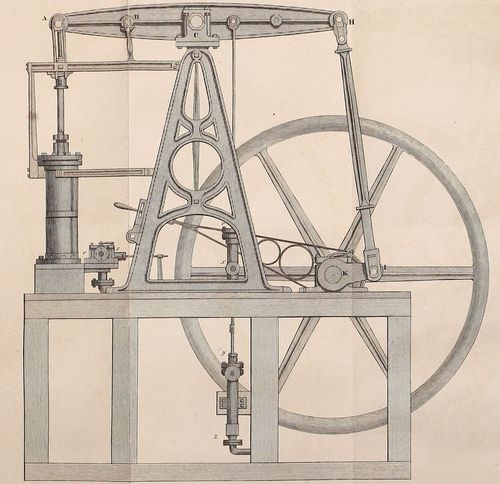

Pl. XIII.

AMERICAN HIGH-PRESSURE ENGINE

Eight horse power. 8 inch Cylinder, 2-1/2 feet Stroke.

THE

STEAM ENGINE

FAMILIARLY EXPLAINED AND ILLUSTRATED;

WITH

AN HISTORICAL SKETCH OF ITS INVENTION AND

PROGRESSIVE IMPROVEMENT;

ITS APPLICATIONS TO

NAVIGATION AND RAILWAYS;

WITH

PLAIN MAXIMS FOR RAILWAY SPECULATORS.

BY THE

REV. DIONYSIUS LARDNER, LL. D., F. R. S.,

FELLOW OF THE ROYAL SOCIETY OF EDINBURGH; OF THE ROYAL IRISH ACADEMY; OF THE ROYAL ASTRONOMICAL SOCIETY; OF THE CAMBRIDGE PHILOSOPHICAL SOCIETY; OF THE STATISTICAL SOCIETY OF PARIS; OF THE LINNÆAN AND ZOOLOGICAL SOCIETIES; OF THE SOCIETY FOR PROMOTING USEFUL ARTS IN SCOTLAND, ETC.

WITH ADDITIONS AND NOTES,

BY JAMES RENWICK, LL. D.,

PROFESSOR OF NATURAL EXPERIMENTAL PHILOSOPHY AND CHEMISTRY IN COLUMBIA COLLEGE, NEW YORK.

ILLUSTRATED BY ENGRAVINGS AND WOODCUTS.

SECOND AMERICAN, FROM THE FIFTH LONDON, EDITION, CONSIDERABLY ENLARGED.

PHILADELPHIA:

E. L. CAREY & A. HART.

1836

Entered, according to the Act of Congress, in the year 1836, by E. L. Carey & A. Hart, in the Clerk's office of the District Court for the Eastern District of Pennsylvania.

Several of the additions, which were made by the Editor to the first American edition, have been superseded by the great extension, which the original has from time to time received from its author. This is more particularly the case, with the sections which had reference to the character of steam at temperatures other than that of boiling water, to the use of steam in navigation, and to its application to locomotion. These sections have of course been omitted. A few new sections, and several notes have been added, illustrative of such points as may be most interesting to the American reader.

Columbia College,

New York, March, 1836.

This volume should more properly be called a new work than a new edition of the former one. In fact the book has been almost rewritten. The change which has taken place, even in the short period which has elapsed since the publication of the first edition, in the relation of the steam engine to the useful arts, has been so considerable as to render this inevitable.

The great extension of railroads, and the increasing number of projects which have been brought forward for new lines connecting various points of the kingdom, as well as the extension of steam navigation, not only through the seas and channels surrounding and intersecting these islands, and throughout other parts of Europe, but through the larger waters which are interposed between our dominions in the East and the countries of Egypt and Syria, have conferred so much interest on the application of steam to transport, that I have thought it adviseable to extend the limits of the present edition considerably beyond those of the last. The chapter on railroads has been enlarged and improved. Three (p. viii) chapters have been added. The twelfth chapter contains a view of steam navigation; the thirteenth contains several important points connected with the economy of steam power, which, when this work was first published, would not have offered sufficient interest to justify their admission into a popular treatise; and the fourteenth chapter contains a series of compendious maxims, for the instruction and guidance of persons desirous of making investments or speculating in railway property.

London, December, 1835.

There are two classes of persons whose attention may be attracted by a treatise on such a subject as the Steam Engine. One consists of those who, by trade or profession, are interested in mechanical science, and who therefore seek information on the subject of which it treats, as a matter of necessity, and a wish to acquire it in a manner and to an extent which may be practically available in their avocations. The other and more numerous class is that part of the public in general, who, impelled by choice rather than necessity, think the interest of the subject itself, and the pleasure derivable from the instances of ingenuity which it unfolds, motives sufficiently strong to induce them to undertake the study of it. Without leaving the former class altogether out of view, it is for the use of the latter principally that the following lectures are designed.

To this class of readers the Steam Engine is a subject which, if properly treated of, must present strong and peculiar (p. x) attractions. Whether we consider the history of its invention as to time and place, the effects which it has produced, or the means by which it has caused these effects, we find everything to gratify our national pride, stimulate our curiosity, excite our wonder, and command our admiration. The invention and progressive improvement of this extraordinary machine, is the work of our own time and our own country; it has been produced and brought to perfection almost within the last century, and is the exclusive offspring of British genius fostered and supported by British capital. To enumerate the effects of this invention, would be to count every comfort and luxury of life. It has increased the sum of human happiness, not only by calling new pleasures into existence, but by so cheapening former enjoyments as to render them attainable by those who before never could have hoped to share them. Nor are its effects confined to England alone: they extend over the whole civilized world; and the savage tribes of America, Asia, and Africa, must ere long feel the benefits, remote or immediate, of this all-powerful agent.

If the effect which this machine has had on commerce and the wealth of nations raise our astonishment, the means by which this effect has been produced will not less excite our admiration. The history of the Steam Engine presents a series of contrivances, which, for exquisite and refined ingenuity, stand without a parallel in the annals of human invention. These admirable contrivances, unlike other results of scientific investigation, have also this peculiarity, that to understand and appreciate their excellence requires little previous or subsidiary knowledge. A simple and clear explanation, (p. xi) divested as far as possible of technicalities, and assisted by well selected diagrams, is all that is necessary to render the principles of the construction and operation of the Steam Engine intelligible to a person of plain understanding and moderate information.

The purpose for which this volume is designed, as already explained, has rendered necessary the omission of many particulars which, however interesting and instructive to the practical mechanic or professional engineer, would have little attraction for the general reader. Our readers require to be informed of the general principles of the construction and operation of Steam Engines, rather than of their practical details. For the same reasons we have confined ourselves to the more striking and important circumstances in the history of the invention and progressive improvement of this machine, excluding many petty disputes which arose from time to time respecting the rights of invention, the interest of which is buried in the graves of their respective claimants.

In the descriptive parts of the work we have been governed by the same considerations. The application of the force of steam to mechanical purposes has been proposed on various occasions, in various countries, and under a great variety of forms. The list of British patents alone would furnish an author of common industry and application with matter to swell his book to many times the bulk of this volume. By far the greater number of these projects have, however, proved abortive. Descriptions of such unsuccessful, though frequently ingenious machines, we have thought it adviseable to exclude from our pages, as not possessing sufficient interest (p. xii) for the readers to whose use this volume is dedicated. We have therefore strictly confined our descriptions either to those Steam Engines which have come into general use, or to those which form an important link in the chain of invention.

December 26, 1827.

CHAPTER I.

PRELIMINARY MATTER.

Motion the Agent in Manufactures. — Animal Power. — Power depending on physical Phenomena. — Purpose of a Machine. — Prime Mover. — Mechanical qualities of the Atmosphere. — Its Weight. — The Barometer. — Fluid Pressure. — Pressure of rarefied Air. — Elasticity of Air. — Bellows. — Effects of Heat. — Thermometer. — Method of making one. — Freezing and Boiling Points. — Degrees. — Dilatation of bodies. — Liquefaction and Solidification. — Vaporisation and Condensation. — Latent Heat of Steam. — Expansion of Water in Evaporating. — Effects of Repulsion and Cohesion. — Effect of Pressure upon Boiling Point. — Formation of a Vacuum by Condensation. Page 17

CHAPTER II.

FIRST STEPS IN THE INVENTION.

Futility of early Claims. — Watt the real Inventor. — Hero of Alexandria. — Blasco Garay. — Solomon De Caus. — Giovanni Branca. — Marquis of Worcester. — Sir Samuel Morland. — Denis Papin. — Thomas Savery. 38

CHAPTER III.

ENGINES OF SAVERY AND NEWCOMEN.

Savery's Engine. — Boilers and their Appendages. — Working Apparatus. — Mode of Operation. — Defects of the Engine. — Newcomen and Cawley. — Atmospheric Engine. — Accidental discovery of Condensation by Jet. — Potter's discovery of the Method of working the Valves. 51

(p. xiv) CHAPTER IV.

ENGINE OF JAMES WATT.

Advantages of the Atmospheric Engine over that of Captain Savery. — It contained no new Principle. — Papin's Engine. — James Watt. — Particulars of his Life. — His first conceptions of the Means of economising Heat. — Principle of his projected Improvements. 69

CHAPTER V.

WATT'S SINGLE-ACTING STEAM ENGINE.

Expansive Principle applied. — Failure of Roebuck, and partnership with Bolton. — Patent extended to 1800. — Counter. — Difficulties in getting the Engines into Use. 80

CHAPTER VI.

DOUBLE-ACTING STEAM ENGINE.

The Single-acting Engine unfit to impel Machinery. — Various Contrivances to adapt it to this Purpose. — Double-Cylinder. — Double-acting Cylinder. — Various modes of connecting the Piston with the Beam. — Rack and Sector. — Double Chain. — Parallel Motion. — Crank. — Sun and Planet Motion. — Fly Wheel. — Governor. 91

CHAPTER VII.

DOUBLE-ACTING STEAM ENGINE,

continued.

On the Valves of the Double-acting Steam Engine. — Original Valves. — Spindle Valves. — Sliding Valve. — D Valve. — Four-Way Cock. 108

CHAPTER VIII.

BOILER AND ITS APPENDAGES.

Level Gauges. — Feeding apparatus. — Steam Gauge. — Barometer Gauge. — Safety Valves. — Self-regulating Damper. — Edelcrantz's Valve. — Furnace. — Smoke-consuming Furnace. — Brunton's Self-regulating Furnace. — Oldham's Modification. 117

(p. xv) CHAPTER IX.

DOUBLE-CYLINDER ENGINES.

Hornblower's Engine. — Woolf's Engine. — Cartwright's Engine. 134

CHAPTER X.

LOCOMOTIVE ENGINES ON RAILWAYS.

High-pressure Engines. — Leupold's Engine. — Trevithick and Vivian. — Effects of Improvement in Locomotion. — Historical Account of the Locomotive Engine. — Blenkinsop's Patent. — Chapman's Improvement. — Walking Engine. — Stephenson's First Engines. — His Improvements. — Liverpool and Manchester Railway Company. — Their Preliminary Proceedings. — The Great Competition of 1829. — The Rocket. — The Sanspareil. — The Novelty. — Qualities of the Rocket. — Successive Improvements. — Experiments. — Defects of the Present Engines. — Inclined Planes. — Methods of surmounting them. — Circumstances of the Manchester Railway Company. — Probable Improvements in Locomotives. — Their capabilities with respect to speed. — Probable Effects of the Projected Railroads. — Steam Power compared with Horse Power. — Railroads compared with Canals. 145

CHAPTER XI.

LOCOMOTIVE ENGINES ON TURNPIKE ROADS.

Railway and Turnpike Roads compared. — Mr. Gurney's inventions. — His Locomotive Steam Engine. — Its performances. — Prejudices and errors. — Committee of the House of Commons. — Convenience and safety of Steam Carriages. — Hancock's Steam Carriage. — Mr. N. Ogle. — Trevithick's invention. — Proceedings against Steam Carriages. — Turnpike Bills. — Steam Carriage between Gloucester and Cheltenham. — Its discontinuance. — Report of the Committee of the Commons. — Present State and Prospects of Steam Carriages. 213

CHAPTER XII.

STEAM NAVIGATION.

Propulsion by paddle-wheels. — Manner of driving them. — Marine Engine. — Its form and arrangement. — Proportion of its cylinder. — Injury to boilers by deposites and incrustation. — Not effectually removed by blowing out. — Mr. Samuel Hall's condenser. — Its advantages. — Originally (p. xvi) suggested by Watt. — Hall's steam saver. — Howard's vapour engine. — Morgan's paddle-wheels. — Limits of steam navigation. — Proportion of tonnage to power. — Average speed. — Consumption of fuel. — Iron Steamers. — American steam raft. — Steam navigation to India. — By Egypt and the Red Sea to Bombay. — By same route to Calcutta. — By Syria and the Euphrates to Bombay. — Steam communication with the United States from the west coast of Ireland to St. Johns, Halifax, and New York. 241

CHAPTER XIII.

GENERAL ECONOMY OF STEAM POWER.

Mechanical efficacy of steam — proportional to the quantity of water evaporated, and to the fuel consumed. — Independent of the pressure. — Its mechanical efficacy by condensation alone. — By condensation and expansion combined — by direct pressure and expansion — by direct pressure and condensation — by direct pressure, condensation, and expansion. — The power of engines. — The duty of engines. — Meaning of horse power. — To compute the power of an engine. — Of the power of boilers. — The structure of the grate-bars. — Quantity of water and steam room. — Fire surface and flue surface. — Dimensions of steam pipes. — Velocity of piston. — Economy of fuel. — Cornish duty reports. 277

CHAPTER XIV.

Plain Rules for Railway Speculators. 307

Motion the Agent in Manufactures. — Animal Power. — Power depending on Physical Phenomena. — Purpose of a Machine. — Prime Mover. — Mechanical qualities of the Atmosphere. — Its Weight. — The Barometer. — Fluid Pressure. — Pressure of Rarefied Air. — Elasticity of Air. — Bellows. — Effects of Heat. — Thermometer. — Method of making one. — Freezing and Boiling Points. — Degrees. — Dilatation of Bodies. — Liquefaction and Solidification. — Vaporisation and Condensation. — Latent heat of Steam. — Expansion of Water in Evaporating. — Effects of Repulsion and Cohesion. — Effect of Pressure upon Boiling-Point. — Formation of a Vacuum by Condensation.

(1.) Of the various productions designed by nature to supply the wants of man, there are few which are suited to his necessities in the state in which the earth spontaneously offers them: if we except atmospheric air, we shall scarcely find another instance: even water, in most cases, requires to be transported from its streams or reservoirs; and food itself, in almost every form, requires culture and preparation. But if, from the mere necessities of physical existence in a primitive state, we rise to the demands of civil and social life,—to say nothing of luxuries and refinements,—we shall find that everything which contributes to our convenience, (p. 18) or ministers to our pleasure, requires a previous and extensive expenditure of labour. In most cases, the objects of our enjoyment derive all their excellences, not from any qualities originally inherent in the natural substances out of which they are formed, but from those qualities which have been bestowed upon them by the application of human labour and human skill.

In all those changes to which the raw productions of the earth are submitted in order to adapt them to our wants, one of the principal agents is motion. Thus, for example, in the preparation of clothing for our bodies, the various processes necessary for the culture of the cotton require the application of moving power, first to the soil, and subsequently to the plant from which the raw material is obtained: the wool must afterwards be picked and cleansed, twisted into threads, and woven into cloth. In all these processes motion is the agent: to cleanse the wool and arrange the fibres of the cotton, the wool must be beaten, teased, carded, and submitted to other processes, by which all the foreign and coarser matter may be separated, and the fibres or threads arranged evenly, side by side. The threads must then receive a rotatory motion, by which they may be twisted into the required form; and finally peculiar motions must be given to them in order to produce among them that arrangement which characterises the cloth which it is our final purpose to produce.

In a rude state of society, the motions required in the infant manufactures are communicated by the immediate application of the hand. Observation and reflection, however, soon suggest more easy and effectual means of attaining these ends: the strength of animals is first resorted to for the relief of human labour. Further reflection and inquiry suggest still better expedients. When we look around us in the natural world, we perceive inanimate matter undergoing various effects in which motion plays a conspicuous part: we see the falls of cataracts, the currents of rivers, the elevation (p. 19) and depression of the waters of the ocean, the currents of the atmosphere; and the question instantly arises, whether, without sharing our own means of subsistence with the animals whose force we use, we may not equally, or more effectually, derive the powers required from these various phenomena of nature? A difficulty, however, immediately presents itself: we require motion of a particular kind; but wind will not blow, nor water fall as we please, nor as suits our peculiar wants, but according to the fixed laws of nature. We want an upward motion; water falls downwards: we want a circular motion; wind blows in a straight line. The motions, therefore, which are in actual existence must be modified to suit our purposes: the means whereby these modifications are produced, are called machines. A machine, therefore, is an instrument interposed between some natural force or motion, and the object to which force or motion is desired to be transmitted. The construction of the machine is such as to modify the natural motion which is impressed upon it, so that it may transmit to the object to be moved that peculiar species of motion which it is required to have. To give a very obvious example, let us suppose that a circular or rotatory motion is required to be produced, and that the only natural source of motion at our command is a perpendicular fall of water: a wheel is provided, placed upon the axle destined to receive the rotatory motion; this wheel is furnished with cavities in its rim; the water is conducted into the cavities near the top of the wheel on one side; and being caught by these, its weight bears down that side of the wheel, the cavities on the opposite side being empty and in an inverted position. As the wheel turns, the cavities on the descending side discharge their contents as they arrive near the lowest point, and ascend empty on the other side. Thus a load of water is continually pressing down one side of the wheel, from which the other side is free, and a continued motion of rotation is produced.

(p. 20) In every machine, therefore, there are three objects demanding attention:—first, The power which imparts motion to it, this is called the prime mover; secondly, The nature of the machine itself; and thirdly, The object to which the motion is to be conveyed. In the steam engine the first mover arises from certain phenomena which are exhibited when heat is applied to liquids; but in the details of the machine and in its application there are several physical effects brought into play, which it is necessary perfectly to understand before the nature of the machine or its mode of operation can be rendered intelligible. We propose therefore to devote the present chapter to the explanation and illustration of these phenomena.

(2.) The physical effects most intimately connected with the operations of steam engines are some of the mechanical properties of atmospheric air. The atmosphere is the thin transparent fluid in which we live and move, and which, by respiration, supports animal life. This fluid is apparently so light and attenuated, that it might be at first doubted whether it be really a body at all. It may therefore excite some surprise when we assert, not only that it is a body, but also that it is one of considerable weight. We shall be able to prove that it presses on every square inch[1] of surface with a weight of about 15lb. avoirdupois.

(3.) Take a glass tube A B (fig. 2.) more than 32 inches long, open at one end A, and closed at the other end B, and let it be filled with mercury (quicksilver.) Let a glass vessel or cistern C, containing a quantity of mercury, be also provided. Applying the finger at A so as to prevent the mercury in the tube from falling out, let the tube be inverted, and the end, stopped by the finger, plunged into the mercury in C. When the end of the tube is below the surface (p. 21) of the mercury in C (fig. 3.) let the finger be removed. It will be found that the mercury in the tube will not, as might be expected, fall to the level of the mercury in the cistern C, which it would do were the end B open so as to admit the air into the upper part of the tube. On the other hand, the level D of the mercury in the tube will be about 30 inches above the level C of the mercury in the cistern.

(4.) The cause of this effect is, that the weight of the atmosphere rests on the surface C of the mercury in the cistern, and tends thereby to press it up, or rather to resist its fall in the tube; and as the fall is not assisted by the weight of the atmosphere on the surface D (since B is closed), it follows, that as much mercury remains suspended in the tube above the level C as the weight of the atmosphere is able to support.

If we suppose the section of the tube to be equal to the magnitude of a square inch, the weight of the column of mercury in the tube above the level C will be exactly equal to the weight of the atmosphere on each square inch of the surface C. The height of the level D above C being about 30 inches, and a column of mercury two inches in height, and having a base of a square inch, weighing about one pound avoirdupois, it follows that the weight with which the atmosphere presses on each square inch of a level surface is about 15lb. avoirdupois.

An apparatus thus constructed, and furnished with a scale to indicate the height of the level D above the level C, is the common barometer. The difference of these levels is subject to a small variation, which indicates a corresponding change in the atmospheric pressure. But we take 30 inches as a standard or average.

(5.) It is an established property of fluids that they press equally in all directions; and air, like every other fluid, participates in this quality. Hence it follows, that since the downward pressure or weight of the atmosphere is about 15lb. on the square inch, the lateral, upward, and oblique (p. 22) pressures are of the same amount. But, independently of the general principle, it may be satisfactory to give experimental proof of this.

Let four glass tubes A, B, C, D, (fig. 4.) be constructed of sufficient length, closed at one end A, B, C, D, and open at the other. Let the open ends of three of them be bent, as represented in the tubes B, C, D. Being previously filled with mercury, let them all be gently inverted so as to have their closed ends up as here represented. It will be found that the mercury will be sustained in all,[2] and that the difference of the levels in all will be the same. Thus the mercury is sustained in A by the upward pressure of the atmosphere, in B by its horizontal or lateral pressure, in C by its downward pressure, and in D by its oblique pressure; and as the difference of the levels is the same in all, these pressures are exactly equal.

(6.) In the experiment described in (3.) the space B D (fig. 3.) at the top of the tube from which the mercury has fallen is perfectly void and empty, containing neither air nor any other fluid: it is called therefore a vacuum. If, however, a small quantity of air be introduced into that space, it will immediately begin to exert a pressure on D, which will cause the surface D to descend, and it will continue to descend until the column of mercury C D is so far diminished that the weight of the atmosphere is sufficient to sustain it, as well as the pressure exerted upon it by the air in the space B D.

The quantity of mercury which falls from the tube in this case is necessarily an equivalent for the pressure of the air introduced, so that the pressure of this air may be exactly ascertained by allowing about one pound per square inch for every two inches of mercury which has fallen from the tube. The pressure of the air or any other fluid above the (p. 23) mercury in the tube, may at once be ascertained by comparing the height of the mercury in the tube with the height of the barometer; the difference of the heights will always determine the pressure on the surface of the mercury in the tube. This principle will be found of some importance in considering the action of the modern steam engines.

The air which we have supposed to be introduced into the upper part of the tube, presses on the surface of the mercury with a force much greater than its weight. For example, if the space B D (fig. 3.) were filled with atmospheric air in its ordinary state, it would exert a pressure on the surface D equal to the whole pressure of the atmosphere, although its weight might not amount to a single grain. The property in virtue of which the air exerts this pressure is its elasticity, and this force is diminished in precisely the proportion in which the space which the air occupies is increased.

Thus it is known that atmospheric air in its ordinary state exerts a pressure on the surface of any vessel in which it is confined, amounting to about 15lb. on every square inch. If the capacity of the vessel which contains it be doubled, it immediately expands and fills the double space, but in doing so it loses half its elastic force, and presses only with the force of 7-1/2lb. on every square inch. If the capacity of the vessel had been enlarged five times, the air would still have expanded so as to fill it, but would exert only a fifth part of its first pressure, or 3lb. on every square inch.

This property of losing its elastic force as its volume or bulk is increased, is not peculiar to air. It is common to all elastic fluids, and we accordingly find it in steam; and it is absolutely necessary to take account of it in estimating the effects of that agent.

(7.) There are numerous instances of the effects of these properties of atmospheric air which continually fall under our observation. If the nozzle and valve-hole of a pair of bellows be stopped, it will require a very considerable force to separate the boards. This effect is produced by the diminished (p. 24) elastic force of the air remaining between the boards upon the least increase of the space within the bellows, while the atmosphere presses, with undiminished force, on the external surfaces of the boards. If the boards be separated so as to double the space within, the elastic force of the included air will be about 7-1/2lb. on every square inch, while the pressure on the external surfaces will be 15lb. on every square inch; consequently, it will require as great a force to sustain the boards in such a position, as it would to separate them if each board were forced against the other, with a pressure of 7-1/2lb. per square inch on their external surfaces.

When boys apply a piece of moistened leather to a stone, so as to exclude the air from between them, the stone, though it be of considerable weight, may be lifted by a string attached to the leather: the cause of which is the atmospheric pressure, which keeps the leather and the stone in close contact.

(8.) The next class of physical effects which it is necessary to explain, are those which are produced when heat is imparted or abstracted from bodies.

In general, when heat is imparted to a body, an enlargement of bulk will be the immediate consequence, and at the same time the body will become warmer to the touch. These two effects of expansion and increase of warmth going on always together, the one has been taken as a measure of the other; and upon this principle the common thermometer is constructed. That instrument consists of a tube of glass, terminated in a bulb, the magnitude of which is considerable, compared with the bore of the tube. The bulb and part of the tube are filled with mercury, or some other liquid. When the bulb is exposed to any source of heat, the mercury contained in it, being warmed or increased in temperature, is at the same time increased in bulk, or expanded or dilated, as it is called. The bulb not having sufficient capacity to contain the increased bulk of mercury, the liquid is (p. 25) forced up in the tube, and the quantity of expansion is determined by observing the ascent of the column in the tube.

An instrument of this kind, exposed to heat or cold, will fluctuate accordingly, the mercury rising as the heat to which it is exposed is increased, and falling by exposure to cold. In order, however, to render it an accurate measure of temperature, it is necessary to connect with it a scale by which the elevation or depression of the mercury in the tube may be measured. Such a scale is constructed for thermometers in this country in the following manner:—Let us suppose the instrument immersed in a vessel of melting ice: the column of mercury in the tube will be observed to fall to a certain point, and there maintain its position unaltered: let that point be marked upon the tube. Let the instrument be now transferred to a vessel of boiling water at a time when the barometer stands at the altitude of 30 inches: the mercury in the tube will be observed to rise until it attain a certain elevation, and will there maintain its position. It will be found, that though the water continue to be exposed to the action of the fire, and continue to boil, the mercury in the tube will not continue to rise, but will maintain a fixed position: let the point to which the mercury has risen, in this case, be likewise marked upon the tube.

The two points, thus determined, are called the freezing and the boiling points. If the distance upon the tube between these two points be divided into 180 equal parts, each of these parts is called a degree; and if this division be continued, by taking equal divisions below the freezing point, until 32 divisions be taken, the last division is called the zero, or nought of the thermometer. It is the point to which the mercury would fall, if the thermometer were immersed in a certain mixture of snow and salt. When thermometers were first invented, this point was taken as the zero point, from an erroneous supposition that the temperature of such a mixture was the lowest possible temperature.

The degrees upon the instrument thus divided are counted (p. 26) upwards from the zero, and are expressed, like the degrees of a circle, by placing a small ° over the number. Thus it will be perceived that the freezing point is 32° of our thermometer, and the boiling-point will be found by adding 180° to 32°; it is therefore 212°.

The temperature of a body is that elevation to which the thermometer would rise when the mercury enclosed in it would acquire the same temperature. Thus, if we should immerse the thermometer, and should find that the mercury would rise to the division marked 100°, we should then affirm that the temperature of the water was 100°.

(9.) The dilatation which attends an increase of temperature is one of the most universal effects of heat. It varies, however, in different bodies: it is least in solid bodies; greater in liquids; and greatest of all in bodies in the aeriform state. Again, different solids are differently susceptible of this expansion. Metals are the most susceptible of it; but metals of different kinds are differently expansible.

As an increase of temperature causes an increase of bulk, so a diminution of temperature causes a corresponding diminution of bulk, and the same body always has the same bulk at the same temperature.

A flaccid bladder, containing a small quantity of air, will, when heated, become quite distended; but it will again resume its flaccid appearance when cold. A corked bottle of fermented liquor, placed before the fire, will burst by the effort of the air contained in it to expand when heated.

Let the tube A B (fig. 5.) open at both ends, have one end inserted in the neck of a vessel C D, containing a coloured liquid, with common air above it; and let the tube be fixed so as to be air-tight in the neck: upon heating the vessel, the warm air inclosed in the vessel C D above the liquid will begin to expand, and will press upon the surface of the liquid, so as to force it up in the tube A B.

In bridges and other structures, formed of iron, mechanical provisions are introduced to prevent the fracture or (p. 27) strain which would take place by the expansion and contraction which the metal must undergo by the changes of temperature at different seasons of the year, and even at different hours of the day.

Thus all nature, animate and inanimate, organized and unorganized, may be considered to be incessantly breathing heat; at one moment drawing in that principle through all its dimensions, and at another moment dismissing it.

(10.) Change of bulk, however, is not the only nor the most striking effect which attends the increase or diminution of the quantity of heat in a body. In some cases, a total change of form and of mechanical qualities is effected by it. If heat be imparted in sufficient quantity to a solid body, that body, after a certain time, will be converted into a liquid. And again, if heat be imparted in sufficient quantity to this liquid, it will cease to exist in the liquid state, and pass into the form of vapour.

By the abstraction of heat, a series of changes will be produced in the opposite order. If from the vapour produced in this case, a sufficient quantity of heat be taken, it will return to the liquid state; and if again from this liquid heat be further abstracted, it will at length resume its original solid state.

The transmission of a body from the solid to the liquid state, by the application of heat, is called fusion or liquefaction, and the body is said to be fused, liquefied, or melted.

The reciprocal transmission from the liquid to the solid state, is called congelation, or solidification; and the liquid is said to be congealed or solidified.

The transmission of a body from the liquid to the vaporous or aeriform state, is called vaporization, and the liquid is said to be vaporized or evaporated.

The reciprocal transmission of vapour to the liquid state is called condensation, and the vapour is said to be condensed.

(p. 28) We shall now examine more minutely the circumstances which attend these remarkable and important changes in the state of body.

(11.) Let us suppose that a thermometer is imbedded in any solid body; for example, in a mass of sulphur; and that it stands at the ordinary temperature of 60 degrees: let the sulphur be placed in a vessel, and exposed to the action of fire. The thermometer will now be observed gradually to rise, and it will continue to rise until it exhibit the temperature of 218°. Here, however, notwithstanding the continued action of the fire upon the sulphur, the thermometer will become stationary; proving, that notwithstanding the supply of heat received from the fire, the sulphur has ceased to become hotter. At the moment that the thermometer attains this stationary point, it will be observed that the sulphur has commenced the process of fusion; and this process will be continued, the thermometer being stationary, until the whole mass has been liquefied. The moment the liquefaction is complete, the thermometer will be observed again to rise, and it will continue to rise until it attain the elevation of 570°. Here, however, it will once more become stationary; and notwithstanding the heat supplied to the sulphur by the fire, the liquid will cease to become hotter: when this happens, the sulphur will boil; and if it continue to be exposed to the fire a sufficient length of time, it will be found that its quantity will gradually diminish, until at length it will all disappear from the vessel which contained it. The sulphur will, in fact, be converted into vapour.

From this process we infer, that all the heat supplied during the processes of liquefaction and vaporization is consumed in effecting these changes in the state of the body; and that under such circumstances, it does not increase the temperature of the body on which the change is produced.

These effects are general: all solid bodies would pass into the liquid state by a sufficient application of heat; and all (p. 29) liquid bodies would pass into the vaporous state by the same means. In all cases the thermometer would be stationary during these changes, and consequently the temperature of the body, in those periods, would be maintained unaltered.

(12.) Solids differ from one another in the temperatures at which they become liquid. These temperatures are called their melting points. Thus the melting point of ice is 32°; that of lead 612°; that of gold 5237°.[3] The heat which is supplied to a body during the processes of fusion or vaporization, and which does not affect the thermometer, or increase the temperature of the body fused or vaporized, is said to become latent. It can be proved to exist in the body fused or vaporized, and may even be taken from that body. In parting with it the body does not fall in temperature, and consequently the loss of this heat is not indicated by the thermometer any more than its reception. The term latent heat is merely intended to express this fact, of the thermometer being insensible to the presence or absence of this portion of heat, and is not intended to express any theoretical notions concerning it.

(13.) In explaining the construction and operation of the steam engine, although it is necessary occasionally to refer to the effects of heat upon bodies in general, yet the body, which is by far the most important to be attended to, so far as the effects of heat upon it are concerned, is water. This body is observed to exist in the three different states, the solid, the liquid, and the vaporous, according to the varying temperature to which it is exposed. All the circumstances which have been explained in reference to metals, and the substance sulphur in particular, will, mutatis mutandis, be applicable to water. But in order perfectly to comprehend the properties of the steam engine, it is necessary to (p. 30) render a more rigorous and exact account of these phenomena, so far as they apply to the changes produced upon water by the effects of heat.

Let us suppose a mass of ice immersed in the mixture of snow and salt which determines the zero point of the thermometer: this mass, if allowed to continue a sufficient length of time submerged in the mixture, will necessarily acquire its temperature, and the thermometer immersed in it will stand at zero. Let the ice be now withdrawn from the mixture, still keeping the thermometer immersed in it, and let it be exposed to the atmosphere at the ordinary temperature, say 60°. At first the thermometer will be observed gradually and continuously to rise until it attain the elevation of 32°; it will then become stationary, and the ice will begin to melt: the thermometer will continue standing at 32° until the ice shall be completely liquefied. The liquid ice and the thermometer being contained in the same vessel, it will be found, when the liquefaction is completed, that the thermometer will again begin to rise, and will continue to rise until it attain the temperature of the atmosphere, viz. 60°. Hitherto the ice or water has received a supply of heat from the surrounding air; but now an equilibrium of temperature having been established, no further supply of heat can be received; and if we would investigate the further effects of increased heat, it will be necessary to expose the liquid to fire, or some other source of heat. But previous to this, let us observe the time which the thermometer remains stationary during the liquefaction of the ice: if noted by a chronometer, it would be found to be a hundred and forty times the time during which the water in the liquid state was elevated one degree; the inference from which is, that in order to convert the solid ice into liquid water, it was necessary to receive from the surrounding atmosphere one hundred and forty times as much heat as would elevate the liquid water one degree in temperature; or, in other words, that to liquefy a given weight of ice requires as much (p. 31) heat as would raise the same weight of water 140° in temperature: or from 32° to 172°.

The latent heat of water acquired in liquefaction is therefore 140°.

(14.) Let us now suppose that, a spirit lamp being applied to the water already raised to 60°, the effects of a further supply of heat be observed: the thermometer will continue to rise until it attain the elevation of 212°, the barometer being supposed to stand at 30 inches. The thermometer having attained this elevation will cease to rise; the water will therefore cease to become hotter, and at the same time bubbles of steam will be observed to be formed at the bottom of the vessel containing the water, near the flame of the spirit lamp. These bubbles will rise through the water, and escape at the surface, exhibiting the phenomena of ebullition, and the water will undergo the process of boiling.

During this process, the thermometer will constantly be maintained at the same elevation of 212°; but if the time be noted, it will be found that the water will be altogether evaporated, if the same source of heat be continued to be applied to it six and a half times as long as was necessary to raise it from the freezing to the boiling-point. Thus, if the application of the lamp to water at 32°, be capable of raising that water to 212° in one hour, the same lamp will require to be applied to the boiling water for six hours and a half, in order to convert the whole of it into steam. Now if the steam into which it is thus converted were carefully preserved in a receiver, maintained at the temperature of 212°, this steam would be found to have that temperature, and not a greater one; but it would be found to fill a space about 1700 times greater than the space it occupied in the liquid state, and it would possess an elastic force equal to the pressure of the atmosphere under which it was boiled; that is to say, it would press the sides of the vessel which contained it with a pressure equivalent to that of a column of (p. 32) mercury of 30 inches in height; or what is the same thing, at the rate of about 15lb. on every square inch of surface.

(15.) As the quantity of heat expended in raising the water from 32° to 212°, is 180°; and as the quantity of heat necessary to convert the same water into steam is six and a half times this quantity, it follows that the quantity of heat requisite for converting a given weight of water into steam, will be found by multiplying 180° by 5-1/2. The product of these numbers being 990°, it follows, that, to convert a given weight of water at 212° into steam of the same temperature, under the pressure of the atmosphere, when the barometer stands at 30 inches, requires as much heat as would be necessary to raise the same water 990° higher in temperature. The heat, not being sensible to the thermometer, is latent heat; and accordingly it may be stated, that the latent heat, necessary to convert water into steam under this pressure is, in round numbers, 1000°.

(16.) All the effects of heat which we have just described may be satisfactorily accounted for, by supposing that the principle of heat imparts to the constituent atoms of bodies a force, by virtue of which they acquire a tendency to repel each other. But in conjunction with this, it is necessary to notice another force, which is known to exist in nature: there is observable among the corpuscles of bodies a force, in virtue of which they have a tendency to cohere, and collect themselves together in solid concrete masses: this force is called the attraction of cohesion. These two forces—the natural cohesion of the particles, and the repulsive energy introduced by heat—are directly opposed to one another, and the state of the body will be decided by the predominance of the one or the other, or their mutual equilibrium. If the natural cohesion of the constituent particles of the body considerably predominate over the repulsive energy introduced by the heat, then the cohesion will take effect; the particles of the body will coalesce, the mass will become rigid and solid, and the particles will hold together in (p. 33) one invariable mass, so that they cannot drop asunder by the mere effect of their weight. In such cases, a more or less considerable force must be applied, in order to break the body, or to tear its parts asunder. Such is the quality which characterises the state, which in mechanics is called the state of solidity.

If the repulsive energy introduced by the application of heat be equal, or nearly equal, to the natural cohesion with which the particles of the body are endued, then the predominance of the cohesive force may be insufficient to resist the tendency which the particles may have to drop asunder by their weight. In such a case, the constituent particles of the body cannot cohere in a solid mass, but will separate by their weight, fall asunder, and drop into the various corners, and adapt themselves to the shape of any vessel in which the body may be contained. In fact, the body will take the liquid form. In this state, however, it does not follow that the cohesive principle will be altogether inoperative: it may, and does, in some cases, exist in a perceptible degree, though insufficient to resist the separate gravitation of the particles. The tendency which particles of liquids have, in some cases, to collect in globules, plainly indicates the predominance of the cohesive principle: drops of water collected upon the window pane; drops of rain condensed in the atmosphere; the tear which trickles on the cheek; drops of mercury, which glide over any flat surface, and which it is difficult to subdivide or scatter into smaller parts; are all obvious indications of the predominance of the cohesive principle in liquids.

By the due application of heat, even this small degree of cohesion may be conquered, and a preponderance of the opposite principle of repulsion may be created. But another physical influence here interposes its aid, and conspires with cohesion in resisting the transmission of the body from the liquid to the vaporous state: this force is no other than the pressure of the atmosphere, already explained. This (p. 34) pressure has an obvious tendency to restrain the particles of the liquid, to press them together, and to resist their separation. The repulsive principle of the heat introduced must therefore not only neutralize the cohesion, but must also impart to the atoms of the liquid a sufficient elasticity or repulsive energy to enable them to fly asunder, and assume the vaporous form in spite of this atmospheric resistance.

Now it is clear, that if this atmospheric resistance be subject to any variation in its intensity, from causes whether natural or artificial, the repulsive energy necessary to be introduced by the heat, will vary proportionally: if the atmospheric pressure be diminished, then less heat will be necessary to vaporize the liquid. If, on the other hand, this pressure be increased, a greater quantity of heat will be required to impart the necessary elasticity.

(17.) From this reasoning we must expect that any cause, whether natural or artificial, which diminishes the atmospheric pressure upon the surface of a liquid, will cause that liquid to boil at a lower temperature: and on the other hand, any cause which may increase the atmospheric pressure upon the liquid, will render it necessary to raise it to a higher temperature before it can boil.

These inferences we accordingly find supported by experience. Under a pressure of 15lb. on the square inch, i. e. when the barometer is at 30 inches, water boils at the temperature of 212° of the common thermometer. But if water at a lower temperature, suppose 180°, be placed under the receiver of an air-pump, and, by the process of exhaustion the atmospheric pressure be removed, or very much diminished, the water will boil, although its temperature still remain at 180°, as may be indicated by a thermometer placed in it.

On the other hand, if a thermometer be inserted air-tight in the lid of a close digester containing water with common atmospheric air above it, when the vessel is heated the air acquires an increased elasticity; and being confined by the (p. 35) cover, presses, with increased force, on the surface of the water. By observing the thermometer while the vessel is exposed to the action of heat, it will be seen to rise considerably above 212°, suppose to 230°, and would continue so to rise until the strength of the vessel could no longer resist the pressure within it.

The temperature at which water boils is commonly said to be 212°, which is called the boiling-point of the thermometer; but, strictly speaking, this is only true when the barometer stands at 30 inches. If it be lower, water will boil at a lower temperature, because the atmospheric pressure is less; and if it be higher, as at 31, water will not boil until it receives a higher temperature, the pressure being greater.

According as the cohesive forces of the particles of liquids are more or less active, they boil at greater or less temperatures. In general the lighter liquids, such as alcohol and ether, boil at lower temperatures. These fluids, in fact, would boil by merely removing the atmospheric pressure, as may be proved by placing them under the receiver of an air-pump, and withdrawing the air. From this we may conclude that these and similar substances would never exist in the liquid state at all, but for the atmospheric pressure.

(18.) The elasticity of vapour raised from a boiling liquid, is equal to the pressure under which it is produced. Thus, steam raised from water at 212°, and, therefore, under a pressure of 15lb. on the square inch, is endued with an elastic force which would exert a pressure on the sides of any vessel which confines it, also equal to 15lb. on the square inch. Since an increased pressure infers an increased temperature in boiling, it follows, that where steam of a higher pressure than the atmosphere is required, it is necessary that the water should be boiled at a higher temperature.

(19.) We have already stated that there is a certain point at which the temperature of a liquid will cease to rise, and that all the heat communicated to it beyond this is consumed in (p. 36) the formation of vapour. It has been ascertained, that when water boils at 212°, under a pressure equal to 30 inches of mercury, a cubic inch of water forms a cubic foot[4] of steam, the elastic force of which is equal to the atmospheric pressure, and the temperature of which is 212°. Since there are 1728 cubic inches in a cubic foot, it follows, that when water at this temperature passes from the liquid to the vaporous state, it is dilated into 1728 times its bulk.

(20.) We have seen that about 1000 degrees of heat must be communicated to any given quantity of water at 212°, in order to convert it into steam of the same temperature, and possessing a pressure amounting to about 15 pounds on the square inch, and that such steam will occupy above 1700 times the bulk of the water from which it was raised. Now we might anticipate, that by abstracting the heat thus employed in converting the liquid into vapour, a series of changes would be produced exactly the reverse of those already described; and such is found to be actually the case. Let us suppose a vessel, the capacity of which is 1728 cubic inches, to be filled with steam, of the temperature of 212°, and exerting a pressure of 15 pounds on the square inch; let 5-1/2 cubic inches of water, at the temperature of 32°, be injected into this vessel, immediately the steam will impart the heat, which it has absorbed in the process of vaporisation to the water thus injected, and will itself resume the liquid form. It will shrink into its primitive dimensions of one cubic inch, and the heat which it will dismiss will be sufficient to raise the 5-1/2 cubic inches of injected water to the temperature of 212°. The contents of (p. 37) the vessel will thus be 6-1/2 cubic inches of water at the temperature of 212°. One of these cubic inches is in fact the steam which previously filled the vessel reconverted into water, the other 5-1/2 are the injected water which has been raised from the temperature of 32° to 212° by the heat which has been dismissed by the steam in resuming the liquid state. It will be observed that in this transmission no temperature is lost, since the cubic inch of water into which the steam is converted has the same temperature as the steam had before the cold water was injected.

These consequences are in perfect accordance with the results already obtained from observing the time necessary to convert a given quantity of water into steam by the application of heat. From the present result it follows, that in the reduction of a given quantity of steam to water it parts with as much heat as is sufficient to raise 5-1/2 cubic inches from 32° to 212°, that is, 5-1/2 times 180° or 990°.

(21.) There is an effect produced in this process to which it is material that we should attend. The steam which filled the space of 1728 cubic inches shrinks when reconverted into water into the dimensions of 1 cubic inch. It therefore leaves 1727 cubic inches of the vessel it contains unoccupied. By this property steam is rendered instrumental in the formation of a vacuum.

By allowing steam to circulate through a vessel, the air may be expelled from it, and its place filled by steam. If the vessel be then closed and cooled the steam will be reduced to water, and, falling in drops on the bottom and sides of the vessel, the space which it filled will become a vacuum. This may be easily established by experiment. Let a long glass tube be provided with a hollow ball at one end, and having the other end open.[5] Let a small quantity of spirits be poured in at the open end, and placing the glass ball over the flame of a lamp, let the spirits be boiled. (p. 38) After some time the steam will be observed to issue copiously from the open end of the tube which is presented upwards. When this takes place, let the tube be inverted, and its open end plunged in a basin of cold water. The heat being thus removed, the cool air will reconvert the steam in the tube into liquid, and a vacuum will be produced, into which the pressure of the atmosphere on the surface of the water in the basin will force the water through the tube, and it will rush up with considerable force, and fill the glass ball.

In this experiment it is better to use spirits than water, because they boil at a lower heat, and expose the glass to less liability to break, and also the tube may more easily be handled.

Futility of early claims. — Watt, the real Inventor. — Hero of Alexandria. — Blasco Garay. — Solomon de Caus. — Giovanni Branca. — Marquis of Worcester. — Sir Samuel Morland. — Denis Papin. — Thomas Savery.

(22.) In the history of the progress of the useful arts and manufactures, there is perhaps no example of any invention the credit of which has been so keenly contested as that of the steam engine. Claims to it have been advanced by different nations, and by different individuals of the same nation. The partisans of the competitors for this honour have argued their pretensions, and pressed their claims, with a zeal which has occasionally outstripped the bounds of discretion; and the contest has not unfrequently been tinged with prejudices, both national and personal, and marked (p. 39) with a degree of asperity quite unworthy of so noble a cause, and altogether beneath the dignity of science.

The efficacy of the steam engine considered as a mechanical agent depends, first, on the several physical properties from which it derives its operation, and, secondly, on the various pieces of mechanism and details of mechanical arrangement by which these properties are rendered practically available. If the merit of the invention must be ascribed to the discoverer and contriver of these, then the contest will be easily decided, because it will be obvious that the prize is not due to any one individual, but must be distributed in different proportions among several. If, however, he is best entitled to the credit of the invention, who has by the powers of his mechanical genius imparted to the machine that form and those qualities from which it has received its present extensive utility, and by which it has become an agent of transcendent power, which has spread its beneficial effects throughout every part of the civilized globe, then the universal consent of mankind will, as it were by acclamation, award the prize to one individual, whose pre-eminent genius places him far above all other competitors, and from the application of whose mental energies to this machine may be dated those grand effects which have rendered it a topic of interest to every individual for whom the progress of human civilization has any attractions. Before the era marked by the discoveries of James Watt, the steam engine, which has since become an object of such universal interest, was a machine of extremely limited power, greatly inferior in importance to most other mechanical contrivances used as prime movers. But from that time it is scarcely necessary here to state that it became a subject not of British interest only, but one with which the progress of the human race became intimately mixed up.

Since, however, the question of the progressive developement of those physical principles on which the steam engine depends, and of their mechanical application, has of late (p. 40) years received some importance, as well from the interest which the public manifest towards them as from the rank of the writers who have investigated them, we have thought it expedient to state briefly, but we trust with candour and fairness, the successive steps which appear to have led to this invention.

The engine as it exists at present is not, strictly speaking, the exclusive invention of any one individual: it is the result of a series of discoveries and inventions which have for the last two centuries been accumulating. When we attempt to trace back its history, and to determine its first inventor, we experience the same difficulty as is felt in tracing the head of a great river: as we ascend its course, we are embarrassed by the variety of its tributary streams, and find it impossible to decide which of those channels into which it ramifies ought to be regarded as the principal stream; and it terminates at length in a number of threads of water, each in itself so insignificant as to be unworthy of being regarded as the source of the majestic object which has excited the inquiry.

From a very early period the effects of heat upon liquids, and more especially the production of steam or vapour, was regarded as a probable source of mechanical power, and numerous speculators directed their attention to it, and exerted their inventive faculties to derive from it an effective mover. It was not, however, until the commencement of the eighteenth century that any invention was produced which was practically applied, even unsuccessfully. All the attempts previous to that time were either suggestions which were limited to paper or experiments confined to models; or, if they exceeded this, they never outlived a single trial on a larger scale. Nevertheless many of these suggestions and experiments being recorded and accessible to future inquirers doubtless offered useful hints and some practical aid to those more successful investigators who subsequently contrived engines in such forms as to be practically available on a large scale for mechanical purposes. It is right and (p. 41) just, therefore—mere suggestions and abortive experiments though they may have been—to record them, that each inventor and discoverer may receive the just credit due to his share in this splendid mechanical invention. We shall then in the present chapter briefly enumerate, in chronological order, the successive steps so far as they have come to our knowledge.

(23.) In a work entitled Spiritalia seu Pneumatica, one of the numerous works of this philosopher which has remained to us, is contained a description of a machine moved by vapour of water. A hollow sphere, of which A B represents a section, is supported on two pivots at A and B, which are the extremities of tubes A C D and B E F, which pass into a boiler where steam is generated. This steam flows through small apertures at the extremities A and B, and fills the hollow sphere. One or more horizontal arms K G, I H, project from this sphere, and are likewise filled with steam, but are closed at their extremities. Conceive a small hole made near the extremity G, but at one side of one of the tubes; the steam confined in the tube and globe would immediately rush from the hole with a force proportionate to its pressure within the globe. On the common principle (p. 42) of mechanics a re-action would be produced, and the tube would recoil in the same manner as a gun when discharged. The tubular arm K G being thus pressed in a direction opposed to that in which the steam issues, the sphere would revolve accordingly, and would continue to revolve so long as the steam would continue to flow from the aperture. The force of recoil would be increased by making a similar aperture in two or more arms, care being taken that all the apertures should be placed so as to cause the sphere to revolve in the same direction.

This motion being once produced might be transmitted by ordinary mechanical contrivance to any machinery which its power might be adequate to move.

This method of using steam is not adopted in any part or any form of the modern steam engine.

(24.) In the year 1826 there appeared in Zach's Correspondence a communication from Thomas Gonsalez, Director of the Royal Archives of Simancas, giving an account of an experiment reported to have been made in the year 1543 by order of Charles V. in the port of Barcelona. Blasco de Garay, a sea captain, had contrived a machine by which he proposed to propel vessels without oars or sails. Garay concealed altogether the nature of the machine which he used: all that was seen during the experiment was that it consisted of a great boiler for water, and that wheels were kept in revolution at each side of the vessel. The experiment was made upon a vessel called the Trinity, of 200 tons burden, and was witnessed by several official personages, whose presence on the occasion was commanded by the king. One of the witnesses reported that it was capable of moving the vessel at the rate of two leagues in three hours, that the machine was too complicated and expensive, and was exposed to the danger of explosion. The other witnesses, however, reported more favourably. The result of (p. 43) the experiment was thought to be favourable: the inventor was promoted, and received a pecuniary reward, besides having all his expenses defrayed.

From the circumstance of the nature of the impelling power having been concealed by the inventor it is impossible to say in what this machine consisted, or even whether steam exerted any agency whatever in it, or, if it did, whether it might not have been, as was most probably the case, a reproduction of Hero's contrivance. It is rather unfavourable to the claims advanced by the advocates of the Spaniard, that although it is admitted that he was rewarded and promoted in consequence of the experiment, yet it does not appear that it was again tried, much less brought into practical use.

(25.) A work entitled "Les Raisons des Forces Mouvantes, avec diverses Machines tant utiles que plaisantes," published at Frankfort in 1615, by Solomon de Caus, a native of France, contains the following theorem:—

"Water will mount by the help of fire higher than its level," which is explained and proved in the following terms:—

"The third method of raising water is by the aid of fire. On this principle may be constructed various machines: I shall here describe one. Let a ball of copper marked A, well soldered in every part, to which is attached a tube and stopcock marked D, by which water may be introduced; and also another tube marked B C, which will be soldered into the top of the ball, and the lower end C of which shall descend nearly to the bottom of the ball without touching it. Let the said ball be (p. 44) filled with water through the tube D, then shutting the stopcock D, and opening the stopcock in the vertical tube B C, let the ball be placed upon a fire, the heat acting upon the said ball will cause the water to rise in the tube B C."

Such is the description of the apparatus of De Caus as given by himself; and on this has been founded a claim to the invention of the steam engine. It will be observed, that neither in the original theorem nor in the description of the machine which accompanies it, is the word steam anywhere used. Now it was well known, by all conversant in physics, long before the date of the publication containing this description, that atmospheric air when heated acquires an increased elastic force. As the experiment is described, the other part of the ball A is filled with atmospheric air; the heat of the fire acting upon the air through the external surface of the ball, and likewise transmitted through the water, would of course raise the temperature of the air contained in the vessel, would thereby increase its elasticity, and would cause the water to rise in the tube B C, upon a physical principle altogether independent of the qualities of steam. The effect produced, therefore, is just what might have been expected by any one acquainted with the common properties of air, though entirely ignorant of those of steam; and, in point of fact, the pressure of the air is as much concerned in this case in raising the water as the pressure of the steam.

This objection, however, is combated by another theorem contained in the same work, in which De Caus speaks of "the strength of the vapour produced by the action of the fire, which causes water to mount; which vapour will issue from the stopcock with great violence after the water has been expelled."

If De Caus be admitted to have understood the elastic property of the vapour of water, and to have attributed the ascent of the water in the tube C B to the pressure of that vapour upon the surface of the water confined in the copper ball, it must be admitted that he suggested one of the ways (p. 45) of using the power of steam as a mechanical agent. In the modern steam engine this pressure is not now used against a liquid surface, but against the solid surface of a piston. This, however, should not take from De Caus whatever credit be due to the suggestion of the physical property in question.

(26.) In a work published at Rome in 1629, entitled "Le Machine del G. Branca," is contained a description of a machine for propelling a wheel by a blast of steam. This contrivance consists of a wheel furnished with flat vanes upon its rim, like the boards of a paddle-wheel. The steam is produced in a close vessel, and made to issue with violence from the extremity of a pipe. Being directed against the vanes, it causes the wheel to revolve, and this motion may be imparted by the usual mechanical contrivances to any machinery which it was intended to move.

This contrivance has no analogy whatever to any part of the modern steam engines in any of their various forms.

(27.) Of all the individuals to whom the invention of the steam engine has been ascribed the most celebrated was the Marquis of Worcester, the author of a work entitled "The Scantling of One Hundred Inventions," but which is more commonly known by the title "A Century of Inventions." It is to him that by far the greater number of writers and inquirers on this subject ascribe the merit of the discovery of the invention. This contrivance is described in the following terms in the sixty-eighth invention in the work above named:—

"I have invented an admirable and forcible way to drive up water by fire; not by drawing or sucking it upwards, for that must be, as the philosopher terms it, infra spæram (p. 46) activitatis, which is but at such a distance. But this way hath no bounder if the vessels be strong enough. For I have taken a piece of whole cannon whereof the end was burst, and filled it three quarters full of water, stopping and screwing up the broken end, as also the touch-hole and making a constant fire under it; within twenty-four hours, it burst and made a great crack. So that, having a way to make my vessels so that they are strengthened by the force within them, and the one to fill after the other, I have seen the water run like a constant fountain stream forty feet high. One vessel of water rarefied by fire driveth up forty of cold water, and a man that tends the work has but to turn two cocks; that one vessel of water being consumed, another begins to force and refill with cold water, and so successively; the fire being tended and kept constant, which the self-same person may likewise abundantly perform in the interim between the necessity of turning the said cocks."

These experiments must have been made before the year 1663, in which the "Century of Inventions" was published. The description of the machine here given, like other descriptions in the same work, was only intended to express the effects produced, and the physical principle on which their production depends. It is, however, sufficiently explicit to enable any one conversant with the subsequent contrivance of Savery, to perceive that Lord Worcester must have contrived a machine containing all that part of Savery's engine in which the direct force of steam is employed. As in the above description, the separate boiler or generator of steam is distinctly mentioned; that the steam from this is conducted into another vessel containing the cold water to be raised; that this water is raised by the pressure of steam acting upon its surface; that when one vessel of water has thus been discharged, the steam acts upon the water contained in another vessel, while the first is being replenished; and that a continued upward current of water is maintained by causing the steam to act alternately upon two (p. 47) vessels, employing the interval to fill one while the water is discharged from the other.

On comparing this with the contrivance previously suggested by De Caus, it will be observed, that even if De Caus knew the physical agent by which the water was driven upwards in the apparatus contrived by him, still it was only a means of causing a vessel of boiling water to empty itself; and before a repetition of the process could be obtained, the vessel should be refilled, and again boiled. In the contrivance of Lord Worcester, on the other hand, the agency of the steam was employed in the same manner as it is in the steam engines of the present day, being generated in one vessel, and used for mechanical purposes in another. Nor must this distinction be regarded as trifling and insignificant, because on it depends the whole practicability of using steam as a mechanical agent. Had its action been confined to the vessel in which it was produced, it never could have been employed for any useful purpose.

(28.) It appears, by a MS. in the Harleian Collection in the British Museum, that a mode of applying steam to raise water was proposed to Louis XIV. by Sir Samuel Morland. It contains, however, nothing more than might have been collected from Lord Worcester's description, and is only curious, because of the knowledge the writer appears to have had of the expansion which water undergoes in passing into steam. The following is extracted from the MS.:

"The principles of the new force of fire invented by Chevalier Morland in 1682, and presented to his Most Christian Majesty in 1683:—'Water being converted into vapour by the force of fire, these vapours shortly require a greater space (about 2000 times) than the water before occupied, and sooner than be constantly confined would split a piece of cannon. But being duly regulated according to (p. 48) the rules of statics, and by science reduced to measure, weight, and balance, then they bear their load peaceably (like good horses,) and thus become of great use to mankind, particularly for raising water, according to the following table, which shows the number of pounds that may be raised 1800 times per hour to a height of six inches by cylinders half filled with water, as well as the different diameters and depths of the said cylinders.'"

(29.) Denis Papin, a native of Blois in France, and professor of mathematics at Marbourg, had been engaged about this period in the contrivance of a machine in which the atmospheric pressure should be made available as a mechanical agent by creating a partial vacuum in a cylinder under a piston. His first attempts were directed to the production of this vacuum by mechanical means, having proposed to apply a water-wheel to work an air-pump, and so maintain the degree of rarefaction required. This, however, would eventually have amounted to nothing more than a mode of transmitting the power of the water-wheel to another engine, since the vacuum produced in this way could only give back the power exerted by the water-wheel diminished by the friction of the pumps; still this would attain the end first proposed by Papin, which was merely to transmit the force of the stream of a river, or a fall of water, to a distant point, by partially exhausted pipes or tubes. He next, however, attempted to produce a partial vacuum by the explosion of gunpowder; but this was found to be insufficient, since so much air remained in the cylinder under the piston, that at least half the power due to a vacuum would have been lost. "I have, therefore," proceeds Papin, "attempted to attain this end by another method. Since water being converted into steam by heat acquires the property of elasticity like air, and may afterwards be recondensed so perfectly by cold (p. 49) that there will no longer remain the appearance of elasticity in it, I have thought that it would not be difficult to construct machines in which, by means of a moderate heat, and at a small expense, water would produce that perfect vacuum which has been vainly sought by means of gunpowder."

Papin accordingly constructed the model of a machine, consisting of a small pump, in which was placed a solid piston, and in the bottom of the cylinder under the piston was contained a small quantity of water. The piston being in immediate contact with this water, so as to exclude the atmospheric air, on applying fire to the bottom of the cylinder steam was produced, the elastic force of which raised the piston to the top of the cylinder: the fire being then removed, and the cylinder being cooled by the surrounding air, the steam was condensed and reconverted into water, leaving a vacuum in the cylinder into which the piston was pressed by the force of the atmosphere. The fire being applied and subsequently removed, another ascent and descent were accomplished; and in the same manner the alternate motion of the piston might be continued. Papin described no other form of machine by which this property could be rendered available in practice; but he states generally that the same end may be attained by various forms of machines easy to be imagined.[6]

(30.) The discovery of the method of producing a vacuum by the condensation of steam was reproduced before 1688, by Captain Thomas Savery, to whom a patent was granted in that year for a steam engine to be applied to the raising of water, &c. Savery proposed to combine the machine described by the Marquis of Worcester, with an apparatus (p. 50) for raising water by suction into a vacuum produced by the condensation of steam.

Savery appears to have been ignorant of the publication of Papin, in 1695, and states that his discovery of the condensing principle arises from the following circumstance:—

Having drunk a flask of Florence at a tavern and flung the empty flask on the fire, he called for a basin of water to wash his hands. A small quantity which remained in the flask began to boil and steam issued from its mouth. It occurred to him to try what effect would be produced by inverting the flask and plunging its mouth in the cold water. Putting on a thick glove to defend his hand from the heat, he seized the flask, and the moment he plunged its mouth in the water, the liquid immediately rushed up into the flask and filled it. (21.)

Savery stated that this circumstance immediately suggested to him the possibility of giving effect to the atmospheric pressure by creating a vacuum in this manner. He thought that if, instead of exhausting the barrel of a pump by the usual laborious method of a piston and sucker, it was exhausted by first filling it with steam and then condensing the same steam, the atmospheric pressure would force the water from the well into the pump-barrel and into any vessel connected with it, provided that vessel were not more than about 34 feet above the elevation of the water in the well. He perceived, also, that, having lifted the water to this height, he might use the elastic force of steam in the manner described by the Marquis of Worcester to raise the same water to a still greater elevation, and that the same steam which accomplished this mechanical effect would serve by its subsequent condensation to repeat the vacuum and draw up more water. It was on this principle that Savery constructed the first engine in which steam was ever brought into practical operation.

Savery's Engine. — Boilers and their appendages. — Working apparatus. — Mode of Operation. — Defects of the Engine. — Newcomen and Cawley. — Atmospheric Engine. — Accidental Discovery of Condensation by Jet. — Potter's Discovery of the Method of Working the Valves.