PORTRAIT OF A. H. FRANCKE

For many years there has been both a need and a call for a book on Lutheran missions, which could be used as a text book and also as a book of reference. Mrs. Lewars has met this need and answered this call with The Story of Lutheran Missions. It is fitting that this book should make its appearance in the Quadricentennial Year of the Reformation and that it should be the first book issued by the first Co-operative Literature Committee of the Woman’s Missionary Societies of the Lutheran Church, representing the General Synod, the General Council, and the United Synod in the South.

The courage and devotion of our self-sacrificing missionary pioneers has been little known even among Lutherans. Our hearts must be thrilled as we read of the superb courage and the unselfish devotion of the brave men and women who, surrounded by indifference were fired with unquenchable missionary zeal to carrying the Word to the ends of the earth.

“Through peril, toil and pain,” they blazed the way for Protestant missions. May this study of the Reformation of the sixteenth century and the subsequent efforts to carry the Word into all of the world help to unite our Lutheran forces in a determined missionary purpose to hasten the transformation of the twentieth century.

| Foreword | |

| List of Illustrations | |

| Chapter I | The Beginnings |

| Chapter II | Pioneers and Methods |

| Chapter III | The Lutheran Church in India |

| Chapter IV | The Lutheran Church in Africa |

| Chapter V | The Lutheran Church in China, Japan and Elsewhere |

| Chapter VI | Lutheran Foreign Missions on the Western Continent |

The author acknowledges her indebtedness to the many persons who have furnished data for The Story of Lutheran Missions, and to those who have read the manuscript. The authorities consulted have been chiefly The History of Protestant Missions by Gustav Warneck, D.D., The History of Christian Missions by C. H. Robinson, D.D., The History of Lutheran Missions by the Rev. Preston A. Laury, Geschichte der evangelischen Heidenmission by R. Gareis, The Lutheran Encyclopedia and the Encyclopedia of Missions, beside numerous magazine articles and reports. Only enough statistics have been included to indicate the size of each mission. With the book should be used such admirable books and pamphlets as Missionary Heroes of the Lutheran Church, Our First Decade in China, The United Norwegian Mission Field in China, Our Colored Mission, Our India Story, and the many interesting illustrated mission reports. Above all, maps should be constantly referred to.

If the study of The Story of Lutheran Missions gives to the reader, as its preparation has given to the author, a sense of the essential unity of the Lutheran Church and a renewed love for her and her history, it will achieve its purpose.

BARTHOLOMEW ZIEGENBALG.

CHRISTIAN FREDERICK SCHWARTZ.

|Purpose of the Book.| It is the object of this book to give a general survey of the missionary labors of the Lutheran Church in all lands. A knowledge of the work of our own Church is of first importance, both that we may be well informed concerning those enterprises which we support and that we may through them become interested in the achievements of other churches.

This account of Lutheran missions cannot be exhaustive. Volumes have been written upon the history of many Lutheran missions. Many names which deserve record must be omitted and those heroes who have been selected for mention are no more devoted, no more noble than many others whose names are lost to human recollection.

|The Missionary Impulse.| Even if the specific commands of our Lord were lacking, we believe that every good Christian would find in his own heart a missionary impulse which could not be denied. There is no good news which we do not hasten to tell; the man who would withhold from his neighbors that which would benefit them is rightly condemned. Would it not be strange if we told all good news but the greatest? The Christian has found peace and life and hope in the Gospel, surely it is his duty and it should be his chief joy to tell the good news to others.

|The Benefits of Missionary Study.| The study of missions is a fascinating pursuit. Its subject matter is the noblest in the world--the history of the evangelizing and Christianizing of mankind. The characters are heroes and heroines. The effect of such study is not only inspiring but improving. The student will gain through diligent attention to the courses offered by mission boards a mass of general information which could be gained so easily in no other way. He will visit all the countries of the world; he will hear something of their history, their geography, their flora and fauna. He will see Eliot and Campanius preaching to the American Indians, he will see Hans Egede laboring among the Greenlanders, he will hear of the wise colonial policy of England, of the amazing devotion and great learning of the Germans, he will observe the daily life of the mission stations where the sick are healed, where lepers are cared for, where to everyone the Gospel is preached. The opening of windows into the wide world is not the least of the rewards for a study of missions.

Before beginning the actual history of Lutheran missions we will review briefly Christian missions before the establishment of the Protestant Church, so that the student may connect the present with the past.

|Salvation Intended for the Whole World.| Christ did not present to the Jews the first intimation of salvation for the whole world. Just as all spiritual truths which He elaborated and fulfilled were shadowed forth in the Old Testament, so was the missionary idea. Here we find the hidden seeds, the promises and prophecies which were to mature and to be fulfilled in the New Testament. God is revealed as the Creator of the whole world. It was all mankind which sinned in Adam, the mankind which God had made “of one blood”. Saint Paul makes clear to the Ephesians the fact that the Gentiles are “fellow heirs and fellow members of the body”. God said to Abraham that in him should “all the families of the earth be blessed.”

|Israel’s Conception of God’s Purpose.| Gradually in the nation of Israel there developed the idea of a new covenant of grace. With the growth of this it became more and more clear to Israel’s prophets and seers that Israel was the center of a great kingdom which God should gather from all nations. Many testimonies may be found to this new consciousness. “For the earth shall be filled with the knowledge of the glory of the Lord as the waters cover the sea.” “For from the rising of the sun even unto the going down of the same, my name shall be great among the Gentiles.” In the Prophet Jonah we have an Old Testament missionary, proud and unwilling, but a witness, nevertheless, to the fact that God’s mercy extended not alone to Israel but to all His works.

|The Jew as a Missionary.| Unconsciously to themselves the Jews were engaged in missionary work. Trained in seclusion, then carried into captivity or trading in all known quarters of the world, they continued to worship the living God. They worshipped Him in private and in public, their synagogues rising plain and austere among the impure temples of the heathen deities. Long-suffering, devout, faithful, they did God’s great task.

|The Septuagint.| About two hundred years before the birth of Christ the Jews accomplished an important missionary work. They were now no longer in Judea alone, but lived all over the Roman Empire. For this scattered host the rabbis translated the Hebrew Scriptures into Greek, the common speech. The translation is called the Septuagint because it was made by seventy men. Here is the first great spreading of the Living Word. The Septuagint was read not only by the Jews but by many learned Greeks, who, while they did not accept its teachings, yet admired its eloquence. One of the greatest factors in the success of the early Christian Church was this acquaintance of the Greeks with the Hebrew Scriptures.

|The Roman Empire.| For the fulfillment of Old Testament prophecies the world was preparing in other ways. The Roman Empire was at the height of its power, its roads led everywhere, it had pushed back the boundaries of the world, it was adding to itself great barbarian nations, little dreaming that all its pride was to serve the will of the Hebrew’s God!

|The Supreme Missionary.| When the time was ripe, God sent His Son into the world, the Supreme Missionary. To convince a doubter of the divine authority for missions, one need go no farther than to point to Christ’s earthly life.

|The Disciples Sent Abroad.| Just as God had sent His Son into the world, so Christ sent abroad His disciples. Their appointment was made directly by Him. The command is positive. “All authority hath been given unto me in heaven and on earth. Go ye therefore and make disciples of all nations, baptizing them into the name of the Father and of the Son and of the Holy Ghost.” “Thus it is written, and thus it behooved Christ to suffer ... that repentance and remission of sins should be preached in His name among all nations beginning at Jerusalem.” “As my Father hath sent me, even so send I you.” “Ye shall receive power, after that the Holy Ghost is come upon you, and ye shall be witnesses unto me, both in Jerusalem and all Judea, and in Samaria and unto the uttermost parts of the earth.”

|The Record of Their Missionary Work.| We have in the Acts of the Apostles a record of the work of the first missionaries appointed by Christ. It describes the disciples gathered together waiting for the promise of the Father. It describes the pentecostal visitation with its mighty wind, its tongues of fire, its strange speech, Parthians and Medes and Elamites, Mesopotamians, Judeans and Cappadocians, Asians, Egyptians, Cretans and Arabians speaking each in his own tongue “the mighty works of God”. It tells the history of the Church, of its early work in Jerusalem, of its miracles and persecutions, of the death of its first martyr. It tells of the missionary work of Peter among the Jews, the beginning of work among the Gentiles. It tells of the conversion of one Saul, a Jew, who had been laying waste the new Church.

|Saint Paul.| In the crises of history, great characters seem to be almost a special creation. Such a man was Lincoln, such a man was Luther, such a man was the apostle Paul. Paul was a Jew of the straitest sect of the Pharisees who had kept the most minute provision of the law and who had felt that the law was unable to solve the problem of sin. He was acquainted also with the wisdom of the Greeks. To him it became clear after his conversion that in Christ lay the fulfillment of the Jewish law and the way of salvation for mankind.

To those outside the law Paul became the first missionary. Through his teaching Christianity was made a universal religion, by his personal work he evangelized a large part of Asia Minor and the chief cities of Greece. His accomplished task was but a small part of that which he planned. His longing eyes turned toward the West, toward the “utmost ramparts of the world”. When the sword of the executioner ended his life in Rome, only a small part of his dreams had been realized.

LOUIS HARMS.

HERMANNSBURG PARSONAGE.

|The Early Church.| Not only the apostles but the whole of the early Christian Church was filled with the missionary spirit. To that early period our eyes turn with longing desire to penetrate farther into the story of devotion, of passion for the things of Christ, of persecution, of martyrdom and of eventual triumph. To us glorious and pathetic relics remain in tradition, in a few written accounts and in inscriptions on tombs and funeral urns. In Thessalonica (now Saloniki), that city in which Paul and Barnabas were said to have “turned the world upside down,” were found two funeral urns of this period. Upon one was the inscription “No hope”; on the other, “Christ my life.” What a mighty hope had been born in the hearts of men!

|Its Extent.| It is impossible to know exactly the size and extent of the Christian Church at any of the early periods of its history. It is estimated by the conservative that at the end of the First Century there were in the Roman Empire two hundred thousand Christians, and at the end of the Second perhaps eight millions, which was about one fifteenth of the population. By the time of the Emperor Constantine, Christianity had become so vast in its extent and so tremendous in influence that he made it in 313 A.D. the State Church of the Empire.

|A Change in Method.| As we study the history of the Christian Church during the next centuries, we observe a new method of Christianizing. The apostles had built up small churches, had watched and nourished them, had chidden the backsliders, had permitted no sacrifice of the cardinal Christian principles. Now there were added to the Empire barbarian countries upon whose people the Christian religion was imposed, whether or not they were truly converted, whether or not, indeed, they were willing to receive it. There were not lacking, of course, many individual conversions, there were not lacking hundreds of Christians who labored with apostolic diligence and devotion and who doubtless deplored the growing union of their religion with the corrupt politics of a great empire.

|Early Missionaries.| Among the famous missionaries of this period were Gregory, the Illuminator, a missionary to the Armenians about the year 300; Ulfilas, who invented a Gothic alphabet so that he might translate the Scriptures into Gothic; Chrysostom, who founded in Constantinople a missionary institution, and Saint Patrick, who converted Ireland. From the secluded churches of Ireland and the Scottish Highlands there went forth to Iceland, to the Faroe Islands, and far into the barbarian sections of the Empire a new band, Columba, Aidan, Columbanus and Trudpert. From the young English Church went Wilfrid to Friesland, Willibrord to the neighborhood of Utrecht, and Boniface to Germany. Further to the east the Gospel was proclaimed under fearful difficulties. At one time it seemed that Christianity might become one of the religions of old China.

|Church and State.| Gradually the alliance of the Church and State came to its inevitable conclusion. The Church began to share the ambitions of the State. Christianity armed itself with the sword and strove to wrest from the Moslem the sepulcher of the Prince of Peace. A measure of the true spirit of the Nazarene remained in such as Raymond Lull, who protested against extending God’s kingdom by the sword and testified to his convictions by giving up his life. The great missionary societies of the Church, the Jesuit, the Dominican, the Capuchin, accepted in the main the Church’s theory of conquest, a theory made enormously advantageous by the discovery of new continents. The missionary enterprises of Spain and Portugal were marked by hideous oppression of those who would not accept the offered religion.

Upon the ministers of the Church the alliance with the State wrought its evil effect. The ambitions of a bishop of Rome led him in 442 to ask the weak Emperor that he be made the head of western Christendom. Henceforth the See of Rome grew more and more powerful. The Church lost entirely the democratic quality of its early life. Pope Gregory claimed toward the end of the Eleventh Century that he had power not only over the souls of men but over all rulers. The lives of great prelates grew evil, the administration of ecclesiastical affairs venal, the pure Gospel was obscured. A mistaken emphasis was put upon good works as a means of winning that forgiveness of sin which God had promised for Christ’s sake. Before the missionary stream could flow for the blessing and healing of mankind, a clear passage must be opened to its Source.

|Boniface.| Among the missionaries who had set out full of zeal from the English Church in the Eighth Century was Boniface, a man of extraordinary energy and power. Among the fields in which he worked was that of Thuringia in Germany. Here, among the dark forests, encouraged and supported by the Pope and by the ruler, Charles Martel, he preached the Gospel, converting thousands and binding them to Rome. With the Gospel he gave them a new sort of superstition, an idolatrous reverence for Rome and a deep awe of the sacred relics which he brought with him. He established monasteries, synods, schools, and required not only faith but knowledge of the forms of the Church, such as the Lord’s Prayer and the Creed. When an old man, he went to visit the country of Friesland which had rejected his early preaching and there with his companions was murdered.

|The Church of Germany.| His Church, however, continued. Closely bound to the great Roman See, it reproduced all the evils of that powerful organization. Here were the great celibate orders, here collections of relics, here a constant demand for money to build magnificent churches and to support an idle and ignorant priesthood. Here, especially, was a tremendous traffic in indulgences by which in exchange for money the sinner could secure not only release from penance on earth and pain in purgatory, but, to the minds of the ignorant, actual pardon for sin. The essential truths of Christ’s teaching were forgotten while men busied themselves with a thousand non-essentials and found no peace for their souls.

Now, as in other times of dire need God provided a man should point to the true way of salvation.

|Martin Luther.| In Germany, as well as in all other parts of the Church, there were many simple, devout Christians whose superstition was underlaid by a deep and childlike faith. To two such pious souls, Hans and Margaret Luther, there was born in 1483, seven hundred years after Boniface had died, a son, Martin. Hans Luther was a poor miner who had moved before Martin’s birth from Möhra to the village of Eisleben. For this son Hans and Margaret were ambitious. They wished him to possess first of all a good character and to that end trained him strictly. His mother taught him simple prayers and hymns and that God for Christ’s sake forgives sin. They wished in the second place that the lad should rise above their humble estate and for that reason sent him to school, first to Mansfield and Magdeburg, then to Eisenach.

|University Days.| When he was eighteen years old Martin entered the University of Erfurt. His father had become more prosperous and continued in his determination that the boy should have every possible opportunity.

Luther was popular among his mates. He won his bachelor’s then his master’s degree and began the study of the law for which his father intended him. Suddenly with crushing disappointment to that ambitious father and to the amazed disapproval of his friends, he abandoned together the study of the law and the world itself and entered a monastery.

|“What Must I Do to be Saved?”| It had not been his studies alone which had occupied the young man during his university course, but meditation upon the needs of his own despairing soul. We have every evidence that he led a pure and godly life, yet the weight of that sin to which all mankind is heir lay heavily upon him. To a man of his time there was but one way of escape--the monastery, in which he might work out his salvation. Vowed to celibacy, to poverty, to obedience, devoting himself to prayer and fasting, he might hope to be saved.

If “Brother Augustine,” as he was called, had any fault as a monk, he erred upon the side of too strict obedience. He followed all the rules of the order, he fasted, he scourged himself cruelly. But still he found no peace. God appeared to him an implacable judge, whose laws it was impossible to keep. He wearied his fellow-priests with confessions and inquiries, but his heart was not at rest.

|The Answer.| Finally, however, he found an answer to his question. Partly by the help of his superiors, chiefly by the aid of the Scriptures, which, contrary to the custom of the time, he studied diligently, he saw a new light. God was a kind Father who required only that his children should throw themselves in faith upon His grace, accepting Christ’s sacrifice for them. Good works were simply the natural expression of a soul already reconciled with God and could have in themselves no merit. If one simply believed, one was justified by his faith. That this doctrine was not that of the Church, Martin did not realize.

But he was soon to learn that his discovery was not acceptable to his superiors. There came into the neighborhood a monk, Tetzel by name, selling those indulgences which had become a menace to spiritual life. Against him and his traffic Luther protested, first in a sermon and then in a series of ninety-five theses which he nailed to the door of the Castle Church.

|A New Evangel.| The sale of indulgences began promptly to decline, and the money, intended partly for the building of St. Peter’s Church at Rome, ceased to flow into the treasury. The local clergy took alarm, the alarm reached to Rome. Threatened, cajoled, greatly disturbed, but steadfast, Luther clung to his conviction. “The Christian man who has true repentance has already received pardon from God altogether apart from an indulgence and does not need one; Christ demands true repentance from every one,” said Luther. At once came a stern reply. It was the Pope and not Luther who had the right to decide this and all other questions. Thus reproved, Luther began to investigate the claims of the Pope upon the lives and fortunes of men. Excommunicated, threatened, with the fate of the martyr Huss in store for him, but gathering courage each day, he persisted until he had separated essentials from non-essentials and, thrusting aside the judgments and traditions of men, had founded his theology upon the Word of God. Tearing out the weeds of false doctrine and false practice, he cleared the stream of the Gospel to its clear and living Spring.

|The Bible Translated.| Luther not only opened the stream, but provided for its continued freedom. To his German people he gave their Bible. His was not the first German translation, but it was the first which was at once readable and true to the original. With the most painstaking care and with the aid of his friends, Luther prepared his version, drawn from the original languages, true to the German idiom, a joy to laity and scholars alike.

|Luther and Missions.| The interest of Luther in missions has been the subject of much unnecessary discussion. There are fervent admirers who claim for him a missionary enthusiasm which he did not possess. There are others who deny for him all interest in this vital question. The truth lies midway.

Missionary enterprise was not one of the first activities of the new Church, nor was it to be expected that it should be. The turmoil and difficulties connected with the establishment of the evangelical religion occupied fully the minds of the reformers. Germany was practically an inland nation and a divided nation. It had no ships, no foreign possessions, no communication with the heathen world. There were not for the early Protestants as for the early Christians great Roman roads leading the imagination afar, there were no large cities where men of many nations touched elbows. The newly discovered lands were the possession of Catholic countries in whose domain the new Gospel, which was really the old Gospel, would have had no hearing.

Not only Luther but other reformers in other lands were concerned chiefly with the heathenized Church about them. For it they labored and prayed. The business of laying a sound foundation absorbed them. That the foundation was well laid, the missions of later centuries will show. In the words of Doctor Gustav Warneck: “The Reformation not only restored the true substance of missionary preaching by its earnest proclamation of the Gospel, but also brought back the whole work of missions to Apostolic lines.”

|The Beginnings.| There is always a difference of opinion about the actual beginnings of a great work. Modern missions offer no exception to this rule. General historians are unwilling to find any indication that even in the Seventeenth Century the Church of the Reformation felt an obligation to heathen nations. Lutheran historians, searching the matter more thoroughly and with a less prejudiced spirit, have discovered various individuals to whom missions were a matter of deep concern.

|In Europe and Asia.| As early as 1557, Primus Truber translated into the language of the Croats and Wends to the east of Germany the Gospel, Luther’s Catechism and a book of spiritual songs. In 1559, Gustavus Vasa, King of Sweden, and later Gustavus Adolphus, endeavored to bring into the Lutheran Church the Lapps, who, though nominally Roman Catholic, had been in reality heathen, but the effort was not successful. Denmark, which had acquired possessions in India, provided for a minister to the colony, whose chief concern should be the spiritual needs of the natives. The creditable undertaking was brought to naught by the wickedness of the appointed ministers. In 1658, Eric Bredal, a Norwegian bishop, began preaching to the Lapps. Some of his assistants were killed; he died and his work came to no earthly fruitage. But the missionary spirit was none the less clearly exhibited.

|In Africa.| In 1634 Peter Heiling of Lübeck journeyed to Abyssinia to try to rouse once more the churches of the East whose spiritual life had almost ceased. There, after translating the New Testament into Amharic, he died a martyr.

|In North America.| In 1638 the Swedes established “New Sweden” on the banks of the Delaware River in America. That there existed in their minds an interest in the spiritual welfare of the Indians surrounding them is recorded in one of the resolutions for the government of the colony. “The wild nations bordering upon all other sides, the Governor shall understand how to treat with all humanity and respect, that no violence or wrong be done to them ... but he shall rather, at every opportunity exert himself that the same wild people may gradually be instructed in the truths and worship of the Christian religion, and in other ways be brought to civilization and good government, and in this manner properly guided.” Among the Swedish Lutheran pastors who obeyed this injunction was John Campanius who translated in 1648 Luther’s Small Catechism into the language of the Virginia Indians, a work which antedated by thirteen years the publication of John Eliot’s translation of the New Testament for the Indians of Massachusetts. The work among the Indians lasted for over a hundred years.

|In South America. Justinian von Welz.| The most important name of the Seventeenth Century in our study of Lutheran missions is that of Justinian von Welz, a German nobleman. To him there came clearly the true vision of the indissoluble relation of living Christianity and Christian missions. In 1664 he issued two pamphlets, one bearing the title, “An invitation for a society of Jesus to promote Christianity and the conversion of heathendom,” the other “A Christian and true-hearted exhortation to all right-believing Christians of the Augsburg Confession respecting a special association by means of which, with God’s help, our evangelical religion might be extended.” In the latter pamphlet there were such questions as these: “Is it right that we evangelical Christians hold the Gospel for ourselves alone?” “Is it right that in all places we have so many theological students, and do not induce them to labor elsewhere in the garden of the Lord?” “Is it right that we evangelical Christians expend so much on all sorts of dress, delicacies in eating and drinking, etc., but have hitherto thought of no means for the spread of the Gospel?”

|His Appeal Ridiculed.| When this appeal was met with opposition and ridicule, von Welz issued a still stronger manifesto. He called upon the court preachers, the learned professors and others in authority to establish a missionary school where oriental languages, the lives of the early missionaries, geography and kindred missionary subjects might be studied. Alas! von Welz was considered now more fanatical and insane than before. When he suggested the sending out of artisans and laymen to tell the Gospel story, since the learned and influential leaders would not go, he was thought to be quite mad.

|A Martyr.| Forsaking his noble rank, this eager soul turned away from his own country to Holland, where he found a minister to ordain him as “an apostle to the Gentiles”. Arranging his affairs so that all his wealth might be applied to his great endeavor, he set sail as a missionary to Dutch Guiana in South America. There in a few months he found a lonely grave.

|A Hero.| In Justinian von Welz the Church of the Reformation possesses one of her worthiest and least known heroes. It was not until 1786, more than a century later, that the Baptist William Carey, considered the first standard bearer of modern missions, lifted up his admonishing voice. Of von Welz, Doctor Warneck, the greatest of all missionary historians, speaks thus: “The indubitable sincerity of his purposes, the noble enthusiasm of his heart, the sacrifice of his position, his fortune, his life for the yet unrecognized duty of the Church to missions, insure for him an abiding place of honor in missionary history.” To him another German missionary historian pays this tribute: “Sometimes in a mild December a snow drop lifts its head, yet is spring far away. Frost and snow will hold field and garden in chains for many months. But have patience. Only a little while and Spring will be here!”

|The Spring at Hand.| Von Welz’s labors and prayers were to bear fruit. His teaching sank into the hearts of some of those who read. In a period of dreary rationalism which followed there began to spring up the seeds which he had sowed. Missions became more and more a subject of discussion among learned men. Among those who gave the theories of von Welz his earnest attention was the German scientist Leibnitz who urged the sending of missionaries to China through Russia. When men began not only to think and to discuss but to pray, the Spring was really at hand.

|Philip Spener.| To two Lutherans above all other men the world owes the impulse to modern Protestant missions. If Philip Jacob Spener and August Herman Francke had not lived, the preaching of the pure Gospel to the heathen, already long delayed, would have had a still later Spring.

Philip Spener was born in 1635 and died in 1705. He was a man of deep piety and great learning. Occupying many important positions, among them that of court preacher at Dresden, he preached and taught constantly that pure living must be added to pure doctrine, urging that the “rigid and externalized” orthodoxy of the Church be transmuted into practical piety which should include Bible study and all sorts of Christian work. He held in his own house meetings for the study of the Bible and the exchanging of personal religious experiences. From the name of these meetings, collegia pietatis, the name of Pietists was given in ridicule to him and his followers.

Among the practical manifestations of a true Christian spirit which Spener urged was the sending of missionaries to the heathen. On the Feast of the Ascension he preached as follows:

“We are thus reminded that although every preacher is not bound to go everywhere and preach, since God has knit each of us to his congregation, yet the obligation rests on the whole Church to have care as to how the Gospel shall be preached in the whole world, and that to this end no diligence, labor, or cost be spared in behalf of the poor heathen and unbelievers. That almost no thought has been given to this, and that great potentates, as the earthly heads of the Church, do so very little therein, is not to be excused, but is evidence how little the honor of Christ and of humanity concerns us; yea, I fear that in that day unbelievers will cry for vengeance upon Christians who have been so utterly without care for their salvation.”

|A. H. Francke.| Most famous among the followers and admirers of Spener was August Herman Francke, who was born in 1663 and died in 1727. He showed as a child extraordinary powers of mind, being prepared to enter the university at the age of fourteen. In 1685 he graduated from the University of Leipsic after having studied there and at Erfurt and Kiel. In 1688 he spent two months with Spener at Dresden and became deeply impressed with pietistic theories. In 1691 he was appointed professor of Greek and Oriental languages in the University of Halle, then recently founded. Here he became pastor of a church in a neighboring village, an undertaking which was to have world-wide importance.

The villagers in this town of Glaucha were degraded, poor, untaught. Moved by their need, Francke opened a school for the children in one room. He had little money but he trusted God. In a short while it was necessary to add another room, then two. He next established a home for orphans, then he added homes for the destitute and fallen. As fast as his enterprises increased, so rapidly came the necessary support.

|The School at Halle.| It is not possible to tell here the amazing history of the Halle institutions which sheltered even before the death of Francke more than a thousand souls, much less of the enormous Inner Mission institutions in other parts of Germany which had here their inspiration. That activity of this remarkable man with which we are chiefly concerned is his missionary labors. In the words of Doctor Warneck: “He knew himself to be a debtor to both, Christians and non-Christians. In him there personified that connection of rescue work at home with missions to the heathen--a type of the fact that they who do the one do not leave the other undone. Home and foreign missions have from the beginning been sisters who work reciprocally into each other’s hands.”

JOHN EVANGELIST GOSSNER.

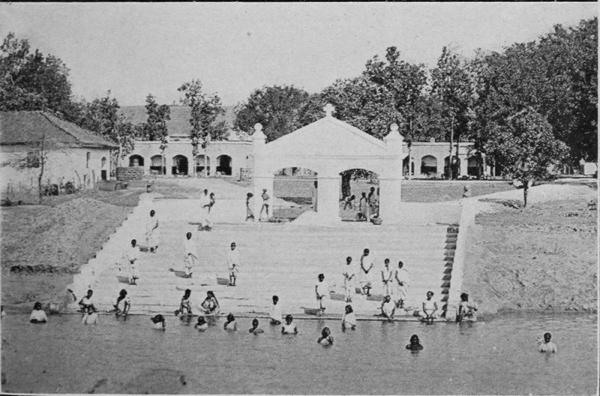

MEN’S BATHING GHAT AT PURULIA.

Francke’s institution became a training school for Christian workers. There was no specific instruction for such undertakings, but “in those that came in near contact with him he stirred a spirit of absolute devotion to divine service, such as he himself possessed in highest measure, and which made them ready to go wherever there was need of them.” There came into the school later, as a lad, the Moravian Zinzendorf, afterwards a zealous missionary, who describes thus the effect of the surroundings upon him: “The daily opportunity in Professor Francke’s house of hearing edifying tidings of the kingdom of Christ, of speaking with witnesses from all lands, of making acquaintance with missionaries, of seeing men who had been banished and imprisoned, as also the institutions then in their bloom, and the cheerfulness of the pious man himself in the work of the Lord ... mightily strengthened within me zeal for the things of the Lord.”

From Halle there went forth during the following century about sixty missionaries, among them Ziegenbalg, Fabricius, Jaenicke, Gericke and Schwartz, whose careers we shall study. Here also was trained Muhlenberg, the patriarch of the Lutheran Church in America, who intended first to go as a missionary to India. Here were published in 1710 the earliest missionary reports in a little periodical which was continued under different titles until 1880, one hundred and seventy years. Among those for whom the heart of Francke yearned were the Jews, in whose interest he founded the Institua Judiaca. From Halle there spread an influence not only through Germany but through the world which is difficult to estimate but almost impossible to exaggerate. By no means the least of the missionary activities which had there their inspiration was that of the Moravian Church, the most ardent in missionary work of all Churches.

The missionary influence did not have any means free course. The opposition shown to the theories of Justinian von Welz continued. Francke was considered no less of a fanatic. This contrary spirit may be shown by the expression of a deeply pious clergyman who concluded an Ascension sermon with the following couplet:

|The First Missionary Hymn.| But even in poetic form missionary activity was soon to find an expression. In Halle a Lutheran Karl Heinrich von Bogatsky wrote in 1750 the first Protestant missionary hymn.

Before this time, however, the first call for missionary workers had come to Halle from outside Germany.

Pioneers.

Methods.

German Societies

Scandinavian Societies

Finnish, Polish and other societies.

American Societies

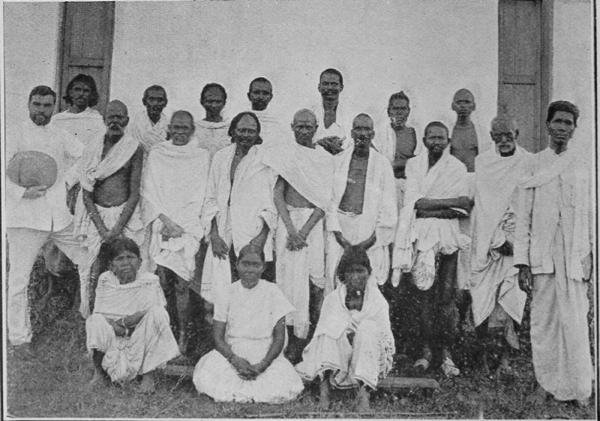

|A Danish Colony.| In 1526, nine years after Luther had nailed his theses to the church door at Wittenberg, the King of Denmark accepted the Evangelical faith. Subsequently the Lutheran Church was made the State Church. About a hundred years later Denmark acquired by purchase an Indian fishing village, Tranquebar, on the east coast of southern India. There a Danish colony was established, there a Lutheran church called Zion Church was built, and thither two preachers were sent to minister to the Danes. Eighty years later the heart of a pious King, Frederick IV, became concerned for the spiritual welfare of the heathen in this colony. His court chaplain, Doctor Lütken, who was also deeply interested, set about securing men who would be willing to undertake the work. Failing to meet with a response in Denmark, he applied to friends in Berlin. They recommended a young German Bartholomew Ziegenbalg.

|The Son of a Pious Mother.| Young Ziegenbalg had been influenced, as most candidates for the ministry are influenced, by a pious mother. Both his mother and father had died so early that he could remember very little about them. One recollection, however, was clear in his mind. Dying, his mother had called her children to her bedside and had commended to them her Bible, with the words: “Dear children, I am leaving to you a treasure, a very great treasure.” Earnest and pious, anxious for communion with God, the young man, who was brought up by a sister, prepared himself for the ministry. He studied at Berlin and afterwards at Halle. There his poor health was a cause of deep discouragement, but Francke reminded him that though he might not be able to work in Germany he might seek a field in some foreign country with a more equable climate.

|Called to the Mission Field.| When his health failed, Ziegenbalg left Halle and took up the work of a private tutor. He continued his devotional studies, however, and held such meetings as Spener had begun. He formed a friendship at this time with Henry Plütschau, another Halle student. Together the two covenanted “never to seek anything but the glory of God, the spread of His kingdom and the salvation of mankind, and constantly to strive after personal holiness, no matter where they might be or what crosses they might have to bear.” In 1705, Ziegenbalg accepted a call to a congregation near Berlin. It was here that he was found by the inquiry of the Danish court chaplain Lütken. He accepted at once, declaring that if his going brought about the conversion of but one heathen he would consider it worth while. His friend Plütschau was anxious to go also, and, ordained by the Danish Church, the two sailed from Copenhagen on the ship “Sophia Hedwig” November 29, 1705, for Tranquebar.

|A Long Journey.| The journey round the Cape of Good Hope consumed seven months, during which time each of the young missionaries wrote a book. On July 9, 1706, they arrived at their destination. There, owing to a difficulty with the captain who had resented their admonitions, they could not land for two days. It was well that they did not know that he had been instructed by the trading company under which he sailed to hinder their work in all possible ways. Unwillingly received by the Danish governor, they settled in a little house near the city wall.

Beside the Danish of the traders, two languages were spoken in Tranquebar: the Portugese of the first foreign settlers and the native Tamil language. Leaving the easier task to his companion who was the older, Ziegenbalg set to work to learn the native tongue. His progress was rapid; in a year he had completed a translation of the Catechism and in a few months over a year had preached his first sermon. By this time he had baptized fourteen souls.

|Busy Days.| The record of his busy days seems almost incredible when we remember that he was a man of delicate health.

“After morning prayers I begin my work. From six to seven I explain Luther’s Catechism to the people in Tamil. From seven to eight I review the Tamil words and phrases which I have learned. From eight to twelve I read nothing but Tamil books, new to me, under the guidance of a teacher who must explain things to me with a writer present, who writes down all words and phrases which I have not had before. From twelve to one I eat, and have the Bible read to me while doing so. From one till two I rest for the heat is very oppressive then. From two to three I have a catechisation in my house. From three to five I again read Tamil books. From five to six we have our prayer-meeting. From six to seven we have a conference together about the day’s happenings. From seven to eight I have a Tamil writer read to me, as I dare not read much by lamplight. From eight to nine I eat, and while doing so have the Bible read to me. After that I examine the children and converse with them.”

When the two missionaries felt that it was necessary to build a church, each gave for that purpose half of the two hundred dollars which was his salary. The church was dedicated on August 4, 1707, and by the end of the year it had thirty-five members. Now Ziegenbalg began to work in the villages of the Danish possessions outside Tranquebar and established a school for the education of Christian children in the city.

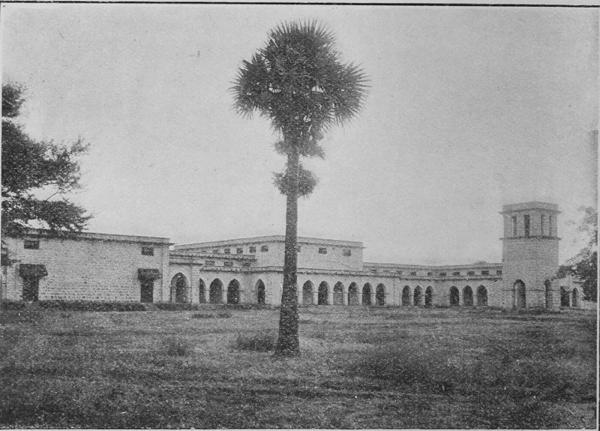

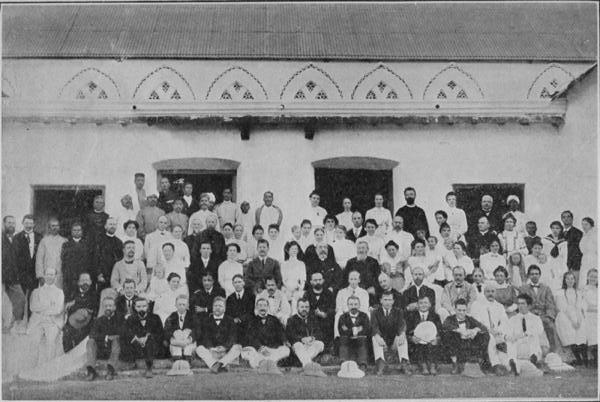

STALL HIGH SCHOOL FOR GIRLS, GUNTUR, INDIA.

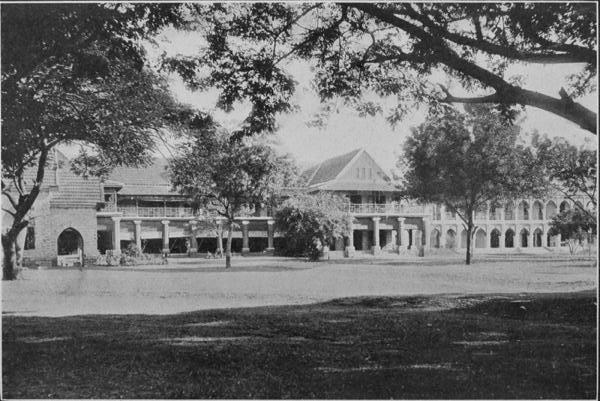

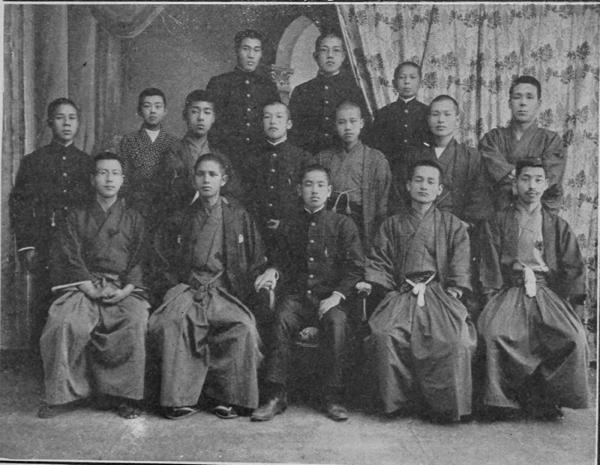

FACULTY OF WATTS MEMORIAL COLLEGE FOR MEN, GUNTUR.

|Early Trials.| The work was not without its hard trials. When the first financial help arrived, two years after the missionaries had landed, the drunken captain upset in the harbor the chest of treasure and it was lost. The work of the missionaries was opposed by the Danish chaplains and by the Roman Catholics. On account of his defense of a poor widow who had been cheated, Ziegenbalg was cast into prison for four months.

That the faith of these pioneers was unfailing may be shown by a prayer, written by one of them on the fly leaf of a mission church-book in 1707.

“O Thou exalted and majestic Savior, Lord Jesus Christ! Thou Redeemer of the whole human race! Thou who through Thy holy apostles hast everywhere, throughout the whole world, gathered a holy congregation out of all peoples for Thy possession, and hast defended and maintained the same even until now against all the might of hell, and moreover assurest Thy servants that Thou wilt uphold them even to the end of the world, and in the very last times wilt multiply them by calling many of the heathen to the faith! For such goodness may Thy name be eternally praised, especially also because Thou, through Thy unworthy servants in this place, dost communicate to Thy Holy Word among the heathen Thy blessing, and hast begun to deliver some souls out of destructive blindness, and to incorporate them with the communion of Thy holy Church. Behold, it is Thy Word, do Thou support it with divine power, so that by Thy power many thousand souls may be born to Thee in these mission stations, which bear the names of Jerusalem and Bethlehem, souls which afterwards may be admitted out of this earthly Jerusalem into Thy heavenly Jerusalem with everlasting and exultant joy. Do this, O Jesus, for the sake of Thy gracious promise and Thy holy merit. Amen.”

|Literary Work.| Ziegenbalg prepared an order of service and a hymnal and translated the New Testament into Tamil--the first translation of the New Testament into an East Indian tongue. An English missionary society, hearing of his labors, sent him a printing press. By 1712 he had composed or had translated thirty-eight books or pamphlets. Among his original works was an account of the native religions. The value of this treatise has become more appreciated as men have realized the importance of a thorough knowledge of those religious principles which unchristianized peoples already possess. To such knowledge was due much of Saint Paul’s success among the Greeks.

|Travels.| Ziegenbalg travelled as far as Madras. On this journey he talked with native rulers and British governors and preached to all who would hear about the only true God.

|Reinforcements.| In 1709 three missionaries were sent to his aid. Of the three John Ernst Gründler proved most able. When in 1711 it seemed best for one of the missionaries to return to Europe to present the needs of the mission, Plütschau was selected to go. There he accepted a pastorate. The testimony of Ziegenbalg to his faithful work accompanied him.

In 1714 Ziegenbalg visited Denmark, leaving the mission in charge of Gründler. Upon his return in 1716 he brought with him a plan for the regular government of the mission, the assurance of ample financial support and a helpmate, Maria Dorothea Saltzmann, who was the first woman ever sent to a foreign field.

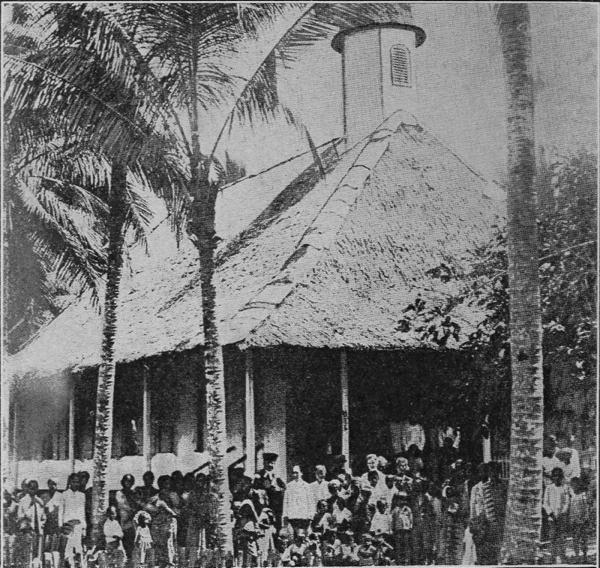

|The New Jerusalem Church.| In February 1717, Ziegenbalg had the satisfaction of dedicating a large native church, the New Jerusalem Church, which is used to this day. He preached the sermon and the newly appointed governor laid the corner stone. He continued to establish village schools, he opened a seminary for the training of native preachers and he provided work by which the poorest of his converts could earn a living. Except for medical work his mission settlement included all the activities of the most complete missionary enterprises at the present time.

For two more years Ziegenbalg labored, growing meanwhile aware that his life was drawing to a close. The record of his service leads us to expect that when his death took place in February 1719 we should find him an old man. It is with a shock that we realize that he was only thirty-six. He was buried in the New Jerusalem Church.

|A Crowded Life.| The extraordinary accomplishment of Ziegenbalg has been far less well known than it deserves to be. Even if we do not take into account his frail health, the extent of his labors is little short of marvelous. His literary work alone would seem to have been enough to fill to the full the thirteen years of his missionary activity. In addition, he preached constantly; he made long journeys; he gave constant thought and effort to his schools; he looked after the poor; he established a theological seminary. From home came many criticisms. It was said that he made concessions to the caste system on the one hand; on the other he was criticised for not gathering in converts as rapidly as did the Roman Catholic missionaries who allowed their converts to keep all their old customs. He was reproached because he paid so much attention to the schools. The criticisms, however, which caused him anxiety and grief serve to-day but to call attention to his splendid common sense and excellent judgment, which later missionary experience has tested. The community of two hundred Christians which he left was not only converted--it was instructed and established in the faith.

|A Second Grave.| The death of Ziegenbalg left his friend, John Ernst Gründler, in charge of the mission. He had been a teacher at Halle and partook of the devotion of all connected with that great institution. For a short time he labored in Tranquebar alone. Soon after the arrival of three new missionaries he died and was buried in 1720 beside his beloved friend in the new church.

Of the three new missionaries, Benjamin Schultze assumed the management of the mission. He resembled Ziegenbalg in the variety of his talents. Like Ziegenbalg he felt the necessity for a careful instruction of the natives. He continued the work of translation, completing the Tamil Old Testament and translating a part of the Bible into Telugu and the whole into Hindustani. After doing faithful work, Schultze, being unwilling to accept the rulings of the mission which had sent him to India, entered the service of an English mission. After sixteen years in India he returned to Halle.

|The Mission Grows.| During the service of Schultze a mission station was established at Cuddalore in Madras. In 1733 the first native preacher who had been baptized by Ziegenbalg was ordained to the ministry. Schools were enlarged and another church was erected. Presently work was begun in Madura to the southeast of Tranquebar. By 1740, thirty-four years after Ziegenbalg had begun his work, the mission counted five thousand six hundred Christians.

In 1741 John Philip Fabricius arrived in India. He came from a godly family in Hesse and like Luther had given up the study of the law for the study of theology. For theology he had gone to Halle and there had heard the call of missions. On Good Friday in 1742 he preached his first Tamil sermon and on Christmas in that year he was assigned to the station established by Schultze in Madras where he remained till his death in 1791. Like his predecessors he became a thorough student in the native tongues.

|A Scholar.| He revised the translations of Ziegenbalg and Schultze in a form which remains unchanged to this day. To his translations the adjective “golden” has been applied. He translated also many hymns for the use of his congregation.

Together with a childlike simplicity and amiability Fabricius possessed great courage. He shared the hardships and dangers of his people during the “Thirty Years’ War in South India”, defending his congregation upon one occasion at the risk of his life.

Another Fabricius whose name should be recorded was that of Sebastian, the brother of John Philip, who was for many years the missionary secretary in Halle and the devoted friend of all missionaries.

Christian William Gericke, “a great and gifted man”, arrived in India in 1767, coming like his predecessors from Halle. His first field of labor was Cuddalore where he preached until war made necessary the abandonment of the mission. Gericke remained throughout the conflict, still preaching and exhorting and supporting his children in the faith. He saw his converts suffering cruelly and was compelled to watch the soldiers changing his church into a powder magazine.

In Madras whither he was invited he took over the work of Fabricius, who was now old and infirm. From there he was able to visit occasionally the scattered members of his Cuddalore flock.

|An Evangelist.| The number of his converts amounted in a short time to three thousand. It was said that whole villages followed him when he conducted mission tours, which were likened to triumphal processions. In some villages temples were stripped of their idols and converted into houses of worship. When he approached a village the entire population frequently awaited him. It is related that the heathen never came to their temples as they came to this man of God. Worn out, he died in 1803 at the age of sixty-one.

|Another Pious Mother.| As in the case of Bartholomew Ziegenbalg so in the case of Christian Frederick Schwartz, the impulse to the Christian ministry came from a godly mother. She died when the lad was but five years old, but she had made her husband promise that her boy should be prepared for the ministry.

Like Ziegenbalg and Luther and many other religious heroes, Schwartz suffered in his youth from the weight of sin and the fear of God’s judgment. Like them also he came, after study of God’s Word and earnest prayer, to rest his soul upon the almighty promises. At Halle he met Benjamin Schultze who called upon him to aid in his revision of the Tamil Bible. Urged by his teachers to consider a call to the mission field, he felt himself at first to be unworthy. Finally, however, he agreed to go. When he informed his father of his intention he met with dismay and refusal. The elder Schwartz had three children, of these one son had just died, a daughter was about to be married and now the third proposed to go to distant India! Finally the father was won over and, giving his son his blessing, charged him to win many souls for Christ. How many times in missionary history has this drama of unwillingness, persuasion and final yielding been enacted!

|A Father’s Sacrifice.| May all fathers and mothers who give their children to the great cause have reason for gratitude as did the elder Schwartz!

In January, 1750, Schwartz and two companions sailed, only to return on account of fearful storms. In March they set out once more and reached Tranquebar at the end of July.

|A Diligent Student.| The first work assigned to the young man was the teaching of the children in the schools. He longed to go into the wilderness of heathendom outside the city and there do pioneer work, and in preparation for the day when he should be allowed to go, he applied himself to a study of the people, their language and their religion. As a result of his thorough comprehension of their nature and their needs he was to have a deep and lasting influence upon them. For twelve years he worked in Tranquebar and the outlying villages.

In 1755, by the persuasion of the wife of a German officer, Schwartz and his companions were allowed to pay a short visit to Tanjore, the city which was the seat of the native government and which had hitherto been closed to missionaries.

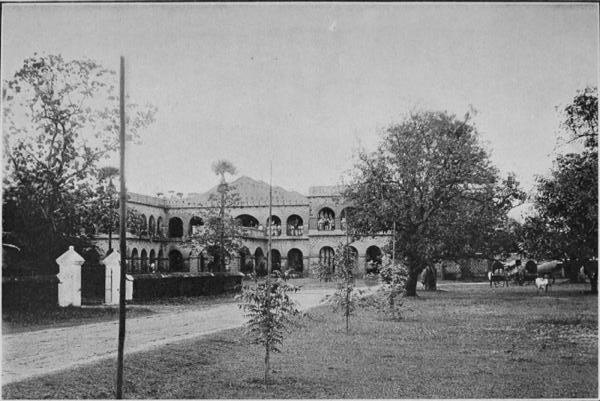

HOSPITAL FOR WOMEN AND CHILDREN, GUNTUR.

|Opening Doors.| In 1762 they went on a similar visit to a little company of native Christians who had settled in Trichinopoli, for which England and France had contended for many years. The city was a center for idolatrous worship and contained great temples to the elephant god Genesa, to Siva and to Vishnu. Here also there was a popular Mohammedan shrine. Well might the visitors feel that all the evil of heathendom was gathered to greet them.

At that time the English had control of the city and to the joy of the visitors they besought them to stay, promising that they would build them a church. It was decided that Schwartz should remain.

|A True Lutheran.| In making this change an important question had to be solved by Schwartz. In order to take up the work which seemed offered by Providence, he would have to sever connection with the Danish Lutheran society whose missionary he had hitherto been and become a missionary of the Church of England. In the end he decided that he would accept English support but he stipulated that he would remain a true Lutheran, preaching the doctrines of his own faith. He was the first of many efficient German Lutherans who laid the foundations for the work of other churches, and who thus furnished an example of true brotherliness which has often been forgotten or overlooked.

|At Trichinopoli.| Schwartz had always been diligent, but now it seemed that his labors became superhuman. He had prayed for opportunity--here was unlimited opportunity! He had studied diligently--here were men of many tongues to whom he might preach. With true wisdom he began his work. With the methods of the Apostles as his model he trained the best of his converts to become missionaries to their own people. Each morning he sent them out, two by two, and each evening he listened to an account of their work. He added Hindustani and Persian to the languages which he already knew so that he might reach the Mohammedans and the court, and studied to improve his broken English so that he might preach to the English soldiers at the garrison. His ministrations to them after a serious explosion and a battle brought him gifts from the government and the soldiers. Presently he built at the foot of the mighty rock upon which stood a heathen temple a Christian church.

|At Tanjore.| Schwartz was now fifty-two years old. He had accomplished large tasks, yet the chief labors of his life were still before him. He learned to his amazement that the spirit at Tanjore had changed and he was urged to return, not for a short visit as before but to remain. The new Rajah of Tanjore sought his advice about the settlement of certain political differences, and finding a divine call in this summons, Schwartz left his work at Trichinopoli in the hands of others and took up his abode in Tanjore in a house presented by the rajah. Here, supported by the rajah, who, however, could not bring himself quite to the point of becoming a Christian, Schwartz lived for twelve years.

Here the English garrison was transformed as the garrison at Trichinopoli had been. Two churches were founded, one for the European residents, the other for native Christians. School houses were built in which English and Tamil were taught and where the Christian religion was openly proclaimed. These schools became the models for the great school system of the English government. A tribe of professional robbers forsook their evil lives as the result of Schwartz’s preaching, sent their children to the schools and settled down to the cultivation of the soil and to silk culture. With the city as a center Schwartz travelled in all directions encouraging, advising, aiding. He established a congregation at Tinnevelli, to the south, of which we shall hear later.

|The Missionary Statesman.| In the history of India Schwartz is described as the missionary statesman. Such without any will of his own, but on account of circumstances and his remarkable character, he became. Foreseeing war with a neighboring ruler in which Tanjore was likely to be besieged, he stored away quantities of rice upon which the people fed and which saved multitudes from death. When the rajah grew old the governor of the Madras presidency made Schwartz the head of a commission which was to rule in his stead, and when the rajah died he himself made Schwartz regent during the minority of his son. Schwartz tried to avoid this heavy responsibility, until the rajah’s brother proved cruel and incapable of governing. Then the mission house became the capitol of the province and for two years the “king-priest” reigned. After the heir had come to the throne, he consulted Schwartz on all important questions.

The character of this missionary hero is beautifully described by his biographer, Dr. Charles E. Hay.[1]

1. In Missionary Heroes of the Lutheran Church. Philadelphia: Lutheran Publication Society.

“In undertaking all the secular duties thus imposed upon him, the missionary was never lost in the statesman. He still gathered his children and catechumens about him daily, preached whenever a little company of people could be assembled and superintended the labors of the increasing number of missionaries sent by various European societies to India. These all recognized him as their real leader, and it was universally felt that the first preparatory step for successful missionary labor in southern India was to catch the inspiration and receive the counsel of the untitled missionary bishop at Tanjore. Around his residence building after building was erected--chapels, schoolhouses, seminaries, missionary homes, etc.--all set in a beautiful garden, filled with rare tropical plants. What a refuge for the wearied and perhaps discouraged catechist! What a scene of beauty and peace to allure the steps of the hopeless devotee of a heartless idolatry! But the center of attraction for all alike was the radiant countenance of the grand old man upon whom his seventy years rested never so lightly--never too tired to entertain the humblest visitor, always ready to help by word or deed in any perplexity.”

|Illness and Death.| In October, 1797, the old man fell ill. Thinking that his end was at hand he sent for the young rajah whose guardian he had been and urged him once more to hear the heavenly invitation. Would that we could record that this young man answered, like so many of his humble subjects, “I believe”! Improving somewhat, Schwartz summoned his pupils once more and went on with his work. The end came at last in February, 1798. With his grieving mission family gathered about him, he fell asleep, his last words being, “Into Thy hands I commend my spirit. Thou has redeemed me, Thou faithful God.”

|A Noble Tribute.| Claiming him for their own, those for whom he had labored provided for his burial. The rajah who followed the bier as chief mourner built a handsome monument on which he is represented as kissing the hand of his dying friend. The East India Company placed a memorial in the church at Madras with the inscription, “Sacred to the Memory of Christian Frederick Schwartz whose life was one continued effort to imitate the example of his blessed Master. He, during a period of fifty years, ‘went about doing good.’ In him religion appeared not with a gloomy aspect or forbidding mien, but with a graceful form and placid dignity. Beloved and honored by Europeans, he was, if possible, held in still deeper reverence by the natives of this country of every degree and sect. The poor and injured looked up to him as an unfailing friend and advocate. The great and powerful concurred in yielding him the highest homage ever paid in this quarter of the globe to European virtue.”

Thus died this godly man. To those whose aim is heavenly peace we commend such a life as his. To those whose ambition includes a desire for earthly honor we commend him also. The young rajah added to his handsome memorial another tribute composed by him and engraved on the stone which covers his body.

|Work for Another Church.| Aiding and succeeding Christian Frederick Schwartz in the English mission was his adopted son, the Rev. J. B. Kohlhoff, who arrived at Tranquebar in 1737 and worked among the Tamils for fifty-three years. His son, John Caspar, was ordained by Schwartz. Together Schwartz and the two Kohlhoffs worked in India for an aggregate period of one hundred and fifty-six years. Still another Lutheran in the English service was W. T. Ringeltaube, who was trained at Halle. Upon the foundation which he laid the London Missionary Society has built nobly and has now after a hundred years a Christian community of seventy thousand.

|A Period of Neglect.| It is estimated that at the end of the Eighteenth Century the Danish-Halle mission in India numbered fifteen thousand Christians. Then a period of rationalism in Europe brought about indifference and neglect of the mission fields. From England came the first wave of mounting missionary zeal and into English hands passed a large part of the work of the Danish-Halle missionaries. While we acknowledge that they have continued the work with zeal and with marked success, yet we cannot but regret that so much that was ours, so much that was won by the devotion of Ziegenbalg and Schwartz, no longer bears the Lutheran name.

|Another Steadfast Lutheran.| In the service of the English mission was Karl Ewald Rhenius, a German Lutheran who was sent soon after the opening of the new century to that field which had passed partly from Danish-Halle to English hands. He went first to Tranquebar and thence to Madras, where for five years he preached and studied. At the end of this time he was transferred to Palmacotta, the chief city of the Tinnevelli district. Here he began an original work, the founding of Christian villages. As soon as sufficient natives were converted, land was bought and they were settled upon it so that they might be removed from former associations and temptations. Presently a native organization was formed the object of which was the aid of new Christian settlements.

In 1832 Mr. Rhenius withdrew from service as a missionary of the English society, the chief ground of difficulty being the demand of the society that he be ordained by the English Church, and for four years he conducted an independent mission. In character and capacity for work Rhenius was not unlike Christian Frederick Schwartz. Beside a great amount of translating he had time to prepare a valuable essay on the “Principles of Translating the Holy Scriptures”. He is notable also as one of the earliest missionaries to take a decided stand against the observance of caste.

The appeal of Rhenius for his independent Lutheran mission in India was one of the influences in the first missionary activity of the American Lutheran Church. Upon his death his followers returned to the English Mission. In Tinnevelli where Christian Frederick Schwartz laid the foundation and Rhenius helped to build upon it, there are now over one hundred thousand Christians belonging to the Church of England.

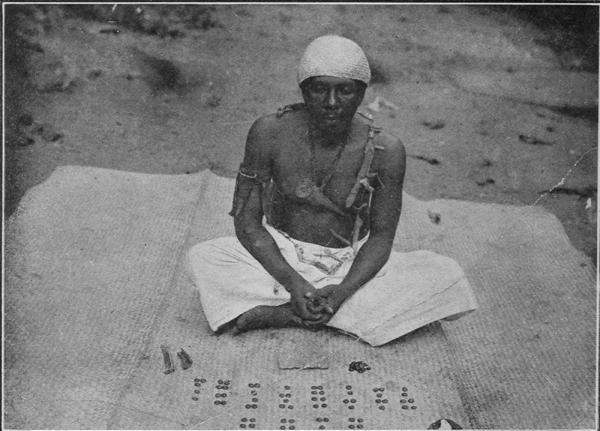

|In the Far North.| It was in 1704 that the Danish King Frederick IV. turned his thoughts to the Christianizing of his East India possessions. Soon after this time his attention was drawn to a need nearer at hand. Among the Lapps who lived in the arctic lands to the north there was great destitution, both spiritual and material. Here idolatry and sacrifices to the evil spirits were common and the official transferral of the country from the Roman to the Evangelical Church had had no effect, since both before and after the natives were at heart heathen. Those who were most devout in spirit had worshipped both the heathen and the Christian gods, feeling that thus were they safe.

A commission was appointed by the King of Denmark-Norway in 1714 to inquire into the state of these northern people. To Finland was sent in 1716 Thomas von Westen, who had himself presented vividly the misery of these poor Esquimaux. Among them he found Isak Olsen, a devoted school master who had been engaged for fourteen years in missionary work, and who now offered his services for von Westen’s undertaking.

Concerning this Isak Olsen, it is related in Stockfleth’s Diary (Dagbog) that he had labored “with apostolic fervor and faithfulness; in poverty and self-denial; in perils at sea, and in perils on land. The Finns hated him because he discovered their idolatry and their places of sacrifice; almost as a pauper, and frequently half clothed, he travelled about among them. When, as it frequently happened, he was compelled to journey across the mountains, they gave him the most refractory reindeer, in order that he might perish on the journey. By all kinds of maltreatment, they sought to shorten his life, and to weary him out. In this purpose, however, they were not successful; for God was with Isak, and labored with him, so that his toil prospered.” He not only instructed the Finns in Christianity, but he taught a number of Finnish youths to write, an art which very few Norsemen had acquired at that time. In 1716, von Westen took him to Throndhjem, Norway, where he translated the Catechism and the Athanasian Creed into the language of the Lapps.

Travelling from place to place, von Westen won the affection of the benighted people whom he loved. He exposed before them the foolishness of the sorcerers, built churches, educated the children and sent young men to Throndhjem to prepare themselves to be ministers to their people. The hardships of three missionary journeys undertaken and carried out in a few years so wore upon him that he was added at the age of forty-five to those who have gone to their reward.

To Swedish Lapland went Per Fjellström (died 1764) who did not only valuable missionary work himself, but who laid the foundation for all future work by his translations of the New Testament, the Catechism and many of the Psalms. Through him and his associates the whole of Swedish Lapland heard the pure Gospel.

In 1739, a royal directorate was appointed to guide and supervise the Church and school system of Swedish Lapland. It designated Per Holmbom and Per Högström, as missionaries to that district. Högström, who died in 1784, is the best known of Per Fjellström’s associates. He gained great renown among the Lapps. He has described his mission labors among them, and his Question Book in the Lapp language, is a catechetical work of merit.

To the west of the Scandinavian countries lies Iceland, which needed no missionaries. Visiting Europe in the Sixteenth Century, Icelanders carried back to their country the story of the Reformation. They introduced at once the Danish Lutheran liturgy and translated and printed the Bible. After some opposition, the work of the Reformation became complete.

|A Zealous Soul.| Beyond Iceland lies Greenland with its snowy fields, its great glaciers, its long dark night and its bitter cold. In the Ninth Century a colony of Norwegians settled there, but in the course of time perished from cold or starvation or by the hand of enemies. Their fate was unknown and they were forgotten when Hans Egede, a Lutheran pastor at Vaagen in Norway, read of their settlement and became possessed of a desire to preach to them that Gospel which had proved so great a blessing to his own land. In 1710 he wrote to the King and to several bishops urging that he be allowed to go as a missionary to these distant folk.

The King was in sympathy with his desire, but not so his people. The plan was thought to be impractical, if not insane. Egede’s own family bitterly opposed him.

But Egede was at once gentle and persistent. Supported by the devotion of his wife he continued to urge his cause. He visited the King, but the interview had a contrary result from that which he hoped. The King asked those who opposed the project to send in the reasons for their objection to the court, and so promptly and fully did they respond that Egede became an object of even greater derision.

|The Ship “Hope”.| Finally Egede persuaded a few men to subscribe two hundred dollars apiece; he gave from his scanty store six hundred, and all together ten thousand dollars was gathered. In a vessel which he called “The Hope” he set out May, 1721, accompanied by his wife and little children and some colonists, in all about forty souls. After a perilous voyage partly among masses of ice floating in a stormy sea they landed in Greenland in July. The situation which they met was uncomfortable and depressing. “As many as twenty natives occupied one tent, their bodies unwashed, their hair uncombed and both their persons and their clothing dripping with rancid oil. The tents were filled and surrounded with seal flesh in all stages of decomposition and the only scavengers were the dogs. Few had any thought beyond the routine of their daily life. No article that could be carried off was safe within their reach, and lying was open and shameless. Skillful in derision and mimicry, and despising men, who, so they said, spent their time in looking at a paper or scratching it with a feather, they did not study gentle modes of giving expression to their feelings. They wanted nothing but plenty of seals, and as for the fire of hell, that would be a pleasant contrast to their terrible cold. When the missionary asked them to deal truly with God, they asked when he had seen Him last.

“The cold as winter drew near was terrific. The eiderdown pillows stiffened with frost, the hoarfrost extended to the mouth of the stove and alcohol froze upon the table. The sun was invisible for two months. There was no change in the dreary night.”[2]

2. Hans Egede: the Rev. Thomas Laurie, Missionary Review of the World, December, 1889.

|The Reward of Faith.| The devotion of Egede to these degraded people was not shared by the colonists and traders who had come with him. When the expected ship failed to appear in the spring they announced that they would return. They had already begun to tear down the buildings preparatory to their departure when the faith of Egede was rewarded. A ship arrived and with it the welcome news that the mission would be supported.

During the summer, Egede, in his exploration of the various bays which indent the coast, discovered the ruins of one of the settlements which he had read about and which had seemed to beckon him to Greenland. There were only ruins remaining, but it seemed to this devoted soul that he could hear the echoes of Norwegian hymns and Norwegian prayers. The next year in a journey along the coast he found many other ruins, among them those of a church fifty by twenty feet with walls six feet thick. Nearby in the churchyard rested the bones of pastor and people.

|A Devoted Wife.| Preaching, translating, trying to establish better methods of agriculture, now receiving aid from home, now apparently forgotten, Egede labored for fifteen years. Beside the heavenly assurance of ultimate victory his chief solace was the devotion of his wife. “She was confined to the monotony of their humble home, while he was called here and there by the duties of his office; but though its comforts were very scanty, she saw the ships from Norway come and go, and heard tidings from her native land without any desire to desert her work. Amid all his troubles her husband ever found her face serene and her spirit rejoicing in God. His greatest trial was the want of success in his work. Though many pretended to believe, he could find little change in heart or life, for those who affected to hear the Word with joy, among their own people still spoke of his instructions and prayers with derision.”[3]

3. Ibid.

Presently a fort was established to protect the colony and the island from other nations, but the presence of armed men drove the islanders farther away. After the death of Frederick IV., the colonists were commanded to return to Denmark. Egede declined to go. In 1733 hope was once more kindled by the announcement that trade would be renewed and the mission be supported.

|A Sad Heart.| But greater misfortunes were at hand. A fearful epidemic of smallpox ravaged the country. “In their despair some stabbed themselves, others plunged into the sea. In one hut an only son died and the father enticed his wife’s sister in and murdered her, as having bewitched his son and so caused his death. In this great trial Egede and his son went everywhere, nursing the sick, comforting the bereaved and burying the dead. Often they found only empty houses and unburied corpses. On one island they found only one girl with her three little brothers. After burying the rest of the people, the father lay down in the grave he had prepared for himself and his infant child, both sick with the plague and bade the girl cover them with skins and stones to protect their bodies from wild beasts. Egede sent the survivors to the colony, lodged as many as his house would hold and nursed them with care. Many were touched by such kindness, and one who had often mocked the good man, said to him now, ‘You have done for us more than we do for our own people; you have buried our dead and have told us of a better life.’” Finally the missionary’s wife fell also a victim to the plague. Dying she blessed him and his work.

In 1736, broken in health, Egede returned to Denmark, invited by the King. There by pen and tongue he continued to work for Greenland until his death.

|The Church of Greenland.| Upon the foundation laid by Egede missionaries of a closely-related Church built a noble superstructure. Appealing to the heart rather than to the intellect, the heroic Moravians won the country for Christ. Soon spring dawned in that wintry land. When a Moravian missionary dwelt upon the love of God and the agony of Christ, an Esquimaux stepped forward asking eagerly, “How was that? Tell me that again, for I also would be saved.”

The mission to Greenland offers not only records of noble devotion and sacrifice but a touching and remarkable conclusion. In 1899 the Moravians handed back to the Danish Lutheran Church the work which the Lutherans had begun. The missionary task was complete; with no selfish desire to hold for themselves in ease what they had won in great difficulty, the Moravians turned their labors into other fields among the many which they have so diligently harvested. The Lutheran Church which has sent so many laborers into other mission fields has here had a brotherly return.

|A Malady.| The latter part of the Eighteenth Century offers a less happy missionary spectacle than the earlier part. Upon religious life, not only in Lutheran countries but in other Protestant countries fell the blight of indifference and of rationalism. When men do not believe the doctrines of the Scriptures, when a future life becomes a matter of doubt and personal salvation the subject of amusement, they cease to feel an obligation to those who are less favorably situated, and the carrying of the Gospel message becomes a useless or worse than useless undertaking.

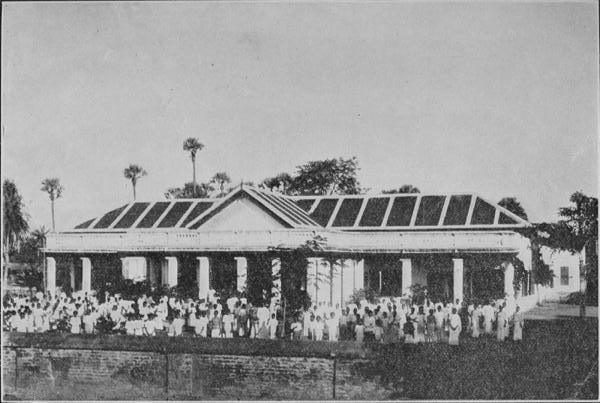

HOSPITAL FOR WOMEN AND CHILDREN, RAJAHMUNDRY.

This malady of unbelief affected the Church, however, for only a short time. By the beginning of the Nineteenth Century men were already returning to the hope which they had rejected. With the return came once more that sense of obligation to the heathen world which had been so clearly seen by von Welz, Francke, Ziegenbalg and Schwartz.

|A Missionary School.| The new light shone out in the opening year of the new century. Then John Jaenicke, who was called “Father” Jaenicke, established in Berlin a missionary school, the first Protestant institution whose object was primarily the direct training of missionaries. For many years Jaenicke had been the only believing preacher of the Gospel in Berlin. In spite of a disease which threatened constantly a fatal hemorrhage, he labored with a humorous disregard of his physical disability--and lived to be eighty years old! His church in Berlin was composed partly of Bohemians, and to these he preached in the morning in Bohemian, his native tongue. In the afternoon he preached in German and on Monday evening he gave a powerful review of his Sunday sermons, dwelling constantly on two cardinal points, human sin and divine grace, and crying earnestly to his people. “You are sinners, you need a Savior, here in the Scriptures Christ offers Himself to you!”

Visiting the sick, giving alms to the needy, comforting the desolate, and alas! constantly laughed at and mocked, this godly man pursued the course which he had set for himself. As in the case of Francke, so in the case of Jaenicke an abounding charity concerned itself not only with those at hand but with those afar off. From his missionary school, he sent out in twenty-seven years about eighty missionaries. Before his death the beauty of his character and the softening heart of his country enabled men to see him as he was.

The Jaenicke school exists no more as such, but in the impulse given to missions and in a successor, the Berlin Missionary Society, it still lives.