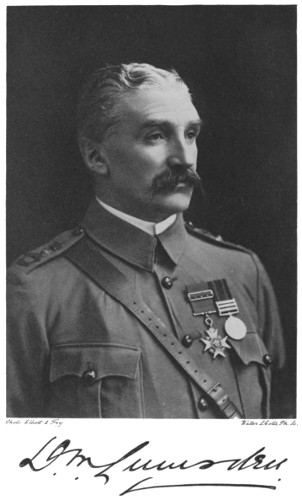

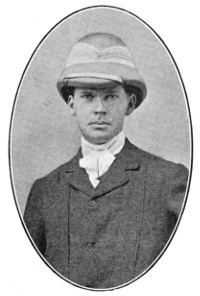

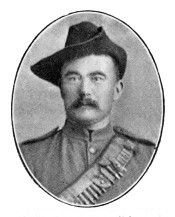

D.M. Lumsden.

Errors, when reasonably attributable to the printer, have been corrected. The corrections appear as words underlined with a light gray. The original text will be shown when the mouse is over the word. Please see the transcriber’s note at the end of this text for details.

The illustrations have been moved to avoid falling within a paragraph. The full page plates were printed with a blank page on its reverse, and both pages were included in the pagination. The page numbers for both are skipped here, since they are not likely to be accurate.

A large map and accompanying legend was bound as a fold-out inside the end cover. The image as printed is given here, in a reduced size. The Reference is given here in text. A larger version of the map itself can be viewed via the link provided below the image.This version of the text does not provide support for an expanded view of the map.

The cover has been fabricated and is placed in the public domain.

D.M. Lumsden.

Although this History of Lumsden’s Horse embraces a period in the South African campaign that was crowded with great issues, it makes no pretence to rank among the many able and comprehensive works dealing with those events. Elaborate descriptions and criticisms of operations as a whole have been purposely avoided, except so far as they serve to explain and emphasise actions in which the corps took part.

First of all, the book is intended to be no more than a regimental record, enlivened by the personal experiences of men who helped to make history at a time when the whole British Empire was moved by one impulse. India’s part in that movement is the inspiring theme, and one object has been to show how the idea of organising an Indian Volunteer Contingent for service in South Africa passed from inception to accomplishment, through the efforts of a Committee in Calcutta which made itself responsible for every financial liability in connection with the corps from its formation to its disbandment.

The cost of publication is being defrayed out of a balance of funds remaining in the hands of the Committee, and each member of the corps will receive a copy as a souvenir of his interesting experiences and a proof that his services are still remembered. Publication, however, is not restricted to members of the corps, and the Editor ventures to think that this book will suggest to general readers many points worthy of consideration. viIt illustrates the facility with which British subjects in India are able to band themselves together, and affords yet another instance of many in which the Indian Government has shown itself capable of utilising instantly its resources for the Empire’s benefit. And, more than this, it will stand as a proof of the cordiality with which the Indian public—British and Native—came forward at a time of Imperial need with offers of personal service or liberal subscriptions, which enabled the Committee to raise and despatch a Mounted Contingent completely equipped in every detail.

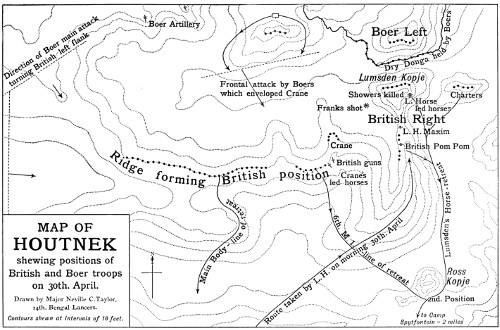

Among those who have assisted the Editor with information that has enabled him to produce this History, he has especially to thank the Committee, the Adjutant of the Regiment (Major Neville Taylor, 14th Bengal Lancers), whose sketch-map of the positions at Houtnek was made from personal reconnaissance, and Messrs. D.S. Fraser, Graves, Burn-Murdoch, Kirwan, and Preston. He is also indebted to Major Ross, C.B., Durham Light Infantry, for interesting material. Acknowledgment is due to Messrs. Johnston & Hoffmann, Messrs. F. Kapp & Co., Messrs. Bourne & Shepherd, and Messrs. Harrington & Co., of Calcutta, and others, who have kindly placed photographs at the Editor’s disposal; and to the proprietors of the ‘Englishman,’ ‘Pioneer,’ ‘Indian Daily News,’ ‘Statesman,’ ‘Times of India,’ and ‘Madras Daily Mail,’ for permission to reproduce from their columns the personal narratives that brighten many pages of this book.

Arts Club, London: January 1903.

| CHAPTER | PAGE | |

| INTRODUCTION | 1 | |

| I. | HOW THE CORPS WAS RAISED AND EQUIPPED | 7 |

| II. | PREPARING FOR THE FRONT—DEPARTURE FROM CALCUTTA | 40 |

| III. | OUTWARD BOUND | 68 |

| IV. | NEARING THE GOAL—DISEMBARKATION AT CAPE TOWN AND EAST LONDON | 85 |

| V. | AN INTERLUDE—THE RESULTS OF SANNA’S POST | 96 |

| VI. | BY RAIL AND ROUTE MARCH TO BLOEMFONTEIN | 109 |

| VII. | IMPRESSIONS OF BLOEMFONTEIN—JOIN THE 8TH MOUNTED INFANTRY REGIMENT ON OUTPOST | 127 |

| VIII. | THE BAPTISM OF FIRE—LUMSDEN’S HORSE AT OSPRUIT (HOUTNEK) | 144 |

| IX. | AFTER OSPRUIT—SOME TRIBUTES TO MAJOR SHOWERS AND OTHER HEROES | 175 |

| X. | PRISONERS OF WAR | 191 |

| XI. | TOWARDS PRETORIA—LUMSDEN’S HORSE SCOUTING AHEAD OF THE ARMY FROM BLOEMFONTEIN TO THE VAAL RIVER | 208 |

| XII. | JOHANNESBURG AND PRETORIA IN OUR HANDS | 230 |

| XIII. | ON LINES OF COMMUNICATION AT IRENE, KALFONTEIN, ZURFONTEIN, AND SPRINGS—THE PRETORIA PAPER-CHASE | 248 |

| XIV. | ALARMS AND EXCURSIONS—BOER SCOUTING—A RECONNAISSANCE TO CROCODILE RIVER—FAREWELL TO COLONEL ROSS | 270 |

| XV. | A MARCH UNDER MAHON OF MAFEKING TO RUSTENBURG AND WARMBATHS—IN PURSUIT OF DE WET | 286 |

| viiiXVI. | EASTWARD TO BELFAST AND BARBERTON UNDER GENERALS FRENCH AND MAHON | 313 |

| XVII. | MARCHING AND FIGHTING—FROM MACHADODORP TO HEIDELBERG AND PRETORIA UNDER GENERALS FRENCH AND DICKSON | 340 |

| XVIII. | HOMEWARD BOUND—APPROBATION FROM LORD ROBERTS—CAPE TOWN’S ACKNOWLEDGMENTS—FAREWELL TO SOUTH AFRICA | 359 |

| XIX. | THE RETURN TO INDIA—WELCOME HOME—HONOURS AND ORATIONS—DISBANDMENT | 377 |

| XX. | A STIRRING SEQUEL—THE STORY OF THOSE WHO STAYED—MEMORIAL TRIBUTES TO THOSE WHO HAVE GONE | 409 |

| I. | ROLL OF LUMSDEN’S HORSE, INCLUDING TRANSPORT | 427 |

| II. | MOBILISATION SCHEME FOR LUMSDEN’S HORSE | 437 |

| III. | THE ADJUTANT’S NOTE-BOOK | 446 |

| IV. | LIST OF OFFICERS, N.C.O.S, AND MEN WHO HAVE BEEN AWARDED DECORATIONS, COMMISSIONS, OR CIVIL APPOINTMENTS | 454 |

| V. | HONOURS AND PROMOTIONS | 456 |

| VI. | HONORARY RANK IN THE ARMY | 461 |

| VII. | LUMSDEN’S HORSE EQUIPMENT FUND | 462 |

| VIII. | FRIENDS AND SUPPORTERS OF THE CORPS | 476 |

| IX. | LUMSDEN’S HORSE RECEPTION COMMITTEE | 480 |

| X. | THE FINAL ACCOUNTS | 483 |

| XI. | REPORT OF TRANSPORT SERGEANT | 485 |

| XII. | TOPICAL SONG BY A TROOPER | 490 |

| INDEX | 491 |

From Drawings, and from Photographs by Messrs. Johnston & Hoffmann, Kapp & Co., Bourne & Shepherd, and Harrington & Co., Calcutta; Messrs. Elliott & Fry, London, and others.

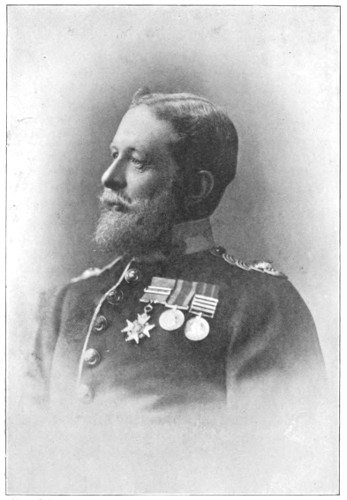

| LIEUTENANT-COLONEL D.M. LUMSDEN, C.B. (Photogravure) | Frontispiece | |

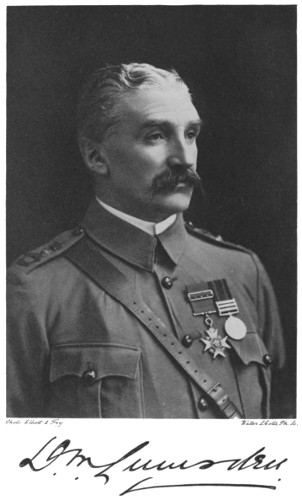

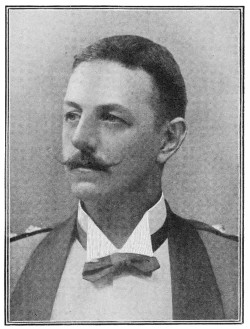

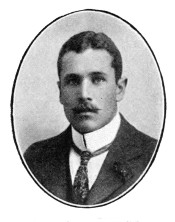

| SIR PATRICK PLAYFAIR, C.I.E. | facing page | 1 |

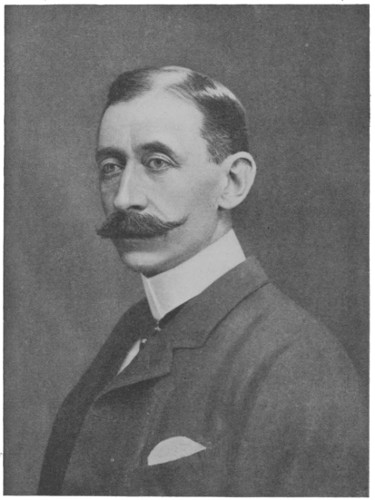

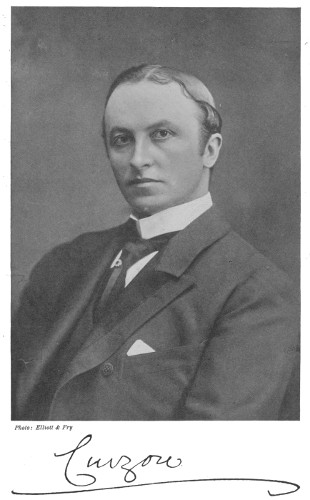

| HIS EXCELLENCY LORD CURZON, VICEROY OF INDIA | ” | 8 |

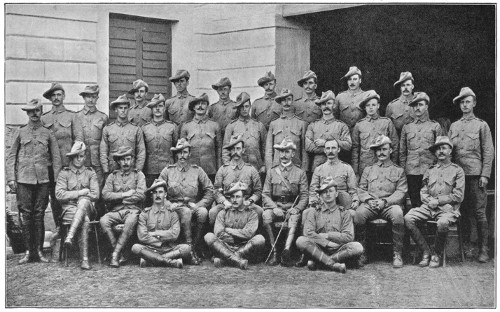

| BEHAR CONTINGENT OF LUMSDEN’S HORSE | ” | 14 |

| MYSORE AND COORG CONTINGENT | ” | 18 |

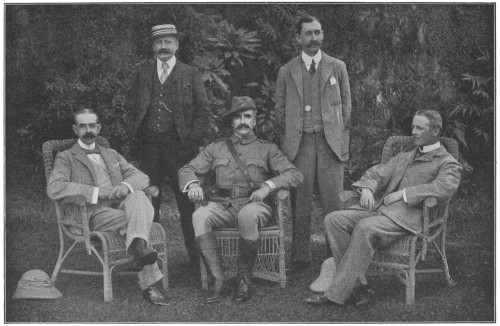

| THE EXECUTIVE COMMITTEE | ” | 26 |

| COLONEL LUMSDEN, C.B., SIR PATRICK PLAYFAIR, C.I.E., COLONEL MONEY, MAJOR EDDIS, MR. HARRY STUART | ||

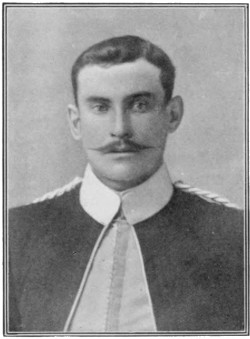

| OFFICERS OF THE CORPS | ” | 30 |

| COLONEL LUMSDEN, MAJOR SHOWERS, CAPTAINS TAYLOR, BERESFORD, NOBLETT, RUTHERFOORD, CHAMNEY, CLIFFORD, AND STEVENSON, LIEUTENANTS CRANE, NEVILLE, SIDEY, AND PUGH | ||

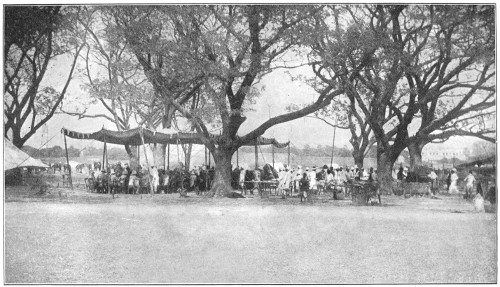

| MESSING AT CALCUTTA | ” | 34 |

| HORSES IN CAMP AT CALCUTTA | ” | 40 |

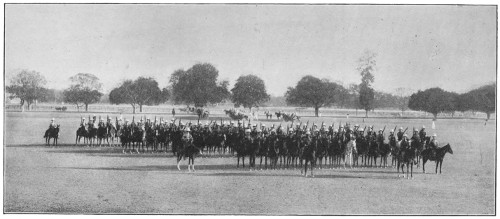

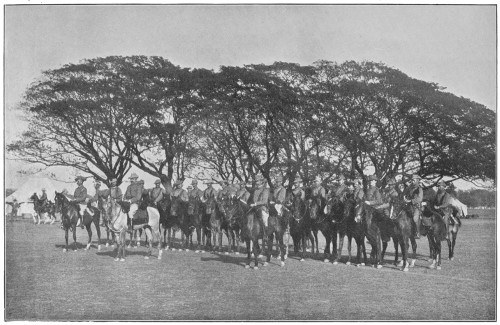

| ON PARADE, CALCUTTA | ” | 44 |

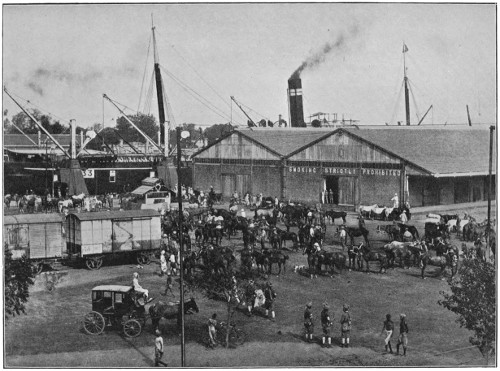

| TAKING HORSES ON BOARD TRANSPORT 28 | ” | 52 |

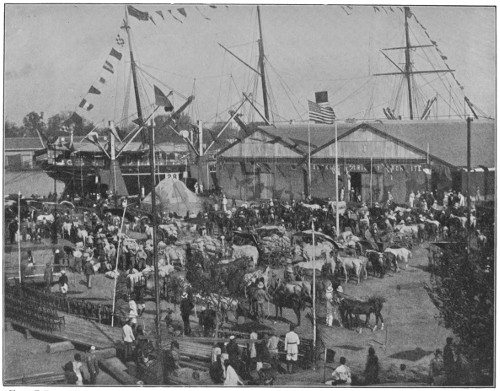

| EMBARKATION AT CALCUTTA | ” | 56 |

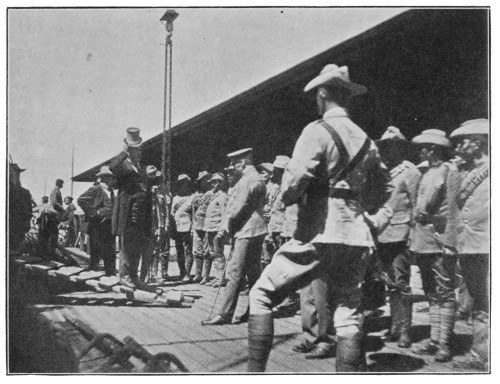

| H.E. THE VICEROY ADDRESSING THE CORPS | ” | 60 |

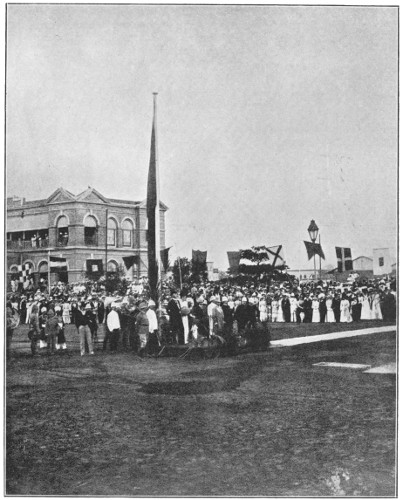

| B COMPANY LUMSDEN’S HORSE LEAVING CALCUTTA | ” | 64 |

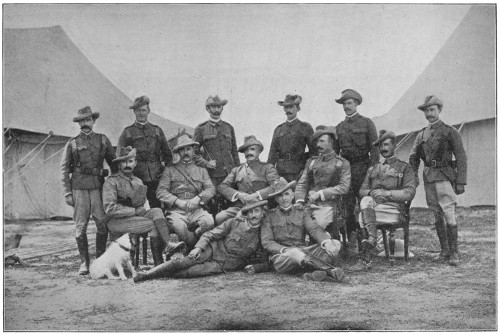

| THE REGIMENT IN CALCUTTA | ” | 72 |

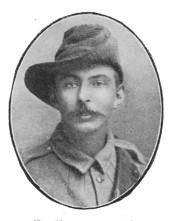

| MAXIM-GUN CONTINGENT | ” | 76 |

| CAPTAIN HOLMES, SERGEANT DALE, C.V.S. DICKENS, N.J. BOLST, P.T. CORBETT | ||

| SURMA VALLEY LIGHT HORSE. CONTINGENT OF LUMSDEN’S B COMPANY | ” | 80 |

| xMAJOR (LOCAL COLONEL) W.C. ROSS, C.B. | ” | 117 |

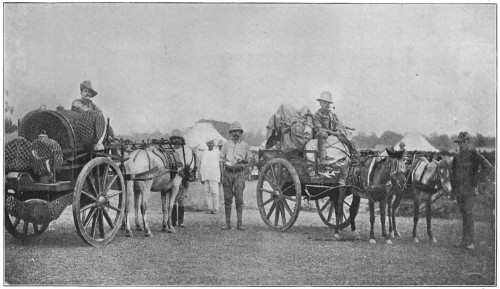

| TRANSPORT AND WATER CARTS | ” | 132 |

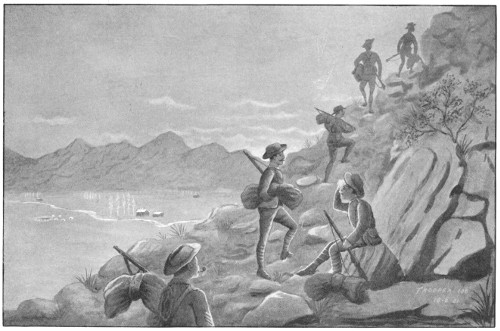

| OUTLYING PICKET TAKING UP POSITION | ” | 136 |

| HOUTNEK, SHOWING POSITIONS OF BRITISH AND BOER TROOPS | ” | 144 |

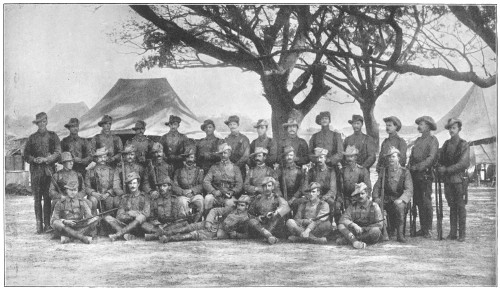

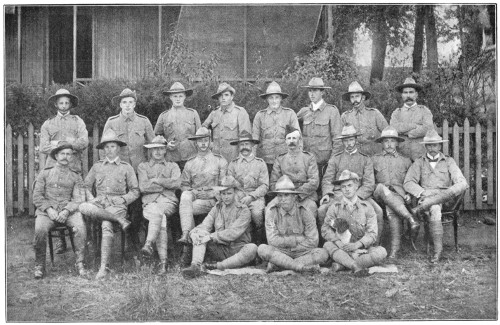

| N.C.O.S AND TROOPERS | ” | 156 |

| SERGEANT F.S. McNAMARA, LANCE-SERGEANT J.S. ELLIOTT, CORPORAL A. MACGILLIVRAY, R.U. CASE, C.A. WALTON, A.F. FRANKS, J.S. SAUNDERS, R.N. MACDONALD, L. GWATKIN WILLIAMS | ||

| BRINGING HALF-RATIONS UP TO NORMAL | ” | 213 |

| N.C.O.S AND TROOPERS | ” | 214 |

| H.J. MOORHOUSE, A.K. MEARES, W.K. MEARES, H.W. PUCKRIDGE, R.G. DAGGE, R.P. WILLIAMS, R.C. NOLAN, T.G. PETERSEN, S. DUCAT | ||

| N.C.O.S AND TROOPERS | ” | 230 |

| CORPORAL L.E. KIRWAN, J.S. CAMPBELL, C.E. TURNER, E.S. CHAPMAN, G. INNES WATSON, C.E. STUART, C. CARY-BARNARD, E.S. CLIFFORD, H. GOUGH | ||

| INVALIDED HOME AFTER THE SURRENDER OF PRETORIA | ” | 248 |

| J. SKELTON, R.P. HAINES, H.W. THELWALL, C.K. MARTIN, H.S. CHESHIRE, H.B. OLDHAM, M.H. LOGAN, J.V. JAMESON, H. HOWES | ||

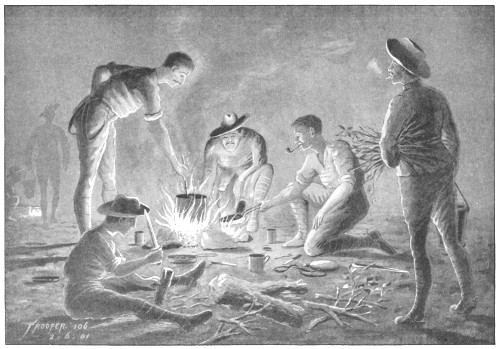

| NIGHT IN CAMP | ” | 296 |

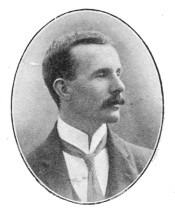

| PHILIP STANLEY | ” | 306 |

| TRANSPORT DRIVERS | ” | 320 |

| T. HARE SCOTT, H.G. PHILLIPS, R.P. ESTABROOKE, J. BRAINE, R. PRINGLE, W. BURNAND | ||

| TRANSPORT DRIVERS | ” | 324 |

| L. DAVIS, LEO H. BRADFORD, C.W. LOVEGROVE, S.W. CULLEN, F.C. MANVILLE, F.C. THOMPSON | ||

| THE LAUNDRY | ” | 328 |

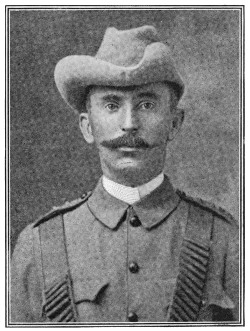

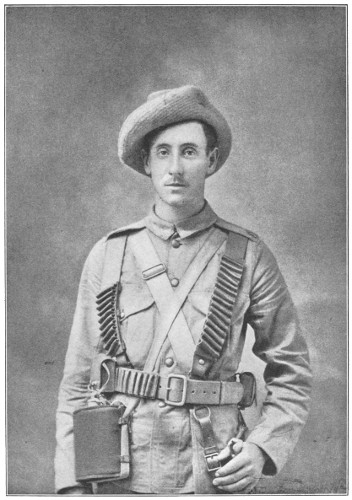

| H.P. BROWN, A TYPICAL TROOPER | ” | 340 |

| N.C.O.S AND TROOPERS | ” | 346 |

| SERGEANT A.H. LUARD, CORPORAL G. LAWRIE, F.G. BATEMAN, L. KINGCHURCH, IAN SINCLAIR, PERCY COBB, HARVEY DAVIES, C.E. CONSTERDINE, D. ROBERTSON | ||

| N.C.O.S AND TROOPERS | ” | 360 |

| SERGEANT G.E. THESIGER, CORPORAL W.T. SMITH, E.B. MOIR-BYRES, J.A. BROWN, H. EVETTS, J.L. STEWART, H.N. SHAW, E.S. CLARKE, B.E. JONES | ||

| xiGAZETTED TO THE REGULAR ARMY | ” | 366 |

| CORPORAL F.S. MONTAGU BATES, H.S.N. WRIGHT, J.D.L. ARATHOON, S.L. INNES, F.W. WRIGHT, R.G. COLLINS, A.E. NORTON, W. DOUGLAS-JONES, T.B. NICHOLSON | ||

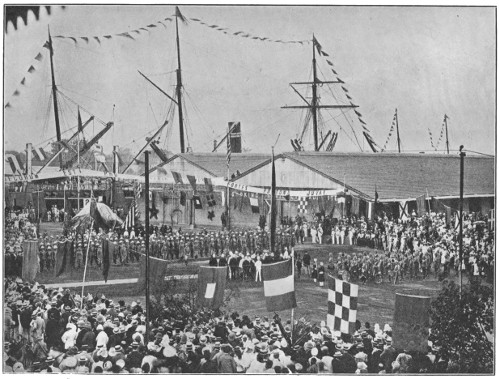

| RECEIVING THE MAYOR OF CAPE TOWN’S FAREWELL ADDRESS ON THE SOUTH ARM | ” | 372 |

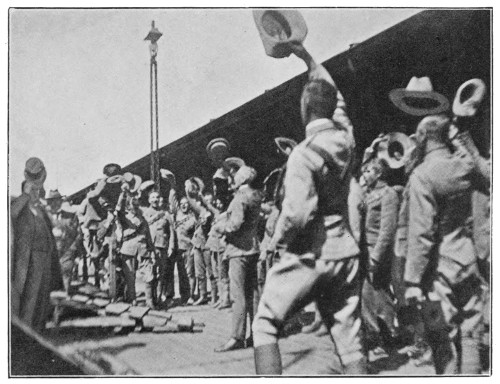

| CHEERING IN RESPONSE | ” | 372 |

| HOME FROM SOUTH AFRICA—N.C.O.S AND TROOPERS | ” | 378 |

| SERGEANTS STOWELL, DONALD, RUTHERFOORD, FOX, FARRIER-SERGEANT EDWARDS, LANCE-CORPORAL GODDEN, S.C. GORDON, E.A. THELWALL, A.P. COURTENAY | ||

| HOME FROM SOUTH AFRICA—N.C.O.S AND TROOPERS | ” | 384 |

| SERGEANT J. BRENNAN, H. NICOLAY, A. ATKINSON, C.H. JOHNSTONE, G. SMITH, N.V. REID, W.R. WINDER, R.M. CRUX, L.K. ZORAB | ||

| MEMBERS OF LUMSDEN’S HORSE WHO JOINED THE JOHANNESBURG POLICE, DECEMBER 1900 | ” | 410 |

| SILVER STATUETTE, PRESENTED TO LIEUTENANT-COLONEL LUMSDEN | ” | 418 |

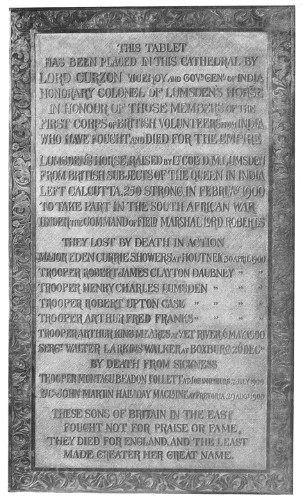

| TABLET IN ST. PAUL’S CATHEDRAL, CALCUTTA | ” | 424 |

| PAGE | |

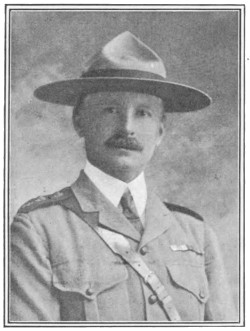

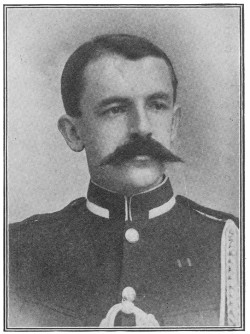

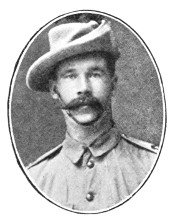

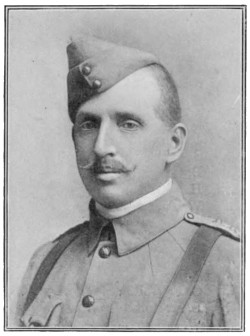

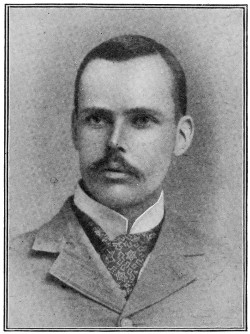

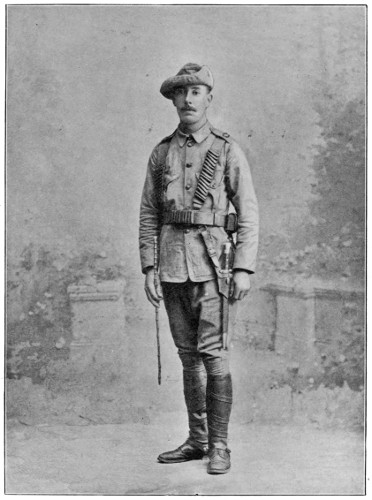

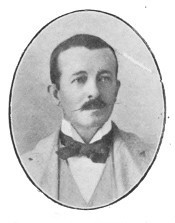

| CAPTAIN NOBLETT (MAJOR ROYAL IRISH RIFLES), COMMANDING B COMPANY LUMSDEN’S HORSE | 142 |

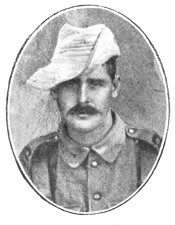

| CAPTAIN H. CHAMNEY | 152 |

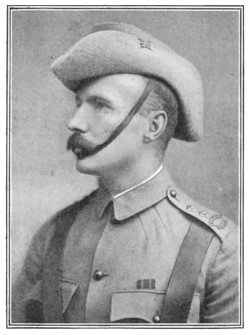

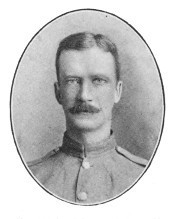

| CAPTAIN NEVILLE C. TAYLOR | 156 |

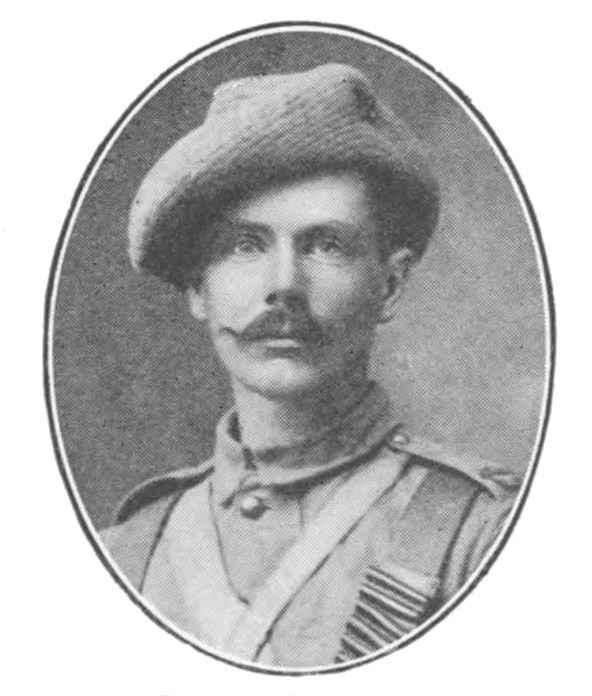

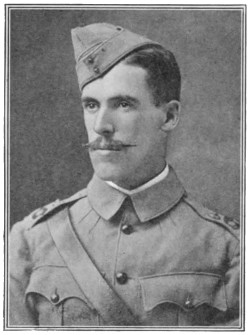

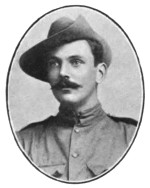

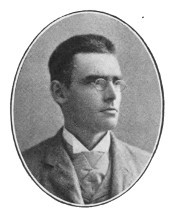

| H.C. LUMSDEN (KILLED IN ACTION, HOUTNEK, APRIL 30, 1900) | 159 |

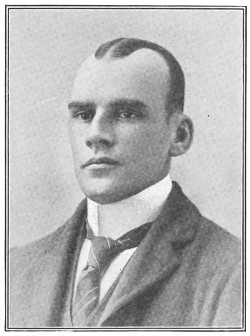

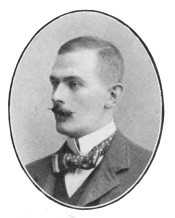

| LIEUTENANT C.E. CRANE | 162 |

| J.H. BURN-MURDOCH | 163 |

| HERBERT N. BETTS, D.C.M. | 167 |

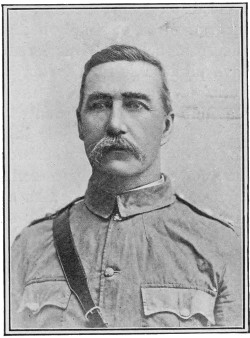

| MAJOR EDEN C. SHOWERS (KILLED AT HOUTNEK) | 175 |

| BUGLER R.H. MACKENZIE | 187 |

| E.B. PARKES | 187 |

| DAVID STEWART FRASER | 193 |

| WATERVAL PRISON, PRETORIA | 206 |

| xiiPERCY JONES, D.C.M. | 228 |

| LIEUTENANT G.A. NEVILLE | 234 |

| LIEUTENANT H.O. PUGH, D.S.O. | 242 |

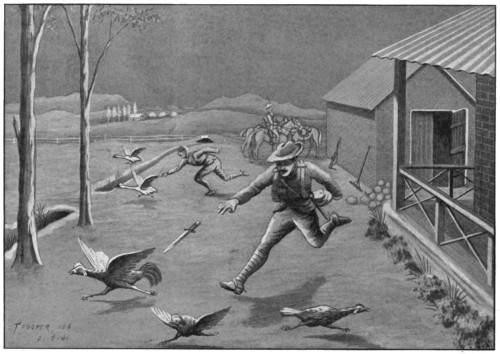

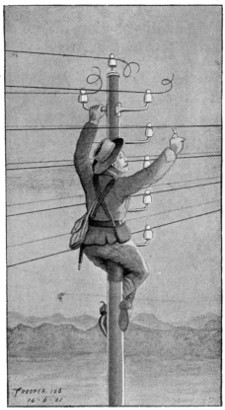

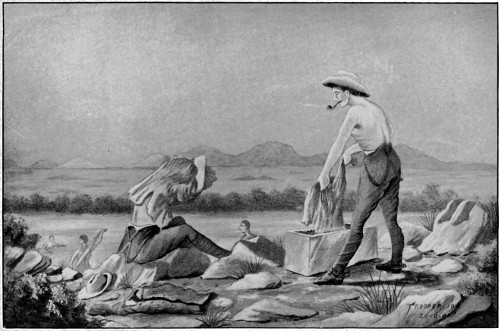

| WALTER DEXTER, D.C.M., CUTTING THE TELEGRAPH WIRES AT ELANDSFONTEIN | 243 |

| P.C. PRESTON, D.C.M. | 244 |

| CAPTAIN RUTHERFOORD, D.S.O. | 263 |

| CAPTAIN W. STEVENSON, VETERINARY SURGEON | 268 |

| SERGEANT ERNEST DAWSON | 269 |

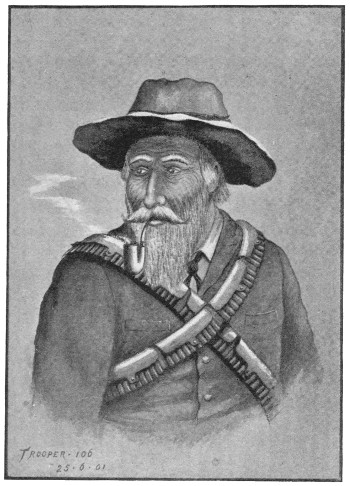

| A TYPICAL BOER | 275 |

| CAPTAIN CLIFFORD | 277 |

| J.A. GRAHAM, D.C.M. | 278 |

| BERNARD CAYLEY | 279 |

| L.C. BEARNE | 280 |

| A HALT ON THE MARCH TO BARBERTON: GENERAL MAHON AND COLONEL WOOLLS-SAMPSON | 339 |

| SERGEANT STEPHENS | 346 |

| CAPTAIN C. LYON SIDEY | 352 |

| D. MORISON | 354 |

| CORPORAL J. GRAVES | 355 |

| LANCE-CORPORAL JOHN CHARLES | 376 |

| J.S. COWEN | 382 |

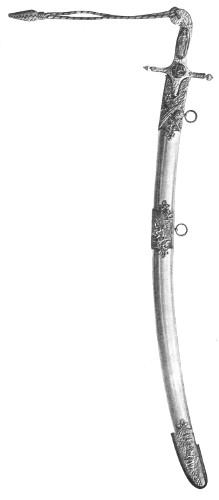

| SWORD OF HONOUR PRESENTED TO LIEUTENANT-COLONEL LUMSDEN | 407 |

| A. NICHOLSON | 414 |

| G.D. NICOLAY | 416 |

| H. KELLY | 417 |

| K. BOILEAU | 418 |

| PART OF SOUTH AFRICA, SHOWING THE ROUTES TAKEN BY LUMSDEN’S HORSE | facing page | 490 |

Photo: Elliott & Fry

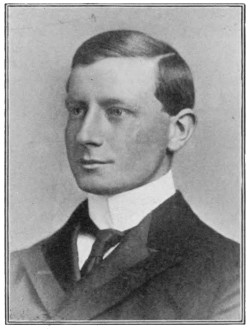

SIR PATRICK PLAYFAIR, C.I.E.

To Lumsden’s Horse belongs the high honour of having represented all India in a movement the magnitude and far-reaching effects of which we are only beginning to appreciate. While the stubborn struggle for supremacy in South Africa lasted, no true sons of the Empire allowed themselves to count the cost. Some were prepared to pay it in blood, others in treasure, to make success certain, and none allowed himself to harbour even the shadow of a thought that failure, with all its inevitable disasters, could befall us so long as the Mother Country and her offshoots held together. At the outset only those blessed with exceptional foresight could have believed in the completeness of a federation the elements of which were bound together by no other ties than sentiment. Selfish interests were merged in combined efforts for the common weal, and, while the necessity for action lasted, few cared to reckon the price they were paying for an idea.

Even the long-looked-for advent of Peace has hardly brought home to us a knowledge of all that War in South Africa meant, not only in a military sense, but also in its greater imperial significance. The men who fought and bled for the noble sentiment of British brotherhood never dreamed that they were doing more than duty demanded, though they had perhaps given up every chance of success in life to answer the call of patriotism; and among those who stayed at home there are millions untouched by the bitterness of personal bereavement who can have no conception of the sacrifices that were made to 2keep our Empire whole. Casualty lists, with all their details of killed and wounded, do not tell half the story. To know it all we must dip deep into the private records of every contingent, British and Colonial, that volunteered for active service, and deeper still to fathom the motives of men who, when their country seemed to need them, threw aside all other considerations and rallied to her standard.

Continental critics may sneer at us for making much of this idea, but none know better than they do the difference between loyalty expressed in such a noble form and the mere instinct of self-preservation that too often passes current for patriotism. They tell us that it is every citizen’s duty to be a soldier and every soldier’s duty to die, if necessary, for his country; but when they see self-governing nations from every quarter of the world coming into line by their own free will and all welded together by one sentiment, they have no better name for it than lust of empire. Nevertheless, they know it for what it is, a thing of which they had previously no conception, and they recognise in the impulses that led to this mighty manifestation the secret of Great Britain’s world-wide power. Let envious rivals say what they will. Let them magnify our reverses and minimise our triumphs, if the process pleases them. In spite of everything, the South African War stands a great epoch of an age that will some day come to be reckoned among the greatest in British History, and all who have helped towards the shaping of events at this memorable time can at least claim to have earned the gratitude of posterity.

And India may well be proud of her share in the work. Measured by the mere number of men whom she sent to the war, her contribution seems perhaps comparatively small; but when we remember the sources from which that contingent was drawn, the munificence of gifts from Europeans and natives alike for its equipment and maintenance, and all the sacrifices that war-service involved for every member of the little force, we cannot but admire the spirit that called it into being. A great crisis was not necessary to convince us that British residents in India would fight, if called upon, with all the valour that distinguished Outram’s Volunteers of old. Few, however, would have been bold enough to predict that for any conceivable cause hundreds 3of men would readily relinquish all that they had struggled for, give up the fruits of half a life’s labour, and calmly face the certainty of irreparable losses, without asking for anything in return, except the opportunity of serving their country on a soldier’s meagre pay. Still less could anybody have imagined that a time might come when Indian natives, debarred from the chance of proving their loyalty by personal service, would give without stint towards a fund for equipping a force to fight in a distant land against the enemies of the British Raj. If Indian princes had been permitted to raise troops for the war in South Africa, our Eastern contingent would have numbered thousands instead of hundreds. What natives were not allowed to give in men they gave in cash and in substance, according to their means, thereby showing that they were with us in a desire to defend the Empire against any assailant. In reality this meant more than an offer of armed forces, and to that extent it was worthy to rank with the self-sacrifice of Anglo-Indians who gave personal service, and thereby took upon themselves a burden the weight of which cannot be readily estimated. It must not be forgotten that raising a corps of Volunteers in India is a very different matter from the enrolment of a similar force at home, or wherever there are dense populations and ‘leisured classes’ to be drawn upon. There are no idle men in India, everyone having gone there to fill an appointment and earn his livelihood. When the call came, therefore, it could only be answered by sacrifices or not at all, and nobody is more conscious of this fact than the man whose laconic appeal for Volunteers brought three or four times more offers than he could possibly accept. In his opinion ‘the men who vacated appointments worth from 300 to 500 rupees a month and went to fight for their country on 1s. 2d. a day have given a much larger contribution to the War Fund than they could afford.’ As an instance he mentions three members of the medical profession, Doctors Charteris, Moorhouse, and Woollright, each of whom threw up a lucrative practice and joined the ranks as a trooper. These are not exceptional but simply typical cases. Scores of other men gave up equally remunerative appointments with the same noble unselfishness to enrol themselves in Lumsden’s Horse.

4To Colonel Lumsden alone belongs the honour of having evoked this splendid manifestation of patriotic feeling. The idea of forming a corps of Indian Volunteers was his; and though similar thoughts may have been in many minds at the same moment, nobody had given a practical turn to them until his message—electric in every sense—startled all Anglo-Indians into active and cordial co-operation. How all that came about will be told with fuller circumstances in its proper place, but some reference must be made here to the man whose firm faith in the patriotism and soldierly qualities of Indian Volunteers led him to the inception of a scheme which events have so abundantly justified.

Lieutenant-Colonel Dugald McTavish Lumsden, C.B., needs no introduction to the East, where the best, and perhaps the happiest, years of his life have been spent. Without some details concerning him, however, completeness could not be claimed for any record of the corps which is now identified with his name. The eldest son of the late Mr. James Lumsden, of Peterhead, Aberdeenshire, he was born in 1851. At the age of twenty-two he obtained an appointment on the Borelli Tea Estate, in the Tezpur District of Assam, and sailed for India. Consciously or unconsciously, he must have taken with him some military ambitions imbibed through intimate association with leaders of the Volunteer movement in Scotland. At any rate, he soon became known as a keen Volunteer in the land of his adoption, and when in 1887 the Durrung Mounted Rifles was formed, he was given a captaincy. A year later that corps lost its identity, as other local units did, in the territorial title of Assam Valley Light Horse, with Colonel Buckingham, C.I.E., as commandant, while Captain Lumsden got his majority and took command of F Squadron in the Durrung District. Subsequently he commanded the regiment for a time, and, though he left India in 1893, he did not lose touch with his old comrades. Every year he returned to spend the cold weather among his friends in Assam, showing always undiminished interest in the welfare of his old regiment. Thus, when the time came for a call to active service, he had no sort of doubt what the response would be from the hardy, sport-loving planters of Northern Bengal. Himself an enthusiastic shikari and first-rate shot, he knew how to value 5the qualities that are developed in hunting and stalking wild game. And his experience of Indian Volunteers was not confined to his own district. He knew every corps in Bengal by reputation, and could thus gauge with an approach to accuracy the numbers on which he would be able to draw for the formation of an Indian contingent. Much travel in many lands had also made him a good judge of men, as evidenced by the first thing he did when the idea of calling upon India to take up her share of the Imperial burden came to him.

At that time he was travelling in Australia, and had no means of knowing how deeply the feelings of British residents and natives of the East had been stirred by news of the reverses to our arms in South Africa. The dark days of Stormberg and Magersfontein had thrown their shadow over Australia as over England, chilling the hearts of people who until then had refused to believe that British troops could be baulked by any foes, notwithstanding the stern lesson of Ladysmith’s investment. Through that darkness they were groping sullenly towards the light, and wondering what national sacrifices would have to be made before the humiliation could be wiped out. It is in such moments of emergency that natural leaders come to the front. Among the few in England or the Colonies who realised the military value of Volunteers was Colonel Lumsden. Though thousands of miles away from the scenes of early associations, his thoughts turned at once to the bold riders and skilful marksmen with whom he had so often shared the exciting incidents of the chase. He made up his mind at once that the planters, on whose spirit he could rely, were the very men wanted for South African fighting. On the parade ground they might not be all that soldiers whose minds are fettered by rules and traditions would desire, but he knew how long days of exercise in the open air at their ordinary avocations, varied by polo, pig-sticking, and big-game hunting, had toughened their fibre and hardened their nerves. He could count on every one of them also for keen intelligence, which he rightly regarded as more important than mere obedience to orders, where every man might be called upon to think and act for himself. Colonel Lumsden would be the last to depreciate Regular soldiers, or undervalue their discipline, but experience had taught him that men who can exercise 6self-restraint and develop powers of endurance for the mere pleasure of excelling in manly sports, adapt themselves readily enough to military duties. To them, at any rate, the prospect of hardships or privations would be no deterrent, the imminence of danger only an additional incentive. On December 15, 1899—a day to be afterwards borne in mournful memory—Colonel Lumsden made up his mind that the time for action had come to every Briton who could see his way to giving the Mother Country a helpful hand. He cabled at once to his friend Sir Patrick Playfair in Calcutta his proposal to raise a corps of European Mounted Infantry for service in South Africa, and backed it with an offer, not only to take the field himself, but to contribute a princely sum in aid of a fund for equipping any force the Government might sanction. Then, without waiting to know whether his services had been accepted, he took passage by the next steamer for India.

Offer Government fifty thousand rupees and my services any capacity towards raising European Mounted Infantry Contingent, India, service Cape. Wire Melbourne Club, Melbourne.—Leaving nineteenth, due Calcutta January 9. Do not divulge name until my arrival.—Lumsden.

These were the stirring words of Colonel Lumsden’s laconic message flashed by cable from Australia to Calcutta at a time when all India was ripe for any movement in aid of the Empire, and only waiting for a lead in the course it should take. No wonder that the spirit of a man whose enthusiastic confidence was expressed in an offer so munificent communicated itself to all whom Sir Patrick Playfair consulted on the subject. Still, official susceptibilities, ever prone to look askance at anything that seems like civilian interference with military prerogatives, had to be considered. Tact was necessary at the very outset to avoid all possibility of friction. Colonel Lumsden had evidently foreseen this when he selected as the recipient of his cable message an Anglo-Indian of diplomatic temperament, great social influence, and varied experience. Few men, if any, could have been better qualified for the delicate negotiations, or could have appealed to the Indian public, Native and European, with more certainty of success than Sir Patrick Playfair, whose services then and for months afterwards entitle him to a niche in India’s Walhalla beside the founder of Lumsden’s Horse. Even at the sacrifice of continuity, it is appropriate to quote here an appreciative comment by one who knew how much Sir Patrick Playfair did towards the formation and equipment of a thoroughly representative force. From the moment of receiving Colonel Lumsden’s telegram he displayed the keenest interest 8in its object, and endeavoured to ensure a successful issue with all the energy that has characterised him in his advocacy and support of many public enterprises during a brilliant career. He was the prime mover in every social function organised in honour of Lumsden’s Horse, and in everything done for their benefit apart from military details while they remained in India. After their departure for the front he never lost an opportunity of identifying himself with them in every way, and none would have been keener than he to share their dangers and hardships if his position had enabled him to accompany them. In this connection Sir Patrick had an entertaining dialogue one day with General Patterson, of the United States army, who said, ‘What I have been wondering about is why you did not go yourself, Sir Patrick.’ To this the knight replied, ‘Well, you know, I am a busy man. Of course I should have liked to go above all things, but with my engagements it was impossible.’ ‘Ah, yes!’ said the General; ‘I guess you’re like Artemus Ward’s friend, the Baldinsville editor, who would “delight to wade in gore,” but whose country bade him stay at home and announce week by week the measures taken by Government, or, like Artemus himself, who, having given two cousins to the war, was ready to sacrifice his wife’s brother and shed the blood of all his able-bodied relations “rather’n not see the rebellyin krusht.”’ As it was, Sir Patrick took the pains to publish every item of interest sent to him by the officer commanding throughout the campaign. When, after twelve months of honourable service, the corps turned homewards again, he took the initiative in preparing a welcome worthy of them, and after Lumsden’s Horse had been disbanded he showed a kindly interest in the men by endeavouring to procure appointments for all who needed assistance of that kind, and thereby won their gratitude as he had long before gained their esteem. This is anticipating events, but, like the prologue to a play, it may help to give some idea of a character whose influence on the whole story is potent though not often in evidence.

Photo: Elliott & Fry

CURZON

Sir Patrick Playfair’s first step was to approach General P.J. MaitlandP.J. Maitland, C.B., Military Secretary to the Government of India, to whom he made known Colonel Lumsden’s offer and explained something of its probable scope. General Maitland, 11who warmly supported the proposal, said he would place it before His Excellency the Viceroy, but intimated that the matter would then have to be referred to the War Office, without whose consent the Government of India could do nothing in connection with the war. At that time Colonel Lumsden was on his way to Calcutta, and had telegraphed again from Albany to find out what progress was being made, but got no answer. Sir Patrick, knowing his man, had no misgivings that he might turn back discouraged by the prospect of an official cold shoulder. Lord Curzon was still absent from Calcutta on tour, and the Commander-in-Chief, the late Sir William Lockhart, had not returned from his official round of inspection in Burma, so that no immediate opportunity occurred for placing the proposal before either of them at a personal interview. General Maitland, however, did more than he had promised by so urging the case in a communication to the Viceroy that His Excellency took it up, and immediately on his arrival in Calcutta telegraphed to the Commander-in-Chief, who thereupon gave his approval promptly. The headquarters authorities asked how many men were to go, and Sir Patrick said he thought from two hundred and fifty to three hundred. That suggestion was embodied in a telegram to the War Office, which, as usual, took time to consider it. Again Colonel Lumsden, who had then reached Colombo, cabled for information as to the state of affairs, but again no reply was vouchsafed. So he came on, fully prepared to meet disappointment at the end of his journey. When he got within sight of land, however, all India knew of his splendid offer and its acceptance by the Home Government. The whole story had been published in every newspaper two days before Colonel Lumsden steamed up the Hooghly to find himself a hero. Crowds of his friends and admirers were there to welcome him as chief of a corps that had neither a local habitation nor a name, nor even a substantial existence at the moment. With characteristic abnegation of self, he had offered his services in any capacity, but nobody doubted from the hour of his arrival in Calcutta that whatever force India might send to the front would have Lumsden for its leader. The newspapers even began to give his name to the contingent before it had assumed bodily shape or anybody knew exactly how it was to be raised. Some days 12later the popular choice was confirmed by publication of a War Office order couched in the following words:

‘Her Majesty’s‘Her Majesty’s Government having accepted the offer of the Government of India to provide a force of Mounted Volunteers for service in South Africa, two companies of Mounted Infantry, to be called the Indian Mounted Infantry Corps (Lumsden’s Horse), will be raised immediately at Calcutta under the command of Lieut.-Colonel D. McT. Lumsden, of the Volunteer Force of India, Supernumerary List, Assam Valley Light Horse.’

With this order, giving unqualified approval of the project, came a mobilisation scheme in which the Government undertook to provide the necessary sea-kit for use on board ship only, the transport, the daily rations as for other soldiers, the weapons, the munitions of war, and pay at the rate of 1s. 2d. a day, but nothing else. The rest was left to private enterprise working on popular enthusiasm and the loyal sentiments of a great community. Towards the sum requisite for the complete equipment and maintenance of a mounted force in the field, even half a lakh of rupees would not go very far. The spirit that had prompted one man to offer that sum and his own services to boot proved contagious, however, and Colonel Lumsden had so little doubt what the result would be that he immediately announced his readiness to receive applications from men who might be willing to serve in South Africa for a year, or ‘for not less than the period of the war.’ That call was published by Indian newspapers on January 10, 1900, and in response Volunteers sent their names from every district far and near, until Colonel Lumsden might have enrolled a thousand as easily as the two or three hundred sanctioned by Government. His one difficulty, indeed, was that of selection, and there the experience he had gained from studying character closely under many different conditions came in. He was assisted by suggestions from officers commanding the Calcutta Light Horse, the Assam Valley Light Horse, the Surma Valley Light Horse, the Behar Light Horse, the Punjab, the Mysore, and the Rangoon Volunteer Corps. Authorities at home had by that time learned a very important lesson, the outcome of which was expressed in a phrase very different from the unlucky telegram that gave 13so much offence to Australians a few weeks earlier. Colonel Lumsden was told ‘preference will be given to Volunteers from mounted Volunteer Corps, but Volunteers belonging to Infantry corps who may possess the requisite qualifications will also be eligible.’ One of the qualifications laid down was that they should be ‘good riders’ before joining Lumsden’s Horse. Here the value of previous training in military duties and of something more than haphazard horsemanship was recognised; and happily Colonel Lumsden knew exactly the sort of men who would meet both requirements, especially as the limits of age (between twenty and forty) brought the best of those who had the riding and shooting experiences incidental to a planter’s life into the category. It is not surprising if he showed a partiality for them when rival claims had to be decided upon. The fact that many of them offered to bring their own horses weighed nothing with him, though he knew that the companies would have to be mounted somehow and that the Government had explicitly declined to provide horses for that purpose. Either by private contributions in kind or by public subscription toward the necessary funds for purchasing, a horse for each trooper had to be furnished; but this consideration did not weigh for a moment against the chances of a man who could only give himself to the Empire’s service, so long as he had in essential points better qualifications than other candidates could boast. The wife of a prominent and popular soldier—now a general—asked, as a great favour, that her brother might be allowed to serve as a trooper in the corps. To such a pleader Sir Patrick could not say ‘no,’ so he arranged a little dinner at which the fascinating lady was to sit beside Colonel Lumsden. Whether her gentle persuasions prevailed or the brother’s merits were too obvious to be disregarded, it is certain that he joined the ranks of Lumsden’s Horse, and so completely justified the choice that he is now an officer of the Regular army and a Companion of the Distinguished Service Order. Naturally, the selection of two hundred and fifty men to represent all India from among a thousand who were anxious for the opportunity of seeing active service gave rise to much jealousy and heart-burning on the part of the rejected. Reading some of their vituperations, one might imagine that they had been aspirants to posts of high distinction, 14or at least to lucrative sinecures, rather than candidates for the khaki jackets of privates in a regiment about to share the hardships of a perilous campaign. One disappointed applicant, whose martial ardour was not to be quenched by rejection, wrote angrily to the ‘Englishman,’ suggesting that there was gross favouritism in the preference shown for planters over townsmen. His letter is worth quoting at length as typical of the fighting spirit that had been aroused everywhere by Colonel Lumsden’s patriotic manifesto. Thus he wrote:

Sir,—I hope I am in time to draw the attention of the Government to the Bahadur[1] style in which the selection to the ‘Indian Yeomanry Corps’ of Volunteers is being conducted. Because a man is the son of his father, and owns a few ponies and a few hundred rupees, is he to be given the preference as a fighting unit?

There are to-day in India, even in the city of Calcutta, men of unquestionable merit, men who are sons and the recipients of a heritage of blood shed in England’s and her Most Gracious Majesty’s cause from fathers who had bled and died for England and England’s prestige, and I beg to ask you, Sir, are these men to be shelved to suit the convenience of a few planters? I am not a planter, and, as an outsider, I put my claims forward as a test of merit. I am willing to shoot a match up the range with the best man selected from Behar, run him a given distance, ride him on strange nags (catch weights), and in the end with my weight and other recommendations beat him.

Photo: Bourne & Shepherd

BEHAR CONTINGENT OF LUMSDEN’S HORSE

There is quite a ring of mediaeval chivalry about that challenge to ‘shoot up the range.’ One cannot mistake its blood-thirsty significance, and perhaps it is lucky for the Champion of Behar that he did not take up the gauntlet thus ruthlessly thrown down. It will be noticed that this duel, after the manner suggested by one of Bret Harte’s heroes, was to precede all other events in the prolonged ordeal; and imagination shudders at the picture of awful slaughter that would have been wrought, as the picked marksmen of Behar and Hyderabad and Oudh and Assam went down one by one, if they had dared to face the deadly rifle of that truculent citizen of Calcutta, without getting a chance to 17prove whether he could run or ride. Happily, the selected two hundred and fifty kept their heads, so that the trial by single combat never came off; but one must hope that a place was found in Lumsden’s Horse for the self-confident challenger, and that he proved as formidable on the field as in a printed column. Readers may scan the names of troopers, whose occupations before enlistment are all given in the Appendix, and yet be left speculating whether or not the writer of that letter was among the chosen after all. He will not be found in the first or second section of Company A, composed almost to a man of indigo-planters, or in the third section, whose tea-planters, mainly from Assam, have not a townsman among them; and the planters who make up an overwhelming majority of three sections in Company B would equally disclaim all knowledge of the fire-eating citizen. Can it be that he figures in the more casual fourth section of either company, under the vague designation of a ‘gentleman’ or a ‘journalist’? A little levity may be pardoned now in reference to a matter which, at the time, aroused some acrimony. All that, however, was swept away by the wave of enthusiasm, leaving no bitterness behind it, even in the minds of those who at first thought themselves humiliated by rejection. If Lumsden’s Horse were almost entirely a corps of planters, few questioned the care and discretion with which Colonel Lumsden had chosen his men, and none could deny that they made a goodly show at manœuvres on the Maidan, where their camp was pitched within easy reach of the city. Though quartered there for six weeks in circumstances that exposed them to many temptations, those troopers behaved in a manner that would have been considered exemplary for the best regiment of disciplined Regulars. This is not surprising when we consider that in civil life they had been accustomed to exercise, command, and to exact obedience from others, even at the risk of their own lives. At the outset Colonel Lumsden made it a condition that he would have none but unmarried men in the ranks, and to this rule there were few known exceptions, though some Benedicts crept in undeclared. As a regiment, Lumsden’s Horse had an esprit de corps to maintain from the day of its birth under auspices that made the occasion imperial, and every man of it was tacitly pledged to prove himself a worthy recipient 18of the honour conferred upon him as one of India’s chosen representatives. How that feeling prevailed over all other considerations in the moment when Lumsden’s Horse played their manful part in battle for the first time, and how it held them together in a comradeship that was akin to brotherhood through after-months of hard campaigning, will appear as the narrative unfolds itself. It began to have an influence while the corps was as yet but an invertebrate skeleton, and it helps to explain the anxiety of Indian Volunteers to join the ranks of a force that was destined by the nature of things to become historical. One can understand, therefore, the alternations of hope and depression that passed over certain districts where men who had offered their services waited anxiously for the decision on which their chances of distinction hung. Some glimpses of this may be got through the letters received by Colonel Lumsden from all parts of India at that time, and from the diaries in which thoughts as well as actions are recorded by the men themselves. One begins his notes—two days after Colonel Lumsden’s call for Volunteers had been published—with the entry: ‘An express came from —— to say he had sent in the names of twenty men from C Company.’ After waiting impatiently several days for news that did not come, the diarist got his friend to send two telegrams, one to Colonel Lumsden, the other direct to the Adjutant-General at Calcutta, offering a complete company. The next day somebody turned up with news that they had been accepted. Jubilation on this score, however, lasted no longer than twenty-four hours, when it gave place to dejection caused by rumours that they ‘were not accepted after all.’ This wave of depression passed away as speedily in its turn, dispelled by the rays of hope that burst out radiantly on receipt of a chit from —— ‘asking me to come in at once.’ Under the next day’s date comes the crowning triumph of that anxious time, told very simply but in a way that makes one feel the nerves of those men throbbing through every word. ‘Started for Chick,’ runs the entry; ‘met ——, who told me we really were accepted. Then we met —— dashing along on his bike. He had already upset a woman.’ A week later, after many festive farewells, that contingent was on its way to Calcutta and foregathering with other contingents, whose experiences had 21all been the same, for every man of them was buoyant at the prospect of seeing active service, and would have regarded it as a personal slight, if not an indelible stigma on his reputation for courage, if he had been left behind.

MYSORE AND COORG CONTINGENT

So day by day the ranks of Lumsden’s Horse gained strength until their numbers were complete and recruiting had to be stopped; while many candidates whom the Colonel would gladly have taken tried in vain for admission. It was a regiment of which any commanding officer might be proud, whether judged by physical or mental standards. A corps of planters it might have been justly called, for they outnumbered all of other occupations; but it represented many classes, and nearly every district in India where sport-loving Britishers are to be found. In its ranks were fifty-five indigo-planters, sixty-one tea-planters, thirty-one coffee-planters, and five of similar occupation not specifically designated. Beside these, the sixteen Civil Service men of various grades, three bank assistants, twelve railway officials, including civil engineers, three medical men from the planting districts, one inspector of mounted police, a brewer, a tutor, a journalist, and a few others whose peaceful days until then had been devoted to commerce, form a comparatively small proportion. Thus considerably more than half the fighting strength were planters. Among the remainder, townsmen must have been fairly represented, to say nothing of artificers who formed the Maxim Gun detachment under command of Captain Bernard Willoughby Holmes, whose services had been placed at Colonel Lumsden’s disposal by consent of the East India Railway Company. The Mercantile Marine also furnished its quota in the persons of a captain, a chief officer, a second officer, and two engineers of the British India Steam Navigation Company’s fleet, and a chief officer of the Hajee Cassim Line. A veterinary surgeon, police inspectors, policemen, clerks in the Military Accounts Department, travelling agents, hotel assistants, a photographer, a theatrical agent, and a superintendent of the Rangoon Boating Club joined the Transport, from which two very smart fellows were drawn into the ranks as troopers during the campaign, and one of them was subsequently gazetted to the West India Regiment as second lieutenant. Counting all these, the enrolled strength was just 300.

22Then came the difficult and delicate task of appointing company officers and section commanders—a difficulty enhanced by the fact that many Volunteer officers had enlisted as troopers. I have said that the Government had given its unqualified approval to Colonel Lumsden’s project. This statement, however, applies only to the general scheme. It must be remembered that he had made no stipulation as to his own rank, or the right of selecting officers, and it was not in the nature of a British War Office to let the prerogative of veto slip entirely out of its hands. Colonel Lumsden’s own appointment as commanding officer came directly from headquarters, on the suggestion probably of Lord Curzon. Two other conditions, not very irksome, the military authorities made at Colonel Lumsden’s urgent request. These were that captains commanding companies should be Regular officers on active service, and that the adjutant, who would also act as quartermaster, should be appointed from the Staff Corps or have graduated in it. These nominations were left to the Commander-in-Chief in India, and in the ordinary course of things they involved the appointment of Regular non-commissioned officers as quartermaster-sergeants and company sergeant-majors. Other subordinate posts for which military experience or special training is necessary were also filled by Regulars, who thus relieved the Volunteer troopers of some laborious duties. An officer second in command, four captains acting as senior subalterns, four lieutenants, a medical officer, and a veterinary surgeon had still to be selected, and the choice must have involved many anxious moments, seeing how much depended on the unknown qualities that are hidden in all men and may lie dormant for years, only to be developed for good or ill in the crisis of an emergency. How Colonel Lumsden succeeded in this, as in every other preliminary task that he imposed upon himself, is now a matter of history to be dealt with in proper sequence. The wisdom of his selections could only be proved by events, and to these, as narrated by men who were best able to judge, appeal may be confidently made. Naturally, some who had held commissioned rank previously, and thought their claims to consideration indisputable, felt sore at being passed over in favour of others who were junior to them in the Volunteer service. But this irritation was not allowed to 23show itself or interfere with loyal subordination in all military duties.

To the inviolable pages of his diary one, whose merits were not at the time so well known as they ought to have been, confides the pregnant sentence: ‘Heard to-day that —— was to be a captain, I a corporal.’ There the entry ends, leaving a blank more eloquent than any scathing comment could have been. For all that, the captain and the corporal remained on the best of terms, and, though they ceased for discipline’s sake to call each other by their Christian names, there is reason to believe that both soon came to the conclusion that no very serious mistake had been made in estimating their relative fitness for command. At any rate, after a little friction they shaped themselves like round pegs to round holes. But that is the habit of Britishers, who, however unaccustomed to discipline, are not slow in recognising its inevitable necessity and its inestimable value. They come to see that without it no concerted movement, whether big or small, is certain of success. You cannot conduct military operations to a definite end, any more than you can navigate a ship or rule a family, if individuality is allowed to take the form of insubordination. These lessons Colonel Lumsden began to inculcate in his peculiarly persuasive way directly he had got his men together and placed officers in authority over them.

Men and officers, however, are not the only things necessary to keep a fighting unit going when once it has been formed and organised. Sir Patrick Playfair found the full equipment of such a force no less costly than he had estimated. Fortunately, however, he had foreseen all difficulties in this connection and provided for them. After consultation with General Maitland, General Wace (Director-General of Ordnance), Sir Alfred Gaselee (then Quartermaster-General), Sir E.R. Elles (Adjutant-General), and the late Surgeon-General Harvey, it was decided that nearly a thousand rupees per man would be necessary for equipping the force, buying horses in addition to those brought in by troopers themselves, and establishing a reserve fund sufficient for all emergencies that might arise while the men remained on active service. This meant that a sum amounting to two and a half lakhs of rupees, or about sixteen thousand five hundred pounds sterling, 24would have to be got together by public subscription. Until this campaign proved the depth and sincerity of Imperial sentiments among nearly all classes of the community, few people, even in England, believed that such a sum would be given to send a mere handful of Volunteers on active service far from their home. And most people, having but a superficial knowledge of Indian affairs, would have ridiculed the suggestion that native princes or merchants would contribute in proportion little less than Johannesburg millionaires to uphold British supremacy in South Africa.

Sir Patrick Playfair, however, knowing by experience how liberal had been the response of those people to all calls on their generosity, and gauging with remarkable insight the genuineness of their loyal devotion in a time of possible peril to the Empire, had no doubt what the result would be. But even he was not prepared for anything like the unanimity of enthusiasm that his appeal evoked. It took simply the form of a general invitation to subscribe. The marvellous rapidity with which the subscription list filled may therefore be taken as a voluntary expression by Europeans and natives alike of staunch fidelity to the cause for which Lumsden’s Horse were being enrolled as a fighting unit. The contributors included His Excellency the Viceroy (Lord Curzon of Kedleston), His Excellency the Governor of Bombay (Lord Sandhurst), His Excellency the Commander-in-Chief in India (the late Sir William Lockhart), their Honours the Lieutenant-Governor of Bengal (Sir John Woodburn), the Lieutenant-Governor of the Punjab (Sir W. Mackworth Young), the Lieutenant-Governor of the North-West Provinces and Oudh (the Bight Honourable Sir A.P. MacDonnell, P.C.), and the Lieutenant-Governor of Burma (Sir F.W.R. Fryer). Princes, rajahs, landowners, mercantile firms, and European residents almost without exception, came forward, subscribing munificently, until the sum of 227,000 rupees had been promised and received in cash, besides contributions from tradesmen in kind amounting to another 100,000 rupees.

No single subscription rivalled Colonel Lumsden’s splendid offer, or came anywhere near it in amount; but Sir Seymour King, K.C.I.E., M.P., on account of Messrs. Henry S. King & Co., 25London, and two allied firms in Bombay and Calcutta, gave a lump sum of 10,000 rupees, while Maharajah Sir Jotendro Mohun Tagore, K.C.S.I., Rajah Sir Sourindro Mohun Tagore, Knt., C.I.E., Nawab Sir Sidi Ahmed Khan, K.C.S.I., Mr. F. Verner, Messrs. Apcar & Co., and Kumar Rada Prosad Roy sent 5,000 rupees each. The last named, a zemindar, or landed proprietor, was quite diffident and doubtful whether he ought to subscribe without being asked directly, but he expressed a hope that his contribution would be accepted. A great many merchants and others who were only known to Sir Patrick Playfair by name sent cheques for amounts varying from fifty to 2,500 rupees. No fewer than twenty-eight mercantile firms in Calcutta subscribed 1,000 rupees each, and among the most liberal donors were native princes of nearly every State in the three Presidencies.

His Highness the Maharajah of Bhownagar, whose palace is 2,500 miles distant from Calcutta, sent fifty Arab chargers and saddlery; the Maharani Regent of Mysore, twenty-two country-bred and Arab horses; and other potentates, like the Maharajah Bahadur of Soubarsa and the Rajah of Mearsa, gave handsome presents of a similar kind according to the resources of their studs. The natives of Aligarh, clubbing together, sent twenty-seven horses and one mule; while one, Mohammed Mazamullah Khan, gave two horses, a mule, a donkey, and two small sleeping tents, accompanied by a touchingly simple letter saying, ‘They are all I have to help to conquer the enemies of the Great White Queen.’ Other contributions in kind ranged from tents sufficient for the whole force presented by the Elgin cotton mills of Cawnpore, rough serge cloth for all coats requisite from the Egerton woollen mills at Cawnpore, puttees from Kashmir and Cawnpore, gaiters, Cardigan jackets, hats, horseshoes and nails, forage, tea, coffee, beer, whisky, and cigars, down to matches, of which no fewer than 7,000 boxes were sent by one thoughtful gentleman. The India General Steam Navigation Company, the River Steam Navigation Company, the East India Railway, and the Eastern Bengal State Railway combined to carry men and horses free of charge from all parts of India to Calcutta.

A small executive committee was formed by Colonel Lumsden 26to carry out the arrangements for the equipment and despatch of the corps. Its members were:

The work of organising naturally fell to Colonel Lumsden, who was also busily engaged in selecting officers and enrolling men; while Sir Patrick Playfair undertook the entire management of the collection of subscriptions in cash and in kind, assisted by Mr. Shirley Tremearne, Editor of ‘Capital,’ whose local knowledge enabled him to render valuable aid in appealing to the mercantile community where personal appeals were necessary, and in collecting the promised subscriptions for which personal application had to be made in accordance with traditional etiquette. Mr. Harry Stuart, formerly executive manager of the Bengal State Railway, took charge of all arrangements for receiving and messing the different detachments on their arrival in Calcutta from distant districts until a camp could be formed.

Photo: Bourne & Shepherd

Mr. Harry Stuart Sir Patrick Playfair, C.I.E.

Col. Money Col. Lumsden, C.B. Major Eddis

THE EXECUTIVE COMMITTEE

Though the mobilisation scheme—drawn up by the Indian Headquarters Staff and sent to Colonel Lumsden after approval by the War Office in London—promised no more substantial assistance than the provision of arms, ammunition, rations, and transport to South Africa, it furnished many suggestions of the greatest importance, and, as a model for use on any similar occasion hereafter, it is reproduced at length in the Appendix. This document will be found of interest also as giving a comprehensive idea of the many requirements for which provision had to be made by Colonel Lumsden and his colleagues. Their labours were lightened by the cordial co-operation of military officials, who went out of their way to render every possible assistance. Without the advice and practical aid thus given by heads of departments of the Government of India, it would have been impossible for Colonel Lumsden, or any other commanding officer in his position, to have carried out all the War Office conditions economically. Major-General Wace, C.B., as head of 29the Ordnance Department, gave every facility for Colonel Lumsden to indent on Government stores for clothing and accoutrements at regulation prices, and not only so, but he and Colonel Buckland, the Superintendent of Army Clothing, with Major-General T.F. Hobday, Commissary-General, and Surgeon-General Robert Harvey, C.B., were ready to place the fruits of their long experience and special knowledge of various details at the service of Colonel Lumsden whenever he felt the need of advice in such matters; and Captain A.L. Phillips, an officer on the Staff of Sir Alfred Gaselee, Q.M.G., was untiring in his efforts to make the movement a success so far as his personal efforts and influence could avail. So everything went well from the beginning, thanks in great measure to the lively interest taken in the corps by Lord Curzon, who was pleased to become its Honorary Colonel, and by all officers of his personal Staff. Her Excellency Lady Curzon was equally zealous and lent her influence to every good work by which the ladies of Calcutta sought to express their admiration, and perhaps their tender regard, for the heroes who were going forth to fight. What form that expression should take was a subject much debated and long in doubt. Of course Sir Patrick Playfair had to be consulted by a deputation of charming damsels. He thought a bazaar might give them the opportunity they wanted. Yes! that was just the thing; but then—and then came a string of fatal objections. A smoking-concert was next suggested, and the young ladies thought that idea splendid, only—well, in short, it wouldn’t do. Then, as if it were the last resource to be thought of—a sort of forlorn hope—Sir Patrick hinted that a dance might meet the case. To that his fair interviewers demurred most effusively; but then and without any hypnotic suggestion, so Sir Patrick avers, they began to see that something might be urged in favour of it, and at last, with a unanimity that was wonderful, they decided that a dance was the only means of fitly celebrating the occasion. Having come to that conclusion, all their coy objections vanished in a moment. Sir Patrick saw his opportunity and seized it to persuade them that, as it was to be a ladies’ enterprise, they must manage it entirely themselves. Thereupon they formed a committee, of which Miss Pugh was elected Honorary Secretary, invited Lady Curzon of Kedleston 30to become patroness, and set to work with an energy which no mere man could hope to rival. They had of course to enlist masculine services for subordinate duties. This they did with a sweet despotism that made revolt impossible. The men had to accept without a murmur the positions assigned to them as stewards, and obeyed every mandate like the willing slaves we all should be in similar circumstances. The committee of ladies showed a business-like promptitude in settling every detail and a faculty for organisation which won from a military admirer the approving comment that they could conduct a campaign if they would only give their minds to it. This or some other feminine attribute had such an effect on the wine merchants of Calcutta that they sent champagne for the ball-supper and gallantly refused to accept payment. So the Calcutta Ball in honour of Lumsden’s Horse became an assured success almost from the moment of its happy inception. Brilliant beyond the dreams of a débutante, it left on many a susceptible heart impressions which neither time nor the changing scenes of warfare could dim, as the secret archives, to which an editor alone has access, attest; and in a less romantic way it proved the unselfish devotion of those ladies, who, after paying all expenses, handed over a balance of 6,000 rupees to the war-chest of Lumsden’s Horse.

Photo: Harrington & Co.

Such financial aids came not amiss at the moment. Government transports chartered by the Royal Indian Marine for taking troops to Natal were delayed on the return, and, one vessel having broken down, Colonel Lumsden found that he would have to encamp his men on the Maidan for two or three weeks longer than he had anticipated, and this entailed an additional expenditure of nearly 1,000l. for extra rations and comforts. To soldiers of Spartan mould, who pride themselves on discarding luxuries at the first call to arms, this might have seemed like pampering the Volunteer troopers; but it must be remembered that in India men cannot give up the habits of a lifetime all at once and come down to bare soldier’s rations without danger to their health. And Colonel Lumsden’s first object after getting his men was to keep them fit. His care in this respect was justified by events no less than his judgment in the selection of men for mental and physical attributes. At the 33end of a year’s campaigning he was able to boast that his losses from sickness were proportionately less than in any other regiment. This delay had its advantages in so far as it gave Colonel Lumsden and his officers a chance of training the troopers for their duties and accustoming them to their horses before the day of embarkation. The postponement, we may be sure, was no disappointment to the people of Calcutta, who felt that the Maidan would be a cheerless blank without Lumsden’s Horse. It will be well to give here a few details of organisation. By War Office order the corps was to consist of two companies, each commanded by a Regular officer, and the Government also appointed a Regular adjutant to assist Colonel Lumsden in executive work; while Colonel Eden C. Showers, Commandant of the Surma Valley Light Horse, offered to serve as Major, and was gazetted with that rank as second in command. When other officers had been selected, chiefly on the recommendation of commandants under whom they had served in Volunteer Corps, they were posted in the following order:

Staff.—Lieutenant-Colonel Dugald McTavish Lumsden, Commandant.

Major Eden C. Showers, Second in Command.

Captain Neville C. Taylor, 14th Bengal Lancers, Adjutant and Quartermaster.

Captain Samuel Arthur Powell, Medical Officer.

Veterinary Captain William Stevenson, M.R.C.V.S., Veterinary Surgeon.

A Company.—Captain James Hugh Brownlow Beresford, 3rd Sikhs (commanding), Captain John Brownley Rutherfoord, Lieutenants Charles Edward Crane and George Augustus Neville.

B Company.—Captain Louis Hemington Noblett, Royal Irish Rifles (commanding), Captain Henry Chamney, Captain Frank Clifford, Lieutenants Charles Lyon Sidey and Herbert Owain Pugh.

Maxim Gun Detachment.—Captain Bernard Willoughby Holmes (commanding).

Each company had a Regular non-commissioned officer as Company Sergeant-Major and another Regular as Company Quartermaster-Sergeant for office duties under the Regimental 34Quartermaster-Sergeant. Regulars from the Artillery, Cavalry, and Infantry were also attached as Farrier-Sergeants, Saddlers, and Signallers, and from the Indian Commissariat as Transport Sergeant. The Maxim Gun Contingent, under Captain Holmes was raised and equipped by the East India Railway Company, who offered its services to Colonel Lumsden. The Calcutta Committee had decided, with the sanction of the Government, that Lumsden’s Horse should not want for adequate regimental transport in the field, but, on the contrary, should leave India as a thoroughly organised unit in that respect, with a complete train of transport carts, ponies, and pack mules, all properly equipped. It is hardly necessary to say that the grant of transport, saddlery, and draught harness, for which provision was made in the mobilisation order, did not comprise all that the committee desired; but the inexhaustible Ordnance Stores were again open to be requisitioned ‘on payment,’ and carts of the Indian Army Transport pattern were drawn in a similar way from the Commissariat Department. The ponies and mules, however, had to be collected by agents in the hill districts of Assam and Thibet, a distance of 1,000 miles from Calcutta. When all this was done, the corps could justly be considered fit for active service, and it is certain that no contingent, Volunteer or Regular, landed in South Africa with a more efficient transport than Lumsden’s Horse. It came near being upset, however, by a War Office decision. Almost at the last minute Colonel Lumsden was told that the native drivers would not be permitted to accompany the corps, and that no natives could go except one personal servant for each officer and a limited number of syces, or grooms, in the proportion of one to each charger, as laid down in the mobilisation scheme. This allowance of three native attendants to every officer was on a sufficiently liberal scale, but it did not meet the requirements for transport purposes. Therefore Colonel Lumsden had to enlist European drivers, of whom twenty-six were needed for each company. In ordinary circumstances Anglo-Indian prejudices would have combined to make this an insuperable difficulty; but so keen was the anxiety of men to see war service in South Africa that they volunteered to go in any capacity not necessarily menial, and so Colonel Lumsden got the full complement of drivers together just as 37readily as lie had filled the ranks with fighting men. War Office conditions stipulated that officers and troopers of the corps must provide their own horses and saddlery, though nearly all of the latter might be drawn from Ordnance Stores at cost price. Naturally the supply of suitable animals for Mounted Infantry work had to be made a corps affair from the outset. Very few of the enlisted troopers owned horses of a class that they would have cared to ride through the rough work of a campaign, even if they could be always sure of having their own; and Colonel Lumsden was not likely to countenance any claims of private ownership when once horses were numbered as of the troop. He therefore informed every man who brought a horse with him that it must be considered corps property, and might not be appropriated by its owner without the commanding officer’s sanction. No other arrangement could have worked satisfactorily. In consideration of this understanding Colonel Lumsden promised that he would endeavour to obtain from Government a scale of compensation for horses thus appropriated, and in the event of being successful the sums obtained under this head would be returned pro rata to the owners of horses. It may be mentioned in passing that Colonel Lumsden’s efforts to this end were ultimately successful, the Government consenting to allow an average of 30l. per horse to the corps, so that every man who brought his own charger was compensated at last.

Photo: F. Kapp & Co.

MESSING AT CALCUTTA

Under the Shamiana

The men having drawn their Lee-Metford rifles with short bayonets and an abundant supply of ·303 ball cartridges, both for practice and the sterner work to come, were duly clothed and equipped, much to their satisfaction.

Not many of these things, in addition to rifles and ammunition, were free gifts from Government, whose contributions in kind had to be supplemented by purchases out of store at the cost of corps funds and by gifts from the appreciative public to whom no appeals were made in vain. The troopers, at any rate, were troubled not a whit about these things, being quite satisfied with the completeness of their personal outfit, even before Mrs. Pugh and the ladies of Calcutta bethought them to work woollen comforters for presentation to every man of Lumsden’s Horse on the day of embarkation. They did not, however, take so kindly at first to the Lee-Metford rifle. It was a new weapon 38to most of the men, who had never handled anything more complicated than the old Martini carbine. So batches of men went to the ranges every morning to practise and accustom themselves to the peculiarities of a firearm that made no more noise than the crack of a whip and ‘had no kick in it.’ This was a time of gradual but sometimes painful initiation to the hardships and discomforts inseparable from camp life. Lessons, however distasteful, had to be learned, and it must be said that Lumsden’s Horse took the rough with the smooth cheerily enough, enlivening their daily routine with many pleasantries. They were always ready to laugh at a comrade or with him in a merry jest at their own expense. Some literary contributions from the ranks to local papers were amusing in their fanciful exaggerations, which nobody enjoyed more than did the troopers whose foibles were thus humorously railed at. For sanitary reasons they were one day ordered, by medical authority, to strike their camp and pitch it on fresh ground, whereupon one of them wrote:

Like a bolt from the blue has fallen upon this camp the Æsculapian decree that we must go hence! It happened to-day that the medical eye of Lumsden’s Horse opened wide, and beheld strange sights. What the vision was has not been recorded owing to no ink being found in camp capable of expressing its blackness, but it is no secret that microbes as big as mastodons were observed freely gambolling in the immediate vicinity of the commissariat tent. The marvel is that a number of men can have lived on such a spot for ten days without coming to more serious harm.

The green sward on the banks of the Tolly’s Nullah has presented an animated appearance within the last few days, for every train arriving in Calcutta has brought its quota to swell the corps. A number of men from the Assam Valley Light Horse are now in camp. The Mysore contingent is also established, while the Behar lads are expected to-morrow by 10 o’clock. These will number a few over fifty, and will prove no doubt the crème de la crème of the corps. In a day or two the Maxim gun will come into quarters, and Oakley, of Kooch Behar and Tirah fame, has gone to some up-country sequestered spot whence comes a particularly quiet jat of pony, where he will choose animals of gentle temperament and so small that falling off them won’t hurt—for Maxim gun men scorn to ride.

This question of riding is no small one, and many gallant sportsmen may be seen tearing down the lines trying to get there before their 39horses. One like this was advised by a real Tommy Atkins to sit further back and so enjoy a longer ride. Not the least pleasurable sight in the camp is when bold Volunteers begin grooming their own horses. Some never do more than the neck, because of the risk attached to venturing within range of hind feet, with which country-bred horses are notoriously handy—if it may be so said of feet. Then saddling troubles others, because of the difficulty in distinguishing between cantle and pommel when a saddle hasn’t a horse inside to illustrate the difference.

There is a touch of boyish imagination about that sketch, but it is not altogether fanciful. Some of the Volunteers who joined first were by no means experienced horse-masters, and, to nearly all, the equipments for Mounted Infantry in full campaigning kit were not less strange than military technicalities. There was a rich fund of amusement for Lumsden’s Horse in the unauthorised version of ordinary commands as one trooper construed them. When sections in line were crowding too much upon him he would say, ‘Fall off, man! Fall off to the left.’ The comrade thus admonished would murmur, ‘Hang it all, man, that is just what I am trying not to do.’ Still, young Malaprop would repeat, in defiance of the Sergeant-Major’s peremptory request for silence in the ranks, ‘Fall off! fall off!’ meaning all the time ‘Ease off.’ These simple incidents of every day gave a piquancy to camp ‘gup,’ and were the cause of more mirth than the elaborate jokes concocted by literary troopers could arouse. One civilian, in a playfully prophetic mood, devised a new coat of arms for Lumsden’s Horse, which was published in the ‘Indian Daily News’ as a clever play upon the cant of Heraldry; though the Earl Marshal and all the Kings-at-Arms and all the learned pursuivants of Heralds’ College might have been puzzled if called upon to emblazon the quaint conceit with its complicated quarterings, its proper shield of pretence, and its lurid crest of augmentation.

Life in camp on the Maidan was becoming somewhat monotonous to men whose ardent spirits panted for opportunities of distinction in the Empire’s service, and for freer movement on the vast South African veldt. For traces of this yearning one may search in vain through pages of diaries, to which men do not commit all their secret thoughts. Perhaps they regarded a parade of warlike sentiments as bad form even in the written impressions that were intended only for private perusal. So they contented themselves with noting briefly the minor events of listless days and the mild excitements of evenings that passed swiftly enough in such social pleasures as dining, theatre-going, or listening to the latest London melodies at a smoking-concert organised in aid of the war fund. Even a flower-show was regarded by some as an amusement. We come across frequent references to baths at the Swimming Club, tiffin at Pelité’s, and luxurious little dinners at the Bristol, the Continental, or the Grand; but only by inference, from the sudden importance given to these everyday incidents of civilian life, can we gather what a contrast they were to the coarser fare and rougher surroundings of meals in camp. There is not a hint of discontent at being reduced for the first time in their lives to soldiers’ rations or at the hard fatigue work they were put to as a necessary part of the daily routine. These manly young troopers were beginning to learn the soldier’s lessons of subjection to discipline and endurance of discomforts that must have seemed sufficiently like hardships to most of them, but they had not acquired the habit of grumbling which is Tommy’s cherished privilege. The visits of crowds to that camp on the Maidan every Sunday were evidence enough of the great interest taken by all classes of citizens in Lumsden’s 43Horse, who were properly appreciative of those attentions, and not quite insensible to the sweet flattery of admiring glances from pretty eyes. The motto that ‘None but the brave deserve the fair’ is one in which gallant soldiers from all time have found encouragement, and Lumsden’s Horse were beginning to appropriate it with other soldierly attributes, for were they not all brave and resolved to prove it? Their only fear was that the chance of doing knightly deeds might not come to them, and that they would land in South Africa only in time to learn that the war had been finished before the tardy transports could get there. Nevertheless, we know that they relaxed no efforts to make themselves fit for the fray. From contributions by troopers to the Indian papers we may learn how zealous they were to master the least attractive duties of military life, and Staff officers bear witness to the sincerity and success of these endeavours. Mere forms of discipline might have been lacking, and one cannot wonder that men who had lived similar lives, sharing the same sports and social pleasures, found it difficult at first to fall into their relative positions, some as officers, others as troopers, and to keep each his own proper groove, ignoring old associations. But the right spirit of subordination was there, and a commander of Irregulars does not ask for more if he has the true capacity for leadership. The daily routine of duties in camp on the Maidan was designed to foster this spirit without making the yoke of essential discipline too galling. A description of it as given by one in the ranks will show that Lumsden’s Horse were by no means pampered Sybarites even at that early stage of their soldiering:

At 6 the ‘rouse’ sounds, and, some minutes later, men clad in khaki breeches, putti gaiters, and flannel shirts issue from the little bell tents into the clammy mist of early morning, and after obtaining a cup of tea at the mess, remove the jhools—which are a most necessary protection against the heavy dew—from their horses, and give them a rub down. At 7 we hear the bugle call ‘Saddle up,’ and at 7.30 the men are all fallen in on the Maidan in column of sections, and go through the various evolutions, special attention being given to mounting and dismounting on saddles packed with full kit, and the leading of horses, the correct and rapid performance of which is so important in Mounted Infantry work. The regiment is divided into two companies, each company consisting of 120 men formed into four sections, and these again divided into permanent 44sub-sections of four men each. As a rule the sections work independently, each under its own commander. Blank ammunition is liberally expended in order to accustom the horses to the rattle of musketry. Most of the men are mounted on country-breds; but several ride shapely walers averaging 14.2. Considering that 50 per cent. of the horses are quite untrained as chargers, they are astonishingly quiet and well-behaved; the C.B.s—with the exception of an occasional kicker, which plays havoc in the ranks, and is a source of some danger to his unfortunate companions, both men and horses—are quick, handy little brutes, and already they have learnt to lead steadily and well. There are, of course, a good number of trained horses in the ranks; the Mysore men, for instance, being almost without exception mounted on Silidar horses, which are proving most satisfactory chargers and are expected to do well in Africa. After parade the horses are watered, fed, and groomed by their respective owners, and then, as Mr. Pepys would have said, ‘to breakfast,’ under a large shamiana placed at one end of the camp in the shade of sycamore-fig trees. The morning passes quickly while men are drawing and marking kit, cleaning rifles, or doing fatigue duty at pitching tents and other healthy exercises. At noon we water and feed the horses, and 1 o’clock is the tiffin hour. At 4.30 there is an afternoon parade, sometimes by companies, and sometimes the whole regiment parading under the Colonel or Major, after which water, feed and bed-down, and then dinner, and an early retirement to bed. But not for all is this happy rest. There are two guard tents, at opposite ends of the camp, each company providing a sergeant and three men for guard every twenty-four hours, while a man from each company is on sentry throughout the night, his duty being to see that the horses are properly secured—head and heel—and be on hand in case of sickness.

Photo: F. Kapp & Co.

HORSES IN CAMP AT CALCUTTA