The Pioneer 10 and 11 spacecraft, launched in 1972 and 1973, respectively, were well named: they made the first crossings of the asteroid belt and were the first to encounter Jupiter and its intense radiation belts. Pioneer 11’s trajectory, bent into a hairpin curve by Jupiter’s powerful gravitational field, allowed it to recross the solar system to make the first flyby of Saturn almost a billion miles from Earth where it came within 13,300 miles of the cloud tops.

Assembled in this publication is a selection of the pictures returned by Pioneer 11 of Saturn and its largest moon, Titan. These images are of great beauty as well as of great scientific interest, serving to whet our appetite for the more detailed observations to be made by Voyager in 1980 and 1981. Tracking of both Pioneers will continue for many more years, providing fundamental data on the nature of interplanetary space in the depths of the solar system. The results of these outer-planet Pioneer missions have far exceeded our hopes and expectations of a decade ago when the program was initiated.

Robert A. Frosch, Administrator

National Aeronautics and Space Administration

September 1979

NASA

National Aeronautics and Space Administration

Ames Research Center

Moffett Field. California 94035

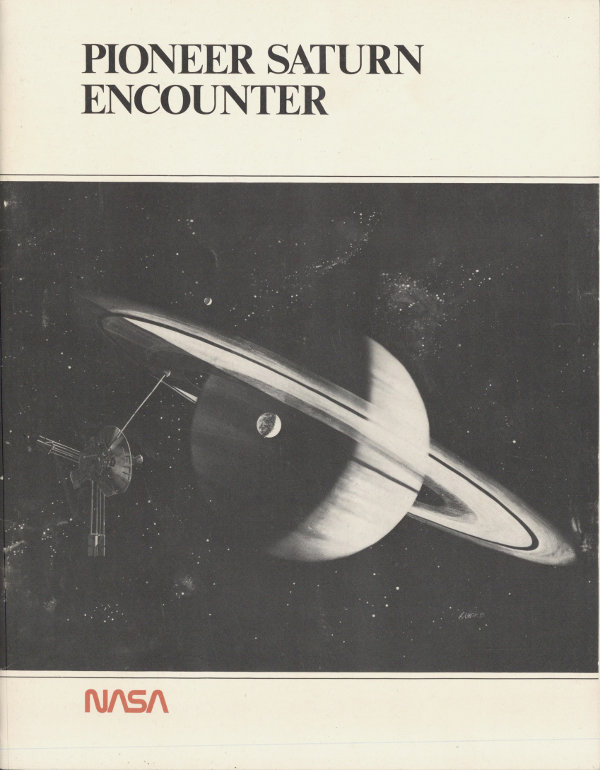

Artist’s drawing of Saturn and its rings showing the Pioneer Saturn spacecraft passing under the rings and nearing closest approach to the planet. Actual pictures could not be obtained at this time because of the high speed of the spacecraft.

We have entered into a new era of space exploration. Missions undertaken during the lunar exploration of the 1960’s typically lasted a matter of days with commands issued and carried out in near real time. Now, a decade later, planetary voyages may last for many years as the spiraling trajectories of the spacecraft make periodic intersections with the orbits of the planets. Communicating with us across the vastness of space, these spacecraft report to us their experiences as they traverse the outer reaches of the solar system.

Among these deep space travelers, Pioneers 10 and 11 are appropriately named, for they truly are pioneering the exploration of the outer solar system. Launched in 1972 and in 1973, respectively, they were the first spacecraft to fly by Jupiter (in 1973 and 1974). At Jupiter, Pioneer 11’s trajectory was carefully targeted to swing it toward Saturn for an encounter in September 1979. We see some of the early results in this publication.

Other spacecraft are following along the trail blazed by Pioneer Saturn. Voyager 1 passed by Jupiter in March 1979 and will reach Saturn in November 1980. Voyager 2 has also passed beyond Jupiter and will encounter Saturn in August 1981, with the further possibility of traveling on to Uranus (a 1986 encounter). Under development are the Galileo orbiter and atmospheric entry probe, destined to journey to Jupiter where the orbiter will return more detailed information, including high-resolution pictures of the Galilean satellites, and the probe will penetrate deep below the Jovian clouds.

In the coming years, each of these follow-on missions will enrich our understanding of the solar system, greatly supplementing the observations of Pioneers 10 and 11. But one thing will never change. The Pioneers were first.

Thomas A. Mutch

Associate Administrator for Space Science

National Aeronautics and Space Administration

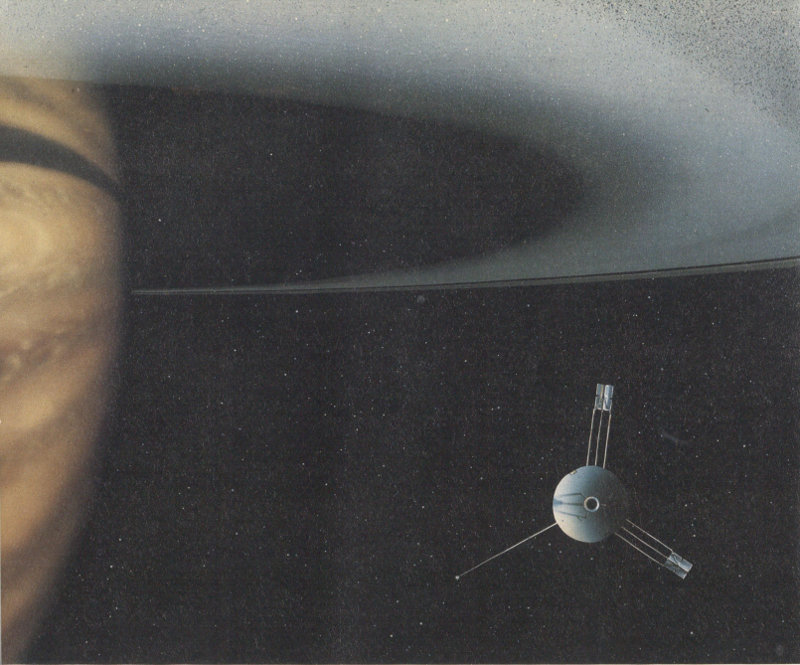

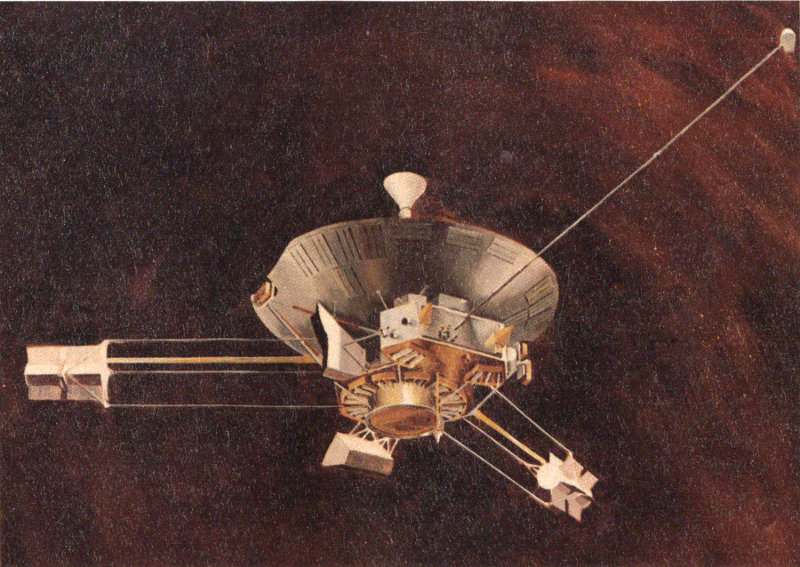

Pioneer Saturn spacecraft.

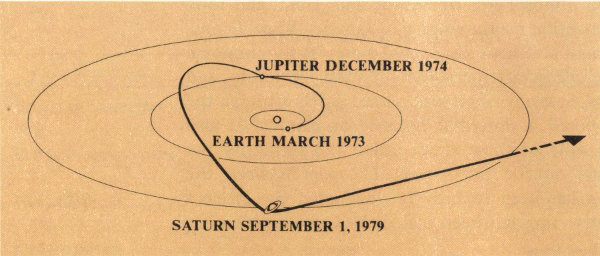

Pioneer Saturn has given us our first close view of the spectacular ringed planet Saturn and its system of moons. The spacecraft began its journey to the giant planets Jupiter and Saturn on April 5, 1973, as Pioneer 11. It reached Jupiter on December 2, 1974, passing within 42,760 km of the Jovian cloud tops and taking the only existing pictures of Jupiter’s polar regions. Jupiter’s massive gravitational field was used to swing Pioneer 11 back across the solar system toward Saturn. Additional maneuvers were executed in 1975 and 1976 to place the spacecraft on a suitable trajectory, with the final aimpoint selected in 1977.

From the many possible targeting options for the first Saturn flyby, two aimpoints were considered, both of which would result in a near-equatorial flyby that would give the best mapping of the high-energy particles and the magnetic field near the planet. The difference between these two aimpoints, which came to be known as the “inside” and “outside” options, was their relationship to Saturn’s unique ring system first discovered by Galileo in 1610. The “outside” option was finally selected because it was considered to be of less risk to the spacecraft and more valuable in planning the subsequent encounter of Saturn by Voyager 2, which will reach Saturn in 5 1981. Final targeting was completed during early 1978, when a series of timed rocket thrusts locked Pioneer into the desired trajectory.

Pioneer Saturn voyage.

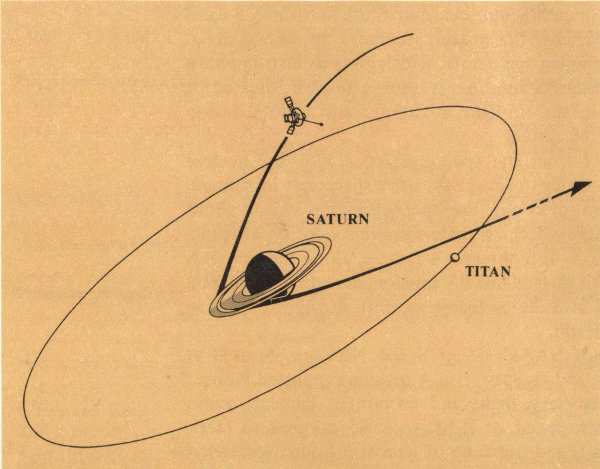

Encounter trajectory.

On September 1, 1979, the spacecraft, now designated Pioneer Saturn, reached Saturn after 6 years in flight. It passed through the ring plane outside the edge of Saturn’s A-ring and then swung in under the rings from 2,000 to 10,000 km below them. At the point of closest approach, it attained a speed of 114,100 km/h (71,900 mi/h) and came within 21,400 km of the planet’s cloud tops. While it was approaching, encountering, and leaving Saturn, the spacecraft took the first closeup pictures of the planet, showing 6 20 to 30 times more detail than the best pictures taken from Earth, and made the first close measurements of its rings and several of its moons, including the largest moon, the planet-sized Titan. Titan, along with Mars, has been considered by many scientists to be the most likely place to find life in the solar system.

Pioneer Saturn unraveled many mysteries. It determined that Saturn has a magnetic field and trapped radiation belts, measured the mass of Saturn and some of its moons, and studied the character of Saturn’s interior. It confirmed the presence and determined the magnitude of an internal heat source for Saturn. Its instruments studied the temperature distribution, composition, and other properties of the clouds and atmospheres of Saturn and Titan, and took photometric and polarization measurements of Iapetus, Rhea, Dione, and Tethys. Pioneer may also have discovered a previously unknown moon of Saturn. The spacecraft measured the mass, structure, and other characteristics of Saturn’s rings, and passed safely through the outer E-ring, which posed a potential hazard for Pioneer. It also discovered new rings. One of these rings, called the F-ring by the Pioneer team, lies just outside the A-ring. The gap between the F-ring and the A-ring has been tentatively designated the Pioneer Division. The other new ring has been called the G-ring, which lies well outside the F-ring.

Pioneer carries a scientific payload of 11 operating instruments; another instrument, the asteroid/meteoroid detector, was turned off in 1975. Two other experiments, celestial mechanics and S-band occultation of Saturn, use the spacecraft radio to obtain data. Pioneer Saturn is a spinning spacecraft, which gives its instruments a full-circle scan 7.8 times a minute. It uses a nuclear source for electric power because the sunlight at Jupiter and beyond is too weak for a solar-powered system.

Two booms project from the spacecraft to deploy the nuclear power source about 3 meters from the sensitive spacecraft instrumentation. A third boom positions the magnetometer sensor about 6 meters from the spacecraft. Six thrusters provide velocity, attitude, and spin-rate control. A dish antenna is located along the spin axis and looks back at Earth throughout the mission, adjusting its view by changes in spacecraft attitude as the spacecraft and Earth move in their orbits around the sun.

Tracking facilities of NASA’s Deep Space Network, located at Goldstone, California, and in Spain and Australia, supported Pioneer Saturn during interplanetary flight and encounter. Pioneer’s radio signals, traveling at the speed of light, took 85 minutes to reach Earth from Saturn, a round-trip time of almost 3 hours, somewhat complicating ground control of the spacecraft. Almost 10,000 commands were sent to the spacecraft in the 2-week period before 7 closest approach. Continued communications should be possible through at least the mid 1980’s.

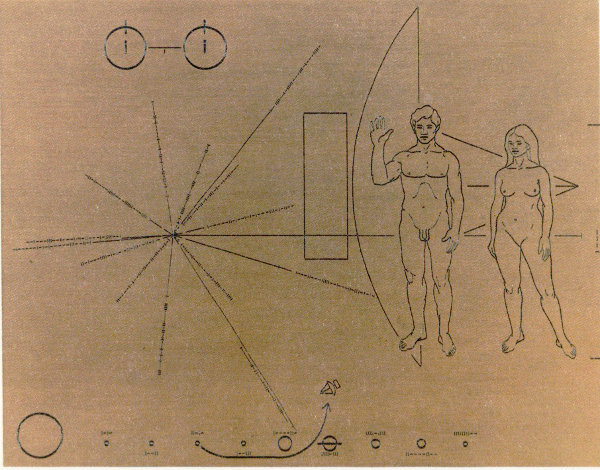

After the spacecraft passed Saturn, it headed out of the solar system, traveling in the direction the solar system moves with respect to the local stars in our galaxy and in approximately an opposite direction from its sister spacecraft, Pioneer 10. Both spacecraft have plaques attached to them which contain a message from Earth for any intelligent species that may intercept the spacecraft during their endless journeys through interstellar space.

| Pioneer Saturn Scientific Instruments | ||

|---|---|---|

| Instrument | Principal Investigator | Experiment Objective |

| Helium vector magnetometer | Edward J. Smith Jet Propulsion Laboratory | Magnetic fields |

| Fluxgate magnetometer | Mario Acuña Goddard Space Flight Center | Magnetic fields |

| Plasma analyzer | John H. Wolfe Ames Research Center | Solar plasma |

| Charged particle | John A. Simpson University of Chicago | Charged particle composition |

| Cosmic ray telescope | Frank B. McDonald Goddard Space Flight Center | Cosmic ray energy spectra |

| Geiger tube telescope | James A. Van Allen University of Iowa | Charged particles |

| Trapped radiation detector | R. Walker Fillius University of California, San Diego | Trapped radiation |

| Asteroid/meteoroid detector[1] | Robert K. Soberman General Electric Co. and Philadelphia Drexel University | Asteroid/meteoroid astronomy |

| Meteoroid detector | William H. Kinard Langley Research Center | Meteoroid detection |

| Radio transmitter and DSN | John D. Anderson Jet Propulsion Laboratory | Celestial mechanics |

| Ultraviolet photometer | Darrell L. Judge University of Southern California Los Angeles | Ultraviolet photometry |

| Imaging photopolarimeter | Tom Gehrels University of Arizona, Tucson | Photo imaging and polarimetry |

| Infrared radiometer | Andrew Ingersoll California Institute of Technology | Infrared thermal structure |

| Radio transmitter and DSN | Arvydas J. Kliore Jet Propulsion Laboratory | S-band occultation |

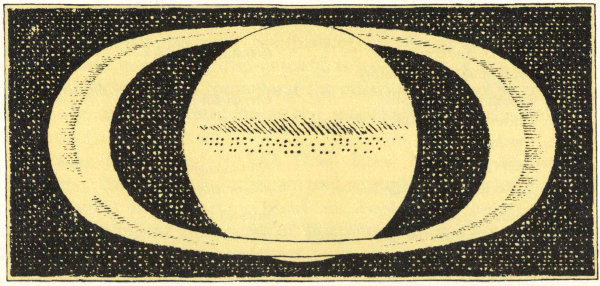

Saturn, called the wonder of the heavens by early astronomers, has been studied from Earth for many centuries. When Galileo first focused his telescope on Saturn in 1610, he realized that the appearance of the planet was unusual, but he never knew its real character because the power of his homemade telescope was far too low. He thought he was looking at three globes, one large and two small, which seemed to change slowly in appearance. In 1655, Huygens, after years of observing the planet, finally realized that these projections were actually a flat ring slightly separated from the main globe.

First sketch of Saturn (Galileo, 1610).

First sketch showing a division in the rings (Cassini, 1675).

In 1675, Cassini found the first breach in the supposedly solid, rigid, and opaque ring when he discovered that it was divided into 9 two parts by a dark line, now known as Cassini’s Division. In later years he also detected some of Saturn’s moons.

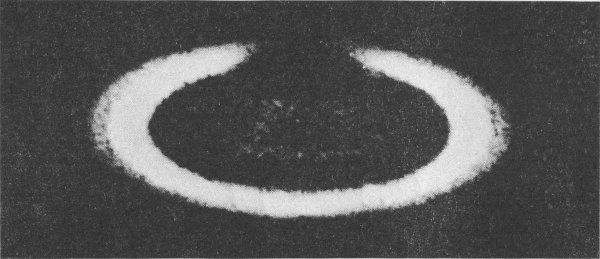

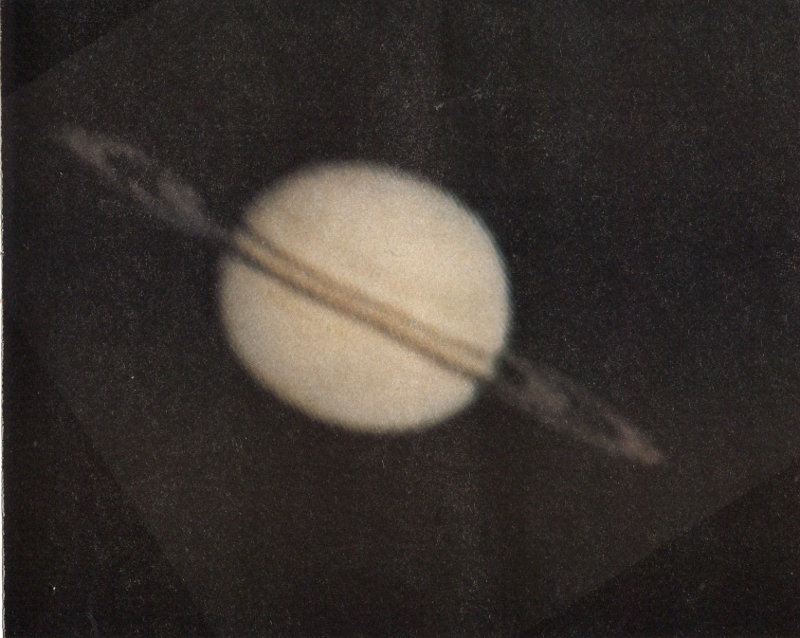

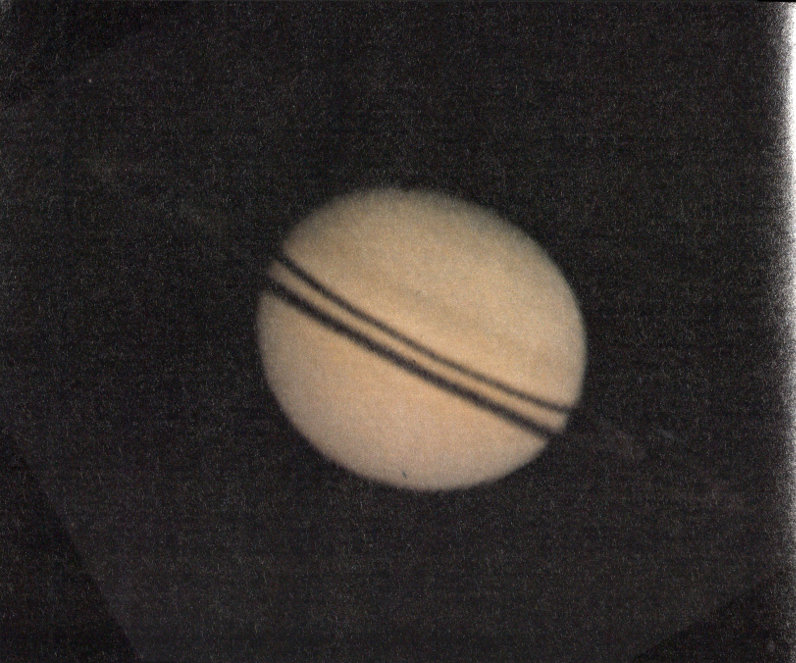

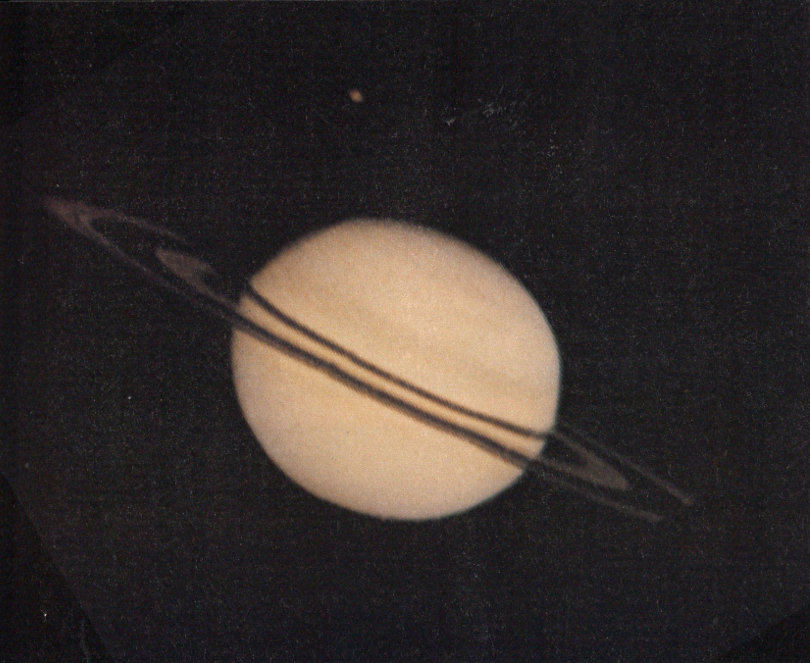

First successful photograph of Saturn (Andrew Common, 1883). (Discovering the Universe, Colin A. Ronan, Copyright 1971 by Colin A. Ronan, Basic Books, Inc., Publishers, New York.)

The earliest successful photograph of Saturn was taken in 1883 by Andrew Common. In 1895, James Keeler suggested that the rings are in fact a swarm of particles in near-independent orbits. These rings, until the recent discoveries of faint ring systems around Jupiter and Uranus, were considered unique in the solar system.

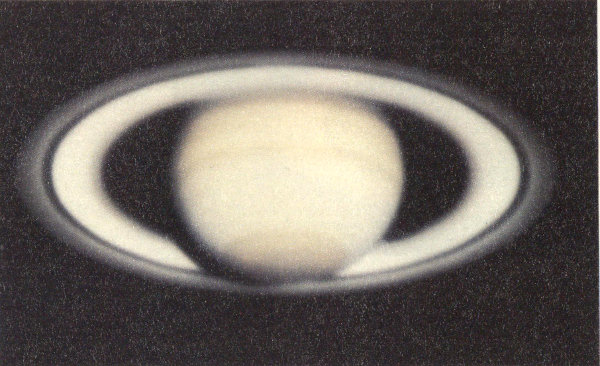

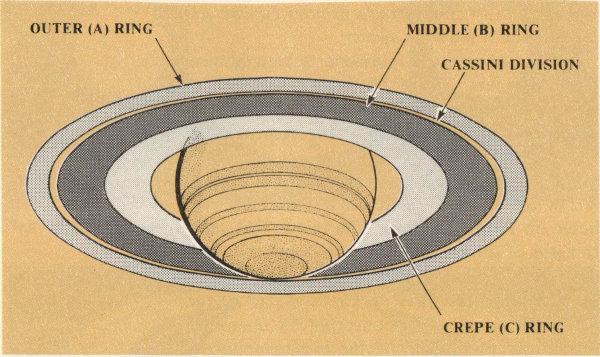

Since Galileo first used his homemade telescope to view Saturn, there have been many observers. There have also been major advances in telescopes; a resulting modern view of Saturn is shown on the next page. The corresponding sketch shows the nomenclature of the brightest rings.

Now the planet has been seen for the first time not from Earth, but in much closer views by an instrument on a spacecraft, the imaging photopolarimeter on Pioneer Saturn. The instrument separately measures the strengths of the red and blue components of sunlight scattered from the clouds of Saturn and converts this information into numbers. The data are transmitted to Earth as part of the spacecraft telemetry. The signals are then converted by computer into shades of gray on photographic film, and the two components plus a synthesized green image can be recombined into a color image that approximates the planet’s true color. Some of the resulting images are shown on the pages following the Earth-based view. These pictures were produced by a scientific team from the University of Arizona.

These images, while helping to unravel some of the mystery surrounding the planet, have created even more interest regarding it. We are really just beginning to know Saturn. It is up to future spacecraft to more completely reveal her secrets and solve her mysteries.

High-quality contemporary Earth-based view of Saturn (Photo: Catalina Observatory, University of Arizona).

Nomenclature of bright rings.

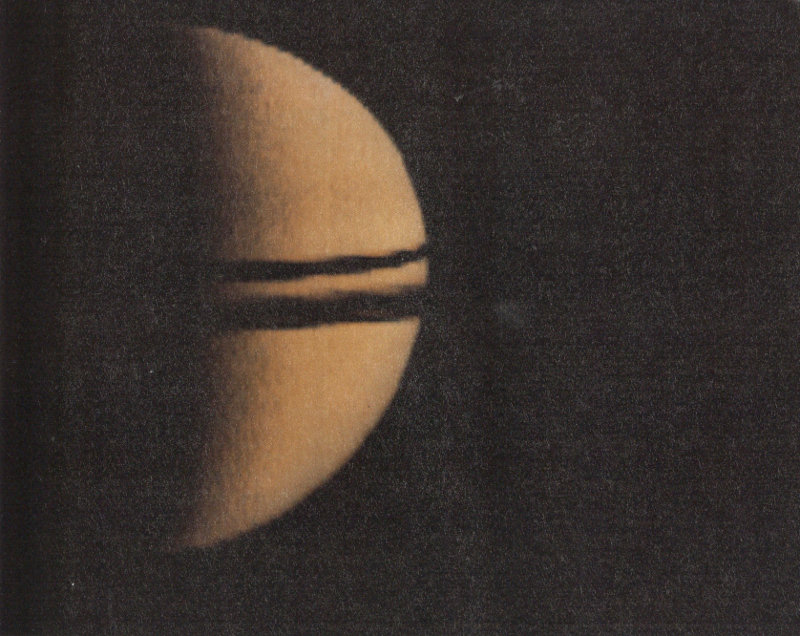

Pioneer Saturn image of Saturn and its rings from a distance of 8,400,000 km (August 22, 1979, 10 days before closest approach). Resolution has not yet reached Earth-based quality. Faint banding is visible on the disk of the planet. The silhouette of the rings can be seen in front of the planet. Slightly above this silhouette is the shadow of the rings on the disk. Beyond the disk, structure can be seen in the rings. The rings have a distinctly different appearance in this and subsequent images than in Earth-based pictures because they are illuminated from below rather than from above as we view them from Earth. The A-ring and C-ring are bright, and between them the B-ring is dark. The Cassini Division at the inner edge of the A-ring is also bright, but is blended with the ring at this distance.

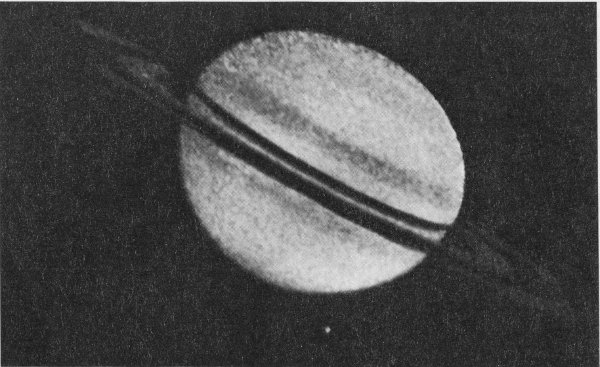

Pioneer Saturn image of Saturn and its rings from a distance of 5,500,000 km (August 26, 1979, 6 days before closest approach). Resolution of features is beginning to be approximately equal to that of Earth-based pictures. Belts on the planet are becoming more distinct, and considerable structure can be seen in the rings. The small blue spot at the bottom of the planet is due to incomplete data and will be corrected by further processing. A notch appears at the top left of the planet, which may be a data transmission problem or the shadow of one of Saturn’s moons.

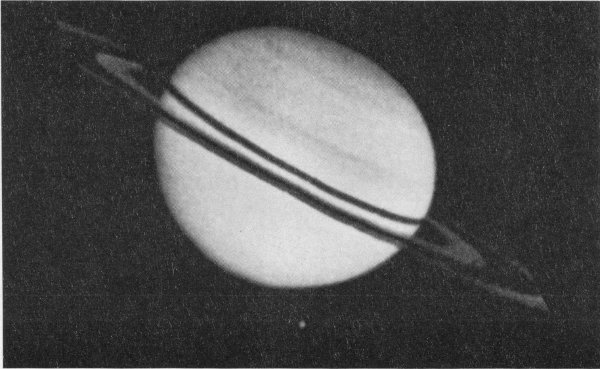

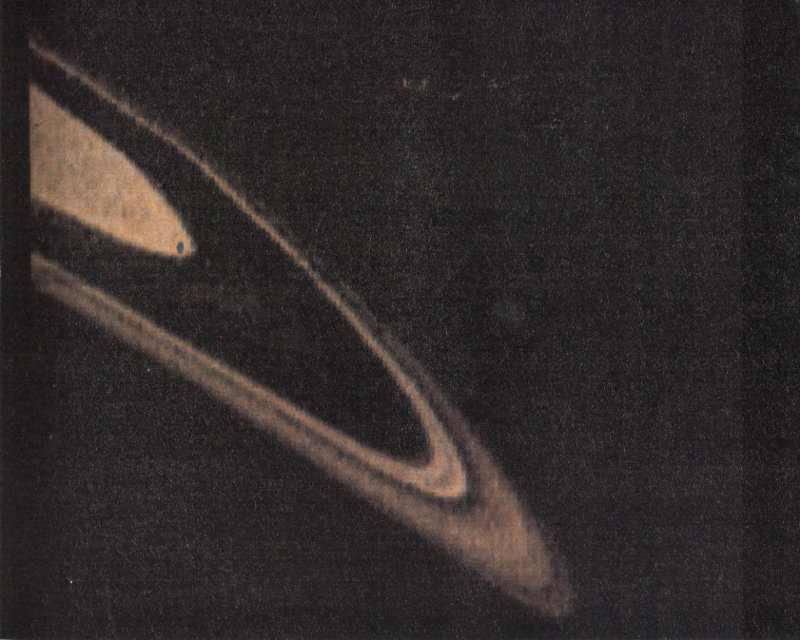

Pioneer Saturn image of Saturn and its rings from a distance of 2,800,000 km (August 29, 1979, 72 hours before closest approach). The Cassini Division at the inner edge of the A-ring is clearly resolved and is bright. The A-ring is dark outside the Cassini Division because it has more particulate matter there. Polar belts are becoming more visible on the face of the planet. Irregularities that appear in the ring silhouette and shadow are due to stepping anomalies in the imaging photopolarimeter and will be removed in further processing. The small round image that appears above the planet is the moon Titan.

These pictures of Saturn and its rings were taken by Pioneer Saturn from a distance of 2,500,000 km (August 29, 1979, 58 hours before closest approach). The imaging photopolarimeter gathers data using the red and blue components of the light reflected from Saturn. These two views are from the two color components (upper, blue; lower, red). The banded structure on the planet is particularly evident in the upper image. Because the spacecraft is nearing the planet, the rings are partially outside the field of view of the instrument. The speck of light below the planet is Saturn’s moon Rhea, which is 1450 km in diameter, about one-half the size of Earth’s moon.

This image was produced by combining the two images on the facing page, adding a synthesized green component, and adjusting the intensity of each to obtain an approximation to Saturn’s true color. (The same process was used in all of the Pioneer color images of Saturn shown here.) Although not evident on this reproduction, scientists believe that, from detailed study of both the uncombined and the combined images, they can begin to see evidence of jet streams in Saturn’s upper atmosphere. The slight blue edge is an artifact from the computer-enhancement procedure.

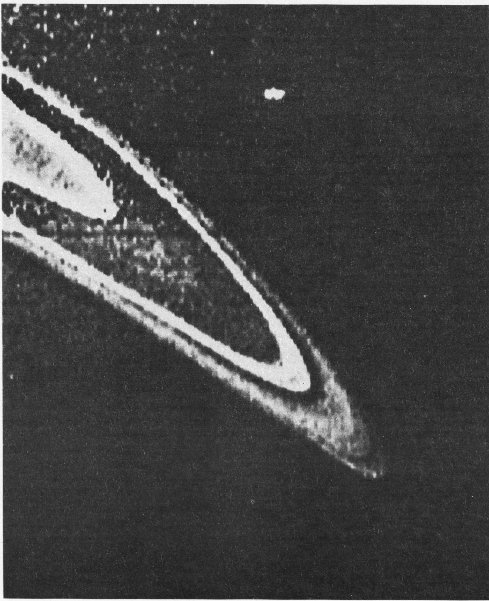

Pioneer Saturn view showing the structure of Saturn’s ring system in detail never before seen. The image was taken from a distance of 943,000 km (August 31, 1979, about 44 hours before encounter). The moon Tethys, seen at the top of the image, is 1200 km in diameter. There is a very faint unidentified Saturnian moon at the lower right, just off the tip of the bright A-ring (may not be visible in this print). The newly defined F-ring appears faintly just outside the bright edge of the A-ring. The region between the A-ring and the F-ring has been tentatively named the Pioneer Division. This print has been processed to enhance detail of the main rings.

A color print of a version of the same image as shown on the facing page. The blue dot at the outer edge of the C-ring is an artifact. This image has not been computer processed to the same extent as the facing image. Tethys, for example, is only faintly visible, and the F-ring cannot be seen.

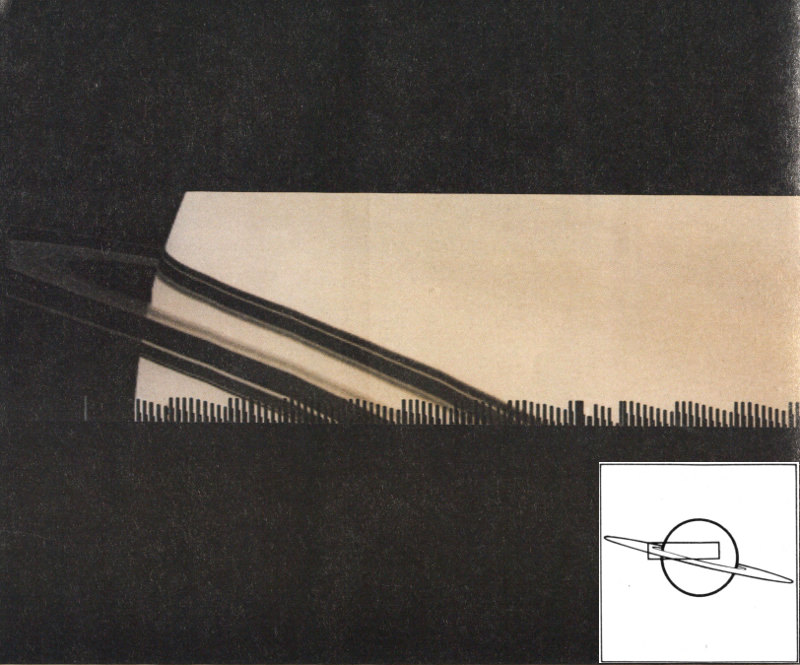

Close-up image from Pioneer Saturn of Saturn from a distance of 400,000 km (September 1, 1979, a few hours before closest approach). Inset shows the location of the image on the planet. The part of the disk shown is about 25,000 by 70,000 km. The sawtooth pattern is an artifact. The vertical stripe on the disk is due to a gain change in the instrument. The image has not had its final corrections for shape. The rings and their shadows cut diagonal swaths across the image with the upper swath being the shadow. The rings, seen from the unlit side, are visible in the foreground. The ring shadow shows clearly that Saturn’s rings have two major divisions: the Cassini Division dividing the outer A-ring from the middle B-ring, and a second division (previously controversial) dividing the B-ring from the inner C-ring. These divisions show as parallel pinstripes in the broad black band of the rings’ shadow, with the upper stripe being the Cassini Division. Some shearing in the bands and belts on Saturn’s disk is beginning to appear, although the low contrast on the planet (due to its high-altitude haze) does not make this highly evident.

Post-encounter image of Saturn from a distance of 850,000 km (September 2, 1979, 15 hours after encounter). As planned, during the encounter Saturn’s gravitational field turned the spacecraft’s trajectory behind the planet and out toward the edge of the solar system at approximately a right angle to the inbound trajectory. Thus, the planet is now illuminated from the side, and the view is of a crescent Saturn with the terminator on the right of the picture. The rings appear dim when compared with the previous inbound pictures because of the different angle between the sun, the rings, and the spacecraft. When this picture was taken, the spacecraft, as seen from Earth, was about to pass behind the sun, and solar activity was interfering with spacecraft communications. The image quality, therefore, is not as good as for pictures taken inbound. With this farewell image from Pioneer, Saturn waits for the Voyager spacecraft in 1980 and 1981.

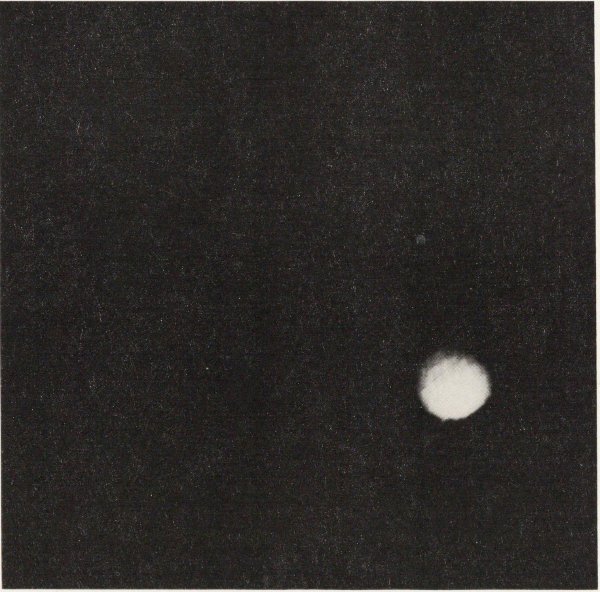

This image of cloud-covered Titan is one of the “firsts” for the Pioneer Saturn mission. Titan is the largest of Saturn’s moons. Because of its great distance from Earth, however, Titan can be seen only as a point of light in Earth-based pictures. The Pioneer trajectory could not be adjusted to allow passage close to Titan, and imaging of the planet from the spacecraft was at the outer range of capability of the imaging instrument. Thus, the fuzzy edges and contrast variations on the moon should not be construed as surface features.

Titan was imaged in the spirit of exploration and discovery. With this image, which is now a part of recorded history, our visual information on Titan is materially increased, but is still only roughly equal to Galileo’s information on Saturn itself in 1610 at the time that he prepared his first sketch. Better images of Titan will be obtained by the Voyager spacecraft.

Pioneer Saturn has already greatly expanded our knowledge of Saturn, its rings and moons. We now know that Saturn, in many ways, represents an intermediate case between Jupiter, the largest planet in the solar system, and Earth. The composition of Saturn’s interior is essentially the same as Jupiter’s, differing only in the size and extent of the various internal layers. Measurements for Saturn are consistent with a central core of molten heavy elements (probably mostly iron) which is the approximate size of the entire Earth, but about three times more massive. Surrounding the central core is an outer core of highly compressed hot, liquefied volatiles such as methane, ammonia, and water. This outer core is equivalent to approximately nine Earth masses. These core regions, however, represent a very small fraction of the planet, which is composed primarily of the very lightest gases, hydrogen and helium, and is almost 100 times the mass of the Earth. Because of the high pressure in Saturn’s interior, the hydrogen is transformed to its liquid metallic state. Above this metallic hydrogen shell are liquid molecular hydrogen and Saturn’s gaseous atmosphere and clouds, which make up the rest of the planet.

Electrical currents set up within the metallic hydrogen shell produce Saturn’s magnetic field, which was measured by Pioneer. In spite of Saturn’s large size, the magnetic field at the cloud tops is only slightly weaker than the field at the Earth’s surface. Saturn is unique in that its magnetic axis is nearly aligned with its rotation axis, unlike Earth and Jupiter.

Saturn’s magnetic field is also much more regular in shape than the fields of the other planets. At large distances from Saturn, the magnetic field is deformed by the inward pressure of the solar wind. Near the noon meridian (close to the inbound Pioneer trajectory), the solar wind causes a compression of the field; in the dawn meridian (close to the outbound trajectory), the field is swept back and presumably forms a long magnetic tail. In both cases, Pioneer Saturn crossed the outer boundary of the magnetic field several times as the field moved in and out, responding to changing solar wind pressure. Pioneer also observed inward and outward boundaries.

The magnetic envelope surrounding Saturn is intermediate in size and energetic particle population between those of the Earth and Jupiter, the only two other planets known to be strongly magnetized. The three other planets investigated thus far (Venus, Mars, and Mercury) and Earth’s moon have little or no magnetism. Virtually all 22 our knowledge of Saturn’s magnetic environment has been obtained by Pioneer. The spacecraft found rings of particulate material and several small moons near the rings, which strongly affect Saturn’s trapped radiation. These features provide important diagnostic capabilities. A unique finding is the nearly total absence of radiation belt particles at distances closer to the planet than the outer edge of the visible rings.

The inner region of the thick magnetic envelope of Saturn, called the magnetosphere, contains trapped high-energy electrons and protons, with some evidence for heavier nuclei. The overall form of the magnetosphere is simple and compact, more similar to that of Earth than of Jupiter. The unique measuring capabilities of the Pioneer Saturn radiation detectors led directly to the discovery of a diffuse new ring of particulate matter in the region from about 10 to 15 planetary radii (1 Saturn radius = 60,000 km) from Saturn. This ring has been tentatively designated as the G-ring. The G-ring clearly causes particle absorption near the equatorial region. Moreover, Pioneer discovered another region inside 7 or 8 planetary radii in which the radiation belt particles were subjected to a strong loss or absorption, presumably caused by the presence of an extensive cloud of plasma corotating with the planet.

Inside about 10 planetary radii, the trapped radiation shows a high degree of axial symmetry around Saturn and is consistent with the centered dipole magnetic field observed by Pioneer. Saturn’s rings annihilate all trapped radiation at the outer edge of the A-ring, leaving a shielded region close to the planet in which the radiation intensity is the lowest so far encountered in this mission. This shielding prevents the further buildup of electron intensities at lower altitudes, which otherwise would have been present and would have made Saturn a strong radio source observable from Earth.

Pioneer found that several of Saturn’s moons absorb trapped particles from the radiation belts, producing prominent dips in the intensity. The effectiveness of absorption at the moons Tethys and Enceladus is particularly astonishing, and supports the idea that radiation belt particles are drifting inward slowly across the moons’ orbits.

A precipitous decrease in particle intensity, lasting only for about 12 seconds, was observed over a wide range of energies for both protons and electrons at a distance near 2.53 Saturn radii, 23 minutes after Pioneer crossed the Saturn ring plane inbound. At about the same time, an anomaly was also observed in the magnetic field measurements. These phenomena have been tentatively interpreted as indicating the presence of a nearby massive body absorbing the trapped radiation and perturbing Saturn’s magnetic field. The estimated radius of this object lies in the range of 100 to 300 km, 23 based on the effectiveness with which it absorbed the high-energy radiation. The total radiation dose received at Saturn was equivalent to only 2 minutes in the Jovian radiation belts because Saturn’s radiation belts were so much weaker.

In addition to images of Saturn, the brightness, color, and polarization of the reflected light were also measured by the imaging photopolarimeter on Pioneer Saturn. These measurements are used to study the cloud layers of Saturn and Titan and to model the vertical structure of the atmospheres of these two bodies. In the scans that made the images, the banded structures of Saturn and of the rings were obtained in fine detail. These are essential in studying the atmosphere, rings, and moons. A new Saturnian ring, which has been tentatively designated the F-ring, was discovered in the images. It is narrower than 500 km in width, but is important because it forms an outside barrier to the bright A- and B-rings. The gap between the F- and A-rings has been designated the Pioneer Division by the Pioneer team. A small moon, which either was previously unknown or had been previously discovered from Earth but lost again, was found in the Pioneer Saturn images. After its initial discovery, this new moon continued on its 17-hour orbit around the planet and passed near Pioneer as the spacecraft entered the ring system. It is quite conceivable that this moon is the same one that perturbed the radiation belt particles and produced the anomaly in the magnetic field measurements.

Infrared observations obtained during the Saturn flyby revealed the temperatures in the atmospheres of Saturn and the rings and in the atmosphere of Titan. It was found that Saturn has a temperature of about 100 K (about 280°F below zero) and, according to these observations, has an internal heat source of enough strength that the planet emits approximately 2.5 times as much energy as it absorbs from the sun. The equatorial yellowish band observable in many of the images was found to be several degrees colder than the planet at other latitudes and is probably a zone of high clouds resembling similar zones on Jupiter. As expected, the rings were extremely cold, 65 to 75 K (about 330°F below zero), at the time of encounter. The temperature differences between the illuminated and unilluminated sides of the rings, and the rate of cooling as the ring particles go into Saturn’s shadow, suggest that the ring particles are at least several centimeters in diameter and the rings themselves are many particle diameters thick. The very minor perturbation to Pioneer’s trajectory, as it passed under the visible rings, indicates that the rings probably consist of ices.

As Pioneer passed through Saturn’s ring system, very sensitive meteoroid detectors observed the impact of five particles on the spacecraft, particles that were about 10 micrometers (0.0005 inch) 24 in diameter. Two impacts occurred while the spacecraft was above the rings and three while the spacecraft was below the rings. No impacts were detected going through the ring plane, but the Pioneer instrument cannot detect individual impacts that occur less than 77 minutes apart. This characteristic would have prevented detection of ring particles because of the impacts detected just before both ring plane crossings. It is uncertain whether the micrometeoroids detected by Pioneer Saturn were stray ring particles deflected out of Saturn’s ring plane or whether they were particles from interplanetary space drawn inward toward Saturn by its strong gravitational field.

Close to the point of closest approach to Saturn, the spacecraft’s radio transmissions were affected by Saturn’s ionosphere. The manner in which the radio signals were absorbed indicates that Saturn has an extensive ionosphere composed of ionized atomic hydrogen with a temperature of about 1250 K in its upper regions. This high temperature requires an extensive energy source other than the sun. This phenomenon was also observed at Jupiter.

Pioneer measured ultraviolet glow throughout the Saturnian system. This ultraviolet glow is due to the scattering of the light from the sun by atomic hydrogen. The observations of ultraviolet emission from an extensive cloud of hydrogen gas surrounding Saturn’s visible rings are especially interesting. The rings themselves are presumably the source of this hydrogen. On the planet’s disk, the ultraviolet observations show significant latitude variations, suggesting the possibility of aurora near Saturn’s polar regions. A similar extensive cloud of hydrogen was also seen partially surrounding Titan’s orbit.

These very preliminary findings by Pioneer Saturn represent only a small fraction of what will ultimately be learned about Saturn and its environment as the spacecraft data are analyzed in greater detail over the weeks and months ahead.

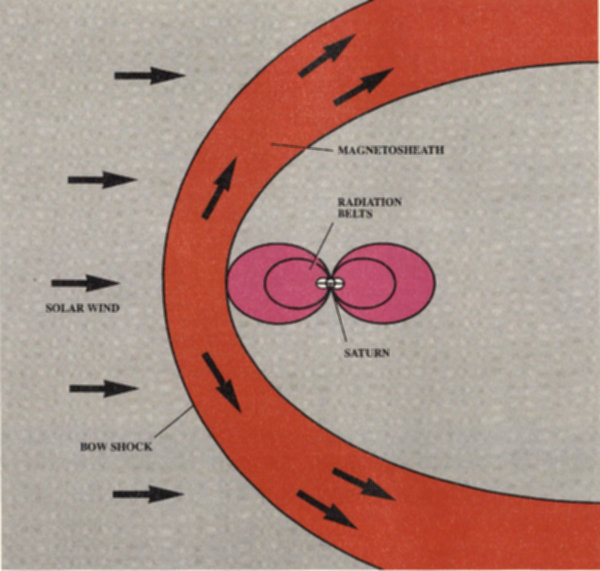

Schematic of the solar wind interaction with Saturn’s magnetosphere. The solar wind arrives from the direction of the sun, is deflected at Saturn’s bow shock, and flows around Saturn in the magnetosheath (orange region), as indicated by the arrows. The sizes of the magnetosheath and radiation belts change in response to the external solar-wind pressure, becoming smaller when the external pressure is larger and vice versa.

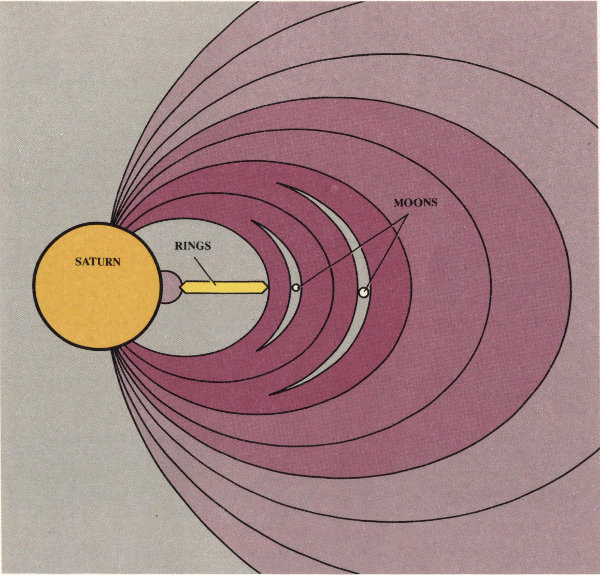

Diagram of Saturn’s inner trapped radiation belts. The energetic particle fluxes generally become more intense closer to Saturn. Decreases in particle flux at the locations of Saturn’s moons are due to the sweeping up of the energetic particles caused by particles striking the moons and being absorbed by them. Also, there are decreases in particle flux at the outer edge of the rings, where the energetic particles are also absorbed, so that a region free of trapped radiation is created from the outer edge of the rings to Saturn.

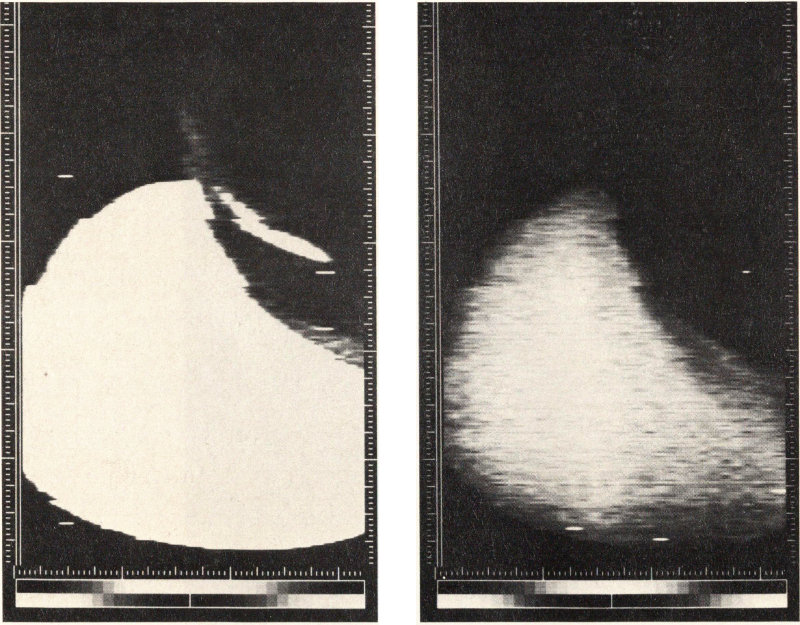

Infrared radiometer image of Saturn and its rings. Brightness in the image is related to temperature, with the brightest areas at about 100 K (about -280°F). The left version shows contrast in the colder regions (the rings). The right version shows contrast in the warmer regions (the planet). The image contains many separate scans from top to bottom. Each scan is displaced to the right from the one before by the motion of the spacecraft. The spacecraft was below the ring plane during most of the 3-hour observation period and was much closer to the planet at the end of the period (right of image) than at the start (left of image). Thus, the images are quite distorted. The small-scale pattern is instrument noise. In the left image, the warm infrared radiation from the planet is seen through Cassini’s Division between the A- and B-rings. The brightness level in the right image implies that Saturn emits heat at a rate that is 2.5 times the rate that it absorbs energy from the sun.

After increasing our knowledge of the Saturnian system manyfold, the spacecraft is now outward bound. It carries a message, engraved on a plaque, from Earth to any inhabitants of another star system who might discover the spacecraft. With its journey far from over, Pioneer Saturn travels on—to the outer reaches of space.

The Pioneer Project is managed by the Ames Research Center for the National Aeronautics and Space Administration. The spacecraft was built by TRW Systems, Redondo Beach, California.

National Aeronautics and Space Administration

Ames Research Center

Moffett Field, California 94035

Official Business

Penalty for Private Use, $300

Postage and Fees Paid

National Aeronautics and Space Administration

NASA-451