*** START OF THE PROJECT GUTENBERG EBOOK 54196 ***

[Pg. i]

THE

PRACTICAL BOOK

OF ORIENTAL RUGS

FOURTH EDITION

[Pg. ii]

THE

PRACTICAL BOOKS

OF HOME LIFE ENRICHMENT

EACH PROFUSELY ILLUSTRATED,

HANDSOMELY BOUND.

Octavo. Cloth. In a slip case.

THE PRACTICAL BOOK

OF EARLY AMERICAN

ARTS AND CRAFTS

BY HAROLD DONALDSON EBERLEIN

AND ABBOT MCCLURE

THE PRACTICAL BOOK

OF ARCHITECTURE

BY C. MATLACK PRICE

THE PRACTICAL BOOK

OF ORIENTAL RUGS

BY DR. G. GRIFFIN LEWIS

New Edition, Revised and Enlarged

THE PRACTICAL BOOK OF

GARDEN ARCHITECTURE

BY PHEBE WESTCOTT HUMPHREYS

THE PRACTICAL BOOK

OF PERIOD FURNITURE

BY HAROLD DONALDSON EBERLEIN

AND ABBOT MCCLURE

THE PRACTICAL BOOK OF

OUTDOOR ROSE GROWING

BY GEORGE C. THOMAS, JR.

New Revised Edition

THE PRACTICAL BOOK OF

INTERIOR DECORATION

[Pg. iv]

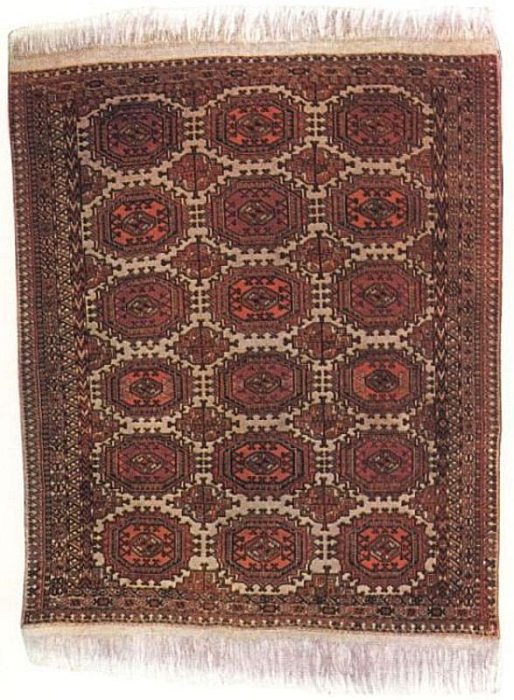

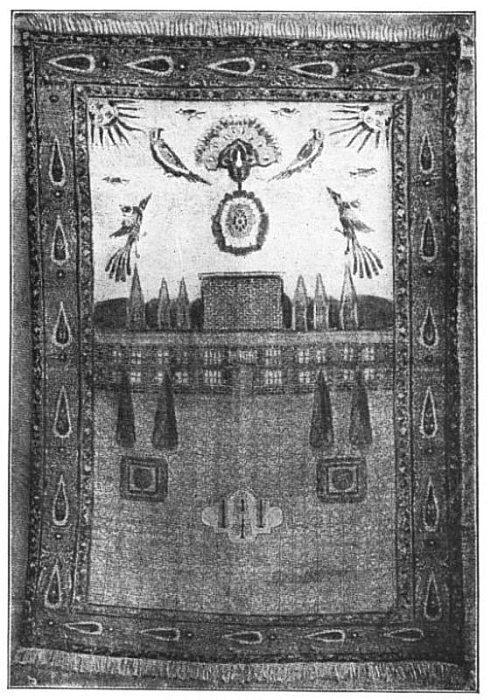

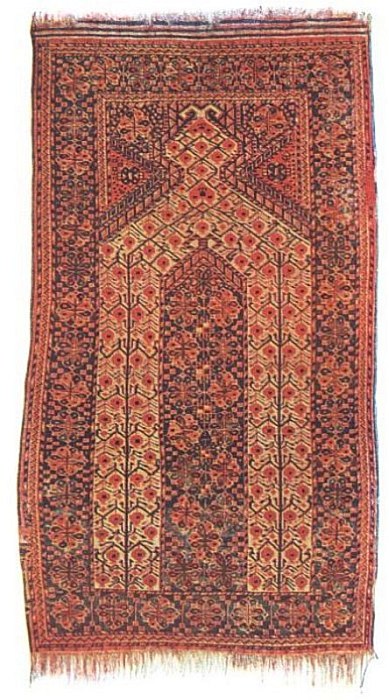

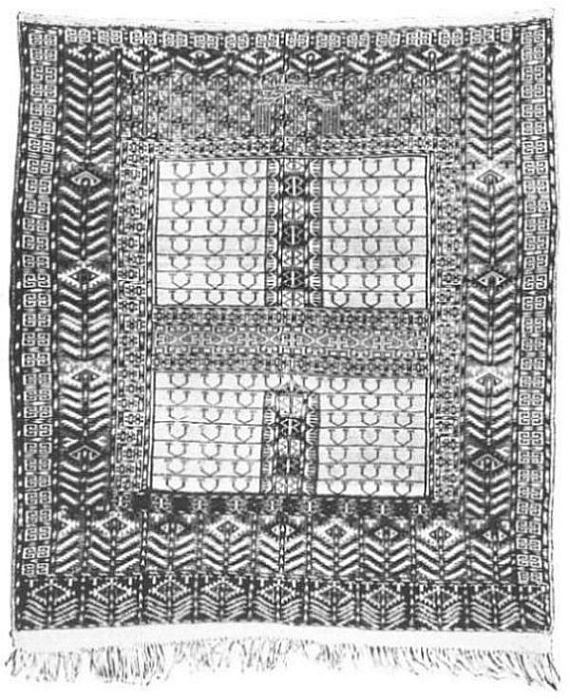

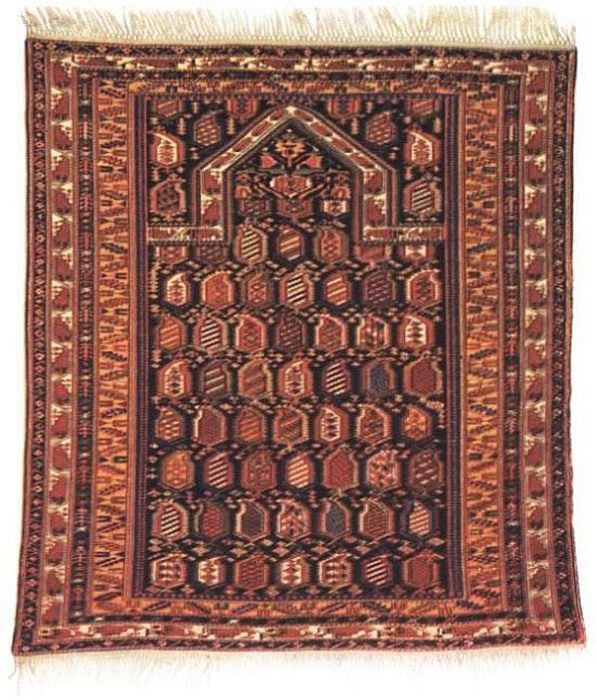

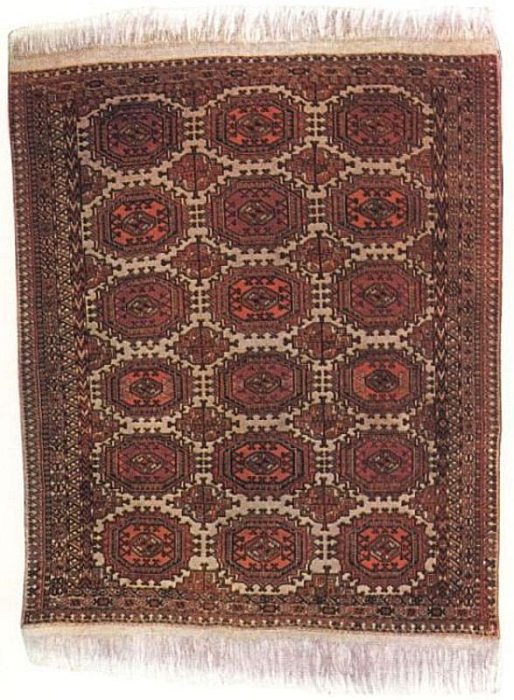

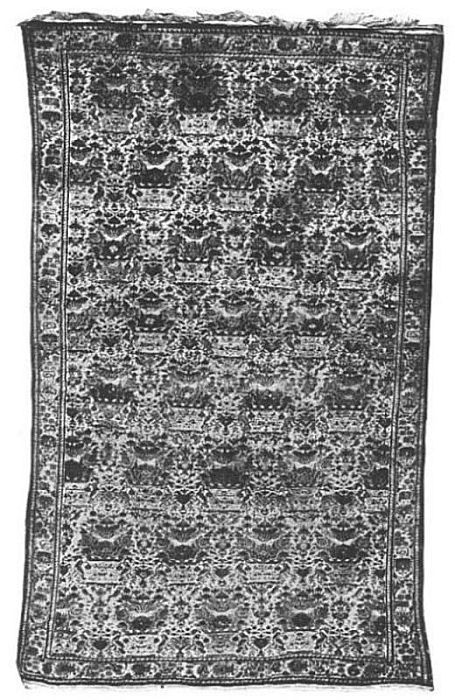

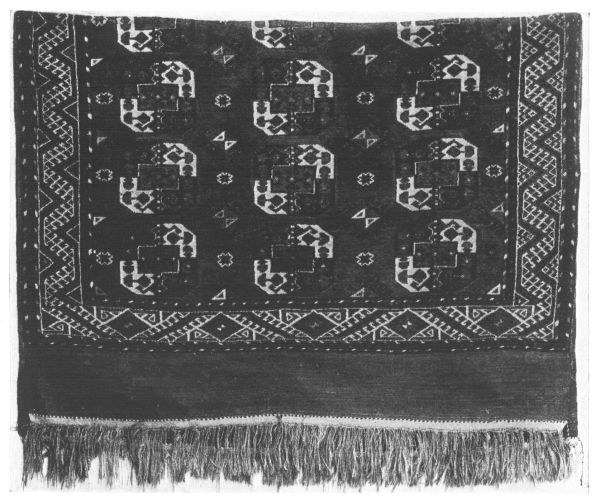

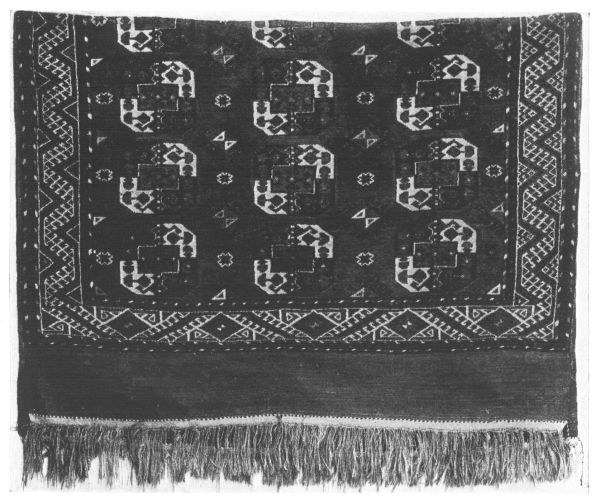

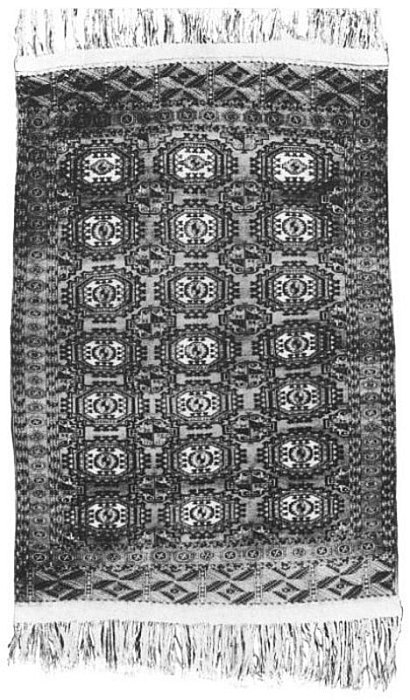

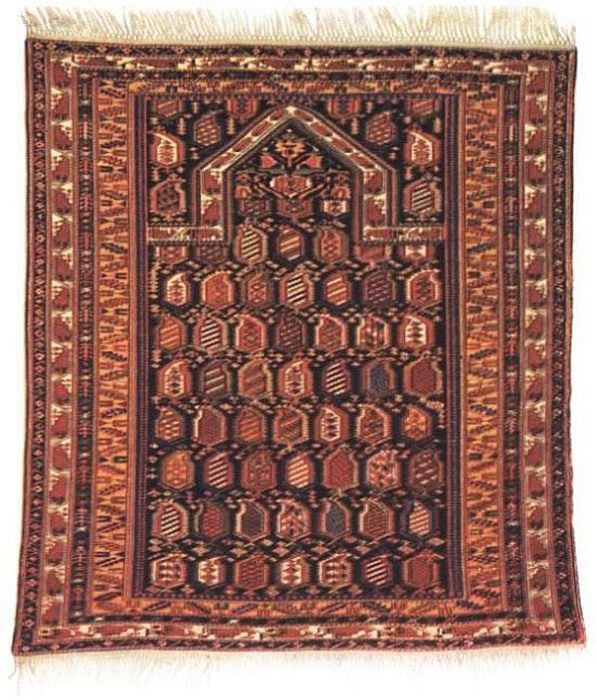

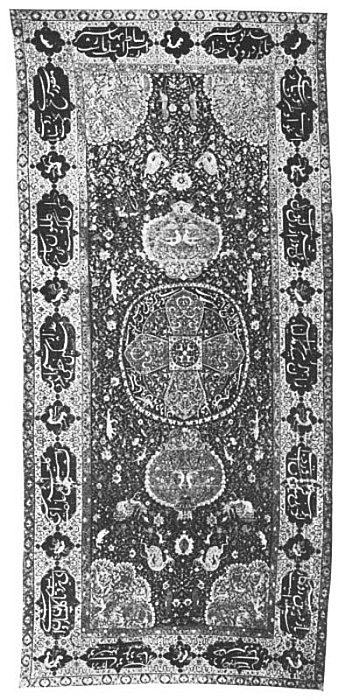

TEKKE BOKHARA RUG

TEKKE BOKHARA RUG

Size 5'6" × 6'4"

PROPERTY OF MR. F. A. TURNER, BOSTON, MASS.

This piece is unusual in many ways. The background of old

ivory both in the borders and in the field; the old rose color of the

octagons; the difference in the number of border stripes and in the

designs of same on the sides and ends are all non-Turkoman features.

It is the only so called "white Bokhara" of which we have

any knowledge.

[Pg. 1]

THE

PRACTICAL BOOK

OF ORIENTAL RUGS

BY

DR. G. GRIFFIN LEWIS

With 20 Illustrations In Color, 93 In Doubletone

70 Designs In Line, Chart And Map

NEW EDITION, REVISED AND ENLARGED

PHILADELPHIA & LONDON

J. B. LIPPINCOTT COMPANY

[Pg. 2]

COPYRIGHT, 1911, BY J. B. LIPPINCOTT COMPANY

COPYRIGHT, 1913, BY J. B. LIPPINCOTT COMPANY

PRINTED BY J. B. LIPPINCOTT COMPANY

AT THE WASHINGTON SQUARE PRESS

PHILADELPHIA, U.S.A.

[Pg. 3]

PREFACE TO THE REVISED EDITION

It is most gratifying to both author and publishers

that the first edition of "The Practical

Book of Oriental Rugs" has been so quickly exhausted.

Its rather remarkable sale, in spite of the

fact that within the past decade, no less than seven

books on the subject have been printed in English,

proves that it is the practical part of the book that

appeals to the majority.

The second edition has been prepared with the

same practical idea paramount and quite a few

new features have been introduced.

The color plates have been increased from ten

to twenty; a chapter on Chinese rugs has been inserted;

descriptions of three more rugs have been

added and numerous changes and additions have

been made to the text in general.

[Pg. 4]

Oriental rugs have become as much a necessity

in our beautiful, artistic homes as are the

paintings on the walls and the various other works

of art. Their admirers are rapidly increasing,

and with this increased interest there is naturally

an increased demand for more reliable information

regarding them.

The aim of the present writer has been practical—no

such systematized and tabulated information

regarding each variety of rug in the market

has previously been attempted. The particulars

on identification by prominent characteristics

and detail of weaving, the detailed chapter

on design, illustrated throughout with text cuts,

thus enabling the reader to identify the different

varieties by their patterns; and the price per

square foot at which each variety is held by retail

dealers, are features new in rug literature. Instructions

are also given for the selection, purchase,

care and cleaning of rugs, as well as for

the detection of fake antiques, aniline dyes, etc.

[Pg. 5]

In furtherance of this practical idea the illustrations

are not of museum pieces and priceless

specimens in the possession of wealthy collectors,

but of fine and attractive examples which with

knowledge and care can be bought in the open

market to-day. These illustrations will therefore

be found of the greatest practical value to modern

purchasers. In the chapter on famous rugs some

few specimens illustrative of notable pieces have

been added.

In brief, the author has hoped to provide within

reasonable limits and at a reasonable price a

volume from which purchasers of Oriental rugs

can learn in a short time all that is necessary

for their guidance, and from which dealers and

connoisseurs can with the greatest ease of reference

refresh their knowledge and determine points

which may be in question.

For many valuable hints the author wishes to

acknowledge indebtedness to the publications referred

to in the bibliography; to Miss Lillian

Cole, of Sivas, Turkey; to Major P. M. Sykes, the

English Consulate General at Meshed, Persia;

to B. A. Gupte, F. Z. S., Assistant Director of

Ethnography at the Indian Museum, Calcutta,

India; to Prof. du Bois-Reymond, of Shanghai,

China; to Dr. John G. Wishard, of the American

[Pg. 6]

Hospital at Teheran, Persia; to Miss Alice C.

Bewer, of the American Hospital at Aintab, Turkey;

to Miss Annie T. Allen, of Brousa, Turkey;

to Mr. Charles C. Tracy, president of Anatolia

College, Morsovan, Turkey; to Mr. John Tyler,

of Teheran, Persia; to Mr. E. L. Harris, United

States Consulate General of Smyrna, Turkey; to

Dr. J. Arthur Frank, Hamadan, Persia; and to

Miss Kate G. Ainslie, of Morash, Turkey.

For the use of some of the plates and photographs

acknowledgment is made to Mr. A. U.

Dilley, of Boston, Mass.; to H. B. Claflin & Co.,

of New York City; to Mr. Charles Quill Jones, of

New York City; to Miss Lillian Cole, of Sivas,

Turkey; to Maj. P. M. Sykes, of Meshed, Persia;

to Maj. L. B. Lawton, of Seneca Falls, N. Y.; to

the late William E. Curtis, of Washington, D. C.;

to The Scientific American and to Good Housekeeping

magazines; while thanks are due Mr. A. U.

Dilley, of Boston, Mass.; to Liberty & Co., of London;

to the Simplicity Co., of Grand Rapids, Mich.;

to the Tiffany Studios and to Nahigian Bros., of

Chicago, Ill., for some of the colored plates, and to

Clifford & Lawton, of New York City, for the map

of the Orient.

[Pg. 7]

TABLE OF CONTENTS

PART I

|

| |

Introduction |

17 |

| |

|

Age of the weaving art; Biblical reference to the weaving

art; a fascinating study; the artistic worth and other

advantages of the Oriental products over the domestic;

annual importation.

|

|

| I. |

Cost And Tariff |

25 |

| |

|

Upon what depends the value; the various profits made;

transportation charges; export duties; import duties;

cost compared with that of domestic products; some

fabulous prices.

|

|

| II. |

Dealers And Auctions |

31 |

| |

|

Oriental shrewdness; when rugs are bought by the bale;

the auction a means of disposing of poor fabrics; fake

bidders.

|

|

| III. |

Antiques |

35 |

| |

|

The antique craze; why age enhances value; what constitutes

an antique; how to determine age; antiques in

the Orient; antiques in America; celebrated antiques;

American collectors; artificial aging.

|

|

| IV. |

Advice To Buyers |

43 |

| |

|

Reliable dealers; difference between Oriental and domestic

products; how to examine rugs; making selections;

selection of rugs for certain rooms.

|

|

| V. |

The Hygiene Of The Rug |

55 |

| |

|

The hygienic condition of Oriental factories and homes;

condition of rugs when leaving the Orient; condition of

rugs when arriving in America; United States laws regarding

the disinfection of hides; the duties of retailers.

|

|

| [Pg. 8]

VI. |

The Care of Rugs |

63 |

| |

|

Erroneous ideas regarding the wearing qualities of

Oriental rugs; treatment of rugs in the Orient compared

with that in America; how and when cleaned;

how and when washed; moths; how straightened; removal

of stains, etc.

|

|

| VII. |

The Material of Rugs |

69 |

| |

|

Wool, goats' hair, camels' hair, cotton, silk, hemp;

preparation of the wool; spinning of the wool.

|

|

| VIII. |

Dyes and Dyers |

75 |

| |

|

Secrets of the Eastern dye pots; vegetable dyes; aniline

dyes; Persian law against the use of aniline; the

process of dyeing; favorite colors of different rug-weaving

nations; how to distinguish between vegetable and

aniline dyes; symbolism of colors; the individual dyes

and how made.

|

|

| IX. |

Weaving and Weavers |

87 |

| |

|

The present method compared with that of centuries

ago; Oriental method compared with the domestic;

pay of the weavers; the Eastern loom; the different

methods of weaving.

|

|

| X. |

Designs and Their Symbolism |

97 |

| |

|

Oriental vs. European designs; tribal patterns; the

migration of designs; characteristics of Persian designs;

characteristics of Turkish designs; characteristics of

Caucasian designs; characteristics of Turkoman designs;

dates and inscriptions; quotations from the

Koran; description and symbolism of designs alphabetically

arranged, with an illustration of each.

|

|

| XI. |

The Identification of Rugs |

147 |

|

A few characteristic features of certain rugs; table

showing the distinguishing features of all rugs; an

example.

|

|

PART II

|

| XII. |

General Classification |

161 |

| |

How they receive their names; trade names; geographical

classification of all rugs.

|

|

| [Pg. 9]

XIII. |

Persian Classification |

169 |

| |

Persian characteristics; the knot; the weavers; factories

in Persia; Persian rug provinces; description

of each Persian rug, as follows: Herez, Bakhshis,

Gorevan, Serapi, Kara Dagh, Kashan, Souj Bulak,

Tabriz, Bijar (Sarakhs, Lule), Kermanshah, Senna,

Feraghan (Iran), Hamadan, Ispahan (Iran), Joshaghan,

Saraband (Sarawan, Selvile), Saruk, Sultanabad

(Muskabad, Mahal, Savalan), Niris (Laristan),

Shiraz (Mecca), Herat, Khorasan, Meshed, Kirman,

Kurdistan.

|

|

| XIV. |

Turkish Classification |

217 |

| |

The rug-making districts of Turkey in Asia; annual

importation of Turkish rugs; Turkish weavers; the

knot; Turkish characteristics; the Kurds; description

of each Turkish rug, as follows: Kir Shehr, Oushak,

Karaman, Mujur, Konieh, Ladik, Yuruk, Ak Hissar

(Aksar), Anatolian, Bergama, Ghiordes, Kulah,

Makri, Meles (Carian), Smyrna (Aidin, Brousa),

Mosul.

|

|

| XV. |

Caucasian Classification |

253 |

| |

The country; the people; Caucasian characteristics;

description of each Caucasian rug, as follows: Daghestan,

Derbend, Kabistan (Kuban), Tchetchen

(Tzitzi, Chichi), Baku, Shemakha (Soumak, Kashmir),

Shirvan, Genghis (Turkman), Karabagh, Kazak.

|

|

| XVI. |

Turkoman Classification |

277 |

| |

Turkoman territory; Turkoman characteristics; description

of each Turkoman rug, as follows: Khiva

Bokhara (Afghan), Beshir Bokhara, Tekke Bokhara,

Yomud (Yamut), Kasghar, Yarkand, Samarkand

(Malgaran).

|

|

| XVII. |

Beluchistan Rugs |

295 |

| |

The country; the people; Beluchistan characteristics;

description and cost of Beluchistan rugs.

|

|

| XVIII. |

Chinese Rugs |

301 |

| |

Slow to grow in public favor; exorbitant prices;

geographical classification; classification according to

designs; Chinese designs and their symbolism; the

materials; the colors.

|

|

| [Pg. 10]

XIX. |

Ghileems, Silks, and Felts |

311 |

| |

How made; classification, characteristics, uses, description

of each kind.

|

|

| |

Silks |

316 |

| |

Classification, colors, cost, wearing qualities. |

|

| |

Felts |

318 |

| |

How made; their use; cost.

|

|

| XX. |

Classification According to Their Intended Use |

321 |

| |

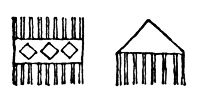

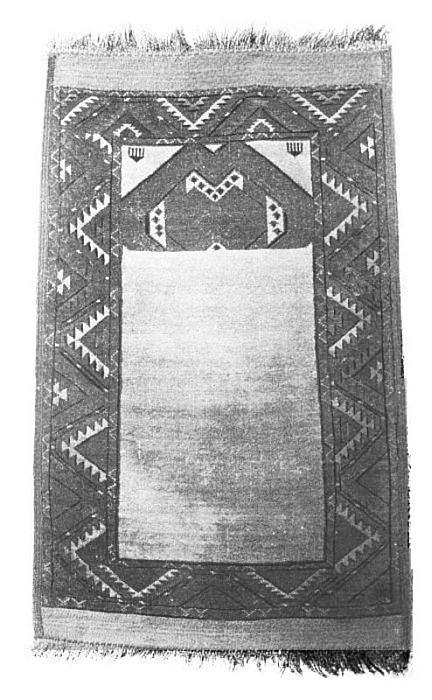

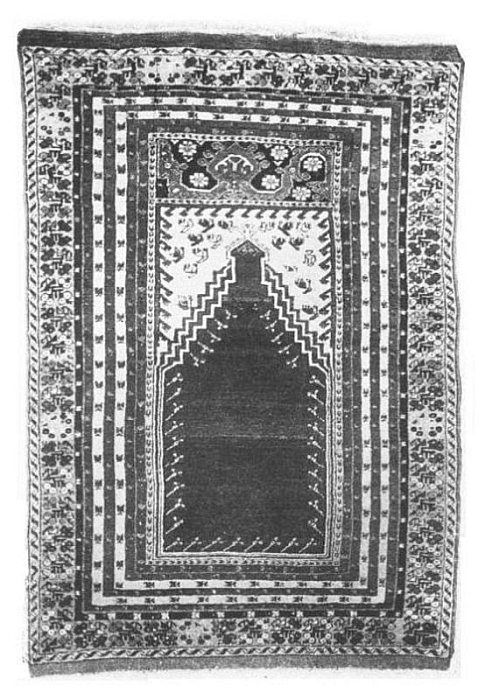

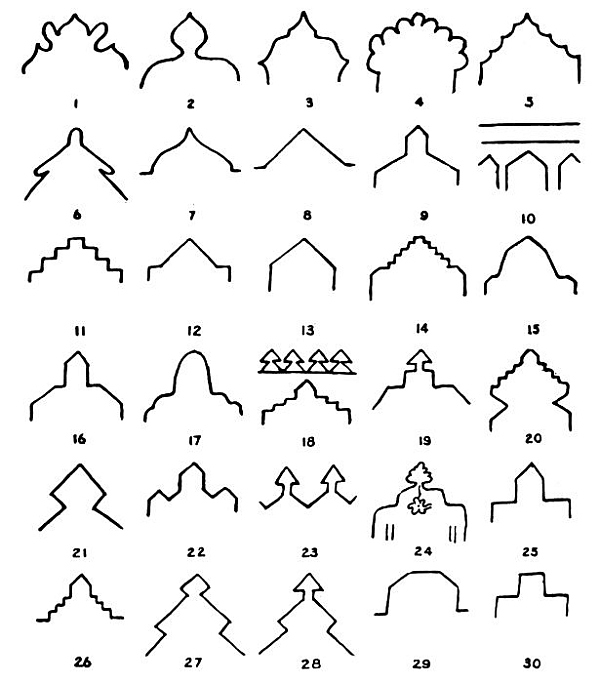

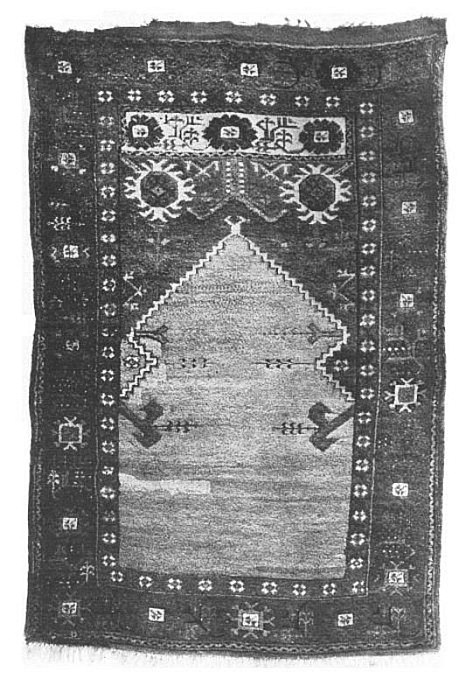

Prayer Rugs. How used; the niche; designs; how classified;

prayer niche designs with key.

Hearth Rugs, Grave Rugs, Dowry or Wedding Rugs,

Mosque Rugs, Bath Rugs, Pillow Cases, Sample Corners,

Saddle Bags, Floor Coverings, Runners, Hangings.

|

|

| XXI. |

Famous Rugs |

331 |

| |

Museum collections; private collections; the recent

Metropolitan Museum exhibit; age and how determined;

description and pictures of certain famous

rugs.

|

|

| Glossary |

341 |

| |

Giving all rug names and terms alphabetically arranged,

with the proper pronunciation and explanation.

|

|

| Bibliography |

359 |

| |

Giving an alphabetically arranged list of all rug literature

in the English language.

|

|

| Index |

363 |

[Pg. 11]

LIST OF ILLUSTRATIONS

| |

| RUGS |

| |

| COLORED PLATES |

PAGE

|

| Tekke Bokhara rug |

Frontispiece |

|

| Meshed prayer rug |

22 |

| Khorasan carpet |

32 |

| Saruk rug |

40 |

| Shiraz rug |

52 |

| Anatolian mat |

60 |

| Ghiordes prayer rug |

66 |

| Ladik prayer rug |

74 |

| Daghestan rug |

84 |

| Kazak rug |

94 |

| Kazak rug |

144 |

| Shirvan rug |

158 |

| Saruk rug |

166 |

| Kulah hearth rug |

216 |

| Shirvan rug |

250 |

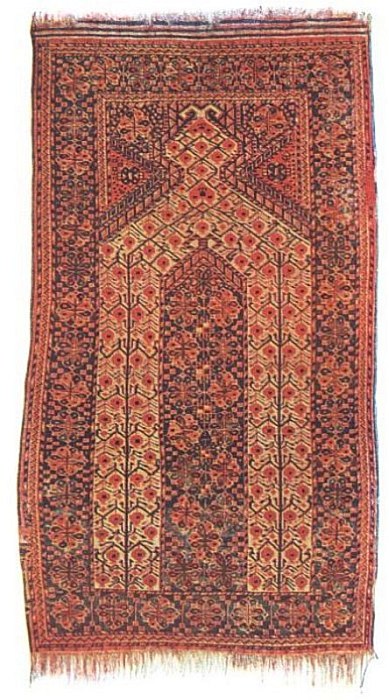

| Beshir Bokhara prayer rug |

274 |

| Daghestan prayer rug |

292 |

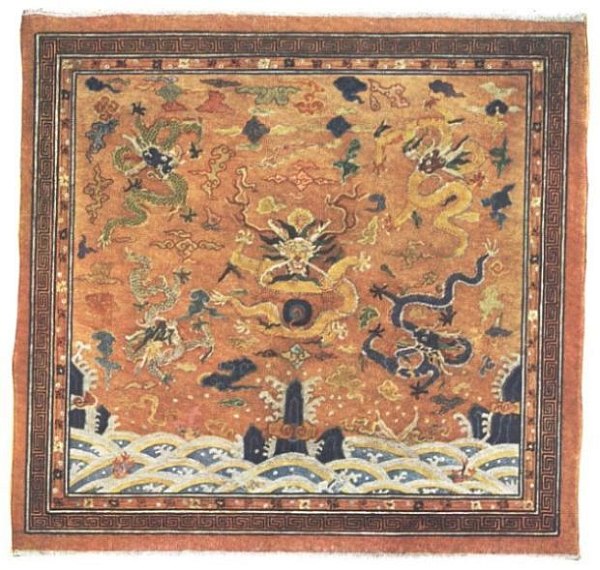

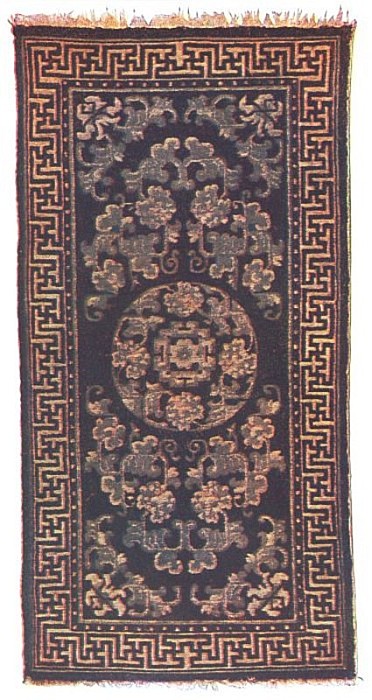

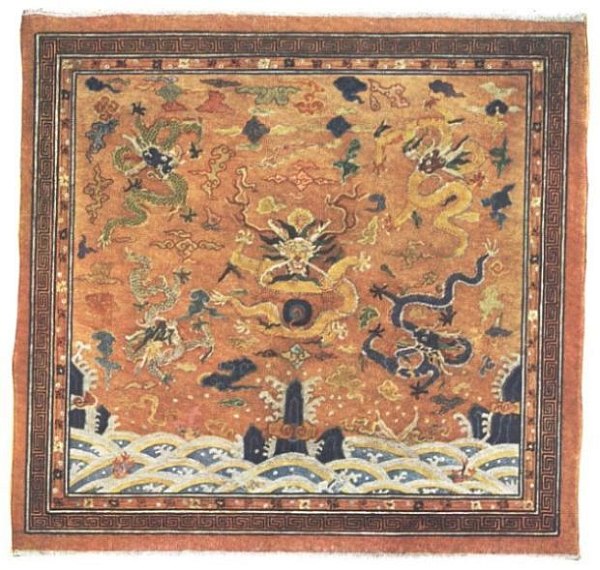

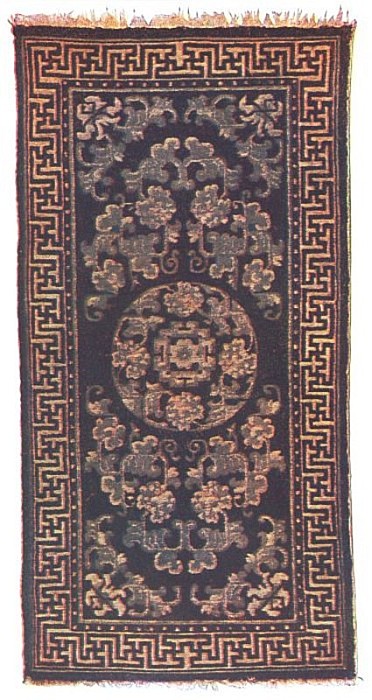

| Chinese rug |

300 |

| Chinese rug |

306 |

Chinese cushion rug

|

318

|

DOUBLETONES

|

| The Metropolitan animal rug |

26 |

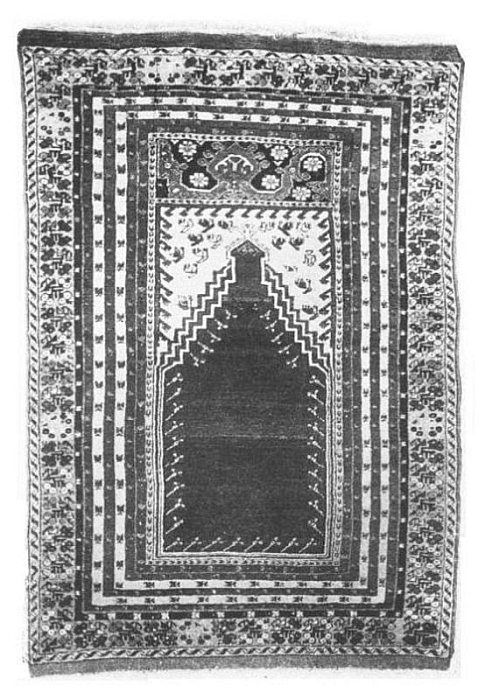

| Bergama prayer rug |

46 |

| Symbolic Persian silk (Tabriz) rug |

48 |

| Symbolic Persian silk rug |

98 |

| Semi-Persian rug (European designs) |

100 |

| Shiraz prayer rug |

104 |

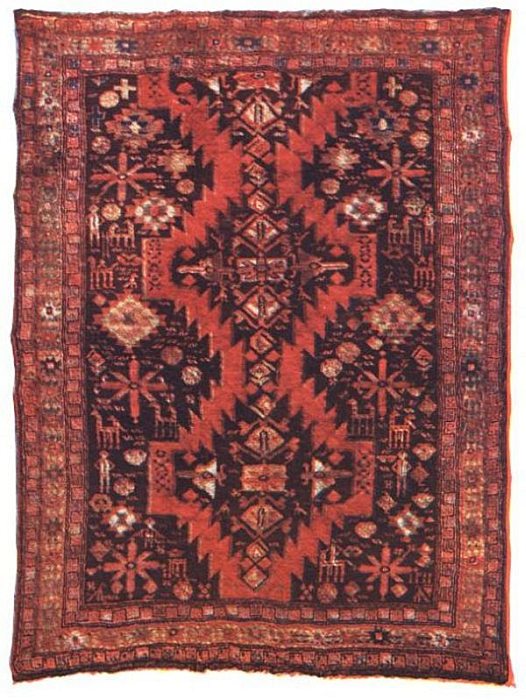

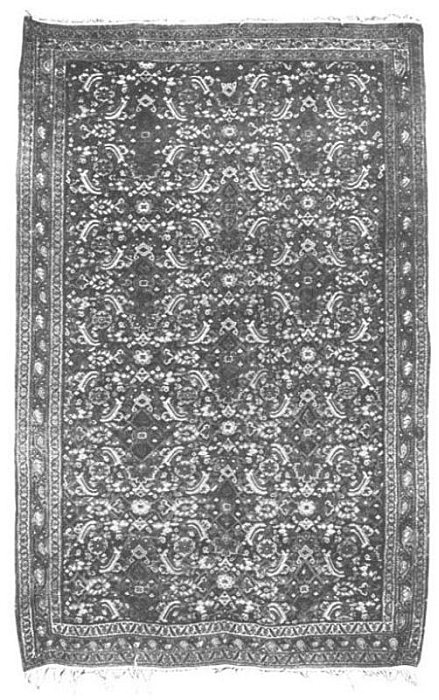

| Hamadan rug |

110 |

| Feraghan rug |

114 |

| Kermanshah rug (modern) |

118 |

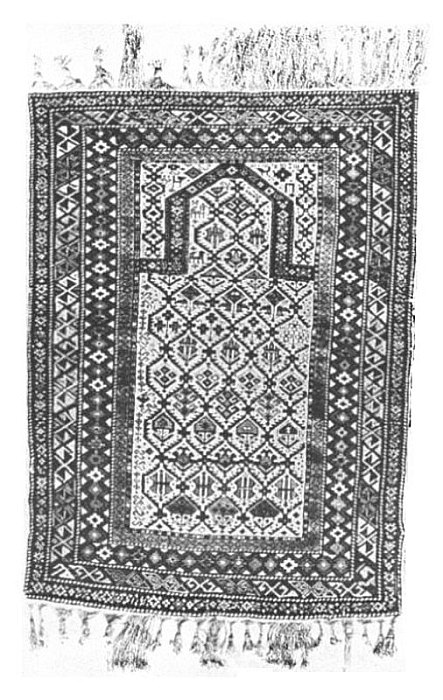

| Khiva prayer rug |

120 |

| [Pg. 12]

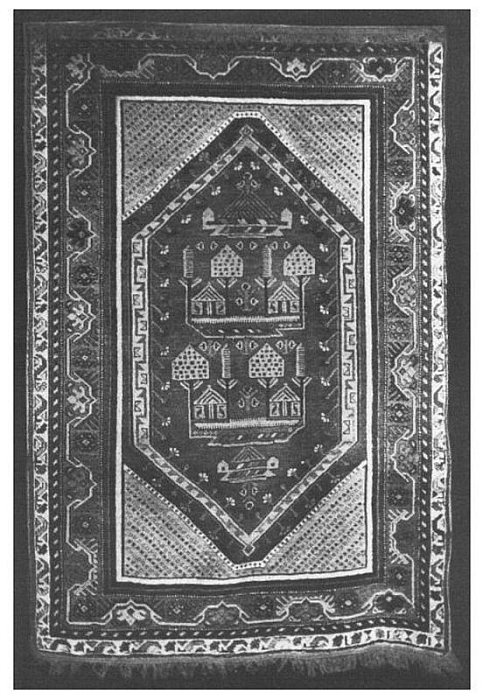

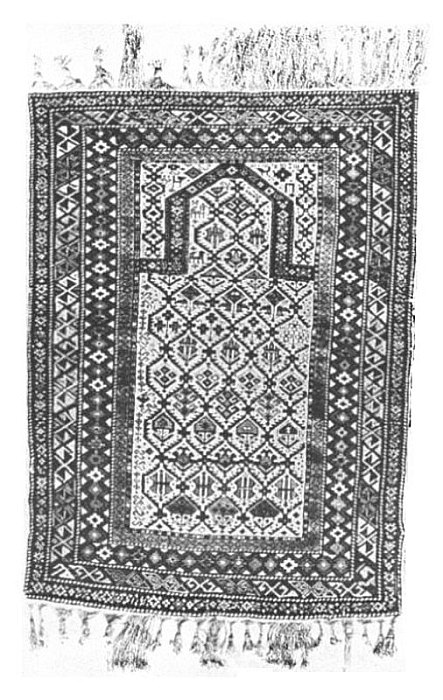

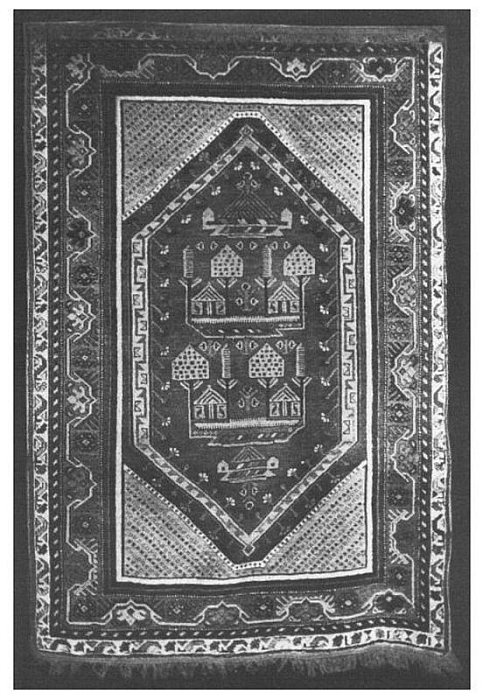

Kir Shehr prayer rug |

130 |

| Konieh prayer rug |

138 |

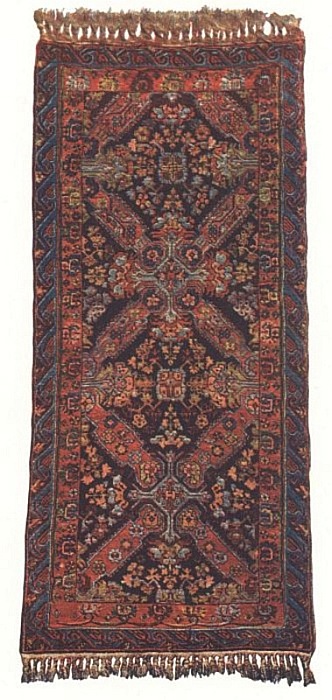

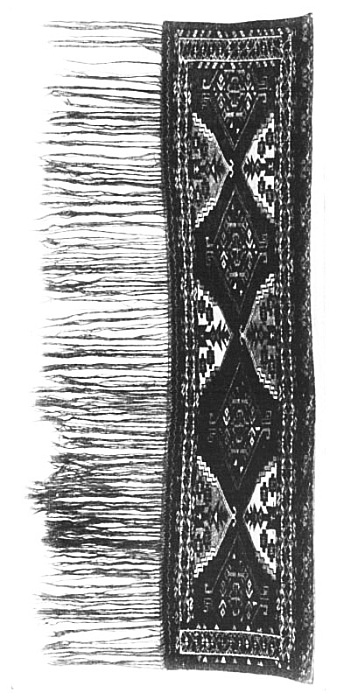

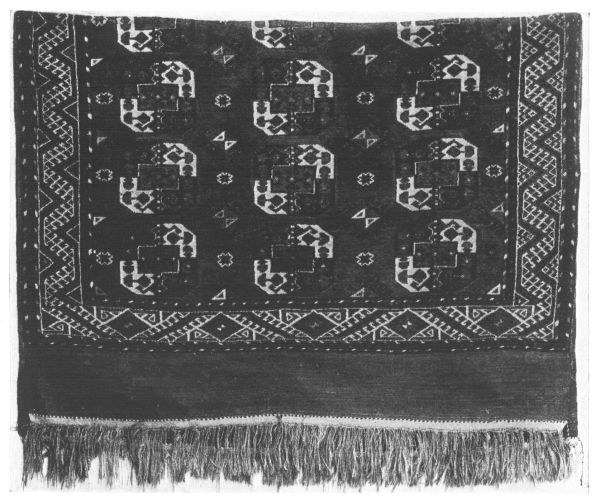

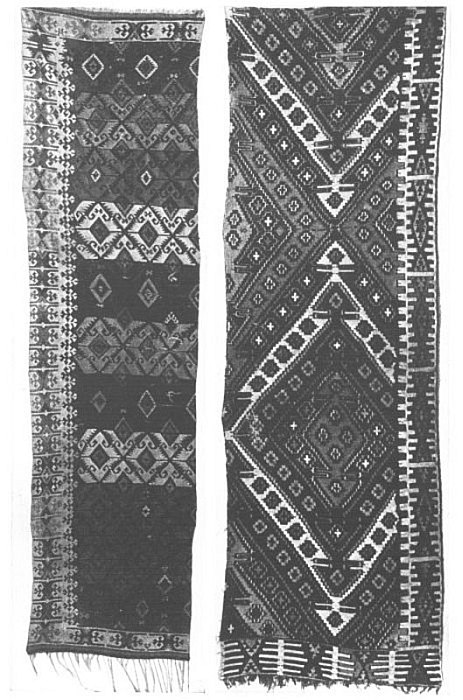

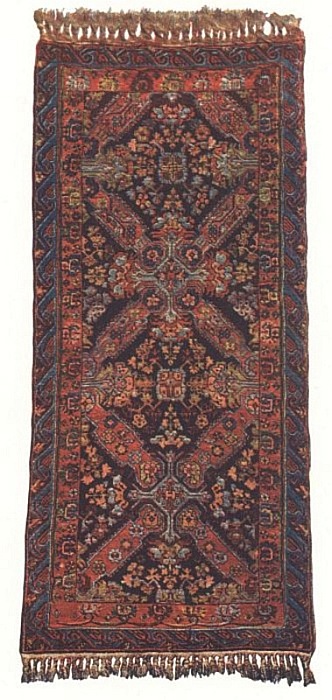

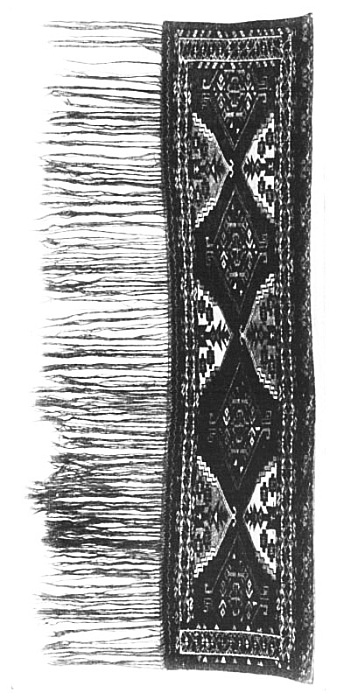

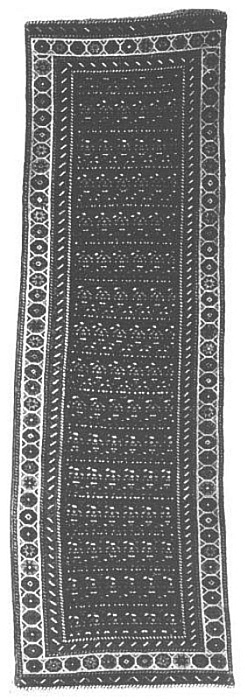

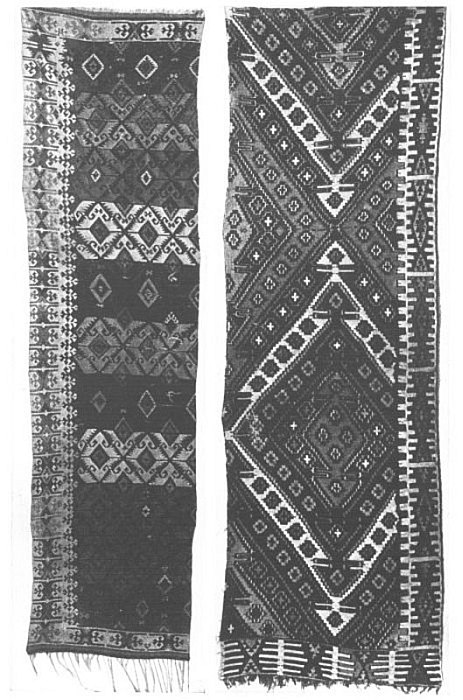

| Tekke Bokhara strip |

150 |

| Tekke Bokhara saddle half |

162 |

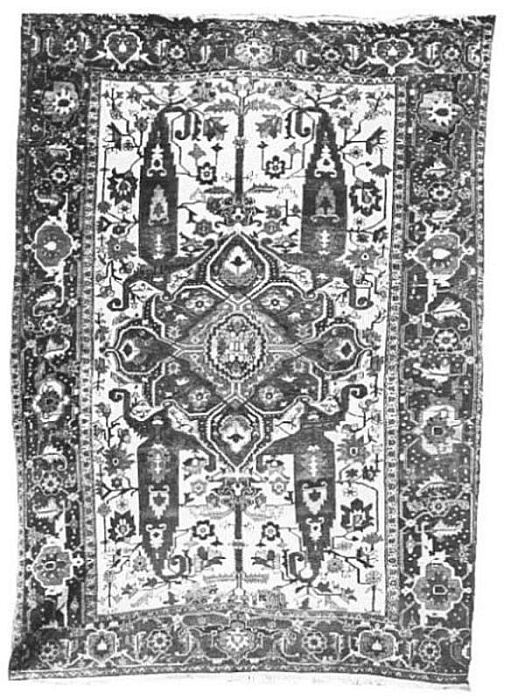

| Herez carpet |

172 |

| Gorevan carpet |

176 |

| Serapi carpet |

178 |

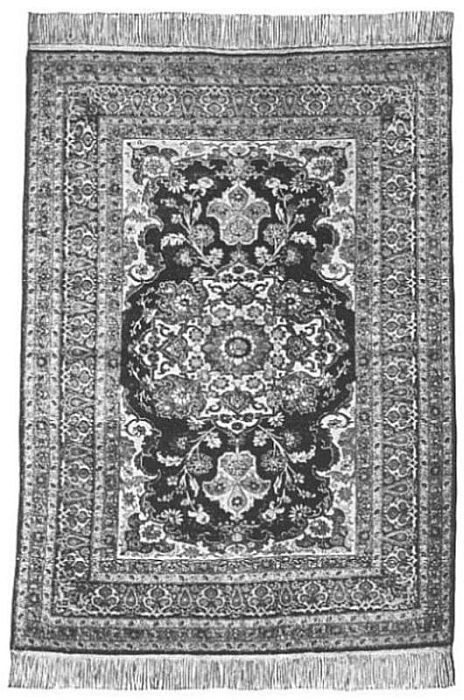

| Kashan silk rug |

180 |

| Tabriz rug |

182 |

| Bijar rug |

186 |

| Senna rug |

188 |

| Feraghan rug |

190 |

| Hamadan rug |

192 |

| Ispahan rug |

194 |

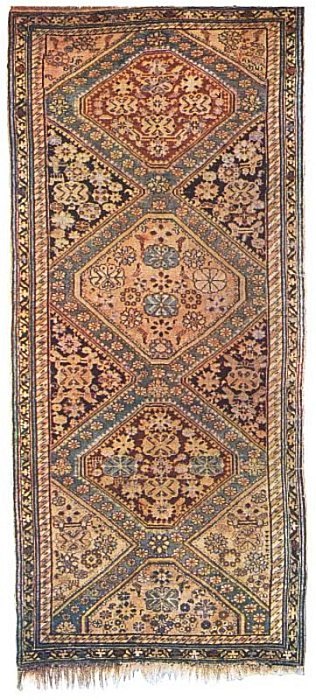

| Saraband rug |

198 |

| Mahal carpet |

202 |

| Niris rug |

204 |

| Shiraz rug |

206 |

| Shiraz rug |

208 |

| Kirman prayer rug |

210 |

| Kirman rug |

212 |

| Kurdistan rug (Mina Khani design) |

214 |

| Kir Shehr prayer rug |

220 |

| Kir Shehr hearth rug |

222 |

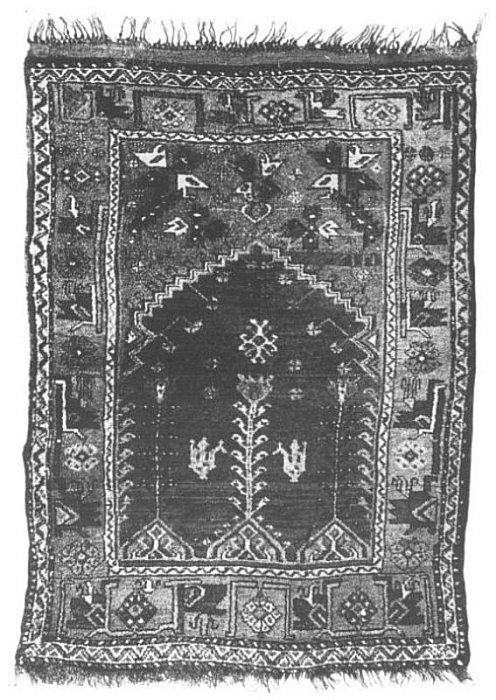

| Konieh prayer rug |

224 |

| Maden (Mujur) prayer rug |

226 |

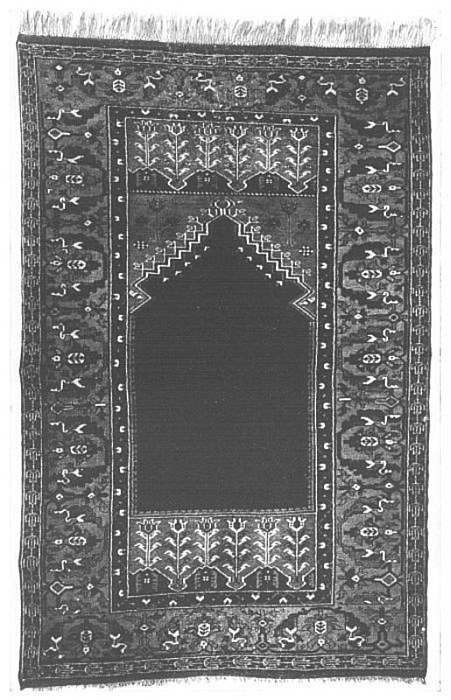

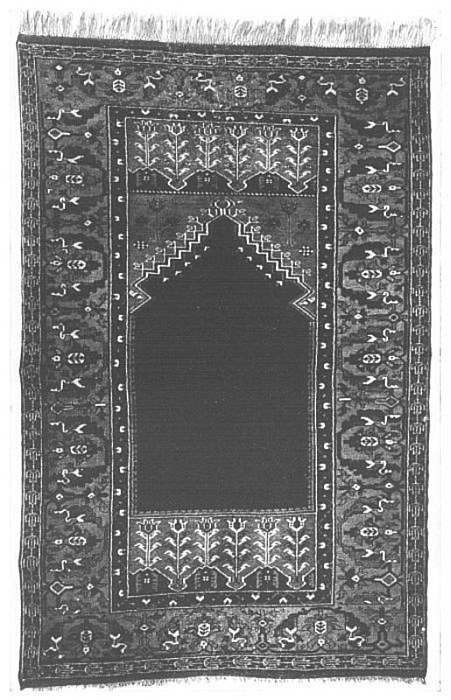

| Ladik prayer rug |

228 |

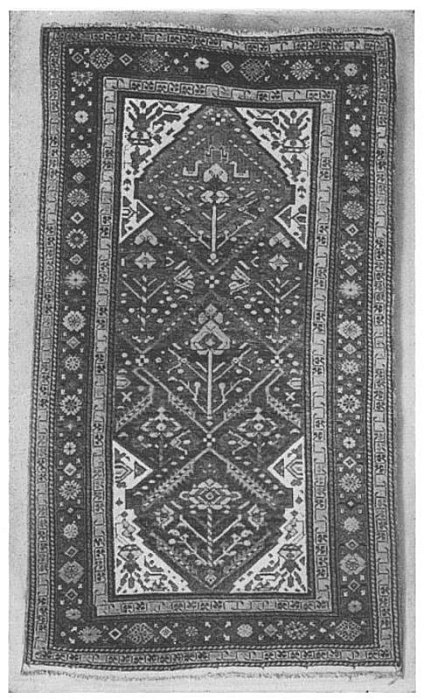

| Yuruk rug |

230 |

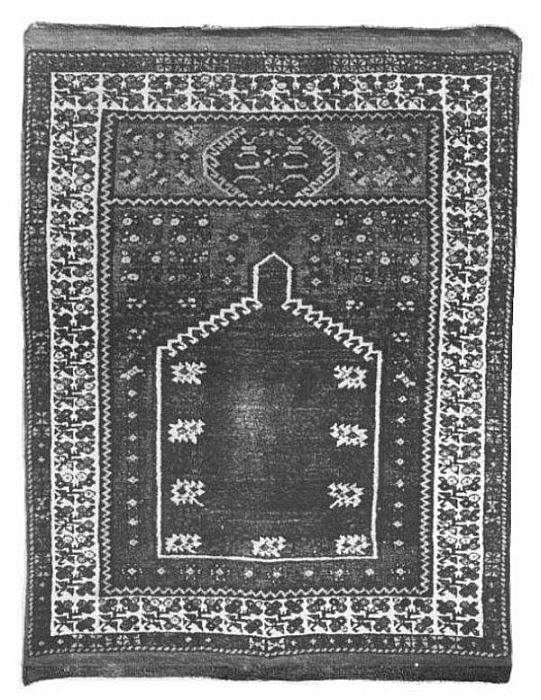

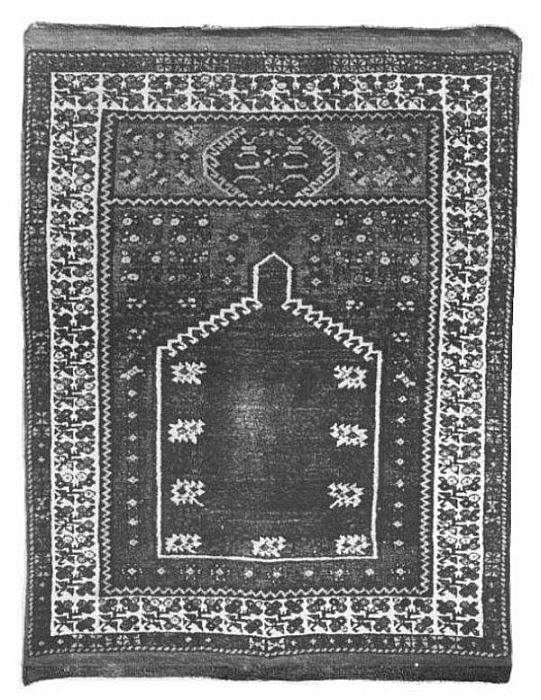

| Ak Hissar prayer rug |

232 |

| Bergama rug |

236 |

| Ghiordes prayer rug |

238 |

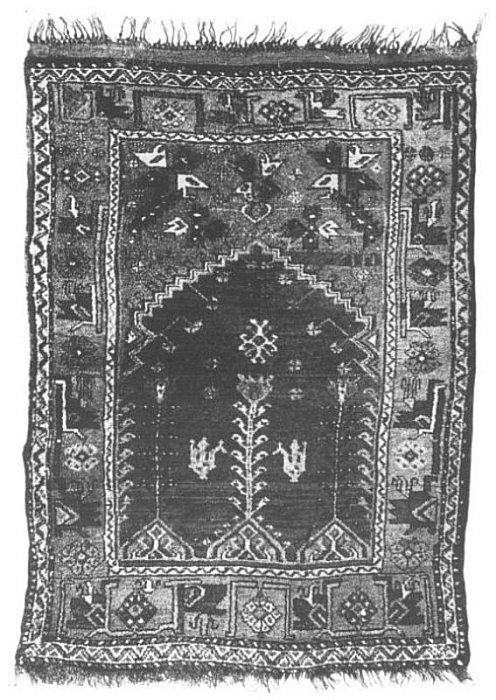

| Kulah prayer rug |

240 |

| Meles rug |

242 |

| Meles rug |

244 |

| Makri rug |

246 |

| Mosul rug |

248 |

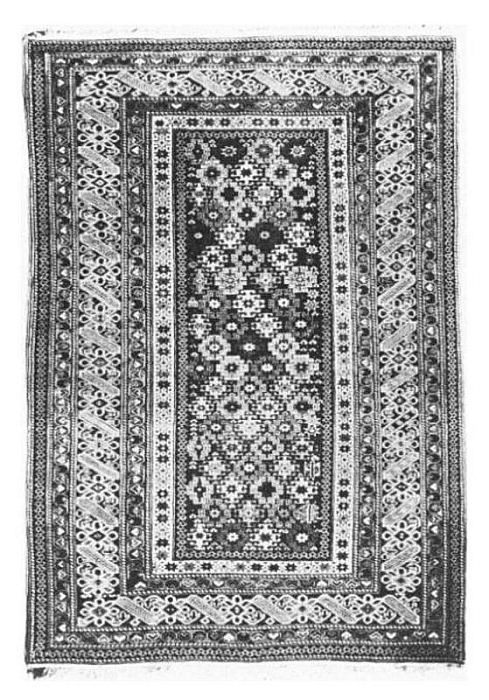

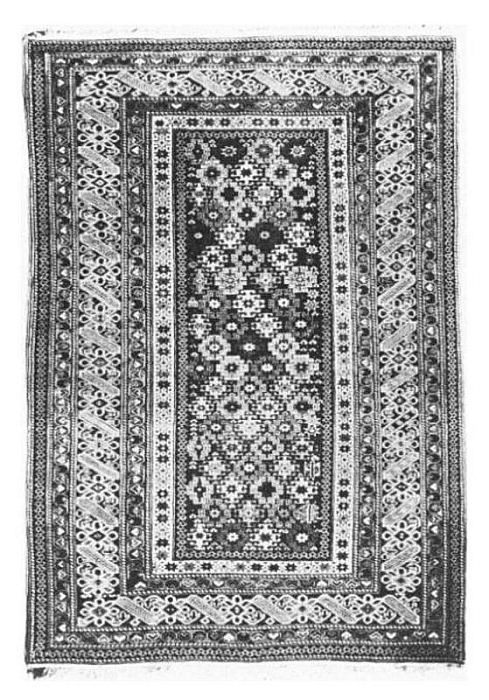

| Daghestan rug |

254 |

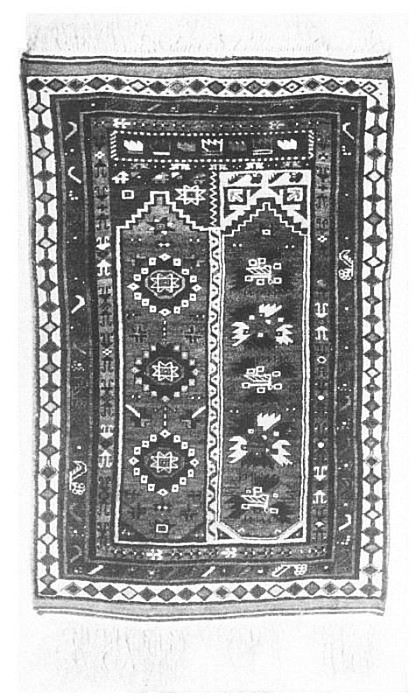

| Daghestan prayer rug |

256 |

| Kabistan rug |

258 |

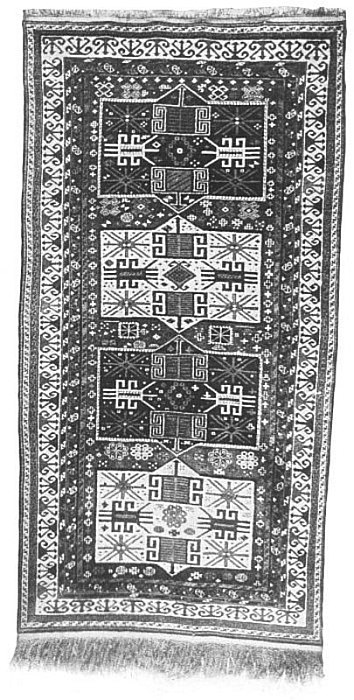

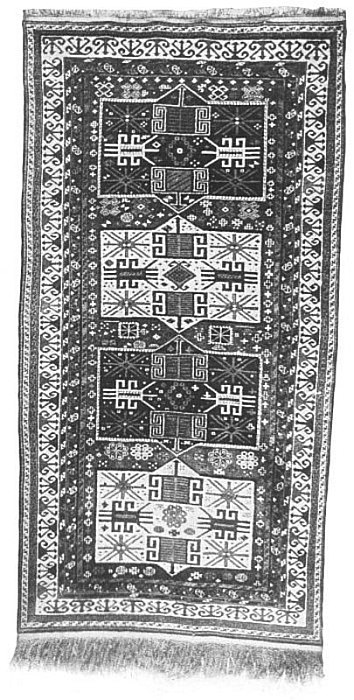

| Tchetchen or Chichi rug |

260 |

| Baku rug |

262 |

| Shemakha, Sumak or Cashmere rug |

264 |

| Shirvan rug |

266 |

| Genghis rug |

268 |

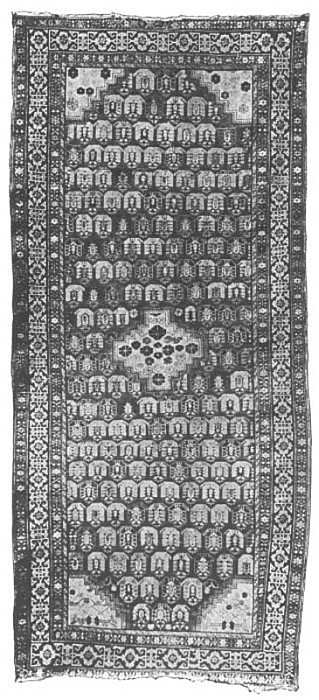

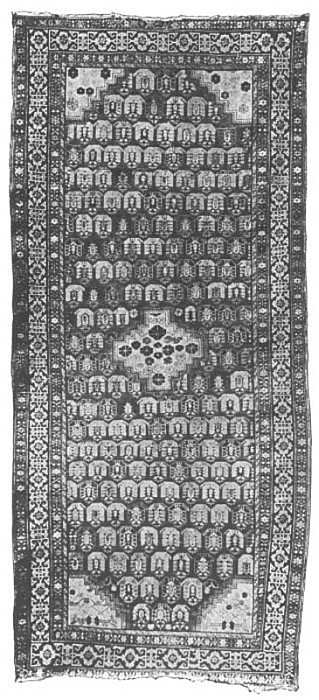

| Karabagh rug |

270 |

| [Pg. 13]

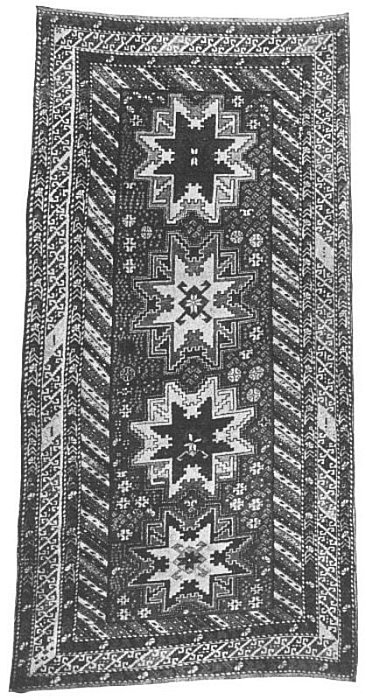

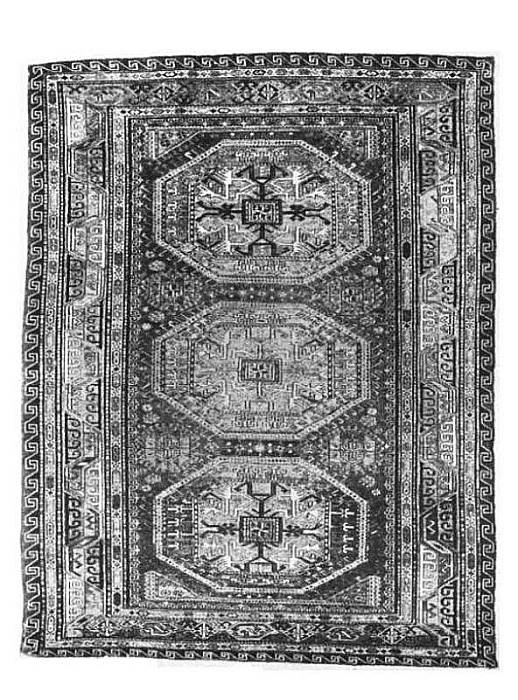

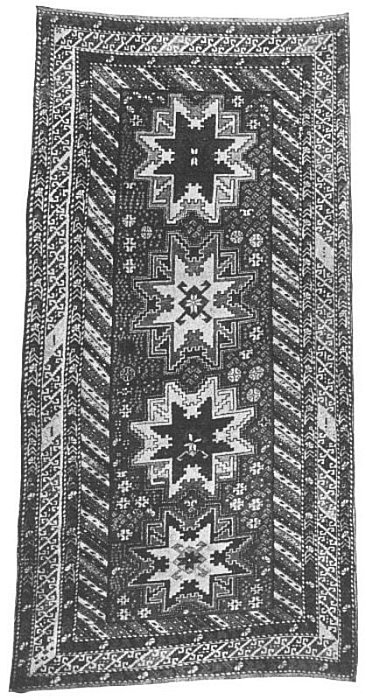

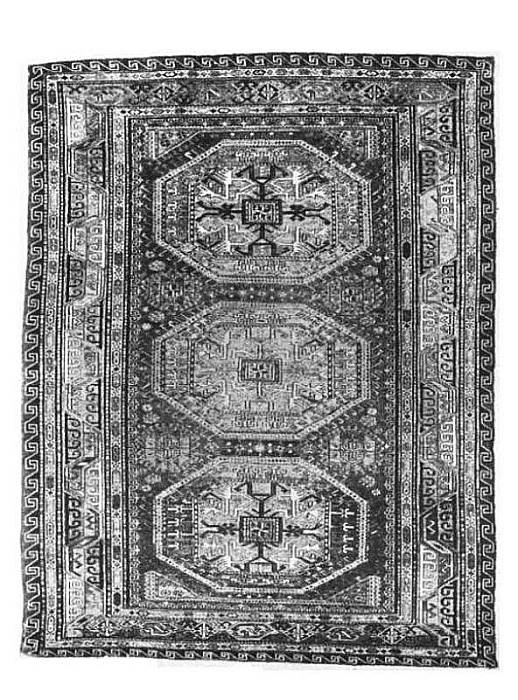

Kazak rug (Palace design) |

272 |

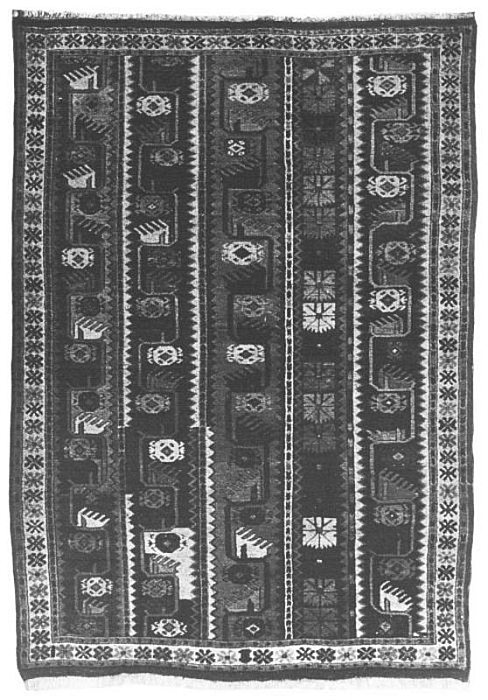

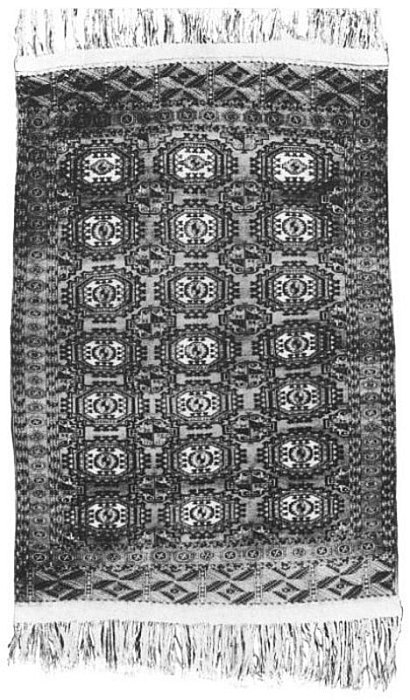

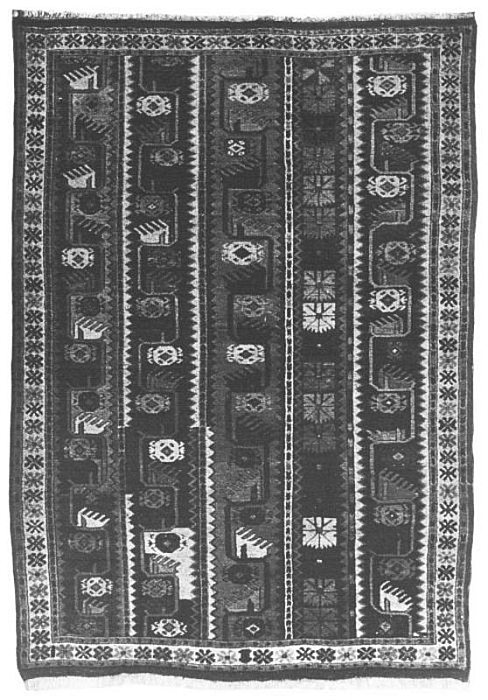

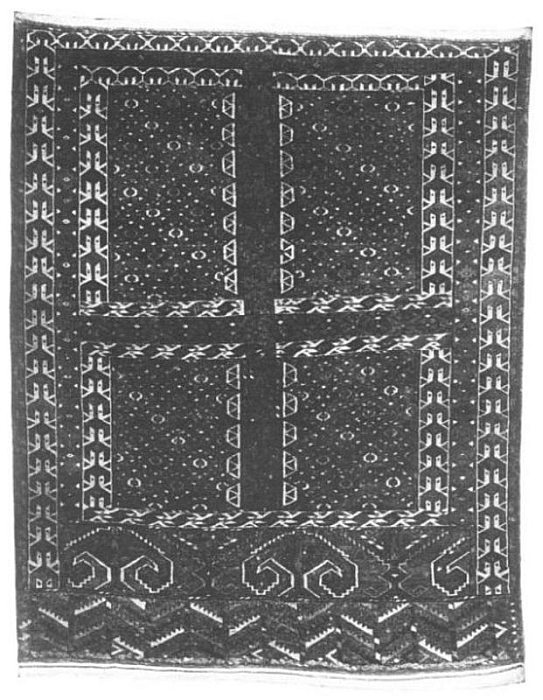

| Khiva Bokhara rug |

278 |

| Beshir Bokhara rug |

280 |

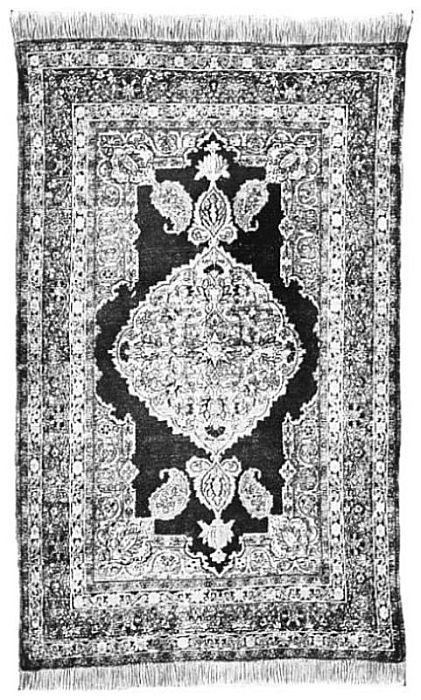

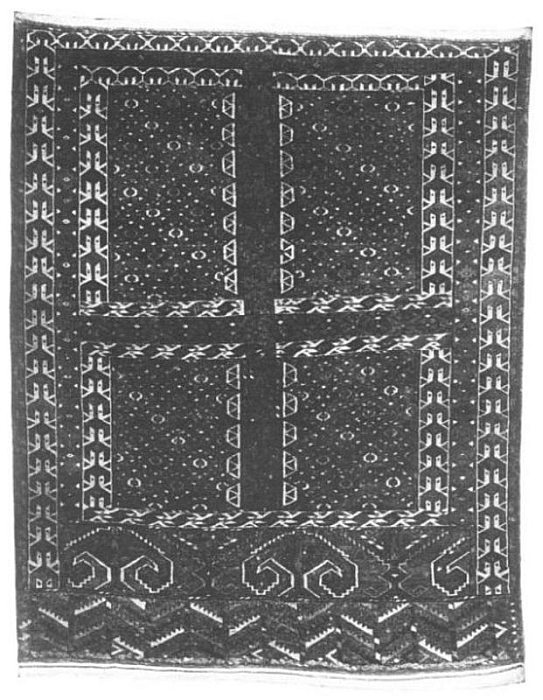

| Tekke Bokhara rug |

282 |

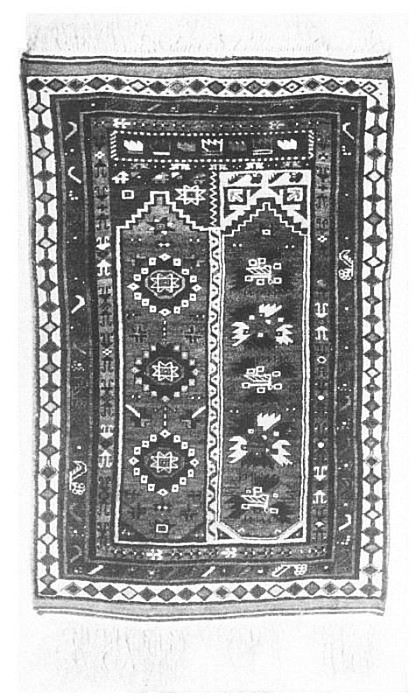

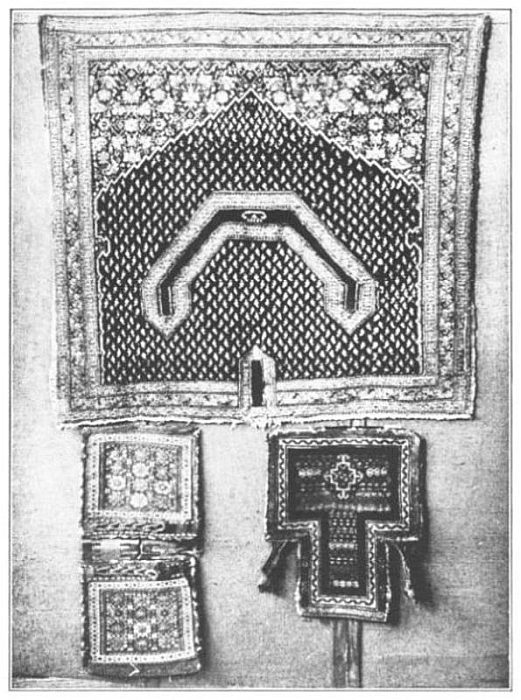

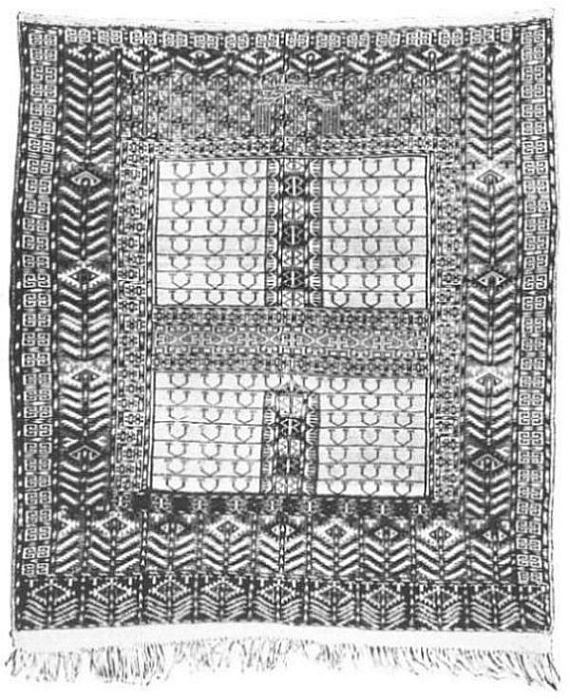

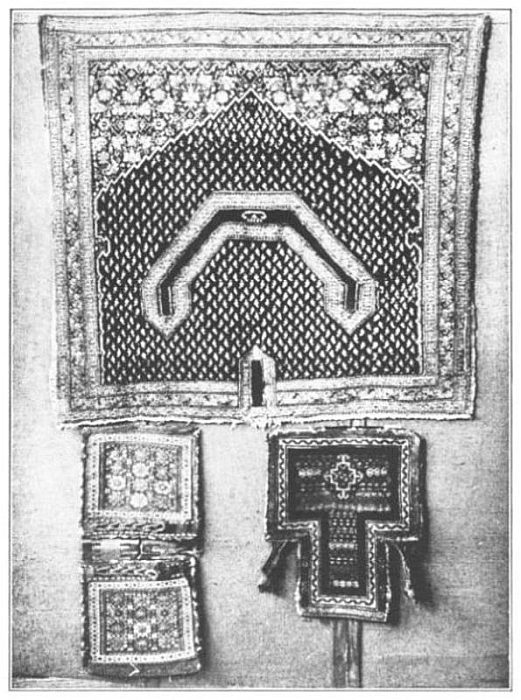

| Tekke Bokhara (Princess Bokhara, Khatchlie) prayer rug |

284 |

| Yomud rug |

286 |

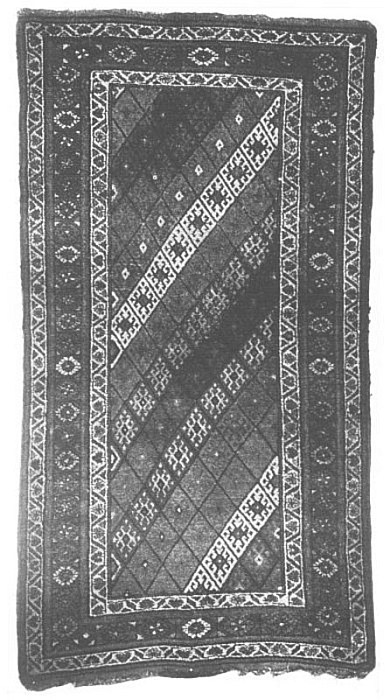

| Samarkand rug |

290 |

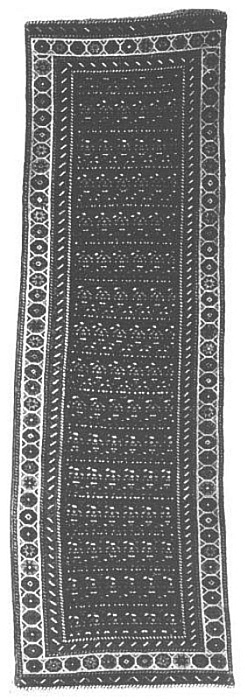

| Beluchistan rug |

296 |

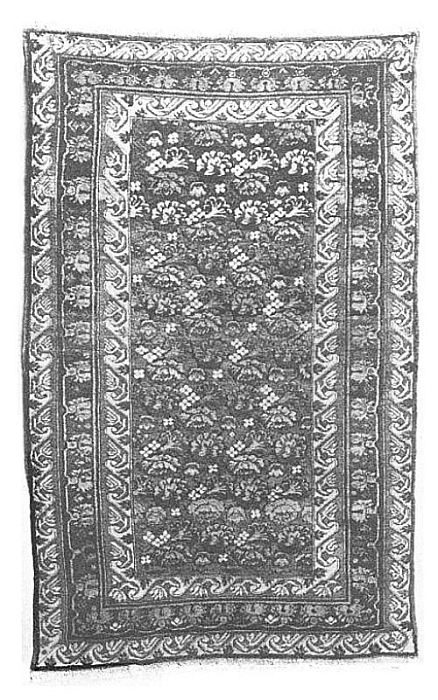

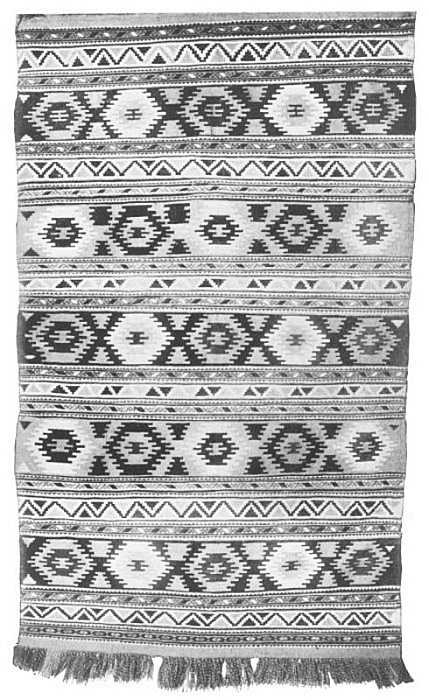

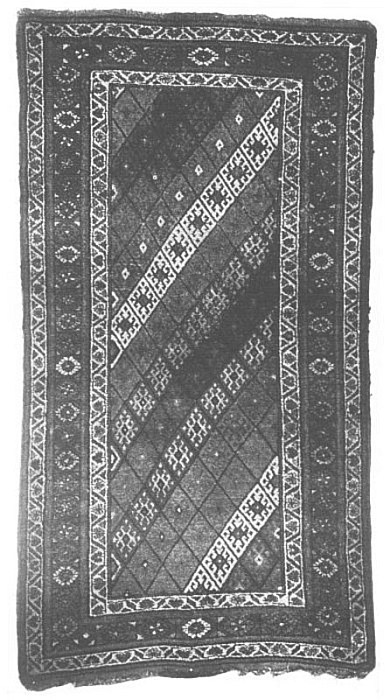

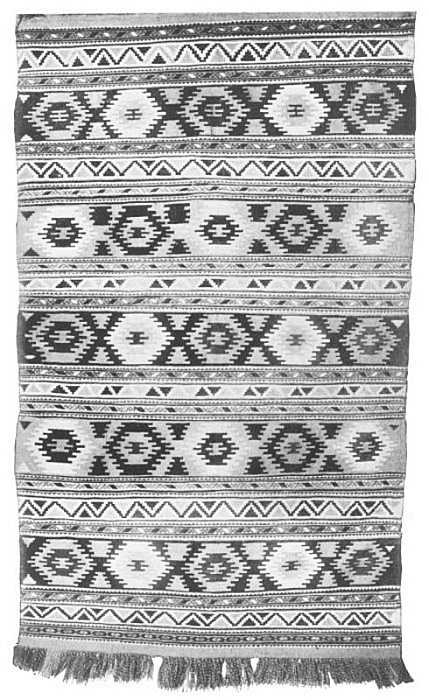

| Senna Ghileem rug |

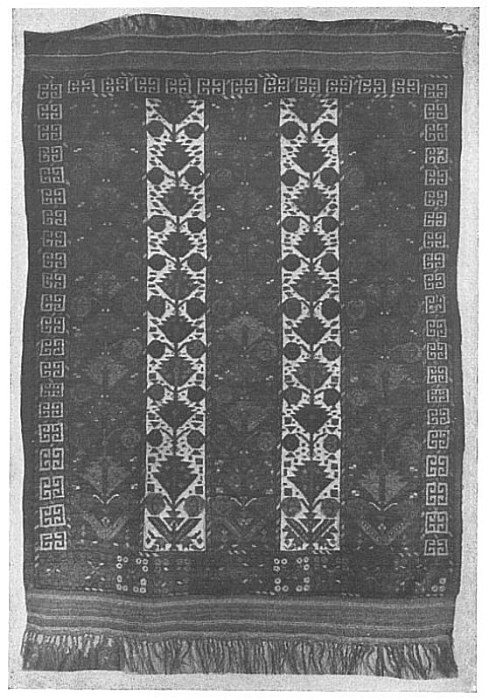

312 |

| Kurdish Ghileem rug |

314 |

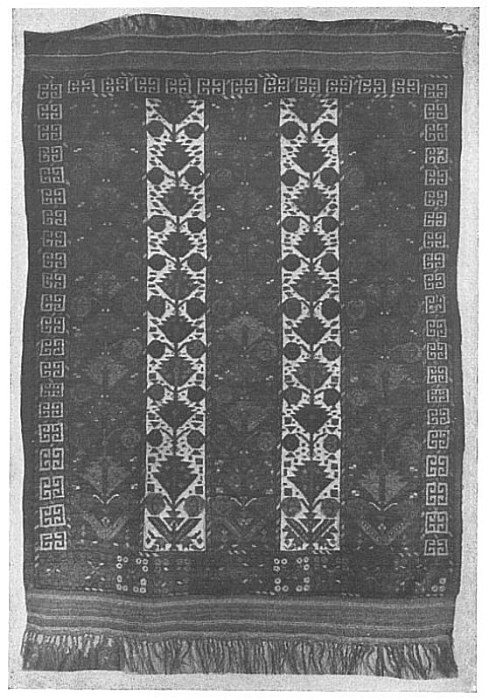

| Merve Ghileem rug |

316 |

| Kurdish Ghileem rug |

316 |

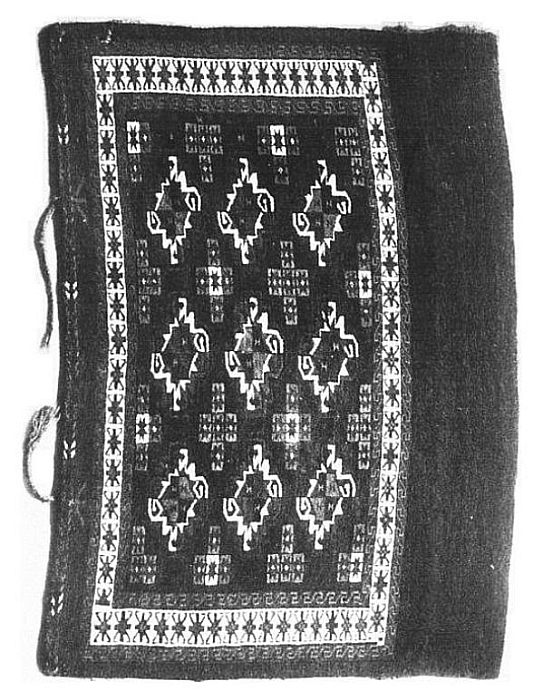

| Saddle cloth, saddle bags and powder bag |

324 |

| Kirman saddle bags |

326 |

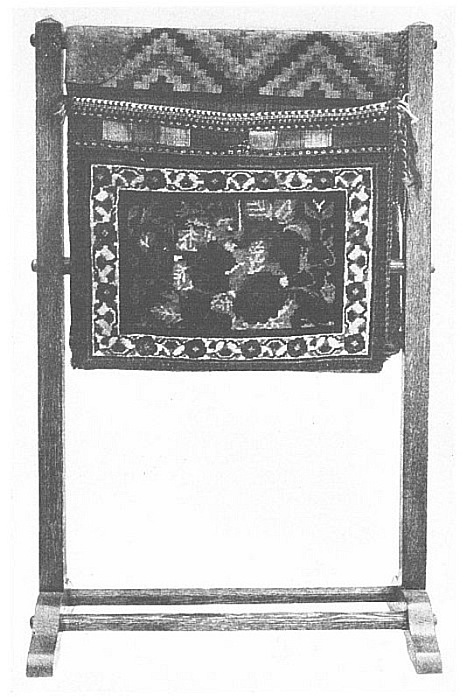

| Bijar sample corner |

328 |

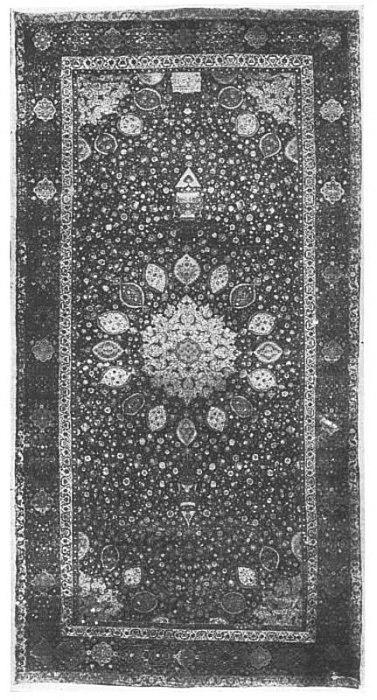

| Ardebil Mosque carpet |

330 |

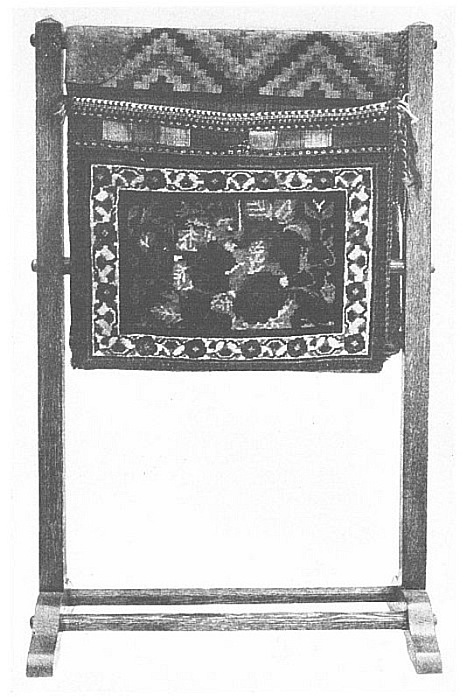

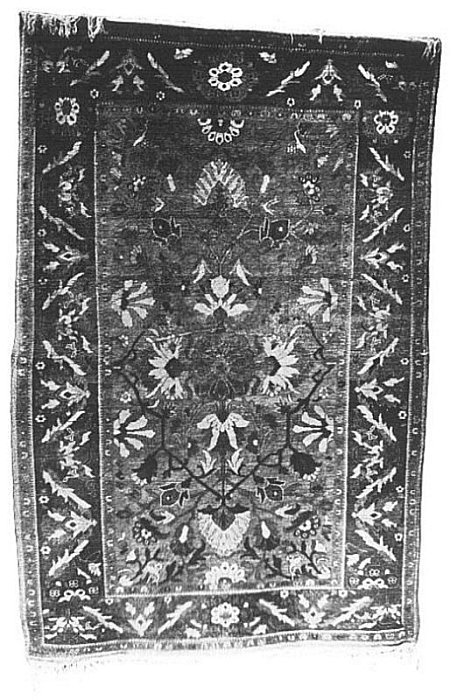

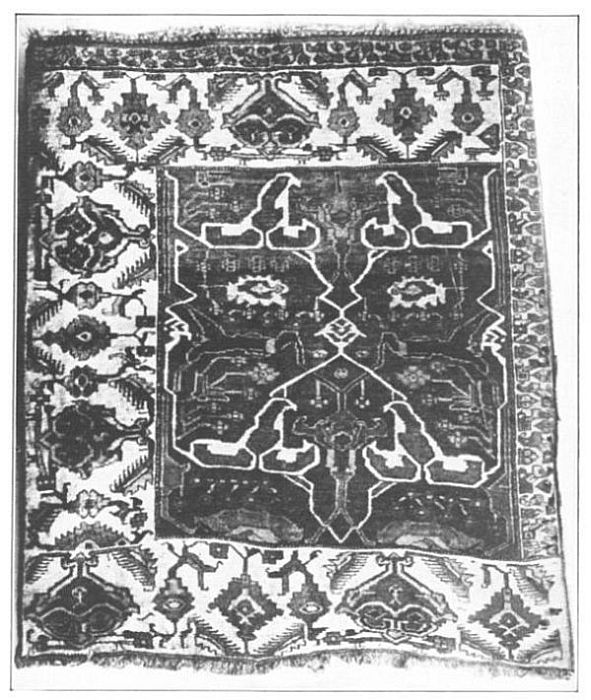

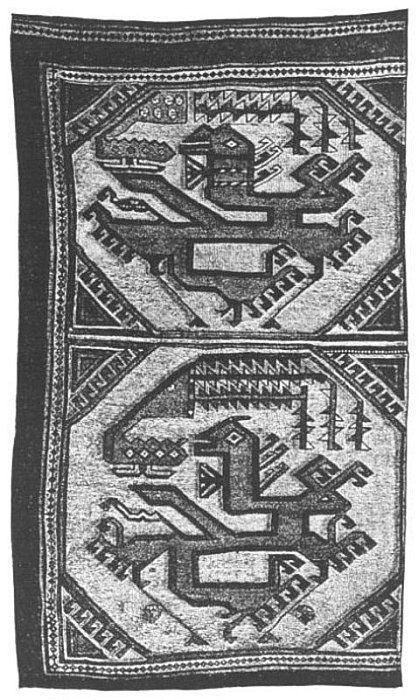

| Berlin Dragon and Phœnix rug |

332 |

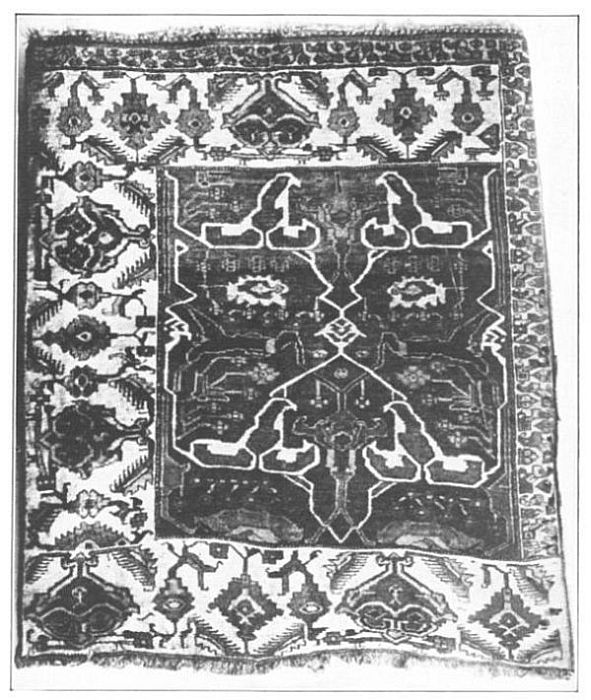

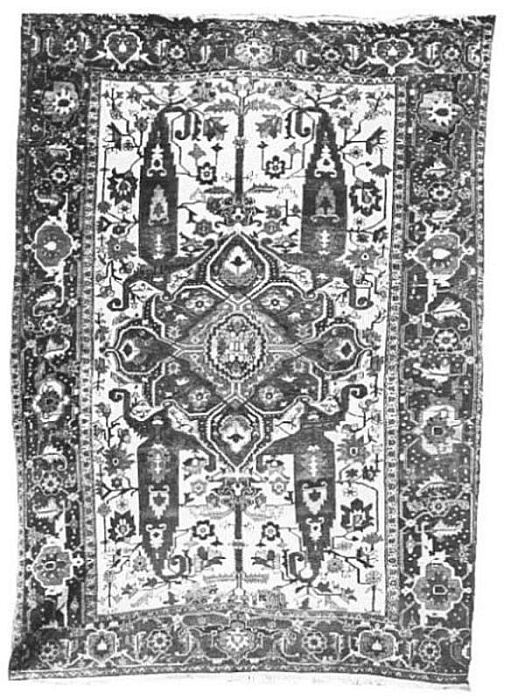

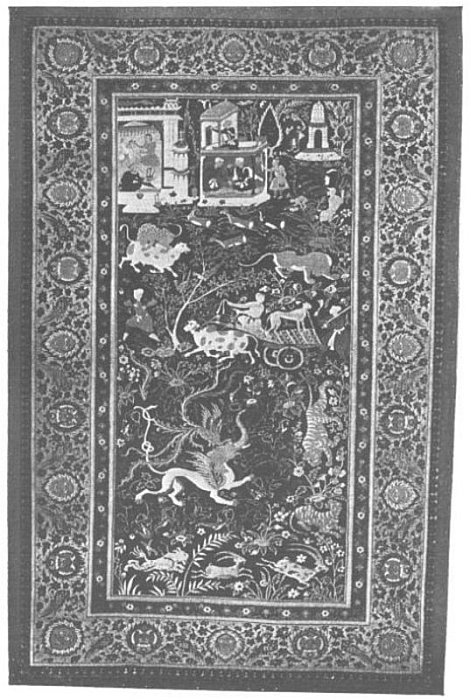

| East Indian hunting rug |

334 |

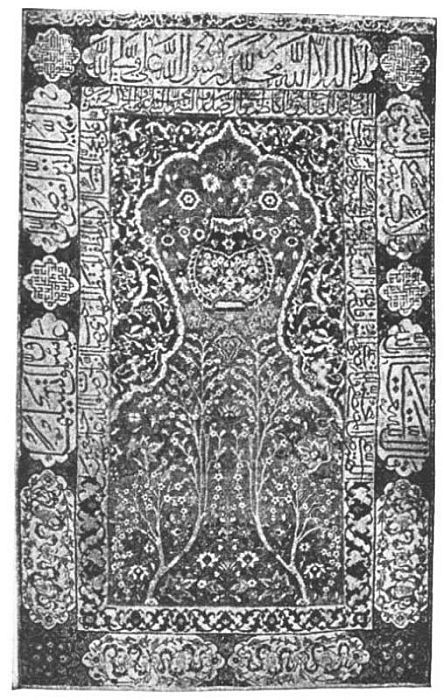

| The Altman prayer rug |

336 |

The Baker hunting rug

|

338

|

RUG MAKING, ETC.

|

| A Persian rug merchant |

38 |

| Expert weaver and inspector |

38 |

| Spinning the wool |

72 |

| Persian dye pots |

80 |

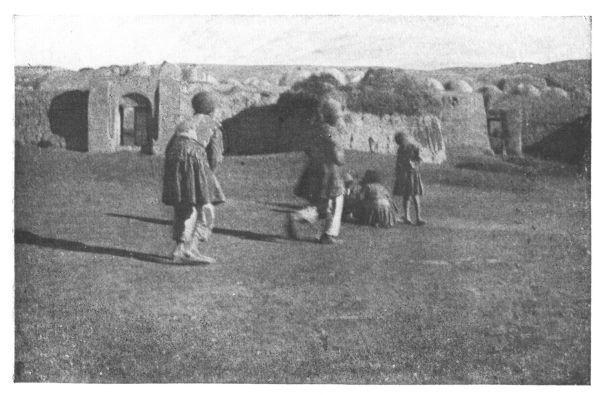

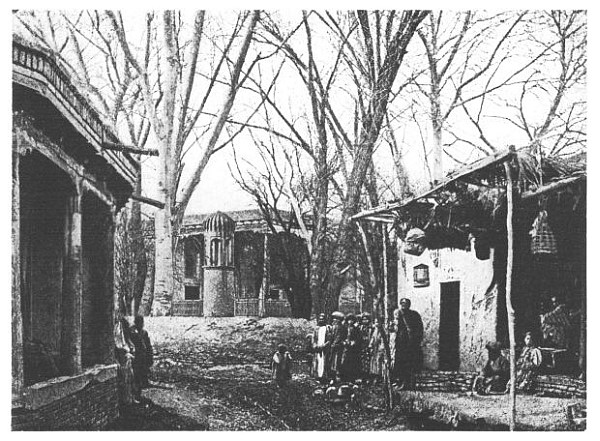

| A Persian village |

80 |

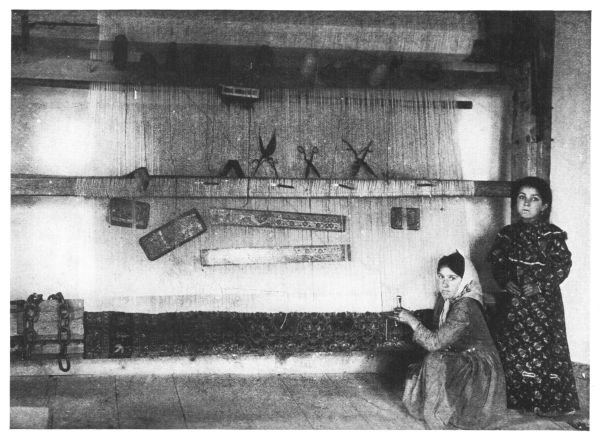

| A Turkish loom |

88 |

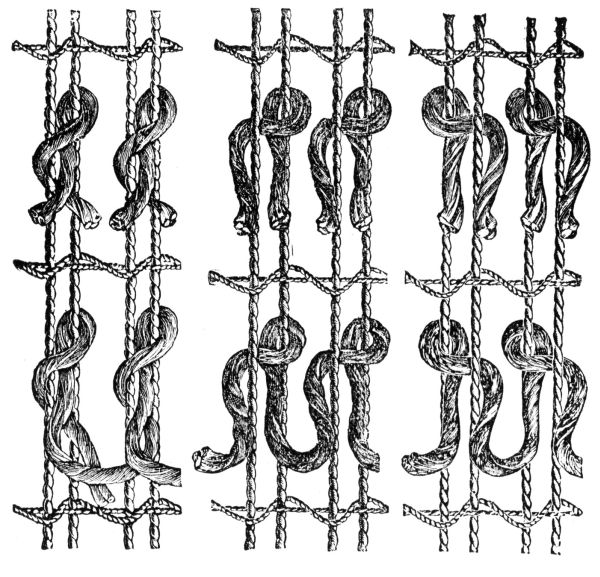

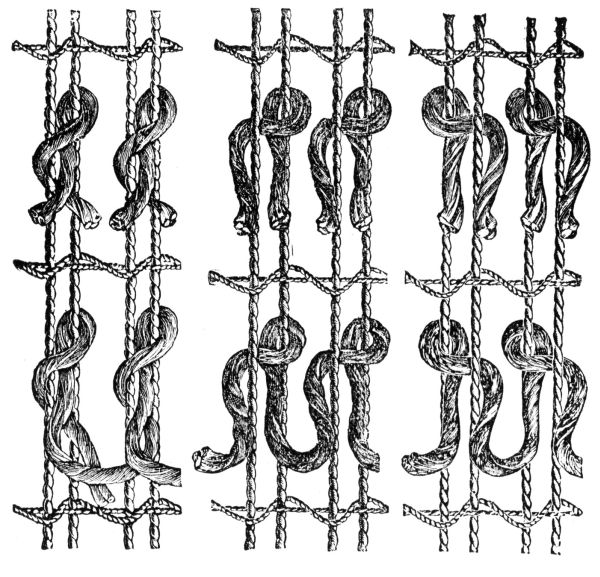

| The Senna and Ghiordes knots |

90 |

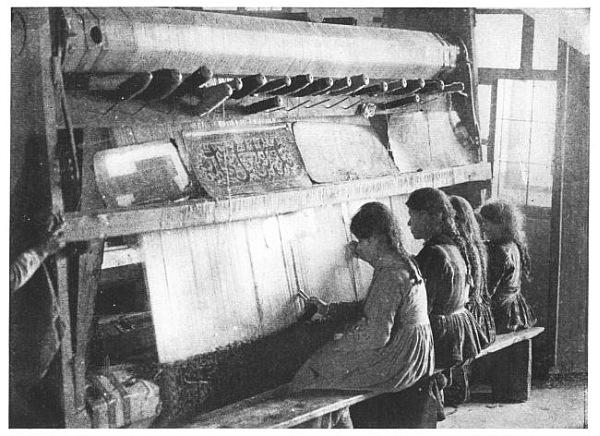

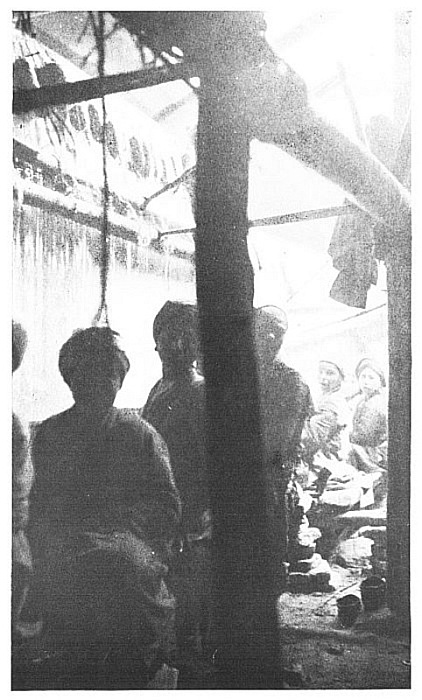

| Youthful weavers |

90 |

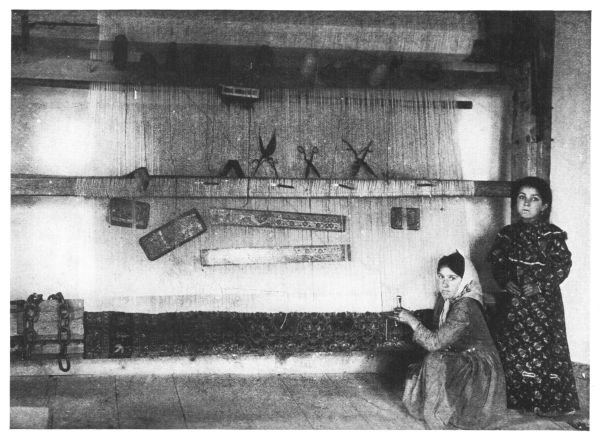

| A Persian loom |

92 |

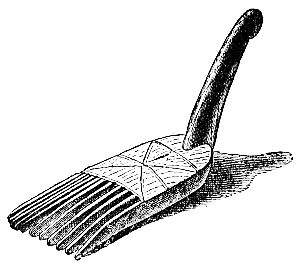

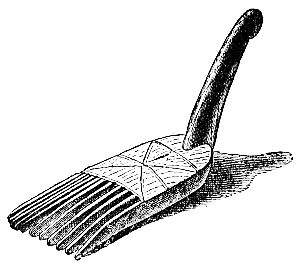

| A wooden comb |

92 |

| A Kurdish guard |

124 |

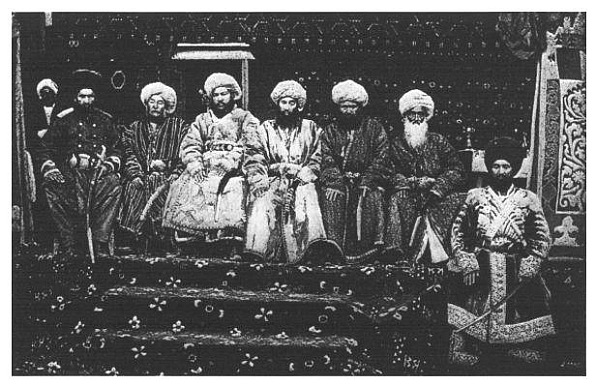

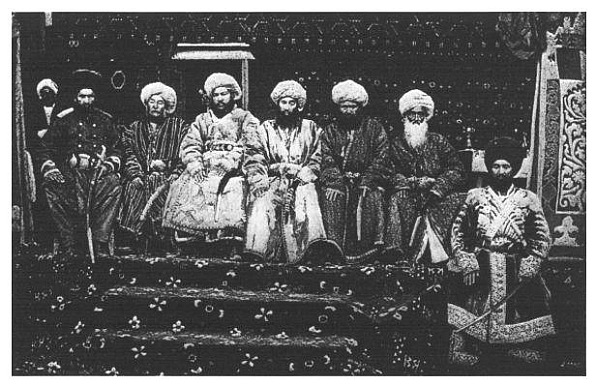

| The Emir of Bokhara and his ministers |

134 |

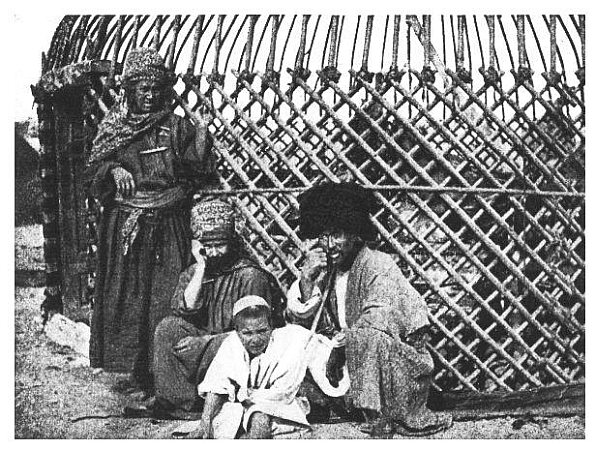

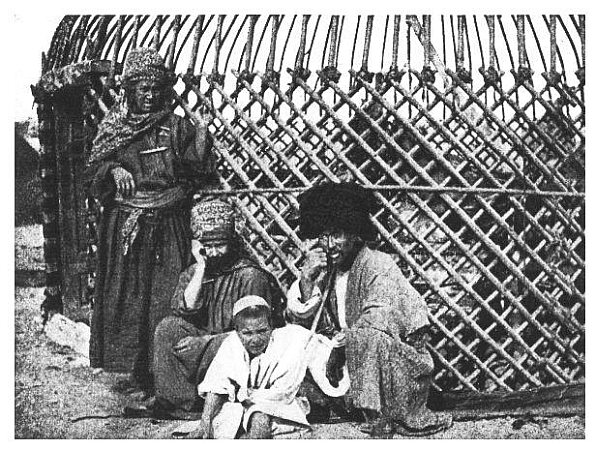

| Turkomans at home |

134 |

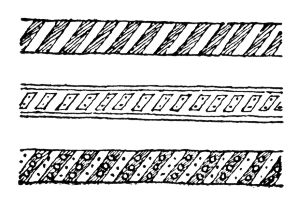

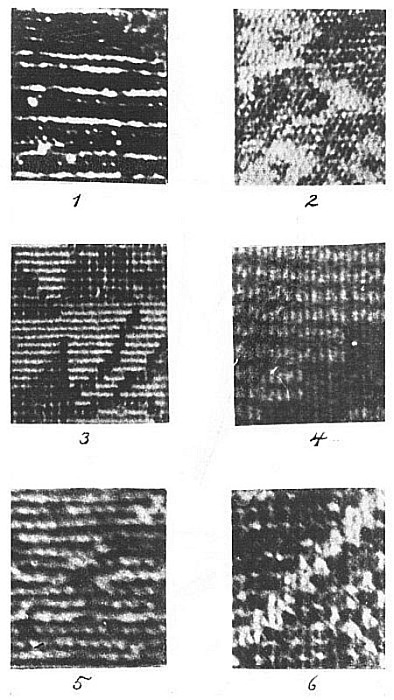

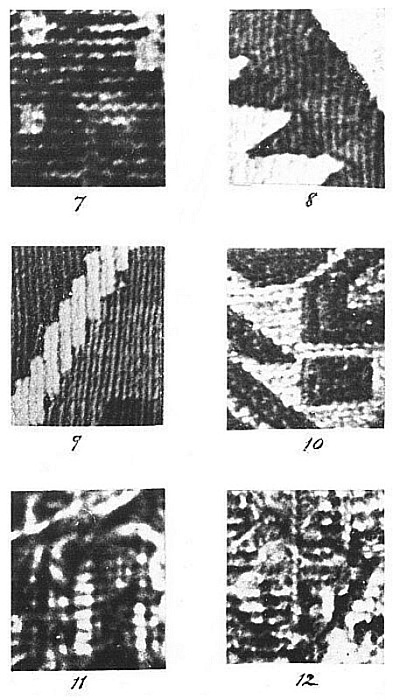

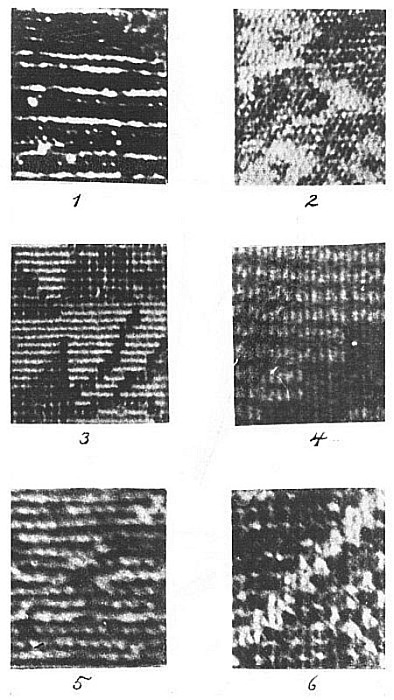

| Characteristic backs of rugs |

152 |

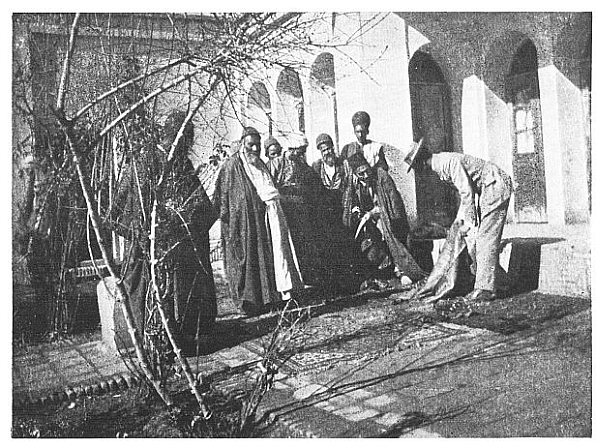

| Inspecting rugs at Ispahan |

170 |

| Persian villages near Hamadan |

170 |

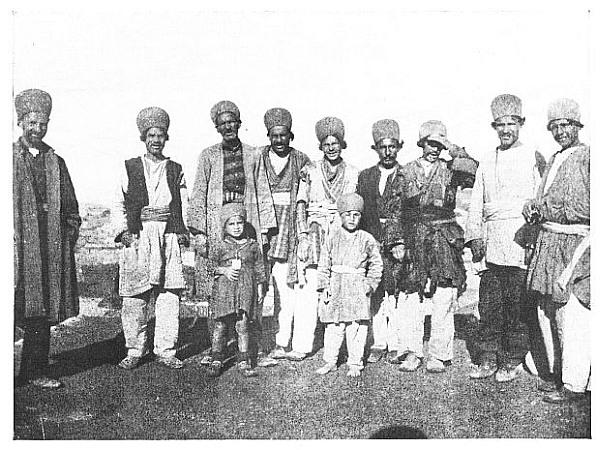

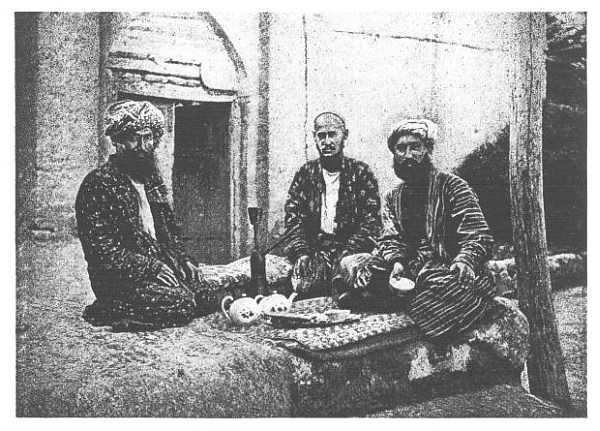

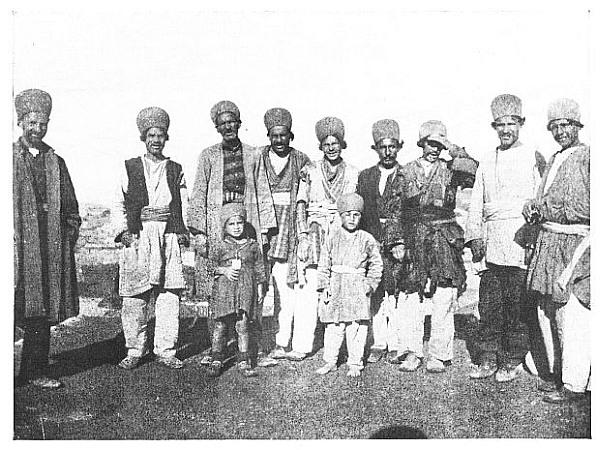

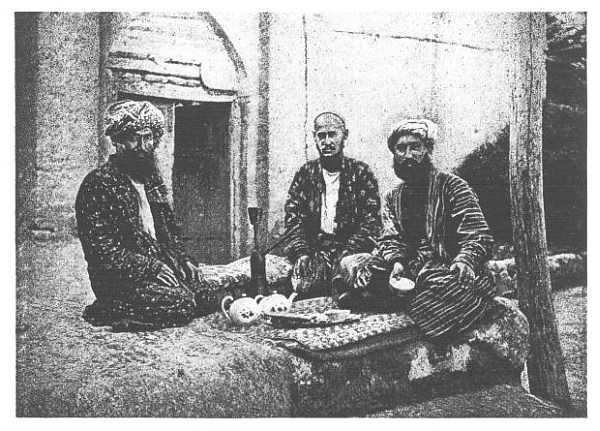

| Turkomans |

276 |

| Having a pot of tea at Bokhara |

288 |

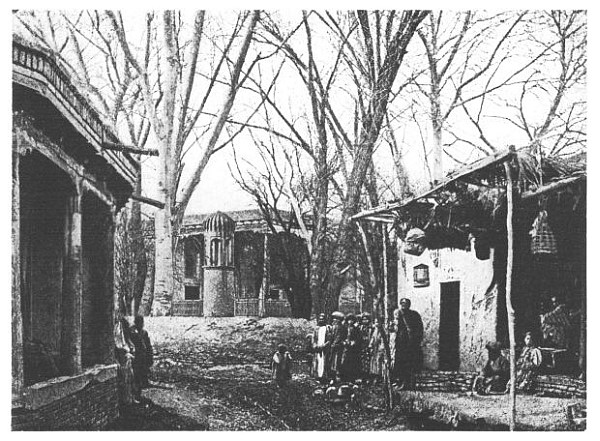

| A street in Samarkand |

288 |

The rug caravan

|

376

|

[Pg. 14]

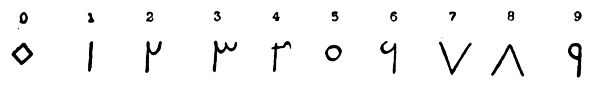

DESIGNS

|

| |

| Angular hook |

101 |

| Barber-pole stripe |

102 |

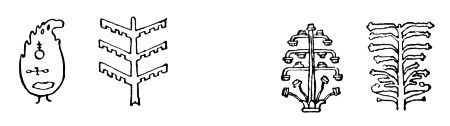

| Bat |

103 |

| Beetle |

103 |

| Butterfly border design |

104 |

| Caucasian border design |

105 |

| Chichi border design |

105 |

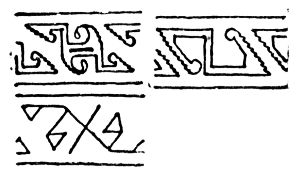

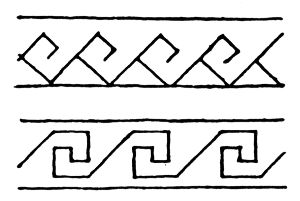

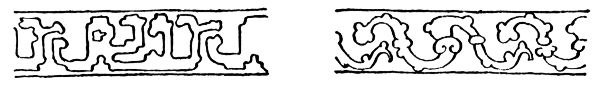

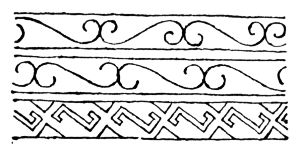

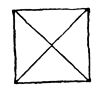

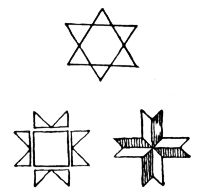

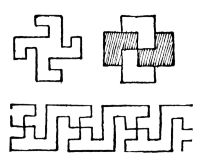

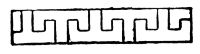

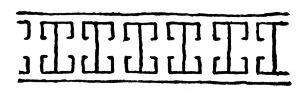

| Chinese fret |

106 |

| Chinese cloud band |

106 |

| Comb |

108 |

| Crab border design |

108 |

| Greek cross |

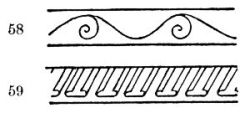

109 |

| Fish bone border design |

112 |

| Galley border design |

112 |

| Georgian border design |

112 |

| Ghiordes border design |

113 |

| Herati border design |

114 |

| Herati field design |

114 |

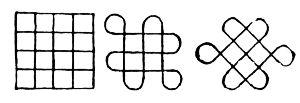

| Knot of destiny |

116 |

| Kulah border design |

116 |

| Lamp |

117 |

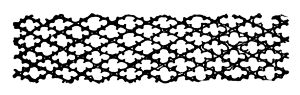

| Lattice field |

117 |

| Link |

118 |

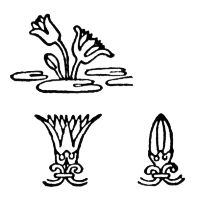

| Lotus |

118 |

| Lotus border design |

119 |

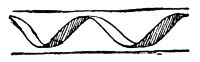

| Greek meander |

119 |

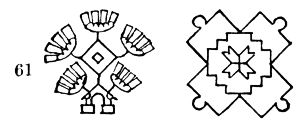

| Pole medallion |

120 |

| Mir or Saraband border design |

120 |

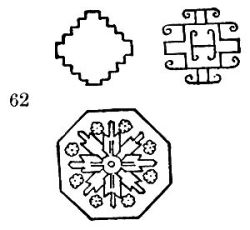

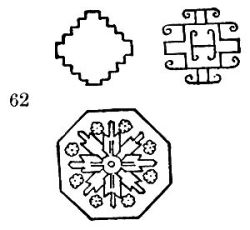

| Octagon |

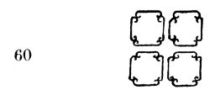

122 |

| Palace or sunburst |

122 |

| Pear |

123 |

| Pear border design |

124 |

| Reciprocal saw-teeth |

126 |

| Reciprocal trefoil |

126 |

| Lily or Rhodian field design |

126 |

| Lily or Rhodian border design |

126 |

| Ribbon border design |

127 |

| Rooster |

127 |

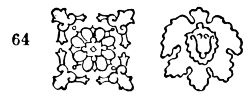

| Rosette |

128 |

| S forms |

129 |

| Scorpion border design |

129 |

| Shirvan border design |

130 |

| Shou |

131 |

| Solomon's seal |

131 |

| [Pg. 15]

Star |

133 |

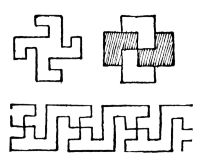

| Swastika |

134 |

| T forms |

134 |

| Tae-kieh |

135 |

| Tarantula |

135 |

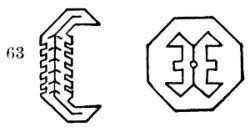

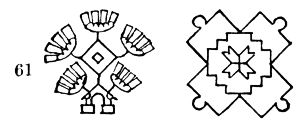

| Tekke border designs |

135 |

| Tekke field designs |

135 |

| Tomoye |

136 |

| Tortoise border designs |

136 |

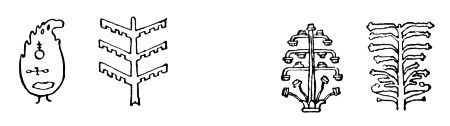

| Tree designs |

137 |

| Wine-glass border designs |

138 |

| Winged disc |

139 |

| Y forms |

139 |

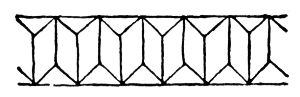

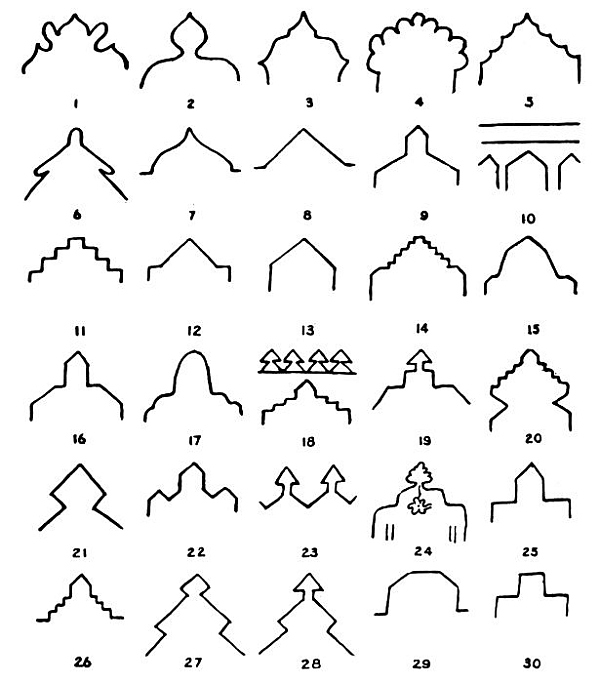

Various forms of prayer-niche in rugs

|

322

|

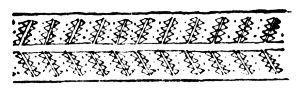

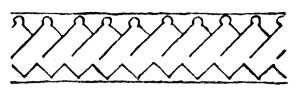

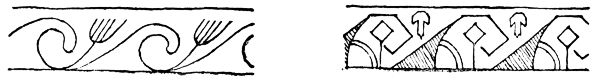

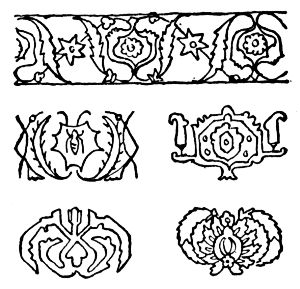

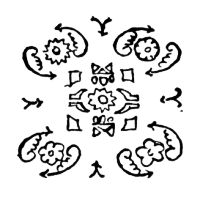

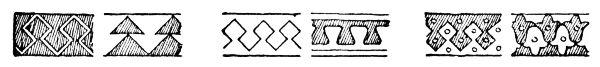

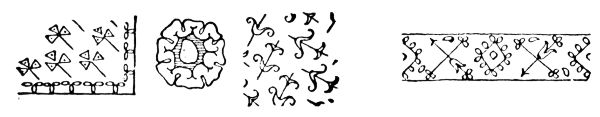

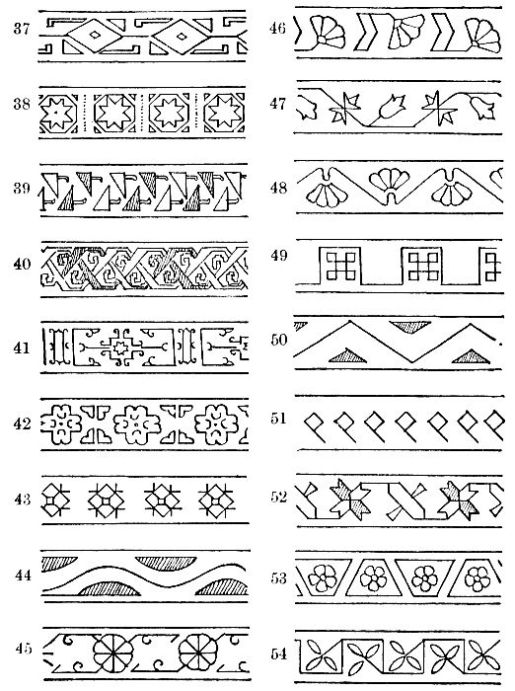

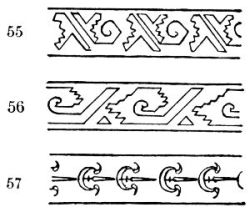

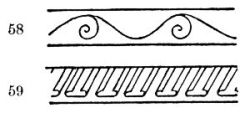

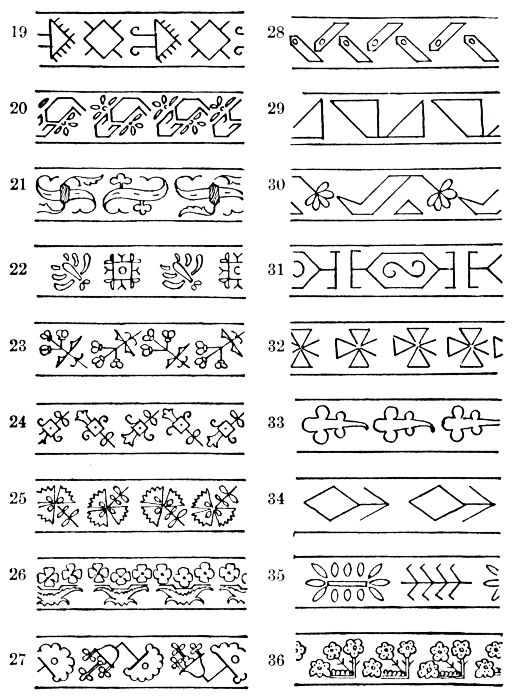

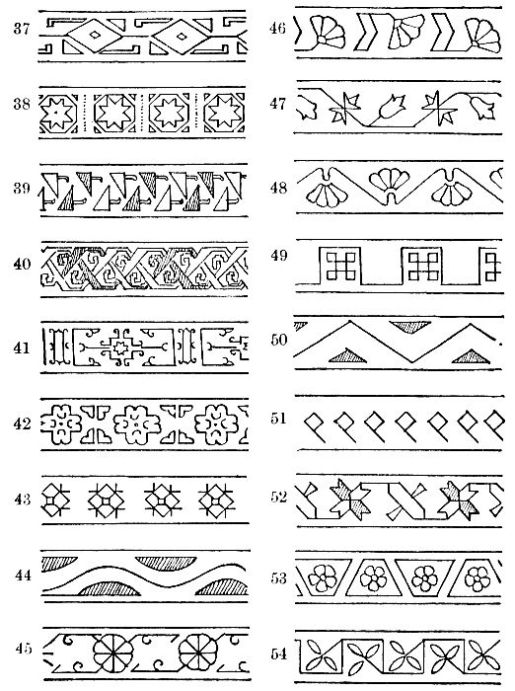

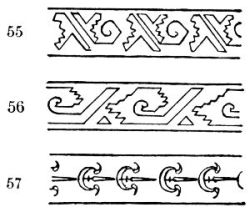

NAMELESS DESIGNS

|

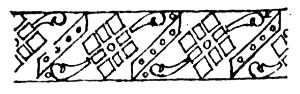

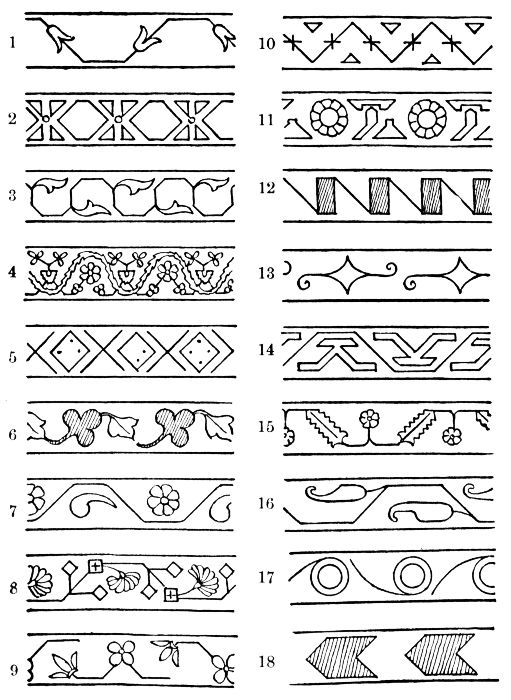

| Persian border designs |

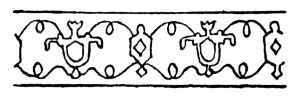

140 |

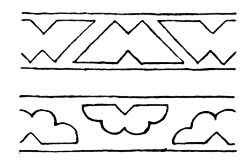

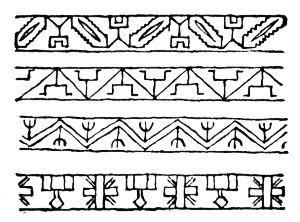

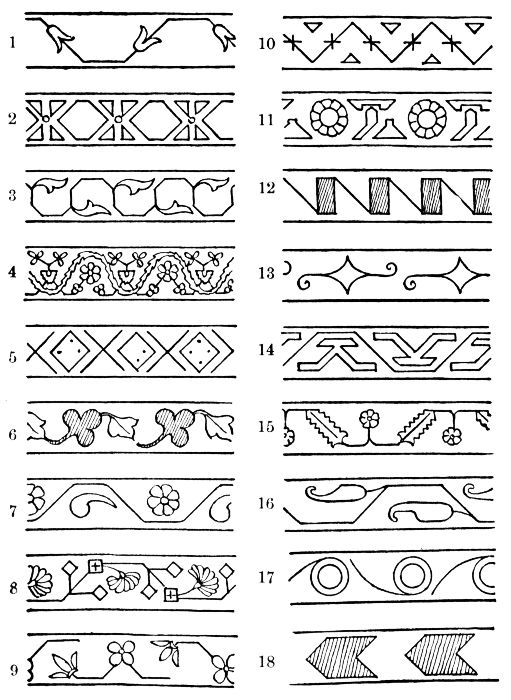

| Turkish border designs |

141 |

| Caucasian border designs |

142 |

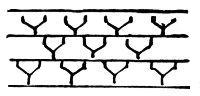

| Turkoman border designs |

143 |

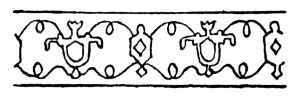

| Chinese border designs |

143 |

| Chinese field design |

143 |

| Kurdish field designs |

143 |

| Caucasian field design |

143 |

| Turkish field designs |

143 |

Persian field designs

|

143

|

CHART

|

Showing the distinguishing features of the different rugs

|

156

|

MAP

|

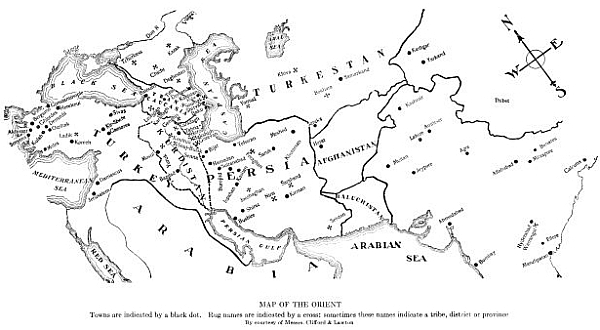

| The Orient | |

At end of volume |

[Pg. 16]

[Pg. 17]

INTRODUCTION

Just when the art of weaving originated is an

uncertainty, but there seems to be a consensus of

opinion among archæologists in general that it

was in existence earlier than the 24th century

before Christ. The first people which we have

been able with certainty to associate with this art

were the ancient Egyptians. Monuments of

ancient Egypt and of Mesopotamia bear witness

that the products of the hand loom date a considerable

time prior to 2400 B.C., and on the tombs

of Beni-Hassan are depicted women weaving

rugs on looms very much like those of the Orient

at the present time. From ancient literature we

learn that the palaces of the Pharaohs were ornamented

with rugs; that the tomb of Cyrus, founder

of the ancient Persian monarchy, was covered

with a Babylonian carpet and that Cleopatra was

carried into the presence of Cæsar wrapped in a

rug of the finest texture. Ovid vividly described

the weaver's loom. In Homer's Iliad we find these

words: "Thus as he spoke he led them in and

placed on couches spread with purple carpets

o'er." The woman in the Proverbs of Solomon

said, "I have woven my bed with cords, I have

[Pg. 18]

covered it with painted tapestry from Egypt."

Job said: "My days are swifter than the weaver's

shuttle and are spent without hope." Other

places in the Bible where reference is made to

the art of weaving are, Ex. 33, 35, Sam. 17, 7,

and Isa. 38, 12. Besides Biblical writers, Plautus,

Scipio, Horace, Pliny and Josephus all speak

of rugs.

The Egyptian carpets were not made of the

same material and weave as are the so-called

Oriental rugs of to-day. The pile surface was

not made by tying small tufts of wool upon the

warp thread. The Chinese seem to have been the

first to have made rugs in this way. Persia

acquired the art from Babylon many centuries

before Christ, since which time she has held the

foremost place as a rug weaving nation.

There is no more fascinating study than that

of Oriental rugs and there are few hobbies that

claim so absorbing a devotion. To the connoisseur

it proves a veritable enchantment: to the

busy man a mental salvation. He reads from his

rugs the life history of both a bygone and a living

people. A fine rug ranks second to no other creation

as a work of art and although many of them

are made by semi-barbaric people, they possess

rare artistic beauty of design and execution to

which the master hand of Time puts the finishing

touches. Each masterpiece has its individuality,

[Pg. 19]

no two being alike, although each may be true in

general to the family patterns, and therein consists

their enchantment. The longer you study

them the more they fascinate. Is it strange then

that this wonderful reproduction of colors appeals

to connoisseurs and art lovers of every country?

Were some of the antique or even the modern

pieces endowed with the gift of speech what wonderfully

interesting stories they could tell and yet

to the connoisseur the history, so to speak, of

many of these gems of the Eastern loom is

plainly legible in their weave, designs and colors.

The family or tribal legends worked out in the

patterns, the religious or ethical meaning of the

blended colors, the death of a weaver before the

completion of his work, which is afterwards taken

up by another, the toil and privation of which

every rug is witness, are all matters of interest

only to the student.

Americans have been far behind Europeans in

recognizing the artistic worth and the many other

advantages of the Oriental rug over any other

kind. Twenty-five years ago few American homes

possessed even one. Since then a marked change

in public taste has taken place. All classes have

become interested and, according to their resources,

have purchased them in a manner characteristic

of the American people, so that now

some of the choicest gems in existence have found

[Pg. 20]

a home in the United States. To what extent this

is true may be shown by the custom house

statistics, which prove that, even under a tariff

of nearly 50 per cent., the annual importation exceeds

over five million dollars and New York City

with the possible exception of London has become

the largest rug market of the world. This importation

will continue on even a larger scale until

the Orient is robbed of all its fabrics and the Persian

rug will have become a thing of the past.

Already the western demand has been so great

that the dyes, materials and quality of workmanship

have greatly deteriorated and the Orientals

are even importing machine made rugs from

Europe for their own use. It therefore behooves

us to cherish the Oriental rugs now in our possession.

Both Europe and the United States are manufacturing

artistic carpets of a high degree of excellence,

but they never have and never will be

able to produce any that will compare with those

made in the East. They may copy the designs

and match the shades, to a certain extent, but they

lack the inspiration and the knack of blending,

both of which are combined in the Oriental

product.

Only in a land where time is of little value and

is not considered as an equivalent to money, can

such artistic perfection be brought about.

[Pg. 21]

PART I

[Pg. 22]

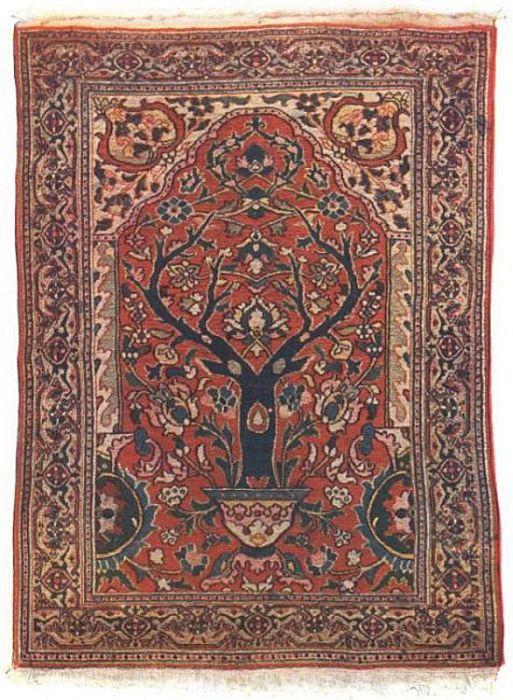

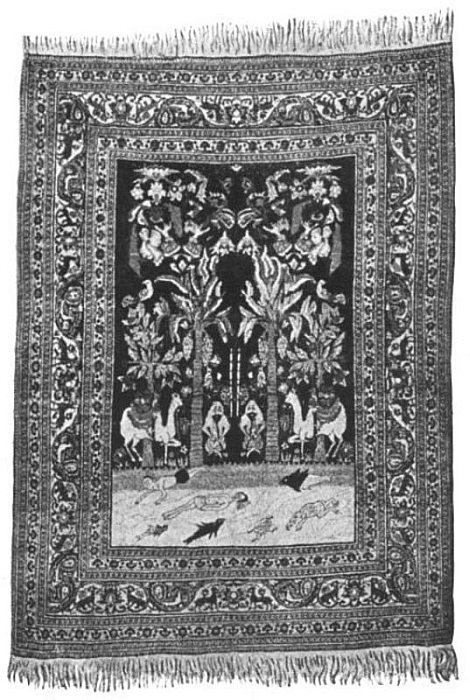

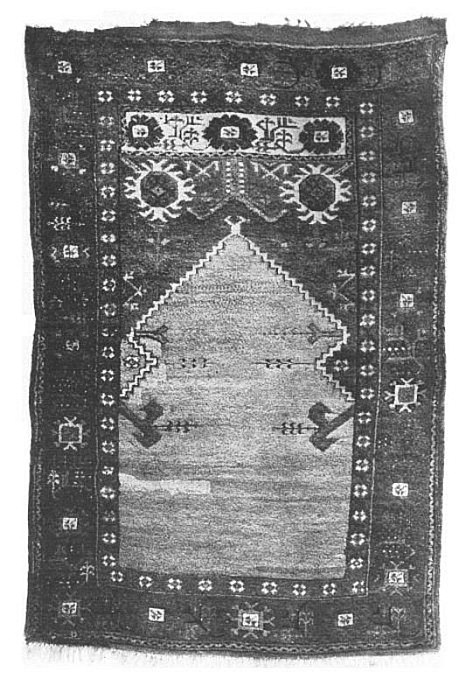

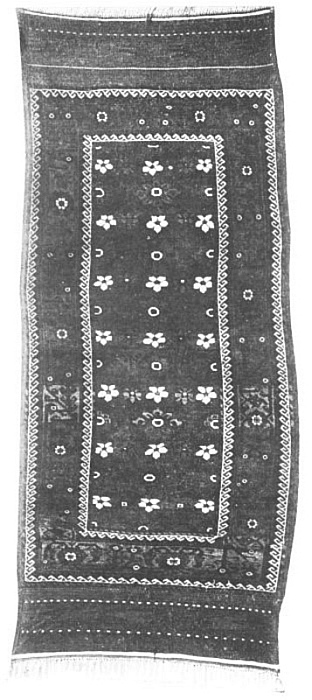

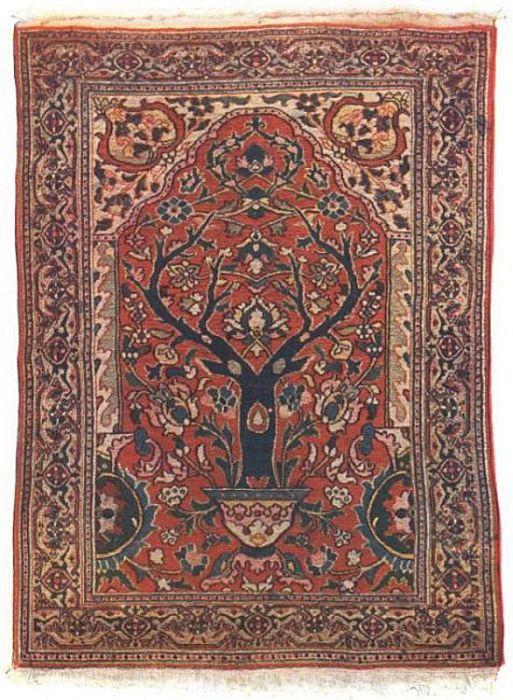

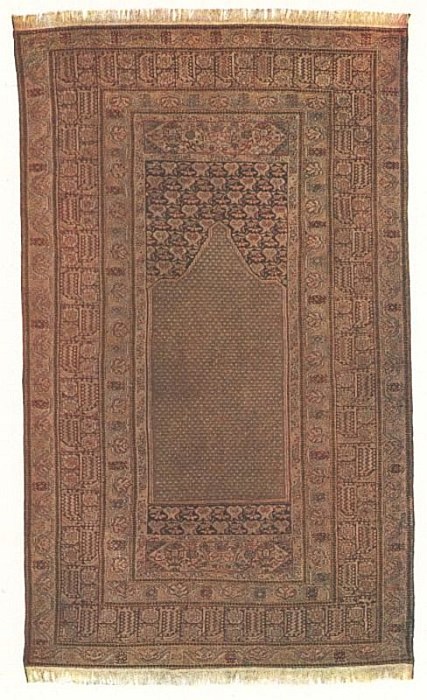

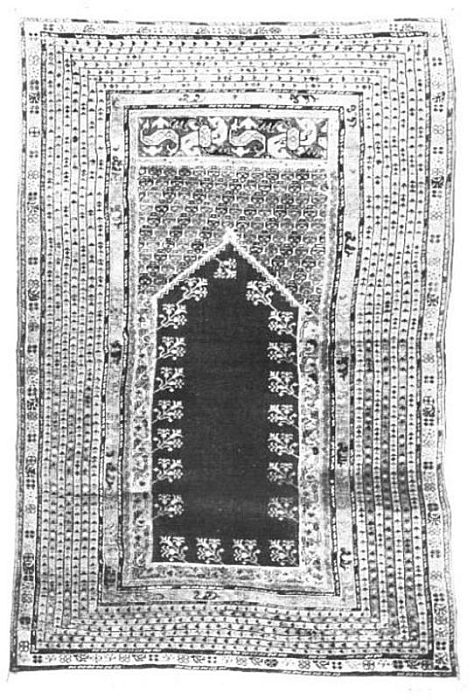

MESHED PRAYER RUG

MESHED PRAYER RUG

Size 4' × 3'

FROM THE COLLECTION OF THE AUTHOR

Prayer rugs of this class are exceedingly rare. This is the only

one the author has ever seen. It is extremely fine in texture, having

twenty-eight Senna knots to the inch vertically and sixteen horizontally,

making four hundred and forty-eight knots to the square inch,

tied so closely that it is quite difficult to separate the pile sufficiently

to see the wool or warp threads. The central field consists of the

tree of life in dark blue with red, blue and pink flowers upon a background

of rich red.

The main border stripe carries the Herati design in dark

blue and dark red upon a pale blue ground on each side of which

are narrow strips of pink carrying alternate dots of red and blue.

(See page 209)

[Pg. 24]

[Pg. 25]

The Practical Book of

Oriental Rugs

COST AND TARIFF

The value of an Oriental rug cannot be gauged

by measurement any more than can that of a fine

painting; it depends upon the number of knots to

the square inch, the fineness of the material, the

richness and stability of its colors, the amount of

detail in design, its durability and, last but not

least, its age. None of these qualifications being at

sight apparent to the novice, he is unable to make

a fair comparison of prices, as frequently rugs

which appear to him to be quite alike and equally

valuable may be far apart in actual worth.

When we consider that from the time a rug

leaves the weavers' hands until it reaches the

final buyer there are at least from five to seven

profits to pay besides the government tariffs

thereon, it is no wonder that the prices at times

seem exorbitant. The transportation charges

amount to about ten cents per square foot.

[Pg. 26]

The Turkish government levies one per cent.

export duty and the heavily protected United

States levies forty per cent. ad valorem and ten

cents per square foot besides, all of which alone

adds over fifty per cent. to the original cost in

America, and yet should we estimate the work

upon Oriental rugs by the American standard of

wages they would cost from ten to fifty times their

present prices.

To furnish a home with Oriental rugs is not

as expensive as it would at first seem. They can

be bought piece by piece at intervals, as circumstances

warrant, and when a room is once provided

for it is for all time, whereas the carpet

account is one that is never closed.

In the United States good, durable Eastern

rugs may be bought for from sixty cents to ten

dollars per square foot, and in England for much

less. Extremely choice pieces may run up to the

thousands. At the Marquand sale in New York

City in 1902, a fifteenth century Persian rug

(10-10 x 6-1) was sold for $36,000, nearly $550 a

square foot. The holy carpet of the Mosque at

Ardebil, woven at Kashan in 1536 and now owned

by the South Kensington Museum, of London, is

valued at $30,000. The famous hunting rug,

which was presented some years ago by the late

Ex-Governor Ames of Massachusetts to the Boston

Museum of Fine Arts, is said to have cost $35,000.

The late Mr. Yerkes of New York City paid

$60,000 for his "Holy Carpet," the highest price

ever paid for a rug. Mr. J. P. Morgan recently

paid $17,000 for one 20 x 15. Two years ago

H. C. Frick paid $160,000 for eight small Persians,

$20,000 apiece. Senator Clark's collection cost

$3,000,000, H. O. Havemeyer's $250,000, and O.

H. Payne's $200,000.

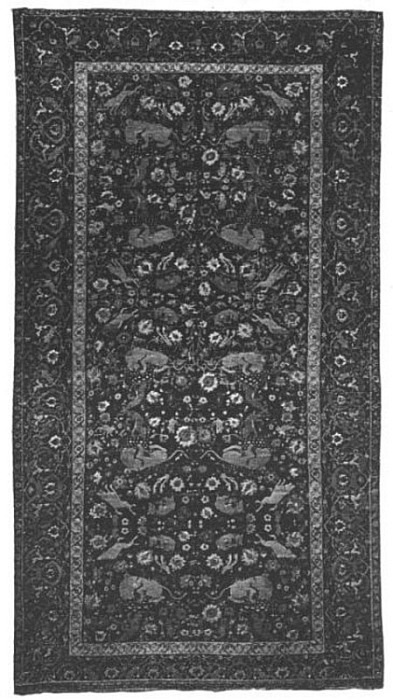

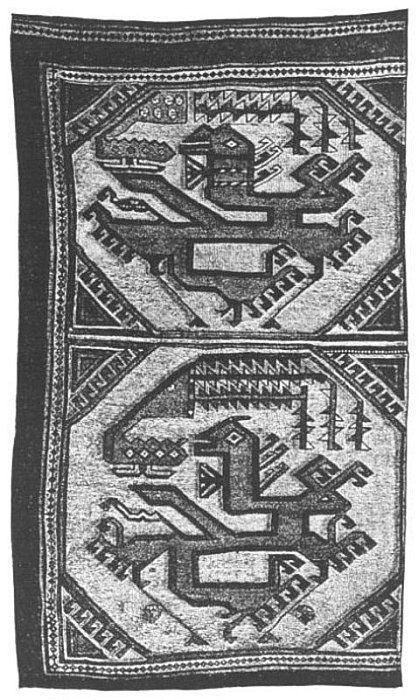

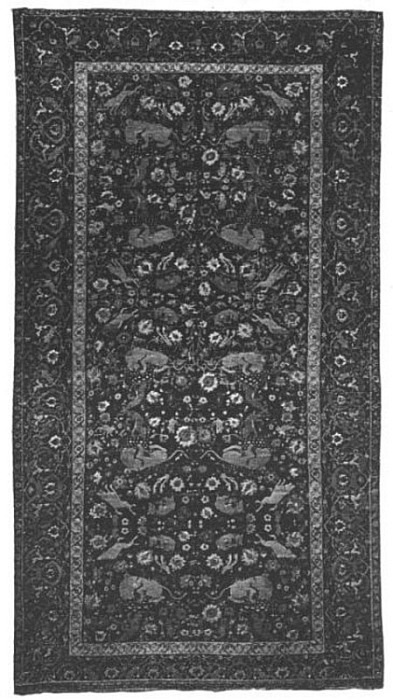

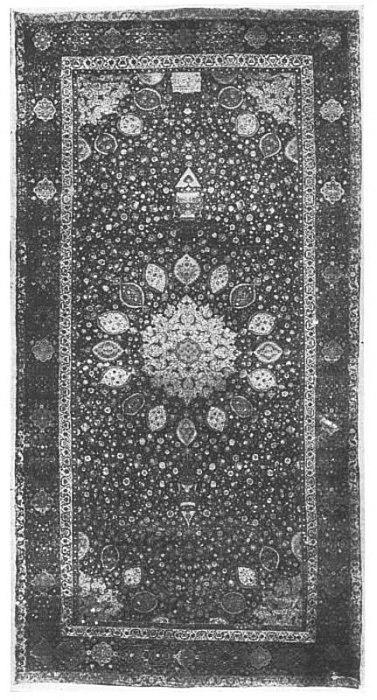

THE METROPOLITAN ANIMAL RUG

BY COURTESY OF THE METROPOLITAN MUSEUM OF FINE ARTS

THE METROPOLITAN ANIMAL RUG

BY COURTESY OF THE METROPOLITAN MUSEUM OF FINE ARTS

NEW YORK CITY

(See page 337)

[Pg. 27]

Everything considered, the difference in cost

per square foot between the average Oriental and

the home product amounts to little in comparison

to the difference in endurance. If one uses the

proper judgment in selecting, his money is much

better spent when invested in the former than

when invested in the latter. While the nap of

the domestic is worn down to the warp the

Oriental has been improving in color and sheen as

well as in value. This is due to the fact that the

Eastern product is made of the softest of wool

and treated with dyes which have stood the test

of centuries and which preserve the wool instead

of destroying it as do the aniline dyes.

In comparing the cost of furnishing a home

with Oriental rugs or with carpets one should

further take into consideration the fact that with

[Pg. 28]

carpets much unnecessary floor space must be

covered which represents so much waste money.

Also the question of health involved in the use of

carpets is a very serious one. They retain dust

and germs of all kinds and are taken up and

cleaned, as a rule, but once a year. With rugs

the room is much more easily kept clean and the

furniture does not have to be moved whenever

sweeping time comes around.

[Pg. 30]

[Pg. 31]

DEALERS AND AUCTIONS

Few Europeans or Americans penetrate to the

interior markets of the East where home-made

rugs find their first sale. Agents of some of the

large importers have been sent over to collect

rugs from families or small factories and the

tales of Oriental shrewdness and trickery which

they bring back are many and varied. We have

in this country many honest, reliable foreign

dealers, but occasionally one meets with one of

the class above referred to. In dealing with such

people it is safe never to bid more than half and

never to give over two-thirds of the price they ask

you. Also never show special preference for any

particular piece, otherwise you will be charged

more for it. No dealer or authority may lay claim

to infallibility, but few of these people have any

adequate knowledge of their stock and are, as a

rule, uncertain authorities, excepting in those

fabrics which come from the vicinity of the

province in which they lived. They buy their stock

in large quantities, usually by the bale at so much

a square foot, and then mark each according to

their judgment so as to make the bale average up

[Pg. 32]

well and pay a good profit. So it is that an expert

may occasionally select a choice piece at a bargain

while the novice usually pays more than the actual

worth. Every rug has three values, first the art

value depending upon its colors and designs,

second the collector's value depending upon its

rarity, and third the utility value depending upon

its durability. No dealer can buy rugs on utility

value alone and he who sells Oriental rugs very

cheap usually sells very cheap rugs.

It might be well right here to state that when

rugs are sold by the bale the wholesaler usually

places a few good ones in the bale for the purpose

of disposing of the poor ones. Dealers can always

find an eager market for good rugs, but poor ones

often go begging, and in order to dispose of them

the auction is resorted to. They are put up under

a bright reflected light which shows them off to

the best advantage; the bidder is allowed no

opportunity for a thorough examination and

almost invariably there are present several fake

bidders. This you can prove to your own satisfaction

by attending some auction several days

in succession and you will see the same beautiful

Tabriz bid off each time at a ridiculously low

price, while those that you actually see placed into

the hands of the deliveryman will average in price

about the same as similar rugs at a retail store.

[Pg. 33]

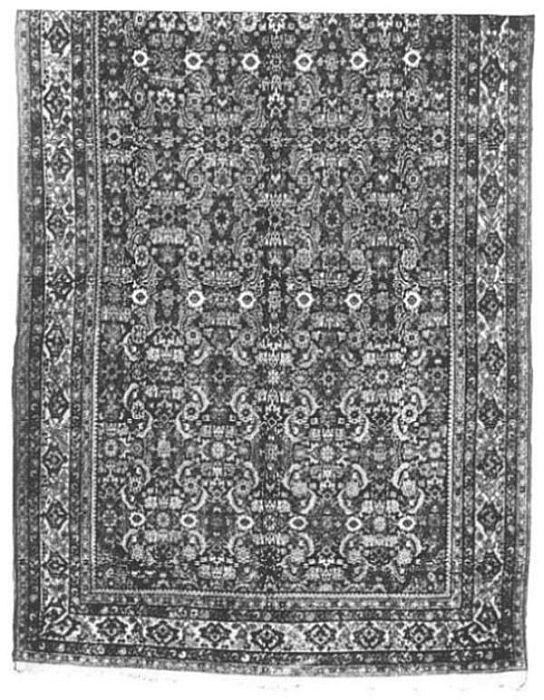

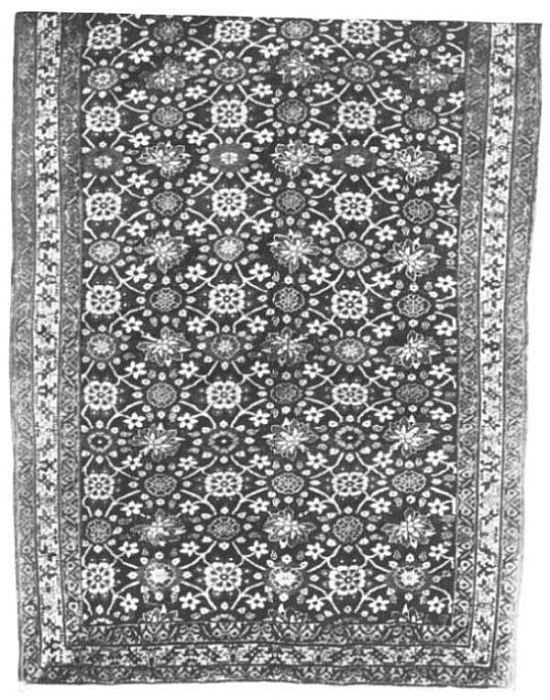

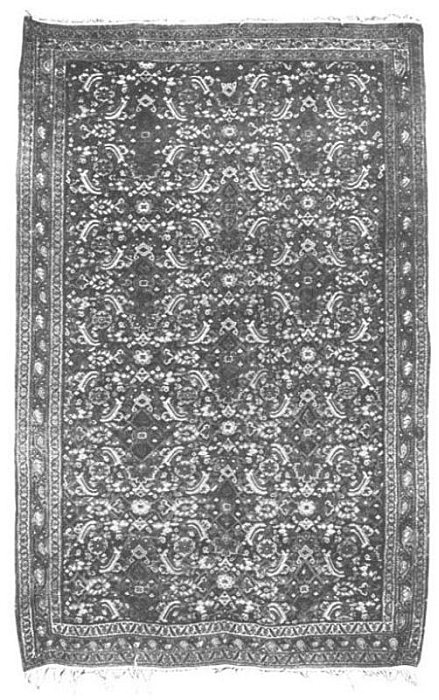

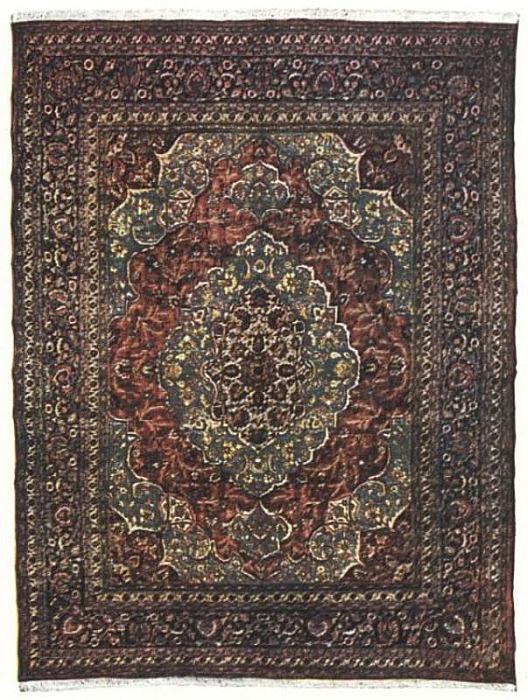

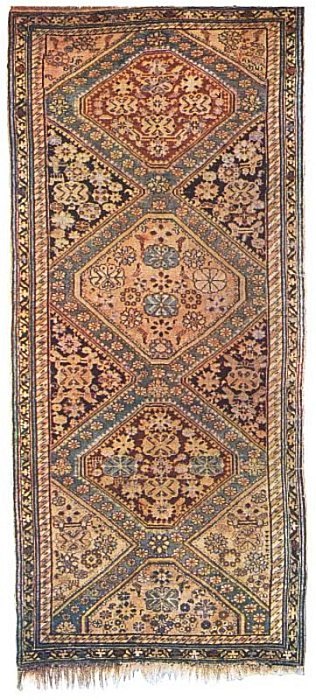

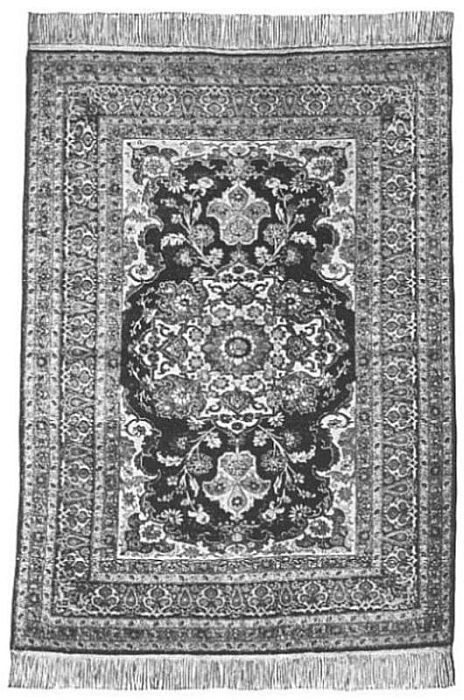

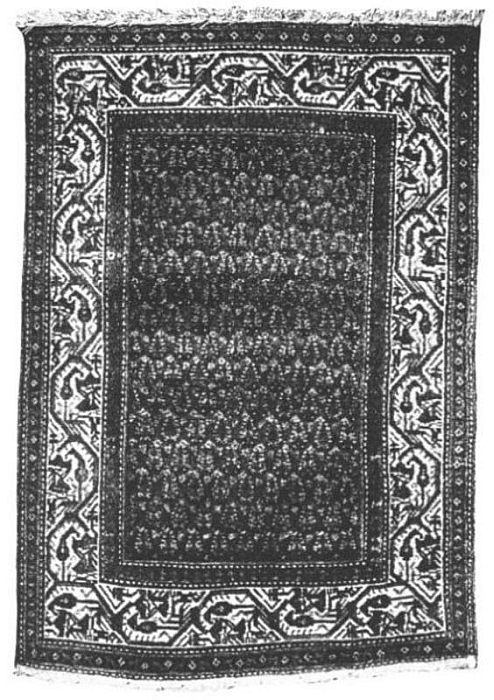

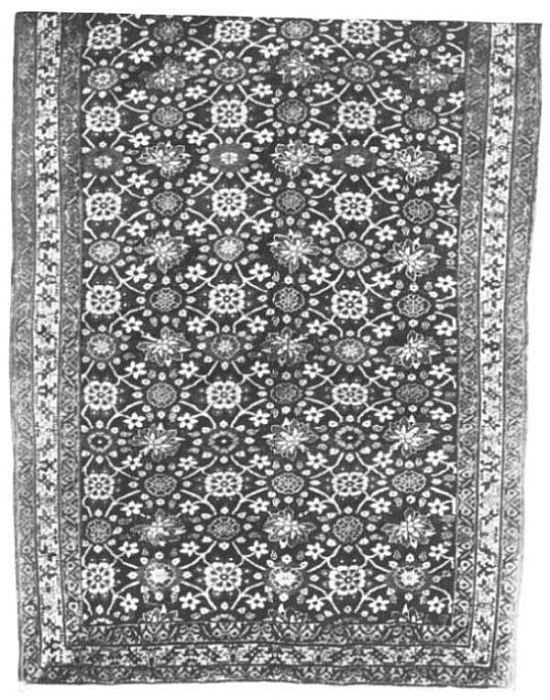

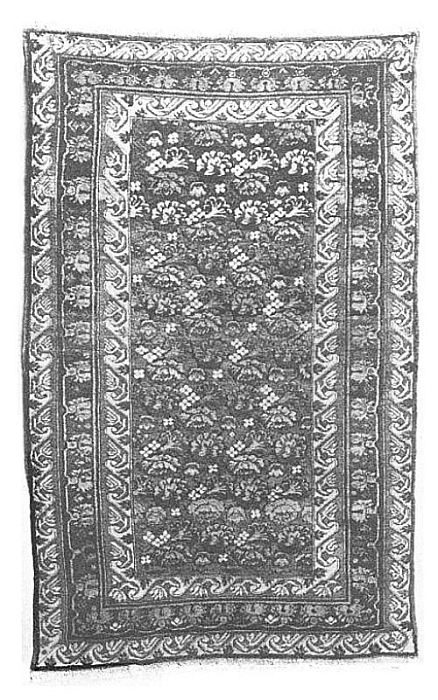

KHORASAN CARPET

KHORASAN CARPET

Size 14' × 10'

LOANED BY A. U. DILLEY & CO.

OWNER'S DESCRIPTION

An East Persian rug of especially heavy weave in robin egg

blue, soft red and cream.

Design: Serrated centre medallion, confined by broad blue

corner bands and seven border strips. A rug of elaborate conventionalized

floral decoration, with a modern rendition of Shah Abbas

design in border.

(See page 207)

[Pg. 34]

ANTIQUES

[Pg. 35]

The passion for antiques in this country has in

the past been so strong that rugs showing signs

of hard wear, with ragged edges and plenty of

holes, were quite as salable as those which were

perfect in every respect and the amateur collector

of so-called "antiques" was usually an easy

victim. Of late, however, the antique craze seems

to be dying out and the average buyer of to-day

will select a perfect modern fabric in preference

to an imperfect antique one.

There is no question that age is an important

factor in the beauty of a rug and that an antique

in a state of good preservation is much more

valuable than a modern fabric, especially to the

collector, to whom the latter has little value. In

order to be classed as an antique a rug should be

at least fifty years old, having been made before

the introduction of aniline dyes. An expert can

determine the age by the method of weaving, the

material used, the color combination, and the

design, with more certainty than can the art connoisseur

tell the age of certain European pictures,

[Pg. 36]

to which he assigns dates by their peculiarities in

style. Every time a design is copied it undergoes

some slight change until, perhaps, the original

design is lost. This modification of designs also

affords great assistance in determining their age.

In the Tiffany studios in New York City can be

seen a series of Feraghan rugs showing the

change in design for several generations.

As a rule more knowledge concerning the age

of a rug can be obtained from the colors and the

materials employed than from the designs. An

antique appears light and glossy when the nap

runs from you, whereas it will appear dark and

rich but without lustre when viewed from the

other end. Such rugs are usually more or less

shiny on the back and their edges are either

somewhat ragged or have been overcast anew.

With the exception of a few rare old pieces

which may be found in the palaces of rulers and

certain noblemen, the Orient has been pretty well

stripped of its antiques. Mr. Charles Quill Jones,

who has made three trips through the Orient in

search of old rugs, reports that region nearly bare

of gems. During his last sojourn in those parts

he has succeeded in collecting a considerable

number of valuable pieces, but his success may be

attributed to the poverty and disruption of households

[Pg. 37]

occasioned by the losses of the recent revolution

in Persia. As especially rare he writes of

having secured five pieces which were made during

the reign of Shah Abbas in the 16th century.

In England, France, Germany, Russia, Austria,

Poland, and especially Bavaria, there are many

fine old pieces, those of London, Paris, Berlin,

Vienna, and Budapest being particularly noteworthy.

The Rothschild collection in Paris contains

many matchless pieces and the Ardebil

Mosque carpet, which is in the South Kensington

Museum, London, is without doubt the most

famous piece of weaving in the world. According

to the inscription upon it, it was woven by

Maksoud, the slave of the Holy Place of Kashan,

in 1536. It measures thirty-four feet by seventeen

feet six inches and contains 32,000,000 knots. No

doubt there are more good genuine antiques in

Europe and America than in the entire Orient.

They are to be found, as a rule, in museums and

in private collections. A number of really old and

very valuable pieces may be seen at the Metropolitan

Museum of Fine Arts in New York City.

The Yerkes collection of Oriental rugs, which has

recently been disposed of at public sale by the

American Art Galleries, contained nothing but

Polish fabrics and Persian carpets of royal origin,

[Pg. 38]

made at some early date prior to the seventeenth

century. Some of the most prominent collectors

of the United States are Mr. J. Pierpont Morgan

of New York City, who has one of the most valuable

collections in the world; Mr. H. C. Frick of

Pittsburg, Pa., Miss A. L. Pease of Hartford,

Conn., Mr. C. F. Williams of Morristown, Pa.,

the Hon. W. A. Clark and Mr. Benjamin Altman

of New York City, Mr. Theodore M. Davis of

Newport, R. I., Mr. Frank Loftus, Mr. F. A.

Turner and Mr. L. A. Shortell of Boston; Mr. J. F.

Ballard of St. Louis and Mr. P. A. B. Widener of

Elkins Park, Pa. The late Ex-Governor Ames

of Massachusetts was an enthusiastic collector

and possessed many fine pieces.

The late A. T. Sinclair of Allston, Mass.,

possessed over one hundred and fifty antiques,

which he himself collected over twenty years ago

from the various districts of Persia, Asia Minor,

the Caucasus, Turkestan, and Beluchistan. Many

of these pieces are from one hundred and fifty to

two hundred and fifty years old and every one is

a gem.

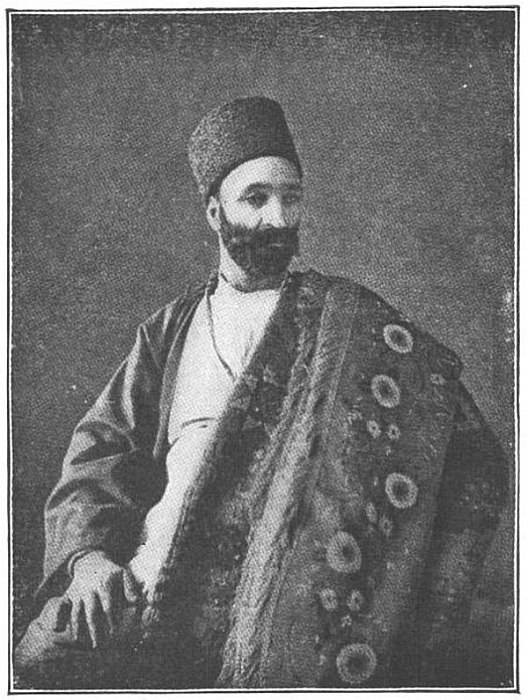

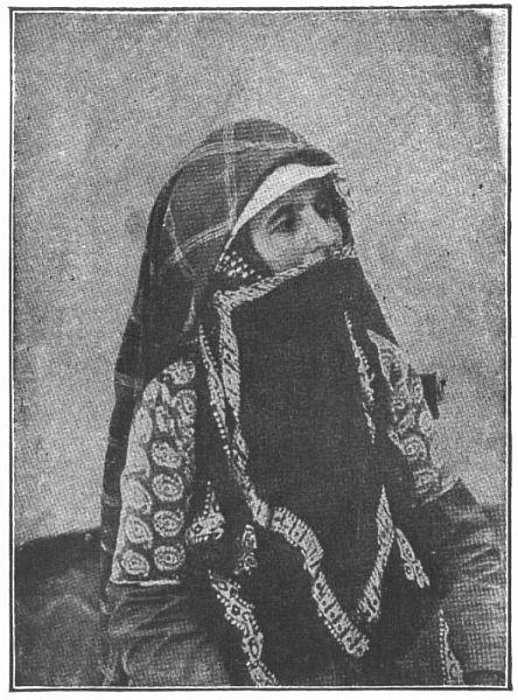

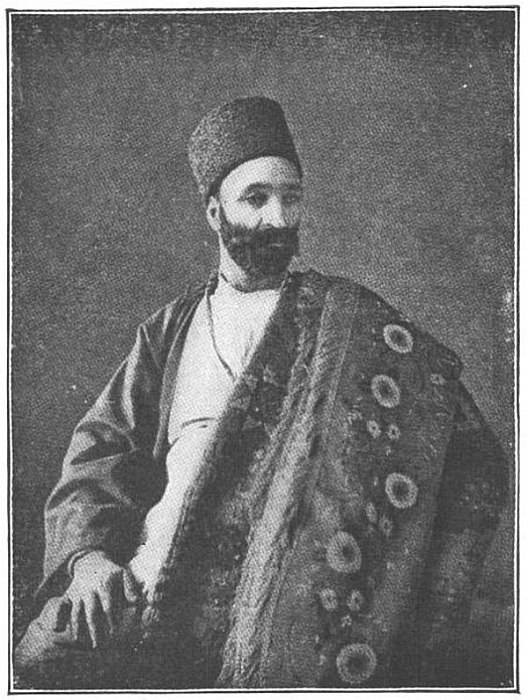

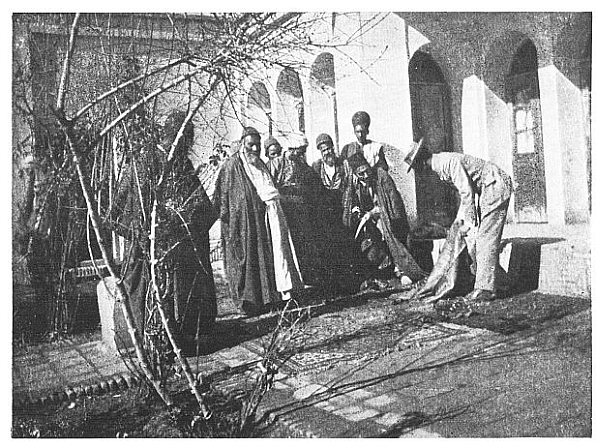

A PERSIAN RUG MERCHANT

A PERSIAN RUG MERCHANT

EXPERT WEAVER AND INSPECTOR

EXPERT WEAVER AND INSPECTOR

[Pg. 39]

With the exception of an occasional old

Ghiordes, Kulah, Bergama or Mosul, for which

are asked fabulous prices, few antiques can now

be found for sale. It is on account of the enormous

prices which antiques bring that faked

antiques have found their way into the market.

Rugs may be artificially aged but never without

detriment to them. The aging process is mostly

done by cunning adepts in Persia or Constantinople

before they are exported, although in recent

years the doctoring process has been practised to

quite an extent in the United States, and a large

portion of the undoctored rugs which reach these

shores are soon afterwards put through this

process. The majority of dealers will tell you

that there is comparatively little sale for the

undoctored pieces. The chemically subdued tones

and artificial sheen appeal to most people who

know little about Oriental rugs.

For toning down the bright colors they use

chloride of lime, oxalic acid or lemon juice; for

giving them an old appearance they use coffee

grounds, and for the creation of an artificial sheen

or lustre the rugs are usually run between hot rollers

after the application of glycerine or paraffin

wax; they are sometimes buried in the ground for

a time, and water color paints are frequently used

to restore the color in spots where the acid has

acted too vigorously. Such rugs usually show a

slight tinge of pink in the white.

There is a class of modern rugs of good quality,

[Pg. 40]

good material, and vegetable dyed, but with colors

too bright for Occidental taste. Such rugs are

sometimes treated with water, acid, and alkali.

The effect of the acid is here neutralized by the

alkali in such a way that the colors are rendered

more subdued and mellow in tone without resulting

injury to the material.

What the trade speaks of as a "washed" rug

is not necessarily a "doctored" one. There is a

legitimate form of washing which is really a finishing

process and which does not injure the

fabric. It merely washes out the surplus color

and sets the rest. The belief that only aniline

dyes will rub off when wet and that vegetable ones

will not do so is erroneous. If a rug is new and

never has been washed the case is quite the opposite.

For the reader's own satisfaction, let him

moisten and rub a piece of domestic carpet. He

will find that the aniline of the latter fabric is

comparatively fast, whereas, in a newly made

vegetable dyed Oriental, certain colors, especially

the blues, reds and greens, will wipe off to a

certain extent. After this first washing out,

however, nothing other than a chemical will disturb

the vegetable color.

[Pg. 41]

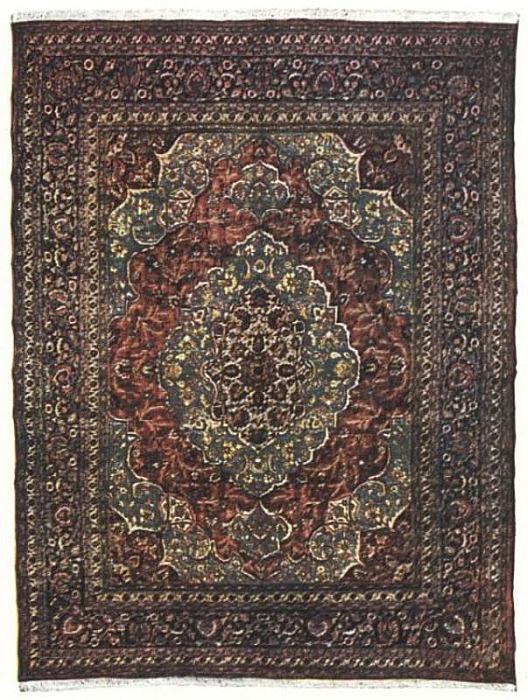

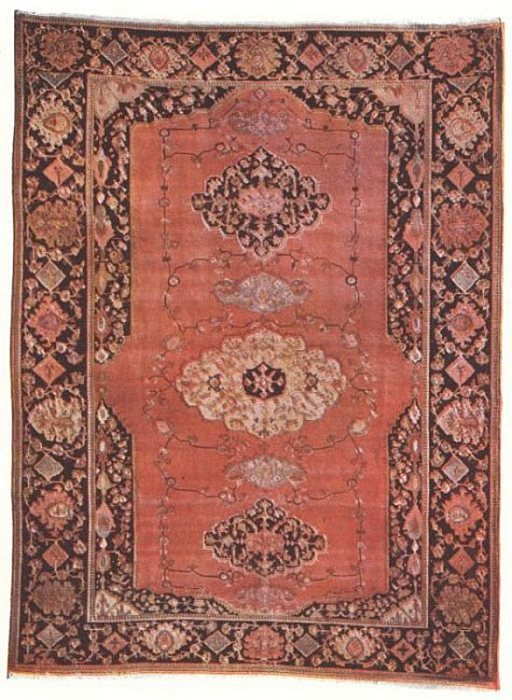

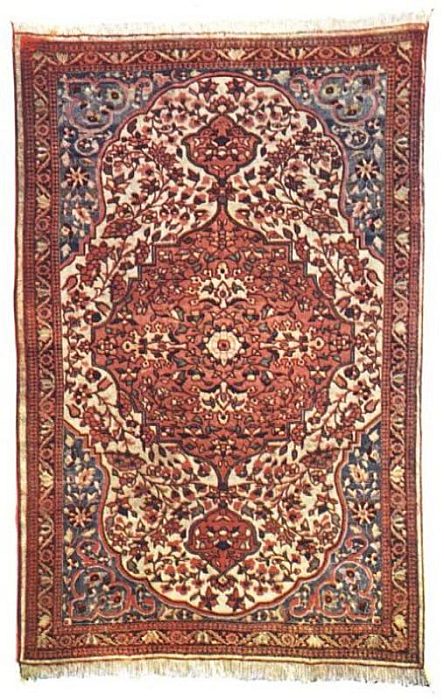

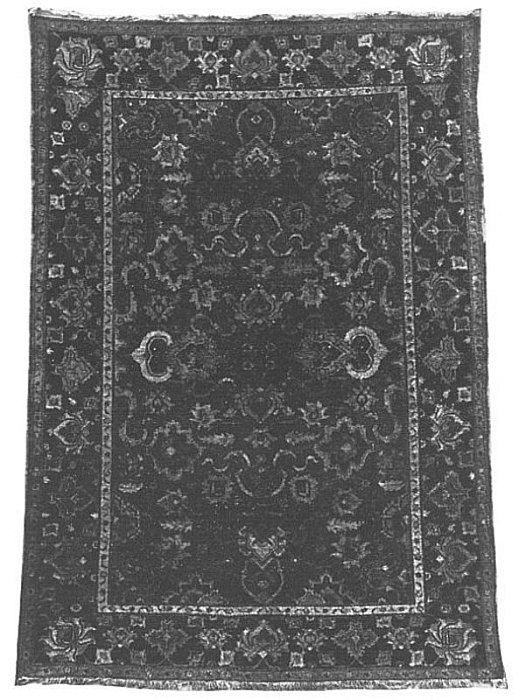

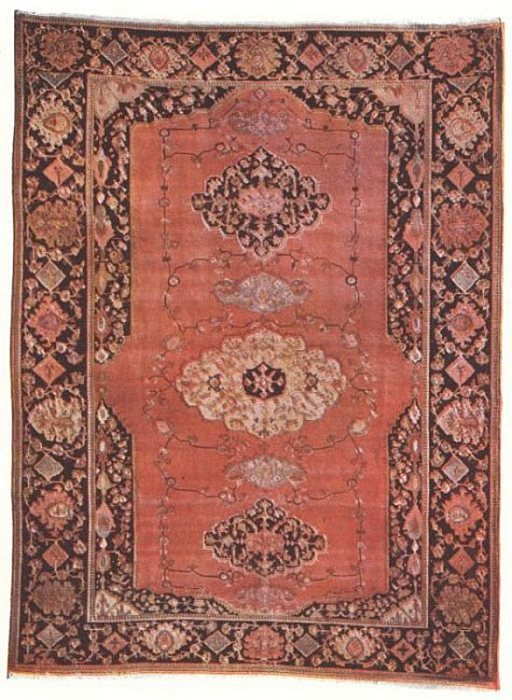

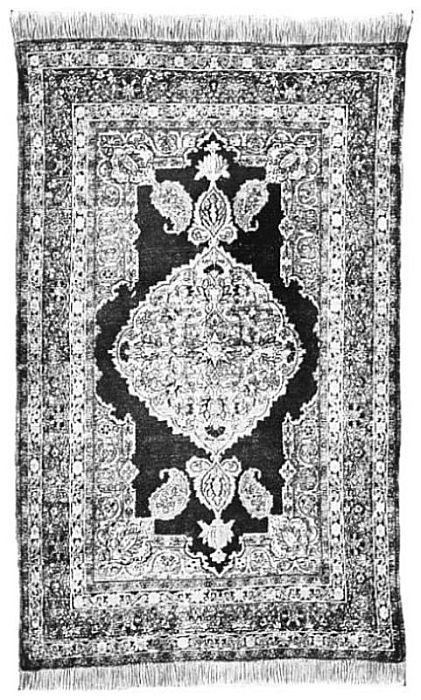

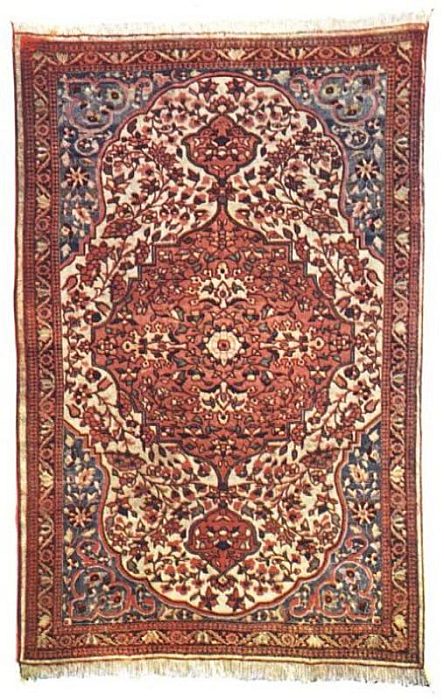

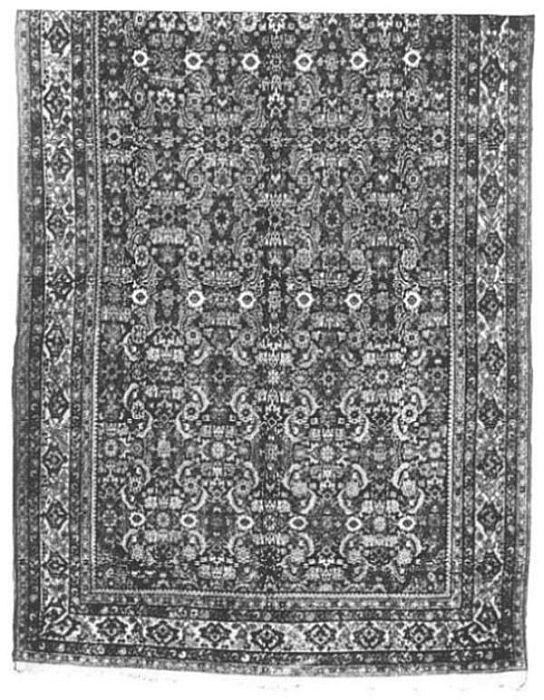

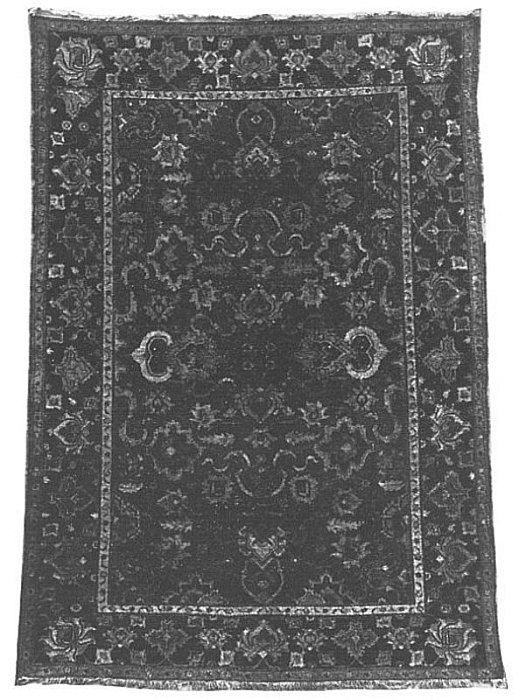

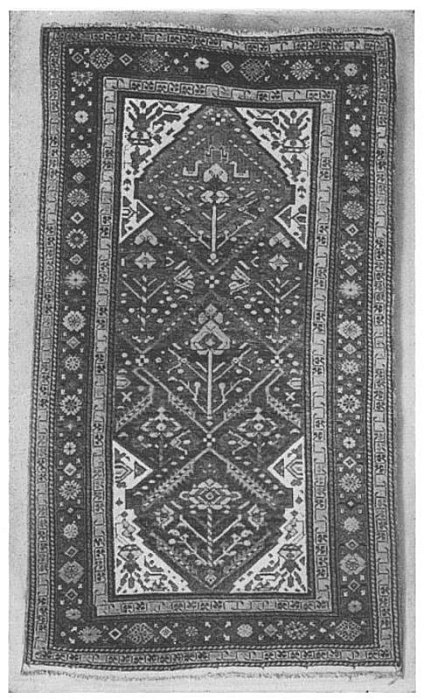

SARUK RUG

SARUK RUG

Size 14' × 10'

LOANED BY A. U. DILLEY & CO.

OWNER'S DESCRIPTION

The field: Three fawn and blue flower colored medallions and

four arabesques in a line arrangement on a rose-colored background,

strewn with garlands.

The border: One broad stripe, carrying elaborate floral sprays

and arabesques, separated by four elongated corner designs in blue.

An elegant combination of brilliant color and ornate floral design.

Cotton foundation and wool pile.

(See page 200)

[Pg. 43]

ADVICE TO BUYERS

No set of rules can be furnished which will

fully protect purchasers against deception. It is

well, however, for one, before purchasing, to

acquire some knowledge of the characteristics of

the most common varieties as well as of the

different means employed in examining them.

In the first place, avoid dealers who fail to

mark their goods in plain figures. Be on the safe

side and go to a reliable house with an established

reputation. They will not ask you fancy prices. If

it is in a department store be sure you deal with

some one who is regularly connected with the

Oriental rug department. You would never dream

of buying a piano of one who knows nothing of

music. So many domestic rugs copy Oriental patterns

that many uninformed people cannot tell the

difference. The following are some of the characteristics

of the Eastern fabrics which are not possessed

by the Western ones. First, they show

their whole pattern and color in detail on the back

side; second, the pile is composed of rows of

distinctly tied knots, which are made plainly

visible by separating it; third, the sides are either

overcast with colored wool or have a narrow

[Pg. 44]

selvage; and fourth, the ends have either a selvage

or fringe or both.

In buying, first select what pleases you in size,

color, and design, then take time and go over it as

thoroughly as a horseman would over a horse

which he contemplates buying. Lift it to test the

weight. Oriental rugs are much heavier in proportion

to their size than are the domestics. See

if it lies straight and flat on the floor and has no

folds. Crookedness detracts much from its value.

Take hold of the centre and pull it up into a sort

of cone shape. If compactly woven it will stand

alone just as a piece of good silk will. Examine

the pile and see whether it is long, short or worn

in places down to the warp threads; whether it

lies down as in loosely woven rugs or stands up

nearly straight as in closely woven rugs; also

note the number of knots to the square inch and

whether or not they are firmly tied. The wearing

qualities depend upon the length of the pile and

the compactness of weaving. Separate the pile,

noting whether the wool is of the same color but

of a deeper shade near the knot than it is on the

surface or if it is of an entirely different color.

Vegetable dyes usually fade to lighter shades of

the original color, while anilines fade to different

colors, one or another of the dyes used in combination

entirely disappearing at times and others

[Pg. 45]

remaining. This will also be noticeable, to a

certain extent, when one end of the fabric is

turned over and the two sides are compared.

Two rugs may be almost exactly alike in every

respect excepting the dye, the one being worth

ten to fifteen times as much as the other.

A good way to test the material is to slightly

burn its surface with a match, thus producing a

black spot. If the wool is good the singed part

can be brushed off without leaving the slightest

trace of the burn. The smell of the burnt wool

will also easily be recognized. Ascertain the

relative strength of the material, making sure

that the warp is the heaviest and strongest, the

pile next and the woof the lightest. If the warp

is lighter than the pile it will break easily or if

the warp is light and the weaving loose it will

pucker. Rugs whose foundation threads are dry

and rotten from age are worthless. In such pieces

the woof threads, which are the lightest, will break

in seams along the line of the warp when slightly

twisted.

Examine the selvage. It will often indicate

the method of its manufacture, showing whether

it is closely or loosely woven, for the selvage is a

continuation of the groundwork of the rug itself.

Also notice the material, whether of hair, wool or

cotton. Separate the pile and examine the woof,

[Pg. 46]

noting the number of threads between each row

of knots. If possible pull one of them out. In

the cheaper grade of rugs you will often find two

strands of cotton and one of wool twisted together.

Such rugs are very likely some time to bunch up,

especially if washed. See if the selvage or warp

threads on the sides are broken in places. If so

it would be an unwise choice. Now turn the rug

over and view it from the back, noting whether

repairs have been made and, if so, to what extent.

View it from the back with the light shining into

the pile to see if there are any moths. Pat it and

knock out the dust. In some instances you will

be surprised how thoroughly impregnated it will

be with the dust of many lands and how much

more attractive the colors are after such a patting.

Rub your hand over the surface with the

nap. If the wool is of a fine quality a feeling of

electric smoothness will result, such as is experienced

when stroking the back of a cat in cold

weather.

Finally, before coming to a decision regarding

its purchase, have it sent to your home for a few

days. There you can study it more leisurely and

may get an idea as to whether or not you would

soon tire of the designs or colors. While you have

it there do not forget to take soap, water and a

stiff brush and scrub well some portion of it,

selecting a part where some bright color such as

green, blue or red joins a white. After the rug

has thoroughly dried notice whether or not the

white has taken any of the other colors. If so,

they are aniline.

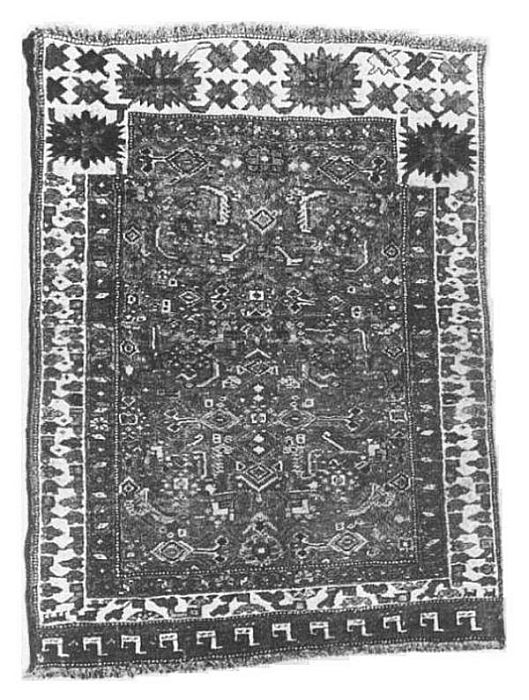

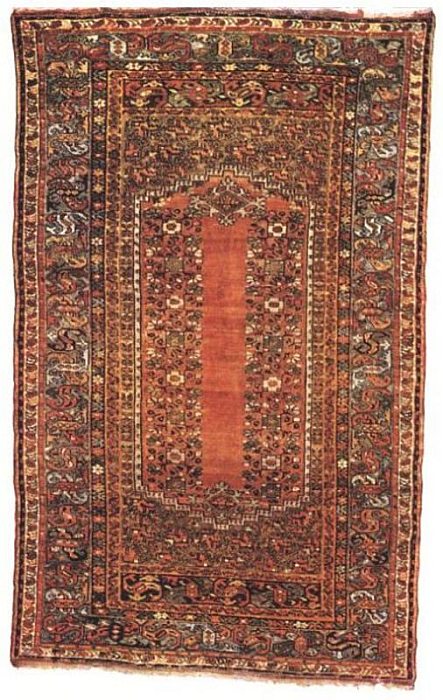

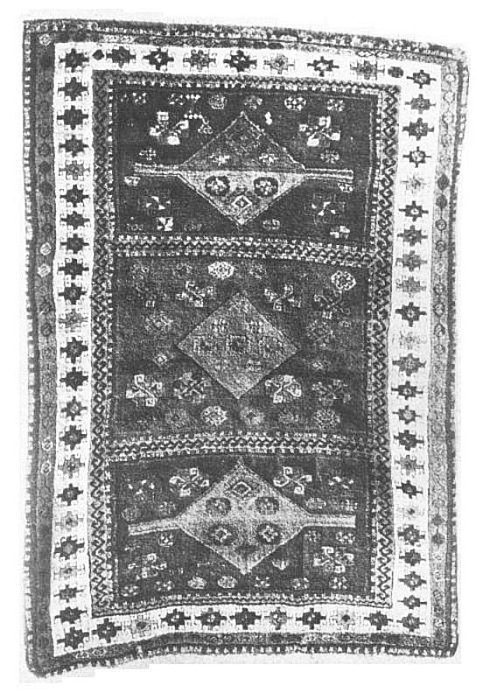

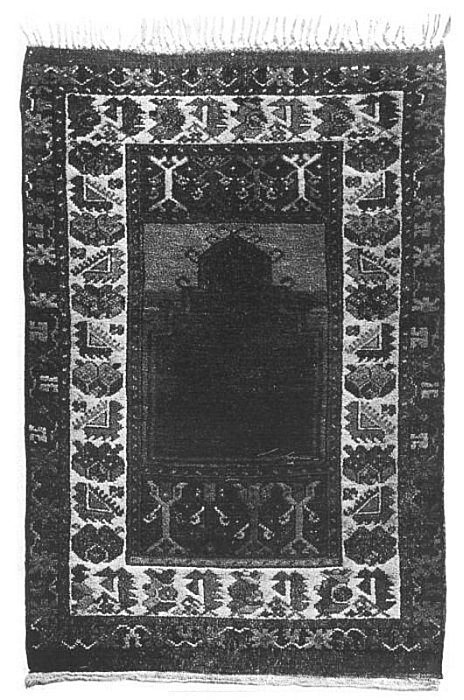

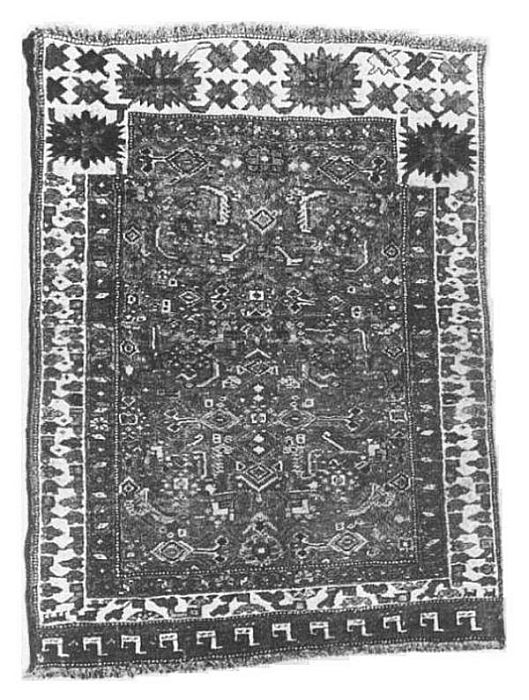

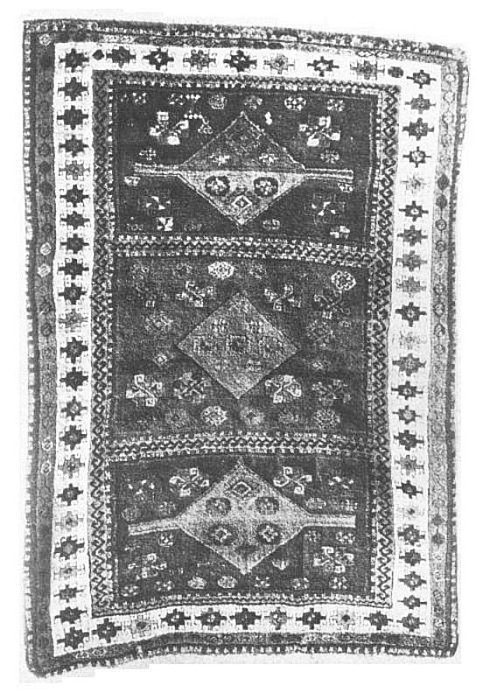

BERGAMA PRAYER RUG

BERGAMA PRAYER RUG

Size 3'8" × 2'7"

PROPERTY OF MR. GEORGE BAUSCH

(See page 237)

[Pg. 47]

A rather vulgar but very good way of telling

whether a rug is doctored or not is to wet it with

saliva and rub it in well. If chemically treated it

will have a peculiar, disagreeable, pungent odor.

A fairly accurate way of determining the claim

of the fabric to great age is to draw out a woof

thread and notice how difficult it is to straighten it,

even after days of soaking in water. Unless one is

an expert, he should refrain from relying upon his

own judgment in buying a rug for an antique.

It may be interesting to know the meaning

of the tags and seals so frequently found on rugs.

The little square or nearly square cloth tag that is

so frequently attached at one corner to the under

surface by two wire clasps has on it the number

given to that particular piece for the convenience

of the washer, the exporter, the importer and the

custom officials. The rug is recorded by its

number instead of by its name to avoid confusion

and to save labor. The round lead seal

which is frequently attached to one corner of the

rug by a flexible wire or a string, especially among

[Pg. 48]

the larger pieces, is the importer's seal, on one

side of which will be found his initials. These

also are of great assistance to the custom officials.

Before closing this chapter a few words in

regard to the selection of rugs for certain rooms

might be acceptable, though this is, to a large

extent, a matter of individual taste; yet in making

a selection one should have some consideration

for the decorations and furniture of the room in

which the rugs are to be laid and they should

harmonize with the side walls, whether the harmony

be one of analogy or of contrast. The floor

of a room is the base upon which the scheme of

decoration is to be built. Its covering should

carry the strongest tones. If a single tint is to

be used the walls must take the next gradation

and the ceiling the last. These gradations must

be far enough removed from each other in depth

of tone to be quite apparent but not to lose their

relation. Contrasting colors do not always harmonize.

A safe rule to follow would be to select

a color with any of its complementary colors.

For instance, the primary colors are red, blue, and

yellow. The complementary color of red would

be the color formed by the combination of the

other two, which in this case would be green

composed of yellow and blue; therefore red

and green would form a harmony of contrast.

Likewise red and blue make violet, which would

harmonize with yellow; red and yellow make

orange, which would harmonize with blue, etc.

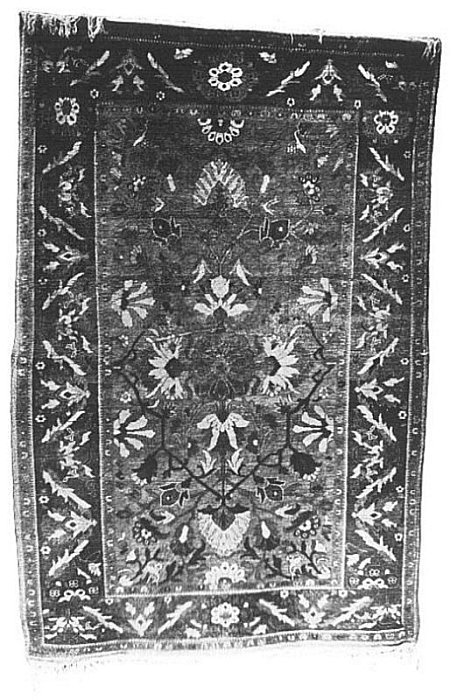

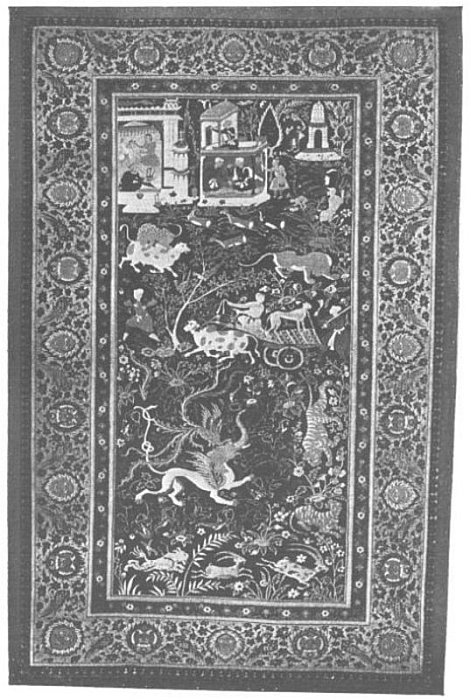

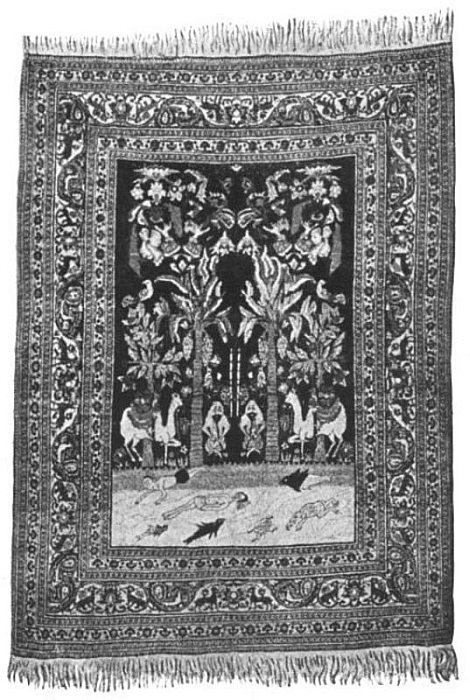

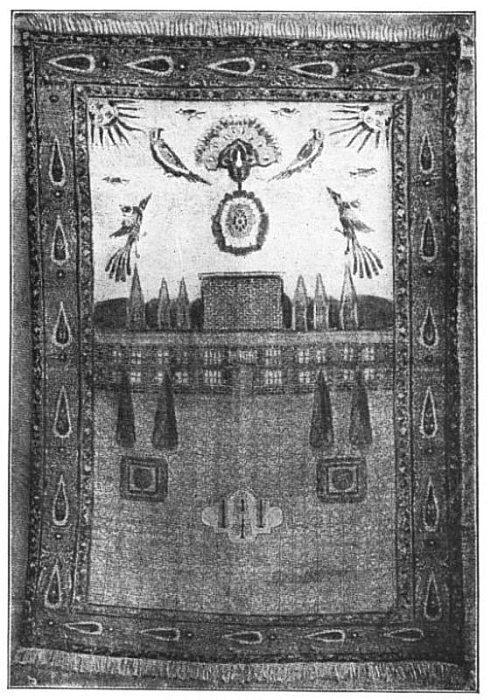

SYMBOLIC PERSIAN SILK (TABRIZ) RUG

(See page 316)

SYMBOLIC PERSIAN SILK (TABRIZ) RUG

(See page 316)

[Pg. 49]

Light rooms of Louis XVI style would hardly

look as well with bright, rich colored rugs as they

would with delicately tinted Kirmans, Saruks,

and Sennas. Nor would the latter styles look as

well in a Dutch dining room, finished in black oak,

as would the rich, dark Bokharas and Feraghans.

Mission rooms also require the dark colored rugs.

If the room is pleasing in its proportion and one

rug is used it should conform as nearly in proportion

as possible. If the room is too long for its

width select a rug which will more nearly cover

the floor in width than it will in length. A rug

used in the centre of a room with considerable

floor area around it decreases the apparent size of

the room. Long rugs placed lengthwise of a room

increase its apparent length, while short rugs

placed across a room decrease its apparent length,

and rugs with large patterns, like wall paper with

large patterns, will dwarf the whole apartment.

The following ideas are merely offered as suggestions

without any pretension whatever to superiority

of judgment.

For a Vestibule a long-naped mat, which

[Pg. 50]

corresponds in shape to the vestibule and covers

fully one-half of its surface, such for instance as

a Beluchistan or a Mosul. Appropriate shorter

naped pieces may be found among the Anatolians,

Meles, Ladiks or Yuruks. As a rule the dark

colored ones are preferable.

Hall.—If the hall is a long, narrow one, use

long runners which cover fully two-thirds of its

surface. Such may be found among the Mosuls,

Sarabands, Hamadans, Ispahans, Shirvans, and

Genghis.

For a reception hall a Khiva Bokhara, a

Yomud, a dark colored Mahal, or several Kazaks

or Karabaghs would look well if the woodwork is

dark. If the woodwork is light several light colored

Caucasian or Persian pieces such as the

Daghestans, Kabistans, Sarabands, Hamadans,

or Shiraz would be appropriate.

Reception Room.—A light colored Kermanshah,

Tabriz, Saruk, Senna, or Khorasan. Usually

one large piece which covers from two-thirds

to three-fourths of the floor surface is the most

desirable.

Living Room.—For this room, which is the

most used of any in the home, we should have

the most durable rugs and as a rule a number of

small or medium sized pieces, which can be easily

[Pg. 51]

shifted from one position to another, are preferable.

Here, too, respect must be had for harmony

with the side walls, woodwork and furniture, as

it is here that the family spend most of their

time and decorative discord would hardly add to

one's personal enjoyment. Many appropriate

selections may be made from the Feraghans,

Ispahans, Sarabands, Shiraz, Mosuls, Daghestans,

Kabistans, and Beluchistans.

Dining Room.—Ordinarily nothing would be

more appropriate than one of the Herez or Sultanabad

productions unless the room be one of

the Mission style, in which case a Khiva Bokhara

would be most desirable. Small pieces would not

be suitable.

Library or Den.—One large or several small

pieces, usually the dark rich shades are preferable,

such for instance as are found in the Khivas,

Yomuds, Kurdistans, Feraghans, Shiraz, Kazaks,

Beluchistans or Tekke Bokharas, the predominating

color selected according to the decorations

of the room.

Bath Room.—One heavy long-piled, soft piece

such as are some of the Bijars or Mosuls in light

colors.

Bedrooms.—For chambers where colors rather

than period styles are dominant and where large

[Pg. 52]

rugs are never appropriate, prayer rugs like those

of the Kulah, Ghiordes, Ladik, Anatolian, or

Daghestan varieties are to be desired. Those

with yellow as the predominating color blend

especially well with mahogany furniture if the

walls are in buff or yellow tones. The Nomad

products are especially desirable for bedrooms

on account of the comfort which they afford.

Being thick and soft the sensation to the tread is

luxurious. An occasional Anatolian, Ladik, Bergama,

Meles, or Bokhara mat placed before a

dresser or a wash-stand; a Shiraz pillow on the

sofa; a Senna Ghileem thrown over a divan; a

Shiraz, Mosul, or Beluchistan saddle-bag on a

Mission standard as a receptacle for magazines;

a silk rug as a table spread, etc., will all add

greatly to the Oriental effect.

[Pg. 53]

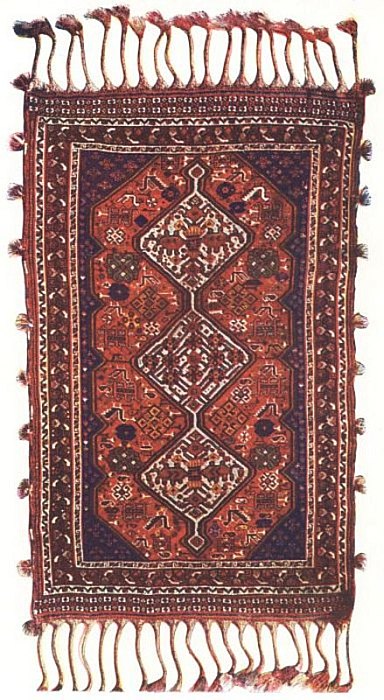

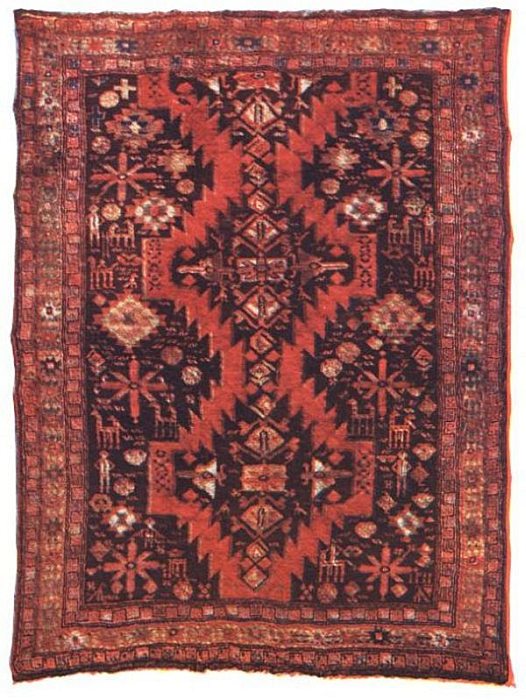

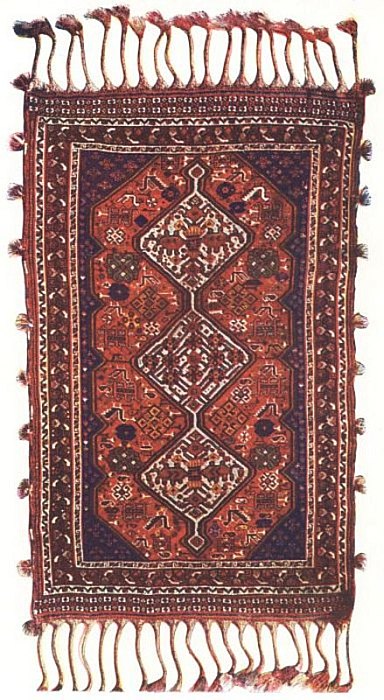

SHIRAZ RUG

SHIRAZ RUG

BY COURTESY OF NAHIGIAN BROS., CHICAGO, ILL.

This piece is typical of its class with the small tassels of wool on

the side edging; with the ornamental web and the braided warp

threads at each end, also the pole medallion and the numerous

bird forms throughout the field.

(See page 204)

[Pg. 55]

THE HYGIENE OF THE RUG

In all the literature on Oriental Rugs no mention

has been made of their sanitary condition

when laid on the floors of our homes. In response

to a letter of inquiry, one of our American missionaries,

a young lady stationed at Sivas, Turkey

in Asia, who very modestly objects to the use of

her name, so well explained the condition of

affairs that portions of her letter given verbatim

will prove most interesting. She says:

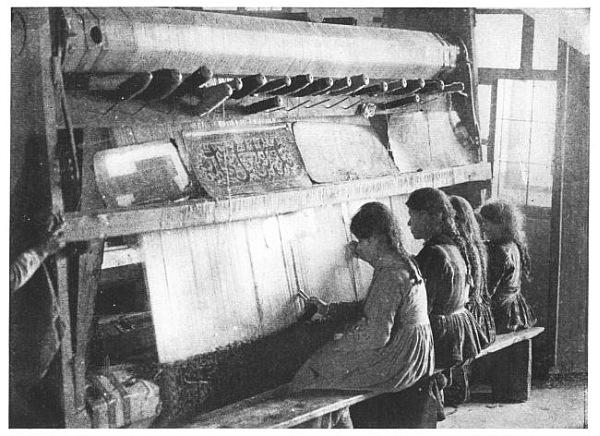

"In Sivas there are a number of rug factories

in which are employed many thousand little girls,

ages ranging from four years upward. They

work from twelve to fourteen hours a day and I

believe the largest amount received by them is

five piasters (less than twenty cents) and the small

girls receive ten to twenty paras (a cent or two).

These factories are hotbeds of tuberculosis and

we have many of these cases in our Mission Hospital.

Of course this amount of money scarcely

keeps them in bread and in this underfed condition,

working so long in ill ventilated rooms, they

quickly succumb to this disease. These girls are

[Pg. 56]

all Armenians in that region. The Turks do not

allow their women and children to work in public

places. The Armenians are going to reap a sad

harvest in the future in thus allowing the future

wives and mothers of their race to undermine

their health working in these factories. These

rugs are all exported to Europe and America.

"No matter what part of the city you pass

through this time of the year you will see looms

up in the different homes and most of the family,

especially the women and children, working on

these rugs, and it is very interesting to watch

them and to see how skilful even the small children

grow in weaving these intricate patterns.

Making rugs in the homes is quite different from

making them in the factories, for in the summer at

least they have plenty of fresh air.

"No doubt many rugs made in these homes

are filled with germs of contagious diseases, for

they use no precautions here when they have such

diseases in the family, and usually the poor people

only have one room, and if a member of the family

is stricken with smallpox or scarlet fever the rest

of the family continue to work on the rug often

in the same room."

Another correspondent from Marash, Turkey

in Asia, says, "If you are interested in humanity

[Pg. 57]

as well as in rugs, please put in a strong plea

against some of these factories which are employing

children who can scarcely speak. These little

babies sit from morning till evening tying and

cutting knots in damp and poorly ventilated

places. Is it a wonder that diseases, especially

tuberculosis, are developing rapidly among

them?"

A third correspondent says, "Often rugs upon

which patients have died from contagious diseases

are sold without cleaning. In fact, they are

rarely cleaned."

Upon receipt of the above a letter of inquiry

was at once sent to the Treasury Department at

Washington regarding the disinfection of textiles

from the Orient immediately upon their arrival

into this country, to which we were informed that

"The Surgeon-General of the Public Health and

Marine Hospital Service stated that such rugs,

if originating in parts or places infected with

quarantinable diseases, would be required to be

disinfected under the quarantine laws." This

sounds sensible, but when the rugs are sent from

all parts of the Orient to Constantinople, from

whence they are shipped in bales to the United

States, pray how can the Surgeon-General discriminate?

The only safe way is for the government

[Pg. 58]

to have strict laws regarding their immediate

and thorough disinfection. We already

have a law which requires the disinfection of

hides before they are shipped to this country. It

reads: "Officers of the customs are directed to

treat hides of neat cattle shipped to the United

States without proper disinfection as prohibited

importations, and to refuse entry of such hides."

Also, "the disinfection of such hides in this country

or storage of the same in general order warehouses

will not be permitted, for the reason that

the passage of diseased hides through the country

or their storage with other goods will tend to the

dissemination of cattle disease in the United

States." (See Section 12 of the Tariff Act of

August 5, 1909.)

Ex-President Taft once recommended a new

department of public health whose duty it would

be to consider all matters relating to the health of

the nation. If his suggestions are carried out no

doubt the question of disinfecting Oriental imports

will be satisfactorily disposed of.

Until then we should see to it that all Oriental

rugs are at least clean and free from dust before

allowing them to be delivered in our homes. The

great majority of these rugs, when leaving the

[Pg. 59]

Orient, are impregnated with dust from their

adobe floors and, if free of this dust, they have in

all probability been pretty thoroughly cleaned by

some reliable importer or dealer, the majority of

whom are beginning to realize the importance of

this procedure.

[Pg. 60]

[Pg. 61]

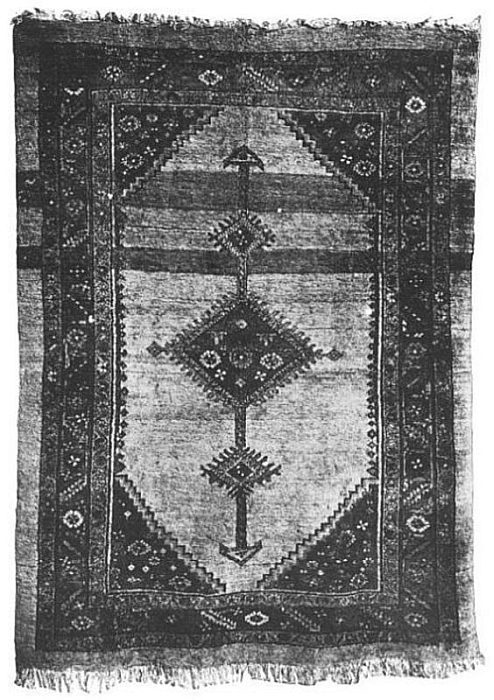

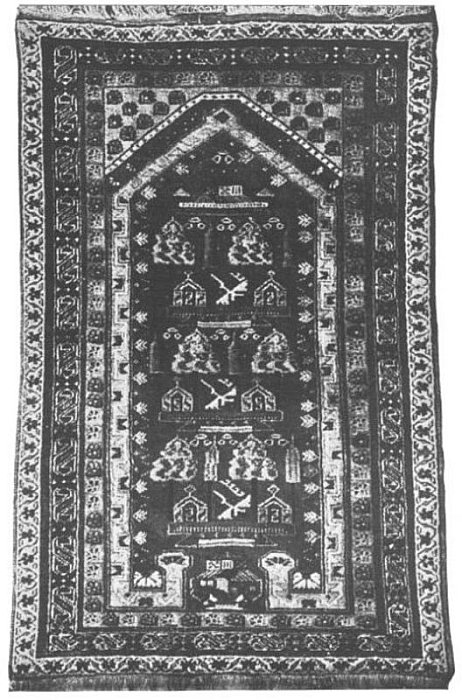

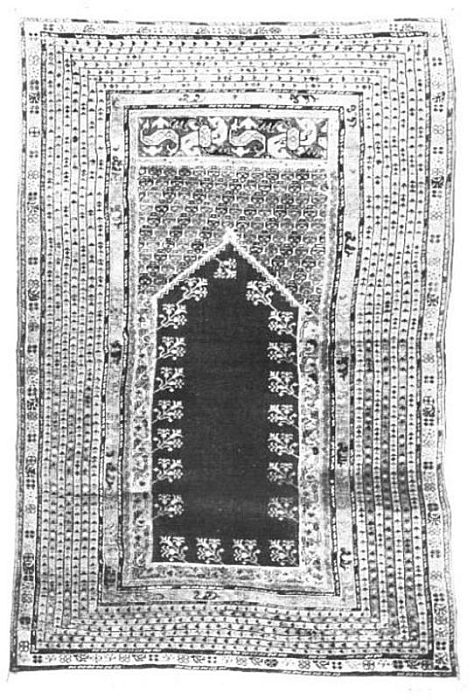

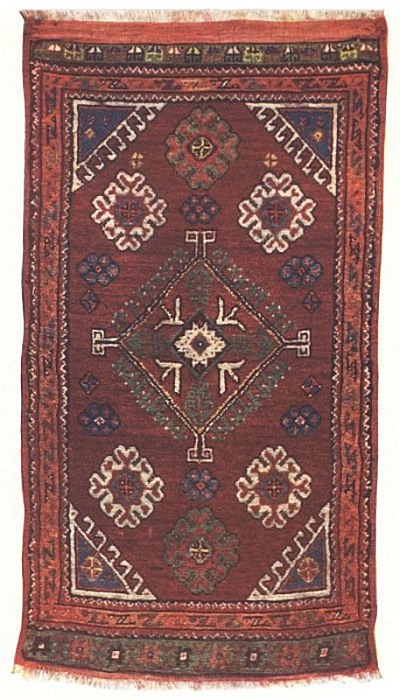

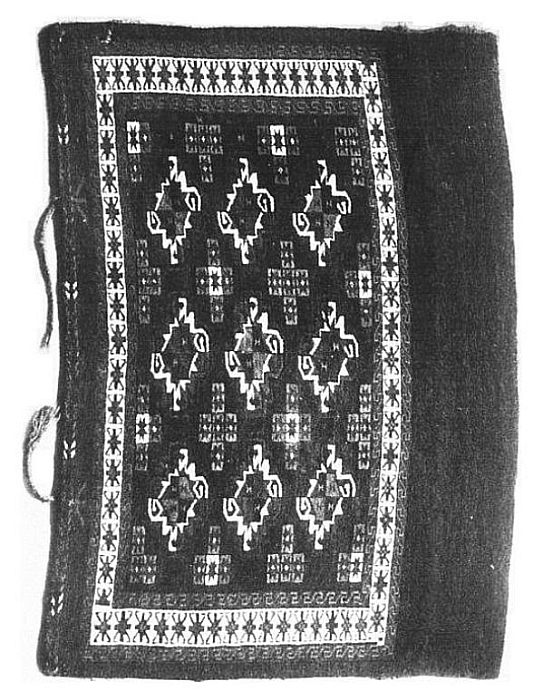

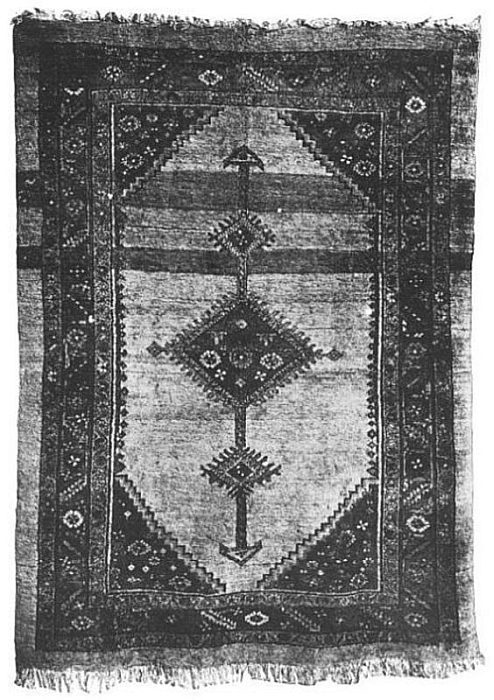

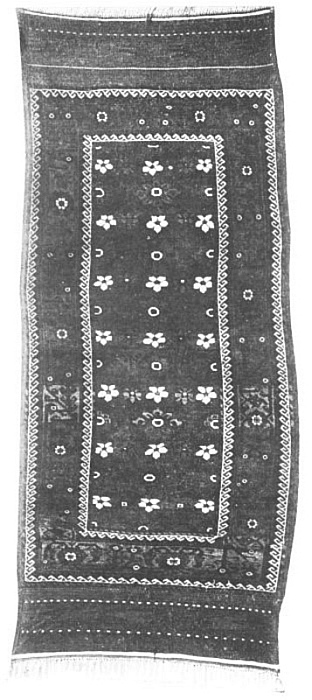

ANTIQUE ANATOLIAN MAT

Size 3'5" × 1'10"

ANTIQUE ANATOLIAN MAT

Size 3'5" × 1'10"

FROM THE COLLECTION OF THE AUTHOR

Knot. Nine to the inch vertically and eight horizontally, making

seventy-two to the square inch.

This is a most unusual piece. It has a long nap, is tied with the

Turkish knot and in many respects resembles the Bergama while on

the back it has a distinctly Khorasan appearance. It is an old piece

with a most lustrous sheen and the colors are of the best, every one

being of exactly the same tint on the surface as it is down next to

the warp threads.

The prevailing color is a rich terra cotta with figures of lilies in

olive-green, old rose, blue and white. There are also a number of

six-petaled flowers in red, white and blue. In the centre there is a

diamond-shaped medallion with triangular corner pieces to match,

all of which are outlined in natural black wool. The nap is so cut

as to give the surface the characteristic hammered-brass appearance

so common in many of the antique Bergamas and the lustre is

such as is only found in the very old pieces.

(See page 234)

[Pg. 63]

THE CARE OF RUGS

There is a popular idea that an Oriental rug

will never wear out and that the harder it is used

the more silky it will grow. This is an erroneous

idea and many rugs that would be almost priceless

now are beyond repair, having fallen into the

hands of people who did not appreciate them and

give them the proper care. Oriental rugs cannot

be handled and beaten like the domestics without

serious injury. In the Orient they receive much

better treatment than they do at our hands.

There they are never exposed to the glare of a

strong light and are never subjected to the contact

of anything rougher than the bare feet. The

peculiar silkiness of the nap so much admired in

old pieces is due to the fact that the Oriental

never treads on them with his shoes.

Large rugs, having a longer pile, resist more

the wear and tear from the shoes, but they must

be handled with greater care than the small ones,

as, being heavier, the warp or woof threads are

more liable to break.

As a rule rugs should be cleaned every week

or two. Never shake them or hang them on a line,

[Pg. 64]

as the foundation threads may break, letting the

knots slip and spread apart. There are more rugs

worn out in this way than by actual service. Lay

them face downward on the grass or on a clean

floor and gently beat them with something pliable

like a piece of rubber hose cut in strips. With a

clean broom sweep the back, then turning them

over, sweep across the nap each way, then with

the nap. Brushing against the nap is most harmful,

as it may loosen the knots and force the dust

and dirt into the texture. Finally dampen the

broom or, better still, dampen a clean white cloth

in water to which a little alcohol has been added,

and wipe over the entire rug in the direction in

which the nap lies. The sweeping process keeps

the end of the pile clean and bright and gives it

a silky, lustrous appearance. Sometimes clean,

dampened sawdust can be used and, in the winter

time, nothing is better than snow, which will clean

and brighten them wonderfully.

Many rugs are improved by an occasional

washing. It is usually advisable to have some

reliable man, who understands this work, to do it

for you, as it is quite a task and few homes have a

suitable place for it. A good concrete floor will

answer nicely. With a stiff brush, a cake of

castile or wool soap and some warm water give

[Pg. 65]

the pile a thorough scrubbing in every direction

excepting against the nap. Rinse with warm

water, then with cold, turning the hose upon it for

fifteen or twenty minutes. Soft water is preferable

if it can be obtained. Finally, with a smooth stick

or a wooden roller, squeeze the water out by stroking

it in the direction of the nap. This stroking

process should be continued for some time, after

which the rug is spread out on a roof face upward

for several clear days.

Unless rugs are frequently moved or cleaned

moths are sure to get into them. Sweeping alone

is not always sufficient to keep them out. For this

purpose the compressed air method is par

excellence.

If you expect to close your home for several

weeks or months do not leave your rugs on the

floor. After having all necessary repairs made,

have them thoroughly cleaned by the compressed

air process, then place them in canvas or strong

paper bags, sealing them tightly. A large rug

may be wrapped with clean white paper, then

with tar paper. It is better to roll than to fold

them, but if folded always see that the pile is on

the inside, else bad creases may be made in them

which may never come out. They should be stored

[Pg. 66]

in a dry, airy room, as they readily absorb

moisture.

When a rug shows a tendency to curl on the

corners only, a very good idea is to weight it

down with tea lead which is folded in such a way

as to make a piece about four inches long, one

inch wide and one-eighth of an inch thick. This

is inclosed in a cloth pocket which is sewed to

the under side of the rug at the corners so that

its length lies in the direction of the warp.

Many rugs that are crooked may easily be

straightened by tacking them face downward in

the proper shape and wetting them. They should

be kept in that position until thoroughly dried and

shrunken to the proper shape. Obstinate and

conspicuous stains may be removed by clipping

the discolored pile down flat to the warp, carefully

pulling out the knots from the back of the rug and

having new ones inserted. This, however, with all

other extensive repairs, should be done by one

especially skilled in that line.

Considering the rapid increase in the price of

good Oriental rugs within the past few years we

should appreciate and care for all the fine examples

which we already have in our possession.

[Pg. 67]

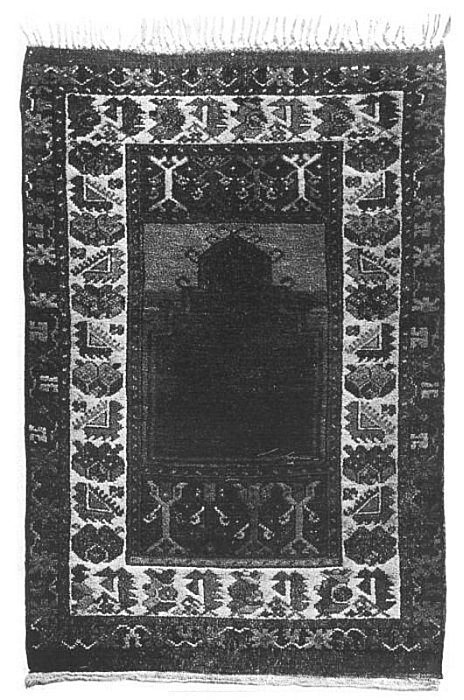

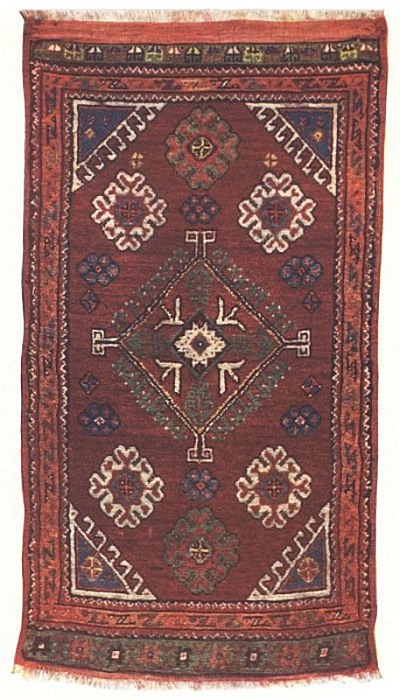

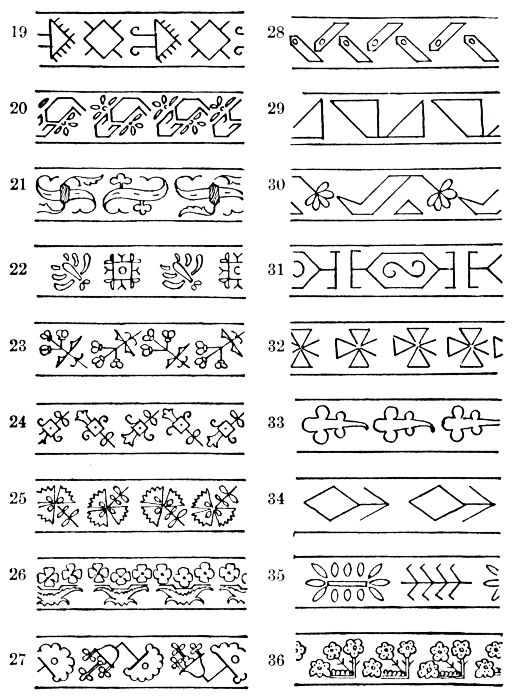

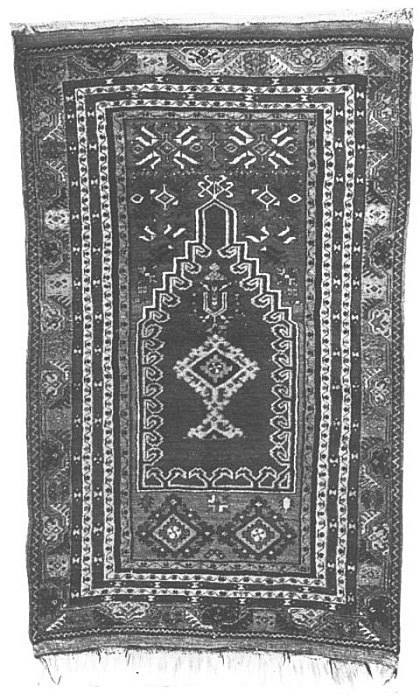

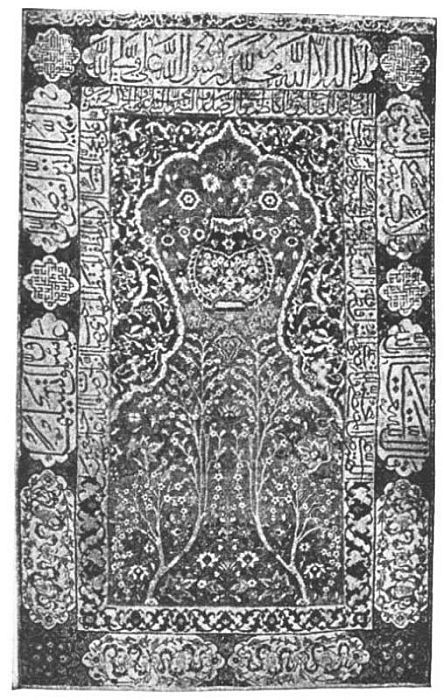

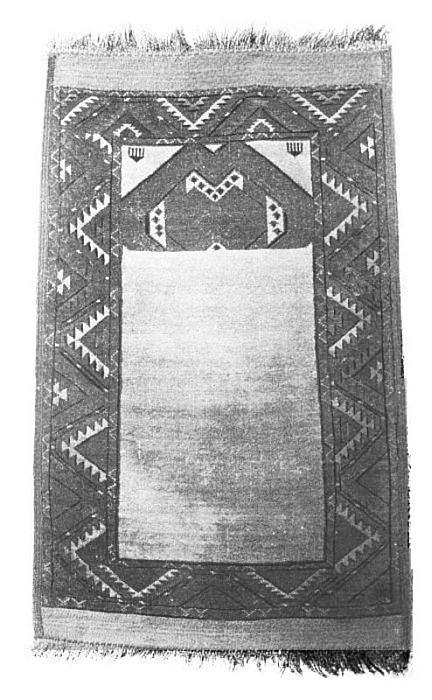

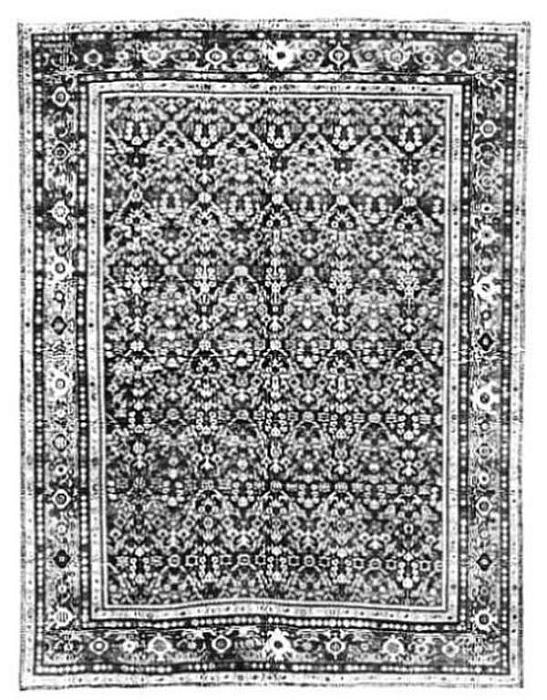

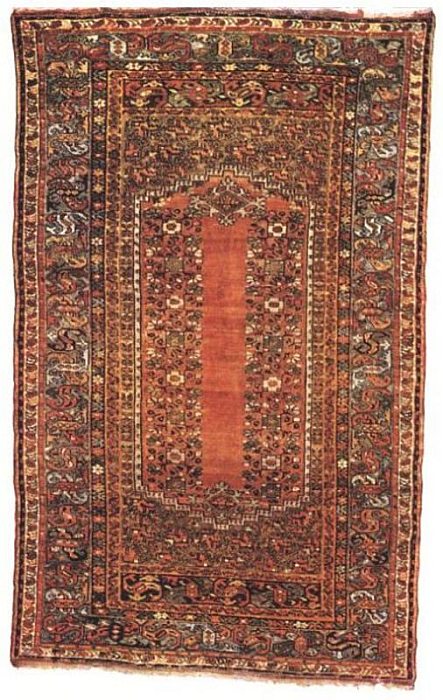

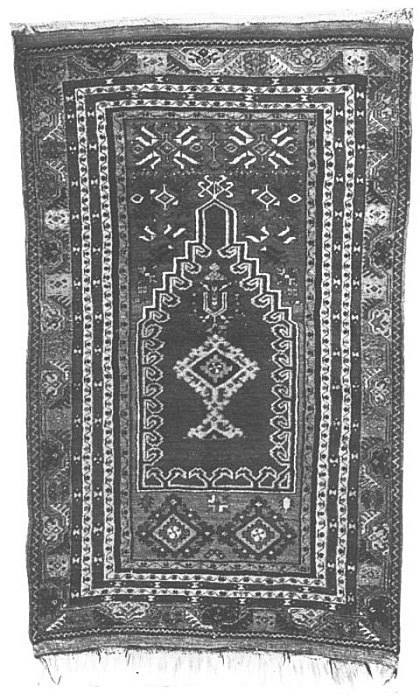

GHIORDES PRAYER RUG

PROPERTY OF LIBERTY & CO., LONDON, ENGLAND.

GHIORDES PRAYER RUG

PROPERTY OF LIBERTY & CO., LONDON, ENGLAND.

The prayer niche, the cross panels and the main border stripe

are all characteristic of its class.

(See page 238)

[Pg. 69]

THE MATERIAL OF RUGS

The materials from which rugs are made,

named in order of the ratio in which they are used,

are wool, goats' hair, camels' hair, cotton, silk,

and hemp.

Wool.—The wool produced in the colder provinces

is softer and better than that produced in

the warmer provinces. Likewise that produced

at a high altitude is superior to that from a lower

altitude. The quality of the pasturage plays a

most important part in the quality of the wool.

For this reason no better wool is to be found

anywhere in the world than from the provinces

of Khorasan and Kurdistan. Very often the

sheep are covered over with a sheet to protect and

keep the wool in a clean, lustrous condition. The

quality of the wool also depends to no small extent

upon the age of the sheep from which it is

taken, that from the young lambs being softer and

more pliable than that from the older animals.

The softest and most lustrous wool is that which

is obtained by combing the sheep in winter and is

[Pg. 70]

known as kurk. From this some of the choicest

prayer rugs are made.

Goats' Hair.—From the goats of some localities,

especially in Asia Minor and Turkestan, is

obtained a soft down which is used to a large

extent in the manufacture of rugs. The straight

hair of the goat is also used. It is of a light brown

color and, as it will not dye well, is sometimes

used without dyeing to produce brown grounds, as

in some of the Kurdistan products. It is quite

commonly used as a selvage and fringe in the

Turkoman products. When wet it curls so tightly

that it is difficult to spin it, therefore it is not

always washed. This accounts for the strong

odor which is especially noticeable in warm

weather.

Mohair is obtained from the Angora goat of

Asia Minor, while cashmere consists of the soft

under-wool of the Cashmere goat of Tibet.

Camels' Hair.—In Eastern Persia, Afghanistan,

and Beluchistan are camels which produce a

long woolly hair suitable for rug weaving which

is never dyed, is silky and soft, has phenomenal

durability and is used quite freely in the Hamadan,

Mosul, and Beluchistan products. It is more

expensive than sheep's wool but has one great

drawback in that on the muggy days of summer it

[Pg. 71]

has a disagreeable odor. Most of the alleged

camels' hair of commerce is a goats' hair pure

and simple.

Cotton.—The majority of the finer Persian

rugs have cotton warp and woof. It makes a much

lighter, better and more compact foundation on

which to tie the pile, and a rug with such a foundation

will hold its shape much better. Seldom

is cotton used for the pile excepting once in a

great while a Bokhara may be found with small

portions of the white worked in cotton.

Silk.—In the regions bordering on the Caspian

Sea and in some parts of China where silk

is plentiful it is used to quite an extent in the

making of rugs, not only for the nap but frequently

for the warp and woof as well. It makes

a beautiful fabric, but of course will not wear like

wool.

Hemp.—Hemp is seldom used in rug making

for the reason that it rots quickly after being wet

and the entire fabric is soon gone.

Preparation of the Wool.—After being

sorted, the wool is taken to a brook and washed

thoroughly at intervals in the cold running water

for several times until all foreign matters are

removed, leaving the animal fat which gives it

the soft, silky appearance. The results of washing

[Pg. 72]

depend to a certain extent upon the quality of

the water used in the process, soft water giving

much better results than does the hard.

After a thorough bleaching in the sun's rays

it is placed in a stone vessel, covered with a mixture

of flour and starch, then pounded with

wooden mallets, after which it is again washed

in running water for several hours and again

dried in the sun. Under this process it shrinks in

weight from forty to fifty per cent., and after

being spun the yarn is sold everywhere for the

same price as twice the amount of the raw

material.

It is spun in three different ways. That which

is intended for the warp is spun tightly and of

medium thickness, that for the woof rather fine,

and that for the pile heavy and loose.

There are so many different natural shades

of wool that much of it can be utilized in its

natural color. The dyeing is always done in the

yarn, never in the loose fibres, and will be explained

in the chapter under Dyes.

SPINNING THE WOOL

COURTESY OF PUSHMAN BROS., CHICAGO.

SPINNING THE WOOL

COURTESY OF PUSHMAN BROS., CHICAGO.

[Pg. 74]

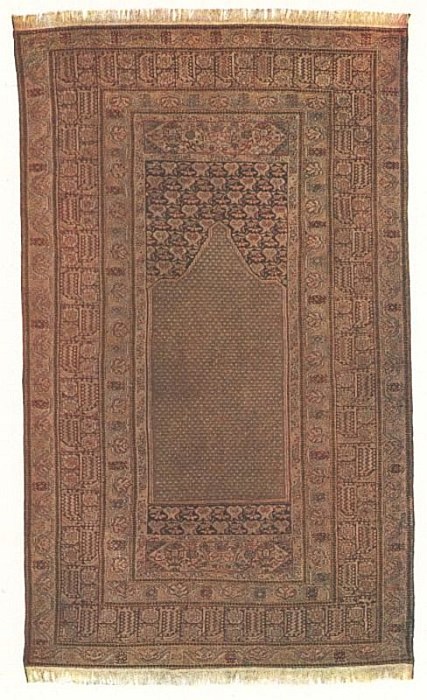

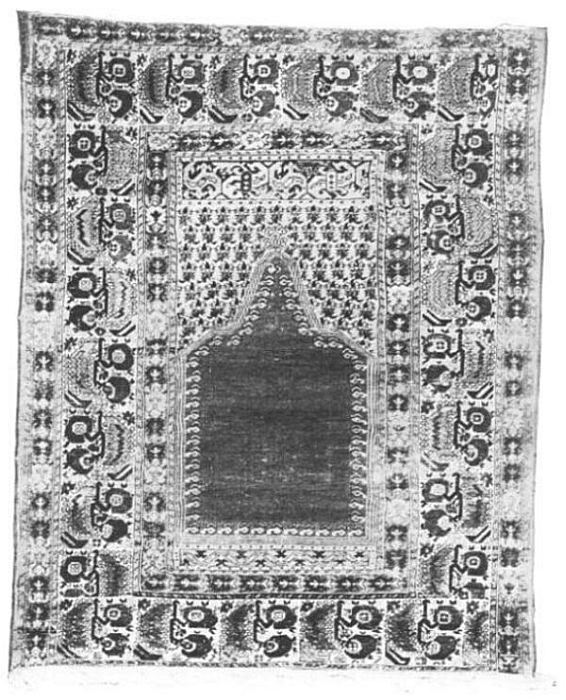

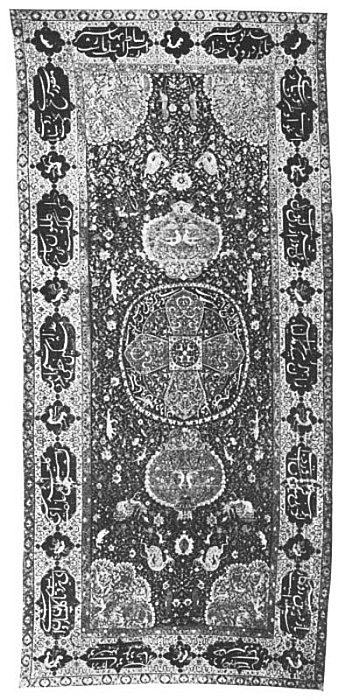

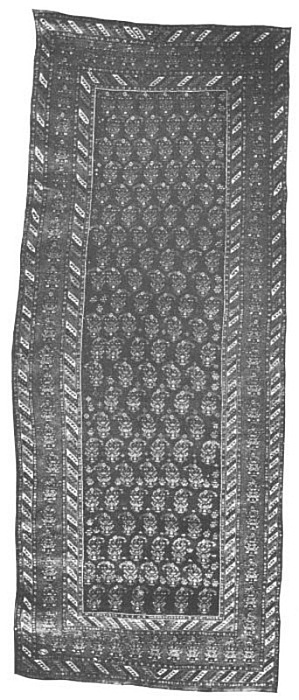

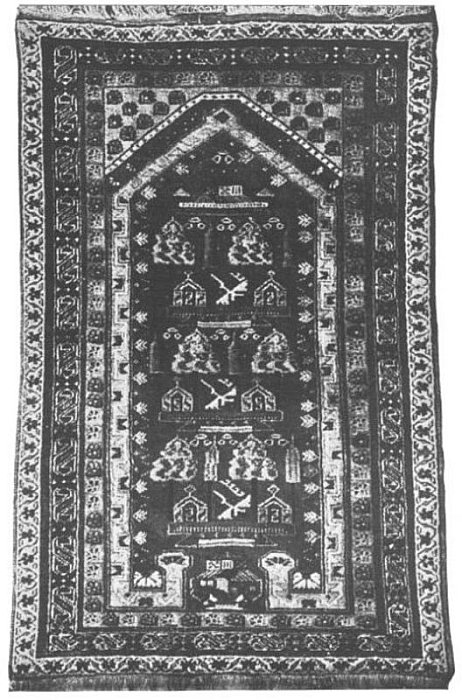

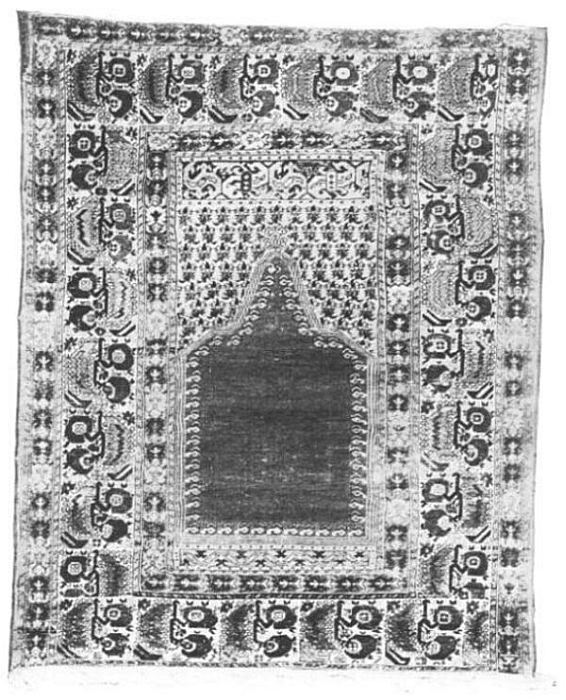

LADIK PRAYER RUG

Size 7'2" × 4'

LADIK PRAYER RUG

Size 7'2" × 4'

BY COURTESY OF NAHIGIAN BROS., CHICAGO, ILL.

Owners' Description.—These rare rugs, so renowned for their

splendid coloring, are well represented by this specimen. The very

unusual shade of green, the sacred color, the deep ivory, and the

rich reds and blues are blended into each other in an artistic

manner.

In and above the "Mihrab" or niche will be noted the "Ubrech"

or pitcher, a most interesting design. It is from this "Ubrech" that

water is poured upon the hands of the Mohammedan as he makes

his ablutions. Wash basins are unknown in the Orient and no

follower of Mohammed will consent to wash in anything except

running water.

So the "Ubrech" is almost as important as the prayer rug itself,

and the four reproductions on this rug emphasize to the devout

Mohammedan owner that cleanliness is next important to Godliness.

Rhodian lilies, with long stems and inverted in the frieze below

the "Mihrab" or niche, are an often noted feature of the Ladik

prayer rugs.

(See page 228)