UNITED STATES DEPARTMENT OF THE INTERIOR

Stewart L. Udall, Secretary

NATIONAL PARK SERVICE

Conrad L. Wirth, Director

HISTORICAL HANDBOOK NUMBER TWENTY-THREE

This publication is one of a series of handbooks describing the historical and archeological areas in the National Park System administered by the National Park Service of the United States Department of the Interior. It is printed by the Government Printing Office and may be purchased from the Superintendent of Documents, Washington 25, D. C. Price 25 cents.

by Kittridge A. Wing

NATIONAL PARK SERVICE HISTORICAL HANDBOOK SERIES No. 23

Washington, D. C., 1955

Reprint 1961

The National Park System, of which Bandelier National Monument is a unit, is dedicated to conserving the scenic, scientific, and historic heritage of the United States for the benefit and enjoyment of its people.

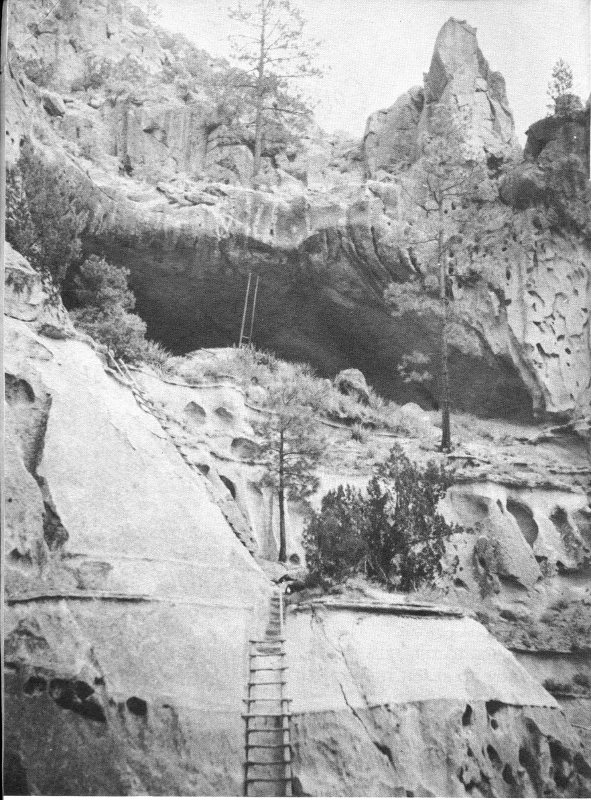

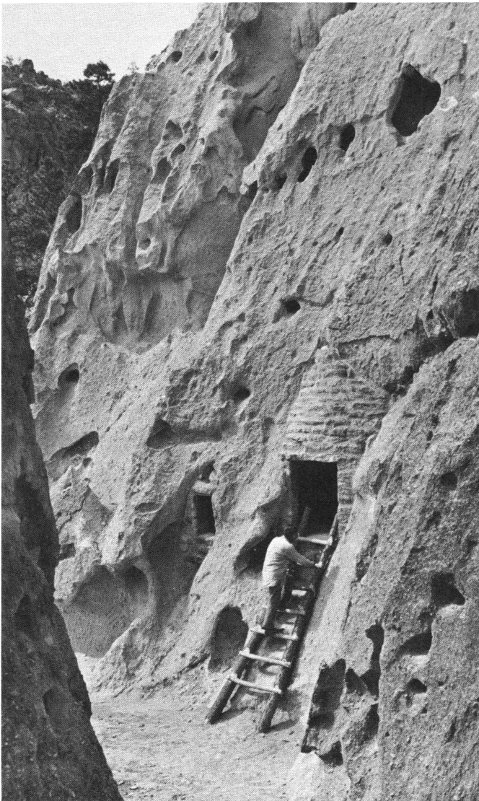

Ceremonial Cave, reached by a series of ladders extending 150 feet above the floor of Frijoles Canyon.

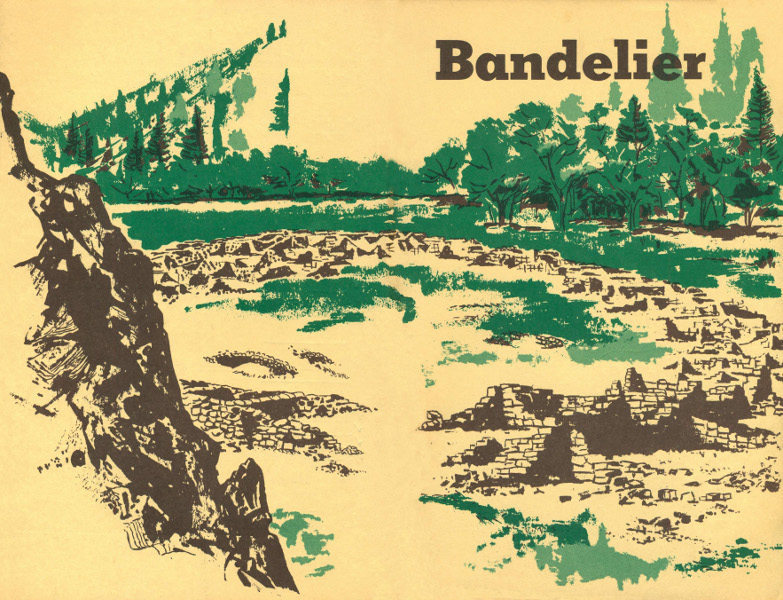

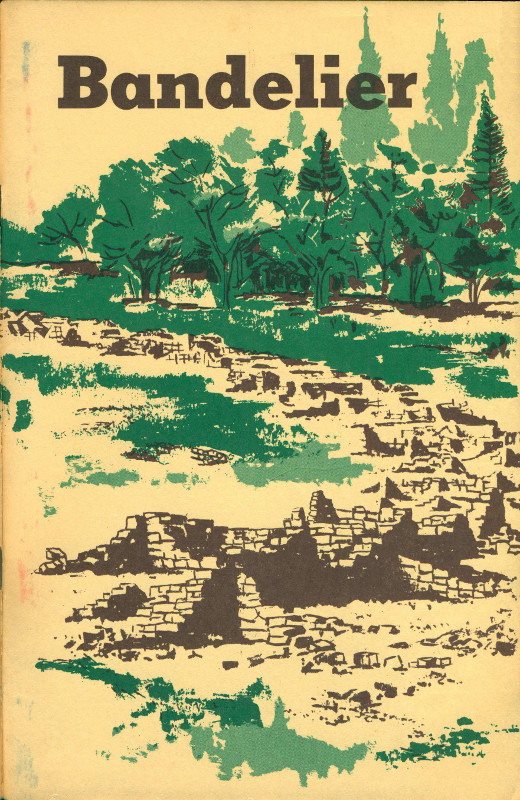

In the picturesque canyon and mesa country of the Pajarito Plateau, west of the Rio Grande from Santa Fe, N. Mex., are found the ruined dwellings of one of the most extensive prehistoric Indian populations of the Southwest. Bandelier National Monument, in the heart of the plateau, includes and protects several of the largest of these ruins, in particular the unique cave and cliff dwellings in the canyon of the Rito de los Frijoles.

The Indian farmers who built and occupied the numerous villages of the Pajarito Plateau flourished there for some 300 years, beginning in the 1200’s. By A. D. 1540, when historic times open with the coming of Coronado and his adventurers from Mexico, the Indian people had already started to leave their canyon fastnesses for new homes on the Rio Grande.

From all evidence it seems that modern Pueblo Indians living along the Rio Grande today are descended in part from the ancient inhabitants of the Pajarito area. Thus Bandelier National Monument preserves ruins which link historic times to prehistoric, and which further link the modern Pueblo Indian with his ancestors from regions to the west, whence came the first migrants to the Bandelier environs. The continuity of Pueblo life traces from origins in northwest New Mexico and the Mesa Verde country of southwest Colorado, through the Bandelier region, to the living towns of Cochiti to the south, San Ildefonso to the northeast, and other local Indian communities.

The evidences of ancient human occupation in the Bandelier neighborhood are apparent even to the most casual observer. When driving over the approach road to the monument headquarters one cannot fail to observe cave rooms in the cliffs on every hand; the continuing spectacle of smoke-blackened chambers dug into the rock provides the stimulus of discovery en route. But the roadside introduction is an infinitesimal preview of the total scope of prehistoric man’s activity in the region. In actuality, all of the ruins contained within the national monument represent but a small fraction of the ruins of the surrounding plateau.

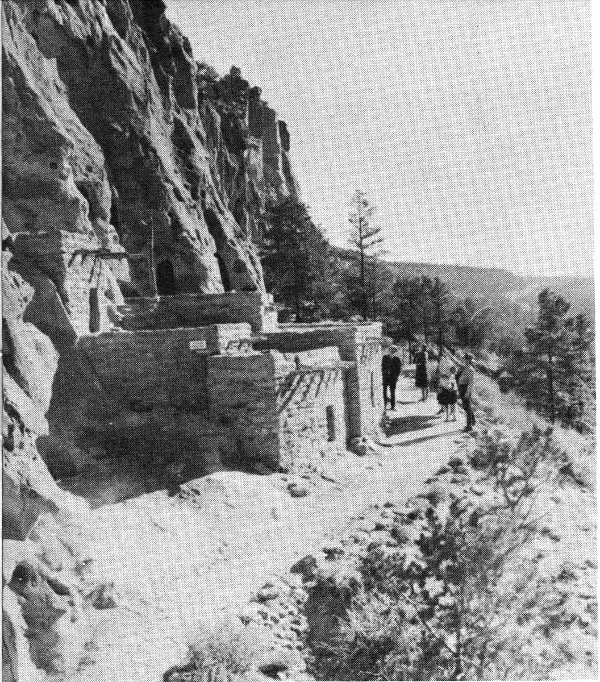

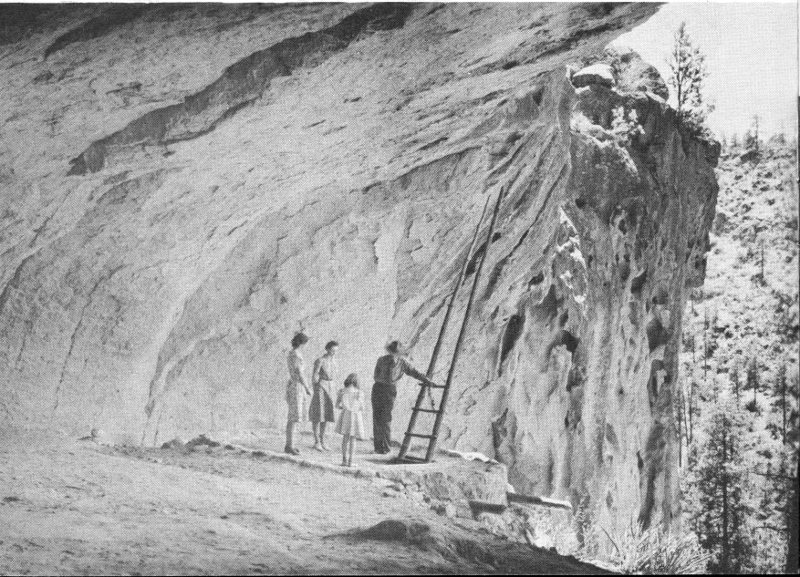

Park ranger and visitors at the Big Kiva in Frijoles Canyon.

The entire eastern slope of the Jemez Mountains to the west, throughout the zone of moderate elevations from 7,000 feet down to the Rio Grande at 5,500 feet, appears to have been thickly settled in prehistoric times; this eastern slope has been given the name of Pajarito Plateau. The extent of the plateau is, very roughly, 30 miles north to south, and 10 miles east to west (from the Rio Grande west to the crest of the Jemez). From Santa Clara Creek on the north of the monument to the Canada de Cochiti on the south of the monument, this tract of forested mesas and canyons contains Indian ruins which, if not innumerable, at least at this writing have not yet been totaled. It perhaps may be said, to emphasize the concentration of these ruins, that an observant person can hardly walk a quarter of a mile in any direction through the once-inhabited zone without noticing some sort of ancient structure or handiwork of prehistoric man.

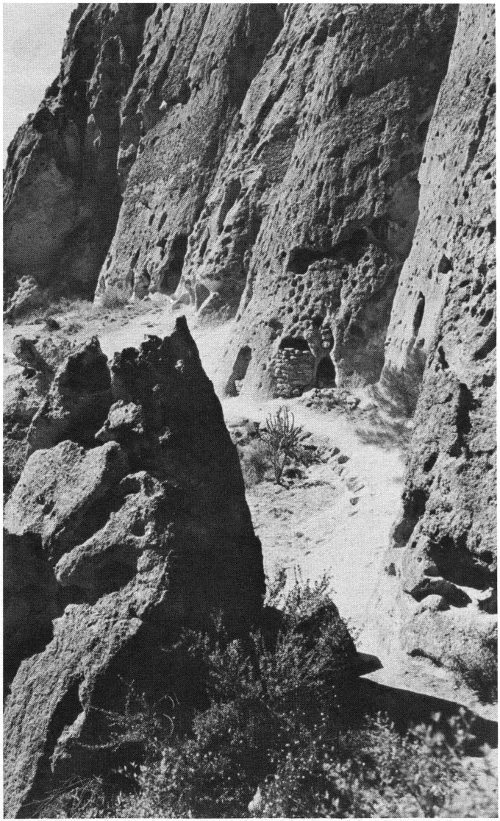

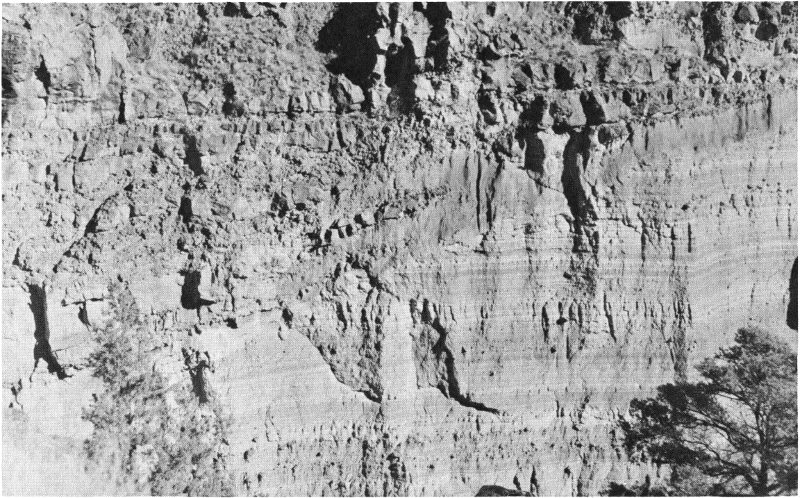

Base of a cliff of volcanic tuff, showing several cave rooms.

The habitations of the early people were of two types, basically: the cliff or cave dwelling, and the masonry or open pueblo structure. But these two types were frequently blended into composite dwellings, part cave and part masonry, wherein a cliff formed the back wall of the building. It is this third type, called a talus house, which is conspicuous along the canyon sides within and near the national monument.

The rock which forms the walls of all the Pajarito canyons is a cemented volcanic ash called tuff, with many erosion cavities which can be readily enlarged with tools of hard stone. It might be logical to assume that early migrants to the Pajarito country, 700 years ago, first took shelter in the natural cavities, then presently improved these crude holes into more livable chambers. There is, however, no evidence to support the idea that the cave rooms were lived in first. In fact, some authorities reason that since the firstcomers had been living in masonry dwellings in their earlier homes, they would first have built the familiar communal buildings on arrival here, leaving the caves to be taken up later by overflow population.

Whatever the sequence of construction, many thousands of cave rooms were prepared, involving the removal of thousands of cubic yards of tuff—an industrious people, these. Although some rooms are found with a long dimension of over 10 feet, the great majority of them are smaller. A typical room measures about 6 by 9 feet, with ceiling height perhaps 5 feet, 8 inches. Such a chamber has a doorway not over 3 feet high and only half as wide; there is an opening or two in the front wall near the ceiling to permit escape of smoke; and there may be a corresponding hole at floor level near the door to admit a draft of air to the fireplace. The appointments of the typical home are completed with a cupboard niche dug into the rear wall, a coat of mud plaster on floor and walls, and a covering of soot all over the ceiling—this last an inescapable penalty of cave living.

A room of such size might have provided sleeping quarters for a family of 5 or 6, considering the fact that no furniture took up space within. Frequently two cave rooms are found connected by a doorway cut through the interior wall, suggesting the expansion of a family beyond the limits of a single room.

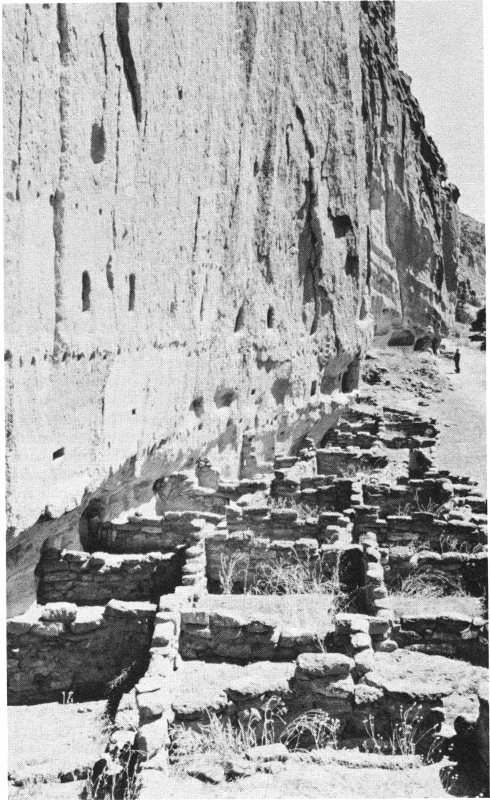

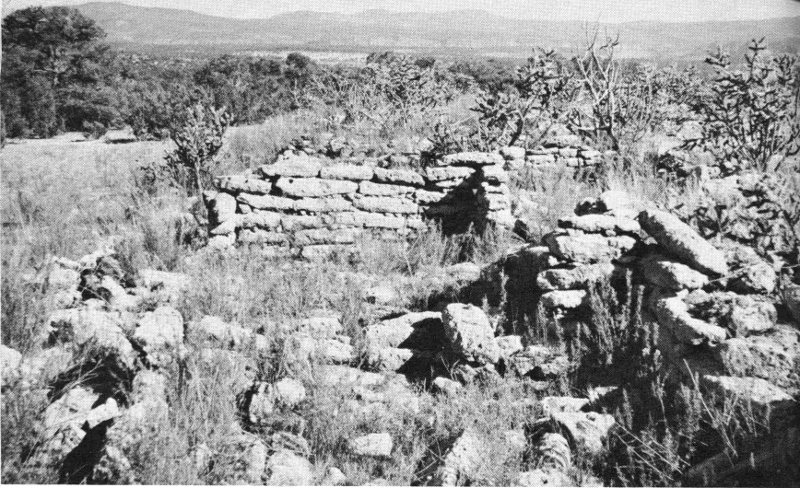

The ruins of Long House, once a dwelling of some 300 rooms.

The most impressive ruins of the Pajarito country are the remains of communal masonry dwellings of pueblo architecture. (Pueblo is Spanish for village or town. The first Spanish explorers applied the word to the permanent dwellings or settlements of farming Indians; by association, the word pueblo has come to designate also the builders of these dwellings and their modern Indian successors.) At least one of these great buildings contained over 600 rooms; there are several which had over 500 rooms, to a height of 3 stories. These multistory towns were built of the local tuff, shattered and pecked into convenient size for masonry use, and laid with mud mortar. The great houses were situated both on mesa-tops and in canyon bottoms; some were designed as hollow squares or circles, others had only a haphazard ground plan. None of these dwellings today is more than one story high, so that their original height is unknown in detail, but great massivity and considerable defensive strength are apparent even from the remaining mounds of rubble.

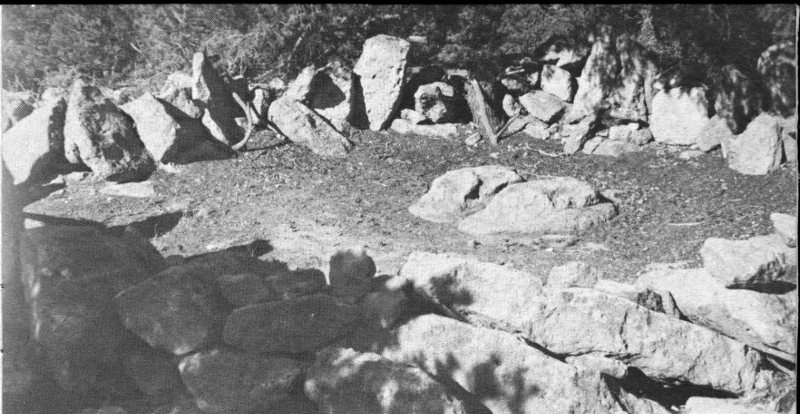

The unexcavated ruin of Yapashi.

The rooms of the community houses were scarcely larger than the cave rooms already described; almost none of the surviving ground-floor rooms are more than 10 by 12 feet, and the typical room measures perhaps 7 by 10 feet. These chambers were quite dark and unventilated, since there were almost no windows or even connecting doorways between rooms; almost every room of the ground floor was entered by a ladder through an opening in its ceiling. It is conjectured that these first-floor cells were designed in this fashion to serve as storage places for foodstuffs, more secure from rodents by reason of having only one opening in the roof. Moreover, the lower-floor walls were a stronger foundation for the upper floors when built without door or window openings. Finally, this design provided maximum security for defense against human marauders.

It has been mentioned that a composite type of building, combining 7 cave rooms and masonry walls, is common in the area. This sort of construction was responsible for the many rows of small holes still to be seen in the cliffs, evenly spaced some 2 feet apart above the cave doorways. These holes were cut and used as sockets to support the ends of roof beams extending forward from the cliff and providing ceilings for the masonry rooms which once stood there. These evenly spaced holes, which you first see along many of the canyon walls, give mute evidence of the early aboriginal occupation of this area. Many of these talus dwellings reached a height of 3 stories and pushed out from the cliff 3 and 4 rooms deep, so that the cave rooms which were occupied first became relegated to storage space in the dark rear interiors.

To conclude this general summation of ruin types, some description should be made of kivas. Kivas were, and are, the ceremonial chambers of the Pueblo people; as such, they are universally present in the Pajarito communities and their design makes them identifiable even in the ruined state. The local kivas were always round and were dug almost full-depth into the ground, except for certain examples which were excavated into the relatively soft bedrock of cliff or mesa-top. The circular depressions still to be found in the plazas of the great communal houses are the remains of kivas with their roofs collapsed and with the wind-borne debris of centuries accumulated in the hollows. A more complete discussion of kivas and their functions will be found on page 12.

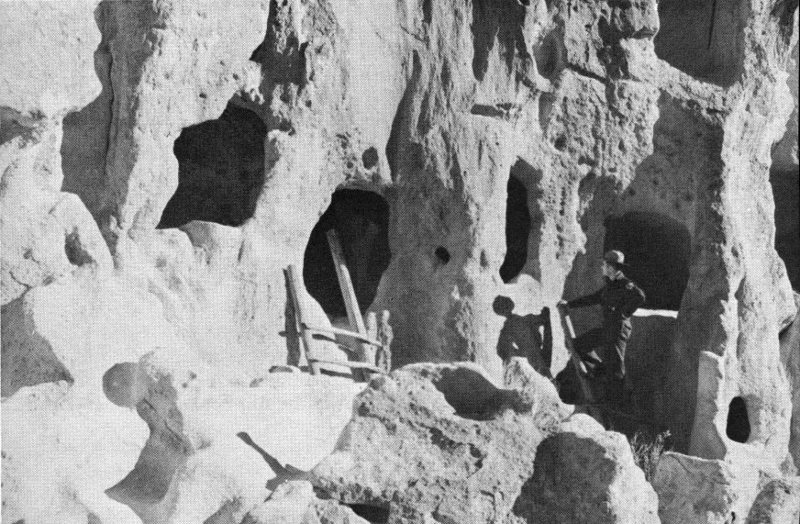

Entrances to cave rooms.

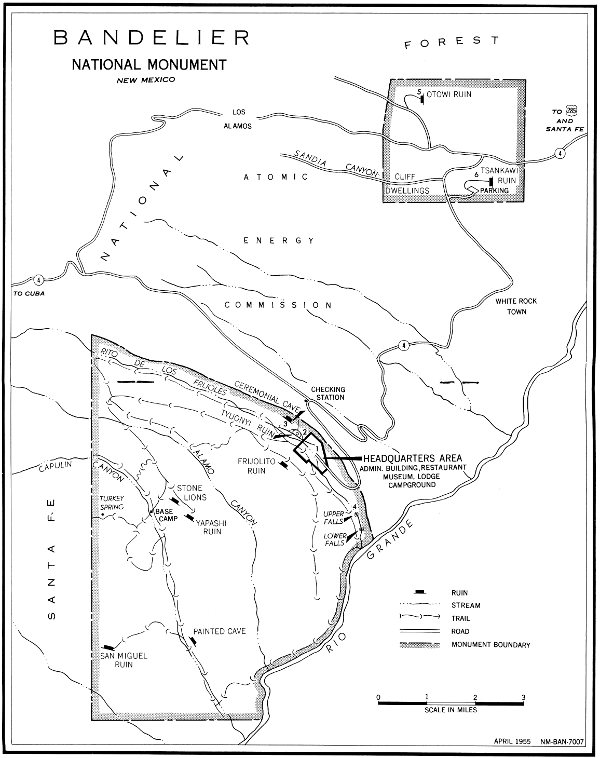

Bandelier National Monument is divided into two parcels of land: the Otowi section of about 9 square miles and the Frijoles section of nearly 33 square miles. Within these two areas are contained great concentrations of ruins, including several of the largest on the plateau. A number of the Bandelier ruins have been excavated, so there is quite a detailed knowledge of the culture which once flourished on the monument lands.

Tyuonyi Ruin, with the Big Kiva at left rear, and the trees of the campground at top of the picture.

The most frequently visited part of the monument is the canyon of the Rito de los Frijoles, wherein is located the monument headquarters. In this well-watered and wooded canyon are to be found ruins of the three types described above, which had well over 1,000 rooms in their prime some 500 years ago. Here also is the excavated remnant of the largest kiva found anywhere in the Pajarito country—a chamber which perhaps was the community center of religious practice for the entire canyon.

On the floor of Frijoles Canyon, a little upstream from the headquarters museum, is Tyuonyi, the chief building of the area, and one of the most impressive pueblo ruins in the Rio Grande drainage. Situated on a level bench of open ground, perhaps 100 feet from the Rito and 15 feet above the water, Tyuonyi at one time contained over 400 rooms, to a height of 3 stories in part. Its modern aspect is greatly reduced in height; although excavated, no walls have been restored, so that only the ground floor is still evident, with outer and inner walls standing to a height of 4 or 5 feet throughout.

The ruins trail; the south rim of Frijoles Canyon shows in the background.

To appreciate the size and lay-out of Tyuonyi, you should climb the nearby slope until a bird’s-eye view reveals the entire ground plan of the huge circle. From above, more than 250 rooms can be counted, placed in concentric rows around a central plaza. The most massive part of the circle is 8 rooms across, narrowing to 4 rooms in breadth at the brook side. The 2- and 3-story parts of the building, as computed from the height of the original rubble, were at the massive eastern side.

One of the most striking features of Tyuonyi is the entrance passage through the eastern part of the circle. This passage was apparently the only access to the central plaza, other than by ladders across the rooftops. An arrangement of this sort, of course, suggests a concern for defensive strength on the part of Tyuonyi’s builders; certainly the circle of windowless, doorless walls would have presented a problem to attackers, once the ladders were drawn up and the single passageway blocked.

It is believed that a good part of the first-floor rooms of Tyuonyi were storage chambers of the type previously discussed. This belief is borne out by the fact that during excavation many of these rooms were found to be without fireplaces, a condition which would have made such rooms unlivable in cold weather. The problem of smoke clearance was very serious in the larger pueblos, since the builders had no knowledge of modern fireplaces with chimney flues; hence the building of fires on the lower floors of multistory buildings worked a hardship on upstairs occupants and must have been avoided whenever possible.

The age of the Tyuonyi construction has been fairly well established by the tree-ring method of dating, so widely and successfully used by archeologists in the Southwest. Ceiling-beam fragments recovered from various rooms give dates between A. D. 1383 and 1466. This general period seems to have been a time of much building in Frijoles Canyon; a score of tree-ring dates from Rainbow House ruin, which is down the canyon a half mile, fall in the early and middle 1400’s. Perhaps the last construction anywhere in Frijoles Canyon occurred close to A. D. 1500, with a peak of population reached near that time or shortly thereafter.

On the talus directly above Tyuonyi to the north, at the foot of the prominent cliff, there once stood a cluster of houses. The group here had as its nucleus 12 or 15 cave rooms which were supplemented by at least as many masonry rooms at the front. Excavation 11 of these rooms was completed in 1909 and the name Sun House was given to the building, because of a prominent Sun-symbol petroglyph carved on the cliff above. A part of this house group has been restored on the old foundations, with its new ceiling beams placed in the ancient holes in the cliff. This restoration work, done by the Museum of New Mexico in 1920, serves to show faithfully the original appearance of this typical specimen of a talus house. Here again the rooms are small (by modern standards) with doors only large enough to squeeze through, and no windows. During the 1400’s, it is probable that several such dwellings were occupied along a 2-mile stretch of this cliff.

A restored talus house.

About one-fourth of a mile up the canyon from Tyuonyi, also against the northern and sun-warmed cliff, is the ruin of one of the largest combination cave-and-masonry dwellings to be found anywhere on the plateau. This great ruin is known as Long House for an obvious reason—it stretches almost 800 feet in a continuous block of rooms. For all of this distance, the masonry walls are backed by a sheer and largely smooth wall of tuff some 150 feet high. Into this cliff are dug many cave rooms, several kivas, and a variety of storage niches, all of which were incorporated into a single dwelling of over 300 rooms, rising 3 stories high. At Long House the rows of viga (roof-beam) holes in the cliff are particularly conspicuous, defining the onetime roof levels for hundreds of feet at a stretch. The site of Long House is 12 especially pleasing, having an elevation of 40 or 50 feet above the canyon bottom, but close enough to the creek so that the sound of running water may be heard, and near enough to the huge stream-bordering cottonwoods to partake of the coolness of their foliage. If it is conceivable to envy any of the people of prehistoric times, surely we should envy the dwellers of Long House.

Associated with the numerous ruins in Frijoles Canyon are various kivas, both in the canyon floor and in the cliffs. The large kiva previously mentioned is a short distance east of Tyuonyi, very nearly in the center of the widest part of the canyon floor. The rock-walled circular pit is 42 feet across and 8 feet deep, with a ventilation shaft at the east side and a narrow entranceway opposite. When the roof was intact above the chamber, there must have been little evidence of the existence of the subterranean room; perhaps a ladder protruding from a center hole in the roof was the only conspicuous indication of the kiva below. In its present and partially restored state, this kiva shows the butt ends of six roof columns similar to those which once bore the load of the roof, as well as the stub ends of roof stringers. The restoration work in this kiva was accomplished by the Civilian Conservation Corps, which was responsible for much valuable work in the monument during the late 1930’s.

Of particular interest in Frijoles Canyon are the unique kivas in the cliffs. Of the thousands of kivas found throughout the ancient land of the pueblos, there are no others of this cave style. The largest of the cave kivas in the monument is a few hundred feet north of Tyuonyi, at the base of a fantastically eroded block of tuff. The oval chamber, nearly 20 feet across its long dimension, has been restored by the replacement of rock work around its doorway and ventilation openings. The interior effect now presented, with soot-blackened ceiling, mud-plastered lower walls, and looms set in their ancient positions, must closely approximate the appearance of the kiva in the days when it was used. Many such kivas were decorated with painted or incised designs on the plaster of the walls. Although this particular kiva does not show evidence of mural paintings, it does still contain scratched designs in the plaster, unidentifiable because covered in part by later replastering.

A restored kiva of very different type may be found up the canyon nearly a mile. By climbing a series of ladders to a ledge 150 feet above the stream, the great rock overhang known as Ceremonial Cave can be reached. Under the shelter of this arch a number of masonry dwellings and a kiva were once built; the subterranean kiva, excavated and reroofed, is very small but would have served the needs of the few families who lived on this impregnable balcony.

Entrance to Cave Kiva.

Other noteworthy remains of the monument area lie outside Frijoles Canyon, accessible only by foot or horse trail across the mesas to the south. Perhaps the most frequently visited of these antiquities is the shrine of the Stone Lions, 10 miles from monument headquarters. Here on the mesa-top near an extensive ruin are two life-size crouching mountain lion effigies carved side by side out of the soft bedrock. This work of sculpture must have been accomplished many centuries ago, for long weathering and erosion have left small semblance of a true likeness. The shrine here is known to modern Indians, being visited occasionally by hunters who leave prayer offerings for success in their hunt. A second pair of stone lions was carved on a mesa-top several miles to the south, outside the monument boundary. These two pairs of life-size stone effigies are unique in the Southwest.

The restored kiva in Ceremonial Cave. The ranger and party are standing on the roof of the circular chamber.

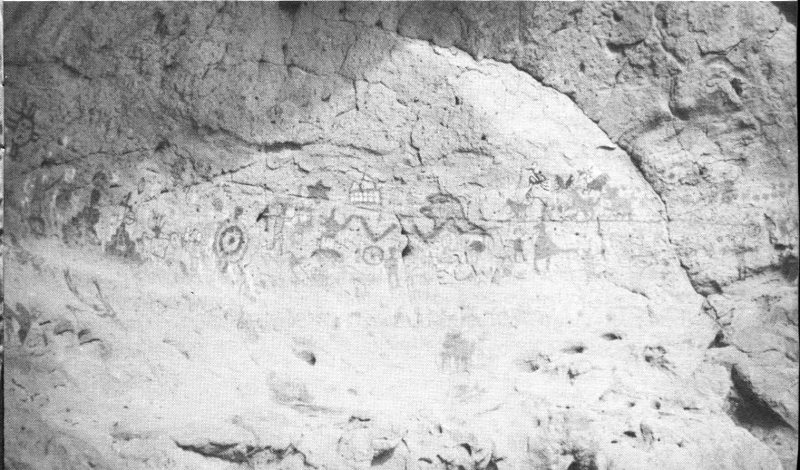

A final feature of particular interest in the back country of the monument is the Painted Cave. This art gallery in the cliffs decorates a canyon wall some 12 miles from headquarters. Once a large population inhabited this canyon of Capulin Creek, but most of the evidences of habitation have vanished except for the extensive pictographs on the weatherproof back wall of the Painted Cave. The 15 arch of the cave is shallow but wide, so that a smooth area over 50 feet long was available to the artists; several dozen drawings in a variety of reds and blacks adorn this surface. It is probable that many generations of artists used the cave, since space finally ran out and later drawings are superimposed on their faded predecessors. Moreover, evidence of historic, or post-Spanish, artistry is here—a sketch of a conquistador on horseback, another of a mission church complete with cross.

The shrine of the Stone Lions: Twin effigies of mountain lions in a walled enclosure.

Painted Cave.

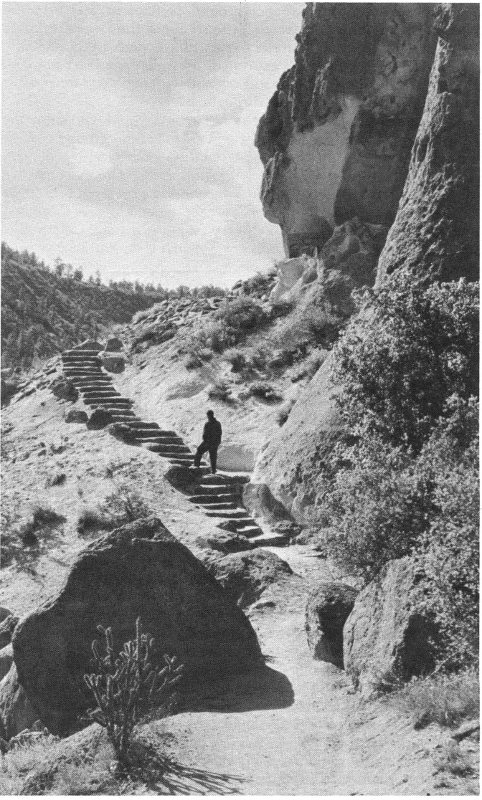

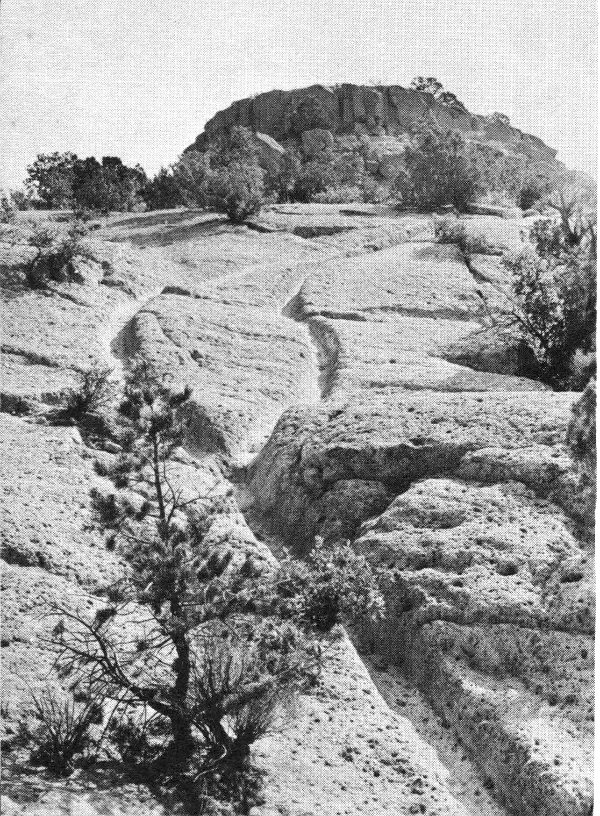

Trail worn into the rock, near Tsankawi Ruin.

The smaller section of Bandelier National Monument, lying some 15 miles from the headquarters area, takes its name from the Otowi ruin, the largest pueblo on the monument. Although not so impressive as the Tyuonyi ruin at first glance, the great spread and complexity of the rubble mounds surely dwarf all other ruined dwellings of the vicinity. Probably 450 ground-floor rooms were here, with an indeterminate number of upper-floor rooms—perhaps 600 rooms altogether is a reasonable estimate. The Otowi rooms have not been excavated to any great extent, but two burial mounds south of the building group have been investigated with spectacular results—over 150 interments were found in a space about 80 by 100 feet. With these burials was found a great variety of offerings to the dead, ranging from food bowls to bone awls and ceremonial pipes. Specimens of these handicrafts may be seen at the National Park Service museum at monument headquarters and at the Museum of New Mexico in Santa Fe.

The Otowi house-group occupies a site atop a low ridge walled in by the cliffsides of steep Pueblo Canyon. Its nearest neighbor, Tsankawi, is sited on a very different terrain: Tsankawi is very near to being a “sky-city” in the style of the modern Acoma in western New Mexico. Not as large as Otowi, this ruin has equal majesty by reason of its commanding position on top of a cliff-ringed island mesa overlooking a vast north-south sweep of the Rio Grande and the Sangre de Cristo Mountains beyond. The location and the ground plan suggest defense as a first consideration. Of masonry construction in a rough hollow square, Tsankawi would have presented a serious problem to enemy besiegers. On the other hand, a siege would have cut off the defenders from their water supply, far in the canyon below. There is, however, some evidence of a rain-catchment basin close outside the eastern walls, and excavation may in future confirm the existence of an ingenious water-storage system.

The most memorable sight at Tsankawi lies along the trail that climbs from the end of the access road to the mesa-top. Here for 100 yards the path, crossing a bald slope of soft gray tuff, is worn down for almost 18 inches by the climbing and descending feet of thousands of Indian passersby. Granted that the rock is extremely porous and soft, it is nonetheless almost beyond the scope of imagination to conceive the vast traffic required to so entrench the path. Today, when you climb this trail, you cannot but visualize a procession of Indian farmers over several generations traveling to and from their fields, their sandaled feet scuffing each year a fractional inch deeper into the calendar of the rock.

The great number of Indian ruins in the Bandelier vicinity, some of which have been described, give evidence of the presence and labor of thousands of prehistoric people. Who were these people? Whence did they come, and where have they gone? A myriad of questions is inspired by the far-flung ruins—and in the ruins, of course, are the answers to these questions, answers which have been gradually unearthed by scientists over the past 75 years. Beginning with Adolph Bandelier, the Swiss-American ethnologist for whom the monument is named, a succession of scientists has brought to light many facts once buried beneath the rubble of the ruins.

Before entering upon a description of the life and times of the early Bandelier dwellers, it may be well to discuss briefly the efforts of the archeologists and others who have built up the picture of this long-lost culture. The work of the archeologist is essentially historical detective work—in his digging and searching he 18 must find, assemble, and interpret clues. Some of these clues will be tangible, like pottery fragments. Other clues will be intangible—the very absence of pottery fragments in an ancient dwelling tells a story. The correct evaluation and interpretation of multitudinous clues by many experts over two generations have at last given us a very considerable knowledge of Southwestern prehistory—and the knowledge is being added to daily. H. M. Wormington, in Prehistoric Indians of the Southwest, wrote “... the development of archaeology in the Southwest may be compared to the putting together of a great jig-saw puzzle. First came a period of general examination of the pieces, then a concentration on the larger and more highly colored pieces, and finally a carefully planned approach to the puzzle as a whole with serious attempts to fill in specific blank areas.”

As a result of such concerted study and deduction, there exists today a fairly solid understanding of the general course of human events in the Southwest for the past 2,000 years. Many details are still missing, and some will always be, but the general outline of Indian life and customs is established back to the early centuries of the Christian era; beyond that, the picture becomes hazy. Those earlier years were seemingly times of a seminomadic, hunting-gathering existence for the early Southwesterners; only from about 3,000 years ago is there clear evidence of the advent of intensive farming and a settled life.

As soon as agriculture became their primary sustenance, the people began to live more or less permanently in one place. From certain early cave-shelters are derived the clues which begin to formulate the story of the days before history. Human burials have been found in the earth floors of shallow caves scattered through the San Juan river drainage; and in these same caves are found storage chambers prepared to protect the foodstuffs, principally corn. Their outstanding handicraft was basketry, as far as remaining evidence shows. Because of the great numbers of skilfully worked baskets found in their homesites, archeologists have named these people Basketmakers. It is now quite certain that the Indians who came much later to live in the Bandelier vicinity can claim as ancestors the Basketmaker people of the area to the west.

The life of these ancestral farmers was a primitive one, even by the standards which prevailed in Frijoles Canyon 1,000 years later. For one thing, no permanent dwellings appear to have been constructed until late in Basketmaker times, and even then dwellings were of crude pithouse type—an excavation some 3 feet into the ground, walled up and roofed with logs, brush, and earth. Further, the bow and arrow was not used by these people until perhaps A. D. 600; the early weapon of hunting and warfare was the spear and spear-thrower (atlatl). 19 For the greater part of Basketmaker times, pottery was unknown; only after A. D. 400 was true fired pottery introduced in the northern Southwest.

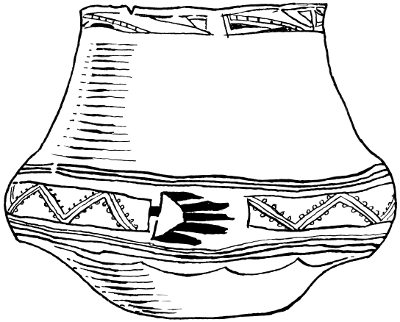

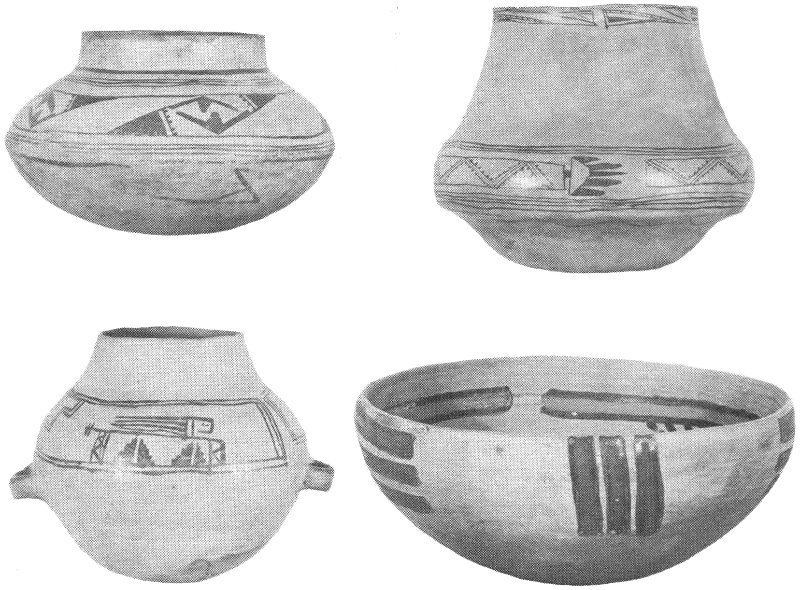

Typical prehistoric pottery vessels made in the Bandelier vicinity.

Photo courtesy Museum of New Mexico.

The production of decorated pottery late in Basketmaker times began a development which has had the greatest archeological significance. The long-enduring fragments of painted pottery found in subsequent housesites have been a principal tool by which students have pieced together the relative chronology of ruins and the migrations of the pottery-makers.

With successive introduction of pottery, the bow and arrow, and other new traits in the approximate period A. D. 450 to 750, the character of Basketmaker life became so modified that a new name—the Pueblos—was applied to the subsequent peoples. Presently they began to move from the Basketmaker pithouse into masonry chambers above ground, perhaps with several rooms connected, the old pithouse surviving in use as the ceremonial kiva. Cotton came under cultivation and was woven into garments. Hoes and axes of stone with serviceable handles came into use. Turkeys and dogs were by this time commonly domesticated, the former being valued primarily for feathers which served to make warm robes and ceremonial garb.

BANDELIER NATIONAL MONUMENT, NEW MEXICO

High-resolution Map

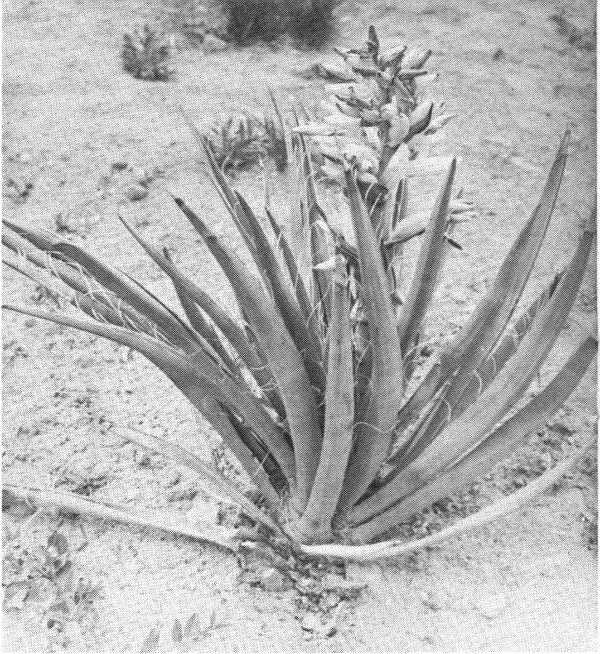

The useful yucca plant.

The stage was now set for the great flowering of the Pueblo people; the way of life which had taken rough shape from A. D. 450 to 1050 now reached culmination in the Great Pueblo period. For about 200 years, or until around A. D. 1250, fortune smiled on the farming towns of the Four Corners country. The population grew and spread, and the handicraft arts reached a stage of impressive proficiency. The centers of this classic period which are today best known lie in three different States: Mesa Verde (in Mesa Verde National Park, Colo.), Chaco Canyon (in Chaco Canyon National Monument, N. Mex.), and the vicinity of Betatakin and Keet Seel (in Navajo National Monument, Ariz.) These three areas, all now under the jurisdiction of the National Park Service, contain the great cliff dwellings and communal houses which mark the highest development of prehistoric Indian attainments in the northern Southwest.

It is beyond the scope of this handbook to present an adequate description of the Great Pueblo towns and their inhabitants. Although almost contemporaneous, the three largest centers differed greatly in development, so that the total story becomes most complex. In general it may be said that the skills of farming and production of foodstuffs became highly efficient, allowing the people more leisure in 23 which to experiment with and improve their arts and crafts and their ceremonial rituals. Much elaboration and refinement of the potter’s craft, for example, is traceable to these years; some of the world’s finest ceramic art, ancient or modern, comes from Chaco Canyon and the Mesa Verde. Again, in the field of jewelry-making and personal adornment, the craftsman of the 1100’s produced shell- and turquoise-inlay work which would have earned the admiration of Cellini. Finally, a multiplicity of kivas is to be found in all the great houses of the period, as well as a number of Great Kivas embodying various elaborate altar features. This expenditure of effort to crowd the towns with ceremonial rooms would seem to indicate something of a preoccupation with religion. The numerous discoveries of carved stone fetishes and other ceremonial objects serve to bear out a concept of elaborate ritual and unending dedication to the service of their gods.

It seems, however, that the gods were fickle. Some two centuries of growth and prosperity were all that were to be allowed the farmers of the Great Pueblo centers. In the last quarter of the 13th century, a period of drought came to the high plateaus of the Pueblo people. From the evidence of the tree rings of the time, the majority of the years between A. D. 1276 and 1299 were so deficient in rainfall that the Indian corn crops could not have matured. Although this drought was not actually continuous, and varied between regions, there was undoubtedly much starvation, and a decimation of the inhabitants of the great towns, perhaps from enemy raids as well as hunger. There were undoubtedly numerous migrations from the drought-stricken areas into places with reliable streams.

These troubled times in the western centers and emigrations therefrom were responsible in large part for the settling of the Pajarito Plateau and the canyons of what is now Bandelier National Monument. The streams of the Jemez Mountains continued to flow during the dry time, apparently, for large-scale colonization of well-watered canyons such as Frijoles appears to date from the end of the 13th century. The drift of the emigrants from the western areas is impossible to trace in detail, continuing as it did for several generations and originating from many sources. The Bandelier region may have been something of a melting pot, assimilating migrants from various distant places. A study of the pottery types produced in the early days of residence here affords the best clue to possible origins. Among these types are found precise copies of decoration styles from a number of the western centers, indicating that the women potters carried on their respective traditional decorations upon arrival in their new homes. One particular kind of black-on-white pottery can hardly be distinguished even by microscopic examination from a similar ware made in the Mesa Verde country.

The upsurge of population and the main construction activity in Bandelier began after A. D. 1300. Large towns grew up and down the Rio Grande drainage, and their people achieved in most respects as high a standard of living as their forebears had known in the Great Pueblo centers of 200 years earlier. Very possibly the Rio Grande pueblos might have gone ahead to a new peak of cultural development if they had not been interrupted and demoralized by the coming of the Spanish. In 1598, some 400 farmers and soldiers led by Don Juan de Onate, the first permanent Spanish settlers, came from Mexico, and with the entry of these land-seekers the ascendancy of the Pueblos was finished.

The typical male inhabitant of Frijoles Canyon in the early 1300’s, then, was a newcomer to the area. He was a man of Mongoloid cast of countenance, about 5 feet 4 or 5 inches in height, with medium red-brown skin and black hair. His wife measured 5 feet or perhaps a little less, and was inclined to a stout build. A few children and a dog or two completed the family circle. These newcomers had arrived in their chosen valley with only such belongings as they could carry on their backs, and were immediately faced with the problems of wresting a livelihood from a somewhat grudging environment. In the pattern of all mankind before and since, this Indian migrant’s first requirements were food, water, shelter, and clothing for himself and his family.

As a practicing farmer, the man’s chief reliance for food had been the crops of corn, beans, and squash that he knew how to raise. Perhaps the family had managed to bring some remnants of their most recent harvests with them to Frijoles; but these remnants had to be saved for seed, to insure crops for the coming year. What did the family eat meanwhile? In the warm season, a diet of sorts could have been pieced together by gathering various plants and fruit and nut crops. Spring brought out of the ground several annuals such as the mustard and bee plants which can be boiled for vegetable-greens while young. A bit later the local berry crop came into fruit—currants, gooseberries, chokecherries, and a few raspberries. The ever-present yucca offered its bananalike pod of fruit toward August. When fall arrived, the countryside, in good years, abounded with wild produce: pinyon-nuts and juniper berries, the staples, with trimmings of prickly pears, acorns, and many other seed and nut crops. The ingenuity of the modern Pueblo Indian in coaxing sustenance out of his familiar native plants is extraordinary; very few things that grow are not of 25 some use to him as food or medicine. It may surely be assumed that the Pueblo ancestor of 600 years ago was equally resourceful.

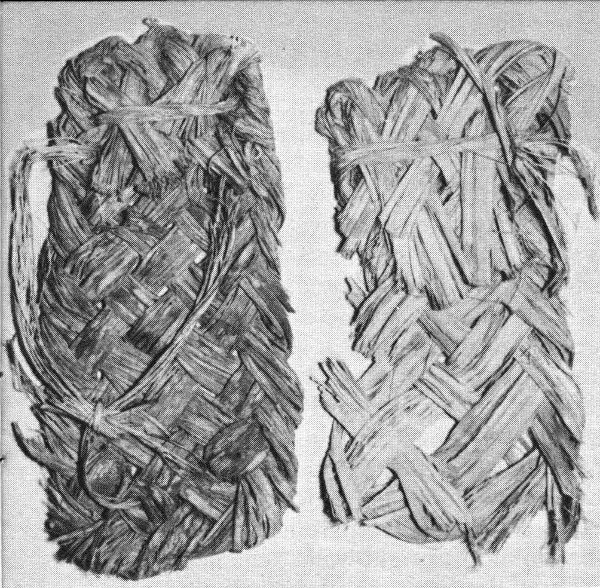

Ancient sandals, made from yucca leaves.

Fortunately, however, this ancient Frijoles resident was not restricted to the collection of wild crops to feed his family. He was a hunter as well as a gatherer. He was armed with bow and arrow, and was undoubtedly an expert shot. Other tools were snares and nets for small game and birds. If he did not bring cordage with him on his migration he promptly wove it from the useful yucca plant, and set out a trapline. Many small animals which moderns would disdain were important food items to the early Pueblos: the once-common prairie dog and the still-common pack rat were eaten in great numbers, if the evidence of bones in ancient trash heaps can be believed. Perhaps only the skunk escaped the designs of the early food-seeker, for a reason which was as valid then as it is today. Of larger animals, the deer was most taken, although elk and antelope were not immune. The remains of game pits, dug into the soft bedrock to entrap larger beasts, have been found in several places in the monument. One of these pits is 15 feet deep with a bottom diameter of 8 feet, narrowing to a smaller bottleneck opening above. The preparation of such a trap as this was obviously a laborious community enterprise, and suggests an occasional community deer-drive to herd the victims across the concealed mouth of the pit.

All this work of hunting and gathering was secondary to planting and tending crops, once the growing season arrived. The Pueblos had discovered, many centuries before, that their best defense against hunger was in growing corn—so the Frijoles hunter became a farmer in 26 late May or June. With digging stick and stone hoe, he prepared the ground to grow his corn, beans, and squash. Not only were the moist canyon bottoms thus cultivated, but also the mesa-tops wherever a sufficient depth of soil had accumulated. This agriculture was not assisted by irrigation systems of any sort that have been discovered here, although irrigation was practiced on the Mesa Verde a century earlier. Apparently the local rains in summer were adequate in Frijoles to bring a crop to maturity. Climatologists believe that there was a little more precipitation over most of the Southwest 500 years ago than there is today, and possibly the ancient corn was more drought-resistant. In any case, in good years the local farmer managed to harvest enough of his three crops in September to tide his family over the privations of winter—if no human marauders descended to loot the granary.

The harvesting of the corn by no means concluded the labors concerned with it. A place of storage safe from rodents was a first requisite, bringing about the building of tight-walled chambers both in the cliffs and in the pueblo understory; then long grinding with stone metate and mano on the part of the housewife was called for to convert the kernels to cornmeal. One ancient use of this cornmeal no doubt is duplicated in the modern Pueblo cooking of Piki—a thin crisp paperlike bread baked on a hot stone griddle. Traces of such griddle-stoves are to be found in some of the ancient pueblos.

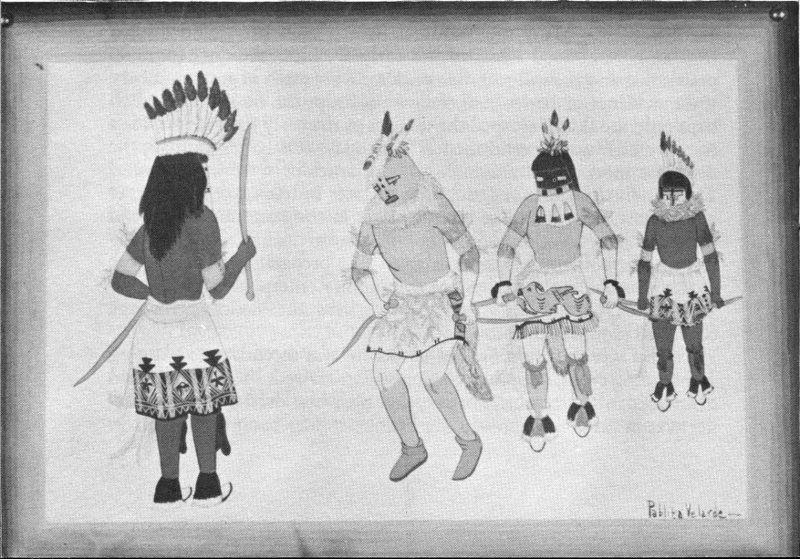

A modern Indian dance, with masked figures, as seen by a Pueblo artist.

Photo of a sketch by Pablita Velarde.

With his food needs taken care of, the new Frijoles resident thought next of shelter from the weather. Either he organized with some of his neighbors to construct a masonry dwelling in the traditional style of the west country, or he took shelter in a natural cave of the tuff cliff. In the latter case, a few days of scraping and chipping at the soft rock would normally suffice to level off the floor and raise the ceiling; final trimmings, such as fireplace and rocked-up doorway, could be completed at leisure. As years passed and the family grew, it may be assumed that the sooty cave became crowded and was supplemented with rooms in front, built up from rock fragments lying close by, mortared together with adobe from down the slope. For ceiling beams, pinyons and junipers were large enough, since the span needed to be only 6 or 8 feet; even these small timbers were hard enough to cut and trim with a stone axe. Above the beams, small sticks, mostly willow, were tightly laid, then grass or bark was spread to take the final layer of earth which weatherproofed the ceiling, or which made the floor for the room above. The design of the ceilings in the modern buildings at monument headquarters is of this type, a style of Pueblo architecture, largely derived from ancient Indian models, which is commonly seen throughout the Southwest.

It is uncertain which type of construction is the older—the talus house or the open pueblo on the canyon floor. But one thing is evident—a building of the size of Tyuonyi, previously described, was worked on and occupied by scores of families. In troubled times, this massive structure would have served better for mutual defense than scattered or smaller houses.

The rock of which the Bandelier masonry walls were made is not an easy material to build with. Unlike sandstone or even limestone, it refuses to fracture into clean straight lines or right angles. To employ it as building stone, the Indians had to find small miscellaneous blocks and chip these odd pieces into some semblance of usable shape. This chipping or pecking was done with hammerstones and axes of harder lava. The work required to fashion the walls of Tyuonyi, crude though they are, must have been prodigious.

The third basic requirement of the Frijoles newcomer was clothing, particularly warm clothing to combat the winter. Traveling into this area in the warm months, presumably, he may or may not have been able to bring along a full cold-weather wardrobe. If he did not, the materials to contrive warm clothes were available here for the taking. Ingenuity and work would have produced the necessary garments.

The obvious coverings were skins and hides of the game animals which the hunters collected. A bear skin was a most desirable cold-weather protection—but there were certainly never enough bear in 28 this part of the country to take care of all the Indian needs. Other long-haired animals, such as wolf, coyote, fox, and bobcat, no doubt played a minor part in the clothing schemes of the local people. But the real mainstay of fur-robe manufacture, of which there is fragmentary evidence in many ruins, was the lowly rabbit.

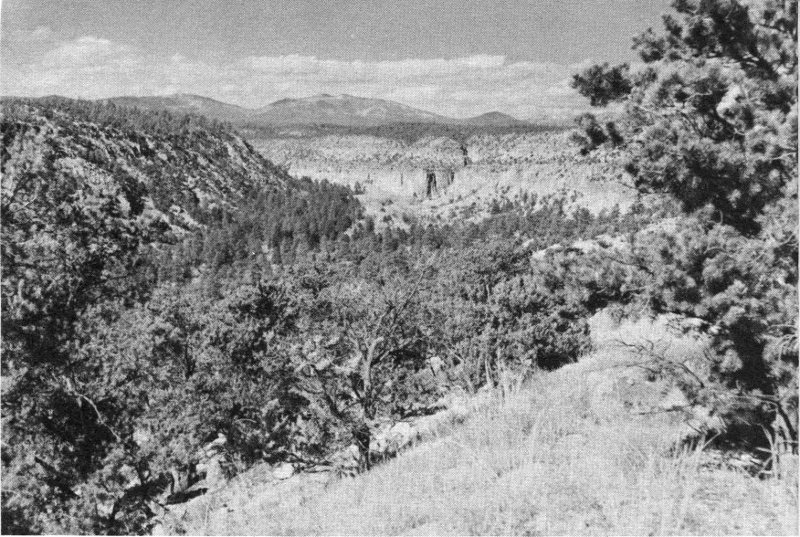

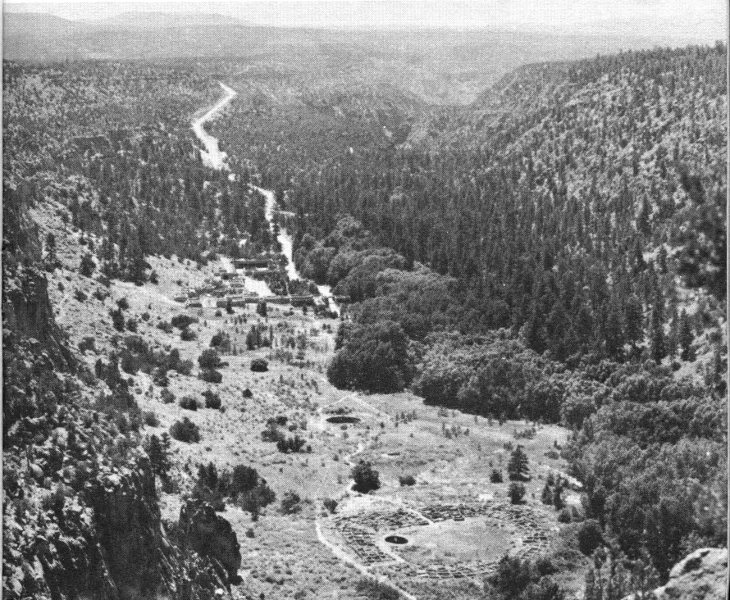

Frijoles Canyon and the Jemez Mountains.

Rabbit skins apparently were not used in one piece, but rather were cut into long strips about one-quarter inch wide. These strips were then spirally wound about a core of yucca-fiber rope, the resulting fur cable being woven by loose twining into a pliant and comfortable blanket. The same technique was used with turkey feathers to produce an equally warm and much lighter-weight garment. The Bandelier people for many years domesticated the wild turkey in order to have an abundant supply of feathers, both for utilitarian and ceremonial garments.

Summer clothing was most conspicuous by its near absence. Since about A. D. 700, however, the Pueblo world had known cotton and had developed considerable skill in weaving it, so that the Frijoles dweller of the 1300’s was able to produce such fabric as he required from cotton, which could be obtained by trade with low-country people only 50 miles down the Rio Grande. Weaving techniques have apparently been passed down to the modern Pueblo people from their 29 prehistoric ancestors. Present-day Pueblo men, particularly in the Hopi towns of Arizona, produce cotton blankets, belts, and ceremonial clothing of a very high standard, on looms of the ancient type.

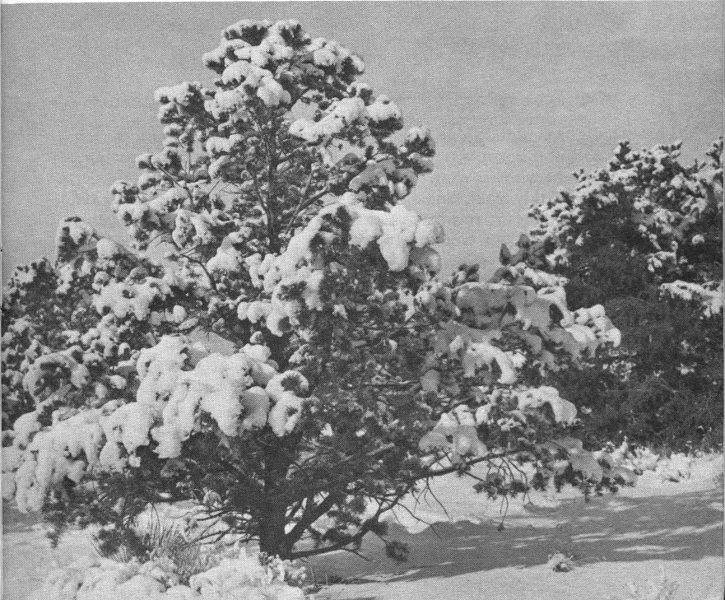

A pinyon-juniper woodland in winter.

The items of wearing apparel most important to the early people, perhaps, were sandals. In the Southwest it is difficult, if not out of the question, to go barefoot outdoors; even the toughened Indian feet could not have been impervious to cactus spines. A great deal of time and skill was expended, therefore, in the devising of footgear. From the days of the Basketmakers, the sandal most in favor had been woven of yucca, the plant with slender swordlike leaves sometimes known as Spanish-bayonet. Yucca is to be found in one species or another throughout the one-time land of the Pueblos. Such intensive use was made of it by the early people that it is almost surprising that it could have survived. As mentioned previously, yucca was the favorite fiber for cordage, and essentially it was cordage which made up the best types of sandals. A twilled weave of small-diameter cords was carefully shaped to the foot, the edges were neatly bound, then lashings 30 to tie around the ankle and over the toes were made to finish the job. A sole of this sort was durable and had remarkable nonskid qualities, as anyone who has worn modern rope-soled shoes can testify. Cruder, more quickly made sandals were plaited together from the unworked blades of the narrow-leaf yucca, the resulting weave looking rather like modern palm-frond matting.

Mule deer.

It has been said that “Man cannot live by bread alone.” Nowhere is the truth of this better illustrated than in the history of the Pueblo Indian who, in spite of appalling difficulties to achieve the physical sustenance of life, found much time to develop a spiritual life. The principal evidences of a widespread ancient religion are, of course, the remains of kivas, found in all the old communities. Although details of the use of prehistoric kivas cannot be established, some ideas of their use can be inferred from the part that kivas play in the modern Pueblo religion. The kiva rituals practiced today are traditional in the highest degree, and in all likelihood have descended in their basic form from centuries-old origins.

Hence it is perhaps valid to assume that the following conditions prevailed here at Bandelier 600 years ago: The principal social and religious organization was a society or clan; each such organization had its own kiva; and in their kiva the men of the group conducted ceremonies to honor and propitiate many deities, which were personified in birds and beasts, the elements, and natural forces.

Certain parts of these ceremonies were very likely performed outside the kiva, so that others of the village might also participate—and thus originated the spectacular public dance dramas which visitors nowadays so greatly enjoy at the modern pueblos. Indian dances, as the 20th-century Southwest knows them, are usually short-term public displays of long-term private rituals entailing days of prayer and chanting in the privacy of the kiva. The best known of these Pueblo ceremonies is chiefly a prayer for rain—The Hopi Snake Dance. Others may be prayers for success in the hunt, for productivity of crops, or for healing the sick.

The complexity of the Pueblo religion is increased by the fact that it is indivisibly allied to social and family organization. In the Pueblo scheme of worship, there is not, and seemingly never was, any elite group of “medicine men” or chief practitioners of religion; each person has a part in religious observances, his respective role growing more important as he advances in seniority within a ceremonial organization. With responsibility for the conduct of worship thus placed on all the people, religion is an extremely pervasive force and enters into much of the daily life of each individual.

Two hummingbirds on a nest at the end of a pine twig. Several species of these birds are common at Bandelier.

In the foregoing attempt to portray the origins and modes of life of the Bandelier dwellers, it has been necessary to generalize and abbreviate to a degree which may occasionally lead a reader astray. Particularly in the matter of dating periods of habitation and 32 migration, it has been impossible to detail the many exceptions to the general chronology. It is suggested that the reader who wishes to investigate further the history of the Pueblo people make reference to the publications included in the list on pages 43-44. These represent, of course, only a small fraction of the written material which exists on the subject. Further publication of new findings will increase our knowledge and alter present-day ideas as the years go by.

The countryside in and around Bandelier National Monument is wholly forested and even in dry months is cool and green. Lying at an elevation of nearly 7,000 feet, about one-third of the monument receives sufficient rain and snow to support a handsome stand of ponderosa pine. Over the remaining two-thirds of the area, where the slopes are too warm and dry for the big pine, the hardy pinyon pine and the juniper produce the “pygmy forest” growth common in the middle elevations of the Southwest.

Summer at Bandelier is the shower season. From the first of July until well into September, there is an impressive display of lofty cumulus clouds and thunderheads almost every afternoon. Fortunately for your comfort, these cloud displays do not always result in showers on the monument every day. As is the habit of southwestern thunderstorms, the rains usually cling to the higher peaks, leaving the midelevations cooled but not drenched. The spring and fall are relatively dry seasons, when the skies may remain entirely cloudless for weeks at a time.

In the fall, the great range of temperature from night to day is particularly noticeable; at monument headquarters a difference of 50° between afternoon high and night low is not unusual. This condition is still evident even in midwinter, when the sun may send the thermometer up far above freezing even after a below-zero night. Partly for this reason, the snows of winter at Bandelier are not long-lasting. The usual snowfall of a few inches will quite commonly melt away in a day or so after the sun has returned. Even the snows of blizzard proportions do not interfere for long with access to monument headquarters, for the typical snow of New Mexico is light and dry, easily cleared from the highways.

There is a great variety of herbs, shrubs, and trees within the monument, as a result of the varied terrain and the range of elevation from the bank of the Rio Grande up to the summit of the San Miguel Mountains on the west boundary. Three life zones, or climatic 33 zones, are encountered in traveling the central part of the monument; the Upper Sonoran zone of pinyon and juniper by the river, the Transition Zone of ponderosa pines on the higher mesas, and, highest of all, the Canadian Zone of spruce, fir, and aspen near Boundary Peak. Each of these zones has its characteristic mammals and birds, so that the population of wildlife is likewise varied and extensive.

Group of cave rooms between Long House and Ceremonial Cave.

Of the larger animals, the mule deer are most commonly seen, becoming quite bold in Frijoles Canyon, where humans are familiar to them. Black bears are encountered occasionally on the trails in the back country, but are too wary to invade much-traveled areas. The shyest of them all, the mountain lion, leaves his footprints here and there, but is rarely seen. Smaller predators such as coyotes and foxes are numerous, as is the bobcat. These small hunters get most of their living from a large population of rabbits and small rodents such as ground squirrels and wood rats. For the visitor, one of the most popular wild residents is the tufted-eared Abert squirrel, which circulates decoratively through the pines and cottonwoods of the public campground during the summer.

A cross section of sandstone overlain by lava, Frijoles Canyon.

The trees lining the Rito de los Frijoles through the Bandelier campground are a haven for birds as well as squirrels. In some spots, the shrubbery by the stream becomes jungle-thick, making a perfect small-bird habitat. Probably the most common of the Frijoles Canyon songbirds, after the robin, is the black-headed grosbeak. Next in numbers comes the hermit thrush, followed by warblers, vireos, and western tanagers. But the bird most commonly heard in the canyon, and frequently seen around the ruins, is the canyon wren; the melody of his song brings life and brightness to the crumbled walls and the gloomy caves of the vanished people.

During the colder part of the year, the forests of Bandelier become the home of flocks of wild turkeys. These great birds stay high on the Jemez crest during the summer, but come down into the zone of oaks and pinyons to feed on nuts and acorns when the crops ripen in the fall. The turkeys are also very fond of the purple berries of the juniper, as are many other birds and virtually all of the small rodents of the locality.

Down along the Rio Grande, which makes the southeast boundary for the main part of the monument, there is a rewarding variety of plants and animals for those who wish to walk or ride horseback the 3 miles from headquarters. The river at this point is midway in its passage through White Rock Canyon, a roadless stretch of steep walls and boulder-strewn rapids. Here, the fringing willows and cottonwoods are festooned with wild grape vines; these green tangles provide food and shelter for a great community of birds, insects, and reptiles. Flycatchers are everywhere over the river in the summer, taking water-dwelling gnats and insects from the air. Swallows and swifts further the inroads on the insect population. On shore, water snakes and an occasional rattler take the sun and keep watch for the unwary lizard or rodent which will make a next meal.

The river is a major flyway for migrating water birds, and in the course of 12 months a large traffic of ducks, geese, and shore birds may be seen going north or south. There is other wild traffic along the Rio Grande, mostly evidenced by tracks left on the mudbanks and sand bars—mink, beaver, and rarely an otter follow the stream in their water-borne prowlings. The beavers seem to be resident on the monument in White Rock Canyon, although the Rio Grande is too large to allow them to build dams; the unmistakable beaver-tooth pattern on sapling stumps is frequently seen along the riverside. On the headwaters of the Rito de los Frijoles, about 9 miles above monument headquarters, a permanent colony of beavers is established, pioneered long ago by some migrant pair who left the big river to venture up the tiny tributary.

The landscape of the Bandelier area is predominantly one of cliffs and canyons; as a visitor to the plateau you will be made conscious of the involved structure and contour of the region in the 36 course of the auto trip over the approach highway. The impression you may get on arrival is of a vast confusion of canyons separated by equally confused mesas and ridges. The topography, however, is not so mixed as first appearance would indicate, for there is a regularity to the pattern of the drainage which becomes apparent from study of a map or aerial photo. The geology, on the other hand, is extremely complex and can be outlined only in general terms in this handbook.

The dominating feature of the landscape is the uplift of the Jemez Mountains, forming the western skyline as one approaches the monument from the east. These mountains are the remains of a great volcano which erupted during the past million years. As seen from a distance, there is very little to suggest a volcano in the profile of the present mountains; only by traveling some 15 miles west of Bandelier into the central valley of the range can the nature of the eruption be visualized. Here is a basin of grassland ringed with forested hills, on a scale so large that its extent is difficult to appreciate. This is the Valle Grande—“great valley” of the Spanish discoverers, who could not have known that they had found one of the largest calderas in the world. Although the Valle Grande now has superficial characteristics of a volcanic crater, there was no single crater here in the days of the eruption—rather a vast dome of a mountain which poured from its flanks such a quantity of lava and other materials that its roof finally fell in. The dimensions of the caldera, a rough oval, are approximately 16 by 18 miles. It is estimated that at least 10 cubic miles of lava and ashes were ejected here to produce the cavity which now exists. The ring of hills around the oval are the remnants of the ancient volcano’s perimeter, which remained elevated after the central areas collapsed.

The volcano, then, played the chief role in fashioning the landscape of the Pajarito Plateau. It provided an uplift of the land at the caldera, by the same means establishing a down-slope from the center outwards, along which the lavas of the eruption avalanched in fire and smoke. Interspersed between the flows of heavy lavas were other avalanches and showerings of volcanic ashes in great depth. When cooled and welded together as they are today, they are called tuff. This process of earth-building went on intermittently for many centuries until the volcano had exhausted its violence and had distributed its many cubic miles of outpourings in encircling deposits around its flanks. With the subsidence of volcanism, the great earth-removing force of erosion became the predominant factor in forming the landscape.

The first rains and snows which fell upon this ancestral uplift found relatively smooth slopes descending outward from the rim of the central caldera. These rains and melted snows began to drain downhill, finding whatever slight channels or irregularities there were in the surface. As the centuries passed, the little water-channels became 37 gullies, then ravines, trending east and southeast through the Bandelier quadrant, down the natural fall-line of the Pajarito slopes. In less than a million years, the plateau has eroded into its present form and the drainage pattern of canyons radiating from the Jemez ridge and emptying into the Rio Grande has become well defined. Such canyons as Frijoles, then, are the products primarily of water erosion, etched into a one-time smooth slope of volcanic deposits.

During the early years of this erosion process, the caldera itself became a lake, entrapping the runoff of waters within its circle. This body of water eventually found an outlet to the south, through the guarding rim of the basin, and in its outflow began the present system of canyons of the Jemez River. A modern example of a caldera containing a lake is to be seen in Crater Lake National Park in Oregon, but the Valle Grande Lake had nearly six times as great an area.

Headquarters area in Frijoles Canyon, showing, from bottom upwards, Tyuonyi Ruin, the Big Kiva, the Museum, and the Lodge.

Many of the almost sheer canyon walls of the monument provide good cross sections of the lava and ash deposits exposed in cliffs several hundred feet high. In simplest form, these cross sections reveal at 38 their base a flow of lava or basalt, overlain by perhaps 200 vertical feet of tuff, and capped by another flow of lava forming the rimrock of the mesa-top. In most places, the alternating layers of lava and tuff were deposited several successive times, variously distributed, and complicated by later faulting and interim periods of erosion, so that the interpretation of the rock layers is not everywhere as simple as in the example given above.

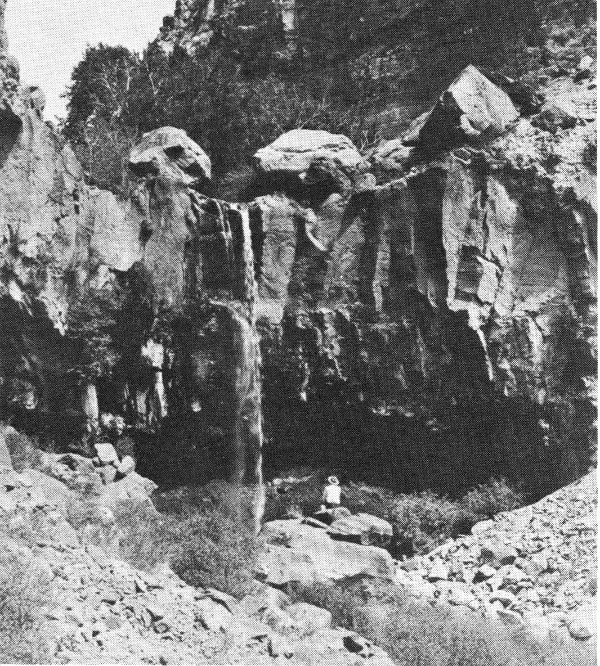

The Lower Falls of the Rito de los Frijoles.

One difficulty you may encounter in understanding the makeup of the Pajarito cliffs stems from the very different appearance of the two opposite walls of such a canyon as Frijoles. In the north wall, facing the sun, the cliffs stand bold and somewhat barren; in the south and shadowed wall, there are no prominent cliffs, but rather a rough slope of boulders overgrown with trees and brush. Because of this contrast, it might be difficult for you to realize that the two walls are made up of nearly identical rocks. The difference in appearance is due simply to the difference in exposure. The north wall, hot and dry in the sun and subject to extremes of temperature, has never had a heavy vegetative cover and has eroded into a cliff; the south wall, relatively cool and moist, has been able to support a growth of plants which have held and produced soil sufficient to mask the underlying rocks.

As mentioned earlier, the geology of this locality is complicated to such a degree that the foregoing discussion should be considered as 39 only a general outline. The whole story of the Jemez volcano has not yet been worked out in detail, for the eruptive activity was on a scale so vast and involved such complex forces that geologists are continuing to evolve new concepts as new facts come to light.

Monument headquarters are at the terminus of the approach road, on the floor of Frijoles Canyon. This center of development is the focal point of activity throughout the year. Listed below are the features of interest to be found in and around the headquarters area; reference to the map on pages 20-21 will help to locate the points mentioned.

1. Administration Building and Museum. This building contains a reception information desk manned by park rangers and a lobby from which visitors leave to walk to the ruins. Reference books are available from the monument library on request, and a stock of publications on pertinent subjects is for sale.

The museum occupies a part of the headquarters building. Three rooms of exhibits present Indian artifacts and information on the life and origins of the prehistoric people, and on the modern Pueblo Indians of the vicinity. A visit to the museum is advisable before making a trip to any of the ruins, since the exhibits provide a background against which the ruins are better understood and appreciated.

2. Tyuonyi Ruin lies about 500 yards by trail up the canyon from headquarters. This ruin is one of the principal way-stations on the loop trail over which the trips are routed. Other features on this same loop are an unexcavated ruin, the Big Kiva, Sun House, Cave Kiva, and Long House.

3. Ceremonial Cave is reached by trails either along the Rito or along the north cliffs, approximately 1 mile above headquarters. A walk to this cave is very popular with hikers of modest ambitions, and is particularly rewarding to the photographer. There are a number of tall ladders to climb to reach the cave; consequently, rubber-soled shoes and a degree of caution are recommended.

4. The Upper Falls are downstream from headquarters about a mile and a half. The trail follows the Rito down through some of the handsomest forest glades on the monument, crossing the stream several times. The falls, in a deep lava cleft, are about 80 feet high. The Lower Falls, a quarter-mile farther down, are only half as high. Along the trail between the two falls, a geologically interesting exposure of the canyon wall is conspicuous.

Two large ruins, Tsankawi and Otowi, are the principal features to visit on this detached section of the monument. The 40 main access road from Santa Fe to monument headquarters passes through this section and close to the Tsankawi Ruin. Distance from this ruin to headquarters is 16 miles.

5. Otowi Ruin lies between Pueblo and Bayo Canyons on a disused road. Inquire of a park ranger before attempting to make the trip.

6. Tsankawi Ruin is reached by a spur road and foot trail branching from State Route 4. At the end of the road, a stand contains booklets for the self-guiding trail which leads up onto the mesa to the ruins, a round trip walk of about three-quarters of a mile.

A network of some 50 miles of foot and horseback trails reaches out from monument headquarters into the roadless southern areas of the monument. Hikers and horseback parties frequently make a loop trip of 2 days, visiting the Stone Lions and Yapashi Ruins, and spending the night at Base Camp in Capulin Canyon, where a National Park Service fire guard is on duty during the summer. The return trip may be made past Painted Cave to the Rio Grande, then up White Rock Canyon to Frijoles Canyon and point of beginning.

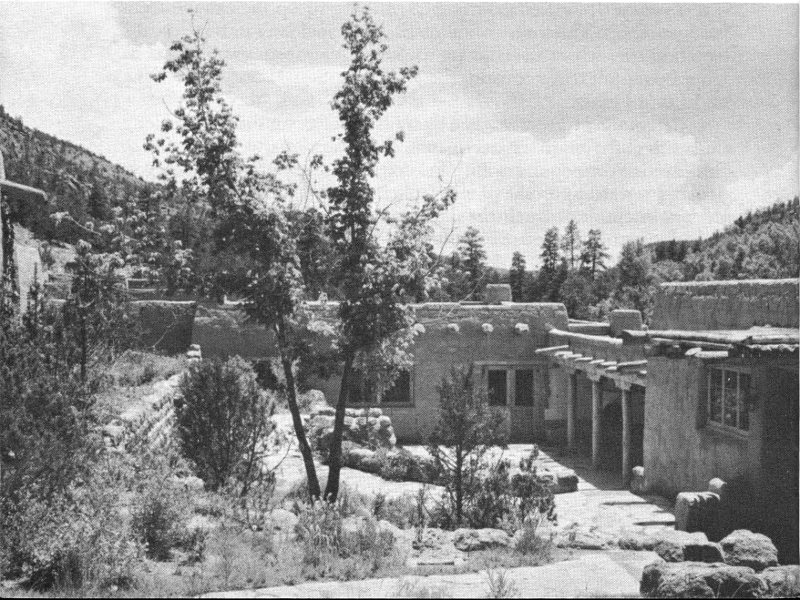

Frijoles Canyon Lodge, one of several verdant patios.

The Valle Grande is 15 miles west from the Frijoles Canyon checking station, on State Route 4, toward Cuba, 41 N. Mex. This drive across the Jemez ridge cannot be made in the winter, for the road is never cleared of snow.

Los Alamos, the atomic city, borders the monument on the north. At the time of this writing (1955), visitors are not allowed to enter the gates of Los Alamos without special passes.

San Ildefonso, the modern Indian Pueblo nearest to the monument, will make an interesting side trip when you either enter or leave Bandelier. The village lies one mile north of State Route 4, just east of the Rio Grande. This is the home of Maria Martinez, the woman whose pottery-making skill has won nationwide awards and who was instrumental in reestablishing the production of high-quality pottery in the Rio Grande pueblos.

Bandelier National Monument is 46 miles west of Santa Fe, N. Mex., by way of U. S. 285 to Pojoaque, then left onto State Route 4. Coming from Taos and the north, leave U. S. 285 at Espanola, turning right across the Rio Grande. During the summer, access is possible from the south via Jemez Springs and through the Valle Grande on unimproved gravel roads.

The monument is open every day of the year. The administration building and museum are open daily from 8 a. m. to 5 p. m. (from 8 a. m. to 9 p. m. in summer). Monument literature is available at the reception desk.

Interpretive services include self-guided tours to the principal ruins of Frijoles Canyon. Make application at the reception desk for the booklet and map which describe the walk.

Two other interpretive trails are provided, one visiting the ruins of Rainbow House immediately down canyon from headquarters; the other, in the Otowi Section, climbing to the mesa on which Tsankawi is situated. At the latter place, a booklet will guide you along the trail and tell you the archeological story, point by point.

Each evening from mid-June until Labor Day a program is presented at the administration building by a ranger or archeologist of the monument staff. The subjects of these informal talks range through many fields, from wildlife or botany to Indian ceremonials. Slides or movies are usually shown.

A campground is maintained near headquarters along the Rito de los Frijoles. Campsites are available in the shade of the grove which lines the stream; and fireplaces, tables, and firewood are provided. Housetrailers can be accommodated, and free toilet, shower, and laundry facilities are nearby.

Frijoles Canyon Lodge and Restaurant, directly opposite the administration building, provide excellent accommodations and meals under a concession contract from the National Park Service. The lodge is built of native stone in pueblo architecture, surrounding several landscaped patios; it is one of the more picturesque resorts of the Santa Fe region. The season for these accommodations is May 1 to October 15; no meals or rooms are available in the monument during the balance of the year. For reservations and further information write Frijoles Canyon Lodge, Bandelier National Monument, Santa Fe, N. Mex.

Horseback riding is very popular over the 50-mile network of trails. A saddle-horse concession is operated from April into October. Although the majority of riders take horses for the day only, overnight trips into the back country can be arranged.

Adolph Bandelier, a Swiss-American historian and ethnologist, gave the first prominence to the Pajarito Plateau ruins as a result of his explorations and descriptions during the 1880’s. Around the turn of the century a bill was introduced in Congress to create here a Cliff Cities National Park, it being apparent that some protection of the area was necessary to reduce the vandalism of the ruins. The bill, however, failed to pass. Presently, attention was again drawn to the area by the archeological work in Frijoles Canyon from 1909 to 1912, directed by the late Dr. Edgar L. Hewett. The renewed interest resulted in a proposal by the Secretary of Agriculture, in 1915, that a national monument be created. The Smithsonian Institution strongly supported this idea and recommended the name Bandelier in honor of the pioneer student of the region. The Secretary of Interior concurred, and as a result, on February 11, 1916, Bandelier National Monument was established by Presidential proclamation.

From 1916 until 1932, the monument was administered by the Forest Service of the United States Department of Agriculture. In 1952, the area was transferred to the National Park Service of the United States Department of the Interior, with a small adjustment of boundaries. The total area is now slightly over 27,000 acres. Since 1932, a National Park Service superintendent has been resident at monument headquarters in Frijoles Canyon. The monument has a small complement of rangers and fire guards for protection of the 43 ruins, the wildlife, and the forests; in the summer, several temporary rangers are employed to aid in archeological interpretation.

Requests for further information should be addressed to the Superintendent, Bandelier National Monument, Santa Fe, N. Mex.

A number of other southwestern areas in the National Park System have been established for the protection of prehistoric structures. These include Mesa Verde National Park, in southwestern Colorado, and the following national monuments: Aztec Ruins, Chaco Canyon, and Gila Cliff Dwellings, in New Mexico; Canyon de Chelly, Casa Grande, Montezuma Castle, Navajo, Tonto, Tuzigoot, Walnut Canyon, and Wupatki, in Arizona.

| Caldera | (cahl-DEHR-ah) | Spanish | Caldron—a volcano that has collapsed upon itself |

| Canada | (cahn-YAH-dah) | Spanish | Wide shallow canyon |

| Chaco | (CHAH-coh) | Unknown | A canyon in northwestern New Mexico |

| Cochiti | (COH-chee-tee) | Indian | A pueblo south of Bandelier |

| Frijoles | (free-HOH-less) | Spanish | Beans |

| Hopi | (HOH-pee) | Indian | A pueblo Indian tribe |

| Jemez | (HAY-mess) | Indian | A mountain range west of Bandelier and an Indian pueblo |

| Kiva | (KEE-vah) | Indian | Ceremonial chamber or room |

| Mano | (MAH-noh) | Spanish | Hand |

| Mesa | (MAY-sah) | Spanish | Table; hence, a tableland |

| Metate | (Meh-TAH-teh) | Spanish from Aztec | A large grinding stone |

| Otowi | (OH-toh-wee) | Indian | A ruin in Bandelier |

| Pajarito | (PAH-hah-REE-toh) | Spanish | Little bird. The plateau between Jemez Mountains and the Rio Grande |

| Pueblo | (Pooh-EB-loh) | Spanish | Village or people |

| Rio, Rito | (REE-oh) (REE-toh) | Spanish | River, creek |

| San Ildefonso | (San ILL-de-FON-soh) | Spanish | A pueblo near Bandelier |

| San Juan | (san WHAHN) | Spanish | A river and a pueblo |

| Tyuonyi | (tchew-OWN-yee) | Indian | A ruin in Frijoles Canyon |

| Valle Grande | (VAH-yeh GRAHN-deh) | Spanish | Great Valley |

| Viga | (VEE-gah) | Spanish | Roofbeam |

(Price lists of National Park Service publications may be obtained from the Superintendent of Documents, Washington 25, D.C.)