THE JACK OF ALL TRADES

OR

NEW IDEAS FOR AMERICAN BOYS

Books by Daniel C. Beard

THE JACK OF ALL TRADES; or, New Ideas for American Boys. Profusely Illustrated by the Author. Square 8vo. $2.00.

THE OUTDOOR HANDY BOOK, for Playground, Field and Forest. With 300 Illustrations by the Author. New Edition. Square 8vo. $2.00.

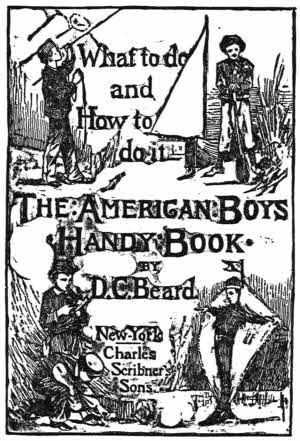

THE AMERICAN BOY’S HANDY BOOK; or, What to Do and How to Do It. With more than 300 Illustrations by the Author. Square 8vo. $2.00.

By the Misses Beard

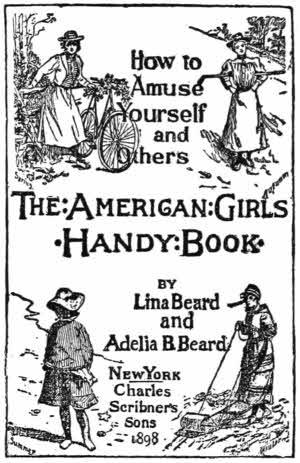

THE AMERICAN GIRL’S HANDY BOOK; or, How to Amuse Yourself and Others. With more than 300 Illustrations. New and Enlarged Edition. Square 8vo. $2.00.

BY

D. C. Beard

New York

Charles Scribner’s Sons.

1900

Copyright, 1900, by

CHARLES SCRIBNER’S SONS

It was not the author’s original intention to produce a series of boys’ books. On the contrary, he expected that his work in this line would begin and end with “The American Boy’s Handy Book.”

The great popularity of that book is a constant source of gratification and pleasure to the author; but he was not a little surprised and embarrassed when he discovered that in place of satisfying the lads he had only whetted their appetite for more material in the same line. Letters from boys in many parts of the British Provinces, and from all over the United States, convinced the writer that he had yet work to do for them, and the revised and enlarged edition of “The American Boy’s Handy Book” was issued. After a brief period of time the quaintly worded letters in boyish handwriting began again to increase the mail left at the author’s studio, and this time he laid aside his brush and pencil to produce “The Outdoor Handy Book.”

It is hoped that the present demand for new ideas for boys will be fully satisfied by “The Jack of All Trades.” To the best of the author’s knowledge and belief there is not a thing described in this book which has not been proved practical by the experiments of himself or some boy[vi] or boys. Parts of this book have appeared in various periodicals, but all these chapters have been revised and enlarged.

It is now a generally accepted truth that the so-called skill of the hand is in reality the skill of a trained mind. The necessity, in work or play, of constantly overcoming new obstacles and solving new problems, develops a strong and normal mind and body. There can be little doubt that the rude schooling and hard knocks of a pioneer’s life rejuvenated our race and developed those qualities in the characters of Americans, without which Washington would have been but a country gentleman and Lincoln a village store-keeper. Had little Abe Lincoln been reared under the care of a foreign woman with cap and ribbons (i.e. a French nurse), his strong manly character would never have been developed and our country would have lost one of its grandest patriots and history its most unique figure.

Aside from these vitally important facts, art demands that our youth should be encouraged to do things for themselves, to produce things by their own labor. The most finished product of the machine cannot appeal to the heart of a real artist as does some useful and homely object which still bears the marks of its maker’s hands.

For these reasons the author hopes that parents will allow their boys to be boyish boys; and in order to keep them out of mischief they will cater to the lads’ natural and healthy desire for entertainment by encouraging them in all rational projects and supplying them with tools and[vii] materials, so that the boys may all become juvenile Jacks of All Trades.

It is the object of the author, in the chapters devoted to animal life, to teach the boys to look upon all animals with the same thoughtful kindness with which they might view their own undeveloped brothers.

To Harper & Brothers, and to The Ladies’ Home Journal the thanks of the author are due for the careful preservation and return of such original drawings as were used by them in their respective publications, and without which this work would be incomplete.

D. C. B.

Flushing, June 1, 1900.

| PART I. | |

| FAIR WEATHER IDEAS. | |

| CHAPTER I. | |

| PAGE | |

| Tree-Top Club Houses | 3 |

| The River Rats, 5; A Tree-top Retreat, 6; The Secret Grape-vine Route, 7; A Club-house in the Tree-tops, 8; A Two-tree House, 9; How to Build the Foundation, 14; The One-tree House, 16; A Three- and Four-tree Foundation, 18. | |

| CHAPTER II. | |

| Hunting Without a Gun | 19 |

| How to Capture and Trap Small Live Animals, 19; Rodents or Gnawers, 21; A Smudge, 22; Flying Squirrels, 23; White-footed Mice, 25; Short-tailed Meadow-rats, 26; Jumping Mice, 27; Woodchucks, 27; A Box Trap, 30; Musk-rats, 31. | |

| CHAPTER III. | |

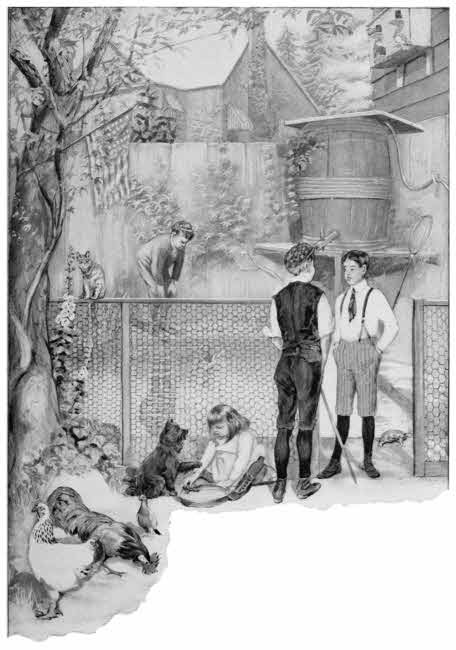

| The Back-yard Zoo | 33 |

| [x]The Study of Living Animals, 33; Size of Lot, 35; Galvanized Iron Wire Cloth or Netting, 36; The Mesh, 36; To Make a Cage of Galvanized Wire Netting, 39; The Door, 40; The Doors for the Runway, 40; Toads, 43; Frogs, 44; Peepers, 44; The Tree-frog, 45; The Anderson Frog, 45; Lizards, 45. | |

| CHAPTER IV. | |

| A Back-yard Fish-pond | 48 |

| How to Make a Fish-pond, 48; By Sinking a Wooden Tank in the Ground, 49; Best Form for Such a Tank, 49; To Prevent Wood from Decay, 50; When to Stock, 52; Fresh-water Clams, 53. | |

| CHAPTER V. | |

| Pigeon Lofts and Bantam Coops | 54 |

| A Pigeon Loft and Bantam Coop, 55; Lumber, 56; Pigeon-loft Floor, 56; Shutter Frames, 56; Roofing Material, 57; Doors, 58; The Shutters, 59; Cleanliness, 59; The Hen’s Nest, 59; The Pigeon’s Nest, 60; For a Hen Roost, 60; Drinking Troughs, 61; Flying Cage, 62. | |

| CHAPTER VI. | |

| How to Make a Back-yard Aviary | 63 |

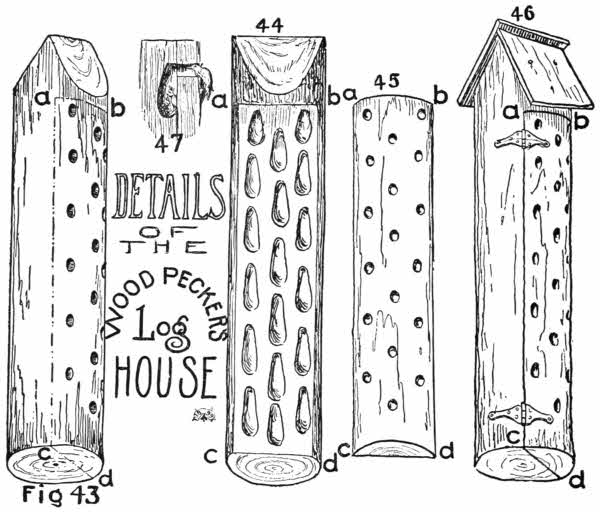

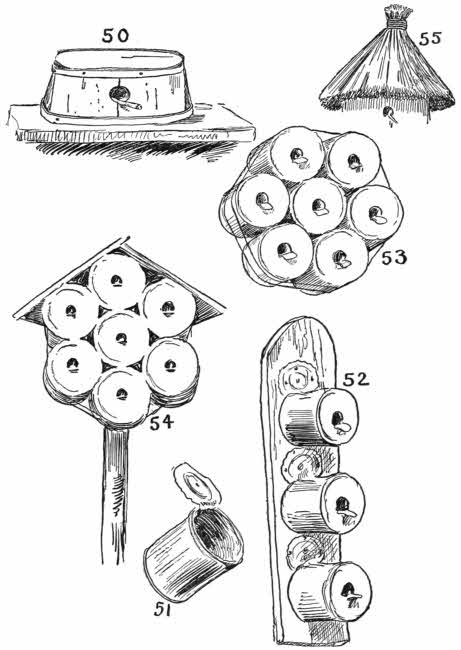

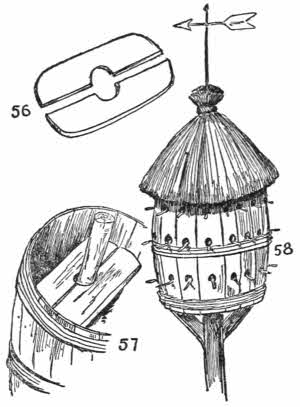

| Birds’ Nests in Washington’s Coat, 63; Nests in Speaking Horn, 63; A Woodpecker’s House, 64; Martin Houses, 66; The Wren House, 66; Tin-can Bird-house, 68; A House of Straw, 68; A Barrel for a Martin House, 68. | |

| CHAPTER VII. | |

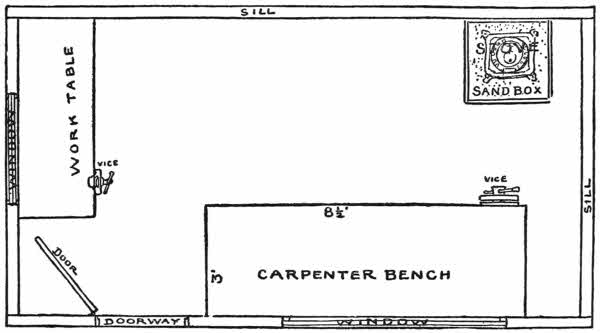

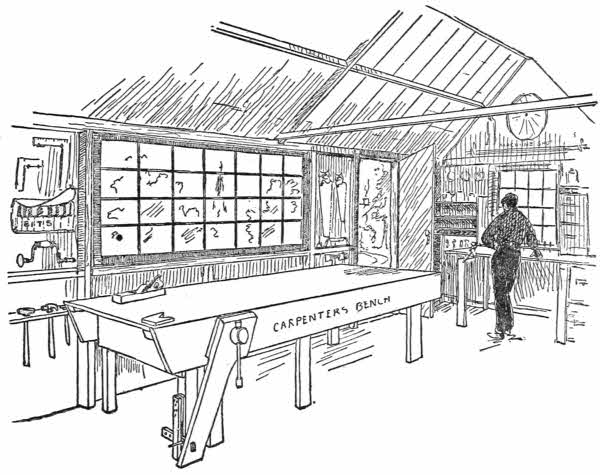

| A Boy’s Back-yard Workshop | 72 |

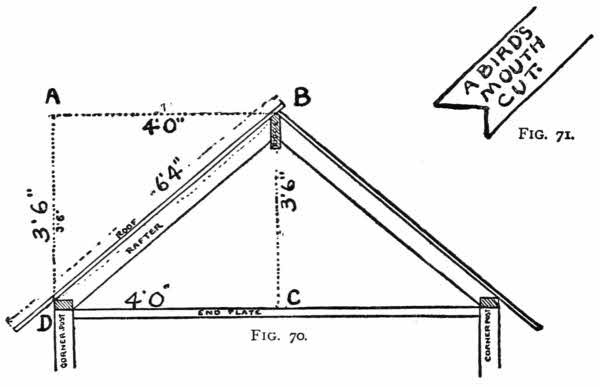

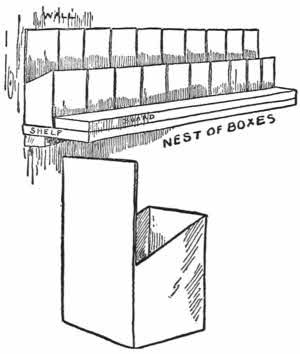

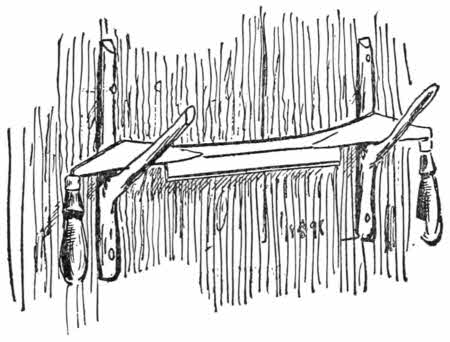

| How to Make Buildings Plumb and Level, 72; Tools, 73; A Level, 74; A Foundation, 76; How to Build the House, 77; Corner Posts, 81; The Window, 82; Side Plate, 82; The Rafters, 84; Machine-Shop, 85; Tool Rack, 86. | |

| CHAPTER VIII. | |

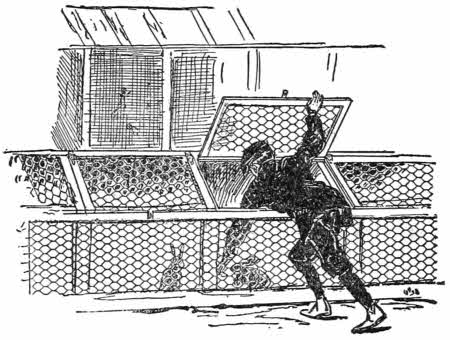

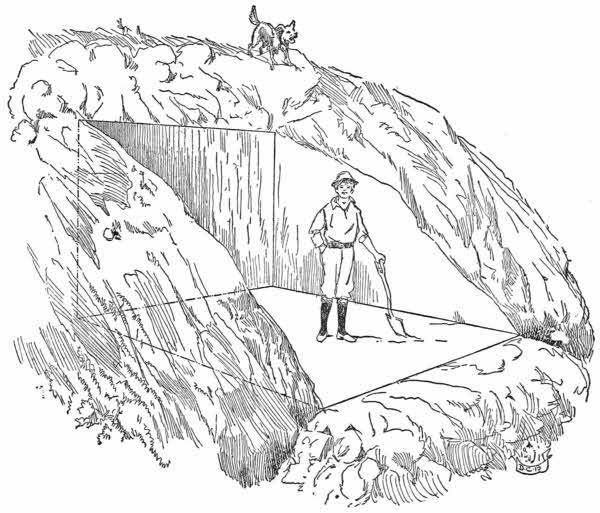

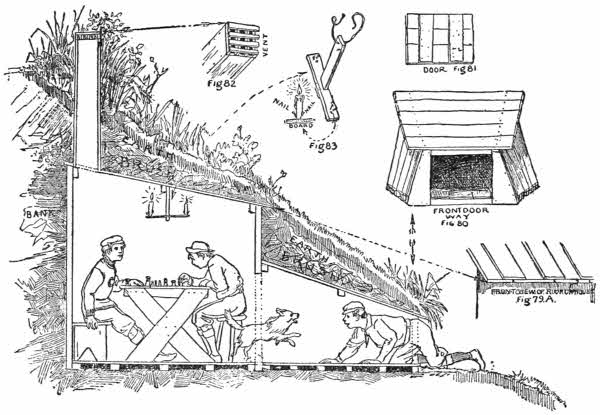

| How to Build an Underground Club-house | 89 |

| [xi]A Doorway at the Top, 89; The Trap-door, 90; Dimensions of House, 90; New Lumber, 92; Framing, 92; Passageway, 93; Windows, 94; The Roof, 94; A Ventilator, 95; Dangerous Caves, 96. | |

| CHAPTER IX. | |

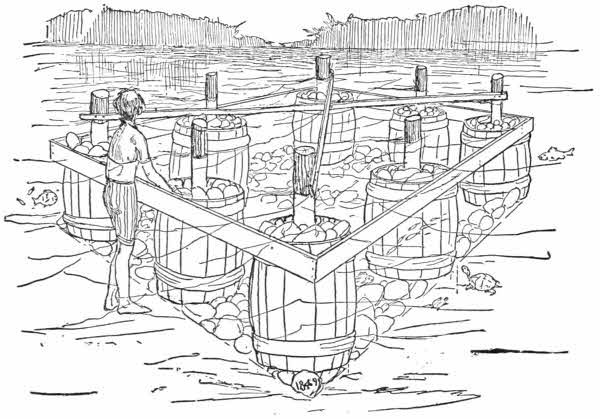

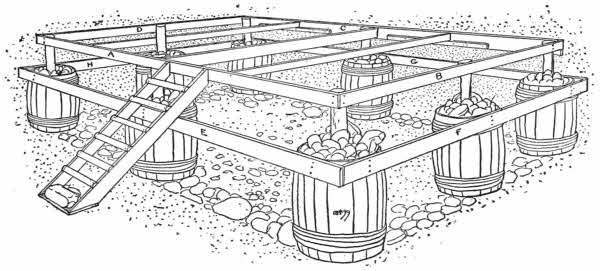

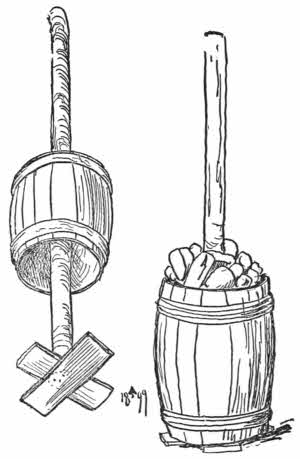

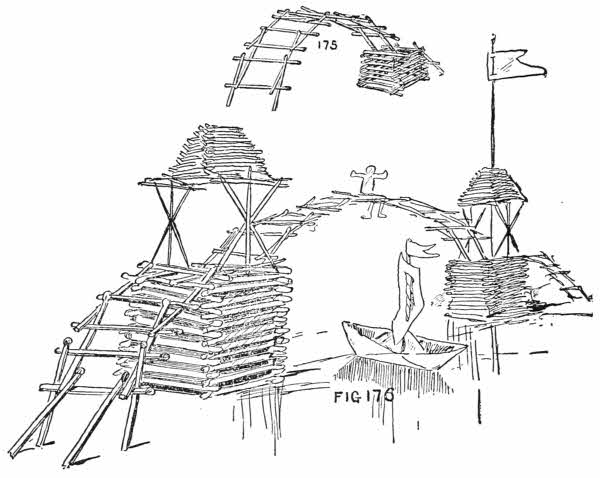

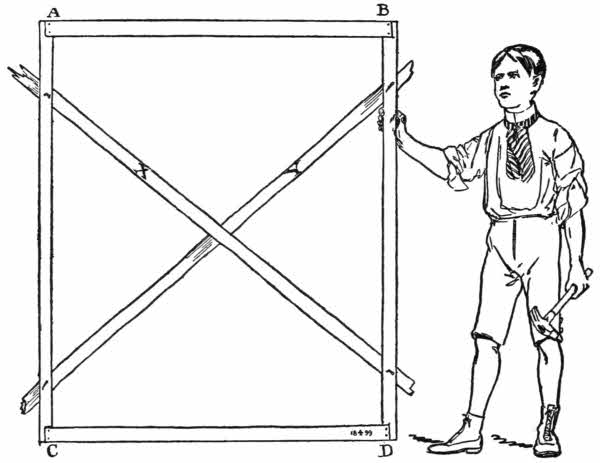

| A Boys’ Club-house on the Water | 97 |

| Crusoe Clubs, 97; Foundation of Club-house, 97; The Building Material, 98; The Foundation Posts, 100; The Bottom of the Pond, 101; Temporary Diagonal Braces, 103; An Artificial Island, 104. | |

| CHAPTER X. | |

| How to Have Fun on a Picnic | 105 |

| Joggling Board, 105; Turnpike Loo, 106; Dinner Box, 106; Rhode Island Clam Bake, 107; Pennsylvania Pond Stew, 107; Burgoo, 107; How to Cook a Burgoo, 108; A Game of Jack Fagots, 110; Old Dan Tucker, 110; Pitch-peg-pin Pitching, 112; Lawn Hab-enihan, 114. | |

| CHAPTER XI. | |

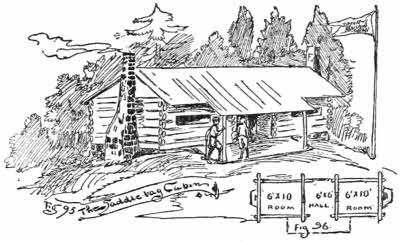

| How to Build and How to Furnish a Daniel Boone Cabin | 116 |

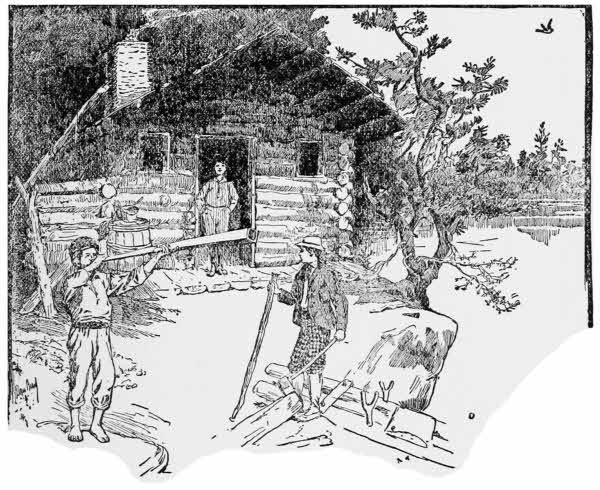

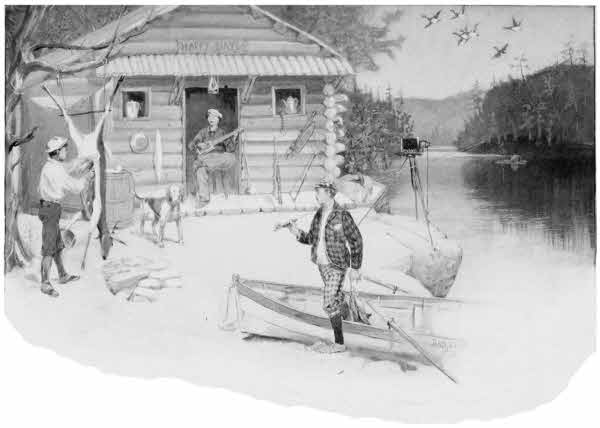

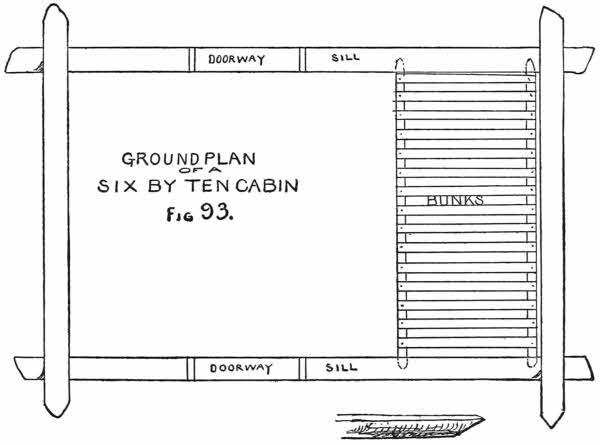

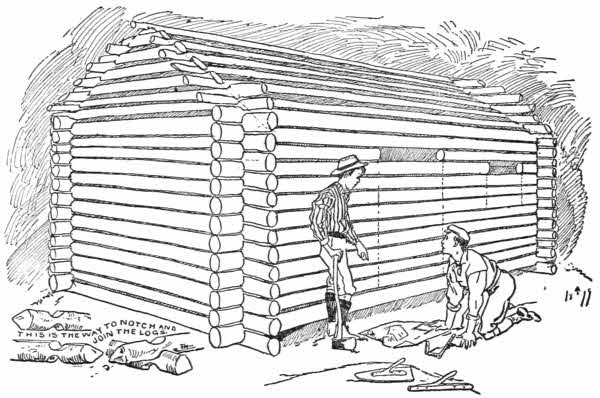

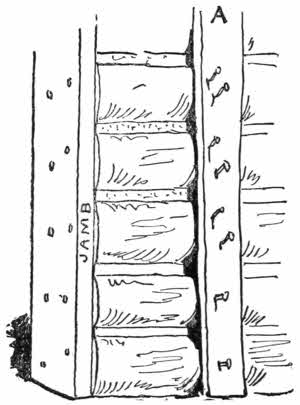

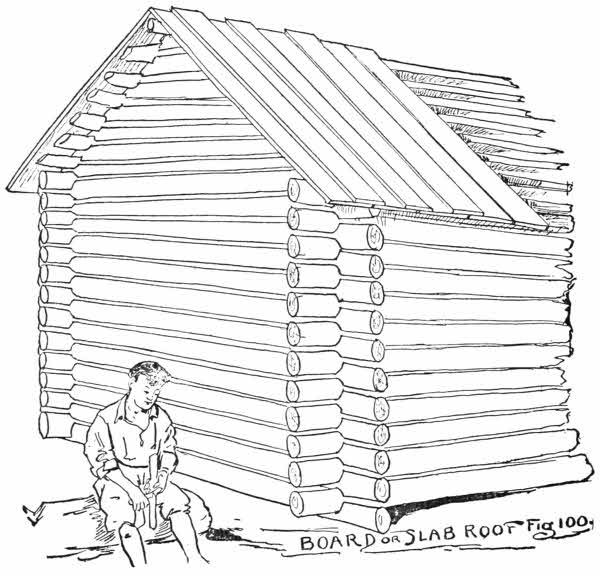

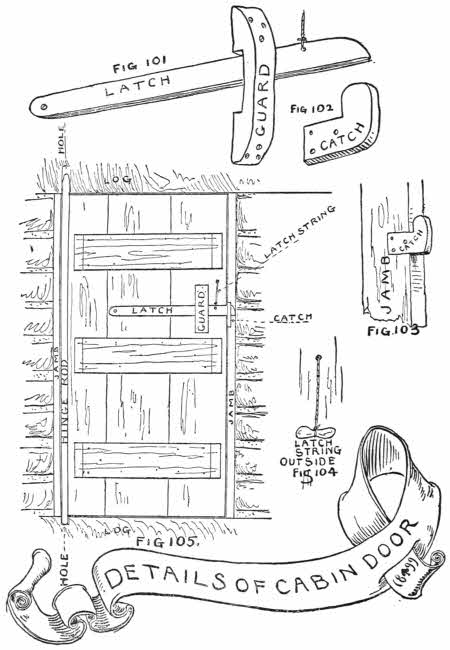

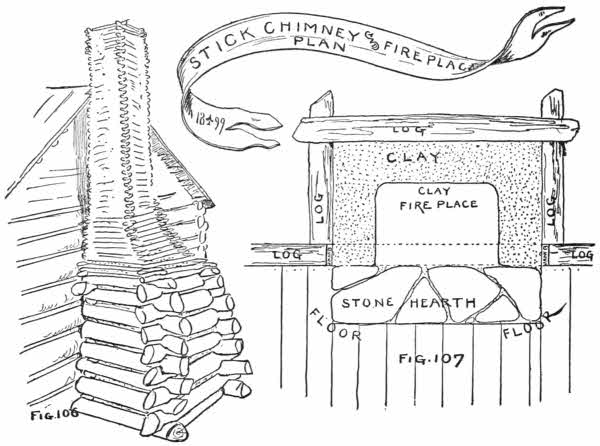

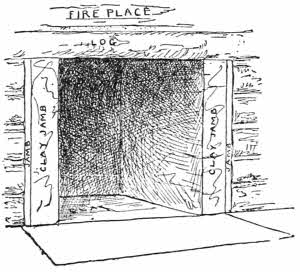

| The Ghosts of the Fireplace, 116; The Log House, 118; Suitable Timber, 118; The “Skid,” 118; The Foundation, 120; Floor Joists, 120; Floor Supports, 120; Log Rolling, 121; Door and Window Openings, 121; The Fireplace, 122; The Roof, 123; The Bunks, 123; A Lincoln Bed, 124; The Door, 125; The Lamp, 127; The Chimney, 130; A Table, 131; General Camp Notes for Old Boys, 132; How the Women Should Dress, 133; The Requirements for a Camp, 133; Making the Shack, 135; The Brush Covered Lean-to, 136; Tents with Roofed Verandas, 136; What is needed for Table and Larder, 137. | |

| CHAPTER XII. | |

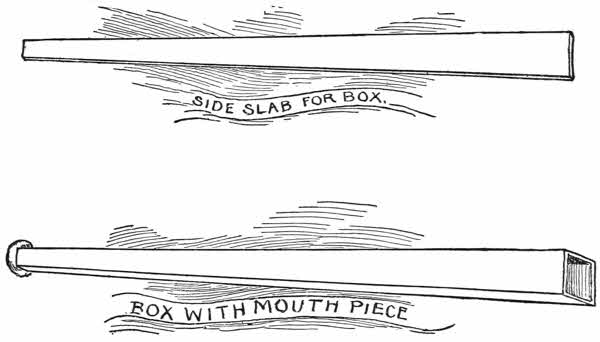

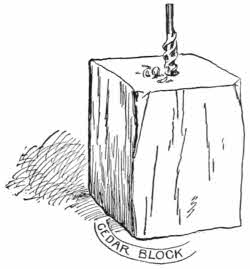

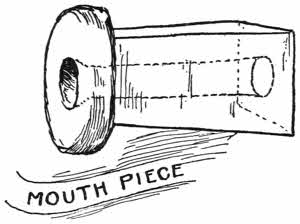

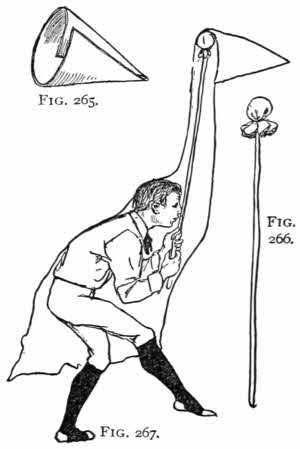

| Flat-boatman’s Horn | 137 |

| [xii]Whittling, 137; Wooden Bugles, 141; The Old Wooden Horn of Captain Bob Collins, 142; The Wabash Horn, 143; How to Make a Wabash Horn, 144; The Mouth-piece, 144. | |

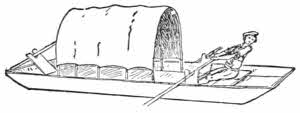

| CHAPTER XIII. | |

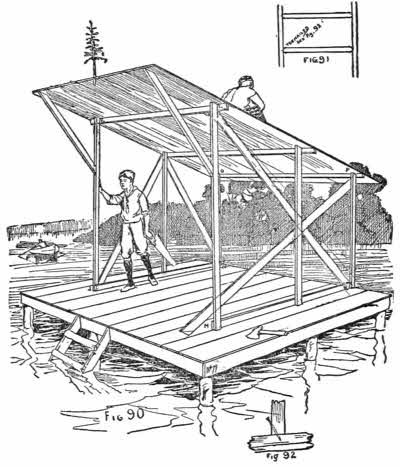

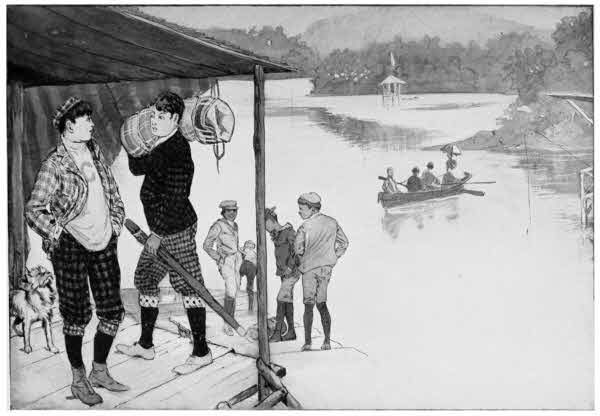

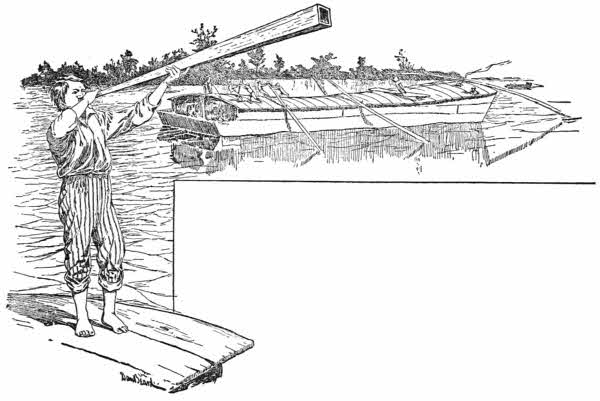

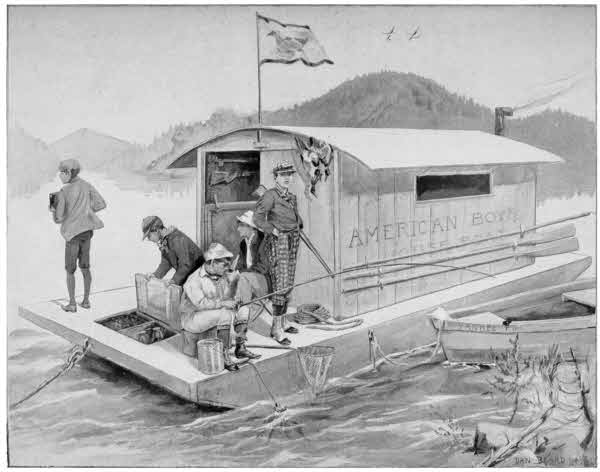

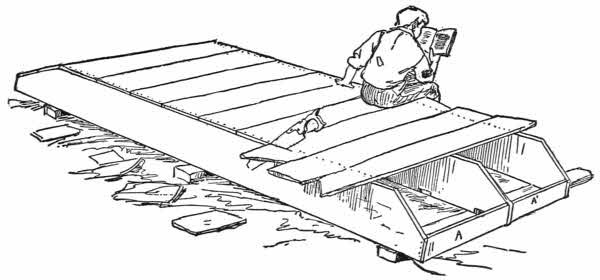

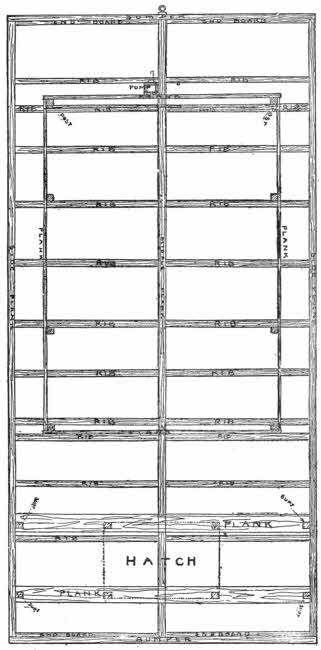

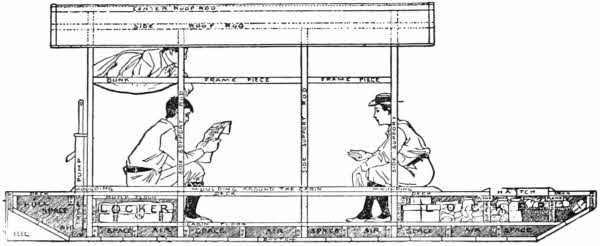

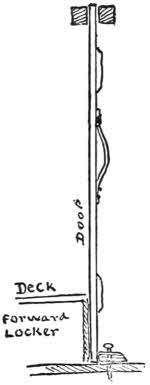

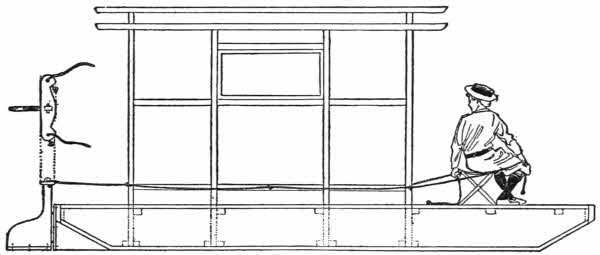

| The American Boy’s House-boat | 146 |

| Building Material, 150; The Centre-piece, 151; The Sides, 151; The Bottom, 154; The Cabin, 157; Deck-ribs, 157; The Keel, 159; Flooring, 159; The Hatch, 160; Upper Deck, 160; The Rafters, 160; The Rudder, 163; Rowlocks, 163; Ash Poles, 164; The Locker, 164; Canvas-cabined House-boat, 166; The Cost of House-boats, 167; For People of Limited Means, 168. | |

| CHAPTER XIV. | |

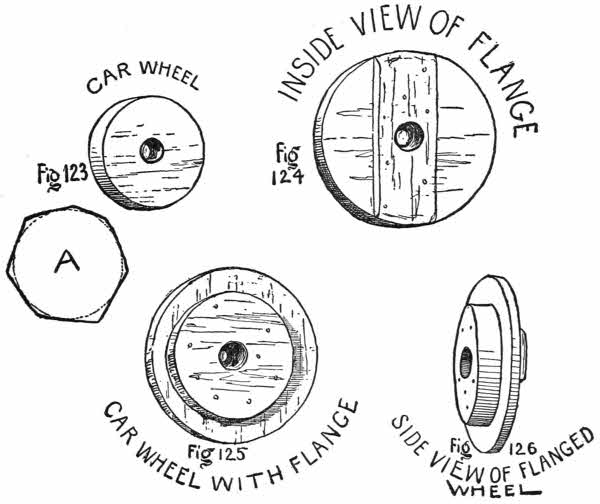

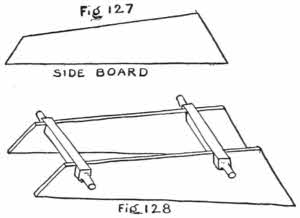

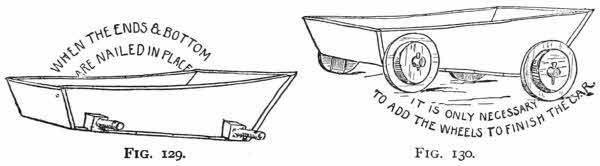

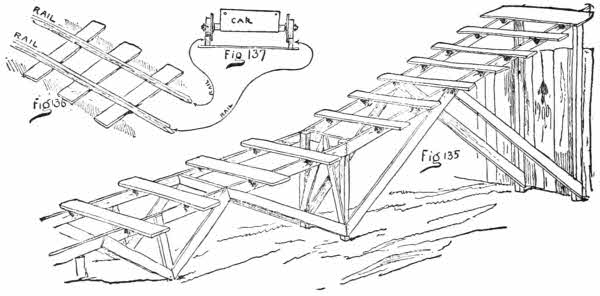

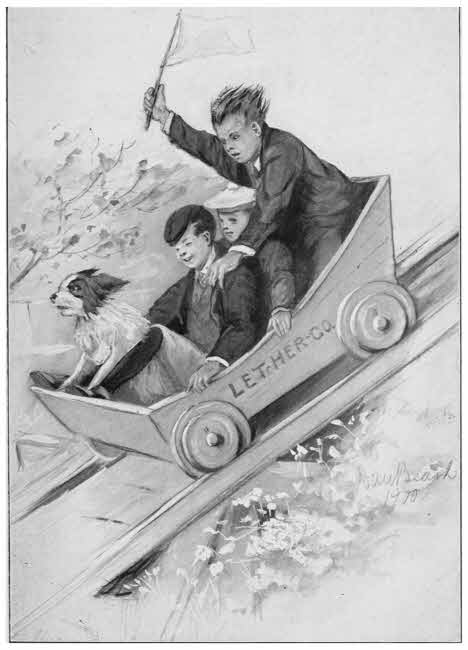

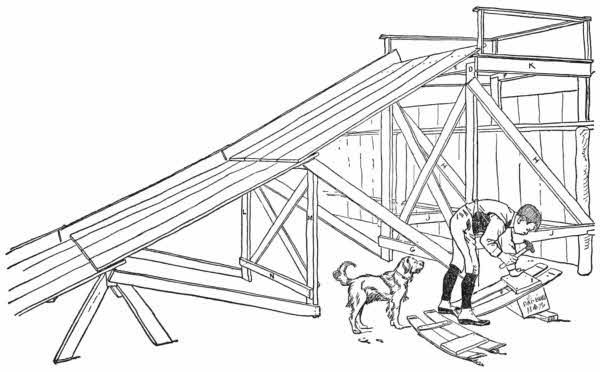

| A Back-yard Switchback | 170 |

| The Wheels, 170; The Flange, 171; The Axles, 172; The Bottom of the Car, 172; Starting Platform, 173; The Track, 178; A Curved Track, 178; Cross-ties or Sleepers, 179; Ticket-chopper’s Box, 180. | |

| CHAPTER XV. | |

| How to Build a Toboggan-slide in the Back-yard | 182 |

| Slipperies, 182; A War-time Slippery, 182; Tropical Toboggan-slide, 184; A Frame, 185; A Toboggan Room, 186; Packing the Slide or Chute, 186. | |

| PART II. | |

| RAINY DAY IDEAS. | |

| CHAPTER XVI. | |

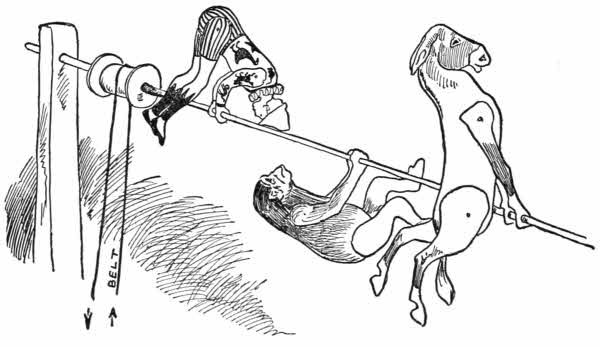

| A Home-made Circus | 191 |

| The Bath-tub as a Receiving-tank, 191; A Water-wheel, 192; The Shaft, 192; Paddles, 193; Hanging-bars, 194; Figures which Move, 198. | |

| CHAPTER XVII. | |

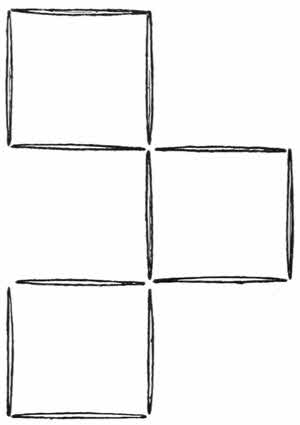

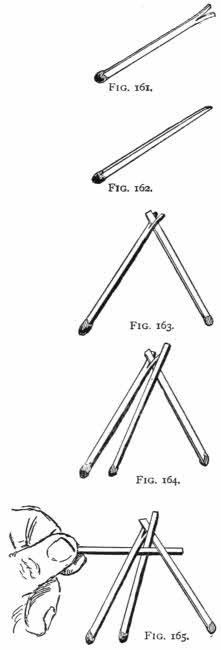

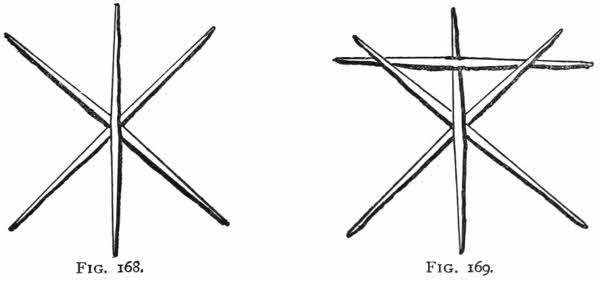

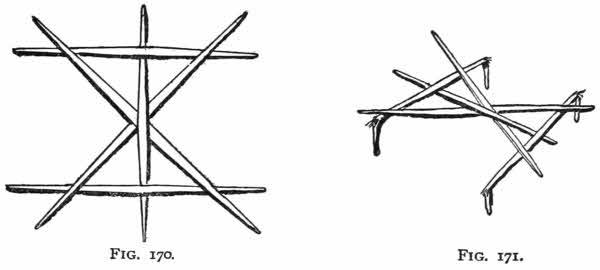

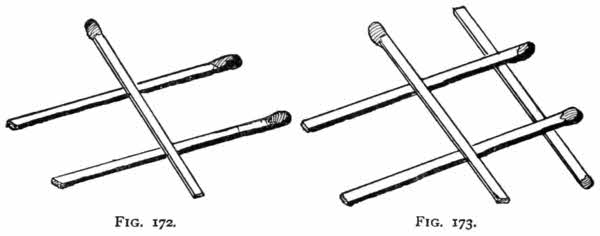

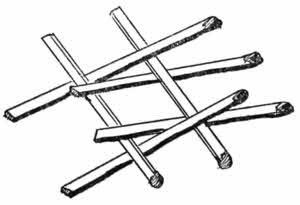

| Good Games with Toothpicks and Matches | 201 |

| [xiii]A Simple Toothpick Example, 203; To Lift Three Safety-matches with One Toothpick, 203; A Spring-bed, 204; Artificial Water, 206; A Bridge of Matches, 206; The Piers, 207; The Approaches, 207; The Roof, 207; A Pioneer Settlement, 208; The Chimneys, 208. | |

| CHAPTER XVIII. | |

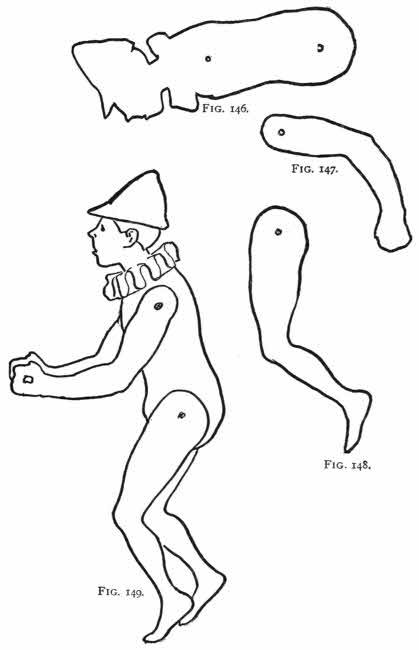

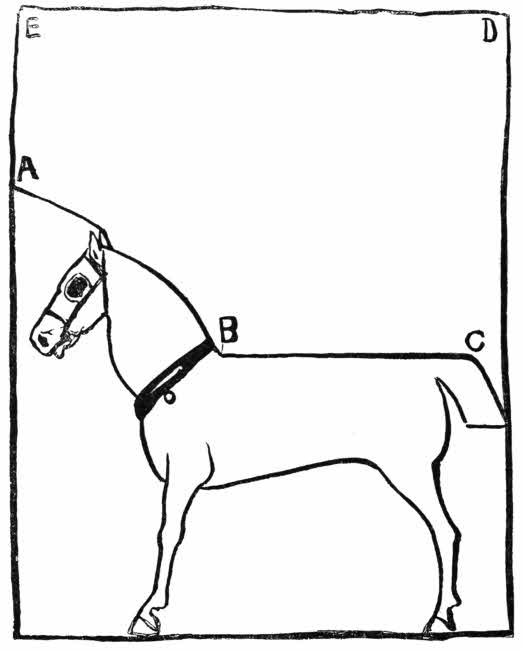

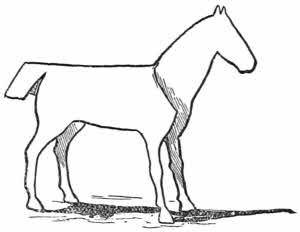

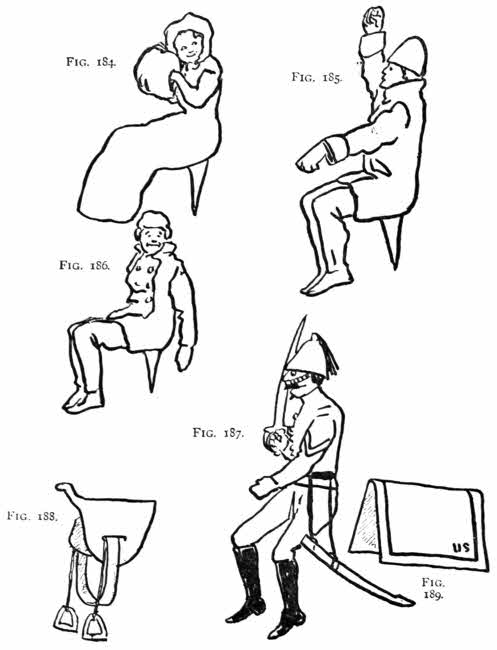

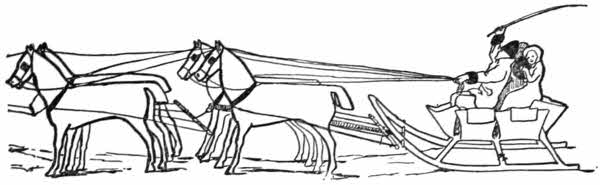

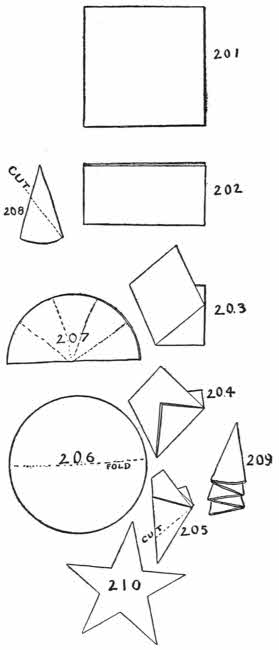

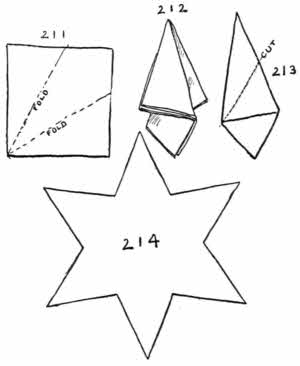

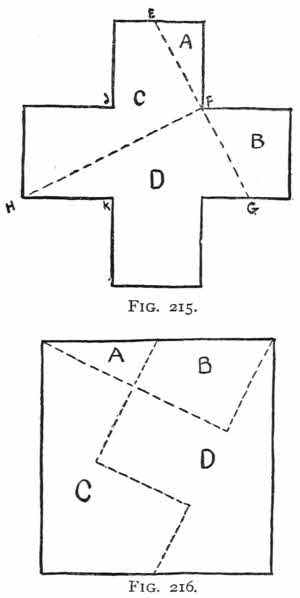

| Fun with Scissors and Pasteboard and Paper | 210 |

| How to Make the Sleigh, 211; How to Make the Horses, 212; To Cut out the Horse, 213; The Pole, 213; The Driver’s Whip, 215; Pasteboard Soldiers, 215; Stirrups, 216; How to Make the Soldiers, 216; To Make an Army, 217; Grandmother’s Reticule, 218; To Cut a Five-pointed Star with One Clip of the Scissors, 220; To Make a Cross Into a Square with Two Cuts, 221. | |

| CHAPTER XIX. | |

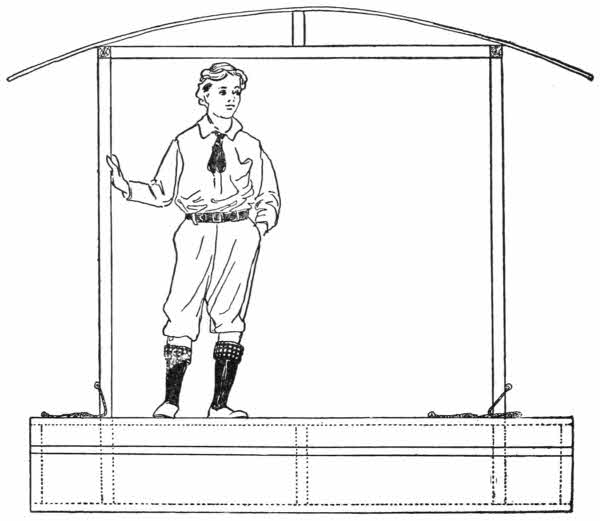

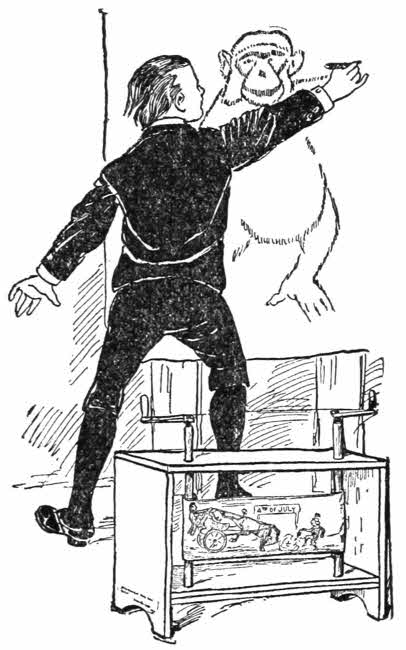

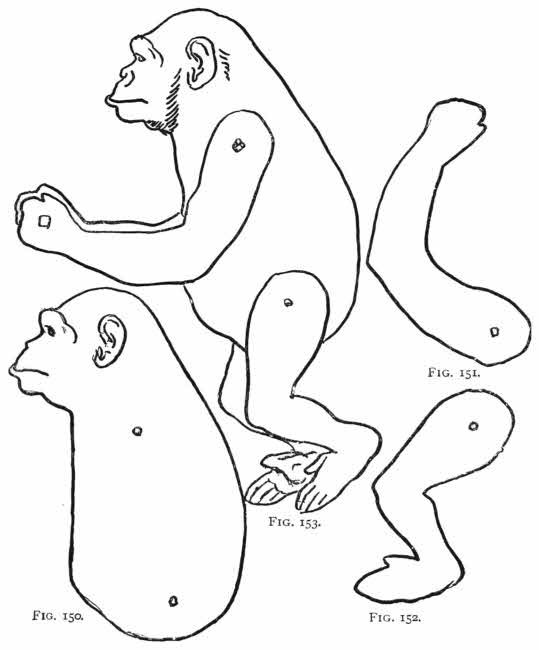

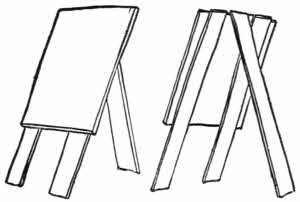

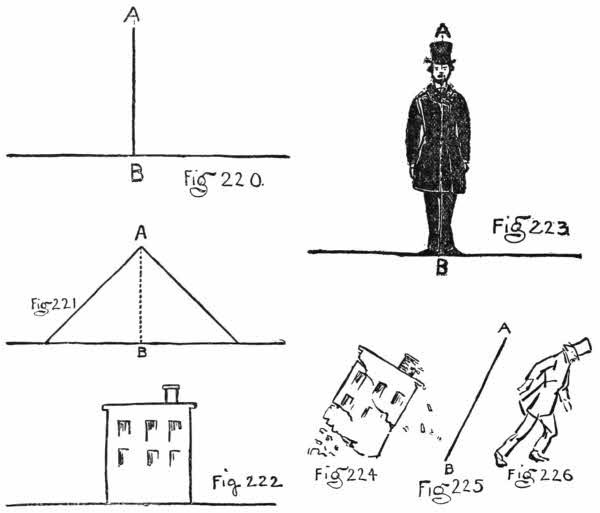

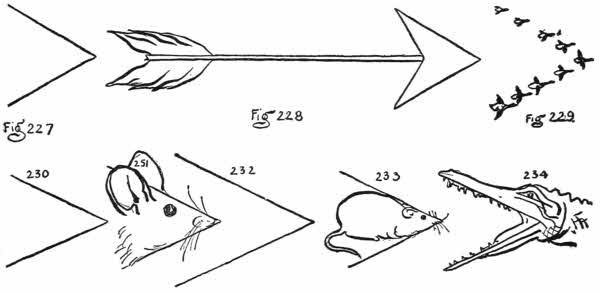

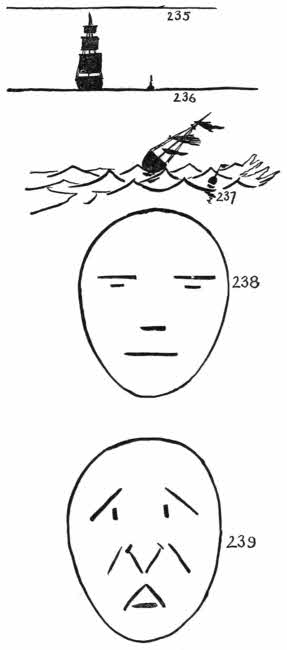

| How to Prepare and Give a Boys’ Chalk-talk | 222 |

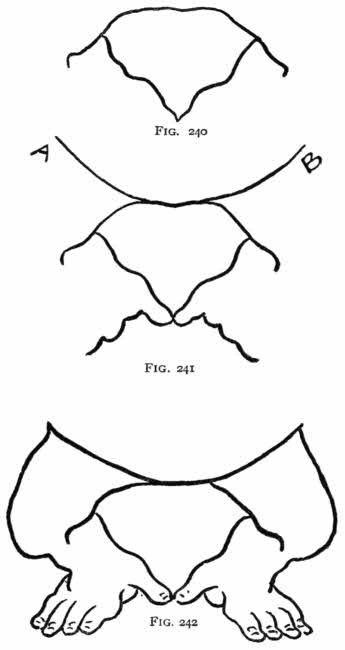

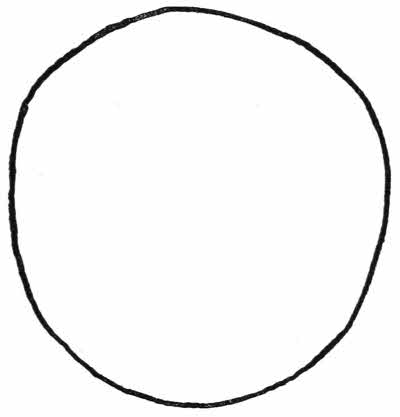

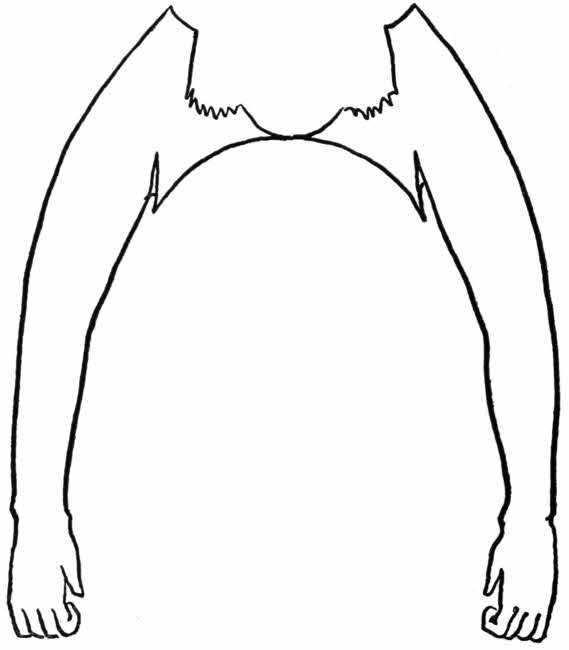

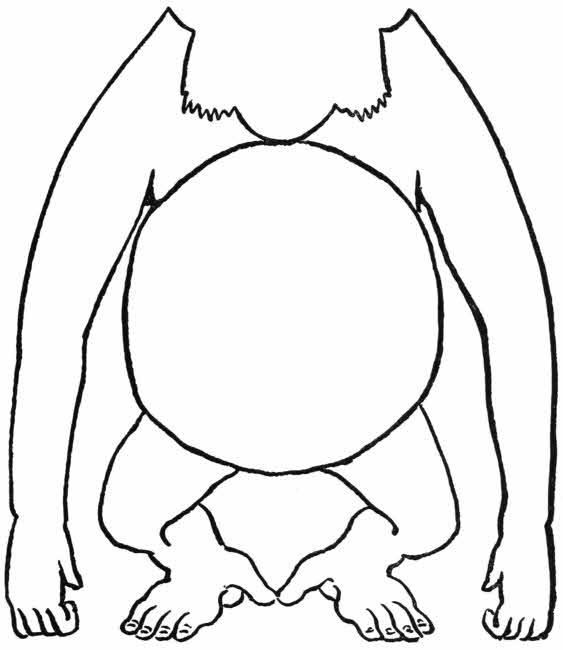

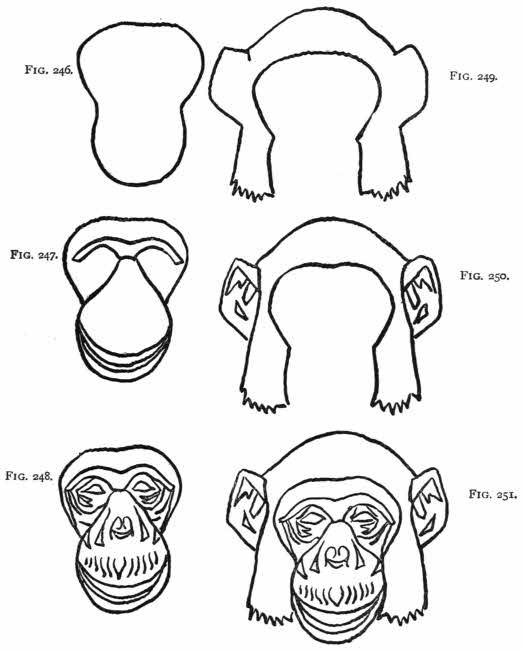

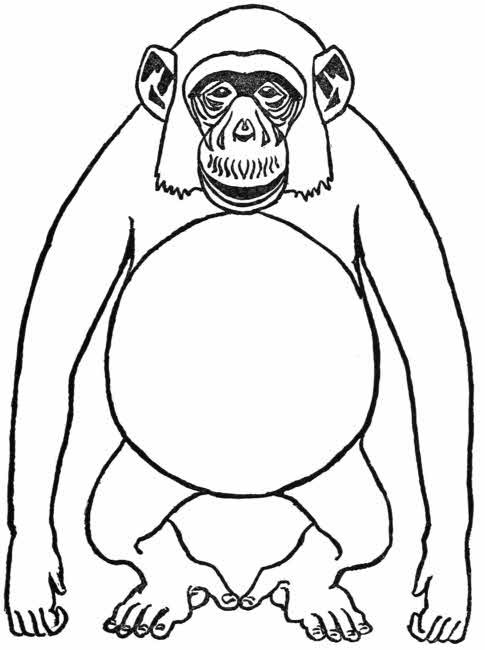

| The Name Chalk-talk, 224; Drawing-board, 225; Size of Board, 226; Height of Easel, 226; The Drawings Themselves, 227; How to Begin, 227; A Stationary Object, 229; Motion, 230; Evolution of the Ape, 234. | |

| CHAPTER XX. | |

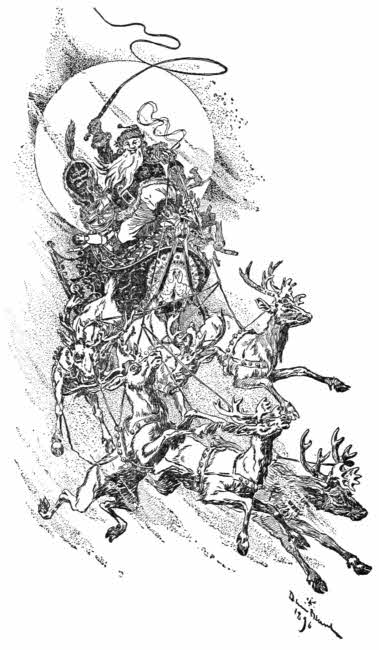

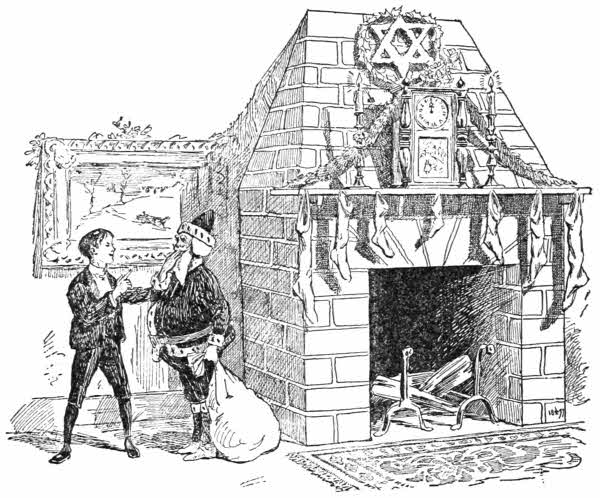

| A Christmas Novelty for Boys | 237 |

| How to Build and Decorate a Fireplace for Santa Claus, 237; The First Start, 237; Back of the Chimney, 238; The Front Frame, 240; The Covering, 243; To Line the Inside of the Fireplace, 243; Our American St. Nicholas, 243; Costume for Santa Claus, 245; How to Put on the Clothes, 246. | |

| CHAPTER XXI. | |

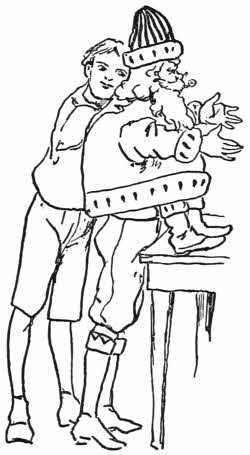

| How to Make Two Boys into One Santa Claus | 248 |

| How the Legs are Made, 249; The Wig and Beard, 249; The Curtains, 249; The Sleigh, 250; The Signal for Legs, 251; The Distribution of the Presents, 251. | |

| CHAPTER XXII. | |

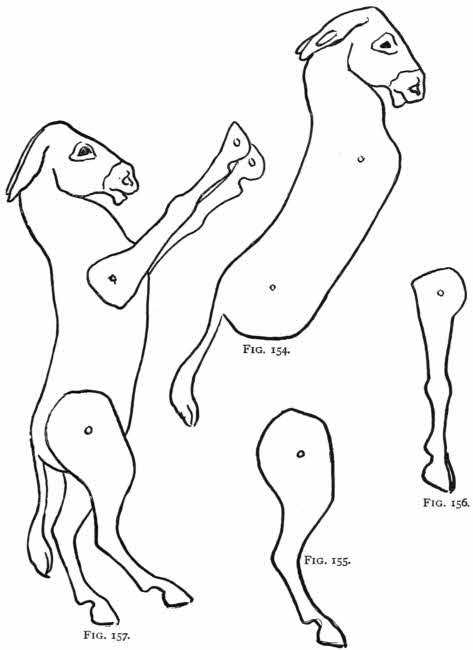

| A Circus in the Attic | 253 |

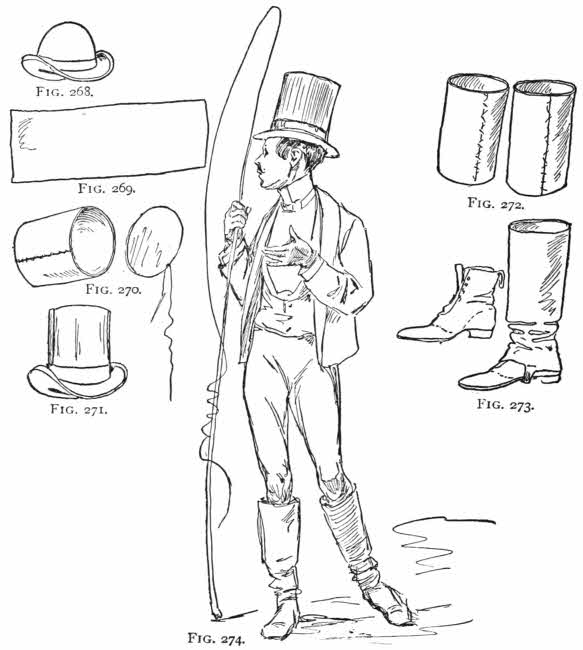

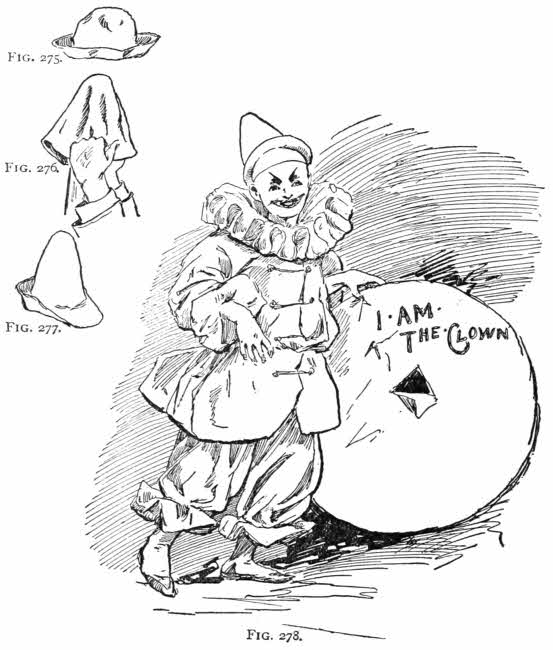

| [xiv]How to Make the Horses and Other Animals, and How to Make the Costumes, 253; The Goat, 253; The Arab Steed, 254; The Neck-bones, 255; The Ribs, 255; The Frame, 256; The Reins, 256; To Make the Giant Bird of New Zealand, 257; The Manicora, 257; The Ring-master and his Costume, 259; Making Up, 262. | |

| CHAPTER XXIII. | |

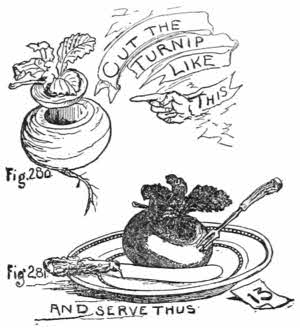

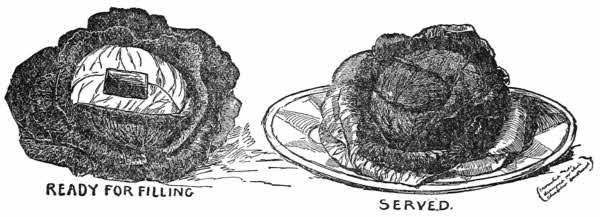

| A Boys’ Stag-party | 263 |

| Target Shooting, 263; To Make the Target, 263; Carpet Tacks as Darts for the Blow-gun, 264; Vegetable Bonbon Boxes, 265; A “Fake” Cake, 266; The Shooting, 267; The Spread, 268; The Explosion of the “Fake” Cake, 268. | |

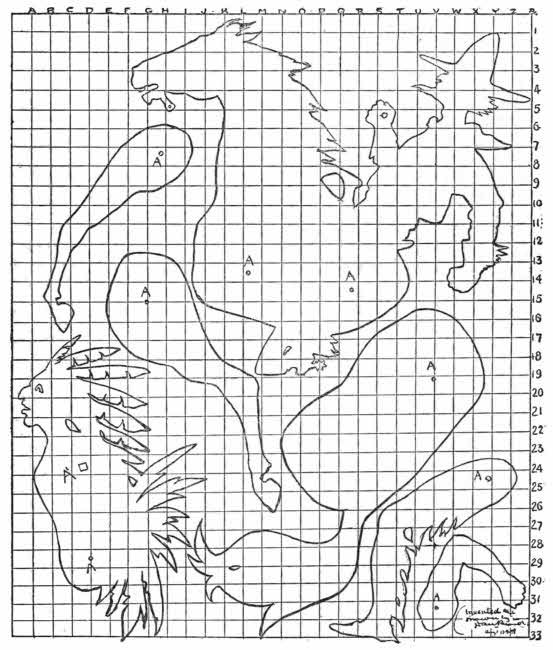

| CHAPTER XXIV. | |

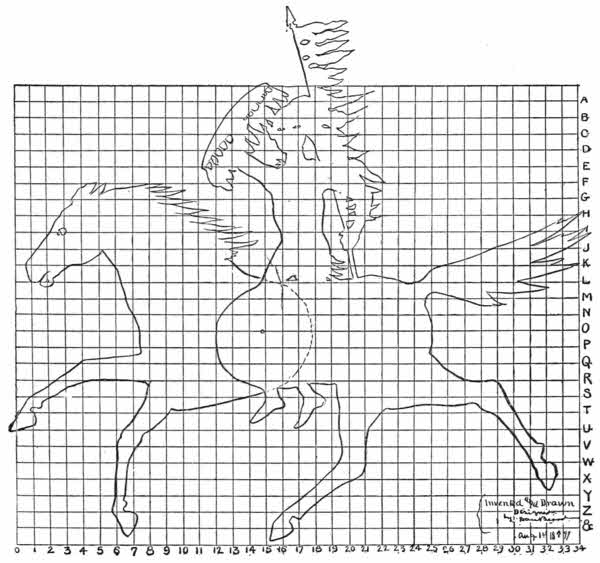

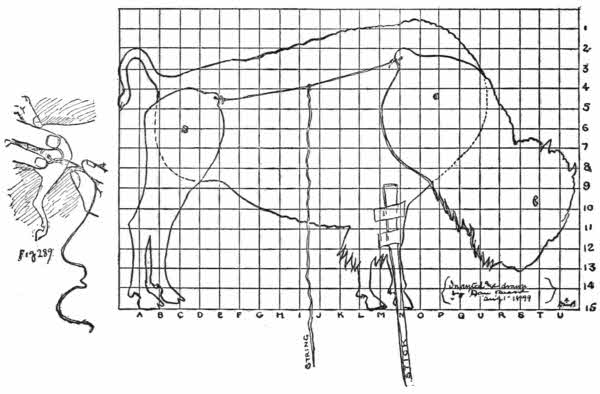

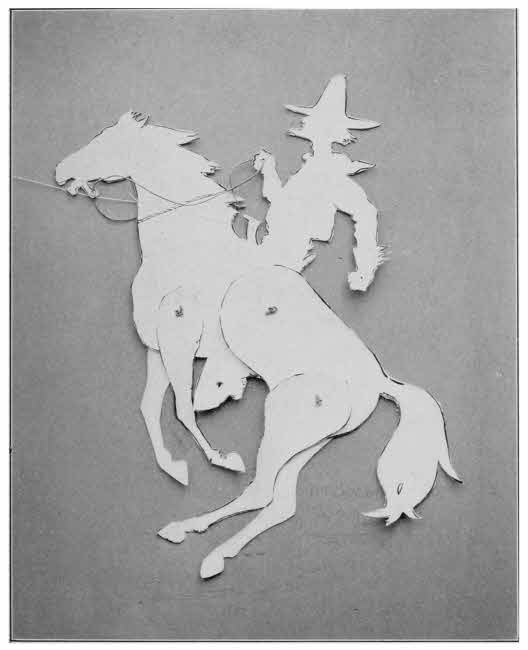

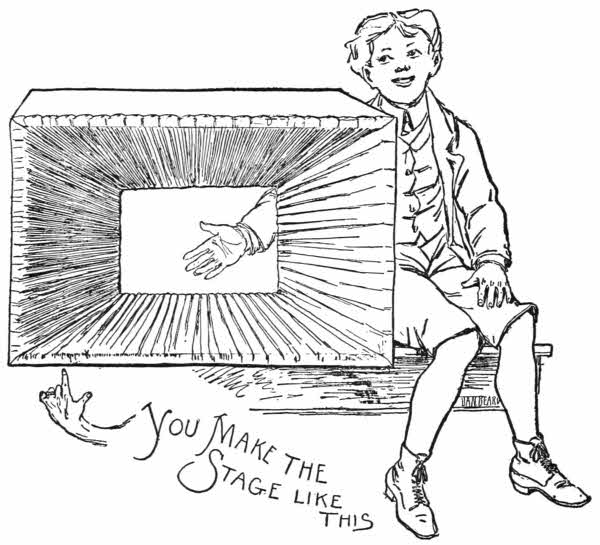

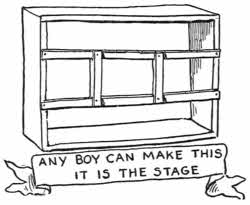

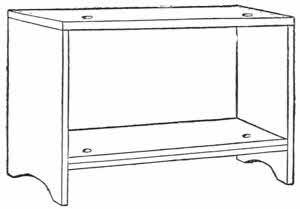

| A Wild West Show in the House | 270 |

| How to Reproduce the Patterns, 270; Making the Cowboy, Horse, and Indian, 273; For a Bridle, 274; The Indian Horseman, 275; The Buffalo, 276; The Stage, 277. | |

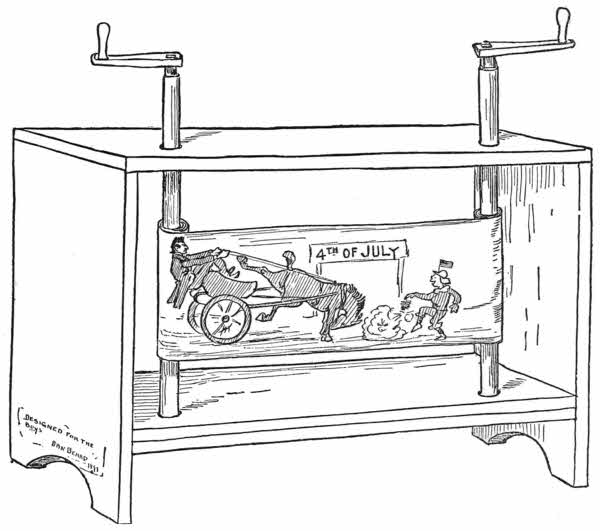

| CHAPTER XXV. | |

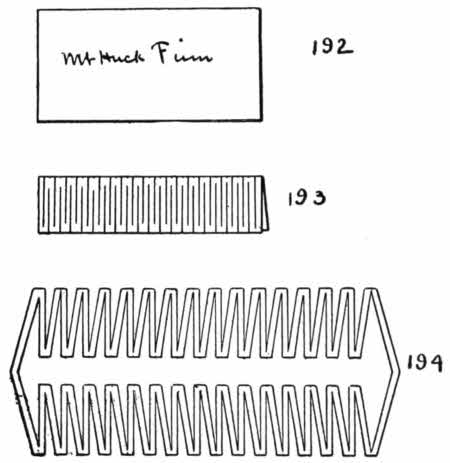

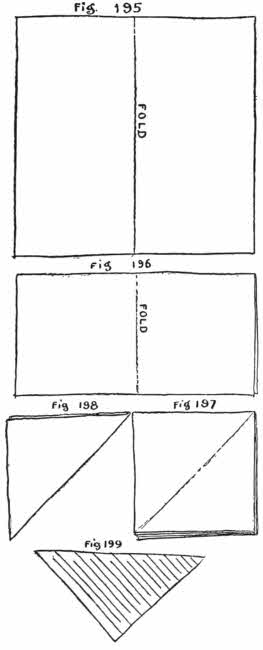

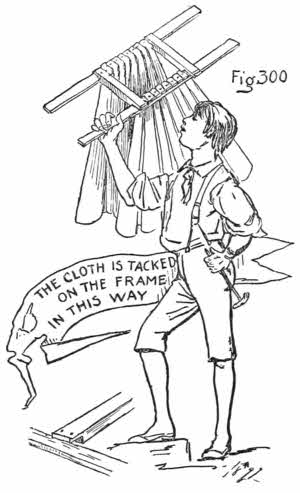

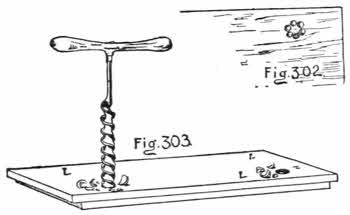

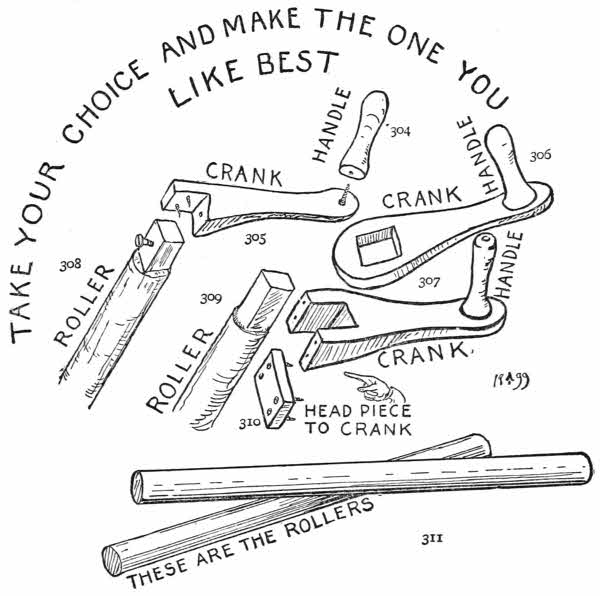

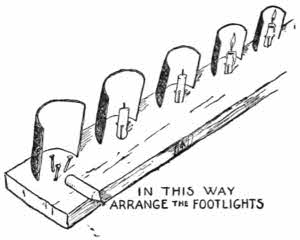

| How to Have a Panorama Show | 278 |

| Choice of Subject, 278; Hunting Suitable Pictures, 279; Colored Figures, 280; The Works of the Panorama, 281; The Stage, 282; Footlights, 282; How the Panorama Box is Built, 283; The Rollers, 284; Show-bills, 286; The Lecture, 287. | |

| Index | 289 |

PART I.

FAIR WEATHER IDEAS.

The Jack of All Trades.

It is now over thirty years since the writer was first initiated into the delights of a boys’ club-house in the tree-tops, and it happened in this way:

The war of the Rebellion was over; for four years the fathers, big brothers, teachers, and policemen of the border States had had so much serious fighting on their own hands that little or no attention was paid to the growing generation of boys, and they were left to fight their own battles in their own way.

For four eventful years these boys were under practically no other restraint than the little their poor half-distracted mothers could enforce. The boys, however, did not appear to miss the discipline, nor desire it, and, as far as their physical health was concerned, they throve and developed into lusty lads, though many of them recognized no law but that of physical force.

Gangs of young toughs, under the leadership of local bullies, frequented the play-grounds and roamed along the river-fronts, where they hunted down, pillaged, and beat every unprotected lad they could catch out of sight of his own home.

In spite of the fact that the river-fronts were the favorite resorts of the lawless element, those places presented so many attractions to the juvenile mind that they were the popular play-grounds of all the boys living within reach of their muddy banks and turbid waters.

About this time three boys of a Kentucky town, who were devoted to boating and bathing, put their curly heads together to devise a plan by which they might enjoy their favorite pastimes, and at the same time secure a safe place of refuge where they could hide when the enemy approached in numbers too strong for the three boys to resist.

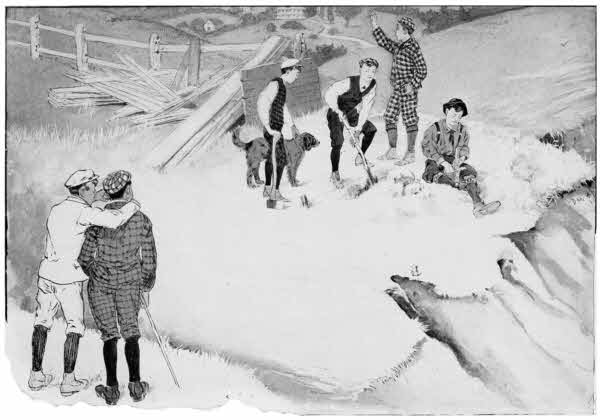

After many conferences, and references to “Robinson Crusoe,” “Swiss Family Robinson,” “The Coral Islands,” and other undoubted authorities, they decided to build an underground house,[1] and armed with spades and shovels, they immediately began work right in the heart of the enemy’s country.

They worked, as only boys can when they think their work is fun, and soon excavated a great hole in the river-bank. Not far off were the remains of a flat-boat, and to the heavy pieces of timber the boys harnessed themselves and hauled the lumber over the top of their cave to serve for a roof.

With spade and shovel they carefully concealed the timber by a thick layer of earth, leaving only a square hole with a trap-door as an entrance and exit. The dirt was then smoothed down, and drift-wood, dried weeds, and other rubbish scattered over in such a manner that no one, without careful inspection, would suspect that the bank had been tampered with.

But the enemy was alert, and spies had been stealthily[5] watching the work progress, and patiently waiting the completion of the secret hiding-place. No sooner was the last handful of rubbish strewn over the roof than, with wild yells and whoops of delight, the “River Rats” charged upon the surprised workers.

“Big Red” Resmere in the lead, with “Squinty” Quinn and “Spotty,” the freckled-face, close behind, while the rear was brought up with a rabble of less noted characters, who more than made up for their own lack of courage by their terror-inspiring yells. It was too formidable a crowd for the three cave-diggers to parley with, so they ingloriously fled up the bank, leaving the product of their hard work in the hands of the despoilers.

used the cave as headquarters, and for a long time afterward would suddenly sally forth from the concealment of the hole and surprise and beat any strange lad who was incautious enough to venture in the neighborhood unprotected by a company of friends. This adventure taught us several things, and one night, at the “dark of the moon,” we met in a smoke-house and formed ourselves into a secret society. Over a bottle of strained honey we made solemn vows, and the secrets of the society have never been divulged until now.

The name, the purpose, and the fact of there being any society were the three great secrets. The name was “The Three Ancient Mariners.” The object was to stand by each other to the crack of doom, and the seal, 3·A·M, was tattooed on each member’s good right arm.

The vows were religiously kept, and many a bruised face and discolored eye proved our loyalty to each other, for the River Rats made constant war upon us, and our[6] peaceful plans for fun were often rudely upset by the sudden appearance of a bright red head, followed by a freckled face and a gang of retainers.

This persecution caused the production of

which, I believe, has never yet been discovered by the enemy, nor any one else.[2] To reach our secret camp and club-house we had to trudge along the dusty turnpike in the hot sun, with no shade but that afforded by our wide-brimmed straw hats. After passing an old-fashioned inn, with its swinging sign decorated with a picture of the battle of Buena Vista, we cut cross-lots over the forts and rifle-pits on the hill-side, built by the Union soldiers at the time of the Morgan raid. At the end of the lowest rifle-pit we slid down the cut to the railroad track, and followed it to the fence, with a hollow gate-post, where the bluebirds always built their nests. Here we left the railway and entered a cool belt of woods in which the dainty maidenhair-ferns grew on the damp rotten logs and the gray squirrels scolded us from the branches overhead. Following a private trail, we reached an immense beech-tree which had grown around a shaggy-barked hickory in such a manner that only the roots and branches of the hickory could be seen, the whole trunk being embedded and concealed by the smooth bark of the beech, giving it the novel appearance of a tree bearing two entirely different kinds of nuts.

Under the spreading branches of this compound tree we generally rested awhile and took a look about us, to be certain that the River Rats were not on our trail; then[7] diving into the hazel thicket, we emerged on the banks of a tributary to the Licking River. A giant tulip-tree stood on the bank of the creek, and a wild grape-vine, as thick as your arm, dangled from the branches, which spread like an umbrella sixty or seventy feet above us. The vine had been cut loose from its roots on the shore, and its severed end hung over a deep, dark pool.

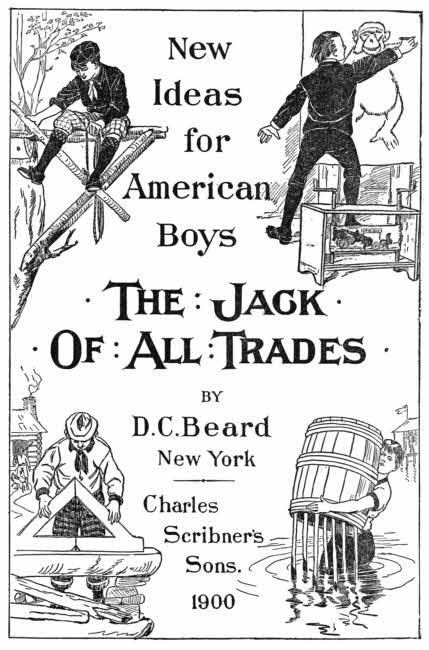

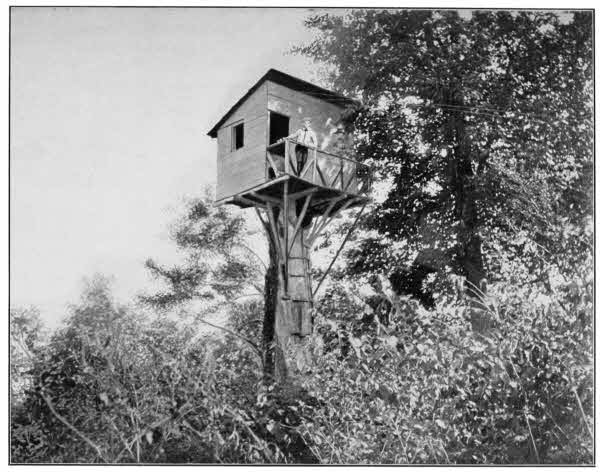

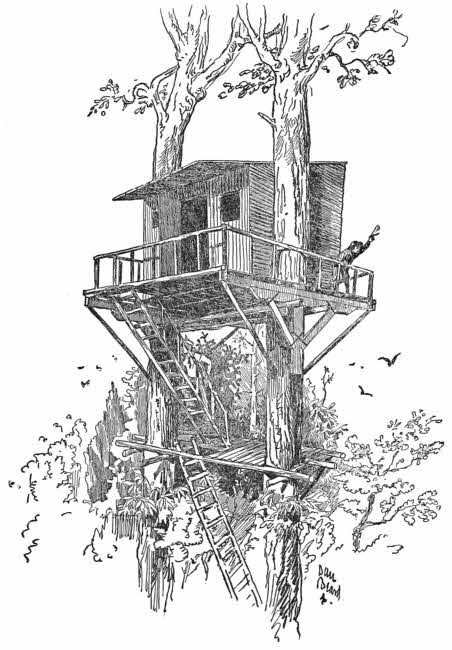

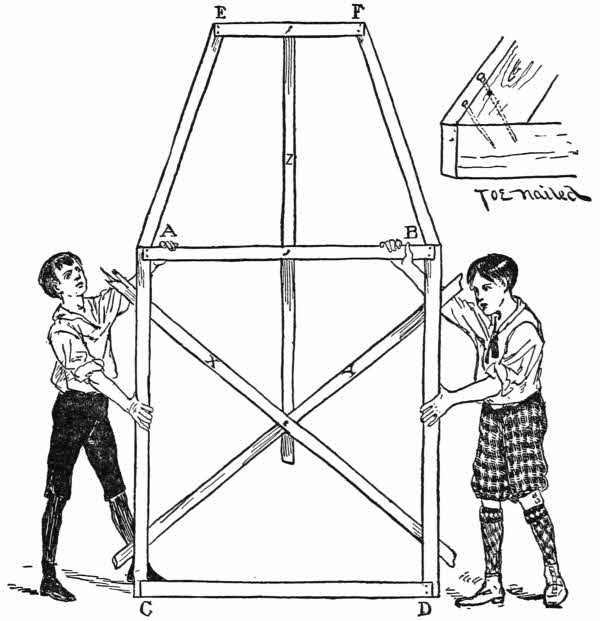

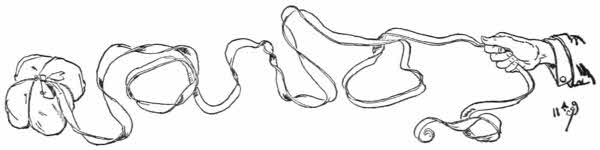

Fig. 1.—Beginning a Two-tree Foundation.

No boy, outside the members of the 3·A·M’s, would look twice at the great snake-like vine hanging over the “lick,” and if he should, the vine was far out of reach, and would be passed by as suggesting no possibilities of fun.

Well, that is where he would make his mistake. Concealed in the underwood back of the tulip-tree was a long pole with a hook on one end, and by means of this implement we could grapple the grape-vine and pull the end within reach of our hands, and then one of us at a time would grasp the vine securely with both hands, and stepping back on the bank, give a short run, spring out into mid-air and sail away across the deep hole to drop with a thud upon the opposite bank.

Of course all this was unnecessary, for there were plenty of shallow riffs near by where we could wade across; but[8] no lad with any romance in his soul would be guilty of such baby-work when he knew the secret of the grape-vine route.

Once across we would peer carefully around in the most approved Indian-scout fashion, and when satisfied the coast was clear we would crouch down and make a wide detour that would bring us to a large sycamore-tree, which had been uprooted by the wind and fallen so that its top rested in the fork of a towering oak-tree. The spreading roots of the fallen sycamore made a wall of clay fully fifteen feet high, which, with the surrounding underbrush and foliage, effectually concealed the fact that in the branches of the oak-tree rested a large and strange nest—a nest built by wingless birds, for it was the club-house of the Three Ancient Mariners! The leaning trunk of the uprooted tree made a firm though slippery substitute for a ladder, and here among the branches many a jolly day was passed, and many a meal of fried fish, fresh from the neighboring “lick,” was devoured by three happy, sunburned boys.

Except in the neighborhood of large cities, there is nowadays not much danger from gangs of brutal, half-grown boys, but in those times the law seldom bothered any one.

However, even now, privacy and exemption from unwelcome interruption are desirable, and this can be best secured by

for when the ladder is pulled up no one, without the aid of “climbers,” such as line-men use, can hope to gain access to the cosey little house in the branches.

If you can find a tree with three or four strong spreading[9] branches, the problem of erecting a house is not a difficult one. If there are four straight trees the proper distance apart, it is a comparatively simple work to erect your house between their trunks, high enough to be out of reach of River Rats; but trees, as a rule, do not regulate their growth to suit any set of boys, and the boys must use their ingenuity to adapt their houses to the forms and growth of the available trees.

Tree-top House. 6 × 10 feet, 35 feet from ground to floor.

First choose your location, and see that it is a desirable one to all the club members; then, if there are any lofty trees at

you will certainly find an opportunity for a four-tree, three-tree, two-tree, or one-tree house.

The tree or trees for the purpose must be so tall, that when the bottom ladder is pulled up the house will be out of reach of unwelcome callers, and big enough to prevent the wind from so swaying the house as to give a feeling of insecurity.

Let us suppose that there are only two trees in the proper location which fulfil the requirements, and that these are tall pines with no branches of any importance below their feather-duster-like tops. This presents one of the most difficult problems to solve; but when you know how, you can erect a most enchanting “crow’s-nest” away up the tall trunks, where the fresh breeze blows over the tops of the smaller trees, and where a good view can be had of the surrounding country, and the enemy, if there be one, may be seen while yet a long distance off, giving ample time to the club members to pull up the ground ladder and place themselves in position to laugh at the foe.

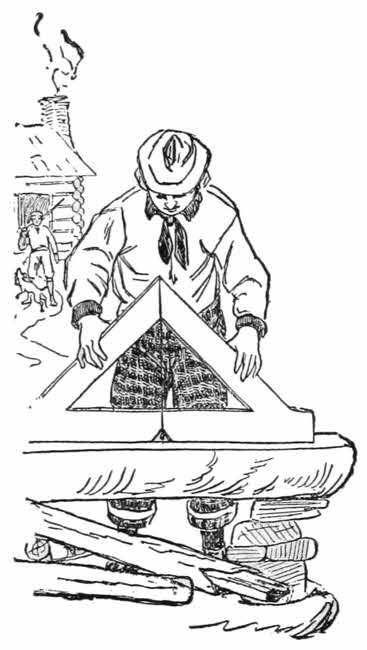

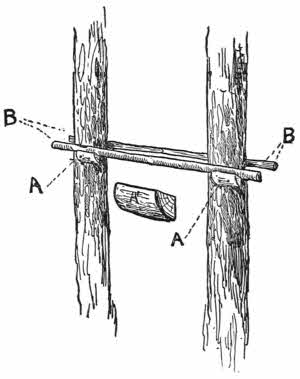

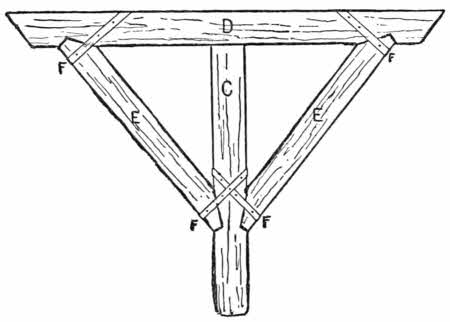

Fig. 2.—King Posts and Corbel.

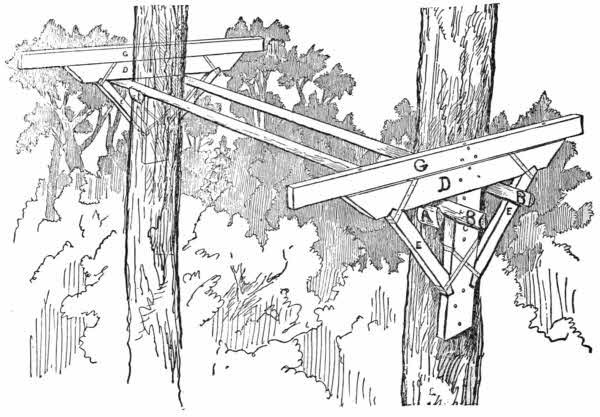

With an accomplished woodsman the whole edifice may be erected with the use of no other tool than an axe; but, as a rule, the more tools you have at your disposal the better you can do your work. If you possess a tape-line, measure the distance with it between the two tree-trunks. If you have no tape but have a two-foot ruler, make yourself a longer measure by marking off the feet and half-feet upon a ten or twelve-foot pole, and use it to measure between the trees. If, however, you have neither, use your legs and pace the distance, and then cut two long, strong poles, and see that they are long enough to span the distance between the trees, leaving plenty of wood to project beyond each tree. Flatten one side of each pole as shown in the diagram B, B, Fig. 1. Next, select a sound log, a foot or so in diameter, quarter it, and make four

each about two feet long. See A, A, and A′, Fig. 1.

As it is best to have the bottom of your house level, you must manage to nail the A blocks the same distance above the ground on each side of each tree—that is, if the ground is level; if not, you must allow for the slant of the earth. Spike the blocks securely to the trees with six-inch nails, using about three nails to each block.

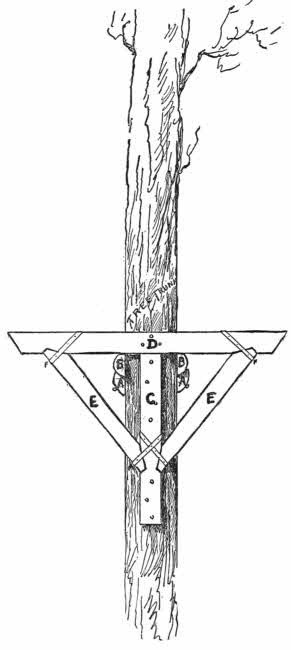

Fig. 3.—End View of Corbel Resting on B Sticks.

The foundation of the house may be higher than your ladder will reach. In this case cut two more poles and four more blocks, and at the point where the top of your ladder reaches spike on the blocks, and then rest

on them on each side of the two trees, as in Fig. 1. Nail the B poles securely to the tree, and with plank or half-round sticks floor the space between the trees, and you will have a good landing below your house (see Fig. 5) from which a ladder may be run to the proposed foundation. After the upper rods have been nailed to the trees and a ladder adjusted, and for security nailed fast to[12] the tree and lower platform, you are ready to begin the serious work of building. Take a good strong plank, two inches thick, and cut two pieces about six feet long, and shaped as shown by

in Fig. 2; then cut four struts (E, E, in Fig. 2) and two king-posts (C, Fig. 2). Shave off the ends of the struts, as shown in the diagram, to fit the notches cut in the corbel pieces and the king-posts.

Fig. 4.—Perspective View of Corbels Resting on B Sticks.

It is not necessary to spike this frame together—the big nails might split the timber—they may be fastened together slightly with wire nails and strengthened by a piece of hoop-iron nailed on with small nails, as shown in Fig. 2[14] at F, F, F, F, and this will keep the pieces from accidentally slipping out of their bearings, or holes may be bored and the parts held together with screws. The real strain being an up-and-down thrust on the notches, the weight will not bear upon the iron bands or screws. Great care must be taken to make neat-fitting joints.

Fig. 5.—A Two-Tree House.

When the two pieces of the form of Fig. 2 are completed, make fast a line to them and haul them up the tree; then slip the ends of the rods B and B under the corbels D, until the king-post C lies flat against the side of the tree-trunk. Spike C securely to the tree-trunk, as shown in Fig. 3; do the same with the other frame on the far side of the other tree, and you have a firm foundation that will hold more weight than you are liable to put upon it. Now cut two more pieces of two-inch plank, say, ten feet long by four inches broad; hoist them up and spike them to the top of the corbel pieces D, D, so that they will project the same distance beyond the tree at each end, as in Fig. 4.

From G to G you may now lay the planks of your floor, if the distance is short: if not, put two poles across each side of the trees and nail them to the trunks, and two more across at each end of the pieces G, G, and nail them to G and G, and then put your flooring on parallel to the G planks.

The rest of the work is simple. To shed the rain your roof must incline one way or the other—to the front, as in Fig. 5, or to the back, as in the one-tree house, Fig. 6. Nail on an A block to each tree, and give them the same incline; then place two poles for rafters on the A blocks[15] and nail them, each with a single nail, to the tree-trunk; this will hold them in place until you cut four straight poles for the uprights at the four corners of your house; set these up under the ends of the rafters, and nail the[16] rafter to them and to the trees; then drive two or three nails, slantingly, in the foot of the upright to secure them to the floor (toe-nail, Fig. 92, Chap. IX.). A cross-piece on top of the front and rear completes the skeleton of your house, which may be roofed and the sides covered with boards, or only the roof made of boards with narrow strips over the cracks and the sides covered with poles, by nailing the latter to the uprights as in Fig. 5. This gives a fine rustic effect, but unless ceiled or boarded up on the inside it will allow the wind and rain to beat through.

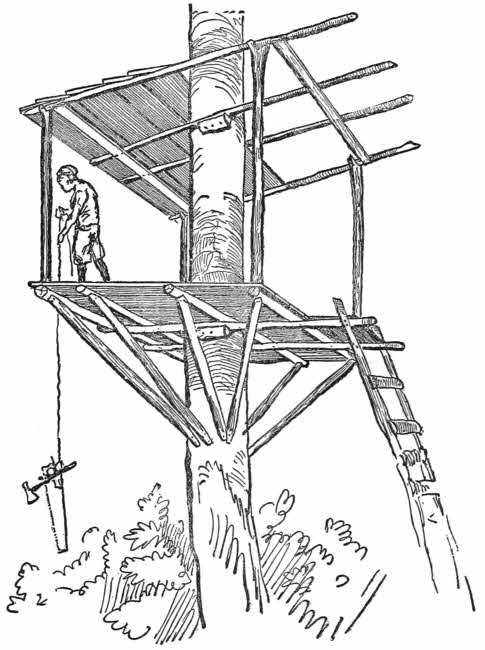

Fig. 6.—Frame of a One-Tree House.

If the trees are further apart than desirable, the house can be built between the trees, as in Fig. 5, but if the space is no more than required, the house can be built so that the sides enclose the tree-trunks, as the railing of the platform does in Fig. 5.

It is really not necessary to use any plank or boards except for the roof and floor. A boy who can handle an axe and hatchet well can make the frame, Fig. 2, from timber cut in the woods, but unless he is an expert, or can get the services of an expert axeman, he had better use plank as directed.

at first thought seems to be an even more serious problem than the two-tree house, but a glance at Fig. 6 will show how it can be built without much trouble.

First we nail the two A blocks on to the trunk, then the two B sticks. After the two B sticks are placed upon the A blocks and nailed to the tree, two more B poles must be laid over the first at right angles to them, so as to enclose[17] the tree-trunk within a square of B sticks. Nail all four sticks securely to the tree. You will notice that in this case many of the sticks are notched near the ends, as D is in Fig. 2, and for a similar purpose, to receive and hold the ends of the struts, which are nailed at their lower ends to the king-post (trunk of the tree). It is unnecessary to notch or mar the trunk of the tree, for the ends of the struts are cut on an angle to rest flat against the trunk where they are nailed, and the nails will not injure the tree in the least.

Fig. 6 shows the roof boards laid clinker, or lap-streak fashion, from side to side. Where a roof is laid in this manner it is not necessary or desirable to nail strips over the cracks, as these are fully protected by the overlapping boards.

Wherever it seems necessary to add to the stability of the foundation of any of the club-houses described, it can be done by struts from the tree-trunk to the ends of the B sticks or other poles supporting the structure.

Fig. 7.—Three-Tree House.

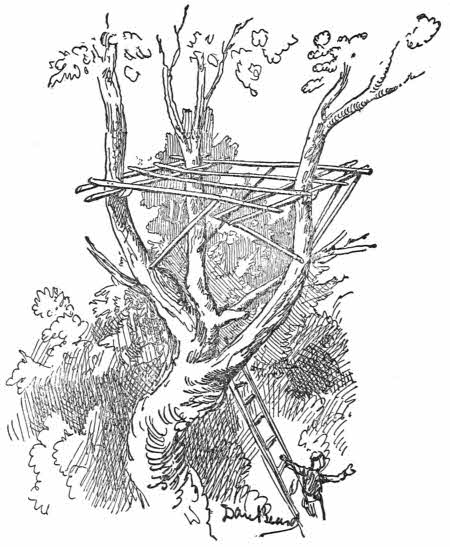

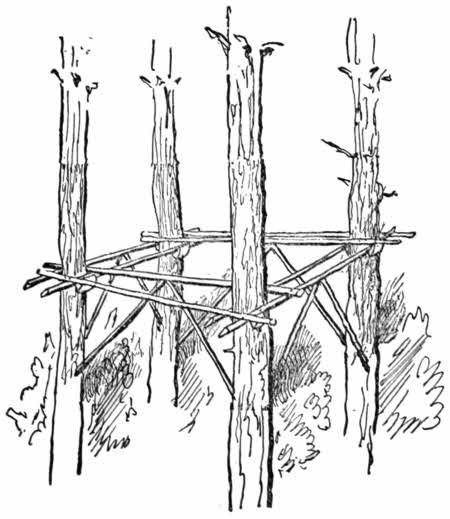

Figs. 7 and 8 show, respectively,

equally applicable to a three or four branch foundation. It is, of course, impossible for the writer to give exact figures and iron-clad rules for this style of building, owing to the variable nature and growth of the trees, but the most difficult problems are here solved, and any other combination of trees or branches will be found to be only variations of the ones here illustrated and described.

Fig. 8.—Four-Tree House.

As I remember our little house in the Kentucky oak-tree, it must have been but a rude affair, yet it was dearer to the hearts of the 3·A·M’s than a house and lot on Fifth Avenue would be now to the only living member of the club formed over thirty years ago.

A boy who can spend part of his time out of town, and is the fortunate owner of a mongrel cur, forms a combination for enjoyment and fun hard to be beaten by anything in nature. A good yellow dog, unencumbered by any aristocratic ancestors, is an ideal companion in the wood, and field: it can scent a woodchuck leagues away, it knows just how to head a chipmonk off from its retreat, and there is not a trick known to the professional poacher which is not familiar to the real country plebeian cur.

There is a potent charm in those words, which can iron the wrinkles out of an old brow, and soften the hard lines in the face of a careworn professional or business man.

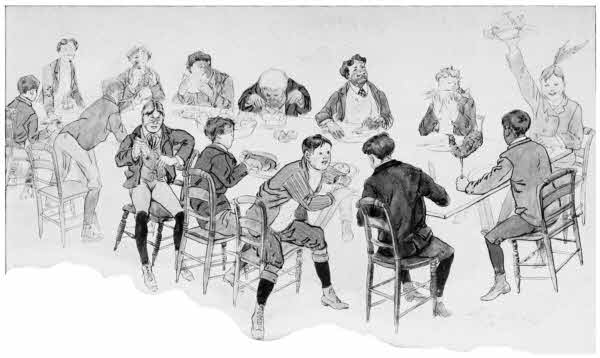

Not long ago I attended a dinner given by the

and there I found ranged around the table an array of veteran hunters. There were men there who had hunted the royal Bengal tiger in the jungles of India, men who had fought with rogue elephants, men who had followed the lions to their dens in Africa, men who had tracked the white[20] bear to its lair in the far frozen North. There were gentlemen who hunted for pleasure, cowboys and scouts—Coquina Shields, “Wolf” Thompson, “Curio” Brown, “Yellowstone” Kelly, Andrew J. Stone, and many others equally well-known in the forests or on the plains were seated at the big round table.[3]

That they were real simon-pure sportsmen could be seen at a glance, and yet, when the after-dinner speeches were made, the sentiments which received the most enthusiastic applause were those which DENOUNCED THE KILLING OF MAN OR BEAST. It could readily be seen that these men only used the gun when it was necessary to procure food or in self-defence. They all indorsed the use of the camera for the hunt in place of the murderous gun; as one of them remarked, “With a kodak every good shot is registered with the click of the shutter, and an album of good shots is a thing of which any man may be proud.”

With a little private zoo of captured live game you may have a living album, which attests the skill of the collector and his knowledge of woodcraft as accurately as any album of photographs.

The next chapter tells how to build a back-yard zoo, and now we must learn how to stock one. If the reader will[21] examine the plans in the chapter mentioned, he will see that there is one compartment marked

Making a Capture.

This is the place where our new captures find temporary shelter until their regular quarters are prepared for them.

The most accessible game for boys belongs to the

These animals can be readily distinguished by their long, chisel-like front teeth. A familiar example of this family may be found in every town and city, and is known as the common rat, the Norway rat, or the brown rat.

Formerly the common rat of the United States was black, but his brown relative has about exterminated the more graceful black one. The only black rat I ever saw was a dead one, which I found one summer in an unoccupied house in the mountains of Pennsylvania. But there are plenty of beautiful little gnawers around us everywhere. There are the soft, furry, big-eyed flying-squirrels, which leave their warm nests at dusk and sail through the air from tree to tree, or romp among the branches until daylight. Just at dawn they return to their beds, to sleep away the day in their dark holes, secure from the garish sunlight.

Of course any boy with money can purchase flying-squirrels, but no boy with any pride would stoop to buy his live game, unless he is so unfortunate as to be unable to leave the densely populated city. I well remember the two boys[4] who gave me my first lessons in hunting flying-squirrels.[22] I followed them across meadows, over hills, through the woods, down into the dank and dark swamps, until we found some old hollow cedars on the edge of the water. Here one of the lads armed himself with a small wand, and the other busied himself gathering old dry leaves and bits of moist bark to make a smudge. The boy armed with the wand probed the hollow trees until he discovered a hole from which the wand would bring forth some bits of the fine shredded inner bark of the cedar. We all know that neither the inner bark nor any other kind of bark grows in the hollow of trees, and when it is discovered there you can wager that it was put there by some animal.

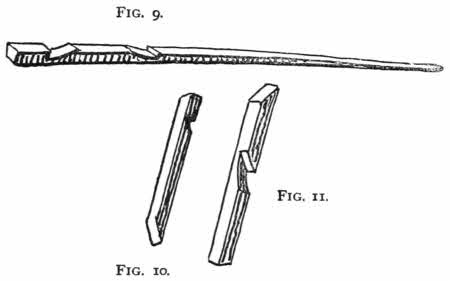

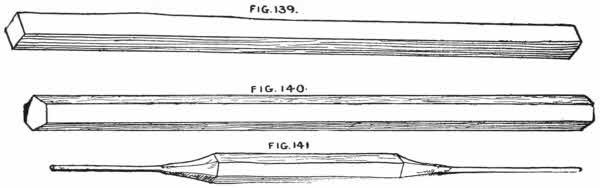

Figs. 9-11.

This stringy, soft stuff is famous material for a nest, and both the white-footed mice and the flying-squirrels are fully aware of its good properties.

When some of this nesting is found in a tree, it is safe to say that there is a nest inside.

is now lighted and the hollow tree is filled with smoke. As soon as this is thoroughly done, you may safely thrust your arm into the hollow and bring out the stupefied inmates.

I never knew the smoke to cause the squirrels any serious harm. The little captives soon revive, when brought out into the open air.

when tame, make the most gentle pets, but when wild, and rudely seized by hand, they have a vicious way of using their chisel-like teeth which induces more caution the next time. A smoke-stupefied squirrel is much more pleasant to handle than a wild one, frantic with fright.

If, however, you protect your hand with an ordinary bicycle or golf cap, you can seize almost any small animal with impunity. I caught nine flying-squirrels in one night, with no protection for my hand but an old cloth cap.

Do not try to throw the cap over the animal, or it will escape from beneath, but use the cap as a protection to your hand, then grasp the creature by a quick movement, closing your fingers tightly over its body, being careful not to squeeze hard enough to injure the terrified little squirrel. The advantage of this mode of capture is that, having the game in your hand, you can easily thrust it into the cloth bag you carry for that purpose.

is a most convenient thing; it is easy to carry, allows plenty of air, and the little creatures never think of gnawing out while you carry them.

I have carried

and white-footed mice for miles, tied up in my handkerchief, and no attempt was made by my prisoners to use their teeth to assist them in escaping.

The gentle, graceful little jumping-mice, white-footed mice, short-tailed meadow-rats, and flying squirrels are all[24] to be found inside the city limits of Greater New York, and some of their relatives are to be found in almost any rural place in this country. These interesting little creatures can be captured with ordinary box-traps, figure fours, or the square or round wire mouse-traps. The white-footed mice or deer-mice may be found in the abandoned nests of other rodents, in hollow logs, in old corn-stacks, in holes in the fence-rails, and under clods of old ploughed fields, or beneath brush-heaps in the fence corners.

In the late autumn, before the first snow comes, they have a very pretty way of

by filling them with the soft down from the cat-tails of a neighboring marsh, or with moss and wood fibres, thistledown, or the silky feathers from the seed of the milk-weed. Like flying-squirrels, the little deer-mice bury themselves in the soft nests, and sleep away the day, emerging at night for food and exercise.

Fig. 12.

If the branch upon which the nest is located is but touched, the brown-backed, nimble-footed little squatter will poke his head from the middle of the nest, look inquiringly around, and if no danger appears the head is withdrawn, and the mouse resumes its slumbers; but if it is deemed that there is cause for serious alarm, it will spring from the nest, and with the agility of a squirrel run lightly up a branch, and from this point of vantage turn its[25] bright eyes on the intruder with a sort of “please don’t” expression. If further frightened it will hastily leap to the ground and disappear in the brush and dry leaves.

Sometimes I have found birds’-nests with a neatly laid thatch roof over the bowl, and a round doorway gnawed through the side of the nest for a means of access to the interior, where, snugly curled up in a warm bed of down, the little white-footed mouse was sleeping.

Once, while skating on a pond, I discovered a pair of deer-mice keeping house in the walls of the mound of mud and roots reared by musk-rats for their winter quarters.

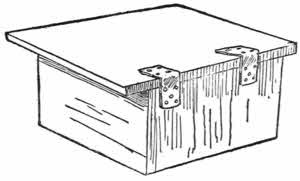

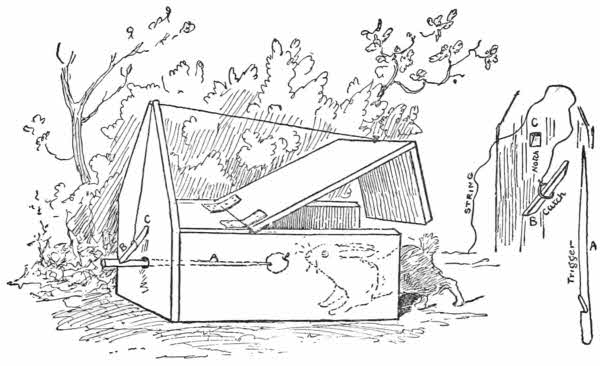

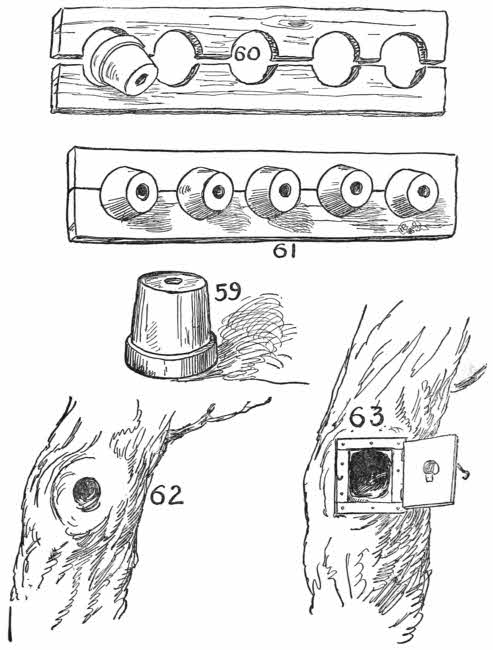

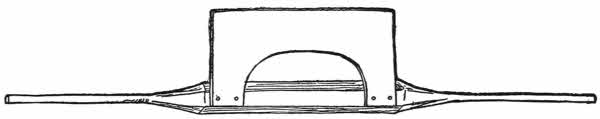

Fig. 12A.—The Old Figure-Four Trap.—Any old box will do for a figure-four trap; but much trouble is avoided by using a box with a large lid for live game, as shown in Fig. 12. This is set upside down, as shown above. The lid is considerably larger than the box, and attached to it by a couple of leather hinges which are tacked to the lid and the box, as shown in the illustration. Fig. 9 is the spindle or trigger, and shows the manner in which the notches are cut. Fig. 10 is the catch, and Fig. 11 is the upright. In Fig. 12A you see this old-fashioned trap, set and ready for business. A small door in the box will make it easy to remove captives.

You may capture these little fellows by hand, if you use due caution in approaching their habitation, and shield your hand with an ordinary pocket-handkerchief.

They will make beautiful pets, and you will find them much more interesting than the common white mice.

Give them a tall narrow cage, with plenty of head room, wire a branch containing a last summer’s bird’s-nest to the side of their cage for sleeping quarters, and feed the mice with bread, seed, and grain.

frequent the salt meadows, where their grass-roofed paths may be found intersecting each other everywhere. After the blunt-headed little creatures have been discovered, by uncovering their runways, you may capture them with your hand, shielded by a cloth cap.

Beware of their teeth, for they are savage biters and plucky fighters.

Meadow-rats are not climbers. Put them in a flat cage with a good wide expanse of bottom covered with sod of growing grass, the roots of which they will eagerly devour. Feed them garden vegetables, when grass roots are not available.

If you are an expert it is sometimes possible to catch chipmonks by hand. I never succeeded but once in capturing one in this manner. They will enter almost any ordinary sort of a trap, and can be best captured in that way. Set the trap near the hole known to be occupied by one of these scolding little rodents, and give your captives a roomy cage, with a dark corner for a nest. They make gentle and amusing pets. Feed them on acorns and nuts. Crack the hardest nuts for them.

when discovered, are off like a flash, and are too swift of foot to be captured by hand—at least this has been my experience. They may sometimes be found under clods of an old ploughed field, in fence corners, or under loose brush and stones. Like the white-footed mice and flying-squirrels, they are nocturnal in their habits, and there may be thousands living all around you, and you will never suspect their presence until your cat brings one in from the field, or you find their half-devoured remains in the screech-owl’s nest in the old apple-tree.

Jumping-mice have been known to make their nests in a beehive, and I know of one short-tailed meadow-rat which chose the same sort of sweet home.

In winter the jumping-mouse becomes torpid and apparently dead, and you may lay him away in a box of cotton, where it will remain until the bursting bud and freshening grass announce the approach of spring. Then your little pet will wake up, and be as full of life as if it had only taken a noon nap.

Although quite vicious, and dangerous to handle in their wild state,

make very gentle and comical pets. One celebrated woodchuck-hunter had great success by using a stuffed woodchuck as a decoy. A very good substitute for a stuffed animal may be made of gray Canton flannel, stuffed with cotton.

Set your decoy up in plain view of the woodchuck’s hole, and sprinkle fresh clover around. Then conceal yourself behind the hole, and be ready with a strong ring-net on a pole to capture your game when it appears.

The watchful old fellow will see the decoy sitting on its haunches, and reasoning that where it is safe for one “chuck” it is safe for another, he will sally forth to enjoy the clover. Then the fun begins. You must jump between the woodchuck and his hole, and net him as best you can, after which transfer him to a meal-bag, and carry him to his cage.

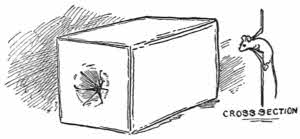

Fig. 13.—The Wooden Box-Trap.—Dotted lines show arrangement inside. A is the trigger, or spindle, which passes through a hole in the rear end of the box. B is the catch with a ring slipped over its middle, to which a string is attached to hold open the trap-door when the trap is set. There is a notch in the back board of the trap at C, and another near the rear end of the trigger, in which the bevelled edges of the catch are caught and held in place by the string attached to the trap-door. Fig. 13 1/2 shows the details of Fig. 13. The box-trap is an old “stand-by” with the boys, is simple in construction, and can be made by any lad who can handle tools. This drawing was made from a trap built by a country lad, twelve years of age. A serviceable trap can be improvised from an old tin can, or, better still, one of those square tin boxes used so generally now for holding fancy groceries.

Woodchucks can run rapidly for eight or ten yards; then they have a habit of suddenly coming to a stop, assuming[29] their favorite upright pose, and darting off again in another direction.

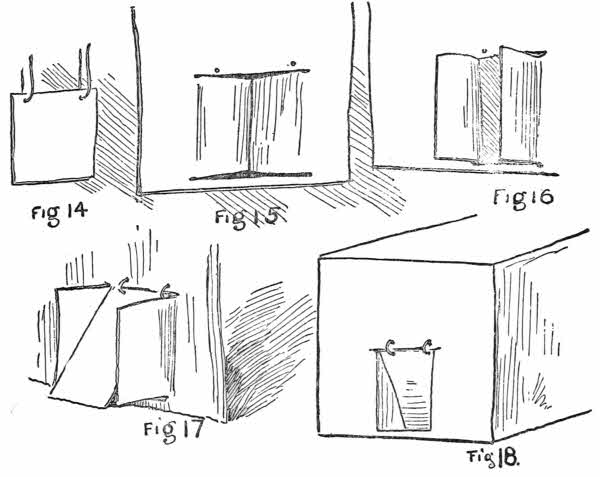

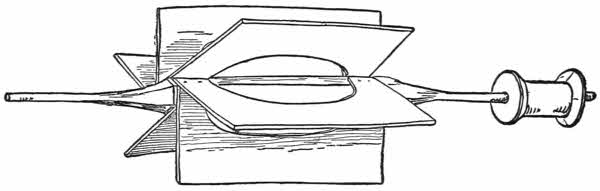

The Tin Can-Trap.—Make a door of a square or rectangular piece of tin. With a nail make two holes in the top of the door for the wire hinges (Fig. 14). With a heavy knife cut a doorway a trifle smaller than the door. Cut three slashes as shown in Fig. 15. Bend the two sides in as shown in Fig. 16, then hang the door with the wire hinges. Fig. 17 shows the door from the inside of the tin box, and Fig. 18 shows the same from the outside. The door, as may be readily seen, can be pushed up from the outside to admit the game, but when the prisoners attempt to get out they cannot push the door open, for the trap opens but one way. Do not leave space enough below the side-pieces for the animal to thrust his nose or paws under, or it may lift the door in this way and escape. If, as in the diagrams, it is necessary to cut a little above the bottom of the box, put a flat stone, or some similar object, inside for the side-pieces and the door to rest upon. Fig. 19 shows the manner of cutting the tin. Another door can be made by cutting a star in the tin, and then bending the pointed pieces in far enough to allow the game to squeeze through. The points will not allow anything to crawl out, however, and it must remain there until released (Fig. 20). These diagrams are given so that the young hunters may make their own traps, in case the ordinary mice and rat-traps to be found in shops are inaccessible.

June is the time to capture the young ones, as they play about their home hole.

may be successfully used to capture both young and old.

However fierce an old wild “ground-hog” may be, one that is taken young and reared in captivity is remarkably gentle. It is fond of a noonday nap, but when the sun sinks in the west, and the long shadows creep across the fields, it will rouse from its slumber, sit up, wash its face like a mouse or a squirrel, and be ready for a frolic.

Fig. 19.—How the Tin is Cut.

When cold weather approaches, the woodchuck, ground-hog, marmot, or siffleur, as it is variously called, will prepare for a long winter sleep by rolling itself into a ball. In this condition you may pack it away like the jumping-mouse, and when friends call you can take the ground-hog out and even roll it around the floor without seeing any signs of life displayed by the hairy ball. But when spring returns, your Rip Van Winkle pet will awaken, and after sitting up on its haunches, and washing its face with its front paws, will be ready for a breakfast of clover or other food.

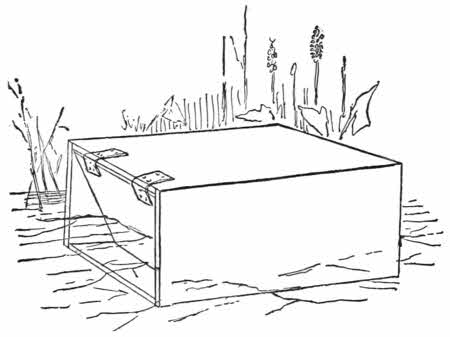

Rare old Captain John Smith, in his quaint “History of New England and the Summer Isles,” published in London in 1624, gives, probably, the first written account of the musk-rat. He says that “the mussascus is a beast of the form and nature of our (English) water-rat;” and he adds, “some of them smell exceedingly strong of musk.” These animals may be caught in almost any sort of a trap baited with sweet apples or parsnips.

have very strong teeth, and can use them on wood effectively, so it is wise to protect all corners and cracks in your wooden traps with pieces of tin or sheet-iron. They have good noses, and can smell an apple a long distance off. Place your traps in the shallow water at the edge of the mill-pond or stream inhabited by these rats, and they will doubtless find it without difficulty.

Young musk-rats are very gentle and playful, and may be handled without fear; they do not grow fierce with age if reared in captivity and accustomed to gentle treatment.

Fig. 20.—The Tin Box-Trap.

When kept in confinement give them a roomy cage, with a tank of water to swim in. Build the tank after the manner of the one described in the “Back-yard Fish-Pond.”

There is one other little animal, familiar to most boys, and which they are too apt to value only for its skin. In truth, this creature generally has a very bad name, and, personally, I owe it a grudge for stealing all my live bait, on more than one occasion.

Nevertheless, when domesticated and supplied with plenty of food, like many a poor two-legged wretch, it will turn honest, and give up its bad habit of robbing hen-roosts. This long-bodied little animal is the mink, which, like those animals already described, is not difficult to capture in almost any sort of a trap.

When caught young it becomes very gentle, and even affectionate. It is passionately fond of frogs, and these batrachians make a good bait for mink-traps. Minks will[32] eat fish and when domesticated will not hurt your chickens, but will wage a relentless war upon rats and mice.

You need not confine your mink, for it will make chums of your dog and cat, and is fond of a cosey spot in the chimney corner.

Fig. 21.—Turtle-Trap.—This is simply a box with a door, like Fig. 10. The trap is set in shallow water, and baited with meat. It is very effective.

While I was sketching on the coast of Maine I spent a whole day at my easel, between two great rocks. I soon discovered that I was watched by some creatures, and it was not long before my neighbors made up their minds that the two-legged thing was a harmless sort of animal, and, before I finished my sketch, they amused themselves by jumping back and forth over my feet. At first I was more afraid of them than they were of me, but soon discovered that they meant no harm: so I painted away, with a pair of wild mink playing about my feet like tame kittens.

The king of beasts and the royal Bengal tiger are neither of them able to inspire such universal terror among the wild creatures of the forest as does man.

Bitter experience and terrible examples of man’s ferocious cruelty to all wild animals have taught even the most humble and inoffensive of them to dread the approach of the bloodthirsty two-legged destroyer.

It is high time that we redeem

It is time we ceased our wasteful, senseless slaughter of every wild thing to be met with in field and forest. It is time we began to study live animals, in place of uncanny dried skins and badly upholstered “specimens,” so-called.

belongs to the past. A new era has commenced, and real naturalists now drop their dry bones and moth-eaten skins to enjoy the study of live, healthy animals.

The boy who is really fond of animals never ill-treats his pets, or abuses and makes a slave of his dog. On the contrary, his dog is his companion and playmate.

The boy knows that a dog’s master is a god in the eyes of the poor brute, and is

which again and again has been proved faithful unto death. Such knowledge makes the boy just and kind. But a dog is only a domesticated wolf, and the wolf is not the only wild creature which can be domesticated; neither is the wolf the only animal which

The same care which transforms a red-mouthed wolf into a faithful dog can transform other undomesticated beasts into useful creatures. As soon as an animal learns that you are contributing to its comfort, you may notice it will greet you with a milder expression. As soon as you can make the wildest and fiercest beast understand that the use of jaws, claws, or sting is unnecessary, it will refrain from using them. It is not always possible to come to this understanding with the larger beasts, and such animals are not fitted for back-yard zoos.

A lad who loves his pets will bestow upon the little creatures that affection which shows itself in a sympathy which can understand their wants and necessities. Such a lad can perform wonders; birds will come at his call, the small beasts of the field will follow at his heels, and no child will fear him.

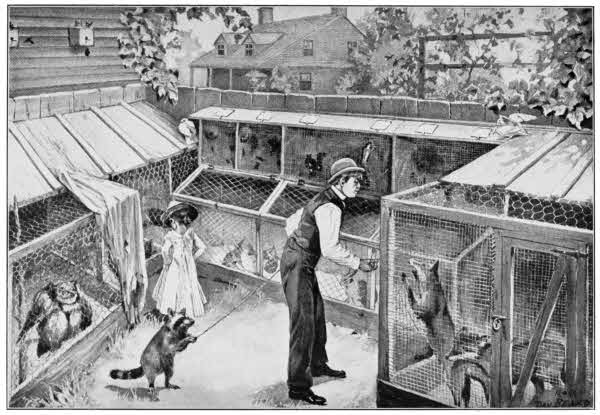

Visiting the Animals.

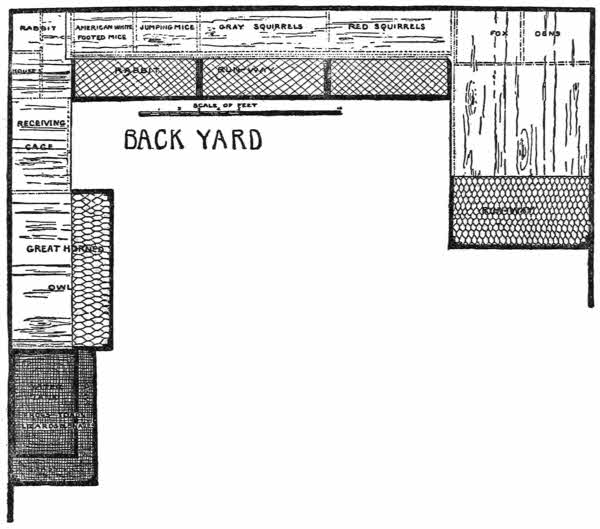

Unfortunately, in spite of the amount of land on this continent, it is difficult for any but the very wealthy to have access to much of it, hence many readers will say, “We have no yard in which to keep pets,” or, “Our yard is too small.” Of course, if you are living in a flat you must go without a zoo, but if you have a yard it will probably not be less than twenty-five feet wide, and Fig. 22 shows how a very comprehensive[35] zoo can be placed in the rear of a twenty-five foot lot, without materially interfering with such domestic matters as the drying of clothes on wash-day. A city

Fig. 22.—Arrangement of Dens in the Back-yard.

is usually one hundred feet deep; this will allow plenty of room for the house and the clothes-lines, and still leave the end of the lot for a famous back-yard zoölogical garden.

When the writer was building back-yard zoos on the banks of the muddy Licking River, in old Kentucky, wire-cloth and wire-netting were unknown, and a few old barrels and dry-goods boxes, a saw, hatchet, and some nails, constituted the materials and tools with which he and his playmates made cages for pets, frog-ponds, and dove-cots.

The writer’s

of the work, and incidentally learned all the weak spots in the structures, a knowledge which they were not slow to use when the sheds and coops were finished, and occupied by creatures fascinatingly interesting to crows and dogs.

But you boys are lucky fellows! Everything that youth wants is now on the market at reasonable prices. Wire-cloth and galvanized wire-netting with double-twisted selvages, with meshes of any size to suit the occasion, and wire of any dimensions to suit the purpose, are now manufactured especially for the building of cages.

comes in rolls, with either square or hexagonal mesh; in other words, the openings between the wires are in the form of a square, or are six-sided.

Fig. 23.—Temporary Frame of Cage.

Wire is numbered from the very heavy, No. 000, which is over a third of an inch in diameter, to No. 40, which is only .00725 of an inch in diameter. It is not very likely that you will use either of these wires, unless your collection includes some very large and strong beasts and some very small insects. The wires which you will probably need will be between No. 14 and No. 22. No. 14 is eighth-tenths of an inch in diameter, and No. 22 is a little more than two-tenths of an inch in diameter.

is the distance from centre to centre of the wire. No. 5 mesh means five meshes to the lineal inch—that is, a piece of netting five inches long will contain twenty-five meshes. The “space” means the opening between the wires—that is, the distance from wire to wire.

This is explained because some of the readers may not live near any dealer in wire-goods, and will be compelled to order what they want by letter. To do this intelligently they should understand the trade terms. Galvanized wire-netting, used for small bird-cages, comes in one-half, five-eighth and three-quarter-inch mesh, and is made of from No. 18 to No. 22 wire. The width of this netting varies from two feet to four feet. One-and-one-quarter-inch mesh is used for pigeon-houses, and the netting is from two feet to six feet wide. One-inch mesh is used for quail, ruffed grouse, pheasants, prairie-chickens, etc. A two-inch mesh is usually used for chicken-coops.

Figs. 24 and 25.

As a rule, the mesh which has square spaces is called wire-cloth, and that which has six-sided spaces is called netting. For mice, rats, chipmonks, flying-squirrels, gray and red squirrels, use about No. 2 1/2 square mesh of No. 17 galvanized wire.

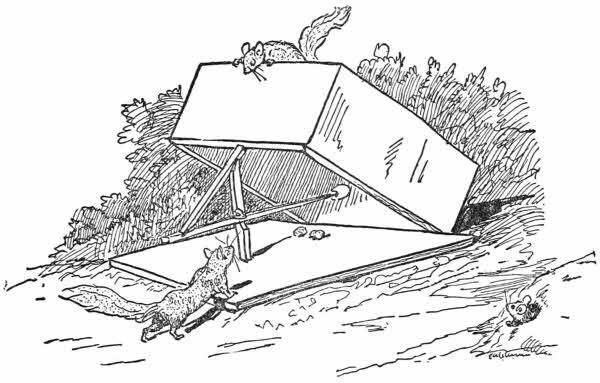

For woodchucks and musk-rats use a rather small mesh and pretty heavy wire, for their teeth are strong chisels, and you will be surprised to see what skilled mechanics they are in the use of the tools with which nature has supplied them. For rabbits, a two-inch mesh or any of the nettings used for poultry answers all purposes; but for foxes, if you use a two-inch mesh, be careful to have it of heavy wire. The writer’s Skye terrier pup gnawed its way through the[38] chicken-coop wire-netting on various occasions, and a fox has all the energy of a terrier, coupled with a most surprising amount of ingenuity and skill in jail-breaking.

I once owned could undo any knot or catch that I could invent with which to fasten them, and I was only made aware of the fact from the complaints of lost chickens which came from our neighbors.

While the neighbors were protesting, Faust and Mrs. Faust lay in front of their den, staring innocently at us with their great brown eyes, but investigation proved that the chains which apparently confined them were attached to nothing but their collars; and, furthermore, when I pushed the foxes aside with my foot, sundry quills and feathers, protruding from the fresh earth of their bed, showed only too plainly that our neighbors were not without reason in suspecting my innocent-looking rascally pets. I at last solved the problem by chaining the foxes together, and in spite of all their cunning, they never learned to go through the same opening in the fence, but each chose a different exit, and both were then held by their chain.

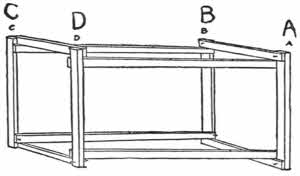

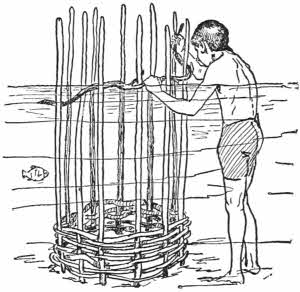

the reader makes will, of necessity, be of a form peculiar to his purpose and the location where it is placed. If it is for a fence-corner there will be but two sides to cover with wire-netting; if it be against the fence there will be three sides of netting: the fence forming the other side. In a hundred different ways will the surroundings modify the form of the cages, so, to simplify matters, we will suppose the proposed pen is to stand in the centre of the yard. In this case,

you first decide upon the wire and the mesh which are needed for this particular coop, next decide what are to be the dimensions; then, with a hand-saw, cut four wooden uprights exactly the same length, and fasten these posts together, temporarily, as shown in Fig. 23, A, B, C, D.

Fig. 26.—Cages and Runway.

The strips connecting the uprights, and forming a box-like frame, should be only secure enough to keep the frame in shape. The nails in the strips must be driven just far enough to hold, leaving the head and enough of each nail above-board to render it a simple task to withdraw the nails when you wish to remove the strips.

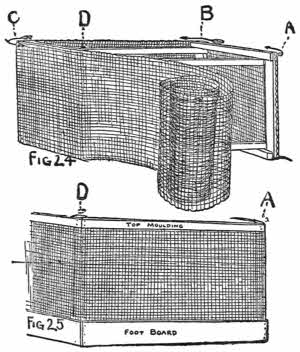

When the temporary frame or mould is finished (Fig. 23), fasten the end of the wire-netting securely to the front of the upright A with staple tacks, then pass the roll to B (Fig. 24), draw it tight, and with more staple tacks secure it to this upright; continue the same process at C and D, ending at A, as shown in Fig. 24. The arrows show the direction to be observed in passing the netting around the uprights.

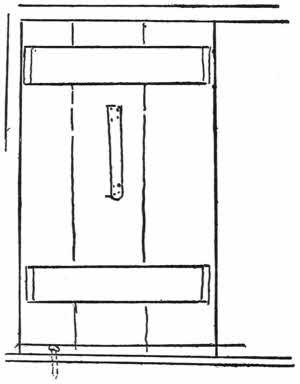

When all is snug and fastened firmly, nail a footboard and top moulding on, as shown in Fig. 25, after which remove the temporary inside strips, and your coop is done. It has no roof or floor as yet, but the roof can be made of[40] wood or netting, as the occasion may require; the floor may be of wood or earth, to suit the purposes for which it is to be used. In large cages the doors must be framed and set in, as shown in the picture of fox-dens in the illustration of the back-yard zoo, but in small cages a small hole may be cut in the netting—this can be done with an old pair of shears. The square piece of netting from the cut can then be used as a door by fastening one edge with loops of wire to the edge of the opening just made. Picture-wire and copper wire are best for such purpose, because they are pliable and easily handled.

can, if desired, be made very neat by the following method: Cut some tin into strips of the proper dimensions, then fold the strips on their centre, lengthwise. Punch a series of holes by placing the folded strips of tin on a block of wood and driving a nail through. Slip the folded tin over the exposed edges of the wire-netting, and sew it in place by threading a fine wire through the holes. Bind the edges of the door in the same manner, then put a loop of wire on the door for a hasp, and a smaller one on the cage near the edge of the doorway for a staple, and the door may be fastened with a peg of wood or a nail; or, better still, wire a hook on the door in place of a hasp, and arrange it so as to hook into the loop on the cage.

It is often handy to have doors in the roof of a cage, as in the roofs of the gnawers’ cages, over the rabbit runway, in the illustration.

to the rabbit-house are on top, and open like a door to a bin, as shown in the illustration and in Fig. 26. While we[41] are at the rodents’, or gnawers’, quarters, it is well to remember certain peculiarities about the habits of these animals. Rats, mice, squirrels, and their kind, will invariably seek a crack, angle or corner to commence work for a hole; knowing this, it is well to protect all such places by pieces of metal or tin, and none of the little fellows will make his escape, unless the door is left open.

Rabbits will seldom gnaw out, but if they have an opportunity they will tunnel out.

To prevent diggers from escaping, allow your wire-netting to extend a foot and a half underground, below the footboard.

need not be more than three feet high. It is not shown in the illustration, but may be built as described and shown in Figs. 23, 24, and 25, after which a roof of wire-cloth must be added.

Into this house you put your turtles, frogs, toads, lizards, and snakes, and as most, if not all, of these require water in considerable quantity, it is well to have a tank for their use. But as every boy does not know how to build the tank, he may learn by following the directions in the following chapter, describing a back-yard fish-pond.

Be careful to set the tank level and pack it around with good hard earth. It is well to sod the ground on three sides, and cover the earth on the remaining side with clean sand and gravel.

There should be a strip of land at least two feet wide all around the tank, as a runway. When this is all arranged spread a layer of sand all over the bottom of the tank, fill it with water, and place the cage over all. You should have

or some similar covering, for the cage, to be used when your sand is in danger of being washed away by a downpour of rain.

Everything is now ready, and you can turn loose in the enclosure

of frogs, toads, lizards, and snakes, and they will soon make themselves at home. You must not be surprised if your pets in this cage feed upon one another. I once owned an old bull-frog who would attempt to swallow anything that moved, with the exception of snakes. This frog swallowed two live mice in one day, but he did not get hungry again for two weeks.[5]

There are but few poisonous snakes in our country, and in the Northern States we have but two kinds—copperheads and rattlesnakes. Neither of these will add to the interest of your collection, and must be left out and let alone.[6]

There are many beautiful and harmless little snakes to be found in every field. They abound within the city limits of New York.[7] I saw two sunning themselves on a neighbor’s lawn, and discovered their home in the gate-post.

You will be surprised at the many varieties of frogs you can find when you start to collect these comical little creatures.[43] Some of them are very difficult to catch, and they often turn up in the oddest of places. I found a big toad in the top of a tree which I had climbed after young crows. It was a common hop-toad, not a tree-frog.

It is high time that the American boys, in the dawn of the twentieth century, should forget all the fabulous stories of snakes with the power to “charm” persons, toads with death-dealing breath, deadly swifts and venomous lizards. All such yarns are handed down to us by our superstitious ancestors, and are a part of the witch belief of the old Salem folk. There are people living now who will tell you that they have seen a hoop-snake with his tail in his mouth, rolling down hill, and these people really believe what they say; but so did the Salem folks believe in witches.

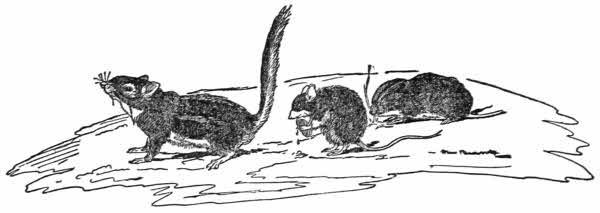

Chipmonk. White-footed Mouse. Short-tail Meadow-Rat.

If our comical, insect-destroying toads were venomous, the hand which pens these lines would have perished while it was still a chubby, dimpled, baby’s hand.

otherwise the writer’s hands would be far too warty to wield either a pen or a brush; but in spite of the hundreds of toads handled by the writer he never was afflicted with warts on either hands or body.

In Pennsylvania there is a toad which has occupied the same back-dooryard for over ten years, and he will eat his own weight in “bugs” in a very short time.

The funniest toad ever owned by the writer was a Kentucky hop-toad with five well-developed legs, and the largest frog the writer ever caught was a New York bull-frog, which weighed one pound.

St. Paul and Minneapolis are the great frog markets of the world. The receipts there last year, according to the daily papers, were something over six million frogs!

In the neighborhood of New York City one of the earliest frogs is the little brown cricket-frog. Next come the mysterious and shrill-voiced peepers, which make each marshy spot fairly shriek with their high-keyed notes.

are hard to capture, because you can seldom see them. A dip-net run through the water where you have heard peepers will generally reward you with two or three little dusky imps, who, when captured, will sing in your coat-pocket, and the writer has had them sing while imprisoned in his hands.

A loud, coarse trill announces the appearance of

and this batrachian makes a most interesting addition to the collection. It is said that the tree-toad has the power of changing color, varying from ash-white, dull-gray or a brown to a bright-green hue.

You must look for the hermit-frogs or spade-frogs where they hide in holes in the ground, and in the damp wood you can hunt the lean-flanked, beautifully-spotted leopard-frog, his cousin, the pickerel-frog, and the brown wood-frog.

The bright-green-tree specimen, known as

is considered by frog-hunters as a great prize, and specimens can only be captured at rare intervals. When you secure a rare frog do not put him in the same place with larger frogs, for the latter will swallow their smaller companions the first time they feel hungry.

Put your finger in a frog’s mouth and you can distinctly feel a number of fine, sharp teeth, but if you put your finger in a toad’s mouth you will find no teeth; a frog grabs his prey with his jaws, a toad snips it up with his tongue.

Besides the common, funny old hop-toad, there are the Rocky Mountain hop-toads, the Southern hop-toads, and the hop-toads from Northeastern Massachusetts, which differ sufficiently from the common hop-toad to be classed by naturalists as sub-species.

With the exception of the Gila Monster there are no poisonous lizards known, and although many of the little[46] creatures will try to bite you, their teeth are as harmless as so many needle points, and cannot be felt through a glove. Put on an old glove when handling them and you can hold them better; but be very careful and not be rude, or you may be surprised to find you have a stump-tailed lizard in your hand while the caudal appendage will be twisting around in a most astonishing manner at your feet.

Many beautiful and interesting lizards may be captured in all parts of the Union.

That it is not cruel to capture and confine wild animals is proved by the fact that almost all wild creatures, after they have become thoroughly familiar with their quarters, will not voluntarily leave their artificial homes for any protracted period. I have had wild pigeons return after giving them their freedom, and have had foxes return after securing their own freedom, by skill and cunning superior to that exercised by me in confining them. As for crows, coons, squirrels, and numerous other creatures possessed by me at different times, only death or forcible detention ever prevented them from returning to the place where plenty of food and kindness awaited them.

It is not necessary, or even desirable, to build all your cages at one time, for it is hardly possible that you will know just what you need until you have secured the creatures you wish to keep confined in the proposed pens and enclosures.

Allow your cages to grow naturally, by adding additions or new ones as the occasion requires. Acting upon this plan the receiving-cage will be the first to be erected, and it should be strong enough to securely confine the largest of your captives, while the mesh of the wire-cloth should[47] be fine enough to prevent the escape of the smallest pocket-mouse. The angles and corners should be well protected with metal, to resist the teeth of the gnawers, and the bottom protected with wire-cloth, to defeat the attempts of the diggers.

This cage will, at different times, furnish lodging for all the varieties of beasts or birds which are from time to time included in your ever-growing collection. Your new animals are first put in the receiving-cage, and must live there until suitable quarters are built for them.

Build all your cages as roomy as your available space and material will allow, and study to make their interiors as like the natural haunts of the imprisoned animals as is practicable. Avoid all attempts at ornamenting the cages, for no cage looks better and more artistic than the strictly practical one, built solely with a view to usefulness.

Clean sand will be found very useful for spreading over the floors of the wooden-bottomed cages, and a large box of it, kept in a dry place, will add greatly to your ability to keep things tidy.

Be particular about the nesting of your mice and squirrels; frequently remove the old nests and burn them, at the same time supplying the little creatures with a fresh lot of clean cotton, wool, fine grass, or even paper, and they will arrange a new bed for themselves out of the fresh material.

You will soon discover that all beasts prefer to keep clean, and have methods of their own by which they endeavor to keep themselves neat and presentable, without the use of soap. Any disagreeable odor proceeding from their cages simply means neglect on the part of the keeper of the zoo.

Although the writer has made frequent journeys to the wonderful dreamland of his boyhood, and has ruthlessly taken and brought to earth many of its air-castles for the use of the boys of the present day, there are still a number of things left, and among the latter is the back-yard fish-pond, which we shall now seize, and, bringing the idea down to your back-yard, make it water-tight, so that you can stock it with real live fish.

with a broad surface exposed to the air will support, in health many more inhabitants than a deep hole, with small exposed surface. Remember that it is easier to keep a fish alive in a shallow basin than it is in a bottle holding exactly the same amount of water.

in your yard and fill it with water, it will be a mud-hole, in which no self-respecting fish will live: besides which the soil will soon soak up the water and leave the mud to bake in the hot summer sun.

in the ground and filling it with water a pond may be made. But any old box will not answer, for, unless you are a much[49] better mechanic than the writer was at your age, you will not be able to prevent an ordinary box from leaking.

However, if you really want a back-yard fish-pond, you may make a box or tank which will hold water, and the

The Back-yard Fish Pond.

is that of a wide, flat-bottomed scow. This scow may be of any dimensions you choose to build it, but I would advise you to make your first one not more than six feet long by four feet wide, and two feet deep.

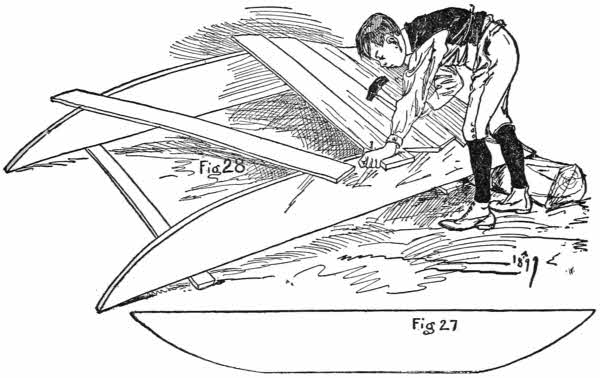

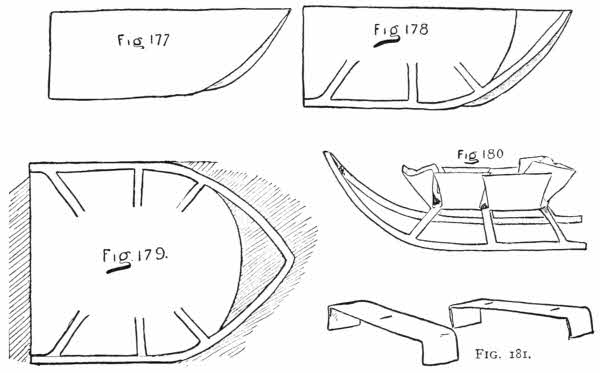

Figs. 27 and 28.—The Side-boards must be Duplicates.

In selecting lumber for the scow, pick out pieces which are comparatively free from knots or blemishes. Reserve two one-and-a-half-inch planks, and keep the half-inch boards for the bottom.

A saw, a plane, and a sharp hatchet are necessary, but[50] other tools, if not absolutely needed, should not on that account be ignored, as they may come in very handy at times.

Trim off your two side-boards to exactly the same length—say six feet; they should then be six feet by two feet. On the edge which is to be the bottom measure toward the centre from each end of each board two feet, and mark the points; then rule a line diagonally from each of these points to the corners of the boards on the upper edge; this will mark out a sort of double-ended sled-runner, as shown in the illustrations, and when you saw off the triangular pieces marked on the boards you will have

Set these runners side to side, on their long edges, and round off the angles with your plane, until the boards look like rockers (see Fig. 27). The side-boards must be exact duplicates of each other (Fig. 28).

Set the two side-pieces four feet apart and nail two or three temporary cross-pieces across their top (longest) edges to hold them in position; then turn them over and nail on the bottom-boards (Fig. 28).

You must use the greatest care in fitting the bottom-boards edge to edge, but you need not trouble yourself about the ends of the boards; allow them to project upon each side, as chance may direct. After the boards are all securely nailed to the bottom the ends may be sawed off flush with the sides of the scow (Fig. 29).

it is well to melt some tar over a fire, and, with a small mop made of rags tied to the end of a stick, paint the bottom of[51] the scow with hot tar, being careful to see that all the cracks and crevices are thoroughly filled.

Fig. 29.—The Ends may be Sawed off Flush.

you can find in the back-yard dig a hole for your tank. Make the bottom level. Set your tank in place and pack the earth well around the edges. Cover the bottom of the pond with about one inch depth of sand, and the surface of the sand with a coating of gravel; then carefully fill the tank, without disturbing the sand, and allow the water to settle; after which a few aquatic plants may be introduced and a wire fence built around the pond to keep out intruders of the two-footed and four-footed kind. If you have a few small frogs and turtles the mesh of the wire in the fence must be small.

After the water has stood for three or four days, and the aquatic plants have started to grow in their new quarters, you can stock the pond with sunfish, rock-bass, dace, small catfish, crawfish, carp, and goldfish. The two last-named are the most stupid of the fish, and the rock-bass is one of the most intelligent fish I have ever kept in captivity.

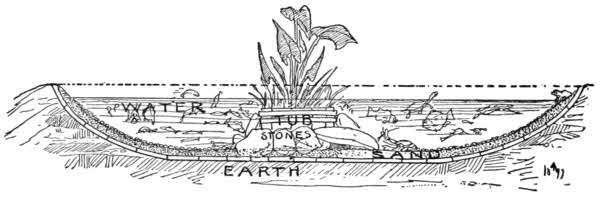

Fig. 30.—Cross-Section of Tank.

The inclined ends of the scow-shaped tank give two sloping shores (Fig. 30), which will be appreciated by the crawfish, turtles, and frogs; and if you build a little rockery in the centre the more timid fish will thank you for your thoughtfulness in providing them a safe retreat.

If it is possible for you to

do not waste your money buying stupid goldfish. The fun of hunting for other small fish, capturing them and taming them, is more than half the pay for the work, in the pleasure it will afford you. However, if you are so situated that[53] you cannot go fishing yourself, the aquarium stores in the big cities will supply you with almost any sort of aquatic creature.

or mussels will live in confinement, and a few make an interesting addition to a collection. Water-snails act as scavengers for the under-water settlement, and a handful of them may be added to form a sort of street-cleaning department. Caddice worms and the little fresh-water shrimp which you find among the water-plants make excellent food for your fish.

stones, and shells, for the salts they contain are injurious to fresh-water creatures. Do not change the water in the tank after it is in running order; but as it evaporates replenish with fresh water.

The best place in the world for boys is out-doors, breathing good fresh air, and the best place in the world for pigeons and chickens is out-doors, breathing good fresh air. Our modern environments too often limit the amount of out-door space which boys can occupy, and also limit the supply of fresh air they can furnish their pets.

In making designs for the latter we must take into consideration the limited space of a city back-yard, as well as the fact that during the extreme cold weather pigeons, chickens, and boys, all need some warm retreat where they may roost or sleep.

Indeed, chickens really

more than either boys or pigeons; the former have been known to thrive and grow lusty and strong when living like the wild animals of the forests, and every boy knows of some location where pigeons have taken up their abode with no better shelter than that afforded by an open shed, or the overhanging eaves of a house.

coming originally from tropical woods, will thrive better where their delicate combs and toes are not liable to be frost-bitten, and one is more certain not to lose his fantails,[55] pouters, ruff-necks, tumblers, and homing pigeons, if he has a suitable loft in which to confine his pets. These considerations lead to the designing of a combined pigeon-house and bantam-coop suitable for the limited space of the diminutive city back-yards, or even appropriate for the roof of a rear extension, where there is no back-yard to the dwelling.

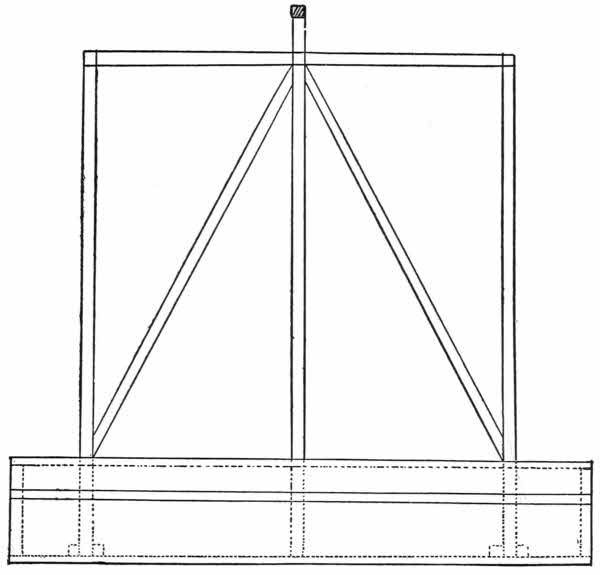

Fig. 31.—Frame of Bantam-Coop and Pigeon-Loft.

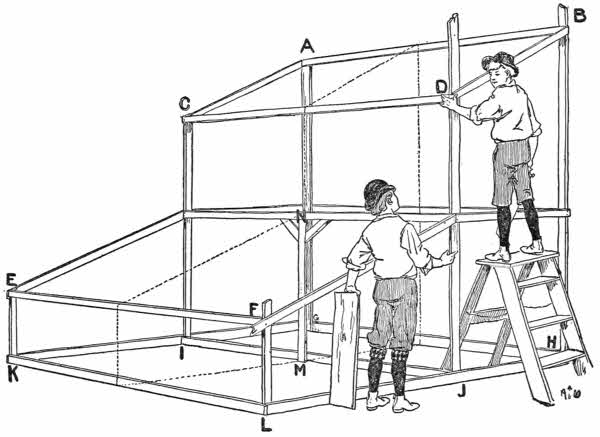

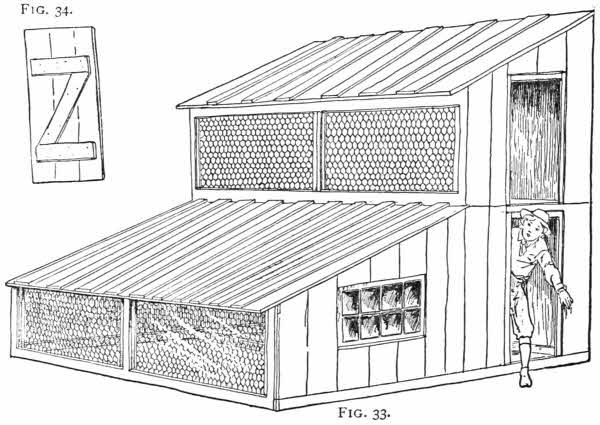

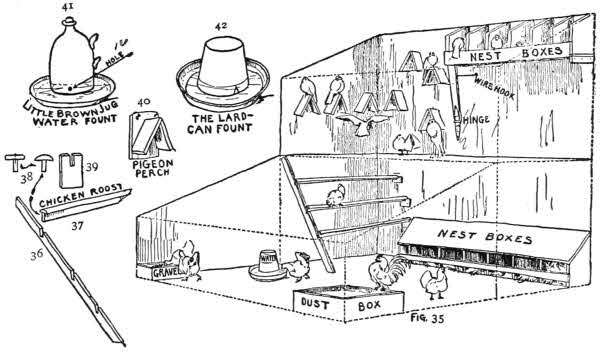

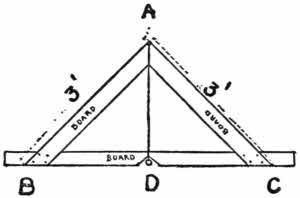

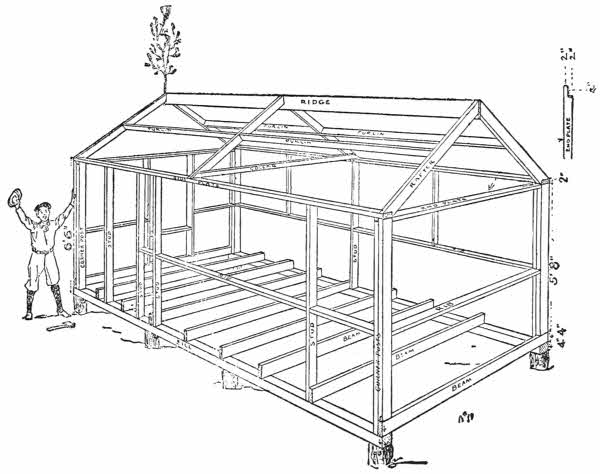

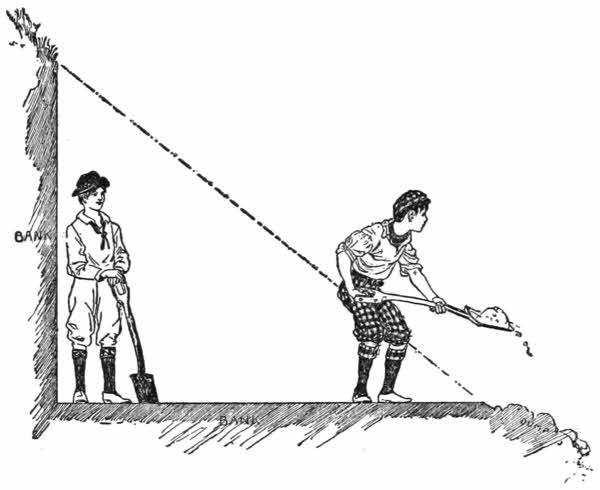

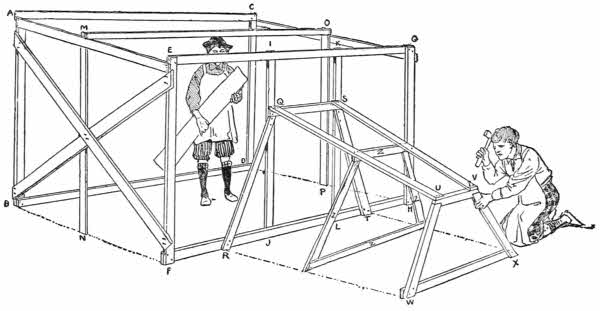

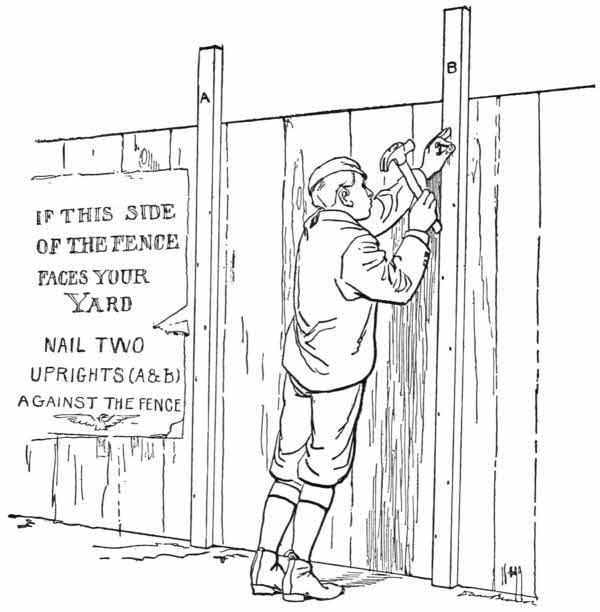

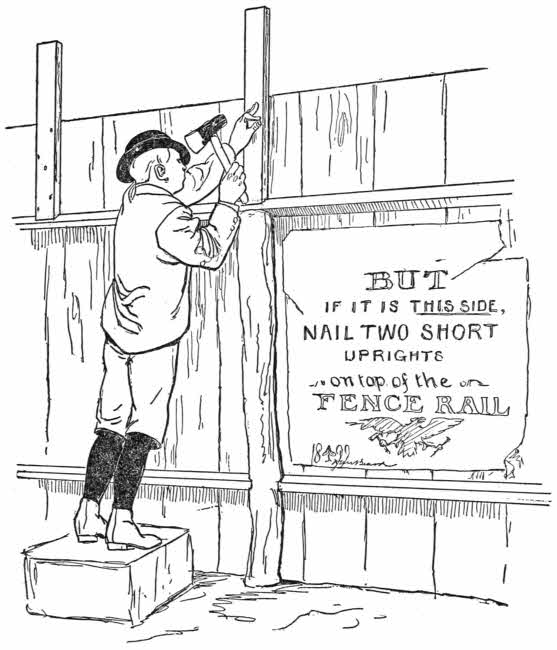

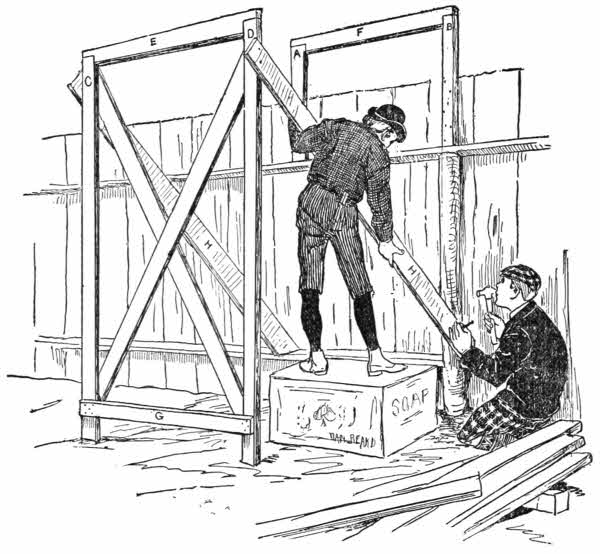

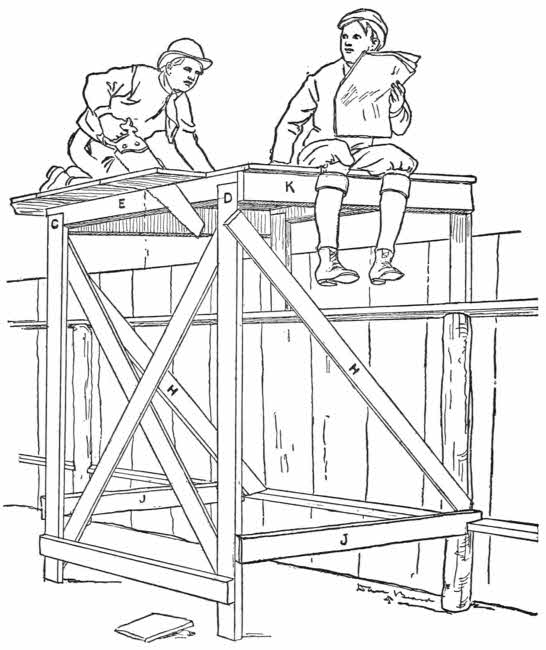

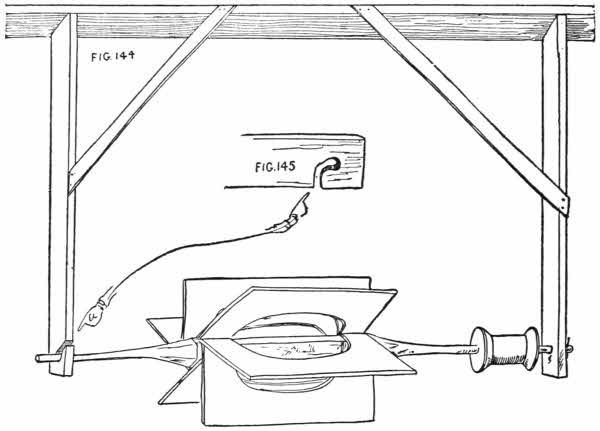

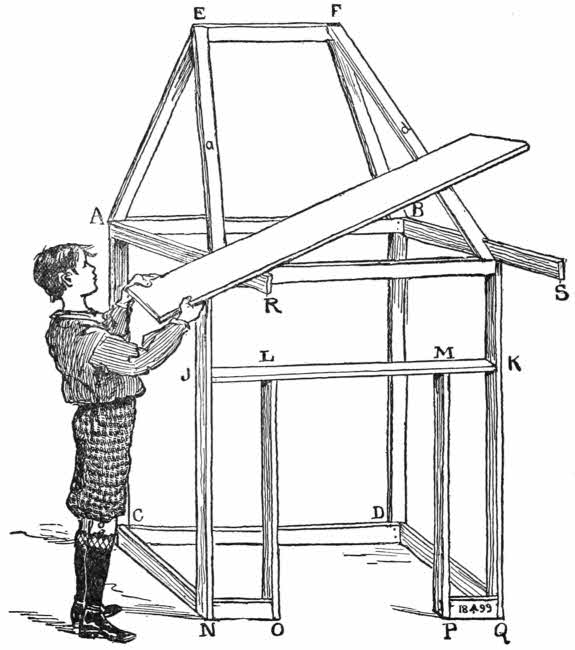

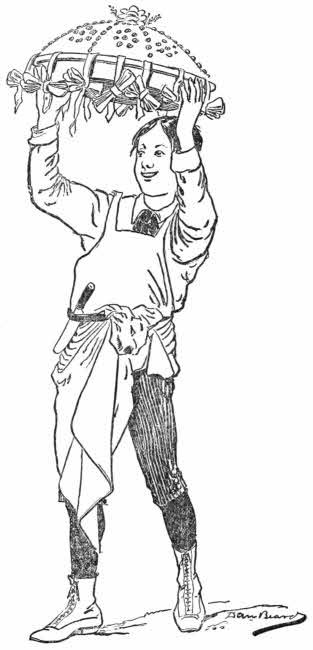

By referring to Fig. 31 you will see two boys at work upon the frame of

which is capable of holding with comfort enough pets to gladden the heart of any healthy boy.

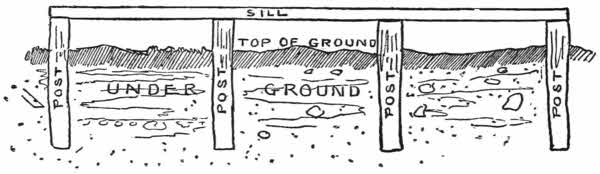

The longest posts, A G and B H, are supposed to be about nine or ten feet high and nailed fast to the back[56] fence. The dotted line, which cuts the frame in half, is to show that a building half the size of the one in the drawing will be plenty large enough for quite commodious quarters for the birds. After the frame has been nailed together and the protruding ends of the timbers all sawed off even with the rest of the frame, a floor must be laid to the pigeon-loft and securely nailed in place.

It is not even necessary to have smoothed lumber for the flooring or any part of the house, but matched and planed boards will make a much neater piece of work. The uprights and all the frame are supposed to be built of “two-by-four” (two inches thick by four inches wide), but even this is not necessary, and in the country, where trimmed lumber is scarce, the whole frame may be built of poles cut in the woods.

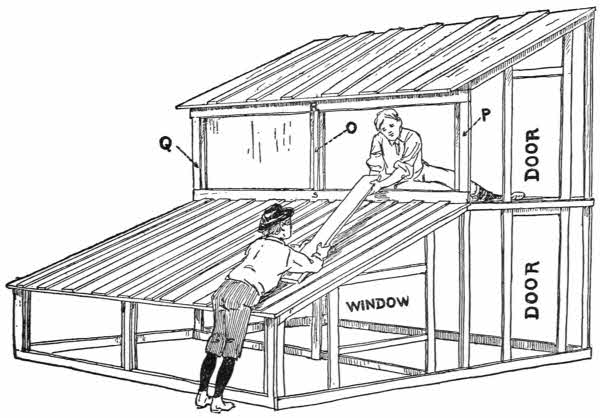

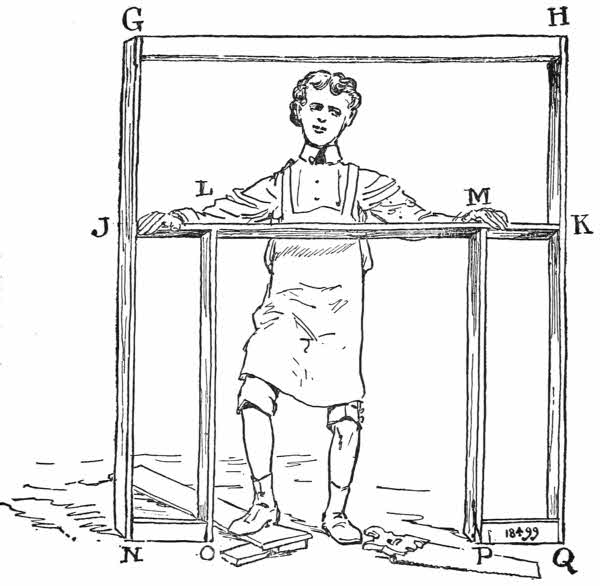

When the

is nailed down, set the door-jambs in place, between D J and B H, and the window-jambs between D J and F L, as shown by Fig. 32. Nail the jambs fast to the rest of the frame, toe-nailing the loft door-jamb to the floor of the loft, and the coop jamb to the ceiling of the coop, also the two horizontal jambs of the window-frame to the two upright jambs of the same.