DEBORAH

By James M. Ludlow

Along the Friendly Way. Reminiscences and impressions. Illustrated, $2.00.

Avanti! Garibaldi's Battle Cry. A Tale of the Resurrection of Sicily—1860. 12mo, cloth, net $1.25.

Sicily, the picturesque in the time of Garibaldi, is the scene of this stirring romance.

Sir Raoul. A Story of the Theft of an Empire. Illustrated. 12mo, cloth, net $1.50.

"Adventure succeeds adventure with breathless rapidity."—New York Sun.

Deborah. A Tale of the Times of Judas Maccabæus. Illustrated, net $1.50.

"Nothing in the class of fiction to which 'Deborah' belongs, exceeds it in vividness and rapidity of action."—The Outlook.

Judge West's Opinion. Cloth, net $1.00.

Jesse ben David. A Shepherd of Bethlehem. Illustrated, cloth, boxed, net $1.00.

Incentives for Life. Personal and Public. Cloth, $1.25.

The Baritone's Parish. Illustrated, .35.

The Discovery of Self. Paper-board, net .50.

A TALE OF THE TIMES

of

JUDAS MACCABAEUS

by

JAMES M. LUDLOW

AUTHOR OF

THE CAPTAIN OF THE JANIZARIES

ETC

NEW YORK CHICAGO TORONTO

FLEMING H. REVELL COMPANY

Copyright, 1901, by

FLEMING H. REVELL COMPANY

New York: 158 Fifth Avenue

Chicago: 17 North Wabash Ave.

London: 21 Paternoster Square

Edinburgh: 75 Princes Street

| CHAPTER | PAGE |

| I.—The City of Pride, | 11 |

| II.—The City of Desolation, | 22 |

| III.—The Little Blind Seer, | 32 |

| IV.—The Discus Throw, | 39 |

| V.—A Flower in a Torrent, | 46 |

| VI.—A Jewish Cupid, | 54 |

| VII.—In the Toils of Apollonius, | 63 |

| VIII.—Deborah Discovers Herself, | 71 |

| IX.—The Nasi's Triumph, | 79 |

| X.—Judas Maccabæus, | 91 |

| XI.—The Priest's Knife, | 106 |

| XII.—The Fort of the Rocks, | 111 |

| XIII.—The Daughter of the Voice, | 120 |

| XIV.—The Spy, | 130 |

| XV.—The Battle of the Wady, | 140 |

| XVI.—The Battlefield of a Heart, | 146 |

| XVII.—A Fair Washerwoman, | 160 |

| XVIII.—High Priest! High Devil! | 171 |

| XIX.—The Renegade, | 179 |

| XX.—A Female Symposium, | 185 |

| XXI.—Battle of Bethhoron, | 193 |

| XXII.—A Prelude Without the Play, | 200 |

| XXIII.—The Greed of Glaucon, | 205 |

| XXIV.—Lessons in Diplomacy, | 209 |

| XXV.—A Jewess Takes No Orders from the Enemy, | 215 |

| XXVI.—To Unmask the Princess, | 221 |

| XXVII.—The Queen of the Grove, | 227 |

| XXVIII.—A Prisoner, | 234 |

| XXIX.—A Raid, | 243 |

| XXX.—Foiled, | 250 |

| XXXI.—The Sheikhs, | 258 |

| XXXII.—The Castle of Masada, | 266 |

| XXXIII.—With Ben Aaron, | 276 |

| XXXIV.—Quick Love: Quick Hate! | 282 |

| XXXV.—Worship Before Battle, | 289 |

| XXXVI.—The Temptress, | 298 |

| XXXVII.—"If I Were a Jew," | 304 |

| XXXVIII.—The Poisoner, | 309 |

| XXXIX.—Battle of Emmaus, | 313 |

| XL.—"A Little Child Shall Lead Them," | 321 |

| XLI.—A Strange Visitor, | 327 |

| XLII.—A Close Call for Dion, | 332 |

| XLIII.—Battle of Bethzur, | 339 |

| XLIV.—A Wife? | 346 |

| XLV.—The Trial, | 354 |

| XLVI.—Disentangled Threads, | 363 |

| XLVII.—A Queen of Israel? | 367 |

| XLVIII.—A Broken Sentence Finished, | 377 |

| XLIX.—The Hidden Hand, | 386 |

| L.—The Vengeance of Judas, | 392 |

| LI.—A King, Indeed, | 401 |

| Author's Note, | 407 |

DEBORAH

King Antiochus, self-styled Epiphanes, the Glorious, was in a humor that ill-suited that title. He cursed his scribe who had just read to him a letter, kicked away the cushions where his royal and gouty feet had been resting, and strode about the chamber declaring that, by all the gods! he would make such a show in Antioch that the whole world would be agog with amazement.

The letter which exploded the temper of his majesty was from Philippi, in Macedonia, and told how the Romans, those insolent republicans of the West, had made a magnificent fête to commemorate their conquest of the country of Perseus, the last of the kings of Greece.

Epiphanes was a compound of pusillanimity and conceit. He could forget the insult offered by a Roman officer who drew about "The Glorious" a circle in the sand, and threatened to thrash the kingship out of him if he did not at once desist from a certain attempt upon Egypt; but he could not endure that another should outshine him in the pomp for which Antioch was famous. This Eagle of Syria, as he liked to be called, would rather have his talons cut than lose any of his plumage.

Hence that great oath of the king. So loud and ominous was it that the pet jackanapes sprang to the shoulder of the statue of the Syrian Venus, and clung with his hairy arms about her marble neck. The giant guardsmen in the adjacent court, who, half asleep, stood leaning upon their pikes, were startled into spasmodic motion, and shouldered their weapons, before their contemptuous glances showed that they understood the words that rang out to them.

"By all the gods! if Rome has the power, and Alexandria the commerce, Antioch shall be queen in splendor, though it takes all the gold of all the provinces to dress her."

The scribe smiled blandly and bowed his appreciation of this new-coming glory of his master. The jackanapes took heart, and, after annihilating some of his own personal enemies with vigorous scratching of his haunches, leaped from the statue to the arm of the King's chair. So the grand pageant was ordered.

All the world was invited to the Syrian capital. For an entire month such splendors and sports were seen at Daphne, the famous pleasure-grounds near to Antioch, that ever after the capital was called Epidaphne, the City by the Grove. The heights of Silpius, on whose lower slope Antioch lay like a jewel in the lap of a queen, blazed by day with a thousand banners, and at night with fires whose reflection turned the Orontes that flowed below the city into a stream of molten gold.

One day was devoted to military display. There were fifty thousand soldiers of many nations, from the perfectly formed Greek of the Peloponnesus to the Persian, who made up for his lack of muscle by[13] the superior glitter of his spear, and the lithe and swarthy Arabs from all the deserts between the Ægean and the Euphrates. Plumes of gold nodded above shields of bronze and silver. Hundreds of chariots glowed like rainbows in their parti-colored enamel, and were drawn by horses buckled and bossed with precious gems. Droves of elephants armored in dazzling steel carried upon their backs howdahs like thrones.

A stalwart young Greek stood looking at this martial display. He wore the chiton, or under-garment, cut short above the knees, and belted at the loins, where hung a stout sword indicating that he too was a soldier.

"What think you, Dion?" asked a comrade.

"Why, that the body-guard of our King Perseus, though numbering but three thousand, could have annihilated this whole mongrel horde as readily as Alexander did the million when he won this land for his degenerate successors. But I must not criticise the service I am enrolled to enter."

Following the soldiery in the procession came a thousand young men, each wearing a crown of seeming gold, clad in glistening white silk, and holding aloft a huge tusk of ivory. These symboled the trade wealth of Syria.

But the army having passed by, the Greek was soon wearied with the rest of the display; and, bidding his companion farewell, with a few sage suggestions about the temptations of the Grove at night, such as one young fellow might give another, went into the city.

The second day's festivities were of a less valiant, though not less fascinating sort. It was the Day of[14] Beauty. Hundreds of fair women, in balconies that overhung the narrow streets of the city, or grouped upon platforms here and there throughout the Grove, flung into the air the dust of sandalwood and other spiceries, or sprinkled the crowds with drops of aromatic ointments. At the crossing of the paths were great vessels of nard and cinnamon and oils, scented with marjoram and lily, that even the paupers might delight themselves with the perfume of princes. Tanks of wine and tables spread with viands were as free as they were costly.

But the King himself was the most extravagant provision of the show. In him the dignity of a king was less than the vanity of the man: his coxcomb more than his crown. It cut him to the quick that a courtier should outdress him, a charioteer better manage his steeds, or a fakir set the mouths of the crowd more widely gaping. In the military procession yesterday he had sat between the tusks of an enormous elephant, and pricked the brute's trunk with a golden prod. He had also ridden a famous stallion,—tightly curbed, it is true, and flanked by six athletic grooms.

His majesty's originality was especially shown on the Day of Beauty by his riding beside Clarissa, the famous dancer, in the chariot where she reclined as Queen of the Grove, an apparition of Astarte herself. The extemporized divinity of love wore a moon-shaped tiara of silver, the symbol of the Queen of Heaven; Epiphanes put on an aureole of gold to represent the glory of the Sun. A score of women whose forms were familiar to all the frequenters of the dancing gardens of Daphne lay at their feet.

Dion was an onlooker. He had caught so much of the spirit of the day as to curl his locks and drape a purple himation or outer cloak from his left shoulder.

"That's the Macedonian," said one of Clarissa's satellites, as from her float she spied the graceful form in the crowd.

"A perfect Apollo!" was the critical response, which drew a jealous glance from even The Glorious, who made the unkingly comment:

"No. His nose isn't true. Has the snout of a Jew."

His Majesty deserved to hear, though he did not, the comment the Greek was at the same moment making to his comrade:

"Humph! Epiphanes, the Glorious! Well do the people call him Epimanes, the Fool."

Captain Dion, notwithstanding the contemptuous sentiments thus far awakened by the great show, was an observer the day following; for the spectacular greatness of the affair would have drawn a Diogenes into the crowd.

This was All-Gods Day. The various deities of the nations which Epiphanes' fathers had conquered for him, and those of lands which the ambitious monarch claimed, though he had not yet subdued them,—these were represented by their statues, or by living personages who were apparelled in celestial hues; that is, so far as the King's costumers were acquainted with the fashions of the world beyond the clouds.

One float bore a tableau in which Mount Olympus appeared, peopled with divinities, among whom Jupiter sat with uplifted hand holding a sheaf of[16] golden spears for lightning bolts, which the shaking of the float made to menace the spectators with celestial ire. A bull-headed Moloch of brass was contributed by the adjacent Phœnician city of Sidon; this was followed by a stone Winged Bull from Babylon.

Lesser divinities held their court before the gaping crowds, as if heaven were trailing its banners beneath the greater glory of the earthly monarch. Indeed, the vanity of Epiphanes did not hesitate to make this monstrous pretension. He was magnificently enthroned, his head canopied by a device in which a golden sun and silvery planets were made to float through fleecy azure. At his feet on a lower platform were priests representing every religion in his wide domain—those of the Phœnician Baal in white robes with fluted skirts slashed diagonally with violet scarfs, their heads covered with close-fitting caps of knitted hair-work, as if of a piece with their black beards; Greek priests with gloomy brows inspecting the entrails of the sacrifice; and naked Bacchantes, crowned with the leaves of the vine.

Among these sacred officials was Menelaos, the High Priest of the Jews, clad in the beauty of the ancient pontificate; his white tunic partly covered with the blue robe; his head surmounted with the flower-shaped turban. Menelaos was not the rightful High Priest of his people. His brother, the sainted Onias, had held that office, until, after long captivity in the prison of Daphne, he was murdered by Menelaos' order, not far from the spot the fratricide was now passing.

As on the previous days, Dion, the Macedonian,[17] had his station as a spectator on the raised platform by the splendid gate of Daphne. By his side was a young man. He was of decided Jewish countenance, of slight form, head uncovered except for the silver band which held his artificially curled hair close down upon his forehead—the fashion of Antiochian fops of the time; from his shoulders a yellow himation buckled with an enormous jewel and cornered with purple devices.

"I take it, Glaucon," said Dion, "that you are in feather with the High Priest of your people. If I mistook it not, you gave him a knowing nod, which he would have returned had not his pose at the feet of the King prevented."

"Yes," replied the Jew, "Menelaos and I are good friends. And well we may be, for, next to his own, my family is the noblest in Jerusalem. Menelaos has great influence with the King, and has brought me into much favor in Antioch."

"Such favor you will doubtless need, if reports be true," replied Dion. "They say that General Apollonius has made your city of Jerusalem a butcher's pen. That surely might have been avoided, since Menelaos, and your house—the house of——"

"The house of Elkiah, the Nasi," quickly interjected Glaucon.

The Greek continued: "Since such great families as yours have been induced to accept the lordship of Antioch, why not all others? I fear that Apollonius is given to the wearing of the bones on the outside of his hand."

"Well he may be," replied Glaucon, "for my people are obdurate,—stupidly so. Many of them are crazed with their religious bigotry. For the precept[18] of some dead Rabbi they would live in the tombs. They would cut off their flesh rather than part with a traditional hem of the garment. They are so proud that one of them would not marry Astarte herself. But a few of us are wiser. We are going to introduce the Greek customs which are so beautiful and joyous; learn your philosophy; adorn our Temple with your art. Young Jewry hears the call of the Greek civilization, as does all the rest of the world. Old Jewry is soured with its traditions, as milk is from too long standing."

"I am glad that I am not a Jew," replied Dion. "I fear that my love of fight would make me a rebel."

"Not you, Captain Dion," said the Jew, looking with admiration into the Greek's handsome face and his blue eyes, that were as full of frolic as of fire. "You, Dion, could fight for a woman, if she were beautiful; but not for a gray-walled temple, and a lot of psalm-snoring priests."

"Well," replied Dion, "I shall soon have a chance to study your strange people; for I am ordered by the King to join Apollonius. I sail to-morrow on the Eros, from the harbor of Seleucia to Joppa."

"Then I am in high luck," replied the Jew enthusiastically, "since I will have you for a fellow-passenger. One night more in Daphne! I assure you that I shall play the true Greek, and fill myself with the best that is left in Antioch, since to-morrow I pay tribute to Neptune. You will join me at sunset, Captain? Celanus' wines are excellent."

"Impossible," replied Dion. "I must keep my legs steady under me, and my brain-pan level, for to-morrow I shall have to take charge of a hundred of[19] the most villainous wretches that the King ever got together. And he calls them 'Greek soldiers,' though there isn't a man of them that can tell his race two generations back. A lot of pirates, robbers, mine-slaves, and old wine-skins on legs! Greek soldiers! When Mars turns chambermaid to a stable we Greeks will be such soldiers. But they may be good enough for the work that Apollonius has for them in Jerusalem. Farewell! To-morrow at noon on deck!"

Even a king must sometimes work. So Antiochus, the Glorious, laid aside the trappings of divinity and attended to business. A vast empire, such as he had inherited through several generations from Alexander the Great, needed care. So far as possible the King farmed out the government of the provinces to those who would return the largest revenue, and trouble him least about the method of their gathering it. Yet something was left for even the King to do.

First in the royal interest, after he had returned to his palace, was the report of the chief of the city spies—old Briareus, he fondly called him, since he was as one that had a hundred arms, and a thousand fingers on them, which were in all the private affairs of the inhabitants of the capital. Having satisfied himself with his chief's account, and feeling confident that the royal throat was in no immediate danger of being cut by any of the multitude he was daily outraging, the King turned to less interesting matters, such as the whereabouts of his many armies, their victories and defeats.

"Your tablets, Timon."

The scribe read:

"Apollonius reports all quiet at Jerusalem. Executed two hundred yesterday."

"Good!" said the King. "Bid him leave not so much as a ghost of a Jew above Hades; and then let him hasten the work in the country to the north. The Jewish peasants are unsubdued. It is not safe for a single company of our troops to go over land to Judea. I have had to send the detachment tomorrow by water down the coast."

"There is the matter of Glaucon, son of the Nasi. You recall your Majesty's promise to spare his property. It was a part of the bargain with Menelaos, the Priest."

"To Hades with the Priest!" cried the King.

"Would it be wise to break with Menelaos?" timidly suggested the scribe.

"You are right, Timon. The High Priest will be convenient in Jerusalem,—like the handle to a blade. Has Menelaos paid up all he promised?"

"Yes; the nine hundred talents are safe."

"Nine hundred talents! That rascal must have robbed the Temple."

"Well, if he did, it will save your Majesty the trouble of finding the hidden coffers. They say that the old King Solomon put his gold into wells as deep as the earth, and that only the High Priest knows where they are."

"A good thought!" said the Glorious, thumping the bald head of the scribe with the royal seal. "Your skull, Timon, is as full of wisdom as a beggar's is of fleas. When Menelaos has gobbled down all the gold there is in Jerusalem, we will open his crop and let out the shekels, as they do corn grains[21] from a turkey's gullet. A good thought! But enough of these things. They tire me. Business is for slaves, not for kings. Did you note to-day how the people looked as I appeared in the procession?"

"Your Majesty's glory can but grow upon the multitude. It is like that of a mountain,—of a sunset—of—of the Great Sea when the glowing orb of day with rays like the dishevelled hair——"

"Stop, good Timon; no flattery. You know I never could abide flattery."

"No words could flatter your Majesty." The scribe bowed upon the marble floor, and kissed the feet of his master.

"Now begone," said the King. "Let everything be ready for to-night. Clarissa, the Queen of the Grove, comes with a troop of her dancers."

With a wave of the royal hand the scribe vanished, and instead came the King's costumers and physician; for the body of the Glorious must be re-apparelled, and his stomach put in order for feasting.

The streets of Jerusalem in every age have been thronged with the same motley multitude: cool-looking, white-shirted market venders from the stalls; no shirted sweat-hot artisans from the cellar workshops; dyers, designated by their badges of bright-colored threads; tailors, in heraldry of ornamented needles; carpenters, wearing their symbol of square and compass—of which they were as proud as the scribe was of the pen stuck behind his ear; fishermen from Galilee and the coast jostling the fruiterers with great baskets on their heads; bare-legged, dirt-tanned laborers from the fields; half-naked children of either sex, playing with equal carelessness whether they knocked over the piles of fruit and black bread that stood upon the stone pavement, or were themselves knocked over by the sharp hoofs of asses or the spongy feet of camels. These exponents of common, toiling humanity made way for the gay tunic-clad aristocrats of the Upper City of Sion, white-robed priests from the Temple Mount, gray-sheeted women from the Cheesemakers Street, and ladies in black silken garments and caps of coins, who were borne in palanquins from the more fashionable Street of David.

But in the year 167 before our Era all these had disappeared,—as suddenly and completely as the sea-[23]mullets and blackfish are driven out of the shallows in the bay of Joppa by an invasion of sharks.

The costumes and speech of the new crowd on the streets were foreign, chiefly those of Greek and Syrian soldiers, with broad-brimmed hats, loose-knit, iron-linked corsage, tight leather leggings, and short, stout cleaver-like swords hanging from their girdles. Here and there one stood stock still, sentinelling his corner of the street, with the point of his sarissa or long spear gleaming ten cubits above his head, while his broad circular shield held abreast made an eddy in the living current as it swept around him. These were the soldiers of Antiochus Epiphanes.

Mingled with them were many foreign civilians, as their dress indicated; merchants whose belts were well filled with gold to purchase what the soldiers might steal; colonists to resettle the lands from which the conquered people were expelled; and hordes of hucksters and harlots who followed the armies of the time as dust clouds come after chariots.

Nor were there wanting in the crowd those whose curved noses contradicted the disguise of their newly cropped hair, and proclaimed them to be renegade Jews: men who preferred to retain their ancestral property by denying the faith of their fathers.

One afternoon the crowd in the Street of David became suddenly congested. Through it a man, venerable with age, was vainly trying to make his way. His long white locks, which curled downward in front of his ears and mingled with the snowy beard upon his bosom, betokened his Jewish race; while the broad fringes of white and hyacinth upon his outer garment designated him as one of the[24] Chasidim or Purists, who preferred to part with their blood rather than with their religion. The old patriot made no retort to the jostling and gibes of the crowd, but his deep-set eyes flashed hatred from beneath their shaggy brows, and told of the tragedy in his soul even more eloquently than if his lips had poured forth fiery speech.

"You can't swim up this stream, old man," said a soldier, giving the frail form a twirl that made it face the other way.

"It is the Nasi himself, Chief of the Rabbis," whispered a young Jew in Greek cloak to a soldier. "Herakles club me, if you haven't caught the biggest rat left in the hole. But Apollonius has given protection to the Nasi's house. Be careful."

"Protection to his house! Why then did he come out of it? Fetch him along. Strip him naked, and warm his toad's blood in the new gymnasium."

With this insult the soldier tore the outer garment from the old man's back. The Jew was dazed for the instant by the Greek's audacity, and mumbled within his sunken lips the words of the Prophet: "I gave my back to the smiters, and my cheek to them that plucked off the hair."

He then raised his eyes heavenward, apparently unconscious of a staggering blow between his shoulders from the flat of a sword. He stood a moment until he had completed the sacred sentence: "For the Lord God shall help me; therefore shall I not be confounded; therefore have I set my face like a flint."

"'Face like a flint,' does he say? Let's see if it will strike fire like a flint," shouted one, smiting the old patriot on the mouth with the palm of his hand.

This dastardly deed drew blood which stained his white beard. But it brought a quick retaliation from an unexpected direction; for a blow like that of a catapult fell upon the assailant's head.

"By the thunderbolt of Zeus! that made you see fire," cried a comrade, as the coward reeled into his arms. "Captain Dion's fist is as heavy as the hammer of Hephæstus, the blacksmith of the gods, and makes the sparks fly as well. I'll wager, Ajax, that you saw the sky full of stars, or else your head is harder than an anvil."

By the side of the venerable Jew now stood a young Greek officer. If Hephæstus had need of an assistant blacksmith the shoulders of Dion would have attracted his notice; yet it is doubtful if the goddesses of Olympus would have allowed so graceful a man to be consigned to the celestial workshop. His face, too, was peculiarly attractive. Topped with a brush of light hair and lighted by his blue eyes, it was beautiful, but without a trace of femininity; a blending of dignity, intelligence, courage, and kindly feeling, though the latter quality was just then outglowed by rage.

On his well-curled head was a chaplet of myrtle, for he was returning as victor in the day's sports at the new gymnasium which, as an intended insult to the religious prejudices of the people, the Governor, Apollonius, had recently built against the southern wall of the Temple plaza.

"Bravo, Dion! If you had hit the Theban boxer yesterday like that, they wouldn't have called for another round."

Dion faced the crowd, and with utmost detestation in his voice, exclaimed: "If I had been here[26] yesterday, this crew of cowardly knaves had not hanged the babes to their mothers' necks, and thrown them from the walls. Let one of you garlic chewers dare confess any part in that beastly business, and I will heave him over the walls into Gehenna, where other carcasses rot. Who touched those women?"

As Dion looked from face to face his blue eyes flashed like the sword-point of a fencer feeling for an exposed spot in the breast of his antagonist. The challenge was not taken, one venturing to say:

"It was done at the Governor's orders."

"I pronounce that a lie. Who repeats it?" cried Captain Dion.

A fellow-officer suggested that it might have been ordered by Apollonius, since the women had plainly broken the new law and had circumcised their brats.

"Shame on you, comrade!" said Dion. "They were women and mothers, and I would say as much to the King's face."

The old Jew, hearing the reference to the scene which he himself had been compelled the day before to witness, turned boldly to the crowd of Greeks, and, with uplifted hands, repeated this imprecation from one of the Psalms of his people:

"Let your children be fatherless and your wives be widows! Let your children be vagabonds and——"

But Dion's hand was firmly laid upon the speaker's mouth.

"Nay, hold your breath, old man. If you give us much of it that way, this crowd will take the rest of it with the hangman's rope."

Dion gently took the Jew's arm. "You must go back to your house. Come, I will see you safely within doors, if you will stay there."

"No, I will go to the house of the Lord, and worship, for it is the ninth hour," replied the determined man.

"That you cannot do," said Dion, kindly. "Don't you see that the Temple gate is burned, and that soldiers are guarding the opening? Your worship is no longer permitted there. Your sort of priests are all gone."

"Then," said the patriot, "I will be my own priest. Surely the Lord will accept an old man's last worship on earth before he goes hence."

"Nay, my good man, but the priests of the new religion are at the Temple. To-morrow they celebrate the feast of Bacchus. If you go there, they will crown you with ivy, and make you drunk in honor of the god. You must go home, and stay within doors."

"Then let me go—to my own house! My God! Why was it not my sepulchre ere I saw what the Prophet foretold?"

Captain Dion led him safely along the Street of David, the crowd giving way as it gazed upon the two and remarked the contrast between the half-mummied saint and the strong-limbed, festive-crowned youth.

"Old Elkiah is about the last of this damnable race left in Jerusalem. It is a wonder that Apollonius has given him tether so long."

"Perhaps Dion knows the Jew," responded some one. "The captain is as good a Greek as ever drew sword or loved a woman, but his nose isn't straight[28] on a line with his forehead. See, it has a Jewish twist."

"A fine observation," laughed another, "for one always follows his nose, and that may account for Dion's kindness to some of these rebels."

"Don't insult Captain Dion!" said one. "He's close in with Apollonius. Besides, he's a good fellow. He always gives a weaker man his handicap in the arena without having it ordered."

"True, or you would not have won yesterday. But I wish he wouldn't interfere with the sport of the men. I know that it is cruel, but the sooner the bigots are exterminated the sooner it will cease. Were it not for Dion's friendship for that Glaucon—as Elkiah's fool of a son now calls himself—we would soon find out what the old Jew's house has for us. They say his cellar is as good as a gold-mine."

"Better kill off Glaucon, and let the old man die himself. You saw that his life is about burned out, and his old body only like a heap of ashes with a spark in it," was the humane response.

Dion paused by the oaken door in the wall of the Jew's house. He took from a little pouch at his belt a pinch of aromatic sawdust of sandalwood, and dropped it upon a small square altar whose brazier emitted a thin curl of white smoke, clouding the entrance. This was an altar to Zeus which the Governor had commanded to be placed at all the houses which were still occupied by the Jews. Just above the altar the lintel had been torn by the destruction of the Mezuzah or wooden box which, according to the Hebrew custom, contained the sacred sentences from the Law, and through the small apertures in which a visitor to any Jewish home could see the[29] word "Shaddai," the Almighty One, and thus make the common salutation, "Peace be to this house," into a prayer. Dion's worship at the little altar by the gate was marred by a muttered curse upon Apollonius for the needless insult perpetrated by this act of sacrilege.

The Greek had scarcely time to knock at the outer entrance when the door flew open, and with the cry "Father!" a young girl's arms were about the old man.

She drew him inside, and stood with her left arm supporting, while she raised her right hand as if it were a shield to protect him.

Captain Dion was familiar with the finest statuary in Athens and Antioch, but thought he had never seen anything to match this,—the white head and beard of age shielded by the raven locks of youth and beauty. He would tell Laertes, his sculptor friend, of this pose.

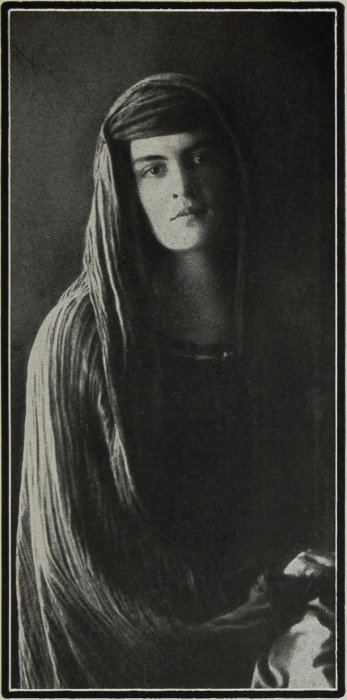

The girl was apparently about seventeen years of age, tall and lithe, with sufficient muscle to give that exquisite grace which only accompanies strength. Her hair, bound about the temples with a single fillet of silver, fell in wavy profusion of jet black upon a white linen chiton. This was gathered at the shoulders, and left fully exposed a neck which might have illuminated a copy of Solomon's Song. Beneath the breasts the garment was girdled with a rope of golden threads, and thence fell below the knees. Her ankles were wound with long white sandal lacings, which were in harmony with the silver band that bound her brow. Her arms were bare. In her haste she had not put on her outer garment, and thus stood revealed in a more exquisite modelling of[30] nature than she would have chosen had she known that she was to be beneath so critical an eye. Yet she could not have been more charming had she practised for hours before her mirror of polished brass, and passed her proud old nurse Huldah's inspection before she made her début at the gate.

Dion noted that the girl's features were perfect, but strictly on the Semitic model. Her face might be a hard one, for it well fitted the tragic feeling of the moment; or it might be sweet as any he had loved to dream about, for it also fitted the intensity of filial affection and solicitude she now displayed. The Greek seemed transfixed by her eyes. These were enlarged by her surprise, and their pupils gleamed from their deep black irises with the fire of excitement.

"A Jewish Athena!" thought Dion, as in a brief sentence or two he begged the girl to be more prudent in the care of her father. Surely there was no scorn of the Jewish race in the profound bow with which he took his departure, nor in the hasty glance he stole as the door was closing.

He plucked a leaf from his myrtle crown and dropped it upon the altar. As he went away he sighed a prayer for the maiden, and grumbled another curse upon the King's cruelty. Then he whistled a sort of musical accompaniment to his thought, which ran something like this:

"That girl is Glaucon's sister. He never told me that he had one." He shrugged his shoulders. "Well, in that he was wise, since he only knows me for a Greek adventurer, and thinks my honor like his own, a spur on the heel, to be used or not according to one's inclination. But, by the arm of Aphrodite![31] what a woman! Beautiful as a lioness, and as brave too. Strange that the Jew could be father of both her and Glaucon—of a lioness and a jackal! Glaucon and I must be good friends, though I despise the fool. Why doesn't he fight for his house? I would—especially with that woman in it."

Dion stopped and stood a long time looking at the narrow strip of sky visible between Elkiah's house and those which lined the opposite side of the street. There were no angels in the blue ether; but something prompted him to take from his bosom a piece of onyx enclosed in a casket of gold, and to look at a sweet face cut into the stone.

"I wonder if she was anything like Elkiah's daughter!"

He put the intaglio back into its pocket and went away.

The house of Elkiah was one of the most stately in Jerusalem, though inferior to the structure which, in more ancient days, rose from the same foundations. Whenever Elkiah told of his ancestral dignities he was apt to show his listeners what were now the cellars and sub-cellars of the house, the great stones of which, by the flat indentations chiselled about the borders, proved that they were as old as the days when Solomon built the Temple, and perhaps wrought by the same Phœnician workmen. The second story, and the battlements which enclosed the roof, were of newer construction, and had evidently been made of the débris of a former and more palatial edifice, for an occasional huge and broidered stone showed upon the street in ancient architectural pride—just as some moderately circumstanced people wear an occasional jewel left them by their richer forebears.

The residence of Elkiah thus maintained a relation to the other and ordinary houses of the city not unlike that which its occupant held to his fellow-citizens. He traced his blood to the days when another Elkiah stood high in the court of Solomon, and thence back to the settlement of the land by the emigrants from Egypt. This could be attested by the official records, and was illustrated by numer[33]ous priceless antiques now stored away in secret closets cut into the solid walls, but which in safer times had ornamented the house from battlement to court.

For many years Elkiah had been the Nasi, or President of the Sanhedrin, that combined ecclesiastical and secular court of seventy-two men who legislated for and judged the people. Of late years the Sanhedrin itself had become utterly debauched by the gold of Egyptian Ptolemies and Syrian Antiochuses, in their rivalry for the possession of Palestine. Most of the members of this sacred council had become Hellenized, and adopted Greek philosophies and customs; and now that the Syrian monarch had invaded the city, these renegades saved themselves from being despoiled by becoming despoilers of their brethren. A former High Priest, Joshua, had changed his name to the Greek Jason, as the Greeks scornfully said, for the sake of the "Golden Fleece." The present incumbent of the sacred office, Menelaos, had been circumcised as Onias, and was now the chief of the traitors in the sacrilegious extinction of the national religion.

The crowning grief of the venerable Elkiah was the apostasy of his own first-born son, Benjamin, who had taken the heathen name of Glaucon, and thus shamed the house of his fathers while he protected it from the general pillage.

The late afternoon of the day following that of Dion's rescue of Elkiah from the mob the old man was reclining upon the thick rug and pillows which Deborah—for so was his fair daughter called—had spread upon the roof. Here he loved to lie, sheltered from view by the parapets, while his eyes fol[34]lowed the white clouds which flecked the deep blue of the sky—"Jehovah's banners," he called them—or caught the gleam of the Temple roof when he was disposed to pray.

"Where is Caleb?" he asked.

A lad of some ten years was lying in the upper chamber, the room which, like a little house by itself, occupied half of the roof upon which it opened. Hearing his father's call, the child sprang up, and in an instant was by Elkiah's side.

"Here am I, father!"

With his long black hair clustering upon his white chiton, and his large black eyes, the boy resembled his sister. One would have noted, however, a strange look; the pupils too widely expanded, as when one tries to see in the dark. And this the child had been doing ever since, five years ago, his sight was destroyed by a strange malady which not even the physician Samuel could cure, for all that this learned man was skilled in the potencies of herbs, the baleful and blessed beams of the stars, and even the deeper mysteries of the words of the Rabbis.

Little Caleb was marvellously beautiful in spite of the stare of his blind eyes and the marble pallor of his face. It was a child's face, yet there was in it the placid sweetness of a woman's look, and at times it seemed to glow with the intelligence of riper years—for the boy had thought and felt more than most men had done.

Caleb knelt down by his father's side, and kissed his forehead. The old man's harsher features relaxed at the touch of the young lips, and tears sprang to his eyes as he drew the lad to his breast.

"Blessed be God, who has left me this fair image of my Miriam! Come, Caleb, and look for me. Your blind eyes are better than mine, which my sins have smitten. Can you see the chariots of the Lord?"

"Nay, father, but you have taught me to trust in Him who is Himself like 'the mountains round about Jerusalem.' What need have we for chariots? Can He not save by His word as well as by war?"

"True, child! Yet I myself once saw, when the impious Apollodorus raged through our street, slaughtering all he met, and no one could stand against him, I saw—or do I dream it?—I saw a heavenly warrior, clad from head to foot in solid silver, waving a sword of fire, who stood before the wicked man, and smote him to the ground. But when they lifted the heathen there was not the sign of the stroke upon him, though he breathed no more. Would that the Avenger might come again, and speedily! But until He come—until He come—we must trust the word, only the word. Bring the Roll of the Prophet. It surely tells of the times that are now passing."

The boy felt for his sister's hand. Taking it, he pressed it against his blind eyes—a way he had of checking his own too violent feeling. He whispered, as he felt her comforting touch:

"Sister, the troubles have surely broken our father's mind. He does not remember even yesterday."

Then, raising his voice, "You have forgotten, father, that the soldiers came and searched the house and took the Books away."

Elkiah passed his hands over his forehead as if to smooth the mirror of his memory. Recollection came, but with it a rage that shook his decrepit form until Deborah's kiss allayed his emotion.

"No matter for the Roll, father," said Caleb. "You know that I can repeat what the Books say. Now that I am blind, I keep in memory all that I hear. In that way God lets me have more, perhaps, than if I could see even to white Hermon there in the north."

"Bless the eyes which the Spirit of the Lord has opened!" cried the old man. "Tell me, child, what says the Prophet of this monster who calls himself our King—Epiphanes, the Glorious—for shame!"

"The Prophet says," replied Caleb, quoting the words of Daniel, "that his heart shall be against the Holy Covenant, and they shall pollute the Sanctuary of Strength, and shall take away the daily sacrifice, and shall place the Abomination that maketh desolate."

"Woe! Woe upon Jerusalem!" cried Elkiah. "Why did I not slay the impious Apollonius, that child of Satan, when he rode into our Holy of Holies? Alas! the breath of the Lord has withered the arm of Elkiah that it cannot smite. But the Avenger will come. He will come yet. What says the Prophet further, my son?"

Caleb continued, "And such as do wickedly against the covenant shall be corrupt with flatteries."

"Ah!" groaned the old patriot, his voice gurgling in his throat like the growl of a wild beast. "And my own son, the son of Miriam, corrupted by the flatteries of the Greek! My Benjamin turned into a[37] Glaucon! God forgive me for having begotten a traitor!"

Elkiah sat upright on the rug. With averted palm he swept the air, as if he would banish from his heart its paternal instinct. He then covered his face with his hands and cried: "O my Miriam! I thank Thee, O God, that Thou didst take her ere she knew this. But, Lord, why didst Thou take my Miriam, and leave me that—that—traitor? But read on, child."

Waiting a moment until his father's paroxysm had passed, Caleb completed the prediction: "But the people that do know their God shall be strong, and shall do exploits."

"Do exploits? Be strong? That we shall," shrieked the old man. "Your hand, Deborah! My sword! I will go and smite the Syrian."

"Nay, father, that cannot be," said Deborah, as she laid the exhausted form back upon the pillows. "Let the children fulfil the Prophet's word."

"The children! My children!" muttered the old man. "One of them a heathen, another blind, and the other only a girl. Deborah, oh, that thou wert a man, or could wear a sword like the Deborah of old!"

Deborah summoned Ephraim, an old servant of the house, who with Huldah his wife assisted in bringing Elkiah into the roof chamber; for the air grew cold as the sun dropped behind the citadel by the Joppa gate, and left only his golden glow on the top of Olivet eastward.

Little Caleb stood a while leaning over the parapet, his face showing the tremendous movement of his soul, now expressing some ineffable longing, and[38] now hardening under some heroic purpose. He turned toward the Temple as if he could see the sacred precincts: but suddenly his great blind orbs were directed southward. As his sister returned to the roof he called to her.

"Deborah, there is a strange noise beyond the city gate, over Ophel!"

"Dear child, you are not yet familiar with the cries at the heathen games. The shouts come from the gymnasium."

"Why, sister, I know all sounds. I know by the dog's barking whether he has the fox on the run or at bay, or has lost him in the hole. And men cry just as the brutes do. I don't need to hear words. I sometimes follow the games in the gymnasium off there. Now it is the hum of the crowd before the contests begin; now the cheer for the runners; the laugh when the wrestlers tumble; the rage of the losers; the joy of the crowd when a favorite wins—I hear it all. But, Deborah, somebody has been hurt over there. Can't you hear something sad in the murmur on Ophel? It is as the fir-trees moan when a storm is coming."

The sound which Caleb heard will be interpreted if we tell of Captain Dion's doings that day.

The high plateau of Ophel swells out from the southern wall of the Temple, and looks down upon the vales of Hinnom and Kedron, which come together at its base, five hundred feet below. From this promontory one can see for miles through the deep valley, which is lined near the city with rock-hewn tombs, and in the distance with whitish-gray cliffs, as if the Kedron had become a leper outcast from the company of the beautiful hills and vales which elsewhere surround Jerusalem. Down, down the valley it goes until lost to sight amid the mountains of stone and sand that make the wilderness of Judea. There the leper dies and is buried in the Dead Sea. Whichever way lies the wind, except from the north, it sweeps this promontory of Ophel with refreshing coolness. Here in the olden time the sages and saints of Israel had been accustomed to walk, their meditations on the judgments of God perhaps more sombre because of the gloomy grandeur of the scene; and here the multitudes had thronged, with hearts gladdened by the contrast of joy of their city with the distant desolation.

But now, by the orders of Apollonius, the Governor under Antiochus, the top of Ophel had been levelled for the stately building of the gymnasium.

To one looking up from the valley of the Kedron,[40] the graceful Greek porticos must have showed against the old gray walls of the Temple like vines on the scarp of a mountain boulder. In front of the structure lay the athletic field, dotted with many colored pennants which denoted the places reserved for the various games. At one end of the field was the stadium, the running track, some six hundred feet in length. Adjoining this was an open court in which were practised wrestling, throwing the discus, swinging the great hanging stone, hurling the javelin, archery, sword play, boxing, and the like. By the side of this court were baths, and near them great caldrons supplying the luxury of heated water.

In shaded porches were raised platforms upon which at stated hours rhetoricians who plumed themselves upon their eloquence discoursed of philosophy and poetry and love. Here, too, professors of the calisthenic art exhibited in their own persons and those of their pupils the graces of the human form.

Captain Dion emerged from the Street of the Cheesemakers upon the athletic field. He saluted the banner of Apollonius, which flaunted from its tall staff, then cast a spray of ivy at the foot of the statue of Hermes, the god of the race. He was at once hailed by a group of young men with whom he was evidently a favorite.

Among these was Glaucon. A broad-brimmed hat topped his head. Artificially curled black locks stuccoed his brow. A white chlamys, or outer robe, of linen broadly bordered with purple was draped from his shoulder in the latest style of the capital.

"Ah, Glaucon, well met! How has it fared with you since we parted at Joppa?" was Dion's greeting.[41] "Has the sea jog gotten out of your legs yet? If the mountains of Carmel and Cassius on the coast had been turned to water the waves could not have tossed us more than when we came from Antioch."

"Jerusalem is a poor exchange for Antioch," replied Glaucon. "One day at Daphne for a lifetime here, but for a few good fellows like you, Captain."

"Did you succeed in getting the order for confiscation reversed?" asked the Greek.

"Oh, yes, I shall hold the property; that is, if I can keep the old man, my father, within doors, so that he doesn't bring a mob about our ears as he did yesterday. Apollonius—Pluto take him!—mulcted me heavily of shekels last night as a guarantee that the old bigot would keep the peace. I wish that you would give the Governor a fair word for me, Dion. You see, I have not come into the estate yet, and haven't many gold feathers to drop. Apollonius seems to think that I am moulting all my ancestral wealth."

"I think I can get the Governor to at least pare your nails without cutting the quick hereafter," replied his friend.

"My thanks. I shall need your help, Captain, in all ways, for though I have donned the King's livery, you Greeks look on me as a Jew. I am like to fall between the upper and nether millstones. My people have cast me off, and, by Hercules! yours do not take to me as they should."

"Never fear, Glaucon," replied Dion. "A man who can swear 'By Hercules!' instead of 'As the Lord liveth!' will soon have the favor of our gods."

"And goddesses, too, I hope," laughed Glaucon. "But I have not thanked you, Dion, for saving my[42] father from his crazy venture on the streets yesterday. The shade of Anchises bless you for that!"

"Well up in the poets, too, I see," said the Captain, slapping his comrade on the back. "Your brain is Greek if your blood be Hebrew. But let us hear what this blabber is saying."

The men stood a moment listening to an orator who, with well-oiled locks and classically arranged toga, was addressing a small group within a portico. He was just saying: "Hear then the words of the divine Plato, 'When a beautiful soul harmonizes with a beautiful body, and the two are cast into the same mould, that will be the fairest of sights to him that has an eye to contemplate the vision.' Truly the soul is made fair by the fairness of the body. Thought glows when the eye sparkles. Heroism is bred of conscious strength of muscle. Love burns within the arms of beauty, and with the kisses scented with the sweet breath of health. Think you that the gods would dwell within the statues if the sculptors did not shape the marble and ivory to exquisite proportions?

"Behold, then, the stupidity of these Jews whose foul nests we are destroying. They read their Rolls, but they gain no wisdom. They pray, yet remain impious. It is because they know not the first of maxims, namely, that the body is the matrix of the mind."

"The fool!" was Dion's comment. "There are better declaimers in any Greek village. And"—more to himself than to his comrade, as a band of Jews, among them even some renegade priests, stripped naked, ran by them on their way to the racing stadium—"yet see, there are bigger fools!"

When the two men passed into the gymnasium proper, the crowd on the benches raised the cry of "Dion! Dion!" until the crossbeam shook down its dust of applause.

The Captain gracefully acknowledged the compliment by taking from his brow the chaplet, now well withered, and flinging it from him into the crowd with the exclamation: "I will win it again before I wear it."

The magnanimous challenge brought the champion another ovation.

The chief gymnasiarch approached, and read from his tablets the names of the day's victors in the various contests that had already taken place. He bade Dion select an antagonist from the list.

"I will throw the discus," said the Captain.

"Then your competitor will be Yusef, the Lebanon giant," read the gymnasiarch. He shouted:

"Hear ye! Yusef of Damascus is challenged by Dion of Philippi."

Divesting himself of his garment the Greek now stood naked among his compeers.

"Adonis has descended," shouted one, in a tone that might have been taken for either admiration or contempt.

An alipta came and rubbed Dion's arms and back with oil mingled with dust.

"Better rub him against the Jew. He'll get both grease and dirt at a touch," sneered some one.

Dion turned, and, fronting the group whence the insult came, scanned the faces one by one; but there was no response to his mute challenge.

As he moved away one ventured to say, loud enough to be heard by a few about him:

"The Jewish renegade is protected by special order of the King, or, by the club of Herakles! I would grind his face with my fists."

"The Captain seems to be the pimp's special body-guard just now," was a reply; after which the knot of men talked in low tones among themselves, casting furtive glances in the direction of Dion.

"Yusef stands on his record of this morning," shouted the gymnasiarch. "He need not throw again unless Dion shall pass him."

The Greek balanced in his hand two circular pieces of bronze, in order to select one of them. The crowd densely lined the way the missile was to fly. There was eager rivalry for places at the goal end, where the friends of the contestants craned their necks to see the exact spot the discus would strike, ready to applaud or dispute it. In this group Glaucon had secured a foremost stand, and waited, leaning with the crowd.

"Here's your chance to stick the pig of a Jew," whispered one to his neighbor, who stood just behind Glaucon.

Dion held the bright bronze in his right hand, his fingers grasping tightly the outer rim, while the weight fell upon his open palm and wrist. Raising his left arm the more perfectly to balance his weight, he pivoted himself upon his left foot, then, swinging the discus backward in almost a complete circle, and combining the muscles of arm and trunk and leg in one tremendous return motion, he flung the metal gleaming through the air.

At the same instant Glaucon was thrust by those behind him headlong into the path of the flying missile. The swift swirl of the disc together with[45] its weight made its impact as dangerous as that of a sword blade. It struck the falling form of Glaucon, terribly bruising the base of his head, and laying open a ghastly wound in his neck and shoulder.

Dion strode down the line. He glanced an instant at the prostrate form of his friend, turned as quickly as a bear, seized two of the throng of bystanders, dashed their heads together until they were half-stunned, then flung them sprawling apart. They lay moaning and cursing on the ground amid the derisions of the crowd until the gymnasiarch ordered them under arrest.

The gymnastæ, or surgeons of the field of sports, were summoned; but the case of Glaucon was beyond the present need of their splints and unguents.

Dion bade them carry the apparently lifeless form to Elkiah's house, and himself led the way. It was this sad company which the clairvoyant mind of the blind boy detected before the searching gaze of Deborah saw the approaching litter.

It is Benjamin! Benjamin is hurt!" cried Caleb, leaning an instant over the parapet. While Deborah was looking into the street he felt his way to the steps leading down from the roof into the open court around which the house was built. He darted across this as quickly and silently as a flash from the brass mirror, not even waking Ephraim, the servant, who had fallen asleep watching the ripples in the great basin of the fountain that stood in the centre of the court. In another instant the boy had raised the crossbar from the lintels and was hasting down the narrow street. Extending his hands he guided himself through the crowds, keeping always in the centre of the way as infallibly as a stick floats in the middle of a wild rushing torrent. In vain did Deborah, as she saw him, call him from the parapet. She flew down the stone stairway and out into the street.

"What haste, my black-eyed beauty?" said an impudent soldier, blocking her way.

By a quick movement Deborah eluded him, but only to be stopped scarcely twenty paces beyond by another, who stretched out his arms and seized her by the wrists. She stood as if paralyzed by her wrath at this indignity, for never before had a rude hand touched her; then, with sudden agility and[47] strength which seemed beyond a woman's, she wrenched herself from her captor. Taking time and breath for one indignant cry, "You coward!" she ran on, while the crowd was temporarily diverted by their jeers at the discomfited soldier.

"The eunuchs are stronger than you, man, for they can keep the women from running away from the harems."

"Her fire-eyes burnt out your heart, did they? Open your corselet, and let's see if it be charred."

Deborah turned into the Cheesemakers Street. Here she met a company of officers.

"Catch the gazelle! She is my spoil!" shouted the leader.

Her arms were instantly seized from behind.

"Apollonius has captured the very Daughter of Jerusalem that the Jews talk about," remarked one.

"Apollonius?" cried Deborah, looking at one whose gorgeous plumage indicated that he was the chief officer.

He was a man of prepossessing appearance. His brow was broad, features finely proportioned; a man evidently trained to think and govern. In younger days he must have been exceedingly handsome, but middle life showed the effects of dissipation. A furtive flicker in his eyes belied his assumption of self-command. His lips were swollen from too frequent communion with the spirit of the vine.

"Apollonius!" cried Deborah. "Does Apollonius dare to break his own orders? Is it true, then, as men say, that there is neither honor nor mercy in a Syrian?" fixing her gaze unflinchingly upon the Governor's face.

"Ah! and who is my charmer? Beautiful as a leopard at bay, or Aphrodite herself is a hag. Come, can you leap as high as my arms?" said the Governor, amid the laughter of his attendants.

"I am the daughter of Elkiah," said Deborah, "whose house you have given your sworn word to spare, if you be indeed General Apollonius."

"By all the nymphs this side of Olympus! I am sorry to hear it," replied he. "If I had known that the old bigot had so fair a daughter, I would have qualified my order. But let her pass, my men. We must keep our word, of course."

A counter commotion was heard down the street.

"Way for the litter! Way for the litter!" shouted those coming.

With a sharp outcry, Deborah darted from the soldiers about her and ran to the side of the wounded man.

"It is Benjamin!" she exclaimed, throwing her arms about the insensible form which the bearers had for the moment put down. "Speak to me, my brother!"

The girl's grief at first seemed inconsolable. But suddenly she was transformed into a Fury. She stood straight but trembling, with hands clenched, and glared upon the bystanders. For a little her passion prevented speech. Then she broke forth, with tone and gesture and look which fitted her words:

"A curse upon his murderer! Who struck this cowardly blow?"

She raised her hand as if to smite any one who dared confess the deed.

"It was but an accident, fair daughter of Elkiah,"[49] responded Dion, with a manner that disarmed her rage. "Your brother is not dead. See, he lives."

He bent over his friend with evident joy as the Jew opened his eyes and gazed, at first with stupidity and then curiously, at the Greek and his sister. The glance at Dion was with the flicker of a smile; that upon his sister brought an expression of pain. The next moment he put his hand to his head, and, uttering a sharp cry, lapsed into unconsciousness.

Deborah and Dion stood one on either side of the litter. Their hands touched as they stroked the forehead of the sufferer. They looked into each other's faces. With her it was only the recognition of a common sympathy.

But Dion had other thoughts. The vision of the face he had seen at Elkiah's doorway had not faded for an instant from his imagination. Now his impression of her beauty was reinforced by the revelation of her soul. What courage! what audacity! yet not beyond a woman's right! Had he struck a wilful blow at Glaucon, he thought that her wrath would have killed him, so just would it have been, and so imperious was her voice and action. Yet what love this woman was capable of! She seemed to him like some goddess weeping at her own altar which had been despoiled; for surely Glaucon was not worthy of this outpouring of her affection. Dion thought that he knew women. To him the most were but as stagnant pools, with surface glistening in the sunlight, while the depths—if there were any—were soiled. But he imagined that this woman's soul was transparent, limpid, and infinitely deep; pouring itself out spontaneously, with as[50] little self-consciousness as that of a fountain when it throws aloft its white spray.

Yet he had injured this woman—unintentionally, it was true; but his hand had thrown the fatal disc which cut its way into her soul, as really as into the flesh of her brother. How could he atone for this?

There came also to Dion a deeper anxiety. Glaucon would recover; but what of this girl's coming life? A Jewish maiden left alone amid the license of Antiochus' soldiers! A dove in the serpent's nest would be as safe. Glaucon could not protect her. With Elkiah's death the renegade son would—as he had heard frequently in the camp—quickly "be cashed," and another estate rattle as coin in Apollonius' belt. Then what of this girl? Dion felt as if a hand from the sky was ordaining him her protector. Yet what power had he?

Upon hearing the commotion about the litter Apollonius turned back. As if to redeem his repute for the dastardly insult of a few moments before, he now made most respectful salaam to the young woman, and, with the semblance of kindly solicitude for Glaucon, gave orders detailing Captain Dion to act as guard for the wounded man. Thus, having assumed by his manner the credit for what Dion had already done, he rejoined his suite.

The men were about to lift the litter when Deborah startled them with the cry:

"But Caleb! Where is the blind boy? Surely he came this way."

"We have seen none such. He must have passed by another street. Doubtless he has gone home," was the Greek's response.

"Oh, I must find him!"

There was a maternal depth in the girl's tones.

"Where could he have gone? Help me, good sir, and the blessing of the Lord will be upon you."

"We could not find him in these streets," said Dion. "Let us go first to your home. If he is not there we will search elsewhere. And I think that my name will open any place where he may be detained."

"Quick, then; let us haste!"

The girl in her eagerness led the way. Reaching the house, she opened the outer door, which had not been fastened after her exit a little while before, and sped across the open court. Elkiah was calling.

"Here am I, father!" and in an instant more she was beside him on the roof.

"My daughter, where have you been? Have the Gentiles bewitched even my Deborah, that she should go out of doors to gaze at them? Nay, veil your face with shame, child. Henceforth you must abide strictly in the house. It may be our sepulchre, but I would rather my daughter died here, than that the same sun should greet her eyes and theirs, except that she hated them. But for a daughter of Jerusalem to so much as look upon their garments is to play the wanton."

"Speak not such words, my father," cried Deborah, kneeling by his side, and placing his hands upon her forehead in claiming his blessing.

"It is Benjamin, father. They have brought him back to us, and——"

"Benjamin!" cried the old man, his voice failing in utterance until it became almost a hiss. "Benjamin! I have no son Benjamin. He has disowned his[52] name; I disown his blood. What does the traitor Glaucon do in the house of Elkiah? Let him be gone! I charge thee, Deborah, if thou be a true daughter, banish him from our house."

"But, father——"

"Nay, let him be gone!"

"But, father, Benjamin is harmed; wounded; it may be he is killed."

The venerable man raised himself on his arm, and stared about him. Deborah laid him gently back upon the pillows.

"Oh, father, do not curse him. It may be he will not live. Do not curse him."

He gazed at her, taking her face between his hands and drawing it close to his.

"Aye, my Miriam again! Would God, Deborah, you had been my son!"

"But, father, pity our Benjamin. He is grievously hurt."

A change passed over the features of Elkiah. Suddenly the tears dimmed his sight, and he said:

"Benjamin hurt? My boy? The child of Miriam harmed? Where is he? Help me, that I may go to him."

He vainly tried to rise. His hands clenched as he muttered:

"The Lord avenge the house of Elkiah upon the heads of the heathen! The Lord spare my child! Benjamin! Benjamin! Would God I had died for thee!"

When she had seen the wounded man brought safely into the lower chamber, Deborah quickly searched every part of the house, and her cry for Caleb rang from the roof to the court.

"He is not here. I will go again to the street."

The strong, but kind, hand of Dion blocked the way: "Nay, good maiden, you cannot return to the city. I will go where you could not. I swear to search the streets and camps if you will but pledge me to abide here."

"A pledge to a Greek!"

But the look of scorn passed quickly from her face, as she saw the solicitude in his. After a little thought, in which her agitated manner told that she could keep such a promise only with her body, and that her whole soul would go with Dion in his search, she replied:

"It is well. I see it is my duty to stay here, sir. But hasten! Hasten, and I will pray for you every step. The Lord bless you, good sir!"

"Your own blessing were enough," said Dion, as he ran down the steps.

Dion knew that a personal search for the lad among the crowds of soldiers, who were lodged in half the houses of the city, and in hundreds of tents beyond the walls, would be a long, if not a useless one, since, if any persons had captured the child, they would have reason for concealing his whereabouts. Dion went, therefore, at once to the headquarters of Apollonius, that he might obtain an order that none would dare disregard.

The house appropriated to the Governor's use was the palace on Mount Sion. Though the finest residential structure in Jerusalem, like Elkiah's house, it was but a sorry scion of its architectural pedigree. For instead of the colonnades where Solomon once walked, and the golden roof which had sheltered the harem of that pious libertine, where now the lime whitened walls and domes of what, but for its site, might have been taken for a caravansery.

Captain Dion passed through the court, with its broken ancient fountains and cheap reproductions of recent Greek statuary. He was greeted by Apollonius at the entrance to the hall of audience.

"Welcome, Dion! In time to sup with me to-night. After the feast we will have a symposium that will make the dead Alexander come to life with envy. He would risk another death by fever for the[55] sake of a draught of such wines as the King has sent me from Antioch."

Dion excused himself, and stated the purpose of his visit.

"Nay; so jovial and witty a comrade as yourself cannot be let off," cried the roystering commandant. "Nor need you trouble yourself about the boy. I will issue the order that he be brought here. It will be a quicker way and more certain—that is, if the circumcised dog be living, which we may doubt; for, since the permission given yesterday, the men are making short work of all this Jewish spawn."

Dion changed his tack, and urged that he must return to take care of his friend Glaucon.

"What care you for the traitor Glaucon?" replied the General. "If that man betrays his own race he will not be true to you. It is enough that such creatures as Glaucon are allowed to live, and keep their property, which should be our common spoil. Let him die of his hurt; we shall all be the better off, with one Jew less and houses more. But stay you shall, Dion, or, by Herakles! I will issue orders to cut the boy's throat when found. No carouse is complete if Dion be absent," he said, throwing his arm about him. "Come now, it's a treaty with you. I know that your friendship is not for Glaucon, but for the black-eyed Diana, his sister, whom I saw to-day. Drink with us you shall, or I shall be jealous as Zeus is of his Hera, and send your Jewish goddess straight to Antiochus as a gift. Go, then, get your ivy and head-grease, and come back quickly; for see, the gnomon already casts shadow of six paces—the hour the gods themselves have set for supper."

"Then I must eat your dainty meats," said Dion, seeing the futility of opposing the distempered will of his superior. Veiling his resentment under a forced hilarity, he retired, and a half-hour later returned in company with the other guests.

These were high officers in gorgeous togas, and caps whose tasselled tops lapped down to their shoulders. Each of these revellers was accompanied to the palace by one or more slaves, who would wait upon their masters at the feast, and take them home when drunk. A few subalterns were invited who, like Dion, compensated for lack of rank by their ready wit and their repertoire of stories and songs.

As the guests reclined upon the cushions their shoes were unlaced and removed by Apollonius' menials, their feet washed in scented water, and gently rubbed with towels, while their caps were displaced by crowns of bay leaves gemmed with the pearly berries. Then the low tables were drawn within reach, laden with all that the distant markets of Antioch could furnish; for the conquered land of Judea gave them not so much as a fig or date. The Jews had left for the invaders only fish and game; but woe to the Syrian soldier who should venture beyond his camps to drop a line in lake or send an arrow after beast or bird!

The viands were quickly disposed of, for, following the Greek custom, no wine was poured until the meats and spicy condiments had created abundant thirst.

"A soldier's hunger is soon satisfied, but his thirst is like the river Oceanus that runs round the earth and has no end," cried Apollonius. "Let's to the potation. Who shall be master of the feast?"

"Dion! Dion!" was shouted, with clapping and cheers.

Apollonius whispered to his next neighbor:

"The master of the feast, according to custom, must remain sober. We must have Dion's tongue loosened with wine, or we shall not skim the cream of his wit. Call for Kallisthenes. He is duller drunk than sober."

"Kallisthenes! Kallisthenes!" went round the table, as the suggestion of the host was whispered from one to another.

"This is a deserved honor," shouted Apollonius, "for the man who fired the gates of the Jews' Temple."

"Aye, it was a valiant deed, for there wasn't so much as a lame Jew to stop him," said Sotades to Dion, who reclined next to him.

"If Apollonius is scattering heroic honors to-night, he should send for the High Priest, Menelaos, for he stole the golden candlesticks from the Holy Place before we could get hold of them," said another.

"Menelaos! The Jew turned Greek! Dion says he once frightened an Ethiopian into a white man. So Menelaos became a Greek. That Jew's lips would poison the wine. Let him get ready for his feast with the worms of Gehenna," grunted the Governor.

Kallisthenes at once assumed the prerogative of Ruler of the Feast. He put on a chaplet of ivy, and proclaimed the laws for the hour.

"Hear ye, my subjects, the rules of the feast, which all shall obey under penalty of the wrath of the gods. May Bacchus and Aphrodite both desert the wretch who fails in his duty."

"Law the first—The wine shall not be mixed with more than half water."

"What goblets shall we use?" asked one. "If the larger ones, I vote for one part wine to three parts water, as Hesiod recommends."

"A frog's drink, as Pharecrates called it," replied the Ruler. "Half and half it shall be, and he who shirks the large goblet shall drink from the crater itself. Are we not all philosophers? And did not Socrates drink from the wine cooler?"

"Agreed! Agreed!" echoed round the circle.

One ruddy-faced veteran knelt in mock adoration at the feet of the Feast Master:

"I humbly crave that, since I was born in distant Phrygia, we to-night follow the custom of the barbarians, and drink no water at all. Let us be inspired with the unadulterated soul of the god."

"Bacchus pardon thy gluttony for the sake of thy piety," said the Master.

"Law the second—Whereas wine should be drunk either hot or cold, and whereas, these Jews who are still above Hades have stopped the way to the mountains where lies the snow to chill it, therefore it is ordained that all drinks shall be heated with both fire and spice."

"Agreed! Agreed!"

"Law the third—Every goblet shall be quaffed from brim to bottom between two breaths."

"It is agreed!"

"Oh! my paunch!" cried one. "Do you think me a Deucalion to stand the deluge?"

Servants poured the water and wine in equal quantities into the crater, or great bowl, from[59] which it was ladled into the large goblets, holding half a quart each.

"A bumper first to Bacchus."

It was drunk with avidity. One started a song from the old poet Anacreon:

"Eros follows Bacchus," cried the Feast Master. "Now a cup to the Syrian goddess Astarte, since we are in her land, or to Aphrodite, Venus, or whatever name each one calls his lady-love."

"Aye, a cup to Bathsheba! if any one has found a Jewess to his taste," shouted Apollonius, lifting his goblet toward Dion.

Songs and comic speeches, extemporized pantomimes, riddles and stories, as the wine happened to stir the peculiar talent or caprice of the guest, interspersed the drinking.

As the hours advanced the curtains at the doorway were swung aside, and a troop of dancing girls entered. They were of various races; the fair Caucasian from the Euxine, the Egyptian whose hue was the reflection of her desert sands, swarthy half-black Arabs from beyond Jordan, and Nubians whose faces seemed cut from solid jet—slaves whom Apollonius had captured or exchanged for other spoil of battle. These rendered the various songs and dances of their native lands. One performed the hazardous exploit of stepping to the throbbing of the zither between a score of sword blades, set with[60] points upward. Another honored Apollonius by advancing on her hands, seizing the ladle of the wine jar between her toes, and dexterously filling with its contents the empty cup of the commandant.

"Let Apollonius, the valiant conqueror of Jerusalem, show us a daughter of Israel. He is making a harem of them, if report be true," cried one.

"Jewish maidens will not dance on anything except the thin air. So we had to hang a score of them yesterday," replied Apollonius. "But I will show you a genuine Jewish Cupid."

"A circumcised Cupid! Apollonius' wit is as sharp as his knife," cried Kallisthenes.

The Governor whispered to an attendant. In a few moments there was thrust into the room a naked boy. His limbs were exquisitely moulded. His large distended pupils shone with strange lustre in the flashing lights of the jewelled lanterns. His outstretched hands and cautious step showed that there was no sight in his eyes.

"Bravo! Bravo! Cupid is blind! Well thought, Apollonius! Let us see to whom he has brought a message from the goddess," said Sotades.

At this moment Kallisthenes uttered a cry of surprise and horror. He leaped to his feet and pointed to the great bowl from which the wine was taken.

The servant, whose attention had been unduly drawn to the revellers, had inadvertently laid the ladle across the brim of the crater,—a thing regarded as ominous of dire calamity to some one of the guests, the evil to be averted only by the instant cessation of the revelry.

The feasters looked, and echoed the consternation of the Feast Master.

The guests unceremoniously rose, and were hastening as fast as their uncertain legs and frightened attendants could carry them, when Apollonius recalled them. "A curse on the slave! Let us appease our Nemesis of the feast with the offal of the villain who has broken its rules!" and lifting the crater he felled the unfortunate man who had perpetrated the dire omen.

As the guests, half sobered by the scene, stood about the prostrate body Apollonius said:

"Hear you, good friends, to-morrow we will treat you to something more ominous still. We will offer another sacrifice,—a sow upon the Jews' altar in the Temple, court. Attend me there. Farewell! Bacchus protect his own!"

Dion took the hand of Apollonius.

"My thanks, General, for your aid in recovering this child, whom I will return to his home."

The Governor lowered his voice:

"Serve me as well when occasion requires, Captain Dion; and if Elkiah's daughter does not reward your service with her favor, tell her what she owes to Apollonius, and I will cast my bait."

The revellers dispersed to their various quarters, some to the citadel, some to the camps outside the walls, and some to the mansions from which they had ejected the owners. One or two of the slaves lighted torches of resinous wood to guide the feet of their masters along the stones, which were slippery with the sewage thrown from the doorways, or poured over the roof parapets into the street. But most of the servants were fully occupied in sup[62]porting the limp bodies of their lords, and now and then lifting them out of the holes where, once fallen, they insisted upon sitting, while they called for more wine, or relieved themselves of what they had already taken.

Dion hastened toward the house of Elkiah, leading the blind child by the hand. As they threaded their way through the narrow streets, Caleb told his story of the day's adventures. He had been seized in the afternoon, and taken somewhere beyond the walls, among the soldiers in the tents. He overheard his captors talking of the reward that Elkiah would give for the return of his son, and intimating how much more they could wring from Glaucon, when some one claimed him in the name of Apollonius. He was led away, as he supposed, to be killed, and was surprised at being conducted to the palace.

Dion plied him with questions, but could elicit no further information. The Captain knew Apollonius too well to believe that the introduction of a Jewish Cupid at the feast, and the rescue of the lad, were all there was to his purpose. He pondered the problem in the light of the Governor's well-known selfishness and sensuality. Did his design reach to the possession of Deborah?

Coming to the house of Elkiah they were surprised to find the outer door unfastened. Caleb ran up the stairs and heralded his coming with many shouts.

Elkiah was sitting beside the wounded Benjamin in the darkness.

"The Lord be praised! His mercy endureth forever!" ejaculated the father as Caleb flung himself into his arms.

"But where is Deborah?" cried the lad.

"Is not your sister with you? Then how came you hither, child?" replied the old man, in that quick terror to which the events of recent days had made him susceptible.

"I brought him here, sir. I, Dion."