By MURRAY LEINSTER

Illustrated by HARRY ROSENBAUM

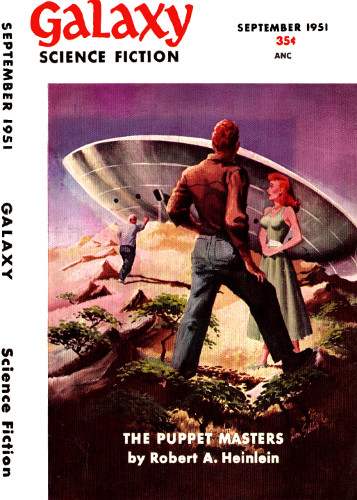

[Transcriber's Note: This etext was produced from

Galaxy Science Fiction September 1951.

Extensive research did not uncover any evidence that

the U.S. copyright on this publication was renewed.]

You'd love Earthmen to pieces, for they

may look pretty bad to themselves, but

not to you. You'd even want to be one!

Up to the very last minute, I can't imagine that Moklin is going to be the first planet that humans get off of, moving fast, breathing hard, and sweating awful copious. There ain't any reason for it. Humans have been on Moklin for more than forty years, and nobody ever figures there is anything the least bit wrong until Brooks works it out. When he does, nobody can believe it. But it turns out bad. Plenty bad. But maybe things are working out all right now.

Maybe! I hope so.

At first, even after he's sent off long reports by six ships in a row, I don't see the picture beginning to turn sour. I don't get it until after the old Palmyra comes and squats down on the next to the last trip a Company ship is ever going to make to Moklin.

Up to that very morning everything is serene, and that morning I am sitting on the trading post porch, not doing a thing but sitting there and breathing happy. I'm looking at a Moklin kid. She's about the size of a human six-year-old and she is playing in a mud puddle while her folks are trading in the post. She is a cute kid—mighty human-looking. She has long whiskers like Old Man Bland, who's the first human to open a trading post and learn to talk to Moklins.

Moklins think a lot of Old Man Bland. They build him a big tomb, Moklin-style, when he dies, and there is more Moklin kids born with long whiskers than you can shake a stick at. And everything looks okay. Everything!

Sitting there on the porch, I hear a Moklin talking inside the trade room. Talking English just as good as anybody. He says to Deeth, our Moklin trade-clerk, "But Deeth, I can buy this cheaper over at the other trading post! Why should I pay more here?"

Deeth says, in English too, "I can't help that. That's the price here. You pay it or you don't. That's all."

I just sit there breathing complacent, thinking how good things are. Here I'm Joe Brinkley, and me and Brooks are the Company on Moklin—only humans rate as Company employees and get pensions, of course—and I'm thinking sentimental about how much humaner Moklins are getting every day and how swell everything is.

The six-year-old kid gets up out of the mud puddle, and wrings out her whiskers—they are exactly like the ones on the picture of Old Man Bland in the trade room—and she goes trotting off down the road after her folks. She is mighty human-looking, that one.

The wild ones don't look near so human. Those that live in the forest are greenish, and have saucer eyes, and their noses can wiggle like an Earth rabbit. You wouldn't think they're the same breed as the trading post Moklins at all, but they are. They crossbreed with each other, only the kids look humaner than their parents and are mighty near the same skin color as Earthmen, which is plenty natural when you think about it, but nobody does. Not up to then.

I don't think about that then, or anything else. Not even about the reports Brooks keeps sweating over and sending off with every Company ship. I am just sitting there contented when I notice that Sally, the tree that shades the trading post porch, starts pulling up her roots. She gets them coiled careful and starts marching off. I see the other trees are moving off, too, clearing the landing field. They're waddling away to leave a free space, and they're pushing and shoving, trying to crowd each other, and the little ones sneak under the big ones and they all act peevish. Somehow they know a ship is coming in. That's what their walking off means, anyhow. But there ain't a ship due in for a month, yet.

They're clearing the landing field, though, so I start listening for a ship's drive, even if I don't believe it. At first I don't hear a thing. It must be ten minutes before I hear a thin whistle, and right after it the heavy drone that's the ground-repulsor units pushing against bedrock underground. Lucky they don't push on wet stuff, or a ship would sure mess up the local countryside!

I get off my chair and go out to look. Sure enough, the old Palmyra comes bulging down out of the sky, a month ahead of schedule, and the trees over at the edge of the field shove each other all round to make room. The ship drops, hangs anxious ten feet up, and then kind of sighs and lets down. Then there's Moklins running out of everywhere, waving cordial.

They sure do like humans, these Moklins! Humans are their idea of what people should be like! Moklins will wrestle the freight over to the trading post while others are climbing over everything that's waiting to go off, all set to pass it up to the ship and hoping to spot friends they've made in the crew. If they can get a human to go home with them and visit while the ship is down, they brag about it for weeks. And do they treat their guests swell!

They got fancy Moklin clothes for them to wear—soft, silky guest garments—and they got Moklin fruits and Moklin drinks—you ought to taste them! And when the humans have to go back to the ship at takeoff time, the Moklins bring them back with flower wreaths all over them.

Humans is tops on Moklin. And Moklins get humaner every day. There's Deeth, our clerk. You couldn't hardly tell him from human, anyways. He looks like a human named Casey that used to be at the trading post, and he's got a flock of brothers and sisters as human-looking as he is. You'd swear—

But this is the last time but one that a Earth ship is going to land on Moklin, though nobody knows it yet. Her passenger port opens up and Captain Haney gets out. The Moklins yell cheerful when they see him. He waves a hand and helps a human girl out. She has red hair and a sort of businesslike air about her. The Moklins wave and holler and grin. The girl looks at them funny, and Cap Haney explains something, but she sets her lips. Then the Moklins run out a freight-truck, and Haney and the girl get on it, and they come racing over to the post, the Moklins pushing and pulling them and making a big fuss of laughing and hollering—all so friendly, it would make anybody feel good inside. Moklins like humans! They admire them tremendous! They do everything they can think of to be human, and they're smart, but sometimes I get cold shivers when I think how close a thing it turns out to be.

Cap Haney steps off the freight-truck and helps the girl down. Her eyes are blazing. She is the maddest-looking female I ever see, but pretty as they make them, with that red hair and those blue eyes staring at me hostile.

"Hiya, Joe," says Cap Haney. "Where's Brooks?"

I tell him. Brooks is poking around in the mountains up back of the post. He is jumpy and worried and peevish, and he acts like he's trying to find something that ain't there, but he's bound he's going to find it regardless.

"Too bad he's not here," says Haney. He turns to the girl. "This is Joe Brinkley," he says. "He's Brooks' assistant. And, Joe, this is Inspector Caldwell—Miss Caldwell."

"Inspector will do," says the girl, curt. She looks at me accusing. "I'm here to check into this matter of a competitive trading post on Moklin."

"Oh," I says. "That's bad business. But it ain't cut into our trade much. In fact, I don't think it's cut our trade at all."

"Get my baggage ashore, Captain," says Inspector Caldwell, imperious. "Then you can go about your business. I'll stay here until you stop on your return trip."

I call, "Hey, Deeth!" But he's right behind me. He looks respectful and admiring at the girl. You'd swear he's human! He's the spit and image of Casey, who used to be on Moklin until six years back.

"Yes, sir," says Deeth. He says to the girl, "Yes, ma'am. I'll show you your quarters, ma'am, and your baggage will get there right away. This way, ma'am."

He leads her off, but he don't have to send for her baggage. A pack of Moklins come along, dragging it, hopeful of having her say "Thank you" to them for it. There hasn't ever been a human woman on Moklin before, and they are all excited. I bet if there had been women around before, there'd have been hell loose before, too. But now the Moklins just hang around, admiring.

There are kids with whiskers like Old Man Bland, and other kids with mustaches—male and female both—and all that sort of stuff. I'm pointing out to Cap Haney some kids that bear a remarkable resemblance to him and he's saying, "Well, what do you know!" when Inspector Caldwell comes back.

"What are you waiting for, Captain?" she asks, frosty.

"The ship usually grounds a few hours," I explain. "These Moklins are such friendly critters, we figure it makes good will for the trading post for the crew to be friendly with 'em."

"I doubt," says Inspector Caldwell, her voice dripping icicles, "that I shall advise that that custom be continued."

Cap Haney shrugs his shoulders and goes off, so I know Inspector Caldwell is high up in the Company. She ain't old, maybe in her middle twenties, I'd say, but the Caldwell family practically owns the Company, and all the nephews and cousins and so on get put into a special school so they can go to work in the family firm. They get taught pretty good, and most of them really rate the good jobs they get. Anyhow, there's plenty of good jobs. The Company runs twenty or thirty solar systems and it's run pretty tight. Being a Caldwell means you get breaks, but you got to live up to them.

Cap Haney almost has to fight his way through the Moklins who want to give him flowers and fruits and such. Moklins are sure crazy about humans! He gets to the entry port and goes in, and the door closes and the Moklins pull back. Then the Palmyra booms. The ground-repulsor unit is on. She heaves up, like she is grunting, and goes bulging up into the air, and the humming gets deeper and deeper, and fainter and fainter—and suddenly there's a keen whistling and she's gone. It's all very normal. Nobody would guess that this is the last time but one a Earth ship will ever lift off Moklin!

Inspector Caldwell taps her foot, icy. "When will you send for Mr. Brooks?" she demands.

"Right away," I says to her. "Deeth—"

"I sent a runner for him, ma'am," says Deeth. "If he was in hearing of the ship's landing, he may be on the way here now."

He bows and goes in the trade room. There are Moklins that came to see the ship land, and now have tramped over to do some trading. Inspector Caldwell jumps.

"Wh-what's that?" she asks, tense.

The trees that crowded off the field to make room for the Palmyra are waddling back. I realize for the first time that it might look funny to somebody just landed on Moklin. They are regular-looking trees, in a way. They got bark and branches and so on. Only they can put their roots down into holes they make in the ground, and that's the way they stay, mostly. But they can move. Wild ones, when there's a water shortage or they get too crowded or mad with each other, they pull up their roots and go waddling around looking for a better place to take root in.

The trees on our landing field have learned that every so often a ship is going to land and they've got to make room for it. But now the ship is gone, and they're lurching back to their places. The younger ones are waddling faster than the big ones, though, and taking the best places, and the old grunting trees are waving their branches indignant and puffing after them mad as hell.

I explain what is happening. Inspector Caldwell just stares. Then Sally comes lumbering up. I got a friendly feeling for Sally. She's pretty old—her trunk is all of three feet thick—but she always puts out a branch to shade my window in the morning, and I never let any other tree take her place. She comes groaning up, and uncoils her roots, and sticks them down one by one into the holes she'd left, and sort of scrunches into place and looks peaceful.

"Aren't they—dangerous?" asks Inspector Caldwell, pretty uneasy.

"Not a bit," I says. "Things can change on Moklin. They don't have to fight. Things fight in other places because they can't change and they get crowded, and that's the only way they can meet competition. But there's a special kind of evolution on Moklin. Cooperative, you might call it. It's a nice place to live. Only thing is everything matures so fast. Four years and a Moklin is grown up, for instance."

She sniffs. "What about that other trading post?" she says, sharp. "Who's back of it? The Company is supposed to have exclusive trading rights here. Who's trespassing?"

"Brooks is trying to find out," I says. "They got a good complete line of trade goods, but the Moklins always say the humans running the place have gone off somewhere, hunting and such. We ain't seen any of them."

"No?" says the girl, short. "I'll see them! We can't have competition in our exclusive territory! The rest of Mr. Brooks' reports—" She stops. Then she says, "That clerk of yours reminds me of someone I know."

"He's a Moklin," I explain, "but he looks like a Company man named Casey. Casey's Area Director over on Khatim Two now, but he used to be here, and Deeth is the spit and image of him."

"Outrageous!" says Inspector Caldwell, looking disgusted.

There's a couple of trees pushing hard at each other. They are fighting, tree-fashion, for a specially good place. And there's others waddling around, mad as hell, because somebody else beat them to the spots they liked. I watch them. Then I grin, because a couple of young trees duck under the fighting big ones and set their roots down in the place the big trees was fighting over.

"I don't like your attitude!" says Inspector Caldwell, furious.

She goes stamping into the post, leaving me puzzled. What's wrong with me smiling at those kid trees getting the best of their betters?

That afternoon Brooks comes back, marching ahead of a pack of woods-Moklins with greenish skins and saucer eyes that've been guiding him around. He's a good-looking kind of fellow, Brooks is, with a good build and a solid jaw.

When he comes out of the woods on the landing field—the trees are all settled down by then—he's striding impatient and loose-jointed. With the woods-Moklins trailing him, he looks plenty dramatic, like a visi-reel picture of a explorer on some unknown planet, coming back from the dark and perilous forests, followed by the strange natives who do not yet know whether this visitor from outer space is a god or what. You know the stuff.

I see Inspector Caldwell take a good look at him, and I see her eyes widen. She looks like he is a shock, and not a painful one.

He blinks when he sees her. He grunts. "What's this? A she-Moklin?"

Inspector Caldwell draws herself up to her full five-foot-three. She bristles.

I say quick, "This here is Inspector Caldwell that the Palmyra dumped off here today. Uh—Inspector, this is Brooks, the Head Trader."

They shake hands. He looks at her and says, "I'd lost hope my reports would ever get any attention paid to them. You've come to check my report that the trading post on Moklin has to be abandoned?"

"I have not!" says Inspector Caldwell, sharp. "That's absurd! This planet has great potentialities, this post is profitable and the natives are friendly, and the trade should continue to increase. The Board is even considering the introduction of special crops."

That strikes me as a bright idea. I'd like to see what would happen if Moklins started cultivating new kinds of plants! It would be a thing to watch—with regular Moklin plants seeing strangers getting good growing places and special attention! I can't even guess what'll happen, but I want to watch!

"What I want to ask right off," says Inspector Caldwell, fierce, "is why you have allowed a competitive trading post to be established, why you did not report it sooner, and why you haven't identified the company back of it?"

Brooks stares at her. He gets mad.

"Hell!" he says. "My reports cover all that! Haven't you read them?"

"Of course not," says Inspector Caldwell. "I was given an outline of the situation here and told to investigate and correct it."

"Oh!" says Brooks. "That's it!"

Then he looks like he's swallowing naughty words. It is funny to see them glare at each other, both of them looking like they are seeing something that interests them plenty, but throwing off angry sparks just the same.

"If you'll show me samples of their trade goods," says Inspector Caldwell, arrogant, "and I hope you can do that much, I'll identify the trading company handling them!"

He grins at her without amusement and leads the way to the inside of the trading post. We bring out the stuff we've had some of our Moklins go over and buy for us. Brooks dumps the goods on a table and stands back to see what she'll make of them, grinning with the same lack of mirth. She picks up a visi-reel projector.

"Hmm," she says, scornful. "Not very good quality. It's...." Then she stops. She picks up a forest knife. "This," she says, "is a product of—" Then she stops again. She picks up some cloth and fingers it. She really steams. "I see!" she says, angry. "Because we have been on this planet so long and the Moklins are used to our goods, the people of the other trading post duplicate them! Do they cut prices?"

"Fifty per cent," says Brooks.

I chime in, "But we ain't lost much trade. Lots of Moklins still trade with us, out of friendship. Friendly folks, these Moklins."

Just then Deeth comes in, looking just like Casey that used to be here on Moklin. He grins at me.

"A girl just brought you a compliment," he lets me know.

"Shucks!" I says, embarrassed and pleased. "Send her in and get a present for her."

Deeth goes out. Inspector Caldwell hasn't noticed. She's seething over that other trading company copying our trade goods and underselling us on a planet we're supposed to have exclusive. Brooks looks at her grim.

"I shall look over their post," she announces, fierce, "and if they want a trade war, they'll get one! We can cut prices if we need to—we have all the resources of the Company behind us!"

Brooks seems to be steaming on his own, maybe because she hasn't read his reports. But just then a Moklin girl comes in. Not bad-looking, either. You can see she is a Moklin—she ain't as convincing human as Deeth is, say—but she looks pretty human, at that. She giggles at me.

"Compliment," she says, and shows me what she's carrying.

I look. It's a Moklin kid, a boy, just about brand-new. And it has my shape ears, and its nose looks like somebody had stepped on it—my nose is that way—and it looks like a very small-sized working model of me. I chuck it under the chin and say, "Kitchy-coo!" It gurgles at me.

"What's your name?" I ask the girl.

She tells me. I don't remember it, and I don't remember ever seeing her before, but she's paid me a compliment, all right—Moklin-style.

"Mighty nice," I say. "Cute as all get-out. I hope he grows up to have more sense than I got, though." Then Deeth comes in with a armload of trade stuff like Old Man Bland gave to the first Moklin kid that was born with long whiskers like his, and I say, "Thanks for the compliment. I am greatly honored."

She takes the stuff and giggles again, and goes out. The kid beams at me over her shoulder and waves its fist. Mighty humanlike. A right cute kid, any way you look at it.

Then I hear a noise. Inspector Caldwell is regarding me with loathing in her eyes.

"Did you say they were friendly creatures?" she asks, bitter. "I think affectionate would be a better word!" Her voice shakes. "You are going to be transferred out of here the instant the Palmyra gets back!"

"What's the matter?" I ask, surprised. "She paid me a compliment and I gave her a present. It's a custom. She's satisfied. I never see her before that I remember."

"You don't?" she says. "The—the callousness! You're revolting!"

Brooks begins to sputter, then he snickers, and all of a sudden he's howling with laughter. He is laughing at Inspector Caldwell. Then I get it, and I snort. Then I hoot and holler. It gets funnier when she gets madder still. She near blows up from being mad!

We must look crazy, the two of us there in the post, just hollering with laughter while she gets furiouser and furiouser. Finally I have to lay down on the floor to laugh more comfortable. You see, she doesn't get a bit of what I've told her about there being a special kind of evolution on Moklin. The more disgusted and furious she looks at me, the harder I have to laugh. I can't help it.

When we set out for the other trading post next day, the atmosphere ain't what you'd call exactly cordial. There is just the Inspector and me, with Deeth and a couple of other Moklins for the look of things. She has on a green forest suit, and with her red hair she sure looks good! But she looks at me cold when Brooks says I'll take her over to the other post, and she doesn't say a word the first mile or two.

We trudge on, and presently Deeth and the others get ahead so they can't hear what she says. And she remarks indignant, "I must say Mr. Brooks isn't very cooperative. Why didn't he come with me? Is he afraid of the men at the other post?"

"Not him," I says. "He's a good guy. But you got authority over him and you ain't read his reports."

"If I have authority," she says, sharp, "I assure you it's because I'm competent!"

"I don't doubt it," I says. "If you wasn't cute, he wouldn't care. But a man don't want a good-looking girl giving him orders. He wants to give them to her. A homely woman, it don't matter."

She tosses her head, but it don't displease her. Then she says, "What's in the reports that I should have read?"

"I don't know," I admit. "But he's been sweating over them. It makes him mad that nobody bothered to read 'em."

"Maybe," she guesses, "it was what I need to know about this other trading post. What do you know about it, Mr. Brinkley?"

I tell her what Deeth has told Brooks. Brooks found out about it because one day some Moklins come in to trade and ask friendly why we charge so much for this and that. Deeth told them we'd always charged that, and they say the other trading post sells things cheaper, and Deeth says what trading post? So they up and tell him there's another post that sells the same kind of things we do, only cheaper. But that's all they'll say.

So Brooks tells Deeth to find out, and he scouts around and comes back. There is another trading post only fifteen miles away, and it is selling stuff just like ours. And it charges only half price. Deeth didn't see the men—just the Moklin clerks. We ain't been able to see the men either.

"Why haven't you seen the men?"

"Every time Brooks or me go over," I explain, "the Moklins they got working for them say the other men are off somewhere. Maybe they're starting some more posts. We wrote 'em a note, asking what the hell they mean, but they never answered it. Of course, we ain't seen their books or their living quarters—"

"You could find out plenty by a glimpse at their books!" she snaps. "Why haven't you just marched in and made the Moklins show you what you want to know, since the men were away?"

"Because," I says, patient, "Moklins imitate humans. If we start trouble, they'll start it too. We can't set a example of rough stuff like burglary, mayhem, breaking and entering, manslaughter, or bigamy, or those Moklins will do just like us."

"Bigamy!" She grabs on that sardonic. "If you're trying to make me think you've got enough moral sense—"

I get a little mad. Brooks and me, we've explained to her, careful, how it is admiration and the way evolution works on Moklin that makes Moklin kids get born with long whiskers and that the compliment the Moklin girl has paid me is just exactly that. But she hasn't listened to a word.

"Miss Caldwell," I says, "Brooks and me told you the facts. We tried to tell them delicate, to spare your feelings. Now if you'll try to spare mine, I'll thank you."

"If you mean your finer feelings," she says, sarcastic, "I'll spare them as soon as I find some!"

So I shut up. There's no use trying to argue with a woman. We tramp on through the forest without a word. Presently we come on a nest-bush. It's a pretty big one. There are a couple dozen nests on it, from the little-bitty bud ones no bigger than your fist, to the big ripe ones lined with soft stuff that have busted open and have got cacklebirds housekeeping in them now.

There are two cacklebirds sitting on a branch by the nest that is big enough to open up and have eggs laid in it, only it ain't. The cacklebirds are making noises like they are cussing it and telling it to hurry up and open, because they are in a hurry.

"That's a nest-bush," I says. "It grows nests for the cacklebirds. The birds—uh—fertilize the ground around it. They're sloppy feeders and drop a lot of stuff that rots and is fertilizer too. The nest-bush and the cacklebirds kind of cooperate. That's the way evolution works on Moklin, like Brooks and me told you."

She tosses that red head of hers and stamps on, not saying a word. So we get to the other trading post. And there she gets one of these slow-burning, long-lasting mads on that fill a guy like me with awe.

There's only Moklins at the other trading post, as usual. They say the humans are off somewhere. They look at her admiring and polite. They show her their stock. It is practically identical with ours—only they admit that they've sold out of some items because their prices are low. They act most respectful and pleased to see her.

But she don't learn a thing about where their stuff comes from or what company is horning in on Moklin trade. And she looks at their head clerk and she burns and burns.

When we get back, Brooks is sweating over memorandums he has made, getting another report ready for the next Company ship. Inspector Caldwell marches into the trade room and gives orders in a controlled, venomous voice. Then she marches right in on Brooks.

"I have just ordered the Moklin sales force to cut the price on all items on sale by seventy-five per cent," she says, her voice trembling a little with fury. "I have also ordered the credit given for Moklin trade goods to be doubled. They want a trade war? They'll get it!"

She is a lot madder than business would account for. Brooks says, tired, "I'd like to show you some facts. I've been over every inch of territory in thirty miles, looking for a place where a ship could land for that other post. There isn't any. Does that mean anything to you?"

"The post is there, isn't it?" she says. "And they have trade goods, haven't they? And we have exclusive trading rights on Moklin, haven't we? That's enough for me. Our job is to drive them out of business!"

But she is a lot madder than business would account for. Brooks says, very weary, "There's nearly a whole planet where they could have put another trading post. They could have set up shop on the other hemisphere and charged any price they pleased. But they set up shop right next to us! Does that make sense?"

"Setting up close," she says, "would furnish them with customers already used to human trade goods. And it furnished them with Moklins trained to be interpreters and clerks! And—" Then it come out, what she's raging, boiling, steaming, burning up about. "And," she says, furious, "it furnished them with a Moklin head-clerk who is a very handsome young man, Mr. Brooks! He not only resembles you in every feature, but he even has a good many of your mannerisms. You should be very proud!"

With this she slams out of the room. Brooks blinks.

"She won't believe anything," he says, sour, "except only that man is vile. Is that true about a Moklin who looks like me?"

I nod.

"Funny his folks never showed him to me for a compliment-present!" Then he stares at me, hard. "How good is the likeness?"

"If he is wearing your clothes," I tell him, truthful, "I'd swear he is you."

Then Brooks—slow, very slow—turns white. "Remember the time you went off with Deeth and his folks, hunting? That was the time a Moklin got killed. You were wearing guest garments, weren't you?"

I feel queer inside, but I nod. Guest garments, for Moklins, are like the best bedroom and the drumstick of the chicken among humans. And a Moklin hunting party is something. They go hunting garlikthos, which you might as well call dragons, because they've got scales and they fly and they are tough babies.

The way to hunt them is you take along some cacklebirds that ain't nesting—they are no good for anything while they're honeymooning—and the cacklebirds go flapping around until a garlikthos comes after them, and then they go jet-streaking to where the hunters are, cackling a blue streak to say, "Here I come, boys! Hold everything until I get past!" Then the garlikthos dives after them and the hunters get it as it dives.

You give the cacklebirds its innards, and they sit around and eat, cackling to each other, zestful, like they're bragging about the other times they done the same thing, only better.

"You were wearing guest garments?" repeats Brooks, grim.

I feel very queer inside, but I nod again. Moklin guest garments are mighty easy on the skin and feel mighty good. They ain't exactly practical hunting clothes, but the Moklins feel bad if a human that's their guest don't wear them. And of course he has to shed his human clothes to wear them.

"What's the idea?" I want to know. But I feel pretty unhappy inside.

"You didn't come back for one day, in the middle of the hunt, after tobacco and a bath?"

"No," I says, beginning to get rattled. "We were way over at the Thunlib Hills. We buried the dead Moklin over there and had a hell of a time building a tomb over him. Why?"

"During that week," says Brooks, grim, "and while you were off wearing Moklin guest garments, somebody came back wearing your clothes—and got some tobacco and passed the time of day and went off again. Joe, just like there's a Moklin you say could pass for me, there's one that could pass for you. In fact, he did. Nobody suspected either."

I get panicky. "But what'd he do that for?" I want to know. "He didn't steal anything! Would he have done it just to brag to the other Moklins that he fooled you?"

"He might," says Brooks, "have been checking to see if he could fool me. Or Captain Haney of the Palmyra. Or—"

He looks at me. I feel myself going numb. This can mean one hell of a mess!

"I haven't told you before," says Brooks, "but I've been guessing at something like this. Moklins like to be human, and they get human kids—kids that look human, anyway. Maybe they can want to be smart like humans, and they are." He tries to grin, and can't. "That rival trading post looked fishy to me right at the start. They're practicing with that. It shouldn't be there at all, but it is. You see?"

I feel weak and sick all over. This is a dangerous sort of thing! But I say quick, "If you mean they got Moklins that could pass for you and me, and they're figuring to bump us off and take our places—I don't believe that! Moklins like humans! They wouldn't harm humans for anything!"

Brooks don't pay any attention. He says, harsh, "I've been trying to persuade the Company that we've got to get out of here, fast! And they send this Inspector Caldwell, who's not only female, but a redhead to boot! All they think about is a competitive trading post! And all she sees is that we're a bunch of lascivious scoundrels, and since she's a woman there's nothing that'll convince her otherwise!"

Then something hits me. It looks hopeful.

"She's the first human woman to land on Moklin. And she has got red hair. It's the first red hair the Moklins ever saw. Have we got time?"

He figures. Then he says, "With luck, it ought to turn up! You've hit it!" And then his expression sort of softens. "If that happens—poor kid, she's going to take it hard! Women hate to be wrong. Especially redheads! But that might be the saving of—of humanity, when you think of it."

I blink at him. He goes on, fierce, "Look, I'm no Moklin! You know that. But if there's a Moklin that looks enough like me to take my place.... You see? We got to think of Inspector Caldwell, anyhow. If you ever see me cross my fingers, you wiggle your little finger. Then I know it's you. And the other way about. Get it? You swear you'll watch over Inspector Caldwell?"

"Sure!" I say. "Of course!"

I wiggle my little finger. He crosses his. It's a signal nobody but us two would know. I feel a lot better.

Brooks goes off next morning, grim, to visit the other trading post and see the Moklin that looks so much like him. Inspector Caldwell goes along, fierce, and I'm guessing it's to see the fireworks when Brooks sees his Moklin double that she thinks is more than a coincidence. Which she is right, only not in the way she thinks.

Before they go, Brooks crosses his fingers and looks at me significant. I wiggle my little finger back at him. They go off.

I sit down in the shade of Sally and try to think things out. I am all churned up inside, and scared as hell. It's near two weeks to landing time, when the old Palmyra ought to come bulging down out of the sky with a load of new trade goods. I think wistful about how swell everything has been on Moklin up to now, and how Moklins admire humans, and how friendly everything has been, and how it's a great compliment for Moklins to want to be like humans, and to get like them, and how no Moklin would ever dream of hurting a human and how they imitate humans joyous and reverent and happy. Nice people, Moklins. But—

The end of things is in sight. Liking humans has made Moklins smart, but now there's been a slip-up. Moklins will do anything to produce kids that look like humans. That's a compliment. But no human ever sees a Moklin that's four or five years old and all grown up and looks so much like him that nobody can tell them apart. That ain't scheming. It's just that Moklins like humans, but they're scared the humans might not like to see themselves in a sort of Moklin mirror. So if they did that at all, they'd maybe keep it a secret, like children keep secrets from grownups.

Moklins are a lot like kids. You can't help liking them. But a human can get plenty panicky if he thinks what would happen if Moklins get to passing for humans among humans, and want their kids to have top-grade brains, and top-grade talents, and so on....

I sweat, sitting there. I can see the whole picture. Brooks is worrying about Moklins loose among humans, outsmarting them as their kids grow up, being the big politicians, the bosses, the planetary pioneers, the prettiest girls and the handsomest guys in the Galaxy—everything humans want to be themselves. Just thinking about it is enough to make any human feel like he's going nuts. But Brooks is also worrying about Inspector Caldwell, who is five foot three and red-headed and cute as a bug's ear and riding for a bad fall.

They come back from the trip to the other trading post. Inspector Caldwell is baffled and mad. Brooks is sweating and scared. He slips me the signal and I wiggle my little finger back at him, just so I'll know he didn't get substituted for without Inspector Caldwell knowing it, and so he knows nothing happened to me while he was gone. They didn't see the Moklin that looks like Brooks. They didn't get a bit of information we didn't have before—which is just about none at all.

Things go on. Brooks and me are sweating it out until the Palmyra lets down out of the sky again, meanwhile praying for Inspector Caldwell to get her ears pinned back so proper steps can be taken, and every morning he crosses his fingers at me, and I wiggle my little finger back at him.... And he watches over Inspector Caldwell tender.

The other trading post goes on placid. They sell their stuff at half the price we sell ours for. So, on Inspector Caldwell's orders, we cut ours again to half what they sell theirs for. So they sell theirs for half what we sell ours for, so we sell ours for half what they sell theirs for. And so on. Meanwhile we sweat.

Three days before the Palmyra is due, our goods are marked at just exactly one per cent of what they was marked a month before, and the other trading post is selling them at half that. It looks like we are going to have to pay a bonus to Moklins to take goods away for us to compete with the other trading post.

Otherwise, everything looks normal on the surface. Moklins hang around as usual, friendly and admiring. They'll hang around a couple days just to get a look at Inspector Caldwell, and they regard her respectful.

Brooks looks grim. He is head over heels crazy about her now, and she knows it, and she rides him hard. She snaps at him, and he answers her patient and gentle—because he knows that when what he hopes is going to happen, she is going to need him to comfort her. She has about wiped out our stock, throwing bargain sales. Our shelves are almost bare. But the other trading post still has plenty of stock.

"Mr. Brooks," says Inspector Caldwell, bitter, at breakfast, "we'll have to take most of the Palmyra's cargo to fill up our inventory."

"Maybe," he says, tender, "and maybe not."

"But we've got to drive that other post out of business!" she says, desperate. Then she breaks down. "This—this is my first independent assignment. I've got to handle it successfully!"

He hesitates. But just then Deeth comes in. He beams friendly at Inspector Caldwell.

"A compliment for you, ma'am. Three of them."

She goggles at him. Brooks says, gentle, "It's all right. Deeth, show them in and get some presents."

Inspector Caldwell splutters incredulous, "But—but—"

"Don't be angry," says Brooks. "They mean it as a compliment. It is, actually, you know."

Three Moklin girls come in, giggling. They are not bad-looking at all. They look as human as Deeth, but one of them has a long, droopy mustache like a mate of the Palmyra—that's because they hadn't ever seen a human woman before Inspector Caldwell come along. They sure have admired her, though! And Moklin kids get born fast. Very fast.

They show her what they are holding so proud and happy in their arms. They have got three little Moklin kids, one apiece. And every one of them has red hair, just like Inspector Caldwell, and every one of them is a girl that is the spit and image of her. You would swear they are human babies, and you'd swear they are hers. But of course they ain't. They make kid noises and wave their little fists.

Inspector Caldwell is just plain paralyzed. She stares at them, and goes red as fire and white as chalk, and she is speechless. So Brooks has to do the honors. He admires the kids extravagant, and the Moklin girls giggle, and take the compliment presents Deeth brings in, and they go out happy.

When the door closes, Inspector Caldwell wilts.

"Oh-h!" she wails. "It's true! You didn't—you haven't—they can make their babies look like anybody they want!"

Brooks puts his arms around her and she begins to cry against his shoulder. He pats her and says, "They've got a queer sort of evolution on Moklin, darling. Babies here inherit desired characteristics. Not acquired characteristics, but desired ones! And what could be more desirable than you?"

I am blinking at them. He says to me, cold, "Will you kindly get the hell out of here and stay out?"

I come to. I says, "Just one precaution."

I wiggle my little finger. He crosses his fingers at me.

"Then," I says, "since there's no chance of a mistake, I'll leave you two together."

And I do.

The Palmyra booms down out of the sky two days later. We are all packed up. Inspector Caldwell is shaky, on the porch of the post, when Moklins come hollering and waving friendly over from the landing field pulling a freight-truck with Cap Haney on it. I see other festive groups around members of the crew that—this being a scheduled stop—have been given ship-leave for a couple hours to visit their Moklin friends.

"I've got the usual cargo—" begins Cap Haney.

"Don't discharge it," says Inspector Caldwell, firm. "We are abandoning this post. I have authority and Mr. Brooks has convinced me of the necessity for it. Please get our baggage to the ship."

He gapes at her. "The Company don't like to give in to competition—"

"There isn't any competition," says Inspector Caldwell. She gulps. "Darling, you tell him," she says to Brooks.

He says, lucid, "She's right, Captain. The other trading post is purely a Moklin enterprise. They like to do everything that humans do. Since humans were running a trading post, they opened one too. They bought goods from us and pretended to sell them at half price, and we cut our prices, and they bought more goods from us and pretended to sell at half the new prices.... Some Moklin or other must've thought it would be nice to be a smart businessman, so his kids would be smart businessmen. Too smart! We close up this post before Moklins think of other things...."

He means, of course, that if Moklins get loose from their home planet and pass as humans, their kids can maybe take over human civilization. Human nature couldn't take that! But it is something to be passed on to the high brass, and not told around general.

"Better sound the emergency recall signal," says Inspector Caldwell, brisk.

We go over to the ship and the Palmyra lets go that wailing siren that'll carry twenty miles. Any crew member in hearing is going to beat it back to the ship full-speed. They come running from every which way, where they been visiting their Moklin friends. And then, all of a sudden, here comes a fellow wearing Moklin guest garments, yelling, "Hey! Wait! I ain't got my clothes—"

And then there is what you might call a dead silence. Because lined up for checkoff is another guy that comes running at the recall signal, and he is wearing ship's clothes, and you can see that him and the guy in Moklin guest garments are just exactly alike. Twins. Identical. The spit and image of each other. And it is for sure that one of them is a Moklin. But which?

Cap Haney's eyes start to pop out of his head. But then the guy in Palmyra uniform grins and says, "Okay, I'm a Moklin. But us Moklins like humans so much, I thought it would be nice to make a trip to Earth and see more humans. My parents planned it five years ago, made me look like this wonderful human, and hid me for this moment. But we would not want to make any difficulties for humans, so I have confessed and I will leave the ship."

He takes it as a joke on him. He talks English as good as anybody. I don't know how anybody could tell which was the human guy and which one the Moklin, but this Moklin grins and steps down, and the other Moklins admire him enormous for passing even a few minutes as human among humans.

We get away from there so fast, he is allowed to keep the human uniform.

Moklin is the first planet that humans ever get off of, moving fast, breathing hard, and sweating copious. It's one of those things that humans just can't take. Not that there's anything wrong with Moklins. They're swell folks. They like humans. But humans just can't take the idea of Moklins passing for human and being all the things humans want to be themselves. I think it's really a false alarm. I'll find out pretty soon.

Inspector Caldwell and Brooks get married, and they go off to a post on Briarius Four—a swell place for a honeymoon if there ever was one—and I guess they are living happy ever after. Me, I go to the new job the Company assigns me—telling me stern not to talk about Moklin, which I don't—and the Space Patrol orders no human ship to land on Moklin for any reason.

But I've been saving money and worrying. I keep thinking of those three Moklin kids that Inspector Caldwell knows she ain't the father of. I worry about those kids. I hope nothing's happened to them. Moklin kids grow up fast, like I told you. They'll be just about grown now.

I'll tell you. I've bought me a little private spacecruiser, small but good. I'm shoving off for Moklin next week. If one of those three ain't married, I'm going to marry her, Moklin-style, and bring her out to a human colony planet. We'll have some kids. I know just what I want my kids to be like. They'll have plenty of brains—top-level brains—and the girls will be real good-looking!

But besides that, I've got to bring some other Moklins out and start them passing for human, too. Because my kids are going to need other Moklins to marry, ain't they? It's not that I don't like humans. I do! If the fellow I look like—Joe Brinkley—hadn't got killed accidental on that hunting trip with Deeth, I never would have thought of taking his place and being Joe Brinkley. But you can't blame me for wanting to live among humans.

Wouldn't you, if you was a Moklin?