In the html version of this eBook, images with blue borders are linked to higher-resolution illustrations.

Three Years

IN

Tibet

with the original Japanese illustrations

BY

THE SHRAMANA EKAI KAWAGUCHI

Late Rector of Gohyakurakan Monastery, Japan.

PUBLISHED BY

THE THEOSOPHIST OFFICE, ADYAR, MADRAS.

THEOSOPHICAL PUBLISHING SOCIETY, BENARES AND LONDON.

1909.

(Registered Copyright.)

PRINTED BY ANNIE BESANT AT THE VASANTA PRESS, ADYAR, MADRAS, S. INDIA.

I was lately reading the Holy Text of the Saḍḍharma-Puṇdarīka (the Aphorisms of the White Lotus of the Wonderful or True Law) in a Samskṛṭ manuscript under a Boḍhi-tree near Mṛga-Ḍāva (Sāranāṭh), Benares. Here our Blessed Lord Buḍḍha Shākya-Muni taught His Holy Ḍharma just after the accomplishment of His Buḍḍhahood at Buḍḍhagayā. Whilst doing so, I was reminded of the time, eighteen years ago, when I had read the same text in Chinese at a great Monastery named Ohbakusang at Kyoto in Japan, a reading which determined me to undertake a visit to Tibet.

It was in March, 1891, that I gave up the Rectorship of the Monastery of Gohyakurakan in Tokyo, and left for Kyoto, where I remained living as a hermit for about three years, totally absorbed in the study of a large collection of Buḍḍhist books in the Chinese language. My object in doing so was to fulfil a long-felt desire to translate the texts into Japanese in an easy style from the difficult and unintelligible Chinese.

But I afterwards found that it was not a wise thing to rely upon the Chinese texts alone, without comparing them with Tibetan translations as well as with the original Samskṛṭ texts which are contained in Mahāyāna Buḍḍhism. The Buḍḍhist Samskṛṭ texts were to be found in Tibet and Nepāl. Of course, many of them had been discovered by European Orientalists in Nepāl and a few in other parts of India and Japan. But those texts had not yet been found which included the most important manuscripts of which Buḍḍhist scholars were in great want. Then again, the Tibetan texts were famous for being[vi] more accurate translations than the Chinese. Now I do not say that the Tibetan translations are superior to the Chinese. As literal translations, I think that they are superior; but, for their general meaning, the Chinese are far better than the Tibetan. Anyhow, it was my idea that I should study the Tibetan language and Tibetan Buḍḍhism, and should try to discover Samskṛṭ manuscripts in Tibet, if any were there available.

With these objects in view, I made up my mind to go to Tibet, though the country was closed not only by the Local Government but also by the surrounding lofty mountains. After making my preparations for some time, I left Japan for Tibet in June, 1897, and returned to my country in May, 1903. Then in October, 1904, I again left Japan for India and Nepāl, with the object of studying Samskṛṭ, hoping, if possible, again to penetrate into Tibet, in search of more manuscripts.

On my return to Japan, my countrymen received me with great enthusiasm, as the first explorer of Tibet from Japan. The Jiji, a daily newspaper in Tokyo, the most well-known, influential and widely read paper in Japan, and also a famous paper in Ōsaka, called the Maimichi, published my articles every day during 156 issues. After this, I collected all these articles and gave them for publication in two volumes to Hakubunkwan, a famous publisher in Tokyo. Afterwards some well-known gentlemen in Japan, Mr. Sutejiro Fukuzawa, Mr. Sensuke Hayakawa and Mr. Eiji Asabuki, proposed to me to get them translated into English. They also helped me substantially in this translation, and I take this opportunity of expressing my grateful thanks to them for the favor thus conferred upon me.

When my translation was finished, the British expedition to Tibet had been successful, and reports regarding it were soon afterwards published. I therefore stopped the[vii] publication of my English translation, for I thought that my book would not be of any use to the English-reading public.

Recently, the President of the Theosophical Society, my esteemed friend Mrs. Annie Besant, asked me to show her the translation. On reading it she advised me to publish it quickly. I then told her that it would be useless for me to publish such a book, as there were already Government reports of the Tibetan expedition, and as Dr. Sven Hedin of Sweden would soon publish an excellent book of his travels in Tibet. But she was of opinion that such books would treat of the country from a western point of view, whilst my book would prove interesting to the reader from the point of view of an Asiatic, intimately acquainted with the manners, the customs, and the inner life of the people. She also pointed out to me that the book would prove attractive to the general reader for its stirring incidents and adventures, and the dangers I had had to pass through during my travels.

Thus then I lay this book before the English-knowing public. I take this opportunity of expressing my grateful thanks to Mrs. Besant for her continued kindness to me in looking over the translation, and for rendering me help in the publication. Were it not for her, this book would not have seen the light of day.

Here also I must not fail to express my sincere thanks to my intimate friend Professor Jamshedji N. Unwalla, M.A., of the Central Hinḍū College, Benares; for he composed all the verses of the book from my free English prose translation, and looked over all the proof-sheets carefully with me with heartiest kindness.

I must equally thank those people who helped me in my travels in a substantial manner, as well as those who rendered me useful assistance in my studies; nay, even those who threw obstacles in my way, for they, after all,[viii] unconsciously rewarded me with the gift of the power to accomplish the objects I had in view, by surmounting all the difficulties I had to go through during my travels.

With reference to this publication, whilst reading the Aphorisms of the White Lotus of the Wonderful Law this day, I cannot but feel extremely sorry in my heart when I am reminded of those people who suffered a great deal for my sake, some being even imprisoned for their connexion with me when I was in Tibet. But on the other hand, it is really gratifying to me, as well as to them, to know that, after all, their sufferings for my sake will be amply compensated by the good karma they have certainly acquired for themselves through their acts of charity and benevolence, that have enabled me to read and carefully study with greater knowledge, accuracy and enthusiasm, the most sacred texts of our Holy Religion, than was possible for me before my travels in Tibet. I assert this with implicit faith in the fact that good deeds, according to the Sacred Canon, have indubitably the power to purify Humanity, sunk in the illusions of this world, often compared in our Holy Scriptures to a muddy and dirty pond; at the same time I believe that that power to purify rests with the Glorious Lotus of the Awe-inspiring Law, suffusing all with its brilliant effulgence; and with sweet odor, itself, amidst its muddy surroundings, remaining for ever stainless and unsullied.

EKAI KAWAGUCHI.

Central Hindu College,

Staff Quarters,

Benares City, 1909.

| CHAPTER | PAGE | |

| I. | Novel farewell Presents. | 1 |

| II. | A Year in Darjeeling. | 11 |

| III. | A foretaste of Tibetan barbarism. | 15 |

| IV. | Laying a false scent. | 21 |

| V. | Journey to Nepāl. | 25 |

| VI. | I befriend Beggars. | 35 |

| VII. | The Sublime Himālaya. | 40 |

| VIII. | Dangers ahead. | 44 |

| IX. | Beautiful Tsarang and Dirty Tsarangese. | 51 |

| X. | Fame and Temptation. | 60 |

| XI. | Tibet at Last. | 69 |

| XII. | The World of Snow. | 77 |

| XIII. | A kind old Dame. | 81 |

| XIV. | A holy Cave-Dweller. | 86 |

| XV. | In helpless Plight. | 90 |

| XVI. | A Foretaste of distressing Experiences. | 96 |

| XVII. | A Beautiful Rescuer. | 99 |

| XVIII. | The Lighter Side of the Experiences. | 104 |

| XIX. | The largest River of Tibet. | 108 |

| XX. | Dangers begin in Earnest. | 112 |

| XXI. | Overtaken by a Sand-Storm. | 116 |

| XXII. | 22,650 Feet above Sea-level. | 123 |

| XXIII. | I survive a Sleep in the Snow. | 127 |

| XXIV. | ‘Bon’ and ‘Kyang’. | 131 |

| XXV. | The Power of Buḍḍhism. | 135 |

| XXVI. | Sacred Mānasarovara and its Legends. | 139 |

| XXVII. | Bartering in Tibet. | 144 |

| XXVIII. | A Himālayan Romance. | 150 |

| XXIX. | On the Road to Nature’s Grand Maṇdala. | 162 |

| XXX. | Wonders of Nature’s Maṇdala. | 167 |

| [x]XXXI. | An Ominous Outlook. | 178 |

| XXXII. | A Cheerless Prospect. | 187 |

| XXXIII. | At Death’s Door. | 191 |

| XXXIV. | The Saint of the White Cave revisited. | 204 |

| XXXV. | Some easier Days. | 211 |

| XXXVI. | War Against Suspicion. | 218 |

| XXXVII. | Across the Steppes. | 227 |

| XXXVIII. | Holy Texts in a Slaughter-house. | 233 |

| XXXIX. | The Third Metropolis of Tibet. | 236 |

| XL. | The Sakya Monastery. | 241 |

| XLI. | Shigatze. | 249 |

| XLII. | A Supposed Miracle. | 257 |

| XLIII. | Manners and Customs. | 264 |

| XLIV. | On to Lhasa. | 280 |

| XLV. | Arrival in Lhasa. | 285 |

| XLVI. | The Warrior-Priests of Sera. | 291 |

| XLVII. | Tibet and North China. | 297 |

| XLVIII. | Admission into Sera College. | 304 |

| XLIX. | Meeting with the Incarnate Boḍhisaṭṭva. | 311 |

| L. | Life in the Sera Monastery. | 323 |

| LI. | My Tibetan Friends and Benefactors. | 329 |

| LII. | Japan in Lhasa. | 335 |

| LIII. | Scholastic Aspirants. | 345 |

| LIV. | Tibetan Weddings and Wedded Life. | 351 |

| LV. | Wedding Ceremonies. | 362 |

| LVI. | Tibetan Punishments. | 374 |

| LVII. | A grim Funeral and grimmer Medicine. | 388 |

| LVIII. | Foreign Explorers and the Policy of Seclusion. | 397 |

| LIX. | A Metropolis of Filth. | 407 |

| LX. | Lamaism. | 410 |

| LXI. | The Tibetan Hierarchy. | 417 |

| LXII. | The Government. | 428 |

| LXIII. | Education and Castes. | 435 |

| LXIV. | Tibetan Trade and Industry. | 447 |

| LXV. | Currency and Printing-blocks. | 461 |

| [xi]LXVI. | The Festival of Lights. | 467 |

| LXVII. | Tibetan Women. | 472 |

| LXVIII. | Tibetan Boys and Girls. | 479 |

| LXIX. | The Care of the Sick. | 484 |

| LXX. | Outdoor Amusements. | 489 |

| LXXI. | Russia’s Tibetan Policy. | 493 |

| LXXII. | Tibet and British India. | 509 |

| LXXIII. | China, Nepāl and Tibet. | 519 |

| LXXIV. | The Future of Tibetan Diplomacy. | 526 |

| LXXV. | The “Monlam” Festival. | 531 |

| LXXVI. | The Tibetan Soldiery. | 549 |

| LXXVII. | Tibetan Finance. | 554 |

| LXXVIII. | Future of the Tibetan Religions. | 561 |

| LXXIX. | The Beginning of the Disclosure of the Secret. | 566 |

| LXXX. | The Secret Leaks Out. | 574 |

| LXXXI. | My Benefactor’s Noble Offer. | 584 |

| LXXXII. | Preparations for Departure. | 590 |

| LXXXIII. | A Tearful Departure from Lhasa. | 599 |

| LXXXIV. | Five Gates to Pass. | 618 |

| LXXXV. | The First Challenge Gate. | 623 |

| LXXXVI. | The Second and Third Challenge Gates. | 636 |

| LXXXVII. | The Fourth and Fifth Challenge Gates. | 642 |

| LXXXVIII. | The Final Gate passed. | 647 |

| LXXXIX. | Good-bye, Tibet! | 652 |

| XC. | The Labche Tribe. | 660 |

| XCI. | Visit to my Old Teacher. | 667 |

| XCII. | My Tibetan Friends in Trouble. | 671 |

| XCIII. | Among Friends. | 677 |

| XCIV. | The Two Kings of Nepāl. | 682 |

| XCV. | Audience of the Two Kings. | 685 |

| XCVI. | Second Audience. | 688 |

| XCVII. | Once more in Kātmāndu. | 692 |

| XCVIII. | Interview with the Acting Prime Minister. | 697 |

| XCIX. | Painful News from Lhasa. | 700 |

| [xii]C. | The King betrays his suspicion. | 703 |

| CI. | Third Audience. | 709 |

| CII. | Farewell to Nepāl and its Good Kings. | 714 |

| CIII. | All’s well that ends well. | 718 |

| PAGE | ||

| 1. | Author’s departure from Japan. | 6 |

| 2. | The Lama’s execution. | 18 |

| 3. | On the banks of the Bichagori river. | 32 |

| 4. | A horse in difficulties. | 49 |

| 5. | Tsarangese village girls. | 57 |

| 6. | Entering Tibet from Nepāl. | 75 |

| 7. | To a tent of nomad Tibetans. | 79 |

| 8. | A night in the open and a snow-leopard. | 92 |

| 9. | Attacked by dogs and saved by a lady. | 100 |

| 10. | Nearly dying of thirst. | 114 |

| 11. | A sand-storm. | 117 |

| 12. | Struggle in the river. | 121 |

| 13. | Meditating in the face of death. | 125 |

| 14. | A ludicrous race. | 132 |

| 15. | Lake Mānasarovara. | 140 |

| 16. | Religion v. Love. | 151 |

| 17. | Near Mount Kailasa. | 169 |

| 18. | Quarrel between brothers. | 181 |

| 19. | Attacked by robbers. | 192 |

| 20. | The cold moon reflected on the ice. | 202 |

| 21. | Fallen into a muddy swamp. | 210 |

| 22. | Meeting a furious wild yak. | 229 |

| 23. | Outline of the monastery of Tashi Lhunpo. | 249 |

| 24. | Reading the Texts. | 266 |

| 25. | Priest fighting with hail. | 274 |

| 26. | Outline of the residence of the Dalai Lama. | 287 |

| 27. | A vehement philosophical discussion. | 306 |

| 28. | An audience with the Dalai Lama. | 316 |

| 29. | Inner room of the Dalai Lama’s country house. | 320 |

| 30. | Room in the finance secretary’s house. | 335 |

| [xiv]31. | Unexpected meeting with friends. | 341 |

| 32. | Girl weeping at being suddenly commanded to marry. | 356 |

| 33. | At the bridegroom’s gate. Throwing an imitation sword at the bride. | 366, 367 |

| 34. | The wife of an Ex-Minister punished in public. | 378, 379 |

| 35. | Funeral ceremonies: cutting up the dead body. | 390, 391 |

| 36. | Lobon Padma Chungne. | 411 |

| 37. | Je Tsong-kha-pa. | 414 |

| 38. | A soothsayer under mediumistic influence falling senseless. | 426 |

| 39. | Flogging as a means of education. | 443 |

| 40. | Priest-traders loading their yaks. | 459 |

| 41. | New year’s reading of the Texts for the Japanese Emperor’s welfare. | 465 |

| 42. | Naming ceremony of a baby. | 480 |

| 43. | A picnic party in summer. | 491 |

| 44. | Prime Minister. | 502 |

| 45. | A corrupt Chief Justice of the monks. | 534 |

| 46. | The final ceremony of the Monlam. | 538 |

| 47. | A scene from the Monlam festival. | 541 |

| 48. | Procession of the Panchen or Tashi Lama in Lhasa. | 568 |

| 49. | Critical meeting with Tsa Rong-ba and his wife. | 580 |

| 50. | Revealing the secret to the Ex-Minister. | 585 |

| 51. | A mysterious Voice in the garden of Sera. | 596 |

| 52. | A distant view of Lhasa. | 605 |

| 53. | Farewell to Lhasa from the top of Genpala. | 606 |

| 54. | Crossing a mountain at midnight. | 610 |

| 55. | Night scene on the Chomo-Lhari and Lham Tso. | 616 |

| 56. | Beautiful scenery in the Tibetan Himālayas. | 634 |

| 57. | The fortress of Nyatong. | 649 |

| 58. | On the way to the snowy Jela-peak. | 654 |

| [xv]59. | Accidental meeting with a friend and compatriot. | 679 |

| 60. | Struggle with a Nepālese soldier. | 690 |

| 61. | Meeting again with an old friend, Lama Buḍḍha Vajra. | 695 |

| 62. | The author and his friend Buḍḍha Vajra enjoying the brilliant snow at Kātmāndu. | 704 |

| 63. | Nāgārjuna’s cave of meditation in Nepāl. | 716 |

| TO FACE PAGE | ||

| 1. | The Author in 1909. | Frontispiece. |

| 2. | The Author just before leaving Japan. | 1 |

| 3. | Rai Bahāḍur Saraṭ Chanḍra Ḍās. | 11 |

| 4. | Lama Sengchen Dorjechan. | 15 |

| 5. | The Author meditating under the Boḍhi-tree. | 25 |

| 6. | Passport in Tibetan for the Author’s return to Tibet in the future. | 645 |

| 7. | The Author as a Tibetan Lama at Darjeeling on his return. | 667 |

| 8. | The Author performing ceremonies in Tibetan costume. | 669 |

| 9. | The Prime Minister of Nepāl, H. H. Chanḍra Shamsīr. | 685 |

| 10. | The Commander-in-Chief of Nepāl, H. E. Bhim Shamsīr. | 697 |

| 11. | Mount Gaurīshaṅkara, the highest peak in the world. (At the end of the volume). | |

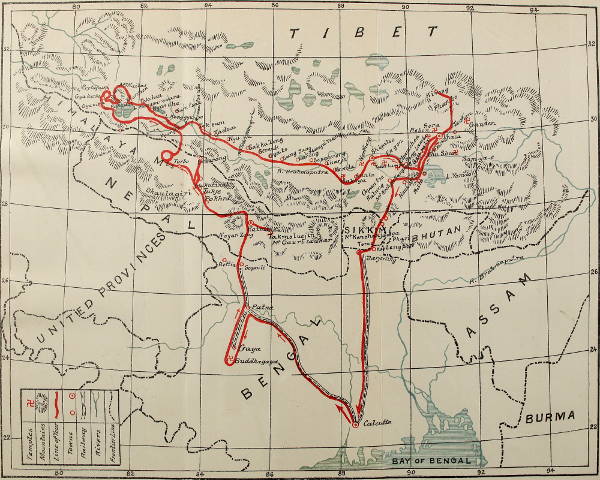

| 1. | Chart of the Route followed by the Author. (At the end of the volume.) |

In the month of May, 1897, I was ready to embark on my journey, which promised nought but danger and uncertainty. I went about taking leave of my friends and relatives in Tokyo. Endless were the kind and heartfelt words poured on me, and many were the presents offered me to wish me farewell; but the latter I uniformly declined to accept, save in the form of sincerely given pledges. From those noted for excessive use of intoxicants, I exacted a promise of absolute abstinence from “the maddening water;” and from immoderate smokers I asked the immediate discontinuance of the habit that would end in nicotine poisoning. About forty persons willingly granted my appeal for this somewhat novel kind of farewell presents. Many of these are still remaining true to the word then given me, and others have apparently forgotten them since. At all events, I valued these “presents” most exceedingly. In Osaka, whither I went after leaving Tokyo, I also succeeded in securing a large number of them. Three of them I particularly prized, and should not fail to mention them here; for, as I think of them now, I cannot help fancying that they had transformed themselves into unseen powers that saved me from the otherwise certain death.

While still in Tokyo I called on Mr. Takabe Tona, a well-known manufacturer of asphalt. Mr. Takabe had been a born fisher, especially skilled in the use of the “shot-net,” and to catch fish had been the joy and pleasure of his life. On the occasion of the leave-taking[2] visit which I paid him, I found him in a very despondent mood. He volunteered to tell me that he had just lost a three-year old child of his, and the loss had left his wife the most distracted woman in the world, while he himself could not recover the peace of his mind, even fishing having become devoid of its former charms for him. I said to my host, who had always been a very intimate friend of mine and a member of my former flock: “Do you really find it so hard to bear the death of your child? What would you think of a person who dared to bind up and kill a beloved child of yours, and roast and eat its flesh?” “Oh! devilish! The devil only could do that; no man could,” answered he. I quickly rejoined: “You are a fiend then, at least, to the fishes of the deep”. Strong were the words I used then, but it was in the fulness of my heart that I spoke them, and Mr. Takabe finally yielded and promised me to fish no more. He was very obdurate at first; but when I pointed out to him that it was at the risk of my life that I was going to Tibet, and that for the sake of my religion, which was also his, he stood up with a look of determination. He excused himself from my presence for awhile, and then returned with some fishing-nets, which he forthwith handed over to me, saying that those were the weapons of murder with which he had caused the death of innumerable denizens of the brine, and that I might do with them as I liked, for he had no longer any use for them. I thereupon asked a daughter of the host’s to build a fire for me in the yard; and, when it was ready, I consigned the nets to flames in the presence of all—there were all the members of the family and some visitors, besides, to witness the scene. Among the visitors was Mr. Ogawa Katsutaro, a relative of the family. This gentleman had also been an excellent sportsman, with[3] both gun and nets. He had seen the dramatic scene before him and heard me pray for my host. As the nets went up in smoke, Mr. Ogawa rose and said impressively: “Let me too wish that you fare well in Tibet, by making to you the gift of a pledge: I pledge myself that I will never more take the lives of other creatures for amusement; should I prove false to these words let ‘Fudo Myo-oh’ visit me with death.” I had never before felt so honored and gratified as I felt when I heard this declaration. Then in Sakai, while taking leave of Mr. Ito Ichiro, an old and lifelong friend of mine, who, also, counted net-fishing among his favorite sports, I told him all about the burning of Mr. Takabe’s nets; and he, too, did me the favor of following the example set by my Tokyo friends. Then I called on Mr. Watanabe Ichibei at Osaka. He is, as he has always been, a very wealthy man, now dealing chiefly in stocks and trade with Korea. His former business was that of a poultry-man, not in the sense of one who raises fowls, etc., but of one who keeps an establishment where people go to have a poultry dinner. His business throve wonderfully; but I knew that his circumstances were such that he could well afford to forego such a sinful business as one which involved the lives of hundreds of fowls every day, especially as he had been a zealous believer of our religion. Several times previously I had written him, beseeching him to give up his brutal business, and I repeated the appeal on the occasion of my last visit to him before my departure for Tibet, when he promised, to my great gratification, that, as speedily as possible, he would change his business, though to do so immediately was impracticable. I was still more gratified when I learned that he had proved the genuineness of his promise about a year and a half after my departure. Ordinarily considered, my conduct in exacting these pledges might[4] appear somewhat presumptuous; but it ought to be remembered that the sick always need a medicine too strong for a person in normal health, and the two classes of people must always be treated differently in spiritual ministration as in corporeal pathology. Be that as it may, I cannot help thinking of these gifts of effective promises, as often as I recall my adventures in the Himālayas and in Tibet, which often brought me to death’s door. I know that the great love of the merciful Buḍḍha has always protected me in my dangers; yet, who knows but that the saving of the lives of hundreds and thousands of finny and feathered creatures, as the result of these promises, contributed largely toward my miraculous escapes.

Farewell visits over, I was ready to start, but for some money. I had had a small sum of one hundred yen of my own savings; but this amount was swelled to 530 yen, by the generosity of Messrs. Watanabe, Harukawa, and Kitamura of Osaka, Hige, Ito, Noda, and Yamanaka of Sakai, and others. Of this total, I spent about one hundred in fitting myself out for a peculiarly problematical journey, and the very modest sum of half a thousand was all I had with me on my departure.

It is curious how little people believe your words, until you actually begin to carry them out, especially when your attempt is a venturesome one, and how they protest, expostulate, and even ridicule you, often predicting failure behind your back, when they see that you are not to be dissuaded. And I had the pleasure of going through these curious experiences; for many indeed were those who came to me almost at the last moment to advise, to ask, to beg me to change my mind and give up my Tibetan trip, and I could see that they were all in earnest. For instance, on the very eve of my departure, while spending my last night at[5] Mr. Maki’s in Osaka, a certain judge of the Local Court of Wakayama came on purpose to tell me that I was bound to end my venture in making myself a laughing-stock of the world by meeting death out of fool-hardiness, and that I would do far better by staying at home and engaging in my ecclesiastical work, a work which, he said, I had full well qualified myself to undertake; to do the latter was especially advisable for me, because the Buḍḍhist circle of Japan was in great need of earnest and capable men, and so on. Seeing that I was not to be moved in my determination, the judge said: “Suppose you lose your life in the attempt? you will not be able to accomplish anything.” “But it is just as uncertain whether I die, or I survive my venture. If I die, well and good; it will be like the soldier’s death in a battle-field, and I should be gratified to think that I fell in the cause of my religion,” I answered. Then the judge gave me up for incorrigible and went away, after wishing me farewell in a substantial manner. That was on the night of June 24th, 1897. Early on the following morning I left Osaka, and on the next day I embarked on the Idzumi-maru at Kobe, seen off by my friends and well-wishers already mentioned. Among them was Mr. Noda Giichiro, who told me that he was very glad as well as very sorry for this departure of mine, and that his words could not give adequate expression to the feelings uppermost in his heart. I thought these touching words expressed the feelings shared by my other friends also.

Hats and handkerchiefs grew smaller and fainter until they went out of sight, as the good ship Idzumi steamed westward. Past Wada promontory, my old acquaintances, the peaks of Kongo, Shigi and Ikoma, in turn, disappeared in the rounding sea. In due time Moji was reached and then, out of the Strait of Genkai,[7] our ship headed direct for Hongkong. At Hongkong, Mr. Thompson, an Englishman, boarded our ship, and his advent proved to be a welcome change in the monotony of the voyage. He said he had lived eighteen years in Japan, and he spoke Japanese exceedingly well. I found in him an earnest and enthusiastic Christian; and, as may be imagined, he and I came to spend much of our time in religious controversies, which, as they were carried on, it may be needless to add, in a most friendly way, became a source of much pleasure and information, not only to ourselves, but also to all on board. Another interesting experience which I went through during the voyage was when I preached—and I preached quite a number of times—before the officers and men of the ship, who proved the most willing and interested audience I had ever come across.

On the 12th of July, the Idzumi entered the port of Singapore, and I put up at the Fusokwan Hotel there. On the 15th, I called at the Japanese Consulate in the port, and saw Mr. Fujita Toshiro, our then Consul there. Mr. Fujita had heard of me from the Idzumi’s captain, and he said to me: “I hear you are going to Tibet. I do not know how you have got your venture mapped out, but I know it is a very difficult thing to reach and enter that country. Even Col. Fukushima (now Lieutenant-General, of trans-Siberian fame) made a halt at Darjeeling, and had to retrace his steps thence, acknowledging practically the impossibility of a Tibetan exploration, and I cannot see how you can fare better. But if you must, I think there are only two ways of accomplishing your purpose: namely, to force your way by the sheer force of arms at the head of an expedition, for one; and to go as a beggar, for the other. May I ask you about your programme?” I answered Mr. Fujita to the effect that being a Buḍḍhist priest, as I was, the first[8] of the methods he had mentioned was out of the question for me, and that my idea at the time was to follow the second course; although I was far from having anything like a definite programme of my journey. I told him, further, that I intended to wander on as the course of events might lead me. I left the Consul in a very meditative mood.

I stayed a week in Fusokwan, and it was on the last day but one before leaving it that I narrowly escaped a serious, even mortal, accident. As a priest, I made it, as I make it now, my practice to do preaching whenever and wherever an opportunity presented itself, and my rigid adherence to this practice greatly pleased the proprietor of that Singapore establishment. In consequence of this, I was treated with special regard while there, and every day, when the bath was ready, I was the first to be asked to have the warm water ablution, which is always so welcome to a Japanese. On the 18th, the usual invitation was extended to me, but I was just at that moment engaged in reading the Text, and could not comply with it at once. The invitation was repeated a second time, but, somehow or other, I was not ready to take my bath, and remained in my room. Meanwhile, I heard a great noise, with a thud that shook the whole building. A few moments later, I ascertained that the sound and quaking were caused by the collapse and fall of the bath-room from the second floor, where it had been situated, to the ground below, with its bath, basin, and all the other contents, among which the most important and unfortunate was a Japanese lady, who, as I had been neglectful in accepting the invitation, was asked to have her bath first. The lady was, as I afterward learned, very dangerously hurt, buried, as she was, under débris of falling stones, bricks and timber, and she was taken to a local hospital, where she[9] lay with very little hope of recovery. I often shudder to think of what would have become of me and of my Tibetan adventure, had I been more prompt, as I had always been till then, in responding to all invitations of the kind. I felt exceedingly sorry for the lady, who met the awful accident practically in my stead; withal I look back to the incident as one that augured well for my Tibetan undertaking, which, indeed, ended in success.

The day after the accident, on the 19th of July, I took passage on an English steamer, the Lightning, which, after calling at Penang, brought me to Calcutta on the 25th of the month. Placing myself under the care of the Mahāboḍhi Society of Calcutta, I spent several days in that city, in the course of which I learned from Mr. Chanḍra Bose, a Secretary of the Society, that I could not do better for my purpose than to go to Darjeeling, and make myself a pupil of Rai Bahāḍur Saraṭ Chanḍra Ḍās, who, as I was told, had some time before spent several months in Tibet, and was then compiling a Tibetan-English dictionary at his country house in Darjeeling. Mr. Chanḍra Bose was good enough to write a letter of introduction to the scholar at Darjeeling in my favor, and, with it and also with kind parting wishes of my countrymen in the city and others, I left Calcutta on August 2nd, by rail. Heading north, the train in almost no time brought its passengers to the river Gaṅgā. We crossed the mighty stream in a steamer, and then boarded another train on the other side. Heading north still, the train now passed through cocoanut groves and green paddy-fields, over which, as night came on, giant fire-flies, the like of which in size are not to be found in Japan, flew about in immense swarms. The sight was especially interesting after the moon had disappeared. The following morning, that is, on the 3rd of August, the train pulled up at Siligree Station, and there its passengers, including myself, were transferred to[10] a train of small mountaineering cars, which, faring ever northward, forthwith began its tortuous ascent of the Himālayas, or rather, of the outer skirt of the mighty range. With its bends and turns and climbings, as the train labored onward and upward through the famous “ḍalai-jungle,” it looked like some amphibian monster on its war path, as I fancied, while the grind of the car wheels, with its sound echoed and re-echoed, seemed to spread quaking terror over peaks and dales. By 3 P. M., the train had made a climb of fifty miles and then landed us at Darjeeling, which place is 380 miles distant from Calcutta. At the station I hired a ḍanlee, which is a sort of mountaineering palanquin, and, borne in it, I soon afterward arrived at Rai Saraṭ’s retreat, Lhasa Villa, which I found to be a magnificent mansion.

It was just after the great earthquake in Assam, India, that I arrived in Darjeeling, and, as I could see from a large number of entirely collapsed and partly destroyed houses, this latter place also had had its share of the seismic disturbances. As for the Saraṭ Villa, it too had suffered more or less, and repair was already in progress. For all that, I was received there with a whole-hearted welcome. An evening’s talk was sufficient, however, to make my intentions clear to my kind host, and, as my time was precious, Rai Saraṭ took me out, the very next day after my arrival, to a temple called Ghoompahl, where I was introduced to an aged Mongolian priest, who lived there and was renowned for his scholarly attainments and also as a teacher of the Tibetan language. The priest was then seventy-eight years of age, and his name, which was Serab Gyamtso (Ocean of Knowledge), happened by a curious coincidence to mean in the Tibetan tongue the same thing as my own name Ekai meant. This discovery, at our first meeting, greatly pleased my Tibetan tutor, as the old priest was thenceforth to be. Our talk naturally devolved upon Buḍḍhism, but the conversation proved to be a rather awkward affair, for though Rai Saraṭ kindly acted the part of an interpreter for us, it had to be carried on, on my part, in very rudimentary English. As it was, the first day of my tutelage ended in my making the acquaintance of the Tibetan alphabet, and from that time onward, I became a regular attendant at the temple, daily walking three miles from and back to the Saraṭ mansion. One day, about a month after this, Rai Saraṭ had me in his room and spoke to me thus: “Well, Mr. Kawaguchi, I would advise you to give[12] up your intention of going to Tibet. It is a very risky undertaking, which it would be worth risking if there were any chance of accomplishing it; but chances are almost entirely against you. You can acquire all the knowledge of the Tibetan language you want, here, and you can go back to Japan, where you will be respected as a Tibetan scholar.” I told my host that my purpose was not only to learn the Tibetan language, but that it was to complete my studies in Buḍḍhism. “That may be,” said my host, “and a very important thing it no doubt is with you; but what is the use of attempting a thing when there is no hope of accomplishing it? If you go into Tibet, the only thing you can count upon is that you will be killed!” I retorted: “Have you not been there yourself? I do not see why I cannot do the same thing.” Rai Saraṭ’s rejoinder was: “Ah! That is just where you are mistaken; you must know that the times are different, Mr. Kawaguchi. The ‘closed door’ policy is in full operation, and is being carried out with the most jealous strictness in Tibet to-day, and I know that I will never be able again to undertake another trip into that country. Besides, when I made my trip, I had with me an excellent pass, which I was fortunate to secure through certain means, but there is no means, nor even hope, any longer of procuring such a pass. Under the circumstances I should think it is to your own interest to go home from here, after you have completed the study of the Tibetan language.” I knew that my good host meant all that he said; but I could not allow myself to be prevailed upon. Instead, I utilised the occasion in telling him that further tutelage under Lama Serab was not to my mind, because the aged priest was more anxious to teach me the Tibetan Buḍḍhism than the Tibetan language. I asked Rai Saraṭ to kindly devise for me some way, by which I might acquire[13] the vernacular Tibetan language. Finding me resolute in my purpose, Rai Saraṭ, with his unswerving kindness, cheerfully agreed to my request, and arranged for me that I should have a new private teacher, besides a regular schooling. It was in this way. Just below Rai Saraṭ’s mansion was a residence which consisted of two small but pretty buildings. The residence belonged to a Lama called Shabdung, who just then happened not to live there, but in a house in the business quarters of Darjeeling. Rai Saraṭ sent for this Lama and asked him to teach the “Japan Lama” the Tibetan language, the Lama returning to his residence just mentioned with his entire household. Lama Shabdung was only too pleased to do as was requested, and I was forthwith installed a member of his household, that I might have ample opportunity of learning the popular Tibetan language. On the other hand, I at the same time matriculated into the Government School of Darjeeling, and was there given systematic lessons in the same language by Prof. Tumi Onden, the Head Teacher of the language department of Tibetans in that School. I should not forget to mention here that, while I paid out of my own pocket all the tuition fees and school expenses, as it was quite proper that I should, I was made a beneficiary of my friend Rai Saraṭ so far as my board was concerned, that good man insisting that to do a little kindness in favor of such a “pure and noble-hearted man as you are”—as he said—was to increase his own happiness. Not too well stocked with the wherewithal as I was, I gratefully allowed myself to be prevailed upon to accept his generosity. Indeed, I had only three hundred yen with me when I arrived at Darjeeling; but, as it was, that amount supported me for the seventeen months of my stay there. Had I had to pay my own board, I would have had to cut down my stay there to half the length of time.

At Lama Shabdung’s I lived as though back in my boyhood, attending the school in the morning, and doing my lessons at home in the company of the children of the family in the afternoon. It is a well known thing that the best way to learn a foreign language is to live among the people who speak it, but a discovery—as it was to me—that I made while at Shabdung’s was that the best teachers of everyday language are children. As a foreigner you ask them to teach you their language; and you find that, led on by their instinctive curiosity and kindness, not unmingled with a sense of pride, they are always the most anxious and untiring teachers, and also that in their innocence they are the most exacting and intolerant teachers, as they will brook no mis-pronunciation or mis-accent, even the slightest errors. Next to children, women are, I think, the best language teachers. At least such are the conclusions I arrived at from the experiences of my ‘schooling days’ in Darjeeling. For in six or seven months after my instalment in the Shabdung household, I had become able to carry on all ordinary conversation in the Tibetan tongue, with more ease than in my English of two years’ hard learning, and I regard Tibetan as a more difficult language than English. True, I made myself a most willing and zealous pupil all through the tutelage; withal, I consider the progress I made in that short space of time as quite remarkable, and that progress was the gift of my female and juvenile teachers in the Shabdung family. The more progress I made in my linguistic acquirement, the more eager student I became in things Tibetan, and I found in my host a truly charming conversationalist, himself fond of talking. Evening after evening I sat, an absorbed listener to Lama Shabdung’s flowing and inexhaustible store of narratives about Tibet.

To give one of Lama Shabdung’s favourite recitals about Tibet: my host, while there, studied Buḍḍhism under a high Lama of great virtues and the most profound learning, called Sengchen Dorjechan (Great-Lion Diamond-Treasury), who had been the tutor of the Secondary or Deputy Pope, so to say, of Tibet. No man in Tibet was held in higher esteem and deeper reverence than this holy man. It was this holy man himself who taught my friend and benefactor Rai Saraṭ, when he was in Tibet. Though Rai Saraṭ’s pupilage under the high Lama lasted only for a short time, it had the most tragical consequences. For, after his return to India, the Tibetan Government discovered to its own mortification that Rai Saraṭ was an emissary of the British Government, and the parties who had become in any way connected with his visit, more particularly the man who had secretly furnished him with a pass, another in whose house he had lodged and boarded, and the high Lama, were all thrown into prison, the last named having afterward had to pay with his life for his innocent crime.

Many are the reminiscences of this holy Lama, which show that he was indeed a person very firm and enlightened in the Buḍḍhist faith, and to that degree was the most lovable and adorable of men. But more especially affecting, even sublimely beautiful, are the episodes immediately preceding and surrounding his death, for the truth of which I depend not on the narrative of Lama Shabdung alone, but largely also upon what I was able to learn from persons of unquestionable reliability, during my disguised stay in the capital of[16] Tibet. To mention a few of these: when an unpleasant rumor had just begun to be circulated, soon after Rai Saraṭ’s departure from Tibet, about his secret mission, the high Lama Sengchen knew at once that death was at his door, but was not afraid. For, when it was hinted at by his friends that he would become involved in a serious predicament, owing to his acquaintance with Rai Saraṭ, he replied that he had always considered it his heaven-ordained work to try to propagate and to perpetuate Buḍḍhism, not among his own countrymen only, but among the whole human race; that whether or not Saraṭ Chanḍra Ḍās was a man who had entered Tibet with the object of “stealing away Buḍḍhism,” or to play the part of a spy, was not his concern—the question had in any case never occurred to him—and that if he were to suffer death for having done what he had regarded it as his duty to do, he could not help it. That this holy Lama was an advocate of active propagandism may be gathered from the fact that, besides sending various Buḍḍhistic images and ritualistic utensils to India, he had caused several persons to go out there as missionaries, my teacher, the Manchurian Lama Serab Gyamtso, in the Ghoompahl Temple of Darjeeling, being one of these. Unfortunately, this undertaking did not prove a success, but none the less it shows the lofty aspirations which actuated the high Lama, who, as I was told, had deeply lamented the decadence, or rather the almost entire disappearance, of Buḍḍhism in the land of its origin, and was sincerely anxious to revive it there. It is nothing uncommon in Japan to meet with Buḍḍhist priests interested in the work or idea of foreign propagandism; but a person so minded is an extreme rarity in that hermit-country Tibet, and that Lama Sengchen was such a one indicates the greatness of his character, and that he was a man above sectarian differences and inter[17]national prejudices, solely given to the noble idea of universal brotherhood under Buḍḍhism. Being the man he was, he had many enemies among the high officials of the hierarchical Government, who were in constant watch for an opportunity to bring about his downfall. To these, his enemies, the rumor about Prof. Saraṭ was a welcome one, which they lost no time in turning to account. In all haste they despatched men to Darjeeling, and ascertained that, in truth, Rai Saraṭ had smuggled himself into and out of Tibet, and that, as the fact was, he had done so at the request of the British Government of India. Then followed the incarceration, already mentioned, of all those who had had anything to do with Rai Saraṭ, the final upshot of which was sentence of death upon the high Lama Sengchen Dorjechan, on the ground that the latter had harbored in his temple, and divulged national secrets to, a foreign emissary. The holy man’s execution was carried out on a certain day of June, 1887, and took the form of sinking him till he became drowned in the river Konbo, which is a local name given to the great Brahmapuṭra. As I recall the scene of that occasion, as I heard it described, I see before my eyes the tear-drenched face of my friend Lama Shabdung, who, struggling with emotion, would often tell me what he witnessed on that day. Surrounded by an immense crowd of sympathising and sobbing people, the noble Lama was found seated, and reading the sacred Text, on a large piece of rock overhanging a side of the river, as the hour of his execution approached. He was clothed in a coarse white fabric, and looked serenely calm and perfectly composed, as he gave an order to his executioners in these words: “When, in a little while, I have finished reading the holy Text, I will shake this my finger three times thus, and that[19] will be the signal for you to sink me in the river.” The instruction was in response to a question, if the high Lama wanted to say or have done anything ere his execution, asked by one of the executioners, who was already tying around the holy man’s body one end of a thick rope, with which he was to be lowered under the water. In the meantime, the suspense grew intense and the great multitude that had gathered around had become blind to everything but the mighty, cruel waters of the Brahmapuṭra, the executioners, and the holy priest, and deaf to all but their own sobbings and wailings. They saw before them a man of their hearts, of national esteem, profound in learning and saintly in behavior, who, as a priest of the highest order, should wear three layers of red and yellow silk, but who was wrapped in an unclean prison-suit of white, and was now to die a victim to his enemies’ malice. They knew all was not right, but they knew not how to undo the wrong, and they appealed to their own tears. As it happened, the day had been cloudy, and rain had even begun to come down in drops as the high Lama raised one of his hands, the purpose of which act was all too evident, and lamentation became loud and universal. Once, twice, and three times the noble prisoner had shaken his finger, but none of the executioners dared to come forward—they were in tears themselves. Then the high Lama said: “My time is come: what are ye doing? Speed me under water.” Thereupon, with heavy hands and heavier hearts the executioners, after having weighted the high Lama’s loins with a large stone, slowly lowered the whole burden into the rushing waters of the Brahmapuṭra. After a while they pulled up what they expected to have become the remains of the saintly man, but finding that life had not yet departed, they[20] again went through the drowning process. When for a second time they raised the body, they found life still lingering in it. The multitude, which saw how things went, became clamorous in their demand that the holy man be now saved; while the executioners themselves seemed unnerved and unable to go to their cruel duty a third time. As the moments of indecision sped by, the high Lama, most wonderful to tell, recovered sufficient strength to speak, and say: “Lament ye not my death. For my phase of activity having come to an end, I now depart with gratification, and that means that my evil past ceases, so that my good future may begin—it is not ye that kill me. All that I wish for, after my death, is a greater and ever-growing prosperity for Buḍḍhism in Tibet. Now make ye haste, and sink me under the water.” Thus urged, the executioners, sorrow-ridden, obeyed the order, and they saw that life, in sooth, had departed at the third raising of the body. Then, as the custom is in Tibet, they severed all the limbs from the high Lama’s remains, and threw the different parts separately into the stream, thus ending the grim business of execution. It will be admitted by all, especially by all Buḍḍhists, that there was something loftily admirable in the personality of a man who had done and given his all for his faith and religion, and yet uttered not a word of complaint against Providence or man, but, in serene, noble meekness, met his most unmerited and most agonising death. As for me, besides finding it most affecting, I felt a peculiarly direct interest in the story of this high Lama’s execution, from the moment when I was told of it for the first time. For, was I not on my way to Tibet? Should I succeed in my purpose? Who could tell but that there might be a repetition of that sad and cruel scene?

I rose early on the New Year’s day of 1898, and spent the greater part of the morning, as was usual with me, in reading the sacred Text in honor of the day, and also in praying for the health and long life of their Majesties the Emperor and the Empress, and his Highness, the Crown Prince, and for the prosperity of Japan. The New Year’s uta[1] which I composed on the occasion was as follows:

I spent the twelve months following in closely devoting myself to the study, and in efforts at the practical mastery, of the Tibetan tongue, with the result that, toward the close of the year, I had become fairly confident of my own proficiency in the use of the language both in its literary and vernacular forms; and I made up my mind to start for my destination with the coming of the year 1899. Then, it became a momentous question for me to decide upon the route to take in entering Tibet.

Besides the secret path, the Khambu-Rong, i. e., ‘Peach Valley’ pass, there are three highways which one may choose in reaching Tibet from Darjeeling. These are: first, the main road, which turns north-east directly after leaving Darjeeling and runs through Nyatong; second, that which traverses the western[22] slope of Kañcheñjunga, the second highest snow-capped peaks in the Range and brings the traveller to Warong, a village on the frontier of Tibet; and the third, which takes one direct from Sikkim through Khampa-Jong to Lhasa. As, however, each of these roads is jealously guarded either with a fortified gate or some sentinels, at its Tibetan terminus, it is a matter of practical impossibility for a foreigner to gain admittance into the hermit-country by going along any of them. Rai Saraṭ was of opinion that, if I were to present myself at the Nyatong gate, tell the guards there that I was a Japanese priest who wished to visit their country for the sole purpose of studying Buḍḍhism, I might possibly be allowed to pass in, provided that I was courteously persistent in my solicitations; but I had reasons for thinking little of this suggestion. At all events, what I had learned from my Tibetan tutors did not sustain my friend’s view; instead, however, my own information led me to a belief that a road to suit my purpose could be found by proceeding through either the Kingdom of Bhūṭan or of Nepāl. It appeared to me, further, that the route most advantageous to me would be by way of Nepāl; for Bhūṭan had never been visited by the Buḍḍha, and there was there little to learn for me in that connexion, though that country had at one time or another been travelled over by Tibetan priests of great renown; but the latter fact had nothing of importance for me. I had been told, however, that Nepāl abounded in the Buḍḍha’s footsteps, and that there was in existence there complete sets of the Buḍḍhist Texts in Samskṛṭ. These were inducements which I could turn to account, in the case of failure to enter Tibet. Moreover, no Japanese had ever been in Nepāl before me, though it had been visited by some Europeans and Americans. So I decided on a route viâ Nepāl.

The decision made, it would have been all I could wish for, if it were possible for me to journey to Nepāl direct from Darjeeling; there was on the way grand and picturesque scenery incidentally to enjoy, besides places sacred to Buḍḍhist pilgrims. But to do so was not possible for me, or at least implied serious dangers. For most of the Tibetans living in Darjeeling—and there were quite a number of them there—knew that I was learning their language with the intention of some day visiting their country; and it was perfectly manifest that the moment I left that town with my face towards Tibet, they, or some of them at the least, would come after me as far as some point where they might make short work of me, or follow me into Tibet and there betray me to the authorities, for they would be richly rewarded for so doing. To meet the necessity of the case, I gave it out that, owing to an unexpected occurrence, I was obliged to go home at once, and I left Darjeeling for Calcutta, which place I reached on the 5th of January, 1899. I, of course, let Rai Saraṭ into my secret, and he alone knew that the day I left Darjeeling I started on my Tibetan journey in real earnest, though back to Calcutta I took fare in sooth. On leaving Darjeeling, my good host Rai Saraṭ Chanḍra earnestly wished me complete success in my travels to Tibet, and gave vent to his hearty and sincere pleasure in finding in me one, who, as bold and adventurous as himself, was starting on a perilous but interesting expedition to that hitherto unknown country. Previous to my departure from Darjeeling, I received there 630 Rupees, which had been collected and forwarded to me through the kind and never-failing efforts of my friends at home, Messrs. Hige, Ito, Watanabe and others.

During my second and short stay in Calcutta I had the good luck of being introduced to a Nepālese named Jibbahaḍur, who was then a Secretary of the Nepāl Government, but who is now the Minister Resident of that country in Tibet. He was kind enough to write two letters introducing me to a certain gentleman of influence in Nepāl.

On the 20th of January, 1899, I came to the famous Buḍḍhagayā, sacred to Holy Shākyamuni Buḍḍha, and there met Mr. Dharmapala of Ceylon, who happened to be there on a visit. I had a very interesting conversation with him. On learning that I was on my way to Tibet, he asked me to do him the favor of taking some presents for him to the Dalai Lama. The presents consisted of a small relic of the Buḍḍha, enclosed in a silver casket which was in the form of a miniature pagoda, and a volume of the sacred Text written on palm leaves. I, of course, willingly complied with the request of the Sinhalese gentleman, who expressed himself as being very anxious to visit Tibet, but thought it useless to attempt a trip thither, unless he were invited to do so. The night of that day I spent meditating on the ‘Diamond Seat’ under the Boḍhi-tree—the very tree under which, and the very stone on which, about two thousand five hundred years ago, the holy Buḍḍha sat and reached Buḍḍhahood. The feeling I then experienced is indescribable: all I can say is that I sat the night out in the most serene and peaceful extasy. I saw the tell-tale moon lodged, as it were, among the branches of the Boḍhi-tree, shedding its pale light on the ‘Diamond[26] Seat,’ and the scene was superbly picturesque, and also hallowing, when I thought of the days and nights the Buḍḍha spent in holy meditation at that very spot.

After a few days’ stay in Buḍḍhagayā, I took the railway-train for Nepāl, and a ride of a day and a night brought me to Sagauli, on the morning of January 23. Sagauli is a station at a distance of two days’ journey from the Nepālese border. Here one boundary of the linguistic territory of English was reached, and beyond neither that language nor the Tibetan tongue was of any use—one had to speak either Hinḍūsṭāni or Nepālese to be understood, and I knew neither. So it became a necessary part of my Tibetan adventure to stop a while at Sagauli, and make myself master of working Nepālese. It was like forging the chain after catching a criminal. But up to then, my time had been all taken up in learning Tibetan, and I had had no moment to spare for anything else. By good fortune, however, my stay there was not to be a long one. I found the postmaster of Sagauli, a Bengālī, to be proficient both in English and Nepālese. As the thing had to be done in the most expeditious way possible, I started my work by noting down every Nepālese word the postmaster would teach me. The next day after my arrival at Sagauli, while I was out on a walk near the station with my note-book in hand, I noticed, among those who got off a train, a company of three men, one of whom was a gentleman, apparently of forty[27] years of age and dressed in a Tibetan costume, another a priest about fifty years old, and the third unmistakably their servant. Thereupon a thought flashed on me that it would be a good thing for me if I could travel with these Tibetans, as I took them to be, and I immediately made bold to go up to them and ask whither they were going. I was told that their destination was Nepāl, that they had not just then come from Tibet, but that one of them was a Tibetan. It then became their turn to question me, their opening enquiry being as to what country I belonged. I replied that I was a Chinese. “Which direction did you come from then?—did you travel by land or by sea?” was the rejoinder sharply put to me next. That was a question I had to answer with caution. For the rule then in force in Tibet was to admit into that country no Chinaman coming by the sea. So I answered: “By land.” As we conversed, so we walked, and presently we came in front of where I was lodging. In that part of the world there is no such smart thing as a hotel or an inn; all the accommodation one can get in this respect is a shanty of a rather primitive type, with bamboo posts and a straw roof. There are a number of these simple structures there, standing on the roadside and intended only for travellers, who have, however, nothing to pay for lodging in them—they only pay the price of eatables and fuel, should they procure any. It was in one of these shanties that I was stopping, and when I excused myself from the company of my newly made acquaintances, the latter betook themselves into another on the opposite side of the street. After a while the gentleman and the priest came out of their shanty and called on me, evidently bent on finding out who, or rather what, I was. For the first question with which they challenged me was to what part of China I belonged.[28] “To Fooshee,” I replied, realising full well that I was to go through the ordeal of an inquisition. “You speak Chinese, of course?” then asked the gentleman. My reply in the affirmative caused him at once to talk to me in quite fluent Chinese, which put me in no little consternation in secret. Compelled by necessity, I ventured calmly: “You must be talking in the official Peking dialect, while I can talk only in the common Fooshee tongue, and I do not understand you at all.” He was not to let me off yet. Says he next: “You can write in Chinese, I suppose.” Yes, I could, and I wrote. Some of my characters were intelligible enough to my guests, and some not, and after all it was agreed that it was best to confine ourselves to Tibetan. As our conversation progressed, my principal guest came to the crucial part of the inquisition and asked: “You say you have come from the landward side: well, from what part of Tibet have you come?” “In sooth, from Lhasa, sir; I have been on a pilgrimage through Darjeeling to Buḍḍhagayā, and from thence here,” I replied. I was requested to say, then, in what part of the city of Lhasa I lived. Being informed that I was in the grand Sera monastery, he wanted to know if I was acquainted with an old priest who was the Tatsang Kenpo (grand teacher) of that institution. I was bold enough to say that I was not a perfect stranger to the priest in question, and made a right good use of what I had learned from Lama Shabdung at Darjeeling. So far I managed to keep up my disguise, but each moment that passed only added to my fear of being trapped, and compelled to give myself away. To avoid this danger, I felt it important to head off my inquisitorial visitors by dispelling their suspicion, if they entertained any, about me. I was remarkably successful in this, the information obtained from Lama Shabdung again doing me excellent service. For, when[29] I told my guests, in a most knowing way, all about Shabbe Shata’s intrigue against the Tangye-ling, which was designed to increase his own power, and the secret of which affair was not then generally known, the recital seemed to make a great impression on them, and to have had the effect of convincing them that I was the person I pretended to be. So my ordeal was at an end; but there was yet in store for me the most unexpected discovery I was to make about these men.

No longer curious as to my antecedents, my gentleman guest now asked me: “You say you are going to Nepāl: may I ask you who is the person you are directed to, and if you have ever been in that country?” I had never been there before, but I had a letter of introduction with me. From whom, to whom, could that be? The letters, I said—for I had had two given me—were written in favor of me by Mr. Jibbahaḍur, an official of the Nepālese Government, then residing in Calcutta, and addressed to the Lama of the Great Tower of Mahāboḍha in Nepāl, whose name, though I just happened to forget it, was on the letters. This piece of information seemed greatly to interest the gentleman, who could not help saying: “Why, that is strange! Mr. Jibbahaḍur is a friend of mine: I wonder who can be the person to whom the letters are addressed; will you permit me to look at them?” And the climax came when I, in all willingness, took out the letters and showed them to my guest, for he ejaculated: “Well, whoever would have thought it? These are for me!”

I may here observe that in Nepāl, as I found out afterwards, the word friend conveys a much deeper meaning, probably, than in any other country. To be a friend there means practically the same thing as being a brother, and the natives have a curious custom of observing a special ceremony when any two of them tie the knot of friendship between them. The ceremony[30] resembles very much that of marriage, and its celebration is made an occasion for a great festival, in which the relatives and connexions of the parties concerned take part. To be brief, the ceremony generally takes the form of exchanging glasses of the native drink between the mutually chosen two, and they each have to extend their liberalities even to their servants in honor of the occasion. It is only after the observance of these formalities—which signify a great deal to the natives—that any two Nepālese may each call themselves the friend of the other.

It so happened that my erstwhile inquisitor proved to be the official owner and Lama-Superior of the Great Tower above mentioned, who stood in the relationship of a ‘friend’ to Mr. Jibbahaḍur. It was most unexpected, but the discovery was none the less welcome to me, and I besought him to take me, henceforth, under his care and protection. Thus I came to be no longer a stranger and a solitary pilgrim, but a guest, a companion, to a high personage of Nepāl. My newly acquired friend, as I should call the Lama in our language, proposed that we should start for Nepāl the next morning. This proposal was agreeable to me, as was another that we should go afoot instead of on horse-back, so that we might the better enjoy each other’s company, and perchance, also, the grand scenery on the way. I say that all this was agreeable to me, because, in addition to the obvious benefit I was sure to derive from being in the company of these men, I entertained a secret hope that I might learn a great deal, which would help me in executing the main part of my adventures, yet to come.

While our talk was progressing in this fashion, two servants of the Lama’s came in, running and all pale, with the unwelcome piece of news that a thief had broken into their shed. This caused my callers to take[31] precipitate leave of me. I afterwards learned that the Lamas had had three hundred and fifty rupees in cash, and some books and clothes, stolen between them. I was in luck on that occasion, for the owner of my shed told me subsequently that the thief, who caused such a loss to the Lamas, had been on the look-out for a chance to loot my lodging, and, as it happened, he finally made my newly made friends suffer for me; I felt exceedingly sorry for them.

In the meantime I learned that the gentleman Lama’s name was Buḍḍha Vajra (Enlightened Diamond), and that the old priest, whose name was Mayar, and who was full of jokes, was a Doctor of Divinity of the Debon monastery in Lhasa.

Early on the 25th of January we started on our journey, and proceeded due north across the plain in which Sagauli stands. The next day we arrived at a place called Beelganji, where stood the first guarded gate of the Nepālese frontier. There I was given a pass, as for a Chinaman living in Tibet. We passed the night of the following day in a village situated a little way this side of the famous Dalai Jungle, which may be regarded as an entrance to the great Himālayas. On the 28th we proceeded past Simla, a village at the outer edge of the great jungle, and thence, straight across the jungle itself, which has a width of full eight miles, until we came to a village on the bank of a mountain stream called Bichagori, where we took up our lodgings for the night. About ten o’clock that night, while writing up my diary, I happened to look out of the window of my shanty. The moon in her pale splendor was shining brightly over the great jungle, and there was something indescribably weird in the scene, whose silence was broken only by a rushing stream. Suddenly I then heard a detonation, tremendous in its volume and depth, which, as I felt, almost shook[33] the ground. In reply to my query, I was told by our innkeeper that the sound came from a tiger, which evidently had just finished a fine repast on its victim, and, having come to have a draught of river-water, could not help giving vent to its sense of enjoyment. So an uta came to me:

For two days more the road lay now through a dale on the bank of a river, then across a deep forest, and over a mountain, until we reached a stage station called Binbit. So far the road was up a slow, gradual incline, and horse-carriages and bullock-carts could be driven over it; but now the ascent became so steep that it could be made only on foot, or in a mountain-palanquin. We went on foot, commencing our climb as early as four o’clock in the morning. After an ascent of something more than three and a half miles, we came to a guarded gate named Tispance. Here was a custom-house and a fortress, garrisoned by quite a number of soldiers, and we had to go through an examination. Thence we climbed a peak called Tisgari, from the top of which I, for the first time, beheld with wonder the sublime sight of the mighty Himālayas, shining majestically with their snow of ages. The grandeur of the scene was so utterly beyond imagination, that the memory of what I had seen at Darjeeling and Tiger Hill came back to me only as a faint vision. Down Tisgari we came to Marku station, where we took lodging for the night.

Early on the 1st of February, we climbed up the peak C̣hanḍra Giri, or Moon Peak, whose sides are covered[34] with the flowers of the rhododendron, the chief characteristic of the Himālayan Range. Thence I saw again the snow-covered range of Himālaya, ever grand and majestic. Just a little way down from the top of the peak, I saw, spread before me like a picture, Kātmāndu the capital of Nepāl and the country around. I saw also in that panorama two gilded towers rising conspicuously against the sky, and Lama Buḍḍha Vajra told me that one of them was the tomb of Kāṣyapa Buḍḍha, and the other that of Ṣikhī Buḍḍha. On coming down the steep slope of the hill, we were met by four or five men with two horses. They were men sent thither in advance to wait for the return of Buḍḍha Vajra, and I was given one of the horses, while my host took the other. We were met by about thirty more men on entering a village, not far from the foot of the hill. The distance from Sagauli railway station to this spot is roughly one hundred and twenty-five miles.

The village that surrounds the great Kāṣyapa tower is generally known by the name of Boḍḍha. Lama Buḍḍha Vajra, I found, was the Headman of that village as well as the Superior of that mausoleum tower, which in Tibetan is called Yambu Chorten Chenpo. Yambu is the general name by which Kātmāndu is known in Tibet; and Chorten Chenpo means great tower. The real name of the tower in full is, however, Ja Rung Kashol Chorten Chenpo, which may be translated into: “Have finished giving order to proceed with.” The tower has an interesting history of its own, which explains this strange name. It is said in this history that Kāṣyapa was a Buḍḍha that lived a long time before Shākyamuni Buḍḍha. After Kāṣyapa Buḍḍha’s demise, a certain old woman, with her four sons, interred this great sage’s remains at the spot over which the great mound now stands, the latter having been built by the woman herself. Before starting on the work of construction, she petitioned the King of the time, and obtained permission to “proceed with” building a tower. By the time that, as the result of great sacrifices on the part of the woman and her four sons, the groundwork of the structure had been finished, those who saw it were astonished at the greatness of the scale on which it was undertaken. Especially was this the case with the high officials of the government and the rich men of the country, who all said that if such a poor old dame were to be allowed to complete building such a stupendous tower, they themselves would have to dedicate a temple as great as a mountain, and so they decided to ask the King to disallow the further progress[36] of the work. When the King was approached on the matter his Majesty replied: “I have finished giving the order to the woman to proceed with the work. Kings must not eat their words, and I cannot undo my orders now.” So the tower was allowed to be finished, and hence its unique name, “Ja Rung Kashol Chorten Chenpo.” I rather think, however, that the tower must have been built after the days of Shākyamuni Buḍḍha, for the above description from Tibetan books is different from the records in Samskṛṭ, which are more reliable than the Tibetan.

Every year, between the middle of September and the middle of the following February of the lunar calendar, crowds of visitors from Tibet, Mongolia, China and Nepāl come to this place to pay their respects to the great temple. The reason why they choose the most apparently unfavorable season for their travel thither is because they are liable to catch malarial fever if they come through the Himālayan passes during the summer months. By far the greatest number of the visitors are Tibetans, of whom, however, only a few are nobles and grandees, the majority being impecunious pilgrims and beggars, who eke out their existence by a sort of nomadic life, passing their winter in the neighborhood of the tower and going back to Tibet in summer.

In Nepāl I had now arrived, and the reason of my presence there was, of course, to choose a route for my purpose, for there are many highways and pathways running between that country and Tibet. My purpose was such that I could take nobody there into my confidence, not even my kind and obliging host. For, to Lama Buḍḍha Vajra I was a well-qualified Chinaman, who was to go back to Lhasa by openly taking one of the public roads, and go on thence to China. Besides, I knew that the Lama was a Tibetan interpreter to His Highness[37] the King of Nepāl, and that were I to divulge to him my secret, he was in duty bound to tell it to his royal master, who, it was plain, would not only not lend himself to my venture, but would at once put an end to the further progress of my journey. I may note here that the Nepālese fondly call Lama Buḍḍha Vajra, Gya Lama, which means “Chinese Lama,” for he was a son born to a Chinese priest who married a Nepālese lady, after having become the Superior of the tower. My host’s father belonged to the old school, and enjoyed the privilege of marriage. It was thus that Lama Buḍḍha Vajra came to take a fancy, and show special favors, to me, considering me as a countryman of his. Be that as it may, there remained for me the necessity of discovering a secret path to Tibet. I was in luck again.

It occurred to me that the begging Tibetans, who go on pilgrimage in and out of their country, could not be in possession of the pass that gave them open passage through the numerous frontier gates. I remembered also that no unprivileged person—even the natives—could obtain permission to pass through these gates, either way, unless he would bribe the guards heavily, and it was plain that these homeless wanderers could not do this. Encouraged by these considerations, I took to befriending the Tibetan mendicants, of whom there was then a large number hanging about the Kāṣyapa Buḍḍha tower, and my liberality to them soon made me very popular among them. Demurring at first, they became quite communicative afterwards, when they had found out, as I presume, that there was nothing to dread in me. I learned of many secret passages, but none which I could consider safe for me. For instance, they spoke of the Nyallam bye-path. By taking this clandestine route one may avoid the Kirong gate, but one is in danger of being challenged at a gate further in the interior. The[38] Sharkongpo path, on the other hand, brings the traveller to the Tenri gate. So on with other paths, and it appeared an impossibility to discover a route which would enable a person to reach the capital of Tibet from that of Nepāl, without having to pass through some challenge gate. The pass and bribery being beyond them, the native beggars and pilgrims have one more resource left to them, and that is imploring a passage, with prayer and supplication, when they come upon a challenge post, and they generally succeed at the interior gates, I was told. It would be different with me: there was every danger of my disguise being detected while pleading with the guards. My persistent efforts finally brought me, however, their reward. I ascertained that by taking a somewhat roundabout way I might reach Lhasa without encountering the perils of these challenge gates. Ordinarily, one should take a north-east course after leaving the Nepālese capital, in order to make a direct journey to Lhasa; but the one I have just referred to lay in the opposite direction of north-west, through Lo, a border province of Nepāl, thence across Jangtang, the north plain (but really the west plain) of Tibet, and finally around the lake Mānasarovara. This bye-route I made up my mind to take.

So far so good. But it would be courting suspicion to say that I chose this particularly circuitous and dangerous route with no obvious reason for it. Fortunately a good pretext was at hand for me. For I happened to think of the identity of the lake Mānasarovara with the Anavatapta Lake that often occurs in the Buḍḍhist Texts. However divided the scholastic views are about this identity, it is popularly accepted, and that was enough for my purpose. The identity granted, it could be argued that Mount Kailāsa, by the side of the lake, was nature’s Maṇdala, sacred to the memory of the Buḍḍha, which formed an important station for Buḍḍhist pilgrims. So one day I said to my[39] host: “Having come thus far, I should always regret a rare opportunity lost, were I to make a stork’s journey from here to Lhasa, and thence to China. The Chinese Text speaks of Mount Kailāsa (Tib. Kang Rinpo Che) rising high on the shore of lake Mānasarovara (Tib. Maphamyumtsho). I want to visit that sacred mountain on my way home. So I should be very much obliged to you if you would kindly get men to carry my luggage for me.” The answer I got in reply was not encouraging, though sympathetic. Gya Lama, in short, bade me give up my purpose, because, as he said, the north-west plain was pathless and full of marauding robbers; it had been his long-entertained desire to visit the sacred mountain himself, but the difficulties mentioned had, so far, prevented him from carrying it out, and he would strongly advise me against my rash decision; to venture a trip through that region, with only one or two servants, was like seeking death. My retort was that, it being one of Buḍḍha’s teachings that “born into life, thou art destined to die,” I was not afraid of death; in fact, death might overtake me at any time, even while living comfortably under the Lama’s care; so that I should consider myself well repaid if I met death while on a pilgrimage to a holy place. Finding dissuasion useless with me, my host complimented me on the firmness of my resolution, and took it upon himself to secure for me reliable carriers. Then, after careful enquiries, he hired for me a pilgrim party, consisting of two men and an old woman, the latter of whom, in spite of her sixty years of age, was strong enough to brave the hardships of an exceptionally difficult road. These people were from Kham, a country noted for its robbers, but I was assured of the perfect honesty and good intentions of the particular three I was to engage. As a mark of his special kindness, Gya Lama promised to let a trustworthy man under him accompany me as far as a place called Tukje, to see that my two pilgrim servants served me faithfully.

It was in the beginning of the month of March, 1899, that, followed by a retinue of three men and one old dame, I bade farewell to my kind host and, seated on a snow-white pony, given me by my fatherly friend, left the Kāṣyapa Buḍḍha tower. I was not in good health that day, on account of fever and weakness, but I was obliged to start from Kātmāndu, for it was very dangerous for me to stay there any longer, as I was quite a stranger to the Nepālese, and they might find out my nationality, and stop me from proceeding further. So I took the assistance of the horse; and the good animal proved to be a splendid mountaineer, and carried me up steep ascents and down abrupt descents in perfect safety. We directed our course towards the north-west, through the British Residency, the most beautiful and clean quarter in Kātmāndu, and through Nagar-yon, a hill famous for a cave where Nāgārjuna, a great Boḍhi-Saṭṭva, used to meditate. We arrived at a village called Jittle-Pedee in the evening, and passed the night under the eaves of a shop-keeper’s house.

The present Ruler of Nepāl is a Hinḍū, and keeps the caste system as rigidly as it is kept in India, where the people belonging to that religion do not allow a foreigner to enter their rooms, or to eat with them. Therefore we were obliged to pass the night outside a house, or under a rock, or in the forests. Here I must not omit some interesting things about my travels among the Himālayan mountains from Kātmāndu to the lake Mānasarovara through Nepāl. The country being extra-territorial, I believe no bold European or American had trodden this precipitous path before me; hence I would like to mention[41] everything connected therewith, but as my object is Tibet, I cannot spend much space on the inner Himālayas of Nepāl. I shall only mention briefly what will be considered interesting by my readers in general.