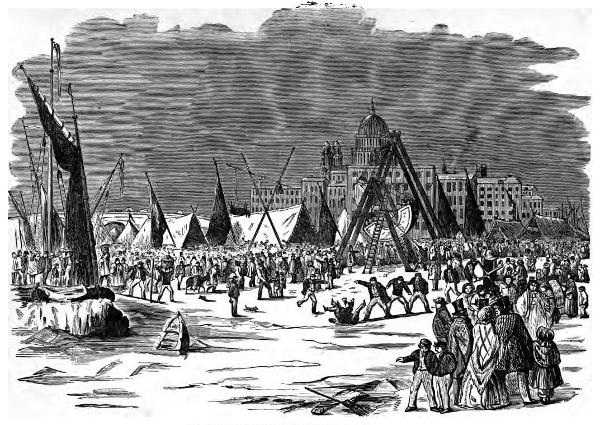

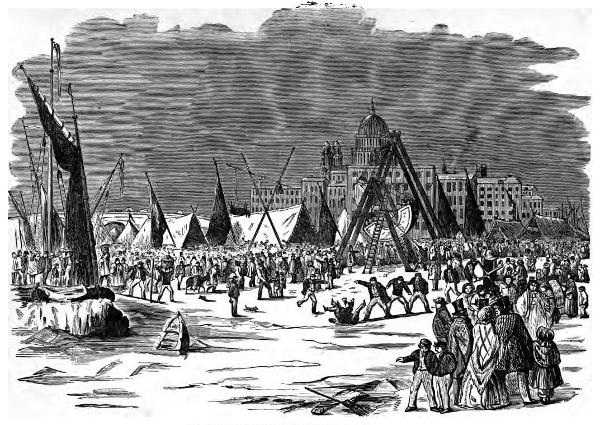

FROST FAIR ON THE RIVER THAMES, IN 1814.

Number 389

Of Four-Hundred Copies printed.

FROST FAIR ON THE RIVER THAMES, IN 1814.

FAMOUS FROSTS

AND

FROST FAIRS

IN

GREAT BRITAIN.

Chronicled from the Earliest to the Present Time.

BY

WILLIAM ANDREWS, F.R.H.S.,

Author of “Historic Romance,” “Modern Yorkshire Poets,” etc.

LONDON:

GEORGE REDWAY, YORK STREET, COVENT GARDEN.

1887.

The aim of this book is to furnish a reliable account of remarkable frosts occurring in this country from the earliest period in our Annals to the present time. In many instances, I have given particulars as presented by contemporary writers of the scenes and circumstances described.

In the compilation of this Chronology, several hundred books, magazines, and newspapers, have been consulted, and a complete list would fill several pages. I must not, however, omit to state that I have derived much valuable information from a scarce book printed on the Ice of the River Thames, in the year 1814, and published under the title of “Frostiana.” I have gleaned information from the late Mr. Cornelius Walford’s “Famines of the World,” which includes a carefully prepared summary of “The Great Frosts of History.” Some of the poems in my pages, bibliographical notes and facts, are culled from Dr. Rimbault’s “Old Ballads Illustrating the Great Frost of 1683-4,” issued by the Percy Society. It will be also observed that I have drawn curious information from Parish Registers and old Parish Accounts.

Several ladies and gentlemen have rendered me great assistance, and amongst the number must be named, with gratitude, Mrs. George Linnæus Banks, author of “The Manchester Man;” Mr. Jesse Quail, F.S.S., editor of the Northern Daily Telegraph; Mr. C. H. Stephenson, actor, author, and antiquary; Mr W. H. K. Wright, F.R.H.S., editor of the Western Antiquary; Mr. W. G. B. Page, of the Hull Subscription[viii] Library; Mr. Frederick Ross, F.R.H.S., and Mr. Ernest E. Baker, editor of the “Somersetshire Reprints.” Mr. E. H. Coleman kindly prepared for me a long list of books and magazines containing articles on this subject. I have to thank Mr. Mason Jackson, the author of “The Pictorial Press,” for kindly presenting to me the quaint cut which appears on page 29 of my work.

In 1881, the greater part of the matter contained in this book appeared in the Bradford Times, a well-conducted journal, under the able editorship of Mr. W. H. Hatton, F.R.H.S. The articles attracted more than local attention, and I was pressed to reproduce them in a volume, but owing to various circumstances, I have not been able to comply with the request until now. The record is now brought up to date, and many facts and particulars, gleaned since the articles appeared, have been added.

WILLIAM ANDREWS.

Rose Cottage, Hessle, Hull,

January, 1887.

Thames frozen over for two months.

Very severe frost, lasting nearly three months. English rivers frozen, including the Thames.

A frost lasted three months, and was followed by a dearth.

A continuous frost of five months in Britain.

Thames frozen for nine weeks.

Severe frost lasted six weeks. English rivers frozen.

The frost very severe in England and Scotland. It lasted fourteen weeks in the latter country.

Four months’ frost, and great snow.

Frost lasted two months: rivers frozen.

Thames frozen for six weeks.

A frost lasting four months, followed by dearth in Scotland: also very severe in England.

“A fatal frost.”—Short.

Thames frozen for six weeks, and booths erected on the ice.

Frost from October 1st, 759, to February 26th, 760.

Great frost after two or three weeks’ rain.

Thames frozen for nine weeks.

The greater part of the English rivers frozen for two months.

Thames frozen for thirteen weeks.

The frost this year was so great as to cause a famine.

Severe frost.

This year is notable for a frost lasting one hundred and twenty days.

Thames frozen for five weeks.

Very severe frost.

Short says: “Frost on Midsummer day; all grass and grain and fruit destroyed; a dearth.”

Great frost, followed by a severe plague and famine.

Thames frozen for seven weeks.

Fourteen weeks’ frost: Thames frozen.

Frost lasted from 1st November, 1076, to 15th April, 1077. It is recorded in the “Harleian Miscellany,” iii, page 167, that: “In the tenth year of his [William the Conqueror] reign, the cold of winter was exceeding memorable, both for sharpness and for continuance; for the earth remained hard from the beginning of November until the midst of April then ensuing.”

According to Walford’s “Insurance Cyclopædia,” “The weather was so inclement that in the unusual efforts made to warm the houses, nearly all the chief cities of the kingdom were destroyed by fire, including a great part of London and St. Paul’s.”

In this year occurred a famous frost, and it is stated, in the quaint language of an old chronicler, that “the great streams [of England] were congealed[4] in such a manner that they could draw two hundred horsemen and carriages over them; whilst at their thawing, many bridges, both of wood and stone, were borne down, and divers water-mills were broken up and carried away.”

Very severe winters.

The following is from an “Old Chronicle:” “Great frost; timber bridges broken down by weight of ice. This year was the winter so severe with snow and frost, that no man who was then living ever remembered one more severe; in consequence of which there was great destruction of cattle.”

A severe frost killed the grain crops. A famine followed.

Very severe frost.

Frost lasted from 10th December to 19th February.

A great frost.

A frost lasted from Christmas to Candlemas.

In Stow’s “Chronicle,” it is recorded that on the 14th day of January, 1205, “began a frost which continued[5] till the 20th day of March, so that no ground could be tilled; whereof it came to passe that, in the summer following, a quarter of wheat was sold for a mark of silver in many places of England, which for the most part, in the days of King Henry II., was sold for twelve pence; a quarter of oats for forty pence, that were wont to be sold for fourpence. Also the money was so sore clipped that there was no remedy but to have it renewed.” Short states, “Frozen ale and wine sold by weight.”

Fifteen weeks’ frost.

A long and hard winter followed by dearth.

Severe frost.

Severe frost and snow.

Frost lasted until Candlemas.

Penkethman gives the following particulars of this frost: “18 Henry III. was a great frost at Christmasse, which destroyed the corne in the ground, and the roots and hearbs in the gardens, continuing till Candlemasse without any snow, so that no man could plough the ground, and all the yeare after was unseasonable weather, so that[6] barrenesse of all things ensued, and many poor folks died for the want of victualls, the rich being so bewitched with avarice that they could yield them no reliefe.”

A great frost after a heavy fall of snow.

Very severe frost.

A severe frost from 1st January to 14th March.

On St. Nicholas’s Day a month’s hard frost set in.

A frost lasted from 30th November to the 2nd February.

“From Christmas to the Purification of Our Lady, there was such a frost and snow as no man living could remember the like: where, through five arches of London Bridge, and all Rochester Bridge, were borne downe and carried away by the streame; and the like hapned to many other bridges in England. And, not long after, men passed over the Thames between Westminster and Lambeth dryshod.”—Stow, edited by Howes, 1631.

Great frost and snow.

Severe frost without snow.

Twelve weeks’ frost, after rain.

A frost from 6th December to 12th March.

“Very terrible” frost from 16th September to 6th April.

A frost lasted fourteen weeks.

It is recorded in the “Chronicles of the Grey Friars of London,” as follows: “Thys yere was the grete frost and ise, and most sharpest winter that ever man sawe, and it duryd fourteen wekes, so that men myght in dyvers places both goo and ryde over the Temse.”

Stow records that the Thames was frozen, from below London Bridge to Gravesend, from December 25th to February 10th, when the merchandise which came to the Thames mouth was carried to London by land.

A long frost.

We find this entry in the “Chronicles of Grey Friars of London”: “Such a sore snowe and a frost that men myght goo with carttes over the Temse and horses, and it lastyed tylle Candlemas.”

The Thames frozen, and carts crossed on the ice to and from Lambeth to Westminster.

Very severe frost.

Interesting particulars of this severe frost are given in Stow’s “Annals,” and Holinshed’s “Chronicle.” The latter historian says that the frost continued to such an extremity that, on New Year’s Eve, “People went over and alongst the Thames on the ise, from London Bridge to Westminster. Some plaied at the football as boldlie there, as if it had been on the drie land; divers of the court being then at Westminster, shot dailie at prickes set upon the Thames; and the people, both men and women, went on the Thames in greater numbers than in anie street of the Citie of London. On the third daie of January, at night, it began to thaw, and on the fifth there was no ise to be seene betweene London Bridge and Lambeth, which sudden thaw caused great floods, and high waters, that bare downe bridges and houses, and drowned manie people in England, especiallie in Yorkshire. Owes Bridge was borne awaie, with others.” There is a tradition that Queen Elizabeth walked upon the ice.

An old tradition still lingers in Derbyshire, respecting the famous Bess of Hardwick, to the effect that a fortune teller told her that her death would not happen as long as she continued building. She caused to be erected[9] several noble structures, including Hardwick and Chatsworth, two of the most stately homes of old England. Her death occurred in the year 1607, during a very severe frost, when the workmen could not continue their labours, although they tried to mix their mortar with hot ale.

Malt liquor in the days of yore was believed to add to the durability of mortar, and items bearing on this subject occur in parish accounts. The following entries are extracted from the parish books of Ecclesfield, South Yorkshire:—

| Itm. 7 metts [i.e. bushels] of lyme for poynting some places in the church wall, and on the leades | ijs. | iiijd. |

| Itm. For 11 gallands of strong liquor for the blending of the lyme | iijs. | viijd. |

Two years later we find mention of “strong liquor” for pointing and ale for drinking:—

| For a secke of malt for pointing steeple | viijs. | |

| To Boy wyfe for Brewing itt | vjd. | |

| For xvij gallons of strong Lycker | vijs. | 4d. |

| For sixe gallons of ale wch. we besttowed of the workmen whilst they was pointing steeple | ijs. | |

| For egges for poynting church | ijs. |

Many of the old parish accounts contain items similar to the foregoing.

The following is an abstract from Drake’s “Eboracum; or, the History and Antiquities of York;” “About Martinmass (1607) began an extream frost; the river Ouze was wholly frozen up, so hard that you might have passed with cart and carriage as well as upon firm ground. Many sports were practised upon the ice, as shooting at eleven score, says my ancient authority, bowling, playing at football, cudgels, &c. And a horse-race was run from the tower at S. Mary[’s] Gate End along and under the great arch of the bridge to the Crain at Skeldergate postern.”

This year a frost fair was held upon the Thames. Edmund Howes, in his “Continuation of the Abridgement of Stow’s English Chronicle,” 1611, p. 481, gives the following curious account of it: “The 8th of December began a hard frost, and continued untill the 15th of the same, and then thawed; the 22nd of December it began againe to freeze violently, so as divers persons went halfe way over the Thames upon the ice: and the 30th of December, at every ebbe, for the flood removed the ice, and forced the people daily to tread new paths, except only betweene Lambeth and the ferry at Westminster, the which, by[11] incessant treading, became very firm, and free passage, untill the great thaw: and from Sunday, the tenth of January, untill the fifteenth of the same, the frost grew so extreme, as the ice became firme, and removed not, and then all sorts of men, women, and children, went boldly upon the ice in most parts; some shot at prickes, others bowled and danced, with other variable pastimes; by reason of which concourse of people were many that set up boothes and standings upon the ice, as fruit-sellers, victuallers, that sold beere and wine, shoemakers, and a barber’s tent, etc.” It is also stated that the tents &c. had fires in them. The artichokes in the gardens about London were killed by the frost. The ice lasted until the afternoon of the 2nd of February. Gough presented to the Bodleian Library, a rare tract containing a wood-cut representation of the Thames in its frozen state, with a view of London Bridge in the distance. It is entitled: “Cold Doings in London, except it be at the Lottery, with Newes out of the Country. A familliar talk between a Countryman and a Citizen, touching this terrible Frost, and the Great Lottery, and the effect of them.” London, 1608, quarto.

Great frost commenced in October, and lasted four months. The Thames frozen, and heavy carriages driven over it.

It is recorded in Drake’s “Eboracum” as follows: “On the 16th of January the same year [1614] it began to snow and freeze, and so by intervals snowing without any thaw till the 7th of March following; at which time was such a heavy snow upon the earth as was not remembered by any man then living. It pleased God that at the thaw fell very little rain, nevertheless the flood was so great, that the Ouze ran down North Street and Skeldergate with such violence as to force all the inhabitants of those streets to leave their houses. This inundation chanced to happen in the Assize week, John Armitage, Esquire, being then High Sheriff of Yorkshire. Business was hereby much obstructed; at Ouze bridge end were four boats continually employed in carrying people [a]cross the river; the like in Walmgate [a]cross the Foss. Ten days this inundation continued at the height, and many bridges were driven down by it in the country, and much land overflown. After this storm, says my manuscript, followed such fair and dry weather, that in April the ground was as dusty as in any time of summer. This drought continued till the 20th of August following without any rain at all; and made such a scarcity of hay, beans, and barley, that the former was sold at York for 30s. and 40s.[13] a wayne load, and at Leeds for four pounds.”

A severe frost from the 17th January to 7th March. In 1814 a tract was republished entitled “The Cold Yeare: a Deep Snow in which Men and Cattle perished; written in Dialogue between a London Shopkeeper and a North-countryman.” 1615. 4to.

“This year a frost enabled the Londoners to carry on all manner of sports and trades upon the river.” “Old and New London,” by E. Walford, M.A., v 3, p. 312.

Says a contributor to “Notes and Queries” in the Nottingham Guardian, the following is an extract from Prynne’s “Divine Tragedie lately acted,” 1636:—“On January the 25th, 1634, being the Lord’s Day, in the time of the last great frost, fourteen young men, presuming to play at football on the river Trent, near Gainsborough, coming altogether in a scuffle, the ice suddenly broke, and there were eight of them drowned.” The “Divine Tragedie,” like several other works of that period, was written to show how judgments were overtaking the people because of the recent order that the Book of Liberty should be read in churches, which legalised sports on Sunday after service.

John Evelyn wrote in his “Diary;” “Now was the Thames frozen over, and horrid tempests of wind.”

From the 28th January to 11th February, severe frost. Samuel Pepys records in his “Diary,” “8th February being very hard frost; 28th August, cold all night and this morning, and a very great frost they say, abroad; which is much, having had no summer at all, almost.”

Severe frost from 28th December to 7th February. Pepys says, 6 February: “One of the coldest days, they say, ever felt in England.”

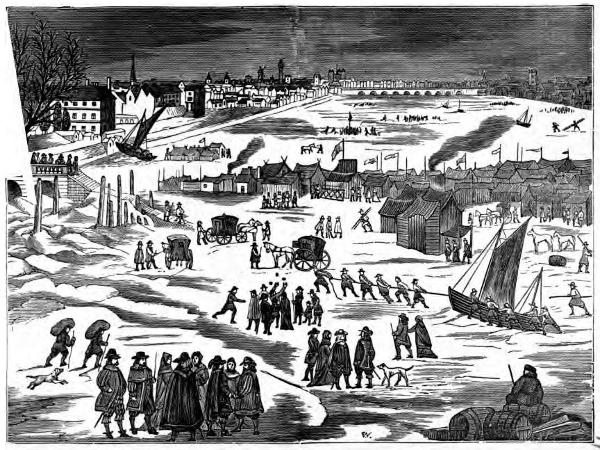

FROST FAIR ON THE THAMES IN THE REIGN OF CHARLES II.

In the December of 1672 occurred in the West of England, an uncommon kind of shower of freezing rain, or raining ice. It is recorded that this rain, as soon as it touched anything above ground, as a bough or the like, immediately settled into ice; and by multiplying and enlarging the icicles broke down with its weight. The rain that fell on the snow immediately froze into ice, without sinking in the snow at all. It made an incredible destruction of trees, beyond anything in all history. “Had it concluded with some gust of wind” says a gentleman on the spot, “it might have been of terrible consequence. I weighed the sprig of an ash tree, of just three quarters of[17] a pound, the ice of which weighed sixteen pounds. Some were frighted with the noise of the air till they discerned it was the clatter of icy boughs dashed against each other.” Dr. Beale says, that there was no considerable frost observed on the ground during the whole time; whence he concludes that a frost may be very intense and dangerous on the tops of some hills and plains; while in other places, it keeps at two, three or four feet distance above the ground, rivers, lakes, &c. The frost was followed by a forwardness of flowers and fruits.

The foregoing appears to have escaped the notice of the compiler of an interesting and informing little book entitled “Odd Showers.” London, 1870.

From the beginning of December until the 5th of February, to use the words of Maitland, frost “congealed the river Thames to that degree, that another city, as it were, was erected thereon; where, by the great number of streets and shops, with their rich furniture, it represented a great fair, with a variety of carriages, and diversions of all sorts; and near Whitehall a whole ox was roasted on the ice.” Evelyn gives perhaps the best account of this’ great frost. Writing in his[18] “Diary” under date of January 24th, 1684, he observes, “the frost continuing more and more severe, the Thames before London, was still planted with boothes in formal streetes, all sorts of trades and shops furnish’d and full of commodities, even to a printing presse, where the people and ladyes tooke a fancy to have their names printed, and the day and yeare set down when printed on the Thames: this humour tooke so universally, that ’twas estimated the printer gain’d £5 a day, for printing a line onely, at sixpence a name, besides what he got by ballads, etc. Coaches plied from Westminster to the Temple, and from several other staires, to and fro, as in the streetes, sleds, sliding with skeetes, a bull-baiting, horse and coach races, puppet-plays, and interludes, cookes, tipling, and other lewd places, so that it seem’d to be a bacchanalian triumph, or carnival on the water.” Evelyn tells how the traffic and festivity were continued until February the 5th, when he states that “it began to thaw, but froze again. My coach crossed from Lambeth to the horse-ferry, at Milbank, Westminster. The boothes were almost all taken downe, but there was just a map, or landskip, cut in copper, representing all the[19] manner of the camp, and the several actions, sports, pastimes, thereon, in memory of so signal a frost.”

King Charles visited the sports on the Thames, in company with members of his family and of the royal household. They had their names printed on a quarto sheet of Dutch paper, measuring three and a half inches by four. The following is a copy of the interesting document:—

| Charles, | King. |

| James, | Duke. |

| Katherine, | Queen. |

| Mary, | Dutchess. |

| Ann, | Princesse. |

| George, | Prince. |

| Hans in Kelder. | |

London: Printed by G. Croom, on the ICE, on the River Thames, January 31, 1684.

In the foregoing list of names we have Charles the Second; his brother James, Duke of York, afterwards James the Second; Queen Catherine, Infanta of Portugal; Mary D’Este, sister of Francis, Duke of Modena, James’s second duchess;[20] the Princess Anne, second daughter of the Duke of York, afterwards Queen Anne; and her husband Prince George of Denmark. It has been suggested that the last name displays a touch of the King’s humour, and signifies “Jack in the Cellar,” alluding to the pregnant situation of Anne of Denmark.

In some quaint lines, entitled “Thamasis’s Advice to the Painter, from her frigid zone, etc.” “printed by G. Croom, on the river of Thames,” occurs:

Landskip, mentioned by Evelyn, is entitled “An exact and lively Mapp or Representation of Boothes, and all the Varieties of Showes and Humours upon the Ice, on the River of Thames by London, during that memorable Frost, 35th yeare of the Reign of his Sacred Majesty King Charles the Second. Anno Dni MDCLXXXIII. With an Alphabetical Explanation of the most remarkable figures.” It consists of a whole-sheet copper-plate engraving, the view extending from[21] the Temple-stairs and Bankside to London-bridge. In an oval cartouche at the top within the frame of the print, is the title; and below the frame are the alphabetical references, with the words “Printed and sold by William Warter, Stationer, at the signe of the Talbott, under the Mitre Tavern in Fleete street, London.” In the foreground of this representation of Frost Fair appear extensive circles of spectators surrounding a bull-baiting, and the rapid revolution of a whirling-chair or car, drawn by several men, by a long rope fastened to a stake fixed in the ice. Large boats, covered with tilts, capable of containing a considerable number of passengers, and decorated with flags and streamers, are represented as being used for sledges, some being drawn by horses, and others by watermen, lacking their usual employment. Another sort of boat was mounted on wheels; and one vessel, called “the drum boat,” was distinguished by a drummer placed at the prow. The pastimes of throwing at a cock, sliding and skating, roasting an ox, football, skittles, pigeon-holes, cups and balls, &c., are represented as being carried on in various parts of the river; whilst a sliding-hutch, propelled by a stick; a chariot, moved by a screw; and stately coaches filled with visitors, appear to be rapidly[22] moving in various directions, and sledges with coals and wood are passing between London and Southwark shores. An impression of this plate will be found in the Royal Collection of Topographical Prints and Drawings, given by George the Fourth to the British Museum, vol. xxvii., art. 39. There is also a variation of the same engraving in the City Library at Guildhall, divided with common ink into compartments, as if intended to be used as cards, and numbered in the margin, in type with Roman numerals, in sets of ten each, with two extra.

This famous frost gave rise to many pictures and poems. In the British Museum is a broadside as follows:

“A True Description of Blanket Fair upon the River Thames, in the time of the Great Frost in the Year of our Lord, 1683.”

London: Printed by H. Brugis, in Green Arbor, Little Old Bayly. 1684.

The following is a copy of a broadside preserved in the British Museum:—

GREAT BRITAIN’S WONDER: OR, LONDON’S ADMIRATION.

Being a true Representation of a prodigious Frost, which began about the beginning of December, 1683, and continued till the fourth day of February following, and held on with such violence, that men and beasts, coaches and carts, went as frequently thereon, as boats were wont to pass before. There was also a street of booths built from the Temple to Southwark, where were sold all sorts of goods imaginable, namely, cloaths, plate, earthenware, meat, drink, brandy, tobacco, and a hundred sorts of other commodities not here inserted: it being the wonder of this present age, and a great consternation to all the spectators.

Printed by M. Haly and J. Miller, and sold by Robert Waltor, at the Globe, on the north side of St. Paul’s Church, near that end towards Ludgate, where you may have all sorts and sizes of maps, coppy-books, and prints, not only in English, but Italian, French, and Dutch; and by John Seller, on the west side of the Royal Exchange. 1684.

[1] Two lines omitted.

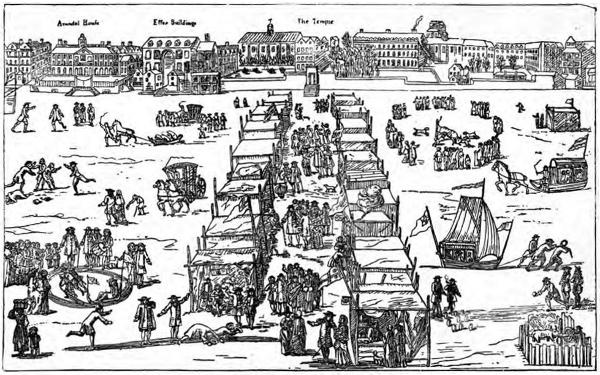

The foregoing is illustrated with a quaint wood-cut, roughly executed. It is reproduced in Mr. Mason Jackson’s “Pictorial Press,” (London, 1885), and by his courtesy we are able to include it in this work.

FROST FAIR ON THE THAMES.

Copy of an engraving from a broadside entitled: “Great Britain’s Wonder, London’s Admiration. Being a True Representation of a prodigious Frost, which began about the beginning of December, 1683 and continued till the fourth day of February following.” etc.

The following is a copy of a broadside preserved in the Ashmolean Museum. It was printed for J. Shad, London, in 1684.

A WINTER WONDER; OR THE THAMES FROZEN OVER, WITH REMARKS ON THE RESORT THERE.

The title of another broadside was the “Wonders of the Deep,” illustrated with a rude wood-cut, representing the Frost Fair. This intimated that it was “an exact Representation of the River Thames, as it appeared during the memorable Frost, which[35] began about the middle of December, and ended on the 28th of February, anno 1683-4.” The lines under the picture are as follow:—

THE WONDERS OF THE DEEP.

Printed in the year 1684.

In the parish register of Holy-rood Church, Southampton, is the following record of this winter’s remarkable frost:

“1683-4 This yeare was a great Frost, which began before Christmasse, soe that yᵉ 3rd and 4th dayes of this month February yᵉ River of Southampton was frossen all over and covered with ice from Calshott Castle to Redbridge and Tho: Martaine maʳ of a vessell went upon yᵉ ice from[37] Berry near Marchwood to Milbrook-point. And yᵉ river at Ichen Ferry was so frossen over that severall persons went from Beauvois-hill to Bittern Farme, forwards and backwards.”

The following curious extract is from the Parochial Register at Ubley, near Wrington: “In the yeare 1683 was a mighty great frost, the like was not seene in England for many ages. It came upon a very deep snow, which fell imediately after Christmas, and it continued untill a Lady-day. The ground was not open nor the snow cleane gone off the earth in thirteene weeks. Somm of the snow remained at mindipe till midsummer. It was soe deepe and driven with the winde a gainst the hedges and stiles, that the next morning after it fell men could not goe to their grounds to serve their cattell without great danger of being buried, for it was above head and shoulders in many places—sum it did burie—did betooken the burieing of many more which came to pass before the end of the yeare; but in few days the frost came soe fearce, that people did goe upon the top of it over wals and stiles as on levell ground, not seeing hardly where they was, and many men was forced to keep their cattell untill the last, in the same ground that they was in at first, because they could not drive them to any other place, and did[38] hew the ice every day for water, by reason of the sharpness of the frost and the deepness of the snow. Som that was travelling on mindipe did travell till they could travell no longer, and then lye down and dye, but mortality did prevaill most among them that could travell worst, the sharpness of the season tooke off the most parte of them that was aged and of them that was under infermities, the people did die so fast, that it was the greatest parte of their work (which was appointed to doe that worke) to burie the dead; it being a day’s work for two men, or two days’ work for one man, to make a grave. It was almost as hard a work to hew a grave out, in the earth, as in the rock, the frost was a foot and halfe and two foot deepe in the dry earth, and where there was moister and watter did runn, the ice was a yard and fower foot thick, in soe much that ye people did keepe market on the River at London; ‘God doth scatter his ice like morsels, man cannot abide his cold.’—Psalme, 147, 17.”

The following are particulars of the chief publications issued in connection with this frost:—

A large copper-plate, entitled “A Map of the River Thames, merrily call’d Blanket Fair, as it was frozen in the memorable year 1683-4, describing the booths, footpaths, coaches, sledges, bull-baiting,[39] and other remarks upon that famous river.” Dedicated to Sir Henry Hulse, Knt., and Lord Mayor, by James Moxon, the engraver.

“A wonderfull Fair, or a Fair of Wonders; being new and true illustration and description of the several things acted and done on the river of Thames in the time of the terrible frost, which began about the beginning of Dec., 1683, and continued till Feb. 4, and held on with such violence, that men and beasts, coaches and sledges, went common thereon. There was also a street of booths from the Temple to Southwark, where was sold all sorts of goods; likewise bull-baiting and an ox roasted whole, and many other things, as the map and description do plainly show.” Engraved and printed on a sheet, 1684.

A small copper-plate representation of Frost Fair, with the figure of Erra Pater in the foreground. At the top, are the words, “Erra Pater’s Prophesy, or Frost Faire in 1683,” and underneath, the following lines:

Printed for James Norris, at the King’s Armes, without Temple Barr.

Timbs, in his “Curiosities of London,” records a great frost, lasting from 20th December to 6th February. Pools were frozen eighteen inches thick, and the Thames ice was covered with streets of shops, bull-baiting, shows and tricks; hackney coaches plied on the ice-roads, and a coach with six horses was driven from Whitehall almost to London Bridge; yet in two days all the ice disappeared.

The Thames frozen over, and some persons crossed it on the ice. In the Crowle Pennant is a coarse bill, within a wood-cut border of rural subjects, bearing the inscription, “Mr. John Heaton, printed on the Thames at Westminster, January 7th, 1709.” The frost lasted three months. It is somewhat remarkable to find that there was very little frost this year in Scotland and Ireland.

Thames again frozen over. At the time of this frost an advertisement appeared as follows: “This is to give notice to gentlemen and others that pass[41] upon the Thames during this frost, that over against Whitehall-stairs they may have their names printed, fit to paste in any book, to hand down the memory of the season to future ages.

The following account of this frost is drawn from Dawks’s News-Letter of January 14th, 1716: “The Thames seems now a solid rock of ice; and booths for the sale of brandy, wine, ale, and other exhilarating liquors, have been for some time fixed thereon; but now it is in a manner like a town: thousands of people cross it, and with wonder view the mountainous heaps of water, that now lie congealed into ice. On Thursday, a great cook’s-shop was erected, and gentlemen went as frequently to dine there, as at any ordinary.”

“Over against Westminster, Whitehall, and Whitefriars, Printing-presses are kept upon the ice, where many persons have their names printed, to transmit the wonders of the season to posterity.”

It is further recorded of the Thames that “coaches, waggons, carts, &c., were driven on it, and an enthusiastic preacher held forth to a motley congregation on the mighty[42] waters, with a zeal fiery enough to have thawed himself through the ice, had it been susceptible to religious warmth. This, with other pastimes and diversions, attracted the attention of many of the nobility, and even brought the Prince of Wales, to visit Frost Fair. On that day, there was an uncommonly high spring-tide, which overflowed the cellars on the banks of the river, and raised the ice full fourteen feet, without interrupting the people from their pursuits. The Protestant Packet of this period, observes that the theatres were almost deserted. The News-letter of February 15, announces the dissolution of the ice, and with it the ‘baseless fabric’ on which Momus had held his temporary reign; the above paper then proclaims the good fare, and various articles to be seen, and purchased.”

The chief illustrations of this frost are as follows:—

A copper plate representing London Bridge on the right hand, and a line of tents on the left, leading from Temple Stairs. In front, another line of tents, marked “Thames Street,” and the various sports, &c., before them: below the print are alphabetical references, with the words “Printed on the Thames, 1715-16;” and above[44] it, “Frost Fair on the River Thames.”

A copper-plate of much larger dimensions, representing London at St. Paul’s, with the tents, &c., and with alphabetical references; “Printed and sold by John Bowles, at the Black Horse, in Cornhill.” In the right-hand corner above, the arms and supporters of the City; and on the left a cartouche, with the words “Frost Fayre, being a True Prospect of the Great Varietie of Shops and Booths for Tradesmen, with other Curiosities and Humors, on the Frozen River of Thames, as it appeared before the City of London, in that memorable Frost in yᵉ year of the Reigne of Our Sovereigne Lord King George, Anno Domini 1716.”

“An exact and lively View of the Booths, and all the variety of Shows, &c., on the ice, with an alphabetical explanation of the most remarkable figures, 1716.” A copper-plate.

“Frost Fair; or a View of the Booths on the Frozen Thames in the 2nd year of King George, 1716.” A wood-cut.

The following is a list of the most important memorials of this famous frost fair:—

A copper-plate, representing a view of the Thames at Westminster, with the tents, sports,[45] &c., and alphabetical references, entitled “Ice Fair.” Printed on yᵉ River Thames, now frozen over. Jan. 31, 1739-40.

A coarse copper-plate, entitled “The view of Frost Fair,”—scene taken from York-buildings Water Works; twelve verses beneath.

A small copper-plate, representing an altar-piece with ten commandments, engraven between the figures of Moses and Aaron; and beneath, on a cartouche, “Printed on the Ice, on the River of Thames, Janʳʸ 15, 1739.”

A small copper-plate, representing an ornamental border with a female head, crowned at the top; and below two designs of the letter press and rolling press. In the centre, in type, “Upon the Frost in the year 1739-40,” six verses, and then, “Mr. John Cross, aged 6. Printed on the ice upon the Thames, at Queen-Hithe, January the 29th, 1739-40.”

A coarse copper-plate engraving, looking down the river, entitled “Frost Fair,” with eight lines of verse beneath, and above, “Printed upon the River Thames when frozen, Janu. the 28, 1739-40.”

“An Extract Draught of Frost Fair on the River Thames, as it appears from Whitehall Stairs, in the year 1740,” with twelve lines of verse underneath. “Printed and sold by Geoᵉ Foster, Printseller, in St. Paul’s Church-yard, London.”

“The English Chronicle, or Frosty Kalender; a broadside containing a memorial of the principal frosts, with a view of the fair from the Southwark side of the river, opposite St. Paul’s. Printed on the Thames, 1739-40.”

The winter of 1739-40 was one of great severity. The frost commenced on Christmas-day, and lasted until the 17th February following. It caused much distress amongst the poor, coals could hardly be obtained for money, and water was equally scarce. It is recorded that “the watermen and fishermen, with a peterboat in mourning, and the carpenters, bricklayers, &c., with their tools and utensils in mourning, walked through the streets in large bodies, imploring relief for their own and families’ necessities; and, to the honour of the British character, this was[47] liberally bestowed. Subscriptions were also made in the different parishes, and great benefactions bestowed by the opulent, through which the calamities of the season were much mitigated. A few days after the frost had set in, great damage was done among the shipping in the river Thames by a high wind, which broke many vessels from their moorings, and drove them foul of each other, while the large sheets of ice that floated on the stream, overwhelmed various boats and lighters, and sunk several corn and coal vessels. By these accidents many lives were lost; and many others were also destroyed by the intensity of the cold, both on land and water.

Above the Bridge, the Thames was completely frozen over, and tents and numerous booths were erected on it for selling liquors, &c., to the multitudes that daily flocked thither for curiosity or diversion. The scene here displayed was very irregular, and had more the appearance of a fair on land, than of a frail exhibition, the only basis of which was congealed water.”

Sports were enjoyed on the ice, and shops opened for the sale of fancy articles, food and drink. A printing press was in active operation, and amongst the papers printed was the following:

The noble Art and mystery of Printing, was first invented by J. Faust, 1441, and publicly practised by John Gottenburgh, a soldier of Mentz, in High Germany, anno. 1450. King Henry VI. (anno. 1457) sent two private messengers with fifteen hundred marks, to procure one of the workmen. These prevailed on Frederick Corsellis to leave the Printing-house in disguise; who immediately came over with them, and first instructed the English in this most famous Art, at Oxford, in the year 1459.

WILLIAM NOBLE, M.A.

Printed upon the river Thames, Jan. 29th, in the thirteenth year of the reign of King George the IId. Anno Dom. 1740.

“Some venturers in the Strand,” says Timbs, “bought a large ox in Smithfield, to be roasted whole on the ice; and one, Hodgeson, claimed the privilege of felling or knocking down the beast as a right inherent in his family, his father having knocked down the one roasted on the river in the Great Frost, 1684, near Hungerford Stairs: Hodgeson to wear a laced cambric apron, a silver-handled steel, and a hat and feathers.”

At the thaw a number of persons fell victims to their rashness, amongst those who lost their lives[49] may be mentioned Doll, the noted pippin woman. Gay, in his “Trivia,” book ii, thus alludes to her death:—

Many of the houses which, at this period, stood on London Bridge, as well as the bridge itself, sustained considerable damage.

Thomas Gent, the celebrated printer and historian, in his Life, relates how he set up a printing press on the river Ouse at York during this frost. “In January, 1739,” [1740 n.s.] he says, “the frost having been extremely intense, the river became so frozen, that I printed names upon the ice. It was a dangerous spot on the south side of the bridge, where I first set up, as it were, a kind of press—only a roller wrapped about with blankets. Whilst reading the verses I had[50] made to follow the names—wherein King George was most loyally inserted—some soldiers round about made great acclamation, with other good people; but the ice suddenly cracking, they almost as quickly ran away, whilst I, who did not hear well, neither guessed the meaning, fell to work, and wondered at them as much for retiring so precipitately as they did at me for staying; but, taking courage, they shortly returned back, brought company, and I took some pence amongst them. After this I moved my shop to and fro, to the great satisfaction of young gentlemen and ladies, and others, who were very liberal on the occasion.”

It will not, we think, be without interest to reproduce particulars of a palace which was built solely of ice at this period. “In the year 1740, the Empress Anne of Russia, caused a palace of ice to be erected upon the banks of the Neva. This extraordinary edifice was fifty-two feet in length, sixteen in breadth, and twenty feet high, and constructed of large pieces of ice cut in the manner of freestone. The walls were three feet thick. The several apartments were furnished with tables, chairs, beds, and all kinds of household furniture of ice. In front of this edifice, besides pyramids and statues, stood six cannon, carrying balls of six pounds weight, and two mortars,[51] entirely made of ice. As a trial from one of the former, a cannon ball, with only a quarter of a pound of powder, was fired off, the ball of which went through a two-inch board, at sixty paces from the mouth of the piece, which remained completely uninjured by the explosion. The illumination of this palace at night was astonishingly grand.”

“All frost or rain from 15th September to 1st February.”

A severe frost for some weeks. It is recorded in the Gentleman’s Magazine, 18 December, 1742: “The frost having continued near three weeks, the streets in some parts of the city, though there had been no snow, were rendered very incommodious, and several accidents happened.”

A very severe frost this year, especially at Bath and in the south-west of England.

The frost lasted ninety-four days. According to the Gentleman’s Magazine it set in on Saturday, 25th December, 1762. It is thus described: “A most intense frost with easterly wind, which has since continued, with very little intermission, until the end of January. Some experiments have been tried during the course of it, which prove that on some[52] days it was no less severe than that of 1740, though upon the whole it has not been attended with the same calamitous circumstances. On Friday, 31st December, a glass of water placed upon the table in the open air, in six minutes froze so hard as to bear 5 shillings upon it; a glass of red port wine placed upon the same table froze in two hours; and a glass of brandy in six, both with hard ice.” It is mentioned that in Cornwall, Wales, and Ireland, this frost was felt but slightly.

Both these years opened with severe frosts, which caused provisions to increase greatly in price. Navigation on the Thames was suspended, and great damage done to the small craft by the ice. It is chronicled that “many persons perished by the severity of the weather, both on the water and on the shore. During the latter frost, the price of butchers’ meat grew so exorbitant that the Hon. Thomas Harley, Lord Mayor, proposed that bounties should be given for bringing fish to Billingsgate market; and this plan having been carried into effect, the distresses of the poor were greatly alleviated, by the cheap rates at which the markets were supplied.”

We read in White’s “Selborne,” under date of January, 1768: “We have had very severe frost and deep snow this month; my thermometer was[53] one day 14½ degrees below freezing point, within doors. The tender evergreens were injured pretty much. It was very providential that the air was still, and the ground well covered with snow, else vegetation in general must have suffered prodigiously. There is reason to believe that some days were more severe than any since the year 1739-40.” The frost this year was very severe in Scotland.

The following “Icy Epitaph” is said to be from the graveyard of Bampton, Devonshire:—

In memory of the Clerk’s son,

Bless my i, i, i, i, i, i,

Here I lies

In a sad pickle

Killed by an icicle,

In the year of Anno Domini 1776.

The Plymouth correspondent of the Gentleman’s Magazine wrote under date of 16th February, 1782: “The most intense frost ever known … The grass, which on Friday was as green and flourishing as if it had been midsummer, on Sunday morning seemed to be entirely killed. This is mentioned by our correspondent as very unusual in that part of the country; and the snow lay on the ground in many places.”

The frost lasted eighty-nine days. It commenced in December, continued through January and[54] February, and in March there was snow, and cold cutting winds. We gather from the Gentleman’s Magazine that it was general. In the February number it is reported: “From different parts of the country we have accounts of more persons having been found dead in the roads, and others dug out of the snow, than ever was known in any one year in the memory of man.” On January 6th, “Thames not quite frozen over, but navigation stopped by ice.” The frost from the 10th to 20th February was extremely severe. The Thames frozen and traffic crossed in several places.

On the fifth bell of Tadcaster peal is recorded: “It is remarkable that these bells were moulded in the great frost, 1783. C. and R. Dalton, Fownders, York.”

In the Gentleman’s Magazine for February the following appears: “From 10th December, 1783, to this day it has been 63 days’ frost; of these it snowed nineteen, and twelve days’ thaw, whereof it rained nine. Had the frost continued at 13 degrees as on the 31st December during the night, it would have frozen over the Thames in twenty-four hours.”

On the 25th November, 1788, a frost set in which lasted seven weeks. It is recorded that the thermometer stood at eleven degrees below[55] freezing point in the very midst of the city. The Thames was frozen below London Bridge, and the ice on the river assumed all the appearance of a frost fair. A variety of amusements were provided for the visitors, including puppet-shows and the exhibition of wild beasts. In the Gentleman’s Magazine for 1789 the following diary of remarkable events which transpired during this frost, is given:—

“Saturday, January 10, 1789—Thirteen men brought a waggon with a ton of coals from Loughborough in Leicestershire, to Carlton House, as a present to His Royal Highness the Prince of Wales. As soon as they were emptied into the cellars, Mr. Weltjie, clerk of the cellars, gave them four guineas, and as soon as the Prince was informed of it, his Highness sent them twenty guineas, and ordered them a pot of beer each man. They performed their journey, which is 111 miles, in 11 days, and drew it all the way without any relief.

Monday 12.—A young bear was baited on the ice, opposite to Redriff, which drew multitudes together, and fortunately no accident happened to interrupt their sport.

Tuesday 13.—The Prince of Wales transmitted £1000 to the Chamberlain for the benefit of the[56] poor, during the severe frost.

Saturday 17.—The captain of a vessel lying off Rotherhithe, the better to secure the ship’s cables, made an agreement with a publican for fastening a cable to his premises; in consequence, a small anchor was carried on shore and deposited in the cellar, while another cable was fastened round a beam in another part of the house. In the night the ship veered about, and the cables holding fast, carried away the beam and levelled the house with the ground; by which accident five persons asleep in their beds were killed.”

In the Common Place Notes for February, 1789, is the following:—“With the new year, new entertainments commenced, or more properly speaking, old sports were revived in the neighbourhood of London. The river Thames, which at this season usually exhibits a dreary scene of languor and indolence, was this year the stage on which there were all kinds of diversions, bear-baiting, festivals, pigs and sheep roasted, booths, turnabouts, and all the various amusements of Bartholomew fair multiplied and improved; from Putney-bridge in Middlesex, down to Redriff, was one continued scene of merriment and jollity; not a gloomy face to be seen, nor a countenance expressive of want; but all cheerfulness, originating[57] apparently from business and bustle. From this description the reader is not, however, to conclude that all was as it seemed. The miserable inhabitants that dwelt in houses on both sides the river during these thoughtless exhibitions, were many of them experiencing extreme misery; destitute of employment, though industrious, they were with families of helpless children, for want of employment, pining for want of bread; and though in no country in the world the rich are more benevolent than in England, yet their benefactions could bear no proportion to the wants of numerous poor, who could not all partake of the common bounty. It may, however, be truly said, that in no great city or country on the continent of Europe, the poor suffered less from the rigour of the season, than the inhabitants of Great Britain and London. Yet even in London, the distresses of the poor were very great; and though liberal subscriptions were raised for their relief, many perished through want and cold.

On this occasion, the City of London subscribed fifteen hundred pounds towards supporting those persons who were not in the habit of receiving alms.”

We cull from the Public Advertiser of January 15th, 1789, the following piece of drollery, in the[58] shape of an inscription on a temporary building on the Thames: “This Booth to Let. The present possessor of the Premises is Mr. Frost. His affairs, however, not being on a permanent footing, a dissolution, or bankruptcy may soon be expected, and a final settlement of the whole entrusted to Mr. Thaw.”

The printing-press was again at work on the ice, and in Crowle’s “Illustrated Pennant,” there is a bill, having a border of type flowers, containing the following lines:—

“On the Ice, at the Thames Printing-Office, opposite St. Catherine’s Stairs, in the severe Frost January, 1789. Printed by me, William Bailey.”

In the same collection is a stippled engraving entitled: “A View of the Thames from Rotherhithe Stairs, during the frost in 1789. Painted by G. Samuel, and engraved by W. Birch, enamel-painter.”

The end of the Fair we find thus described in the London Chronicle of January 15th, 1789, “Perhaps the breaking up of the fair upon the Thames last Tuesday night below bridge, exceeded every[59] idea that could be formed of it, as it was not until after the dusk of the evening that the busy crowd was persuaded of the approach of a thaw. This, however, with the crackling of some ice about eight o’clock, made the whole a scene of the most perfect confusion; as men, beasts, booths, turnabouts, puppet-shows, &c., &c., were all in motion, and pouring towards the shore on each side. The confluence here was so sudden and impetuous, that the watermen who had formed the toll-bars over the sides of the river, where they had broken the ice for that purpose, not being able to maintain their standard from the crowd, &c., pulled up the boards, by which a number of persons who could not leap, or were borne down by the press, were soused up to the middle.”

The next issue of the paper records that “on Thursday, January 15th, the ice was so powerful as to cut the cables of two vessels lying at the old Rose Chair, and drive them through the great arch of London bridge; when their masts becoming entangled with the balustrades, both were broken and many persons hurt.” The river remained frozen for some time after this.

The Antiquarian Society of Newcastle-on-Tyne recorded that the ice on the river Tyne was twenty inches thick. The Thames frozen.

We find in “Frostiana” the following particulars of the curious effect of cold on the feathered tribe:—“In February, 1809, a boy, in the service of Mr. W. Newman, miller, at Leybourne, near Malling, went into a field, called the Forty Acres, and saw a number of rooks on the ground very close together. He made a noise to drive them away, but they did not appear alarmed; he threw snow-balls to make them rise, still they remained. Surprised at this apparent indifference, he went in among them, and actually picked up twenty-seven rooks; and also in several parts of the same field, ninety larks, a pheasant, and a buzzard hawk. The cause of the inactivity of the birds, was a thing of rare occurrence in this climate; a heavy rain fell on Thursday afternoon, which, freezing as it came down, so completely glazed over the bodies of the birds, that they were fettered in a coat of ice, and completely deprived of the power of motion. Several of the larks were dead, having perished from the intensity of the cold. The buzzard hawk being strong, struggled hard for his liberty, broke his icy fetters and effected his escape.”

In January this year the Thames frozen over.—Timbs.

On the evening of the 27th of December, 1813, a great fog commenced in London, and the greatest frost of the century set in. We have taken from a work compiled during the frost, the following reliable account of it:—

“On the night of 27th the darkness was so dense that the Prince Regent, who desired to pay a visit to the Marquis of Salisbury at Hatfield House, was obliged to return back to Carlton House, not, however, until one of his outriders had fallen into a ditch on the side of Kentish Town. The short excursion occupied several hours. Mr. Croker, of the Admiralty, intending to go northward, wandered in the dark for some hours without making more than three or four miles progress.”

On the night of the 28th of December, the Maidenhead coach, on its return from town, missed the road near Harford Bridge, and was overturned. Amongst the injured passengers was Lord Hawarden.

It took, on the 29th of December, the Birmingham mail nearly seven hours in going a couple of miles past Uxbridge, or a distance of about twenty miles.

On this and other evenings in London, a couple of persons with links ran by each horse’s head; yet with this and other precautions some serious and many whimsical accidents occurred. Pedestrians[62] even carried links or lanterns, and a number who were not provided with lights lost themselves in the most frequented and at other times well-known streets. Hackney coachmen mistook the pathway for the road, and vice versa—the greatest possible confusion took place.

The state of the Metropolis on the night of the 31st of December was in consequence truly alarming. It required both great care and knowledge of the public streets to enable anyone to proceed any distance, and those obliged to venture out carried torches. The usual lamps appeared through the haze not larger than small candles. Many of the hackney coachmen led their horses, and others drove only at walking pace. Until the 3rd of January, 1814, lasted this tremendous fog, or “darkness that might be felt.”

Immediately on the cessation of the fogs, a heavy fall of snow commenced. A writer of the time said, “There is nothing in the memory of man to equal these falls.” With the exception of a few short intervals, the snow continued incessantly for forty-eight hours, and this, too, after the ground was covered with a condensation, the result of nearly four weeks’ continued frost. Nearly the whole of the time the wind blew from the north and north-east, and was intensely cold.

The state of the streets was rendered dangerous by a thaw which lasted about a day. The mass of snow and water became so thick, that it was with difficulty that the carriages could progress even with the aid of an additional horse each. Nearly all trades and callings carried on out of doors were stopped, which considerably increased the distress of the lower orders. The frost continued and skating occupied the chief attention of the people. It will be interesting to furnish an account of the state of the river Thames at this period.

Sunday, January 30th: Immense masses of ice that had floated from the upper parts of the river, in consequence of the thaw on the two preceding days, now blocked up the Thames between Blackfriars and London Bridges, and afforded every probability of its being frozen over in a day or two. Some venturous persons even now walked on different parts of the ice.

Monday, January 31st: This expectation was realised. During the whole of the afternoon, hundreds of people were assembled on Blackfriars and London Bridges, to see several adventurous men cross and recross the Thames on the ice; at one time seventy persons were counted walking from Queenhithe to the opposite[64] shore. The frost on Sunday night so united the vast mass as to render it immovable by the tide.

Tuesday, February 1st: The floating masses of ice with which the Thames was covered, having been stopped by London Bridge, now assumed the shape of a solid surface over that part of the river which entered from Blackfriars Bridge to some distance below Three Crane Stairs, at the bottom of Queen-street, Cheapside. The watermen, taking advantage of the circumstance, placed notices at the end of all the streets leading to the city side of the river, announcing safe footway over the river, which, as might be expected, attracted immense crowds to witness so novel a scene. Many were induced to venture on the ice, and the example thus afforded soon led thousands to perambulate the rugged plain, where a variety of amusements were prepared for their entertainment.

Among the more curious of these was the ceremony of roasting a small sheep, which was toasted, or rather burnt over a coal fire, placed in a large iron pan. For a view of this extraordinary spectacle, sixpence was demanded, and willingly paid. The delicate meat when done was sold at a shilling a slice, and termed Lapland mutton.

Of booths there was a great number, which were ornamented with streamers, flags, and signs, and in which there was a plentiful store of those favourite luxuries, gin, beer and gingerbread.

Opposite Three Crane Stairs there was a complete and well-frequented thoroughfare to Bankside, which was strewed with ashes, and apparently afforded a very safe, although a very rough path.

Near Blackfriars Bridge, however, the path did not appear to be equally safe, for one young man, a plumber, named Davis, having imprudently ventured to cross with some lead in his hands, he sank between two masses of ice, to rise no more. Two young women nearly shared a similar fate, but were happily rescued from their perilous situation by the prompt efforts of a waterman. Many a fair nymph, indeed, was embraced in the very arms of old Father Thames; three prim young quakeresses had a sort of semi-bathing near London Bridge, and when landed on terra firma, made the best of their way through the Borough, amid the shouts of an admiring populace, to their residence at Newington. In consequence of the impediments to the current of the river at London Bridge, the tide did not ebb for some days more than one half the usual mark.

Wednesday, February 2nd: The Thames presented a complete Frost Fair. The grand mall or walk was from Blackfriars Bridge; this was named the City-road, and lined on each side with tradesmen of all descriptions. Eight or ten printing presses were erected, and numerous pieces commemorative of the great frost were actually printed on the ice. Some of these frosty typographers displayed considerable taste in the specimens.

At one press an orange-coloured standard was hoisted, with the watch word “Orange Boven” in large characters, and the following papers were issued from it:—

Frost Fair.

Another:—

Another of these stainers of paper addressed the spectators in the following terms:—

“Friends, now is your time to support the freedom of the press. Can the press have greater[67] liberty? Here you find it working in the middle of the Thames; and if you encourage us by buying our impressions, we will keep it going in the true spirit of liberty during the frost.”

One of the articles printed and sold contained the following lines:—

Besides the above the Lord’s Prayer and several other pieces were issued from these ice bated printing offices, and were bought with the greatest avidity.

Thursday, February 3rd: The adventurers were still more numerous. Swings, book-stalls, dancing in a barge, suttling-booths, playing at skittles, and almost every appendage of a fair on land was now transferred to the Thames. Thousands of people flocked to behold this singular spectacle, and to partake of the various sports and pastimes. The ice now became like a solid rock of adamant, and presented a truly picturesque appearance. The view of St. Paul’s and of the city with its white foreground had a very singular effect; in many parts mountains of ice were upheaved, and these fragments bore a strong[68] resemblance to the rude interior of a stone quarry.

Friday, February, 4th: Every day brought a fresh accession of “pedlars to sell their wares,” and the greatest rubbish of all sorts was raked up and sold at double and treble the original cost. Books and toys labelled “bought on the Thames” were seen in profusion. The waterman profited exceedingly, for each person paid a toll of 2d. or 3d. before he was admitted to the Frost Fair. Some douceur also was expected on your return. These men were said to have taken £6 each in the course of a day.

This afternoon, about five o’clock three persons, an old man and two lads, having ventured on a piece of ice above London Bridge, it suddenly detached itself from the main body, and was carried by the tide through one of the arches. The persons on the ice, who laid themselves down for safety, were observed by the boatmen at Billingsgate, who with laudable activity, put off to their assistance, and rescued them from their danger.

One of them was able to walk, but the other two were carried in a state of insensibility to a public-house in the neighbourhood, where they received every attention their situation required.

Many persons were seen on the ice till late at[69] night, and the effect by moonlight was singularly picturesque and beautiful. With a little stretch of imagination, we might have transported ourselves to the frozen climes of the north—to Lapland, Sweden or Holland.

Saturday, February 5th: The morning of this day augured rather unfavourably for the continuance of Frost Fair. The wind had shifted to the south, and a light fall of snow took place. The visitors of the Thames, however, were not to be deterred by trifles. Thousands again returned, and there was much life and bustle on the frozen element.

The footpath in the centre of the river was hard and secure, and among the pedestrians we observed four donkeys which trotted at a nimble pace and produced considerable merriment. At every glance, the spectator met with some pleasing novelty. Gaming in all its branches threw out different allurements, while honesty was out of the question. Many of the itinerant admirers of the profit gained by E. O. Tables, wheel of fortune, the garter, &c., were industrious in their avocations, leaving their kind customers without a penny to pay their passage over a plank to the shore. Skittles was played by several parties, and the drinking tents filled by females[70] and their companions, dancing reels to the sound of fiddles, while others sat round large fires, drinking rum, grog, and other spirits. Tea, coffee, and eatables were provided in ample order, while passengers were invited to eat by way of recording their visit. Several respectable tradesmen also attended with their wares, selling books, toys, and trinkets of every description.

Towards evening the concourse became thinned; rain fell in some quantity; Maister Ice gave some loud cracks, and floated with the printing presses, booths, &c., to the no small dismay of publicans, typographers, &c. In short, this icy palace of Momus, this fairy frost work, was soon to be dissolved, and doomed to vanish like the baseless fabric of a vision, but leaving some “wrecks behind.”

A short time before the thaw, a gentleman standing by one of the printing presses, and supposed to be a limb of the law, handed the following jeu d’esprit to its conductor, requesting that it might be printed on the Thames. The prophecy which it contains has been most remarkably fulfilled:—

“To Madam Tabitha Thaw.

Dear dissolving dame,—

Father Frost and Sister Snow have[71] boneyed my borders, formed an idol of ice upon my bosom, and all the Lords of London came to make merry: now, as you love mischief, treat the multitude with a few cracks by a sudden visit, and obtain the prayers of the poor upon both banks. Given at my press the 5th February, 1814. Thomas Thames.”

It was evident that a thaw was rapidly taking place, yet such was the indiscretion and heedlessness of some persons that one fatal accident occurred.

Two genteel looking young men fell victims to their temerity in venturing on the ice above Westminster Bridge, notwithstanding the warnings of the waterman. A large mass on which they stood, and which had been loosened by the flood-tide, gave way, and they floated down the stream. As they passed under Westminster Bridge they cried out most piteously for help. They had not gone far before they sat down, but, going too near the edge, they overbalanced the mass, and were precipitated into the stream, sinking not to appear again.

This morning, also, Mr. Lawrence, of the Feathers, in High Timber street, Queenhithe, erected a booth on the Thames opposite Brook’s Wharf, for the accommodation of the curious.[72] At nine at night he left it to the care of two men, taking away all liquors, except some gin, which he gave them for their own use.

Sunday, February 6th: At two o’clock this morning, the tide began to flow with great rapidity at London Bridge; the thaw assisted the efforts of the tide, and the booth just mentioned was hurried along with the quickness of lightning towards Blackfriars Bridge. There were nine men in it, and in their alarm they neglected the fire and candles, which, communicating with the covering, set it in a flame. The men succeeded in getting into a lighter which had broken from its moorings, but it was dashed to pieces against one of the piers of Blackfriars Bridge, on which seven of them got, and were taken off safely; the other two got into a barge while passing Puddle Dock.

On this day, the Thames towards high tide (about 3 p.m.) presented a very tolerable idea of the frozen ocean; grand masses of ice floating along, added to the great height of the water and afforded a striking sight for contemplation.

Thousands of disappointed persons thronged the banks; and many a ’prentice boy and servant maid sighed unutterable things at the sudden and unlooked-for destruction of Frost Fair.

Monday, February, 7th: Large masses of ice are yet floating, and numerous lighters, broken from their moorings, are seen in different parts of the river, many of them complete wrecks. The damage done to the craft and barges is supposed to be very great. From London Bridge to Westminster, twenty thousand pounds will scarcely make good the losses that have been sustained.

An interesting account of an “Ice Festival” is given in the pages of The Champion of February 6th, 1814. It is chronicled that “Saturday se’nnight afforded to the inhabitants of Kelso a scene to which there has been nothing similar for the last 73 years. The late severe weather having frozen the Tweed completely over, a number of the respectable inhabitants were desirous of dining on the ice, and gave orders to Mr. Lander, of the Queen’s Head Inn, to provide what was necessary for the occasion. He accordingly erected an enormous tent in the midst of the river, opposite Ednam House, and served up an excellent and hot dinner to a numerous and respectable company. The tent, which was well heated by stoves, was surmounted by an orange flag, and the union flags of England and Holland were displayed on tables. From forty to fifty sat down to dinner. The following toasts were drunk with glee:—[74]‘General Frost, who so signally fought last winter for the deliverance of Europe, and who now supports the present company.’ ‘Both sides of the Tweed, and God preserve us in the middle.’ The company were much gratified by seeing among them an old inhabitant of the town who was present at the last entertainment given under similar circumstances, in the winter of the year 1740, when part of an ox was roasted on the ice. No accident happened to disturb the pleasures of the scene.”

From a scene of rejoicing let us turn to a record of a painful death occurring at this period. We find in the “Annals of Manchester,” edited by W. E. A. Axon, (pub. 1886) a note as follows, under the year 1814:—“Miss Lavinia Robinson was found drowned in the Irwell, near the Mode Wheel, February 8. This young lady, who possessed superior mental accomplishments, as well as personal beauty, was engaged to Mr. Holroyd, a surgeon, but on the eve of her intended marriage she disappeared from her home in Bridge Street, December 6th, and owing to the long frost, her body remained under the ice for a long period. It appears most probable that the rash act of the ‘Manchester Ophelia’ was due to a quarrel in which her betrothed had repeated[75] some slanderous statements respecting her. There was, however, a strong suspicion that she had met with foul play. The slanders were shown to be baseless, and the feeling against Mr. Holroyd was so strong that he had to leave the town. (Procter’s ‘Bygone Manchester,’ pages 268, 269. ‘City News Notes and Queries,’ vol. I., p. 265.)”

We extract from the Newcastle Weekly Chronicle the following lines by an anonymous author:—

TYNE FAIR;

OR, THE GREAT FROST, JAN. 31, AND FEB. 1, 1814.

The frost here commemorated began about the 8th December, 1813, and continued in a gentle manner until the morning of the 14th January, 1814, when a stronger frost covered the Tyne below bridge with a smooth and perfect sheet of ice, on which, the succeeding day, a number of people ventured, and skaters, for three successive days. A partial thaw came on which damped the ardour of skaters, until the night of the 29th of January, when again a severe frost considerably strengthened the ice, and presented a glassy surface above bridge. On Monday, 31st January, no less than seven tents were erected on it for the sale of spirits, and fires kindled on that and the succeeding day. Parties dined in various of the[76] tents. The desire of recreation shone forth in every face. Horse shoes, football, “toss or buy,” rolly polly, fiddlers, pipers, razor grinders, recruiting parties, and racers with and without skates, were all alive to the moment. Hats, breeches, shifts, stockings, ribbons, and even legs of mutton, were the rewards of the racers, who turned night into day; the brilliancy of the full moon contributing to their diversions until late beyond midnight. A horse and sledge above bridge added to the novelty of the scene; and it is worthy of remark that not one accident of consequence happened, although thousands ventured their persons upon the ice. Owing to the severity of the season, the London Mail for Friday, the 21st January, and three following days, was brought to Newcastle on the fifth day, in the Lord Wellington Coach, with eight horses; a circumstance quite new to the inhabitants of canny Newcastle.

The winter very severe in Ireland.

On the 7th January a very severe frost set in and continued a month. This frost was predicted in “Murphy’s Almanack,” and the fulfilment of the prediction rendered the publication extremely popular. A rhyme of the period was as follows—

It is recorded in January this year, that the thermometer at Walton, near Claremont, fell to 14 deg. below zero; at Beckenham it was 13½ deg. below zero; at Wallingford, 5 deg. below zero; at Greenwich, 4 deg. below zero; and at Glasgow 1 deg. below zero.

The principal rivers of this country were frozen over. This winter is frequently called “Murphy’s winter.”

On January 16th a very strong frost commenced, and prevailed for about six weeks. Rivers were frozen over, and inland navigation was entirely suspended. The working classes were subject to many privations on account of the dearness of food and depression of trade. In London 10,000 dock porters were out of work, and such was their sufferings that bread-riots occurred in the east end of the town. During this frost traffic was established on the Ure in Lincolnshire to the distance of thirty-five miles.

Very severe frost from 20th December to 5th January. Says the Northern Daily Telegraph, in a recent article on “Old Fashioned Winters” “on the 25th of December, 1860, the thermometer in[80] London fell to 15 degrees Fahrenheit, which is 17 degrees below freezing point. In the country the same intensity of cold was felt, and a certain meteorologist wrote to the Times stating that at Boston, in Nottinghamshire, the temperature four feet above the ground was 8 degrees below zero, whilst on the grass it was 13 degrees, or 45 degrees of frost. Fortunately this extreme cold only lasted three days, and the inconveniences attending it—in themselves bad enough—were not to be compared with the miseries which accompanied the great Frost Fair.”

In the middle of January, 1880, it was expected by many that a Frost Fair would once more be held on the Thames. The last two months of 1879 and the opening month of 1880 were extremely cold. The President of the Meteorological Society in his report, 1880, says, “The period through which we have been passing since October, 1878, has been one of great cold, in many respects without precedent during nearly a quarter of a century. The harvest of 1879 is recorded as the worst ever known. Shrubs, even hollies, little short of 100 years old were killed. Birds were destroyed, Robin Redbreasts took shelter in our houses; all the rivers in England were frozen over. It is stated that Major Slack of[81] the 63rd Regiment, at Oakamoor Station, railway lamps were frozen out, and that rabbits pushed for food had attacked the oil and grease on the station crane.” At Chirmside Bridge a temperature of 6° below zero was observed. Peach trees 60 years old were killed to the roots. The evergreens, laurels, rhododendrons, hollies in many instances, Wellingtonias, and many others were all killed, and many people frozen to death. This frost began on the 22nd November, 1879, and on the 2nd February, 1880, a thaw began.

Severe frost from the 7th to the 27th January. Snow fell daily from the 9th to the 27th of the month.

The concluding pages of this work are being written and printed during a hard frost. The closing days of the past year, and the early days of the current year will long be remembered amongst severe winters.

Perhaps we cannot more fitly close our account of “Famous Frosts and Frost Fairs,” than by quoting the following lines from the facile pen of Edith May, culled from the pages of Hale’s “Selections of Female Writers,” published in 1853.

FROST PICTURES.

Charles H. Barnwell, Printer, Bond Street, Hull.