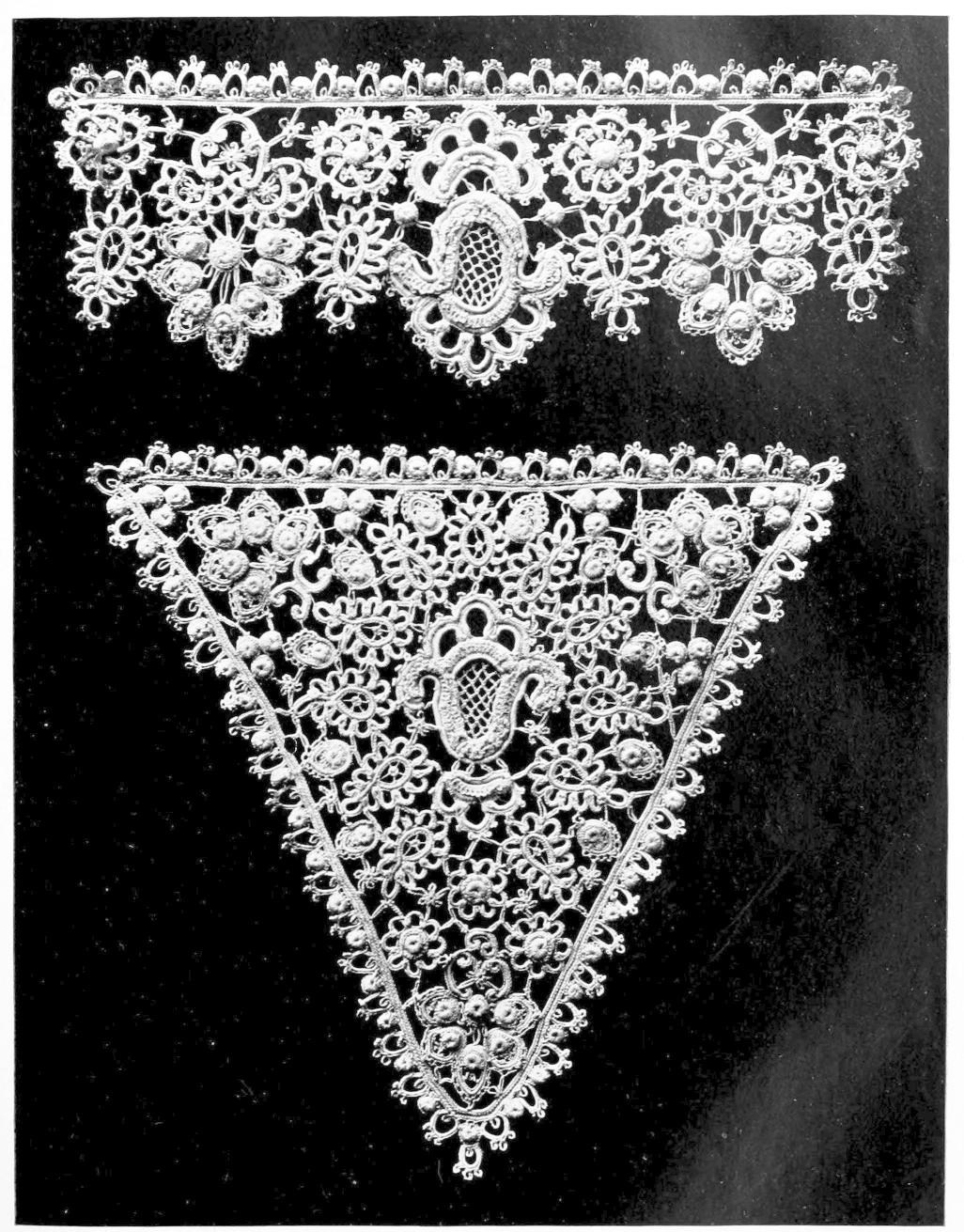

| Maltese.—Modern Bobbin-made |

" XXVIII |

88 |

| Bobbin Lace (Ceylon) |

Fig. 42 |

89 |

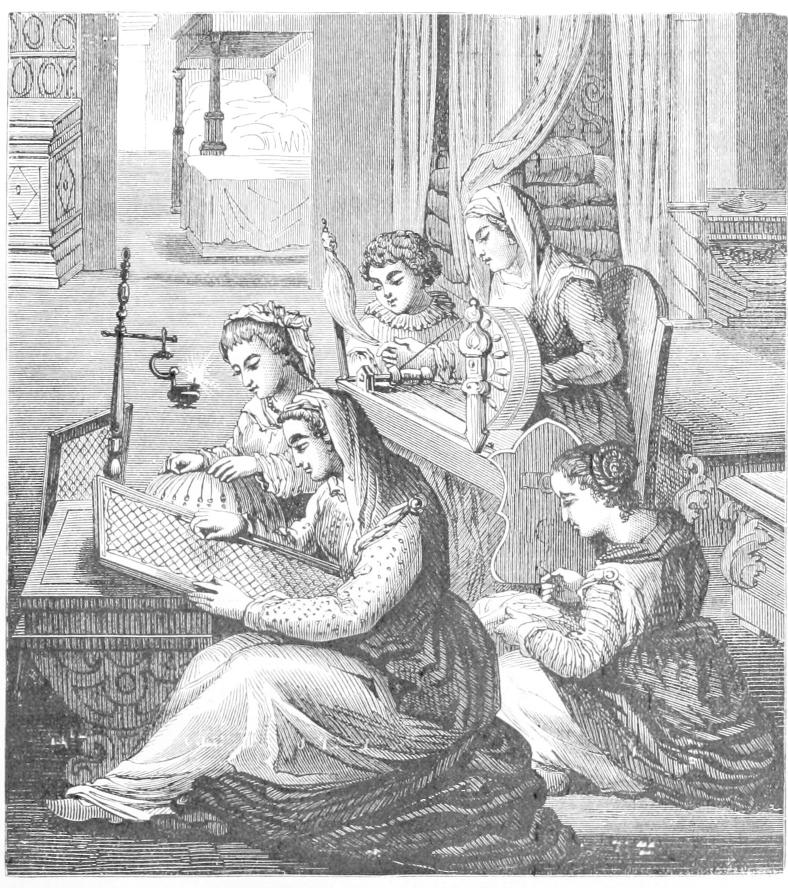

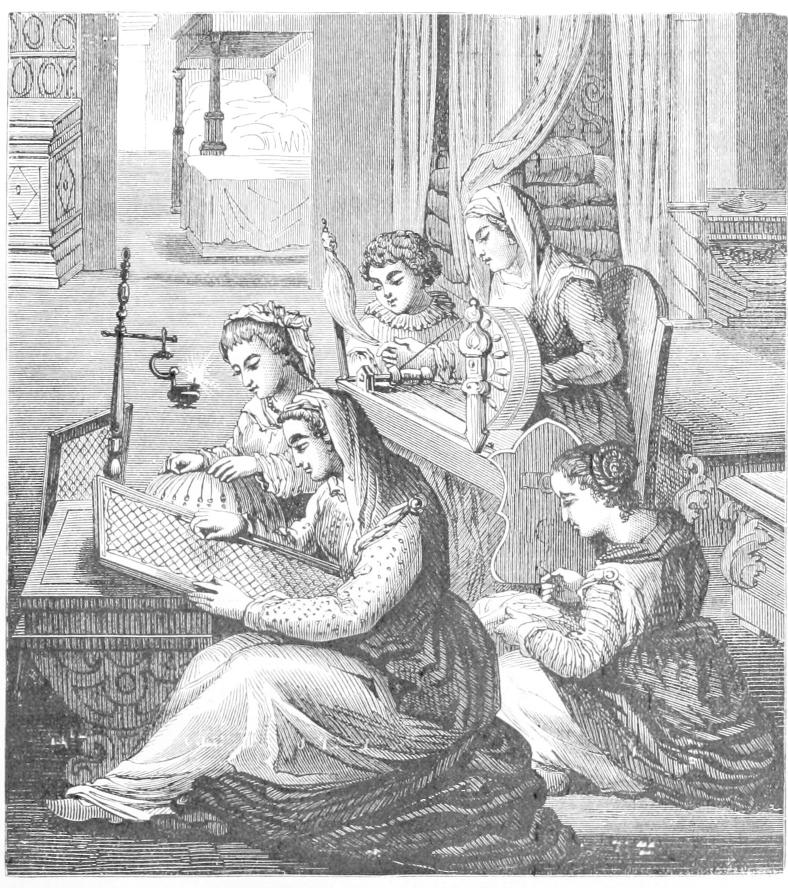

| The Work Room (16th century engraving) |

" 43 |

91 |

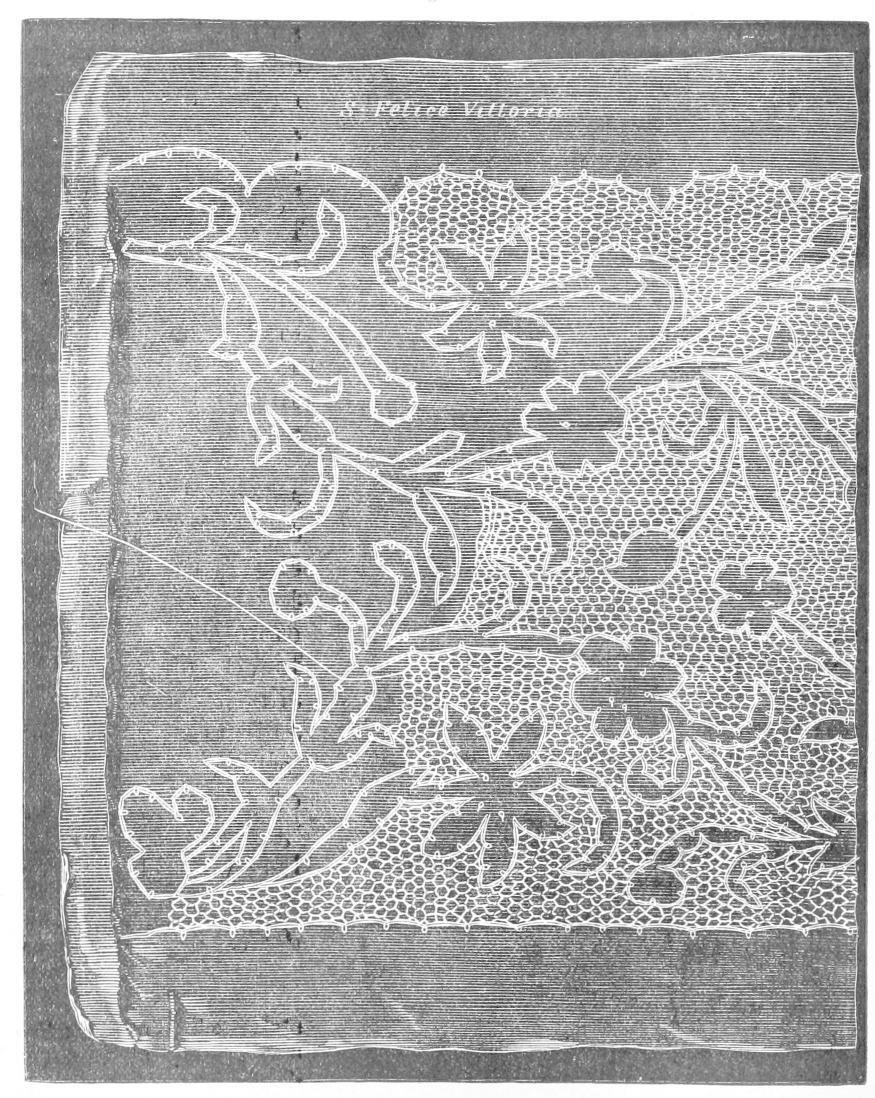

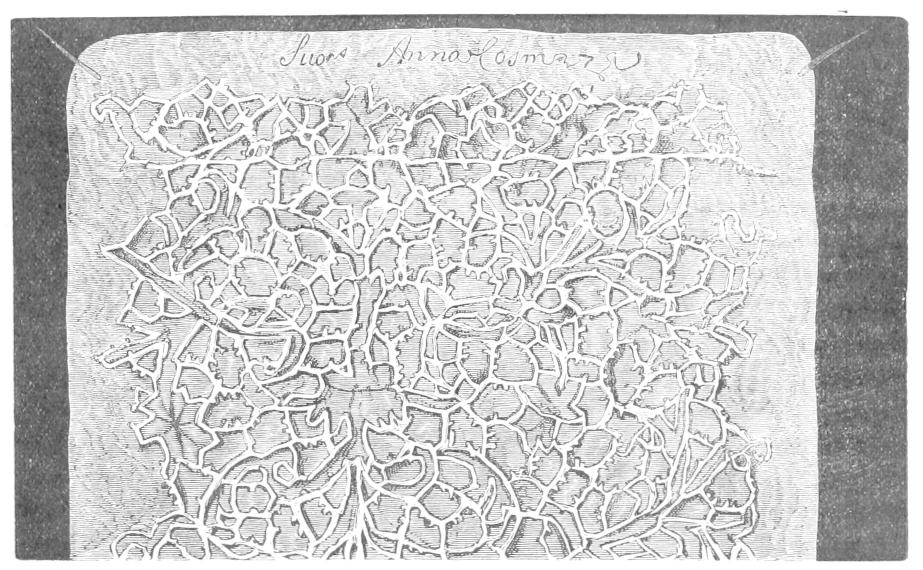

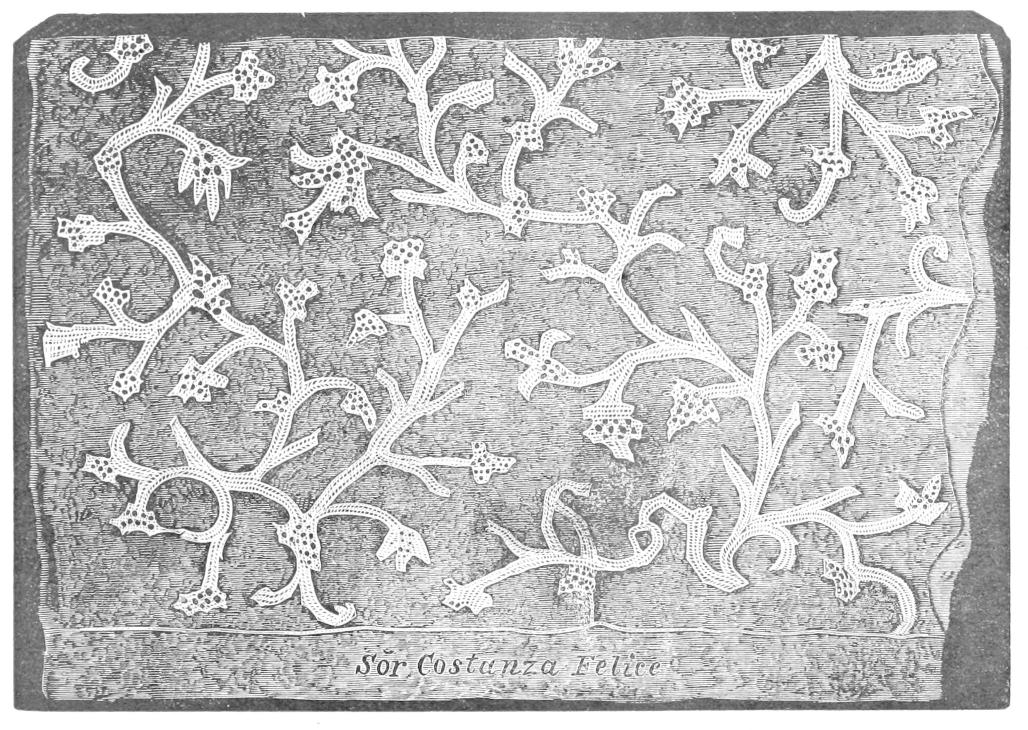

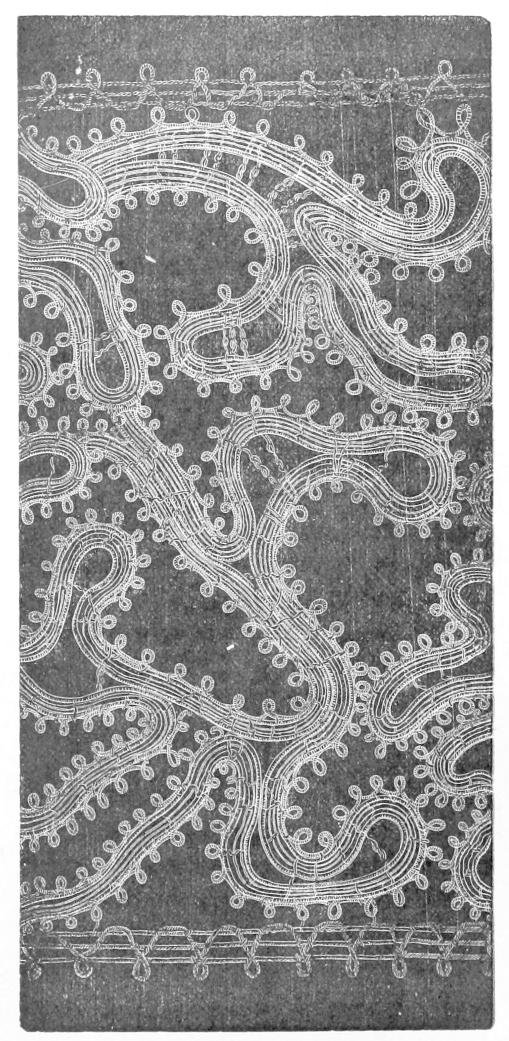

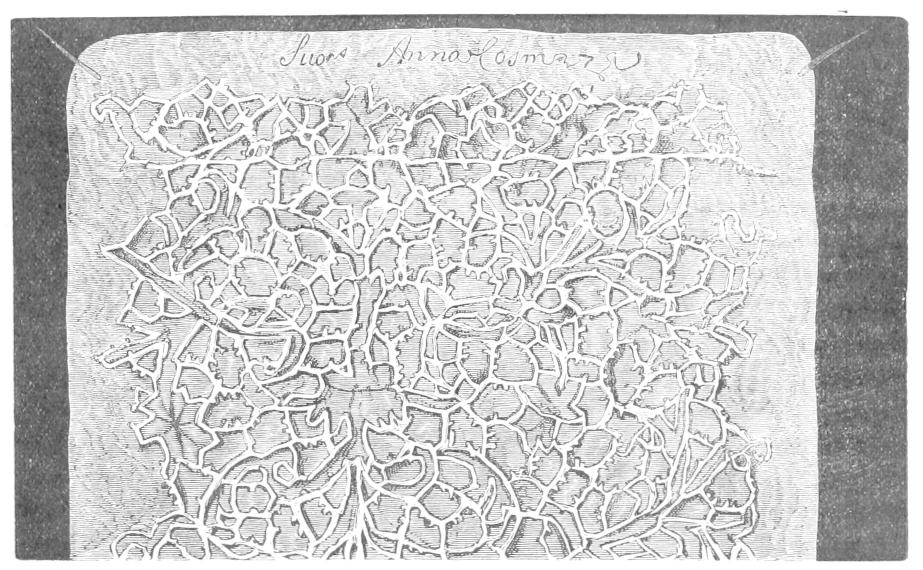

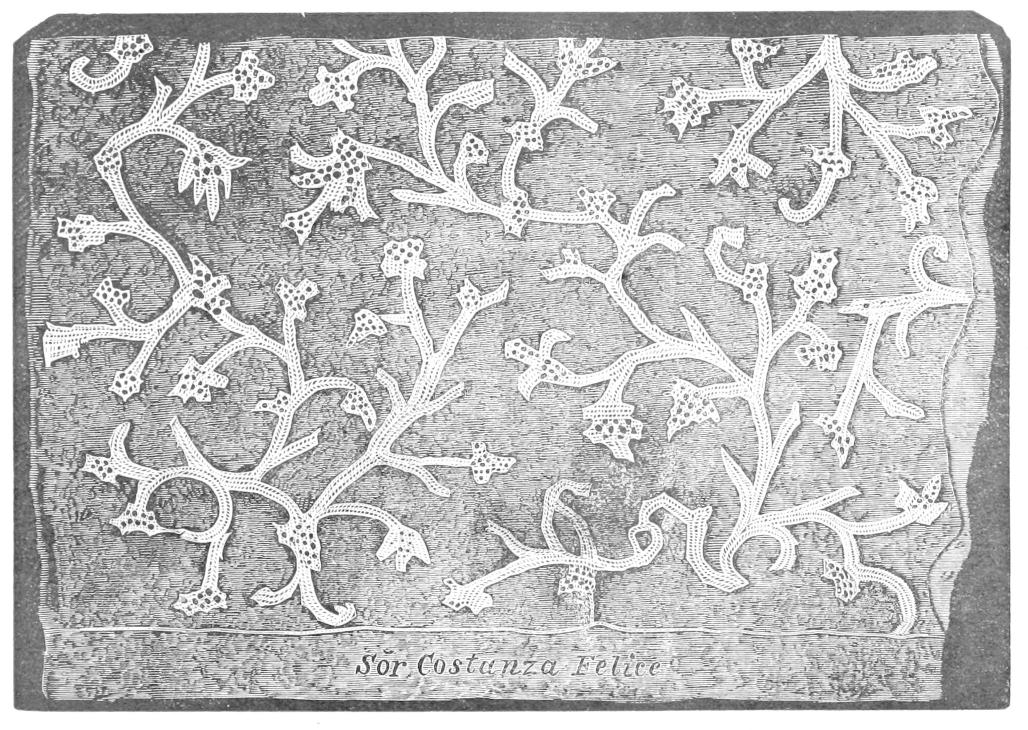

| Unfinished Work of a Spanish Nun |

" 44 |

94 |

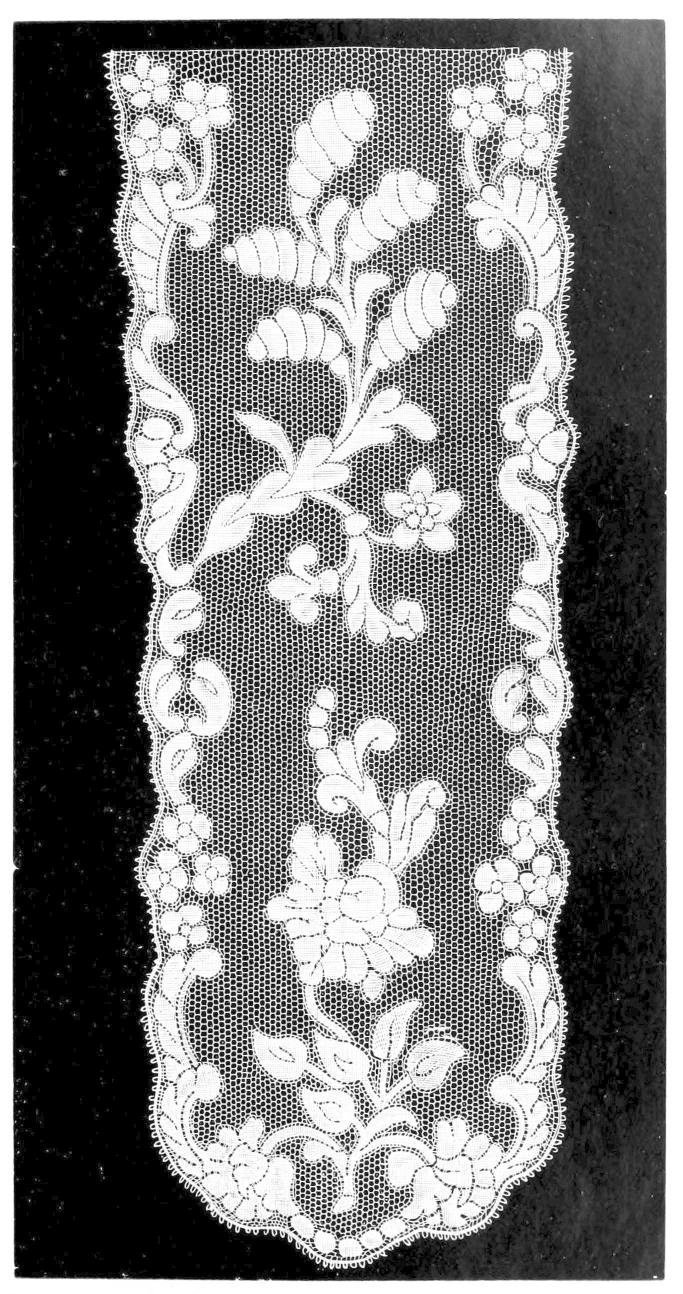

| Spanish.—Modern Thread Bobbin Lace |

Plate XXIX |

94 |

| Spanish, Blonde.—White Silk Darning on Machine

Net |

" XXX |

94 |

| Unfinished Work of a Spanish Nun |

Fig. 45 |

95 |

| Unfini"hed Work"of a Span" |

" 46 |

96 |

| Old Spanish Pillow Lace |

" 47 |

100 |

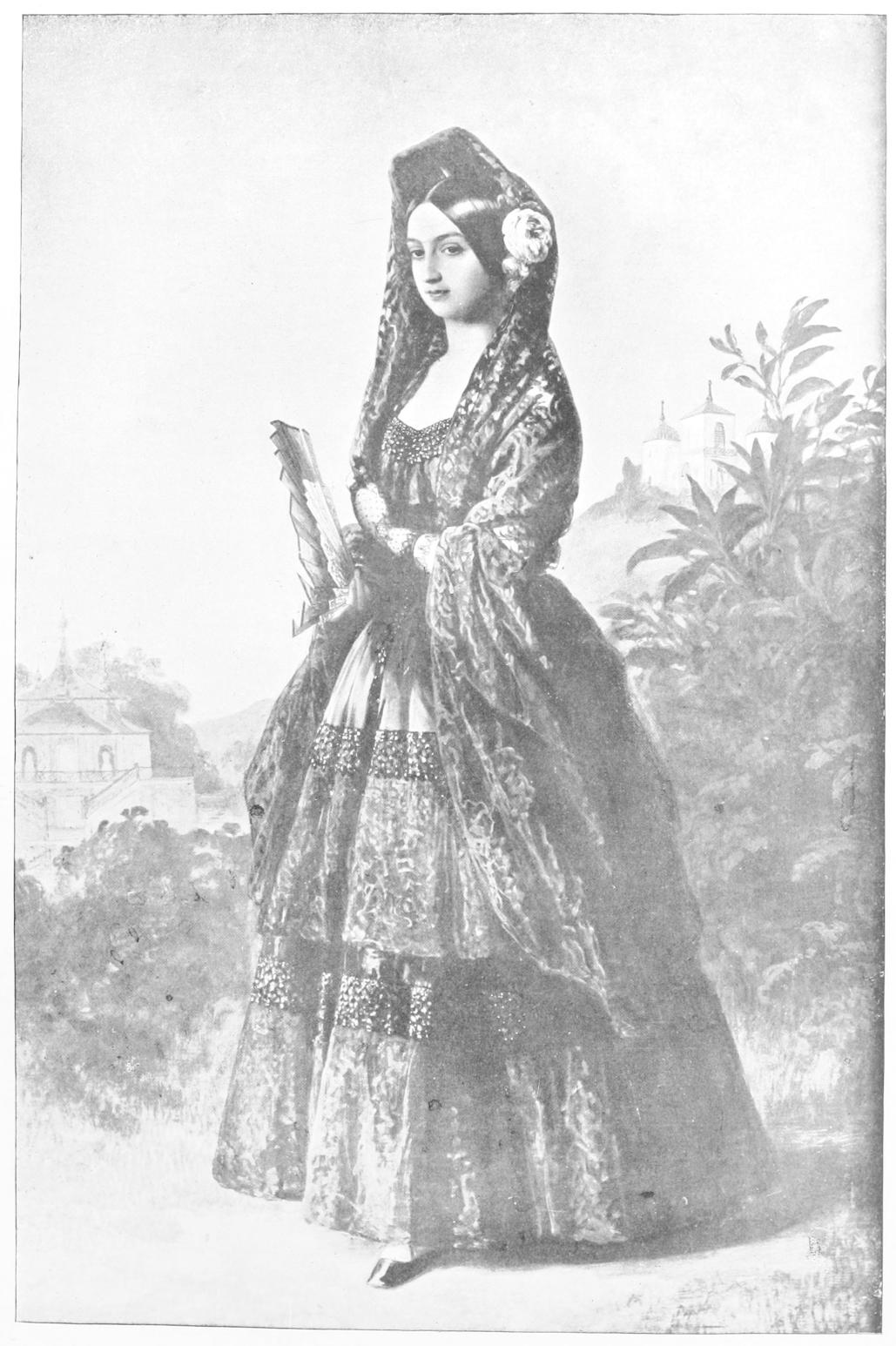

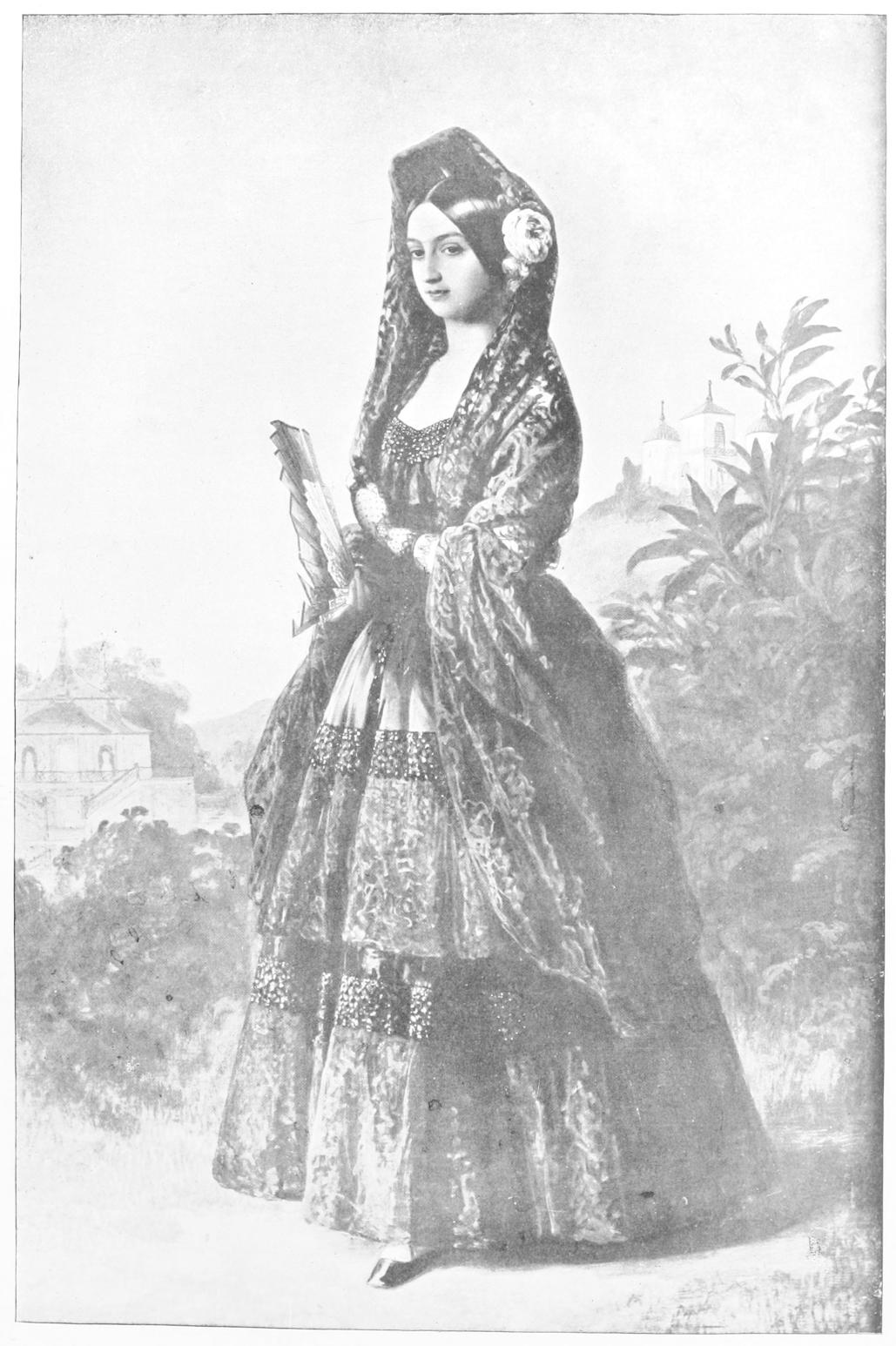

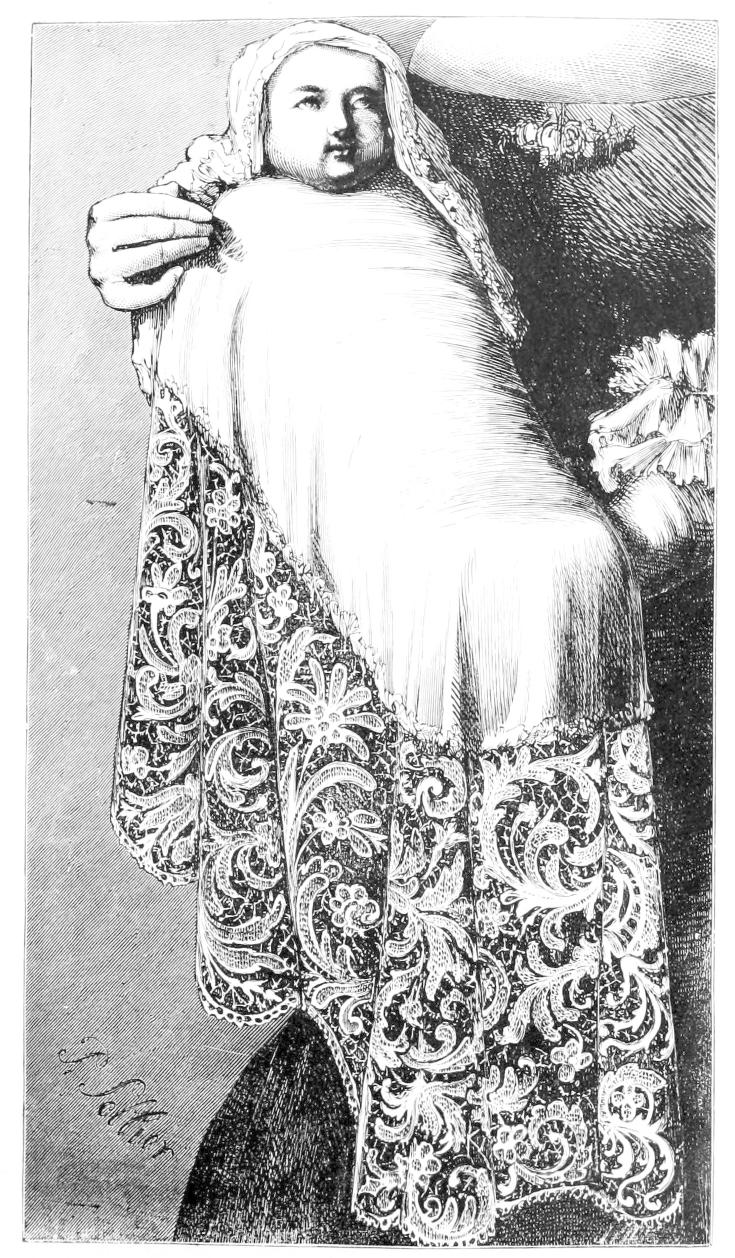

| Portrait, Duchesse de Montpensier |

Plate XXXI |

100 |

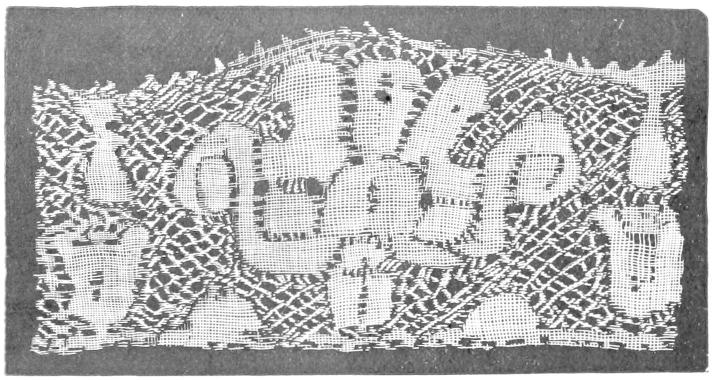

| Jewish |

" IXXXII |

104 |

| Spanish |

" XXXIII |

104 |

| Bobbin Lace (Madeira) |

Fig. 48 |

106 |

| Bobbin"Lace (Brazil) |

" 49 |

107 |

| Spanish.—Pillow-made 19th Century |

Plate XXXIV |

108 |

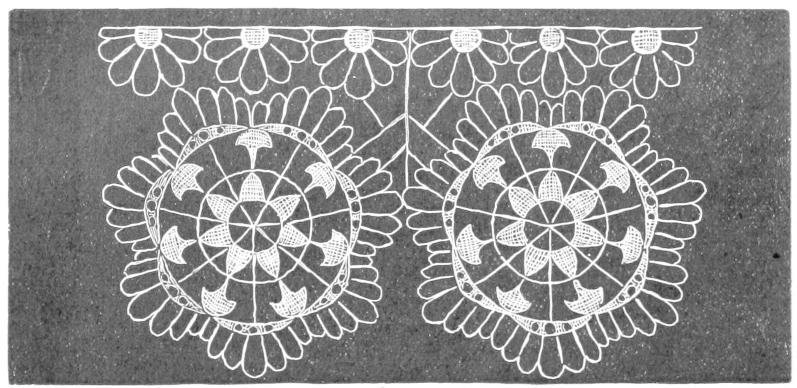

| Paraguay.—"Nauduti" |

" XXXV |

108 |

| Lace-making |

Fig. 50 |

110 |

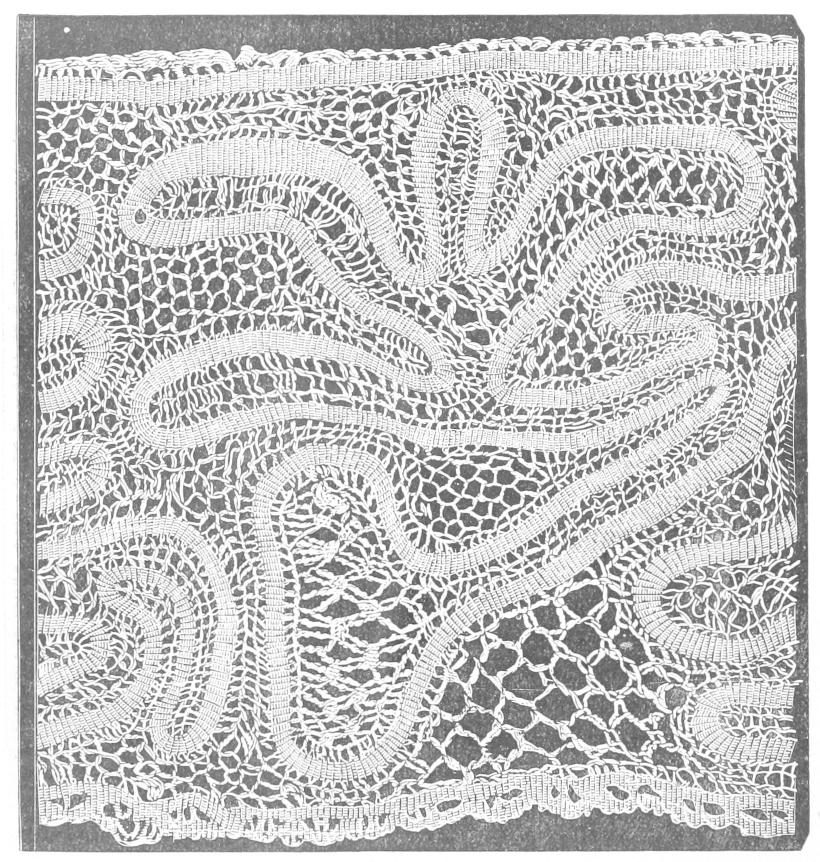

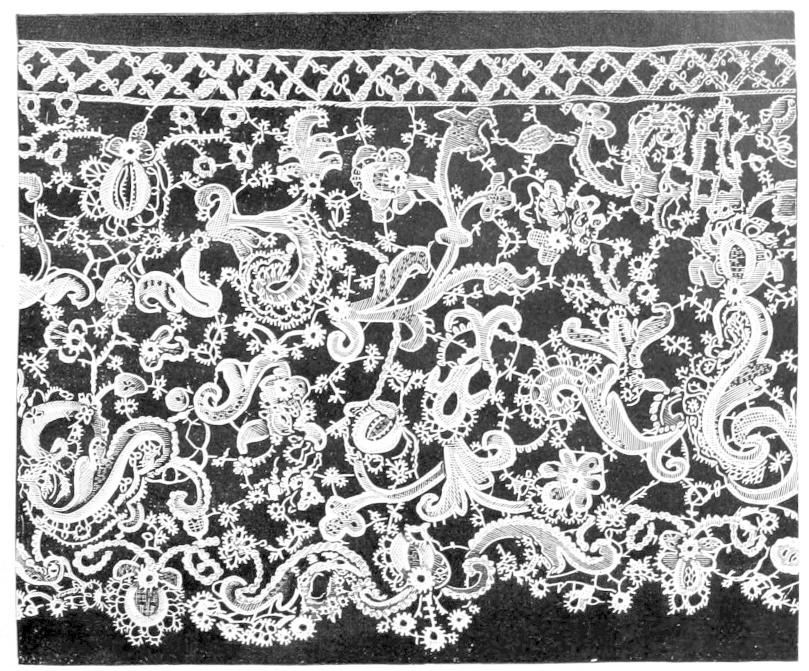

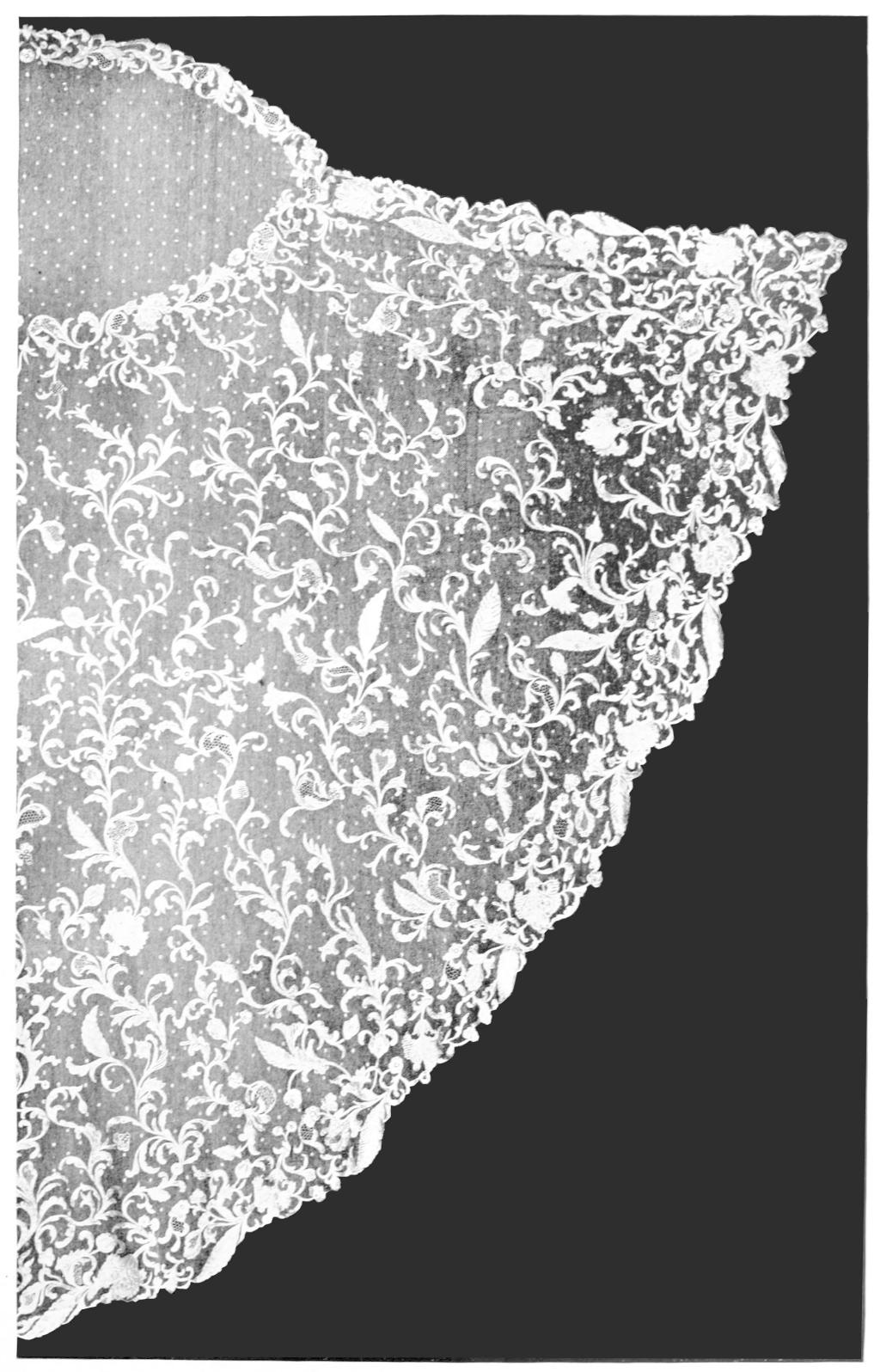

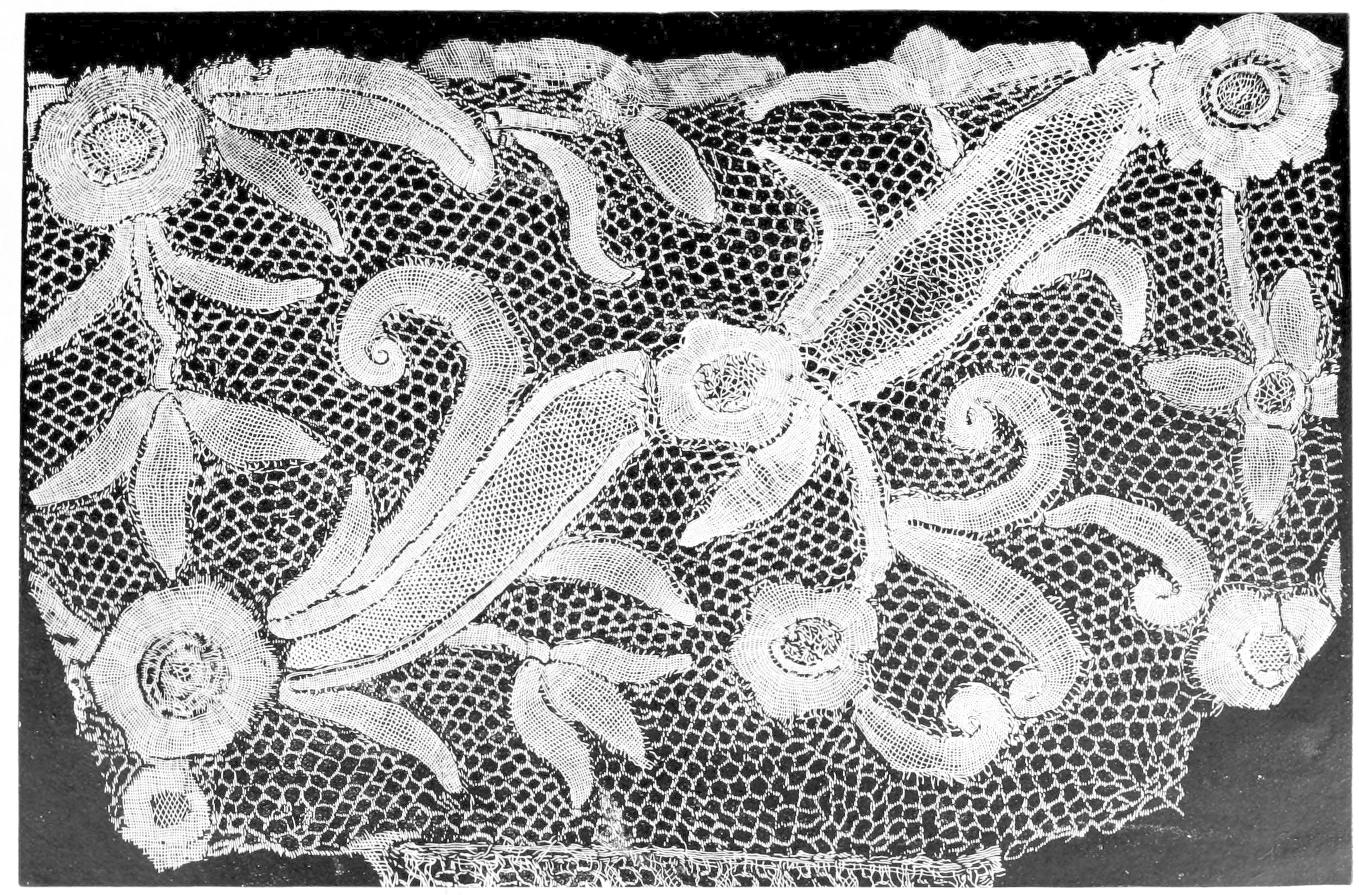

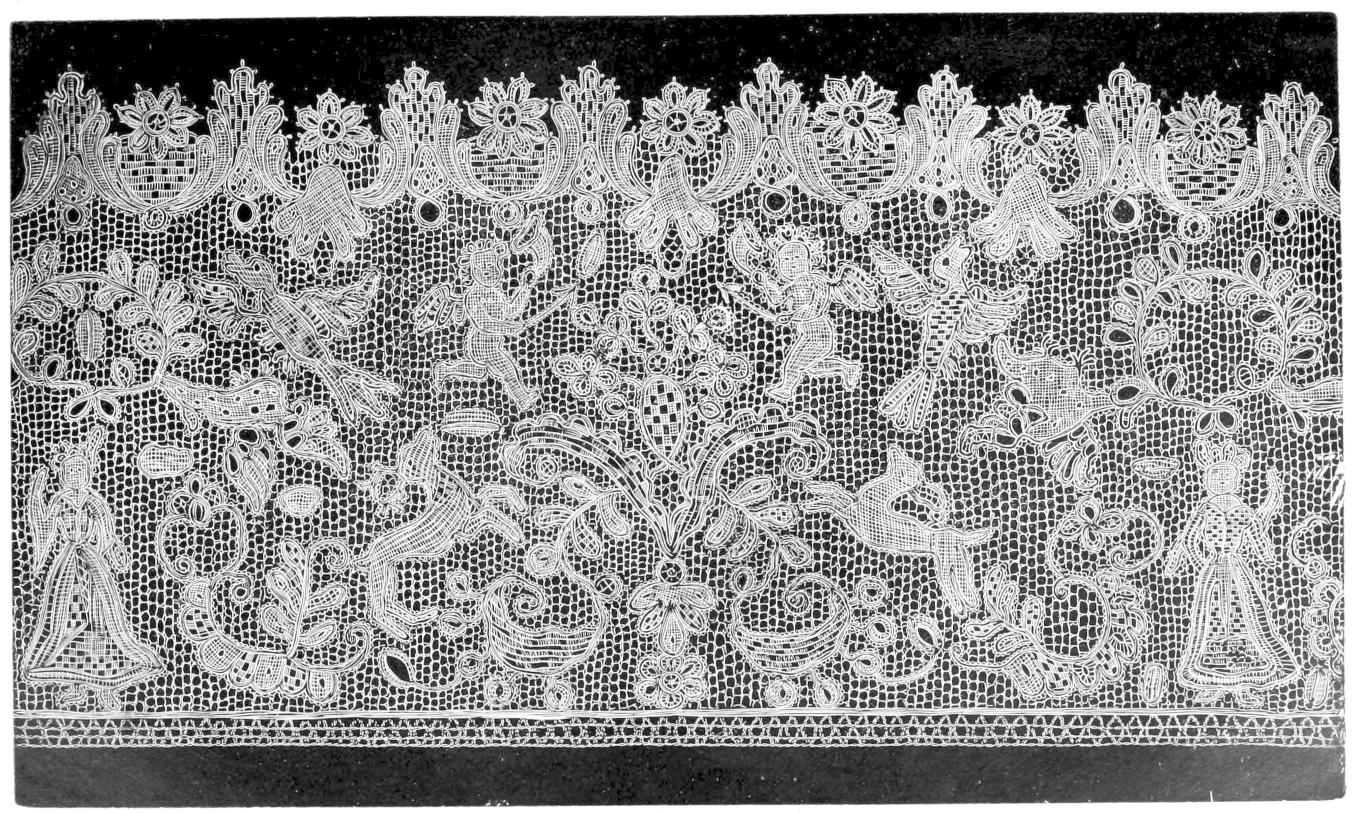

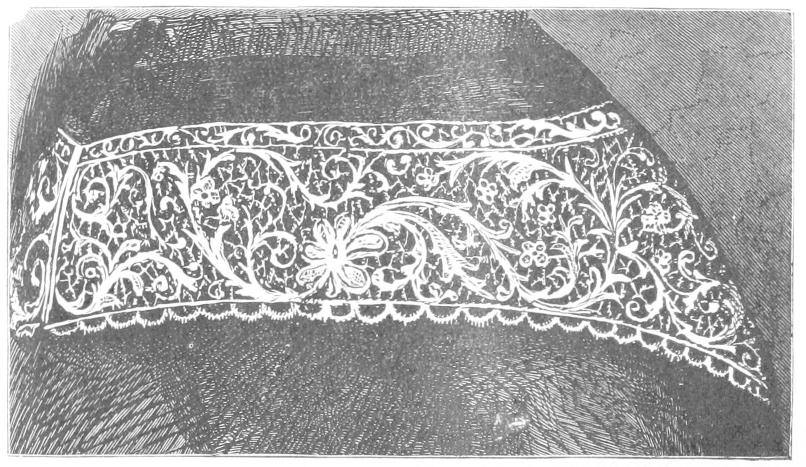

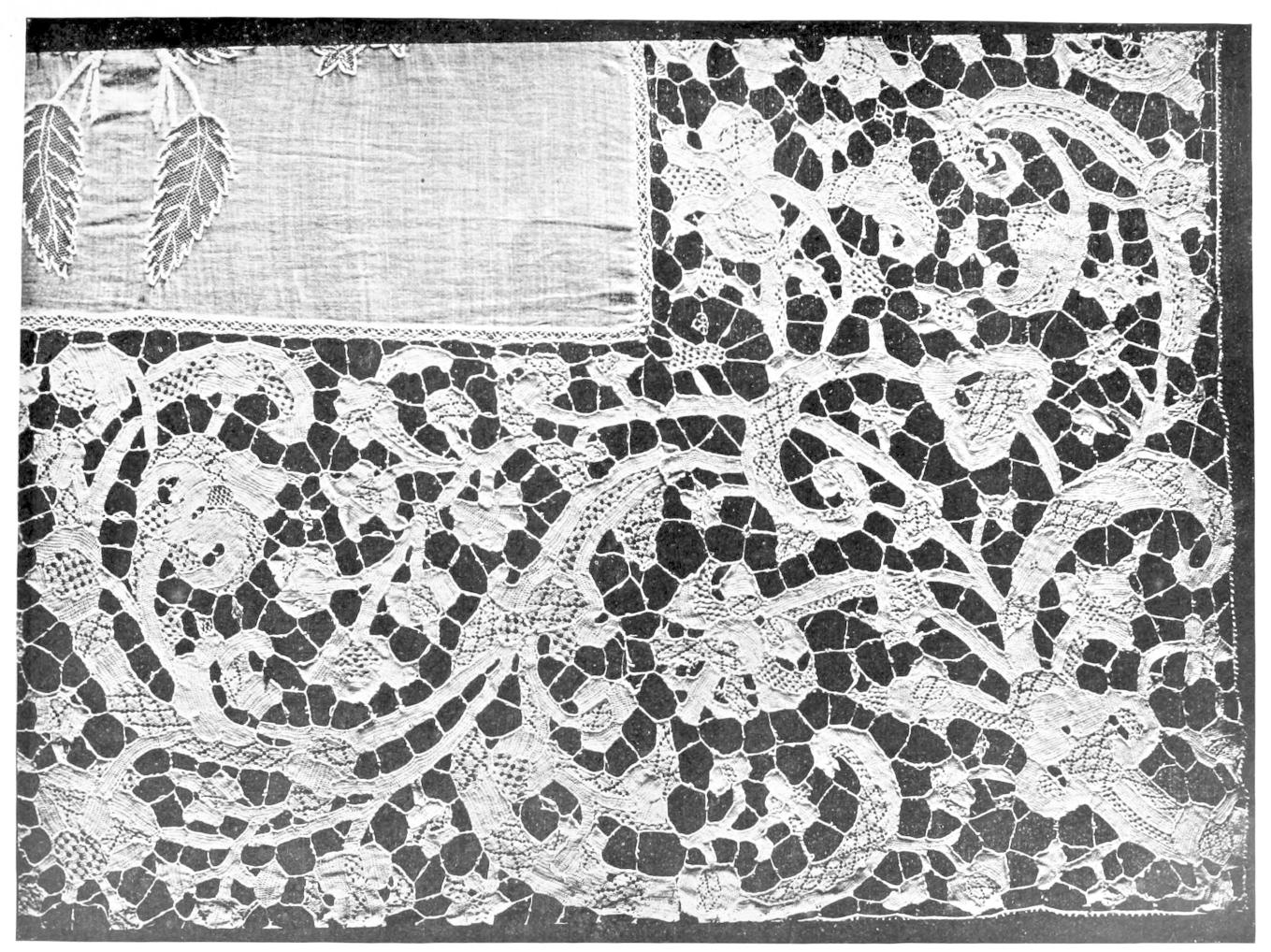

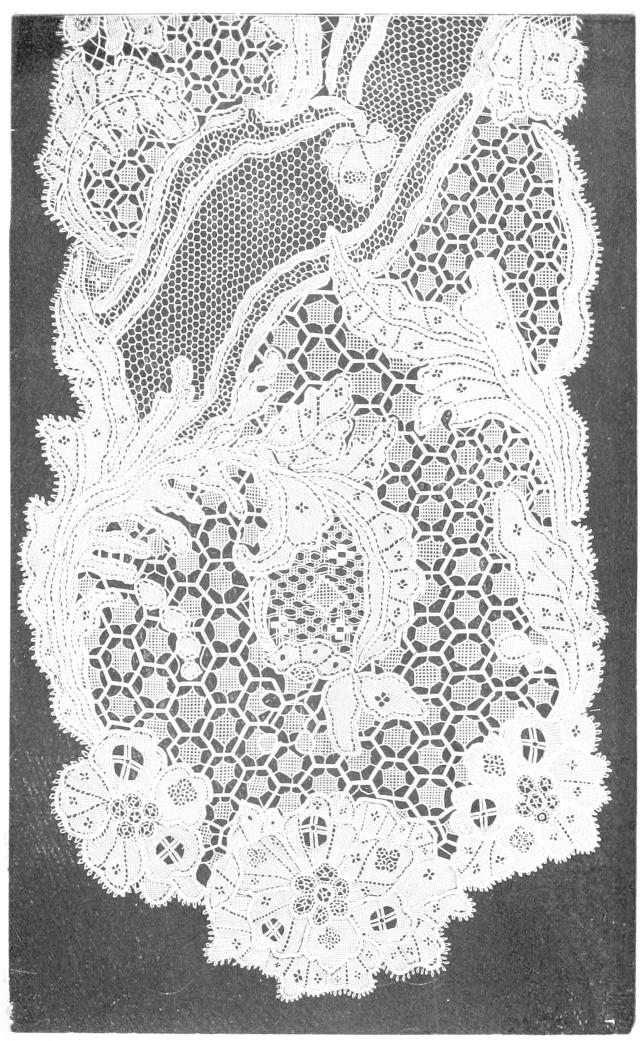

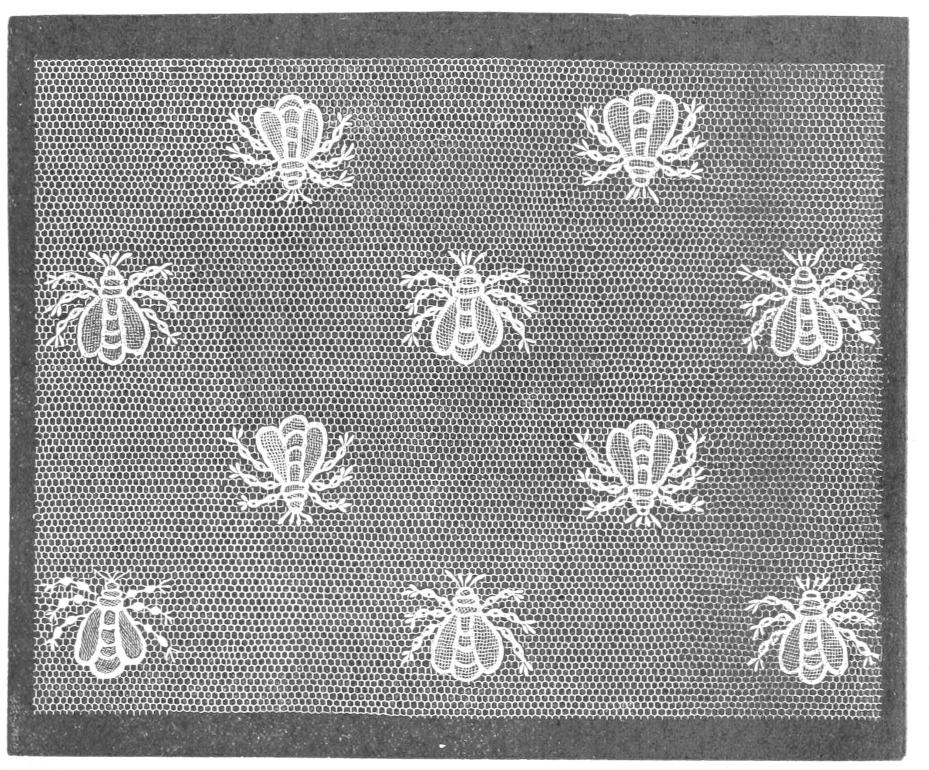

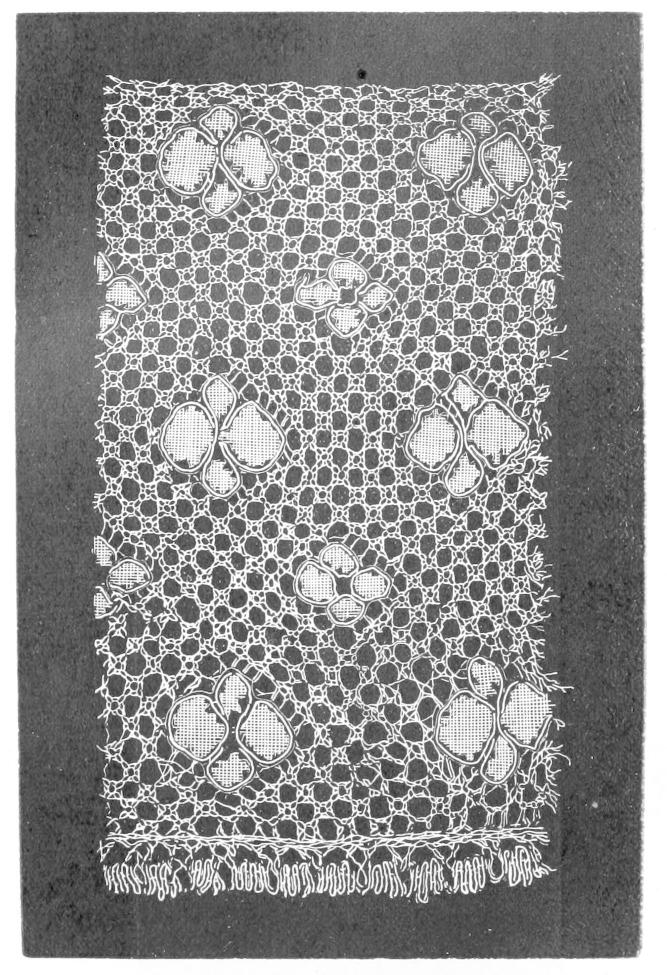

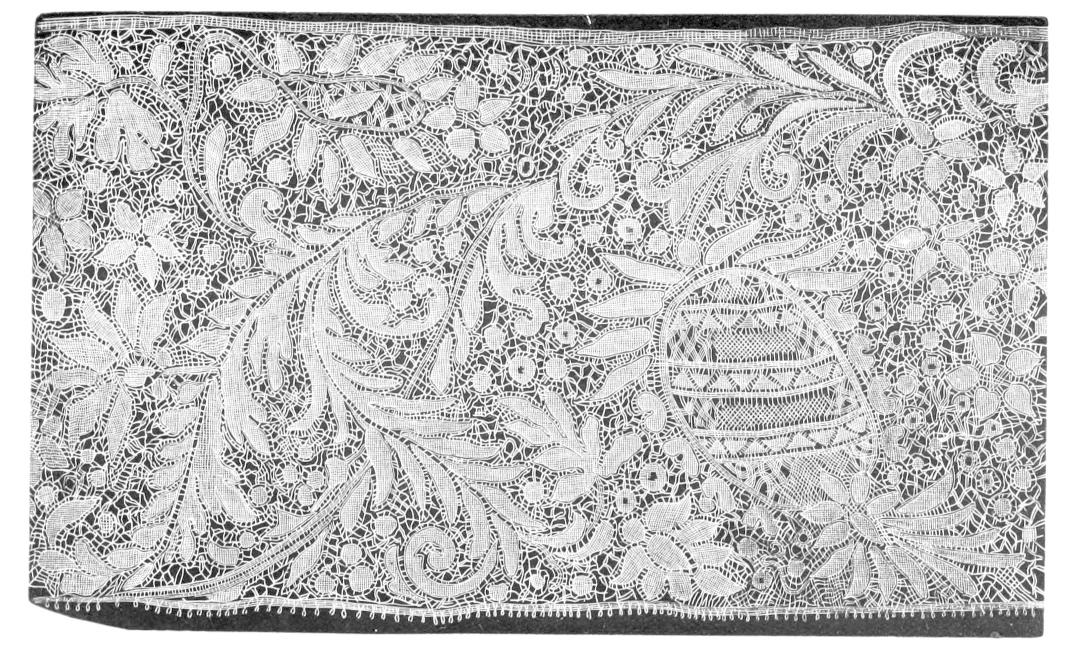

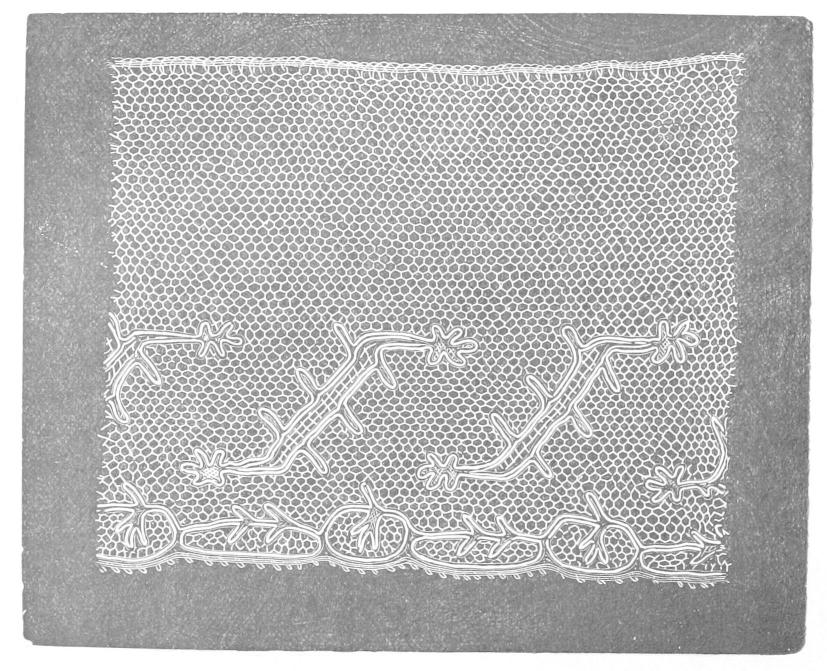

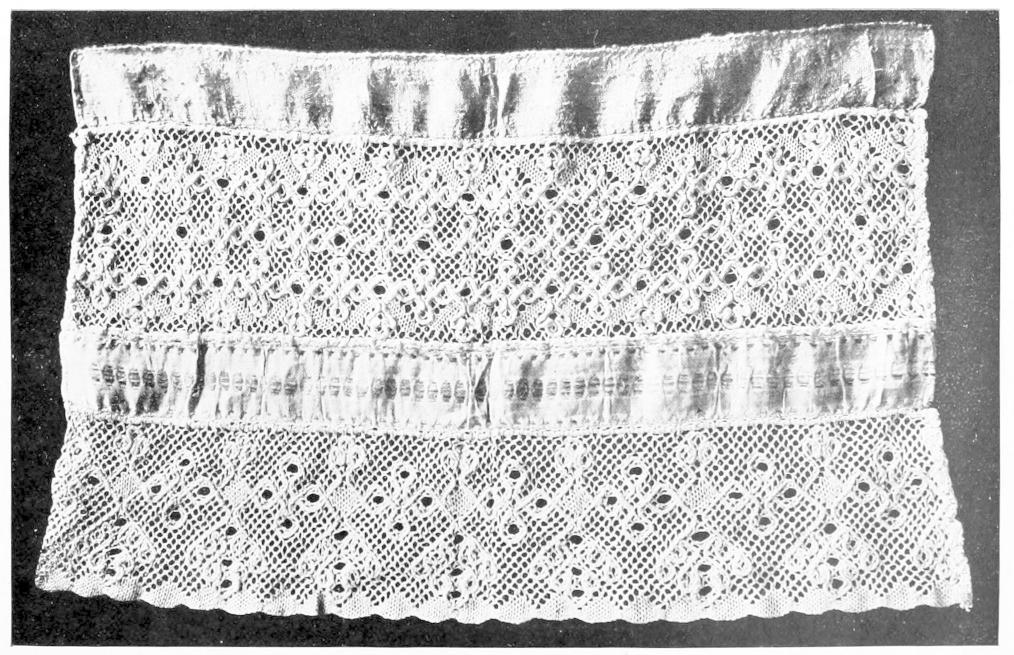

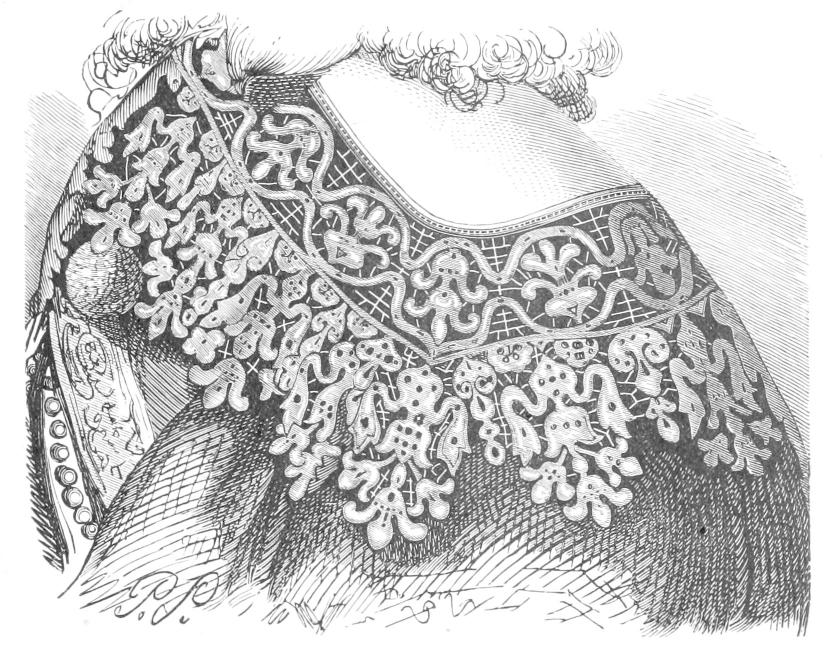

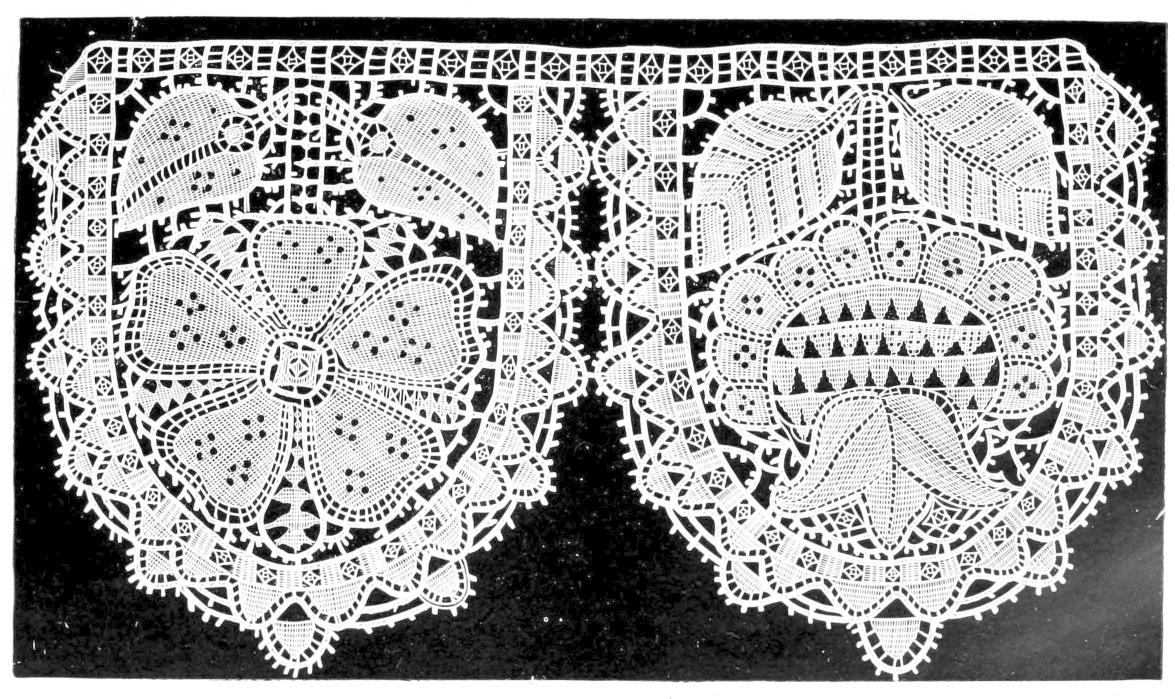

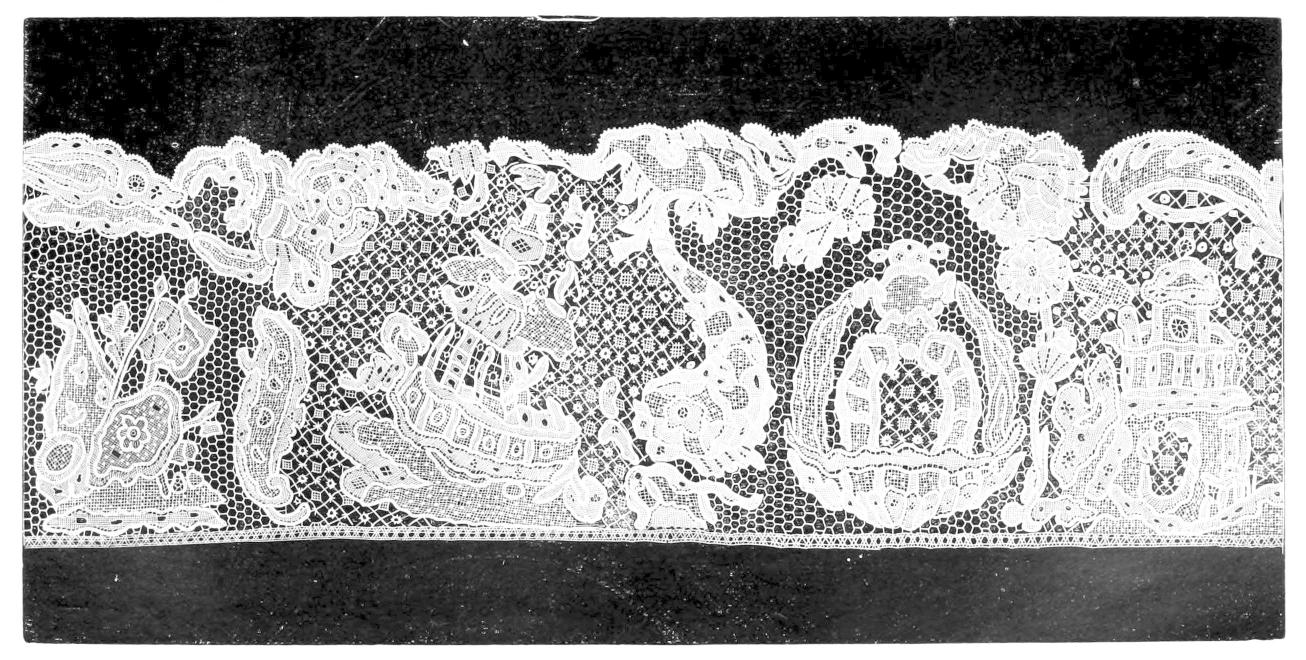

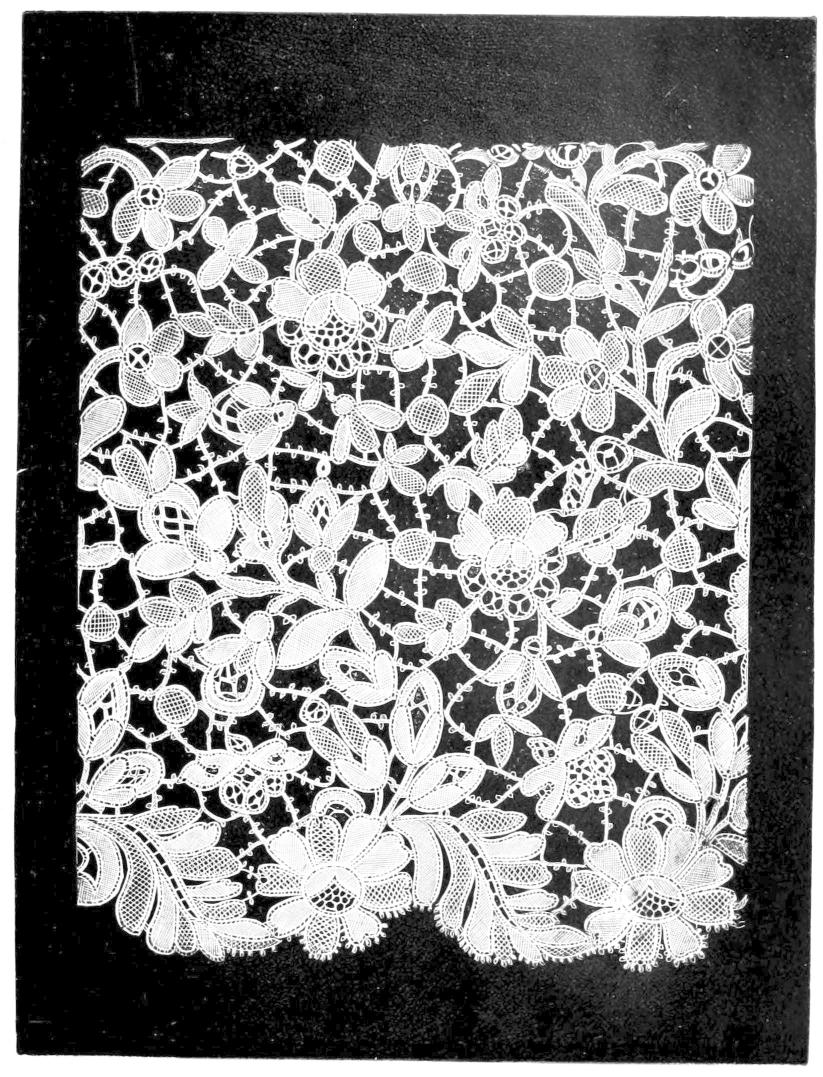

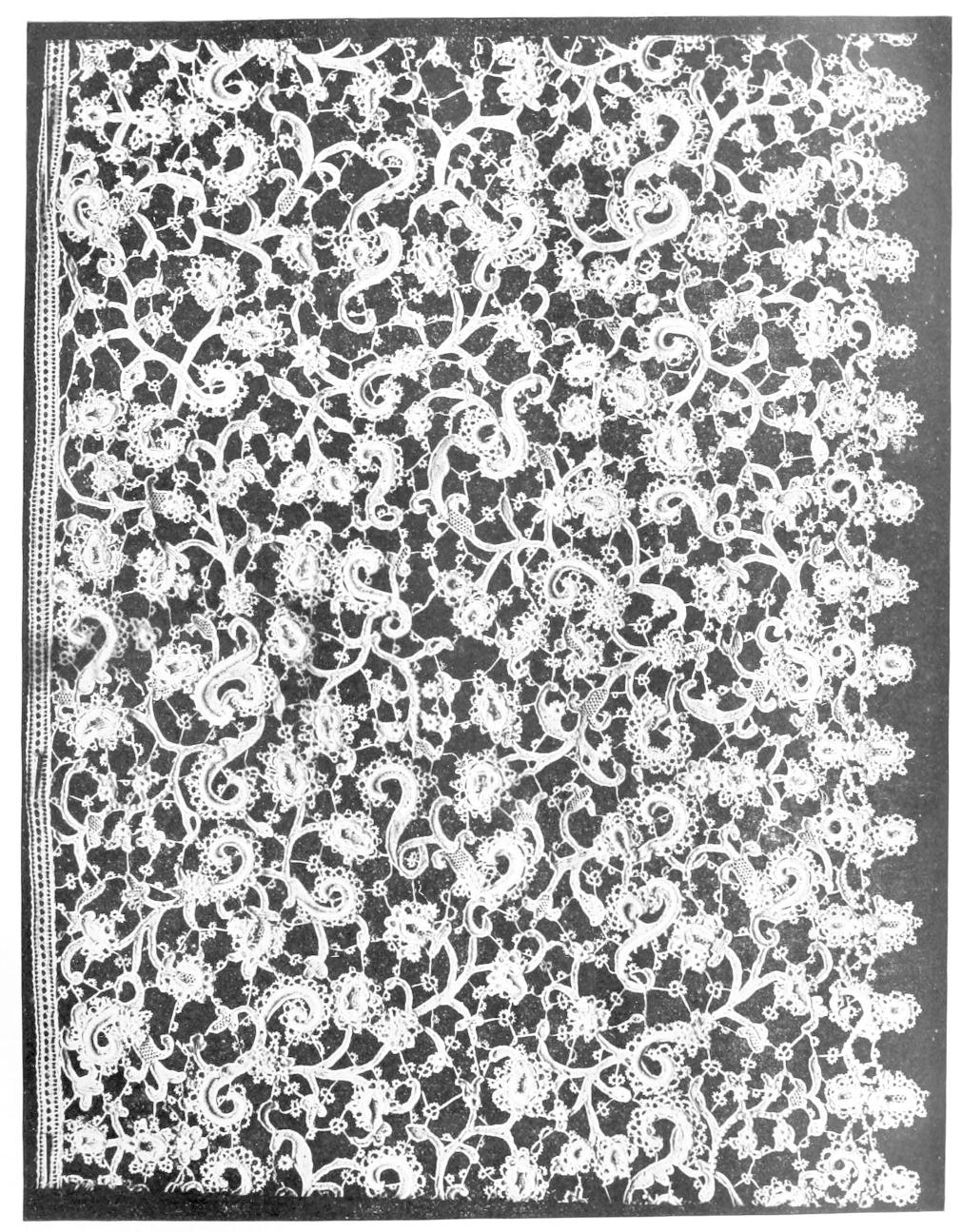

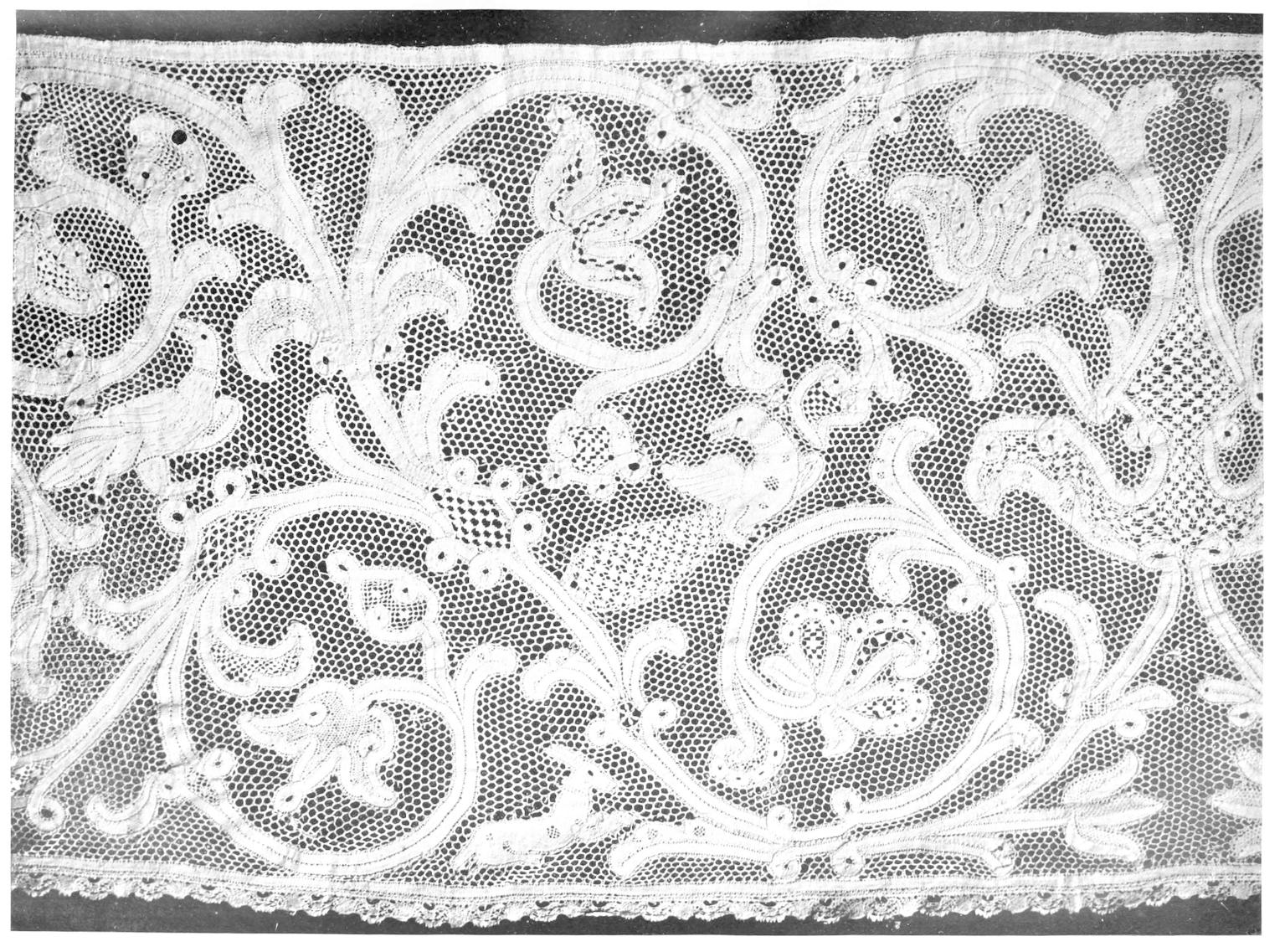

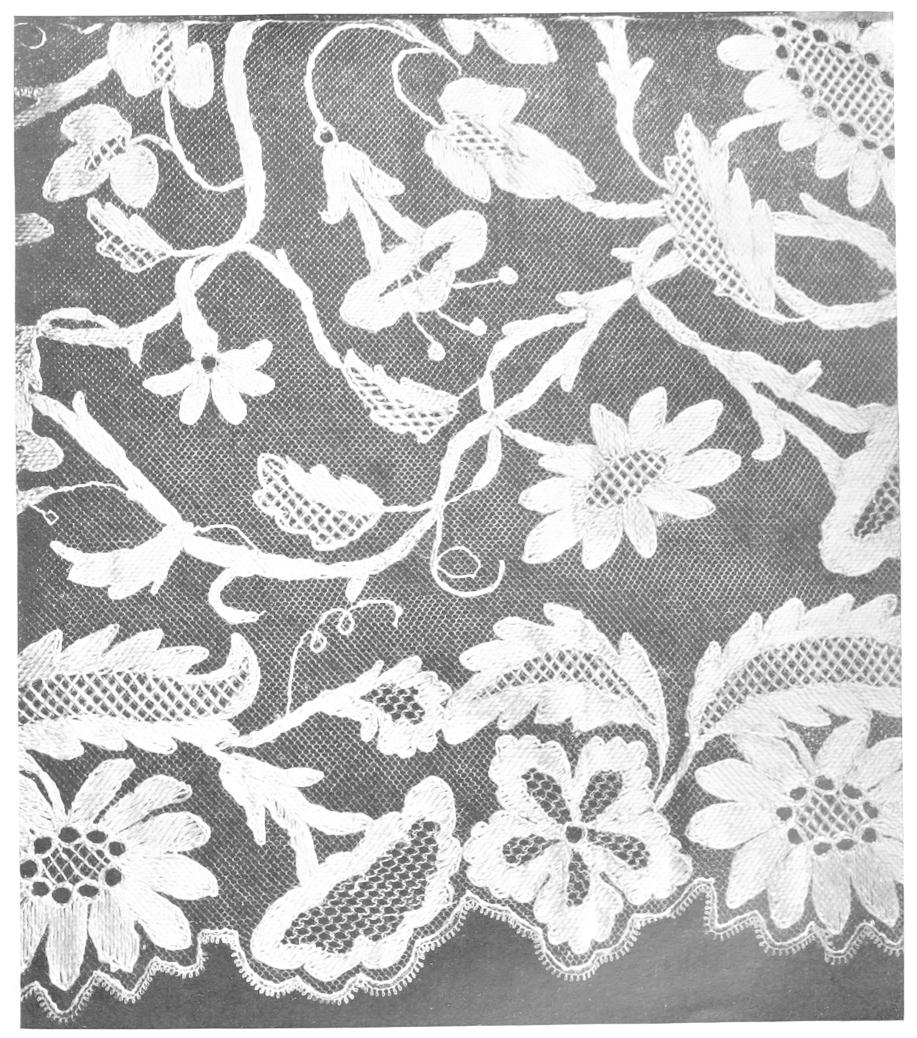

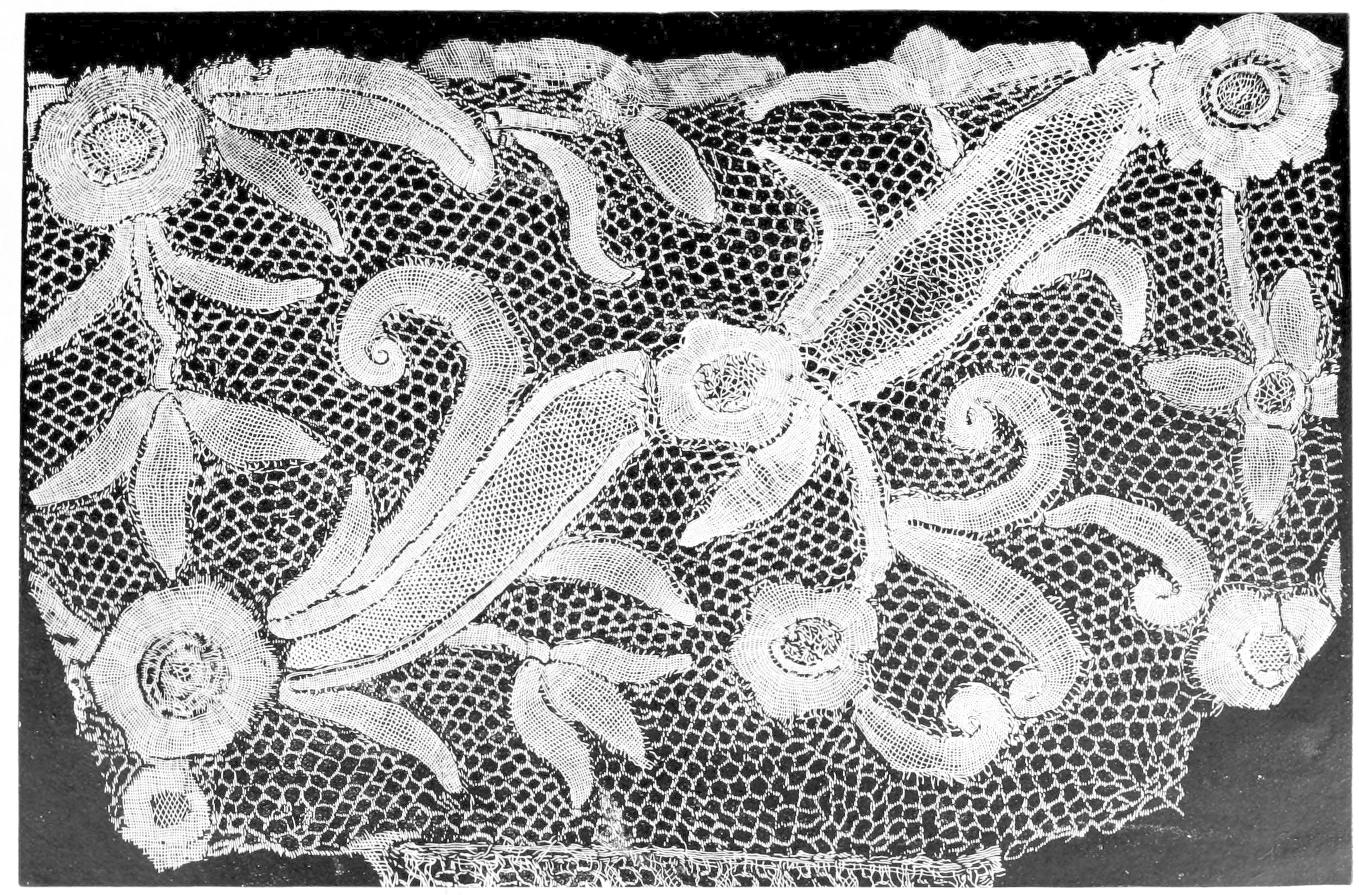

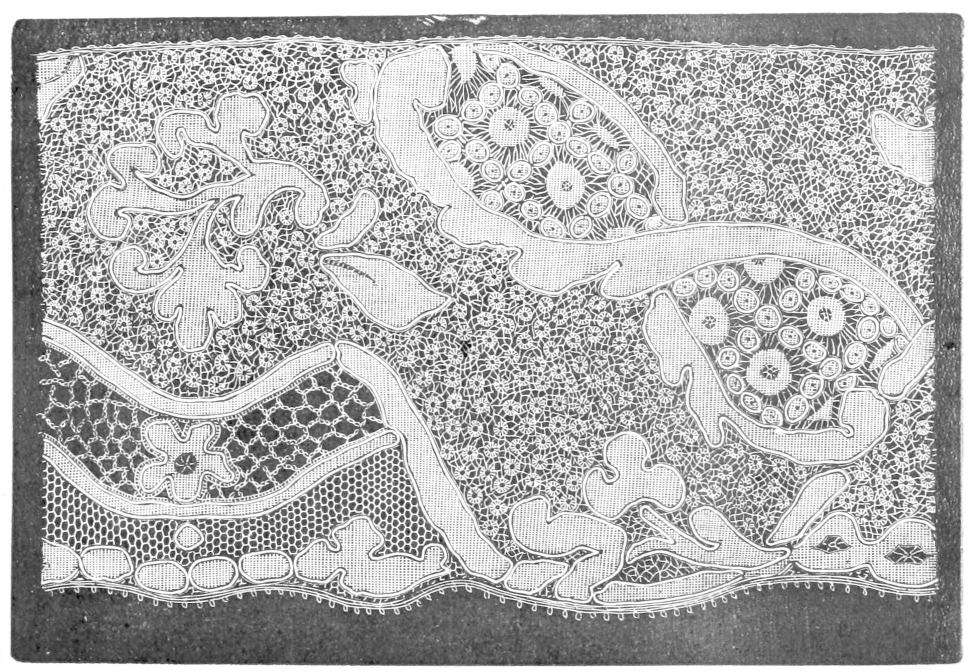

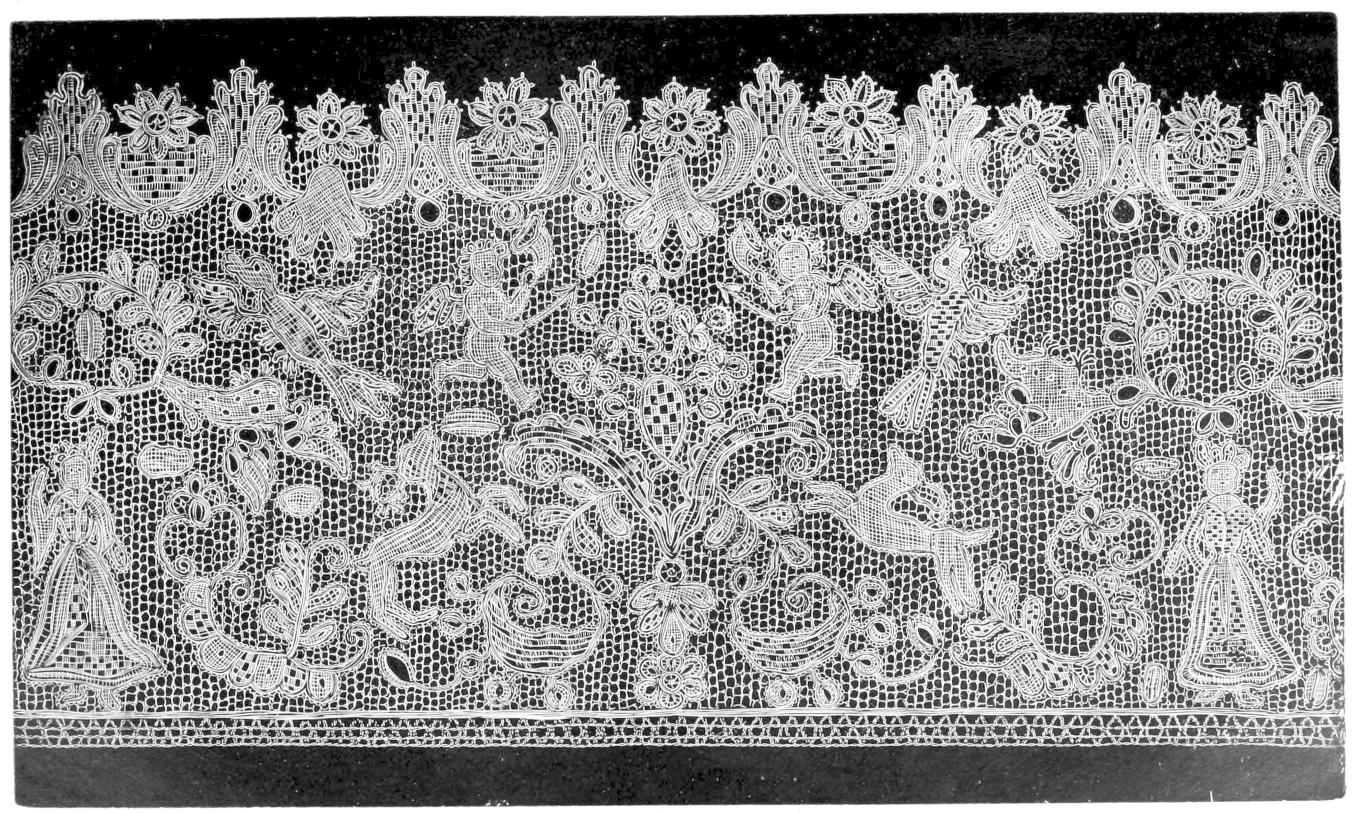

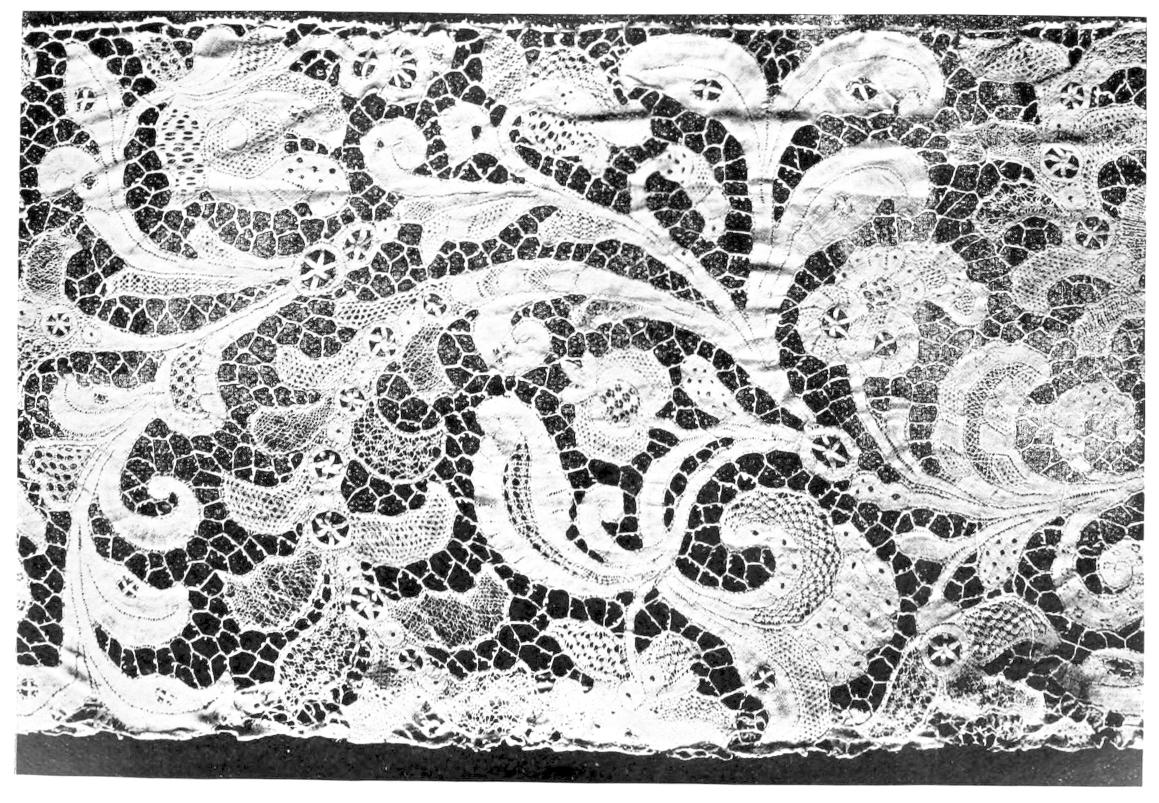

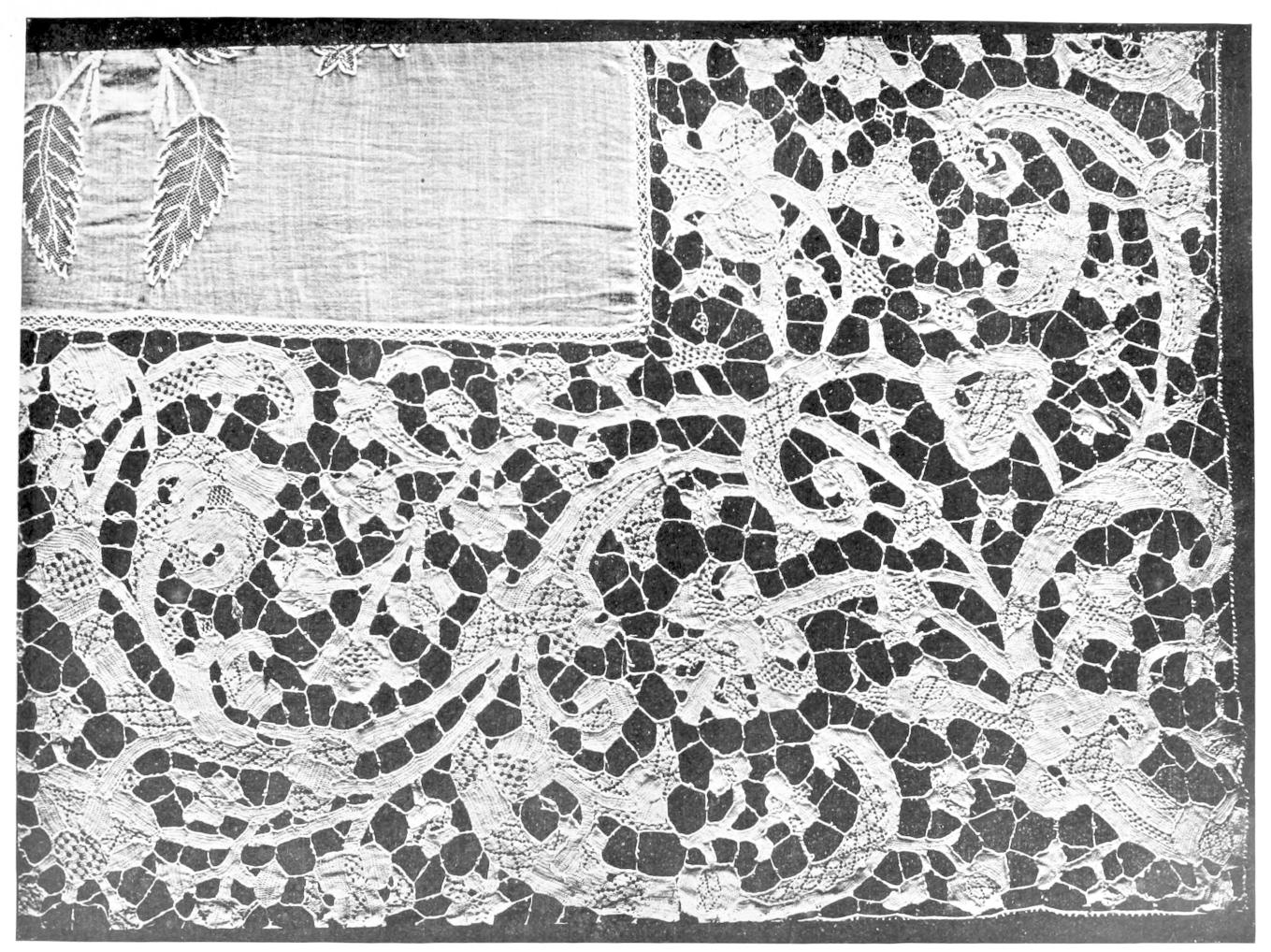

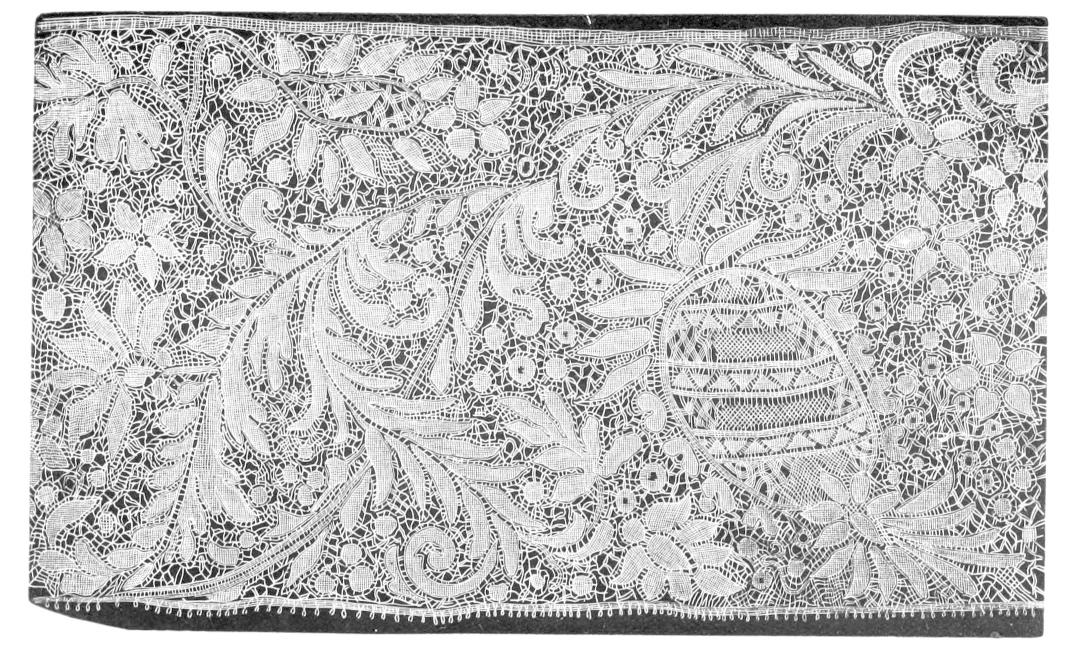

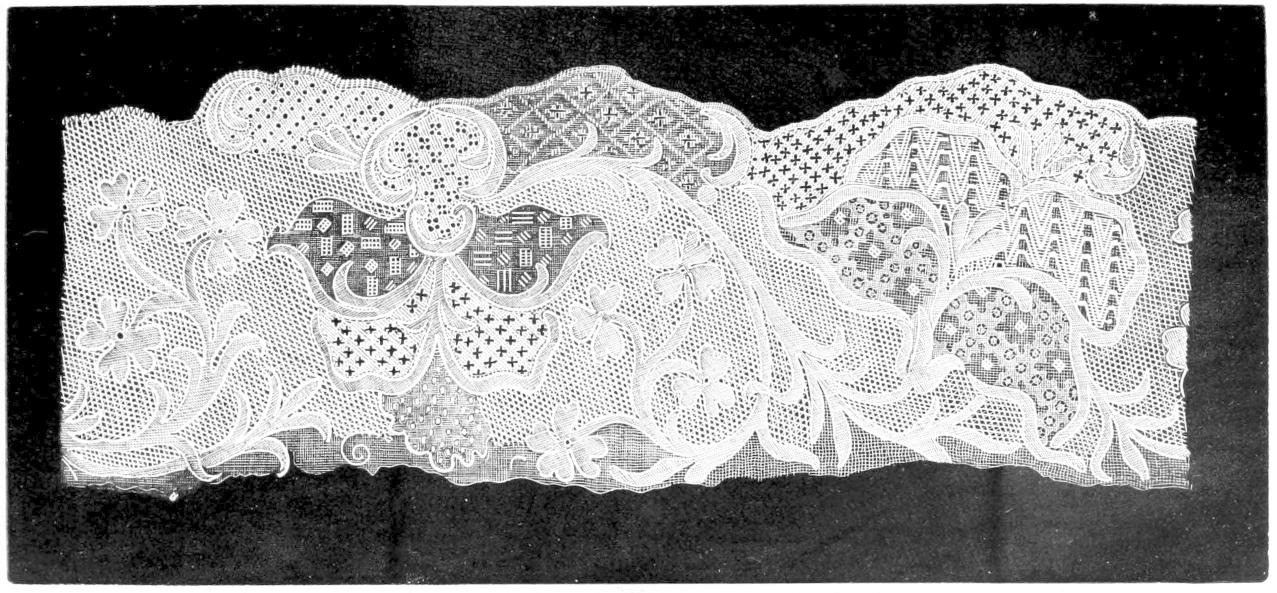

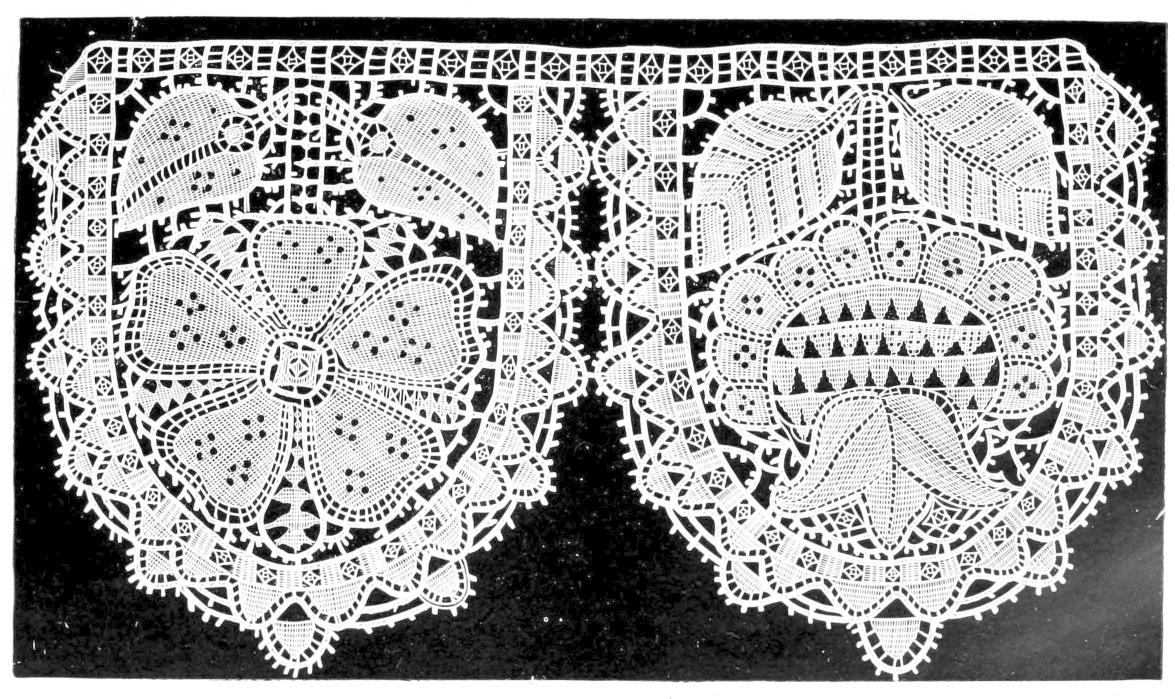

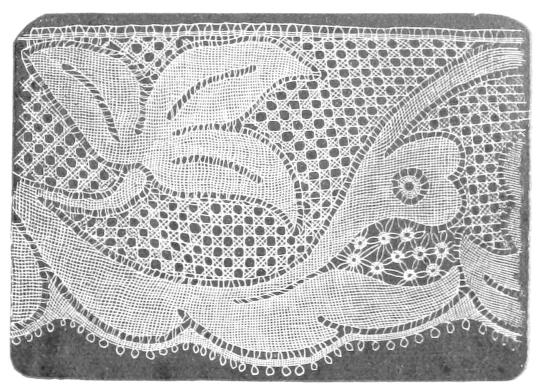

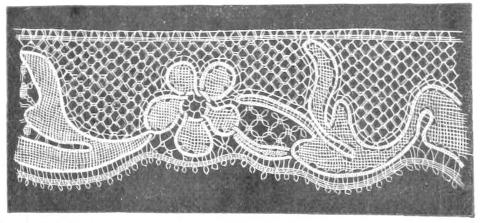

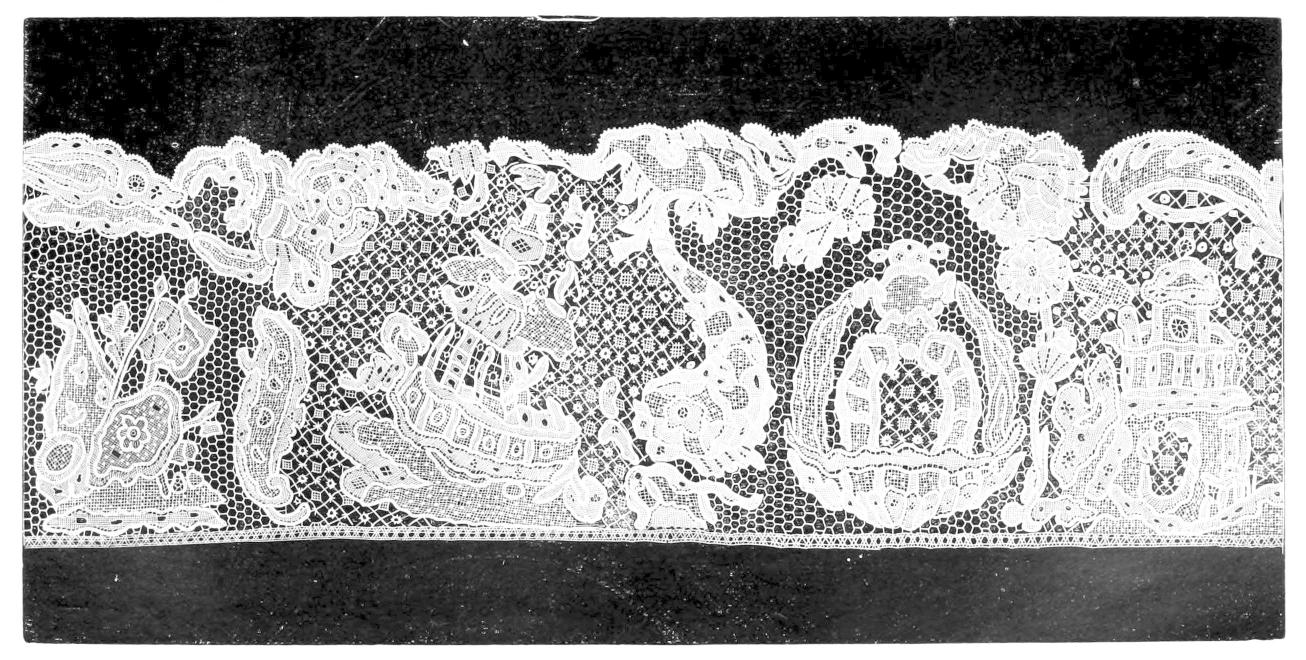

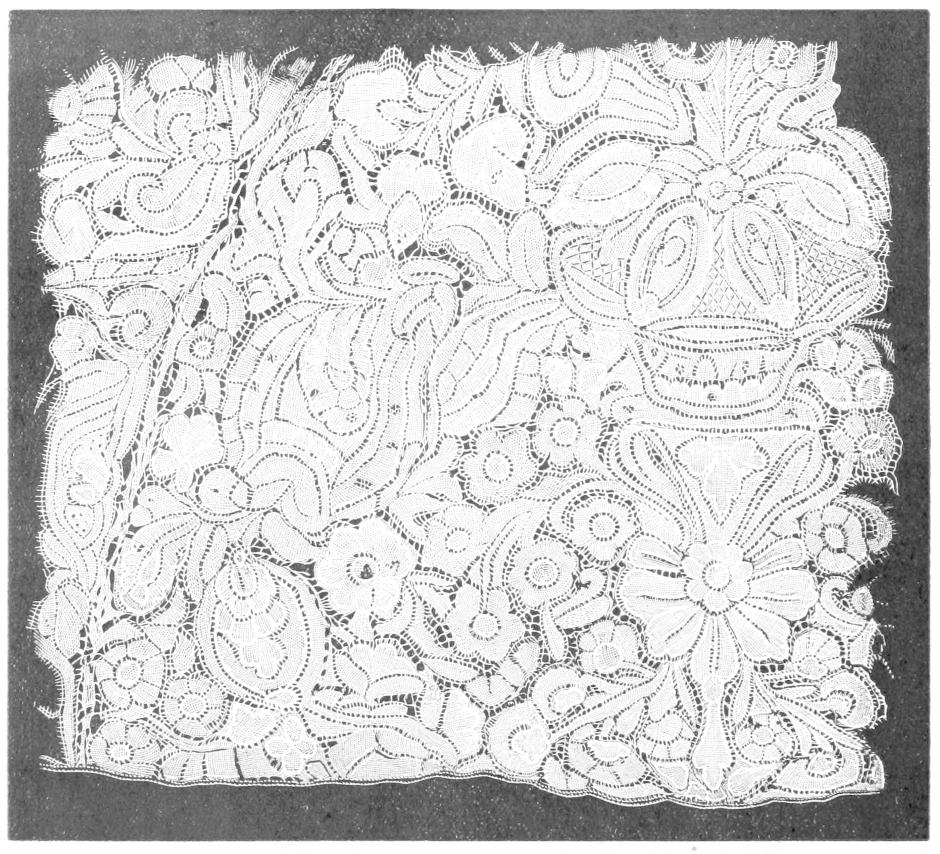

| Flemish.—Portion of Bed-Cover |

Plate XXXVI |

110 |

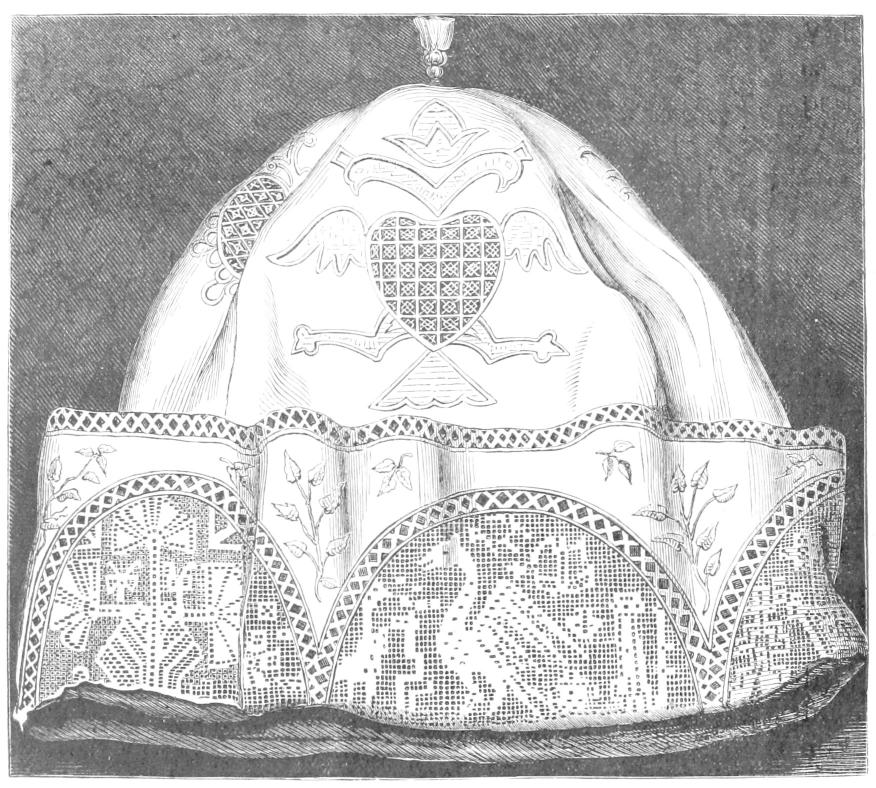

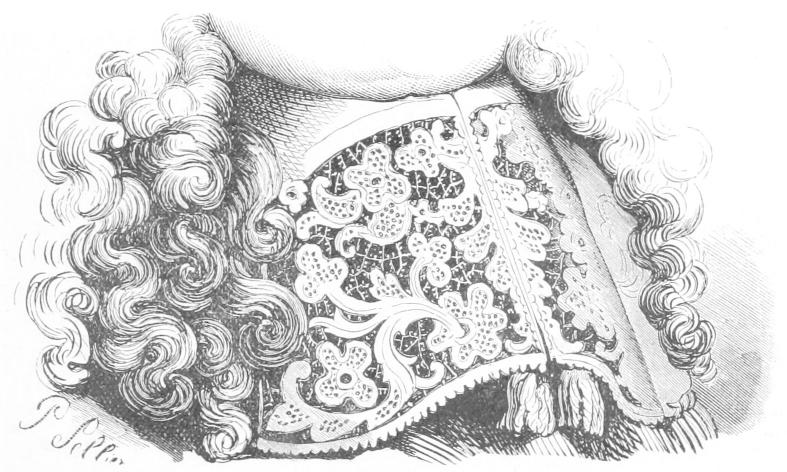

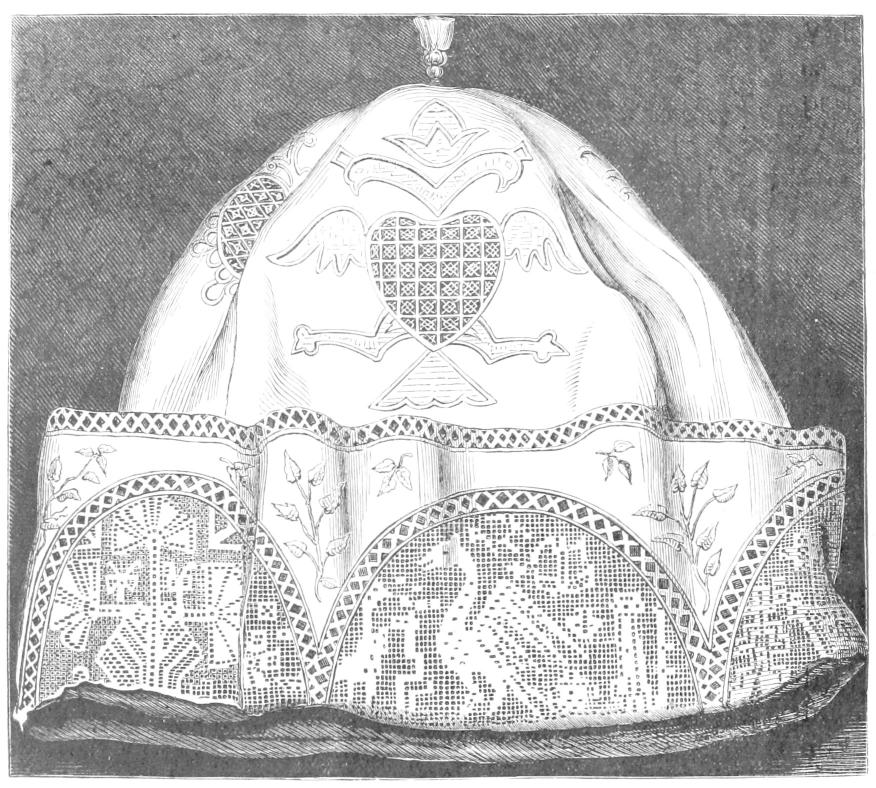

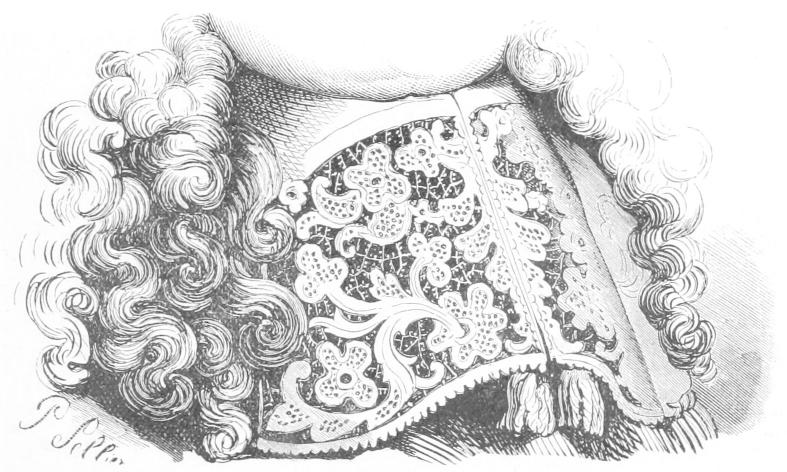

| Cap of Emperor Charles V. |

Fig. 51 |

112 |

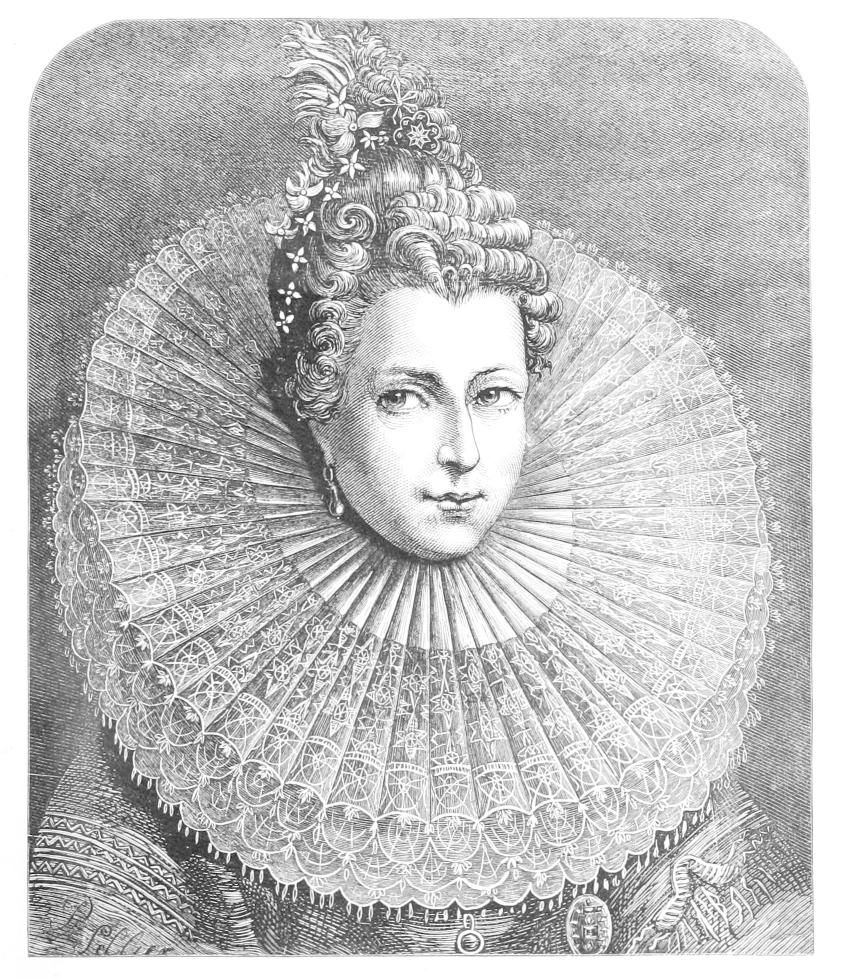

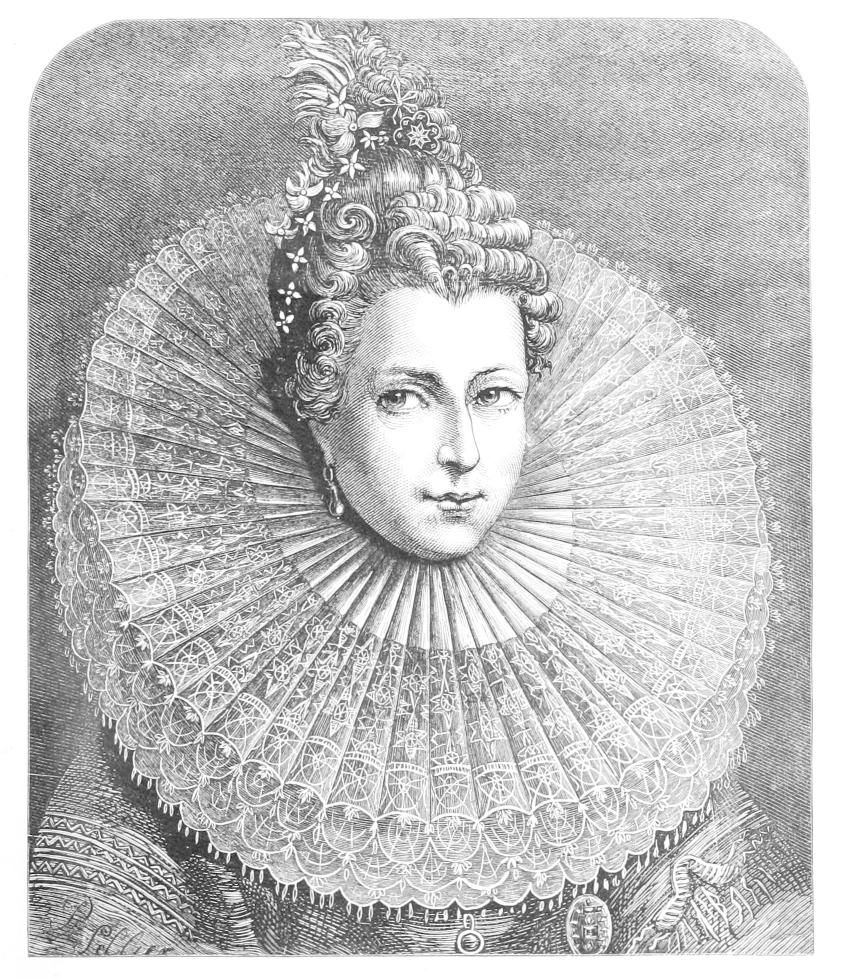

| Isabella Clara Eugenia, Daughter of Philip II. |

" 52 |

112 |

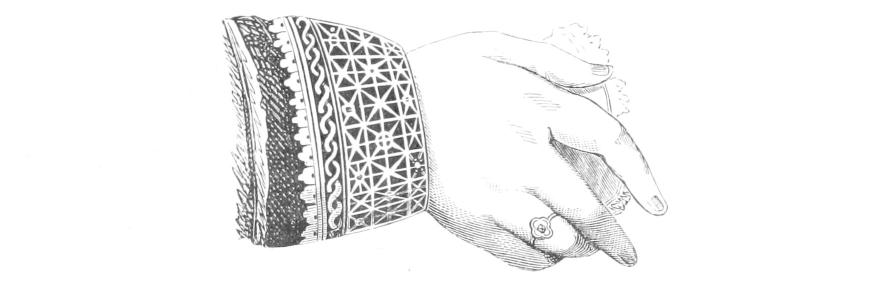

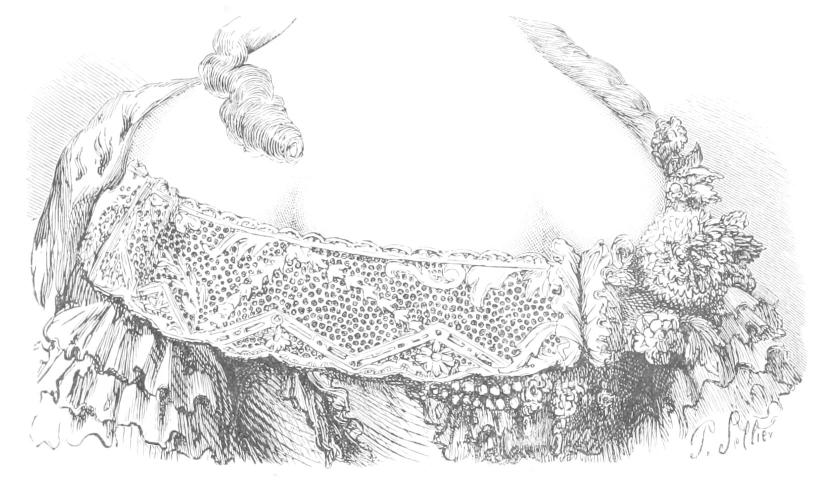

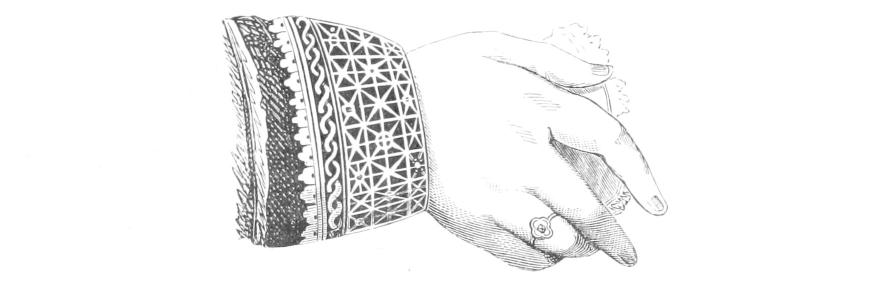

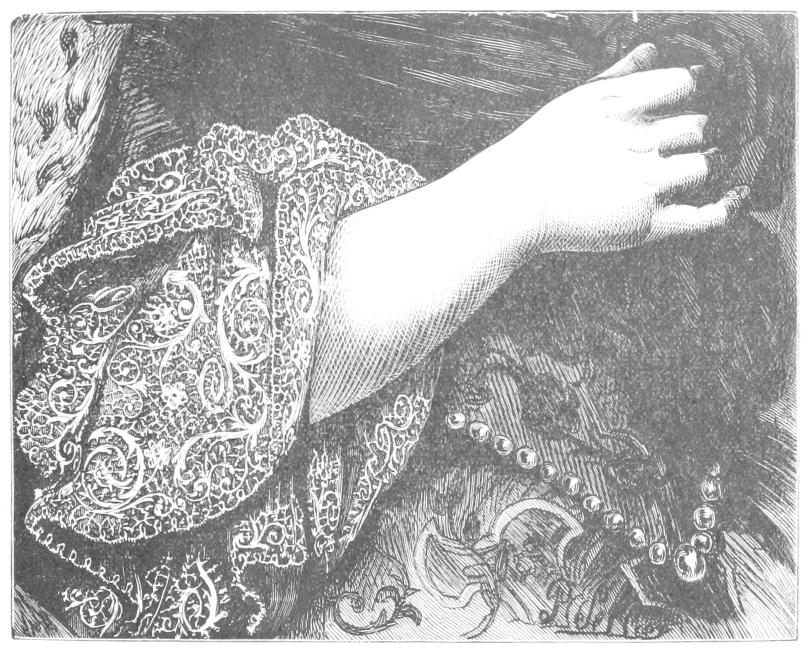

| Mary, Queen of Hungary, Cuff |

" 53 |

113 |

|

Belgian Lace School

|

" 54 |

114 |

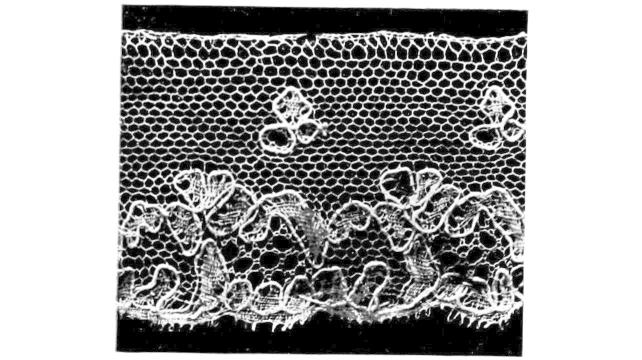

| Old Flemish Bobbin Lace |

" 55 |

114 |

| Old Flemish.—Trolle Kant |

" 56 |

115 |

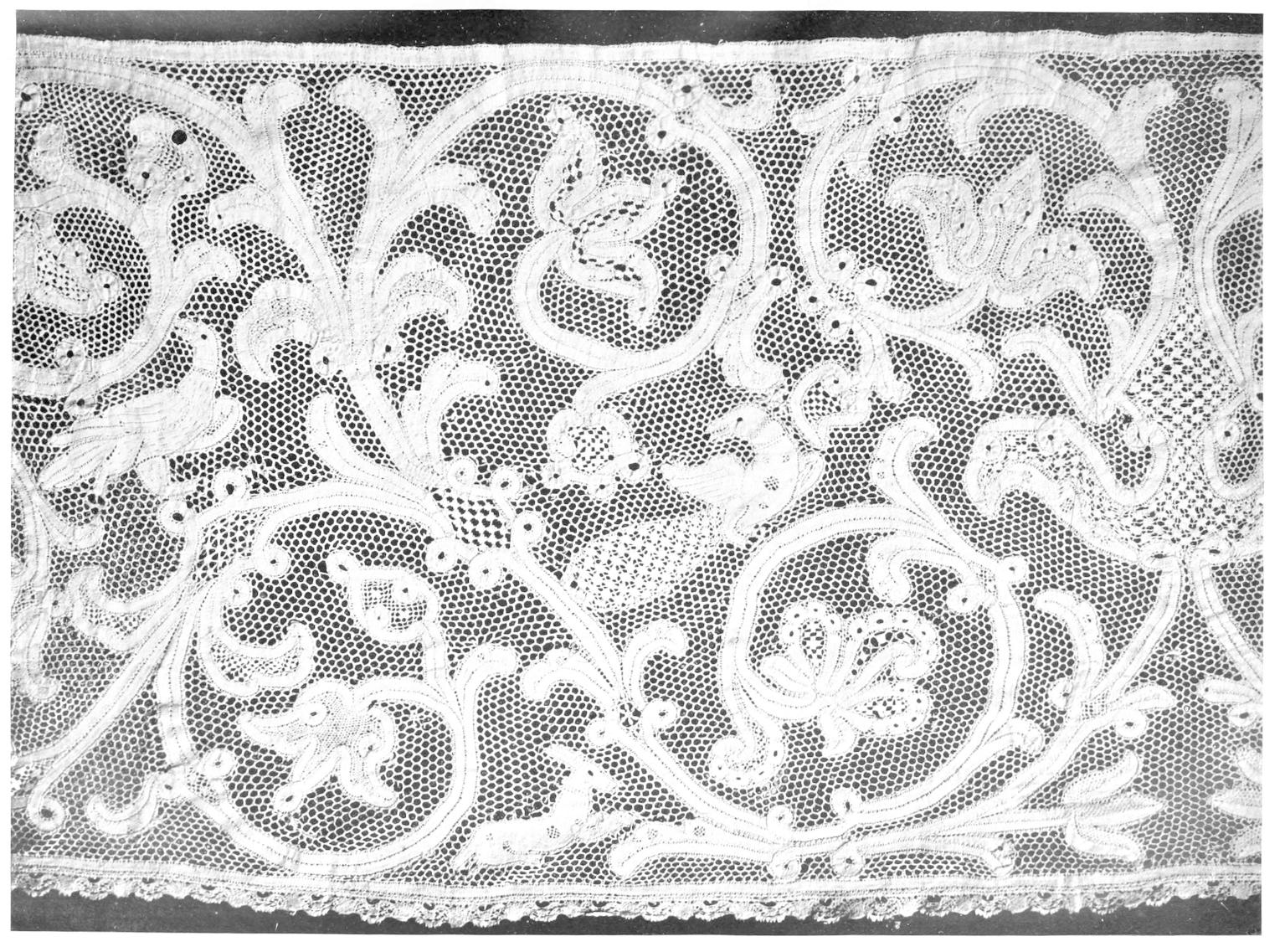

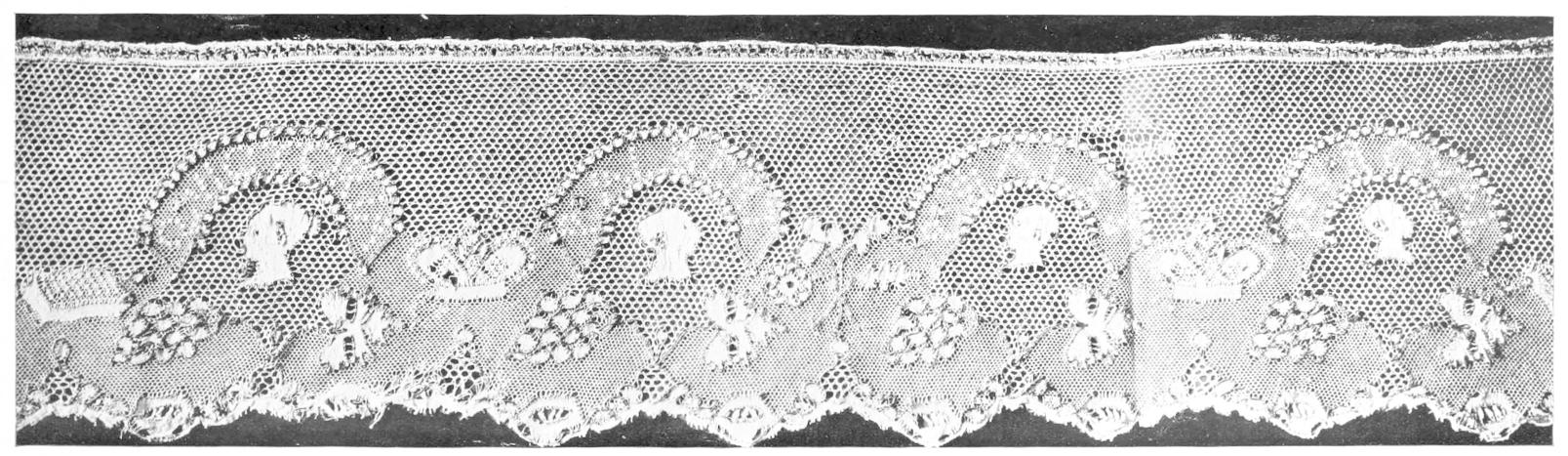

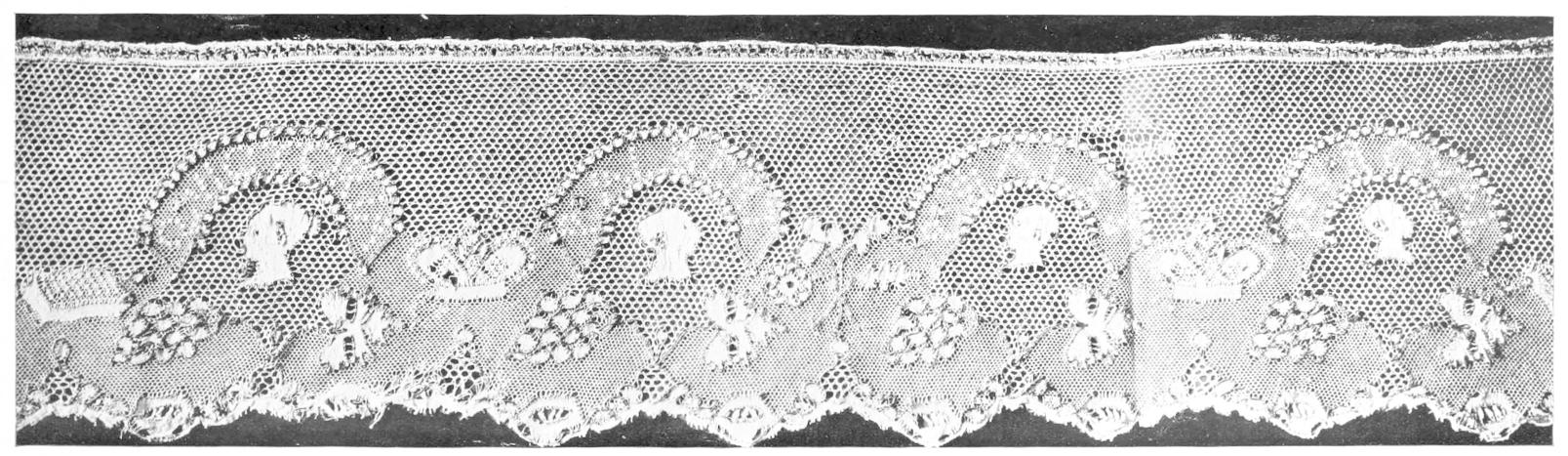

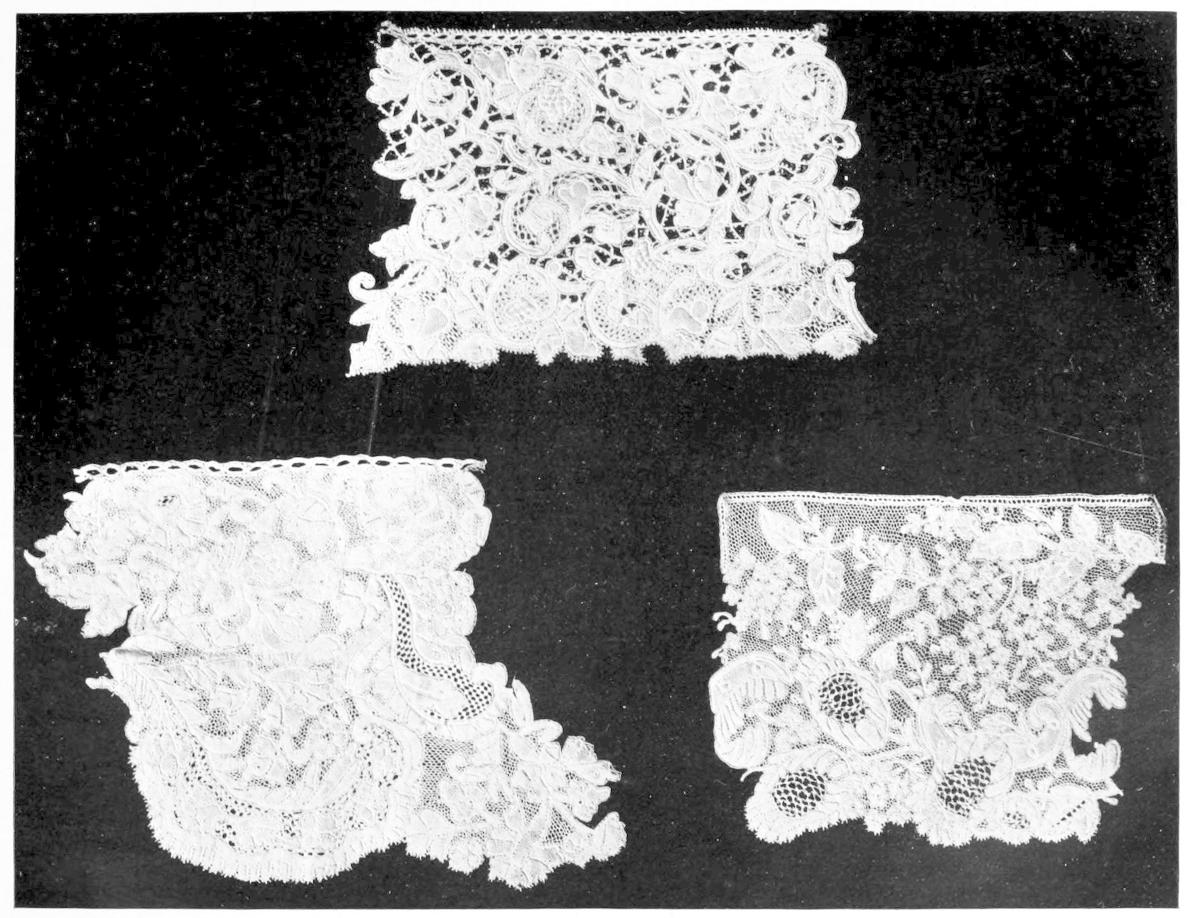

| Brussels.—Point d'Angleterre à Brides |

Plate XXXVII |

116 |

| Flemish.—Tape Lace, Bobbin-made |

" XXXVIII |

116 |

| Brussels Needle-Point |

Fig. 57 |

118 |

| Brussel" Needle-" |

" 58 |

120 |

| Brussels.—Point à l'Aiguille |

" 58 |

A |

120 |

| Old Brussels.—Point d'Angleterre |

" 59 |

122 |

| Old Br"ssels.—P"int d'Ang" |

" 60 |

124 |

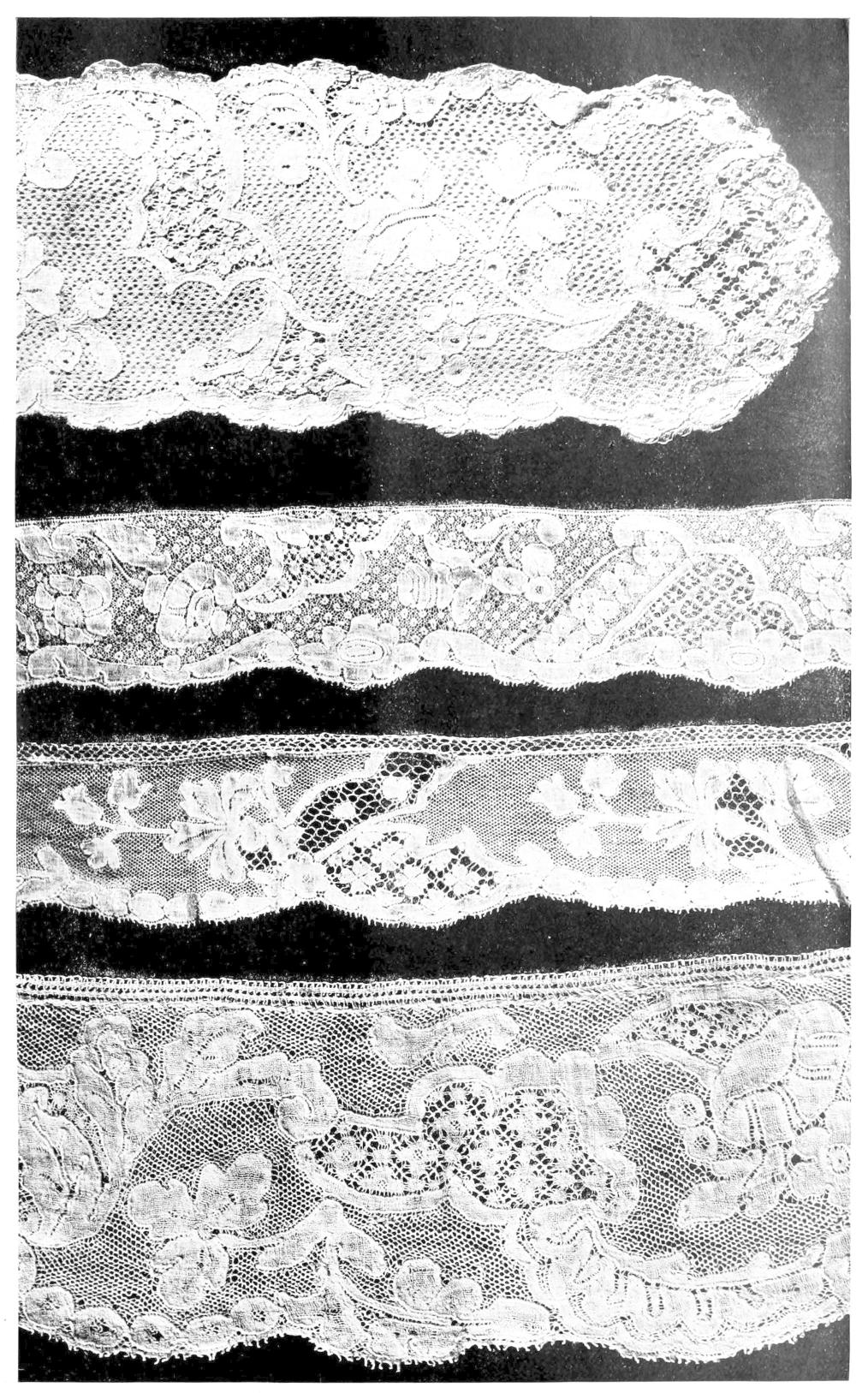

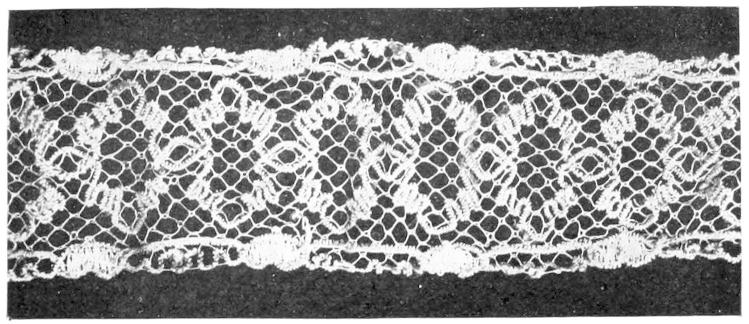

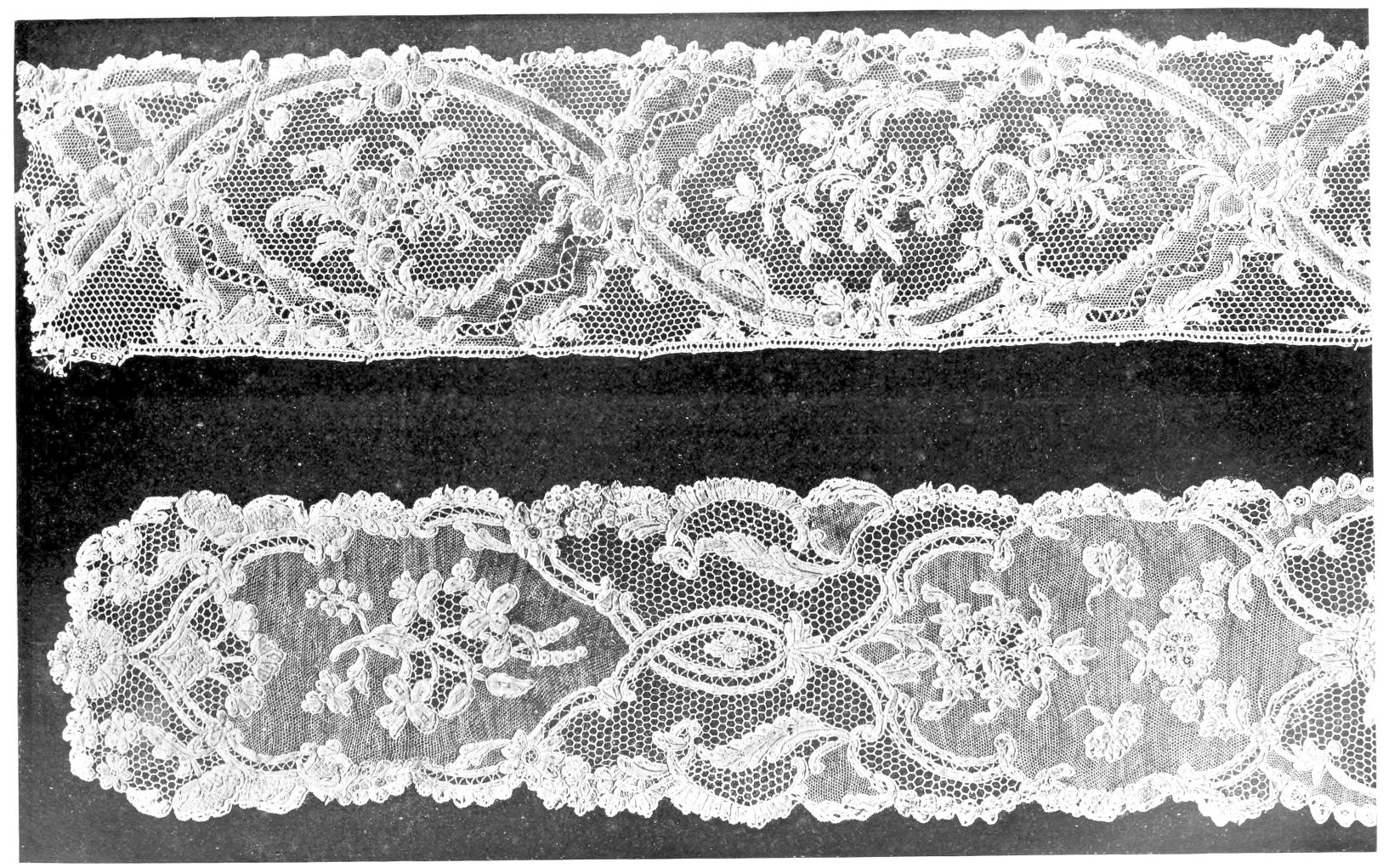

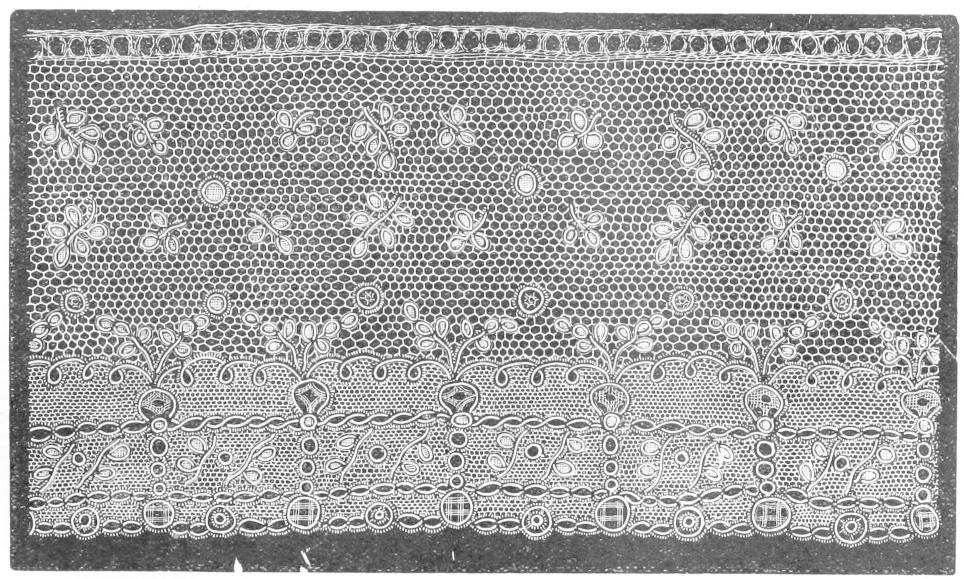

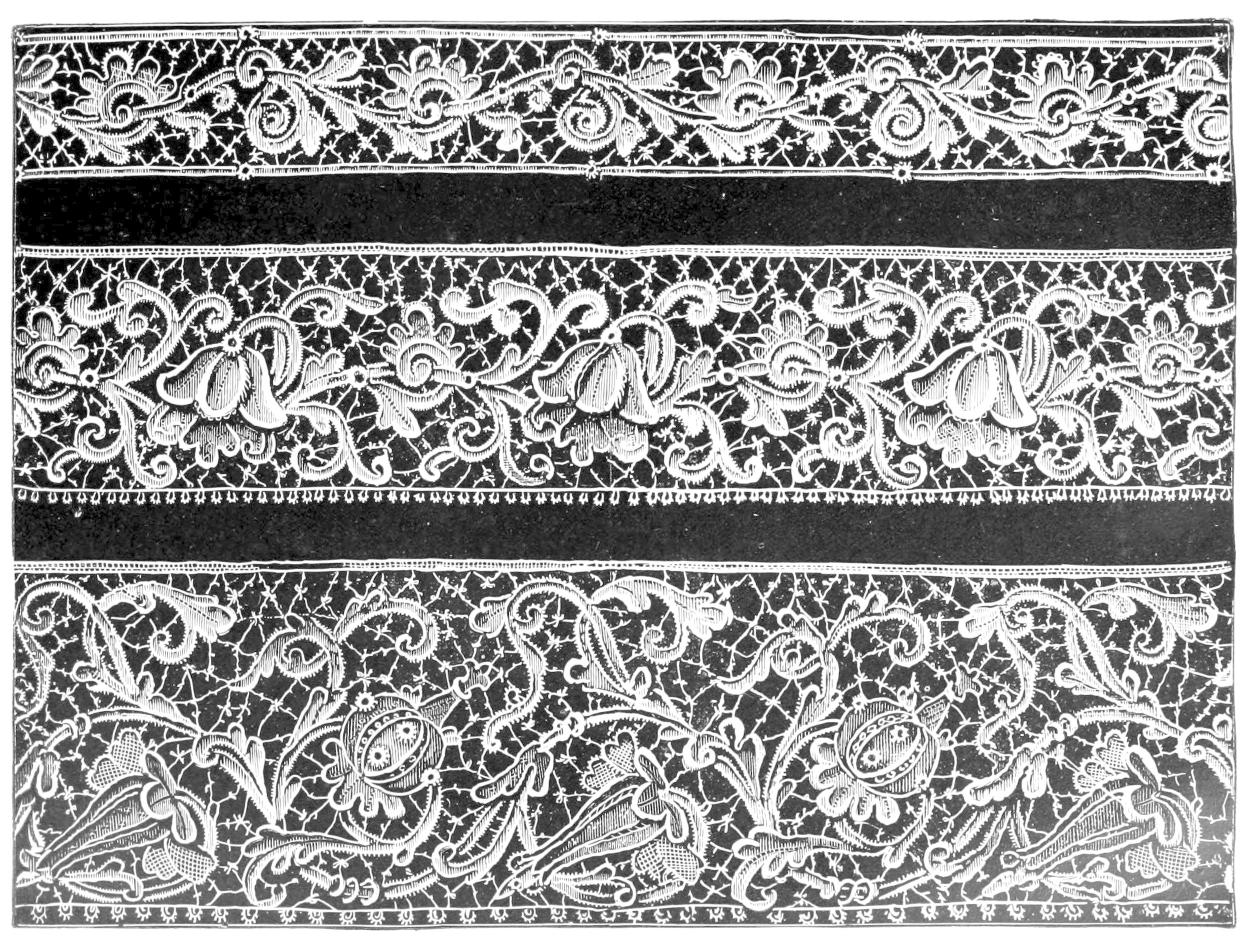

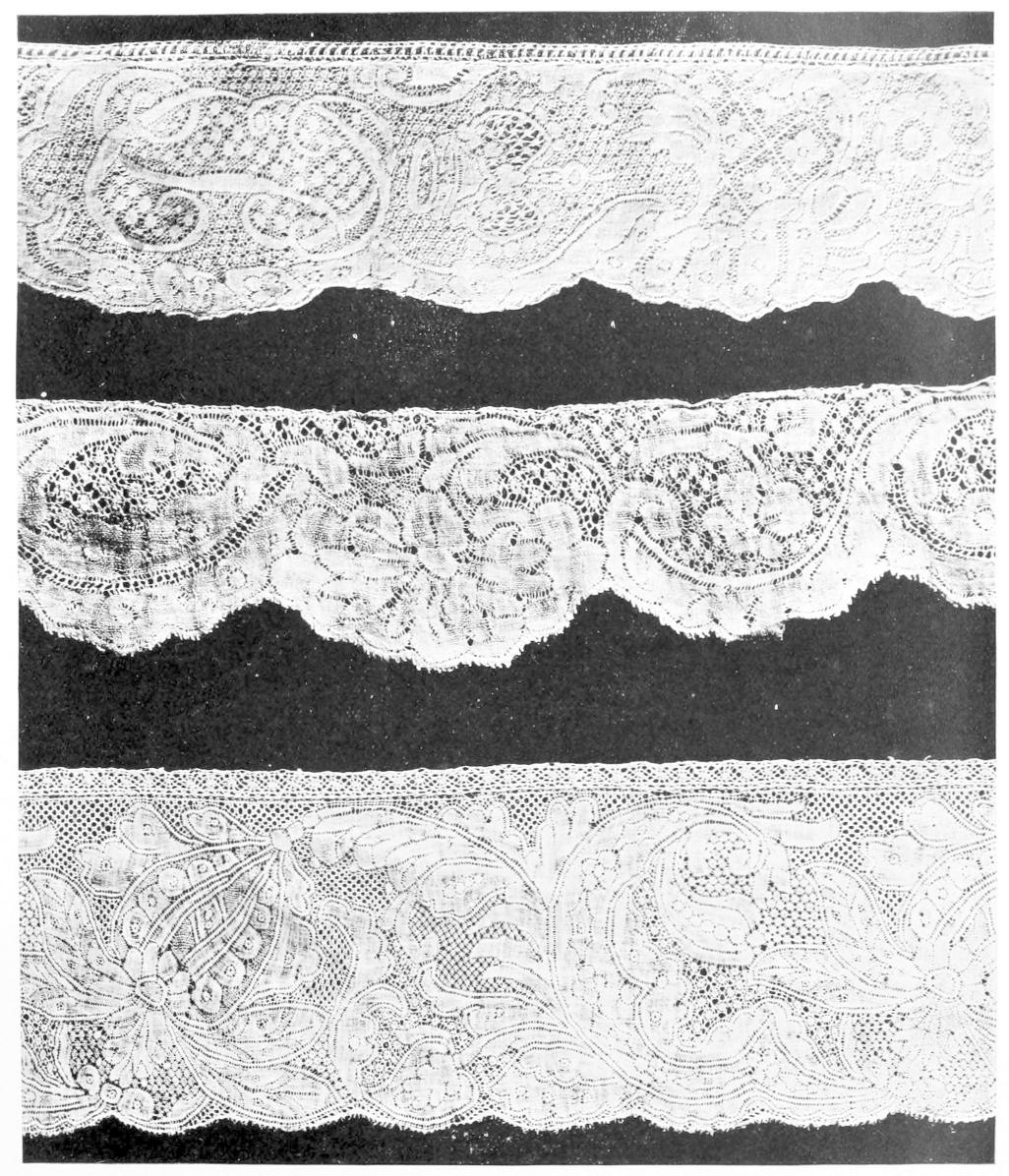

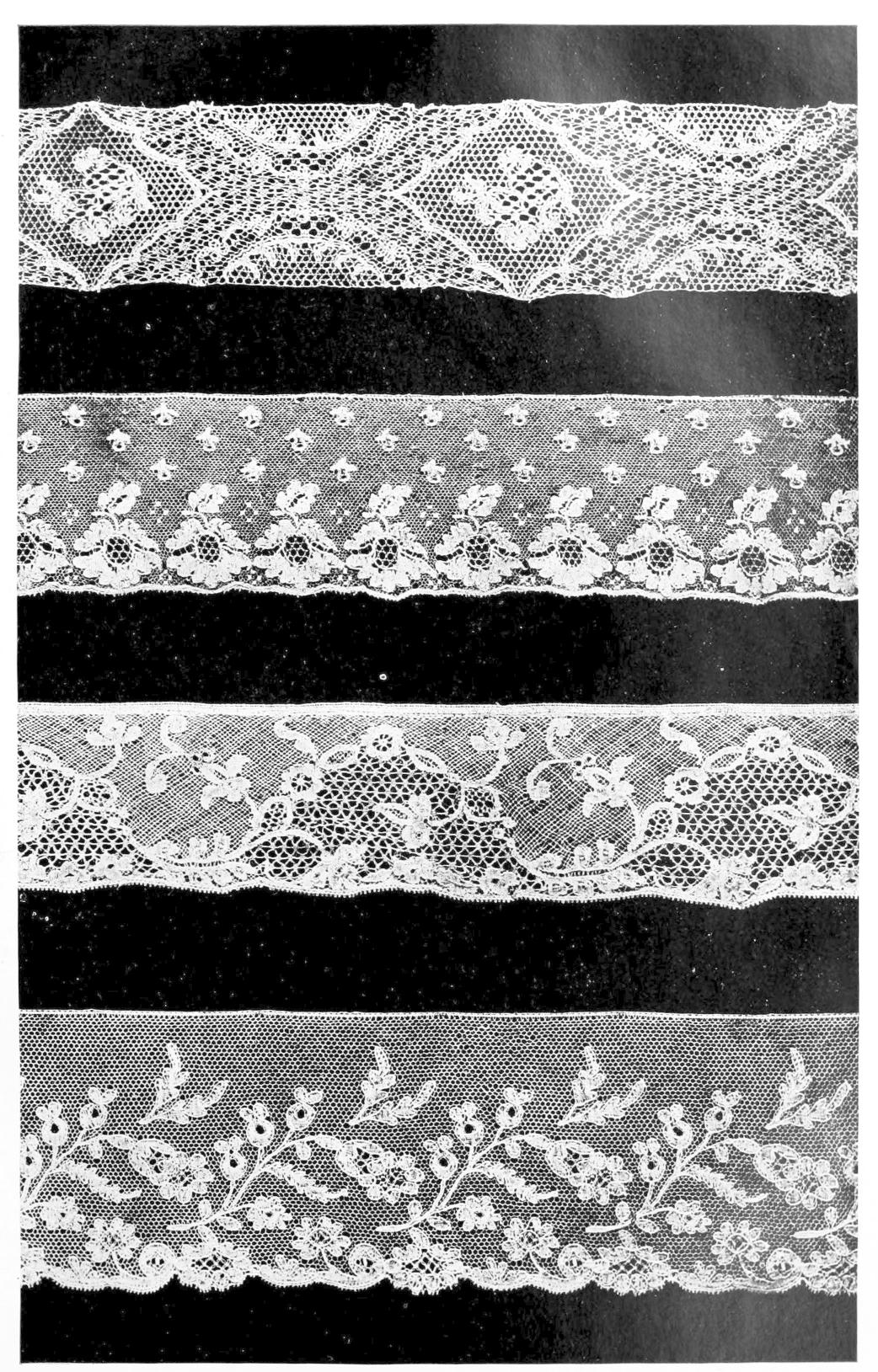

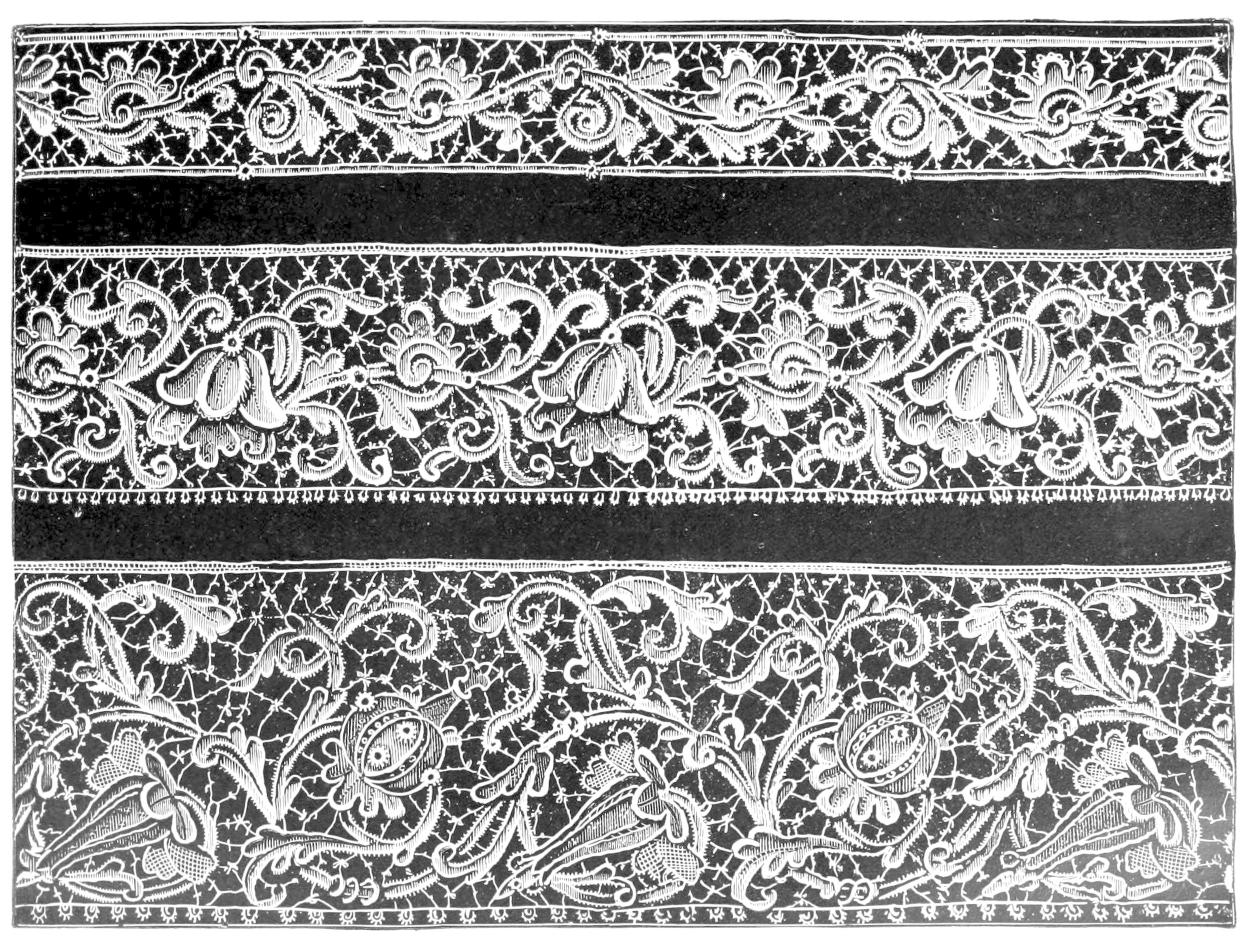

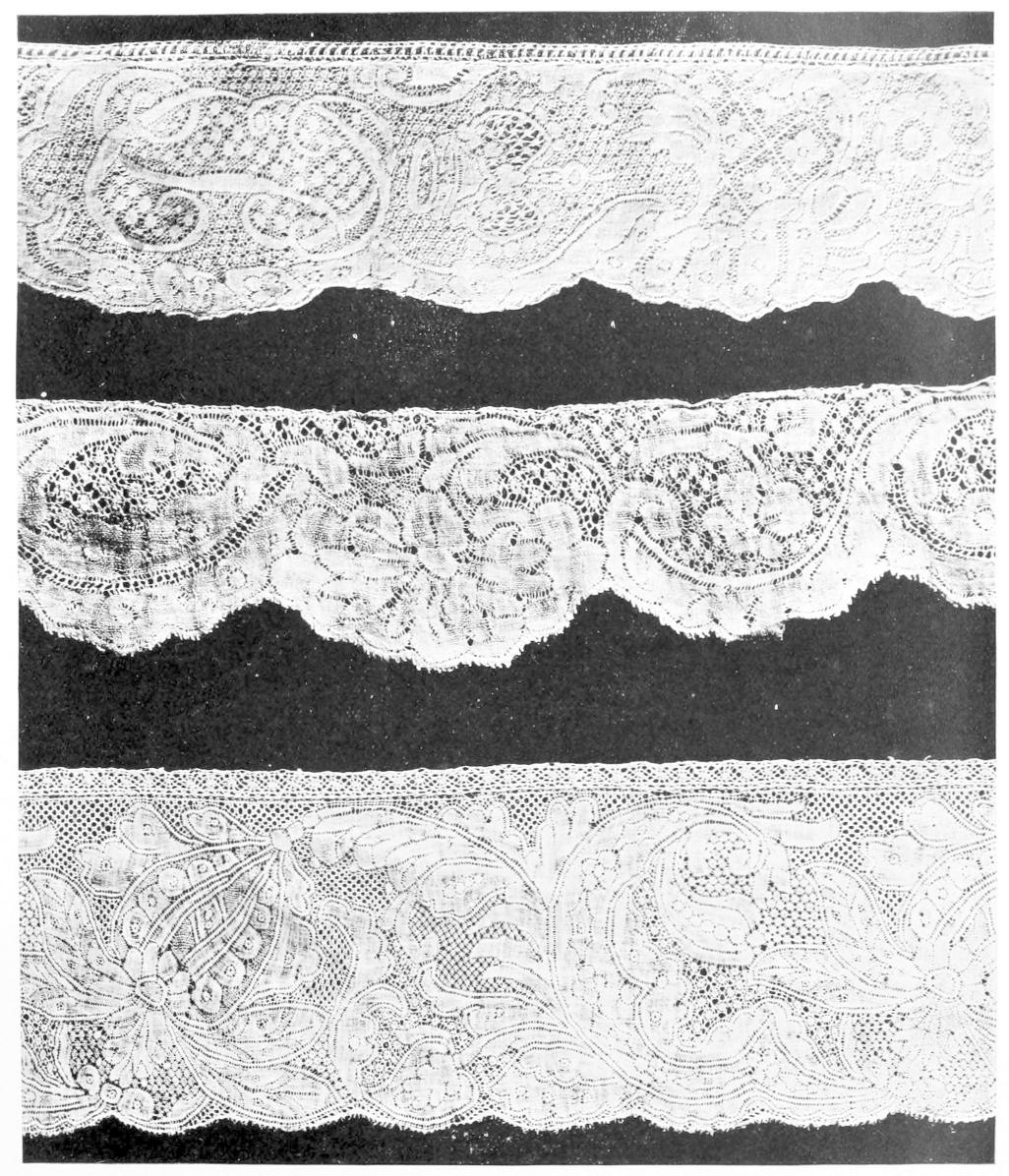

| Mechlin, 17th and 18th Century |

Plate XXXIX |

126 |

| Mechlin.—Period Louis XVI. |

Fig. 61 |

127 |

| Mechlin, formerly belonging to H.M. Queen Charlotte |

" 62 |

128 |

| Mechlin.—Three Specimens From Victoria and Albert

Museum |

Plate XL |

128 |

| A Lady of Antwerp |

Fig. 63 |

130 |

| Antwerp Pot Lace |

" 64 |

130 |

| Valenciennes Lace of Ypres |

" 65 |

132 |

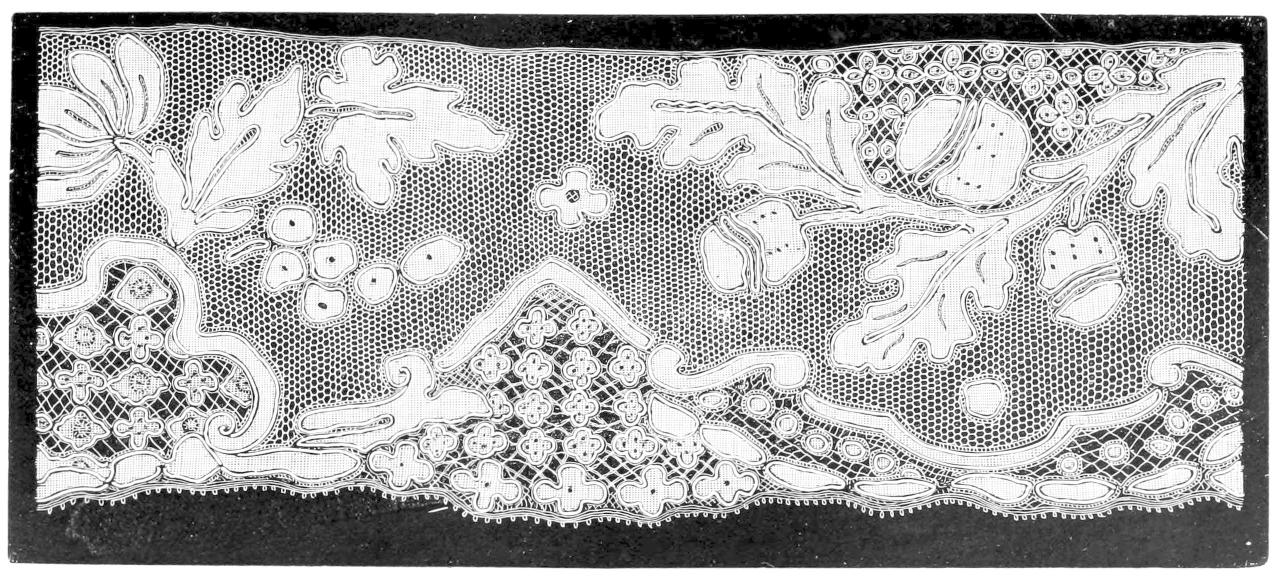

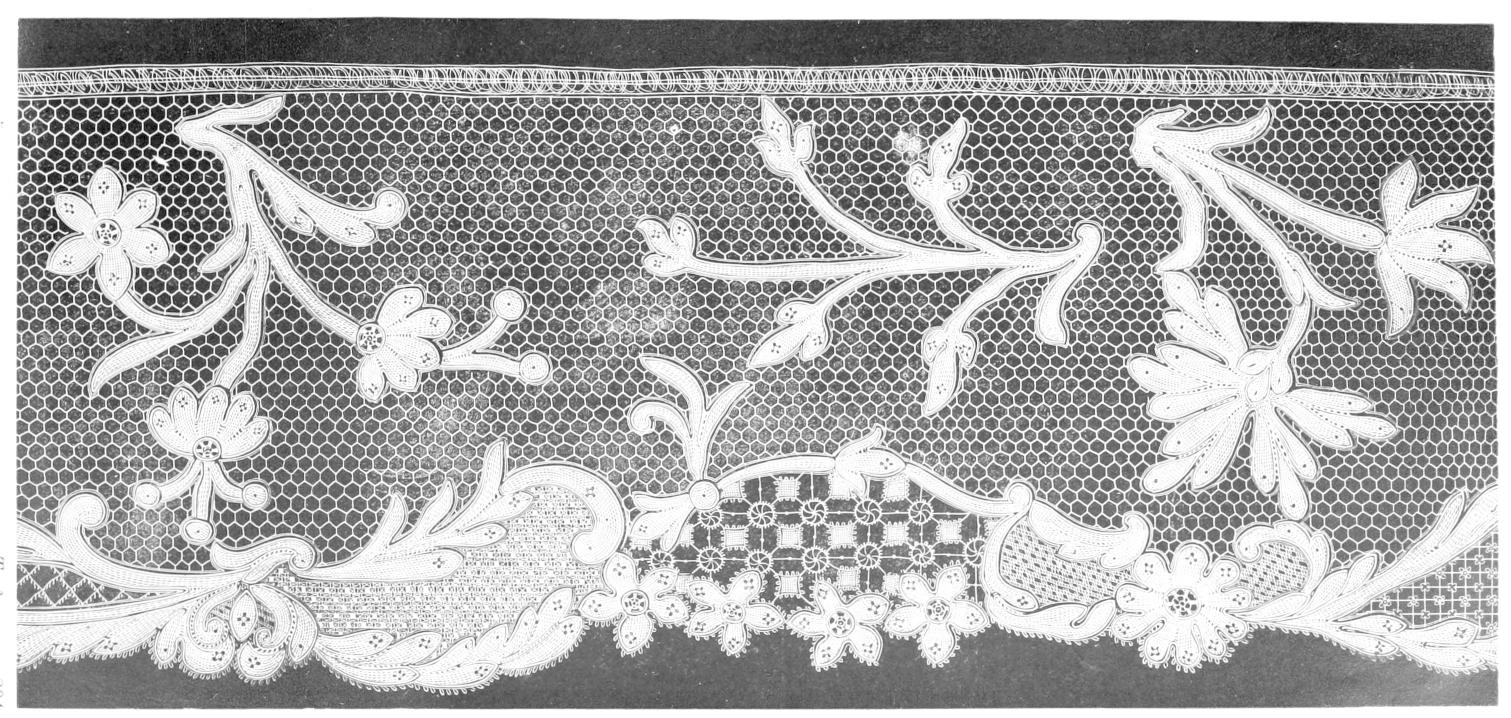

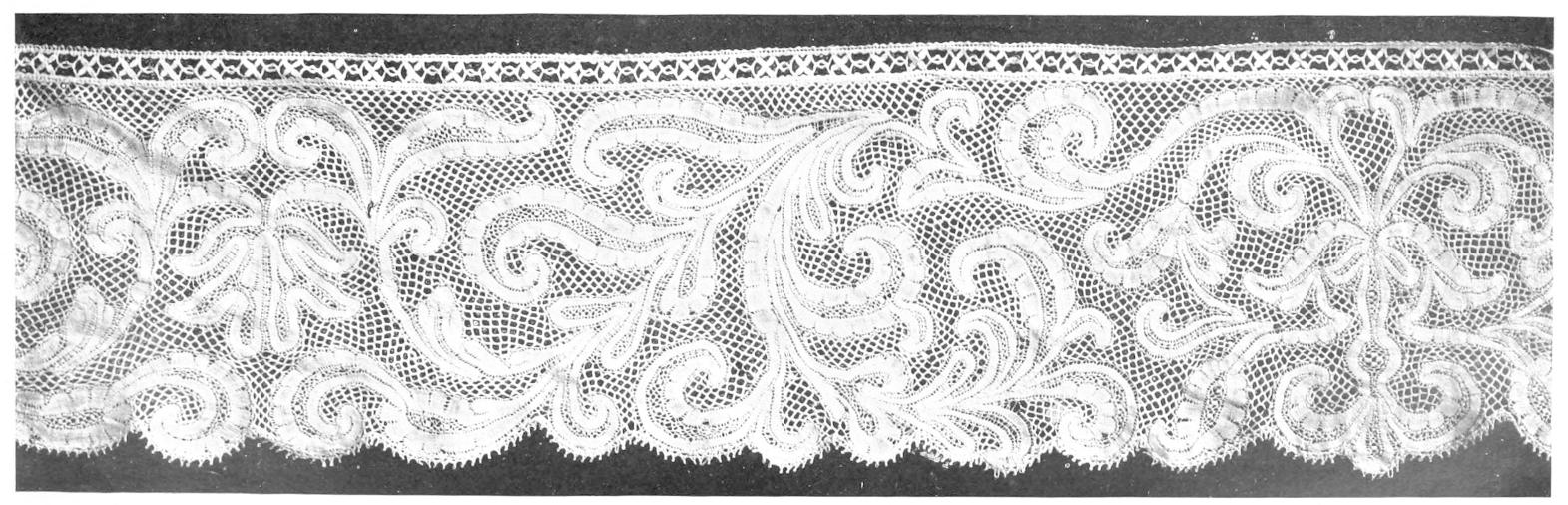

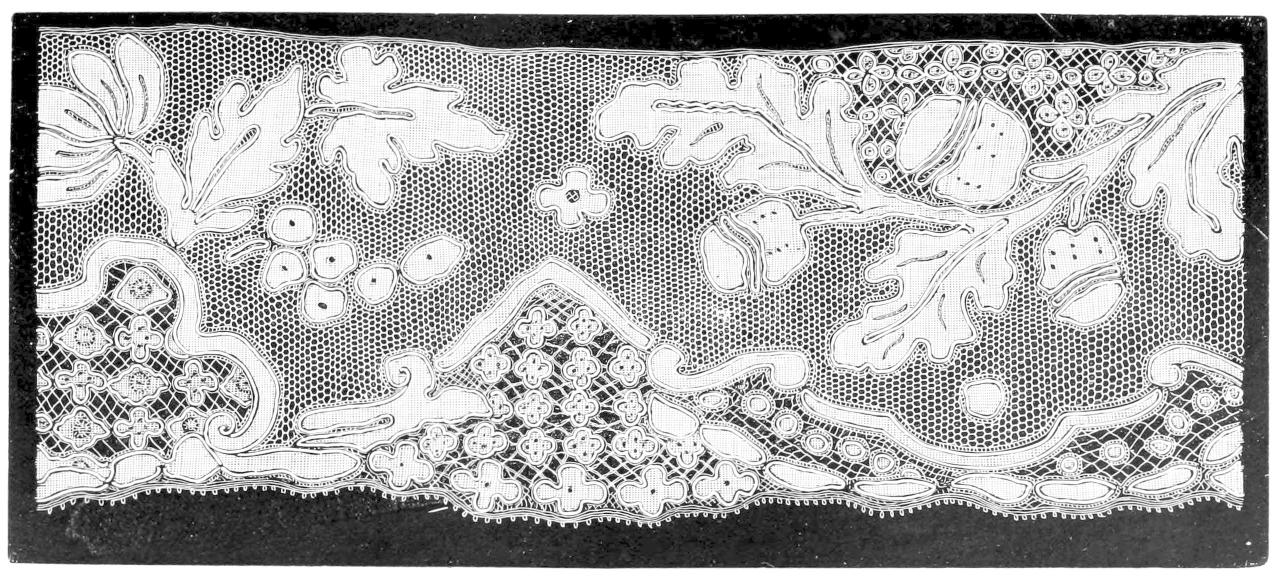

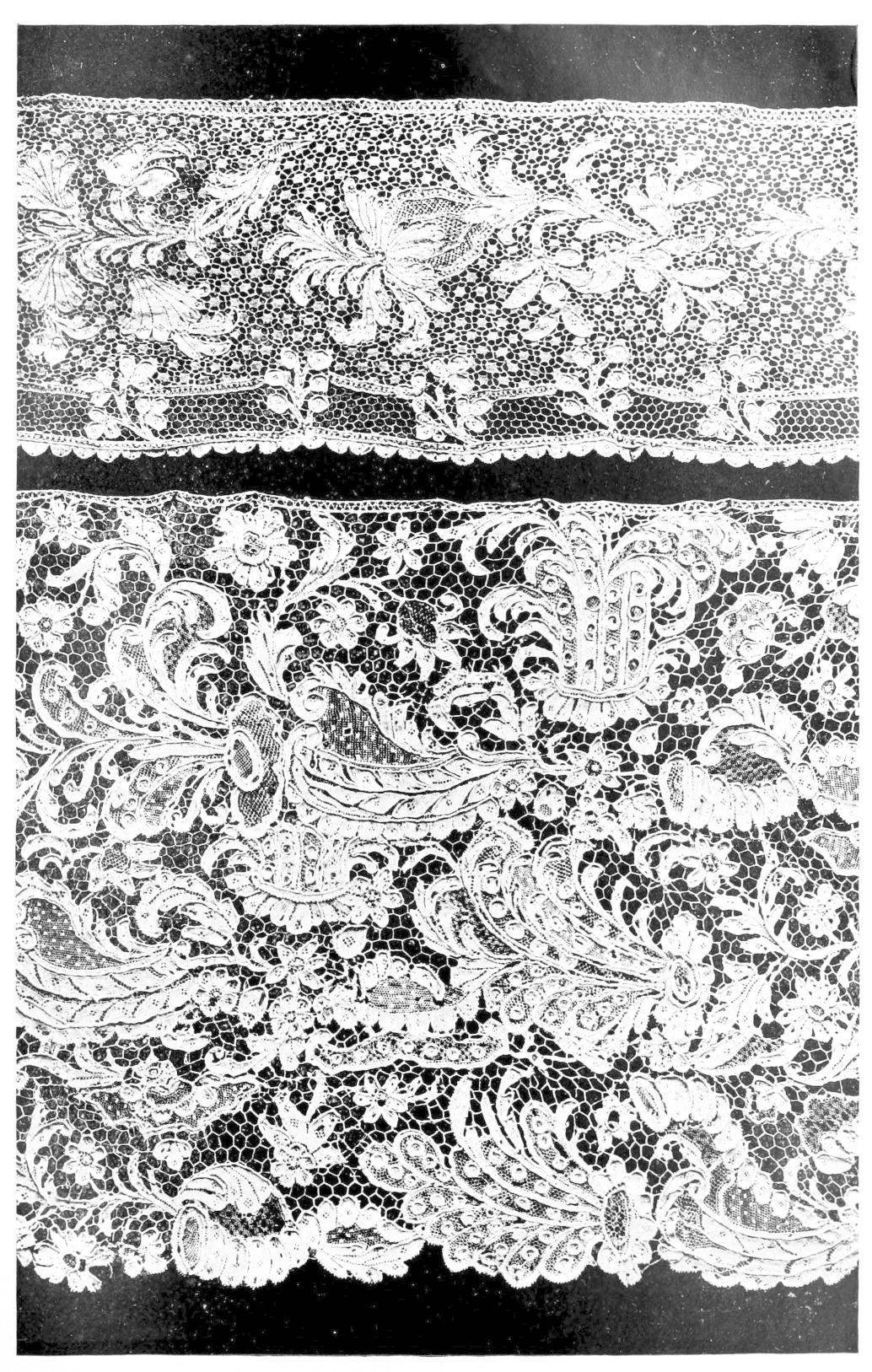

| Flemish.—Flat Spanish Bobbin Lace |

Plate XLI |

132 |

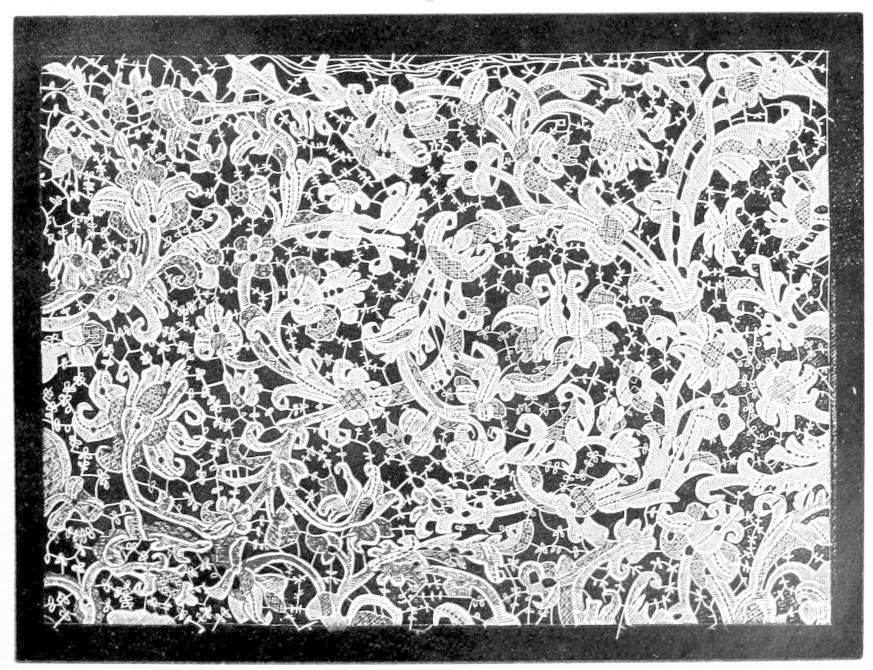

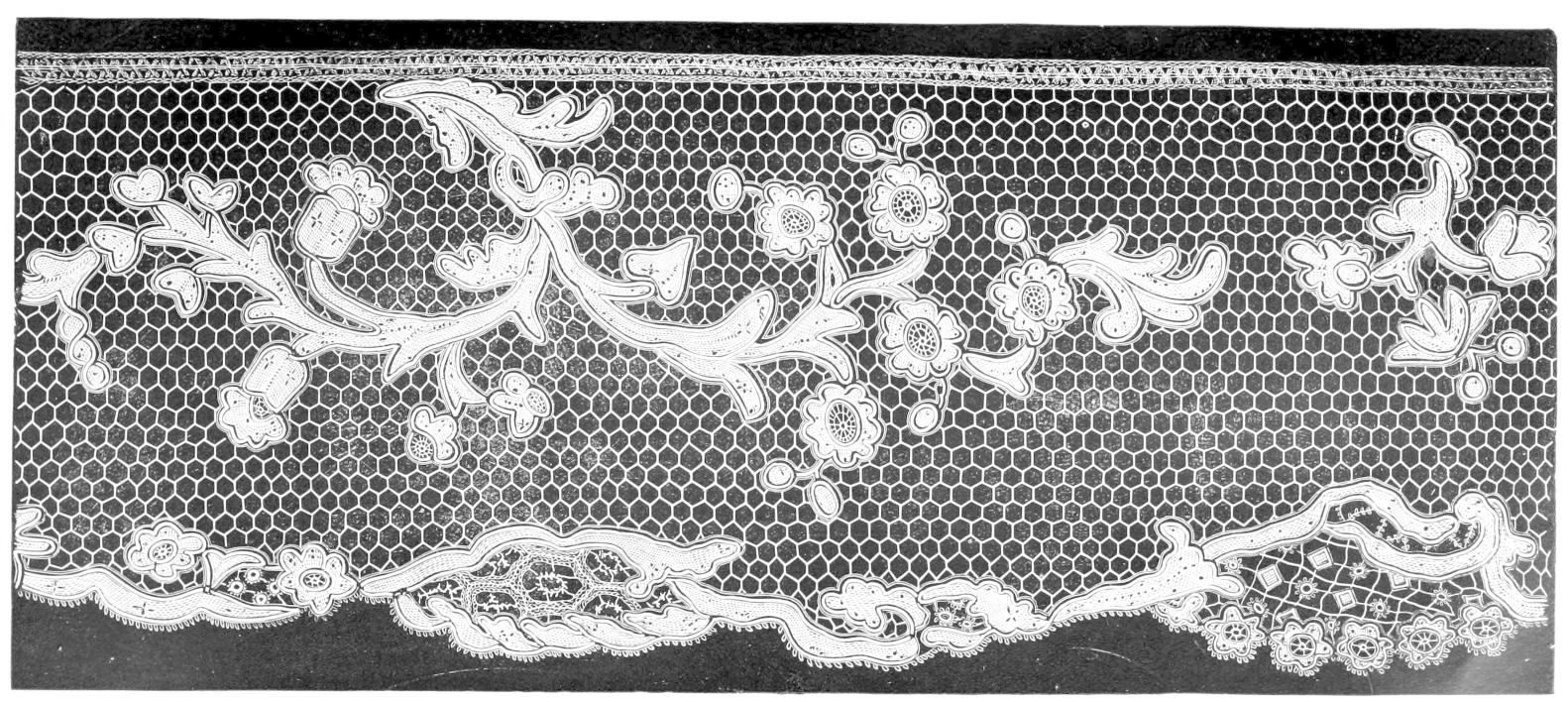

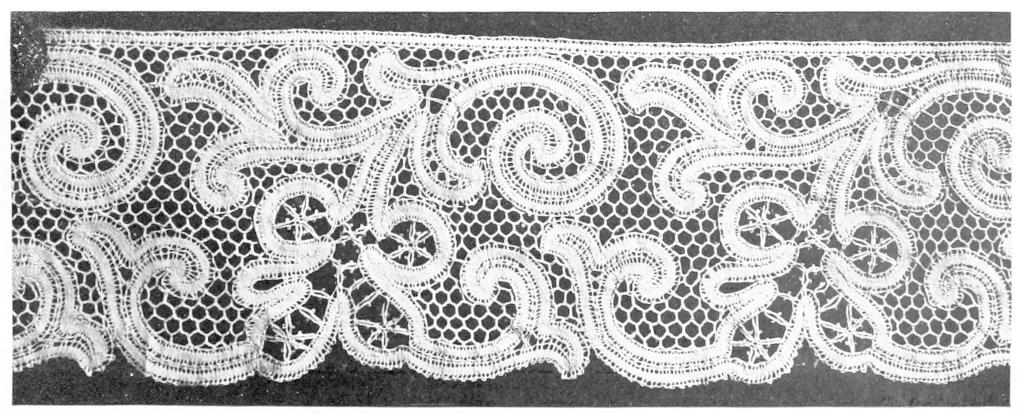

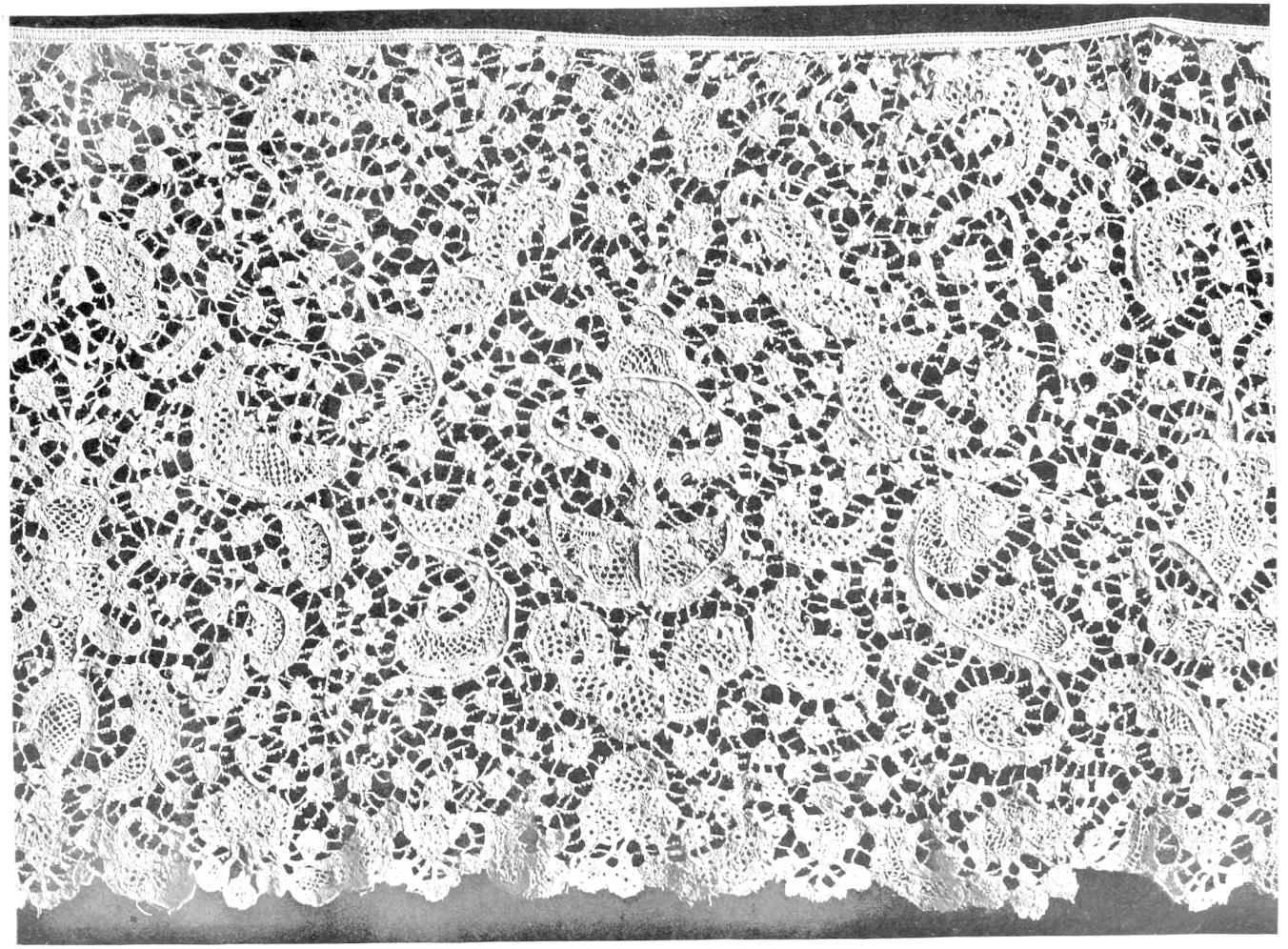

| Flemish.—Guipure de Flandre |

" VXLII |

134 |

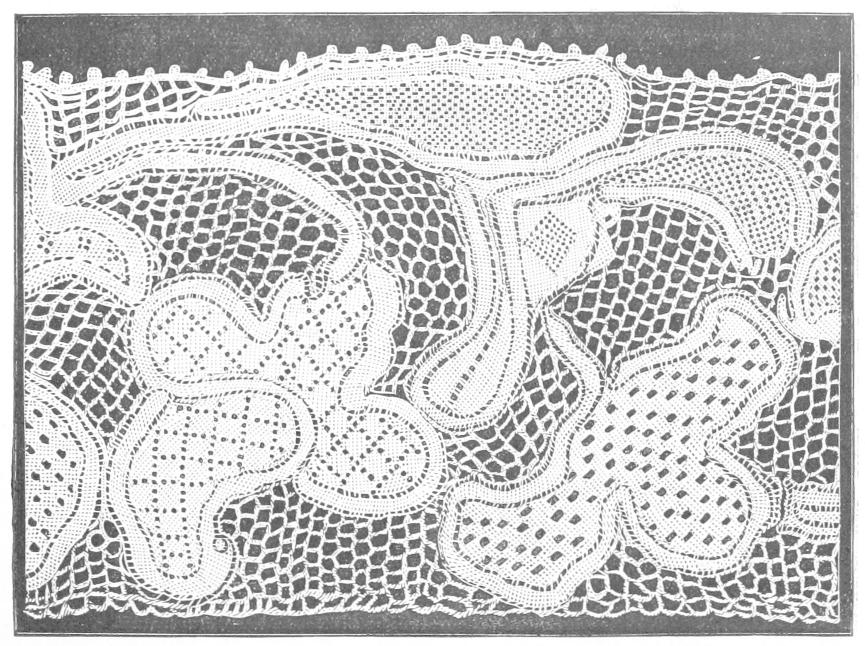

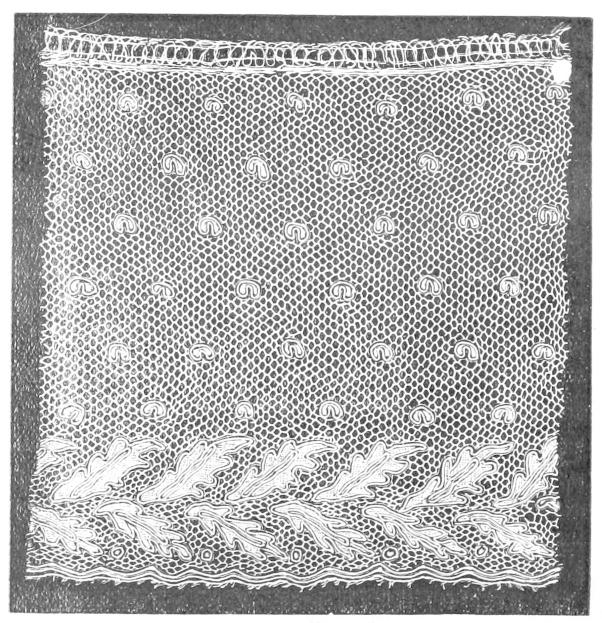

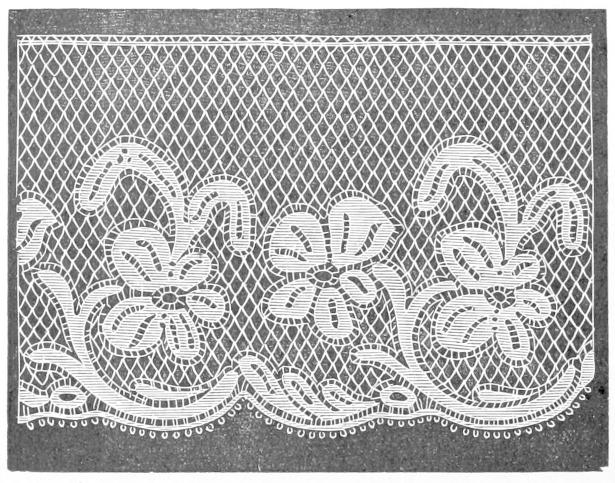

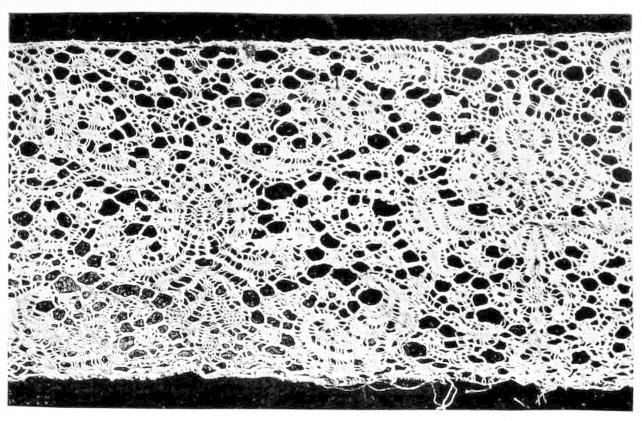

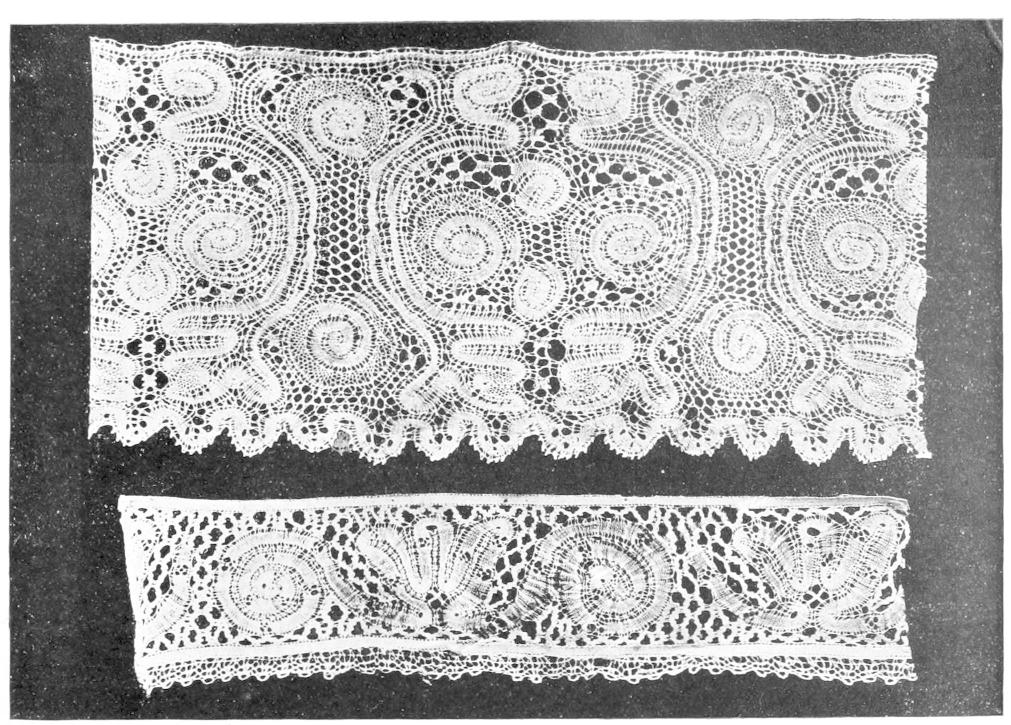

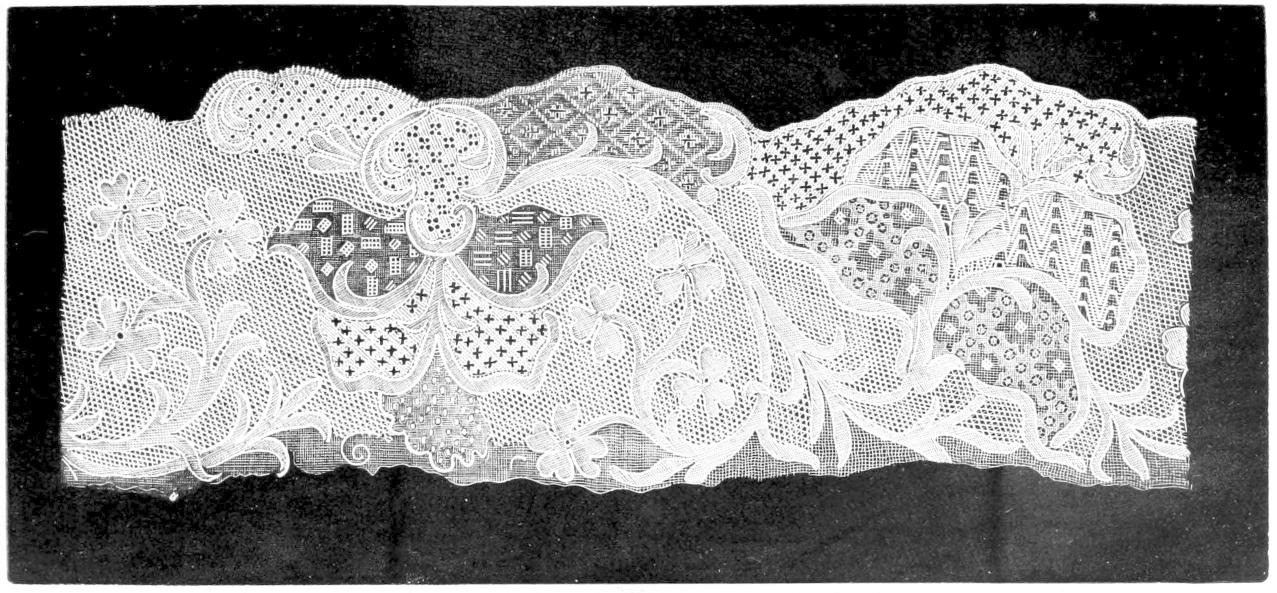

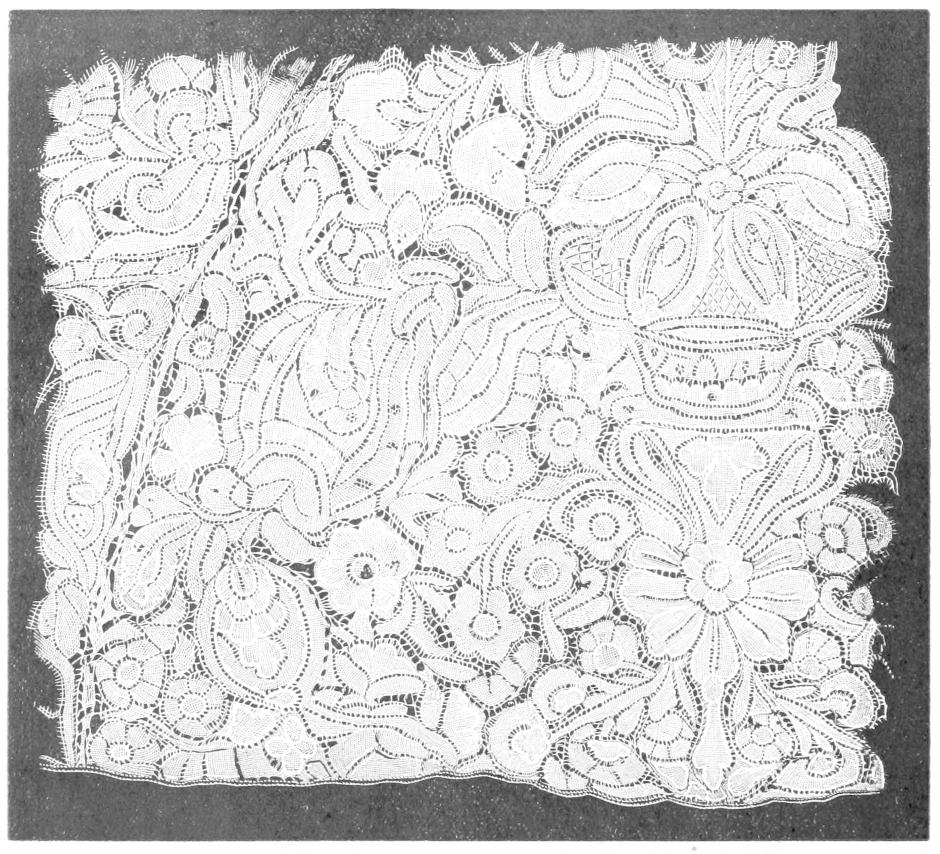

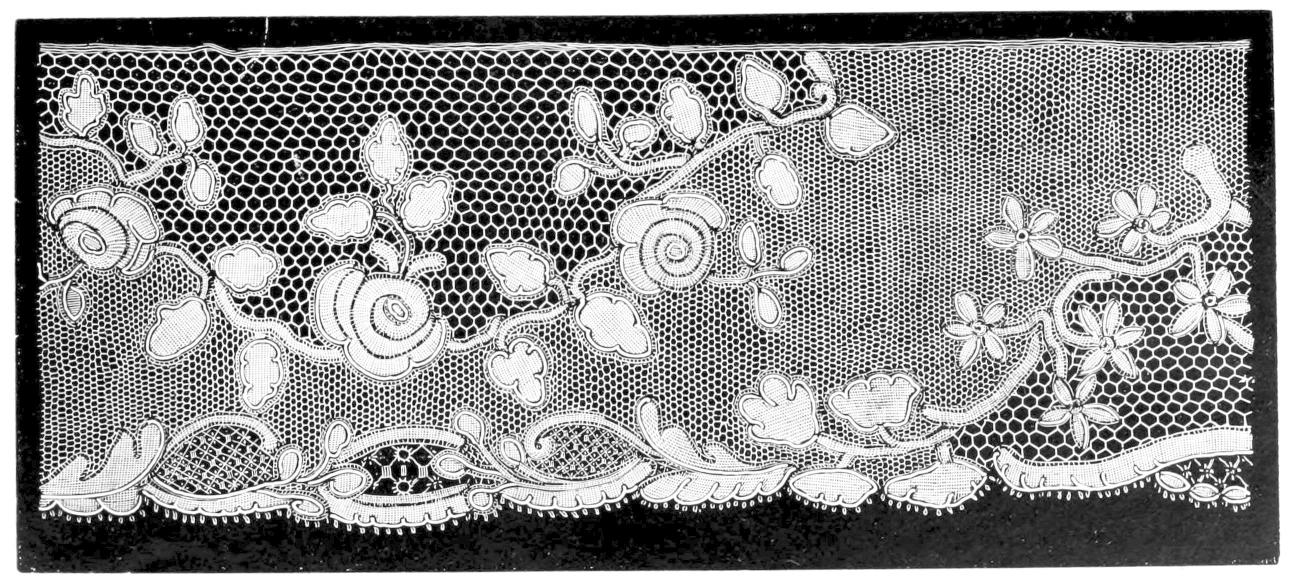

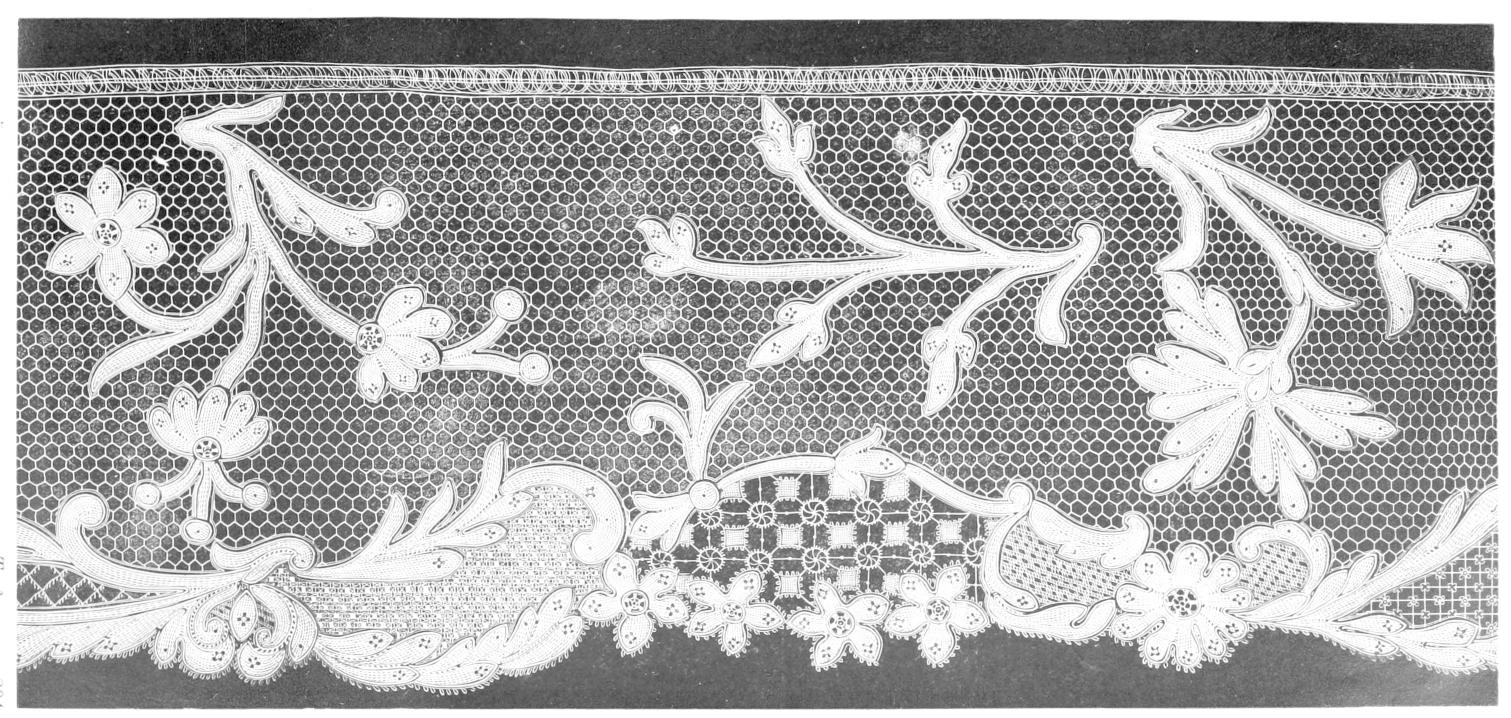

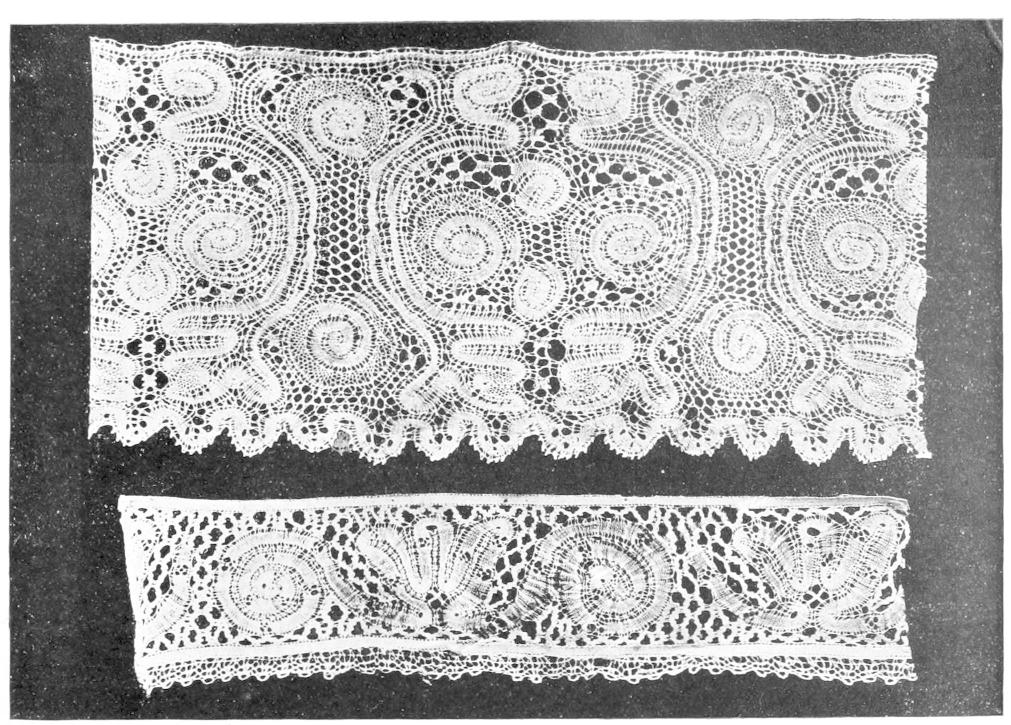

| Belgian.—Bobbin-made, Binche |

" IXLIII |

136 |

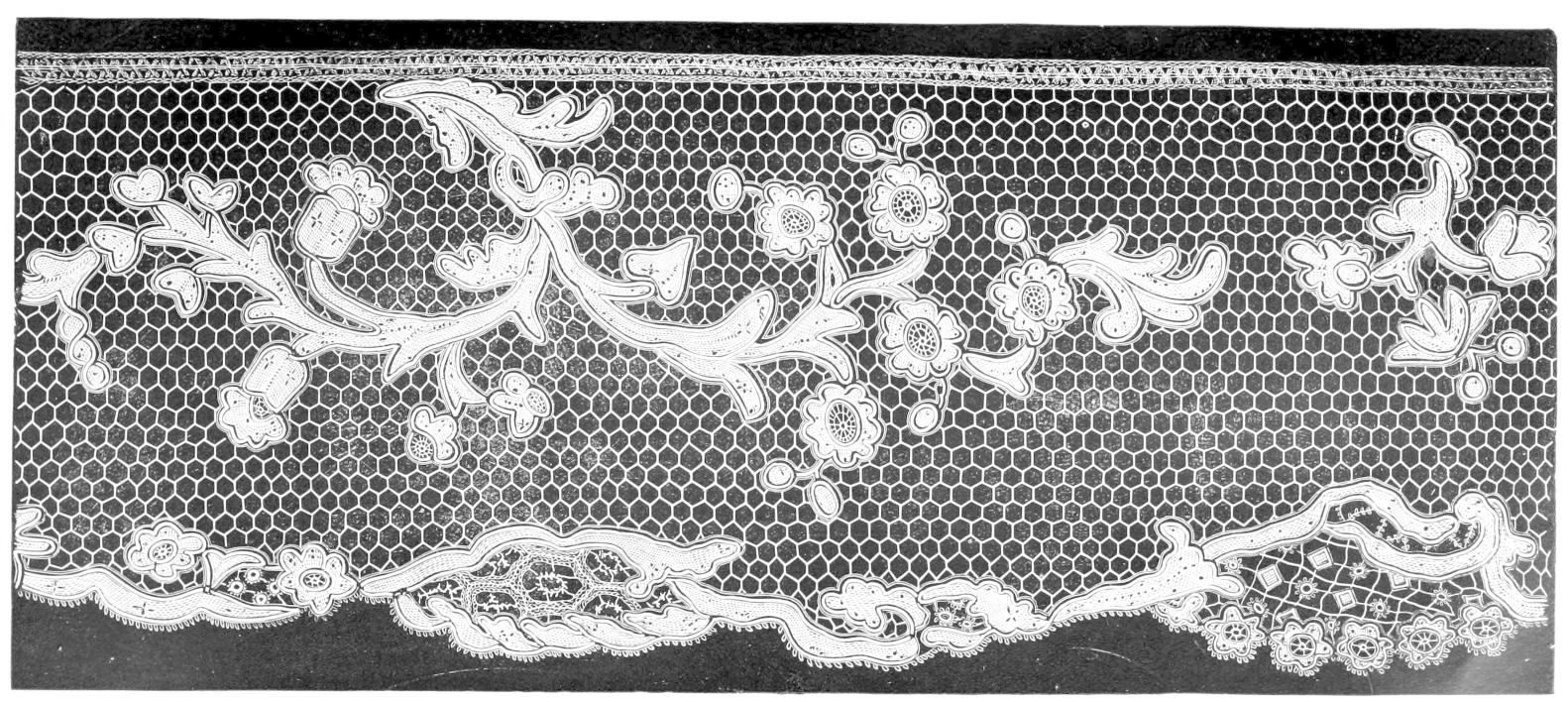

| Belgia".—Bobbi"-made, Marche |

" IXLIV |

136 |

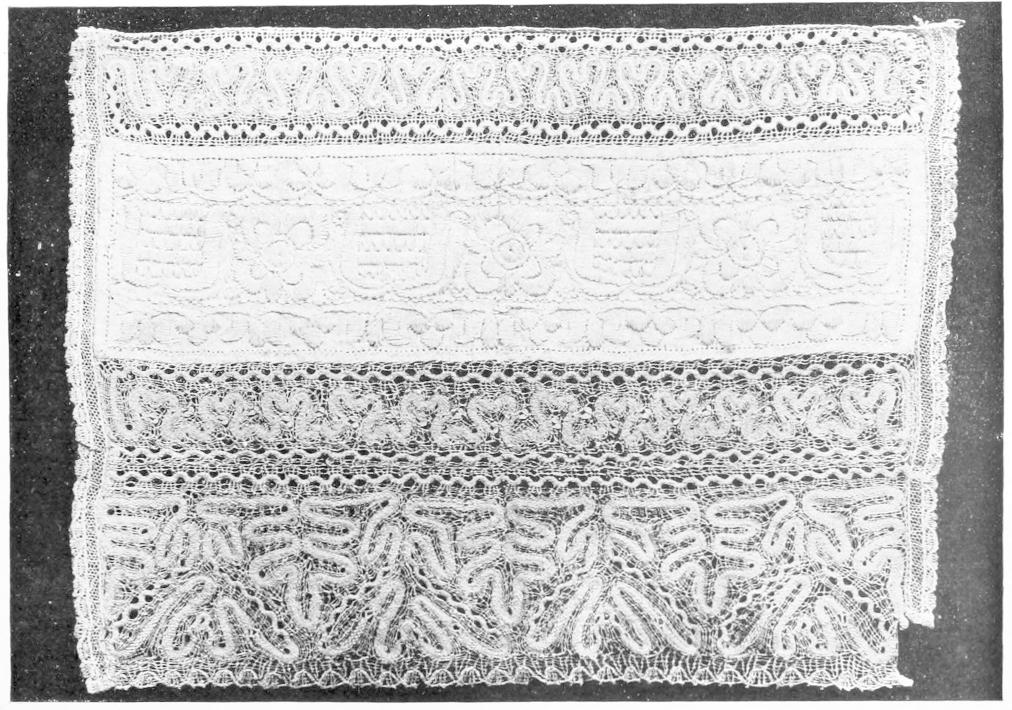

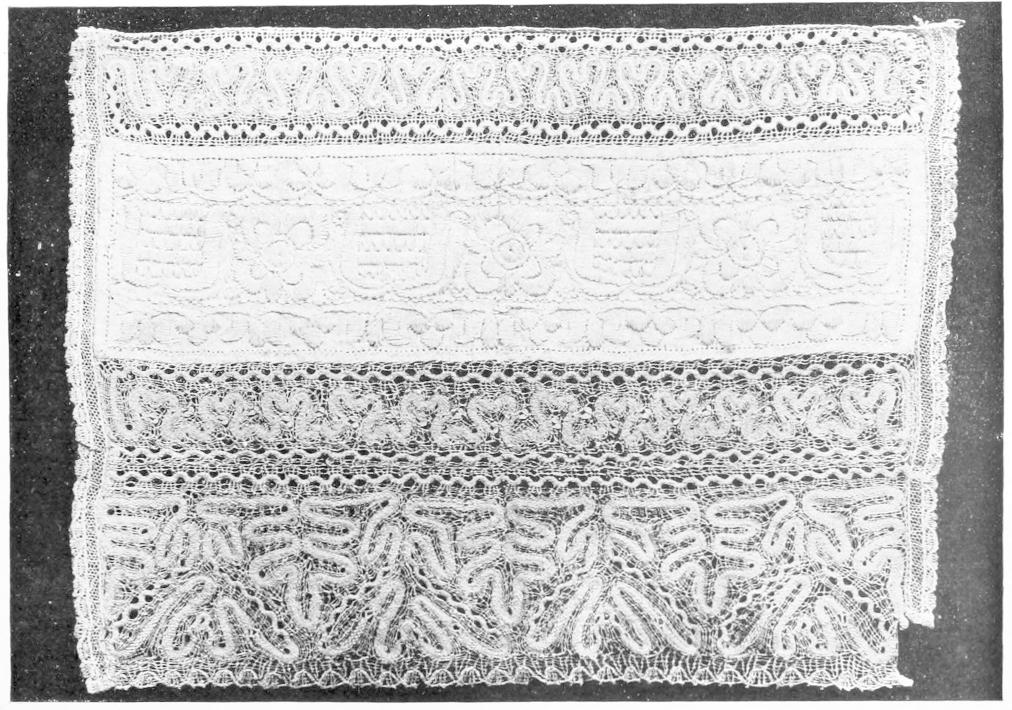

| Drawn and Embroidered Muslin, Flemish |

" IIXLV |

136 |

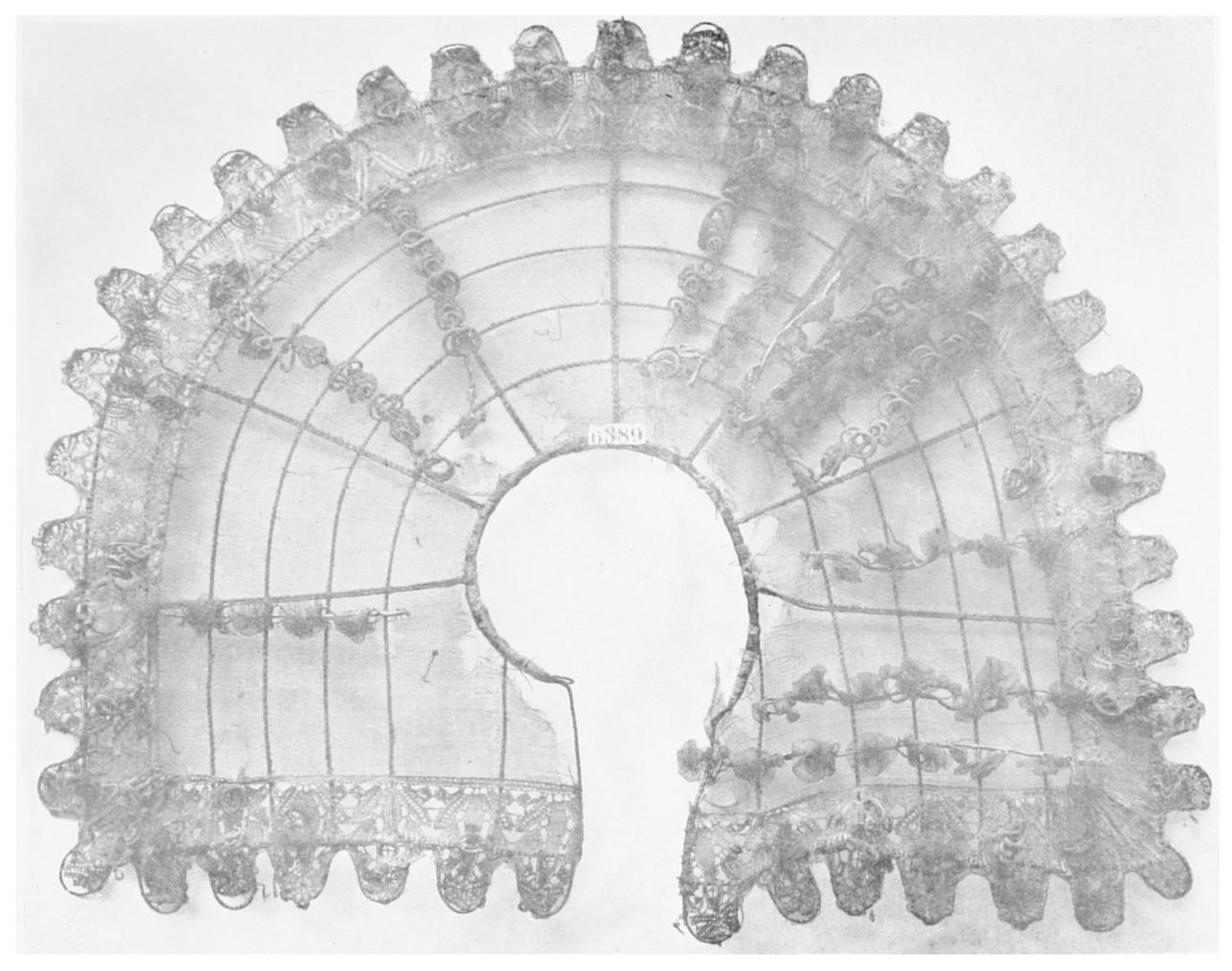

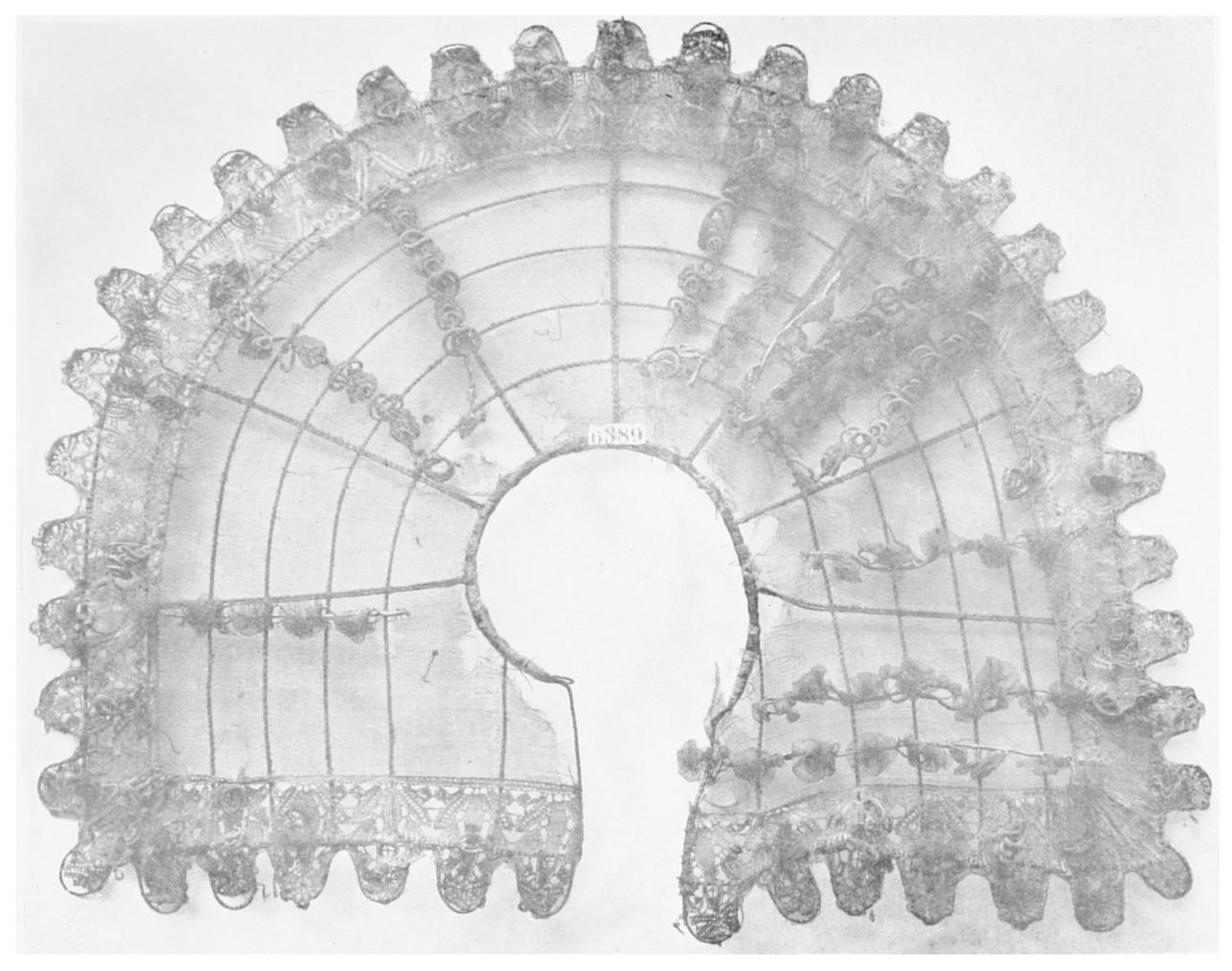

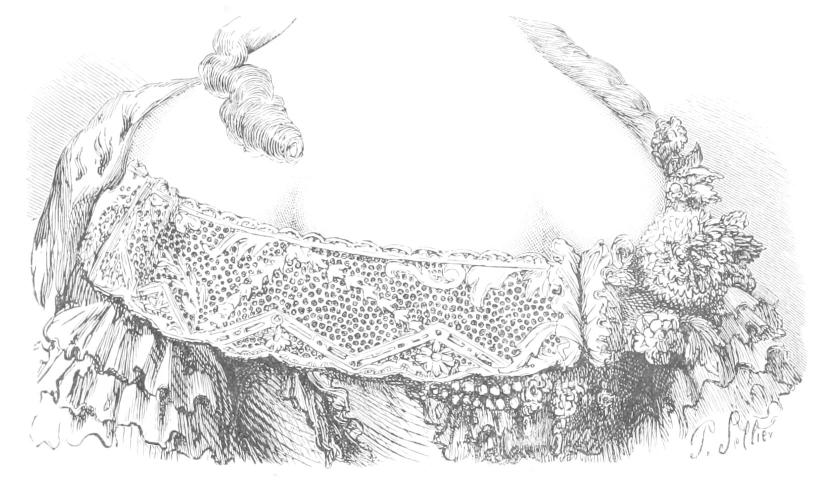

| Ruff, Edged With Lace |

" IXLVI |

142 |

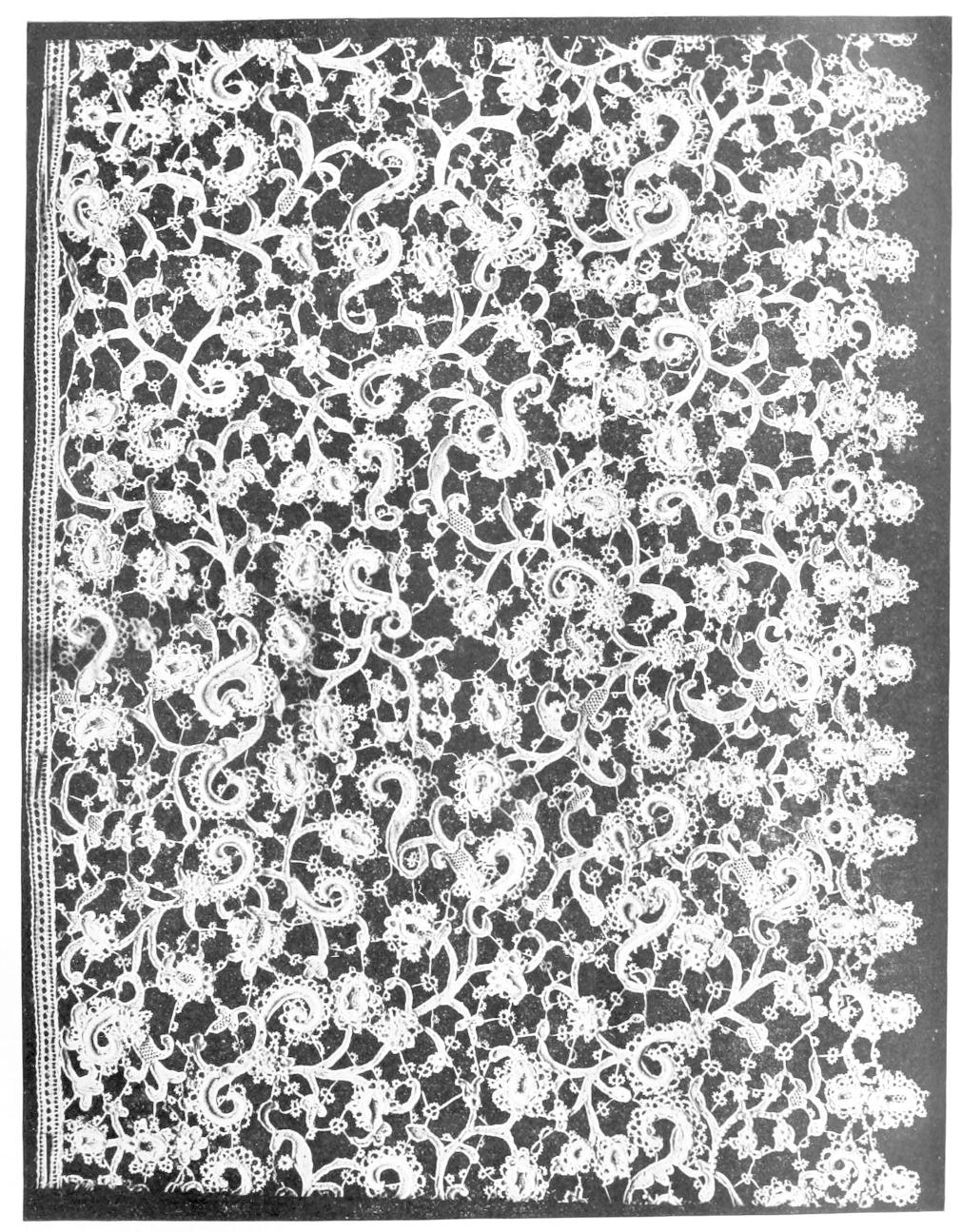

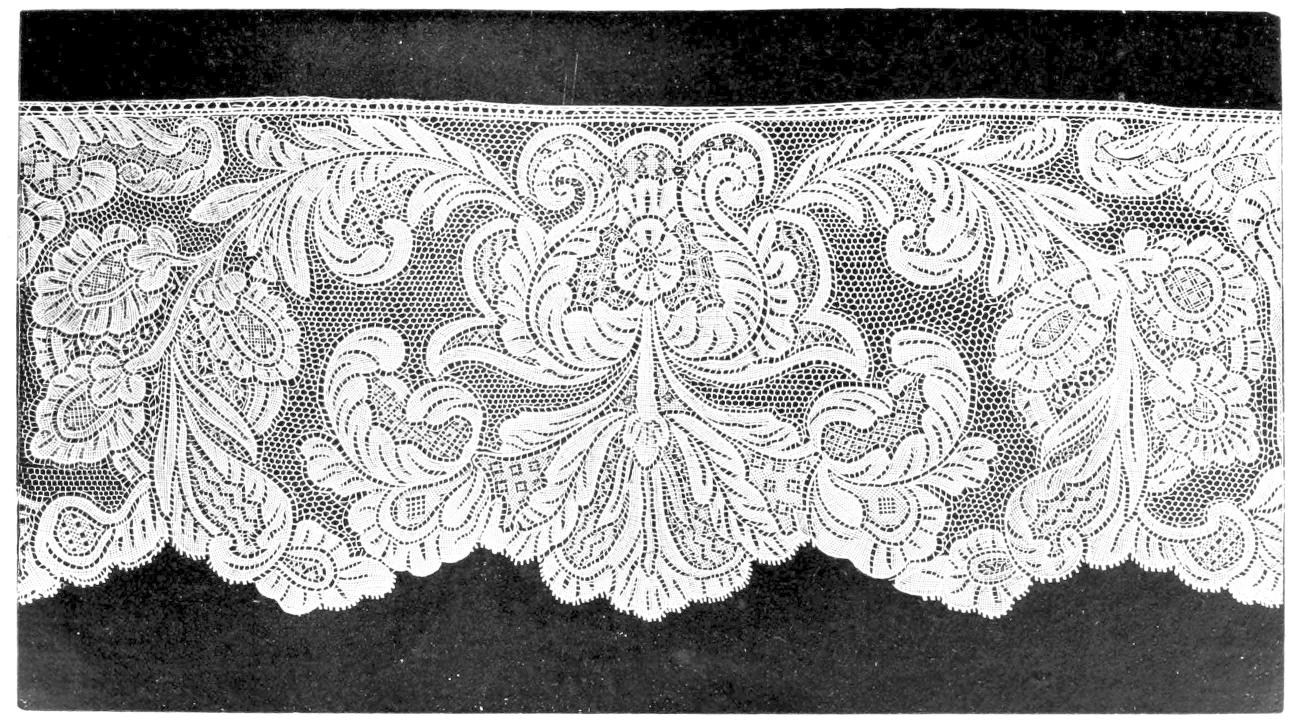

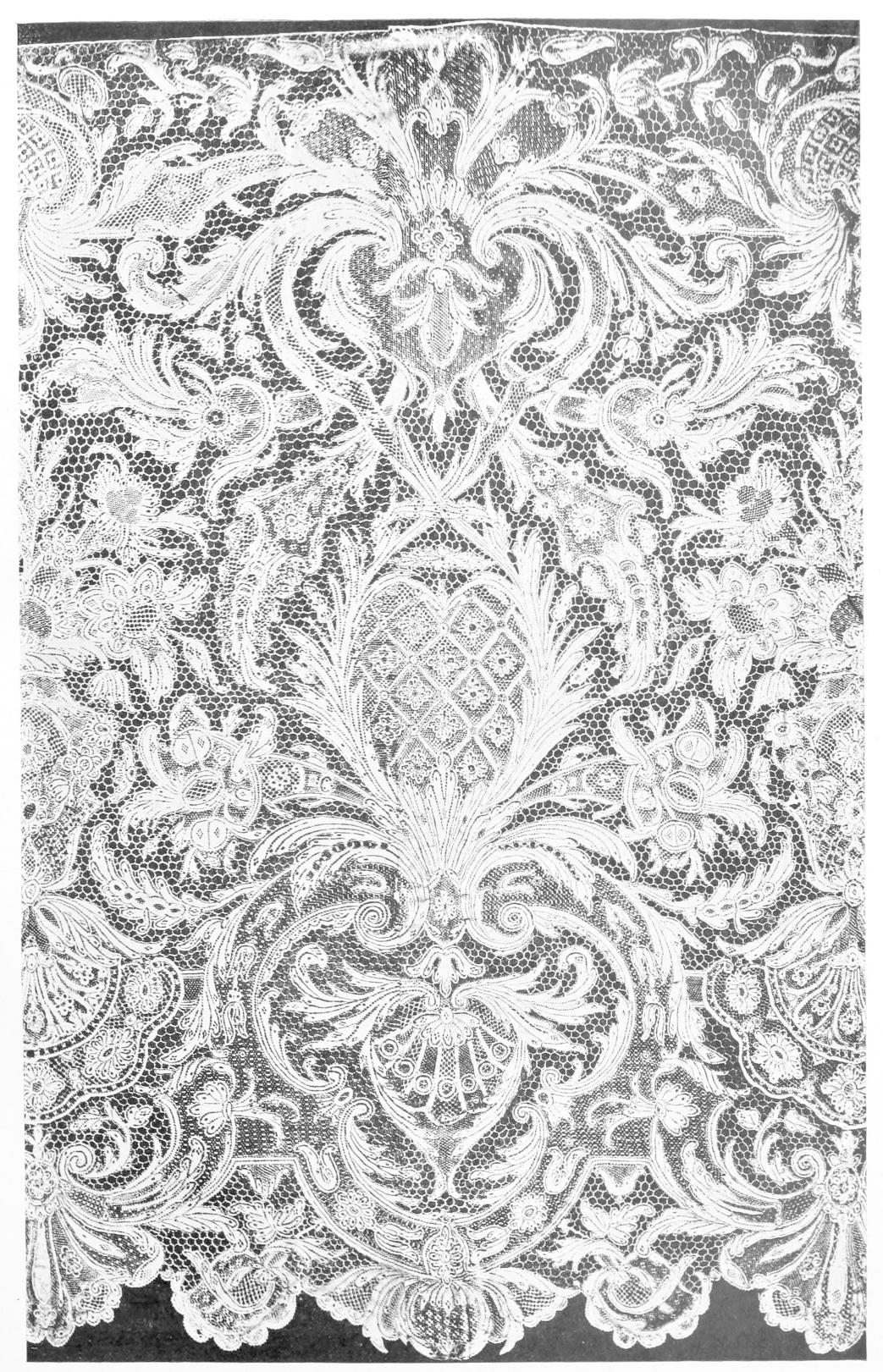

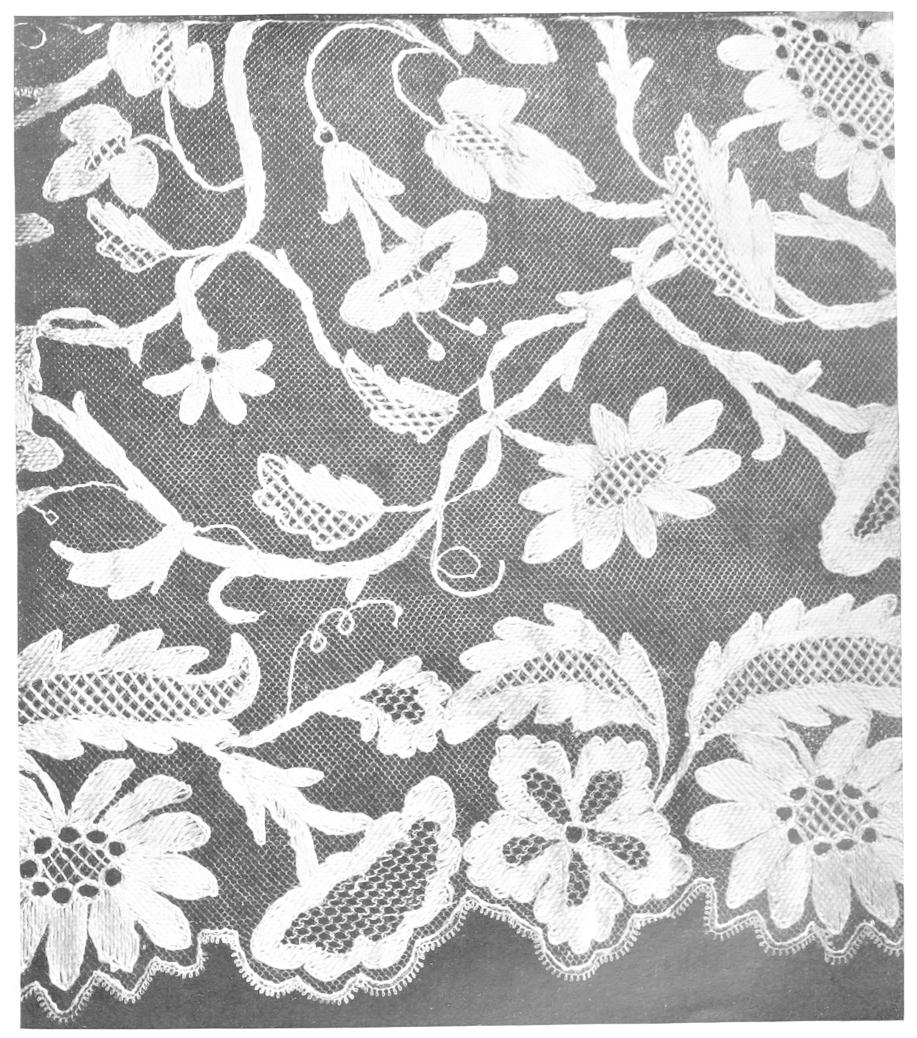

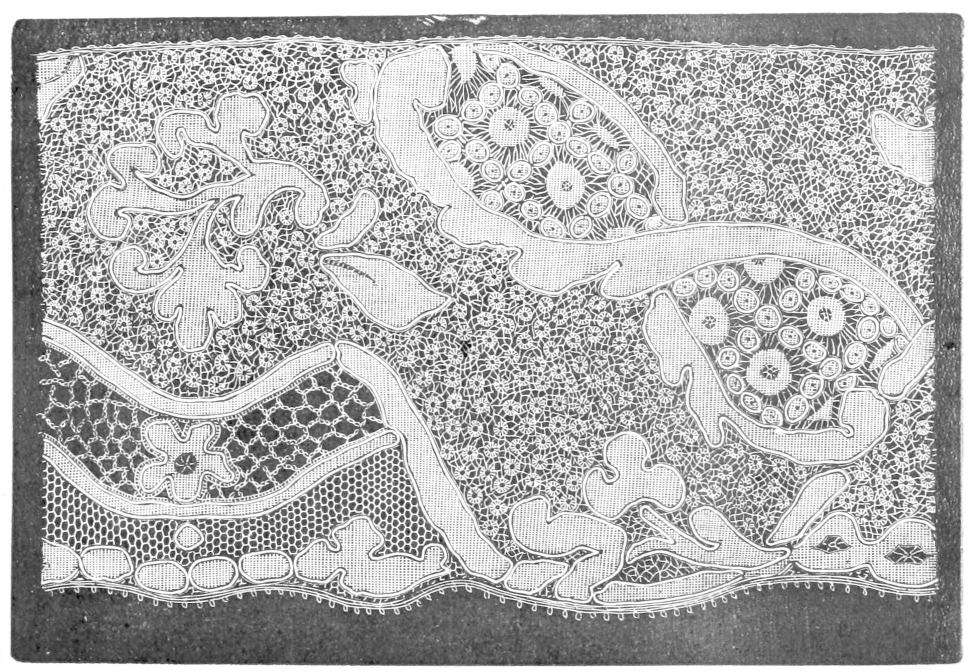

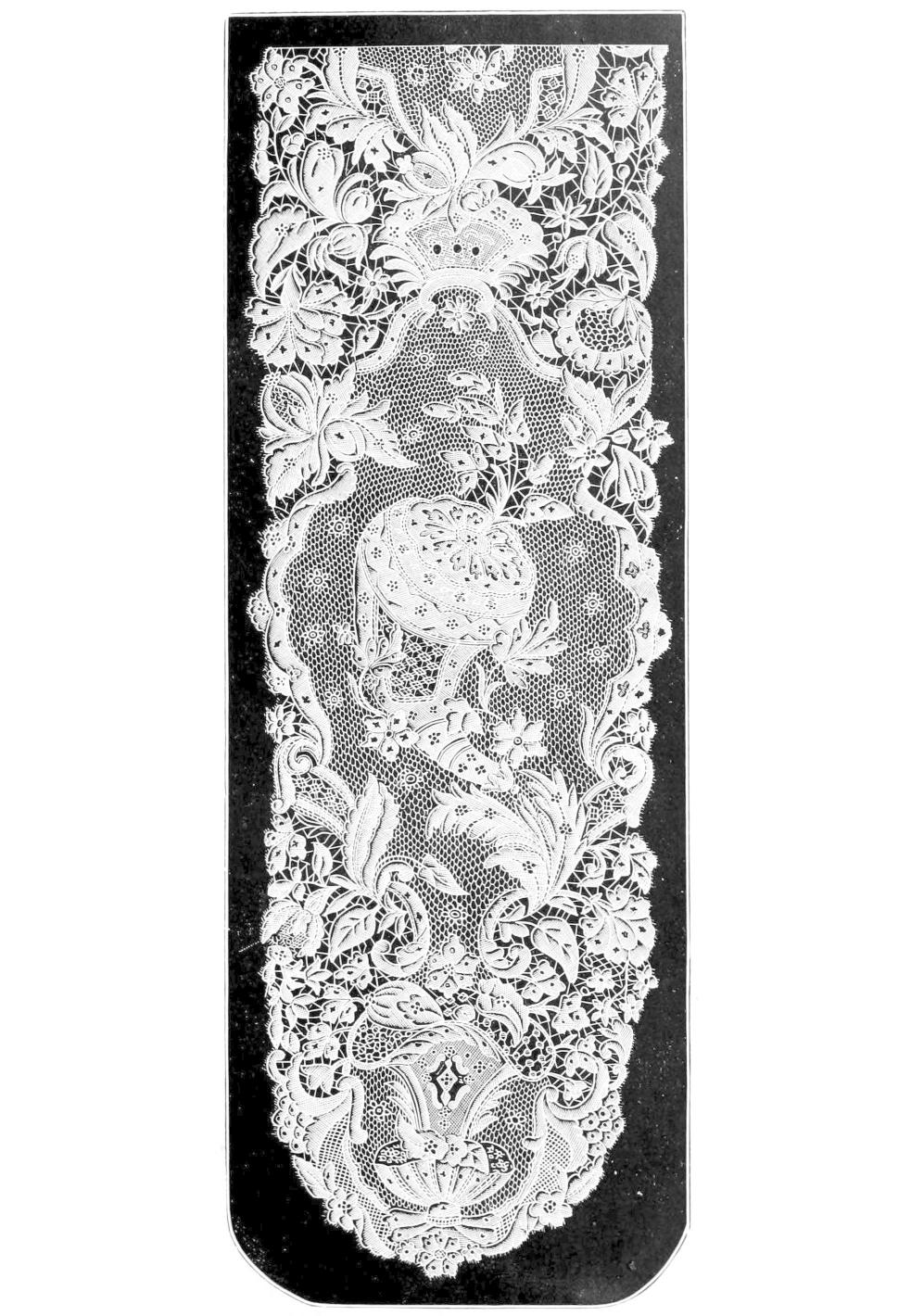

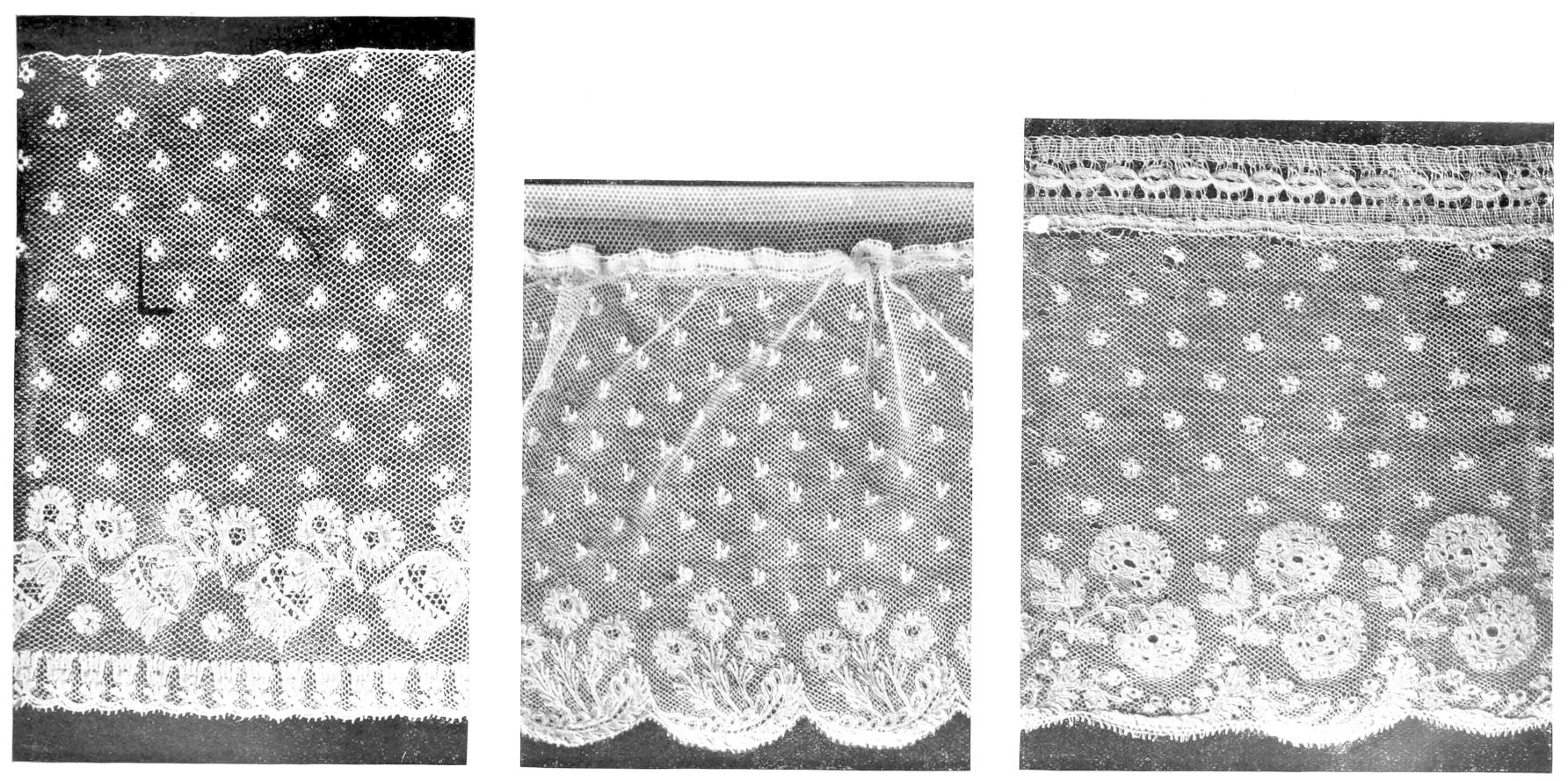

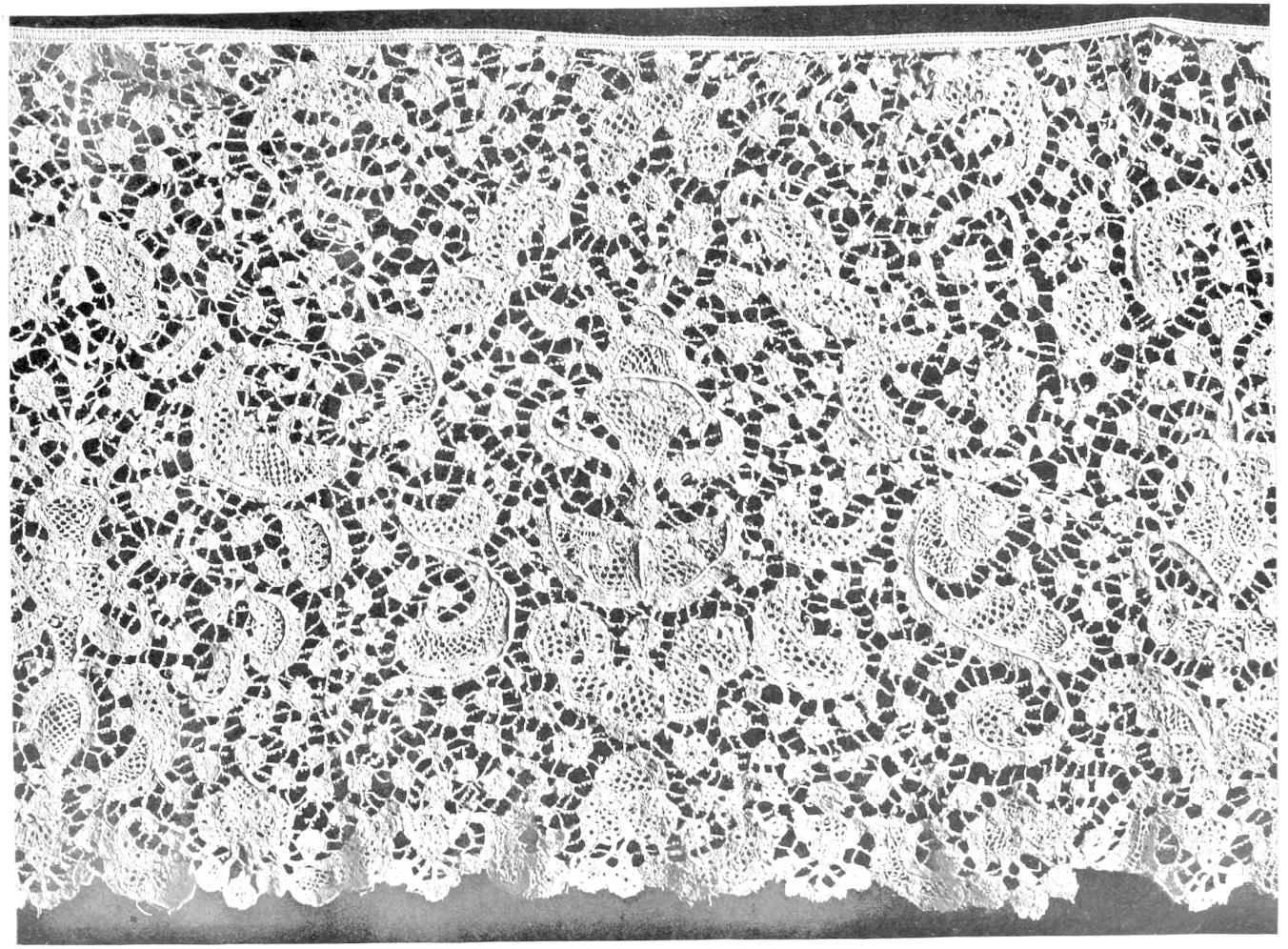

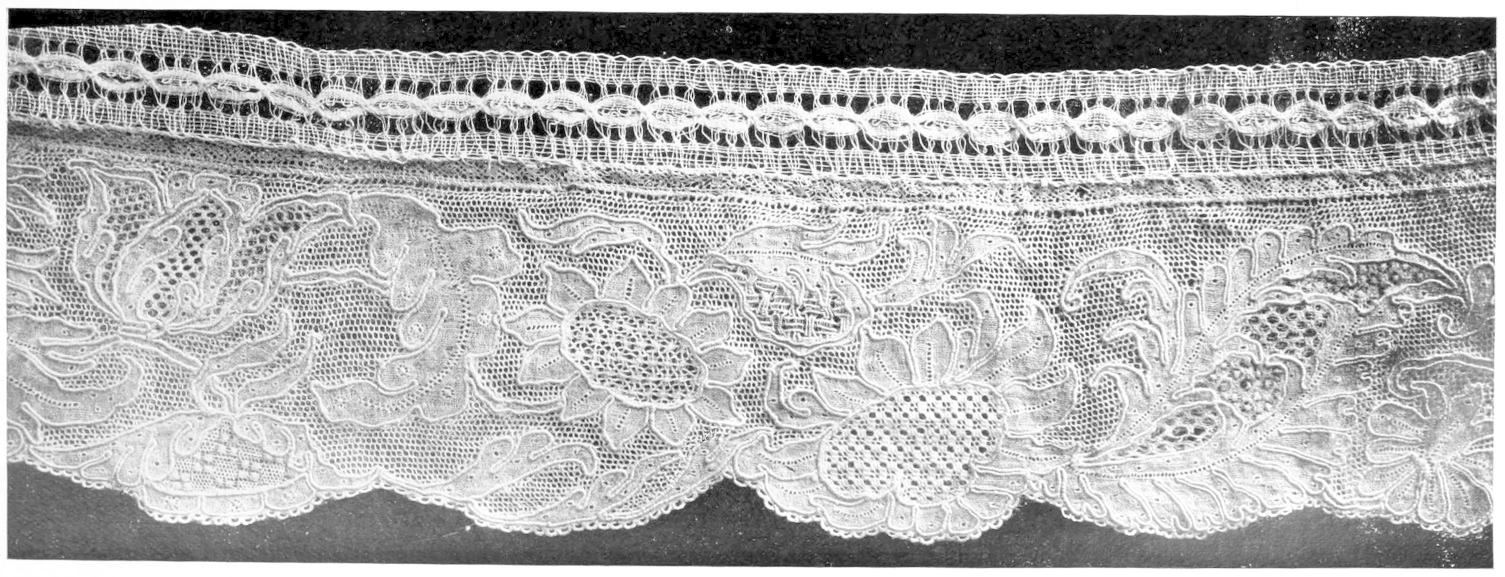

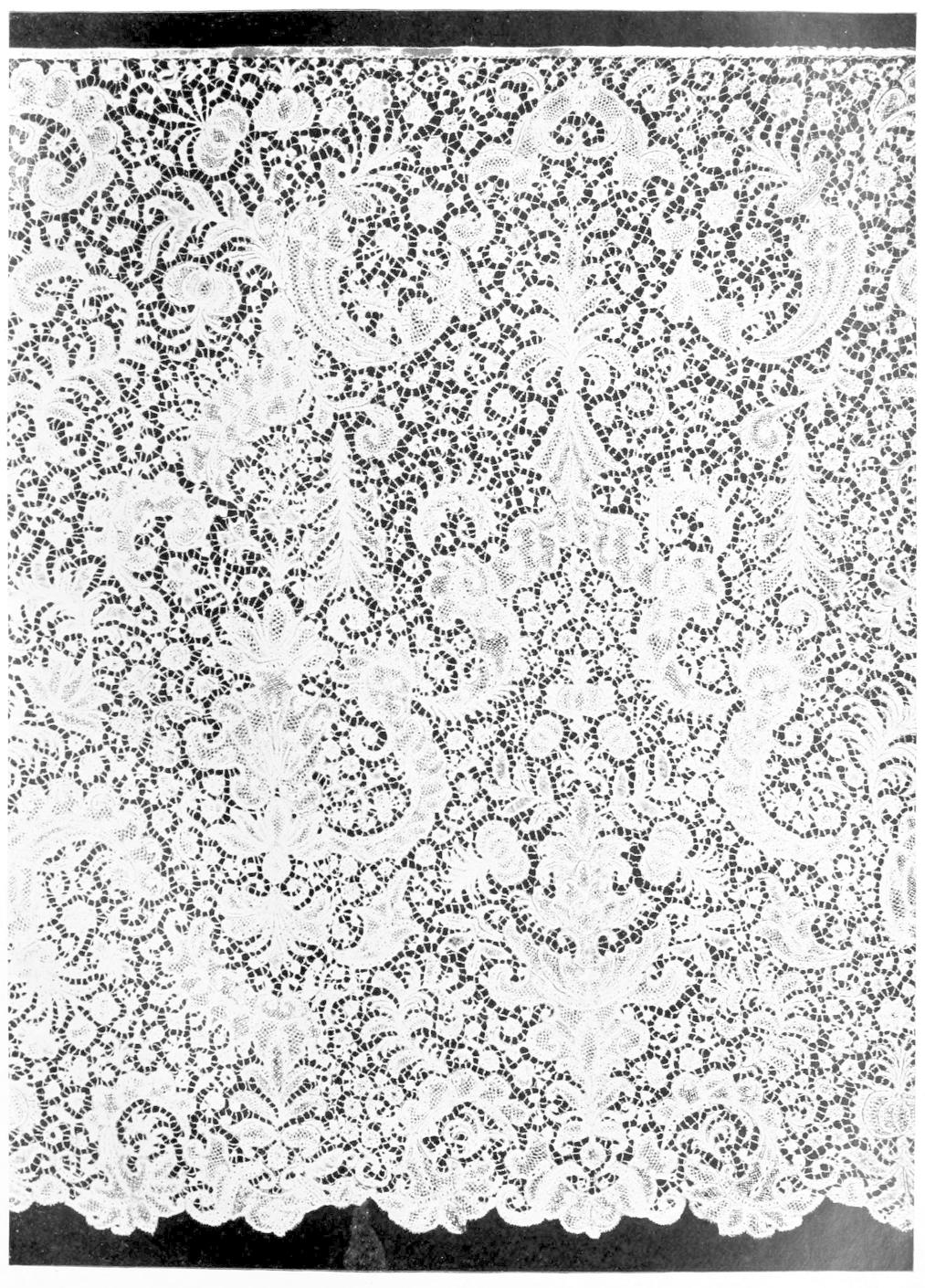

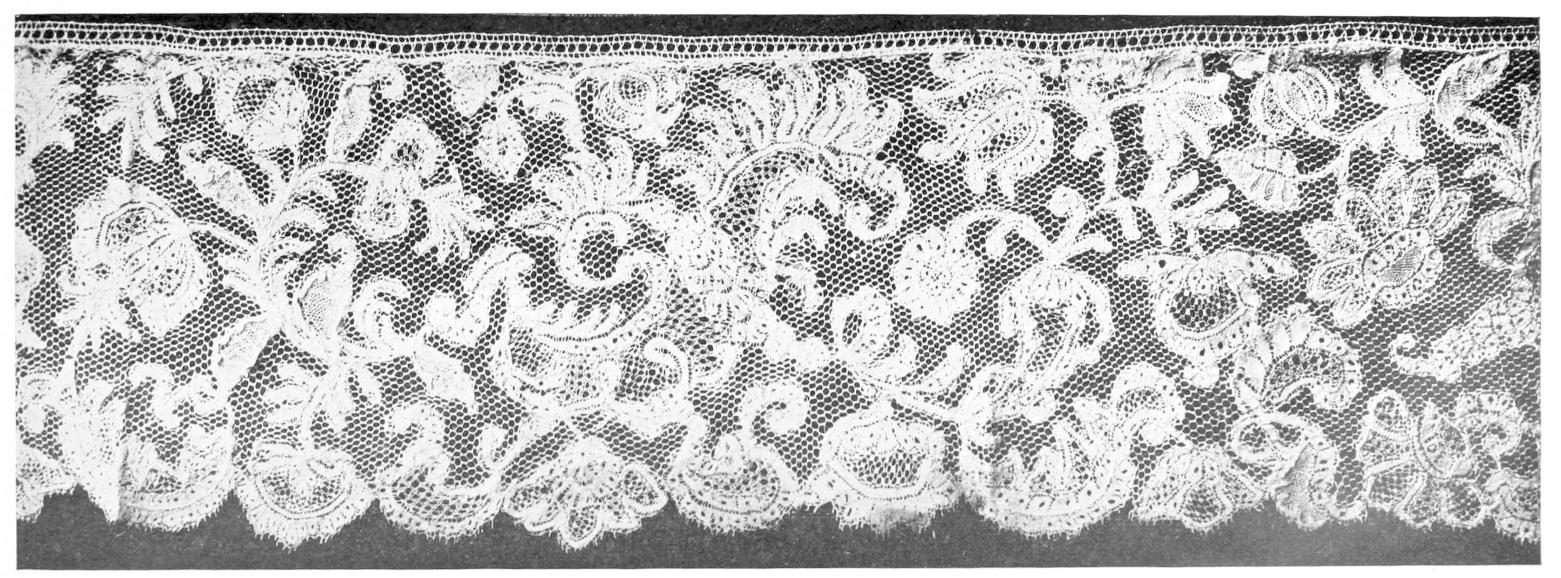

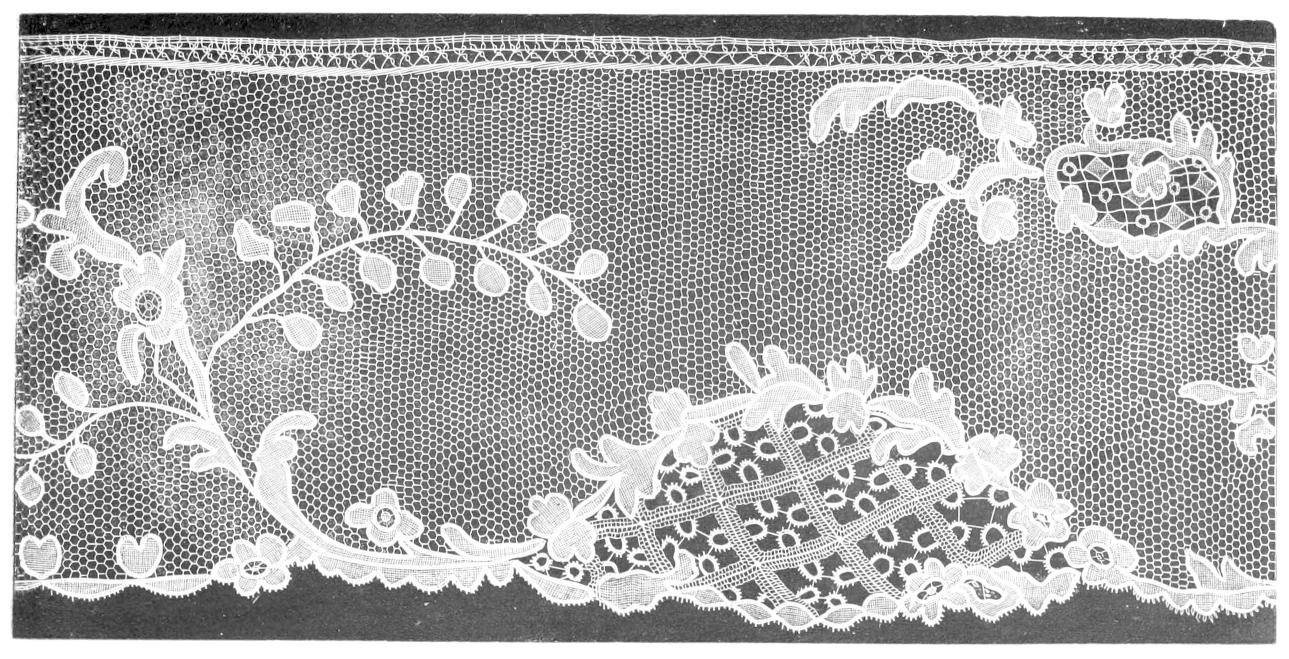

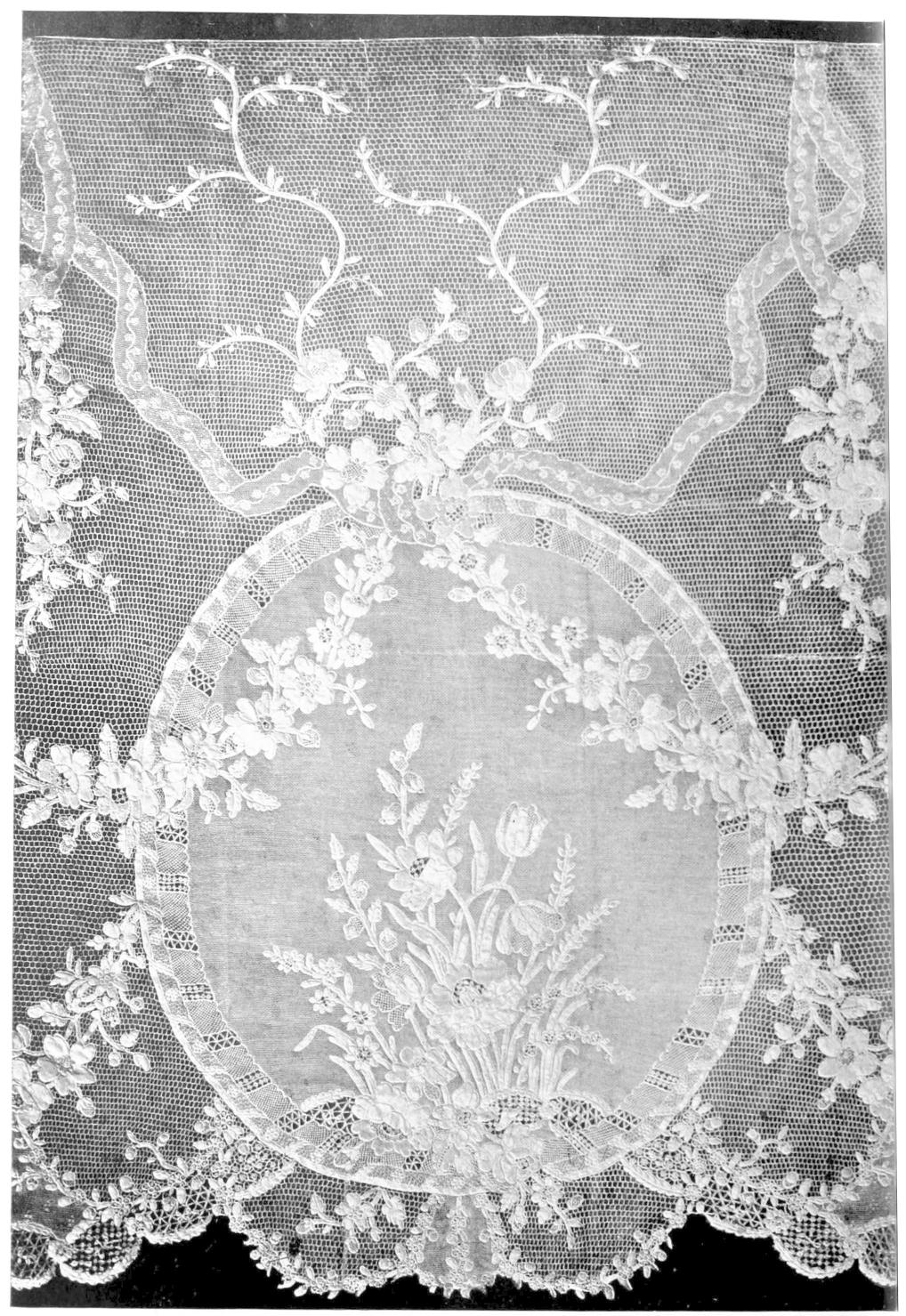

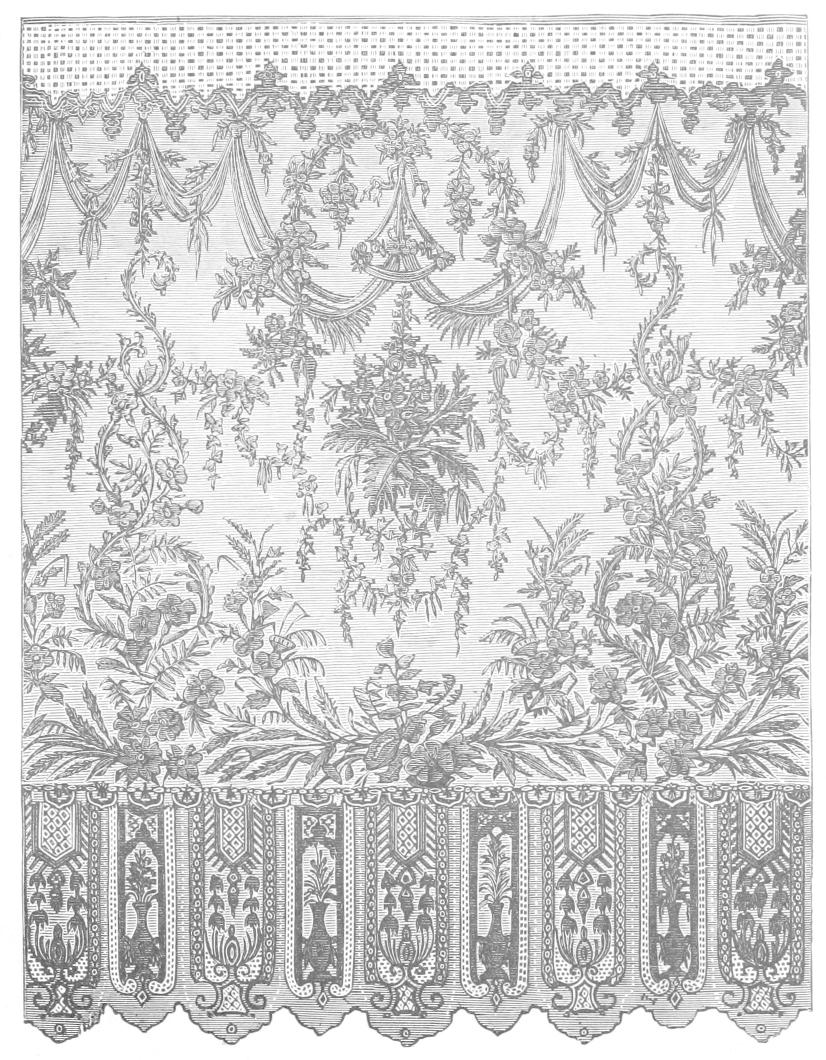

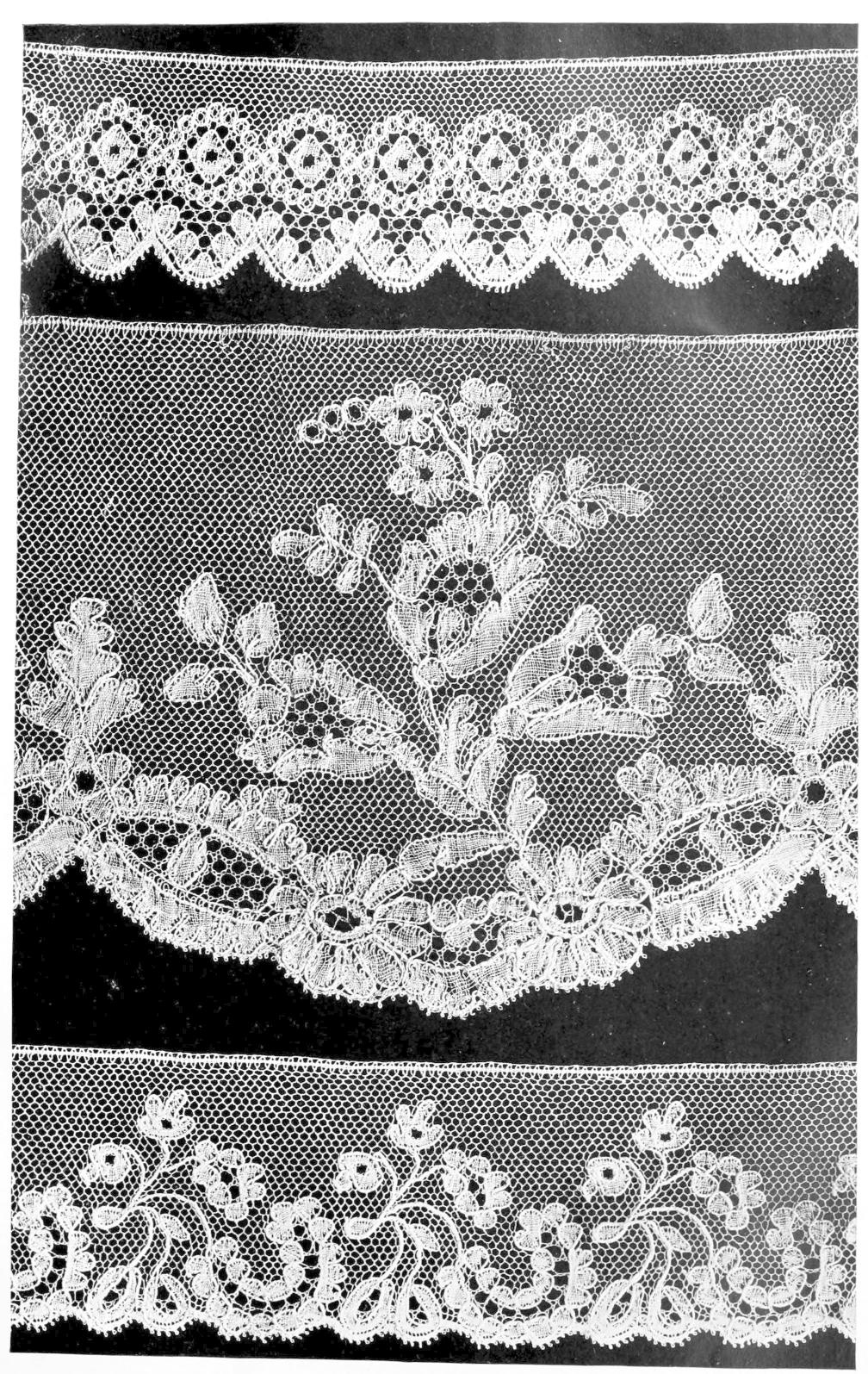

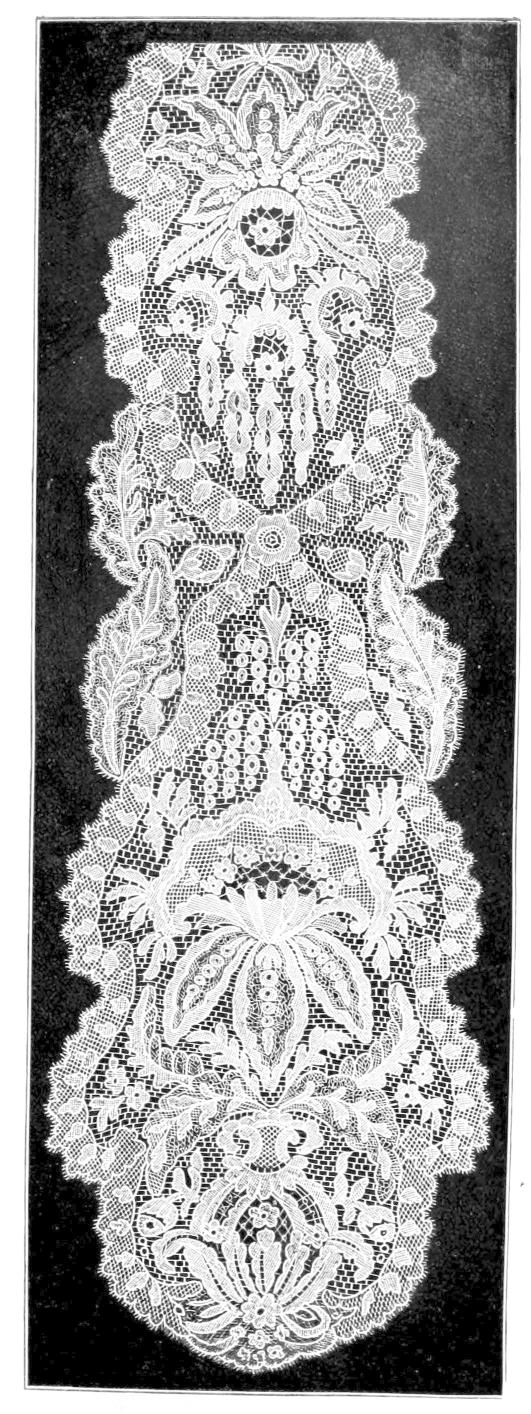

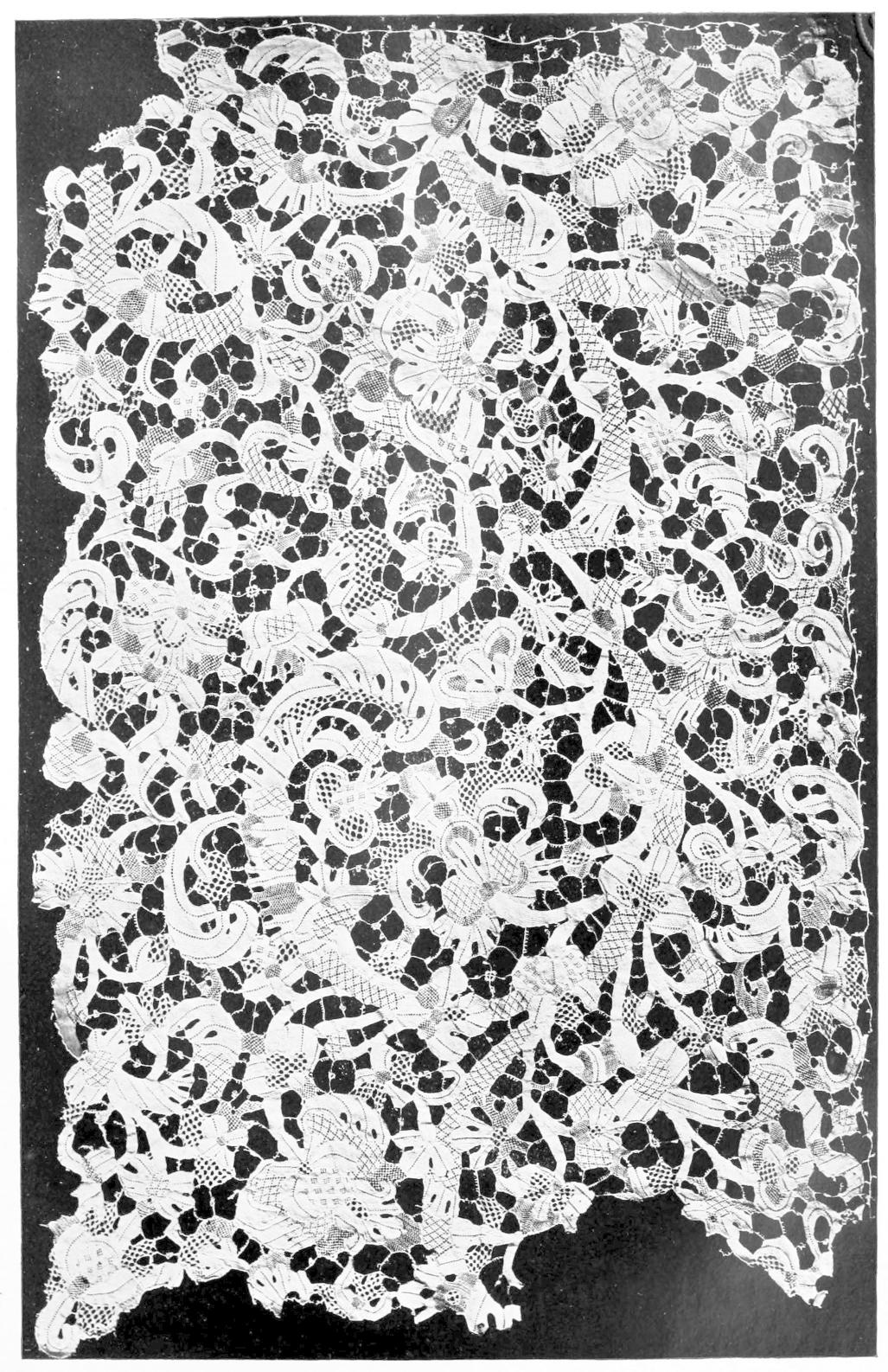

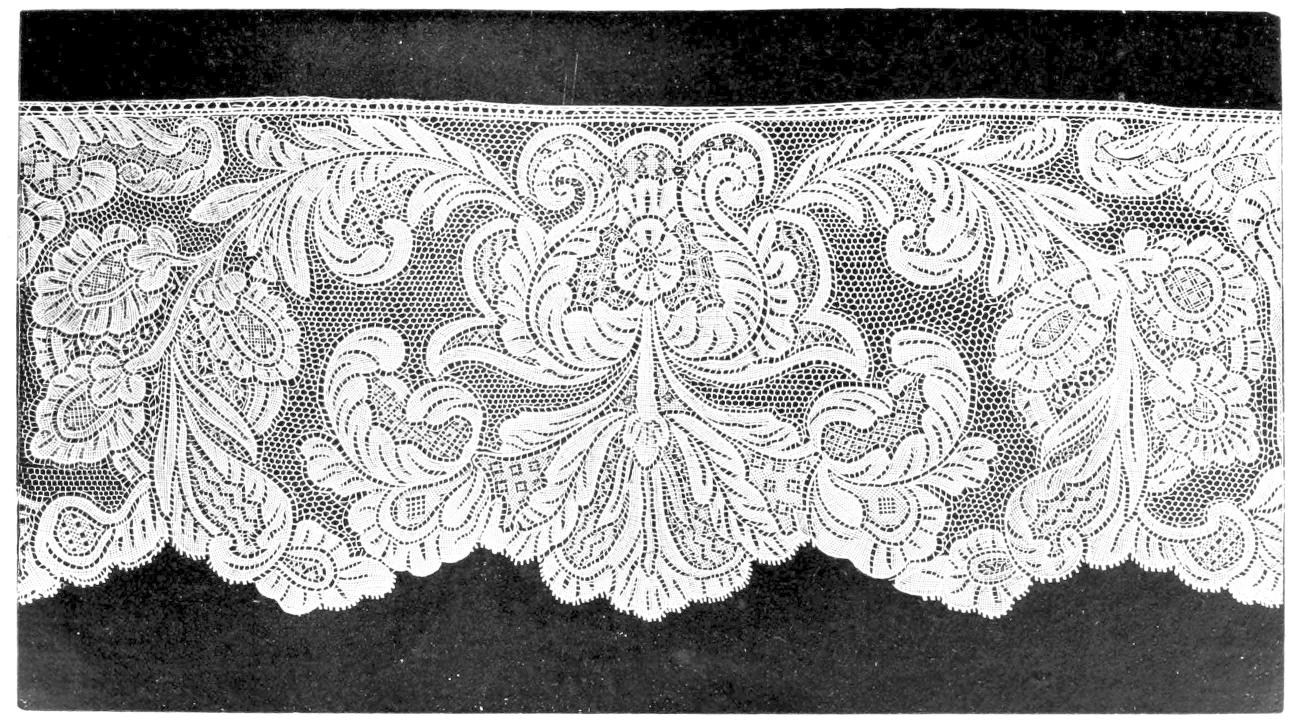

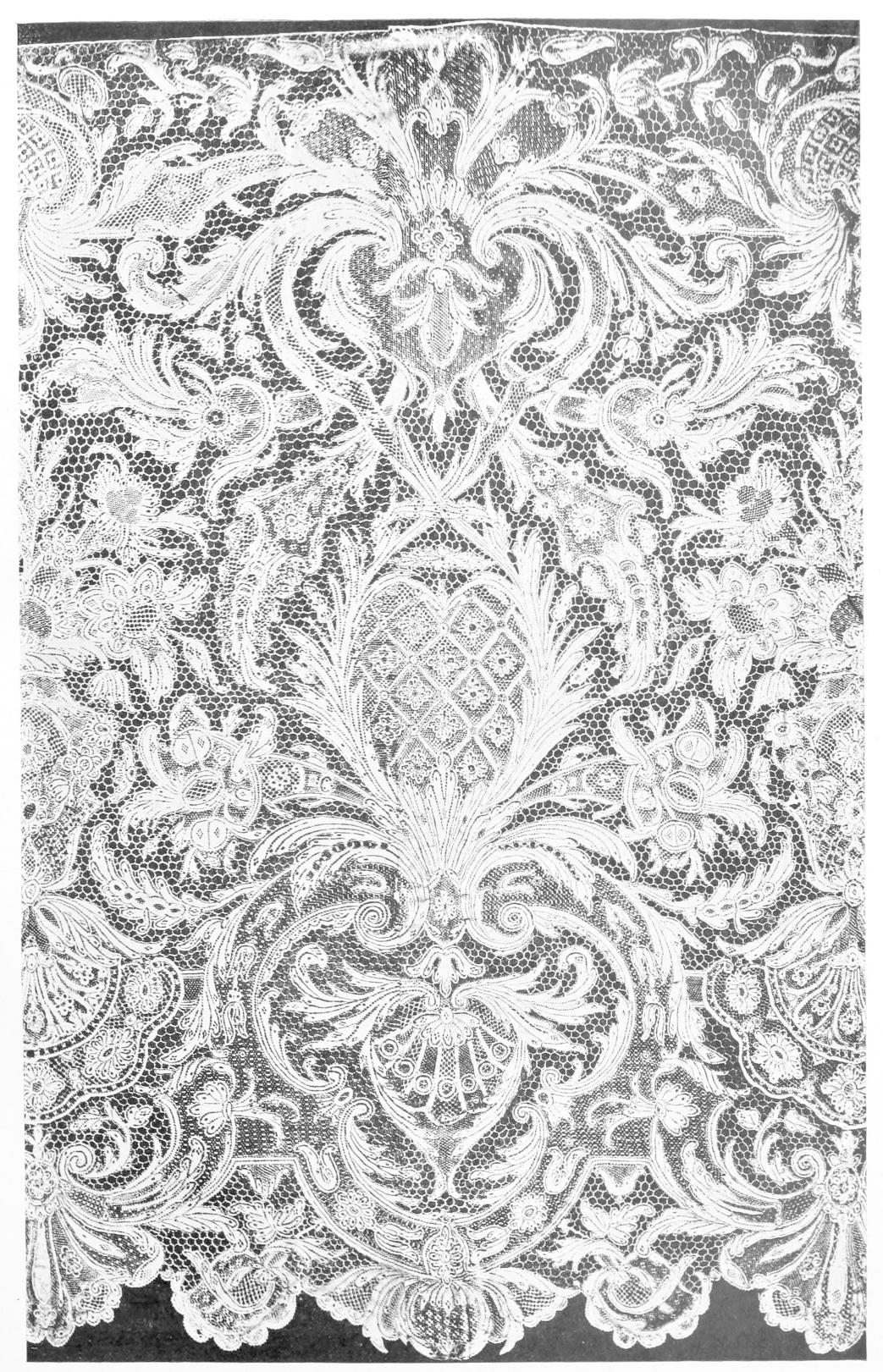

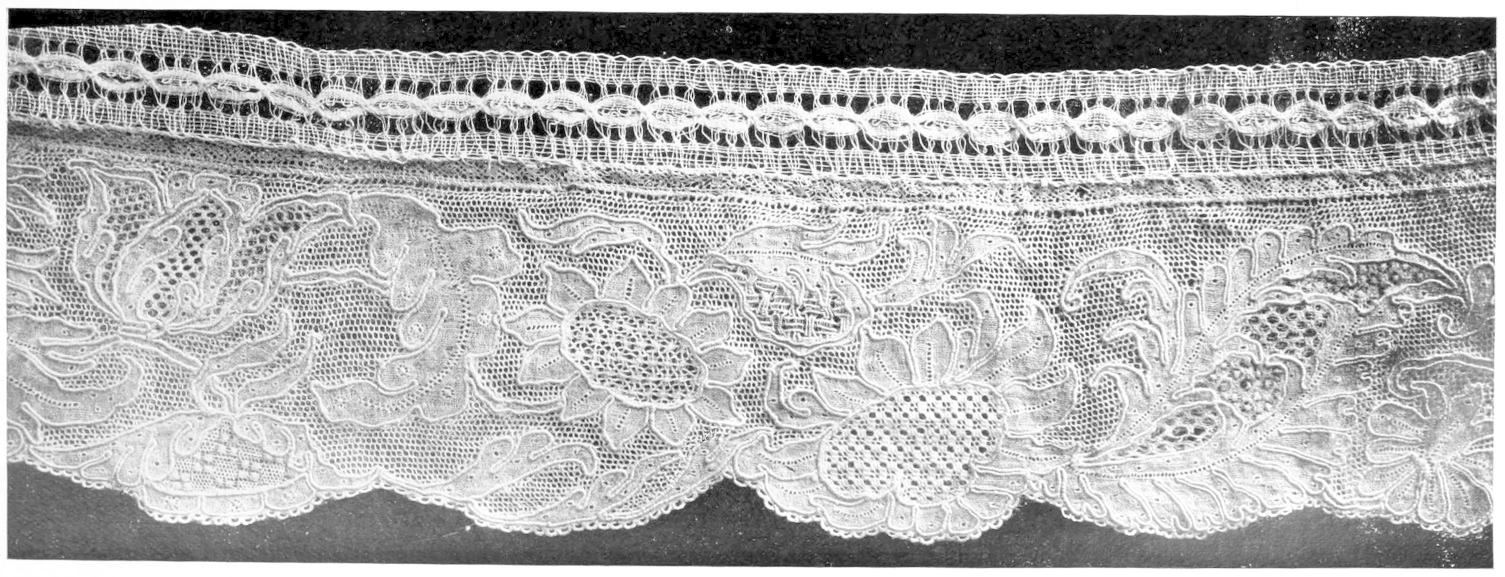

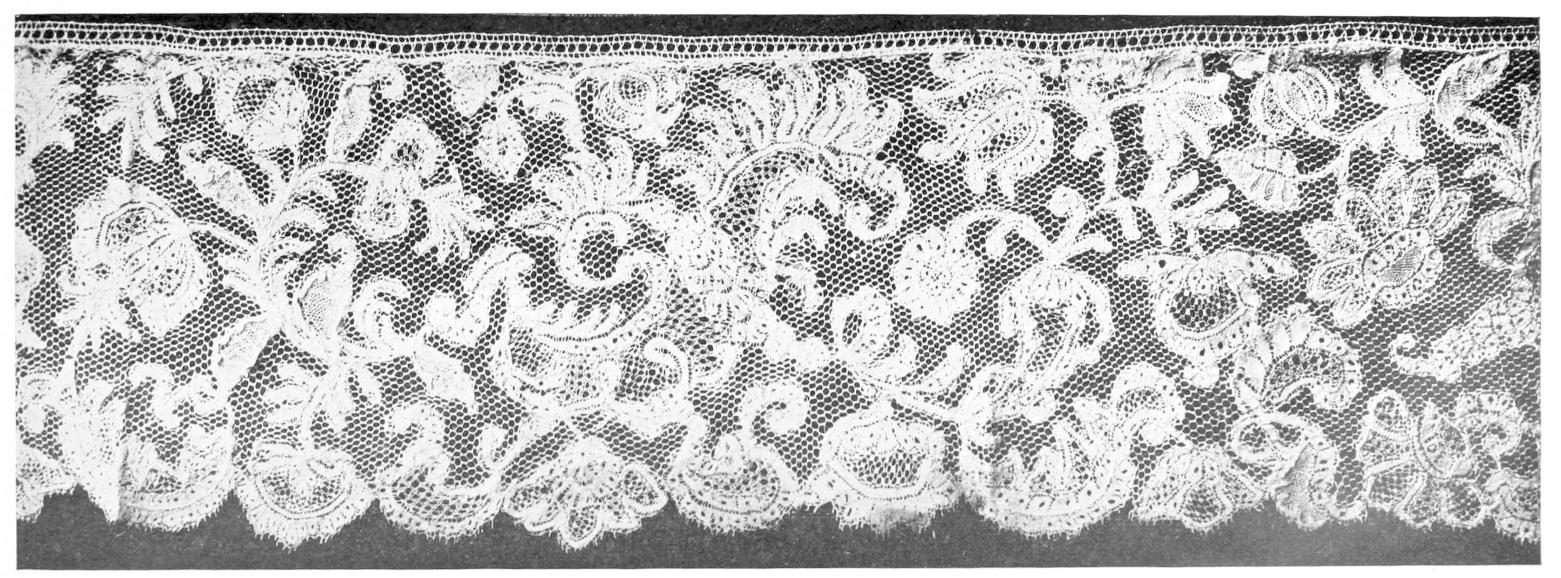

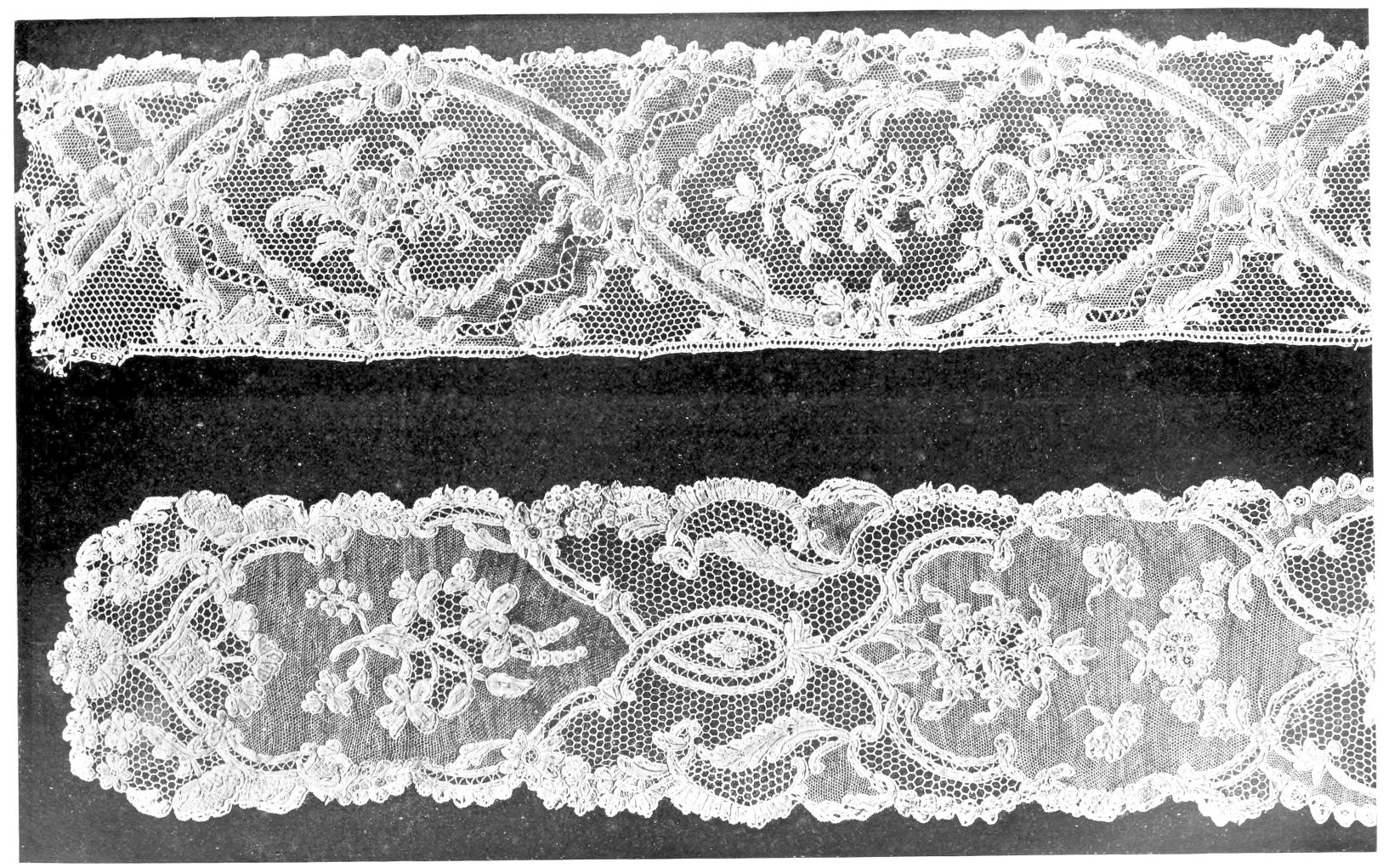

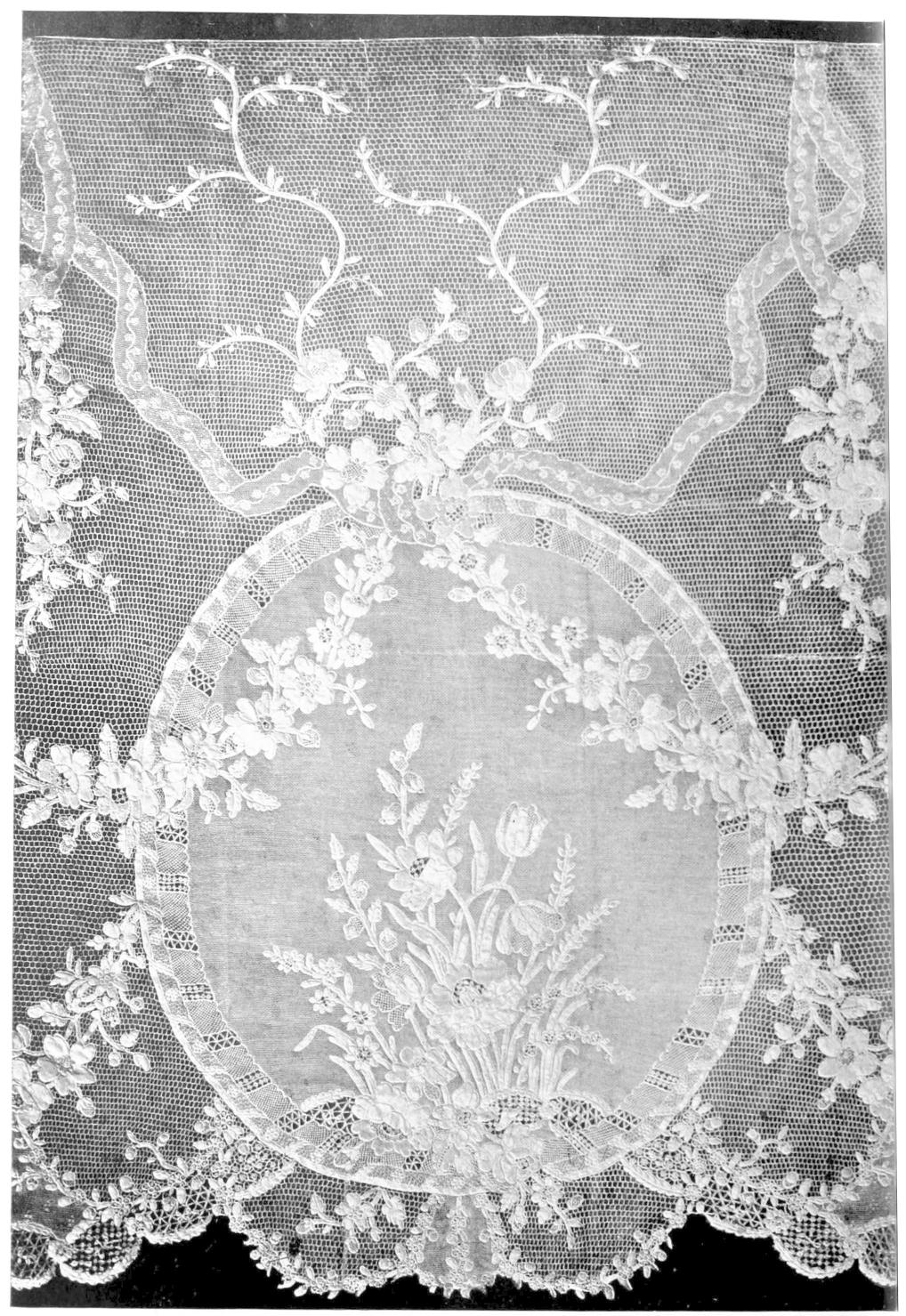

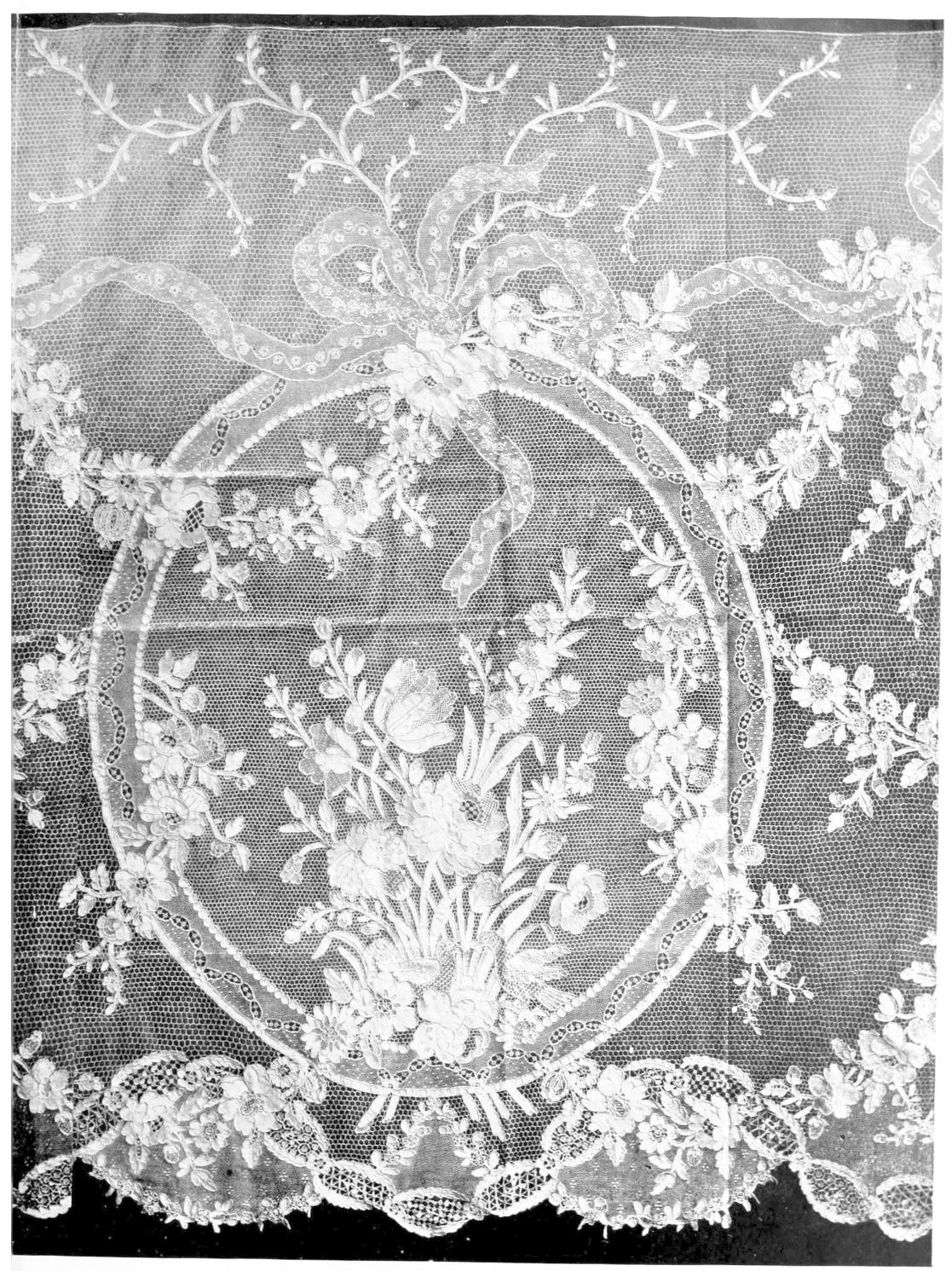

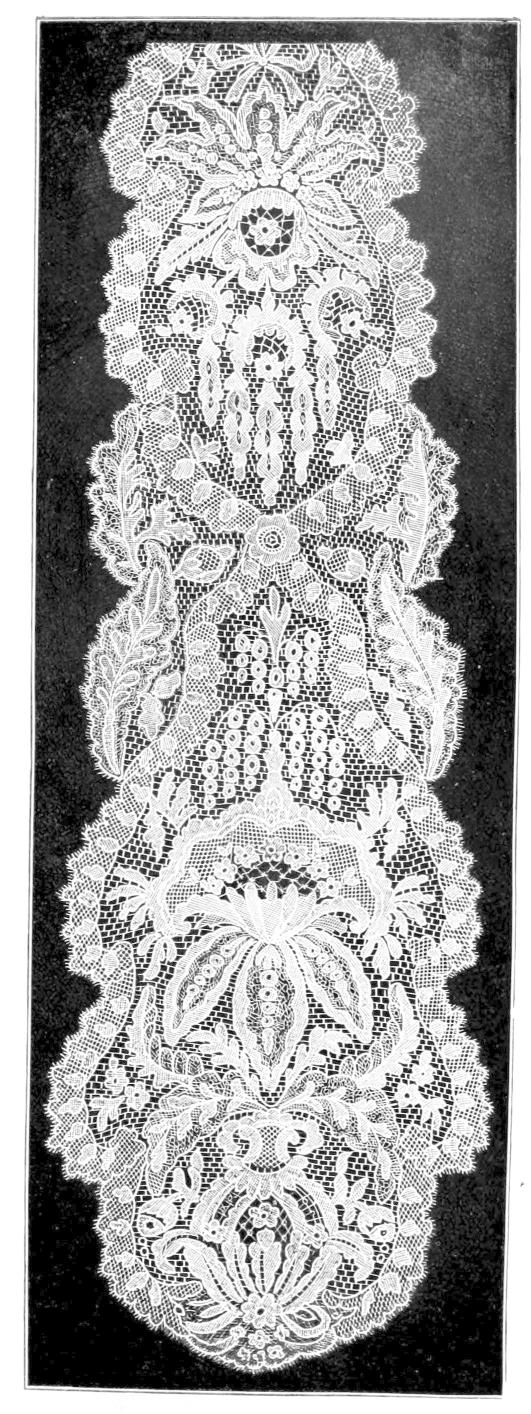

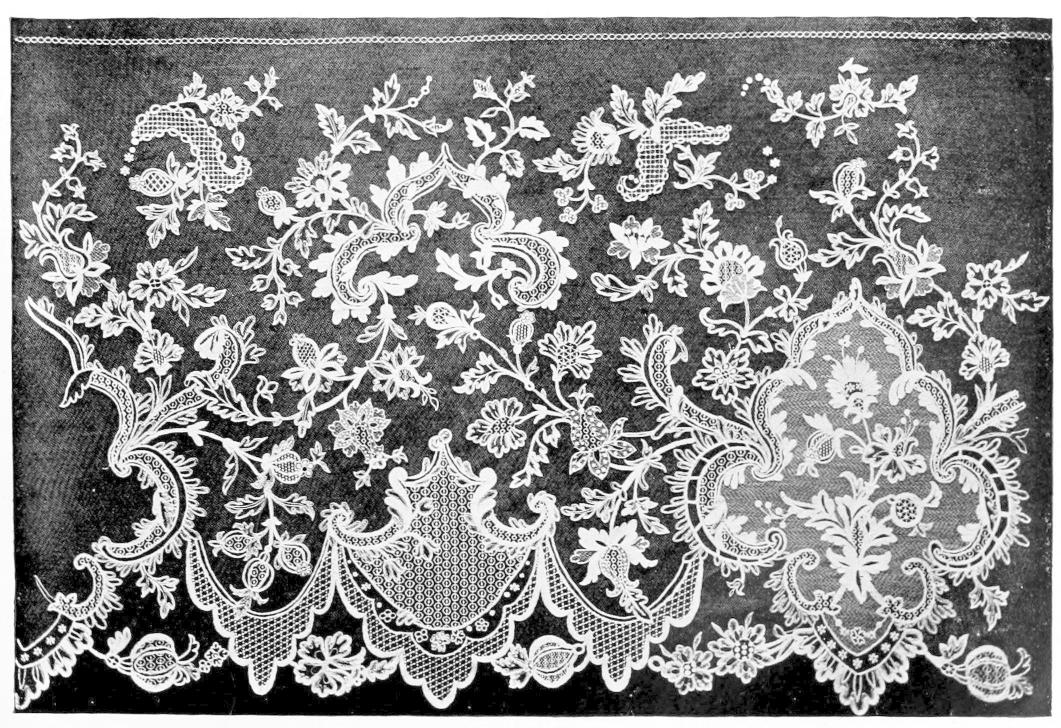

| Brussels.—Flounce, Bobbin-made |

" XLVII |

144 |

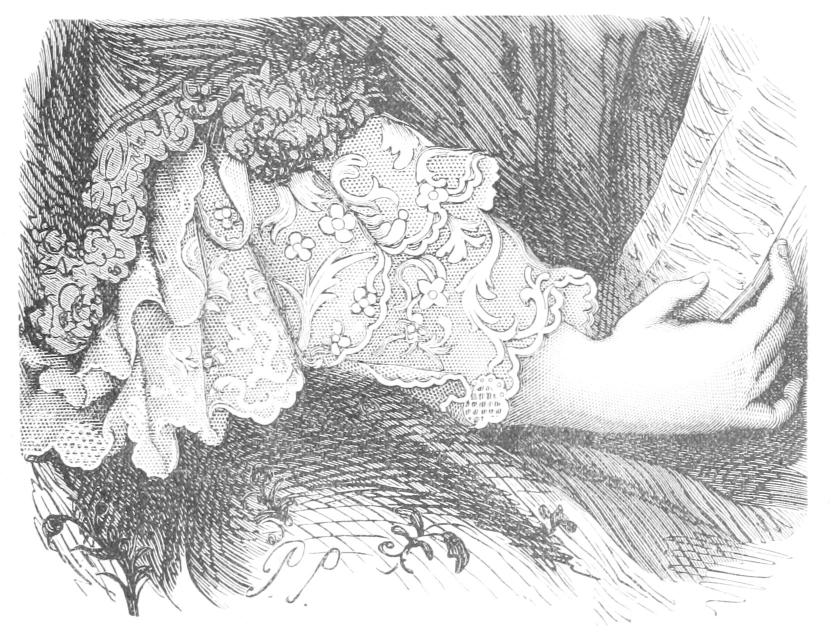

| Cinq-Mars.—M. de Versailles |

Fig. 66 |

145 |

| Cinq"Mars.—After his

portrait by Le Wain |

" 67 |

146 |

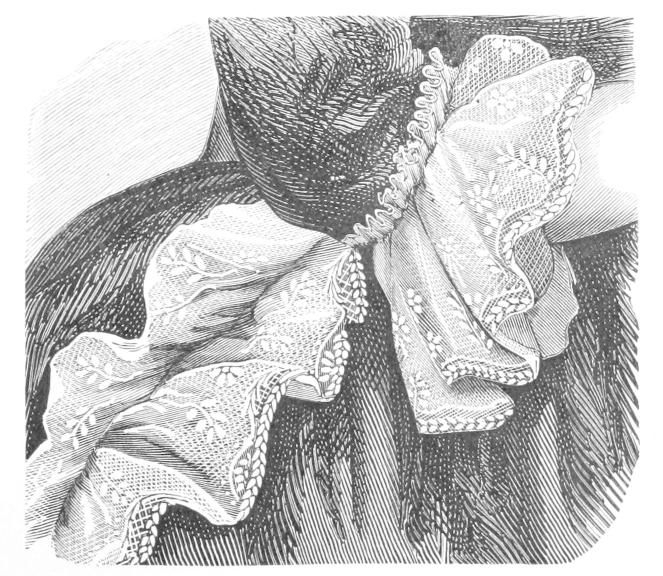

| Lace Rose and Garter |

" 68 |

147 |

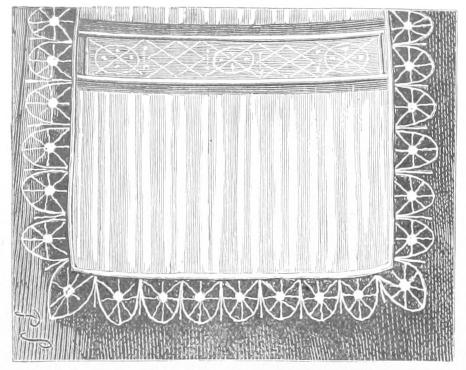

| Young Lady's Apron, time of Henry III |

" 69 |

148 |

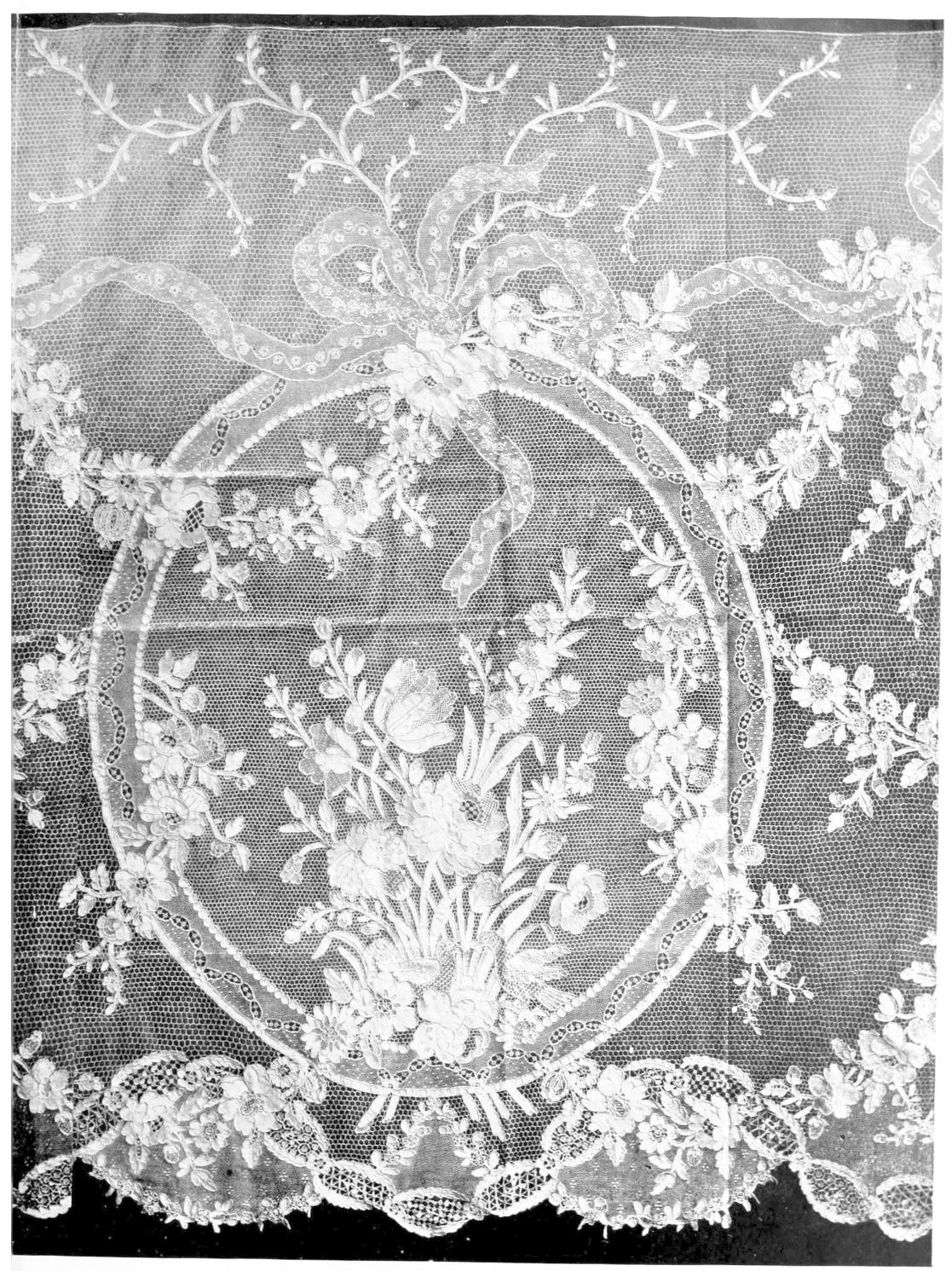

| Brussels.—Bobbin-made, Period Louis XIV. |

Plate XLVIII |

150 |

| Bru"els.—Point d'Angleterre à Réseau |

" XLIX |

150 |

| Anne of Austria |

Fig. 70 |

151 |

| A Courtier of the Regency |

" 71 |

152 |

| Canons of Louis XIV |

" 72 |

154 |

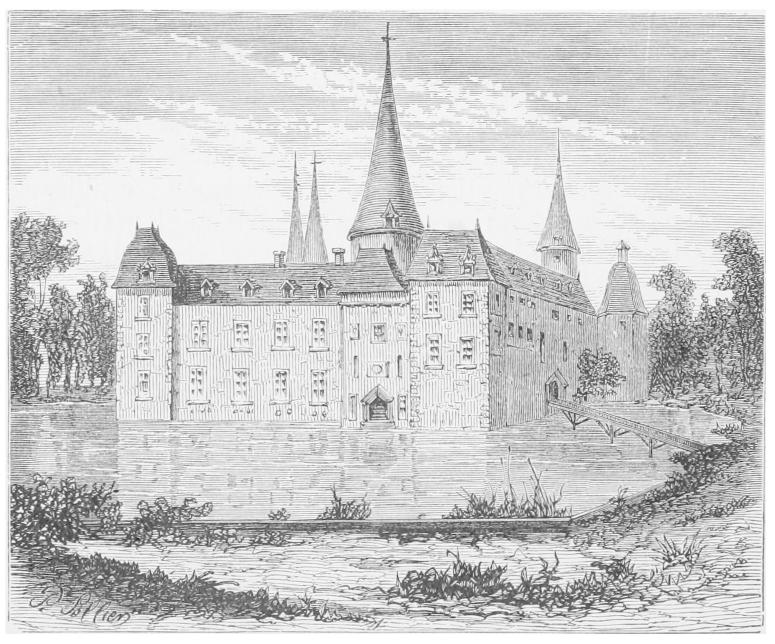

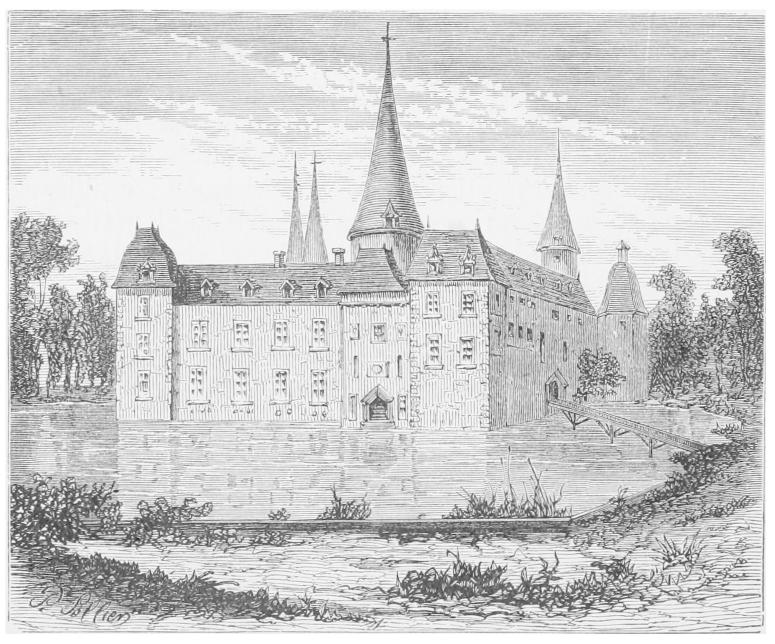

| Chateau de Louvai |

" 73 |

156 |

| Chenille Run on a Bobbin-ground |

Plate L |

156 |

| Brussels.—Bobbin-made |

" LI |

156 |

| Le Grand Bébé |

Fig. 74 |

162 |

| Louvois, 1691 |

" 75 |

163 |

| Madame de Maintenon |

" 76 |

164 |

| Lady in Morning déshabille |

" 77 |

165 |

| Le Grand Dauphin en Steinkerque |

" 78 |

168 |

| Madame du Lude en Steinkerque |

" 79 |

168 |

| Madame Palatine |

" 80 |

169 |

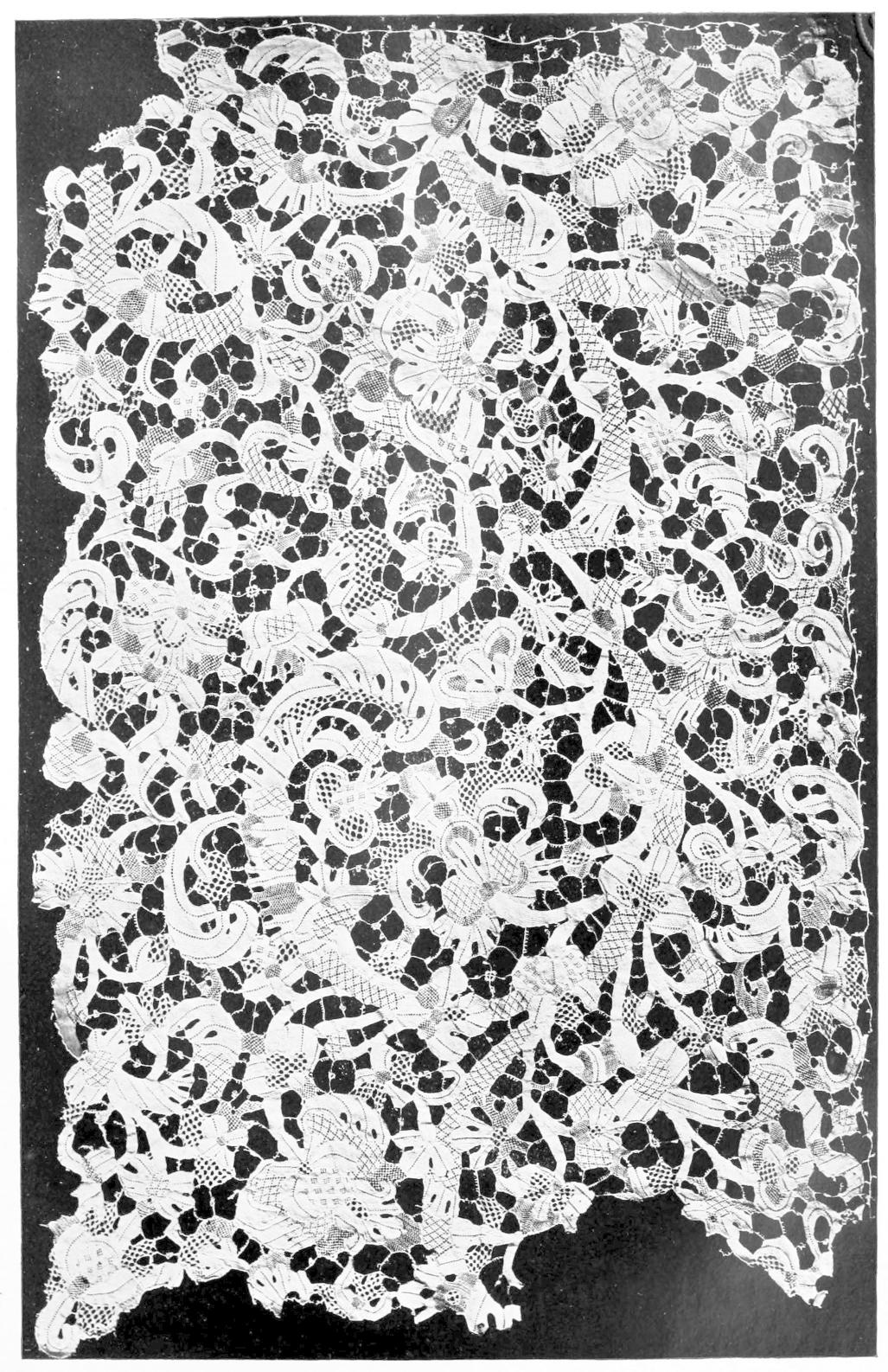

| Brussels.—Modern Point de Gaze |

Plate LII |

170 |

| Madame Sophie de France, 1782 |

Fig. 81 |

175 |

| Madame Adélaide de France |

" 82 |

176 |

| Madame Louise de France |

Plate LIII |

176 |

| Madame Thérèse |

Fig. 83 |

177 |

| Marie-Antoinette |

" 84 |

179 |

| Madame Adélaide de France |

" 85 |

182 |

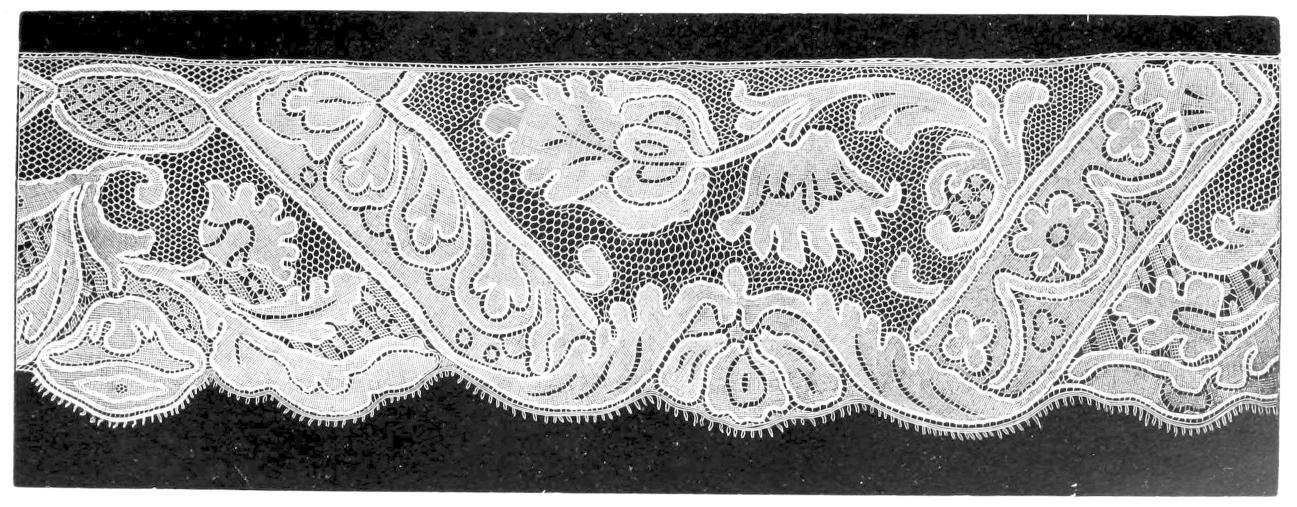

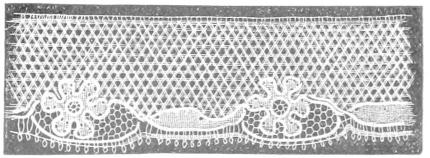

|

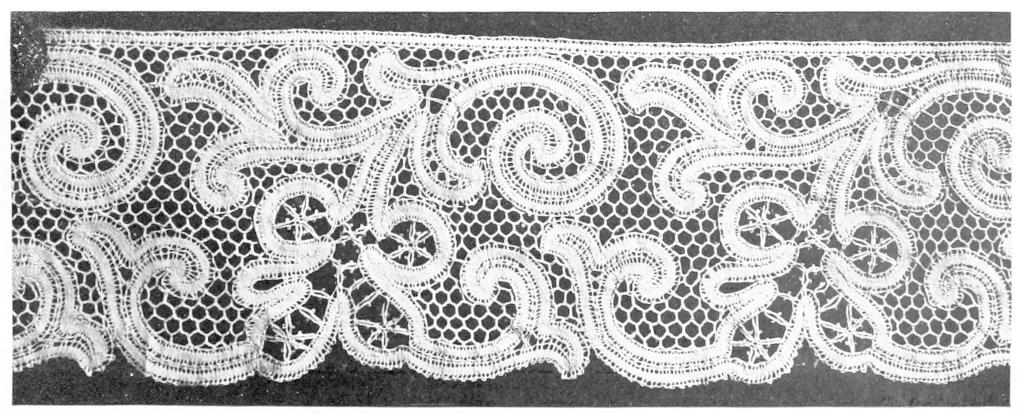

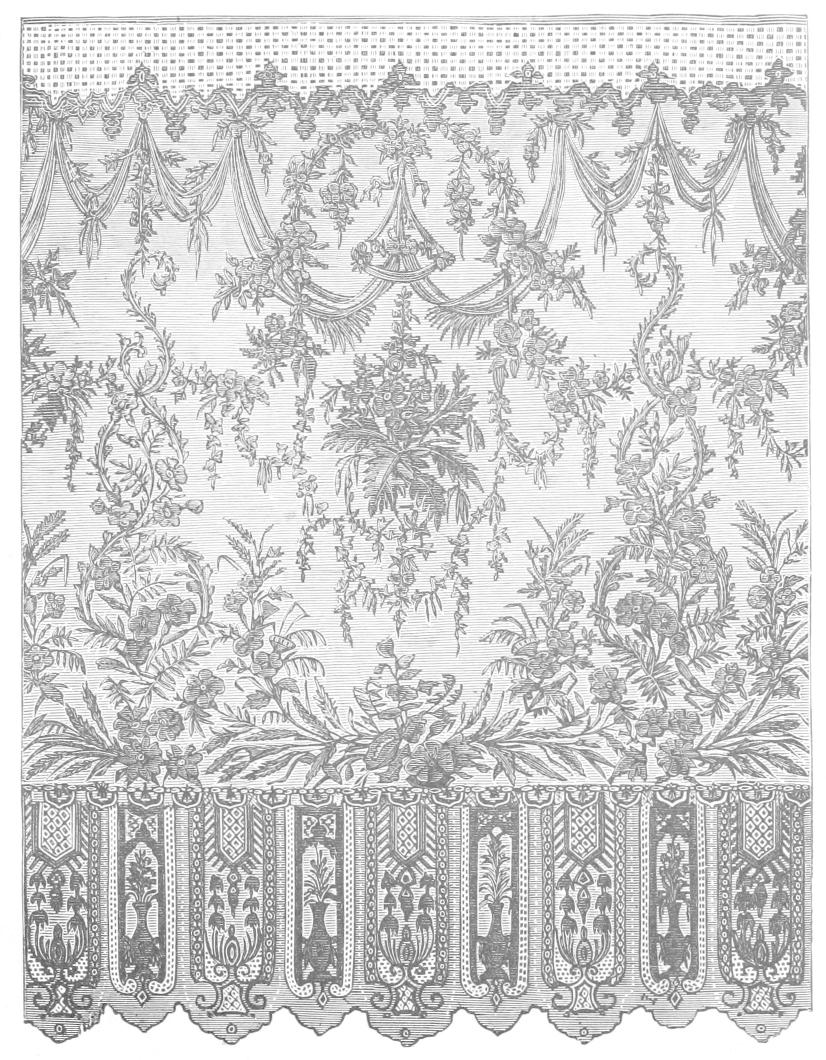

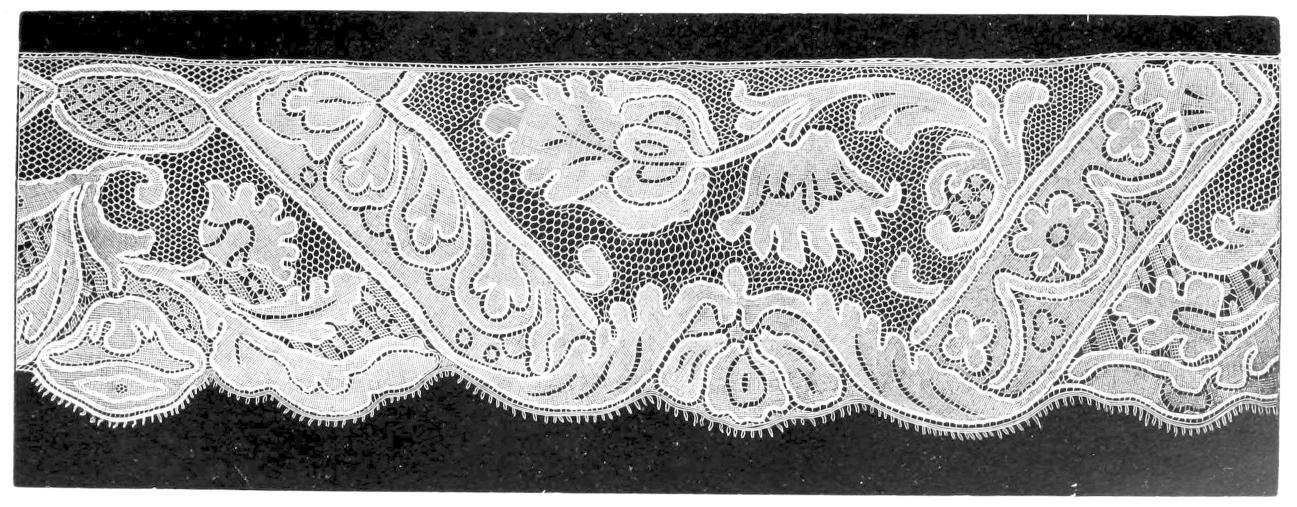

French.—Border of Point Plat de France

|

Plate LIV |

188 |

| Colbert, + 1683 |

Fig. 86 |

189 |

| Venice Point |

" 87 |

191 |

| French.—Point d'Alençon |

Plate LV |

192 |

| Argentella, or Point d'Alençon à Réseau Rosacé |

Fig. 88 |

194 |

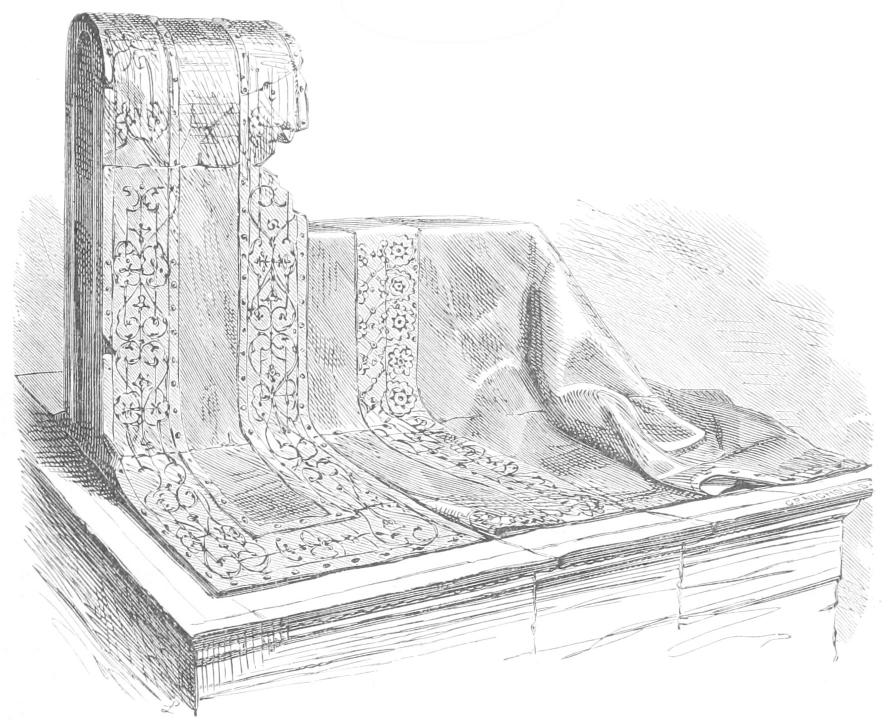

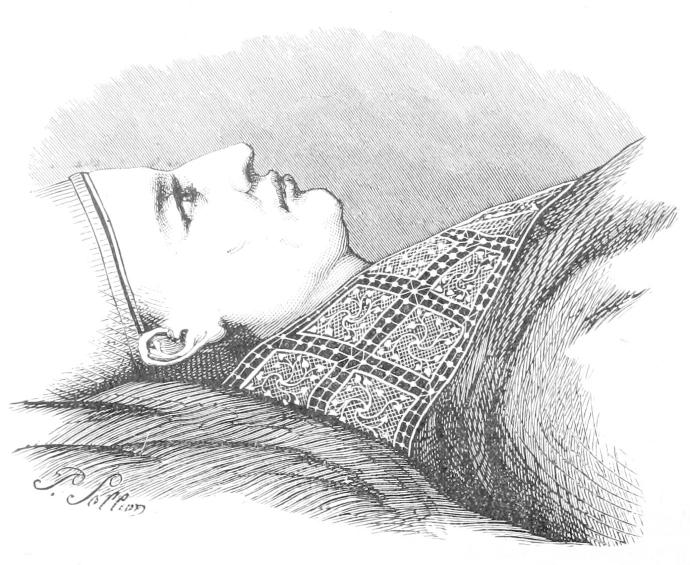

| Bed made for Napoleon I. |

" 89 |

197 |

| Alençon Point à Petites Bredes |

" 90 |

200 |

| Point d'Alençon, Louis XV. |

" 91 |

200 |

| Point d'Alençon. Flounce |

Plate LVI |

202-3 |

| Point d'Argentan |

Fig. 92 |

204 |

| Poi"t d'Arg"ntan. Grande Bride ground |

" 93 |

206 |

| French.—Point d'Argentan, 18th Century |

Plate LVII |

208 |

| Point de Paris |

Fig. 94 |

210 |

| Point de France |

" 95 |

210 |

| French (or Dutch).—Victoria and Albert

Museum |

Plate LVIII |

212 |

| Chantilly |

Fig. 96 |

214 |

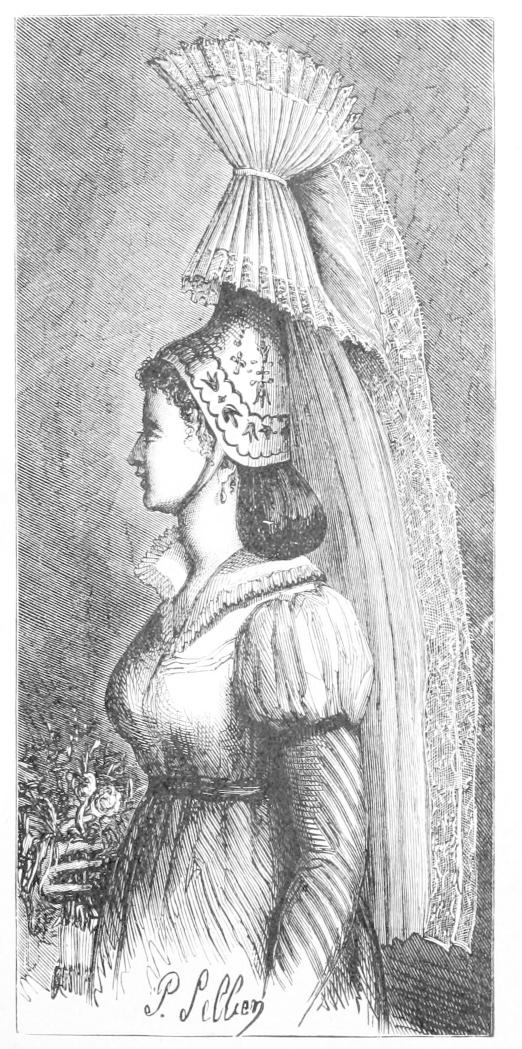

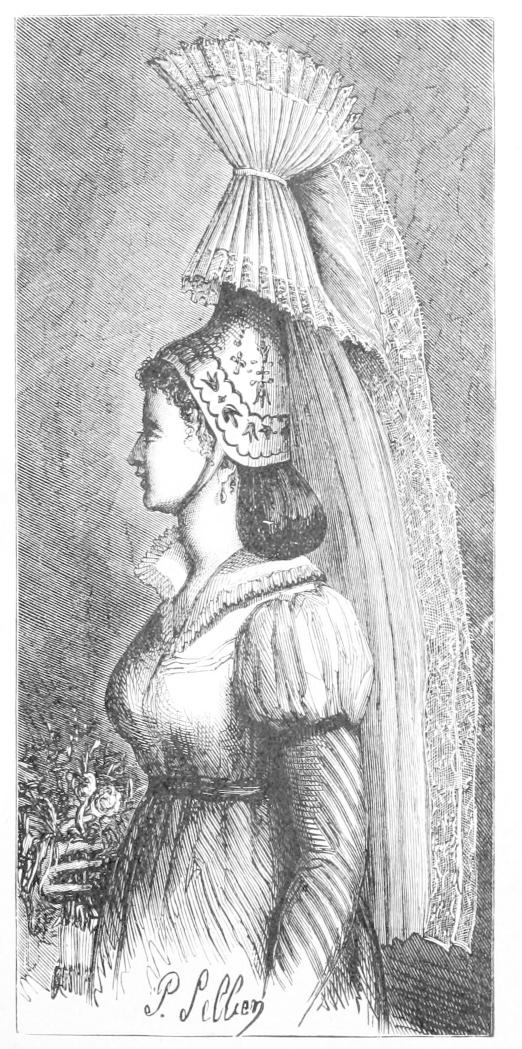

| Cauchoise |

" 97 |

217 |

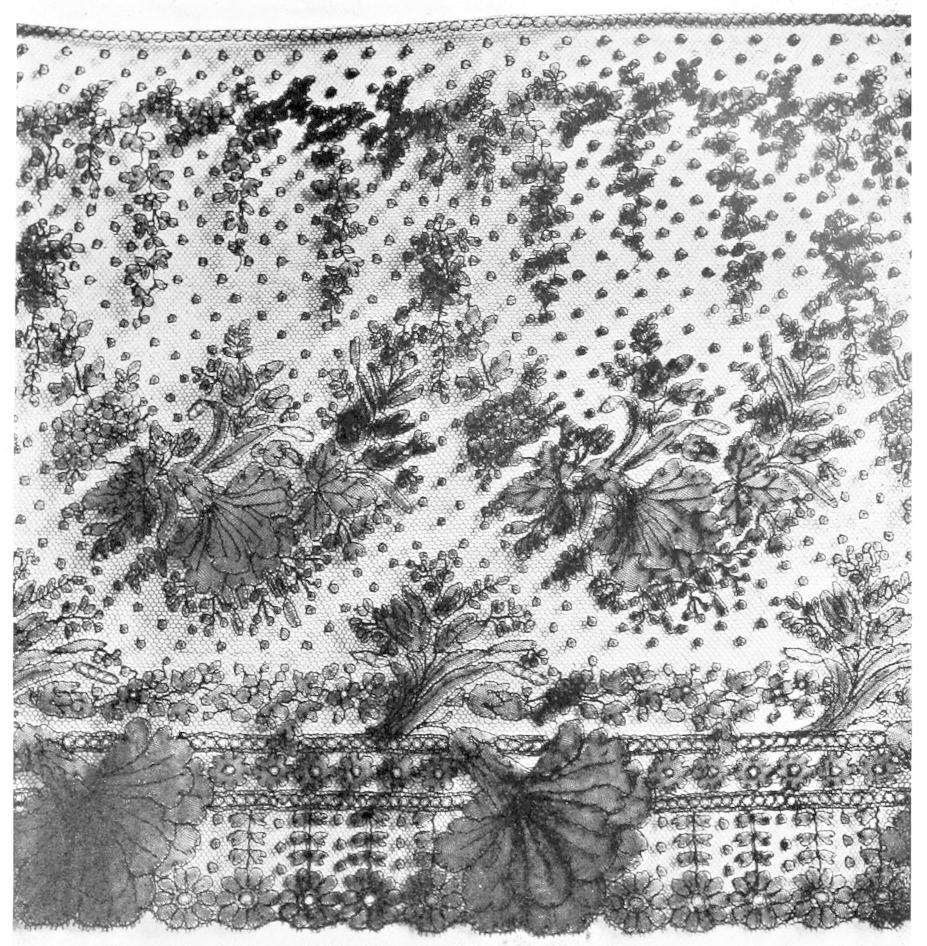

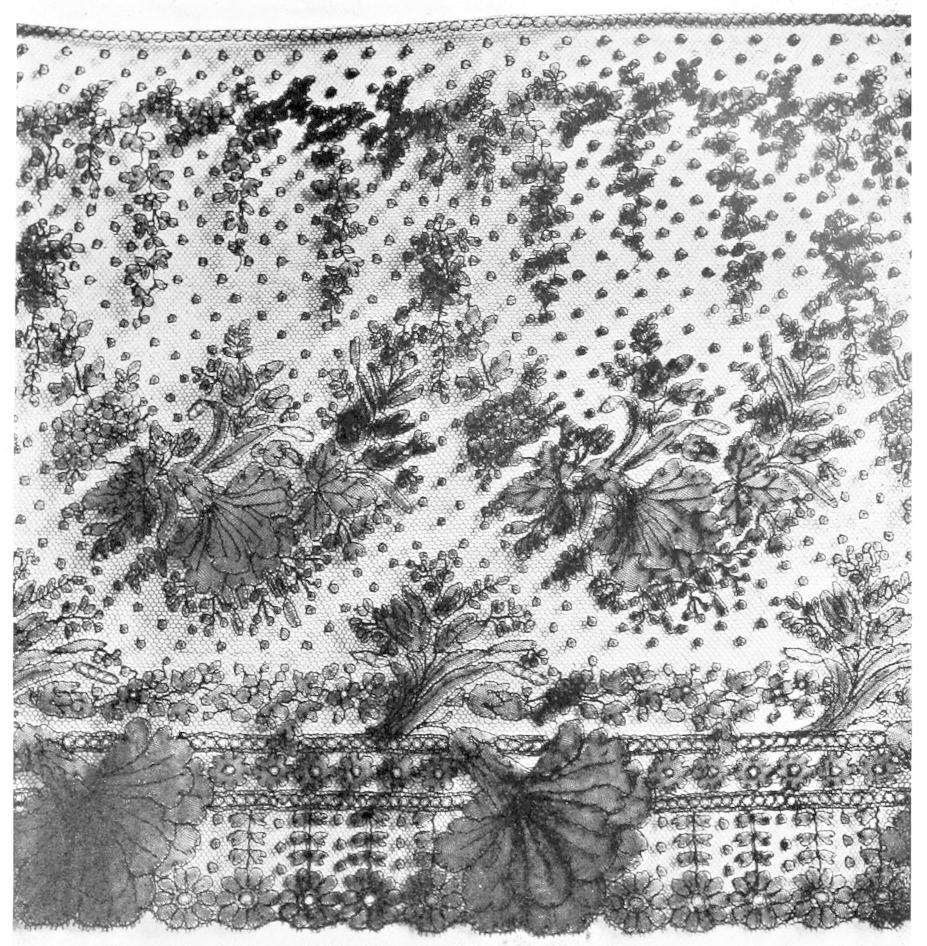

| French, Chantilly.—Flounce |

Plate LIX |

218 |

| French, Le Puy.—Black Silk Guipure |

" LX |

218 |

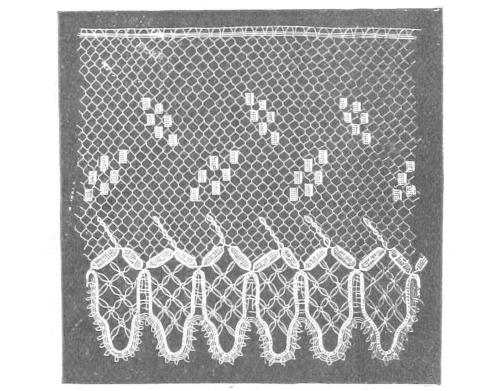

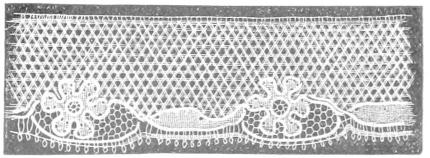

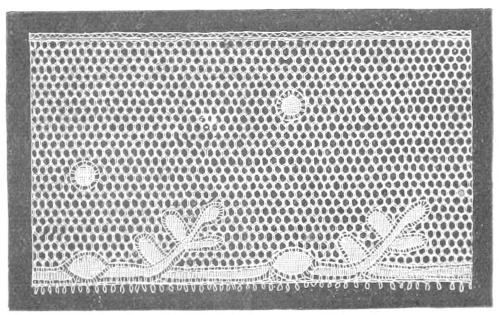

| Petit Poussin, Dieppe |

Fig. 98 |

219 |

| Ave Maria, Dieppe |

" 99 |

220 |

| Point de Dieppe |

" 100 |

221 |

| Dentelle à la Vierge |

" 101 |

222 |

| Duc de Peuthièvre |

" 102 |

223 |

| French.—Blonde Male, in Spanish Style |

Plate LXI |

226 |

| Modern Black Lace of Bayeux |

Fig. 103 |

227 |

| Point Colbert |

" 104 |

228 |

| Valenciennes, 1650-1780 |

" 105 |

230 |

| Valen"iennes, Period, Louis

XIV. |

" 106 |

232 |

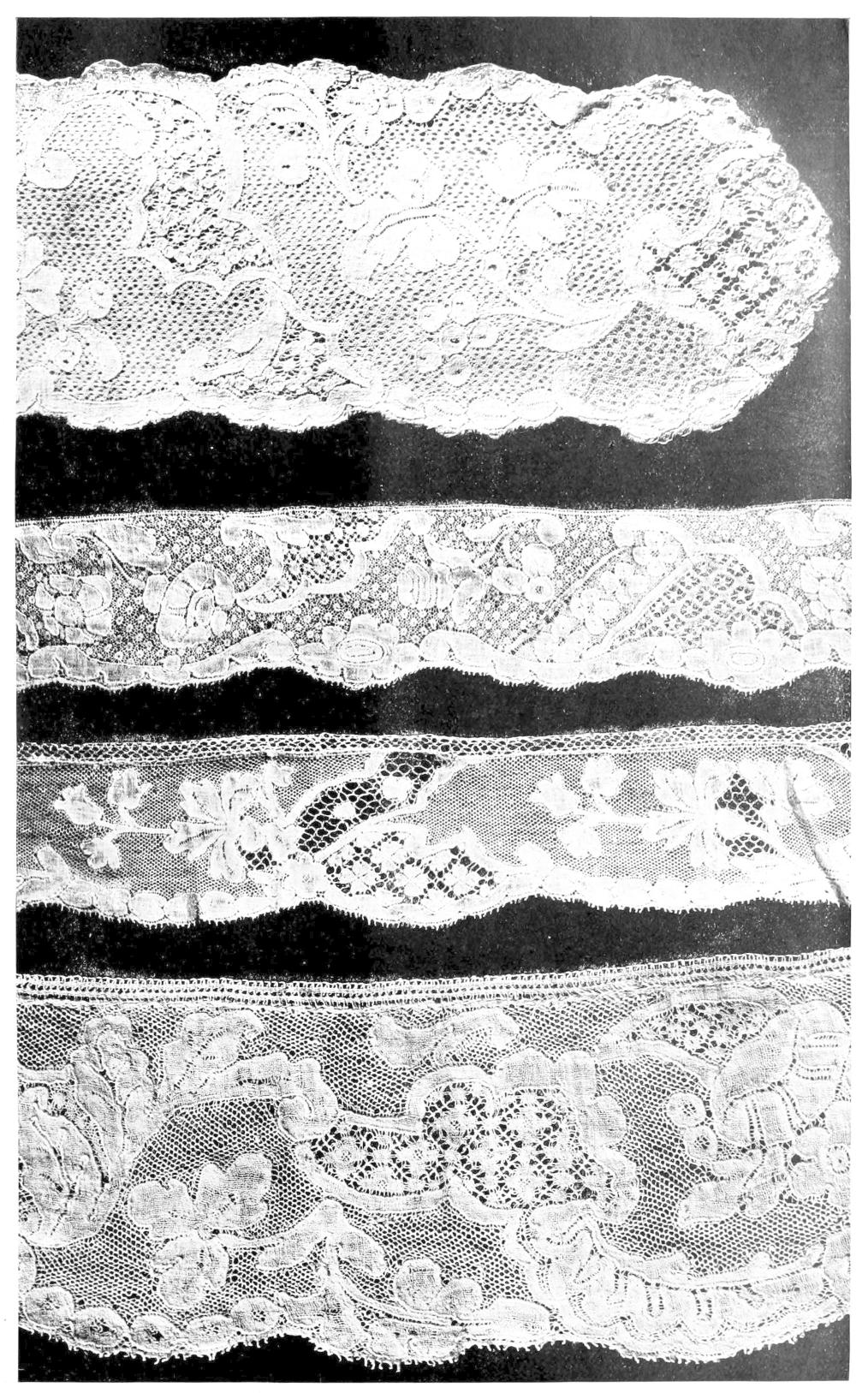

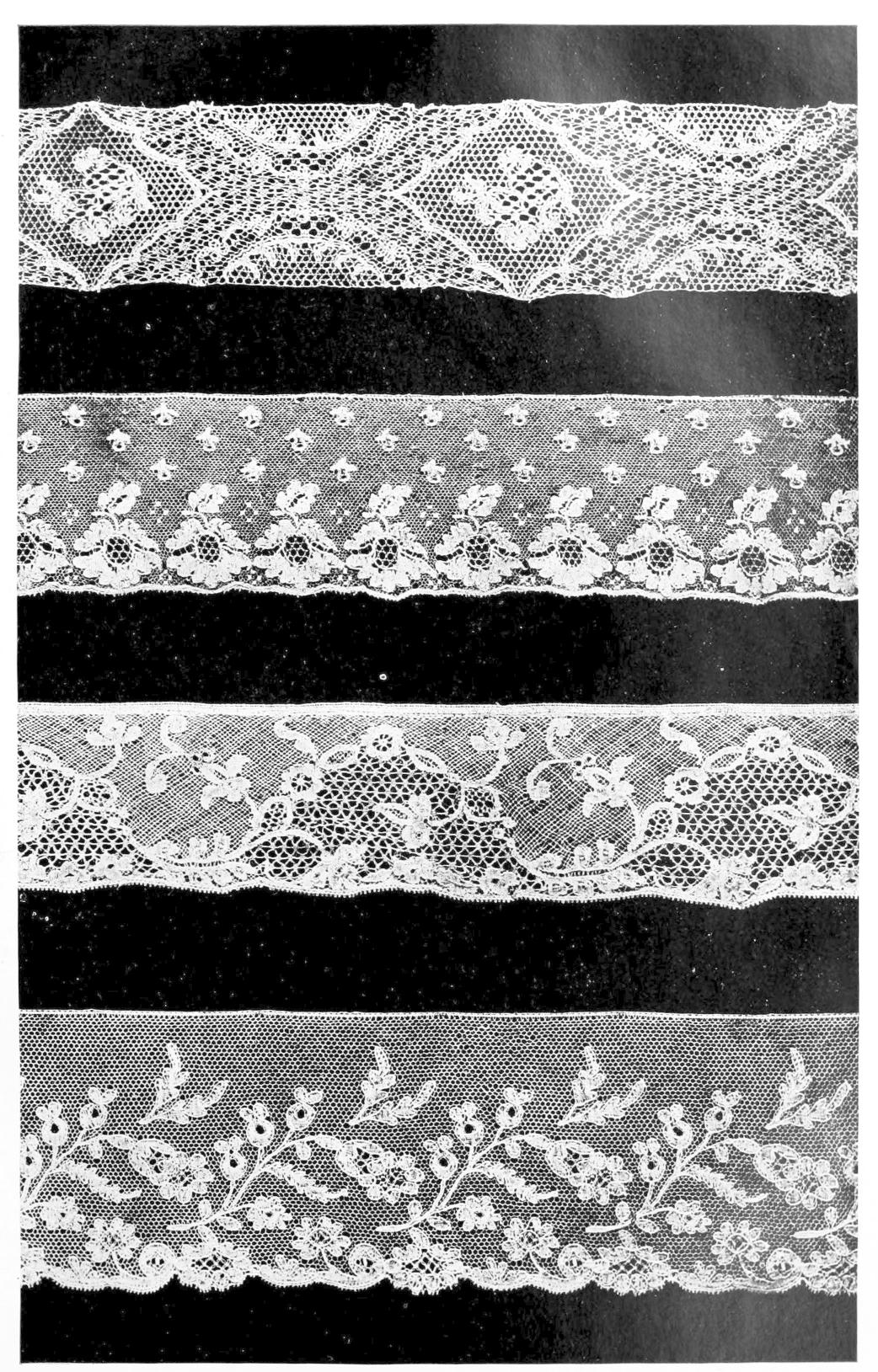

| Valen"iennes, 17th and 18th Century |

Plate LXII |

232 |

| Valen" |

Fig. 107 |

234 |

| Valenciennes Lappet |

" 108 |

234 |

| Lille |

" 109 |

236 |

| Li" |

" 110 |

238 |

| Arras |

" 111 |

240 |

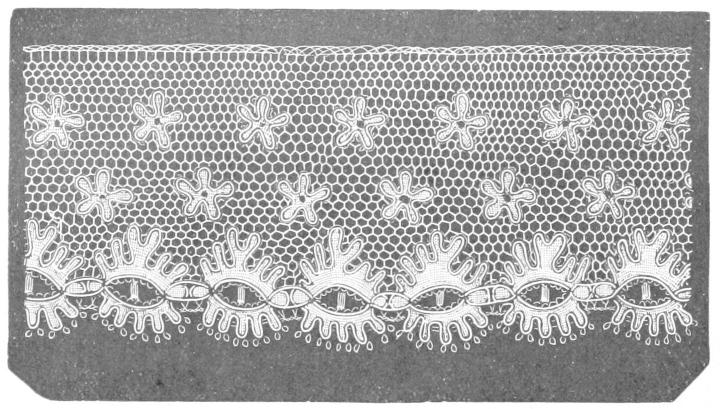

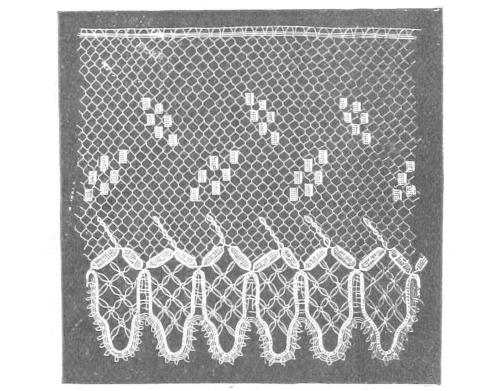

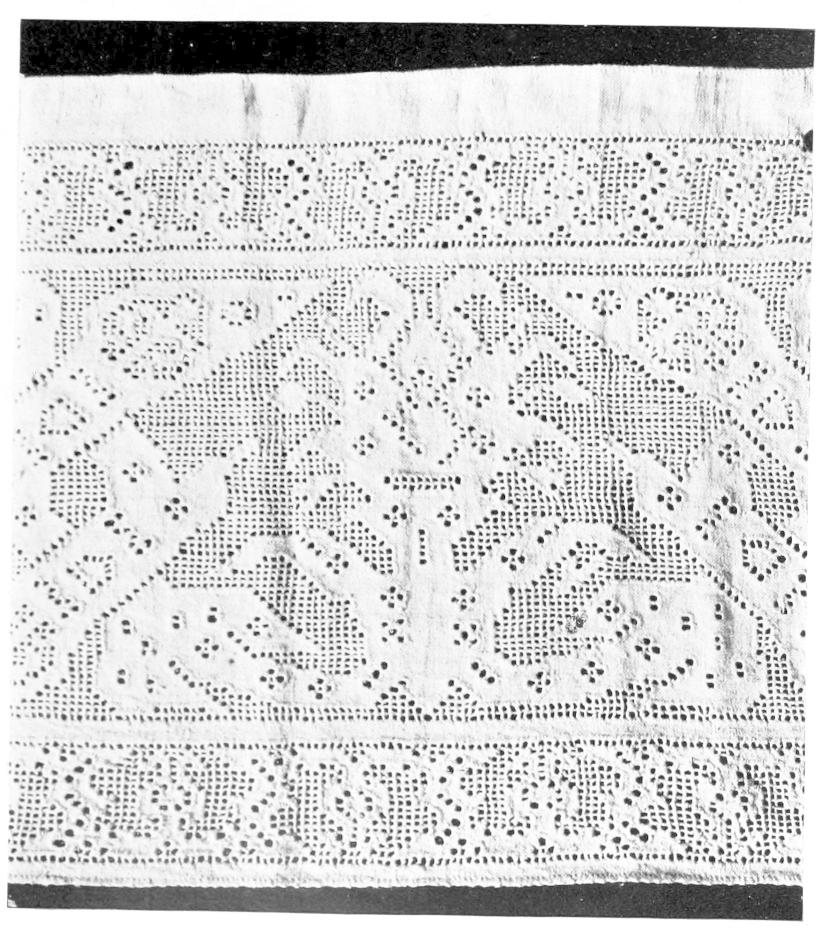

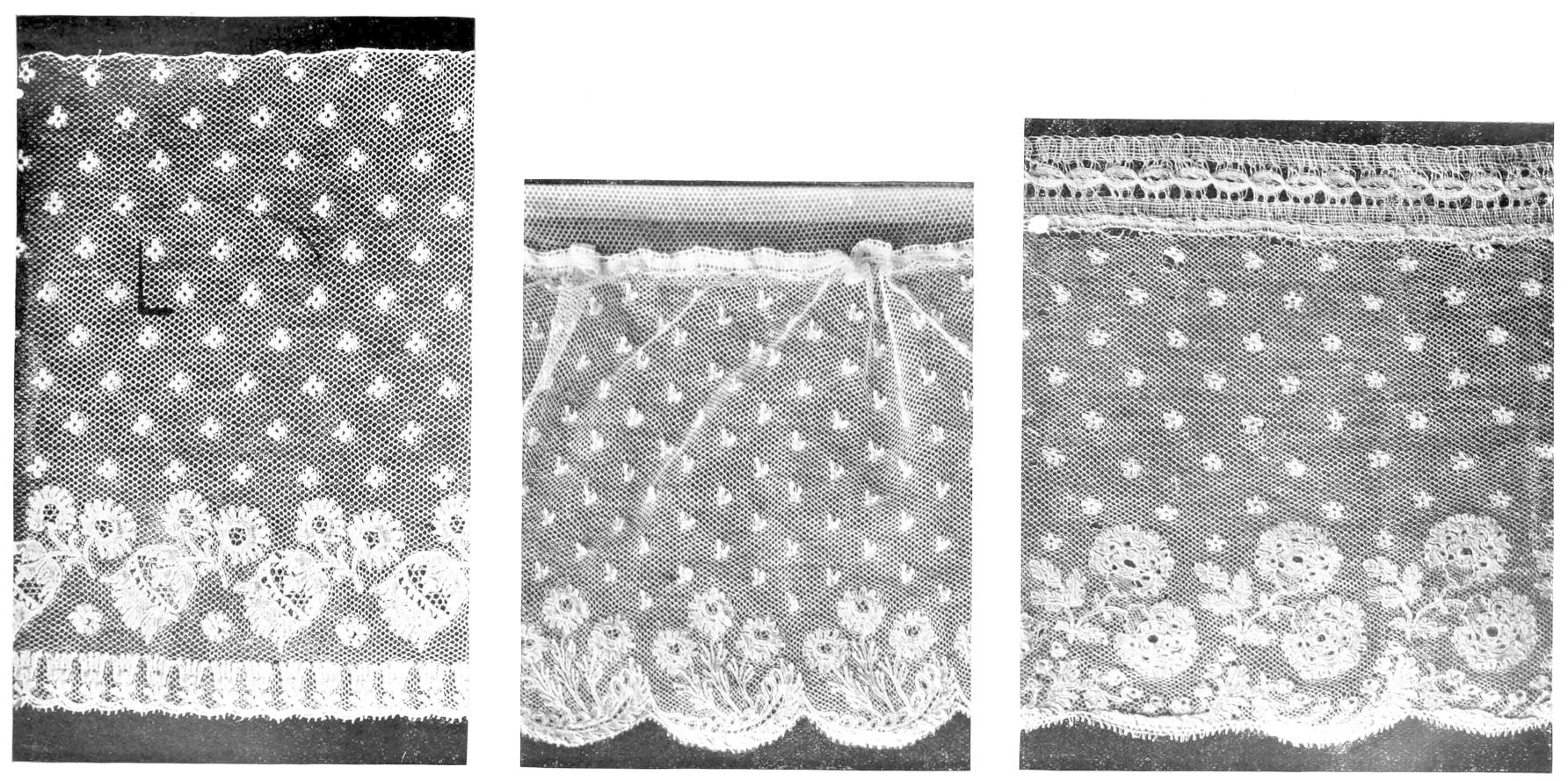

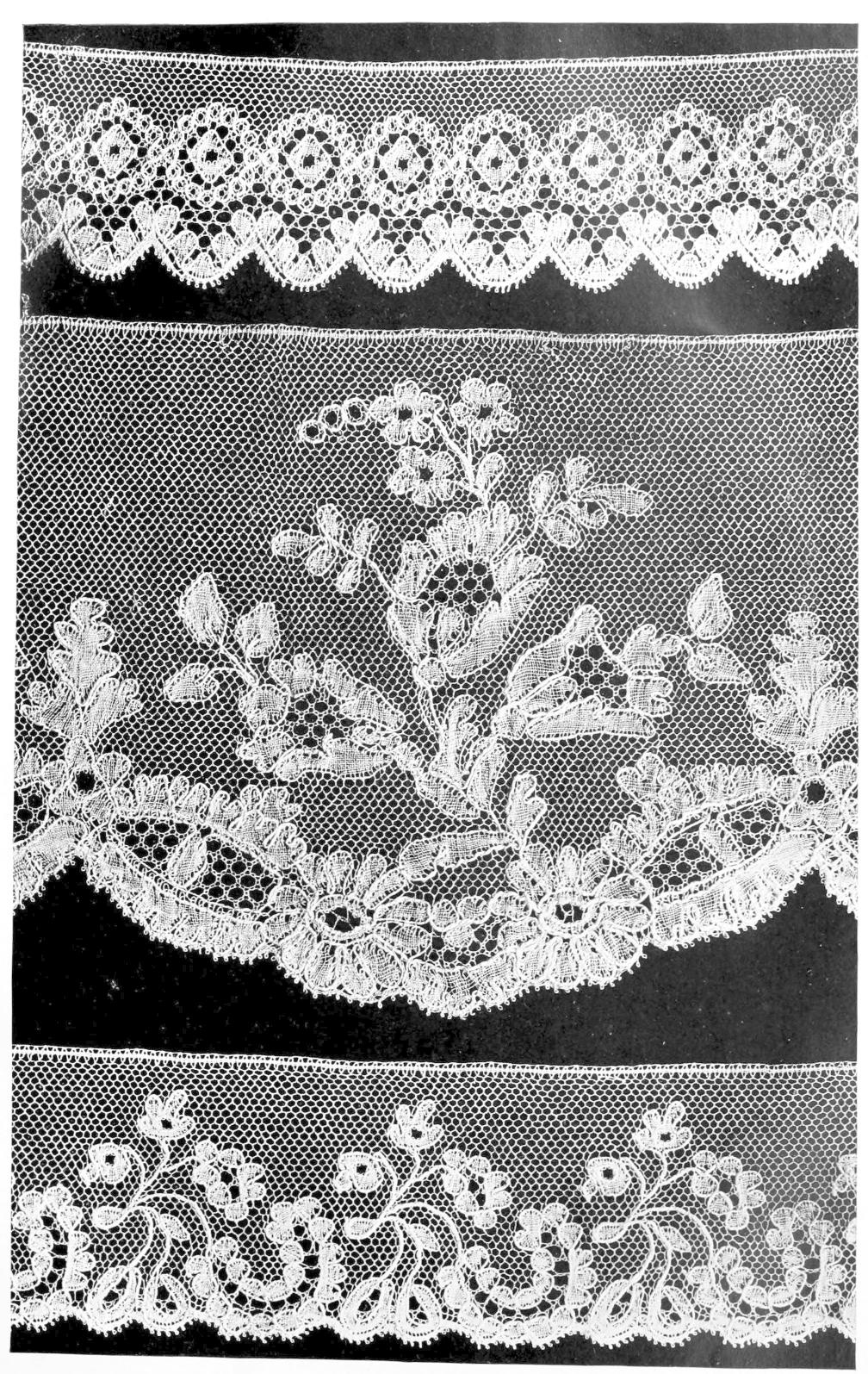

| French, Cambrai |

Plates LXIII, LXIV |

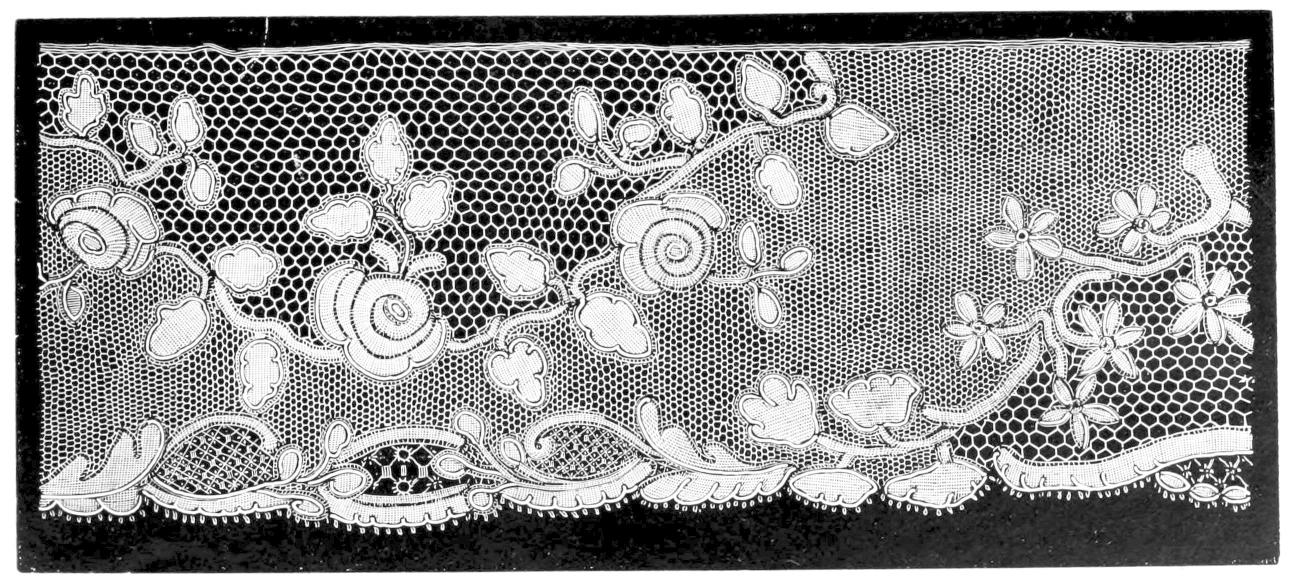

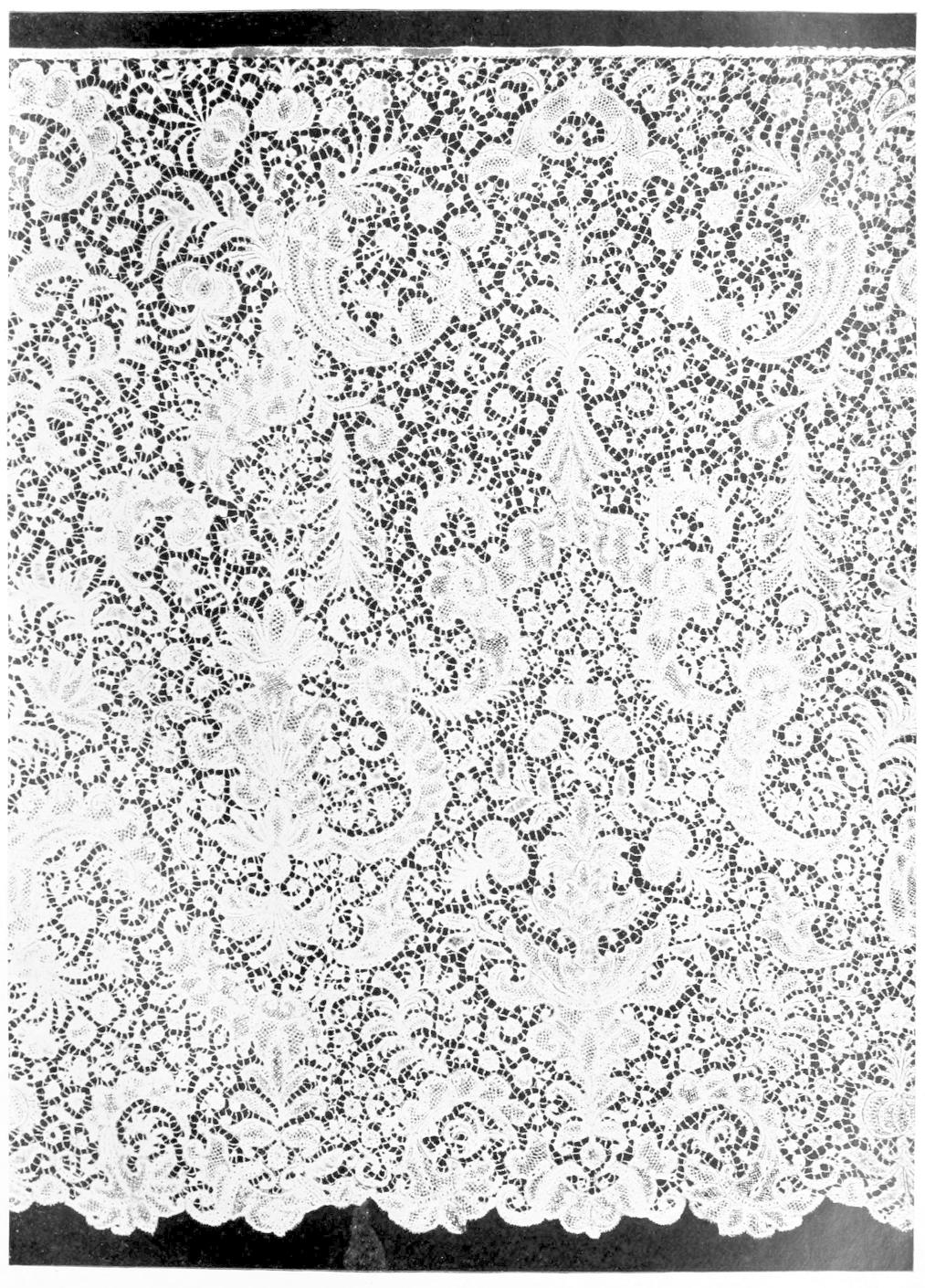

246 |

| French, le Puy |

Plate LXV |

246 |

| Point de Bourgogne |

Fig. 112 |

256 |

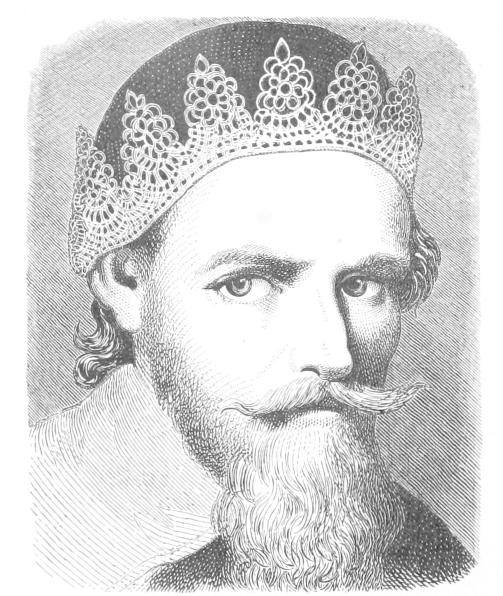

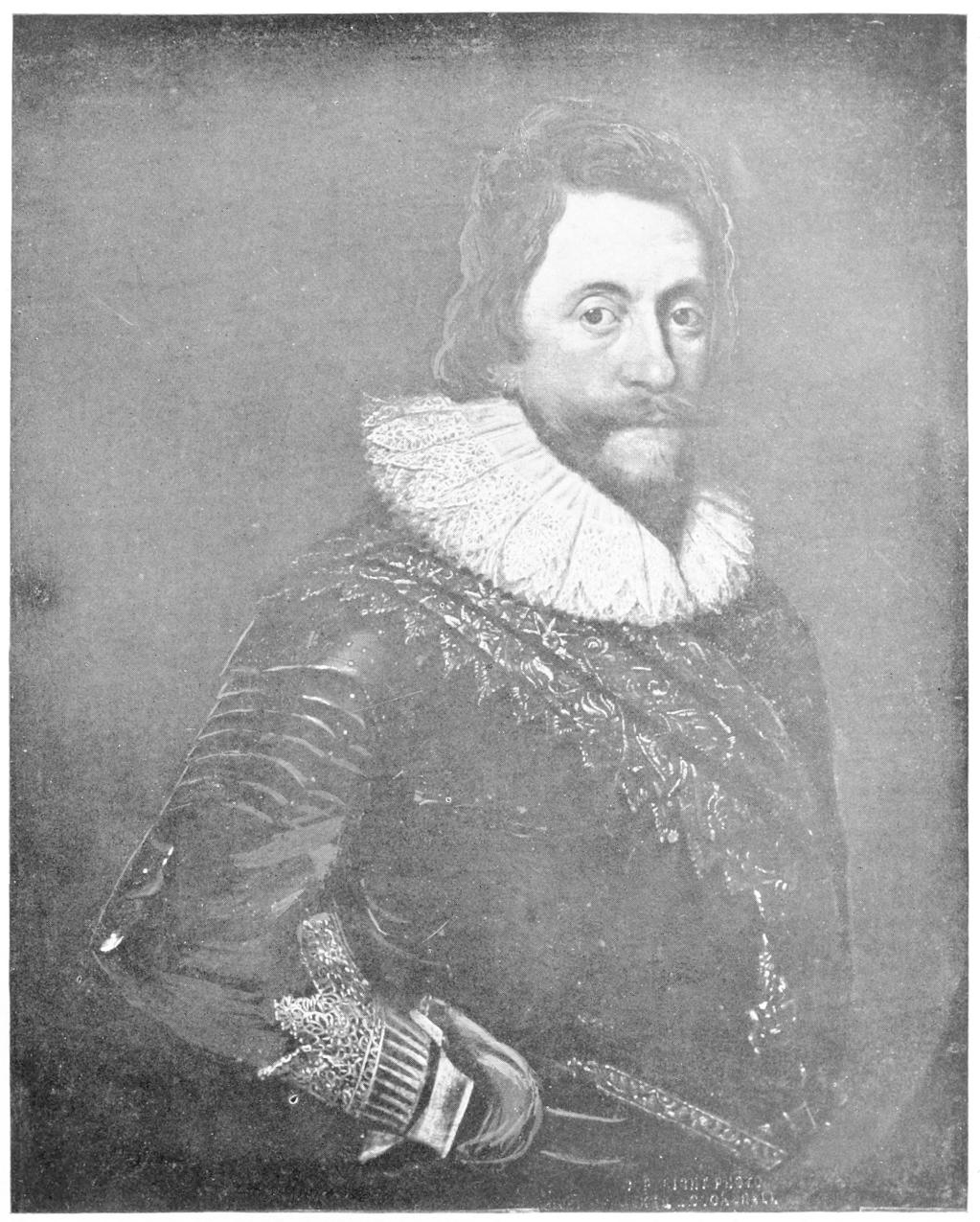

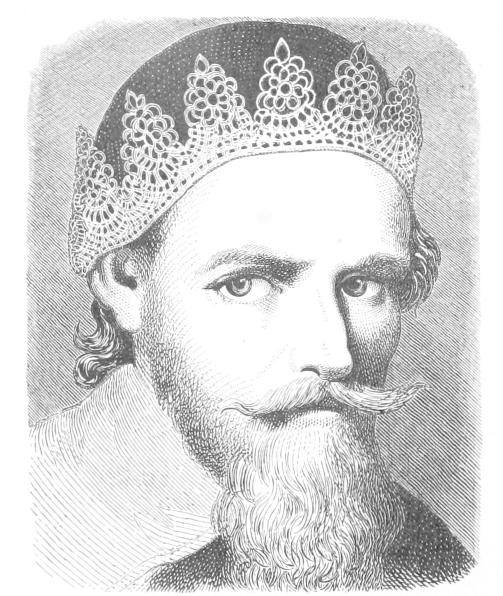

| William, Prince of Orange |

Plate LXVI |

258 |

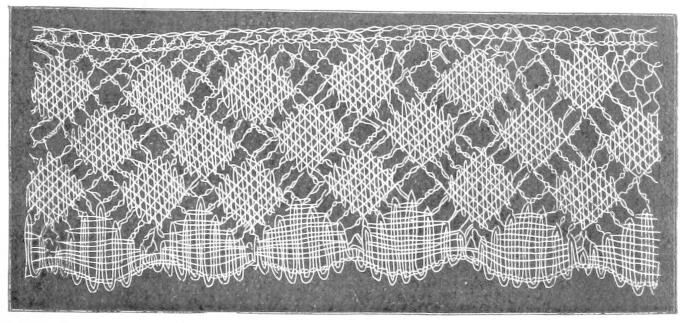

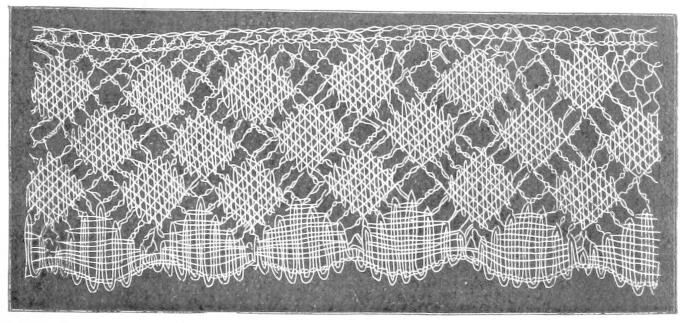

| Dutch Bobbin Lace |

Fig. 113 |

260 |

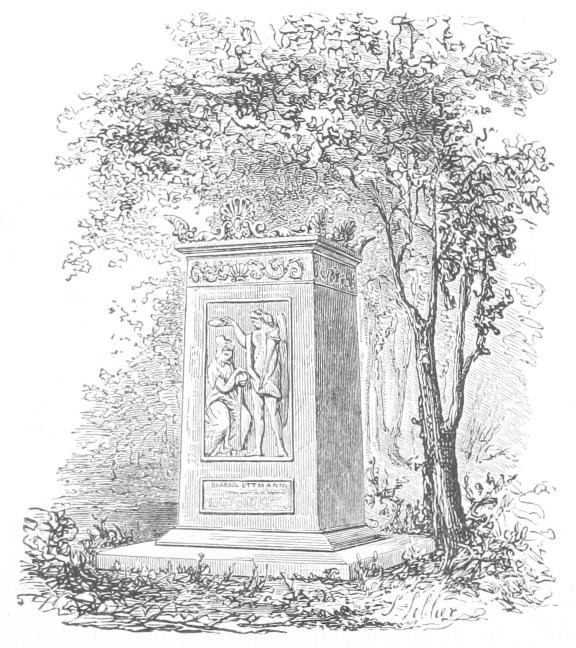

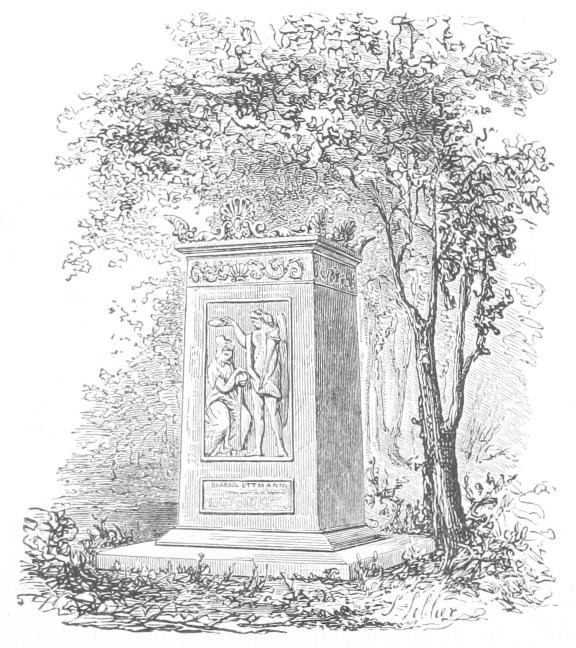

| Tomb of Barbara Uttmann |

" 114 |

261 |

| Barbara Uttmann |

" 114 |

A |

262 |

| Swiss, Neuchatel |

Plate LXVII |

264 |

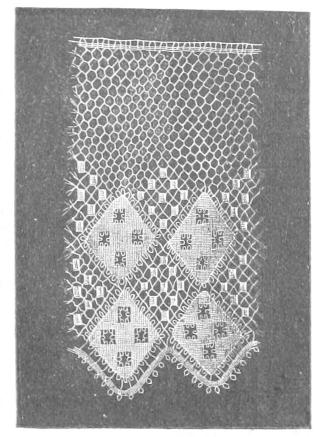

| German, Nuremberg |

" ILXVIII |

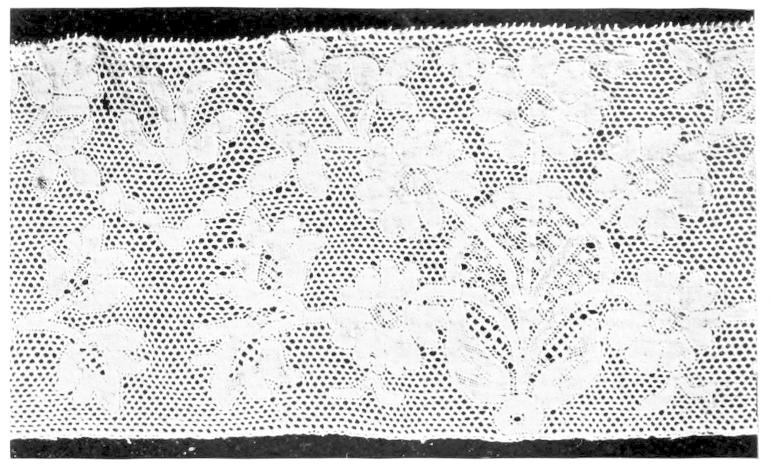

264 |

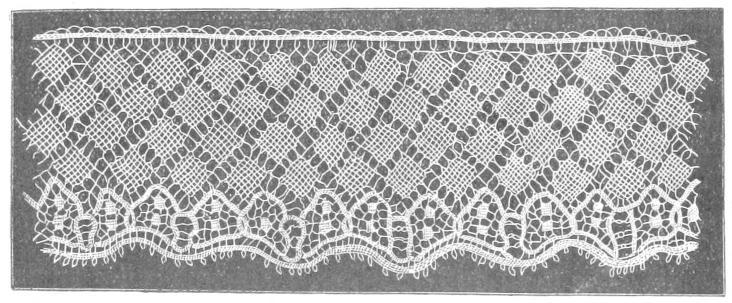

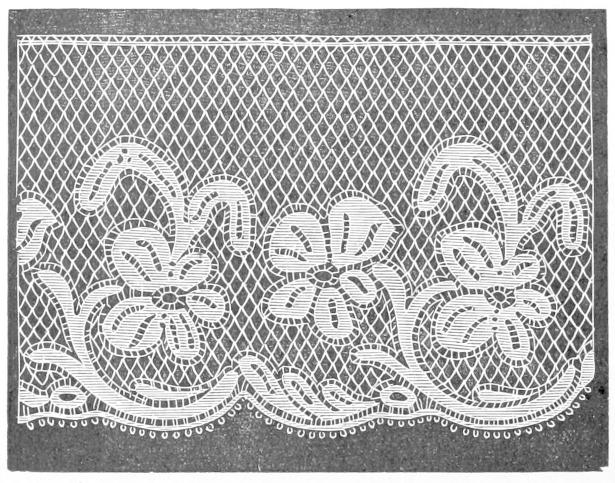

| English, Bucks |

" IIILXIX |

264 |

| Hungarian.—Bobbin Lace |

" IIIILXX |

268 |

| Austro-Hungarian |

" IIILXXI |

268 |

| Shirt Collar of Christian IV. |

Fig. 115 |

273 |

| Tönder Lace, Drawn Muslin |

" 116 |

274 |

| Russian—Needlepoint; German—Saxon |

Plate LXXII |

276 |

| Russian, Old Bobbin-made |

" LXXIII |

276 |

|

Russian, Bobbin-made in Thread

|

" LXXIV |

280 |

| Dalecarlian Lace |

Fig. 117 |

281 |

| Collar of Gustavus Adolphus |

" 118 |

282 |

| Russia, Bobbin-made, 19th Century |

" 119 |

284 |

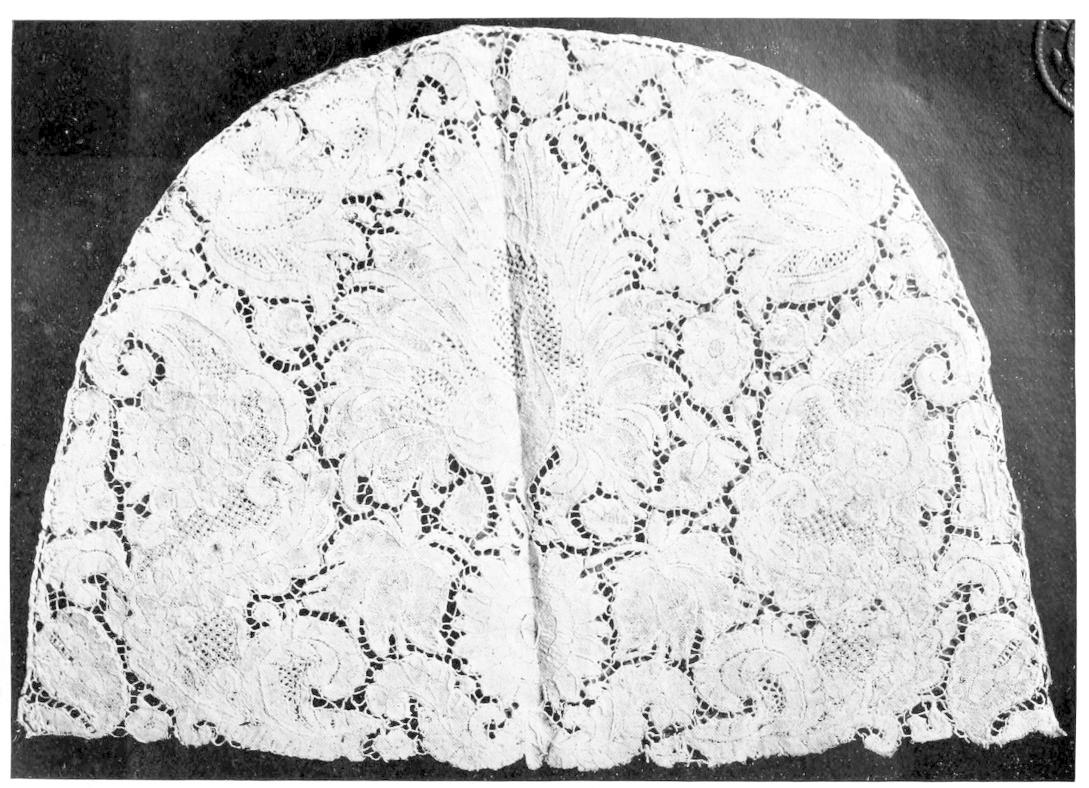

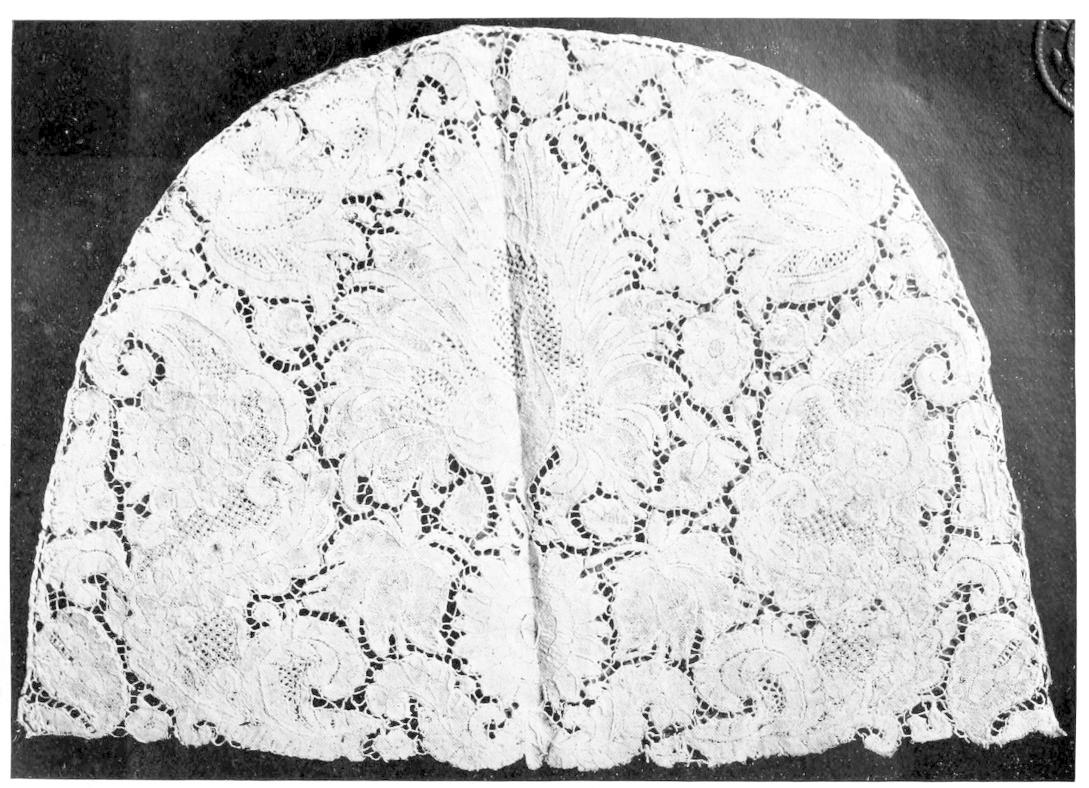

| Cap, Flemish or German |

Plate XXV |

288 |

| Fisher, Bishop of Rochester |

Fig. 120 |

292 |

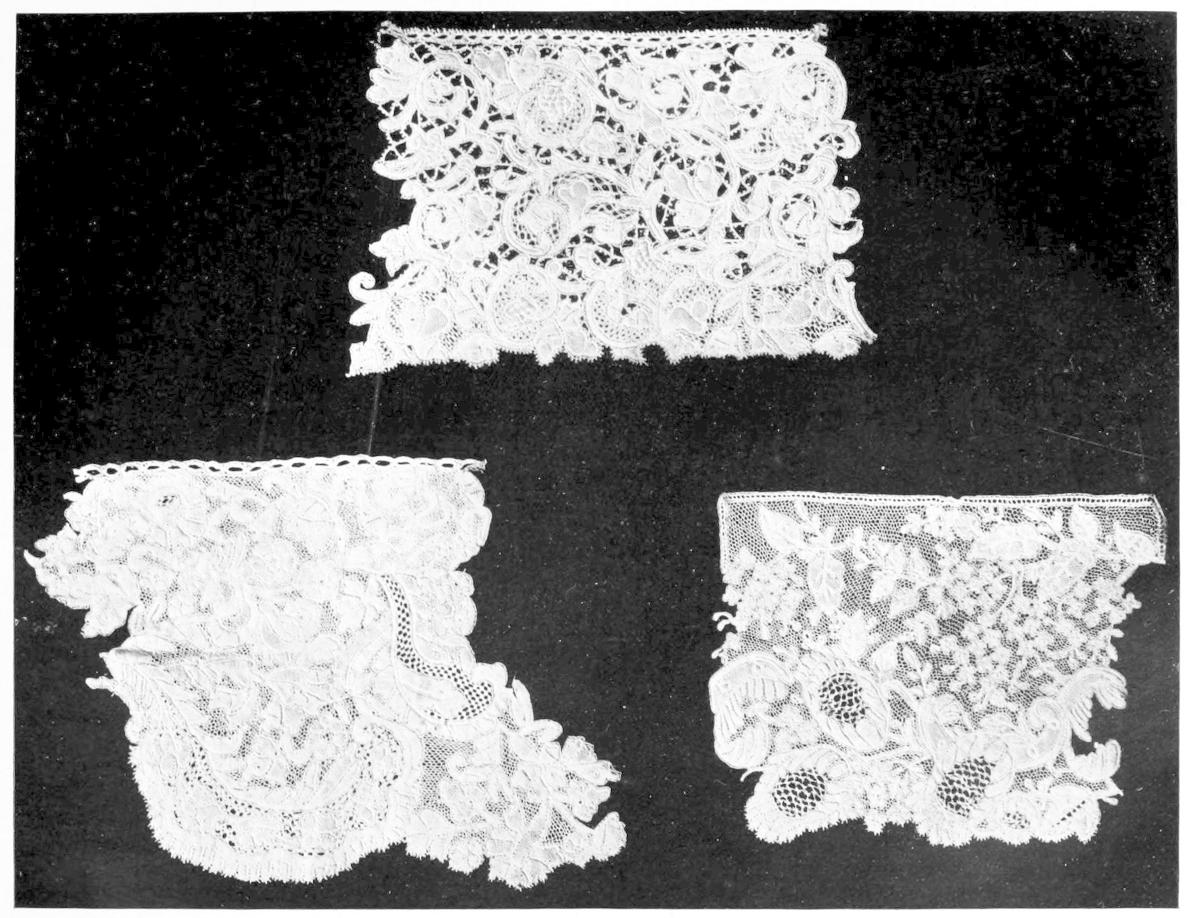

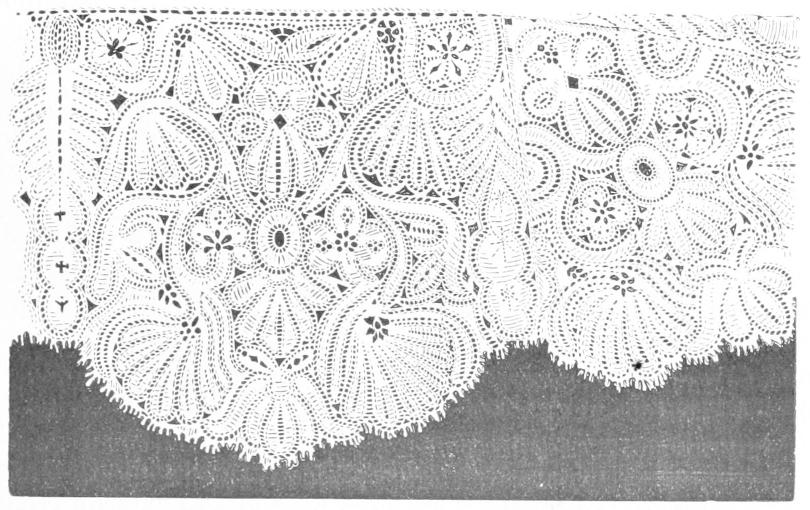

| English.—Cutwork and Needle-point |

Plate LXXVI |

292 |

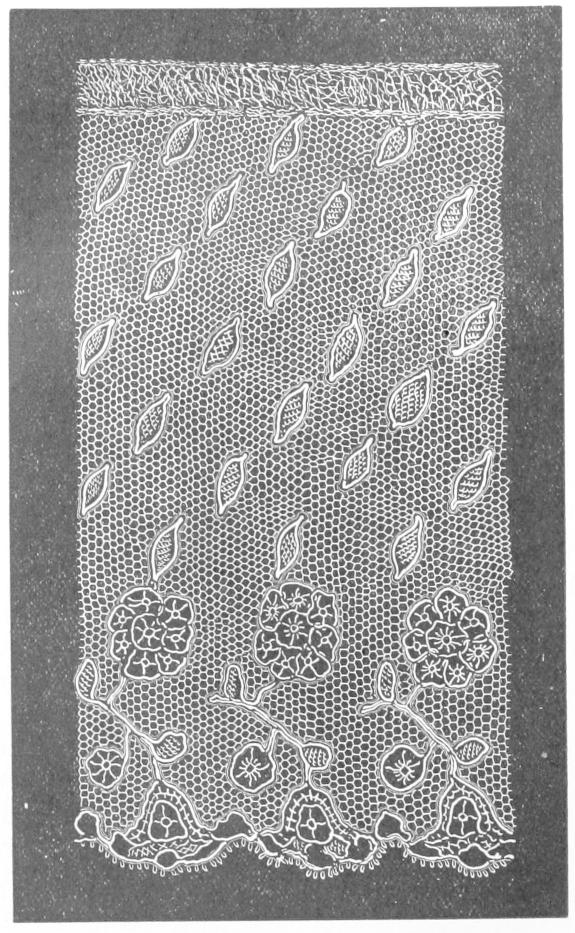

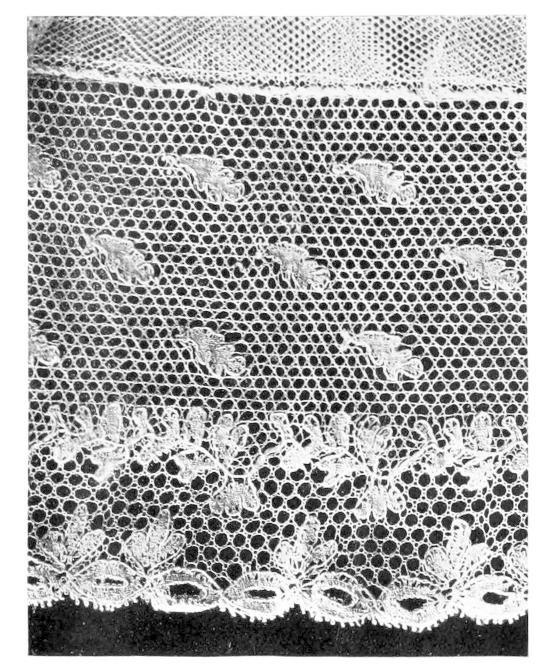

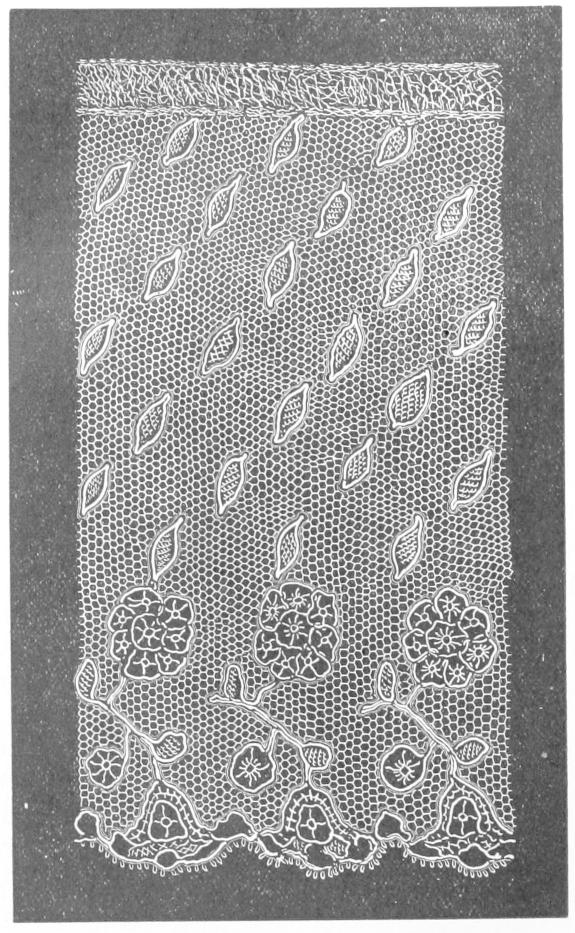

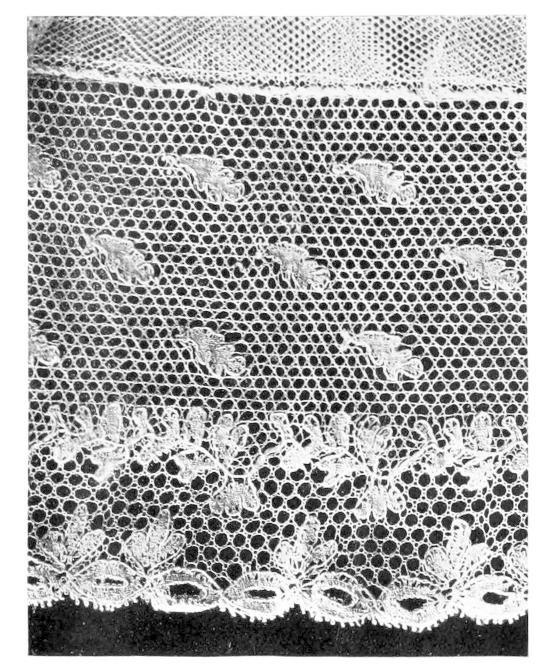

| English.—Devonshire "Trolly." |

" LXXVII |

292 |

| Fisher, Bishop of Rochester |

Fig. 121 |

293 |

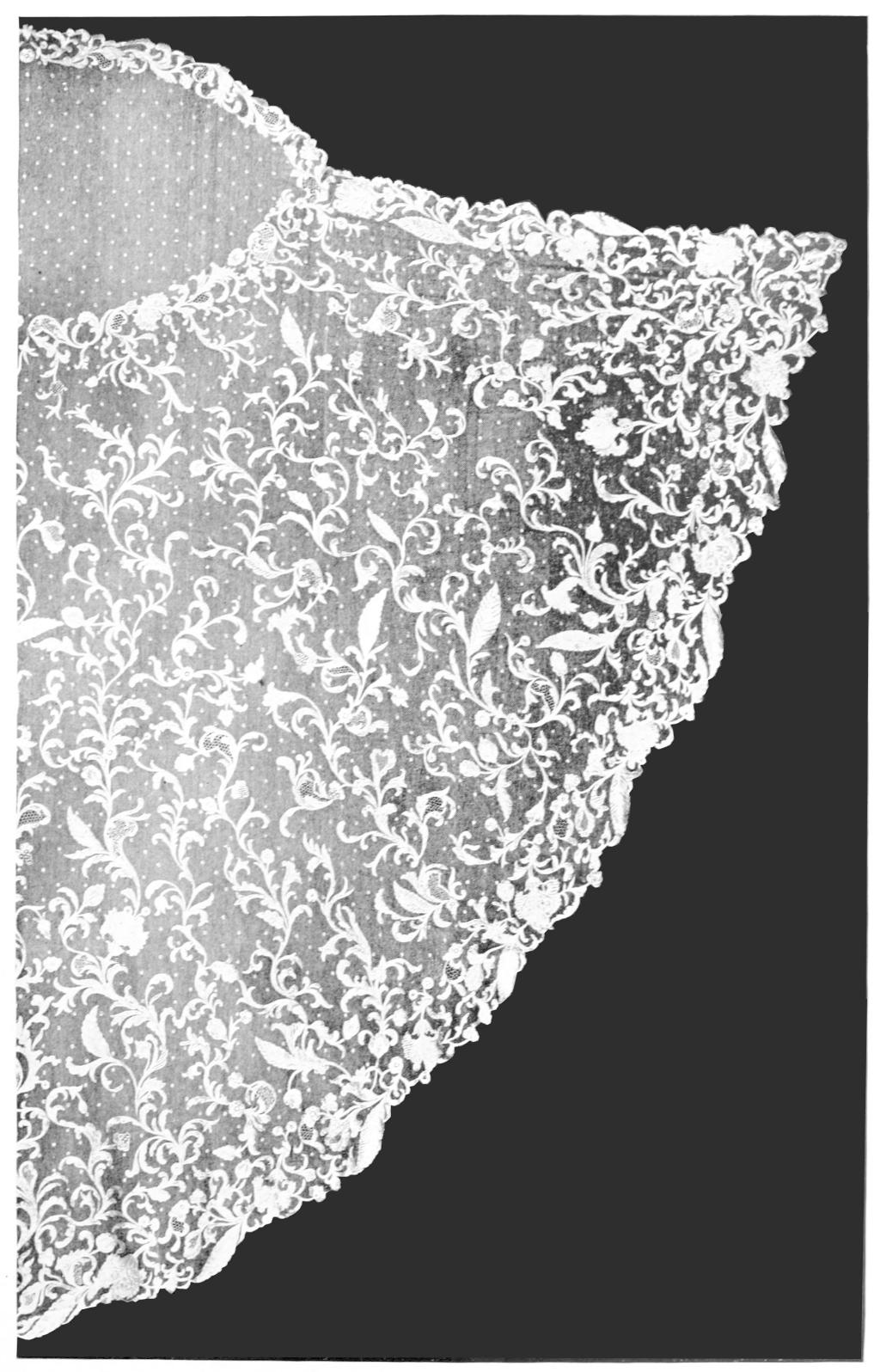

| Marie de Lorraine |

Plate LXXVIII |

298 |

| Queen Elizabeth's Smock |

Fig. 122 |

308 |

| Christening Caps, Needle-made Brussels |

Figs. 123, 124 |

309 |

| Mary Sidney, Countess of Pembroke |

Plate LXXIX |

316 |

| Henry Wrothesley, Third Earl of Southampton |

" LXXX |

320 |

| Monument of Princess Sophia |

Fig. 125 |

321 |

| Mon"ment "f Pri"cess Mary |

" 126 |

322 |

| Mary, Countess of Pembroke |

" 127 |

323 |

| Elizabeth, Princess Palatine |

Plate LXXXI |

326 |

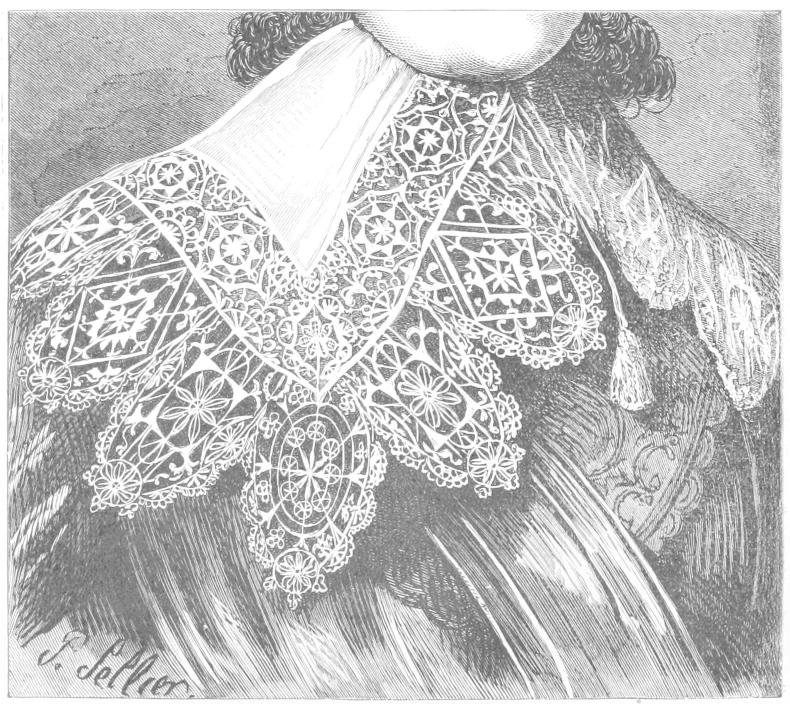

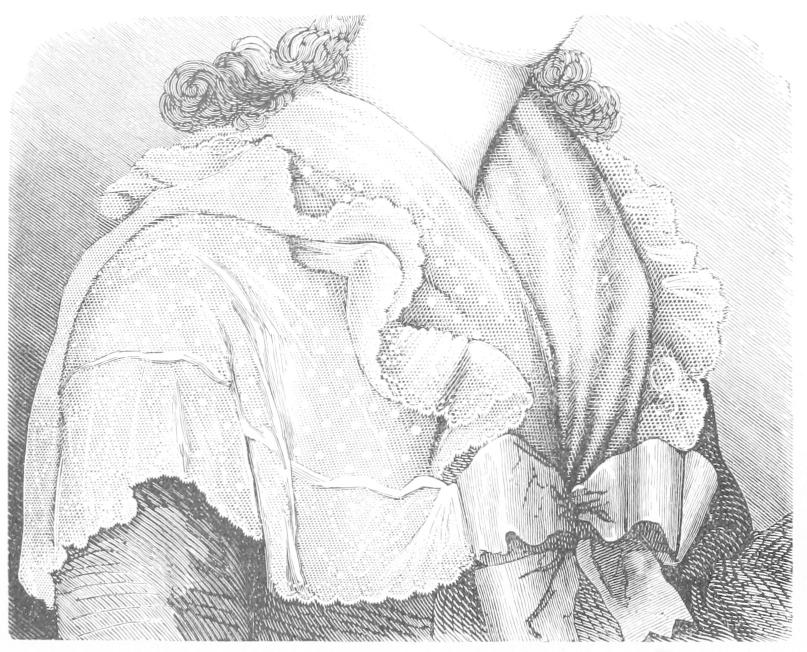

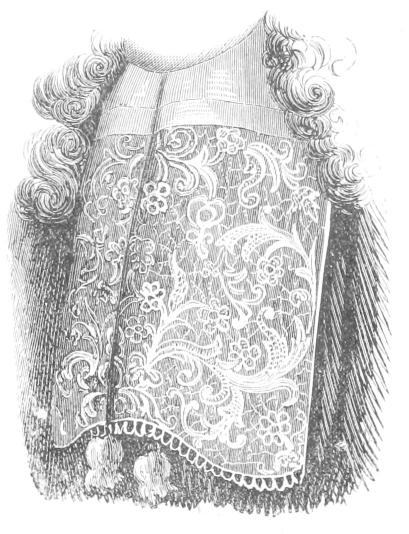

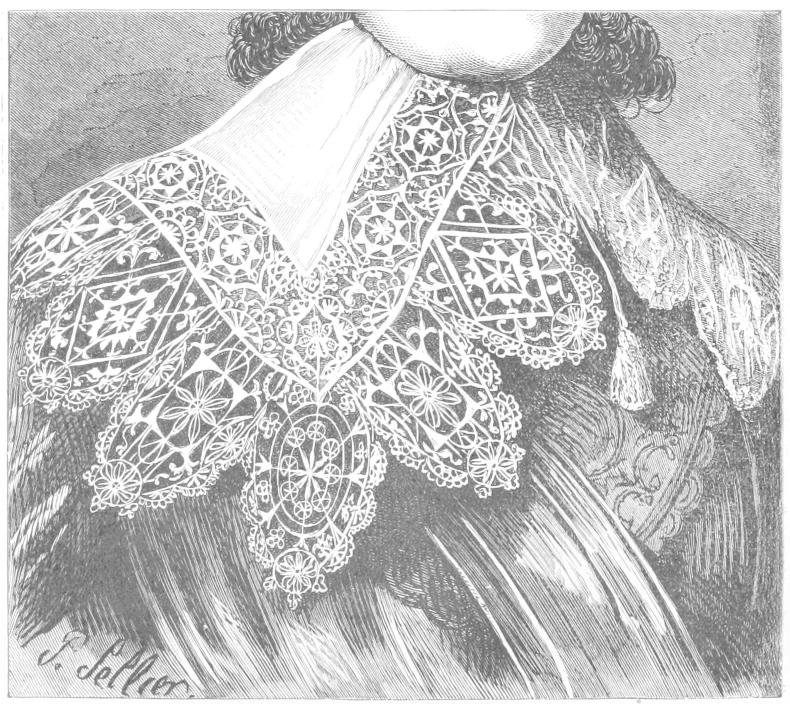

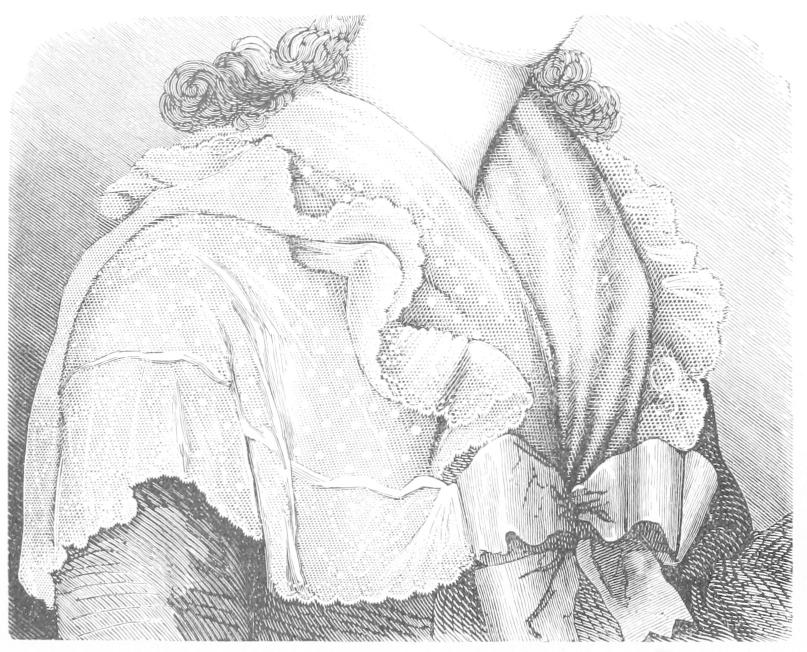

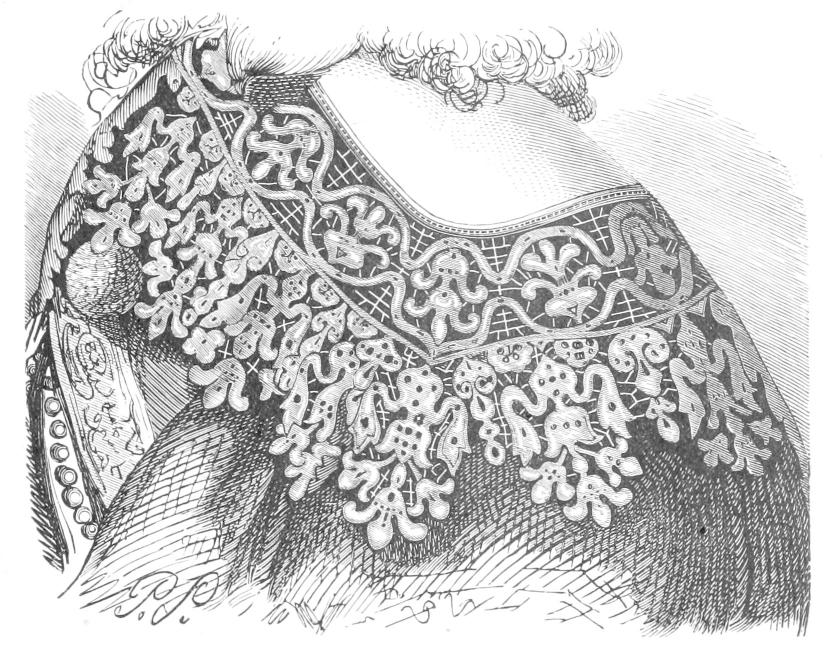

| Falling Collar of the 17th Century |

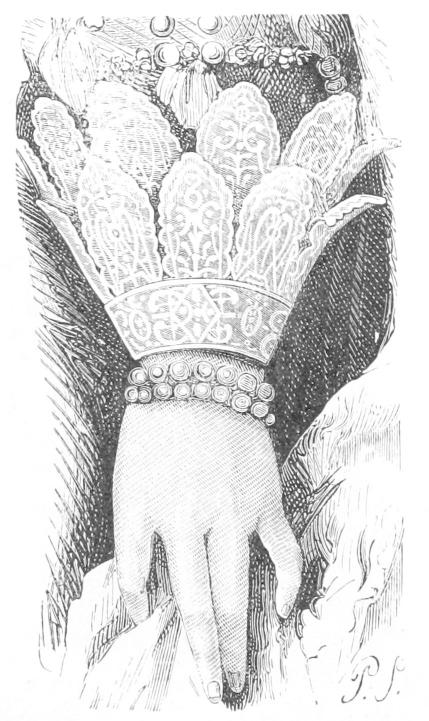

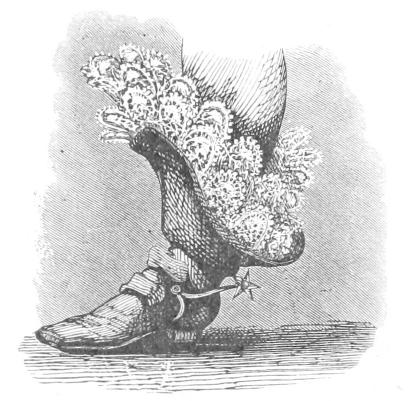

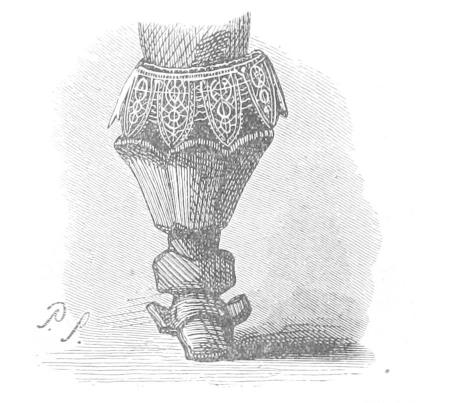

Fig. 128 |

327 |

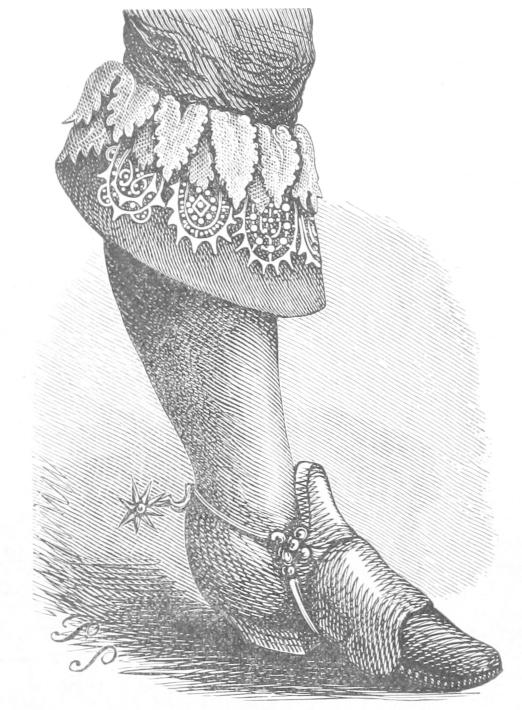

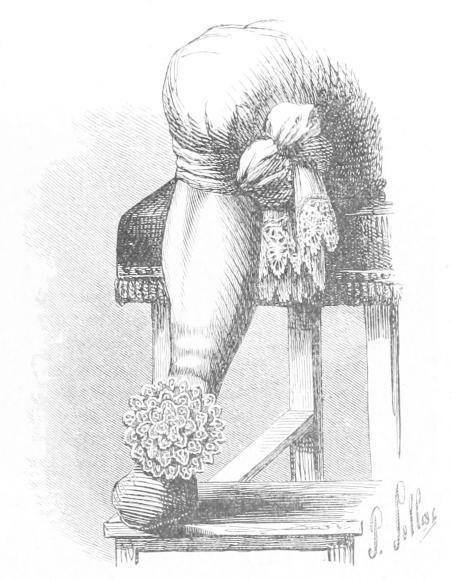

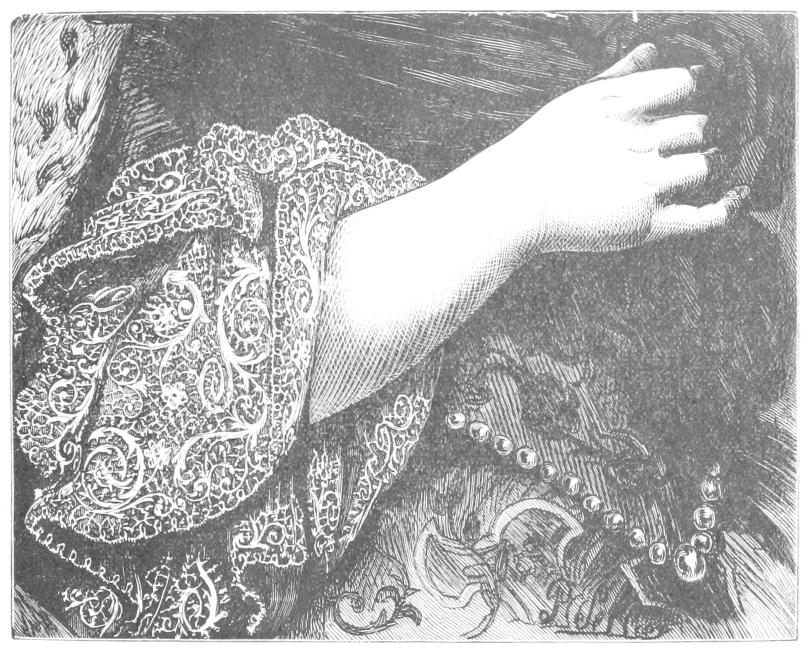

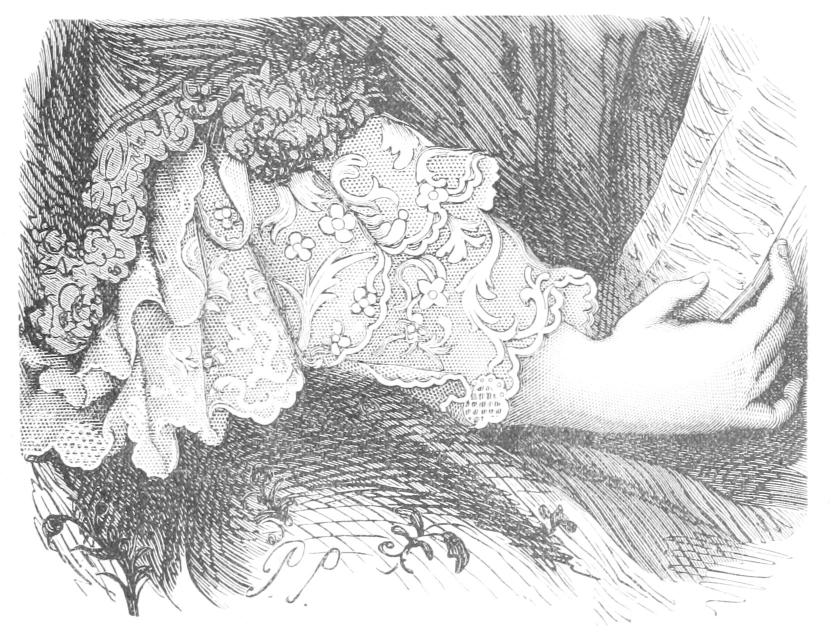

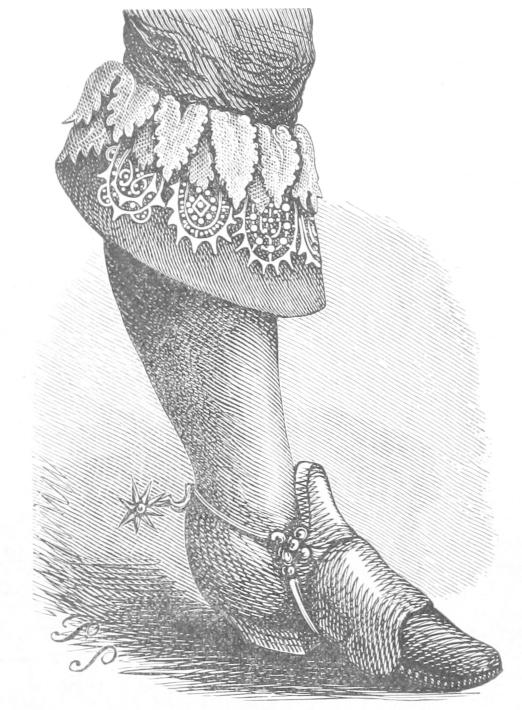

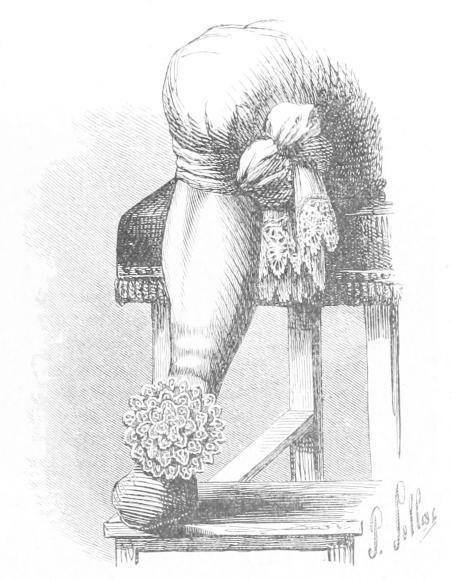

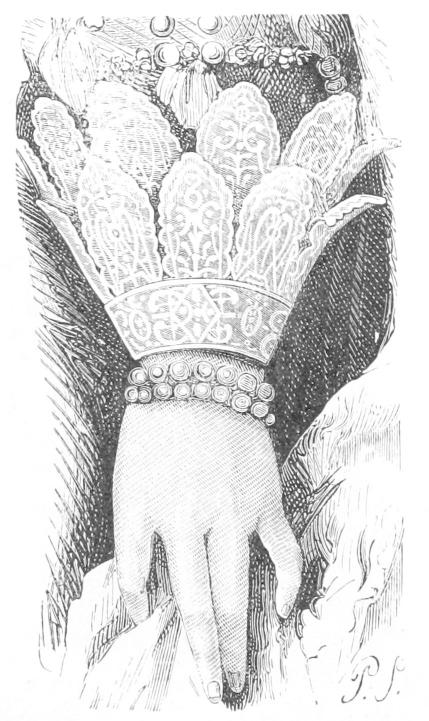

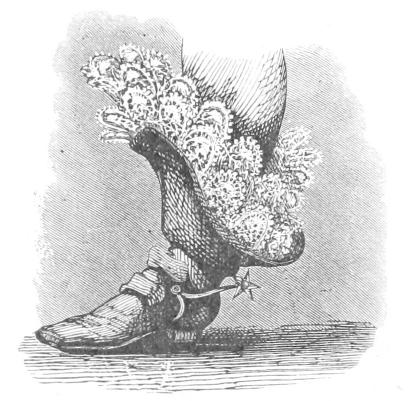

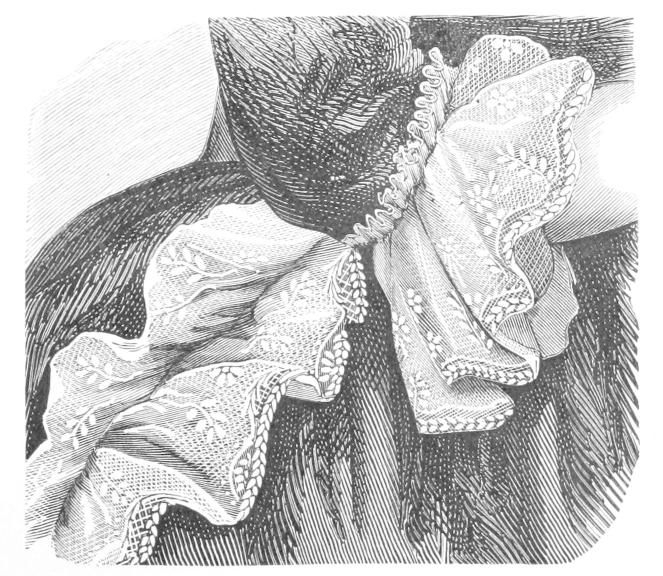

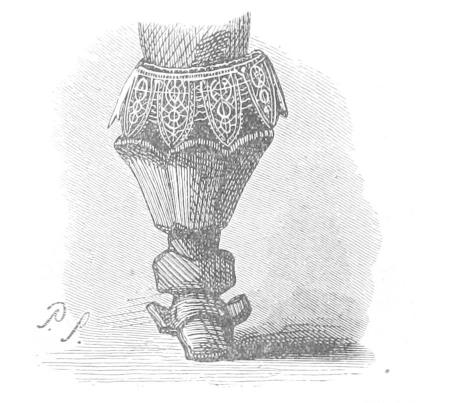

| Boots, Cuffs |

Figs. 129, 130 |

328 |

| English Needle-made Lace |

Fig. 131 |

328 |

| James Harrington |

Plate LXXXII |

332 |

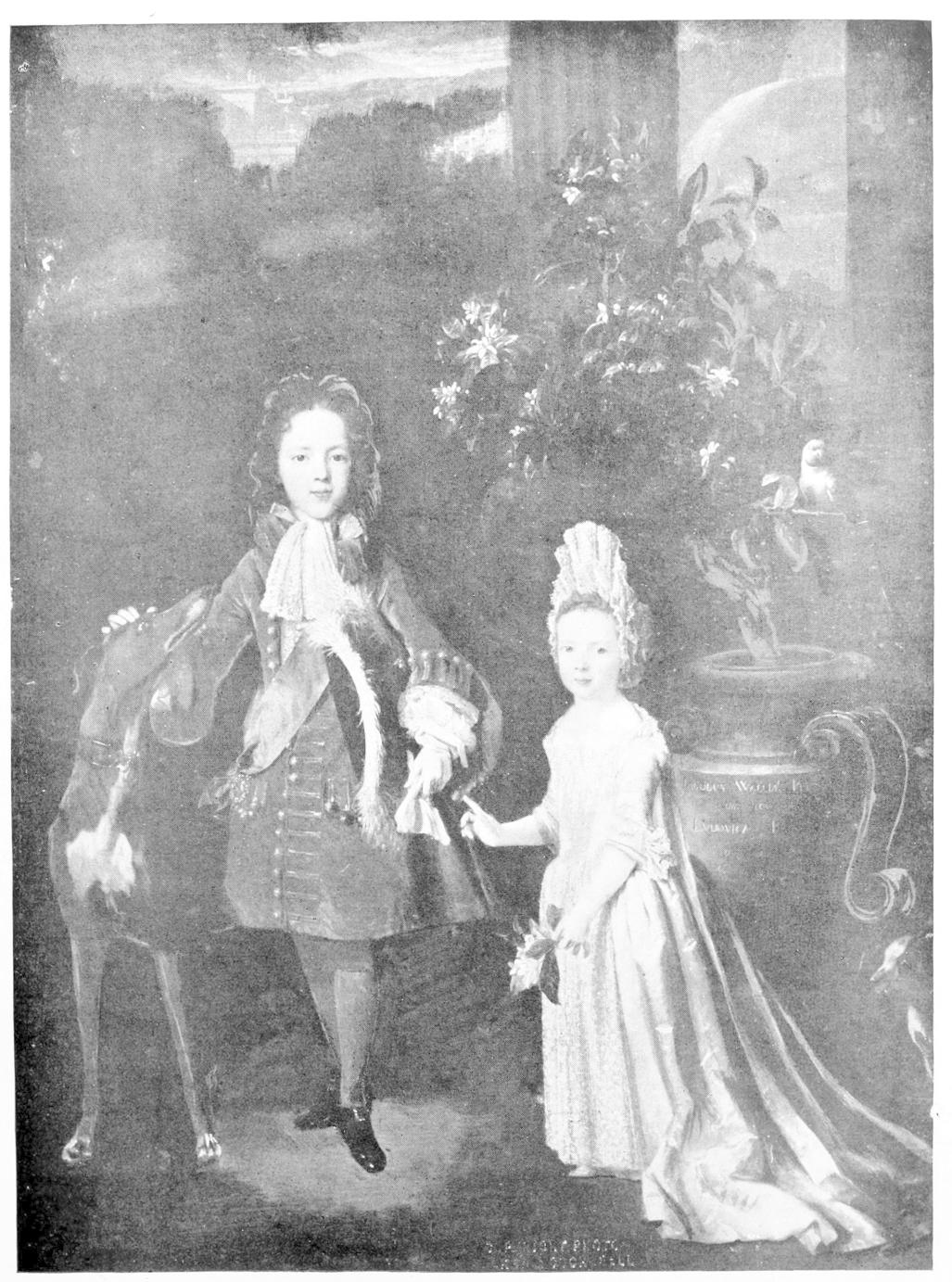

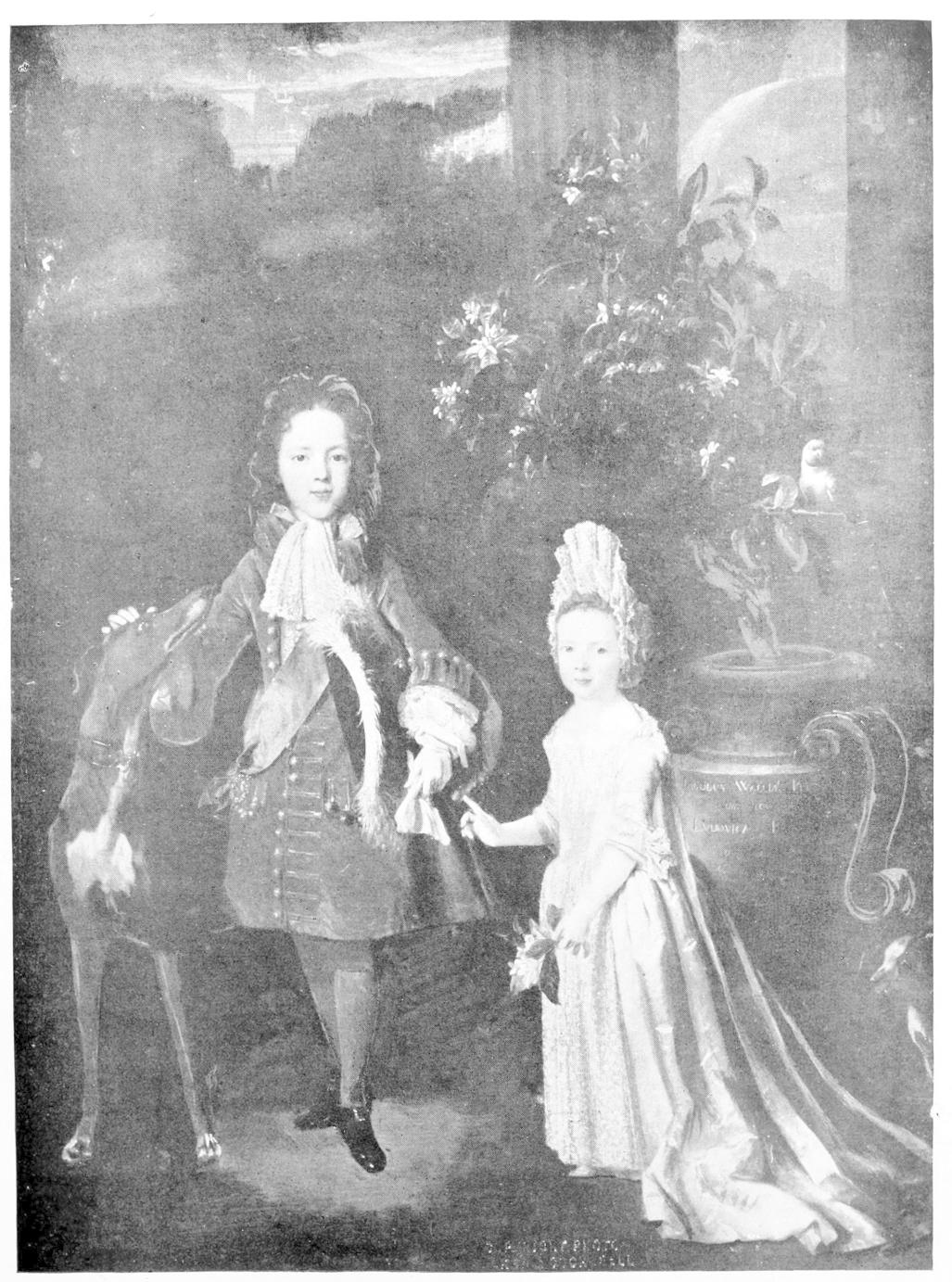

| James, the Old Pretender, and His Sister, Princess

Louisa |

" LXXXIII |

344 |

| John Law, the Paris Banker |

" LXXXIV |

352 |

| Ripon |

Fig. 132 |

373 |

| English, Buckinghamshire, Bobbin Lace |

Plate LXXXV |

374 |

| Buckinghamshire Trolly |

Fig. 133 |

381 |

| Bucking"amshire Point |

" 134 |

382 |

| Bucking"amshire Po" |

" 135 |

383 |

| English, Northamptonshire, Bobbin Lace |

Plate LXXXVI |

384 |

| Old Flemish |

Fig. 136 |

385 |

| Old Brussels |

" 137 |

385 |

| "Run" Lace, Newport Pagnell |

" 138 |

386 |

| English Point, Northampton |

" 139 |

386 |

| "Baby" Lace, Northampton |

" 140 |

387 |

| nB"byn L"ce Beds |

" 141 |

387 |

| nB"byn L"ce Bucks |

" 142 |

387 |

| Wire Ground, Northampton |

" 143 |

388 |

| Valenciennes " |

" 144 |

388 |

| Regency Point, Bedford |

" 145 |

389 |

| Insertion, " |

" 146 |

389 |

| Plaited Lace, " |

" 147 |

392 |

| Raised Plait, " |

" 148 |

393 |

| English, Suffolk, Bobbin Lace |

Plate LXXXVII |

394 |

| English Needle-made Lace |

Fig. 149 |

396 |

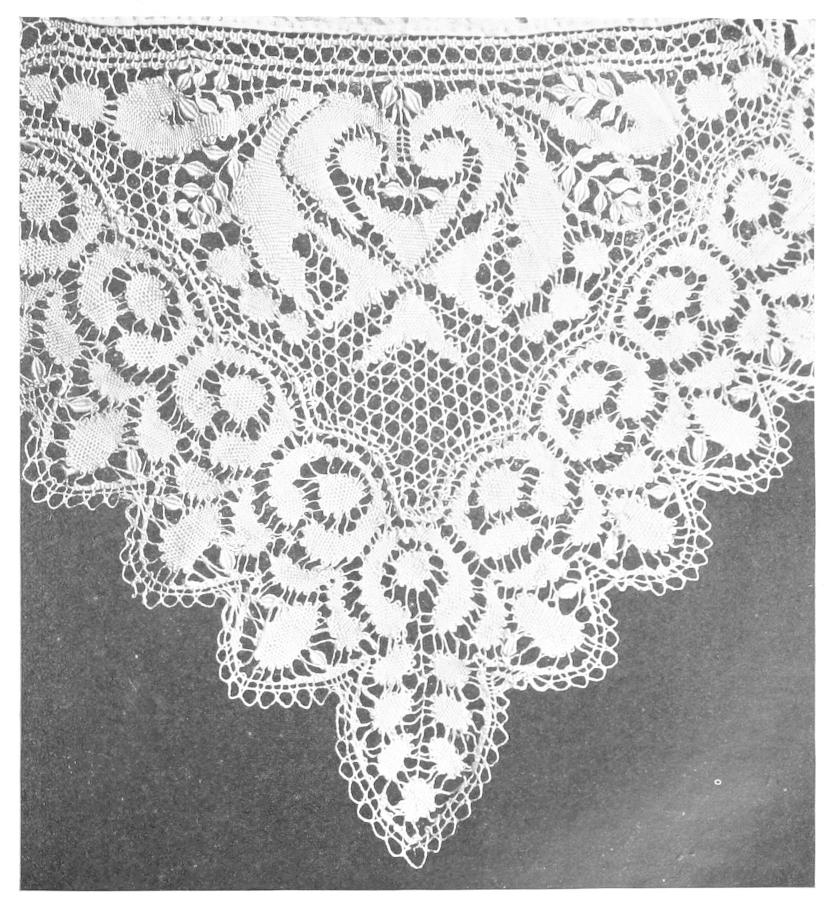

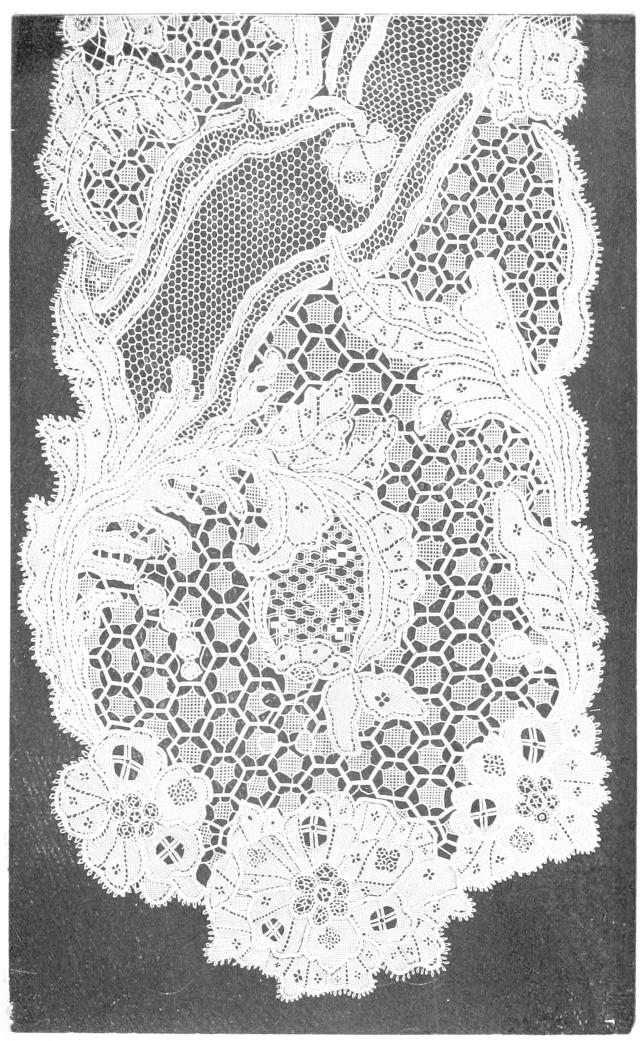

| Honiton With the Vrai Réseau |

Plate LXXXVIII |

402 |

| Bone Lace from Cap, Devonshire |

Fig. 150 |

404 |

| Monument of Bishop Stafford, Exeter Cathedral |

" 151 |

406 |

| Monument of Lady Doddridge Exe"er

Cath" |

" 152 |

407 |

| Honiton, sewn on plain pillow ground |

" 153 |

408 |

|

Old Devonshire

|

" 154 |

408 |

| Honiton Guipure |

" 155 |

410 |

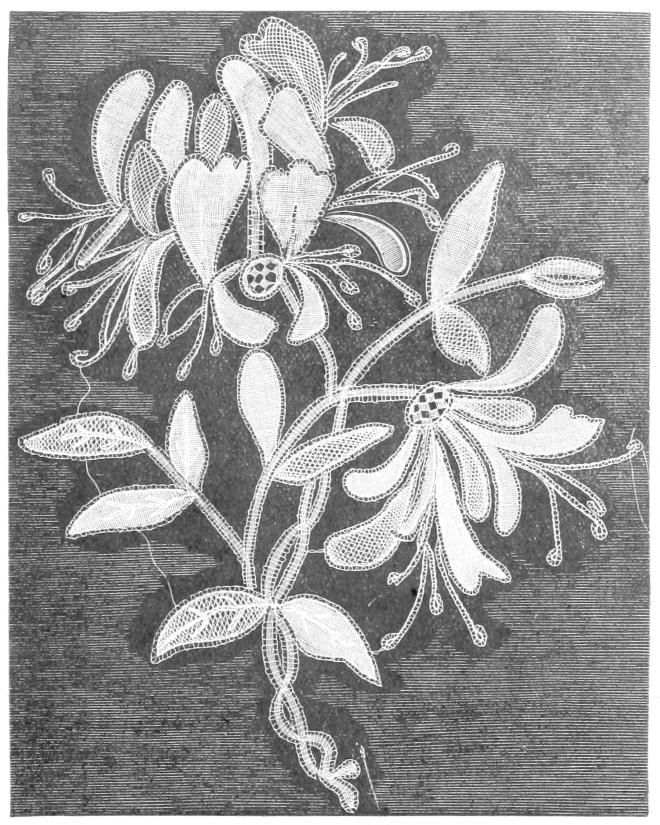

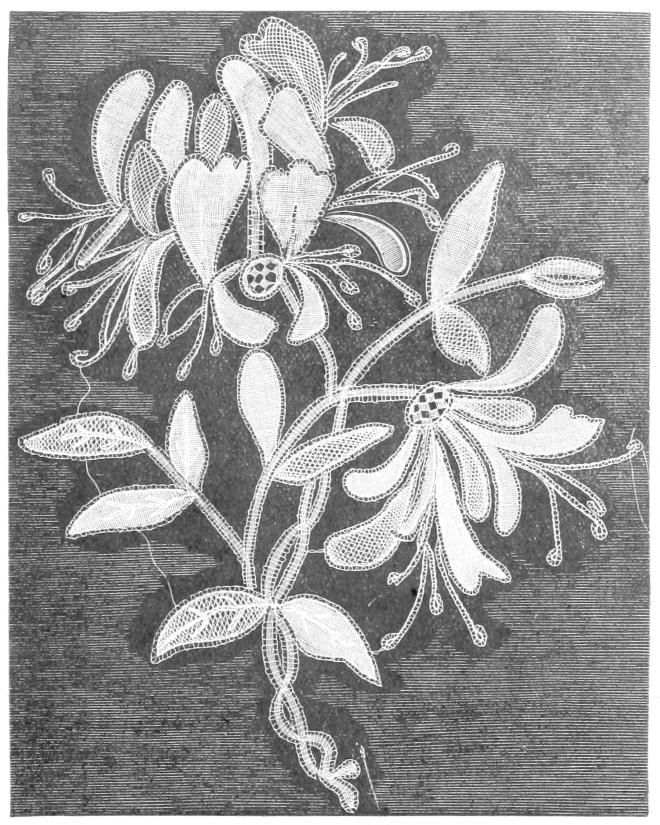

| Honeysuckle, Sprig of Modern Honiton |

" 156 |

411 |

| Old Devonshire Point |

" 157 |

412 |

| Lappet made by the late Mrs. Treadwin of Exeter |

" 158 |

412 |

| Venetian Relief in Point |

" 159 |

414 |

| English.—Devonshire. Fan Made at Beer for the Paris

Exhibition, 1900 |

Plate LXXXIX |

416 |

| Sir Alexander Gibson |

Fig. 160 |

424 |

| Scotch, Hamilton |

" 161 |

431 |

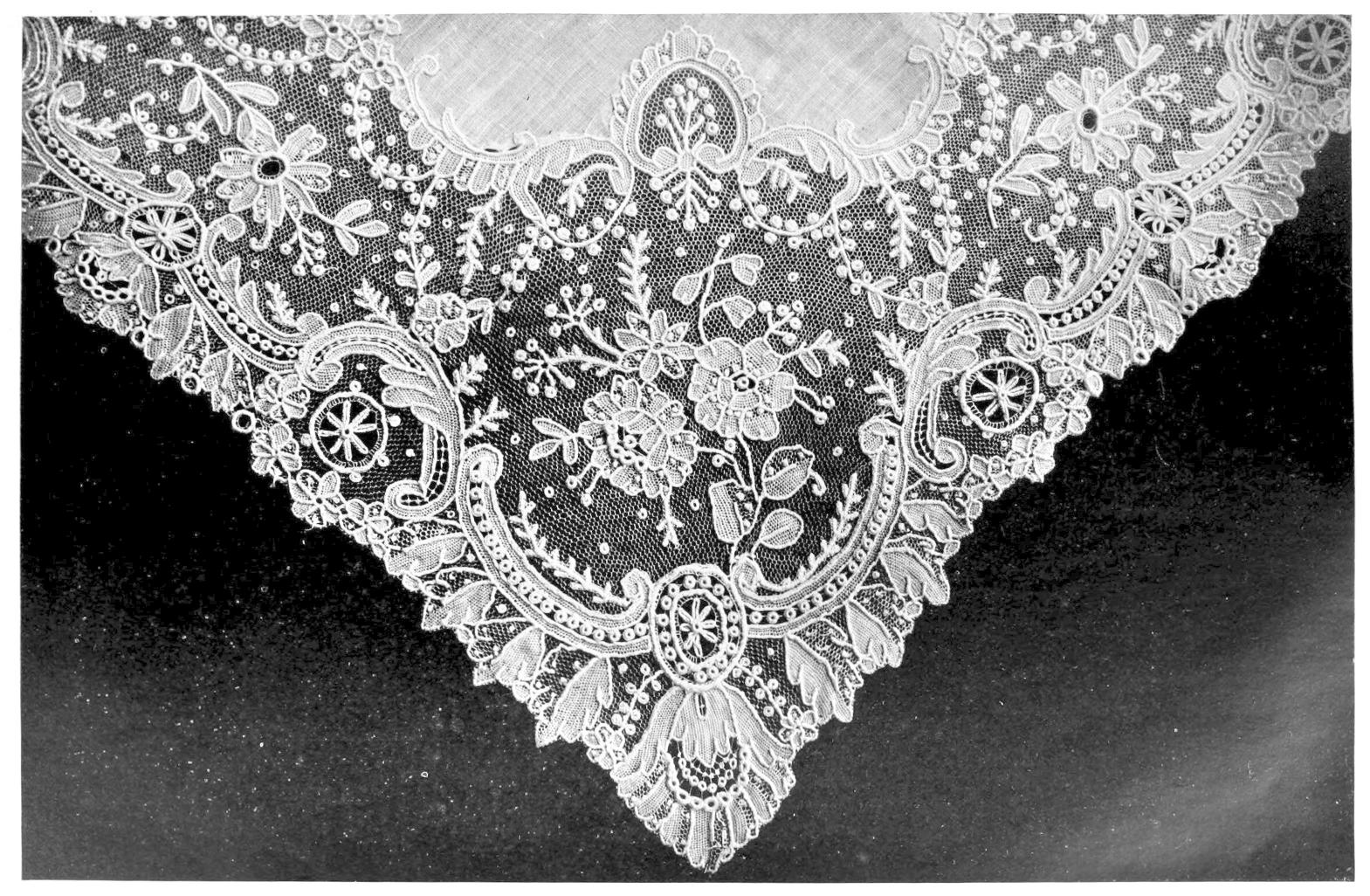

| Irish, Youghal |

Plate XC |

436 |

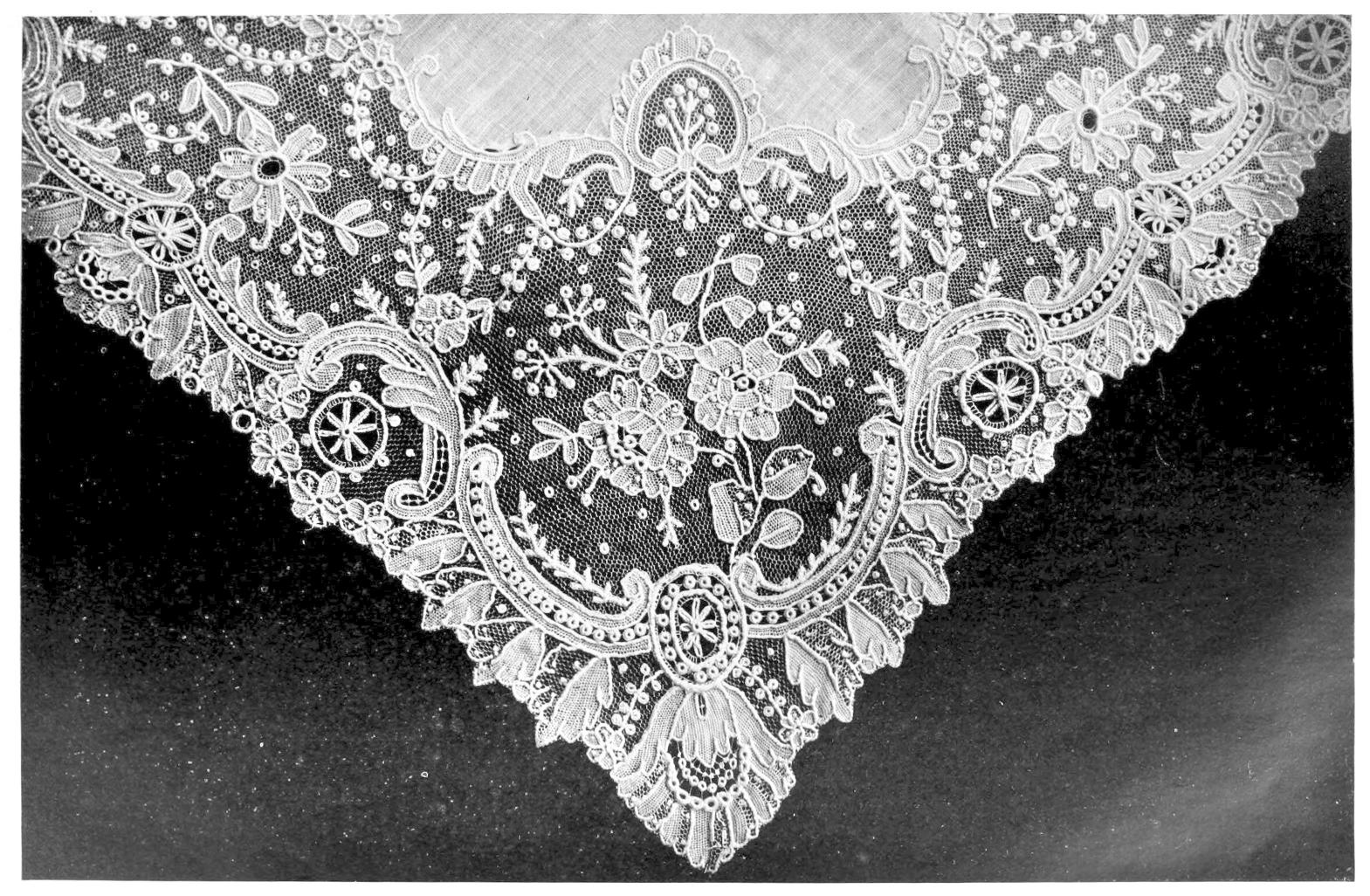

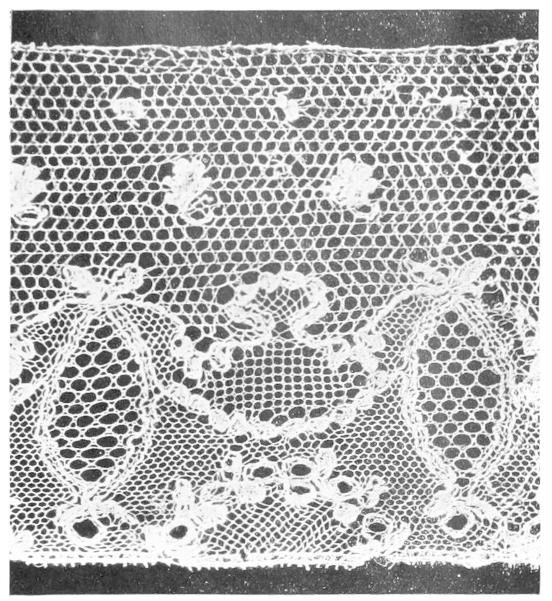

| Irish, Carrickmacross |

" IIXCI |

442 |

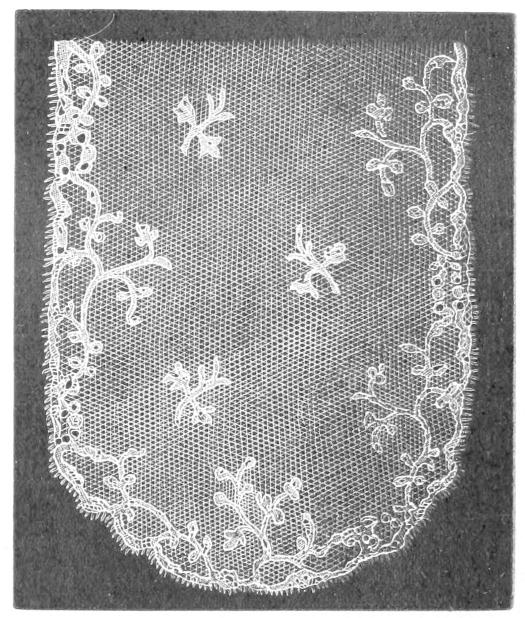

| Irish, Limerick Lace |

" IXCII |

442 |

| Irish, Crochet Lace |

" XCIII |

446 |

| Arms of the Framework Knitters' Company |

Fig. 162 |

447 |

| The Lagetta, or Lace-bark Tree |

" 163 |

456 |

| Metre P. Quinty |

Figs. 164, 165 |

460 |

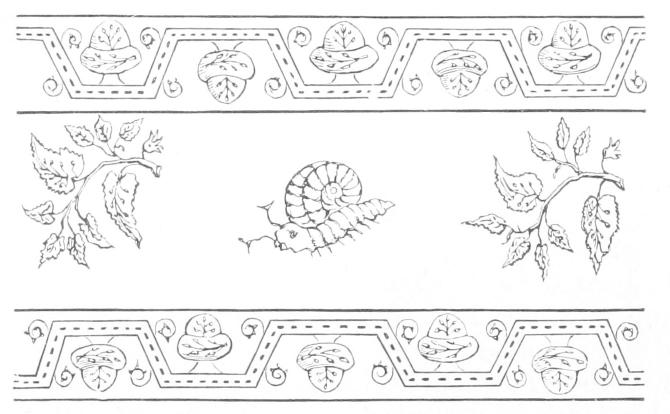

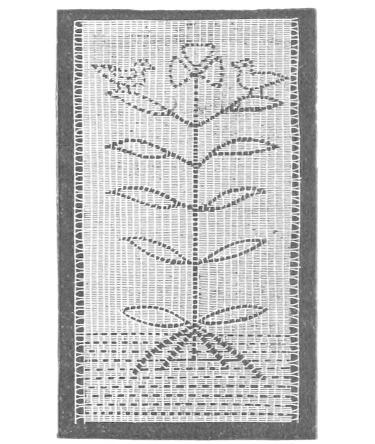

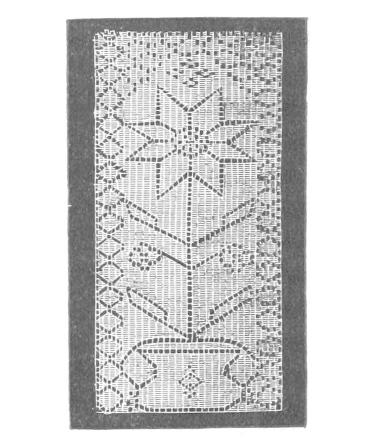

| Pattern Book, Augsburg |

" 166, 167 |

462 |

| Augsburg |

Fig. 168 |

463 |

| Le Pompe, 1559 |

" 169 |

473 |

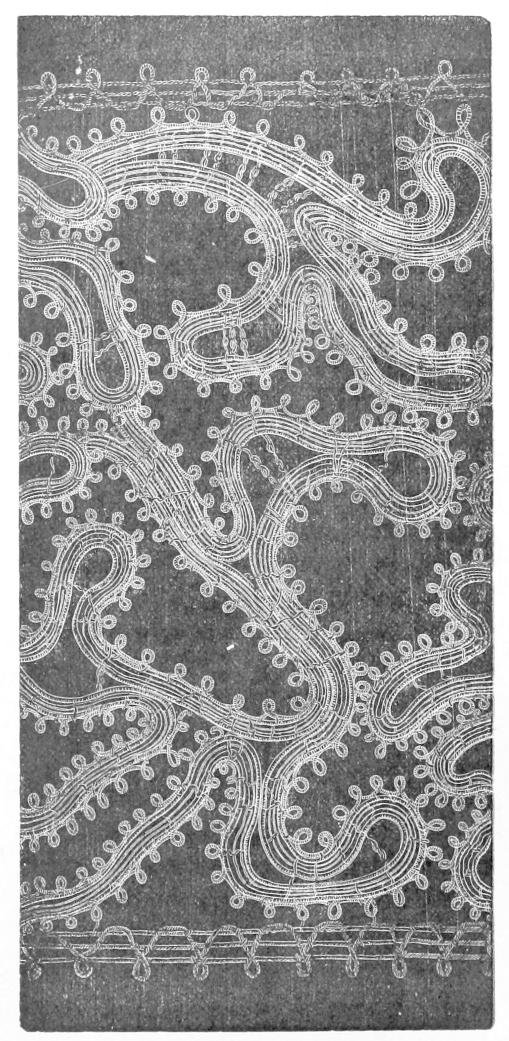

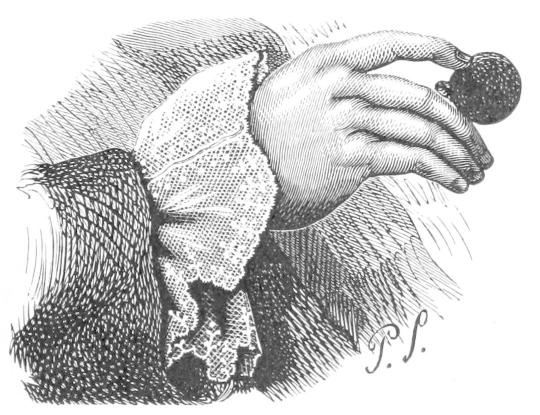

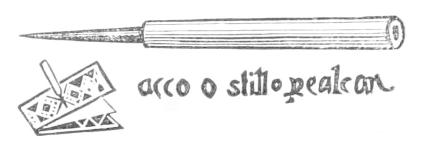

| Manner of Pricking Pattern |

" 170 |

486 |

| Frankfort-on-the-Main, 1605 |

" 171 |

492 |

| Monogram |

" 172 |

492 |

| "Bavari," from "Ornamento nobile" of Lucretia Romana |

" 173 |

498 |

{1}

HISTORY OF LACE.

CHAPTER I.

NEEDLEWORK.

"As ladies wont

To finger the fine needle and nyse thread."—Faerie Queene.

The art of lace-making has from the earliest times been so interwoven with the art of

needlework that it would be impossible to enter on the subject of the present work without giving

some mention of the latter.

With the Egyptians the art of embroidery was general, and at Beni Hassan figures are

represented making a sort of net—"they that work in flax, and they that weave network."[1] Examples of elaborate netting have been found in

Egyptian tombs, and mummy wrappings are ornamented with drawn-work, cut-work, and other open

ornamentation. The outer tunics of the robes of state of important personages appear to be

fashioned of network darned round the hem with gold and silver and coloured silks. Amasis, King of

Egypt, according to Herodotus,[2] sent to Athene of

Lindus a corslet with figures interwoven with gold and cotton, and to judge from a passage of

Ezekiel, the Egyptians even embroidered the sails of their galleys which they exported to Tyre.[3]

{2}

The Jewish embroiderers, even in early times, seem to have carried their art to a high standard

of execution. The curtains of the Tabernacle were of "fine twined linen wrought with needlework,

and blue, and purple, and scarlet, with cherubims of cunning work."[4] Again, the robe of the ephod was of gold and blue and purple and

scarlet, and fine twined linen, and in Isaiah we have mention of women's cauls and nets of

checker-work. Aholiab is specially recorded as a cunning workman, and chief embroiderer in blue,

and in purple, and in scarlet, and in fine linen,[5] and

the description of the virtuous woman in the Proverbs, who "layeth her hands to the spindle" and

clotheth herself in tapestry, and that of the king's daughter in the Psalms, who shall be "brought

unto the king in a raiment of needlework," all plainly show how much the art was appreciated

amongst the Jews.[6] Finally Josephus, in his Wars of

the Jews, mentions the veil presented to the Temple by Herod (B.C. 19), a Babylonian curtain fifty cubits high, and sixteen broad,

embroidered in blue and red, "of marvellous texture, representing the universe, the stars, and the

elements."

In the English Bible, lace is frequently mentioned, but its meaning must be qualified by

the reserve due to the use of such a word in James I.'s time. It is pretty evident that the

translators used it to indicate a small cord, since lace for decoration would be more commonly

known at that time as purls, points, or cut-works.[7]

"Of lace amongst the Greeks we seem to have no evidence. Upon the well-known red and black

vases are all kinds of figures clad in costumes which are bordered with ornamental patterns, but

these were painted upon, woven into, or embroidered upon the fabric. They were not lace. Many

centuries elapsed before a marked and elaborately ornamental character infused itself into

twisted, plaited, or looped thread-work. During such a period the fashion of ornamenting borders

of costumes and hangings existed, and underwent a few phases, as, for instance, in the Elgin

marbles, where crimped {3}edges appear along the flowing

Grecian dresses." Embroidered garments, cloaks, veils and cauls, and networks of gold are

frequently mentioned in Homer and other early authors.[8]

The countries of the Euphrates were renowned in classical times for the beauty of their

embroidered and painted stuffs which they manufactured.[9] Nothing has come down to us of these Babylonian times, of which

Greek and Latin writers extolled the magnificence; but we may form some idea, from the statues and

figures engraved on cylinders, of what the weavers and embroiderers of this ancient time were

capable.[10] A fine stone in the British Museum is

engraved with the figure of a Babylonian king, Merodach-Idin-Abkey, in embroidered robes, which

speak of the art as practised eleven hundred years B.C.[11] Josephus writes that the veils given by Herod for the Temple

were of Babylonian work (πεπλος

βαβυλωνιος)—the women

excelling, according to Apollonius, in executing designs of varied colours.

The Sidonian women brought by Paris to Troy embroidered veils of such rich work that Hecuba

deemed them worthy of being offered to Athene; and Lucan speaks of the Sidonian veil worn by

Cleopatra at a feast in her Alexandrine palace, in honour of Cæsar.[12]

Phrygia was also renowned for its needlework, and from the shores of Phrygia Asiatic and

Babylonian embroideries were shipped to Greece and Italy. The toga picta, worked with

Phrygian embroidery, was worn by Roman generals at their triumphs and by the consuls when they

celebrated the games; hence embroidery itself is styled "Phrygian,"[13] {4}and the Romans knew

it under no other name (opus Phrygianum).[14]

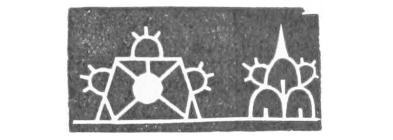

Gold needles and other working implements have been discovered in Scandinavian

tumuli. In the London Chronicle of 1767 will be found a curious account of the opening of a

Scandinavian barrow near Wareham, in Dorsetshire. Within the hollow trunk of an oak were

discovered many bones wrapped in a covering of deerskins neatly sewn together. There were also the

remains of a piece of gold lace, four inches long and two and a half broad. This lace was black

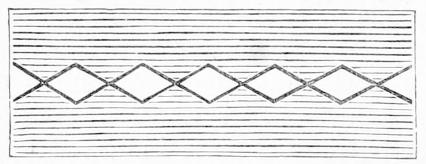

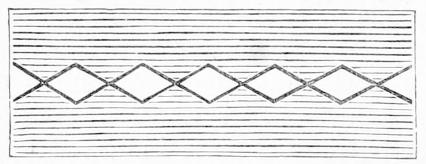

and much decayed, of the old lozenge pattern,[15] that

most ancient and universal of all designs, again found depicted on the coats of ancient Danes,

where the borders are edged with an open or net-work of the same pattern.

Fig. 1.

Gold Lace Found in a Barrow.

Passing to the first ages of the Christian era, we find the pontifical ornaments, the altar and

liturgical cloths, and the draperies then in common use for hanging between the colonnades and

porches of churches all worked with holy images and histories from the Holy Writ. Rich men chose

sacred subjects to be embroidered on their dress, and one senator wore 600 figures worked upon his

robes of state. Asterius, Bishop of Amasus, thunders against those Christians "who wore the

Gospels upon their backs instead of in their hearts."[16]

In the Middle Ages spinning and needlework were the occupation of women of all degrees. As

early as the sixth {5}century the nuns in the diocese of

St. Césaire, Bishop of Arles, were forbidden to embroider robes enriched with paintings, flowers,

and precious stones. This prohibition, however, was not general. Near Ely, an Anglo-Saxon lady

brought together a number of maidens to work for the monastery, and in the seventh century an

Abbess of Bourges, St. Eustadiole, made vestments and enriched the altar with the work of her

nuns. At the beginning of the ninth century St. Viborade, of St. Gall, worked coverings for the

sacred books of the monastery, for it was the custom then to wrap in silk and carry in a linen

cloth the Gospels used for the offices of the Church.[17] Judith of Bavaria, mother of Charles the Bold, stood sponsor for

the Queen of Harold, King of Denmark, who came to Ingelheim to be baptised with all his family,

and gave her a robe she had worked with her own hands and studded with precious stones.

"Berthe aux grands pieds," the mother of Charlemagne, was celebrated for her skill in

needlework,[18]

"à ouvrer si com je vous dirai

N'avoit meillor ouvriere de Tours jusqu'à Cambrai;"

while Charlemagne[19]—

"Ses filles fist bien doctriner,

Et aprendre keudre et filer."

Queen Adelhaïs, wife of Hugh Capet (987-996), presented to the Church of St. Martin at Tours a

cope, on the back of which she had embroidered the Deity, surrounded by seraphim and cherubim, the

front being worked with an Adoration of the Lamb of God.[20]

Long before the Conquest, Anglo-Saxon women were skilled with the needle, and gorgeous are the

accounts of the gold-starred and scarlet-embroidered tunics and violet sacks worked by the nuns.

St. Dunstan himself designed the ornaments of a stole worked by the hands of a noble Anglo-Saxon

lady, Ethelwynne, and sat daily in her bower with her maidens, directing the work. The four

daughters of {6}Edward the Elder are all praised for their

needle's skill. Their father, says William of Malmesbury, had caused them in childhood "to give

their whole attention to letters, and afterwards employed them in the labours of the distaff and

the needle." In 800 Denbert, Bishop of Durham, granted the lease of a farm of 200 acres for life

to an embroideress named Eanswitha for the charge of scouring, repairing, and renewing the

vestments of the priests of his diocese.[21] The

Anglo-Saxon Godric, Sheriff of Buckingham, granted to Alcuid half a hide of land as long as he

should be sheriff on condition she taught his daughter the art of embroidery. In the tenth century

Ælfleda, a high-born Saxon lady, offered to the church at Ely a curtain on which she had wrought

the deeds of her husband, Brithnoth, slain by the Danes; and Edgitha, Queen of Edward the

Confessor, was "perfect mistress of her needle."

The famous Bayeux Tapestry or embroidery, said to have been worked by Matilda, wife of William

the Conqueror, is of great historical interest.[22] It

is, according to the chroniclers, "Une tente très longue et estroite de telle a broderies de

ymages et escriptaux faisant représentation du Conquest de l'Angleterre"; a needle-wrought epic of

the Norman Conquest, worked on a narrow band of stout linen over 200 feet long, and containing

1,255 figures worked on worsted threads.[23] Mr. Fowke

gives the Abbé Rue's doubts as to the accepted period of the Bayeux tapestry, which he assigns to

the Empress Matilda. Mr. Collingwood Bruce is of opinion that the work is coeval with the events

it records, as the primitive furniture, buildings, etc., are all of the eleventh century. That the

tapestry is not found in any catalogue before 1369 is only a piece of presumptive evidence against

the earlier date, and must be weighed with the internal evidence in its favour.

After the Battle of Hastings William of Normandy, on {7}his first appearance in public, clad himself in a richly-wrought cloak of

Anglo-Saxon embroidery, and his secretary, William of Poictiers, states that "the English women

are eminently skilful with the needle and in weaving."

The excellence of the English work was maintained as time went on, and a proof of this is found

in an anecdote preserved by Matthew of Paris.[24]

"About this time (1246) the Lord Pope (Innocent IV.) having observed the ecclesiastical ornaments

of some Englishmen, such as choristers' copes and mitres, were embroidered in gold thread after a

very desirable fashion, asked where these works were made, and received in answer, in England.

'Then,' said the Pope, 'England is surely a garden of delights for us. It is truly a never-failing

spring, and there, where many things abound, much may be extracted.' Accordingly, the same Lord

Pope sent sacred and sealed briefs to nearly all the abbots of the Cistercian order established in

England, requesting them to have forthwith forwarded to him those embroideries in gold which he

preferred to all others, and with which he wished to adorn his chasuble and choral cope, as if

these objects cost them nothing," an order which, adds the chronicler, "was sufficiently pleasing

to the merchants, but the cause of many persons detesting him for his covetousness."

Perhaps the finest examples of the opus anglicanum extant are the cope and maniple of

St. Cuthbert, taken from his coffin in the Cathedral of Durham, and now preserved in the Chapter

library. One side of the maniple is of gold lace stitched on, worked apparently on a parchment

pattern. The Syon Monastery cope, in the Victoria and Albert Museum, is an invaluable example of

English needlework of the thirteenth century. "The greater portion of its design is worked in a

chain-stitch (modern tambour or crochet), especially in the faces of the figures, where the stitch

begins in the centre, say, of a cheek, and is then worked in a spiral, thus forming a series of

circular lines. The texture so obtained is then, by means of a hot, small and round-knobbed iron,

pressed into indentations at the centre of each spiral, and an effect of relief imparted to it.

The general {8}practice was to work the draperies in

feather-stitch (opus plumarium)."[25]

In the tenth century the art of pictorial embroidery had become universally spread. The

inventory of the Holy See (in 1293) mentions the embroideries of Florence, Milan, Lucca, France,

England, Germany, and Spain, and throughout the Middle Ages embroidery was treated as a fine art,

a serious branch of painting.[26] In France the

fashion continued, as in England, of producing groups, figures and portraits, but a new

development was given to floral and elaborate arabesque ornament.[27]

It was the custom in feudal times[28] for knightly

families to send their daughters to the castles of their suzerain lords, there to be trained to

spin, weave and embroider under the eye of the lady châtelaine, a custom which, in the more

primitive countries, continued even to the French Revolution. In the French romances these young

ladies are termed "chambrières," in our English, simply "the maidens." Great ladies prided

themselves upon the number of their attendants, and passed their mornings at work, their labours

beguiled by singing the "chansons à toile," as the ballads written for those occasions were

termed.[29]

{9}

In the wardrobe accounts of our kings appear constant entries of working materials purchased

for the royal ladies.[30] There is preserved in the

cathedral at Prague an altar-cloth of embroidery and cut-work worked by Anne of Bohemia, Queen of

Richard II.

During the Wars of the Roses, when a duke of the blood royal is related to have begged alms in

the streets of the rich Flemish towns, ladies of rank, more fortunate in their education, gained,

like the French emigrants of more modern days, their subsistence by the products of their

needle.[31]

Without wishing to detract from the industry of mediæval ladies, it must be owned that the

swampy state of the country, the absence of all roads, save those to be traversed in the fine

season by pack-horses, and the deficiency of all suitable outdoor amusement but that of hawking,

caused them to while away their time within doors the best way they could. Not twenty years since,

in the more remote provinces of France, a lady who quitted her house daily would be remarked on.

"Elle sort beaucoup," folks would say, as though she were guilty of dissipation.

So queens and great ladies sewed on. We hear much of works of adornment, more still of piety,

when Katharine of Aragon appears on the scene. She had learned much in her youth from her mother,

Queen Isabella, and had probably {10}assisted at those

"trials" of needlework[32] established by that

virtuous queen among the Spanish ladies:—

"Her days did pass

In working with the needle curiously."[33]

It is recorded how, when Wolsey, with the papal legate Campeggio, going to Bridewell, begged an

audience of Queen Katharine, on the subject of her divorce, they found her at work, like Penelope

of old, with her maids, and she came to them with a skein of red silk about her neck.[34]

Queen Mary Tudor is supposed, by her admirers, to have followed the example of her illustrious

mother, though all we find among the entries is a charge "to working materials for Jane the Fole,

one shilling."

No one would suspect Queen Elizabeth of solacing herself with the needle. Every woman, however,

had to make one shirt in her lifetime, and the "Lady Elizabeth's grace," on the second anniversary

of Prince Edward's birth, when only six years of age, presented her brother with a cambric smock

wrought by her own hands.

The works of Scotland's Mary, who early studied all female accomplishments under her governess,

Lady Fleming, {11}are too well known to require notice.

In her letters are constant demands for silk and other working materials wherewith to solace her

long captivity. She had also studied under Catherine de Médicis, herself an unrivalled

needlewoman, who had brought over in her train from Florence the designer for embroidery,

Frederick Vinciolo. Assembling her daughters, Claude, Elizabeth and Margaret, with Mary Stuart,

and her Guise cousins, "elle passoit," says Brantôme, "fort son temps les apres-disnées à besogner

apres ses ouvrages de soye, où elle estoit tant parfaicte qu'il estoit possible."[35] The ability of Reine Margot[36] is sung by Ronsard, who exalts her as imitating Pallas in the

art.[37]

Many of the great houses in England are storehouses of old needlework. Hatfield, Penshurst, and

Knole are all filled with the handiwork of their ladies. The Countess of Shrewsbury, better known

as "Building Bess," Bess of Hardwick, found time to embroider furniture for her palaces, and her

samplar patterns hang to this day on their walls.

Needlework was the daily employment of the convent. As early as the fourteenth century[38] it was termed "nun's work"; and even now, in

secluded parts of the kingdom, ancient lace is styled by that name.[39]

Nor does the occupation appear to have been solely {12}confined to women. We find monks commended for their skill in embroidery,[40] and in the frontispieces of some of the early

pattern books of the sixteenth century, men are represented working at frames, and these books are

stated to have been written "for the profit of men as well as of women."[41] Many were composed by monks,[42] and in the library[43] of St. Geneviève at Paris, are several works of this class,

inherited from the monastery of that name. As these books contain little or no letterpress, they

could scarcely have been collected by the monks unless with a view to using them.

At the dissolution of the monasteries, the ladies of the great Roman Catholic families came to

the rescue. Of the widow of the ill-fated Earl of Arundel it is recorded: "Her gentlewomen and

chambermaids she ever busied in works ordained for the service of the Church. She permitted none

to be idle at any time."[44]

Instructions in the art of embroidery were now at a premium. The old nuns had died out, and

there were none to replace them.

Mrs. Hutchinson, in her Memoirs, enumerates, among the eight tutors she had at seven

years of age, one for needlework, while Hannah Senior, about the same period, entered the service

of the Earl of Thomond, to teach his daughters the use of their needle, with the salary of £200 a

year. The money, however, was never paid; so she petitions the Privy Council for leave to sue

him.[45]

When, in 1614, the King of Siam applied to King James for an English wife, a gentleman of

"honourable parentage" offers his daughter, whom he describes of excellent parts for "music, her

needle, and good discourse."[46] And these are the

sole accomplishments he mentions. The bishops, however, shocked at the proceeding, interfered,

and put an end to the projected alliance.

|

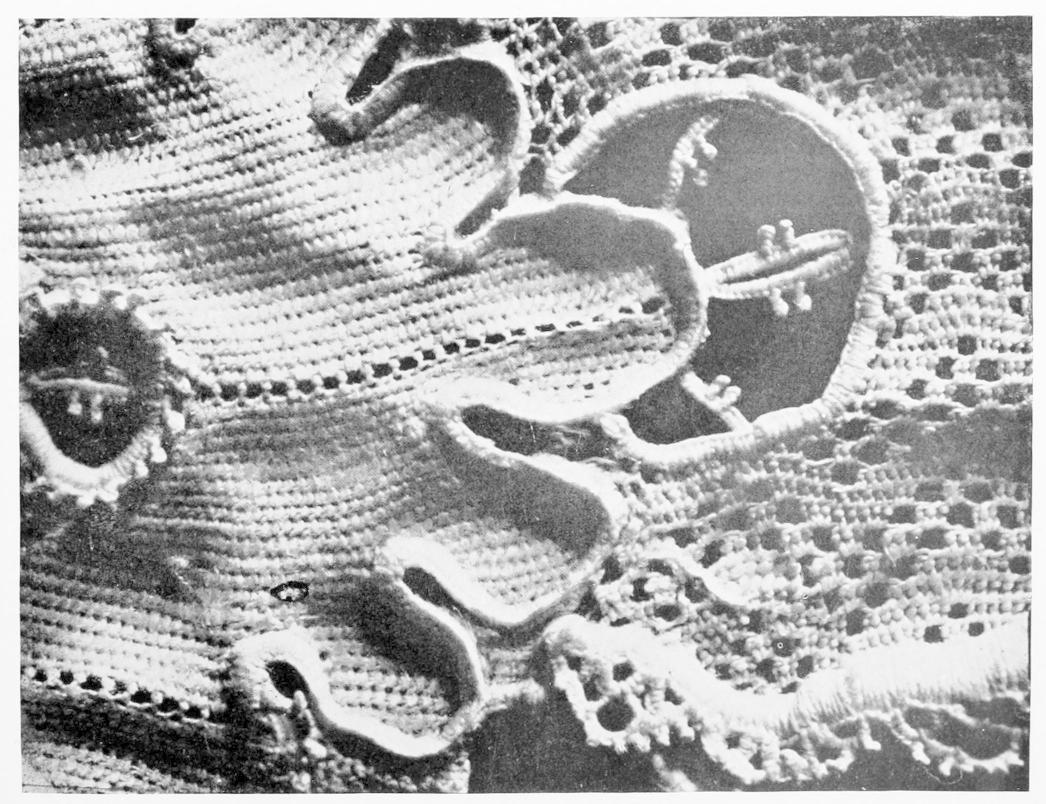

Plate I. |

|

|

Argentan.—Showing buttonhole stitched réseau

and "brides bouclées."

|

Circular Bobbin Réseau.—Variety of

Mechlin.

|

{13}

No ecclesiastical objection, however, was made to the epitaph of Catherine Sloper—she

sleeps in the cloisters of Westminster Abbey, 1620:—

"Exquisite at her needle."

Till a very late date, we have ample record of the esteem in which this art was held.

In the days of the Commonwealth, Mrs. Walker is described to have been as well skilled in

needlework "as if she had been brought up in a convent." She kept, however, a gentlewoman for

teaching her daughters.

Evelyn, again, praises the talent of his daughter, Mrs. Draper. "She had," writes he, "an

extraordinary genius for whatever hands could do with a needle."

The queen of Charles I. and the wives of the younger Stuarts seem to have changed the simple

habits of their royal predecessors, for when Queen Mary, in her Dutch simplicity, sat for hours at

the knotted fringe, her favourite employment, Bishop Burnet, her biographer, adds, "It was a

strange thing to see a queen work for so many hours a day," and her homely habits formed a

never-ending subject of ridicule for the wit of Sir Charles Sedley.[47]

From the middle of the last century, or rather apparently from the French

Revolution, the more artistic style of needlework and embroidery fell into decadence. The

simplicity of male costume rendered it a less necessary adjunct to female or, indeed, male

education. However, two of the greatest generals of the Republic, Hoche and Moreau, followed the

employment of embroidering satin waistcoats long after they had entered the military service. We

may look upon the art now as almost at an end.

{14}

CHAPTER II.

CUT-WORK.

"These workes belong chiefly to gentlewomen to passe away

their time in vertuous exercises."

"Et lors, sous vos lacis à mille fenestrages

Raiseuls et poinct couppés et tous vos clairs ouvrages."

—Jean Godard, 1588.

It is from that open-work embroidery which in the sixteenth century came into such universal

use that we must derive the origin of lace, and, in order to work out the subject, trace it

through all its gradations.

This embroidery, though comprising a wide variety of decoration, went by the general name of

cut-work.

The fashion of adorning linen has prevailed from the earliest times. Either the edges were

worked with close embroidery—the threads drawn and fashioned with a needle in various

forms—or the ends of the cloth unravelled and plaited with geometric precision.

To judge from the description of the linen grave-clothes of St. Cuthbert,[48] as given by an eye-witness to his disinterment in

the twelfth century, they were ornamented in a manner similar to that we have described. "There

had been," says the chronicler, "put over him a sheet ... this sheet had a fringe of linen thread

of a finger's length; upon its sides and ends were woven a border of projecting workmanship

fabricated of the thread itself, bearing the figures of birds and beasts so arranged that between

every two pairs there were interwoven among them the representation of a branching tree which

divides the figures. This tree, so tastefully depicted, appears to be putting forth its leaves,"

etc. There can be no doubt that this sheet, for many centuries preserved in the cathedral church

of Durham, was a specimen of cut-work, which, though later it came into general use, was, at an

early period of our history, alone used for ecclesiastical purposes, and an art which was, till

the dissolution of monasteries, looked upon as a church secret.

|

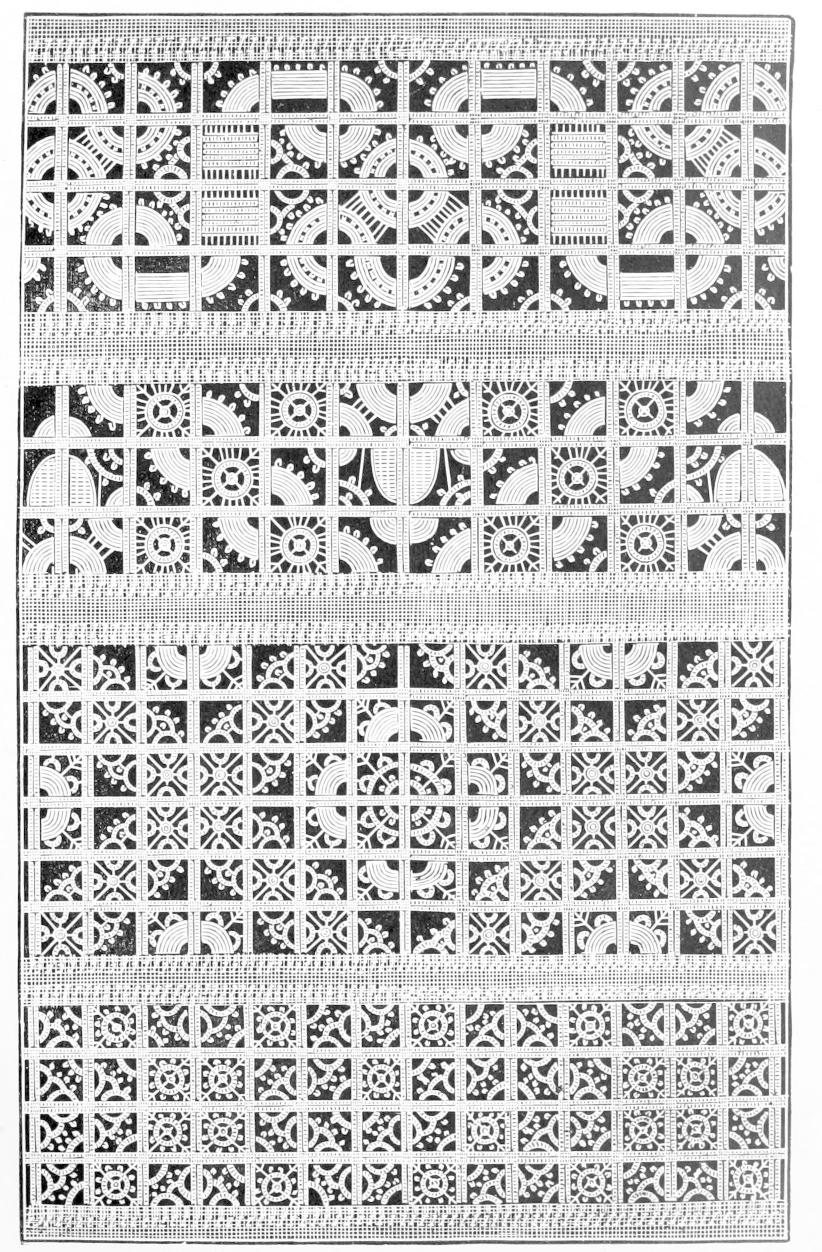

Plate II. |

|

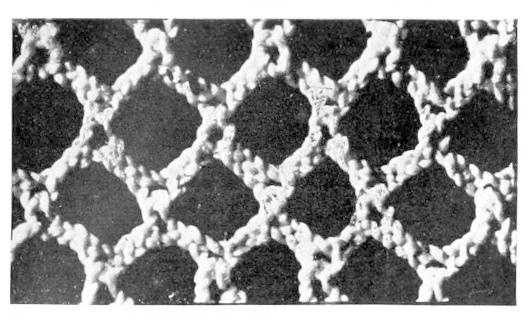

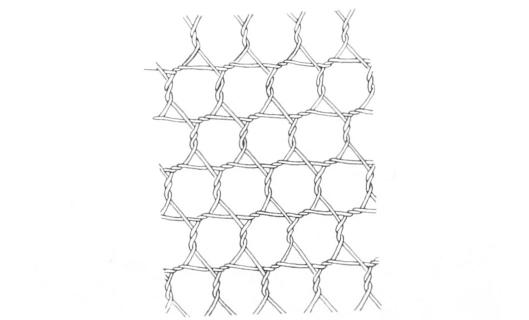

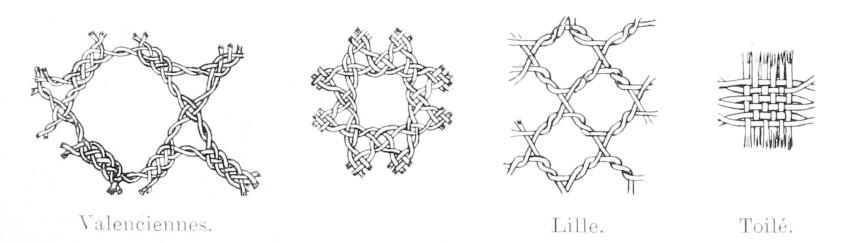

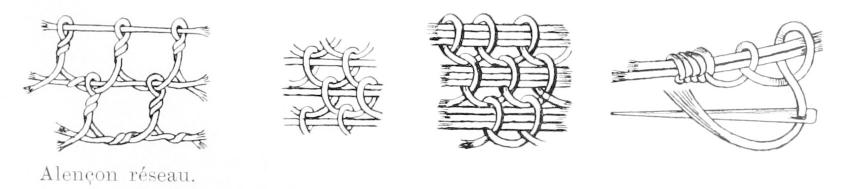

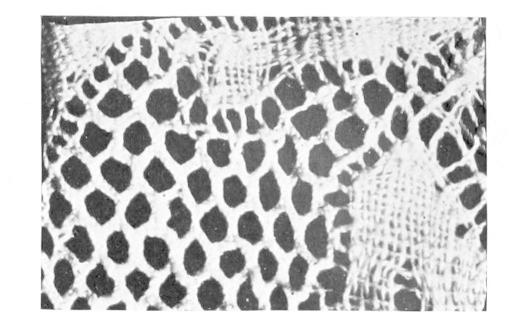

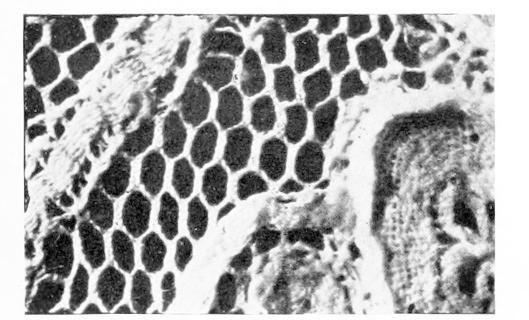

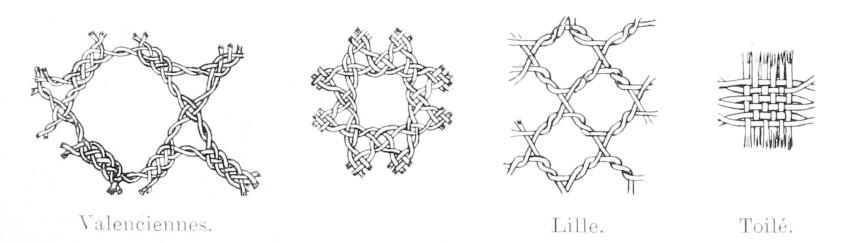

|

|

|

Six-pointed Star-meshed Bobbin

Réseau.—Variety of Valenciennes.

|

|

|

|

|

Fond chant of Chantilly and Point de Paris.

|

Details of Bobbin Réseau and Toilé.

Details of Needle Réseau and Buttonhole Stitches.

{15}

Though cut-work is mentioned in Hardyng's Chronicle,[49] when describing the luxury in King Richard II.'s reign, he

says:—

"Cut werke was greate both in court and townes,

Both in menes hoddis and also in their gownes,"

yet this oft-quoted passage, no more than that of Chaucer, in which he again accuses the

priests of wearing gowns of scarlet and green colours ornamented with cut-work, can scarcely be

received as evidence of this mode of decoration being in general use. The royal wardrobe accounts

of that day contain no entries on the subject. It applies rather to the fashion of cutting out[50] pieces of velvet or other materials, and sewing them

down to the garment with a braid like ladies' work of the present time. Such garments were in

general use, as the inventories of mediæval times fully attest.

The linen shirt or smock was the special object of adornment, and on the decoration of the

collar and sleeves much time and ingenuity were expended.

In the ancient ballad of "Lord Thomas,"[51] the

fair Annette cries:—

"My maids, gae to my dressing-room,

And dress me in my smock;

The one half is o' the Holland fine,

The other o' needlework."

Chaucer, too, does not disdain to describe the embroidery of a lady's smock—

"White was her smocke, embrouded all before

And eke behynde, on her colar aboute,

Of cole blacke sylke, within and eke without."

The sums expended on the decoration of this most necessary article of dress sadly excited the

wrath of {16}Stubbes, who thus vents his indignation:

"These shirtes (sometymes it happeneth) are wrought throughout with needlework of silke, and such

like, and curiously stitched with open seame, and many other knackes besides, more than I can

describe; in so much, I have heard of shirtes that have cost some ten shillynges, some twenty,

some forty, some five pounds, some twenty nobles, and (which is horrible to heare) some ten pound

a pece."[52]

Up to the time of Henry VIII. the shirt was "pynched" or plaited—

"Come nere with your shirtes bordered and displayed,

In foarme of surplois."[53]

These,[54] with handkerchiefs,[55] sheets, and pillow-beres,[56] (pillow-cases), were embroidered with silks of various {17}colours, until the fashion gradually gave place to

cut-work, which, in its turn, was superseded by lace.

The description of the widow of John Whitcomb, a wealthy clothier of Newbury, in Henry VIII.'s

reign, when she laid aside her weeds, is the first notice we have of cutwork being in general use.

"She came," says the writer, "out of the kitchen in a fair train gown stuck full of silver pins,

having a white cap upon her head, with cuts of curious needlework, the same an apron, white as the

driven snow."

We are now arrived at the Renaissance, a period when so close a union existed between the fine

arts and manufactures; when the most trifling object of luxury, instead of being consigned to the

vulgar taste of the mechanic, received from artists their most graceful inspirations. Embroidery

profited by the general impulse, and books of designs were composed for that species which, under

the general name of cut-work, formed the great employment for the women of the day. The volume

most generally circulated, especially among the ladies of the French court, for whose use it was

designed, is that of the Venetian Vinciolo, to whom some say, we know not on what authority,

Catherine de Médicis granted, in 1585, the exclusive privilege of making and selling the

collerettes gaudronnées[57] she had herself

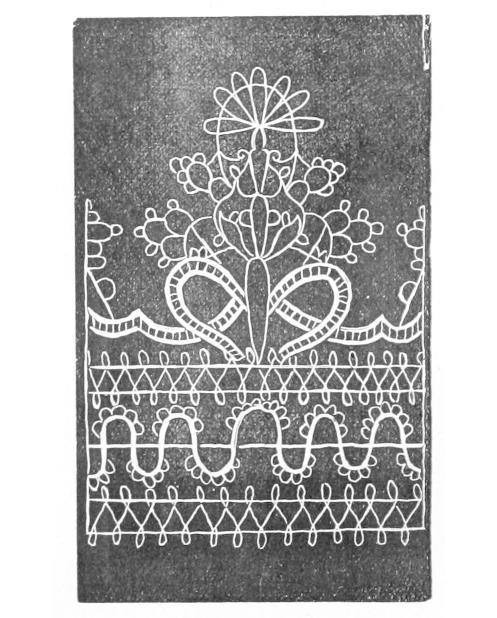

introduced. This work, which passed through many editions, dating from 1587 to 1623, is entitled,

"Les singuliers et nouveaux pourtraicts et ouvrages de Lingerie. Servans de patrons à faire toutes

sortes de poincts, couppé, Lacis & autres. Dedié à la Royne. Nouvellement inventez, au proffit

et contentement des nobles Dames et Demoiselles & autres gentils esprits, amateurs d'un tel

art. Par le Seigneur Federic de Vinciolo Venitien. A Paris. Par Jean le Clerc le jeune, etc.,

1587."

Two little figures, representing ladies in the costume of the period, with working-frames in

their hands, decorate the title-page.[58]

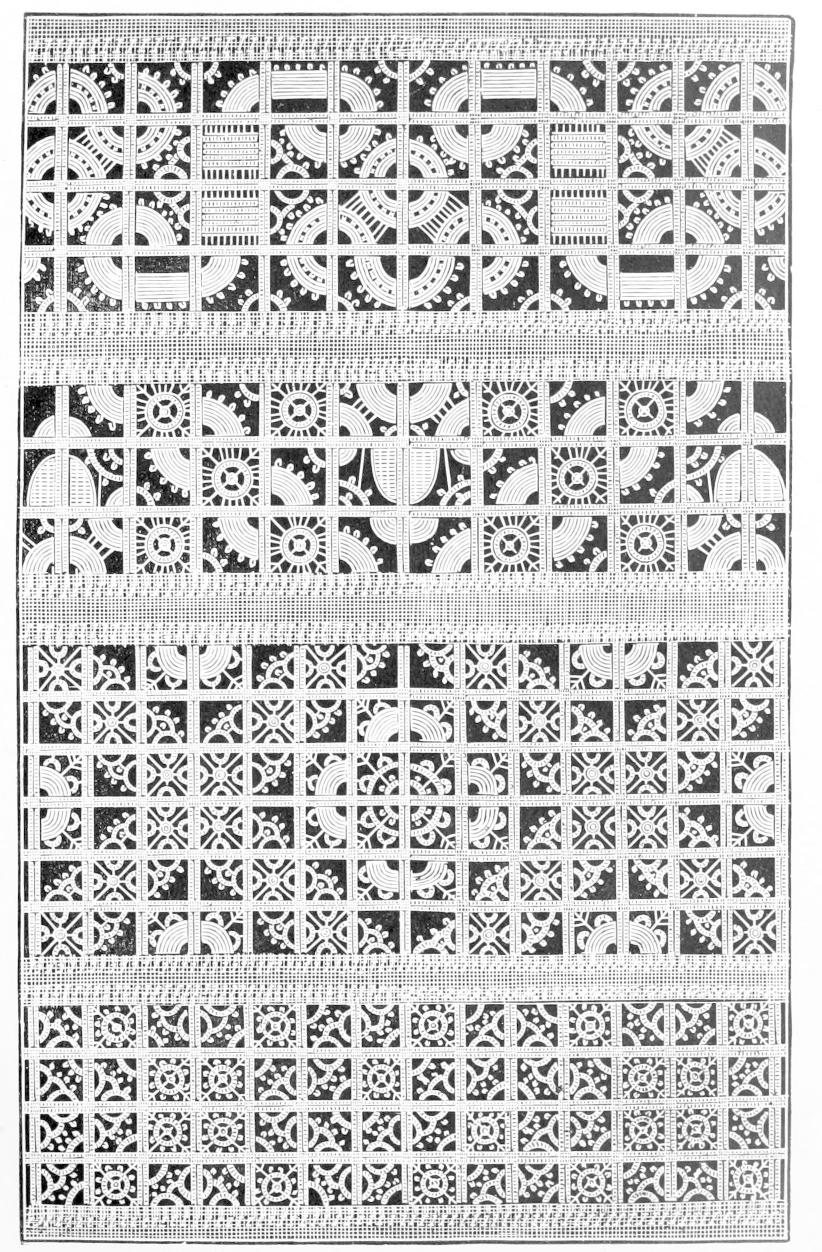

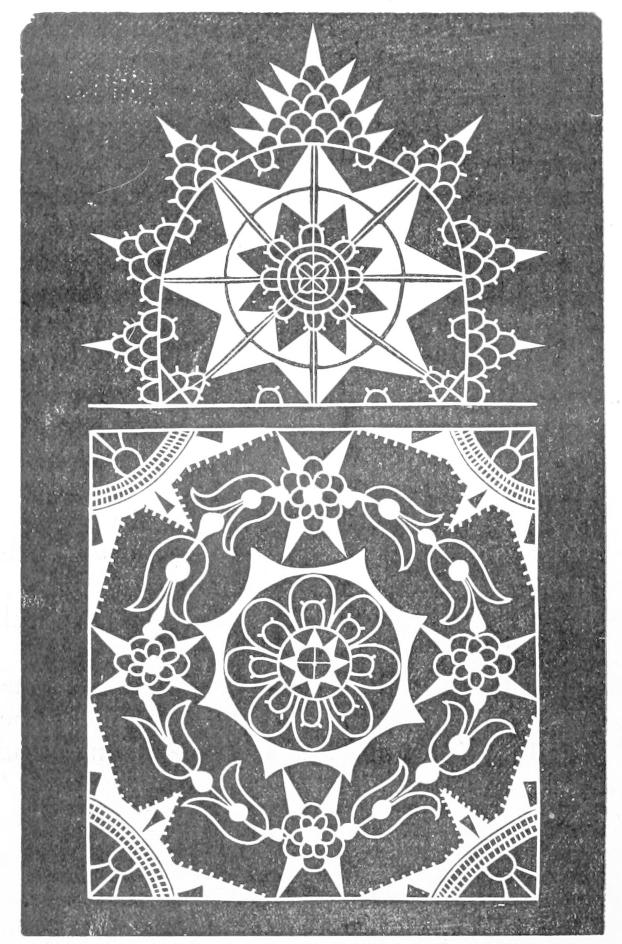

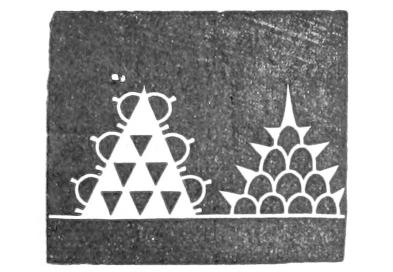

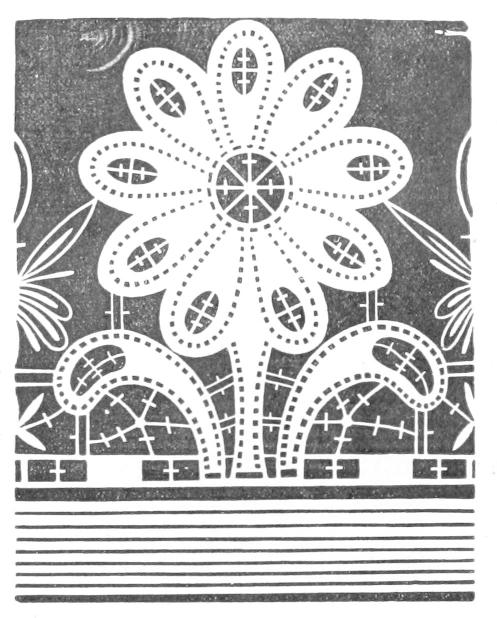

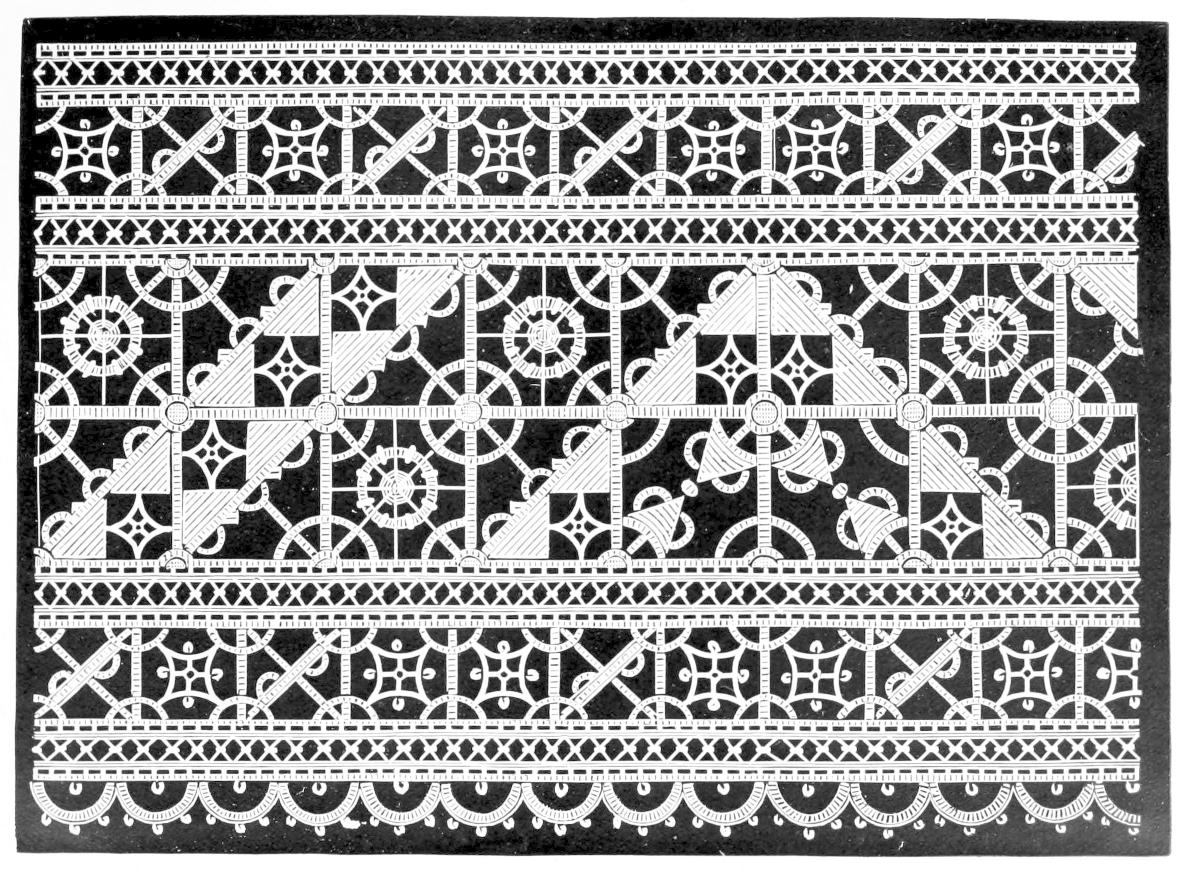

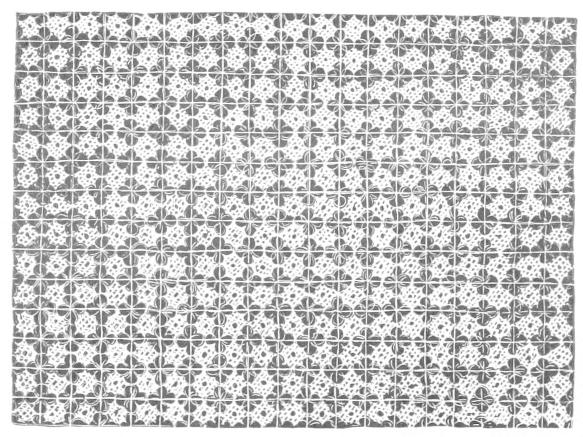

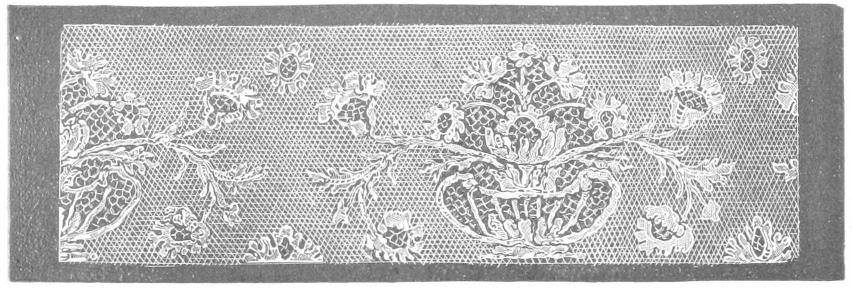

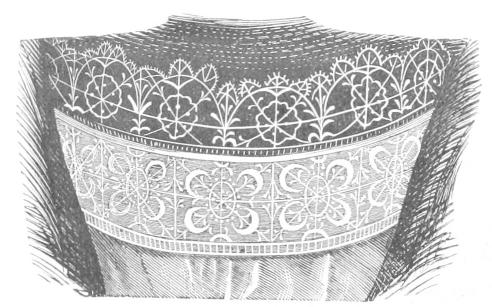

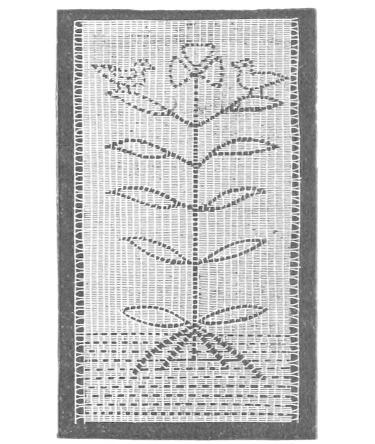

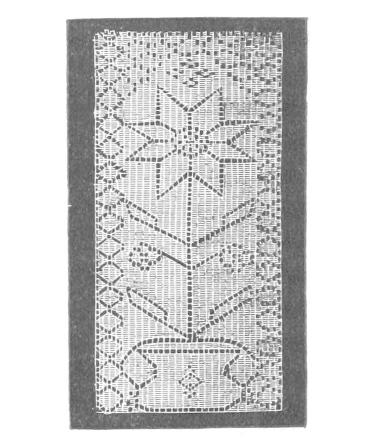

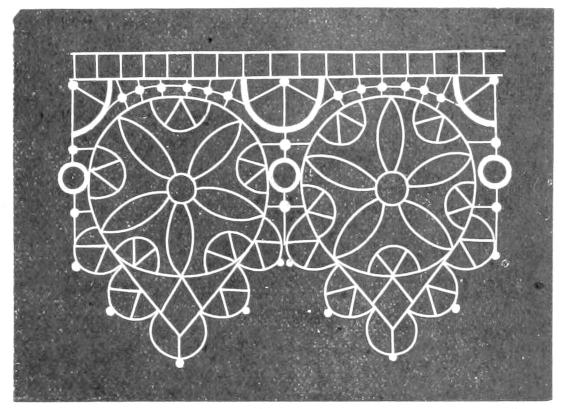

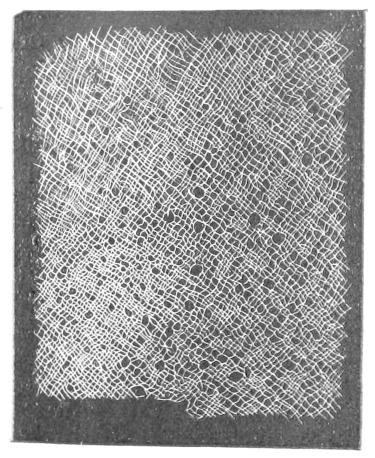

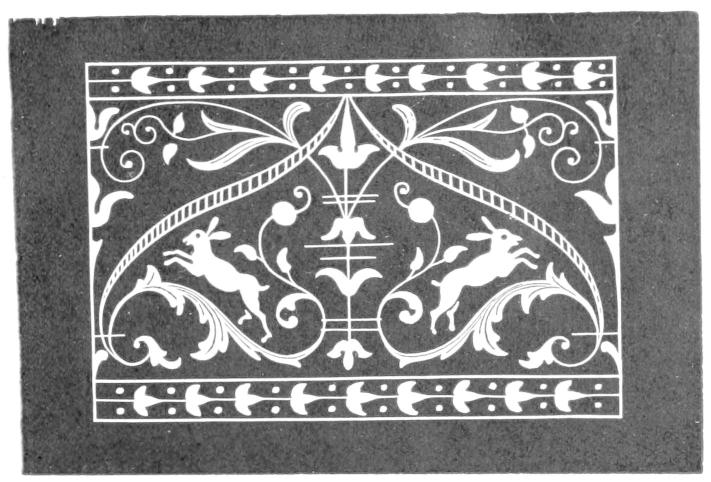

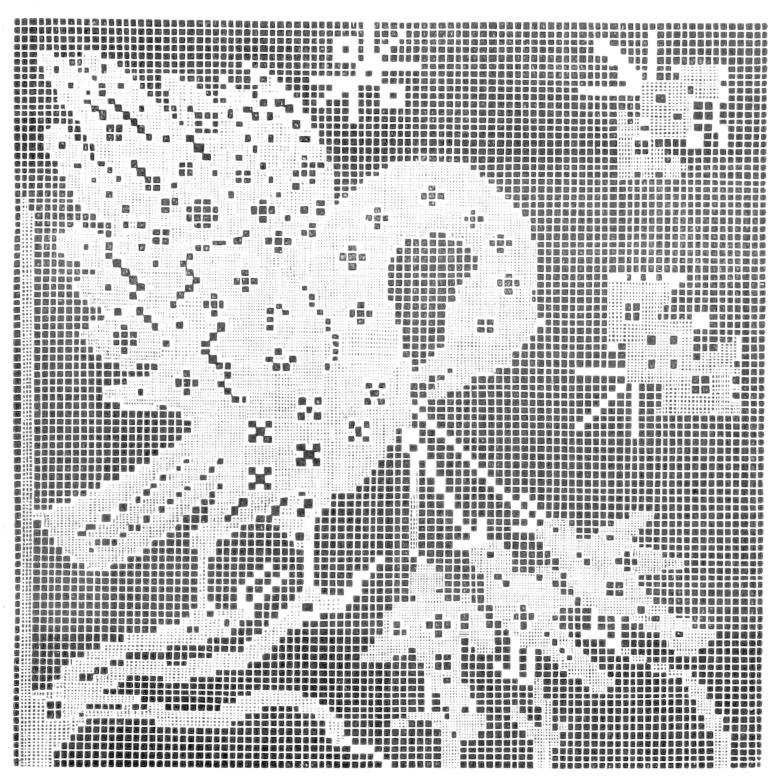

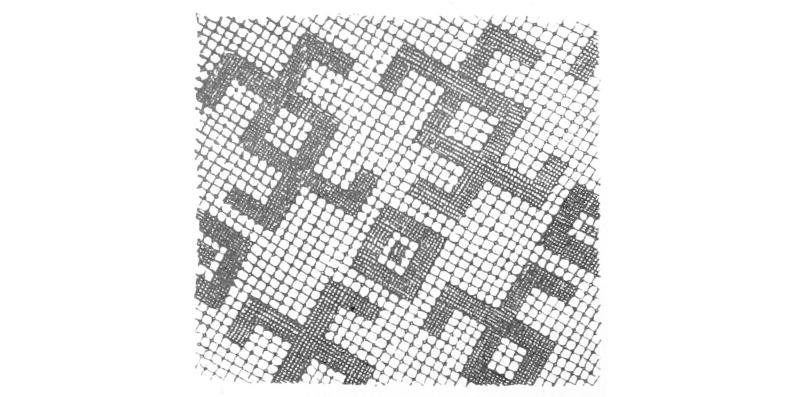

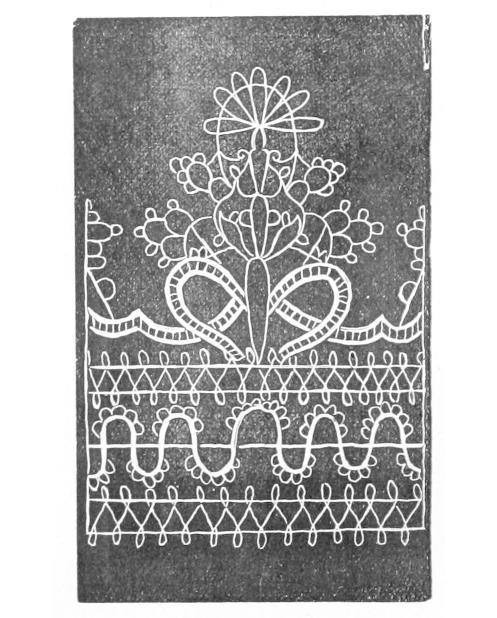

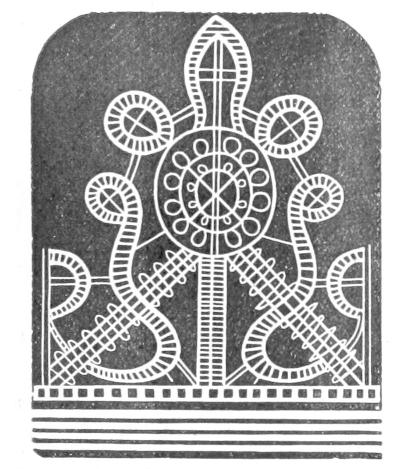

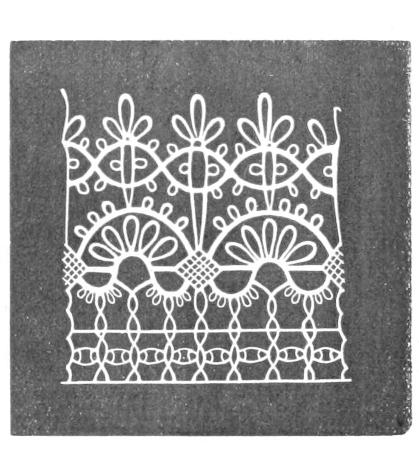

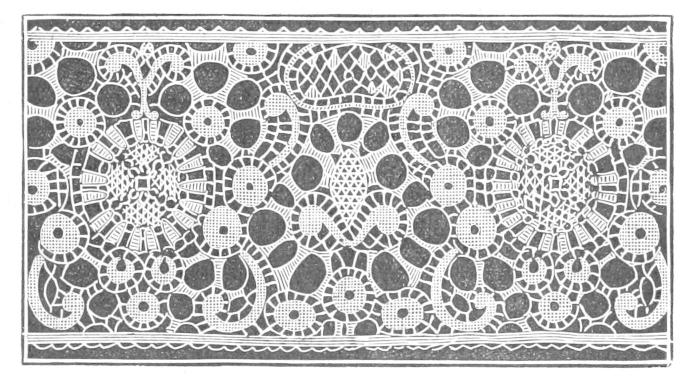

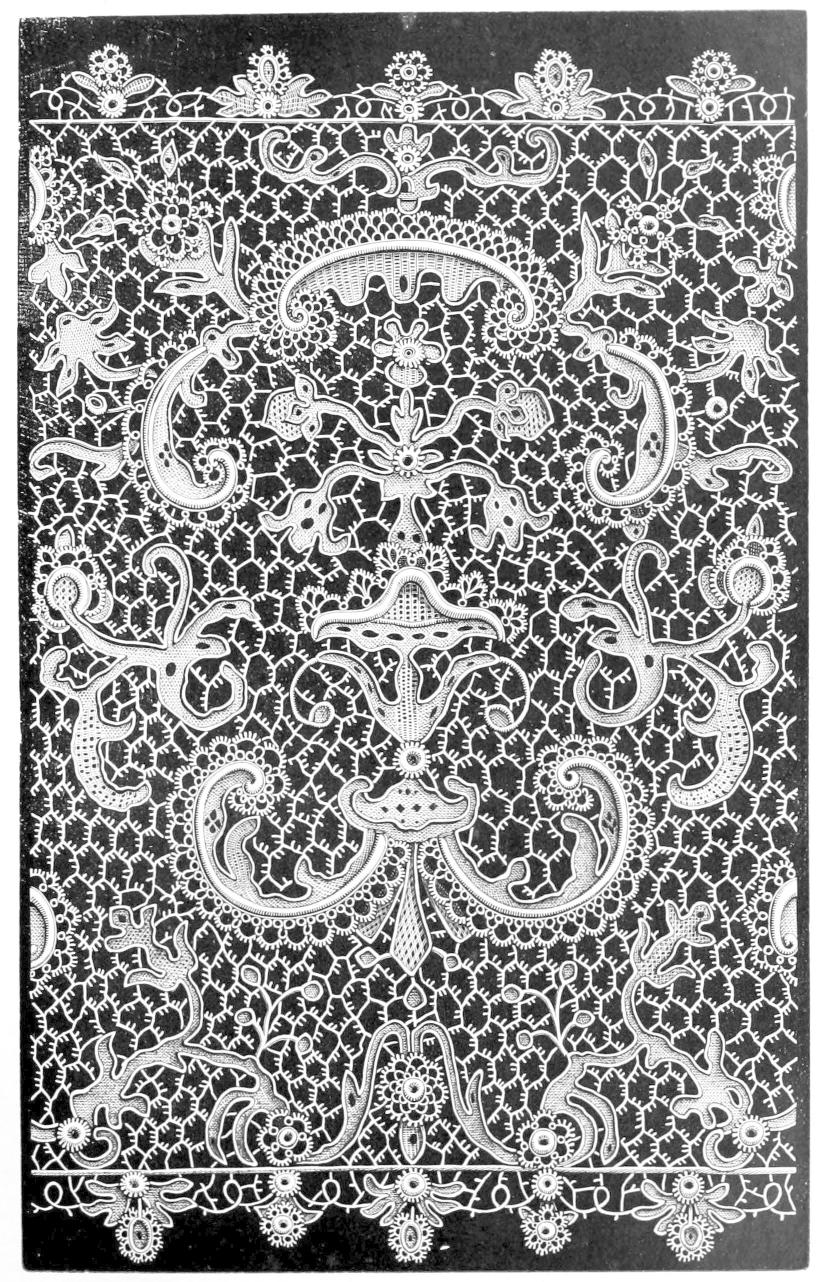

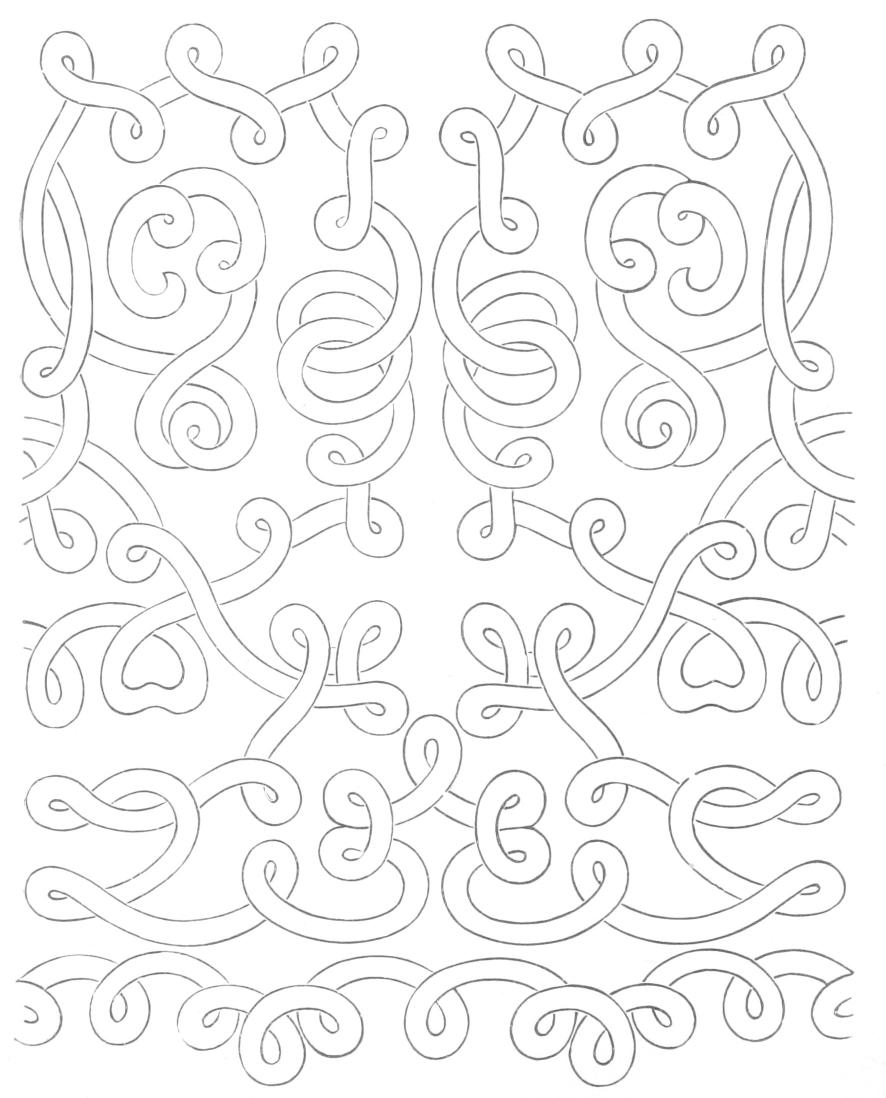

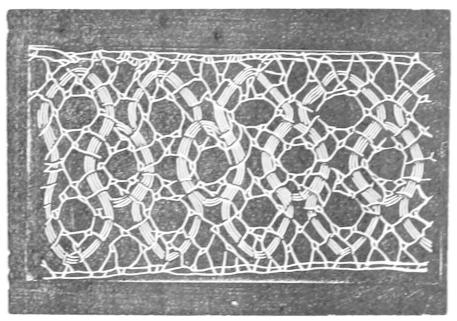

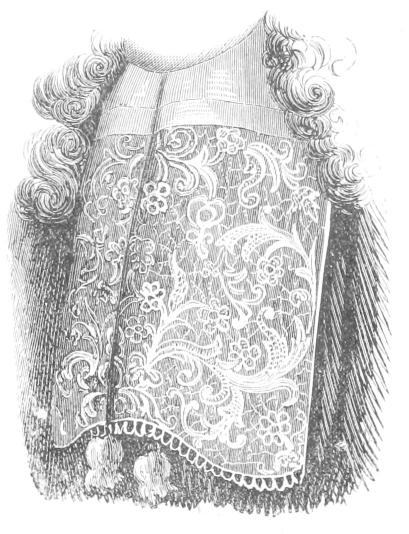

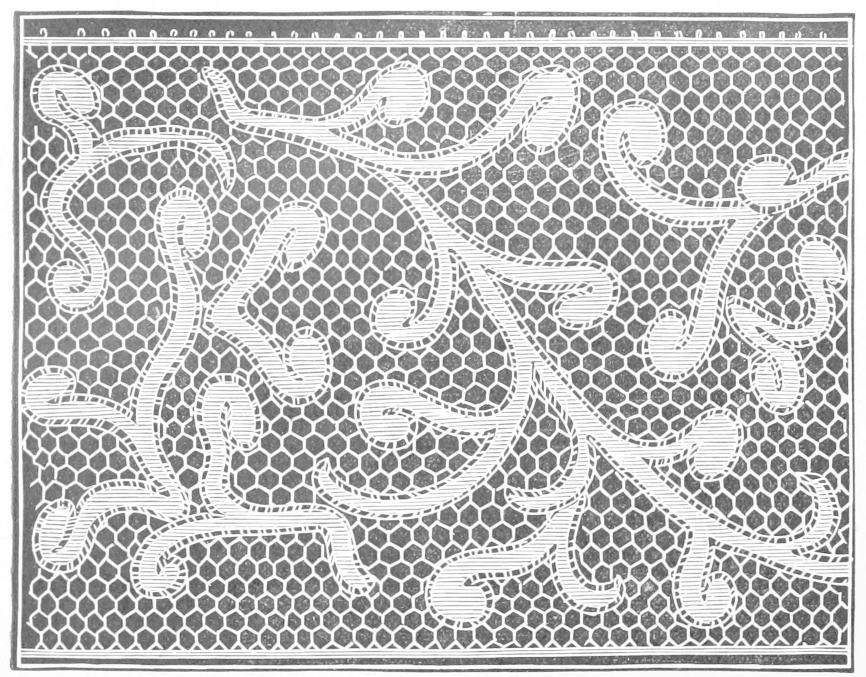

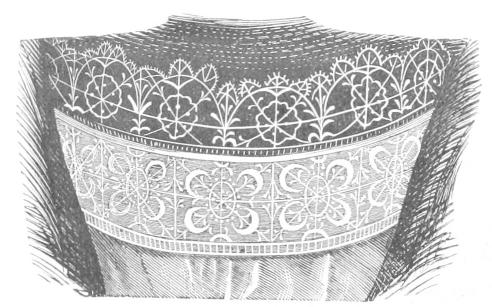

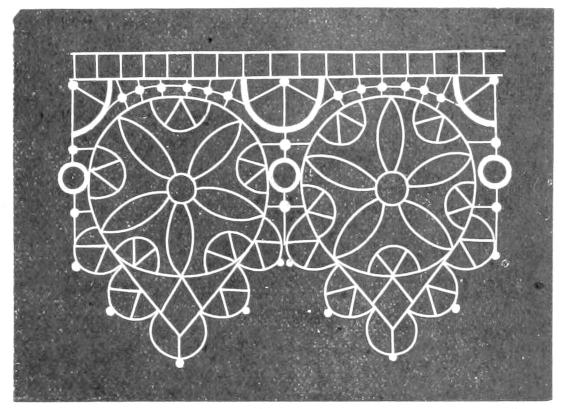

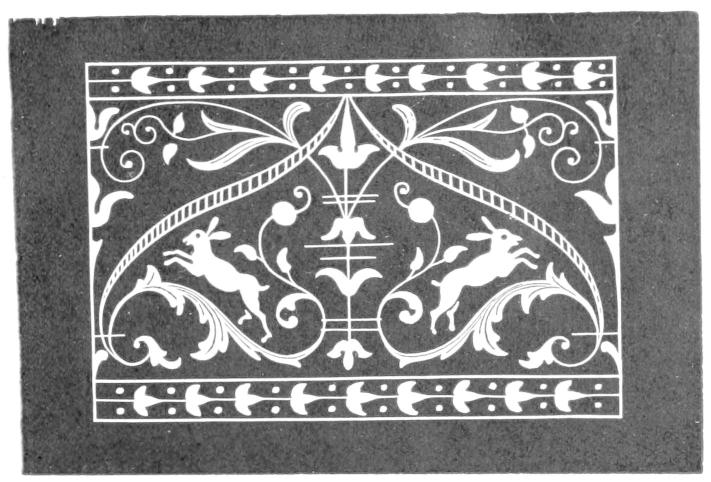

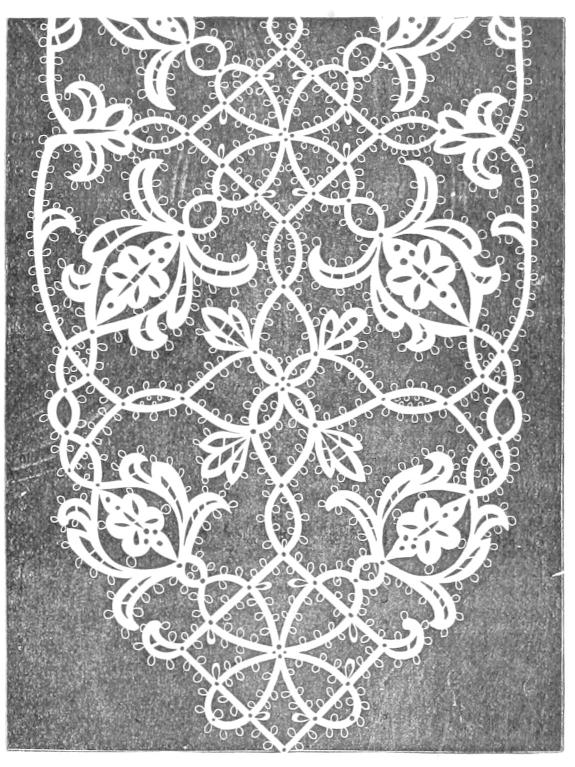

The work is in two books: the first of Point Coupé, or {18}rich geometric patterns, printed in white upon a black ground (Fig. 2); the

second of Lacis, or subjects in squares (Fig. 3), with counted stitches, like the patterns for

worsted-work of the present day—the designs, the seven planets, Neptune, and various

squares, borders, etc.

Vinciolo dedicates his book to Louise de Vaudemont, the neglected Queen of Henry III., whose

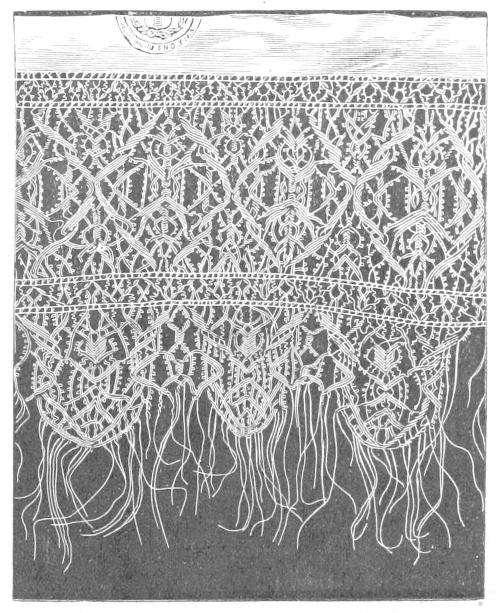

portrait, with that of the king, is added to the later editions.

Various other pattern-books had already been published. The earliest bearing a date

is one printed at Cologne in 1527.[59]

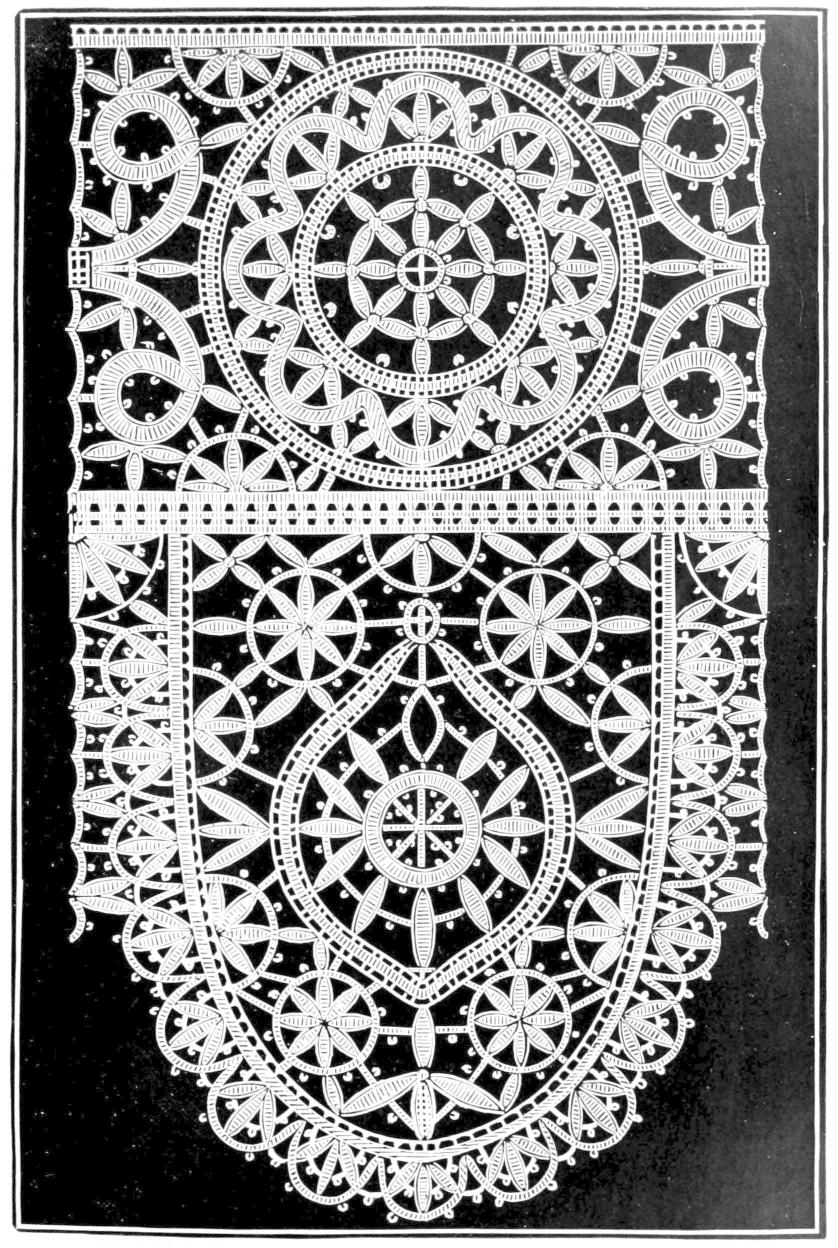

Fig. 2.

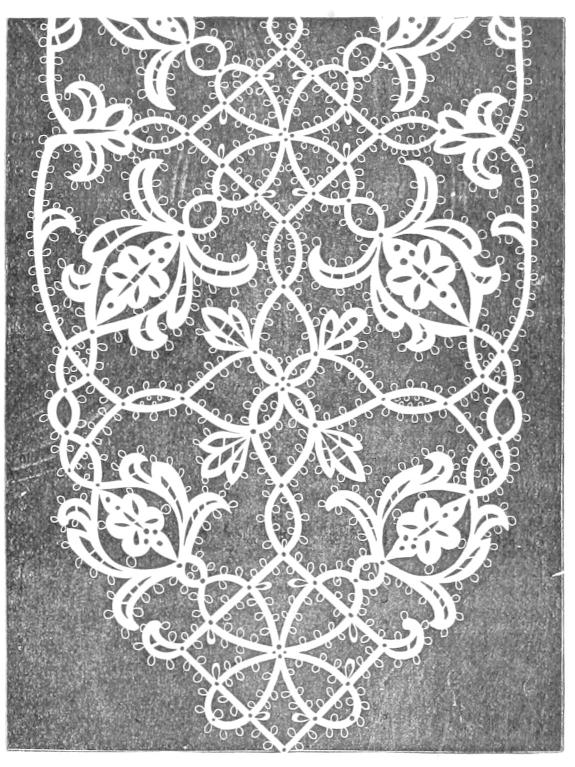

These books are scarce; being designed for patterns, and traced with a metal style, or pricked

through, many perished in the using. They are much sought after by the collector as among the

early specimens of wood-block printing. We give therefore in the Appendix a list of those we find

recorded, or of which we have seen copies, observing that the greater number, though generally

composed for one particular art, may be applied indifferently to any kind of ornamental work.

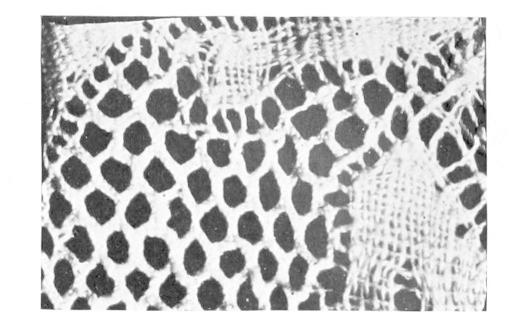

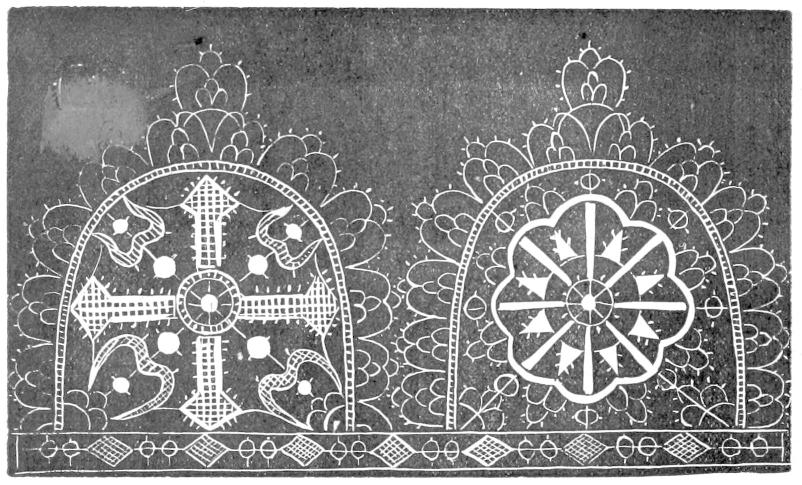

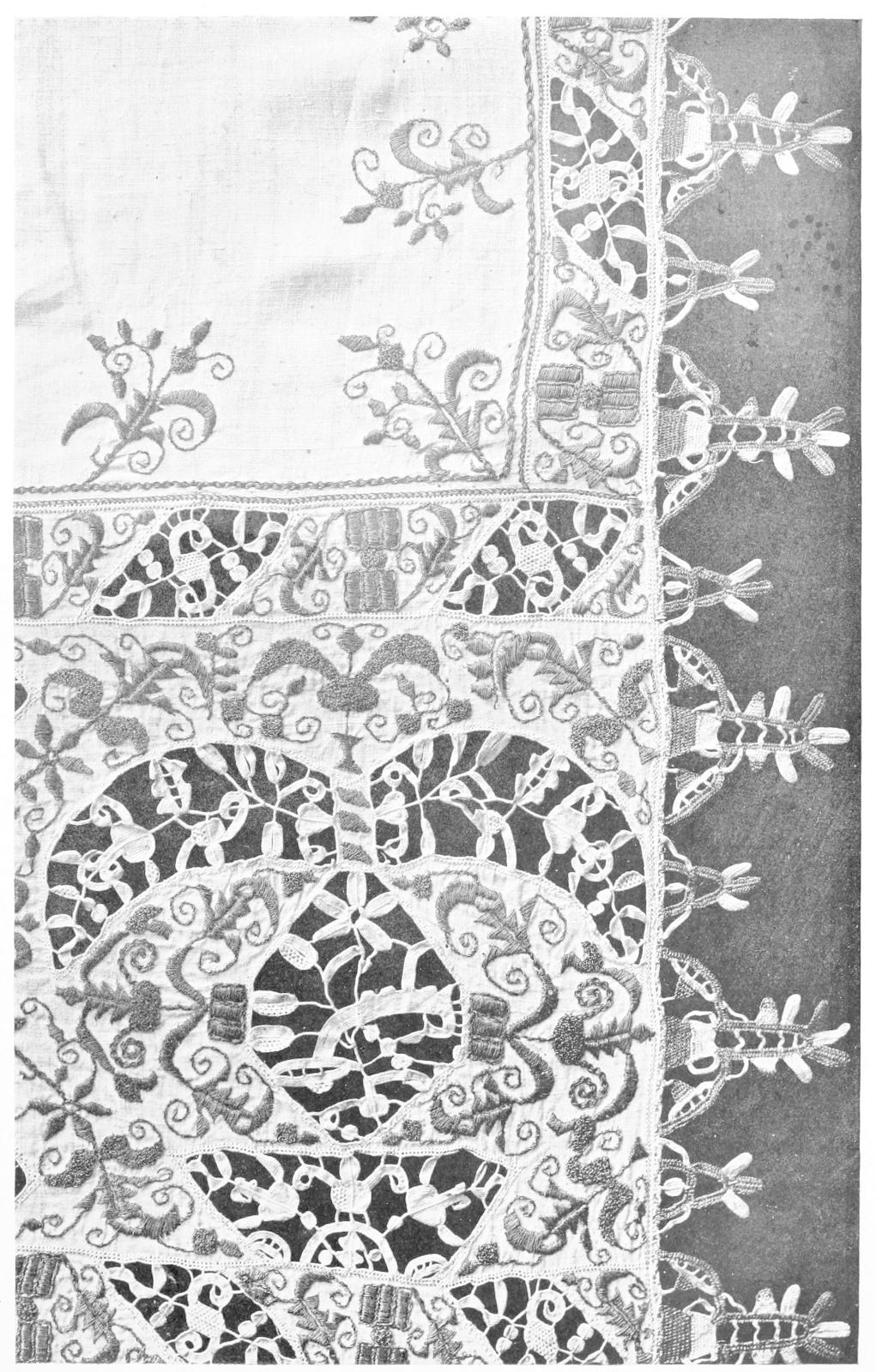

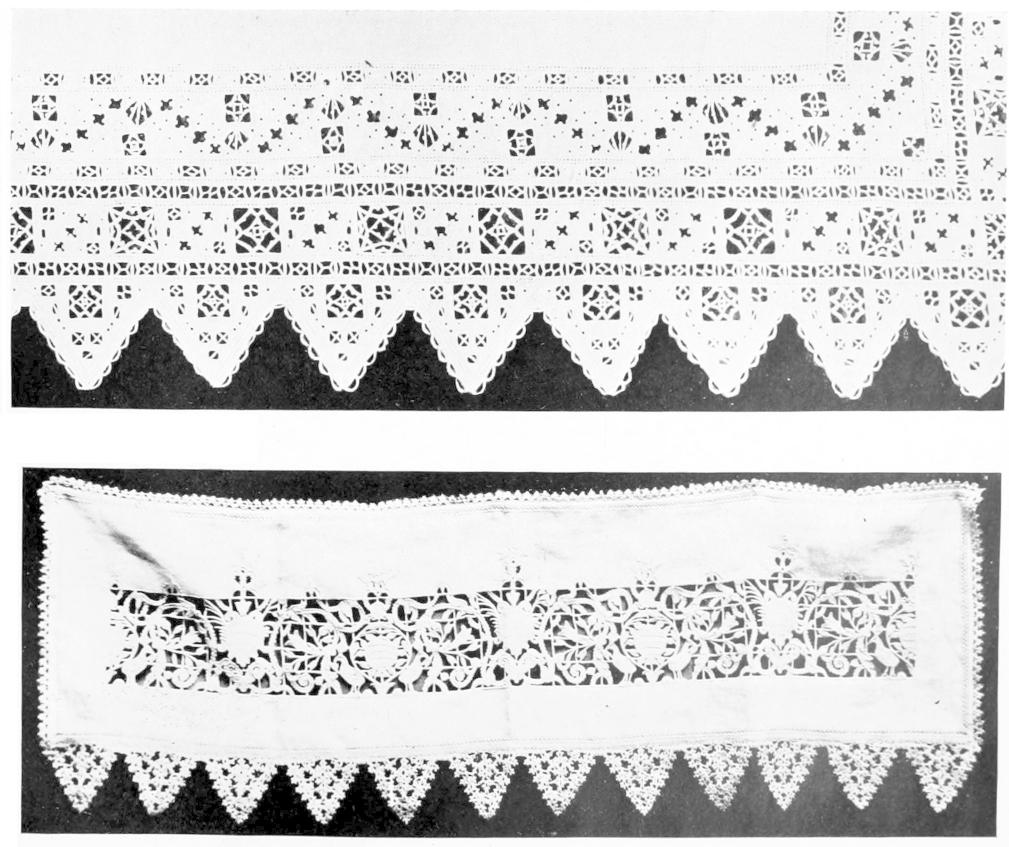

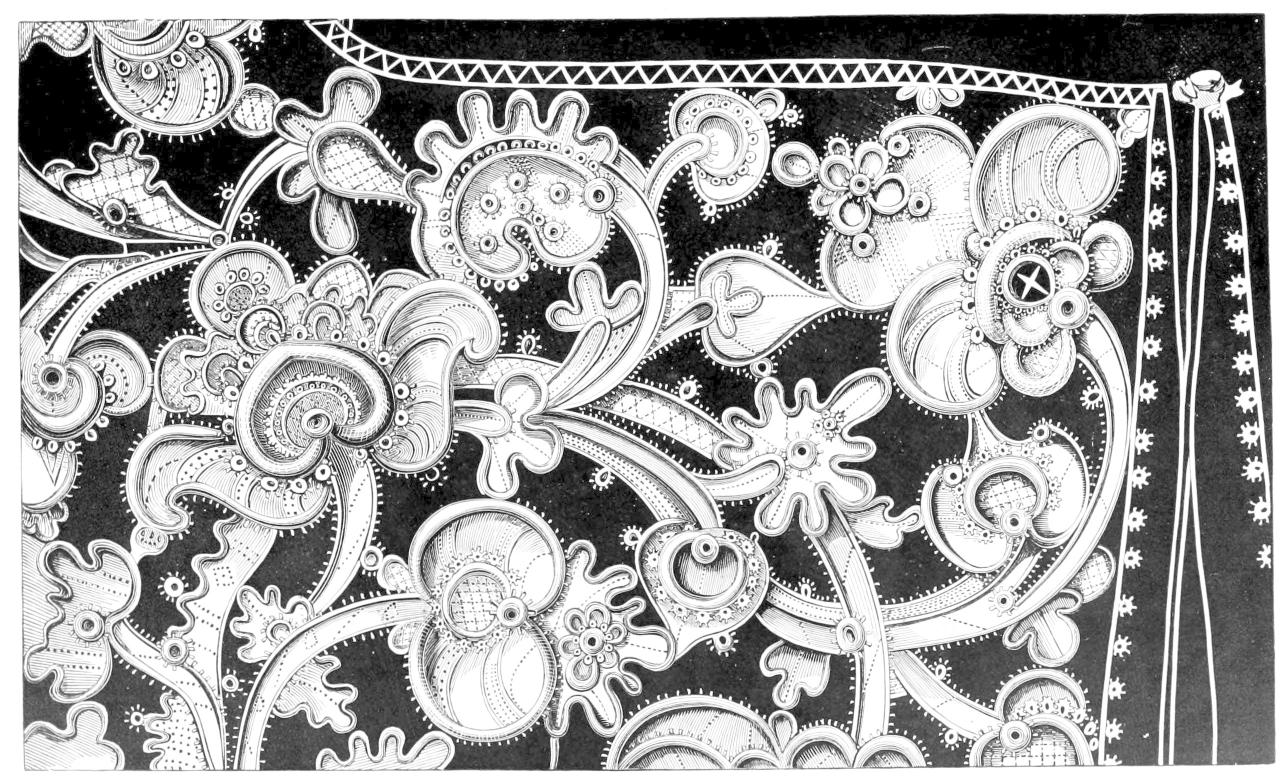

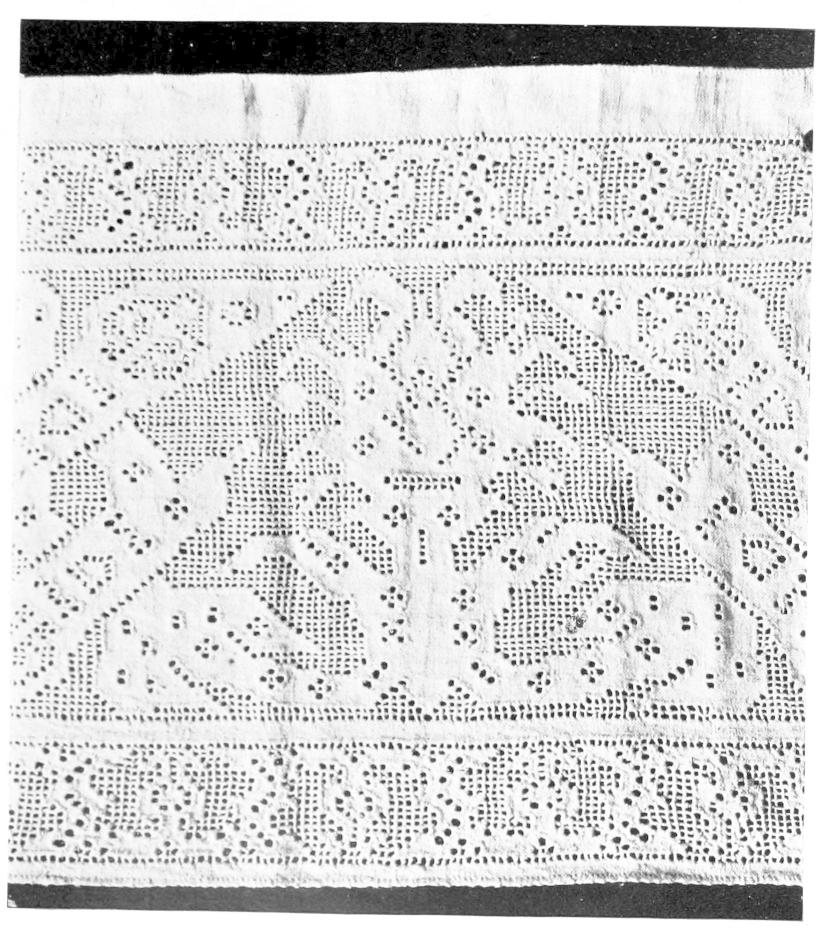

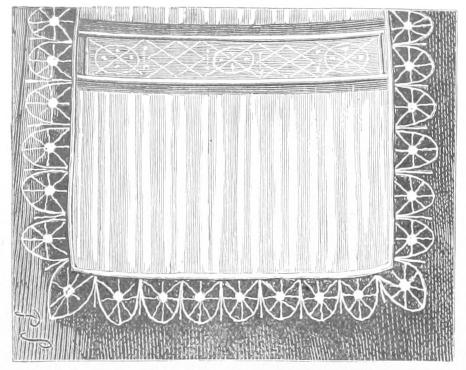

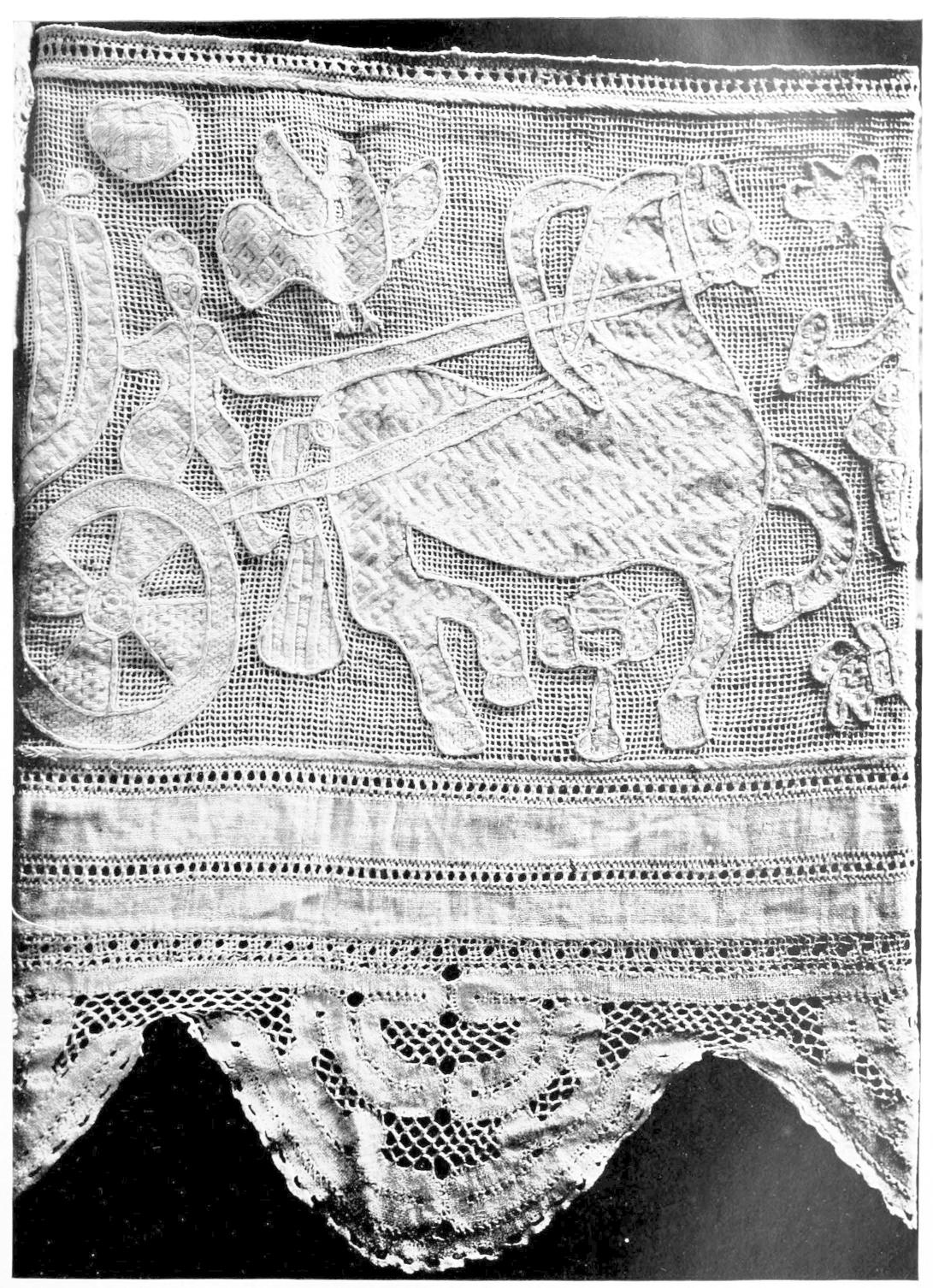

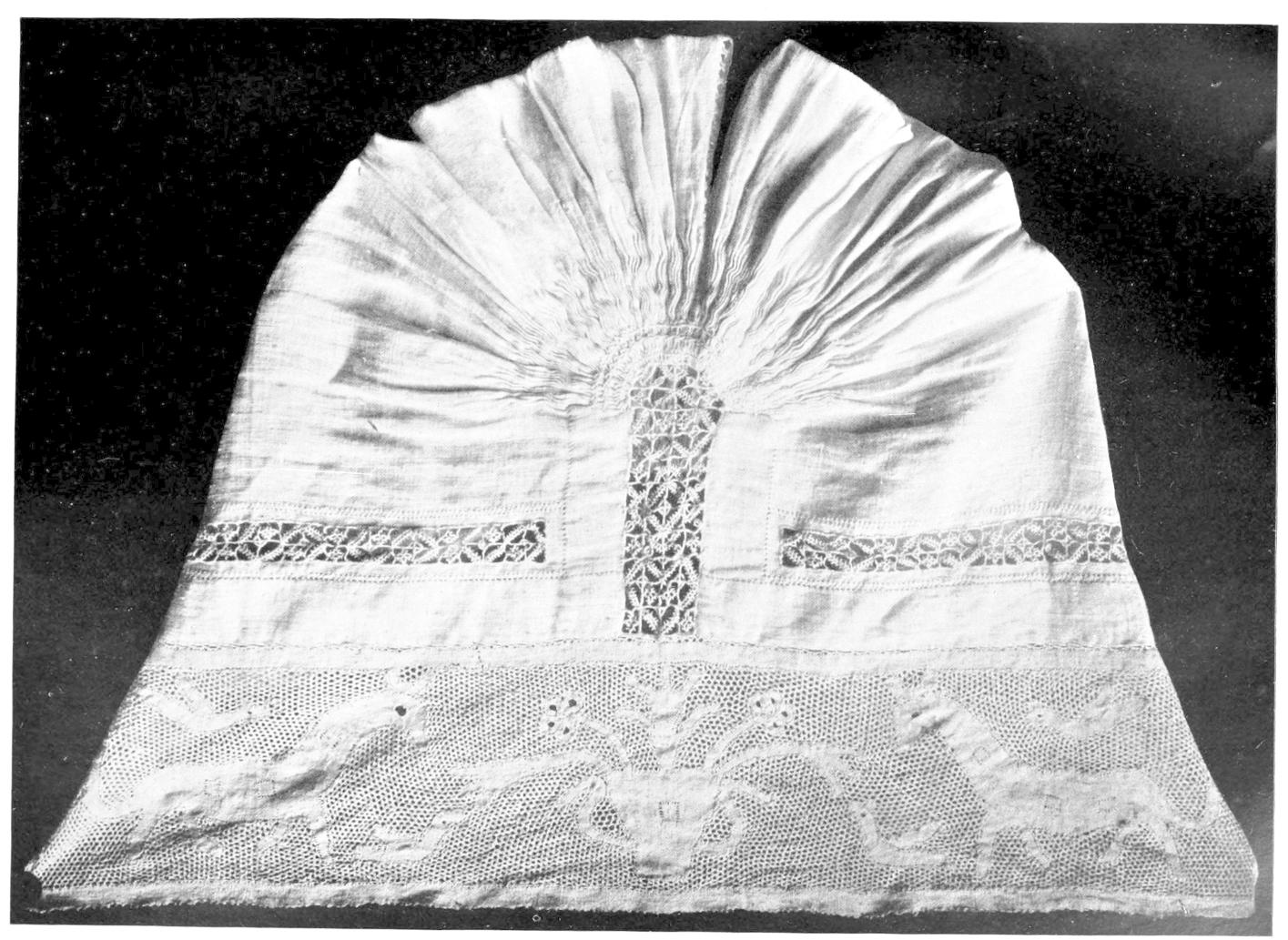

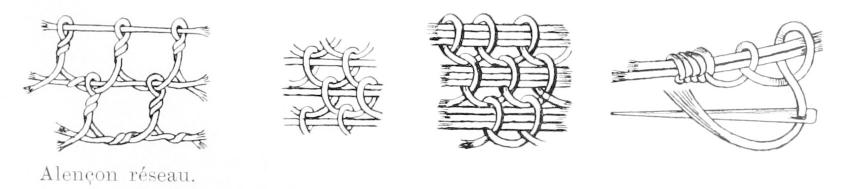

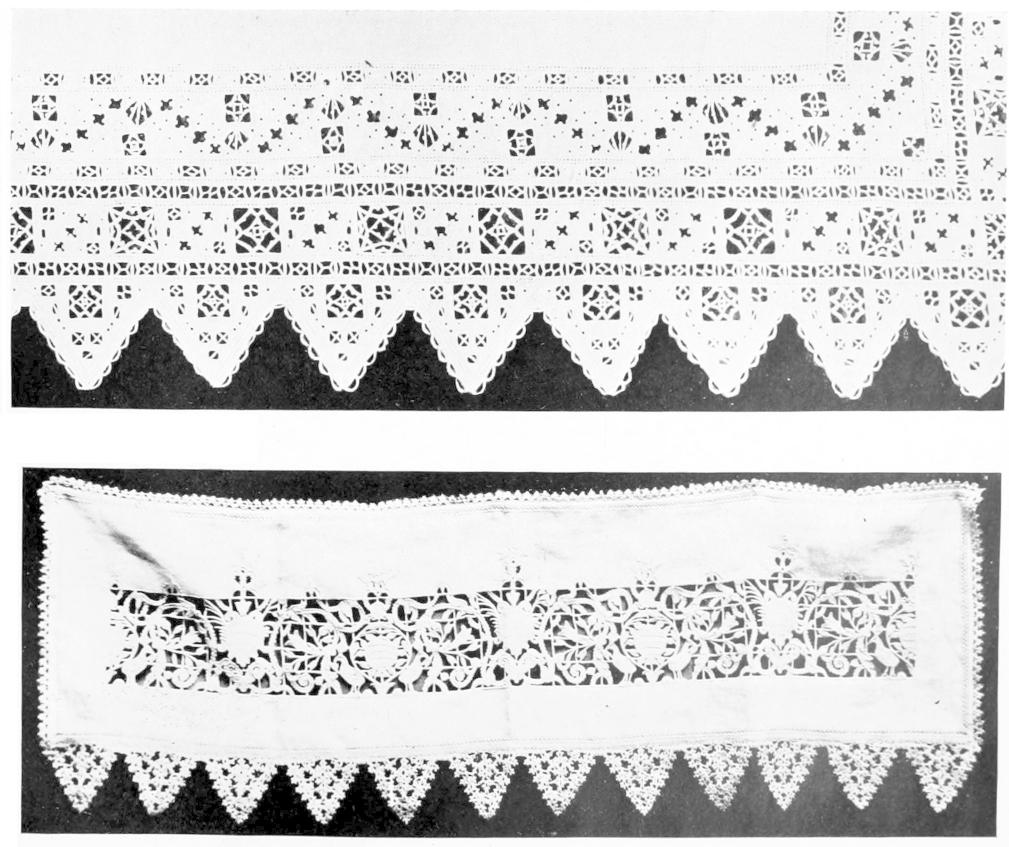

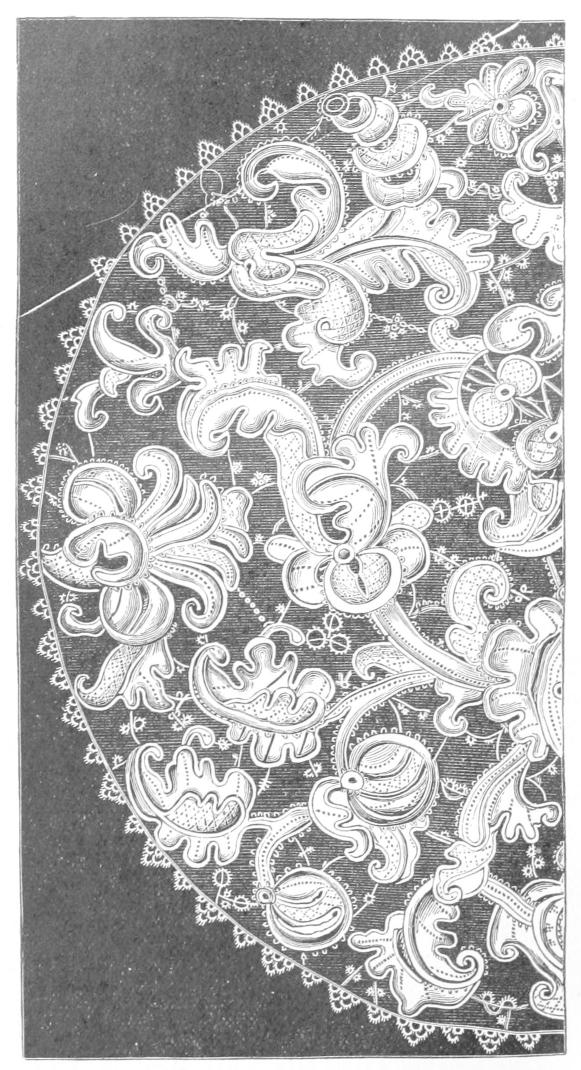

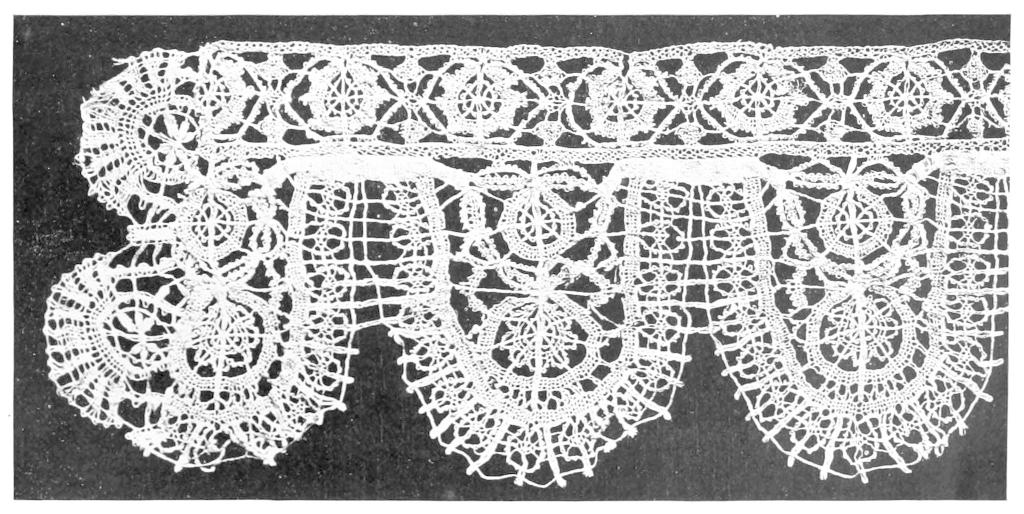

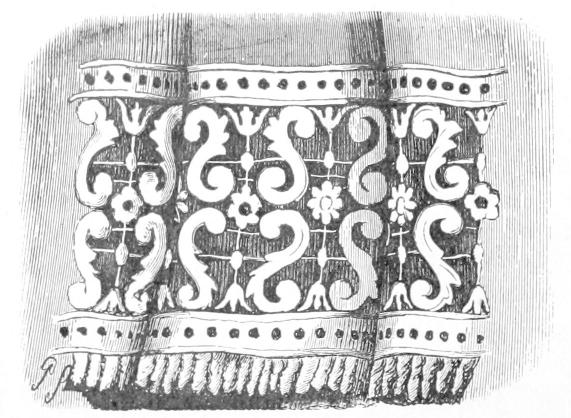

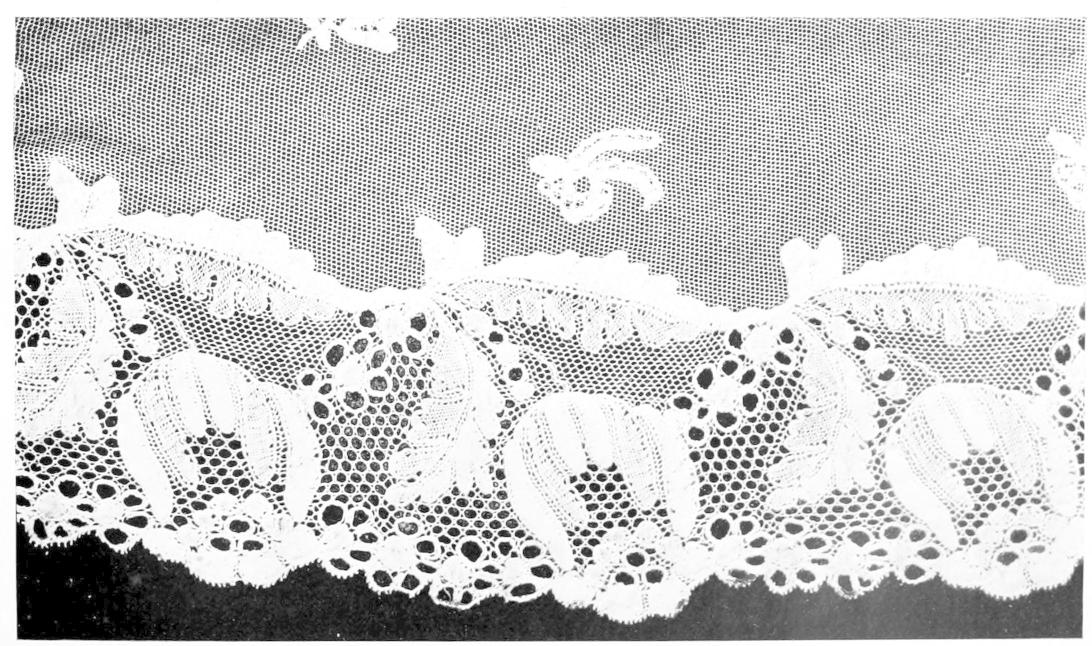

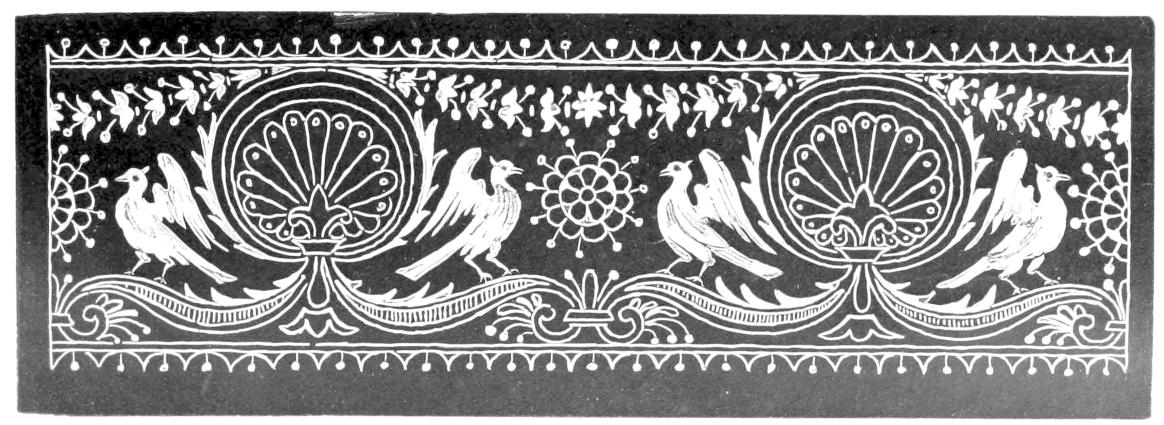

Plate III.

Altar or Table Cloth of fine linen embroidered with gold thread, laid, and in satin

stitches on both sides. The Cut out spaces are filled with white thread needle-point lace.

The edging is alternated of white and gold thread needle-point lace. Probably Italian. Late

sixteenth century.—Victoria and Albert Museum.

To face page 18

{19}

Cut-work was made in several manners. The first consisted in arranging a network

of threads upon a small frame, crossing and interlacing them into various complicated patterns.

Beneath this network was gummed a piece of fine cloth, called quintain,[60] from the town in Brittany where it was made. Then, with a

needle, the network was sewn to the quintain by edging round those parts of the pattern that were

to remain thick. The last operation was to cut away the superfluous cloth; hence the name of

cut-work.

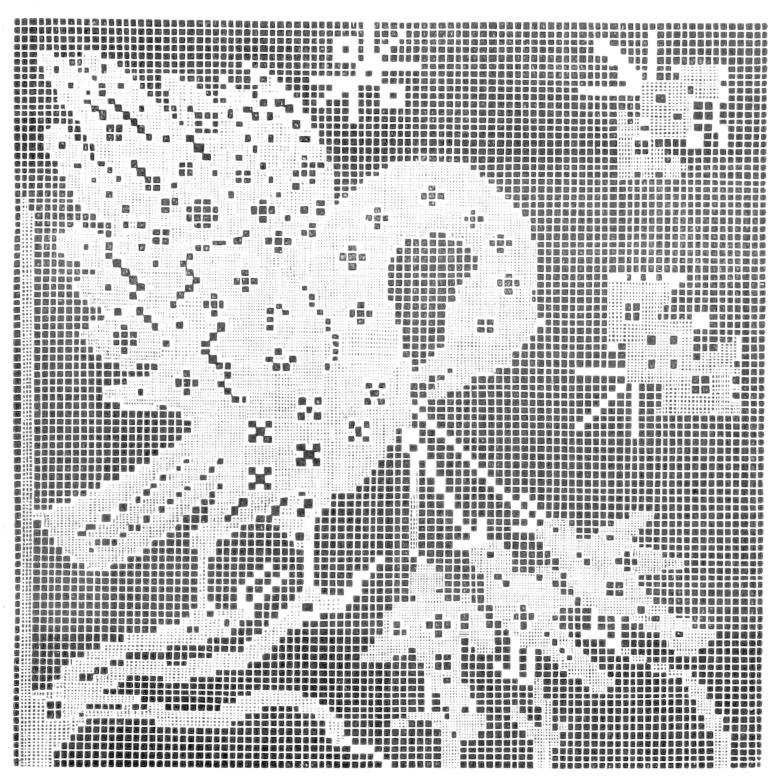

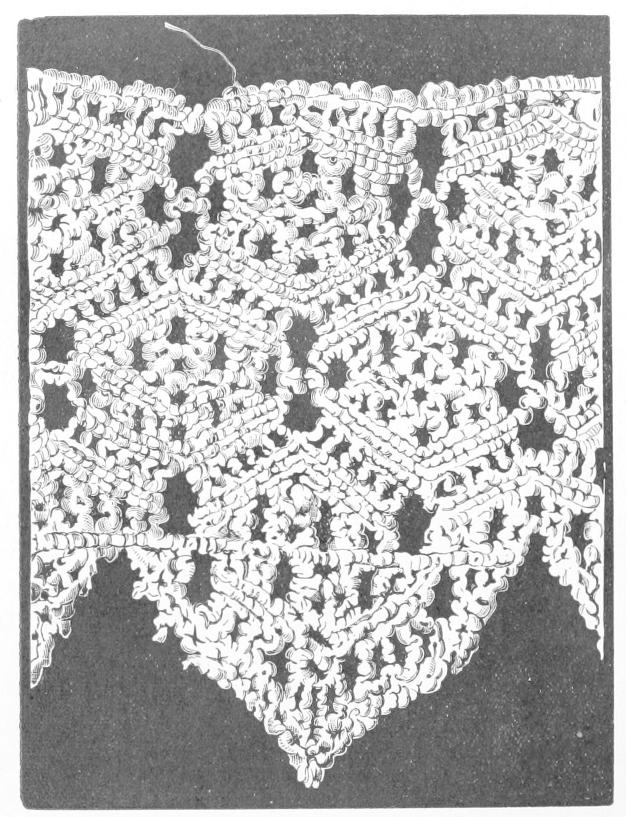

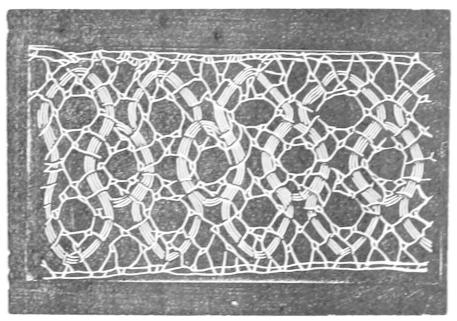

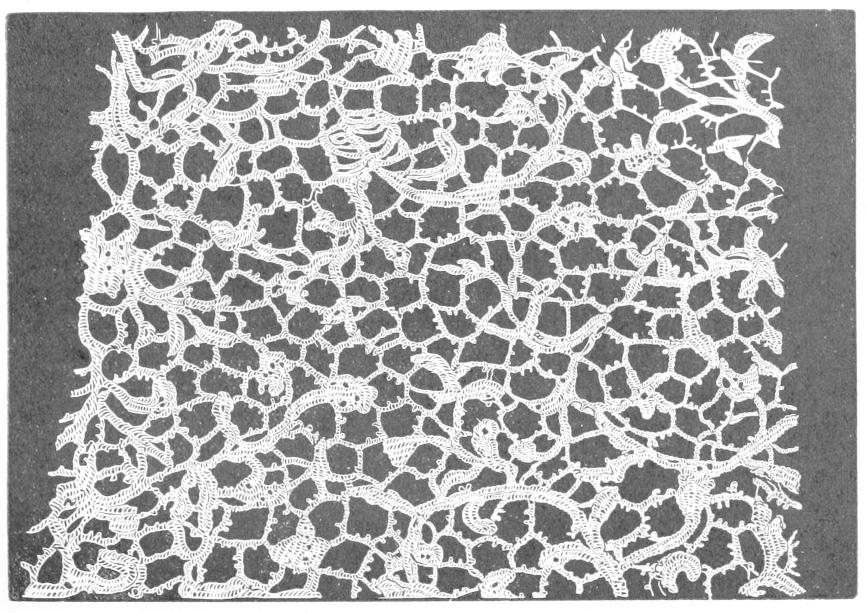

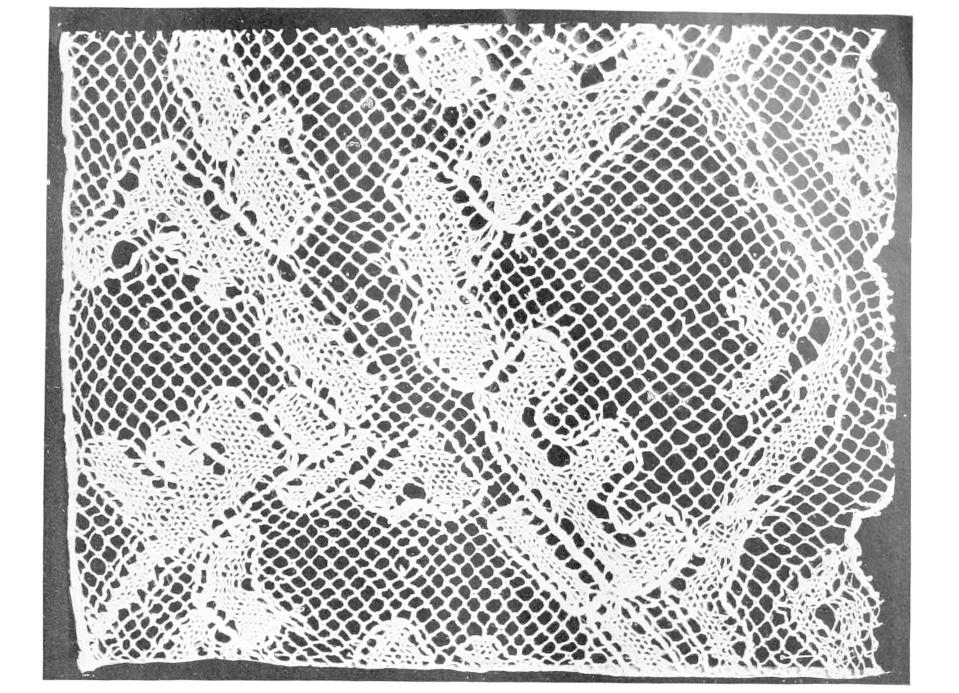

Fig. 3.

Lacis.—(Vinciolo. Edition 1588.)

Ce Pelican contient en longueur 70 mailles et en hauteur 65.

{20}

The author of the Consolations aux Dames, 1620, in addressing the ladies, thus specially

alludes to the custom of working on quintain:—

"Vous n'employiez les soirs et les matins

A façonner vos grotesques quaintains,

O folle erreur—O despence excessive."

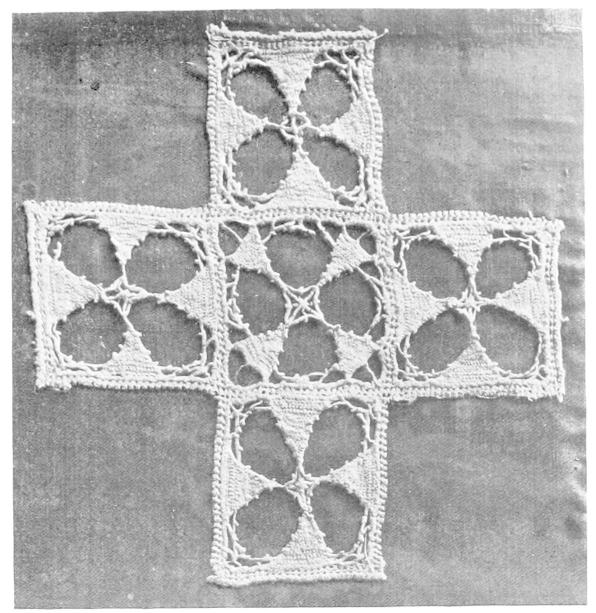

Again, the pattern was made without any linen at all; threads, radiating at equal distances

from one common centre, served as a framework to others which were united to them in squares,

triangles, rosettes, and other geometric forms, worked over with button-hole stitch (point

noué), forming in some parts open-work, in others a heavy compact embroidery. In this class

may be placed the old conventual cut-work of Italy, generally termed Greek lace, and that of

extraordinary fineness and beauty which is assigned to Venice. Distinct from all these geometric

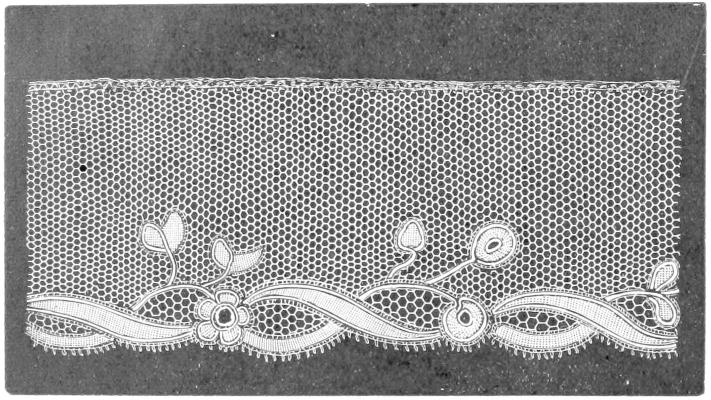

combinations was the lacis[61] of the sixteenth

century, done on a network ground (réseau), identical with the opus araneum or

spider-work of continental writers, the "darned netting" or modern filet brodé à reprises

of the French embroiderers.

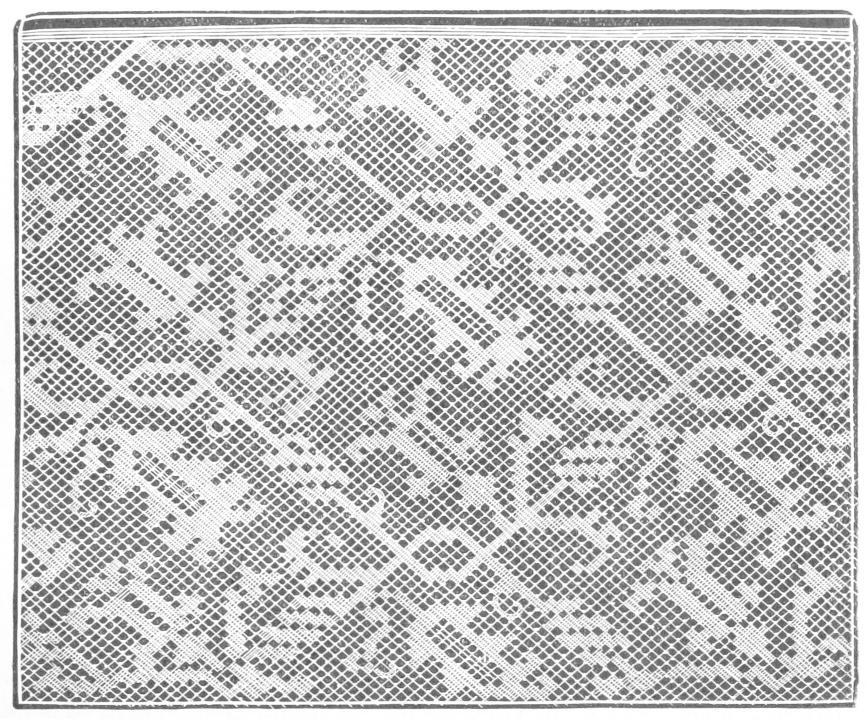

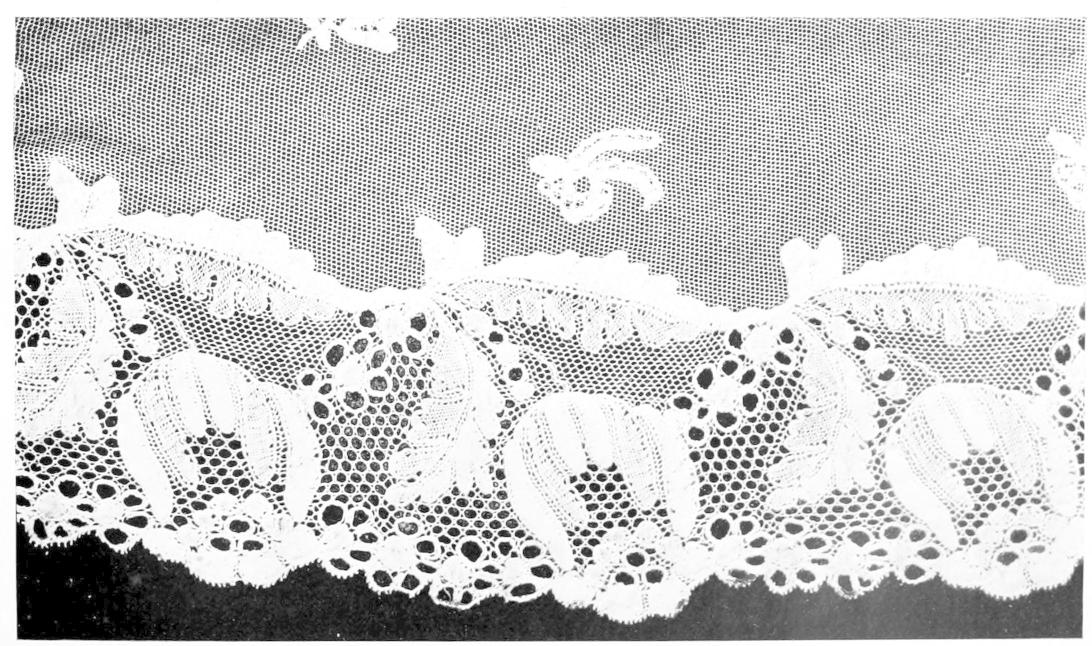

The ground consisted of a network of square meshes, on which was worked the pattern, sometimes

cut out of linen and appliqué,[62] but more usually

darned with stitches like tapestry. This darning-work was easy of execution, and the stitches

being regulated by counting the meshes,[63] effective

geometric patterns could be produced. Altar-cloths, baptismal napkins, as well as bed coverlets

and table-cloths, were decorated with these squares of net embroidery. In the Victoria and Albert

Museum there are several {21}gracefully-designed borders

to silk table-covers in this work, made both of white and coloured threads, and of silk of various

shades. The ground, as we learn from a poem on lacis, affixed to the pattern-book of "Milour

Mignerak,"[64] was made by beginning a single stitch,

and increasing a stitch on each side until the required size was obtained. If a strip or long

border was to be made, the netting was continued to its prescribed length, and then finished off

by reducing a stitch on each side till it was decreased to one, as garden nets are made at the

present day.

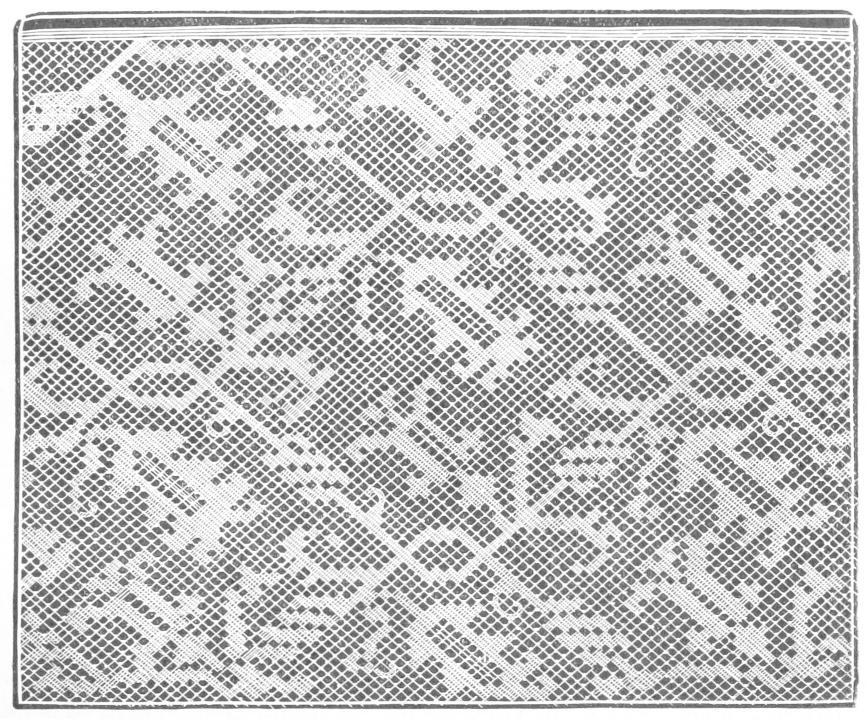

This plain netted ground was called réseau, rézel, rézeuil,[65] and was much used for bed-curtains, vallances, etc.

In the inventory of Mary Stuart, made at Fotheringay,[66] we find, "Le lict d'ouvrage à rezel"; and again, under the care

of Jane Kennethee, the "Furniture of a bedd of network and Holland intermixed, not yet

finished."

When the réseau was decorated with a pattern, it was termed lacis, or darned

netting, the Italian punto ricamato a maglia quadra, and, combined with point-coupé,

was much used for bed-furniture. It appears to have been much employed for church-work,[67] for the sacred emblems. The Lamb and the Pelican are

frequently represented.[68]

{22}

In the inventory of Sir John Foskewe (modern Fortescue), Knight, time of Henry VIII., we find

in the hall, "A hanging of green saye, bordered with darning."

Queen Mary Stuart, previous to the birth of James I. (1560), made a will, which still exists,[69] with annotations in her own handwriting. After

disposing of her jewels and objects of value, she concludes by bequeathing "tous mes ouvrages

masches et collets aux 4 Maries, à Jean Stuart, et Marie Sunderland, et toutes les

filles";—"masches,"[70] with punti a

maglia, being among the numerous terms applied to this species of work.

These "ouvrages masches" were doubtless the work of Queen Mary and her ladies. She had learned

the art at the French court, where her sister-in-law, Reine Margot, herself also a prisoner for

many life-long years, appears to have occupied herself in the same manner, for we find in her

accounts,[71] "Pour des moulles et esguilles pour

faire rezeuil la somme de iiii. L. tourn." And again, "Pour avoir monté une fraize neufve de

reseul la somme de X. sols tourn."

Catherine de Médicis had a bed draped with squares of reseuil or lacis, and it is recorded that

"the girls and servants of her household consumed much time in making squares of reseuil." The

inventory of her property and goods includes a coffer containing three hundred and eighty-one of

such squares unmounted, whilst in another were found five hundred and thirty-eight squares, some

worked with rosettes or with blossoms, and others with nosegays.[72]

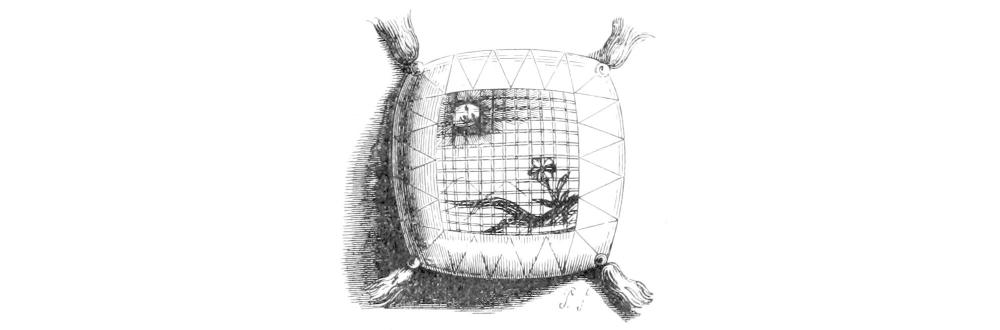

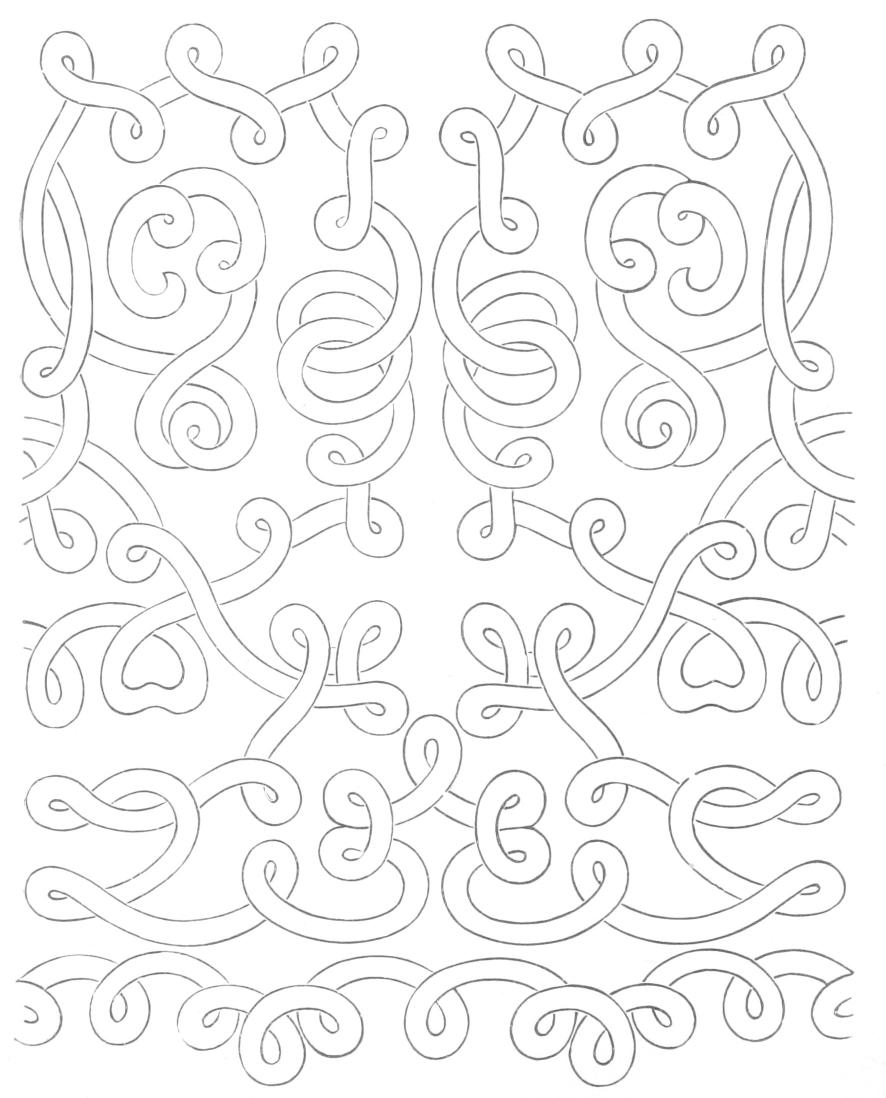

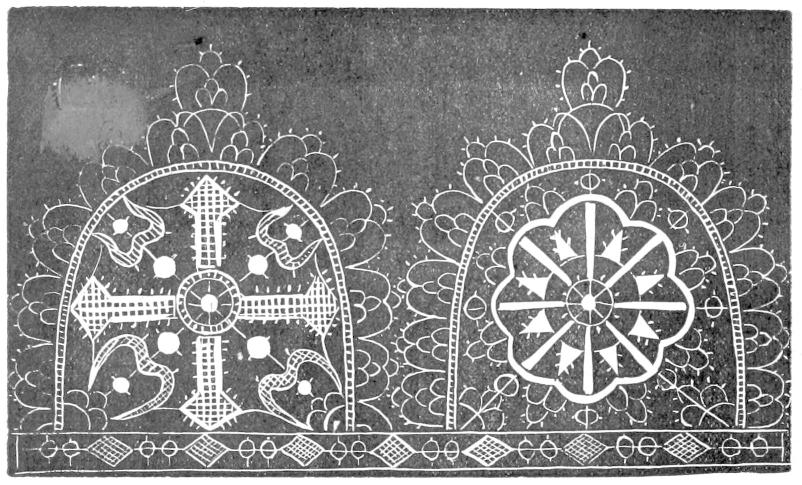

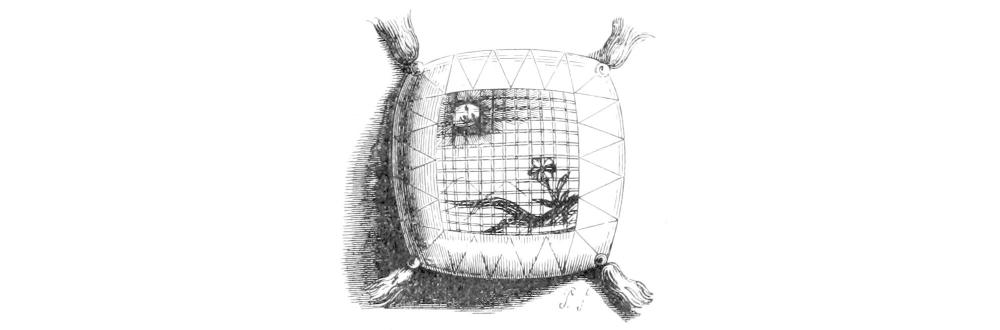

Though the work of Milour Mignerak, already quoted, is dedicated to the

Trés-Chrestienne Reine de France et de Navarre, Marie de Médicis, and bears her cipher and arms,

yet in the decorated frontispiece is a cushion with a piece of lacis in progress, the pattern a

daisy looking at the sun, the favourite impresa of her predecessor, the divorced Marguerite, now,

by royal ordinance, "Marguerite Reine, Duchesse de Valois." (Fig. 4.)

Fig. 5.

To face page 22.

{23}

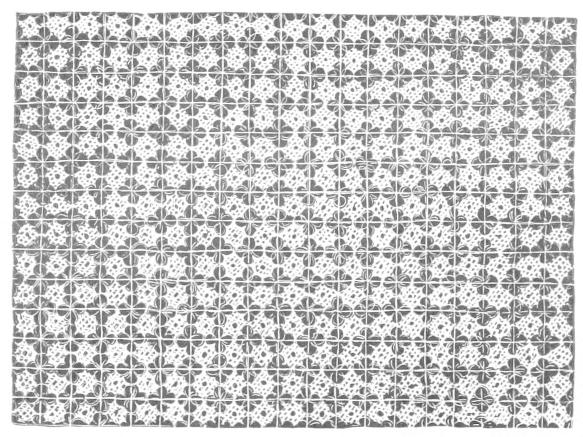

These pattern-books being high in price and difficult to procure, teachers of the art soon

caused the various patterns to be reproduced in "samcloths,"[73] as samplars were then termed, and young ladies worked at them

diligently as a proof of their competency in the arts of cut-work, lacis and réseuil, much as a

dame-school child did her A B C in the country villages some years ago. Proud mothers caused these

chefs-d'œuvre of their children to be framed and glazed; hence many have come down

to us hoarded up in old families uninjured at the present time. (Fig. 5.)

A most important specimen of lacis was exhibited at the Art International

Exhibition of 1874, by Mrs. Hailstone, of Walton Hall, an altar frontal 14 feet by 4 feet,

executed in point conté, representing eight scenes from the Passion of Christ, in all fifty-six

figures, surrounded by Latin inscriptions. It is assumed to be of English workmanship.

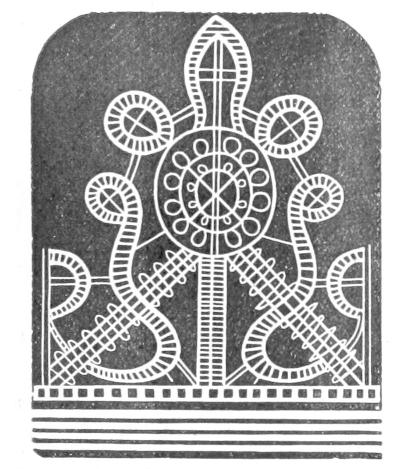

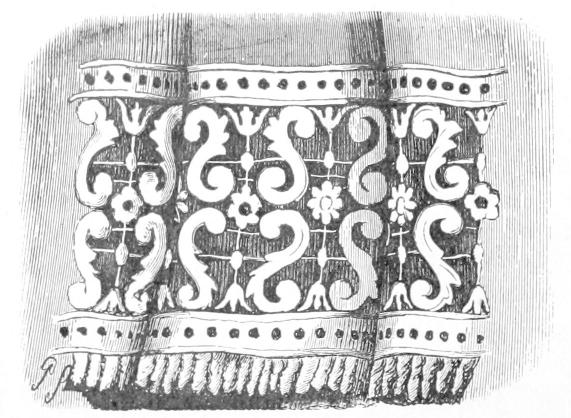

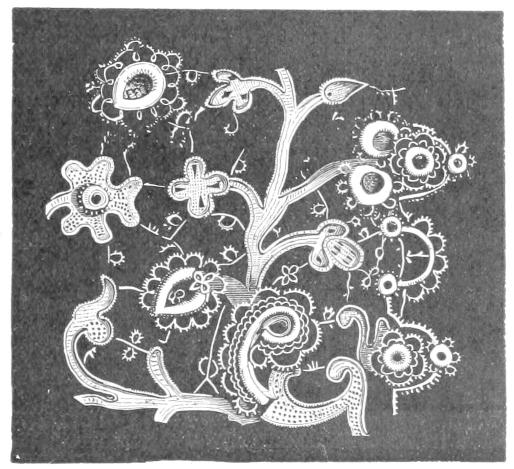

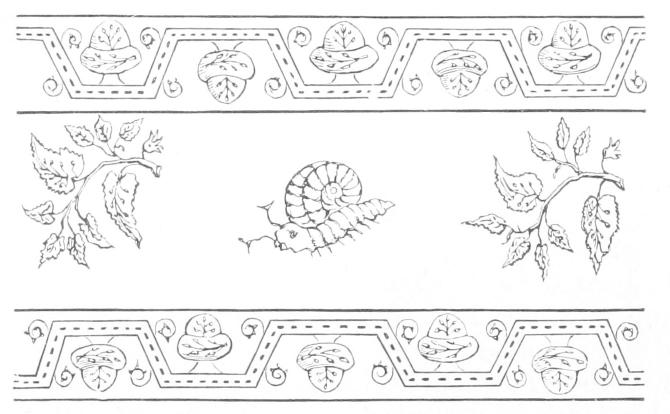

Fig. 4.

Impresa of Queen Margaret of Navarre in

Lacis.—(Mignerak.)

Some curious pieces of ancient lacis were also exhibited (circ. 1866) at the Museum of

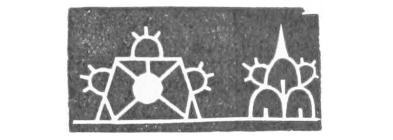

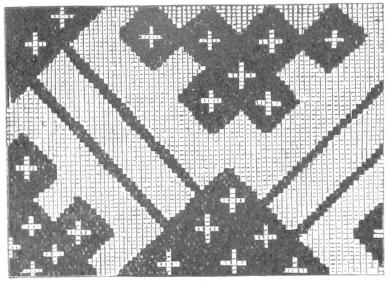

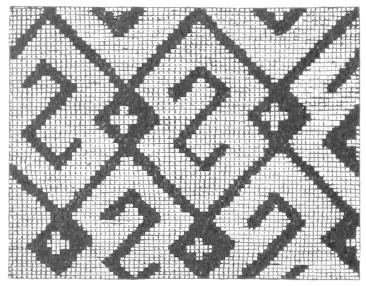

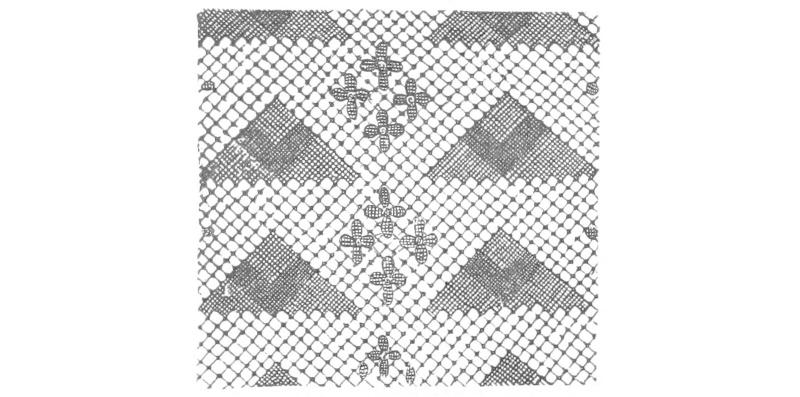

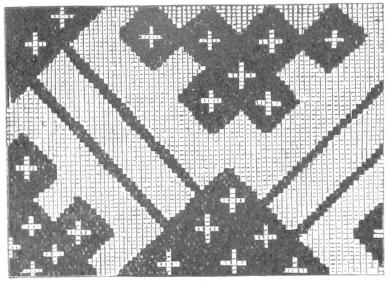

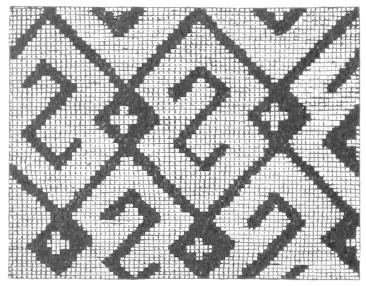

South Kensington by Dr. Bock, of Bonn. Among others, two specimens of coloured silk network, the

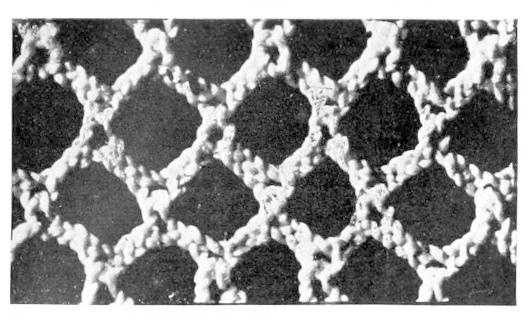

one ornamented with small embroidered shields and crosses (Fig. 6), the other with the mediæval

gammadion pattern (Fig. 7). In the same collection was a towel or altar-cloth of ancient German

work—a coarse net ground, worked over with the lozenge pattern.[74]

{24}

But most artistic of all was a large ecclesiastical piece, some three yards in length. The

design portrays the Apostles, with angels and saints. These two last-mentioned objects are of the

sixteenth century.

When used for altar-cloths, bed-curtains, or coverlets, to produce a greater effect it was the

custom to alternate the lacis with squares of plain linen.

"An apron set with many a dice

Of needlework sae rare,

Wove by nae hand, as ye may guess,

Save that of Fairly fair."

Ballad of Hardyknute.

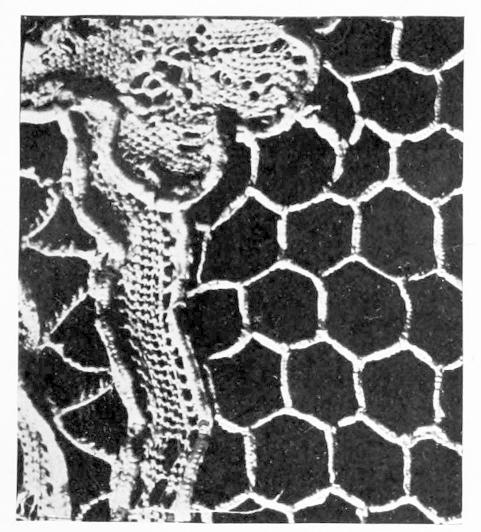

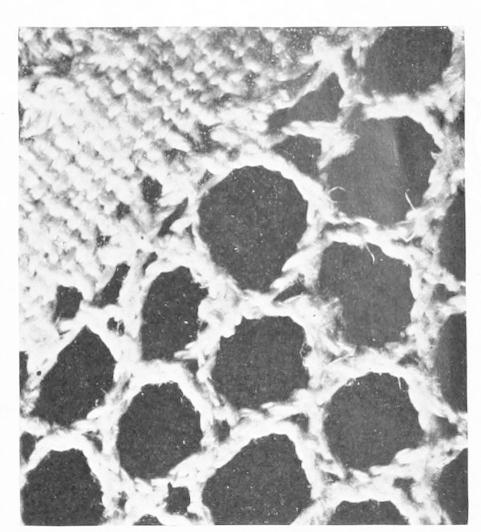

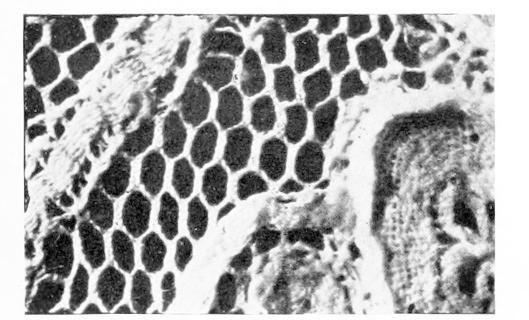

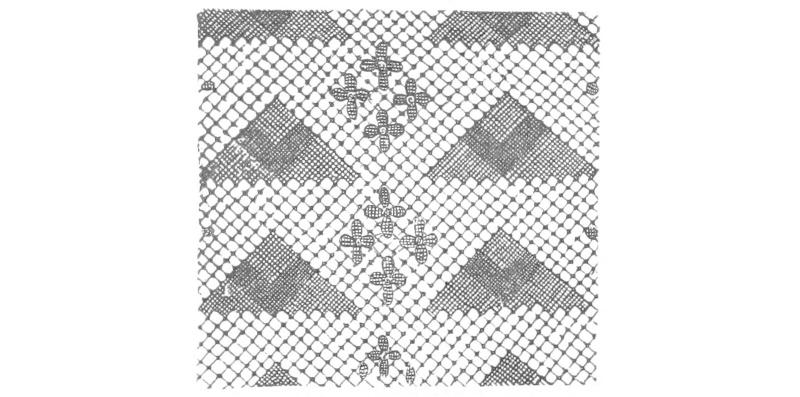

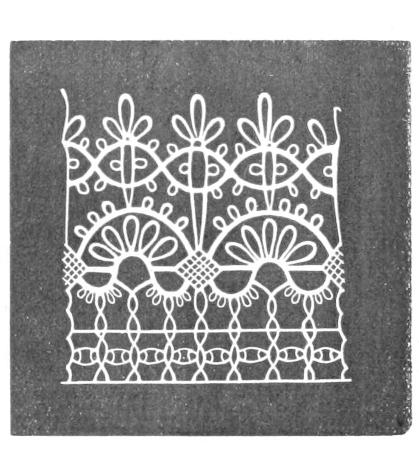

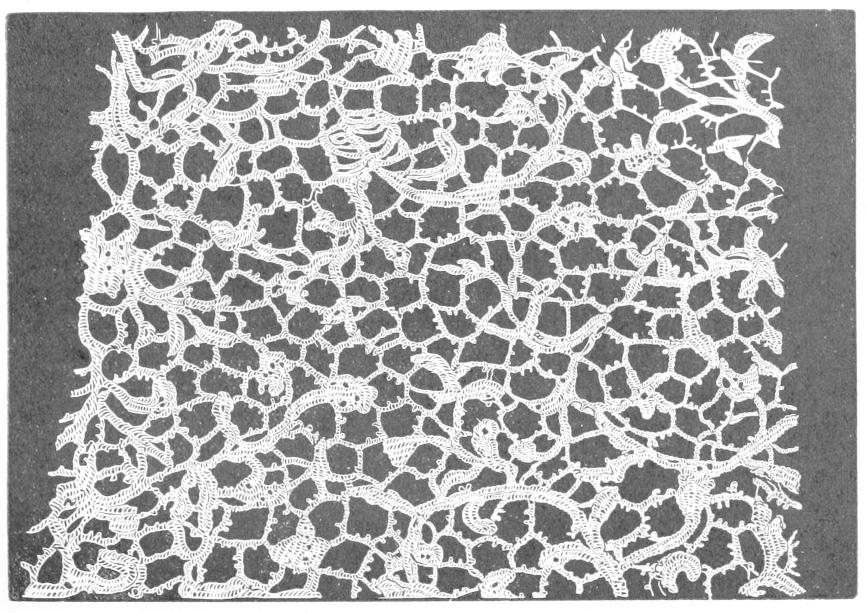

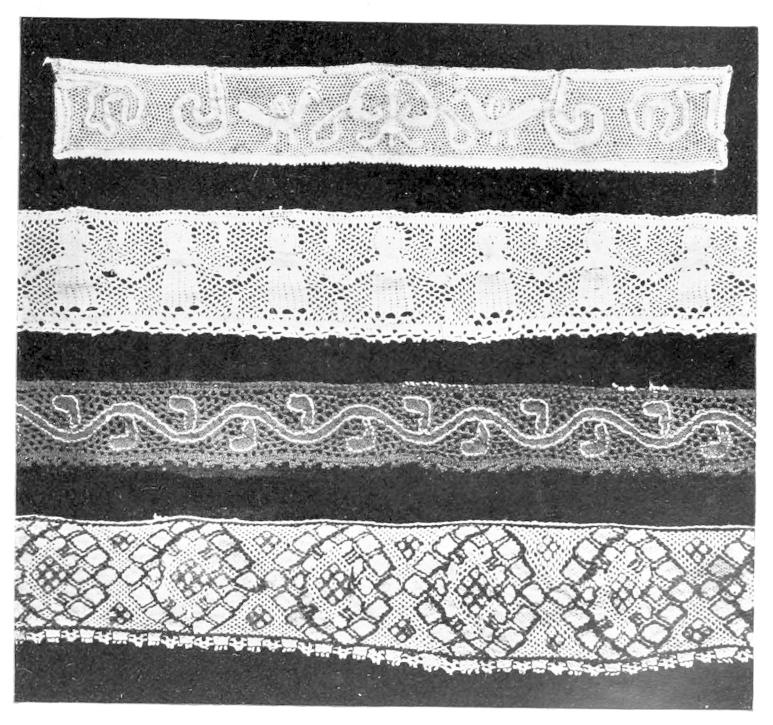

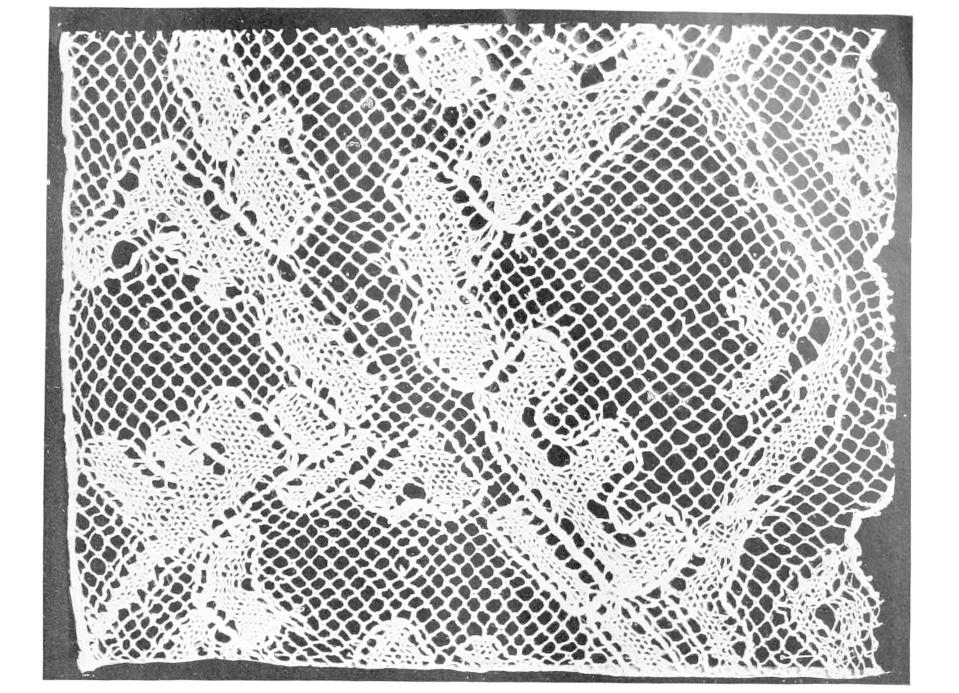

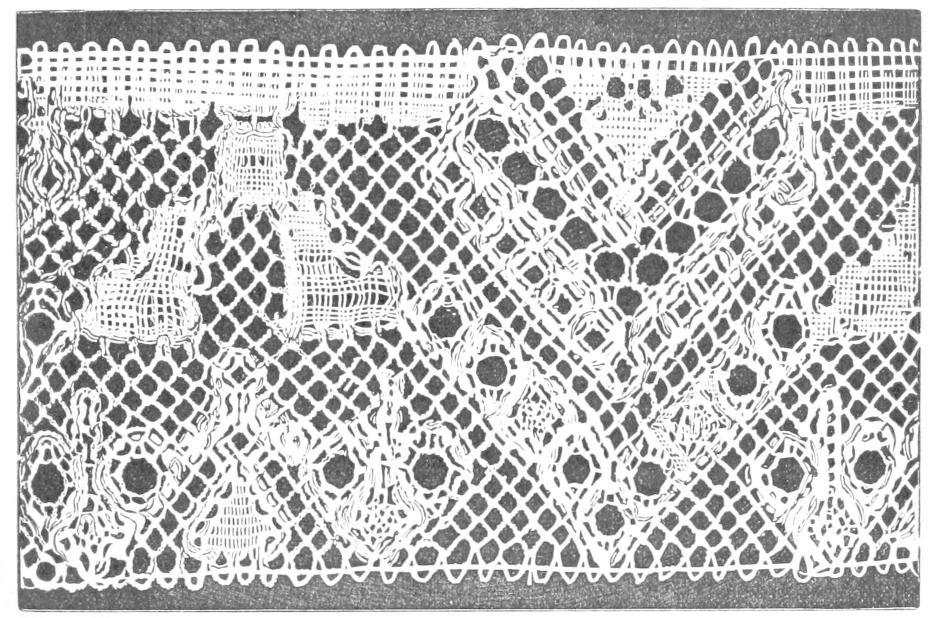

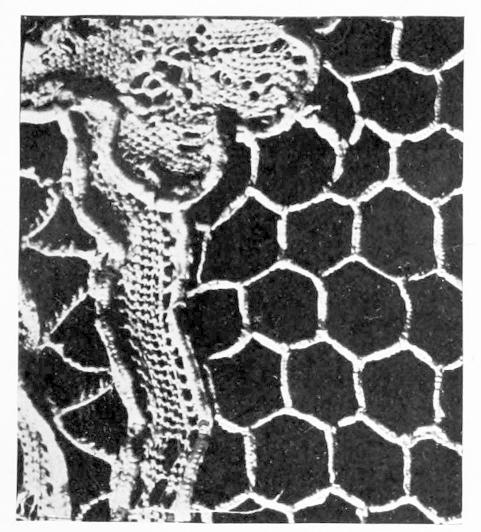

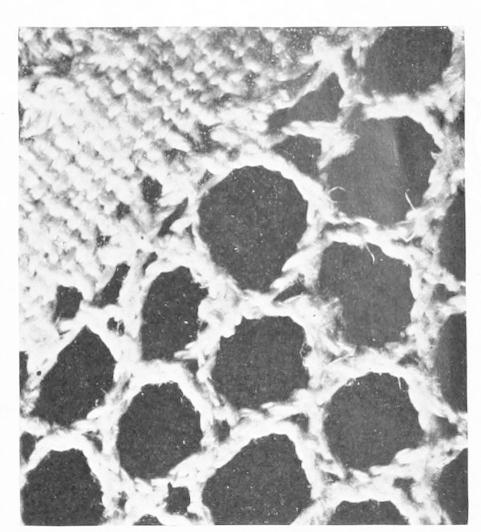

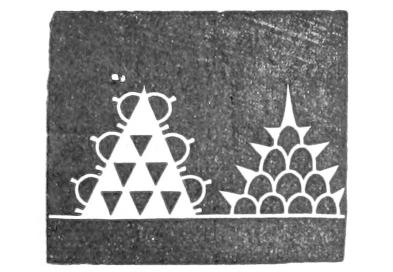

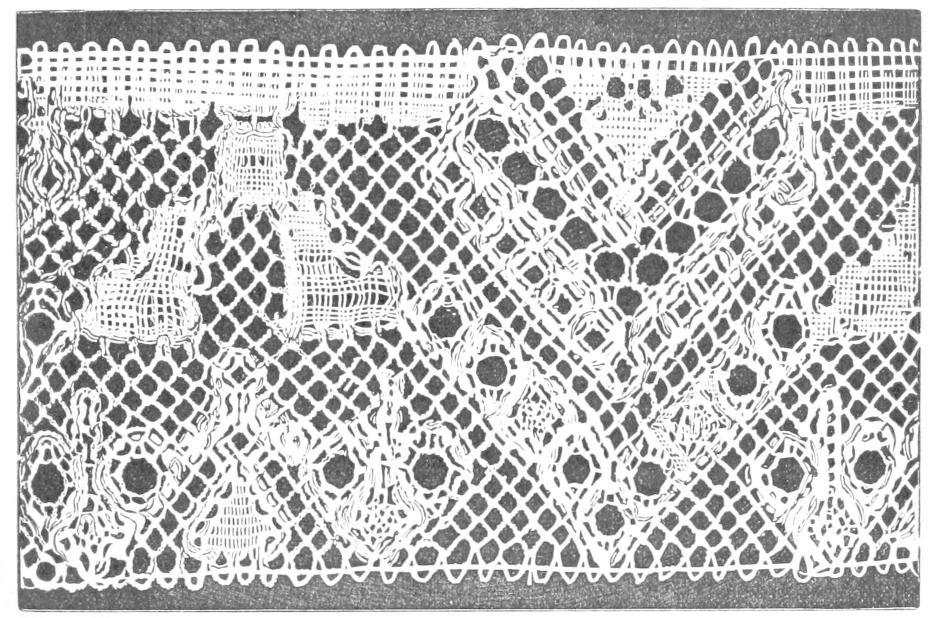

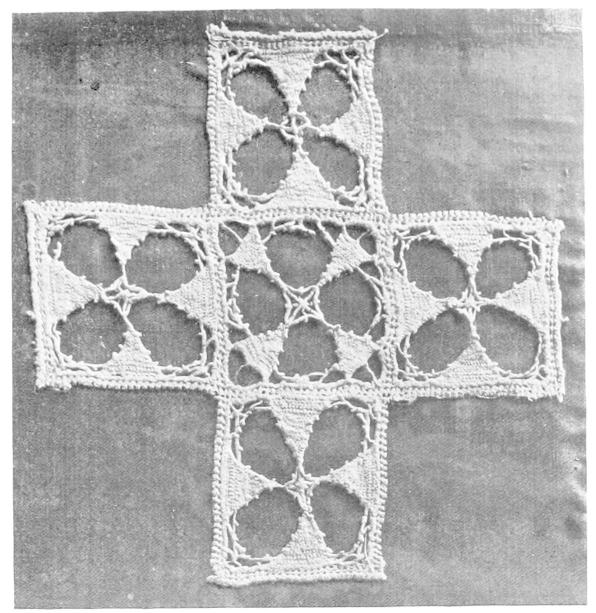

| Fig. 6. |

Fig. 7. |

|

|

"Spiderwork," thirteenth century.—(Bock Coll.

South Kensington Museum).

|

"Spiderwork," fourteenth century.—(Bock Coll.

South Kensington Museum.)

|

This work formed the great delight of provincial ladies in France. Jean Godard, in his poem on

the Glove,[75] alluding to this occupation, says:—

"Une femme gantée œuvre en tapisserie

En raizeaux deliez et toute lingerie

Elle file—elle coud et fait passement

De toutes les fassons...."

The armorial shield of the family, coronets, monograms, the beasts of the Apocalypse, with

fleurs-de-lys, sacrés cœurs, for the most part adorned those pieces destined for the use of

the Church. If, on the other hand, intended for a pall, death's-heads, cross-bones and tears, with

the sacramental cup, left no doubt of the destination of the article.

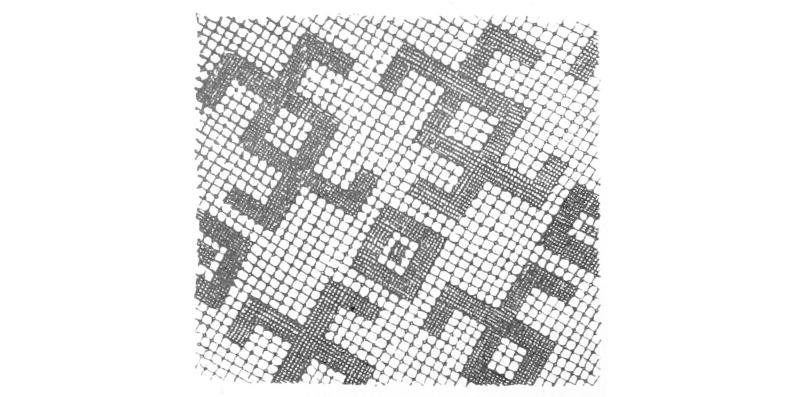

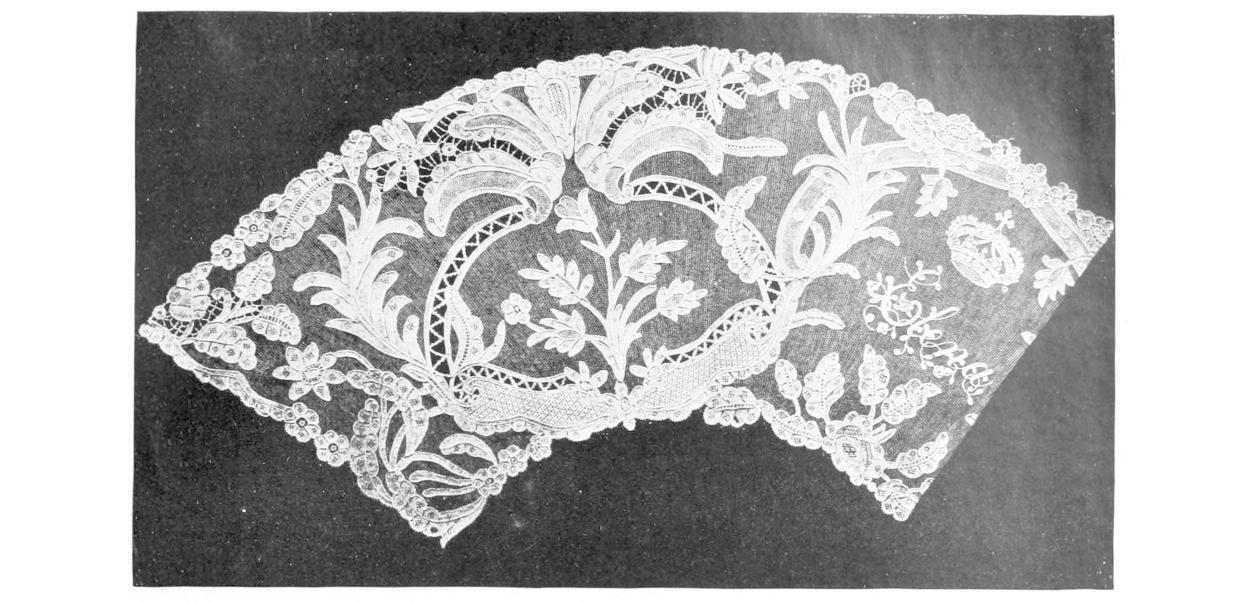

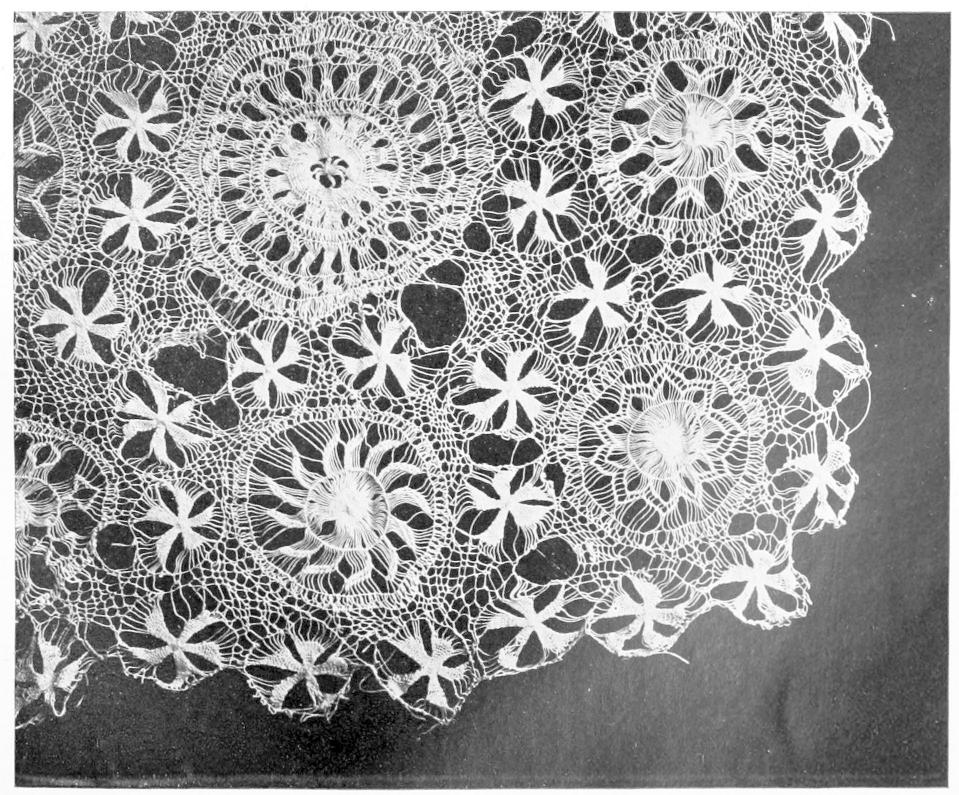

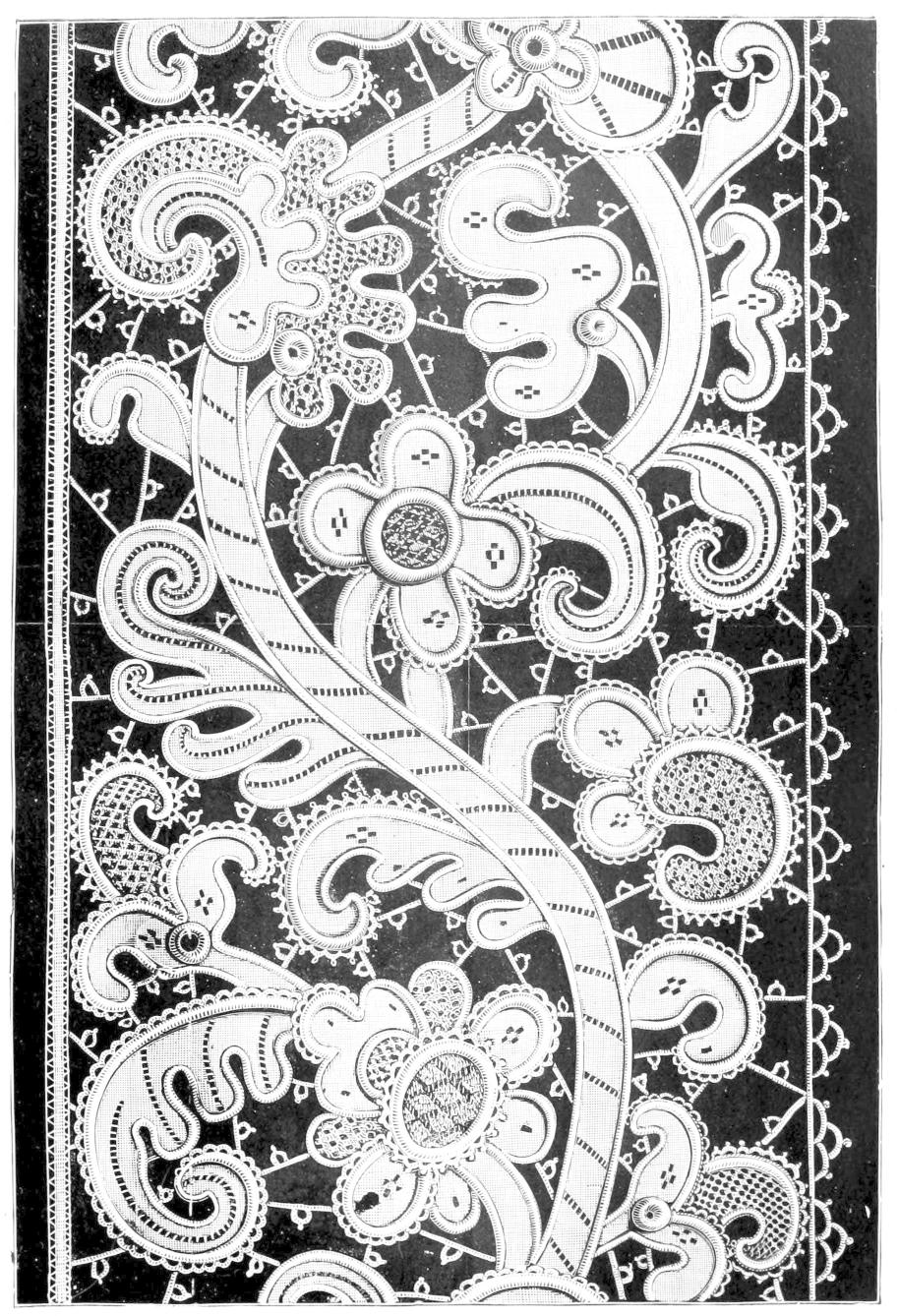

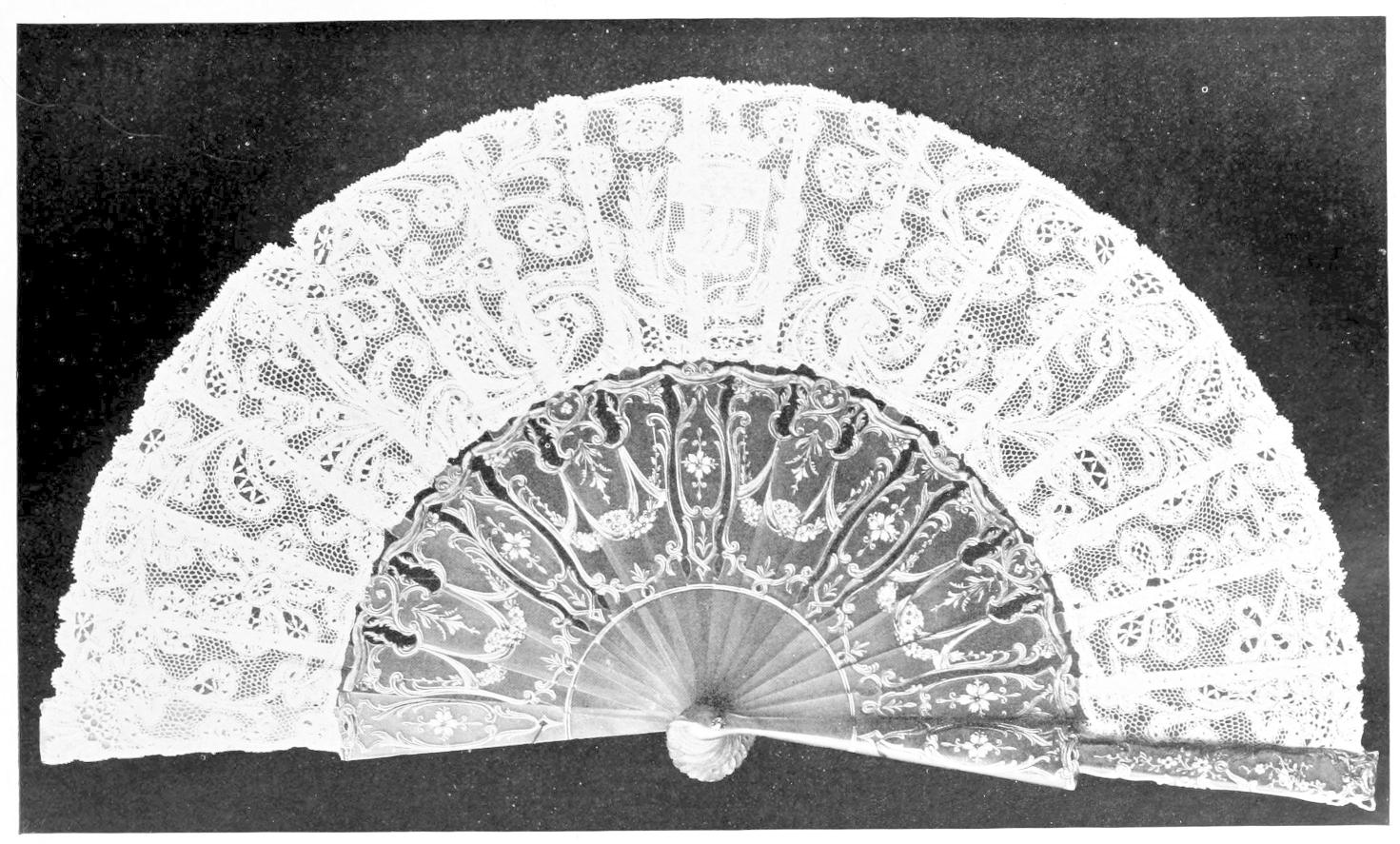

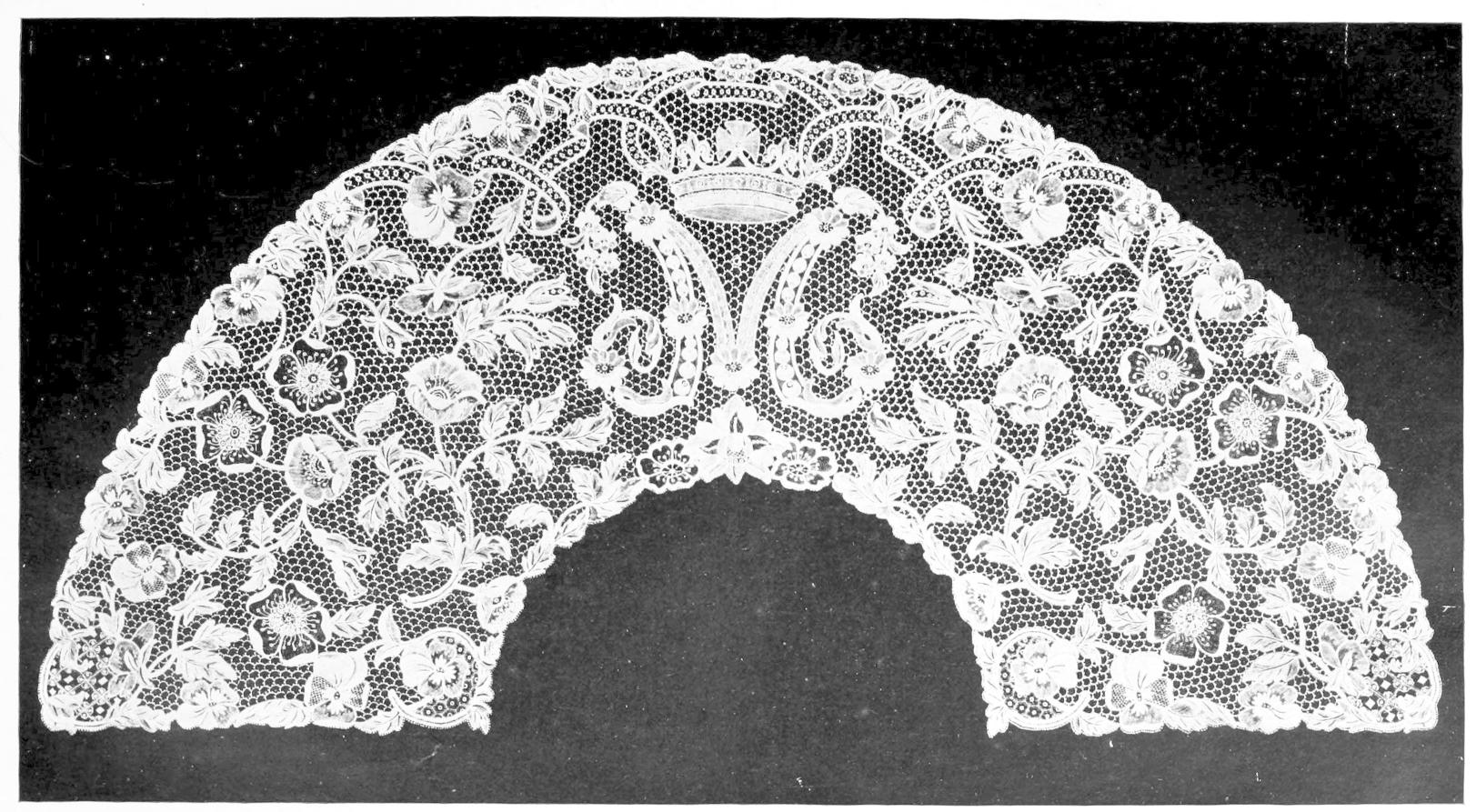

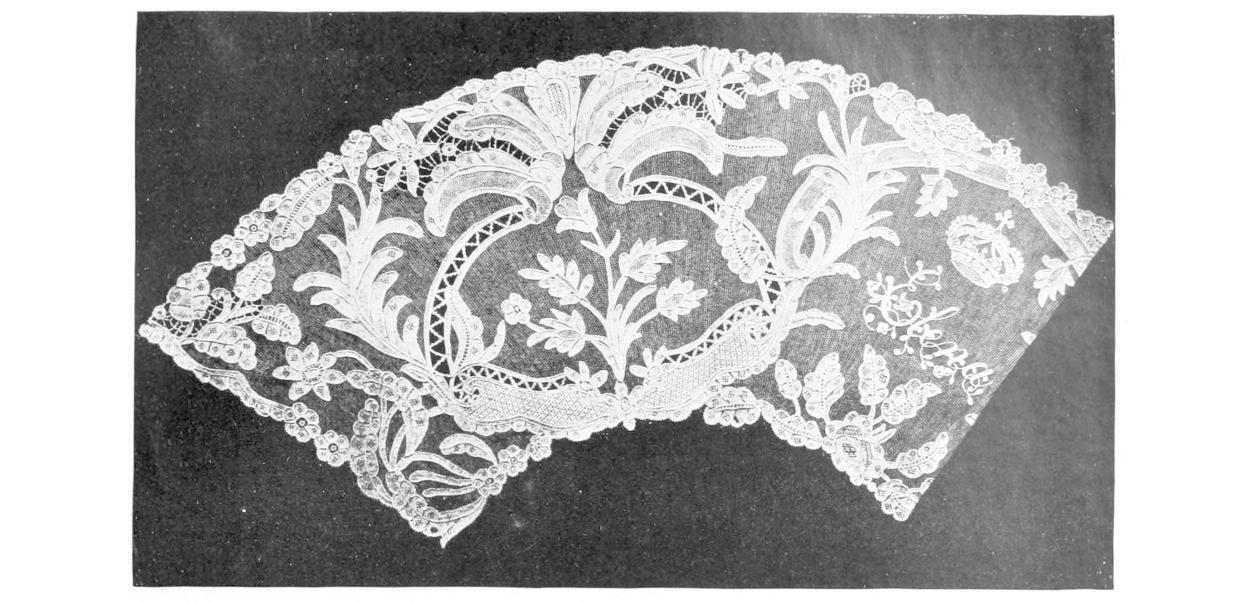

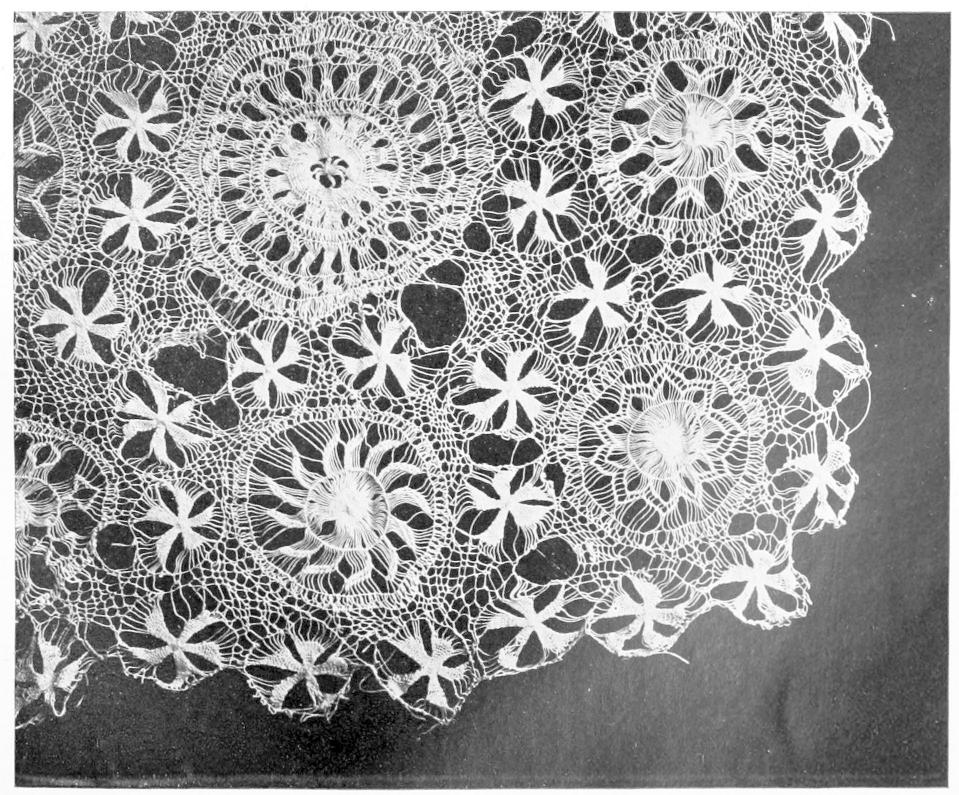

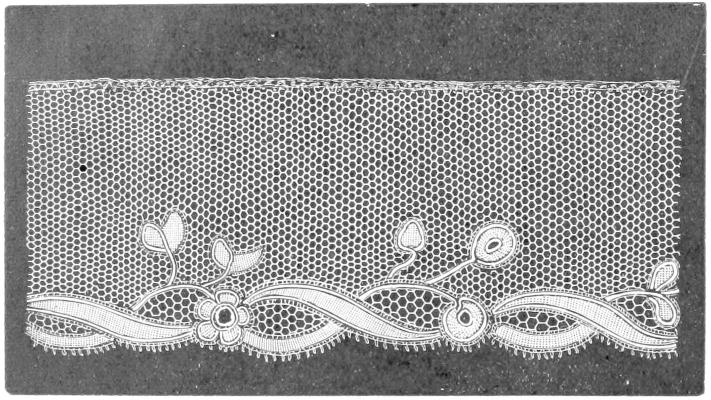

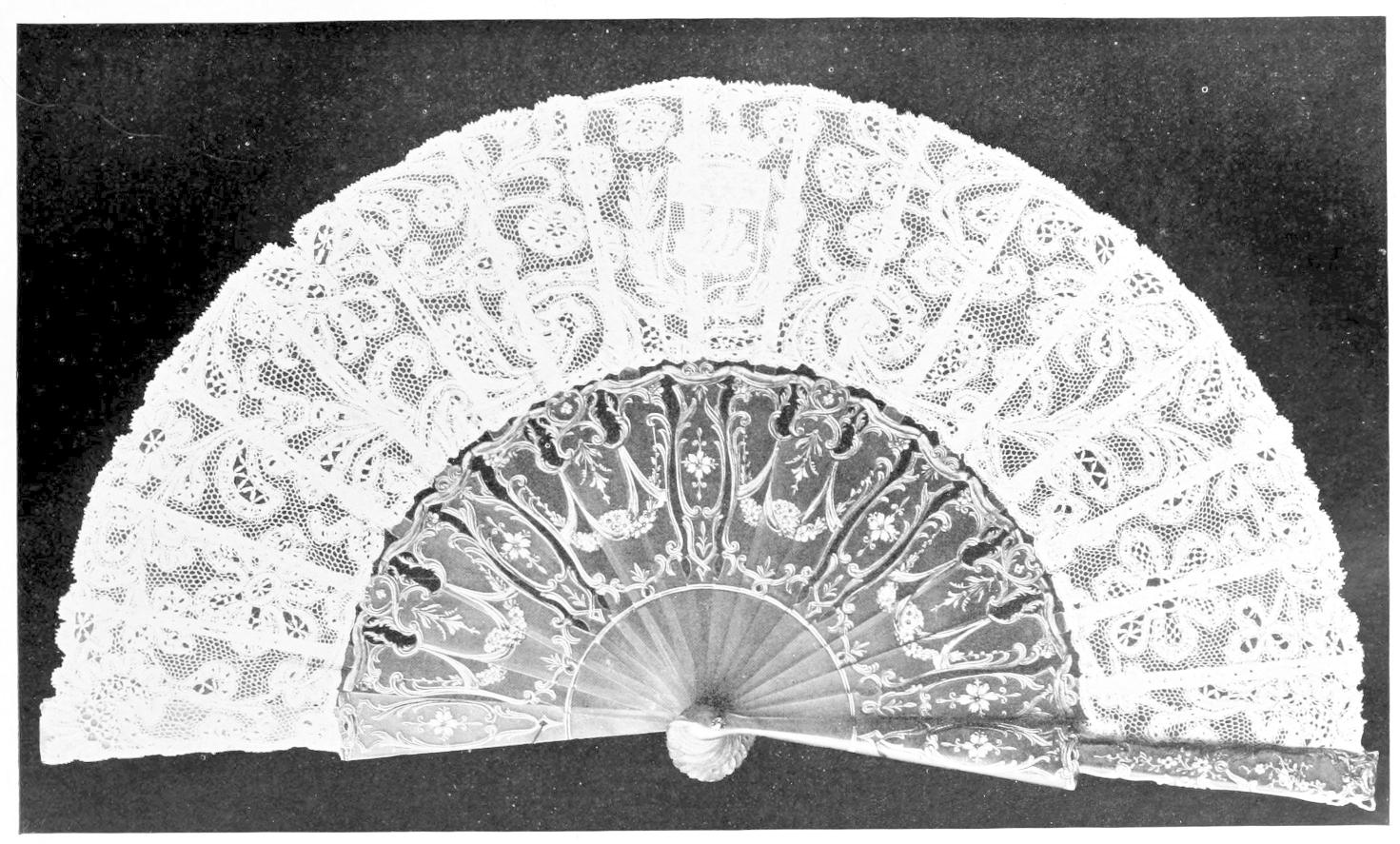

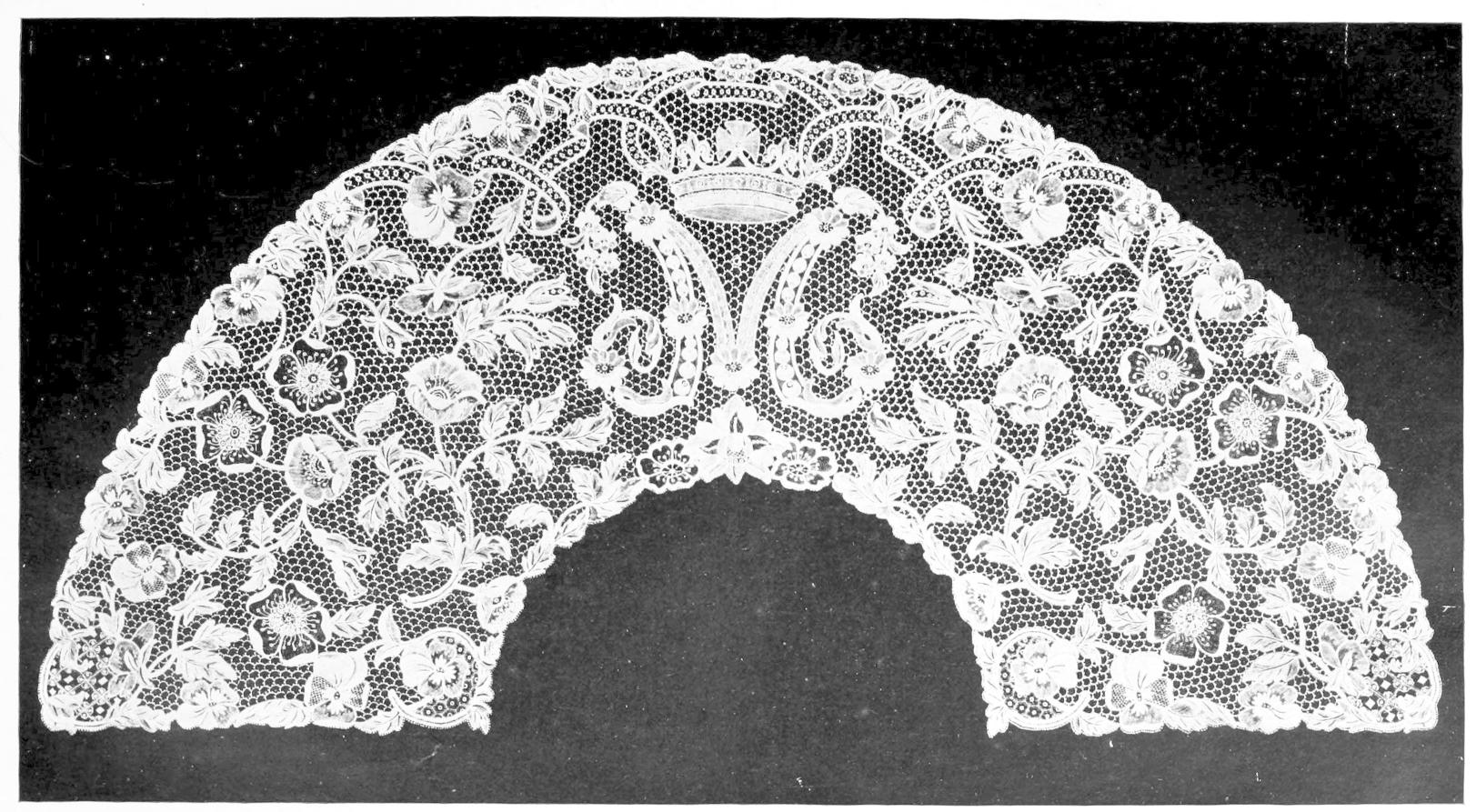

Plate IV.

Fan made at Burano and presented to Queen Elena of Italy on her Marriage,

1896.

Photo by the Burano School.

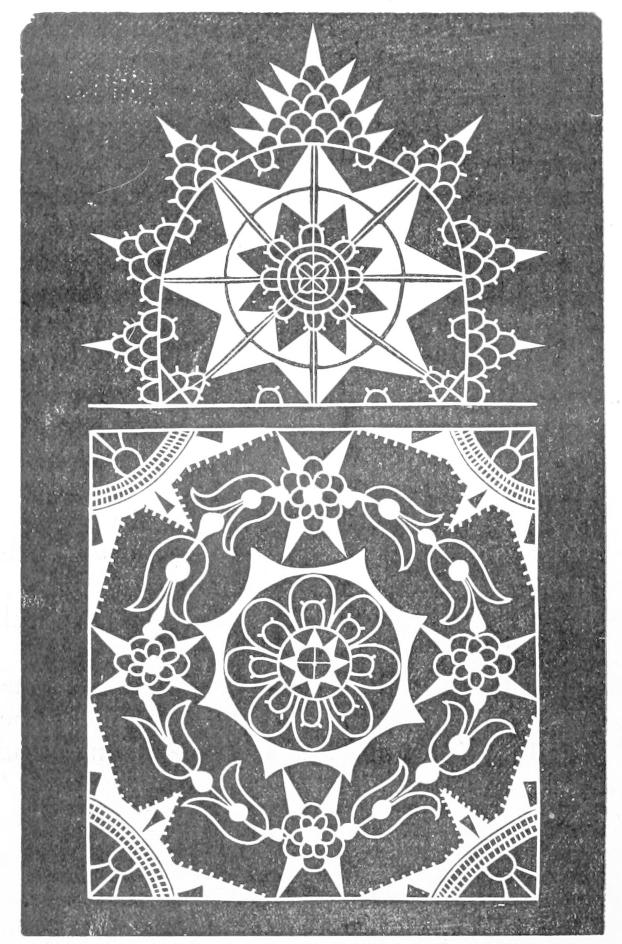

Plate V.

Italian. Punto Reale.—Modern reproduction by the Society

Æmilia Ars, Bologna.

Photo by the Society.

To face page 24.

{25}

As late as 1850, a splendid cut-work pall still covered the coffins of the fishers when borne

in procession through the streets of Dieppe. It is said to have been a votive offering worked by

the hands of some lady saved from shipwreck, and presented as a memorial of her gratitude.

In 1866, when present at a peasant's wedding in the church of St. Lo (Dép. Manche), the author

observed that the "toile d'honneur," which is always held extended over the heads of the married

pair while the priest pronounces the blessing, was of the finest cut-work, trimmed with lace.

Both in the north and south of Europe the art still lingers on. Swedish housewives pierce and

stitch the holiday collars of their husbands and sons, and careful ladies, drawing the threads of

the fine linen sheets destined for the "guest-chamber," produce an ornament of geometric

design.

Scarce fifty years since, an expiring relic of this art might be sometimes seen on the white

smock-frock of the English labourer, which, independent of elaborate stitching, was enriched with

an insertion of cut-work, running from the collar to the shoulder crossways, like that we see

decorating the surplices of the sixteenth century.

Drawn-thread embroidery is another cognate work. The material in old drawn-work is usually

loosely-woven linen. Certain threads were drawn out from the linen ground, and others left, upon

and between which needlework was made. Its employment in the East dates from very early times, and

withdrawing threads from a fabric is perhaps referred to in Lucan's Pharsalia:—[76]

"Candida Sidonio perlucent pectora filo,

Quod Nilotis acus compressum pectine Serum

Solvit, et extenso laxavit stamina velo."

"Her white breasts shine through the Sidonian fabric, which pressed down with the

comb (or sley) of the Seres, the needle of the Nile workman has separated, and has loosened the

warp by stretching out (or withdrawing) the weft."

{26}

CHAPTER III.

LACE.

"Je demandai de la dentelle:

Voici le tulle de Bruxelles,

La blonde, le point d'Alençon,

Et la Maline, si légère;

L'application d'Angleterre

(Qui se fait à Paris, dit-on);

Voici la guipure indigène,

Et voici la Valenciennes,

Le point d'esprit, et le point de Paris;

Bref les dentelles

Les plus nouvelles

Que produisent tous les pays."

Le Palais des Dentelles (Rothomago).

Lace[77] is defined as a plain or ornamental

network, wrought of fine threads of gold, silver, silk, flax, or cotton, interwoven, to which may

be added "poil de chèvre," and also the fibre of the aloe, employed by the peasants of Italy and

Spain. The term lacez rendered in the English translation of the Statutes[78] as "laces," implying braids, such as were used for uniting the

different parts of the dress, appears long before lace, properly so called, came into use. The

earlier laces, such as they were, were defined by the word "passament"[79]—a general term for gimps and braids, as well as for lace.

Modern industry has separated these two classes of work, but their being formerly so confounded

renders it difficult in historic researches to separate one from the other.

The same confusion occurs in France, where the first lace was called passement, because

it was applied to the same {27}use, to braid or lay flat

over the coats and other garments. The lace trade was entirely in the hands of the "passementiers"

of Paris, who were allowed to make all sorts of "passements de dentelle sur l'oreiller aux

fuseaux, aux épingles, et à la main, d'or, d'argent, tant fin que faux, de soye, de fil blanc, et

de couleur," etc. They therefore applied the same terms to their different products, whatever the

material.

The word passement continued to be in use till the middle of the seventeenth century, it

being specified as "passements aux fuseaux," "passements à l'aiguille"; only it was more

specifically applied to lace without an edge.

The term dentelle is also of modern date, nor will it be found in the earlier French

dictionaries.[80] It was not till fashion caused the

passament to be made with a toothed edge that the expression of "passement dentelé" first

appears.

In the accounts of Henry II. of France, and his queen, we have frequent notices of "passement

jaulne dantellé des deux costez,"[81] "passement de

soye incarnat dentellé d'un costé,"[82] etc., etc.,

but no mention of the word "dentelle." It does, however, occur in an inventory of an earlier date,

that of Marguerite de France, sister of Francis I., who, in 1545, paid the sum of VI. livres "pour soixante aulnes, fine dantelle de Florance pour mettre à

des colletz."[83]

After a lapse of twenty years and more, among the articles furnished to Mary Stuart in 1567, is

"Une pacque de petite dentelle";[84] and this is the

sole mention of the word in all her accounts.

{28}

We find like entries in the accounts of Henry IV.'s first queen.[85]

Gradually the passement dentelé subsided into the modern dentelle.

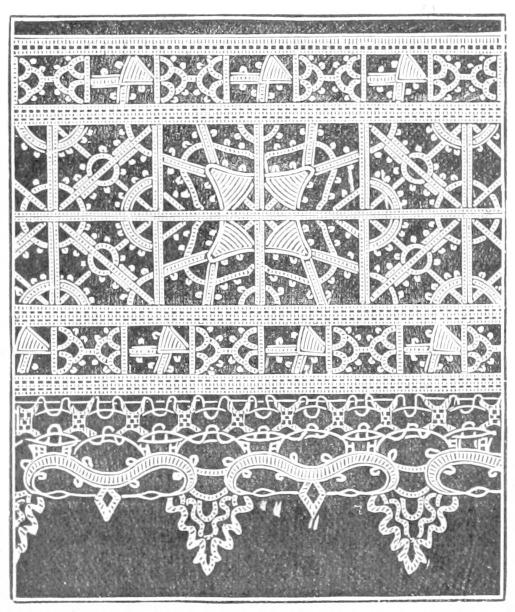

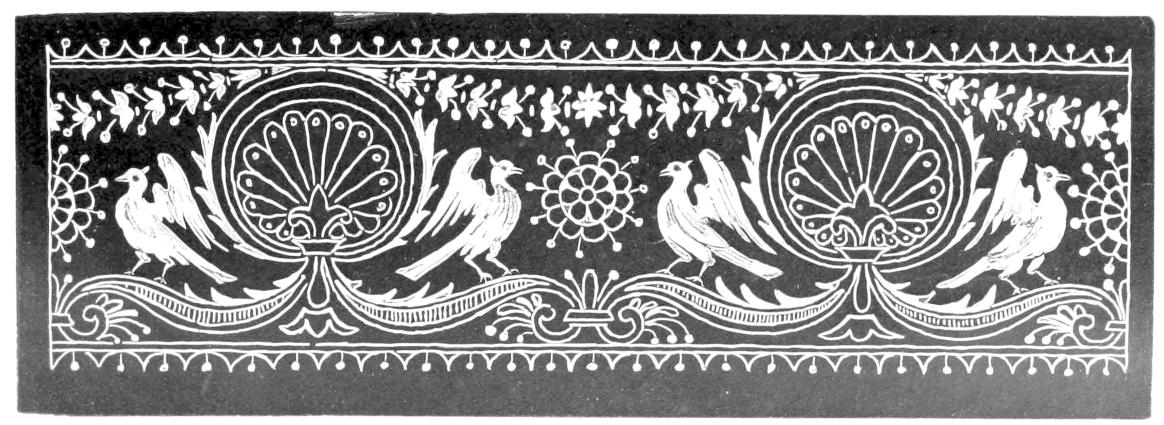

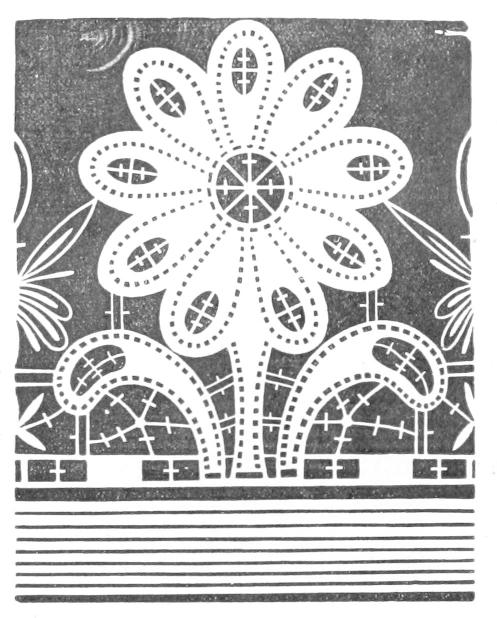

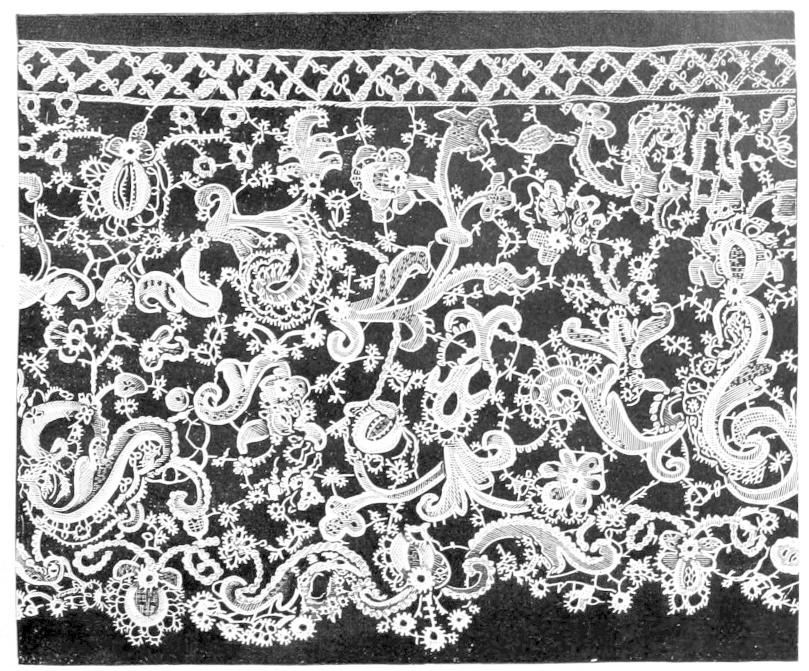

Fig. 8.

Grande Dantelle au point devant

l'Aiguille.—(Montbéliard, 1598.)

It is in a pattern book, published at Montbéliard in 1598,[86] we first find designs for "dantelles." It contains {29}twenty patterns, of all sizes, "bien petites, petites"

(Figs. 9, 10, 11, 12), "moyennes, et grosses" (Fig. 8).

| Fig. 9. |

Fig. 10. |

|

|

|

|

|

The word dentelle seems now in general use; but Vecellio, in his Corona, 1592,

has "opere a mazette," pillow lace, and Mignerak first gives the novelty of "passements au

fuzeau," pillow lace (Fig. 13), for which Vinciolo, in his edition of 1623, also furnishes

patterns (Figs. 14 and 15); and Parasoli, 1616, gives designs for "merli a piombini" (Fig.

16).

| Fig. 11. |

Fig. 12. |

|

|

|

|

|

In the inventory of Henrietta Maria, dated 1619,[87] appear a variety of laces, all qualified under the name of

"passement"; and in that of the Maréchal La Motte, 1627, we find the term applied to every

description of lace.

{30}

"Item, quatre paires de manchettes garnyes de passement, tant de Venise, Gennes, et de

Malines."[88]

Lace consists of two parts, the ground and the pattern.

The plain ground is styled in French entoilage, on account of its containing the flower

or ornament, which is called toilé, from the flat close texture resembling linen, and also

from its being often made of that material or of muslin.

| Fig. 13. |

Fig. 14. |

|

|

Passement au Fuseau.—(Mignerak, 1605.)

|

Passement au Fuseau.—(Vinciolo,

Edition 1623.)

|

The honeycomb network or ground, in French fond, champ,[89] réseau, treille, is of various kinds: wire ground,

Brussels ground, trolly ground, etc., fond clair, fond double, etc.

{31}

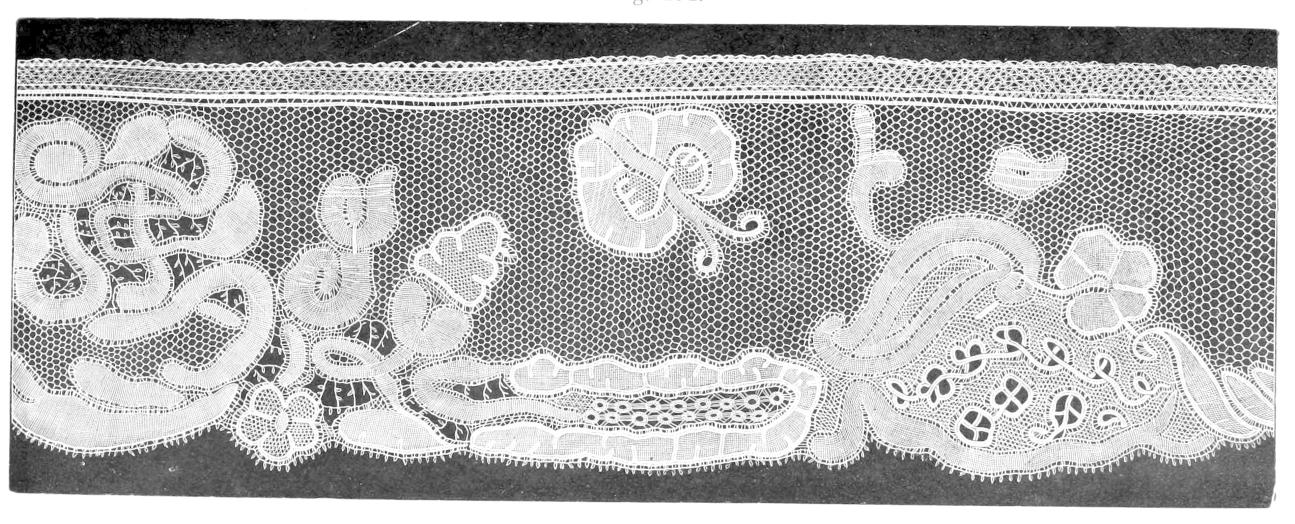

Some laces, points and guipures are not worked upon a ground; the flowers are connected by

irregular threads overcast (buttonhole stitch), and sometimes worked over with pearl loops

(picot). Such are the points of Venice and Spain and most of the guipures. To these uniting

threads, called by our lace-makers "pearl ties"—old Randle Holme[90] styles them "coxcombs"—the Italians give the name of

"legs," the French that of "brides."[91]

| Fig. 15. |

Fig. 16. |

|

|

Passement au Fuseau.—(Vinciolo,

Edition 1623.)

|

Merletti a Piombini.—(Parasole, 1616.)

|

The flower, or ornamental pattern, is either made together with the ground, as in Valenciennes

or Mechlin, or separately, and then either worked in or sewn on (appliqué), as in Brussels.

The open-work stitches introduced into the pattern are called modes, jours; by

our Devonshire workers, "fillings."

All lace is terminated by two edges, the pearl, picot,[92] or couronne—a row of little points at equal distances, and

the footing or engrêlure—a narrow lace, which serves to keep the stitches of the

ground firm, and to sew the lace to the garment upon which it is to be worn.

{32}

Lace is divided into point and pillow (or more correctly bobbin) lace. The term pillow gives

rise to misconceptions, as it is impossible to define the distinction between the "cushion" used

for some needle-laces and the "pillow" of bobbin-lace. The first is made by the needle on a

parchment pattern, and termed needle-point, point à l'aiguille, punto in aco.

The word is sometimes incorrectly applied to pillow-lace, as point de Malines, point de

Valenciennes, etc.

Point also means a particular kind of stitch, as point de Paris,[93] point de neige, point d'esprit,[94] point à la Reine, point à carreaux, à chaînette, etc.

"Cet homme est bien en points," was a term used to denote a person who wore rich laces.[95]

The mention of point de neige recalls the quarrel of Gros René and Marinette, in the Dépit

Amoureux[96] of Molière:—

"Ton beau galant de neige,[97] avec ta nonpareille,

Il n'aura plus l'honneur d'être sur mon oreille."

Gros René evidently returns to his mistress his point de neige nightcap.

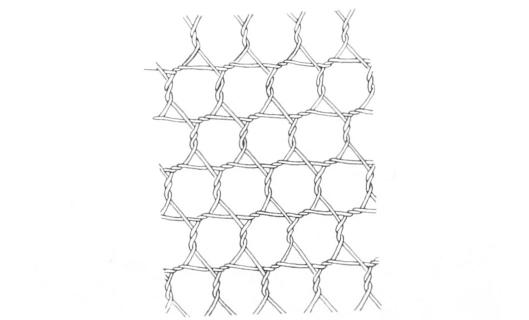

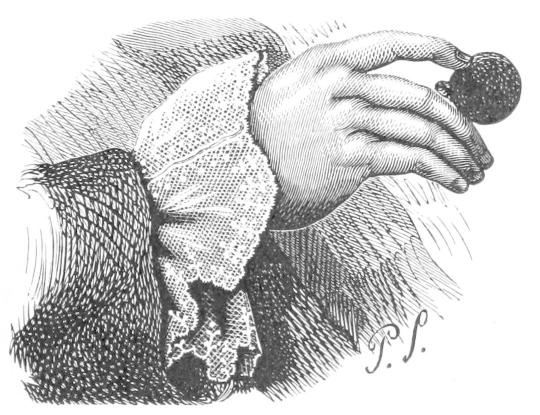

The manner of making bobbin lace on a pillow[98]

need hardly be described. The "pillow"[99] is a round

or oval board, stuffed so as to form a cushion, and placed upon the knees of the workwoman. On

this pillow a stiff piece of parchment is fixed, with small holes pricked through to mark the

pattern. Through these holes pins are stuck into the cushion. The threads with which the lace is

formed are wound upon "bobbins," formerly bones,[100] now small round pieces of wood, about the size of a pencil,

having round their upper ends a deep groove, so formed as to reduce the bobbin to a thin neck, on

which the thread is wound, a separate bobbin being used for each thread.

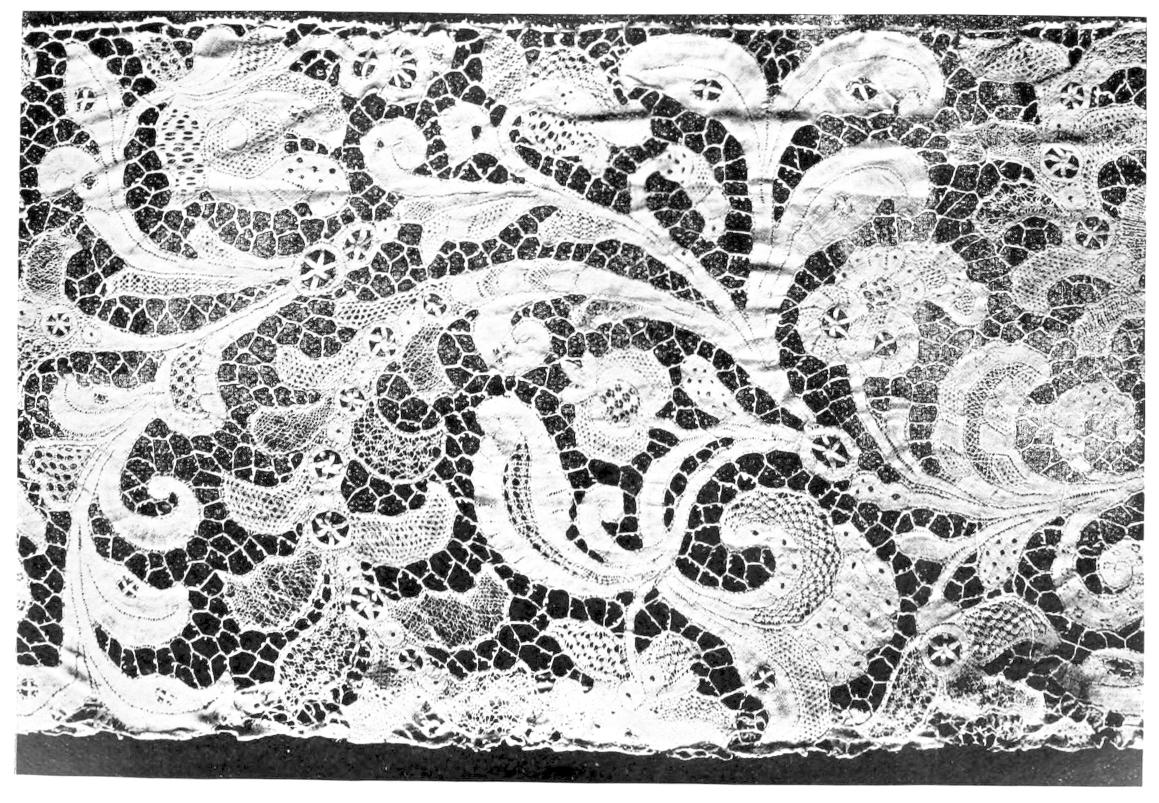

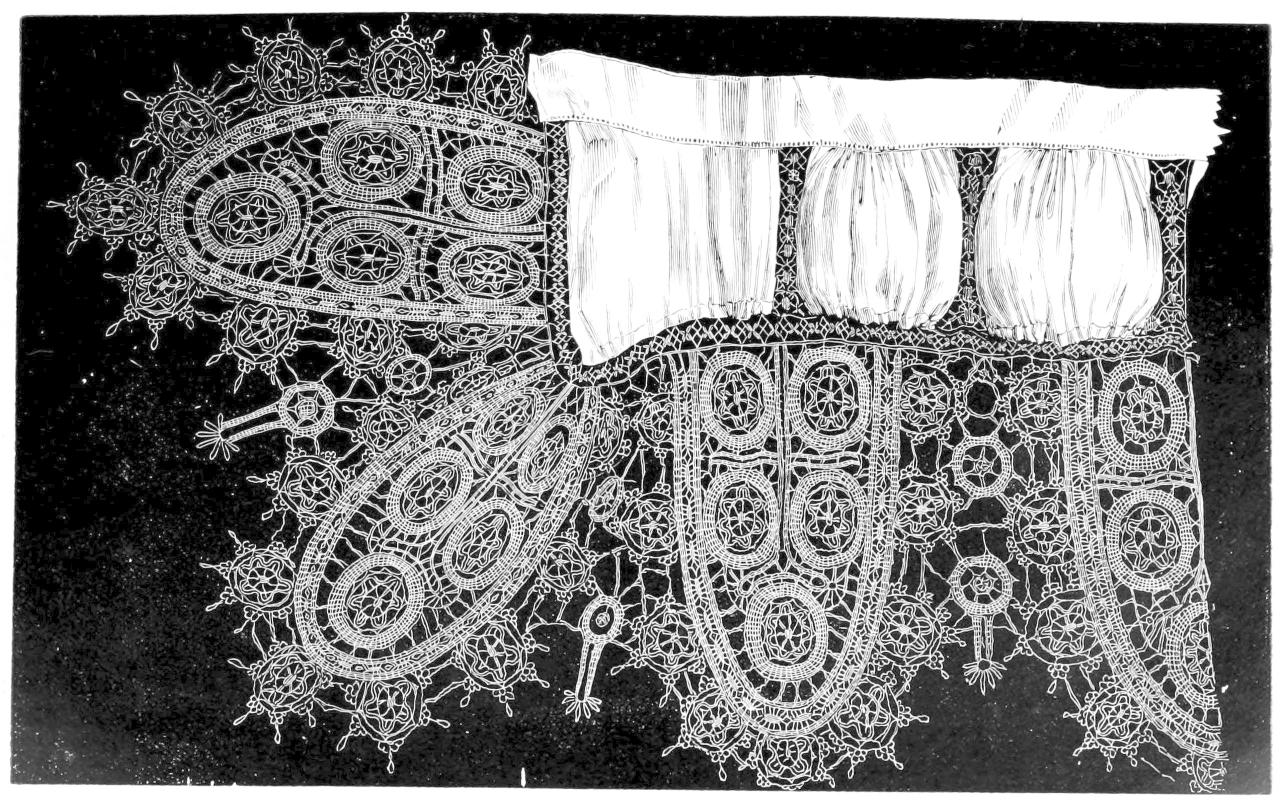

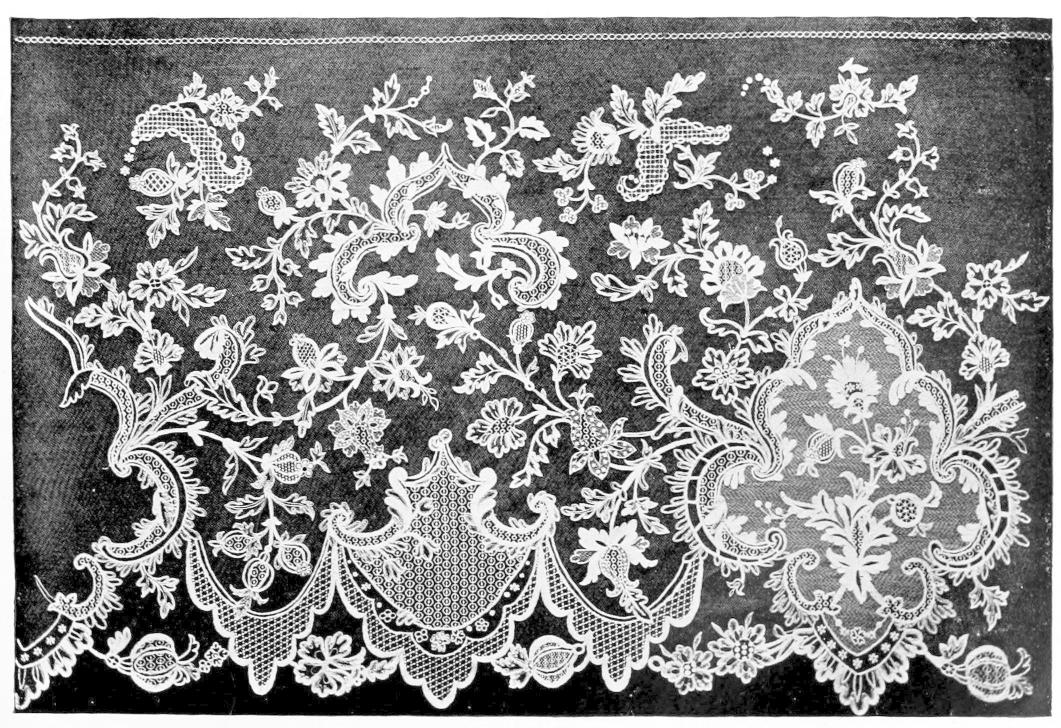

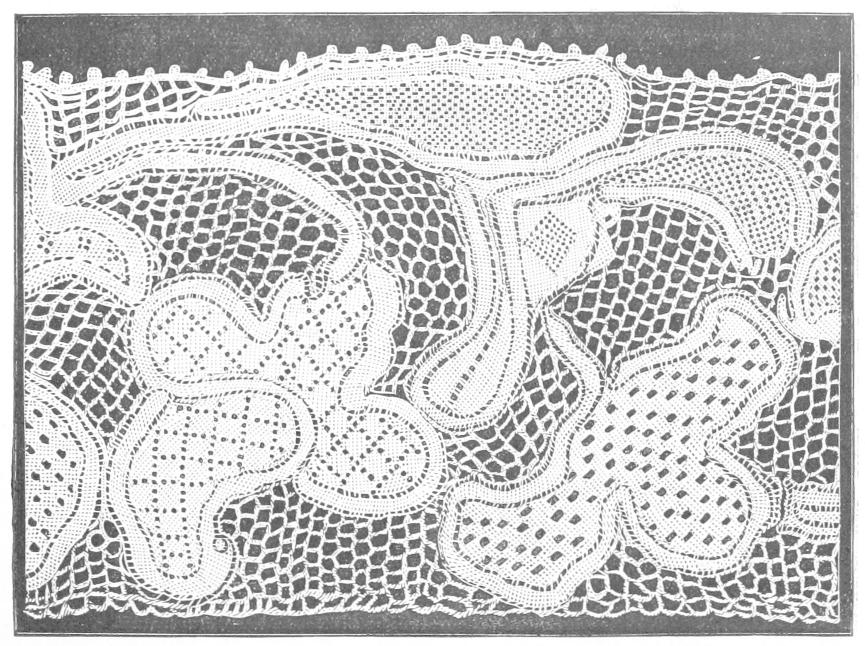

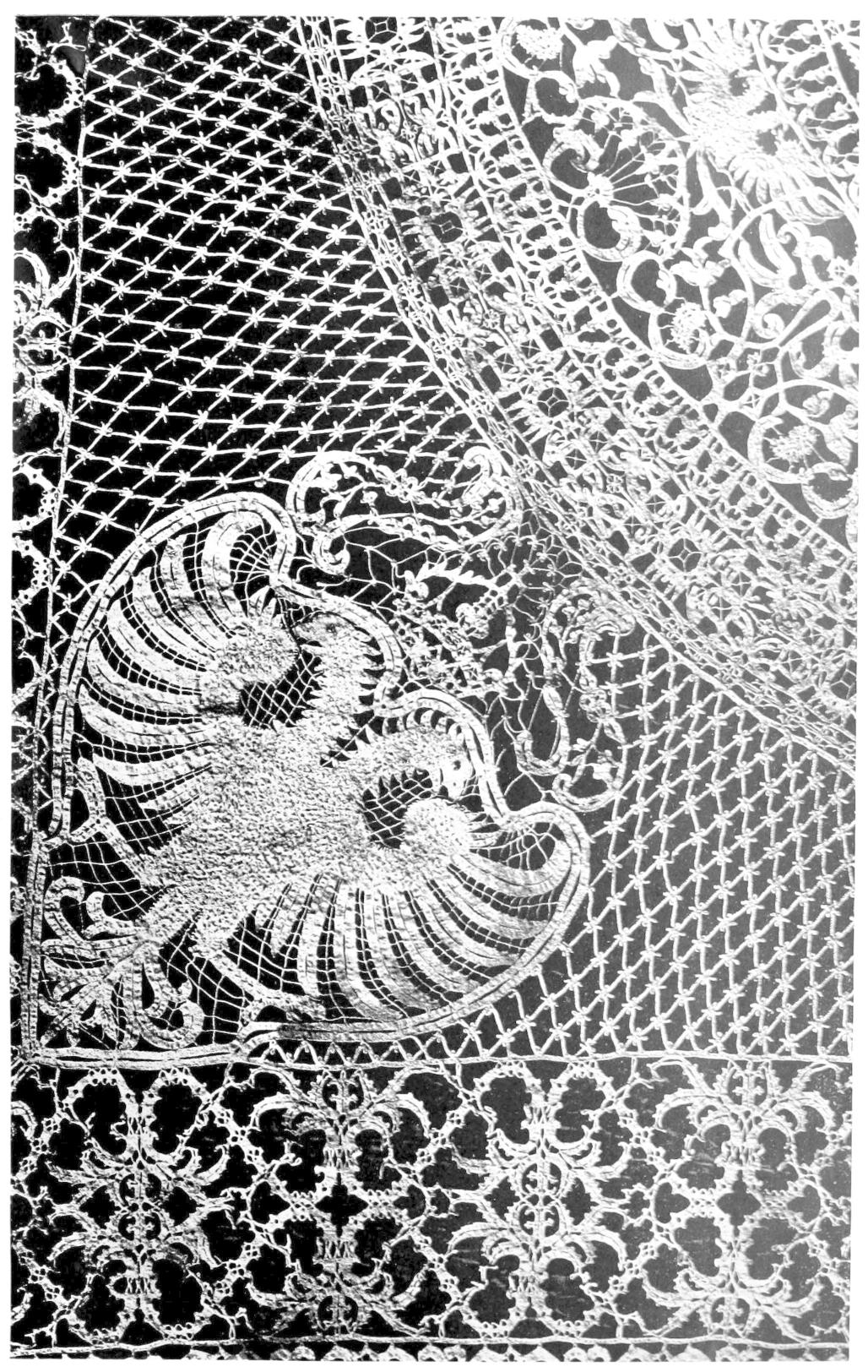

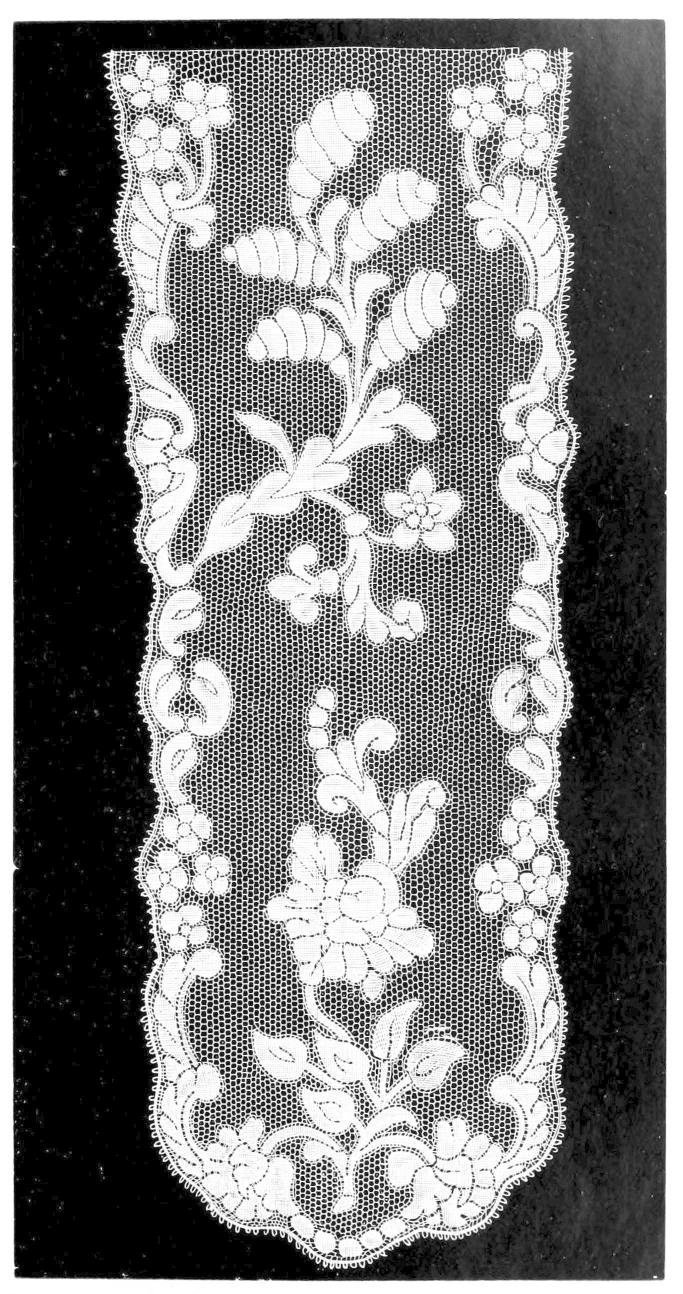

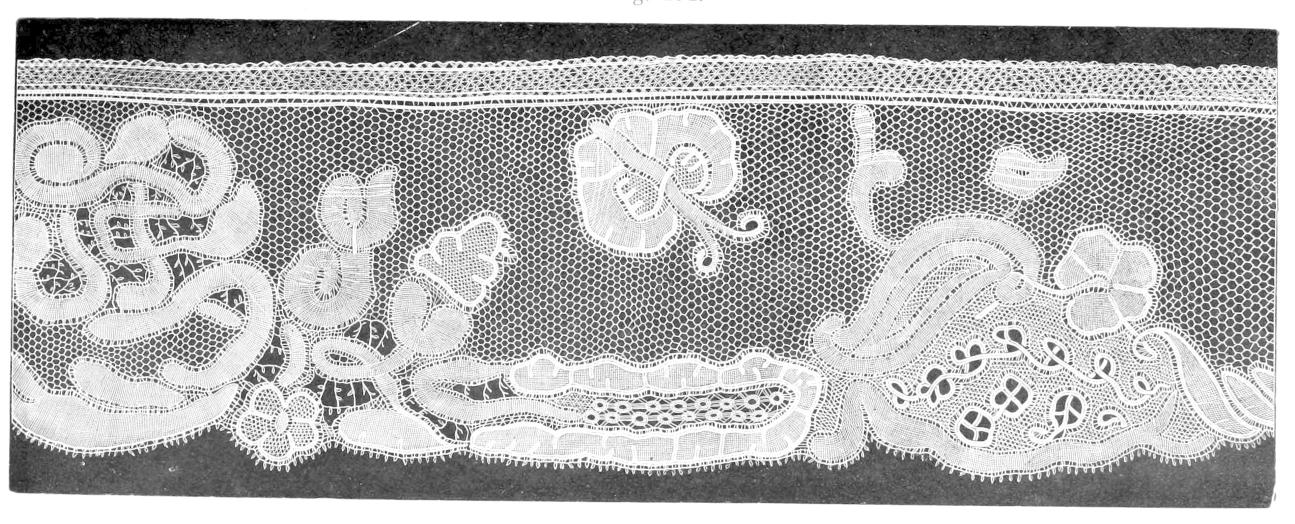

Plate VI.

Italian.—Modern reproduction at Burano of Point de Venise à

la feuille et la rose, of seventeenth century.

Width, 8 in. Photo by the Burano School.

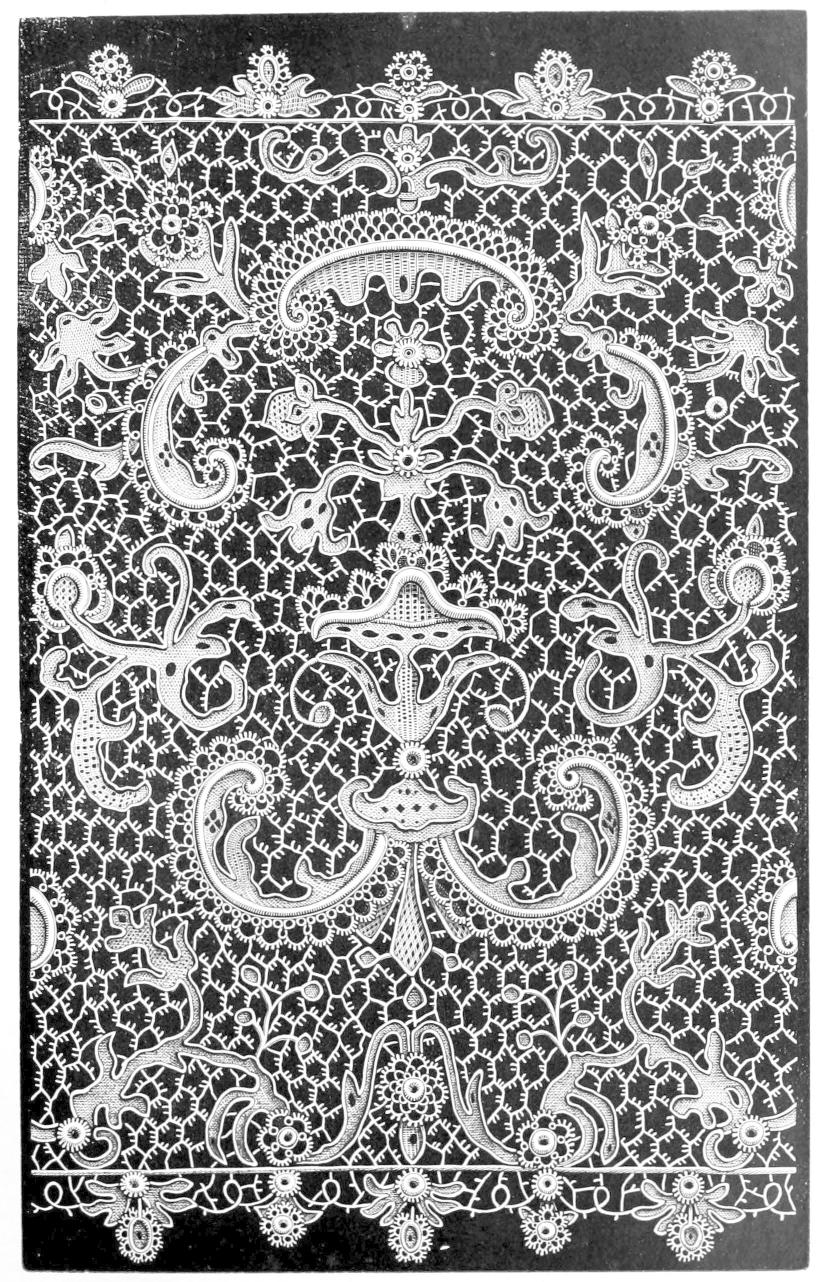

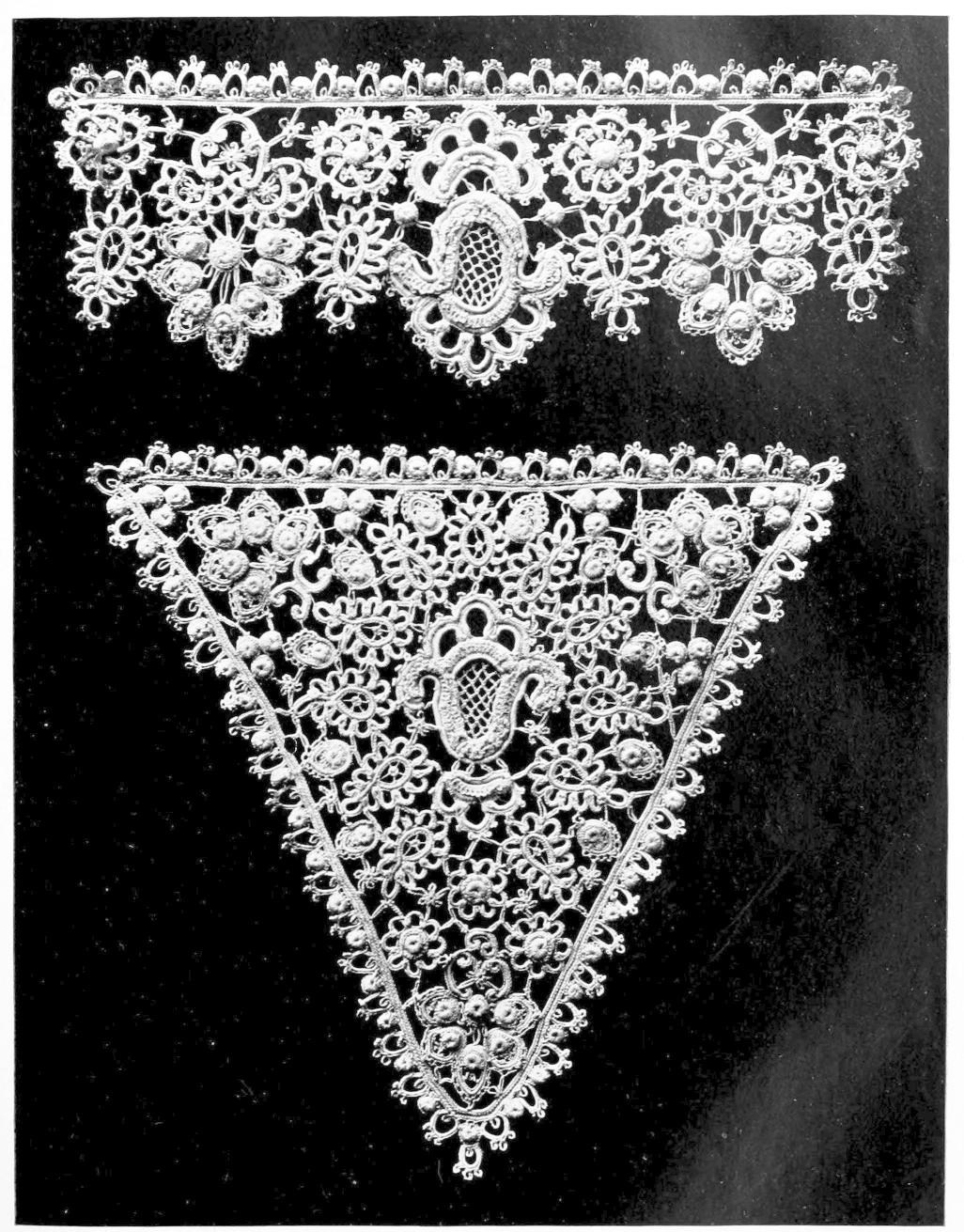

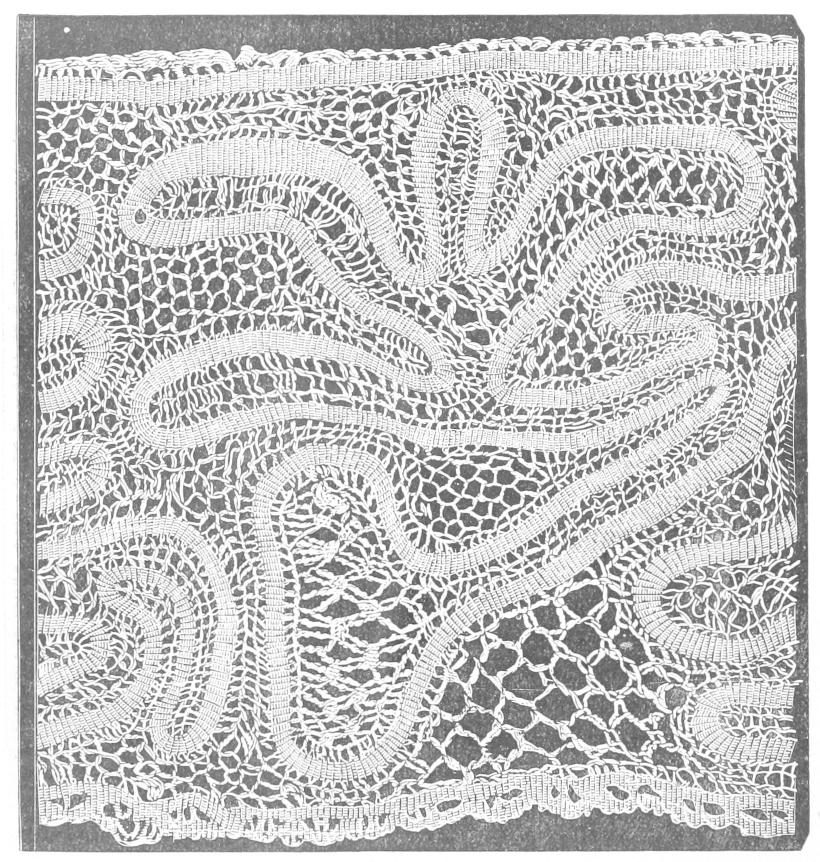

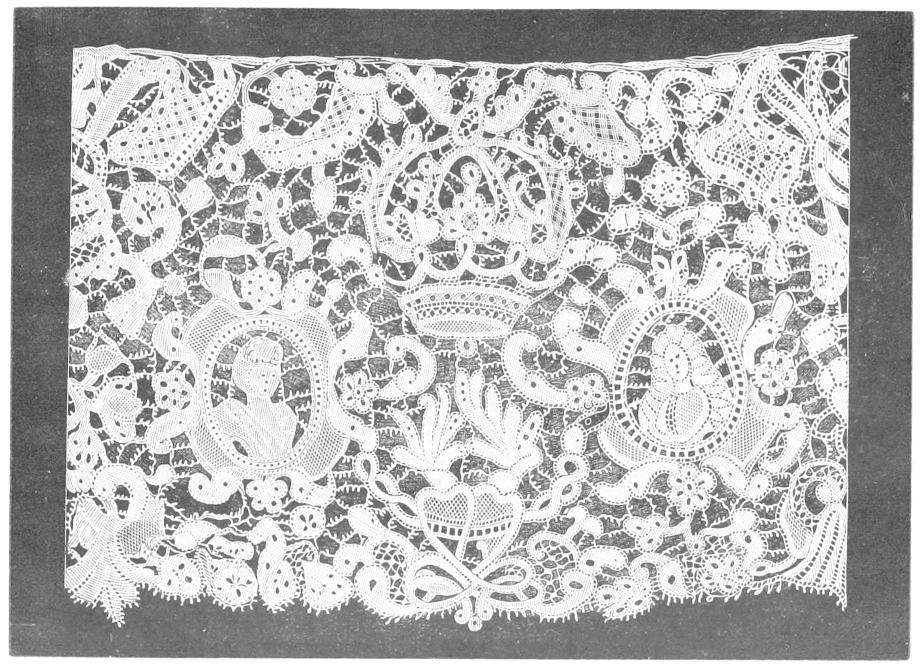

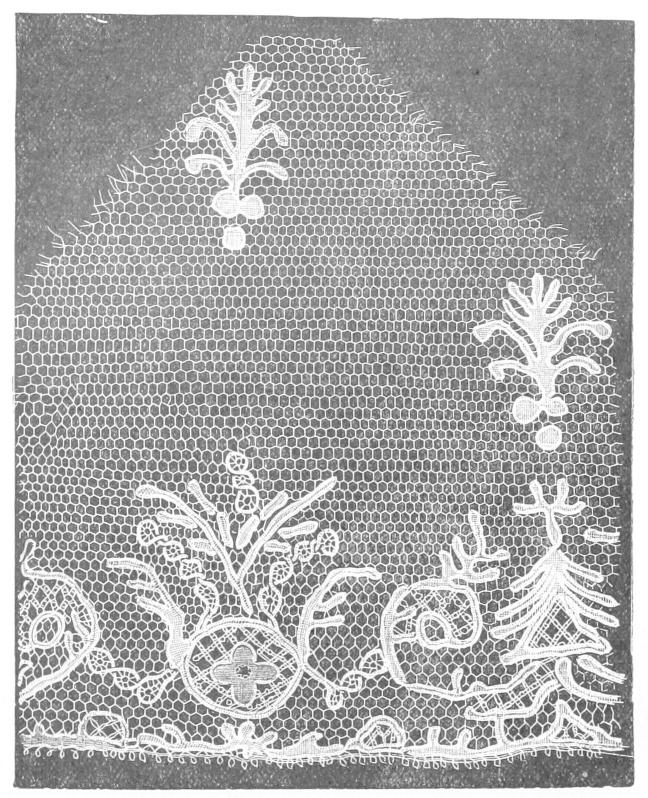

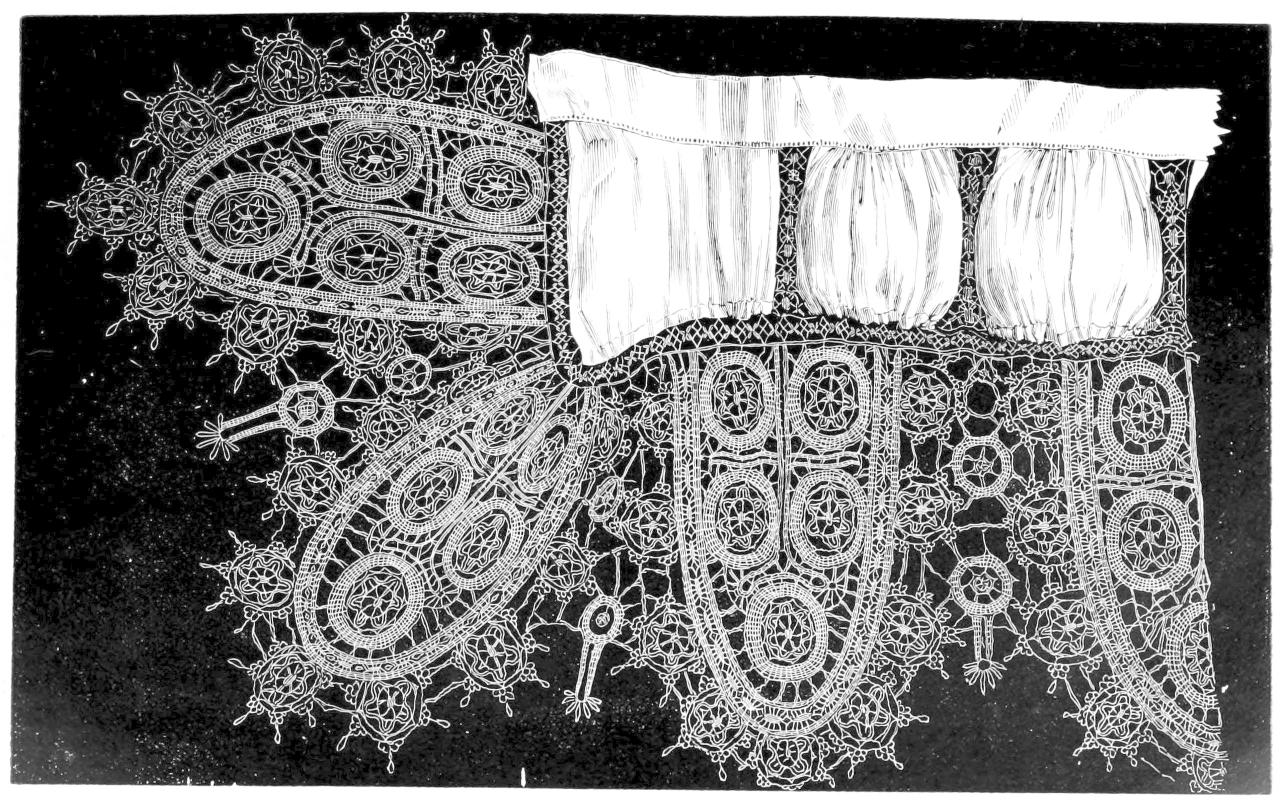

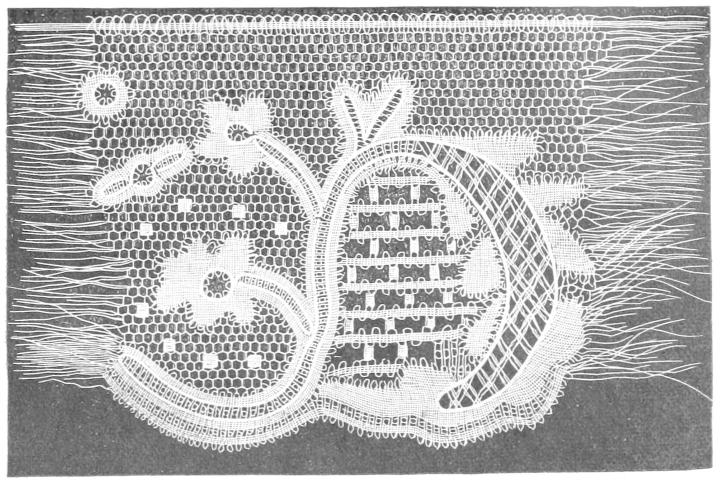

Plate VII.

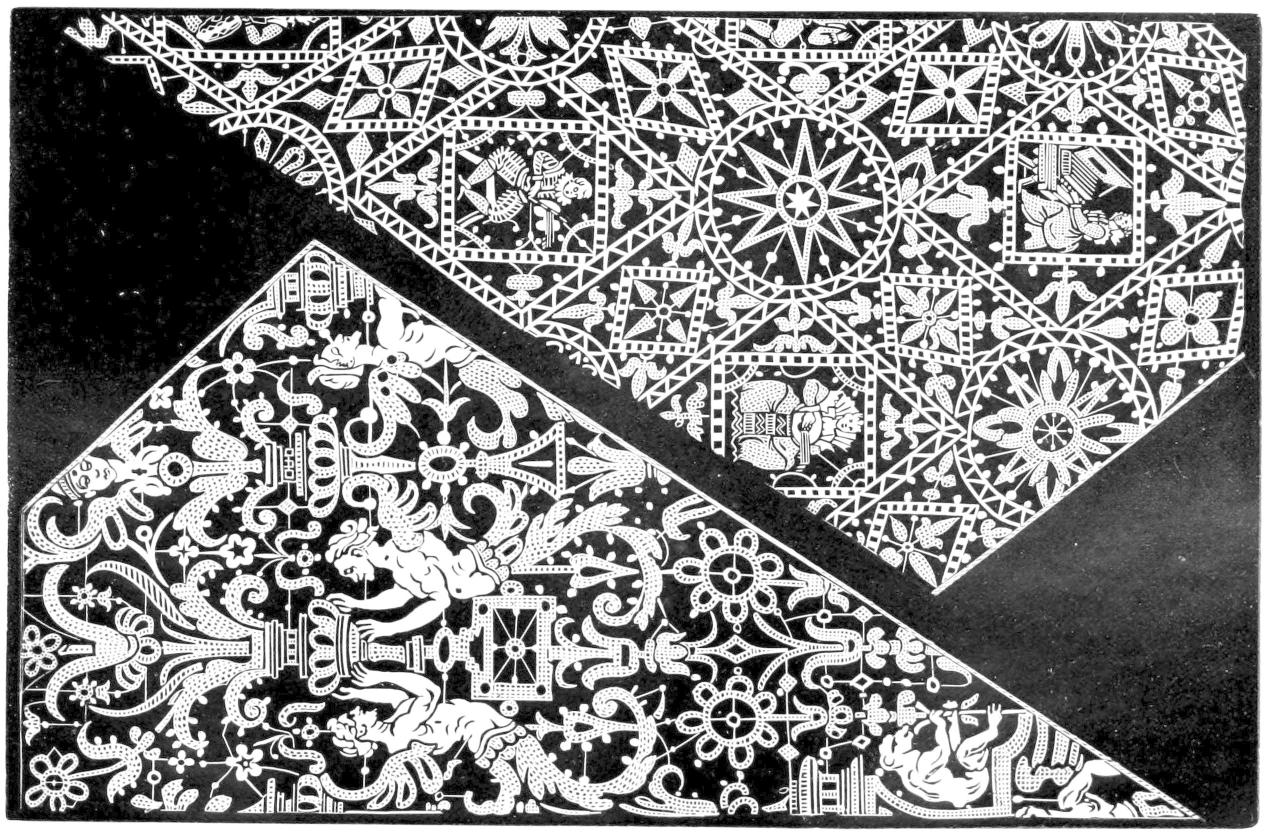

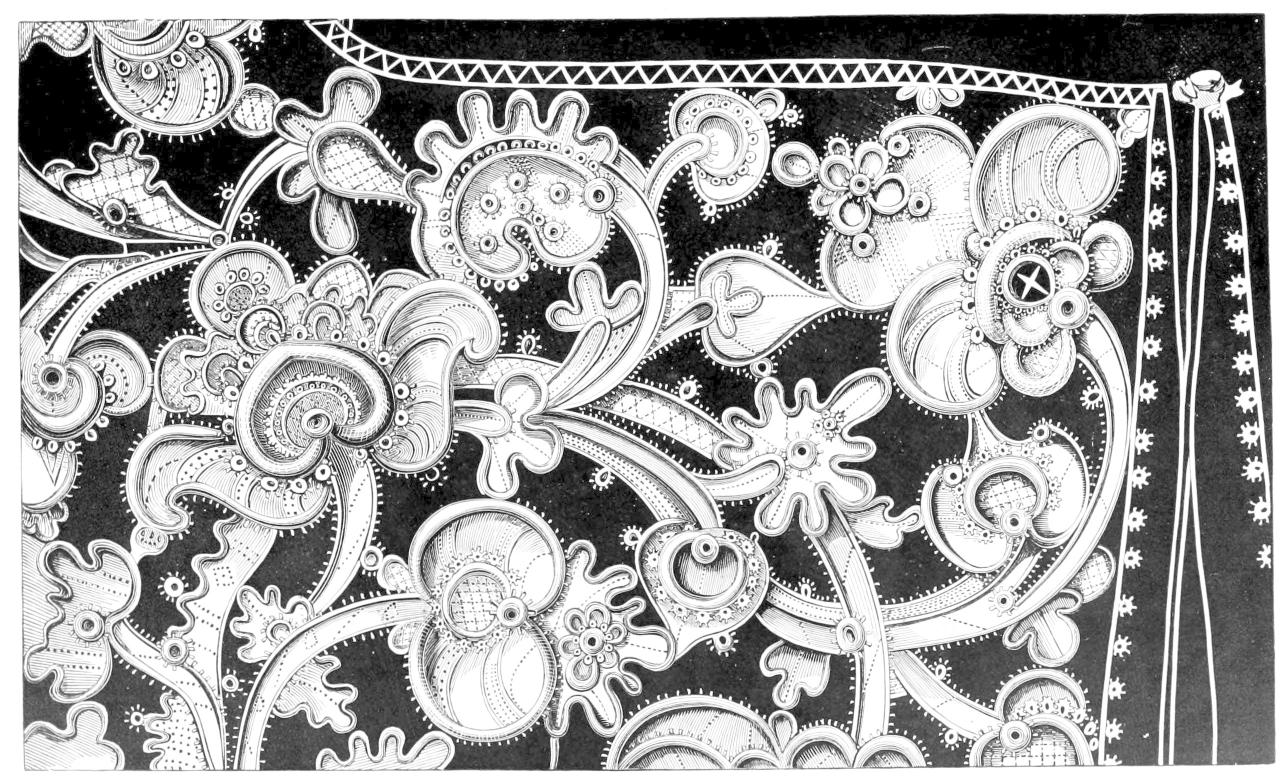

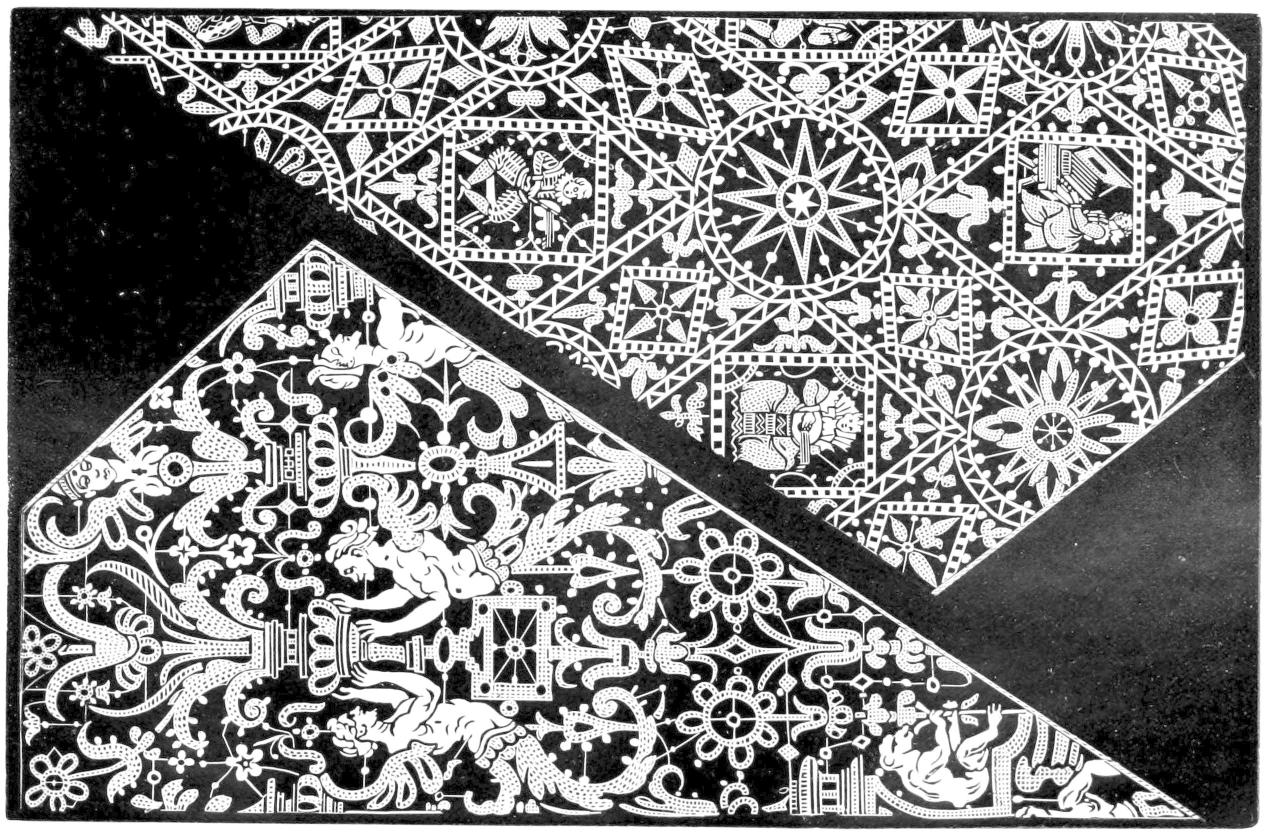

Heraldic (carnival lace), was made in Italy. This appears to be a specimen, though the

archaic pattern points to a German origin. The réseau is twisted and knotted. Circ.

1700. The Arms are those of a Bishop.

Photo by A. Dryden from private collection.

To face page 32.

{33}

By the twisting and crossing of these threads the ground of the lace is formed. The pattern or

figure, technically called "gimp," is made by interweaving a thread much thicker than that forming

the groundwork, according to the design pricked out on the parchment.[101] Such has been the pillow and the method of using it, with but

slight variation, for more than three centuries.

To avoid repetition, we propose giving a separate history of the manufacture in each country;

but in order to furnish some general notion of the relative ages of lace, it may be as well to

enumerate the kinds most in use when Colbert, by his establishment of the Points de France, in

1665, caused a general development of the lace manufacture throughout Europe.

The laces known at that period were:—

1. Point.—Principally made at Venice, Genoa, Brussels, and in Spain.

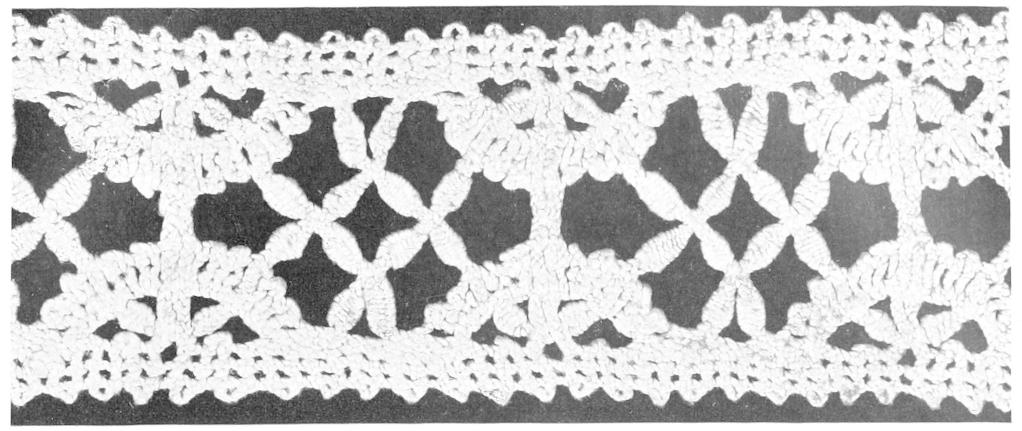

2. Bisette.—A narrow, coarse thread pillow lace of three qualities, made in the environs

of Paris[102] by the peasant women, principally for

their own use. Though proverbially of little value—"ce n'est que de la bisette"[103]—it formed an article of traffic with the

mercers and lingères of the day.

3. Gueuse.—A thread lace, which owed to its simplicity {34}the name it bore. The ground was network, the flowers a loose, thick

thread, worked in on the pillow. Gueuse was formerly an article of extensive consumption in

France, but, from the beginning of the last century, little used save by the lower classes. Many

old persons may still remember the term, "beggars' lace."

4. Campane.[104]—A white, narrow, fine,

thread pillow edging, used to sew upon other laces, either to widen them, or to replace a worn-out

picot or pearl.

Campane lace was also made of gold, and of coloured silks, for trimming mantles, scarfs, etc.

We find, in the Great Wardrobe Accounts of George I., 1714,[105] an entry of "Gold Campagne buttons."

Evelyn, in his "Fop's Dictionary," 1690, gives, "Campane, a kind of narrow, pricked lace;" and

in the "Ladies' Dictionary," 1694, it is described as "a kind of narrow lace, picked or

scalloped."[106]

In the Great Wardrobe Account of William III., 1688-9, we have "le poynt campanie tæniæ."

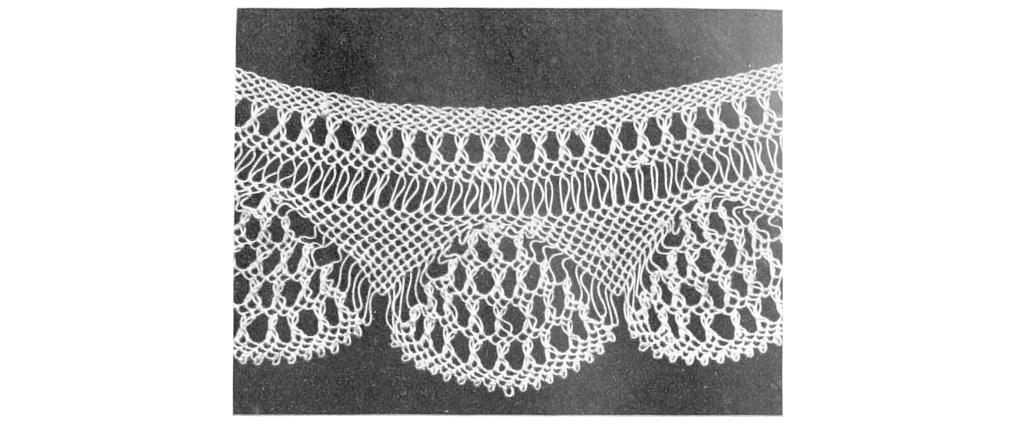

5. Mignonette.[107]—A light, fine, pillow

lace, called blonde de fil,[108] also point de

tulle, from the ground resembling that {35}fabric. It was

made of Lille thread, bleached at Antwerp, of different widths, never exceeding two to three

inches. The localities where it was manufactured were the environs of Paris, Lorraine, Auvergne,

and Normandy.[109] It was also fabricated at Lille,

Arras, and in Switzerland. This lace was article of considerable export, and at times in high

favour, from its lightness and clear ground, for headdresses[110] and other trimmings. It frequently appears in the

advertisements of the last century. In the Scottish Advertiser, 1769, we find enumerated

among the stock-in-trade, "Mennuet and blonde lace."

6. Point double, also called point de Paris and point des champs: point double, because it

required double the number of threads used in the single ground; des champs, from its being made

in the country.

7. Valenciennes.—See Chapter XV.

Fig. 17.

8. Mechlin.—All the laces of Flanders, with the exception of those of Brussels and the

point double, were known in commerce at this period under the general name of Mechlin. (Fig.

17.)

9. Gold lace.

10. Guipure.

{36}

GUIPURE.

Guipure, says Savary, is a kind of lace or passement made of "cartisane" and twisted silk.

Cartisane is a little strip of thin parchment or vellum, which was covered over with silk,

gold, or silver thread, and formed the raised pattern.

The silk twisted round a thick thread or cord was called guipure,[111] hence the whole work derived its name.[112]

Guipure was made either with the needle or on the pillow like other lace, in various patterns,

shades and colours, of different qualities and several widths.

The narrowest guipures were called "Têtes de More."[113]

The less cartisane in the guipure, the more it was esteemed, for cartisane was not durable,

being only vellum covered over with silk. It was easily affected by the damp, shrivelled, would

not wash, and the pattern was destroyed. Later, the parchment was replaced by a cotton material

called canetille.

Savary says that most of the guipures were made in the environs of Paris;[114] that formerly, he writes in 1720, great quantities were

consumed in the kingdom; but since the fashion had passed away, they were mostly exported to

Spain, Portugal, Germany, and the Spanish Indies, where they were much worn.[115]

Guipure was made of silk, gold and silver; from its costliness, therefore, it was only worn by

the rich.

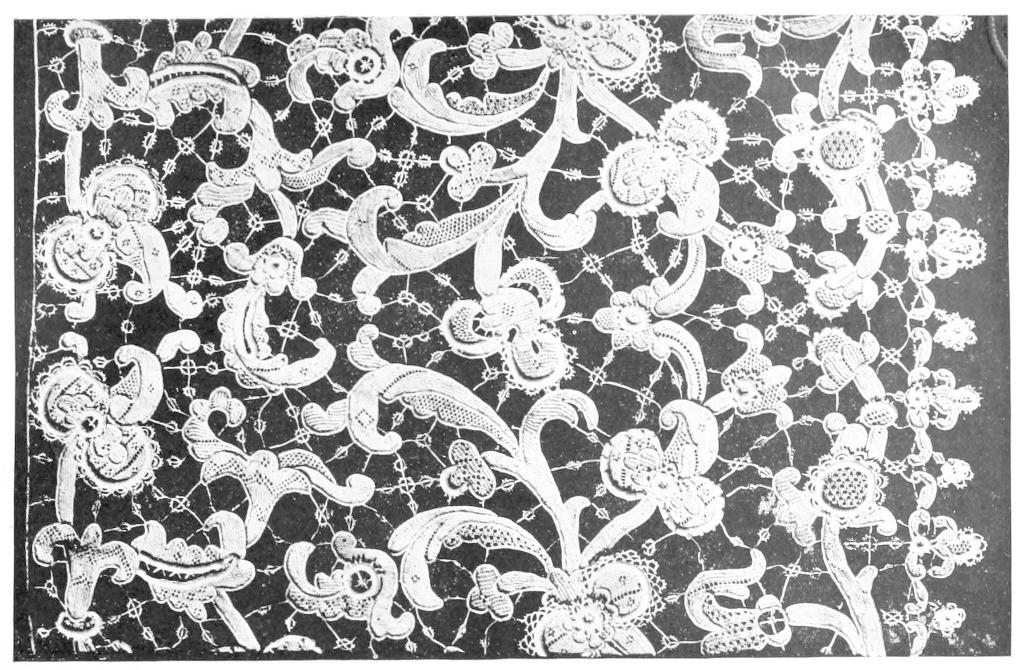

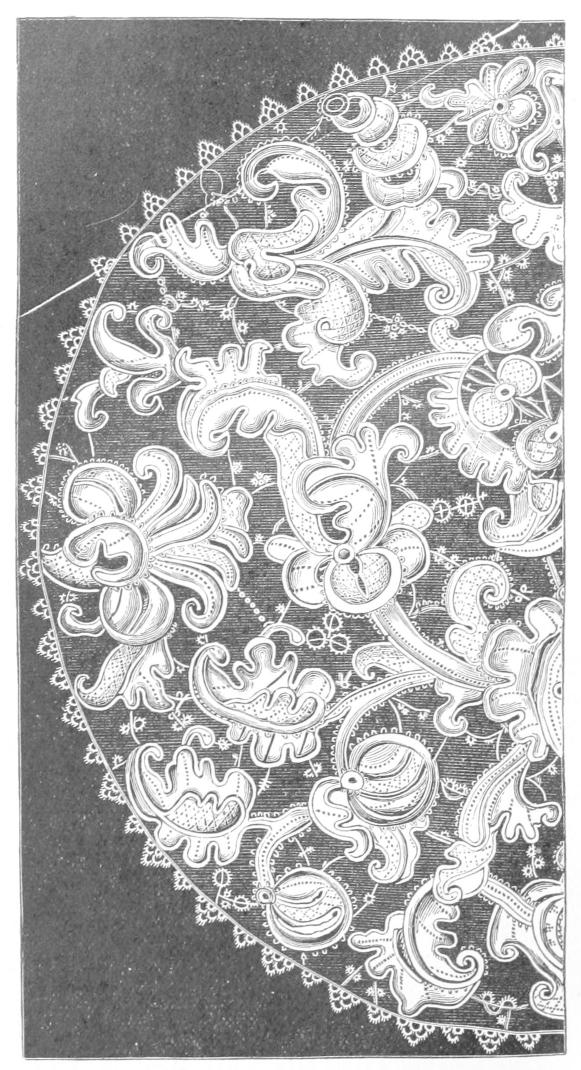

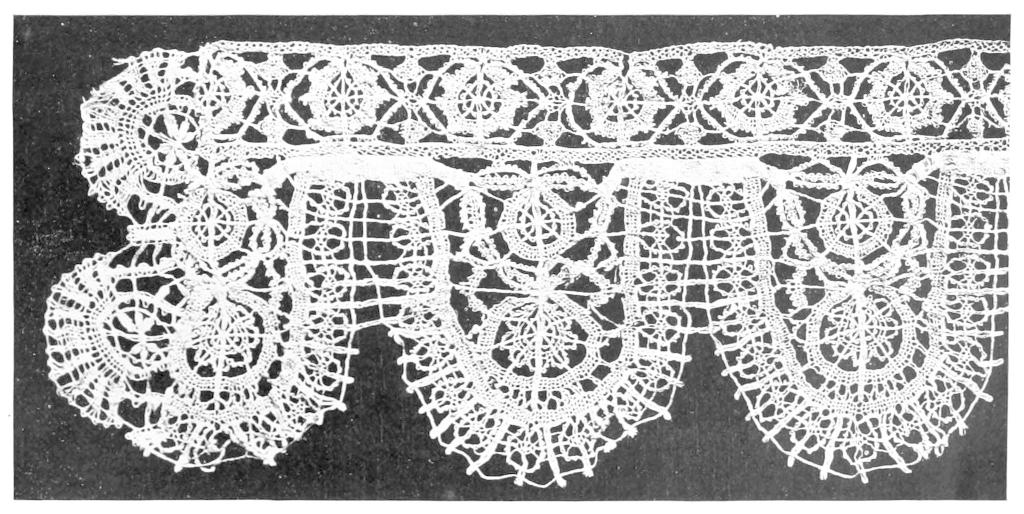

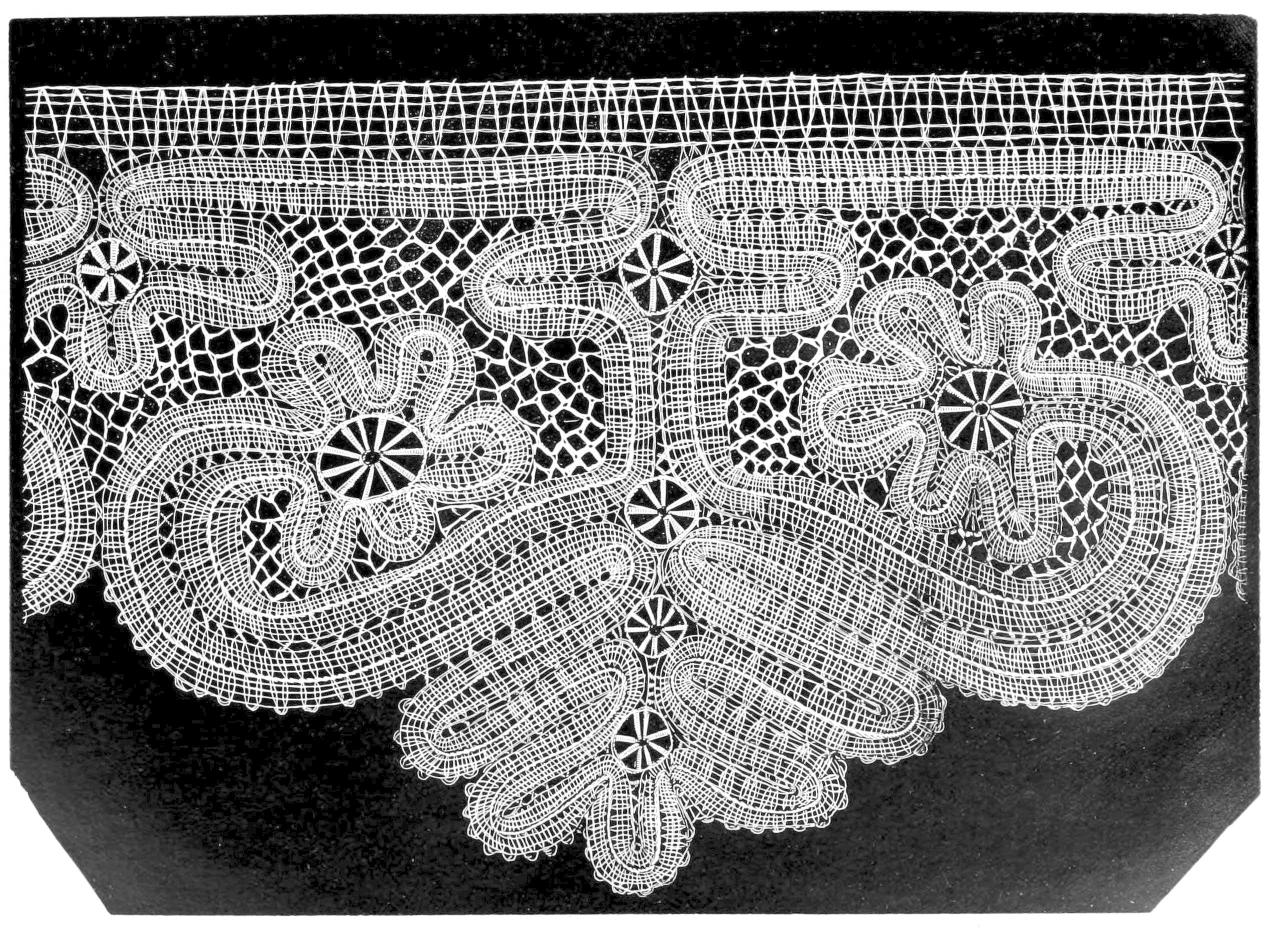

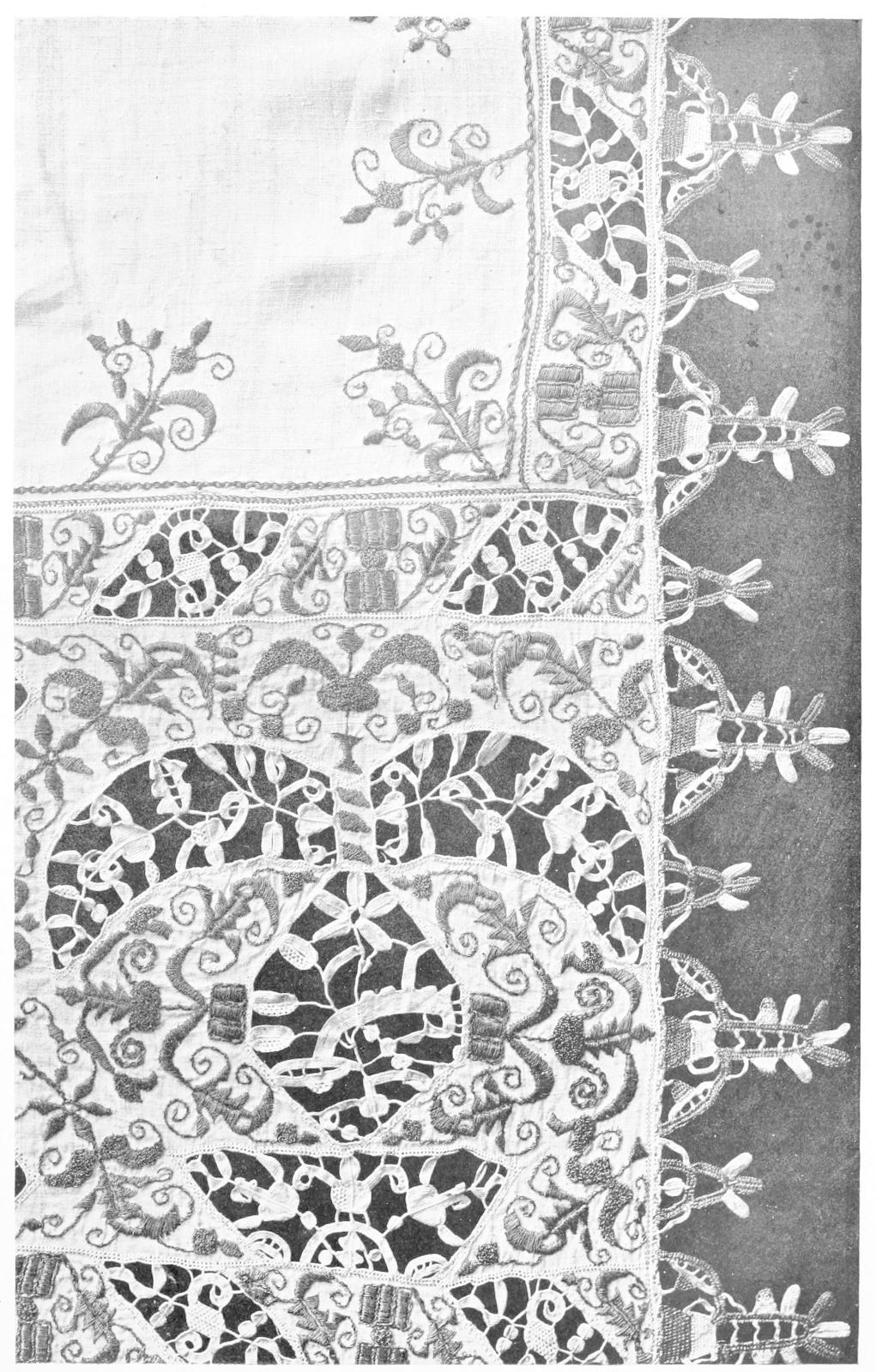

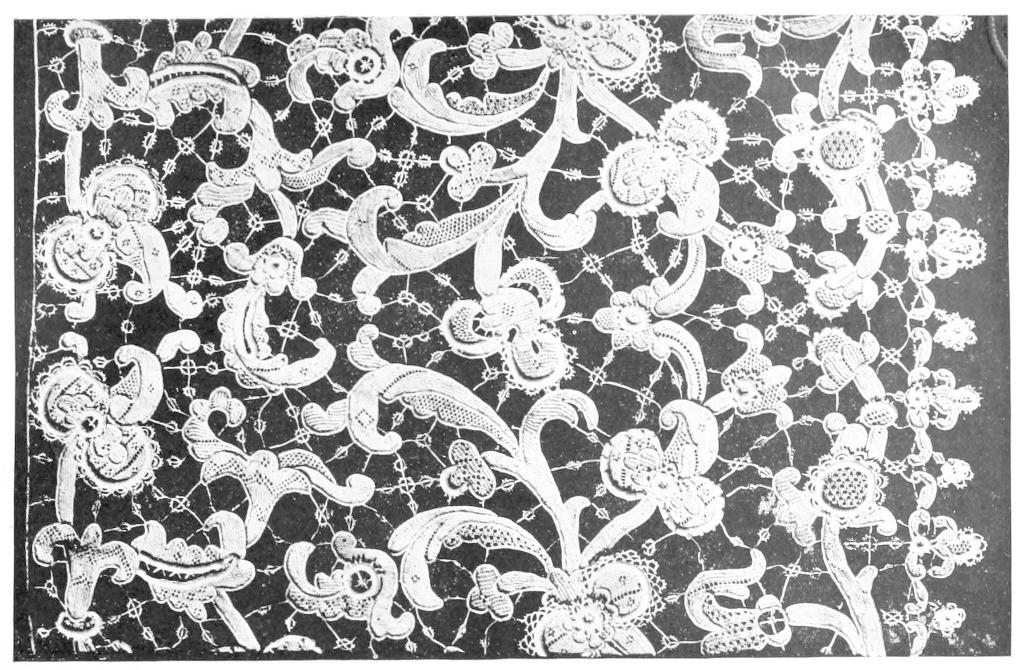

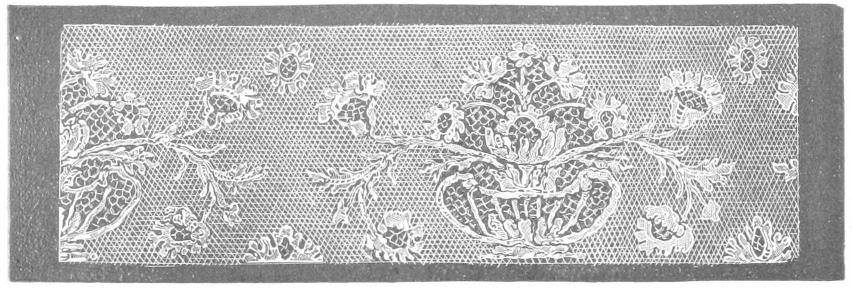

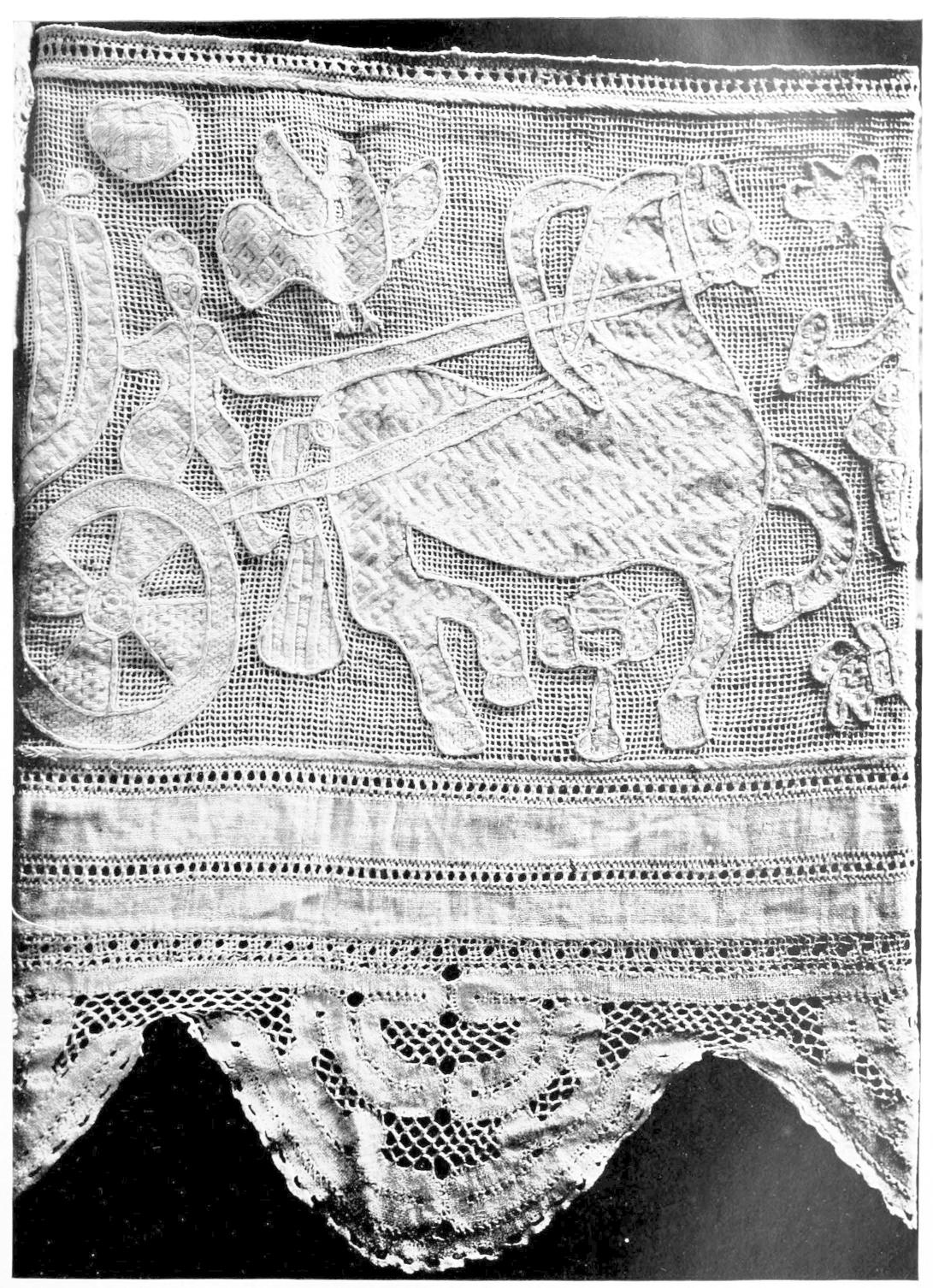

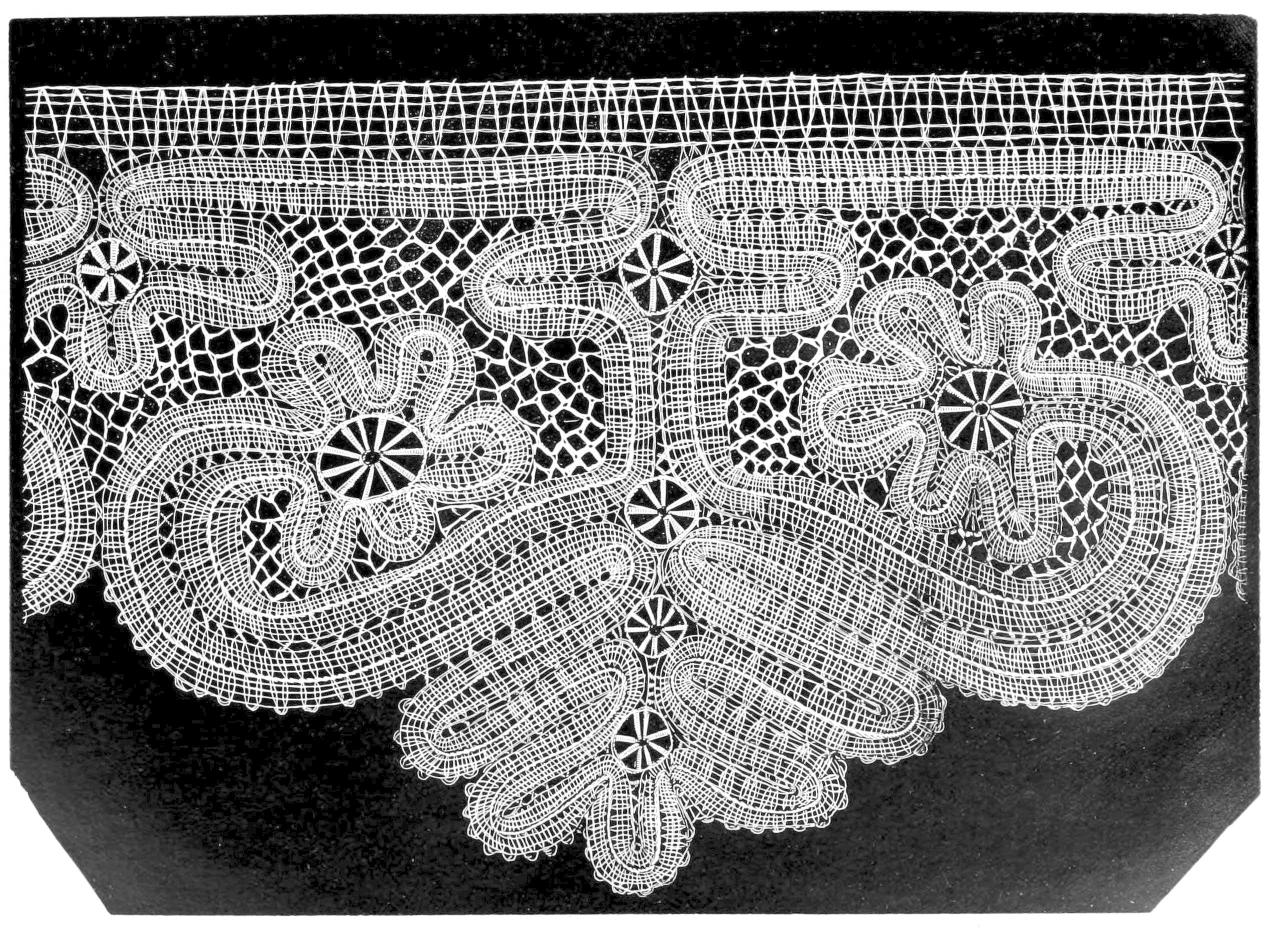

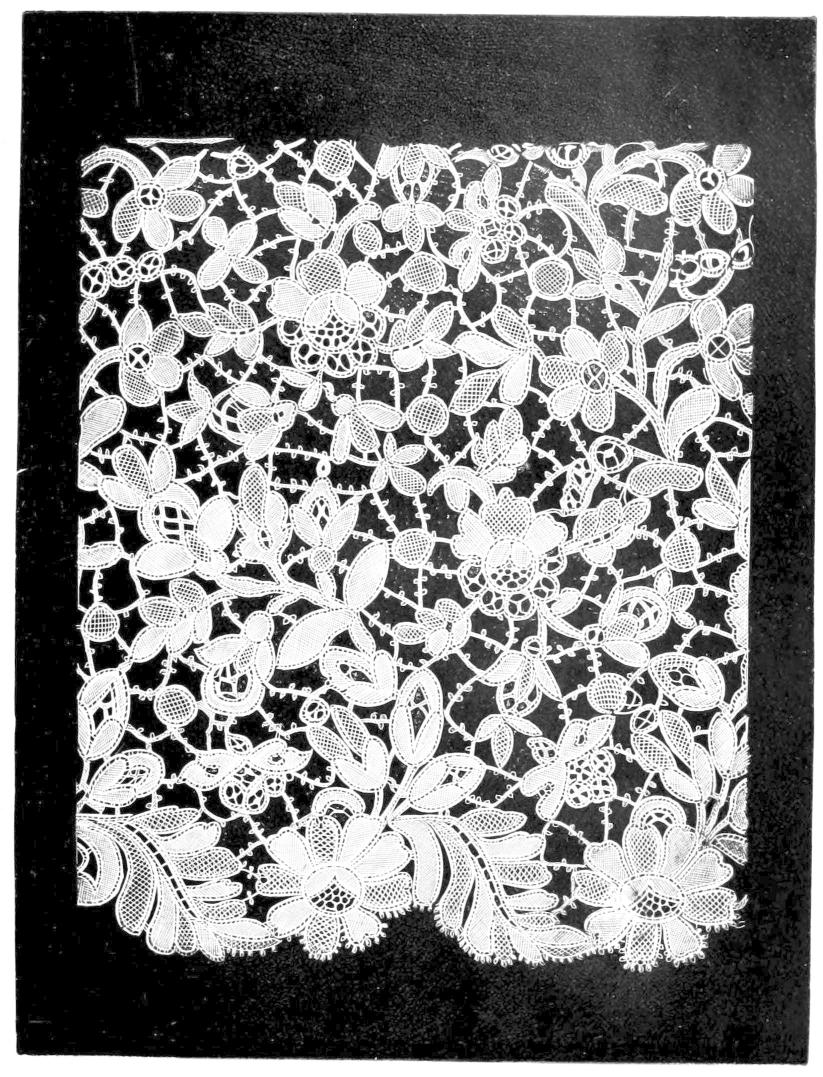

Plate VIII.

Italian, Venetian, Flat Needle-point Lace. "Punto

in Aria."—The design is held together by plain "brides." Date, circ. 1645.

Width, 11⅝ in.

Victoria and Albert Museum.

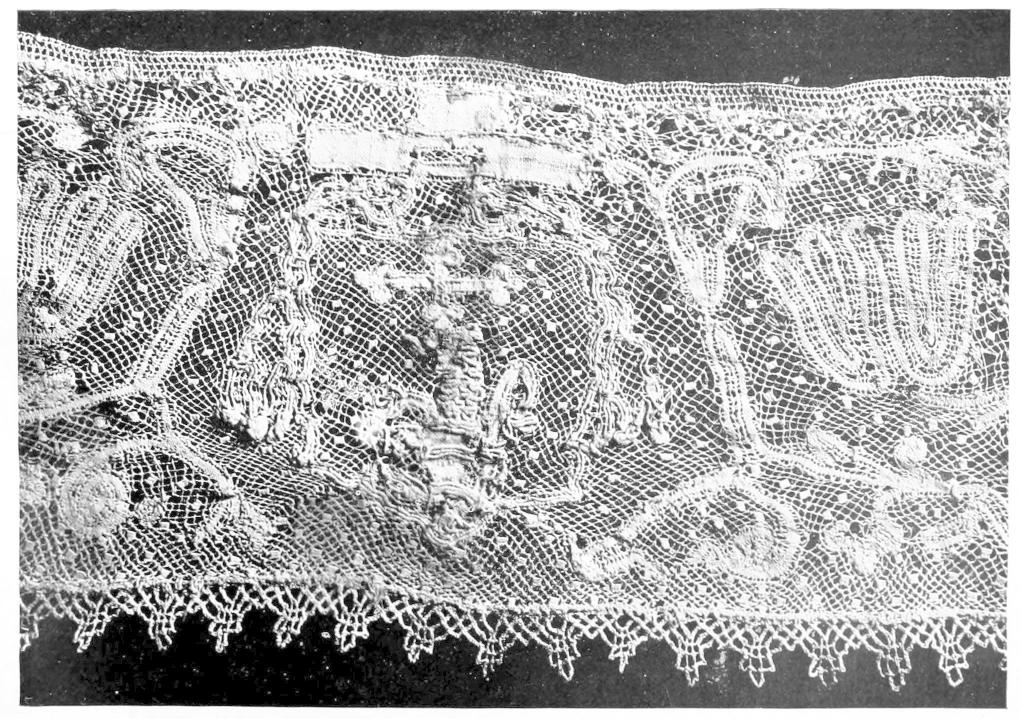

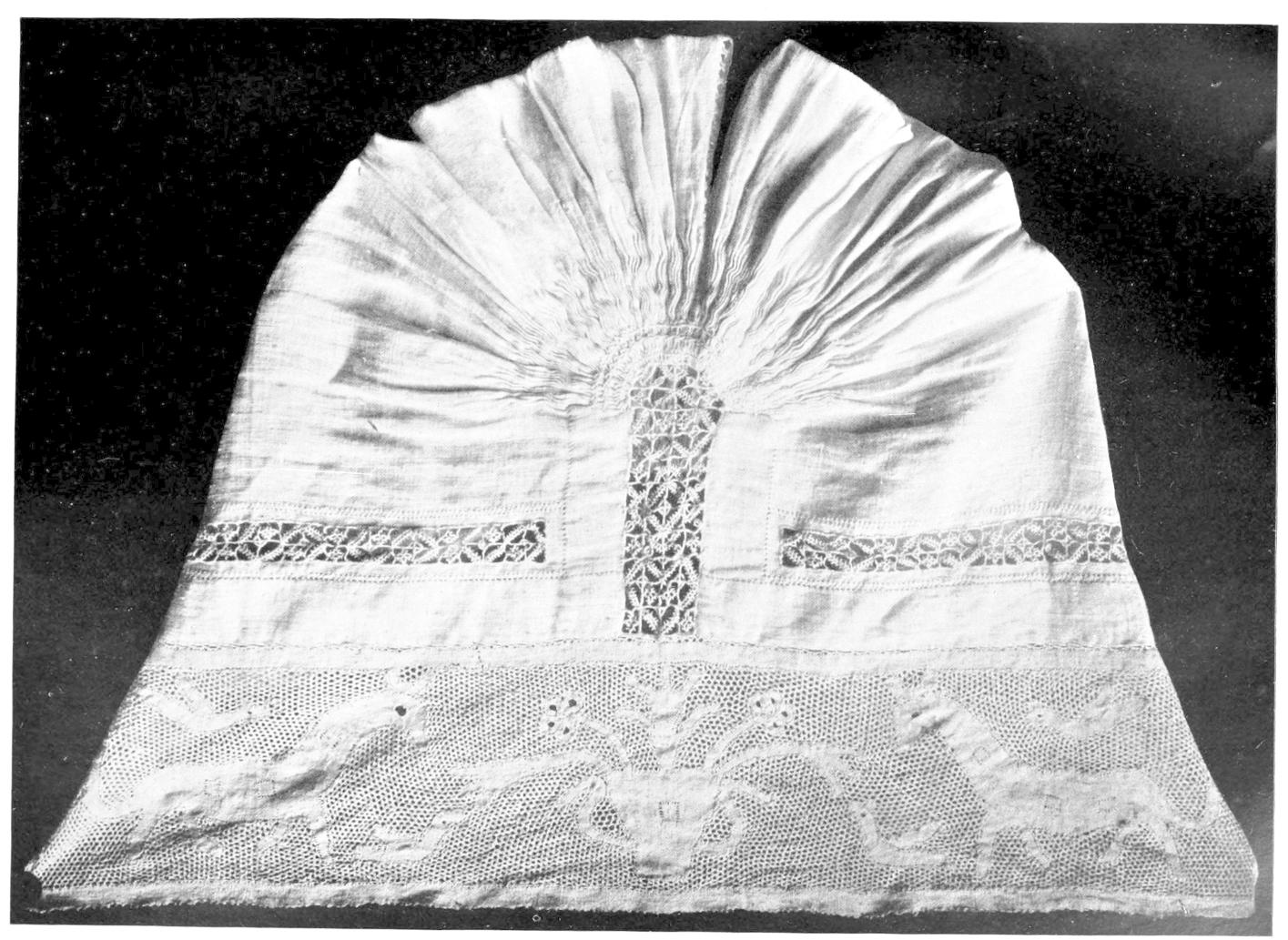

Plate IX.

Portion of a Band of Needle-point Lace representing the Story of Judith

and Holofernes.—The work is believed to be Italian, made for a Portuguese, the

inscription being in Portuguese. Date, circ. 1590. Width, 8 in. The property of Mr.

Arthur Blackborne.

Photo by A. Dryden.

To face page 36.

{37}

At the coronation of Henry II. the front of the high altar is described as of crimson velvet,

enriched with "cuipure d'or"; and the ornaments, chasuble, and corporaliers of another altar as

adorned with a "riche broderie de cuipure."[116]

On the occasion of Henry's entry into Paris, the king wore over his armour a surcoat of cloth

of silver ornamented with his ciphers and devices, and trimmed with "guippures d'argent."[117]

In the reign of Henry III. the casaques of the pages were covered with guipures and passements,

composed of as many colours as entered into the armorial bearings of their masters; and these silk

guipures, of varied hues, added much to the brilliancy of their liveries.[118]

Guipure seems to have been much worn by Mary Stuart. When the Queen was at Lochleven, Sir

Robert Melville is related to have delivered to her a pair of white satin sleeves, edged with a

double border of silver guipure; and, in the inventory of her clothes taken at the Abbey of

Lillebourg,[119] 1561-2, we find numerous velvet and

satin gowns trimmed with "gumpeures" of gold and silver.[120]

It is singular that the word guipure is not to be found in our English inventories or wardrobe

accounts, a circumstance which leads us to infer, though in opposition to higher authorities, that

guipure was in England termed "parchment lace"—a not unnatural conclusion, since we know it

was sometimes called "dentelle à cartisane,"[121]

from the slips of parchment of which it was partly composed. Though Queen Mary would use the

French term, it does not seem to have been adopted in England, whereas "parchment lace" is of

frequent occurrence.

From the Privy Purse Expenses of the Princess Mary,[122] we find she gives to Lady Calthorpe a pair of sleeves of

"gold, {38}trimmed with parchment lace," a favourite

donation of hers, it would appear, by the anecdote of Lady Jane Grey.

"A great man's daughter," relates Strype[123]

"(the Duke of Suffolk's daughter Jane), receiving from Lady Mary, before she was Queen, goodly

apparel of tinsel, cloth of gold, and velvet, laid on with parchment lace of gold, when she saw

it, said, 'What shall I do with it?' Mary said, 'Gentlewoman, wear it.' 'Nay,' quoth she, 'that

were a shame to follow my Lady Mary against God's word, and leave my Lady Elizabeth, which

followeth God's word.'"

In the list of the Protestant refugees in England, 1563 to 1571,[124] among their trades, it is stated "some live by making matches

of hempe stalks, and parchment lace."

Again, Sir Robert Bowes, "once ambassador to Scotland," in his inventory, 1553, has "One

cassock of wrought velvet with p'chment lace of gold."[125]

"Parchment lace[126] of watchett and syllver at

7s. 8d. the ounce," appears also among the laces of Queen Elizabeth.[127]