In Part collected by the late J. G. FENNELL; now largely augmented with manifold matters of singular note and worthy memory by the Author and his friend J. M. D——.

HAT

the history and curiosities of Ale

and Beer should fill a bulky volume,

may be a subject for surprise to the

unthinking reader; and that surprise

will probably be intensified, on his

learning that great difficulty has been

experienced in keeping this book within

reasonable limits, and at the same time doing anything like

justice to the subject. Since the dawn of our history Barley-wine has

been the “naturall drinke” for an “Englysshe man,” and has had

no unimportant influence on English life and manners. It is, therefore,

somewhat curious that up to the present, among the thousands of

books published annually, no comprehensive work on the antiquities

of ale and beer has found place.

HAT

the history and curiosities of Ale

and Beer should fill a bulky volume,

may be a subject for surprise to the

unthinking reader; and that surprise

will probably be intensified, on his

learning that great difficulty has been

experienced in keeping this book within

reasonable limits, and at the same time doing anything like

justice to the subject. Since the dawn of our history Barley-wine has

been the “naturall drinke” for an “Englysshe man,” and has had

no unimportant influence on English life and manners. It is, therefore,

somewhat curious that up to the present, among the thousands of

books published annually, no comprehensive work on the antiquities

of ale and beer has found place.

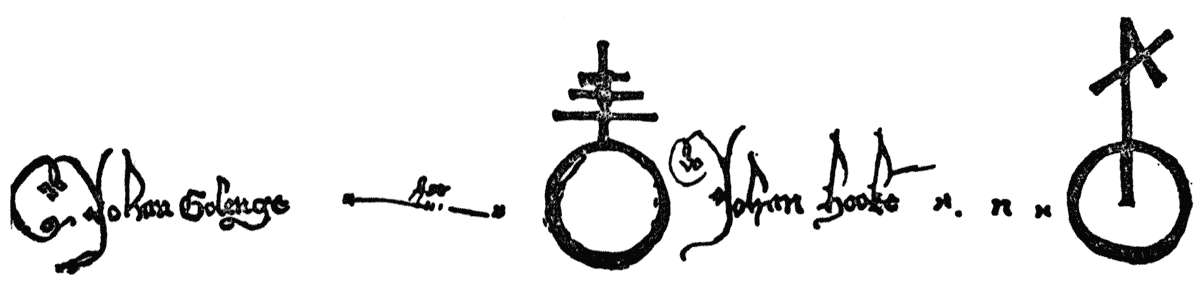

Some years ago this strange neglect of so excellent a theme was observed by the late John Greville Fennell, best known as a contributor to The Field, and who, like “John of the Dale,” was a “lover of ale.” With him probably originated the idea of filling this void in our literature. As occasion offered he made extracts from works bearing on the subject, and in time amassed a considerable amount of material, which was, however, devoid of arrangement. Old age overtaking him before he was able to commence writing his proposed book, he asked me to undertake that which from failing health he was unable to accomplish. To this I assented, and at the end of some months had prepared a complete scheme of the book, with the materials for each chapter carefully grouped. That arrangement, for which I am responsible, has, with a few slight modifications, been carefully adhered to. The work did not then proceed further, as to carry out my scheme a large amount of additional matter, from sources not then available, was required. A few months later my friend was taken seriously ill, and, finding his end approaching, directed that on his decease all papers connected with the book should be placed at my disposal. His death seems to render a statement of our respective shares in the book desirable.

When able to resume work on the book, with the object of hastening its publication, I obtained the assistance of my friend, Mr. J. M. D——. By the collection of fresh matter, in amplification of that already arranged, and the addition of several new features, we have considerably increased the scope of the work, and, it is to be hoped, added to its attractiveness. To my friend’s researches in the City of London and other Records is due the bringing to light of many curious facts, so far as I am aware, never before noticed. He has also rendered me great assistance in those portions of the book in which the antiquities of the subject are specially treated.

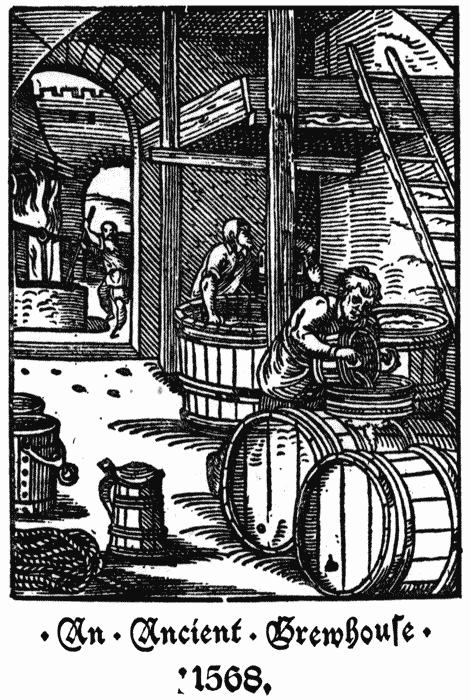

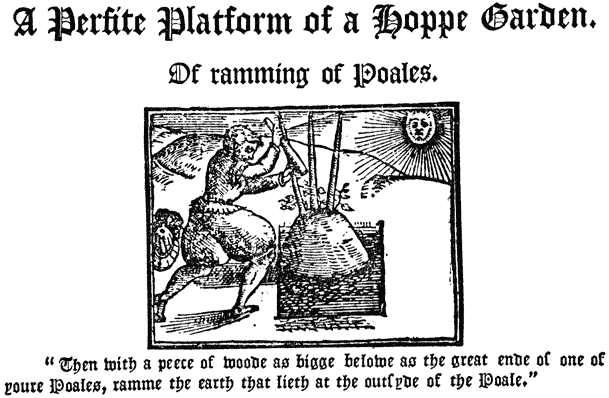

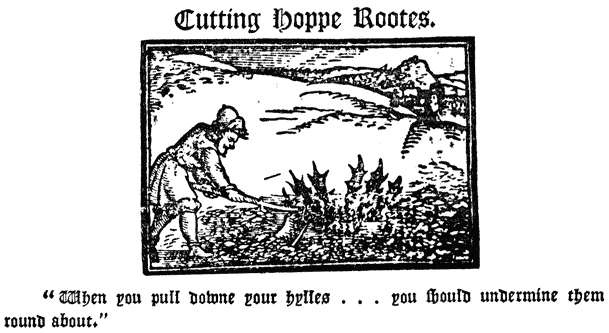

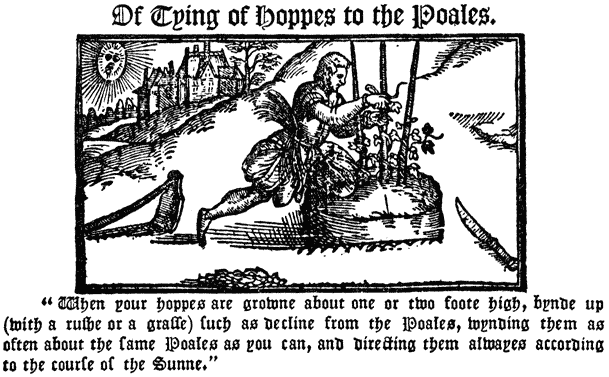

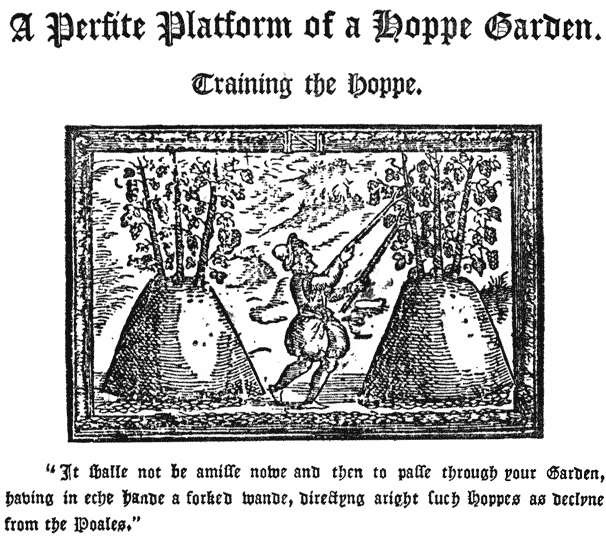

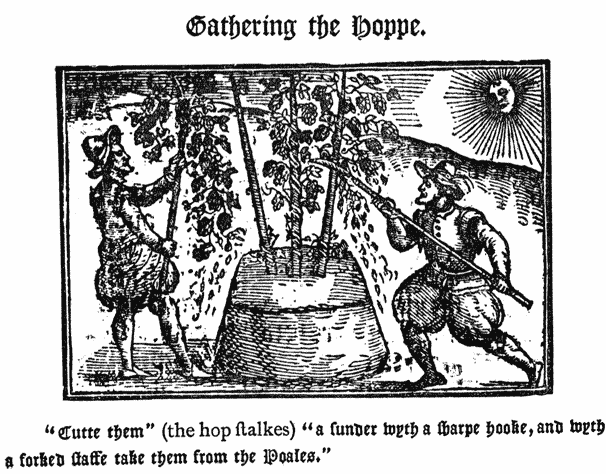

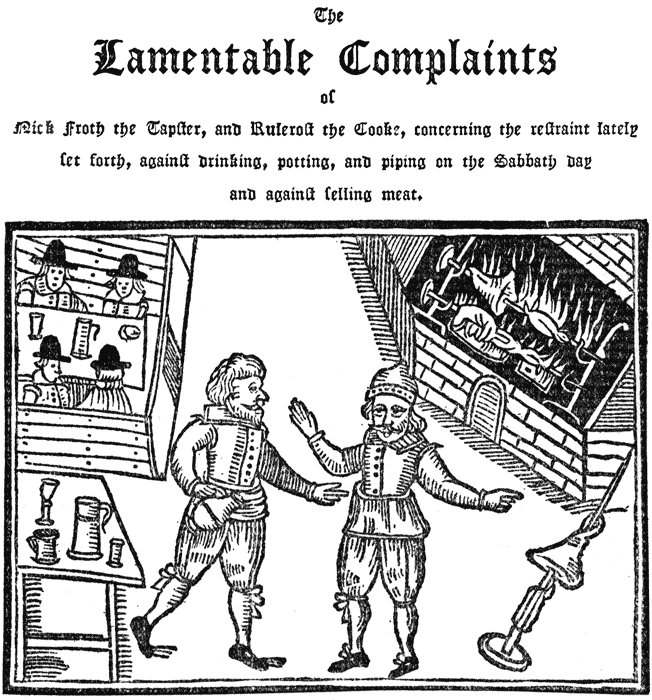

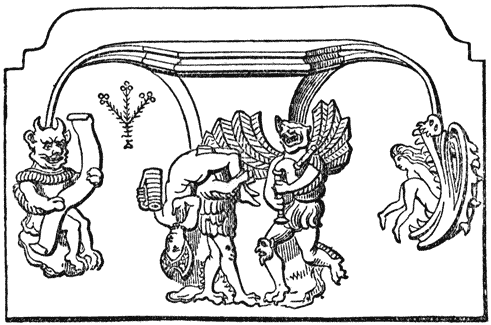

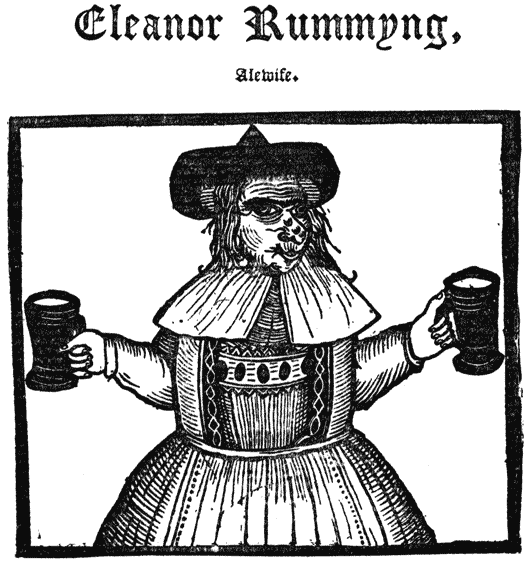

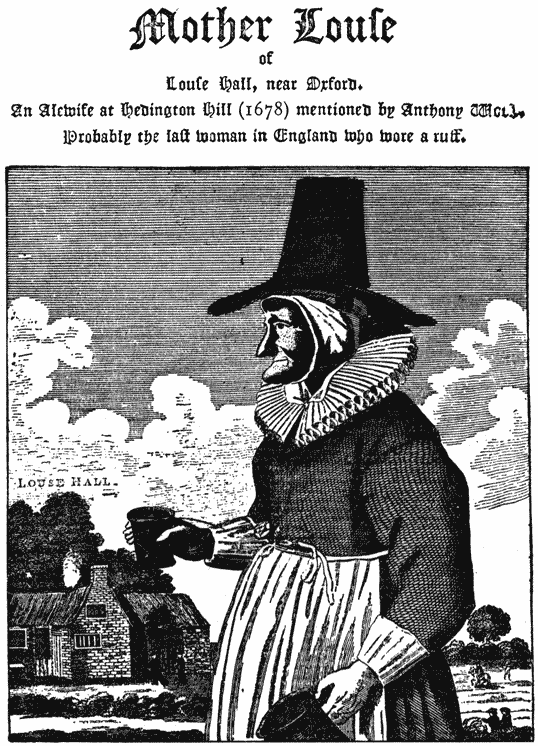

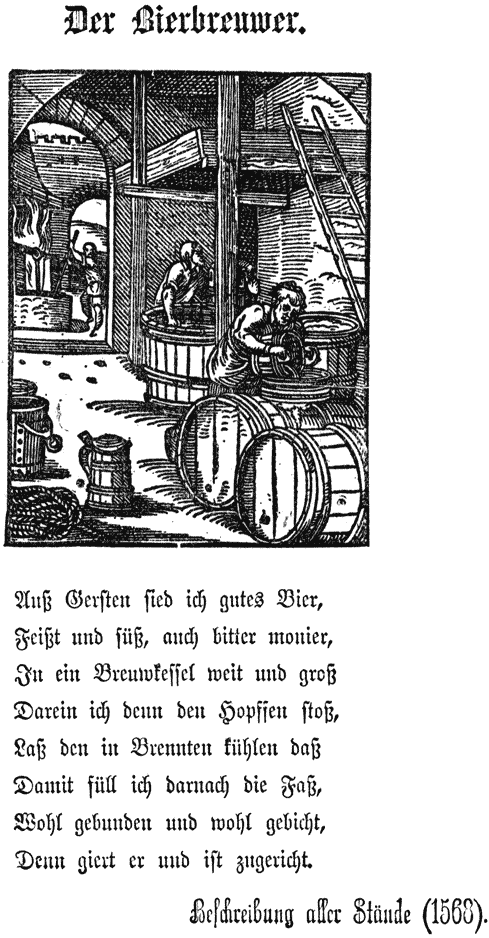

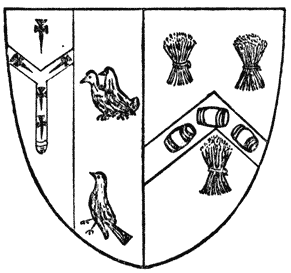

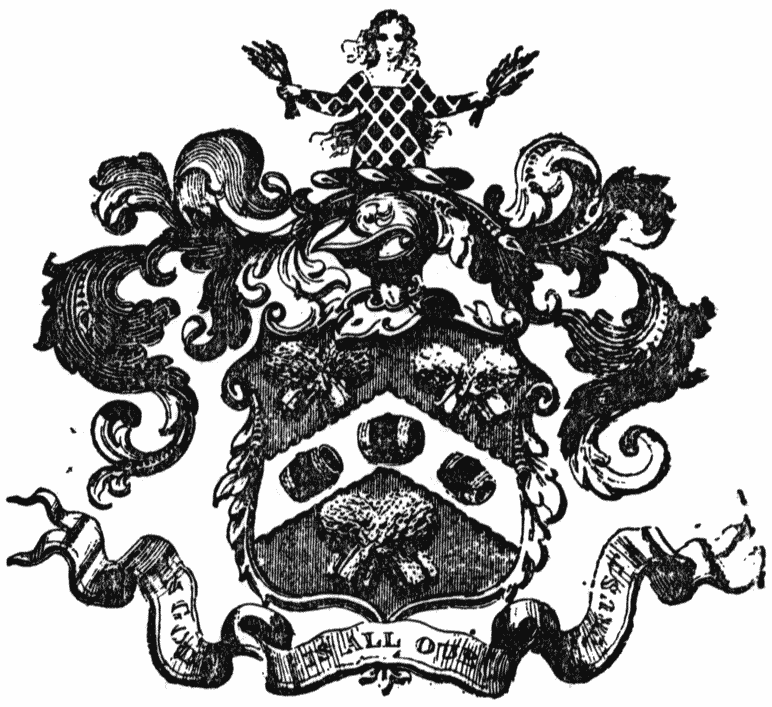

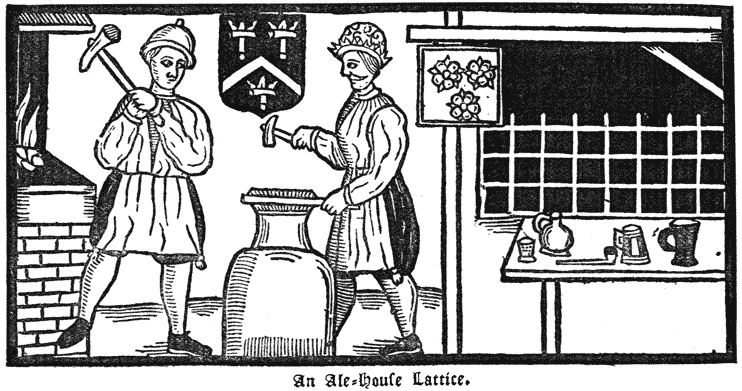

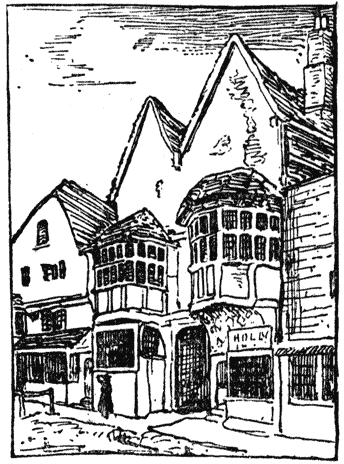

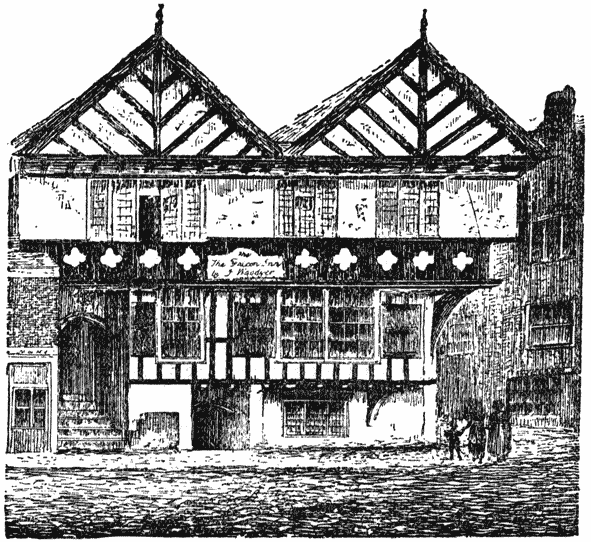

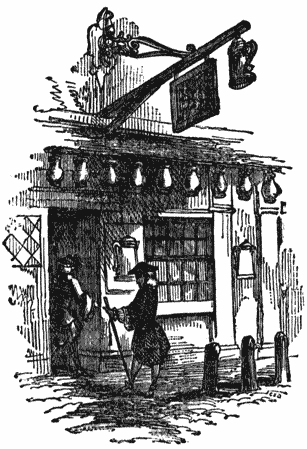

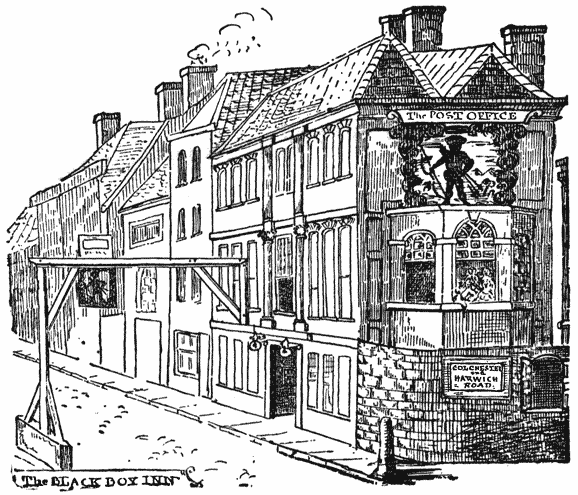

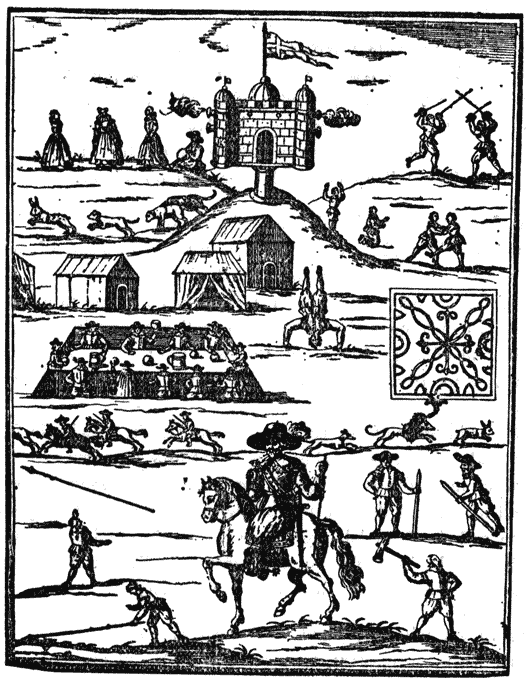

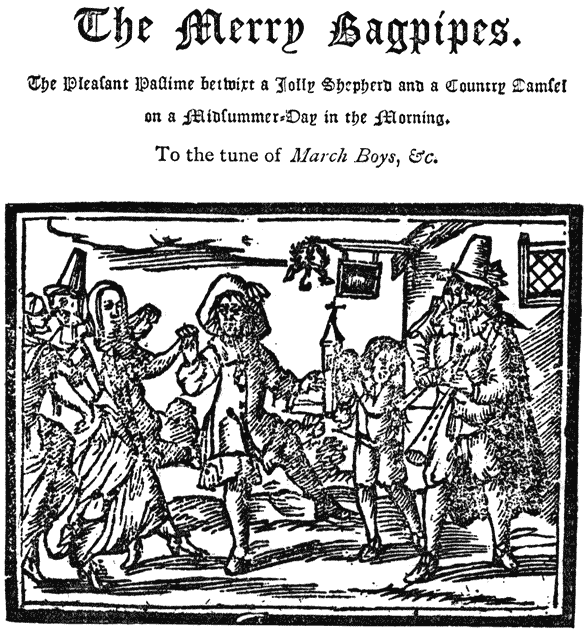

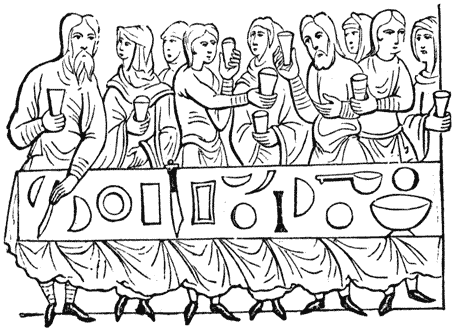

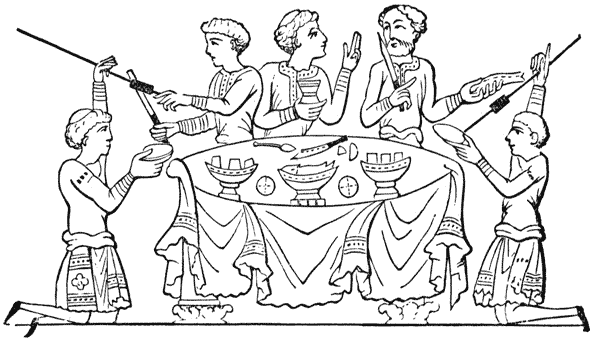

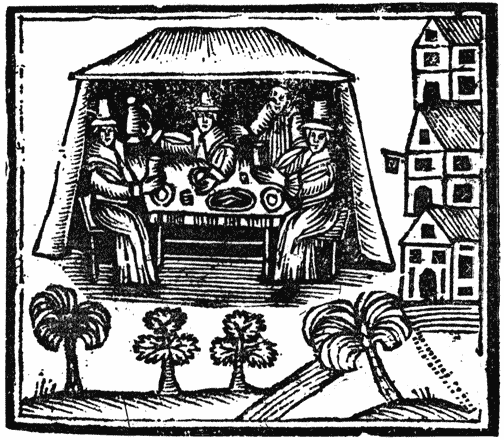

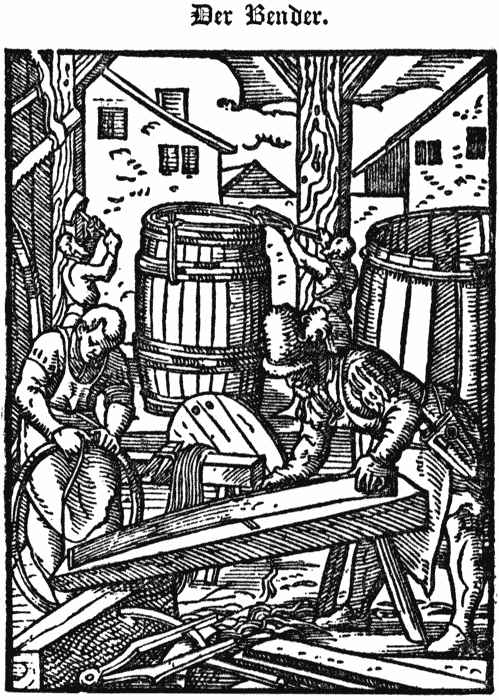

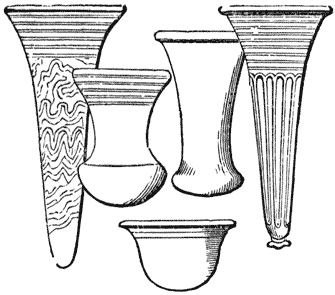

The illustrations have been in most part taken from rare old works. As any smoothing away of defects in such relics of the past would be deemed by many an offence against the antiquarian code of morality, they have been reproduced in exact fac-simile, and will no doubt appeal to those interested in the art of the early engraver, and amuse many with their quaintness.

As aptly terminating the chapter devoted to an account of the medicinal qualities of ale and beer, I have ventured to enter upon a short consideration of the leading teetotal arguments. In extending their denunciations to ale and beer drinkers, the total abstainers are, in my opinion, working a very grievous injury on the labouring classes, who for centuries have found the greatest benefit from the use of malt liquors. Barley-broth should be looked upon as the temperance drink of the people or, in other words, the drink of the temperate.

I have gratefully to acknowledge the kindness and courtesy accorded me during the preparation of this work by the authorities of the British Museum, by Dr. Sharpe, Records Clerk of the City of London, by Mr. Higgins, Clerk of the Brewers’ Company, and by several eminent brewers and a large number of correspondents.

JOHN BICKERDYKE.

SUPPRESSION OF BEER SHOPS IN EGYPT 2,000 B.C. — BREWING IN A TEAPOT. — ALE SONGS. — DISTINCTIONS BETWEEN ALE AND BEER. — ALE-KNIGHTS’ OBJECTION TO SACK. — HOGARTH AND TEMPERANCE. — IMPORTANCE OF ALE TO THE AGRICULTURAL LABOURER. — SIR JOHN BARLEYCORNE INTRODUCED TO THE READER.

OUR thousand years ago,

if old inscriptions and papyri lie not, Egypt was convulsed by the

high-handed proceedings of certain persons in authority who inclined to

the opinion that the beer shops were too many. Think of it, ye modern

Suppressionists! ’Tis now forty centuries since first your theories saw

the light, and yet there is not a town in our happy country without its

alehouse.

OUR thousand years ago,

if old inscriptions and papyri lie not, Egypt was convulsed by the

high-handed proceedings of certain persons in authority who inclined to

the opinion that the beer shops were too many. Think of it, ye modern

Suppressionists! ’Tis now forty centuries since first your theories saw

the light, and yet there is not a town in our happy country without its

alehouse.

While those disturbing members of the Egyptian community were waxing wrath over the beer shops, our savage ancestors probably contented themselves with such drinks as mead made from wild honey, {2} or cyder from the crab tree. But when Ceres sent certain of her votaries into our then benighted land to initiate our woad-dressed forefathers into the mysteries of grain-growing, the venerable Druids quickly discovered the art of brewing that beverage which in all succeeding years has been the drink of Britons.

most truly wrote an Oxford poet, whose name has not been handed down to posterity.

Almost every inhabitant of this country has tasted beer of some kind or another, but on the subject of brewing the great majority have ideas both vague and curious. About one person out of ten imagines that pale ale consists solely of hops and water; indeed, more credit is given by most persons to the hop than to the malt. In order to give a proper understanding of our subject, and at the risk of ruining the brewing trade, let us then, in ten lines or so, inform the world at large how, with no other utensils than a tea-kettle and a saucepan, a quart or two of ale may be brewed, and the revenue defrauded.

Into your tea-kettle, amateur brewer, cast a quart of malt, and on it pour water, hot, but not boiling; let it stand awhile and stir it. Then pour off the sweet tea into the saucepan, and add to the tea-leaves boiling water again, and even a third time, until possibly a husband would rebel at the weak liquid which issues from the spout. The saucepan is now nearly full, thanks to the frequent additions from the tea-kettle, so on to the fire with it, and boil up its contents for an hour or two, not forgetting to add of hops half-an-ounce, or a little more. This process over, let the seething liquor cool, and, when at a little below blood-heat, throw into it a small particle of brewer’s yeast. The liquor now ferments; at the end of an hour skim it, and lo! beneath the scum is bitter beer—in quantity, a quart or more. After awhile bottle the results of your brew, place it in a remote corner of your cellar, and order in a barrel of XXX. from the nearest brewer.

If the generality of people have ideas of the vaguest on the subject of brewing, still less do we English know of the history of that excellent compound yclept ale.

Old ballad makers have certainly sung in its praise, but it is a subject which few prose writers have touched upon, except in the most superficial manner. Modern song writers rarely take ale as their theme. The reason is not far to seek. The ale of other days—not the single beer rightly stigmatised as “whip-belly vengeance,” nor even the doble beer, but the doble-doble beer brewed against law, and beloved by the ale-knights of old—was of such mightiness that whoso drank of it, more often than not dashed off a verse or two in its praise. Now most people drink small beer which exciteth not the brain to poesy. Could one of the ancient topers be restored to life, in tasting a glass of our most excellent bitter, he would, in all likelihood, make a wry face, for hops were not always held in the estimation they obtain at present. There is no doubt, however, that we could restore his equanimity and make him tolerably happy with a gallon or two of old Scotch or Burton ale, double stout or, better still, a mixture of the three with a little aqua vitæ added.

In these pages it will be our task, aided or unaided by strong ale as the case may be, to remove the reproach under which this country rests; for surely a reproach it is that the history of the bonny nut-brown ale, to which we English owe not a little, should have been so long left unwritten.

Now ale has a curious history which, as we have indicated, will be related anon, together with other matters pertaining to the subject. At present let us only chat awhile concerning the great Sir John Barleycorn, malt liquors of the past and present, their virtues, and importance to the labouring classes. Also may we consider the foolish ideas of certain worthy but misguided folk, halting now and again, should we find ourselves growing too serious, to chant a jolly old drinking song, that the way may be more enlivened. If on reaching the first stage of our journey you, dear reader, and ourselves remain friends, let us in each other’s company pass lightly and cheerfully over the path which Sir John Barleycorn has traversed, and fight again his battles, rejoicing at his victories; grieving over his defeats—if any there be. If, on the other hand, it so happens that by the time we arrive at our first halting place you should grow weary of us—which the Spirit of Malt forbid!—let us at once part company, friends none the less, and consign us to a place high up on your bookshelf, or with kindly words present us to the President of the United Kingdom Alliance.

In accusing modern poets of neglecting to sing the praises of our {4} national drink, we must not forget that in one place is kept up the good old custom of brewing strong beer and glorifying it in verse. At Brasenose College, Oxford, beer of the strongest, made of the best malt and hops, is brewed once a year, distributed ad. lib., and verses are written in its praise. Mr. Prior, the college butler, to whom is due the honour of having kept alive the custom for very many years, writes us1 that it is proposed to pull down the old college brewery. Should this happen, Brasenose ale will become a thing of the past.

wrote a Brasenose poet. Alas, that both poets and ale should soon become extinct!

Among the few prose writers past or present who have taken ale for their subject, John Taylor, of whom a good deal will be heard in these pages, stands pre-eminent. His little work, Drinke and Welcome, written some two hundred years ago, and which glorifies ale in a manner most marvellous, is one of the most curious literary productions it has ever been our good fortune to read. “Ale is rightly called nappy,” says the old Thames waterman and innkeeper, “for it will set a nap upon a man’s threed-bare eyes when he is sleepy. It is called Merry-goe-downe, for it slides downe merrily; It is fragrant to the Sent, it is most pleasing to the taste. The flowring and mantling of it (like chequer worke) with the verdant smiling of it, is delightefull to the Sight, it is Touching or Feeling to the Braine and Heart; and (to please the senses all) it provokes men to singeing and mirth, which is contenting to the Hearing. The speedy taking of it doth comfort a heavy and troubled minde; it will make a weeping widowe laugh and forget sorrow for her deceas’d husband. . . . . It will set a Bashfull Suiter a wooing; It heates the chill blood of the Aged; It will cause a man to speake past his owne or any other man’s capacity, or understanding; It sets an Edge upon Logick and Rhetorick; It is a friend to the Muses; It inspires the poore Poet, that cannot compasse the price of Canarie or Gascoign; It mounts the Musician ’bove Eccla; It makes the Balladmaker Rime beyond Reason; It is a Repairer of a {5} decaied Colour in the face; It puts Eloquence into the Oratour; It will make the Philosopher talke profoundly, the Scholler learnedly, and the Lawyer acute and feelingly. Ale at Whitsontide, or a Whitson Church Ale, is a repairer of decayed Countrey Churches; It is a great friend to Truth; so they that drinke of it (to the purpose) will reveale all they know, be it never so secret to be kept; It is an Embleme of Justice, for it allowes, and yeelds measure; It will put Courage into a Coward, and make him swagger and fight; It is a Seale to many a good Bargaine. The Physittian will commend it; the Lawyer will defend it; It neither hurts or kils any but those that abuse it unmeasurably and beyond bearing; It doth good to as many as take it rightly; It is as good as a Paire of Spectacles to cleare the Eyesight of an old Parish Clarke; and in Conclusion, it is such a nourisher of Mankinde, that if my Mouth were as bigge as Bishopsgate, my Pen as long as a Maypole, and my Inke a flowing spring, or a standing fishpond, yet I could not with Mouth, Pen or Inke, speake or write the true worth and worthiness of Ale.” Bravo, John Taylor! He would be a bold man who could lift up his voice against our honest English nappy, after reading your vigorous lines.

It is not uninteresting to compare this sixteenth century work with a passage taken from By Lake and River, the author of which rarely loses an opportunity of eulogising beer. Anglers and many more will cordially agree with Mr. Francis Francis in his remarks. “Ah! my beloved brother of the rod,” he writes, “do you know the taste of beer—of bitter beer—cooled in the flowing river? Not you; I warrant, like the ‘Marchioness,’ hitherto you have only had ‘a sip’ occasionally—and, as Mr. Swiveller judiciously remarks, ‘it can’t be tasted in a sip.’ Take your bottle of beer, sink it deep, deep in the shady water, where the cooling springs and fishes are. Then, the day being very hot and bright, and the sun blazing on your devoted head, consider it a matter of duty to have to fish that long, wide stream (call it the Blackstone stream, if you will); and so, having endued yourself with high wading breeks, walk up to your middle, and begin hammering away with your twenty-foot flail. Fish are rising, but not at you. No, they merely come up to see how the weather looks, and what o’clock it is. So fish away; there is not above a couple of hundred yards of it, and you don’t want to throw more than about two or three-and-thirty yards at every cast. It is a mere trifle. An hour or so of good hard hammering will bring you to the end of it, and then—let me ask you avec impressement—how about that beer? Is it cool? Is it refreshing? Does it {6} gurgle, gurgle, and ‘go down glug,’ as they say in Devonshire? Is it heavenly? Is it Paradise and all the Peris to boot? Ah! if you have never tasted beer under these or similar circumstances, you have, believe me, never tasted it at all.”

A word or two now as to the distinctions between the beverages known as ale and beer. Going back to the time of the Conquest, or earlier, we find that both words were applied to the same liquor, a fermented drink made usually from malt and water, without hops. The Danes called it ale, the Anglo-Saxons beer. Later on the word beer dropped almost out of use. Meanwhile, in Germany and the Netherlands, the use of hops in brewing had been discovered; and in the fifteenth and sixteenth centuries, the Flemings having introduced their bier into England, the word “beer” came to have in this country a distinct meaning—viz., hopped ale. The difference was quaintly explained by Andrew Boorde in his Dyetary, written about the year 1542. “Ale,” said Andrew, “is made of malte and water; and they which do put any other thynge to ale than is rehersed, except yest, barme, or godesgood, doth sofystical theyr ale. Ale for an Englysshe man is a naturall drinke. Ale must have these propertyes: it must be fresshe and cleare, it muste not be ropy nor smoky, nor it must have no weft nor tayle. Ale shuld not be dronke vnder v. dayes olde. Newe ale is vnholsome for all men. And sowre ale, and deade ale the which doth stande a tylt, is good for no man. Barly malte maketh better ale then oten malte or any other corne doth: it doth ingendre grose humoures; but yette it maketh a man stronge.”

“Bere is made of malte, of hoppes, and water; it is the naturall drynke for a Dutche man, and nowe of late dayes it is moche vsed in Englande to the detryment of many Englysshe people; specyally it kylleth them the which be troubled with the colycke, and the stone, and the strangulion; for the drynke is a colde drynke; yet it doth make a man fat, and doth inflate the bely, as it doth appere by the Dutche men’s faces and belyes. If the bere be well serued, and be fyned, and not new, it doth qualyfy heat of the liquer.”

The distinction between ale and beer as described by Boorde lasted for a hundred years or more. As hops came into general use, though malt liquors generally were now beer, the word ale was still retained, and was used whether the liquor it was intended to designate was {7} hopped or not. At the present day beer is the generic word, which includes all malt liquors; while the word ale includes all but the black or brown beers—porter and stout. The meanings of the words are, however, subject to local variations. This subject is further treated of in Chapter VII.

The union of hops and malt is amusingly described in one of the Brasenose College alepoems:―

In John Taylor’s time there seems to have existed among ale drinkers a wholesome prejudice against wine in general, and more especially sack. The water poet writes very bitterly on the subject:―

Another poet wrote in much the same strain:―

Oh let them come and taste this beer

And water henceforth they’ll forswear.

Oh let them come and taste this beer

And water henceforth they’ll forswear.

Our ancestors seem, indeed, almost to have revered good malt liquor. Richard Atkinson gave the following excellent advice to Leonard Lord Dacre in the year 1570: “See that ye keep a noble house for beef and beer, that thereof may be praise given to God and to your honour.”

The same subject—comparison of sack with ale to the disadvantage of the former—is still better treated in an old ale song by Beaumont; it is such a good one of its kind that we give it in full:―

“Wine is but single broth, ale is meat, drink and cloth,” was a proverbial saying in the sixteenth and seventeenth centuries, and occurs in many writings, both prose and poetical. John Taylor, for instance, writes that ale is the “warmest lining of a naked man’s coat.” “Barley broth” and “oyle of barley” were very common expressions for ale. “Dagger ale” was very strong malt liquor. The word “ale-tasters” will be fully explained later on. {10}

The nearest approach in modern times to a denunciation of wine by an ale-favouring poet occurs in a few lines—by whom written we know not—cleverly satirising the introduction of cheap French wines into this country. Cheap clarets command, thanks to an eminent statesman, a considerable share of popular favour. If unadulterated, they are no doubt wholesome enough, and suitable for some specially constituted persons. Let those who like them drink them, by all means.

Among famous ale songs of the past, Jolly Good Ale and Old, which has been wrongly attributed to Bishop Still, stands pre-eminent. Of the eight double stanzas composing the song, four were incorporated in “a ryght pithy, plesaunt, and merie comedie, intytuled, Gammer Gurton’s Nedle, played on stage not longe ago, in Christe’s Colledge, in Cambridge. Made by Mr. S——, Master of Art” (1575). According to Dyer, who possessed a MS., giving the song in its complete form, “it is certainly of an earlier date,” and could not have been by Mr. Still (afterwards Bishop of Bath and Wells), the Master of Trinity College, who was probably the writer of the play. The “merrie comedie” well illustrates the difference of tone and thought which divides those days from the present, and it is a little difficult to understand how it could have been produced by the pen of a High Church dignitary. The prologue of the play is very quaint, it runs thus:―

The song, Jolly Good Ale and Old, four stanzas of which occur in the second act, is a good record of the spirit of those hard-drinking days, now passed away, in which a man who could not, or did not, consume vast quantities of liquor was looked upon as a milksop. It is given as follows in the Comedy:―

Back and syde go bare, go bare, &c., &c.

Back and syde go bare, go bare, &c., &c.

Back and syde go bare, go bare, &c., &c.

Back and syde go bare, go bare, &c., &c.

2 Alluding to the drunkenness of the clergy.

3 Cf:

4 The word “trowle” was used of passing the vessel about, as appears by the beginning of an old catch:

Charles Dibdin the younger has, in a couple of verses, told a very amusing little story of an old fellow who, in addition to finding that ale was meat, drink and cloth, discovered that it included friends as well—or, at any rate, when he was without ale he was without friends, which comes to much the same thing.

For the sake of contrast with the foregoing songs, if for nothing else, the following poem (save the mark!) by George Arnold, a Boston rhymster, is worthy of perusal. The “gurgle-gurgle” of the athletic salmon-fisher, described by Mr. Francis, is replaced by the “idle sipping” (fancy sipping beer!) of the beer-garden frequenter.

The new generation of American poets do not mean, it would appear, to be confined in the old metrical grooves. Very different in style are the verses written on ale by Thomas Wharton, in 1748. A Panegyric on Oxford Ale is the title of the poem, which is prefaced by the lines from Horace:―

The poem opens thus:―

There exist, sad to relate, persons who, with the notion of promoting temperance, would rob us of our beer. Many of these individuals may act with good motives, but they are weak, misguided bodies who, if they but devoted their energies to promoting ale-drinking as opposed to spirit-drinking, would be doing useful service to the State, for malt liquors are the true temperance drinks of the working classes. The Bill (for the encouragement of private tippling) so long sought to be introduced by the teetotal party, was cleverly hit off in Songs of the Session, published in The World some years back:―

Of course, in asserting malt liquors to be the temperance drink, or drink of the temperate, it must be understood that we refer to the ordinary ales and beers of to-day, in which the amount of alcohol is small, and which are very different from the potent liquor drank by the topers of the past, who were rightly designated malt worms.

It has been said that even pigs drank strong ale in those days, but the only evidence of the truth of that statement is the tradition that Herrick, a most charming but little read poet, succeeded in teaching a favourite pig to drink ale out of a jug. Old ale is now out of fashion, its chief strongholds being the venerable centres of education. We all know the tale of the don who, about once a week, reminded the butler of a certain understanding between them, in these words: “Mind, when I say ‘beer’—the old ale.” Ancient writers are full of allusions to the potent character of the strong ales of their day. Nor are more modern authors wanting in that respect. Peter Pindar, who wrote during the reign of George III., when ale was still of a “mightie” character, thus sings:―

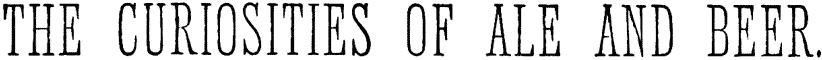

Hogarth, who was perhaps the most accurate and certainly the most powerful delineator of mankind’s virtues and vices that the world has ever seen, has left us in his pictures of “Beer Street” and “Gin Lane” striking illustrations of the advantages attending the use of our national beverage, and the misery and want brought about by dram drinking. In Beer Street everybody thrives, and everything has an air of prosperity. There is one exception—the pawnbroker, gainer by the poverty of others. He, poor man, with barricaded doors and {17} propped-up walls, awaits in terror the arrival of the Sheriff’s officer, fearing only that his house may collapse meanwhile. Through a hole in the door which he is afraid to open, a potboy hands him a mug of ale, at once the cause and consolation of his woes. The bracket which supports the pawnbroker’s sign is awry, and threatens every minute to fall. Apart from this unfortunate all else flourishes. The burly butcher, seated outside the inn with no fear of the Sheriff in his heart, quaffs his pewter mug of foaming ale, and casts now and again an eye on the artist who is repainting the signboard. The sturdy smith, the drayman, the porter and the fishwife—all are well clad and prosperous. Houses are being built, others are being repaired, and health and wealth are visible on every side.

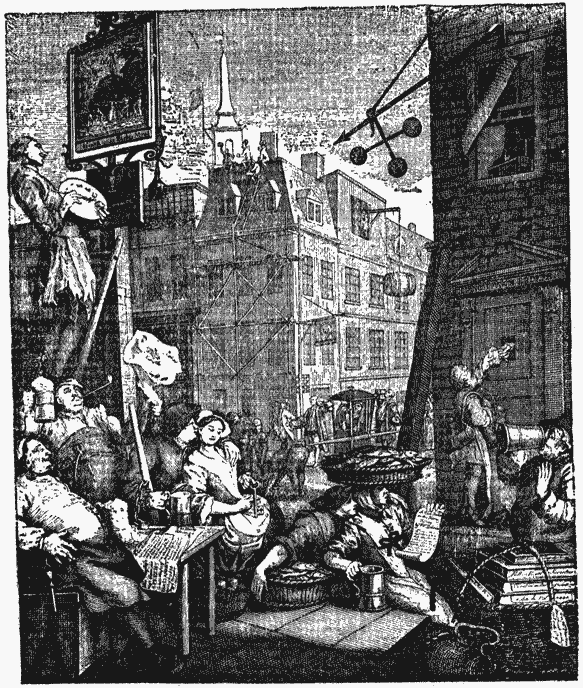

Look now at the noisome slum where the demon Gin reigns triumphant. Squalor, poverty, hunger, wretchedness and sin are depicted on all sides. Here flourish the pawnbroker and the keeper of the gin-palace—but the picture is too speaking a one to need comment.

A medical writer of some thirty years ago says:―

“There are well-meaning persons who wish now-a-days to rob, not only the poor, but the rich man of his beer. I am content to remember that Mary, Queen of Scots, was solaced in her dreary captivity at Fotheringay by the brown beer of Burton-on-Trent; that holy Hugh {19} Latimer drank a goblet of spiced ale with his supper the night before he was burned alive; that Sir Walter Raleigh took a cool tankard with his pipe, the last pipe of tobacco, on the very morning of his execution; and that one of the prettiest ladies with whom I have the honour to be acquainted, when escorting her on an opera Saturday to the Crystal Palace I falteringly suggested chocolate, lemonade and vanilla ices for her refreshment, sternly replied, ‘Nonsense, sir! Get me a pint of stout immediately.’ If the ladies only knew how much better they would be for their beer, there would be fewer cases of consumption for quacks to demonstrate the curability of.”

The question of beer drinking as opposed to total abstinence, is one intimately connected with the welfare of the agricultural labourer. The lives of the majority of these persons are, it is to be feared, somewhat dull and cheerless. From early morn to dewy eve—work; the only prospect in old age—the workhouse. Weary in mind and body, the labourer returns to his cottage at nightfall. At supper he takes his glass of mild ale. It nourishes him, and the alcohol it contains, of so small a quantity as to be absolutely harmless, invigorates him and causes the too often miserable surroundings to appear bright and cheerful. Contentedly he smokes his pipe, chats sociably with his wife, and forgets for awhile the many long days of hard work in store for him. Soon the soporific influence of the hop begins to take effect, and the toiler retires to rest, to sleep soundly, forgetful of the cares of life.

Then there is Saturday night, when the villagers meet at the alehouse, not perhaps so much to drink as to converse, and, with church-wardens in mouth and tankard at elbow, to settle the affairs of the State. The newspaper, a week old, is produced, and one, probably the village tailor or maybe the barber, reads passages from it. “A party of fuddled rustics in a beer-shop,” exclaims the teetotaler, with a sneer. Not so; one or two may have had their pewter tankards filled more often than is prudent, but the majority will be moderate, drinking no more than is good for them. Drunkenness and crime are not the outcome of the village alehouse; for them, go to the gin-palaces of the towns. Nothing, we feel certain, more tends to keep our agricultural labourers from intemperance than the easy means of obtaining cheap but pure beer. What we may term temperance legislation (unless it be of a criminal character, punishing excess by fines) will always defeat its own object. Shut up the alehouses, Sundays or week-days, and the poorer classes at once take to dram drinking. This subject will be found fully considered in the last chapter. {20}

One does not hear much now-a-days of that gallant Knight, Sir John Barleycorn. The song writers of the past were, however, loud in his praises, and Sir John used to be as favourite a myth with the people of England as was our patron saint, St. George. Elton’s play of Paul the Poacher commences with the following charming verses:―

A whimsical old pamphlet, the writer of which must have possessed keen powers of observation, is “The Arraigning and Indicting of Sir John Barleycorn, Knight, printed for Timothy Tosspot.” Sir John is described as of noble blood, well-beloved in England, a great support to the Crown, and a maintainer of both rich and poor. The trial takes place at the sign of the “Three Loggerheads,” before Oliver {21} and Old Nick his holy father. Sir John, of course, pleads not guilty to the charges made against him, which are, in effect, that he has compassed the death of several of his Majesty’s loving subjects, and brought others to ruin. Vulcan the blacksmith, Will the weaver, and Stitch the tailor, are called by the prosecution, and depose that after being first friendly with Sir John, they quarrel with him, and in the end get knocked down, bruised, their bones broken, and their pockets picked. Mr. Wheatley, the baker, complains that, whereas he was the most esteemed by Lords, Knights and Squires, he is now supplanted by the prisoner. Sir John, being called on for his defence, asks that his brother Malt may be summoned, and indicates that the fault, if any, lies mostly at Malt’s door. Malt is thereupon summoned, and thus addresses the Court:―

“My Lords, I thank you for the liberty you now indulge me with, and think it a great happiness, since I am so strongly accused, that I have such learned judges to determine these complaints. As for my part, I will put the matter to the Bench—First, I pray you consider with yourselves, all tradesmen would live; and although Master Malt does make sometimes a cup of good liquor, and many men come to taste it, yet the fault is neither in me nor my brother John, but in such as those who make this complaint against us, as I shall make it appear to you all.

“In the first place, which of you all can say but Master Malt can make a cup of good liquor, with the help of a good brewer; and when it is made, it will be sold. I pray you which of you all can live without it? But when such as these, who complain of us, find it to be good, then they have such a greedy mind, that they think they never have enough, and this overcharge brings on the inconveniences complained of, makes them quarrelsome one with another, and abusive to their very friends, so that we are forced to lay them down to sleep. From hence it appears it is from their own greedy desires all these troubles arise, and not from wicked designs of our own.”

Court.—“Truly we cannot see that you are in the fault. Sir John Barleycorn, we will show you as much favour that, if you can bring any person of reputation to speak to your character, the court is disposed to acquit you. Bring in your evidence, and let us hear what they can say in your behalf.”

Thomas the Ploughman.—“May I be allowed to speak my thoughts freely, since I shall offer nothing but the truth?”

Court.—“Yes, thou mayest be bold to speak the truth, and no {22} more, for that is the cause we sit here for; therefore speak boldly, that we may understand thee.”

Ploughman.—“Gentlemen, Sir John is of an ancient house, and is come of a noble race; there is neither lord, knight, nor squire, but they love his company and he theirs: as long as they don’t abuse him he will abuse no man, but doth a great deal of good. In the first place, few ploughmen can live without him; for if it were not for him we should not pay our landlords their rent; and then what could such men as you do for money and clothes? Nay, your gay ladies would care but little for you if you had not your rents coming in to maintain them; and we could never pay but that Sir John Barleycorn feeds us with money; and you would not seek to take away his life? For shame! let your malice cease and pardon his life, or else we are all undone.”

Bunch the Brewer.—“Gentlemen, I beseech you, hear me. My name is Bunch, a brewer; and I believe few of you can live without a cup of good liquor, nor more than I can without the help of Sir John Barleycorn. As for my own part, I maintain a great charge and keep a great many men at work; I pay taxes forty pounds a-year to his Majesty, God bless him, and all this is maintained by the help of Sir John; then how can any man for shame seek to take away his life?”

Mistress Hostess.—“To give evidence on behalf of Sir John Barleycorn gives me pleasure, since I have an opportunity of doing justice to so honourable a person. Through him the administration receives large supplies; he likewise greatly supports the labourer, and enlivens his conversation. What pleasure could there be at a sheep-clipping without his company, or what joy at a feast without his assistance? I know him to be an honest man, and he never abused any man if they abused not him. If you put him to death all England is undone, for there is not another in the land can do as he can do, and hath done; for he can make a cripple go, the coward fight, and a soldier feel neither hunger nor cold. I beseech you, gentlemen, let him live, or else we are all undone; the nation likewise will be distressed, the labourer impoverished, and the husbandman ruined.”

Court.—“Gentlemen of the jury, you have now heard what has been offered against Sir John Barleycorn, and the evidence that has been produced in his defence. It you are of opinion that he is guilty of those wicked crimes laid to his charge, and has with malice prepense conspired and brought about the death of several of his Majesty’s loving subjects, you are then to find him guilty; but, if, on the contrary, you are of {23} opinion that he had no real intention of wickedness, and was not the immediate, but only the accidental cause of these evils laid to his charge, then, according to the statute law of this kingdom you ought to acquit him.”

Verdict—Not Guilty.

A somewhat lengthy extract has been given from the report of the trial, because the facetious little narrative contains a moral as applicable at the present time as on the day on which the worthy Knight was acquitted.

And now, dear reader, your introduction to Sir John Barleycorn being complete, it is for you, should the inclination be present, to become acquainted with all that pertains to him, from the barley-wine of the Egyptians and other nations of the far past to those excellent beverages in which the people of this country do now delight. On the way you will meet with strange things and strange people, queer customs and quaint sayings and songs; you will watch malting and brewing as it was carried on five hundred years ago; you will stand by while the Flemings, who have just come to London, brew beer with the assistance of a “wicked weed called hoppes;” meanwhile Parliament will re-enact strange sumptuary laws and order that you brew only two kinds of ale or beer; you will be at times in the bad company of dissolute alewives who will whisper sad scandals in your ear; fleeing from them, you will find yourself in a solemn place where lines on stone tell how, when he lived, he brewed good ale; then being perhaps sad at heart, you shall pass into the village ale-house and join the ploughboys in their merry chorus, or sit awhile with the roystering blades in some London tavern; later you shall see the sign and learn its signification and history, and delay a moment to read the verses over the door and admire the quaint architecture and curious carving. In the ale-house you will have tasted and drank wisely, let it be hoped, of London or Dublin black beer, of Plymouth white ale, of old Nappy and Yorkshire Stingo, and as many more as your head can stand.

Then you shall take part in ancient ceremonies—wassailing, Church ales, bride ales, and the like; the merry sheep-shearers will sing for you, and for you the villagers shall dance round the ale-stake; then the old ballad-writers will lay before you their ballads praising ale, and headed with wood-cuts, humorous, but sometimes fearful to look upon. Having rested awhile in perusing these relics of the past, the doors of John Barleycorn’s greatest palaces will fly open before you, and while exploring these wonders of the present, you will chat pleasantly with {24} their founders, Dr. Johnson joining in with ponderous remarks on the brewery of his friend Thrale. The history of porter shall then be unfolded to you, after which you shall be introduced to the college butler, who is in the very act of compounding a noble wassail-bowl, and who, good man, whispers in your willing ear instructions for the making of a score or more of ale-cups; then the old Saxon leeches and their successors shall be summoned, and, in a language strange to modern ears, they shall relate how ale and certain herbs will cure all diseases; then shall you see a curious but not a wondrous sight—water passing through holes in teetotal arguments; and lastly the great French savant shall take you into his laboratory, and shall make you see in a grain of yeast a world of wonders. Last of all we beg you to treasure up in your memory these old lines:―

“What hath been and now is used by the English, as well since the Conquest, as in the days of the Britons, Saxons and Danes.”—Drinke and Welcome.—Taylor.

ORIGIN AND ANTIQUITY OF ALE AND BEER

E must go back several thousand years into the

past to trace the origin of our modern ale and beer. The

ancient Egyptians, as we learn from the Book of the

Dead, a treatise at least 5,000 years old, understood the

manufacture of an intoxicating liquor from grain. This

liquor they called hek, and under the slightly modified

form hemki the name has been used in Egypt for beer until

comparatively modern times. An ancient Egyptian medical

manual, of about the same date as the Book of the Dead,

contains frequent mention of the use of Egyptian beer in

medicine, and at a period about 1,000 years later, the

papyri afford conclusive evidence of the existence even in

that early age, of a burning liquor question in Egypt, for

it is recorded that intoxication had become so common that

many of the beer shops had to be suppressed.

E must go back several thousand years into the

past to trace the origin of our modern ale and beer. The

ancient Egyptians, as we learn from the Book of the

Dead, a treatise at least 5,000 years old, understood the

manufacture of an intoxicating liquor from grain. This

liquor they called hek, and under the slightly modified

form hemki the name has been used in Egypt for beer until

comparatively modern times. An ancient Egyptian medical

manual, of about the same date as the Book of the Dead,

contains frequent mention of the use of Egyptian beer in

medicine, and at a period about 1,000 years later, the

papyri afford conclusive evidence of the existence even in

that early age, of a burning liquor question in Egypt, for

it is recorded that intoxication had become so common that

many of the beer shops had to be suppressed.

Herodotus, after stating that the Egyptians used “wine made from barley” because there were no vines in the country, mentions a tradition that Osiris, the Egyptian Bacchus, first taught the Egyptians how to brew, to compensate them for the natural deficiencies of their native land. Herodotus, however, was frequently imposed upon by the persons from whom he derived his narrative, and no trace of any such tradition is to be found elsewhere. Wine was undoubtedly made in Egypt two or three thousand years before his time. {26}

It is maintained by some that the Hebrew word sicera, which occurs in the Bible and is in our version translated “strong drink,” was none other than the barley-wine mentioned in Herodotus, and that the Israelites brought from Egypt the knowledge of its use. Certain it is that they understood the manufacture of sicera shortly after the exodus, for we find in Leviticus that the priests are forbidden to drink wine or “strong drink” before they go into the tabernacle, and in the Book of Numbers the Nazarenes are required not only to abstain from wine and “strong drink,” but even from vinegar made from either; and in all the passages where the word occurs it is formally distinguished from wine. It may be mentioned in passing, that this word sicera has been regarded as being the equivalent of the word cider. The passage in Numbers is translated in Tyndale’s version, “They shall drink neither wyn ne sydyr,” and it is this rendering that has earned for Tyndale’s translation the name of the cider Bible.

It seems highly probable that the word sicera signified any intoxicating liquor other than wine, whether made from corn, honey or fruit.

In support of the theory that beer was known amongst the Jews, may be mentioned the Rabbinical tradition that the Jews were free from leprosy during the captivity in Babylon by reason of their drinking “siceram veprium, id est, ex lupulis confectam,” or sicera made with hops, which one would think could be no other than bitter beer.

Speaking of this old Egyptian barley-wine, Aeschylus seems to imply that it was not held in very high esteem, for he says that only the women-kind would drink it.5 Evidently the phrase, “to be learned in all the learning of the Egyptians,” had no reference to a competent knowledge of brewing. Before leaving the land of the Pharaoh, it may be mentioned that in that country the labourers still drink a kind of beer extracted from unmalted barley. A traveller in Egypt some years ago recorded in one of the London daily papers that his crew on the Nile made an intoxicating liquor from the fermentation of bread in water; he says that it was called boozer, but whether by himself or crew is not clear. {27}

A goodly number of instances may be found in various old Greek writers of the mention of barley-wine under the various terms of κρίθινον πεπωκότες οινον,6 ἐκ κριθῶν μεθυ, βρῦτον ἐκ τῶν κριθῶν, but it does not appear that beer was ever a popular beverage in Hellas. Further north, the Thracians, as Archilochus tells, brewed and drank a good deal of beer.

Among the Greek writers, Xenophon gives the most interesting and complete account of beer in the year 401 B.C. In describing the retreat of the Ten Thousand, he tells how, on approaching a certain village in Armenia which had been allotted to him, he selected the most active of his troops, and making a sudden descent upon the place captured all the villagers and their headman. One man alone escaped—the bridegroom of the headman’s daughter, who had been married nine days, and was gone out to hunt hares. The snow was six feet deep at the time. Xenophon goes on to describe the dwellings of this singular people. Their houses were under ground, the entrance like that of a well, but wide below. There were entrances dug out for the cattle, but the men used to get down by a ladder. And in the houses were goats, sheep, oxen, fowls and their young ones, and all the animals were fed inside with fodder. And there was wheat, and barley, and pulse, and barley-wine (οἶνος κρίθινος) in bowls. And the malt, too, itself was in the bowl, and level with the brim. And reeds lay in it, some long, some short, with no joints, and when anyone was thirsty he had to take a reed in his hand and suck. The liquor was very strong, says Xenophon, unless one poured water into it, and the drink was pleasant to one accustomed to it. And whenever anyone in friendliness wished to drink to his comrade, he used to drag him to the bowl, where he must stoop down and drink, gulping it down like an ox. The inhabitants of the Khanns district of Armenia, through which Xenophon’s world-famed march was made, still pursue much the same life as they did more than two thousand years ago. They live in these curious subterranean dwellings with all their live stock about them, but, alas! modern travellers aver that they have lost the art of making barley-wine.

Enough has been said as to the use of beer among Eastern nations to disprove the theory of the old author of the Haven of Health, who asserts, quoting “Master Eliote” as his authority, that ale was never used as a common drink in any other country than in “England, Scotland, Ireland, and Poile.” {28}

Ale or beer was in common use in Germany in the time of Tacitus, and Pliny, who may have tasted beer while serving in the army in Germany, says, “All the nations who inhabit the west of Europe have a liquor with which they intoxicate themselves, made of corn and water (fruge madida). The manner of making this liquor is somewhat different in Gaul, Spain, and other countries, and it is called by various names; but its nature and properties are everywhere the same. The people of Spain in particular brew this liquor so well that it will keep good for a long time. So exquisite is the ingenuity of mankind in gratifying their vicious appetites, that they have thus invented a method of making water itself intoxicate.” Among the many various kinds of drink so made were zythum, cœlia, ceria, Cereris vinum, curmi, and cerevisia. All these names, except zythum, are probably merely local variations of one word, whose British representative may be found in the Welsh cwrw.

Turning to the earliest records of the use of malt liquors in this country, we find that, according to Diodorus Siculus, the Britons made use of a very simple diet which consisted chiefly of milk and venison. Their usual drink was water; but upon festive occasions they drank a kind of fermented liquor, made of barley, honey, or apples, and were very quarrelsome in their cups. Dioscorides wrote in the first century that the Britons, instead of wine, use “curmi,” a liquor made from barley. Pytheas (300 B.C.) said a fermented grain liquor was made in Thule.

The drinks in use in this island at the time of its conquest by the Romans seem to have been metheglin, cider, and ale. Metheglin, or mead, was probably the most ancient and universally used of all intoxicating drinks among European nations. Cider is in all probability the next in order of antiquity of the drinks in use amongst our Celtic predecessors. It was made from wild apples, but its use was probably not so wide-spread as that of either mead or ale.

The two drinks, mead and cider, are appropriate to nations who have made but slight advances on the path of civilisation. Tribes of nomads, or of hunters, would find the wherewithal for their manufacture—the honey in the hollow tree, the crabs growing wild in the woods. The manufacture of ale, however, indicates another step forward; it implies the settlement in particular districts, and the knowledge and practice of agriculture. It is, therefore, not surprising to find that the Celtic inhabitants of the midland and northern parts of this country, at the time of the first Roman attack, knew no drink but mead and cider; while, in the southern districts, where contact with {29} the outer world had brought about a somewhat more advanced civilisation and a more settled mode of life, agriculture was practised, and cerevisia, or ale, was added to the list of beverages.

Given below is a metrical version of the origin of ale. It is put in this place between the account of the use of ale by the Britons and its use by the Saxons, because our anonymous poet does not seem to have quite made up his mind whether he is recording a British or a Saxon myth. The name of the king would seem to point to a British origin, whilst some of the gods on whom he calls are Teutonic.

In the sister Island are to be found very early references to ale. The Senchus Mor, which contains some of the oldest and most important of the ancient laws of Ireland, has the following passages in which mention of this drink occurs:―

“What is a human banquet? The banquet of each one’s feasting-house to his chief according to his due (i.e., the chief’s), to which his (i.e., the tenant’s) deserts entitle him; viz., a supper with ale, a feast without ale, a feast by day. The feast without ale is divided; it is distributed according to dignity; the feeding of the assembly of the forces of a territory, assembled for the purpose of demanding proof and law, and answering to illegality. Suppers with ale, feasts without ale, are the fellowship of the Feini.” It is difficult to understand the ideas contained in these old Erse laws and customs, but the main thing for the present purpose is the evidence they give that ale was known and commonly used in Ireland as early as the fifth century.7

From the Brehon law tracts it may be gathered that the privileges of an Irish king included the right to have his ale supplied him with food;8 he was also to have a brave army and an inebriating ale-house. The Irish chief is always to have two casks in his house, one of ale, another of milk; he should also have three sacks—a sack of malt, a sack of salt, and a sack of charcoal.

7 The Senchus Mor was composed in the time of Lœghaire, son of Niall, King of Erin, about A.D. 430, a few years after the arrival of St. Patrick in Ireland.

8 Doubtless an allusion to the old food rents once common in Ireland.

Wales was also to some extent an ale-producing country, and we find in Anglo-Saxon times Welsh ale frequently alluded to as a luxury. When Offa renders the lands at Westbury and Stanbury to the church of Worcester, he accepts at Westbury these services: 2 tunne full of clear Ale, and a cumbe (16 quarts) full of smaller Ale, and a cumbe of Welsh Ale, besides other services. There was a payment to the said church also out of the lands at Breodune of 3 cuppes full of Ale, 111 dolea Brytannicæ cervissiæ (i.e., casks of British Ale), and 3 hogsheads of {31} Welsh Ale, quorum unum fit melle dulcoratum (i.e., of which one was to be sweetened with honey). Henry, in his History of England, in treating of the drinks used in England and Wales during five centuries before the Norman Conquest, remarks on the rarity of the use of ale in Wales at that time. “Mead,” he says, “was still one of their favourite liquors, and bore a high price; for a cask of mead, by the laws of Wales, was valued at 120 pence, equal in quantity of silver to thirty shillings of our present money, and in efficacy to fifteen pounds. The dimensions of a cask of mead must be nine palms in height, and so capacious as to serve the King and one of his counsellors for a bathing tub.” By another law its diameter is fixed at eighteen palms. The Welsh had also two kinds of ale, called common ale and spiced ale, and their value was thus ascertained by law—“If a farmer hath no mead (to pay part of his rent) he shall pay two casks of spiced ale, or four casks of common ale for one cask of mead.” By the same law, a cask of spiced ale, nine palms in height and eighteen palms in diameter, was valued at a sum equal in efficacy to seven pounds ten shillings of our present money; and a cask of common ale, of the same dimensions, at a sum equal to three pounds fifteen shillings. This is a sufficient proof that even common ale at this period was an article of luxury among the Welsh which could only be obtained by the great and opulent. Wine seems to have been quite unknown even to the Kings of Wales at this period, as it is not so much as once mentioned in their laws; though Giraldus Cambrensis, who flourished about a century after the Conquest, acquaints us that there was a vineyard in his time, at Maenarper, near Pembroke, in South Wales.

Before leaving the subject of the British use of ale, it will perhaps amuse some of our readers to find that the very name of Britain has been derived by some from the word βρῡτον, the Greek for beer. The following extract from Hearne’s Discourses is a good instance of that reckless ingenuity in guessing derivations, for which our older school of philologists was ever so justly famed:—“There is one thing,” he says, “which upon this occasion the antiquaries should have observed, and that is our Mault Liquor, called βρῡτον in Athenæus. Which being so, it is humbly offered to the consideration of more judicious persons whether our Britannia might not be denominated from βρῡτον, the whole nation being famous for such sort of drink. ’Tis true, Athenæus does not mention the Britains among those that drunk mault drink; and the reason is, because he had not met with any writer that had {32} celebrated them upon that account, whereas the others that he mentions to drink it were put down in his Authors. Nor will it seem a wonder, that even those people he speaks of were not called Britaines from the said liquor, since it was not their constant and common drink, but was only used by them upon occasion, whereas it was always made use of in Britain, and it was looked upon as peculiar to this Island, and other liquors were esteemed as foreign, and not so agreeable to the nature of the country. And I have some reason to think that those few other people that drunk it abroad did it only in imitation of the Britains, though we have no records remaining upon which to ground this opinion.”

It is rather unfortunate that, in the cause of science, our author did not inform us what that “some reason to think” of his in fact was. However, let us honour his patriotism if we may not his learning.

It would appear that ale and beer were different words signifying the same thing, ale being the Saxon ealu and Danish öl, probably connected with our word oil, and beer being the Saxon beor. Horne Tooke, in his Diversions of Purley, says that “ale” is derived from a Saxon verb ælan, which signifies to inflame.

The word “beer” has been the occasion of some ingenuity and not a little diversity of opinion among the philologists. Goldast derived it a pyris, because (he asserts) beer was first made from pears; Vossius from the Latin bibere, to drink, thus: Bibere, Biber and (extrito b) Bier; Somner from the Hebrew Bar, corn. Probably the true derivation is that which connects the word with the root of the verb, to brew. However this may be, the connection of the word barley with the word beere—denoting a coarse kind of barley—is unmistakeable. Beer was originally used to denote the beverage and also the plant from which it was brewed. Beere or bigge is still to be found growing in some parts of Scotland and Ireland, but in England it has given place to the more refined barley (i.e., beer-lec or beer plant).

The attempt to connect the word “yule” with “ale” is probably fanciful, and may have originated from the use of the word “ale” as denoting not only the liquor, but also any festival at which it formed the principal beverage (e.g. the Whitsun Ale). Yule or Jule is probably derived, along with the festival it represents, from the Celts. It was a feast in honour of the sun, the Celtic name for which was heol or houl and was designed to celebrate the time when the Sun-god, after sinking to his lowest point in the heavens in mid-winter, begins again to ascend the sky, ushering in a period of warmth and plenty. When the Saxons {33} were converted to Christianity, their teachers, instead of entirely doing away with the older forms of religion, allowed them to remain, adapting them to the new faith. This was very usual in early days of Christianity, and thus we find the heathen “Yule” merged in the great Christian festival of Christmas.

The very ancient Anglo-Saxon poem entitled Beowulf, a poem which may be said to be the earliest considerable fragment of our language now extant, shows that ale was the chief drink amongst our Anglo-Saxon ancestors in the far-off days, before they had seized upon this land of England. It contains a mythological account of the rescue by the hero Beowulf of his friends from the Grendel, a monster who was constantly slaughtering and carrying some of them away. The feast is thus described: “Then was for the sons of the Geats, altogether, a bench cleared in the beer-hall; there the bold in spirit went to sit; the thane observed his office, he that in his hand bare the twisted ale-cup; he poured the bright sweet liquor.” Further on, the Danish queen comes in to greet the victors. “There was laughter of heroes, the noise was modulated, words were winsome; Wealtheow, Hrothgar’s queen, went forth; mindful of their races, she, hung round with gold, greeted the men in the hall; and the freeborn lady gave the cup first to the prince of the East Danes; she bade him be blithe at the service of beer, dear to his people. He, the king, proud of victory, joyfully received the feast and hall-cup . . .”

That it was customary among our ancestors for the lady of the house herself to fill the guests’ cups after dinner, may be gathered from the poem called the Geste of Kyng Horn, which in its present form is of thirteenth century date, but is probably founded upon a much earlier work. The poem thus describes Rymenhild, the queen and wife of King Horn, performing this duty:―

9 Schenche = to pour out.

10 Sale = hall.

These lines also show that ale and beer were used at that time as interchangeable words.

Our Saxon ancestors seem to have made use of several kinds of beverage; they had wine and mead, cider, which they called æppelwin, and piment, which was a compound of wine, honey, and spices. Ale and beer, however, seem, to use the quaint words of old Harrison, to have “borne the brunt in drincking,” and to have formed the national beverage of the English people from the earliest times to the present day. Ale, honest English ale, was the general drink, and wine was a luxury of the rich, as may be gathered from the old Anglo-Saxon dialogue, entitled Alfric’s Colloquy, in which a lad, on being asked what his drink is, replies, “Ale, if I have it, water, if I have it not.” To the question why he does not drink wine his answer is, “I am not so rich that I can buy me wine; and wine is not the drink of children or the weak-minded, but of the elders and the wise.”

The Exeter Book, which contains a collection of Anglo-Saxon songs and poems, and was presented to the church at Exeter by Bishop Leofric in the eleventh century, contains one of those curious rhyming riddles so popular among the Saxons, which were known as Symposii Ænigmata. It is as follows:―

Those who remember the more elaborate legend of John Barleycorn will not have far to seek for the solution of this somewhat ponderous riddle.

The Anglo-Saxons, before their conversion to Christianity, believed that some of the chief blessings to be enjoyed by departed heroes were the frequent and copious draughts of ale served round to them in the halls of Odin. Even after the spread of Christianity had dispelled this heathen notion, all the evidence available seems to point rather to an enlarged than a diminished consumption of malt liquors. Whether our forefathers, practically-minded like their descendants, resolved to make up here upon earth for the loss of the expected joys of which their new creed had robbed them, it is impossible at this distance of time to determine; but certain it is that the popularity of our national beverage has gone on increasing from that day to this.

In these early days rents were not infrequently paid in ale. In 852 the Abbot of Medeshampstede (Peterborough) let certain lands at Sempringham to one Wulfred, on this condition, amongst others, that he should each year deliver to the minster two tuns of pure ale and ten mittans (measures) of Welsh ale. The ale-gafol mentioned in the laws of Ine was a tribute or rent of ale paid by the tenant to the lord of the manor. By an ancient charter granted in the time of King Alfred, the tenants of Hysseburne, amongst other services, rendered six church-mittans of ale.

Ale was also in olden days frequently liable to the payment of a toll (tollester) to the lord of the manor. In a Gloucestershire manor it was customary for a tenant holding in villeinage to pay as toll to the lord gallons of ale, whenever he brewed ale to sell. At Fiskerton, in Notts, if {36} an ale-wife brews ale to sell she is to satisfy the lord for tollester. In the manor of Tidenham, in Saxon times the villein is to pay to the lord at the Martinmass six sesters of malt; and in the same manor, in the reign of Edward I., we find the rent changed into a toll, the tenant at the later period being bound to render to the lord 8 gallons of beer at every brewing.

Similarly, wages were in some manors paid in kind. At Brissingham, Norfolk, the tenants, amongst other services, might perform 125 ale-beeves in the year, i.e., carting-days, on which attendance was not compulsory, but on which the tenants, if they did attend, were entitled to bread and ale in lieu of wages. The word “bever” still occurs in some places, denoting a harvest-man’s drink between breakfast and dinner.

The Saxons and Danes were of a social disposition, and delighted in forming themselves into fraternities or guilds. An important feature of these institutions was the meeting for convivial purposes, and their object was to promote good fellowship among the members. The laws for the regulation of some of these bodies are still in existence, and it seems were enforced by fines of honey, or malt, to be used in the making of mead or ale for the use of the members of the confraternity. It seems that both clergy and laity were members of certain of the guilds, at any rate at one period of their history, and allusion is probably made to these mixed fraternities in the Canons of Archbishop Walter, A.D. 1200, in which he directs “that clerks go not to taverns and drinking bouts, for from thence come quarrels, and then laymen beat clergymen, and fall under the Canon.”

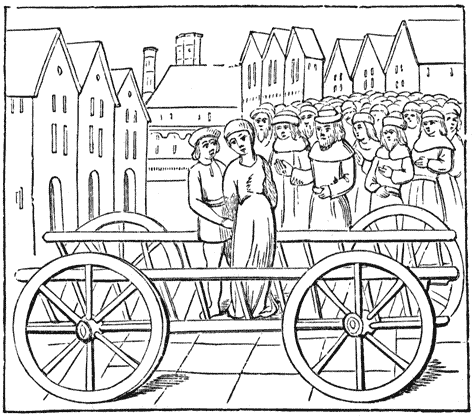

During the Middle Ages ale was the usual drink of all classes of Englishmen, and the wines of France were a luxury, in general only consumed by the upper classes. In France, however, wine was the common drink, and ale a luxury. William Fitz-Stephen, in his Life of Thomas à Becket, states that when the latter went on an embassy to France, he took with him two waggons laden with beer in iron-bound casks, as a present to the French, “who admire that kind of drink, for it is wholesome, clear, of the colour of wine, and of a better taste.”

As an instance of the fame which English ale had attained abroad in the twelfth century, may be cited the reply of Pope Innocent III. to those who were arguing before him the case of the Bishop of Worcester’s claims against the Abbey of Evesham. “Holy father,” said they, “we have learnt in the schools, and this is the opinion of our masters, that there is no prescription against the rights of bishops.” His Holiness’s reply was blunt and somewhat personal: “Certainly, both you and your masters had drunk too much English ale when you learnt this.” {37}

A curious extract may here be added as indicative of the fame of English ale amongst foreigners in the fourteenth and fifteenth centuries. It is taken from a work entitled “A Relation; or rather a true account of the Island of England, A.D. 1500, translated from the Italian by C. A. Sneyd.” “The deficiency of wine, however,” says our author, “is amply supplied by the abundance of ale and beer, to the use of which these people have become so habituated, that at an entertainment where there is plenty of wine, they will drink them in preference to it, and in great quantities. Like discreet people, however, they do not offer them to Italians, unless they should ask for them, and they think that no greater honour can be conferred, or received, than to invite others to eat with them, or be invited themselves; and they would sooner give five or six ducats to provide an entertainment for a person, than a groat to assist him in any distress. They are not without vines; and I have eaten grapes from one, and wine might be made in Southern parts, but it would probably be harsh. The natural deficiency of the country is supplied by a great quantity of excellent wines from Candia, Germany, France, and Spain; besides which, the common people make two beverages from Wheat, Barley, and Oats, one of which is called beer, and the other Ale; and these liquors are much liked by them, nor are they disliked by foreigners, after they have drank them four or six times; they are most agreeable to the palate, when a person is by some chance rather heated.”

The regulations of the religious houses nearly always make reference to ale; and it may be inferred from the evidence we possess, that the holy fathers, who were always strong sticklers for the rights and privileges of their order, would brook no interference either with the quantity or quality of their liquor. In the Institutes of the Abbey of Evesham, drawn up by Abbot Randulf about the year 1223, the directions as to the diet of the inmates of the Abbey, are of great particularity. The Prior is to have one measure of ale at supper (except when he shall sup with the Abbot). Each of the fraternity shall every day receive two measures of ale, each of which shall contain two pittances, of which pittances six make up a “sextarium regis.” In the same rules it is laid down that the monks are to have “two semes of beans from Huniburne, to make puddings throughout all Lent.” Bean-pudding seems indeed a mortification of the flesh! Further on we find: “On every day every two brethren shall have one measure of ale from the cellar, but after being let blood they shall have one for dinner and another for supper. The servant who shall let the monks’ blood shall have bread and ale {38} from the cellar, if he have blooded more than one.” A further account of the monks as brewers will be found in the succeeding chapter.

The Proverbs of Hendyng (thirteenth century) give good advice as of the duties of charity and hospitality:―

In the fourteenth century taxes seem to have been occasionally levied on ale for certain specific purposes. In 1363 the inhabitants of Abbeville were granted a tax on ale for the purpose of repairing their fortifications. For each lotus of ale of gramville the tax was one penny Parisien; for each lotus of god-ale the tax was ½d. (Rhymer 2. 712.).

In a curious old poem of the early part of the fourteenth century entitled De Baptismo, by William of Shoreham, it appears to the poet, necessary to lay down that ale must not be used for purposes of baptism, but “kende water” (i.e., natural water) only. The verse is as follows:―

12 Male = bag or wallet.

14 See p. 401.

This old English requires some little explanation, and may be rendered thus:—Therefore man may not renounce (his sins) through christening in wine, in cider, nor in perry, nor in anything that never was water, nor yet in ale, for though this (i.e., ale) was water first, it is acounted water no longer. {39}

Whilst Christmas, as far as eating was concerned, always had its specialities, its liquor carte seems even in the thirteenth century to have been of a very varied character. An old carolist of the period thus sings (we follow Douce’s translation):―

Piers the Ploughman, a poem by William Longland, written towards the close of the fourteenth century, contains a curious confession of the tricks played by the ale-sellers upon their customers:―

This, being interpreted, in modern English would read somewhat as follows:—I bought her barley they brew it to sell; Peny ale (i.e., ale at a penny a gallon) and small perry she poured together for labourers and poor folk that live by themselves. The best lay in the bed chamber by the wall, whoso drank thereof bought it (i.e., the penny ale) by the sample (i.e., of the best) a gallon for a groat, God knows, no less, when it came in by cupfulls; such craft I used.

Piers the Ploughman, in describing the scarcity of labour after the great plague in the fourteenth century and the independence of the labouring men that arose from the high wages they were enabled to demand, says that after harvest they would eat none but the finest bread,

15 As we should say, “hot and hot,” for chill of their stomach.

Chaucer has many references to ale. The Cook, who was no mean proficient in his proper art, was a judge of ale as well:―

The Miller prepares himself to tell his tale aright by swallowing mighty draughts of the same liquor. He knows he is drunk, and is not ashamed, thinking it quite sufficient excuse to lay the blame upon that seductive fluid, “the ale of Southwerk”:―

The two Cambridge students who lodge a night at the miller of Trompington’s are feasted by their host in this wise:―

They soupen and they speken of solace,

And drinken ever strong ale at the best.

Abouten midnight wente they to rest.

They soupen and they speken of solace,

And drinken ever strong ale at the best.

Abouten midnight wente they to rest.

Before they went, however, they had “dronken all that was in crouke,” and the miller, who appears to have had the lion’s share, had decidedly imbibed too much.

This miller hath so wisely bibbed ale,

That as an hors he snorteth in his slepe.

This miller hath so wisely bibbed ale,

That as an hors he snorteth in his slepe.

Geoffrey Chaucer, along with other poets and writers of his times, was unsparing in his denunciations of the vices of the clergy, their sloth, gluttony, drunkenness and other grievous lapses.

Piers the Ploughman, in his Crede, which is a satire upon the clergy, makes the Franciscan say, in contrasting his own order with other religious bodies:―

The frequent directions to the monks and clergy to abstain from taverns, from drinking bouts and revels, all point to the necessity then felt of tightening the bonds of church discipline, and show the laxity that had prevailed.

John Taylor, the Water Poet, frequently selected ale as his theme, and, when once mounted on his favourite hobby, soon travelled into such realms of marvellous history and miraculous philology, that it almost takes away one’s breath to follow him. The chief work in which he glorifies our English Ale has for its full title,

After speaking of cider, perry, &c., the author goes on to speak of ale, which “hath been and now is used by the English, as well since the Conquest as in the times of the Brittains, Saxons, and Danes (for the former-recited drinks are to this day confined to the Principality) so as we enjoy them onely by a Statute called the courtesie of Wales. And to perfect any discourse in this I shall onely induce them into two heads, viz., the unparalleled liquor called Ale with his abstract Beere; whose antiquity amongst a sort of Northerne pated fellowes, is, if not altogether contemptible, of very little esteeme; this humour served the scurrilous pen of a shamelesse writer16 in the raigne of King Henry the third; detractingly to inveigh against this unequal’d liquor. Thus

16 Henry D’Avranches.

“Of all the Authors that I have ever yet read, this is the only one that hath attempted to brand the glorious splendour of that Ale-beloved decoction; but observe this fellow, by the perpetuall use of water (which was his accustomed drinke) he fell into such convulsions and lethargick diseases, that he remained in opinion a dead man; however, the knowing Physicians of that time, by the frequent and inward application of Ale, not onely recouvered him to his pristine state of health, but also enabled him in body and braine for the future, that he became famous in his writings, which for the most part were afterwards spent with most Aleoquent and Alaborate commendation of that admired and most superexcellent Imbrewage.”

“Some there are,” he says, “that affirme that Ale was first invened by Alexander the Great, and that in his conquests this liquor did infuse such vigour and valour into his souldiers. Others say that famous Physician of Piemont (named Don Alexis) was the founder of it. But it is knowne that it was of that singular use in the time of the Saxons that none were allowed to brewe it but such whose places and qualities were most Eminent, insomuch that we finde that one of them had the credit to give the name of a Saxon Prince, who in honour of that rare quality, he called Alle. Some aleadge that it being our drinke when our land was called Albion, that it had the name of the countrey; Twiscus in his Euphorbinum will have it from Albanta or Epirus, Wolfgang Plashendorph of Gustenburg, saies that Alecto (one of the three furies) gave the receipt of it to Albumazar, a Magician, and he (having Aliance {43} with Aladine, the Soldan at Aleppo) first brew’d it there, whereto may be Aleuded, the story how Alphonsus of Scicily, sent it from thence to the battell of Alcazar. My Authour is of Anaxagoras’ opinion, that Ale is to be held in high price for the nutritive substance that it is indued withall, and how precious a nurse it is in generall to Mankinde.

“It is true that the overmuch taking of it doth so much exhilerate the spirits, that a man is not improperly said to be in the Aletitude (observe the word, I pray you, and all the words before or after for you shall find their first syllable to be Ale), and some writers are of opinion that the Turkish Alcoran was invented by Mahomet, out of such furious raptures as Ale inspired him withall; some affirme Bacchus (Al’as Liber Pater) was the first Brewer of it, among the Indians, who being a stranger to them they nam’d it Ale, as brought by an Alien: in a word, Somnus altus signifies dead sleepe: Quies alta, Great rest; Altus and Alta, noble and excellent: It is (for the most part) extracted out of the spirit of a Graine called Barley, which was of that estimation amongest the ancient Galles that their Prophets (whom they called Bards) used it in their most important prophesies and ceremonies: This Graine, after it had beene watered and dryed, was at first ground in a Mill in the island of Malta, from whence it is supposed to gaine the name of Malt; but I take it more proper from the word Malleolus, which signifies a Hammer or Maule, for Hanniball (that great Carthaginian Captaine) in his sixteene yeeres warres against the Romans, was called the Maule of Italie, for it is conjectured that he victoriously Mauld them by reason that his army was daily refreshed with the Spiritefull Elixar of Mault.

“It holds very significant to compare a man in the Aletitude to be in a planetarie height, for in a Planet, the Altitude is his motion in which he is carried from the lowest place of Heaven or from the Center of the Earth, into the most highest place, or unto the top of his circle, and then it is said to be in Apogee, that is the most Transcendant part of all, so the Sublunarie of a Stupified Spirit, being elevated by the efficacious vigour of this uncontrolleable vertue, renders him most capable for high actions.”

After much more in the same vein, sufficient to astonish the most reckless of modern punsters, our author winds up his account of the antiquity of ale as follows:―

“I will therefore shut up with that admirable conclusion insisted upon in our time by a discreet Gentleman in a Solemne Assembly, who by a Politick observation, very aptly compares Ale and Cakes with Wine and {44} Waters, neither doth he hold it fit that it should stand in competition with the meanest wines, but with that most excellent composition which the Prince of Physicians Hippocrases had so ingeniously compounded for the preservation of Mankinde, and which (to this day) speakes the Author by the name of Hippocras. So that you see for Antiquity—Ale was famous amongst the Troians, Brittaines, Romans, Saxons, Normans, Englishmen, Welch, besides in Scotland, from the highest and Noblest Palace to the poorest and meanest Cottage.”

Other curious details with respect to the use of ale in the Middle Ages and in modern times will be found in their appropriate places, and having established clearly enough the highly respectable antiquity of the Prince of liquors, old or new, it is time, in the elegant language of the Water Poet, to “shut up” this portion of the subject; and so we pass on, concluding here with an extract from the Philosopher’s Banquet, on the pre-eminence of ale:―

HOME-BREWED ALES. — OLD RECEIPTS. — HISTORICAL FACTS. — DEAN SWIFT ON HOME-BREW. — CHRISTOPHER NORTH’S BREW-HOUSE.

OGARTH’S

Farmer’s Return represents

the worthy man just come in from his

morning round or from distant market

town. As he rests awhile in the farmhouse

kitchen he draws sweet solace from

the pipe brought him by his daughter,

while he eyes with keen expectance the

jug of foaming home-brew which his

buxom wife, in her hurry to serve her

lord, is spilling on the tiled floor. These two old friends, firm supporters

of each other, the farmers and home-brewed ale, have almost

parted company. Home-brew, indeed, has become, in some places, an

extinct and almost forgotten beverage. It is a curious fact, however,

that between the years 1884 and 1886 there was a slight increase in the

number of persons brewing

their own ale. {46}

OGARTH’S

Farmer’s Return represents

the worthy man just come in from his

morning round or from distant market

town. As he rests awhile in the farmhouse

kitchen he draws sweet solace from

the pipe brought him by his daughter,

while he eyes with keen expectance the

jug of foaming home-brew which his

buxom wife, in her hurry to serve her

lord, is spilling on the tiled floor. These two old friends, firm supporters

of each other, the farmers and home-brewed ale, have almost

parted company. Home-brew, indeed, has become, in some places, an