*** START OF THE PROJECT GUTENBERG EBOOK 49723 ***

THE POEMS

OF

OLIVER GOLDSMITH

THE

POEMS

OF

OLIVER GOLDSMITH

THE POEMS

OF

OLIVER GOLDSMITH.

EDITED BY

ROBERT ARIS WILLMOTT,

AUTHOR OF THE “PLEASURES OF LITERATURE,” “SUMMER TIME IN THE COUNTRY,”

ETC., ETC.

A NEW EDITION,

WITH ILLUSTRATIONS BY

BIRKET FOSTER AND H. N. HUMPHREYS,

PRINTED IN COLOURS BY EDMUND EVANS.

LONDON AND NEW YORK

GEORGE ROUTLEDGE AND SONS.

1877.

EDMUND EVANS

ENGRAVER & PRINTER

ix

PREFACE

Oliver Goldsmith, the fifth child of Charles and Ann

Goldsmith, was born at Pallas, a hamlet of the parish of

Forney, county of Longford, Ireland, November 10th, 1728. His

father, the “Preacher” of the “Deserted Village,” having been

presented to the Rectory of Kilkenny-West, about the year 1730,

removed his family to Lissoy, the “Auburn” of the Poet. The

“modest mansion” is a ruin, or, by this time, has quite disappeared.

His first schoolmaster is described, by one who remembered

him, as a man “stern to view,” in whose “morning face”

the disasters of the day might be easily read. Goldsmith made

small progress under the ferule of Paddy Burns, and, after being

for some time a pupil in the diocesan school of Elphin, he

was placed with a competent teacher at Athlone, where he remained

two years. He was then transferred to the care of

Mr. Hughes, vicar of Shruel, who treated him with kindness, and

whom he always mentioned with respect and gratitude. His

eldest sister has given a specimen of her brother’s early and

ready humour. A large company of young people had assembled

in his uncle’s house, at Elphin, and Oliver, then nine years old,

was desired to dance a hornpipe, under very unfavourable circumstances,

for his figure was short and thick, and the marks of recent

small-pox were still conspicuous. A young man, who played thex

violin, compared him to Æsop dancing; but Oliver, stopping

short in the performance, immediately disabled his satirist with

a sharp epigram:—

“Our herald hath proclaim’d this saying,

See Æsop dancing, and his monkey playing.”

On the 11th of June, 1745, he was admitted a Sizar of Trinity

College, Dublin—a fact which denoted a considerable proficiency

in classical learning; but he was unfortunate in his tutor, who

deserved, and has won, the title of “Savage;” and, perhaps, the

promise of Oliver was blighted by his severity. He neglected

his studies, and was seen “perpetually lounging about the college

gates.” We find him elected, June 15th, 1747, to an Exhibition,

on the foundation of Erasmus Smith, obtaining a premium at the

Christmas examination, and, after a delay of two years, taking his

Bachelor’s degree, February 27th, 1750. His father died in 1747,

but he found a second parent in the Rev Thomas Contarine, who

was descended from a noble ancestry in Venice, and had been a

contemporary and friend of Berkeley. The relatives of the poet

now advised him to “go into orders,” and yielding to the persuasion

of Mr. Contarine, he presented himself before the Bishop

of Elphin, and was rejected. Tradition ascribes the failure to his

uncanonical costume, and the episcopal dislike of scarlet breeches.

His kind friends might now, as he afterwards wrote, be perfectly

satisfied that he was undone; but they did not abandon

him. He was enabled to proceed to Edinburgh, towards the end

of 1752, where he attended the lectures of Monro and the other

Medical Professors. Scotland did not please him. “Shall I tire

you,” he wrote to a friend, “with a description of this unfruitful

country, where I must lead you over their hills all brown with

heath, or their valleys scarcely able to feed a rabbit? Man alone

seems to be the only creature who has arrived to the natural size

in this poor soil.”

His design of completing his studies at Leyden was nearly

frustrated by an act of generous imprudence, from which two

college friends set him free. From Leyden, in the April or Mayxi

of 1754, he sent a letter to Mr. Contarine, containing an account

of his journey, and some lively sketches of the “downright Hollander,”

with lank hair, laced hat, no coat, and seven waistcoats,

the lady with her portable stove, the lugubrious Harlequin, and

the domestic interior, which reminded him of a magnificent

Egyptian temple dedicated to an ox. He remained in Leyden

nearly a year, deriving small benefit from the instruction of the

Professors, who, with the exception of Gaubius, the teacher of

Chemistry, were as indolent as himself. Meanwhile, the necessaries

of life were costly, and the attractions of the gaming-table

proved to be overpowering and ruinous. At length, having

emptied his purse, and reduced his wardrobe to a single shirt,

he boldly resolved to make the tour of Europe. This characteristic

chapter of the Poet’s history is yet to be written, if his

lost letters should ever be recovered. The interesting and

copious narrative which he communicated to Dr. Radcliff is

known to have been destroyed by fire.

He commenced his travels about February, 1755. “A good

voice,” adopting his own account of an earlier adventurer, “and

a trifling skill in music, were the only finances he had to support

an undertaking so extensive.” Thus he journeyed, and at night

sang at the doors of peasants’ houses, to get himself a lodging.

Once or twice, he “attempted to play to people of fashion,” but

they despised his performance, and never rewarded him even

with a trifle. We are told by Bishop Percy, that he reached

Padua, and visited all the northern parts of Italy, returning, on

foot, through France, and landing at Dover, about the beginning

of the war, in 1756. We may believe his own assurance, that

he fought his way homewards, examining mankind with near eyes,

and seeing both sides of the picture.

He appeared in London, without means or interest. England,

he complained, was a country, where being born an Irishman

was sufficient to keep a man unemployed. With much difficulty

he obtained the situation of usher at a school. Johnson did not

remember the occupation with a fiercer disgust; and the redolent

French teacher, papering his curls at night, was a frequentxii

spectre of his memory. A migration from the school-room to the

chemist’s shop slightly improved his condition. Better days were

coming. By the aid of an Edinburgh acquaintance, Dr. Sleigh,

and other friends, he was “set up” as a practitioner at Bankside,

Southwark, where, in his pleasant confession, he got plenty of

patients, but no fees. A physician, Dr. Farr, who had known

him in Scotland, thus describes his appearance:—“He called

upon me one morning, before I was up, and, on entering the

room, I recognized my old acquaintance, dressed in a rusty, full-trimmed

black suit, with his pockets full of papers, which instantly

reminded me of the poet in Garrick’s farce of ‘Lethe.’

On this occasion he read portions of a ‘Tragedy,’ and talked

of a journey to decipher the inscriptions on the Written Mountains.”

In later days, when writing an “Essay on the advantages

to be derived from sending a judicious traveller into Asia,”

Goldsmith professed to feel the difficulty of choosing a proper

person for such an enterprise, and indicated the qualifications

demanded:—“He should be a man of a philosophical turn, one

apt to deduce consequences of general utility from particular

occurrences—neither swollen with pride, nor hardened by prejudice—neither

wedded to one particular system, nor instructed

only in one particular science—neither wholly a botanist, nor

wholly an antiquarian; his mind should be tinctured with miscellaneous

knowledge, and his manners humanized by an intercourse

with men. He should be, in some measure, an enthusiast to

the design; fond of travelling, from a rapid imagination and an

innate love of change; furnished with a body capable of sustaining

every fatigue, and a heart not easily terrified at danger.”

With the year 1757, the prospects of Goldsmith brightened,

and the papers which filled the pockets of the rusty black coat

began to get abroad. He wrote several articles for the “Monthly

Review,” translated the “Mémoires d’un Protestant,” and composed

his “Enquiry into the Present State of Polite Learning

in Europe.” The object of the work was special. He had obtained

the appointment of physician to a factory on the coast

of Coromandel, and was providing funds for the voyage. Axiii

considerable sum was needed. The Company’s warrant cost ten

pounds, and the passage and equipment required one hundred

and thirty pounds in addition; but the emoluments were expected

to be large. The salary was one hundred pounds; the

average returns of the general practice amounted to a thousand;

there was an opening for commercial enterprise, and invested

money brought twenty per cent. These were flattering inducements;

but time deadened their charm, and he shrank from so

distant a banishment, and beginning life again at the age of

thirty-one. Eight years of anxiety and trial had done their work

on his face and temper. His picture of himself was most discouraging.

He had “contracted a hesitating, disagreeable manner

of speaking, and a visage that looked ill-nature itself.” Home

news deepened his melancholy, for his mother was almost blind.

The “Enquiry” appeared, without the Author’s name, April,

1759—a small volume, price half-a-crown; and in the autumn

of the same year, the commencement of a weekly paper, called

“The Bee,” afforded him an opportunity of showing his skill as

an Editor. His plan was to “rove from flower to flower, with

seeming inattention, but concealed choice, expatiate over all the

beauties of the season, and make his industry his amusement.”

The “Bee” expired with its eighth number, but he was more

successful in his next enterprise. To the “Public Ledger,” of

which the first number appeared January 12th, 1760, Goldsmith

contributed one hundred and twenty-three letters, which were

afterwards collected as the “Citizen of the World.”

The last day of May, 1761, was memorable in his life, as witnessing

the commencement of his intimacy with Johnson. His

miscellaneous productions in 1762–4 included a “Life of Richard

Nash, of Bath,” an “Introduction to Natural History,” an “Abridgment

of Plutarch,” a “History of England,” and the “Traveller.”

For the poem he received only twenty guineas, but the applause

of its readers was loud and unanimous. “I was glad,” said Sir

Joshua, “to hear Sir Charles Fox say it was one of the finest

poems in the English language.” A fourth edition was required

within eight months, and the Author lived to see the ninth. Inxiv

1764, he wrote the “Captivity,” for which the sum of ten guineas

was paid by Dodsley.

Poetry kept him poor, and we still see him writing for bread

in a garret, and expecting to be “dunned for a milk score.”

However, he cleared and warmed the future with the hopefulness

of his genial nature, and comforted himself by the recollection

that while Addison wrote the “Campaign” in a third storey, he

had only got to the second. Reckless improvidence multiplied

his difficulties. “Those who knew him,” he told a correspondent,

“knew his principles to differ from those of the rest of mankind,

and while none regarded the interest of his friend more, none

regarded his own less.”

Among his disappointments, at this period, are to be numbered

an unsuccessful application for a Gresham Lectureship,

and Garrick’s refusal of the “Good-Natured Man.” But Colman

put the drama on the stage, January 29th, 1768, and the Professorship

of Ancient History in the Royal Academy was agreeably

bestowed. His “Roman History,” published in 1769, was

received with favour; and in the May of 1770, the “Deserted

Village” appeared.

In that year, Gray travelled through a part of England and

South Wales, and Mr. Norton Nichols was with him at Malvern

when he received the new poem, which he desired his friend to

read to him. He listened with fixed attention, and soon exclaimed,

“This man is a Poet.” In twelve days the poem was

reprinted, and before the 5th of August the public admiration

exhausted a fifth impression. His comedy, the “Mistakes of a

Night” (represented March 15th, 1773), obtained a success, of its

kind, not inferior. Johnson said that it answered the great end

of a comedy—“making an audience merry.” For an impertinent

letter in the “London Packet,” Goldsmith caned the editor;

having found, was the remark of a friend, a new pleasure, for he

believed that it was the “first time he had beat,” though “he may

have been beaten before.”

I may add, that the Ballad of “Edwin and Angelina,” having

been privately printed for the amusement of the Countess ofxv

Northumberland, was inserted in the “Vicar of Wakefield,” when

that charming fiction first came out, March 27th, 1766, to delight

the young by its adventures, and the old by its wisdom. For

two years the manuscript had lain in the desk of the Publisher,

until the fame of the “Traveller” encouraged him to send it to the

press.

He was now engaged in the compilation of the “History of

the Earth and Animated Nature,” for which he was to receive

eight hundred guineas; and about this time, according to Percy,

he wrote “the ‘Haunch of Venison,’ ‘Retaliation,’ and some

other little sportive sallies, which were not printed until after his

death.” Mr. Peter Cunningham1 has, for the first time, related

the true story of “Retaliation,” in the original words of Garrick:—A

party of friends, at the St. James’s Coffee House, were diverting

themselves with the peculiar oddities of Goldsmith, who insisted

upon trying his epigrammatic powers with Garrick. Each was to

write the other’s epitaph. Garrick immediately spoke the following

lines:—

“Here lies Nolly Goldsmith, for shortness call’d Noll,

Who wrote like an angel, and talk’d like poor Poll.”

The company laughed, and Goldsmith grew serious; he went to

work, and some weeks after produced “Retaliation,” which was

not written in anger, but with the utmost good humour.

His path seemed now to be winding out of gloom into the

full sunlight,—but, of a sudden, there rose up in it the “Shadow

feared of man.” He was busy with projects, and had prepared

a “Prospectus of an Universal Dictionary of Arts and Science,”

when a complaint, from which he had previously suffered, returned

with extreme severity. His unskilful treatment of the disorder was

aggravated by the agitation of his mind, and he gradually sank,

until Monday, April 4th, 1774, when death released him, in the

forty-sixth year of his age. His remains were interred in the

burial-ground of the Temple; Nollekens carved his profile in

marble, and Johnson wrote a Latin inscription for the monument,xvi

which was erected in the south transept of Westminster Abbey.

The epitaph is thus given in English:—

OF OLIVER GOLDSMITH—

Poet, Naturalist, and Historian,

who left scarcely any style of writing

untouched,

and touched nothing that he did not adorn;

of all the passions,

whether smiles were to be moved,

or tears,

a powerful yet gentle master;

in genius, sublime, lively, versatile;

in style, elevated, clear, elegant—

the love of companions,

the fidelity of friends,

and the veneration of readers,

have by this monument honoured the memory.

He was born in Ireland,

at a place called Pallas,

[in the parish] of Forney, [and county] of Longford,

On the 29th Nov., 1731;2

educated at [the university of] Dublin;

and died in London,

4th April, 1774.

Goldsmith, in the judgment of a friendly, but severe observer,

always seemed to do best that which he was doing. Does he

write History? He tells shortly, and with a pleasing simplicity

of narrative, all that we want to know. Does he write Essays?

He clothes familiar wisdom with an easy and elegant diction, of

which the real difficulty is only known by those who seek to

obtain it. Does he write the story of Animated Nature? He

makes it “amusing as a Persian tale.” Does he write a Novel?

Dr. Primrose sits in our chimney-corner to celebrate his biographer.

Does he write Comedy? Laughter “holds both its

sides” at the Incendiary Letter to “Muster Croaker.” Does he

write Poetry? The big tears on the rugged face of Johnsonxvii

bear witness to its tenderness, dignity, and truth. The naturalness

of the Author pervaded the Man. Whose vanity was so transparent,

and yet so harmless? He honestly believed himself qualified

to explore Asia, and would have undertaken to read, at sight,

the Manuscripts of Mount Athos. His tailor’s bill is a commentary

on his life. But under the bloom-coloured coat beat the large

heart of a kindly and generous nature, throwing up the spontaneous

and abundant fruitfulness of charity to the needy, and

sympathy with all. Thieves had only to plunder a stranger, to

make him a neighbour. In reading Goldsmith, or reading of him,

the touch of nature changes us into his kindred, and we do not

more admire the Writer, than we love the Brother.

St. Catherine’s,

September 15th, 1858.

HERE LIES OLIVER GOLDSMITH

xviii

CONTENTS

| |

PAGE |

| The Traveller |

1 |

| The Deserted Village |

29 |

| The Hermit |

57 |

| The Captivity |

67 |

| The Haunch of Venison |

85 |

| Retaliation |

91 |

| The Double Transformation |

99 |

| The Gift to Iris |

104 |

| The Logicians Refuted |

105 |

| An Elegy on the Death of a Mad Dog |

108 |

| Threnodia Augustalis |

110 |

| A New Simile |

122 |

| On a Beautiful Youth struck Blind by Lightning |

125 |

| Stanzas on Woman |

126 |

| Translation from Scarròn |

126 |

| Stanzas on the Taking of Quebec |

127 |

| Epitaph on Edward Purdon |

128xix |

| Translation of a South American Ode |

128 |

| Epitaph on Thomas Parnell |

129 |

| Description of an Author’s Bed-chamber |

130 |

| Song, from the Comedy of “She Stoops to Conquer” |

131 |

| Answer to an Invitation to Dinner. |

133 |

| Song, intended to have been sung in “She Stoops to Conquer” |

135 |

| From the Latin of Vida |

135 |

| An Elegy on Mrs. Mary Blaize |

136 |

| Answer to an Invitation to pass the Christmas at Barton |

138 |

| On Seeing a Lady Perform a Certain Character |

141 |

| Birds |

142 |

| Prologue written and spoken by the Poet Laberius |

143 |

| Prologue to “Zobeide” |

144 |

| Epilogue to “The Sister” |

146 |

| Epilogue intended for “She Stoops to Conquer” |

148 |

| Another Intended Epilogue |

153 |

| Epilogue to “She Stoops to Conquer” |

155 |

| Epilogue to “The Good-natured Man” |

157 |

| On the Death of the Right Hon. —— |

159 |

| Epilogue Written for Mr. Charles Lee Lewes |

163 |

xx

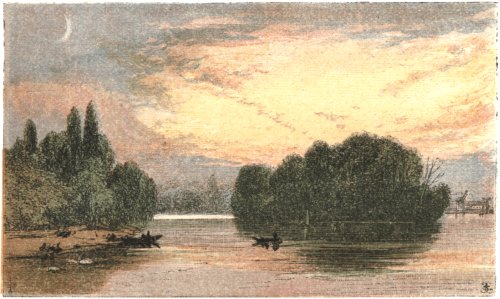

ILLUSTRATIONS

ENGRAVED BY EDMUND EVANS,

FROM DRAWINGS BY BIRKET FOSTER.

| MILL AT LISSOY (Frontispiece). |

| |

PAGE |

| GOLDSMITH’S TOMB IN THE TEMPLE CHURCHYARD |

xvii |

| THE TRAVELLER. |

| Or where Campania’s plain forsaken lies |

5 |

| Bless’d that abode, where want and pain repair |

6 |

| Even now, where Alpine solitudes ascend |

7 |

| Ye lakes, whose vessels catch the busy gale |

8 |

| The shuddering tenant of the frigid zone |

9 |

| Basks in the glare, or stems the tepid wave |

10 |

| While oft some temple’s mouldering tops between |

12 |

| In florid beauty groves and fields appear |

13 |

| A mistress or a saint in every grove |

14xxi |

| Where the bleak Swiss their stormy mansions tread |

16 |

| With patient angle trolls the finny deep |

17 |

| How often have I led thy sportive choir |

18 |

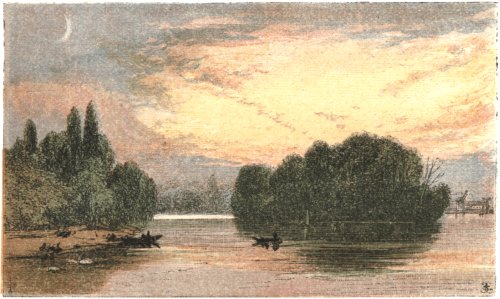

| The willow-tufted bank, the gliding sail |

21 |

| There gentle music melts on every spray |

24 |

| Where wild Oswego spreads her swamps around |

27 |

| THE DESERTED VILLAGE. |

| The never-failing brook, the busy mill |

32 |

| The shelter’d cot, the cultivated farm |

33 |

| And many a gambol frolick’d o’er the ground |

34 |

| The hollow-sounding bittern guards its nest |

35 |

| Where once the cottage stood, the hawthorn grew |

37 |

| The swain responsive as the milk-maid sung |

38 |

| And fill’d each pause the nightingale had made |

39 |

| To pick her wintry faggot from the thorn |

40 |

| The village preacher’s modest mansion rose |

41 |

| Thus to relieve the wretched was his pride |

42 |

| At church, with meek and unaffected grace |

43 |

| Low lies that house, where nut-brown draughts inspir’d |

45 |

| No more the farmer’s news, the barber’s tale |

45 |

| Space for his lake, his park’s extended bounds |

48 |

| Where the poor houseless, shivering female lies |

50 |

| Her modest looks the cottage might adorn |

51 |

| Where crouching tigers wait their hapless prey |

52 |

| The cooling brook, the grassy-vested green |

53 |

| And left a lover’s for a father’s arms |

54xxii |

| Downward they move, a melancholy band |

56 |

| THE HERMIT. |

| Then turn, to-night, and freely share whate’er my cell bestows |

58 |

| The hermit trimm’d his little fire, and cheer’d his pensive guest |

61 |

| And when, beside me in the dale; he caroll’d lays of love |

64 |

| THE CAPTIVITY. |

| Ye hills of Lebanon, with cedars crown’d |

69 |

| Fierce is the tempest rolling along the furrow’d main |

74 |

| As panting flies the hunted hind, where brooks refreshing stray |

80 |

| O Babylon! how art thou fall’n |

83 |

| THE HAUNCH OF VENISON |

90 |

| THE DOUBLE TRANSFORMATION |

102 |

| AN ELEGY ON THE DEATH OF A MAD DOG |

109 |

| THRENODIA AUGUSTALIS |

116 |

| ON A BEAUTIFUL YOUTH STRUCK BLIND BY LIGHTNING |

125 |

| SONG—“THE THREE PIGEONS” |

130 |

| BIRDS |

142 |

| EPILOGUE WRITTEN FOR MR. CHARLES LEE LEWES |

162 |

The Ornamental Illustrations designed by H. Noel Humphreys1

3

THE TRAVELLER

DEDICATION.

TO THE REV. HENRY GOLDSMITH.

Dear Sir,

I am sensible that the friendship between us can acquire no

new force from the ceremonies of a dedication; and perhaps it demands an

excuse thus to prefix your name to my attempts, which you decline giving

with your own. But as a part of this poem was formerly written to you

from Switzerland, the whole can now, with propriety, be only inscribed

to you. It will also throw a light upon many parts of it, when the reader

understands that it is addressed to a man who, despising fame and fortune,

has retired early to happiness and obscurity with an income of forty pounds

a year.

I now perceive, my dear brother, the wisdom of your humble choice.

You have entered upon a sacred office, where the harvest is great, and the

labourers are but few; while you have left the field of ambition, where the

labourers are many, and the harvest not worth carrying away. But of all

kinds of ambition—what from the refinement of the times, from different

systems of criticism, and from the divisions of party—that which pursues

poetical fame is the wildest.

Poetry makes a principal amusement among unpolished nations; but in

a country verging to the extremes of refinement, Painting and Music come

in for a share. As these offer the feeble mind a less laborious entertainment,

they at first rival Poetry, and at length supplant her: they engross all

that favour once shown to her; and, though but younger sisters, seize upon

the elder’s birthright.

Yet, however this art may be neglected by the powerful, it is still in

greater danger from the mistaken efforts of the learned to improve it. What4

criticisms have we not heard of late in favour of blank verse and pindaric

odes, choruses, anapests, and iambics, alliterative care and happy negligence!

Every absurdity has now a champion to defend it; and as he is

generally much in the wrong, so he has always much to say—for error is

ever talkative.

But there is an enemy to this art still more dangerous; I mean party.

Party entirely distorts the judgment and destroys the taste. When the mind

is once infected with this disease, it can only find pleasure in what contributes

to increase the distemper. Like the tiger, that seldom desists from

pursuing man after having once preyed upon human flesh, the reader who

has once gratified his appetite with calumny, makes ever after the most agreeable

feast upon murdered reputation. Such readers generally admire some

half-witted thing, who wants to be thought a bold man, having lost the

character of a wise one. Him they dignify with the name of poet: his

tawdry lampoons are called satires; his turbulence is said to be force, and

his frenzy fire.

What reception a poem may find, which has neither abuse, party, nor

blank verse to support it, I cannot tell; nor am I solicitous to know. My

aims are right. Without espousing the cause of any party, I have attempted

to moderate the rage of all. I have endeavoured to show that there may be

equal happiness in states that are differently governed from our own; that

every state has a particular principle of happiness; and that this principle in

each may be carried to a mischievous excess. There are few can judge better

than yourself how far these positions are illustrated in this poem.

I am, dear Sir,

Your most affectionate brother,

Oliver Goldsmith.

5

THE TRAVELLER

Remote, unfriended, melancholy, slow—

Or by the lazy Scheldt, or wandering Po,

Or onward where the rude Carinthian boor

Against the houseless stranger shuts the door,

6

Or where Campania’s plain forsaken lies,

A weary waste expanding to the skies—

Where’er I roam, whatever realms to see,

My heart, untravell’d, fondly turns to thee;

Still to my brother turns, with ceaseless pain,

And drags at each remove a lengthening chain.

Eternal blessings crown my earliest friend,

And round his dwelling guardian saints attend:

Bless’d be that spot, where cheerful guests retire

To pause from toil, and trim their evening fire;

Bless’d that abode, where want and pain repair,

And every stranger finds a ready chair;

Bless’d be those feasts, with simple plenty crown’d,

Where all the ruddy family around

Laugh at the jests or pranks that never fail,

Or sigh with pity at some mournful tale,

Or press the bashful stranger to his food,

And learn the luxury of doing good.

7

But me, not destin’d such delights to share,

My prime of life in wandering spent and care,

Impell’d with steps unceasing to pursue

Some fleeting good that mocks me with the view,

That, like the circle bounding earth and skies,

Allures from far, yet, as I follow, flies—

My fortune leads to traverse realms alone,

And find no spot of all the world my own.

Even now, where Alpine solitudes ascend,

I sit me down a pensive hour to spend;

And plac’d on high, above the storms career,

Look downward where an hundred realms appear—

8

Lakes, forests, cities, plains extending wide,

The pomp of kings, the shepherd’s humbler pride.

When thus Creation’s charms around combine,

Amidst the store should thankless pride repine?

Say, should the philosophic mind disdain

That good which makes each humbler bosom vain?

Let school-taught pride dissemble all it can,

These little things are great to little man;

And wiser he whose sympathetic mind

Exults in all the good of all mankind.

Ye glittering towns with wealth and splendour crown’d,

Ye fields where summer spreads profusion round,

9

Ye lakes whose vessels catch the busy gale,

Ye bending swains that dress the flowery vale—

For me your tributary stores combine;

Creation’s heir, the world, the world is mine!

As some lone miser, visiting his store,

Bends at his treasure, counts, recounts it o’er—

Hoards after hoards his rising raptures fill,

Yet still he sighs, for hoards are wanting still—

Thus to my breast alternate passions rise,

Pleas’d with each good that Heaven to man supplies;

Yet oft a sigh prevails, and sorrows fall,

To see the hoard of human bliss so small;

And oft I wish, amidst the scene, to find

Some spot to real happiness consign’d,

Where my worn soul, each wandering hope at rest,

May gather bliss to see my fellows blest.

But where to find that happiest spot below,

Who can direct, when all pretend to know?

10

The shuddering tenant of the frigid zone

Boldly proclaims that happiest spot his own,

Extols the treasures of his stormy seas,

And his long nights of revelry and ease;

The naked negro, panting at the line,

Boasts of his golden sands and palmy wine,

Basks in the glare, or stems the tepid wave,

And thanks his gods for all the good they gave.

Such is the patriot’s boast, where’er we roam,

His first, best country ever is at home;

And yet, perhaps, if countries we compare,

And estimate the blessings which they share,

Though patriots flatter, still shall wisdom find

An equal portion dealt to all mankind—

As different good, by art or nature given

To different nations, makes their blessings even.

11

Nature, a mother kind alike to all,

Still grants her bliss at labour’s earnest call:

With food as well the peasant is supplied

On Idria’s cliffs as Arno’s shelvy side;

And, though the rocky-crested summits frown,

These rocks, by custom, turn to beds of down.

From art, more various are the blessings sent—

Wealth, commerce, honour, liberty, content;

Yet these each other’s power so strong contest,

That either seems destructive of the rest:

Where wealth and freedom reign, contentment fails,

And honour sinks where commerce long prevails.

Hence every state, to one lov’d blessing prone,

Conforms and models life to that alone;

Each to the favourite happiness attends,

And spurns the plan that aims at other ends—

Till, carried to excess in each domain,

This favourite good begets peculiar pain.

But let us try these truths with closer eyes,

And trace them through the prospect as it lies:

Here, for a while my proper cares resign’d,

Here let me sit in sorrow for mankind;

Like yon neglected shrub, at random cast,

That shades the steep, and sighs at every blast.

Far to the right, where Apennine ascends,

Bright as the summer, Italy extends:

Its uplands sloping deck the mountain’s side.

Woods over woods in gay theatric pride,

12

While oft some temple’s mouldering tops between

With venerable grandeur mark the scene.

Could Nature’s bounty satisfy the breast,

The sons of Italy were surely bless’d.

Whatever fruits in different climes are found,

That proudly rise, or humbly court the ground—

Whatever blooms in torrid tracts appear,

Whose bright succession decks the varied year—

Whatever sweets salute the northern sky,

With vernal lives, that blossom but to die—

13

These, here disporting, own the kindred soil,

Nor ask luxuriance from the planter’s toil;

While sea-born gales their gelid wings expand,

To winnow fragrance round the smiling land.

But small the bliss that sense alone bestows,

And sensual bliss is all the nation knows;

In florid beauty groves and fields appear—

Man seems the only growth that dwindles here!

Contrasted faults through all his manners reign;

Though poor, luxurious; though submissive, vain

Though grave, yet trifling; zealous, yet untrue—

And even in penance planning sins anew.

14

All evils here contaminate the mind,

That opulence departed leaves behind;

For wealth was theirs—nor far remov’d the date

When commerce proudly flourish’d through the state,

At her command the palace learn’d to rise,

Again the long-fall’n column sought the skies,

The canvas glow’d beyond even nature warm,

The pregnant quarry teem’d with human form;

Till, more unsteady than the southern gale,

Commerce on other shores display’d her sail,

While nought remain’d of all that riches gave,

But towns unmann’d, and lords without a slave—

15

And late the nation found, with fruitless skill,

Its former strength was but plethoric ill.

Yet, still the loss of wealth is here supplied

By arts, the splendid wrecks of former pride:

From these the feeble heart and long-fall’n mind

An easy compensation seem to find.

Here may be seen, in bloodless pomp array’d,

The pasteboard triumph and the cavalcade;

Processions form’d for piety and love—

A mistress or a saint in every grove:

By sports like these are all their cares beguil’d;

The sports of children satisfy the child.

Each nobler aim, repress’d by long control,

Now sinks at last, or feebly mans the soul;

While low delights, succeeding fast behind,

In happier meanness occupy the mind.

As in those domes, where Cæsars once bore sway,

Defac’d by time and tottering in decay,

There in the ruin, heedless of the dead,

The shelter-seeking peasant builds his shed;

And, wondering man could want the larger pile,

Exults, and owns his cottage with a smile.

My soul, turn from them, turn we to survey

Where rougher climes a nobler race display—

Where the bleak Swiss their stormy mansions tread,

And force a churlish soil for scanty bread.

No product here the barren hills afford,

But man and steel, the soldier and his sword;

16

No vernal blooms their torpid rocks array,

But winter lingering chills the lap of May;

No zephyr fondly sues the mountain’s breast,

But meteors glare, and stormy glooms invest.

Yet still, even here, content can spread a charm,

Redress the clime, and all its rage disarm.

Though poor the peasant’s hut, his feasts though small,

He sees his little lot the lot of all;

Sees no contiguous palace rear its head,

To shame the meanness of his humble shed—

No costly lord the sumptuous banquet deal,

To make him loathe his vegetable meal—

But calm, and bred in ignorance and toil,

Each wish contracting, fits him to the soil.

17

Cheerful at morn, he wakes from short repose,

Breasts the keen air, and carols as he goes;

With patient angle trolls the finny deep;

Or drives his venturous ploughshare to the steep;

Or seeks the den where snow-tracks mark the way,

And drags the struggling savage into day.

At night returning, every labour sped,

He sits him down the monarch of a shed;

Smiles by his cheerful fire, and round surveys

His children’s looks, that brighten at the blaze—

While his lov’d partner, boastful of her hoard,

Displays her cleanly platter on the board:

And haply too some pilgrim, thither led,

With many a tale repays the nightly bed.

Thus every good his native wilds impart

Imprints the patriot passion on his heart;

And even those ills, that round his mansion rise,

Enhance the bliss his scanty fund supplies:

18

Dear is that shed to which his soul conforms,

And dear that hill which lifts him to the storms;

And as a child, when scaring sounds molest,

Clings close and closer to the mother’s breast—

So the loud torrent and the whirlwind’s roar

But bind him to his native mountains more.

Such are the charms to barren states assign’d—

Their wants but few, their wishes all confin’d;

Yet let them only share the praises due,

If few their wants, their pleasures are but few;

For every want that stimulates the breast

Becomes a source of pleasure when redress’d.

Whence from such lands each pleasing science flies,

That first excites desire, and then supplies;

Unknown to them, when sensual pleasures cloy,

To fill the languid pause with finer joy;

Unknown those powers that raise the soul to flame,

Catch every nerve, and vibrate through the frame:

19

Their level life is but a smouldering fire,

Unquench’d by want, unfann’d by strong desire;

Unfit for raptures, or, if raptures cheer,

On some high festival of once a year,

In wild excess the vulgar breast takes fire,

Till, buried in debauch, the bliss expire.

But not their joys alone thus coarsely flow—

Their morals, like their pleasures, are but low;

For, as refinement stops, from sire to son

Unalter’d, unimprov’d, the manners run—

And love’s and friendship’s finely pointed dart

Fall blunted from each indurated heart.

Some sterner virtues o’er the mountain’s breast

May sit, like falcons cowering on the nest;

But all the gentler morals, such as play

Through life’s more cultur’d walks, and charm the way—

These, far dispers’d, on timorous pinions fly,

To sport and flutter in a kinder sky.

To kinder skies, where gentler manners reign,

I turn; and France displays her bright domain.

Gay sprightly land of mirth and social ease,

Pleas’d with thyself, whom all the world can please—

How often have I led thy sportive choir,

With tuneless pipe, beside the murmuring Loire,

Where shading elms along the margin grew,

And, freshen’d from the wave, the zephyr flew!

And haply, though my harsh touch, faltering still,

But mock’d all tune, and marr’d the dancers’ skill—

20

Yet would the village praise my wondrous power,

And dance, forgetful of the noontide hour.

Alike all ages: dames of ancient days

Have led their children through the mirthful maze;

And the gay grandsire, skill’d in gestic lore,

Has frisk’d beneath the burden of threescore.

So bless’d a life these thoughtless realms display;

Thus idly busy rolls their world away.

Theirs are those arts that mind to mind endear,

For honour forms the social temper here:

Honour, that praise which real merit gains,

Or even imaginary worth obtains,

Here passes current—paid from hand to hand,

It shifts, in splendid traffic, round the land;

From courts to camps, to cottages it strays,

And all are taught an avarice of praise—

They please, are pleas’d, they give to get esteem,

Till, seeming bless’d, they grow to what they seem.

But while this softer art their bliss supplies,

It gives their follies also room to rise;

For praise too dearly lov’d, or warmly sought,

Enfeebles all internal strength of thought—

And the weak soul, within itself unbless’d,

Leans for all pleasure on another’s breast.

Hence ostentation here, with tawdry art,

Pants for the vulgar praise which fools impart;

Here vanity assumes her pert grimace,

And trims her robes of frieze with copper lace;

21

Here beggar pride defrauds her daily cheer,

To boast one splendid banquet once a year:

The mind still turns where shifting fashion draws,

Nor weighs the solid worth of self-applause.

To men of other minds my fancy flies,

Embosom’d in the deep where Holland lies.

Methinks her patient sons before me stand,

Where the broad ocean leans against the land;

And, sedulous to stop the coming tide,

Lift the tall rampire’s artificial pride.

22

Onward, methinks, and diligently slow,

The firm connected bulwark seems to grow,

Spreads its long arms amidst the watery roar,

Scoops out an empire, and usurps the shore—

While the pent ocean, rising o’er the pile,

Sees an amphibious world beneath him smile;

The slow canal, the yellow-blossom’d vale,

The willow-tufted bank, the gliding sail,

The crowded mart, the cultivated plain—

A new creation rescued from his reign.

Thus, while around the wave-subjected soil

Impels the native to repeated toil,

Industrious habits in each bosom reign,

And industry begets a love of gain.

Hence all the good from opulence that springs,

With all those ills superfluous treasure brings,

Are here display’d. Their much-lov’d wealth imparts

Convenience, plenty, elegance, and arts;

But view them closer, craft and fraud appear—

Even liberty itself is barter’d here.

At gold’s superior charms all freedom flies;

The needy sell it, and the rich man buys:

A land of tyrants, and a den of slaves,

Here wretches seek dishonourable graves;

And, calmly bent, to servitude conform,

Dull as their lakes that slumber in the storm.

Heavens! how unlike their Belgic sires of old—

Rough, poor, content, ungovernably bold,

23

War in each breast, and freedom on each brow;

How much unlike the sons of Britain now!

Fir’d at the sound, my genius spreads her wing,

And flies where Britain courts the western spring;

Where lawns extend that scorn Arcadian pride,

And brighter streams than fam’d Hydaspes glide.

There, all around, the gentlest breezes stray;

There gentle music melts on every spray;

Creation’s mildest charms are there combin’d;

Extremes are only in the master’s mind.

Stern o’er each bosom reason holds her state,

With daring aims irregularly great.

Pride in their port, defiance in their eye,

I see the lords of human kind pass by,

Intent on high designs—a thoughtful band,

By forms unfashion’d, fresh from Nature’s hand,

Fierce in their native hardiness of soul,

True to imagin’d right, above control;

While even the peasant boasts these rights to scan,

And learns to venerate himself as man.

Thine, freedom, thine the blessings pictur’d here;

Thine are those charms that dazzle and endear;

Too bless’d indeed were such without alloy,

But, foster’d even by freedom, ills annoy.

That independence Britons prize too high

Keeps man from man, and breaks the social tie:

The self-dependent lordlings stand alone—

All claims that bind and sweeten life unknown.

24

Here, by the bonds of nature feebly held,

Minds combat minds, repelling and repell’d;

Ferments arise, imprison’d factions roar,

Repress’d ambition struggles round her shore—

Till, over-wrought, the general system feels

Its motions stopp’d, or frenzy fire the wheels.

Nor this the worst. As nature’s ties decay,

As duty, love, and honour fail to sway,

Fictitious bonds, the bonds of wealth and law,

Still gather strength, and force unwilling awe.

Hence all obedience bows to these alone,

And talent sinks, and merit weeps unknown;

Till time may come, when stripp’d of all her charms,

The land of scholars, and the nurse of arms—

Where noble stems transmit the patriot flame,

Where kings have toil’d, and poets wrote for fame—

25

One sink of level avarice shall lie,

And scholars, soldiers, kings, unhonour’d die.

Yet think not, thus when freedom’s ills I state,

I mean to flatter kings, or court the great.

Ye powers of truth, that bid my soul aspire,

Far from my bosom drive the low desire;

And thou, fair freedom, taught alike to feel

The rabble’s rage, and tyrant’s angry steel—

Thou transitory flower, alike undone

By proud contempt, or favour’s fostering sun—

Still may thy blooms the changeful clime endure!

I only would repress them to secure;

For just experience tells, in every soil,

That those who think must govern those that toil—

And all that freedom’s highest aims can reach

Is but to lay proportion’d loads on each:

Hence, should one order disproportion’d grow,

Its double weight must ruin all below.

Oh, then, how blind to all that truth requires,

Who think it freedom when a part aspires!

Calm is my soul, nor apt to rise in arms,

Except when fast-approaching danger warms;

But, when contending chiefs blockade the throne,

Contracting regal power, to stretch their own—

When I behold a factious band agree

To call it freedom when themselves are free—

Each wanton judge new penal statutes draw,

Laws grind the poor, and rich men rule the law—

26

The wealth of climes, where savage nations roam,

Pillag’d from slaves, to purchase slaves at home—

Fear, pity, justice, indignation start,

Tear off reserve, and bare my swelling heart;

Till, half a patriot, half a coward grown,

I fly from petty tyrants to the throne.

Yes, brother! curse with me that baleful hour,

When first ambition struck at regal power;

And thus, polluting honour in its source,

Gave wealth to sway the mind with double force.

Have we not seen, round Britain’s peopled shore,

Her useful sons exchang’d for useless ore?

Seen all her triumphs but destruction haste,

Like flaring tapers, brightening as they waste?

Seen opulence, her grandeur to maintain,

Lead stern depopulation in her train—

And over fields, where scatter’d hamlets rose,

In barren solitary pomp repose?

Have we not seen, at pleasure’s lordly call,

The smiling long-frequented village fall?—

Beheld the duteous son, the sire decay’d,

The modest matron, and the blushing maid,

Forc’d from their homes, a melancholy train,

To traverse climes beyond the western main—

Where wild Oswego spreads her swamps around,3

And Niagara stuns with thundering sound?

27

Even now, perhaps, as there some pilgrim strays

Through tangled forests, and through dangerous ways,

Where beasts with man divided empire claim,

And the brown Indian marks with murderous aim—

There, while above the giddy tempest flies,

And all around distressful yells arise—

The pensive exile, bending with his woe,

To stop too fearful, and too faint to go,

Casts a long look where England’s glories shine,

And bids his bosom sympathize with mine.

Vain, very vain, my weary search to find

That bliss which only centres in the mind.

Why have I stray’d from pleasure and repose,

To seek a good each government bestows?

In every government, though terrors reign,

Though tyrant-kings or tyrant-laws restrain,

How small, of all that human hearts endure,

That part which laws or kings can cause or cure!

Still to ourselves in every place consign’d,

Our own felicity we make or find:

28

With secret course, which no loud storms annoy,

Glides the smooth current of domestic joy;

The lifted axe, the agonizing wheel,

Zeck’s iron crown, and Damiens’ bed of steel,4

To men remote from power but rarely known—

Leave reason, faith, and conscience, all our own.

29

THE DESERTED VILLAGE

30

DEDICATION.

TO SIR JOSHUA REYNOLDS.

Dear Sir,

I can have no expectation, in an address of this kind, either

to add to your reputation or to establish my own. You can gain nothing

from my admiration, as I am ignorant of that art in which you are said

to excel; and I may lose much by the severity of your judgment, as few

have a juster taste in poetry than you. Setting interest therefore aside,

to which I never paid much attention, I must be indulged at present in

following my affections. The only dedication I ever made was to my

brother, because I loved him better than most other men. He is since

dead. Permit me to inscribe this poem to you.

How far you may be pleased with the versification and mere mechanical

parts of this attempt, I do not pretend to inquire: but I know you will

object—and indeed several of our best and wisest friends concur in the

opinion—that the depopulation it deplores is nowhere to be seen, and the

disorders it laments are only to be found in the poet’s own imagination.

To this I can scarce make any other answer, than that I sincerely believe

what I have written; that I have taken all possible pains in my country

excursions, for these four or five years past, to be certain of what I allege;

and that all my views and inquiries have led me to believe those miseries

real, which I here attempt to display. But this is not the place to enter

into an inquiry, whether the country be depopulating or not; the discussion

would take up much room, and I should prove myself, at best, but an indifferent

politician to tire the reader with a long preface, when I want his

unfatigued attention to a long poem.

31

In regretting the depopulation of the country, I inveigh against the

increase of our luxuries; and here also I expect the shout of modern politicians

against me. For twenty or thirty years past, it has been the fashion

to consider luxury as one of the greatest national advantages, and all the

wisdom of antiquity, in that particular, as erroneous. Still, however, I must

remain a professed ancient on that head, and continue to think those luxuries

prejudicial to states, by which so many vices are introduced, and so many

kingdoms have been undone. Indeed, so much has been poured out of late

on the other side of the question, that, merely for the sake of novelty and

variety, one would sometimes wish to be in the right.

I am, dear Sir,

Your sincere friend and ardent admirer,

Oliver Goldsmith.

32

THE DESERTED VILLAGE

Sweet Auburn! loveliest village of the plain,

Where health and plenty cheer’d the labouring swain,

Where smiling spring its earliest visit paid,

And parting summer’s lingering blooms delay’d—

33

Dear lovely bowers of innocence and ease,

Seats of my youth, when every sport could please—

How often have I loiter’d o’er thy green,

Where humble happiness endear’d each scene;

How often have I paus’d on every charm—

The shelter’d cot, the cultivated farm,

The never-failing brook, the busy mill,

The decent church that topp’d the neighbouring hill,

The hawthorn-bush, with seats beneath the shade,

For talking age and whispering lovers made;

How often have I bless’d the coming day,

When toil remitting lent its turn to play,

And all the village train, from labour free,

Led up their sports beneath the spreading tree—

While many a pastime circled in the shade,

The young contending as the old survey’d,

34

And many a gambol frolick’d o’er the ground,

And sleights of art and feats of strength went round:

And still, as each repeated pleasure tir’d,

Succeeding sports the mirthful band inspir’d—

The dancing pair, that simply sought renown

By holding out to tire each other down,

The swain mistrustless of his smutted face,

While secret laughter titter’d round the place,

The bashful virgin’s side-long looks of love,

The matron’s glance that would those looks reprove.

These were thy charms, sweet village! sports like these,

With sweet succession, taught even toil to please;

35

These round thy bowers their cheerful influence shed,

These were thy charms—but all these charms are fled.

Sweet smiling village, loveliest of the lawn,

Thy sports are fled, and all thy charms withdrawn;

Amidst thy bowers the tyrant’s hand is seen,

And desolation saddens all thy green;

One only master grasps the whole domain,

And half a tillage stints thy smiling plain.

No more thy glassy brook reflects the day,

But chok’d with sedges works its weedy way;

Along thy glades, a solitary guest,

The hollow-sounding bittern guards its nest;

Amidst thy desert walks the lapwing flies,

And tires their echoes with unvaried cries;

Sunk are thy bowers in shapeless ruin all,

And the long grass o’ertops the mouldering wall;

And, trembling, shrinking from the spoiler’s hand,

Far, far away thy children leave the land.

36

Ill fares the land, to hastening ills a prey,

Where wealth accumulates, and men decay:

Princes and lords may flourish, or may fade—

A breath can make them, as a breath has made;

But a bold peasantry, their country’s pride,

When once destroy’d, can never be supplied.

A time there was, ere England’s griefs began,

When every rood of ground maintain’d its man:

For him light labour spread her wholesome store,

Just gave what life requir’d, but gave no more;

His best companions, innocence and health,

And his best riches, ignorance of wealth.

But times are alter’d; trade’s unfeeling train

Usurp the land, and dispossess the swain:

Along the lawn, where scatter’d hamlets rose,

Unwieldy wealth and cumbrous pomp repose;

And every want to luxury allied,

And every pang that folly pays to pride.

Those gentle hours that plenty bade to bloom,

Those calm desires that ask’d but little room,

Those healthful sports that grac’d the peaceful scene,

Liv’d in each look, and brighten’d all the green—

These, far departing, seek a kinder shore,

And rural mirth and manners are no more.

Sweet Auburn! parent of the blissful hour,

Thy glades forlorn confess the tyrant’s power.

Here, as I take my solitary rounds,

Amidst thy tangling walks and ruin’d grounds,

37

And, many a year elaps’d, return to view

Where once the cottage stood, the hawthorn grew—

Remembrance wakes with all her busy train,

Swells at my breast, and turns the past to pain.

In all my wanderings round this world of care,

In all my griefs—and God has given my share—

I still had hopes, my latest hours to crown,

Amidst these humble bowers to lay me down;

To husband out life’s taper at the close,

And keep the flame from wasting, by repose.

I still had hopes, for pride attends us still,

Amidst the swains to show my book-learn’d skill—

Around my fire an evening group to draw,

And tell of all I felt, and all I saw;

And as an hare, whom hounds and horns pursue,

Pants to the place from whence at first she flew,

38

I still had hopes, my long vexations past,

Here to return—and die at home at last.

O bless’d retirement, friend to life’s decline,

Retreats from care, that never must be mine!

How happy he who crowns, in shades like these,

A youth of labour with an age of ease;

Who quits a world where strong temptations try,

And, since ’tis hard to combat, learns to fly.

For him no wretches, born to work and weep,

Explore the mine, or tempt the dangerous deep;

39

No surly porter stands, in guilty state,

To spurn imploring famine from the gate;

But on he moves, to meet his latter end,

Angels around befriending virtue’s friend—

Bends to the grave with unperceiv’d decay,

While resignation gently slopes the way—

And, all his prospects brightening to the last,

His heaven commences ere the world be past.

Sweet was the sound, when oft at evening’s close

Up yonder hill the village murmur rose.

There as I pass’d, with careless steps and slow,

The mingled notes came soften’d from below;

The swain responsive as the milk-maid sung,

The sober herd that low’d to meet their young,

The noisy geese that gabbled o’er the pool,

The playful children just let loose from school,

The watch-dog’s voice, that bay’d the whispering wind,

And the loud laugh that spoke the vacant mind—

These all in sweet confusion sought the shade,

And fill’d each pause the nightingale had made.

40

But now the sounds of population fail,

No cheerful murmurs fluctuate in the gale,

No busy steps the grass-grown footway tread,

For all the bloomy flush of life is fled—

All but yon widow’d, solitary thing,

That feebly bends beside the plashy spring;

She, wretched matron, forc’d in age, for bread,

To strip the brook with mantling cresses spread,

To pick her wintry faggot from the thorn,

To seek her nightly shed, and weep till morn—

41

She only left of all the harmless train,

The sad historian of the pensive plain!

Near yonder copse, where once the garden smil’d,

And still where many a garden flower grows wild,

There, where a few torn shrubs the place disclose,

The village preacher’s modest mansion rose.

A man he was to all the country dear,

And passing rich with forty pounds a year.

Remote from towns he ran his godly race,

Nor e’er had chang’d, nor wish’d to change, his place;

Unpractis’d he to fawn, or seek for power

By doctrines fashion’d to the varying hour;

Far other aims his heart had learn’d to prize—

More skill’d to raise the wretched than to rise.

His house was known to all the vagrant train;

He chid their wanderings, but reliev’d their pain;

The long-remember’d beggar was his guest,

Whose beard descending swept his aged breast;

The ruin’d spendthrift, now no longer proud,

Claim’d kindred there, and had his claim allow’d;

42

The broken soldier, kindly bade to stay,

Sat by his fire, and talk’d the night away—

Wept o’er his wounds, or, tales of sorrow done,

Shoulder’d his crutch, and show’d how fields were won.

Pleas’d with his guests, the good man learn’d to glow,

And quite forgot their vices in their woe;

Careless their merits or their faults to scan,

His pity gave ere charity began.

Thus to relieve the wretched was his pride,

And even his failings lean’d to virtue’s side—

But in his duty, prompt at every call,

He watch’d and wept, he pray’d and felt for all;

And, as a bird each fond endearment tries,

To tempt its new-fledg’d offspring to the skies,

He tried each art, reproved each dull delay,

Allur’d to brighter worlds, and led the way.

43

Beside the bed where parting life was laid,

And sorrow, guilt, and pain by turns dismay’d,

The reverend champion stood: at his control

Despair and anguish fled the struggling soul;

Comfort came down the trembling wretch to raise,

And his last faltering accents whisper’d praise.

At church, with meek and unaffected grace,

His looks adorn’d the venerable place;

Truth from his lips prevail’d with double sway,

And fools who came to scoff remain’d to pray.

The service pass’d, around the pious man,

With ready zeal, each honest rustic ran;

Even children follow’d with endearing wile,

And pluck’d his gown, to share the good man’s smile:

His ready smile a parent’s warmth express’d,

Their welfare pleas’d him, and their cares distress’d.

To them his heart, his love, his griefs were given,

But all his serious thoughts had rest in heaven:

As some tall cliff, that lifts its awful form,

Swells from the vale, and midway leaves the storm.

44

Though round its breast the rolling clouds are spread,

Eternal sunshine settles on its head.

Beside yon straggling fence that skirts the way,

With blossom’d furze unprofitably gay—

There, in his noisy mansion, skill’d to rule,

The village master taught his little school.

A man severe he was, and stern to view;

I knew him well, and every truant knew:

Well had the boding tremblers learn’d to trace

The day’s disasters in his morning face;

Full well they laugh’d with counterfeited glee

At all his jokes, for many a joke had he;

Full well the busy whisper, circling round,

Convey’d the dismal tidings when he frown’d:

Yet he was kind, or if severe in aught,

The love he bore to learning was in fault.

The village all declar’d how much he knew;

’Twas certain he could write, and cipher too,

Lands he could measure, terms and tides presage—

And even the story ran that he could gauge.

In arguing too, the parson own’d his skill,

For even though vanquish’d, he could argue still;

While words of learned length and thundering sound

Amaz’d the gaping rustics rang’d around—

And still they gaz’d, and still the wonder grew,

That one small head could carry all he knew.

But pass’d is all his fame: the very spot,

Where many a time he triumph’d, is forgot.

45

Near yonder thorn, that lifts its head on high,

Where once the sign-post caught the passing eye,

Low lies that house where nut-brown draughts inspir’d,

Where grey-beard mirth and smiling toil retir’d,

Where village statesmen talk’d with looks profound,

And news much older than their ale went round.

46

Imagination fondly stoops to trace

The parlour splendours of that festive place;

The whitewash’d wall, the nicely sanded floor,

The varnish’d clock that click’d behind the door—

The chest contriv’d a double debt to pay,

A bed by night, a chest of drawers by day—

The pictures plac’d for ornament and use,

The twelve good rules, the royal game of goose—

The hearth, except when winter chill’d the day,

With aspen boughs, and flowers, and fennel gay—

While broken tea-cups, wisely kept for show,

Rang’d o’er the chimney, glisten’d in a row.

Vain transitory splendours! could not all

Reprieve the tottering mansion from its fall?

Obscure it sinks; nor shall it more impart

An hour’s importance to the poor man’s heart:

Thither no more the peasant shall repair,

To sweet oblivion of his daily care;

No more the farmer’s news, the barber’s tale,

No more the woodman’s ballad shall prevail;

No more the smith his dusky brow shall clear,

Relax his ponderous strength, and lean to hear;

The host himself no longer shall be found

Careful to see the mantling bliss go round;

Nor the coy maid, half willing to be press’d,

Shall kiss the cup to pass it to the rest.

Yes! let the rich deride, the proud disdain,

These simple blessings of the lowly train—

47

To me more dear, congenial to my heart,

One native charm, than all the gloss of art.

Spontaneous joys, where nature has its play,

The soul adopts, and owns their first-born sway—

Lightly they frolic o’er the vacant mind,

Unenvied, unmolested, unconfin’d;

But the long pomp, the midnight masquerade,

With all the freaks of wanton wealth array’d,

In these, ere triflers half their wish obtain,

The toiling pleasure sickens into pain—

And, even while fashion’s brightest arts decoy,

The heart distrusting asks, if this be joy.

Ye friends to truth, ye statesmen who survey

The rich man’s joys increase, the poor’s decay—

’Tis yours to judge, how wide the limits stand

Between a splendid and a happy land.

Proud swells the tide with loads of freighted ore,

And shouting folly hails them from her shore;

Hoards even beyond the miser’s wish abound,

And rich men flock from all the world around;

Yet count our gains: this wealth is but a name,

That leaves our useful products still the same.

Not so the loss. The man of wealth and pride

Takes up a space that many poor supplied—

Space for his lake, his park’s extended bounds,

Space for his horses, equipage, and hounds;

The robe that wraps his limbs in silken sloth

Has robb’d the neighbouring fields of half their growth;

48

His seat, where solitary sports are seen,

Indignant spurns the cottage from the green;

Around the world each needful product flies,

For all the luxuries the world supplies:

While thus the land adorn’d for pleasure—all

In barren splendour feebly waits the fall.

As some fair female, unadorn’d and plain,

Secure to please while youth confirms her reign,

Slights every borrow’d charm that dress supplies,

Nor shares with art the triumph of her eyes—

But when those charms are pass’d, for charms are frail,

When time advances, and when lovers fail—

She then shines forth, solicitous to bless,

In all the glaring impotence of dress.

Thus fares the land, by luxury betray’d:

In nature’s simplest charms at first array’d—

49

But verging to decline, its splendours rise,

Its vistas strike, its palaces surprise;

While, scourg’d by famine, from the smiling land,

The mournful peasant leads his humble band—

And while he sinks, without one arm to save,

The country blooms—a garden and a grave.

Where, then, ah! where shall poverty reside,

To ’scape the pressure of contiguous pride?

If to some common’s fenceless limits stray’d,

He drives his flock to pick the scanty blade,

Those fenceless fields the sons of wealth divide,

And even the bare-worn common is denied.

If to the city sped—what waits him there?—

To see profusion that he must not share;

To see ten thousand baneful arts combin’d

To pamper luxury, and thin mankind;

To see those joys the sons of pleasure know,

Extorted from his fellow-creatures’ woe:

Here, while the courtier glitters in brocade,

There the pale artist plies the sickly trade;

Here, while the proud their long-drawn pomps display,

There the black gibbet glooms beside the way.

The dome where pleasure holds her midnight reign,

Here, richly deck’d, admits the gorgeous train—

Tumultuous grandeur crowds the blazing square,

The rattling chariots clash, the torches glare:

Sure scenes like these no troubles e’er annoy;

Sure these denote one universal joy!

50

Are these thy serious thoughts?—ah! turn thine eyes,

Where the poor houseless shivering female lies:

She once, perhaps, in village plenty bless’d,

Has wept at tales of innocence distress’d—

Her modest looks the cottage might adorn,

Sweet as the primrose peeps beneath the thorn;

Now lost to all—her friends, her virtue fled,

Near her betrayer’s door she lays her head—

And, pinch’d with cold, and shrinking from the shower,

With heavy heart deplores that luckless hour,

When idly first, ambitious of the town,

She left her wheel, and robes of country brown.

Do thine, sweet Auburn! thine, the loveliest train,

Do thy fair tribes participate her pain?

Even now, perhaps, by cold and hunger led,

At proud men’s doors they ask a little bread.

51

Ah, no! to distant climes, a dreary scene,

Where half the convex world intrudes between,

Through torrid tracts with fainting steps they go,

Where wild Altama5 murmurs to their woe.

Far different there from all that charm’d before,

The various terrors of that horrid shore;

Those blazing suns that dart a downward ray,

And fiercely shed intolerable day—

52

Those matted woods where birds forget to sing,

But silent bats in drowsy clusters cling—

Those poisonous fields with rank luxuriance crown’d,

Where the dark scorpion gathers death around—

Where at each step the stranger fears to wake

The rattling terrors of the vengeful snake—

Where crouching tigers wait their hapless prey,

And savage men, more murderous still than they—

While oft in whirls the mad tornado flies,

Mingling the ravag’d landscape with the skies.

Far different these from every former scene—

The cooling brook, the grassy-vested green,

The breezy covert of the warbling grove,

That only shelter’d thefts of harmless love.

53

Good Heaven! what sorrows gloom’d that parting day

That call’d them from their native walks away;

When the poor exiles, every pleasure pass’d,

Hung round their bowers, and fondly look’d their last—

And took a long farewell, and wish’d in vain

For seats like these beyond the western main—

And shuddering still to face the distant deep,

Return’d and wept, and still return’d to weep.

The good old sire, the first, prepar’d to go,

To new-found worlds, and wept for others’ woe—

But for himself, in conscious virtue brave,

He only wish’d for worlds beyond the grave;

His lovely daughter, lovelier in her tears,

The fond companion of his helpless years,

Silent went next, neglectful of her charms,

And left a lover’s for a father’s arms.

With louder plaints the mother spoke her woes,

And bless’d the cot where every pleasure rose.

54

And kiss’d her thoughtless babes with many a tear,

And clasp’d them close, in sorrow doubly dear—

Whilst her fond husband strove to lend relief,

In all the silent manliness of grief.

O luxury! thou curs’d by Heaven’s decree,

How ill exchang’d are things like these for thee;

How do thy potions, with insidious joy,

Diffuse their pleasures only to destroy!

Kingdoms by thee to sickly greatness grown,

Boast of a florid vigour not their own;

At every draught more large and large they grow,

A bloated mass of rank unwieldy woe—

55

Till sapp’d their strength, and every part unsound,

Down, down they sink, and spread a ruin round.

Even now the devastation is begun,

And half the business of destruction done;

Even now, methinks, as pondering here I stand,

I see the rural virtues leave the land:

Down, where yon anchoring vessel spreads the sail,

That idly waiting flaps with every gale,

Downward they move—a melancholy band—

Pass from the shore, and darken all the strand;

Contented toil, and hospitable care,

And kind connubial tenderness are there—

And piety with wishes plac’d above,

And steady loyalty, and faithful love.

And thou, sweet poetry! thou loveliest maid,

Still first to fly where sensual joys invade,

Unfit in these degenerate times of shame

To catch the heart, or strike for honest fame—

Dear charming nymph, neglected and decried,

My shame in crowds, my solitary pride—

Thou source of all my bliss, and all my woe,

That found’st me poor at first, and keep’st me so—

Thou guide by which the nobler arts excel.

Thou nurse of every virtue—fare thee well.

Farewell! and oh! where’er thy voice be tried,

On Tornea’s cliffs, or Pambamarca’s side,6

56

Whether where equinoctial fervours glow,

Or winter wraps the polar world in snow,

Still let thy voice, prevailing over time,

Redress the rigours of the inclement clime.

Aid slighted truth: with thy persuasive strain

Teach erring man to spurn the rage of gain;

Teach him that states, of native strength possess’d,

Though very poor, may still be very bless’d;

That trade’s proud empire hastes to swift decay,

As ocean sweeps the labour’d mole away—

While self-dependent power can time defy,

As rocks resist the billows and the sky.7

57

[A correspondent of the St. James’s Chronicle having accused Goldsmith of imitating

a ballad by Percy, he addressed the following letter to the Editor. In a later edition

of the “Reliques,” Percy vindicated his friend from the charge, and said, “If there is

any imitation in the case, they will be found both to be indebted to the beautiful old

ballad, ‘Gentle Herdsman,’ which the Doctor had much admired in manuscript, and has

finely improved.”

Sir,—A correspondent of yours accuses me of having taken a ballad, I published some

time ago, from one (the “Friar of Orders Gray”) by the ingenious Mr. Percy. I do not

think there is any great resemblance between the two pieces in question. If there be

any, his ballad is taken from mine. I read it to Mr. Percy, some years ago; and he (as

we both considered these things as trifles at best) told me, with his usual good humour,

the next time I saw him, that he had taken my plan to form the fragments of Shakspere

into a ballad of his own. He then read me his little cento, if I may so call it, and I highly

approved it. Such petty anecdotes as these are scarce worth printing; and, were it not

for the busy disposition of some of your correspondents, the public should never have

known that he owes me the hint of his ballad, or that I am obliged to his friendship

and learning for communications of a much more important nature.

I am, Sir, yours, &c.

Oliver Goldsmith.]

58

“Turn, gentle hermit of the dale,

And guide my lonely way,

To where yon taper cheers the vale

With hospitable ray;

“For here, forlorn and lost, I tread,

With fainting steps and slow—

Where wilds, immeasurably spread,

Seem lengthening as I go.”

59

“Forbear, my son,” the hermit cries,

“To tempt the dangerous gloom;

For yonder faithless phantom flies

To lure thee to thy doom.

“Here to the houseless child of want

My door is open still;

And, though my portion is but scant,

I give it with good will.

“Then turn, to-night, and freely share

Whate’er my cell bestows—

My rushy couch and frugal fare,

My blessing and repose.

“No flocks that range the valley free

To slaughter I condemn—

Taught by that Power who pities me,

I learn to pity them;

“But, from the mountain’s grassy side

A guiltless feast I bring—

A scrip with herbs and fruits supplied,

And water from the spring.

“Then, pilgrim, turn, thy cares forego;

All earth-born cares are wrong:

Man wants but little here below,

Nor wants that little long.”

60

Soft as the dew from heaven descends,

His gentle accents fell;

The modest stranger lowly bends,

And follows to the cell.

Far, in a wilderness obscure,

The lonely mansion lay;

A refuge to the neighbouring poor,

And strangers led astray.

No stores beneath its humble thatch

Requir’d a master’s care;

The wicket, opening with a latch,

Receiv’d the harmless pair.

And now, when busy crowds retire

To take their evening rest,

The hermit trimm’d his little fire,

And cheer’d his pensive guest;

And spread his vegetable store,

And gaily press’d, and smil’d;

And, skill’d in legendary lore,

The lingering hours beguil’d.

Around, in sympathetic mirth,

Its tricks the kitten tries—

The cricket chirrups in the hearth,

The crackling faggot flies;

61

But nothing could a charm impart

To soothe the stranger’s woe—

For grief was heavy at his heart,

And tears began to flow.

His rising cares the hermit spied—

With answering care opprest;

“And whence, unhappy youth,” he cried,

“The sorrows of thy breast?

“From better habitations spurn’d,

Reluctant dost thou rove?

Or grieve for friendship unreturn’d,

Or unregarded love?

“Alas! the joys that fortune brings

Are trifling, and decay—

And those who prize the paltry things,

More trifling still than they;

62

“And what is friendship but a name,