THE

STATELY HOMES OF ENGLAND

THE STATELY

HOMES OF ENGLAND

BY

LLEWELLYNN JEWITT, F.S.A., Etc., Etc.

AND

S. C. HALL, F.S.A.

COMPLETE IN TWO SERIES.

ILLUSTRATED WITH

THREE HUNDRED AND EIGHTY ENGRAVINGS ON WOOD

NEW YORK

A. W. LOVERING, IMPORTER.

INTRODUCTION.

ENGLAND is rich—immeasurably richer than any other country under the sun—in its “Homes;” and these homes, whether of the sovereign or of the high nobility, of the country squire or the merchant-prince, of the artisan or the labourer, whether, in fact, they are palace or cottage, or of any intermediate grade, have a character possessed by none other. England, whose

“Home! sweet home!”

has become almost a national anthem—so closely is its sentiment entwined around the hearts of the people of every class—is, indeed, emphatically a Kingdom of Homes; and these, and their associations and surroundings, and the love which is felt for them, are its main source of true greatness. An Englishman feels, wherever he may be, that

“Home is home, however lowly;”

and that, despite the attractions of other countries and the glare and brilliancy of foreign courts and foreign phases of society, after all

“There’s no place like home”

in his own old fatherland.

Beautifully has the gifted poet, Mrs. Hemans, sung of English “Homes,” and charmingly has she said—

“The Stately Homes of England,

How beautiful they stand

Amidst their tall ancestral trees

O’er all the pleasant land!”

and thus given to us a title for our present work. Of these “Stately Homes” of our “pleasant land” we have chosen some few for illustration, not for their stateliness alone, but because the true nobility of their owners allows their beauties, their splendour, their picturesque surroundings, and their treasures of art to be seen and enjoyed by all.

Whether “stately” in their proportions or in their style of architecture, in their internal decorations or their outward surroundings, in the halo of historical associations which encircle them, or in the families which have made their greatness, and whose high and noble characters have given them an enduring interest, these “Homes” are indeed a fitting and pleasant subject for pen and pencil. The task of their illustration has been a peculiarly grateful one to us, and we have accomplished it with loving hands, and with a sincere desire to make our work acceptable to a large number of readers.

In the first instance, our notices of these “Stately Homes” appeared in the pages of the Art-Journal, for which, indeed, they were specially prepared, with the ultimate intention, now carried out, of issuing them in a collected form. They have, however, now been rearranged, and have received considerable, and in many instances very important, additions. The present volume may be looked upon as the first of a short series of volumes devoted to this pleasant and fascinating subject; others of a similar character, embracing many equally beautiful, equally interesting, and equally “stately” Homes will follow.

LLEWELLYNN JEWITT.

Winster Hall, Derbyshire.

CONTENTS OF FIRST SERIES.

| PAGE | |||

| I. | — | Alton Towers, Staffordshire | 1 |

| II. | — | Cobham Hall, Kent | 37 |

| III. | — | Mount Edgcumbe, Devonshire | 54 |

| IV. | — | Cothele, Cornwall | 70 |

| V. | — | Alnwick Castle, Northumberland | 78 |

| VI. | — | Hardwick Hall, Derbyshire | 116 |

| VII. | — | Arundel Castle, Sussex | 153 |

| VIII. | — | Penshurst, Kent | 172 |

| IX. | — | Warwick Castle, Warwickshire | 192 |

| X. | — | Haddon Hall, Derbyshire | 221 |

| XI. | — | Hatfield House, Hertfordshire | 294 |

| XII. | — | Cassiobury, Hertfordshire | 308 |

| XIII. | — | Chatsworth, Derbyshire | 322 |

LIST OF ILLUSTRATIONS.

FIRST SERIES.

| Page | |

| I.—ALTON TOWERS. | |

| Lion Fountain | 1 |

| Ruins of Alton Castle | 2 |

| Alton Towers, from the Terrace | 4 |

| ———”–——from the Lake | 6 |

| The Octagon | 8 |

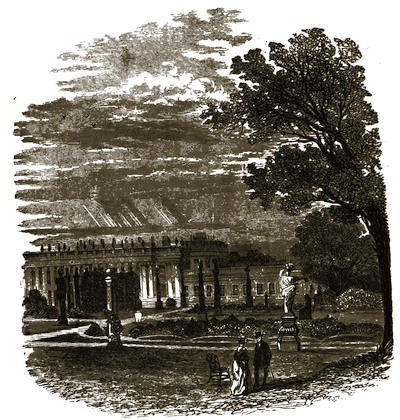

| The Conservatories and Alcove | 11 |

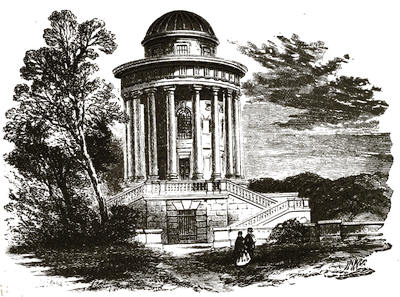

| The Temple | 19 |

| The Conservatories | 22 |

| The Pagoda | 24 |

| Choragic Temple | 27 |

| View from the Lower Terrace | 29 |

| The Gothic Temple | 31 |

| Part of the Grounds | 33 |

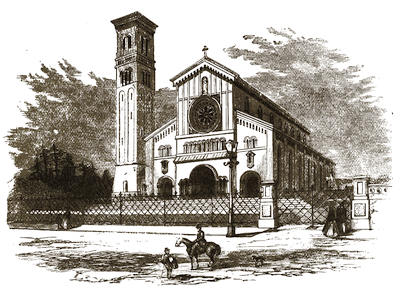

| Hospital of St. John | 34 |

| II.—COBHAM HALL. | |

| Initial Letter | 37 |

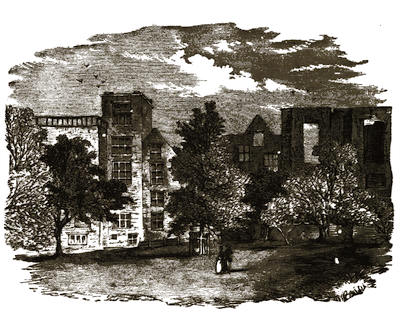

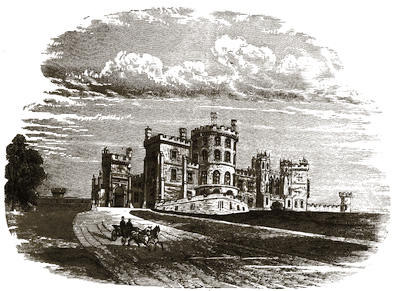

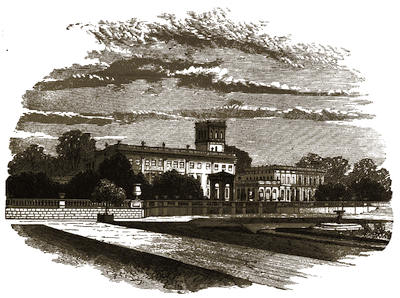

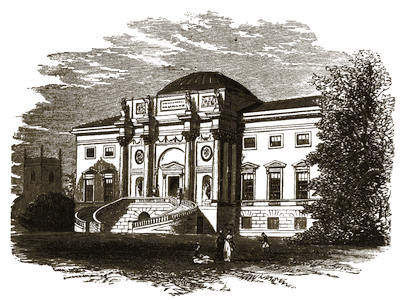

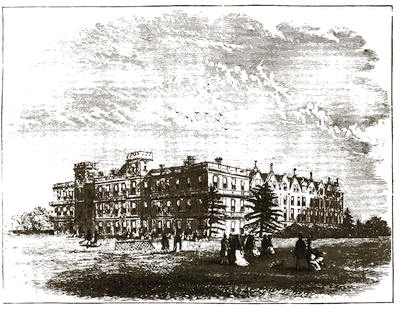

| Cobham Hall | 38 |

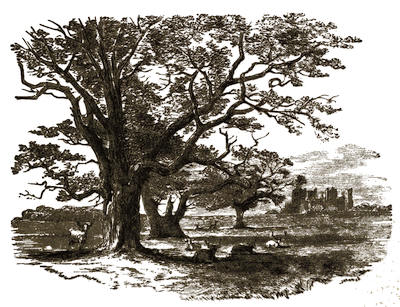

| The Three Sisters | 43 |

| The Lodge | 45 |

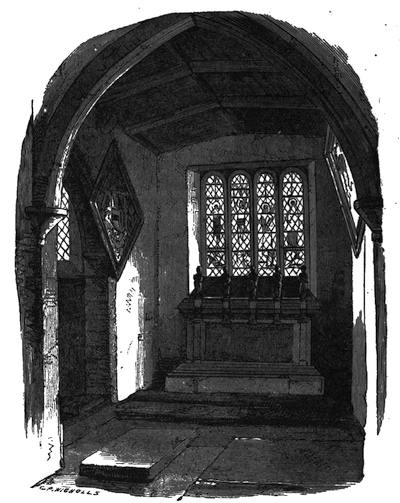

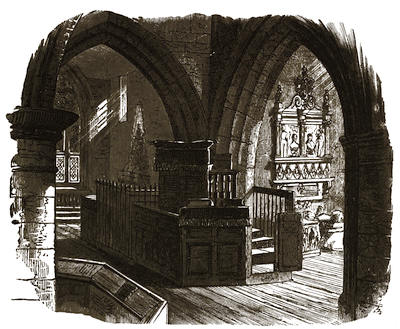

| Interior of the Church | 48 |

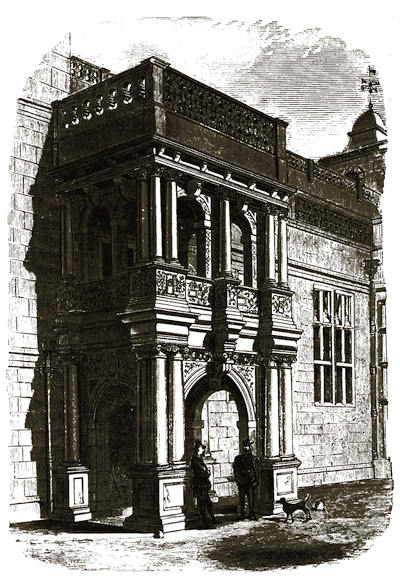

| The College Porch | 50 |

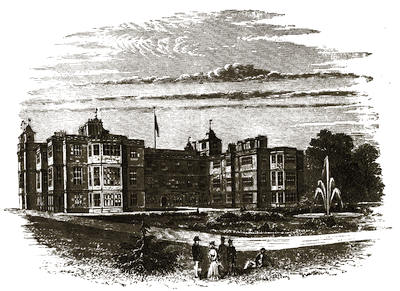

| The College | 52 |

| III.—MOUNT EDGCUMBE. | |

| The Eddystone Lighthouse | 54 |

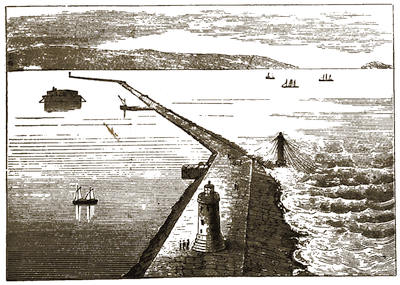

| Plymouth Breakwater | 57 |

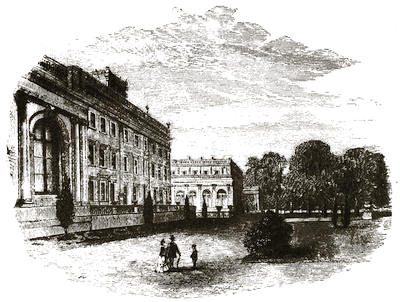

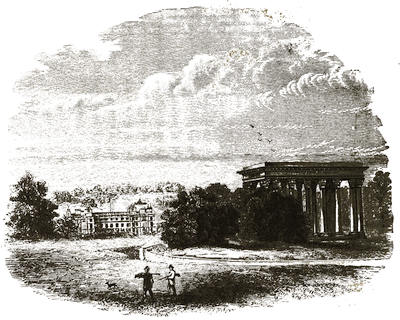

| Mount Edgcumbe, from Stonehouse Pier | 59 |

| The Mansion | 61 |

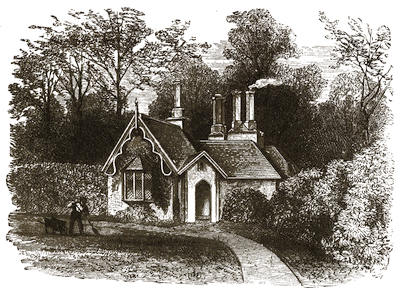

| Lady Emma’s Cottage | 64 |

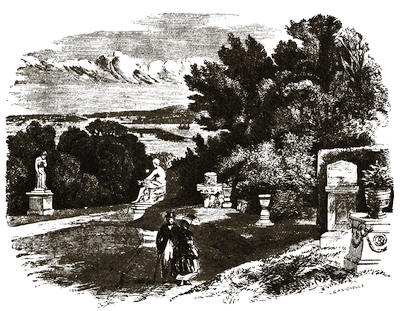

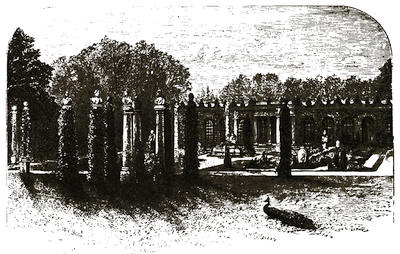

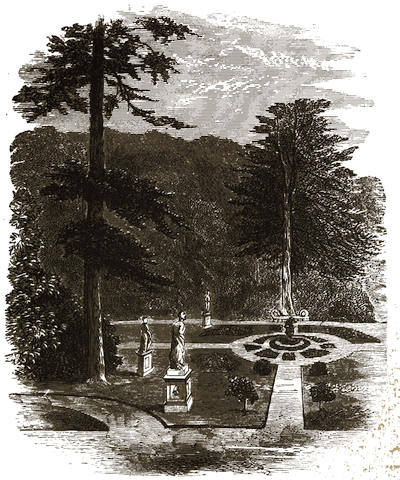

| The Gardens | 65 |

| The Ruin, the Sound, Drake’s Island, &c. | 68 |

| The Salute Battery | 69 |

| IV.—COTHELE. | |

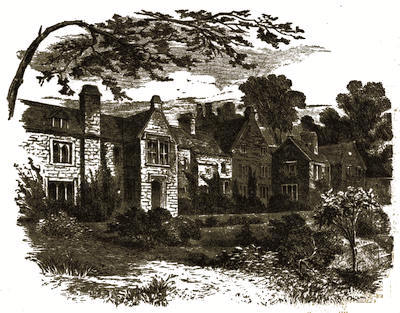

| The Mansion | 73 |

| The Landing Place | 75 |

| V.—ALNWICK CASTLE. | |

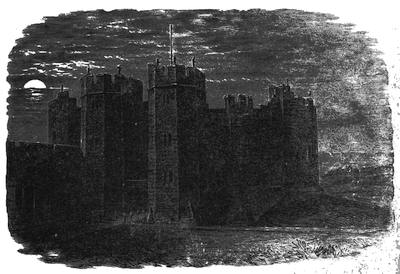

| Lighting the Beacon | 78 |

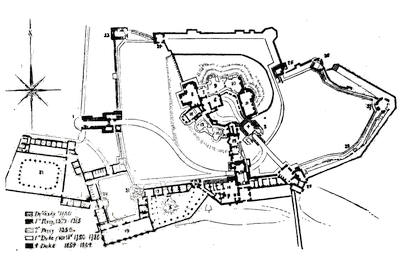

| Plan of Alnwick Castle | 80 |

| Alnwick Castle, from the River Aln | 81 |

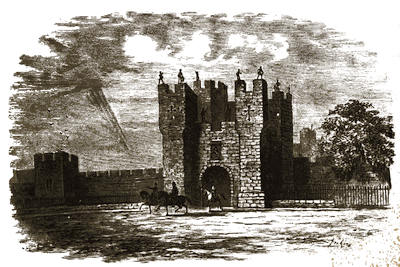

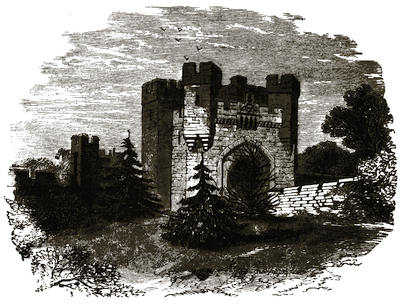

| The Barbican | 83 |

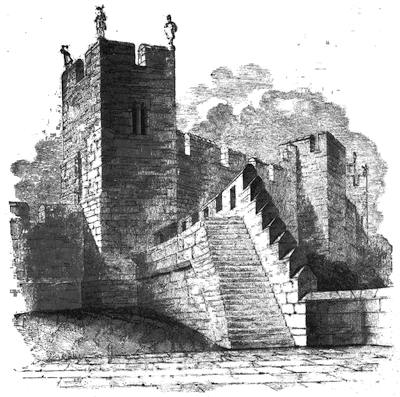

| The Prudhoe Tower and Chapel | 85 |

| The Keep | 87 |

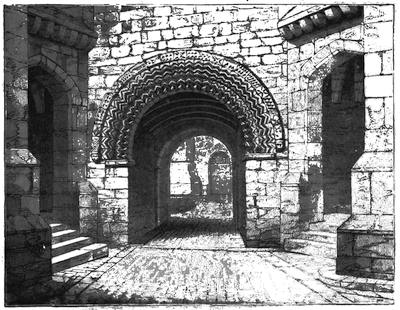

| Norman Gateway in the Keep | 89 |

| The Armourer’s Tower | 91 |

| Figure of Warrior on the Barbican | 93 |

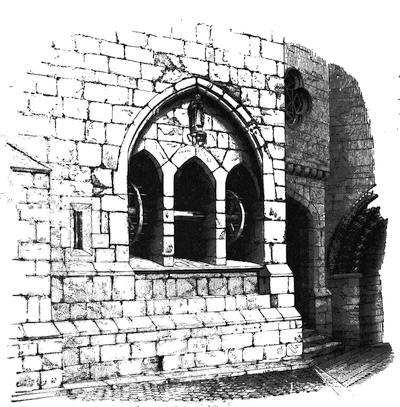

| The Well in the Keep | 94 |

| The Constable’s Tower | 95 |

| Figure of Warrior on the Barbican | 96 |

| The East Garret | 98 |

| The Garden Gate, or Warder’s Tower | 99 |

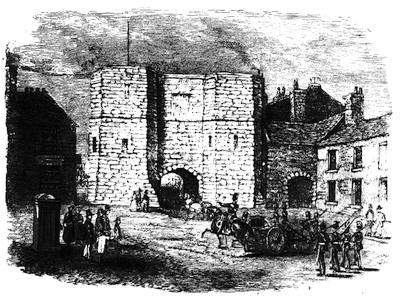

| Bond Gate: “Hotspur’s Gate” | 103 |

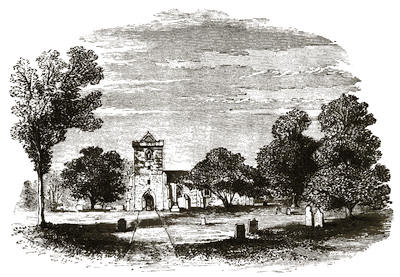

| Alnwick Abbey | 105 |

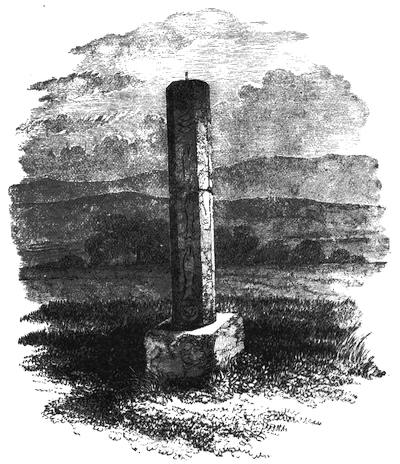

| The Percy Cross | 107 |

| Hulne Abbey: The Percy Tower | 109 |

| ———”–——The Church | 111 |

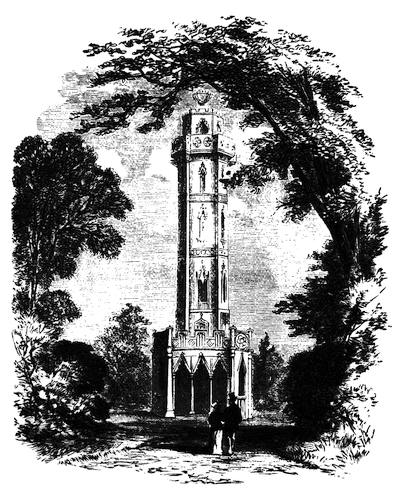

| The Brislee Tower | 114 |

| VI.—HARDWICK HALL. | |

| Ancient Pargetting, and Arms of Cavendish | 116 |

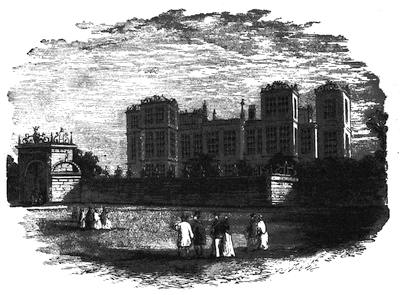

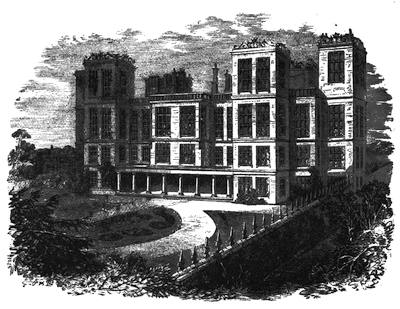

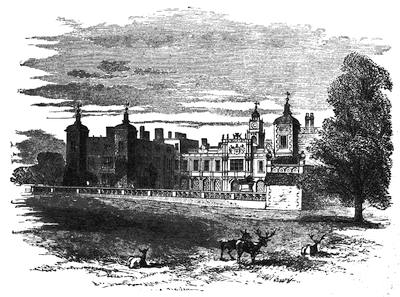

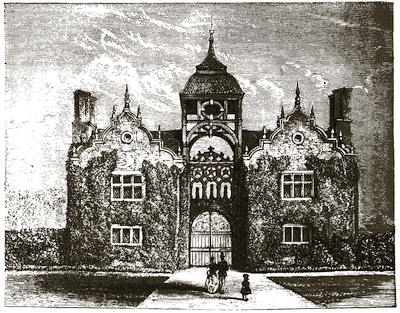

| Hardwick Hall, with the Entrance Gateway | 118 |

| The West Front | 122 |

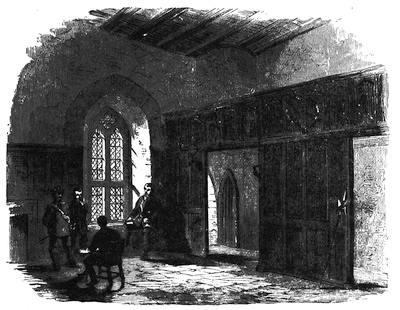

| The Great Hall | 125 |

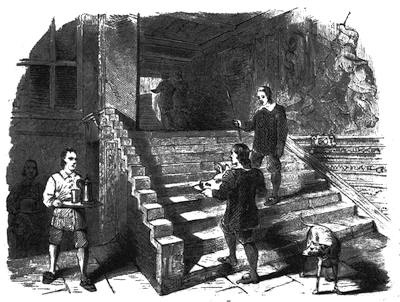

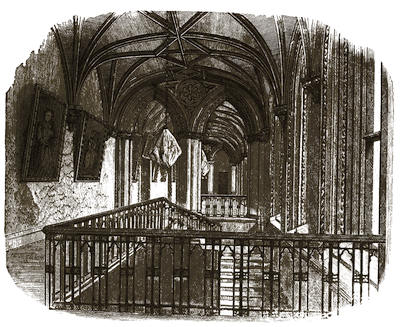

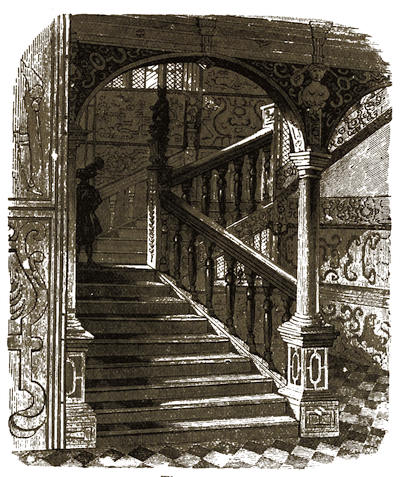

| The Grand Staircase | 127 |

| The Chapel | 129 |

| The Presence Chamber[x] | 131 |

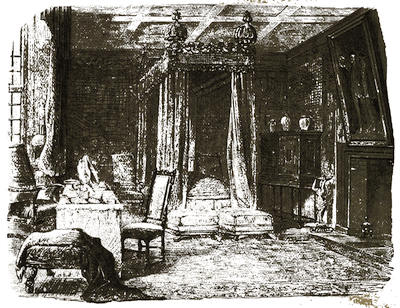

| Mary Queen of Scots’ Room | 133 |

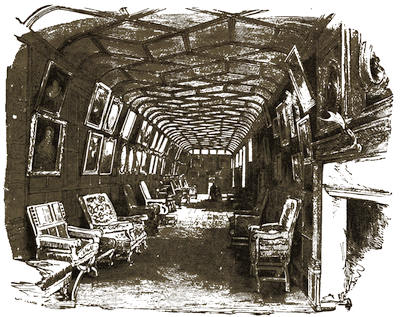

| The Picture Gallery | 135 |

| Ancient Lock, and Arms of Hardwick | 137 |

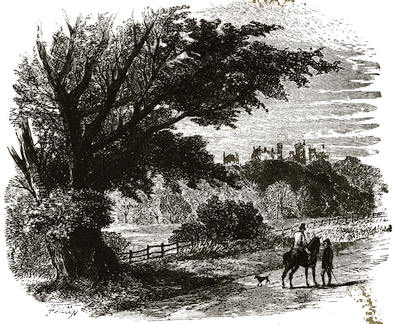

| Hardwick Hall, from the Park | 139 |

| The Old Hall at Hardwick | 142 |

| Interior of the Old Hall | 144 |

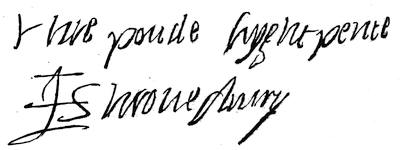

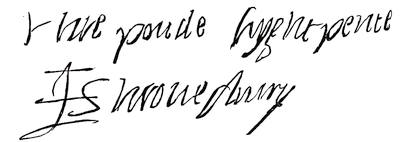

| Fac-simile of the Countess of Shrewsbury’s Signature | 145 |

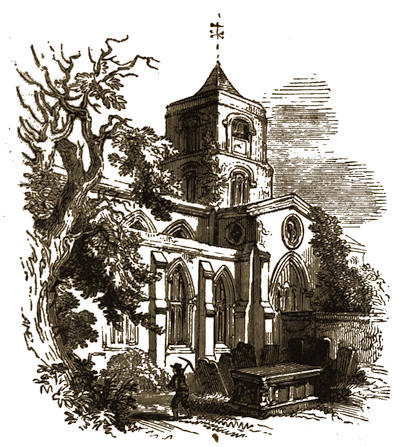

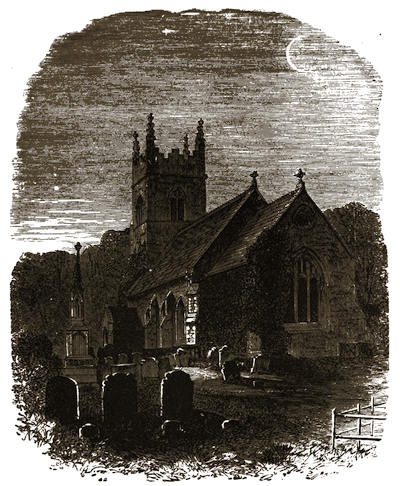

| Hault Hucknall Church | 146 |

| The Grave of Hobbes of Malmesbury in Hault Hucknall Church | 148 |

| VII.—ARUNDEL CASTLE. | |

| Horned Owls in the Keep | 153 |

| The Quadrangle | 156 |

| Entrance Gate, from the Interior | 158 |

| The Keep | 160 |

| The Library | 163 |

| The Church of the Holy Trinity | 169 |

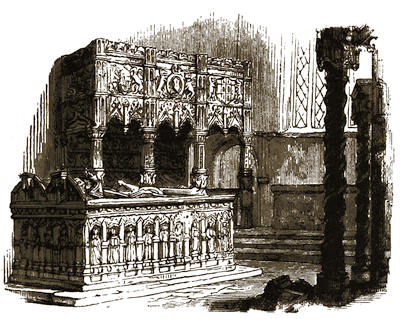

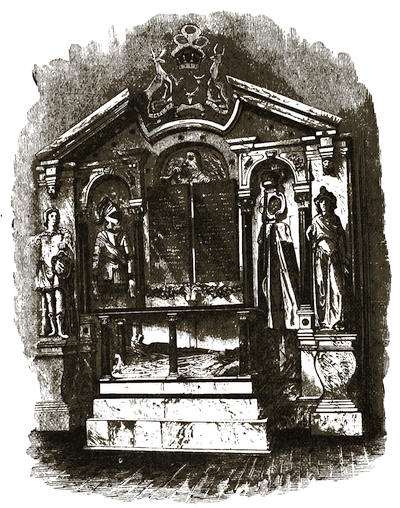

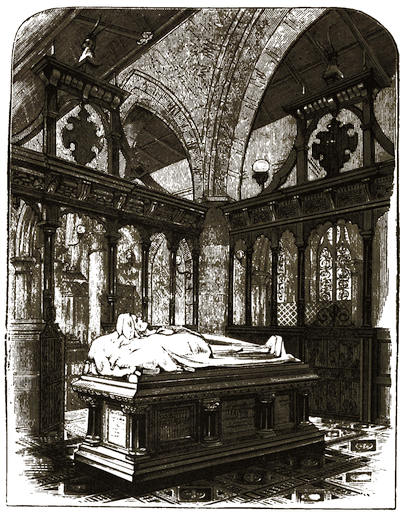

| Tombs of Thomas Fitzalan and Lady Beatrix in Arundel Church | 171 |

| VIII.—PENSHURST. | |

| The Bell | 172 |

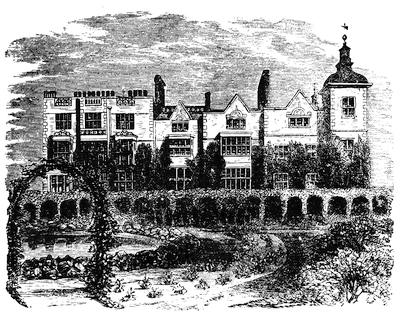

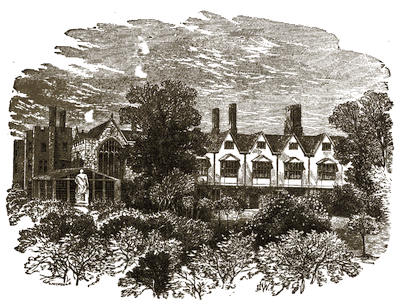

| Penshurst, from the President’s Court | 174 |

| North and West Fronts | 177 |

| View from the Garden | 179 |

| The Baron’s Court | 182 |

| The Village and Entrance to Churchyard | 185 |

| The Record Tower and the Church, from the Garden | 186 |

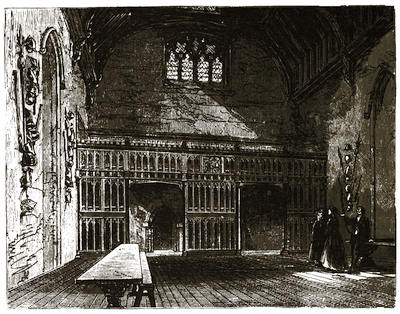

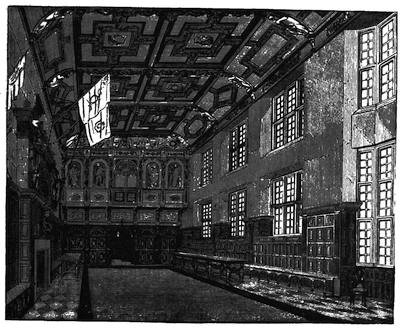

| The Hall and Minstrels’ Gallery | 188 |

| IX.—WARWICK CASTLE. | |

| The Swan of Avon | 192 |

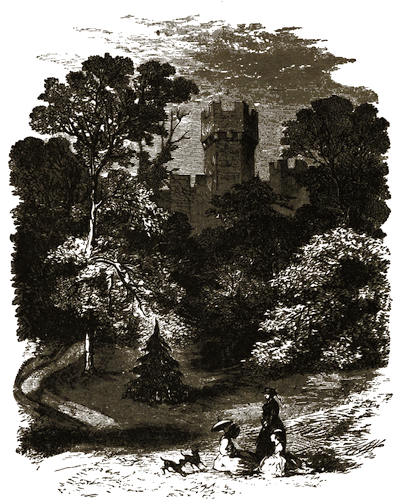

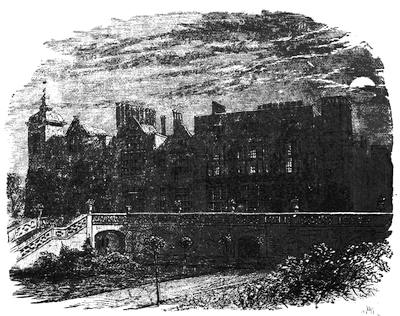

| The Castle, from the Temple Field | 194 |

| The Keep, from the Inner Court | 196 |

| Earl of Warwick and Humphrey, Duke of Gloucester | 198 |

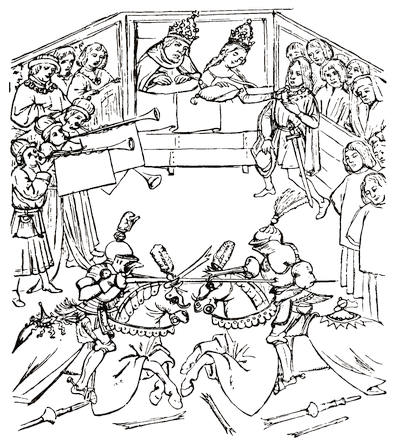

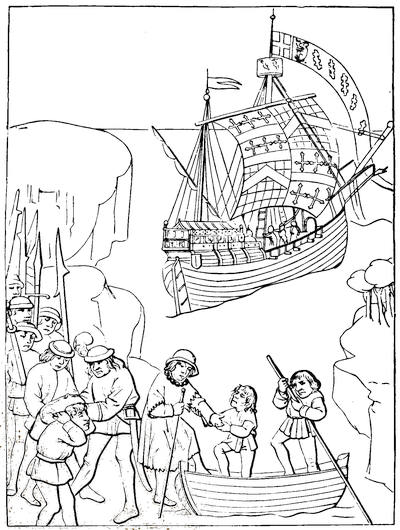

| Earl of Warwick’s Combat before the Emperor Sigismund and the Empress | 199 |

| Earl of Warwick Departing on a Pilgrimage to the Holy Land | 200 |

| Badge of the Earl of Warwick | 201 |

| Cæsar’s Tower | 202 |

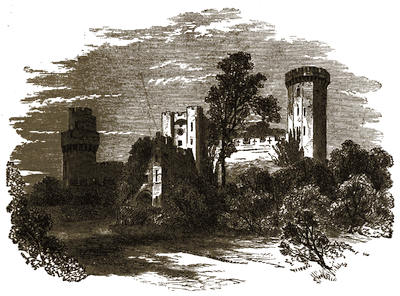

| The Castle, from the Bridge | 203 |

| The Castle, from the Island | 205 |

| Guy’s Tower | 206 |

| The Warder’s Horn | 207 |

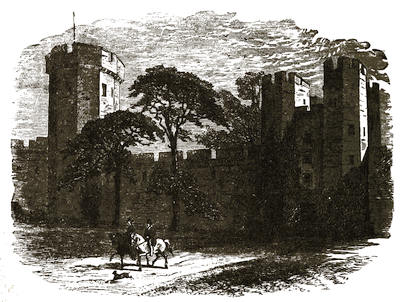

| The Castle, from the Outer Court | 209 |

| The Inner Court, from the Keep | 211 |

| Guy’s and the Clock Tower, from the Keep | 212 |

| The Castle, from the banks of the Avon | 214 |

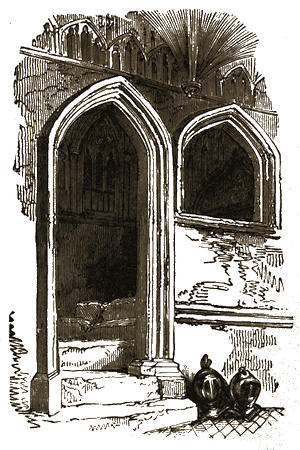

| The Beauchamp Chapel; Monument of the Founder | 216 |

| The Confessional | 217 |

| The Oratory | 218 |

| Warwick: The East Gate | 219 |

| X.—HADDON HALL. | |

| Dorothy Vernon’s Door | 221 |

| Haddon, from the Meadows on the Bakewell Road | 223 |

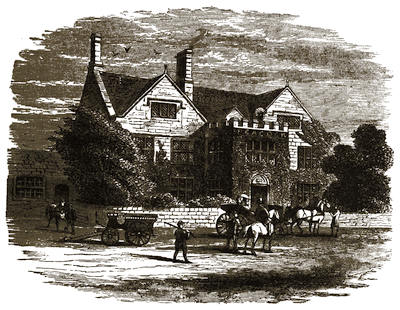

| The “Peacock” at Rowsley | 225 |

| Haddon, from the Rowsley Road | 226 |

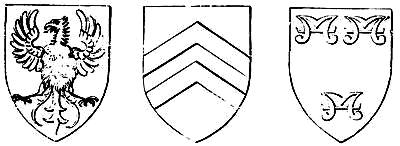

| Arms of Vernon quartering Avenell | 227 |

| Arms of Lord Vernon | 230 |

| Haddon, from the Meadows | 234 |

| The Main Entrance | 235 |

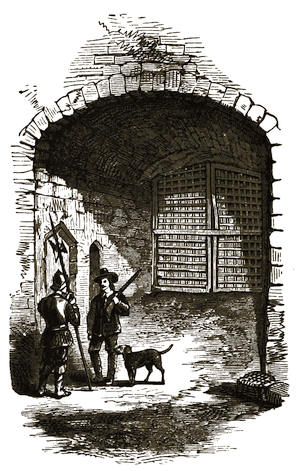

| Inside of Gateway | 236 |

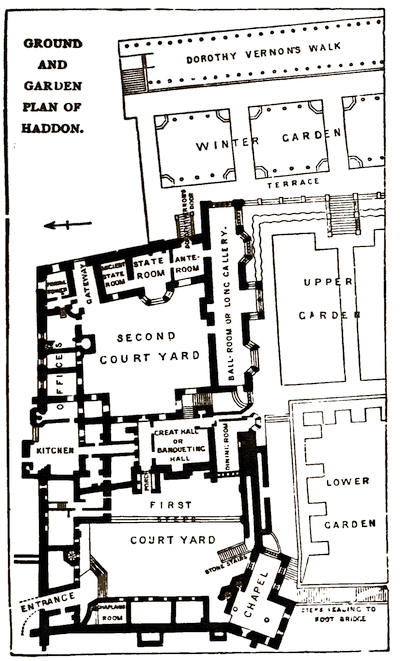

| Ground and Garden Plan of Haddon | 237 |

| The first Court-yard | 239 |

| Gateway under the Eagle Tower | 240 |

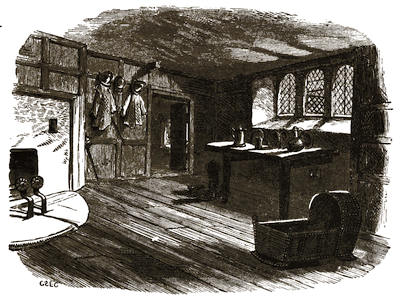

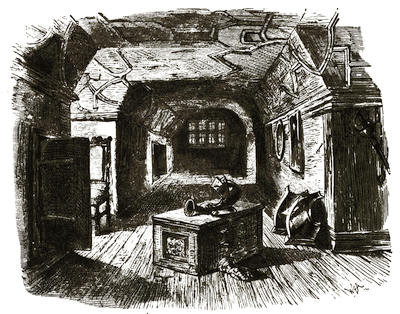

| The Chaplain’s Room | 241 |

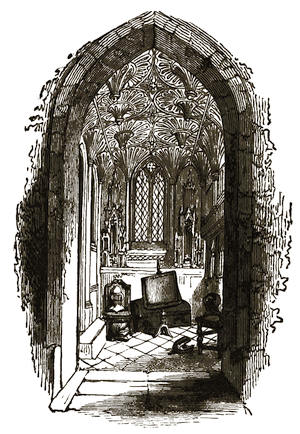

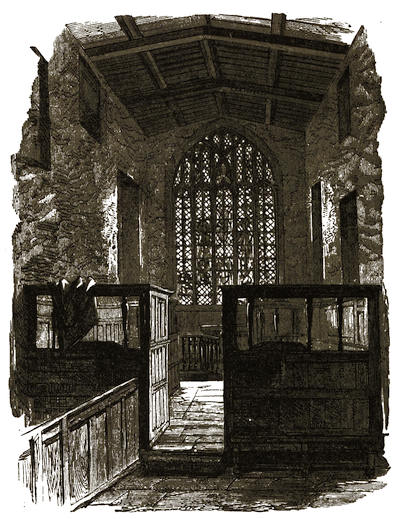

| The Chapel | 242 |

| Norman Font in the Chapel | 244 |

| Wall-paintings in the Chapel | 248 |

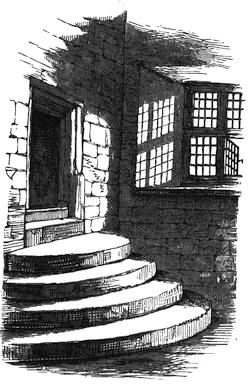

| Steps to State Apartments | 249 |

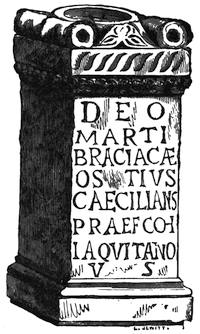

| Roman Altar, Haddon Hall | 250 |

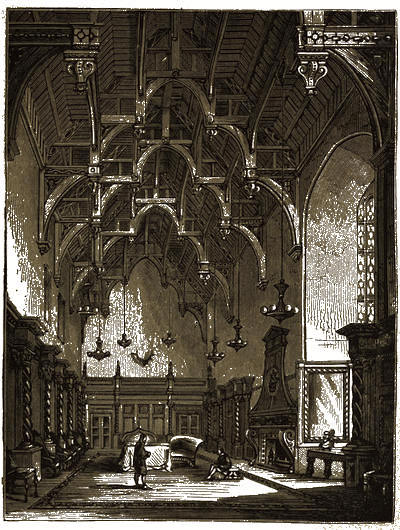

| The Banqueting-Hall: with the Minstrels’ Gallery | 251 |

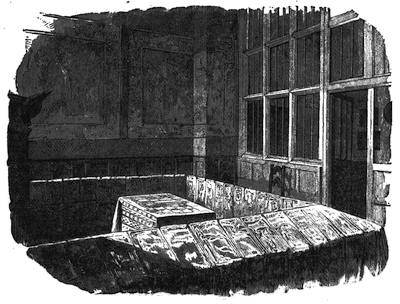

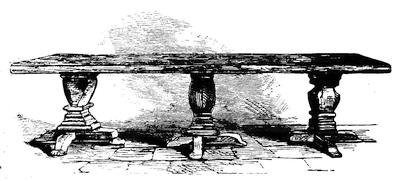

| Old Oak-table in the Banqueting-Hall | 252 |

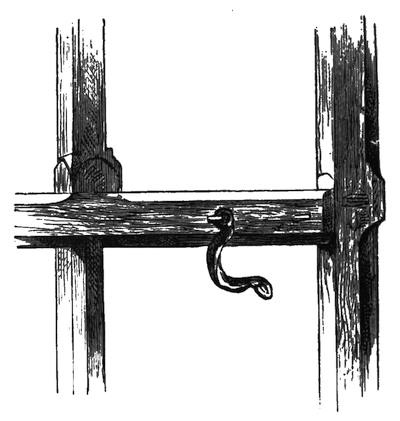

| The Hand-lock in the Banqueting-Hall | 252 |

| Staircase to Minstrels’ Gallery | 253 |

| Oriel Window in the Dining-room | 255 |

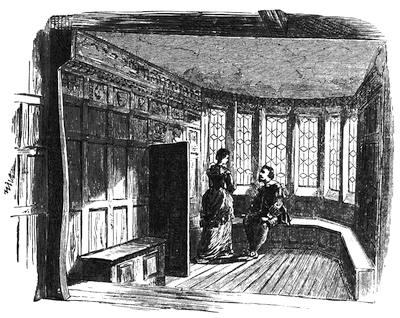

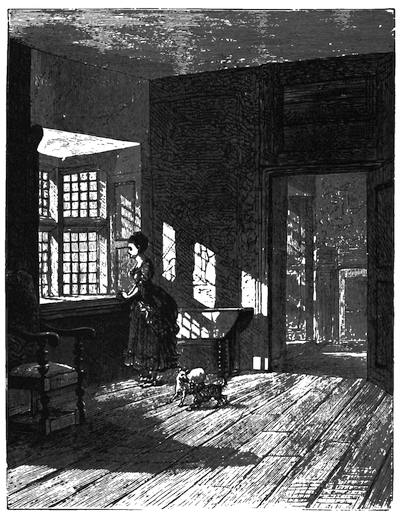

| Ante-room to the Earl’s Bed-room | 256 |

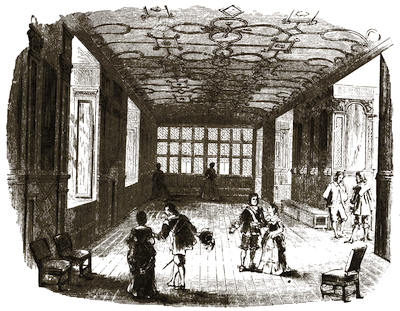

| The Ball-room, or Long Gallery | 257 |

| Steps to the Ball-room | 259 |

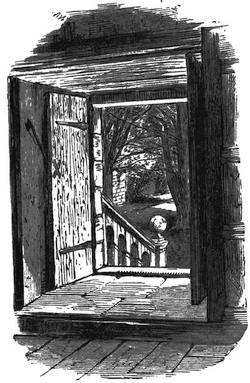

| Dorothy Vernon’s Door: Interior | 260 |

| Dorothy Vernon’s Door: Exterior | 261 |

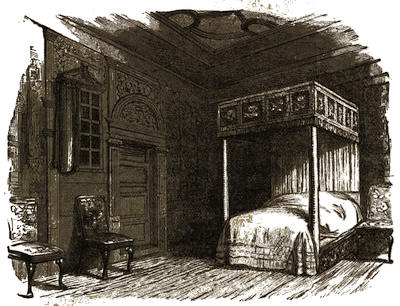

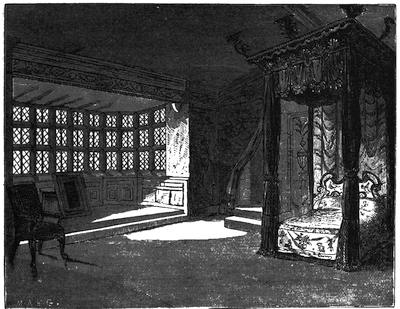

| The State Bed-room | 263 |

| The Archers’ Room, for Stringing Bows, &c. | 264 |

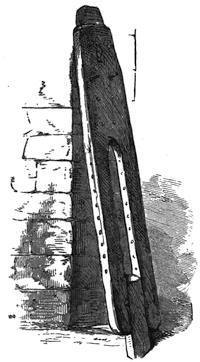

| The Rack for Stringing the Bows | 265 |

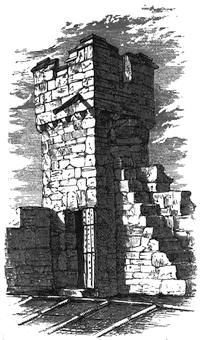

| The Eagle, or Peverel Tower[xi] | 266 |

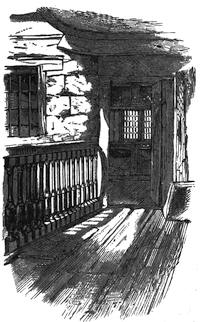

| Gallery across Small Yard | 267 |

| Room over the Entrance Gateway | 268 |

| The Terrace | 270 |

| The Hall from the Terrace | 271 |

| Arms of Family of Manners | 272 |

| Arms of the Duke of Rutland | 278 |

| The Foot-Bridge | 279 |

| Ring found at Haddon Hall | 280 |

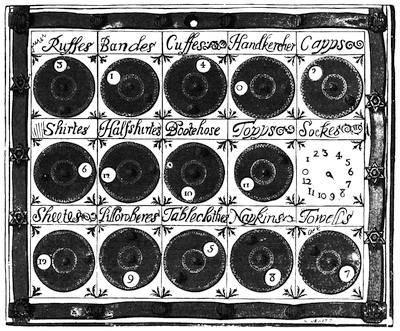

| Washing-Tally found at Haddon Hall | 281 |

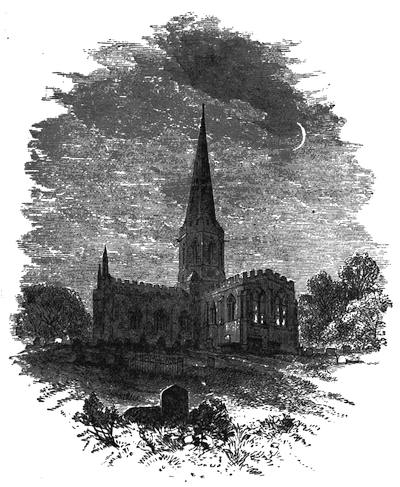

| Bakewell Church | 283 |

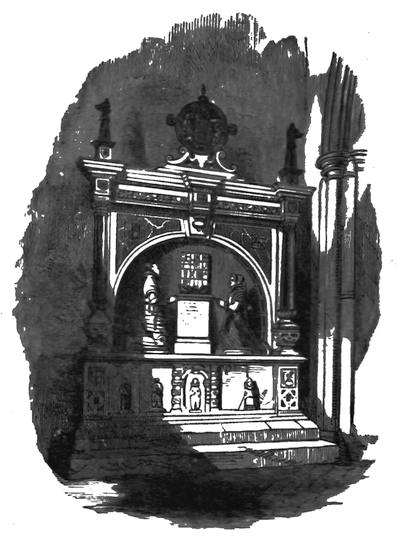

| Monument of Sir John Manners and his Wife, Dorothy Vernon | 286 |

| Ancient Cross, Bakewell Churchyard | 290 |

| XI.—HATFIELD HOUSE. | |

| Armed Knight | 294 |

| The Old Palace at Hatfield | 295 |

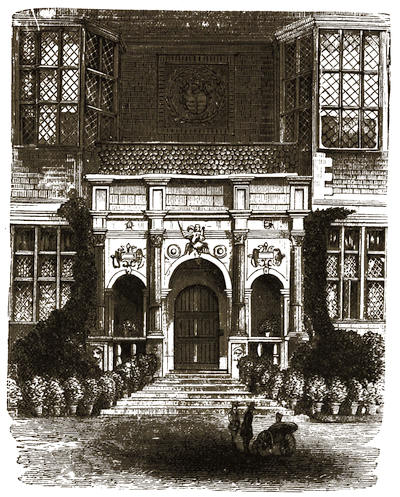

| The Front View | 297 |

| The Garden front of Hatfield House | 299 |

| The East View | 302 |

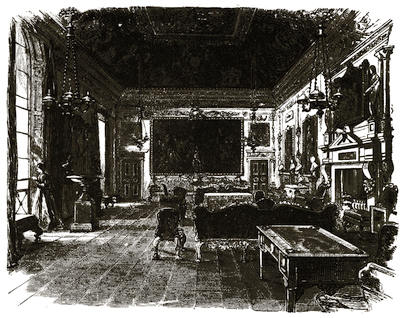

| The Gallery | 304 |

| The Hall | 305 |

| XII.—CASSIOBURY. | |

| Crest of the Earl of Essex | 308 |

| Back View | 310 |

| From the Wood Walks | 313 |

| From the South-west | 315 |

| The Swiss Cottage | 317 |

| The Lodge | 318 |

| Monument in the Church at Watford | 320 |

| XIII.—CHATSWORTH. | |

| Entrance to the Stables | 322 |

| The Old Hall as it formerly stood | 325 |

| Chatsworth from the River Derwent | 333 |

| The Entrance Gates | 335 |

| The Grand Entrance-Lodge at Baslow | 340 |

| Edensor Mill Lodge and Beeley Bridge | 341 |

| Entrance Gate | 342 |

| The Bridge over the River Derwent, in the Park | 343 |

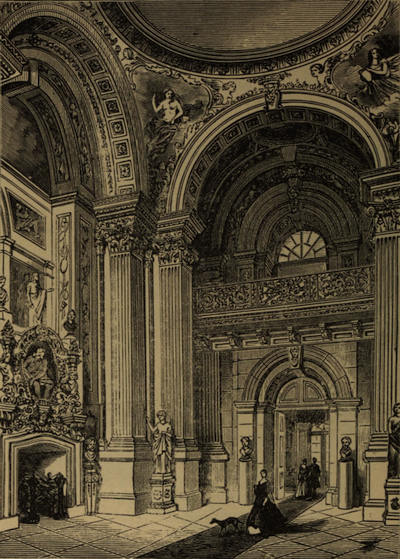

| The Great Hall and Staircase | 344 |

| Vista of the State Apartments | 346 |

| Grinling Gibbons’ Masterpiece | 348 |

| The Old State Bed-room | 349 |

| The State Drawing-room | 351 |

| The State Dining room | 352 |

| The Drawing-room | 355 |

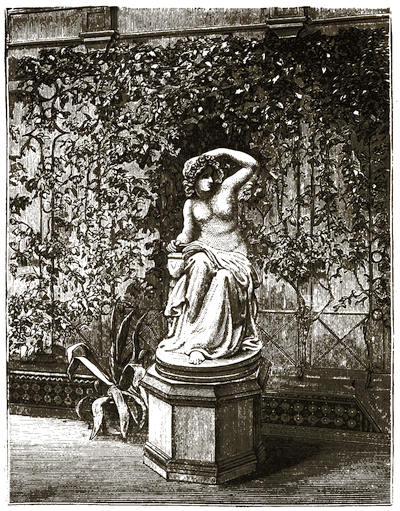

| The Hebe of Canova | 356 |

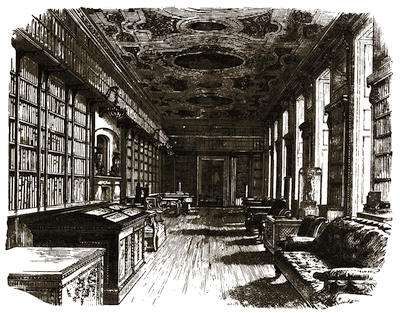

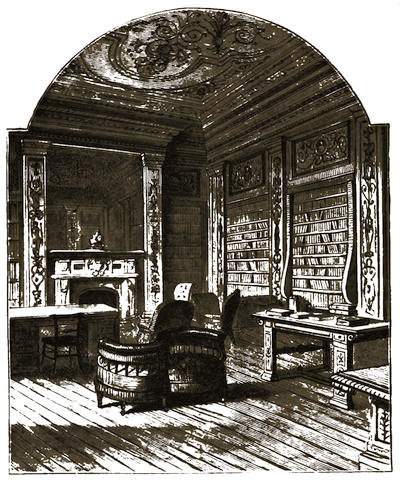

| The Library | 357 |

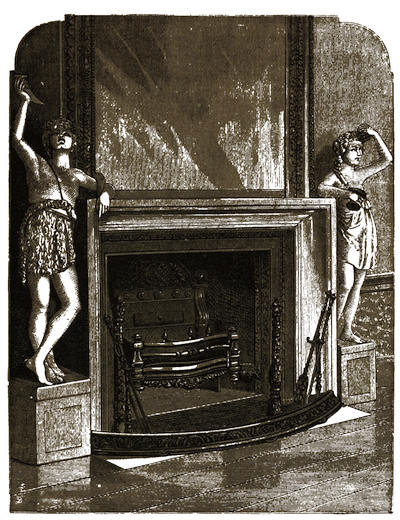

| Fireplace by Westmacott in the Dining-room | 359 |

| The Sculpture Gallery | 360 |

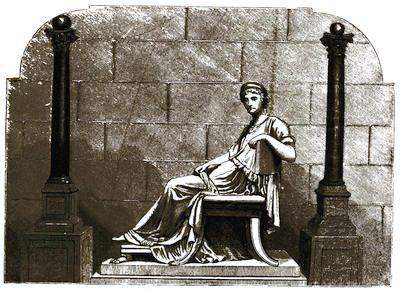

| Mater Napoleonis | 361 |

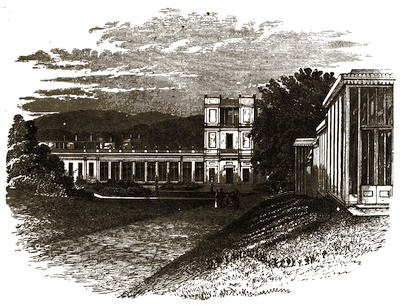

| The Pavilion and Orangery, from the East | 363 |

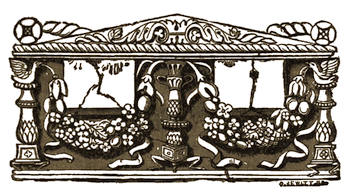

| Carving over one of the Doors of the Chapel | 365 |

| Carving over one of the Doors of the Chapel | 366 |

| Carvings in the Chapel | 367 |

| The Private or West Library | 370 |

| The Sculpture Gallery and Orangery | 372 |

| Bust of the late Duke of Devonshire | 373 |

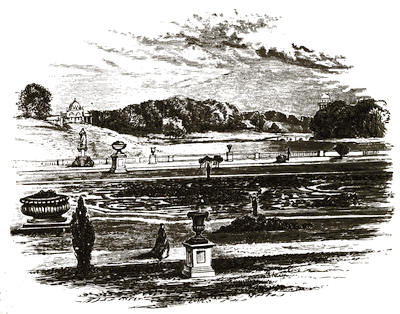

| The French Garden | 374 |

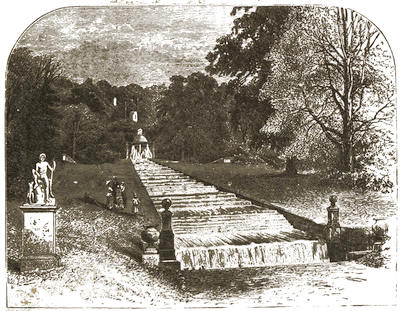

| The Great Cascade | 375 |

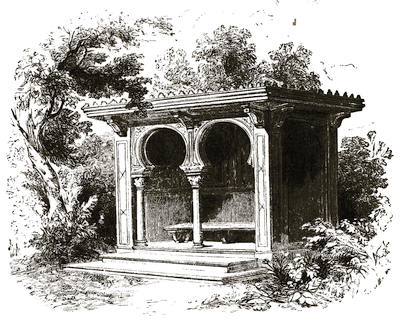

| The Alcove | 376 |

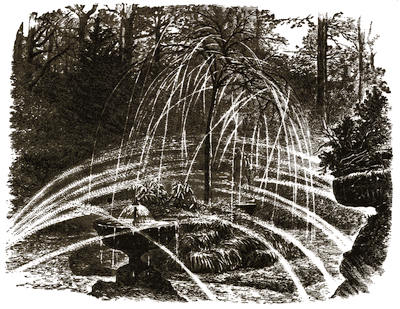

| Waterworks—The Willow Tree | 377 |

| Part of the Rock-work | 378 |

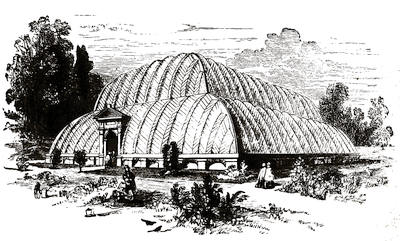

| The Great Conservatory | 379 |

| Part of the Rock-work—The Rocky Portal | 380 |

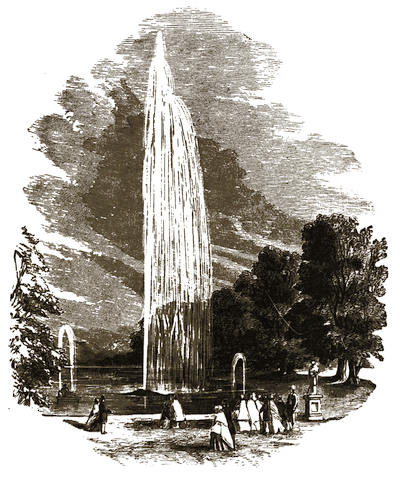

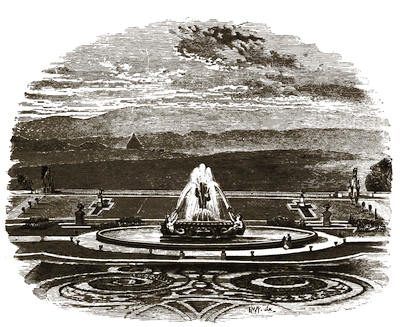

| The Emperor Fountain | 381 |

| The Garden on the West Front | 382 |

| West Front from the South | 383 |

| The Hunting Tower | 384 |

| Mary Queen of Scots’ Bower | 385 |

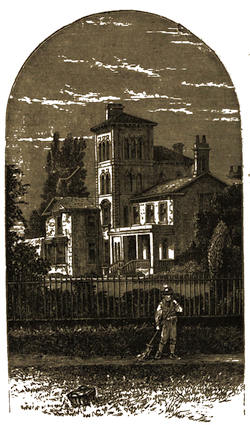

| The late Sir Joseph Paxton’s House | 386 |

| The Victoria Regia | 388 |

| Edensor Church and Village | 389 |

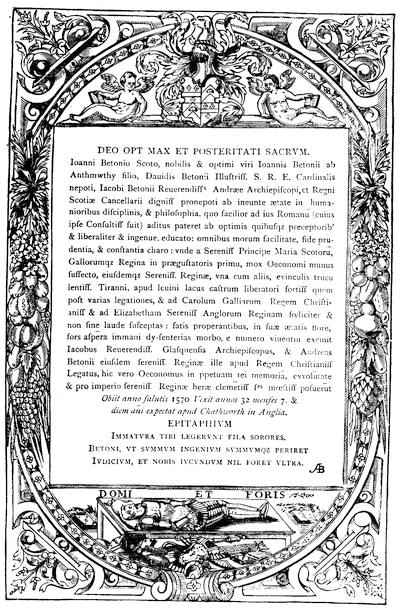

| Monumental Brass to John Beton | 391 |

| Cavendish Monument, Edensor Church | 392 |

| Tomb of the Sixth Duke of Devonshire | 393 |

| The Chatsworth Hotel, Edensor | 395 |

ALTON TOWERS.

WE commence this series with Alton Towers, one of the most interesting of the many Stately Homes of England that dignify and glorify the Kingdom; deriving interest not alone from architectural grandeur and the picturesque and beautiful scenery by which it is environed, but as a perpetual reminder of a glorious past—its associations being closely allied with the leading heroes and worthies of our country.

The Laureate asks, apparently in a tone of reproach—

“Why don’t these acred sirs

Throw up their parks some dozen times a year,

And let the people breathe?”

The poet cannot be aware that a very large number of the “parks” of the nobility and gentry of England are “thrown up” not a “dozen times” but a hundred times in every year; and that, frequently, thousands of “the people” breathe therein—as free to all the enjoyments they supply as the owners themselves. Generally, also, on fixed days, the chief rooms, such as are highly decorated or contain pictures—the State Apartments—are open also; and all that wealth has procured, as far as the eye is concerned, is as much the property of the humblest artisan as it is of the lord of the soil.

And what a boon it is to the sons and daughters of toil—the hard-handed men—with their wives and children—workers at the forge, the wheel, and the[2] loom,—who thus make holiday, obtain enjoyment, and gain health, under the shadows of “tall ancestral trees” planted centuries ago by men whose names are histories.

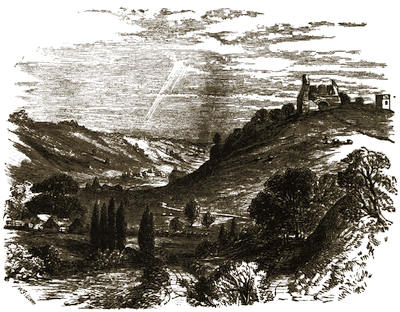

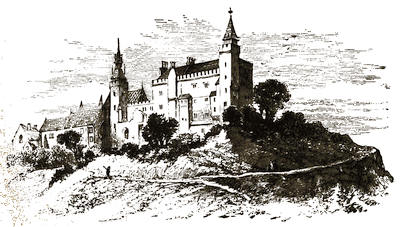

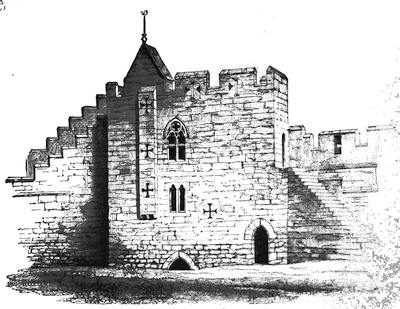

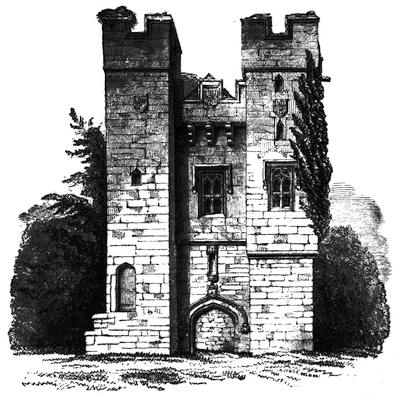

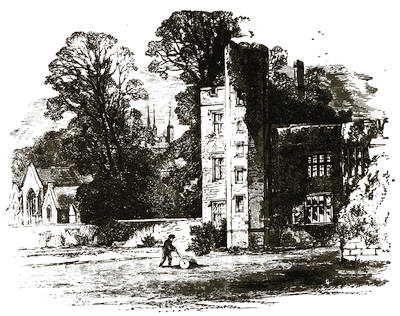

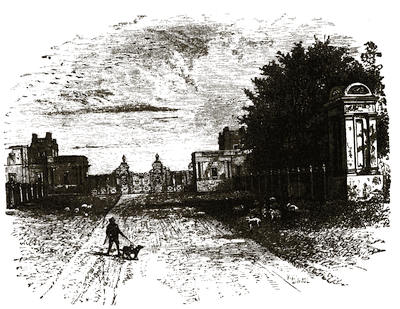

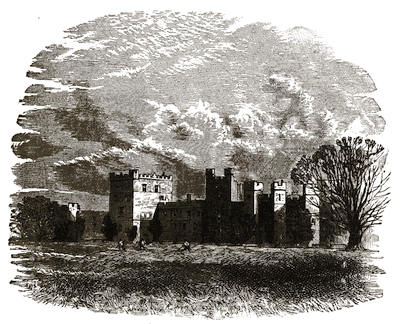

Ruins of Alton Castle.

Indeed a closed park, and a shut-up mansion, are, now, not the rule, but the exception; the noble or wealthy seem eager to share their acquisitions with the people; and continually, as at Alton Towers, picturesque and comfortable “summer houses” have been erected for the ease, shelter, and refreshment of all comers. Visitors of any rank or grade are permitted to wander where they will, and it is gratifying to add, that very rarely has any evil followed such license. At Alton Towers, a few shillings usually pays the cost consequent upon an inroad of four thousand modern “iconoclasts:” the grounds being frequently visited by so many in one day.

The good that hence arises is incalculable: it removes the barriers that[3] separate the rich from the poor, the peer from the peasant, the magnate from the labourer; and contributes to propagate and confirm the true patriotism that arises from holy love of country.

Alton, Alveton, Elveton, or Aulton, was held by the Crown at the time of taking the Domesday survey, but, it would appear, afterwards reverted to its original holders; Rohesia, the only child of the last of whom, brought Alton, by marriage, to Bertram de Verdon, who had been previously married to Maude, daughter of Robert de Ferrars, first Earl of Derby. Alveton thus became the caput baroniæ of the Verdon family, its members being Wooton, Stanton, Farley, Ramsor, Coton, Bradley, Spon, Denston, Stramshall, and Whiston.

From the Verdons, through the Furnivals and Neviles, Alton passed to the Earls of Shrewsbury, as will be seen from the following notice of the Verdon family. Godfreye Compte le Verdon, surnamed de Caplif, had a son, Bertram de Verdon, who held Farnham Royal, Bucks, by grand sergeantry, circa 1080. He had three sons, one of whom, Norman de Verdon, Lord of Weobly, co. Hereford, married Lasceline, daughter of Geoffrey de Clinton, and by her had, with other issue, Bertram de Verdon, who was a Crusader, and founded Croxden, or Crokesden, Abbey, near Alton, in the twenty-third year of Henry II., anno 1176. He married twice: his first wife being Maude, daughter of Robert de Ferrars, first Earl of Derby (who died without issue in 1139), and his second being Rohesia, daughter and heiress of a former possessor of Alton, through which marriage he became possessed of that manor, castle, &c. He was Sheriff of the counties of Warwick and Leicester, and, dying at Joppa, was buried at Acre. By his wife Rohesia (who died in 1215) he had issue—William; Thomas, who married Eustachia, daughter of Gilbert Bassett; Bertram; Robert; Walter, who was Constable of Bruges Castle; and Nicholas, through whom the line is continued through John de Verdon, who, marrying Marjorie, one of the co-heiresses of Walter de Lacie, Lord Palatine of the county of Meath, had issue by her—Sir Nicholas de Verdon of Ewyas-Lacie Castle; John de Verdon, Lord of Weobly; Humphrey; Thomas; Agnes; and Theobald, who was Constable of Ireland, 3rd Edward I., and was in 1306 summoned as Baron Verdon. He died at Alton in 1309, and was buried at Croxden Abbey. His son, Theobald de Verdon, by his first wife, Elizabeth, widow of John de Burgh, Earl of Ulster, and daughter and one of the co-heiresses of Gilbert de Clare, Earl of Gloucester, by “Joane de Acres,” had a daughter, married to[4] Lord Ferrars of Groby; and, by his second wife, Maude, daughter of Edmund, first Baron Mortimer of Wigmore, had issue, besides three sons who died during his lifetime, three daughters, who became his co-heiresses.

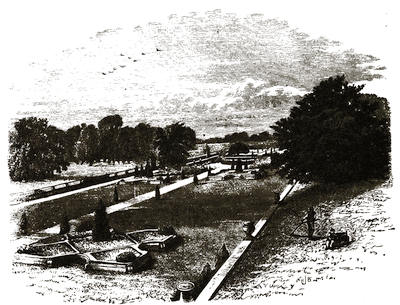

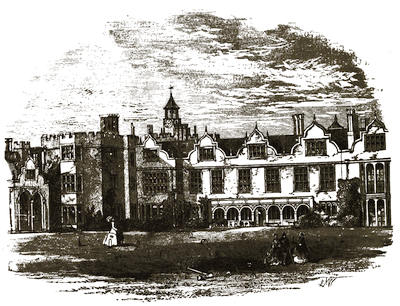

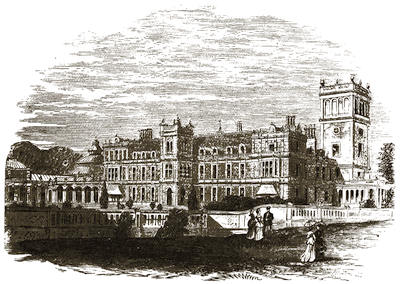

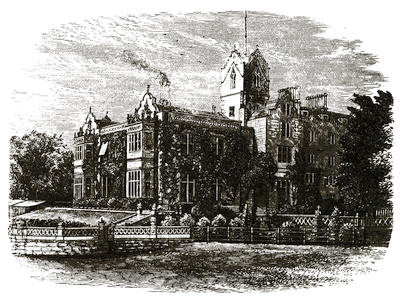

Alton Towers, from the Terrace.

One of these, Margaret (who married three times), had Weobly Castle for her portion; another, Elizabeth, married to Lord de Burghersh, had Ewyas-Lacie Castle for her portion; and the other, Joan, had for her portion Alton, with its castle and dependencies. This lady (Joan de Verdon) married, firstly, William de Montague; and, secondly, Thomas, second Lord Furnival, who, for marrying her without the king’s licence, was fined in the sum of £200. She had by this marriage two sons, Thomas and William, who were successively third and fourth Barons Furnival, lords of Hallamshire. This William, Lord Furnival, married Thomasin, daughter and heiress of Nicholas, second Baron Dagworth of Dagworth, and had by her a sole daughter and heiress,[5] Joan de Furnival, who, marrying Thomas Neville of Hallamshire, brother to the Earl of Westmoreland, conveyed to him the title and estates, he being summoned in 1383 as fifth Baron Furnival. By her he had issue, two daughters and co-heiresses, the eldest of whom, Maude, “Lady of Hallamshire,” married, in 1408, John Talbot, afterwards first Earl of Shrewsbury and sixth Baron Talbot of Goderich—“Le Capitaine Anglais.” This nobleman, whose military career was one of the most brilliant recorded in English history, was summoned as Baron Furnival of Sheffield in 1409; created Earl of Shrewsbury, 1442; and Earl of Waterford, &c., 1446. He was slain, aged eighty, at Chatillon, in 1453, and was buried at Whitchurch. This Earl of Shrewsbury, who so conspicuously figures in Shakespeare’s Henry VI., enjoyed, among his other titles, that of “Lord Verdon of Alton”—a title which continued in the family, the Alton estates having now for nearly five centuries uninterruptedly belonged to them.

The titles of this great Earl of Shrewsbury are thus set forth by Shakespeare, when Sir William Lucy, seeking the Dauphin’s tent, to learn what prisoners have been taken, and to “survey the bodies of the dead,” demands—

“Where is the great Alcides of the field,

Valiant Lord Talbot, Earl of Shrewsbury?

Created, for his rare success in arms,

Great Earl of Washford, Waterford, and Valence

Lord Talbot of Goodrig and Urchinfield,

Lord Strange, of Blackmere, Lord Verdun of Alton,

Lord Cromwell of Wingfield, Lord Furnival of Sheffield,

The thrice victorious Lord of Falconbridge;

Knight of the noble order of Saint George,

Worthy Saint Michael, and the Golden Fleece;

Great Mareshal to Henry the Sixth

Of all his wars within the realm of France.”

To which, it will be remembered, La Pucelle contemptuously replies—

“Here is a silly stately style indeed!

The Turk, that two-and-fifty kingdoms hath—

Writes not so tedious a style as this—

Him that thou magnifiest with all these titles,

Stinking and fly-blown, lies here at our feet.”

From this John, Earl of Shrewsbury,—“the scourge of France,” “so much feared abroad that with his name the mothers still their babes,”—the manor and estates of Alton and elsewhere passed to his son, John, second earl, who married Elizabeth Butler, daughter of James, Earl of Ormond, and was succeeded by his son, John, third earl, who married Catherine Stafford, daughter of Humphrey, Duke of Buckingham; and was in like manner succeeded by his son, George, fourth earl, K.G., &c., who was only five years of age at his[6] father’s death. He was succeeded, as fifth earl, by his son, Francis; who, dying in 1560, was succeeded by his son, George, as sixth earl.

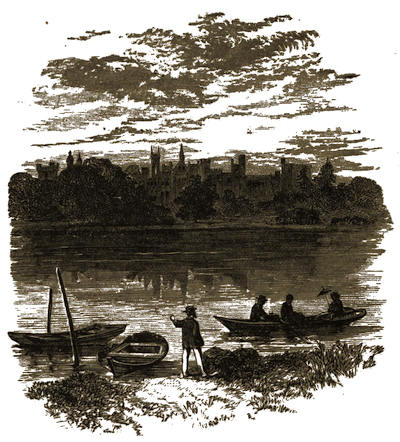

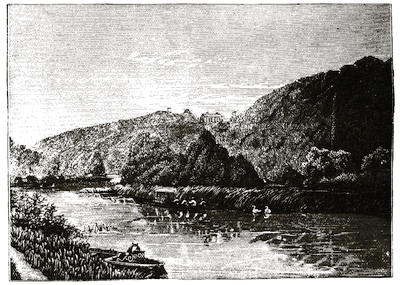

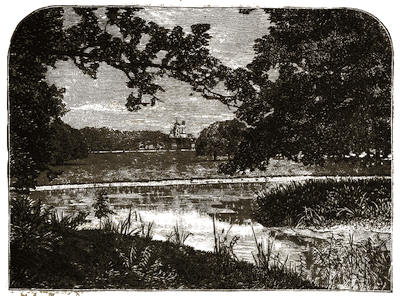

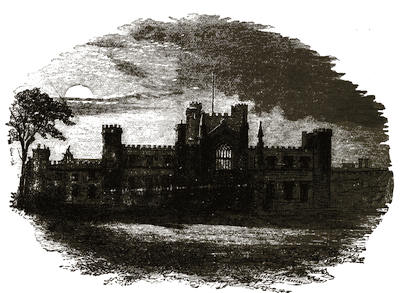

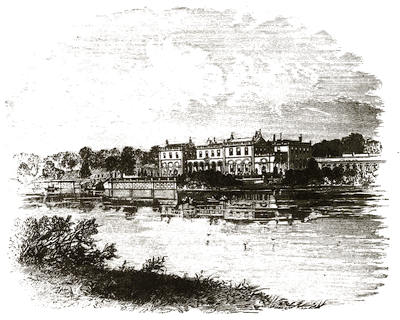

Alton Towers, from the Lake.

This nobleman married, first, Gertrude Manners, daughter of Thomas, Earl of Rutland; and, second, Elizabeth (generally known as “Bess of Hardwick,” for an account of whom, see the article on Hardwick Hall in the present volume), daughter of John Hardwick, of Hardwick Hall, Derbyshire, and successively widow, first, of Robert Barlow, of Barlow; second, of Sir William Cavendish, of Chatsworth; and, third, of Sir William St. Loe. She was the builder of Chatsworth and of Hardwick Hall. To him was confided the care of Mary Queen of Scots. He was succeeded by his son Gilbert, as seventh earl. This young nobleman was married before he was fifteen to Mary,[7] daughter of Sir William Cavendish of Chatsworth. He left no surviving male issue, and was succeeded by his brother, Edward, as eighth earl, who, having married Jane, daughter of Cuthbert, Lord Ogle, died, without issue, being the last of this descent, in 1617. The title then passed to a distant branch of the family, in the person of George Talbot, of Grafton; who, being descended from Sir Gilbert Talbot, third son of the second earl, succeeded as ninth earl. From him the title descended in regular lineal succession to Charles, twelfth earl, who was created by George I. Duke of Shrewsbury and Marquis of Alton, and a K.G. At his death, the dukedom and marquisate expired, and from that time, until 1868, the earldom has never passed directly from a father to a son. The thirteenth earl was a Jesuit priest, and he was succeeded by his nephew as fourteenth earl. Charles, fifteenth earl, dying without issue, in 1827, was succeeded by his nephew, John (son of John Joseph Talbot, Esq.), who became sixteenth earl. That nobleman died in 1852, and was succeeded as seventeenth earl, by his cousin, Bertram Arthur Talbot (nephew of Charles, fifteenth earl), who was the only son of Lieut.-Colonel Charles Thomas Talbot. This young nobleman was but twenty years of age when he succeeded to the title and estates, which he enjoyed only four years, dying unmarried at Lisbon, on the 10th of August, 1856. Earl Bertram, who, like the last few earls his predecessors, was a Roman Catholic, bequeathed the magnificent estates of Alton Towers to the infant son of the Duke of Norfolk, Lord Edward Howard, also a Roman Catholic; but Earl Talbot (who was opposed in his claim by the Duke of Norfolk, acting for Lord Edward Howard; by the Princess Doria Pamphili, of Rome, the only surviving child of Earl John; and by Major Talbot, of Talbot, co. Wexford) claimed the peerage and estates as rightful heir. After a long-protracted trial, Earl Talbot’s claim was admitted by the House of Lords, in 1858; and after another trial his lordship took formal possession of Alton Towers and the other estates of the family, and thus became eighteenth Earl of Shrewsbury, in addition to his title of third Earl of Talbot.

His lordship (the Hon. Henry John Chetwynd Talbot, son of Earl Talbot) was born in 1803. He served in the Royal Navy, and became an admiral on the reserved list. He was also a Knight of the Order of St. Anne of Russia, and of St. Louis of France, a Knight of the Bath, and a Privy Councillor. In 1830, his lordship, then Mr. Talbot, represented Thetford in Parliament; and in the following year was elected for Armagh and for Dublin; and from[8] 1837 until 1849, when he entered the Upper House as Earl Talbot, he represented South Staffordshire. In 1852 his lordship was made a Lord in Waiting to the Queen; in 1858 Captain of the Corps of Gentlemen at Arms; and was also Hereditary Lord High Steward of Ireland.

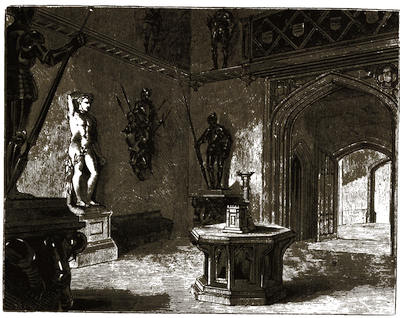

The Octagon.

He married in 1828 Lady Sarah Elizabeth Beresford, eldest daughter of the second Marquis of Waterford, and by her had issue living four sons, viz.—Charles John, present, nineteenth, Earl of Shrewsbury; the Hon. Walter Cecil Talbot, who, in 1869, assumed, by Royal Sign Manual, the surname of Carpenter in lieu of[9] that of Talbot, on his succeeding to the Yorkshire estates of the late Countess of Tyrconnell; the Hon. Reginald Arthur James Talbot, M.P. for Stafford; and the Hon. Alfred Talbot; and three daughters, viz.: Lady Constance Harriet Mahunesa, married to the Marquis of Lothian; Lady Gertrude Frances; and Lady Adelaide, married at her father’s death-bed, June 1st, 1868, to the Earl Brownlow. The eighteenth Earl died in June, 1868, and was succeeded by his son, Charles John, Viscount Ingestre, M.P., as nineteenth earl.

The present peer, the noble owner of princely Alton, of Ingestre, and of other mansions, Charles John Talbot, nineteenth Earl of Shrewsbury, fourth Earl of Talbot, of Hemsoll, in the county of Glamorgan, Earl of Waterford, Viscount Ingestre, of Ingestre, in the county of Stafford, and Baron Talbot, of Hemsoll, in the county of Glamorgan, Hereditary Lord High Steward of Ireland, and Premier Earl in the English and Irish peerages, was born in 1830, and was educated at Eton and at Merton College, Oxford. In 1859 he became M.P. for North Staffordshire, and, in 1868, for the borough of Stamford. In 1868 he succeeded his father in the titles and estates, and entered the Upper House. He formerly held a commission in the 1st Life Guards. His lordship married, in 1855, Anne Theresa, daughter of Commander Richard Howe Cockerell, R.N., and has issue one son, Charles Henry John, Viscount Ingestre, born in 1860; and three daughters, the Hon. Theresa Susey Helen Talbot, born in 1856; the Hon. Gwendoline Theresa Talbot, born in 1858; and the Hon. Muriel Frances Louisa Talbot, born in 1859.

The Earl of Shrewsbury is patron of thirteen livings, eight of which are in Staffordshire, two in Worcestershire, and one each in Oxfordshire, Berkshire, and Shropshire.

The arms of the earl are, gules, a lion rampant within a bordure engrailed, or. Crest, on a chapeau, gules, turned up, ermine, a lion statant, with the tail extended, or. Supporters, two talbots, argent.

We have thus given a history of this illustrious family from its founder to the present day, and proceed to describe its principal seat in Staffordshire—the beautiful and “stately home” of Alton Towers.

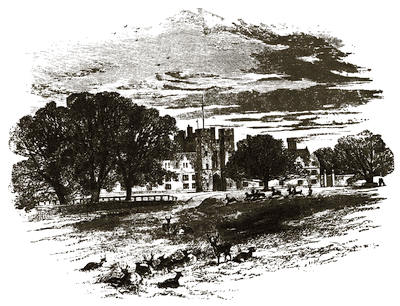

The castle of the De Verdons, which was dismantled by the army of the Parliament, stood on the commanding and truly picturesque eminence now occupied by the unfinished Roman Catholic Hospital of St. John and other conventual buildings, &c. A remarkably interesting view, showing the commanding site of the castle, and the valley of Churnet, with Alton Church, &c.,[10] is fortunately preserved in an original painting from which our first engraving is made.

The site of Alton Towers was originally occupied by a plain house, the dwelling of a steward of the estate. A hundred and forty years ago it was known as “Alveton (or Alton) Lodge,” and was evidently a comfortable homestead, with farm buildings adjoining.

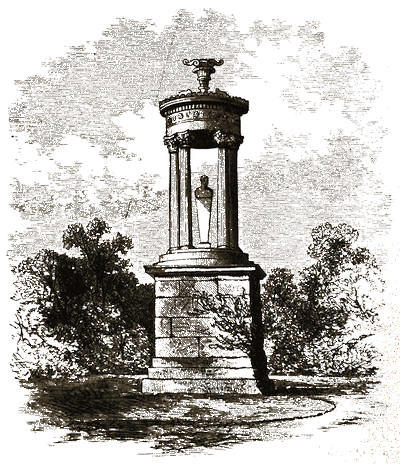

When Charles, fifteenth Earl of Shrewsbury, succeeded to the titles and estates of his family, in the beginning of the present century, he made a tour of his estates, and on visiting Alton was so much pleased with the natural beauties of the place, and its surrounding neighbourhood, that he determined upon improving the house and laying out the grounds, so as to make it his summer residence.[1] With that view he added considerably to the steward’s dwelling, and having, with the aid of architects and landscape gardeners, converted that which was almost wilderness into a place of beauty, he called it “Alton Abbey,”—a name to which it had no right or even pretension. To his taste, the conservatories, the temples, the pagoda, the stone circle, the cascades, the fountains, the terraces, and most of the attractive features of the grounds, owe their origin, as do many of the rooms of the present mansion. A pleasant memory of this excellent nobleman is preserved at the entrance to the gardens, where, in a noble cenotaph, is a marble bust, with the literally true inscription—

“He made the desert smile.”

After his death, in 1827, his successor, Earl John, continued the works at Alton, and, by the noble additions he made to the mansion, rendered it what it now is—one of the most picturesque of English seats. In 1832 his lordship consulted Pugin as to some of the alterations and additions, and this resulted in his designing some new rooms, and decorating and altering the interior of others. Mr. Fradgley and other architects had also previously been employed, and to their skill a great part of the beauty of Alton Towers is attributable. The parts executed by Pugin are the balustrade at the great entrance, the parapet round the south side, the Doria apartments over Lady Shrewsbury’s rooms, on the south-east side of the house, called sometimes the “plate-glass drawing-room,” the apartments over the west end of the great gallery, and the conservatory, &c. The fittings and decorations of many of[11] the other rooms and galleries, including the unfinished dining-hall and the chapel, are also his. The entrance lodges near the Alton Station are likewise from Pugin’s designs.

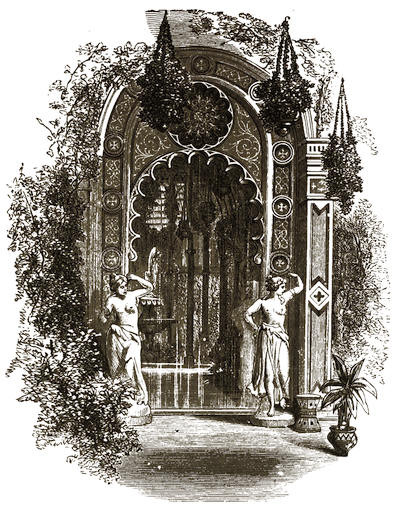

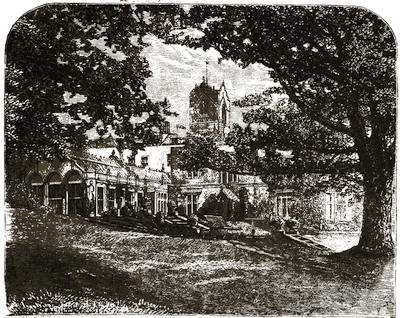

The Conservatories and Alcove.

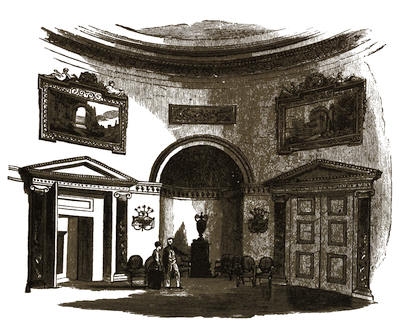

The principal, or state, entrance to the mansion is on the east side, but the private foot entrance from the park is by the drawbridge, while that from the gardens and grounds is by a path leading over the entrance gateway or tower. To reach the state entrance the visitor on leaving the park, passes a noble gateway in an embattled and machicolated tower, with side turrets and embrasures, near to which he will notice the sculptured arms of De Verdon, of Furnival, and of Raby, and on the inner side of the tower, those of Talbot, with the date, 1843. Passing between embattled walls, the entrance to the[12] right is a majestic tower, bearing sculptured over the doorway the armorial bearings, crest, supporters, with mantling, &c., of the Earl of Shrewsbury. The steps leading to the doorway are flanked on either side by a life-size “talbot,” bearing the shield and the family arms, while on the pedestals, &c., are the monogram of Earl John, and the motto “Prest d’accomplir.” Passing through the doors the visitor enters the Entrance Tower, a square apartment of extremely lofty proportions. “The doors being closed after him, he will at once notice the most striking feature of this hall to be, that the entrance-doors and the pair of similar folding-doors facing them—each of which is some twenty feet high, and of polished oak—are painted on their full size with the arms, supporters, &c., of the Earl of Shrewsbury. This fine effect, until the place was dismantled a few years since, was considerably heightened by the assemblage of arms, and armour, and of stags’ antlers, &c., with which the walls were decorated. In this apartment the old blind Welsh harper, a retainer of the family, with his long dress, covered with medals and silver badges, sat for years and played his native strains on the ancient bardic instrument of his country.

“From this apartment one of the immense pairs of heraldic doors opens into ‘The Armoury,’ a fine Gothic apartment of about 120 feet in length, with oak roof, the arches of which spring from carved corbels, while from the central bosses hang a series of pendant lanterns. The ‘armoury’ is lit on its north side by a series of stained-glass windows, the first of which bears, under a canopy, &c., the portrait and armorial bearings of William the Conqueror; the next those of ‘Marescallus pater Gilberti Marescalli Regis Henrici Primi, temp. Willm. Conqr.;’ the third, those of Donald, King of Scotland, 1093; the fourth, those of Raby; the fifth, those of De Verdun, the founder of the castle of Alton (‘Verdun fund: Cast: de Alveton, originalis familiæ de Verdun, temp. Will. Conqr.’); and the sixth, of Lacy—‘Summa soror et heres Hugonis de Lacy, fundatoris de Lanthony in Wallia; Mater Gilberti de Lacy, temp. Will. Conqr.’ In this apartment, from which a doorway leads to the billiard and other rooms, hang a number of funeral and other banners of the house of Talbot, and at one end is the Earl’s banner as Lord High Seneschal or Lord High Steward of Ireland—a blue banner bearing the golden harp of ‘Old Ireland’ which was borne by the Earl of Shrewsbury at the funeral of King William IV. In the palmy days of Alton this apartment was filled with one of the most magnificent assemblages of arms and armour ever got together, amongst which not the least noticeable feature was a life-size equestrian figure[13] of ‘the great Talbot’ in full armour, and bearing on his head an antique coronet, in his hand a fac-simile of the famous sword which he wielded so powerfully while living, bearing the words—

‘Ego sum Talboti pro vincere inimicos meos

and on his shoulders his magnificent ‘Garter’ mantle, embroidered with heraldic insignia. The horse was fully armed and caparisoned, the trappings bearing the arms and insignia of its noble owner. The figure was placed on a raised oak platform, richly carved; and on this, at the horse’s feet, lay the fine war helmet of the grand old Earl. At the farther or west end of the armoury, a pair of open screen-work doors of large size, formed of spears and halberds, and surmounted by a portcullis—the whole being designed by a former Countess of Shrewsbury—opens into—

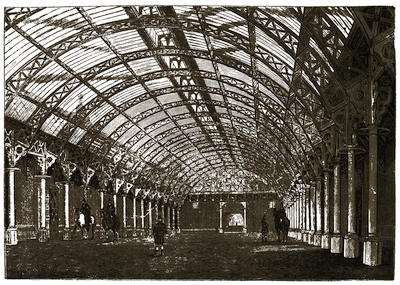

“The Picture-Gallery.—This noble gallery, about 150 feet in length, has a fine oak and glass ceiling, supported by a series of arches, which spring from corbels formed of demi-talbots, holding in their paws shields with the Talbot arms, while in each spandrel of the roof are also the same arms. The room is lit with sumptuous chandeliers. In this gallery was formerly a series of tables, containing articles of vertu and a large assemblage of interesting objects, while the walls were literally covered with paintings of every school, including the collection formed by Letitia Buonaparte, which was purchased in Paris by Earl John. It is now entirely denuded of this treasure of art. From the Picture-Gallery a pair of Gothic screen-work oak and glass folding-doors, with side lights to correspond, opens into—

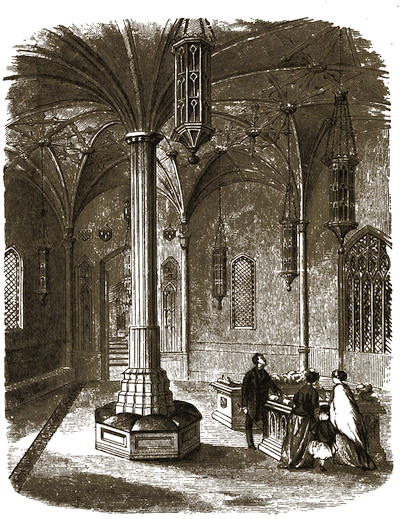

“The Octagon (sometimes called the ‘Saloon,’ or ‘Sculpture-Gallery’), an octagonal room designed to some extent from the splendid Chapter House at Wells Cathedral. Like this it has a central pier, or clustered column, of sixteen shafts, from the foliated capital of which the ribs of the vaulted roof radiate. Other radiating ribs spring from shafts at the angles of the room; and where the radiations meet and cross are sculptured bosses, while a series of geometric cuspings fills in between the intersecting ribs at the points of the arches. Around the base of the central column is an octagonal seat, and stone benches are placed in some parts of the sides. It is lit with pendant Gothic lanterns.

“The ‘Octagon’ opens on its east side into the ‘Picture-Gallery;’ on its west into the ‘Talbot Gallery;’ and on its north into the ‘Conservatory.’ On its south is a fine large window of Perpendicular tracery filled with stained[14] glass, while on the other four sides are small windows, diapered in diagonal lines, with the motto, ‘Prest d’Accomplir,’ alternating with monograms and heraldic devices of the family. Over the Picture-Gallery doorway the following curious verses—a kind of paraphrase of the family motto, ‘Prest d’Accomplir,’ which is everywhere inscribed—are painted in old English characters on an illuminated scroll:—

“‘The redie minde regardeth never toyle,

But still is Prest t’accomplish heartes intent;

Abrode, at home, in every coste or soyle.

The dede is done, that inwardly is meante;

Which makes me saye to every vertuous dede,

I am still Prest t’accomplish what’s decreede.

“‘But byd to goe I redie am to roune,

But byd to roune I redie am to ride;

To goe, roune, ride, or what else to bee done.

Speke but the word, and sone it shall be tryde;

Tout prest je suis pour accomplix la chose,

Par tout labeur qui vous peut faire repose.

“‘Prest to accomplish what you shall commande,

Prest to accomplish what you shall desyre,

Prest to accomplish your desires demande,

Prest to accomplish heaven for happy hire;

Thus do I ende, and at your will I reste,

As you shall please, in every action Prest.’

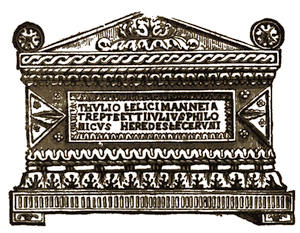

“Above this, and other parts of the walls, are the emblazoned arms of Talbot, Furnivall, De Verdun, Lacy, Raby, and the other alliances of the family; while in the large stained-glass window on the south side are splendid full-length figures of six archbishops and bishops of the Talbot family, with their arms and those of the sees over which they presided. Beneath this window are two beautiful models, full size, of ancient tombs of the great Talbots of former days. One of these is the famous tomb, from Whitchurch, of John, first Earl of Shrewsbury, who was killed in battle July 7, 1453. It bears a full-length effigy of the Earl in his Garter robes and armour, and bears on its sides and ends a number of emblazoned shields of the Talbot alliances, and the following inscription:—

“‘Orate pro anima prœnobilis domini, domini Johanis Talbot, Comitis Salopiæ, domini Furnival, domini Verdun, domini Strange de Blackmere, et Mareschalli Franciæ; qui obiit, in bello apud Burdeux VII Julii MCCCCLIII.’

“It is related that when this noble warrior was slain, his herald passing over the battle-field to seek the body, at length found it bleeding and lifeless,[15] when he kissed it, and broke out into these passionate and dutiful expressions:—‘Alas! it is you: I pray God pardon all your misdoings. I have been your officer of arms forty years or more. It is time I should surrender it to you.’ And while the tears trickled plentifully down his cheek, he disrobed himself of his coat of arms and flung it over his master’s body. This is the knight of whom we read—

“‘Which Sir John Talbote, first Lord Fournivall,

Was most worthie warrior we read of all.

For by his knigh thode and his chivalrye

A Knight of the Garter first he was made;

And of King Henry, first Erle Scrovesberye.

To which Sir John, his sone succession hade,

And his noble successors now therto sade;

God give them goode speede in their progresse,

And Heaven at their ende, both more or lesse.

The live to report of this foresaid lorde

How manly hee was, and full chivalrose:

What deedes that he did I cannot by worde

Make rehersal, by meter ne prose;

How manly, how true, and how famose,

In Ireland, France, Normandy, Lyon, and Gascone

His pere so long renyng I rede of none.

*******

Which while he reigned was most knight

That was in the realme here many yere,

Most dughty of hand and feresest in fight,

Most drede of all other with French men of werr

In Ireland, France, Gyon; whose soule God absolve

And bring to that Llyss that will not dissolve.’

“From the north side of the ‘Octagon’ a flight of stone steps leads up to a glass doorway, which opens into a glass vestibule, forming a part of the ‘Conservatory,’ of which I shall speak a little later on. This conservatory leads into the ‘Dining-room’ and the suite on the north side, and the view along it from the Octagon is charming in the extreme, not the least striking and sweetly appropriate matter being the motto painted above the flowers and around the cornice of the vestibule:—

“‘The speech of flowers exceeds all flowers of speech.’

“On the west side a similar flight of steps and doorway open into

“The Talbot Gallery, a magnificent apartment of about the same size and proportions as the ‘Picture-Gallery.’ It has a fine Gothic ceiling of oak and glass, supported, like that of the Picture-Gallery, on arches springing from demi-talbots bearing shields. The walls, to about two-thirds of their height, are covered with a rich arabesque paper of excellent design, while the upper[16] part is painted throughout its entire surface in diagonal lines with the Talbot motto ‘Prest d’Accomplir,’ alternating with the initials T. (Talbot) and S. (Shrewsbury). On this diapered groundwork are painted, at regular intervals, shields of arms, fully blazoned, with tablets beneath them containing the names of their illustrious bearers. The series of arms on the south side shows the descent of the Earl of Shrewsbury from the time of the Conquest, while those on the north side exhibit the armorial bearings of the alliances formed by the females of the House of Talbot. As these series are of great importance, and have only heretofore been given in Mr. Jewitt’s work upon Alton Towers, from which the whole of the description of the interior here given is copied, I have carefully noted them for the reader’s information. On the south side, commencing at the end next the ‘Octagon,’ the arms are as follows, the arms being all impaled:—

“William the Conqueror and Matilda of Flanders.

King Henry I. and Matilda of Scotland.

Geoffrey Plantagenet, Earl of Anjou, and Matilda, daughter of King Henry I.

King Henry II. and Eleanor of Aquitaine.

King John and Isabella d’Angoulême.

King Henry III. and Eleanor of Provence.

King Edward I. and Eleanor of Castile.

Humphrey Bohun, Earl of Hereford, and Elizabeth, daughter of King Edward I.

James Butler, Earl of Ormond, and Eleanor, daughter of the Earl of Hereford.

James, Earl of Ormond, and Elizabeth, daughter of the Earl of Kildare.

James, Earl of Ormond, and Anne, daughter of Baron Welles.

James, Earl of Ormond, and Joane, daughter of William de Beauchamp.

John Talbot, Earl of Shrewsbury, and Elizabeth, daughter of the Earl of Ormond.

Sir Gilbert Talbot, Knight of the Garter, and Audrey Cotton.

Sir John Talbot and Ada Troutbecke.

Sir John Talbot and Frances Clifford.

John Talbot and Catherine Petre.

John Talbot and Eleanor Baskerville.

John, Earl of Shrewsbury, and Mary Fortescue.

Gilbert Talbot and June Flatsbury.

George, Earl of Shrewsbury, and Mary Fitzwilliam.

Charles Talbot and Mary Mostyn.

John Joseph Talbot and Mary Clifton.

‘John, now Earl of Shrewsbury, Waterford, and Wexford,’ and Maria Talbot.

Richard, Baron Talbot, ancestor of the Earl of Shrewsbury, and Elizabeth Cummin.

John, father of Elizabeth Cummin, and Joane de Valence.

William de Valletort, Earl of Pembroke, and Joane Mountchesney.

Hugh, Count de la Marche, and Isabel d’Angoulême.

Aymer, Count d’Angoulême, and Alice de Courteney.

Peter, fils de France, and the Heiress of Courteney.

[17]Louis VI., King of Fiance, father of Peter de Courteney.

Richard Talbot and Eva, daughter of Gerrard de Gournay.

Hugh Talbot and Beatrix, daughter of William de Mandeville.

Richard Talbot and Maud, daughter of Stephen Bulmer.

Richard Talbot and Aliva, daughter of Alan Bassett.

William Talbot and Gwendiline, daughter of Rhys ap Griffith, Prince of Wales.

Richard Baron Talbot and Elizabeth Cummin.

John Cummin, grandfather of Elizabeth, and Margery Baliol.

John Baliol and Dorvegillia, Lady of Galloway.

David the First, King of Scotland, and the Lady of Galloway.

“On the north side, beginning at the west end, the arms of the female alliances are as on the other side—impaled—and are as follows:—

“Joane Talbot, married to John Carew.

Joane Talbot to John de Dartmouth.

Elizabeth Talbot to Waren Archdekene.

Katherine Talbot to Sir Roger Chandos.

Phillippa Talbot to Sir Matthew Gournay.

Jane Talbot to Sir Nicholas Poynings.

Anne Talbot to Hugh, Earl of Devon.

Mary Talbot to Sir Thomas Greene.

Elizabeth Talbot to Sir Thomas Barre.

Jane Talbot to Hugh de Cokesay.

Elizabeth Talbot to Thomas Gray, Viscount Lisle.

Margaret Talbot to Sir George Vere.

Anne Talbot to Sir Henry Vernon.

Margaret Talbot to Thomas Chaworth.

Eleanor Talbot to Thomas, Baron Sudeley.

Margaret Talbot to Henry, Earl of Cumberland.

Mary Talbot to Henry, Earl of Northumberland.

Elizabeth Talbot to Lord Dacre of Gilsland.

Anne Talbot to Peter Compton.

Anne Talbot to William, Earl of Pembroke.

Anne Talbot to John, Baron Bray.

Anne Talbot to Thomas, Lord Wharton.

Catherine Talbot to Edward, Earl of Pembroke.

Mary Talbot to Sir George Saville.

Grace Talbot to Henry Cavendish.

Mary Talbot to William, Earl of Pembroke.

Elizabeth Talbot to Henry, Earl of Kent.

Alatheia Talbot to Thomas, Earl of Arundel.

Gertrude Talbot to Robert, Earl of Kingston.

Mary Talbot to Thomas Holcroft.

Mary Talbot to Sir William Airmine.

Margaret Talbot to Robert Dewport.

Elizabeth Talbot to Sir John Littleton.

Mary Talbot to Thomas Astley.

[18]Joane Talbot to Sir George Bowes.

Mary Talbot to Mervin, Earl of Castlehaven.

Barbara Talbot to James, Lord Aston.

Mary Talbot to Charles, Baron Dormer.

Mary Alathea Beatrix Talbot to Prince Filippo Doria Pamfili.

Gwendaline Catherine Talbot to Prince Marc Antonio Borghese.

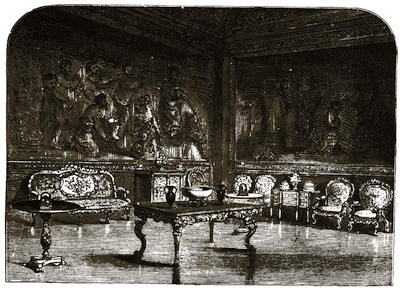

“On and over the doorway are the arms and quarterings of the Talbots, and the sculptured stone chimney-pieces are of the most exquisite character, having Talbots supporting enamelled banners of arms under Gothic canopies, and shields on the cuspings. At the top also is a shield, supported by two angels. The fire-place is open, and has fire-dogs; and the tiles are decorated alternately with the letter S for Shrewsbury, and I T conjoined, for John Talbot.

“At the west end is a splendid stained-glass window, exhibiting the names, armorial bearings, and dates of Earl John and nine of his ancestors, who have been Knights of the Garter—the garter encircling each of the shields. The names are Gilbert, Lord Talbot, 19 Henry VI.; John, Earl of Shrewsbury, 1460; George, 4th Earl of Shrewsbury; George Talbot; Francis, 5th Earl of Shrewsbury; Sir Gilbert Talbot, 1495; George, 6th Earl of Shrewsbury; Gilbert, 7th Earl of Shrewsbury, 1592; Charles, Earl of Shrewsbury, 1604; and John, Earl of Shrewsbury, 1840.

“In the palmy days of Alton Towers, this room, the Talbot Gallery, contained a splendid collection of choice paintings, a fine assemblage of rare china, some exquisite sculpture, and a large number of articles of vertu of every imaginable class and character. From the north side a small door opens into—

“The Oak Corridor, a narrow passage leading in a straight line to the North Library, and having doorways opening on its left into both of the state-rooms. The first of these rooms, after passing the ‘waiting-room’ or ‘ante-room,’ is—

“The State Boudoir, an octagonal apartment with a magnificent carved, painted, and gilt Gothic ceiling. This, in former days, when it contained some fine old cabinets, a service of regal Sèvres china, and some exquisite portraits, and was filled with sumptuous furniture, was one of the most charming rooms imaginable. Next to this is—

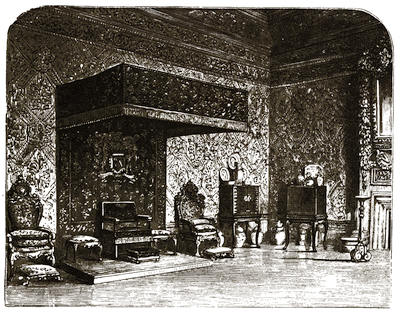

“The State Bed-room.—The ceiling is panelled, being divided by deep ribs into squares, having the ground painted a pale blue; rich tracery of oak and gold stretches toward the centre of each compartment, and terminates with a gold leaf; the hollow mouldings of the ribs are crimson, studded with[19] gold; below is a deep cornice of vine-leaves and fruit picked out green and gold; and the walls are hung with paper of an azure ground, relieved with crimson and gold.

The Temple.

“The State Bed, which is about 18 feet in height and 9 feet in width, is a sumptuous piece of massive Gothic furniture, all gilt in every part and massively carved. Around the canopy hangs the most costly of bullion fringe, and the hangings, as well as those of the windows and other furniture, are of the richest possible golden Indian silk. This room formerly contained a toilet service of gold, and the whole of the furniture and decorations were of the grandest character. The chimney-piece is of white marble, exquisitely carved, and bearing on the spandrels the Talbot arms—a lion rampant within a bordure engrailed. The furniture is all gilt like the bed, with which also the drapery is en suite. The windows, as do also those of the boudoir, look out upon a perfect sea of magnificent rhododendrons. One door opens into the Oak Corridor, and another into—

“The Dining-Room, from which, by a doorway, the Oak Corridor is also[20] entered, and from which, by a light staircase, access to the upper suite of sleeping apartments, including the ‘Arragon room’ (and to the lower rooms) is gained. From this ante-room—

“The West Library is entered. This apartment, a fine, sombre, quiet-looking room, has a panelled ceiling, at the intersections of the ribs of which are carved heraldic bosses. In the centre is a large and massive dark oak table, and around the sides of the room are ranged fine old carved and inlaid cabinets and presses for books. Over these presses, and in different parts of this room and of the ‘North Library,’ are a number of well-chosen mottoes, than which for a library nothing could well be more appropriate. Thus, in these mottoes, among others we read—

“‘Study wisdom and make thy heart joyful.’

“‘The wise shall inherit glory, but shame shall be the portion of fools.’

“‘They that be wise shall shine as the firmament.’

“‘Blessed is the man that findeth wisdom, and is rich in prudence.’

“‘The heart of the wise shall instruct his mouth and add grace to his lips.’

“‘Take hold on instruction; leave it not; keep it because it is thy life.’

“‘Knowledge is a fountain of life to him that possesseth it.’

“From this fine apartment the North Library is entered by two open archways. This room is similar in its appointments to the West Library, and with it forms one magnificent whole. At the north-west corner of this room (in the tower) is a charming apartment, connected with the library by an open archway, called—

“The Poet’s Bay or ‘Poet’s Corner,’ which is one of the most charming of all imaginable retreats. The bay window overlooks the park and the distant country for miles away, while the side windows overlook parts of the grounds and buildings. The ceiling is of the most elaborate character, covered with minute tracery and exquisite pendents picked out in gold and colours. At the west end of the library is a stained-glass window with full-length figures of ‘Gilbert Talbot’ and the ‘Lady Joan,’ with their arms under Gothic canopies. From this room a door on the south side opens into the ‘Oak Corridor,’ while two open arches at the east end connect it with—

“The Music-Room, the ceiling of which is an elegant example of flamboyant tracery, the ground being blue, and the raised tracery white and gold. The chimney-piece of white marble is elaborately sculptured, and from it rises a majestic pier-glass. On either side are portraits of Earl John and his Countess, life-size, surmounted by their coronets. The furniture which[21] remains is of remarkably fine character, carved and gilt, and the walls are here and there filled in with mirrors, which add much to the effect. On the south side is a large and deeply-recessed bay window, like the rest, of Gothic design, with stained glass in its upper portion, representing King David playing on the harp, St. Cecilia, and angels with various musical instruments. In front of this window is a beautiful parterre of flowers, the Conservatory being to the left, and the state-rooms to the right. From the ‘Music-Room,’ glass doors, in a Gothic screen, open into a small library, with Gothic presses and stained-glass window with Talbot arms, &c. From this room another similar door opens into—

“The Drawing-Room, a remarkably fine and strikingly grand Gothic apartment, with a ceiling of flamboyant tracery of very similar design to the one already named. To the right, on entering, a central door of Gothic screen-work and glass opens into the Conservatory, which, as I have before said, connects this room and those on the north side with the Octagon and those on the south side. The Conservatory is entirely of glass, both roof and sides, and has a central transept. It is filled with the choicest plants, and in every part, except the vestibule, the sweetly pretty and appropriate text, ‘Consider the lilies of the field how they grow; they toil not, neither do they spin, yet I say unto you, that even Solomon in all his glory was not arrayed like unto one of these,’ is painted around the cornice. In the vestibule, as I have said, the motto is, ‘The speech of flowers exceeds all flowers of speech.’ Over the Conservatory door, in stained glass, are the arms of Talbot, Verdun, &c.; the crowned rose and thistle; and other devices. Opposite to the Conservatory, on the north side, is the ‘Saloon.’ The furniture of the ‘Drawing-room,’ the chairs, couches, and seats, are all of the most costly character, some of them draped with the arms, supporters, &c., of the earl in gold and crimson damask. On a table in this room are arranged the various addresses, in cabinets, &c., presented to the late Earl of Shrewsbury on his accession to the earldom and estates after the trial in 1860, and a magnificent ancient casket, the outer glass case of which bears the inscription—‘La casset Talbot presente par Jean, premier Comte de Shreusburie, sur son mariage a Marguerite Beauclerc.’ On the walls, besides other paintings, is a fine full-length seated figure of Queen Adelaide. The ends of the room are Gothic screen-work, with doors and mirrors. One of these, at the east end, leads into another small library, and so on by a small gallery, denuded of its objects of interest, to the Chapel Corridor (elaborately groined and panelled in[22] oak), from which the private apartments are gained, and which also leads direct to—

“The Chapel, which, although ruthlessly shorn of its relics, its paintings, its altar, its shrines, and all its more interesting objects, is still one of the most gorgeous and beautiful of rooms. It is enough to say that it is one of Pugin’s masterpieces, and that the stained glass is perhaps the finest that even Willement, by whom it was executed, ever produced. It is impossible to conceive anything finer than was the effect of this chapel when it was in perfect order.

The Conservatories.

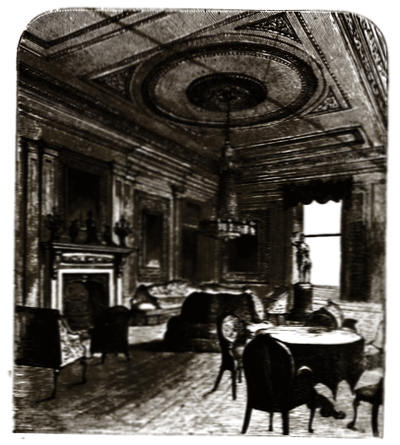

“With the drawing-room, as I have said, an open archway connects another magnificent apartment, the Saloon, which has a fine oak-groined ceiling, with elegantly carved, gilt, and painted bosses. In the centre of the[23] west side is a fine stained-glass window, representing Edward, the Black Prince, full length, in armour, and with his garter robes, painted by Muss; and opposite to this a doorway opens into a corridor leading to the drawing and other rooms. The view from the north end of the saloon, looking down its full length, across the splendid drawing-room, down the long vista of the conservatory, and into the octagon at the farthest end, is fine in the extreme, and is indeed matchless.

“The Corridor, of which I have just spoken, is one of the most dainty and minutely beautiful ‘bits’ of the whole building. It is of oak, the sides are panelled and gilt, and from small clustered pilasters rises the elaborate oak groining of the ceiling, the groining being what can only be expressed as ‘skeleton groining,’ the ribs alone being of oak, partly painted and gilt, and the space between them being filled in with a minute geometric pattern in stained glass. From this corridor a door in the north side opens into the—

“Small or Family Dining-Room, a fine sombre-looking apartment, about 25 feet square, and furnished with a magnificent central table, and every accompaniment that wealth can desire. The ceiling is of oak, panelled, and has a rich armorial cornice, with arms of Talbot, running around it. The chimney-piece, of dark oak, is a splendid piece of ancient carving. From the corridor another doorway leads to a staircase connecting other private apartments above, while at its east end it opens into—

“The Grand Dining-Hall, near which are the kitchens. This hall, which was being remodelled and altered by Pugin at the time of the Earl’s death, remains to this day in an unfinished state, but shows how truly grand in every way it would have been had it been completed. The roof is one of the finest imaginable, and from its centre rises a majestic louvre, which at once admits a subdued light and acts as a ventilator. It is of truly noble proportions, and the fire-places and carved stone chimney-pieces are grand in the extreme—the latter bearing the arms, crest, supporters, motto, chapeau, &c., of the Earl of Shrewsbury. The sides of the room were intended to be panelled, as was also the minstrels’ gallery, with carved oak, and a part of this is already placed. At the north end is a fine large window, the upper part of which is filled with armorial bearings, but the lower part has never been completed, and is filled in with plain quarries. The arms in this window are those of Talbot Earl of Shrewsbury, Clifford, Beauchamp, De Valence, Comyn, Mountchesny, Nevile, Middleham, Clifford, Bohun, Strange of Blackmere, Tailebot, Troutbeke, Claveringe, Buckley, Pembroke, Borghese, Doria, Lovetoft, Mareschal, Strongbow,[24] King Donald, Raby, Lacy, De Verdun, Castile and Leon, D’Angoulême, William the Conqueror, Bagot, Mexley, Aylmer, and others.

The Pagoda.

“From here a short corridor leads to a small vestibule, from which the other private apartments extend. Of these the principal one is the Boudoir of the Countess of Shrewsbury—a charming apartment, replete with every luxury and with every appliance which taste and art can dictate. The ‘Doria’ and other apartments are reached from near this by a circular staircase. From[25] the vestibule the private entrance to the Towers is gained, and from it is the private way across the entrance gateway into the grounds; and also through the small tower and across the drawbridge the park is reached. The drawbridge crosses the moat, and the entrance is fully guarded, and has all the appliances of an old baronial castle.”[2]

And now let us speak briefly of the situation of Alton Towers, and of its grounds of matchless charms. Situate almost in the centre of England—in busy Staffordshire, but on the borders of picturesque Derbyshire—Alton Towers is within easy reach of several populous cities and towns, the active and laborious denizens of which frequently “breathe” in these always open gardens and grounds the pure and fragrant air.

The roads to it are, moreover, full of interest and surpassing beauty; approached from any side, the traveller passes through a country rich in the picturesque. Those who reach it from thronged and toiling Manchester, from active and energetic Derby, from the potteries of busy Staffordshire, are regaled by Nature on their way, and are refreshed before they drink from the full cup of loveliness with which the mansion and its grounds and gardens supply them.

The route from Derby passes by way of Egginton; Tutbury, whose grand old church and extensive ruins of the castle are seen to the left of the line; Sudbury, where the seat of Lord Vernon (Sudbury Hall) will be noticed to the right; Marchington, Scropton, and Uttoxeter. Here, at Uttoxeter Junction, the passenger for Alton Towers will alight, and, entering another carriage, proceed on his way, passing the town of Uttoxeter on his left, and Doveridge Hall, the seat of Lord Waterpark, on his right, by way of Rocester (where the branch line for Ashbourne and Dove-Dale joins in), to the Alton Station. Arrived here, he will notice, a short distance to the left, high up on a wooded cliff, the unfinished Roman Catholic Hospital of St. John, and on the right, close to the station, the entrance lodge to the Towers.

From Manchester the visitor proceeds by way of Stockport and Macclesfield to the North Rode Junction, and so on by Leek and Oakamoor, &c., through the beautiful scenery of the Churnet valley, to Alton Station, as before.

From the Staffordshire Potteries the visitor, after leaving Stoke-upon-Trent, will pass through Longton, another of the pottery towns, Blythe Bridge, Cresswell, and Leigh, to Uttoxeter, whence he will proceed in the same manner as if travelling from Derby.

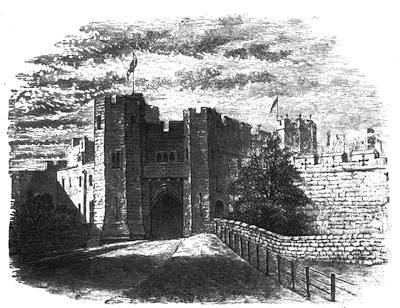

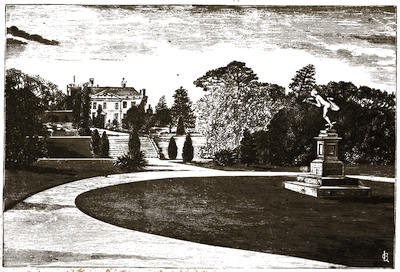

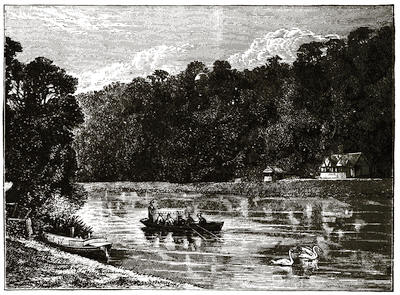

There are, besides others of less note, two principal entrances to the park and grounds of Alton Towers. One of these, the “Quicksall” Lodge, is on the Uttoxeter Road, about a quarter of a mile from Ellastone. By this the “Earl’s Drive” is entered, and it is, for length and beauty, the most charming of the roads to the house. The drive is about three miles in length from the lodge to the house, and passes through some truly charming scenery along the vale and on the heights of the Churnet valley—the river Churnet being visible at intervals through the first part of its route. Within about half a mile of the house, on the right, will be seen the conservatory, ornamented with statues, busts, and vases, and on the left a lake of water. A little farther on is the Gothic temple, close to the road-side. At this point Alton Towers and the intervening gardens burst upon the eye in all their magnificence and beauty. It is a peep into a terrestrial paradise. Proceeding onwards another quarter of a mile through a plantation of pines, the noble mansion stands before us in all the fulness of its splendour. The lake, the lawn, the arcade bridge, the embattled terrace, the towers, and the surrounding foliage come broadly and instantaneously upon the view—a splendid and imposing picture—a place to be gazed on and wondered at. By this drive the Towers are reached by way of the castellated stable-screen, and so on over the bridge and the entrance to the gardens.

The other, and usual, lodge, is close by the Alton Station on the Churnet Valley (North Staffordshire) Railway. This lodge, designed by Pugin, and decorated with the sculptured arms of the family, is about a mile from the house, and the carriage-drive up the wood is on the ascent all the way. A[27] path, called “the steps,” for foot passengers, turns off from the lodge, and winds and “zig-zags” its way up, arriving at the house opposite to the Clock Tower, and passing on its way some charming bits of rocky and wooded scenery.

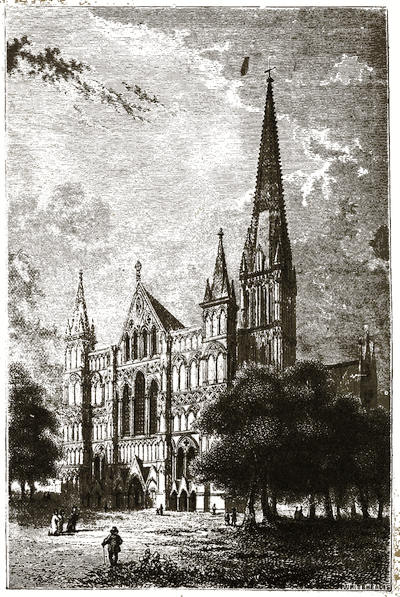

The Choragic Temple.

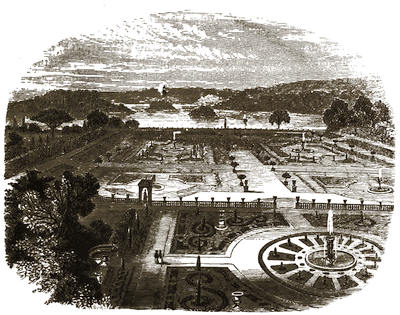

The gardens are entered from the park by a pair of gates (on either side of which is a superb cedar) in an archway, under the “Earl’s Drive” Bridge. Near this spot is the Choragic Temple, designed from the Choragic monument of Lysicrates, at Athens; it contains a bust of Earl Charles, the founder of the gardens, with the appropriate inscription—“He made the desert smile.” From here the visitor then proceeds along a winding path with an arcaded[28] wall on one side, and the valley, from which come up the music of the stream and the bubbling of the miniature fountains, on the other. This passes between myriads of standard roses on either side, and long continuous beds of “ribbon gardening,” or what, from its splendid array of continuous lines of colours, may very appropriately be termed “rainbow gardening,” and pathways winding about in every direction, among roses, hollyhocks, and shrubs and flowers of divers kinds, to a pleasant spot to the left, where is a terrace garden approached by steps with pedestals bearing choice sculptures. In the centre is a sundial; behind this, a fine group of sculpture, and behind this again a fountain, surmounted by a lion. The wall is covered with luxuriant ivy, and headed by innumerable vases of gay-coloured flowers, above which, a little to the back, rises one of the many conservatories that are scattered over this portion of the grounds.

Passing onwards, the visitor soon afterwards reaches the Grand Conservatories—a splendid pile of buildings on his left. These conservatories are three hundred feet in length, and consist of a central house for palm-trees, and other plants of a similar nature; two glass-roofed open corridors filled with hardy plants, and decorated with gigantic vases filled with flowers; and, at one end, a fine orangery, and at the other end a similar house filled with different choice plants and trees. In front of the Grand Conservatory the grounds are terraced to the bottom of the valley, and immediately opposite, on the distant heights, is the “Harper’s Cottage.” At the end of the broad terrace-walk, in front of the conservatory, is The Temple—a semi-open temple, or alcove, of circular form, fitted with seats and central table. From this charming spot, which the visitor will find too tempting to pass by without a rest, a magnificent view of the grounds is obtained. Immediately beneath are the terraces, with their parterres, ponds, arcades, and fountains, receding gently from the view till they are lost in the deep valley, beyond which rise the wooded heights, terrace on terrace, on the other side, and terminated with tall trees and the buildings of the tower. From the temple a broad pathway leads on to the Gothic Temple, and so to the modern Stonehenge—an imitation Druidical circle—and other interesting objects. Retracing his path, the visitor will do well to descend by the steps to a lower terrace, where he will find an open alcove beneath the temple. From here many paths diverge amid beds of the choicest flowers laid out with the most exquisite taste, and of every variety of form, and studded in all directions with vases and statuary.

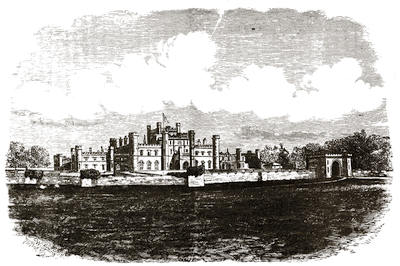

Alton Towers, from the Lower Terrace.

Descending a flight of steps beneath a canopy of ivy, a rosery, arched behind an open arcade of stone, is reached. This arcade is decorated with gigantic vases and pedestals, and from here, arcade after arcade, terrace after terrace, and flight of steps after flight of steps, lead down to the bottom of the valley, where the “lower lake,” filled with water-lilies and other aquatic plants, is found. In this lake stands the Pagoda, or Chinese Temple. Before reaching this, about halfway down the hill-side, will be seen the “upper lake,” a charming sheet of water, filled with water-lilies and other plants, and containing, among its other beauties, a number of fish and water-fowl. Over this lake is a prettily[30] designed foot-bridge forming a part of what is called “Jacob’s Ladder”—a sloping pathway with innumerable turnings, and twinings, and flights of steps. Arrived at the Pagoda Fountain, the visitor will choose between returning by the same route, or crossing or going round the lake, and pursuing his way up the opposite side, by winding and zig-zag pathways and small plateau, to the top of the heights.

The ornamental grounds are, as will have been gathered from this description, a deep valley or ravine, which, made lovely in the highest and wildest degree by nature, has been converted by man into a kind of earthly paradise. The house stands at one end or edge of this ravine, and commands a full view of the beauties with which it is studded. These garden grounds, although only some fifty or sixty acres in extent, are, by their very character, and by their innumerable winding pathways, and their diversified scenery, made to appear of at least twice that extent. Both sides of the ravine or gorge, are formed into a series of terraces, each of which is famed for some special charm of natural or artificial scenery it contains or commands; while temples, grottoes, fountains, rockeries, statues, vases, conservatories, refuges, alcoves, steps, and a thousand-and-one other beauties, seem to spring up everywhere and add their attractions to the general scene. Without wearying the visitor by taking him along these devious paths—which he will follow at will—a word or two on some of the main features of the gardens, besides those of which we have already spoken, will suffice. Some of these are:—

The Harper’s Cottage, in which the Welsh harper—a fine old remnant of the bardic race of his country, and an esteemed retainer of the family—resided, is near the summit of the heights opposite to the “Grand Conservatories.” It is in the Swiss style, and commands one of the most gorgeous views of the grounds and their surroundings. It was built from the designs of Mr. Fradgley, who was employed during no less than twenty-two years on works at Alton Towers.

The Corkscrew Fountain, standing in the midst of a pool filled with aquatic plants, is a column of unequal thickness of five tiers, each of which is fluted up its surface in a spiral direction, giving it a curious and pleasing effect.

The Gothic Temple, at the summit of the heights, on the opposite side from the “Harper’s Cottage,” and closely adjoining the “Earl’s Drive,” is a light and picturesque building of four stories in height, with a spiral staircase leading to the top. From it a magnificent view of the grounds, the towers, and the surrounding country, is obtained.

The Refuge is a pretty little retreat—a recessed alcove with inner room in fact—which the visitor, if weary with “sight-seeing,” or, for a time, satiated with beauty, will find pleasant for a rest.

The Gothic Temple.

The Pagoda Fountain is built in form of a Chinese pagoda. It is placed in the lower lake, and from its top rises a majestic jet of water which falls down into the lake and adds much to the beauty of the place.

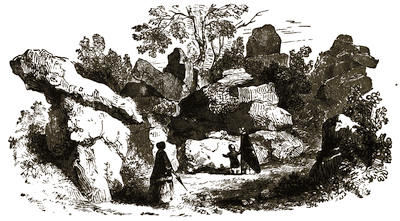

Stonehenge.—This is an imitation “Druidic Circle” formed of stones, of[32] about nine tons in weight each; it is highly picturesque, and forms a pleasing feature. Near to it is the upper lake.

The Flag Tower, near the house, is a prospect-tower of six stories in height. It is a massive square building with circular turrets at its angles. The view from the top is one of the most beautiful and extensive which the country can boast—embracing the house, gardens, grounds, and broad domains of Alton Towers; the village of Alton with its church and parsonage; the ruins of the old castle of the De Verduns; the new monastic buildings—the Hospital of St. John, the Institution, the Nunnery, and the Chapel; the valley of the Churnet; Toot Hill; and the distant country stretching out for miles around.

Ina’s Rock is one of the many interesting spots in the grounds. It is about three-quarters of a mile from the Towers, on what is called the “Rock Walk.” It is said that after a great battle fought near the spot (on a place still called the “battle-field”), between Ceolred and Ina, Kings of Mercia and Wessex, the latter chieftain held a parliament at this rock; whence it takes its names. We have thus guided the reader through the house and grounds of Alton Towers.

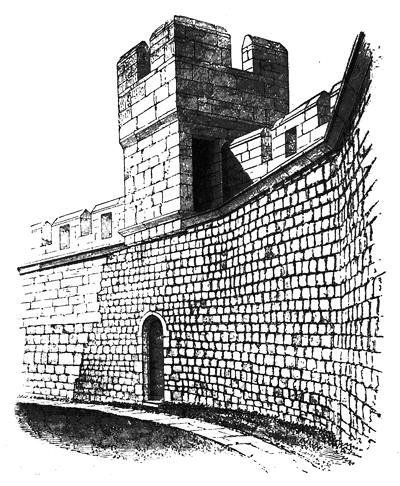

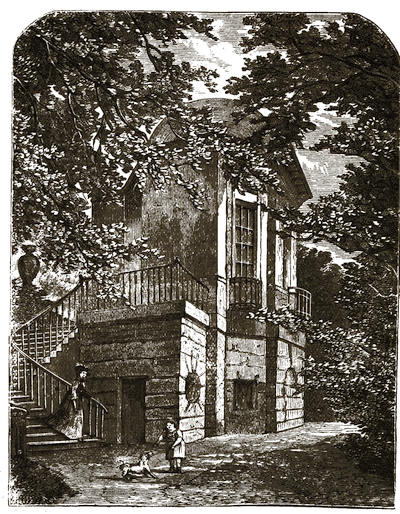

The district around Alton Towers is rich in interesting places, and in beautiful localities where the visitor may while away many an hour in enjoyment. The monastic buildings, on the site of old Alton Castle, are charmingly situated, and deserve a few words at our hands. These we quote from Mr. Jewitt’s “Alton Towers:”—“The monastic buildings, which form such a striking and picturesque object from the railway station, and indeed from many points in the surrounding neighbourhood, were erected from the designs, and under the immediate superintendence, of the late Mr. Pugin, and are, for stern simplicity and picturesque arrangement, perhaps the most successful of all his works. The buildings have never been—and probably never will be—completed, and they remain a sad instance of the mutability of human plans. Commenced at the suggestion, and carried out at the expense, of a Roman Catholic nobleman; planned and erected by a Roman Catholic architect; and intended as a permanent establishment for Roman Catholic priests, &c., &c., the buildings rose in great pride and beauty, and were continued with the utmost spirit, until the death of Earl Bertram, when, after the trials I have recounted, the estates passed into Protestant hands, the works were at once discontinued, and the buildings have since been allowed, with the exception of the chapel and the apartments devoted to the residence of a priest (and the[33] school), to become dilapidated. The castle grounds on which these buildings are erected are situated near the church, the buildings forming three sides of a quadrangle—one being the school and institution, and the others the cloisters, priest’s house, chapel, and other buildings. From this the moat is crossed by a wooden bridge to the ruins of the castle and the hospital of St. John. The buildings are beautifully shown on the engraving on the next page.

Part of the Grounds.

“The erection of these Roman Catholic buildings gave rise to much annoyance, and much ill-feeling was engendered in the neighbourhood; and a hoax[34] was played on Pugin, whose susceptibilities were strong and hasty. It was as follows: One day—of all days ‘April fool day’—he received the following letter:—

Alton—Hospital of St. John.

“‘Dear Sir—It is with deep sorrow that I venture to inform you of a circumstance which has just come to my knowledge; and, though an entire stranger, I take the liberty of addressing you, being aware of your zeal for the honour and welfare of the Catholic Church. What, then, will be your grief and indignation (if you have not already heard it) at being told that—fearing the bazaar, in behalf of the Monastery of St. Bernard, may prove unsuccessful—it has been thought that more people would be drawn to it were the monks to hold the stalls! Was there ever such a scandal given to our most holy religion? It may have been done ignorantly or innocently; but it is enough to make a Catholic of feeling shudder! I am not in a situation to have the slightest influence in putting an end to this most dreadful proceeding; but knowing you to be well acquainted with the head of the English Catholics—the good Earl of Shrewsbury—would you not write to him, and request him to use his influence (which must be great) in stopping the sacrilege, for such it really is? Think of your Holy Church thus degraded and made a by-word in the mouths of Protestants! I know how you love and venerate her. Aid her then now, and attempt to rescue her from this calamity! Pray excuse the freedom with which I have written, and believe me, dear sir, A Sincere[35] Lover of my Church, but an Enemy to the Protestant Principle of Bazaars.’

“Pugin wrote immediately to the earl in an impassioned strain, but, in reference to this trick, when the light had at length dawned upon him, in writing to Lord Shrewsbury, he says—‘I have found out at last that the alarm about the monks at the bazaar was all a hoax; and rumour mentions some ladies, not far distant from the Towers, as the authors. I must own it was capitally done, and put me into a perfect fever for some days. I only read the letter late in the day, and sent a person all the way to the General Post Office to save the post. I never gave the day of the month a moment’s consideration. I shall be better prepared for the next 1st of April.’

“The school, which was intended also as a literary institution, a hall, and a lecture-room for Alton, will be seen to the right on entering the grounds; the house, to the left, now occupied as a convent, being intended for a residence of the schoolmaster. In the original design the cloistered part of the establishment was intended to be the convent (the chapel being a nuns’ chapel), and the parish church of Alton was intended to be rebuilt in the same style as the splendid church at Cheadle. The hospital was to be for decayed priests. The chapel is a beautiful little building, highly decorated in character, and remarkably pure and good in proportions. In it, to the north of the altar, are buried Earl John and his Countess, and to the south Earl Bertram. The following are the inscriptions on the brasses to their memory:—

“‘Hic jacet corpus Johannis quondam Comitis Salopiæ XVI. qui hunc Sacellum et hospitium construere fecit A.D. MDCCCXLIV. Orate pro anima misserimi peccatoris obiit Neapoli die IX No MDCCCLII Ætatis suæ LXI.’

“‘In Memoriam Mariæ Teresiæ, Johannis Comitis Salopiæ Viduæ, Natæ Wexfordiæ XXII Maii MDCCXCV. Parissis obiit IV Junii MDCCCLVI quorum animas Viventium Amor Sanctissimus incor unum conflasse Videbatur corpora eodem sepulchro deposita misericordiam ejusdem redemptoris expectant. R.I.P.’

“‘Orate pro anima Bertrami Artheri Talbot XVII Com: Salop: ob: die: 10º August 1856. Requiescat in pace.’

“In the cloisters is another beautiful brass, on which is the following inscription:—

“‘Good Christian people of your charity pray for the soul of Mistress Anne Talbot wife of Willm Talbot Esquire of Castle Talbot Wexford who died on the V day of May A.D. MDCCCXLIV. Also for the soul of the above named Willm Talbot Esqre who died the IInd day of Augt MDCCCXLIX aged LXXXVI years. May they rest in peace.’

“On a slab on the floor:—

“‘Of your charity pray for the soul of Sister Mary Joseph Healy of the Order of Mercy. Who died 4th August 1857 in the 31st year of her age, and the 5th of her Religious Profession. R.I.P.’

“On a brass:—

“‘Orato pro anima Domini Caroli quondam Comitis Salopiæ qui obiit VI die Aprilis anno domini MDCCCXXVII Ætatis suæ LXIV.’”[3]

Alton Church is also worthy of a visit, not because of any special architectural features which it contains, but because of its commanding situation and its near proximity to the Castle. It is of Norman foundation. The village itself (visitors to the locality will be glad to learn that it contains a very comfortable inn, the “Wheatsheaf”) is large and very picturesque, and its immediate neighbourhood abounds in delightful walks and in glorious “bits” of scenery.

Demon’s Dale—a haunted place concerning which many strange stories are current—is also about a mile from Alton, and is highly picturesque.